problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prove that any real solution of

$$

x^{3}+p x+q=0

$$

satisfies the inequality $4 q x \leq p^{2}$.

|

Let $x_{0}$ be a root of the qubic, then $x^{3}+p x+q=\left(x-x_{0}\right)\left(x^{2}+a x+b\right)=$ $x^{3}+\left(a-x_{0}\right) x^{2}+\left(b-a x_{0}\right) x-b x_{0}$. So $a=x_{0}, p=b-a x_{0}=b-x_{0}^{2},-q=b x_{0}$. Hence $p^{2}=b^{2}-2 b x_{0}^{2}+x_{0}^{4}$. Also $4 x_{0} q=-4 x_{0}^{2} b$. So $p^{2}-4 x_{0} q=b^{2}+2 b x_{0}^{2}+x_{0}^{4}=\left(b+x_{0}^{2}\right)^{2} \geq 0$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prove that any real solution of

$$

x^{3}+p x+q=0

$$

satisfies the inequality $4 q x \leq p^{2}$.

|

Let $x_{0}$ be a root of the qubic, then $x^{3}+p x+q=\left(x-x_{0}\right)\left(x^{2}+a x+b\right)=$ $x^{3}+\left(a-x_{0}\right) x^{2}+\left(b-a x_{0}\right) x-b x_{0}$. So $a=x_{0}, p=b-a x_{0}=b-x_{0}^{2},-q=b x_{0}$. Hence $p^{2}=b^{2}-2 b x_{0}^{2}+x_{0}^{4}$. Also $4 x_{0} q=-4 x_{0}^{2} b$. So $p^{2}-4 x_{0} q=b^{2}+2 b x_{0}^{2}+x_{0}^{4}=\left(b+x_{0}^{2}\right)^{2} \geq 0$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Prove that any real solution of

$$

x^{3}+p x+q=0

$$

satisfies the inequality $4 q x \leq p^{2}$.

|

As the equation $x_{0} x^{2}+p x+q=0$ has a root $\left(x=x_{0}\right)$, we must have $D \geq 0 \Leftrightarrow p^{2}-4 q x_{0} \geq 0$. (Also the equation $x^{2}+p x+q x_{0}=0$ having the root $x=x_{0}^{2}$ can be considered.)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prove that any real solution of

$$

x^{3}+p x+q=0

$$

satisfies the inequality $4 q x \leq p^{2}$.

|

As the equation $x_{0} x^{2}+p x+q=0$ has a root $\left(x=x_{0}\right)$, we must have $D \geq 0 \Leftrightarrow p^{2}-4 q x_{0} \geq 0$. (Also the equation $x^{2}+p x+q x_{0}=0$ having the root $x=x_{0}^{2}$ can be considered.)

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $x, y$ and $z$ be positive real numbers such that $x y z=1$. Prove that

$$

(1+x)(1+y)(1+z) \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

|

Put $a=b x, b=c y$ and $c=a z$. The given inequality then takes the form

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)\left(1+\frac{b}{c}\right)\left(1+\frac{c}{a}\right) & \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{b^{2}}{a c}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{c^{2}}{a b}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{a^{2}}{b c}}\right) \\

& =2\left(1+\frac{a+b+c}{3 \sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

By the AM-GM inequality we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)\left(1+\frac{b}{c}\right)\left(1+\frac{c}{a}\right) & =\frac{a+b+c}{a}+\frac{a+b+c}{b}+\frac{a+b+c}{c}-1 \\

& \geq 3\left(\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right)-1 \geq 2 \frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}+3-1=2\left(1+\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $x, y$ and $z$ be positive real numbers such that $x y z=1$. Prove that

$$

(1+x)(1+y)(1+z) \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

|

Put $a=b x, b=c y$ and $c=a z$. The given inequality then takes the form

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)\left(1+\frac{b}{c}\right)\left(1+\frac{c}{a}\right) & \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{b^{2}}{a c}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{c^{2}}{a b}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{a^{2}}{b c}}\right) \\

& =2\left(1+\frac{a+b+c}{3 \sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

By the AM-GM inequality we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)\left(1+\frac{b}{c}\right)\left(1+\frac{c}{a}\right) & =\frac{a+b+c}{a}+\frac{a+b+c}{b}+\frac{a+b+c}{c}-1 \\

& \geq 3\left(\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right)-1 \geq 2 \frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}+3-1=2\left(1+\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt[3]{a b c}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $x, y$ and $z$ be positive real numbers such that $x y z=1$. Prove that

$$

(1+x)(1+y)(1+z) \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

|

Expanding the left side we obtain

$$

x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geq 2\left(\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

As $\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}} \leq \frac{1}{3}\left(y+\frac{1}{x}+1\right)$ etc., it suffices to prove that

$$

x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geq \frac{2}{3}\left(x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z}\right)+2

$$

which follows from $a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $x, y$ and $z$ be positive real numbers such that $x y z=1$. Prove that

$$

(1+x)(1+y)(1+z) \geq 2\left(1+\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

|

Expanding the left side we obtain

$$

x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geq 2\left(\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{z}{y}}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{x}{z}}\right)

$$

As $\sqrt[3]{\frac{y}{x}} \leq \frac{1}{3}\left(y+\frac{1}{x}+1\right)$ etc., it suffices to prove that

$$

x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geq \frac{2}{3}\left(x+y+z+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z}\right)+2

$$

which follows from $a+\frac{1}{a} \geq 2$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be positive real numbers. Prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c}+\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a}+\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b} .

$$

|

First we prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c} \leq \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right)

$$

which is equivalent to $0 \leq b(a-c)^{2}+c(a-b)^{2}$, and therefore holds true. Now we turn to the inequality

$$

\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c} \leq \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}\right),

$$

which by multiplying by $2 a b c$ is seen to be equivalent to $0 \leq(a-b)^{2}+(a-c)^{2}$. Hence we have proved that

Analogously we have

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c} \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}\right) .

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a} & \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}+\frac{a}{b c}\right) \\

\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} & \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 c}{a b}+\frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

and it suffices to sum the above three inequalities.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $a, b, c$ be positive real numbers. Prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c}+\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a}+\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b} .

$$

|

First we prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c} \leq \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}\right)

$$

which is equivalent to $0 \leq b(a-c)^{2}+c(a-b)^{2}$, and therefore holds true. Now we turn to the inequality

$$

\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c} \leq \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}\right),

$$

which by multiplying by $2 a b c$ is seen to be equivalent to $0 \leq(a-b)^{2}+(a-c)^{2}$. Hence we have proved that

Analogously we have

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c} \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}\right) .

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a} & \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}+\frac{a}{b c}\right) \\

\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} & \leq \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{2 c}{a b}+\frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

and it suffices to sum the above three inequalities.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be positive real numbers. Prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c}+\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a}+\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b} .

$$

|

As $a^{2}+b c \geq 2 a \sqrt{b c}$ etc., it is sufficient to prove that

$$

\frac{1}{\sqrt{b c}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{a c}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{a b}} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}

$$

which can be obtained by "inserting" $\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}$ between the left side and the right side.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $a, b, c$ be positive real numbers. Prove that

$$

\frac{2 a}{a^{2}+b c}+\frac{2 b}{b^{2}+c a}+\frac{2 c}{c^{2}+a b} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b} .

$$

|

As $a^{2}+b c \geq 2 a \sqrt{b c}$ etc., it is sufficient to prove that

$$

\frac{1}{\sqrt{b c}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{a c}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{a b}} \leq \frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{c a}+\frac{c}{a b}

$$

which can be obtained by "inserting" $\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{b}+\frac{1}{c}$ between the left side and the right side.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

A sequence $\left(a_{n}\right)$ is defined as follows: $a_{1}=\sqrt{2}, a_{2}=2$, and $a_{n+1}=a_{n} a_{n-1}^{2}$ for $n \geq 2$. Prove that for every $n \geq 1$ we have

$$

\left(1+a_{1}\right)\left(1+a_{2}\right) \cdots\left(1+a_{n}\right)<(2+\sqrt{2}) a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n} .

$$

|

First we prove inductively that for $n \geq 1, a_{n}=2^{2^{n-2}}$. We have $a_{1}=2^{2^{-1}}$, $a_{2}=2^{2^{0}}$ and

$$

a_{n+1}=2^{2^{n-2}} \cdot\left(2^{2^{n-3}}\right)^{2}=2^{2^{n-2}} \cdot 2^{2^{n-2}}=2^{2^{n-1}} .

$$

Since $1+a_{1}=1+\sqrt{2}$, we must prove, that

$$

\left(1+a_{2}\right)\left(1+a_{3}\right) \cdots\left(1+a_{n}\right)<2 a_{2} a_{3} \cdots a_{n} .

$$

The right-hand side is equal to

$$

2^{1+2^{0}+2^{1}+\cdots+2^{n-2}}=2^{2^{n-1}}

$$

and the left-hand side

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+2^{2^{0}}\right) & \left(1+2^{2^{1}}\right) \cdots\left(1+2^{2^{n-2}}\right) \\

& =1+2^{2^{0}}+2^{2^{1}}+2^{2^{0}+2^{1}}+2^{2^{2}}+\cdots+2^{2^{0}+2^{1}+\cdots+2^{n-2}} \\

& =1+2+2^{2}+2^{3}+\cdots+2^{2^{n-1}-1} \\

& =2^{2^{n-1}}-1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

The proof is complete.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

A sequence $\left(a_{n}\right)$ is defined as follows: $a_{1}=\sqrt{2}, a_{2}=2$, and $a_{n+1}=a_{n} a_{n-1}^{2}$ for $n \geq 2$. Prove that for every $n \geq 1$ we have

$$

\left(1+a_{1}\right)\left(1+a_{2}\right) \cdots\left(1+a_{n}\right)<(2+\sqrt{2}) a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n} .

$$

|

First we prove inductively that for $n \geq 1, a_{n}=2^{2^{n-2}}$. We have $a_{1}=2^{2^{-1}}$, $a_{2}=2^{2^{0}}$ and

$$

a_{n+1}=2^{2^{n-2}} \cdot\left(2^{2^{n-3}}\right)^{2}=2^{2^{n-2}} \cdot 2^{2^{n-2}}=2^{2^{n-1}} .

$$

Since $1+a_{1}=1+\sqrt{2}$, we must prove, that

$$

\left(1+a_{2}\right)\left(1+a_{3}\right) \cdots\left(1+a_{n}\right)<2 a_{2} a_{3} \cdots a_{n} .

$$

The right-hand side is equal to

$$

2^{1+2^{0}+2^{1}+\cdots+2^{n-2}}=2^{2^{n-1}}

$$

and the left-hand side

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+2^{2^{0}}\right) & \left(1+2^{2^{1}}\right) \cdots\left(1+2^{2^{n-2}}\right) \\

& =1+2^{2^{0}}+2^{2^{1}}+2^{2^{0}+2^{1}}+2^{2^{2}}+\cdots+2^{2^{0}+2^{1}+\cdots+2^{n-2}} \\

& =1+2+2^{2}+2^{3}+\cdots+2^{2^{n-1}-1} \\

& =2^{2^{n-1}}-1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

The proof is complete.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $n \geq 2$ and $d \geq 1$ be integers with $d \mid n$, and let $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$ be real numbers such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+\cdots+x_{n}=0$. Prove that there are at least $\left(\begin{array}{l}n-1 \\ d-1\end{array}\right)$ choices of $d$ indices $1 \leq i_{1}<i_{2}<\cdots<i_{d} \leq n$ such that $x_{i_{1}}+x_{i_{2}}+\cdots+x_{i_{d}} \geq 0$.

|

Put $m=n / d$ and $[n]=\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$, and consider all partitions $[n]=A_{1} \cup$ $A_{2} \cup \cdots \cup A_{m}$ of $[n]$ into $d$-element subsets $A_{i}, i=1,2, \ldots, m$. The number of such partitions is denoted by $t$. Clearly, there are exactly $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right) d$-element subsets of $[n]$ each of which occurs in the same number of partitions. Hence, every $A \subseteq[n]$ with $|A|=d$ occurs in exactly $s:=t m /\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right)$ partitions. On the other hand, every partition contains at least one $d$-element set $A$ such that $\sum_{i \in A} x_{i} \geq 0$. Consequently, the total number of sets with this property is at least $t / s=\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right) / m=\frac{d}{n}\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{l}n-1 \\ d-1\end{array}\right)$.

|

\left(\begin{array}{l}n-1 \\ d-1\end{array}\right)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $n \geq 2$ and $d \geq 1$ be integers with $d \mid n$, and let $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$ be real numbers such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+\cdots+x_{n}=0$. Prove that there are at least $\left(\begin{array}{l}n-1 \\ d-1\end{array}\right)$ choices of $d$ indices $1 \leq i_{1}<i_{2}<\cdots<i_{d} \leq n$ such that $x_{i_{1}}+x_{i_{2}}+\cdots+x_{i_{d}} \geq 0$.

|

Put $m=n / d$ and $[n]=\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$, and consider all partitions $[n]=A_{1} \cup$ $A_{2} \cup \cdots \cup A_{m}$ of $[n]$ into $d$-element subsets $A_{i}, i=1,2, \ldots, m$. The number of such partitions is denoted by $t$. Clearly, there are exactly $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right) d$-element subsets of $[n]$ each of which occurs in the same number of partitions. Hence, every $A \subseteq[n]$ with $|A|=d$ occurs in exactly $s:=t m /\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right)$ partitions. On the other hand, every partition contains at least one $d$-element set $A$ such that $\sum_{i \in A} x_{i} \geq 0$. Consequently, the total number of sets with this property is at least $t / s=\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right) / m=\frac{d}{n}\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ d\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{l}n-1 \\ d-1\end{array}\right)$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $X$ be a subset of $\{1,2,3, \ldots, 10000\}$ with the following property: If $a, b \in X, a \neq b$, then $a \cdot b \notin X$. What is the maximal number of elements in $X$ ?

Answer: 9901.

|

If $X=\{100,101,102, \ldots, 9999,10000\}$, then for any two selected $a$ and $b, a \neq b$, $a \cdot b \geq 100 \cdot 101>10000$, so $a \cdot b \notin X$. So $X$ may have 9901 elements.

Suppose that $x_{1}<x_{2}<\cdots<x_{k}$ are all elements of $X$ that are less than 100. If there are none of them, no more than 9901 numbers can be in the set $X$. Otherwise, if $x_{1}=1$ no other number can be in the set $X$, so suppose $x_{1}>1$ and consider the pairs

$$

\begin{gathered}

200-x_{1},\left(200-x_{1}\right) \cdot x_{1} \\

200-x_{2},\left(200-x_{2}\right) \cdot x_{2} \\

\vdots \\

200-x_{k},\left(200-x_{k}\right) \cdot x_{k}

\end{gathered}

$$

Clearly $x_{1}<x_{2}<\cdots<x_{k}<100<200-x_{k}<200-x_{k-1}<\cdots<200-x_{2}<$ $200-x_{1}<200<\left(200-x_{1}\right) \cdot x_{1}<\left(200-x_{2}\right) \cdot x_{2}<\cdots<\left(200-x_{k}\right) \cdot x_{k}$. So all numbers in these pairs are different and greater than 100. So at most one from each pair is in the set $X$. Therefore, there are at least $k$ numbers greater than 100 and $99-k$ numbers less than 100 that are not in the set $X$, together at least 99 numbers out of 10000 not being in the set $X$.

|

9901

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $X$ be a subset of $\{1,2,3, \ldots, 10000\}$ with the following property: If $a, b \in X, a \neq b$, then $a \cdot b \notin X$. What is the maximal number of elements in $X$ ?

Answer: 9901.

|

If $X=\{100,101,102, \ldots, 9999,10000\}$, then for any two selected $a$ and $b, a \neq b$, $a \cdot b \geq 100 \cdot 101>10000$, so $a \cdot b \notin X$. So $X$ may have 9901 elements.

Suppose that $x_{1}<x_{2}<\cdots<x_{k}$ are all elements of $X$ that are less than 100. If there are none of them, no more than 9901 numbers can be in the set $X$. Otherwise, if $x_{1}=1$ no other number can be in the set $X$, so suppose $x_{1}>1$ and consider the pairs

$$

\begin{gathered}

200-x_{1},\left(200-x_{1}\right) \cdot x_{1} \\

200-x_{2},\left(200-x_{2}\right) \cdot x_{2} \\

\vdots \\

200-x_{k},\left(200-x_{k}\right) \cdot x_{k}

\end{gathered}

$$

Clearly $x_{1}<x_{2}<\cdots<x_{k}<100<200-x_{k}<200-x_{k-1}<\cdots<200-x_{2}<$ $200-x_{1}<200<\left(200-x_{1}\right) \cdot x_{1}<\left(200-x_{2}\right) \cdot x_{2}<\cdots<\left(200-x_{k}\right) \cdot x_{k}$. So all numbers in these pairs are different and greater than 100. So at most one from each pair is in the set $X$. Therefore, there are at least $k$ numbers greater than 100 and $99-k$ numbers less than 100 that are not in the set $X$, together at least 99 numbers out of 10000 not being in the set $X$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

There are 2003 pieces of candy on a table. Two players alternately make moves. A move consists of eating one candy or half of the candies on the table (the "lesser half" if there is an odd number of candies); at least one candy must be eaten at each move. The loser is the one who eats the last candy. Which player - the first or the second - has a winning strategy?

Answer: The second.

|

Let us prove inductively that for $2 n$ pieces of candy the first player has a winning strategy. For $n=1$ it is obvious. Suppose it is true for $2 n$ pieces, and let's consider $2 n+2$ pieces. If for $2 n+1$ pieces the second is the winner, then the first eats 1 piece and becomes the second in the game starting with $2 n+1$ pieces. So suppose that for $2 n+1$ pieces the first is the winner. His winning move for $2 n+1$ is not eating 1 piece (according to the inductive assumption). So his winning move is to eat $n$ pieces, leaving the second with $n+1$ pieces, when the second must lose. But the first can leave the second with $n+1$ pieces from the starting position with $2 n+2$ pieces, eating $n+1$ pieces; so $2 n+2$ is a winning position for the first.

Now if there are 2003 pieces of candy on the table, the first must eat either 1 or 1001 candies, leaving an even number of candies on the table. So the second player will be the first player in a game with even number of candies and therefore has a winning strategy.

In general, if there is an odd number $N$ of candies, write $N=2^{m} r+1$, where $r$ is odd. Then the first player wins if $m$ is even, and the second player wins if $m$ is odd: At each move, the player must avoid leaving the other with an even number of candies, so he must eat half of the candies. But this means that the number of candies descend as $2^{m} r+1,2^{m-1} r+1, \ldots, 2 r+1, r+1$, and eventually there is an even number of candies.

|

The second

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

There are 2003 pieces of candy on a table. Two players alternately make moves. A move consists of eating one candy or half of the candies on the table (the "lesser half" if there is an odd number of candies); at least one candy must be eaten at each move. The loser is the one who eats the last candy. Which player - the first or the second - has a winning strategy?

Answer: The second.

|

Let us prove inductively that for $2 n$ pieces of candy the first player has a winning strategy. For $n=1$ it is obvious. Suppose it is true for $2 n$ pieces, and let's consider $2 n+2$ pieces. If for $2 n+1$ pieces the second is the winner, then the first eats 1 piece and becomes the second in the game starting with $2 n+1$ pieces. So suppose that for $2 n+1$ pieces the first is the winner. His winning move for $2 n+1$ is not eating 1 piece (according to the inductive assumption). So his winning move is to eat $n$ pieces, leaving the second with $n+1$ pieces, when the second must lose. But the first can leave the second with $n+1$ pieces from the starting position with $2 n+2$ pieces, eating $n+1$ pieces; so $2 n+2$ is a winning position for the first.

Now if there are 2003 pieces of candy on the table, the first must eat either 1 or 1001 candies, leaving an even number of candies on the table. So the second player will be the first player in a game with even number of candies and therefore has a winning strategy.

In general, if there is an odd number $N$ of candies, write $N=2^{m} r+1$, where $r$ is odd. Then the first player wins if $m$ is even, and the second player wins if $m$ is odd: At each move, the player must avoid leaving the other with an even number of candies, so he must eat half of the candies. But this means that the number of candies descend as $2^{m} r+1,2^{m-1} r+1, \ldots, 2 r+1, r+1$, and eventually there is an even number of candies.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

It is known that $n$ is a positive integer, $n \leq 144$. Ten questions of type "Is $n$ smaller than a?" are allowed. Answers are given with a delay: The answer to the $i$ 'th question is given only after the $(i+1)$ 'st question is asked, $i=1,2, \ldots, 9$. The answer to the tenth question is given immediately after it is asked. Find a strategy for identifying $n$.

|

Let the Fibonacci numbers be denoted $F_{0}=1, F_{1}=2, F_{2}=3$ etc. Then $F_{10}=144$. We will prove by induction on $k$ that using $k$ questions subject to the conditions of the problem, it is possible to determine any positive integer $n \leq F_{k}$. First, for $k=0$ it is trivial, since without asking we know that $n=1$. For $k=1$, we simply ask if $n$ is smaller than 2. For $k=2$, we ask if $n$ is smaller than 3 and if $n$ is smaller than 2; from the two answers we can determine $n$.

Now, in general, our first two questions will always be "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-1}+1$ ?" and "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-2}+1$ ". We then receive the answer to the first question. As long as we receive affirmative answers to the $i-1$ 'st question, the $i+1$ 'st question will be "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-(i+1)}+1$ ?". If at any point, say after asking the $j$ 'th question, we receive a negative answer to the $j-1$ 'st question, we then know that $F_{k-(j-1)}+1 \leq n \leq F_{k-(j-2)}$, so $n$ is one of $F_{k-(j-2)}-F_{k-(j-1)}=F_{k-j}$ consecutive integers, and by induction we may determine $n$ using the remaining $k-j$ questions. Otherwise, we receive affirmative answers to all the questions, the last being "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-k}+1=2$ ?"; so $n=1$ in that case.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

It is known that $n$ is a positive integer, $n \leq 144$. Ten questions of type "Is $n$ smaller than a?" are allowed. Answers are given with a delay: The answer to the $i$ 'th question is given only after the $(i+1)$ 'st question is asked, $i=1,2, \ldots, 9$. The answer to the tenth question is given immediately after it is asked. Find a strategy for identifying $n$.

|

Let the Fibonacci numbers be denoted $F_{0}=1, F_{1}=2, F_{2}=3$ etc. Then $F_{10}=144$. We will prove by induction on $k$ that using $k$ questions subject to the conditions of the problem, it is possible to determine any positive integer $n \leq F_{k}$. First, for $k=0$ it is trivial, since without asking we know that $n=1$. For $k=1$, we simply ask if $n$ is smaller than 2. For $k=2$, we ask if $n$ is smaller than 3 and if $n$ is smaller than 2; from the two answers we can determine $n$.

Now, in general, our first two questions will always be "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-1}+1$ ?" and "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-2}+1$ ". We then receive the answer to the first question. As long as we receive affirmative answers to the $i-1$ 'st question, the $i+1$ 'st question will be "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-(i+1)}+1$ ?". If at any point, say after asking the $j$ 'th question, we receive a negative answer to the $j-1$ 'st question, we then know that $F_{k-(j-1)}+1 \leq n \leq F_{k-(j-2)}$, so $n$ is one of $F_{k-(j-2)}-F_{k-(j-1)}=F_{k-j}$ consecutive integers, and by induction we may determine $n$ using the remaining $k-j$ questions. Otherwise, we receive affirmative answers to all the questions, the last being "Is $n$ smaller than $F_{k-k}+1=2$ ?"; so $n=1$ in that case.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

A lattice point in the plane is a point whose coordinates are both integral. The centroid of four points $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right), i=1,2,3,4$, is the point $\left(\frac{x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}}{4}, \frac{y_{1}+y_{2}+y_{3}+y_{4}}{4}\right)$. Let $n$ be the largest natural number with the following property: There are $n$ distinct lattice points in the plane such that the centroid of any four of them is not a lattice point. Prove that $n=12$.

|

To prove $n \geq 12$, we have to show that there are 12 lattice points $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right)$, $i=1,2, \ldots, 12$, such that no four determine a lattice point centroid. This is guaranteed if we just choose the points such that $x_{i} \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$ for $i=1, \ldots, 6, x_{i} \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$ for

$i=7, \ldots, 12, y_{i} \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$ for $i=1,2,3,10,11,12, y_{i} \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$ for $i=4, \ldots, 9$.

Now let $P_{i}, i=1,2, \ldots, 13$, be lattice points. We have to show that some four of them determine a lattice point centroid. First observe that, by the Pigeonhole Principle, among any five of the points we find two such that their $x$-coordinates as well as their $y$-coordinates have the same parity. Consequently, among any five of the points there are two whose midpoint is a lattice point. Iterated application of this observation implies that among the 13 points in question we find five disjoint pairs of points whose midpoint is a lattice point. Among these five midpoints we again find two, say $M$ and $M^{\prime}$, such that their midpoint $C$ is a lattice point. Finally, if $M$ and $M^{\prime}$ are the midpoints of $P_{i} P_{j}$ and $P_{k} P_{\ell}$, respectively, $\{i, j, k, \ell\} \subseteq\{1,2, \ldots, 13\}$, then $C$ is the centroid of $P_{i}, P_{j}, P_{k}, P_{\ell}$.

|

12

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

A lattice point in the plane is a point whose coordinates are both integral. The centroid of four points $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right), i=1,2,3,4$, is the point $\left(\frac{x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}}{4}, \frac{y_{1}+y_{2}+y_{3}+y_{4}}{4}\right)$. Let $n$ be the largest natural number with the following property: There are $n$ distinct lattice points in the plane such that the centroid of any four of them is not a lattice point. Prove that $n=12$.

|

To prove $n \geq 12$, we have to show that there are 12 lattice points $\left(x_{i}, y_{i}\right)$, $i=1,2, \ldots, 12$, such that no four determine a lattice point centroid. This is guaranteed if we just choose the points such that $x_{i} \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$ for $i=1, \ldots, 6, x_{i} \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$ for

$i=7, \ldots, 12, y_{i} \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$ for $i=1,2,3,10,11,12, y_{i} \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$ for $i=4, \ldots, 9$.

Now let $P_{i}, i=1,2, \ldots, 13$, be lattice points. We have to show that some four of them determine a lattice point centroid. First observe that, by the Pigeonhole Principle, among any five of the points we find two such that their $x$-coordinates as well as their $y$-coordinates have the same parity. Consequently, among any five of the points there are two whose midpoint is a lattice point. Iterated application of this observation implies that among the 13 points in question we find five disjoint pairs of points whose midpoint is a lattice point. Among these five midpoints we again find two, say $M$ and $M^{\prime}$, such that their midpoint $C$ is a lattice point. Finally, if $M$ and $M^{\prime}$ are the midpoints of $P_{i} P_{j}$ and $P_{k} P_{\ell}$, respectively, $\{i, j, k, \ell\} \subseteq\{1,2, \ldots, 13\}$, then $C$ is the centroid of $P_{i}, P_{j}, P_{k}, P_{\ell}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

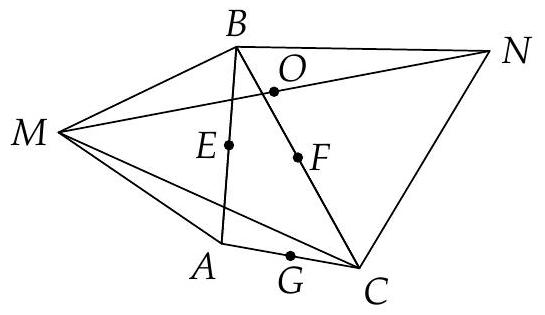

Is it possible to select 1000 points in a plane so that at least 6000 distances between two of them are equal?

Answer: Yes.

|

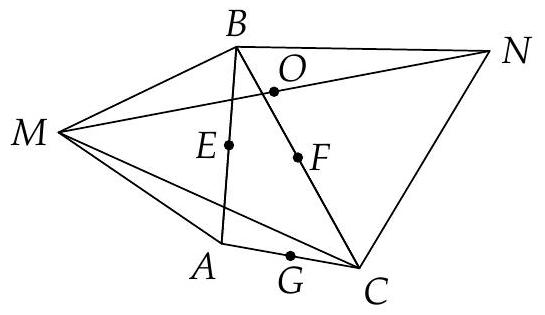

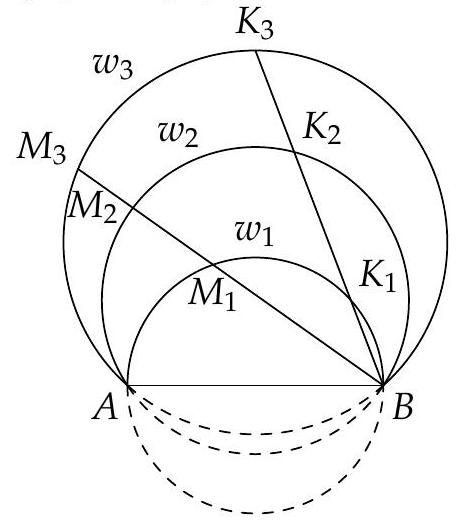

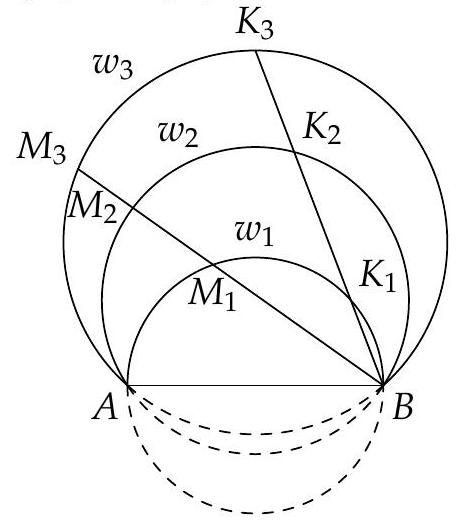

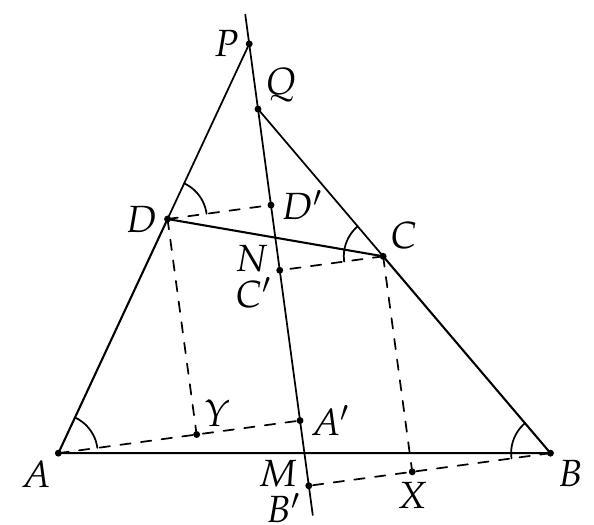

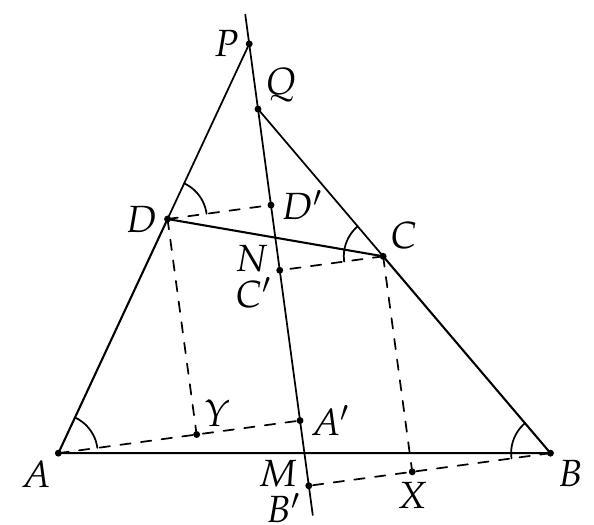

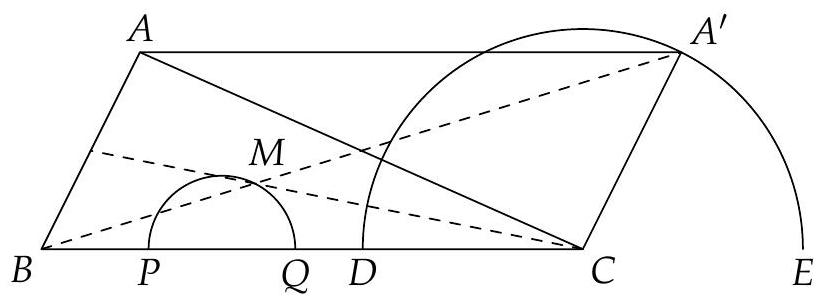

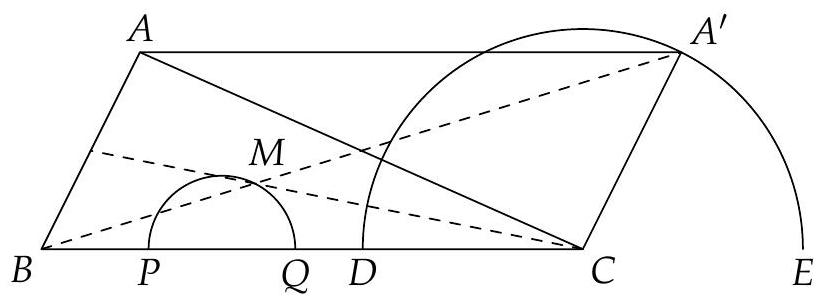

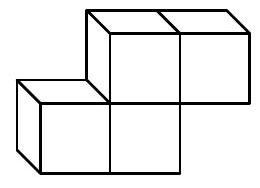

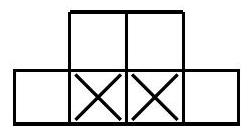

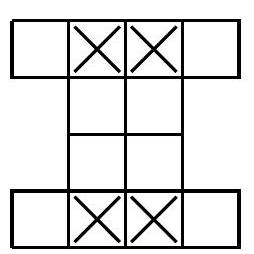

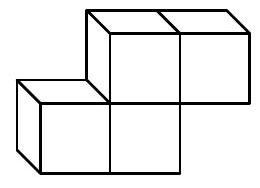

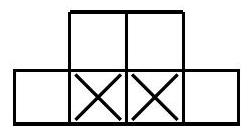

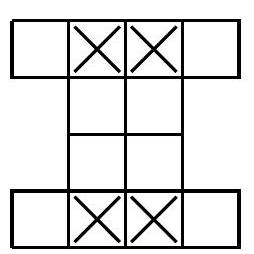

Let's start with configuration of 4 points and 5 distances equal to $d$, like in this figure:

$(\alpha)$

Now take $(\alpha)$ and two copies of it obtainable by parallel shifts along vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b},|\vec{a}|=|\vec{b}|=d$ and $\angle(\vec{a}, \vec{b})=60^{\circ}$. Vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ should be chosen so that no two vertices of $(\alpha)$ and of the two copies coincide. We get $3 \cdot 4=12$ points and $3 \cdot 5+12=27$ distances. Proceeding in the same way, we get gradually

- $3 \cdot 12=36$ points and $3 \cdot 27+36=117$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 36=108$ points and $3 \cdot 117+108=459$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 108=324$ points and $3 \cdot 459+324=1701$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 324=972$ points and $3 \cdot 1701+972=6075$ distances.

|

6075

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Is it possible to select 1000 points in a plane so that at least 6000 distances between two of them are equal?

Answer: Yes.

|

Let's start with configuration of 4 points and 5 distances equal to $d$, like in this figure:

$(\alpha)$

Now take $(\alpha)$ and two copies of it obtainable by parallel shifts along vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b},|\vec{a}|=|\vec{b}|=d$ and $\angle(\vec{a}, \vec{b})=60^{\circ}$. Vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ should be chosen so that no two vertices of $(\alpha)$ and of the two copies coincide. We get $3 \cdot 4=12$ points and $3 \cdot 5+12=27$ distances. Proceeding in the same way, we get gradually

- $3 \cdot 12=36$ points and $3 \cdot 27+36=117$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 36=108$ points and $3 \cdot 117+108=459$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 108=324$ points and $3 \cdot 459+324=1701$ distances;

- $3 \cdot 324=972$ points and $3 \cdot 1701+972=6075$ distances.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\n11.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

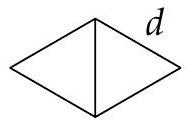

Let $A B C D$ be a square. Let $M$ be an inner point on side $B C$ and $N$ be an inner point on side $C D$ with $\angle M A N=45^{\circ}$. Prove that the circumcentre of $A M N$ lies on $A C$.

|

Draw a circle $\omega$ through $M, C, N$; let it intersect $A C$ at $O$. We claim that $O$ is the circumcentre of $A M N$.

Clearly $\angle M O N=180^{\circ}-\angle M C N=90^{\circ}$. If the radius of $\omega$ is $R$, then $O M=$ $2 R \sin 45^{\circ}=R \sqrt{2}$; similarly $O N=R \sqrt{2}$. Hence we get that $O M=O N$. Then the circle with centre $O$ and radius $R \sqrt{2}$ will pass through $A$, since $\angle M A N=\frac{1}{2} \angle M O N$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a square. Let $M$ be an inner point on side $B C$ and $N$ be an inner point on side $C D$ with $\angle M A N=45^{\circ}$. Prove that the circumcentre of $A M N$ lies on $A C$.

|

Draw a circle $\omega$ through $M, C, N$; let it intersect $A C$ at $O$. We claim that $O$ is the circumcentre of $A M N$.

Clearly $\angle M O N=180^{\circ}-\angle M C N=90^{\circ}$. If the radius of $\omega$ is $R$, then $O M=$ $2 R \sin 45^{\circ}=R \sqrt{2}$; similarly $O N=R \sqrt{2}$. Hence we get that $O M=O N$. Then the circle with centre $O$ and radius $R \sqrt{2}$ will pass through $A$, since $\angle M A N=\frac{1}{2} \angle M O N$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

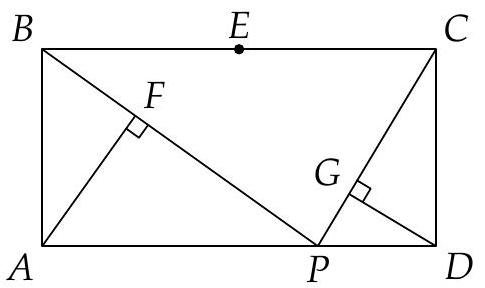

Let $A B C D$ be a rectangle and $B C=2 \cdot A B$. Let $E$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $P$ an arbitrary inner point of $A D$. Let $F$ and $G$ be the feet of perpendiculars drawn correspondingly from $A$ to $B P$ and from $D$ to $C P$. Prove that the points $E, F, P, G$ are concyclic.

|

From rectangular triangle $B A P$ we have $B P \cdot B F=A B^{2}=B E^{2}$. Therefore the circumference through $F$ and $P$ touching the line $B C$ between $B$ and $C$ touches it at $E$.

Analogously, the circumference through $P$ and $G$ touching the line $B C$ between $B$ and $C$ touches it at $E$. But there is only one circumference touching $B C$ at $E$ and passing through $P$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a rectangle and $B C=2 \cdot A B$. Let $E$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $P$ an arbitrary inner point of $A D$. Let $F$ and $G$ be the feet of perpendiculars drawn correspondingly from $A$ to $B P$ and from $D$ to $C P$. Prove that the points $E, F, P, G$ are concyclic.

|

From rectangular triangle $B A P$ we have $B P \cdot B F=A B^{2}=B E^{2}$. Therefore the circumference through $F$ and $P$ touching the line $B C$ between $B$ and $C$ touches it at $E$.

Analogously, the circumference through $P$ and $G$ touching the line $B C$ between $B$ and $C$ touches it at $E$. But there is only one circumference touching $B C$ at $E$ and passing through $P$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\n13.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

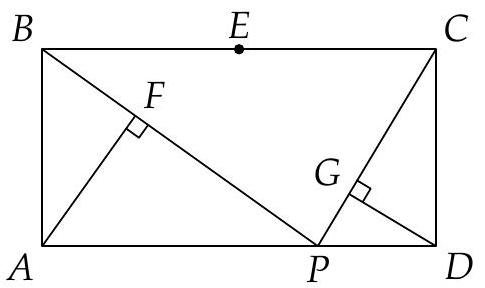

Let $A B C$ be an arbitrary triangle and $A M B, B N C, C K A$ regular triangles outward of $A B C$. Through the midpoint of $M N$ a perpendicular to $A C$ is constructed; similarly through the midpoints of $N K$ resp. KM perpendiculars to $A B$ resp. $B C$ are constructed. Prove that these three perpendiculars intersect at the same point.

|

Let $O$ be the midpoint of $M N$, and let $E$ and $F$ be the midpoints of $A B$ and $B C$, respectively. As triangle $M B C$ transforms into triangle $A B N$ when rotated $60^{\circ}$ around $B$ we get $M C=A N$ (it is also a well-known fact). Considering now the quadrangles $A M B N$ and $C M B N$ we get $O E=O F$ (from Eiler's formula $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=e^{2}+f^{2}+4 \cdot P Q^{2}$ or otherwise). As $E F \| A C$ we get from this that the perpendicular to $A C$ through $O$ passes through the circumcentre of $E F G$, as it is the perpendicular bisector of $E F$. The same holds for the other two perpendiculars.

First solution

Second solution

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an arbitrary triangle and $A M B, B N C, C K A$ regular triangles outward of $A B C$. Through the midpoint of $M N$ a perpendicular to $A C$ is constructed; similarly through the midpoints of $N K$ resp. KM perpendiculars to $A B$ resp. $B C$ are constructed. Prove that these three perpendiculars intersect at the same point.

|

Let $O$ be the midpoint of $M N$, and let $E$ and $F$ be the midpoints of $A B$ and $B C$, respectively. As triangle $M B C$ transforms into triangle $A B N$ when rotated $60^{\circ}$ around $B$ we get $M C=A N$ (it is also a well-known fact). Considering now the quadrangles $A M B N$ and $C M B N$ we get $O E=O F$ (from Eiler's formula $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=e^{2}+f^{2}+4 \cdot P Q^{2}$ or otherwise). As $E F \| A C$ we get from this that the perpendicular to $A C$ through $O$ passes through the circumcentre of $E F G$, as it is the perpendicular bisector of $E F$. The same holds for the other two perpendiculars.

First solution

Second solution

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an arbitrary triangle and $A M B, B N C, C K A$ regular triangles outward of $A B C$. Through the midpoint of $M N$ a perpendicular to $A C$ is constructed; similarly through the midpoints of $N K$ resp. KM perpendiculars to $A B$ resp. $B C$ are constructed. Prove that these three perpendiculars intersect at the same point.

|

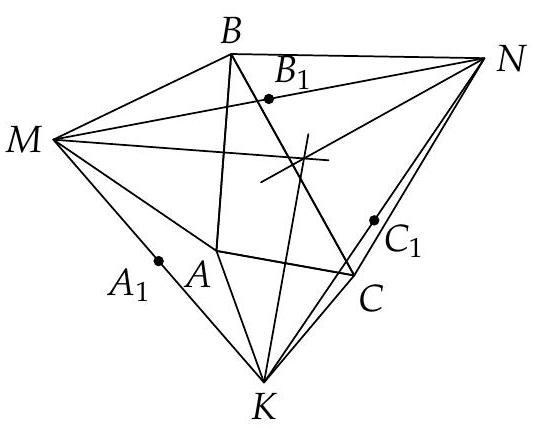

Let us denote the midpoints of the segments $M N, N K, K M$ by $B_{1}, C_{1}, A_{1}$, respectively. It is easy to see that triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$ is homothetic to triangle $N K M$ via the homothety centered at the intersection of the medians of triangle $N M K$ and dilation $-\frac{1}{2}$. The perpendiculars through $M, N, K$ to $A B, B C, C A$, respectively, are also the perpendicular bisectors of these sides, so they intersect in the circumcentre of triangle $A B C$. The desired result follows now from the homothety, and we find that that the common point of intersection is the circumcentre of the image of triangle $A B C$ under the homothety; that is, the circumcentre of the triangle with vertices the midpoints of the sides $A B, B C, C A$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an arbitrary triangle and $A M B, B N C, C K A$ regular triangles outward of $A B C$. Through the midpoint of $M N$ a perpendicular to $A C$ is constructed; similarly through the midpoints of $N K$ resp. KM perpendiculars to $A B$ resp. $B C$ are constructed. Prove that these three perpendiculars intersect at the same point.

|

Let us denote the midpoints of the segments $M N, N K, K M$ by $B_{1}, C_{1}, A_{1}$, respectively. It is easy to see that triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$ is homothetic to triangle $N K M$ via the homothety centered at the intersection of the medians of triangle $N M K$ and dilation $-\frac{1}{2}$. The perpendiculars through $M, N, K$ to $A B, B C, C A$, respectively, are also the perpendicular bisectors of these sides, so they intersect in the circumcentre of triangle $A B C$. The desired result follows now from the homothety, and we find that that the common point of intersection is the circumcentre of the image of triangle $A B C$ under the homothety; that is, the circumcentre of the triangle with vertices the midpoints of the sides $A B, B C, C A$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

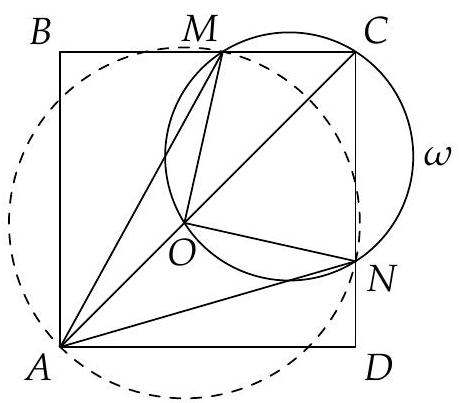

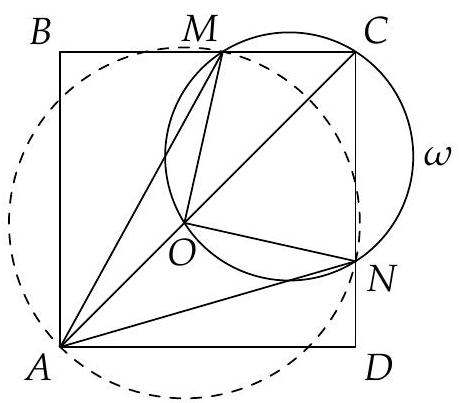

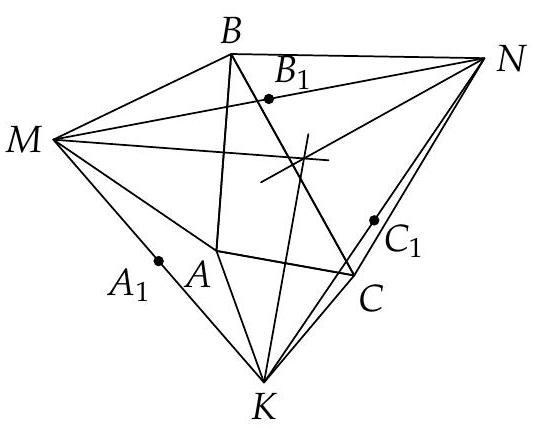

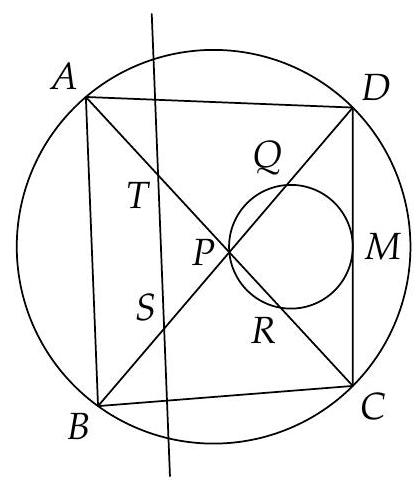

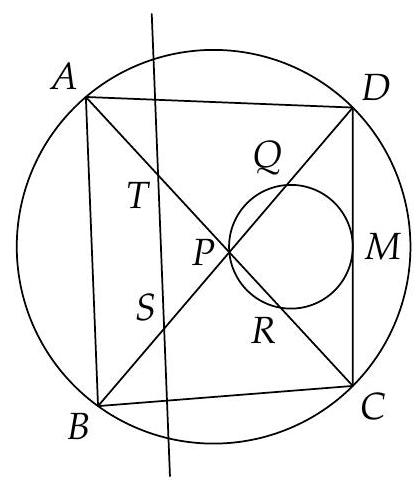

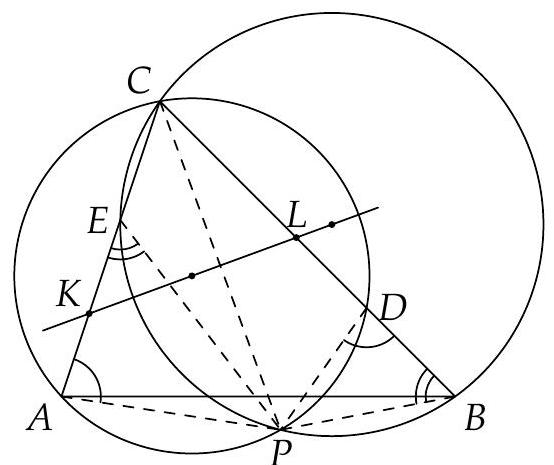

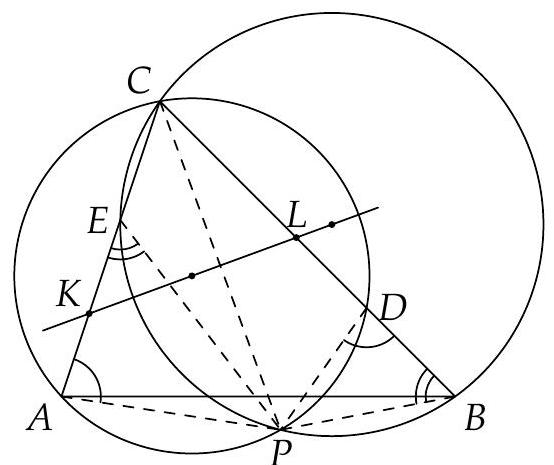

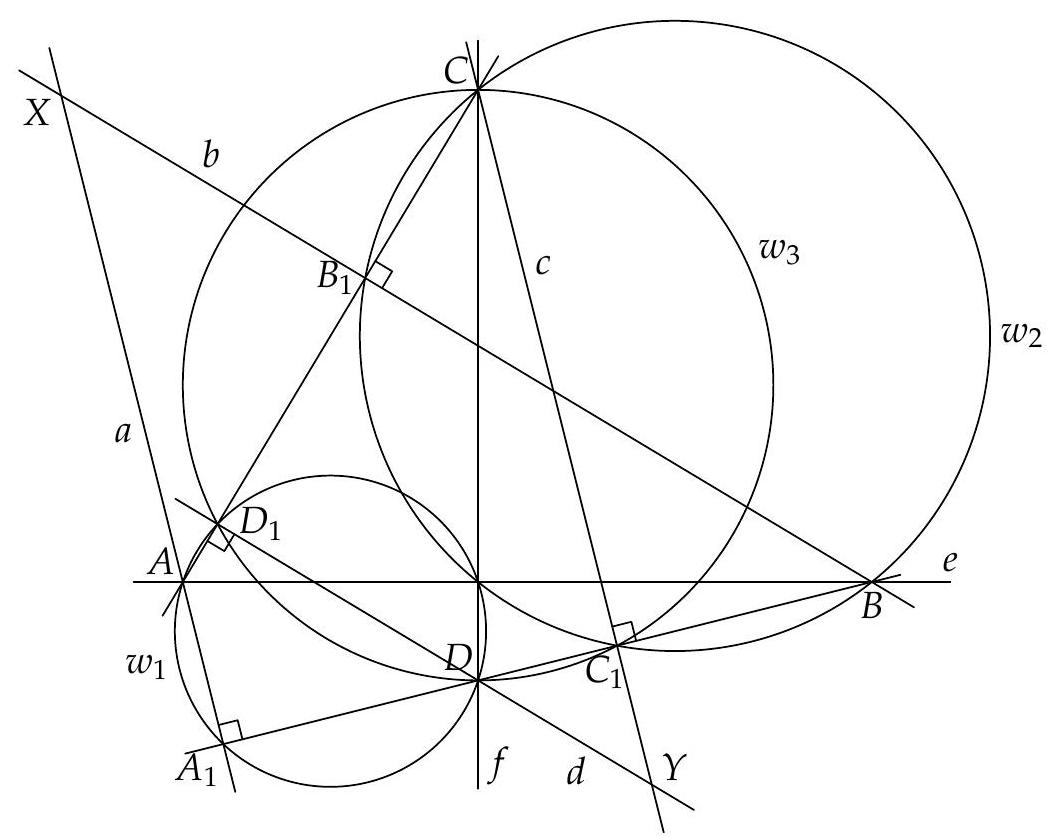

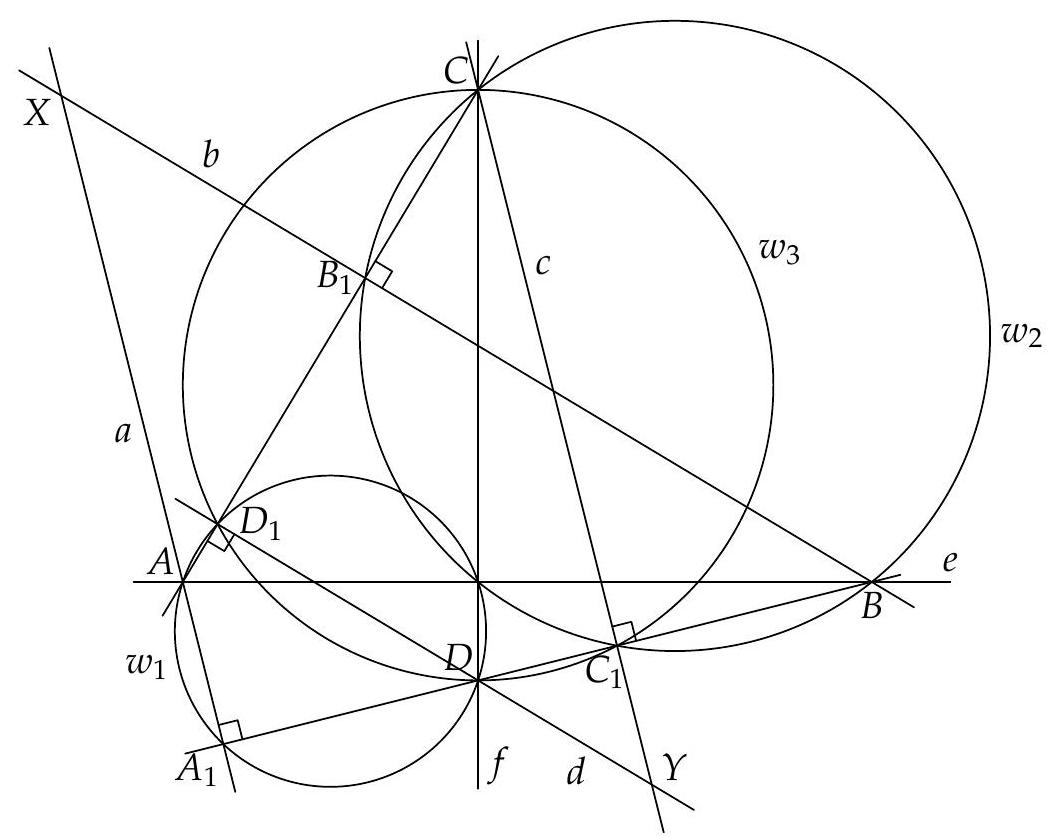

Let $P$ be the intersection point of the diagonals $A C$ and $B D$ in a cyclic quadrilateral. $A$ circle through $P$ touches the side $C D$ in the midpoint $M$ of this side and intersects the segments $B D$ and $A C$ in the points $Q$ and $R$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point on the segment $B D$ such that $B S=D Q$. The parallel to $A B$ through $S$ intersects $A C$ at $T$. Prove that $A T=R C$.

|

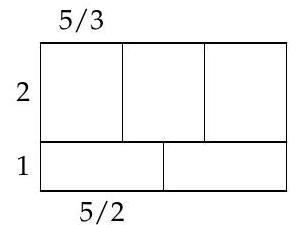

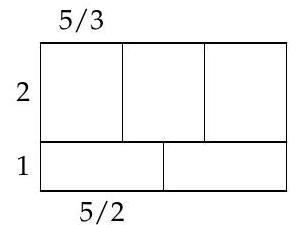

With reference to the figure below we have $C R \cdot C P=D Q \cdot D P=C M^{2}=D M^{2}$, which is equivalent to $R C=\frac{D Q \cdot D P}{C P}$. We also have $\frac{A T}{B S}=\frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A T}{D Q}$, so $A T=\frac{A P \cdot D Q}{B P}$. Since $A B C D$ is cyclic the result now comes from the fact that $D P \cdot B P=A P \cdot C P$ (due to a well-known theorem).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $P$ be the intersection point of the diagonals $A C$ and $B D$ in a cyclic quadrilateral. $A$ circle through $P$ touches the side $C D$ in the midpoint $M$ of this side and intersects the segments $B D$ and $A C$ in the points $Q$ and $R$, respectively. Let $S$ be a point on the segment $B D$ such that $B S=D Q$. The parallel to $A B$ through $S$ intersects $A C$ at $T$. Prove that $A T=R C$.

|

With reference to the figure below we have $C R \cdot C P=D Q \cdot D P=C M^{2}=D M^{2}$, which is equivalent to $R C=\frac{D Q \cdot D P}{C P}$. We also have $\frac{A T}{B S}=\frac{A P}{B P}=\frac{A T}{D Q}$, so $A T=\frac{A P \cdot D Q}{B P}$. Since $A B C D$ is cyclic the result now comes from the fact that $D P \cdot B P=A P \cdot C P$ (due to a well-known theorem).

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Find all pairs of positive integers $(a, b)$ such that $a-b$ is a prime and $a b$ is a perfect square. Answer: Pairs $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$, where $p$ is a prime greater than 2 .

|

Let $p$ be a prime such that $a-b=p$ and let $a b=k^{2}$. Insert $a=b+p$ in the equation $a b=k^{2}$. Then

$$

k^{2}=(b+p) b=\left(b+\frac{p}{2}\right)^{2}-\frac{p^{2}}{4}

$$

which is equivalent to

$$

p^{2}=(2 b+p)^{2}-4 k^{2}=(2 b+p+2 k)(2 b+p-2 k) .

$$

Since $2 b+p+2 k>2 b+p-2 k$ and $p$ is a prime, we conclude $2 b+p+2 k=p^{2}$ and $2 b+p-2 k=1$. By adding these equations we get $2 b+p=\frac{p^{2}+1}{2}$ and then $b=\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}$, so $a=b+p=\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2}$. By checking we conclude that all the solutions are $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$ with $p$ a prime greater than 2 .

|

(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find all pairs of positive integers $(a, b)$ such that $a-b$ is a prime and $a b$ is a perfect square. Answer: Pairs $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$, where $p$ is a prime greater than 2 .

|

Let $p$ be a prime such that $a-b=p$ and let $a b=k^{2}$. Insert $a=b+p$ in the equation $a b=k^{2}$. Then

$$

k^{2}=(b+p) b=\left(b+\frac{p}{2}\right)^{2}-\frac{p^{2}}{4}

$$

which is equivalent to

$$

p^{2}=(2 b+p)^{2}-4 k^{2}=(2 b+p+2 k)(2 b+p-2 k) .

$$

Since $2 b+p+2 k>2 b+p-2 k$ and $p$ is a prime, we conclude $2 b+p+2 k=p^{2}$ and $2 b+p-2 k=1$. By adding these equations we get $2 b+p=\frac{p^{2}+1}{2}$ and then $b=\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}$, so $a=b+p=\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2}$. By checking we conclude that all the solutions are $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$ with $p$ a prime greater than 2 .

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Find all pairs of positive integers $(a, b)$ such that $a-b$ is a prime and $a b$ is a perfect square. Answer: Pairs $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$, where $p$ is a prime greater than 2 .

|

Let $p$ be a prime such that $a-b=p$ and let $a b=k^{2}$. We have $(b+p) b=k^{2}$, so $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=\operatorname{gcd}(b, p)$ is equal either to 1 or $p$. If $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=p$, let $b=b_{1} p$. Then $p^{2} b_{1}\left(b_{1}+1\right)=k^{2}, b_{1}\left(b_{1}+1\right)=m^{2}$, but this equation has no solutions.

Hence $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=1$, and

$$

b=u^{2} \quad b+p=v^{2}

$$

so that $p=v^{2}-u^{2}=(v+u)(v-u)$. This in turn implies that $v-u=1$ and $v+u=p$, from which we finally obtain $a=\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2}, b=\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}$, where $p$ must be an odd prime.

|

(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find all pairs of positive integers $(a, b)$ such that $a-b$ is a prime and $a b$ is a perfect square. Answer: Pairs $(a, b)=\left(\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2},\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}\right)$, where $p$ is a prime greater than 2 .

|

Let $p$ be a prime such that $a-b=p$ and let $a b=k^{2}$. We have $(b+p) b=k^{2}$, so $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=\operatorname{gcd}(b, p)$ is equal either to 1 or $p$. If $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=p$, let $b=b_{1} p$. Then $p^{2} b_{1}\left(b_{1}+1\right)=k^{2}, b_{1}\left(b_{1}+1\right)=m^{2}$, but this equation has no solutions.

Hence $\operatorname{gcd}(b, b+p)=1$, and

$$

b=u^{2} \quad b+p=v^{2}

$$

so that $p=v^{2}-u^{2}=(v+u)(v-u)$. This in turn implies that $v-u=1$ and $v+u=p$, from which we finally obtain $a=\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)^{2}, b=\left(\frac{p-1}{2}\right)^{2}$, where $p$ must be an odd prime.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

All the positive divisors of a positive integer $n$ are stored into an array in increasing order. Mary has to write a program which decides for an arbitrarily chosen divisor $d>1$ whether it is a prime. Let $n$ have $k$ divisors not greater than $d$. Mary claims that it suffices to check divisibility of $d$ by the first $\lceil k / 2\rceil$ divisors of $n$ : If a divisor of $d$ greater than 1 is found among them, then $d$ is composite, otherwise d is prime. Is Mary right?

Answer: Yes, Mary is right.

|

Let $d>1$ be a divisor of $n$. Suppose Mary's program outputs "composite" for $d$. That means it has found a divisor of $d$ greater than 1 . Since $d>1$, the array contains at least 2 divisors of $d$, namely 1 and $d$. Thus Mary's program does not check divisibility of $d$ by $d$ (the first half gets complete before reaching $d$ ) which means that the divisor found lays strictly between 1 and $d$. Hence $d$ is composite indeed.

Suppose now $d$ being composite. Let $p$ be its smallest prime divisor; then $\frac{d}{p} \geq p$ or, equivalently, $d \geq p^{2}$. As $p$ is a divisor of $n$, it occurs in the array. Let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ all divisors of $n$ smaller than $p$. Then $p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ are less than $p^{2}$ and hence less than $d$.

As $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ are all relatively prime with $p$, all the numbers $p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ divide $n$. The numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}, p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ are pairwise different by construction. Thus there are at least $2 k+1$ divisors of $n$ not greater than $d$. So Mary's program checks divisibility of $d$ by at least $k+1$ smallest divisors of $n$, among which it finds $p$, and outputs "composite".

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

All the positive divisors of a positive integer $n$ are stored into an array in increasing order. Mary has to write a program which decides for an arbitrarily chosen divisor $d>1$ whether it is a prime. Let $n$ have $k$ divisors not greater than $d$. Mary claims that it suffices to check divisibility of $d$ by the first $\lceil k / 2\rceil$ divisors of $n$ : If a divisor of $d$ greater than 1 is found among them, then $d$ is composite, otherwise d is prime. Is Mary right?

Answer: Yes, Mary is right.

|

Let $d>1$ be a divisor of $n$. Suppose Mary's program outputs "composite" for $d$. That means it has found a divisor of $d$ greater than 1 . Since $d>1$, the array contains at least 2 divisors of $d$, namely 1 and $d$. Thus Mary's program does not check divisibility of $d$ by $d$ (the first half gets complete before reaching $d$ ) which means that the divisor found lays strictly between 1 and $d$. Hence $d$ is composite indeed.

Suppose now $d$ being composite. Let $p$ be its smallest prime divisor; then $\frac{d}{p} \geq p$ or, equivalently, $d \geq p^{2}$. As $p$ is a divisor of $n$, it occurs in the array. Let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ all divisors of $n$ smaller than $p$. Then $p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ are less than $p^{2}$ and hence less than $d$.

As $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ are all relatively prime with $p$, all the numbers $p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ divide $n$. The numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}, p a_{1}, \ldots, p a_{k}$ are pairwise different by construction. Thus there are at least $2 k+1$ divisors of $n$ not greater than $d$. So Mary's program checks divisibility of $d$ by at least $k+1$ smallest divisors of $n$, among which it finds $p$, and outputs "composite".

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\n17.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Every integer is coloured with exactly one of the colours BLUE, GREEN, RED, YELLOW. Can this be done in such a way that if $a, b, c, d$ are not all 0 and have the same colour, then $3 a-2 b \neq 2 c-3 d$ ?

Answer: Yes.

|

A colouring with the required property can be defined as follows. For a non-zero integer $k$ let $k^{*}$ be the integer uniquely defined by $k=5^{m} \cdot k^{*}$, where $m$ is a nonnegative integer and $5 \nmid k^{*}$. We also define $0^{*}=0$. Two non-zero integers $k_{1}, k_{2}$ receive the same colour if and only if $k_{1}^{*} \equiv k_{2}^{*}(\bmod 5)$; we assign 0 any colour.

Assume $a, b, c, d$ has the same colour and that $3 a-2 b=2 c-3 d$, which we rewrite as $3 a-2 b-2 c+3 d=0$. Dividing both sides by the largest power of 5 which simultaneously divides $a, b, c, d$ (this makes sense since not all of $a, b, c, d$ are 0 ), we obtain

$$

3 \cdot 5^{A} \cdot a^{*}-2 \cdot 5^{B} \cdot b^{*}-2 \cdot 5^{C} \cdot c^{*}+3 \cdot 5^{D} \cdot d^{*}=0,

$$

where $A, B, C, D$ are nonnegative integers at least one of which is equal to 0 . The above equality implies

$$

3\left(5^{A} \cdot a^{*}+5^{B} \cdot b^{*}+5^{C} \cdot c^{*}+5^{D} \cdot d^{*}\right) \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 5) .

$$

Assume $a, b, c, d$ are all non-zero. Then $a^{*} \equiv b^{*} \equiv c^{*} \equiv d^{*} \not \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$. This implies

$$

5^{A}+5^{B}+5^{C}+5^{D} \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

which is impossible since at least one of the numbers $A, B, C, D$ is equal to 0 . If one or more of $a, b, c, d$ are 0 , we simply omit the corresponding terms from (1), and the same conclusion holds.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Every integer is coloured with exactly one of the colours BLUE, GREEN, RED, YELLOW. Can this be done in such a way that if $a, b, c, d$ are not all 0 and have the same colour, then $3 a-2 b \neq 2 c-3 d$ ?

Answer: Yes.

|

A colouring with the required property can be defined as follows. For a non-zero integer $k$ let $k^{*}$ be the integer uniquely defined by $k=5^{m} \cdot k^{*}$, where $m$ is a nonnegative integer and $5 \nmid k^{*}$. We also define $0^{*}=0$. Two non-zero integers $k_{1}, k_{2}$ receive the same colour if and only if $k_{1}^{*} \equiv k_{2}^{*}(\bmod 5)$; we assign 0 any colour.

Assume $a, b, c, d$ has the same colour and that $3 a-2 b=2 c-3 d$, which we rewrite as $3 a-2 b-2 c+3 d=0$. Dividing both sides by the largest power of 5 which simultaneously divides $a, b, c, d$ (this makes sense since not all of $a, b, c, d$ are 0 ), we obtain

$$

3 \cdot 5^{A} \cdot a^{*}-2 \cdot 5^{B} \cdot b^{*}-2 \cdot 5^{C} \cdot c^{*}+3 \cdot 5^{D} \cdot d^{*}=0,

$$

where $A, B, C, D$ are nonnegative integers at least one of which is equal to 0 . The above equality implies

$$

3\left(5^{A} \cdot a^{*}+5^{B} \cdot b^{*}+5^{C} \cdot c^{*}+5^{D} \cdot d^{*}\right) \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 5) .

$$

Assume $a, b, c, d$ are all non-zero. Then $a^{*} \equiv b^{*} \equiv c^{*} \equiv d^{*} \not \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$. This implies

$$

5^{A}+5^{B}+5^{C}+5^{D} \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

which is impossible since at least one of the numbers $A, B, C, D$ is equal to 0 . If one or more of $a, b, c, d$ are 0 , we simply omit the corresponding terms from (1), and the same conclusion holds.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $a$ and $b$ be positive integers. Prove that if $a^{3}+b^{3}$ is the square of an integer, then $a+b$ is not a product of two different prime numbers.

|

Suppose $a+b=p q$, where $p \neq q$ are two prime numbers. We may assume that $p \neq 3$. Since

$$

a^{3}+b^{3}=(a+b)\left(a^{2}-a b+b^{2}\right)

$$

is a square, the number $a^{2}-a b+b^{2}=(a+b)^{2}-3 a b$ must be divisible by $p$ and $q$, whence $3 a b$ must be divisible by $p$ and $q$. But $p \neq 3$, so $p \mid a$ or $p \mid b$; but $p \mid a+b$, so $p \mid a$ and $p \mid b$. Write $a=p k, b=p \ell$ for some integers $k, \ell$. Notice that $q=3$, since otherwise, repeating the above argument, we would have $q|a, q| b$ and $a+b>p q)$. So we have

$$

3 p=a+b=p(k+\ell)

$$

and we conclude that $a=p, b=2 p$ or $a=2 p, b=p$. Then $a^{3}+b^{3}=9 p^{3}$ is obviously not a square, a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $a$ and $b$ be positive integers. Prove that if $a^{3}+b^{3}$ is the square of an integer, then $a+b$ is not a product of two different prime numbers.

|

Suppose $a+b=p q$, where $p \neq q$ are two prime numbers. We may assume that $p \neq 3$. Since

$$

a^{3}+b^{3}=(a+b)\left(a^{2}-a b+b^{2}\right)

$$

is a square, the number $a^{2}-a b+b^{2}=(a+b)^{2}-3 a b$ must be divisible by $p$ and $q$, whence $3 a b$ must be divisible by $p$ and $q$. But $p \neq 3$, so $p \mid a$ or $p \mid b$; but $p \mid a+b$, so $p \mid a$ and $p \mid b$. Write $a=p k, b=p \ell$ for some integers $k, \ell$. Notice that $q=3$, since otherwise, repeating the above argument, we would have $q|a, q| b$ and $a+b>p q)$. So we have

$$

3 p=a+b=p(k+\ell)

$$

and we conclude that $a=p, b=2 p$ or $a=2 p, b=p$. Then $a^{3}+b^{3}=9 p^{3}$ is obviously not a square, a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "\n19.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer such that the sum of all the positive divisors of $n$ (except $n$ ) plus the number of these divisors is equal to $n$. Prove that $n=2 m^{2}$ for some integer $m$.

|

Let $t_{1}<t_{2}<\cdots<t_{s}$ be all positive odd divisors of $n$, and let $2^{k}$ be the maximal power of 2 that divides $n$. Then the full list of divisors of $n$ is the following:

$$

t_{1}, \ldots, t_{s}, 2 t_{1}, \ldots, 2 t_{s}, \ldots, 2^{k} t_{1}, \ldots, 2^{k} t_{s} .

$$

Hence,

$$

2 n=\left(2^{k+1}-1\right)\left(t_{1}+t_{2}+\cdots+t_{s}\right)+(k+1) s-1 .

$$

The right-hand side can be even only if both $k$ and $s$ are odd. In this case the number $n / 2^{k}$ has an odd number of divisors and therefore it is equal to a perfect square $r^{2}$. Writing $k=2 a+1$, we have $n=2^{k} r^{2}=2\left(2^{a} r\right)^{2}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer such that the sum of all the positive divisors of $n$ (except $n$ ) plus the number of these divisors is equal to $n$. Prove that $n=2 m^{2}$ for some integer $m$.

|

Let $t_{1}<t_{2}<\cdots<t_{s}$ be all positive odd divisors of $n$, and let $2^{k}$ be the maximal power of 2 that divides $n$. Then the full list of divisors of $n$ is the following:

$$

t_{1}, \ldots, t_{s}, 2 t_{1}, \ldots, 2 t_{s}, \ldots, 2^{k} t_{1}, \ldots, 2^{k} t_{s} .

$$

Hence,

$$

2 n=\left(2^{k+1}-1\right)\left(t_{1}+t_{2}+\cdots+t_{s}\right)+(k+1) s-1 .

$$

The right-hand side can be even only if both $k$ and $s$ are odd. In this case the number $n / 2^{k}$ has an odd number of divisors and therefore it is equal to a perfect square $r^{2}$. Writing $k=2 a+1$, we have $n=2^{k} r^{2}=2\left(2^{a} r\right)^{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw03sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Given a sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of non-negative real numbers satisfying the conditions

(1) $a_{n}+a_{2 n} \geq 3 n$

(2) $a_{n+1}+n \leq 2 \sqrt{a_{n} \cdot(n+1)}$

for all indices $n=1,2 \ldots$

(a) Prove that the inequality $a_{n} \geq n$ holds for every $n \in \mathbb{N}$.

(b) Give an example of such a sequence.

|

(a) Note that the inequality

$$

\frac{a_{n+1}+n}{2} \geq \sqrt{a_{n+1} \cdot n}

$$

holds, which together with the second condition of the problem gives

$$

\sqrt{a_{n+1} \cdot n} \leq \sqrt{a_{n} \cdot(n+1)}

$$

This inequality simplifies to

$$

\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_{n}} \leq \frac{n+1}{n}

$$

Now, using the last inequality for the index $n$ replaced by $n, n+1, \ldots, 2 n-1$ and multiplying the results, we obtain

$$

\frac{a_{2 n}}{a_{n}} \leq \frac{2 n}{n}=2

$$

or $2 a_{n} \geq a_{2 n}$. Taking into account the first condition of the problem, we have

$$

3 a_{n}=a_{n}+2 a_{n} \geq a_{n}+a_{2 n} \geq 3 n

$$

which implies $a_{n} \geq n$. (b) The sequence defined by $a_{n}=n+1$ satisfies all the conditions of the problem.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Given a sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of non-negative real numbers satisfying the conditions

(1) $a_{n}+a_{2 n} \geq 3 n$

(2) $a_{n+1}+n \leq 2 \sqrt{a_{n} \cdot(n+1)}$

for all indices $n=1,2 \ldots$

(a) Prove that the inequality $a_{n} \geq n$ holds for every $n \in \mathbb{N}$.

(b) Give an example of such a sequence.

|

(a) Note that the inequality

$$

\frac{a_{n+1}+n}{2} \geq \sqrt{a_{n+1} \cdot n}

$$

holds, which together with the second condition of the problem gives

$$

\sqrt{a_{n+1} \cdot n} \leq \sqrt{a_{n} \cdot(n+1)}

$$

This inequality simplifies to

$$

\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_{n}} \leq \frac{n+1}{n}

$$

Now, using the last inequality for the index $n$ replaced by $n, n+1, \ldots, 2 n-1$ and multiplying the results, we obtain

$$

\frac{a_{2 n}}{a_{n}} \leq \frac{2 n}{n}=2

$$

or $2 a_{n} \geq a_{2 n}$. Taking into account the first condition of the problem, we have

$$

3 a_{n}=a_{n}+2 a_{n} \geq a_{n}+a_{2 n} \geq 3 n

$$

which implies $a_{n} \geq n$. (b) The sequence defined by $a_{n}=n+1$ satisfies all the conditions of the problem.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Let $P(x)$ be a polynomial with non-negative coefficients. Prove that if $P\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) P(x) \geq 1$ for $x=1$, then the same inequality holds for each positive $x$.

|

For $x>0$ we have $P(x)>0$ (because at least one coefficient is non-zero). From the given condition we have $(P(1))^{2} \geq 1$. Further, let's denote $P(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+$ $\cdots+a_{0}$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(x) P\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) & =\left(a_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+a_{0}\right)\left(a_{n} x^{-n}+\cdots+a_{0}\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i}^{2}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=0}^{i-1}\left(a_{i-j} a_{j}\right)\left(x^{i}+x^{-i}\right) \\

& \geq \sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i}^{2}+2 \sum_{i>j} a_{i} a_{j} \\

& =(P(1))^{2} \geq 1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $P(x)$ be a polynomial with non-negative coefficients. Prove that if $P\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) P(x) \geq 1$ for $x=1$, then the same inequality holds for each positive $x$.

|

For $x>0$ we have $P(x)>0$ (because at least one coefficient is non-zero). From the given condition we have $(P(1))^{2} \geq 1$. Further, let's denote $P(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+$ $\cdots+a_{0}$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(x) P\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) & =\left(a_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+a_{0}\right)\left(a_{n} x^{-n}+\cdots+a_{0}\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i}^{2}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=0}^{i-1}\left(a_{i-j} a_{j}\right)\left(x^{i}+x^{-i}\right) \\

& \geq \sum_{i=0}^{n} a_{i}^{2}+2 \sum_{i>j} a_{i} a_{j} \\

& =(P(1))^{2} \geq 1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Let $p, q, r$ be positive real numbers and $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Show that if $p q r=1$, then

$$

\frac{1}{p^{n}+q^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{q^{n}+r^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{r^{n}+p^{n}+1} \leq 1

$$

|

The key idea is to deal with the case $n=3$. Put $a=p^{n / 3}, b=q^{n / 3}$, and $c=r^{n / 3}$, so $a b c=(p q r)^{n / 3}=1$ and

$$

\frac{1}{p^{n}+q^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{q^{n}+r^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{r^{n}+p^{n}+1}=\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} .

$$

Now

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}=\frac{1}{(a+b)\left(a^{2}-a b+b^{2}\right)+1}=\frac{1}{(a+b)\left((a-b)^{2}+a b\right)+1} \leq \frac{1}{(a+b) a b+1} .

$$

Since $a b=c^{-1}$,

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1} \leq \frac{1}{(a+b) a b+1}=\frac{c}{a+b+c}

$$

Similarly we obtain

$$

\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1} \leq \frac{a}{a+b+c} \quad \text { and } \quad \frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} \leq \frac{b}{a+b+c}

$$

Hence

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} \leq \frac{c}{a+b+c}+\frac{a}{a+b+c}+\frac{b}{a+b+c}=1,

$$

which was to be shown.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $p, q, r$ be positive real numbers and $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Show that if $p q r=1$, then

$$

\frac{1}{p^{n}+q^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{q^{n}+r^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{r^{n}+p^{n}+1} \leq 1

$$

|

The key idea is to deal with the case $n=3$. Put $a=p^{n / 3}, b=q^{n / 3}$, and $c=r^{n / 3}$, so $a b c=(p q r)^{n / 3}=1$ and

$$

\frac{1}{p^{n}+q^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{q^{n}+r^{n}+1}+\frac{1}{r^{n}+p^{n}+1}=\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} .

$$

Now

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}=\frac{1}{(a+b)\left(a^{2}-a b+b^{2}\right)+1}=\frac{1}{(a+b)\left((a-b)^{2}+a b\right)+1} \leq \frac{1}{(a+b) a b+1} .

$$

Since $a b=c^{-1}$,

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1} \leq \frac{1}{(a+b) a b+1}=\frac{c}{a+b+c}

$$

Similarly we obtain

$$

\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1} \leq \frac{a}{a+b+c} \quad \text { and } \quad \frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} \leq \frac{b}{a+b+c}

$$

Hence

$$

\frac{1}{a^{3}+b^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{b^{3}+c^{3}+1}+\frac{1}{c^{3}+a^{3}+1} \leq \frac{c}{a+b+c}+\frac{a}{a+b+c}+\frac{b}{a+b+c}=1,

$$

which was to be shown.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Let $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$ be real numbers with arithmetic mean $X$. Prove that there is a positive integer $K$ such that the arithmetic mean of each of the lists $\left\{x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{K}\right\},\left\{x_{2}, x_{3}, \ldots, x_{K}\right\}$, $\ldots,\left\{x_{K-1}, x_{K}\right\},\left\{x_{K}\right\}$ is not greater than $X$.

|

Suppose the conclusion is false. This means that for every $K \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$, there exists a $k \leq K$ such that the arithmetic mean of $x_{k}, x_{k+1}, \ldots, x_{K}$ exceeds $X$. We now define a decreasing sequence $b_{1} \geq a_{1}>a_{1}-1=b_{2} \geq a_{2}>\cdots$ as follows: Put $b_{1}=n$, and for each $i$, let $a_{i}$ be the largest largest $k \leq b_{i}$ such that the arithmetic mean of $x_{a_{i}}, \ldots, x_{b_{i}}$ exceeds $X$; then put $b_{i+1}=a_{i}-1$ and repeat. Clearly for some $m, a_{m}=1$. Now, by construction, each of the sets $\left\{x_{a_{m}}, \ldots, x_{b_{m}}\right\},\left\{x_{a_{m-1}}, \ldots, x_{b_{m-1}}\right\}, \ldots,\left\{x_{a_{1}}, \ldots, x_{b_{1}}\right\}$ has arithmetic mean strictly greater than $X$, but then the union $\left\{x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}\right\}$ of these sets has arithmetic mean strictly greater than $X$; a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Let $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$ be real numbers with arithmetic mean $X$. Prove that there is a positive integer $K$ such that the arithmetic mean of each of the lists $\left\{x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{K}\right\},\left\{x_{2}, x_{3}, \ldots, x_{K}\right\}$, $\ldots,\left\{x_{K-1}, x_{K}\right\},\left\{x_{K}\right\}$ is not greater than $X$.

|

Suppose the conclusion is false. This means that for every $K \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$, there exists a $k \leq K$ such that the arithmetic mean of $x_{k}, x_{k+1}, \ldots, x_{K}$ exceeds $X$. We now define a decreasing sequence $b_{1} \geq a_{1}>a_{1}-1=b_{2} \geq a_{2}>\cdots$ as follows: Put $b_{1}=n$, and for each $i$, let $a_{i}$ be the largest largest $k \leq b_{i}$ such that the arithmetic mean of $x_{a_{i}}, \ldots, x_{b_{i}}$ exceeds $X$; then put $b_{i+1}=a_{i}-1$ and repeat. Clearly for some $m, a_{m}=1$. Now, by construction, each of the sets $\left\{x_{a_{m}}, \ldots, x_{b_{m}}\right\},\left\{x_{a_{m-1}}, \ldots, x_{b_{m-1}}\right\}, \ldots,\left\{x_{a_{1}}, \ldots, x_{b_{1}}\right\}$ has arithmetic mean strictly greater than $X$, but then the union $\left\{x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}\right\}$ of these sets has arithmetic mean strictly greater than $X$; a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Determine the range of the function $f$ defined for integers $k$ by

$$

f(k)=(k)_{3}+(2 k)_{5}+(3 k)_{7}-6 k

$$

where $(k)_{2 n+1}$ denotes the multiple of $2 n+1$ closest to $k$.

|

For odd $n$ we have

$$

(k)_{n}=k+\frac{n-1}{2}-\left[k+\frac{n-1}{2}\right]_{n^{\prime}}

$$

where $[m]_{n}$ denotes the principal remainder of $m$ modulo $n$. Hence we get

$$

f(k)=6-[k+1]_{3}-[2 k+2]_{5}-[3 k+3]_{7}

$$

The condition that the principal remainders take the values $a, b$ and $c$, respectively, may be written

$$

\begin{aligned}

k+1 \equiv a & (\bmod 3) \\

2 k+2 \equiv b & (\bmod 5) \\

3 k+3 & \equiv c \quad(\bmod 7)

\end{aligned}

$$

or

$$

\begin{aligned}

& k \equiv a-1 \quad(\bmod 3) \\

& k \equiv-2 b-1 \quad(\bmod 5) \\

& k \equiv-2 c-1 \quad(\bmod 7)

\end{aligned}

$$

By the Chinese Remainder Theorem, these congruences have a solution for any set of $a, b, c$. Hence $f$ takes all the integer values between $6-2-4-6=-6$ and $6-0-0-0=$ 6. (In fact, this proof also shows that $f$ is periodic with period $3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7=105$.)

|

-6 \text{ to } 6

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Determine the range of the function $f$ defined for integers $k$ by

$$

f(k)=(k)_{3}+(2 k)_{5}+(3 k)_{7}-6 k

$$

where $(k)_{2 n+1}$ denotes the multiple of $2 n+1$ closest to $k$.

|

For odd $n$ we have

$$

(k)_{n}=k+\frac{n-1}{2}-\left[k+\frac{n-1}{2}\right]_{n^{\prime}}

$$

where $[m]_{n}$ denotes the principal remainder of $m$ modulo $n$. Hence we get

$$

f(k)=6-[k+1]_{3}-[2 k+2]_{5}-[3 k+3]_{7}

$$

The condition that the principal remainders take the values $a, b$ and $c$, respectively, may be written

$$

\begin{aligned}

k+1 \equiv a & (\bmod 3) \\

2 k+2 \equiv b & (\bmod 5) \\

3 k+3 & \equiv c \quad(\bmod 7)

\end{aligned}

$$

or

$$

\begin{aligned}

& k \equiv a-1 \quad(\bmod 3) \\

& k \equiv-2 b-1 \quad(\bmod 5) \\

& k \equiv-2 c-1 \quad(\bmod 7)

\end{aligned}

$$

By the Chinese Remainder Theorem, these congruences have a solution for any set of $a, b, c$. Hence $f$ takes all the integer values between $6-2-4-6=-6$ and $6-0-0-0=$ 6. (In fact, this proof also shows that $f$ is periodic with period $3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7=105$.)

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

A positive integer is written on each of the six faces of a cube. For each vertex of the cube we compute the product of the numbers on the three adjacent faces. The sum of these products is 1001. What is the sum of the six numbers on the faces?

|

Let the numbers on the faces be $a_{1}, a_{2}, b_{1}, b_{2}, c_{1}, c_{2}$, placed so that $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are on opposite faces etc. Then the sum of the eight products is equal to

$$

\left(a_{1}+a_{2}\right)\left(b_{1}+b_{2}\right)\left(c_{1}+c_{2}\right)=1001=7 \cdot 11 \cdot 13 .

$$

Hence the sum of the numbers on the faces is $a_{1}+a_{2}+b_{1}+b_{2}+c_{1}+c_{2}=7+11+13=$ 31.

|

31

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A positive integer is written on each of the six faces of a cube. For each vertex of the cube we compute the product of the numbers on the three adjacent faces. The sum of these products is 1001. What is the sum of the six numbers on the faces?

|

Let the numbers on the faces be $a_{1}, a_{2}, b_{1}, b_{2}, c_{1}, c_{2}$, placed so that $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are on opposite faces etc. Then the sum of the eight products is equal to

$$

\left(a_{1}+a_{2}\right)\left(b_{1}+b_{2}\right)\left(c_{1}+c_{2}\right)=1001=7 \cdot 11 \cdot 13 .

$$

Hence the sum of the numbers on the faces is $a_{1}+a_{2}+b_{1}+b_{2}+c_{1}+c_{2}=7+11+13=$ 31.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Find all sets $X$ consisting of at least two positive integers such that for every pair $m, n \in X$, where $n>m$, there exists $k \in X$ such that $n=m k^{2}$.

Answer: The sets $\left\{m, m^{3}\right\}$, where $m>1$.

|

Let $X$ be a set satisfying the condition of the problem and let $n>m$ be the two smallest elements in the set $X$. There has to exist a $k \in X$ so that $n=m k^{2}$, but as $m \leq k \leq n$, either $k=n$ or $k=m$. The first case gives $m=n=1$, a contradiction; the second case implies $n=m^{3}$ with $m>1$.

Suppose there exists a third smallest element $q \in X$. Then there also exists $k_{0} \in X$, such that $q=m k_{0}^{2}$. We have $q>k_{0} \geq m$, but $k_{0}=m$ would imply $q=n$, thus $k_{0}=n=m^{3}$ and $q=m^{7}$. Now for $q$ and $n$ there has to exist $k_{1} \in X$ such that $q=n k_{1}^{2}$, which gives $k_{1}=m^{2}$. Since $m^{2} \notin X$, we have a contradiction.

Thus we see that the only possible sets are those of the form $\left\{m, m^{3}\right\}$ with $m>1$, and these are easily seen to satisfy the conditions of the problem.

|

\left\{m, m^{3}\right\}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find all sets $X$ consisting of at least two positive integers such that for every pair $m, n \in X$, where $n>m$, there exists $k \in X$ such that $n=m k^{2}$.

Answer: The sets $\left\{m, m^{3}\right\}$, where $m>1$.

|

Let $X$ be a set satisfying the condition of the problem and let $n>m$ be the two smallest elements in the set $X$. There has to exist a $k \in X$ so that $n=m k^{2}$, but as $m \leq k \leq n$, either $k=n$ or $k=m$. The first case gives $m=n=1$, a contradiction; the second case implies $n=m^{3}$ with $m>1$.

Suppose there exists a third smallest element $q \in X$. Then there also exists $k_{0} \in X$, such that $q=m k_{0}^{2}$. We have $q>k_{0} \geq m$, but $k_{0}=m$ would imply $q=n$, thus $k_{0}=n=m^{3}$ and $q=m^{7}$. Now for $q$ and $n$ there has to exist $k_{1} \in X$ such that $q=n k_{1}^{2}$, which gives $k_{1}=m^{2}$. Since $m^{2} \notin X$, we have a contradiction.

Thus we see that the only possible sets are those of the form $\left\{m, m^{3}\right\}$ with $m>1$, and these are easily seen to satisfy the conditions of the problem.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw04sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Let $f$ be a non-constant polynomial with integer coefficients. Prove that there is an integer $n$ such that $f(n)$ has at least 2004 distinct prime factors.

|