problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

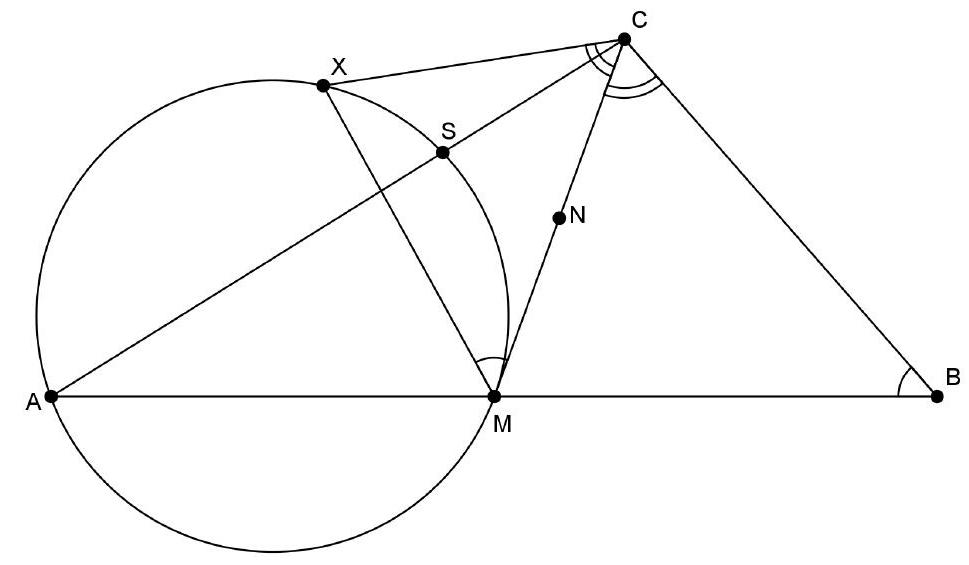

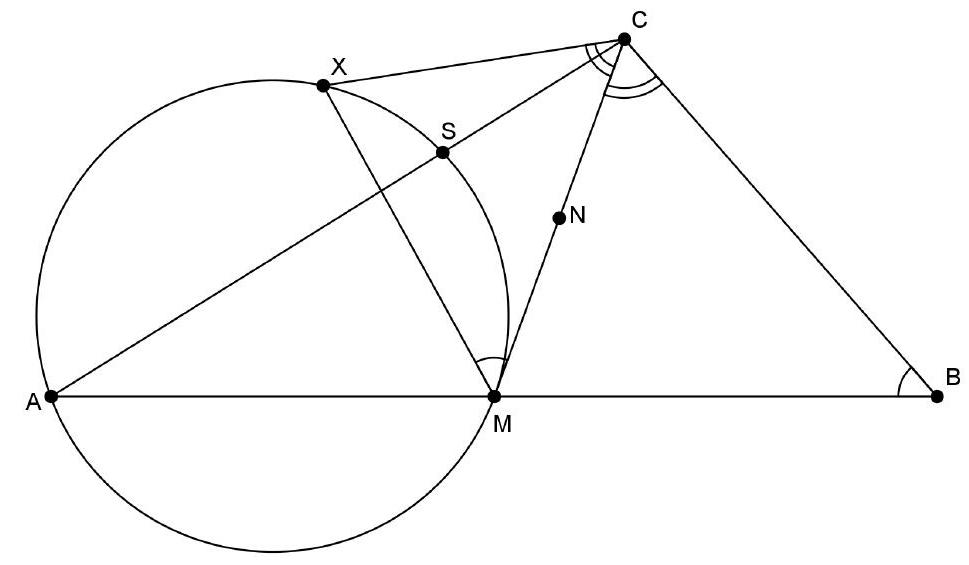

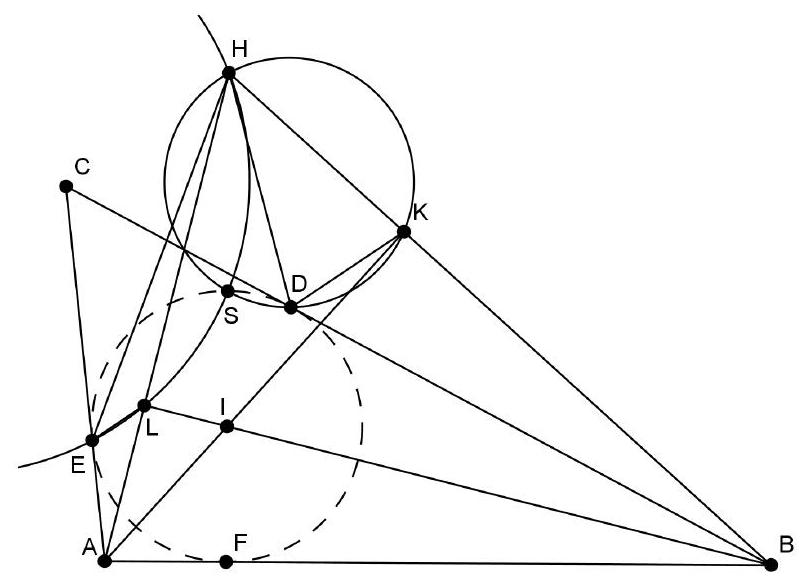

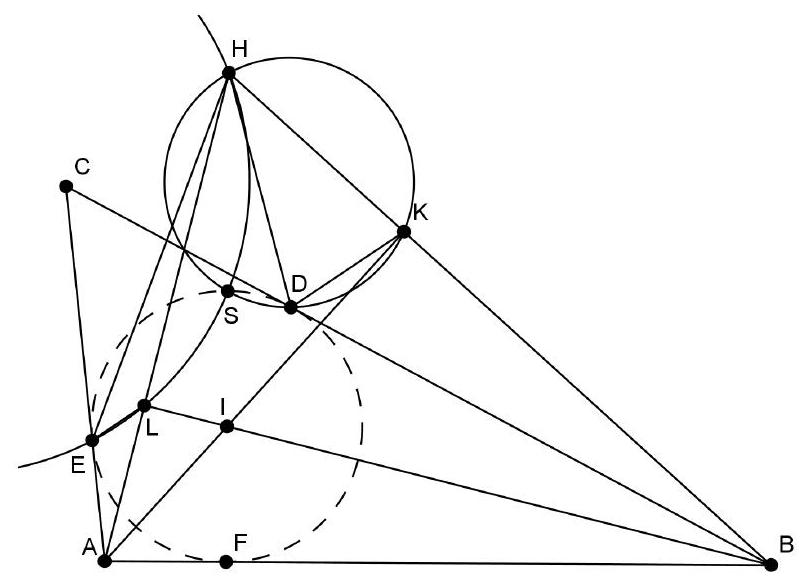

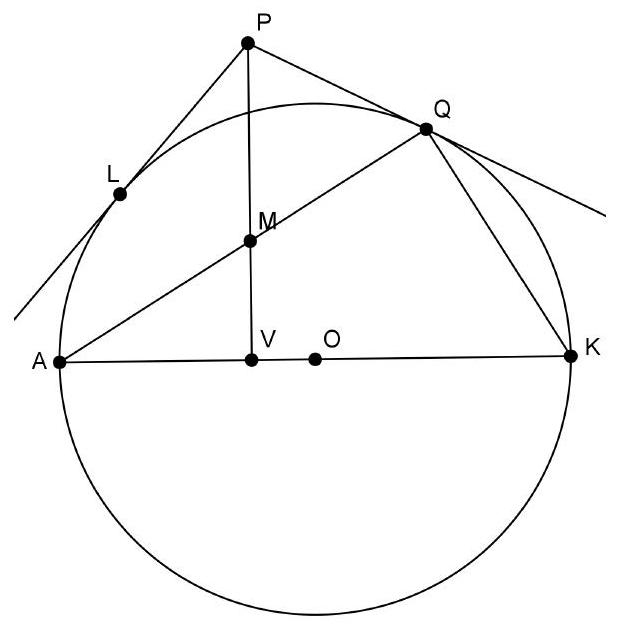

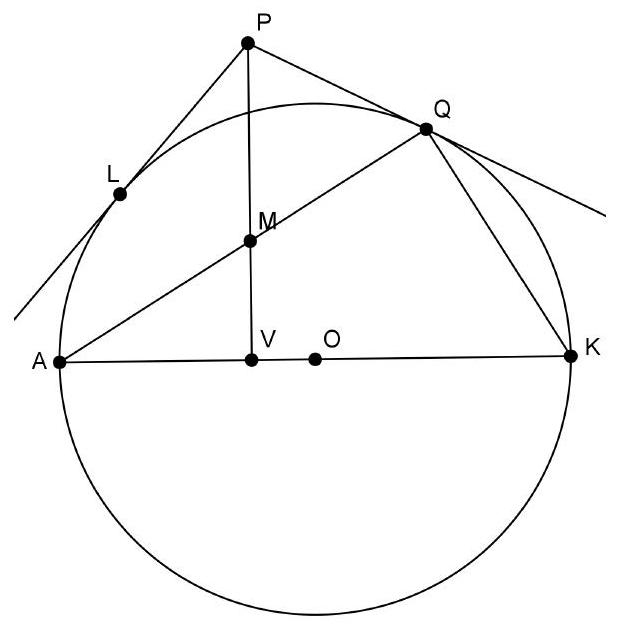

Given is a triangle $ABC$. Let $\Gamma_{1}$ be the circle through $B$ that is tangent to side $AC$ at $A$. Let $\Gamma_{2}$ be the circle through $C$ that is tangent to side $AB$ at $A$. The second intersection point of $\Gamma_{1}$ and $\Gamma_{2}$ is called $D$. The line $AD$ intersects the circumcircle of $\triangle ABC$ again at $E$. Prove that $D$ is the midpoint of $AE$.

|

Due to the tangent-secant angle theorem in $\Gamma_{1}$, we have $\angle D A C=\angle D B A$. Due to the tangent-secant angle theorem in $\Gamma_{2}$, we have $\angle D A B=\angle D C A$. Therefore, $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D(\mathrm{hh})$. Now let $M$ be the midpoint of $A B$ and $N$ the midpoint of $A C$. Then $D M$ is a median in $\triangle D B A$ and $D N$ is the corresponding median in $\triangle D A C$. Therefore, we know that $\angle B D M=\angle A D N$. Thus,

$$

\begin{array}{rlr}

\angle M D N & =\angle M D A+\angle A D N & \text { (splitting the angle) } \\

& =\angle M D A+\angle B D M & \text { (equality from above) } \\

& =\angle B D A & \text { (adding angles) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle A B D-\angle B A D & \text { (angle sum in } \triangle A B D) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle C A D-\angle B A D & \text { (similarity of } \triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle C A B & \text { (adding angles) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle N A M & \text { (same angle.) }

\end{array}

$$

We conclude that $M D N A$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Therefore, $\angle M D A=\angle M N A$. Since $M N$ is a midline in $\triangle A B C$, $\angle M N A=\angle B C A$ and that is equal to $\angle B E A$ by the inscribed angle theorem. Altogether, we have $\angle M D A=\angle B E A$, which means that $M D$ is parallel to $B E$. Since $M$ is the midpoint of $A B$, $D$ must also be the midpoint of $A E$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeven is een driehoek $A B C . \mathrm{Zij} \Gamma_{1}$ de cirkel door $B$ die raakt aan zijde $A C$ in $A$. Zij $\Gamma_{2}$ de cirkel door $C$ die raakt aan zijde $A B$ in $A$. Het tweede snijpunt van $\Gamma_{1}$ en $\Gamma_{2}$ noemen we $D$. De lijn $A D$ snijdt de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle A B C$ nog een keer in $E$. Bewijs dat $D$ het midden is van $A E$.

|

Vanwege de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling in $\Gamma_{1}$ geldt $\angle D A C=\angle D B A$. Vanwege de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling in $\Gamma_{2}$ geldt $\angle D A B=\angle D C A$. Er geldt dus $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D(\mathrm{hh})$. Noem nu $M$ het midden van $A B$ en $N$ het midden van $A C$. Dan is $D M$ een zwaartelijn in $\triangle D B A$ en is $D N$ de corresponderende zwaartelijn in $\triangle D A C$. Daardoor weten we dat $\angle B D M=\angle A D N$. Dus

$$

\begin{array}{rlr}

\angle M D N & =\angle M D A+\angle A D N & \text { (opsplitsen hoek) } \\

& =\angle M D A+\angle B D M & \text { (gelijkheid van hiervoor) } \\

& =\angle B D A & \text { (optellen hoeken) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle A B D-\angle B A D & \text { (hoekensom } \triangle A B D) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle C A D-\angle B A D & \text { (gelijkvormigheid } \triangle A B D \sim \triangle C A D) \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle C A B & \text { (optellen hoeken) } \\

& =180^{\circ}-\angle N A M & \text { (zelfde hoek.) }

\end{array}

$$

We concluderen dat $M D N A$ een koordenvierhoek is. Dus $\angle M D A=\angle M N A$. Omdat $M N$ een middenparallel in $\triangle A B C$ is, is $\angle M N A=\angle B C A$ en dat is wegens de omtrekshoekstelling weer gelijk aan $\angle B E A$. Al met al hebben we $\angle M D A=\angle B E A$, wat betekent dat $M D$ evenwijdig is met $B E$. Aangezien $M$ het midden van $A B$ is, moet nu $D$ ook het midden van $A E$ zijn.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing III.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Let $n \geq 3$ be an integer and consider an $n \times n$ board, divided into $n^{2}$ unit squares. We have for each $m \geq 1$ arbitrarily many $1 \times m$ rectangles (type I) and arbitrarily many $m \times 1$ rectangles (type II) available. We cover the board with $N$ of these rectangles, which do not overlap and do not extend beyond the board. The total number of type I rectangles on the board must be equal to the total number of type II rectangles on the board. (Note that a $1 \times 1$ rectangle is both of type I and of type II.) What is the smallest value of $N$ for which this is possible?

|

We prove that the minimal value $N=2n-1$. First, we construct an example by induction.

Base case. For $n=3$, $N=5$ is possible, by placing a $1 \times 1$ rectangle in the middle field and covering the remaining fields with four $2 \times 1$ and $1 \times 2$ rectangles. There are then three rectangles with height 1 (type I) and three rectangles with width 1 (type II), where the $1 \times 1$ rectangle is counted twice.

Inductive step. Let $k \geq 3$ and assume that we can cover a $k \times k$ board with $2k-1$ rectangles such that all conditions are met. Consider a $(k+1) \times (k+1)$ board and cover the $k \times k$ sub-square at the bottom right according to the inductive hypothesis. Then cover the left column with a rectangle of width 1 and height $k+1$, and cover the remaining space with a rectangle of height 1 and width $k$. We have now used one more rectangle with width 1 and one more rectangle with height 1, so the condition is satisfied and we have used $2k-1+2=2(k+1)-1$ rectangles. This constructs an example for $n=k+1$.

This proves that it is possible to cover the board with $N=2n-1$ rectangles. We now want to prove that it cannot be done with fewer rectangles. Let $k$ be the number of rectangles with width 1 and height greater than 1. Then the number of rectangles with height 1 and width greater than 1 is also $k$. Let $l$ be the number of $1 \times 1$ rectangles. Thus, $N=2k+l$. If $k \geq n$, then $N \geq 2n$, so there is nothing to prove in this case. We therefore assume that $k < n$ and we will prove that then $l \geq 2n-2k-1$, so that $N \geq 2n-1$.

Each rectangle with width 1 can only cover fields in one column. Therefore, there are $n-k$ columns in which no field is covered by a rectangle with width 1 and height greater than 1. Similarly, there are $n-k$ rows in which no field is covered by a rectangle with height 1 and width greater than 1. Consider the $(n-k)^2$ fields that lie in both such a row and such a column. These fields must be covered by $1 \times 1$ rectangles. Thus, $l \geq (n-k)^2$.

We have $(k-n+1)^2 \geq 0$, so $k^2 + n^2 + 1 - 2kn + 2k - 2n \geq 0$, and thus $n^2 - 2kn + k^2 \geq 2n - 2k - 1$. We conclude that $l \geq (n-k)^2 \geq 2n - 2k - 1$, which is exactly what we wanted to prove. Therefore, in all cases, $N \geq 2n-1$, and this proves that the minimal value of $N$ is $2n-1$.

|

2n-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Zij $n \geq 3$ een geheel getal en bekijk een $n \times n$-bord, opgedeeld in $n^{2}$ eenheidsvierkantjes. We hebben voor elke $m \geq 1$ willekeurig veel $1 \times m$-rechthoeken (type I) en willekeurig veel $m \times 1$-rechthoeken (type II) beschikbaar. We bedekken het bord met $N$ van deze rechthoeken, die elkaar niet overlappen en niet uitsteken buiten het bord. Het totaal aantal rechthoeken van type I op het bord moet hierbij gelijk zijn aan het totaal aantal rechthoeken van type II op het bord. (Merk op dat een $1 \times 1$-rechthoek zowel van type I als van type II is.) Wat is de kleinste waarde van $N$ waarvoor dit mogelijk is?

|

We bewijzen dat de minimale waarde $N=2 n-1$ is. We construeren eerst een voorbeeld door middel van inductie.

Inductiebasis. Voor $n=3$ is $N=5$ mogelijk, door in het middelste veld een $1 \times 1$-rechthoek te leggen en de overige velden te bedekken met vier $2 \times 1$ - en $1 \times 2$-rechthoeken. Er zijn dan drie rechthoeken met hoogte 1 (type I) en drie rechthoeken met breedte 1 (type II), waarbij de $1 \times 1$-rechthoek twee keer geteld wordt.

Inductiestap. Zij $k \geq 3$ en neem aan dat we een $k \times k$-bord kunnen bedekken met $2 k-1$ rechthoeken zodat aan alle voorwaarden is voldaan. Bekijk een $(k+1) \times(k+1)$-bord en bedek het $k \times k$-deelvierkant rechtsonder volgens de inductiehypothese. Bedek vervolgens de linkerkolom met een rechthoek met breedte 1 en hoogte $k+1$ en vervolgens de overgebleven ruimte met een rechthoek met hoogte 1 en breedte $k$. We hebben nu één rechthoek met breedte 1 en één rechthoek met hoogte 1 meer gebruikt, dus aan de voorwaarde is voldaan en we hebben $2 k-1+2=2(k+1)-1$ rechthoeken gebruikt. Hiermee hebben we een voorbeeld voor $n=k+1$ geconstrueerd.

Hiermee is bewezen dat het mogelijk is om het bord te bedekken met $N=2 n-1$ rechthoeken. We willen nu nog bewijzen dat het niet met minder rechthoeken kan. Zij $k$ het aantal rechthoeken met breedte 1 en hoogte groter dan 1 . Dan is ook het aantal rechthoeken met hoogte 1 en breedte groter dan 1 , gelijk aan $k$. Zij verder $l$ het aantal rechthoeken van $1 \times 1$. Er geldt dus $N=2 k+l$. Als $k \geq n$, geldt $N \geq 2 n$, dus in dit geval is er niets te bewijzen. We nemen dus aan dat $k<n$ en we gaan bewijzen dat dan $l \geq 2 n-2 k-1$, zodat $N \geq 2 n-1$.

Elke rechthoek met breedte 1 kan alleen velden in één kolom bedekken. Er zijn dus $n-k$ kolommen waarin geen enkel veld wordt bedekt door een rechthoek met breedte 1 en hoogte groter dan 1. Zo ook zijn er $n-k$ rijen waarin geen enkel veld wordt bedekt door een rechthoek met hoogte 1 en breedte groter dan 1. Bekijk de $(n-k)^{2}$ velden die in zowel zo'n rij als zo'n kolom liggen. Deze velden moeten bedekt worden door $1 \times 1$-rechthoeken. Dus $l \geq(n-k)^{2}$.

Er geldt $(k-n+1)^{2} \geq 0$, dus $k^{2}+n^{2}+1-2 k n+2 k-2 n \geq 0$, dus $n^{2}-2 k n+k^{2} \geq 2 n-2 k-1$. We concluderen dat $l \geq(n-k)^{2} \geq 2 n-2 k-1$ en dat is precies wat we wilden bewijzen. Dus in alle gevallen is $N \geq 2 n-1$ en dat bewijst dat de minimale waarde van $N$ gelijk is aan $2 n-1$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Let $a, b$ and $c$ be positive real numbers with $a b c=1$. Prove that

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

Let $x, y$ and $z$ be positive real numbers such that $x^{3}=a, y^{3}=b$ and $z^{3}=c$. Then $x^{3} y^{3} z^{3}=1$, so also $x y z=1$. We can now write $a+2$ as $x^{3}+2 x y z=x\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)$, and similarly we can rewrite $b+2$ and $c+2$, which gives us

\[

(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)=x y z\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right)=\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right).

\]

Now we apply the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality to the positive terms $x^{2}+2 y z, y^{2}+2 z x$ and $z^{2}+2 x y$:

\[

\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right) \leq\left(\frac{x^{2}+2 y z+y^{2}+2 z x+z^{2}+2 x y}{3}\right)^{3}=\left(\frac{(x+y+z)^{2}}{3}\right)^{3}.

\]

So far, we have found:

\[

(a+2)(b+2)(c+2) \leq \frac{1}{27}\left((x+y+z)^{3}\right)^{2}

\]

We will now prove that $(x+y+z)^{3} \leq 9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)$. For those familiar with power means: this follows directly from the inequality between the arithmetic mean and the cubic mean. We have

\[

(x+y+z)^{3}=x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}+3\left(x^{2} y+y^{2} z+z^{2} x+x y^{2}+y z^{2}+z x^{2}\right)+6 x y z.

\]

Using the arithmetic mean-geometric mean inequality on only positive terms, we know that

\[

2 x^{3}+y^{3}=x^{3}+x^{3}+y^{3} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{6} y^{3}}=3 x^{2} y

\]

and similarly $x^{3}+2 y^{3} \geq 3 x y^{2}$. If we cyclically permute these two inequalities, we find

\[

3\left(x^{2} y+y^{2} z+z^{2} x+x y^{2}+y z^{2}+z x^{2}\right) \leq 6\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right).

\]

We also know $x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{3} y^{3} z^{3}}=3 x y z$, so altogether we get

\[

(x+y+z)^{3} \leq\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)+6\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)+2\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)=9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right).

\]

Combining this with (4) we now get

\[

(a+2)(b+2)(c+2) \leq \frac{1}{27}\left(9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)\right)^{2}=3(a+b+c)^{2}.

\]

Dividing both sides by 3 and then taking the square root (both sides are positive) gives us exactly the desired result.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Laat $a, b$ en $c$ positieve reële getallen zijn met $a b c=1$. Bewijs dat

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

Laat $x, y$ en $z$ positieve reële getallen zijn zodat $x^{3}=a, y^{3}=b$ en $z^{3}=c$. Dan geldt $x^{3} y^{3} z^{3}=1$, dus ook $x y z=1$. We kunnen nu $a+2$ schrijven als $x^{3}+2 x y z=x\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)$, en analoog kunnen we $b+2$ en $c+2$ herschrijven, waarmee we krijgen

$(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)=x y z\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right)=\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right)$.

Nu passen we rekenkundig-meetkundig toe op de positieve termen $x^{2}+2 y z, y^{2}+2 z x$ en $z^{2}+2 x y:$

$\left(x^{2}+2 y z\right)\left(y^{2}+2 z x\right)\left(z^{2}+2 x y\right) \leq\left(\frac{x^{2}+2 y z+y^{2}+2 z x+z^{2}+2 x y}{3}\right)^{3}=\left(\frac{(x+y+z)^{2}}{3}\right)^{3}$.

We hebben tot nu toe dus gevonden:

$$

(a+2)(b+2)(c+2) \leq \frac{1}{27}\left((x+y+z)^{3}\right)^{2}

$$

We gaan nu bewijzen dat $(x+y+z)^{3} \leq 9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)$. Voor wie het machtsgemiddelde kent: dit volgt direct uit de ongelijkheid van het rekenkundig gemiddelde en het derdemachtsgemiddelde. Er geldt

$$

(x+y+z)^{3}=x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}+3\left(x^{2} y+y^{2} z+z^{2} x+x y^{2}+y z^{2}+z x^{2}\right)+6 x y z .

$$

Met rekenkundig-meetkundig op alleen maar positieve termen weten we dat

$$

2 x^{3}+y^{3}=x^{3}+x^{3}+y^{3} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{6} y^{3}}=3 x^{2} y

$$

en analoog $x^{3}+2 y^{3} \geq 3 x y^{2}$. Als we deze beide ongelijkheden cyclisch doordraaien, vinden we

$$

3\left(x^{2} y+y^{2} z+z^{2} x+x y^{2}+y z^{2}+z x^{2}\right) \leq 6\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right) .

$$

We weten natuurlijk ook $x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{3} y^{3} z^{3}}=3 x y z$, dus al met al krijgen we

$$

(x+y+z)^{3} \leq\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)+6\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)+2\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)=9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right) .

$$

Gecombineerd met (4) krijgen we nu

$$

(a+2)(b+2)(c+2) \leq \frac{1}{27}\left(9\left(x^{3}+y^{3}+z^{3}\right)\right)^{2}=3(a+b+c)^{2}

$$

Links en rechts delen door 3 en daarna de worteltrekken (beide kanten zijn positief) geeft nu precies het gevraagde.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Let $a, b$ and $c$ be positive real numbers with $a b c=1$. Prove that

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

Note that $a, b$ and $c$ are positive, so we can always apply the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality below. First, we apply the arithmetic-geometric mean to $a^{2}$ and 1:

$$

a^{2}+1 \geq 2 \sqrt{a^{2}}=2 a

$$

We can cyclically permute and add, so we find:

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+3 \geq 2 a+2 b+2 c

$$

Furthermore, we apply the arithmetic-geometric mean to $b c, c a$ and $a b$:

$$

b c+c a+a b \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{a^{2} b^{2} c^{2}}=3

$$

where we have used that $a b c=1$. Also, we apply the arithmetic-geometric mean to $a^{2}, b^{2}$ and $c^{2}$:

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{a^{2} b^{2} c^{2}}=3

$$

Now we take 2 times (5), 4 times (6), and 1 time (7) and add them up. Then we get:

$$

2 a^{2}+2 b^{2}+2 c^{2}+6+4 b c+4 c a+4 a b+a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 4 a+4 b+4 c+12+3

$$

Combining like terms, subtracting 6 from both sides, and adding $2 a b+2 b c+2 c a$ to both sides gives:

$$

3 a^{2}+3 b^{2}+3 c^{2}+6 a b+6 b c+6 c a \geq 2 a b+2 b c+2 c a+4 a+4 b+4 c+9

$$

Now, on the left, we have $3\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+2 a b+2 b c+2 c a\right)=3(a+b+c)^{2}$. On the right, we can write 9 as $8+a b c$, and then we have exactly $(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)$. Finally, dividing both sides by 3 and taking the square root (everything is still positive), we get

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Laat $a, b$ en $c$ positieve reële getallen zijn met $a b c=1$. Bewijs dat

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

Merk op dat $a, b$ en $c$ positief zijn, zodat we hieronder steeds rekenkundigmeetkundig mogen toepassen. Allereerst passen we rekenkundig-meetkundig toe op $a^{2}$ en 1 :

$$

a^{2}+1 \geq 2 \sqrt{a^{2}}=2 a

$$

Dit kunnen we cyclisch doordraaien en optellen, zodat we vinden:

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+3 \geq 2 a+2 b+2 c

$$

Verder passen we rekenkundig-meetkundig toe op $b c, c a$ en $a b$ :

$$

b c+c a+a b \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{a^{2} b^{2} c^{2}}=3

$$

waarbij we gebruikt hebben dat $a b c=1$. Ook passen we rekenkundig-meetkundig toe op $a^{2}, b^{2}$ en $c^{2}$ :

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 3 \sqrt[3]{a^{2} b^{2} c^{2}}=3

$$

Nu nemen we 2 keer (5), 4 keer (6) en 1 keer (7) en tellen dat op. Dan krijgen we:

$$

2 a^{2}+2 b^{2}+2 c^{2}+6+4 b c+4 c a+4 a b+a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 4 a+4 b+4 c+12+3

$$

Gelijke termen bij elkaar nemen, links en rechts 6 aftrekken en links en rechts $2 a b+2 b c+2 c a$ optellen geeft:

$$

3 a^{2}+3 b^{2}+3 c^{2}+6 a b+6 b c+6 c a \geq 2 a b+2 b c+2 c a+4 a+4 b+4 c+9

$$

Nu staat links $3\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+2 a b+2 b c+2 c a\right)=3(a+b+c)^{2}$. Rechts kunnen we 9 schrijven als $8+a b c$ en dan staat daar precies $(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)$. Als we dan ten slotte links en rechts delen door 3 en de wortel trekken (alles is nog steeds positief) dan krijgen we

$$

a+b+c \geq \sqrt{\frac{(a+2)(b+2)(c+2)}{3}}

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Prove that

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{2013} \frac{4026!}{(n!(2013-n)!)^{2}}

$$

is the square of an integer.

|

By replacing 2013 with 1, 2, 3, and 4 and then calculating the sum, you get a hunch for which number squared this sum yields. The factorials suggest that you should look in the binomial coefficients. We prove something more general:

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m} \frac{(2 m)!}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}}=\binom{2 m}{m}^{2}

$$

From this, the desired result follows.

It holds that

$$

\frac{(2 m)!}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}}=\frac{(m!)^{2}}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}} \cdot \frac{(2 m)!}{(m!)^{2}}=\binom{m}{n}^{2} \cdot\binom{2 m}{m}

$$

Thus, it is sufficient to prove that

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m}\binom{m}{n}^{2}=\binom{2 m}{m}

$$

We do this combinatorially. Consider $2 m$ balls numbered from 1 to $2 m$, where the balls from 1 to $m$ are colored blue and the balls from $m+1$ to $2 m$ are colored red. You want to choose a total of $m$ balls. This can be done in $\binom{2 m}{m}$ ways. On the other hand, we can also first choose $n$ blue balls, with $0 \leq n \leq m$, and then choose $m-n$ red balls. This is equivalent to first choosing $n$ blue balls and then not choosing $n$ red balls. Thus, the number of ways to choose $m$ balls is also equal to

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m}\binom{m}{n}^{2}

$$

Therefore, this sum is equal to $\binom{2 m}{m}$. And with that, we have proven (1).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Bewijs dat

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{2013} \frac{4026!}{(n!(2013-n)!)^{2}}

$$

het kwadraat van een geheel getal is.

|

Door 2013 te vervangen door 1, 2, 3 en 4 en de som dan uit te rekenen, krijg je een vermoeden voor welk getal in het kwadraat deze som oplevert. De faculteiten suggereren dat je het in de binomiaalcoëfficiënten moet zoeken. We bewijzen iets algemeners:

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m} \frac{(2 m)!}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}}=\binom{2 m}{m}^{2}

$$

Hieruit volgt het gevraagde.

Er geldt

$$

\frac{(2 m)!}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}}=\frac{(m!)^{2}}{(n!(m-n)!)^{2}} \cdot \frac{(2 m)!}{(m!)^{2}}=\binom{m}{n}^{2} \cdot\binom{2 m}{m}

$$

Het is dus voldoende te bewijzen dat

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m}\binom{m}{n}^{2}=\binom{2 m}{m}

$$

We doen dit combinatorisch. Bekijk $2 m$ ballen genummerd van 1 tot en met $2 m$, waarbij de ballen van 1 tot en met $m$ blauw gekleurd zijn en de ballen van $m+1$ tot en met $2 m$ rood gekleurd zijn. Je wilt hier totaal $m$ ballen van uitkiezen. Dat kan op $\binom{2 m}{m}$ manieren. Anderzijds kunnen we ook eerst $n$ blauwe ballen uitkiezen, met $0 \leq n \leq m$, en vervolgens $m-n$ rode ballen. Dat komt op hetzelfde neer als eerst $n$ blauwe ballen uitkiezen en daarna $n$ rode ballen niet uitkiezen. Dus het aantal manieren om $m$ ballen uit te kiezen is ook gelijk aan

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{m}\binom{m}{n}^{2}

$$

Dus deze som is gelijk aan $\binom{2 m}{m}$. En daarmee hebben we (1) bewezen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

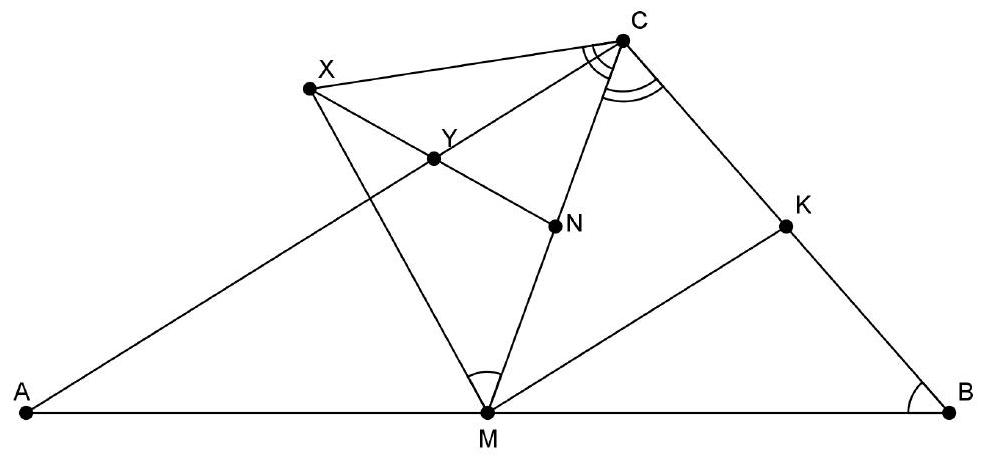

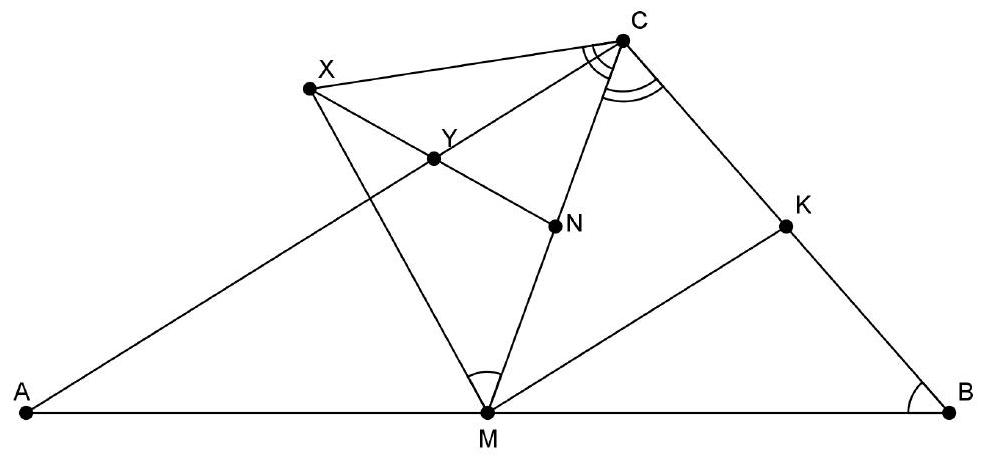

Let $P$ be the intersection of the diagonals of a convex quadrilateral $ABCD$. Let $X, Y$, and $Z$ be points on the interior of $AB, BC$, and $CD$ respectively, such that

$$

\frac{|AX|}{|XB|}=\frac{|BY|}{|YC|}=\frac{|CZ|}{|ZD|}=2

$$

Suppose moreover that $XY$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\triangle CYZ$ and that $YZ$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $\triangle BXY$. Prove that $\angle APD = \angle XYZ$.

|

Due to the tangent-chord angle theorem, $\angle C Z Y = \angle B Y X$ and $\angle B X Y = \angle C Y Z$. From this, it follows first that

$$

\angle X Y Z = 180^{\circ} - \angle B Y X - \angle C Y Z = 180^{\circ} - \angle B Y X - \angle B X Y = \angle X B Y = \angle A B C.

$$

Secondly, we see that $\triangle X B Y \sim \triangle Y C Z$ (AA). This means

$$

\frac{|X B|}{|B Y|} = \frac{|Y C|}{|C Z|}

$$

Given that $|X B| = \frac{1}{3}|A B|$, $|B Y| = \frac{2}{3}|B C|$, $|Y C| = \frac{1}{3}|B C|$, and $|C Z| = \frac{2}{3}|C D|$. Substituting these values gives

$$

\frac{\frac{1}{3}|A B|}{\frac{2}{3}|B C|} = \frac{\frac{1}{3}|B C|}{\frac{2}{3}|C D|}

$$

and thus

$$

\frac{|A B|}{|B C|} = \frac{|B C|}{|C D|}

$$

From the similarity, it also follows that $\angle A B C = \angle X B Y = \angle Y C Z = \angle B C D$. Combining this with the found ratio, we get a new similarity: $\triangle A B C \sim \triangle B C D$ (SAS). Therefore, $\angle C A B = \angle D B C$. This gives

$$

\angle P A B + \angle A B P = \angle C A B + \angle A B D = \angle D B C + \angle A B D = \angle A B C.

$$

We already knew that $\angle A B C = \angle X Y Z$. Using the exterior angle theorem in triangle $A B P$, we now get

$$

\angle B P C = \angle P A B + \angle A B P = \angle A B C = \angle X Y Z.

$$

Since $\angle B P C = \angle A P D$, it follows that $\angle A P D = \angle X Y Z$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $P$ het snijpunt van de diagonalen van een convexe vierhoek $A B C D$. Laat $X, Y$ en $Z$ punten op het inwendige van respectievelijk $A B, B C$ en $C D$ zijn zodat

$$

\frac{|A X|}{|X B|}=\frac{|B Y|}{|Y C|}=\frac{|C Z|}{|Z D|}=2

$$

Veronderstel bovendien dat $X Y$ raakt aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle C Y Z$ en dat $Y Z$ raakt aan de omgeschreven cirkel van $\triangle B X Y$. Bewijs dat $\angle A P D=\angle X Y Z$.

|

Vanwege de raaklijnomtrekshoekstelling is $\angle C Z Y=\angle B Y X$ en $\angle B X Y=$ $\angle C Y Z$. Hieruit volgt ten eerste dat

$$

\angle X Y Z=180^{\circ}-\angle B Y X-\angle C Y Z=180^{\circ}-\angle B Y X-\angle B X Y=\angle X B Y=\angle A B C .

$$

Ten tweede zien we dat $\triangle X B Y \sim \triangle Y C Z$ (hh). Dit betekent

$$

\frac{|X B|}{|B Y|}=\frac{|Y C|}{|C Z|}

$$

Gegeven is dat $|X B|=\frac{1}{3}|A B|,|B Y|=\frac{2}{3}|B C|,|Y C|=\frac{1}{3}|B C|$ en $|C Z|=\frac{2}{3}|C D|$. Dit invullen geeft

$$

\frac{\frac{1}{3}|A B|}{\frac{2}{3}|B C|}=\frac{\frac{1}{3}|B C|}{\frac{2}{3}|C D|}

$$

en dus

$$

\frac{|A B|}{|B C|}=\frac{|B C|}{|C D|}

$$

Uit de gelijkvormigheid volgt ook $\angle A B C=\angle X B Y=\angle Y C Z=\angle B C D$. Als we dit combineren met de gevonden verhouding, krijgen we een nieuwe gelijkvormigheid: $\triangle A B C \sim \triangle B C D$ (zhz). Dus $\angle C A B=\angle D B C$. Dit geeft

$$

\angle P A B+\angle A B P=\angle C A B+\angle A B D=\angle D B C+\angle A B D=\angle A B C .

$$

We wisten al dat $\angle A B C=\angle X Y Z$. Met de buitenhoekstelling in driehoek $A B P$ krijgen we nu

$$

\angle B P C=\angle P A B+\angle A B P=\angle A B C=\angle X Y Z .

$$

Aangezien $\angle B P C=\angle A P D$, geldt $\angle A P D=\angle X Y Z$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Gegeven is een onbekende rij $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ van gehele getallen die voldoet aan de volgende eigenschap: voor elk priemgetal $p$ en elk positief geheel getal $k$ geldt

$$

a_{p k+1}=p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13

$$

Bepaal alle mogelijke waarden van $a_{2013}$.

|

Laat $q$ en $t$ priemgetallen zijn. Vul in $k=q, p=t$ :

$$

a_{q t+1}=t a_{q}-3 a_{t}+13

$$

Vul ook in $k=t, p=q$ :

$$

a_{q t+1}=q a_{t}-3 a_{q}+13

$$

Beide uitdrukkingen rechts zijn dus gelijk aan elkaar, waaruit volgt

$$

t a_{q}-3 a_{t}=q a_{t}-3 a_{q}

$$

oftewel

$$

(t+3) a_{q}=(q+3) a_{t}

$$

In het bijzonder geldt $5 a_{3}=6 a_{2}$ en $5 a_{7}=10 a_{2}$. Vul nu $k=3, p=2$ in:

$$

a_{7}=2 a_{3}-3 a_{2}+13=2 \cdot \frac{6}{5} a_{2}-3 a_{2}+13

$$

Omdat $a_{7}=\frac{10}{5} a_{2}$, vinden we nu

$$

\frac{13}{5} a_{2}=13

$$

dus $a_{2}=5$. Nu geldt voor elk priemgetal $p$ dat $a_{p}=\frac{(p+3) a_{2}}{5}=p+3$.

Vul in $k=4, p=3$ :

$$

a_{13}=3 a_{4}-3 a_{3}+13

$$

We weten dat $a_{13}=16$ en $a_{3}=6$, dus dit geeft $3 a_{4}=21$, oftewel $a_{4}=7$.

Vul ten slotte $k=4$ en $p=503$ in:

$a_{2013}=a_{4 \cdot 503+1}=503 \cdot a_{4}-3 a_{503}+13=503 \cdot 7-3 \cdot(503+3)+13=503 \cdot 4-9+13=2016$.

Dus $a_{2013}=2016$ en dit is de enige mogelijke waarde.

|

2016

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Gegeven is een onbekende rij $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ van gehele getallen die voldoet aan de volgende eigenschap: voor elk priemgetal $p$ en elk positief geheel getal $k$ geldt

$$

a_{p k+1}=p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13

$$

Bepaal alle mogelijke waarden van $a_{2013}$.

|

Laat $q$ en $t$ priemgetallen zijn. Vul in $k=q, p=t$ :

$$

a_{q t+1}=t a_{q}-3 a_{t}+13

$$

Vul ook in $k=t, p=q$ :

$$

a_{q t+1}=q a_{t}-3 a_{q}+13

$$

Beide uitdrukkingen rechts zijn dus gelijk aan elkaar, waaruit volgt

$$

t a_{q}-3 a_{t}=q a_{t}-3 a_{q}

$$

oftewel

$$

(t+3) a_{q}=(q+3) a_{t}

$$

In het bijzonder geldt $5 a_{3}=6 a_{2}$ en $5 a_{7}=10 a_{2}$. Vul nu $k=3, p=2$ in:

$$

a_{7}=2 a_{3}-3 a_{2}+13=2 \cdot \frac{6}{5} a_{2}-3 a_{2}+13

$$

Omdat $a_{7}=\frac{10}{5} a_{2}$, vinden we nu

$$

\frac{13}{5} a_{2}=13

$$

dus $a_{2}=5$. Nu geldt voor elk priemgetal $p$ dat $a_{p}=\frac{(p+3) a_{2}}{5}=p+3$.

Vul in $k=4, p=3$ :

$$

a_{13}=3 a_{4}-3 a_{3}+13

$$

We weten dat $a_{13}=16$ en $a_{3}=6$, dus dit geeft $3 a_{4}=21$, oftewel $a_{4}=7$.

Vul ten slotte $k=4$ en $p=503$ in:

$a_{2013}=a_{4 \cdot 503+1}=503 \cdot a_{4}-3 a_{503}+13=503 \cdot 7-3 \cdot(503+3)+13=503 \cdot 4-9+13=2016$.

Dus $a_{2013}=2016$ en dit is de enige mogelijke waarde.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Given is an unknown sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of integers that satisfies the following property: for every prime number $p$ and every positive integer $k$ it holds that

$$

a_{p k+1}=p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13

$$

Determine all possible values of $a_{2013}$.

|

Leid net als in oplossing I af dat $a_{2}=5$ en $a_{p}=p+3$ voor alle priemgetallen $p$. Dan geldt dus $a_{3}=6$. Invullen van $k=1$ en $p=2$ geeft

$$

a_{3}=2 a_{1}-3 a_{2}+13=2 a_{1}-2,

$$

dus $2 a_{1}=a_{3}+2=8$, dus $a_{1}=4$. Nu hebben we $a_{1}$ en $a_{2}$ berekend. Voor $n \geq 3$ geldt dat er altijd een priemgetal $p$ is met $p \mid n-1$, dus dat we altijd $p$ en $k$ kunnen vinden zodat

$n=k p+1$. Dus ligt de waarde van $a_{n}$ vast als we alle waarden $a_{m}$ met $1 \leq m<n$ al kennen. Er kan dus maar één rij zijn die voldoet. We proberen nu of $a_{n}=n+3$ voldoet. Dan geldt

$$

p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13=p(k+3)-3(p+3)+13=p k+3 p-3 p-9+13=p k+4=a_{p k+1}

$$

Dus dit voldoet inderdaad. De enige rij die voldoet is dus degene met $a_{n}=n+3$ voor alle $n \geq 1$, waaruit volgt dat de enige mogelijke waarde voor $a_{2013}$ gelijk is aan 2016.

Translate the above text into English, keeping the original text's line breaks and formatting:

From the solution I, we can deduce that $a_{2}=5$ and $a_{p}=p+3$ for all prime numbers $p$. Therefore, $a_{3}=6$. Substituting $k=1$ and $p=2$ gives

$$

a_{3}=2 a_{1}-3 a_{2}+13=2 a_{1}-2,

$$

so $2 a_{1}=a_{3}+2=8$, hence $a_{1}=4$. Now we have calculated $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$. For $n \geq 3$, there is always a prime number $p$ such that $p \mid n-1$, so we can always find $p$ and $k$ such that

$n=k p+1$. Therefore, the value of $a_{n}$ is fixed if we already know all values $a_{m}$ with $1 \leq m<n$. Thus, there can only be one sequence that satisfies the condition. We now try to see if $a_{n}=n+3$ satisfies the condition. Then we have

$$

p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13=p(k+3)-3(p+3)+13=p k+3 p-3 p-9+13=p k+4=a_{p k+1}

$$

So this indeed satisfies the condition. The only sequence that satisfies the condition is the one with $a_{n}=n+3$ for all $n \geq 1$, which implies that the only possible value for $a_{2013}$ is 2016.

|

2016

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Gegeven is een onbekende rij $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ van gehele getallen die voldoet aan de volgende eigenschap: voor elk priemgetal $p$ en elk positief geheel getal $k$ geldt

$$

a_{p k+1}=p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13

$$

Bepaal alle mogelijke waarden van $a_{2013}$.

|

Leid net als in oplossing I af dat $a_{2}=5$ en $a_{p}=p+3$ voor alle priemgetallen $p$. Dan geldt dus $a_{3}=6$. Invullen van $k=1$ en $p=2$ geeft

$$

a_{3}=2 a_{1}-3 a_{2}+13=2 a_{1}-2,

$$

dus $2 a_{1}=a_{3}+2=8$, dus $a_{1}=4$. Nu hebben we $a_{1}$ en $a_{2}$ berekend. Voor $n \geq 3$ geldt dat er altijd een priemgetal $p$ is met $p \mid n-1$, dus dat we altijd $p$ en $k$ kunnen vinden zodat

$n=k p+1$. Dus ligt de waarde van $a_{n}$ vast als we alle waarden $a_{m}$ met $1 \leq m<n$ al kennen. Er kan dus maar één rij zijn die voldoet. We proberen nu of $a_{n}=n+3$ voldoet. Dan geldt

$$

p a_{k}-3 a_{p}+13=p(k+3)-3(p+3)+13=p k+3 p-3 p-9+13=p k+4=a_{p k+1}

$$

Dus dit voldoet inderdaad. De enige rij die voldoet is dus degene met $a_{n}=n+3$ voor alle $n \geq 1$, waaruit volgt dat de enige mogelijke waarde voor $a_{2013}$ gelijk is aan 2016.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Determine all integers $n \geq 2$ for which

$$

i+j \equiv\binom{n}{i}+\binom{n}{j} \quad \bmod 2

$$

for all $i$ and $j$ with $0 \leq i \leq j \leq n$.

|

We first show that $n$ satisfies the condition if and only if $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ for all $i$ with $0 \leq i \leq n$. Suppose that $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ for all $i$, then $\binom{n}{i}+\binom{n}{j} \equiv i+1+j+1 \equiv i+j \bmod 2$ for all $i$ and $j$. Thus, $n$ satisfies the condition in the problem. Conversely, suppose that $n$ satisfies the condition. Since $\binom{n}{0}=1$, it follows that $i \equiv 1+\binom{n}{i} \bmod 2$ for all $i$, so $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i-1 \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ for all $i$.

Write $n$ as $n=2^{k}+m$ with $0 \leq m<2^{k}$. Since $n \geq 2$, we may assume $k \geq 1$. Consider

$$

\binom{n}{2^{k}-2}=\binom{2^{k}+m}{2^{k}-2}=\frac{\left(2^{k}+m\right)\left(2^{k}+m-1\right) \cdots(m+4)(m+3)}{\left(2^{k}-2\right)\left(2^{k}-3\right) \cdots 2 \cdot 1} .

$$

The product in the denominator contains $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $2$, $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{4}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $4$, ..., $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2^{k-1}}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $2^{k-1}$, and no factors divisible by $2^{k}$. The product in the numerator consists of $2^{k}-2$ consecutive factors and therefore contains at least $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $2$, at least $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{4}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $4$, ..., at least $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2^{k-1}}\right\rfloor$ factors divisible by $2^{k-1}$. Thus, the product in the numerator contains at least as many factors of $2$ as the product in the denominator. The product in the numerator certainly has more factors of $2$ than the product in the denominator if $2^{k}$ appears as a factor in the numerator. This is the case if $m+3 \leq 2^{k}$, or equivalently if $m \leq 2^{k}-3$. Therefore, if $m \leq 2^{k}-3$, then $\binom{n}{2^{k}-2}$ is even, while $2^{k}-2$ is also even. Thus, $n=2^{k}+m$ does not satisfy the condition.

Therefore, $n$ can only satisfy the condition if there is a $k \geq 2$ such that $2^{k}-2 \leq n \leq 2^{k}-1$. If $n$ is odd, then $\binom{n}{0}+\binom{n}{1}=1+n \equiv 0 \bmod 2$, so $n$ does not satisfy the condition. Therefore, $n$ can only satisfy the condition if it is of the form $n=2^{k}-2$ with $k \geq 2$. Now suppose that $n$ is indeed of this form. We will show that $n$ satisfies the condition. We have

$$

\binom{2^{k}-2}{c}=\frac{\left(2^{k}-2\right)\left(2^{k}-3\right) \cdots\left(2^{k}-c\right)\left(2^{k}-c-1\right)}{c \cdot(c-1) \cdots 2 \cdot 1} .

$$

The number of factors of $2$ in $2^{k}-i$ is equal to the number of factors of $2$ in $i$ for $1 \leq i \leq 2^{k}-1$. Therefore, the number of factors of $2$ in the numerator is equal to the number of factors of $2$ in the product $(c+1) \cdot c \cdot(c-1) \cdots 2$, which is the number of factors of $2$ in the denominator plus the number of factors of $2$ in $c+1$. Thus, $\binom{2^{k}-2}{c}$ is even if and only if $c$ is odd. This means that $n=2^{k}-2$ satisfies the condition.

We conclude that $n$ satisfies the condition if and only if $n=2^{k}-2$ with $k \geq 2$.

|

n=2^{k}-2 \text{ with } k \geq 2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Bepaal alle gehele getallen $n \geq 2$ waarvoor geldt dat

$$

i+j \equiv\binom{n}{i}+\binom{n}{j} \quad \bmod 2

$$

voor alle $i$ en $j$ met $0 \leq i \leq j \leq n$.

|

We laten eerst zien dat $n$ voldoet dan en slechts dan als $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ voor alle $i$ met $0 \leq i \leq n$. Stel dat $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ voor alle $i$, dan geldt $\binom{n}{i}+\binom{n}{j} \equiv$ $i+1+j+1 \equiv i+j \bmod 2$ voor alle $i$ en $j$. Dus $n$ voldoet dan aan de voorwaarde in de opgave. Stel andersom dat $n$ voldoet. Omdat $\binom{n}{0}=1$, geldt dan $i \equiv 1+\binom{n}{i} \bmod 2$ voor alle $i$, dus $\binom{n}{i} \equiv i-1 \equiv i+1 \bmod 2$ voor alle $i$.

Schrijf nu $n$ als $n=2^{k}+m$ met $0 \leq m<2^{k}$. Omdat $n \geq 2$, mogen we aannemen $k \geq 1$. Bekijk

$$

\binom{n}{2^{k}-2}=\binom{2^{k}+m}{2^{k}-2}=\frac{\left(2^{k}+m\right)\left(2^{k}+m-1\right) \cdots(m+4)(m+3)}{\left(2^{k}-2\right)\left(2^{k}-3\right) \cdots 2 \cdot 1} .

$$

Het product in de noemer bevat $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door $2,\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{4}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door $4, \ldots,\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2^{k-1}}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door $2^{k-1}$ en geen factoren deelbaar door $2^{k}$. Het product in de teller bestaat uit $2^{k}-2$ opeenvolgende factoren en bevat daarom minstens $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door 2 , minstens $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{4}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door $4, \ldots$, minstens $\left\lfloor\frac{2^{k}-2}{2^{k-1}}\right\rfloor$ factoren deelbaar door $2^{k-1}$. Het product in de teller bevat dus minstens evenveel factoren 2 als het product in de noemer. Het product in de teller bevat zeker meer factoren 2 dan het product in de noemer als $2^{k}$ voorkomt als factor in de teller. Dat is zo als $m+3 \leq 2^{k}$, oftewel als $m \leq 2^{k}-3$. Dus als $m \leq 2^{k}-3$, dan is $\binom{n}{2^{k}-2}$ even, terwijl $2^{k}-2$ ook even is. Dan voldoet $n=2^{k}+m$ dus niet.

Dus $n$ kan alleen voldoen als er een $k \geq 2$ is met $2^{k}-2 \leq n \leq 2^{k}-1$. Als $n$ oneven is, geldt $\binom{n}{0}+\binom{n}{1}=1+n \equiv 0 \bmod 2$, dus dan voldoet $n$ niet. Dus $n$ kan alleen voldoen als hij van de vorm $n=2^{k}-2$ met $k \geq 2$ is. Stel nu dat $n$ inderdaad van die vorm is. We gaan laten zien dat $n$ voldoet. Er geldt

$$

\binom{2^{k}-2}{c}=\frac{\left(2^{k}-2\right)\left(2^{k}-3\right) \cdots\left(2^{k}-c\right)\left(2^{k}-c-1\right)}{c \cdot(c-1) \cdots 2 \cdot 1} .

$$

Het aantal factoren 2 in $2^{k}-i$ is gelijk aan het aantal factoren 2 in $i$ voor $1 \leq i \leq 2^{k}-1$. Dus het aantal factoren 2 in de teller is gelijk aan het aantal factoren 2 in het product $(c+1) \cdot c \cdot(c-1) \cdots 2$, oftewel het aantal factoren 2 in de noemer plus het aantal factoren 2 in $c+1$. Dus $\binom{2^{k}-2}{c}$ is even dan en slechts dan als $c$ oneven is. Dit betekent dat $n=2^{k}-2$ voldoet.

We concluderen dat $n$ voldoet dan en slechts dan als $n=2^{k}-2$ met $k \geq 2$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

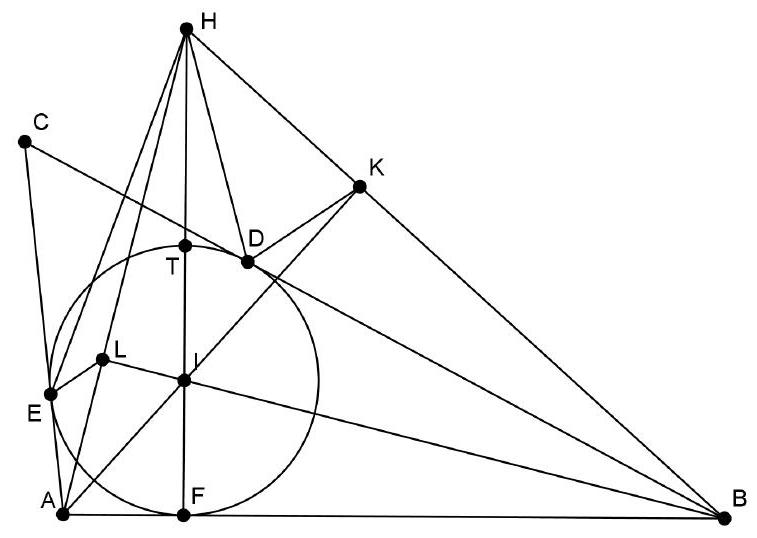

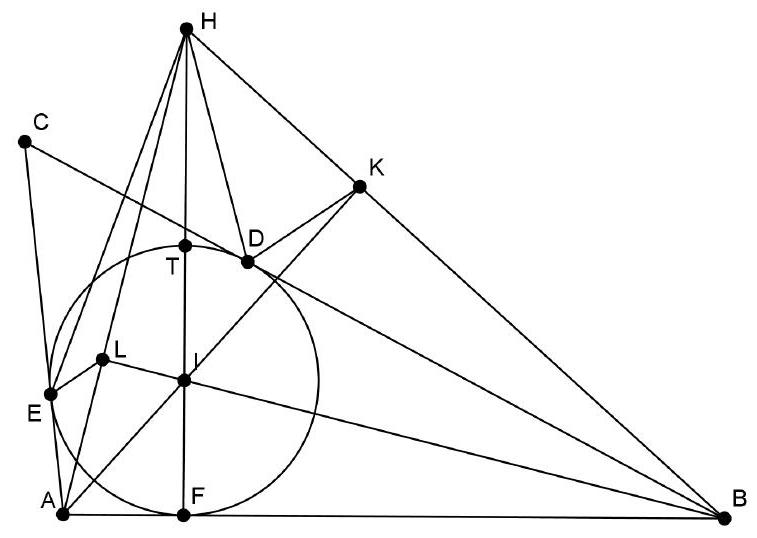

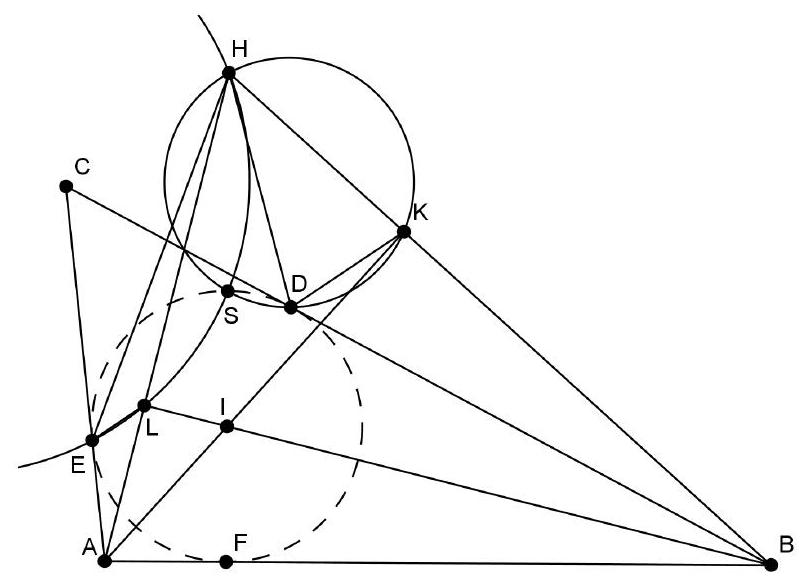

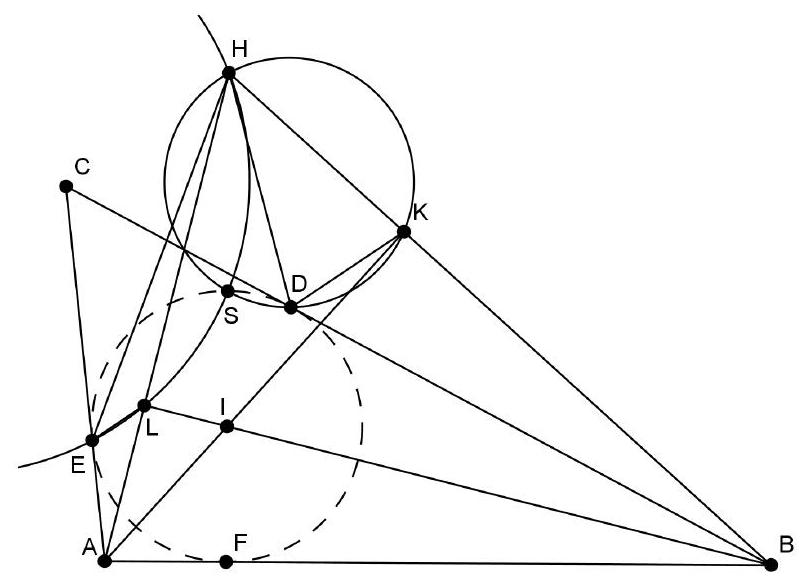

In a cyclic hexagon $A B C D E F$, $A B \perp B D$ and $|B C|=|E F|$. Let $P$ be the intersection of $B C$ and $A D$ and let $Q$ be the intersection of $E F$ and $A D$. Assume that $P$ and $Q$ both lie on the side of $D$ where $A$ does not lie. Let $S$ be the midpoint of $A D$. Let $K$ and $L$ be the centers of the inscribed circles of $\triangle B P S$ and $\triangle E Q S$, respectively. Prove that $\angle K D L=90^{\circ}$.

|

It is useful for this task to analyze what happens when you slide points. You can, for example, slide line segment EF without affecting $K$. Therefore, $L$ can move independently of $K$. Apparently, $L$ always moves along a line through D that is perpendicular to KD. The angle $\angle L D S$ is apparently independent of the position of line segment EF. Since we are dealing with a circle, this suggests that $\angle L D S$ might be equal to a certain inscribed angle. Then $\angle K D S$ would also be equal to an inscribed angle, and these two inscribed angles together would be $90^{\circ}$. In this way, you can get ideas to ultimately arrive at the following proof.

The configuration is fixed by the given order of points $A$ through $F$ on the circle and by the given positions of points $P$ and $Q$ on line $A D$. Therefore, we do not need to distinguish between different configurations. (The points $P$ and $Q$ can be swapped on line $A D$, but this is not relevant.)

First, note that $S$ is the center of the circle, since $\angle A B D=90^{\circ}$, line $A D$ is a diameter, and $S$ is the midpoint of $A D$. We will now prove that $\angle K D S=\angle K B S$. We know that $K S$ is a bisector, so $\angle B S K=\angle K S D$. Furthermore, $|S D|=|S B|$, since both lengths are equal to the radius of the circle. Since also $|S K|=|S K|$, we find $\triangle D S K \cong \triangle B S K$ (SAS). Therefore, $\angle K D S=\angle K B S$.

Since $B K$ is also a bisector, $\angle K B S=\angle C B K=\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$. Thus, $\angle K D S=$ $\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$.

Analogously, we derive that $\angle L D S=\frac{1}{2} \angle Q E S$, which implies that $\angle L D S=\frac{1}{2} \left(180^{\circ}-\angle F E S\right)=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \angle F E S$. Therefore, $\angle L D S+\angle K D S=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \angle F E S+\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$. Furthermore, note that $\triangle S B C \cong \triangle S E F$ (SSS), so $\angle F E S=\angle C B S$. Now we can conclude that $\angle K D L=\angle L D S+\angle K D S=90^{\circ}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

In een koordenzeshoek $A B C D E F$ geldt $A B \perp B D$ en $|B C|=|E F|$. Noem $P$ het snijpunt van $B C$ en $A D$ en noem $Q$ het snijpunt van $E F$ en $A D$. Neem aan dat $P$ en $Q$ allebei aan de kant van $D$ liggen waar $A$ niet ligt. Zij $S$ het midden van $A D$. Laat $K$ en $L$ de middelpunten zijn van de ingeschreven cirkels van respectievelijk $\triangle B P S$ en $E Q S$. Bewijs dat $\angle K D L=90^{\circ}$.

|

Het is bij deze opgave nuttig om te analyseren wat er gebeurt als je met punten schuift. Je kunt namelijk lijnstuk EF verschuiven zonder dat dat invloed op $K$ heeft. Dus L kan onafhankelijk van $K$ bewegen. Kennelijk beweegt $L$ dan wel altijd over een lijn door D die loodrecht op KD staat. De hoek $\angle L D S$ is blijkbaar onafhankelijk van de positie van lijnstuk EF. Omdat we met een cirkel te maken hebben, suggereert dit dat $\angle L D S$ misschien gelijk is aan een bepaalde omtrekshoek. Dan zou $\angle K D S$ ook gelijk aan een omtrekshoek worden, en wel zo dat die twee omtrekshoeken samen $90^{\circ}$ zijn. Op deze manier kun je ideeën krijgen om uiteindelijk tot het volgende bewijs te komen.

De configuratie ligt vast door de gegeven volgorde van de punten $A$ tot en met $F$ op de cirkel en door het gegeven over de punten $P$ en $Q$ op de lijn $A D$. We hoeven dus geen verschillende configuraties te onderscheiden. (De punten $P$ en $Q$ kunnen wel verwisseld worden op de lijn $A D$, maar dat is niet relevant.)

Merk eerst op dat $S$ het middelpunt van de cirkel is, aangezien vanwege $\angle A B D=90^{\circ}$ de lijn $A D$ middellijn is, en $S$ het midden van $A D$ is. We gaan nu bewijzen dat $\angle K D S=\angle K B S$. We weten dat $K S$ een bissectrice is, dus $\angle B S K=\angle K S D$. Verder is $|S D|=|S B|$, omdat beide lengtes gelijk zijn aan de straal van de cirkel. Omdat ook $|S K|=|S K|$, vinden we $\triangle D S K \cong \triangle B S K$ (ZHZ). Dus $\angle K D S=\angle K B S$.

Omdat ook $B K$ een bissectrice is, geldt $\angle K B S=\angle C B K=\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$. Dus $\angle K D S=$ $\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$.

Helemaal analoog leiden we af dat $\angle L D S=\frac{1}{2} \angle Q E S$, waaruit volgt dat $\angle L D S=\frac{1}{2}$. $\left(180^{\circ}-\angle F E S\right)=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \angle F E S$. Dus $\angle L D S+\angle K D S=90^{\circ}-\frac{1}{2} \angle F E S+\frac{1}{2} \angle C B S$. Merk nu verder op dat $\triangle S B C \cong \triangle S E F$ (ZZZ), zodat $\angle F E S=\angle C B S$. Nu kunnen we concluderen dat $\angle K D L=\angle L D S+\angle K D S=90^{\circ}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2013-D_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2013"

}

|

Find all non-negative integers $n$ for which there exist integers $a$ and $b$ such that $n^{2}=a+b$ and $n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}$.

|

Due to the inequality of the arithmetic and geometric mean, applied to $a^{2}$ and $b^{2}$, it holds that $a^{2}+b^{2} \geq 2 a b$. Since $2 a b=(a+b)^{2}-(a^{2}+b^{2})$, it follows that $n^{3} \geq (n^{2})^{2}-n^{3}$, or equivalently $2 n^{3} \geq n^{4}$. This means $n=0$ or $2 \geq n$. Therefore, $n=0, n=1$ and $n=2$ are the only possibilities. For $n=0$ we find $a=b=0$ as a solution, for $n=1$ we find $a=0, b=1$ as a solution, and for $n=2$ we find $a=b=2$ as a solution. The numbers $n$ that satisfy this are thus precisely $n=0, n=1$, and $n=2$.

|

n=0, n=1, n=2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle niet-negatieve gehele getallen $n$ waarvoor er gehele getallen $a$ en $b$ bestaan met $n^{2}=a+b$ en $n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}$.

|

Vanwege de ongelijkheid van het rekenkundig en meetkundig gemiddelde, toegepast op $a^{2}$ en $b^{2}$, geldt $a^{2}+b^{2} \geq 2 a b$. Aangezien $2 a b=(a+b)^{2}-\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)$, volgt hieruit $n^{3} \geq\left(n^{2}\right)^{2}-n^{3}$, oftewel $2 n^{3} \geq n^{4}$. Dit betekent $n=0$ of $2 \geq n$. Dus $n=0, n=1$ en $n=2$ zijn de enige mogelijkheden. Voor $n=0$ vinden we $a=b=0$ als oplossing, voor $n=1$ vinden we $a=0, b=1$ als oplossing en voor $n=2$ vinden we $a=b=2$ als oplossing. De getallen $n$ die voldoen zijn dus precies $n=0, n=1$ en $n=2$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Find all non-negative integers $n$ for which there exist integers $a$ and $b$ such that $n^{2}=a+b$ and $n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}$.

|

Write $b=n^{2}-a$ and substitute it in:

$$

n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2}+\left(n^{2}-a\right)^{2}=a^{2}+n^{4}-2 a n^{2}+a^{2} .

$$

So

$$

2 a^{2}-2 n^{2} a+n^{4}-n^{3}=0 .

$$

This is a quadratic equation in $a$, whose discriminant is equal to

$$

D=\left(-2 n^{2}\right)^{2}-4 \cdot 2 \cdot\left(n^{4}-n^{3}\right)=-4 n^{4}+8 n^{3}=4 n^{2}\left(-n^{2}+2 n\right) .

$$

For $n \geq 3$, we have $-n^{2}+2 n \leq-3 n+2 n=-n<0$, so there is no solution for $a$. Therefore, we must have $n \leq 2$. For $n=0$, we find $a=b=0$ as a solution, for $n=1$, we find $a=0, b=1$ as a solution, and for $n=2$, we find $a=b=2$ as a solution. The numbers $n$ that satisfy the condition are thus precisely $n=0, n=1$, and $n=2$.

|

n=0, n=1, n=2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle niet-negatieve gehele getallen $n$ waarvoor er gehele getallen $a$ en $b$ bestaan met $n^{2}=a+b$ en $n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}$.

|

Schrijf $b=n^{2}-a$ en vul dat in:

$$

n^{3}=a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2}+\left(n^{2}-a\right)^{2}=a^{2}+n^{4}-2 a n^{2}+a^{2} .

$$

Dus

$$

2 a^{2}-2 n^{2} a+n^{4}-n^{3}=0 .

$$

Dit is een kwadratische vergelijking in $a$, waarvan de discriminant gelijk is aan

$$

D=\left(-2 n^{2}\right)^{2}-4 \cdot 2 \cdot\left(n^{4}-n^{3}\right)=-4 n^{4}+8 n^{3}=4 n^{2}\left(-n^{2}+2 n\right) .

$$

Voor $n \geq 3$ geldt $-n^{2}+2 n \leq-3 n+2 n=-n<0$, dus dan is er geen oplossing voor $a$. Er moet dus gelden $n \leq 2$. Voor $n=0$ vinden we $a=b=0$ als oplossing, voor $n=1$ vinden we $a=0, b=1$ als oplossing en voor $n=2$ vinden we $a=b=2$ als oplossing. De getallen $n$ die voldoen zijn dus precies $n=0, n=1$ en $n=2$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0\} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ waarvoor geldt:

$$

x f(x y)+f(-y)=x f(x)

$$

voor alle reële $x, y$ ongelijk aan 0 .

|

Vul in $x=1$, dat geeft $f(y)+f(-y)=f(1)$, oftewel $f(-y)=f(1)-f(y)$ voor alle $y$. Vul nu in $y=-1$, dat geeft $x f(-x)+f(1)=x f(x)$. Als we hierin $f(-x)=$ $f(1)-f(x)$ invullen, krijgen we $x(f(1)-f(x))+f(1)=x f(x)$, dus $x f(1)+f(1)=2 x f(x)$. We zien dat $f$ van de vorm $f(x)=c+\frac{c}{x}$ is voor zekere $c \in \mathbb{R}$. Deze familie van functies controleren we. Links staat dan $x f(x y)+f(-y)=x\left(c+\frac{c}{x y}\right)+c+\frac{c}{-y}=x c+c$ en rechts staat $x f(x)=x\left(c+\frac{c}{x}\right)=x c+c$. Deze twee zijn aan elkaar gelijk, dus deze functie voldoet voor alle $c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

f(x)=c+\frac{c}{x}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0\} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ waarvoor geldt:

$$

x f(x y)+f(-y)=x f(x)

$$

voor alle reële $x, y$ ongelijk aan 0 .

|

Vul in $x=1$, dat geeft $f(y)+f(-y)=f(1)$, oftewel $f(-y)=f(1)-f(y)$ voor alle $y$. Vul nu in $y=-1$, dat geeft $x f(-x)+f(1)=x f(x)$. Als we hierin $f(-x)=$ $f(1)-f(x)$ invullen, krijgen we $x(f(1)-f(x))+f(1)=x f(x)$, dus $x f(1)+f(1)=2 x f(x)$. We zien dat $f$ van de vorm $f(x)=c+\frac{c}{x}$ is voor zekere $c \in \mathbb{R}$. Deze familie van functies controleren we. Links staat dan $x f(x y)+f(-y)=x\left(c+\frac{c}{x y}\right)+c+\frac{c}{-y}=x c+c$ en rechts staat $x f(x)=x\left(c+\frac{c}{x}\right)=x c+c$. Deze twee zijn aan elkaar gelijk, dus deze functie voldoet voor alle $c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

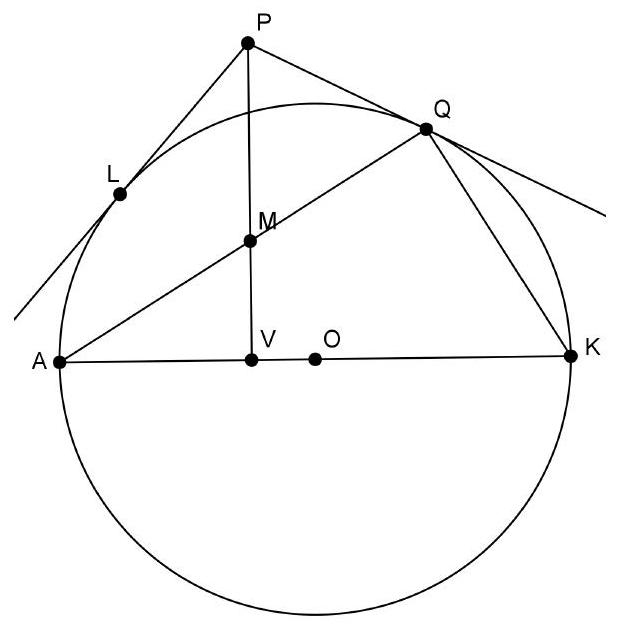

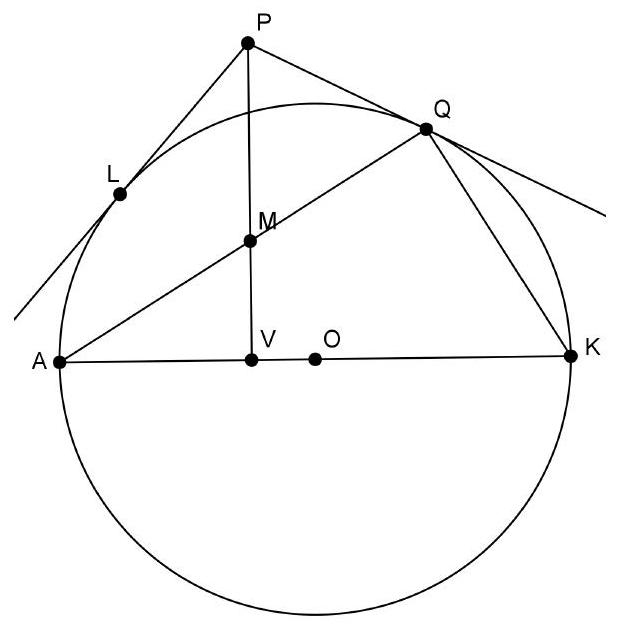

In triangle $A B C$, $I$ is the center of the inscribed circle. A circle is tangent to $A I$ at $I$ and also passes through $B$. This circle intersects $A B$ again at $P$ and $B C$ again at $Q$. The line $Q I$ intersects $A C$ at $R$. Prove that $|A R| \cdot|B Q|=|P I|^{2}$.

|

There is only one configuration. The following applies:

$$

\begin{array}{rlr}

\angle A I P & =\angle I B P & \text { (tangent-secant angle theorem) } \\

& =\angle I B Q & (I B \text { is bisector) } \\

& =\angle I P Q & \text { (cyclic quadrilateral } P B Q I \text { ) }

\end{array}

$$

Thus, due to Z-angles, $A I \| P Q$. This means $\angle I A B=\angle Q P B=\angle Q I B$, where the last equality holds due to the cyclic quadrilateral. We had already seen that $\angle A I P=\angle I B Q$, so $\triangle I A P \sim \triangle B I Q$ (AA). Therefore,

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P I|}=\frac{|Q I|}{|B Q|}

$$

Moreover, $\angle R I A$ is the opposite angle of a tangent angle and is therefore equal to $\angle I P Q$, which we already knew is equal to $\angle A I P$. Thus, $\angle R I A=\angle A I P$. Due to the bisector $A I$, it also holds that $\angle R A I=\angle P A I$, so $\triangle R A I \cong \triangle P A I$ (ASA). This implies $|A R|=|A P|$. Furthermore, $I$ is the midpoint of arc $P Q$, since $B I$ is a bisector, so $|P I|=|Q I|$. We substitute these two into (1):

$$

\frac{|A R|}{|P I|}=\frac{|P I|}{|B Q|}

$$

which implies $|A R| \cdot|B Q|=|P I|^{2}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

In driehoek $A B C$ is $I$ het middelpunt van de ingeschreven cirkel. Een cirkel raakt aan $A I$ in $I$ en gaat verder door $B$. Deze cirkel snijdt $A B$ nogmaals in $P$ en $B C$ nogmaals in $Q$. De lijn $Q I$ snijdt $A C$ in $R$. Bewijs dat $|A R| \cdot|B Q|=|P I|^{2}$.

|

Er is maar één configuratie. Er geldt

$$

\begin{array}{rlr}

\angle A I P & =\angle I B P & \text { (raaklijn-omtrekshoekstelling) } \\

& =\angle I B Q & (I B \text { is bissectrice) } \\

& =\angle I P Q & \text { (koordenvierhoek } P B Q I \text { ) }

\end{array}

$$

dus vanwege Z-hoeken geldt nu $A I \| P Q$. Dit betekent $\angle I A B=\angle Q P B=\angle Q I B$, waarbij de laatste gelijkheid geldt vanwege de koordenvierhoek. We hadden al gezien dat $\angle A I P=\angle I B Q$, dus $\triangle I A P \sim \triangle B I Q$ (hh). Dus

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P I|}=\frac{|Q I|}{|B Q|}

$$

Daarnaast is $\angle R I A$ de overstaande hoek van een raaklijnhoek en daarom gelijk aan $\angle I P Q$, waarvan we al wisten dat die gelijk is aan $\angle A I P$. Dus $\angle R I A=\angle A I P$. Vanwege de bissectrice $A I$ geldt ook $\angle R A I=\angle P A I$, dus $\triangle R A I \cong \triangle P A I$ (HZH). Hieruit volgt $|A R|=|A P|$. Verder is $I$ het midden van boog $P Q$, aangezien $B I$ een bissectrice is, dus $|P I|=|Q I|$. Deze twee dingen vullen we in in (1):

$$

\frac{|A R|}{|P I|}=\frac{|P I|}{|B Q|}

$$

waaruit volgt $|A R| \cdot|B Q|=|P I|^{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $m \geq 3$ and $n$ be positive integers with $n > m(m-2)$. Find the largest positive integer $d$ such that $d \mid n!$ and $k \nmid d$ for all $k \in \{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$.

|

We will prove that $d=m-1$ is the largest that satisfies. First, note that $m-1 \mid n$ ! and for $k \geq m$ we have $k \nmid m-1$, so $d=m-1$ indeed satisfies.

Suppose now that for some $d$ we have: $d \mid n$ ! and $k \nmid d$ for all $k \in\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$. We will prove that $d \leq m-1$. Write $d=p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t}$ with $p_{i}$ prime for all $i$ (not necessarily all distinct). If $t=0$, then $d=1 \leq m-1$, so we may assume $t \geq 1$. From the first condition on $d$ it follows that $p_{i} \leq n$ for all $i$. From the second condition on $d$ it follows that $p_{i} \notin\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$ for all $i$. Thus $p_{i} \leq m-1$ for all $i$. Now consider the numbers $p_{1}, p_{1} p_{2}, \ldots, p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t}$. These are all divisors of $d$ and therefore all different from numbers in $\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$. Furthermore, we know that $p_{1} \leq m-1$. Now consider the largest $j \leq t$ for which $p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} \leq m-1$. If $j<t$ then

$$

p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} p_{j+1} \leq(m-1) p_{j+1} \leq(m-1)(m-1)=m(m-2)+1 \leq n

$$

But that means that $p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} p_{j+1} \leq m-1$ as well. Contradiction with the maximality of $j$. So it must be that $j=t$, i.e., $d=p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t} \leq m-1$.

We conclude that $d=m-1$ is indeed the largest $d$ that satisfies the conditions.

|

m-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Laat $m \geq 3$ en $n$ positieve gehele getallen zijn met $n>m(m-2)$. Vind het grootste positieve gehele getal $d$ zodat $d \mid n$ ! en $k \nmid d$ voor alle $k \in\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$.

|

We gaan bewijzen dat $d=m-1$ de grootste is die voldoet. Merk eerst op dat $m-1 \mid n$ ! en dat voor $k \geq m$ geldt $k \nmid m-1$, dus $d=m-1$ voldoet inderdaad.

Stel nu dat voor zekere $d$ geldt: $d \mid n$ ! en $k \nmid d$ voor alle $k \in\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$. We gaan bewijzen dat $d \leq m-1$. Schrijf $d=p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t}$ met $p_{i}$ priem voor alle $i$ (niet noodzakelijk allemaal verschillend). Als $t=0$, is $d=1 \leq m-1$, dus we mogen aannemen $t \geq 1$. Uit de eerste voorwaarde op $d$ volgt $p_{i} \leq n$ voor alle $i$. Uit de tweede voorwaarde op $d$ volgt dat $p_{i} \notin\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$ voor alle $i$. Dus $p_{i} \leq m-1$ voor alle $i$. Bekijk nu de getallen $p_{1}, p_{1} p_{2}, \ldots, p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t}$. Dit zijn allemaal delers van $d$ en daarom allemaal ongelijk aan getallen uit $\{m, m+1, \ldots, n\}$. Verder weten we dat $p_{1} \leq m-1$. Bekijk nu de grootste $j \leq t$ waarvoor geldt dat $p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} \leq m-1$. Als $j<t$ geldt

$$

p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} p_{j+1} \leq(m-1) p_{j+1} \leq(m-1)(m-1)=m(m-2)+1 \leq n

$$

Maar dat betekent dat ook $p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{j} p_{j+1} \leq m-1$. Tegenspraak met de maximaliteit van $j$. Dus moet gelden $j=t$, oftewel $d=p_{1} p_{2} \cdots p_{t} \leq m-1$.

We concluderen dat $d=m-1$ inderdaad de grootste $d$ is die aan de eisen voldoet.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. Daniel and Merlijn are playing a game. Daniel has $k$ sheets of paper lying next to each other on the table, where $k$ is a positive integer. He writes a number from 1 to $n$ on each sheet (no number is allowed, all numbers are allowed too). On the back of each sheet, he writes exactly the remaining numbers from 1 to $n$. When Daniel is done, Merlijn may flip some of the sheets to show the back (he may also choose not to flip any or to flip all of them). If he can make all the numbers from 1 to $n$ visible at the same time (where duplicates are allowed), he wins.

Determine the smallest $k$ for which Merlijn can always win, regardless of what Daniel does.

|

We give all of Daniel's sheets of paper a different color. Furthermore, we have $n$ boxes with the numbers 1 to $n$ on them. We also provide enough tokens in exactly the colors of Daniel's sheets of paper. For each sheet, he looks at the numbers on the front of the sheet and puts a token of the color of this sheet in each of those boxes. Each box then contains the tokens in the colors of the sheets of paper on which that number is on the front, and precisely not the tokens in the colors of the sheets of paper on which that number is on the back.

If Merlin has laid the sheets of paper he desires with the back side up, he picks from the supply exactly the tokens in the colors of those sheets. A number is not visible on the table precisely if the sheets on which this number is on the front are the sheets that Merlin has turned over, or in other words, precisely if the set of tokens in his hand is equal to the set of tokens in the box of this number. Merlin wins then and only then if the set of tokens in his hand does not occur in any of the boxes, because then all numbers are visible. We claim now that Merlin can win if and only if $2^{k}>n$. The smallest $k$ for which Merlin wins is thus the smallest $k$ with $2^{k}>n$.

Assume that $2^{k}>n$. The number of possible sets of colors is $2^{k}$ and therefore greater than $n$. There are $n$ boxes, so not all sets of colors can be exactly the colors of tokens in a box. Merlin can thus choose a set of colors that does not occur in a box and lay the sheets of those colors with the back side up. Then he wins. Now assume that $2^{k} \leq n$. Daniel first fills the boxes with sets of tokens so that every possible set occurs in a box. This is possible because the number of possible sets is $2^{k}$ and we have at least $2^{k}$ boxes. Now Daniel writes on each colored sheet of paper on the front exactly the numbers of the boxes that contain a token of the correct color, and on the back the rest. In this way, the tokens in the boxes again correspond exactly to the numbers on the front of the sheets. No matter which set of colors Merlin chooses, there is always a box with exactly that set of colors. Merlin can therefore not win.

|

k = \lceil \log_2(n+1) \rceil

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Zij $n$ een positief geheel getal. Daniël en Merlijn spelen een spel. Daniël heeft $k$ vellen papier die naast elkaar op tafel liggen, waarbij $k$ een positief geheel getal is. Hij schrijft op elk vel papier een aantal van de getallen 1 tot en met $n$ (geen enkel getal mag ook, alle getallen mag ook). Op de achterkant van elk vel papier schrijft hij juiste de overige getallen van 1 tot en met $n$. Als Daniël klaar is, mag Merlijn een aantal vellen papier met de achterkant boven leggen (hij mag dit ook bij geen enkel vel of juist alle vellen doen). Als het hem lukt om de getallen 1 tot en met $n$ allemaal tegelijk zichtbaar te maken (waarbij dubbele mogen voorkomen), dan wint hij.

Bepaal de kleinste $k$ waarvoor Merlijn altijd kan winnen, wat Daniël ook doet.

|

We geven de vellen papier van Daniël allemaal een andere kleur. Verder hebben we $n$ doosjes met daarop de getallen 1 tot en met $n$. We zorgen ook voor voldoende beschikbare fiches in precies de kleuren van de vellen papier van Daniël. Per vel bekijkt hij de getallen op de voorkant van het vel en stopt een fiche met de kleur van dit vel in elk van die doosjes. Elk doosje bevat daarna dus de fiches in de kleuren van de vellen papier waar dat getal op de voorkant staat, en juist niet de fiches in de kleuren van de vellen papier waar dat getal op de achterkant staat.

Als Merlijn de door hem gewenste vellen papier met de achterkant boven heeft gelegd, pakt hij uit de voorraad precies de fiches in de kleuren van die vellen. Een getal is niet zichtbaar op tafel precies als de vellen waar dit getal op de voorkant staat, de vellen zijn die Merlijn omgedraaid heeft, oftewel precies als de verzameling fiches in zijn hand gelijk is aan de verzameling fiches in het doosje van dit getal. Merlijn wint dus dan en slechts dan als de verzameling fiches in zijn hand niet voorkomt in één van de doosjes, want dan zijn alle getallen zichtbaar. We beweren nu dat Merlijn kan winnen dan en slechts dan als $2^{k}>n$. De kleinste $k$ waarvoor Merlijn wint, is dan dus de kleinste $k$ met $2^{k}>n$.

Stel dat $2^{k}>n$. Het aantal mogelijke verzamelingen van kleuren is $2^{k}$ en daarom groter dan $n$. Er zijn $n$ doosjes, dus niet alle verzamelingen van kleuren kunnen precies de kleuren van fiches in een doosje zijn. Merlijn kan dus een verzameling kleuren kiezen die niet in een doosje voorkomt en de vellen daarvan met de achterkant boven leggen. Dan wint hij. Stel nu dat $2^{k} \leq n$. Daniël vult nu eerst de doosjes met verzamelingen fiches, zodat elke mogelijke verzameling voorkomt in een doosje. Dat kan, want het aantal mogelijke verzamelingen is $2^{k}$ en we hebben minstens $2^{k}$ doosjes. Nu schrijft Daniël op elk vel gekleurd papier op de voorkant precies de getallen van de doosjes waar een fiche van de juiste kleur in zit, en op de achterkant de rest. Op deze manier corresponderen de fiches in de doosjes weer precies met de getallen op de voorkant van de vellen. Welke verzameling kleuren Merlijn nu ook uitkiest, er is altijd een doosje met precies die verzameling kleuren. Merlijn kan dus niet winnen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. Daniel and Merlijn are playing a game. Daniel has $k$ sheets of paper lying next to each other on the table, where $k$ is a positive integer. He writes a number from 1 to $n$ on each sheet (no number is allowed, all numbers are allowed too). On the back of each sheet, he writes exactly the remaining numbers from 1 to $n$. When Daniel is done, Merlijn may flip some of the sheets to show the back (he may also choose not to flip any or to flip all of them). If he can make all the numbers from 1 to $n$ visible at the same time (where duplicates are allowed), he wins.

Determine the smallest $k$ for which Merlijn can always win, regardless of what Daniel does.

|

We will show that Merlijn can win if and only if $2^{k}>n$. The smallest $k$ for which Merlijn wins is thus the smallest $k$ with $2^{k}>n$.

Suppose that $2^{k}>n$. Merlijn chooses one by one for each sheet whether to flip it or not. For the first sheet, he places the side with the most numbers on top (so at least half of the numbers from 1 to $n$). For each subsequent sheet, he places the side with as many numbers as possible that he has not yet made visible on earlier sheets. Let $b_{j}$ be the number of numbers that are still not visible on sheets 1 to $j$ after Merlijn has made his choices for these sheets. Then $b_{1} \leq \frac{1}{2} n$ and $b_{j} \leq \frac{1}{2} b_{j-1}$ for $j \geq 2$. Thus, $b_{j} \leq \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{j} n$ and in particular $b_{k} \leq \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{k} n$. Since $2^{k}>n$, it follows that $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{k} n<1$, so $b_{k}<1$. Since $b_{k}$ must be an integer, $b_{k}=0$. Therefore, after Merlijn's choice for all $k$ sheets, there are no numbers left that are not visible.

Now we prove that for $2^{k} \leq n$ Daniël can ensure that Merlijn cannot win. We do this by induction on $k$. For $k=1$, we have $n \geq 2$. Daniël writes the number 1 on one side of the sheet and all other numbers (there is at least one) on the other side. Merlijn cannot now turn this sheet in such a way that he can win. This is the base case of the induction. Now let $k \geq 1$ and assume that Daniël can describe $k$ sheets with $n \geq 2^{k}$ numbers such that Merlijn cannot win. We now consider $k+1$ sheets. Describe the first $k$ sheets in such a way with the numbers 1 to $2^{k}$ that Merlijn cannot win with only these numbers; this is possible according to the induction hypothesis. Then write the same numbers on each sheet again, but increased by $2^{k}$, so that these numbers run from $2^{k}+1$ to $2^{k+1}$. Finally, write all numbers $m$ with $2^{k+1}<m \leq n$ on the back of each sheet. Now each of these $k$ sheets contains the numbers 1 to $n$. On sheet number $k+1$, write the numbers 1 to $2^{k}$ on the front and the numbers $2^{k}+1$ to $n$ on the back. Suppose Merlijn leaves the last sheet with the front side up. Then he must at least make the numbers $2^{k}+1$ to $2^{k+1}$ visible on the first $k$ sheets, but this is not possible according to the induction hypothesis. Suppose Merlijn lays the last sheet with the back side up. Then he must make the numbers 1 to $2^{k}$ visible on the first $k$ sheets, but this is also not possible according to the induction hypothesis. Merlijn can therefore not win with these sheets. This completes the proof.

|

2^{k}>n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Zij $n$ een positief geheel getal. Daniël en Merlijn spelen een spel. Daniël heeft $k$ vellen papier die naast elkaar op tafel liggen, waarbij $k$ een positief geheel getal is. Hij schrijft op elk vel papier een aantal van de getallen 1 tot en met $n$ (geen enkel getal mag ook, alle getallen mag ook). Op de achterkant van elk vel papier schrijft hij juiste de overige getallen van 1 tot en met $n$. Als Daniël klaar is, mag Merlijn een aantal vellen papier met de achterkant boven leggen (hij mag dit ook bij geen enkel vel of juist alle vellen doen). Als het hem lukt om de getallen 1 tot en met $n$ allemaal tegelijk zichtbaar te maken (waarbij dubbele mogen voorkomen), dan wint hij.

Bepaal de kleinste $k$ waarvoor Merlijn altijd kan winnen, wat Daniël ook doet.

|

We gaan laten zien dat Merlijn kan winnen dan en slechts dan als $2^{k}>n$. De kleinste $k$ waarvoor Merlijn wint, is dan dus de kleinste $k$ met $2^{k}>n$.

Stel dat $2^{k}>n$. Merlijn kiest één voor één bij elk vel of hij het wel of niet omdraait. Bij het eerste vel legt hij de kant boven waar de meeste getallen op staan (dus minstens de

helft van de getallen 1 tot en met $n$ ). Bij elk volgende vel legt hij de kant naar boven waar zoveel mogelijk getallen op staan die hij nog niet op eerdere vellen zichtbaar had liggen. Laat $b_{j}$ het aantal getallen zijn dat nog niet zichtbaar is op de vellen 1 tot en met $j$ nadat Merlijn voor deze vellen een keuze heeft gemaakt. Dan is $b_{1} \leq \frac{1}{2} n$ en $b_{j} \leq \frac{1}{2} b_{j-1}$ voor $j \geq 2$. Dus $b_{j} \leq\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{j} n$ en in het bijzonder $b_{k} \leq\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{k} n$. Omdat $2^{k}>n$, is $\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{k} n<1$, dus $b_{k}<1$. Omdat $b_{k}$ geheel moet zijn, geldt $b_{k}=0$. Dus na Merlijns keuze voor alle $k$ vellen zijn er geen getallen meer onzichtbaar.

Nu bewijzen we dat voor $2^{k} \leq n$ Daniël kan zorgen dat Merlijn niet kan winnen. Dit doen we met inductie naar $k$. Voor $k=1$ geldt $n \geq 2$. Daniël schrijft nu het getal 1 op de ene kant van het vel en alle andere getallen (dat is er minstens één) op de andere kant. Merlijn kan dit vel nu niet zo draaien dat hij kan winnen. Dat is de inductiebasis. Zij nu $k \geq 1$ en neem aan dat Daniël $k$ vellen zo kan beschrijven met $n \geq 2^{k}$ getallen dat Merlijn niet kan winnen. We bekijken nu $k+1$ vellen. Beschrijf de eerste $k$ vellen op zo'n manier met de getallen 1 tot en met $2^{k}$ dat Merlijn met alleen die getallen niet kan winnen; dit kan volgens de inductiehypothese. Schrijf vervolgens op elk vel weer dezelfde getallen voor en achter, maar dan verhoogd met $2^{k}$, zodat deze getallen van $2^{k}+1$ tot en met $2^{k+1}$ lopen. Schrijf ten slotte alle getallen $m$ met $2^{k+1}<m \leq n$ op de achterkant van elk vel. Nu bevat elk van deze $k$ vellen de getallen 1 tot en met $n$. Op vel nummer $k+1$ schrijven we aan de voorkant de getallen 1 tot en met $2^{k}$ en aan de achterkant de getallen $2^{k}+1$ tot en met $n$. Stel dat Merlijn het laatste vel met de voorkant boven laat liggen. Dan moet hij in ieder geval de getallen $2^{k}+1$ tot en met $2^{k+1}$ nog zichtbaar maken op de eerste $k$ vellen, maar dat kan niet volgens de inductiehypothese. Stel dat Merlijn het laatste vel juist met de achterkant boven legt. Dan moet hij de getallen 1 tot en met $2^{k}$ nog zichtbaar maken op de eerste $k$ vellen, maar dat kan ook weer niet volgens de inductiehypothese. Merlijn kan dus met deze vellen niet winnen. Dit voltooit het bewijs.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-B_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Determine all pairs $(a, b)$ of positive integers for which

$$

a^{2}+b \mid a^{2} b+a \quad \text { and } \quad b^{2}-a \mid a b^{2}+b .

$$

|

From $a^{2}+b \mid a^{2} b+a$ it follows

$$

a^{2}+b \mid\left(a^{2} b+a\right)-b\left(a^{2}+b\right)=a-b^{2}

$$

From $b^{2}-a \mid a b^{2}+b$ it follows

$$

b^{2}-a \mid\left(a b^{2}+b\right)-a\left(b^{2}-a\right)=b+a^{2} .

$$

We see that $a^{2}+b\left|a-b^{2}\right| a^{2}+b$. This means that $a^{2}+b$ is equal to $a-b^{2}$ up to a sign. Therefore, we have two cases: $a^{2}+b=b^{2}-a$ and $a^{2}+b=a-b^{2}$. In the second case, $a^{2}+b^{2}=a-b$. But $a^{2} \geq a$ and $b^{2} \geq b>-b$, so this is impossible. Therefore, we must have the first case: $a^{2}+b=b^{2}-a$. This gives $a^{2}-b^{2}=-a-b$, so $(a+b)(a-b)=-(a+b)$. Since $a+b$ is positive, we can divide by it and get $a-b=-1$, so $b=a+1$. All pairs that can satisfy the conditions are thus of the form $(a, a+1)$ for a positive integer $a$.

We check these pairs. We have $a^{2}+b=a^{2}+a+1$ and $a^{2} b+a=a^{2}(a+1)+a=$ $a^{3}+a^{2}+a=a\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)$, so the first divisibility relation is satisfied. Furthermore, $b^{2}-a=(a+1)^{2}-a=a^{2}+a+1$ and $a b^{2}+b=a(a+1)^{2}+(a+1)=a^{3}+2 a^{2}+2 a+1=$ $a\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)+a^{2}+a+1=(a+1)\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)$, so the second divisibility relation is also satisfied. The pairs $(a, a+1)$ thus satisfy the conditions and are therefore the exact solutions.

|

(a, a+1)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Bepaal alle paren $(a, b)$ van positieve gehele getallen waarvoor

$$

a^{2}+b \mid a^{2} b+a \quad \text { en } \quad b^{2}-a \mid a b^{2}+b .

$$

|

Uit $a^{2}+b \mid a^{2} b+a$ volgt

$$

a^{2}+b \mid\left(a^{2} b+a\right)-b\left(a^{2}+b\right)=a-b^{2}

$$

Uit $b^{2}-a \mid a b^{2}+b$ volgt

$$

b^{2}-a \mid\left(a b^{2}+b\right)-a\left(b^{2}-a\right)=b+a^{2} .

$$

We zien dus dat $a^{2}+b\left|a-b^{2}\right| a^{2}+b$. Dat betekent dat $a^{2}+b$ op eventueel het teken na gelijk is aan $a-b^{2}$. We krijgen dus twee gevallen: $a^{2}+b=b^{2}-a$ en $a^{2}+b=a-b^{2}$. In het tweede geval geldt $a^{2}+b^{2}=a-b$. Maar $a^{2} \geq a$ en $b^{2} \geq b>-b$, dus dit is onmogelijk. We moeten dus wel het eerste geval hebben: $a^{2}+b=b^{2}-a$. Hieruit volgt $a^{2}-b^{2}=-a-b$, dus $(a+b)(a-b)=-(a+b)$. Aangezien $a+b$ positief is, mogen we erdoor delen en krijgen we $a-b=-1$, dus $b=a+1$. Alle paren die kunnen voldoen zijn dus van de vorm $(a, a+1)$ voor een positieve gehele $a$.

We controleren deze paren. Er geldt $a^{2}+b=a^{2}+a+1$ en $a^{2} b+a=a^{2}(a+1)+a=$ $a^{3}+a^{2}+a=a\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)$, dus aan de eerste deelbaarheidsrelatie wordt voldaan. Verder is $b^{2}-a=(a+1)^{2}-a=a^{2}+a+1$ en $a b^{2}+b=a(a+1)^{2}+(a+1)=a^{3}+2 a^{2}+2 a+1=$ $a\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)+a^{2}+a+1=(a+1)\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)$, dus aan de tweede deelbaarheidsrelatie wordt ook voldoen. De paren $(a, a+1)$ voldoen dus en zijn daarmee precies de oplossingen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $\triangle A B C$ be a triangle. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and let $D$ be a point on the interior of side $A B$. The intersection of $A M$ and $C D$ we call $E$. Suppose that $|A D|=|D E|$. Prove that $|A B|=|C E|$.

|

There is only one configuration. Let $N$ be the midpoint of $AC$. Then $MN$ is a midline. Due to Z-angles, $\angle EAD = \angle MAB = \angle AMN$, but also $\angle EAD = \angle DEA = \angle MEC$. Therefore, $\angle AMN = \angle CEM$. If $S$ is the intersection of $MN$ and $CE$, then $\triangle SEM$ is isosceles with $|SE| = |SM|$. Furthermore, $SM$ is a midline in triangle $CDB$, so $2|SM| = |DB|$ and $S$ is the midpoint of $CD$, such that $|CS| = |SD|$. Combining all this, we find

$$

|CE| = |CS| + |SE| = |SD| + |SE| = 2|SE| + |DE| = 2|SM| + |AD| = |DB| + |AD| = |AB|.

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $\triangle A B C$ een driehoek. Zij $M$ het midden van $B C$ en zij $D$ een punt op het inwendige van zijde $A B$. Het snijpunt van $A M$ en $C D$ noemen we $E$. Veronderstel dat $|A D|=|D E|$. Bewijs dat $|A B|=|C E|$.

|

Er is maar één configuratie. Zij $N$ het midden van $A C$. Dan is $M N$ een middenparallel. Wegens Z-hoeken is $\angle E A D=\angle M A B=\angle A M N$, maar ook geldt $\angle E A D=\angle D E A=\angle M E C$. Dus $\angle A M N=\angle C E M$. Als nu $S$ het snijpunt van $M N$ en $C E$ is, dan is $\triangle S E M$ dus gelijkbenig met $|S E|=|S M|$. Verder is $S M$ een middenparallel in driehoek $C D B$, dus $2|S M|=|D B|$ en is $S$ dan het midden van $C D$, zodat $|C S|=|S D|$. Als we dit alles combineren, vinden we

$$

|C E|=|C S|+|S E|=|S D|+|S E|=2|S E|+|D E|=2|S M|+|A D|=|D B|+|A D|=|A B| .

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2014-C_uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",