problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Given positive real numbers $a, b, c, d$ that satisfy equalities

$$

a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c \quad \text { and } \quad a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}

$$

find all possible values of the expression $\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}$.

Answer: $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$.

|

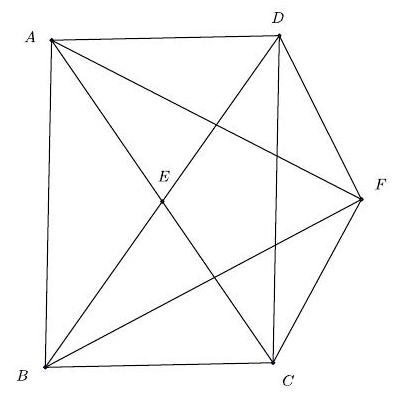

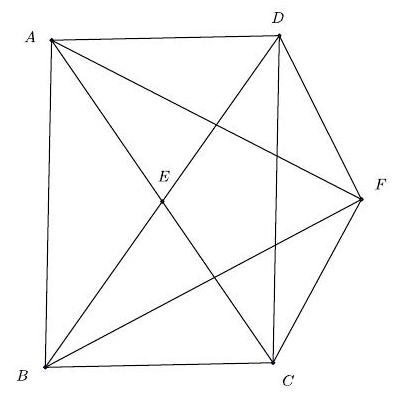

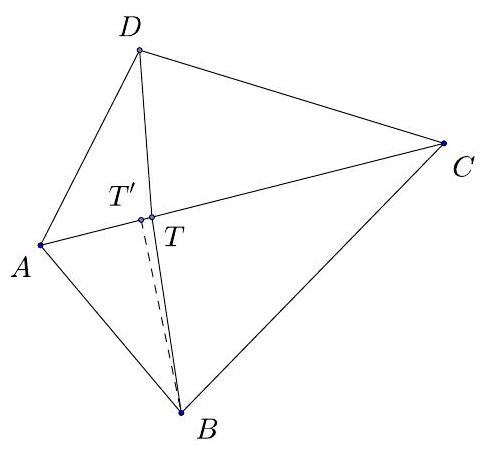

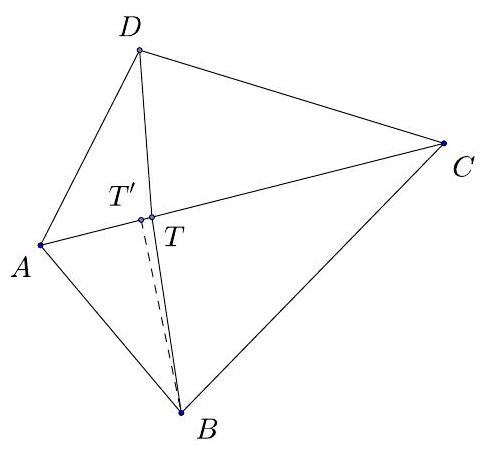

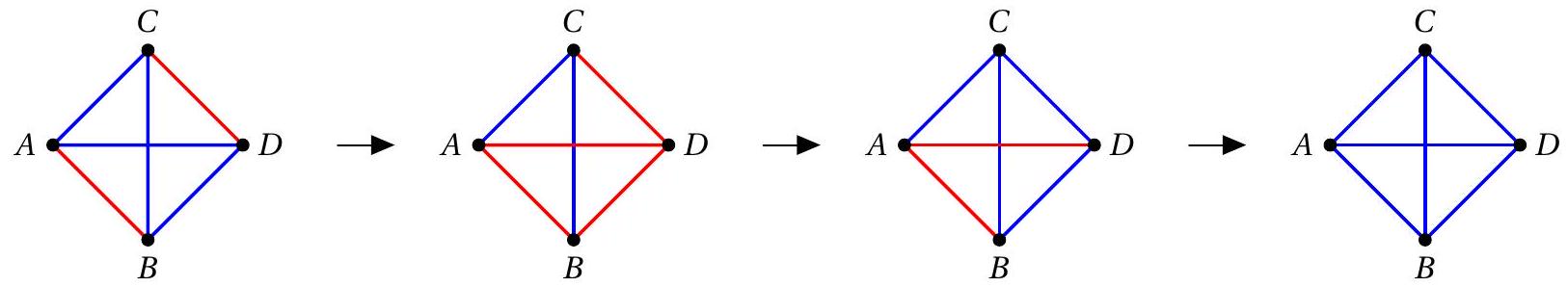

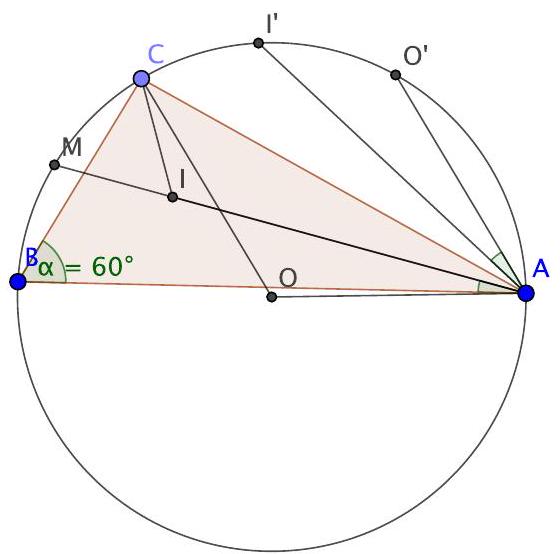

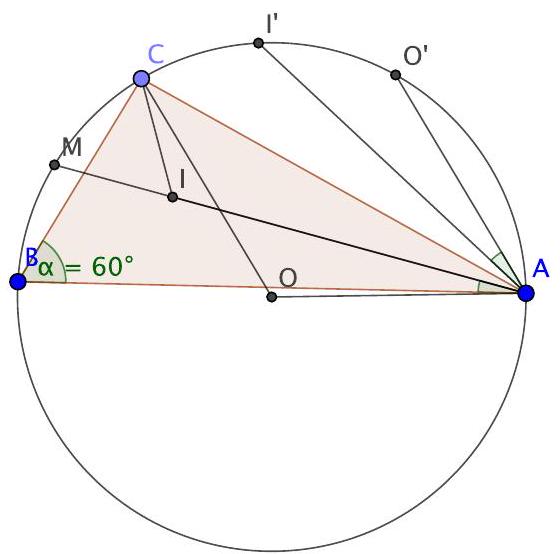

. Let $A_{1} B C_{1}$ be a triangle with $A_{1} B=b, B C_{1}=c$ and $\angle A_{1} B C_{1}=120^{\circ}$, and let $C_{2} D A_{2}$ be another triangle with $C_{2} D=d, D A_{2}=a$ and $\angle C_{2} D A_{2}=60^{\circ}$. By the law of cosines and the assumption $a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c$, we have $A_{1} C_{1}=A_{2} C_{2}$. Thus, the two triangles can be put together to form a quadrilateral $A B C D$ with $A B=b$, $B C=c, C D=d, D A=a$ and $\angle A B C=120^{\circ}, \angle C D A=60^{\circ}$. Then $\angle D A B+\angle B C D=$ $360^{\circ}-(\angle A B C+\angle C D A)=180^{\circ}$.

Suppose that $\angle D A B>90^{\circ}$. Then $\angle B C D<90^{\circ}$, whence $a^{2}+b^{2}<B D^{2}<c^{2}+d^{2}$, contradicting the assumption $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}$. By symmetry, $\angle D A B<90^{\circ}$ also leads to a contradiction. Hence, $\angle D A B=\angle B C D=90^{\circ}$. Now, let us calculate the area of $A B C D$ in two ways: on one hand, it equals $\frac{1}{2} a d \sin 60^{\circ}+\frac{1}{2} b c \sin 120^{\circ}$ or $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}(a d+b c)$. On the other hand, it equals $\frac{1}{2} a b+\frac{1}{2} c d$ or $\frac{1}{2}(a b+c d)$. Consequently,

$$

\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}=\frac{\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}}{\frac{1}{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

$$

|

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Given positive real numbers $a, b, c, d$ that satisfy equalities

$$

a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c \quad \text { and } \quad a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}

$$

find all possible values of the expression $\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}$.

Answer: $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$.

|

. Let $A_{1} B C_{1}$ be a triangle with $A_{1} B=b, B C_{1}=c$ and $\angle A_{1} B C_{1}=120^{\circ}$, and let $C_{2} D A_{2}$ be another triangle with $C_{2} D=d, D A_{2}=a$ and $\angle C_{2} D A_{2}=60^{\circ}$. By the law of cosines and the assumption $a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c$, we have $A_{1} C_{1}=A_{2} C_{2}$. Thus, the two triangles can be put together to form a quadrilateral $A B C D$ with $A B=b$, $B C=c, C D=d, D A=a$ and $\angle A B C=120^{\circ}, \angle C D A=60^{\circ}$. Then $\angle D A B+\angle B C D=$ $360^{\circ}-(\angle A B C+\angle C D A)=180^{\circ}$.

Suppose that $\angle D A B>90^{\circ}$. Then $\angle B C D<90^{\circ}$, whence $a^{2}+b^{2}<B D^{2}<c^{2}+d^{2}$, contradicting the assumption $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}$. By symmetry, $\angle D A B<90^{\circ}$ also leads to a contradiction. Hence, $\angle D A B=\angle B C D=90^{\circ}$. Now, let us calculate the area of $A B C D$ in two ways: on one hand, it equals $\frac{1}{2} a d \sin 60^{\circ}+\frac{1}{2} b c \sin 120^{\circ}$ or $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}(a d+b c)$. On the other hand, it equals $\frac{1}{2} a b+\frac{1}{2} c d$ or $\frac{1}{2}(a b+c d)$. Consequently,

$$

\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}=\frac{\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}}{\frac{1}{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Given positive real numbers $a, b, c, d$ that satisfy equalities

$$

a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c \quad \text { and } \quad a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}

$$

find all possible values of the expression $\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}$.

Answer: $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$.

|

. Setting $T^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}$, where $T>0$, we can write

$$

a=T \sin \alpha, \quad b=T \cos \alpha, \quad c=T \sin \beta, \quad d=T \cos \beta

$$

for some $\alpha, \beta \in(0, \pi / 2)$. With this notation, the first equality gives

$$

\sin ^{2} \alpha+\cos ^{2} \beta-\sin \alpha \cos \beta=\sin ^{2} \beta+\cos ^{2} \alpha+\cos \alpha \sin \beta .

$$

Hence, $\cos (2 \beta)-\cos (2 \alpha)=\sin (\alpha+\beta)$. Since $\cos (2 \beta)-\cos (2 \alpha)=2 \sin (\alpha-\beta) \sin (\alpha+\beta)$ and $\sin (\alpha+\beta) \neq 0$, this yields $\sin (\alpha-\beta)=1 / 2$. Thus, in view of $\alpha-\beta \in(-\pi / 2, \pi / 2)$ we deduce that $\cos (\alpha-\beta)=\sqrt{1-\sin ^{2}(\alpha-\beta)}=\sqrt{3} / 2$.

Now, observing that $a b+c d=\frac{T^{2}}{2}(\sin (2 \alpha)+\sin (2 \beta))=T^{2} \sin (\alpha+\beta) \cos (\alpha-\beta)$ and $a d+b c=T^{2} \sin (\alpha+\beta)$, we obtain $(a b+c d) /(a d+b c)=\cos (\alpha-\beta)=\sqrt{3} / 2$.

|

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Given positive real numbers $a, b, c, d$ that satisfy equalities

$$

a^{2}+d^{2}-a d=b^{2}+c^{2}+b c \quad \text { and } \quad a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}

$$

find all possible values of the expression $\frac{a b+c d}{a d+b c}$.

Answer: $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$.

|

. Setting $T^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+d^{2}$, where $T>0$, we can write

$$

a=T \sin \alpha, \quad b=T \cos \alpha, \quad c=T \sin \beta, \quad d=T \cos \beta

$$

for some $\alpha, \beta \in(0, \pi / 2)$. With this notation, the first equality gives

$$

\sin ^{2} \alpha+\cos ^{2} \beta-\sin \alpha \cos \beta=\sin ^{2} \beta+\cos ^{2} \alpha+\cos \alpha \sin \beta .

$$

Hence, $\cos (2 \beta)-\cos (2 \alpha)=\sin (\alpha+\beta)$. Since $\cos (2 \beta)-\cos (2 \alpha)=2 \sin (\alpha-\beta) \sin (\alpha+\beta)$ and $\sin (\alpha+\beta) \neq 0$, this yields $\sin (\alpha-\beta)=1 / 2$. Thus, in view of $\alpha-\beta \in(-\pi / 2, \pi / 2)$ we deduce that $\cos (\alpha-\beta)=\sqrt{1-\sin ^{2}(\alpha-\beta)}=\sqrt{3} / 2$.

Now, observing that $a b+c d=\frac{T^{2}}{2}(\sin (2 \alpha)+\sin (2 \beta))=T^{2} \sin (\alpha+\beta) \cos (\alpha-\beta)$ and $a d+b c=T^{2} \sin (\alpha+\beta)$, we obtain $(a b+c d) /(a d+b c)=\cos (\alpha-\beta)=\sqrt{3} / 2$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "# Problem 5",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

In how many ways can we paint 16 seats in a row, each red or green, in such a way that the number of consecutive seats painted in the same colour is always odd?

Answer: 1974.

|

Let $g_{k}, r_{k}$ be the numbers of possible odd paintings of $k$ seats such that the first seat is painted green or red, respectively. Obviously, $g_{k}=r_{k}$ for any $k$. Note that $g_{k}=r_{k-1}+g_{k-2}=g_{k-1}+g_{k-2}$, since $r_{k-1}$ is the number of odd paintings with first seat green and second seat red and $g_{k-2}$ is the number of odd paintings with first and second seats green. Moreover, $g_{1}=g_{2}=1$, so $g_{k}$ is the $k$ th element of the Fibonacci sequence. Hence, the number of ways to paint $n$ seats in a row is $g_{n}+r_{n}=2 f_{n}$. Inserting $n=16$ we obtain $2 f_{16}=2 \cdot 987=1974$.

|

1974

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In how many ways can we paint 16 seats in a row, each red or green, in such a way that the number of consecutive seats painted in the same colour is always odd?

Answer: 1974.

|

Let $g_{k}, r_{k}$ be the numbers of possible odd paintings of $k$ seats such that the first seat is painted green or red, respectively. Obviously, $g_{k}=r_{k}$ for any $k$. Note that $g_{k}=r_{k-1}+g_{k-2}=g_{k-1}+g_{k-2}$, since $r_{k-1}$ is the number of odd paintings with first seat green and second seat red and $g_{k-2}$ is the number of odd paintings with first and second seats green. Moreover, $g_{1}=g_{2}=1$, so $g_{k}$ is the $k$ th element of the Fibonacci sequence. Hence, the number of ways to paint $n$ seats in a row is $g_{n}+r_{n}=2 f_{n}$. Inserting $n=16$ we obtain $2 f_{16}=2 \cdot 987=1974$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "# Problem 6",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{30}$ be a permutation of the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 30$. For how many permutations does the equality $\sum_{k=1}^{30}\left|p_{k}-k\right|=450$ hold?

Answer: $(15 !)^{2}$.

|

Let us define pairs $\left(a_{i}, b_{i}\right)$ such that $\left\{a_{i}, b_{i}\right\}=\left\{p_{i}, i\right\}$ and $a_{i} \geqslant b_{i}$. Then for every $i=1, \ldots, 30$ we have $\left|p_{i}-i\right|=a_{i}-b_{i}$ and

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{30}\left|p_{i}-i\right|=\sum_{i=1}^{30}\left(a_{i}-b_{i}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{30} a_{i}-\sum_{i=1}^{30} b_{i}

$$

It is clear that the sum $\sum_{i=1}^{30} a_{i}-\sum_{i=1}^{30} b_{i}$ is maximal when

$$

\left\{a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{30}\right\}=\{16,17, \ldots, 30\} \quad \text { and } \quad\left\{b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{30}\right\}=\{1,2, \ldots, 15\}

$$

where exactly two $a_{i}$ 's and two $b_{j}$ 's are equal, and the maximal value equals

$$

2(16+\cdots+30-1-\cdots-15)=450 .

$$

The number of such permutations is $(15 !)^{2}$.

|

(15 !)^{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $p_{1}, p_{2}, \ldots, p_{30}$ be a permutation of the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 30$. For how many permutations does the equality $\sum_{k=1}^{30}\left|p_{k}-k\right|=450$ hold?

Answer: $(15 !)^{2}$.

|

Let us define pairs $\left(a_{i}, b_{i}\right)$ such that $\left\{a_{i}, b_{i}\right\}=\left\{p_{i}, i\right\}$ and $a_{i} \geqslant b_{i}$. Then for every $i=1, \ldots, 30$ we have $\left|p_{i}-i\right|=a_{i}-b_{i}$ and

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{30}\left|p_{i}-i\right|=\sum_{i=1}^{30}\left(a_{i}-b_{i}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{30} a_{i}-\sum_{i=1}^{30} b_{i}

$$

It is clear that the sum $\sum_{i=1}^{30} a_{i}-\sum_{i=1}^{30} b_{i}$ is maximal when

$$

\left\{a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{30}\right\}=\{16,17, \ldots, 30\} \quad \text { and } \quad\left\{b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{30}\right\}=\{1,2, \ldots, 15\}

$$

where exactly two $a_{i}$ 's and two $b_{j}$ 's are equal, and the maximal value equals

$$

2(16+\cdots+30-1-\cdots-15)=450 .

$$

The number of such permutations is $(15 !)^{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "# Problem 7",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Albert and Betty are playing the following game. There are 100 blue balls in a red bowl and 100 red balls in a blue bowl. In each turn a player must make one of the following moves:

a) Take two red balls from the blue bowl and put them in the red bowl.

b) Take two blue balls from the red bowl and put them in the blue bowl.

c) Take two balls of different colors from one bowl and throw the balls away.

They take alternate turns and Albert starts. The player who first takes the last red ball from the blue bowl or the last blue ball from the red bowl wins. Determine who has a winning strategy.

Answer: Betty has a winning strategy.

|

Betty follows the following strategy. If Albert makes move a), then Betty makes move b) and vice verse. If Albert makes move c) from one bowl, Betty makes move c) from the other bowl. The only exception of this rule is that if Betty can make a winning move, that is, a move where she removes the last blue ball from the red bowl, or the last red ball from the blue bowl, then she makes her winning move.

Firstly, we prove that it is possible to follow this strategy. Let

$$

\begin{aligned}

& b=(\# \text { red balls in the blue bowl, } \# \text { blue balls in the blue bowl }), \\

& r=(\# \text { blue balls in the red bowl, } \# \text { red balls in the red bowl }) .

\end{aligned}

$$

At the beginning $b=r=(100,0)$. If $b=r$ and Albert takes a move a), then it must be possible for Betty to take a move b) and again leave a situation with $b=r$ to Albert. The same happens when Albert takes a move b). If $b=r$ and Albert takes a move c) from one bowl, then it is possible for Betty to take a move c) from the other bowl and again leave a situation with $b=r$. Thus, by following this strategy, Betty always leaves to Albert a situation with $b=r$ if she is not taking a winning move. Notice that there is one situation from which no legal move is possible, that is, $b=r=(1,0)$, but this could not happen, because the number of balls in a bowl is always even. (It is either increased or decreased by 2 , or doesn't change.)

Now, we will prove that, by using this strategy, Betty wins. Assume that at some point Albert wins, that is, he takes a winning move. Since, before his move, we have $b=r$, the situation was either $b=r=(1, s), s \geqslant 1$, or $b=r=(2, t), t \geqslant 0$. But that means that either $b$ or $r$ was either $\left(1, s^{\prime}\right), s^{\prime} \geqslant 1$ (because $1+s^{\prime}$ is even), or $\left(2, t^{\prime}\right), t^{\prime} \geqslant 0$,

before Betty made her last move. This is a contradiction with Betty's strategy, because in this situation Betty would have taken a winning move, and the game would have stopped. Hence, Betty always wins.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Albert and Betty are playing the following game. There are 100 blue balls in a red bowl and 100 red balls in a blue bowl. In each turn a player must make one of the following moves:

a) Take two red balls from the blue bowl and put them in the red bowl.

b) Take two blue balls from the red bowl and put them in the blue bowl.

c) Take two balls of different colors from one bowl and throw the balls away.

They take alternate turns and Albert starts. The player who first takes the last red ball from the blue bowl or the last blue ball from the red bowl wins. Determine who has a winning strategy.

Answer: Betty has a winning strategy.

|

Betty follows the following strategy. If Albert makes move a), then Betty makes move b) and vice verse. If Albert makes move c) from one bowl, Betty makes move c) from the other bowl. The only exception of this rule is that if Betty can make a winning move, that is, a move where she removes the last blue ball from the red bowl, or the last red ball from the blue bowl, then she makes her winning move.

Firstly, we prove that it is possible to follow this strategy. Let

$$

\begin{aligned}

& b=(\# \text { red balls in the blue bowl, } \# \text { blue balls in the blue bowl }), \\

& r=(\# \text { blue balls in the red bowl, } \# \text { red balls in the red bowl }) .

\end{aligned}

$$

At the beginning $b=r=(100,0)$. If $b=r$ and Albert takes a move a), then it must be possible for Betty to take a move b) and again leave a situation with $b=r$ to Albert. The same happens when Albert takes a move b). If $b=r$ and Albert takes a move c) from one bowl, then it is possible for Betty to take a move c) from the other bowl and again leave a situation with $b=r$. Thus, by following this strategy, Betty always leaves to Albert a situation with $b=r$ if she is not taking a winning move. Notice that there is one situation from which no legal move is possible, that is, $b=r=(1,0)$, but this could not happen, because the number of balls in a bowl is always even. (It is either increased or decreased by 2 , or doesn't change.)

Now, we will prove that, by using this strategy, Betty wins. Assume that at some point Albert wins, that is, he takes a winning move. Since, before his move, we have $b=r$, the situation was either $b=r=(1, s), s \geqslant 1$, or $b=r=(2, t), t \geqslant 0$. But that means that either $b$ or $r$ was either $\left(1, s^{\prime}\right), s^{\prime} \geqslant 1$ (because $1+s^{\prime}$ is even), or $\left(2, t^{\prime}\right), t^{\prime} \geqslant 0$,

before Betty made her last move. This is a contradiction with Betty's strategy, because in this situation Betty would have taken a winning move, and the game would have stopped. Hence, Betty always wins.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "# Problem 8",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

What is the least possible number of cells that can be marked on an $n \times n$ board such that for each $m>\frac{n}{2}$ both diagonals of any $m \times m$ sub-board contain a marked cell?

## Answer: $n$.

|

For any $n$ it is possible to set $n$ marks on the board and get the desired property, if they are simply put on every cell in row number $\left\lceil\frac{n}{2}\right\rceil$. We now show that $n$ is also the minimum amount of marks needed.

If $n$ is odd, then there are $2 n$ series of diagonal cells of length $>\frac{n}{2}$ and both end cells on the edge of the board, and, since every mark on the board can at most lie on two of these diagonals, it is necessary to set at least $n$ marks to have a mark on every one of them.

If $n$ is even, then there are $2 n-2$ series of diagonal cells of length $>\frac{n}{2}$ and both end cells on the edge of the board. We call one of these diagonals even if every coordinate $(x, y)$ on it satisfies $2 \mid x-y$ and odd else. It can be easily seen that this is well defined. Now, by symmetry, the number of odd and even diagonals is the same, so there are exactly $n-1$ of each of them. Any mark set on the board can at most sit on two diagonals and these two have to be of the same kind. Thus, we will need at least $\frac{n}{2}$ marks for the even diagonals, since there are $n-1$ of them and $2 \nmid n-1$, and, similarly, we need at least $\frac{n}{2}$ marks for the the odd diagonals. So we need at least $\frac{n}{2}+\frac{n}{2}=n$ marks to get the desired property.

|

n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

What is the least possible number of cells that can be marked on an $n \times n$ board such that for each $m>\frac{n}{2}$ both diagonals of any $m \times m$ sub-board contain a marked cell?

## Answer: $n$.

|

For any $n$ it is possible to set $n$ marks on the board and get the desired property, if they are simply put on every cell in row number $\left\lceil\frac{n}{2}\right\rceil$. We now show that $n$ is also the minimum amount of marks needed.

If $n$ is odd, then there are $2 n$ series of diagonal cells of length $>\frac{n}{2}$ and both end cells on the edge of the board, and, since every mark on the board can at most lie on two of these diagonals, it is necessary to set at least $n$ marks to have a mark on every one of them.

If $n$ is even, then there are $2 n-2$ series of diagonal cells of length $>\frac{n}{2}$ and both end cells on the edge of the board. We call one of these diagonals even if every coordinate $(x, y)$ on it satisfies $2 \mid x-y$ and odd else. It can be easily seen that this is well defined. Now, by symmetry, the number of odd and even diagonals is the same, so there are exactly $n-1$ of each of them. Any mark set on the board can at most sit on two diagonals and these two have to be of the same kind. Thus, we will need at least $\frac{n}{2}$ marks for the even diagonals, since there are $n-1$ of them and $2 \nmid n-1$, and, similarly, we need at least $\frac{n}{2}$ marks for the the odd diagonals. So we need at least $\frac{n}{2}+\frac{n}{2}=n$ marks to get the desired property.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "# Problem 9",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

In a country there are 100 airports. Super-Air operates direct flights between some pairs of airports (in both directions). The traffic of an airport is the number of airports it has a direct Super-Air connection with. A new company, Concur-Air, establishes a direct flight between two airports if and only if the sum of their traffics is at least 100. It turns out that there exists a round-trip of Concur-Air flights that lands in every airport exactly once. Show that then there also exists a round-trip of Super-Air flights that lands in every airport exactly once.

|

Let $G$ and $G^{\prime}$ be two graphs corresponding to the flights of Super-Air and Concur-Air, respectively. Then the traffic of an airport is simply the degree of a corresponding vertex, and the assertion means that the graph $G$ has a Hamiltonian cycle.

Lemma. Let a graph $H$ has 100 vertices and contains a Hamiltonian path (not cycle) that starts at the vertex $A$ and ends in $B$. If the sum of degrees of vertices $A$ and $B$ is at least 100, then the graph $H$ contains a Hamiltonian cycle.

Proof. Put $N=\operatorname{deg} A$. Then $\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100-N$. Let us enumarate the vertices along the Hamiltonian path: $C_{1}=A, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{100}=B$. Let $C_{p}, C_{q}, C_{r}, \ldots$ be the $N$ vertices which are connected directly to $A$. Consider $N$ preceding vertices: $C_{p-1}, C_{q-1}, C_{r-1}, \ldots$ Since the remaining part of the graph $H$ contains $100-N$ vertices (including $B$ ) and $\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100-N$, we conclude that at least one vertex under consideration, say $C_{r-1}$, is connected directly to $B$. Then

$$

A=C_{1} \rightarrow C_{2} \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow C_{r-1} \rightarrow B=C_{100} \rightarrow C_{99} \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow C_{r} \rightarrow A

$$

is a Hamiltonian cycle.

Now, let us solve the problem. Assume that the graph $G$ contains no Hamiltonian cycle. Consider arbitrary two vertices $A$ and $B$ not connected by an edge in the graph $G$ but connected in $G^{\prime}$. The latter means that $\operatorname{deg} A+\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100$ in the graph $G$. Let us add the edge $A B$ to the graph $G$. By the lemma, there was no Hamiltonian path from $A$ to $B$ in the graph $G$. Therefore, the graph $G$ still does not contain a Hamiltonian cycle after adding this new edge. By repeating this operation, we will obtain that all the vertices connected by an edge in the graph $G^{\prime}$ are also connected in the graph $G$ and at the same time the graph $G$ has no Hamiltonian cycle (in contrast to $G^{\prime}$ ). This is a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

In a country there are 100 airports. Super-Air operates direct flights between some pairs of airports (in both directions). The traffic of an airport is the number of airports it has a direct Super-Air connection with. A new company, Concur-Air, establishes a direct flight between two airports if and only if the sum of their traffics is at least 100. It turns out that there exists a round-trip of Concur-Air flights that lands in every airport exactly once. Show that then there also exists a round-trip of Super-Air flights that lands in every airport exactly once.

|

Let $G$ and $G^{\prime}$ be two graphs corresponding to the flights of Super-Air and Concur-Air, respectively. Then the traffic of an airport is simply the degree of a corresponding vertex, and the assertion means that the graph $G$ has a Hamiltonian cycle.

Lemma. Let a graph $H$ has 100 vertices and contains a Hamiltonian path (not cycle) that starts at the vertex $A$ and ends in $B$. If the sum of degrees of vertices $A$ and $B$ is at least 100, then the graph $H$ contains a Hamiltonian cycle.

Proof. Put $N=\operatorname{deg} A$. Then $\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100-N$. Let us enumarate the vertices along the Hamiltonian path: $C_{1}=A, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{100}=B$. Let $C_{p}, C_{q}, C_{r}, \ldots$ be the $N$ vertices which are connected directly to $A$. Consider $N$ preceding vertices: $C_{p-1}, C_{q-1}, C_{r-1}, \ldots$ Since the remaining part of the graph $H$ contains $100-N$ vertices (including $B$ ) and $\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100-N$, we conclude that at least one vertex under consideration, say $C_{r-1}$, is connected directly to $B$. Then

$$

A=C_{1} \rightarrow C_{2} \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow C_{r-1} \rightarrow B=C_{100} \rightarrow C_{99} \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow C_{r} \rightarrow A

$$

is a Hamiltonian cycle.

Now, let us solve the problem. Assume that the graph $G$ contains no Hamiltonian cycle. Consider arbitrary two vertices $A$ and $B$ not connected by an edge in the graph $G$ but connected in $G^{\prime}$. The latter means that $\operatorname{deg} A+\operatorname{deg} B \geqslant 100$ in the graph $G$. Let us add the edge $A B$ to the graph $G$. By the lemma, there was no Hamiltonian path from $A$ to $B$ in the graph $G$. Therefore, the graph $G$ still does not contain a Hamiltonian cycle after adding this new edge. By repeating this operation, we will obtain that all the vertices connected by an edge in the graph $G^{\prime}$ are also connected in the graph $G$ and at the same time the graph $G$ has no Hamiltonian cycle (in contrast to $G^{\prime}$ ). This is a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "# Problem 10",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

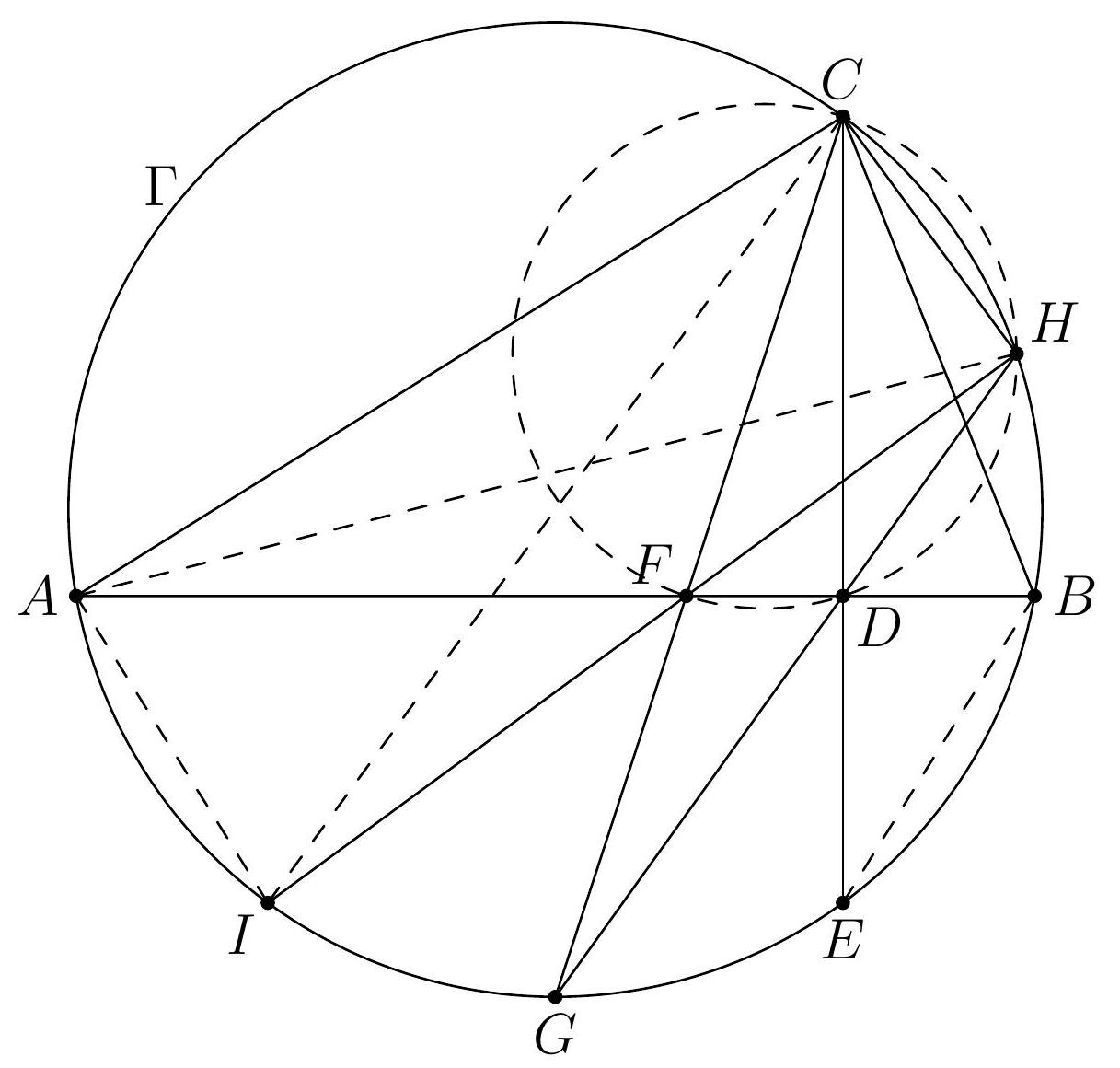

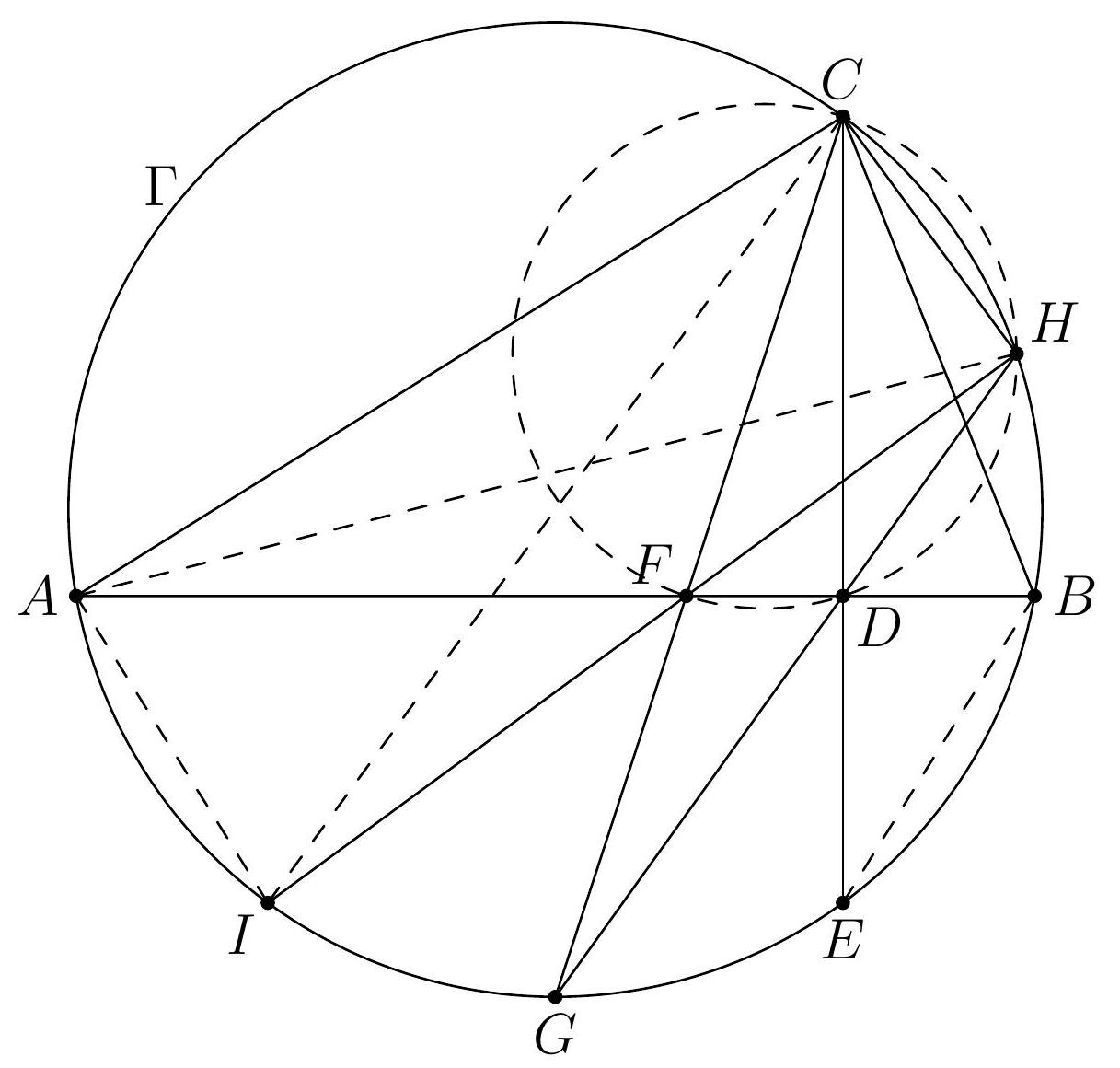

Let $\Gamma$ be the circumcircle of an acute triangle $A B C$. The perpendicular to $A B$ from $C$ meets $A B$ at $D$ and $\Gamma$ again at $E$. The bisector of angle $C$ meets $A B$ at $F$ and $\Gamma$ again at $G$. The line $G D$ meets $\Gamma$ again at $H$ and the line $H F$ meets $\Gamma$ again at $I$. Prove that $A I=E B$.

|

Since $C G$ bisects $\angle A C B$, we have $\angle A H G=\angle A C G=\angle G C B$. Thus, from the triangle $A D H$ we find that $\angle H D B=\angle H A B+\angle A H G=\angle H C B+\angle G C B=\angle G C H$. It follows that a pair of opposite angles in the quadrilateral $C F D H$ are supplementary, whence $C F D H$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Thus, $\angle G C E=\angle F C D=\angle F H D=\angle I H G=$ $\angle I C G$. In view of $\angle A C G=\angle G C B$ we obtain $\angle A C I=\angle E C B$, which implies $A I=E B$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $\Gamma$ be the circumcircle of an acute triangle $A B C$. The perpendicular to $A B$ from $C$ meets $A B$ at $D$ and $\Gamma$ again at $E$. The bisector of angle $C$ meets $A B$ at $F$ and $\Gamma$ again at $G$. The line $G D$ meets $\Gamma$ again at $H$ and the line $H F$ meets $\Gamma$ again at $I$. Prove that $A I=E B$.

|

Since $C G$ bisects $\angle A C B$, we have $\angle A H G=\angle A C G=\angle G C B$. Thus, from the triangle $A D H$ we find that $\angle H D B=\angle H A B+\angle A H G=\angle H C B+\angle G C B=\angle G C H$. It follows that a pair of opposite angles in the quadrilateral $C F D H$ are supplementary, whence $C F D H$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Thus, $\angle G C E=\angle F C D=\angle F H D=\angle I H G=$ $\angle I C G$. In view of $\angle A C G=\angle G C B$ we obtain $\angle A C I=\angle E C B$, which implies $A I=E B$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "# Problem 11",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Triangle $A B C$ is given. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the segment $A B$ and $T$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ not containing $A$ of the circumcircle of $A B C$. The point $K$ inside the triangle $A B C$ is such that $M A T K$ is an isosceles trapezoid with $A T \| M K$. Show that $A K=K C$.

|

Assume that $T K$ intersects the circumcircle of $A B C$ at the point $S$ (where $S \neq T)$. Then $\angle A B S=\angle A T S=\angle B A T$, so $A S B T$ is a trapezoid. Hence, $M K\|A T\| S B$ and $M$ is the midpoint of $A B$. Thus, $K$ is the midpoint of $T S$. From $\angle T A C=\angle B A T=$ $\angle A T S$ we see that $A C T S$ is an inscribed trapezoid, so it is isosceles. Thus, $A K=K C$, since $K$ is the midpoint of $T S$.

|

A K=K C

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Triangle $A B C$ is given. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the segment $A B$ and $T$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ not containing $A$ of the circumcircle of $A B C$. The point $K$ inside the triangle $A B C$ is such that $M A T K$ is an isosceles trapezoid with $A T \| M K$. Show that $A K=K C$.

|

Assume that $T K$ intersects the circumcircle of $A B C$ at the point $S$ (where $S \neq T)$. Then $\angle A B S=\angle A T S=\angle B A T$, so $A S B T$ is a trapezoid. Hence, $M K\|A T\| S B$ and $M$ is the midpoint of $A B$. Thus, $K$ is the midpoint of $T S$. From $\angle T A C=\angle B A T=$ $\angle A T S$ we see that $A C T S$ is an inscribed trapezoid, so it is isosceles. Thus, $A K=K C$, since $K$ is the midpoint of $T S$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "# Problem 12",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $A B C D$ be a square inscribed in a circle $\omega$ and let $P$ be a point on the shorter arc $A B$ of $\omega$. Let $C P \cap B D=R$ and $D P \cap A C=S$. Show that triangles $A R B$ and $D S R$ have equal areas.

|

Let $T=P C \cap A B$. Then $\angle B T C=90^{\circ}-\angle P C B=90^{\circ}-\angle P D B=90^{\circ}-$ $\angle S B D=\angle B S C$, thus the points $B, S, T, C$ are concyclic. Hence $\angle T S C=90^{\circ}$, and, therefore, $T S \| B D$. It follows that

$$

[D S R]=[D T R]=[D T B]-[T B R]=[C T B]-[T B R]=[C R B]=[A R B]

$$

where $[\Delta]$ denotes the area of a triangle $\Delta$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a square inscribed in a circle $\omega$ and let $P$ be a point on the shorter arc $A B$ of $\omega$. Let $C P \cap B D=R$ and $D P \cap A C=S$. Show that triangles $A R B$ and $D S R$ have equal areas.

|

Let $T=P C \cap A B$. Then $\angle B T C=90^{\circ}-\angle P C B=90^{\circ}-\angle P D B=90^{\circ}-$ $\angle S B D=\angle B S C$, thus the points $B, S, T, C$ are concyclic. Hence $\angle T S C=90^{\circ}$, and, therefore, $T S \| B D$. It follows that

$$

[D S R]=[D T R]=[D T B]-[T B R]=[C T B]-[T B R]=[C R B]=[A R B]

$$

where $[\Delta]$ denotes the area of a triangle $\Delta$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "# Problem 13",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

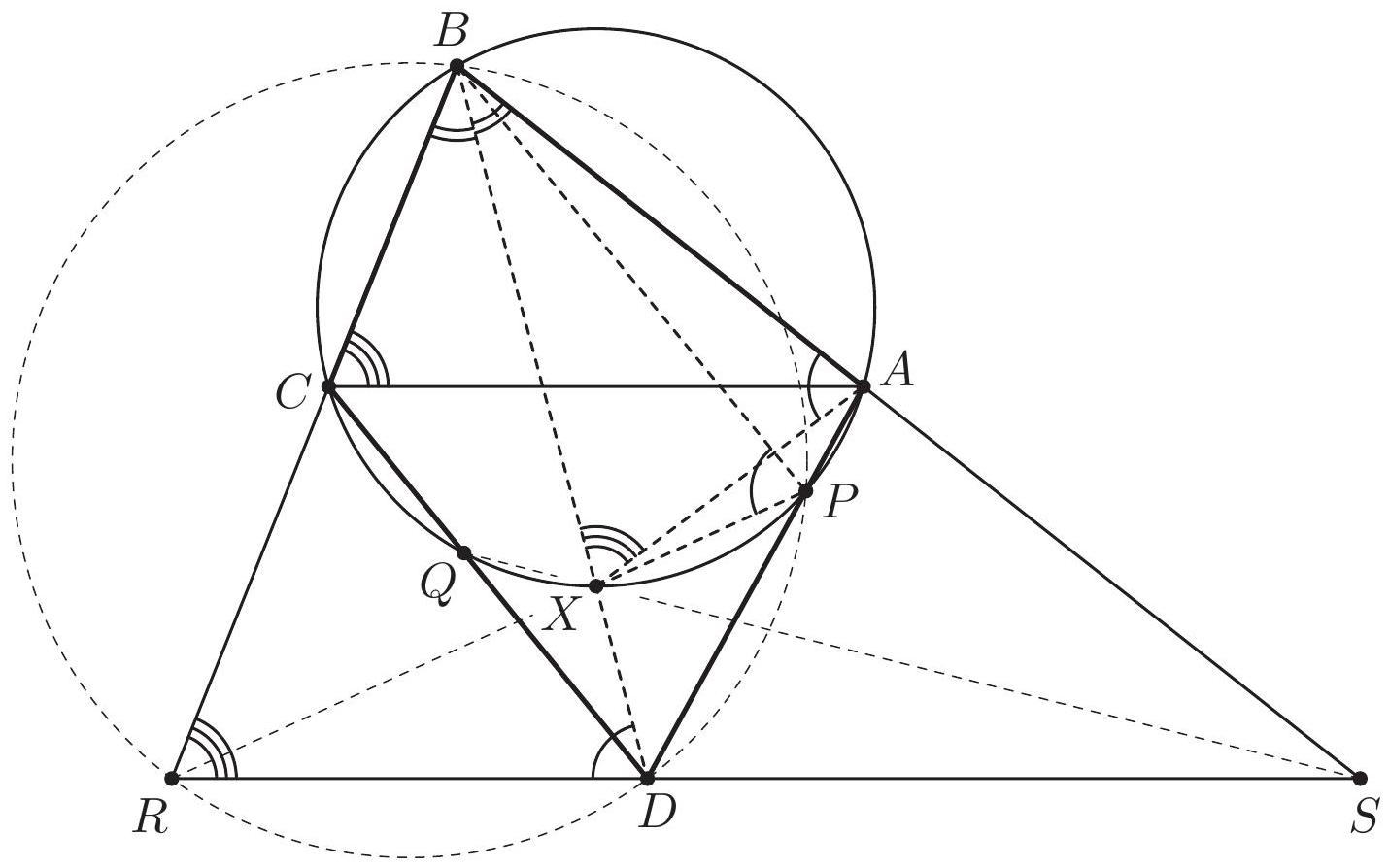

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

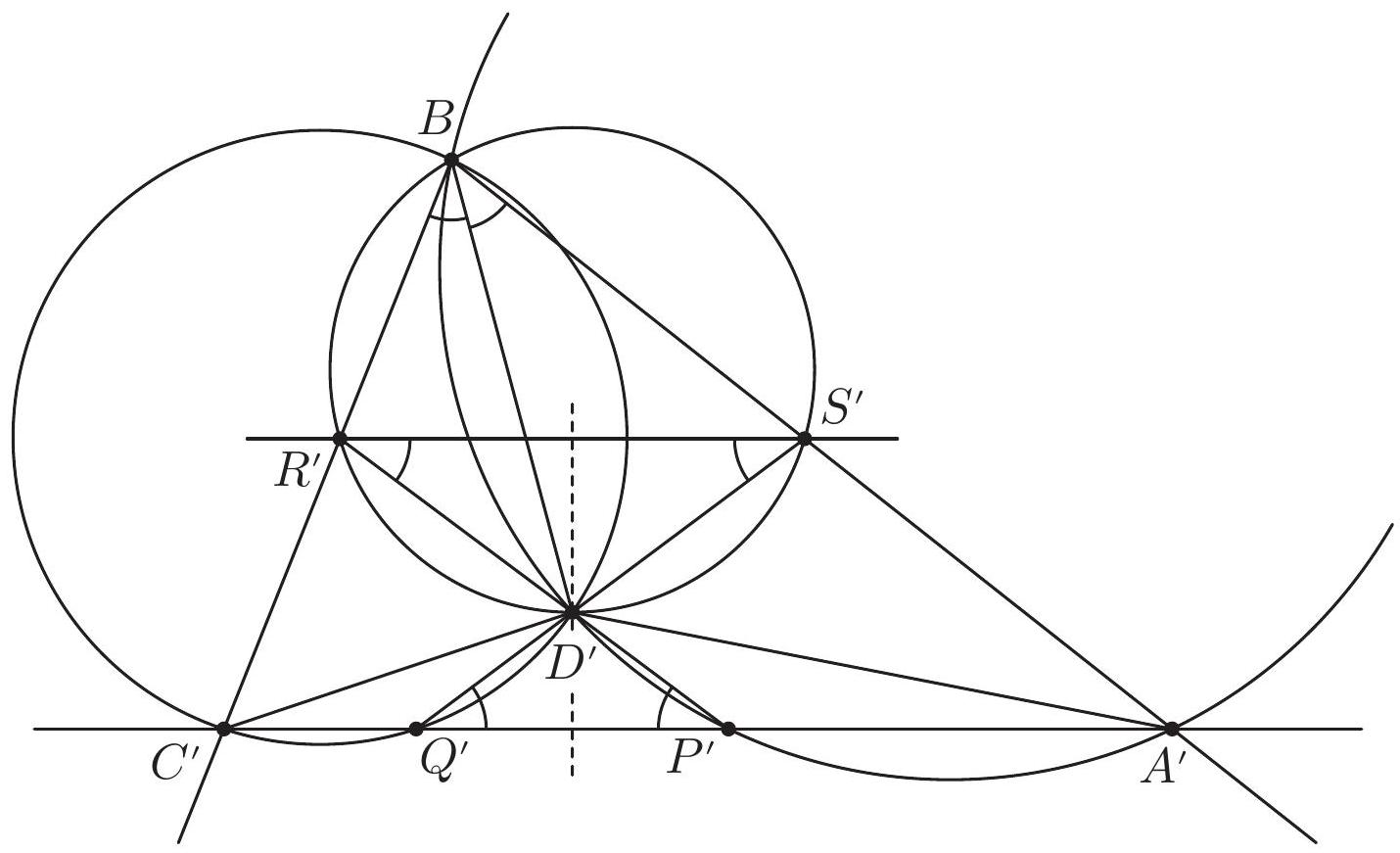

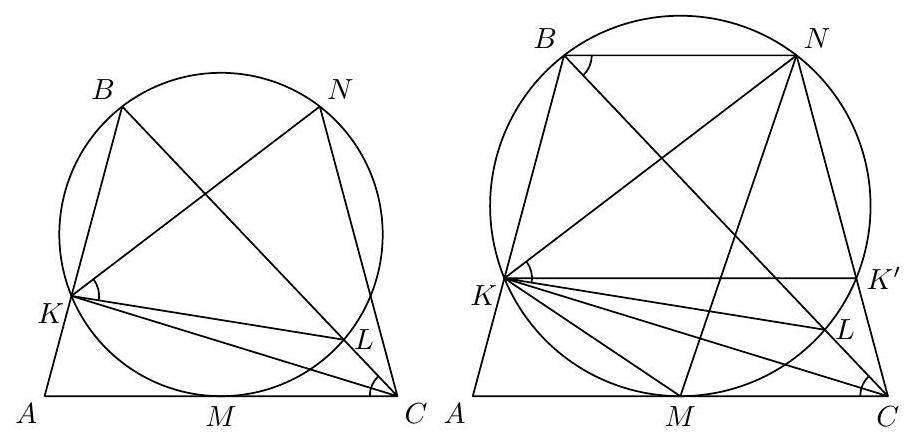

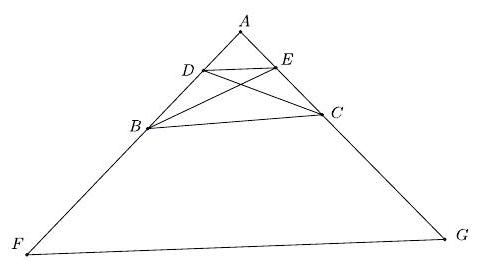

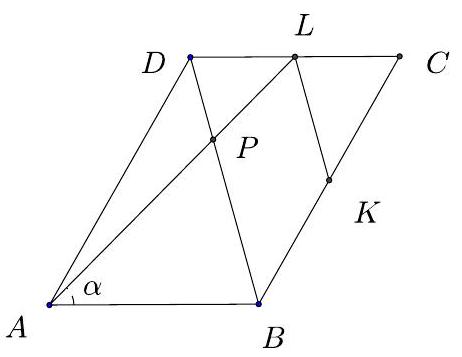

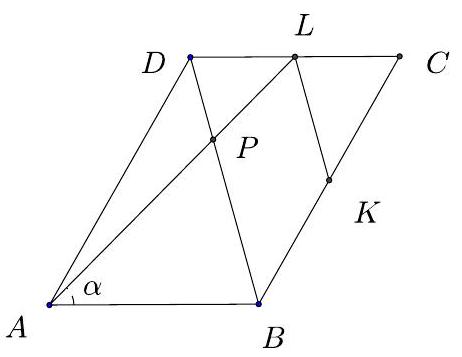

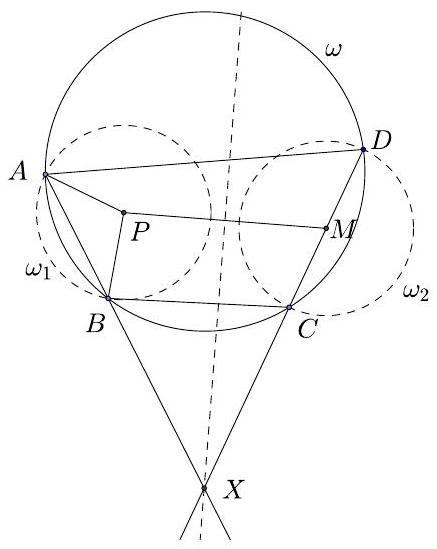

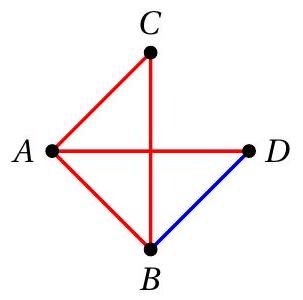

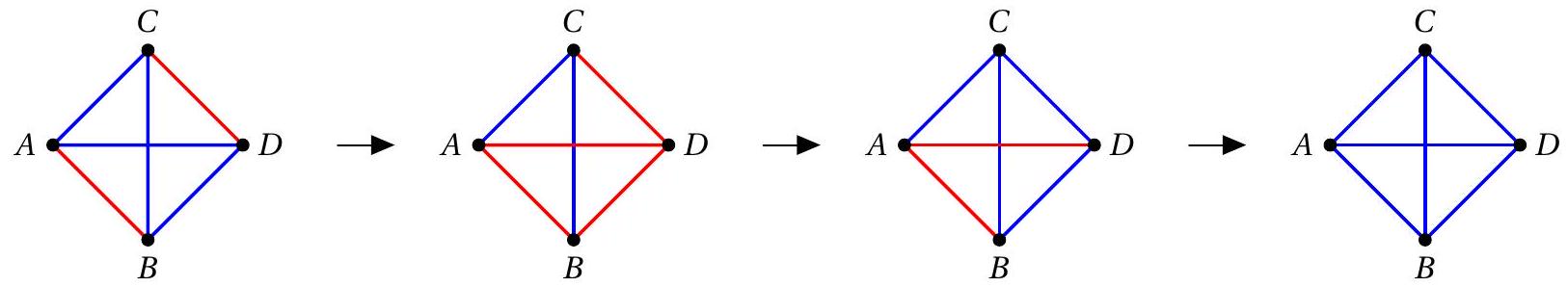

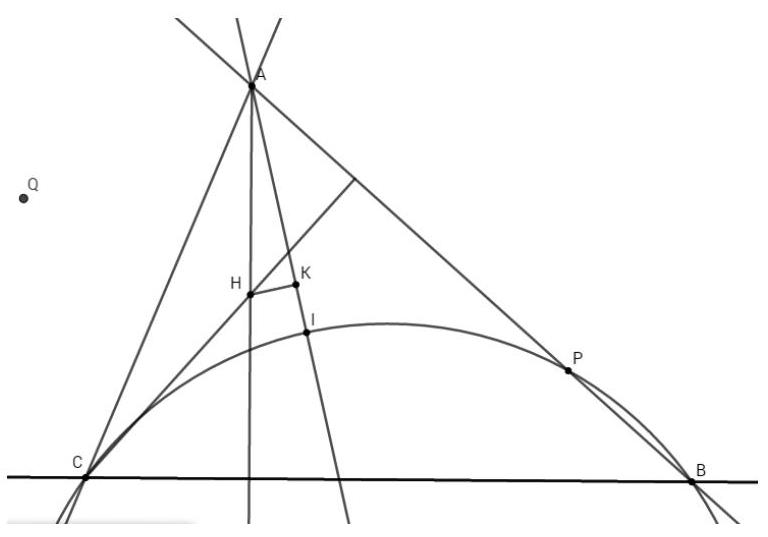

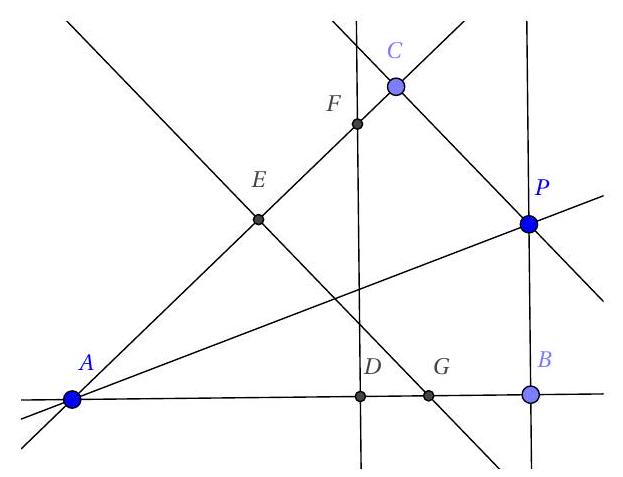

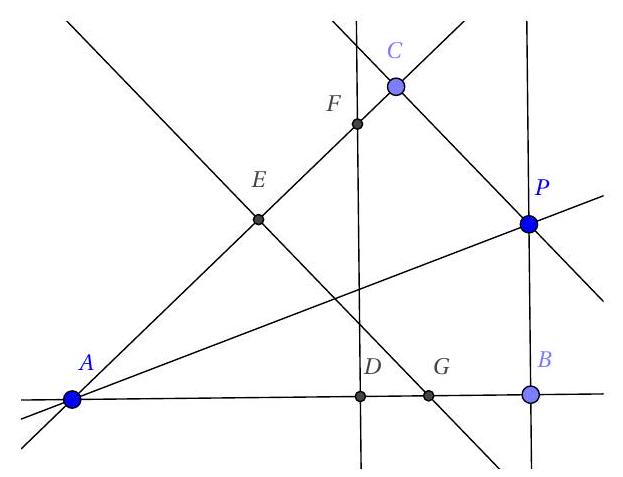

. Since $\angle S D P=\angle C A P=\angle R B P$, the quadrilateral $B R D P$ is cyclic (see Figure 1). Similarly, the quadrilateral $B S D Q$ is cyclic. Let $X$ be the second intersection point of the segment $B D$ with the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$. Then

$$

\angle A X B=\angle A C B=\angle D R B,

$$

and, moreover, $\angle A B X=\angle D B R$. It means that triangles $A B X$ and $D B R$ are similar. Thus

$$

\angle R P B=\angle R D B=\angle X A B=\angle X P B,

$$

which implies that the points $R, X$ and $P$ are collinear. Analogously, we can show that the points $S, X$ and $Q$ are collinear.

Thus, we obtain $R X \cdot X P=D X \cdot X B=S X \cdot X Q$, which proves that the points $P$, $Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

Figure 1

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

. Since $\angle S D P=\angle C A P=\angle R B P$, the quadrilateral $B R D P$ is cyclic (see Figure 1). Similarly, the quadrilateral $B S D Q$ is cyclic. Let $X$ be the second intersection point of the segment $B D$ with the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$. Then

$$

\angle A X B=\angle A C B=\angle D R B,

$$

and, moreover, $\angle A B X=\angle D B R$. It means that triangles $A B X$ and $D B R$ are similar. Thus

$$

\angle R P B=\angle R D B=\angle X A B=\angle X P B,

$$

which implies that the points $R, X$ and $P$ are collinear. Analogously, we can show that the points $S, X$ and $Q$ are collinear.

Thus, we obtain $R X \cdot X P=D X \cdot X B=S X \cdot X Q$, which proves that the points $P$, $Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

Figure 1

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "# Problem 14",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

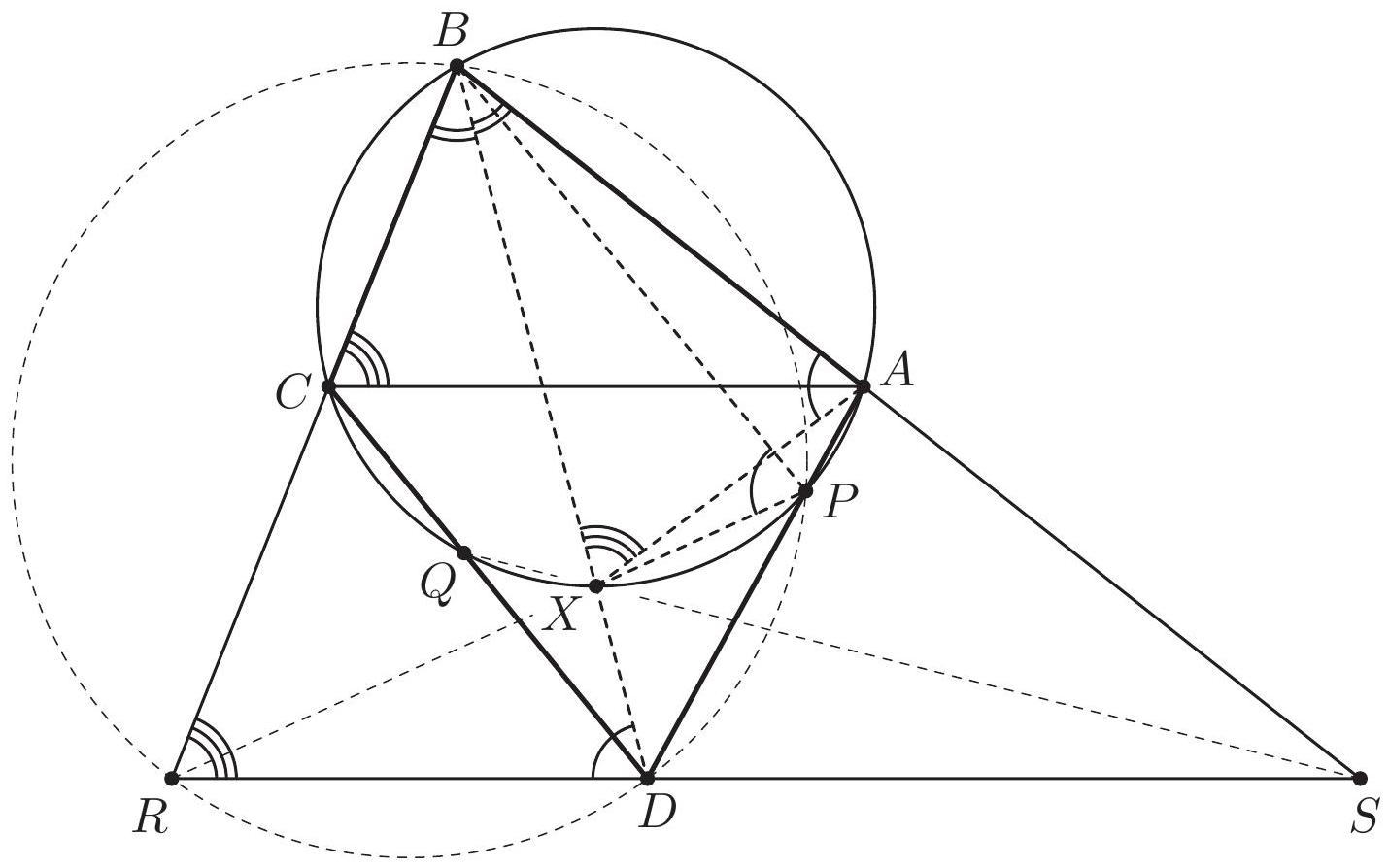

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

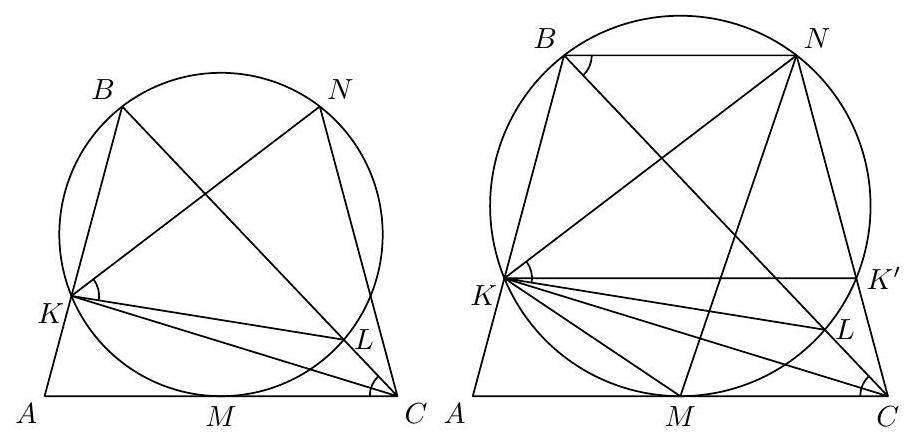

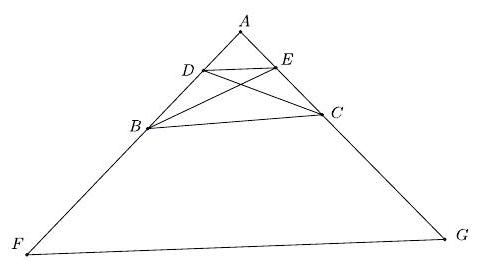

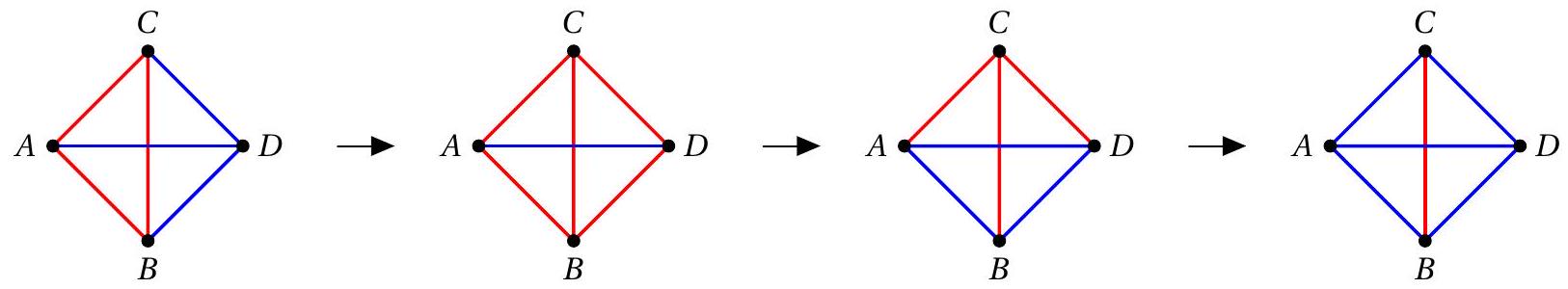

. If $A B=B C$, then the points $R$ and $S$ are symmetric to each other with respect to the line $B D$. Similarly, the points $P$ and $Q$ are symmetric to each other with respect to the line $B D$. Therefore, $R S P Q$ is an isosceles trapezoid, so the claim follows.

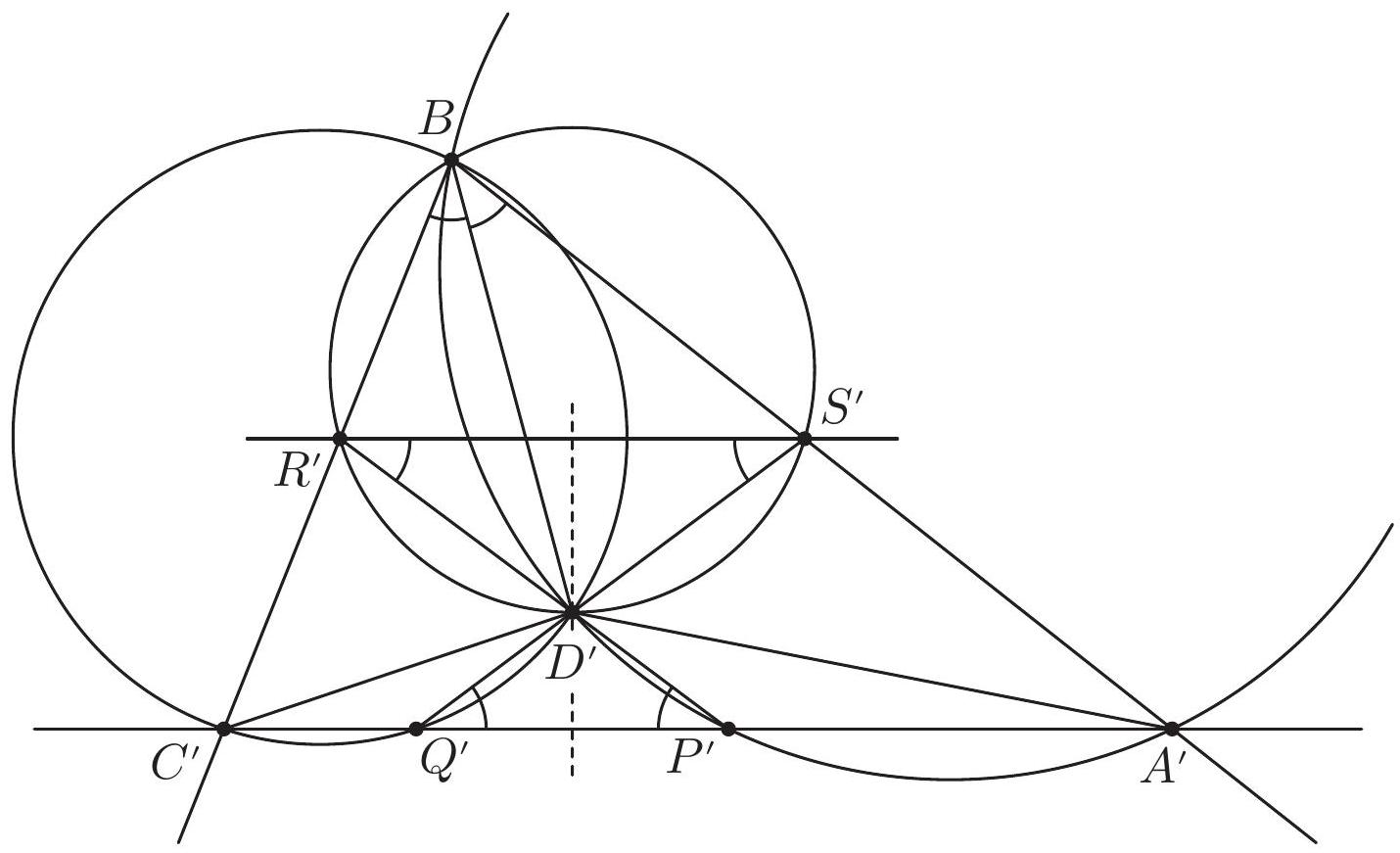

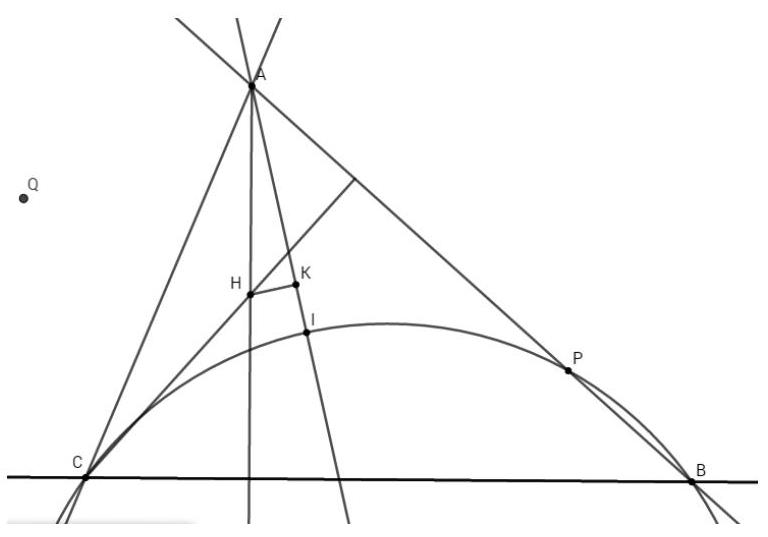

Assume that $A B \neq B C$. Denote by $\omega$ the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$ (see Figure 2). Since the lines $A C$ and $S R$ are parallel, the dilation with center $B$, which takes $A$ to $S$, also takes $C$ to $R$ and the circle $\omega$ to the circumcircle $\omega_{1}$ of $B S R$. This implies that $\omega$ and $\omega_{1}$ are tangent at $B$.

Note that $\angle R D Q=\angle D C A=\angle D P Q$, which means that the circumcircle $\omega_{2}$ of the triangle $P Q D$ is tangent to the line $R S$ at $D$.

Denote by $K$ the intersection point of the line $R S$ with the common tangent to $\omega$ and $\omega_{1}$ at $B$. Then we have

$$

\angle K B D=\angle K B R+\angle C B D=\angle D S B+\angle S B D=\angle K D B,

$$

which implies that $K D=K B$. Therefore, the powers of the point $K$ with respect to the circles $\omega$ and $\omega_{2}$ are equal, so $K$ lies on their radical axis. This implies that the points $K, P$ and $Q$ are collinear. Finally, we obtain

$$

K R \cdot K S=K B^{2}=K D^{2}=K P \cdot K Q,

$$

which shows that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

Figure 2

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

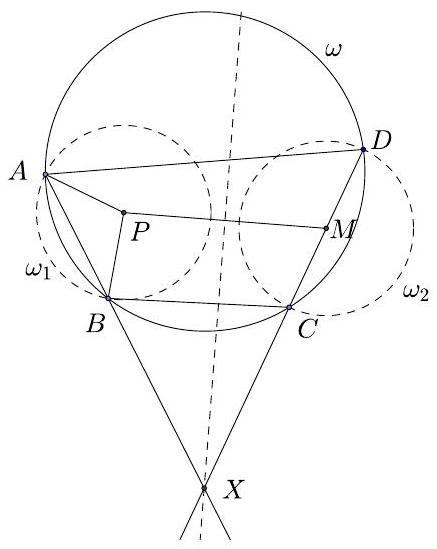

. If $A B=B C$, then the points $R$ and $S$ are symmetric to each other with respect to the line $B D$. Similarly, the points $P$ and $Q$ are symmetric to each other with respect to the line $B D$. Therefore, $R S P Q$ is an isosceles trapezoid, so the claim follows.

Assume that $A B \neq B C$. Denote by $\omega$ the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$ (see Figure 2). Since the lines $A C$ and $S R$ are parallel, the dilation with center $B$, which takes $A$ to $S$, also takes $C$ to $R$ and the circle $\omega$ to the circumcircle $\omega_{1}$ of $B S R$. This implies that $\omega$ and $\omega_{1}$ are tangent at $B$.

Note that $\angle R D Q=\angle D C A=\angle D P Q$, which means that the circumcircle $\omega_{2}$ of the triangle $P Q D$ is tangent to the line $R S$ at $D$.

Denote by $K$ the intersection point of the line $R S$ with the common tangent to $\omega$ and $\omega_{1}$ at $B$. Then we have

$$

\angle K B D=\angle K B R+\angle C B D=\angle D S B+\angle S B D=\angle K D B,

$$

which implies that $K D=K B$. Therefore, the powers of the point $K$ with respect to the circles $\omega$ and $\omega_{2}$ are equal, so $K$ lies on their radical axis. This implies that the points $K, P$ and $Q$ are collinear. Finally, we obtain

$$

K R \cdot K S=K B^{2}=K D^{2}=K P \cdot K Q,

$$

which shows that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

Figure 2

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "# Problem 14",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

. Denote by $X^{\prime}$ the image of the point $X$ under some fixed inversion with center $B$. At the beginning of Solution 2 we noticed that the circumcircles of the triangles $A B C$ and $S B R$ are tangent at the point $B$. Therefore, the images of these two circles

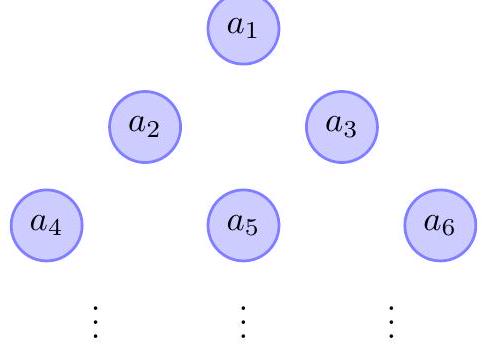

under the considered inversion become two parallel lines $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime} R^{\prime}$ (see Figure 3).

Since $D$ lies on the line $R S$ and also on the angle bisector of the angle $A B C$, the point $D^{\prime}$ lies on the circumcircle of the triangle $B R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ and also on the angle bisector of the angle $A^{\prime} B C^{\prime}$. Since the point $P$, other than $A$, is the intersection point of the line $A D$ and the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$, the point $P^{\prime}$, other than $A^{\prime}$, is the intersection point of the circumcircle of the triangle $B A^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ and the line $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. Similarly, the point $Q^{\prime}$ is the intersection point of the circumcircle of the triangle $B C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ and the line $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$.

Therefore, we obtain

$$

\angle D^{\prime} Q^{\prime} P^{\prime}=\angle C^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle A^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle D^{\prime} P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}

$$

and

$$

\angle D^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}=\angle D^{\prime} B S^{\prime}=\angle R^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle R^{\prime} S^{\prime} D^{\prime} .

$$

This implies that the points $P^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime}$ are symmetric to the points $Q^{\prime}$ and $R^{\prime}$ with respect to the line passing through $D^{\prime}$ and perpendicular to the lines $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime} R^{\prime}$. Thus $P^{\prime} S^{\prime} R^{\prime} Q^{\prime}$ is an isosceles trapezoid, so the points $P^{\prime}, S^{\prime}, R^{\prime}$ and $Q^{\prime}$ lie on a common circle. Therefore, the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ also lie on a common circle.

Figure 3

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral such that the line $B D$ bisects the angle $A B C$. The circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ intersects the sides $A D$ and $C D$ in the points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through $D$ and parallel to $A C$ intersects the lines $B C$ and $B A$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

. Denote by $X^{\prime}$ the image of the point $X$ under some fixed inversion with center $B$. At the beginning of Solution 2 we noticed that the circumcircles of the triangles $A B C$ and $S B R$ are tangent at the point $B$. Therefore, the images of these two circles

under the considered inversion become two parallel lines $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime} R^{\prime}$ (see Figure 3).

Since $D$ lies on the line $R S$ and also on the angle bisector of the angle $A B C$, the point $D^{\prime}$ lies on the circumcircle of the triangle $B R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ and also on the angle bisector of the angle $A^{\prime} B C^{\prime}$. Since the point $P$, other than $A$, is the intersection point of the line $A D$ and the circumcircle of the triangle $A B C$, the point $P^{\prime}$, other than $A^{\prime}$, is the intersection point of the circumcircle of the triangle $B A^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ and the line $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. Similarly, the point $Q^{\prime}$ is the intersection point of the circumcircle of the triangle $B C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ and the line $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$.

Therefore, we obtain

$$

\angle D^{\prime} Q^{\prime} P^{\prime}=\angle C^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle A^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle D^{\prime} P^{\prime} Q^{\prime}

$$

and

$$

\angle D^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}=\angle D^{\prime} B S^{\prime}=\angle R^{\prime} B D^{\prime}=\angle R^{\prime} S^{\prime} D^{\prime} .

$$

This implies that the points $P^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime}$ are symmetric to the points $Q^{\prime}$ and $R^{\prime}$ with respect to the line passing through $D^{\prime}$ and perpendicular to the lines $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime} R^{\prime}$. Thus $P^{\prime} S^{\prime} R^{\prime} Q^{\prime}$ is an isosceles trapezoid, so the points $P^{\prime}, S^{\prime}, R^{\prime}$ and $Q^{\prime}$ lie on a common circle. Therefore, the points $P, Q, R$ and $S$ also lie on a common circle.

Figure 3

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "# Problem 14",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 3",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

The sum of the angles $A$ and $C$ of a convex quadrilateral $A B C D$ is less than $180^{\circ}$. Prove that

$$

A B \cdot C D+A D \cdot B C<A C(A B+A D)

$$

|

. Let $\omega$ be the circumcircle $A B D$. Then the point $C$ is outside this circle, but inside the angle $B A D$. Let us ppply the inversion with the center $A$ and radius 1 . This inversion maps the circle $\omega$ to the line $\omega^{\prime}=B^{\prime} D^{\prime}$, where $B^{\prime}$ and $D^{\prime}$ are images of $B$ and $D$. The point $C$ goes to the point $C^{\prime}$ inside the triangle $A B^{\prime} D^{\prime}$. Therefore, $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}+C^{\prime} D^{\prime}<A B^{\prime}+A D^{\prime}$. Now, due to inversion properties, we have

$$

B^{\prime} C^{\prime}=\frac{B C}{A B \cdot A C}, \quad C^{\prime} D^{\prime}=\frac{C D}{A C \cdot A D}, \quad A B^{\prime}=\frac{1}{A B}, \quad A D^{\prime}=\frac{1}{A D} .

$$

Hence

$$

\frac{B C}{A B \cdot A C}+\frac{C D}{A C \cdot A D}<\frac{1}{A B}+\frac{1}{A D}

$$

Multiplying by $A B \cdot A C \cdot A D$, we obtain the desired inequality.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

The sum of the angles $A$ and $C$ of a convex quadrilateral $A B C D$ is less than $180^{\circ}$. Prove that

$$

A B \cdot C D+A D \cdot B C<A C(A B+A D)

$$

|

. Let $\omega$ be the circumcircle $A B D$. Then the point $C$ is outside this circle, but inside the angle $B A D$. Let us ppply the inversion with the center $A$ and radius 1 . This inversion maps the circle $\omega$ to the line $\omega^{\prime}=B^{\prime} D^{\prime}$, where $B^{\prime}$ and $D^{\prime}$ are images of $B$ and $D$. The point $C$ goes to the point $C^{\prime}$ inside the triangle $A B^{\prime} D^{\prime}$. Therefore, $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}+C^{\prime} D^{\prime}<A B^{\prime}+A D^{\prime}$. Now, due to inversion properties, we have

$$

B^{\prime} C^{\prime}=\frac{B C}{A B \cdot A C}, \quad C^{\prime} D^{\prime}=\frac{C D}{A C \cdot A D}, \quad A B^{\prime}=\frac{1}{A B}, \quad A D^{\prime}=\frac{1}{A D} .

$$

Hence

$$

\frac{B C}{A B \cdot A C}+\frac{C D}{A C \cdot A D}<\frac{1}{A B}+\frac{1}{A D}

$$

Multiplying by $A B \cdot A C \cdot A D$, we obtain the desired inequality.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "# Problem 15",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

The sum of the angles $A$ and $C$ of a convex quadrilateral $A B C D$ is less than $180^{\circ}$. Prove that

$$

A B \cdot C D+A D \cdot B C<A C(A B+A D)

$$

|

. Consider an inscribed quadrilateral $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ with sides of the same lengths as $A B C D$ (such a quadrilateral exists, because we can draw these 4 sides in a big circle and afterwards continuously decrease its radius). Then $\angle B^{\prime}+\angle D^{\prime}=180^{\circ}<\angle B+\angle D$. Therefore, $\angle B^{\prime}<\angle B$ or $\angle D^{\prime}<\angle D$ and hence $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}<A C$, by the cosine theorem.

So the inequality under consideration for $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ is stronger than that for $A B C D$. However, the inequality for $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ follows immediately from Ptolemy's theorem.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

The sum of the angles $A$ and $C$ of a convex quadrilateral $A B C D$ is less than $180^{\circ}$. Prove that

$$

A B \cdot C D+A D \cdot B C<A C(A B+A D)

$$

|

. Consider an inscribed quadrilateral $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ with sides of the same lengths as $A B C D$ (such a quadrilateral exists, because we can draw these 4 sides in a big circle and afterwards continuously decrease its radius). Then $\angle B^{\prime}+\angle D^{\prime}=180^{\circ}<\angle B+\angle D$. Therefore, $\angle B^{\prime}<\angle B$ or $\angle D^{\prime}<\angle D$ and hence $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}<A C$, by the cosine theorem.

So the inequality under consideration for $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ is stronger than that for $A B C D$. However, the inequality for $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime} D^{\prime}$ follows immediately from Ptolemy's theorem.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "# Problem 15",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Determine whether $712 !+1$ is a prime number.

Answer: It is composite.

|

We will show that 719 is a prime factor of given number (evidently, $719<$ $712 !+1$ ). All congruences are considered modulo 719 . By Wilson's theorem, $718 ! \equiv-1$. Furthermore,

$$

713 \cdot 714 \cdot 715 \cdot 716 \cdot 717 \cdot 718 \equiv(-6)(-5)(-4)(-3)(-2)(-1) \equiv 720 \equiv 1 .

$$

Hence $712 ! \equiv-1$, which means that $712 !+1$ is divisible by 719 .

We remark that 719 is the smallest prime greater then 712 , so 719 is the smallest prime divisor of $712 !+1$.

|

719

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Determine whether $712 !+1$ is a prime number.

Answer: It is composite.

|

We will show that 719 is a prime factor of given number (evidently, $719<$ $712 !+1$ ). All congruences are considered modulo 719 . By Wilson's theorem, $718 ! \equiv-1$. Furthermore,

$$

713 \cdot 714 \cdot 715 \cdot 716 \cdot 717 \cdot 718 \equiv(-6)(-5)(-4)(-3)(-2)(-1) \equiv 720 \equiv 1 .

$$

Hence $712 ! \equiv-1$, which means that $712 !+1$ is divisible by 719 .

We remark that 719 is the smallest prime greater then 712 , so 719 is the smallest prime divisor of $712 !+1$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "# Problem 16",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Do there exist pairwise distinct rational numbers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

\frac{1}{(x-y)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(y-z)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(z-x)^{2}}=2014 ?

$$

Answer: No.

|

Put $a=x-y$ and $b=y-z$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{(x-y)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(y-z)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(z-x)^{2}} & =\frac{1}{a^{2}}+\frac{1}{b^{2}}+\frac{1}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\frac{b^{2}(a+b)^{2}+a^{2}(a+b)^{2}+a^{2} b^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\left(\frac{a^{2}+b^{2}+a b}{a b(a+b)}\right)^{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

On the other hand, 2014 is not a square of a rational number. Hence, such numbers $x, y, z$ do not exist.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Do there exist pairwise distinct rational numbers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

\frac{1}{(x-y)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(y-z)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(z-x)^{2}}=2014 ?

$$

Answer: No.

|

Put $a=x-y$ and $b=y-z$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{(x-y)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(y-z)^{2}}+\frac{1}{(z-x)^{2}} & =\frac{1}{a^{2}}+\frac{1}{b^{2}}+\frac{1}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\frac{b^{2}(a+b)^{2}+a^{2}(a+b)^{2}+a^{2} b^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\left(\frac{a^{2}+b^{2}+a b}{a b(a+b)}\right)^{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

On the other hand, 2014 is not a square of a rational number. Hence, such numbers $x, y, z$ do not exist.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "# Problem 17",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $p$ be a prime number, and let $n$ be a positive integer. Find the number of quadruples $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}\right)$ with $a_{i} \in\left\{0,1, \ldots, p^{n}-1\right\}$ for $i=1,2,3,4$ such that

$$

p^{n} \mid\left(a_{1} a_{2}+a_{3} a_{4}+1\right) .

$$

Answer: $p^{3 n}-p^{3 n-2}$.

|

We have $p^{n}-p^{n-1}$ choices for $a_{1}$ such that $p \nmid a_{1}$. In this case for any of the $p^{n} \cdot p^{n}$ choices of $a_{3}$ and $a_{4}$, there is a unique choice of $a_{2}$, namely,

$$

a_{2} \equiv a_{1}^{-1}\left(-1-a_{3} a_{4}\right) \quad \bmod p^{n}

$$

This gives $p^{2 n}\left(p^{n}-p^{n-1}\right)=p^{3 n-1}(p-1)$ of quadruples.

If $p \mid a_{1}$ then we obviously have $p \nmid a_{3}$, since otherwise the condition

$$

p^{n} \mid\left(a_{1} a_{2}+a_{3} a_{4}+1\right)

$$

is violated. Now, if $p \mid a_{1}, p \nmid a_{3}$, for any choice of $a_{2}$ there is a unique choice of $a_{4}$, namely,

$$

a_{4} \equiv a_{3}^{-1}\left(-1-a_{1} a_{2}\right) \quad \bmod p^{n}

$$

Thus, for these $p^{n-1}$ choices of $a_{1}$ and $p^{n}-p^{n-1}$ choices of $a_{3}$, we have for each of the $p^{n}$ choices of $a_{2}$ a unique $a_{4}$. So in this case there are $p^{n-1}\left(p^{n}-p^{n-1}\right) p^{n}=p^{3 n-2}(p-1)$ of quadruples.

Thus, the total number of quadruples is

$$

p^{3 n-1}(p-1)+p^{3 n-2}(p-1)=p^{3 n}-p^{3 n-2} \text {. }

$$

|

p^{3 n}-p^{3 n-2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $p$ be a prime number, and let $n$ be a positive integer. Find the number of quadruples $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}\right)$ with $a_{i} \in\left\{0,1, \ldots, p^{n}-1\right\}$ for $i=1,2,3,4$ such that

$$

p^{n} \mid\left(a_{1} a_{2}+a_{3} a_{4}+1\right) .

$$

Answer: $p^{3 n}-p^{3 n-2}$.

|

We have $p^{n}-p^{n-1}$ choices for $a_{1}$ such that $p \nmid a_{1}$. In this case for any of the $p^{n} \cdot p^{n}$ choices of $a_{3}$ and $a_{4}$, there is a unique choice of $a_{2}$, namely,

$$

a_{2} \equiv a_{1}^{-1}\left(-1-a_{3} a_{4}\right) \quad \bmod p^{n}

$$

This gives $p^{2 n}\left(p^{n}-p^{n-1}\right)=p^{3 n-1}(p-1)$ of quadruples.

If $p \mid a_{1}$ then we obviously have $p \nmid a_{3}$, since otherwise the condition

$$

p^{n} \mid\left(a_{1} a_{2}+a_{3} a_{4}+1\right)

$$

is violated. Now, if $p \mid a_{1}, p \nmid a_{3}$, for any choice of $a_{2}$ there is a unique choice of $a_{4}$, namely,

$$

a_{4} \equiv a_{3}^{-1}\left(-1-a_{1} a_{2}\right) \quad \bmod p^{n}

$$

Thus, for these $p^{n-1}$ choices of $a_{1}$ and $p^{n}-p^{n-1}$ choices of $a_{3}$, we have for each of the $p^{n}$ choices of $a_{2}$ a unique $a_{4}$. So in this case there are $p^{n-1}\left(p^{n}-p^{n-1}\right) p^{n}=p^{3 n-2}(p-1)$ of quadruples.

Thus, the total number of quadruples is

$$

p^{3 n-1}(p-1)+p^{3 n-2}(p-1)=p^{3 n}-p^{3 n-2} \text {. }

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "# Problem 18",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $m$ and $n$ be relatively prime positive integers. Determine all possible values of

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) .

$$

Answer: 1 and 7 .

|

Without restriction of generality we may assume that $m \geqslant n$. It is well known that

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{p}-1,2^{q}-1\right)=2^{\operatorname{gcd}(p, q)}-1,

$$

SO

$$

\begin{aligned}

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) & =\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m-n}-1,2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) \\

& =2^{\operatorname{gcd}\left(m-n, m^{2}+m n+n^{2}\right)}-1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

Let $d \geqslant 1$ be a divisor of $m-n$. Clearly, $\operatorname{gcd}(m, d)=1$, since $m$ and $n$ are relatively prime. Assume that $d$ also divides $m^{2}+m n+n^{2}$. Then $d$ divides $3 m^{2}$. In view of $\operatorname{gcd}(m, d)=1$ the only choices for $d$ are $d=1$ and $d=3$. Hence $\operatorname{gcd}\left(m-n, m^{2}+m n+n^{2}\right)$ is either 1 or 3 . Consequently, $\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right)$ may only assume the values $2^{1}-1=1$ and $2^{3}-1=7$.

Both values are attainable, since $m=2, n=1$ gives

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{2}-2^{1}, 2^{2^{2}+2 \cdot 1+1^{2}}-1\right)=\operatorname{gcd}\left(2,2^{7}-1\right)=1

$$

whereas $m=1, n=1$ gives

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{1}-2^{1}, 2^{1^{2}+1 \cdot 1+1^{2}}-1\right)=\operatorname{gcd}\left(0,2^{3}-1\right)=7

$$

|

1 \text{ and } 7

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $m$ and $n$ be relatively prime positive integers. Determine all possible values of

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) .

$$

Answer: 1 and 7 .

|

Without restriction of generality we may assume that $m \geqslant n$. It is well known that

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{p}-1,2^{q}-1\right)=2^{\operatorname{gcd}(p, q)}-1,

$$

SO

$$

\begin{aligned}

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) & =\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m-n}-1,2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right) \\

& =2^{\operatorname{gcd}\left(m-n, m^{2}+m n+n^{2}\right)}-1 .

\end{aligned}

$$

Let $d \geqslant 1$ be a divisor of $m-n$. Clearly, $\operatorname{gcd}(m, d)=1$, since $m$ and $n$ are relatively prime. Assume that $d$ also divides $m^{2}+m n+n^{2}$. Then $d$ divides $3 m^{2}$. In view of $\operatorname{gcd}(m, d)=1$ the only choices for $d$ are $d=1$ and $d=3$. Hence $\operatorname{gcd}\left(m-n, m^{2}+m n+n^{2}\right)$ is either 1 or 3 . Consequently, $\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{m}-2^{n}, 2^{m^{2}+m n+n^{2}}-1\right)$ may only assume the values $2^{1}-1=1$ and $2^{3}-1=7$.

Both values are attainable, since $m=2, n=1$ gives

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{2}-2^{1}, 2^{2^{2}+2 \cdot 1+1^{2}}-1\right)=\operatorname{gcd}\left(2,2^{7}-1\right)=1

$$

whereas $m=1, n=1$ gives

$$

\operatorname{gcd}\left(2^{1}-2^{1}, 2^{1^{2}+1 \cdot 1+1^{2}}-1\right)=\operatorname{gcd}\left(0,2^{3}-1\right)=7

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "# Problem 19",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Consider a sequence of positive integers $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ such that for $k \geqslant 2$ we have

$$

a_{k+1}=\frac{a_{k}+a_{k-1}}{2015^{i}}

$$

where $2015^{i}$ is the maximal power of 2015 that divides $a_{k}+a_{k-1}$. Prove that if this sequence is periodic then its period is divisible by 3 .

|

If all the numbers in the sequence are even, then we can divide each element of the sequence by the maximal possible power of 2 . In this way we obtain a new sequence of integers which is determined by the same recurrence formula and has the same period, but now it contains an odd number. Consider this new sequence modulo 2. Since the number 2015 is odd, it has no influence to the calculations modulo 2 , so we may think that modulo 2 this sequence is given by the Fibonacci recurrence $a_{k+1} \equiv a_{k}+a_{k-1}$ with $a_{j} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 2)$ for at least one $j$. Then it has the following form $\ldots, 1,1,0,1,1,0,1,1,0, \ldots$ (with period 3 modulo 2), so that the length of the original period of our sequence (if it is periodic!) must be divisible by 3 .

Remark. It is not known whether a periodic sequence of integers satisfying the recurrence condition of this problem exists. The solution of such a problem is apparently completely out of reach. See, e.g., the recent preprint

Brandon Avila and Tanya Khovanova, Free Fibonacci sequences, 2014, preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1403.4614v1.pdf

for more information. (The problem given at the olympiad is Lemma 28 of this paper, where 2015 can be replaced by any odd integer greater than 1.)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Consider a sequence of positive integers $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ such that for $k \geqslant 2$ we have

$$

a_{k+1}=\frac{a_{k}+a_{k-1}}{2015^{i}}

$$

where $2015^{i}$ is the maximal power of 2015 that divides $a_{k}+a_{k-1}$. Prove that if this sequence is periodic then its period is divisible by 3 .

|

If all the numbers in the sequence are even, then we can divide each element of the sequence by the maximal possible power of 2 . In this way we obtain a new sequence of integers which is determined by the same recurrence formula and has the same period, but now it contains an odd number. Consider this new sequence modulo 2. Since the number 2015 is odd, it has no influence to the calculations modulo 2 , so we may think that modulo 2 this sequence is given by the Fibonacci recurrence $a_{k+1} \equiv a_{k}+a_{k-1}$ with $a_{j} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 2)$ for at least one $j$. Then it has the following form $\ldots, 1,1,0,1,1,0,1,1,0, \ldots$ (with period 3 modulo 2), so that the length of the original period of our sequence (if it is periodic!) must be divisible by 3 .

Remark. It is not known whether a periodic sequence of integers satisfying the recurrence condition of this problem exists. The solution of such a problem is apparently completely out of reach. See, e.g., the recent preprint

Brandon Avila and Tanya Khovanova, Free Fibonacci sequences, 2014, preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1403.4614v1.pdf

for more information. (The problem given at the olympiad is Lemma 28 of this paper, where 2015 can be replaced by any odd integer greater than 1.)

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "# Problem 20",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw14sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2014"

}

|

For $n \geq 2$, an equilateral triangle is divided into $n^{2}$ congruent smaller equilateral triangles. Determine all ways in which real numbers can be assigned to the $\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}$ vertices so that three such numbers sum to zero whenever the three vertices form a triangle with edges parallel to the sides of the big triangle.

|

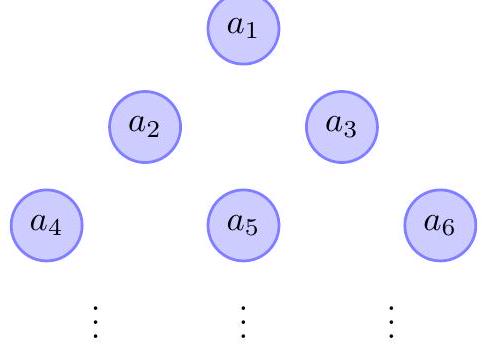

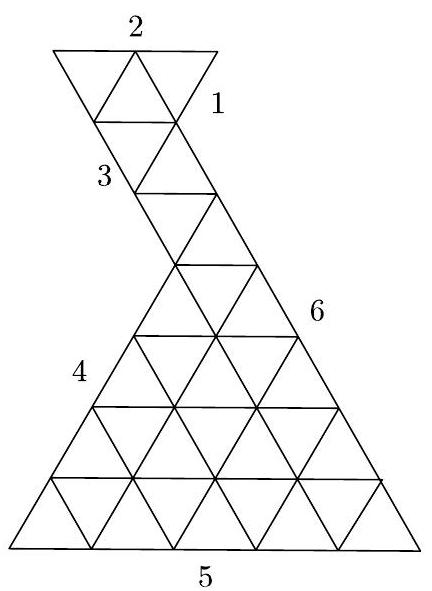

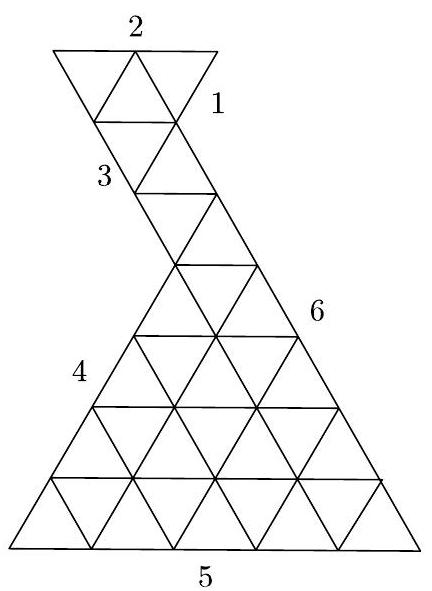

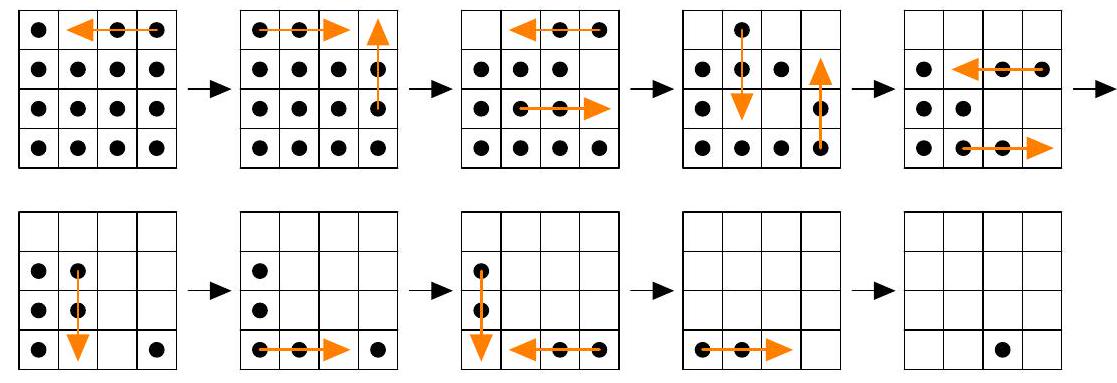

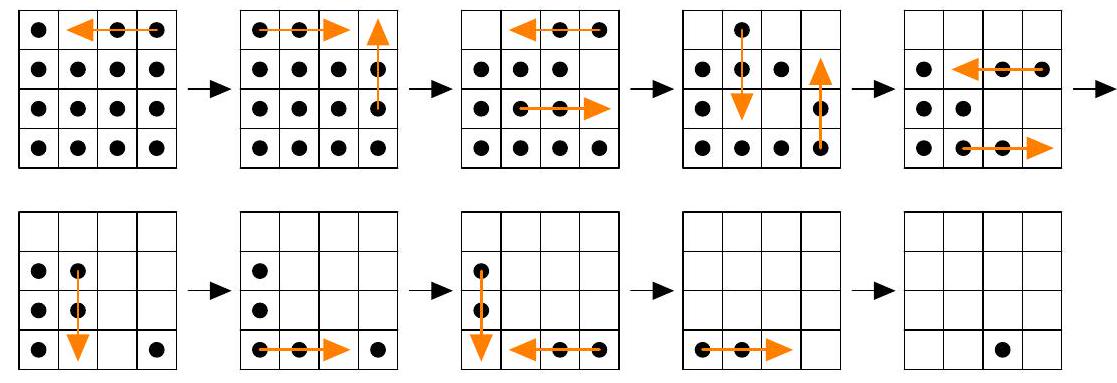

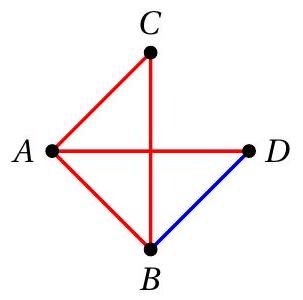

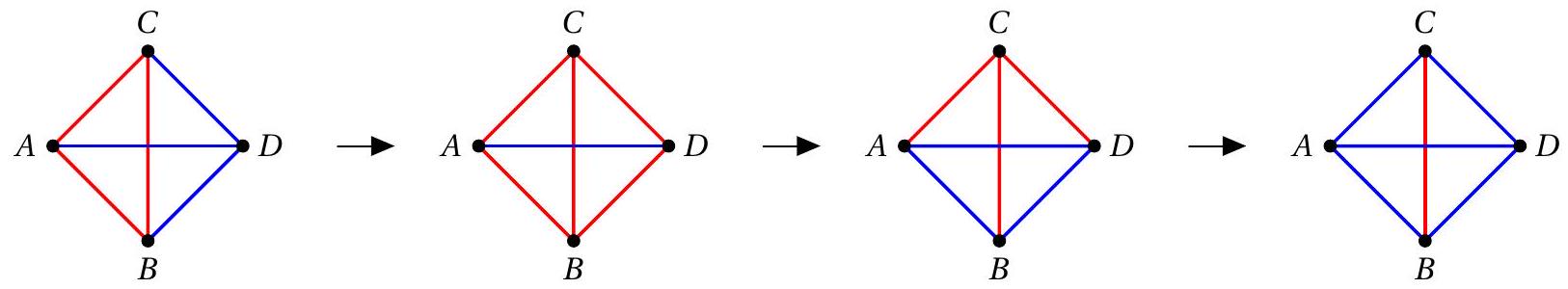

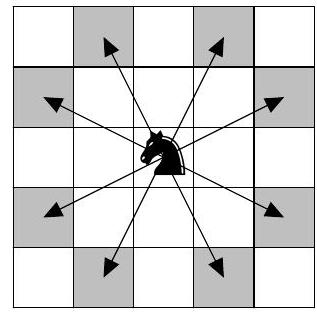

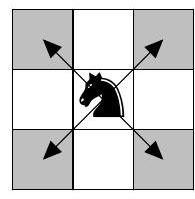

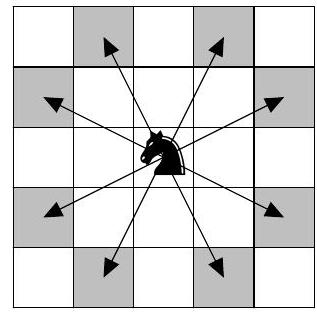

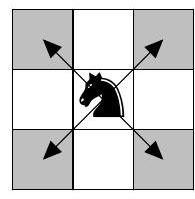

We label the vertices (and the corresponding real numbers) as follows.

For $n=2$, we see that

$$

a_{2}+a_{4}+a_{5}=0=a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{5}

$$

which shows that $a_{3}=a_{4}$ and similarly $a_{1}=a_{5}$ and $a_{2}=a_{6}$. Now the only additional requirement is $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}=0$, so that all solutions are of the following form, for any $x, y$ and $z$ with $x+y+z=0$ :

For $n=3$, observe that $a_{1}=a_{7}=a_{10}$ since they all equal $a_{5}$. Since also $a_{1}+a_{7}+a_{10}=0$, they all equal zero. By considering the top triangle, we get $x=a_{2}=-a_{3}$ and this uniquely determines the rest. It is easily checked that, for any real $x$, this is actually a solution:

For $n \geq 3$ we can apply the same argument as above for any collection of 10 vertices. Any vertex not on the sides of the big triangle has to equal zero, since it is the centre of such a collection of 10 vertices. Any vertex $a$ on the sides of the big triangle forms some parallelogram similar to $a_{4}, a_{2}, a_{5}, a_{8}$, where the point opposite $a$ is in the interior of the big triangle. Since such opposite numbers are equal, all $a_{i}$ have to be zero in this case.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

For $n \geq 2$, an equilateral triangle is divided into $n^{2}$ congruent smaller equilateral triangles. Determine all ways in which real numbers can be assigned to the $\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2}$ vertices so that three such numbers sum to zero whenever the three vertices form a triangle with edges parallel to the sides of the big triangle.

|

We label the vertices (and the corresponding real numbers) as follows.

For $n=2$, we see that

$$

a_{2}+a_{4}+a_{5}=0=a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{5}

$$

which shows that $a_{3}=a_{4}$ and similarly $a_{1}=a_{5}$ and $a_{2}=a_{6}$. Now the only additional requirement is $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}=0$, so that all solutions are of the following form, for any $x, y$ and $z$ with $x+y+z=0$ :

For $n=3$, observe that $a_{1}=a_{7}=a_{10}$ since they all equal $a_{5}$. Since also $a_{1}+a_{7}+a_{10}=0$, they all equal zero. By considering the top triangle, we get $x=a_{2}=-a_{3}$ and this uniquely determines the rest. It is easily checked that, for any real $x$, this is actually a solution:

For $n \geq 3$ we can apply the same argument as above for any collection of 10 vertices. Any vertex not on the sides of the big triangle has to equal zero, since it is the centre of such a collection of 10 vertices. Any vertex $a$ on the sides of the big triangle forms some parallelogram similar to $a_{4}, a_{2}, a_{5}, a_{8}$, where the point opposite $a$ is in the interior of the big triangle. Since such opposite numbers are equal, all $a_{i}$ have to be zero in this case.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Problem 1.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw15sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer and let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers satisfying $0 \leq a_{i} \leq 1$ for $i=1, \ldots, n$. Prove the inequality

$$

\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right) \cdots\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right) \leq\left(1-a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}\right)^{n} .

$$

|

The numbers $1-a_{i}^{n}$ are positive by assumption. AM-GM gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right) \cdots\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right) & \leq\left(\frac{\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)+\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right)+\cdots+\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right)}{n}\right)^{n} \\

& =\left(1-\frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n}\right)^{n} .

\end{aligned}

$$

By applying AM-GM again we obtain

$$

a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n} \leq \frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n} \Rightarrow\left(1-\frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n}\right)^{n} \leq\left(1-a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}\right)^{n}

$$

and hence the desired inequality.

Remark. It is possible to use Jensen's inequality applied to $f(x)=\log \left(1-e^{x}\right)$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer and let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers satisfying $0 \leq a_{i} \leq 1$ for $i=1, \ldots, n$. Prove the inequality

$$

\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right) \cdots\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right) \leq\left(1-a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}\right)^{n} .

$$

|

The numbers $1-a_{i}^{n}$ are positive by assumption. AM-GM gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right) \cdots\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right) & \leq\left(\frac{\left(1-a_{1}^{n}\right)+\left(1-a_{2}^{n}\right)+\cdots+\left(1-a_{n}^{n}\right)}{n}\right)^{n} \\

& =\left(1-\frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n}\right)^{n} .

\end{aligned}

$$

By applying AM-GM again we obtain

$$

a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n} \leq \frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n} \Rightarrow\left(1-\frac{a_{1}^{n}+\cdots+a_{n}^{n}}{n}\right)^{n} \leq\left(1-a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}\right)^{n}

$$

and hence the desired inequality.

Remark. It is possible to use Jensen's inequality applied to $f(x)=\log \left(1-e^{x}\right)$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Problem 2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw15sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Let $n>1$ be an integer. Find all non-constant real polynomials $P(x)$ satisfying, for any real $x$, the identity

$$

P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right) .

$$

|

Answer: $P(x)=x^{m}$ if $n$ is even; $P(x)= \pm x^{m}$ if $n$ is odd.

Consider first the case of a monomial $P(x)=a x^{m}$ with $a \neq 0$. Then

$$

a x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right)=P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=a x^{m} \cdot a x^{2 m} \cdots a x^{n m}=a^{n} x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}

$$

implies $a^{n}=a$. Thus, $a=1$ when $n$ is even and $a= \pm 1$ when $n$ is odd. Obviously these polynomials satisfy the desired equality.

Suppose now that $P$ is not a monomial. Write $P(x)=a x^{m}+Q(x)$, where $Q$ is non-zero polynomial with $\operatorname{deg} Q=k<m$. We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}+Q & \left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right)=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right) \\

& =P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=\left(a x^{m}+Q(x)\right)\left(a x^{2 m}+Q\left(x^{2}\right)\right) \cdots\left(a x^{n m}+Q\left(x^{n}\right)\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

The highest degree of a monomial, on both sides of the equality, is $\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}$. The second highest degree in the right-hand side is

$$

2 m+3 m+\cdots+n m+k=\frac{m(n+2)(n-1)}{2}+k

$$

while in the left-hand side it is $\frac{k n(n+1)}{2}$. Thus

$$

\frac{m(n+2)(n-1)}{2}+k=\frac{k n(n+1)}{2}

$$

which leads to

$$

(m-k)(n+2)(n-1)=0

$$

and so $m=k$, contradicting the assumption that $m>k$. Consequently, no polynomial of the form $a x^{m}+Q(x)$ fulfils the given condition.

|

P(x)=x^{m} \text{ if } n \text{ is even; } P(x)= \pm x^{m} \text{ if } n \text{ is odd.}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $n>1$ be an integer. Find all non-constant real polynomials $P(x)$ satisfying, for any real $x$, the identity

$$

P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right) .

$$

|

Answer: $P(x)=x^{m}$ if $n$ is even; $P(x)= \pm x^{m}$ if $n$ is odd.

Consider first the case of a monomial $P(x)=a x^{m}$ with $a \neq 0$. Then

$$

a x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right)=P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=a x^{m} \cdot a x^{2 m} \cdots a x^{n m}=a^{n} x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}

$$

implies $a^{n}=a$. Thus, $a=1$ when $n$ is even and $a= \pm 1$ when $n$ is odd. Obviously these polynomials satisfy the desired equality.

Suppose now that $P$ is not a monomial. Write $P(x)=a x^{m}+Q(x)$, where $Q$ is non-zero polynomial with $\operatorname{deg} Q=k<m$. We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a x^{\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}}+Q & \left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right)=P\left(x^{\frac{n(n+1)}{2}}\right) \\

& =P(x) P\left(x^{2}\right) P\left(x^{3}\right) \cdots P\left(x^{n}\right)=\left(a x^{m}+Q(x)\right)\left(a x^{2 m}+Q\left(x^{2}\right)\right) \cdots\left(a x^{n m}+Q\left(x^{n}\right)\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

The highest degree of a monomial, on both sides of the equality, is $\frac{m n(n+1)}{2}$. The second highest degree in the right-hand side is

$$

2 m+3 m+\cdots+n m+k=\frac{m(n+2)(n-1)}{2}+k

$$

while in the left-hand side it is $\frac{k n(n+1)}{2}$. Thus

$$

\frac{m(n+2)(n-1)}{2}+k=\frac{k n(n+1)}{2}

$$

which leads to

$$

(m-k)(n+2)(n-1)=0

$$

and so $m=k$, contradicting the assumption that $m>k$. Consequently, no polynomial of the form $a x^{m}+Q(x)$ fulfils the given condition.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw15sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2015"

}

|

A family wears clothes of three colours: red, blue and green, with a separate, identical laundry bin for each colour. At the beginning of the first week, all bins are empty. Each week, the family generates a total of $10 \mathrm{~kg}$ of laundry (the proportion of each colour is subject to variation). The laundry is sorted by colour and placed in the bins. Next, the heaviest bin (only one of them, if there are several that are heaviest) is emptied and its contents washed. What is the minimal possible storing capacity required of the laundry bins in order for them never to overflow?

|

Answer: $25 \mathrm{~kg}$.

Each week, the accumulation of laundry increases the total amount by $K=10$, after which the washing decreases it by at least one third, because, by the pigeon-hole principle, the bin with the most laundry must contain at least a third of the total. Hence the amount of laundry post-wash after the $n$th week is bounded above by the sequence $a_{n+1}=\frac{2}{3}\left(a_{n}+K\right)$ with $a_{0}=0$, which is clearly bounded above by $2 K$. The total amount of laundry is less than $2 K$ post-wash and $3 K$ pre-wash.

Now suppose pre-wash state $(a, b, c)$ precedes post-wash state $(a, b, 0)$, which precedes pre-wash state $\left(a^{\prime}, b^{\prime}, c^{\prime}\right)$. The relations $a \leq c$ and $a^{\prime} \leq a+K$ lead to

$$

3 K>a+b+c \geq 2 a \geq 2\left(a^{\prime}-K\right)

$$

and similarly for $b^{\prime}$, whence $a^{\prime}, b^{\prime}<\frac{5}{2} K$. Since also $c^{\prime} \leq K$, a pre-wash bin, and a fortiori a post-wash bin, always contains less than $\frac{5}{2} K$.

Consider now the following scenario. For a start, we keep packing the three bins equally full before washing. Initialising at $(0,0,0)$, the first week will end at $\left(\frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K, 0\right)$ post-wash, the second week at $\left(\frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K, 0\right)$ post-wash, \&c. Following this scheme, we can get arbitrarily close to the state $(K, K, 0)$ after washing. Supposing this accomplished, placing $\frac{1}{2} K \mathrm{~kg}$ of laundry in each of the non-empty bins leaves us in a state close to $\left(\frac{3}{2} K, \frac{3}{2} K, 0\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{3}{2} K, 0,0\right)$ post-wash. Finally, the next week's worth of laundry is directed solely to the single non-empty bin. It may thus contain any amount of laundry below $\frac{5}{2} K \mathrm{~kg}$.

|

25 \mathrm{~kg}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

A family wears clothes of three colours: red, blue and green, with a separate, identical laundry bin for each colour. At the beginning of the first week, all bins are empty. Each week, the family generates a total of $10 \mathrm{~kg}$ of laundry (the proportion of each colour is subject to variation). The laundry is sorted by colour and placed in the bins. Next, the heaviest bin (only one of them, if there are several that are heaviest) is emptied and its contents washed. What is the minimal possible storing capacity required of the laundry bins in order for them never to overflow?

|

Answer: $25 \mathrm{~kg}$.

Each week, the accumulation of laundry increases the total amount by $K=10$, after which the washing decreases it by at least one third, because, by the pigeon-hole principle, the bin with the most laundry must contain at least a third of the total. Hence the amount of laundry post-wash after the $n$th week is bounded above by the sequence $a_{n+1}=\frac{2}{3}\left(a_{n}+K\right)$ with $a_{0}=0$, which is clearly bounded above by $2 K$. The total amount of laundry is less than $2 K$ post-wash and $3 K$ pre-wash.

Now suppose pre-wash state $(a, b, c)$ precedes post-wash state $(a, b, 0)$, which precedes pre-wash state $\left(a^{\prime}, b^{\prime}, c^{\prime}\right)$. The relations $a \leq c$ and $a^{\prime} \leq a+K$ lead to

$$

3 K>a+b+c \geq 2 a \geq 2\left(a^{\prime}-K\right)

$$

and similarly for $b^{\prime}$, whence $a^{\prime}, b^{\prime}<\frac{5}{2} K$. Since also $c^{\prime} \leq K$, a pre-wash bin, and a fortiori a post-wash bin, always contains less than $\frac{5}{2} K$.

Consider now the following scenario. For a start, we keep packing the three bins equally full before washing. Initialising at $(0,0,0)$, the first week will end at $\left(\frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{1}{3} K, \frac{1}{3} K, 0\right)$ post-wash, the second week at $\left(\frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{5}{9} K, \frac{5}{9} K, 0\right)$ post-wash, \&c. Following this scheme, we can get arbitrarily close to the state $(K, K, 0)$ after washing. Supposing this accomplished, placing $\frac{1}{2} K \mathrm{~kg}$ of laundry in each of the non-empty bins leaves us in a state close to $\left(\frac{3}{2} K, \frac{3}{2} K, 0\right)$ pre-wash and $\left(\frac{3}{2} K, 0,0\right)$ post-wash. Finally, the next week's worth of laundry is directed solely to the single non-empty bin. It may thus contain any amount of laundry below $\frac{5}{2} K \mathrm{~kg}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw15sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbf{R} \rightarrow \mathbf{R}$ satisfying the equation

$$

|x| f(y)+y f(x)=f(x y)+f\left(x^{2}\right)+f(f(y))

$$

for all real numbers $x$ and $y$.

|

Answer: all functions $f(x)=c(|x|-x)$, where $c \geq 0$.

Choosing $x=y=0$, we find

$$

f(f(0))=-2 f(0)

$$