problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

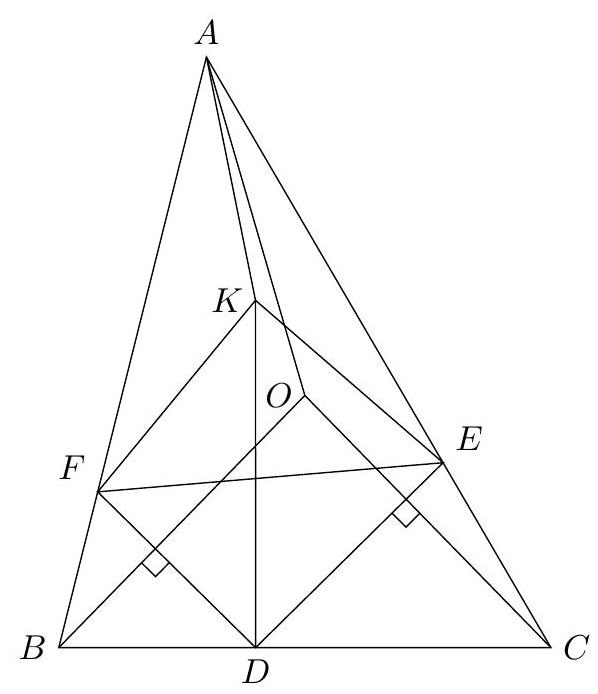

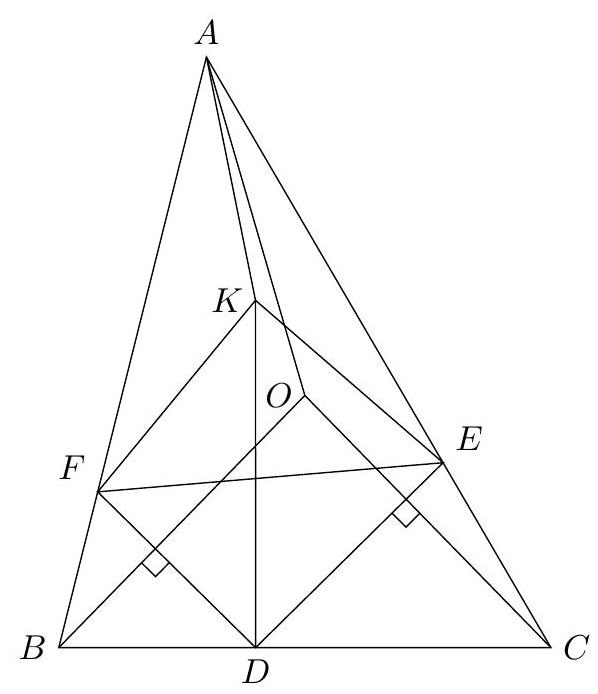

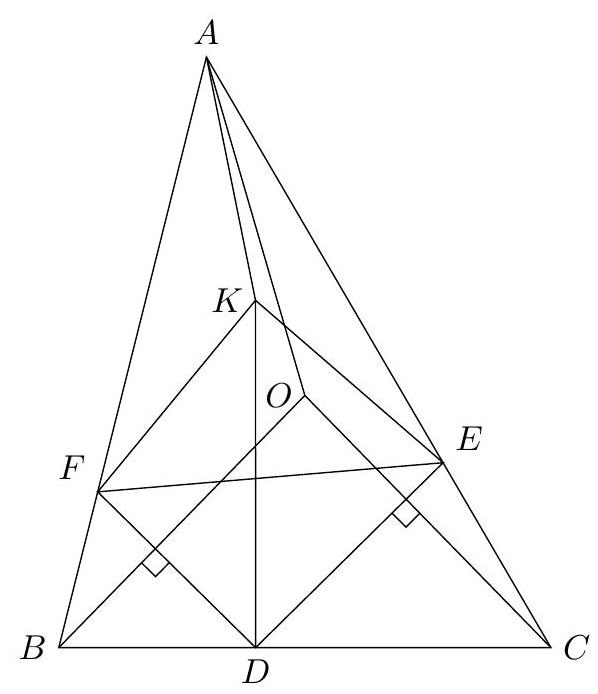

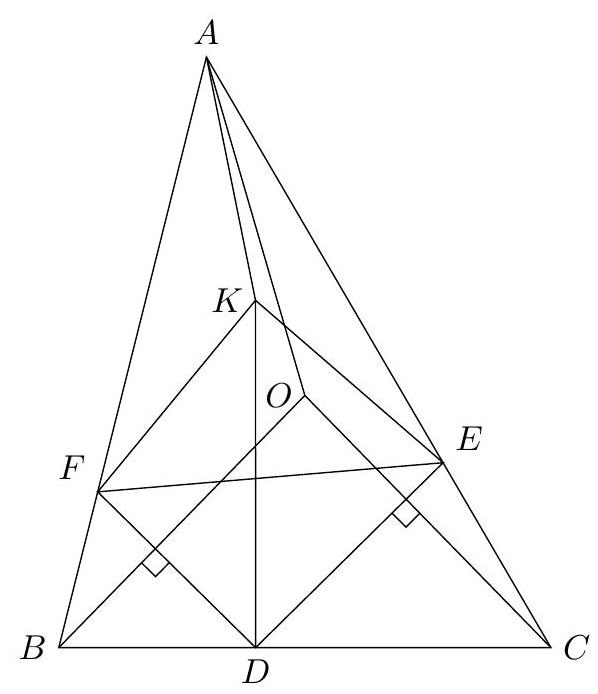

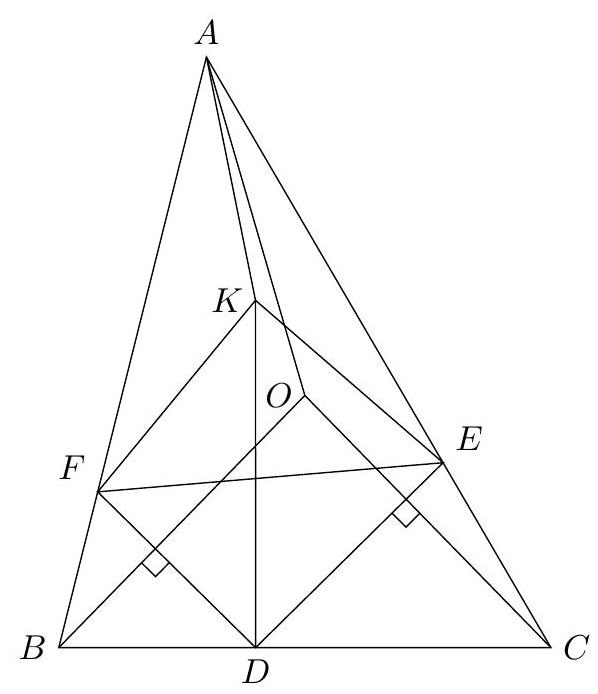

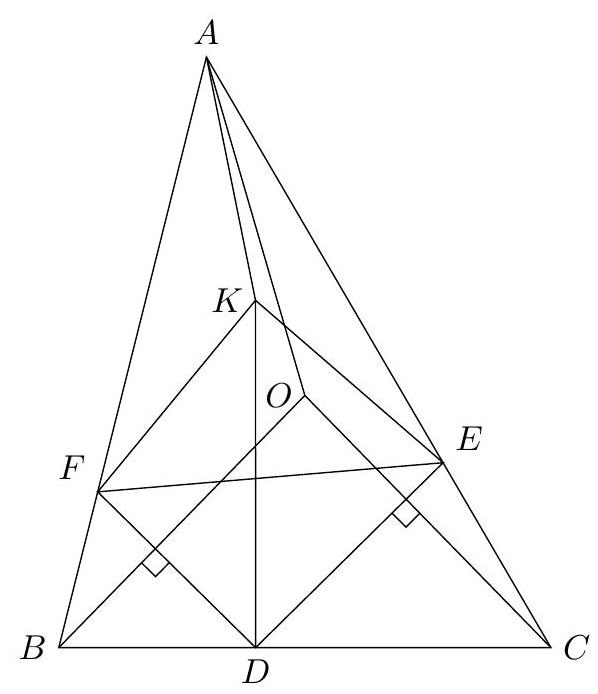

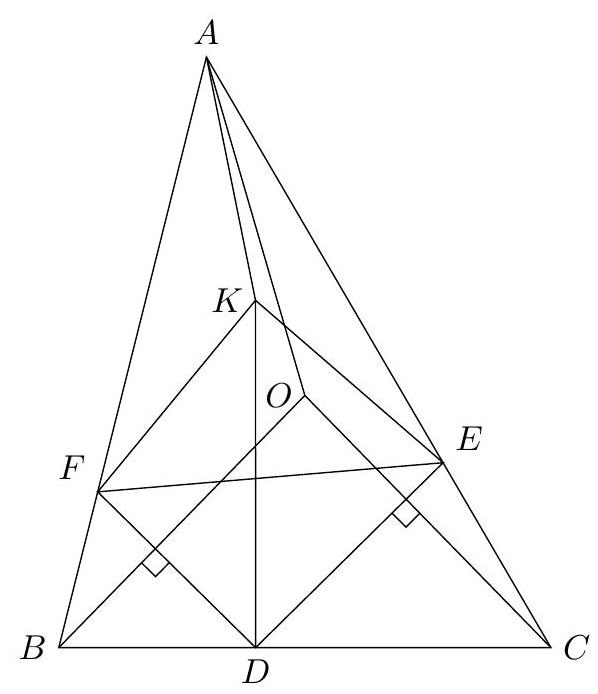

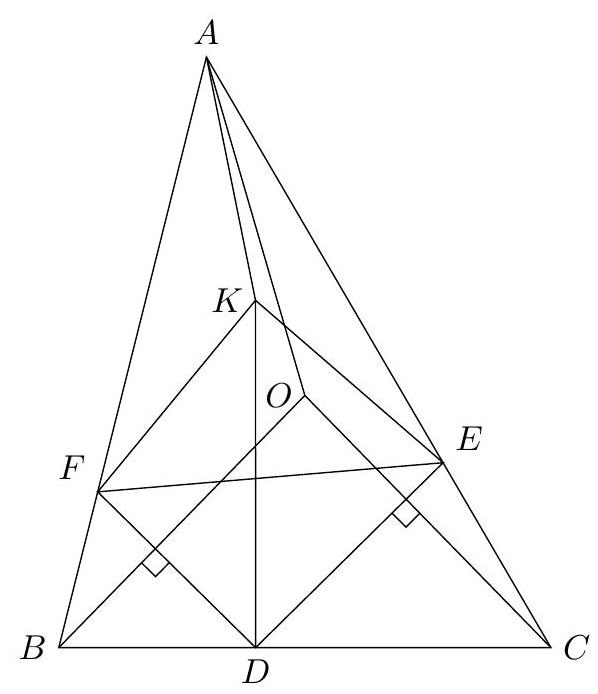

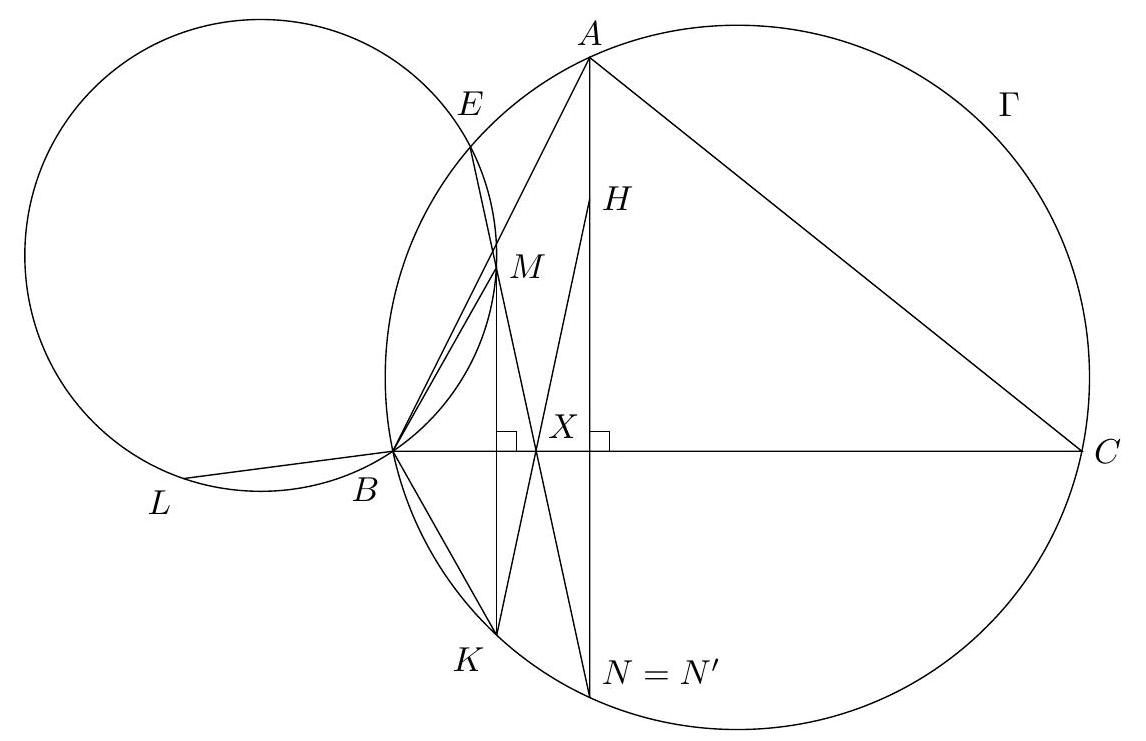

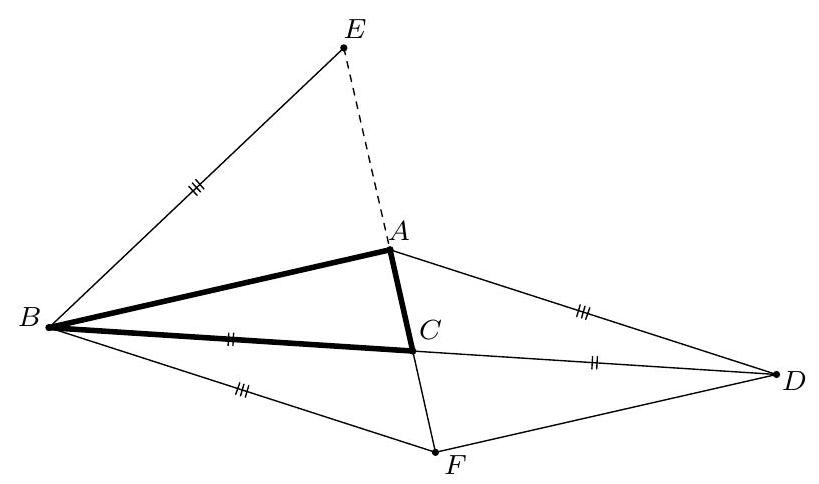

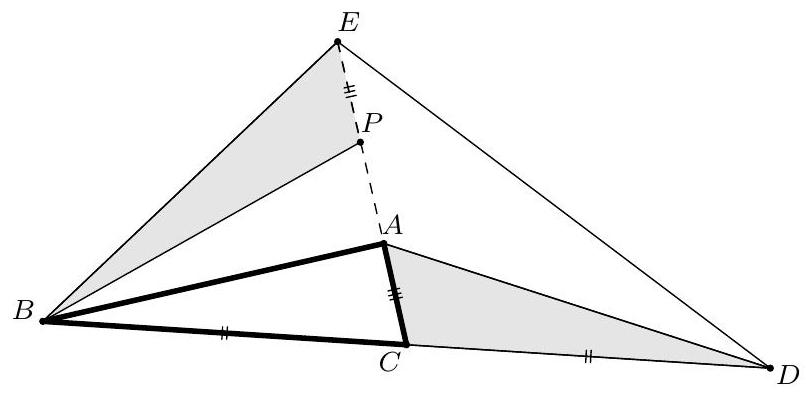

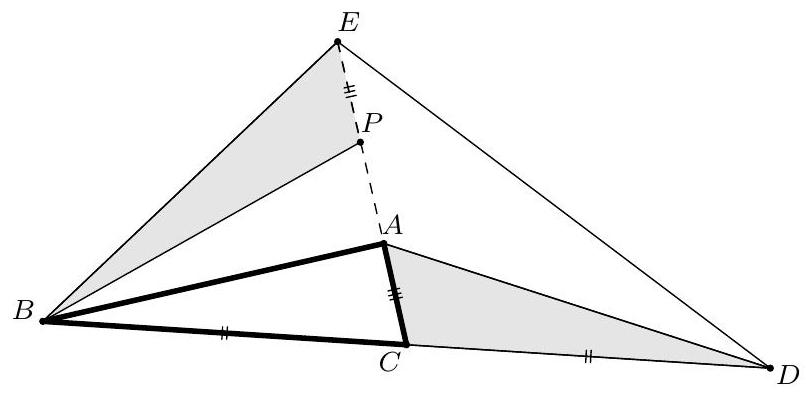

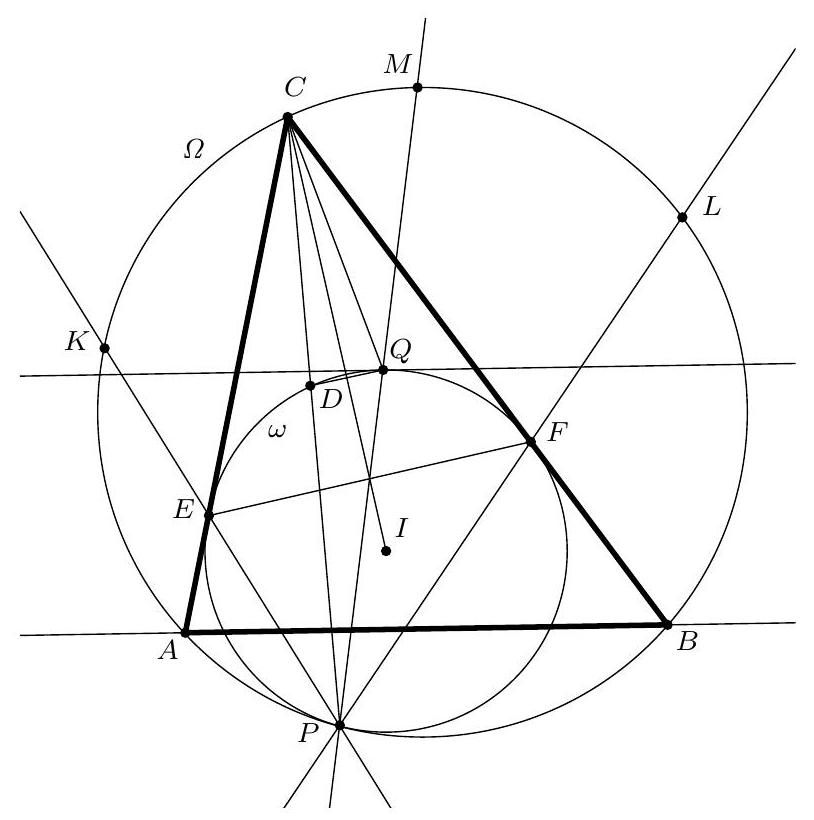

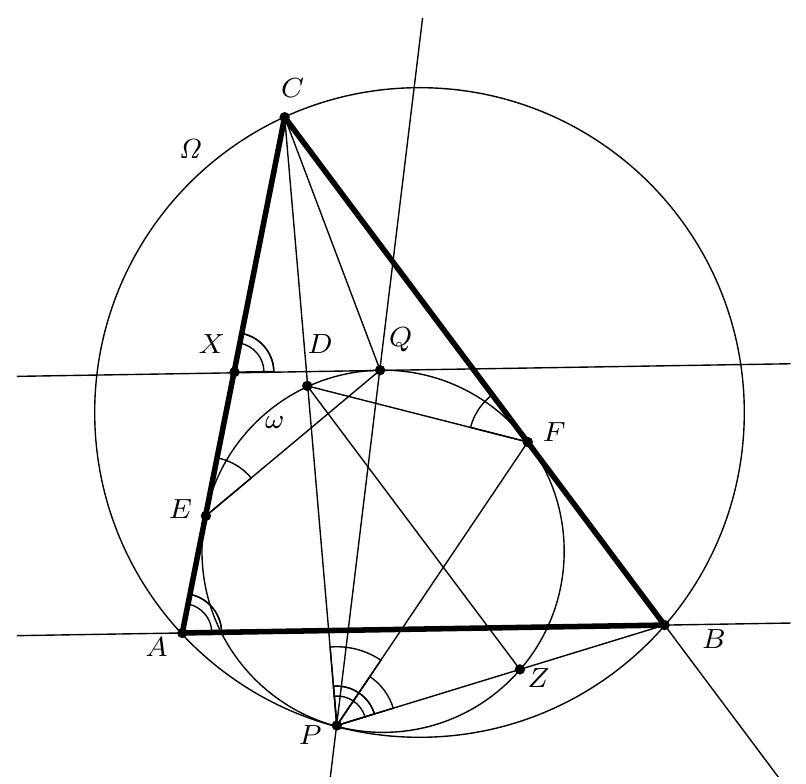

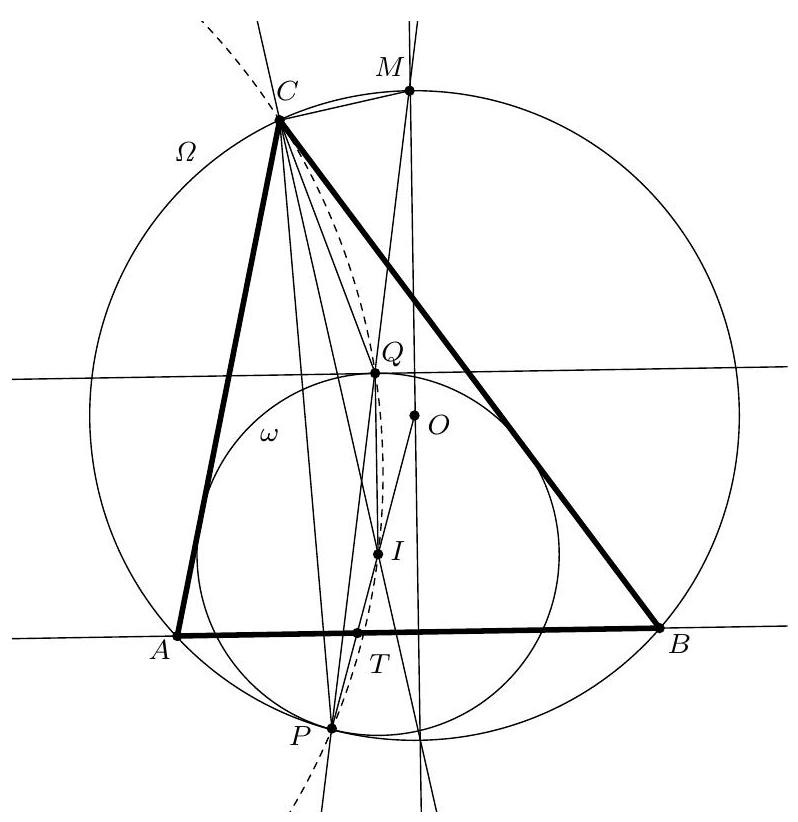

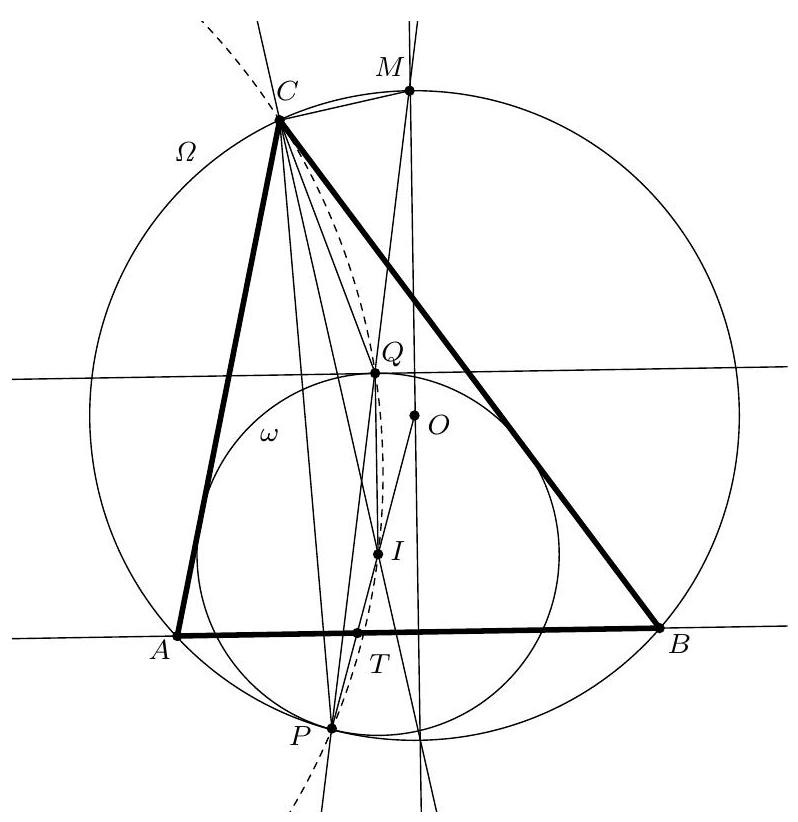

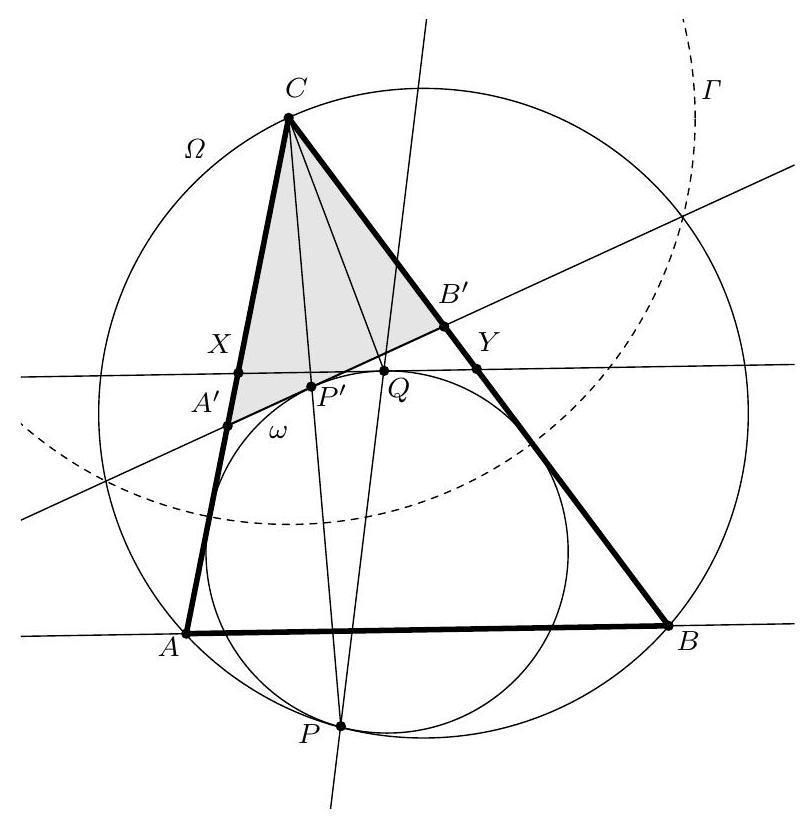

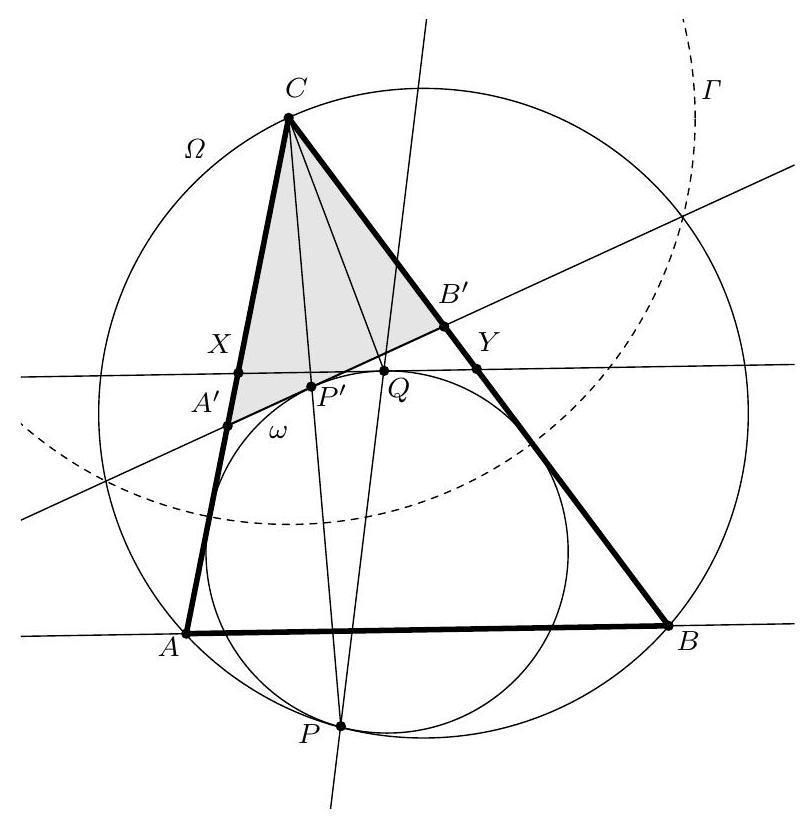

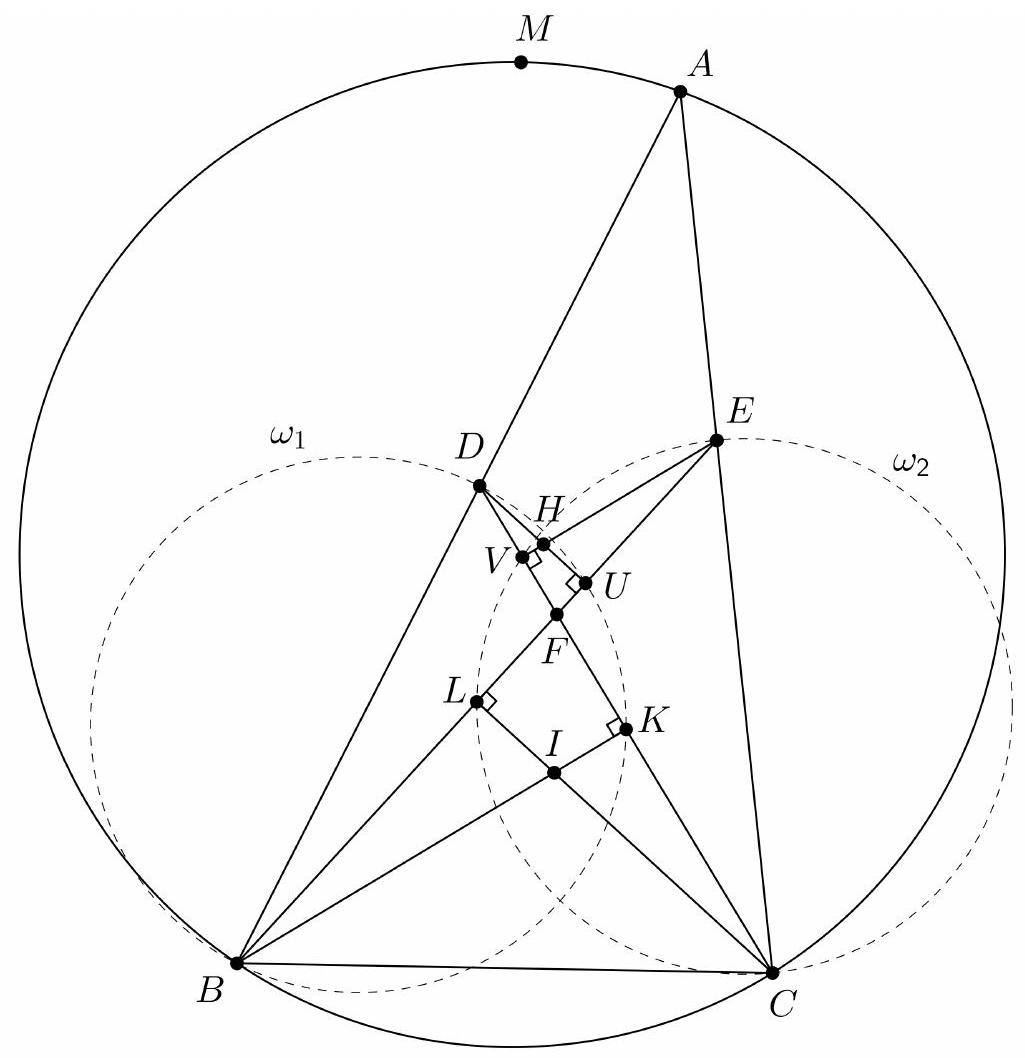

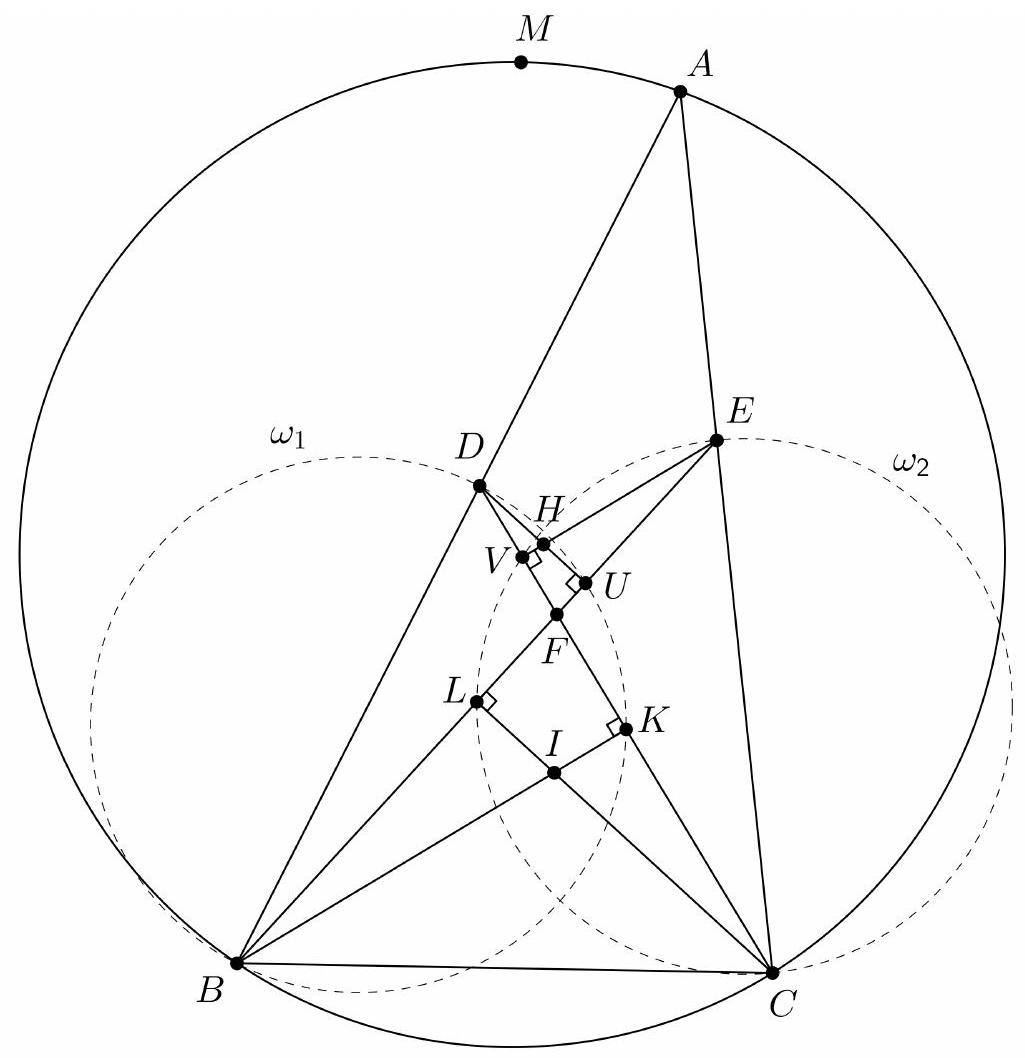

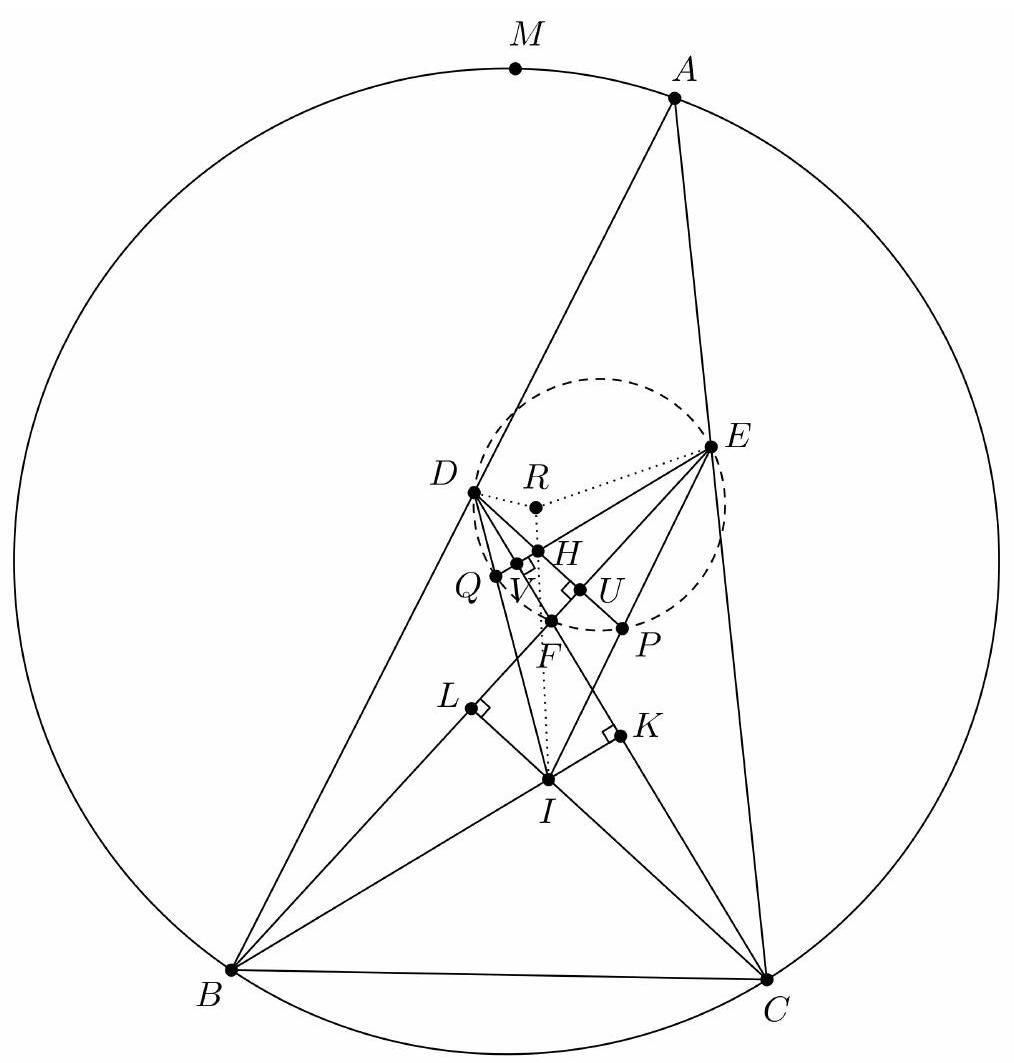

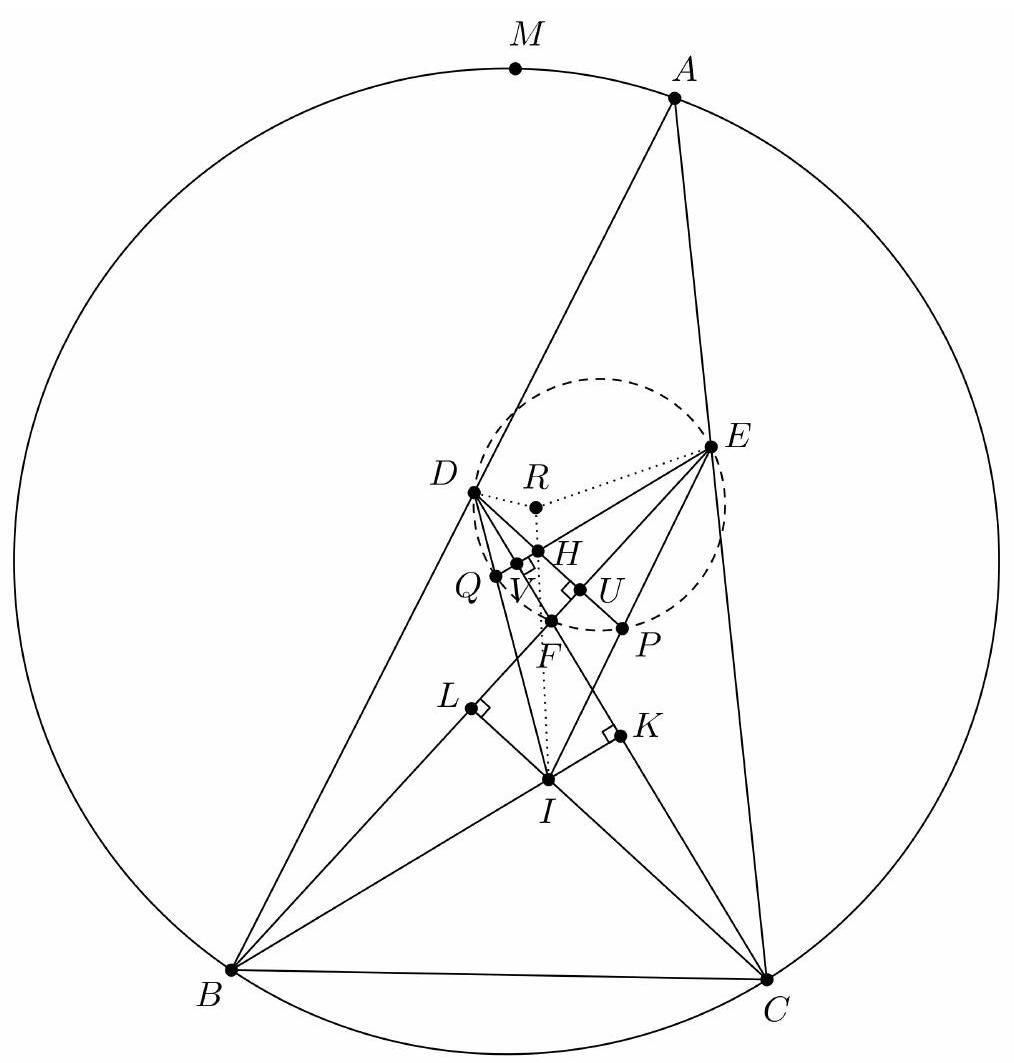

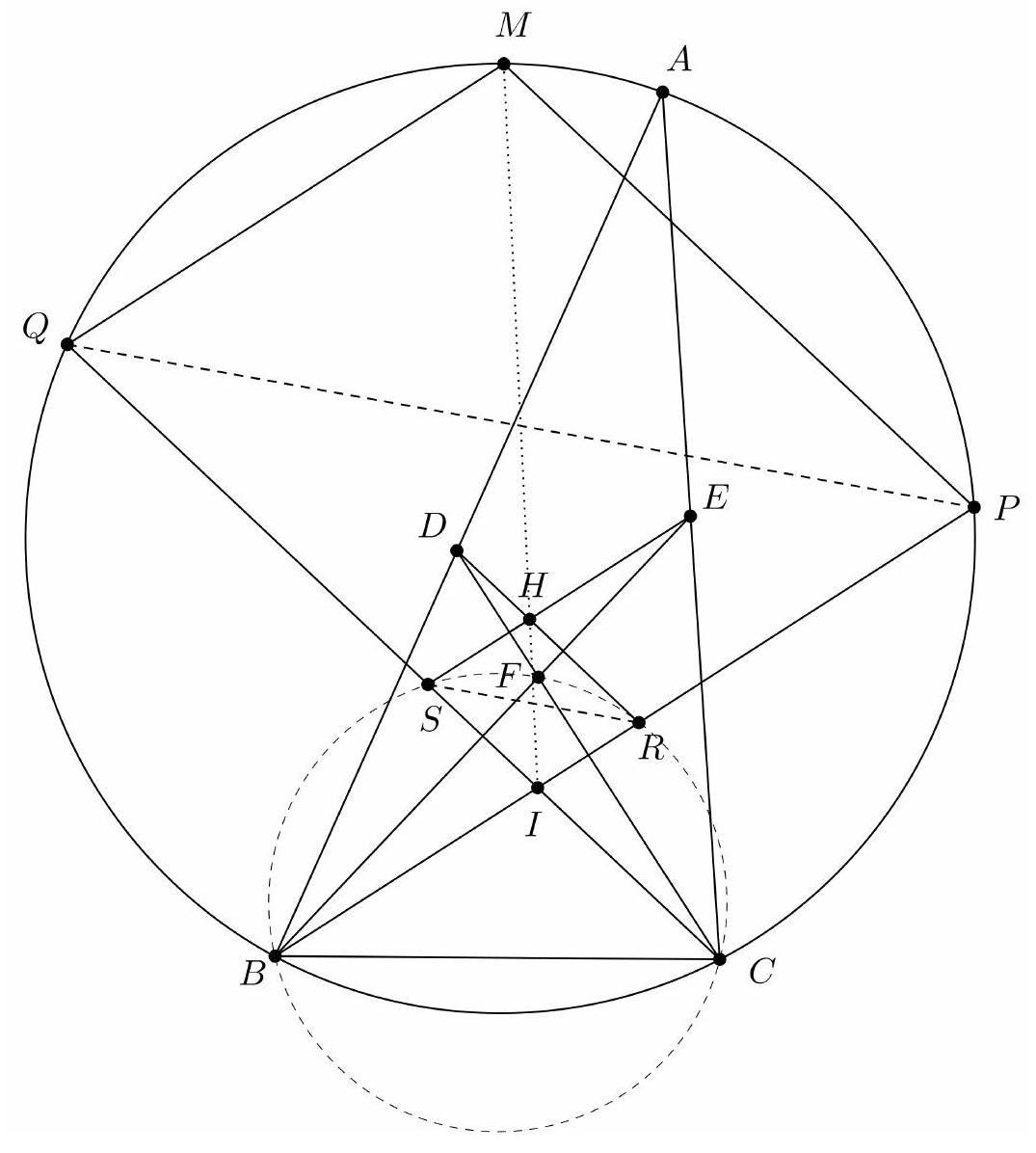

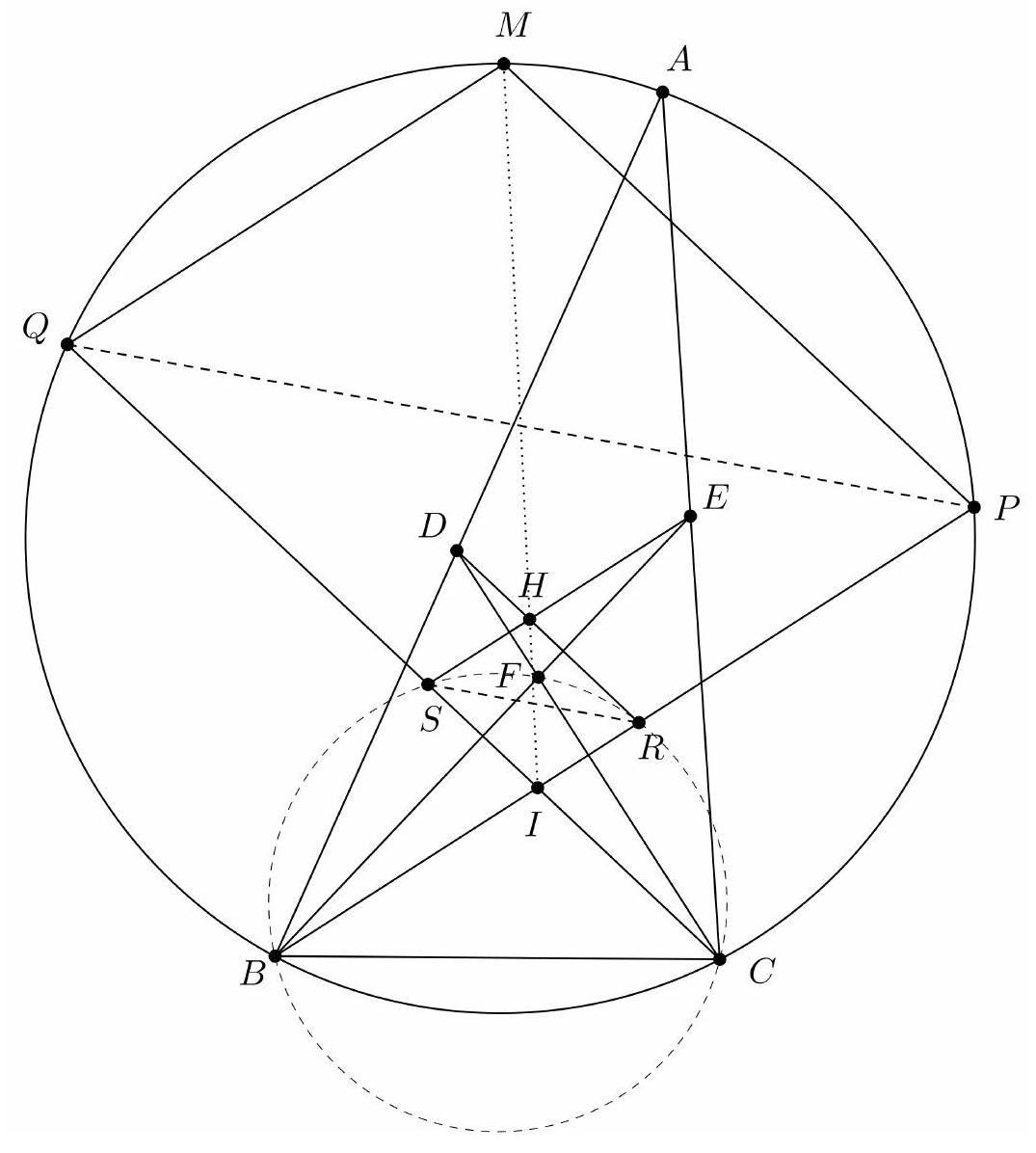

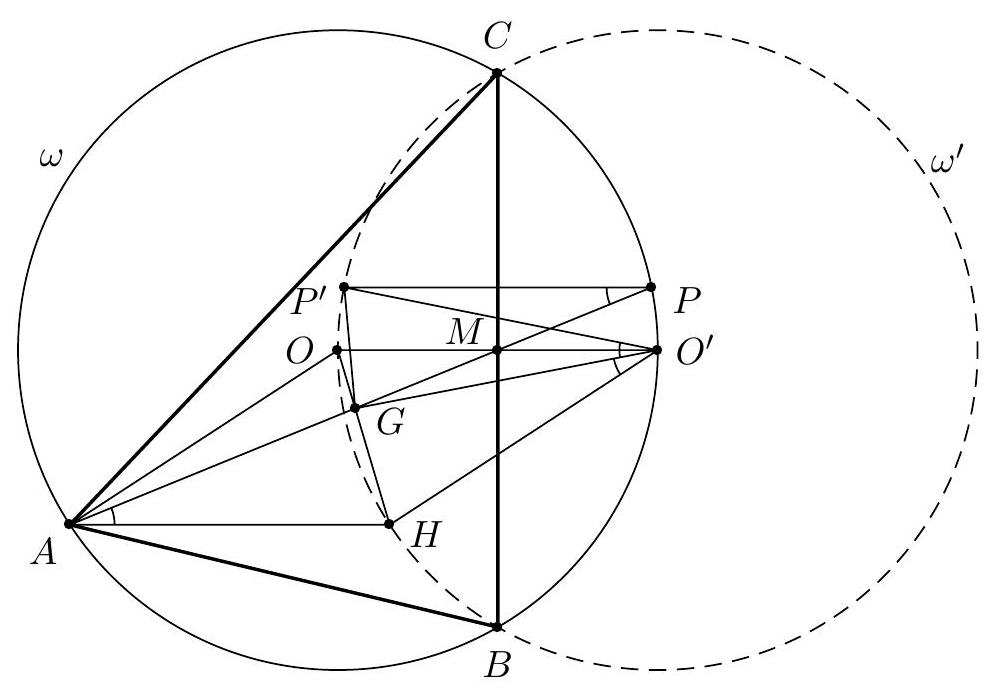

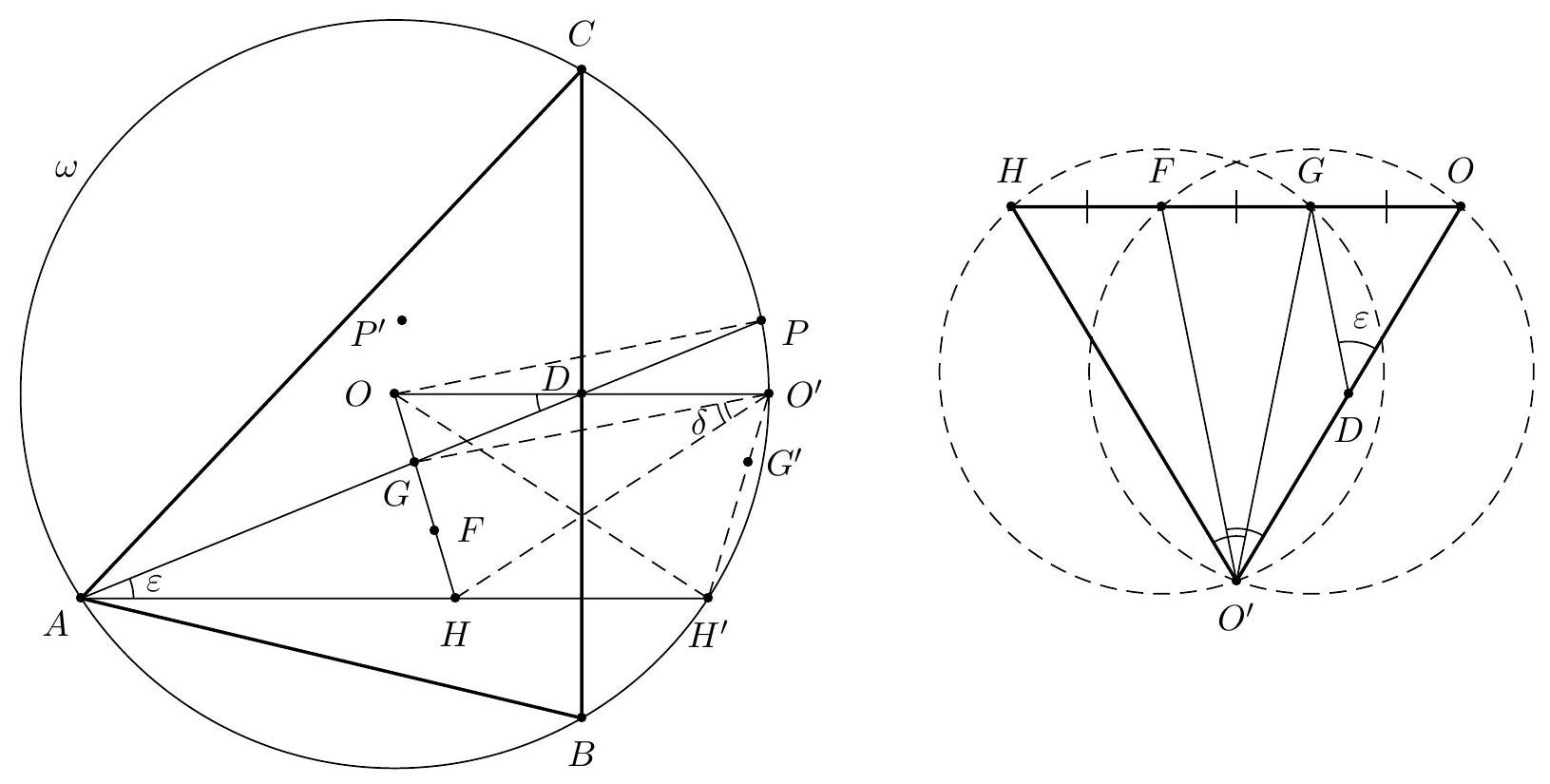

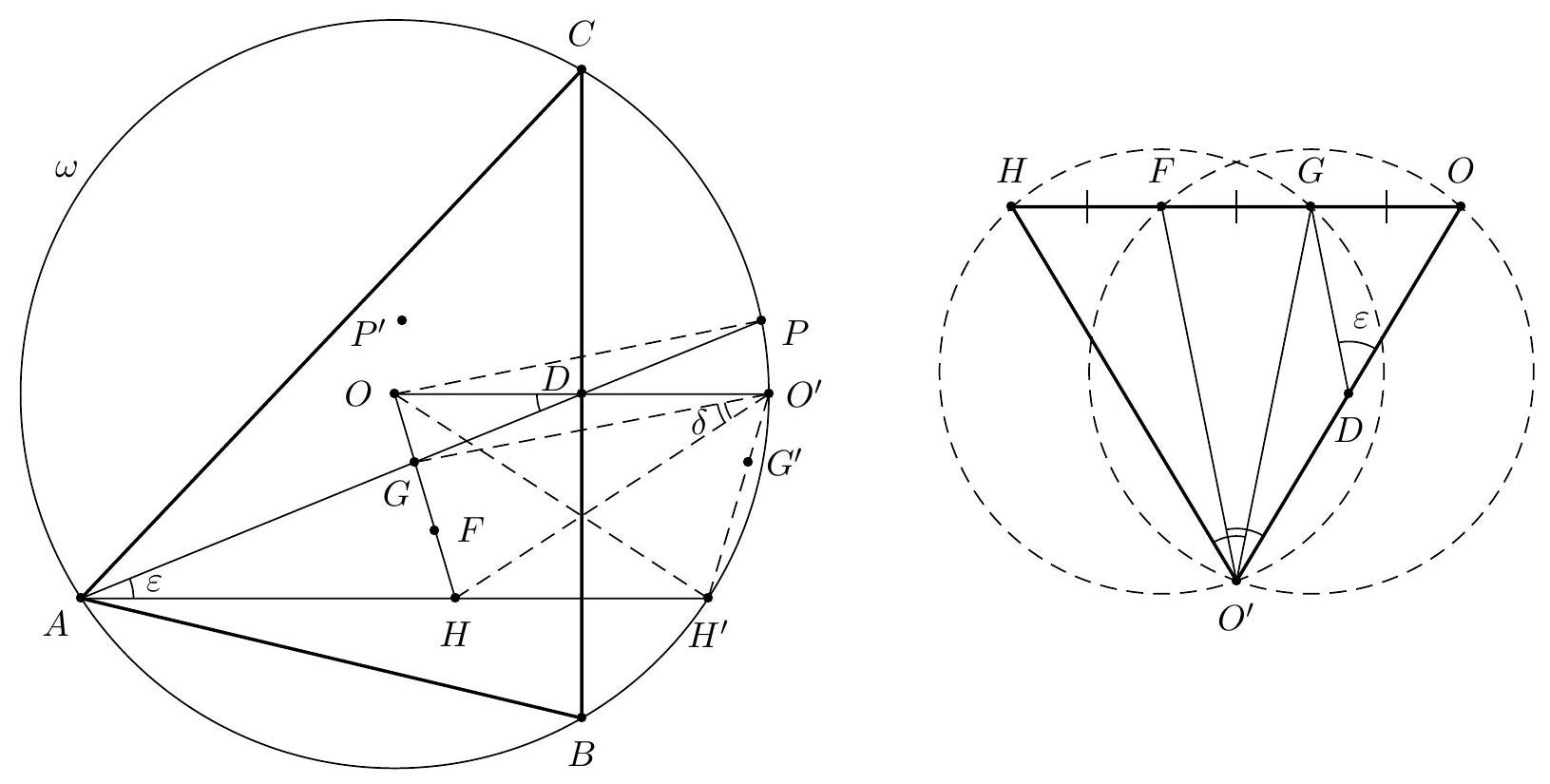

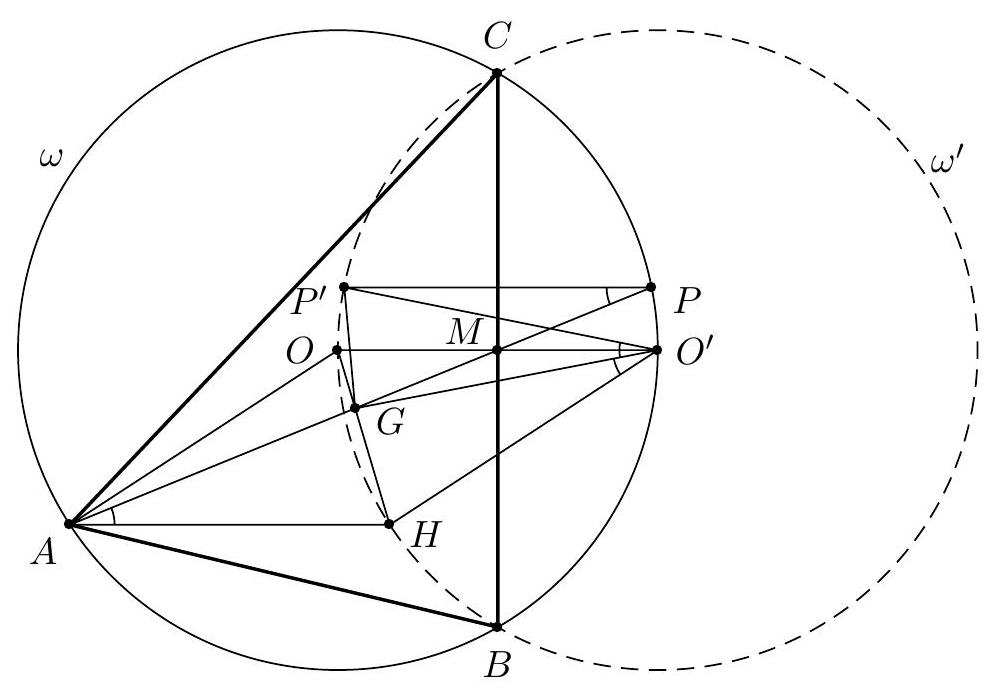

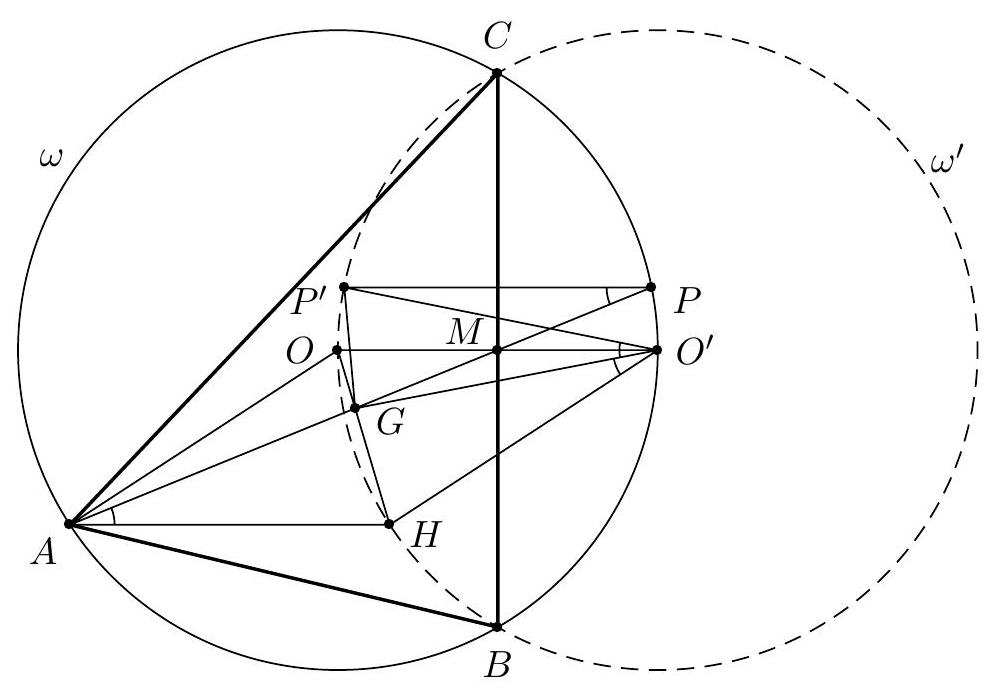

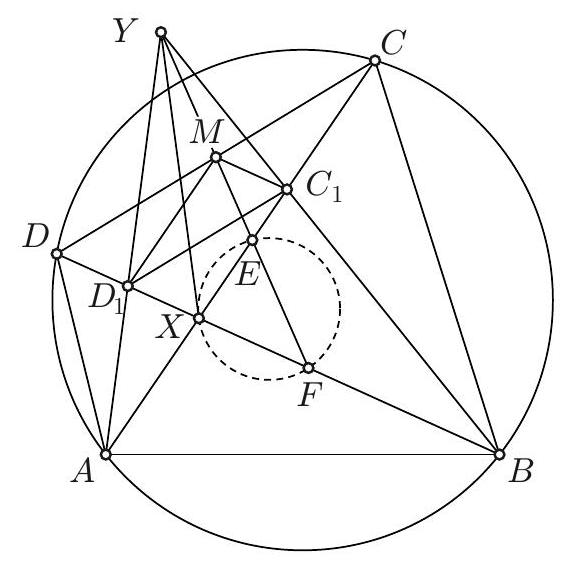

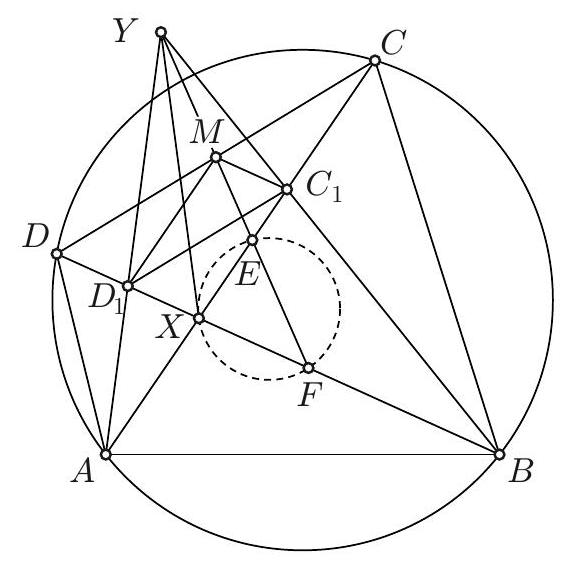

Let \(\triangle ABC\) be an acute triangle such that \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) and \(|AB| < |BC|\). Let \(D\) be the intersection of the angle bisector of \(\angle ABC\) with the side \(AC\). Points \(P\) and \(Q\) lie on the line segment \(BD\) such that \(|BP| = 2|DQ|\). Let \(\ell\) be the line through \(P\) parallel to \(AC\). The line through \(Q\) perpendicular to \(BD\) intersects the line segments \(AB\) and \(BC\) at points \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively. Assume that \(X\) and \(Y\) lie on the opposite side of \(\ell\) from \(B\).

A ant starts its journey at \(X\) and from there goes to a point on \(AC\), then to a point on \(\ell\), then back to a (possibly different) point on \(AC\), and finally to \(Y\). Prove that the length of the shortest possible route of the ant is equal to \(4|XY|\).

|

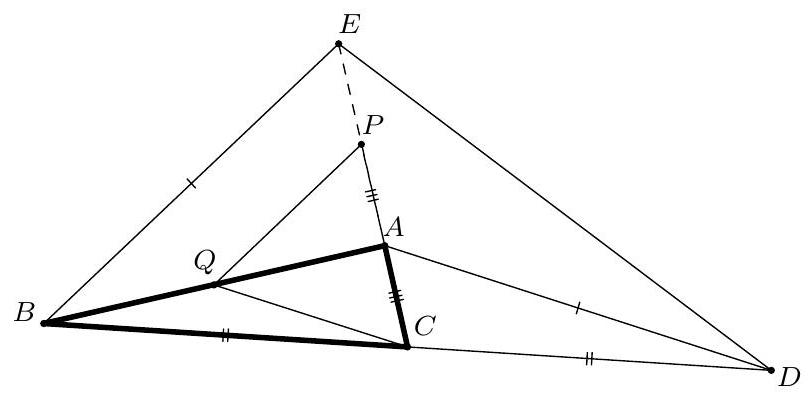

Let \(R\), \(S\), and \(T\) be the points where the ant first reaches \(AC\), first reaches \(\ell\), and secondly reaches \(AC\) again, respectively. Let \(\ell'\) and \(S'\) be the reflections of \(\ell\) and \(S\) in \(AC\), and let \(Y'\) be the reflection of \(Y\) in \(\ell'\). Then, by the triangle inequality for the total length of the ant's path, we have

\[

\begin{align*}

|XR| + |RS| + |ST| + |TY| &= |XR| + |RS'| + |S'T| + |TY| \\

&\ge |XS'| + |S'Y| \\

&= |XS'| + |S'Y'| \\

&\ge |XY'|,

\end{align*}

\]

with equality if \(S'\) lies on \(XY'\), \(R\) lies on \(XS'\), and \(T\) lies on \(S'Y\). Therefore, it remains to prove that \(|XY'| = 4|XY|\).

Now, redefine \(S'\) as the intersection of \(XY'\) and \(\ell'\). By definition, \(\ell'\) is the external angle bisector of \(\angle XS'Y\). We also define \(B'\) as the intersection of \(BQ\) with \(\ell'\). Then \(B'\) also lies on the perpendicular bisector of \(XY\), so \(B'\) is the second Brocard point of \(\triangle XYS'\). (Note that \(BQ\) is neither parallel to \(\ell'\) nor perpendicular to it, because \(\ell' \parallel AC\) and \(\triangle BAC\) is not isosceles. Thus, this Brocard point is well-defined and distinct from \(S'\).) In particular, \(XYB'S'\) is a cyclic quadrilateral. By our definition of \(\ell'\), \(B'\) is also the reflection of

\(P\) in \(D\). Therefore, together with the condition that \(2|QD| = |BP|\), we calculate that

\[

\begin{align*}

|QB'| &= |QD| + |DB'| \\

&= |QD| + |PD| \\

&= |QD| + |PQ| + |QD| \\

&= |BP| + |PQ| \\

&= |BQ|.

\end{align*}

\]

Since \(Q\) is also the midpoint of \(XY\) and the diagonals are perpendicular to each other, we conclude that \(BXB'Y\) is a rhombus. Now we will angle chase with this cyclic quadrilateral, this rhombus, and F-angles:

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle S'XY &= \angle S'B'Y \\

&= \angle S'B'B - \angle YB'B \\

&= \angle CDB - \angle YBB' \\

&= (180^\circ - \frac{1}{2}\angle CBA - \angle ACB) - \frac{1}{2}\angle CBA \\

&= \angle BAC.

\end{align*}

\]

Similarly, \(\angle S'YX = \angle BCA\). Therefore, \(\triangle XYS' \sim \triangle ACB\), and the condition \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) also holds in \(\triangle XYS'\). We conclude that \(|XY'| = |XS'| + |S'Y| = 4|XY|\), which is exactly what we sought. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij \(\triangle ABC\) een scherphoekige driehoek zo dat \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) en \(|AB| < |BC|\). Zij \(D\) het snijpunt van de bissectrice van \(\angle ABC\) met de zijde \(AC\). Punten \(P\) en \(Q\) liggen op het lijnstuk \(BD\) zo dat \(|BP| = 2|DQ|\). Zij \(\ell\) de lijn door \(P\) parallel aan \(AC\). De lijn door \(Q\) loodrecht op \(BD\) snijdt de lijnstukken \(AB\) en \(BC\) in respectievelijk \(X\) en \(Y\). Stel dat \(X\) en \(Y\) aan de andere kant liggen van \(\ell\) dan \(B\).

Een mier begint zijn reis in \(X\) en gaat vanaf daar naar een punt op \(AC\), dan een punt op \(\ell\), dan weer terug naar een (eventueel ander) punt op \(AC\) en uiteindelijk naar \(Y\). Bewijs dat de lengte van de kortst mogelijke route van de mier gelijk is aan \(4|XY|\).

|

Laat \(R\), \(S\) en \(T\) respectievelijk de punten zijn waar de mier de eerste keer op \(AC\) is, op \(\ell\) is en de tweede keer op \(AC\) is. Laat \(\ell'\) en \(S'\) de spiegelingen van \(\ell\) en \(S\) in \(AC\) zijn, en zij \(Y'\) de spiegeling van \(Y\) in \(\ell'\). Dan geldt wegens de driehoekongelijkheid voor de totale lengte van het pad van de mier dat

\[

\begin{align*}

|XR| + |RS| + |ST| + |TY| &= |XR| + |RS'| + |S'T| + |TY| \\

&\ge |XS'| + |S'Y| \\

&= |XS'| + |S'Y'| \\

&\ge |XY'|,

\end{align*}

\]

met gelijkheid als \(S'\) op \(XY'\) ligt, \(R\) op \(XS'\) en \(T\) op \(S'Y\). Dus nu rest ons te bewijzen dat \(|XY'| = 4|XY|\).

Nu herdefiniëren we \(S'\) als het snijpunt van \(XY'\) en \(\ell'\). Dan is \(\ell'\) per definitie de buiten-bissectrice van \(\angle XS'Y\). We definiëren ook \(B'\) als het snijpunt van \(BQ\) met \(\ell'\). Dan ligt \(B'\) ook op de middelloodlijn van \(XY\), dus \(B'\) is het tweede BOM-punt van \(\triangle XYS'\). (Merk op dat \(BQ\) niet parallel is aan \(\ell'\) of er loodrecht op staat, want \(\ell' \parallel AC\) en \(\triangle BAC\) is niet gelijkbenig. Dus dit BOM-punt is goed gedefinieerd en ongelijk aan \(S'\).) In het bijzonder is \(XYB'S'\) een koordenvierhoek. Wegens onze definitie van \(\ell'\) is \(B'\) ook de spiegeling van

\(P\) in \(D\). Dus samen met de voorwaarde dat \(2|QD| = |BP|\) rekenen we uit dat

\[

\begin{align*}

|QB'| &= |QD| + |DB'| \\

&= |QD| + |PD| \\

&= |QD| + |PQ| + |QD| \\

&= |BP| + |PQ| \\

&= |BQ|.

\end{align*}

\]

Omdat \(Q\) ook het midden is van \(XY\) en de diagonalen loodrecht op elkaar staan, concludeer en we dat \(BXB'Y\) een ruit is. Nu gaan we hoekenjagen met deze koordenvierhoek, deze ruit en F-hoeken:

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle S'XY &= \angle S'B'Y \\

&= \angle S'B'B - \angle YB'B \\

&= \angle CDB - \angle YBB' \\

&= (180^\circ - \frac{1}{2}\angle CBA - \angle ACB) - \frac{1}{2}\angle CBA \\

&= \angle BAC.

\end{align*}

\]

Analog geldt dat \(\angle S'YX = \angle BCA\). Dus \(\triangle XYS' \sim \triangle ACB\), waardoor de voorwaarde \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) ook in \(\triangle XYS'\) geldt. We concluderen dat \(|XY'| = |XS'| + |S'Y| = 4|XY'|\), wat precies is wat we zochten. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-C2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Let \(\triangle ABC\) be an acute triangle such that \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) and \(|AB| < |BC|\). Let \(D\) be the intersection of the angle bisector of \(\angle ABC\) with the side \(AC\). Points \(P\) and \(Q\) lie on the line segment \(BD\) such that \(|BP| = 2|DQ|\). Let \(\ell\) be the line through \(P\) parallel to \(AC\). The line through \(Q\) perpendicular to \(BD\) intersects the line segments \(AB\) and \(BC\) at points \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively. Assume that \(X\) and \(Y\) lie on the opposite side of \(\ell\) from \(B\).

A ant starts its journey at \(X\) and from there goes to a point on \(AC\), then to a point on \(\ell\), then back to a (possibly different) point on \(AC\), and finally to \(Y\). Prove that the length of the shortest possible route of the ant is equal to \(4|XY|\).

|

We provide an alternative to the (subtle use of the) BOM-lemma. Define \(B'\) again as the intersection of \(BQ\) with \(\ell'\). Since \(BXB'Y\) is a rhombus and \(Y'\) is the reflection of \(Y\), it follows that \(|B'X| = |B'Y| = |B'Y'|\). Therefore, \(B'\) is the circumcenter of \(\triangle XYY'\). From this, it follows that \(\angle XYY' = \frac{1}{2}\angle XB'Y\). Thus, by the exterior angle theorem, we have \(\angle XS'Y = \angle XYY' + \angle Y'YS' = 2\angle XYY' = \angle XB'Y\). Therefore, \(XYB'S'\) is a cyclic quadrilateral. From here, we proceed as in Solution I. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij \(\triangle ABC\) een scherphoekige driehoek zo dat \(|AB| + |BC| = 4|AC|\) en \(|AB| < |BC|\). Zij \(D\) het snijpunt van de bissectrice van \(\angle ABC\) met de zijde \(AC\). Punten \(P\) en \(Q\) liggen op het lijnstuk \(BD\) zo dat \(|BP| = 2|DQ|\). Zij \(\ell\) de lijn door \(P\) parallel aan \(AC\). De lijn door \(Q\) loodrecht op \(BD\) snijdt de lijnstukken \(AB\) en \(BC\) in respectievelijk \(X\) en \(Y\). Stel dat \(X\) en \(Y\) aan de andere kant liggen van \(\ell\) dan \(B\).

Een mier begint zijn reis in \(X\) en gaat vanaf daar naar een punt op \(AC\), dan een punt op \(\ell\), dan weer terug naar een (eventueel ander) punt op \(AC\) en uiteindelijk naar \(Y\). Bewijs dat de lengte van de kortst mogelijke route van de mier gelijk is aan \(4|XY|\).

|

We geven een alternatief voor het (subtiele gebruik van het) BOM-lemma. Definieer \(B'\) weer als het snijpunt van \(BQ\) met \(\ell'\). Omdat \(BXB'Y\) een ruit is en \(Y'\) de spiegeling van \(Y\), geldt dat \(|B'X| = |B'Y| = |B'Y'|\). Dus \(B'\) is het middelpunt van de omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle XYY'\). Daaruit volgt dat \(\angle XYY' = \frac{1}{2}\angle XB'Y\). Dus met de buitenhoekstelling geldt nu dat \(\angle XS'Y = \angle XYY' + \angle Y'YS' = 2\angle XYY' = \angle XB'Y\). Dus \(XYB'S'\) is een koordenvierhoek. Vanaf hier gaan we weer verder als Oplossing I. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-C2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Determine all integers \(n \ge 2\) for which \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We will prove that the answer is: all \(n \ge 2\) that are not powers of 2. It holds that

\[ \binom{2n-3}{n-1} = \frac{(2n-3)!}{(n-1)!(n-2)!} = \frac{(2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n}{(n-2)(n-3)\cdots2\cdot1}. \qquad (1) \]

Let \(p\) be a prime factor of \(n\) and assume that \(p > 2\). We know that the following expression is an integer:

\[ \binom{2n-3}{n} = \frac{(2n-3)!}{n!(n-3)!} = \frac{(2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)}{(n-3)(n-4)\cdots2\cdot1}. \]

Let \(e_p(N)\) denote the number of factors \(p\) in an integer \(N\). Now we see that

\[ e_p((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)) \ge e_p((n-3)(n-4)\cdots2\cdot1). \]

Furthermore, since \(p \mid n\) and \(p > 2\), it follows that \(p \nmid n-2\), so multiplying by \(n-2\) does not add any factor \(p\). We conclude that

\[ e_p((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_p((n-2)(n-3)\cdots2\cdot1) \ge e_p(n). \]

Thus, \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) contains at least \(e_p(n)\) factors \(p\). Now, \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) if and only if this result also holds for \(p = 2\).

In a product \(a_1a_2\cdots a_m\), the total number of factors 2 is equal to the sum of the number of \(a_i\) divisible by 2, the number of \(a_i\) divisible by 4, the number of \(a_i\) divisible by 8, etc. Consider now \(n = 2^k\) with \(k \ge 1\). In (1), the numerator is the product of \(2^k, 2^k+1, 2^k+2, \ldots, 2^{k+1}-3\), while the denominator is the product of \(1, 2, 3, \ldots, 2^k-2\). For \(1 \le i \le k-1\), the number of integers from \(1, 2, 3, \ldots, 2^k-2\) divisible by \(2^i\) is exactly the same as the number of integers from \(2^k+1, 2^k+2, 2^k+3, \ldots, 2^{k+1}-2\) divisible by \(2^i\). For \(i \ge k\), both counts are 0. Therefore,

\[ e_2(1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots (2^k-2)) = e_2((2^k+1)(2^k+2)(2^k+3) \cdots (2^{k+1}-2)). \]

On the right side, we divide the product by \(2^{k+1}-2\) (one factor 2) and multiply by \(2^k\) (\(k\) factors 2) to get the product in the numerator. We conclude

\[ e_2(2^k(2^k+1)(2^k+2)(2^k+3)\cdots(2^{k+1}-3)) - e_2(1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots (2^k-2)) = k-1, \]

and thus \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) contains exactly \(k-1\) factors 2, which is not enough to be divisible by \(n\). Therefore, \(n = 2^k\) does not satisfy the condition.

Now consider the case where \(n\) is not a power of 2. Let \(2^k\) be the largest power of 2 less than \(n\). We know that \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) is an integer, so for odd \(n\) it holds that

\[ e_2((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_2((n-2)(n-3)\cdots 2\cdot 1) \ge 0 = e_2(n). \]

If \(n\) is even, then there is a maximum \(\ell\) such that \(2^\ell \mid n\). Since \(n\) is not a power of 2, we note that \(2^{\ell+1} < 3 \cdot 2^\ell \le n < 2^{k+1}\). This means that \(\ell < k\). Furthermore, \(2^k \le n-2\) and thus \(n < 2^{k+1} \le 2n-4\), so the numerator in (1) contains \(2^{k+1}\). Now we consider for each \(i\) the number of factors in the numerator and the denominator divisible by \(2^i\):

- \(i = 1\): there are \(n-2\) integers in each of the products, and \(n\) is even, so the number of integers in the product divisible by 2 is the same in the numerator and the denominator.

- \(2 \le i \le \ell\): in the denominator, there are \(\lfloor \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rfloor\) numbers divisible by \(2^i\); in the numerator, there are \(\lceil \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rceil\) numbers divisible by \(2^i\) since the smallest number is divisible by \(2^i\); therefore, there is one more in the numerator than in the denominator.

- \(\ell+1 \le i \le k\): in the denominator, there are \(\lfloor \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rfloor\) numbers divisible by \(2^i\); in the numerator, there are at least as many.

- \(i = k+1\): in the denominator, no number is divisible by \(2^{k+1}\); in the numerator, there is exactly one.

- \(i > k+1\): both the numerator and the denominator contain no numbers divisible by \(2^i\).

All together, we conclude that

\[ e_2((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_2((n-2)(n-3)\cdots 2\cdot 1) \ge \ell - 1 + 1 = \ell = e_2(n). \]

Thus, \(n\) divides \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\). The answer to the question is therefore: all \(n \ge 2\) that are not powers of 2. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle gehele getallen \(n \ge 2\) waarvoor \(n\) een deler is van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We gaan bewijzen dat het antwoord is: alle \(n \ge 2\) die geen macht van 2 zijn. Er geldt

\[ \binom{2n-3}{n-1} = \frac{(2n-3)!}{(n-1)!(n-2)!} = \frac{(2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n}{(n-2)(n-3)\cdots2\cdot1}. \qquad (1) \]

Zij \(p\) een priemfactor van \(n\) en stel dat \(p > 2\). We weten dat de volgende uitdrukking geheel is:

\[ \binom{2n-3}{n} = \frac{(2n-3)!}{n!(n-3)!} = \frac{(2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)}{(n-3)(n-4)\cdots2\cdot1}. \]

Schrijf \(e_p(N)\) voor het aantal factoren \(p\) in een geheel getal \(N\). Nu zien we dat

\[ e_p((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)) \ge e_p((n-3)(n-4)\cdots2\cdot1). \]

Verder geldt, aangezien \(p \mid n\) en \(p > 2\), dat \(p \nmid n-2\), dus vermenigvuldigen met \(n-2\) voegt geen factor \(p\) toe. We concluderen dat

\[ e_p((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_p((n-2)(n-3)\cdots2\cdot1) \ge e_p(n). \]

Dus \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) bevat minstens \(e_p(n)\) factoren \(p\). Nu is \(n\) een deler van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) dan en slechts dan als dit resultaat ook geldt voor \(p = 2\).

In een product \(a_1a_2\cdots a_m\) is het totaal aantal factoren 2 gelijk aan de som van het aantal \(a_i\) deelbaar door 2, het aantal \(a_i\) deelbaar door 4, het aantal \(a_i\) deelbaar door 8, ... Bekijk nu eerst \(n = 2^k\) met \(k \ge 1\). Dan is in (1) de teller het product van \(2^k, 2^k+1, 2^k+2, \ldots, 2^{k+1}-3\), terwijl de noemer het product is van \(1, 2, 3, \ldots, 2^k-2\). Voor \(1 \le i \le k-1\) is het aantal getallen uit \(1, 2, 3, \ldots, 2^k-2\) deelbaar door \(2^i\) precies gelijk aan het aantal getallen uit \(2^k+1, 2^k+2, 2^k+3, \ldots, 2^{k+1}-2\) deelbaar door \(2^i\). Voor \(i \ge k\) zijn beide aantallen 0. Dus

\[ e_2(1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots (2^k-2)) = e_2((2^k+1)(2^k+2)(2^k+3) \cdots (2^{k+1}-2)). \]

Aan de rechterkant delen we het product door \(2^{k+1}-2\) (één factor 2) en vermenigvuldigen met \(2^k\) (\(k\) factoren 2) om het product uit de teller te krijgen. We concluderen

\[ e_2(2^k(2^k+1)(2^k+2)(2^k+3)\cdots(2^{k+1}-3)) - e_2(1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots (2^k-2)) = k-1, \]

en dus bevat \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) precies \(k-1\) factoren 2, wat niet genoeg is om deelbaar te zijn door \(n\). Dus \(n = 2^k\) voldoet niet.

Bekijk nu het geval dat \(n\) geen macht van 2 is. Zij \(2^k\) de grootste macht van 2 kleiner dan \(n\). We weten dat \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) geheel is, dus voor oneven \(n\) geldt dat

\[e_2((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_2((n-2)(n-3)\cdots 2\cdot 1) \ge 0 = e_2(n).\]

Als \(n\) even is, dan is er een maximale \(\ell\) zo dat \(2^\ell \mid n\). Aangezien \(n\) geen tweemacht is, merken we op dat \(2^{\ell+1} < 3 \cdot 2^\ell \le n < 2^{k+1}\). Dat betekent dat \(\ell < k\). Verder is \(2^k \le n-2\) en dus \(n < 2^{k+1} \le 2n-4\), dus de teller van (1) bevat \(2^{k+1}\). Nu bekijken we voor elke \(i\) het aantal factoren in de teller en de noemer deelbaar door \(2^i\):

- \(i = 1\): er zijn \(n-2\) gehele getallen in elk van de producten, en \(n\) is even, dus het aantal getallen in het product deelbaar door 2 is in teller en noemer gelijk.

- \(2 \le i \le \ell\): in de noemer zijn \(\lfloor \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rfloor\) getallen deelbaar door \(2^i\); in de teller zijn er \(\lceil \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rceil\) deelbaar door \(2^i\) aangezien het kleinste getal deelbaar is door \(2^i\); daarom is er in de teller één meer dan in de noemer.

- \(\ell+1 \le i \le k\): in de noemer zijn \(\lfloor \frac{n-2}{2^i} \rfloor\) getallen deelbaar door \(2^i\); in de teller zijn het er minstens zoveel.

- \(i = k+1\): in de noemer is geen getal deelbaar door \(2^{k+1}\); in de teller is het er precies één.

- \(i > k+1\): zowel teller als noemer bevatten geen getallen deelbaar door \(2^i\).

Alles bij elkaar concluderen we dat

\[e_2((2n-3)(2n-4)\cdots(n+1)n) - e_2((n-2)(n-3)\cdots 2\cdot 1) \ge \ell - 1 + 1 = \ell = e_2(n).\]

Dus \(n\) deelt \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\). Het antwoord op de vraag is dus: alle \(n \ge 2\) die geen macht van 2 zijn. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-C2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Determine all integers \(n \ge 2\) for which \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We first note that the number of ways to distribute \(n-2\) identical balls into \(n\) different boxes is equal to \(\binom{(n-2)+(n-1)}{n-1} = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) by the stars and bars principle for \(n \ge 2\). We will examine the symmetries in the set of distributions.

Denote a distribution as \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) with \(x_k\) the number of balls in the \(k\)-th box. The smallest \(1 \le p \le n\) such that \((x_{1+p}, x_{2+p}, \ldots, x_{n+p}) = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) is called the *period* of this distribution, where indices are taken modulo \(n\). Since you return to the original distribution after \(n\) rotations and \(p\) is minimal with this property, \(p\) is a divisor of \(n\). We write \(d = n/p\) and the distribution now consists of \(d\) identical

parts \((x_1, \ldots, x_p) = (x_{p+1}, \ldots, x_{2p}) = \ldots = (x_{n-p+1}, \ldots, x_n)\). In particular, each part contains the same number of balls, so \(d\) is also a divisor of \(n-2\). Since \(\text{gcd}(n, n-2) = \text{gcd}(n, 2)\), \(d\) is equal to 1, or possibly 2 if \(n\) is even.

Let \(A\) be the set of ways to distribute \(n-2\) identical balls into \(n\) different boxes, and let \(A_p\) be the subset of these ways with period \(p\). Then we can summarize the above as follows: for \(n \ge 2\), \(|A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\), if \(n\) is odd, then \(A = A_n\), and if \(n\) is even, then \(A = A_n \cup A_{n/2}\). The crux of the solution is now that for a distribution \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) with period \(p\), the distributions \((x_{1+i}, x_{2+i}, \ldots, x_{n+i})\) for \(0 \le i \le p-1\) are distinct and unique (while \(i = p\) gives the same distribution as \(i = 0\)). Thus, \(p \mid |A_p|\). In particular, \(n \mid |A_n|\), and for all odd \(n \ge 3\), \(n\) is a divisor of \(|A_n| = |A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

Now suppose \(n\) is even, and write \(n = 2m\). Let \(B\) be the set of ways to distribute \(m-1\) identical balls into \(m\) different boxes. Then the restriction \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{2m}) \mapsto (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m)\) to the first \(m\) boxes is a function from \(A_m\) to \(B\). The function \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m) \mapsto (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m, x_1, \ldots, x_m)\) that repeats the first \(m\) boxes is a two-sided inverse. Thus, we have a bijection between these two sets. This means that \(|A_m| = |B|\), and

\[|A| = |A_n| + |A_m| \equiv |A_m| = |B| \mod n.\]

Now we calculate using the stars and bars principle that

\[|B| = \binom{2m-2}{m-1} = \binom{2m-3}{m-2} + \binom{2m-3}{m-1} = 2\binom{2m-3}{m-1}.\]

We conclude that \(n\) is a divisor of \(|A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) if and only if \(n = 2m\) is a divisor of \(|B| = 2\binom{2m-3}{m-1}\), if and only if \(m\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2m-3}{m-1}\).

We had already proven that \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) for all odd \(n \ge 3\). By repeatedly applying the conclusion from the previous paragraph, we now find that \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) for all \(n\) with an odd divisor greater than or equal to 3. On the other hand, for \(n = 2\), we calculate that \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1} = \binom{1}{1} = 1\), which clearly is not divisible by 2. Thus, by repeatedly applying the conclusion from the previous paragraph, \(n\) is not a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) when \(n\) is a power of 2. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle gehele getallen \(n \ge 2\) waarvoor \(n\) een deler is van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We merken als eerste op dat het aantal manieren om \(n-2\) identieke ballen te verdelen over \(n\) verschillende vakjes gelijk is aan \(\binom{(n-2)+(n-1)}{n-1} = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) wegens het paaseierenprincipe voor \(n \ge 2\). We gaan kijken naar de symmetrieën in de verzameling van manieren.

Noteer een verdeling als \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) met \(x_k\) het aantal ballen in het \(k\)-de vakje. De kleinste \(1 \le p \le n\) zo dat \((x_{1+p}, x_{2+p}, \ldots, x_{n+p}) = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) noemen we de *periode* van deze verdeling, waarbij we de indices modulo \(n\) rekenen. Omdat je na \(n\) keer doordraaien ook weer bij de oorspronkelijke verdeling uitkomt en \(p\) minimaal is met deze eigenschap, geldt dat \(p\) een deler is van \(n\). We schrijven \(d = n/p\) en de verdeling bestaat nu uit \(d\) gelijke

delen \((x_1, \ldots, x_p) = (x_{p+1}, \ldots, x_{2p}) = \ldots = (x_{n-p+1}, \ldots, x_n)\). In het bijzonder heeft elk deel evenveel ballen, dus \(d\) is ook een deler van \(n-2\). Aangezien \(\text{gcd}(n, n-2) = \text{gcd}(n, 2)\) is \(d\) gelijk aan 1, of eventueel 2 als \(n\) even is.

Zij \(A\) de verzameling van manieren om \(n-2\) identieke ballen te verdelen over \(n\) verschillende vakjes, en zij \(A_p\) de deelverzameling van deze manieren met periode \(p\). Dan kunnen we het bovenstaande als volgt samenvatten: voor \(n \ge 2\) geldt \(|A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\), als \(n\) oneven is geldt \(A = A_n\), en als \(n\) even is dan \(A = A_n \cup A_{n/2}\). De crux van de oplossing is nu dat voor een verdeling \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\) met periode \(p\) de verdelingen \((x_{1+i}, x_{2+i}, \ldots, x_{n+i})\) voor \(0 \le i \le p-1\) verschillende unieke verdelingen zijn (terwijl \(i = p\) dus juist dezelfde verdeling geeft als \(i = 0\)). Dus \(p \mid |A_p|\). In het bijzonder geldt \(n \mid |A_n|\), en voor alle oneven \(n \ge 3\) dat \(n\) een deler is van \(|A_n| = |A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

Stel nu dat \(n\) even is, en schrijf \(n = 2m\). Zij \(B\) de verzameling van manieren om \(m-1\) identieke ballen te verdelen over \(m\) verschillende vakjes. Dan is de restrictie \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{2m}) \mapsto (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m)\) tot de eerste \(m\) vakjes een functie van \(A_m\) naar \(B\). De functie \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m) \mapsto (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m, x_1, \ldots, x_m)\) die de eerste \(m\) vakjes herhaalt, is een tweezijdige inverse. Dus we hebben een bijectie tussen deze twee verzamelingen. Dit betekent dat \(|A_m| = |B|\), en

\[|A| = |A_n| + |A_m| \equiv |A_m| = |B| \mod n.\]

Nu rekenen we met het paaseirenprincipe uit dat

\[|B| = \binom{2m-2}{m-1} = \binom{2m-3}{m-2} + \binom{2m-3}{m-1} = 2\binom{2m-3}{m-1}.\]

We concluderen dat \(n\) een deler is van \(|A| = \binom{2n-3}{n-1}\), dan en slechts dan als \(n = 2m\) een deler is van \(|B| = 2\binom{2m-3}{m-1}\), dan en slechts dan als \(m\) een deler is van \(\binom{2m-3}{m-1}\).

We hadden al bewezen dat \(n\) een deler is van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) voor alle oneven \(n \ge 3\). Door de conclusie van de vorige alinea herhaaldelijk toe te passen vinden we nu dus dat \(n\) een deler is van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) voor alle \(n\) met een oneven deler groter of gelijk aan 3. Aan de andere kant rekenen we voor \(n = 2\) uit dat \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1} = \binom{1}{1} = 1\), waarvan 2 duidelijk geen deler is. Dus met herhaaldelijk toepassen van de conclusie van de vorige alinea is \(n\) géén deler van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\) wanneer \(n\) een tweemacht is. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-C2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Determine all integers \(n \ge 2\) for which \(n\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We use the notation of solution II. We provide an alternative to the induction for even \(n = 2m\) starting from the realization that \(|A| \equiv |B| \mod n\).

Since \(\text{gcd}(m, m-1) = 1\), there is no partition in \(B\) with a period smaller than \(m\). Thus, \(m \mid |B|\). This means that \(b = |B|/m\) is an integer, and \(n \mid |A|\) if and only if \(b\) is even. Now we compute that

\[b = \frac{1}{m} \binom{2m-2}{m-1} = \frac{1}{m} \frac{(2m-2)!}{(m-1)!(m-1)!} = \frac{1}{(2m-1)} \frac{(2m-1)!}{m!(m-1)!} = \frac{1}{(2m-1)} \binom{2m-1}{m-1}.\]

Since \(b\) is an integer, it follows that \(2m-1\) is a divisor of \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\). And since \(2m-1\) is odd, \(b\) is even if and only if \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\) is even. We rewrite this as \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1} = \frac{(2m-1)!}{m!(m-1)!} = \frac{m}{2m} \frac{(2m)!}{m!m!} = \frac{1}{2} \binom{2m}{m}\). Thus, \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\) is even if and only if 4 is a divisor of \(\binom{2m}{m}\). Let \(2^k\) be the largest power of 2 less than or equal to \(m\). Using the notation of solution I, we compute

\[e_2(\binom{2m}{m}) = e_2(2m!) - 2e_2(m!)\] \[= \sum_{i=1}^{k+1} \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2^i} \right\rfloor - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= \left( \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2} \right\rfloor + \sum_{i=2}^{k+1} \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2^i} \right\rfloor \right) - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= \left( m + \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i}\right\rfloor \right) - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i}\right\rfloor\] \[\geq m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{m}{2^i} = \frac{m}{2^k} \geq 1.\]

The two inequalities in the last line hold with equality if and only if \(m = 2^k\), and thus \(n = 2^{k+1}\). Since 4 is a divisor of \(\binom{2m}{m}\) if and only if \(e_2(\binom{2m}{m}) > 1\), this holds if and only if \(n\) is not a power of 2. \(\square\)

Remark. The formula \(m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\) gives the number of ones in the binary representation of \(m\).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle gehele getallen \(n \ge 2\) waarvoor \(n\) een deler is van \(\binom{2n-3}{n-1}\).

|

We gebruiken de notatie van oplossing II. We geven een alternatief voor de inductie voor even \(n = 2m\) vanaf de realisatie dat \(|A| \equiv |B| \mod n\).

Omdat \(\text{gcd}(m, m-1) = 1\), is er geen enkele verdeling in \(B\) met een periode kleiner dan \(m\). Dus \(m \mid |B|\). Dat betekent dat \(b = |B|/m\) geheel is, en \(n \mid |A|\) dan en slechts dan als \(b\)

even is. Nu rekenen we uit dat

\[b = \frac{1}{m} \binom{2m-2}{m-1} = \frac{1}{m} \frac{(2m-2)!}{(m-1)!(m-1)!} = \frac{1}{(2m-1)} \frac{(2m-1)!}{m!(m-1)!} = \frac{1}{(2m-1)} \binom{2m-1}{m-1}.\]

Aangezien \(b\) geheel is, volgt hieruit dat \(2m-1\) een deler is van \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\). En omdat \(2m-1\) oneven is, is \(b\) even dan en slechts dan als \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\) even is. Dit herschrijven we nog een keer als \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1} = \frac{(2m-1)!}{m!(m-1)!} = \frac{m}{2m} \frac{(2m)!}{m!m!} = \frac{1}{2} \binom{2m}{m}\). Dus \(\binom{2m-1}{m-1}\) is even dan en slechts dan als 4 een deler is van \(\binom{2m}{m}\). Zij \(2^k\) de grootste macht van 2 kleiner dan of gelijk aan \(m\). Met de notatie van oplossing I rekenen we dan uit

\[e_2(\binom{2m}{m}) = e_2(2m!) - 2e_2(m!)\] \[= \sum_{i=1}^{k+1} \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2^i} \right\rfloor - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= \left( \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2} \right\rfloor + \sum_{i=2}^{k+1} \left\lfloor \frac{2m}{2^i} \right\rfloor \right) - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= \left( m + \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i}\right\rfloor \right) - 2 \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\] \[= m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i}\right\rfloor\] \[\geq m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{m}{2^i} = \frac{m}{2^k} \geq 1.\]

In de twee ongelijkheden van de laatste regel geldt gelijkheid dan en slechts dan als \(m = 2^k\), en dus \(n = 2^{k+1}\). Aangezien 4 is een deler van \(\binom{2m}{m}\) dan en slechts dan als \(e_2(\binom{2m}{m}) > 1\), geldt dat dus dan en slechts dan als \(n\) géén tweemacht is. \(\square\)

Opmerking. De formule \(m - \sum_{i=1}^{k} \left\lfloor \frac{m}{2^i} \right\rfloor\) geeft het aantal enen in de binaire notatie van \(m\).

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-C2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing III.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Can a number of the form 44...41, with an odd number of fours followed by a 1, be a square?

|

No. We can write such a number 44...41 as \(4 \cdot \frac{10^{2m}-1}{9} - 3\), with \(m \ge 1\) an integer. Suppose this is a square. Write \(4 \cdot \frac{10^{2m}-1}{9} - 3 = n^2\) with \(n\) a positive integer. Multiplying by 9 gives \(4(10^{2m} - 1) - 27 = 9n^2\), so \(4 \cdot 10^{2m} = 9n^2 + 31\), or \((2 \cdot 10^m)^2 - (3n)^2 = 31\). Write \(x = 2 \cdot 10^m\) and \(y = 3n\), then we get \(x^2 - y^2 = 31\). This can be factored as \((x - y)(x + y) = 31\). So \(x + y \mid 31\), and since \(x + y \ge 2\) we get \(x + y = 31\) and \(x - y = 1\). This yields \(x = 16\), but that is not of the form \(2 \cdot 10^m\). We conclude that a number of the form 44...41 with an odd number of fours cannot be a square. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Kan een getal van de vorm 44...41, met een oneven aantal vieren gevolgd door een 1, een kwadraat zijn?

|

Nee. We kunnen zo'n getal 44...41 schrijven als \(4 \cdot \frac{10^{2m}-1}{9} - 3\), met \(m \ge 1\) geheel. Stel dat dit een kwadraat is. Schrijf \(4 \cdot \frac{10^{2m}-1}{9} - 3 = n^2\) met \(n\) positief geheel. Vermenigvuldigen met 9 geeft \(4(10^{2m} - 1) - 27 = 9n^2\), dus \(4 \cdot 10^{2m} = 9n^2 + 31\), ofwel \((2 \cdot 10^m)^2 - (3n)^2 = 31\). Schrijf nu \(x = 2 \cdot 10^m\) en \(y = 3n\), dan krijgen we dus \(x^2 - y^2 = 31\). Dit kunnen we ontbinden als \((x - y)(x + y) = 31\). Dus \(x + y \mid 31\), en omdat \(x + y \ge 2\) krijgen we dus \(x + y = 31\) en \(x - y = 1\). Dit levert \(x = 16\), maar dat is niet van de vorm \(2 \cdot 10^m\). We concluderen dat een getal van de vorm 44...41 met een oneven aantal vieren geen kwadraat kan zijn. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Can a number of the form 44...41, with an odd number of fours followed by a 1, be a square?

|

We observe that the residue classes of squares modulo 11 are respectively 0, 1, 4, 9, 5, 3, 3, 5, 9, 4, 1. On the other hand, we can compute the residue class of 44...41 by repeatedly subtracting two fours from the number, which does not change the residue class due to \(44 \cdot 10^\ell \equiv 0 \mod 11\). Since the given number has an odd number of fours, it is thus equal to

\[44...41 \equiv 41 \equiv 8 \mod 11.\]

This is not one of the quadratic residue classes, so none of these numbers is a square. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Kan een getal van de vorm 44...41, met een oneven aantal vieren gevolgd door een 1, een kwadraat zijn?

|

We merken op dat de restklassen van kwadraten modulo 11 gelijk zijn aan respectievelijk 0, 1, 4, 9, 5, 3, 3, 5, 9, 4, 1. Aan de andere kant kunnen we de restklasse van 44...41 uitrekenen door steeds twee vieren van het getal af te halen, waardoor de restklasse niet verandert wegens \(44 \cdot 10^\ell \equiv 0 \mod 11\). Omdat het gegeven getal een oneven aantal vieren heeft, is het dus gelijk aan

\[44...41 \equiv 41 \equiv 8 \mod 11.\]

Dit is niet een van de kwadratische restklassen, dus geen van deze getallen is een kwadraat. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

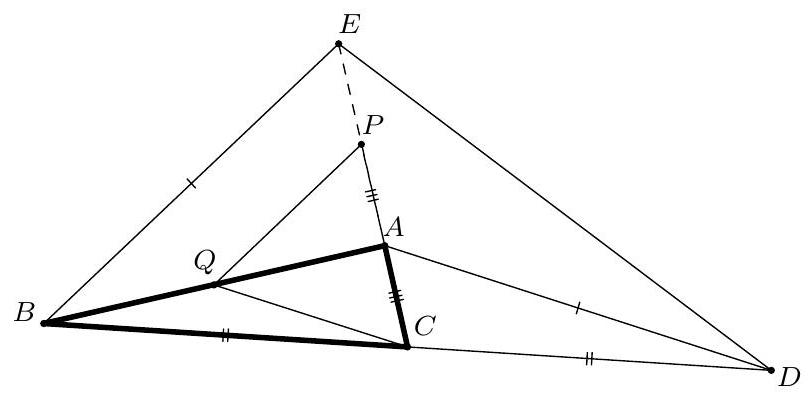

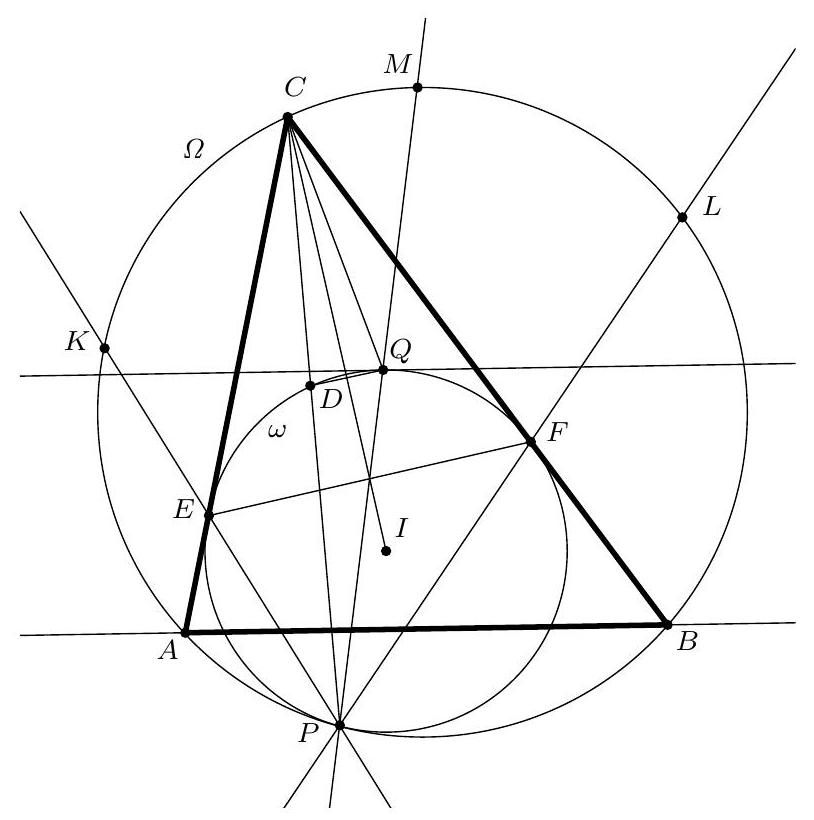

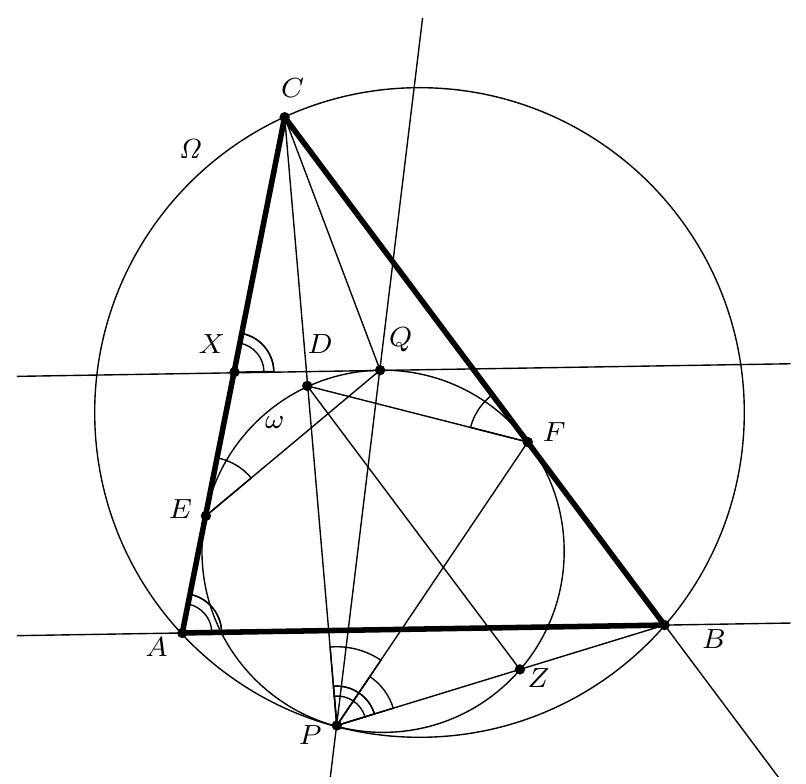

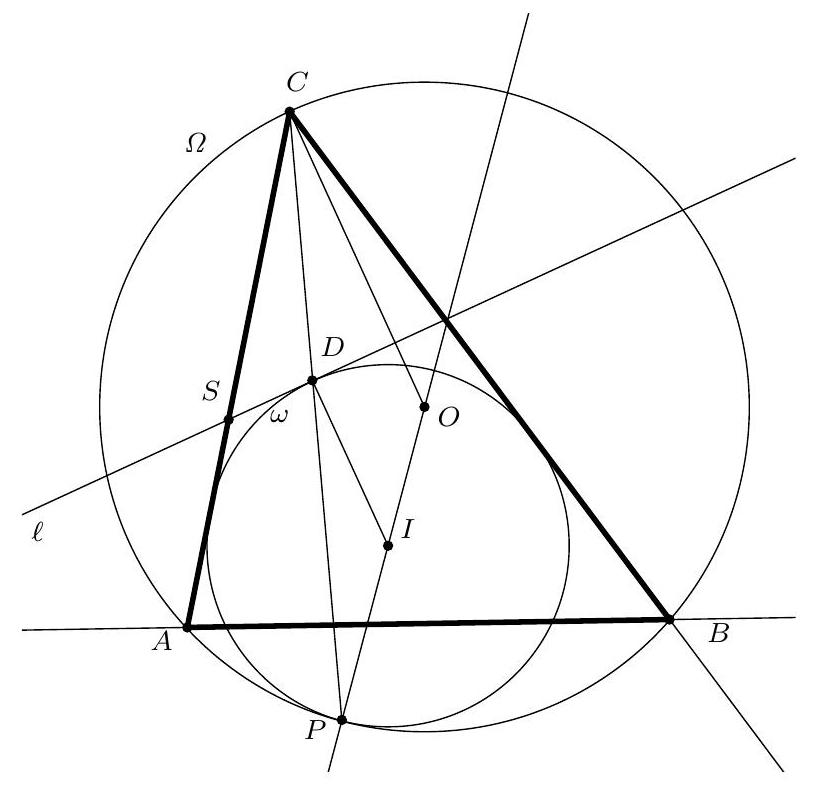

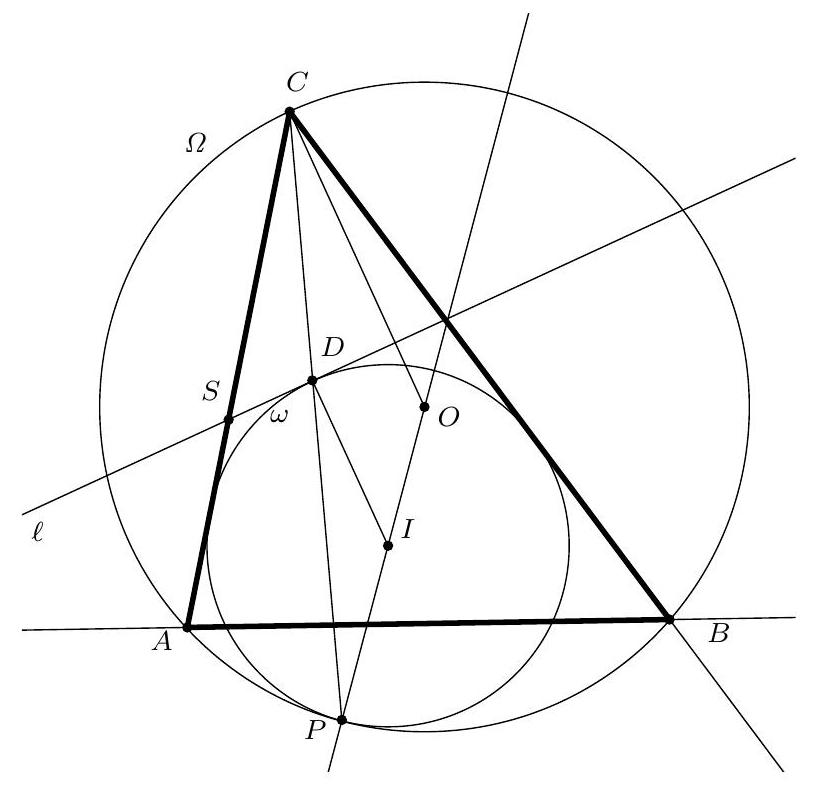

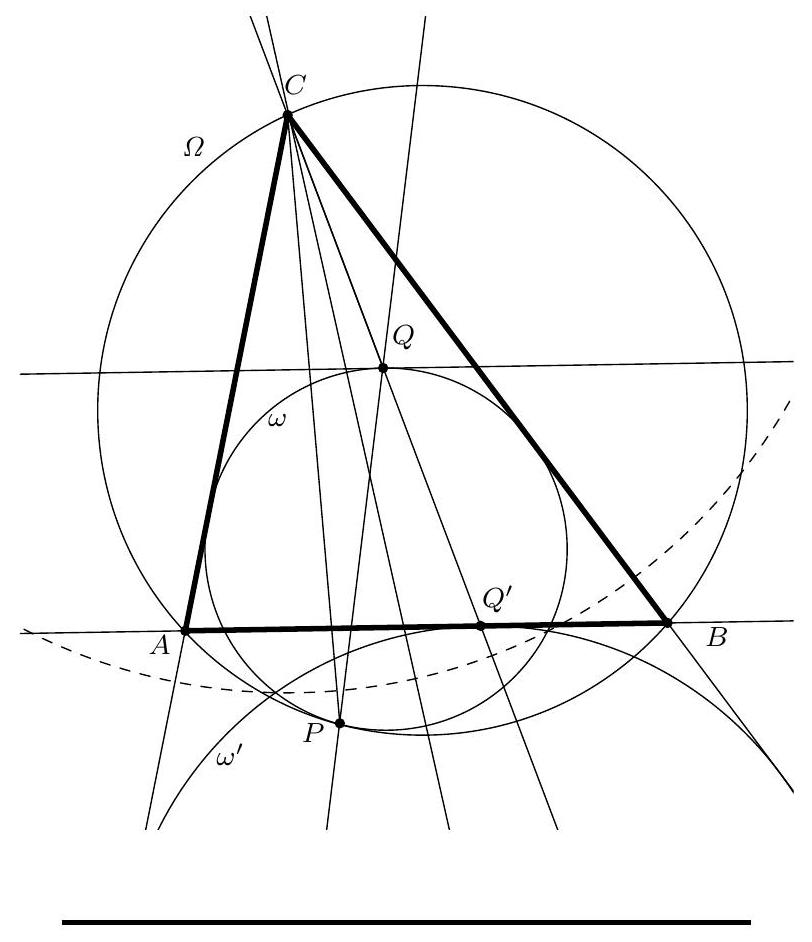

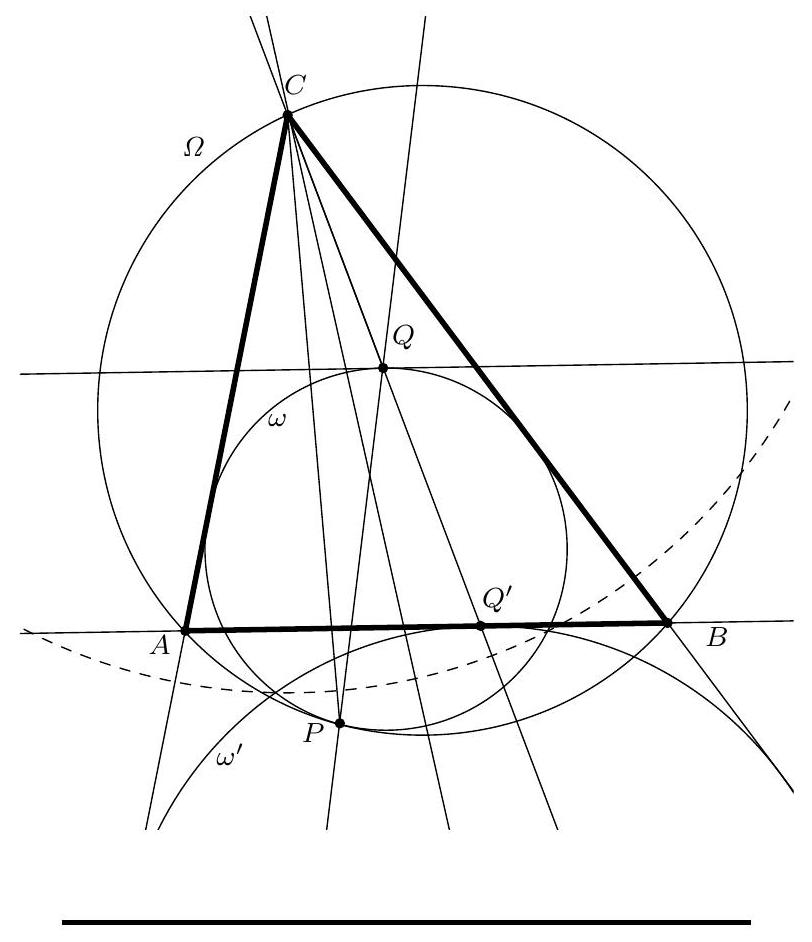

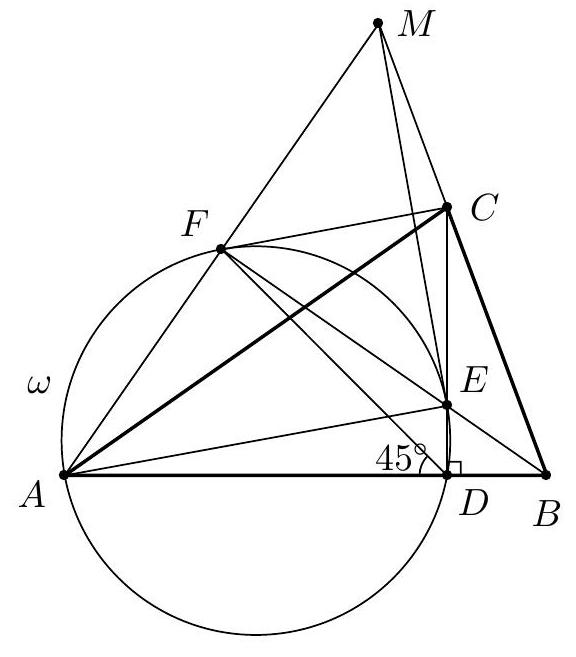

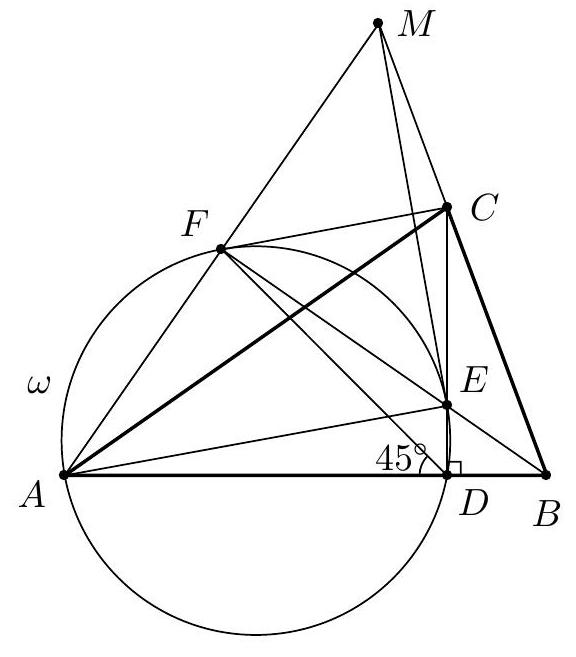

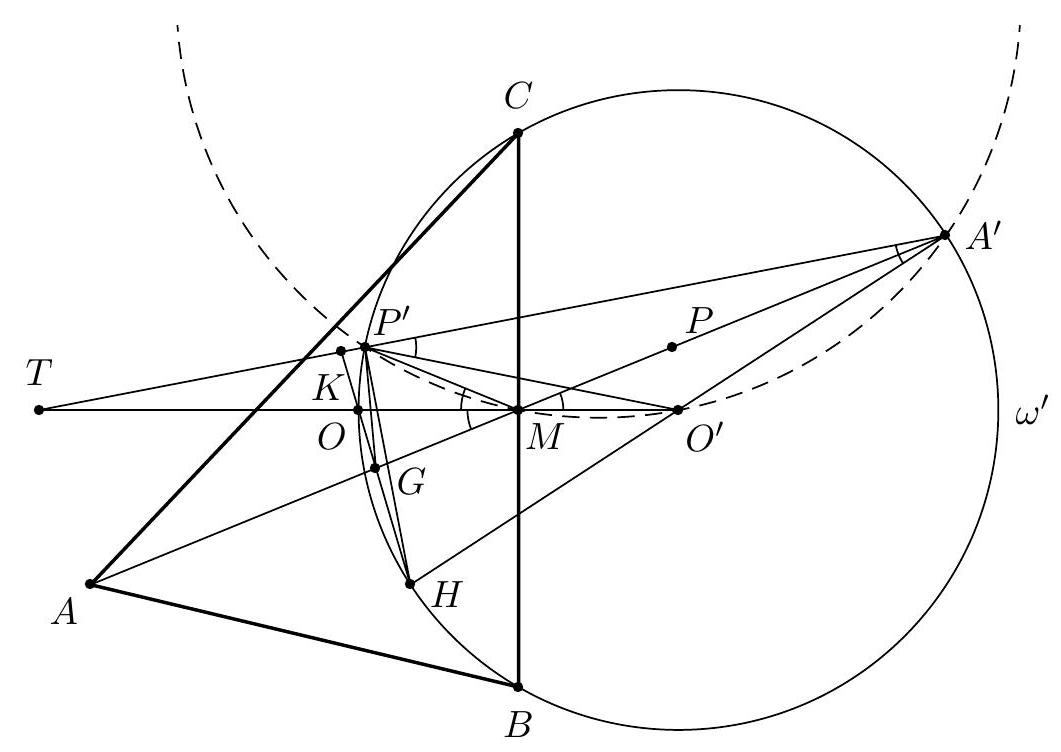

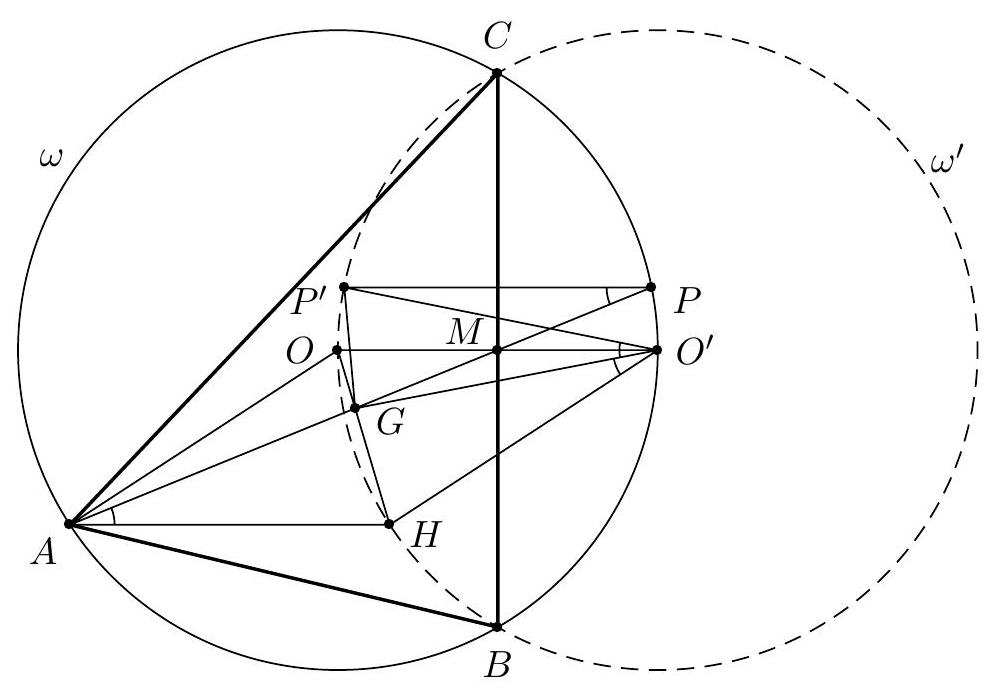

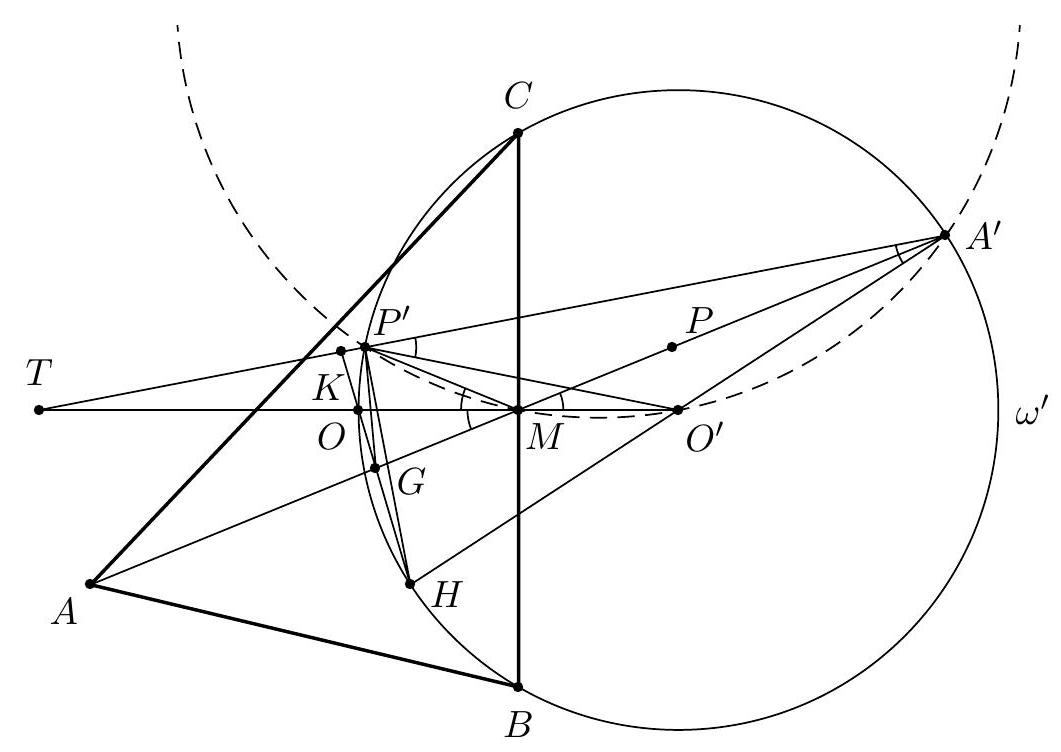

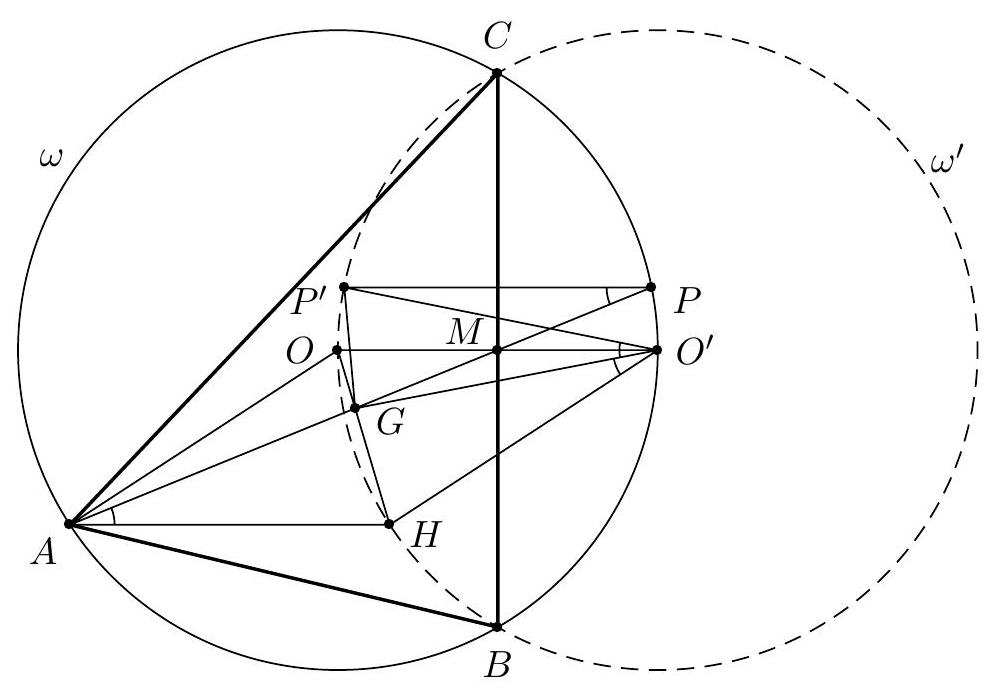

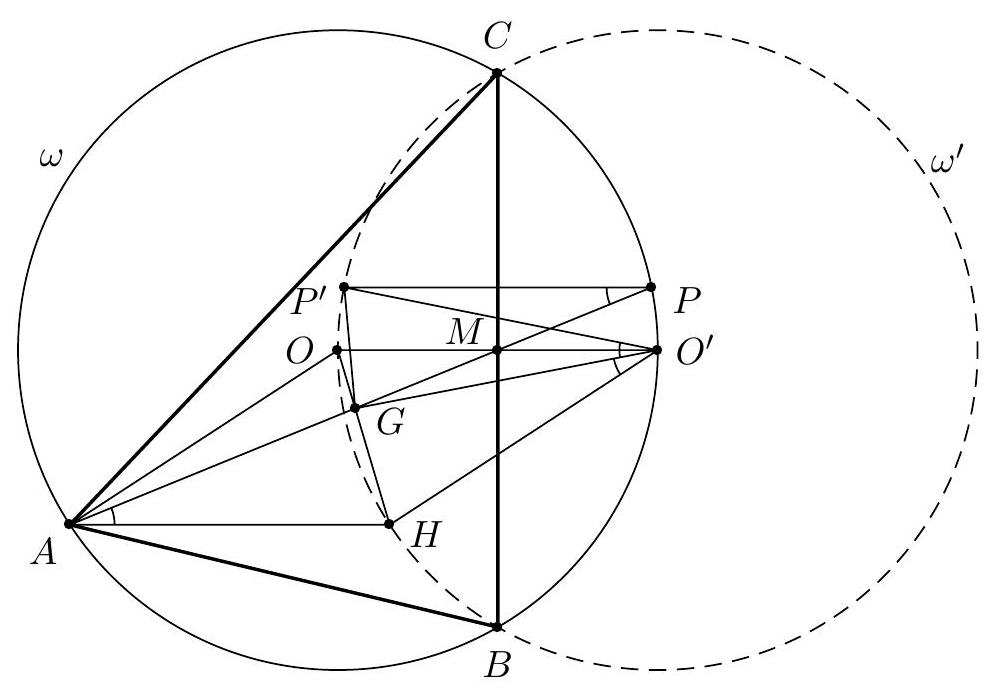

Let \(\triangle ABC\) be an acute triangle with \(|AB| > |AC|\), and let \(\omega\) be the circumcircle of \(\triangle ABC\) with center \(O\). The altitude from \(A\) intersects \(BC\) at \(D\) and intersects \(\omega\) again at \(P\). Define \(H\) as the orthocenter of \(\triangle ABC\) and let \(K\) be the point on segment \(BC\) such that \(|BD| = |KC|\). The circumcircle of \(\triangle PKH\) intersects \(\omega\) again at \(Q\) and intersects line \(BC\) again at \(N\). Let \(T\) be the point on line \(AD\) such that \(TN \perp PQ\).

Prove that the line \(KT\) passes through \(O\).

|

Let \(O\) be the center of \(\omega\). Since \(|BD| = |KC|\), the perpendicular bisectors of \(BC\) and \(KD\) coincide, and in particular, \(|OK| = |OD|\). Let \(T'\) be the reflection of \(K\) in \(O\). By Thales' theorem, \(\angle KDT' = 90^\circ\), so \(T'\) lies on \(AD\).

It is a standard fact that the reflection of \(H\) in \(BC\) lies on the circumcircle. (This can be easily proven by calculating \(\angle BHC\).) This implies that \(\triangle PKH\) maps to itself under reflection in \(BC\). This means that the center \(M\) of the circumcircle of \(\triangle PKH\) lies on \(BC\), and that \(M\) is the midpoint of \(KN\). By definition, \(O\) is the midpoint of \(KT'\), so \(OM\) is a midline in \(\triangle KNT'\); in particular, \(OM \parallel NT'\). Since \(P\) and \(Q\) both lie on \(\omega\) and the circumcircle of \(\triangle PKH\), \(OM\) is the perpendicular bisector of \(PQ\), so \(OM \perp PQ\). It follows that \(NT' \perp PQ\), and we can conclude that \(T'\) is equal to \(T\). \(\square\)

Remark. Let \(\ell\) be the line through \(N\) perpendicular to \(PQ\). For completeness, we show that \(\ell\) is not parallel to \(AD\) and in particular does not coincide (so that \(T\) exists and is unique). Note that \(H\) lies inside \(\triangle ABC\) because it is an acute triangle. This implies that \(D \neq N\), and thus \(\ell\) does not coincide with \(AD\). Since \(D \neq N\) and \(M\) is the midpoint of \(KN\), \(M\) is not the midpoint of \(KD\). Therefore, \(M\) is not the midpoint of \(BC\). Hence, \(OM\) is not perpendicular to \(BC\). Since \(OM \parallel \ell\) and \(AD \perp BC\), we conclude that \(\ell\) is not parallel to \(AD\).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij \(\triangle ABC\) een scherphoekige driehoek met \(|AB| > |AC|\), zij \(\omega\) de omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle ABC\) met middelpunt \(O\). De hoogtelijn vanuit \(A\) snijdt \(BC\) in \(D\) en snijdt \(\omega\) een tweede keer in \(P\). Definieer \(H\) als het hoogtepunt van \(\triangle ABC\) en zij \(K\) het punt op het lijnstuk \(BC\) zodanig dat \(|BD| = |KC|\). De omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle PKH\) snijdt \(\omega\) een tweede keer in \(Q\) en snijdt de lijn \(BC\) een tweede keer in \(N\). Zij \(T\) het punt op de lijn \(AD\) zodanig dat \(TN \perp PQ\).

Bewijs dat de lijn \(KT\) door \(O\) gaat.

|

Zij \(O\) het middelpunt van \(\omega\). Wegens \(|BD| = |KC|\) vallen de middelloodlijnen van \(BC\) en \(KD\) samen en in het bijzonder geldt dus dat \(|OK| = |OD|\). Zij \(T'\) de spiegeling van \(K\) in \(O\). Wegens Thales geldt dan dat \(\angle KDT' = 90^\circ\), dus \(T'\) ligt op \(AD\).

Het is een standaardplaatje dat de spiegeling van \(H\) in \(BC\) op de omgeschreven cirkel ligt. (Eenvoudig te bewijzen door \(\angle BHC\) uit te rekenen.) Hieruit volgt dat \(\triangle PKH\) in zichzelf overgaat onder spiegeling in \(BC\). Dit betekent dat het middelpunt \(M\) van de omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle PKH\) op \(BC\) ligt, en dat \(M\) het midden van \(KN\) is. Per definitie is \(O\) het midden van \(KT'\), dus \(OM\) is een middenparallel in \(\triangle KNT'\); in het bijzonder geldt \(OM \parallel NT'\). Omdat \(P\) en \(Q\) beide op zowel \(\omega\) als de omgeschreven cirkel

van \(\triangle PKH\) liggen, is \(OM\) de middelloodlijn van \(PQ\), dus \(OM \perp PQ\). Nu volgt dat ook \(NT' \perp PQ\), en kunnen we concluderen dat \(T'\) gelijk is aan \(T\). \(\square\)

Opmerking. Zij \(\ell\) de lijn door \(N\) loodrecht op \(PQ\). We laten voor de volledigheid zien dat \(\ell\) niet evenwijdig is met \(AD\) en in het bijzonder niet samenvalt (zodat \(T\) bestaat en uniek vastligt). Merk op dat \(H\) binnen \(\triangle ABC\) ligt, omdat dit een scherphoekige driehoek is. Hieruit volgt dat \(D \neq N\), en dus dat \(\ell\) niet samenvalt met \(AD\). Omdat \(D \neq N\) en \(M\) het midden is van \(KN\), is \(M\) niet het midden van \(KD\). Dus \(M\) is niet het midden van \(BC\). Hierdoor staat \(OM\) niet loodrecht op \(BC\). Omdat \(OM \parallel \ell\) en \(AD \perp BC\) concluderen we dat \(\ell\) niet evenwijdig is met \(AD\).

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Let \(\triangle ABC\) be an acute triangle with \(|AB| > |AC|\), and let \(\omega\) be the circumcircle of \(\triangle ABC\) with center \(O\). The altitude from \(A\) intersects \(BC\) at \(D\) and intersects \(\omega\) again at \(P\). Define \(H\) as the orthocenter of \(\triangle ABC\) and let \(K\) be the point on segment \(BC\) such that \(|BD| = |KC|\). The circumcircle of \(\triangle PKH\) intersects \(\omega\) again at \(Q\) and intersects line \(BC\) again at \(N\). Let \(T\) be the point on line \(AD\) such that \(TN \perp PQ\).

Prove that the line \(KT\) passes through \(O\).

|

For a more direct version of the previous solution, we again note that \(OM \perp PQ \perp TN\). Thus, \(OM \parallel TN\), and since \(M\) is the midpoint of \(KN\), the line \(OM\) is the midline of \(\triangle KNT\) (but \(O\) a priori is not yet on \(KT\)). Therefore, \(OM\) passes through the midpoint of \(KT\), say \(O'\). Furthermore, the perpendicular bisector of \(KD\) is a midline in \(\triangle KDT\), as it passes through the midpoint of \(KD\) and is parallel to \(DT\). Thus, it also passes through \(O'\). The perpendicular bisector of \(KD\) is the same as the perpendicular bisector of \(BC\). This also passes through \(O\), since \(BC\) is a chord of \(\omega\). Since both \(MO\) and the perpendicular bisector of \(BC\) pass through both \(O\) and \(O'\), we conclude that \(O' = O\). Therefore, \(KT\) passes through \(O\). \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij \(\triangle ABC\) een scherphoekige driehoek met \(|AB| > |AC|\), zij \(\omega\) de omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle ABC\) met middelpunt \(O\). De hoogtelijn vanuit \(A\) snijdt \(BC\) in \(D\) en snijdt \(\omega\) een tweede keer in \(P\). Definieer \(H\) als het hoogtepunt van \(\triangle ABC\) en zij \(K\) het punt op het lijnstuk \(BC\) zodanig dat \(|BD| = |KC|\). De omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle PKH\) snijdt \(\omega\) een tweede keer in \(Q\) en snijdt de lijn \(BC\) een tweede keer in \(N\). Zij \(T\) het punt op de lijn \(AD\) zodanig dat \(TN \perp PQ\).

Bewijs dat de lijn \(KT\) door \(O\) gaat.

|

Voor een directere versie van de vorige oplossing, merken we wederom op dat \(OM \perp PQ \perp TN\). Dus \(OM \parallel TN\), en omdat \(M\) het midden is van \(KN\) is de lijn \(OM\) dus de middenparallel van \(\triangle KNT\) (maar \(O\) ligt a priori nog niet op \(KT\)). Dus \(OM\) gaat door het midden van \(KT\), zeg \(O'\). Verder is de middelloodlijn van \(KD\) een middenparallel in \(\triangle KDT\), want hij gaat door het midden van \(KD\) en is evenwijdig aan \(DT\). Dus deze gaat ook door \(O'\). De middelloodlijn van \(KD\) is gelijk aan de middelloodlijn van \(BC\). Deze gaat ook door \(O\), omdat \(BC\) een koorde is van \(\omega\). Omdat \(MO\) en de middelloodlijn van \(BC\) beide door zowel \(O\) als \(O'\) gaan, concluderen we dat \(O' = O\). Dus \(KT\) gaat door \(O\). \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Johan and Quintijn play the following game, taking turns with Johan starting. At the beginning, the numbers \(1, 2, \dots, 2024\) are written on a board. In each turn, the player whose turn it is erases two numbers \(a\) and \(b\) that are on the board, and writes the (possibly negative) difference \(a - b\) on the board. The game ends when only one number remains on the board. If this number is divisible by 3, Johan wins; otherwise, Quintijn wins.

Determine which of the two players has a winning strategy.

|

We will prove that Quintijn has a winning strategy. First, note that only the number of numbers in each residue class modulo 3 is relevant. If \(a \equiv i \mod 3\), \(b \equiv j \mod 3\) and \(a - b \equiv k \mod 3\), we denote the move with \(a\) and \(b\) as \((i, j) \to k\). Let \(x\) be the number of numbers on the board that are *not* divisible by 3. Note that \(x\) can decrease by at most 2 in each turn.

Quintijn can play the game arbitrarily until at the beginning of his turn, \(1 \le x \le 4\). From that point on, he follows the following strategy.

- If \(x = 4\), then Quintijn always makes a move that ensures \(x\) remains 4. To show that this is always possible, note that Quintijn always has an odd number of numbers left at the beginning of his turn. If \(x = 4\), there must also be at least one number on the board that is divisible by 3. Now Quintijn can make a move of the form \((i, 0) \to i\) with \(i \in \{1, 2\}\), and the value of \(x\) does not change.

If Quintijn follows this strategy, Johan must eventually make a move that results in \(x \in \{2, 3\}\), and we are in one of the following cases.

- If \(x = 3\), then without loss of generality, there are two numbers on the board that are congruent to 1 modulo 3. With the move \((1, 1) \to 0\), Quintijn can ensure that \(x = 1\), and there will always be exactly one number that is not divisible by 3 on the board. Therefore, the last number will also not be divisible by 3, and Quintijn wins.

- If \(x = 2\), then we distinguish two subcases.

- The two numbers are in different residue classes modulo 3. Then Quintijn can make the move \((2, 1) \to 1\) so that \(x = 1\), and as we have seen, he wins then.

- The two numbers are in the same residue class modulo 3, say they are both congruent to 1 modulo 3. Since there is an odd number left, there is also a number on the board that is divisible by 3. With the move \((0, 1) \to 2\), Quintijn leaves a situation where \(x = 2\) again, and the numbers are not congruent to each other modulo 3. Now Johan cannot ensure that \(x\) becomes 0, so he leaves a situation where \(x = 1\) or \(x = 2\). If Quintijn follows this strategy, Johan must eventually make a move that leads to the previous subcase or the case \(x = 1\), and thus Quintijn wins.

- If \(x = 1\), then as stated, there will always be one number that is not divisible by 3 on the board, so Quintijn wins.

We conclude that Quintijn indeed has a winning strategy.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Johan en Quintijn spelen het volgende spel, waarbij ze om en om aan de beurt zijn en Johan begint. Aan het begin staan op een bord de getallen \(1, 2, \dots, 2024\) geschreven. In elke beurt veegt de speler die aan de beurt is twee getallen \(a\) en \(b\) die op het bord staan uit, en schrijft het (mogelijk negatieve) verschil \(a - b\) op het bord. Het spel eindigt als er nog maar één getal op het bord staat. Als dit getal deelbaar is door 3, dan wint Johan, en anders wint Quintijn.

Bepaal welke van de twee spelers een winnende strategie heeft.

|

We gaan bewijzen dat Quintijn een winnende strategie heeft. Merk allereerst op dat alleen het aantal getallen in elke restklasse modulo 3 van belang is. Als \(a \equiv i \mod 3\), \(b \equiv j \mod 3\) en \(a - b \equiv k \mod 3\), dan noteren we de zet met \(a\) en \(b\) als \((i, j) \to k\). Zij \(x\) het aantal getallen op het bord die *niet* deelbaar zijn door 3. Merk op dat \(x\) in elke beurt met hoogstens 2 kan afnemen.

Quintijn kan het spel willekeurig spelen totdat aan het begin van zijn beurt geldt dat \(1 \le x \le 4\). Vanaf dat moment houdt hij de volgende strategie aan.

- Als \(x = 4\), dan doet Quintijn altijd een zet die er voor zorgt dat \(x\) gelijk blijft aan 4. Om aan te tonen dat dit altijd kan, merken we op dat Quintijn aan het begin van zijn beurt altijd een oneven aantal getallen over heeft. Als \(x = 4\), moet er dus ook nog minstens één getal op het bord staan dat deelbaar is door 3. Nu kan Quintijn dus een zet doen van de vorm \((i, 0) \to i\) met \(i \in \{1, 2\}\), en verandert de waarde van \(x\) dus niet.

Als Quintijn deze strategie aanhoudt, moet Johan dus op een gegeven moment een zet doen waardoor \(x \in \{2, 3\}\), en bevinden we ons in één van de volgende gevallen.

- Als \(x = 3\), dan staan er zonder verlies van algemeenheid twee getallen op het bord die congruent zijn aan 1 modulo 3. Met de zet \((1, 1) \to 0\) kan Quintijn er voor zorgen dat \(x = 1\), en dan blijft er altijd exact 1 getal dat niet deelbaar is door 3 op het bord staan. Dus is uiteindelijk ook het laatste getal niet deelbaar door 3, en wint Quintijn.

- Als \(x = 2\), dan onderscheiden we twee deelgevallen.

- De twee getallen zitten in verschillende restklassen modulo 3. Dan kan Quintijn de zet \((2, 1) \to 1\) doen zodat \(x = 1\), en zoals we al zagen wint hij dan.

- De twee getallen zitten in dezelfde restklass modulo 3, zeg dat ze beide congruent zijn aan 1 modulo 3. Omdat er een oneven aantal overgebleven is, staat er ook nog een getal op het bord dat deelbaar is door 3. Met de zet \((0, 1) \to 2\) laat Quintijn een situatie over waarin opnieuw \(x = 2\), en de getallen niet congruent aan elkaar zijn modulo 3. Nu kan Johan er niet voor zorgen dat \(x\) gelijk wordt

aan 0, dus laat hij een situatie over waarin \(x = 1\) of \(x = 2\). Als Quintijn deze strategie aanhoudt, dan moet Johan uiteindelijk een zet doen waardoor we in het vorige deelgeval of in het geval \(x = 1\) terecht komen, en dus wint Quintijn.

* Als \(x = 1\), dan blijft er zoals gezegd altijd een getal dat niet deelbaar is door 3 op het bord staan, dus wint Quintijn.

We concluderen dat Quintijn inderdaad een winnende strategie heeft.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Johan and Quintijn play the following game, taking turns with Johan starting. At the beginning, the numbers \(1, 2, \dots, 2024\) are written on a board. In each turn, the player whose turn it is erases two numbers \(a\) and \(b\) that are on the board, and writes the (possibly negative) difference \(a - b\) on the board. The game ends when only one number remains on the board. If this number is divisible by 3, Johan wins; otherwise, Quintijn wins.

Determine which of the two players has a winning strategy.

|

For \(i = 0, 1, 2\), we denote the number of numbers on the board that are congruent to \(i\) modulo 3 by \(x_i\). Note that Johan can only play the remaining numbers that are not divisible by 3 if \(x_1 = 2\) and \(x_2 = 0\), or \(x_1 = 0\) and \(x_2 = 2\). We claim that if \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are not both equal to 0, Quintijn can always make a move that ensures at least one of \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) is odd. As we just saw, Johan cannot then play all the numbers that are not divisible by 3; and in his first turn, this is of course also not possible. By following this strategy, Quintijn wins.

To prove the claim, first assume that both \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are even. Then at least one of the two must be at least 2, say \(x_1 \ge 2\). Since Quintijn always has an odd number of numbers left at the beginning of his turn, there must also be a number on the board that is divisible by 3. With the move \((0, 1) \to 2\), Quintijn ensures that \(x_1\) decreases by 1 and \(x_2\) increases by 1. After this turn, both \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) are thus odd.

Now assume that at least one of \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) is odd. If there are at least 4 numbers left, then there is an \(i\) with \(x_i \ge 2\). By making the move \((i, i) \to 0\), \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) do not change modulo 2, so the claim follows. The last case is that there are exactly 3 numbers left (since Quintijn always has an odd number of numbers left at the beginning of his turn). Then it must be that \(x_0 = x_1 = x_2 = 1\), and Quintijn can make the move \((1, 0) \to 1\).

This completes the proof of the claim, so Quintijn indeed has a winning strategy.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Johan en Quintijn spelen het volgende spel, waarbij ze om en om aan de beurt zijn en Johan begint. Aan het begin staan op een bord de getallen \(1, 2, \dots, 2024\) geschreven. In elke beurt veegt de speler die aan de beurt is twee getallen \(a\) en \(b\) die op het bord staan uit, en schrijft het (mogelijk negatieve) verschil \(a - b\) op het bord. Het spel eindigt als er nog maar één getal op het bord staat. Als dit getal deelbaar is door 3, dan wint Johan, en anders wint Quintijn.

Bepaal welke van de twee spelers een winnende strategie heeft.

|

Voor \(i = 0, 1, 2\) noteren we het aantal getallen op het bord dat congruent is aan \(i\) modulo 3 met \(x_i\). Merk op dat Johan de laatst overgebleven getallen die niet deelbaar zijn door 3 alleen weg kan spelen als \(x_1 = 2\) en \(x_2 = 0\), of \(x_1 = 0\) en \(x_2 = 2\). We beweren nu dat, als \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) niet beide gelijk zijn aan 0, Quintijn altijd een zet kan doen die er voor zorgt dat minstens één van \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) oneven is. Zoals we net zagen, kan Johan dan niet alle getallen die niet deelbaar zijn door 3 wegspelen; en in zijn eerste beurt lukt dit natuurlijk ook niet. Door deze strategie te volgen, wint Quintijn dus.

Om de bewering te bewijzen, stel eerst dat \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) beide even zijn. Dan moet minstens één van de twee minstens gelijk zijn aan 2, zeg \(x_1 \ge 2\). Omdat Quintijn aan het begin van zijn beurt altijd een oneven aantal getallen over heeft, moet er ook nog een getal op het bord staan dat deelbaar is door 3. Met de zet \((0, 1) \to 2\) zorgt Quintijn ervoor dat \(x_1\) met 1 afneemt en \(x_2\) met 1 toeneemt. Na deze beurt zijn \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) dus beide oneven.

Stel nu dat minstens één van \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) oneven is. Als er nog minstens 4 getallen over zijn, dan is er een \(i\) met \(x_i \ge 2\). Door de zet \((i, i) \to 0\) veranderen \(x_1\) en \(x_2\) niet modulo 2, dus volgt de bewering. Het laatste geval is dat er precies 3 getallen over zijn (want Quintijn heeft aan het begin van zijn beurt altijd een oneven aantal getallen over). Dan moet gelden dat \(x_0 = x_1 = x_2 = 1\), en kan Quintijn de zet \((1, 0) \to 1\) doen.

Dit voltooit het bewijs van de bewering, dus Quintijn heeft inderdaad een winnende strategie.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Find all functions \(f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \to \mathbb{Z}_{>0}\) such that for all positive integers \(m, n\) it holds that

\[(f(m))^2 + 2mf(n) + f(n^2)\]

is the square of an integer.

|

Let \(m = n = 1\), then \(f(1)^2 + 3f(1)\) must be a square. Since

\[(f(1) + 1)^2 \le f(1)^2 + 3f(1) < (f(1) + 2)^2,\]

there must be equality on the left, and thus \(f(1) = 1\). Now let \(p = 2k+1\) be an odd prime and substitute \(m = k = (p-1)/2\) and \(n = 1\). Then we see that \(f(k)^2 + p\) must be a square, say \(a^2\) for some positive integer \(a\). This gives \(p = a^2 - f(k)^2 = (a - f(k))(a + f(k))\), and this has the only solution \(a - f(k) = 1\) and \(a + f(k) = p = 2k + 1\). Taking the difference of these gives \(f(k) = k\).

Now we only substitute \(m = k\) (again so that \(2k + 1\) is an odd prime, so \(f(k) = k\)), then we see that \(k^2 + 2kf(n) + f(n^2) = (k + f(n))^2 + f(n^2) - f(n)^2\) is a square. If we choose \(k\) large enough (for a given \(n\)) so that \(1 - 2k - 2f(n) < f(n^2) - f(n)^2 < 1 + 2k + 2f(n)\), then we see that

\[(k + f(n) - 1)^2 < (k + f(n))^2 + f(n^2) - f(n)^2 < (k + f(n) + 1)^2.\]

The middle expression is a square and must therefore be equal to \((k + f(n))^2\), which means that \(f(n^2) = f(n)^2\) for all \(n\). Finally, we substitute \(n = k\), and see that \(f(m)^2 + 2mk + k^2 = (k + m)^2 + f(m)^2 - m^2\) is a square. If we now choose \(k\) large enough again (for a given \(m\)), we see with the same reasoning that \(f(m)^2 = m^2\), so \(f(m) = m\) for all \(m\).

The function \(f(m) = m\) indeed satisfies, because then the desired expression is \((m+n)^2\). □

|

f(m) = m

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle functies \(f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \to \mathbb{Z}_{>0}\) zo dat voor alle positieve gehele getallen \(m, n\) geldt dat

\[(f(m))^2 + 2mf(n) + f(n^2)\]

het kwadraat van een geheel getal is.

|

Vul in \(m = n = 1\), dan moet \(f(1)^2 + 3f(1)\) een kwadraat zijn. Aangezien

\[(f(1) + 1)^2 \le f(1)^2 + 3f(1) < (f(1) + 2)^2,\]

moet er links gelijkheid gelden, en dus is \(f(1) = 1\). Laat nu \(p = 2k+1\) een oneven priemgetal en vul in \(m = k = (p-1)/2\) en \(n = 1\). Dan zien we dat \(f(k)^2 + p\) een kwadraat moet zijn, zeg \(a^2\) voor een positieve gehele \(a\). Dat geeft \(p = a^2 - f(k)^2 = (a - f(k))(a + f(k))\), en dit heeft als enige oplossing \(a - f(k) = 1\) en \(a + f(k) = p = 2k + 1\). Hiervan het verschil nemen geeft \(f(k) = k\).

Nu vullen we alleen \(m = k\) in (weer zodat \(2k + 1\) een oneven priemgetal is, dus zodat \(f(k) = k\)), dan zien we dat \(k^2 + 2kf(n) + f(n^2) = (k + f(n))^2 + f(n^2) - f(n)^2\) een kwadraat is. Als we \(k\) groot genoeg kiezen (voor gegeven \(n\)) zodat \(1 - 2k - 2f(n) < f(n^2) - f(n)^2 < 1 + 2k + 2f(n)\), dan zien we dat

\[(k + f(n) - 1)^2 < (k + f(n))^2 + f(n^2) - f(n)^2 < (k + f(n) + 1)^2.\]

De middelste uitdrukking is een kwadraat en moet dus gelijk zijn aan \((k + f(n))^2\), dat betekent dat \(f(n^2) = f(n)^2\) voor alle \(n\). Tot slot vullen we \(n = k\) in, en zien we dat \(f(m)^2 + 2mk + k^2 = (k + m)^2 + f(m)^2 - m^2\) een kwadraat is. Als we nu \(k\) weer groot genoeg kiezen (voor gegeven \(m\)), zien we met dezelfde redenering dat \(f(m)^2 = m^2\), dus \(f(m) = m\) voor alle \(m\).

De functie \(f(m) = m\) voldoet inderdaad, want dan is het gevraagde gelijk aan \((m+n)^2\). □

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-D2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

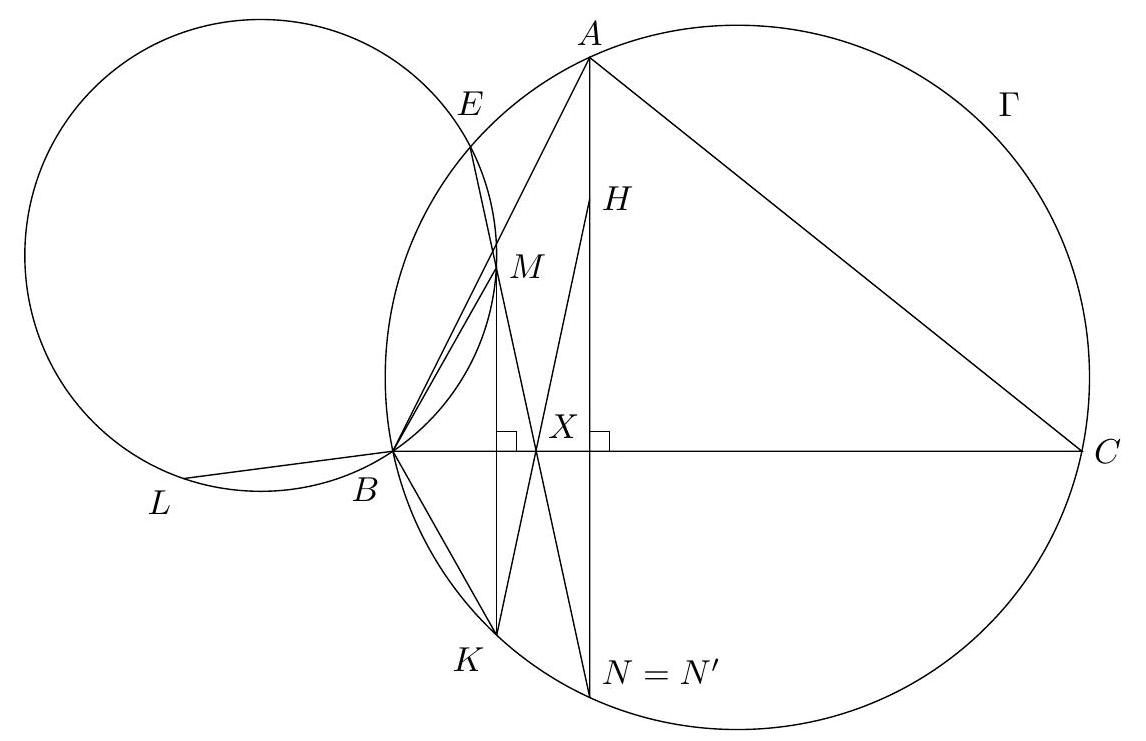

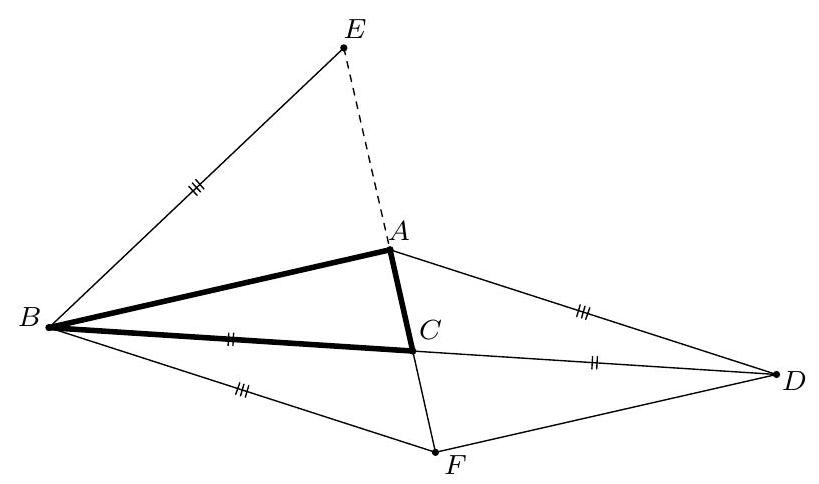

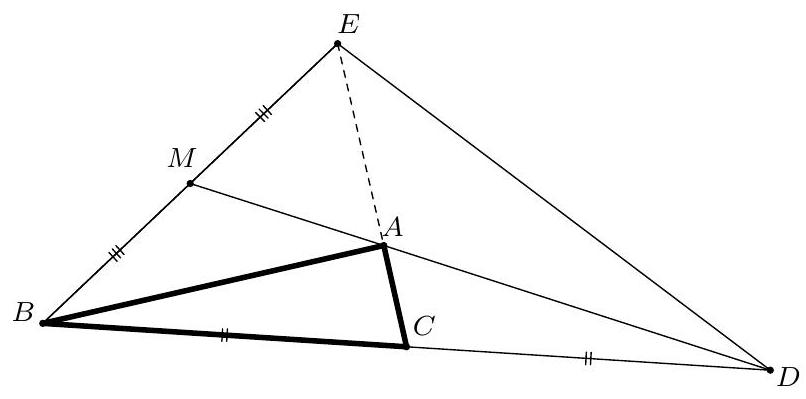

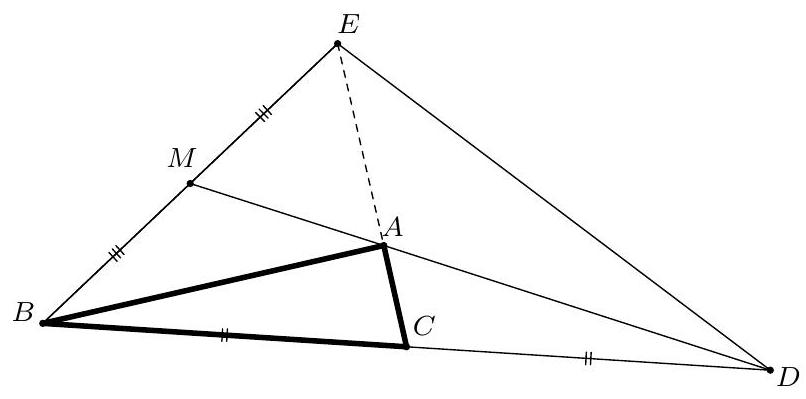

Let \(ABCD\) be a parallelogram and let \(M\) be the intersection of the diagonals. The circumcircle of \(\triangle ABM\) intersects the line segment \(AD\) at \(E \neq A\) and the circumcircle of \(\triangle EMD\) intersects the line segment \(BE\) at the point \(F \neq E\).

Prove that \(\angle ACB = \angle DCF\).

|

We first show that \(CBFD\) is a cyclic quadrilateral. It holds that

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle BCD &= \angle BAD = \angle BAE \quad (\text{parallelogram}) \\

&= 180^\circ - \angle EMB \quad (\text{cyclic quadrilateral theorem in } EABM) \\

&= \angle EMD \quad (\text{straight angle}) \\

&= \angle EFD \quad (\text{inscribed angle theorem in } EFMD) \\

&= 180^\circ - \angle BFD \quad (\text{straight angle}).

\end{align*}

\]

Thus, by the cyclic quadrilateral theorem, \(CBFD\) is a cyclic quadrilateral. With this, we find that

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle ACD &= \angle CAB = \angle MAB \tag{Z-angles} \\

&= \angle MEB = \angle MEF \tag{inscribed angle theorem in EABM} \\

&= \angle MDF = \angle BDF \tag{inscribed angle theorem in EFMD} \\

&= \angle BCF \tag{inscribed angle theorem in CBFD}.

\end{align*}

\]

Thus, \(\angle ACF + \angle FCD = \angle ACD = \angle BCF = \angle BCA + \angle ACF\). If we subtract \(\angle ACF\) from both sides, we find that \(\angle ACB = \angle DCF\), which is what we wanted to prove. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij \(ABCD\) een parallellogram en zij \(M\) het snijpunt van de diagonalen. De omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle ABM\) snijdt het lijnstuk \(AD\) in \(E \neq A\) en de omgeschreven cirkel van \(\triangle EMD\) snijdt het lijnstuk \(BE\) in het punt \(F \neq E\).

Bewijs dat \(\angle ACB = \angle DCF\).

|

We laten eerst zien dat \(CBFD\) een koordenvierhoek is. Er geldt

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle BCD &= \angle BAD = \angle BAE \quad (\text{parallellogram}) \\

&= 180^\circ - \angle EMB \quad (\text{koordenvierhoekstelling in } EABM) \\

&= \angle EMD \quad (\text{gestrekte hoek}) \\

&= \angle EFD \quad (\text{omtrekshoekstelling in } EFMD) \\

&= 180^\circ - \angle BFD \quad (\text{gestrekte hoek}).

\end{align*}

\]

Dus wegens de koordenvierhoekstelling is \(CBFD\) een koordenvierhoek. Daarmee vinden

we dat

\[

\begin{align*}

\angle ACD &= \angle CAB = \angle MAB \tag{Z-hoeken} \\

&= \angle MEB = \angle MEF \tag{omtrekshoekstelling in EABM} \\

&= \angle MDF = \angle BDF \tag{omtrekshoekstelling in EFMD} \\

&= \angle BCF \tag{omtrekshoekstelling in CBFD}.

\end{align*}

\]

Dus \(\angle ACF + \angle FCD = \angle ACD = \angle BCF = \angle BCA + \angle ACF\). Als we hier \(\angle ACF\) van af

halen vinden we dat \(\angle ACB = \angle DCF\), wat we wilden bewijzen. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-E2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

We call an integer \(n \ge 3\) polypythagorean if there are \(n\) distinct positive numbers that can be placed around a circle such that the sum of the squares of each pair of consecutive numbers is a square. For example, 3 is a polypythagorean number because you can use 44, 117, and 240, for which \(44^2 + 117^2 = 125^2\), \(117^2 + 240^2 = 267^2\), and \(240^2 + 44^2 = 244^2\).

Find all polypythagorean numbers.

|

We prove by induction that all integers greater than or equal to 2 are polypythagorean, where we extend the definition to \(n = 2\) in the logical way. As the base case, we take (3, 4) for \(n = 2\) and (44, 117, 240) from the example for \(n = 3\).

Suppose now that \(n\) is polypythagorean with witness numbers \((a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)\). Choose a prime \(p\) that does not divide any of the \(a_i\). Then define \(x = p^2 - 1\) and \(y = 2p\). For these, we have that \(x^2 + y^2 = (p^2 - 1)^2 + (2p)^2 = (p^2 + 1)^2\). By multiplying our \(n\)-tuple by \(x\), we can now insert two numbers:

\[(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n, y a_n, y a_1).\]

We easily check that

\[

\begin{align*} (x a_i)^2 + (x a_{i+1})^2 &= x^2 (a_i^2 + a_{i+1}^2), \\ (x a_n)^2 + (y a_n)^2 &= (x^2 + y^2) a_n, \\ (y a_n)^2 + (y a_1)^2 &= y^2 (a_n^2 + a_1^2), \\ (y a_1)^2 + (x a_1)^2 &= (y^2 + x^2) a_1^2, \end{align*}

\]

are indeed all squares by the induction hypothesis and the definition of \(x\) and \(y\). Since the numbers \(a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n\) are all distinct, the numbers \(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n\) are also all distinct. The numbers \(y a_n\) and \(y a_1\) are also distinct from each other. And since \(y\) is divisible by \(p\), but \(x\) and \(a_i\) are not, \(y a_n\) or \(y a_1\) cannot be equal to any of the \(x a_i\). We conclude that \(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n, y a_n, y a_1\) are all distinct, so \(n + 2\) is polypythagorean.

Since our base case consisted of \(n = 2, 3\), this proves by steps of two that all numbers are polypythagorean. \(\square\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

We noemen een geheel getal \(n \ge 3\) polypythagorees als er \(n\) verschillende positieve getallen zijn die je een cirkel achter elkaar kan zetten zo dat de som van de kwadraten van elk paar opvolgende getallen een kwadraat is. Zo is 3 een polypythagorees getal omdat je bijvoorbeeld met 44, 117 en 240 een drietal hebt waarvoor geldt dat \(44^2 + 117^2 = 125^2\), \(117^2 + 240^2 = 267^2\) en \(240^2 + 44^2 = 244^2\).

Vind alle polypythagorees getallen.

|

We bewijzen met inductie dat alle gehele getallen groter of gelijk aan 2 polypythagorees zijn, waarbij we de definitie uitbreiden naar \(n = 2\) op de logische manier. Als inductiebasis nemen we (3, 4) voor \(n = 2\) en (44, 117, 240) uit het voorbeeld voor \(n = 3\).

Stel nu dat \(n\) polypythagorees is met als getuige de getallen \((a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)\). Kies nu een priemgetal \(p\) dat geen enkele van de \(a_i\) deelt. Dan definiëren we \(x = p^2 - 1\) en \(y = 2p\). Hiervoor geldt dat \(x^2 + y^2 = (p^2 - 1)^2 + (2p)^2 = (p^2 + 1)^2\). Door ons \(n\)-tal met \(x\) te vermenigvuldigen kunnen hiermee nu twee getallen invoegen:

\[(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n, y a_n, y a_1).\]

We controleren eenvoudig dat

\[

\begin{align*} (x a_i)^2 + (x a_{i+1})^2 &= x^2 (a_i^2 + a_{i+1}^2), \\ (x a_n)^2 + (y a_n)^2 &= (x^2 + y^2) a_n, \\ (y a_n)^2 + (y a_1)^2 &= y^2 (a_n^2 + a_1^2), \\ (y a_1)^2 + (x a_1)^2 &= (y^2 + x^2) a_1^2, \end{align*}

\]

inderdaad allemaal kwadraten zijn wegens de inductiehypothese en de definitie van \(x\) en \(y\). Omdat de getallen \(a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n\) allemaal verschillend zijn, zijn de getallen \(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n\) ook allemaal verschillend. De getallen \(y a_n\) en \(y a_1\) zijn ook verschillend van elkaar. En omdat \(y\) deelbaar is door \(p\), maar \(x\) en \(a_i\) niet, kunnen \(y a_n\) of \(y a_1\) niet gelijk zijn aan een van de \(x a_i\). We concluderen dat \(x a_1, x a_2, \dots, x a_n, y a_n, y a_1\) allemaal verschillend zijn, dus \(n + 2\) is polypythagorees.

Aangezien onze inductiebasis bestond uit \(n = 2, 3\) bewijst dit met stappen van twee dat alle getallen polypythagorees zijn. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-E2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

Determine all triples \((x, y, p)\) of positive integers such that \(p\) is a prime number, \(x^2 = p - 1\), and \(y^2 = 2p^2 - 1\).

|

The only triplet that satisfies the condition is \((2, 7, 5)\).

First, we calculate that

\[ (y + x)(y - x) = y^2 - x^2 = (2p^2 - 1) - (p - 1) = 2p^2 - p = p(2p - 1). \quad (1) \]

This means in particular that \(p \mid x + y\) or \(p \mid x - y\).

Assume that \(p \mid y + x\). Then \(y = kp - x\) for some \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\). From the given conditions, however, \(2p > y > p\) and \(x < p\). Therefore, \(2p > y = kp - x > kp - p = (k - 1)p\) and \(kp > kp - x = y > p\), from which we conclude that \(k = 2\). Thus, \(y = 2p - x\). Substituting this into (1) gives us

\[ 2p(2p - x - x) = p(2p - 1). \]

Distributing \(p\) leaves us with \(4(p - x) = 2p - 1\). This is impossible since the left side is even and the right side is odd.

Now assume that \(p \mid y - x\). Then we have \(y = kp + x\). From the given conditions, \(2p > y = kp + x > kp\) and \((k + 1)p = kp + p > kp + x = y > p\). This implies that \(k = 1\), so \(y - x = p\), and from (1) also that \(y + x = 2p - 1\). Solving these, we find \(2x = (y + x) - (y - x) = (2p - 1) - p = p - 1\). We conclude that \(4(p - 1) = 4x^2 = (2x)^2 = (p - 1)^2\). As a quadratic equation in \(p - 1\), this has the solutions \(p - 1 = 0\) and \(p - 1 = 4\). Only in the second case is \(p\) a prime number, namely \(p = 5\). This gives \(x = (p-1)/2 = 2\) and \(y = p + x = 5 + 2 = 7\). This satisfies the condition. \(\square\)

|

(2, 7, 5)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle drietallen \((x, y, p)\) van positieve gehele getallen zo dat \(p\) een

priemgetal is, \(x^2 = p - 1\) en \(y^2 = 2p^2 - 1\).

|

Het enige drietal dat voldoet is \((2, 7, 5)\).

We rekenen eerst uit dat

\[ (y + x)(y - x) = y^2 - x^2 = (2p^2 - 1) - (p - 1) = 2p^2 - p = p(2p - 1). \quad (1) \]

Dat betekent in het bijzonder dat \(p \mid x + y\) of \(p \mid x - y\).

Stel dat \(p \mid y + x\). Dan geldt dat \(y = kp - x\) voor een zekere \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\). Uit het gegeven volgt echter dat \(2p > y > p\) en \(x < p\). Dus \(2p > y = kp - x > kp - p = (k - 1)p\) en \(kp > kp - x = y > p\), waaruit we concluderen dat \(k = 2\). Dus \(y = 2p - x\). Als we dat invullen in (1) krijgen we

\[ 2p(2p - x - x) = p(2p - 1). \]

Als we \(p\) uitdelen, dan houden we over dat \(4(p - x) = 2p - 1\). Dit is onmogelijk aangezien de linkerkant even is en de rechterkant oneven.

Stel nu dat \(p \mid y - x\). Dan hebben we \(y = kp + x\). Uit het gegeven volgt dan \(2p > y = kp + x > kp\) en \((k + 1)p = kp + p > kp + x = y > p\). Hieruit volgt dat \(k = 1\), dus \(y - x = p\), en wegens (1) ook dat \(y + x = 2p - 1\). Als we dat oplossen vinden we \(2x = (y + x) - (y - x) = (2p - 1) - p = p - 1\). We concluderen dat \(4(p - 1) = 4x^2 = (2x)^2 = (p - 1)^2\). Als kwadratische vergelijking in \(p - 1\) heeft dit de oplossingen \(p - 1 = 0\) en \(p - 1 = 4\). Alleen in het tweede geval is \(p\) een priemgetal, namelijk \(p = 5\). Dat geeft verder \(x = (p-1)/2 = 2\) en \(y = p+x = 5+2 = 7\). Deze voldoet. \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-E2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

We say that a sequence \(a_1, \dots, a_n\) of real numbers is decreasingly increasing if for all \(1 < i < n\) it holds that \(0 < a_{i+1} - a_i < a_i - a_{i-1}\). Find for each positive integer \(m\) the smallest positive integer \(k\) for which there exists a decreasingly increasing sequence of length \(k\) such that 1 can be written as the difference of two elements \(a_i\) and \(a_j\) from the sequence in at least \(m\) different ways.

|

We first prove that \(k \ge 2m\). We define \(b_i = a_{i+1} - a_i\). Then \(b_1, b_2, \dots, b_{k-1}\) is a decreasing sequence of positive real numbers. Each of the ways to write 1 in this form is a sum of consecutive elements in this sequence \(b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{j+t-1} = a_{j+t} - a_j = 1\) with \(1 \le j\), \(1 \le t\) and \(j + t \le k\). No two of these ways can start at the same position, because their difference would then be the sum of the last few \(b_i\) of the longer sequence, contradicting that the difference \(1 - 1 = 0\) must be. Also, no two of these ways can be of the same length. In fact, if we order the ways by \(1 \le j_1 < j_2 < \dots < j_m\), then \(1 \le t_1 < t_2 < \dots < t_m\) because the terms in the sequence starting with \(j_h\) are each greater than the terms of the way starting with \(j_{h+1}\). This means that

\[k \ge j_m + t_m \ge m + m = 2m.\]

Now we construct an example for \(k = 2m\). We define the last \(m\) terms of the sequence \(b_1, \dots, b_{2m-1}\) as \(b_{m+i} = \frac{2(m-1)-i}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)}\) for \(0 \le i \le m-1\). Then this is clearly a decreasing sequence and it holds that

\[b_m + b_{m+1} + \dots + b_{2m-1} = \frac{1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} \left((2m-2) + (2m-3) + \dots + m + (m-1)\right) = 1.\]

Now we define recursively \(b_{m-1}, \dots, b_1\) as \(b_i = b_{2i} + b_{2i+1}\). Then we find in particular that

\[b_{m-1} = b_{m+(m-2)} + b_{m+(m-1)} = \frac{m}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} + \frac{m-1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} = \frac{2m-1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} > \frac{2m-2}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} = b_m.\]

And for \(i < m-1\) it holds recursively that \(b_i > b_{i+1}\), because this expression is equivalent to \(b_{2i} + b_{2i+1} > b_{2i+2} + b_{2i+3}\). We conclude that \(b_1, \dots, b_{2m-1}\) is a decreasing sequence. We now prove by induction on \(j\) (decreasing) that

\[b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{2j-1} = 1\]

for all \(1 \le j \le m\). For the base case, we take \(b_m + b_{m+1} + \dots + b_{2m-1} = 1\). For the inductive step, we note that \(b_{j-1} + b_j + \dots + b_{2j-3} = b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{2j-1}\). So if the formula holds for \(j\) then it also holds for \(j-1\). \(\square\)

|

2m

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

We zeggen dat een rij \(a_1, \dots, a_n\) van reële getallen afnemend stijgend is als voor alle \(1 < i < n\) geldt dat \(0 < a_{i+1} - a_i < a_i - a_{i-1}\). Vind voor elk positief geheel getal \(m\) het kleinste positieve gehele getal \(k\) waarvoor er een afnemend stijgende rij bestaat van lengte \(k\) zo dat 1 op zijn minst op \(m\) verschillende manieren geschreven kan worden als het verschil van twee elementen \(a_i\) en \(a_j\) uit de rij.

|

We bewijzen eerst dat \(k \ge 2m\). We definiëren \(b_i = a_{i+1} - a_i\). Dan is \(b_1, b_2, \dots, b_{k-1}\) een dalende rij positieve reële getallen. En elk van de manieren om 1 te schrijven is in deze schrijfwijze een som van opvolgende elementen in deze rij \(b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{j+t-1} = a_{j+t} - a_j = 1\) met \(1 \le j\), \(1 \le t\) en \(j + t \le k\). Geen twee van deze manieren kunnen op dezelfde plek beginnen, want hun verschil is dan de som van de laatste paar \(b_i\) van de langere reeks, in tegenspraak met dat het verschil \(1 - 1 = 0\) moet zijn. Ook geen twee van deze manieren kunnen even lang zijn. Sterker nog als we de manieren ordenen op \(1 \le j_1 < j_2 < \dots < j_m\), dan geldt \(1 \le t_1 < t_2 < \dots < t_m\) want de termen in de reeks beginnend met \(j_h\) zijn stuk voor stuk groter dan de termen van de manier beginnend met \(j_{h+1}\). Dit betekent dat

\[k \ge j_m + t_m \ge m + m = 2m.\]

Nu construeren we een voorbeeld voor \(k = 2m\). We definiëren de laatste \(m\) termen van de rij \(b_1, \dots, b_{2m-1}\) als \(b_{m+i} = \frac{2(m-1)-i}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)}\) voor \(0 \le i \le m-1\). Dan is dit duidelijk een dalende rij en geldt er dat

\[b_m + b_{m+1} + \dots + b_{2m-1} = \frac{1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} \left((2m-2) + (2m-3) + \dots + m + (m-1)\right) = 1.\]

Nu definiëren recursief \(b_{m-1}, \dots, b_1\) als \(b_i = b_{2i} + b_{2i+1}\). Dan vinden we in het bijzonder dat

\[b_{m-1} = b_{m+(m-2)} + b_{m+(m-1)} = \frac{m}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} + \frac{m-1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} = \frac{2m-1}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} > \frac{2m-2}{\frac{3}{2}m(m-1)} = b_m.\]

En voor \(i < m-1\) geldt recursief dat \(b_i > b_{i+1}\), omdat deze uitdrukking equivalent is met \(b_{2i} + b_{2i+1} > b_{2i+2} + b_{2i+3}\). We concluderen we dat \(b_1, \dots, b_{2m-1}\) een dalende rij is. We bewijzen nu met inductie naar \(j\) (aflopend) dat

\[b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{2j-1} = 1\]

voor alle \(1 \le j \le m\). Voor de inductiebasis nemen we \(b_m + b_{m+1} + \dots + b_{2m-1} = 1\). Voor de inductiestap merken we op dat \(b_{j-1} + b_j + \dots + b_{2j-3} = b_j + b_{j+1} + \dots + b_{2j-1}\). Dus als de formule geldt voor \(j\) dan geldt die ook voor \(j-1\). \(\square\)

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2025-E2025_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2025"

}

|

We say that a sequence \(a_1, \dots, a_n\) of real numbers is decreasingly increasing if for all \(1 < i < n\) it holds that \(0 < a_{i+1} - a_i < a_i - a_{i-1}\). Find for each positive integer \(m\) the smallest positive integer \(k\) for which there exists a decreasingly increasing sequence of length \(k\) such that 1 can be written as the difference of two elements \(a_i\) and \(a_j\) from the sequence in at least \(m\) different ways.

|

We present an alternative example. We first choose \(b_1 = 1\). Now we take a \(0 < \epsilon_1 < \frac{1}{6}\) and define \(b_2 = \frac{1}{2} + \epsilon_1\) and \(b_3 = \frac{1}{2} - \epsilon_1\). Then it holds that \(0 < \epsilon_1 < \frac{b_1 - b_2}{2}\).

We define the rest of the sequence recursively. Suppose that for some \(2 \le i \le m-1\) it holds that \(b_1, b_2, \dots, b_{2i-1}\) is a decreasing sequence and that \(0 < \epsilon_{i-1} < \frac{b_{i-1}-b_i}{2}\). Then we choose \(\epsilon_i\) with \(0 < \epsilon_i < \frac{b_i-b_{i+1}}{2}\) and \(\epsilon_i < \frac{b_{i-1}-b_i}{2} - \epsilon_{i-1}\), and define \(b_{2i} = \frac{b_i}{2} + \epsilon_i\) and \(b_{2i+1} = \frac{b_i}{2} - \epsilon_i\). Then both \(b_{2i}\) and \(b_{2i+1}\) are positive. We also see that \(b_{2i-1} = \frac{b_{i-1}}{2} - \epsilon_{i-1} > \frac{b_i}{2} + \epsilon_i = b_{2i}\) and \(b_{2i} = b_{2i+1} + 2\epsilon_i > b_{2i+1}\), so the sequence \(b_1, b_2, \dots, b_{2i+1}\) is decreasing.

Again, it holds that \(b_{2i} + b_{2i+1} = b_i\). If we apply this to \(b_1 = 1\), then we find by induction that

\[b_j + b_{j+1} + \ldots + b_{2j-1} = 1\]

for all \(1 \le j \le m\).

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

We zeggen dat een rij \(a_1, \dots, a_n\) van reële getallen afnemend stijgend is als voor alle \(1 < i < n\) geldt dat \(0 < a_{i+1} - a_i < a_i - a_{i-1}\). Vind voor elk positief geheel getal \(m\) het kleinste positieve gehele getal \(k\) waarvoor er een afnemend stijgende rij bestaat van lengte \(k\) zo dat 1 op zijn minst op \(m\) verschillende manieren geschreven kan worden als het verschil van twee elementen \(a_i\) en \(a_j\) uit de rij.

|

We presenteren een alternatief voorbeeld. We kiezen eerst \(b_1 = 1\). Nu nemen we een \(0 < \epsilon_1 < \frac{1}{6}\) en definiëren we \(b_2 = \frac{1}{2} + \epsilon_1\) en \(b_3 = \frac{1}{2} - \epsilon_1\). Dan geldt er dat \(0 < \epsilon_1 < \frac{b_1 - b_2}{2}\).