problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be a sequence of real numbers such that $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}=0$ and define $b_{i}=a_{1}+\cdots+a_{i}$ for $1 \leq i \leq n$. Suppose that $b_{i}\left(a_{j+1}-a_{i+1}\right) \geq 0$ for all $1 \leq i \leq j \leq n-1$. Prove that

$$

\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq n}\left|a_{\ell}\right| \geq \max _{1 \leq m \leq n}\left|b_{m}\right|

$$

|

Just as in solution I, we find that from $b_{i}>0$ it follows that $a_{i+1}<0$ and from $b_{i}<0$ it follows that $a_{i+1}>0$. Let now $M=\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq n}\left|a_{\ell}\right|$. We prove by induction on $t$ that $\left|b_{t}\right| \leq M$ for $1 \leq t \leq n$. For $t=1$ we have $\left|b_{1}\right|=\left|a_{1}\right| \leq M$. Let now $r \geq 1$ and assume that $\left|b_{r}\right| \leq M$. We now prove that $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. We distinguish three cases. If $b_{r}=0$, then $\left|b_{r+1}\right|=\left|b_{r}+a_{r+1}\right|=\left|a_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. Now suppose $b_{r}>0$. Then we know $a_{r+1}<0$, so $b_{r+1}=b_{r}+a_{r+1}$, hence $a_{r+1}<b_{r+1}<b_{r}$. By the induction hypothesis, $b_{r} \leq M$ and further we know $a_{r+1} \geq-M$, so $-M<b_{r+1}<M$, which means that $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. Finally, suppose that $b_{r}<0$. Then we know $a_{r+1}>0$, so we see in the same way as above $-M \leq b_{r}<b_{r+1}<a_{r+1} \leq M$, thus $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. This completes the induction. We conclude that $\left|b_{t}\right| \leq M$ for all $t$ and from this the desired result follows directly.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

$\mathrm{Zij} a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ een rijtje reële getallen zodat $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}=0$ en definieer $b_{i}=a_{1}+\cdots+a_{i}$ voor $1 \leq i \leq n$. Veronderstel dat $b_{i}\left(a_{j+1}-a_{i+1}\right) \geq 0$ voor alle $1 \leq i \leq$ $j \leq n-1$. Bewijs dat

$$

\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq n}\left|a_{\ell}\right| \geq \max _{1 \leq m \leq n}\left|b_{m}\right|

$$

|

Net als in oplossing I vinden we dat uit $b_{i}>0$ volgt dat $a_{i+1}<0$ en uit $b_{i}<0$ volgt $a_{i+1}>0$. Zij nu $M=\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq n}\left|a_{\ell}\right|$. We bewijzen met inductie naar $t$ dat $\left|b_{t}\right| \leq M$ voor $1 \leq t \leq n$. Voor $t=1$ geldt $\left|b_{1}\right|=\left|a_{1}\right| \leq M$. Zij nu $r \geq 1$ en neem aan dat $\left|b_{r}\right| \leq M$. Nu bewijzen we dat $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. We onderscheiden drie gevallen. Als $b_{r}=0$, dan geldt $\left|b_{r+1}\right|=\left|b_{r}+a_{r+1}\right|=\left|a_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. Stel nu $b_{r}>0$. Dan weten we $a_{r+1}<0$, dan geldt $b_{r+1}=b_{r}+a_{r+1}$, dus $a_{r+1}<b_{r+1}<b_{r}$. Vanwege de inductiehypothese is $b_{r} \leq M$ en verder weten we $a_{r+1} \geq-M$, dus $-M<b_{r+1}<M$, wat betekent dat $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. Stel ten slotte dat $b_{r}<0$. Dan weten we $a_{r+1}>0$, dus zien we op dezelfde manier als hierboven $-M \leq b_{r}<b_{r+1}<a_{r+1} \leq M$, dus $\left|b_{r+1}\right| \leq M$. Dit voltooit de inductie. We concluderen dat $\left|b_{t}\right| \leq M$ voor alle $t$ en daaruit volgt direct het gevraagde.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2017-E_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Determine the product of all positive integers $n$ for which $3(n!+1)$ is divisible by $2 n-5$.

将上面的文本翻译成英文,请保留源文本的换行和格式,直接输出翻译结果。

However, it seems there is a note or an additional request in Chinese at the end of your message. If you need the Chinese text translated as well, please let me know! For now, I'll assume you only need the provided Dutch text translated to English. If that's correct, the translation is as above.

|

The numbers $n=1$ to $n=4$ satisfy the condition, because $2n-5$ is then equal to $-3, -1, 1$, and $3$, respectively, and is always a divisor of $3(n!+1)$. From now on, we only consider $n>4$ and then $2n-5>3$.

We first prove that if $n$ satisfies the condition, then $2n-5$ must be prime. We distinguish two cases. Suppose first that $2n-5$ is not prime and has a prime divisor $p>3$. Since $p \neq 2n-5$ and since $2n-5$ is odd, it follows that $p \leq \frac{2n-5}{3} < n$. Therefore, $p \mid n!$, but then $p \nmid n!+1$ and thus also $p \nmid 3(n!+1)$ since $p \neq 3$. Therefore, $2n-5 \nmid 3(n!+1)$, which means that $n$ does not satisfy the condition. Now suppose that $2n-5$ is not prime but has only prime divisors 3; then it is a power of 3 greater than 3. However, for $n>4$, $3 \nmid n!+1$, so $3(n!+1)$ is divisible by exactly one factor of 3 and no more. We see that $n$ cannot satisfy the condition in this case either.

For an $n>4$ that satisfies the condition, we now know that $2n-5$ is a prime number greater than 3. Let $q=2n-5$. Then $q \mid n!+1$, or $n! \equiv -1 \pmod{q}$. Furthermore, Wilson's theorem states that $(q-1)! \equiv -1 \pmod{q}$. Therefore,

$$

\begin{aligned}

-1 & \equiv (2n-6)! \\

& \equiv (2n-6)(2n-7) \cdots (n+1) \cdot n! \\

& \equiv (-1) \cdot (-2) \cdots (-n+6) \cdot n! \\

& \equiv (-1)^{n-6} \cdot (n-6)! \cdot n! \\

& \equiv (-1)^{n} \cdot (n-6)! \cdot -1 \quad \pmod{q}.

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus, $(n-6)! \equiv (-1)^{n} \pmod{q}$. Since $n! \equiv -1 \pmod{q}$, it follows that $n \cdot (n-1) \cdots (n-5) \equiv (-1)^{n-1} \pmod{q}$. We multiply this by $2^6$:

$$

2n \cdot (2n-2) \cdot (2n-4) \cdot (2n-6) \cdot (2n-8) \cdot (2n-10) \equiv (-1)^{n-1} \cdot 64 \pmod{q}.

$$

Modulo $q=2n-5$, the left side is $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 1 \cdot -1 \cdot -3 \cdot -5 = -225$.

Suppose $n$ is odd. Then we have $-225 \equiv 64 \pmod{q}$, so $q \mid -225-64 = -289 = -17^2$. Therefore, $q=17$ and then $n=\frac{17+5}{2}=11$. Now suppose $n$ is even. Then we have $-225 \equiv -64 \pmod{q}$, so $q \mid -225+64 = -161 = -7 \cdot 23$. Therefore, $q=7$ or $q=23$, which gives $n=6$ and $n=14$, respectively.

We check these three possibilities. For $n=11$ and $2n-5=17$:

$$

\begin{aligned}

11! & = 1 \cdot (2 \cdot 9) \cdot (3 \cdot 6) \cdot (5 \cdot 7) \cdot 4 \cdot 8 \cdot 10 \cdot 11 \\

& \equiv 4 \cdot 8 \cdot 10 \cdot 11 = 88 \cdot 40 \equiv 3 \cdot 6 \equiv 1 \quad \pmod{17}

\end{aligned}

$$

so $n=11$ does not satisfy the condition. For $n=14$ and $2n-5=23$:

$$

\begin{aligned}

14! & = 1 \cdot (2 \cdot 12) \cdot (3 \cdot 8) \cdot (4 \cdot 6) \cdot (5 \cdot 14) \cdot (7 \cdot 10) \cdot 9 \cdot 11 \cdot 13 \\

& \equiv 9 \cdot 11 \cdot 13 = 117 \cdot 11 \equiv 2 \cdot 11 \equiv -1 \quad \pmod{23}

\end{aligned}

$$

so $n=14$ satisfies the condition. For $n=6$ and $2n-5=7$, it follows from Wilson's theorem that $6! \equiv -1 \pmod{7}$, so $n=6$ also satisfies the condition.

We conclude that the numbers $n$ that satisfy the condition are: $1, 2, 3, 4, 6$, and 14. The product of these is 2016.

|

2016

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal het product van alle positieve gehele getallen $n$ waarvoor $3(n!+1)$ deelbaar is door $2 n-5$.

|

De getallen $n=1$ tot en met $n=4$ voldoen, want $2 n-5$ is dan gelijk aan respectievelijk $-3,-1,1$ en 3 , dus altijd een deler dan $3(n!+1)$. Vanaf nu bekijken we alleen $n>4$ en dan is $2 n-5>3$.

We bewijzen eerst dat als $n$ voldoet, dan $2 n-5$ priem moet zijn. We onderscheiden twee gevallen. Stel eerst dat $2 n-5$ niet priem is en een priemdeler $p>3$ heeft. Omdat $p \neq 2 n-5$ en omdat $2 n-5$ oneven is, geldt $p \leq \frac{2 n-5}{3}<n$. Dus $p \mid n!$, maar dan $p \nmid n!+1$ en dus ook $p \nmid 3(n!+1)$ aangezien $p \neq 3$. Dus $2 n-5 \nmid 3(n!+1)$, wat betekent dat $n$ niet voldoet. Stel nu dat $2 n-5$ niet priem is, maar alleen priemdelers 3 heeft; dan is het dus een driemacht groter dan 3. Echter, voor $n>4$ is $3 \nmid n!+1$, dus $3(n!+1)$ is deelbaar door precies één factor 3 en niet meer. We zien dat $n$ ook in dit geval niet kan voldoen.

Voor een $n>4$ die voldoet, weten we nu dat $2 n-5$ een priemgetal groter dan 3 is. Schrijf $q=2 n-5$. Dan $q \mid n!+1$, oftewel $n!\equiv-1 \bmod q$. Verder zegt de stelling van Wilson dat $(q-1)!\equiv-1 \bmod q$. Dus

$$

\begin{aligned}

-1 & \equiv(2 n-6)! \\

& \equiv(2 n-6)(2 n-7) \cdots(n+1) \cdot n! \\

& \equiv(-1) \cdot(-2) \cdots \cdots(-n+6) \cdot n! \\

& \equiv(-1)^{n-6} \cdot(n-6)!\cdot n! \\

& \equiv(-1)^{n} \cdot(n-6)!\cdot-1 \quad \bmod q .

\end{aligned}

$$

Dus $(n-6)!\equiv(-1)^{n} \bmod q$. Omdat $n!\equiv-1 \bmod q$, volgt daaruit $n \cdot(n-1) \cdots \cdot \cdot(n-5) \equiv$ $(-1)^{n-1} \bmod q$. We vermenigvuldigen dit met $2^{6}$ :

$$

2 n \cdot(2 n-2) \cdot(2 n-4) \cdot(2 n-6) \cdot(2 n-8) \cdot(2 n-10) \equiv(-1)^{n-1} \cdot 64 \bmod q .

$$

Modulo $q=2 n-5$ staat links $5 \cdot 3 \cdot 1 \cdot-1 \cdot-3 \cdot-5=-225$.

Stel $n$ is oneven. Dan hebben we dus $-225 \equiv 64 \bmod q$, dus $q \mid-225-64=-289=-17^{2}$. Dus $q=17$ en dan $n=\frac{17+5}{2}=11$. Stel nu $n$ is even. Dan hebben we $-225 \equiv-64 \bmod q$, dus $q \mid-225+64=-161=-7 \cdot 23$. Dus $q=7$ of $q=23$ en dat geeft respectievelijk $n=6$ en $n=14$.

We controleren deze drie mogelijkheden. Voor $n=11$ en $2 n-5=17$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

11! & =1 \cdot(2 \cdot 9) \cdot(3 \cdot 6) \cdot(5 \cdot 7) \cdot 4 \cdot 8 \cdot 10 \cdot 11 \\

& \equiv 4 \cdot 8 \cdot 10 \cdot 11=88 \cdot 40 \equiv 3 \cdot 6 \equiv 1 \quad \bmod 17

\end{aligned}

$$

dus $n=11$ voldoet niet. Voor $n=14$ en $2 n-5=23$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

14! & =1 \cdot(2 \cdot 12) \cdot(3 \cdot 8) \cdot(4 \cdot 6) \cdot(5 \cdot 14) \cdot(7 \cdot 10) \cdot 9 \cdot 11 \cdot 13 \\

& \equiv 9 \cdot 11 \cdot 13=117 \cdot 11 \equiv 2 \cdot 11 \equiv-1 \quad \bmod 23

\end{aligned}

$$

dus $n=14$ voldoet. Voor $n=6$ en $2 n-5=7$ ten slotte volgt $6!\equiv-1 \bmod 7$ uit de stelling van Wilson, dus $n=6$ voldoet ook.

We concluderen dat de getallen $n$ die voldoen, zijn: $1,2,3,4,6$ en 14. Het product daarvan is 2016.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2017-E_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Let $n \geq 2$ be an integer. Determine the smallest positive integer $m$ such that: given $n$ points in the plane, no three on a line, there are $m$ lines to be found, such that no line passes through any of the given points and such that for each pair of given points $X \neq Y$ there is a line such that $X$ and $Y$ lie on opposite sides of the line.

|

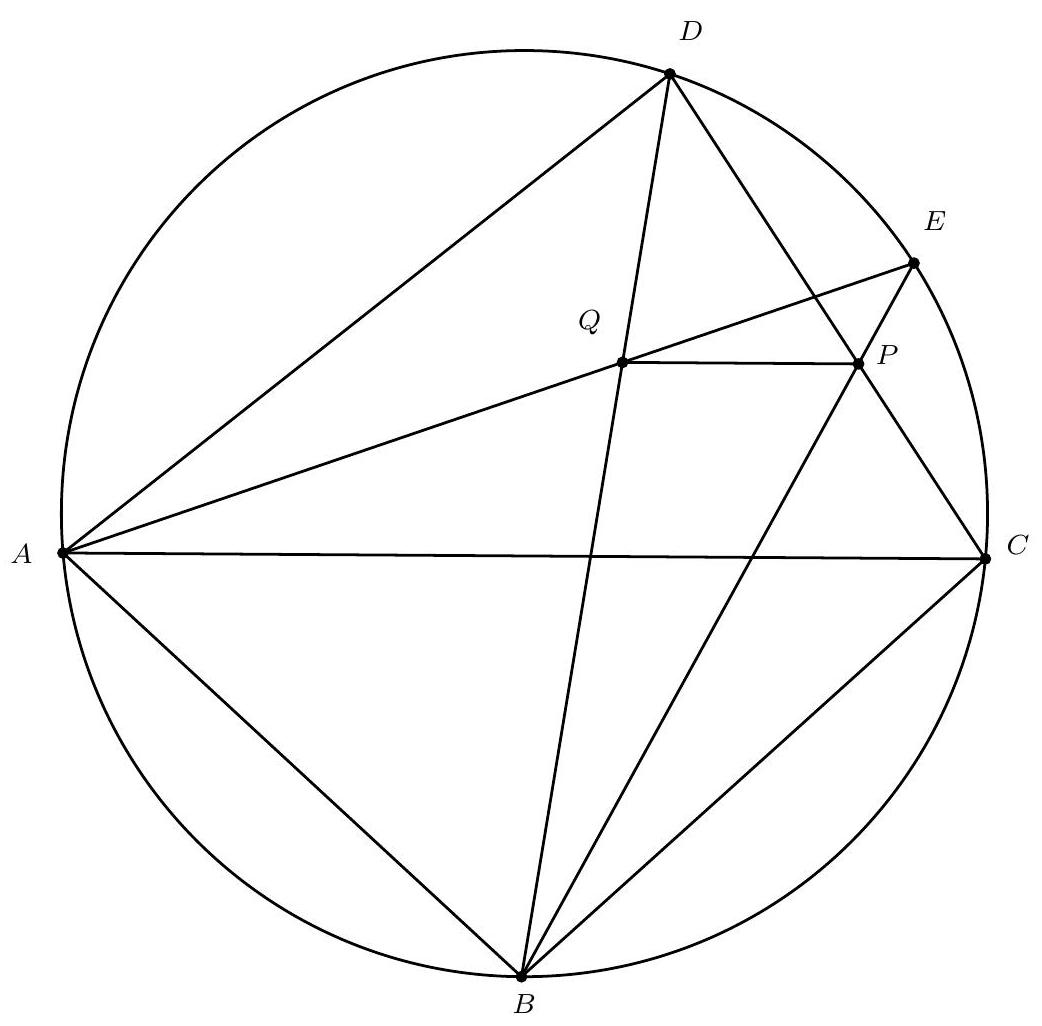

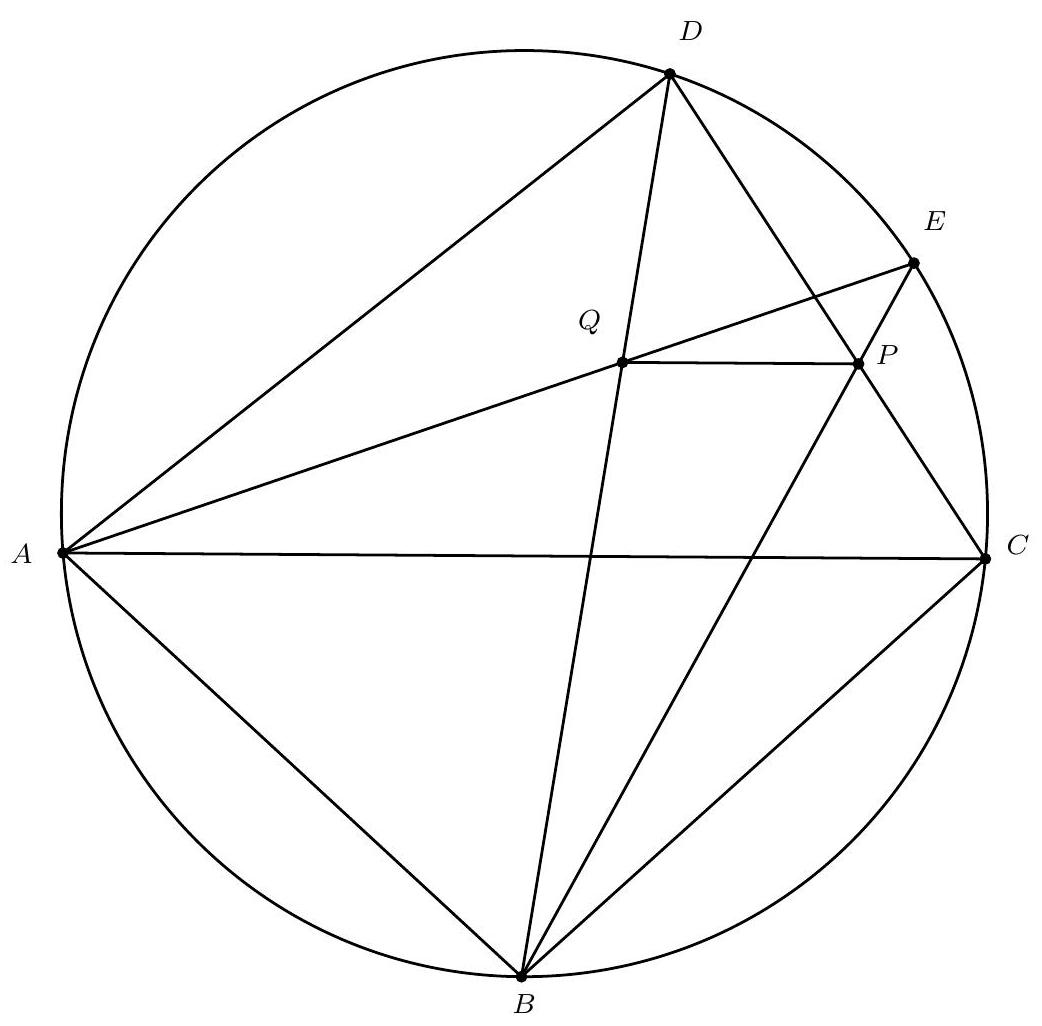

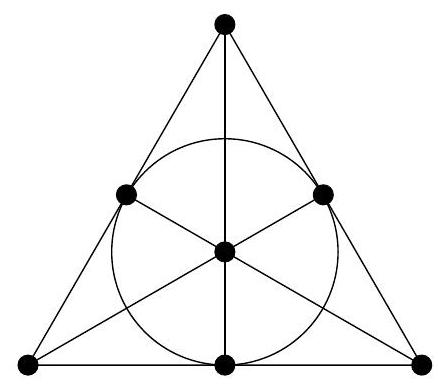

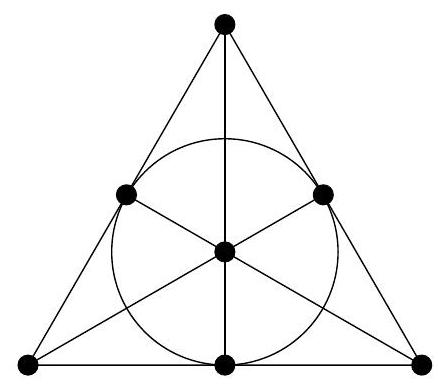

We prove that the smallest $m$ is equal to $\frac{n}{2}$ if $n$ is even and $\frac{n+1}{2}$ if $n$ is odd. Choose the $n$ points all on the same circle and call them $P_{1}, P_{2}, \ldots, P_{n}$ in the order in which they lie on the circle. The $n$ line segments $P_{1} P_{2}, P_{2} P_{3}, \ldots, P_{n} P_{1}$ must all be intersected by at least one line. Each line can intersect at most two such line segments, since each line intersects the circle at most twice. Therefore, the number of lines is at least $\frac{n}{2}$ and thus for odd $n$ at least $\frac{n+1}{2}$.

Now we prove that this is sufficient. First, we show that given four distinct points $P_{1}, P_{2}$ and $Q_{1}, Q_{2}$, there always exists a line such that $P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ lie on opposite sides of the line and $Q_{1}$ and $Q_{2}$ also. For this, take the line through the midpoint of $P_{1} P_{2}$ and through the midpoint of $Q_{1} Q_{2}$. Suppose this line passes through $P_{1}$. Then it also passes through $P_{2}$, but not through $Q_{1}$ or $Q_{2}$, because no three points lie on a line. Shift it slightly so that it no longer passes through the midpoint of $Q_{1} Q_{2}$, but still through the midpoint of $P_{1} P_{2}$, then it no longer passes through any of these four points. Similarly, if the line passes through one of the other three points. If the now chosen line passes through one of the other given points in the plane, shift it (even) a little bit so that it no longer does. Since there are only finitely many points, this is always possible. This line now has $P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ on opposite sides and $Q_{1}$ and $Q_{2}$ also.

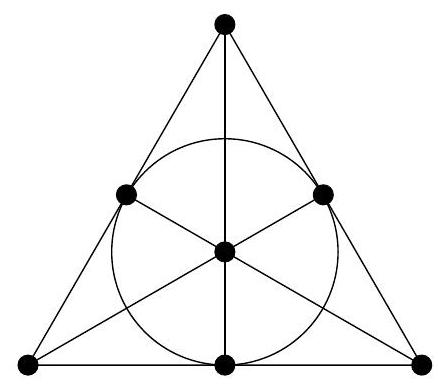

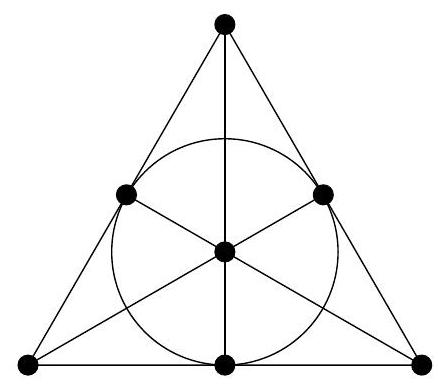

Now assume that $n$ is even; if $n$ is odd, add an arbitrary point (not on a line with two of the other points). The lines we then construct also work if you remove the extra point. We now need to construct $\frac{n}{2}$ lines. Choose a random line in a direction such that no line through two of the given points is parallel to this line (this is possible because there are only finitely many points and thus also finitely many pairs, while there are infinitely many directions to choose from). Now shift the chosen line. In doing so, it encounters the given points one by one. There is thus a moment when there are no points on the line and there are exactly $\frac{n}{2}$ points on either side of the line. We fix this first line at that moment.

The plane is now divided into two regions, let's say the left and right regions. We will now add lines so that each line creates a new subregion in both the left and right regions. (We only count subregions in which at least one point lies.) For this, we always take two points in the left region that are not yet separated by a line and two points in the right region that are not yet separated by a line. We now choose a line such that the two points on the left lie on opposite sides of this line and the two points on the right also; we have shown earlier that this is possible. There is now at least one additional subregion on both the left and right sides, because the subregion with the two points in it is split into two. If at some point there are no two points left on one of the two sides that are not yet separated by a line, we only use points on the other side. Eventually, after adding $\frac{n}{2}-1$ lines, there are at least $\frac{n}{2}$ subregions with at least one point in each on both the left and right sides; there must therefore be exactly one point in each subregion. Each point thus lies in its own subregion, so the condition is satisfied. In total, we have used $\frac{n}{2}$ lines. So with $\frac{n}{2}$ lines, it is always possible to satisfy the condition.

|

m = \frac{n}{2} \text{ if } n \text{ is even and } m = \frac{n+1}{2} \text{ if } n \text{ is odd}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Zij $n \geq 2$ een geheel getal. Bepaal de kleinste positieve gehele $m$ zodat geldt: gegeven $n$ punten in het vlak, geen drie op een lijn, zijn er $m$ lijnen te vinden, zodat geen enkele lijn door één van de gegeven punten gaat en zodat voor elk tweetal gegeven punten $X \neq Y$ geldt dat er een lijn is waarvan $X$ en $Y$ aan weerszijden liggen.

|

We bewijzen dat de kleinste $m$ gelijk is aan $\frac{n}{2}$ als $n$ even is en $\frac{n+1}{2}$ als $n$ oneven. Kies de $n$ punten allemaal op dezelfde cirkel en noem ze $P_{1}, P_{2}, \ldots, P_{n}$ in de volgorde waarin ze op de cirkel liggen. De $n$ lijnstukken $P_{1} P_{2}, P_{2} P_{3}, \ldots, P_{n} P_{1}$ moeten allemaal gesneden worden door minstens één lijn. Elke lijn snijdt hoogstens twee van zulke lijnstukken, aangezien elke lijn de cirkel hoogstens twee keer snijdt. Dus het aantal lijnen is minstens $\frac{n}{2}$ en dus voor oneven $n$ minstens $\frac{n+1}{2}$.

Nu bewijzen we dat dit voldoende is. Eerst laten we zien dat gegeven vier verschillende punten $P_{1}, P_{2}$ en $Q_{1}, Q_{2}$ er altijd een lijn bestaat zodat $P_{1}$ en $P_{2}$ aan weerszijden van de lijn liggen en $Q_{1}$ en $Q_{2}$ ook. Neem hiervoor de lijn door het midden van $P_{1} P_{2}$ en door het midden van $Q_{1} Q_{2}$. Stel dat deze lijn door $P_{1}$ heen gaat. Dan gaat hij ook door $P_{2}$ heen, maar niet door $Q_{1}$ of $Q_{2}$, omdat er nooit drie punten op een lijn liggen. Schuif hem dan een klein stukje op zodat hij net niet door het midden van $Q_{1} Q_{2}$ heen gaat, maar nog wel door het midden van $P_{1} P_{2}$, dan gaat hij niet meer door één van deze vier punten heen. Analoog als de lijn door één van de andere drie punten heen zou gaan. Als de nu gekozen lijn door één van de overige gegeven punten in het vlak gaat, schuif je hem (nog) een heel klein beetje op zodat dat niet meer zo is. Omdat er maar eindig veel punten zijn, lukt dit altijd. Deze lijn heeft nu $P_{1}$ en $P_{2}$ aan weerszijden en $Q_{1}$ en $Q_{2}$ ook.

Neem nu aan dat $n$ even is; als $n$ oneven is, voegen we een willekeurig punt (niet op een lijn met twee van de andere punten) toe. De lijnen die we dan construeren, werken ook als je het extra punt weer weglaat. We moeten dus nu $\frac{n}{2}$ lijnen construeren. Kies een willekeurige lijn in een richting zodat geen enkele lijn door twee van de gegeven punten evenwijdig aan deze lijn loopt (dat kan omdat er maar eindig veel punten zijn en dus ook maar eindig veel tweetallen, terwijl er oneindig veel richtingen te kiezen zijn). Schuif nu de gekozen lijn op. Hierbij komt hij één voor één de gegeven punten tegen. Er is dus een moment dat er geen punten op de lijn liggen en er aan weerszijden van de lijn precies $\frac{n}{2}$ punten liggen. Daar leggen we deze eerste lijn vast.

Het vlak wordt nu in twee gebieden verdeeld, laten we zeggen het linker- en rechtergebied. We gaan nu lijnen toevoegen zodat elke lijn een nieuw deelgebied creëert in zowel het linker- als het rechtergebied. (We tellen alleen deelgebieden waarin minstens één punt ligt.) Hiervoor nemen we steeds twee punten in het linkergebied die nog niet gescheiden worden door een lijn en twee punten in het rechtergebied die nog niet gescheiden worden door een lijn. We kiezen nu een lijn zodat de twee punten links aan weerszijden van deze lijn liggen en de twee punten rechts ook; we hebben eerder laten zien dat dit kan. Er is nu zowel links als rechts minstens één extra deelgebied ontstaan, want het deelgebied met de twee punten erin is in tweeën gesplitst. Mochten er op een gegeven moment aan één van beide kanten geen twee punten meer zijn waar nog geen lijn tussendoor loopt, dan gebruiken we alleen nog punten aan de andere kant. Uiteindelijk hebben we na het toevoegen van $\frac{n}{2}-1$ lijnen

zowel links als rechts minstens $\frac{n}{2}$ deelgebieden met elk minstens één punt erin; er moet dus wel precies één punt in elk deelgebied zitten. Elk punt ligt dus in zijn eigen deelgebied, waardoor aan de voorwaarde voldaan wordt. In totaal hebben we $\frac{n}{2}$ lijnen gebruikt. Dus met $\frac{n}{2}$ lijnen lukt het altijd om aan de voorwaarde te voldoen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2017-E_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

We have 1000 balls in 40 different colors, with exactly 25 balls of each color. Determine the smallest value of $n$ with the following property: if you randomly arrange the 1000 balls in a circle, there will always be $n$ consecutive balls where at least 20 different colors appear.

|

Consider the circle of balls where 25 balls of one color are always next to each other. To have 20 different colors, you need to take at least 18 of these groups plus one ball on one side and one ball on the other side. In total, you need at least \(18 \cdot 25 + 2 = 452\) balls next to each other. Therefore, \(n \geq 452\). Now we prove that in any circle of balls, you need at most 452 balls next to each other to get 20 different colors. For this, consider any random circle of balls and all possible series of balls next to each other that together have exactly 20 colors. (There is at least one such series: take a random ball and add the balls next to it one by one until you have exactly 20 colors.) Take a series with the minimum number of balls. Say the first ball in this series is white. If there is another white ball in the series, we could have omitted the first ball to get a series with the same number of colors but fewer balls. This contradicts the minimality of the series. Therefore, there is no other white ball. In particular, the last ball in the series is not white; say it is black. We see in the same way that no other ball in the series is black. So there is one white ball, one black ball, and balls in 18 other colors, with at most 25 of each color. Together, this is at most \(18 \cdot 25 + 2 = 452\) balls. Therefore, you can always find a series of 452 balls next to each other that contains at least 20 different colors. We conclude that the required minimum \(n\) is 452.

|

452

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

We hebben 1000 ballen in 40 verschillende kleuren, waarbij er van elke kleur precies 25 ballen zijn. Bepaal de kleinste waarde van $n$ met de volgende eigenschap: als je de 1000 ballen willekeurig in een cirkel legt, zijn er altijd $n$ ballen naast elkaar te vinden waarbij minstens 20 verschillende kleuren voorkomen.

|

Bekijk de cirkel van ballen waarbij de 25 ballen van één kleur steeds allemaal naast elkaar liggen. Om nu 20 verschillende kleuren te hebben, moet je minstens 18 van deze groepen nemen plus nog een bal aan de ene kant daarvan en een bal aan de andere kant. Totaal heb je dus minimaal $18 \cdot 25+2=452$ ballen naast elkaar nodig. Dus $n \geq 452$. Nu bewijzen we dat je in elke cirkel van ballen genoeg hebt aan 452 ballen naast elkaar om 20 verschillende kleuren te krijgen. Bekijk daarvoor een willekeurige cirkel van ballen en alle mogelijke series van ballen naast elkaar die samen precies 20 kleuren hebben. (Er bestaat minstens één zo'n serie: pak een willekeurige bal en voeg de ballen ernaast één voor één toe, totdat je precies 20 kleuren hebt.) Neem een serie daarvan met zo min mogelijk ballen erin. Zeg dat de eerste bal daarvan wit is. Als er nog een bal in de serie wit is, dan hadden we de eerste bal kunnen weglaten om een serie te krijgen met evenveel kleuren, maar minder ballen. Dat is een tegenspraak met de minimaliteit van de serie. Dus er is geen enkele andere bal wit. In het bijzonder is ook de laatste bal van de serie niet wit; zeg dat deze zwart is. We zien op dezelfde manier dat geen enkele andere bal in de serie zwart is. Dus er is één witte bal, één zwarte bal en daarnaast nog ballen in 18 andere kleuren, hooguit 25 per kleur. Samen zijn dat hooguit $18 \cdot 25+2=452$ ballen. Dus inderdaad kun je altijd een serie van 452 ballen naast elkaar vinden met daarin minstens 20 verschillende kleuren. We concluderen dat de gevraagde minimale $n$ gelijk is aan 452 .

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

We have 1000 balls in 40 different colors, with exactly 25 balls of each color. Determine the smallest value of $n$ with the following property: if you randomly arrange the 1000 balls in a circle, there will always be $n$ consecutive balls where at least 20 different colors appear.

|

We provide an alternative proof for the second part of the solution. We do this by contradiction. Suppose we have a circle of balls where every series of 452 balls contains at most 19 colors. Since $452=18 \cdot 25+2$, each such series then contains exactly 19 colors, and there are at least two balls of each color. Now consider such a series and shift it one ball at a time. With each shift, one ball leaves the series, say ball $A$, and one ball joins, say ball $B$. The color of ball $A$ appears at least once more in the series, so the color of ball $A$ does not disappear. However, no new color can be added, so ball $B$ must be of a color that is already in the series. Each time we shift by one, the set of colors present in the series remains the same set of 19 colors. If we go around the entire circle this way, we thus encounter only 19 different colors, while there are 40 different colors. Contradiction. Therefore, there is a series of 452 balls with at least 20 different colors.

|

452

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

We hebben 1000 ballen in 40 verschillende kleuren, waarbij er van elke kleur precies 25 ballen zijn. Bepaal de kleinste waarde van $n$ met de volgende eigenschap: als je de 1000 ballen willekeurig in een cirkel legt, zijn er altijd $n$ ballen naast elkaar te vinden waarbij minstens 20 verschillende kleuren voorkomen.

|

We geven een alternatief bewijs voor het tweede deel van de oplossing. We doen dit uit het ongerijmde. Stel dat we een cirkel van ballen hebben waar elke serie van 452 ballen hooguit 19 kleuren bevat. Omdat $452=18 \cdot 25+2$ bevat elk zo'n serie dan precies 19 kleuren en zitten er van elke kleur minstens twee ballen in. Bekijk nu zo'n serie en schuif hem steeds één bal op. Bij zo'n verschuiving verdwijnt één bal uit de serie, zeg bal $A$, en komt er ook eentje bij, zeg bal $B$. De kleur van bal $A$ komt minstens nog een keer voor in de serie, dus de kleur van bal $A$ verdwijnt niet. Maar er mag ook geen extra kleur bijkomen, dus bal $B$ moet van een kleur zijn die al in de serie zat. Elke keer dat we één opschuiven, blijft de verzameling van kleuren die voorkomen in de serie, dus dezelfde verzameling van 19 kleuren. Als we zo de hele cirkel rondgaan, komen we dus maar 19

verschillende kleuren tegen, terwijl er 40 verschillende kleuren zijn. Tegenspraak. Dus er is een serie van 452 ballen met minstens 20 verschillende kleuren.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

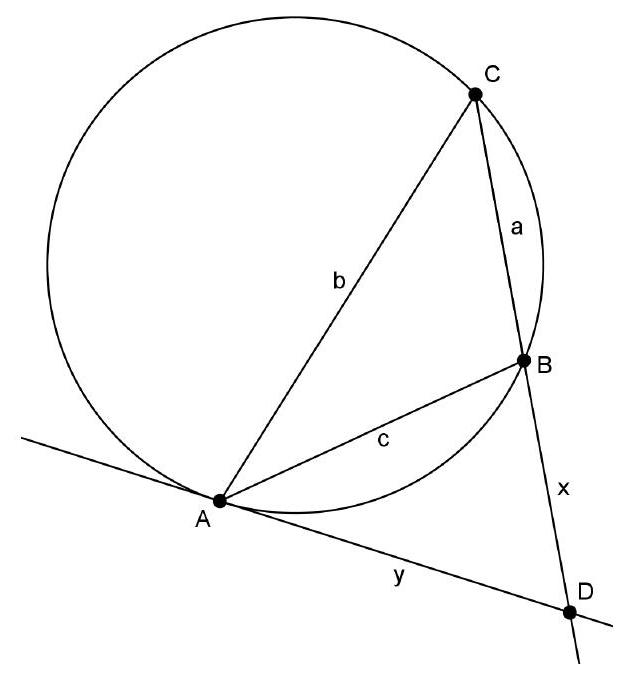

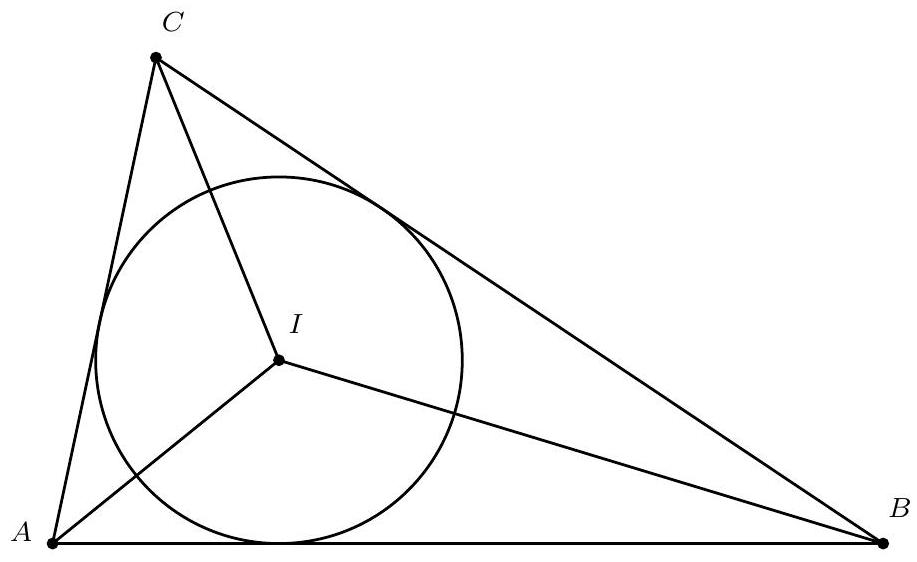

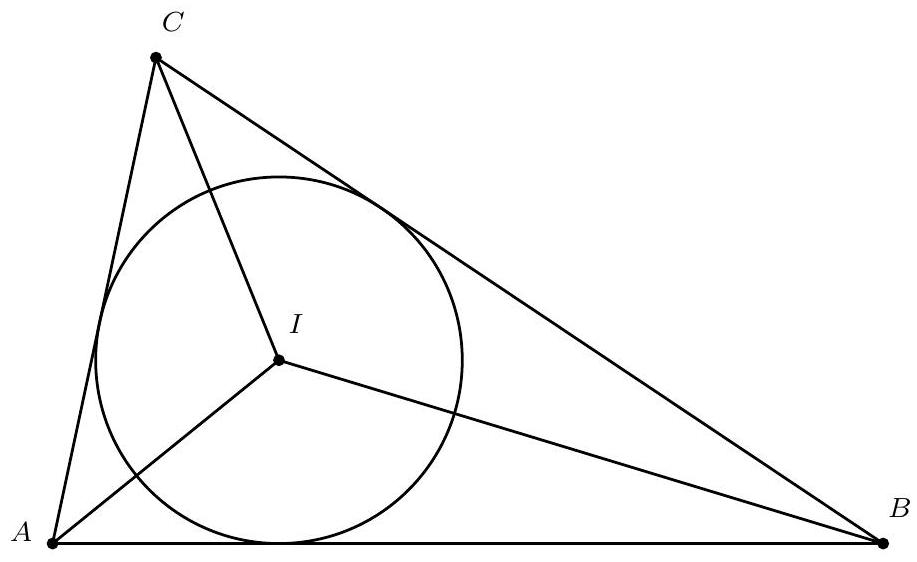

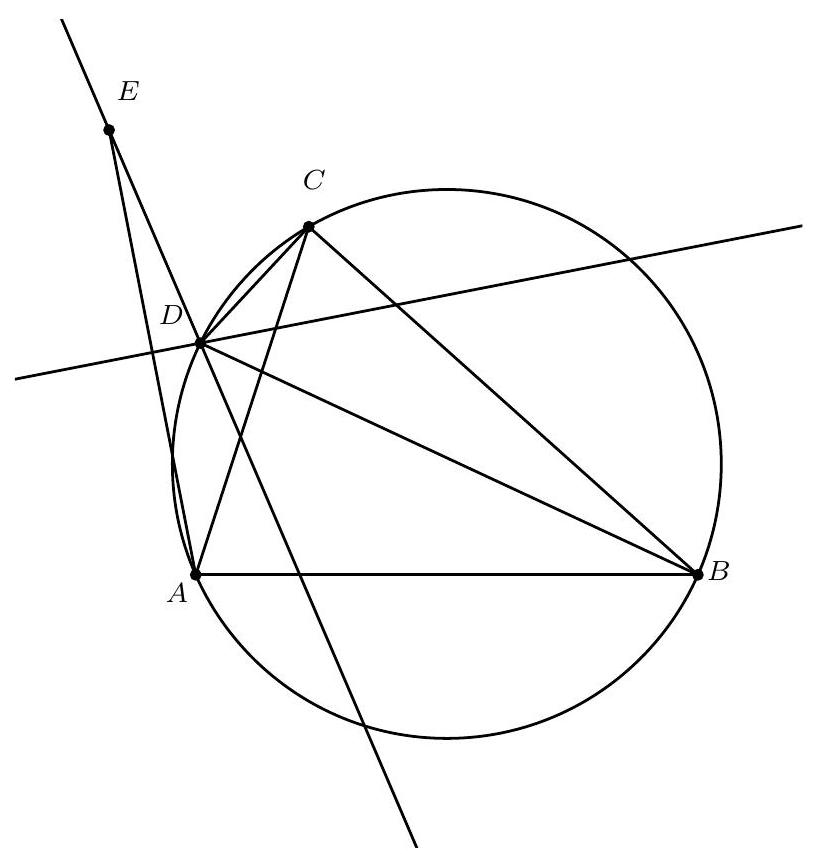

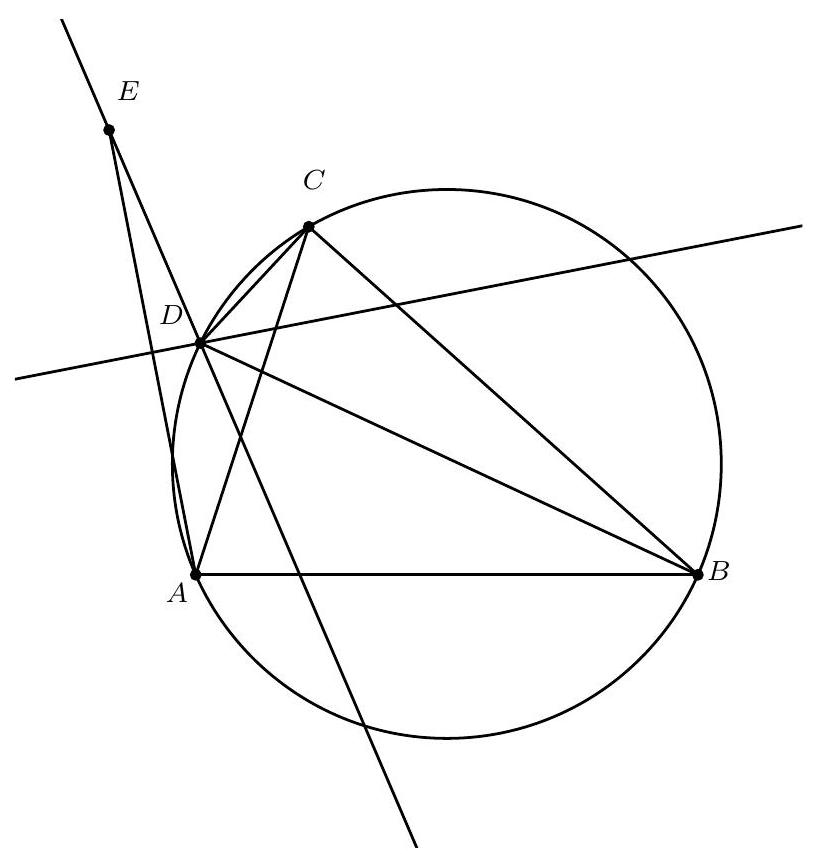

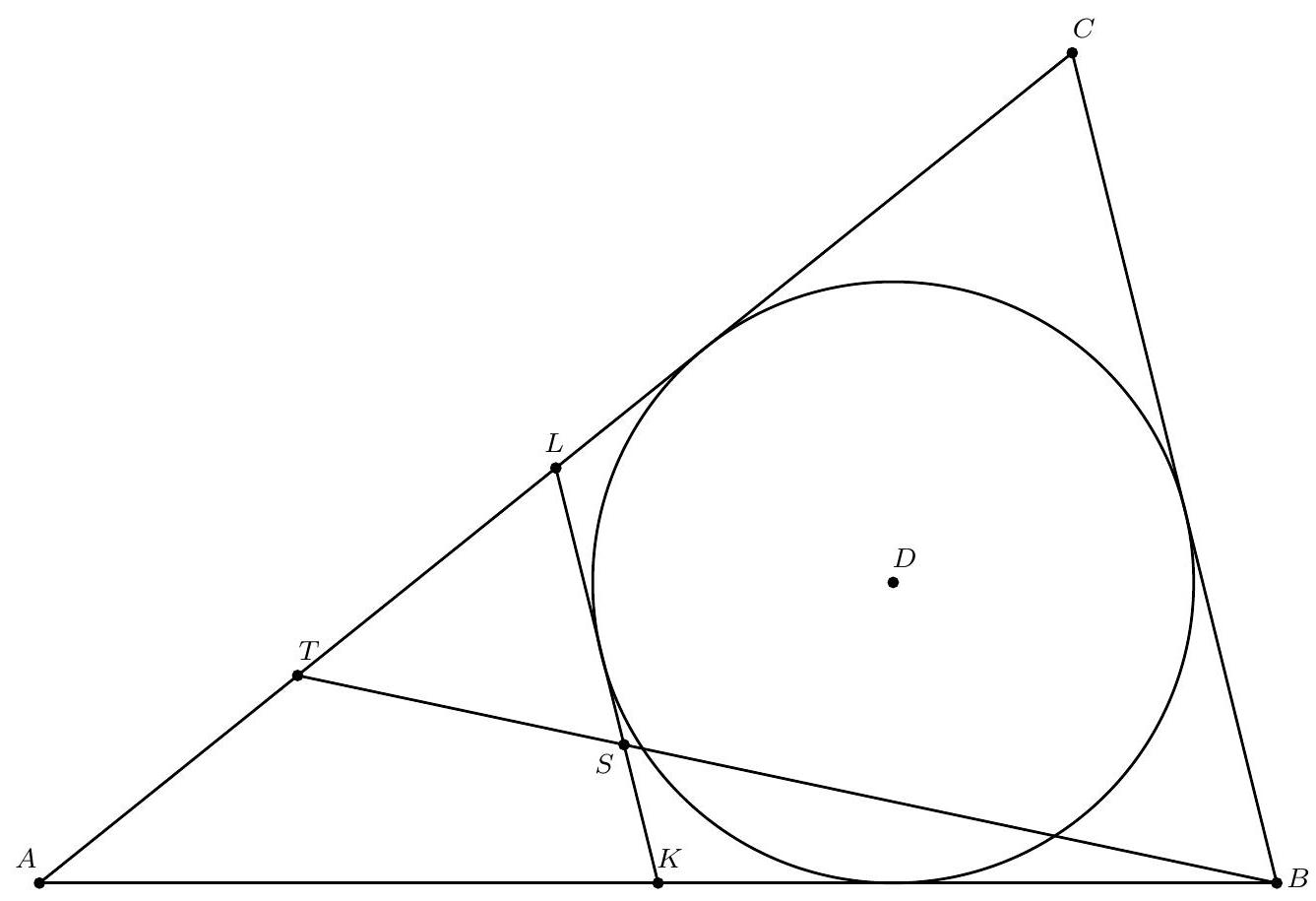

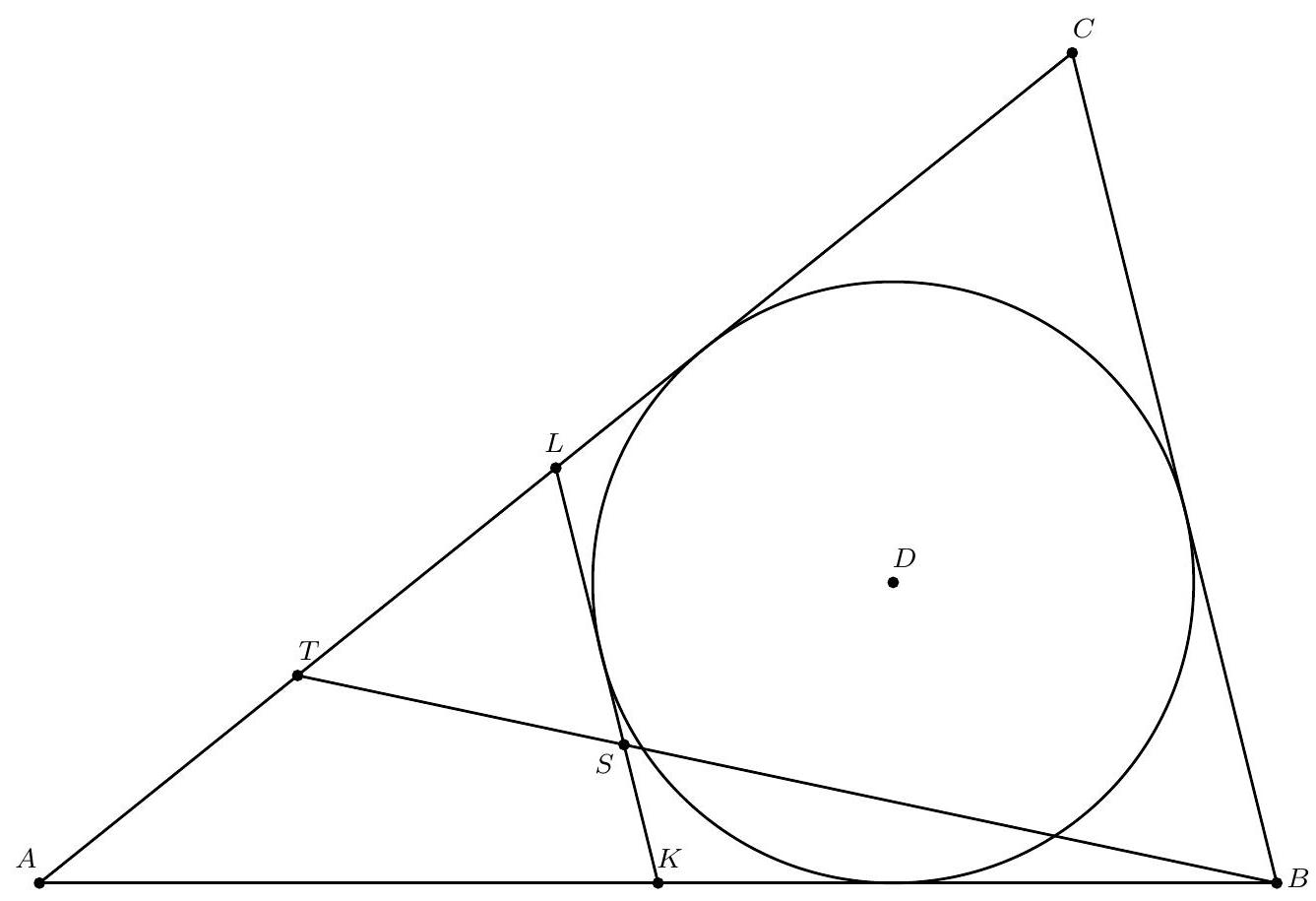

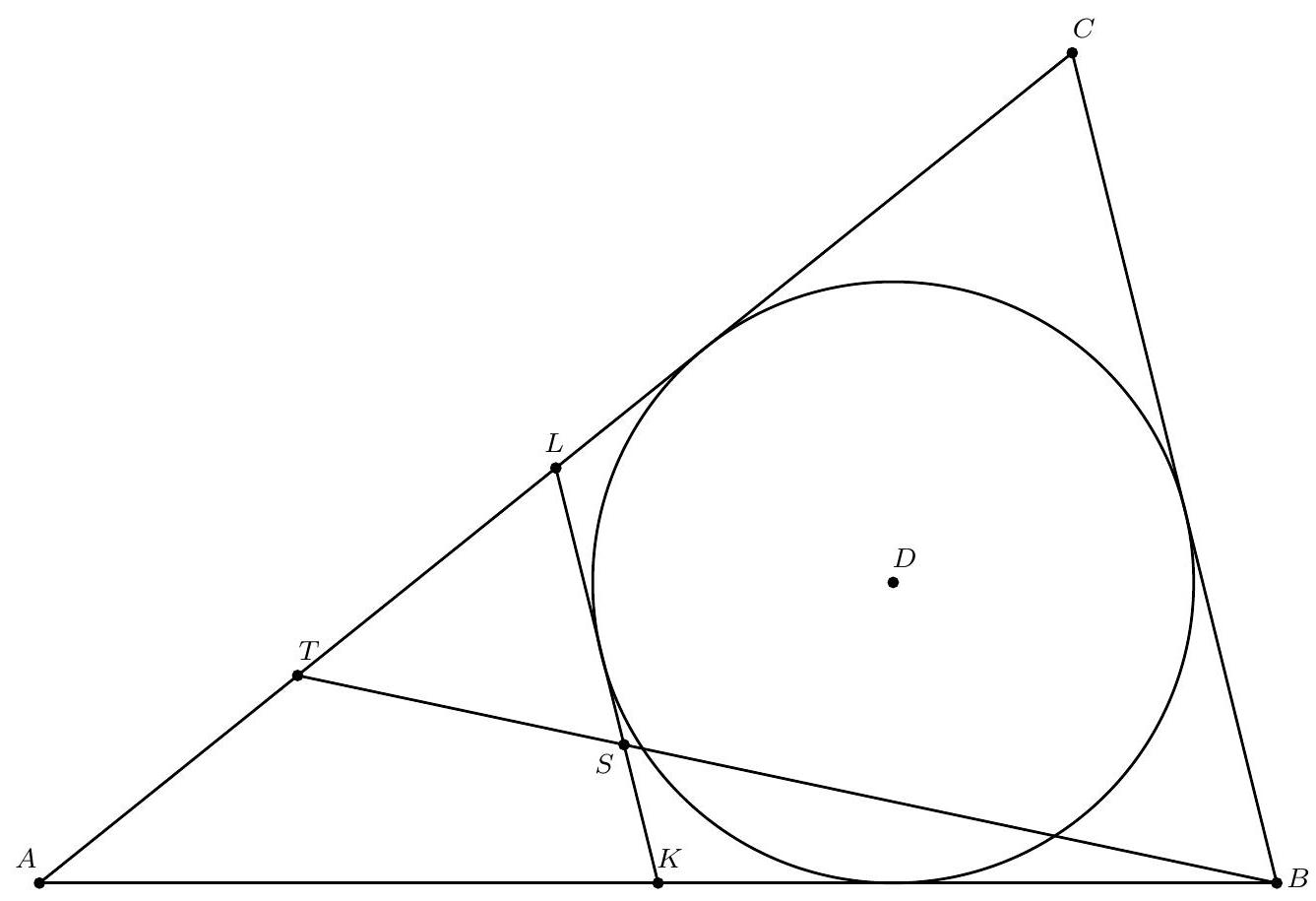

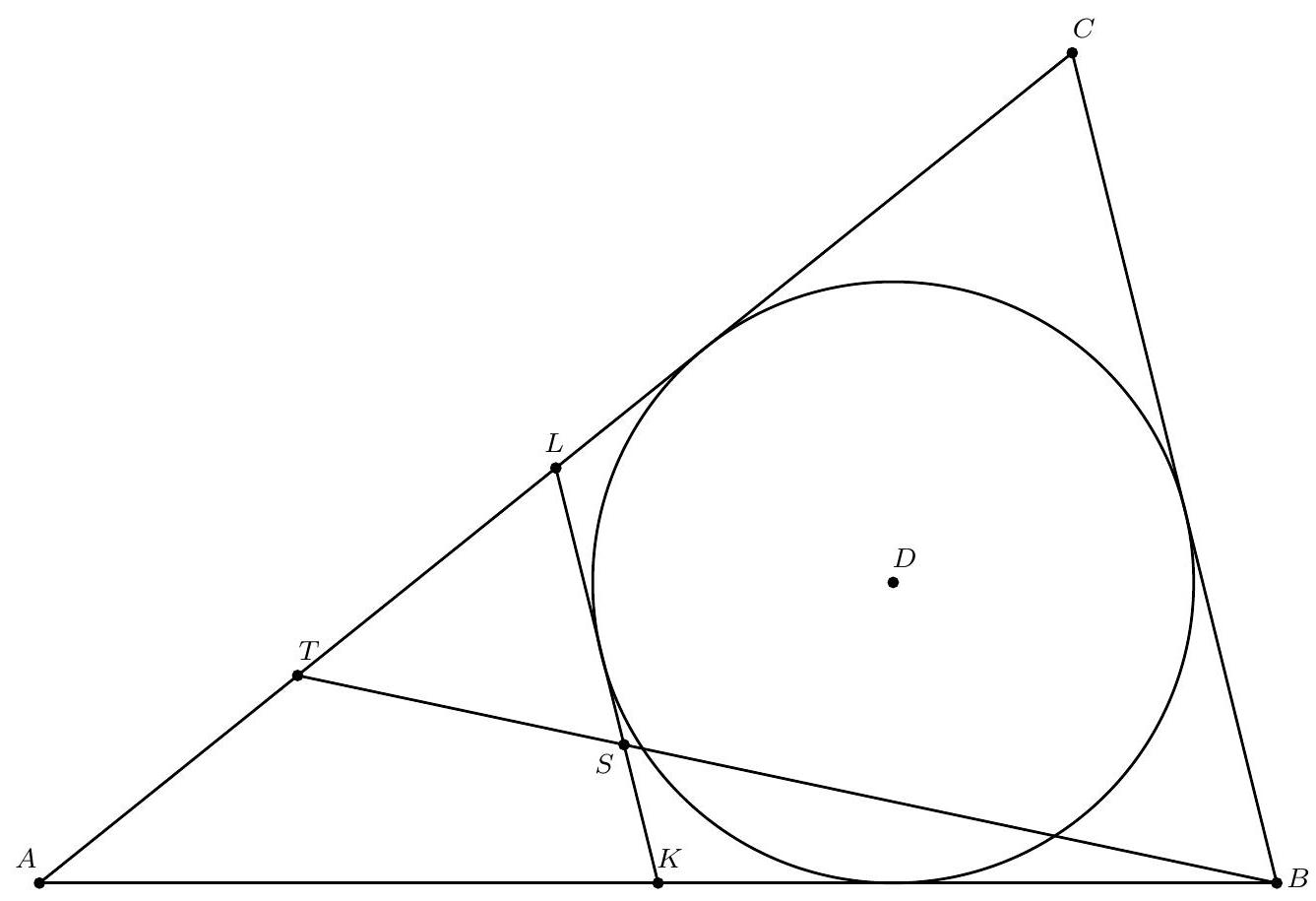

Let $\triangle A B C$ be a triangle with side lengths that are positive integers and pairwise relatively prime. The tangent at $A$ to the circumcircle intersects the line $B C$ at $D$. Prove that $|B D|$ is not an integer.

|

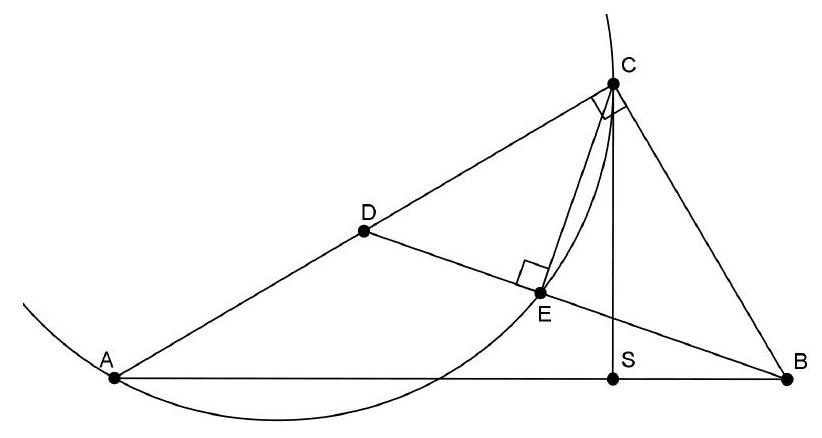

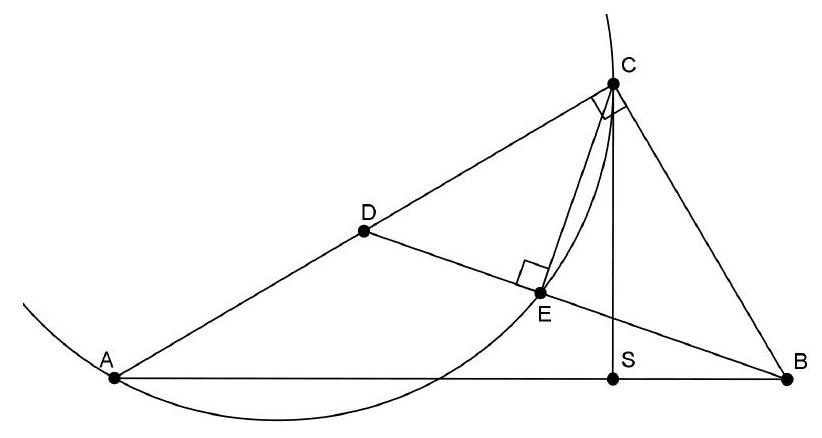

There are two possible configurations. Without loss of generality, assume that $B$ lies between $D$ and $C$. Let $a=|B C|, b=|C A|, c=|A B|, x=|B D|$, and $y=|A D|$. By the tangent-secant angle theorem, $\angle B A D=\angle A C B=\angle A C D$, so $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D(\mathrm{AA})$, hence $\frac{|B D|}{|A D|}=\frac{|A B|}{|C A|}=\frac{|A D|}{|C D|}$, or $\frac{x}{y}=\frac{c}{b}=\frac{y}{a+x}$. From this, we get $y c=b x$ and $a c+x c=b y$, so also $b y c=b^{2} x$ and $a c^{2}+x c^{2}=b y c$. Combining these gives $b^{2} x=a c^{2}+x c^{2}$, or $x\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a c^{2}$.

Now assume for the sake of contradiction that $x$ is an integer. Then $b^{2}-c^{2}$ is a divisor of $a c^{2}$. But we know $\operatorname{gcd}(b, c)=1$, so also $\operatorname{gcd}\left(b^{2}-c^{2}, c\right)=\operatorname{gcd}\left(b^{2}, c\right)=1$. Therefore, $b^{2}-c^{2}$ must be a divisor of $a$. This implies $b^{2}-c^{2} \leq a$. Note that $b^{2}-c^{2}>0$ since $x\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a c^{2}$; thus, $b-c>0$ as well. Therefore, $b^{2}-c^{2}=(b-c)(b+c) \geq 1 \cdot(b+c)$ because $b$ and $c$ are positive integers. Hence, $a \geq b+c$, which contradicts the triangle inequality. Therefore, $x=|B D|$ cannot be an integer.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $\triangle A B C$ een driehoek waarvan de zijdelengtes positieve gehele getallen zijn die paarsgewijs relatief priem zijn. De raaklijn in $A$ aan de omgeschreven cirkel snijdt de lijn $B C$ in $D$. Bewijs dat $|B D|$ geen geheel getal is.

|

Er zijn twee configuraties mogelijk. Neem zonder verlies van algemeenheid aan dat $B$ tussen $D$ en $C$ ligt. Schrijf $a=|B C|, b=|C A|, c=|A B|, x=|B D|$ en $y=|A D|$. Vanwege de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling geldt $\angle B A D=\angle A C B=\angle A C D$, dus $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D(\mathrm{hh})$, dus $\frac{|B D|}{|A D|}=\frac{|A B|}{|C A|}=\frac{|A D|}{|C D|}$, oftewel $\frac{x}{y}=\frac{c}{b}=\frac{y}{a+x}$. We vinden hieruit $y c=b x$ en $a c+x c=b y$, dus ook byc $=b^{2} x$ en $a c^{2}+x c^{2}=b y c$. Dit combineren geeft $b^{2} x=a c^{2}+x c^{2}$, oftewel $x\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a c^{2}$.

Stel nu uit het ongerijmde dat $x$ geheel is. Dan is $b^{2}-c^{2}$ een deler van $a c^{2}$. Maar we weten $\operatorname{ggd}(b, c)=1$, dus ook $\operatorname{ggd}\left(b^{2}-c^{2}, c\right)=\operatorname{ggd}\left(b^{2}, c\right)=1$. Dus $b^{2}-c^{2}$ moet een deler zijn van $a$. Daaruit volgt $b^{2}-c^{2} \leq a$. Merk op dat $b^{2}-c^{2}>0$ aangezien $x\left(b^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a c^{2}$; er geldt dus ook $b-c>0$. Dus $b^{2}-c^{2}=(b-c)(b+c) \geq 1 \cdot(b+c)$ omdat $b$ en $c$ positieve gehele getallen zijn. Dus $a \geq b+c$, wat in tegenspraak is met de driehoeksongelijkheid. Dus $x=|B D|$ kan niet geheel zijn.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $p$ be a prime number. Prove that it is possible to choose a permutation $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{p}$ of $1,2, \ldots, p$ such that the numbers $a_{1}, a_{1} a_{2}, a_{1} a_{2} a_{3}, \ldots, a_{1} a_{2} a_{3} \cdots a_{p}$ all give different remainders when divided by $p$.

|

Let $b_{i}=a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{i}$, for $1 \leq i \leq p$. We prove that it is possible to choose the permutation such that $b_{i} \equiv i \bmod p$ for all $i$. For $i \geq 2$, $a_{i} \equiv b_{i} \cdot b_{i-1}^{-1} \bmod p$ if $b_{i-1} \not \equiv 0 \bmod p$. We now choose $a_{1}=1$ and $a_{i} \equiv i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \bmod p$ for $2 \leq i \leq p$. It is now sufficient to prove that $a_{i} \not \equiv 1 \bmod p$ for all $2 \leq i \leq p$ and $a_{i} \not \equiv a_{j} \bmod p$ for all $2 \leq j<i \leq p$.

Assume for the sake of contradiction that $a_{i} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ for some $2 \leq i \leq p$. Then $i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, so $i \equiv i-1 \bmod p$, so $0 \equiv -1 \bmod p$. Since $p \geq 2$, this is a contradiction. Now assume that $a_{i} \equiv a_{j} \bmod p$ for some $2 \leq j<i \leq p$. Then $i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \equiv j \cdot(j-1)^{-1} \bmod p$ so $i(j-1) \equiv j(i-1) \bmod p$ so $ij - i \equiv ij - j \bmod p$ so $-i \equiv -j \bmod p$. But we had $2 \leq j < i \leq p$, so this cannot be.

We conclude that if we choose the $a_{i}$ as indicated above, all $a_{i}$ will be distinct, making it indeed a permutation of $1, 2, \ldots, p$. Furthermore, by definition, $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{i} \equiv i \bmod p$, so the second condition is also satisfied.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $p$ een priemgetal. Bewijs dat het mogelijk is om een permutatie $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{p}$ van $1,2, \ldots, p$ te kiezen zodat de getallen $a_{1}, a_{1} a_{2}, a_{1} a_{2} a_{3}, \ldots, a_{1} a_{2} a_{3} \cdots a_{p}$ allemaal verschillende resten geven na deling door $p$.

|

Noem $b_{i}=a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{i}$, voor $1 \leq i \leq p$. We bewijzen dat het mogelijk is de permutatie zo te kiezen dat $b_{i} \equiv i \bmod p$ voor alle $i$. Voor $i \geq 2$ is $a_{i} \equiv b_{i} \cdot b_{i-1}^{-1} \bmod p$ als $b_{i-1} \not \equiv 0 \bmod p$. We kiezen nu dus $a_{1}=1$ en $a_{i} \equiv i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \bmod p$ voor $2 \leq i \leq p$. Het is nu voldoende te bewijzen dat $a_{i} \not \equiv 1 \bmod p$ voor alle $2 \leq i \leq p$ en $a_{i} \not \equiv a_{j} \bmod p$ voor alle $2 \leq j<i \leq p$.

Stel uit het ongerijmde dat $a_{i} \equiv 1 \bmod p$ voor zekere $2 \leq i \leq p$. Dan is $i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \equiv 1$ $\bmod p$, dus $i \equiv i-1 \bmod p$, dus $0 \equiv-1 \bmod p$. Omdat $p \geq 2$ is dit een tegenspraak. Stel nu dat $a_{i} \equiv a_{j} \bmod p$ voor zekere $2 \leq j<i \leq p$. Dan geldt $i \cdot(i-1)^{-1} \equiv j \cdot(j-1)^{-1}$ $\bmod p$ dus $i(j-1) \equiv j(i-1) \bmod p$ dus $i j-i \equiv i j-j \bmod p$ dus $-i \equiv-j \bmod p$. Maar we hadden $2 \leq j<i \leq p$, dus dit kan niet.

We concluderen dat als we de $a_{i}$ kiezen zoals hierboven aangegeven, alle $a_{i}$ verschillend worden, zodat het inderdaad een permutatie van $1,2, \ldots, p$ is. Verder geldt nu per definitie dat $a_{1} a_{2} \cdots a_{i} \equiv i \bmod p$, zodat ook aan de tweede eis is voldaan.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

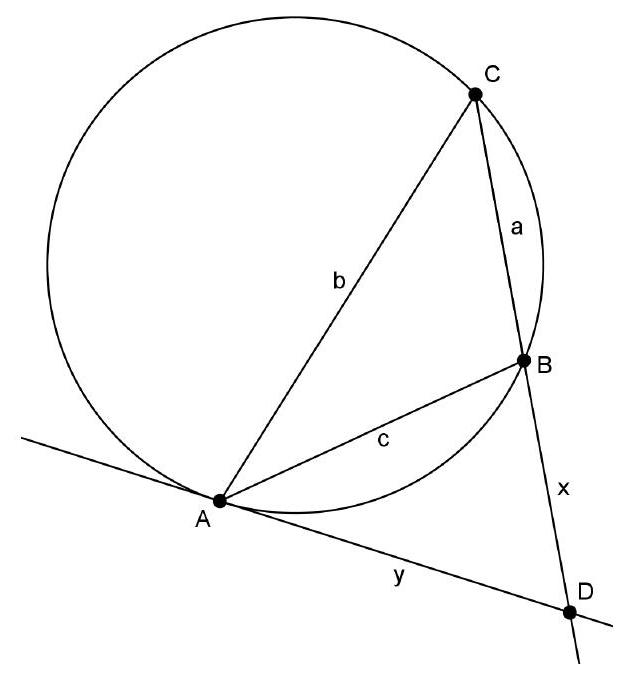

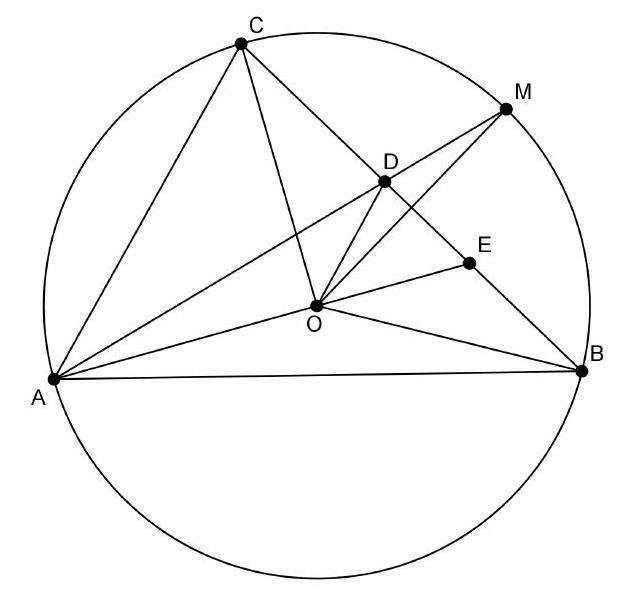

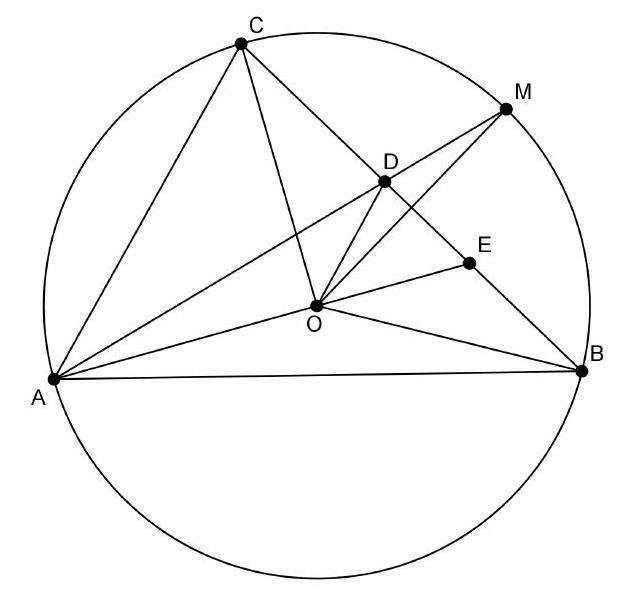

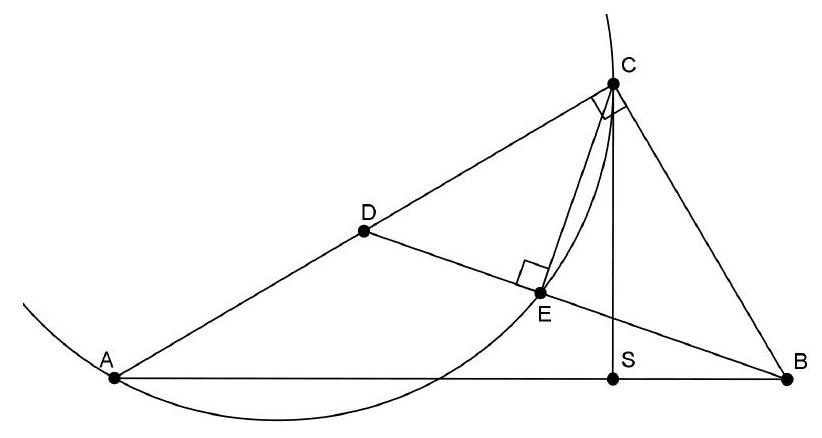

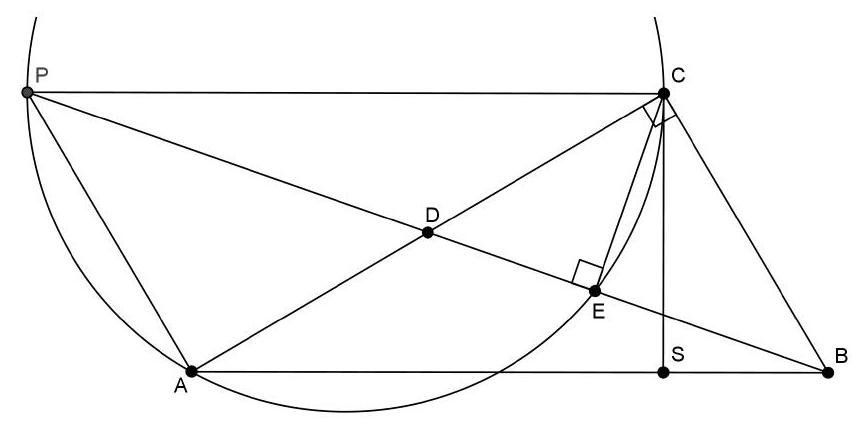

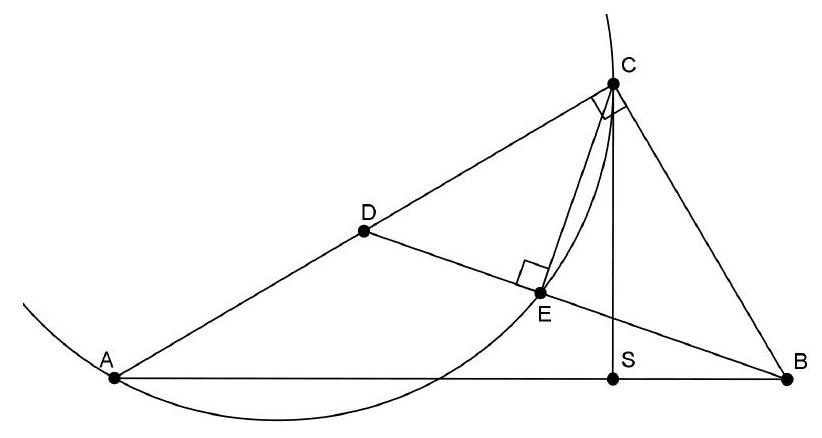

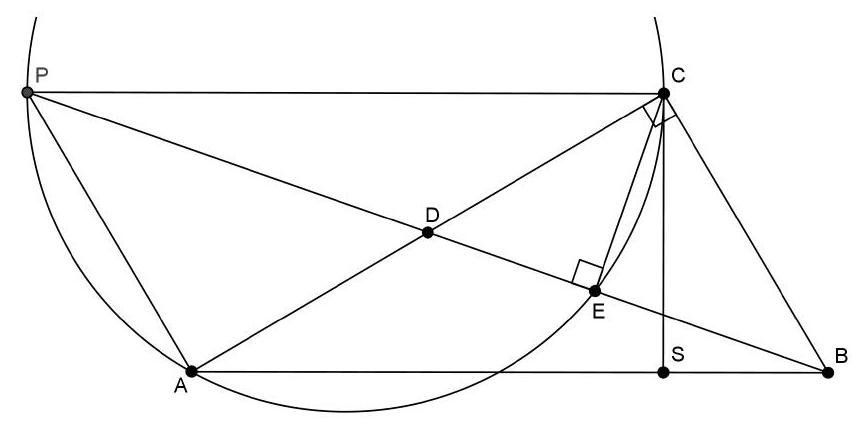

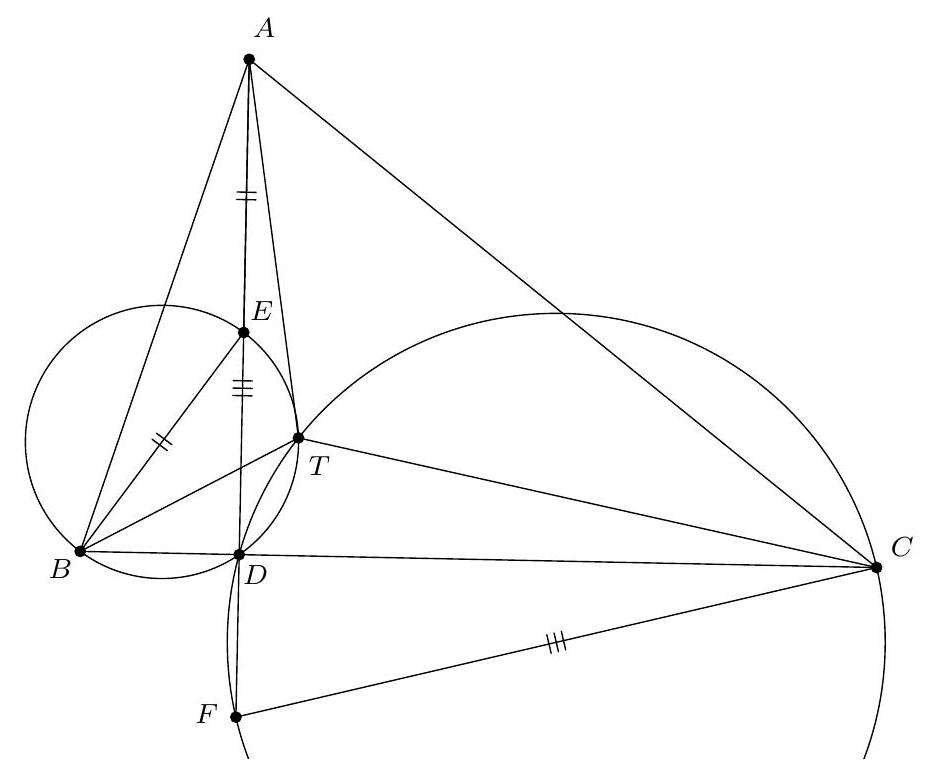

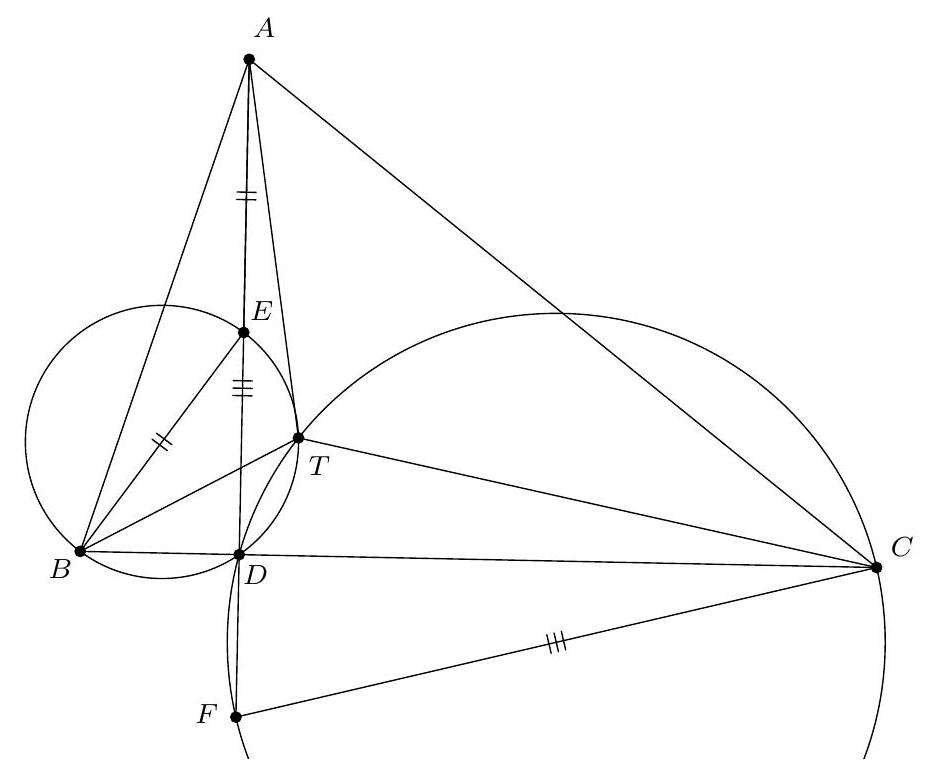

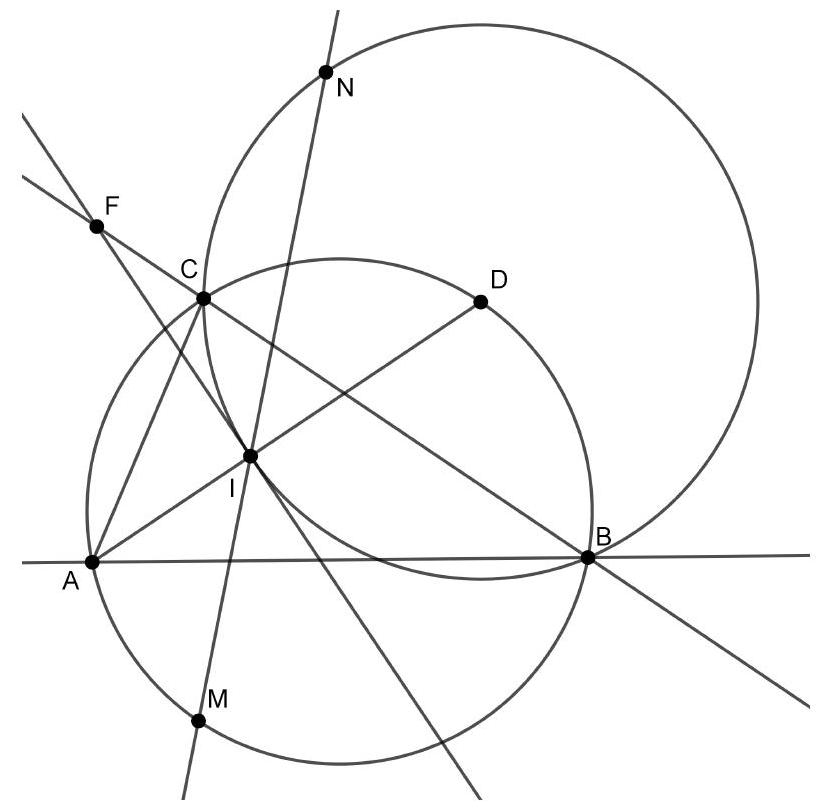

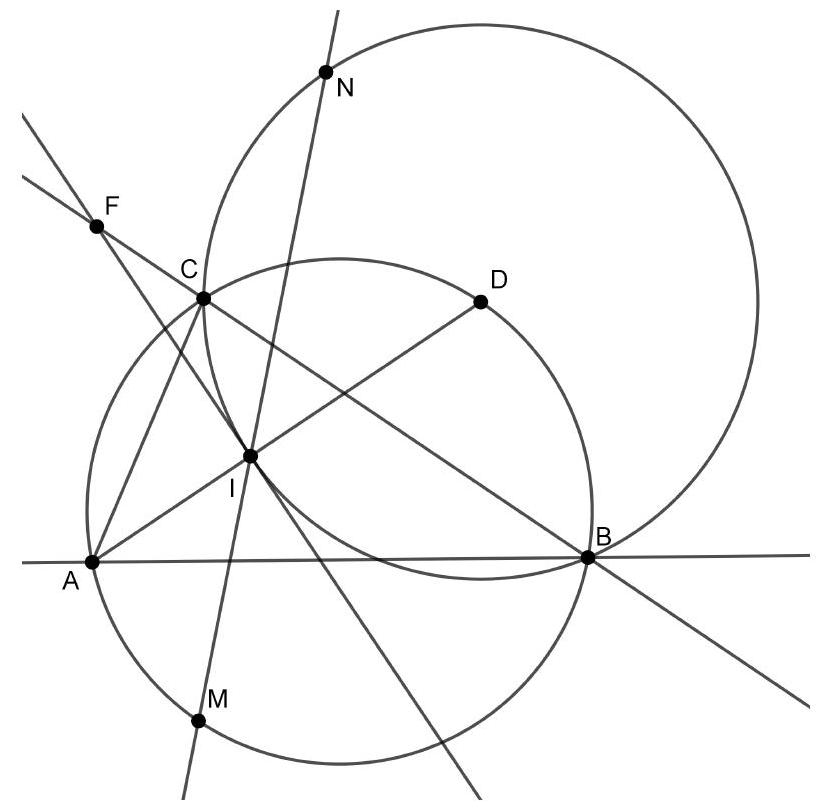

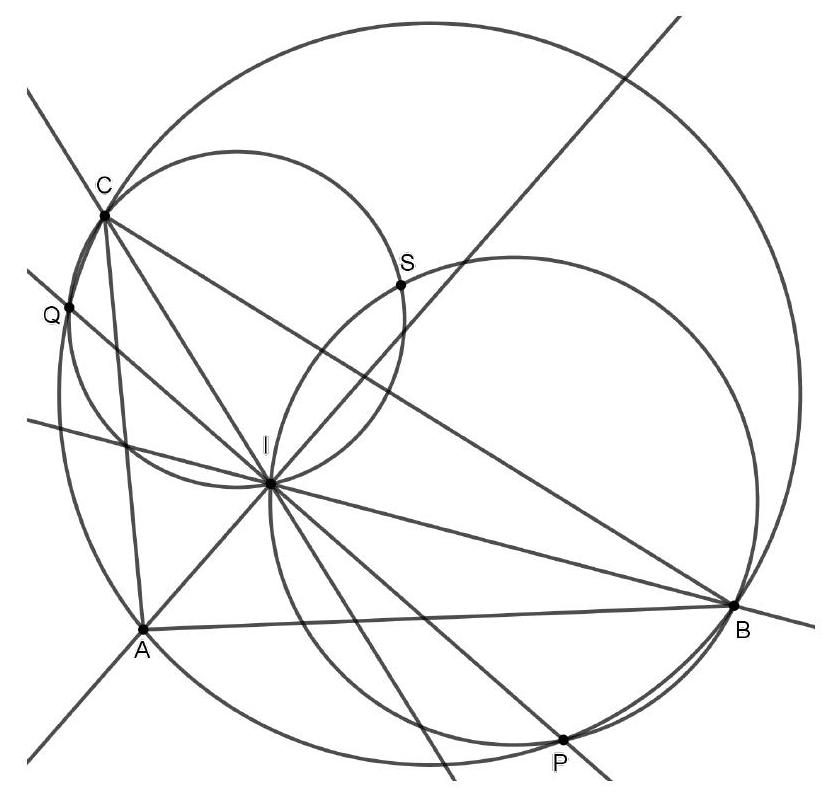

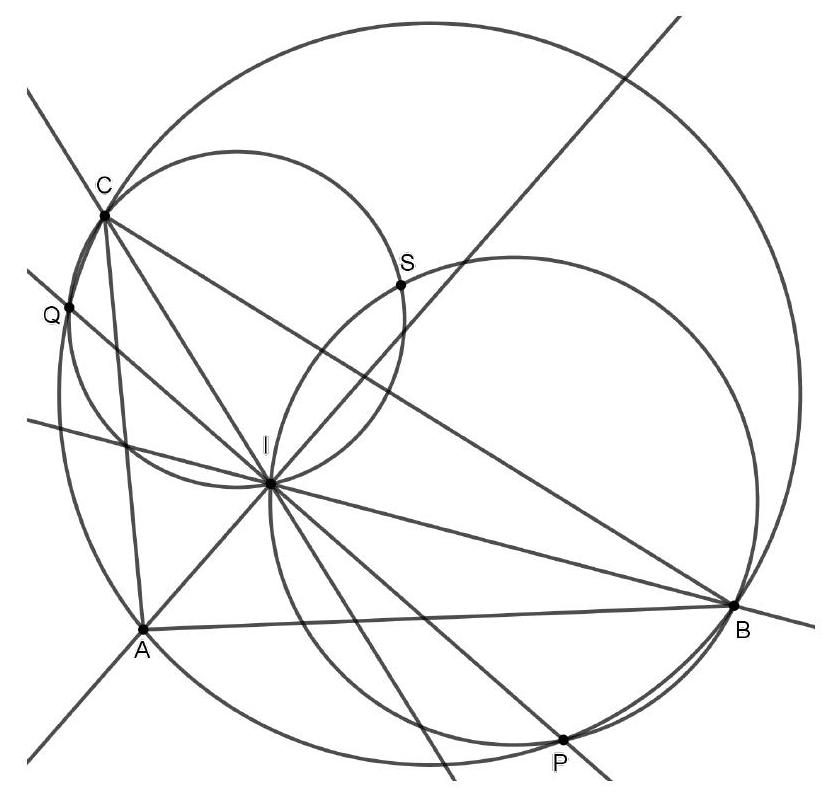

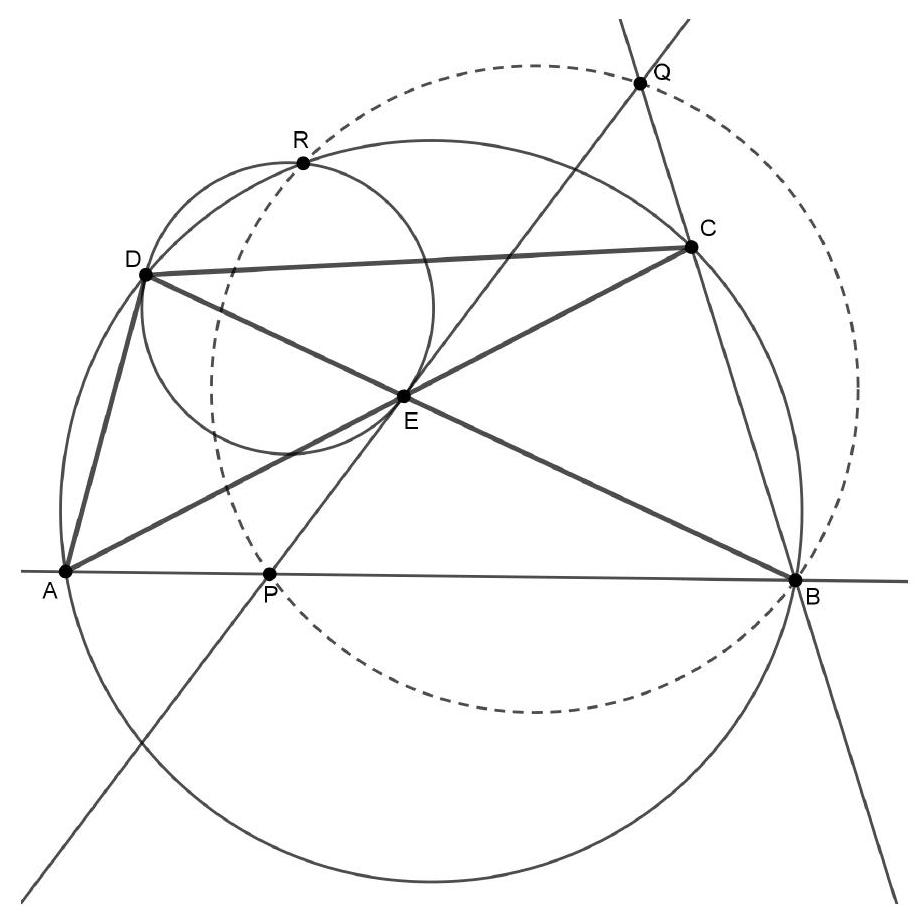

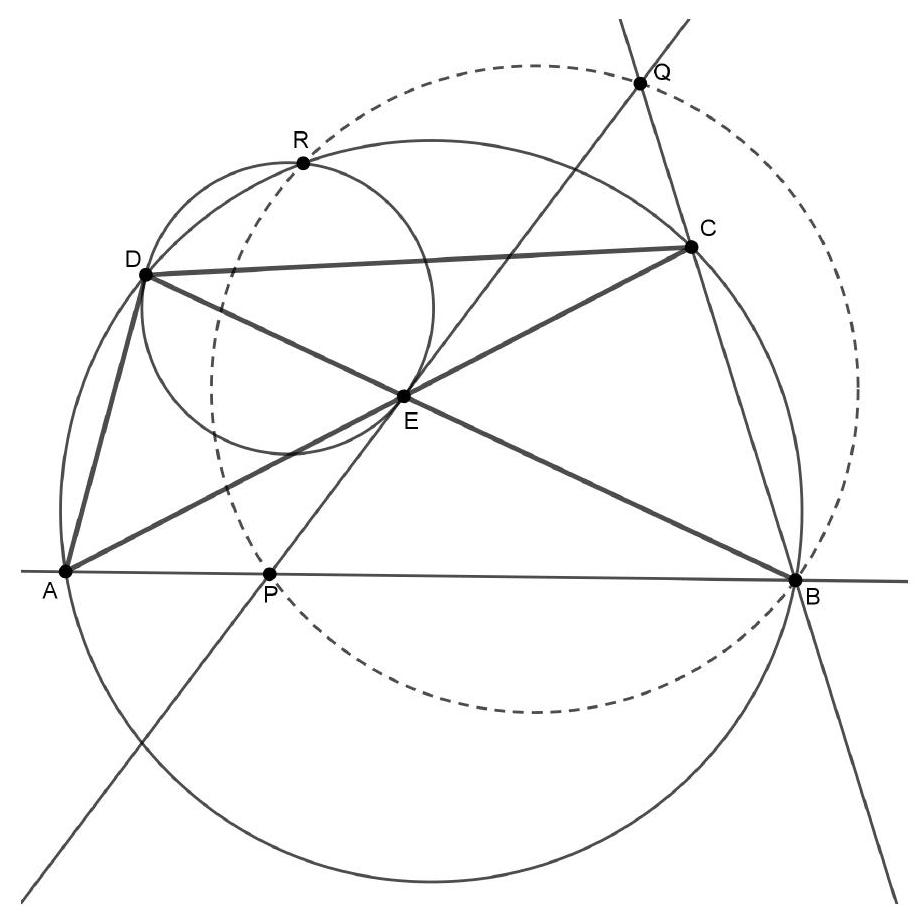

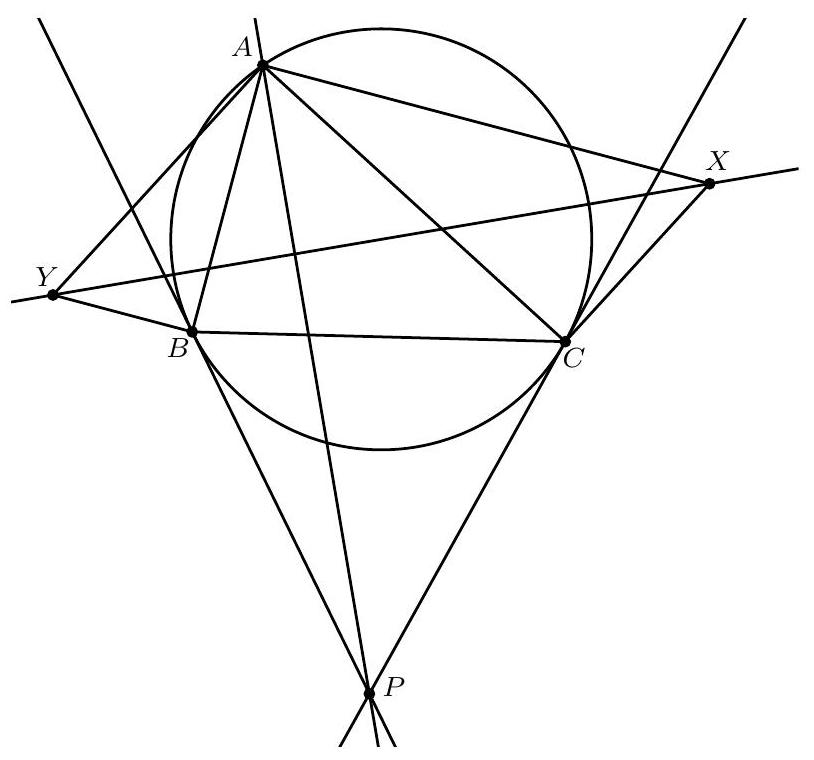

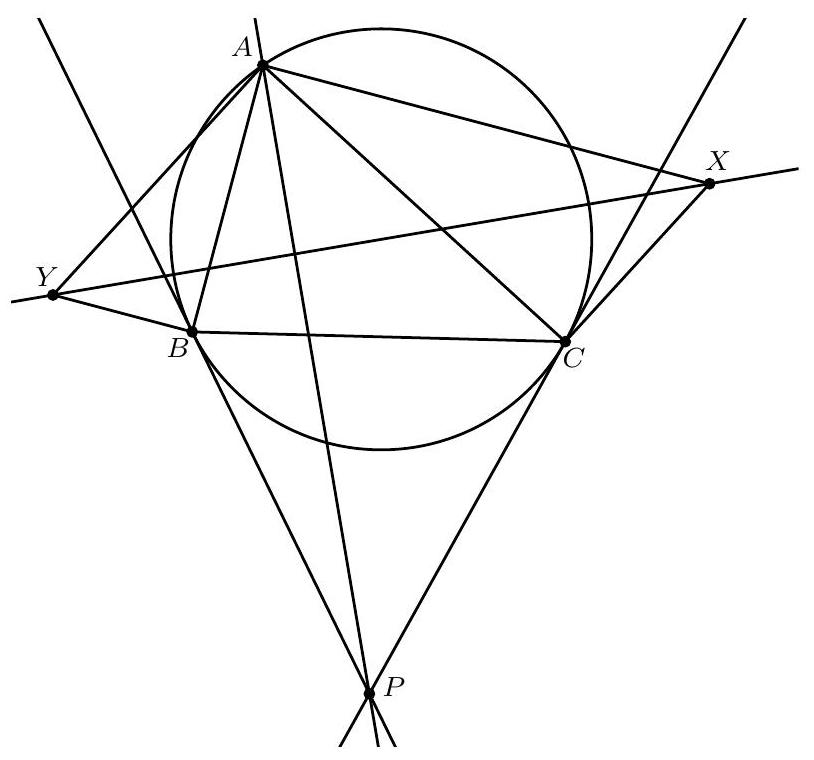

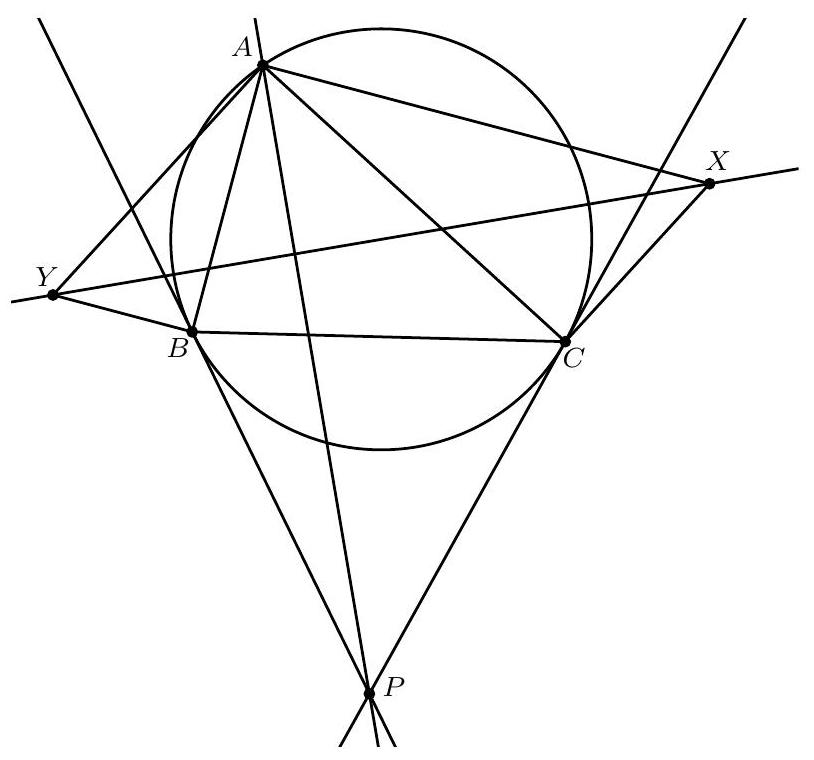

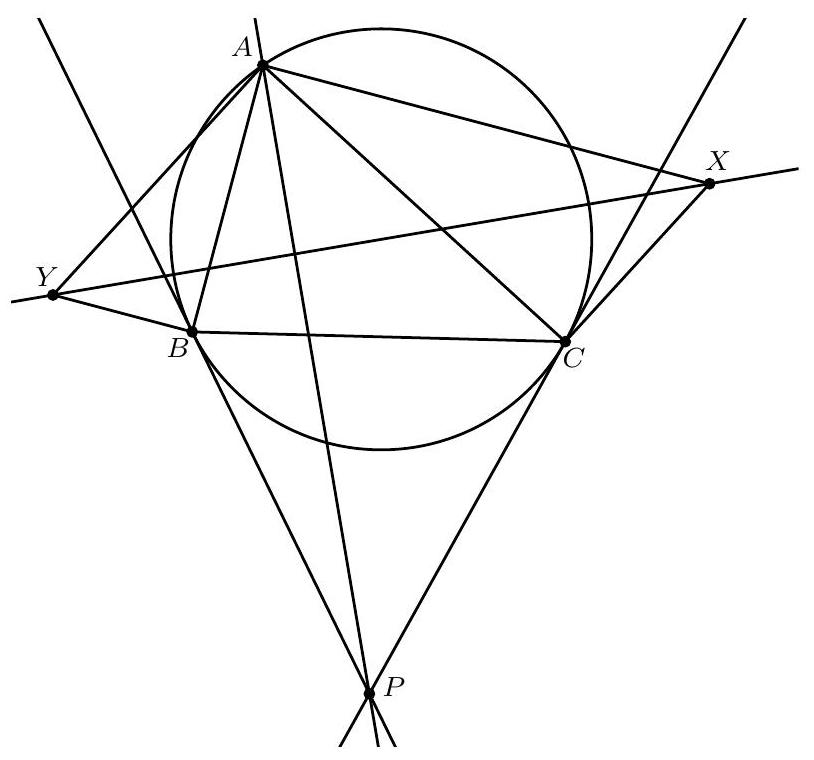

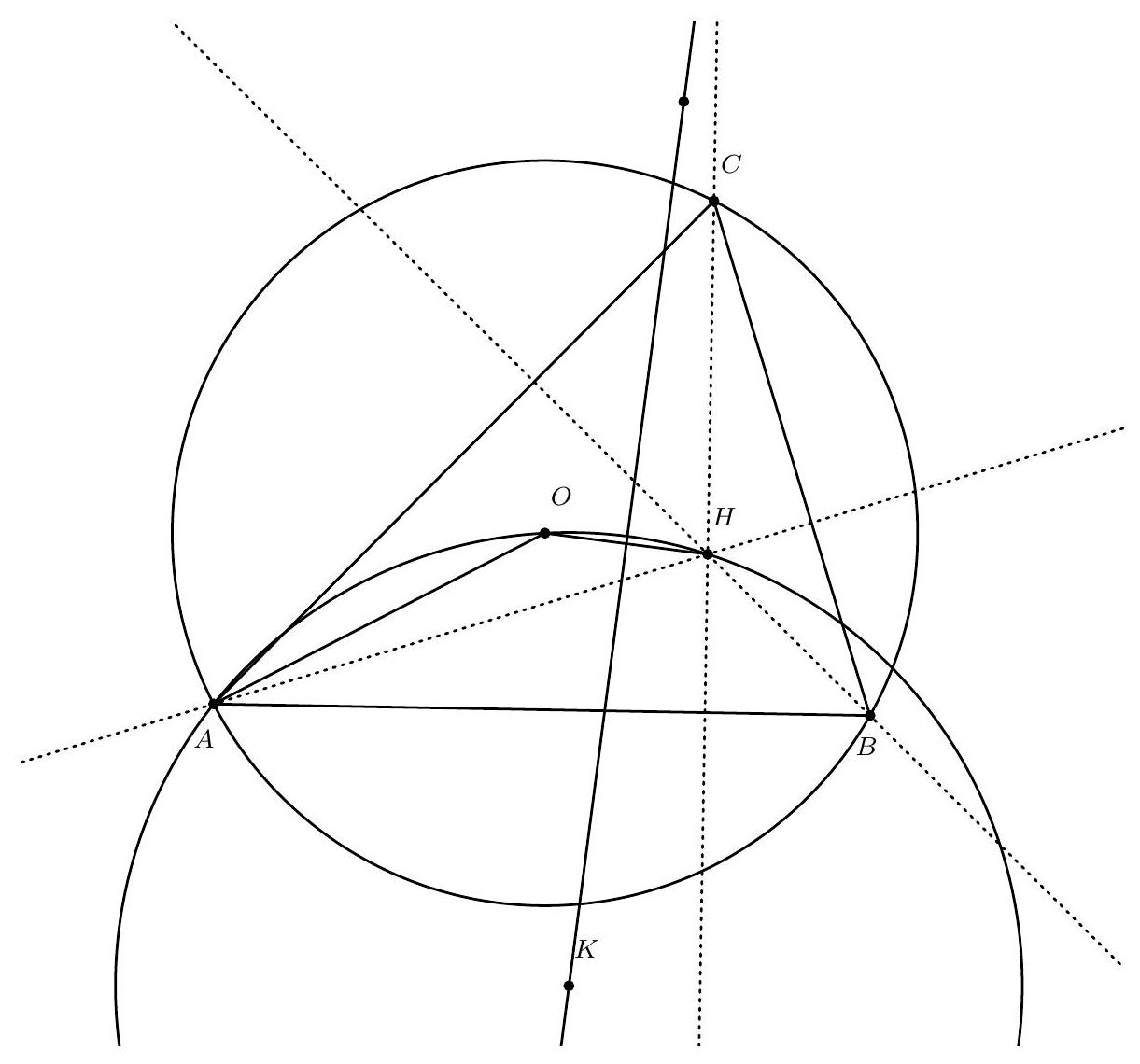

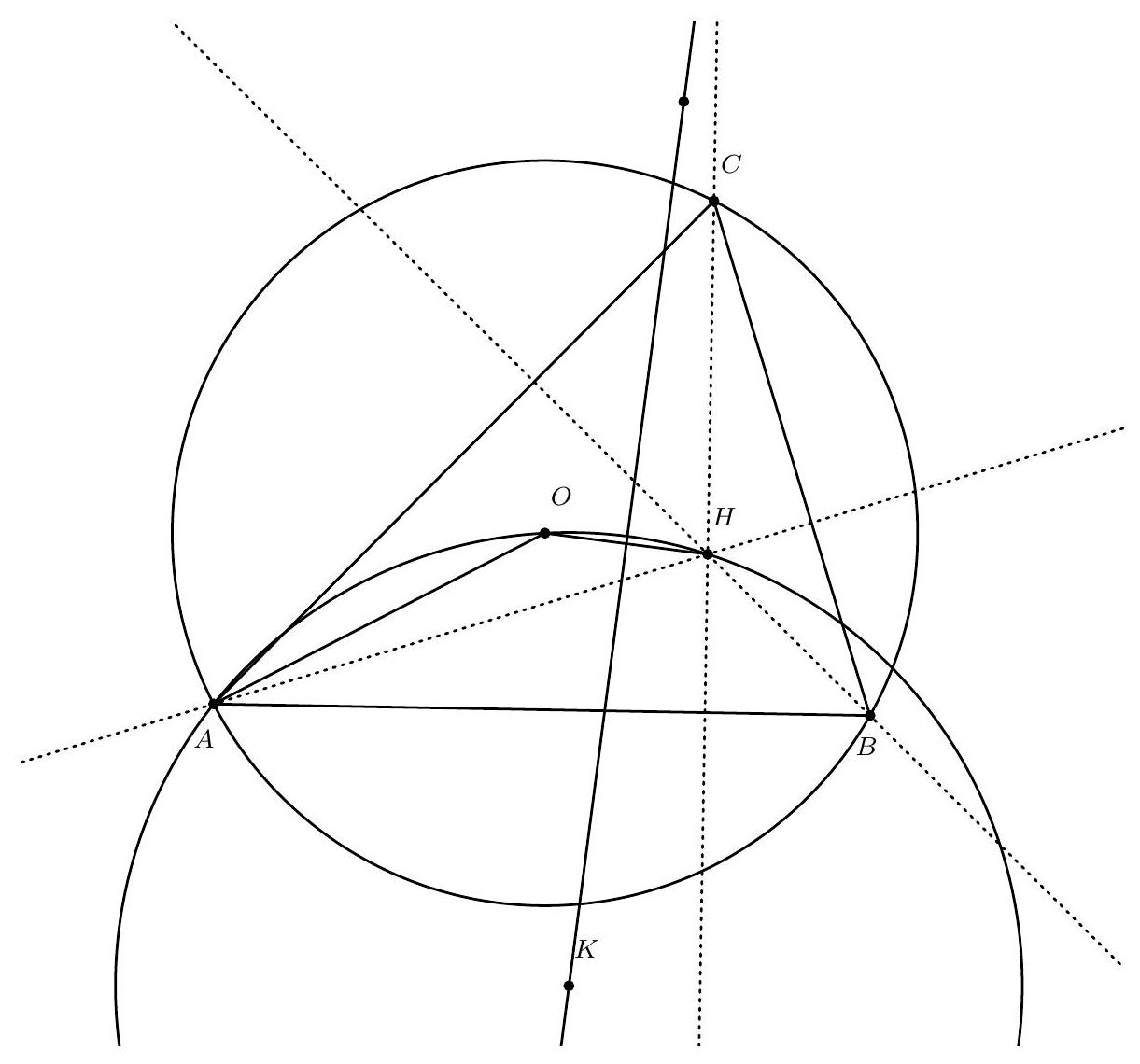

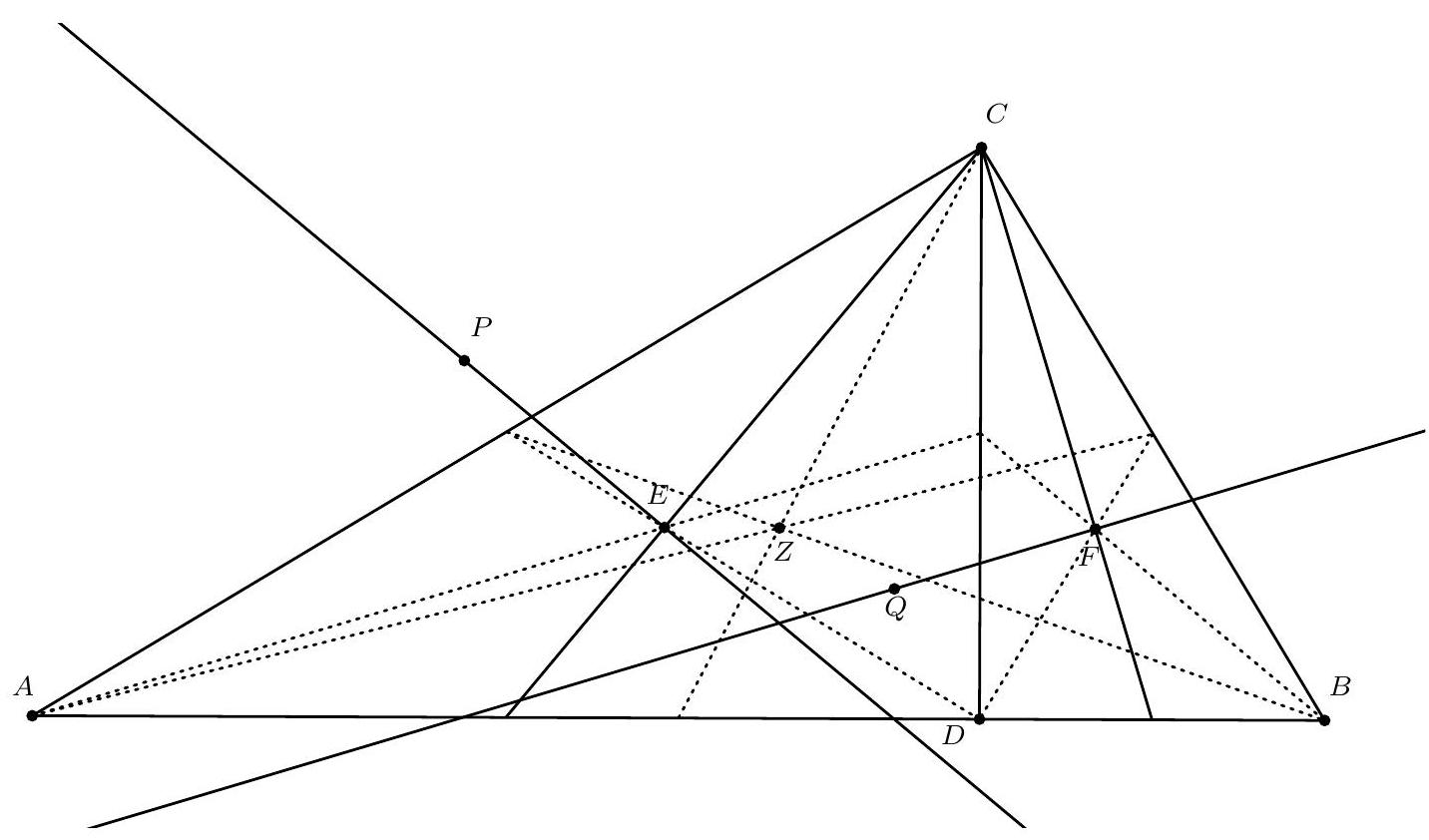

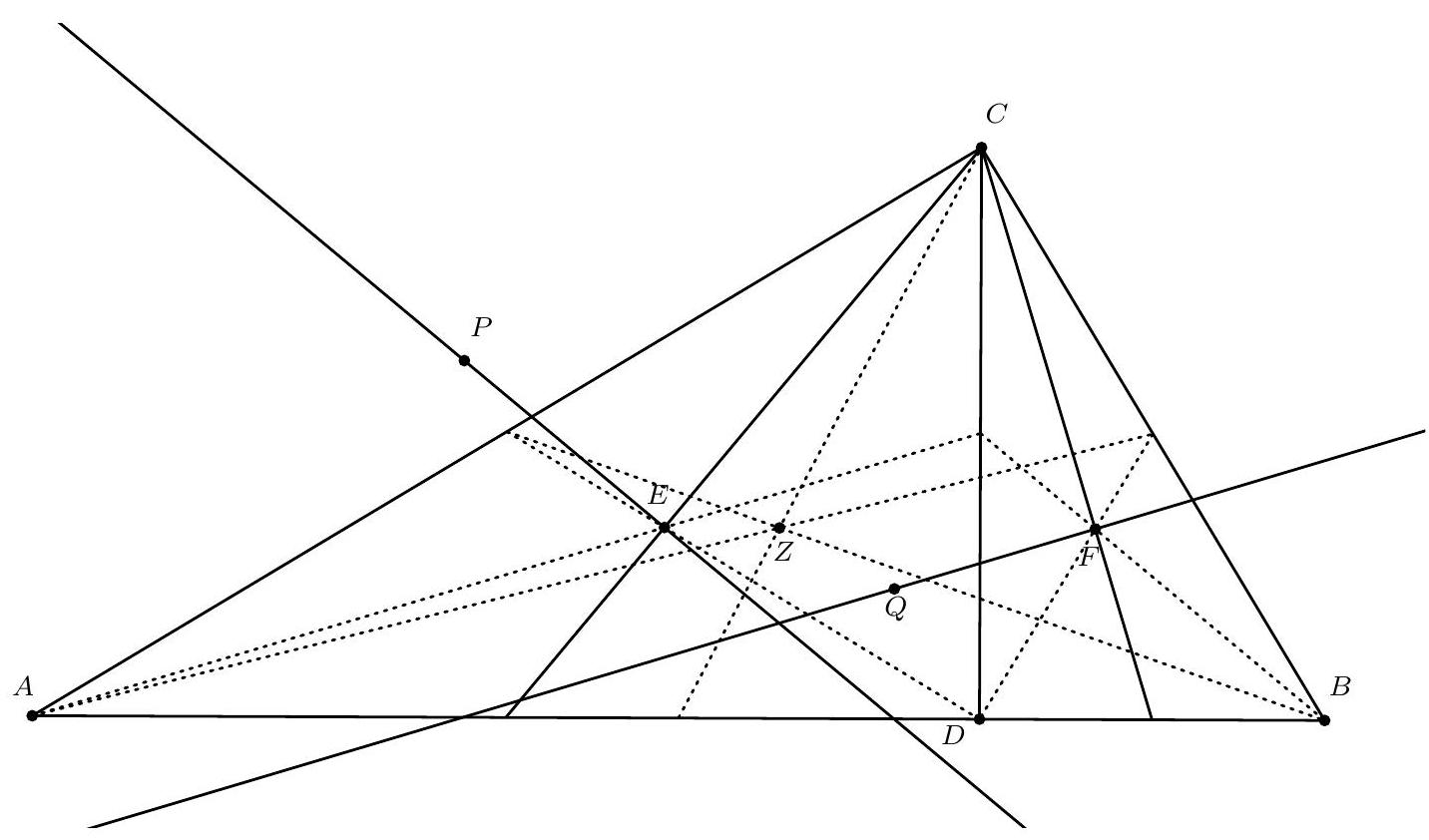

In a non-equilateral triangle $\triangle ABC$, $\angle BAC = 60^{\circ}$. Let $D$ be the intersection of the angle bisector of $\angle BAC$ with side $BC$, $O$ the circumcenter of $\triangle ABC$, and $E$ the intersection of $AO$ with $BC$. Prove that $\angle AED + \angle ADO = 90^{\circ}$.

|

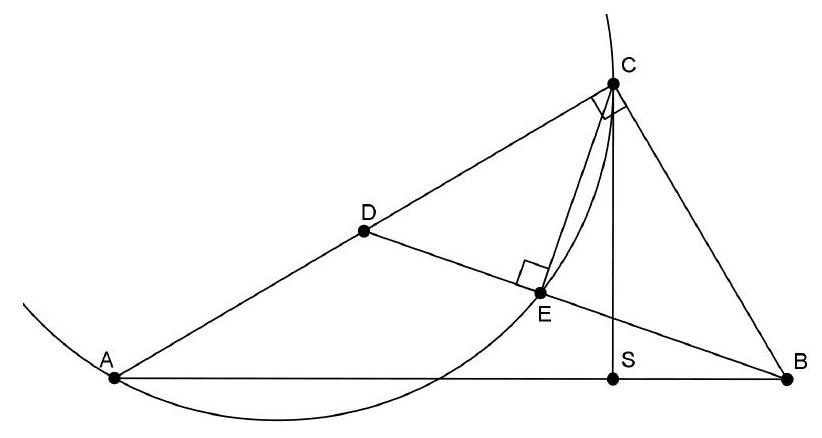

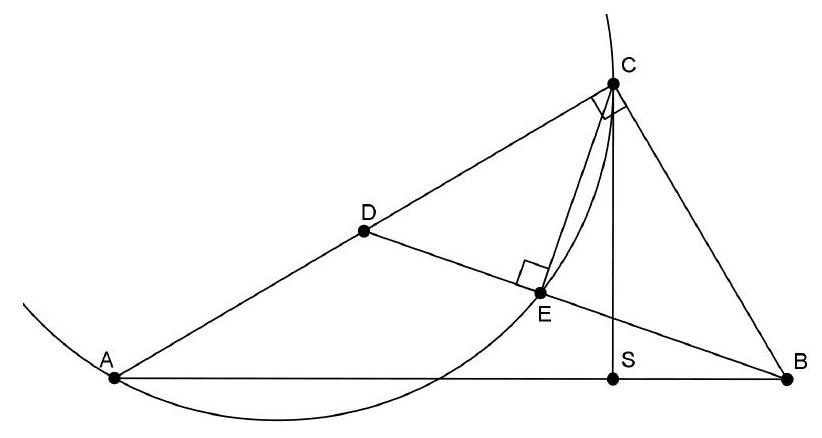

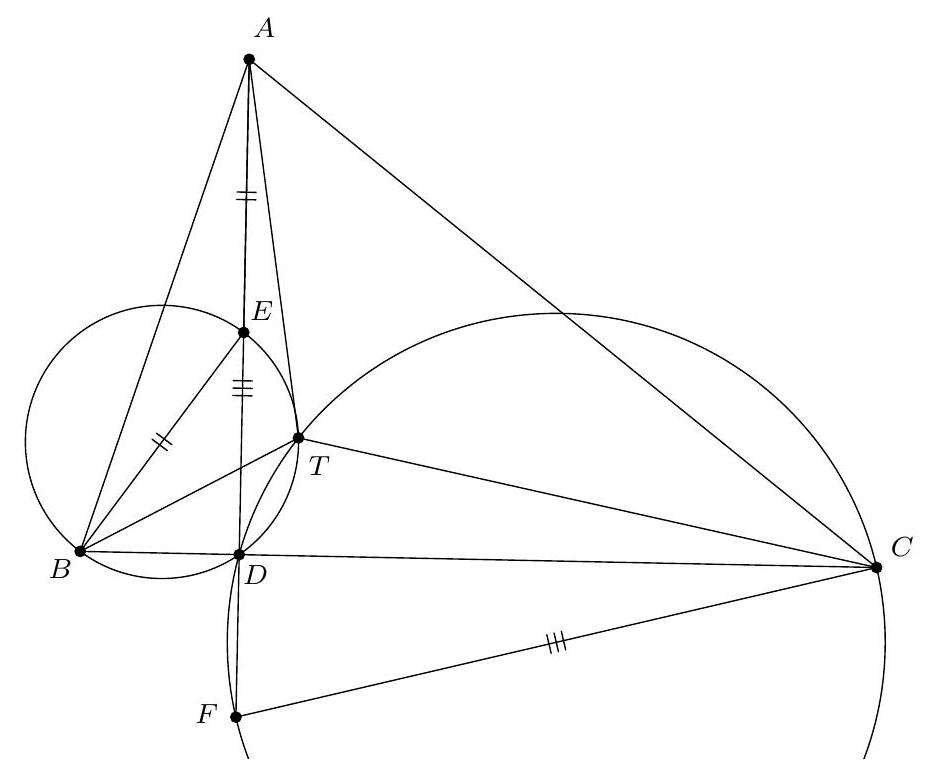

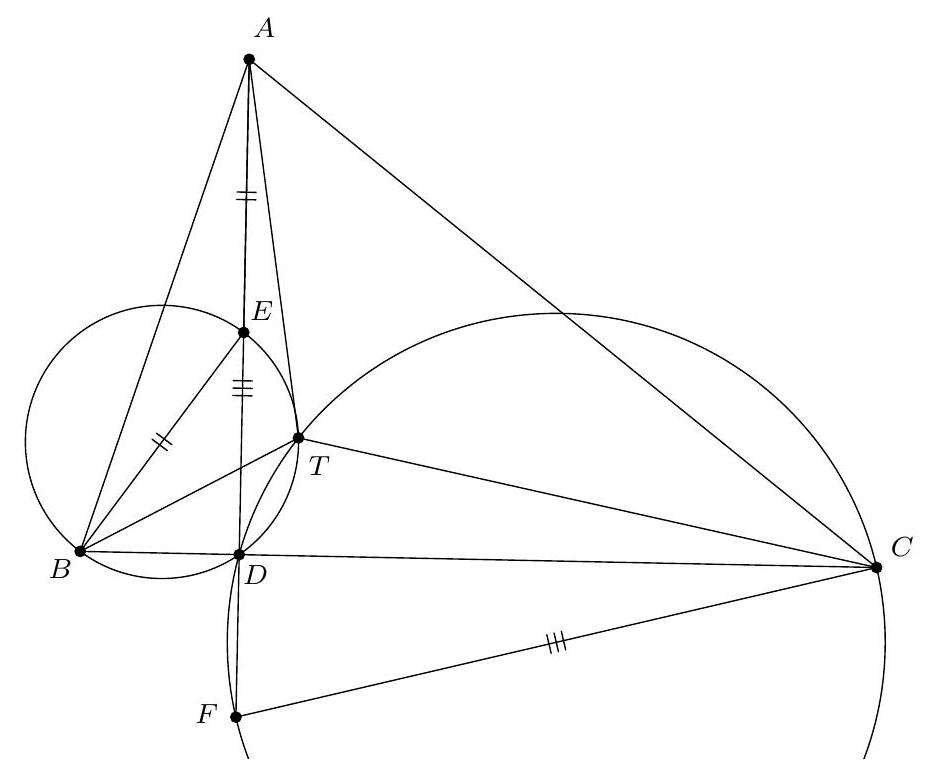

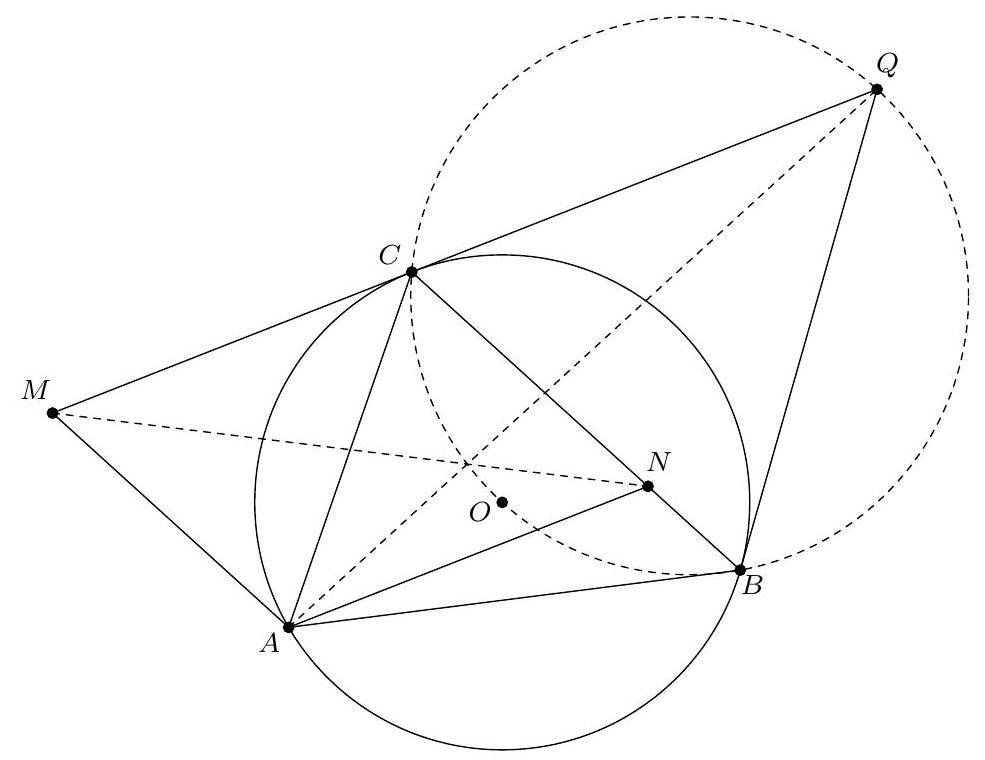

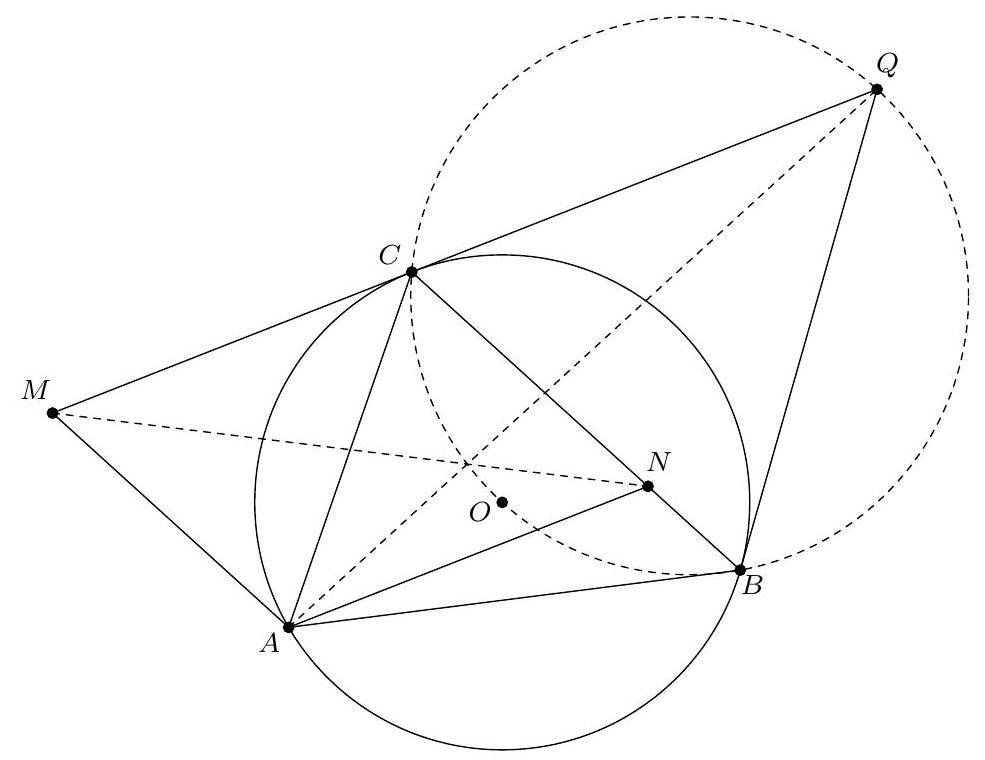

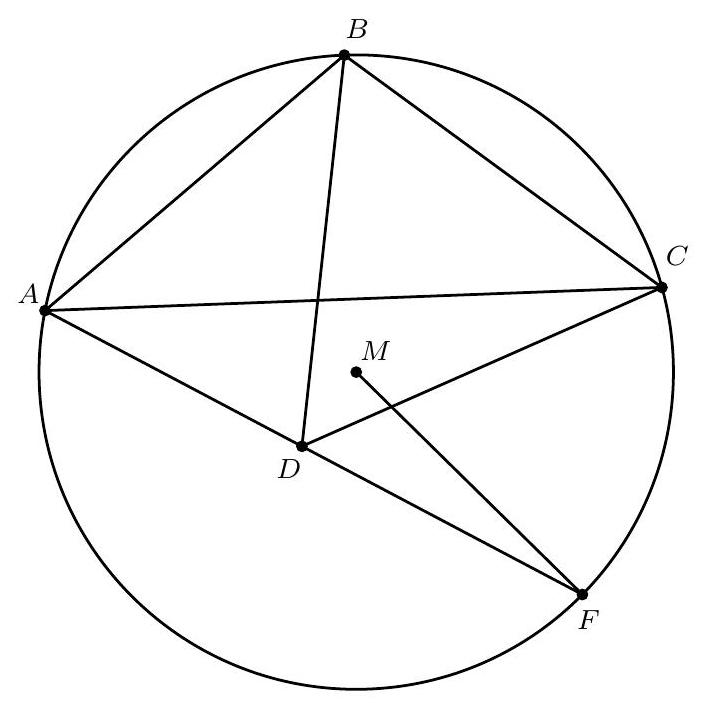

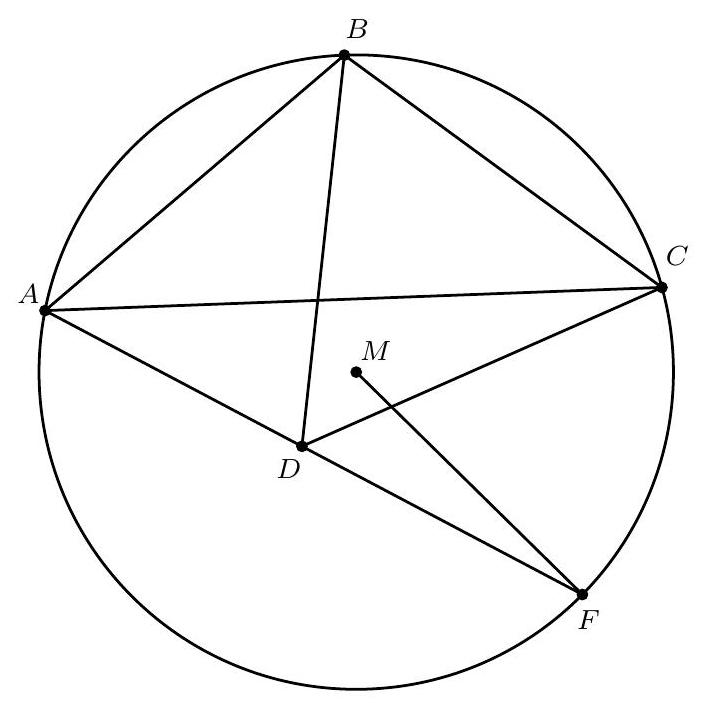

Let $M$ be the second intersection of $A D$ with the circumcircle of $\triangle A B C$. Then $M$ is the midpoint of the arc $B C$ not containing $A$. It now holds that $\angle C O M = \frac{1}{2} \angle C O B = \angle C A B = 60^{\circ}$. Of course, $|O C| = |O M|$, so $\triangle O C M$ is isosceles with a top angle of $60^{\circ}$. This means it is equilateral, so $|C M| = |C O|$. Since $O M$ is perpendicular to $B C$, it follows that $M$ is the reflection of $O$ in side $B C$, and thus $\angle D O M = \angle D M O$.

Furthermore, $\angle D M O = \angle A M O = \angle M A O$ due to $|O A| = |O M|$. We now find $\angle O D E = 90^{\circ} - \angle D O M = 90^{\circ} - \angle D M O = 90^{\circ} - \angle M A O = 90^{\circ} - \angle D A E$. Therefore, $\angle O D E + \angle D A E = 90^{\circ}$. In triangle $A D E$, $180^{\circ} = \angle D A E + \angle A E D + \angle O D E + \angle A D O$, so we conclude that $\angle A E D + \angle A D O = 90^{\circ}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

In een niet-gelijkbenige driehoek $\triangle A B C$ geldt $\angle B A C=60^{\circ}$. Zij $D$ het snijpunt van de bissectrice van $\angle B A C$ met de zijde $B C, O$ het middelpunt van de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A B C$ en $E$ het snijpunt van $A O$ met $B C$. Bewijs dat $\angle A E D+\angle A D O=90^{\circ}$.

|

Zij $M$ het tweede snijpunt van $A D$ met de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A B C$. Dan is $M$ het midden van de boog $B C$ waar $A$ niet op ligt. Er geldt nu $\angle C O M=$ $\frac{1}{2} \angle C O B=\angle C A B=60^{\circ}$. Verder is natuurlijk $|O C|=|O M|$, dus $\triangle O C M$ is gelijkbenig met een tophoek van $60^{\circ}$. Dat betekent dat hij gelijkzijdig is, dus $|C M|=|C O|$. Omdat $O M$ loodrecht op $B C$ staat, volgt hieruit dat $M$ de spiegeling is van $O$ in zijde $B C$, en dus $\angle D O M=\angle D M O$.

Verder geldt $\angle D M O=\angle A M O=\angle M A O$ vanwege $|O A|=|O M|$. We vinden nu $\angle O D E=90^{\circ}-\angle D O M=90^{\circ}-\angle D M O=90^{\circ}-\angle M A O=90^{\circ}-\angle D A E$. Dus $\angle O D E+\angle D A E=90^{\circ}$. In driehoek $A D E$ geldt $180^{\circ}=\angle D A E+\angle A E D+\angle O D E+\angle A D O$, dus we concluderen dat $\angle A E D+\angle A D O=90^{\circ}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Given a positive integer $n$. Determine all positive real numbers $x$ such that

$$

n x^{2}+\frac{2^{2}}{x+1}+\frac{3^{2}}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{(n+1)^{2}}{x+n}=n x+\frac{n(n+3)}{2} .

$$

|

For $1 \leq i \leq n$ we have

$\frac{(i+1)^{2}}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{(i+1)^{2}-(i+1)(x+i)}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{i+1-(i+1) x}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{(i+1)(1-x)}{x+i}$,

so we can rewrite the left side of the given equation to

$$

n x^{2}+2+3+\ldots+(n+1)+\frac{2(1-x)}{x+1}+\frac{3(1-x)}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{(n+1)(1-x)}{x+n}

$$

It holds that $2+3+\ldots+(n+1)=\frac{1}{2} n(n+3)$, so this sum cancels out with $\frac{n(n+3)}{2}$ on the right side of the given equation. Furthermore, we can move $n x^{2}$ to the other side and factor out $1-x$ in all fractions. The equation can thus be rewritten as

$$

(1-x) \cdot\left(\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}\right)=n x-n x^{2} .

$$

The right side can be factored as $n x(1-x)$. We now see that $x=1$ is a solution to this equation. If there were another solution $x \neq 1$, then it would have to satisfy

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}=n x .

$$

However, for $0<x<1$ we have

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}>\frac{2}{2}+\frac{3}{3}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{n+1}=n>n x

$$

while for $x>1$ we have

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}<\frac{2}{2}+\frac{3}{3}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{n+1}=n<n x .

$$

Therefore, there are no solutions with $x \neq 1$. We conclude that for all $n$, the only solution is $x=1$.

|

x=1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Gegeven is een positief geheel getal $n$. Bepaal alle positieve reële getallen $x$ met

$$

n x^{2}+\frac{2^{2}}{x+1}+\frac{3^{2}}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{(n+1)^{2}}{x+n}=n x+\frac{n(n+3)}{2} .

$$

|

Voor $1 \leq i \leq n$ geldt

$\frac{(i+1)^{2}}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{(i+1)^{2}-(i+1)(x+i)}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{i+1-(i+1) x}{x+i}=i+1+\frac{(i+1)(1-x)}{x+i}$,

dus kunnen we de linkerkant van de gegeven vergelijking herschrijven tot

$$

n x^{2}+2+3+\ldots+(n+1)+\frac{2(1-x)}{x+1}+\frac{3(1-x)}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{(n+1)(1-x)}{x+n}

$$

Er geldt $2+3+\ldots+(n+1)=\frac{1}{2} n(n+3)$ dus deze som valt weg tegen $\frac{n(n+3)}{2}$ aan de rechterkant van de gegeven vergelijking. Verder kunnen we $n x^{2}$ naar de andere kant halen en in alle breuken $1-x$ buiten haakjes halen. De vergelijking laat zich dus herschrijven tot

$$

(1-x) \cdot\left(\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}\right)=n x-n x^{2} .

$$

De rechterkant kunnen we ontbinden als $n x(1-x)$. We zien nu dat $x=1$ een oplossing is van deze vergelijking. Als er nog een oplossing $x \neq 1$ zou zijn, dan moet die voldoen aan

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}=n x .

$$

Voor $0<x<1$ geldt echter

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}>\frac{2}{2}+\frac{3}{3}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{n+1}=n>n x

$$

terwijl voor $x>1$ juist geldt

$$

\frac{2}{x+1}+\frac{3}{x+2}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{x+n}<\frac{2}{2}+\frac{3}{3}+\ldots+\frac{n+1}{n+1}=n<n x .

$$

Er zijn dus geen oplossingen met $x \neq 1$. We concluderen dat voor alle $n$ de enige oplossing $x=1$ is.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

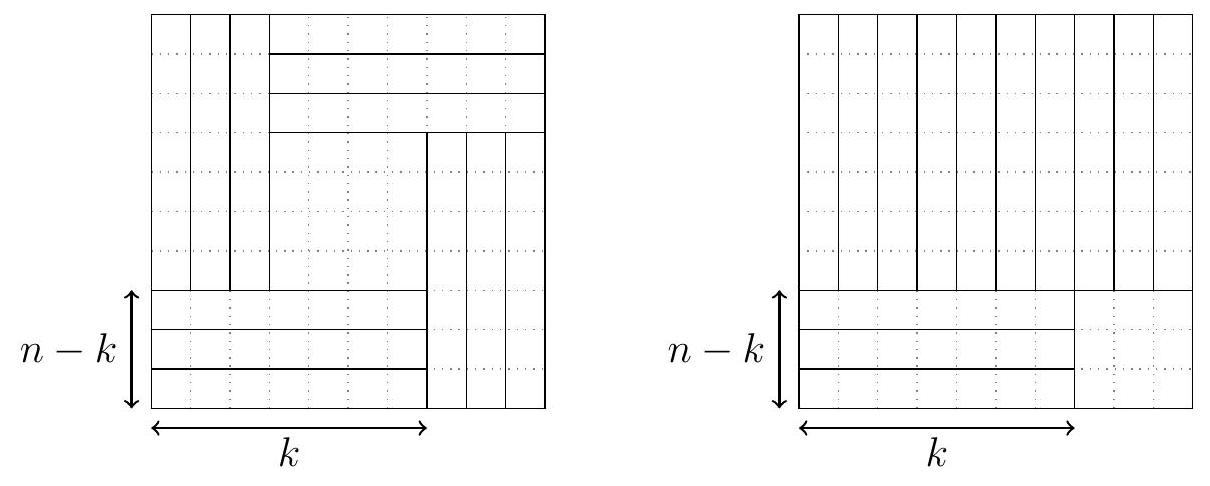

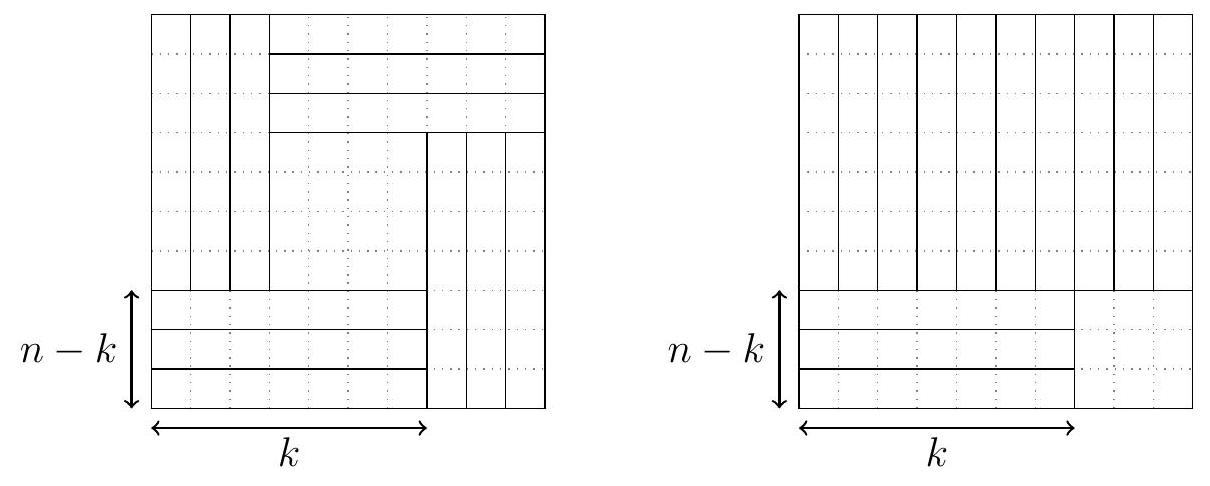

Given is a board with $2 m$ rows and $2 n$ columns, where $m$ and $n$ are positive integers. You may place one pawn on a square of this board, but not on the bottom-left square or the top-right square. Then a snail starts a walk over the board. The snail starts in the bottom-left square and may move horizontally and vertically. The snail does not land on the square with the pawn, but wants to visit every other square exactly once, with the top-right square being its endpoint. On which squares can you place the pawn so that the snail can succeed in its plan?

|

Number the rows from bottom to top with 1 to $2 m$ and number the columns from left to right with 1 to $2 n$. The snail thus starts in square $(1,1)$ and ends in square $(2 m, 2 n)$. Color the squares like a chessboard, where square $(i, j)$ is black if $i+j$ is even and white if $i+j$ is odd. Since $2 m$ and $2 n$ are even, there are as many black as white squares. The snail starts and ends on a black square and visits black and white squares alternately during its walk. The number of black squares it visits is therefore 1 more than the number of white squares it visits. Therefore, the pawn must stand on a white square, i.e., a square $(i, j)$ with $i+j$ odd.

We now show that if the pawn stands on such a square, the snail can always make its walk. Let $1 \leq k \leq m$ and $1 \leq l \leq n$ such that the pawn is in one of the rows $2 k-1$ and $2 k$ and in one of the columns $2 l-1$ and $2 l$. Let the snail run through all rows with row number less than $2 k-1$ in their entirety: the odd rows from left to right, then one square up and the even rows from right to left back. Then one square up again and he is on an odd row again. At some point, the snail arrives in row $2 k-1$ and is then on the far left square. As long as the snail is still in the columns with number less than $2 l-1$, it visits each $2 \times 2$ square (in rows $2 k-1,2 k$) in the order bottom-left-top-left-top-right-bottom-right. And then he arrives at the bottom-left again in the next $2 \times 2$ square. At some point, he arrives in column $2 l-1$. He is then on square $(2 k-1,2 l-1)$ and the pawn cannot stand there, because $2 k-1+2 l-1$ is even. In this $2 \times 2$ square, the pawn stands either top-left or bottom-right. In the first case, the snail walks bottom-left-bottom-right-top-right and in the second case, he walks bottom-left-top-left-top-right. In both cases, he ends up in this $2 \times 2$ square in the top-right square. The rest of the $2 \times 2$ squares in these rows he can visit in the order top-left-bottom-left-bottom-right-top-right. He always ends up top-right. When he eventually arrives in the last column, he goes one row up, to row $2 k+1$. There he arrives at the bottom-right. The remaining rows he runs through again in their entirety: the odd rows from right to left, then one square up and the even rows from left to right back. In row $2 m$ he ends up top-right, exactly as required. We conclude that the pawn can be placed on the squares $(i, j)$ with $i+j$ odd.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Gegeven is een bord met $2 m$ rijen en $2 n$ kolommen, waarbij $m$ en $n$ positieve gehele getallen zijn. Je mag één pion plaatsen op een vakje van dit bord, maar niet het vakje linksonder of het vakje rechtsboven. Vervolgens begint een slak een wandeling te maken over het bord. De slak begint in het vakje linksonder en mag horizontaal en verticaal bewegen. De slak komt niet op het vakje met de pion, maar wil verder elk vakje precies één keer aandoen, waarbij het vakje rechtsboven zijn eindpunt is. Op welke vakjes kun je de pion neerzetten zodat de slak in zijn opzet kan slagen?

|

Nummer de rijen van beneden naar boven met 1 tot en met $2 m$ en nummer de kolommen van links naar rechts met 1 tot en met $2 n$. De slak begint dus in vakje $(1,1)$ en eindigt in vakje $(2 m, 2 n)$. Kleur nu de vakjes als een schaakbord, waarbij vakje $(i, j)$ zwart wordt als $i+j$ even is en wit als $i+j$ oneven is. Omdat $2 m$ en $2 n$ even zijn, zijn er evenveel zwarte als witte vakjes. De slak begint en eindigt op een zwart vakje en bezoekt tijdens zijn wandeling om en om zwarte en witte vakjes. Het aantal zwarte vakjes waar hij komt, is dus 1 groter dan het aantal witte vakjes waar hij komt. Daarom moet de pion wel op een wit vakje staan, dus een vakje $(i, j)$ met $i+j$ oneven.

We laten nu zien dat als de pion op zo'n vakje staat, de slak altijd zijn wandeling kan maken. Zij $1 \leq k \leq m$ en $1 \leq l \leq n$ zo dat de pion in één van de rijen $2 k-1$ en $2 k$ staat en in één van de kolommen $2 l-1$ en $2 l$. Laat de slak alle rijen met rijnummer kleiner dan $2 k-1$ in zijn geheel aflopen: de oneven rijen van links naar rechts, dan één vakje omhoog en de even rijen van rechts naar links terug. Vervolgens weer één vakje omhoog en dan is hij weer op een oneven rij. Op een gegeven moment komt de slak aan in rij $2 k-1$ en staat dan op het vakje helemaal links. Zolang de slak nog in de kolommen met nummer kleiner dan $2 l-1$ zit, bezoekt hij elk $2 \times 2$-vierkantje (in rijen $2 k-1,2 k$ ) in de volgorde linksonder-linksboven-rechtsboven-rechtsonder. En dan komt hij linksonder weer aan in het volgende $2 \times 2$-vierkantje. Op een gegeven moment arriveert hij in kolom $2 l-1$. Hij staat dan op vakje $(2 k-1,2 l-1)$ en daar kan de pion niet staan, want $2 k-1+2 l-1$ is even. In dit $2 \times 2$-vierkantje staat de pion ofwel linksboven ofwel rechtsonder. In het eerste geval loopt de slak linksonder-rechtsonder-rechtsboven en in het tweede geval loopt hij linksonder-linksboven-rechtsboven. In beide gevallen eindigt hij in dit $2 \times 2$-vierkantje in het vakje rechtsboven. De rest van de $2 \times 2$-vierkantjes in deze rijen kan hij dus in de volgorde linksboven-linksonder-rechtsonder-rechtsboven bezoeken. Steeds eindigt hij rechtsboven. Als hij uiteindelijk in de laatste kolom is aangekomen, gaat hij een rij omhoog, naar rij $2 k+1$. Daar komt hij dus rechtsonderin aan. De overige rijen loopt hij weer in z'n geheel af: de oneven rijen van rechts naar links, dan een vakje omhoog en de even rijen van links

naar rechts terug. In rij $2 m$ eindigt hij dus rechtsboven, precies zoals gevraagd. We concluderen dat de pion op de vakjes $(i, j)$ met $i+j$ oneven neergezet kan worden.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

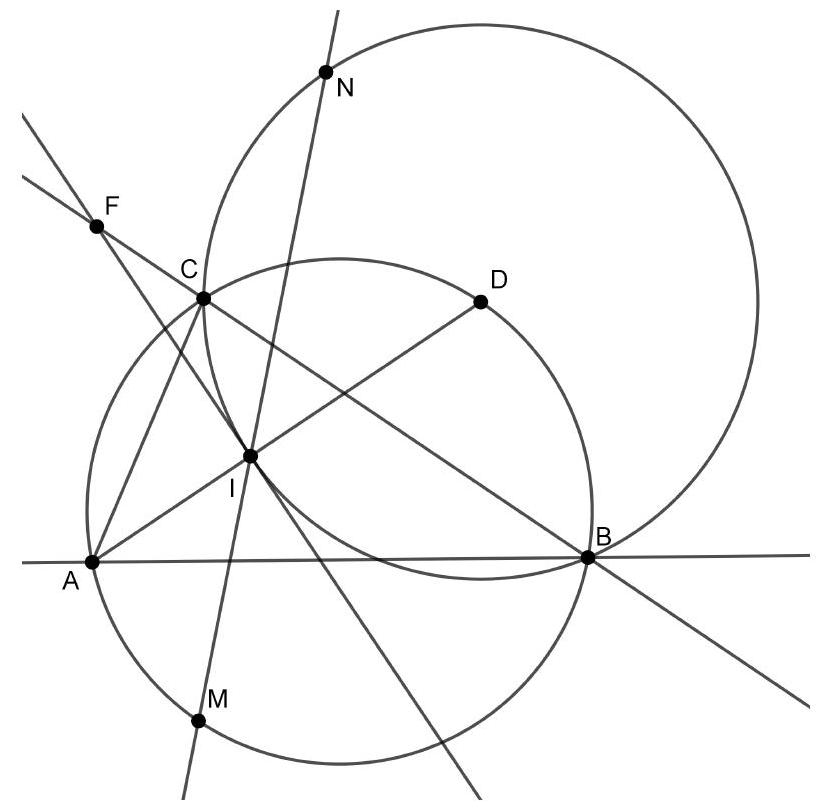

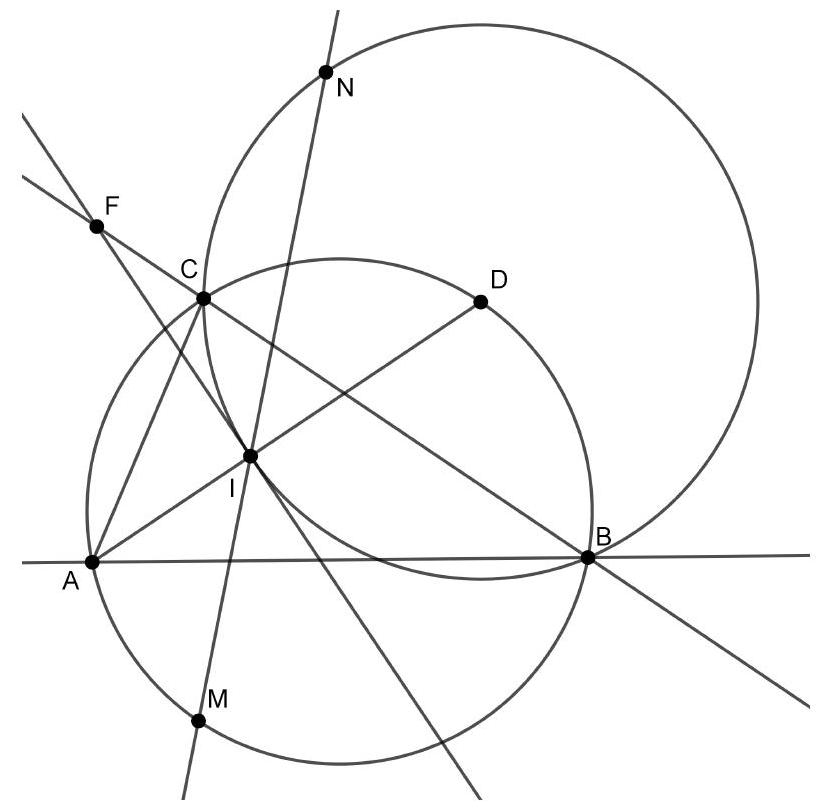

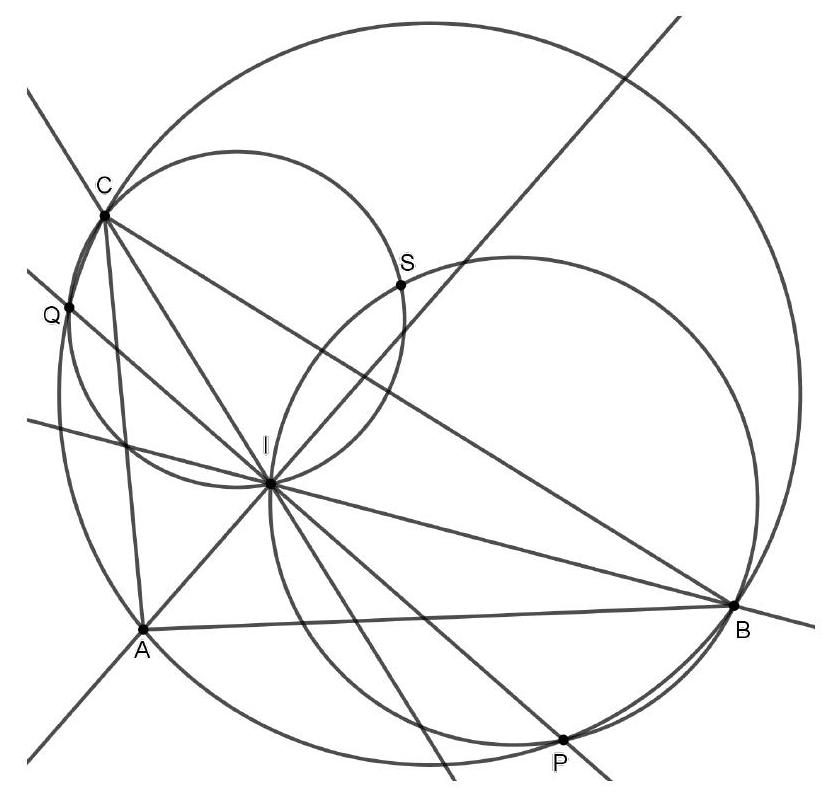

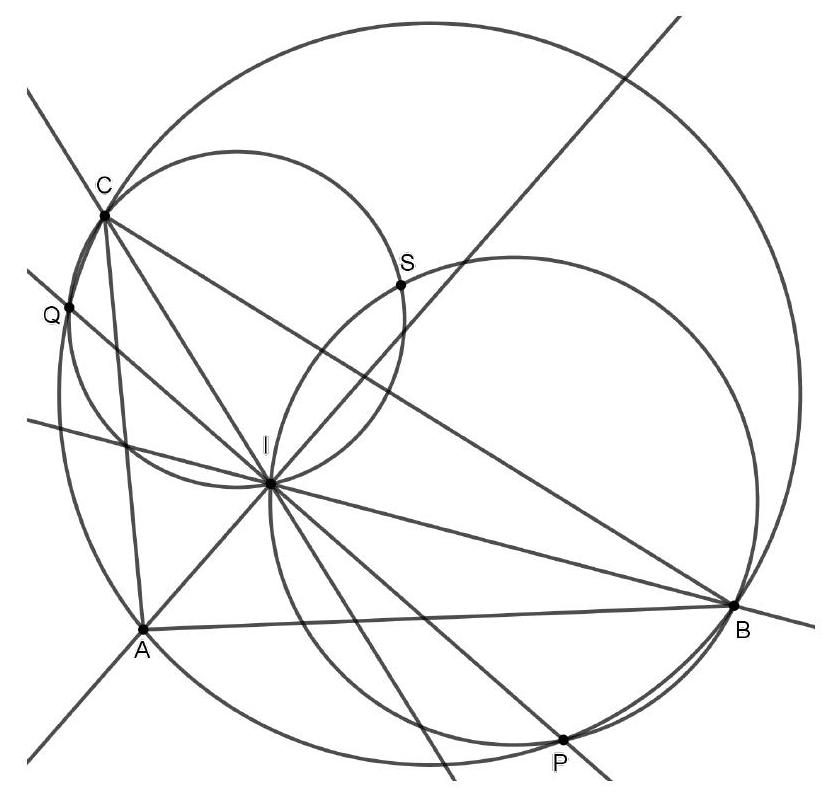

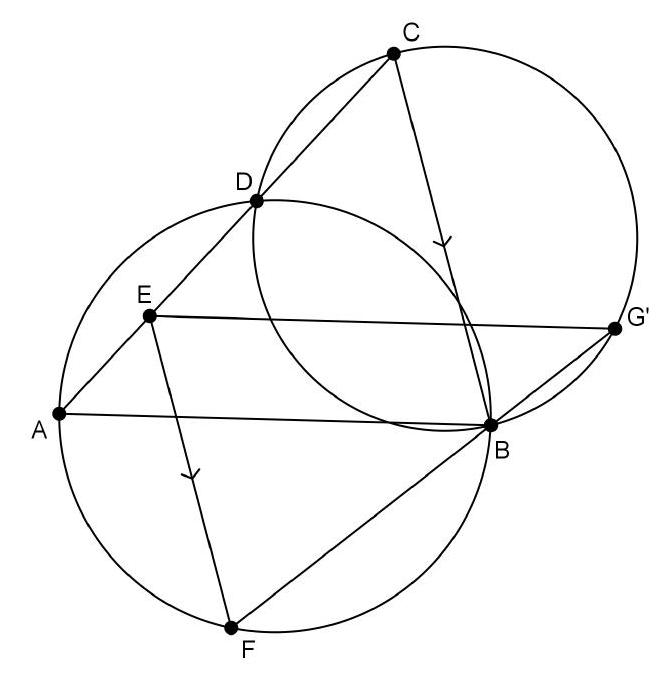

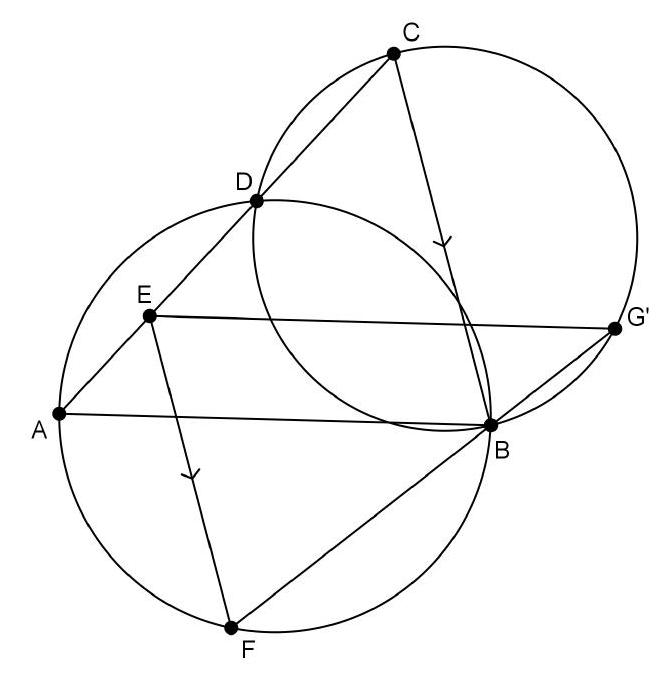

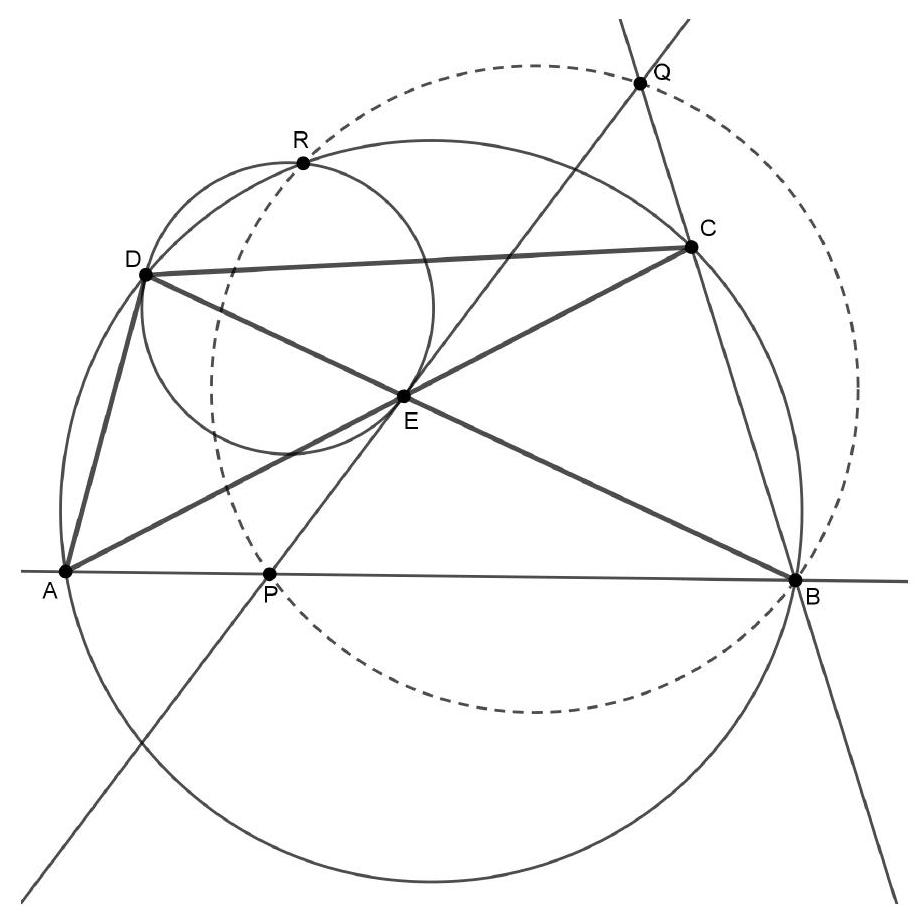

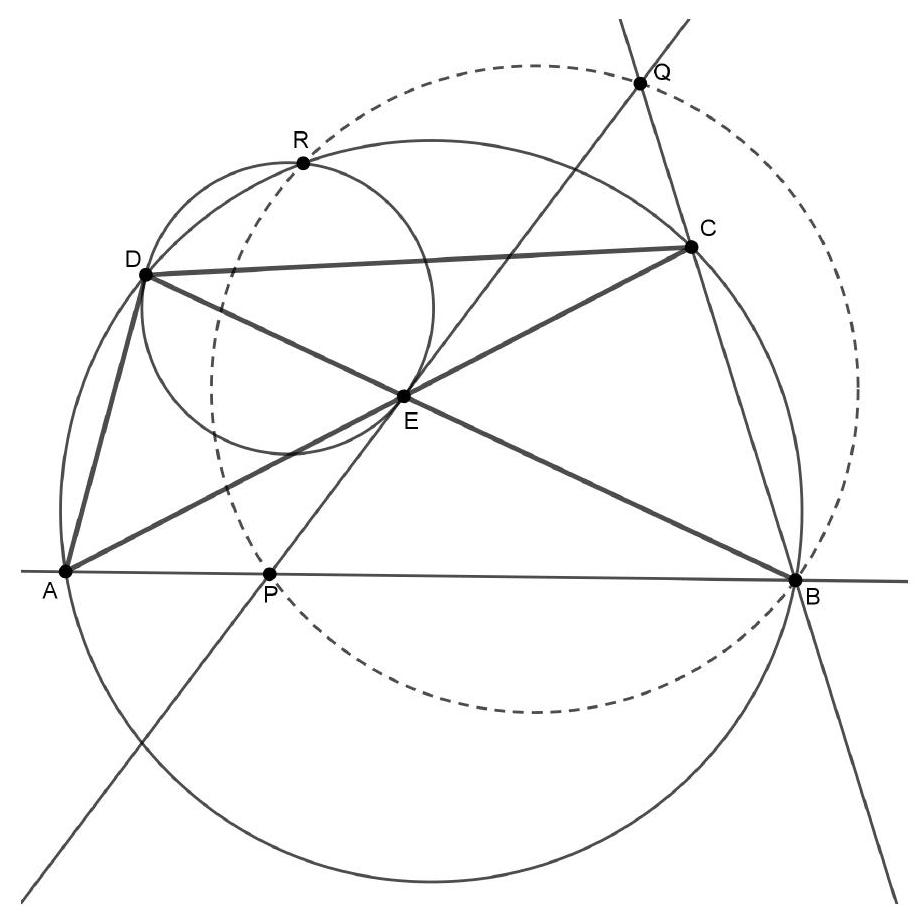

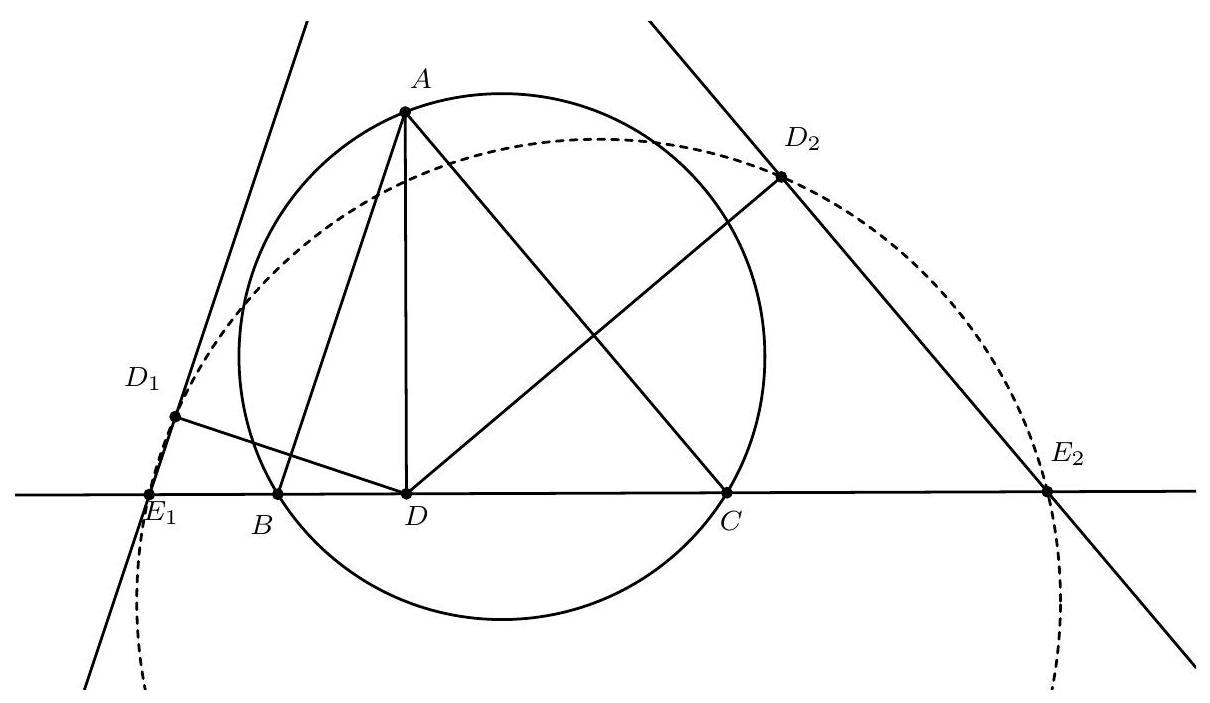

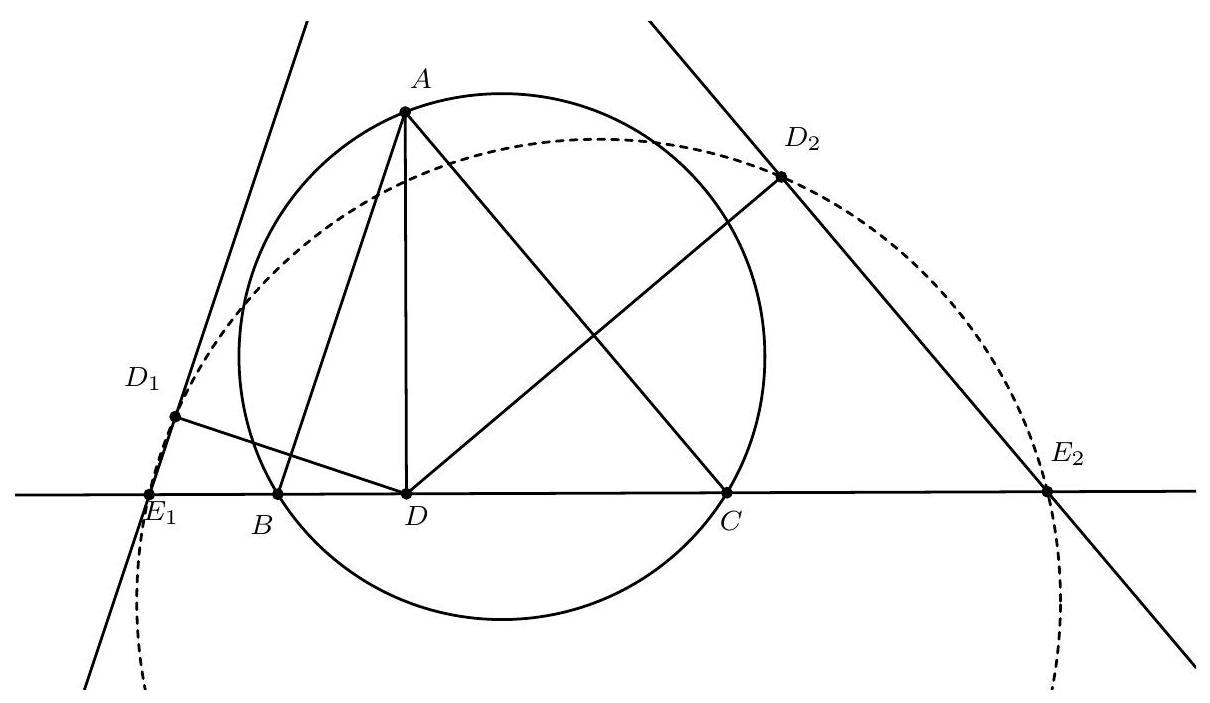

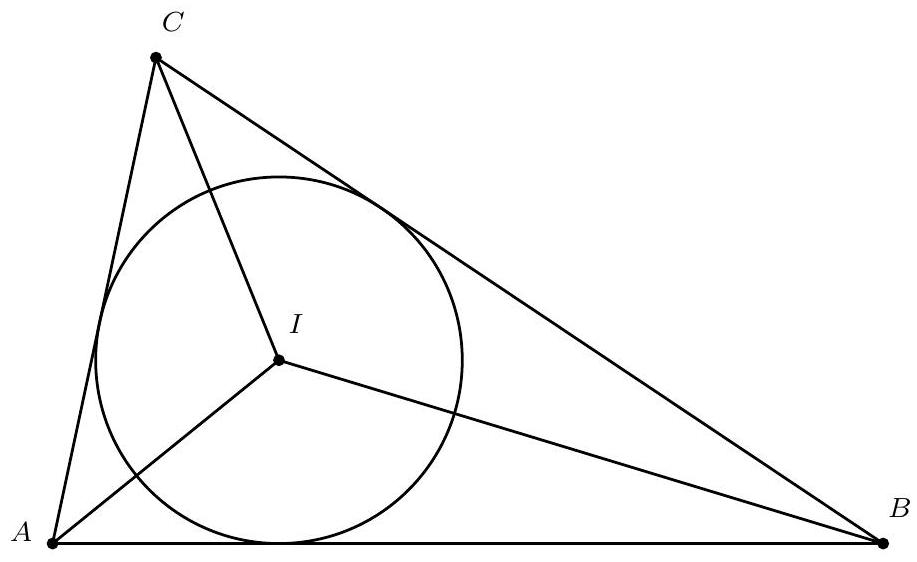

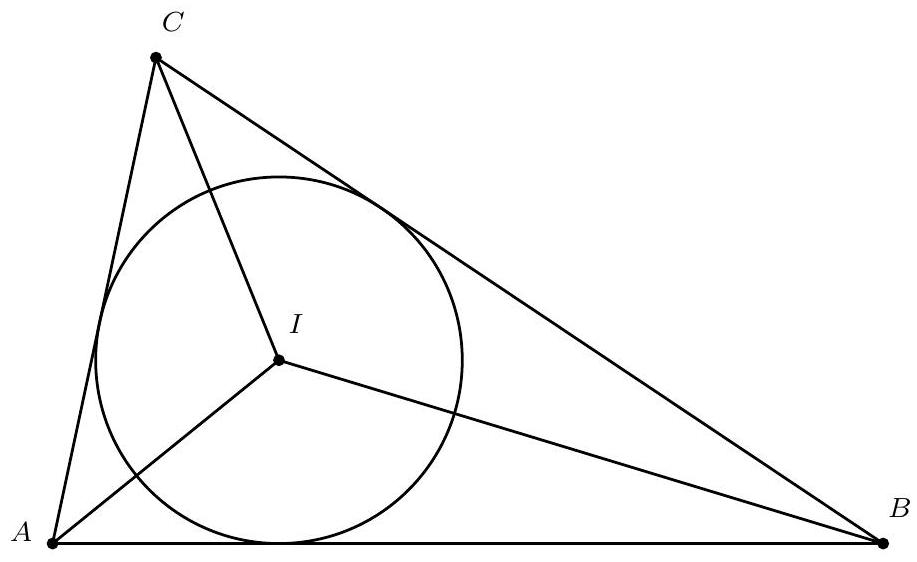

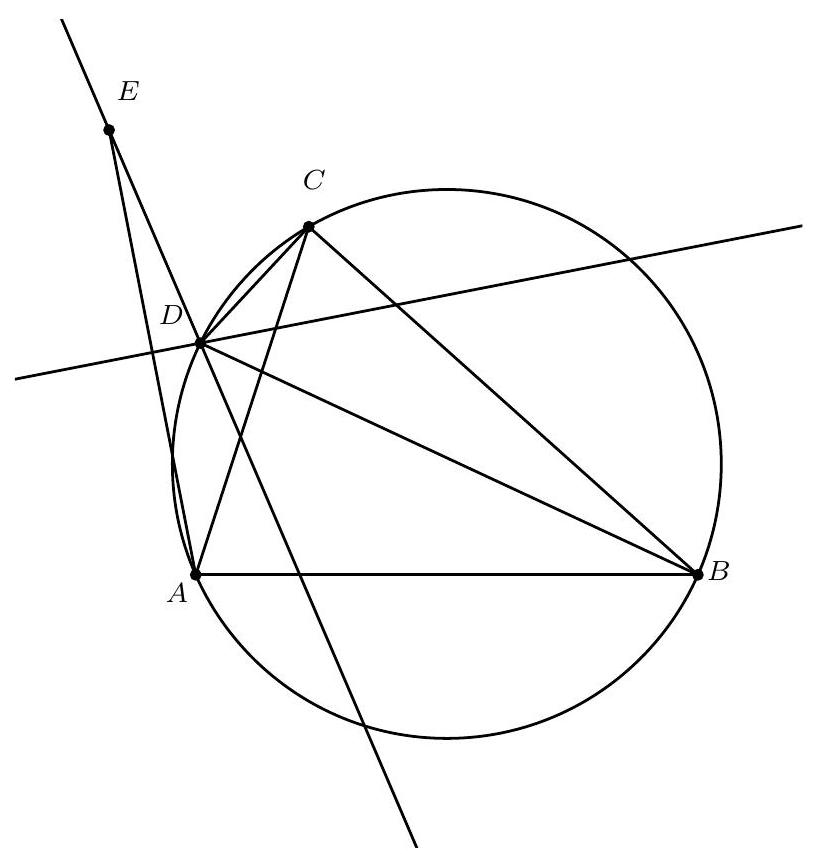

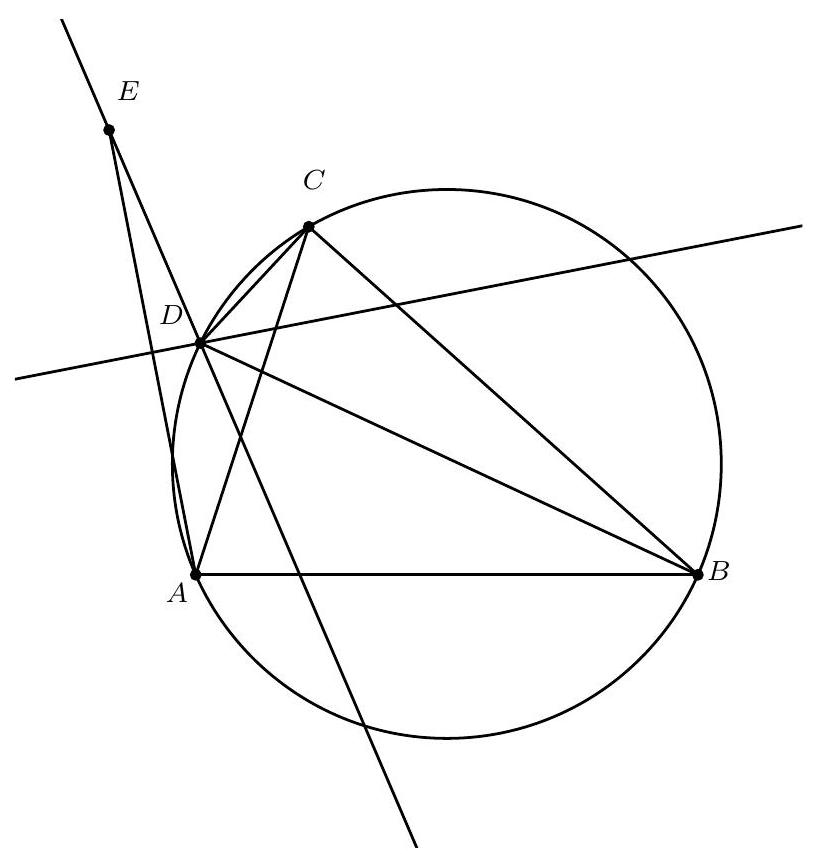

Given is a triangle $\triangle A B C$ with $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. The midpoint of $A C$ is called $D$ and the perpendicular projection of $C$ on $B D$ is called $E$. Prove that the tangent at $C$ to the circumcircle of $\triangle A E C$ is perpendicular to $A B$.

|

Let $S$ be the intersection of the tangent line and $AB$. We need to prove that $\angle BSC=90^{\circ}$.

Since $\angle BCD=90^{\circ}=\angle CED$, we have $\triangle BCD \sim \triangle CED$, so $\frac{|DC|}{|DB|}=\frac{|DE|}{|DC|}$. Because $|DA|=|DC|$, it follows that $\frac{|DA|}{|DB|}=\frac{|DE|}{|DA|}$. Together with $\angle BDA=\angle EDA$, this gives $\triangle ADE \sim \triangle BDA$ (side-angle-side). Therefore, $\angle ABD=\angle EAD$. Since $SC$ is a tangent to the circumcircle of $\triangle AEC$, by the tangent-secant theorem, we also have $\angle EAD=\angle EAC=\angle SCE$. Thus, $\angle SCE=\angle ABD=\angle SBE$. This implies that $SBCE$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Therefore, $\angle BSC=\angle BEC=90^{\circ}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeven is een driehoek $\triangle A B C$ met $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. Het midden van $A C$ noemen we $D$ en de loodrechte projectie van $C$ op $B D$ noemen we $E$. Bewijs dat de raaklijn in $C$ aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A E C$ loodrecht op $A B$ staat.

|

Noem $S$ het snijpunt van de raaklijn en $A B$. We moeten dus bewijzen dat $\angle B S C=90^{\circ}$.

Vanwege $\angle B C D=90^{\circ}=\angle C E D$ geldt $\triangle B C D \sim \triangle C E D$, dus $\frac{|D C|}{|D B|}=\frac{|D E|}{|D C|}$. Omdat $|D A|=|D C|$ volgt hieruit $\frac{|D A|}{|D B|}=\frac{|D E|}{|D A|}$. Samen met $\angle B D A=\angle E D A$ geeft dit $\triangle A D E \sim \triangle B D A$ (zhz). Dus $\angle A B D=\angle E A D$. Omdat $S C$ een raaklijn is aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A E C$ geldt vanwege de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling ook dat $\angle E A D=\angle E A C=\angle S C E$. Dus $\angle S C E=\angle A B D=\angle S B E$. Hieruit volgt dat $S B C E$ een koordenvierhoek is. Dus $\angle B S C=\angle B E C=90^{\circ}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Given is a triangle $\triangle A B C$ with $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. The midpoint of $A C$ is called $D$ and the perpendicular projection of $C$ on $B D$ is called $E$. Prove that the tangent at $C$ to the circumcircle of $\triangle A E C$ is perpendicular to $A B$.

|

Let $P$ be the reflection of $B$ in $D$. Then $AC$ and $PB$ bisect each other, so $CBAP$ is a parallelogram. Therefore, $\angle CAP = \angle ACB = 90^{\circ} = \angle CEP$. This means that $CEAP$ is a cyclic quadrilateral and that $CP$ is a diameter of its circumscribed circle. The tangent at $C$ to this circumscribed circle is perpendicular to the diameter $CP$. Since in the parallelogram $AB \parallel CP$, the tangent is also perpendicular to $AB$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeven is een driehoek $\triangle A B C$ met $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. Het midden van $A C$ noemen we $D$ en de loodrechte projectie van $C$ op $B D$ noemen we $E$. Bewijs dat de raaklijn in $C$ aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A E C$ loodrecht op $A B$ staat.

|

Zij $P$ de spiegeling van $B$ in $D$. Dan snijden $A C$ en $P B$ elkaar middendoor, dus is $C B A P$ een parallellogram. Dus $\angle C A P=\angle A C B=90^{\circ}=\angle C E P$. Dit betekent dat $C E A P$ een koordenvierhoek is en dat $C P$ een middellijn van zijn omgeschreven cirkel is. De raaklijn in $C$ aan deze omgeschreven cirkel staat loodrecht op de middellijn $C P$. Aangezien in het parallellogram $A B \| C P$, staat de raaklijn dus ook loodrecht op $A B$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Given is a triangle $\triangle A B C$ with $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. The midpoint of $A C$ is called $D$ and the perpendicular projection of $C$ on $B D$ is called $E$. Prove that the tangent at $C$ to the circumcircle of $\triangle A E C$ is perpendicular to $A B$.

|

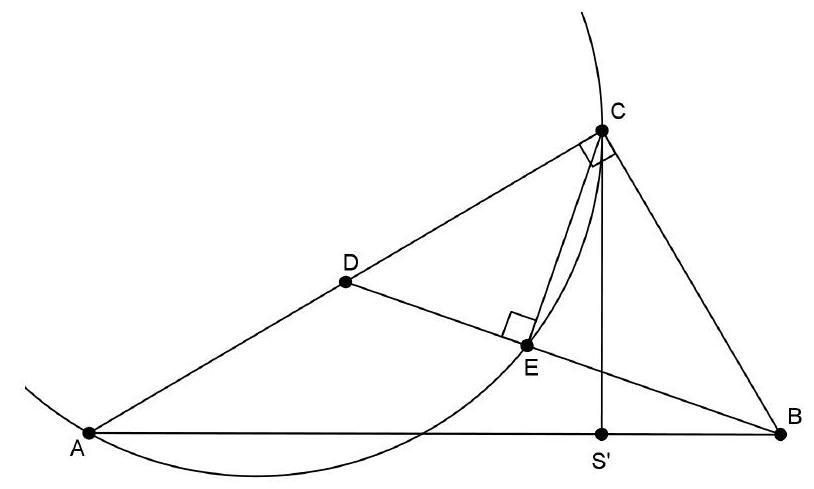

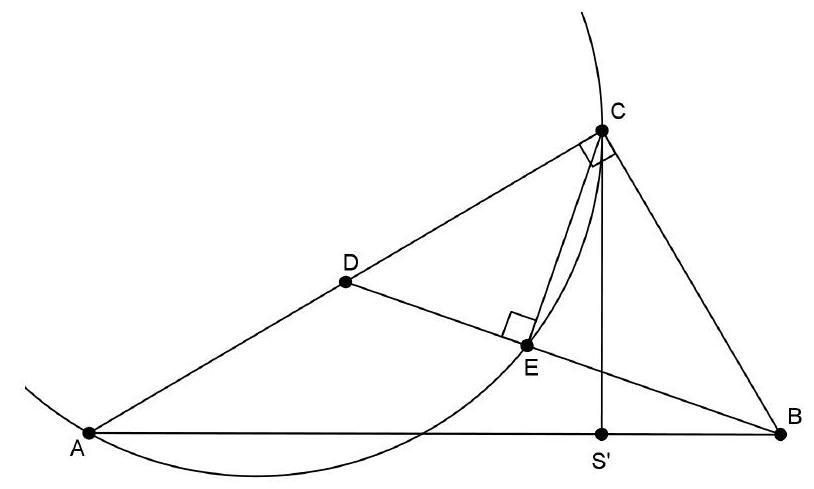

Let $S^{\prime}$ be the orthogonal projection of $C$ on $AB$. Then $\angle B S^{\prime} C = 90^{\circ} = \angle B E C$, so $B C S^{\prime} E$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. It follows that $\angle E D C = 90^{\circ} - \angle E C D = \angle E C B = 180^{\circ} - \angle E S^{\prime} C = \angle E S^{\prime} A$, so $\angle E D A = 180^{\circ} - \angle E D C = 180^{\circ} - \angle E S^{\prime} A$, which implies that $A D E S^{\prime}$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Now, $\angle S^{\prime} A E = \angle S^{\prime} D E$. Furthermore, by Thales' theorem, $D$ is the center of the circle through $A, C$, and $S^{\prime}$, so $\angle D S^{\prime} A = \angle S^{\prime} A D$. These two results together give $\angle E A C = \angle S^{\prime} A C - \angle S^{\prime} A E = \angle S^{\prime} A D - \angle S^{\prime} A E = \angle D S^{\prime} A - \angle S^{\prime} D E$. By the exterior angle theorem in triangle $D S^{\prime} B$, this is equal to $\angle S^{\prime} B D = \angle S^{\prime} B E$, and by the cyclic quadrilateral $B C S^{\prime} E$, this is again equal to $\angle S^{\prime} C E$. Therefore, $\angle E A C = \angle S^{\prime} C E$. By the tangent-secant theorem, it follows that $S^{\prime} C$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\triangle E A C$. This tangent $S^{\prime} C$ is indeed perpendicular to $AB$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeven is een driehoek $\triangle A B C$ met $\angle C=90^{\circ}$. Het midden van $A C$ noemen we $D$ en de loodrechte projectie van $C$ op $B D$ noemen we $E$. Bewijs dat de raaklijn in $C$ aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A E C$ loodrecht op $A B$ staat.

|

Zij $S^{\prime}$ de loodrechte projectie van $C$ op $A B$. Er geldt dan $\angle B S^{\prime} C=$ $90^{\circ}=\angle B E C$, dus $B C S^{\prime} E$ is een koordenvierhoek. Er volgt dat $\angle E D C=90^{\circ}-\angle E C D=$ $\angle E C B=180^{\circ}-\angle E S^{\prime} C=\angle E S^{\prime} A$, dus $\angle E D A=180^{\circ}-\angle E D C=180^{\circ}-\angle E S^{\prime} A$, waaruit volgt dat $A D E S^{\prime}$ een koordenvierhoek is. Nu is $\angle S^{\prime} A E=\angle S^{\prime} D E$. Verder is vanwege Thales $D$ het middelpunt van de cirkel door $A, C$ en $S^{\prime}$, dus is $\angle D S^{\prime} A=\angle S^{\prime} A D$. Deze twee resultaten samen geven $\angle E A C=\angle S^{\prime} A C-\angle S^{\prime} A E=\angle S^{\prime} A D-\angle S^{\prime} A E=\angle D S^{\prime} A-$ $\angle S^{\prime} D E$. Met de buitenhoekstelling in driehoek $D S^{\prime} B$ is dit gelijk aan $\angle S^{\prime} B D=\angle S^{\prime} B E$ en vanwege koordenvierhoek $B C S^{\prime} E$ is dat weer gelijk aan $\angle S^{\prime} C E$. Dus $\angle E A C=\angle S^{\prime} C E$. Met de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling volgt hieruit dat $S^{\prime} C$ raakt aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle E A C$. Deze raaklijn $S^{\prime} C$ staat dus inderdaad loodrecht op $A B$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing III.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $n \geq 0$ be an integer. A sequence $a_{0}, a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ of integers is defined as follows: $a_{0}=n$ and for $k \geq 1$, $a_{k}$ is the smallest integer greater than $a_{k-1}$ such that $a_{k}+a_{k-1}$ is the square of an integer. Prove that there are exactly $\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$ positive integers that cannot be written in the form $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ with $k>\ell \geq 0$.

|

Let $m=\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$. We first prove that the sequence of squares $a_{0}+a_{1}, a_{1}+a_{2}$, ... is exactly the sequence $(m+1)^{2},(m+2)^{2}, \ldots$. Then we show that the differences $a_{i}-a_{i-1}$ form a sequence of consecutive even numbers and a sequence of consecutive odd numbers. With this, we can then prove the desired result.

Note that $a_{0}+a_{1}$ is the smallest square greater than $2 n$. Therefore, $a_{0}+a_{1}=(m+1)^{2}$. We now prove by induction on $i$ that $a_{i-1}+a_{i}=(m+i)^{2}$. For $i=1$, we have just proven this. Suppose that $a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j)^{2}$. This means that $a_{j-1} \geq \frac{(m+j-1)^{2}}{2}$ (otherwise, $a_{j}$ could have been chosen such that $a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j-1)^{2}$) and thus

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{j} & =(m+j)^{2}-a_{j-1} \\

& \leq(m+j)^{2}-\frac{(m+j-1)^{2}}{2} \\

& =\frac{2 m^{2}+4 m j+2 j^{2}-\left(m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}+1-2 m-2 j\right)}{2} \\

& =\frac{m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}-1+2 m+2 j}{2} \\

& <\frac{m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}+1+2 m+2 j}{2} \\

& =\frac{(m+j+1)^{2}}{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

From this, it follows that $a_{j}+a_{j+1} \leq(m+j+1)^{2}$. Moreover, $a_{j}+a_{j+1}>a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j)^{2}$, so $a_{j}+a_{j+1}=(m+j+1)^{2}$. This completes the induction.

Define now $b_{i}=a_{i}-a_{i-1}$ for all $i \geq 1$. Then we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

b_{i+2}-b_{i} & =a_{i+2}-a_{i+1}-a_{i}+a_{i-1} \\

& =\left(a_{i+2}+a_{i+1}\right)+\left(a_{i}+a_{i-1}\right)-2\left(a_{i+1}+a_{i}\right) \\

& =(m+i+2)^{2}+(m+i)^{2}-2(m+i+1)^{2} \\

& =(m+i)^{2}+4(m+i)+4+(m+i)^{2}-2(m+i)^{2}-4(m+i)-2 \\

& =2

\end{aligned}

$$

for all $i \geq 1$. We now see that

$$

\left(b_{1}, b_{3}, b_{5}, \ldots\right)=\left(b_{1}, b_{1}+2, b_{1}+4, \ldots\right), \quad\left(b_{2}, b_{4}, b_{6}, \ldots\right)=\left(b_{2}, b_{2}+2, b_{2}+4, \ldots\right)

$$

We have $b_{1}+b_{2}=\left(a_{2}-a_{1}\right)+\left(a_{1}-a_{0}\right)=\left(a_{2}+a_{1}\right)-\left(a_{1}+a_{0}\right)=(m+2)^{2}-(m+1)^{2}=2 m+3$. In particular, $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$ have different parities. Now, at least all numbers with the same parity as $b_{1}$ and at least as large as $b_{1}$ can be written as $a_{k}-a_{k-1}$ for some $k$. The same holds for the numbers with the same parity as $b_{2}$ and at least as large as $b_{2}$. All numbers of the form $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ with $k \geq \ell+2$ are at least as large as $b_{k}+b_{k-1} \geq b_{1}+b_{2}$ and thus larger than $b_{1}$ and larger than $b_{2}$. In this way, we can no longer create new numbers. The numbers that cannot be written as $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ with $k>\ell \geq 0$ are therefore exactly the numbers with the same parity as $b_{1}$ and smaller than $b_{1}$ and the numbers with the same parity as $b_{2}$ and smaller than $b_{2}$. There are in total

$$

\left\lfloor\frac{b_{1}-1}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{b_{2}-1}{2}\right\rfloor

$$

numbers, where within the brackets of the floor function, exactly one of the two times is an integer. We can thus write this as

$$

\frac{b_{1}-1}{2}+\frac{b_{2}-1}{2}-\frac{1}{2}=\frac{b_{1}+b_{2}-3}{2}=\frac{2 m}{2}=m \text {. }

$$

There are thus exactly $m=\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$ positive integers that cannot be written in the desired form.

|

\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $n \geq 0$ een geheel getal. Een rij $a_{0}, a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ van gehele getallen wordt als volgt gedefinieerd: er geldt $a_{0}=n$ en voor $k \geq 1$ is $a_{k}$ het kleinste gehele getal groter dan $a_{k-1}$ waarvoor $a_{k}+a_{k-1}$ het kwadraat van een geheel getal is. Bewijs dat er precies $\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$ positieve gehele getallen zijn die niet te schrijven zijn in de vorm $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ met $k>\ell \geq 0$.

|

Zij $m=\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$. We bewijzen eerst dat de rij kwadraten $a_{0}+a_{1}, a_{1}+a_{2}$, ... precies de rij $(m+1)^{2},(m+2)^{2}, \ldots$ is. Vervolgens laten we zien dat de verschillen $a_{i}-a_{i-1}$ een rij opeenvolgende even getallen en een rij opeenvolgende oneven getallen vormen. Hiermee kunnen we daarna het gevraagde bewijzen.

Merk op dat $a_{0}+a_{1}$ het kleinste kwadraat is dat groter is dan $2 n$. Er geldt dus $a_{0}+a_{1}=$ $(m+1)^{2}$. We bewijzen nu met inductie naar $i$ dat $a_{i-1}+a_{i}=(m+i)^{2}$. Voor $i=1$ hebben we dit zojuist bewezen. Stel dat $a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j)^{2}$. Dat betekent dat $a_{j-1} \geq \frac{(m+j-1)^{2}}{2}$ (anders had $a_{j}$ zo gekozen kunnen worden dat $\left.a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j-1)^{2}\right)$ en dus

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{j} & =(m+j)^{2}-a_{j-1} \\

& \leq(m+j)^{2}-\frac{(m+j-1)^{2}}{2} \\

& =\frac{2 m^{2}+4 m j+2 j^{2}-\left(m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}+1-2 m-2 j\right)}{2} \\

& =\frac{m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}-1+2 m+2 j}{2} \\

& <\frac{m^{2}+2 m j+j^{2}+1+2 m+2 j}{2} \\

& =\frac{(m+j+1)^{2}}{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hieruit volgt dat $a_{j}+a_{j+1} \leq(m+j+1)^{2}$. Er geldt bovendien $a_{j}+a_{j+1}>a_{j-1}+a_{j}=(m+j)^{2}$, dus $a_{j}+a_{j+1}=(m+j+1)^{2}$. Dit voltooit de inductie.

Definieer nu $b_{i}=a_{i}-a_{i-1}$ voor alle $i \geq 1$. Dan geldt

$$

\begin{aligned}

b_{i+2}-b_{i} & =a_{i+2}-a_{i+1}-a_{i}+a_{i-1} \\

& =\left(a_{i+2}+a_{i+1}\right)+\left(a_{i}+a_{i-1}\right)-2\left(a_{i+1}+a_{i}\right) \\

& =(m+i+2)^{2}+(m+i)^{2}-2(m+i+1)^{2} \\

& =(m+i)^{2}+4(m+i)+4+(m+i)^{2}-2(m+i)^{2}-4(m+i)-2 \\

& =2

\end{aligned}

$$

voor alle $i \geq 1$. We zien nu dat

$$

\left(b_{1}, b_{3}, b_{5}, \ldots\right)=\left(b_{1}, b_{1}+2, b_{1}+4, \ldots\right), \quad\left(b_{2}, b_{4}, b_{6}, \ldots\right)=\left(b_{2}, b_{2}+2, b_{2}+4, \ldots\right)

$$

Er geldt $b_{1}+b_{2}=\left(a_{2}-a_{1}\right)+\left(a_{1}-a_{0}\right)=\left(a_{2}+a_{1}\right)-\left(a_{1}+a_{0}\right)=(m+2)^{2}-(m+1)^{2}=2 m+3$. In het bijzonder hebben $b_{1}$ en $b_{2}$ verschillende pariteit. Nu kunnen in elk geval alle getallen

met dezelfde pariteit als $b_{1}$ en minstens gelijk aan $b_{1}$ geschreven worden als $a_{k}-a_{k-1}$ voor zekere $k$. Hetzelfde geldt voor de getallen met dezelfde pariteit als $b_{2}$ en minstens gelijk aan $b_{2}$. Alle getallen van de vorm $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ met $k \geq \ell+2$ zijn minstens gelijk aan $b_{k}+b_{k-1} \geq b_{1}+b_{2}$ en dus groter dan $b_{1}$ en groter dan $b_{2}$. We kunnen op deze manier dus geen nieuwe getallen meer maken. De getallen die niet te schrijven zijn als $a_{k}-a_{\ell}$ met $k>\ell \geq 0$ zijn dus precies de getallen met dezelfde pariteit als $b_{1}$ en kleiner dan $b_{1}$ en de getallen met dezelfde pariteit als $b_{2}$ en kleiner dan $b_{2}$. Dit zijn in totaal

$$

\left\lfloor\frac{b_{1}-1}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{b_{2}-1}{2}\right\rfloor

$$

getallen, waarbij binnen de haken van de entierfunctie precies één van beide keren een geheel getal staat. We kunnen dit dus schrijven als

$$

\frac{b_{1}-1}{2}+\frac{b_{2}-1}{2}-\frac{1}{2}=\frac{b_{1}+b_{2}-3}{2}=\frac{2 m}{2}=m \text {. }

$$

Er zijn dus precies $m=\lfloor\sqrt{2 n}\rfloor$ positieve gehele getallen die niet op de gevraagde manier te schrijven zijn.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Gegeven is een verzameling $A$ van functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$ bestaat er een $f_{3} \in A$ zodat

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)-x\right)+2 x=f_{3}(x+y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$. Bewijs dat voor alle $f \in A$ geldt:

$$

f(x-f(x))=0

$$

voor alle $x \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Invullen van $x=0$ geeft

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)\right)=f_{3}(y)

$$

dus de $f_{3}$ die bij $f_{1}$ en $f_{2}$ hoort, is blijkbaar de samenstelling $f_{3}(x)=f_{1}\left(f_{2}(x)\right)$. Invullen van $x=-y$ geeft nu dat voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)-2 y=f_{3}(0)=f_{1}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Invullen van $x=f_{2}(y)$ geeft dat er voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$ een $f_{3} \in A$ bestaat met

$$

f_{1}(0)+2 f_{2}(y)=f_{3}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$. We hebben hiervoor gezien dat we $f_{3}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)$ kunnen schrijven als $2 y+f_{3}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)$. Dus

$$

2 f_{2}(y)=2 y+f_{3}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)-f_{1}(0)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$. We concluderen dat er een $d \in \mathbb{R}$ is, onafhankelijk van $y$, zodat $f_{2}(y)=y+d$ voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Dus elke $f \in A$ is van de vorm $f(x)=x+d$ met $d$ een constante. Er geldt dan

$$

f(x-f(x))=f(x-(x+d))=f(-d)=-d+d=0

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Gegeven is een verzameling $A$ van functies $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$ bestaat er een $f_{3} \in A$ zodat

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)-x\right)+2 x=f_{3}(x+y)

$$

voor alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$. Bewijs dat voor alle $f \in A$ geldt:

$$

f(x-f(x))=0

$$

voor alle $x \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Invullen van $x=0$ geeft

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)\right)=f_{3}(y)

$$

dus de $f_{3}$ die bij $f_{1}$ en $f_{2}$ hoort, is blijkbaar de samenstelling $f_{3}(x)=f_{1}\left(f_{2}(x)\right)$. Invullen van $x=-y$ geeft nu dat voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$

$$

f_{1}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)-2 y=f_{3}(0)=f_{1}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Invullen van $x=f_{2}(y)$ geeft dat er voor alle $f_{1}, f_{2} \in A$ een $f_{3} \in A$ bestaat met

$$

f_{1}(0)+2 f_{2}(y)=f_{3}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$. We hebben hiervoor gezien dat we $f_{3}\left(f_{2}(y)+y\right)$ kunnen schrijven als $2 y+f_{3}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)$. Dus

$$

2 f_{2}(y)=2 y+f_{3}\left(f_{2}(0)\right)-f_{1}(0)

$$

voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$. We concluderen dat er een $d \in \mathbb{R}$ is, onafhankelijk van $y$, zodat $f_{2}(y)=y+d$ voor alle $y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Dus elke $f \in A$ is van de vorm $f(x)=x+d$ met $d$ een constante. Er geldt dan

$$

f(x-f(x))=f(x-(x+d))=f(-d)=-d+d=0

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

a) If $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ for positive real numbers $a, b, c$, does it necessarily follow that $a=b=c$?

b) If $a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=c\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ for positive real numbers $a, b, c$, does it necessarily follow that $a=b=c$?

|

a) We claim that $(a, b, c)=(2,2,-1+\sqrt{5})$ satisfies the given equalities. In this triplet, all numbers are positive real and they are not all equal, so the answer to the question is then no.

We calculate $c^{3}=(-1+\sqrt{5})^{3}=-1+3 \cdot \sqrt{5}-3 \cdot 5+5 \sqrt{5}=-16+8 \sqrt{5}$. Now, $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=(-1+\sqrt{5}) \cdot 2 \cdot 8=-16+16 \sqrt{5}$ and $a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)=$ $2 \cdot(-16+8 \sqrt{5}+8)=-16+16 \sqrt{5}$. The given equalities indeed hold.

Here is a possible approach to find this triplet. Assume without loss of generality that $c \leq a, b$. Rewrite $a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ as $a b\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)=c^{3}(b-a)$. If $a \neq b$, we can divide by $b-a$ and get $a b(a+b)=c^{3}$. But $c \leq a, b$ and everything is positive, so $c^{3}<2 c^{3} \leq a^{2} b+a b^{2}=a b(a+b)$, a contradiction. Therefore, it must be that $a=b$. Now we can rewrite $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)$ as $a^{3} c-a c^{3}=a^{4}-a^{3} c$ and then further to $ac \left(a^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a^{3}(a-c)$. Now, $a=c$ (and thus $a=b=c$) or $a c(a+c)=a^{3}$. This second is a quadratic equation in $c$. Solving this gives $c=\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{5}\right) a$. This way we find infinitely many triplets that satisfy the conditions.

b) We will prove that it must always be that $a=b=c$. Assume without loss of generality that $c \leq a, b$. There are two cases (since the given equalities are cyclic but not symmetric).

First, assume that $a \geq b \geq c$. Then,

$$

a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+c^{3}\right)=a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)

$$

so equality must always hold. Since everything is positive, this implies $a=c$ from the first inequality and $b=c$ from the second. Thus, $a=b=c$.

Now, assume that $b \geq a \geq c$. Then,

$$

b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right) \geq c\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)

$$

so equality must always hold. We find $b=c$ from the first inequality and $b=a$ from the second, thus $a=b=c$.

Solution II for b). Assume without loss of generality that $a \geq b, c$. Then,

$$

a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq b\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq b\left(c^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)

$$

so equality must always hold. Since everything is positive, this implies $a=b$ from the first inequality and $a=c$ from the second. Thus, $a=b=c$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

a) Als $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ voor positieve reële getallen $a, b, c$, geldt dan noodzakelijk $a=b=c$ ?

b) Als $a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=c\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ voor positieve reële getallen $a, b, c$, geldt dan noodzakelijk $a=b=c$ ?

|

a) We beweren dat $(a, b, c)=(2,2,-1+\sqrt{5})$ aan de gegeven gelijkheden voldoet. In dit drietal zijn alle getallen positief reëel en ze zijn niet allemaal gelijk, dus het antwoord op de vraag is dan nee.

We berekenen $c^{3}=(-1+\sqrt{5})^{3}=-1+3 \cdot \sqrt{5}-3 \cdot 5+5 \sqrt{5}=-16+8 \sqrt{5}$. Nu geldt $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=(-1+\sqrt{5}) \cdot 2 \cdot 8=-16+16 \sqrt{5}$ en $a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)=$ $2 \cdot(-16+8 \sqrt{5}+8)=-16+16 \sqrt{5}$. De gegeven gelijkheden gelden dus inderdaad.

Hier een mogelijke aanpak om dit drietal te vinden. Neem zonder verlies van algemeenheid aan dat $c \leq a, b$. Herschrijf $a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(c^{3}+a^{3}\right)$ tot $a b\left(b^{2}-a^{2}\right)=c^{3}(b-a)$. Als $a \neq b$ kunnen we delen door $b-a$ en volgt $a b(a+b)=c^{3}$. Maar $c \leq a, b$ en alles is positief, dus $c^{3}<2 c^{3} \leq a^{2} b+a b^{2}=a b(a+b)$, tegenspraak. Er moet dus wel gelden $a=b$. Nu kunnen we $c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)$ herschrijven tot $a^{3} c-a c^{3}=a^{4}-a^{3} c$ en dan verder tot ac $\left(a^{2}-c^{2}\right)=a^{3}(a-c)$. Nu geldt $a=c$ (en dus $a=b=c$ ) of $a c(a+c)=a^{3}$. Dit tweede is een kwadratische vergelijking in $c$. Dit oplossen geeft dat $c=\left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{5}\right) a$. Zo vinden we oneindig veel drietallen die voldoen.

b) We gaan bewijzen dat altijd moet gelden dat $a=b=c$. Neem zonder verlies van algemeenheid aan dat $c \leq a, b$. Nu zijn er twee gevallen (want de gegeven gelijkheden zijn slechts cyclisch en niet symmetrisch).

Stel eerst dat $a \geq b \geq c$. Dan geldt

$$

a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+c^{3}\right)=a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)

$$

dus er moet steeds gelijkheid gelden. Omdat alles positief is, volgt daaruit $a=c$ bij de eerste ongelijkheid en $b=c$ bij de tweede. Dus $a=b=c$.

Stel nu dat $b \geq a \geq c$. Dan geldt

$$

b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right) \geq c\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right) \geq c\left(a^{3}+c^{3}\right)=b\left(b^{3}+c^{3}\right)

$$

dus ook hier moet steeds gelijkheid gelden. We vinden nu $b=c$ bij de eerste ongelijkheid en $b=a$ bij de tweede, dus $a=b=c$.

Oplossing II voor b). Neem zonder verlies van algemeenheid aan dat $a \geq b, c$. Dan geldt

$$

a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq b\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right) \geq b\left(c^{3}+b^{3}\right)=a\left(a^{3}+b^{3}\right)

$$

dus er moet steeds gelijkheid gelden. Omdat alles positief is, volgt daaruit $a=b$ bij de eerste ongelijkheid en $a=c$ bij de tweede. Dus $a=b=c$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find all positive integers $n$ for which there exists a positive integer $k$ such that for every positive divisor $d$ of $n$, $d-k$ is also a (not necessarily positive) divisor of $n$.

|

When $n=1$ or $n$ is a prime number, the only positive divisors of $n$ are 1 and $n$ (which coincide in the case $n=1$). Now take $k=n+1$, then $1-(n+1)=-n$ and $n-(n+1)=-1$ must also be divisors of $n$. This is exactly correct. So $n=1$ and $n$ being prime satisfy the condition with $k=n+1$. If $n=4$, the positive divisors are 1, 2, and 4. We choose $k=3$, so $-2, -1$, and 1 must be divisors of 4, and this is correct. So $n=4$ satisfies the condition with $k=3$. If $n=6$, then the positive divisors are $1, 2, 3$, and 6. We choose $k=4$, so $-3, -2, -1$, and 2 must also be divisors of 6, and this is correct. So $n=6$ satisfies the condition with $k=4$. In summary, we now know that $n \leq 6$ and all prime numbers $n$ satisfy the condition.

Now assume $n>6$ and $n$ is not prime. Suppose $n$ satisfies the condition. Since $n$ is a positive divisor of $n$, $n-k$ is also a divisor of $n$. The largest divisor less than $n$ is at most $\frac{1}{2} n$, so $n-k \leq \frac{1}{2} n$, thus $k \geq \frac{1}{2} n$. Furthermore, 1 is a positive divisor of $n$, so $1-k$ is a divisor of $n$. We now know $1-k \leq 1-\frac{1}{2} n$. Since $n>6$, $\frac{1}{6} n>1$, so $\frac{1}{2} n-\frac{1}{3} n>1$, thus $-\frac{1}{3} n>1-\frac{1}{2} n$. The only divisors that are at most $1-\frac{1}{2} n$ are $-n$ and (if $n$ is even) $-\frac{1}{2} n$. We conclude that $1-k=-n$ or $1-k=-\frac{1}{2} n$.

In the latter case, $k=\frac{1}{2} n+1$, so $n-k=\frac{1}{2} n-1$. However, similarly to the above, there is no divisor equal to $\frac{1}{2} n-1$ for $n>6$ (since after $\frac{1}{2} n$, the next possible divisor is $\frac{1}{3} n$, which is already smaller than $\frac{1}{2} n-1$). Contradiction, because $n-k$ must be a divisor of $n$.

We are left with the case $1-k=-n$. So $k=n+1$. Since $n$ is not prime, there is a divisor $d$ with $1<d<n$. Therefore, $d-k=d-n-1$ is also a divisor. But $d \leq \frac{1}{2} n$, so $d-n-1 \leq -\frac{1}{2} n-1$, and the only divisor less than or equal to $-\frac{1}{2} n-1$ is $-n$. We see that $d-n-1=-n$, so $d=1$, contradiction.

We conclude that all $n$ with $n>6$ and $n$ not prime do not satisfy the condition, so the only solutions are all $n$ with $n \leq 6$ and all $n$ that are prime.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle positieve gehele getallen $n$ waarvoor er een positief geheel getal $k$ bestaat zodat voor iedere positieve deler $d$ van $n$ geldt dat ook $d-k$ een (niet noodzakelijk positieve) deler van $n$ is.

|

Als $n=1$ of $n$ is een priemgetal, dan zijn de enige positieve delers van $n$ gelijk aan 1 en $n$ (die samenvallen in het geval $n=1$ ). Neem nu $k=n+1$, dan moeten $1-(n+1)=-n$ en $n-(n+1)=-1$ ook delers zijn van $n$. Dat klopt precies. Dus $n=1$ en $n$ is priem voldoen met $k=n+1$. Als $n=4$, zijn de positieve delers 1,2 en 4 . We kiezen $k=3$, waardoor $-2,-1$ en 1 delers van 4 moeten zijn en dat klopt. Dus $n=4$ voldoet met $k=3$. Als $n=6$, dan zijn de positieve delers $1,2,3$ en 6 . We kiezen $k=4$, waardoor $-3,-2,-1$ en 2 ook delers van 6 moeten zijn en dat klopt. Dus $n=6$ voldoet met $k=4$. Al met al weten we nu dat $n \leq 6$ en alle priemgetallen $n$ voldoen.

Stel nu dat $n>6$ en $n$ is niet priem. Neem aan dat $n$ voldoet. Omdat $n$ een positieve deler is van $n$, is $n-k$ ook een deler van $n$. De grootste deler kleiner dan $n$ is hoogstens $\frac{1}{2} n$, dus $n-k \leq \frac{1}{2} n$, dus $k \geq \frac{1}{2} n$. Verder is 1 een positieve deler van $n$, dus is $1-k$ een deler van $n$. We weten nu $1-k \leq 1-\frac{1}{2} n$. Aangezien $n>6$, is $\frac{1}{6} n>1$, dus $\frac{1}{2} n-\frac{1}{3} n>1$, dus $-\frac{1}{3} n>1-\frac{1}{2} n$. De enige delers die hoogstens $1-\frac{1}{2} n$ zijn, zijn dus $-n$ en (als $n$ even is) $-\frac{1}{2} n$. We concluderen dat $1-k=-n$ of $1-k=-\frac{1}{2} n$.

In het laatste geval geldt $k=\frac{1}{2} n+1$, dus $n-k=\frac{1}{2} n-1$. Echter, analoog aan het voorgaande is er voor $n>6$ geen deler gelijk aan $\frac{1}{2} n-1$ (want na $\frac{1}{2} n$ is de volgende mogelijke deler $\frac{1}{3} n$ en die is al kleiner dan $\frac{1}{2} n-1$ ). Tegenspraak, want $n-k$ moet een deler van $n$ zijn.

We houden het geval $1-k=-n$ over. Dus $k=n+1$. Omdat $n$ niet priem is, is er een deler $d$ met $1<d<n$. Daarom is $d-k=d-n-1$ ook een deler. Maar $d \leq \frac{1}{2} n$, dus $d-n-1 \leq-\frac{1}{2} n-1$, maar de enige deler kleiner dan of gelijk aan $-\frac{1}{2} n-1$ is $-n$. We zien dat $d-n-1=-n$, dus $d=1$, tegenspraak.

We concluderen dat alle $n$ met $n>6$ en $n$ niet priem niet voldoen, dus de enige oplossingen zijn alle $n$ met $n \leq 6$ en alle $n$ die priem zijn.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2018-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find all positive integers $n$ for which there exists a positive integer $k$ such that for every positive divisor $d$ of $n$, $d-k$ is also a (not necessarily positive) divisor of $n$.

|

Consider an $n \geq 2$ that satisfies the condition. Since 1 is a positive divisor of $n$, $1-k$ is a divisor of $n$. This must be a negative divisor, since $k$ is a positive integer. If we write this divisor as $-d$ with $d$ a positive divisor of $n$, we have $1-k=-d$, so $d+1=k$. Since $n$ is a positive divisor of $n$, $n-k=n-d-1$ is also a divisor of $n$. Note that $\operatorname{gcd}(d, n-d-1)=\operatorname{gcd}(d,-1)=1$ because $d \mid n$. This means that $d(n-d-1)$ is also a divisor of $n$. Therefore, $d(n-d-1) \leq n$.

Suppose $d=n$. Consider the smallest prime divisor $p$ of $n$ and write $n=p m$ with $m$ a positive integer. Now, $m$ is the largest divisor of $n$ that is smaller than $n$, and $p-k=p-d-1=p-n-1$ is a divisor of $n$. But $p-n-1>-n$ and $p-n-1=p-p m-1=p(1-m)-1 \leq 2(1-m)-1=-2 m+1 \leq -m$. However, there are no divisors between $-n$ and $-m$, so equality must hold in the last inequality. This can only happen if $m=1$, which means $n$ is prime.