problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

Choose an arbitrary index $i$ and assume without loss of generality that $a_{i} \leqslant a_{i+1}$. (If the opposite inequality holds, reverse all the inequalities below.) By induction we will show that for each $k \in \mathbb{N}_{0}$ the following two inequalities hold

$$

\begin{gathered}

a_{i+1+k} \geqslant a_{i-k} \\

a_{i+1+k} a_{i+1-k} \geqslant a_{i-k} a_{i+k}

\end{gathered}

$$

(where all indices are cyclic modulo $n$ ). Both inequalities trivially hold for $k=0$.

Assume now that both inequalities hold for some $k \geqslant 0$. The inequality $a_{i+1+k} \geqslant a_{i-k}$ implies $b_{i+1+k} \geqslant b_{i-k}$, so

$$

\frac{a_{i+k}+a_{i+2+k}}{a_{i+1+k}} \geqslant \frac{a_{i-1-k}+a_{i+1-k}}{a_{i-k}} .

$$

We may rearrange this inequality by making $a_{i+2+k}$ the subject so

$$

a_{i+2+k} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+1+k} a_{i-1-k}}{a_{i-k}}+\frac{a_{i+1-k} a_{i+1+k}-a_{i+k} a_{i-k}}{a_{i-k}} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+1+k} a_{i-1-k}}{a_{i-k}},

$$

where the last inequality holds by (2). It follows that

$$

a_{(i+1)+(k+1)} a_{(i+1)-(k+1)} \geqslant a_{i+(k+1)} a_{i-(k+1)},

$$

i.e. the inequality (2) holds also for $k+1$. Using (1) we now get

$$

a_{(i+1)+(k+1)} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+k+1}}{a_{i-k}} a_{i-(k+1)} \geqslant a_{i-(k+1)},

$$

i.e. (1) holds for $k+1$.

Now we use the inequality (1) for $k=n-1$. We get $a_{i} \geqslant a_{i+1}$, and since at the beginning we assumed $a_{i} \leqslant a_{i+1}$, we get that any two consecutive $a$ 's are equal, so all of them are equal.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

Choose an arbitrary index $i$ and assume without loss of generality that $a_{i} \leqslant a_{i+1}$. (If the opposite inequality holds, reverse all the inequalities below.) By induction we will show that for each $k \in \mathbb{N}_{0}$ the following two inequalities hold

$$

\begin{gathered}

a_{i+1+k} \geqslant a_{i-k} \\

a_{i+1+k} a_{i+1-k} \geqslant a_{i-k} a_{i+k}

\end{gathered}

$$

(where all indices are cyclic modulo $n$ ). Both inequalities trivially hold for $k=0$.

Assume now that both inequalities hold for some $k \geqslant 0$. The inequality $a_{i+1+k} \geqslant a_{i-k}$ implies $b_{i+1+k} \geqslant b_{i-k}$, so

$$

\frac{a_{i+k}+a_{i+2+k}}{a_{i+1+k}} \geqslant \frac{a_{i-1-k}+a_{i+1-k}}{a_{i-k}} .

$$

We may rearrange this inequality by making $a_{i+2+k}$ the subject so

$$

a_{i+2+k} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+1+k} a_{i-1-k}}{a_{i-k}}+\frac{a_{i+1-k} a_{i+1+k}-a_{i+k} a_{i-k}}{a_{i-k}} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+1+k} a_{i-1-k}}{a_{i-k}},

$$

where the last inequality holds by (2). It follows that

$$

a_{(i+1)+(k+1)} a_{(i+1)-(k+1)} \geqslant a_{i+(k+1)} a_{i-(k+1)},

$$

i.e. the inequality (2) holds also for $k+1$. Using (1) we now get

$$

a_{(i+1)+(k+1)} \geqslant \frac{a_{i+k+1}}{a_{i-k}} a_{i-(k+1)} \geqslant a_{i-(k+1)},

$$

i.e. (1) holds for $k+1$.

Now we use the inequality (1) for $k=n-1$. We get $a_{i} \geqslant a_{i+1}$, and since at the beginning we assumed $a_{i} \leqslant a_{i+1}$, we get that any two consecutive $a$ 's are equal, so all of them are equal.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 1.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 7. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

We first prove the following claim by induction:

Claim 1: If $a_{k} a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}^{2}$ and $a_{k}<a_{k+1}$, then $a_{j} a_{j+2}<a_{j+1}^{2}$ and $a_{j}<a_{j+1}$ for all $j$.

We assume that $a_{i} a_{i+2}<a_{i+1}^{2}$ and $a_{i}<a_{i+1}$, and then show that $a_{i-1} a_{i+1}<a_{i}^{2}$ and $a_{i-1}<a_{i}$.

Since $a_{i} \leq a_{i+1}$ we have that $b_{i} \leq b_{i+1}$. By plugging in the definition of $b_{i}$ and $b_{i+1}$ we have that

$$

a_{i+1} a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}^{2} \leq a_{i}^{2}+a_{i+2} a_{i}

$$

Using $a_{i} a_{i+2}<a_{i+1}^{2}$ we get that

$$

a_{i+1} a_{i-1}<a_{i}^{2} .

$$

Since $a_{i}<a_{i+1}$ we have that $a_{i-1}<a_{i}$, which concludes the induction step and hence proves the claim.

We cannot have that $a_{j}<a_{j+1}$ for all indices $j$. Similar as in the above claim, one can prove that if $a_{k} a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}^{2}$ and $a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}$, then $a_{j+1}<a_{j}$ for all $j$, which also cannot be the case. Thus we have that $a_{k} a_{k+2} \geq a_{k+1}^{2}$ for all indices $k$.

Next observe (e.g. by taking the product over all indices) that this implies $a_{k} a_{k+2}=a_{k+1}^{2}$ for all indices $k$, which is equivalent to $b_{k}=b_{k+1}$ for all $k$ and hence $a_{k+1}=a_{k}$ for all $k$.

|

a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

We first prove the following claim by induction:

Claim 1: If $a_{k} a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}^{2}$ and $a_{k}<a_{k+1}$, then $a_{j} a_{j+2}<a_{j+1}^{2}$ and $a_{j}<a_{j+1}$ for all $j$.

We assume that $a_{i} a_{i+2}<a_{i+1}^{2}$ and $a_{i}<a_{i+1}$, and then show that $a_{i-1} a_{i+1}<a_{i}^{2}$ and $a_{i-1}<a_{i}$.

Since $a_{i} \leq a_{i+1}$ we have that $b_{i} \leq b_{i+1}$. By plugging in the definition of $b_{i}$ and $b_{i+1}$ we have that

$$

a_{i+1} a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}^{2} \leq a_{i}^{2}+a_{i+2} a_{i}

$$

Using $a_{i} a_{i+2}<a_{i+1}^{2}$ we get that

$$

a_{i+1} a_{i-1}<a_{i}^{2} .

$$

Since $a_{i}<a_{i+1}$ we have that $a_{i-1}<a_{i}$, which concludes the induction step and hence proves the claim.

We cannot have that $a_{j}<a_{j+1}$ for all indices $j$. Similar as in the above claim, one can prove that if $a_{k} a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}^{2}$ and $a_{k+2}<a_{k+1}$, then $a_{j+1}<a_{j}$ for all $j$, which also cannot be the case. Thus we have that $a_{k} a_{k+2} \geq a_{k+1}^{2}$ for all indices $k$.

Next observe (e.g. by taking the product over all indices) that this implies $a_{k} a_{k+2}=a_{k+1}^{2}$ for all indices $k$, which is equivalent to $b_{k}=b_{k+1}$ for all $k$ and hence $a_{k+1}=a_{k}$ for all $k$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 1.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 8. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

Define $c_{i}:=\frac{a_{i}}{a_{i+1}}$, then $b_{i}=c_{i-1}+1 / c_{i}$. Assume that not all $c_{i}$ are equal to 1. Since, $\prod_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}=1$ there exists a $k$ such that $c_{k} \geqslant 1$. From the condition given in the problem statement for $(i, j)=(k, k+1)$ we have

$$

c_{k} \geqslant 1 \Longleftrightarrow c_{k-1}+\frac{1}{c_{k}} \geqslant c_{k}+\frac{1}{c_{k+1}} \Longleftrightarrow c_{k-1} c_{k} c_{k+1}+c_{k+1} \geqslant c_{k}^{2} c_{k+1}+c_{k}

$$

Now since $c_{k+1} \leqslant c_{k}^{2} c_{k+1}$, it follows that

$$

c_{i-1} c_{i} c_{i+1} \geqslant c_{i} \Longrightarrow\left(c_{i-1} \geqslant 1 \text { or } c_{i+1} \geqslant 1\right) .

$$

So there exist a set of at least 2 consecutive integers, such that the corresponding $c_{i}$ are greater or equal to one. By the innitial assumption there must exist an index $\ell$, such that $c_{\ell-1}, c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$ and $c_{\ell+1}<1$. We distinguish two cases:

Case 1: $c_{\ell}>c_{\ell-1} \geqslant 1$

From $c_{\ell-1} c_{\ell} c_{\ell+1}<c_{\ell}^{2} c_{\ell+1}$ and the inequality (5), we get that $c_{\ell+1}>c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$, which is a contradiction to our choice of $\ell$.

Case 2: $c_{\ell-1} \geqslant c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$

Once again looking at the inequality (5) we can find that

$$

c_{\ell-2} c_{\ell-1} c_{\ell} \geqslant c_{\ell-1}^{2} c_{\ell} \Longrightarrow c_{\ell-2} \geqslant c_{\ell-1} .

$$

Note that we only needed $c_{\ell-1} \geqslant c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$ to show $c_{\ell-2} \geqslant c_{\ell-1} \geqslant 1$. So using induction we can easily show $c_{\ell-s-1} \geqslant c_{\ell-s}$ for all $s$.

So

$$

c_{1} \leqslant c_{2} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant c_{n} \leqslant c_{1}

$$

a contradiction to our innitial assumption.

So our innitial assumtion must have been wrong, which implies that all the $a_{i}$ must have been equal from the start.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

There are $n \geqslant 3$ positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$. For each $1 \leqslant i \leqslant n$ we let $b_{i}=\frac{a_{i-1}+a_{i+1}}{a_{i}}$ (here we define $a_{0}$ to be $a_{n}$ and $a_{n+1}$ to be $a_{1}$ ). Assume that for all $i$ and $j$ in the range 1 to $n$, we have $a_{i} \leqslant a_{j}$ if and only if $b_{i} \leqslant b_{j}$.

Prove that $a_{1}=a_{2}=\cdots=a_{n}$.

|

Define $c_{i}:=\frac{a_{i}}{a_{i+1}}$, then $b_{i}=c_{i-1}+1 / c_{i}$. Assume that not all $c_{i}$ are equal to 1. Since, $\prod_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}=1$ there exists a $k$ such that $c_{k} \geqslant 1$. From the condition given in the problem statement for $(i, j)=(k, k+1)$ we have

$$

c_{k} \geqslant 1 \Longleftrightarrow c_{k-1}+\frac{1}{c_{k}} \geqslant c_{k}+\frac{1}{c_{k+1}} \Longleftrightarrow c_{k-1} c_{k} c_{k+1}+c_{k+1} \geqslant c_{k}^{2} c_{k+1}+c_{k}

$$

Now since $c_{k+1} \leqslant c_{k}^{2} c_{k+1}$, it follows that

$$

c_{i-1} c_{i} c_{i+1} \geqslant c_{i} \Longrightarrow\left(c_{i-1} \geqslant 1 \text { or } c_{i+1} \geqslant 1\right) .

$$

So there exist a set of at least 2 consecutive integers, such that the corresponding $c_{i}$ are greater or equal to one. By the innitial assumption there must exist an index $\ell$, such that $c_{\ell-1}, c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$ and $c_{\ell+1}<1$. We distinguish two cases:

Case 1: $c_{\ell}>c_{\ell-1} \geqslant 1$

From $c_{\ell-1} c_{\ell} c_{\ell+1}<c_{\ell}^{2} c_{\ell+1}$ and the inequality (5), we get that $c_{\ell+1}>c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$, which is a contradiction to our choice of $\ell$.

Case 2: $c_{\ell-1} \geqslant c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$

Once again looking at the inequality (5) we can find that

$$

c_{\ell-2} c_{\ell-1} c_{\ell} \geqslant c_{\ell-1}^{2} c_{\ell} \Longrightarrow c_{\ell-2} \geqslant c_{\ell-1} .

$$

Note that we only needed $c_{\ell-1} \geqslant c_{\ell} \geqslant 1$ to show $c_{\ell-2} \geqslant c_{\ell-1} \geqslant 1$. So using induction we can easily show $c_{\ell-s-1} \geqslant c_{\ell-s}$ for all $s$.

So

$$

c_{1} \leqslant c_{2} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant c_{n} \leqslant c_{1}

$$

a contradiction to our innitial assumption.

So our innitial assumtion must have been wrong, which implies that all the $a_{i}$ must have been equal from the start.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 1.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 9. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

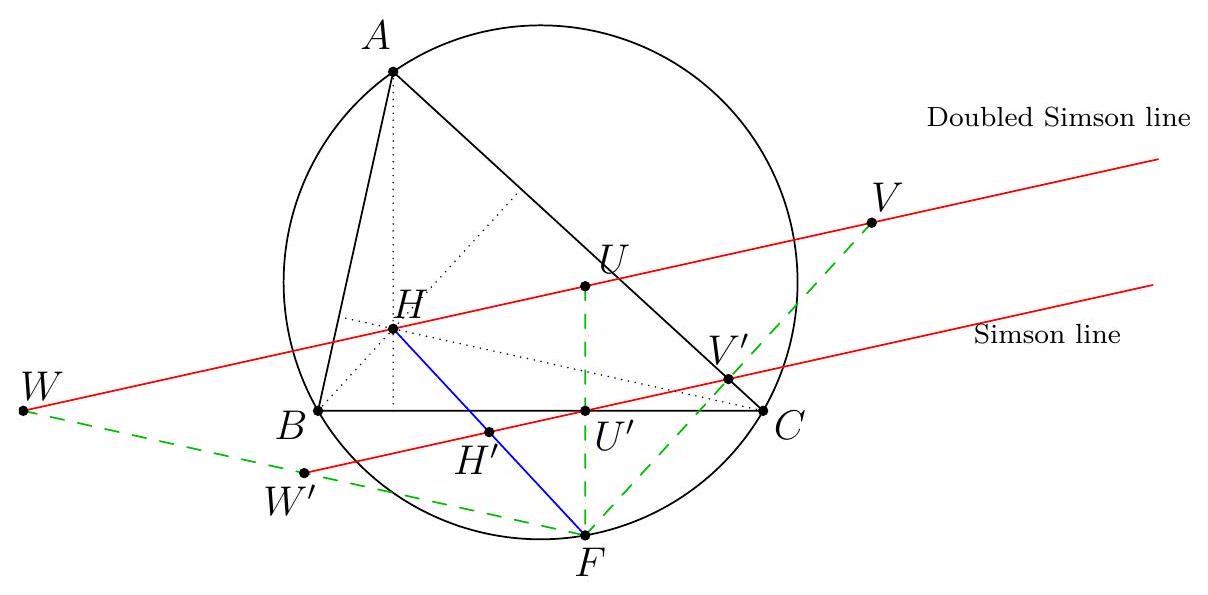

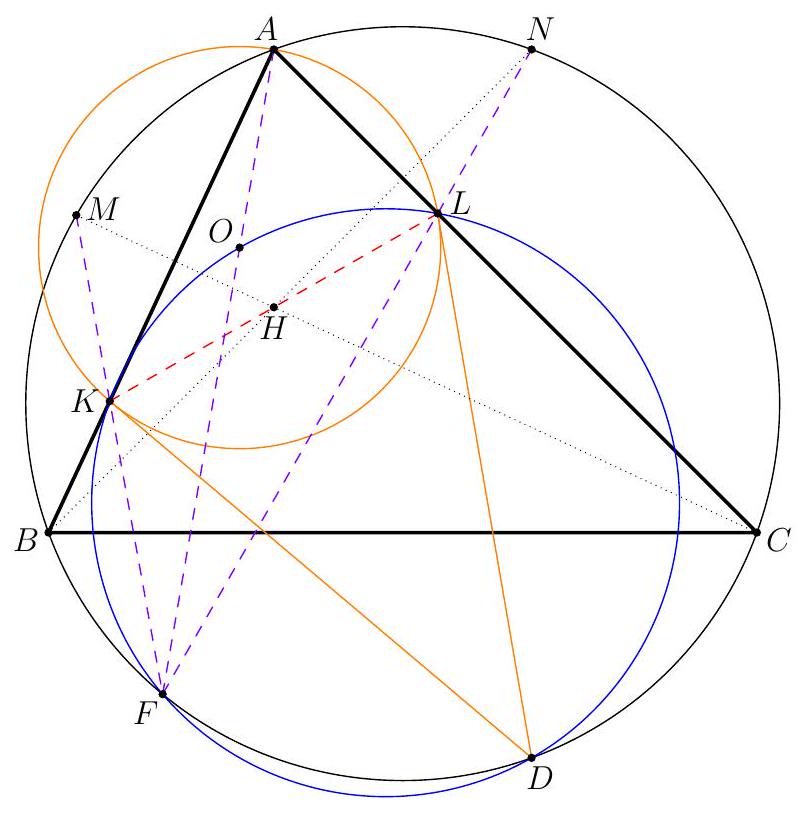

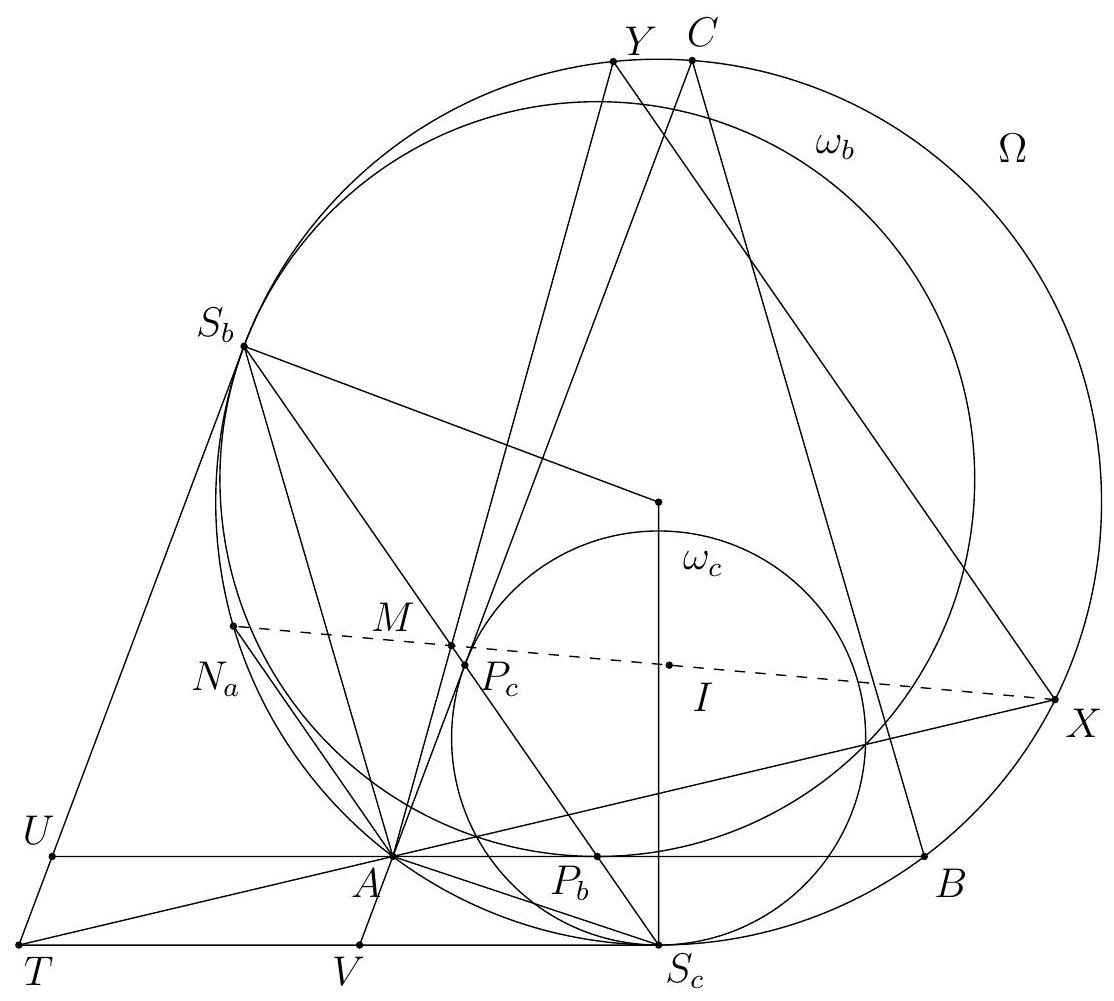

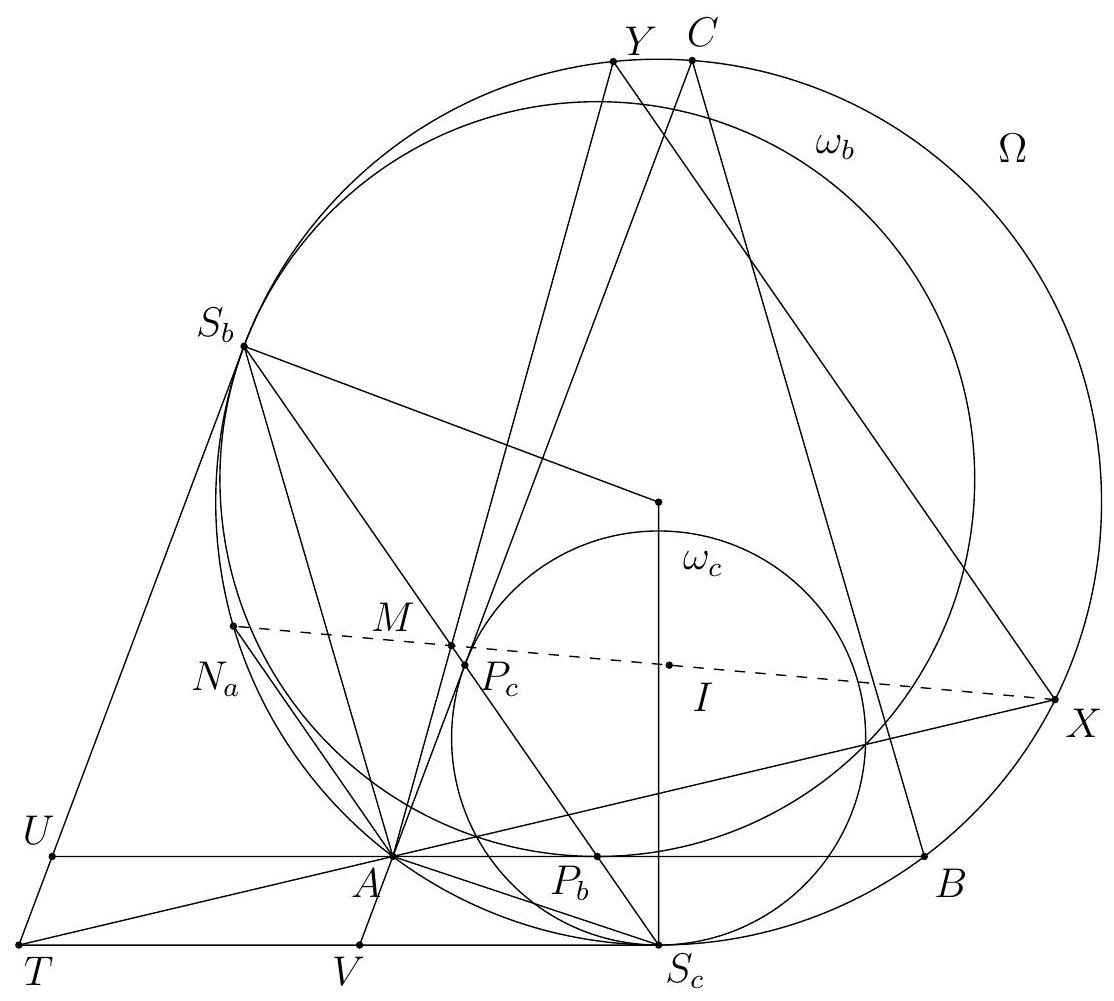

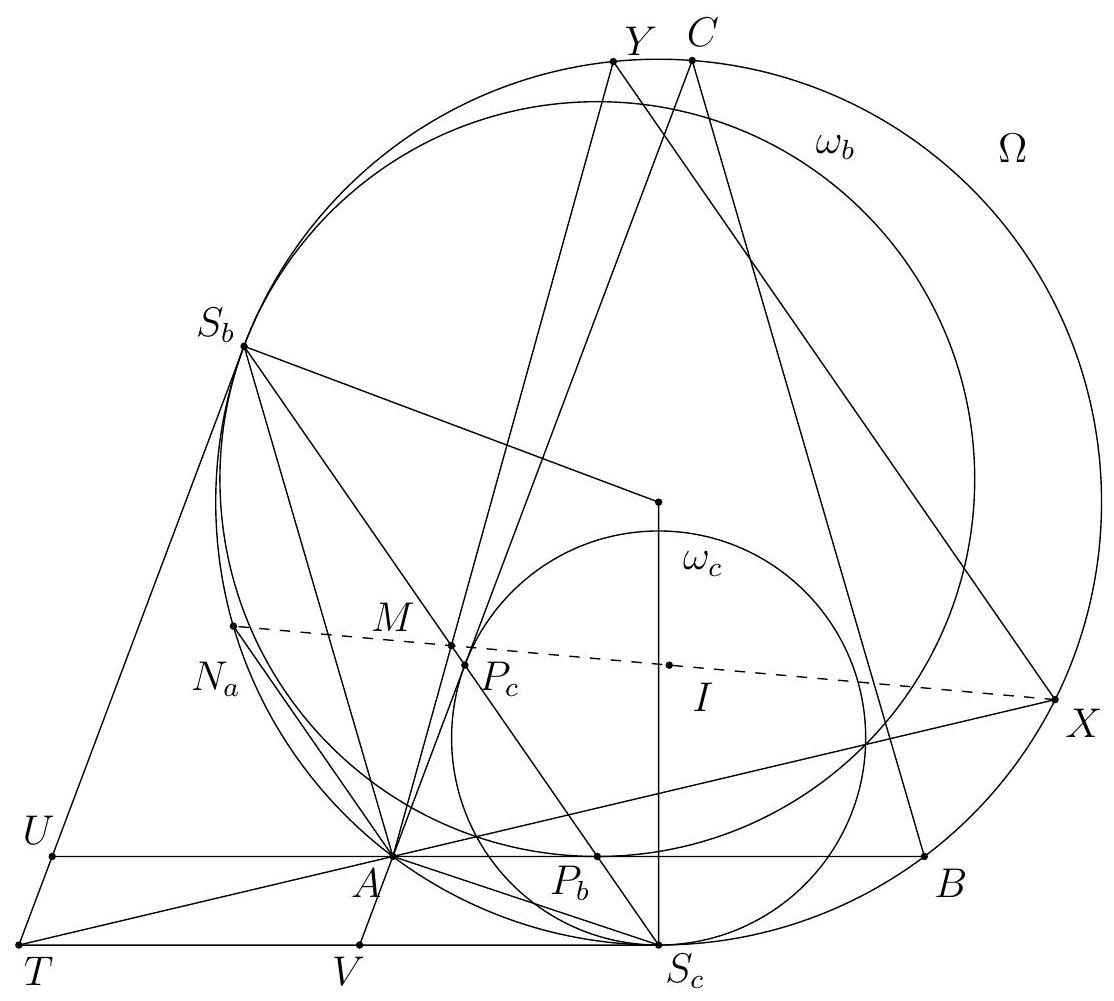

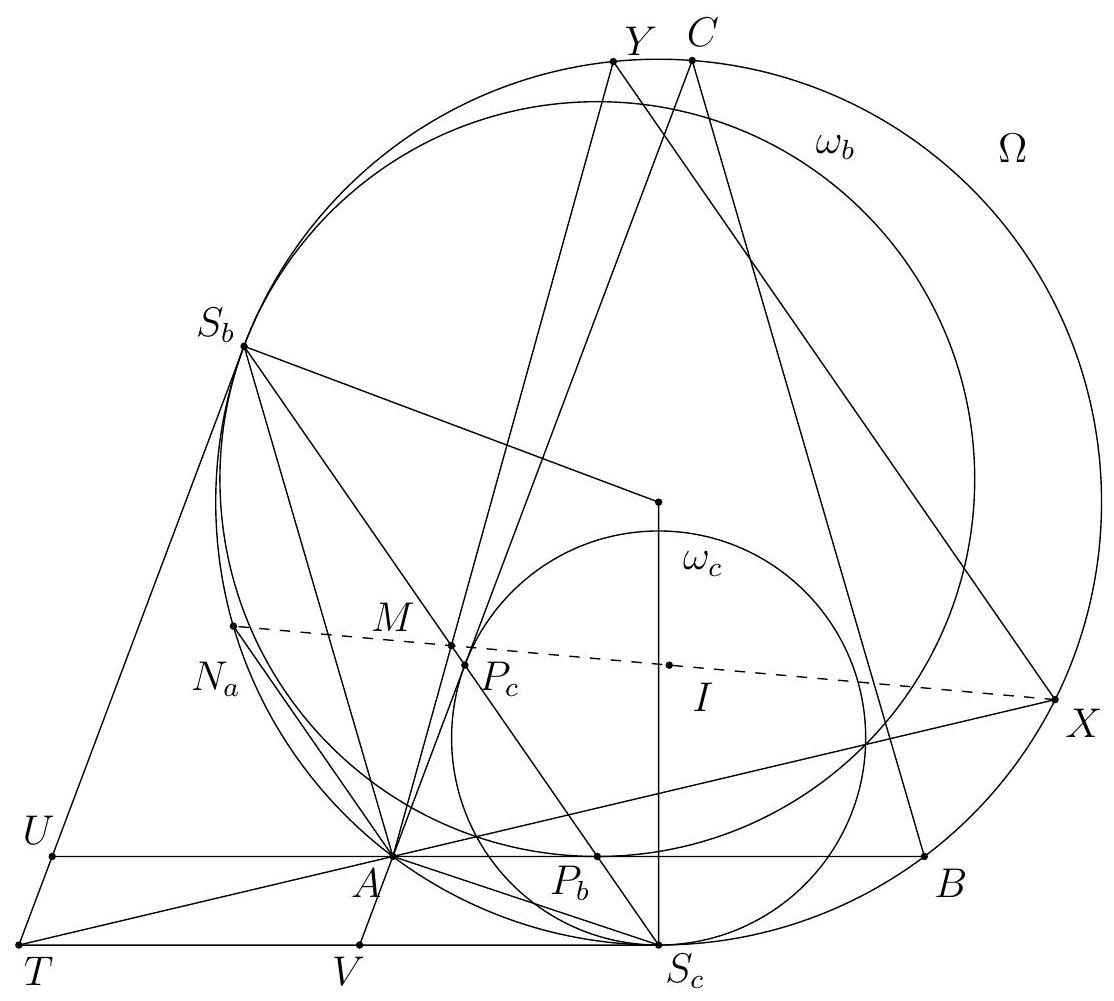

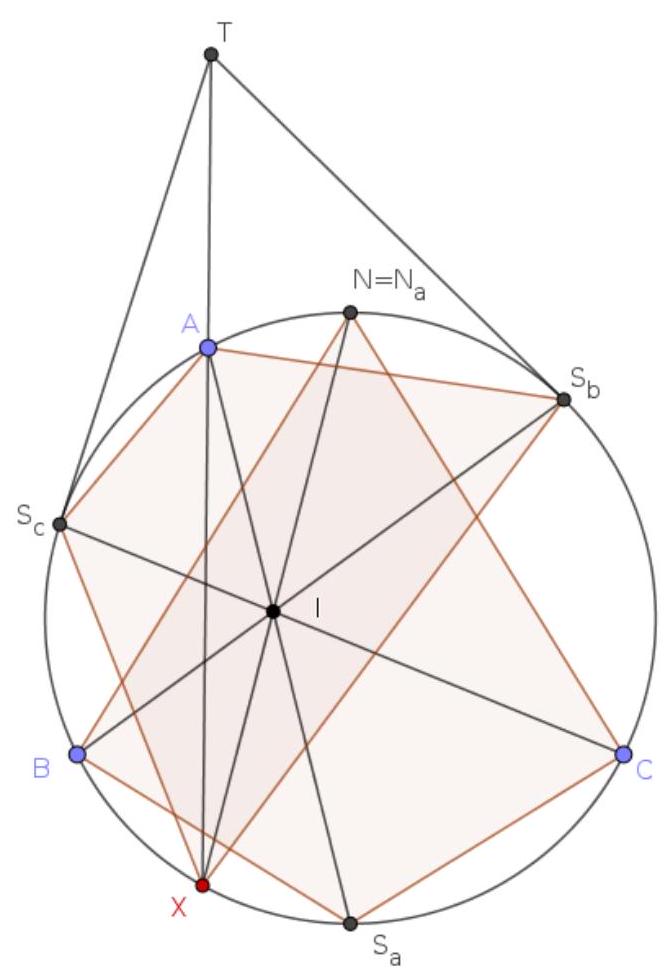

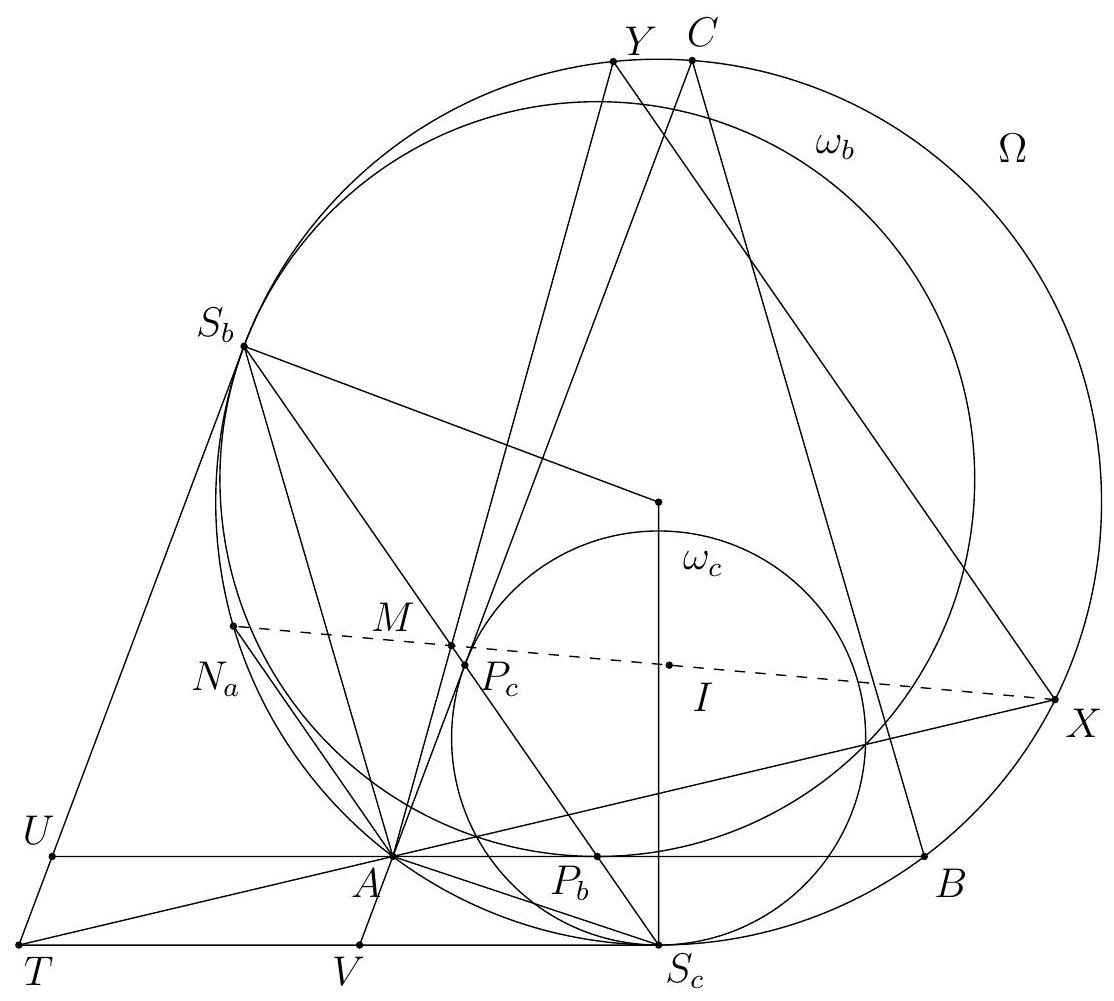

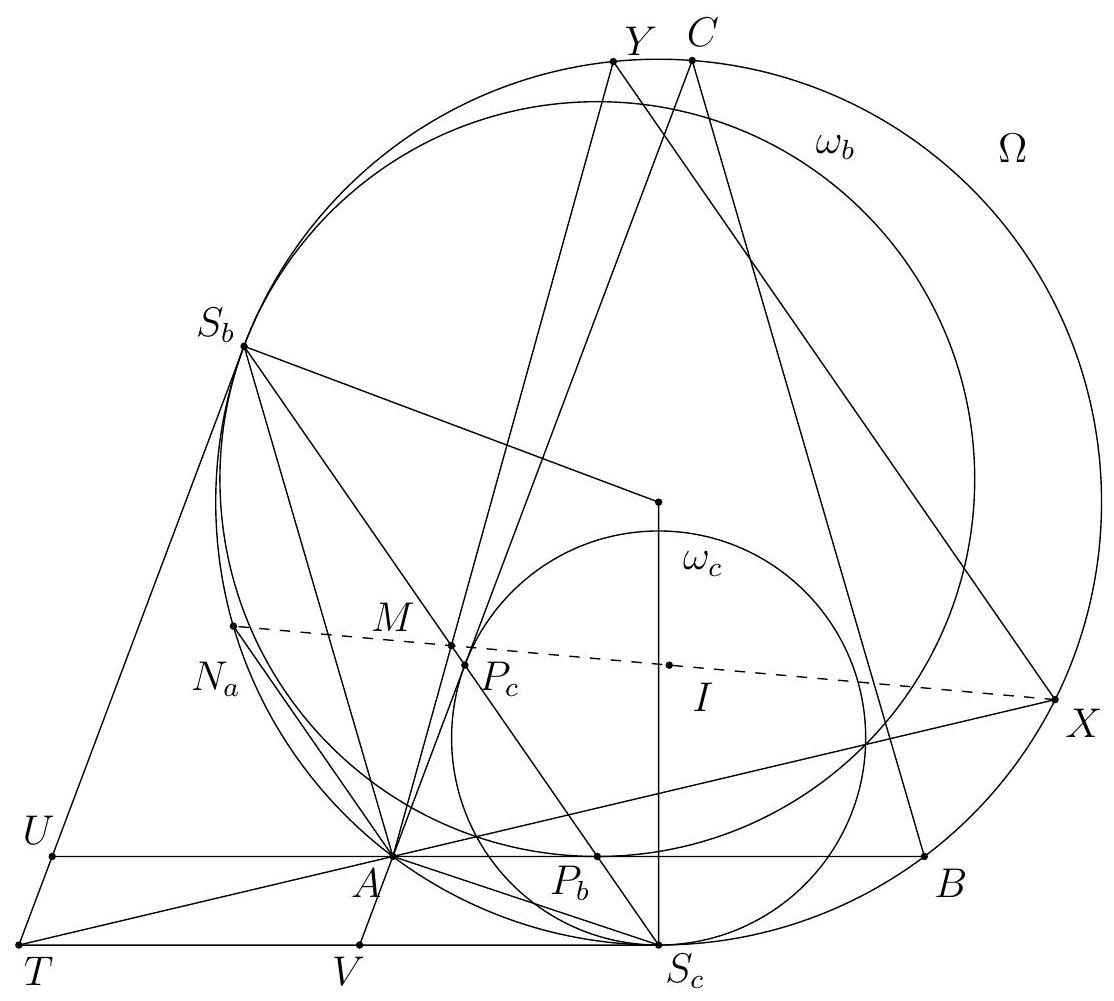

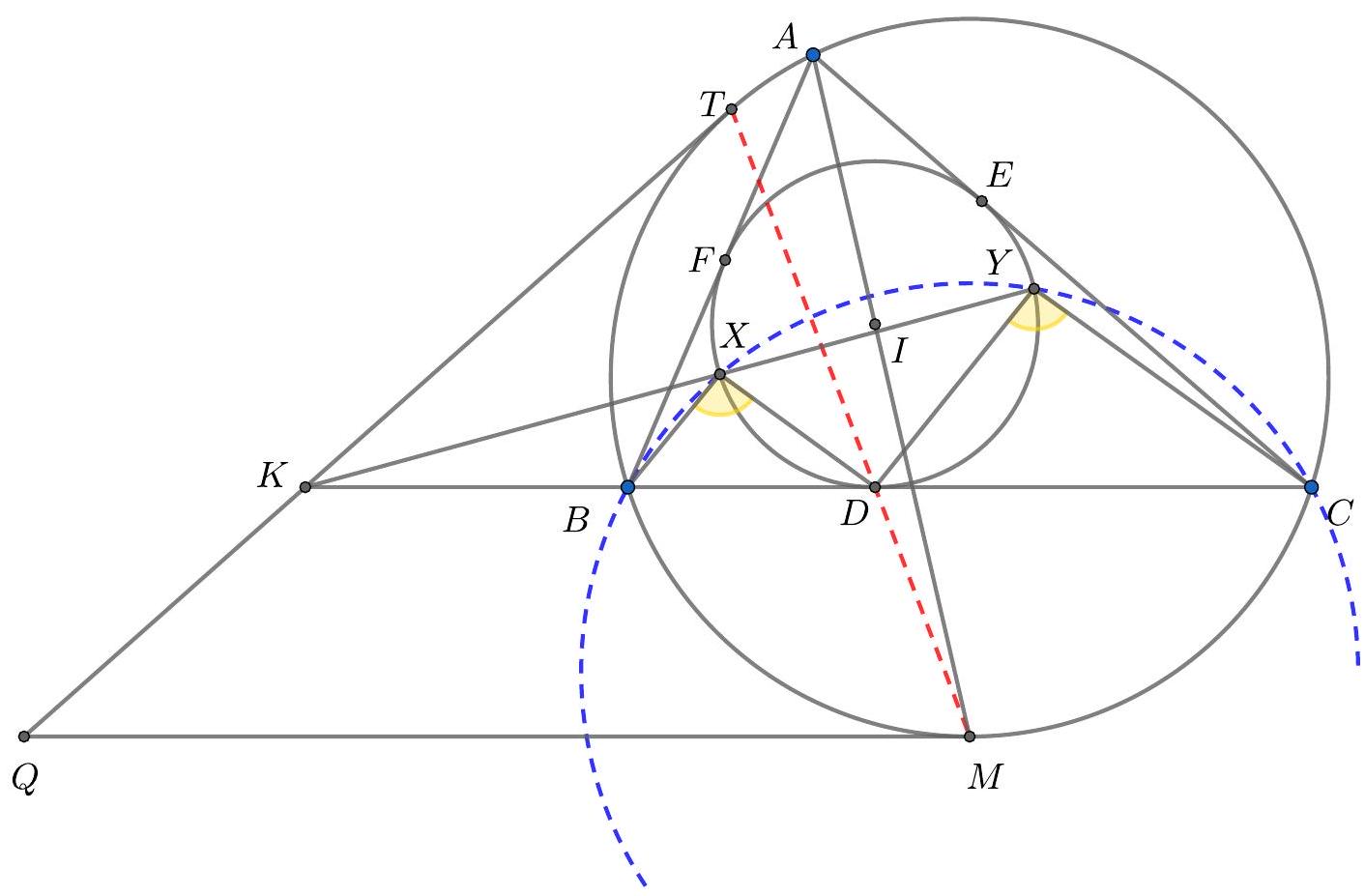

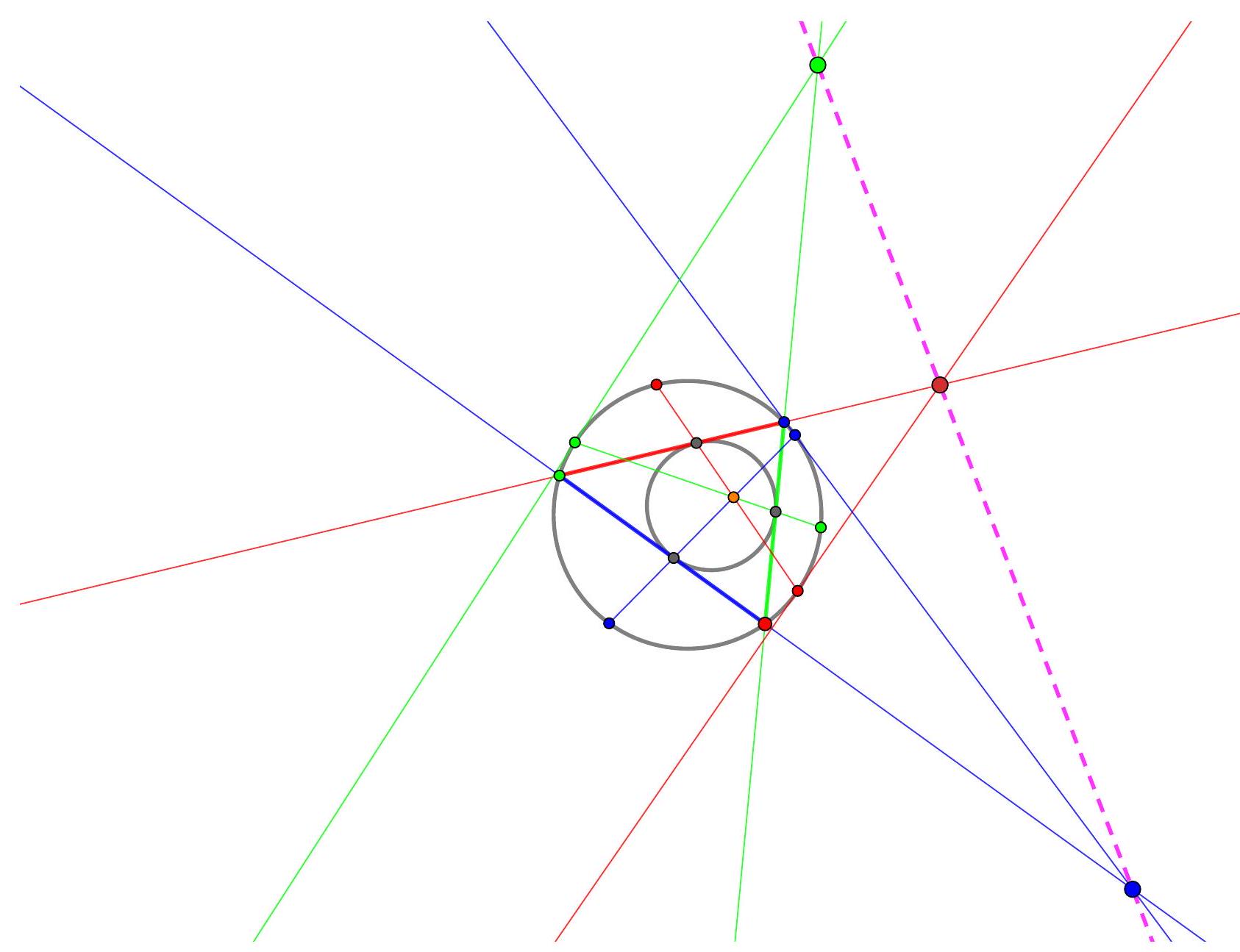

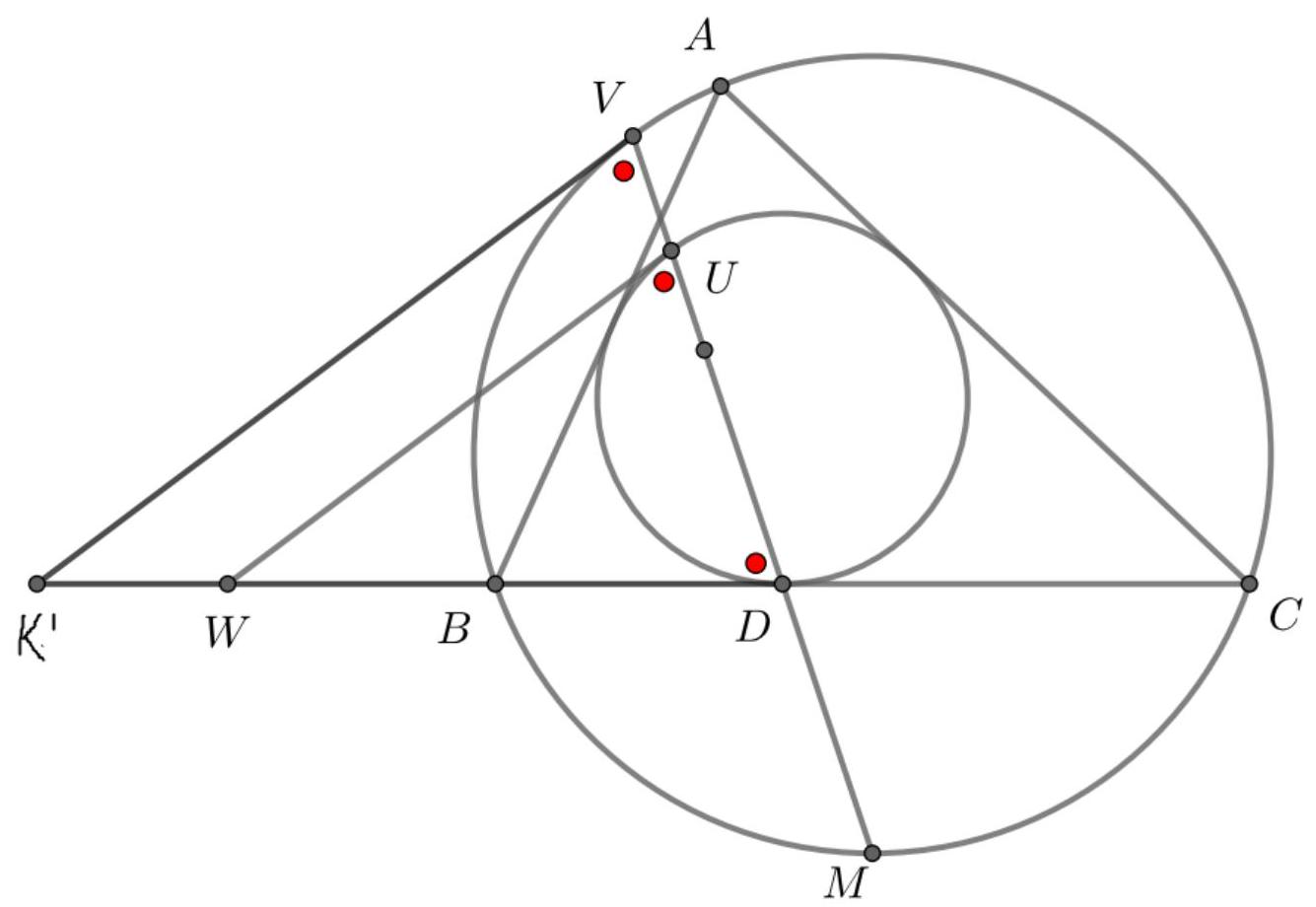

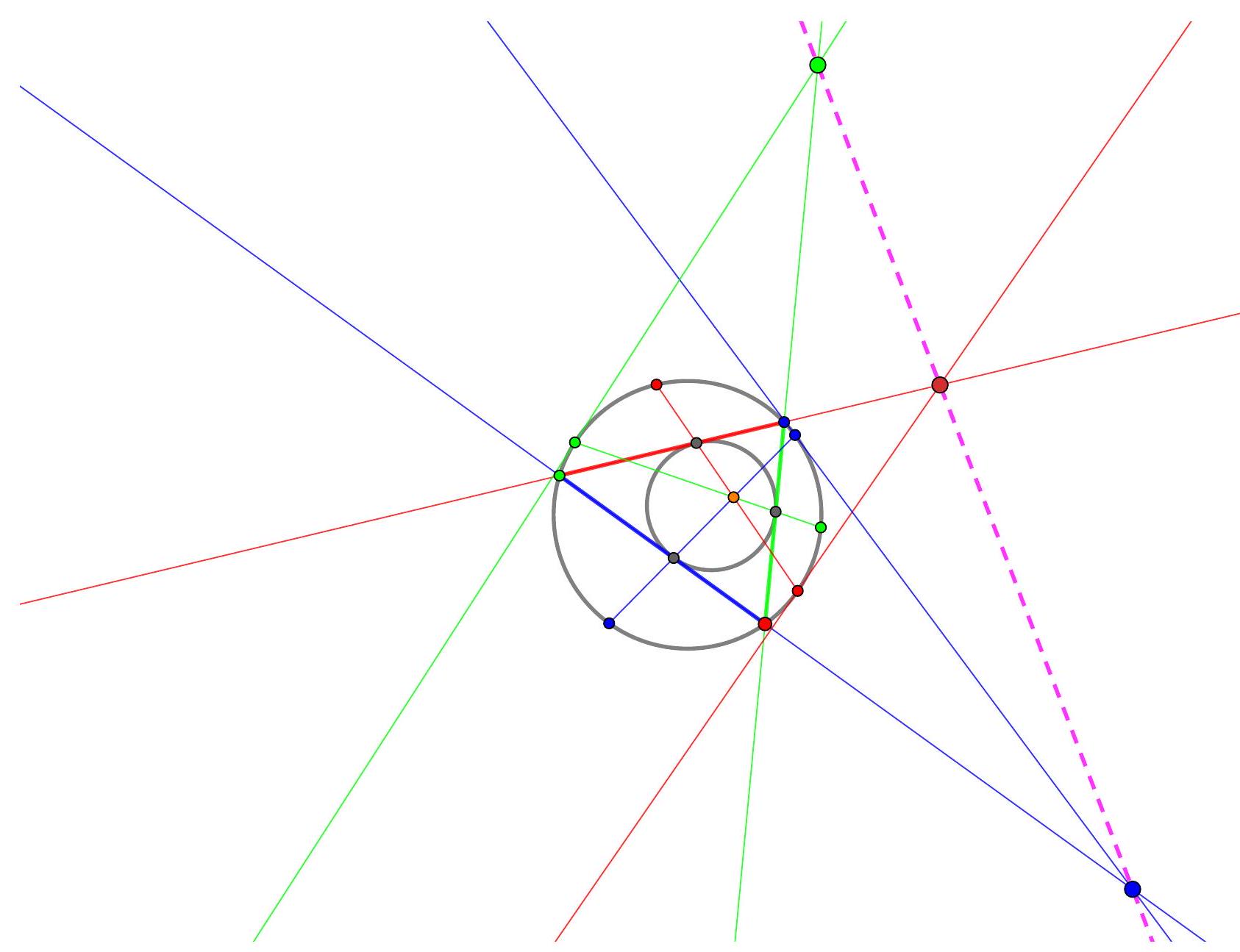

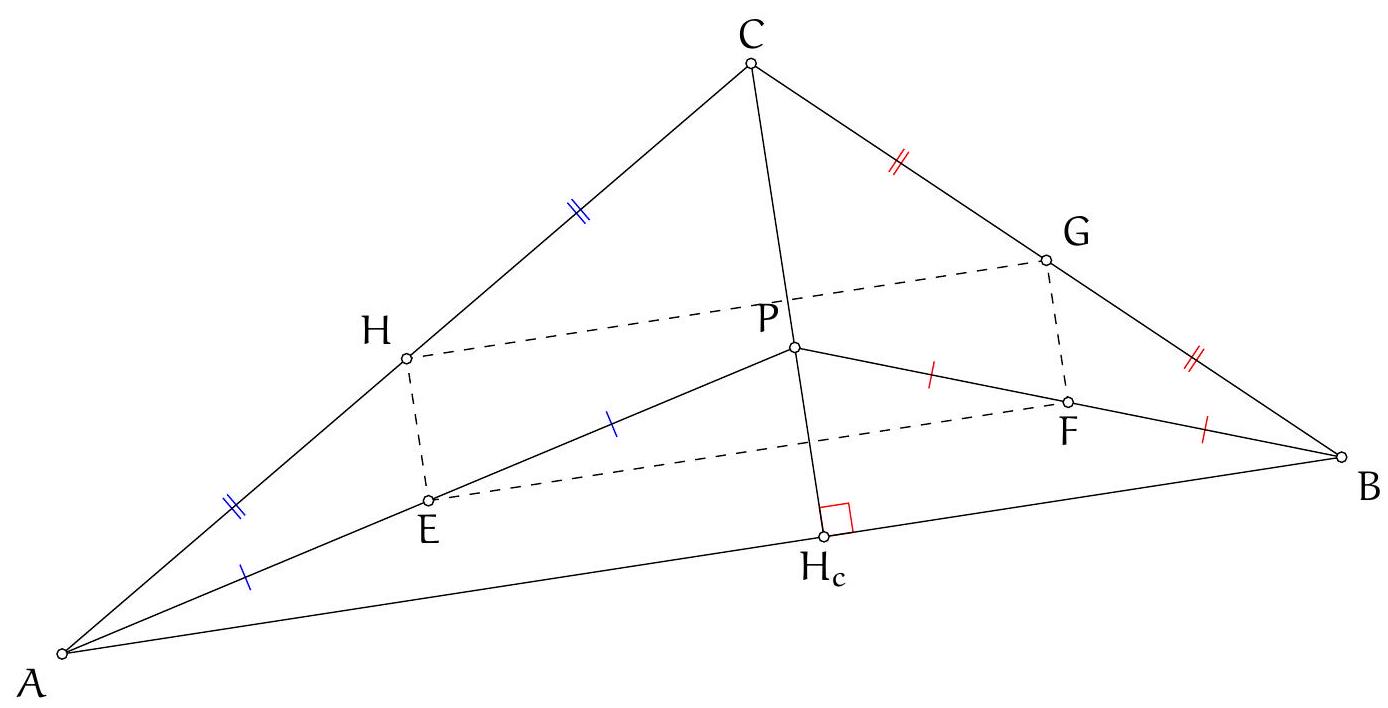

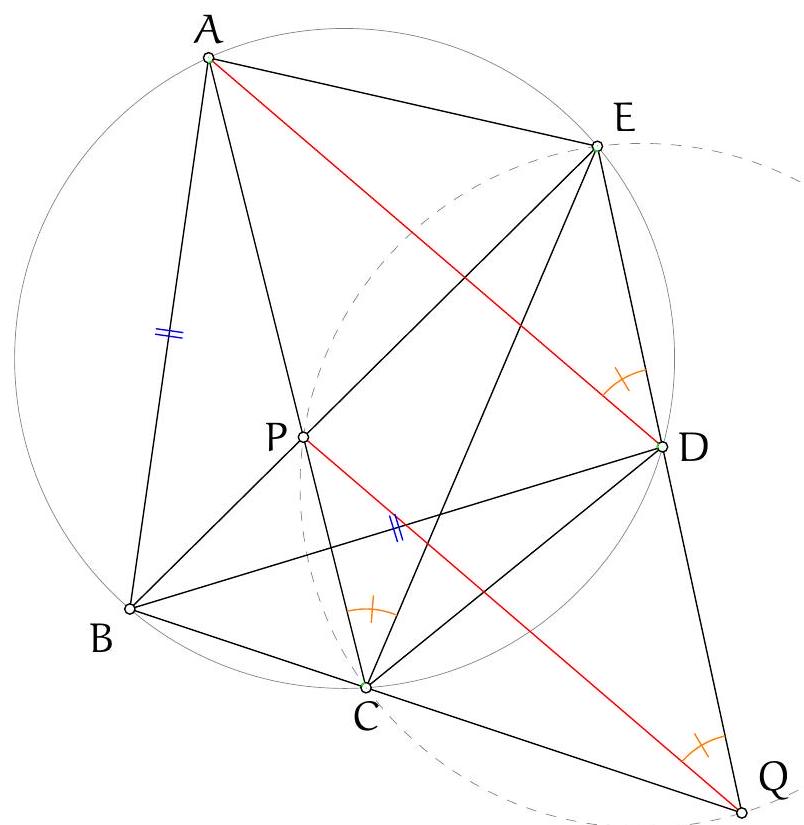

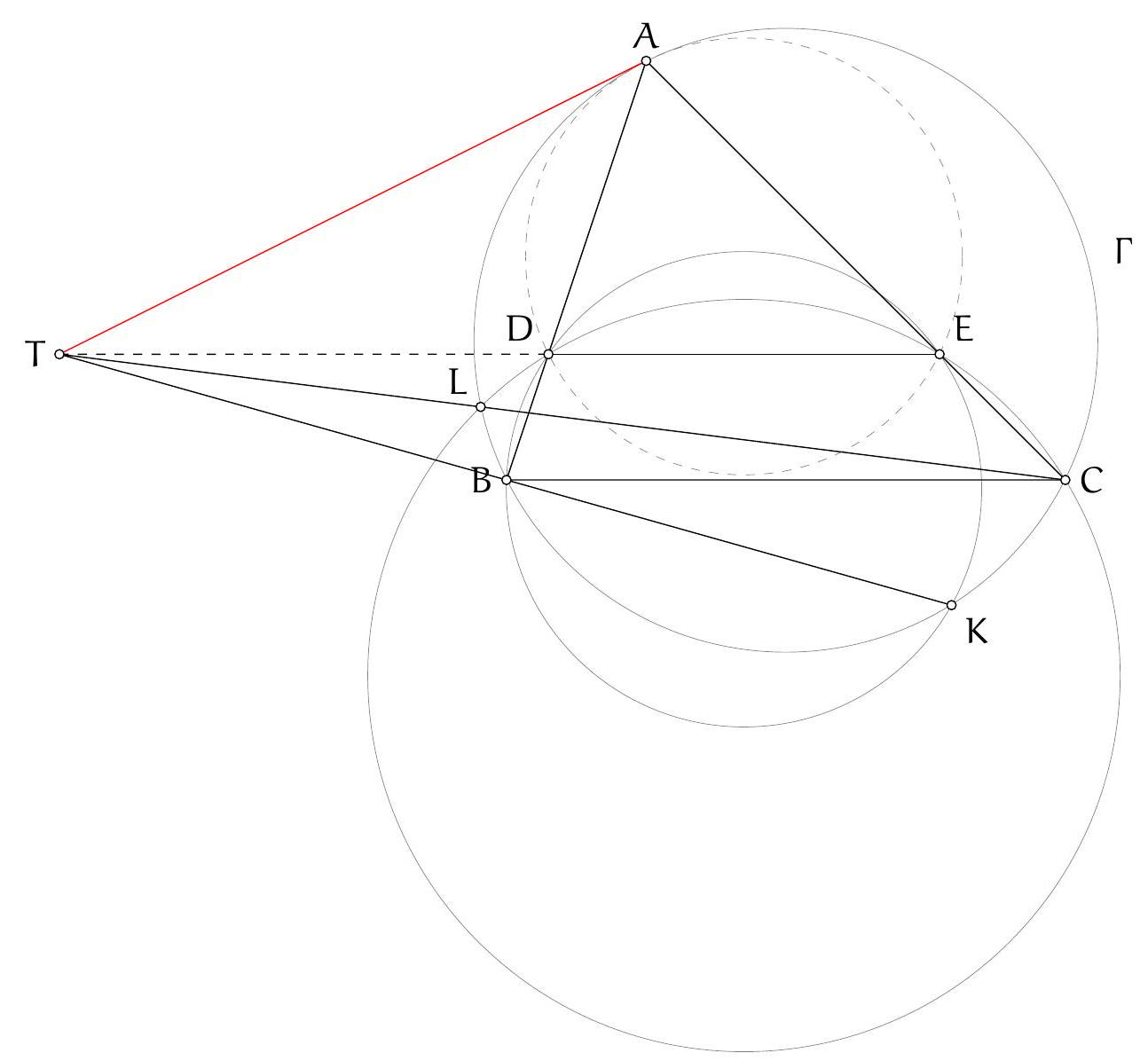

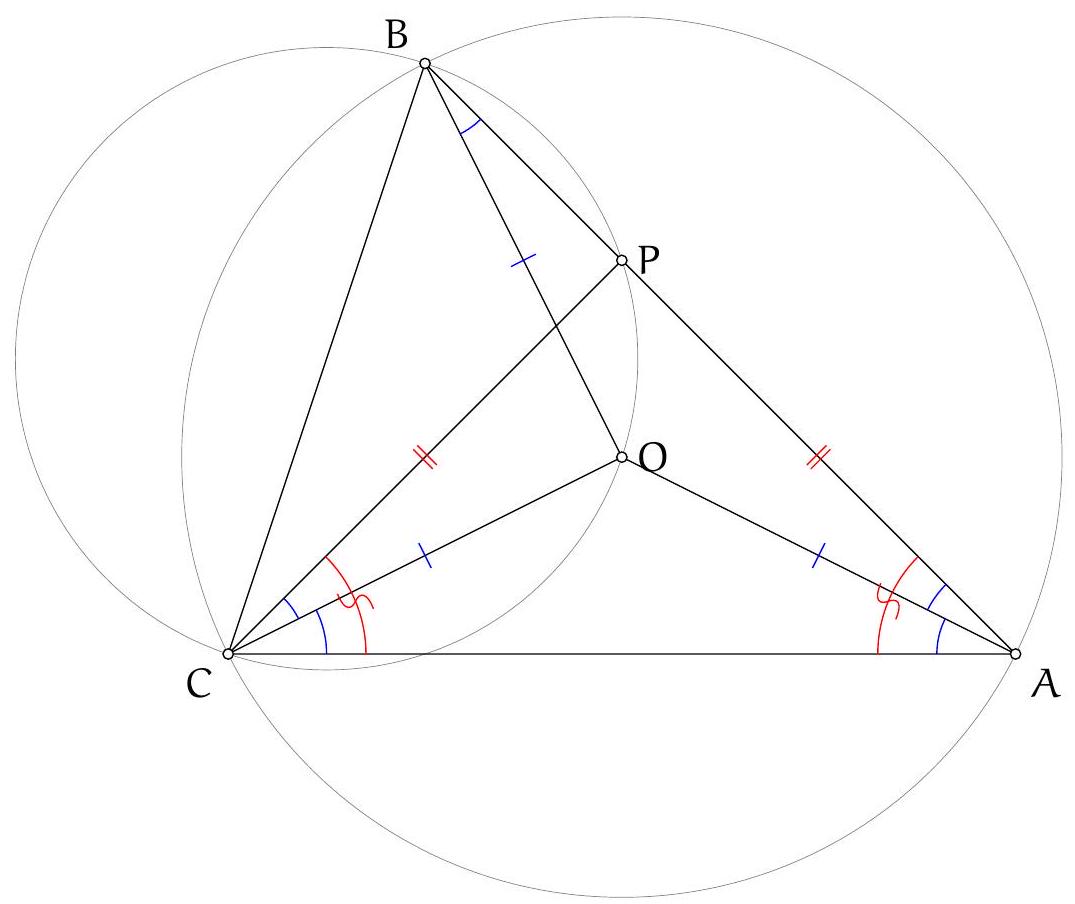

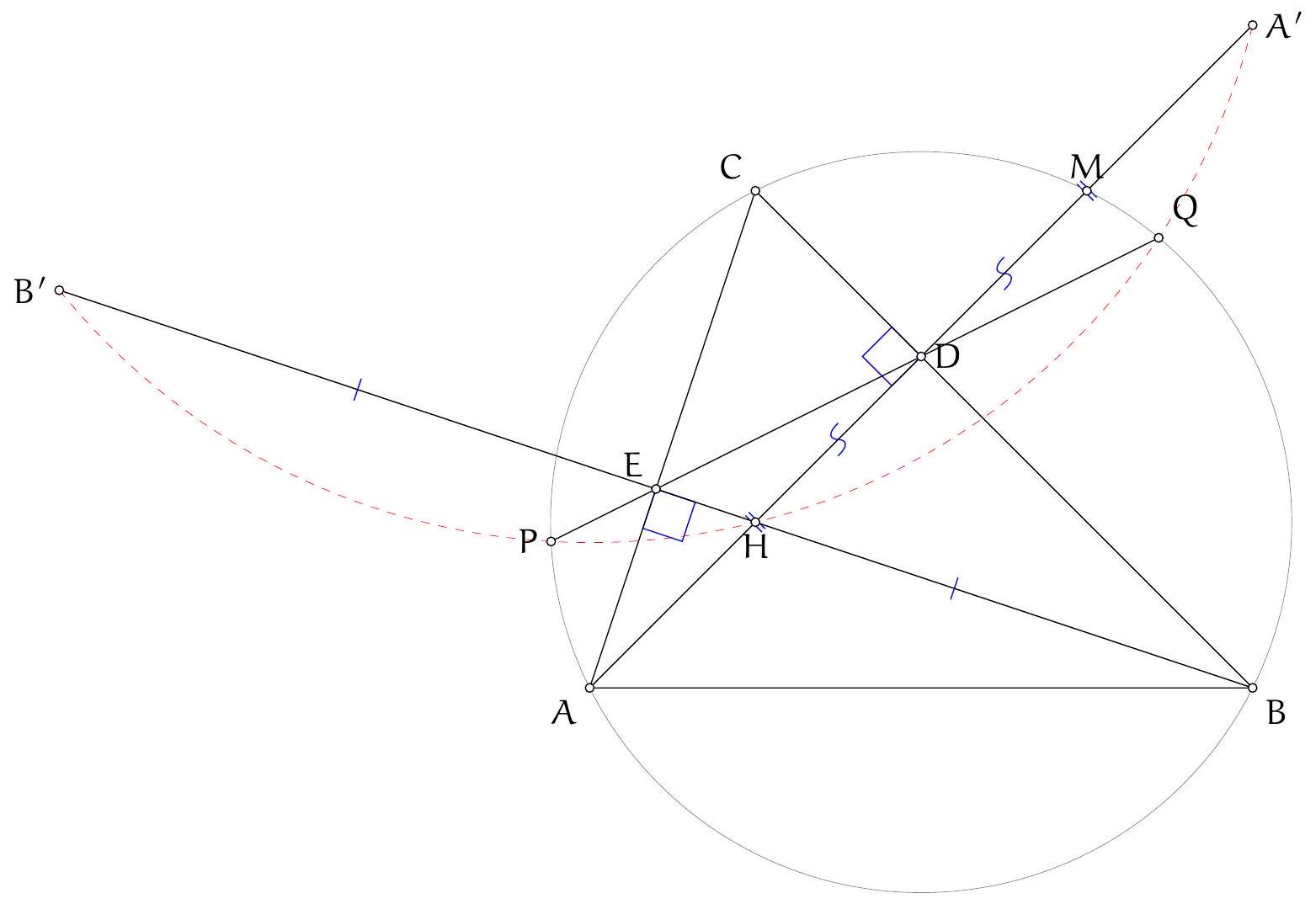

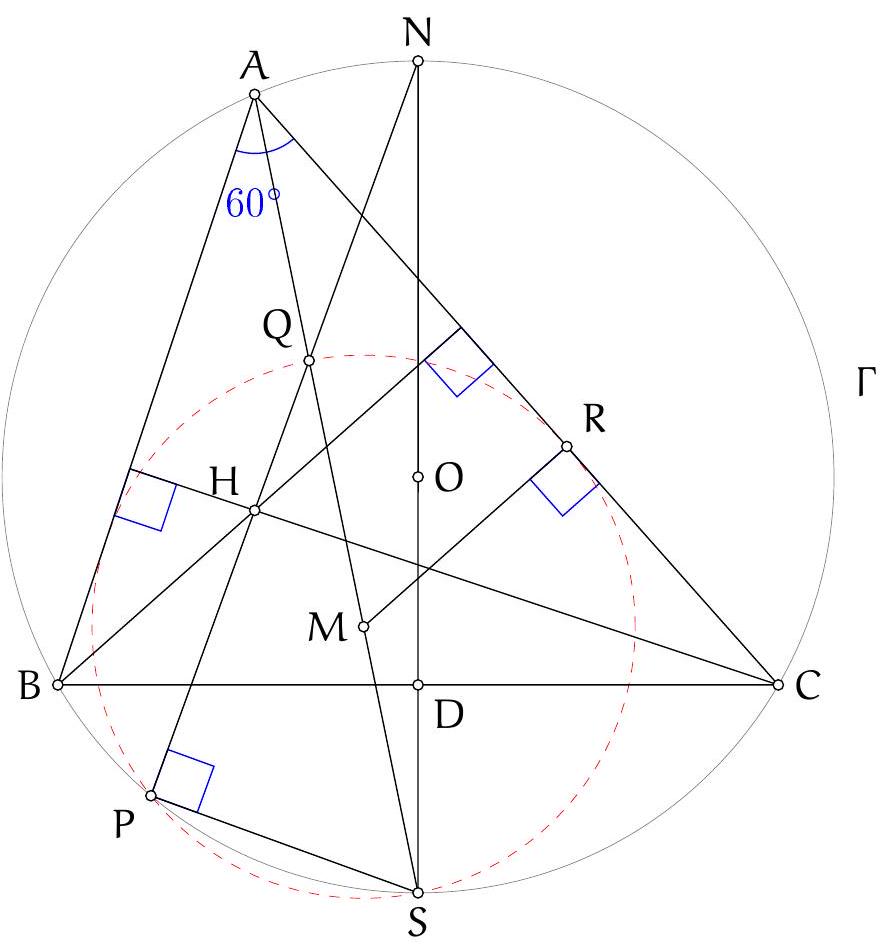

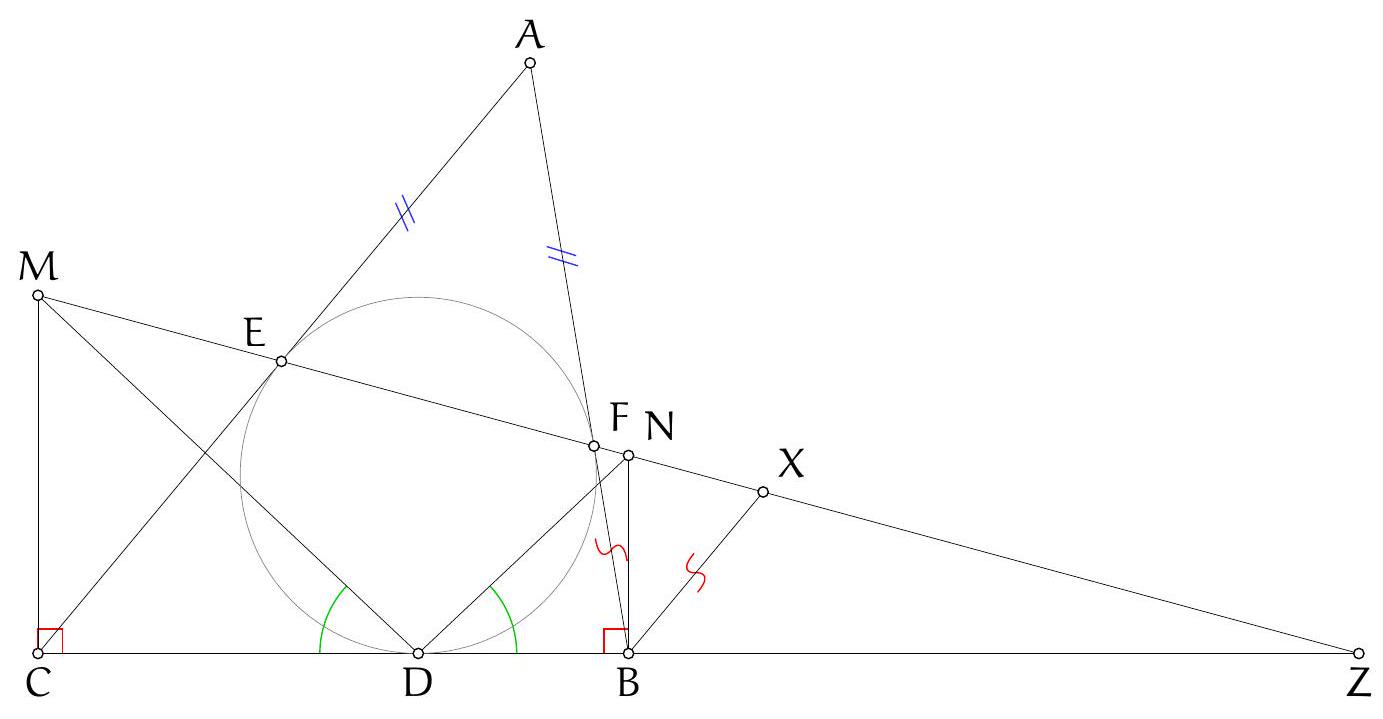

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Let $M$ be the midpoint of $K L$. We will prove that $M$ is the orthocentre of $A B C$. Since $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to the same circle, $|D K|=|D L|$ and hence $D M \perp K L$. The theorem of Thales in circle $A B C$ also gives $D B \perp B A$ and $D C \perp C A$. The right angles then give that quadrilaterals $B D M K$ and $D M L C$ are cyclic.

If $\angle B A C=\alpha$, then clearly $\angle D K M=\angle M L D=\alpha$ by angle in the alternate segment of circle $A K L$, and so $\angle M D K=\angle L D M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha$, which thanks to cyclic quadrilaterals gives $\angle M B K=\angle L C M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha$. From this, we have $B M \perp A C$ and $C M \perp A B$, and so $M$ indeed is the orthocentre of $A B C$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Let $M$ be the midpoint of $K L$. We will prove that $M$ is the orthocentre of $A B C$. Since $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to the same circle, $|D K|=|D L|$ and hence $D M \perp K L$. The theorem of Thales in circle $A B C$ also gives $D B \perp B A$ and $D C \perp C A$. The right angles then give that quadrilaterals $B D M K$ and $D M L C$ are cyclic.

If $\angle B A C=\alpha$, then clearly $\angle D K M=\angle M L D=\alpha$ by angle in the alternate segment of circle $A K L$, and so $\angle M D K=\angle L D M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha$, which thanks to cyclic quadrilaterals gives $\angle M B K=\angle L C M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha$. From this, we have $B M \perp A C$ and $C M \perp A B$, and so $M$ indeed is the orthocentre of $A B C$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Preliminaries

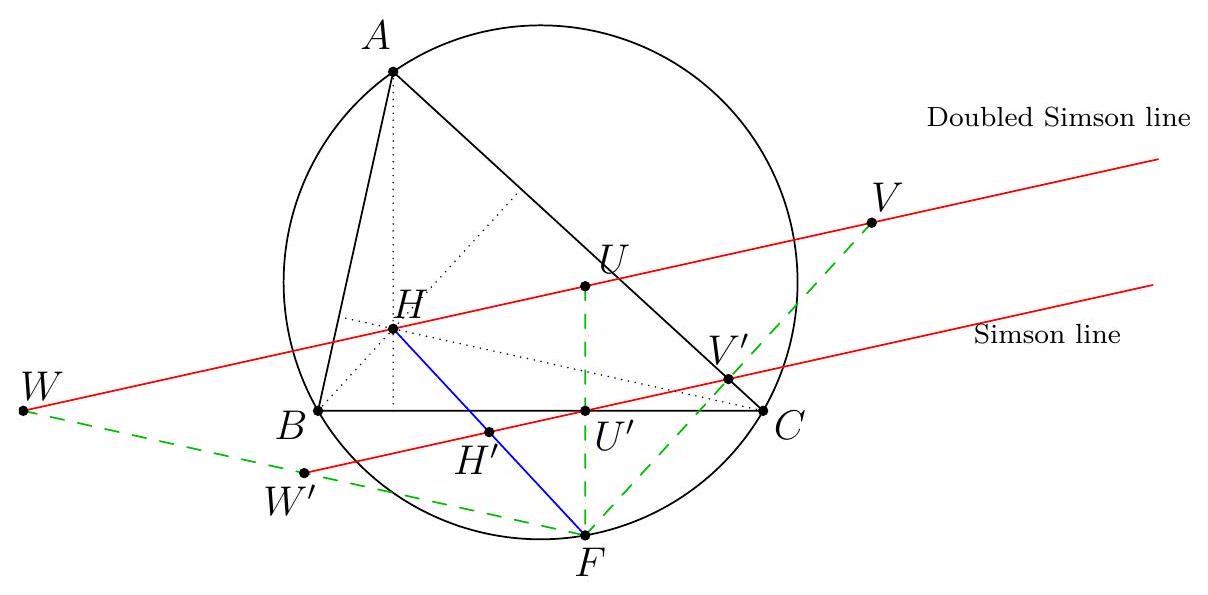

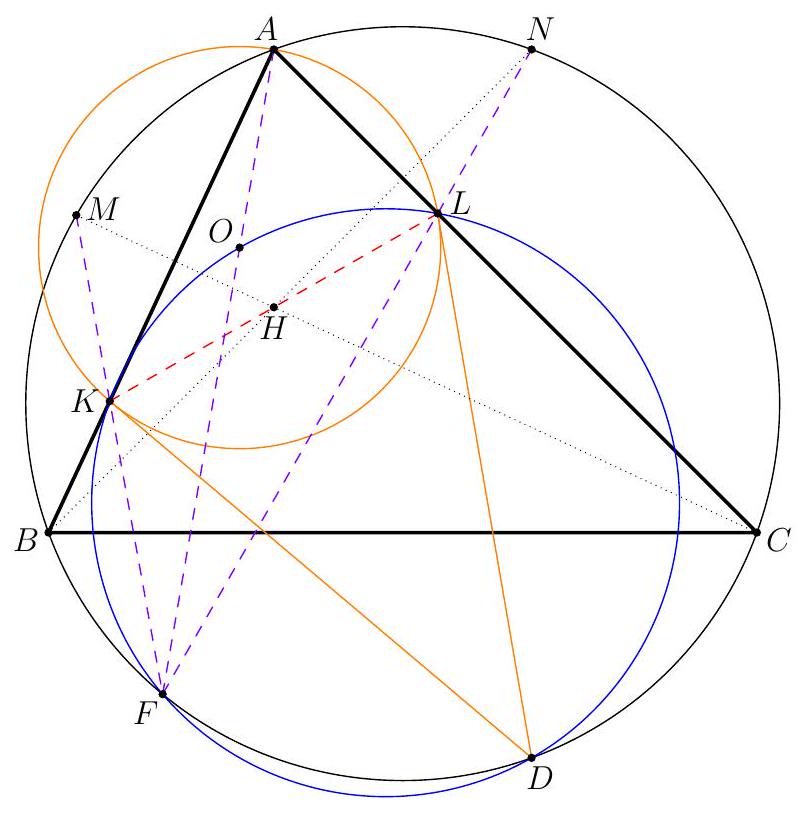

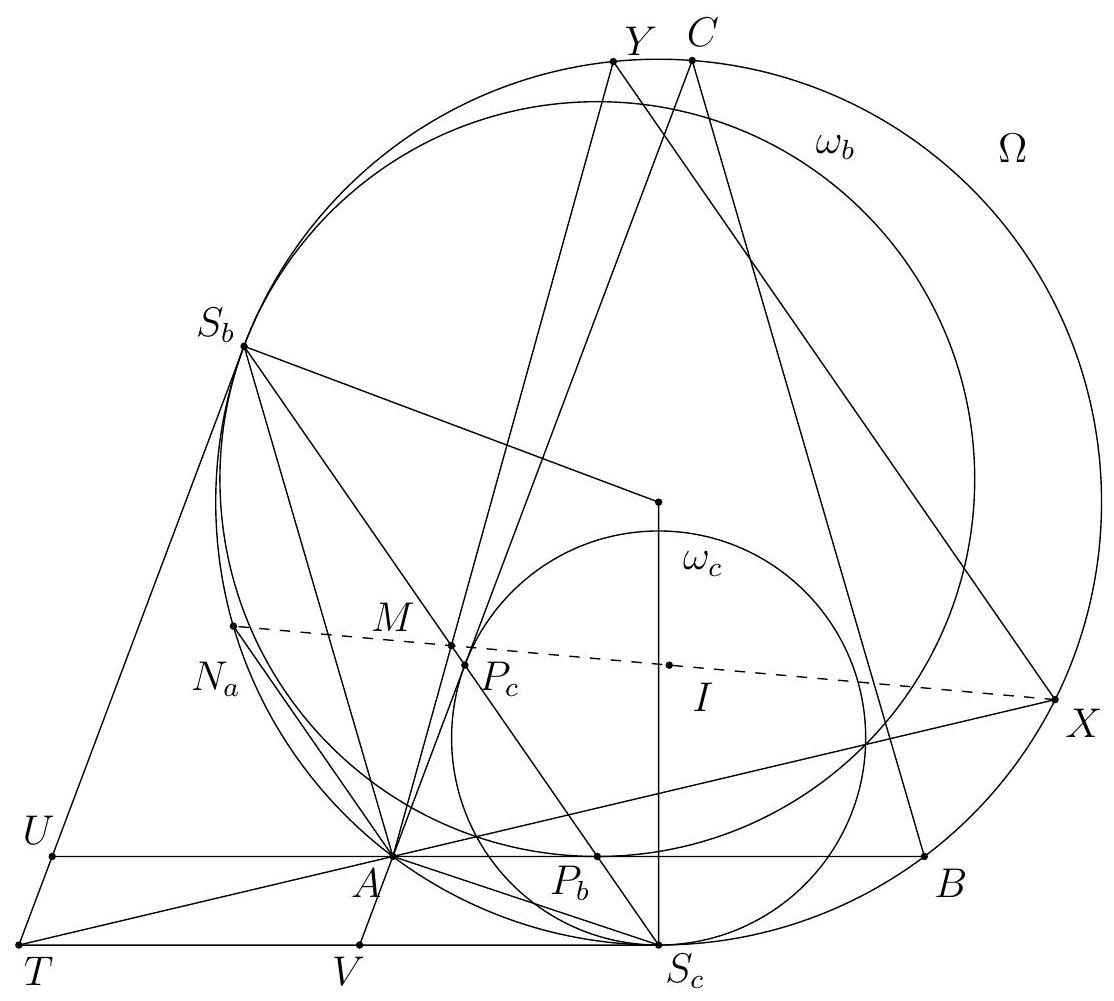

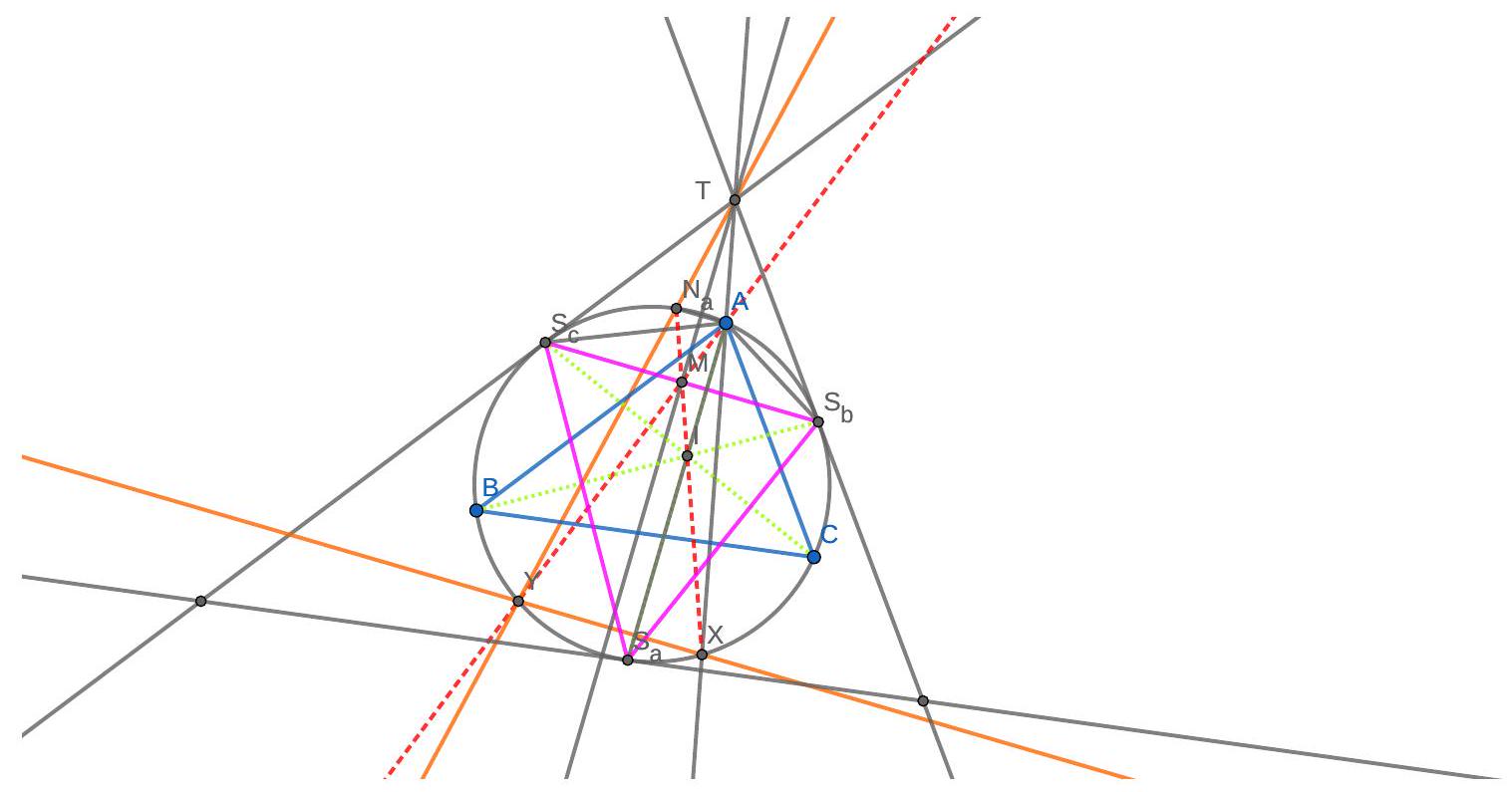

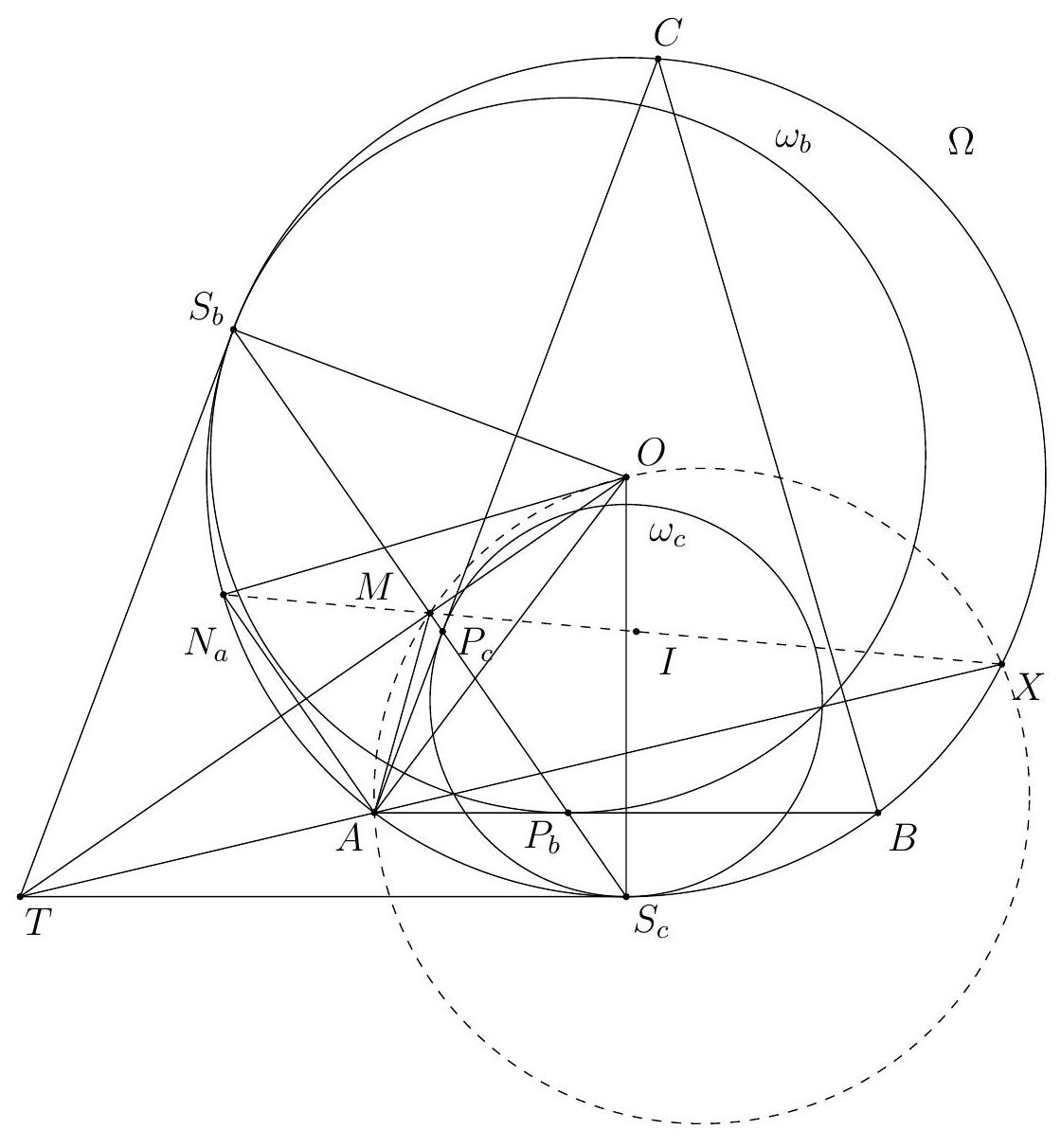

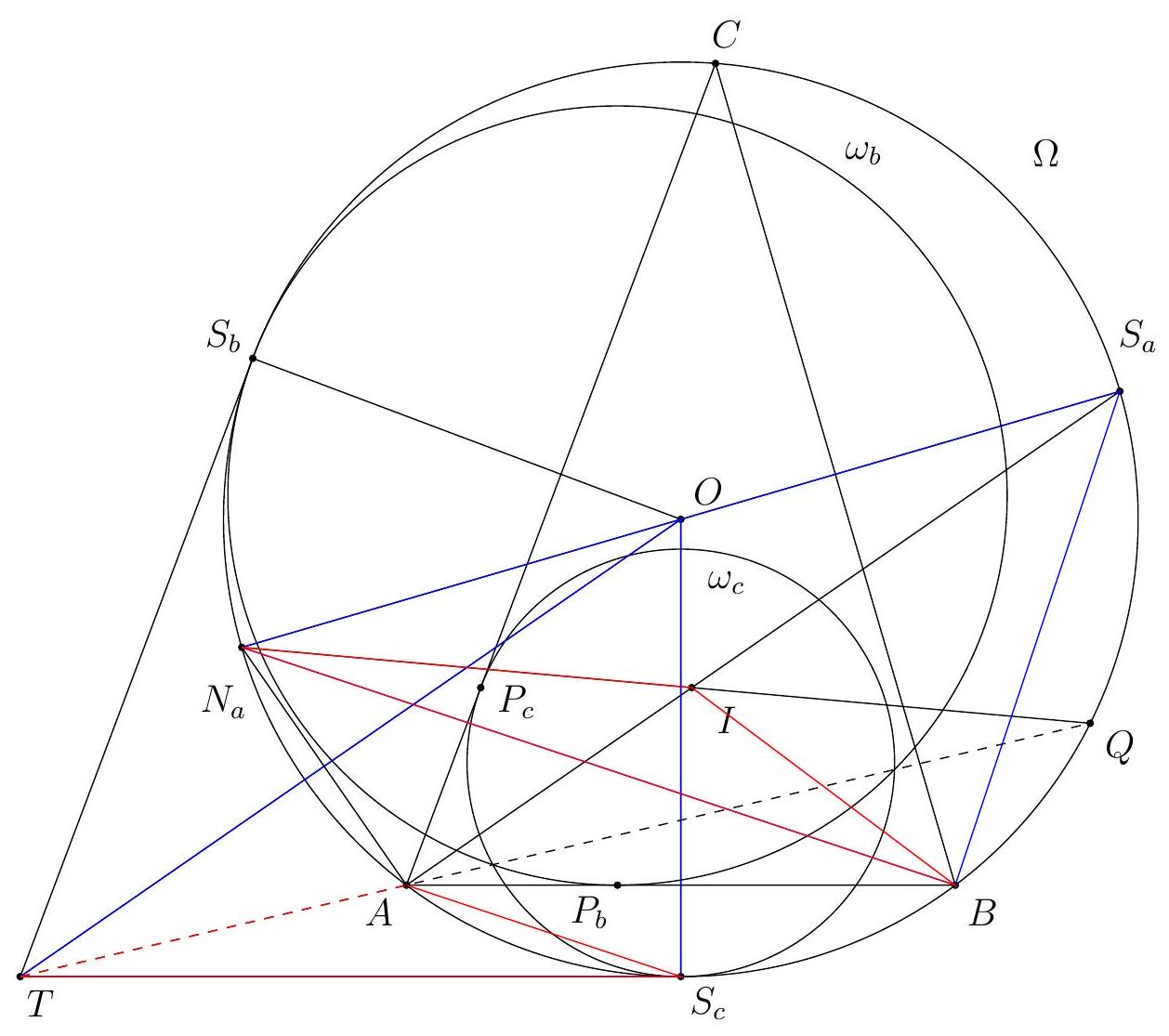

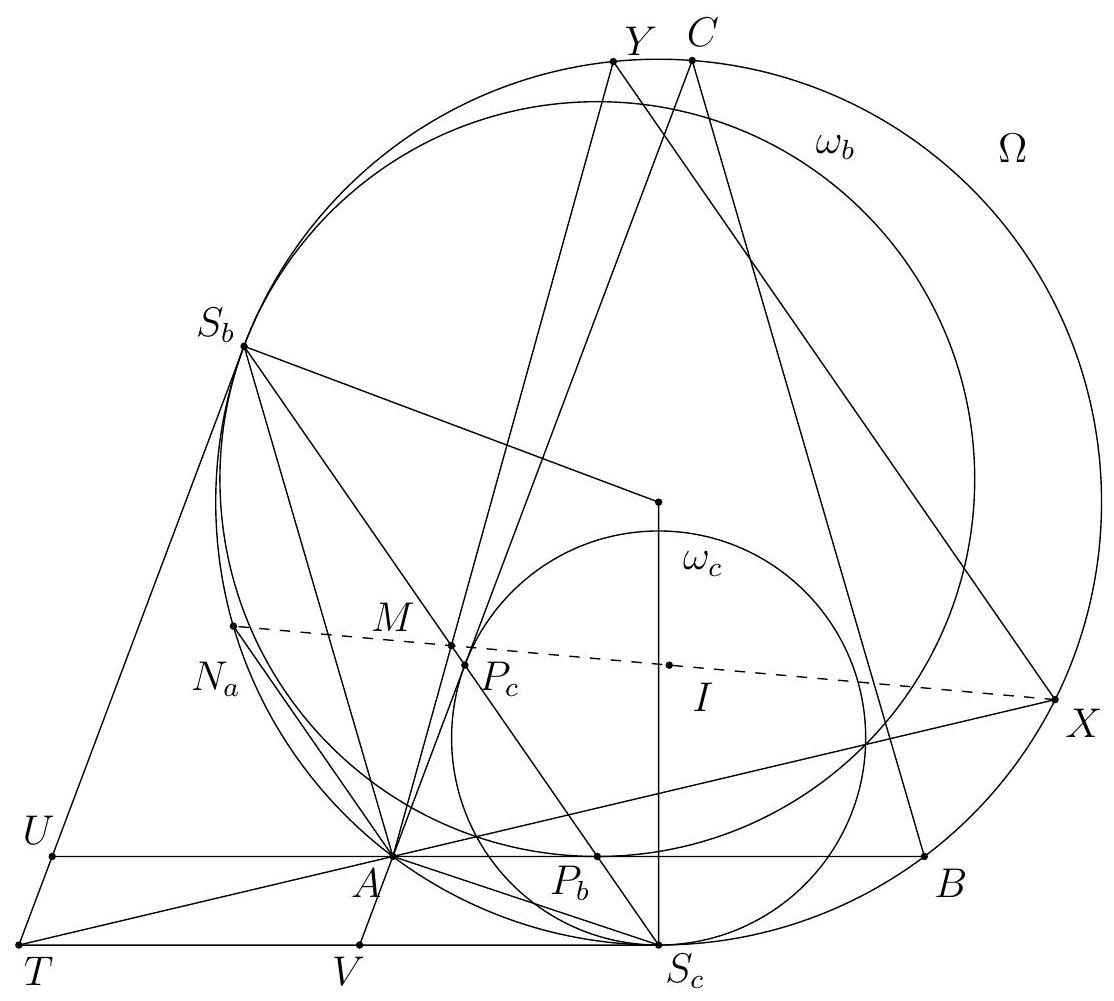

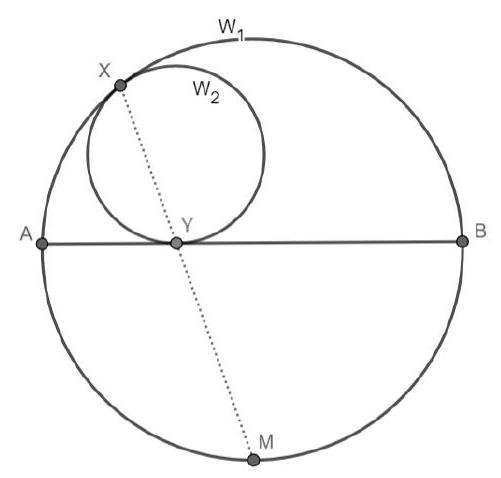

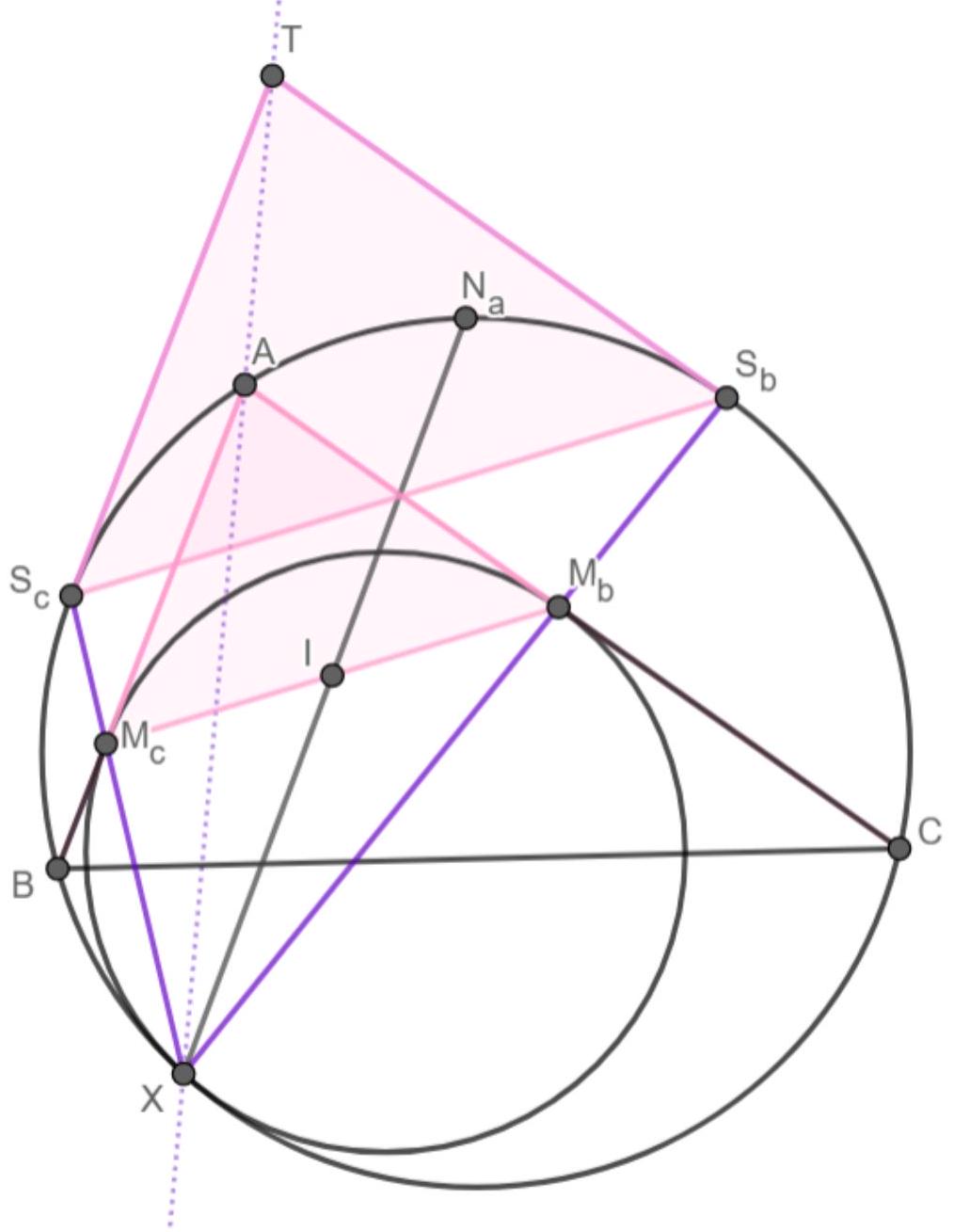

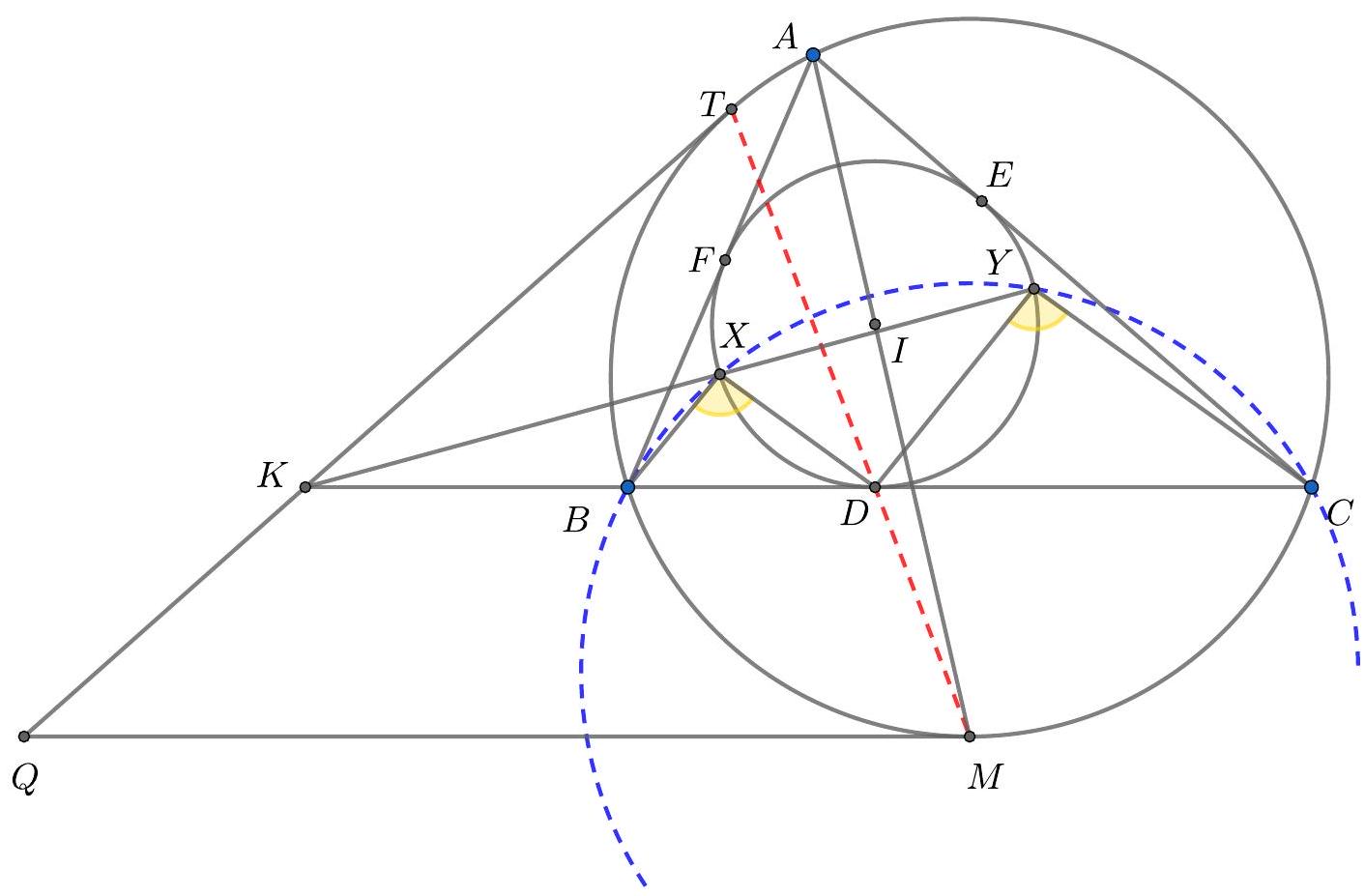

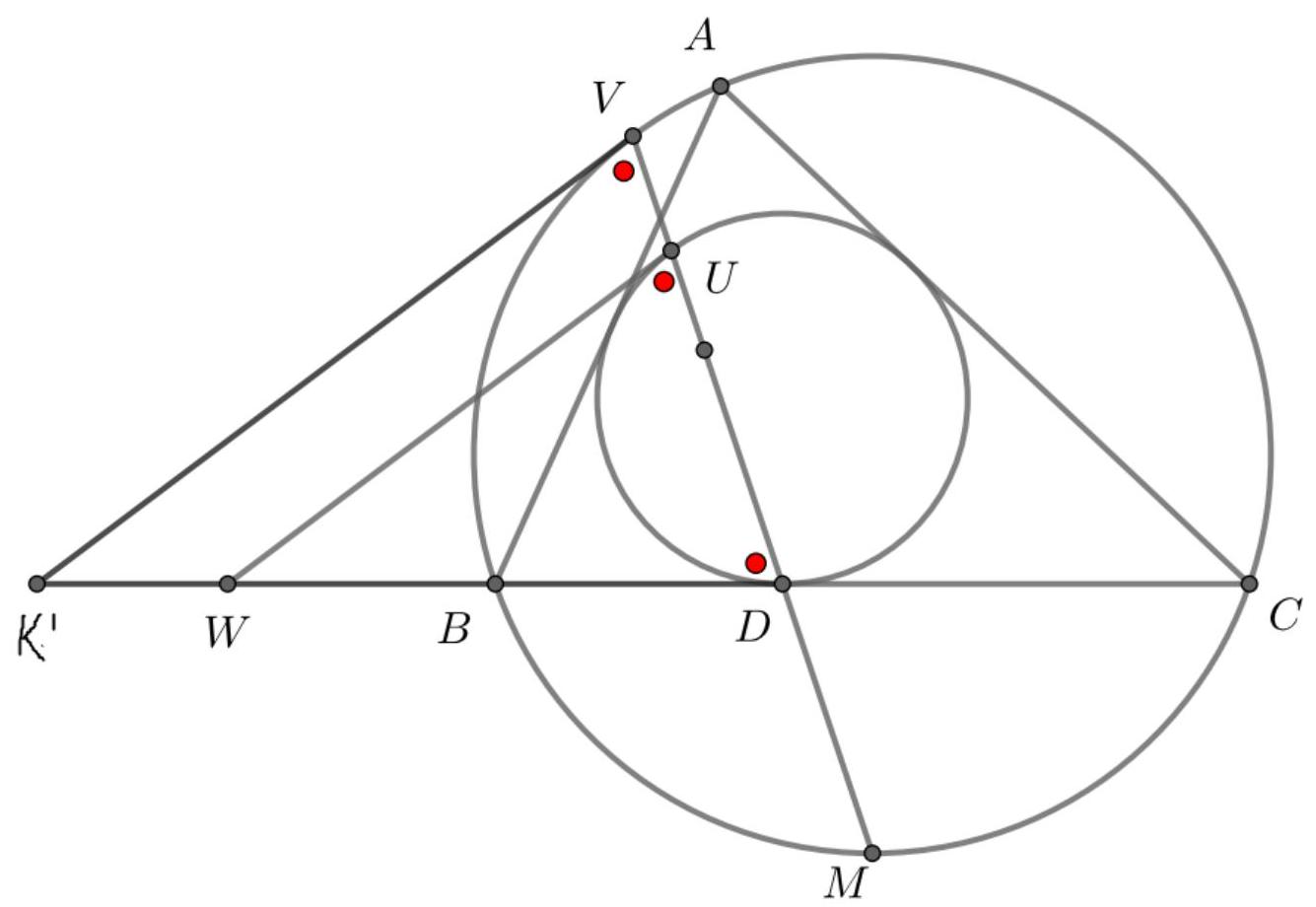

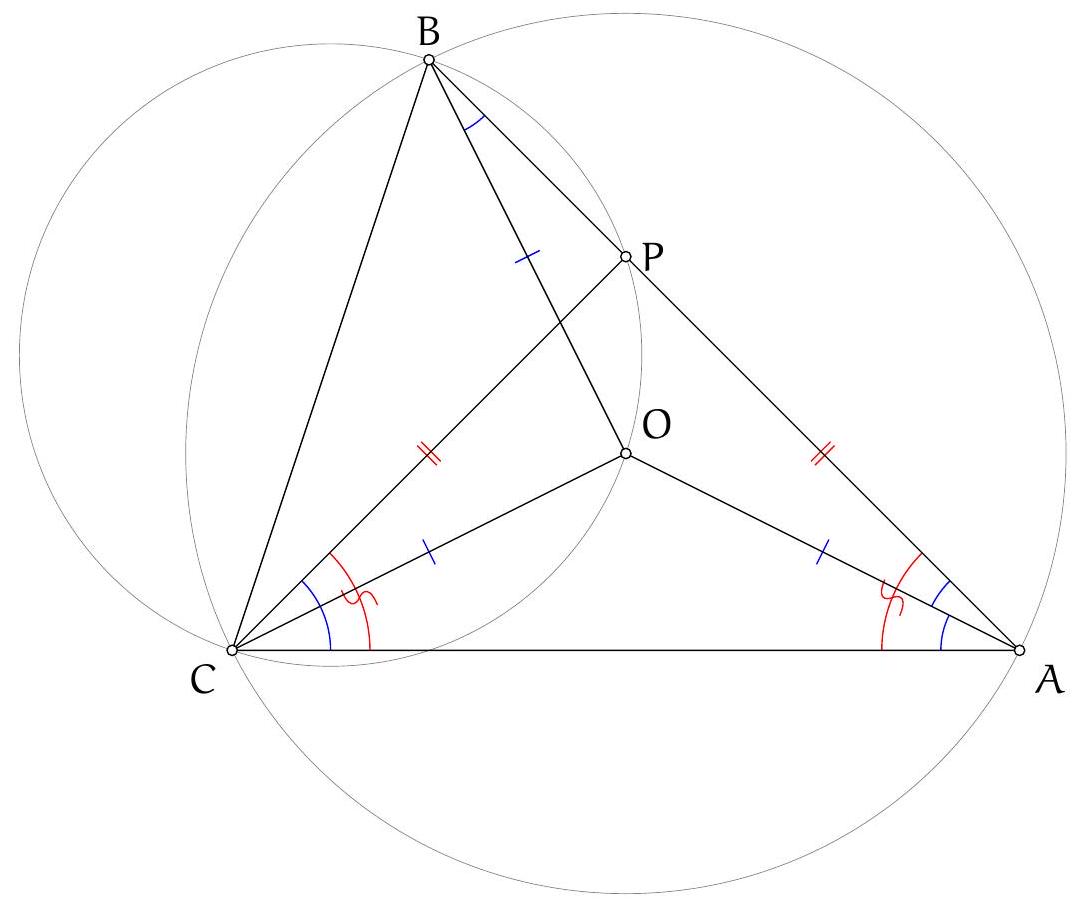

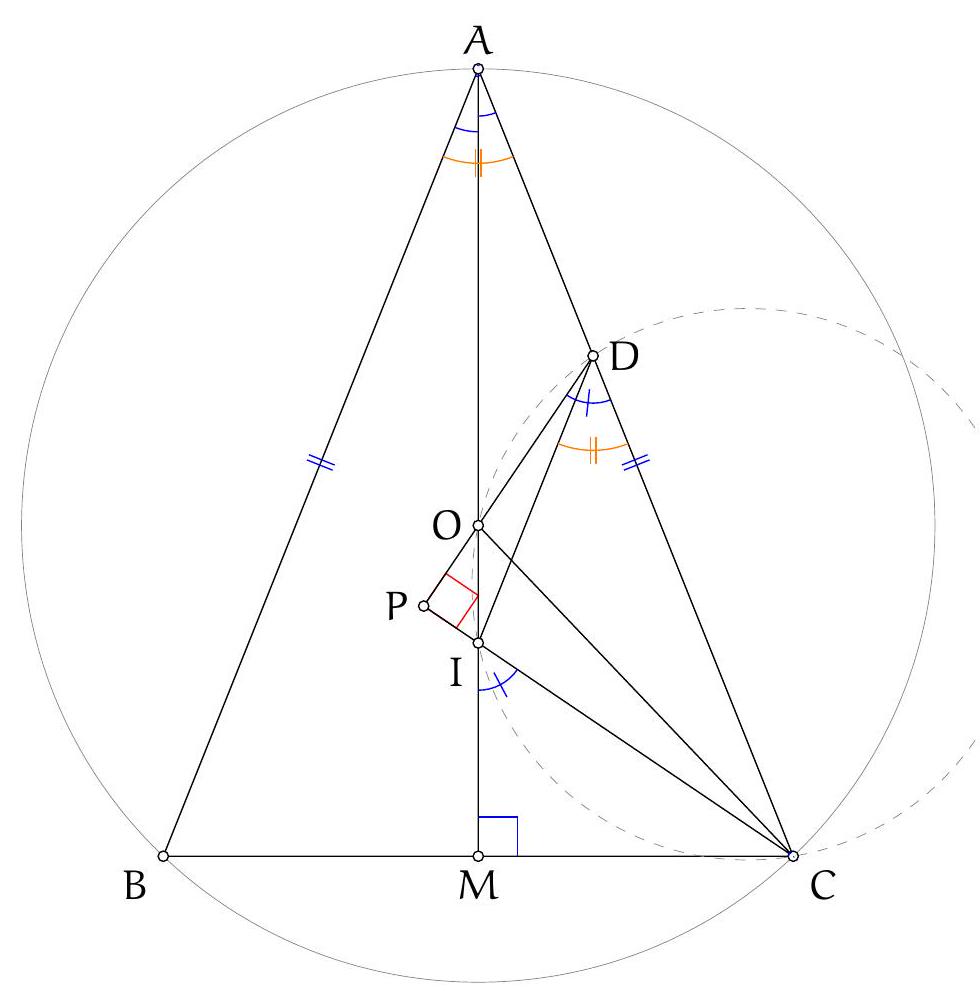

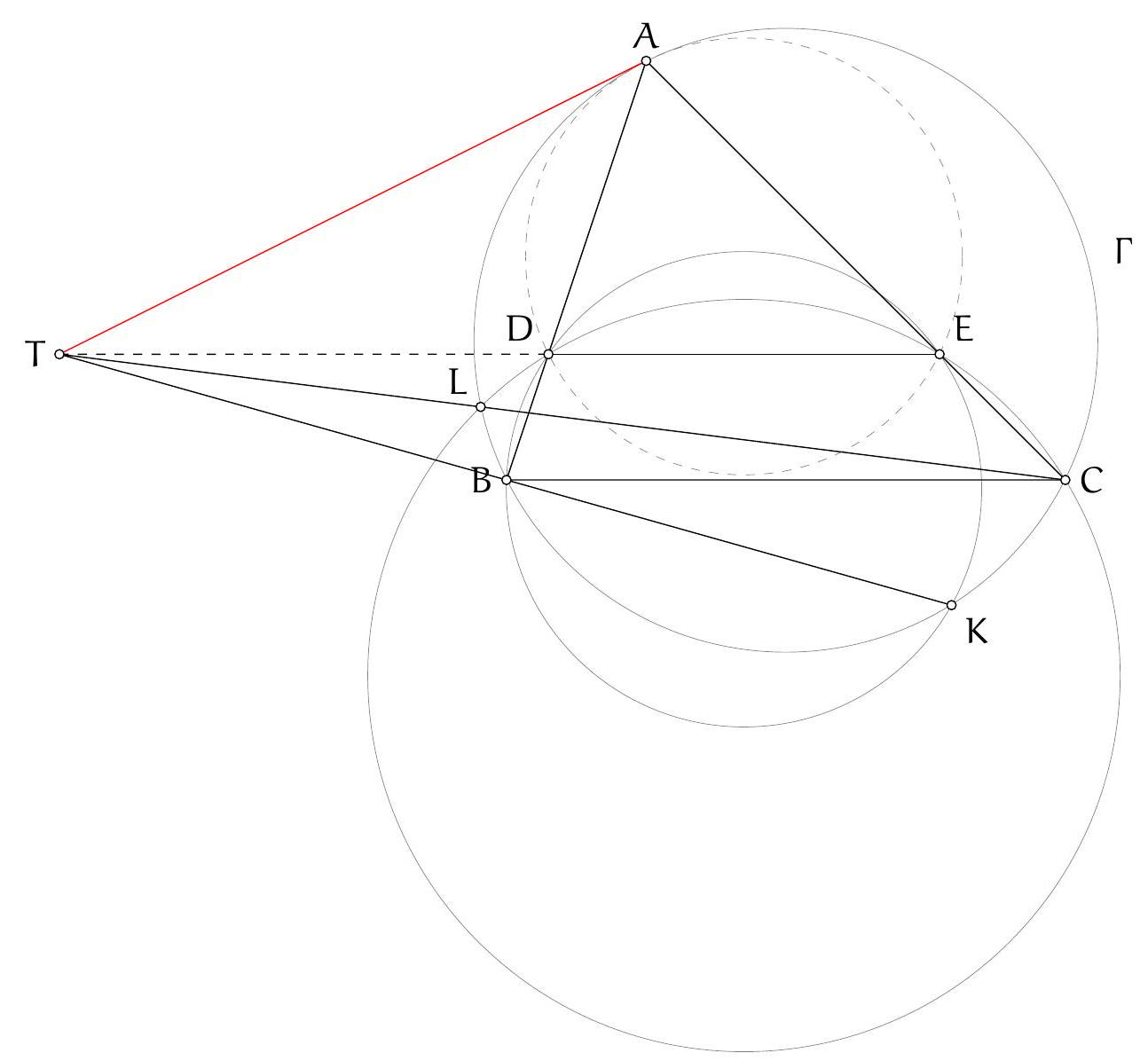

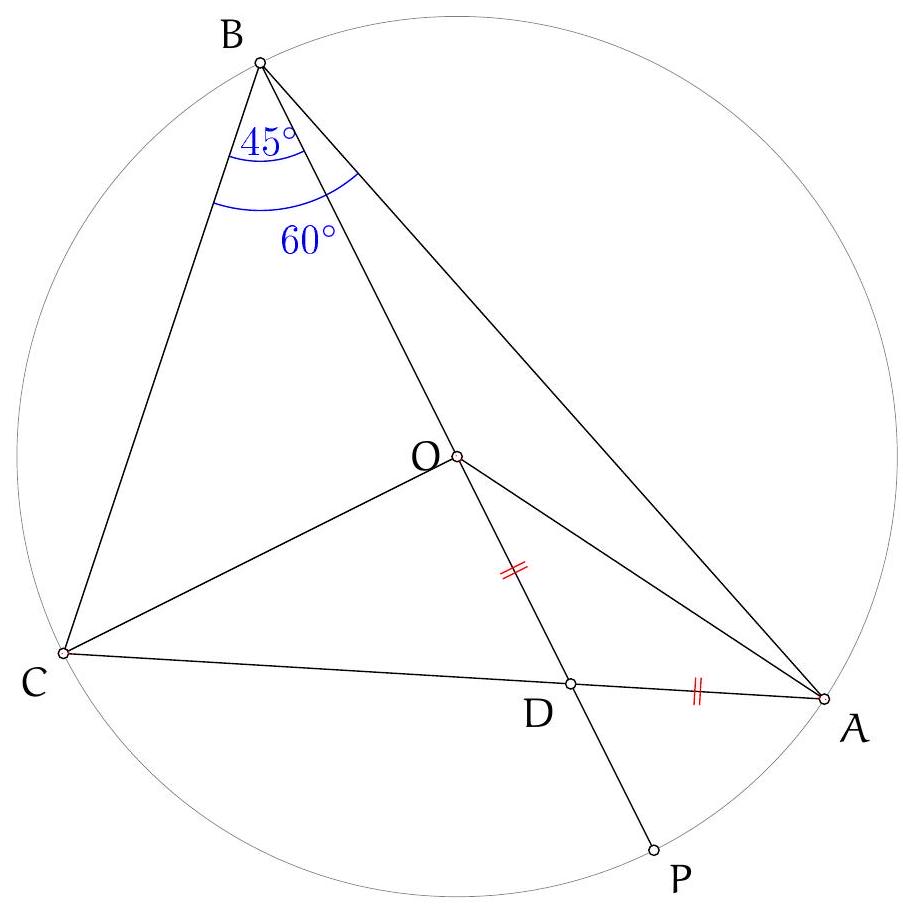

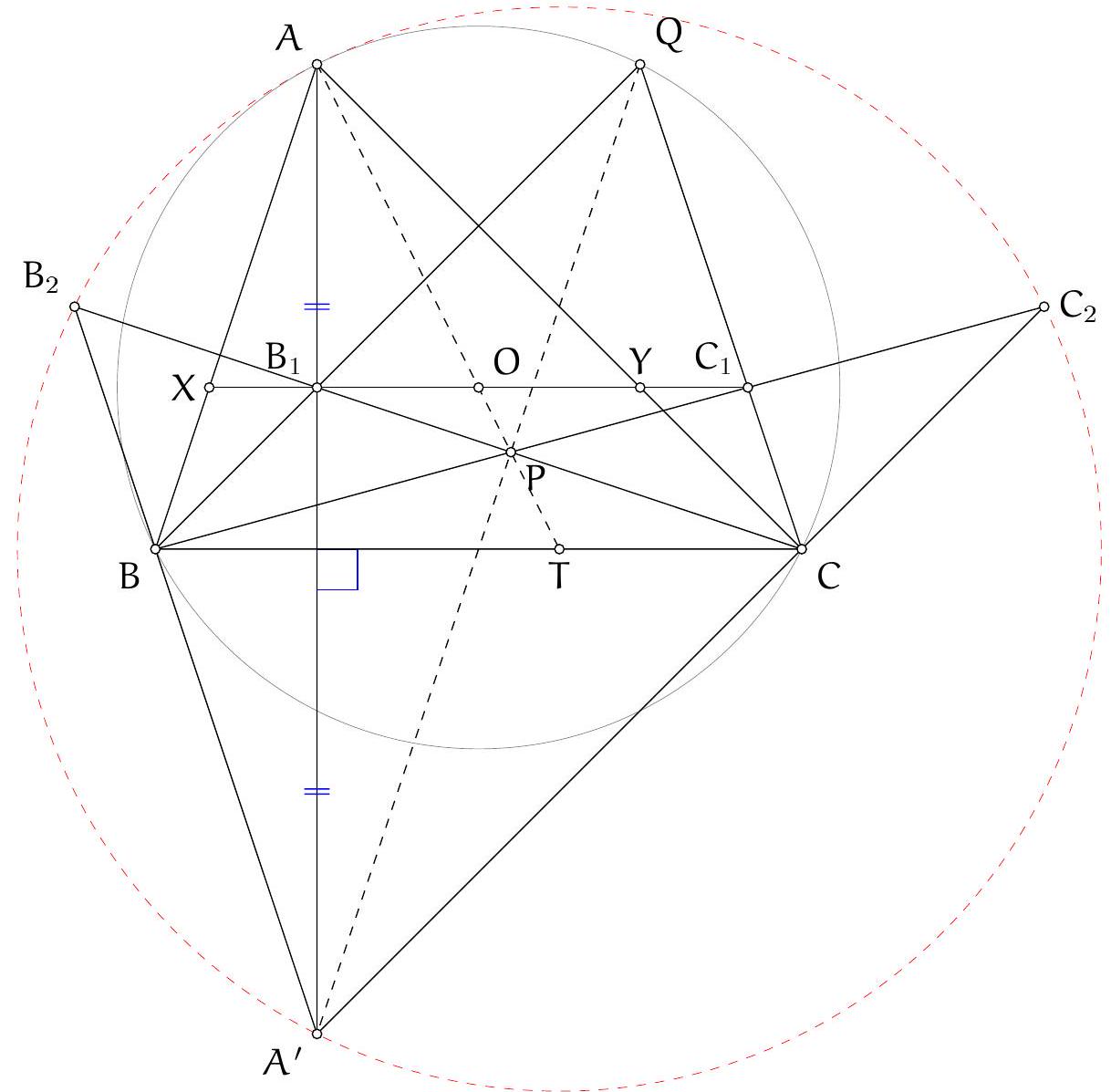

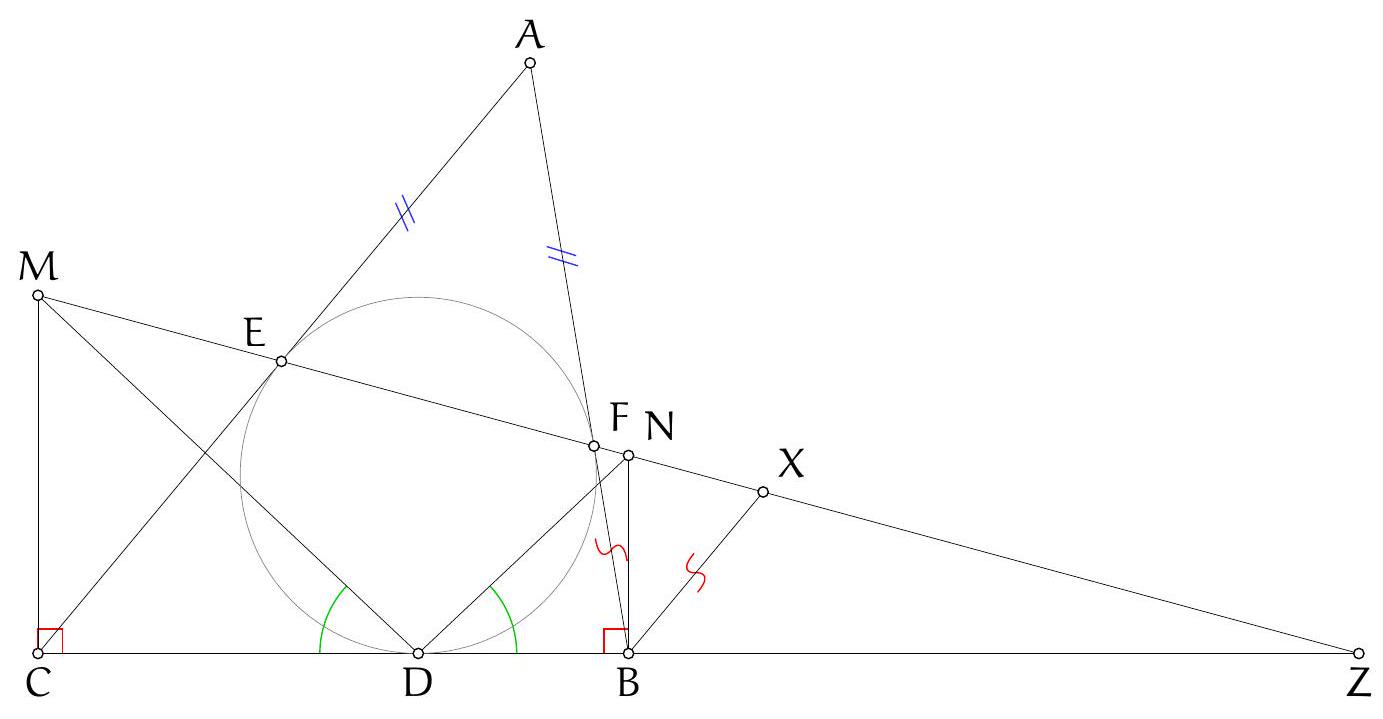

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumcircle $\Gamma$. Let $X$ be a point in the plane. The Simson line (Wallace-Simson line) is defined via the following theorem. Drop perpendiculars from $X$ to each of the three side lines of $A B C$. The feet of these perpendiculars are collinear (on

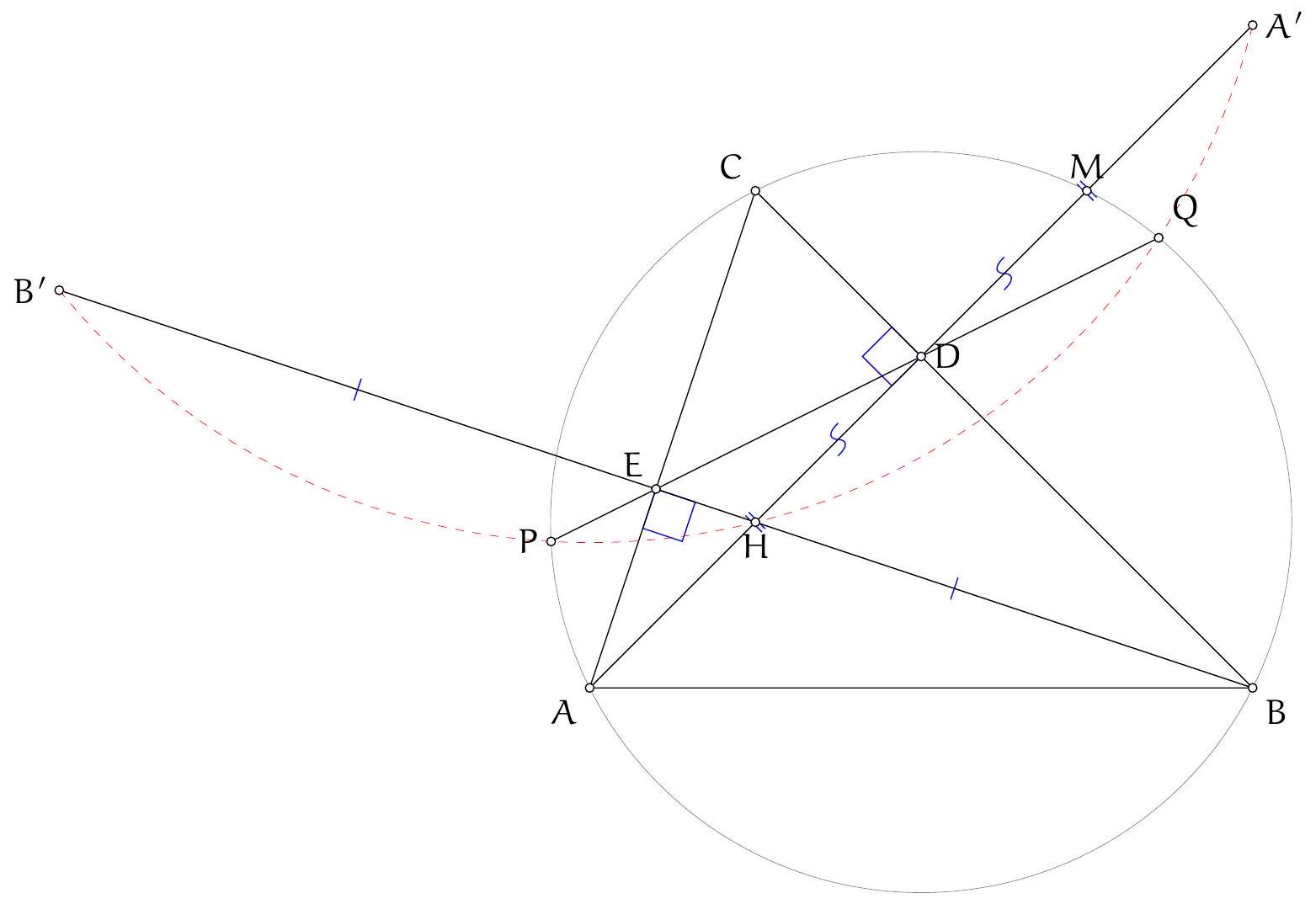

the Simson line of $X$ ) if and only if $X$ lies of $\Gamma$. The Simson line of $X$ in the circumcircle bisects the line segment $X H$ where $H$ is the orthocentre of triangle $A B C$. See Figure 2

Figure 2: The Wallace-Simson configuration

When $X$ is on $\Gamma$, we can enlarge from $X$ with scale factor 2 (a homothety) to take the Simson line to the doubled Simson line which passes through the orthocentre $H$ and contains the reflections of $X$ in each of the three sides of $A B C$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Preliminaries

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumcircle $\Gamma$. Let $X$ be a point in the plane. The Simson line (Wallace-Simson line) is defined via the following theorem. Drop perpendiculars from $X$ to each of the three side lines of $A B C$. The feet of these perpendiculars are collinear (on

the Simson line of $X$ ) if and only if $X$ lies of $\Gamma$. The Simson line of $X$ in the circumcircle bisects the line segment $X H$ where $H$ is the orthocentre of triangle $A B C$. See Figure 2

Figure 2: The Wallace-Simson configuration

When $X$ is on $\Gamma$, we can enlarge from $X$ with scale factor 2 (a homothety) to take the Simson line to the doubled Simson line which passes through the orthocentre $H$ and contains the reflections of $X$ in each of the three sides of $A B C$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

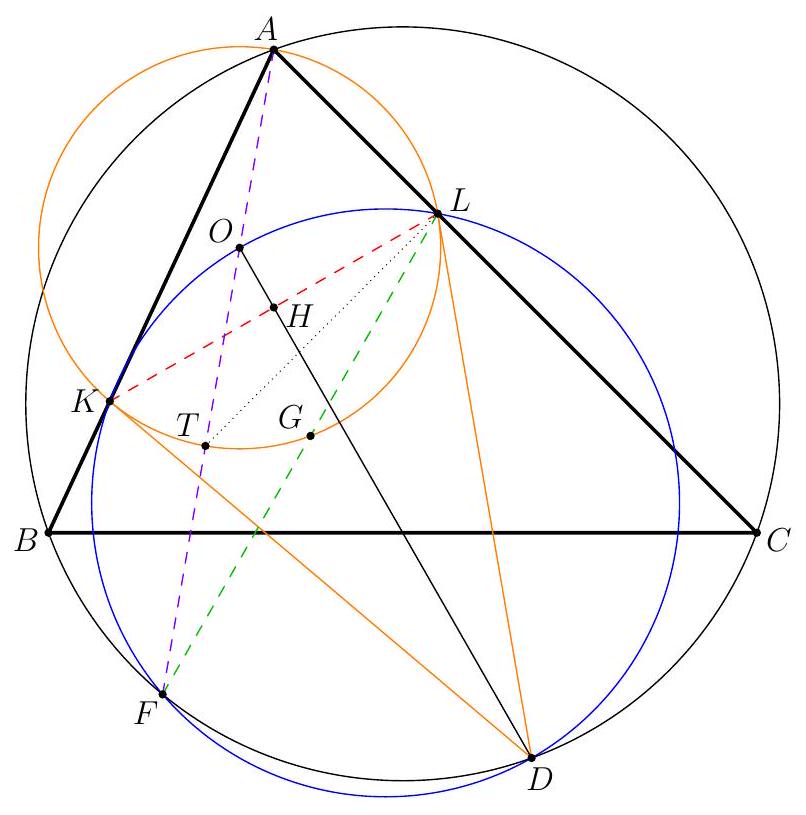

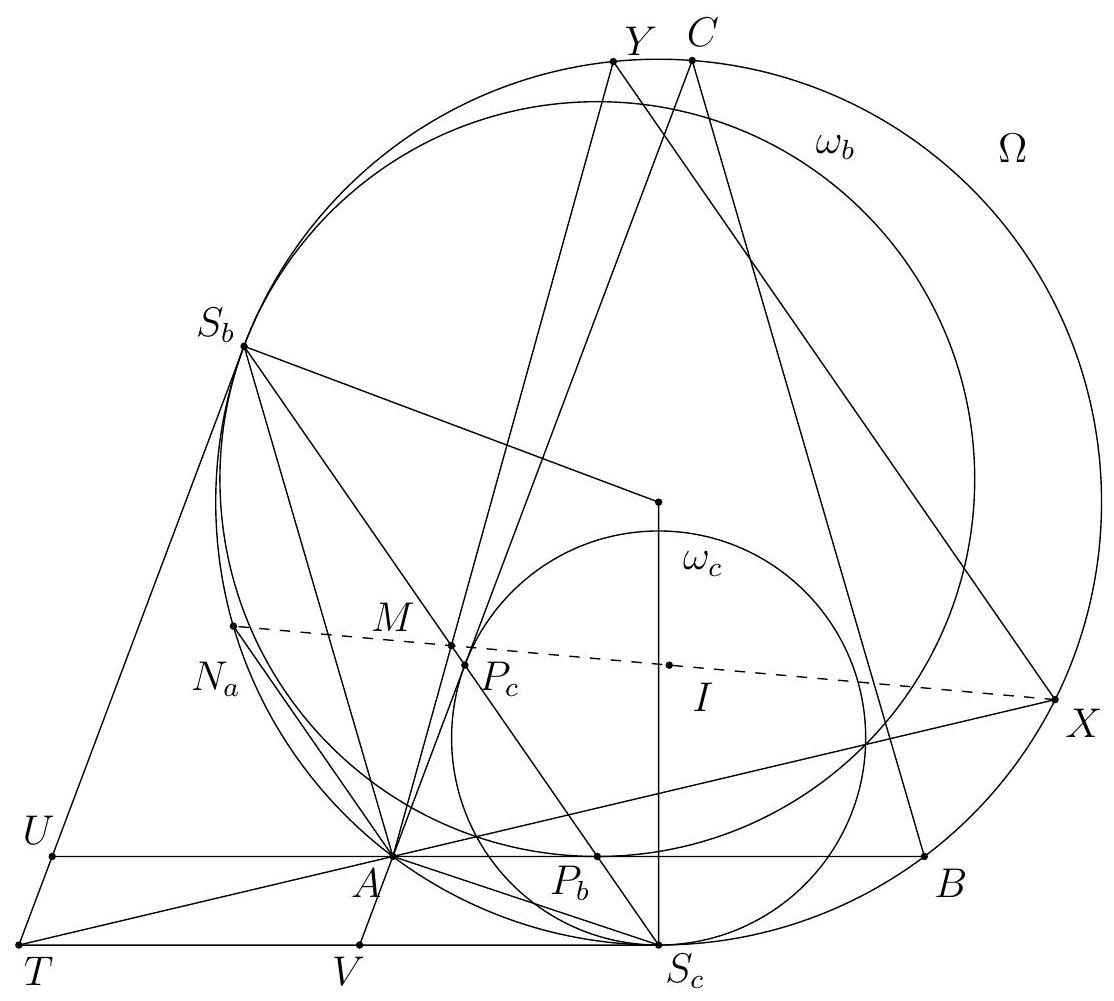

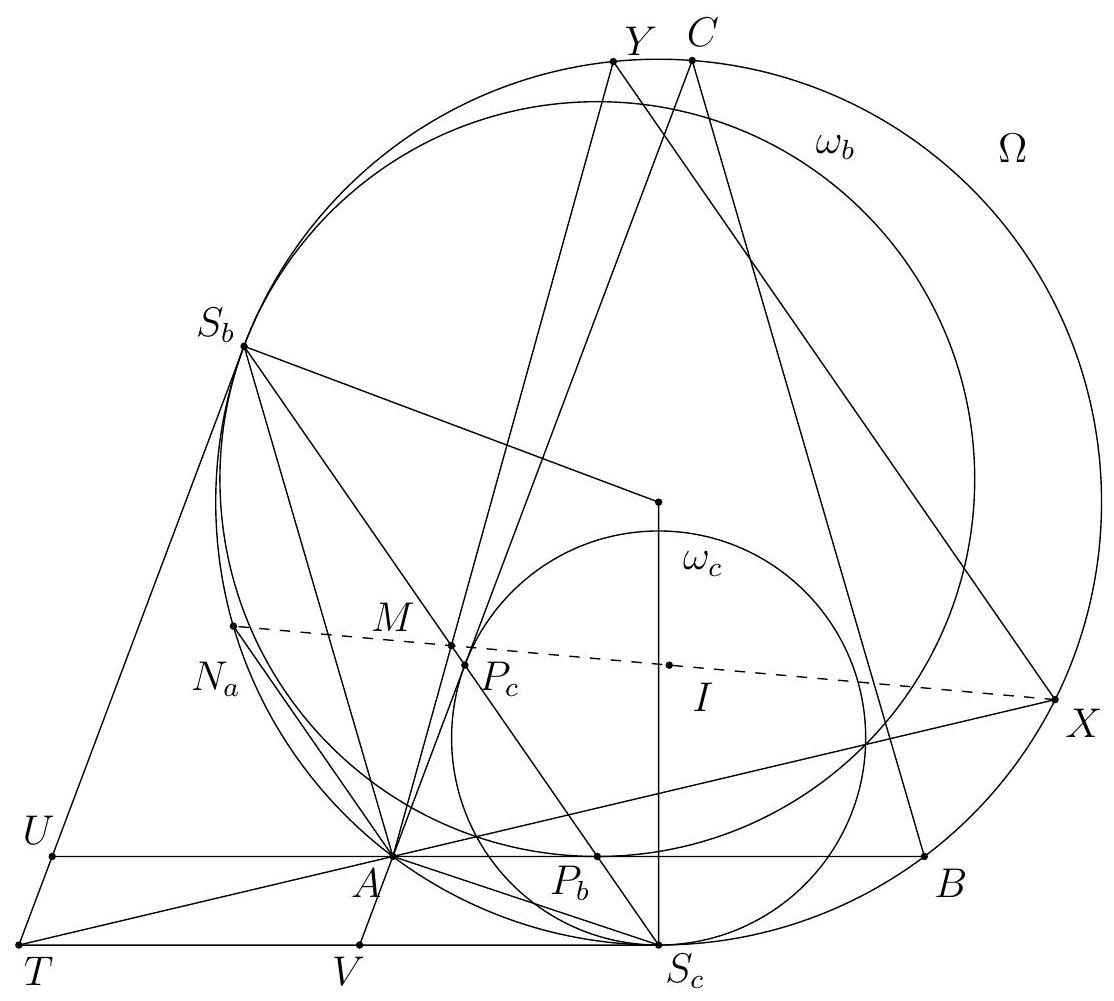

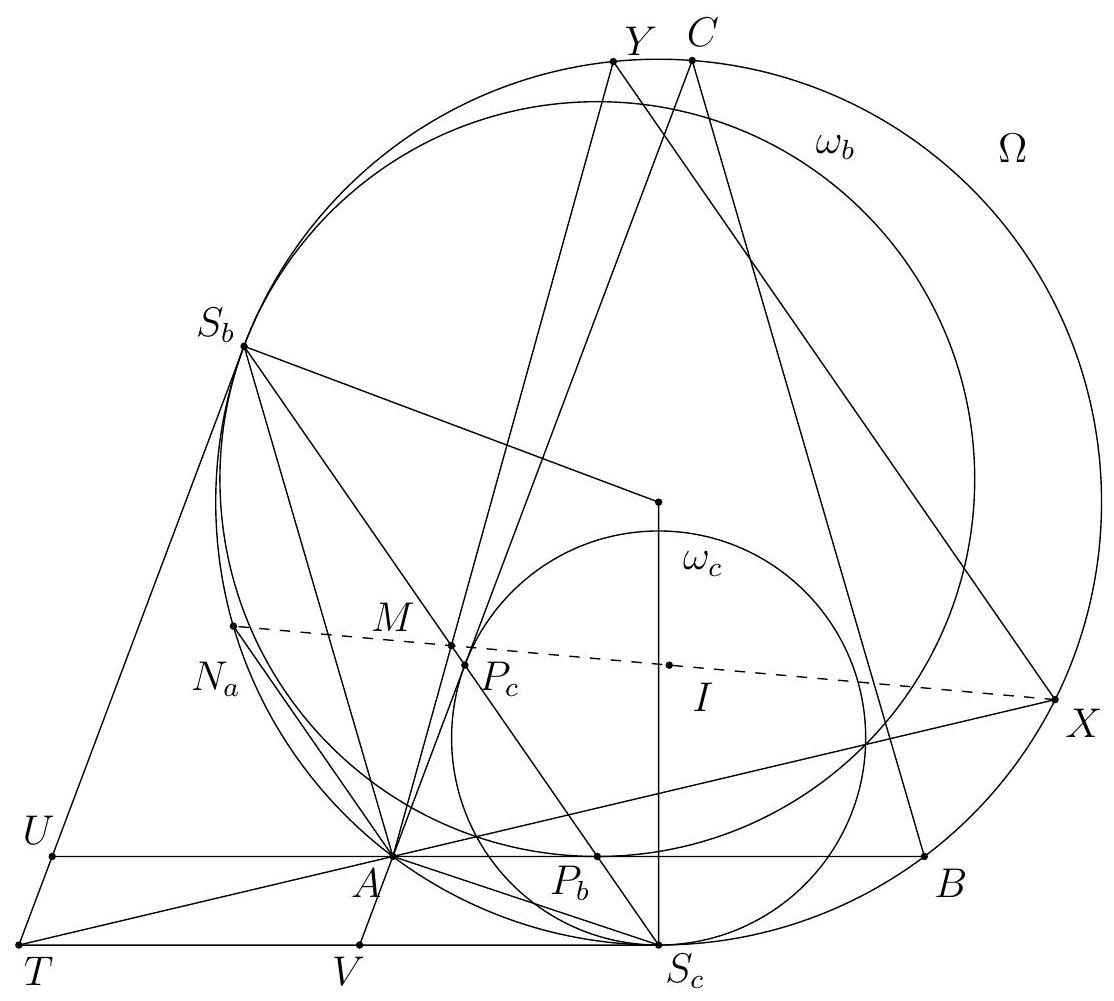

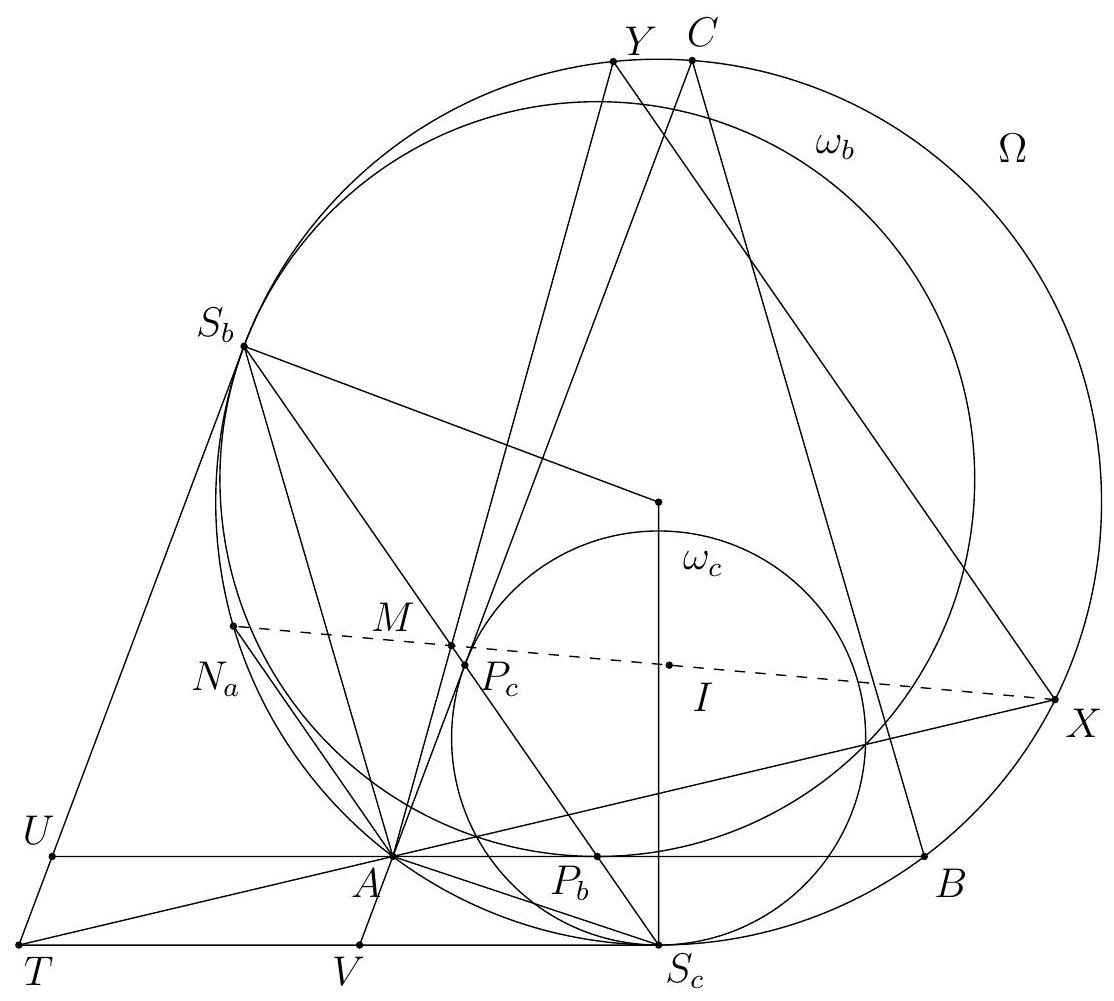

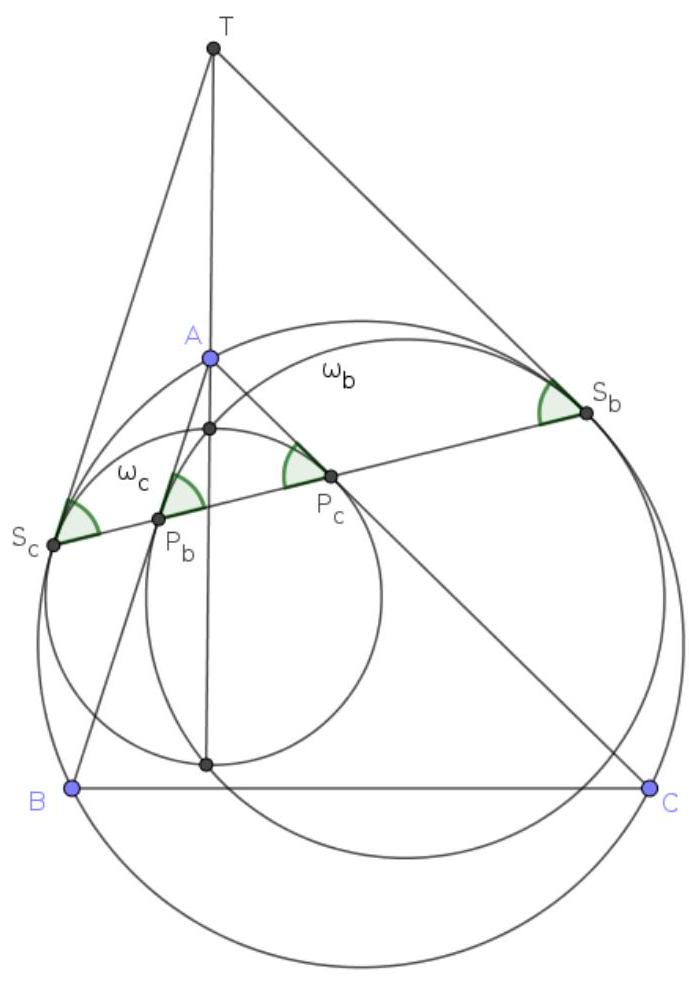

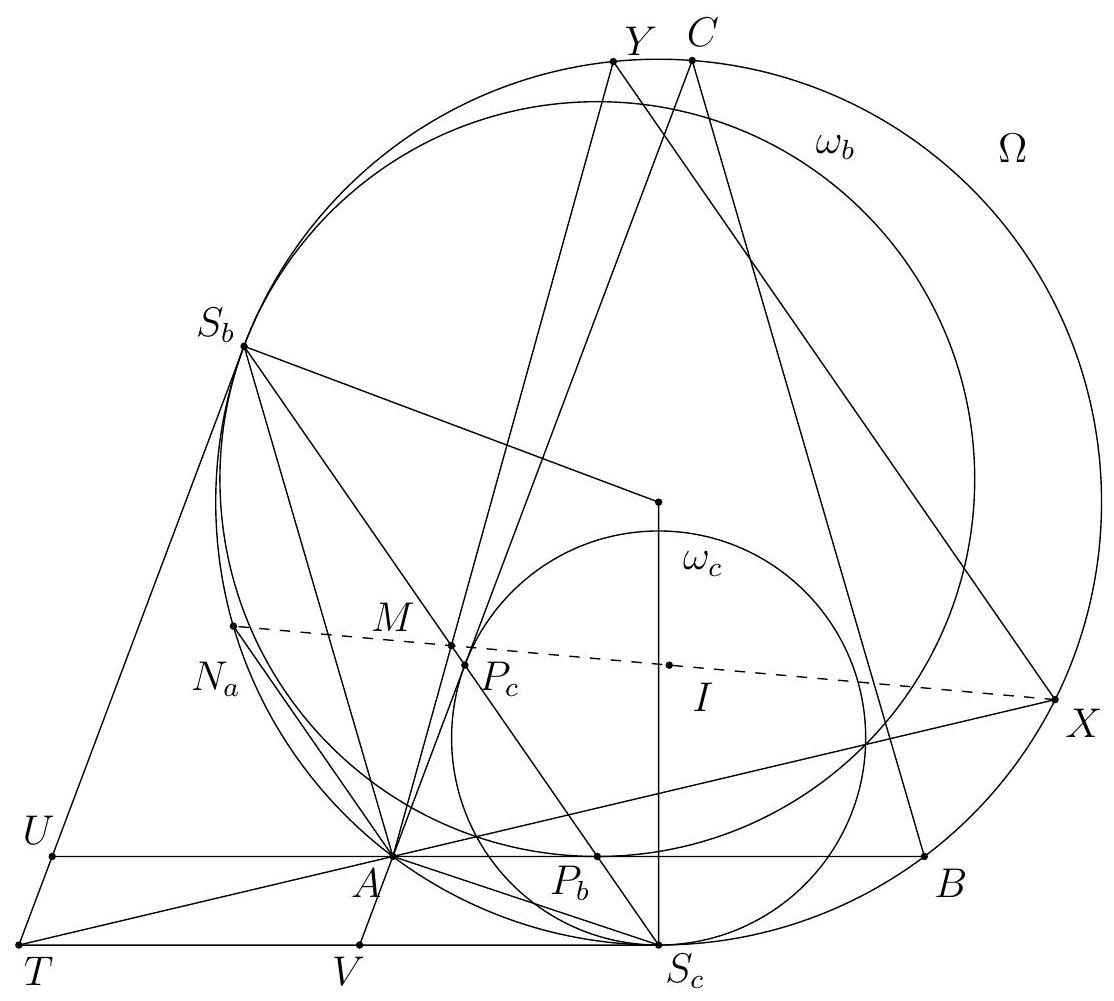

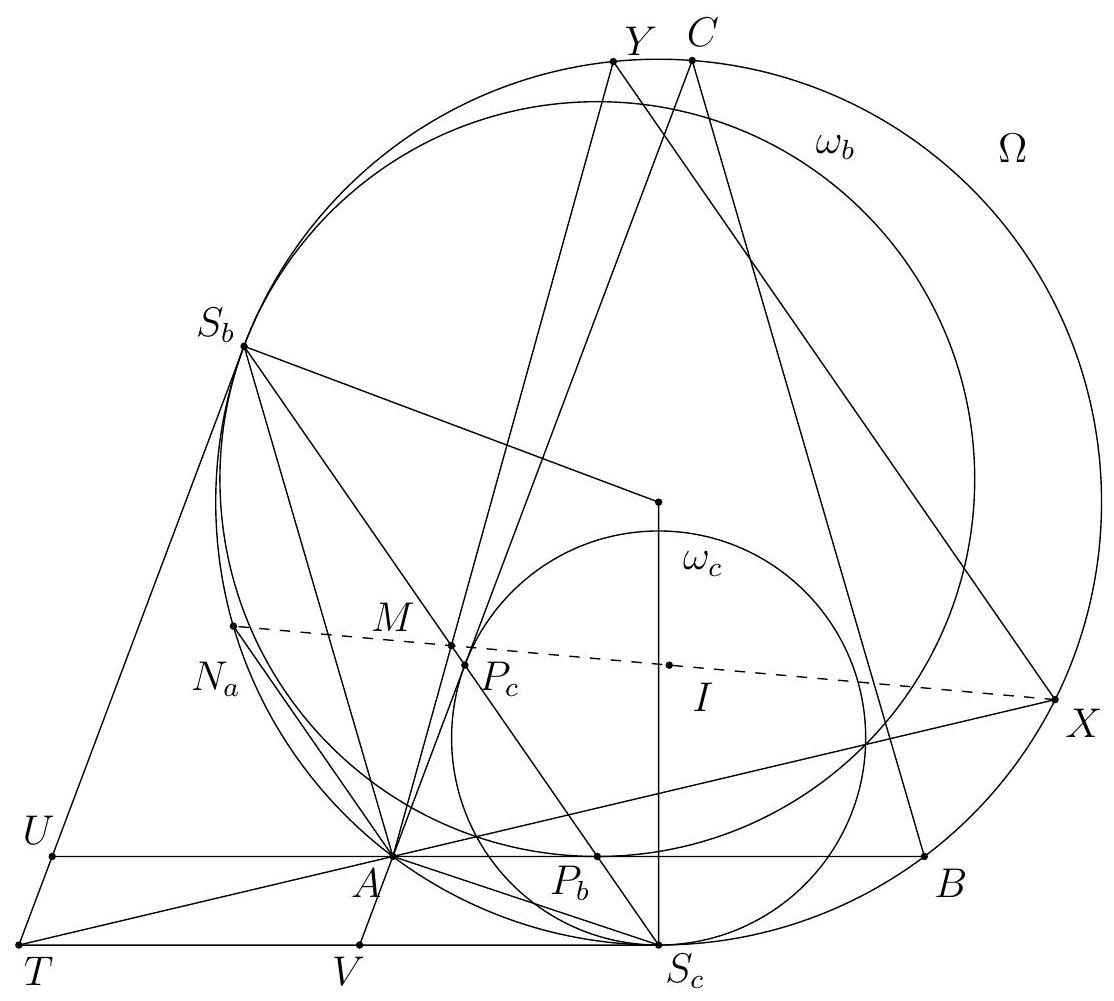

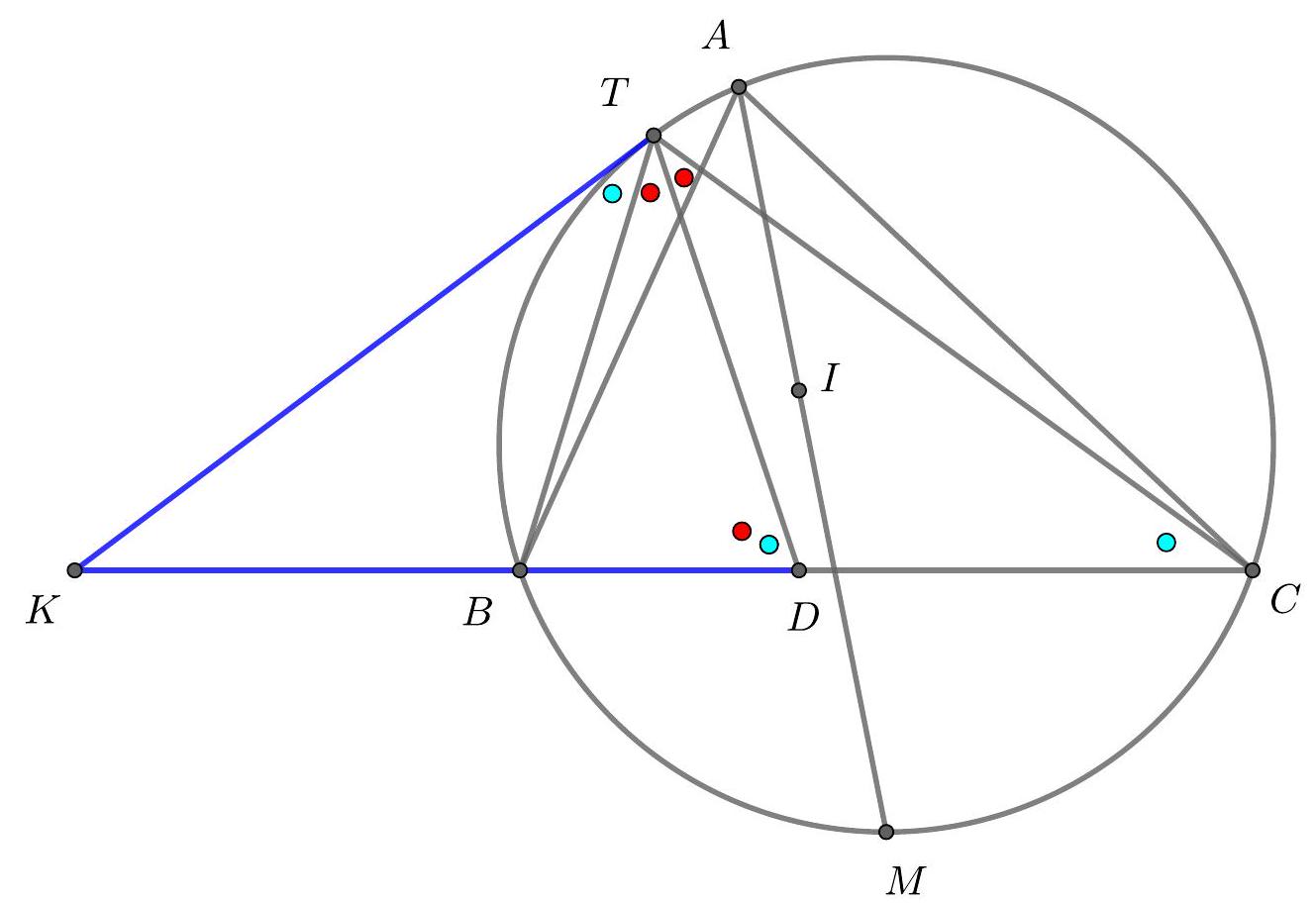

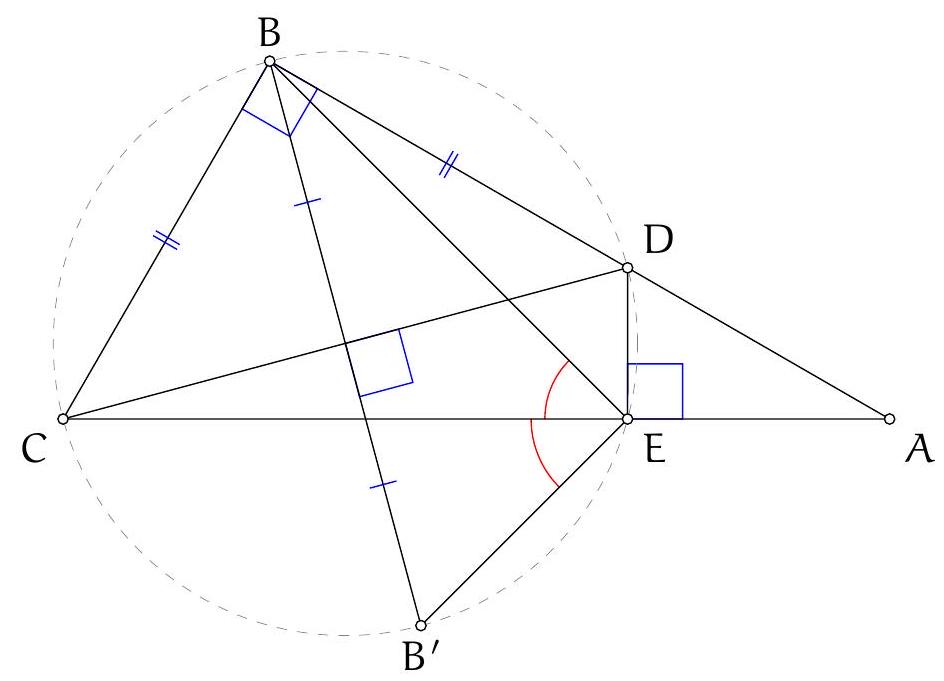

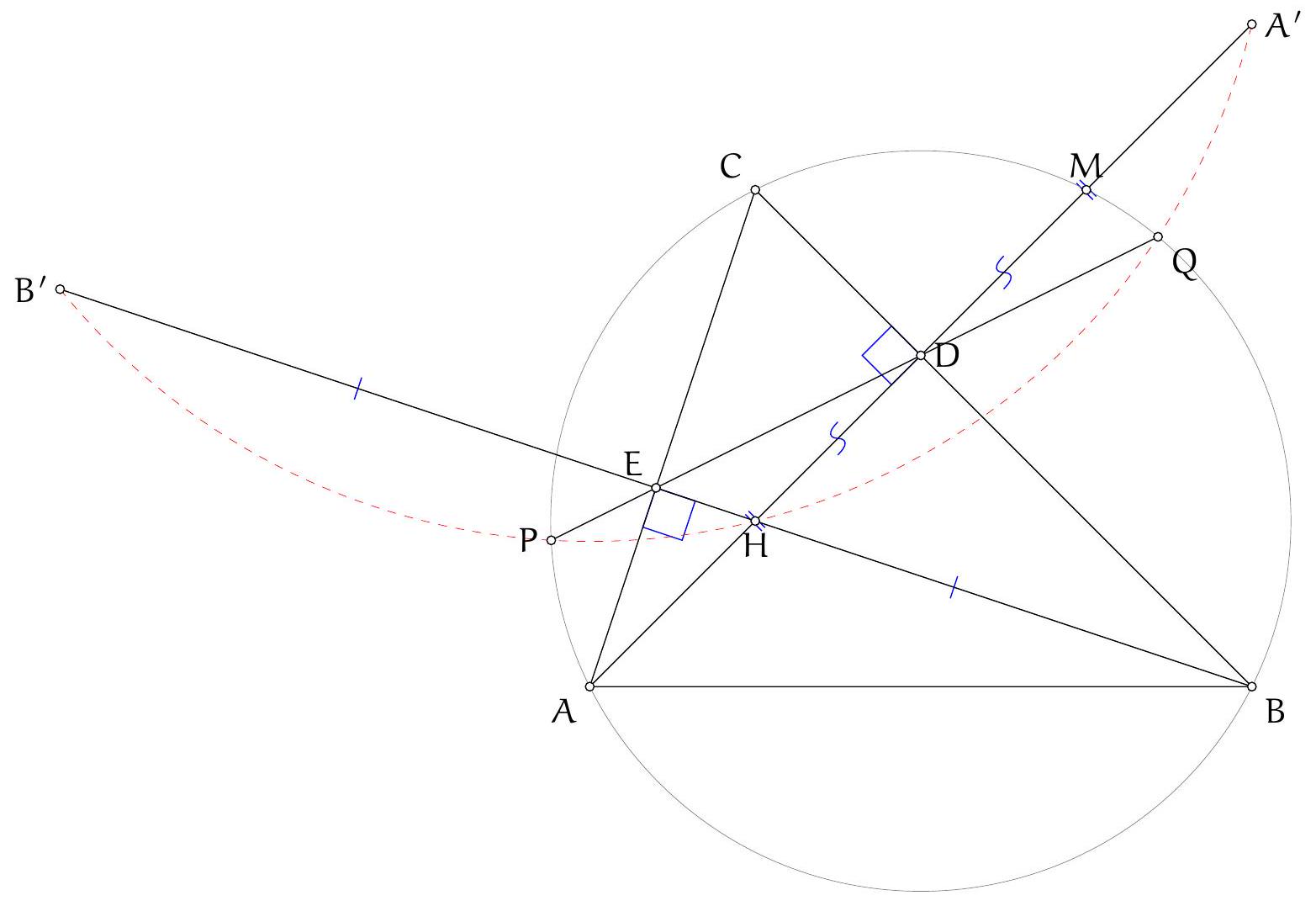

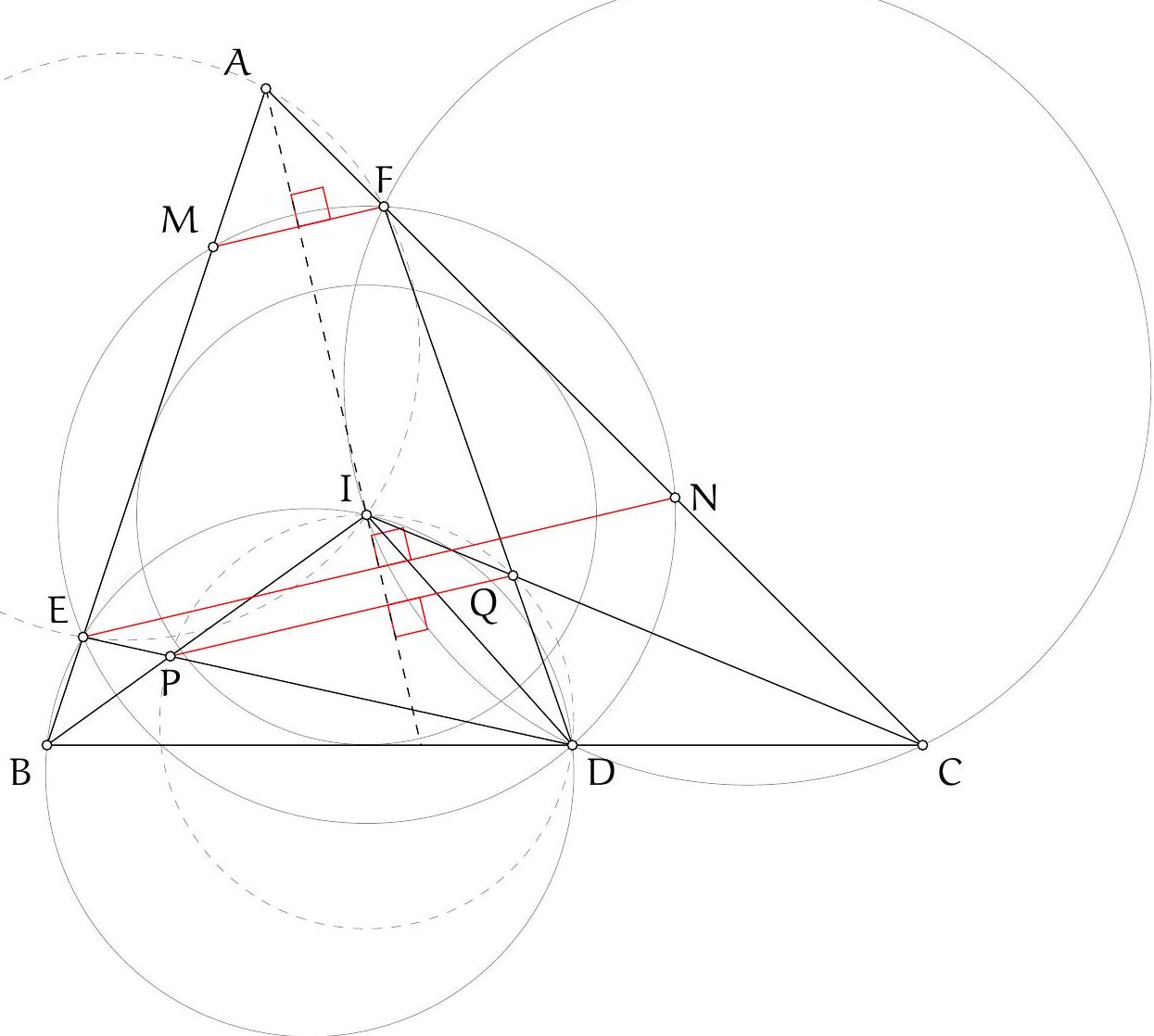

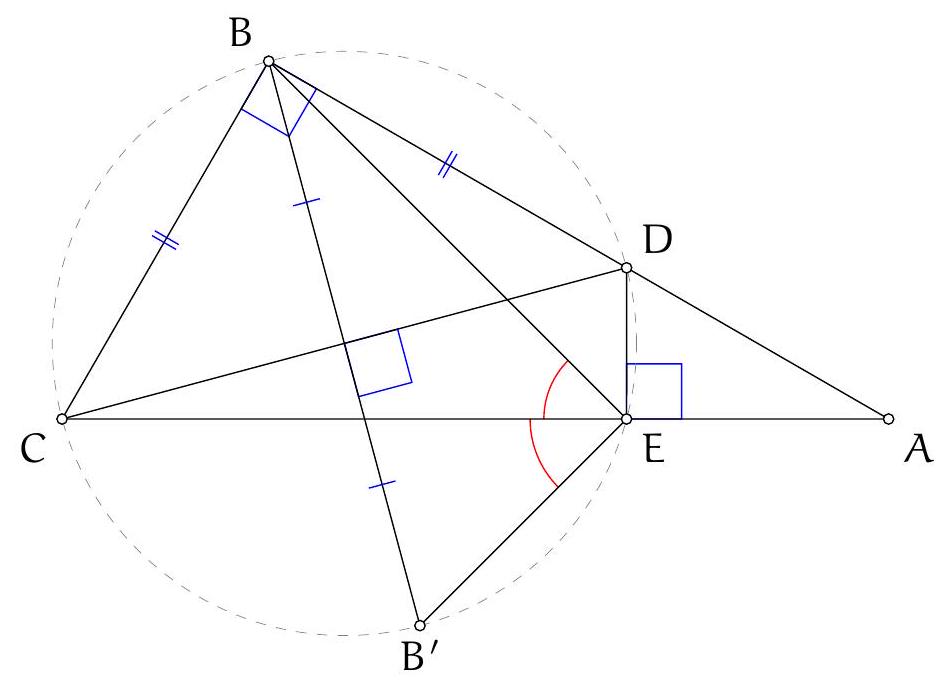

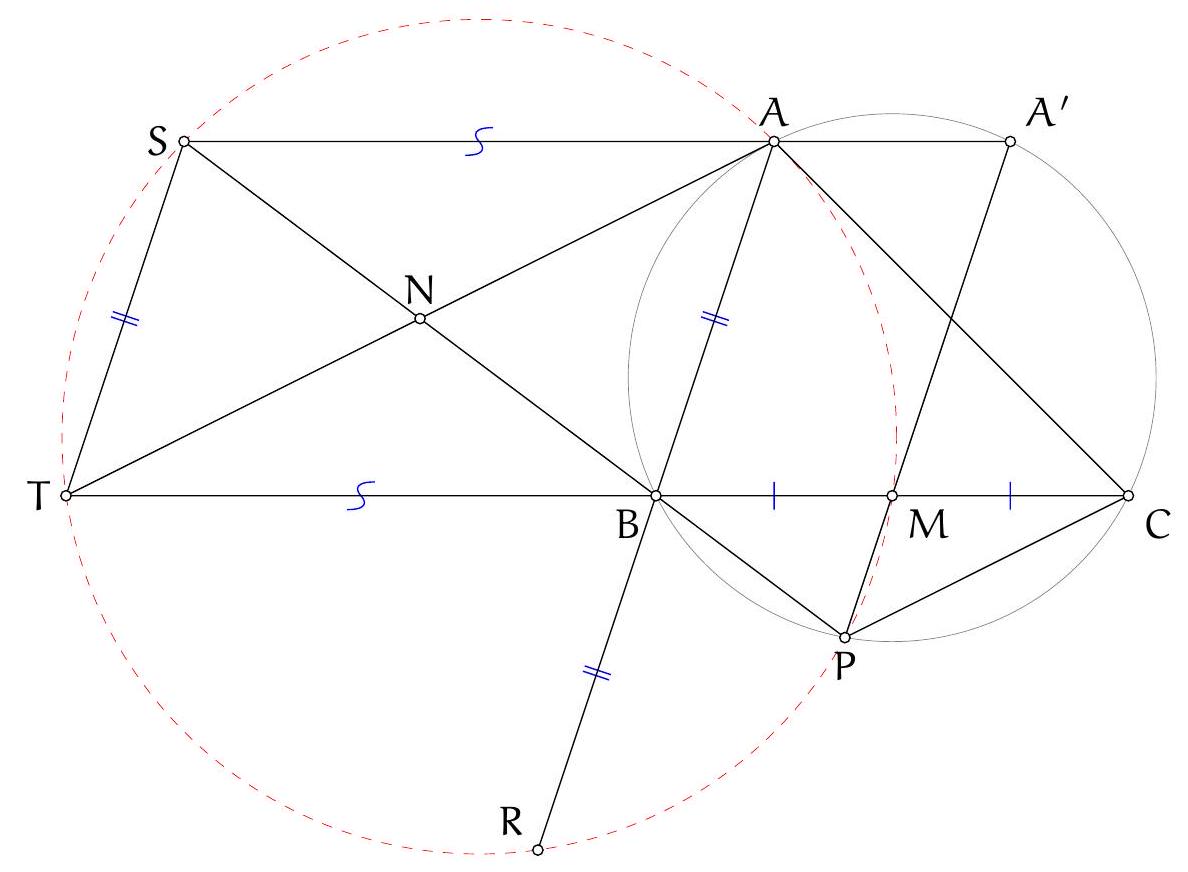

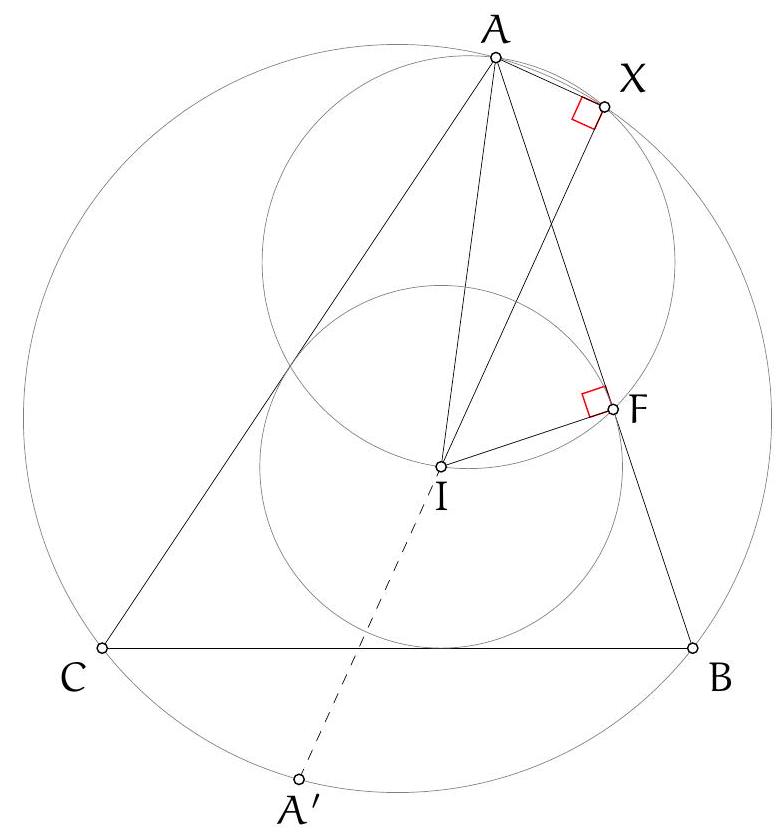

of the problem

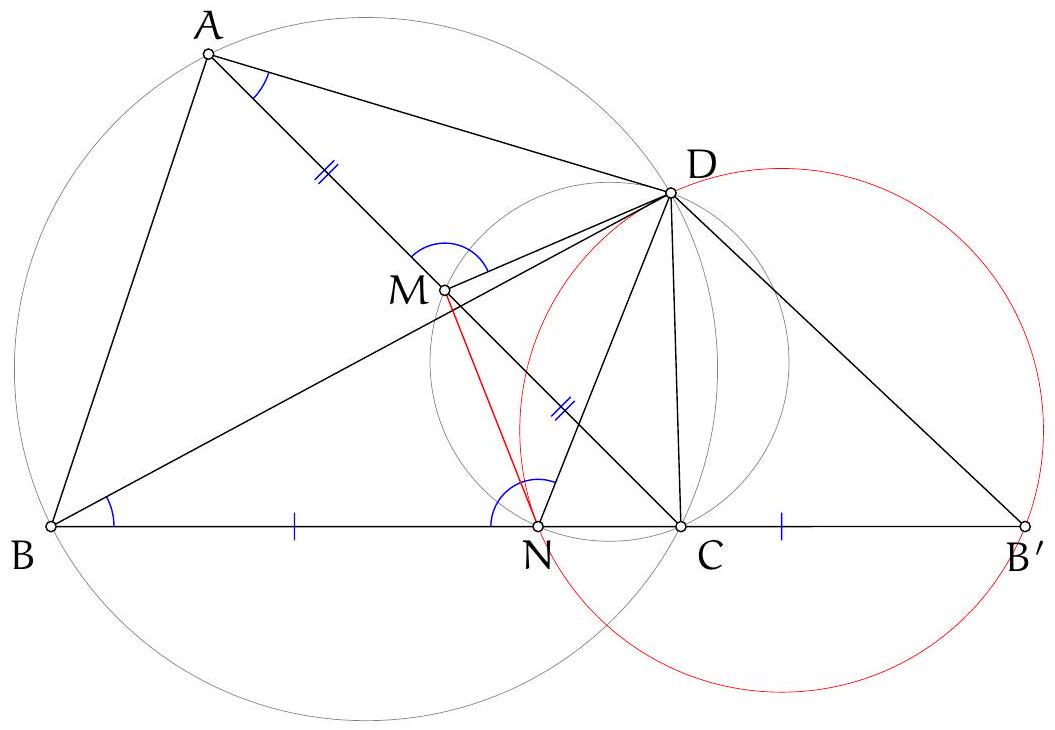

Figure 3: Three circles do the work

Let $\Gamma$ be the circle $A B C, \Sigma$ be the circle $A K L$ with centre $O$, and $\Omega$ be the circle on diameter $O D$ so $K$ and $L$ are on this circle by converse of Thales. Let $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ meet at $D$ and $F$. By Thales in both circles, $\angle A F D$ and $\angle O F D$ are both right angles so $A O F$ is a line. Let $A F$ meet $\Sigma$ again at $T$ so $A T$ (containing $O$ ) is a diameter of this circle and by Thales, $T L \perp A C$.

Let $G$ (on $\Sigma$ ) be the reflection of $K$ in $A F$. Now $A T$ is the internal angle bisector of $\angle G A K$ so, by an upmarket use of angles in the same segment (of $\Sigma$ ), $T L$ is the internal

angle bisector of $\angle G L K$. Thus the line $G L$ is the reflection of the line $K L$ in $T L$, and so also the reflection of $K L$ in the line $A C$ (internal and external angle bisectors).

Our next project is to show that $L G F$ are collinear. Well $\angle F L K=\angle F O K$ (angles in the same segment of $\Omega$ ) and $\angle G L K=\angle G A K$ (angles in the same segment of $\Sigma$ ) $=2 \angle O A K$ ( $A K G$ is isosceles with apex $A)=\angle T O K$ (since $O A K$ is isosceles with apex $O$, and this is an external angle at $O$ ). The point $T$ lies in the interior of the line segment $F O$ so $\angle T O K=\angle F O K$. Therefore $\angle F L K=\angle G L K$ so $L G F$ is a line.

Now from the second paragraph, $F$ is on the reflection of $K L$ in $A C$. By symmetry, $F$ is also on the reflection of $K L$ in $A B$. Therefore the reflections of $F$ in $A B$ and $A C$ are both on $K L$ which must therefore be the doubled Wallace-Simson line of $F$. Therefore the orthocentre of $A B C$ lies on $K L$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

of the problem

Figure 3: Three circles do the work

Let $\Gamma$ be the circle $A B C, \Sigma$ be the circle $A K L$ with centre $O$, and $\Omega$ be the circle on diameter $O D$ so $K$ and $L$ are on this circle by converse of Thales. Let $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ meet at $D$ and $F$. By Thales in both circles, $\angle A F D$ and $\angle O F D$ are both right angles so $A O F$ is a line. Let $A F$ meet $\Sigma$ again at $T$ so $A T$ (containing $O$ ) is a diameter of this circle and by Thales, $T L \perp A C$.

Let $G$ (on $\Sigma$ ) be the reflection of $K$ in $A F$. Now $A T$ is the internal angle bisector of $\angle G A K$ so, by an upmarket use of angles in the same segment (of $\Sigma$ ), $T L$ is the internal

angle bisector of $\angle G L K$. Thus the line $G L$ is the reflection of the line $K L$ in $T L$, and so also the reflection of $K L$ in the line $A C$ (internal and external angle bisectors).

Our next project is to show that $L G F$ are collinear. Well $\angle F L K=\angle F O K$ (angles in the same segment of $\Omega$ ) and $\angle G L K=\angle G A K$ (angles in the same segment of $\Sigma$ ) $=2 \angle O A K$ ( $A K G$ is isosceles with apex $A)=\angle T O K$ (since $O A K$ is isosceles with apex $O$, and this is an external angle at $O$ ). The point $T$ lies in the interior of the line segment $F O$ so $\angle T O K=\angle F O K$. Therefore $\angle F L K=\angle G L K$ so $L G F$ is a line.

Now from the second paragraph, $F$ is on the reflection of $K L$ in $A C$. By symmetry, $F$ is also on the reflection of $K L$ in $A B$. Therefore the reflections of $F$ in $A B$ and $A C$ are both on $K L$ which must therefore be the doubled Wallace-Simson line of $F$. Therefore the orthocentre of $A B C$ lies on $K L$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

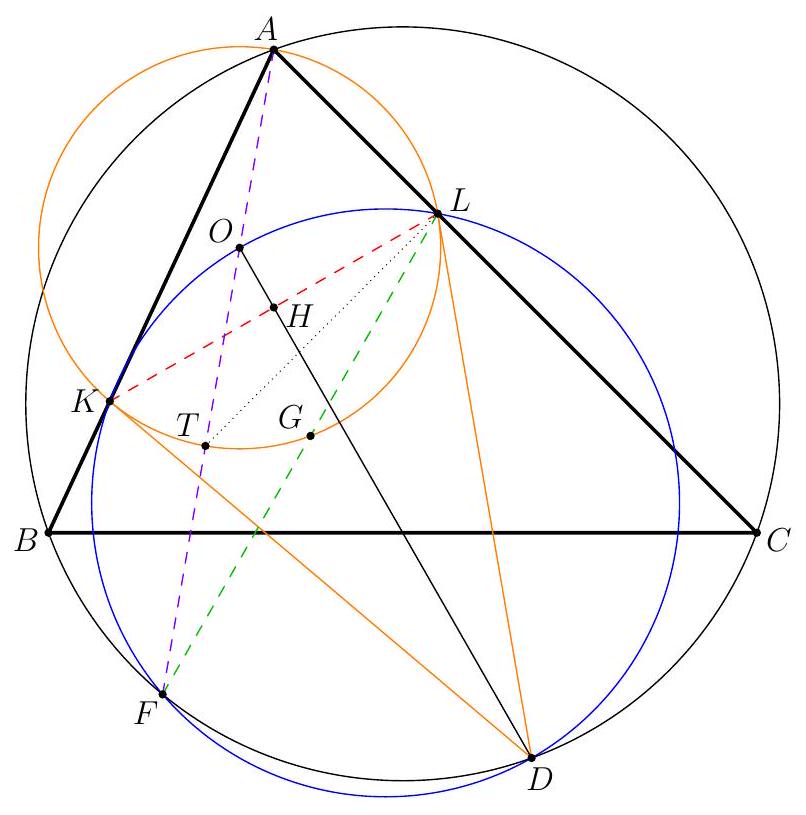

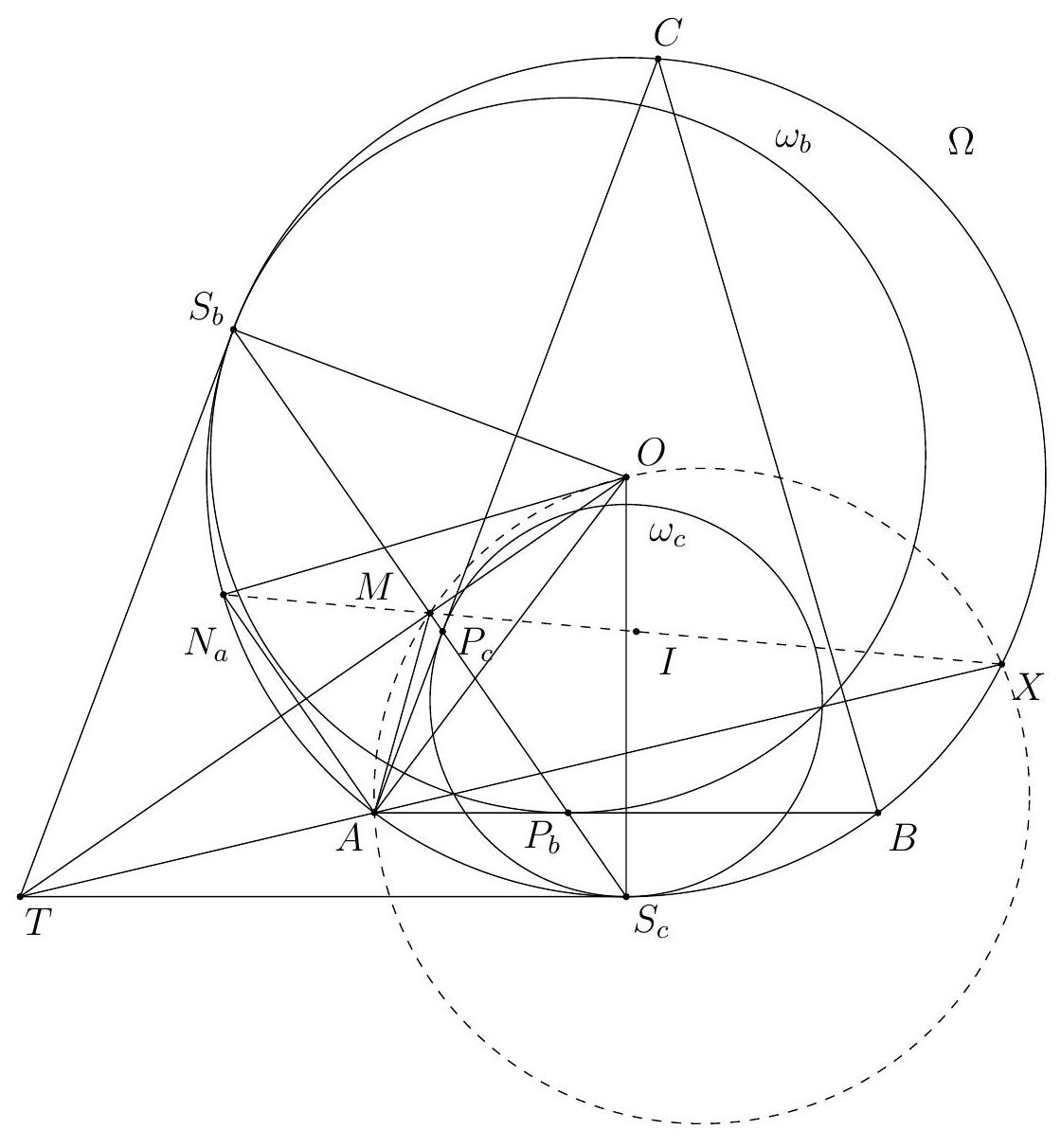

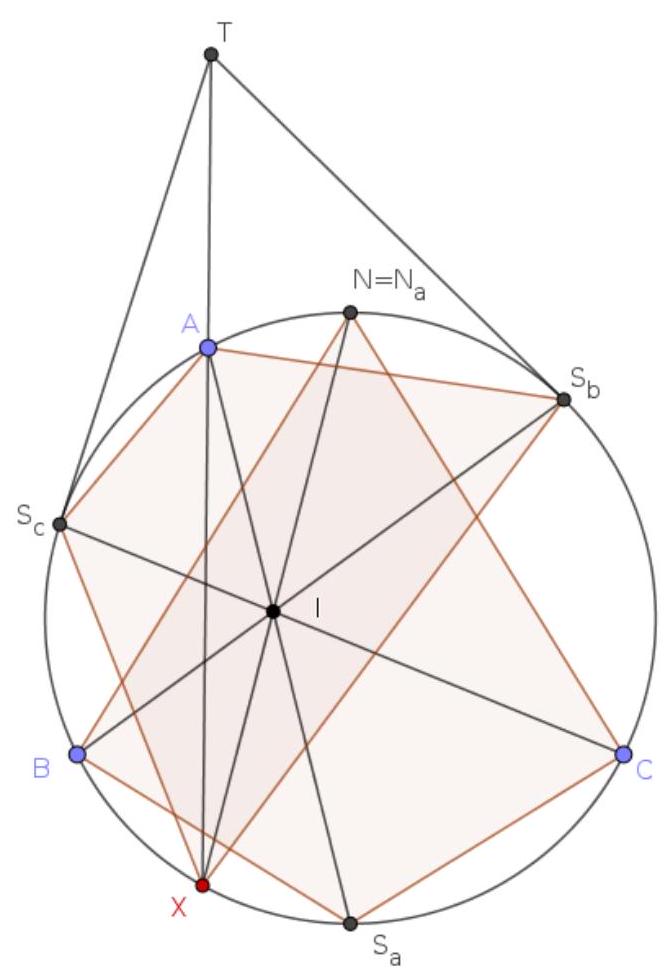

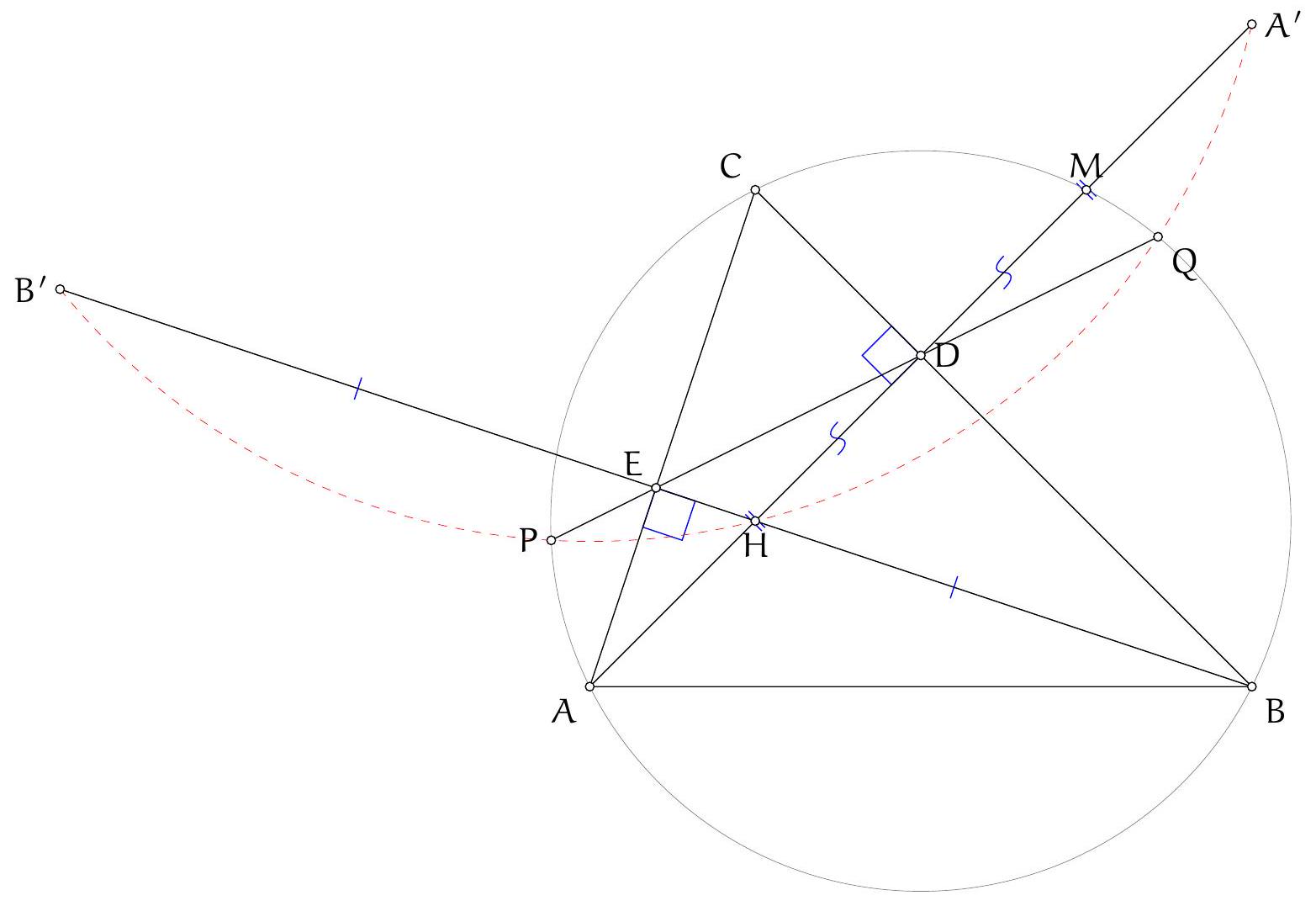

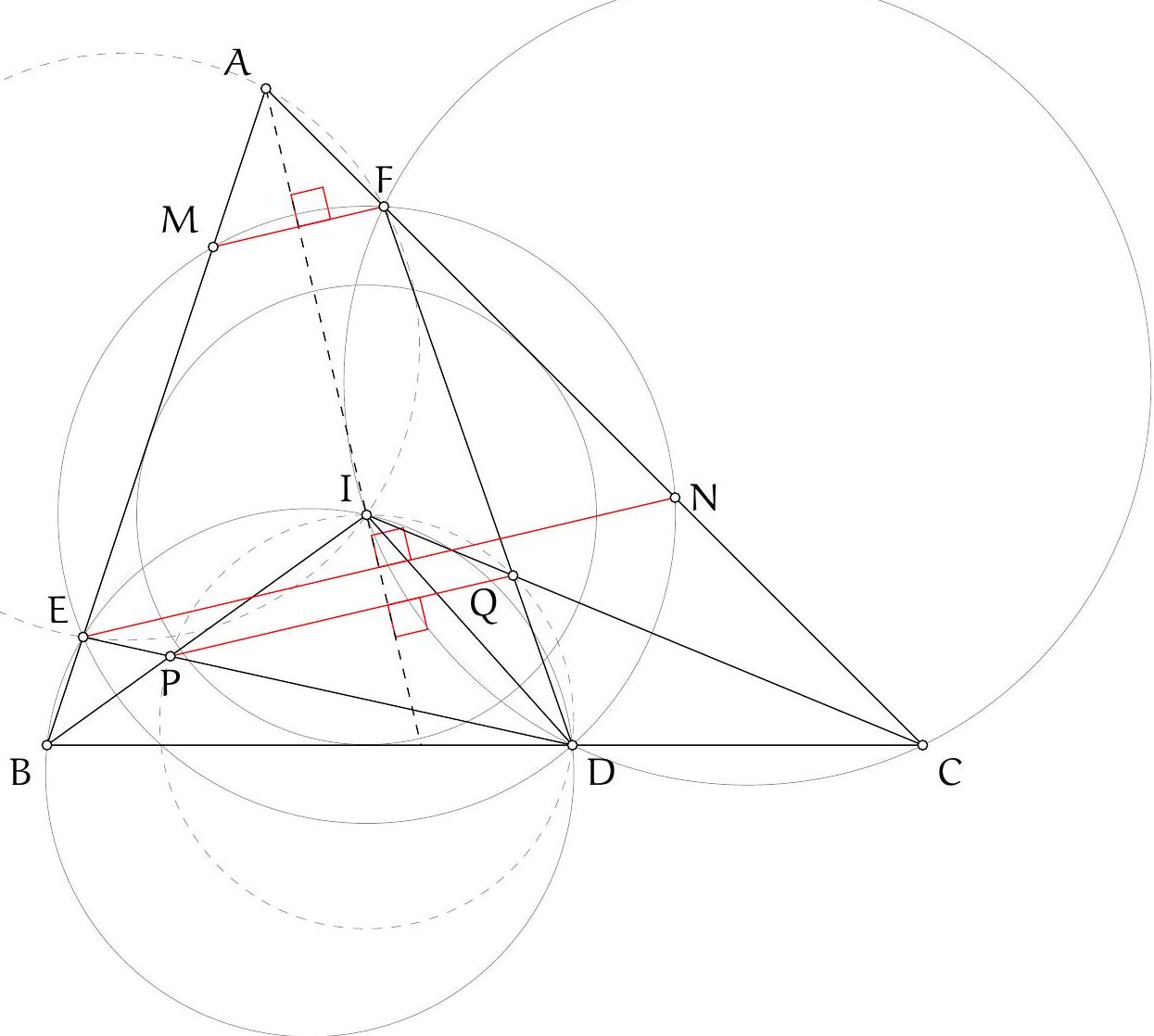

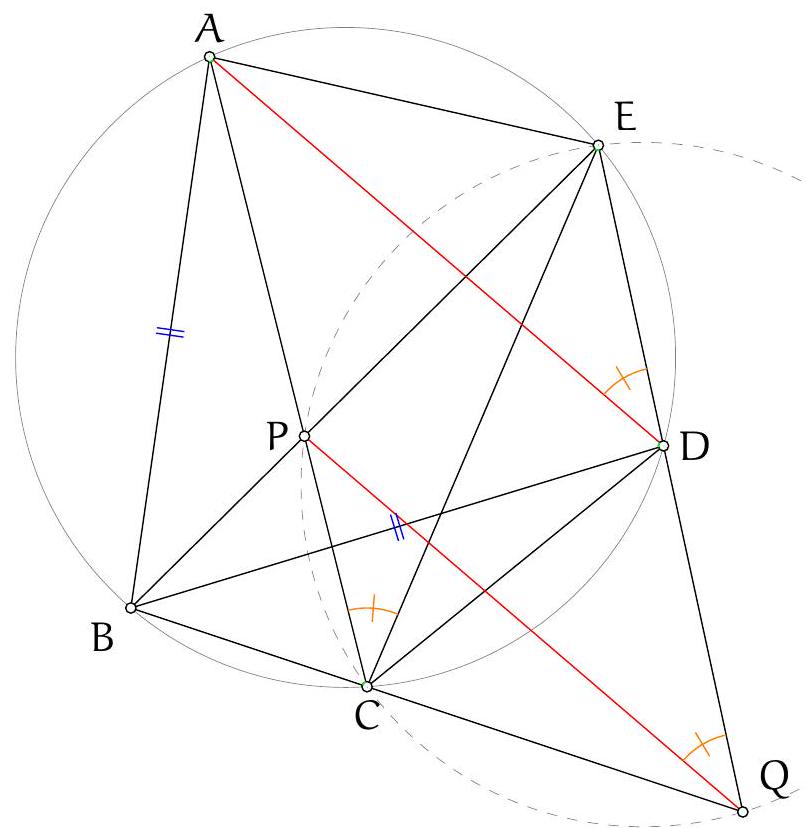

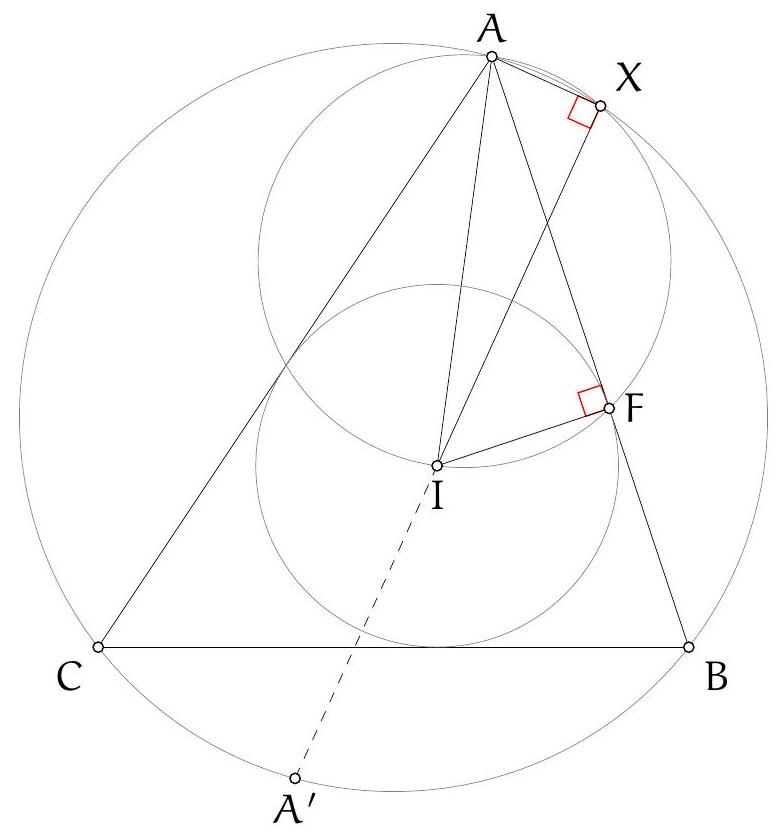

Let $H$ be the orthocentre of triangle $A B C$ and $\Sigma$ the circumcircle of $A K L$ with centre $O$. Let $\Omega$ be the circle with diameter $O D$, which contains $K$ and $L$ by Thales, and let $\Gamma$ be the circumcircle of $A B C$ containing $D$. Denote the second intersection of $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ by $F$. Since $O D$ and $A D$ are diameters of $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ we have $\angle O F D=\frac{\pi}{2}=\angle A F D$, so the points $A, O, F$ are collinear. Let $M$ and $N$ be the second intersections of $C H$ and $B H$ with $\Gamma$, respectively. It is well-known that $M$ and $N$ are the reflections of $H$ in $A B$ and $A C$, respectively (because $\angle N C A=\angle N B A=\angle A C M=\angle A B M$ ). By collinearity of $A, O, F$ and the angles in $\Gamma$ we have

$$

\angle N F O=\angle N F A=\angle N B A=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle B A C=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle K A L

$$

Since $D L$ is tangent to $\Sigma$ we obtain

$$

\angle N F O=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle K L D=\angle L D O,

$$

where the last equality follows from the fact that $O D$ is bisector of $\angle L D K$ since $L D$

Figure 4: Diagram to Solution 3

and $K D$ are tangent to $\Sigma$. Furthermore, $\angle L D O=\angle L F O$ since these are angles in $\Omega$. Hence, $\angle N F O=\angle L F O$, which implies that points $N, L, F$ are collinear. Similarly points $M, K, F$ are collinear. Since $N$ and $M$ are reflections of $H$ in $A C$ and $A B$ we have

$$

\angle L H N=\angle H N L=\angle B N F=\angle B M F=\angle B M K=\angle K H B .

$$

Hence,

$$

\angle L H K=\angle L H N+\angle N H K=\angle K H B+\angle N H K=\pi

$$

and the points $L, H, K$ are collinear.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Let $H$ be the orthocentre of triangle $A B C$ and $\Sigma$ the circumcircle of $A K L$ with centre $O$. Let $\Omega$ be the circle with diameter $O D$, which contains $K$ and $L$ by Thales, and let $\Gamma$ be the circumcircle of $A B C$ containing $D$. Denote the second intersection of $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ by $F$. Since $O D$ and $A D$ are diameters of $\Omega$ and $\Gamma$ we have $\angle O F D=\frac{\pi}{2}=\angle A F D$, so the points $A, O, F$ are collinear. Let $M$ and $N$ be the second intersections of $C H$ and $B H$ with $\Gamma$, respectively. It is well-known that $M$ and $N$ are the reflections of $H$ in $A B$ and $A C$, respectively (because $\angle N C A=\angle N B A=\angle A C M=\angle A B M$ ). By collinearity of $A, O, F$ and the angles in $\Gamma$ we have

$$

\angle N F O=\angle N F A=\angle N B A=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle B A C=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle K A L

$$

Since $D L$ is tangent to $\Sigma$ we obtain

$$

\angle N F O=\frac{\pi}{2}-\angle K L D=\angle L D O,

$$

where the last equality follows from the fact that $O D$ is bisector of $\angle L D K$ since $L D$

Figure 4: Diagram to Solution 3

and $K D$ are tangent to $\Sigma$. Furthermore, $\angle L D O=\angle L F O$ since these are angles in $\Omega$. Hence, $\angle N F O=\angle L F O$, which implies that points $N, L, F$ are collinear. Similarly points $M, K, F$ are collinear. Since $N$ and $M$ are reflections of $H$ in $A C$ and $A B$ we have

$$

\angle L H N=\angle H N L=\angle B N F=\angle B M F=\angle B M K=\angle K H B .

$$

Hence,

$$

\angle L H K=\angle L H N+\angle N H K=\angle K H B+\angle N H K=\pi

$$

and the points $L, H, K$ are collinear.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 3. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

As in Solution 3 let $M$ and $N$ be the reflections of the orthocentre in $A B$ and $A C$. Let $\angle B A C=\alpha$. Then $\angle N D M=\pi-\angle M A N=\pi-2 \alpha$.

Let $M K$ and $N L$ intersect at $F$. See Figure 3.

Claim. $\angle N F M=\pi-2 \alpha$, so $F$ lies on the circumcircle.

Proof. Since $K D$ and $L D$ are tangents to circle $A K L$, we have $|D K|=|D L|$ and $\angle D K L=\angle K L D=\alpha$, so $\angle L D K=\pi-2 \alpha$.

By definition of $M, N$ and $D, \angle M N D=\angle A N D-\angle A N M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha\right)=\alpha$ and analogously $\angle D M N=\alpha$. Hence $|D M|=|D N|$.

From $\angle N D M=\angle L D K=\pi-2 \alpha$ if follows that $\angle L D N=\angle K D M$. Since $|D K|=|D L|$ and $|D M|=|D N|$, triangles $M D K$ and $N D L$ are related by a rotation about $D$ through angle $\pi-2 \alpha$, and hence the angle between $M K$ and $N L$ is $\pi-2 \alpha$, which proved the claim.

We now finish as in Solution 3:

$$

\begin{gathered}

\angle M H K=\angle K M H=\angle F M C=\angle F A C \\

\angle L H N=\angle H N L=\angle B N F=\angle B A F

\end{gathered}

$$

As $\angle B A F+\angle F A C=\alpha$, we have $\angle L H K=\alpha+\angle N H M=\alpha+\pi-\alpha=\pi$, so $H$ lies on $K L$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

As in Solution 3 let $M$ and $N$ be the reflections of the orthocentre in $A B$ and $A C$. Let $\angle B A C=\alpha$. Then $\angle N D M=\pi-\angle M A N=\pi-2 \alpha$.

Let $M K$ and $N L$ intersect at $F$. See Figure 3.

Claim. $\angle N F M=\pi-2 \alpha$, so $F$ lies on the circumcircle.

Proof. Since $K D$ and $L D$ are tangents to circle $A K L$, we have $|D K|=|D L|$ and $\angle D K L=\angle K L D=\alpha$, so $\angle L D K=\pi-2 \alpha$.

By definition of $M, N$ and $D, \angle M N D=\angle A N D-\angle A N M=\frac{\pi}{2}-\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha\right)=\alpha$ and analogously $\angle D M N=\alpha$. Hence $|D M|=|D N|$.

From $\angle N D M=\angle L D K=\pi-2 \alpha$ if follows that $\angle L D N=\angle K D M$. Since $|D K|=|D L|$ and $|D M|=|D N|$, triangles $M D K$ and $N D L$ are related by a rotation about $D$ through angle $\pi-2 \alpha$, and hence the angle between $M K$ and $N L$ is $\pi-2 \alpha$, which proved the claim.

We now finish as in Solution 3:

$$

\begin{gathered}

\angle M H K=\angle K M H=\angle F M C=\angle F A C \\

\angle L H N=\angle H N L=\angle B N F=\angle B A F

\end{gathered}

$$

As $\angle B A F+\angle F A C=\alpha$, we have $\angle L H K=\alpha+\angle N H M=\alpha+\pi-\alpha=\pi$, so $H$ lies on $K L$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 4. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Since $A D$ is a diameter, it is well known that $D B H C$ is a parallelogram (indeed, both $B D$ and $C H$ are perpendicular to $A B$, hence parallel, and similarly for $D C \| B H)$. Let $B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}$ be the reflections of $D$ in lines $A K B$ and $A L C$, respectively; since $A B D$ and $A C D$ are right angles, these are also the factor-2 homotheties of $B$ and $C$ with respect to $D$, hence $H$ is the midpoint of $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. We will prove that $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram: it will then follow that the midpoint of $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$, which is $H$, is also the midpoint of $K L$, and in particular is on the line, as we wanted to show.

We will prove $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram by showing that $B^{\prime} K$ and $C^{\prime} L$ are the same length and direction. Indeed, for lengths we have $K B^{\prime}=K D=L D=L C^{\prime}$, where the first and last equalities arise from the reflections defining $B^{\prime}$ and $C^{\prime}$, and the middle one

is equality of tangents. For directions, let $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ denote the angles of triangle $A K L$. Immediate angle chasing in the circle $A K L$, and the properties of the reflections, yield

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle C^{\prime} L C & =\angle C L D=\angle A K L=\beta \\

\angle B K B^{\prime} & =\angle D K B=\angle K L A=\gamma \\

& \angle L D K=2 \alpha-\pi

\end{aligned}

$$

and therefore in directed angles $(\bmod 2 \pi)$ we have

$\angle\left(C^{\prime} L, B^{\prime} K\right)=\angle C^{\prime} L C+\angle C L D+\angle L D K+\angle D K B+\angle B K B^{\prime}=2 \alpha+2 \beta+2 \gamma-\pi=\pi$

and hence $C^{\prime} L$ and $B^{\prime} K$ are parallel and in opposite directions, i.e. $C^{\prime} L$ and $K B^{\prime}$ are in the same direction, as claimed.

Comment. While not necessary for the final solution, the following related observation motivates how the fact that $H$ is the midpoint of $K L$ (and therefore $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram) was first conjectured. We have $A B^{\prime}=A D=A C^{\prime}$ by the reflections, i.e. $B^{\prime} A C^{\prime}$ is an isosceles triangle with $H$ being the midpoint of the base. Thus $A H$ is the median, altitude and angle bisector in $B^{\prime} A C^{\prime}$, thus $\angle B^{\prime} A K+\angle K A H=\angle H A L+\angle L A C^{\prime}$. Since from the reflections we also have $\angle B^{\prime} A K=\angle K A D$ and $\angle D A L=\angle L A C^{\prime}$ it follows that $\angle H A L=\angle K A D$ and $\angle K A H=\angle D A L$. Since $D$ is the symmedian point in $A K L$, the angle conjugation implies $A H$ is the median line of $K L$. Thus, if $H$ is indeed on $K L$ (as the problem assures us), it can only be the midpoint of $K L$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Since $A D$ is a diameter, it is well known that $D B H C$ is a parallelogram (indeed, both $B D$ and $C H$ are perpendicular to $A B$, hence parallel, and similarly for $D C \| B H)$. Let $B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}$ be the reflections of $D$ in lines $A K B$ and $A L C$, respectively; since $A B D$ and $A C D$ are right angles, these are also the factor-2 homotheties of $B$ and $C$ with respect to $D$, hence $H$ is the midpoint of $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. We will prove that $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram: it will then follow that the midpoint of $B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$, which is $H$, is also the midpoint of $K L$, and in particular is on the line, as we wanted to show.

We will prove $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram by showing that $B^{\prime} K$ and $C^{\prime} L$ are the same length and direction. Indeed, for lengths we have $K B^{\prime}=K D=L D=L C^{\prime}$, where the first and last equalities arise from the reflections defining $B^{\prime}$ and $C^{\prime}$, and the middle one

is equality of tangents. For directions, let $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ denote the angles of triangle $A K L$. Immediate angle chasing in the circle $A K L$, and the properties of the reflections, yield

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle C^{\prime} L C & =\angle C L D=\angle A K L=\beta \\

\angle B K B^{\prime} & =\angle D K B=\angle K L A=\gamma \\

& \angle L D K=2 \alpha-\pi

\end{aligned}

$$

and therefore in directed angles $(\bmod 2 \pi)$ we have

$\angle\left(C^{\prime} L, B^{\prime} K\right)=\angle C^{\prime} L C+\angle C L D+\angle L D K+\angle D K B+\angle B K B^{\prime}=2 \alpha+2 \beta+2 \gamma-\pi=\pi$

and hence $C^{\prime} L$ and $B^{\prime} K$ are parallel and in opposite directions, i.e. $C^{\prime} L$ and $K B^{\prime}$ are in the same direction, as claimed.

Comment. While not necessary for the final solution, the following related observation motivates how the fact that $H$ is the midpoint of $K L$ (and therefore $B^{\prime} K C^{\prime} L$ is a parallelogram) was first conjectured. We have $A B^{\prime}=A D=A C^{\prime}$ by the reflections, i.e. $B^{\prime} A C^{\prime}$ is an isosceles triangle with $H$ being the midpoint of the base. Thus $A H$ is the median, altitude and angle bisector in $B^{\prime} A C^{\prime}$, thus $\angle B^{\prime} A K+\angle K A H=\angle H A L+\angle L A C^{\prime}$. Since from the reflections we also have $\angle B^{\prime} A K=\angle K A D$ and $\angle D A L=\angle L A C^{\prime}$ it follows that $\angle H A L=\angle K A D$ and $\angle K A H=\angle D A L$. Since $D$ is the symmedian point in $A K L$, the angle conjugation implies $A H$ is the median line of $K L$. Thus, if $H$ is indeed on $K L$ (as the problem assures us), it can only be the midpoint of $K L$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 5. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

There are a number of "phantom point" arguments which define $K^{\prime}$ and $L^{\prime}$ in terms of angles and then deduce that these points are actually $K$ and $L$.

Note: In these solutions it is necessary to show that $K$ and $L$ are uniquely determined by the conditions of the problem. One example of doing this is the following:

To prove uniqueness of $K$ and $L$, let us consider that there exist two other points $K^{\prime}$ and $L^{\prime}$ that satisfy the same properties ( $K^{\prime}$ on $A B$ and $L^{\prime}$ on $A C$ such that $D K^{\prime}$ and $D L^{\prime}$ are tangent to the circle $\left.A K^{\prime} L^{\prime}\right)$.

Then, we have that $D K=D L$ and $D K^{\prime}=D L^{\prime}$. We also have that $\angle K D L=\angle K^{\prime} D L^{\prime}=$ $\pi-2 \angle A$. Hence, we deduce $\angle K D K^{\prime}=\angle K D L-\angle K^{\prime} D L=\angle K^{\prime} D L^{\prime}-\angle K^{\prime} D L=\angle L D L^{\prime}$ Thus we have that $\triangle K D K^{\prime} \equiv \triangle L D L^{\prime}$, so we deduce $\angle D K A=\angle D K K^{\prime}=\angle D L L^{\prime}=$ $\pi-\angle A L D$. This implies that $A K D L$ is concyclic, which is clearly a contradiction since $\angle K A L+\angle K D L=\pi-\angle B A C$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

There are a number of "phantom point" arguments which define $K^{\prime}$ and $L^{\prime}$ in terms of angles and then deduce that these points are actually $K$ and $L$.

Note: In these solutions it is necessary to show that $K$ and $L$ are uniquely determined by the conditions of the problem. One example of doing this is the following:

To prove uniqueness of $K$ and $L$, let us consider that there exist two other points $K^{\prime}$ and $L^{\prime}$ that satisfy the same properties ( $K^{\prime}$ on $A B$ and $L^{\prime}$ on $A C$ such that $D K^{\prime}$ and $D L^{\prime}$ are tangent to the circle $\left.A K^{\prime} L^{\prime}\right)$.

Then, we have that $D K=D L$ and $D K^{\prime}=D L^{\prime}$. We also have that $\angle K D L=\angle K^{\prime} D L^{\prime}=$ $\pi-2 \angle A$. Hence, we deduce $\angle K D K^{\prime}=\angle K D L-\angle K^{\prime} D L=\angle K^{\prime} D L^{\prime}-\angle K^{\prime} D L=\angle L D L^{\prime}$ Thus we have that $\triangle K D K^{\prime} \equiv \triangle L D L^{\prime}$, so we deduce $\angle D K A=\angle D K K^{\prime}=\angle D L L^{\prime}=$ $\pi-\angle A L D$. This implies that $A K D L$ is concyclic, which is clearly a contradiction since $\angle K A L+\angle K D L=\pi-\angle B A C$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 6. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

We will use the usual complex number notation, where we will use a capital letter (like $Z$ ) to denote the point associated to a complex number (like z). Consider $\triangle A K L$ on the unit circle. So, we have $a \cdot \bar{a}=k \cdot \bar{k}=l \cdot \bar{l}=1 \quad$ As point $D$ is the intersection of the tangents to the unit circle at $K$ and $L$, we have that

$$

d=\frac{2 k l}{k+l} \text { and } \bar{d}=\frac{2}{k+l}

$$

Defining $B$ as the foot of the perpendicular from $D$ on the line $A K$, and $C$ as the foot of the perpendicular from $D$ on the line $A L$, we have the formulas:

$$

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-k) \bar{d}+\bar{a} k-a \bar{k}}{\bar{a}-\bar{k}}\right)

$$

$$

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-l) \bar{d}+\bar{a} l-a \bar{l}}{\bar{a}-\bar{l}}\right)

$$

Simplyfing these formulas, we get:

$$

\begin{gathered}

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-k) \frac{2}{k+l}+\frac{k}{a}-\frac{a}{k}}{\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1}{k}}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{\frac{2(a-k)}{k+l}+\frac{k^{2}-a^{2}}{a k}}{\frac{k-a}{a k}}\right) \\

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{2 a k}{k+l}+(a+k)\right)=\frac{k(l-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(k+a) \\

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-l) \frac{2}{k+l}+\frac{l}{a}-\frac{a}{l}}{\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1}{l}}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{\frac{2(a-l)}{k+l}+\frac{l^{2}-a^{2}}{a l}}{\frac{l-a}{a l}}\right) \\

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{2 a l}{k+l}+(a+l)\right)=\frac{l(k-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(l+a)

\end{gathered}

$$

Let $O$ be the the circumcenter of triangle $\triangle A B C$. As $A D$ is the diameter of this circle, we have that:

$$

o=\frac{a+d}{2}

$$

Defining $H$ as the orthocentre of the $\triangle A B C$, we get that:

$$

\begin{gathered}

h=a+b+c-2 \cdot o=a+\left(\frac{k(l-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(k+a)\right)+\left(\frac{l(k-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(l+a)\right)-(a+d) \\

h=a+\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{a(k+l)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2} k++\frac{1}{2} l++a-\left(a+\frac{2 k l}{k+l}\right) \\

h=\frac{1}{2}(k+l)

\end{gathered}

$$

Hence, we conclude that $H$ is the midpoint of $K L$, so $H, K, L$ are collinear.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

We will use the usual complex number notation, where we will use a capital letter (like $Z$ ) to denote the point associated to a complex number (like z). Consider $\triangle A K L$ on the unit circle. So, we have $a \cdot \bar{a}=k \cdot \bar{k}=l \cdot \bar{l}=1 \quad$ As point $D$ is the intersection of the tangents to the unit circle at $K$ and $L$, we have that

$$

d=\frac{2 k l}{k+l} \text { and } \bar{d}=\frac{2}{k+l}

$$

Defining $B$ as the foot of the perpendicular from $D$ on the line $A K$, and $C$ as the foot of the perpendicular from $D$ on the line $A L$, we have the formulas:

$$

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-k) \bar{d}+\bar{a} k-a \bar{k}}{\bar{a}-\bar{k}}\right)

$$

$$

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-l) \bar{d}+\bar{a} l-a \bar{l}}{\bar{a}-\bar{l}}\right)

$$

Simplyfing these formulas, we get:

$$

\begin{gathered}

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-k) \frac{2}{k+l}+\frac{k}{a}-\frac{a}{k}}{\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1}{k}}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{\frac{2(a-k)}{k+l}+\frac{k^{2}-a^{2}}{a k}}{\frac{k-a}{a k}}\right) \\

b=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{2 a k}{k+l}+(a+k)\right)=\frac{k(l-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(k+a) \\

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{(a-l) \frac{2}{k+l}+\frac{l}{a}-\frac{a}{l}}{\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1}{l}}\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(d+\frac{\frac{2(a-l)}{k+l}+\frac{l^{2}-a^{2}}{a l}}{\frac{l-a}{a l}}\right) \\

c=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{2 a l}{k+l}+(a+l)\right)=\frac{l(k-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(l+a)

\end{gathered}

$$

Let $O$ be the the circumcenter of triangle $\triangle A B C$. As $A D$ is the diameter of this circle, we have that:

$$

o=\frac{a+d}{2}

$$

Defining $H$ as the orthocentre of the $\triangle A B C$, we get that:

$$

\begin{gathered}

h=a+b+c-2 \cdot o=a+\left(\frac{k(l-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(k+a)\right)+\left(\frac{l(k-a)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2}(l+a)\right)-(a+d) \\

h=a+\frac{2 k l}{k+l}-\frac{a(k+l)}{k+l}+\frac{1}{2} k++\frac{1}{2} l++a-\left(a+\frac{2 k l}{k+l}\right) \\

h=\frac{1}{2}(k+l)

\end{gathered}

$$

Hence, we conclude that $H$ is the midpoint of $K L$, so $H, K, L$ are collinear.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 7. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

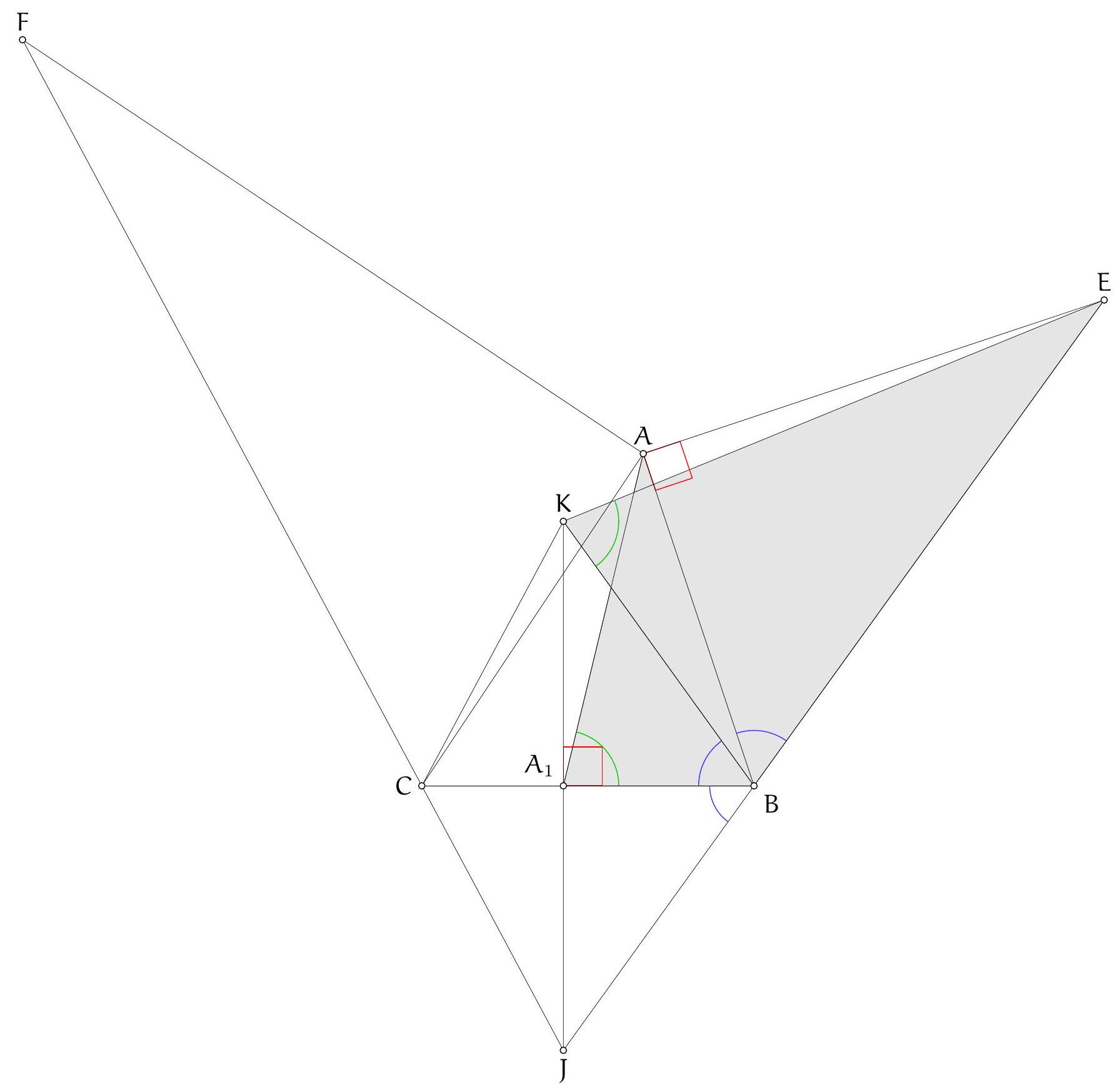

Let us employ the barycentric coordinates. Set $A(1,0,0), K(0,1,0), L(0,0,1)$.

The tangent at $K$ of $(A K L)$ is $a^{2} z+c^{2} x=0$, and the tangent of of $L$ at $(A K L)$ is $a^{2} y+b^{2} x=0$. Their intersection is

$$

D\left(-a^{2}: b^{2}: c^{2}\right)

$$

Since $B \in A K$, we can let $B(1-t, t, 0)$. Solving for $\overrightarrow{A B} \cdot \overrightarrow{B D}=0$ gives

$$

t=\frac{3 b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)} \Longrightarrow B=\left(\frac{-a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, \frac{-a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, 0\right)

$$

Likewise, $C$ has the coordinate

$$

C=\left(\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, 0, \frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}+3 c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right) .

$$

The altitude from $B$ for triangle $A B C$ is

$$

-b^{2}\left(x-z-\frac{-a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)+\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\left(y-\frac{-a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)=0

$$

Also the altitude from $C$ for triangle $A B C$ is

$$

-c^{2}\left(x-y-\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)+\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)\left(z-\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}+3 c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)=0

$$

The intersection of these two altitudes, which is the orthocenter of triangle $A B C$, has the barycentric coordinate

$$

H=(0,1 / 2,1 / 2)

$$

which is the midpoint of the segment $K L$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

We are given an acute triangle $A B C$. Let $D$ be the point on its circumcircle such that $A D$ is a diameter. Suppose that points $K$ and $L$ lie on segments $A B$ and $A C$, respectively, and that $D K$ and $D L$ are tangent to circle $A K L$.

Show that line $K L$ passes through the orthocentre of $A B C$.

The altitudes of a triangle meet at its orthocentre.

Figure 1: Diagram to solution 1

|

Let us employ the barycentric coordinates. Set $A(1,0,0), K(0,1,0), L(0,0,1)$.

The tangent at $K$ of $(A K L)$ is $a^{2} z+c^{2} x=0$, and the tangent of of $L$ at $(A K L)$ is $a^{2} y+b^{2} x=0$. Their intersection is

$$

D\left(-a^{2}: b^{2}: c^{2}\right)

$$

Since $B \in A K$, we can let $B(1-t, t, 0)$. Solving for $\overrightarrow{A B} \cdot \overrightarrow{B D}=0$ gives

$$

t=\frac{3 b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)} \Longrightarrow B=\left(\frac{-a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, \frac{-a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, 0\right)

$$

Likewise, $C$ has the coordinate

$$

C=\left(\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}, 0, \frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}+3 c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right) .

$$

The altitude from $B$ for triangle $A B C$ is

$$

-b^{2}\left(x-z-\frac{-a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)+\left(c^{2}-a^{2}\right)\left(y-\frac{-a^{2}+3 b^{2}+c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)=0

$$

Also the altitude from $C$ for triangle $A B C$ is

$$

-c^{2}\left(x-y-\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)+\left(a^{2}-b^{2}\right)\left(z-\frac{-a^{2}+b^{2}+3 c^{2}}{2\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\right)=0

$$

The intersection of these two altitudes, which is the orthocenter of triangle $A B C$, has the barycentric coordinate

$$

H=(0,1 / 2,1 / 2)

$$

which is the midpoint of the segment $K L$.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 8. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Let $k$ be a positive integer. Lexi has a dictionary $\mathcal{D}$ consisting of some $k$-letter strings containing only the letters $A$ and $B$. Lexi would like to write either the letter $A$ or the letter $B$ in each cell of a $k \times k$ grid so that each column contains a string from $\mathcal{D}$ when read from top-to-bottom and each row contains a string from $\mathcal{D}$ when read from left-to-right.

What is the smallest integer $m$ such that if $\mathcal{D}$ contains at least $m$ different strings, then Lexi can fill her grid in this manner, no matter what strings are in $\mathcal{D}$ ?

|

We claim the minimum value of $m$ is $2^{k-1}$.

Firstly, we provide a set $\mathcal{S}$ of size $2^{k-1}-1$ for which Lexi cannot fill her grid. Consider the set of all length- $k$ strings containing only $A$ s and $B$ shich end with a $B$, and remove the string consisting of $k B$ s. Clearly there are 2 independent choices for each of the first $k-1$ letters and 1 for the last letter, and since exactly one string is excluded, there must be exactly $2^{k-1}-1$ strings in this set.

Suppose Lexi tries to fill her grid. For each row to have a valid string, it must end in a $B$. But then the right column would necessarily contain $k B \mathrm{~s}$, and not be in our set. Thus, Lexi cannot fill her grid with our set, and we must have $m \geqslant 2^{k-1}$.

Now, consider any set $\mathcal{S}$ with at least $2^{k-1}$ strings. Clearly, if $\mathcal{S}$ contained either the uniform string with $k A$ s or the string with $k B \mathrm{~s}$, then Lexi could fill her grid with all of the relevant letters and each row and column would contain that string.

Consider the case where $\mathcal{S}$ contains neither of those strings. Among all $2^{k}$ possible length$k$ strings with $A \mathrm{~s}$ and $B \mathrm{~s}$, each has a complement which corresponds to the string with $B$ s in every position where first string had $A$ s and vice-versa. Clearly, the string with all $A$ s is paired with the string with all $B$ s. We may assume that we do not take the two uniform strings and thus applying the pigeonhole principle to the remaining set of strings, we must have two strings which are complementary.

Let this pair of strings be $\ell, \ell^{\prime} \in \mathcal{S}$ in some order. Define the set of indices $\mathcal{J}$ corresponding to the $A$ s in $\ell$ and thus the $B \mathrm{~s}$ in $\ell^{\prime}$, and all other indices (not in $\mathcal{J}$ ) correspond to $B \mathrm{~s}$ in $\ell$ (and thus $A$ s in $\ell^{\prime}$ ). Then, we claim that Lexi puts an $A$ in the cell in row $r$, column $c$ if $r, c \in \mathcal{J}$ or $r, c \notin \mathcal{J}$, and a $B$ otherwise, each row and column contains a string in $\mathcal{S}$.

We illustrate this with a simple example: If $k=6$ and we have that $A A A B A B$ and $B B B A B A$ are both in the dictionary, then Lexi could fill the table as follows:

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| B | B | B | A | B | A |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| B | B | B | A | B | A |

Suppose we are looking at row $i$ or column $i$ for $i \in \mathcal{J}$. Then by construction the string in this row/column contains $A$ s at indices $k$ with $k \in \mathcal{J}$ and $B$ s elsewhere, and thus is precisely $\ell$. Suppose instead we are looking at row $i$ or column $i$ for $i \notin \mathcal{J}$. Then again

by construction the string in this row/column contains $A$ s at indices $k$ with $k \notin \mathcal{J}$ and $B$ s elsewhere, and thus is precisely $\ell^{\prime}$. So each row and column indeed contains a string in $\mathcal{S}$.

Thus, for any $\mathcal{S}$ with $|\mathcal{S}| \geqslant 2^{k-1}$, Lexi can definitely fill the grid appropriately. Since we know $m \geqslant 2^{k-1}$, $2^{k-1}$ is the minimum possible value of $m$ as claimed.

|

2^{k-1}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $k$ be a positive integer. Lexi has a dictionary $\mathcal{D}$ consisting of some $k$-letter strings containing only the letters $A$ and $B$. Lexi would like to write either the letter $A$ or the letter $B$ in each cell of a $k \times k$ grid so that each column contains a string from $\mathcal{D}$ when read from top-to-bottom and each row contains a string from $\mathcal{D}$ when read from left-to-right.

What is the smallest integer $m$ such that if $\mathcal{D}$ contains at least $m$ different strings, then Lexi can fill her grid in this manner, no matter what strings are in $\mathcal{D}$ ?

|

We claim the minimum value of $m$ is $2^{k-1}$.

Firstly, we provide a set $\mathcal{S}$ of size $2^{k-1}-1$ for which Lexi cannot fill her grid. Consider the set of all length- $k$ strings containing only $A$ s and $B$ shich end with a $B$, and remove the string consisting of $k B$ s. Clearly there are 2 independent choices for each of the first $k-1$ letters and 1 for the last letter, and since exactly one string is excluded, there must be exactly $2^{k-1}-1$ strings in this set.

Suppose Lexi tries to fill her grid. For each row to have a valid string, it must end in a $B$. But then the right column would necessarily contain $k B \mathrm{~s}$, and not be in our set. Thus, Lexi cannot fill her grid with our set, and we must have $m \geqslant 2^{k-1}$.

Now, consider any set $\mathcal{S}$ with at least $2^{k-1}$ strings. Clearly, if $\mathcal{S}$ contained either the uniform string with $k A$ s or the string with $k B \mathrm{~s}$, then Lexi could fill her grid with all of the relevant letters and each row and column would contain that string.

Consider the case where $\mathcal{S}$ contains neither of those strings. Among all $2^{k}$ possible length$k$ strings with $A \mathrm{~s}$ and $B \mathrm{~s}$, each has a complement which corresponds to the string with $B$ s in every position where first string had $A$ s and vice-versa. Clearly, the string with all $A$ s is paired with the string with all $B$ s. We may assume that we do not take the two uniform strings and thus applying the pigeonhole principle to the remaining set of strings, we must have two strings which are complementary.

Let this pair of strings be $\ell, \ell^{\prime} \in \mathcal{S}$ in some order. Define the set of indices $\mathcal{J}$ corresponding to the $A$ s in $\ell$ and thus the $B \mathrm{~s}$ in $\ell^{\prime}$, and all other indices (not in $\mathcal{J}$ ) correspond to $B \mathrm{~s}$ in $\ell$ (and thus $A$ s in $\ell^{\prime}$ ). Then, we claim that Lexi puts an $A$ in the cell in row $r$, column $c$ if $r, c \in \mathcal{J}$ or $r, c \notin \mathcal{J}$, and a $B$ otherwise, each row and column contains a string in $\mathcal{S}$.

We illustrate this with a simple example: If $k=6$ and we have that $A A A B A B$ and $B B B A B A$ are both in the dictionary, then Lexi could fill the table as follows:

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| B | B | B | A | B | A |

| A | A | A | B | A | B |

| B | B | B | A | B | A |

Suppose we are looking at row $i$ or column $i$ for $i \in \mathcal{J}$. Then by construction the string in this row/column contains $A$ s at indices $k$ with $k \in \mathcal{J}$ and $B$ s elsewhere, and thus is precisely $\ell$. Suppose instead we are looking at row $i$ or column $i$ for $i \notin \mathcal{J}$. Then again

by construction the string in this row/column contains $A$ s at indices $k$ with $k \notin \mathcal{J}$ and $B$ s elsewhere, and thus is precisely $\ell^{\prime}$. So each row and column indeed contains a string in $\mathcal{S}$.

Thus, for any $\mathcal{S}$ with $|\mathcal{S}| \geqslant 2^{k-1}$, Lexi can definitely fill the grid appropriately. Since we know $m \geqslant 2^{k-1}$, $2^{k-1}$ is the minimum possible value of $m$ as claimed.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Turbo the snail sits on a point on a circle with circumference 1. Given an infinite sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$, Turbo successively crawls distances $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ around the circle, each time choosing to crawl either clockwise or counterclockwise.

For example, if the sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ is $0.4,0.6,0.3, \ldots$, then Turbo may start crawling as follows:

Determine the largest constant $C>0$ with the following property: for every sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ with $c_{i}<C$ for all $i$, Turbo can (after studying the sequence) ensure that there is some point on the circle that it will never visit or crawl across.

|

The largest possible $C$ is $C=\frac{1}{2}$.

For $0<C \leqslant \frac{1}{2}$, Turbo can simply choose an arbitrary point $P$ (different from its starting point) to avoid. When Turbo is at an arbitrary point $A$ different from $P$, the two arcs $A P$ have total length 1 ; therefore, the larger of the two the arcs (or either arc in case $A$ is diametrically opposite to $P$ ) must have length $\geqslant \frac{1}{2}$. By always choosing this larger arc (or either arc in case $A$ is diametrically opposite to $P$ ), Turbo will manage to avoid the point $P$ forever.

For $C>\frac{1}{2}$, we write $C=\frac{1}{2}+a$ with $a>0$, and we choose the sequence

$$

\frac{1}{2}, \quad \frac{1+a}{2}, \quad \frac{1}{2}, \quad \frac{1+a}{2}, \quad \frac{1}{2}, \quad \ldots

$$

In other words, $c_{i}=\frac{1}{2}$ if $i$ is odd and $c_{i}=\frac{1+a}{2}<C$ when $i$ is even. We claim Turbo must eventually visit all points on the circle. This is clear when it crawls in the same direction two times in a row; after all, we have $c_{i}+c_{i+1}>1$ for all $i$. Therefore, we are left with the case that Turbo alternates crawling clockwise and crawling counterclockwise. If it, without loss of generality, starts by going clockwise, then it will always crawl a distance $\frac{1}{2}$ clockwise followed by a distance $\frac{1+a}{2}$ counterclockwise. The net effect is that it crawls a distance $\frac{a}{2}$ counterclockwise. Because $\frac{a}{2}$ is positive, there exists a positive integer $N$ such that $\frac{a}{2} \cdot N>1$. After $2 N$ crawls, Turbo will have crawled a distance $\frac{a}{2}$ counterclockwise $N$ times, therefore having covered a total distance of $\frac{a}{2} \cdot N>1$, meaning that it must have crawled over all points on the circle.

Note: Every sequence of the form $c_{i}=x$ if $i$ is odd, and $c_{i}=y$ if $i$ is even, where $0<x, y<C$, such that $x+y \geqslant 1$, and $x \neq y$ satisfies the conditions with the same argument. There might be even more possible examples.

|

\frac{1}{2}

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

Turbo the snail sits on a point on a circle with circumference 1. Given an infinite sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$, Turbo successively crawls distances $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ around the circle, each time choosing to crawl either clockwise or counterclockwise.

For example, if the sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ is $0.4,0.6,0.3, \ldots$, then Turbo may start crawling as follows:

Determine the largest constant $C>0$ with the following property: for every sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ with $c_{i}<C$ for all $i$, Turbo can (after studying the sequence) ensure that there is some point on the circle that it will never visit or crawl across.

|

The largest possible $C$ is $C=\frac{1}{2}$.

For $0<C \leqslant \frac{1}{2}$, Turbo can simply choose an arbitrary point $P$ (different from its starting point) to avoid. When Turbo is at an arbitrary point $A$ different from $P$, the two arcs $A P$ have total length 1 ; therefore, the larger of the two the arcs (or either arc in case $A$ is diametrically opposite to $P$ ) must have length $\geqslant \frac{1}{2}$. By always choosing this larger arc (or either arc in case $A$ is diametrically opposite to $P$ ), Turbo will manage to avoid the point $P$ forever.

For $C>\frac{1}{2}$, we write $C=\frac{1}{2}+a$ with $a>0$, and we choose the sequence

$$

\frac{1}{2}, \quad \frac{1+a}{2}, \quad \frac{1}{2}, \quad \frac{1+a}{2}, \quad \frac{1}{2}, \quad \ldots

$$

In other words, $c_{i}=\frac{1}{2}$ if $i$ is odd and $c_{i}=\frac{1+a}{2}<C$ when $i$ is even. We claim Turbo must eventually visit all points on the circle. This is clear when it crawls in the same direction two times in a row; after all, we have $c_{i}+c_{i+1}>1$ for all $i$. Therefore, we are left with the case that Turbo alternates crawling clockwise and crawling counterclockwise. If it, without loss of generality, starts by going clockwise, then it will always crawl a distance $\frac{1}{2}$ clockwise followed by a distance $\frac{1+a}{2}$ counterclockwise. The net effect is that it crawls a distance $\frac{a}{2}$ counterclockwise. Because $\frac{a}{2}$ is positive, there exists a positive integer $N$ such that $\frac{a}{2} \cdot N>1$. After $2 N$ crawls, Turbo will have crawled a distance $\frac{a}{2}$ counterclockwise $N$ times, therefore having covered a total distance of $\frac{a}{2} \cdot N>1$, meaning that it must have crawled over all points on the circle.

Note: Every sequence of the form $c_{i}=x$ if $i$ is odd, and $c_{i}=y$ if $i$ is even, where $0<x, y<C$, such that $x+y \geqslant 1$, and $x \neq y$ satisfies the conditions with the same argument. There might be even more possible examples.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Turbo the snail sits on a point on a circle with circumference 1. Given an infinite sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$, Turbo successively crawls distances $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ around the circle, each time choosing to crawl either clockwise or counterclockwise.

For example, if the sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ is $0.4,0.6,0.3, \ldots$, then Turbo may start crawling as follows:

Determine the largest constant $C>0$ with the following property: for every sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ with $c_{i}<C$ for all $i$, Turbo can (after studying the sequence) ensure that there is some point on the circle that it will never visit or crawl across.

|

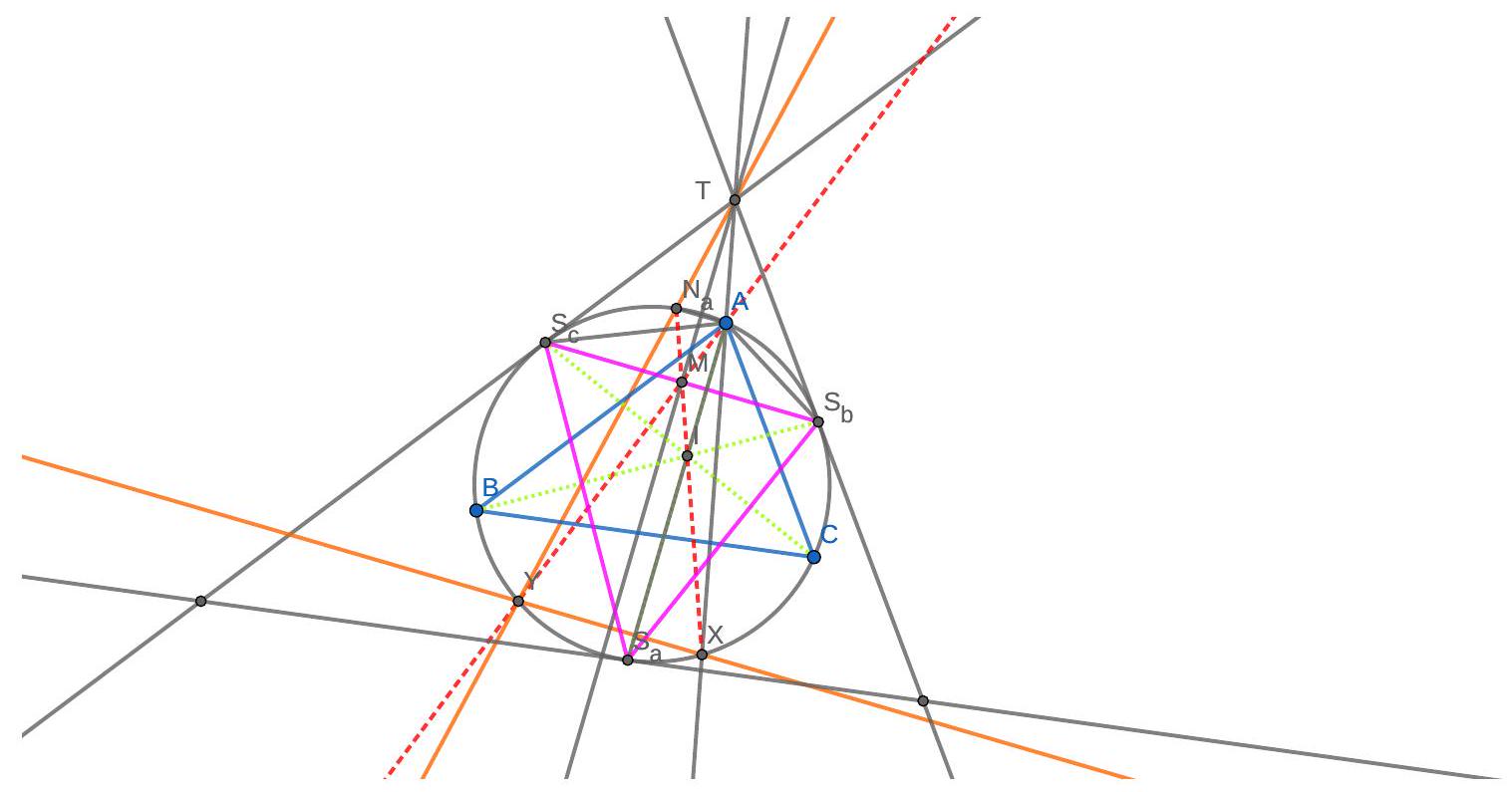

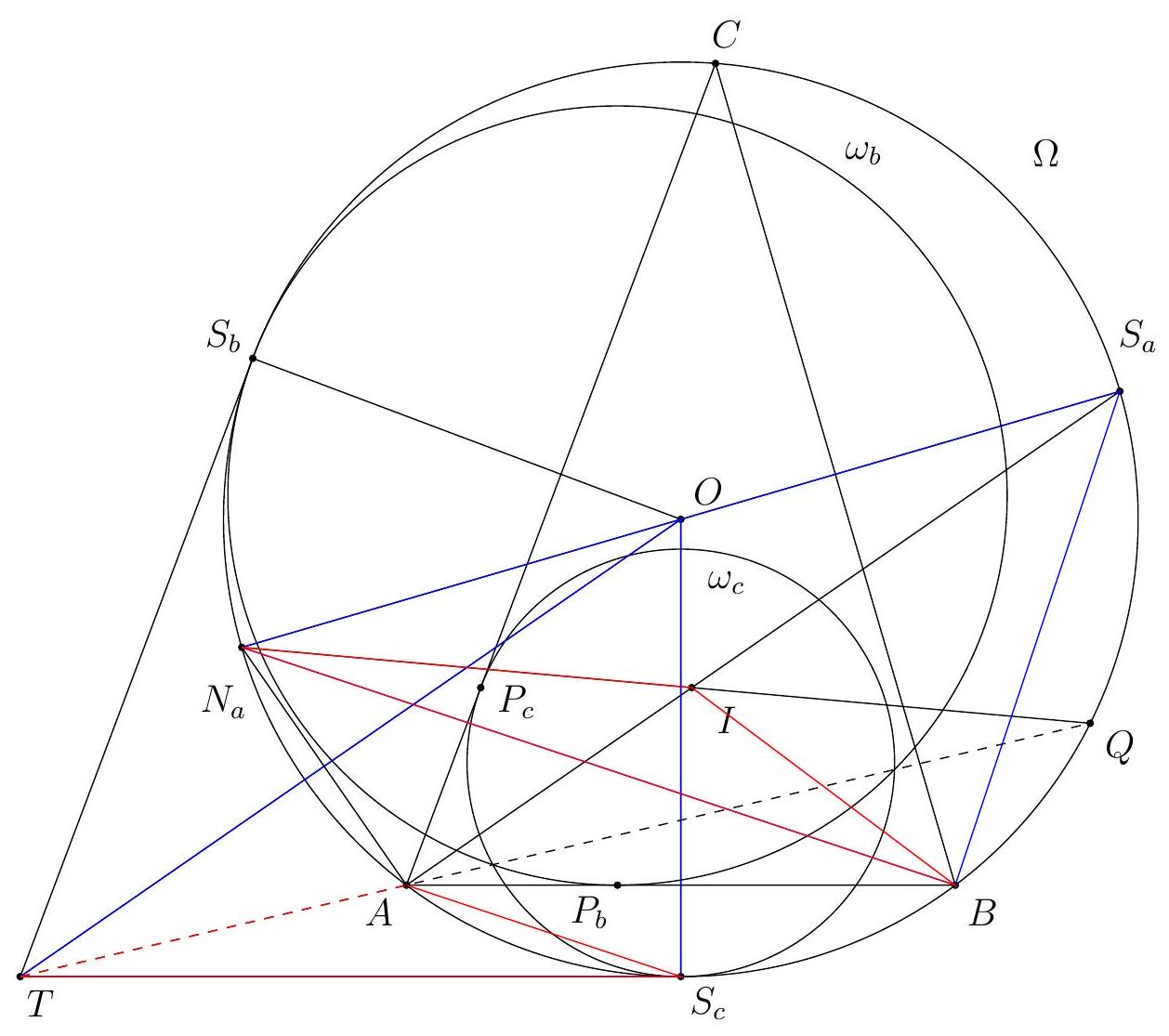

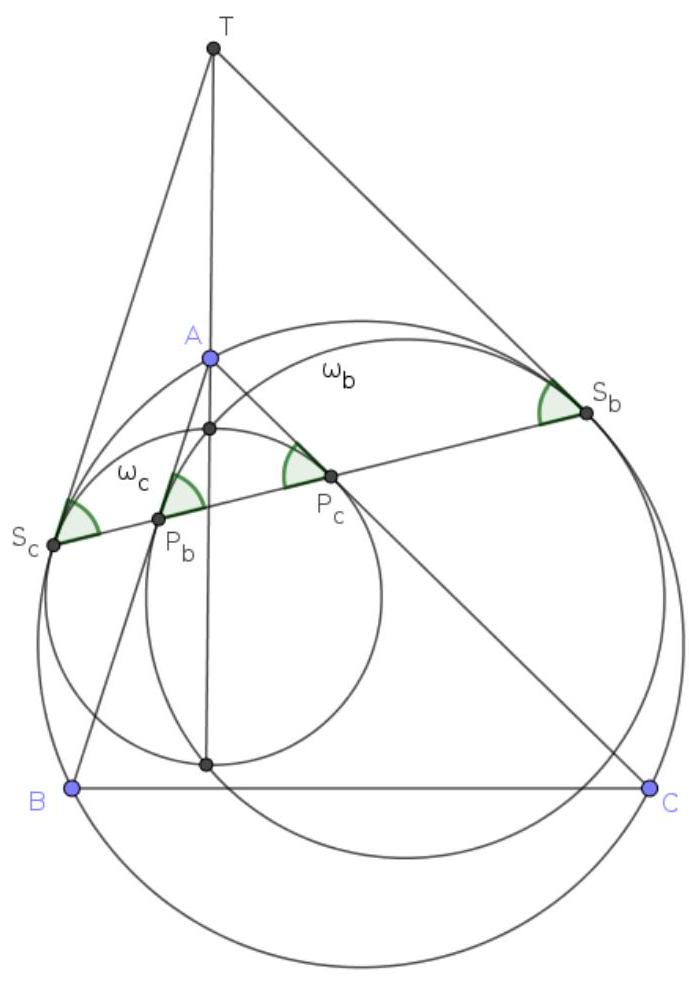

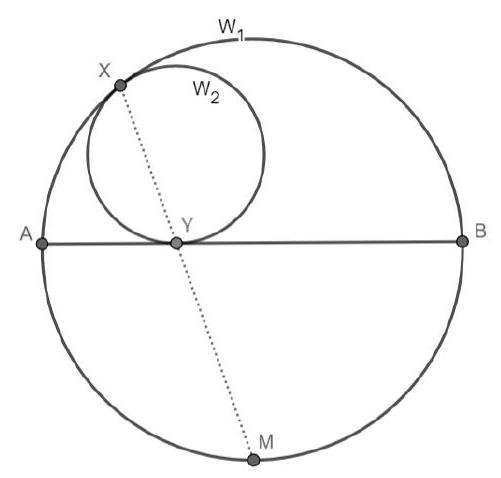

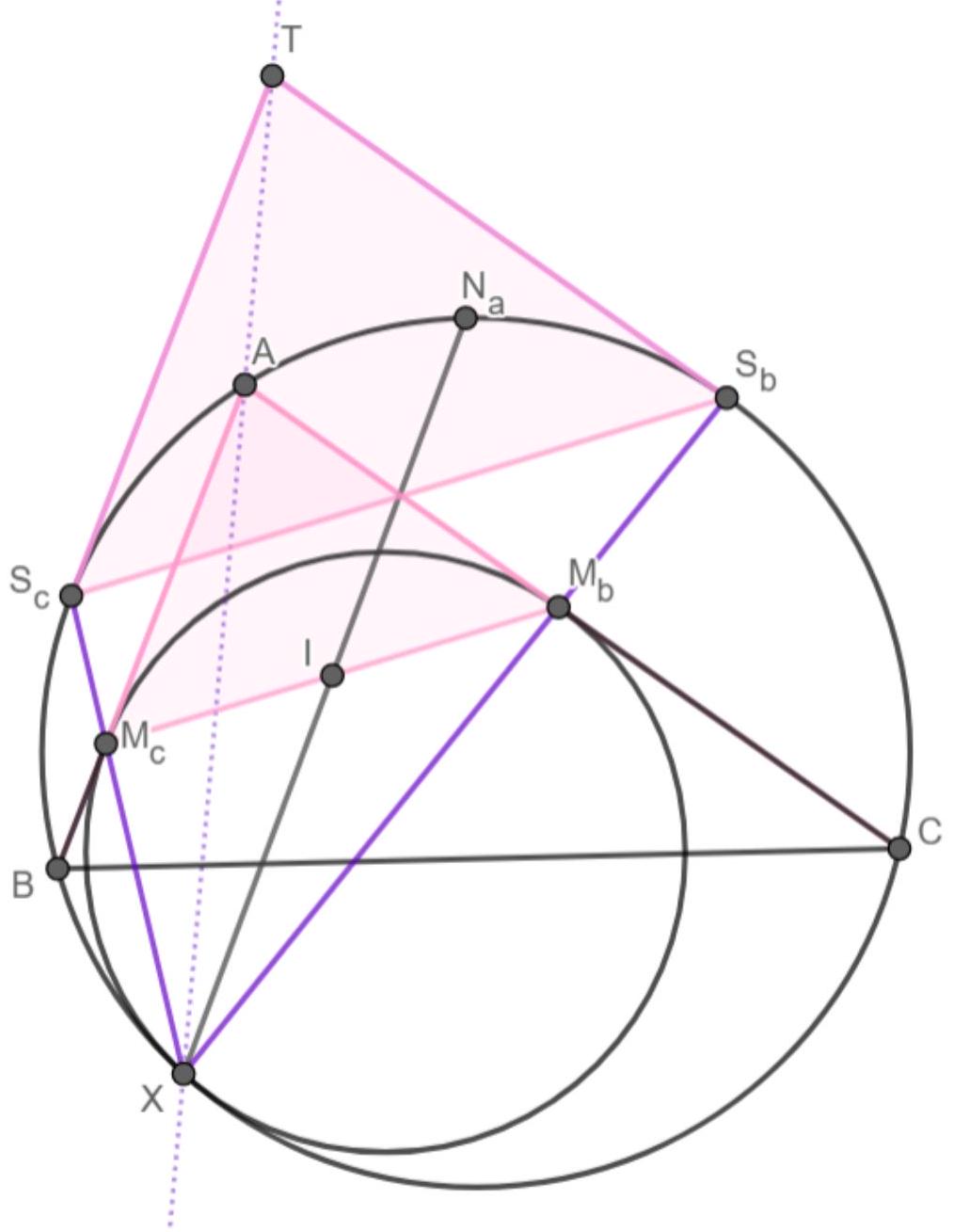

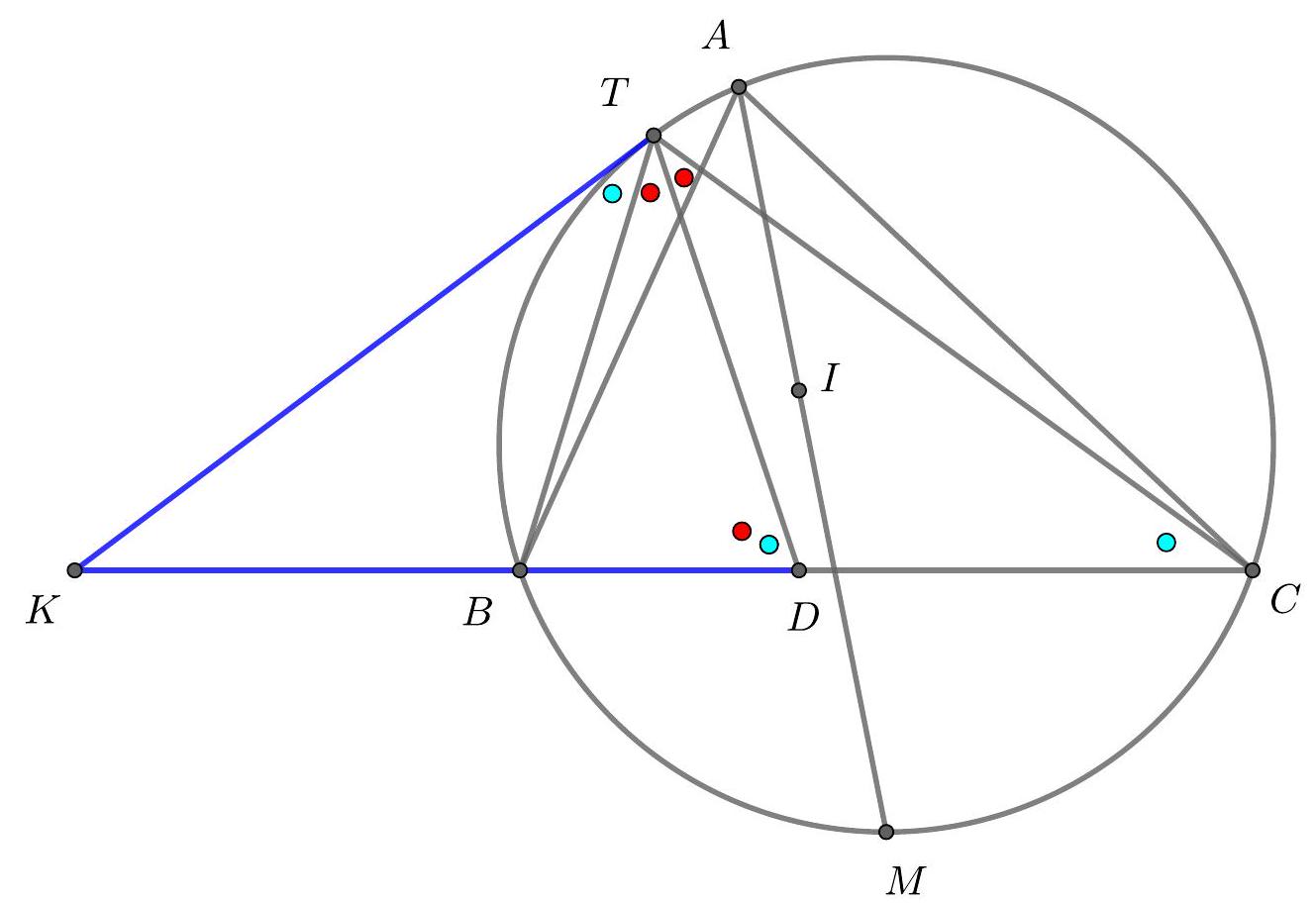

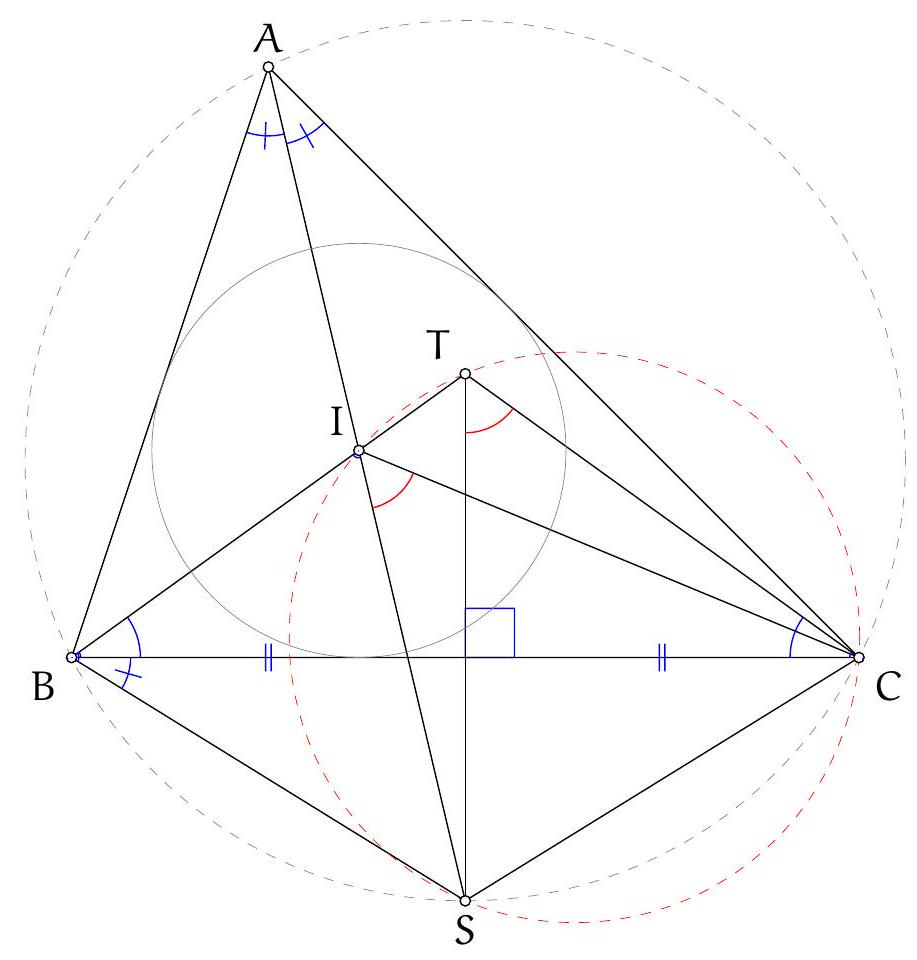

Alternative solution (to show that $C \leqslant \frac{1}{2}$ )

We consider the following related problem:

We assume instead that the snail Chet is moving left and right on the real line. Find the size $M$ of the smallest (closed) interval, that we cannot force Chet out of, using a sequence of real numbers $d_{i}$ with $0<d_{i}<1$ for all $i$.

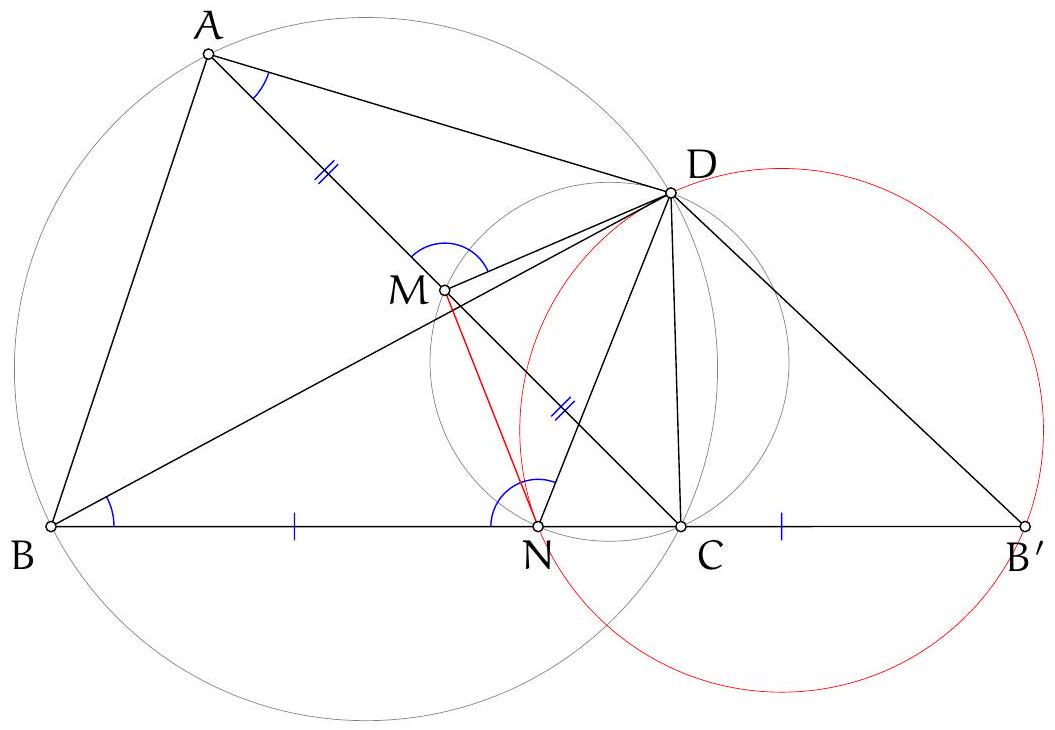

Then $C=1 / M$. Indeed if for every sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, \ldots$, with $c_{i}<C$ there exists a point that Turbo can avoid, then the circle can be cut open at the avoided point and mapped to an interval of size $M$ such that Chet can stay inside this interval for any sequence of the from $c_{1} / C, c_{2} / C, \ldots$, see Figure 5 . However, all sequences $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$ with $d_{i}<1$ can be written in this form. Similarly if for every sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$, there exists an interval of length smaller or equal $M$ that we cannot force Chet out of, this projects to a subset of the circle, that we cannot force Turbo out of using any sequence of the form $d_{1} / M, d_{2} / M, \ldots$. These are again exactly all the sequences with elements in $[0, C)$.

Figure 5: Chet and Turbo equivalence

Claim: $M \geqslant 2$.

Proof. Suppose not, so $M<2$. Say $M=2-2 \varepsilon$ for some $\varepsilon>0$ and let $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$ be a minimal interval, that Chet cannot be forced out of. Then we can force Chet arbitrarily close to $\pm(1-\varepsilon)$. In partiular, we can force Chet out of $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$ by minimality of $M$. This means that there exists a sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$ for which Chet has to leave $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$, which means he ends up either in the interval $\left[-1+\varepsilon,-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right)$ or in the interval $\left(1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon\right]$.

Now consider the sequence,

$$

d_{1}, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad d_{2}, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, d_{3}, \ldots

$$

obtained by adding the sequence $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ in between every two steps. We claim that this sequence forces Chet to leave the larger interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Indeed no two consecutive elements in the sequence $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ can

have the same sign, because the sum of any two consecutive terms is larger than $2-2 \varepsilon$ and Chet would leave the interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. It follows that the $\left(1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon\right.$ )'s and the ( $1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon$ )'s cancel out, so the position after $d_{k}$ is the same as before $d_{k+1}$. Hence, the positions after each $d_{k}$ remain the same as in the original sequence. Thus, Chet is also forced to the boundary in the new sequence.

If Chet is outside the interval $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$, then Chet has to move $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ towards 0 , and ends in $\left[-\frac{1}{6} \varepsilon, \frac{1}{6} \varepsilon\right]$. Chet then has to move by $1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon$, which means that he has to leave the interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Indeed the absolute value of the final position is at least $1-\frac{5}{6} \varepsilon$. This contradicts the assumption, that we cannot force Chet out of $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Hence $M \geqslant 2$ as needed.

|

C \leqslant \frac{1}{2}

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

Turbo the snail sits on a point on a circle with circumference 1. Given an infinite sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$, Turbo successively crawls distances $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ around the circle, each time choosing to crawl either clockwise or counterclockwise.

For example, if the sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ is $0.4,0.6,0.3, \ldots$, then Turbo may start crawling as follows:

Determine the largest constant $C>0$ with the following property: for every sequence of positive real numbers $c_{1}, c_{2}, c_{3}, \ldots$ with $c_{i}<C$ for all $i$, Turbo can (after studying the sequence) ensure that there is some point on the circle that it will never visit or crawl across.

|

Alternative solution (to show that $C \leqslant \frac{1}{2}$ )

We consider the following related problem:

We assume instead that the snail Chet is moving left and right on the real line. Find the size $M$ of the smallest (closed) interval, that we cannot force Chet out of, using a sequence of real numbers $d_{i}$ with $0<d_{i}<1$ for all $i$.

Then $C=1 / M$. Indeed if for every sequence $c_{1}, c_{2}, \ldots$, with $c_{i}<C$ there exists a point that Turbo can avoid, then the circle can be cut open at the avoided point and mapped to an interval of size $M$ such that Chet can stay inside this interval for any sequence of the from $c_{1} / C, c_{2} / C, \ldots$, see Figure 5 . However, all sequences $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$ with $d_{i}<1$ can be written in this form. Similarly if for every sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$, there exists an interval of length smaller or equal $M$ that we cannot force Chet out of, this projects to a subset of the circle, that we cannot force Turbo out of using any sequence of the form $d_{1} / M, d_{2} / M, \ldots$. These are again exactly all the sequences with elements in $[0, C)$.

Figure 5: Chet and Turbo equivalence

Claim: $M \geqslant 2$.

Proof. Suppose not, so $M<2$. Say $M=2-2 \varepsilon$ for some $\varepsilon>0$ and let $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$ be a minimal interval, that Chet cannot be forced out of. Then we can force Chet arbitrarily close to $\pm(1-\varepsilon)$. In partiular, we can force Chet out of $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$ by minimality of $M$. This means that there exists a sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$ for which Chet has to leave $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$, which means he ends up either in the interval $\left[-1+\varepsilon,-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right)$ or in the interval $\left(1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon\right]$.

Now consider the sequence,

$$

d_{1}, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad d_{2}, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, d_{3}, \ldots

$$

obtained by adding the sequence $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ in between every two steps. We claim that this sequence forces Chet to leave the larger interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Indeed no two consecutive elements in the sequence $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon, \quad 1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ can

have the same sign, because the sum of any two consecutive terms is larger than $2-2 \varepsilon$ and Chet would leave the interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. It follows that the $\left(1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon\right.$ )'s and the ( $1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon$ )'s cancel out, so the position after $d_{k}$ is the same as before $d_{k+1}$. Hence, the positions after each $d_{k}$ remain the same as in the original sequence. Thus, Chet is also forced to the boundary in the new sequence.

If Chet is outside the interval $\left[-1+\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon, 1-\frac{4}{3} \varepsilon\right]$, then Chet has to move $1-\frac{7}{6} \varepsilon$ towards 0 , and ends in $\left[-\frac{1}{6} \varepsilon, \frac{1}{6} \varepsilon\right]$. Chet then has to move by $1-\frac{2}{3} \varepsilon$, which means that he has to leave the interval $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Indeed the absolute value of the final position is at least $1-\frac{5}{6} \varepsilon$. This contradicts the assumption, that we cannot force Chet out of $[-1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon]$. Hence $M \geqslant 2$ as needed.

|

{

"exam": "EGMO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 4.",

"resource_path": "EGMO/segmented/en-2023-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2. ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2023"

}

|

We are given a positive integer $s \geqslant 2$. For each positive integer $k$, we define its twist $k^{\prime}$ as follows: write $k$ as $a s+b$, where $a, b$ are non-negative integers and $b<s$, then $k^{\prime}=b s+a$. For the positive integer $n$, consider the infinite sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots$ where $d_{1}=n$ and $d_{i+1}$ is the twist of $d_{i}$ for each positive integer $i$.

Prove that this sequence contains 1 if and only if the remainder when $n$ is divided by $s^{2}-1$ is either 1 or $s$.

|

First, we consider the difference $k-k^{\prime \prime}$. If $k=a s+b$ as in the problem statement, then $k^{\prime}=b s+a$. We write $a=l s+m$ with $m, l$ non-negative numbers and $m \leq s-1$. This gives $k^{\prime \prime}=m s+(b+l)$ and hence $k-k^{\prime \prime}=(a-m) s-l=l\left(s^{2}-1\right)$.

We conclude

Fact 1.1. $k \geq k^{\prime \prime}$ for every every $k \geq 1$

Fact 1.2. $s^{2}-1$ divides the difference $k-k^{\prime \prime}$.

Fact 1.2 implies that the sequences $d_{1}, d_{3}, d_{5}, \ldots$ and $d_{2}, d_{4}, d_{6}, \ldots$ are constant modulo $s^{2}-1$. Moreover, Fact 1.1 says that the sequences are (weakly) decreasing and hence eventually constant. In other words, the sequence $d_{1}, d_{2}, d_{3}, \ldots$ is 2 -periodic modulo $s^{2}-1$ (from the start) and is eventually 2-periodic.

Now, assume that some term in the sequence is equal to 1 . The next term is equal to $1^{\prime}=s$ and since the sequence is 2 -periodic from the start modulo $s^{2}-1$, we conclude that $d_{1}$ is either equal to 1 or $s$ modulo $s^{2}-1$. This proves the first implication.

To prove the other direction, assume that $d_{1}$ is congruent to 1 or $s$ modulo $s^{2}-1$. We need the observation that once one of the sequences $d_{1}, d_{3}, d_{5}, \ldots$ or $d_{2}, d_{4}, d_{6}, \ldots$ stabilises, then their value is less than $s^{2}$. This is implied by the following fact.

Fact 1.3. If $k=k^{\prime \prime}$, then $k=k^{\prime \prime}<s^{2}$.