problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let $f(n)=\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n} \cdot k!}$. Calculate $\sum_{n=2}^{\infty} f(n)$.

|

$3-e$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{n=2}^{\infty} f(n) & =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n} \cdot k!} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n}} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \cdot \frac{1}{k(k-1)} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(k-1)!} \cdot \frac{1}{k^{2}(k-1)}

\end{aligned}

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(k-1)!}\left(\frac{1}{k-1}-\frac{1}{k^{2}}-\frac{1}{k}\right) \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{(k-1)(k-1)!}-\frac{1}{k \cdot k!}-\frac{1}{k!}\right) \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{(k-1)(k-1)!}-\frac{1}{k \cdot k!}\right)-\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \\

& =\frac{1}{1 \cdot 1!}-\left(e-\frac{1}{0!}-\frac{1}{1!}\right) \\

& =3-e

\end{aligned}

$$

|

3-e

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Let $f(n)=\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n} \cdot k!}$. Calculate $\sum_{n=2}^{\infty} f(n)$.

|

$3-e$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{n=2}^{\infty} f(n) & =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n} \cdot k!} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k^{n}} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \cdot \frac{1}{k(k-1)} \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(k-1)!} \cdot \frac{1}{k^{2}(k-1)}

\end{aligned}

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(k-1)!}\left(\frac{1}{k-1}-\frac{1}{k^{2}}-\frac{1}{k}\right) \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{(k-1)(k-1)!}-\frac{1}{k \cdot k!}-\frac{1}{k!}\right) \\

& =\sum_{k=2}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{(k-1)(k-1)!}-\frac{1}{k \cdot k!}\right)-\sum_{k=2}^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!} \\

& =\frac{1}{1 \cdot 1!}-\left(e-\frac{1}{0!}-\frac{1}{1!}\right) \\

& =3-e

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $x(t)$ be a solution to the differential equation

$$

\left(x+x^{\prime}\right)^{2}+x \cdot x^{\prime \prime}=\cos t

$$

with $x(0)=x^{\prime}(0)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}}$. Compute $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)$.

|

$\frac{\sqrt[4]{450}}{5}$ Rewrite the equation as $x^{2}+2 x x^{\prime}+\left(x x^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=\cos t$. Let $y=x^{2}$, so $y^{\prime}=2 x x^{\prime}$ and the equation becomes $y+y^{\prime}+\frac{1}{2} y^{\prime \prime}=\cos t$. The term $\cos t$ suggests that the particular solution should be in the form $A \sin t+B \cos t$. By substitution and coefficient comparison, we get $A=\frac{4}{5}$ and $B=\frac{2}{5}$. Since the function $y(t)=\frac{4}{5} \sin t+\frac{2}{5} \cos t$ already satisfies the initial conditions $y(0)=x(0)^{2}=\frac{2}{5}$ and $y^{\prime}(0)=2 x(0) x^{\prime}(0)=\frac{4}{5}$, the function $y$ also solves the initial value problem. Note that since $x$ is positive at $t=0$ and $y=x^{2}$ never reaches zero before $t$ reaches $\frac{\pi}{4}$, the value of $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)$ must be positive. Therefore, $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=+\sqrt{y\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)}=\sqrt{\frac{6}{5} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}}=\frac{\sqrt[4]{450}}{5}$.

|

\frac{\sqrt[4]{450}}{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Let $x(t)$ be a solution to the differential equation

$$

\left(x+x^{\prime}\right)^{2}+x \cdot x^{\prime \prime}=\cos t

$$

with $x(0)=x^{\prime}(0)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}}$. Compute $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)$.

|

$\frac{\sqrt[4]{450}}{5}$ Rewrite the equation as $x^{2}+2 x x^{\prime}+\left(x x^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=\cos t$. Let $y=x^{2}$, so $y^{\prime}=2 x x^{\prime}$ and the equation becomes $y+y^{\prime}+\frac{1}{2} y^{\prime \prime}=\cos t$. The term $\cos t$ suggests that the particular solution should be in the form $A \sin t+B \cos t$. By substitution and coefficient comparison, we get $A=\frac{4}{5}$ and $B=\frac{2}{5}$. Since the function $y(t)=\frac{4}{5} \sin t+\frac{2}{5} \cos t$ already satisfies the initial conditions $y(0)=x(0)^{2}=\frac{2}{5}$ and $y^{\prime}(0)=2 x(0) x^{\prime}(0)=\frac{4}{5}$, the function $y$ also solves the initial value problem. Note that since $x$ is positive at $t=0$ and $y=x^{2}$ never reaches zero before $t$ reaches $\frac{\pi}{4}$, the value of $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)$ must be positive. Therefore, $x\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=+\sqrt{y\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)}=\sqrt{\frac{6}{5} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}}=\frac{\sqrt[4]{450}}{5}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $f(n)=\sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{1}{k}$. Then there exists constants $\gamma, c$, and $d$ such that

$$

f(n)=\ln (n)+\gamma+\frac{c}{n}+\frac{d}{n^{2}}+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}\right)

$$

where the $O\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}\right)$ means terms of order $\frac{1}{n^{3}}$ or lower. Compute the ordered pair $(c, d)$.

|

$\left(\frac{1}{2},-\frac{1}{12}\right)$ From the given formula, we pull out the term $\frac{k}{n^{3}}$ from $O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$, making $f(n)=$ $\log (n)+\gamma+\frac{c}{n}+\frac{d}{n^{2}}+\frac{k}{n^{3}}+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$. Therefore,

$f(n+1)-f(n)=\log \left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)-c\left(\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}\right)-d\left(\frac{1}{n^{2}}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}\right)-k\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{3}}\right)+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$.

For the left hand side, $f(n+1)-f(n)=\frac{1}{n+1}$. By substituting $x=\frac{1}{n}$, the formula above becomes

$$

\frac{x}{x+1}=\log (1+x)-c x^{2} \cdot \frac{1}{x+1}-d x^{3} \cdot \frac{x+2}{(x+1)^{2}}-k x^{4} \cdot \frac{x^{2}+3 x+3}{(x+1)^{3}}+O\left(x^{4}\right)

$$

Because $x$ is on the order of $\frac{1}{n}, \frac{1}{(x+1)^{3}}$ is on the order of a constant. Therefore, all the terms in the expansion of $k x^{4} \cdot \frac{x^{2}+3 x+3}{(x+1)^{3}}$ are of order $x^{4}$ or higher, so we can collapse it into $O\left(x^{4}\right)$. Using the Taylor expansions, we get

$$

x\left(1-x+x^{2}\right)+O\left(x^{4}\right)=\left(x-\frac{1}{2} x^{2}+\frac{1}{3} x^{3}\right)-c x^{2}(1-x)-d x^{3}(2)+O\left(x^{4}\right) .

$$

Coefficient comparison gives $c=\frac{1}{2}$ and $d=-\frac{1}{12}$.

|

\left(\frac{1}{2},-\frac{1}{12}\right)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Let $f(n)=\sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{1}{k}$. Then there exists constants $\gamma, c$, and $d$ such that

$$

f(n)=\ln (n)+\gamma+\frac{c}{n}+\frac{d}{n^{2}}+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}\right)

$$

where the $O\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}\right)$ means terms of order $\frac{1}{n^{3}}$ or lower. Compute the ordered pair $(c, d)$.

|

$\left(\frac{1}{2},-\frac{1}{12}\right)$ From the given formula, we pull out the term $\frac{k}{n^{3}}$ from $O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$, making $f(n)=$ $\log (n)+\gamma+\frac{c}{n}+\frac{d}{n^{2}}+\frac{k}{n^{3}}+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$. Therefore,

$f(n+1)-f(n)=\log \left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)-c\left(\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}\right)-d\left(\frac{1}{n^{2}}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}\right)-k\left(\frac{1}{n^{3}}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{3}}\right)+O\left(\frac{1}{n^{4}}\right)$.

For the left hand side, $f(n+1)-f(n)=\frac{1}{n+1}$. By substituting $x=\frac{1}{n}$, the formula above becomes

$$

\frac{x}{x+1}=\log (1+x)-c x^{2} \cdot \frac{1}{x+1}-d x^{3} \cdot \frac{x+2}{(x+1)^{2}}-k x^{4} \cdot \frac{x^{2}+3 x+3}{(x+1)^{3}}+O\left(x^{4}\right)

$$

Because $x$ is on the order of $\frac{1}{n}, \frac{1}{(x+1)^{3}}$ is on the order of a constant. Therefore, all the terms in the expansion of $k x^{4} \cdot \frac{x^{2}+3 x+3}{(x+1)^{3}}$ are of order $x^{4}$ or higher, so we can collapse it into $O\left(x^{4}\right)$. Using the Taylor expansions, we get

$$

x\left(1-x+x^{2}\right)+O\left(x^{4}\right)=\left(x-\frac{1}{2} x^{2}+\frac{1}{3} x^{3}\right)-c x^{2}(1-x)-d x^{3}(2)+O\left(x^{4}\right) .

$$

Coefficient comparison gives $c=\frac{1}{2}$ and $d=-\frac{1}{12}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [8]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $S=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}$. How many (potentially empty) subsets $T$ of $S$ are there such that, for all $x$, if $x$ is in $T$ and $2 x$ is in $S$ then $2 x$ is also in $T$ ?

|

180 We partition the elements of $S$ into the following subsets: $\{1,2,4,8\},\{3,6\},\{5,10\}$, $\{7\},\{9\}$. Consider the first subset, $\{1,2,4,8\}$. Say 2 is an element of $T$. Because $2 \cdot 2=4$ is in $S, 4$ must also be in $T$. Furthermore, since $4 \cdot 2=8$ is in $S, 8$ must also be in $T$. So if $T$ contains 2 , it must also contain 4 and 8 . Similarly, if $T$ contains 1 , it must also contain 2,4 , and 8 . So $T$ can contain the following subsets of the subset $\{1,2,4,8\}$ : the empty set, $\{8\},\{4,8\},\{2,4,8\}$, or $\{1,2,4,8\}$. This gives 5 possibilities for the first subset. In general, we see that if $T$ contains an element $q$ of one of these subsets, it must also contain the elements in that subset that are larger than $q$, because we created the subsets for this to be true. So there are 3 possibilities for $\{3,6\}, 3$ for $\{5,10\}, 2$ for $\{7\}$, and 2 for $\{9\}$. This gives a total of $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 2=180$ possible subsets $T$.

|

180

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $S=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}$. How many (potentially empty) subsets $T$ of $S$ are there such that, for all $x$, if $x$ is in $T$ and $2 x$ is in $S$ then $2 x$ is also in $T$ ?

|

180 We partition the elements of $S$ into the following subsets: $\{1,2,4,8\},\{3,6\},\{5,10\}$, $\{7\},\{9\}$. Consider the first subset, $\{1,2,4,8\}$. Say 2 is an element of $T$. Because $2 \cdot 2=4$ is in $S, 4$ must also be in $T$. Furthermore, since $4 \cdot 2=8$ is in $S, 8$ must also be in $T$. So if $T$ contains 2 , it must also contain 4 and 8 . Similarly, if $T$ contains 1 , it must also contain 2,4 , and 8 . So $T$ can contain the following subsets of the subset $\{1,2,4,8\}$ : the empty set, $\{8\},\{4,8\},\{2,4,8\}$, or $\{1,2,4,8\}$. This gives 5 possibilities for the first subset. In general, we see that if $T$ contains an element $q$ of one of these subsets, it must also contain the elements in that subset that are larger than $q$, because we created the subsets for this to be true. So there are 3 possibilities for $\{3,6\}, 3$ for $\{5,10\}, 2$ for $\{7\}$, and 2 for $\{9\}$. This gives a total of $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 2=180$ possible subsets $T$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n1. [2]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

How many positive integers less than or equal to 240 can be expressed as a sum of distinct factorials? Consider 0! and 1! to be distinct.

|

39 Note that $1=0!, 2=0!+1!, 3=0!+2$ !, and $4=0!+1!+2$ !. These are the only numbers less than 6 that can be written as the sum of factorials. The only other factorials less than 240 are $3!=6,4!=24$, and $5!=120$. So a positive integer less than or equal to 240 can only contain 3 !, 4 !, 5 !, and/or one of $1,2,3$, or 4 in its sum. If it contains any factorial larger than 5 !, it will be larger than 240 . So a sum less than or equal to 240 will will either include 3 ! or not ( 2 ways), 4 ! or not ( 2 ways), 5 ! or not ( 2 ways), and add an additional $0,1,2,3$ or 4 ( 5 ways). This gives $2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 5=40$ integers less than 240 . However, we want only positive integers, so we must not count 0 . So there are 39 such positive integers.

|

39

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

How many positive integers less than or equal to 240 can be expressed as a sum of distinct factorials? Consider 0! and 1! to be distinct.

|

39 Note that $1=0!, 2=0!+1!, 3=0!+2$ !, and $4=0!+1!+2$ !. These are the only numbers less than 6 that can be written as the sum of factorials. The only other factorials less than 240 are $3!=6,4!=24$, and $5!=120$. So a positive integer less than or equal to 240 can only contain 3 !, 4 !, 5 !, and/or one of $1,2,3$, or 4 in its sum. If it contains any factorial larger than 5 !, it will be larger than 240 . So a sum less than or equal to 240 will will either include 3 ! or not ( 2 ways), 4 ! or not ( 2 ways), 5 ! or not ( 2 ways), and add an additional $0,1,2,3$ or 4 ( 5 ways). This gives $2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 5=40$ integers less than 240 . However, we want only positive integers, so we must not count 0 . So there are 39 such positive integers.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

How many ways are there to choose 2010 functions $f_{1}, \ldots, f_{2010}$ from $\{0,1\}$ to $\{0,1\}$ such that $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{1}$ is constant? Note: a function $g$ is constant if $g(a)=g(b)$ for all $a, b$ in the domain of $g$.

|

$4^{2010}-2^{2010}$ If all 2010 functions are bijective ${ }^{1}$, then the composition $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{1}$ will be bijective also, and therefore not constant. If, however, one of $f_{1}, \ldots, f_{2010}$ is not bijective, say $f_{k}$, then $f_{k}(0)=f_{k}(1)=q$, so $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1} \circ f_{k} \circ \cdots f_{1}(0)=f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1}(q)=$ $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1} \circ f_{k} \circ \cdots f_{1}(1)$. So the composition will be constant unless all $f_{i}$ are bijective. Since there are 4 possible functions ${ }^{2}$ from $\{0,1\}$ to $\{0,1\}$ and 2 of them are bijective, we subtract the cases where all the functions are bijective from the total to get $4^{2010}-2^{2010}$.

|

4^{2010}-2^{2010}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

How many ways are there to choose 2010 functions $f_{1}, \ldots, f_{2010}$ from $\{0,1\}$ to $\{0,1\}$ such that $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{1}$ is constant? Note: a function $g$ is constant if $g(a)=g(b)$ for all $a, b$ in the domain of $g$.

|

$4^{2010}-2^{2010}$ If all 2010 functions are bijective ${ }^{1}$, then the composition $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{1}$ will be bijective also, and therefore not constant. If, however, one of $f_{1}, \ldots, f_{2010}$ is not bijective, say $f_{k}$, then $f_{k}(0)=f_{k}(1)=q$, so $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1} \circ f_{k} \circ \cdots f_{1}(0)=f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1}(q)=$ $f_{2010} \circ f_{2009} \circ \cdots \circ f_{k+1} \circ f_{k} \circ \cdots f_{1}(1)$. So the composition will be constant unless all $f_{i}$ are bijective. Since there are 4 possible functions ${ }^{2}$ from $\{0,1\}$ to $\{0,1\}$ and 2 of them are bijective, we subtract the cases where all the functions are bijective from the total to get $4^{2010}-2^{2010}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

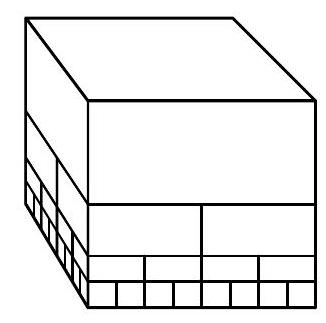

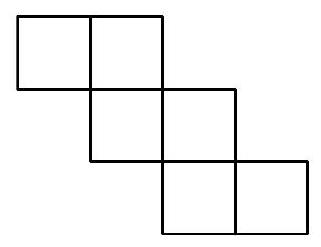

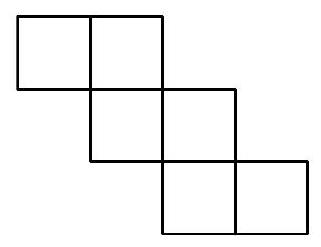

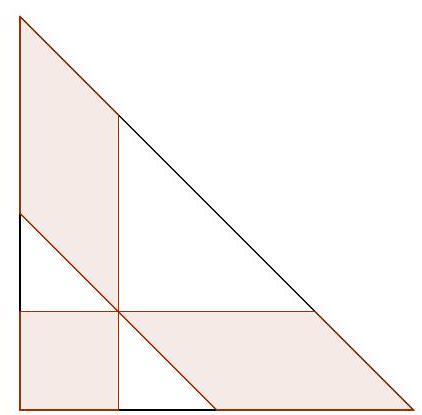

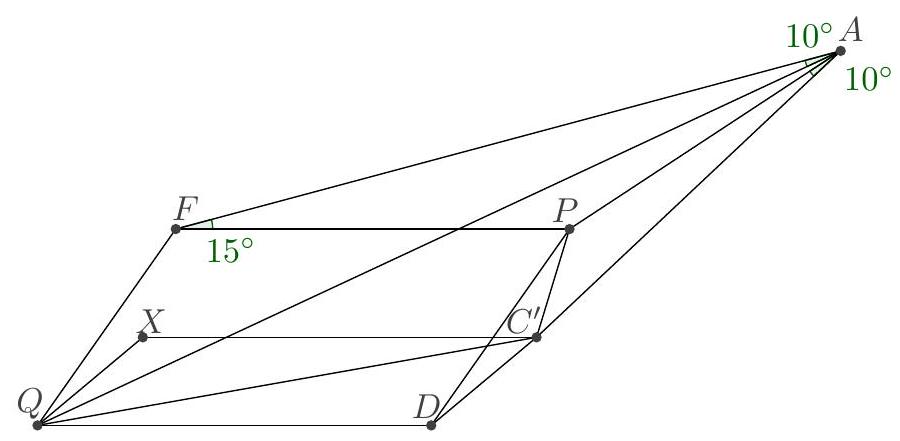

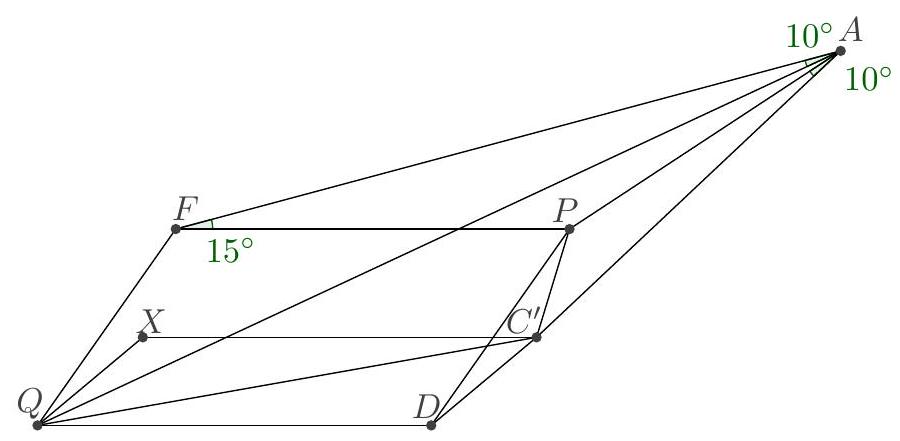

Manya has a stack of $85=1+4+16+64$ blocks comprised of 4 layers (the $k$ th layer from the top has $4^{k-1}$ blocks; see the diagram below). Each block rests on 4 smaller blocks, each with dimensions half those of the larger block. Laura removes blocks one at a time from this stack, removing only blocks that currently have no blocks on top of them. Find the number of ways Laura can remove precisely 5 blocks from Manya's stack (the order in which they are removed matters).

|

3384 Each time Laura removes a block, 4 additional blocks are exposed, increasing the total number of exposed blocks by 3 . She removes 5 blocks, for a total of $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13$ ways. However, the stack originally only has 4 layers, so we must subtract the cases where removing a block on the bottom layer does not expose any new blocks. There are $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=256$ of these (the last factor of 4 is from the 4 blocks that we counted as being exposed, but were not actually). So our final answer is $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13-1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=3384$.

|

3384

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Manya has a stack of $85=1+4+16+64$ blocks comprised of 4 layers (the $k$ th layer from the top has $4^{k-1}$ blocks; see the diagram below). Each block rests on 4 smaller blocks, each with dimensions half those of the larger block. Laura removes blocks one at a time from this stack, removing only blocks that currently have no blocks on top of them. Find the number of ways Laura can remove precisely 5 blocks from Manya's stack (the order in which they are removed matters).

|

3384 Each time Laura removes a block, 4 additional blocks are exposed, increasing the total number of exposed blocks by 3 . She removes 5 blocks, for a total of $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13$ ways. However, the stack originally only has 4 layers, so we must subtract the cases where removing a block on the bottom layer does not expose any new blocks. There are $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=256$ of these (the last factor of 4 is from the 4 blocks that we counted as being exposed, but were not actually). So our final answer is $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13-1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=3384$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

John needs to pay 2010 dollars for his dinner. He has an unlimited supply of 2, 5, and 10 dollar notes. In how many ways can he pay?

|

20503

Let the number of 2,5 , and 10 dollar notes John can use be $x, y$, and $z$ respectively. We wish to find the number of nonnegative integer solutions to $2 x+5 y+10 z=2010$. Consider this equation $\bmod 2$. Because $2 x, 10 z$, and 2010 are even, $5 y$ must also be even, so $y$ must be even. Now consider the equation mod 5 . Because $5 y, 10 z$, and 2010 are divisible by $5,2 x$ must also be divisible by 5 , so $x$ must be divisible by 5 . So both $2 x$ and $5 y$ are divisible by 10 . So the equation is equivalent to $10 x^{\prime}+10 y^{\prime}+10 z=2010$, or $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$, with $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ nonnegative integers. There is a well-known bijection between solutions of this equation and picking 2 of 203 balls in a row on the table (explained in further detail below), so there are $\binom{203}{2}=20503$ ways.

The bijection between solutions of $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$ and arrangements of 203 balls in a row is as follows. Given a solution of the equation, we put $x^{\prime}$ white balls in a row, then a black ball, then $y^{\prime}$ white balls, then a black ball, then $z$ white balls. This is like having 203 balls in a row on a table and picking two of them to be black. To go from an arrangement of balls to a solution of the equation, we just read off $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ from the number of white balls in a row. There are $\binom{203}{2}$ ways to choose 2 of 203 balls to be black, so there are $\binom{203}{2}$ solutions to $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$.

|

20503

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

John needs to pay 2010 dollars for his dinner. He has an unlimited supply of 2, 5, and 10 dollar notes. In how many ways can he pay?

|

20503

Let the number of 2,5 , and 10 dollar notes John can use be $x, y$, and $z$ respectively. We wish to find the number of nonnegative integer solutions to $2 x+5 y+10 z=2010$. Consider this equation $\bmod 2$. Because $2 x, 10 z$, and 2010 are even, $5 y$ must also be even, so $y$ must be even. Now consider the equation mod 5 . Because $5 y, 10 z$, and 2010 are divisible by $5,2 x$ must also be divisible by 5 , so $x$ must be divisible by 5 . So both $2 x$ and $5 y$ are divisible by 10 . So the equation is equivalent to $10 x^{\prime}+10 y^{\prime}+10 z=2010$, or $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$, with $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ nonnegative integers. There is a well-known bijection between solutions of this equation and picking 2 of 203 balls in a row on the table (explained in further detail below), so there are $\binom{203}{2}=20503$ ways.

The bijection between solutions of $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$ and arrangements of 203 balls in a row is as follows. Given a solution of the equation, we put $x^{\prime}$ white balls in a row, then a black ball, then $y^{\prime}$ white balls, then a black ball, then $z$ white balls. This is like having 203 balls in a row on a table and picking two of them to be black. To go from an arrangement of balls to a solution of the equation, we just read off $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ from the number of white balls in a row. There are $\binom{203}{2}$ ways to choose 2 of 203 balls to be black, so there are $\binom{203}{2}$ solutions to $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n5. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

An ant starts out at $(0,0)$. Each second, if it is currently at the square $(x, y)$, it can move to $(x-1, y-1),(x-1, y+1),(x+1, y-1)$, or $(x+1, y+1)$. In how many ways can it end up at $(2010,2010)$ after 4020 seconds?

|

$\binom{4020}{1005}^{2}$ Note that each of the coordinates either increases or decreases the $x$ and $y$ coordinates by 1. In order to reach 2010 after 4020 steps, each of the coordinates must be increased 3015 times and decreased 1005 times. A permutation of 3015 plusses and 1005 minuses for each of $x$ and $y$ uniquely corresponds to a path the ant could take to $(2010,2010)$, because we can take ordered pairs from the two lists and match them up to a valid step the ant can take. So the number of ways the ant can end up at $(2010,2010)$ after 4020 seconds is equal to the number of ways to arrange plusses and minuses for both $x$ and $y$, or $\left(\binom{4020}{1005}\right)^{2}$.

|

\binom{4020}{1005}^{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

An ant starts out at $(0,0)$. Each second, if it is currently at the square $(x, y)$, it can move to $(x-1, y-1),(x-1, y+1),(x+1, y-1)$, or $(x+1, y+1)$. In how many ways can it end up at $(2010,2010)$ after 4020 seconds?

|

$\binom{4020}{1005}^{2}$ Note that each of the coordinates either increases or decreases the $x$ and $y$ coordinates by 1. In order to reach 2010 after 4020 steps, each of the coordinates must be increased 3015 times and decreased 1005 times. A permutation of 3015 plusses and 1005 minuses for each of $x$ and $y$ uniquely corresponds to a path the ant could take to $(2010,2010)$, because we can take ordered pairs from the two lists and match them up to a valid step the ant can take. So the number of ways the ant can end up at $(2010,2010)$ after 4020 seconds is equal to the number of ways to arrange plusses and minuses for both $x$ and $y$, or $\left(\binom{4020}{1005}\right)^{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

For each integer $x$ with $1 \leq x \leq 10$, a point is randomly placed at either $(x, 1)$ or $(x,-1)$ with equal probability. What is the expected area of the convex hull of these points? Note: the convex hull of a finite set is the smallest convex polygon containing it.

|

$\frac{1793}{\frac{1728}{128}}$ Let $n=10$. Given a random variable $X$, let $\mathbb{E}(X)$ denote its expected value. If all points are collinear, then the convex hull has area zero. This happens with probability $\frac{2}{2^{n}}$ (either all points are at $y=1$ or all points are at $y=-1$ ). Otherwise, the points form a trapezoid with height 2 (the trapezoid is possibly degenerate, but this won't matter for our calculation). Let $x_{1, l}$ be the $x$-coordinate of the left-most point at $y=1$ and $x_{1, r}$ be the $x$-coordinate of the right-most point at $y=1$. Define $x_{-1, l}$ and $x_{-1, r}$ similarly for $y=-1$. Then the area of the trapezoid is

$$

2 \cdot \frac{\left(x_{1, r}-x_{1, l}\right)+\left(x_{-1, r}-x_{-1, l}\right)}{2}=x_{1, r}+x_{-1, r}-x_{1, l}-x_{-1, l} .

$$

The expected area of the convex hull (assuming the points are not all collinear) is then, by linearity of expectation,

$$

\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, r}+x_{-1, r}-x_{1, l}-x_{-1, l}\right)=\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, r}\right)+\mathbb{E}\left(x_{-1, r}\right)-\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, l}\right)-\mathbb{E}\left(x_{-1, l}\right) .

$$

We need only compute the expected values given in the above equation. Note that $x_{1, r}$ is equal to $k$ with probability $\frac{2^{k-1}}{2^{n}-2}$, except that it is equal to $n$ with probability $\frac{2^{n-1}-1}{2^{n}-2}$ (the denominator is $2^{n}-2$ instead of $2^{n}$ because we need to exclude the case where all points are collinear). Therefore, the expected value of $x_{1, r}$ is equal to

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} k \cdot 2^{k-1}\right)-n \cdot 1\right) \\

& \quad=\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(1+2+\cdots+2^{n-1}\right)+\left(2+4+\cdots+2^{n-1}\right)+\cdots+2^{n-1}-n\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(2^{n}-1\right)+\left(2^{n}-2\right)+\cdots+\left(2^{n}-2^{n-1}\right)-n\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(n \cdot 2^{n}-\left(2^{n}-1\right)-n\right) \\

& \quad=(n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Similarly, the expected value of $x_{-1, r}$ is also $(n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}$. By symmetry, the expected value of both $x_{1, l}$ and $x_{-1, l}$ is $n+1-(n-1) \frac{\frac{2}{n}^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}$. This says that if the points are not all collinear then the expected area is $2 \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right)$. So, the expected area is

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{2}{2^{n}} \cdot 0+(1- & \left.\frac{2}{2^{n}}\right) \cdot 2 \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right) \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{2^{n-1}-1}{2^{n-1}} \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right) \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{(n-1)\left(2^{n}-1\right)-(n+1)\left(2^{n-1}-1\right)}{2^{n-1}} \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{((2 n-2)-(n+1)) 2^{n-1}+2}{2^{n-1}} \\

& =2 n-6+\frac{1}{2^{n-3}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Plugging in $n=10$, we get $14+\frac{1}{128}=\frac{1793}{128}$.

|

\frac{1793}{128}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

For each integer $x$ with $1 \leq x \leq 10$, a point is randomly placed at either $(x, 1)$ or $(x,-1)$ with equal probability. What is the expected area of the convex hull of these points? Note: the convex hull of a finite set is the smallest convex polygon containing it.

|

$\frac{1793}{\frac{1728}{128}}$ Let $n=10$. Given a random variable $X$, let $\mathbb{E}(X)$ denote its expected value. If all points are collinear, then the convex hull has area zero. This happens with probability $\frac{2}{2^{n}}$ (either all points are at $y=1$ or all points are at $y=-1$ ). Otherwise, the points form a trapezoid with height 2 (the trapezoid is possibly degenerate, but this won't matter for our calculation). Let $x_{1, l}$ be the $x$-coordinate of the left-most point at $y=1$ and $x_{1, r}$ be the $x$-coordinate of the right-most point at $y=1$. Define $x_{-1, l}$ and $x_{-1, r}$ similarly for $y=-1$. Then the area of the trapezoid is

$$

2 \cdot \frac{\left(x_{1, r}-x_{1, l}\right)+\left(x_{-1, r}-x_{-1, l}\right)}{2}=x_{1, r}+x_{-1, r}-x_{1, l}-x_{-1, l} .

$$

The expected area of the convex hull (assuming the points are not all collinear) is then, by linearity of expectation,

$$

\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, r}+x_{-1, r}-x_{1, l}-x_{-1, l}\right)=\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, r}\right)+\mathbb{E}\left(x_{-1, r}\right)-\mathbb{E}\left(x_{1, l}\right)-\mathbb{E}\left(x_{-1, l}\right) .

$$

We need only compute the expected values given in the above equation. Note that $x_{1, r}$ is equal to $k$ with probability $\frac{2^{k-1}}{2^{n}-2}$, except that it is equal to $n$ with probability $\frac{2^{n-1}-1}{2^{n}-2}$ (the denominator is $2^{n}-2$ instead of $2^{n}$ because we need to exclude the case where all points are collinear). Therefore, the expected value of $x_{1, r}$ is equal to

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} k \cdot 2^{k-1}\right)-n \cdot 1\right) \\

& \quad=\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(1+2+\cdots+2^{n-1}\right)+\left(2+4+\cdots+2^{n-1}\right)+\cdots+2^{n-1}-n\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(\left(2^{n}-1\right)+\left(2^{n}-2\right)+\cdots+\left(2^{n}-2^{n-1}\right)-n\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{n}-2}\left(n \cdot 2^{n}-\left(2^{n}-1\right)-n\right) \\

& \quad=(n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Similarly, the expected value of $x_{-1, r}$ is also $(n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}$. By symmetry, the expected value of both $x_{1, l}$ and $x_{-1, l}$ is $n+1-(n-1) \frac{\frac{2}{n}^{n}-1}{2^{n}-2}$. This says that if the points are not all collinear then the expected area is $2 \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right)$. So, the expected area is

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{2}{2^{n}} \cdot 0+(1- & \left.\frac{2}{2^{n}}\right) \cdot 2 \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right) \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{2^{n-1}-1}{2^{n-1}} \cdot\left((n-1) \frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{n-1}-1}-(n+1)\right) \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{(n-1)\left(2^{n}-1\right)-(n+1)\left(2^{n-1}-1\right)}{2^{n-1}} \\

& =2 \cdot \frac{((2 n-2)-(n+1)) 2^{n-1}+2}{2^{n-1}} \\

& =2 n-6+\frac{1}{2^{n-3}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Plugging in $n=10$, we get $14+\frac{1}{128}=\frac{1793}{128}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

How many functions $f$ from $\{-1005, \ldots, 1005\}$ to $\{-2010, \ldots, 2010\}$ are there such that the following two conditions are satisfied?

- If $a<b$ then $f(a)<f(b)$.

- There is no $n$ in $\{-1005, \ldots, 1005\}$ such that $|f(n)|=|n|$.

|

$\cdots$ Note: the intended answer was $\binom{4019}{2011}$, but the original answer was incorrect. The correct answer is:

1173346782666677300072441773814388000553179587006710786401225043842699552460942166630860 5302966355504513409792805200762540756742811158611534813828022157596601875355477425764387 2333935841666957750009216404095352456877594554817419353494267665830087436353494075828446 0070506487793628698617665091500712606599653369601270652785265395252421526230453391663029 1476263072382369363170971857101590310272130771639046414860423440232291348986940615141526 0247281998288175423628757177754777309519630334406956881890655029018130367627043067425502 2334151384481231298380228052789795136259575164777156839054346649261636296328387580363485 2904329986459861362633348204891967272842242778625137520975558407856496002297523759366027

1506637984075036473724713869804364399766664507880042495122618597629613572449327653716600 6715747717529280910646607622693561789482959920478796128008380531607300324374576791477561 5881495035032334387221203759898494171708240222856256961757026746724252966598328065735933 6668742613422094179386207330487537984173936781232801614775355365060827617078032786368164 8860839124954588222610166915992867657815394480973063139752195206598739798365623873142903 28539769699667459275254643229234106717245366005816917271187760792

This obviously cannot be computed by hand, but there is a polynomial-time dynamic programming algorithm that will compute it.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

How many functions $f$ from $\{-1005, \ldots, 1005\}$ to $\{-2010, \ldots, 2010\}$ are there such that the following two conditions are satisfied?

- If $a<b$ then $f(a)<f(b)$.

- There is no $n$ in $\{-1005, \ldots, 1005\}$ such that $|f(n)|=|n|$.

|

$\cdots$ Note: the intended answer was $\binom{4019}{2011}$, but the original answer was incorrect. The correct answer is:

1173346782666677300072441773814388000553179587006710786401225043842699552460942166630860 5302966355504513409792805200762540756742811158611534813828022157596601875355477425764387 2333935841666957750009216404095352456877594554817419353494267665830087436353494075828446 0070506487793628698617665091500712606599653369601270652785265395252421526230453391663029 1476263072382369363170971857101590310272130771639046414860423440232291348986940615141526 0247281998288175423628757177754777309519630334406956881890655029018130367627043067425502 2334151384481231298380228052789795136259575164777156839054346649261636296328387580363485 2904329986459861362633348204891967272842242778625137520975558407856496002297523759366027

1506637984075036473724713869804364399766664507880042495122618597629613572449327653716600 6715747717529280910646607622693561789482959920478796128008380531607300324374576791477561 5881495035032334387221203759898494171708240222856256961757026746724252966598328065735933 6668742613422094179386207330487537984173936781232801614775355365060827617078032786368164 8860839124954588222610166915992867657815394480973063139752195206598739798365623873142903 28539769699667459275254643229234106717245366005816917271187760792

This obviously cannot be computed by hand, but there is a polynomial-time dynamic programming algorithm that will compute it.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are playing a game where they repeatedly flip coins. Rosencrantz wins if 1 heads followed by 2009 tails appears. Guildenstern wins if 2010 heads come in a row. They will flip coins until someone wins. What is the probability that Rosencrantz wins?

|

$\frac{2^{2009}-1}{3 \cdot 2^{2008}-1}$ We can assume the first throw is heads (because neither player can win starting from a string of only tails). Let $x$ be the probability that Rosencrantz wins. Let $y$ be the probability that Rosencrantz wins after HT.

Whenever there is a string of less than 2009 tails followed by a heads, the heads basically means the two are starting from the beginning, where Rosencrantz has probability $x$ of winning.

We also know that $x=y\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right)$. This is because from the initial heads there is a $\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right)$ chance Rosencrantz doesn't lose, and in this case the last two flips are HT, in which case Rosencrantz has probability $y$ of winning.

If the first two throws are HT, there is a $\frac{1}{2^{2008}}$ chance Rosencrantz wins; otherwise, there is eventually a heads, and so we are back in the case of starting from a heads, which corresponds to $x$. Therefore, $y=\frac{1}{2^{2008}}+x\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2008}}\right)$. Putting this together with the previous equation, we get:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x & =\left(\frac{1}{2^{2008}}+x\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2008}}\right)\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right) \\

\Longrightarrow \quad x & =\left(\frac{1+2^{2008} x-x}{2^{2008}}\right)\left(\frac{2^{2009}-1}{\left.2^{2009}\right)}\right. \\

\Longrightarrow \quad 2^{4017} x & =x\left(2^{4017}-2^{2009}-2^{2008}+1\right)+2^{2009}-1 \\

\Longrightarrow \quad x & =\frac{2^{2009}-1}{2^{2009}+2^{2008}-1},

\end{aligned}

$$

so the answer is $\frac{2^{2009}-1}{2^{2009}+2^{2008}-1}=\frac{2^{2009}-1}{3 \cdot 2^{2008}-1}$.

|

\frac{2^{2009}-1}{3 \cdot 2^{2008}-1}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are playing a game where they repeatedly flip coins. Rosencrantz wins if 1 heads followed by 2009 tails appears. Guildenstern wins if 2010 heads come in a row. They will flip coins until someone wins. What is the probability that Rosencrantz wins?

|

$\frac{2^{2009}-1}{3 \cdot 2^{2008}-1}$ We can assume the first throw is heads (because neither player can win starting from a string of only tails). Let $x$ be the probability that Rosencrantz wins. Let $y$ be the probability that Rosencrantz wins after HT.

Whenever there is a string of less than 2009 tails followed by a heads, the heads basically means the two are starting from the beginning, where Rosencrantz has probability $x$ of winning.

We also know that $x=y\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right)$. This is because from the initial heads there is a $\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right)$ chance Rosencrantz doesn't lose, and in this case the last two flips are HT, in which case Rosencrantz has probability $y$ of winning.

If the first two throws are HT, there is a $\frac{1}{2^{2008}}$ chance Rosencrantz wins; otherwise, there is eventually a heads, and so we are back in the case of starting from a heads, which corresponds to $x$. Therefore, $y=\frac{1}{2^{2008}}+x\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2008}}\right)$. Putting this together with the previous equation, we get:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x & =\left(\frac{1}{2^{2008}}+x\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2008}}\right)\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{2009}}\right) \\

\Longrightarrow \quad x & =\left(\frac{1+2^{2008} x-x}{2^{2008}}\right)\left(\frac{2^{2009}-1}{\left.2^{2009}\right)}\right. \\

\Longrightarrow \quad 2^{4017} x & =x\left(2^{4017}-2^{2009}-2^{2008}+1\right)+2^{2009}-1 \\

\Longrightarrow \quad x & =\frac{2^{2009}-1}{2^{2009}+2^{2008}-1},

\end{aligned}

$$

so the answer is $\frac{2^{2009}-1}{2^{2009}+2^{2008}-1}=\frac{2^{2009}-1}{3 \cdot 2^{2008}-1}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

In a $16 \times 16$ table of integers, each row and column contains at most 4 distinct integers. What is the maximum number of distinct integers that there can be in the whole table?

|

49 First, we show that 50 is too big. Assume for sake of contradiction that a labeling with at least 50 distinct integers exists. By the Pigeonhole Principle, there must be at least one row, say the first row, with at least 4 distinct integers in it; in this case, that is exactly 4 , since that is the maximum number of distinct integers in one row. Then, in the remaining 15 rows there must be at least 46 distinct integers (these 46 will also be distinct from the 4 in the first row). Using Pigeonhole again, there will be another row, say the second row, with 4 distinct integers in it. Call the set of integers in the first and second rows $S$. Because the 4 distinct integers in the second row are distinct from the 4 in the first row, there are 8 distinct values in the first two rows, so $|S|=8$. Now consider the subcolumns containing the cells in rows 3 to 16 . In each subcolumn, there are at most 2 values not in $S$, because there are already two distinct values in that column from the cells in the first two rows. So, the maximum number of distinct values in the table is $16 \cdot 2+8=40$, a contradiction. So a valid labeling must have fewer than 50 distinct integers. Below, we show by example that 49 is attainable.

| 1 | 17 | 33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| - | 2 | 18 | 34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | 3 | 19 | 35 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 4 | 20 | 36 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | 5 | 21 | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 22 | 38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 23 | 39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 24 | 40 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | 25 | 41 | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | 26 | 42 | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 27 | 43 | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | 28 | 44 | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | 29 | 45 | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | 30 | 46 |

| 47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 31 |

| 32 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 |

Cells that do not contain a number are colored with color 49 .

|

49

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In a $16 \times 16$ table of integers, each row and column contains at most 4 distinct integers. What is the maximum number of distinct integers that there can be in the whole table?

|

49 First, we show that 50 is too big. Assume for sake of contradiction that a labeling with at least 50 distinct integers exists. By the Pigeonhole Principle, there must be at least one row, say the first row, with at least 4 distinct integers in it; in this case, that is exactly 4 , since that is the maximum number of distinct integers in one row. Then, in the remaining 15 rows there must be at least 46 distinct integers (these 46 will also be distinct from the 4 in the first row). Using Pigeonhole again, there will be another row, say the second row, with 4 distinct integers in it. Call the set of integers in the first and second rows $S$. Because the 4 distinct integers in the second row are distinct from the 4 in the first row, there are 8 distinct values in the first two rows, so $|S|=8$. Now consider the subcolumns containing the cells in rows 3 to 16 . In each subcolumn, there are at most 2 values not in $S$, because there are already two distinct values in that column from the cells in the first two rows. So, the maximum number of distinct values in the table is $16 \cdot 2+8=40$, a contradiction. So a valid labeling must have fewer than 50 distinct integers. Below, we show by example that 49 is attainable.

| 1 | 17 | 33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| - | 2 | 18 | 34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | 3 | 19 | 35 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 4 | 20 | 36 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | 5 | 21 | 37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 22 | 38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 23 | 39 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 24 | 40 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | 25 | 41 | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | 26 | 42 | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 27 | 43 | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | 28 | 44 | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | 29 | 45 | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | 30 | 46 |

| 47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 31 |

| 32 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 |

Cells that do not contain a number are colored with color 49 .

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [8]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Suppose that $x$ and $y$ are positive reals such that

$$

x-y^{2}=3, \quad x^{2}+y^{4}=13

$$

Find $x$.

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{17}}{2}$ Squaring both sides of $x-y^{2}=3$ gives $x^{2}+y^{4}-2 x y^{2}=9$. Subtract this equation from twice the second given to get $x^{2}+2 x y^{2}+y^{4}=17 \Longrightarrow x+y^{2}= \pm 17$. Combining this equation with the first given, we see that $x=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{17}}{2}$. Since $x$ is a positive real, $x$ must be $\frac{3+\sqrt{17}}{2}$.

|

\frac{3+\sqrt{17}}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Suppose that $x$ and $y$ are positive reals such that

$$

x-y^{2}=3, \quad x^{2}+y^{4}=13

$$

Find $x$.

|

$\frac{3+\sqrt{17}}{2}$ Squaring both sides of $x-y^{2}=3$ gives $x^{2}+y^{4}-2 x y^{2}=9$. Subtract this equation from twice the second given to get $x^{2}+2 x y^{2}+y^{4}=17 \Longrightarrow x+y^{2}= \pm 17$. Combining this equation with the first given, we see that $x=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{17}}{2}$. Since $x$ is a positive real, $x$ must be $\frac{3+\sqrt{17}}{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $S=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}$. How many (potentially empty) subsets $T$ of $S$ are there such that, for all $x$, if $x$ is in $T$ and $2 x$ is in $S$ then $2 x$ is also in $T$ ?

|

180 We partition the elements of $S$ into the following subsets: $\{1,2,4,8\},\{3,6\},\{5,10\}$, $\{7\},\{9\}$. Consider the first subset, $\{1,2,4,8\}$. Say 2 is an element of $T$. Because $2 \cdot 2=4$ is in $S, 4$ must also be in $T$. Furthermore, since $4 \cdot 2=8$ is in $S, 8$ must also be in $T$. So if $T$ contains 2 , it must also contain 4 and 8 . Similarly, if $T$ contains 1 , it must also contain 2,4 , and 8 . So $T$ can contain the following subsets of the subset $\{1,2,4,8\}$ : the empty set, $\{8\},\{4,8\},\{2,4,8\}$, or $\{1,2,4,8\}$. This gives 5 possibilities for the first subset. In general, we see that if $T$ contains an element $q$ of one of these subsets, it must also contain the elements in that subset that are larger than $q$, because we created the subsets for this to be true. So there are 3 possibilities for $\{3,6\}, 3$ for $\{5,10\}, 2$ for $\{7\}$, and 2 for $\{9\}$. This gives a total of $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 2=180$ possible subsets $T$.

|

180

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $S=\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10\}$. How many (potentially empty) subsets $T$ of $S$ are there such that, for all $x$, if $x$ is in $T$ and $2 x$ is in $S$ then $2 x$ is also in $T$ ?

|

180 We partition the elements of $S$ into the following subsets: $\{1,2,4,8\},\{3,6\},\{5,10\}$, $\{7\},\{9\}$. Consider the first subset, $\{1,2,4,8\}$. Say 2 is an element of $T$. Because $2 \cdot 2=4$ is in $S, 4$ must also be in $T$. Furthermore, since $4 \cdot 2=8$ is in $S, 8$ must also be in $T$. So if $T$ contains 2 , it must also contain 4 and 8 . Similarly, if $T$ contains 1 , it must also contain 2,4 , and 8 . So $T$ can contain the following subsets of the subset $\{1,2,4,8\}$ : the empty set, $\{8\},\{4,8\},\{2,4,8\}$, or $\{1,2,4,8\}$. This gives 5 possibilities for the first subset. In general, we see that if $T$ contains an element $q$ of one of these subsets, it must also contain the elements in that subset that are larger than $q$, because we created the subsets for this to be true. So there are 3 possibilities for $\{3,6\}, 3$ for $\{5,10\}, 2$ for $\{7\}$, and 2 for $\{9\}$. This gives a total of $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 2=180$ possible subsets $T$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

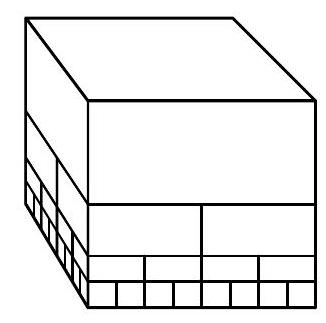

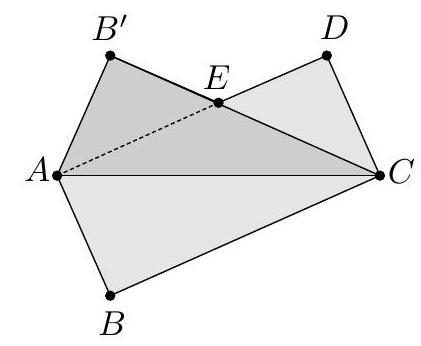

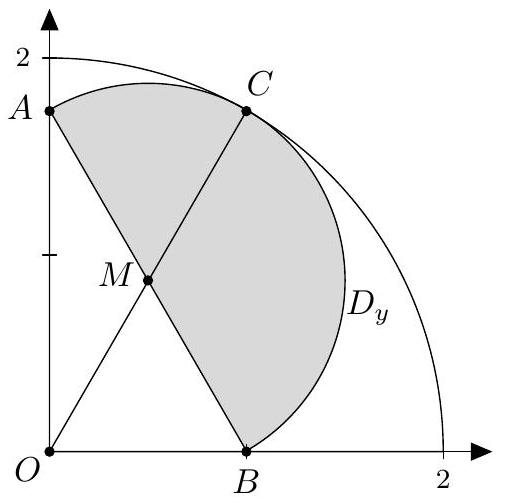

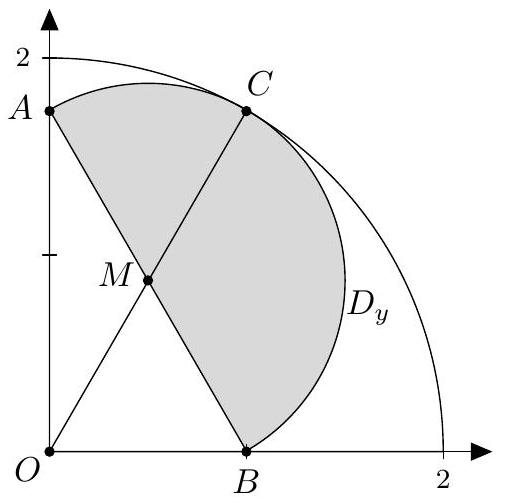

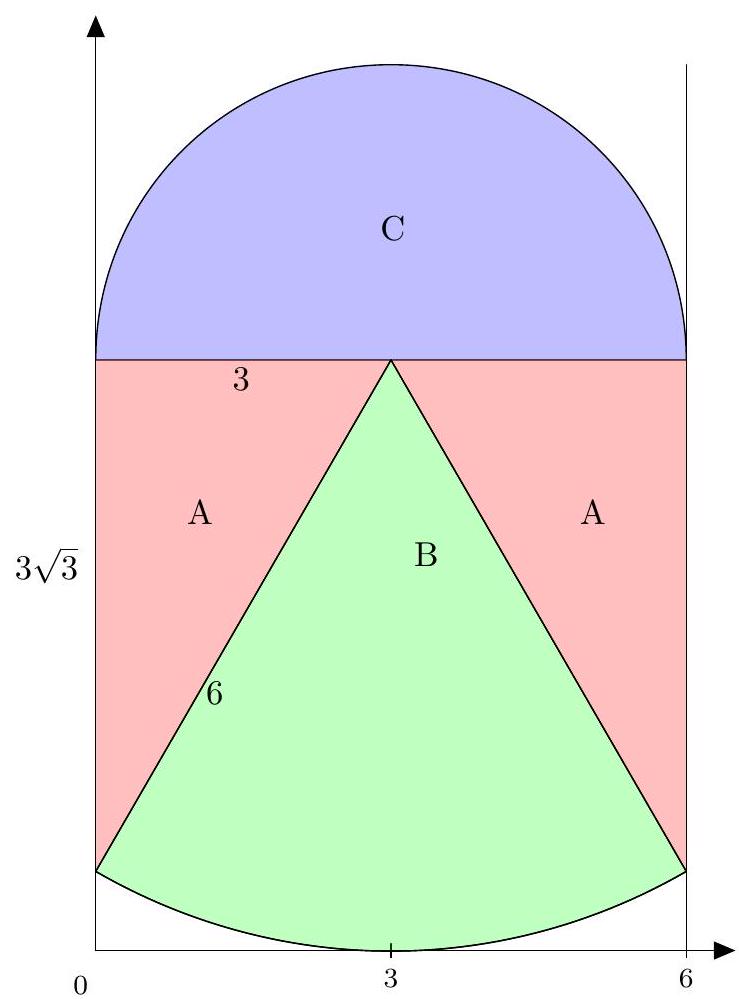

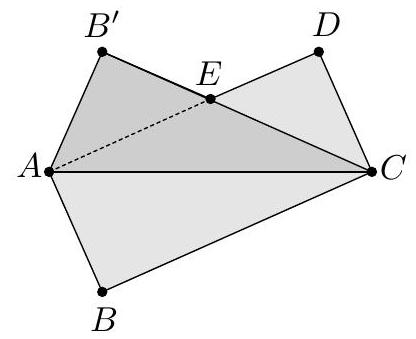

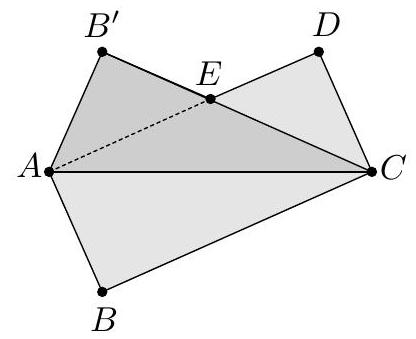

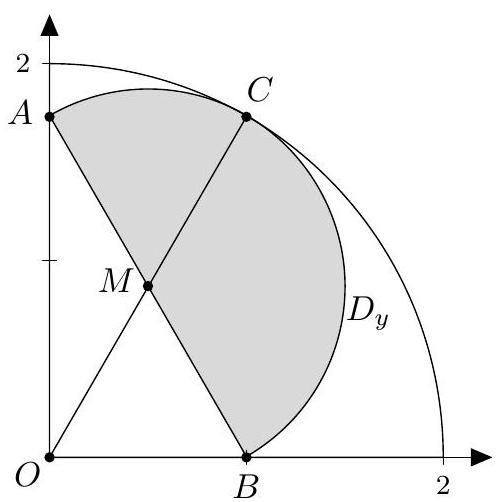

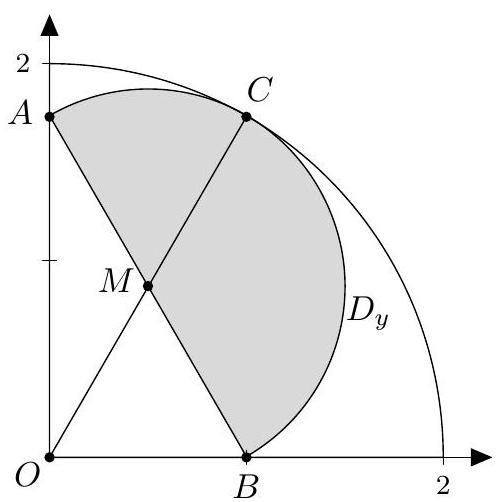

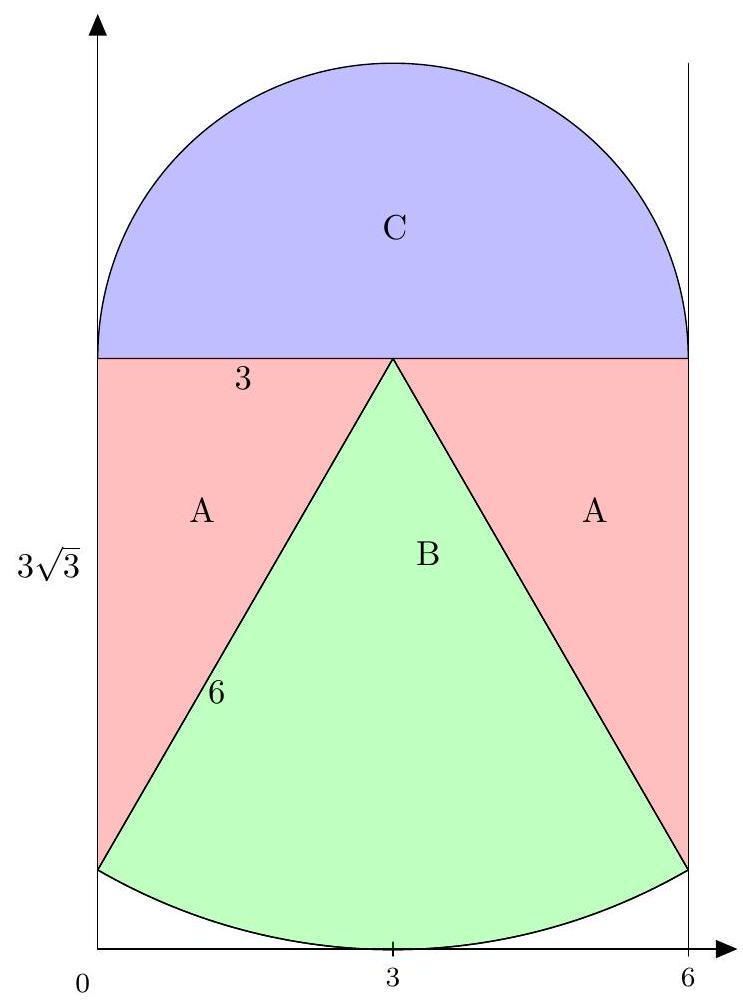

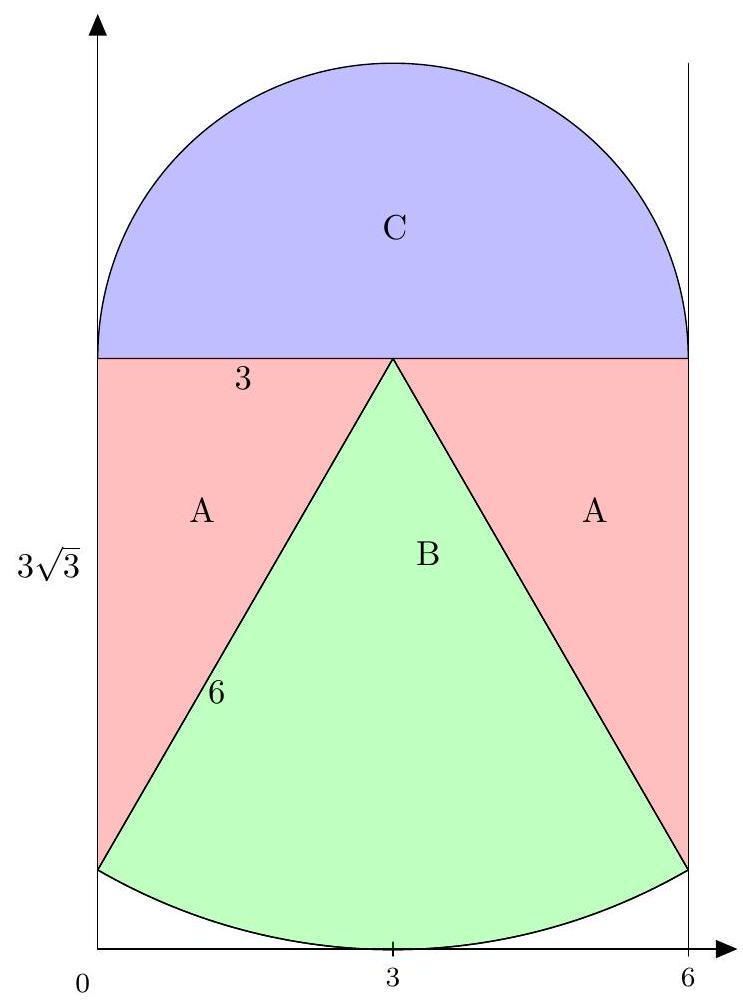

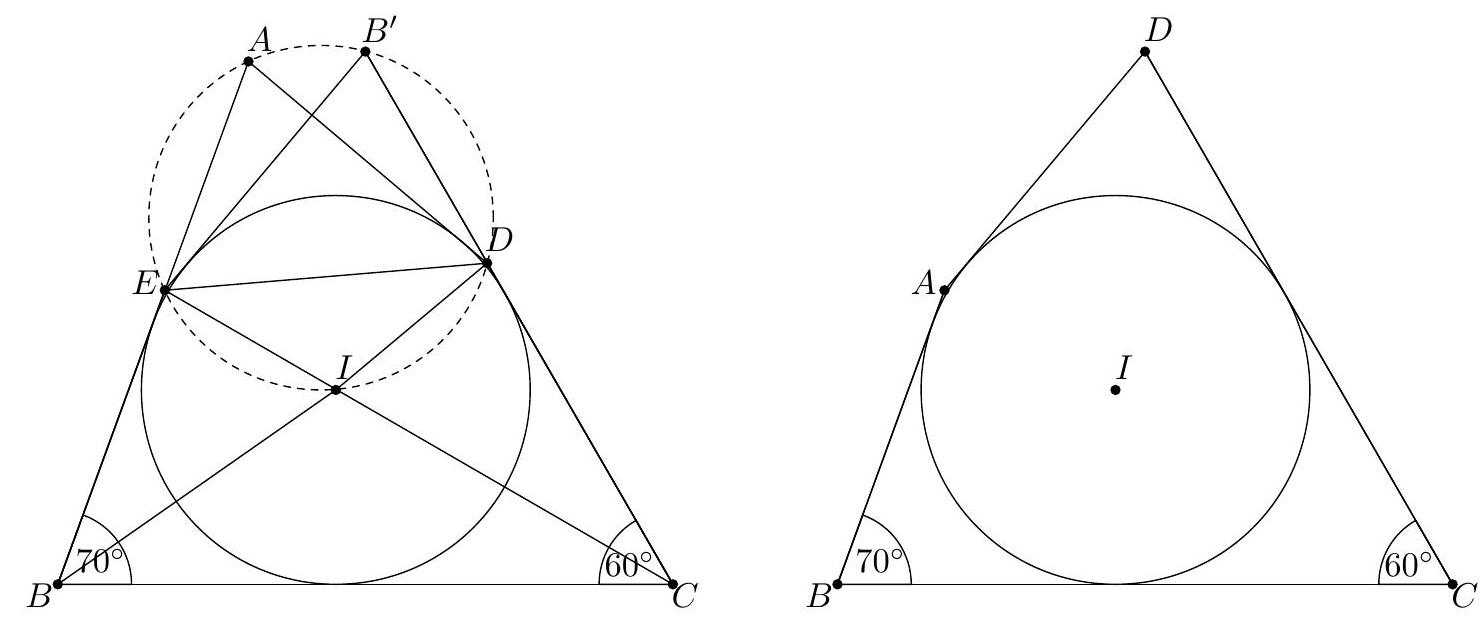

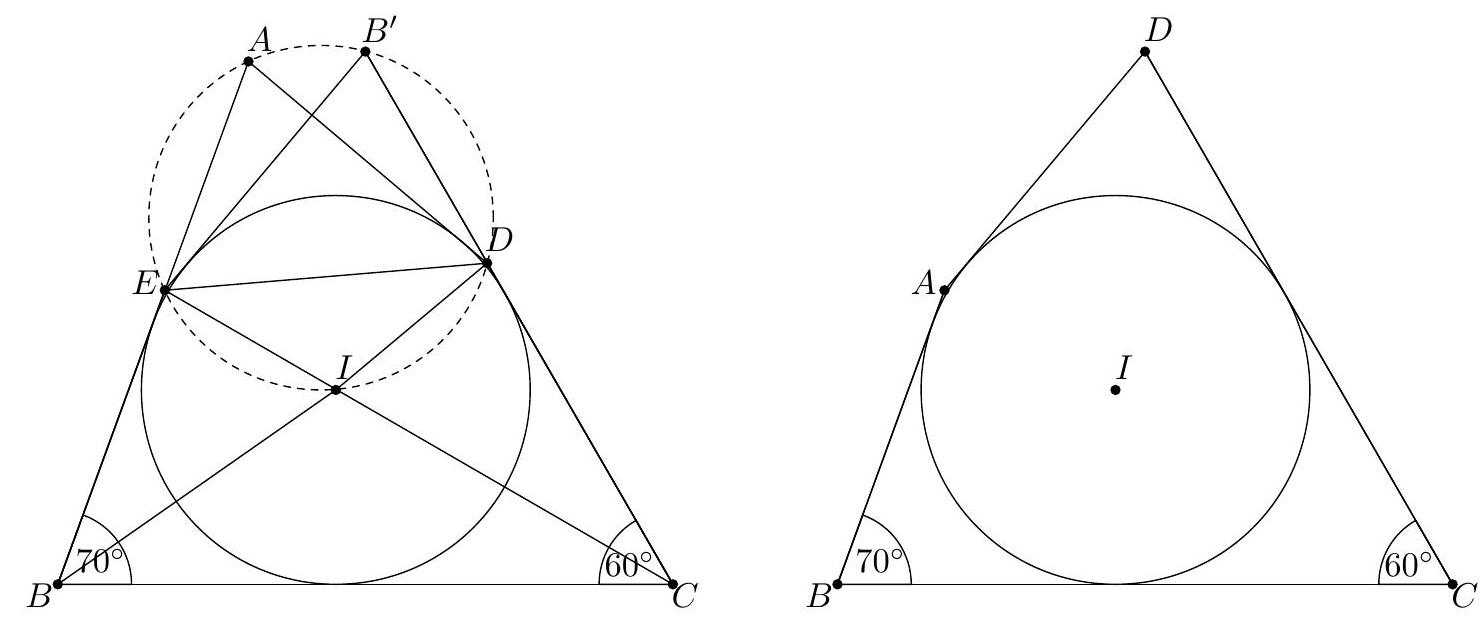

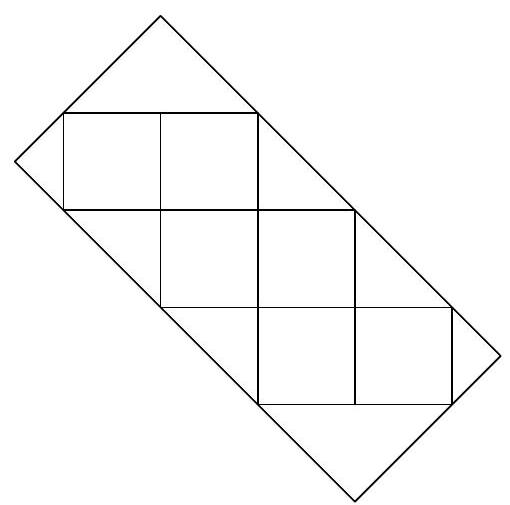

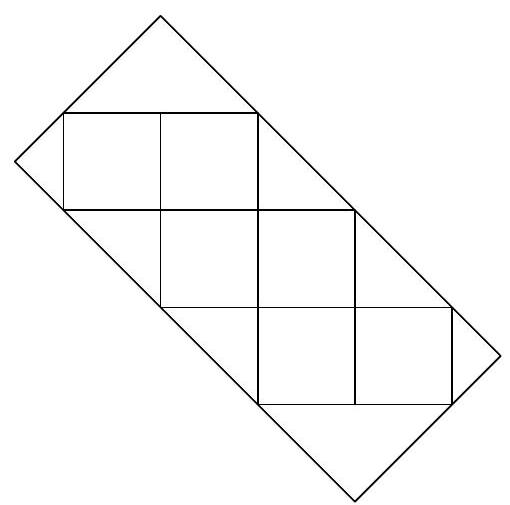

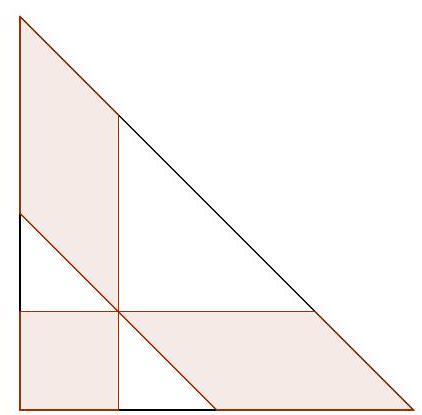

A rectangular piece of paper is folded along its diagonal (as depicted below) to form a non-convex pentagon that has an area of $\frac{7}{10}$ of the area of the original rectangle. Find the ratio of the longer side of the rectangle to the shorter side of the rectangle.

|

$\sqrt{5}$

Given a polygon $P_{1} P_{2} \cdots P_{k}$, let $\left[P_{1} P_{2} \cdots P_{k}\right]$ denote its area. Let $A B C D$ be the rectangle. Suppose we fold $B$ across $\overline{A C}$, and let $E$ be the intersection of $\overline{A D}$ and $\overline{B^{\prime} C}$. Then we end up with the pentagon $A C D E B^{\prime}$, depicted above. Let's suppose, without loss of generality, that $A B C D$ has area 1. Then $\triangle A E C$ must have area $\frac{3}{10}$, since

$$

\begin{aligned}

{[A B C D] } & =[A B C]+[A C D] \\

& =\left[A B^{\prime} C\right]+[A C D] \\

& =\left[A B^{\prime} E\right]+2[A E C]+[E D C] \\

& =\left[A C D E B^{\prime}\right]+[A E C] \\

& =\frac{7}{10}[A B C D]+[A E C],

\end{aligned}

$$

That is, $[A E C]=\frac{3}{10}[A B C D]=\frac{3}{10}$.

Since $\triangle E C D$ is congruent to $\triangle E A B^{\prime}$, both triangles have area $\frac{1}{5}$. Note that $\triangle A B^{\prime} C, \triangle A B C$, and $\triangle C D A$ are all congruent, and all have area $\frac{1}{2}$. Since $\triangle A E C$ and $\triangle E D C$ share altitude $\overline{D C}$, $\frac{D E}{E A}=\frac{[D E C]}{[A E C]}=\frac{2}{3}$. Because $\triangle C A E$ is isosceles, $C E=E A$. Let $A E=3 x$. The $C E=3 x, D E=2 x$, and $C D=x \sqrt{9-4}=x \sqrt{5}$. Then $\frac{A D}{D C}=\frac{A E+E D}{D C}=\frac{3+2}{\sqrt{5}}=\sqrt{5}$.

|

\sqrt{5}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A rectangular piece of paper is folded along its diagonal (as depicted below) to form a non-convex pentagon that has an area of $\frac{7}{10}$ of the area of the original rectangle. Find the ratio of the longer side of the rectangle to the shorter side of the rectangle.

|

$\sqrt{5}$

Given a polygon $P_{1} P_{2} \cdots P_{k}$, let $\left[P_{1} P_{2} \cdots P_{k}\right]$ denote its area. Let $A B C D$ be the rectangle. Suppose we fold $B$ across $\overline{A C}$, and let $E$ be the intersection of $\overline{A D}$ and $\overline{B^{\prime} C}$. Then we end up with the pentagon $A C D E B^{\prime}$, depicted above. Let's suppose, without loss of generality, that $A B C D$ has area 1. Then $\triangle A E C$ must have area $\frac{3}{10}$, since

$$

\begin{aligned}

{[A B C D] } & =[A B C]+[A C D] \\

& =\left[A B^{\prime} C\right]+[A C D] \\

& =\left[A B^{\prime} E\right]+2[A E C]+[E D C] \\

& =\left[A C D E B^{\prime}\right]+[A E C] \\

& =\frac{7}{10}[A B C D]+[A E C],

\end{aligned}

$$

That is, $[A E C]=\frac{3}{10}[A B C D]=\frac{3}{10}$.

Since $\triangle E C D$ is congruent to $\triangle E A B^{\prime}$, both triangles have area $\frac{1}{5}$. Note that $\triangle A B^{\prime} C, \triangle A B C$, and $\triangle C D A$ are all congruent, and all have area $\frac{1}{2}$. Since $\triangle A E C$ and $\triangle E D C$ share altitude $\overline{D C}$, $\frac{D E}{E A}=\frac{[D E C]}{[A E C]}=\frac{2}{3}$. Because $\triangle C A E$ is isosceles, $C E=E A$. Let $A E=3 x$. The $C E=3 x, D E=2 x$, and $C D=x \sqrt{9-4}=x \sqrt{5}$. Then $\frac{A D}{D C}=\frac{A E+E D}{D C}=\frac{3+2}{\sqrt{5}}=\sqrt{5}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $S_{0}=0$ and let $S_{k}$ equal $a_{1}+2 a_{2}+\ldots+k a_{k}$ for $k \geq 1$. Define $a_{i}$ to be 1 if $S_{i-1}<i$ and -1 if $S_{i-1} \geq i$. What is the largest $k \leq 2010$ such that $S_{k}=0$ ?

|

1092 Suppose that $S_{N}=0$ for some $N \geq 0$. Then $a_{N+1}=1$ because $N+1 \geq S_{N}$. The following table lists the values of $a_{k}$ and $S_{k}$ for a few $k \geq N$ :

| $k$ | $a_{k}$ | $S_{k}$ |

| :--- | ---: | :--- |

| $N$ | | 0 |

| $N+1$ | 1 | $N+1$ |

| $N+2$ | 1 | $2 N+3$ |

| $N+3$ | -1 | $N$ |

| $N+4$ | 1 | $2 N+4$ |

| $N+5$ | -1 | $N-1$ |

| $N+6$ | 1 | $2 N+5$ |

| $N+7$ | -1 | $N-2$ |

We see inductively that, for every $i \geq 1$,

$$

S_{N+2 i}=2 N+2+i

$$

and

$$

S_{N+1+2 i}=N+1-i

$$

thus $S_{3 N+3}=0$ is the next $k$ for which $S_{k}=0$. The values of $k$ for which $S_{k}=0$ satisfy the recurrence relation $p_{n+1}=3 p_{n}+3$, and we compute that the first terms of the sequence are $0,3,12,39,120,363,1092$; hence 1092 is our answer.

|

1092

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $S_{0}=0$ and let $S_{k}$ equal $a_{1}+2 a_{2}+\ldots+k a_{k}$ for $k \geq 1$. Define $a_{i}$ to be 1 if $S_{i-1}<i$ and -1 if $S_{i-1} \geq i$. What is the largest $k \leq 2010$ such that $S_{k}=0$ ?

|

1092 Suppose that $S_{N}=0$ for some $N \geq 0$. Then $a_{N+1}=1$ because $N+1 \geq S_{N}$. The following table lists the values of $a_{k}$ and $S_{k}$ for a few $k \geq N$ :

| $k$ | $a_{k}$ | $S_{k}$ |

| :--- | ---: | :--- |

| $N$ | | 0 |

| $N+1$ | 1 | $N+1$ |

| $N+2$ | 1 | $2 N+3$ |

| $N+3$ | -1 | $N$ |

| $N+4$ | 1 | $2 N+4$ |

| $N+5$ | -1 | $N-1$ |

| $N+6$ | 1 | $2 N+5$ |

| $N+7$ | -1 | $N-2$ |

We see inductively that, for every $i \geq 1$,

$$

S_{N+2 i}=2 N+2+i

$$

and

$$

S_{N+1+2 i}=N+1-i

$$

thus $S_{3 N+3}=0$ is the next $k$ for which $S_{k}=0$. The values of $k$ for which $S_{k}=0$ satisfy the recurrence relation $p_{n+1}=3 p_{n}+3$, and we compute that the first terms of the sequence are $0,3,12,39,120,363,1092$; hence 1092 is our answer.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Manya has a stack of $85=1+4+16+64$ blocks comprised of 4 layers (the $k$ th layer from the top has $4^{k-1}$ blocks; see the diagram below). Each block rests on 4 smaller blocks, each with dimensions half those of the larger block. Laura removes blocks one at a time from this stack, removing only blocks that currently have no blocks on top of them. Find the number of ways Laura can remove precisely 5 blocks from Manya's stack (the order in which they are removed matters).

|

3384 Each time Laura removes a block, 4 additional blocks are exposed, increasing the total number of exposed blocks by 3 . She removes 5 blocks, for a total of $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13$ ways. However, the stack originally only has 4 layers, so we must subtract the cases where removing a block on the bottom layer does not expose any new blocks. There are $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=256$ of these (the last factor of 4 is from the 4 blocks that we counted as being exposed, but were not actually). So our final answer is $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13-1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=3384$.

|

3384

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Manya has a stack of $85=1+4+16+64$ blocks comprised of 4 layers (the $k$ th layer from the top has $4^{k-1}$ blocks; see the diagram below). Each block rests on 4 smaller blocks, each with dimensions half those of the larger block. Laura removes blocks one at a time from this stack, removing only blocks that currently have no blocks on top of them. Find the number of ways Laura can remove precisely 5 blocks from Manya's stack (the order in which they are removed matters).

|

3384 Each time Laura removes a block, 4 additional blocks are exposed, increasing the total number of exposed blocks by 3 . She removes 5 blocks, for a total of $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13$ ways. However, the stack originally only has 4 layers, so we must subtract the cases where removing a block on the bottom layer does not expose any new blocks. There are $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=256$ of these (the last factor of 4 is from the 4 blocks that we counted as being exposed, but were not actually). So our final answer is $1 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 10 \cdot 13-1 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4 \cdot 4=3384$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

John needs to pay 2010 dollars for his dinner. He has an unlimited supply of 2, 5, and 10 dollar notes. In how many ways can he pay?

|

20503

Let the number of 2,5 , and 10 dollar notes John can use be $x, y$, and $z$ respectively. We wish to find the number of nonnegative integer solutions to $2 x+5 y+10 z=2010$. Consider this equation $\bmod 2$. Because $2 x, 10 z$, and 2010 are even, $5 y$ must also be even, so $y$ must be even. Now consider the equation $\bmod 5$. Because $5 y, 10 z$, and 2010 are divisible by $5,2 x$ must also be divisible by 5 , so $x$ must be divisible by 5 . So both $2 x$ and $5 y$ are divisible by 10 . So the equation is equivalent to $10 x^{\prime}+10 y^{\prime}+10 z=2010$, or $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$, with $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ nonnegative integers. There is a well-known bijection between solutions of this equation and picking 2 of 203 balls in a row on the table (explained in further detail below), so there are $\binom{203}{2}=20503$ ways.

The bijection between solutions of $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$ and arrangements of 203 balls in a row is as follows. Given a solution of the equation, we put $x^{\prime}$ white balls in a row, then a black ball, then $y^{\prime}$ white balls, then a black ball, then $z$ white balls. This is like having 203 balls in a row on a table and picking two of them to be black. To go from an arrangement of balls to a solution of the equation, we just read off $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ from the number of white balls in a row. There are $\binom{203}{2}$ ways to choose 2 of 203 balls to be black, so there are $\binom{203}{2}$ solutions to $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$.

|

20503

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

John needs to pay 2010 dollars for his dinner. He has an unlimited supply of 2, 5, and 10 dollar notes. In how many ways can he pay?

|

20503

Let the number of 2,5 , and 10 dollar notes John can use be $x, y$, and $z$ respectively. We wish to find the number of nonnegative integer solutions to $2 x+5 y+10 z=2010$. Consider this equation $\bmod 2$. Because $2 x, 10 z$, and 2010 are even, $5 y$ must also be even, so $y$ must be even. Now consider the equation $\bmod 5$. Because $5 y, 10 z$, and 2010 are divisible by $5,2 x$ must also be divisible by 5 , so $x$ must be divisible by 5 . So both $2 x$ and $5 y$ are divisible by 10 . So the equation is equivalent to $10 x^{\prime}+10 y^{\prime}+10 z=2010$, or $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$, with $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ nonnegative integers. There is a well-known bijection between solutions of this equation and picking 2 of 203 balls in a row on the table (explained in further detail below), so there are $\binom{203}{2}=20503$ ways.

The bijection between solutions of $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$ and arrangements of 203 balls in a row is as follows. Given a solution of the equation, we put $x^{\prime}$ white balls in a row, then a black ball, then $y^{\prime}$ white balls, then a black ball, then $z$ white balls. This is like having 203 balls in a row on a table and picking two of them to be black. To go from an arrangement of balls to a solution of the equation, we just read off $x^{\prime}, y^{\prime}$, and $z$ from the number of white balls in a row. There are $\binom{203}{2}$ ways to choose 2 of 203 balls to be black, so there are $\binom{203}{2}$ solutions to $x^{\prime}+y^{\prime}+z=201$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Answer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Suppose that a polynomial of the form $p(x)=x^{2010} \pm x^{2009} \pm \cdots \pm x \pm 1$ has no real roots. What is the maximum possible number of coefficients of -1 in $p$ ?

|

1005 Let $p(x)$ be a polynomial with the maximum number of minus signs.

$p(x)$ cannot have more than 1005 minus signs, otherwise $p(1)<0$ and $p(2) \geq 2^{2010}-2^{2009}-\ldots-2-1=$ 1 , which implies, by the Intermediate Value Theorem, that $p$ must have a root greater than 1.

Let $p(x)=\frac{x^{2011}+1}{x+1}=x^{2010}-x^{2009}+x^{2008}-\ldots-x+1 .-1$ is the only real root of $x^{2011}+1=0$ but $p(-1)=2011$; therefore $p$ has no real roots. Since $p$ has 1005 minus signs, it is the desired polynomial.

|

1005

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Suppose that a polynomial of the form $p(x)=x^{2010} \pm x^{2009} \pm \cdots \pm x \pm 1$ has no real roots. What is the maximum possible number of coefficients of -1 in $p$ ?

|

1005 Let $p(x)$ be a polynomial with the maximum number of minus signs.

$p(x)$ cannot have more than 1005 minus signs, otherwise $p(1)<0$ and $p(2) \geq 2^{2010}-2^{2009}-\ldots-2-1=$ 1 , which implies, by the Intermediate Value Theorem, that $p$ must have a root greater than 1.

Let $p(x)=\frac{x^{2011}+1}{x+1}=x^{2010}-x^{2009}+x^{2008}-\ldots-x+1 .-1$ is the only real root of $x^{2011}+1=0$ but $p(-1)=2011$; therefore $p$ has no real roots. Since $p$ has 1005 minus signs, it is the desired polynomial.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

A sphere is the set of points at a fixed positive distance $r$ from its center. Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a set of 2010dimensional spheres. Suppose that the number of points lying on every element of $\mathcal{S}$ is a finite number $n$. Find the maximum possible value of $n$.

|

2 The answer is 2 for any number of dimensions. We prove this by induction on the dimension.

Note that 1-dimensional spheres are pairs of points, and 2-dimensional spheres are circles.

Base case, $d=2$ : The intersection of two circles is either a circle (if the original circles are identical, and in the same place), a pair of points, a single point (if the circles are tangent), or the empty set. Thus, in dimension 2 , the largest finite number of intersection points is 2 , because the number of pairwise intersection points is 0,1 , or 2 for distinct circles.

We now prove that the intersection of two $k$-dimensional spheres is either the empty set, a $(k-1)$ dimensional sphere, a $k$-dimensional sphere (which only occurs if the original spheres are identical and coincident). Consider two spheres in $k$-dimensional space, and impose a coordinate system such that the centers of the two spheres lie on one coordinate axis. Then the equations for the two spheres become identical in all but one coordinate:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left(x_{1}-a_{1}\right)^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+\ldots+x_{k}^{2}=r_{1}^{2} \\

& \left(x_{1}-a_{2}\right)^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+\ldots+x_{k}^{2}=r_{2}^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

If $a_{1}=a_{2}$, the spheres are concentric, and so they are either nonintersecting or coincident, intersecting in a $k$-dimensional sphere. If $a_{1} \neq a_{2}$, then subtracting the equations and solving for $x_{1}$ yields $x_{1}=\frac{r_{1}^{2}-a_{1}^{2}-r_{2}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}}{2\left(a_{2}-a_{2}\right)}$. Plugging this in to either equation above yields a single equation equation that describes a $(k-1)$-dimensional sphere.

Assume we are in dimension $d$, and suppose for induction that for all $k$ less than $d$, any two distinct $k$-dimensional spheres intersecting in a finite number of points intersect in at most two points. Suppose we have a collection of $d$-dimensional spheres $s_{1}, s_{2}, \ldots, s_{m}$. Without loss of generality, suppose the $s_{i}$ are distinct. Let $t_{i}$ be the intersection of $s_{i}$ and $s_{i+1}$ for $1 \leq i<m$. If any $t_{i}$ are the empty set, then the intersection of the $t_{i}$ is empty. None of the $t_{i}$ is a $d$-dimensional sphere because the $s_{i}$ are distinct. Thus each of $t_{1}, t_{2}, \ldots, t_{m-1}$ is a $(d-1)$-dimensional sphere, and the intersection of all of them is the same as the intersection of the $d$-dimensional spheres. We can then apply the inductive hypothesis to find that $t_{1}, \ldots, t_{m-1}$ intersect in at most two points. Thus, by induction, a set of spheres in any dimension which intersect at only finitely many points intersect at at most two points.

We now exhibit a set of $2^{2009}$ 2010-dimensional spheres, and prove that their intersection contains exactly two points. Take the spheres with radii $\sqrt{2013}$ and centers $(0, \pm 1, \pm 1, \ldots, \pm 1)$, where the sign of each coordinate is independent from the sign of every other coordinate. Because of our choice of radius, all these spheres pass through the points $( \pm 2,0,0, \ldots 0)$. Then the intersection is the set of points $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{2010}\right)$ which satisfy the equations $x_{1}^{2}+\left(x_{2} \pm 1\right)^{2}+\cdots+\left(x_{2010} \pm 1\right)^{2}=2013$. The only solutions to these equations are the points $( \pm 2,0,0, \ldots, 0)$ (since $\left(x_{i}+1\right)^{2}$ must be the same as $\left(x_{i}-1\right)^{2}$ for all $i>1$, because we may hold all but one of the $\pm$ choices constant, and change the remaining one).

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A sphere is the set of points at a fixed positive distance $r$ from its center. Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a set of 2010dimensional spheres. Suppose that the number of points lying on every element of $\mathcal{S}$ is a finite number $n$. Find the maximum possible value of $n$.

|

2 The answer is 2 for any number of dimensions. We prove this by induction on the dimension.

Note that 1-dimensional spheres are pairs of points, and 2-dimensional spheres are circles.

Base case, $d=2$ : The intersection of two circles is either a circle (if the original circles are identical, and in the same place), a pair of points, a single point (if the circles are tangent), or the empty set. Thus, in dimension 2 , the largest finite number of intersection points is 2 , because the number of pairwise intersection points is 0,1 , or 2 for distinct circles.

We now prove that the intersection of two $k$-dimensional spheres is either the empty set, a $(k-1)$ dimensional sphere, a $k$-dimensional sphere (which only occurs if the original spheres are identical and coincident). Consider two spheres in $k$-dimensional space, and impose a coordinate system such that the centers of the two spheres lie on one coordinate axis. Then the equations for the two spheres become identical in all but one coordinate:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left(x_{1}-a_{1}\right)^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+\ldots+x_{k}^{2}=r_{1}^{2} \\

& \left(x_{1}-a_{2}\right)^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+\ldots+x_{k}^{2}=r_{2}^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

If $a_{1}=a_{2}$, the spheres are concentric, and so they are either nonintersecting or coincident, intersecting in a $k$-dimensional sphere. If $a_{1} \neq a_{2}$, then subtracting the equations and solving for $x_{1}$ yields $x_{1}=\frac{r_{1}^{2}-a_{1}^{2}-r_{2}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}}{2\left(a_{2}-a_{2}\right)}$. Plugging this in to either equation above yields a single equation equation that describes a $(k-1)$-dimensional sphere.

Assume we are in dimension $d$, and suppose for induction that for all $k$ less than $d$, any two distinct $k$-dimensional spheres intersecting in a finite number of points intersect in at most two points. Suppose we have a collection of $d$-dimensional spheres $s_{1}, s_{2}, \ldots, s_{m}$. Without loss of generality, suppose the $s_{i}$ are distinct. Let $t_{i}$ be the intersection of $s_{i}$ and $s_{i+1}$ for $1 \leq i<m$. If any $t_{i}$ are the empty set, then the intersection of the $t_{i}$ is empty. None of the $t_{i}$ is a $d$-dimensional sphere because the $s_{i}$ are distinct. Thus each of $t_{1}, t_{2}, \ldots, t_{m-1}$ is a $(d-1)$-dimensional sphere, and the intersection of all of them is the same as the intersection of the $d$-dimensional spheres. We can then apply the inductive hypothesis to find that $t_{1}, \ldots, t_{m-1}$ intersect in at most two points. Thus, by induction, a set of spheres in any dimension which intersect at only finitely many points intersect at at most two points.

We now exhibit a set of $2^{2009}$ 2010-dimensional spheres, and prove that their intersection contains exactly two points. Take the spheres with radii $\sqrt{2013}$ and centers $(0, \pm 1, \pm 1, \ldots, \pm 1)$, where the sign of each coordinate is independent from the sign of every other coordinate. Because of our choice of radius, all these spheres pass through the points $( \pm 2,0,0, \ldots 0)$. Then the intersection is the set of points $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{2010}\right)$ which satisfy the equations $x_{1}^{2}+\left(x_{2} \pm 1\right)^{2}+\cdots+\left(x_{2010} \pm 1\right)^{2}=2013$. The only solutions to these equations are the points $( \pm 2,0,0, \ldots, 0)$ (since $\left(x_{i}+1\right)^{2}$ must be the same as $\left(x_{i}-1\right)^{2}$ for all $i>1$, because we may hold all but one of the $\pm$ choices constant, and change the remaining one).

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n8. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

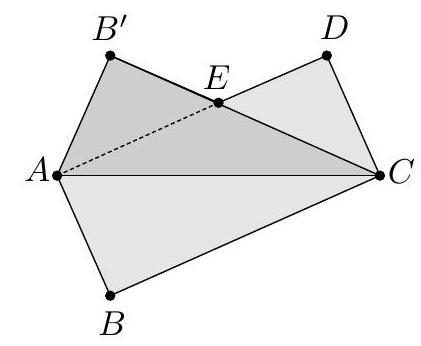

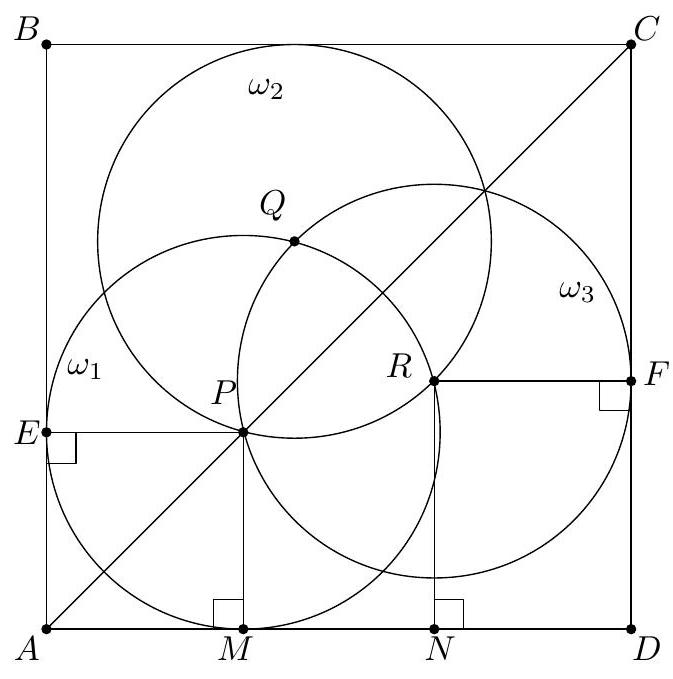

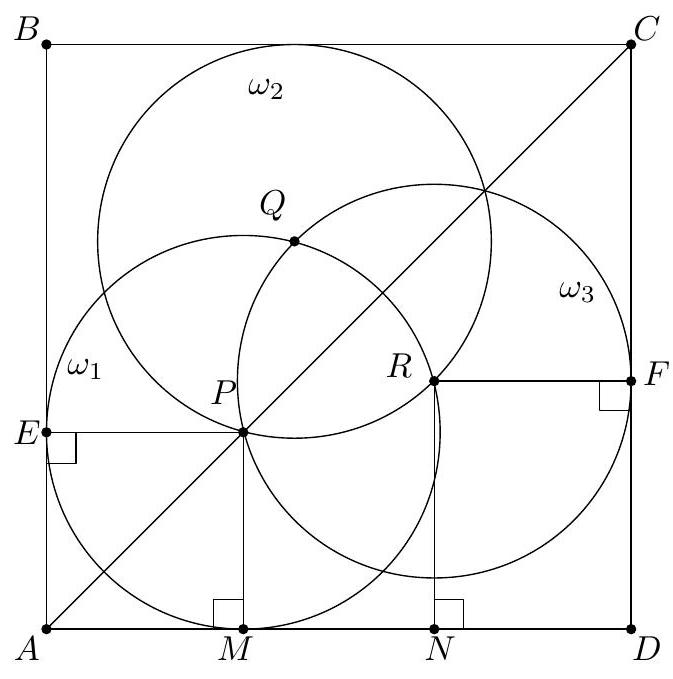

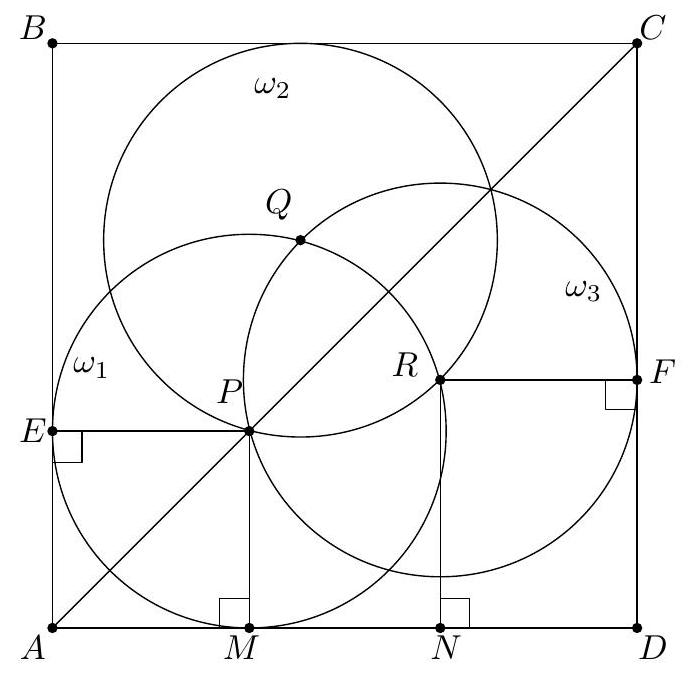

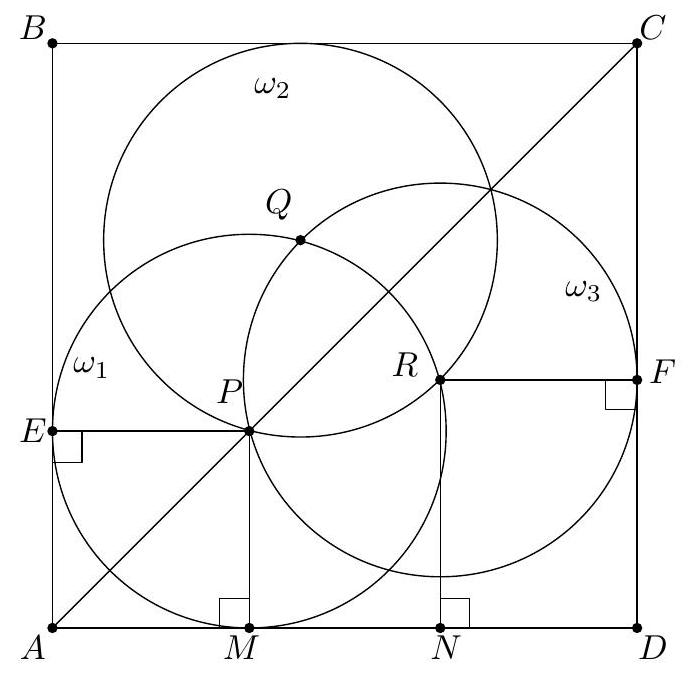

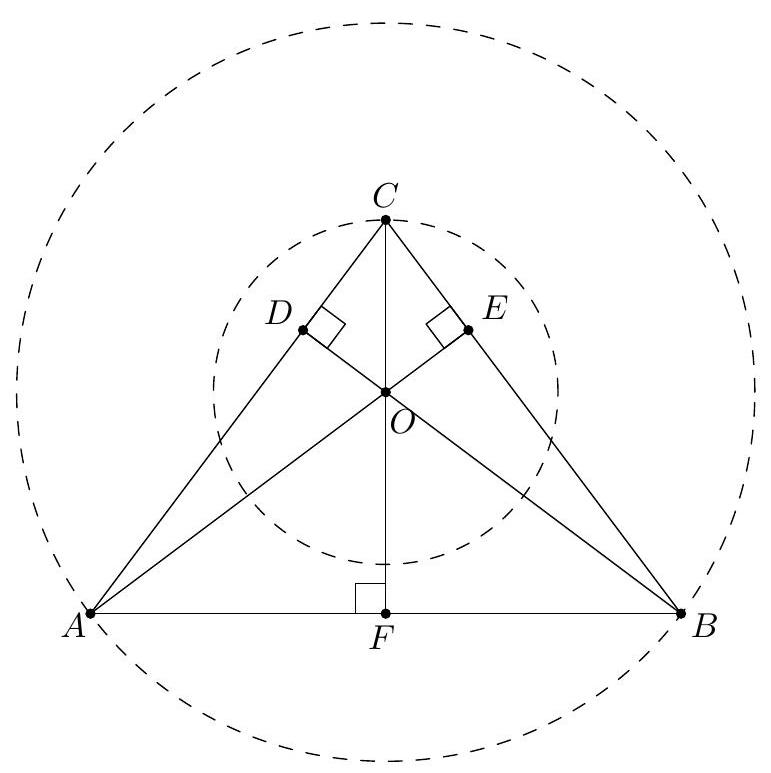

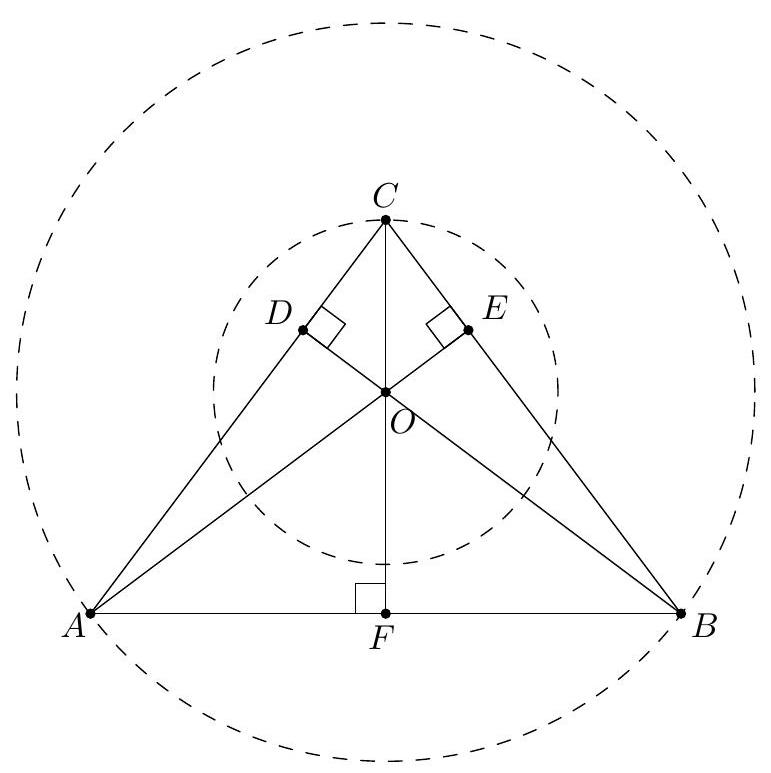

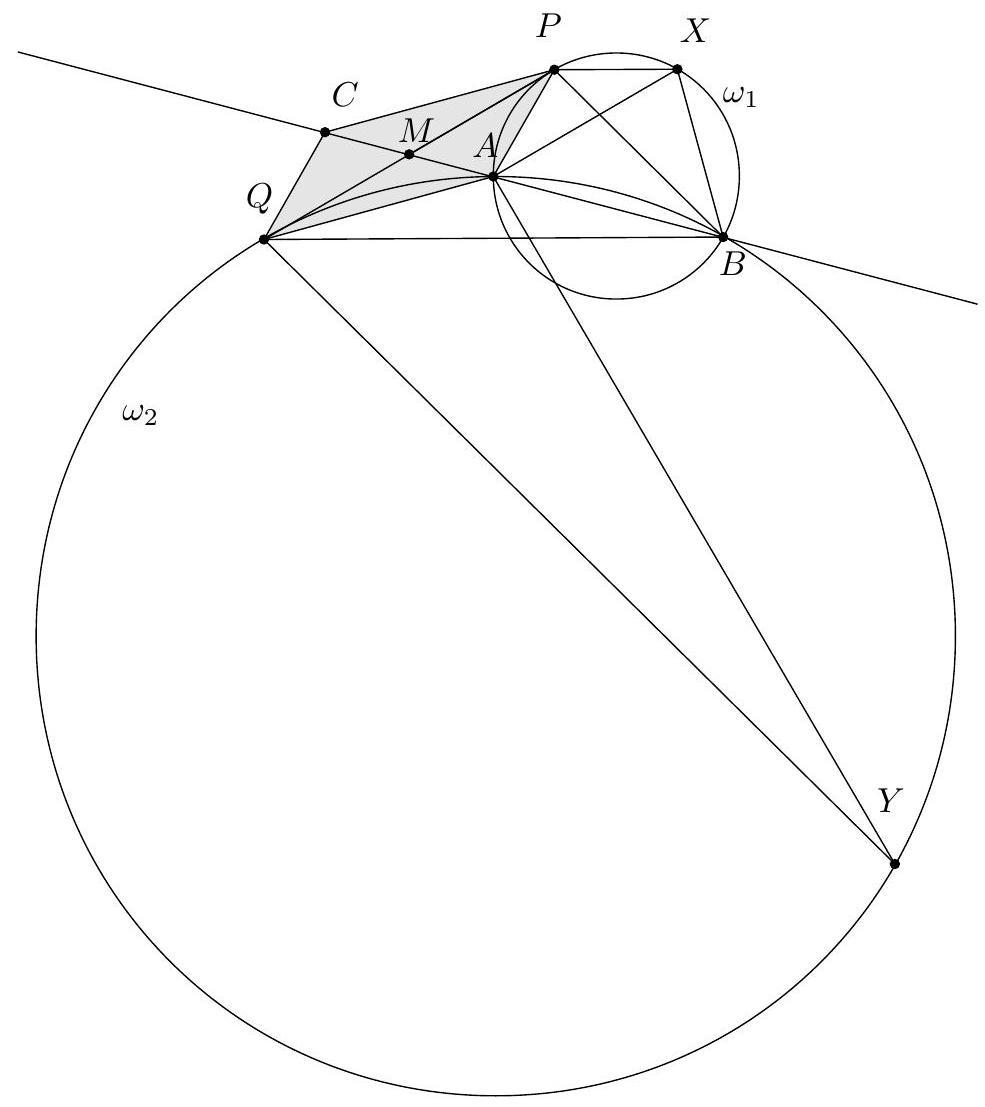

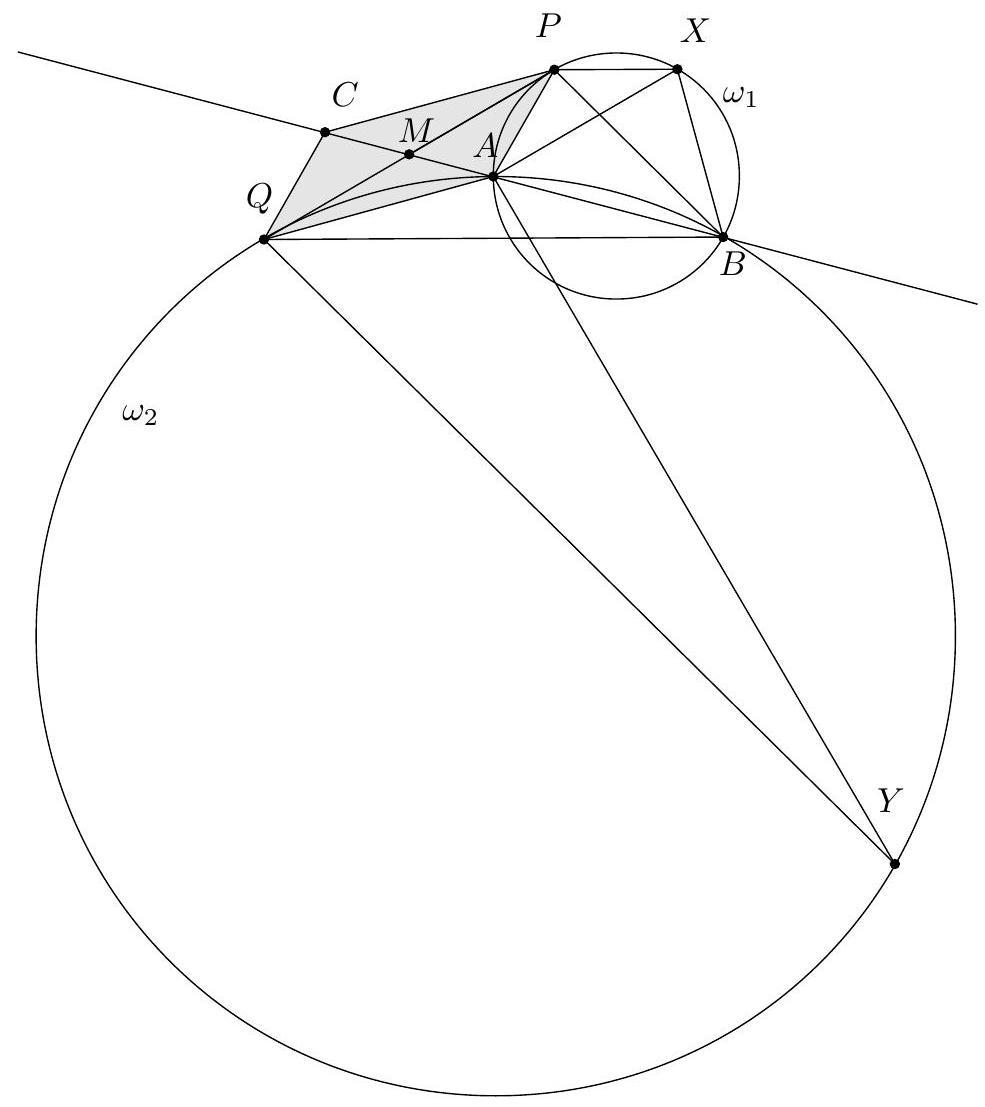

Three unit circles $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$, and $\omega_{3}$ in the plane have the property that each circle passes through the centers of the other two. A square $S$ surrounds the three circles in such a way that each of its four sides is tangent to at least one of $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$. Find the side length of the square $S$.

|

$\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}+8}{4}$

By the Pigeonhole Principle, two of the sides must be tangent to the same circle, say $\omega_{1}$. Since $S$ surrounds the circles, these two sides must be adjacent, so we can let $A$ denote the common vertex of the two sides tangent to $\omega_{1}$. Let $B, C$, and $D$ be the other vertices of $S$ in clockwise order, and let $P, Q$, and $R$ be the centers of $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$, and $\omega_{3}$ respectively, and suppose WLOG that they are also in clockwise order. Then $A C$ passes through the center of $\omega_{1}$, and by symmetry ( since $A B=A D$ ) it

must also pass through the other intersection point of $\omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$. That is, $A C$ is the radical axis of $\omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$.

Now, let $M$ and $N$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $P$ and $R$, respectively, to side $A D$. Let $E$ and $F$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $P$ to $A B$ and from $R$ to $D C$, respectively. Then $P E A M$ and $N R F D$ are rectangles, and $P E$ and $R F$ are radii of $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ respectively. Thus $A M=E P=1$ and $N D=R F=1$. Finally, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

M N & =P R \cdot \cos \left(180^{\circ}-\angle E P R\right) \\

& =\cos \left(180^{\circ}-E P Q-R P Q\right) \\

& =-\cos \left(\left(270^{\circ}-60^{\circ}\right) / 2+60^{\circ}\right) \\

& =-\cos \left(165^{\circ}\right) \\

& =\cos \left(15^{\circ}\right) \\

& =\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}}{4} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus $A D=A M+M N+N D=1+\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}}{4}+1=\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}+8}{4}$ as claimed.

|

\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}+8}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Three unit circles $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$, and $\omega_{3}$ in the plane have the property that each circle passes through the centers of the other two. A square $S$ surrounds the three circles in such a way that each of its four sides is tangent to at least one of $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$. Find the side length of the square $S$.

|

$\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}+8}{4}$

By the Pigeonhole Principle, two of the sides must be tangent to the same circle, say $\omega_{1}$. Since $S$ surrounds the circles, these two sides must be adjacent, so we can let $A$ denote the common vertex of the two sides tangent to $\omega_{1}$. Let $B, C$, and $D$ be the other vertices of $S$ in clockwise order, and let $P, Q$, and $R$ be the centers of $\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}$, and $\omega_{3}$ respectively, and suppose WLOG that they are also in clockwise order. Then $A C$ passes through the center of $\omega_{1}$, and by symmetry ( since $A B=A D$ ) it

must also pass through the other intersection point of $\omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$. That is, $A C$ is the radical axis of $\omega_{2}$ and $\omega_{3}$.

Now, let $M$ and $N$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $P$ and $R$, respectively, to side $A D$. Let $E$ and $F$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $P$ to $A B$ and from $R$ to $D C$, respectively. Then $P E A M$ and $N R F D$ are rectangles, and $P E$ and $R F$ are radii of $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ respectively. Thus $A M=E P=1$ and $N D=R F=1$. Finally, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

M N & =P R \cdot \cos \left(180^{\circ}-\angle E P R\right) \\

& =\cos \left(180^{\circ}-E P Q-R P Q\right) \\

& =-\cos \left(\left(270^{\circ}-60^{\circ}\right) / 2+60^{\circ}\right) \\

& =-\cos \left(165^{\circ}\right) \\

& =\cos \left(15^{\circ}\right) \\

& =\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}}{4} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus $A D=A M+M N+N D=1+\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}}{4}+1=\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}+8}{4}$ as claimed.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-132-2010-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Let $a, b, c, x, y$, and $z$ be complex numbers such that

$$

a=\frac{b+c}{x-2}, \quad b=\frac{c+a}{y-2}, \quad c=\frac{a+b}{z-2} .

$$

If $x y+y z+z x=67$ and $x+y+z=2010$, find the value of $x y z$.

|

-5892 Manipulate the equations to get a common denominator: $a=\frac{b+c}{x-2} \Longrightarrow x-2=$ $\frac{b+c}{a} \Longrightarrow x-1=\frac{a+b+c}{a} \Longrightarrow \frac{1}{x-1}=\frac{a}{a+b+c}$; similarly, $\frac{1}{y-1}=\frac{b}{a+b+c}$ and $\frac{1}{z-1}=\frac{c}{a+b+c}$. Thus

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{x-1}+\frac{1}{y-1}+\frac{1}{z-1} & =1 \\

(y-1)(z-1)+(x-1)(z-1)+(x-1)(y-1) & =(x-1)(y-1)(z-1) \\

x y+y z+z x-2(x+y+z)+3 & =x y z-(x y+y z+z x)+(x+y+z)-1 \\

x y z-2(x y+y z+z x)+3(x+y+z)-4 & =0 \\

x y z-2(67)+3(2010)-4 & =0 \\

x y z & =-5892

\end{aligned}

$$

|

-5892

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $a, b, c, x, y$, and $z$ be complex numbers such that

$$

a=\frac{b+c}{x-2}, \quad b=\frac{c+a}{y-2}, \quad c=\frac{a+b}{z-2} .

$$

If $x y+y z+z x=67$ and $x+y+z=2010$, find the value of $x y z$.