problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Call an $2 n$-digit number special if we can split its digits into two sets of size $n$ such that the sum of the numbers in the two sets is the same. Let $p_{n}$ be the probability that a randomly-chosen $2 n$-digit number is special (we will allow leading zeros in the number).

(a) [25] The sequence $p_{n}$ converges to a constant $c$. Find $c$.

|

$\frac{1}{2}$ We first claim that if a $2 n$-digit number $x$ has at least eight 0 's and at least eight 1's and the sum of its digits is even, then $x$ is special.

Let $A$ be a set of eight 0 's and eight 1 's and let $B$ be the set of all the other digits. We split $b$ arbitrily into two sets $Y$ and $Z$ of equal size. If $\left|\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z\right|>8$, then we swap the biggest element of the set with the bigger sum with the smallest element of the other set. This transposition always decreases the absolute value of the sum: in the worst case, a 9 from the bigger set is swapped for a 0 from the smaller set, which changes the difference by at most 18 . Therefore, after a finite number of steps, we will have $\left|\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z\right| \leq 8$.

Note that this absolute value is even, since the sum of all the digits is even. Without loss of generality, suppose that $\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z$ is $2 k$, where $0 \leq k \leq 4$. If we add $k 0$ 's and $8-k$ 's to $Y$, and we add the other elements of $A$ to $Z$, then the two sets will balance, so $x$ is special.

[^1](b) $[\mathbf{3 0}]$ Let $q_{n}=p_{n}-c$. There exists a unique positive constant $r$ such that $\frac{q_{n}}{r^{n}}$ converges to a constant $d$. Find $r$ and $d$.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Call an $2 n$-digit number special if we can split its digits into two sets of size $n$ such that the sum of the numbers in the two sets is the same. Let $p_{n}$ be the probability that a randomly-chosen $2 n$-digit number is special (we will allow leading zeros in the number).

(a) [25] The sequence $p_{n}$ converges to a constant $c$. Find $c$.

|

$\frac{1}{2}$ We first claim that if a $2 n$-digit number $x$ has at least eight 0 's and at least eight 1's and the sum of its digits is even, then $x$ is special.

Let $A$ be a set of eight 0 's and eight 1 's and let $B$ be the set of all the other digits. We split $b$ arbitrily into two sets $Y$ and $Z$ of equal size. If $\left|\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z\right|>8$, then we swap the biggest element of the set with the bigger sum with the smallest element of the other set. This transposition always decreases the absolute value of the sum: in the worst case, a 9 from the bigger set is swapped for a 0 from the smaller set, which changes the difference by at most 18 . Therefore, after a finite number of steps, we will have $\left|\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z\right| \leq 8$.

Note that this absolute value is even, since the sum of all the digits is even. Without loss of generality, suppose that $\sum_{y \in Y} y-\sum_{z \in Z} z$ is $2 k$, where $0 \leq k \leq 4$. If we add $k 0$ 's and $8-k$ 's to $Y$, and we add the other elements of $A$ to $Z$, then the two sets will balance, so $x$ is special.

[^1](b) $[\mathbf{3 0}]$ Let $q_{n}=p_{n}-c$. There exists a unique positive constant $r$ such that $\frac{q_{n}}{r^{n}}$ converges to a constant $d$. Find $r$ and $d$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. ",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Call an $2 n$-digit number special if we can split its digits into two sets of size $n$ such that the sum of the numbers in the two sets is the same. Let $p_{n}$ be the probability that a randomly-chosen $2 n$-digit number is special (we will allow leading zeros in the number).

(a) [25] The sequence $p_{n}$ converges to a constant $c$. Find $c$.

|

$\left(\frac{1}{4},-1\right)$ To get the next asymptotic term after the constant term of $\frac{1}{2}$, we need to consider what happens when the digit sum is even; we want to find the probability that such a number isn't balanced. We claim that the configuration that contributes the vast majority of unbalanced numbers is when all numbers are even and the sum is $2 \bmod 4$, or such a configuration with all numbers increased by 1. Clearly this gives $q_{n}$ being asymptotic to $-\frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2 n}=-\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^{n}$, so $r=\frac{1}{4}$ and $d=-1$.

To prove the claim, first note that the asymptotic probability that there are at most 4 digits that occur more than 10 times is asymptotically much smaller than $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n}$, so we can assume that there exist 5 digits that each occur at least 10 times. If any of those digits are consecutive, then the digit sum being even implies that the number is balanced (by an argument similar to part (a)).

So, we can assume that none of the numbers are consecutive. We would like to say that this implies that the numbers are either $0,2,4,6,8$ or $1,3,5,7,9$. However, we can't quite say this yet, as we need to rule out possibilities like $0,2,4,7,9$. In this case, though, we can just pair 0 and 7 up with 2 and 4 ; by using the same argument as in part (a), except using 0 and 7 both (to get a sum of 7 ) and 2 and 4 both (to get a sum of 6 ) to balance out the two sets at the end.

In general, if there is ever a gap of size 3 , consider the number right after it and the 3 numbers before it (so we have $k-4, k-2, k, k+3$ for some $k$ ), and pair them up such that one pair has a sum that's exactly one more than the other (i.e. pair $k-4$ with $k+3$ and $k-2$ with $k$ ). Since we again have pairs of numbers whose sums differ by 1 , we can use the technique from part (a) of balancing out the sets at the end.

So, we can assume there is no gap of size 3 , which together with the condition that no two numbers are adjacent implies that the 5 digits are either $0,2,4,6,8$ or $1,3,5,7,9$. For the remainder of the solution, we will deal with the $0,2,4,6,8$ case, since it is symmetric with the other case under the transformation $x \mapsto 9-x$.

If we can distribute the odd digits into two sets $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$ such that (i) the differense in sums of $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$ is small; and (ii) the difference in sums of $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$, plus the sum of the even digits, is divisible by 4 , then the same argument as in part (a) implies that the number is good.

In fact, if there are any odd digits, then we can use them at the beginning to fix the parity mod 4 (by adding them all in such that the sums of the two sets remain close, and then potentially switching one with an even digit). Therefore, if there are any odd digits then the number is good. Also, even if there are no odd digits, if the sum of the digits is divisible by 4 then the number is good.

So, we have shown that almost all non-good numbers come from having all numbers being even with a digit sum that is $2 \bmod 4$, or the analogous case under the mapping $x \mapsto 9-x$. This formalizes the claim we made in the first paragraph, so $r=\frac{1}{4}$ and $d=-1$, as claimed.

[^0]: ${ }^{1}$ This is the maximum possible number of new regions, but it's not too hard to see that this is always attainable.

${ }^{2}$ While the fact that a curve going through a region splits it into two new regions is intuitively obvious, it is actually very difficult to prove. The proof relies on some deep results from algebraic topology and is known as the Jordan Curve Theorem. If you are interested in learning more about this, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan_curve_theorem

[^1]: ${ }^{3}$ See http://www.artofproblemsolving.com/Forum/weblog_entry.php?p=1263378

${ }^{4}$ See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_polynomial

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Call an $2 n$-digit number special if we can split its digits into two sets of size $n$ such that the sum of the numbers in the two sets is the same. Let $p_{n}$ be the probability that a randomly-chosen $2 n$-digit number is special (we will allow leading zeros in the number).

(a) [25] The sequence $p_{n}$ converges to a constant $c$. Find $c$.

|

$\left(\frac{1}{4},-1\right)$ To get the next asymptotic term after the constant term of $\frac{1}{2}$, we need to consider what happens when the digit sum is even; we want to find the probability that such a number isn't balanced. We claim that the configuration that contributes the vast majority of unbalanced numbers is when all numbers are even and the sum is $2 \bmod 4$, or such a configuration with all numbers increased by 1. Clearly this gives $q_{n}$ being asymptotic to $-\frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2 n}=-\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^{n}$, so $r=\frac{1}{4}$ and $d=-1$.

To prove the claim, first note that the asymptotic probability that there are at most 4 digits that occur more than 10 times is asymptotically much smaller than $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{n}$, so we can assume that there exist 5 digits that each occur at least 10 times. If any of those digits are consecutive, then the digit sum being even implies that the number is balanced (by an argument similar to part (a)).

So, we can assume that none of the numbers are consecutive. We would like to say that this implies that the numbers are either $0,2,4,6,8$ or $1,3,5,7,9$. However, we can't quite say this yet, as we need to rule out possibilities like $0,2,4,7,9$. In this case, though, we can just pair 0 and 7 up with 2 and 4 ; by using the same argument as in part (a), except using 0 and 7 both (to get a sum of 7 ) and 2 and 4 both (to get a sum of 6 ) to balance out the two sets at the end.

In general, if there is ever a gap of size 3 , consider the number right after it and the 3 numbers before it (so we have $k-4, k-2, k, k+3$ for some $k$ ), and pair them up such that one pair has a sum that's exactly one more than the other (i.e. pair $k-4$ with $k+3$ and $k-2$ with $k$ ). Since we again have pairs of numbers whose sums differ by 1 , we can use the technique from part (a) of balancing out the sets at the end.

So, we can assume there is no gap of size 3 , which together with the condition that no two numbers are adjacent implies that the 5 digits are either $0,2,4,6,8$ or $1,3,5,7,9$. For the remainder of the solution, we will deal with the $0,2,4,6,8$ case, since it is symmetric with the other case under the transformation $x \mapsto 9-x$.

If we can distribute the odd digits into two sets $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$ such that (i) the differense in sums of $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$ is small; and (ii) the difference in sums of $S_{1}$ and $S_{2}$, plus the sum of the even digits, is divisible by 4 , then the same argument as in part (a) implies that the number is good.

In fact, if there are any odd digits, then we can use them at the beginning to fix the parity mod 4 (by adding them all in such that the sums of the two sets remain close, and then potentially switching one with an even digit). Therefore, if there are any odd digits then the number is good. Also, even if there are no odd digits, if the sum of the digits is divisible by 4 then the number is good.

So, we have shown that almost all non-good numbers come from having all numbers being even with a digit sum that is $2 \bmod 4$, or the analogous case under the mapping $x \mapsto 9-x$. This formalizes the claim we made in the first paragraph, so $r=\frac{1}{4}$ and $d=-1$, as claimed.

[^0]: ${ }^{1}$ This is the maximum possible number of new regions, but it's not too hard to see that this is always attainable.

${ }^{2}$ While the fact that a curve going through a region splits it into two new regions is intuitively obvious, it is actually very difficult to prove. The proof relies on some deep results from algebraic topology and is known as the Jordan Curve Theorem. If you are interested in learning more about this, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jordan_curve_theorem

[^1]: ${ }^{3}$ See http://www.artofproblemsolving.com/Forum/weblog_entry.php?p=1263378

${ }^{4}$ See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_polynomial

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. ",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-team2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Jacob flips five coins, exactly three of which land heads. What is the probability that the first two are both heads?

|

$\frac{3}{10}$ We can associate with each sequence of coin flips a unique word where $H$ represents heads, and T represents tails. For example, the word HHTTH would correspond to the coin flip sequence where the first two flips were heads, the next two were tails, and the last was heads. We are given that exactly three of the five coin flips came up heads, so our word must be some rearrangement of HHHTT. To calculate the total number of possibilities, any rearrangement corresponds to a choice of three spots to place the H flips, so there are $\binom{5}{3}=10$ possibilities. If the first two flips are both heads, then we can only rearrange the last three HTT flips, which corresponds to choosing one spot for the remaining $H$. This can be done in $\binom{3}{1}=3$ ways. Finally, the probability is the quotient of these two, so we get the answer of $\frac{3}{10}$. Alternatively, since the total number of possiblities is small, we can write out all rearrangements: HHHTT, HHTHT, HHTTH, HTHHT, HTHTH, HTTHH, THHHT, THHTH, THTHH, TTHHH. Of these ten, only in the first three do we flip heads the first two times, so we get the same answer of $\frac{3}{10}$.

|

\frac{3}{10}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Jacob flips five coins, exactly three of which land heads. What is the probability that the first two are both heads?

|

$\frac{3}{10}$ We can associate with each sequence of coin flips a unique word where $H$ represents heads, and T represents tails. For example, the word HHTTH would correspond to the coin flip sequence where the first two flips were heads, the next two were tails, and the last was heads. We are given that exactly three of the five coin flips came up heads, so our word must be some rearrangement of HHHTT. To calculate the total number of possibilities, any rearrangement corresponds to a choice of three spots to place the H flips, so there are $\binom{5}{3}=10$ possibilities. If the first two flips are both heads, then we can only rearrange the last three HTT flips, which corresponds to choosing one spot for the remaining $H$. This can be done in $\binom{3}{1}=3$ ways. Finally, the probability is the quotient of these two, so we get the answer of $\frac{3}{10}$. Alternatively, since the total number of possiblities is small, we can write out all rearrangements: HHHTT, HHTHT, HHTTH, HTHHT, HTHTH, HTTHH, THHHT, THHTH, THTHH, TTHHH. Of these ten, only in the first three do we flip heads the first two times, so we get the same answer of $\frac{3}{10}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [2]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

How many sequences $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{8}$ of zeroes and ones have $a_{1} a_{2}+a_{2} a_{3}+\cdots+a_{7} a_{8}=5$ ?

|

9 First, note that we have seven terms in the left hand side, and each term can be either 0 or 1 , so we must have five terms equal to 1 and two terms equal to 0 . Thus, for $n \in\{1,2, \ldots, 8\}$, at least one of the $a_{n}$ must be equal to 0 . If we can find $i, j \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$ such that $a_{i}=a_{j}=0$ and $i<j$, then the terms $a_{i-1} a_{i}, a_{i} a_{i+1}$, and $a_{j} a_{j+1}$ will all be equal to 0 . We did not count any term twice because $i-1<i<j$, so we would have three terms equal to 0 , which cannot happen because we can have only two. Thus, we can find at most one $n \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$ such that $a_{n}=0$. We will do casework on which $n$ in this range have $a_{n}=0$.

If $n \in\{3,4,5,6\}$, then we know that the terms $a_{n-1} a_{n}=a_{n} a_{n+1}=0$, so all other terms must be 1 , so $a_{1} a_{2}=a_{2} a_{3}=\ldots=a_{n-2} a_{n-1}=1$ and $a_{n+1} a_{n+2}=\ldots=a_{7} a_{8}=1$. Because every $a_{i}$ appears in one of these equations for $i \neq n$, then we must have $a_{i}=1$ for all $i \neq n$, so we have 1 possibility for each choice of $n$ and thus 4 possibilities total for this case.

If $n=2$, then again we have $a_{1} a_{2}=a_{2} a_{3}=0$, so we must have $a_{3} a_{4}=a_{4} a_{5}=\ldots=a_{7} a_{8}=1$, so $a_{3}=a_{4}=\ldots=a_{8}=1$. However, this time $a_{1}$ is not fixed, and we see that regardless of our choice of $a_{1}$ the sum will still be equal to 5 . Thus, since there are 2 choices for $a_{1}$, then there are 2 possibilities total for this case. The case where $n=7$ is analogous, with $a_{8}$ having 2 possibilities, so we have another 2 possibilities.

Finally, if $a_{n}=1$ for $n \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$, then we will have $a_{2} a_{3}=a_{3} a_{4}=\ldots=a_{6} a_{7}=1$. We already have five terms equal to 1 , so the remaining two terms $a_{1} a_{2}$ and $a_{7} a_{8}$ must be 0 . Since $a_{2}=1$, then we must have $a_{1}=0$, and since $a_{7}=1$ then $a_{8}=0$. Thus, there is only 1 possibility for this case.

Summing, we have $4+2+2+1=9$ total sequences.

|

9

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

How many sequences $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{8}$ of zeroes and ones have $a_{1} a_{2}+a_{2} a_{3}+\cdots+a_{7} a_{8}=5$ ?

|

9 First, note that we have seven terms in the left hand side, and each term can be either 0 or 1 , so we must have five terms equal to 1 and two terms equal to 0 . Thus, for $n \in\{1,2, \ldots, 8\}$, at least one of the $a_{n}$ must be equal to 0 . If we can find $i, j \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$ such that $a_{i}=a_{j}=0$ and $i<j$, then the terms $a_{i-1} a_{i}, a_{i} a_{i+1}$, and $a_{j} a_{j+1}$ will all be equal to 0 . We did not count any term twice because $i-1<i<j$, so we would have three terms equal to 0 , which cannot happen because we can have only two. Thus, we can find at most one $n \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$ such that $a_{n}=0$. We will do casework on which $n$ in this range have $a_{n}=0$.

If $n \in\{3,4,5,6\}$, then we know that the terms $a_{n-1} a_{n}=a_{n} a_{n+1}=0$, so all other terms must be 1 , so $a_{1} a_{2}=a_{2} a_{3}=\ldots=a_{n-2} a_{n-1}=1$ and $a_{n+1} a_{n+2}=\ldots=a_{7} a_{8}=1$. Because every $a_{i}$ appears in one of these equations for $i \neq n$, then we must have $a_{i}=1$ for all $i \neq n$, so we have 1 possibility for each choice of $n$ and thus 4 possibilities total for this case.

If $n=2$, then again we have $a_{1} a_{2}=a_{2} a_{3}=0$, so we must have $a_{3} a_{4}=a_{4} a_{5}=\ldots=a_{7} a_{8}=1$, so $a_{3}=a_{4}=\ldots=a_{8}=1$. However, this time $a_{1}$ is not fixed, and we see that regardless of our choice of $a_{1}$ the sum will still be equal to 5 . Thus, since there are 2 choices for $a_{1}$, then there are 2 possibilities total for this case. The case where $n=7$ is analogous, with $a_{8}$ having 2 possibilities, so we have another 2 possibilities.

Finally, if $a_{n}=1$ for $n \in\{2,3, \ldots, 7\}$, then we will have $a_{2} a_{3}=a_{3} a_{4}=\ldots=a_{6} a_{7}=1$. We already have five terms equal to 1 , so the remaining two terms $a_{1} a_{2}$ and $a_{7} a_{8}$ must be 0 . Since $a_{2}=1$, then we must have $a_{1}=0$, and since $a_{7}=1$ then $a_{8}=0$. Thus, there is only 1 possibility for this case.

Summing, we have $4+2+2+1=9$ total sequences.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

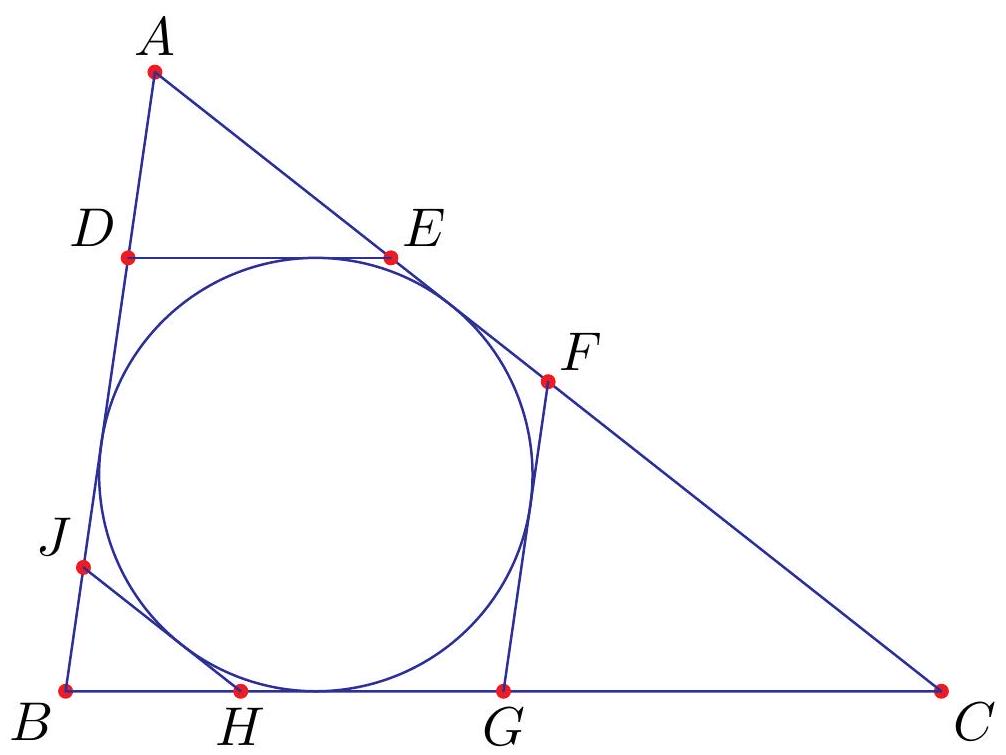

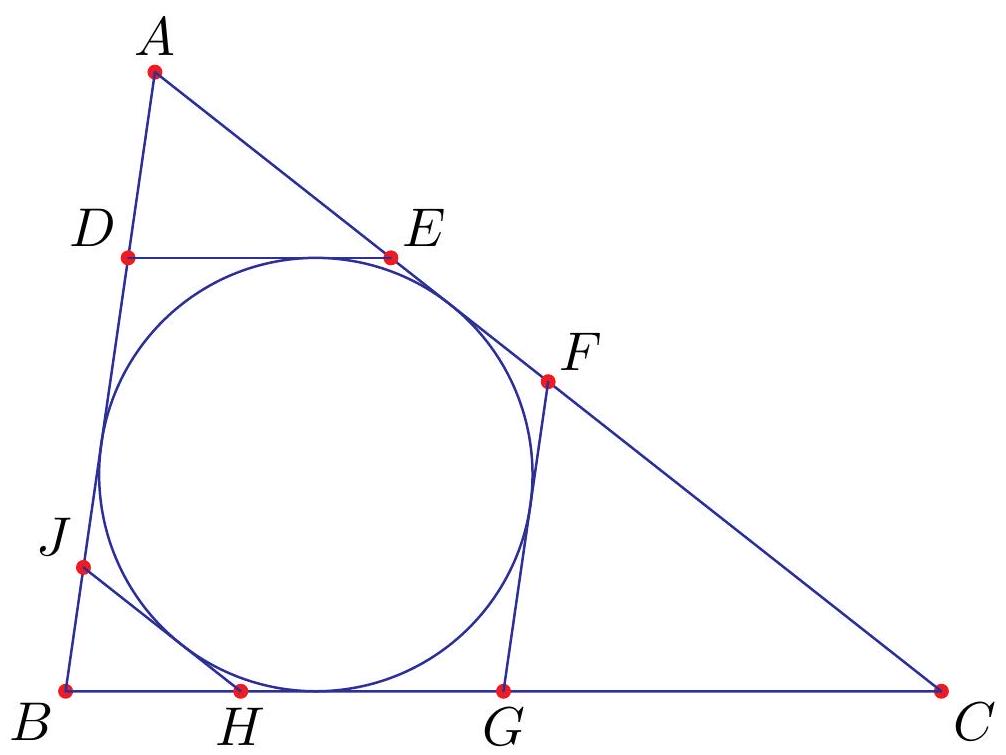

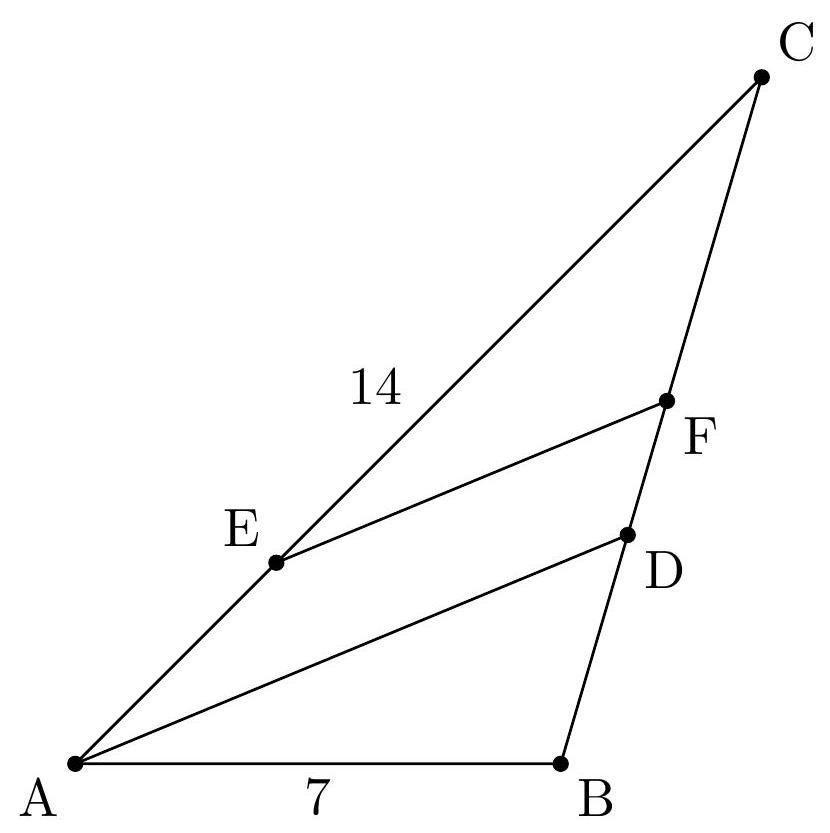

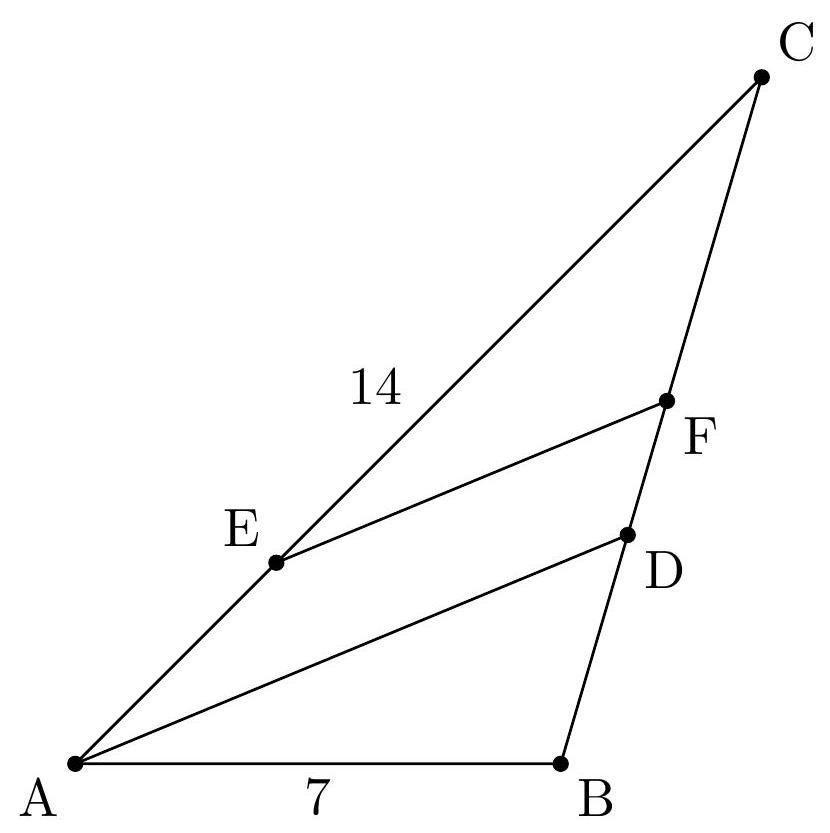

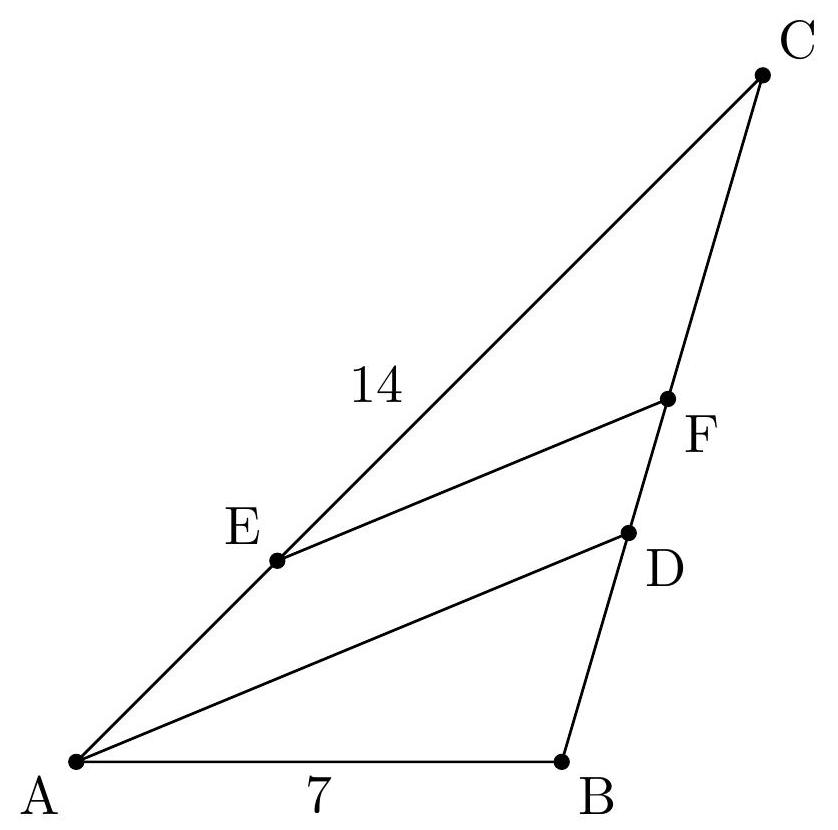

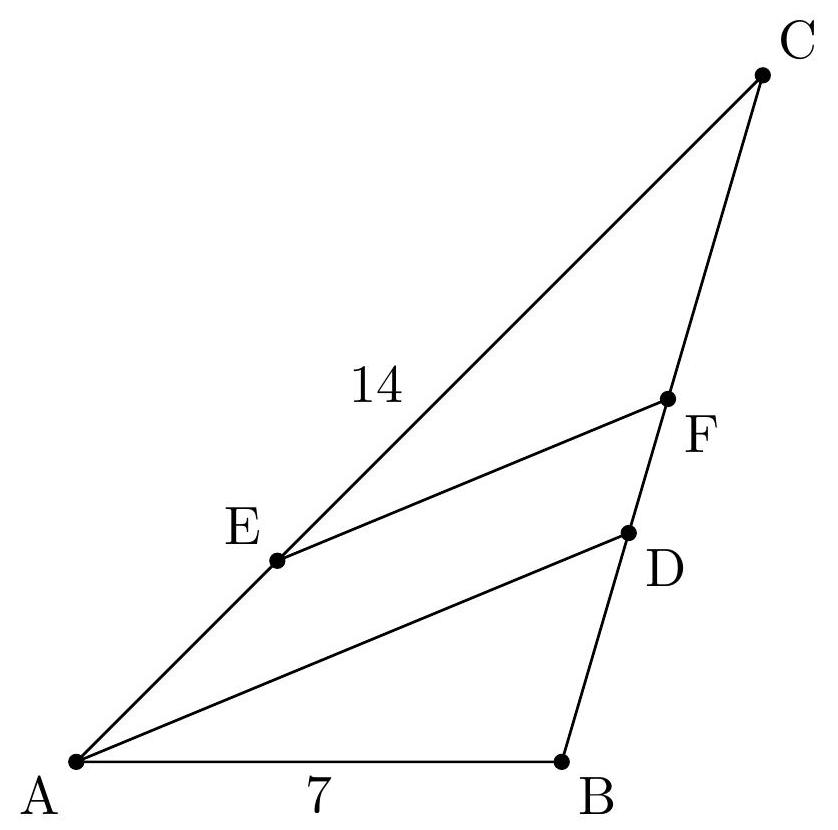

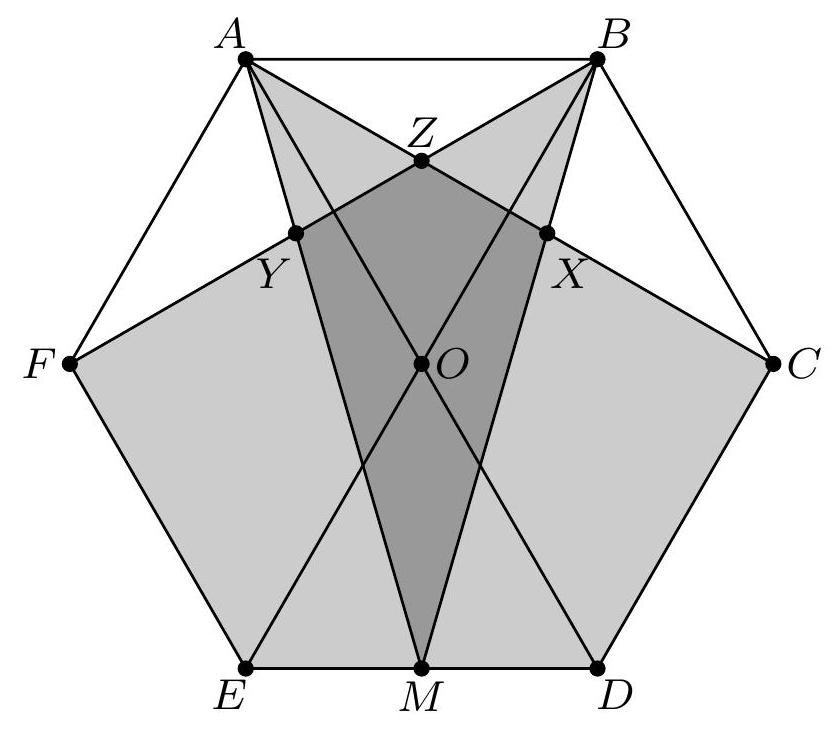

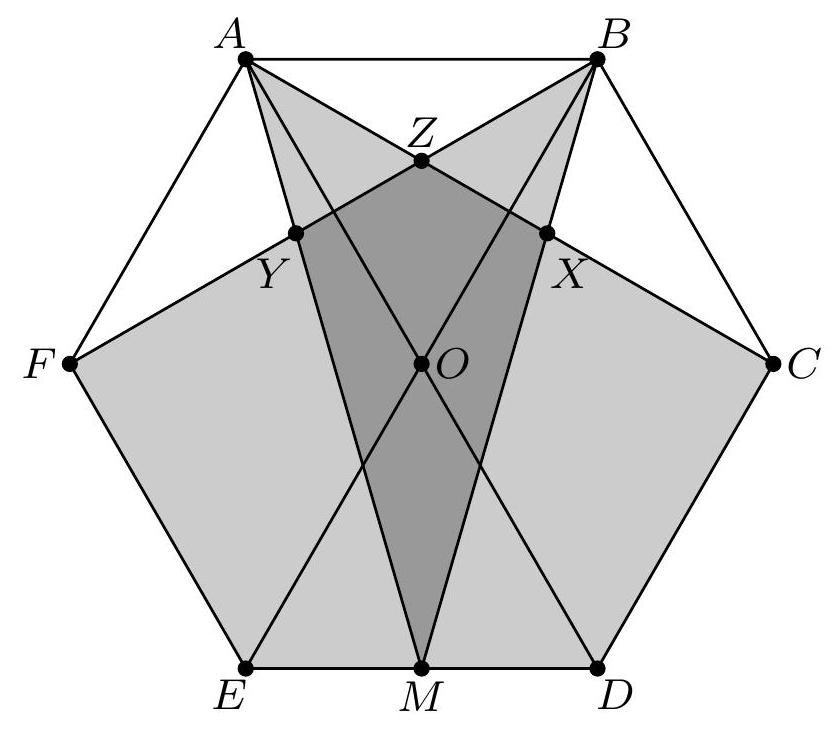

Triangle $A B C$ has $A B=5, B C=7$, and $C A=8$. New lines not containing but parallel to $A B$, $B C$, and $C A$ are drawn tangent to the incircle of $A B C$. What is the area of the hexagon formed by the sides of the original triangle and the newly drawn lines?

|

$\frac{31}{5} \sqrt{3}$

From the law of cosines we compute $\measuredangle A=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{5^{2}+8^{2}-7^{2}}{2(5)(8)}\right)=60^{\circ}$. Using brackets to denote the area of a region, we find that

$$

[A B C]=\frac{1}{2} A B \cdot A C \cdot \sin 60^{\circ}=10 \sqrt{3}

$$

The radius of the incircle can be computed by the formula

$$

r=\frac{2[A B C]}{A B+B C+C A}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{20}=\sqrt{3}

$$

Now the height from $A$ to $B C$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{B C}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{7}$. Then the height from $A$ to $D E$ is $\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{7}-2 r=\frac{6 \sqrt{3}}{7}$. Then $[A D E]=\left(\frac{6 \sqrt{3} / 7}{20 \sqrt{3} / 7}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{9}{100}[A B C]$. Here, we use the fact that $\triangle A B C$ and $\triangle A D E$ are similar.

Similarly, we compute that the height from $B$ to $C A$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{C A}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{8}=\frac{5 \sqrt{3}}{2}$. Then the height from $B$ to $H J$ is $\frac{5 \sqrt{3}}{2}-2 r=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$. Then $[B H J]=\left(\frac{\sqrt{3} / 2}{5 \sqrt{3} / 2}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{1}{25}[A B C]$.

Finally, we compute that the height from $C$ to $A B$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{5}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{5}=4 \sqrt{3}$. Then the height from $C$ to $F G$ is $4 \sqrt{3}-2 r=2 \sqrt{3}$. Then $[C F G]=\left(\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{4 \sqrt{3}}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{1}{4}[A B C]$.

Finally we can compute the area of hexagon $D E F G H J$. We have

$$

\begin{gathered}

{[D E F G H J]=[A B C]-[A D E]-[B H J]-[C F G]=[A B C]\left(1-\frac{9}{100}-\frac{1}{25}-\frac{1}{4}\right)=[A B C]\left(\frac{31}{50}\right)=} \\

10 \sqrt{3}\left(\frac{31}{50}\right)=\frac{31}{5} \sqrt{3} .

\end{gathered}

$$

|

\frac{31}{5} \sqrt{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Triangle $A B C$ has $A B=5, B C=7$, and $C A=8$. New lines not containing but parallel to $A B$, $B C$, and $C A$ are drawn tangent to the incircle of $A B C$. What is the area of the hexagon formed by the sides of the original triangle and the newly drawn lines?

|

$\frac{31}{5} \sqrt{3}$

From the law of cosines we compute $\measuredangle A=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{5^{2}+8^{2}-7^{2}}{2(5)(8)}\right)=60^{\circ}$. Using brackets to denote the area of a region, we find that

$$

[A B C]=\frac{1}{2} A B \cdot A C \cdot \sin 60^{\circ}=10 \sqrt{3}

$$

The radius of the incircle can be computed by the formula

$$

r=\frac{2[A B C]}{A B+B C+C A}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{20}=\sqrt{3}

$$

Now the height from $A$ to $B C$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{B C}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{7}$. Then the height from $A$ to $D E$ is $\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{7}-2 r=\frac{6 \sqrt{3}}{7}$. Then $[A D E]=\left(\frac{6 \sqrt{3} / 7}{20 \sqrt{3} / 7}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{9}{100}[A B C]$. Here, we use the fact that $\triangle A B C$ and $\triangle A D E$ are similar.

Similarly, we compute that the height from $B$ to $C A$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{C A}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{8}=\frac{5 \sqrt{3}}{2}$. Then the height from $B$ to $H J$ is $\frac{5 \sqrt{3}}{2}-2 r=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$. Then $[B H J]=\left(\frac{\sqrt{3} / 2}{5 \sqrt{3} / 2}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{1}{25}[A B C]$.

Finally, we compute that the height from $C$ to $A B$ is $\frac{2[A B C]}{5}=\frac{20 \sqrt{3}}{5}=4 \sqrt{3}$. Then the height from $C$ to $F G$ is $4 \sqrt{3}-2 r=2 \sqrt{3}$. Then $[C F G]=\left(\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{4 \sqrt{3}}\right)^{2}[A B C]=\frac{1}{4}[A B C]$.

Finally we can compute the area of hexagon $D E F G H J$. We have

$$

\begin{gathered}

{[D E F G H J]=[A B C]-[A D E]-[B H J]-[C F G]=[A B C]\left(1-\frac{9}{100}-\frac{1}{25}-\frac{1}{4}\right)=[A B C]\left(\frac{31}{50}\right)=} \\

10 \sqrt{3}\left(\frac{31}{50}\right)=\frac{31}{5} \sqrt{3} .

\end{gathered}

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

An ant starts at the point $(1,0)$. Each minute, it walks from its current position to one of the four adjacent lattice points until it reaches a point $(x, y)$ with $|x|+|y| \geq 2$. What is the probability that the ant ends at the point $(1,1)$ ?

|

$\frac{7}{24}$ From the starting point of $(1,0)$, there is a $\frac{1}{4}$ chance we will go directly to $(1,1)$, a $\frac{1}{2}$ chance we will end at $(2,0)$ or $(1,-1)$, and a $\frac{1}{4}$ chance we will go to $(0,0)$. Thus, if $p$ is the probability that we will reach $(1,1)$ from $(0,0)$, then the desired probability is equal to $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} p$, so we need only calculate $p$. Note that we can replace the condition $|x|+|y| \geq 2$ by $|x|+|y|=2$, since in each iteration the quantity $|x|+|y|$ can increase by at most 1 . Thus, we only have to consider the eight points $(2,0),(1,1),(0,2),(-1,1),(-2,0),(-1,-1),(0,-2),(1,-1)$. Let $p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{8}$ be the probability of

reaching each of these points from $(0,0)$, respectively. By symmetry, we see that $p_{1}=p_{3}=p_{5}=p_{7}$ and $p_{2}=p_{4}=p_{6}=p_{8}$. We also know that there are two paths from $(0,0)$ to $(1,1)$ and one path from $(0,0)$ to $(2,0)$, thus $p_{2}=2 p_{1}$. Because the sum of all probabilities is 1 , we have $p_{1}+p_{2}+\ldots+p_{8}=1$. Combining these equations, we see that $4 p_{1}+4 p_{2}=12 p_{1}=1$, so $p_{1}=\frac{1}{12}$ and $p_{2}=\frac{1}{6}$. Since $p=p_{2}=\frac{1}{6}$, then the final answer is $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{6}=\frac{7}{24}$

|

\frac{7}{24}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

An ant starts at the point $(1,0)$. Each minute, it walks from its current position to one of the four adjacent lattice points until it reaches a point $(x, y)$ with $|x|+|y| \geq 2$. What is the probability that the ant ends at the point $(1,1)$ ?

|

$\frac{7}{24}$ From the starting point of $(1,0)$, there is a $\frac{1}{4}$ chance we will go directly to $(1,1)$, a $\frac{1}{2}$ chance we will end at $(2,0)$ or $(1,-1)$, and a $\frac{1}{4}$ chance we will go to $(0,0)$. Thus, if $p$ is the probability that we will reach $(1,1)$ from $(0,0)$, then the desired probability is equal to $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} p$, so we need only calculate $p$. Note that we can replace the condition $|x|+|y| \geq 2$ by $|x|+|y|=2$, since in each iteration the quantity $|x|+|y|$ can increase by at most 1 . Thus, we only have to consider the eight points $(2,0),(1,1),(0,2),(-1,1),(-2,0),(-1,-1),(0,-2),(1,-1)$. Let $p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{8}$ be the probability of

reaching each of these points from $(0,0)$, respectively. By symmetry, we see that $p_{1}=p_{3}=p_{5}=p_{7}$ and $p_{2}=p_{4}=p_{6}=p_{8}$. We also know that there are two paths from $(0,0)$ to $(1,1)$ and one path from $(0,0)$ to $(2,0)$, thus $p_{2}=2 p_{1}$. Because the sum of all probabilities is 1 , we have $p_{1}+p_{2}+\ldots+p_{8}=1$. Combining these equations, we see that $4 p_{1}+4 p_{2}=12 p_{1}=1$, so $p_{1}=\frac{1}{12}$ and $p_{2}=\frac{1}{6}$. Since $p=p_{2}=\frac{1}{6}$, then the final answer is $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{6}=\frac{7}{24}$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

A polynomial $P$ is of the form $\pm x^{6} \pm x^{5} \pm x^{4} \pm x^{3} \pm x^{2} \pm x \pm 1$. Given that $P(2)=27$, what is $P(3)$ ?

|

439 We use the following lemma:

Lemma. The sign of $\pm 2^{n} \pm 2^{n-1} \pm \cdots \pm 2 \pm 1$ is the same as the sign of the $2^{n}$ term.

Proof. Without loss of generality, let $2^{n}$ be positive. (We can flip all signs.) Notice that $2^{n} \pm 2^{n-1} \pm$ $2^{n-2} \pm \cdots 2 \pm 1 \geq 2^{n}-2^{n-1}-2^{n-2}-\cdots-2-1=1$, which is positive.

We can use this lemma to uniquely determine the signs of $P$. Since our desired sum, 27, is positive, the coefficient of $x^{6}$ must be positive. Subtracting 64 , we now have that $\pm 2^{5} \pm 2^{4} \pm \ldots \pm 2 \pm 1=-37$, so the sign of $2^{5}$ must be negative. Continuing in this manner, we find that $P(x)=x^{6}-x^{5}-x^{4}+x^{3}+x^{2}-x+1$, so $P(3)=3^{6}-3^{5}-3^{4}+3^{3}+3^{2}-3+1=439$.

|

439

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

A polynomial $P$ is of the form $\pm x^{6} \pm x^{5} \pm x^{4} \pm x^{3} \pm x^{2} \pm x \pm 1$. Given that $P(2)=27$, what is $P(3)$ ?

|

439 We use the following lemma:

Lemma. The sign of $\pm 2^{n} \pm 2^{n-1} \pm \cdots \pm 2 \pm 1$ is the same as the sign of the $2^{n}$ term.

Proof. Without loss of generality, let $2^{n}$ be positive. (We can flip all signs.) Notice that $2^{n} \pm 2^{n-1} \pm$ $2^{n-2} \pm \cdots 2 \pm 1 \geq 2^{n}-2^{n-1}-2^{n-2}-\cdots-2-1=1$, which is positive.

We can use this lemma to uniquely determine the signs of $P$. Since our desired sum, 27, is positive, the coefficient of $x^{6}$ must be positive. Subtracting 64 , we now have that $\pm 2^{5} \pm 2^{4} \pm \ldots \pm 2 \pm 1=-37$, so the sign of $2^{5}$ must be negative. Continuing in this manner, we find that $P(x)=x^{6}-x^{5}-x^{4}+x^{3}+x^{2}-x+1$, so $P(3)=3^{6}-3^{5}-3^{4}+3^{3}+3^{2}-3+1=439$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

What is the sum of the positive solutions to $2 x^{2}-x\lfloor x\rfloor=5$, where $\lfloor x\rfloor$ is the largest integer less than or equal to $x$ ?

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{41}+2 \sqrt{11}}{4}$ We first note that $\lfloor x\rfloor \leq x$, so $2 x^{2}-x\lfloor x\rfloor \geq 2 x^{2}-x^{2}=x^{2}$. Since this function is increasing on the positive reals, all solutions must be at most $\sqrt{5}$. This gives us 3 possible values of $\lfloor x\rfloor: 0,1$, and 2 .

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=0$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}=5$, which has positive solution $x=\sqrt{\frac{5}{2}}$. This number is greater than 1 , so its floor is not 0 ; thus, there are no solutions in this case.

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=1$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}-x=5$. Using the quadratic formula, we find the positive solution $x=\frac{1+\sqrt{41}}{4}$. Since $3<\sqrt{41}<7$, this number is between 1 and 2 , so it satisfies the equation.

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=2$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}-2 x=5$. We find the positive solution $x=\frac{1+\sqrt{11}}{2}$. Since $3<\sqrt{11}<5$, this number is between 2 and 3 , so it satisfies the equation.

We then find that the sum of positive solutions is $\frac{1+\sqrt{41}}{4}+\frac{1+\sqrt{11}}{2}=\frac{3+\sqrt{41}+2 \sqrt{11}}{4}$.

|

\frac{3+\sqrt{41}+2 \sqrt{11}}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

What is the sum of the positive solutions to $2 x^{2}-x\lfloor x\rfloor=5$, where $\lfloor x\rfloor$ is the largest integer less than or equal to $x$ ?

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{41}+2 \sqrt{11}}{4}$ We first note that $\lfloor x\rfloor \leq x$, so $2 x^{2}-x\lfloor x\rfloor \geq 2 x^{2}-x^{2}=x^{2}$. Since this function is increasing on the positive reals, all solutions must be at most $\sqrt{5}$. This gives us 3 possible values of $\lfloor x\rfloor: 0,1$, and 2 .

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=0$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}=5$, which has positive solution $x=\sqrt{\frac{5}{2}}$. This number is greater than 1 , so its floor is not 0 ; thus, there are no solutions in this case.

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=1$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}-x=5$. Using the quadratic formula, we find the positive solution $x=\frac{1+\sqrt{41}}{4}$. Since $3<\sqrt{41}<7$, this number is between 1 and 2 , so it satisfies the equation.

If $\lfloor x\rfloor=2$, then our equation becomes $2 x^{2}-2 x=5$. We find the positive solution $x=\frac{1+\sqrt{11}}{2}$. Since $3<\sqrt{11}<5$, this number is between 2 and 3 , so it satisfies the equation.

We then find that the sum of positive solutions is $\frac{1+\sqrt{41}}{4}+\frac{1+\sqrt{11}}{2}=\frac{3+\sqrt{41}+2 \sqrt{11}}{4}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

What is the remainder when $(1+x)^{2010}$ is divided by $1+x+x^{2}$ ?

|

1 We use polynomial congruence $\bmod 1+x+x^{2}$ to find the desired remainder. Since $x^{2}+x+1 \mid x^{3}-1$, we have that $x^{3} \equiv 1\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right)$. Now:

$$

\begin{aligned}

(1+x)^{2010} & \equiv\left(-x^{2}\right)^{2010} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv x^{4020} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv\left(x^{3}\right)^{1340} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv 1^{1340} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv 1 \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus, the answer is 1 .

|

1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

What is the remainder when $(1+x)^{2010}$ is divided by $1+x+x^{2}$ ?

|

1 We use polynomial congruence $\bmod 1+x+x^{2}$ to find the desired remainder. Since $x^{2}+x+1 \mid x^{3}-1$, we have that $x^{3} \equiv 1\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right)$. Now:

$$

\begin{aligned}

(1+x)^{2010} & \equiv\left(-x^{2}\right)^{2010} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv x^{4020} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv\left(x^{3}\right)^{1340} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv 1^{1340} \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right) \\

& \equiv 1 \quad\left(\bmod 1+x+x^{2}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus, the answer is 1 .

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Two circles with radius one are drawn in the coordinate plane, one with center $(0,1)$ and the other with center $(2, y)$, for some real number $y$ between 0 and 1 . A third circle is drawn so as to be tangent to both of the other two circles as well as the $x$ axis. What is the smallest possible radius for this third circle?

|

$3-2 \sqrt{2}$ Suppose that the smaller circle has radius $r$. Call the three circles (in order from left to right) $O_{1}, O_{2}$, and $O_{3}$. The distance between the centers of $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$ is $1+r$, and the distance in their $y$-coordinates is $1-r$. Therefore, by the Pythagorean theorem, the difference in $x$-coordinates

is $\sqrt{(1+r)^{2}-(1-r)^{2}}=2 \sqrt{r}$, which means that $O_{2}$ has a center at $(2 \sqrt{r}, r)$. But $O_{2}$ is also tangent to $O_{3}$, which means that the difference in $x$-coordinate from the right-most point of $O_{2}$ to the center of $O_{3}$ is at most 1. Therefore, the center of $O_{3}$ has an $x$-coordinate of at most $2 \sqrt{r}+r+1$, meaning that $2 \sqrt{r}+r+1 \leq 2$. We can use the quadratic formula to see that this implies that $\sqrt{r} \leq \sqrt{2}-1$, so $r \leq 3-2 \sqrt{2}$. We can achieve equality by placing the center of $O_{3}$ at $(2, r)$ (which in this case is $(2,3-2 \sqrt{2}))$.

|

3-2 \sqrt{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Two circles with radius one are drawn in the coordinate plane, one with center $(0,1)$ and the other with center $(2, y)$, for some real number $y$ between 0 and 1 . A third circle is drawn so as to be tangent to both of the other two circles as well as the $x$ axis. What is the smallest possible radius for this third circle?

|

$3-2 \sqrt{2}$ Suppose that the smaller circle has radius $r$. Call the three circles (in order from left to right) $O_{1}, O_{2}$, and $O_{3}$. The distance between the centers of $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$ is $1+r$, and the distance in their $y$-coordinates is $1-r$. Therefore, by the Pythagorean theorem, the difference in $x$-coordinates

is $\sqrt{(1+r)^{2}-(1-r)^{2}}=2 \sqrt{r}$, which means that $O_{2}$ has a center at $(2 \sqrt{r}, r)$. But $O_{2}$ is also tangent to $O_{3}$, which means that the difference in $x$-coordinate from the right-most point of $O_{2}$ to the center of $O_{3}$ is at most 1. Therefore, the center of $O_{3}$ has an $x$-coordinate of at most $2 \sqrt{r}+r+1$, meaning that $2 \sqrt{r}+r+1 \leq 2$. We can use the quadratic formula to see that this implies that $\sqrt{r} \leq \sqrt{2}-1$, so $r \leq 3-2 \sqrt{2}$. We can achieve equality by placing the center of $O_{3}$ at $(2, r)$ (which in this case is $(2,3-2 \sqrt{2}))$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

What is the sum of all numbers between 0 and 511 inclusive that have an even number of 1 s when written in binary?

|

65408 Call a digit in the binary representation of a number a bit. We claim that for any given $i$ between 0 and 8 , there are 128 numbers with an even number of 1 s that have a 1 in the bit representing $2^{i}$. To prove this, we simply make that bit a 1 , then consider all possible configurations of the other bits, excluding the last bit (or the second-last bit if our given bit is already the last bit). The last bit will then be restricted to satisfy the parity condition on the number of 1 s . As there are 128 possible configurations of all the bits but two, we find 128 possible numbers, proving our claim.

Therefore, each bit is present as a 1 in 128 numbers in the sum, so the bit representing $2^{i}$ contributes $128 \cdot 2^{i}$ to our sum. Summing over all $0 \leq i \leq 8$, we find the answer to be $128(1+2+\ldots+128)=$ $128 \cdot 511=65408$.

|

65408

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

What is the sum of all numbers between 0 and 511 inclusive that have an even number of 1 s when written in binary?

|

65408 Call a digit in the binary representation of a number a bit. We claim that for any given $i$ between 0 and 8 , there are 128 numbers with an even number of 1 s that have a 1 in the bit representing $2^{i}$. To prove this, we simply make that bit a 1 , then consider all possible configurations of the other bits, excluding the last bit (or the second-last bit if our given bit is already the last bit). The last bit will then be restricted to satisfy the parity condition on the number of 1 s . As there are 128 possible configurations of all the bits but two, we find 128 possible numbers, proving our claim.

Therefore, each bit is present as a 1 in 128 numbers in the sum, so the bit representing $2^{i}$ contributes $128 \cdot 2^{i}$ to our sum. Summing over all $0 \leq i \leq 8$, we find the answer to be $128(1+2+\ldots+128)=$ $128 \cdot 511=65408$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

You are given two diameters $A B$ and $C D$ of circle $\Omega$ with radius 1. A circle is drawn in one of the smaller sectors formed such that it is tangent to $A B$ at $E$, tangent to $C D$ at $F$, and tangent to $\Omega$ at $P$. Lines $P E$ and $P F$ intersect $\Omega$ again at $X$ and $Y$. What is the length of $X Y$, given that $A C=\frac{2}{3}$ ?

|

\( \frac{4\sqrt{2}}{3} \). Let \( O \) denote the center of circle \( \Omega \). We first prove that \( OX \perp AB \) and \( OY \perp CD \). Consider the homothety about $P$ which maps the smaller circle to $\Omega$. This homothety takes $E$ to $X$ and also takes $A B$ to the line tangent to circle $\Omega$ parallel to $A B$. Therefore, $X$ is the midpoint of the arc $A B$, and so $O X \perp A B$. Similarly, $O Y \perp C D$.

Let $\theta=\angle A O C$. By the Law of Sines, we have $A C=2 \sin \frac{\theta}{2}$. Thus, $\sin \frac{\theta}{2}=\frac{1}{3}$, and $\cos \frac{\theta}{2}=\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}}=$ $\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$. Therefore,

$$

\begin{aligned}

X Y & =2 \sin \frac{\angle X O Y}{2} \\

& =2 \sin \left(90^{\circ}-\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \\

& =2 \cos \frac{\theta}{2} \\

& =\frac{4 \sqrt{2}}{3}

\end{aligned}

$$

|

\frac{4\sqrt{2}}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

You are given two diameters $A B$ and $C D$ of circle $\Omega$ with radius 1. A circle is drawn in one of the smaller sectors formed such that it is tangent to $A B$ at $E$, tangent to $C D$ at $F$, and tangent to $\Omega$ at $P$. Lines $P E$ and $P F$ intersect $\Omega$ again at $X$ and $Y$. What is the length of $X Y$, given that $A C=\frac{2}{3}$ ?

|

\( \frac{4\sqrt{2}}{3} \). Let \( O \) denote the center of circle \( \Omega \). We first prove that \( OX \perp AB \) and \( OY \perp CD \). Consider the homothety about $P$ which maps the smaller circle to $\Omega$. This homothety takes $E$ to $X$ and also takes $A B$ to the line tangent to circle $\Omega$ parallel to $A B$. Therefore, $X$ is the midpoint of the arc $A B$, and so $O X \perp A B$. Similarly, $O Y \perp C D$.

Let $\theta=\angle A O C$. By the Law of Sines, we have $A C=2 \sin \frac{\theta}{2}$. Thus, $\sin \frac{\theta}{2}=\frac{1}{3}$, and $\cos \frac{\theta}{2}=\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}}=$ $\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$. Therefore,

$$

\begin{aligned}

X Y & =2 \sin \frac{\angle X O Y}{2} \\

& =2 \sin \left(90^{\circ}-\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \\

& =2 \cos \frac{\theta}{2} \\

& =\frac{4 \sqrt{2}}{3}

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [8]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

16 progamers are playing in a single elimination tournament. Each player has a different skill level and when two play against each other the one with the higher skill level will always win. Each round, each progamer plays a match against another and the loser is eliminated. This continues until only one remains. How many different progamers can reach the round that has 2 players remaining?

|

9 Each finalist must be better than the person he beat in the semifinals, both of the people they beat in the second round, and all 4 of the people any of those people beat in the first round. So, none of the 7 worst players can possibly make it to the finals. Any of the 9 best players can make it to the finals if the other 8 of the best 9 play each other in all rounds before the finals. So, exactly 9 people are capable of making it to the finals.

|

9

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

16 progamers are playing in a single elimination tournament. Each player has a different skill level and when two play against each other the one with the higher skill level will always win. Each round, each progamer plays a match against another and the loser is eliminated. This continues until only one remains. How many different progamers can reach the round that has 2 players remaining?

|

9 Each finalist must be better than the person he beat in the semifinals, both of the people they beat in the second round, and all 4 of the people any of those people beat in the first round. So, none of the 7 worst players can possibly make it to the finals. Any of the 9 best players can make it to the finals if the other 8 of the best 9 play each other in all rounds before the finals. So, exactly 9 people are capable of making it to the finals.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

16 progamers are playing in another single elimination tournament. Each round, each of the remaining progamers plays against another and the loser is eliminated. Additionally, each time a progamer wins, he will have a ceremony to celebrate. A player's first ceremony is ten seconds long, and afterward each ceremony is ten seconds longer than the last. What is the total length in seconds of all the ceremonies over the entire tournament?

|

260 At the end of the first round, each of the 8 winners has a 10 second ceremony. After the second round, the 4 winners have a 20 second ceremony. The two remaining players have 30 second ceremonies after the third round, and the winner has a 40 second ceremony after the finals. So, all of the ceremonies combined take $8 \cdot 10+4 \cdot 20+2 \cdot 30+40=260$ seconds.

|

260

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

16 progamers are playing in another single elimination tournament. Each round, each of the remaining progamers plays against another and the loser is eliminated. Additionally, each time a progamer wins, he will have a ceremony to celebrate. A player's first ceremony is ten seconds long, and afterward each ceremony is ten seconds longer than the last. What is the total length in seconds of all the ceremonies over the entire tournament?

|

260 At the end of the first round, each of the 8 winners has a 10 second ceremony. After the second round, the 4 winners have a 20 second ceremony. The two remaining players have 30 second ceremonies after the third round, and the winner has a 40 second ceremony after the finals. So, all of the ceremonies combined take $8 \cdot 10+4 \cdot 20+2 \cdot 30+40=260$ seconds.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Dragoons take up $1 \times 1$ squares in the plane with sides parallel to the coordinate axes such that the interiors of the squares do not intersect. A dragoon can fire at another dragoon if the difference in the $x$-coordinates of their centers and the difference in the $y$-coordinates of their centers are both at most 6 , regardless of any dragoons in between. For example, a dragoon centered at $(4,5)$ can fire at a dragoon centered at the origin, but a dragoon centered at $(7,0)$ can not. A dragoon cannot fire at itself. What is the maximum number of dragoons that can fire at a single dragoon simultaneously?

|

168 Assign coordinates in such a way that the dragoon being fired on is centered at $(0,0)$. Any dragoon firing at it must have a center with $x$-coordinates and $y$-coordinates that are no smaller than -6 and no greater than 6 . That means that every dragoon firing at it must lie entirely in the region bounded by the lines $x=-6.5, x=6.5, y=-6.5$, and $y=6.5$. This is a square with sides of length 13 , so there is room for exactly 169 dragoons in it. One of them is the dragoon being fired on, so there are at most 168 dragoons firing at it.

|

168

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Dragoons take up $1 \times 1$ squares in the plane with sides parallel to the coordinate axes such that the interiors of the squares do not intersect. A dragoon can fire at another dragoon if the difference in the $x$-coordinates of their centers and the difference in the $y$-coordinates of their centers are both at most 6 , regardless of any dragoons in between. For example, a dragoon centered at $(4,5)$ can fire at a dragoon centered at the origin, but a dragoon centered at $(7,0)$ can not. A dragoon cannot fire at itself. What is the maximum number of dragoons that can fire at a single dragoon simultaneously?

|

168 Assign coordinates in such a way that the dragoon being fired on is centered at $(0,0)$. Any dragoon firing at it must have a center with $x$-coordinates and $y$-coordinates that are no smaller than -6 and no greater than 6 . That means that every dragoon firing at it must lie entirely in the region bounded by the lines $x=-6.5, x=6.5, y=-6.5$, and $y=6.5$. This is a square with sides of length 13 , so there is room for exactly 169 dragoons in it. One of them is the dragoon being fired on, so there are at most 168 dragoons firing at it.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

A zerg player can produce one zergling every minute and a protoss player can produce one zealot every 2.1 minutes. Both players begin building their respective units immediately from the beginning of the game. In a fight, a zergling army overpowers a zealot army if the ratio of zerglings to zealots is more than 3 . What is the total amount of time (in minutes) during the game such that at that time the zergling army would overpower the zealot army?

|

1.3 At the end of the first minute, the zerg player produces a zergling and has a superior army for the 1.1 minutes before the protoss player produces the first zealot. At this point, the zealot is at least a match for the zerglings until the fourth is produced 4 minutes into the game. Then, the zerg army has the advantage for the .2 minutes before a second zealot is produced. A third zealot will be produced 6.3 minutes into the game, which will be before the zerg player accumulates the 7 zerglings needed to overwhelm the first 2 zealots. After this, the zerglings will never regain the advantage because the zerg player can never produce 3 more zerglings to counter the last zealot before another one is produced. So, the zerg player will have the military advantage for $1.1+.2=1.3$ minutes.

|

1.3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

A zerg player can produce one zergling every minute and a protoss player can produce one zealot every 2.1 minutes. Both players begin building their respective units immediately from the beginning of the game. In a fight, a zergling army overpowers a zealot army if the ratio of zerglings to zealots is more than 3 . What is the total amount of time (in minutes) during the game such that at that time the zergling army would overpower the zealot army?

|

1.3 At the end of the first minute, the zerg player produces a zergling and has a superior army for the 1.1 minutes before the protoss player produces the first zealot. At this point, the zealot is at least a match for the zerglings until the fourth is produced 4 minutes into the game. Then, the zerg army has the advantage for the .2 minutes before a second zealot is produced. A third zealot will be produced 6.3 minutes into the game, which will be before the zerg player accumulates the 7 zerglings needed to overwhelm the first 2 zealots. After this, the zerglings will never regain the advantage because the zerg player can never produce 3 more zerglings to counter the last zealot before another one is produced. So, the zerg player will have the military advantage for $1.1+.2=1.3$ minutes.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

There are 111 StarCraft progamers. The StarCraft team SKT starts with a given set of eleven progamers on it, and at the end of each season, it drops a progamer and adds a progamer (possibly the same one). At the start of the second season, SKT has to field a team of five progamers to play the opening match. How many different lineups of five players could be fielded if the order of players on the lineup matters?

|

4015440 We disregard the order of the players, multiplying our answer by $5!=120$ at the end to account for it. Clearly, SKT will be able to field at most 1 player not in the original set of eleven players. If it does not field a new player, then it has $\binom{11}{5}=462$ choices. If it does field a new player, then it has 100 choices for the new player, and $\binom{11}{4}=330$ choices for the 4 other players, giving 33000 possibilities. Thus, SKT can field at most $33000+462=33462$ unordered lineups, and multiplying this by 120 , we find the answer to be 4015440 .

## Unfair Coins

|

4015440

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

There are 111 StarCraft progamers. The StarCraft team SKT starts with a given set of eleven progamers on it, and at the end of each season, it drops a progamer and adds a progamer (possibly the same one). At the start of the second season, SKT has to field a team of five progamers to play the opening match. How many different lineups of five players could be fielded if the order of players on the lineup matters?

|

4015440 We disregard the order of the players, multiplying our answer by $5!=120$ at the end to account for it. Clearly, SKT will be able to field at most 1 player not in the original set of eleven players. If it does not field a new player, then it has $\binom{11}{5}=462$ choices. If it does field a new player, then it has 100 choices for the new player, and $\binom{11}{4}=330$ choices for the 4 other players, giving 33000 possibilities. Thus, SKT can field at most $33000+462=33462$ unordered lineups, and multiplying this by 120 , we find the answer to be 4015440 .

## Unfair Coins

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

When flipped, a coin has a probability $p$ of landing heads. When flipped twice, it is twice as likely to land on the same side both times as it is to land on each side once. What is the larger possible value of $p$ ?

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{3}}{6}$ The probability that the coin will land on the same side twice is $p^{2}+(1-p)^{2}=$ $2 p^{2}-2 p+1$. The probability that the coin will land on each side once is $p(p-1)+(p-1) p=$ $2 p(1-p)=2 p-2 p^{2}$. We are told that it is twice as likely to land on the same side both times, so $2 p^{2}-2 p+1=2\left(2 p-2 p^{2}\right)=4 p-4 p^{2}$. Solving, we get $6 p^{2}-6 p+1=0$, so $p=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{3}}{6}$. The larger solution is $p=\frac{3+\sqrt{3}}{6}$.

|

\frac{3+\sqrt{3}}{6}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

When flipped, a coin has a probability $p$ of landing heads. When flipped twice, it is twice as likely to land on the same side both times as it is to land on each side once. What is the larger possible value of $p$ ?

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{3}}{6}$ The probability that the coin will land on the same side twice is $p^{2}+(1-p)^{2}=$ $2 p^{2}-2 p+1$. The probability that the coin will land on each side once is $p(p-1)+(p-1) p=$ $2 p(1-p)=2 p-2 p^{2}$. We are told that it is twice as likely to land on the same side both times, so $2 p^{2}-2 p+1=2\left(2 p-2 p^{2}\right)=4 p-4 p^{2}$. Solving, we get $6 p^{2}-6 p+1=0$, so $p=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{3}}{6}$. The larger solution is $p=\frac{3+\sqrt{3}}{6}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

George has two coins, one of which is fair and the other of which always comes up heads. Jacob takes one of them at random and flips it twice. Given that it came up heads both times, what is the probability that it is the coin that always comes up heads?

|

\( \frac{4}{5} \). In general, \( P(A|B) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(B)} \), where \( P(A|B) \) is the probability of \( A \) given \( B \) and $P(A \cap B)$ is the probability of $A$ and $B$ (See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conditional_probability for more information). If $A$ is the event of selecting the "double-headed" coin and $B$ is the event of Jacob flipping two heads, then $P(A \cap B)=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)(1)$, since there is a $\frac{1}{2}$ chance of picking the doubleheaded coin and Jacob will always flip two heads when he has it. By conditional probability, $P(B)=$ $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)(1)+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)=\frac{5}{8}$, so $P(A \mid B)=\frac{1 / 2}{5 / 8}=\frac{4}{5}$.

|

\frac{4}{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

George has two coins, one of which is fair and the other of which always comes up heads. Jacob takes one of them at random and flips it twice. Given that it came up heads both times, what is the probability that it is the coin that always comes up heads?

|

\( \frac{4}{5} \). In general, \( P(A|B) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(B)} \), where \( P(A|B) \) is the probability of \( A \) given \( B \) and $P(A \cap B)$ is the probability of $A$ and $B$ (See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conditional_probability for more information). If $A$ is the event of selecting the "double-headed" coin and $B$ is the event of Jacob flipping two heads, then $P(A \cap B)=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)(1)$, since there is a $\frac{1}{2}$ chance of picking the doubleheaded coin and Jacob will always flip two heads when he has it. By conditional probability, $P(B)=$ $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)(1)+\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)=\frac{5}{8}$, so $P(A \mid B)=\frac{1 / 2}{5 / 8}=\frac{4}{5}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Allison has a coin which comes up heads $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time. She flips it 5 times. What is the probability that she sees more heads than tails?

|

\(\frac{6}{81}\). The probability of flipping more heads than tails is the probability of flipping 3 heads, 4 heads, or 5 heads. Since 5 flips will give $n$ heads with probability $\binom{5}{n}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{5-n}$, our answer is $\binom{5}{3}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{3}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}+\binom{5}{4}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{4}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{1}+\binom{5}{5}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{5}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{0}=\frac{64}{81}$.

|

\frac{64}{81}

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Allison has a coin which comes up heads $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time. She flips it 5 times. What is the probability that she sees more heads than tails?

|

\(\frac{6}{81}\). The probability of flipping more heads than tails is the probability of flipping 3 heads, 4 heads, or 5 heads. Since 5 flips will give $n$ heads with probability $\binom{5}{n}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{n}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{5-n}$, our answer is $\binom{5}{3}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{3}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}+\binom{5}{4}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{4}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{1}+\binom{5}{5}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{5}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{0}=\frac{64}{81}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Newton and Leibniz are playing a game with a coin that comes up heads with probability $p$. They take turns flipping the coin until one of them wins with Newton going first. Newton wins if he flips a heads and Leibniz wins if he flips a tails. Given that Newton and Leibniz each win the game half of the time, what is the probability $p$ ?

|

$\frac{\frac{3-\sqrt{5}}{2}}{}$ The probability that Newton will win on the first flip is $p$. The probability that Newton will win on the third flip is $(1-p) p^{2}$, since the first flip must be tails, the second must be heads, and the third flip must be heads. By the same logic, the probability Newton will win on the $(2 n+1)^{\text {st }}$ flip is $(1-p)^{n}(p)^{n+1}$. Thus, we have an infinite geometric sequence $p+(1-p) p^{2}+(1-p)^{2} p^{3}+\ldots$ which equals $\frac{p}{1-p(1-p)}$. We are given that this sum must equal $\frac{1}{2}$, so $1-p+p^{2}=2 p$, so $p=\frac{3-\sqrt{5}}{2}$ (the other solution is greater than 1).

|

\frac{3-\sqrt{5}}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Newton and Leibniz are playing a game with a coin that comes up heads with probability $p$. They take turns flipping the coin until one of them wins with Newton going first. Newton wins if he flips a heads and Leibniz wins if he flips a tails. Given that Newton and Leibniz each win the game half of the time, what is the probability $p$ ?

|

$\frac{\frac{3-\sqrt{5}}{2}}{}$ The probability that Newton will win on the first flip is $p$. The probability that Newton will win on the third flip is $(1-p) p^{2}$, since the first flip must be tails, the second must be heads, and the third flip must be heads. By the same logic, the probability Newton will win on the $(2 n+1)^{\text {st }}$ flip is $(1-p)^{n}(p)^{n+1}$. Thus, we have an infinite geometric sequence $p+(1-p) p^{2}+(1-p)^{2} p^{3}+\ldots$ which equals $\frac{p}{1-p(1-p)}$. We are given that this sum must equal $\frac{1}{2}$, so $1-p+p^{2}=2 p$, so $p=\frac{3-\sqrt{5}}{2}$ (the other solution is greater than 1).

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Justine has a coin which will come up the same as the last flip $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time and the other side $\frac{1}{3}$ of the time. She flips it and it comes up heads. She then flips it 2010 more times. What is the probability that the last flip is heads?

|

| $\frac{3^{2010}+1}{2 \cdot 3^{2010}}$ | Let the "value" of a flip be 1 if the flip is different from the previous flip and let |

| :---: | :---: | it be 0 if the flip is the same as the previous flip. The last flip will be heads if the sum of the values of all 2010 flips is even. The probability that this will happen is $\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}$.

We know that

$$

\begin{gathered}

\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}+\binom{2010}{2 i+1}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i+1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-(2 i+1)}= \\

\sum_{k=0}^{2010}\binom{2010}{k}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{k}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-k}=\left(\frac{1}{3}+\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010}=1

\end{gathered}

$$

and

$$

\begin{gathered}

\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}-\binom{2010}{2 i+1}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i+1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-(2 i+1)}= \\

\sum_{k=0}^{2010}\binom{2010}{k}\left(\frac{-1}{3}\right)^{k}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-k}=\left(\frac{-1}{3}+\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010}=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2010}

\end{gathered}

$$

Summing these two values and dividing by 2 gives the answer $\frac{1+\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2010}}{2}=\frac{3^{2010}+1}{2 \cdot 3^{2010}}$.

|

\frac{3^{2010}+1}{2 \cdot 3^{2010}}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Justine has a coin which will come up the same as the last flip $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time and the other side $\frac{1}{3}$ of the time. She flips it and it comes up heads. She then flips it 2010 more times. What is the probability that the last flip is heads?

|

| $\frac{3^{2010}+1}{2 \cdot 3^{2010}}$ | Let the "value" of a flip be 1 if the flip is different from the previous flip and let |

| :---: | :---: | it be 0 if the flip is the same as the previous flip. The last flip will be heads if the sum of the values of all 2010 flips is even. The probability that this will happen is $\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}$.

We know that

$$

\begin{gathered}

\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}+\binom{2010}{2 i+1}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i+1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-(2 i+1)}= \\

\sum_{k=0}^{2010}\binom{2010}{k}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{k}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-k}=\left(\frac{1}{3}+\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010}=1

\end{gathered}

$$

and

$$

\begin{gathered}

\sum_{i=0}^{1005}\binom{2010}{2 i}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-2 i}-\binom{2010}{2 i+1}\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2 i+1}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-(2 i+1)}= \\

\sum_{k=0}^{2010}\binom{2010}{k}\left(\frac{-1}{3}\right)^{k}\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010-k}=\left(\frac{-1}{3}+\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2010}=\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2010}

\end{gathered}

$$

Summing these two values and dividing by 2 gives the answer $\frac{1+\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2010}}{2}=\frac{3^{2010}+1}{2 \cdot 3^{2010}}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

David, Delong, and Justin each showed up to a problem writing session at a random time during the session. If David arrived before Delong, what is the probability that he also arrived before Justin?

|

$\sqrt[2]{3}$ Let $t_{1}$ be the time that David arrives, let $t_{2}$ be the time that Delong arrives, and let $t_{3}$ be the time that Justin arrives. We can assume that all times are pairwise distinct because the probability of any two being equal is zero. Because the times were originally random and independent before we were given any information, then all orders $t_{1}<t_{2}<t_{3}, t_{1}<t_{3}<t_{2}, t_{3}<t_{1}<t_{2}, t_{2}<t_{1}<t_{3}$, $t_{2}<t_{3}<t_{1}, t_{3}<t_{2}<t_{1}$ must all be equally likely. Since we are given that $t_{1}<t_{2}$, then we only have the first three cases to consider, and $t_{1}<t_{3}$ in two cases of these three. Thus, the desired probability is $\frac{2}{3}$.

|

\frac{2}{3}

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

David, Delong, and Justin each showed up to a problem writing session at a random time during the session. If David arrived before Delong, what is the probability that he also arrived before Justin?

|

$\sqrt[2]{3}$ Let $t_{1}$ be the time that David arrives, let $t_{2}$ be the time that Delong arrives, and let $t_{3}$ be the time that Justin arrives. We can assume that all times are pairwise distinct because the probability of any two being equal is zero. Because the times were originally random and independent before we were given any information, then all orders $t_{1}<t_{2}<t_{3}, t_{1}<t_{3}<t_{2}, t_{3}<t_{1}<t_{2}, t_{2}<t_{1}<t_{3}$, $t_{2}<t_{3}<t_{1}, t_{3}<t_{2}<t_{1}$ must all be equally likely. Since we are given that $t_{1}<t_{2}$, then we only have the first three cases to consider, and $t_{1}<t_{3}$ in two cases of these three. Thus, the desired probability is $\frac{2}{3}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

A circle of radius 6 is drawn centered at the origin. How many squares of side length 1 and integer coordinate vertices intersect the interior of this circle?

|

132 By symmetry, the answer is four times the number of squares in the first quadrant. Let's identify each square by its coordinates at the bottom-left corner, $(x, y)$. When $x=0$, we can have $y=0 \ldots 5$, so there are 6 squares. (Letting $y=6$ is not allowed because that square intersects only the boundary of the circle.) When $x=1$, how many squares are there? The equation of the circle is $y=\sqrt{36-x^{2}}=\sqrt{36-1^{2}}$ is between 5 and 6 , so we can again have $y=0 \ldots 5$. Likewise for $x=2$ and $x=3$. When $x=4$ we have $y=\sqrt{20}$ which is between 4 and 5 , so there are 5 squares, and when $x=5$ we have $y=\sqrt{11}$ which is between 3 and 4 , so there are 4 squares. Finally, when $x=6$, we have $y=0$, and no squares intersect the interior of the circle. This gives $6+6+6+6+5+4=33$. Since this is the number in the first quadrant, we multiply by four to get 132 .

|

132

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A circle of radius 6 is drawn centered at the origin. How many squares of side length 1 and integer coordinate vertices intersect the interior of this circle?

|

132 By symmetry, the answer is four times the number of squares in the first quadrant. Let's identify each square by its coordinates at the bottom-left corner, $(x, y)$. When $x=0$, we can have $y=0 \ldots 5$, so there are 6 squares. (Letting $y=6$ is not allowed because that square intersects only the boundary of the circle.) When $x=1$, how many squares are there? The equation of the circle is $y=\sqrt{36-x^{2}}=\sqrt{36-1^{2}}$ is between 5 and 6 , so we can again have $y=0 \ldots 5$. Likewise for $x=2$ and $x=3$. When $x=4$ we have $y=\sqrt{20}$ which is between 4 and 5 , so there are 5 squares, and when $x=5$ we have $y=\sqrt{11}$ which is between 3 and 4 , so there are 4 squares. Finally, when $x=6$, we have $y=0$, and no squares intersect the interior of the circle. This gives $6+6+6+6+5+4=33$. Since this is the number in the first quadrant, we multiply by four to get 132 .

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Jacob flipped a fair coin five times. In the first three flips, the coin came up heads exactly twice. In the last three flips, the coin also came up heads exactly twice. What is the probability that the third flip was heads?

|

| $\frac{4}{5}$ |

| :---: |

| How many sequences of five flips satisfy the conditions, and have the third flip be heads? | We have __H_- , so exactly one of the first two flips is heads, and exactly one of the last two flips is heads. This gives $2 \times 2=4$ possibilities. How many sequences of five flips satisfy the conditions, and have the third flip be tails? Now we have __T__, so the first two and the last two flips must all be heads. This gives only 1 possibility. So the probability that the third flip was heads is $\frac{4}{(4+1)}=\frac{4}{5}$

|

\frac{4}{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Jacob flipped a fair coin five times. In the first three flips, the coin came up heads exactly twice. In the last three flips, the coin also came up heads exactly twice. What is the probability that the third flip was heads?

|

| $\frac{4}{5}$ |

| :---: |

| How many sequences of five flips satisfy the conditions, and have the third flip be heads? | We have __H_- , so exactly one of the first two flips is heads, and exactly one of the last two flips is heads. This gives $2 \times 2=4$ possibilities. How many sequences of five flips satisfy the conditions, and have the third flip be tails? Now we have __T__, so the first two and the last two flips must all be heads. This gives only 1 possibility. So the probability that the third flip was heads is $\frac{4}{(4+1)}=\frac{4}{5}$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $x$ be a real number. Find the maximum value of $2^{x(1-x)}$.

|

$\sqrt[4]{2}$ Consider the function $2^{y}$. This is monotonically increasing, so to maximize $2^{y}$, you simply want to maximize $y$. Here, $y=x(1-x)=-x^{2}+x$ is a parabola opening downwards. The vertex of the parabola occurs at $x=(-1) /(-2)=1 / 2$, so the maximum value of the function is $2^{(1 / 2)(1 / 2)}=\sqrt[4]{2}$.

|

\sqrt[4]{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $x$ be a real number. Find the maximum value of $2^{x(1-x)}$.

|

$\sqrt[4]{2}$ Consider the function $2^{y}$. This is monotonically increasing, so to maximize $2^{y}$, you simply want to maximize $y$. Here, $y=x(1-x)=-x^{2}+x$ is a parabola opening downwards. The vertex of the parabola occurs at $x=(-1) /(-2)=1 / 2$, so the maximum value of the function is $2^{(1 / 2)(1 / 2)}=\sqrt[4]{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-141-2010-nov-guts-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

An icosahedron is a regular polyhedron with twenty faces, all of which are equilateral triangles. If an icosahedron is rotated by $\theta$ degrees around an axis that passes through two opposite vertices so that it occupies exactly the same region of space as before, what is the smallest possible positive value of $\theta$ ?

|

$72^{\circ}$ Because this polyhedron is regular, all vertices must look the same. Let's consider just one vertex. Each triangle has a vertex angle of $60^{\circ}$, so we must have fewer than 6 triangles; if we had 6 , there would be $360^{\circ}$ at each vertex and you wouldn't be able to "fold" the polyhedron up (that is, it would be a flat plane). It's easy to see that we need at least 3 triangles at each vertex, and this gives a triangular pyramid with only 4 faces. Having 4 triangles meeting at each vertex gives an octahedron (two square pyramids with the squares glued together) with 8 faces. Therefore, an icosahedron has 5 triangles meeting at each vertex, so rotating by $\frac{360^{\circ}}{5}=72^{\circ}$ gives another identical icosahedron.

Alternate solution: Euler's formula tells us that $V-E+F=2$, where an icosahedron has $V$ vertices, $E$ edges, and $F$ faces. We're told that $F=20$. Each triangle has 3 edges, and every edge is common to 2 triangles, so $E=\frac{3(20)}{2}=30$. Additionally, each triangle has 3 vertices, so if every vertex is common to $n$ triangles, then $V=\frac{3(20)}{n}=\frac{60}{n}$. Plugging this into the formula, we have $\frac{60}{n}-30+20=2$, so $\frac{60}{n}=12$ and $n=5$. Again this shows that the rotation is $\frac{360^{\circ}}{5}=72^{\circ}$

|

72^{\circ}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

An icosahedron is a regular polyhedron with twenty faces, all of which are equilateral triangles. If an icosahedron is rotated by $\theta$ degrees around an axis that passes through two opposite vertices so that it occupies exactly the same region of space as before, what is the smallest possible positive value of $\theta$ ?

|