problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

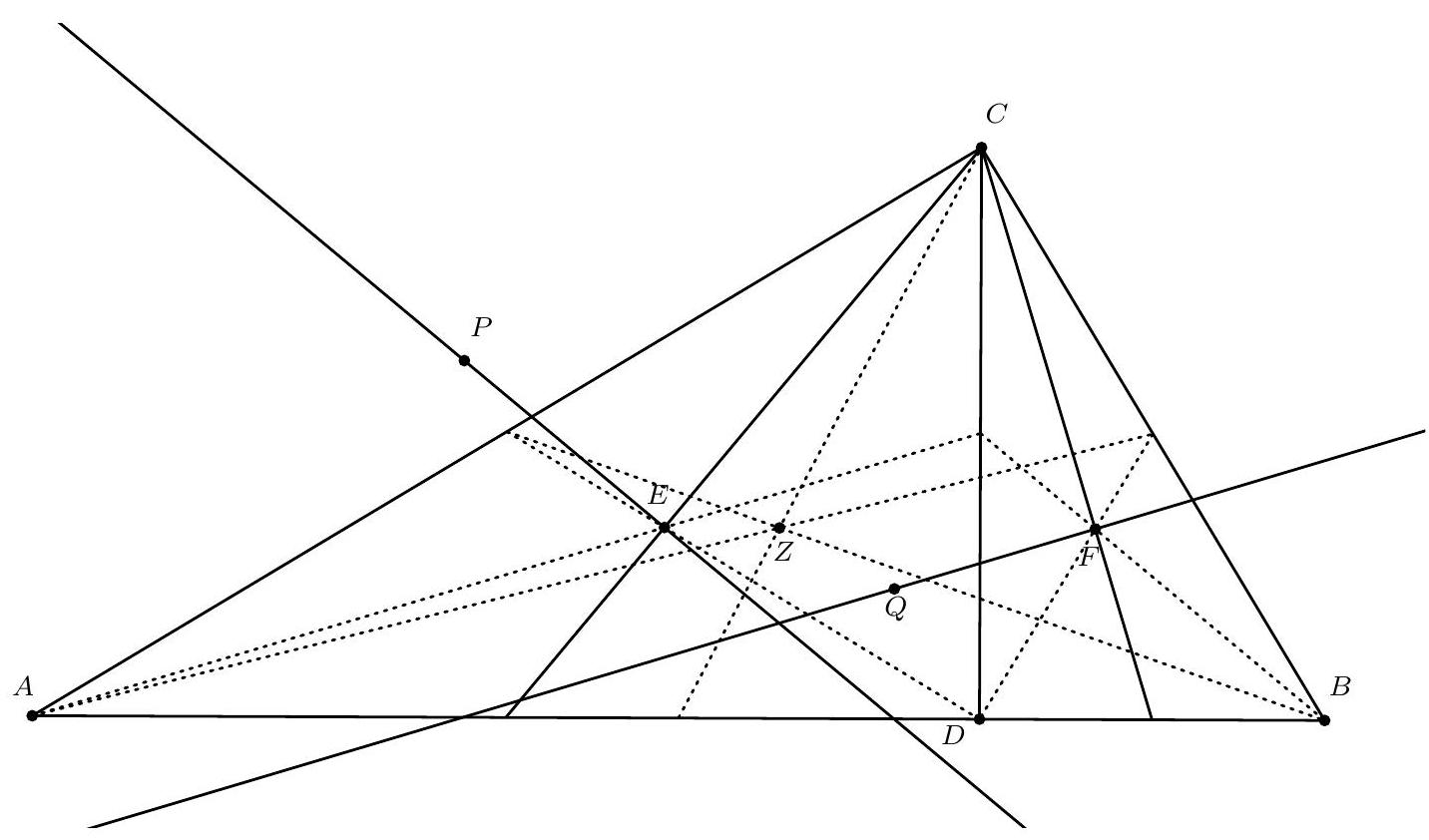

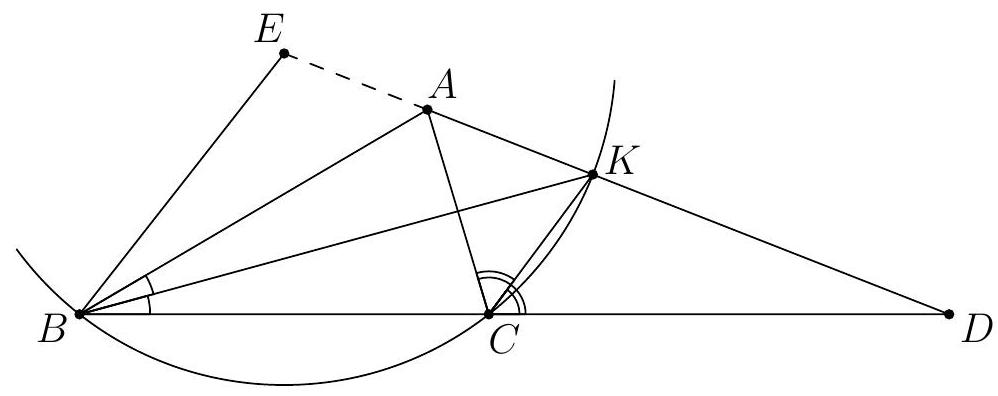

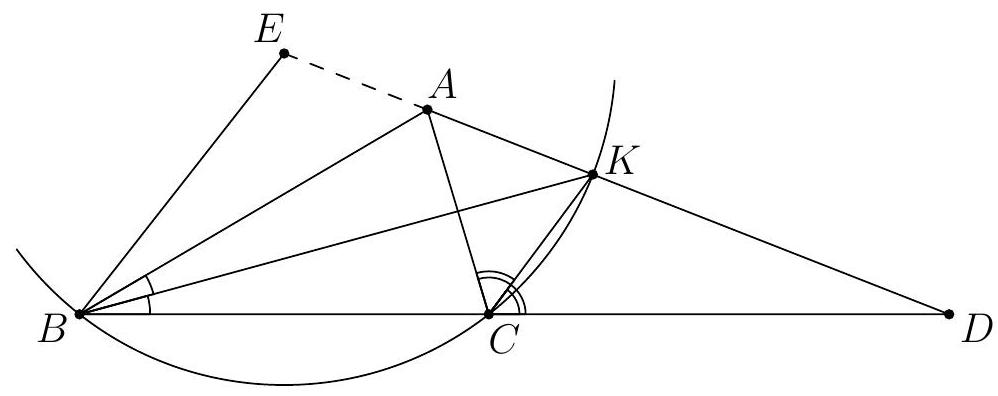

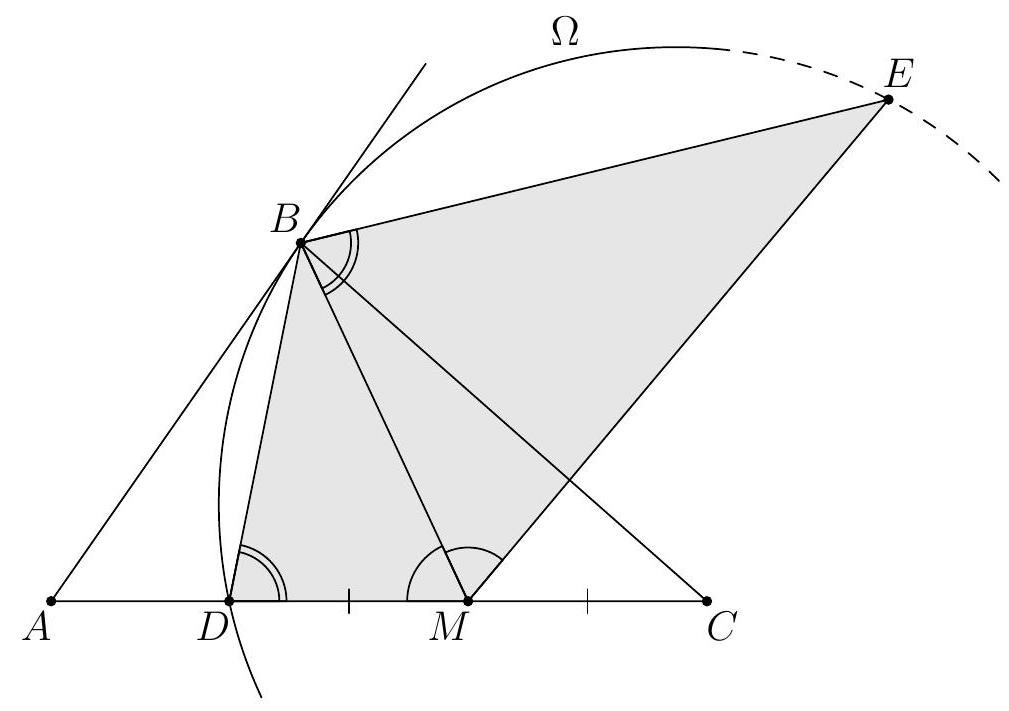

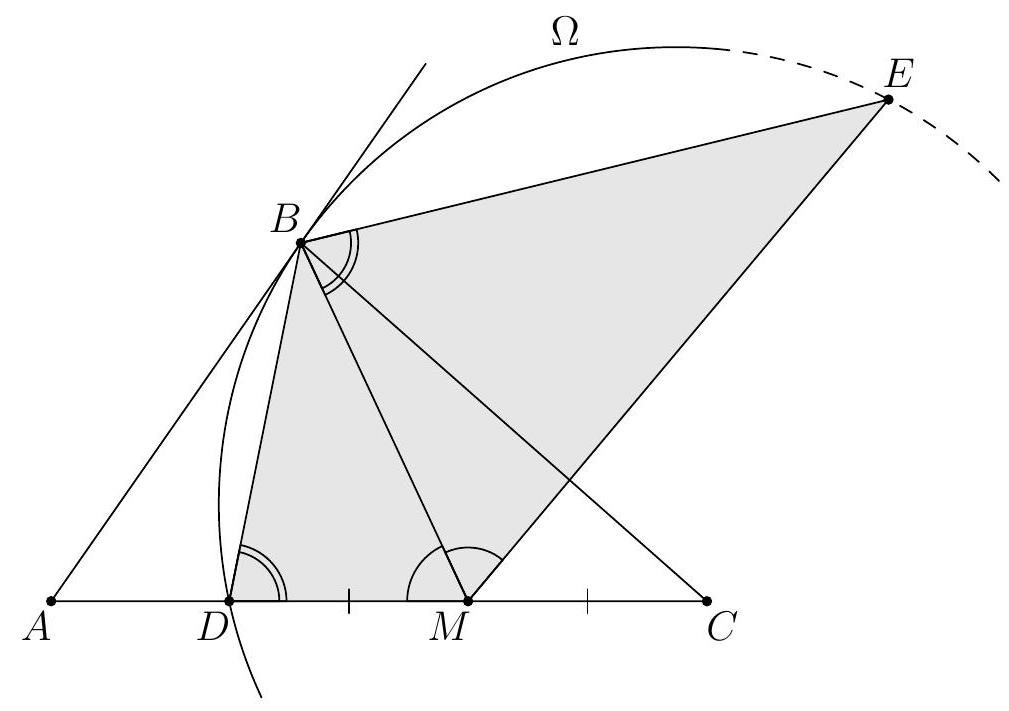

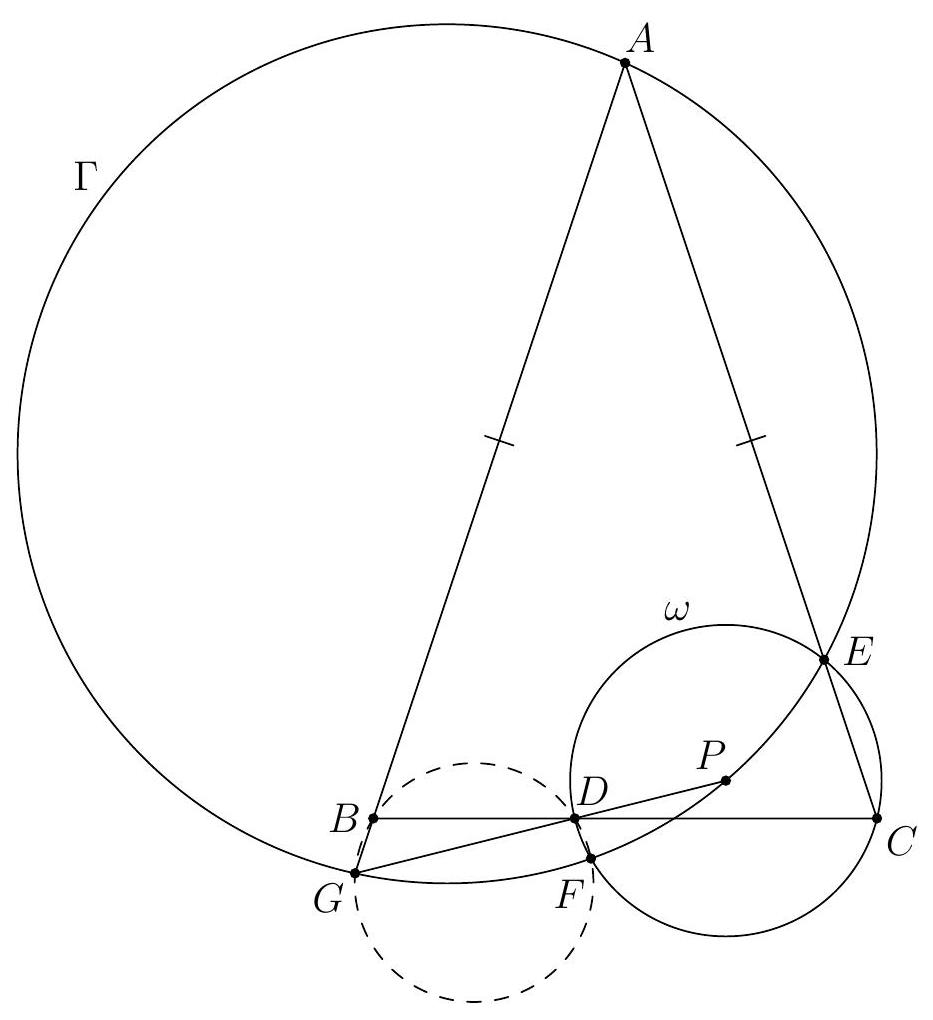

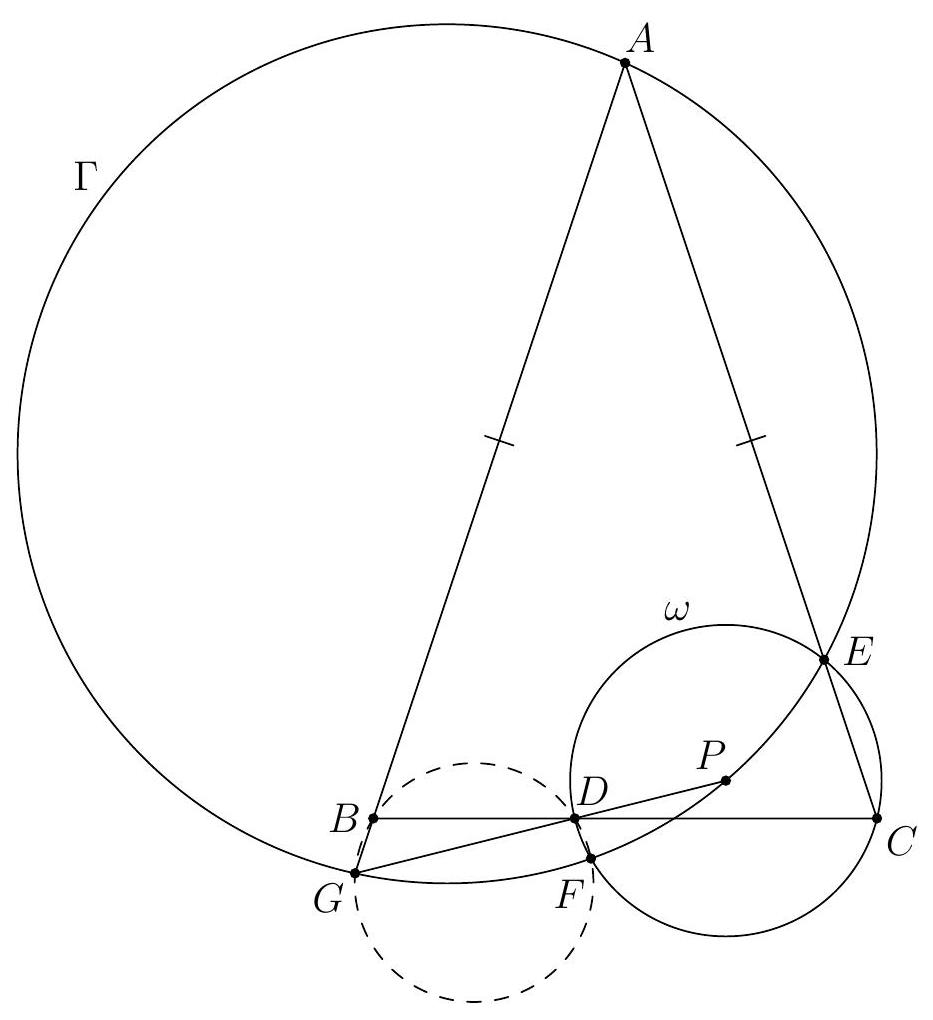

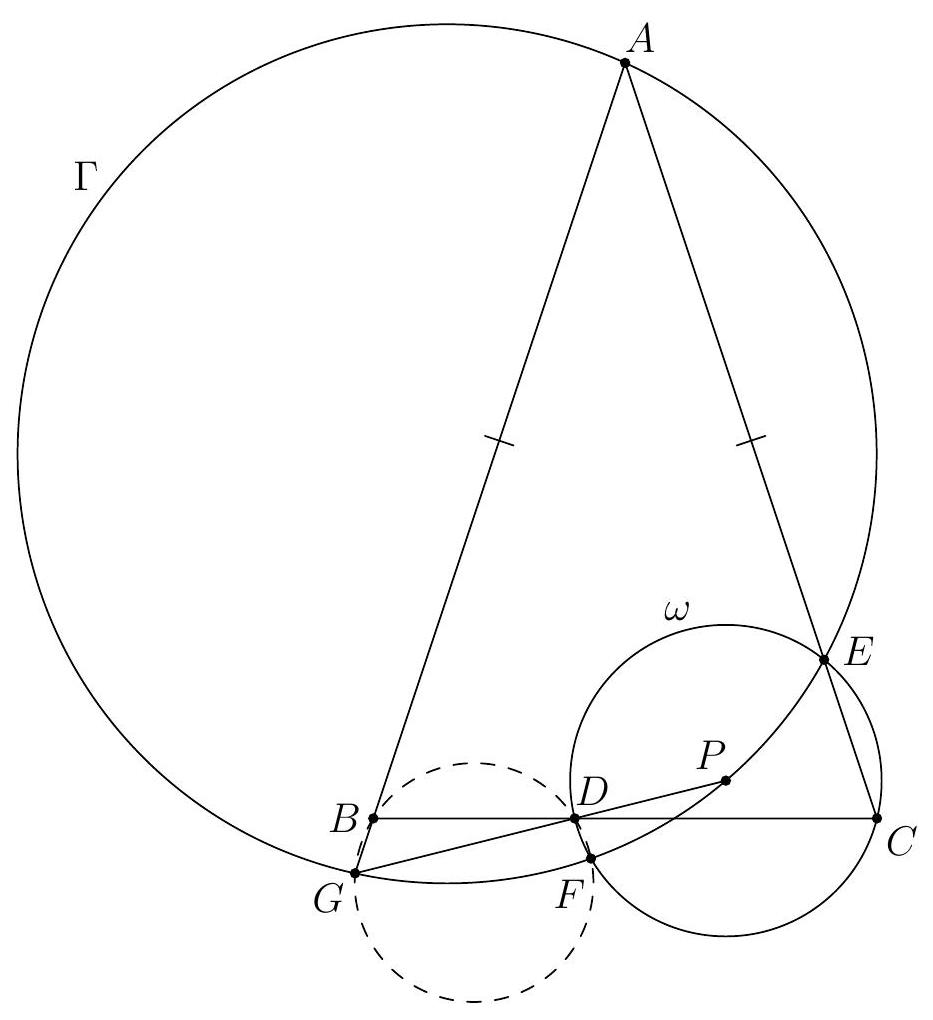

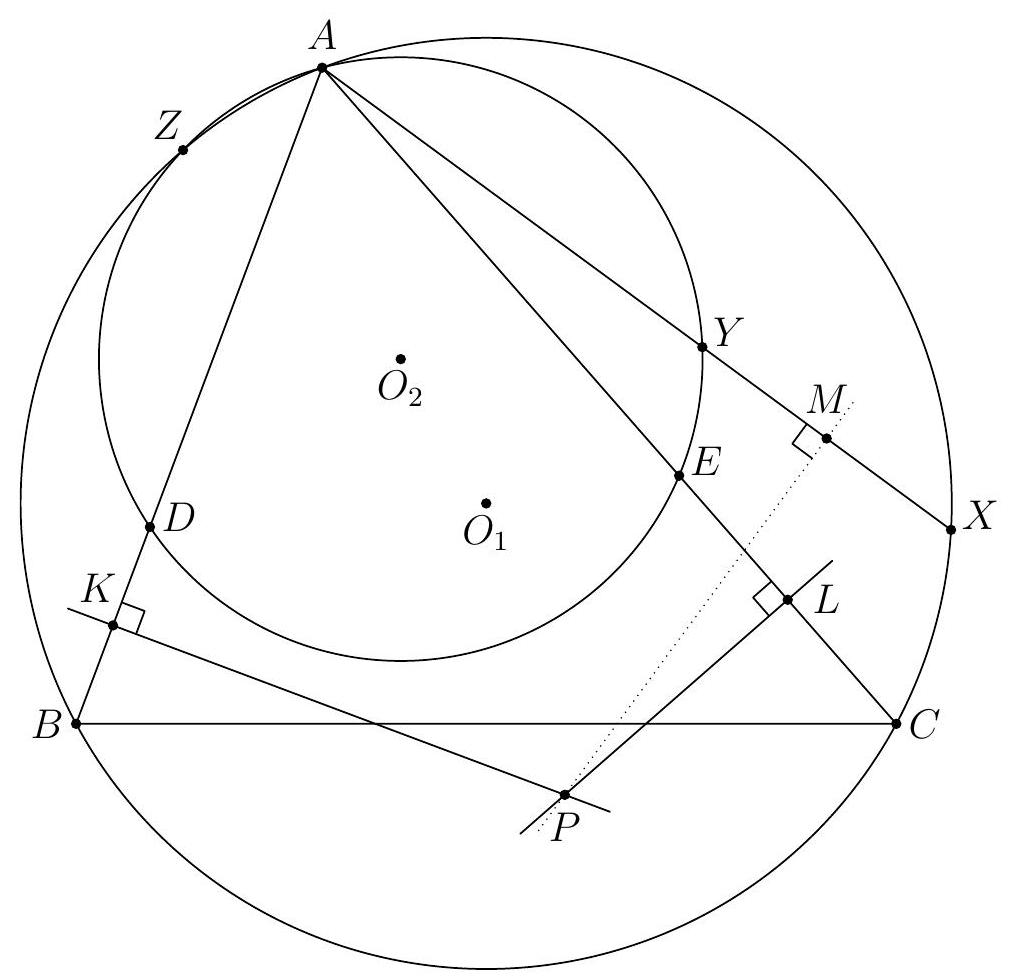

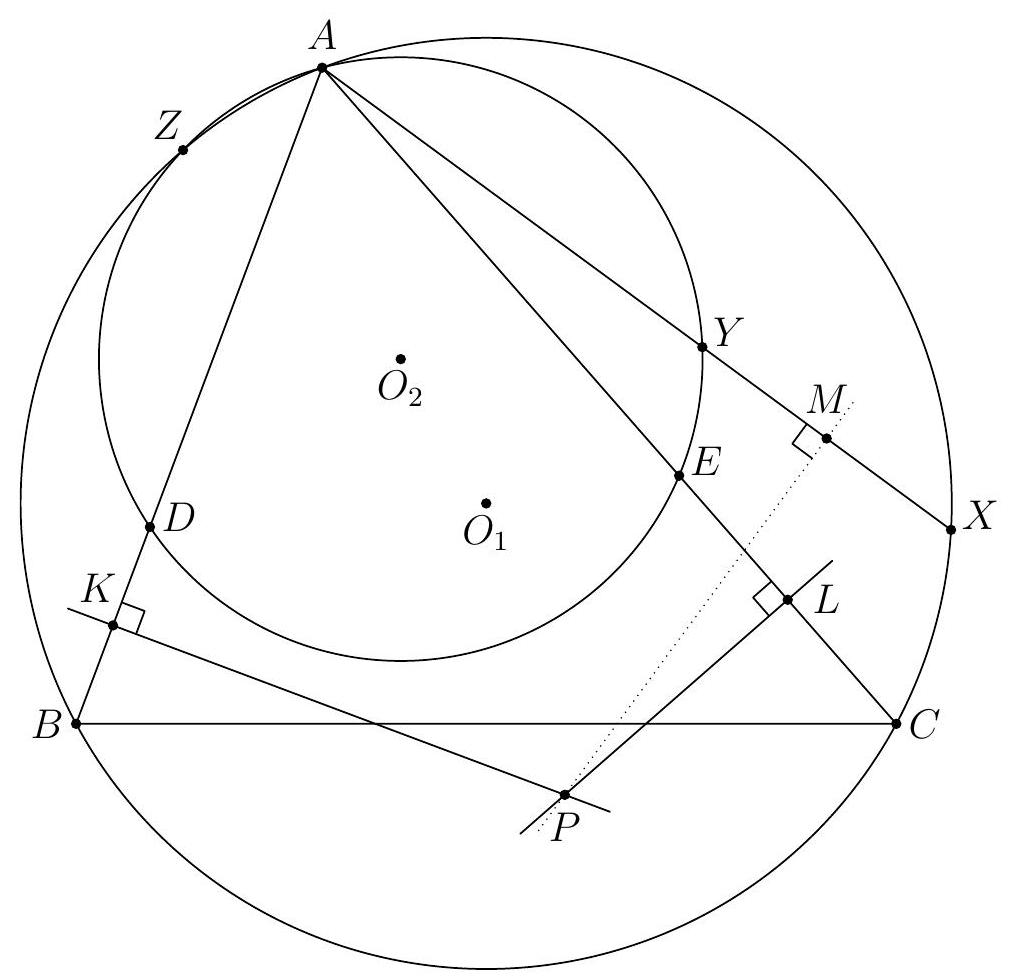

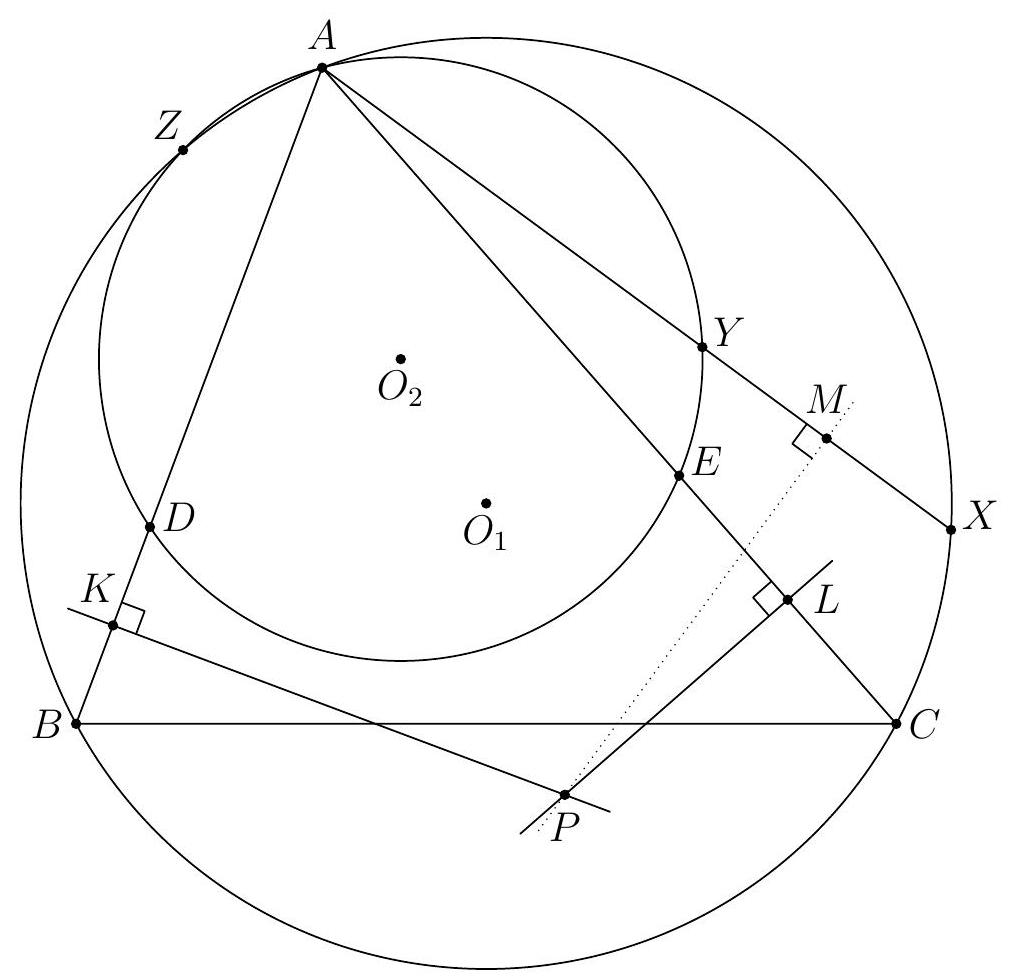

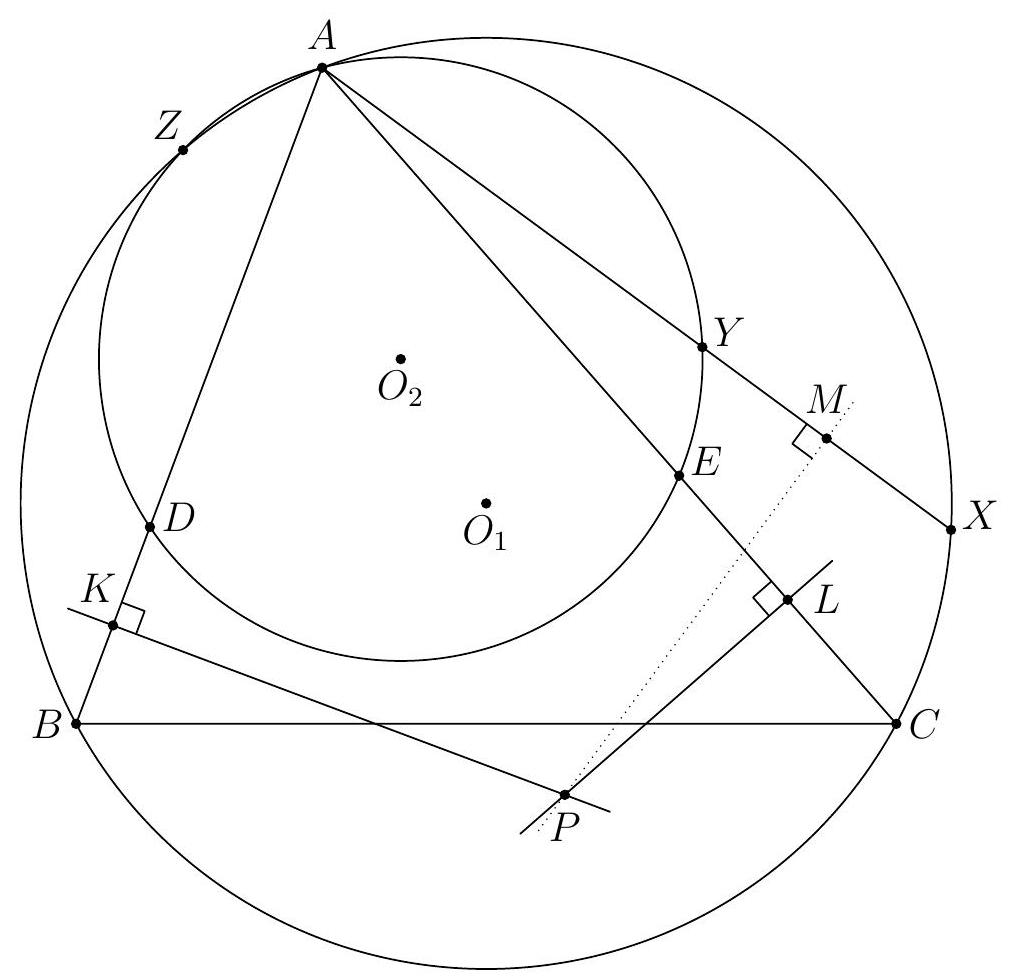

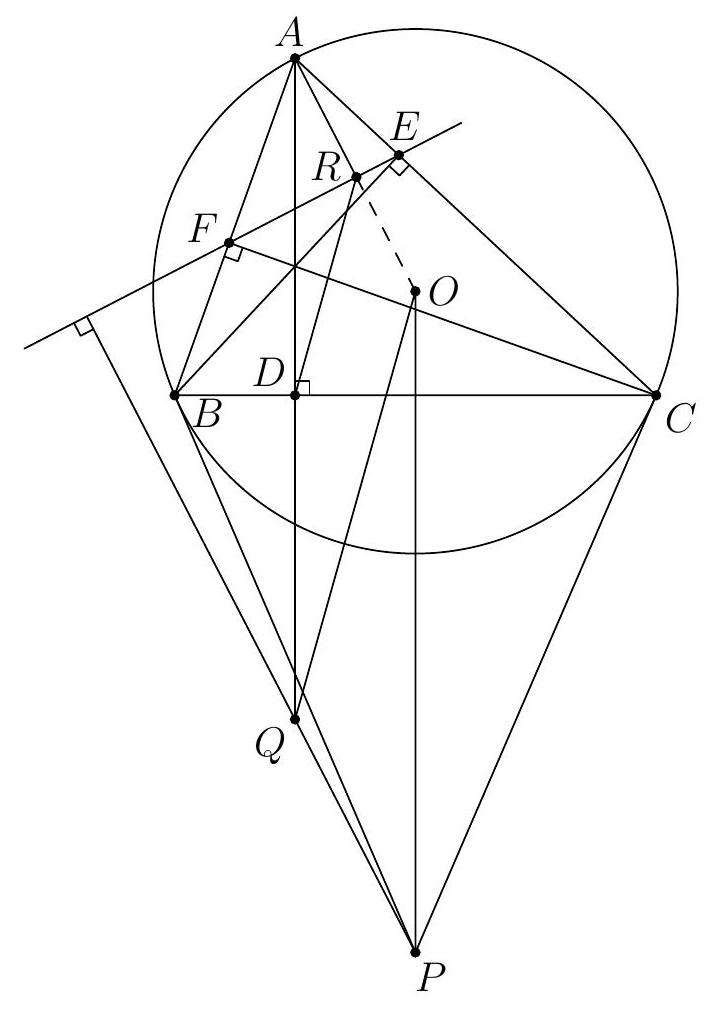

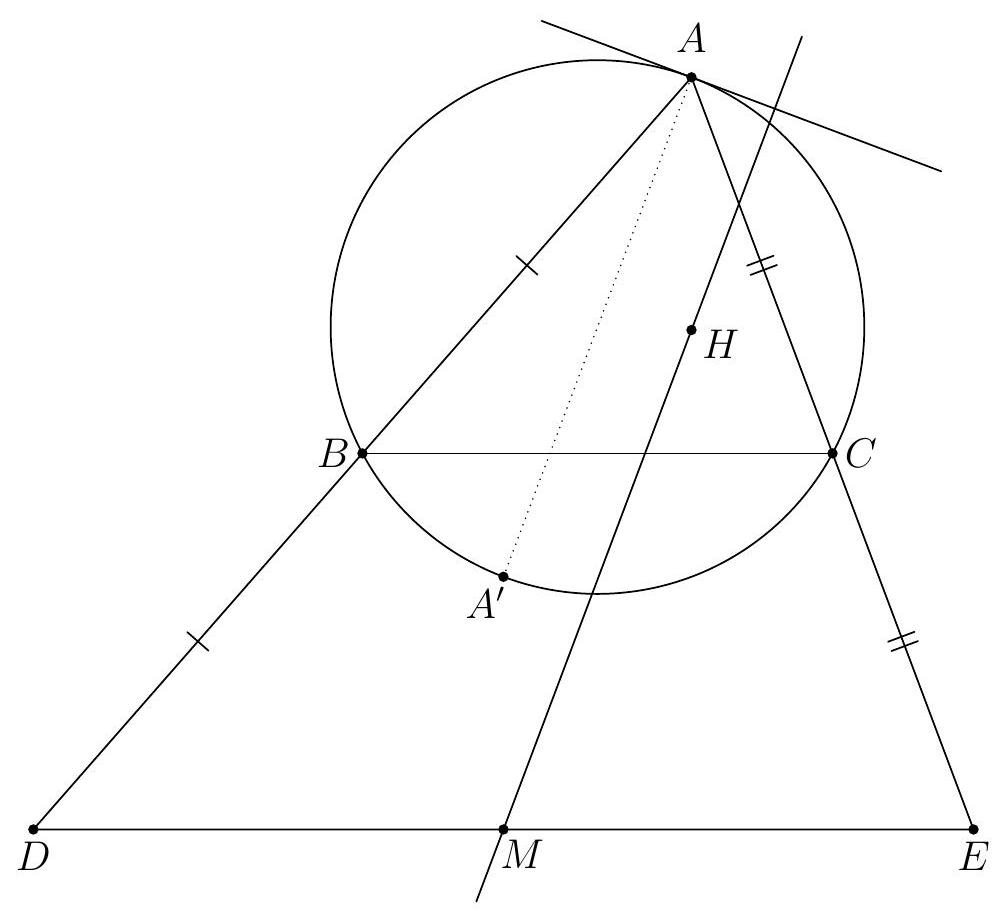

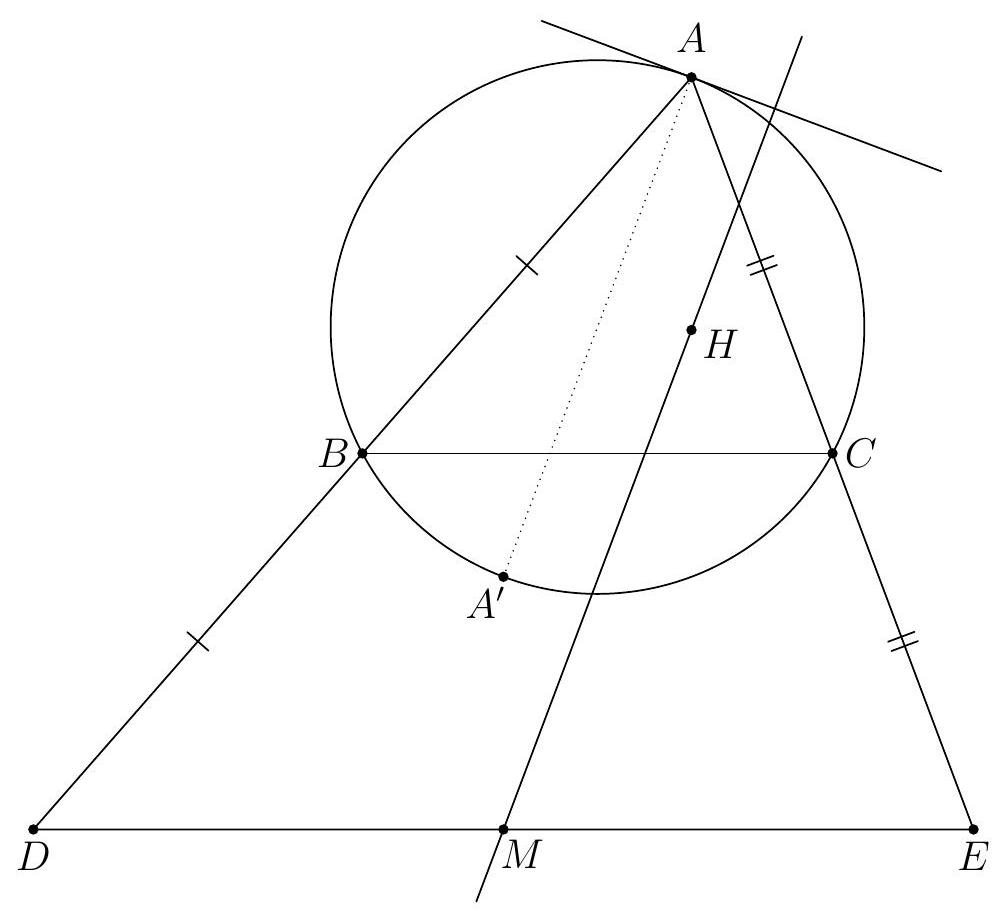

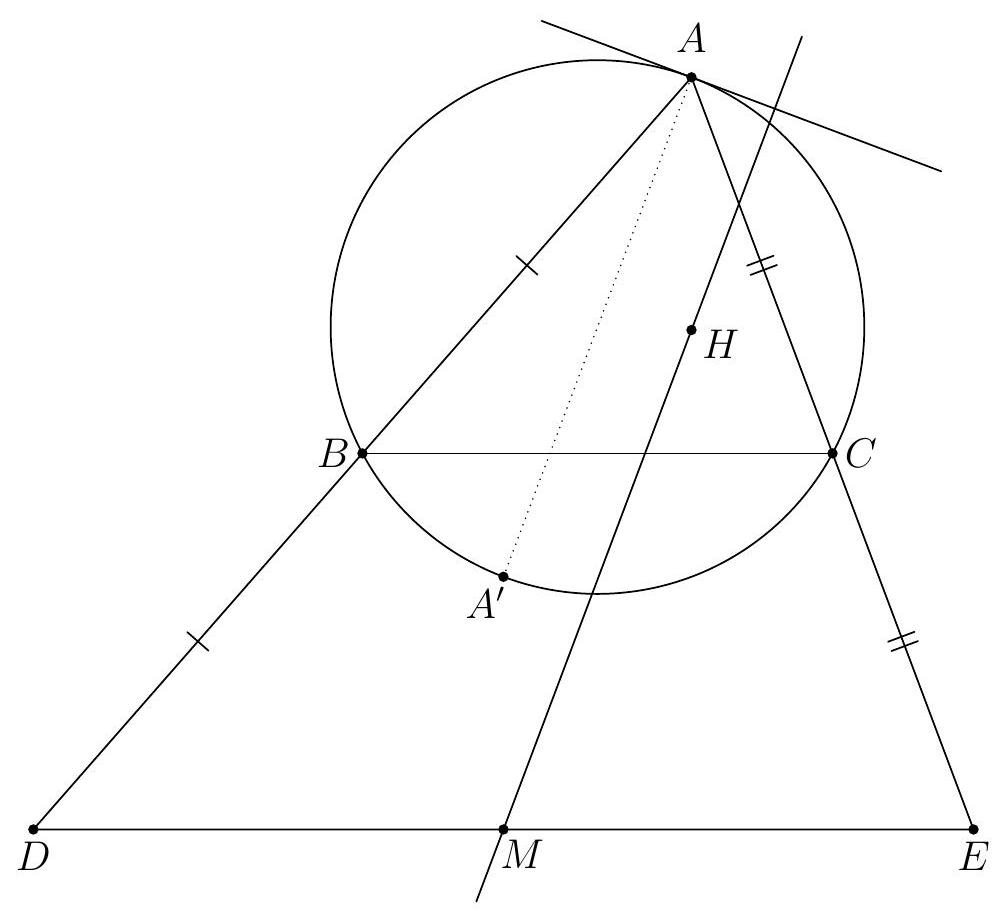

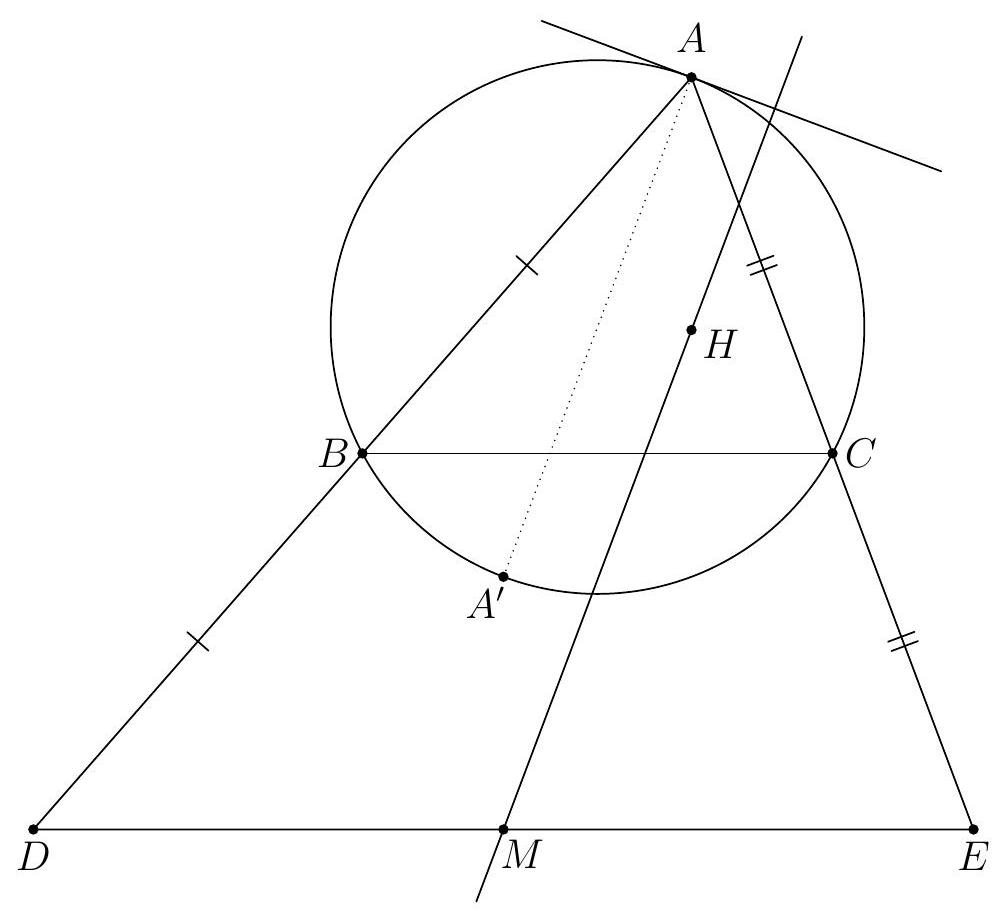

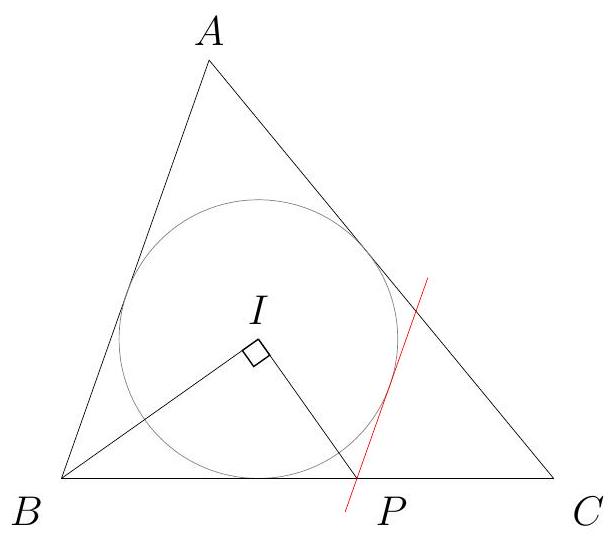

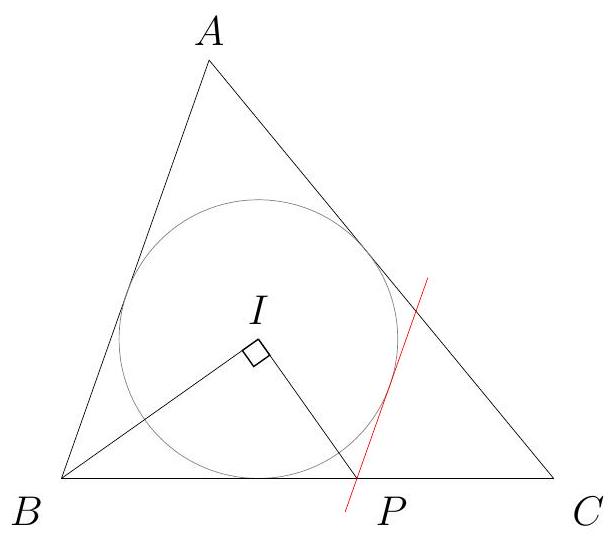

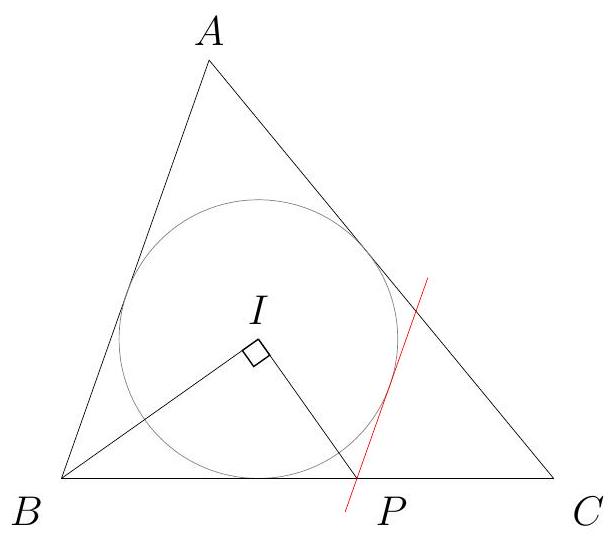

Let $A B C$ be a right triangle with $\angle C=90^{\circ}$ and let $D$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$. Let $E$ be the centroid of triangle $A C D$ and let $F$ be the centroid of triangle $B C D$. The point $P$ satisfies $\angle C E P=90^{\circ}$ and $|C P|=|A P|$, while the point $Q$ satisfies $\angle C F Q=90^{\circ}$ and $|C Q|=|B Q|$.

Show that $P Q$ passes through the centroid of triangle $A B C$.

|

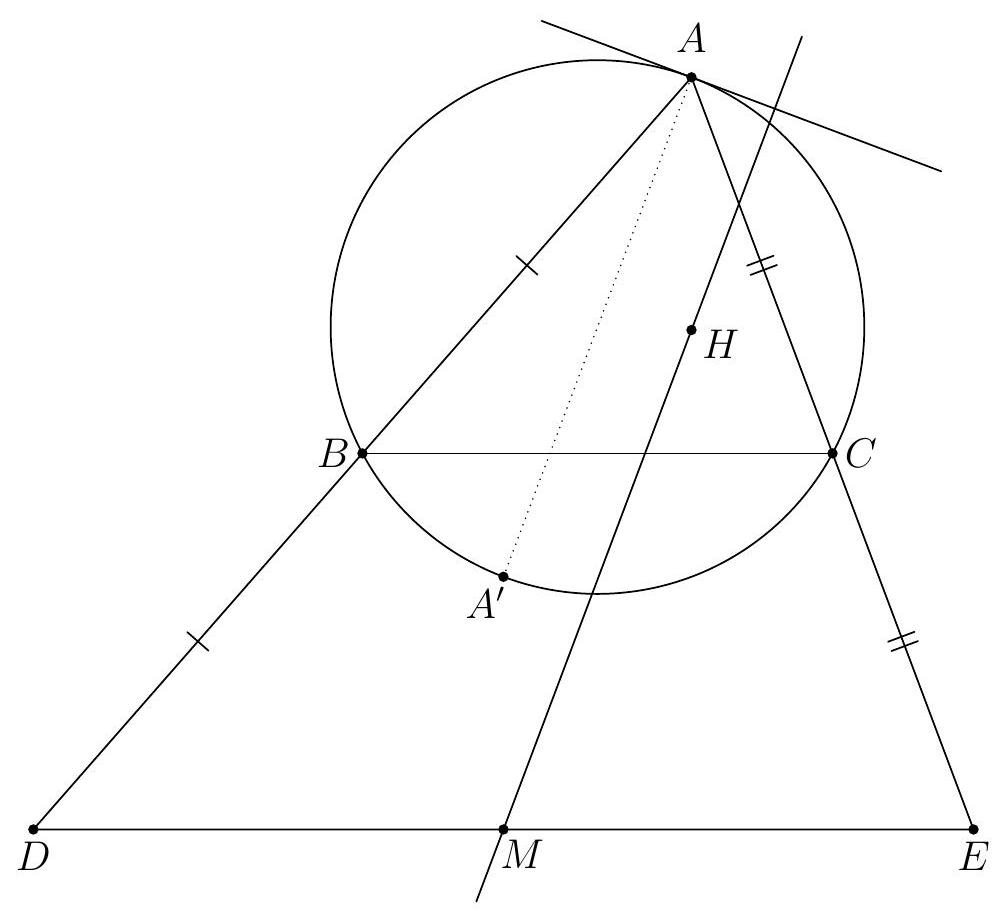

Let $M, N, K$ and $L$ be the midpoints of sides $B C, C A, A B$ and $C D$, respectively. Let $Z$ be the centroid of $\triangle A B C$. Since $M L$ is a midline in triangle $B C D$, we have $M L \| B D$ and thus $M L \| A B$. Similarly, $N L \| A B$, so $M, N$ and $L$ lie on a line $\ell$ parallel to $A B$. Furthermore, because $M L \| B D$, $\triangle B D F \sim \triangle L M F$, and the scaling factor between these two triangles is 2. Therefore, the distance from $F$ to $\ell$ (which is the line $M L$) is half the distance from $F$ to $A B$ (which is the line $B D$). Similarly, the distance from $E$ to $\ell$ is half the distance from $E$ to $A B$, and the same applies to $Z$. Thus, $E, F$ and $Z$ all lie on a line parallel to $A B$ that is twice as far from $A B$ as from $\ell$.

(Another way to see this is by using the fact that centroids always lie at $\frac{1}{3}$ of the altitude from the corresponding vertex. The points $E, F$ and $Z$ all lie at $\frac{1}{3}$ of the altitude from $C$, which leads to the same conclusion.)

In particular, this implies that $\angle C Z E = \angle C K A$ (F-angles). We will use this to show that the points $Z, E, N$ and $C$ lie on a circle. For this, consider the similar triangles $\triangle A B C$ and $\triangle A C D$. We have $\frac{|A K|}{|A N|} = \frac{|A B|}{|A C|} = \frac{|A C|}{|A D|}$, so $\triangle A K C \sim \triangle A N D$ (SAS). This gives $\angle C K A = \angle D N A$. Altogether, we find

$$

\angle C Z E = \angle C K A = \angle D N A = 180^{\circ} - \angle D N C = 180^{\circ} - \angle E N C,

$$

so $C Z E N$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.

Since $|C P| = |A P|$, $P$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $A C$. Therefore, $\angle C N P = 90^{\circ} = \angle C E P$, which means that $C, E, N$ and $P$ lie on a circle. We have just seen that $Z$ also lies on this circle. Thus, $\angle C Z P = \angle C E P = 90^{\circ}$. Similarly, $\angle C Z Q = 90^{\circ}$. Together, we can conclude that $P, Z$ and $Q$ lie on a line.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een rechthoekige driehoek met $\angle C=90^{\circ}$ en zij $D$ het voetpunt van de hoogtelijn uit $C$. Zij $E$ het zwaartepunt van driehoek $A C D$ en zij $F$ het zwaartepunt van driehoek $B C D$. Het punt $P$ voldoet aan $\angle C E P=90^{\circ}$ en $|C P|=|A P|$, terwijl het punt $Q$ voldoet aan $\angle C F Q=90^{\circ}$ en $|C Q|=|B Q|$.

Toon aan dat $P Q$ door het zwaartepunt van driehoek $A B C$ gaat.

|

Noem $M, N, K$ en $L$ de middens van respectievelijk zijden $B C, C A, A B$ en $C D$. Zij $Z$ het zwaartepunt van $\triangle A B C$. Omdat $M L$ een middenparallel in driehoek $B C D$ is, geldt $M L \| B D$ en dus $M L \| A B$. Zo is ook $N L \| A B$, dus $M, N$ en $L$ liggen op een lijn $\ell$ evenwijdig aan $A B$. Verder geldt vanwege $M L \| B D$ dat $\triangle B D F \sim \triangle L M F$, waarbij de vermenigvuldigingsfactor tussen deze twee driehoeken gelijk aan 2 is. Dus de afstand van $F$ tot $\ell$ (wat de lijn $M L$ is) is twee keer zo klein als de afstand van $F$ tot $A B$ (wat de lijn $B D$ is). Net zo is de afstand van $E$ tot $\ell$ twee keer zo klein als de afstand van $E$ tot $A B$, en hetzelfde geldt voor $Z$. Dus $E, F$ en $Z$ liggen allemaal op een lijn evenwijdig aan $A B$ die twee keer zo ver van $A B$ af ligt als van $\ell$.

(Een andere manier om dit in te zien, is door gebruik te maken van het feit dat zwaartepunten altijd op $\frac{1}{3}$ hoogte van een zwaartelijn liggen. De punten $E, F$ en $Z$ liggen allemaal op $\frac{1}{3}$ hoogte van de corresponderende zwaartelijnen uit $C$, waaruit het gestelde volgt.)

Hieruit volgt in het bijzonder dat $\angle C Z E=\angle C K A$ (F-hoeken). We gaan dit gebruiken om aan te tonen dat de punten $Z, E, N$ en $C$ samen op een cirkel liggen. Bekijk hiervoor eerst de gelijkvormige driehoeken $\triangle A B C$ en $\triangle A C D$. Er geldt nu $\frac{|A K|}{|A N|}=\frac{|A B|}{|A C|}=\frac{|A C|}{|A D|}$, dus $\triangle A K C \sim \triangle A N D$ (zhz). Hieruit volgt $\angle C K A=\angle D N A$. Al met al vinden we nu

$$

\angle C Z E=\angle C K A=\angle D N A=180^{\circ}-\angle D N C=180^{\circ}-\angle E N C,

$$

dus $C Z E N$ is een koordenvierhoek.

Omdat $|C P|=|A P|$ ligt $P$ op de middelloodlijn van $A C$. Er geldt dus $\angle C N P=90^{\circ}=$ $\angle C E P$, wat betekent dat $C, E, N$ en $P$ op een cirkel liggen. We hebben zojuist gezien dat $Z$ ook op deze cirkel ligt. Dus geldt $\angle C Z P=\angle C E P=90^{\circ}$. Analoog volgt $\angle C Z Q=90^{\circ}$. Samen kunnen we hieruit concluderen dat $P, Z$ en $Q$ op een lijn liggen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2021-E2021_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ met

$$

f(x+y f(x+y))=y^{2}+f(x) f(y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Merk op dat de functie $f(x)=0$ voor alle $x$ niet voldoet. Er is dus een $a$ met $f(a) \neq 0$. Vul $x=a$ en $y=0$ in, dat geeft $f(a)=f(a) f(0)$, dus $f(0)=1$. Vul nu $x=1$ en $y=-1$ in, dat geeft $f(1-f(0))=1+f(1) f(-1)$. Omdat $f(0)=1$, staat hier $1=1+f(1) f(-1)$, dus $f(1)=0$ of $f(-1)=0$. We onderscheiden deze twee gevallen.

Stel eerst dat $f(1)=0$. Vul $x=t$ en $y=1-t$ in, en vervolgens $x=1-t$ en $y=t$, dan krijgen we de twee vergelijkingen

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(t) & =(1-t)^{2}+f(t) f(1-t) \\

f(1-t) & =t^{2}+f(t) f(1-t)

\end{aligned}

$$

Deze van elkaar afhalen geeft $f(t)-f(1-t)=(1-t)^{2}-t^{2}=1-2 t$, dus $f(1-t)=f(t)+2 t-1$. Dit invullen in de eerste van bovenstaande twee vergelijkingen geeft

$$

f(t)=(1-t)^{2}+f(t)^{2}+(2 t-1) f(t)

$$

wat we kunnen herschrijven tot

$$

f(t)^{2}+(2 t-2) f(t)+(1-t)^{2}=0

$$

oftewel $(f(t)-(1-t))^{2}=0$. We concluderen dat $f(t)=1-t$. Controleren van deze functie in de oorspronkelijke functievergelijking geeft links $1-(x+y(1-x-y))=1-$ $\left(x+y-x y-y^{2}\right)=1-x-y+x y+y^{2}$ en rechts $y^{2}+(1-x)(1-y)=y^{2}+1-x-y+x y$ en dat is hetzelfde, dus de functie voldoet.

Stel nu $f(-1)=0$. Vul $x=t$ en $y=-1-t$ in, en vervolgens $x=-1-t$ en $y=t$, dan krijgen we de twee vergelijkingen

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(t) & =(-1-t)^{2}+f(t) f(-1-t), \\

f(-1-t) & =t^{2}+f(t) f(-1-t)

\end{aligned}

$$

Deze van elkaar afhalen geeft $f(t)-f(-1-t)=(-1-t)^{2}-t^{2}=1+2 t$, dus $f(-1-t)=$ $f(t)-2 t-1$. Dit invullen in de eerste van bovenstaande twee vergelijkingen geeft

$$

f(t)=(-1-t)^{2}+f(t)^{2}+(-2 t-1) f(t)

$$

wat we kunnen herschrijven tot

$$

f(t)^{2}-(2 t+2) f(t)+(t+1)^{2}=0

$$

oftewel $(f(t)-(t+1))^{2}=0$. We concluderen dat $f(t)=t+1$. Controleren van deze functie in de oorspronkelijke functievergelijking geeft links $x+y(x+y+1)+1=x+x y+y^{2}+y+1$ en rechts $y^{2}+(x+1)(y+1)=y^{2}+x y+x+y+1$ en dat is hetzelfde, dus de functie voldoet.

We concluderen dat er precies twee oplossingen zijn: $f(x)=1-x$ voor alle $x$ en $f(x)=x+1$ voor alle $x$.

|

f(x)=1-x \text{ en } f(x)=x+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ met

$$

f(x+y f(x+y))=y^{2}+f(x) f(y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Merk op dat de functie $f(x)=0$ voor alle $x$ niet voldoet. Er is dus een $a$ met $f(a) \neq 0$. Vul $x=a$ en $y=0$ in, dat geeft $f(a)=f(a) f(0)$, dus $f(0)=1$. Vul nu $x=1$ en $y=-1$ in, dat geeft $f(1-f(0))=1+f(1) f(-1)$. Omdat $f(0)=1$, staat hier $1=1+f(1) f(-1)$, dus $f(1)=0$ of $f(-1)=0$. We onderscheiden deze twee gevallen.

Stel eerst dat $f(1)=0$. Vul $x=t$ en $y=1-t$ in, en vervolgens $x=1-t$ en $y=t$, dan krijgen we de twee vergelijkingen

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(t) & =(1-t)^{2}+f(t) f(1-t) \\

f(1-t) & =t^{2}+f(t) f(1-t)

\end{aligned}

$$

Deze van elkaar afhalen geeft $f(t)-f(1-t)=(1-t)^{2}-t^{2}=1-2 t$, dus $f(1-t)=f(t)+2 t-1$. Dit invullen in de eerste van bovenstaande twee vergelijkingen geeft

$$

f(t)=(1-t)^{2}+f(t)^{2}+(2 t-1) f(t)

$$

wat we kunnen herschrijven tot

$$

f(t)^{2}+(2 t-2) f(t)+(1-t)^{2}=0

$$

oftewel $(f(t)-(1-t))^{2}=0$. We concluderen dat $f(t)=1-t$. Controleren van deze functie in de oorspronkelijke functievergelijking geeft links $1-(x+y(1-x-y))=1-$ $\left(x+y-x y-y^{2}\right)=1-x-y+x y+y^{2}$ en rechts $y^{2}+(1-x)(1-y)=y^{2}+1-x-y+x y$ en dat is hetzelfde, dus de functie voldoet.

Stel nu $f(-1)=0$. Vul $x=t$ en $y=-1-t$ in, en vervolgens $x=-1-t$ en $y=t$, dan krijgen we de twee vergelijkingen

$$

\begin{aligned}

f(t) & =(-1-t)^{2}+f(t) f(-1-t), \\

f(-1-t) & =t^{2}+f(t) f(-1-t)

\end{aligned}

$$

Deze van elkaar afhalen geeft $f(t)-f(-1-t)=(-1-t)^{2}-t^{2}=1+2 t$, dus $f(-1-t)=$ $f(t)-2 t-1$. Dit invullen in de eerste van bovenstaande twee vergelijkingen geeft

$$

f(t)=(-1-t)^{2}+f(t)^{2}+(-2 t-1) f(t)

$$

wat we kunnen herschrijven tot

$$

f(t)^{2}-(2 t+2) f(t)+(t+1)^{2}=0

$$

oftewel $(f(t)-(t+1))^{2}=0$. We concluderen dat $f(t)=t+1$. Controleren van deze functie in de oorspronkelijke functievergelijking geeft links $x+y(x+y+1)+1=x+x y+y^{2}+y+1$ en rechts $y^{2}+(x+1)(y+1)=y^{2}+x y+x+y+1$ en dat is hetzelfde, dus de functie voldoet.

We concluderen dat er precies twee oplossingen zijn: $f(x)=1-x$ voor alle $x$ en $f(x)=x+1$ voor alle $x$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2021-E2021_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ met

$$

f(x+y f(x+y))=y^{2}+f(x) f(y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Net als in de eerste oplossing leiden we af dat $f(0)=1$ en dat $f(1)=0$ of $f(-1)=0$.

Stel eerst dat $f(1)=0$. Invullen van $x=t-1$ en $y=1$ geeft $f(t-1+f(t))=1$. Anderzijds geldt ook $f(0)=1$. We laten nu zien dat $f(z)=1$ impliceert dat $z=0$. Stel $f(z)=1$. Invullen van $x=1$ en $y=z-1$ geeft $f(1+(z-1) f(z))=(z-1)^{2}$, dus $f(z)=(z-1)^{2}$, oftewel $1=(z-1)^{2}$. Dus $z=0$ of $z=2$. Stel $z=2$, dan geeft invullen van $x=0$ en $y=2$ dat $f(2 f(2))=4+f(0) f(2)$, wat met $f(2)=f(z)=1$ leidt tot $f(2)=5$, in tegenspraak met $f(2)=1$. Dus $z=0$. In het bijzonder volgt uit $f(t-1+f(t))=1$ dus dat $t-1+f(t)=0$, dus $f(t)=1-t$. Deze functie voldoet (zie eerste oplossing).

Stel nu dat $f(-1)=0$. Invullen van $x=t+1$ en $y=-1$ geeft $f(t+1-f(t))=1$. Anderzijds geldt ook $f(0)=1$. We laten nu wederom zien dat $f(z)=1$ impliceert dat $z=0$. Stel $f(z)=1$. Invullen van $x=-1$ en $y=z+1$ geeft $f(-1+(z+1) f(z))=(z+1)^{2}$, dus $f(z)=(z+1)^{2}$, oftewel $1=(z+1)^{2}$. Dus $z=0$ of $z=-2$. Stel $z=-2$, dan geeft invullen van $x=0$ en $y=-2$ dat $f(-2 f(-2))=4+f(0) f(-2)$, wat met $f(-2)=f(z)=1$ leidt tot $f(-2)=5$, in tegenspraak met $f(-2)=1$. Dus $z=0$. In het bijzonder volgt uit $f(t+1-f(t))=1$ dus dat $t+1-f(t)=0$, dus $f(t)=t+1$. Deze functie voldoet ook (zie eerste oplossing).

|

f(t)=1-t \text{ or } f(t)=t+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ met

$$

f(x+y f(x+y))=y^{2}+f(x) f(y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Net als in de eerste oplossing leiden we af dat $f(0)=1$ en dat $f(1)=0$ of $f(-1)=0$.

Stel eerst dat $f(1)=0$. Invullen van $x=t-1$ en $y=1$ geeft $f(t-1+f(t))=1$. Anderzijds geldt ook $f(0)=1$. We laten nu zien dat $f(z)=1$ impliceert dat $z=0$. Stel $f(z)=1$. Invullen van $x=1$ en $y=z-1$ geeft $f(1+(z-1) f(z))=(z-1)^{2}$, dus $f(z)=(z-1)^{2}$, oftewel $1=(z-1)^{2}$. Dus $z=0$ of $z=2$. Stel $z=2$, dan geeft invullen van $x=0$ en $y=2$ dat $f(2 f(2))=4+f(0) f(2)$, wat met $f(2)=f(z)=1$ leidt tot $f(2)=5$, in tegenspraak met $f(2)=1$. Dus $z=0$. In het bijzonder volgt uit $f(t-1+f(t))=1$ dus dat $t-1+f(t)=0$, dus $f(t)=1-t$. Deze functie voldoet (zie eerste oplossing).

Stel nu dat $f(-1)=0$. Invullen van $x=t+1$ en $y=-1$ geeft $f(t+1-f(t))=1$. Anderzijds geldt ook $f(0)=1$. We laten nu wederom zien dat $f(z)=1$ impliceert dat $z=0$. Stel $f(z)=1$. Invullen van $x=-1$ en $y=z+1$ geeft $f(-1+(z+1) f(z))=(z+1)^{2}$, dus $f(z)=(z+1)^{2}$, oftewel $1=(z+1)^{2}$. Dus $z=0$ of $z=-2$. Stel $z=-2$, dan geeft invullen van $x=0$ en $y=-2$ dat $f(-2 f(-2))=4+f(0) f(-2)$, wat met $f(-2)=f(z)=1$ leidt tot $f(-2)=5$, in tegenspraak met $f(-2)=1$. Dus $z=0$. In het bijzonder volgt uit $f(t+1-f(t))=1$ dus dat $t+1-f(t)=0$, dus $f(t)=t+1$. Deze functie voldoet ook (zie eerste oplossing).

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2021-E2021_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Let $p>10$ be a prime number. Prove that there exist positive integers $m$ and $n$ with $m+n<p$ such that $p$ is a divisor of $5^{m} 7^{n}-1$.

|

Due to Fermat's little theorem, $a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ for all $a$ with $p \nmid a$. Since $p>10$, $p$ is odd, so $p-1$ is even. It holds that

$$

\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-1\right)\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}+1\right)=a^{p-1}-1 \equiv 0 \quad \bmod p

$$

Thus $p \left\lvert\,\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-1\right)\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}+1\right)\right.$, so $p$ is a divisor of at least one of the two factors. Therefore, $a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}$ is congruent to 1 or -1 modulo $p$.

We apply this to $a=5$ and $a=7$. Note that $p>10$ so $p \neq 5,7$. If $5^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1$ $\bmod p$ and $7^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, then we take $m=n=\frac{p-1}{2}$ and that satisfies. The same applies if they are both $-1 \bmod p$. The remaining case is when one is 1 and the other is -1. Assume $5^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ and $7^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv-1 \bmod p$. The case where it is the other way around proceeds analogously.

If there is an $n$ with $0<n<\frac{p-1}{2}$ and $7^{n} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, then we choose this $n$ and further $m=\frac{p-1}{2}$. That satisfies. Otherwise, there can also be no $n$ with $\frac{p-1}{2}<n<p-1$ and $7^{n} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, because then $7^{p-1-n} \equiv 7^{p-1} \cdot\left(7^{n}\right)^{-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, while $0<p-1-n<\frac{p-1}{2}$, a contradiction. Furthermore, there can now be no $i$ and $j$ with $1 \leq i<j \leq p-1$ such that $7^{i} \equiv 7^{j} \bmod p$, because if they did exist, then $7^{j-i} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ with $1 \leq j-i<p-1$. We conclude that $7^{i}$ with $1 \leq i \leq p-1$ all take different values modulo $p$, and the value 0 is not among them, so they are precisely all the values from 1 to $p-1$.

In particular, there is an $n$ such that $7^{n} \equiv 5^{-1} \bmod p$. It holds that $n \leq p-2$, because $7^{p-1} \equiv 1 \not \equiv 5^{-1}$ $\bmod p$. We now choose this $n$ and further $m=1$ and then $7^{n} \cdot 5^{m} \equiv 5^{-1} \cdot 5 \equiv 1 \bmod p$.

We see that it is possible in all cases to find $m$ and $n$ that satisfy the conditions.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $p>10$ een priemgetal. Bewijs dat er positieve gehele getallen $m$ en $n$ met $m+n<p$ bestaan waarvoor $p$ een deler is van $5^{m} 7^{n}-1$.

|

Wegens de kleine stelling van Fermat geldt $a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ voor alle $a$ met $p \nmid a$. Omdat $p>10$ is $p$ oneven, dus $p-1$ is even. Er geldt

$$

\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-1\right)\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}+1\right)=a^{p-1}-1 \equiv 0 \quad \bmod p

$$

Dus $p \left\lvert\,\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-1\right)\left(a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}+1\right)\right.$, dus $p$ is een deler van minstens één van beide factoren. Dus $a^{\frac{p-1}{2}}$ is modulo $p$ congruent aan 1 of -1 .

We passen dit toe op $a=5$ en $a=7$. Merk op dat $p>10$ dus $p \neq 5,7$. Als $5^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1$ $\bmod p$ en $7^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, dan nemen we $m=n=\frac{p-1}{2}$ en dat voldoet. Hetzelfde geldt als ze beide $-1 \bmod p$ zijn. Blijft over het geval dat één van beide 1 en de ander -1 is. Neem aan dat $5^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ en $7^{\frac{p-1}{2}} \equiv-1 \bmod p$. Het geval waarin het andersom is, gaat precies analoog.

Als er een $n$ is met $0<n<\frac{p-1}{2}$ en $7^{n} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, dan kiezen we deze $n$ en verder $m=\frac{p-1}{2}$. Dat voldoet. Zo niet, dan kan er ook geen $n$ zijn met $\frac{p-1}{2}<n<p-1$ en $7^{n} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, want dan zou $7^{p-1-n} \equiv 7^{p-1} \cdot\left(7^{n}\right)^{-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, terwijl $0<p-1-n<\frac{p-1}{2}$, tegenspraak. Verder kunnen er nu geen $i$ en $j$ zijn met $1 \leq i<j \leq p-1$ zodat $7^{i} \equiv 7^{j} \bmod p$, want als die wel zouden bestaan, dan is $7^{j-i} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ met $1 \leq j-i<p-1$. We concluderen dat $7^{i}$ met $1 \leq i \leq p-1$ allemaal verschillende waarden aanneemt modulo $p$, en daar zit waarde 0 niet bij, dus het zijn precies alle waarden van 1 tot en met $p-1$.

In het bijzonder is er een $n$ zodat $7^{n} \equiv 5^{-1} \bmod p$. Er geldt $n \leq p-2$, want $7^{p-1} \equiv 1 \not \equiv 5^{-1}$ $\bmod p$. We kiezen nu deze $n$ en verder $m=1$ en dan geldt $7^{n} \cdot 5^{m} \equiv 5^{-1} \cdot 5 \equiv 1 \bmod p$.

We zien dat het in alle gevallen mogelijk is om $m$ en $n$ te vinden die aan de voorwaarden voldoen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2021-E2021_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Let $p>10$ be a prime number. Prove that there exist positive integers $m$ and $n$ with $m+n<p$ such that $p$ is a divisor of $5^{m} 7^{n}-1$.

|

We consider all numbers of the form $5^{i} 7^{j}$ for $1 \leq i, j \leq p-1$. These are $(p-1)^{2}$ numbers. Modulo $p$ these numbers never take the value 0, because for $p>10$ we have $p \neq 5,7$. Therefore, modulo $p$ there are at most $p-1$ different values assumed. By the pigeonhole principle, there is now a value $k$ such that at least $\frac{(p-1)^{2}}{p-1}=p-1$ of these pairs $(i, j)$ satisfy $5^{i} 7^{j} \equiv k \bmod p$. We call these pairs $k$-valued.

Take such a $k$-valued pair $(i, j)=(a, b)$. We will first show that not all $k$-valued pairs are of the form $(x, b)$. For example, $(a+1, b)$ (and similarly $(a-1, b)$ if it happens that $a=p-1$) is not $k$-valued, because from $5^{a+1} 7^{b} \equiv 5^{a} 7^{b} \bmod p$ it would follow that $5 \equiv 1 \bmod p$ so $p \mid 4$, a contradiction. Since there are at least $p-1$ $k$-valued pairs, it follows that not all $k$-valued pairs can be of the form $(x, b)$. Therefore, there is a $k$-valued pair $(c, d)$ with $d \neq b$. Similarly, there is a $k$-valued pair $(e, f)$ with $e \neq a$. If $a \neq c$, then $(a, b)$ and $(c, d)$ are two pairs with two different numbers in the first component and two different numbers in the second component. If $b \neq f$, then $(a, b)$ and $(e, f)$ are such pairs. If $a=c$ and $b=f$, then precisely $(c, d)=(a, d)$ and $(e, f)=(e, b)$ are such pairs.

Thus, we can always find two $k$-valued pairs $\left(i_{1}, j_{1}\right)$ and $\left(i_{2}, j_{2}\right)$ with $i_{1} \neq i_{2}$ and $j_{1} \neq j_{2}$. It now follows that

$$

5^{i_{1}-i_{2}} 7^{j_{1}-j_{2}} \equiv 5^{i_{1}}\left(5^{i_{2}}\right)^{-1} \cdot 7^{j_{1}}\left(7^{j_{2}}\right)^{-1} \equiv k \cdot k^{-1} \equiv 1 \quad \bmod p .

$$

From Fermat's little theorem, it follows that $u^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ if $u \in\{5,7\}$. For $t \in \mathbb{Z}$, we have $u^{p-1+t} \equiv u^{p-1} u^{t} \equiv u^{t} \bmod p$. Write $m^{\prime}=i_{1}-i_{2}$ if $i_{1}>i_{2}$ and $m^{\prime}=p-1+i_{1}-i_{2}$ if $i_{1}<i_{2}$, then $5^{m^{\prime}} \equiv 5^{i_{1}-i_{2}} \bmod p$. Furthermore, $1 \leq m^{\prime} \leq p-2$. Similarly, we define $n^{\prime}$ so that $7^{n^{\prime}} \equiv 7^{j_{1}-j_{2}} \bmod p$ and $1 \leq n^{\prime} \leq p-2$. We now have $5^{m^{\prime}} 7^{n^{\prime}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$.

If $n^{\prime}+m^{\prime}<p$, then we choose $m=m^{\prime}$ and $n=n^{\prime}$ and we are done. Otherwise, we choose $m=p-1-m^{\prime}$ and $n=p-1-n^{\prime}$ and it follows that $5^{m} 7^{n} \equiv 5^{p-1}\left(5^{m^{\prime}}\right)^{-1} \cdot 7^{p-1}\left(7^{n^{\prime}}\right)^{-1} \equiv 1 \cdot 1^{-1} \equiv 1$ $\bmod p$. Now $n+m=2(p-2)-\left(n^{\prime}+m^{\prime}\right) \leq 2 p-4-p=p-4$, so we are also done.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $p>10$ een priemgetal. Bewijs dat er positieve gehele getallen $m$ en $n$ met $m+n<p$ bestaan waarvoor $p$ een deler is van $5^{m} 7^{n}-1$.

|

We bekijken alle getallen van de vorm $5^{i} 7^{j}$ voor $1 \leq i, j \leq p-1$. Dit zijn $(p-1)^{2}$ getallen. Modulo $p$ nemen deze getallen nooit de waarde 0 aan, want vanwege $p>10$ geldt $p \neq 5,7$. Dus modulo $p$ worden er hooguit $p-1$ verschillende waarden aangenomen. Vanwege het ladenprincipe is er nu een waarde $k$ zodat minstens $\frac{(p-1)^{2}}{p-1}=p-1$ van deze paren $(i, j)$ voldoen aan $5^{i} 7^{j} \equiv k \bmod p$. Noem deze paren $k$-waardig.

Neem zo'n $k$-waardig paar $(i, j)=(a, b)$. We gaan eerst laten zien dat niet alle $k$-waardige paren van de vorm $(x, b)$ zijn. Bijvoorbeeld $(a+1, b)$ (en net zo goed $(a-1, b)$ als net toevallig $a=p-1$ ) is niet $k$-waardig, want uit $5^{a+1} 7^{b} \equiv 5^{a} 7^{b} \bmod p$ zou volgen dat $5 \equiv 1$

$\bmod p$ dus $p \mid 4$, tegenspraak. Omdat er minstens $p-1$ paren $k$-waardig zijn, volgt nu dat niet alle $k$-waardige paren van de vorm $(x, b)$ kunnen zijn. Dus er is een $k$-waardig paar $(c, d)$ met $d \neq b$. Net zo bestaat er een $k$-waardig paar $(e, f)$ met $e \neq a$. Als nu $a \neq c$, dan zijn $(a, b)$ en $(c, d)$ twee paren met twee verschillende getallen in de eerste component en twee verschillende getallen in de tweede component. Als $b \neq f$, zijn $(a, b)$ en $(e, f)$ zulke paren. Als $a=c$ en $b=f$, dan zijn juist $(c, d)=(a, d)$ en $(e, f)=(e, b)$ zulke paren.

We kunnen dus altijd twee $k$-waardige paren $\left(i_{1}, j_{1}\right)$ en $\left(i_{2}, j_{2}\right)$ vinden met $i_{1} \neq i_{2}$ en $j_{1} \neq j_{2}$. Er geldt nu

$$

5^{i_{1}-i_{2}} 7^{j_{1}-j_{2}} \equiv 5^{i_{1}}\left(5^{i_{2}}\right)^{-1} \cdot 7^{j_{1}}\left(7^{j_{2}}\right)^{-1} \equiv k \cdot k^{-1} \equiv 1 \quad \bmod p .

$$

Uit de kleine stelling van Fermat volgt $u^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ als $u \in\{5,7\}$. Voor $t \in \mathbb{Z}$ geldt nu $u^{p-1+t} \equiv u^{p-1} u^{t} \equiv u^{t} \bmod p$. Schrijf $m^{\prime}=i_{1}-i_{2}$ als $i_{1}>i_{2}$ en $m^{\prime}=p-1+i_{1}-i_{2}$ als $i_{1}<i_{2}$, dan geldt dus $5^{m^{\prime}} \equiv 5^{i_{1}-i_{2}} \bmod p$. Verder is $1 \leq m^{\prime} \leq p-2$. Analoog definiëren we $n^{\prime}$ zodat $7^{n^{\prime}} \equiv 7^{j_{1}-j_{2}} \bmod p$ en $1 \leq n^{\prime} \leq p-2$. We hebben nu $5^{m^{\prime}} 7^{n^{\prime}} \equiv 1 \bmod p$.

Als $n^{\prime}+m^{\prime}<p$, dan kiezen we $m=m^{\prime}$ en $n=n^{\prime}$ en zijn we klaar. Zo niet, dan kiezen we $m=p-1-m^{\prime}$ en $n=p-1-n^{\prime}$ en geldt $5^{m} 7^{n} \equiv 5^{p-1}\left(5^{m^{\prime}}\right)^{-1} \cdot 7^{p-1}\left(7^{n^{\prime}}\right)^{-1} \equiv 1 \cdot 1^{-1} \equiv 1$ $\bmod p$. Nu geldt $n+m=2(p-2)-\left(n^{\prime}+m^{\prime}\right) \leq 2 p-4-p=p-4$, dus zijn we ook klaar.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2021-E2021_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ for which $f(n) \mid f(m)-n$ if and only if $n \mid m$ for all positive integers $m$ and $n$.

|

When we substitute $m=n$, we find that $f(n) \mid f(n)-n$, so for all natural numbers, $f(n) \mid n$. If we use this again on the original functional condition, we find that $f(n) \mid f(m)$ if and only if $n \mid m$.

Now we prove that $f(n)=n$ by induction on the number of prime divisors of $n$ counted with multiplicity. As the base case, we have that $f(1) \mid 1$, so indeed $f(1)=1$. Suppose that $f(k)=k$ for all numbers $k$ with fewer divisors than $n$ and that $f(n) \mid n$ is a strict divisor of $n$. Then there exists a prime number $p$ such that $f(n) \mid n / p=f(n / p)$ by the induction hypothesis. But $n$ is not a divisor of $n / p$, so our assumption that $f(n) \neq n$ leads to a contradiction.

We check that $f(n)=n$ is indeed a solution: $n \mid m$ if and only if $n \mid m-n$.

|

f(n)=n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ waarvoor geldt dat $f(n) \mid f(m)-n$ dan en slechts dan als $n \mid m$ voor alle natuurlijke getallen $m$ en $n$.

|

Als we $m=n$ invullen, dan vinden we dat $f(n) \mid f(n)-n$, dus voor alle natuurlijke getallen geldt $f(n) \mid n$. Als we dat weer gebruiken op de originele functievoorwaarde vinden we dat $f(n) \mid f(m)$ dan en slechts dan als $n \mid m$.

Nu bewijzen we dat $f(n)=n$ via inductie naar het aantal priemdelers van $n$ geteld met multipliciteit. Als inductiebasis hebben we dat $f(1) \mid 1$, dus inderdaad $f(1)=1$. Stel dat $f(k)=k$ voor alle getallen $k$ met minder delers dan $n$ en dat $f(n) \mid n$ een strikte deler is van $n$. Dan bestaat er dus een priemgetal $p$ zo dat $f(n) \mid n / p=f(n / p)$ door de inductiehypothese. Maar $n$ is geen deler van $n / p$, dus onze aanname dat $f(n) \neq n$ leidt tot een tegenspraak.

We controleren dat $f(n)=n$ inderdaad een oplossing is: $n \mid m$ dan en slechts dan als $n \mid m-n$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ for which $f(n) \mid f(m)-n$ if and only if $n \mid m$ for all positive integers $m$ and $n$.

|

We can also perform strong induction on $n$. The base case is the same as above. Suppose that $f(k)=k$ for all $k<n$ (this is the induction hypothesis). To derive a contradiction, we also assume that $f(n)<n$. Then by taking $k=f(n)$, we have that $f(f(n))=f(n)$. In particular, this means that $f(n) \mid f(f(n))$. Since $f(n) \mid f(m)$ if and only if $n \mid m$, it follows that $n \mid f(n)$. But this is in contradiction with $f(n)<n$, so $f(n)=n$.

|

f(n)=n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ waarvoor geldt dat $f(n) \mid f(m)-n$ dan en slechts dan als $n \mid m$ voor alle natuurlijke getallen $m$ en $n$.

|

We kunnen ook sterke inductie doen naar $n$. De basis is hetzelfde als hierboven. Stel dat $f(k)=k$ voor alle $k<n$ (dat is de inductiehypothese). Om een tegenspraak af te leiden stellen we ook dat $f(n)<n$. Dan geldt door $k=f(n)$ te nemen dat $f(f(n))=f(n)$. En in het bijzonder dus dat $f(n) \mid f(f(n))$. Doordat $f(n) \mid f(m)$ dan en slechts dan als $n \mid m$ volgt hieruit dat $n \mid f(n)$. Maar dat is in tegenspraak met $f(n)<n$, dus $f(n)=n$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

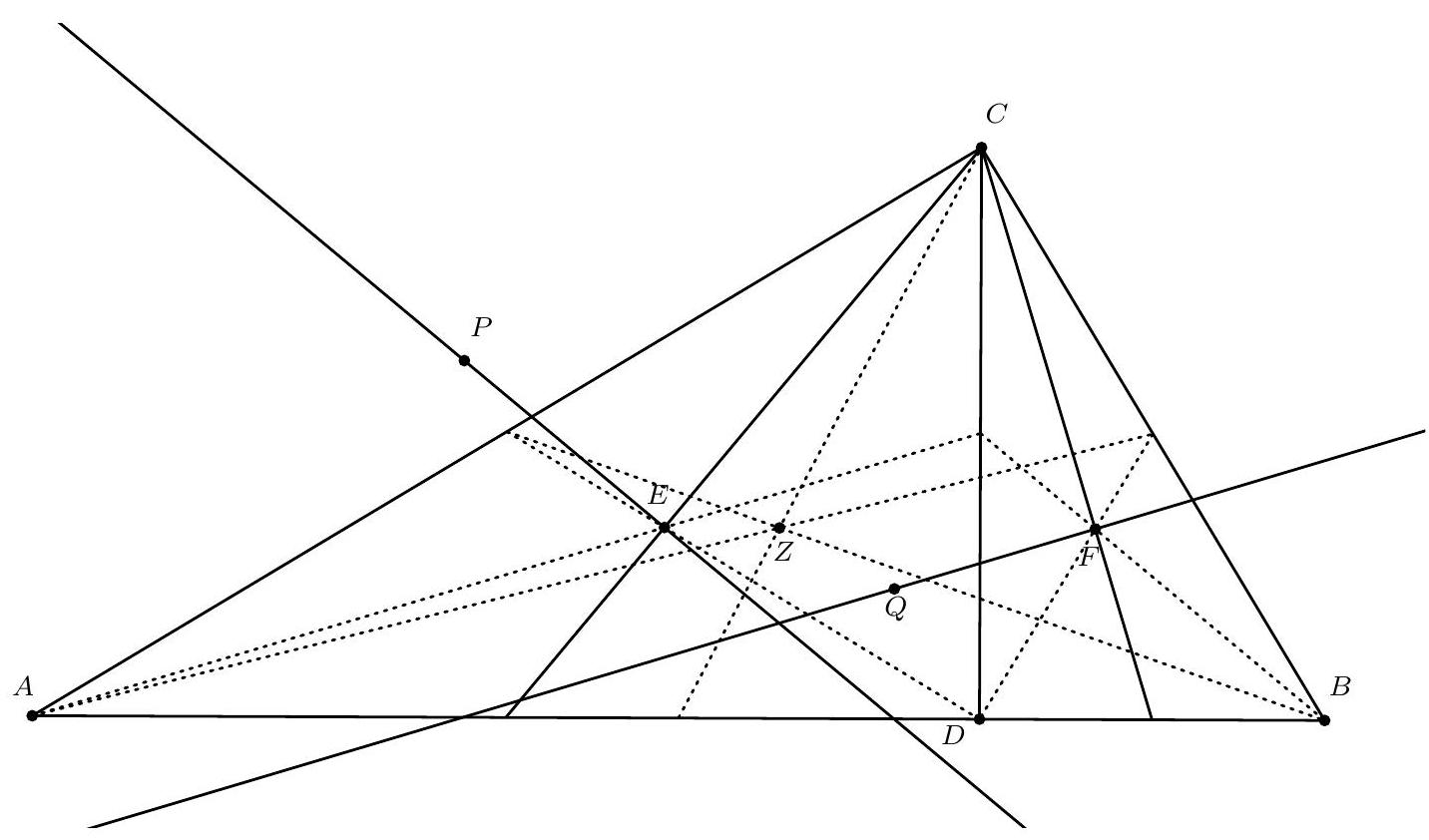

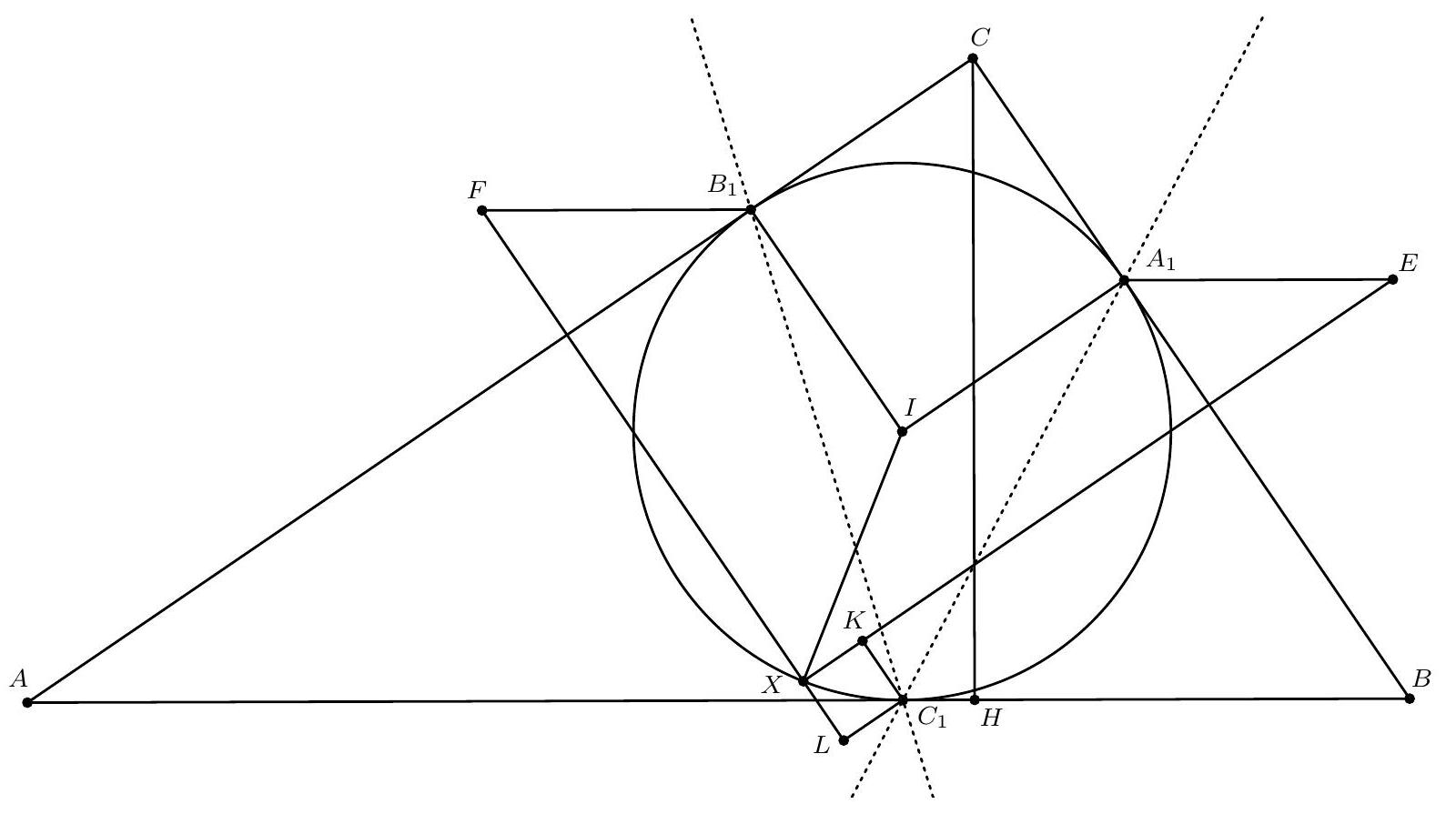

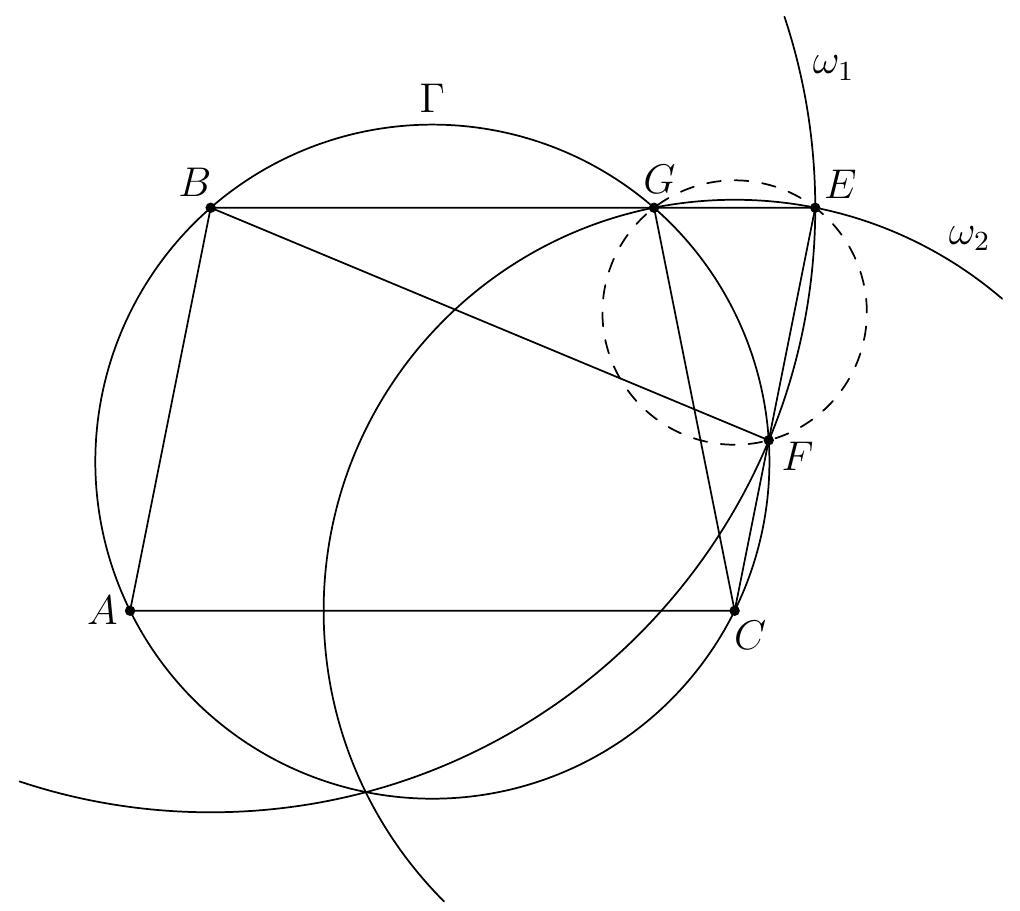

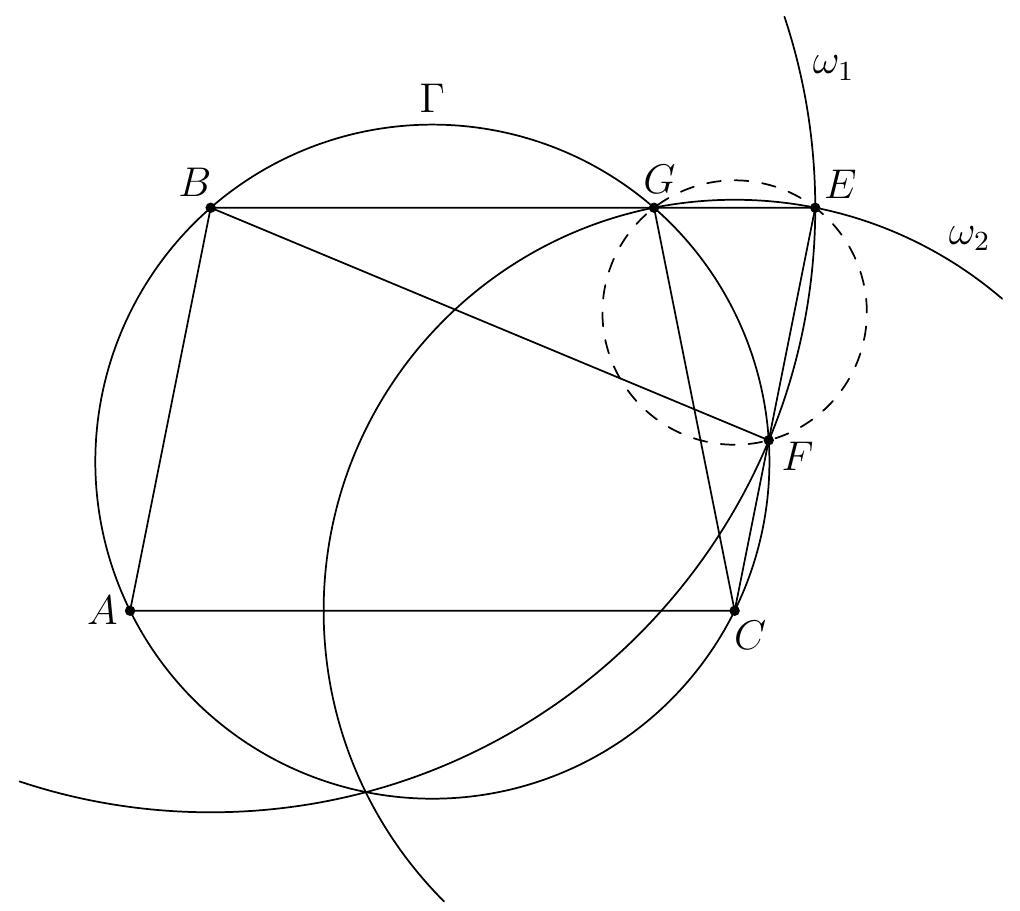

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with $D$ the foot of the altitude from $A$. The circle centered at $A$ passing through $D$ intersects the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ at $X$ and $Y$, such that the order of the points on this circumcircle is: $A, X, B, C, Y$. Prove that $\angle B X D=\angle C Y D$.

|

Since the ray $A D$ is perpendicular to $B C$, $B C$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\triangle D X Y$. Due to the tangent-secant theorem, the angle between the tangent and the chord $D X$ is equal to the inscribed angle on this chord, i.e., $\angle X D B = \angle X Y D$. Furthermore, we know that $B C Y X$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. This means that the opposite angles add up to $180^{\circ}$, so $\angle C B X + \angle X Y C = 180^{\circ}$. From the angle sum in $\triangle B D X$, we find that $\angle B X D = 180^{\circ} - \angle D B X - \angle X D B = (180^{\circ} - \angle C B X) - \angle X D B = \angle X Y C - \angle X Y D$, where we have used the two derived equations. We can simply subtract these two angles: $\angle X Y C - \angle X Y D = \angle D Y C$, from which it follows that $\angle B X D = \angle D Y C$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een scherphoekige driehoek met $D$ het voetpunt van de hoogtelijn vanuit $A$. De cirkel met middelpunt $A$ die door $D$ gaat, snijdt de omgeschreven cirkel van driehoek $A B C$ in $X$ en $Y$, waarbij de volgorde van de punten op deze omgeschreven cirkel is: $A, X, B, C, Y$. Bewijs dat $\angle B X D=\angle C Y D$.

|

Omdat de straal $A D$ loodrecht staat op $B C$, raakt $B C$ aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle D X Y$. Wegens de raaklijn-omtrekshoekstelling geldt daardoor dat de hoek tussen de raaklijn en de koorde $D X$ gelijk is aan de omtrekshoek op deze koorde, oftewel $\angle X D B=$ $\angle X Y D$. Verder weten we dat $B C Y X$ een koordenvierkhoek is. Dat betekent dat de overstaande hoeken optellen tot $180^{\circ}$, dus $\angle C B X+\angle X Y C=180^{\circ}$. Vanwege de hoekensom in $\triangle B D X$ vinden we dan dat $\angle B X D=180^{\circ}-\angle D B X-\angle X D B=\left(180^{\circ}-\angle C B X\right)-$ $\angle X D B=\angle X Y C-\angle X Y D$ waar we de twee gevonden vergelijkingen hebben gebruikt. Deze laatste twee hoeken kunnen we gewoon van elkaar aftrekken: $\angle X Y C-\angle X Y D=$ $\angle D Y C$, waaruit volgt dat $\angle B X D=\angle D Y C$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with $D$ the foot of the altitude from $A$. The circle centered at $A$ passing through $D$ intersects the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ at $X$ and $Y$, such that the order of the points on this circumcircle is: $A, X, B, C, Y$. Prove that $\angle B X D=\angle C Y D$.

|

Let $S$ be the second intersection of $XD$ and the circumcircle of $\triangle ABC$. Let $T$ be the second intersection of $YD$ and the circumcircle of $\triangle ABC$. Then, $\angle DST = \angle XST = \angle XYT = \angle XYD$. Furthermore, $AD \perp BC$ and $A$ is the center of the circle through $D, X$, and $Y$, so $BC$ is tangent to this circle. Using the tangent-secant angle theorem, we find that $\angle XYD = \angle XDB$. Therefore, $\angle DST = \angle XDB$, from which it follows with F-angles that $BD$ is parallel to $ST$.

Thus, $BC$ and $ST$ are parallel, from which it follows by Julian's theorem that $|BS| = |CT|$. The inscribed angles on these chords are equal, that is, $\angle BXS = \angle CYT$. This means that $\angle BXD = \angle CYD$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een scherphoekige driehoek met $D$ het voetpunt van de hoogtelijn vanuit $A$. De cirkel met middelpunt $A$ die door $D$ gaat, snijdt de omgeschreven cirkel van driehoek $A B C$ in $X$ en $Y$, waarbij de volgorde van de punten op deze omgeschreven cirkel is: $A, X, B, C, Y$. Bewijs dat $\angle B X D=\angle C Y D$.

|

Zij $S$ het tweede snijpunt van $X D$ en de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A B C$. Zij $T$ het tweede snijpunt van $Y D$ en de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A B C$. Dan geldt $\angle D S T=\angle X S T=\angle X Y T=\angle X Y D$. Verder geldt $A D \perp B C$ en $A$ is het middelpunt van de cirkel door $D, X$ en $Y$, dus $B C$ raakt aan deze cirkel. Met de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling vinden we dan $\angle X Y D=\angle X D B$. Dus $\angle D S T=\angle X D B$, waaruit met F-hoeken volgt dat $B D$ evenwijdig aan $S T$ is.

Dus $B C$ en $S T$ zijn evenwijdig, waaruit met de stelling van Julian volgt dat $|B S|=|C T|$. De omtrekshoeken op deze koorden zijn gelijk, oftewel $\angle B X S=\angle C Y T$. Dit betekent dat $\angle B X D=\angle C Y D$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Find all pairs of prime numbers $(p, q)$ for which

$$

p\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)=q(2 q+3)

$$

|

Answer: the only solution is $(p, q)=(13,31)$.

If $p=q$, then it must also hold that $p^{2}-p-1=2 q+3=2 p+3$. This can be factored as $(p-4)(p+1)=0$. Since 4 and -1 are not prime numbers, this does not yield any solutions.

In the other case, we have $p \mid 2 q+3$ and $q \mid p^{2}-p-1$. Since $2 q+3$ and $p^{2}-p-1$ are positive, it follows that $p \leq 2 q+3$ and $q \leq p^{2}-p-1$. To find a sharper lower bound for $p$, we multiply the two relations

$$

\begin{aligned}

p q & \mid(2 q+3)\left(p^{2}-p-1\right) \\

& \mid 2 q p^{2}-2 q p-2 q+3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right) \\

& \mid 3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q,

\end{aligned}

$$

where we have discarded terms with a factor of $p q$. Note now that $3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q \geq$ $3 q-2 q=q>0$. This means that the above divisibility relation leads to

$$

\begin{aligned}

p q & \leq 3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q \\

& =3 p^{2}-3 p-(2 q+3) \\

& \leq 3 p^{2}-3 p-p \\

& =3 p^{2}-4 p .

\end{aligned}

$$

If we move $4 p$ to the other side and divide by $p$, we find that $q+4 \leq 3 p$, or

$$

\frac{2 q+3}{6}<\frac{q+4}{3} \leq p

$$

Since $p$ is a divisor of $2 q+3$, we deduce that $2 q+3=k p$ with $k \in\{1,2,3,4,5\}$. If $k=1$, then we have $2 q+3=p$ and thus also $q=p^{2}-p-1$. But then it would hold that $p=2 q+3=2\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)+3=2 p^{2}-2 p+1$. This can be factored as $(2 p-1)(p-1)=0$, which has no solutions with $p$ prime. If $k=2$ or $k=4$, then $k p$ is even. But $2 q+3$ is odd, so these cases are ruled out. If $k=3$, then from $2 q+3=3 p$ it follows that $q$ must be a multiple of 3. Since $q$ is prime, we then have $q=3$, and thus also $p=(2 q+3) / 3=3$. Checking shows that this is not a solution to the original equation.

The last case is $k=5$. Then we have $5 p=2 q+3$ and from the original equation, we have $5 q=p^{2}-p-1$. If we substitute this, we get $25 p=5(2 q+3)=$ $2\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)+15=2 p^{2}-2 p+13$. This can be factored as $(p-13)(2 p-1)=0$. This gives the possible solution $p=13$ with $q=(5 p-3) / 2=31$. We check that $(p, q)=(13,31)$ is indeed a solution to the problem.

|

(13,31)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle paren priemgetallen $(p, q)$ waarvoor geldt dat

$$

p\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)=q(2 q+3)

$$

|

Antwoord: de enige oplossing is $(p, q)=(13,31)$.

Als $p=q$, dan moet ook gelden dat $p^{2}-p-1=2 q+3=2 p+3$. Dit kunnen we ontbinden als $(p-4)(p+1)=0$. Omdat 4 en -1 geen priemgetallen zijn, levert dit dus geen oplossingen op.

In het andere geval hebben we $p \mid 2 q+3$ en $q \mid p^{2}-p-1$. Omdat $2 q+3$ en $p^{2}-p-1$ positief zijn, volgt hieruit dat $p \leq 2 q+3$ en $q \leq p^{2}-p-1$. Om een scherpere ondergrens voor $p$ te vinden vermenigvuldigen we de twee relaties

$$

\begin{aligned}

p q & \mid(2 q+3)\left(p^{2}-p-1\right) \\

& \mid 2 q p^{2}-2 q p-2 q+3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right) \\

& \mid 3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q,

\end{aligned}

$$

waarbij we termen met een factor $p q$ hebben weggegooid. Merk nu op dat $3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q \geq$ $3 q-2 q=q>0$. Dat betekent dat de bovenstaande deelrelatie leidt tot

$$

\begin{aligned}

p q & \leq 3\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)-2 q \\

& =3 p^{2}-3 p-(2 q+3) \\

& \leq 3 p^{2}-3 p-p \\

& =3 p^{2}-4 p .

\end{aligned}

$$

Als we $4 p$ naar de andere kant halen en delen door $p$ vinden we dus dat $q+4 \leq 3 p$, oftewel

$$

\frac{2 q+3}{6}<\frac{q+4}{3} \leq p

$$

Aangezien $p$ een deler is van $2 q+3$ leiden we hieruit af dat $2 q+3=k p$ met $k \in\{1,2,3,4,5\}$. Als $k=1$, dan hebben we $2 q+3=p$ en dus ook $q=p^{2}-p-1$. Maar dan zou gelden dat $p=2 q+3=2\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)+3=2 p^{2}-2 p+1$. Dat kunnen we ontbinden als $(2 p-1)(p-1)=0$, wat geen oplossingen heeft met $p$ priem. Als $k=2$ of $k=4$, dan is $k p$ even. Maar $2 q+3$ is oneven, dus die vallen af. Als $k=3$, dan volgt uit $2 q+3=3 p$ dat $q$ een drievoud moet zijn. Omdat $q$ priem is, hebben we dan $q=3$, en dus ook $p=(2 q+3) / 3=3$. Controleren geeft dat dit geen oplossing is van de oorspronkelijke vergelijking.

Het laatste geval is $k=5$. Dan hebben we $5 p=2 q+3$ en wegens de oorspronkelijke vergelijking dus dat $5 q=p^{2}-p-1$. Als we dat invullen, vinden we $25 p=5(2 q+3)=$ $2\left(p^{2}-p-1\right)+15=2 p^{2}-2 p+13$. Dit kunnen we ontbinden als $(p-13)(2 p-1)=0$. Dit geeft als mogelijke oplossing $p=13$ met daarbij $q=(5 p-3) / 2=31$. We controleren dat $(p, q)=(13,31)$ inderdaad een oplossing is van de opgave.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Given positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ with $n \geq 2$ for which $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}=1$. Prove that

$$

\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}+\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-1}+\ldots+\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}+\left(\frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}\right)^{n-1} \geq a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}

$$

and determine when equality holds.

|

We take the arithmetic-mean on $\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)$ terms:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{(n-1)\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}+(n-2)\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-1}+\ldots+\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}}{\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)} & \geq\left(\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{(n-1)^{2}}\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{(n-1)(n-2)} \cdots\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n(n-1)}} \\

& =\left(\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-2} \cdots\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)\right)^{\frac{2}{n}} \\

& =\left(a_{1}^{n-1} a_{2}^{-1} a_{3}^{-1} \cdots a_{n}^{-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n}} \\

& =a_{1}^{2}\left(a_{1}^{-1} a_{2}^{-1} a_{2}^{-1} \cdots a_{n}^{-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Since it is given that $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}=1$, this is equal to $a_{1}^{2}$. By cyclically rotating this inequality, we get one inequality for each $a_{i}^{2}$. Adding these $n$ inequalities gives exactly what is required: the right-hand side is clearly $a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}$, and on the left-hand side, we only have terms of the form $\left(\frac{a_{i}}{a_{i+1}}\right)^{n-1}$, each with a factor $\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)}((n-1)+(n-2)+\ldots+1)=1$.

Equality holds if and only if equality holds for each of the $n$ inequalities. For each of these $n$ inequalities, equality holds when the $n-1$ different terms are equal. For $n=2$, this is trivially true, so equality holds for all $a_{1}, a_{2}$ with $a_{1} a_{2}=1$. For $n>2$, the equality cases are the cyclic permutations of $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}=\ldots=\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}$. If we combine two permutations, we get $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}=\ldots=\frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}=a$ for some positive real $a$, and then the equality also holds for all permutations. The product of all these fractions can be calculated as $a^{n}=\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}} \frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}} \cdots \frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}=1$, so $a=1$. We conclude that all $a_{i}$ must be the same. Given the condition, they are all equal to 1.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Gegeven zijn positieve, reële getallen $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ met $n \geq 2$ waarvoor geldt dat $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}=1$. Bewijs dat

$$

\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}+\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-1}+\ldots+\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}+\left(\frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}\right)^{n-1} \geq a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}

$$

en bepaal wanneer gelijkheid geldt.

|

We nemen het rekenkundig-meetkundig gemiddelde op $\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)$ termen:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{(n-1)\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}+(n-2)\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-1}+\ldots+\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}}{\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)} & \geq\left(\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{(n-1)^{2}}\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{(n-1)(n-2)} \cdots\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)^{n-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n(n-1)}} \\

& =\left(\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{n-1}\left(\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}\right)^{n-2} \cdots\left(\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}\right)\right)^{\frac{2}{n}} \\

& =\left(a_{1}^{n-1} a_{2}^{-1} a_{3}^{-1} \cdots a_{n}^{-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n}} \\

& =a_{1}^{2}\left(a_{1}^{-1} a_{2}^{-1} a_{2}^{-1} \cdots a_{n}^{-1}\right)^{\frac{2}{n}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Aangezien gegeven is dat $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{n}=1$ is dit gelijk aan $a_{1}^{2}$. Als we deze ongelijkheid cyclisch roteren krijgen we één ongelijkheid voor elke $a_{i}^{2}$. Het optellen van deze $n$ ongelijkheden geeft precies het gevraagde: de rechterkant is duidelijk $a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}$ en aan de linkerkant krijgen hebben we alleen termen van de vorm $\left(\frac{a_{i}}{a_{i+1}}\right)^{n-1}$ elk met een factor $\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2} n(n-1)}((n-1)+(n-2)+\ldots+1)=1$.

Er geldt gelijkheid dan en slechts dan als er gelijkheid geldt voor elk van de $n$ ongelijkheden. Voor elk van deze $n$ ongelijkheden geldt gelijkheid wanneer de $n-1$ verschillende termen gelijk zijn. Voor $n=2$ is dit triviaal waar, dus geldt er gelijkheid voor alle $a_{1}, a_{2}$ met $a_{1} a_{2}=1$. Voor $n>2$ zijn de gelijkheidsgevallen de cyclische permutaties van $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}=\ldots=\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_{n}}$. Als we twee permutaties combineren krijgen we $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}=\ldots=\frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}=a$ voor een zekere positieve reële $a$, en dan geldt de gelijkheid ook voor alle permutaties. Het product van al deze breuken kunnen we dan uitrekenen als $a^{n}=\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}} \frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}} \cdots \frac{a_{n}}{a_{1}}=1$, dus $a=1$. We concluderen dat alle $a_{i}$ hetzelfde moeten zijn. Wegens de voorwaarde zijn ze dan allemaal gelijk aan 1.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

At a fish market, there are 10 stalls, all selling the same 10 types of fish. All the fish are caught in either the North Sea or the Mediterranean Sea, and each stall has only one sea of origin for each type of fish. A number, $k$, of customers buy one fish from each stall such that they have one fish of each type. Furthermore, we know that each pair of customers has at least one fish of a different origin. We consider all possible ways to stock the stalls according to the above rules.

What is the maximum possible value of $k$?

|

The answer is $2^{10}-10$. First, we note that there are $2^{10}$ possible combinations for the origins of each fish species. We will show that there are always at least 10 exceptions (possibilities that are ruled out) and that there is a market setup where there are exactly 10 exceptions.

We order both the stalls and the fish from 1 to 10. For a stall $i$, we define the sequence $a_{i} \in\{M, N\}^{10}$ as the origins of the 10 fish species in this stall (for example, $a_{1}=(M, M, M, N, M, N, N, M, M, M)$). Let $c_{i}$ be the complement of this sequence: we replace all $M$ with $N$ and vice versa. Since every customer has bought a fish from stall $i$, no customer can have the sequence $c_{i}$. If the sequences $c_{i}$ with $1 \leq i \leq 10$ are all different, then we have 10 exceptions.

On the other hand, suppose that stalls $i$ and $j$ sell fish from exactly the same seas, i.e., $a_{i}=a_{j}$. Then also $c_{i}=c_{j}$. We define the sequences $d_{k}$ with $1 \leq k \leq 10$ by swapping the origin of fish $k$ in the sequence $c_{i}$. These are precisely the sequences that match the sequence $a_{i}=a_{j}$ in exactly one sea. If a customer has bought a sequence $d_{k}$, then there can be at most one fish from stall $i$ or $j$ in that sequence. This contradicts the fact that the customer has bought a fish from both stalls. We conclude that in this case, we also have at least 10 exceptions $d_{k}$ (and in fact also $c_{i}$).

We construct a market as follows where you can buy $2^{10}-10$ different combinations of fish origins as described in the problem: stall $i$ sells only fish from the North Sea, with the exception of fish $i$ from the Mediterranean Sea. Let $b \in\{M, N\}^{10}$ be a sequence of origins such that it does not contain exactly one $N$. We will show that we can buy 10 different fish from 10 different stalls so that $b$ is the sequence of origins. We split the fish in $b$ into a set $A$ from the Mediterranean Sea and a set $B$ from the North Sea, that is, $A$ is the set of indices where $b$ has an $M$ and $B$ is the set of indices where $b$ has an $N$. For $i \in A$, we buy fish species $i$ from stall $i$, so we indeed get a fish from the Mediterranean Sea. If $B$ is empty, then we are done. Otherwise, $B$ has at least two elements, and we write $B=\left\{i_{1}, \ldots, i_{n}\right\} \subset\{1, \ldots, 10\}$. For $i_{k} \in B$, we buy fish species $i_{k}$ from stall $i_{k+1}$, where we compute the indices modulo $n$. Since $n \neq 1$, it holds that $i_{k+1} \neq i_{k}$, so this fish indeed comes from the North Sea.

|

2^{10}-10

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Op een vismarkt staan 10 kraampjes die allemaal dezelfde 10 vissoorten verkopen. Alle vissen zijn gevangen in de Noordzee of de Middellandse Zee, en elk kraampje heeft per vissoort maar één zee van afkomst. Een aantal, $k$, klanten koopt van elk kraampje één vis zo dat ze één vis van elke soort hebben. Verder weten we dat elk tweetal klanten een vissoort hebben met verschillende afkomst. We beschouwen alle mogelijke manieren om de kraampjes te vullen volgens de bovenstaande spelregels.

Wat is de maximaal mogelijke waarde van $k$ ?

|

Het antwoord is $2^{10}-10$. Ten eerste merken we op dat er $2^{10}$ mogelijke combinaties zijn voor de afkomsten per vissoort. We gaan laten zien dat er altijd minstens 10 uitzonderingen zijn (mogelijkheden die afvallen) en dat er een marktopzet is waarbij er precies 10 uitzonderingen zijn.

We ordenen zowel de kraampjes als de vissen van 1 tot 10. Voor een kraampje $i$ definiëren we het rijtje $a_{i} \in\{M, N\}^{10}$ als de afkomsten van de 10 vissoorten in dit kraampje (bijvoorbeeld $a_{1}=(M, M, M, N, M, N, N, M, M, M)$ ). Zij $c_{i}$ het complement van dit rijtje: we vervangen alle $M$ door $N$ en vice versa. Aangezien elke klant een vis heeft gekocht van kraampje $i$ kan geen enkele klant het rijtje $c_{i}$ hebben. Als de rijtjes $c_{i}$ met $1 \leq i \leq 10$ allemaal verschillend zijn, dan hebben we dus 10 uitzonderingen.

Stel aan de andere kant dat kraampjes $i$ en $j$ vissen van precies dezelfde zeeën verkopen, oftewel $a_{i}=a_{j}$. Dan ook $c_{i}=c_{j}$. Dan definiëren we de rijtjes $d_{k}$ met $1 \leq k \leq 10$ door in het rijtje $c_{i}$ de afkomst van vis $k$ te wisselen. Dit zijn precies de rijtjes die één zee overeenkomstig hebben met het rijtje $a_{i}=a_{j}$. Als een klant een rijtje $d_{k}$ heeft ingekocht, dan kan daar dus maximaal één vis tussen zitten van kraampje $i$ of $j$. Dit is in tegenspraak met het feit dat de klant bij beide kraampjes een vis heeft gekocht. We concluderen dat we in dat geval ook minstens 10 uitzonderingen $d_{k}$ hebben (en in feite ook nog $c_{i}$ ).

We construeren als volgt een markt waar je $2^{10}-10$ verschillende combinaties van afkomsten van vissen kan kopen zoals in de opgave: kraampje $i$ verkoopt alleen vis uit de Noordzee met uitzondering van vis $i$ uit de Middellandse Zee. Zij $b \in\{M, N\}^{10}$ een rijtje afkomsten zo dat er niet precies één $N$ in voorkomt. We gaan laten zien dat we 10 verschillende vissen van 10 verschillende kraampjes kunnen kopen zo dat $b$ het rijtje afkomsten is. We splitsen de vissen in $b$ op in een verzameling $A$ uit de Middellandse Zee en een verzameling $B$ uit de Noordzee, dat wil zeggen $A$ is de verzameling indices waar in $b$ een $M$ staat en $B$ is de verzameling indices waar een $N$ staat. Voor $i \in A$ kopen we vissoort $i$ bij kraampje $i$, zodat we inderdaad een vis uit de Middellandse Zee krijgen. Als $B$ leeg is, dan zijn we klaar. Anders heeft $B$ minstens twee elementen en schrijven we $B=\left\{i_{1}, \ldots, i_{n}\right\} \subset\{1, \ldots, 10\}$. Voor $i_{k} \in B$ kopen we vissoort $i_{k}$ bij kraampje $i_{k+1}$, waarbij we de indices modulo $n$ rekenen. Omdat $n \neq 1$ geldt dat $i_{k+1} \neq i_{k}$, dus deze vis komt inderdaad uit de Noordzee.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-B2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Determine all positive integers $n \geq 2$ for which there exists a positive divisor $m \mid n$ such that

$$

n=d^{3}+m^{3},

$$

where $d$ is the smallest divisor of $n$ greater than 1.

|

The smallest divisor of $n$ greater than 1 is the smallest prime that is a divisor of $n$, so $d$ is prime. Furthermore, $d \mid n$, so $d \mid d^{3}+m^{3}$, thus $d \mid m^{3}$. This implies that $m>1$. On the other hand, $m \mid n$, so $m \mid d^{3}+m^{3}$, thus $m \mid d^{3}$. Since $d$ is prime and $m>1$, we see that $m$ is equal to $d, d^{2}$, or $d^{3}$.

In all cases, the parity of $m^{3}$ is the same as that of $d^{3}$, so $n=d^{3}+m^{3}$ is even. This means that the smallest divisor of $n$ greater than 1 is equal to 2, so $d=2$. We now find the possible solutions: in the case $m=d$, the number $n=2^{3}+2^{3}=16$; in the case $m=d^{2}$, the number $n=2^{3}+2^{6}=72$; and in the case $m=d^{3}$, the number $n=2^{3}+2^{9}=520$. These indeed satisfy the conditions: they are even, so $d=2$, and $2|16 ; 4| 72$ and $8 \mid 520$, so $m \mid n$.

|

16, 72, 520

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle positieve gehele getallen $n \geq 2$ waarvoor er een positieve deler $m \mid n$ bestaat met

$$

n=d^{3}+m^{3},

$$

waarbij $d$ de kleinste deler van $n$ groter dan 1 is.

|

De kleinste deler van $n$ groter dan 1 is het kleinste priemgetal dat een deler is dan $n$, dus $d$ is priem. Verder geldt dat $d \mid n$, dus $d \mid d^{3}+m^{3}$, dus $d \mid m^{3}$. Hieruit volgt dat $m>1$. Anderzijds is $m \mid n$, dus $m \mid d^{3}+m^{3}$, dus $m \mid d^{3}$. Omdat $d$ priem is en $m>1$, zien we nu dat $m$ gelijk is aan $d, d^{2}$ of $d^{3}$.

In alle gevallen is de pariteit van $m^{3}$ hetzelfde als die van $d^{3}$, dus $n=d^{3}+m^{3}$ is even. Dat betekent dat de kleinste deler van $n$ groter dan 1 gelijk is aan 2 , dus $d=2$. We vinden nu als mogelijke oplossingen in geval $m=d$ het getal $n=2^{3}+2^{3}=16$, in geval $m=d^{2}$ het getal $n=2^{3}+2^{6}=72$, en in geval $m=d^{3}$ het getal $n=2^{3}+2^{9}=520$. Deze voldoen daadwerkelijk: ze zijn even zodat inderdaad $d=2$, en $2|16 ; 4| 72$ en $8 \mid 520$, zodat inderdaad $m \mid n$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-C2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

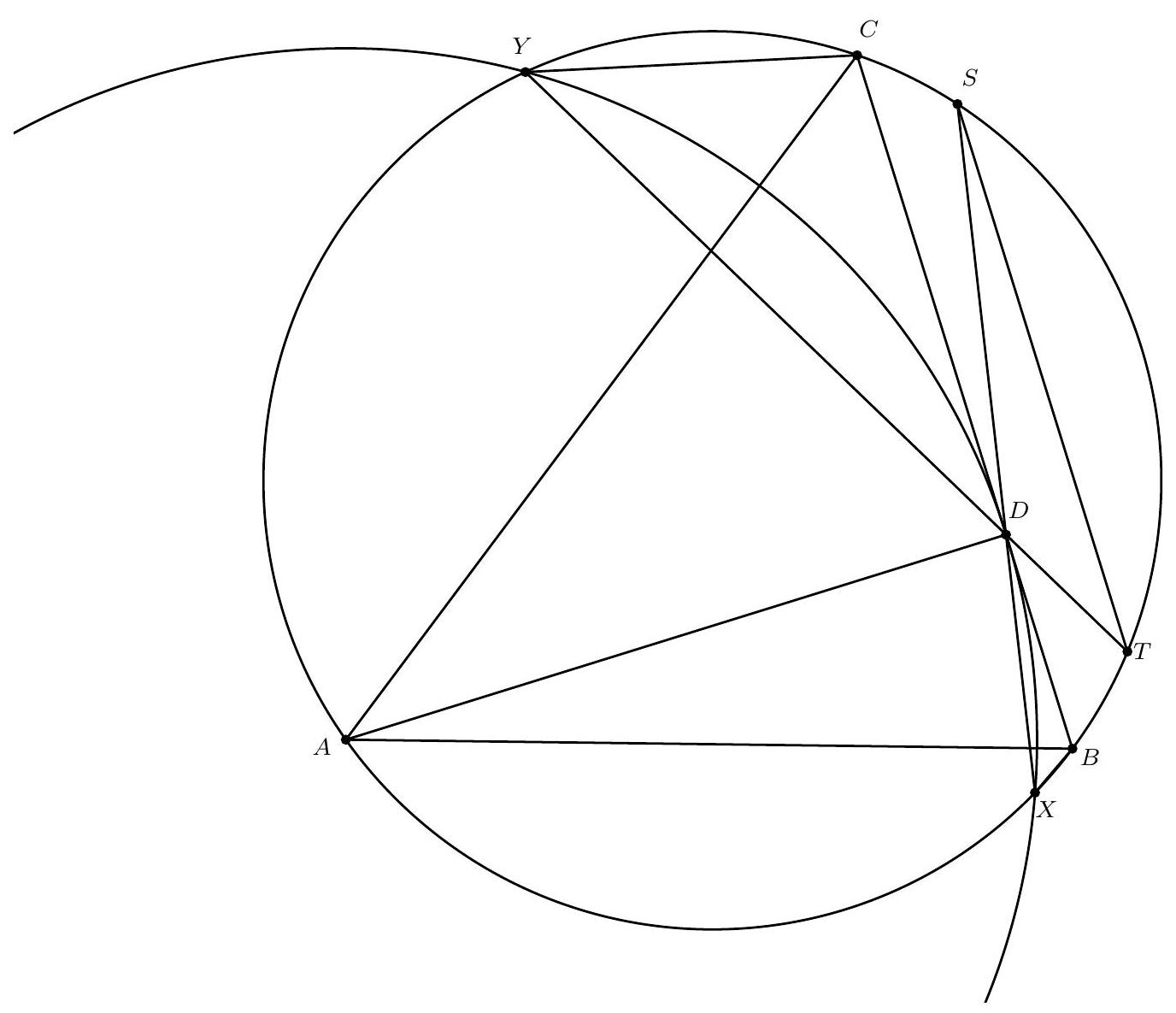

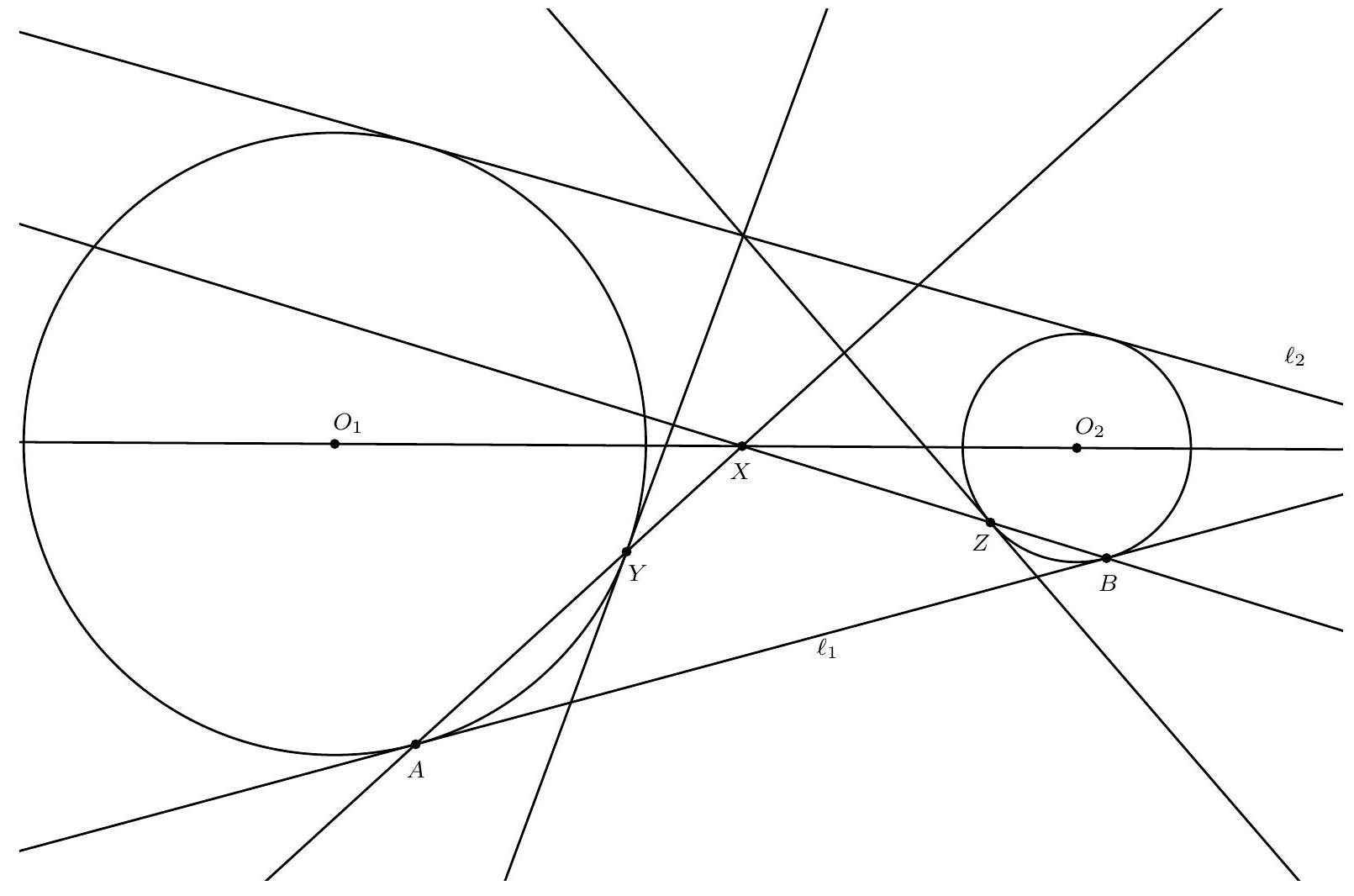

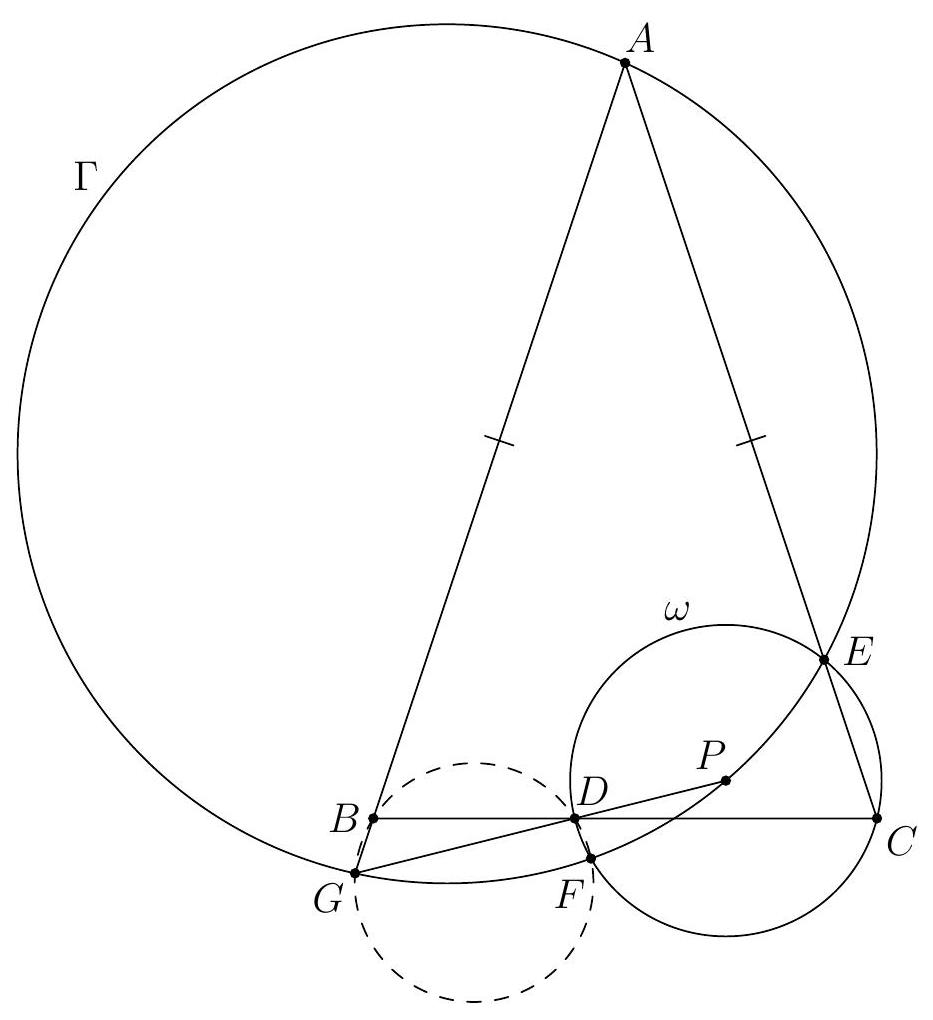

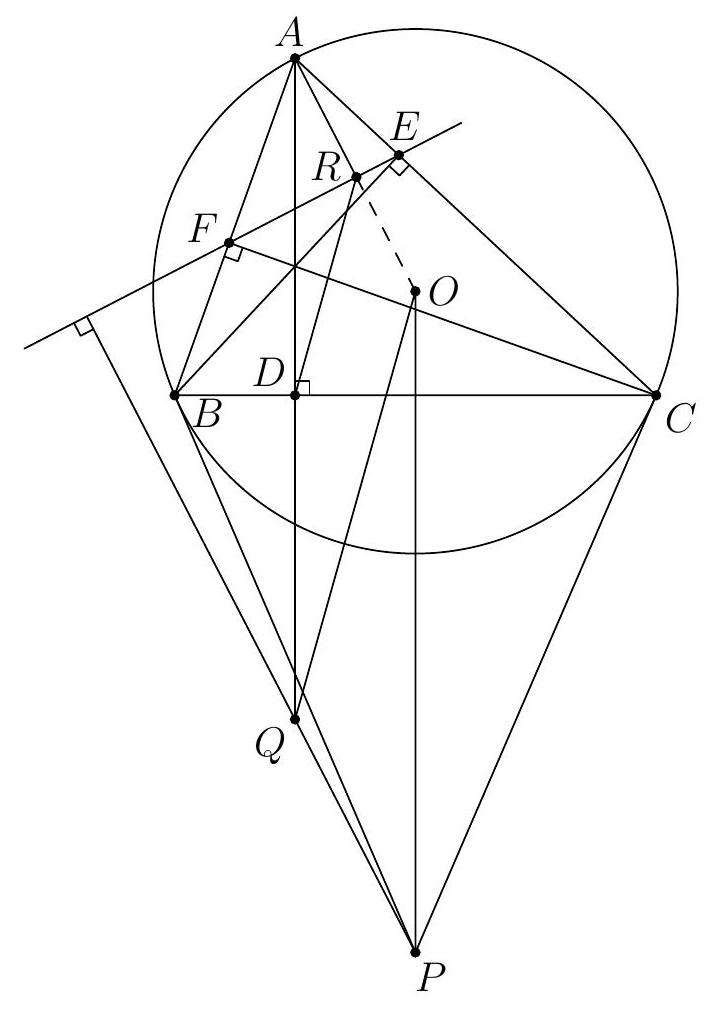

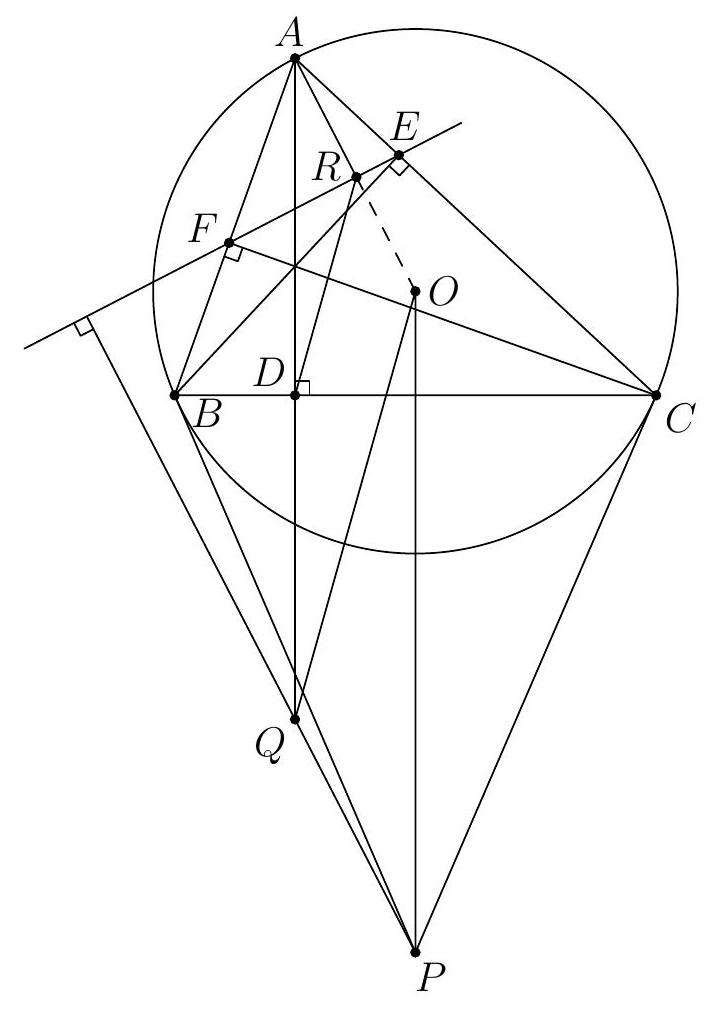

Given are two circles $\Gamma_{1}$ and $\Gamma_{2}$ with centers $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$ and common external tangents $\ell_{1}$ and $\ell_{2}$. The line $\ell_{1}$ is tangent to $\Gamma_{1}$ at $A$ and to $\Gamma_{2}$ at $B$. Let $X$ be a point on the segment $O_{1} O_{2}$, but not on $\Gamma_{1}$ or $\Gamma_{2}$. The segment $A X$ intersects $\Gamma_{1}$ at $Y \neq A$ and the segment $B X$ intersects $\Gamma_{2}$ at $Z \neq B$.

Prove that the tangent line at $Y$ to $\Gamma_{1}$ and the tangent line at $Z$ to $\Gamma_{2}$ intersect on $\ell_{2}$.

|

We consider the configuration where $Y$ lies between $A$ and $X$; other configurations proceed analogously. Let $C$ be the point of tangency of $\ell_{2}$ with $\Gamma_{1}$. Then $C$ is the reflection of $A$ in $O_{1} O_{2}$. We have

$$

\begin{array}{rrr}

\angle O_{1} Y X & =180^{\circ}-\angle O_{1} Y A & \text { (straight angle) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle Y A O_{1} & \text { (isosceles triangle } \left.O_{1} Y A\right) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle X A O_{1} & \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle X C O_{1} & \left(A \text { and } C \text { are reflections of each other in } O_{1} X\right)

\end{array}

$$

which implies that $O_{1} C X Y$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.

Now let $S$ be the intersection of the tangent to $\Gamma_{1}$ at $Y$ and $\ell_{2}$. Then both $S C$ and $S Y$ are tangent to $\Gamma_{1}$, so $\angle S C O_{1}=90^{\circ}=\angle S Y O_{1}$, hence $O_{1} C S Y$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.

We see that both $X$ and $S$ lie on the circle through $O_{1}, C$ and $Y$. Therefore, $\angle S X O_{1}=$ $\angle S Y O_{1}=90^{\circ}$. We conclude that $S X$ is perpendicular to $O_{1} O_{2}$. Analogously, for the intersection $S^{\prime}$ of the tangent to $\Gamma_{2}$ at $Z$ and $\ell_{2}$, we can deduce that $S^{\prime} X$ is perpendicular to $O_{1} O_{2}$. Since $S$ and $S^{\prime}$ both lie on $\ell_{2}$, it follows that $S=S^{\prime}$. Thus, the two tangents intersect on $\ell_{2}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeven zijn twee cirkels $\Gamma_{1}$ en $\Gamma_{2}$ met middelpunten $O_{1}$ en $O_{2}$ en gemeenschappelijke uitwendige raaklijnen $\ell_{1}$ en $\ell_{2}$. De lijn $\ell_{1}$ raakt $\Gamma_{1}$ in $A$ en $\Gamma_{2}$ in $B$. Zij $X$ een punt op het lijnstuk $O_{1} O_{2}$, maar niet op $\Gamma_{1}$ of $\Gamma_{2}$. Het lijnstuk $A X$ snijdt $\Gamma_{1}$ in $Y \neq A$ en het lijnstuk $B X$ snijdt $\Gamma_{2}$ in $Z \neq B$.

Bewijs dat de raaklijn in $Y$ aan $\Gamma_{1}$ en de raaklijn in $Z$ aan $\Gamma_{2}$ elkaar snijden op $\ell_{2}$.

|

We bekijken de configuratie waarbij $Y$ tussen $A$ en $X$ ligt; andere configuraties gaan analoog. Zij $C$ het raakpunt van $\ell_{2}$ aan $\Gamma_{1}$. Dan is $C$ de spiegeling van $A$ in $O_{1} O_{2}$. Er geldt

$$

\begin{array}{rrr}

\angle O_{1} Y X & =180^{\circ}-\angle O_{1} Y A & \text { (gestrekte hoek) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle Y A O_{1} & \text { (gelijkbenige driehoek } \left.O_{1} Y A\right) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle X A O_{1} & \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle X C O_{1} & \left(A \text { en } C \text { elkaars gespiegelde in } O_{1} X\right)

\end{array}

$$

waaruit volgt dat $O_{1} C X Y$ een koordenvierhoek is.

Noem nu $S$ het snijpunt van de raaklijn aan $\Gamma_{1}$ in $Y$ en $\ell_{2}$. Dan raakt zowel $S C$ als $S Y$ aan $\Gamma_{1}$, dus geldt $\angle S C O_{1}=90^{\circ}=\angle S Y O_{1}$, dus $O_{1} C S Y$ is een koordenvierhoek.

We zien dat zowel $X$ als $S$ op de cirkel door $O_{1}, C$ en $Y$ ligt. Er geldt dus $\angle S X O_{1}=$ $\angle S Y O_{1}=90^{\circ}$. We concluderen dat $S X$ loodrecht op $O_{1} O_{2}$ staat. Analoog kunnen we nu voor het snijpunt $S^{\prime}$ van de raaklijn aan $\Gamma_{2}$ in $Z$ en $\ell_{2}$ afleiden dat $S^{\prime} X$ loodrecht op $O_{1} O_{2}$ staat. Aangezien $S$ en $S^{\prime}$ ook beide op $\ell_{2}$ liggen, geldt $S=S^{\prime}$. Dus de twee raaklijnen snijden elkaar op $\ell_{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-C2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

For real numbers $x$ and $y$, we define $M(x, y)$ as the maximum of the three numbers $x y, (x-1)(y-1)$, and $x+y-2 x y$. Determine the smallest possible value of $M(x, y)$ over all real numbers $x$ and $y$ with $0 \leq x, y \leq 1$.

|

We show that the minimum value is $\frac{4}{9}$. This value can be achieved by taking $x=y=\frac{2}{3}$. Then we have $x y=\frac{4}{9}, (x-1)(y-1)=\frac{1}{9}$, and $x+y-2 x y=\frac{4}{9}$, so the maximum is indeed $\frac{4}{9}$.

Now we will prove that $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$ for all $x$ and $y$. Let $a=x y, b=(x-1)(y-1)$, and $c=x+y-2 x y$. If we replace $x$ and $y$ with $1-x$ and $1-y$, then $a$ and $b$ are swapped and $c$ remains the same, because $(1-x)+(1-y)-2(1-x)(1-y)=2-x-y-2+2 x+2 y-2 x y=x+y-2 x y$. Thus, $M(1-x, 1-y)=M(x, y)$. We have $x+y=2-(1-x)-(1-y)$, so at least one of $x+y$ and $(1-x)+(1-y)$ is greater than or equal to 1, which means we can assume without loss of generality that $x+y \geq 1$.

Now write $x+y=1+t$ with $t \geq 0$. We also have $t \leq 1$, because $x, y \leq 1$ so $x+y \leq 2$. From the inequality of the arithmetic and geometric means, we get

$$

x y \leq\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{(1+t)^{2}}{4}=\frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{4}

$$

We have $b=x y-x-y+1=x y-(1+t)+1=x y-t=a-t$, so $b \leq a$. Furthermore,

$$

c=x+y-2 x y \geq(1+t)-2 \cdot \frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{4}=\frac{2+2 t}{2}-\frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{2}=\frac{1-t^{2}}{2}.

$$

If $t \leq \frac{1}{3}$, then $c \geq \frac{1-t^{2}}{2} \geq \frac{1-\frac{1}{9}}{2}=\frac{4}{9}$, and thus $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

The remaining case is $t>\frac{1}{3}$. We have $c=x+y-2 x y=1+t-2 a>\frac{4}{3}-2 a$. We have $M(x, y) \geq \max \left(a, \frac{4}{3}-2 a\right)$, so

$$

3 M(x, y) \geq a+a+\left(\frac{4}{3}-2 a\right)=\frac{4}{3},

$$

which implies that $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

We conclude that the minimum value of $M(x, y)$ is $\frac{4}{9}$.

|

\frac{4}{9}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Voor reële getallen $x$ en $y$ definiëren we $M(x, y)$ als het maximum van de drie getallen $x y,(x-1)(y-1)$ en $x+y-2 x y$. Bepaal de kleinst mogelijke waarde van $M(x, y)$ over alle reële getallen $x$ en $y$ met $0 \leq x, y \leq 1$.

|

We laten zien dat de minimale waarde $\frac{4}{9}$ is. Deze waarde kan bereikt worden door $x=y=\frac{2}{3}$ te nemen. Dan geldt $x y=\frac{4}{9},(x-1)(y-1)=\frac{1}{9}$ en $x+y-2 x y=\frac{4}{9}$, dus dan is het maximum inderdaad $\frac{4}{9}$.

Nu gaan we bewijzen dat $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$ voor alle $x$ en $y$. Schrijf $a=x y, b=(x-1)(y-1)$ en $c=x+y-2 x y$. Als we $x$ en $y$ vervangen door $1-x$ en $1-y$, dan worden $a$ en $b$ verwisseld en blijft $c$ gelijk, omdat $(1-x)+(1-y)-2(1-x)(1-y)=2-x-y-2+2 x+2 y-2 x y=x+y-2 x y$. Dus $M(1-x, 1-y)=M(x, y)$. Er geldt $x+y=2-(1-x)-(1-y)$, dus minstens één $\operatorname{van} x+y$ en $(1-x)+(1-y)$ is groter of gelijk aan 1 , wat betekent dat we zonder verlies van algemeemheid mogen aannemen dat $x+y \geq 1$.

Schrijf nu $x+y=1+t$ met $t \geq 0$. Er geldt ook $t \leq 1$, want $x, y \leq 1$ dus $x+y \leq 2$. Uit de ongelijkheid van het rekenkundig en meetkundig gemiddelde volgt

$$

x y \leq\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}=\frac{(1+t)^{2}}{4}=\frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{4}

$$

Er geldt $b=x y-x-y+1=x y-(1+t)+1=x y-t=a-t$, dus $b \leq a$. Verder is

$$

c=x+y-2 x y \geq(1+t)-2 \cdot \frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{4}=\frac{2+2 t}{2}-\frac{t^{2}+2 t+1}{2}=\frac{1-t^{2}}{2} .

$$

Als nu $t \leq \frac{1}{3}$, dan geldt $c \geq \frac{1-t^{2}}{2} \geq \frac{1-\frac{1}{9}}{2}=\frac{4}{9}$ en dus ook $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

Blijft over het geval $t>\frac{1}{3}$. Er geldt $c=x+y-2 x y=1+t-2 a>\frac{4}{3}-2 a$. Er geldt $M(x, y) \geq \max \left(a, \frac{4}{3}-2 a\right)$, dus

$$

3 M(x, y) \geq a+a+\left(\frac{4}{3}-2 a\right)=\frac{4}{3},

$$

waaruit volgt dat $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

We concluderen dat de minimale waarde van $M(x, y)$ gelijk is aan $\frac{4}{9}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-C2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

For real numbers $x$ and $y$, we define $M(x, y)$ as the maximum of the three numbers $x y, (x-1)(y-1)$, and $x+y-2 x y$. Determine the smallest possible value of $M(x, y)$ over all real numbers $x$ and $y$ with $0 \leq x, y \leq 1$.

|

We show that the minimum value is $\frac{4}{9}$. Just like in the first solution, we see that this value can be achieved by taking $x=y=\frac{2}{3}$. Now we will prove that $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$ for all $x$ and $y$. We do this by comparing the level curves on which the expressions $x y$, $(1-x)(1-y)$, and $x+y-2 x y$ take the value $\frac{4}{9}$.

First, we consider the case $0 \leq x<\frac{1}{2}$. Note that in this case $1-2 x>0$. If $(1-x)(1-y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$, then we are done. Suppose now that $(1-x)(1-y)<\frac{4}{9}$. Then $1-y<\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$, so $y>1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$. We now show that $1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x} \geq \frac{\frac{4}{9}-x}{1-2 x}$. Since the denominators are positive, it suffices to prove that $\left(1-x-\frac{4}{9}\right)(1-2 x) \geq\left(\frac{4}{9}-x\right)(1-x)$, or equivalently $2 x^{2}-\frac{19}{9} x+\frac{5}{9} \geq x^{2}-\frac{13}{9} x+\frac{4}{9}$, which simplifies to $x^{2}-\frac{2}{3} x+\frac{1}{9} \geq 0$. The left side is $\left(x-\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}$, which proves this inequality and thus the desired inequality. Now we are done, because from $y>1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$ it follows that $y>\frac{\frac{4}{9}-x}{1-2 x}$, so $y(1-2 x)>\frac{4}{9}-x$, or equivalently $x+y-2 x y>\frac{4}{9}$. Therefore, in any case, $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

If $x=\frac{1}{2}$, then $x+y-2 x y=\frac{1}{2}+y-2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} y=\frac{1}{2}>\frac{4}{9}$.

Finally, we consider the case $\frac{1}{2}<x \leq 1$. Note that in this case $2 x-1>0$. If $x y \geq \frac{4}{9}$, then we are done. Suppose now that $x y<\frac{4}{9}$. Then $y<\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{x}$. We now show that $\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{x} \leq \frac{x-\frac{4}{9}}{2 x-1}$. For this, it suffices to show that $\frac{4}{9}(2 x-1) \leq x\left(x-\frac{4}{9}\right)$, or equivalently $\frac{8}{9} x-\frac{4}{9} \leq x^{2}-\frac{4}{9} x$, which simplifies to $0 \leq x^{2}-\frac{4}{3} x+\frac{4}{9}$. The right side is $\left(x-\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2}$, which proves this inequality and thus the desired inequality. Now we are done, because from $y<\frac{x-\frac{4}{9}}{2 x-1}$ it follows that $y(2 x-1)<x-\frac{4}{9}$, or equivalently $x+y-2 x y>\frac{4}{9}$. Therefore, in any case, $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

|

\frac{4}{9}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Voor reële getallen $x$ en $y$ definiëren we $M(x, y)$ als het maximum van de drie getallen $x y,(x-1)(y-1)$ en $x+y-2 x y$. Bepaal de kleinst mogelijke waarde van $M(x, y)$ over alle reële getallen $x$ en $y$ met $0 \leq x, y \leq 1$.

|

We laten zien dat de minimale waarde $\frac{4}{9}$ is. Net als in de eerste oplossing zien we dat deze waarde bereikt kan worden door $x=y=\frac{2}{3}$ te nemen. Nu gaan we bewijzen dat $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$ voor alle $x$ en $y$. Dit doen we in feite door de niveaukrommen te vergelijken waarop de uitdrukkingen $x y,(1-x)(1-y)$ respectievelijk $x+y-2 x y$ de waarde $\frac{4}{9}$ aannemen.

We bekijken eerst het geval $0 \leq x<\frac{1}{2}$. Merk op dat nu geldt dat $1-2 x>0$. Als $(1-x)(1-y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$, dan zijn we klaar. Stel nu dat $(1-x)(1-y)<\frac{4}{9}$. Dan geldt $1-y<\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$, dus $y>1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$. We laten nu zien dat $1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x} \geq \frac{\frac{4}{9}-x}{1-2 x}$. Omdat de noemers positief zijn, is het voldoende om te bewijzen dat $\left(1-x-\frac{4}{9}\right)(1-2 x) \geq\left(\frac{4}{9}-x\right)(1-x)$, oftewel $2 x^{2}-\frac{19}{9} x+\frac{5}{9} \geq x^{2}-\frac{13}{9} x+\frac{4}{9}$, wat neerkomt op $x^{2}-\frac{2}{3} x+\frac{1}{9} \geq 0$. Aan de linkerkant staat $\left(x-\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}$, waarmee deze ongelijkheid en dus ook de gevraagde ongelijkheid bewezen is. Nu zijn we klaar, want hieruit volgt wegens $y>1-\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{1-x}$ dat $y>\frac{\frac{4}{9}-x}{1-2 x}$, dus $y(1-2 x)>\frac{4}{9}-x$, oftewel $x+y-2 x y>\frac{4}{9}$. Dus hoe dan ook geldt $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

Als $x=\frac{1}{2}$, dan is $x+y-2 x y=\frac{1}{2}+y-2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} y=\frac{1}{2}>\frac{4}{9}$.

We bekijken ten slotte het geval $\frac{1}{2}<x \leq 1$. Merk op dat nu juist geldt dat $2 x-1>0$. Als $x y \geq \frac{4}{9}$, dan zijn we klaar. Stel nu dat $x y<\frac{4}{9}$. Dan geldt $y<\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{x}$. We laten nu zien dat $\frac{\frac{4}{9}}{x} \leq \frac{x-\frac{4}{9}}{2 x-1}$. Hiervoor is het voldoende om te laten zien dat $\frac{4}{9}(2 x-1) \leq x\left(x-\frac{4}{9}\right)$, oftewel $\frac{8}{9} x-\frac{4}{9} \leq x^{2}-\frac{4}{9} x$, wat neerkomt op $0 \leq x^{2}-\frac{4}{3} x+\frac{4}{9}$. Aan de rechterkant staat $\left(x-\frac{2}{3}\right)^{2}$, waarmee deze ongelijkheid en dus ook de gevraagde ongelijkheid bewezen is. Nu zijn we klaar, want hieruit volgt dat $y<\frac{x-\frac{4}{9}}{2 x-1}$, dus $y(2 x-1)<x-\frac{4}{9}$, oftewel $x+y-2 x y>\frac{4}{9}$. Dus ook nu geldt hoe dan ook $M(x, y) \geq \frac{4}{9}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-C2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

In a sequence of numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{1000}$ consisting of 1000 different numbers, a pair $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ with $i<j$ is called increasing if $a_{i}<a_{j}$ and decreasing if $a_{i}>a_{j}$. Determine the largest positive integer $k$ with the property that in any sequence of 1000 different numbers, there are at least $k$ non-overlapping increasing pairs or at least $k$ non-overlapping decreasing pairs.

|

We will prove that the largest $k$ is equal to 333. First, consider the sequence $1000, 999, 998, \ldots, 669, 668, 1, 2, 3, \ldots, 666, 667$. The first 333 numbers in the sequence are not usable in an increasing pair, because for each of these numbers, only larger numbers are to the left and only smaller numbers are to the right. Therefore, only the last 667 numbers are available for increasing pairs, and this yields at most 333 non-overlapping increasing pairs. For a decreasing pair $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ with $i<j$, $a_{i}$ cannot be one of the numbers from 1 to 667, because for each of these numbers, only larger numbers are to the right. Thus, $a_{i}$ must be one of the first 333 numbers, which means there are at most 333 non-overlapping decreasing pairs. We conclude that $k>333$ cannot be satisfied.

Now we prove that for all $t \geq 1$, in a sequence of $3t-1$ different numbers, there are always at least $t$ non-overlapping increasing pairs or $t$ non-overlapping decreasing pairs. We prove this by induction on $t$. For $t=1$, the sequence has length 2, and this pair of numbers is either increasing or decreasing, so it holds. Now let $r \geq 1$ and assume the statement is true for $t=r$. We now consider $t=r+1$ and take an arbitrary sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{3r+2}$ with $3r+2$ different numbers. If the sequence is completely increasing, we can divide the sequence into adjacent pairs, all of which are increasing. There are $\left\lfloor\frac{3r+2}{2}\right\rfloor \geq \frac{2r+2}{2}=r+1$ such pairs. If the sequence is completely decreasing, there are analogously at least $r+1$ decreasing pairs. If the sequence is neither completely increasing nor completely decreasing, there is a point in the sequence where it first increases and then decreases, or vice versa, i.e., there are numbers $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, a_{i+2}$ in the sequence with $a_{i}<a_{i+1}>a_{i+2}$ or $a_{i}>a_{i+1}<a_{i+2}$. In both cases, among these three numbers, there is both an increasing pair and a decreasing pair. Now apply the induction hypothesis to the sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{i-1}, a_{i+3}, a_{i+4}, \ldots, a_{3r+2}$. This is a sequence with $3r+2-3=3r-1$ different numbers, so there are $r$ non-overlapping increasing pairs or $r$ non-overlapping decreasing pairs. In the first case, we add the increasing pair from $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, a_{i+2}$ to these, and in the second case, we add the decreasing pair. This gives us $r+1$ non-overlapping increasing pairs or $r+1$ non-overlapping decreasing pairs. This completes the induction.

Now substitute $t=333$ into this result: in a sequence of 998 different numbers, there are always at least 333 non-overlapping increasing pairs or at least 333 non-overlapping decreasing pairs. This also holds for a sequence of 1000 numbers (ignore the last two numbers in the sequence). Therefore, $k=333$ satisfies the condition and is thus the largest $k$ that satisfies it.

|

333

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In een getallenrij $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{1000}$ van 1000 verschillende getallen heet een paar $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ met $i<j$ stijgend als $a_{i}<a_{j}$ en dalend als $a_{i}>a_{j}$. Bepaal de grootste positieve gehele $k$ met de eigenschap dat in elke rij van 1000 verschillende getallen ten minste $k$ niet-overlappende stijgende paren te vinden zijn of ten minste $k$ niet-overlappende dalende paren.

|

We gaan bewijzen dat de grootste $k$ gelijk aan 333 is. Bekijk ten eerste de rij $1000,999,998, \ldots, 669,668,1,2,3, \ldots, 666,667$. De eerste 333 getallen in de rij zijn niet bruikbaar in een stijgend paar, omdat voor elk van deze getallen geldt dat links van dit getal alleen maar grotere getallen staan en rechts van dit getal alleen maar kleinere getallen. Voor de stijgende paren zijn dus alleen de laatste 667 getallen beschikbaar en dat levert hooguit 333 niet-overlappende stijgende paren op. Voor een dalend paar $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ met $i<j$ geldt dat $a_{i}$ niet één van de getallen 1 tot en met 667 kan zijn, want voor elk van deze getallen geldt dat er rechts van dit getal alleen maar grotere getallen staan. Dus $a_{i}$ moet één van de eerste 333 getallen zijn, waaruit volgt dat er hooguit 333 niet-overlappende dalende paren zijn. We concluderen dat $k>333$ niet kan voldoen.

Nu bewijzen we voor alle $t \geq 1$ dat er in een getallenrij van $3 t-1$ verschillende getallen altijd minstens $t$ niet-overlappende stijgende paren of $t$ niet-overlappende dalende paren te vinden zijn. We bewijzen dit met inductie naar $t$. Voor $t=1$ geldt dat de getallenrij lengte 2 heeft en dit paar getallen is ofwel stijgend ofwel dalend, dus het klopt. Zij nu $r \geq 1$ en veronderstel dat de bewering waar is voor $t=r$. We bekijken nu $t=r+1$ en nemen een willekeurige getallenrij $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{3 r+2}$ met $3 r+2$ verschillende getallen. Als de rij volledig stijgend is, dan kunnen we de rij opdelen in buurparen en die zijn allemaal stijgend. Dit zijn er $\left\lfloor\frac{3 r+2}{2}\right\rfloor \geq \frac{2 r+2}{2}=r+1$. Als de rij volledig dalend is, zijn er analoog minstens $r+1$ dalende paren. Als de rij niet volledig stijgend, maar ook niet volledig dalend is, dan is er een plek in de rij waar de rij eerst stijgt en dan daalt of andersom, oftewel: er zijn getallen $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, a_{i+2}$ in de rij met $a_{i}<a_{i+1}>a_{i+2}$ of $a_{i}>a_{i+1}<a_{i+2}$. In beide gevallen zit er in deze drie getallen zowel een stijgend paar als een dalend paar. Pas nu de inductiehypothese toe op de rij $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{i-1}, a_{i+3}, a_{i+4}, \ldots, a_{3 r+2}$. Dit is een rij met $3 r+2-3=3 r-1$ verschillende getallen, dus zijn er $r$ niet-overlappende stijgende paren te vinden of $r$ niet-overlappende dalende paren. In het eerste geval voegen we hier het stijgende paar uit $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, a_{i+2}$ aan toe en in het tweede geval juist het dalende paar. Daarmee hebben we dan $r+1$ niet-overlappende stijgende paren of $r+1$ niet-overlappende dalende paren gevonden. Dat voltooit de inductie.

Vul nu $t=333$ in dit resultaat in: in een rij van 998 verschillende getallen zijn altijd minstens 333 niet-overlappende stijgende paren of minstens 333 niet-overlappende dalende paren te vinden. In een rij van 1000 getallen geldt dit dus ook (negeer de laatste twee getallen in de rij). Dus $k=333$ voldoet en is daarmee de grootste $k$ die voldoet.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2022-C2022_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2022"

}

|

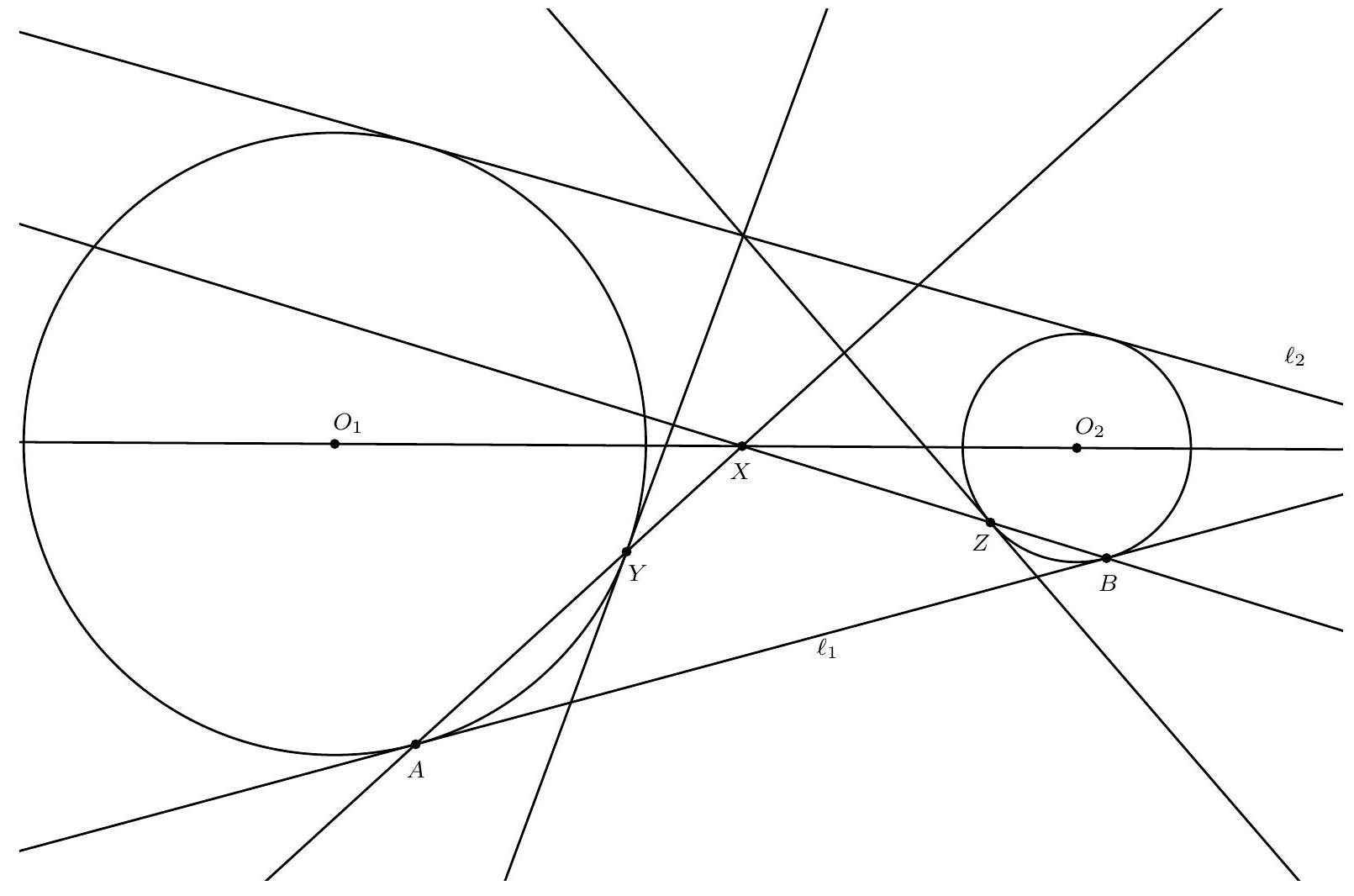

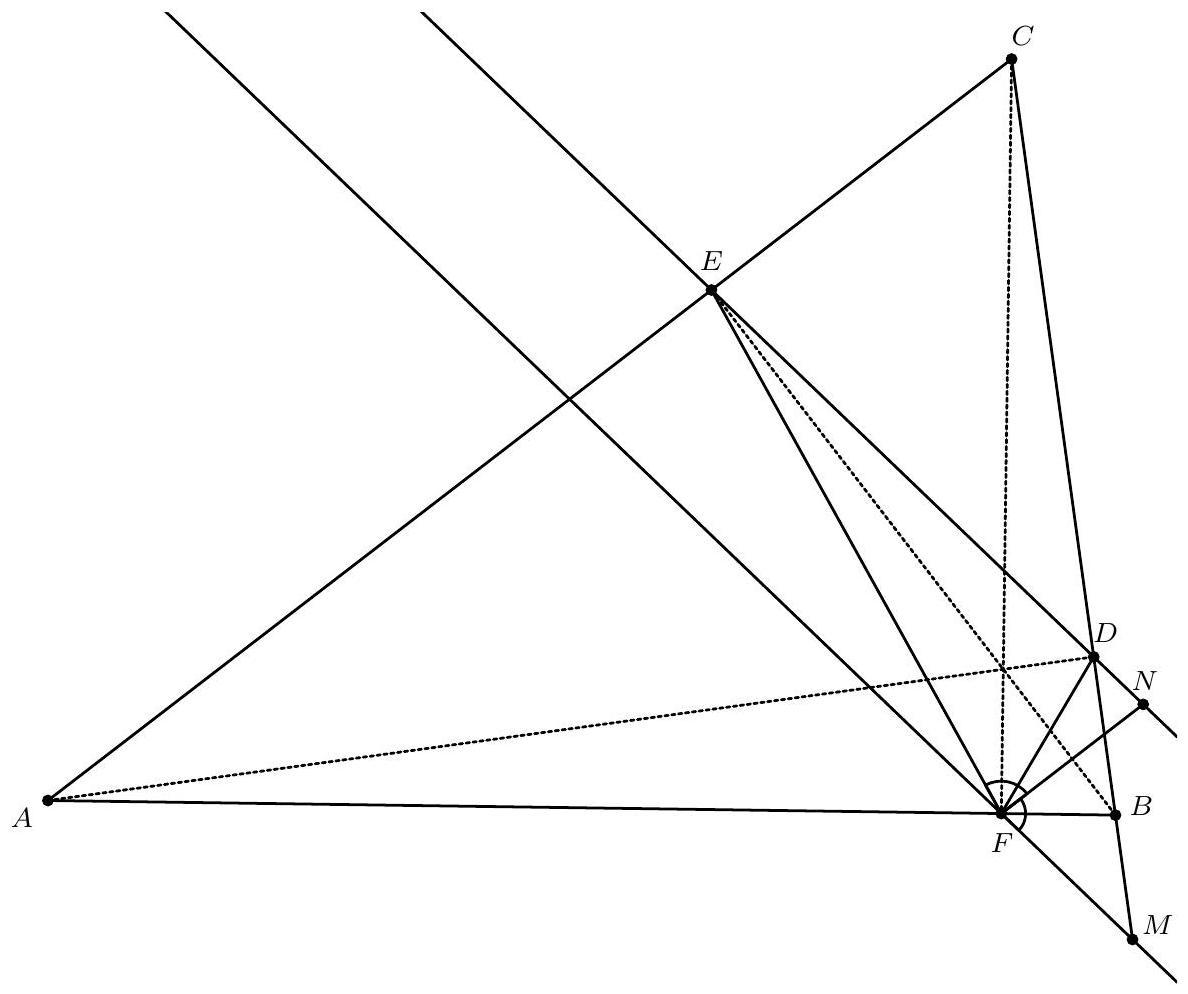

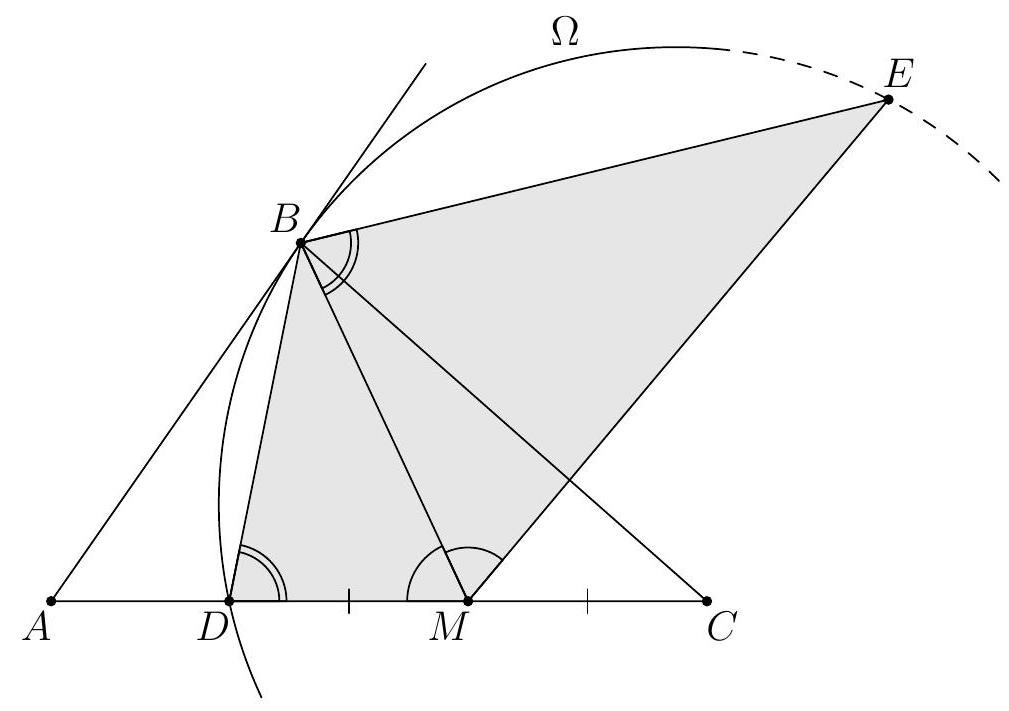

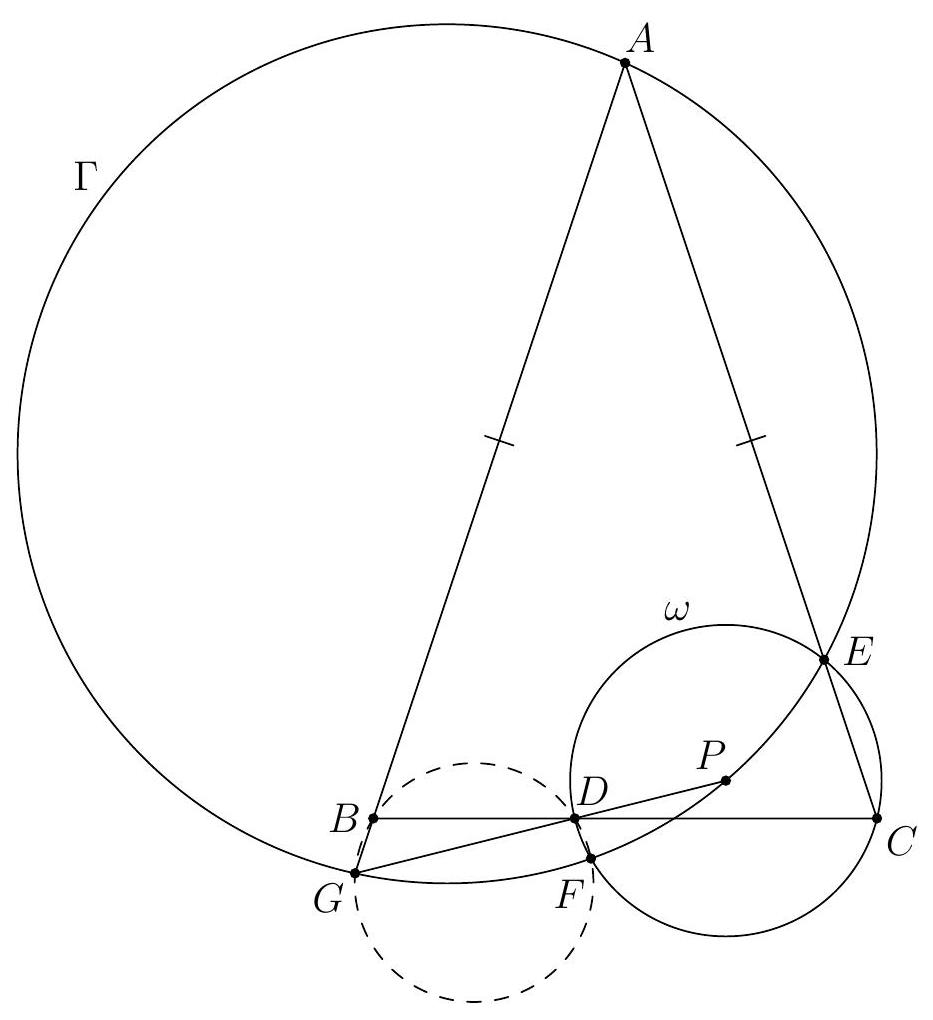

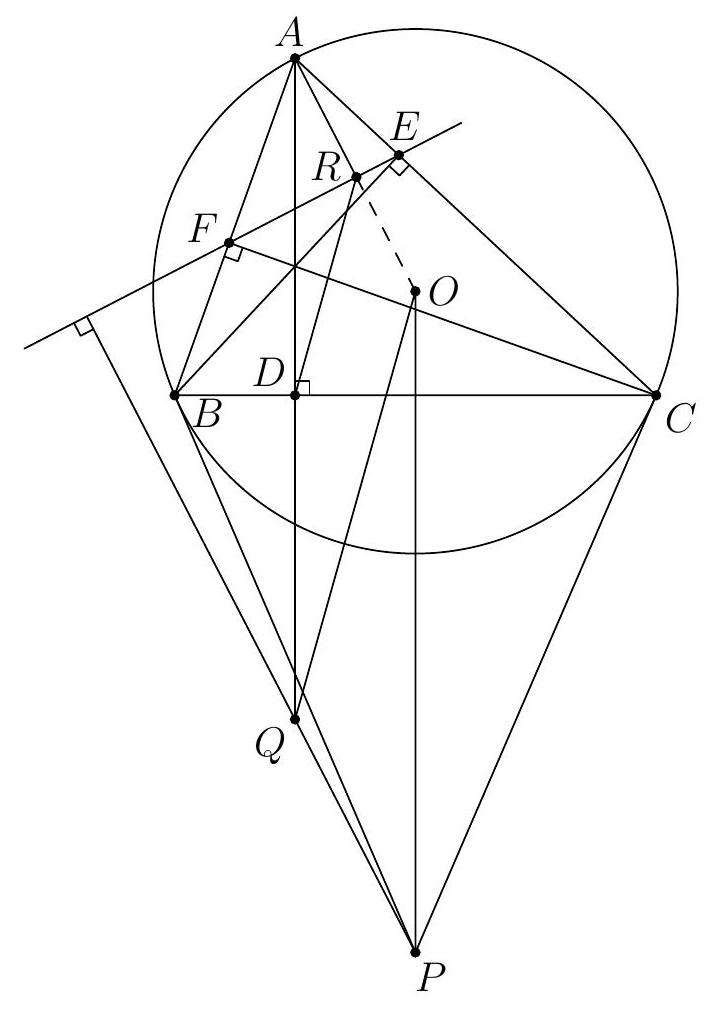

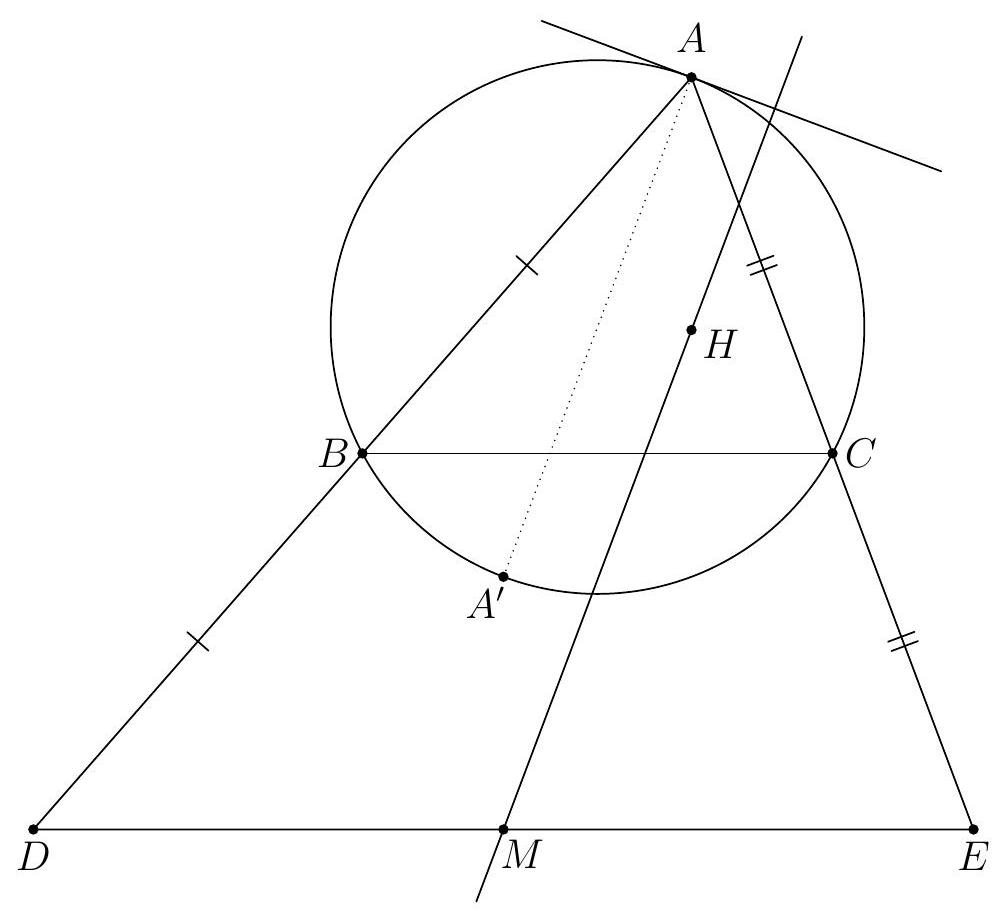

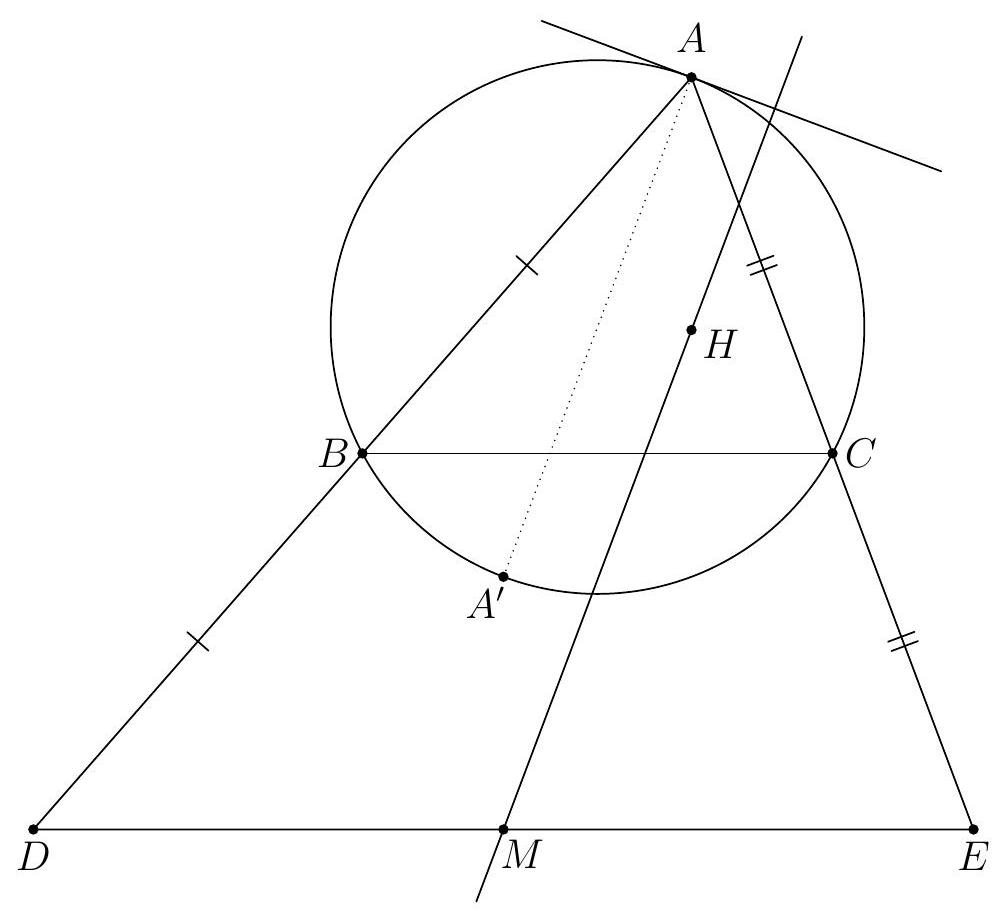

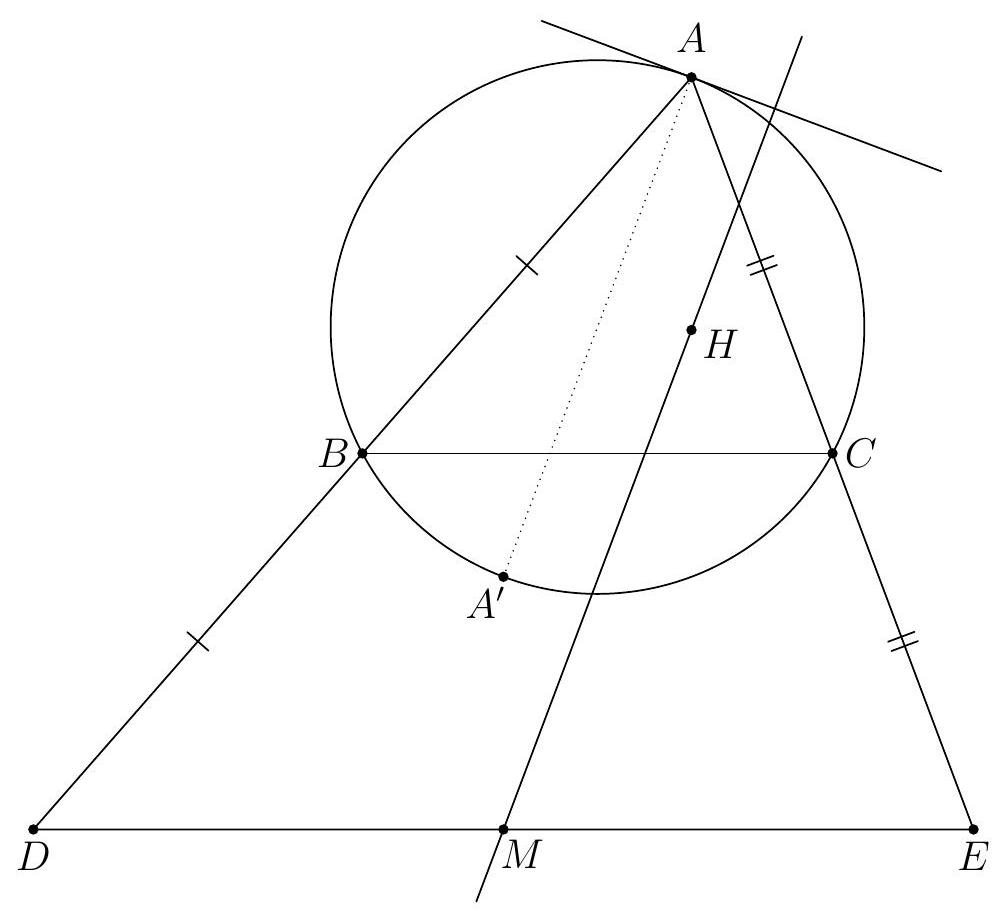

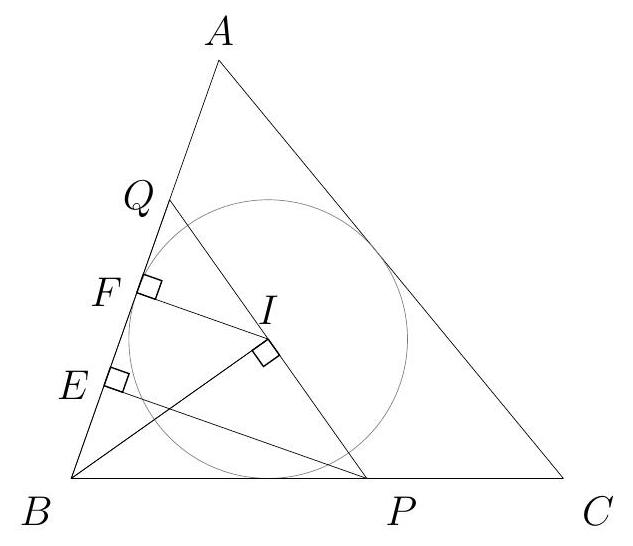

In an acute-angled triangle $ABC$, it holds that $|AB| > |CA| > |BC|$. The points $D, E$, and $F$ are the feet of the altitudes from $A, B$, and $C$ respectively. The line through $F$ parallel to $DE$ intersects $BC$ at $M$. The bisector of $\angle MFE$ intersects $DE$ at $N$. Prove that $F$ is the circumcenter of $\triangle DMN$ if and only if $B$ is the circumcenter of $\triangle FMN$.

|

Due to the length requirement in the problem, the configuration is fixed: $M$ lies on the ray $CB$ beyond $B$, and $N$ lies on the ray $ED$ beyond $D$. See the figure. Let $\alpha = \angle BAC$ and $\beta = \angle ABC$. Furthermore, let $H$ be the orthocenter of the triangle (i.e., the intersection of $AD$, $BE$, and $CF$). By Thales' theorem, $AFHE$, $BDHF$, $CEHD$, $ABDE$, $BCEF$, and $CAFD$ are cyclic quadrilaterals. Due to cyclic quadrilateral $ABDE$, $\angle CED = 180^\circ - \angle AED = \angle ABD = \beta$ and due to cyclic quadrilateral $BCEF$, $\angle AEF = 180^\circ - \angle CEF = \angle CBF = \beta$. Similarly, $\angle CDE$ and $\angle BDF$ are equal to $\alpha$.

From $\angle CED = \beta = \angle AEF$, it follows that $\angle DEH = 90^\circ - \beta = \angle FEH$. Therefore, $EH$ is the angle bisector of $\angle DEF$. Since $DE \parallel FM$, by alternate interior angles, $\angle MFE = 180^\circ - \angle FED = 180^\circ - 2(90^\circ - \beta) = 2\beta$. Since $FN$ is the angle bisector of $\angle MFE$, $\angle EFN = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2\beta = \beta$. Given that $\angle FEH = 90^\circ - \beta$, we see that $FN$ and $EH$ are perpendicular to each other, so $EH$ is not only the angle bisector in $\triangle FEN$ but also the altitude. This line is thus the perpendicular bisector of $FN$. Since $B$ lies on this line, $|BF| = |BN|$.

We have previously seen that $\angle CDE = \alpha = \angle BDF$. Since $DE \parallel FM$, $\angle BMF = \angle CDE = \alpha$, so $\angle DMF = \angle BMF = \angle BDF = \angle MDF$. Therefore, $|FM| = |FD|$.

Let $S$ be the intersection of $AC$ and $MF$. Then $\angle BFM = \angle AFS$ and since $DE \parallel FM$, $\angle CED = \angle CSF$. By the exterior angle theorem in triangle $AFS$, we also have $\angle CSF = \angle SAF + \angle AFS = \alpha + \angle AFS$. Combining all this, we find $\angle CED = \alpha + \angle BFM$. On the other hand, we know that $\angle CED = \beta$, so $\angle BFM = \beta - \alpha$. We also know that $\angle BMF = \alpha$. We conclude that $|BF| = |BM|$ if and only if $\beta - \alpha = \alpha$ or if and only if $\beta = 2\alpha$. Since we already know that $|BF| = |BN|$, we have: $B$ is the circumcenter of $\triangle FMN$ if and only if $\beta = 2\alpha$.