problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Show that there are infinitely many integers $n$ such that the base 4 representation of $n^{2}$ contains only 1s and 2s.

|

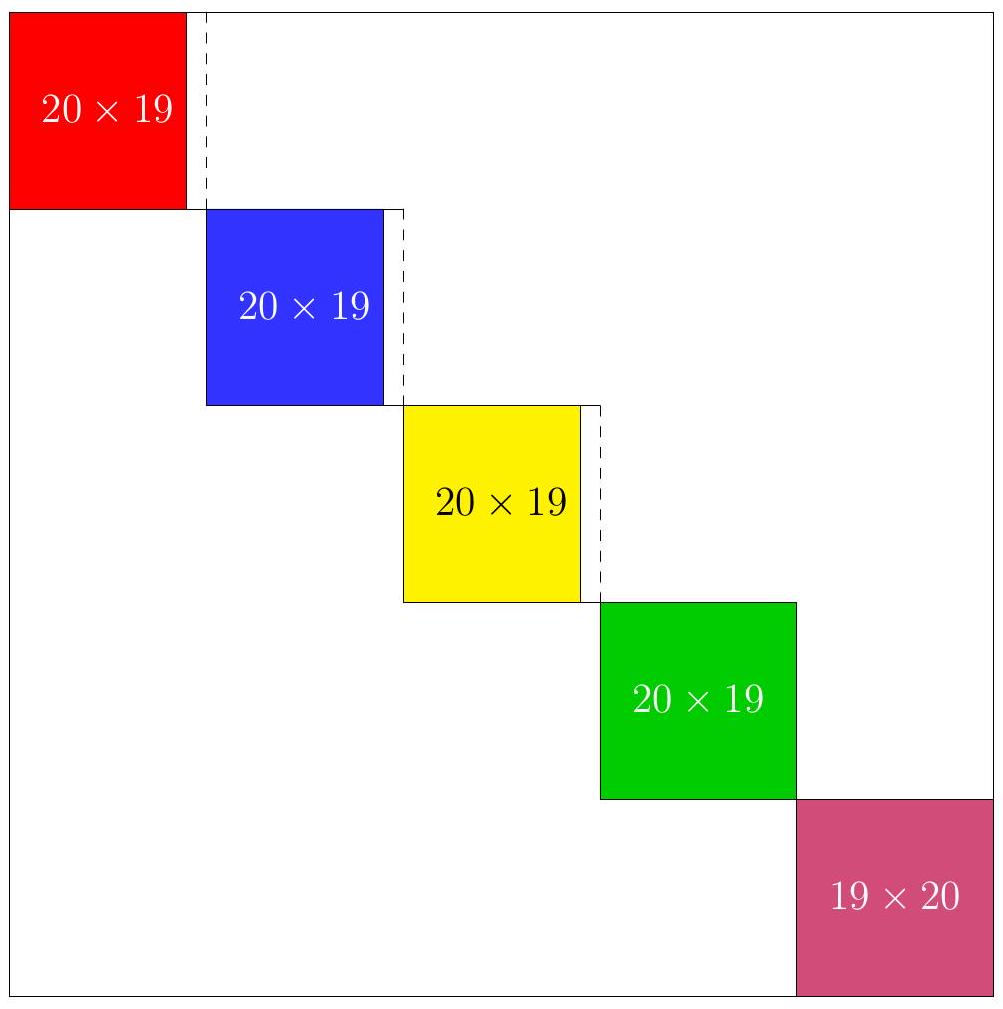

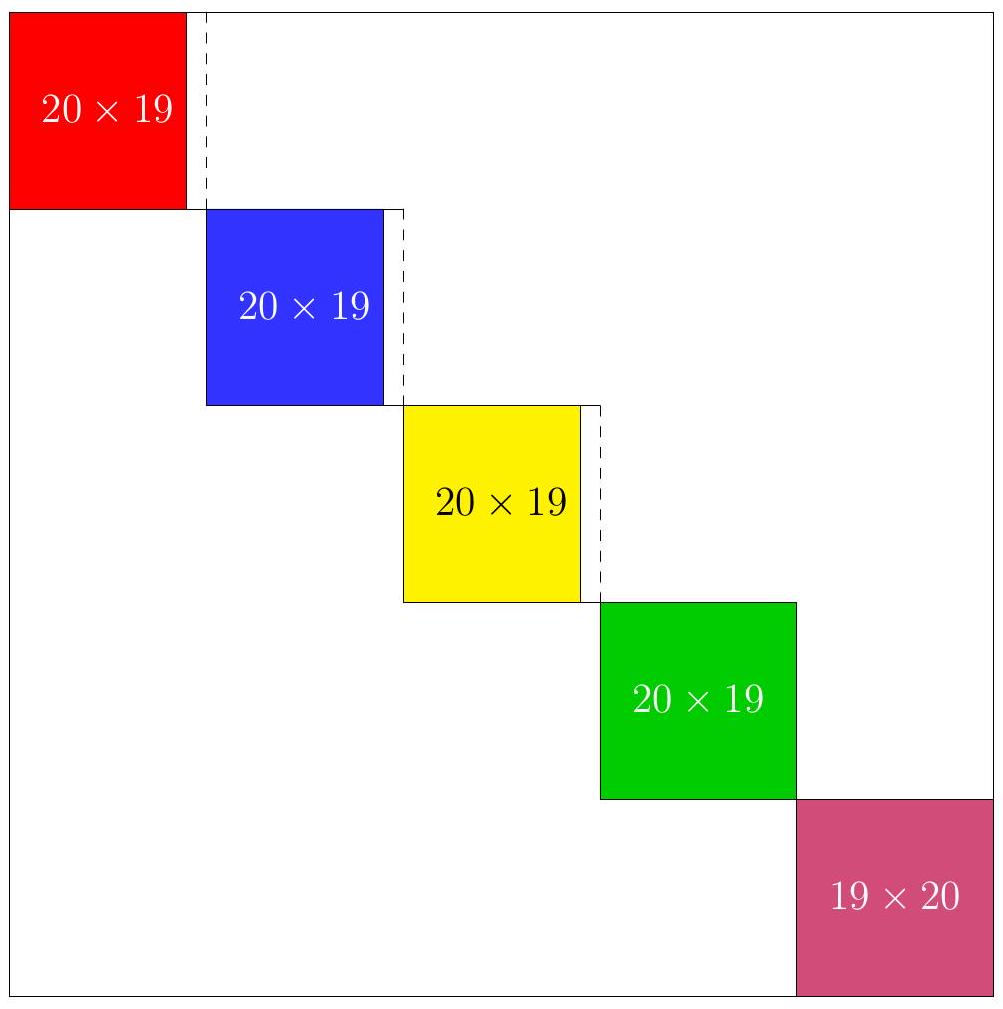

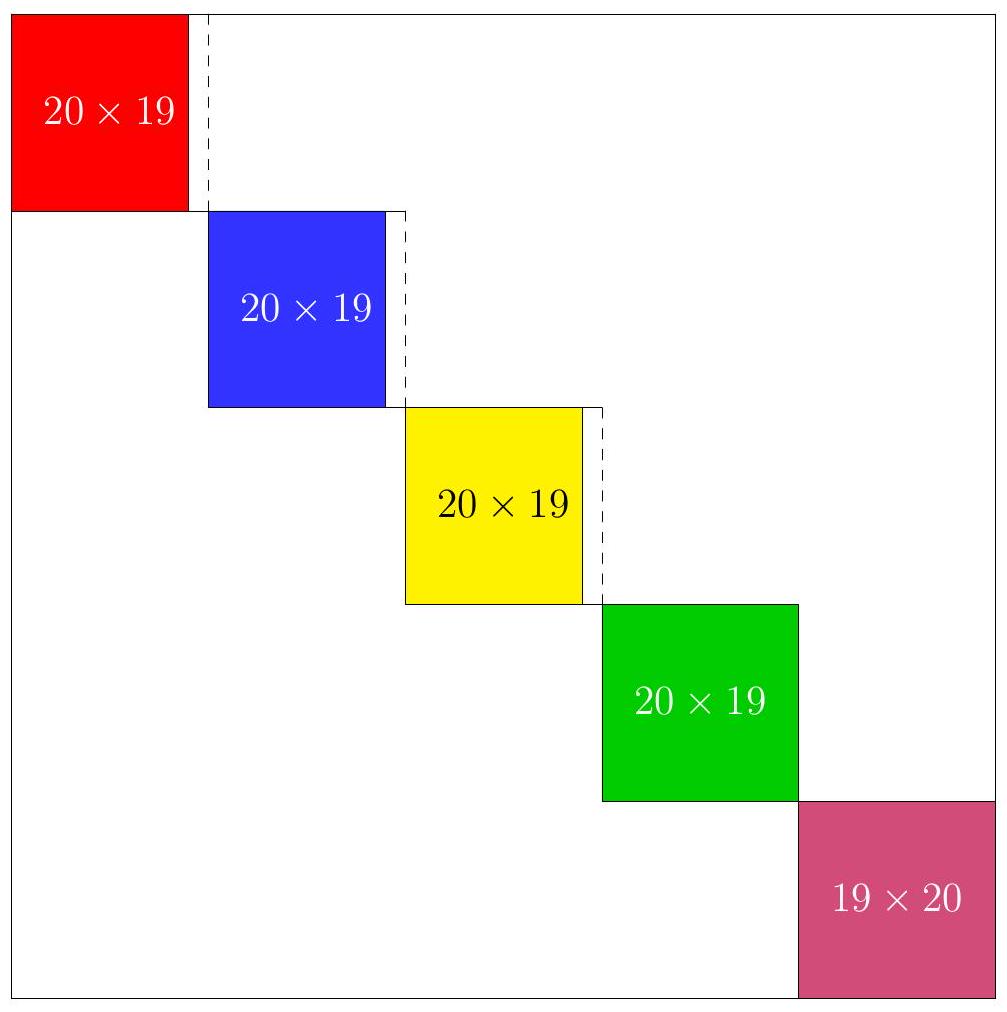

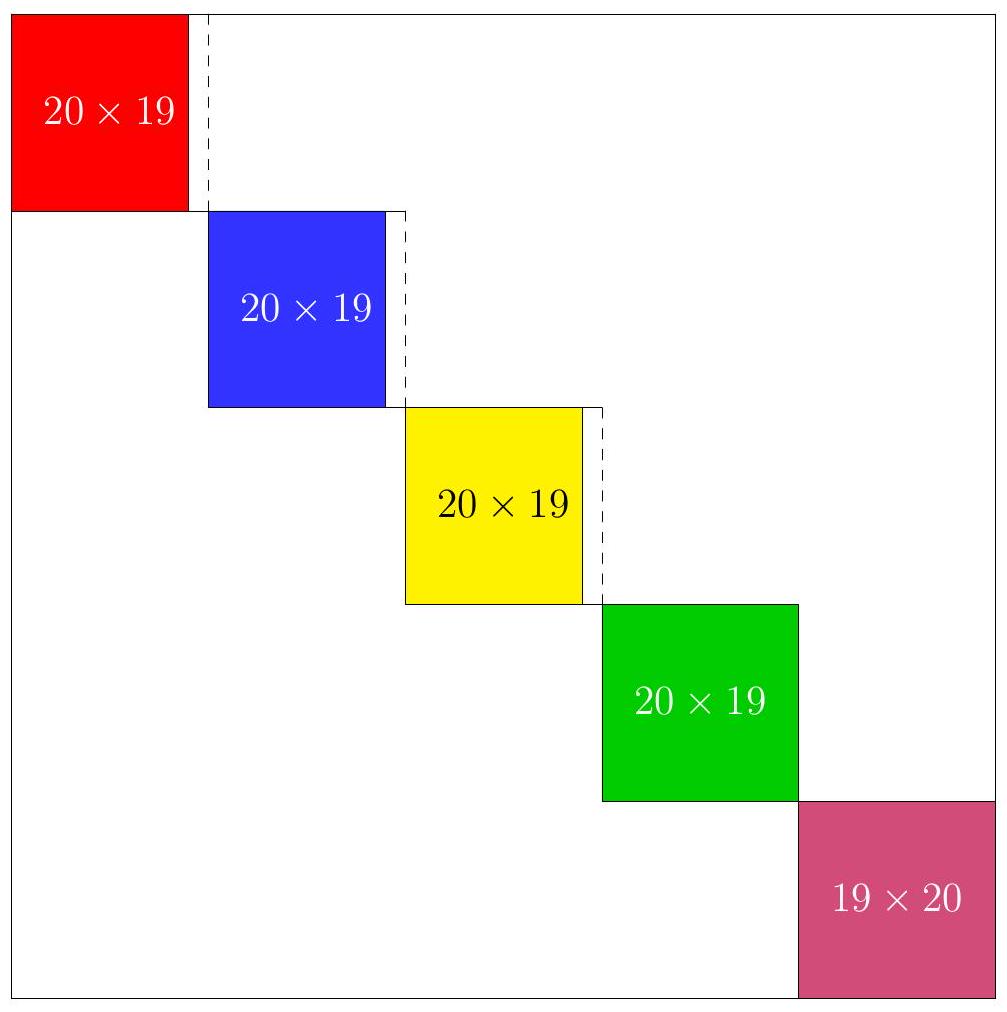

We show a slightly stronger result, which is better suited for an inductive reasoning: there are infinitely many integers $n$ such that the base 4 representation of $n^{2}$ contains only 1s and 2s, and such that the first and last digit of the base 4 representation of $n^{2}$ is 1. A first example is the number $5^{2}=25=121_{4}$. Then, we show that if we have such an $n$, we can construct a new one that is strictly greater, which will prove that there are infinitely many integers with the desired property.

Let $n$ be such that the base 4 representation of $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ contains only 1s and 2s, and starts and ends with a 1. Suppose this representation contains $k$ digits. We then set $m=2^{2 k-1} \cdot n+n$. We have

$$

\mathrm{m}^{2}=4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}+4^{\mathrm{k}} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}+\mathrm{n}^{2}

$$

In base 4, $m^{2}$ is thus made up of three copies of $n^{2}$, with $n^{2}$ and $4^{k} \cdot n^{2}$ being two adjacent disjoint copies, and $4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}$ and $4^{\mathrm{k}} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}$ sharing exactly one power of 4 in their representation, namely $4^{2 k-1}$. But by hypothesis, the coefficients in front of 1 and in front of $4^{k-1}$ of $n^{2}$ are 1s, so the coefficient in front of $4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1}$ of $\mathrm{m}^{2}$ is a 2. Furthermore, all other coefficients in the base 4 representation of $\mathrm{m}^{2}$ appeared in that of $\mathrm{n}^{2}$, and are therefore indeed 1s or 2s. Finally, the first and last coefficients of the base 4 representation of $\mathrm{m}^{2}$, namely the coefficients in front of $4^{0}$ and $4^{3 \mathrm{k}-2}$, are indeed 1s by the inductive hypothesis.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Montrer qu'il existe une infinité d'entiers $n$ tels que l'écriture de $n^{2}$ en base 4 ne contient que des 1 et des 2 .

|

On montre un résultat un peu plus fort, qui se prête mieux à un raisonnement par récurrence : il existe une infinité d'entiers $n$ tels que l'écriture de $n^{2}$ en base 4 ne contient que des 1 et des 2 , et tels que le premier et le dernier chiffre de l'écriture en base 4 de $n^{2}$ vaut 1 . Un premier exemple est le nombre $5^{2}=25=121_{4}$. Ensuite, on montre que si l'on a un tel n , on peut en construire un nouveau qui lui est strictement supérieur, ce qui montrera bien qu'il existe une infinité d'entiers ayant la propriété recherchée.

Soit donc n tel que l'écriture de $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ en base 4 ne contient que des 1 et des 2 , et commence et se termine par un 1 . On suppose que cette écriture contient $k$ chiffres. On pose alors $m=2^{2 k-1} \cdot n+n$. On a

$$

\mathrm{m}^{2}=4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}+4^{\mathrm{k}} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}+\mathrm{n}^{2}

$$

En base $4, m^{2}$ est donc constitué de trois copies de $n^{2}$, avec $n^{2}$ et $4^{k} \cdot n^{2}$ qui sont deux copies disjointes adjacentes, et $4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}$ et $4^{\mathrm{k}} \cdot \mathrm{n}^{2}$ qui ont exactement une puissance de 4 en commun dans leur écriture, à savoir $4^{2 k-1}$. Mais par hypothèse, les coefficients devant 1 et devant $4^{k-1}$ de $n^{2}$ sont des 1 , donc le coefficient devant $4^{2 \mathrm{k}-1}$ de $\mathrm{m}^{2}$ est un 2 . En outre, tous les autres coefficients de l'écriture en base 4 de $\mathrm{m}^{2}$ apparaissaient dans celle de $\mathrm{n}^{2}$, et sont donc bien des 1 ou des 2 . Enfin, les premiers et derniers coefficients de l'écriture en base 4 de $\mathrm{m}^{2}$, à savoir les coefficients devant $4^{0}$ et $4^{3 \mathrm{k}-2}$, sont bien des 1 par hypothèse de récurrence.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 17.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-5-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 17",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

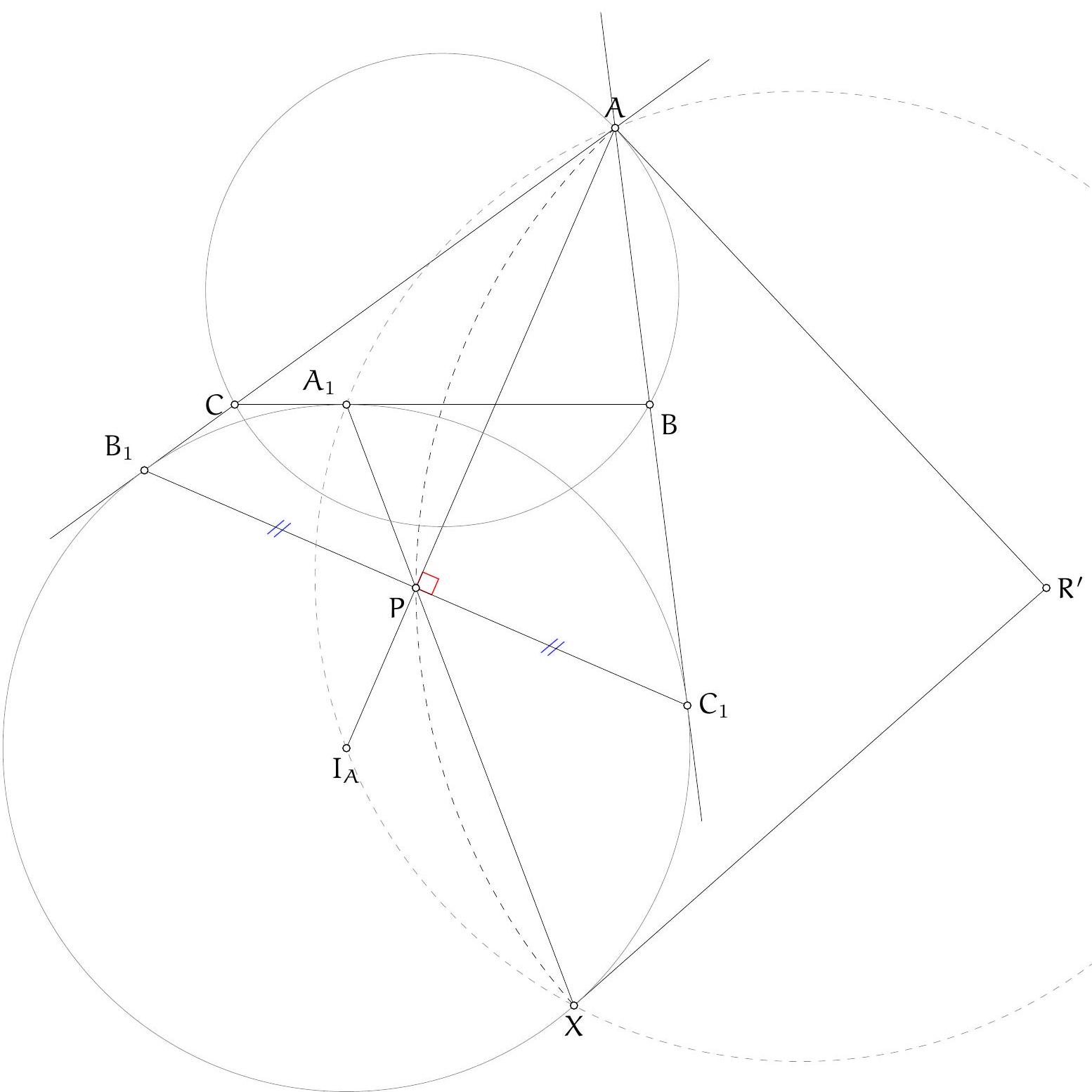

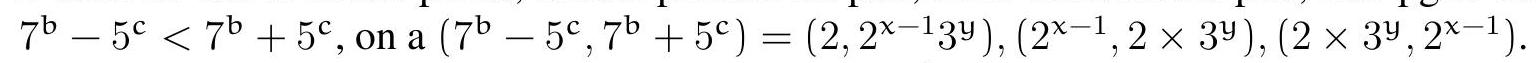

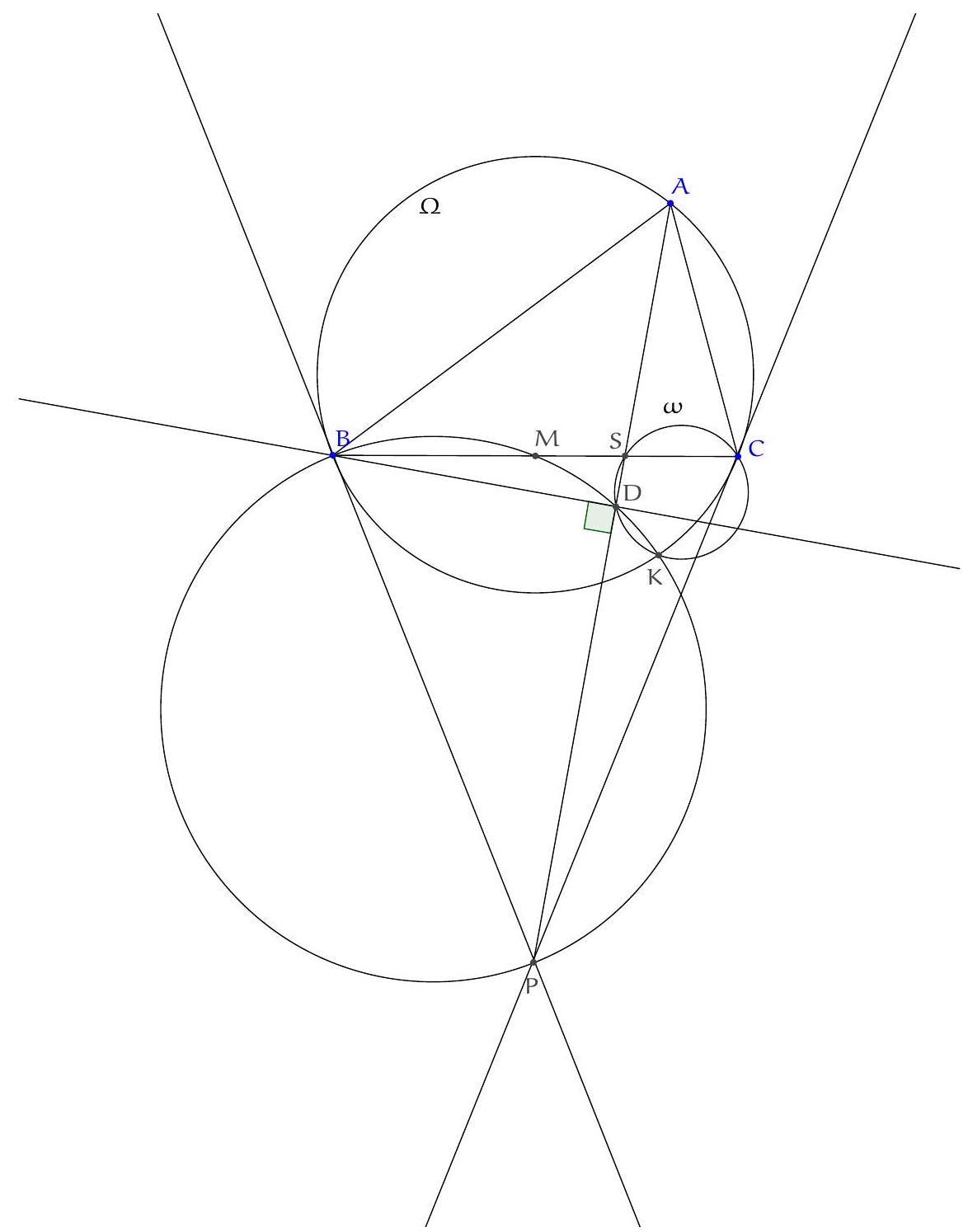

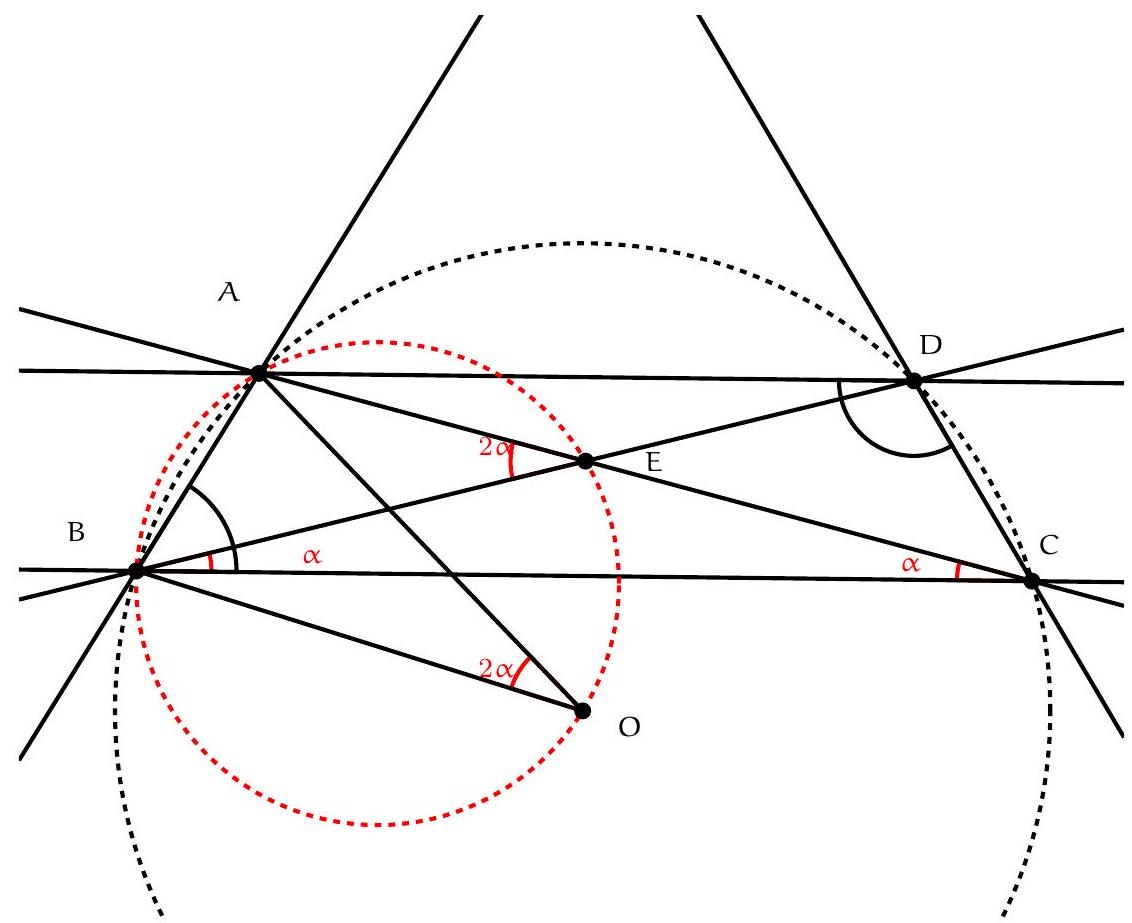

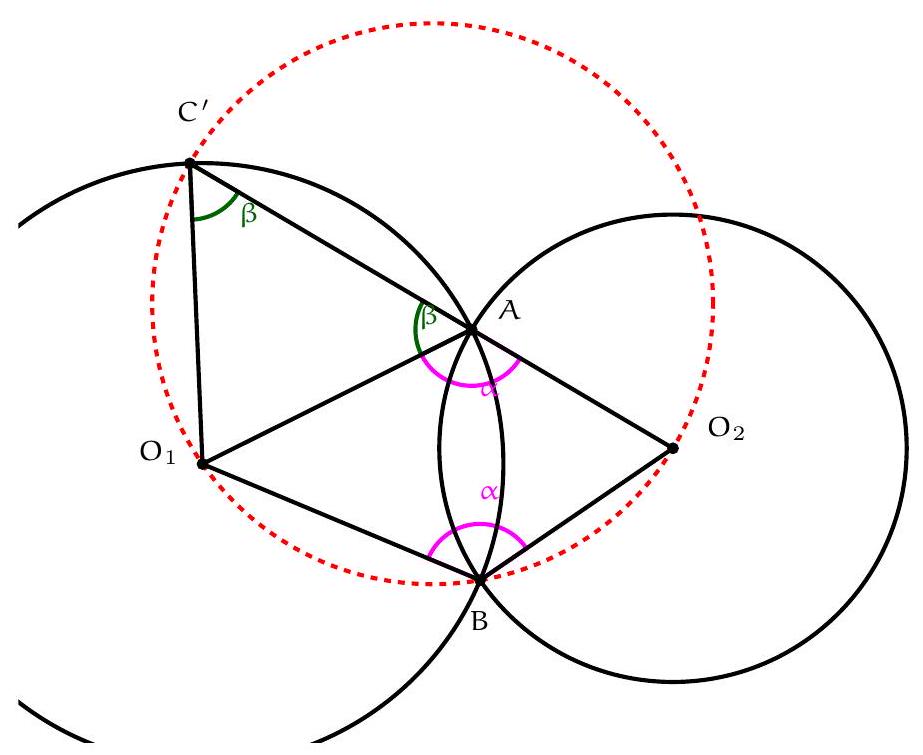

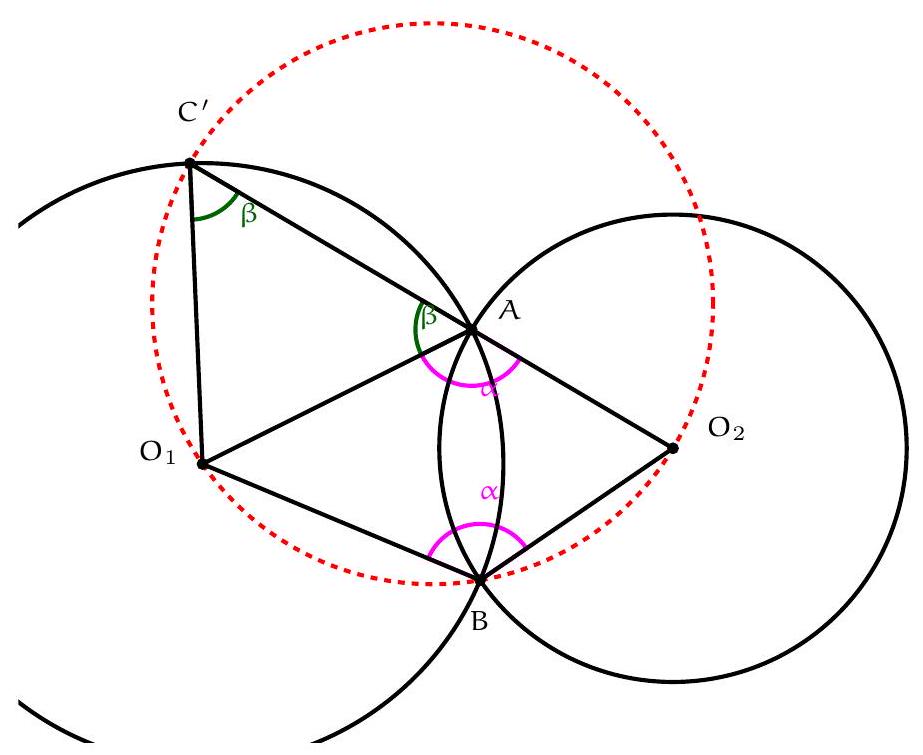

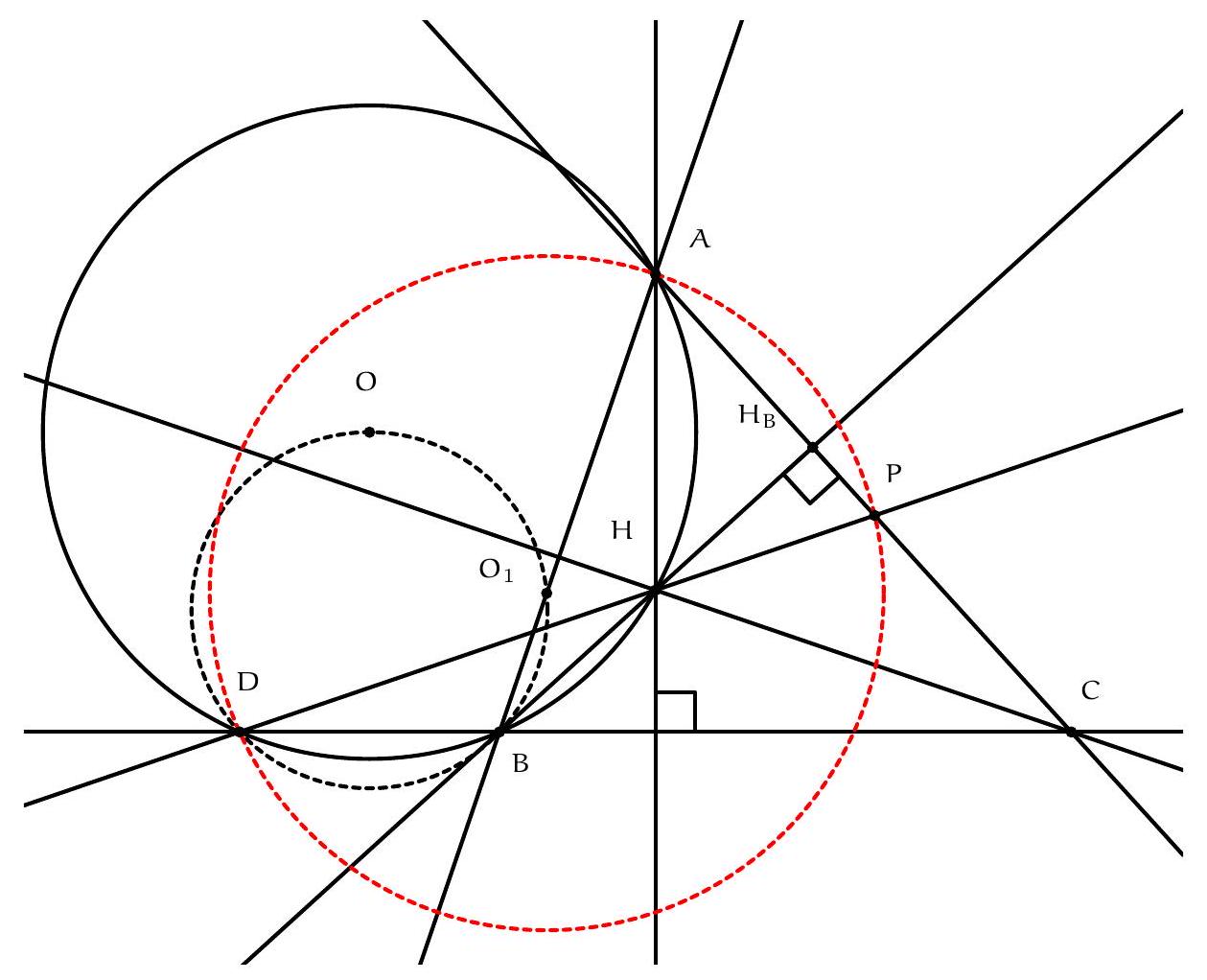

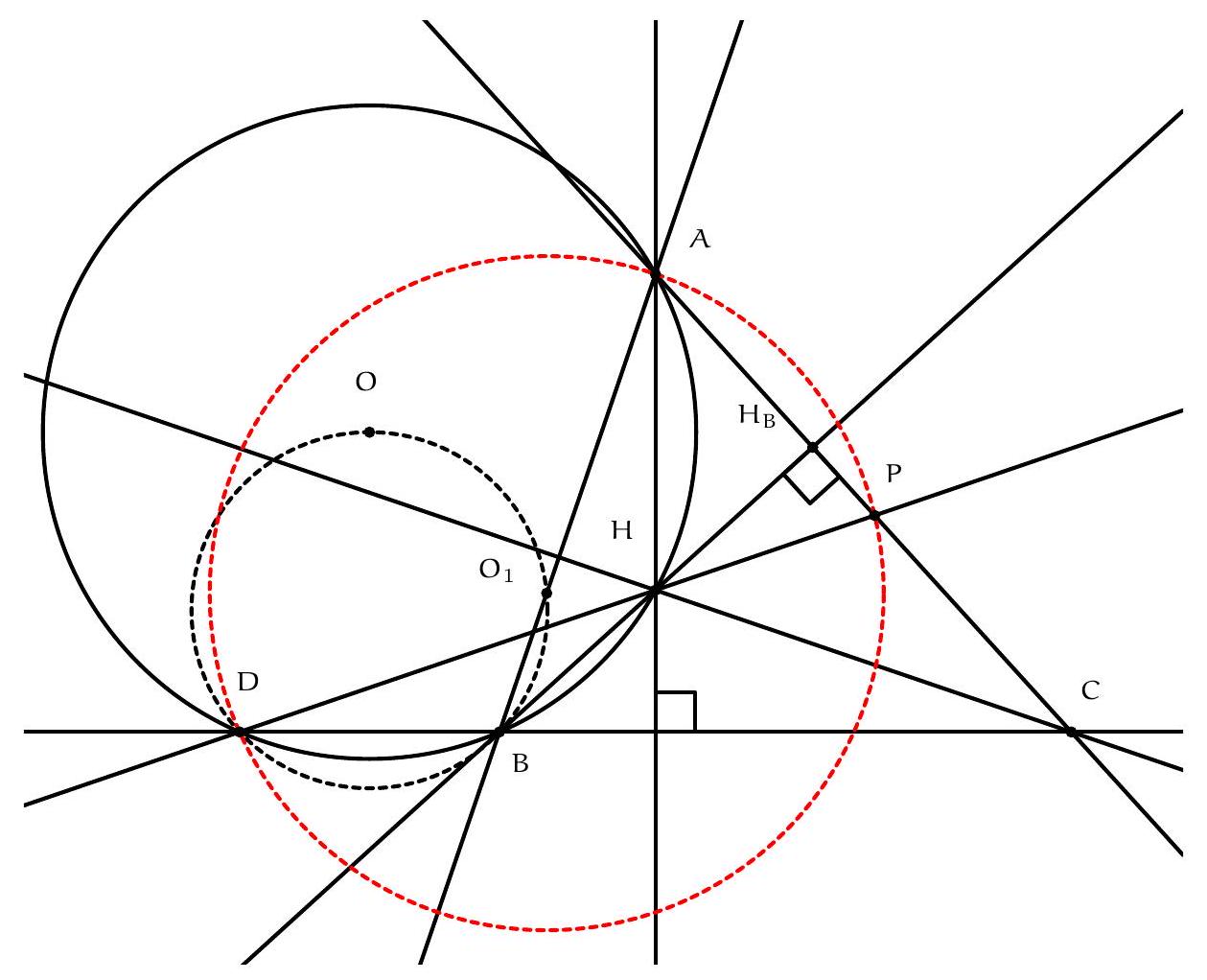

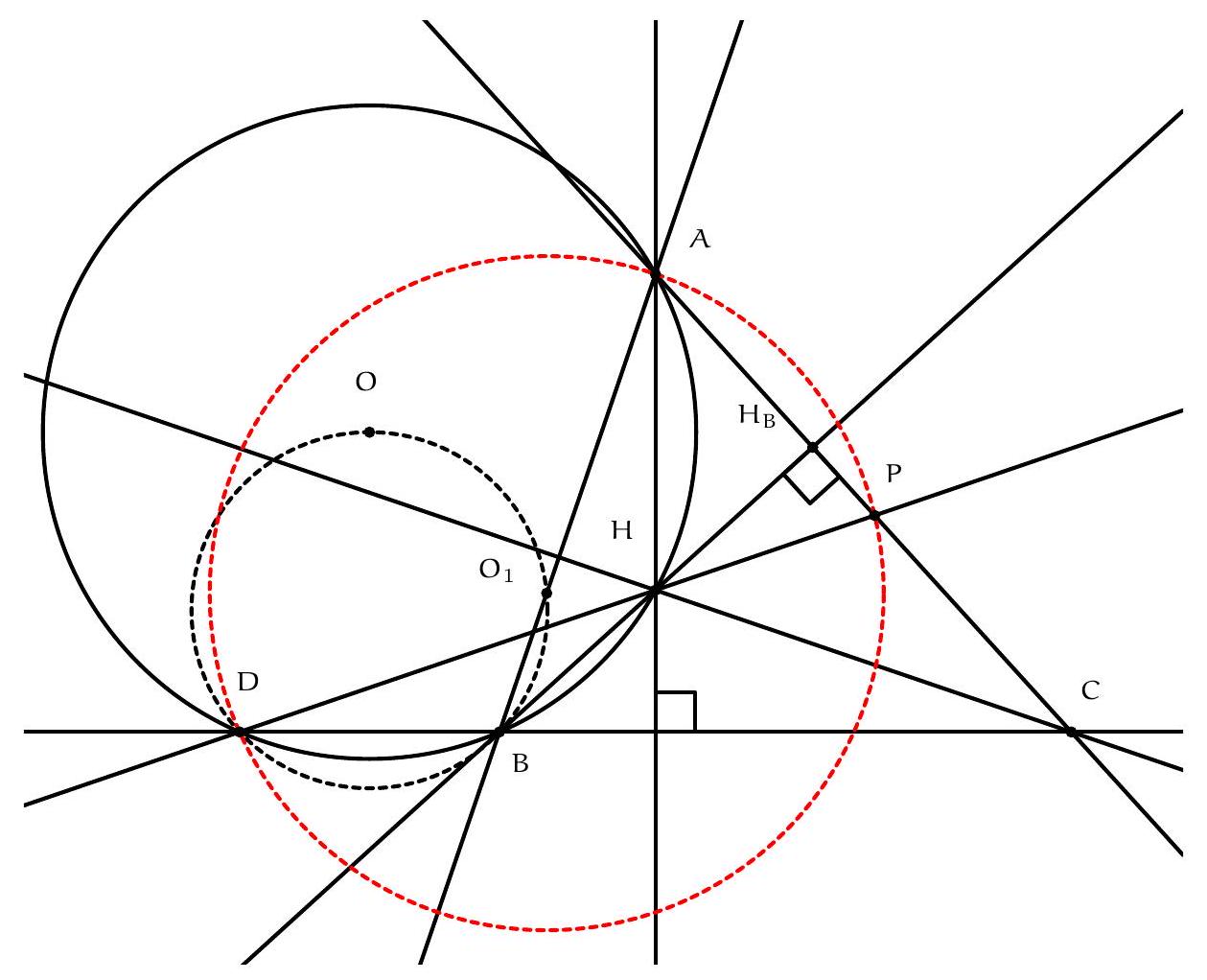

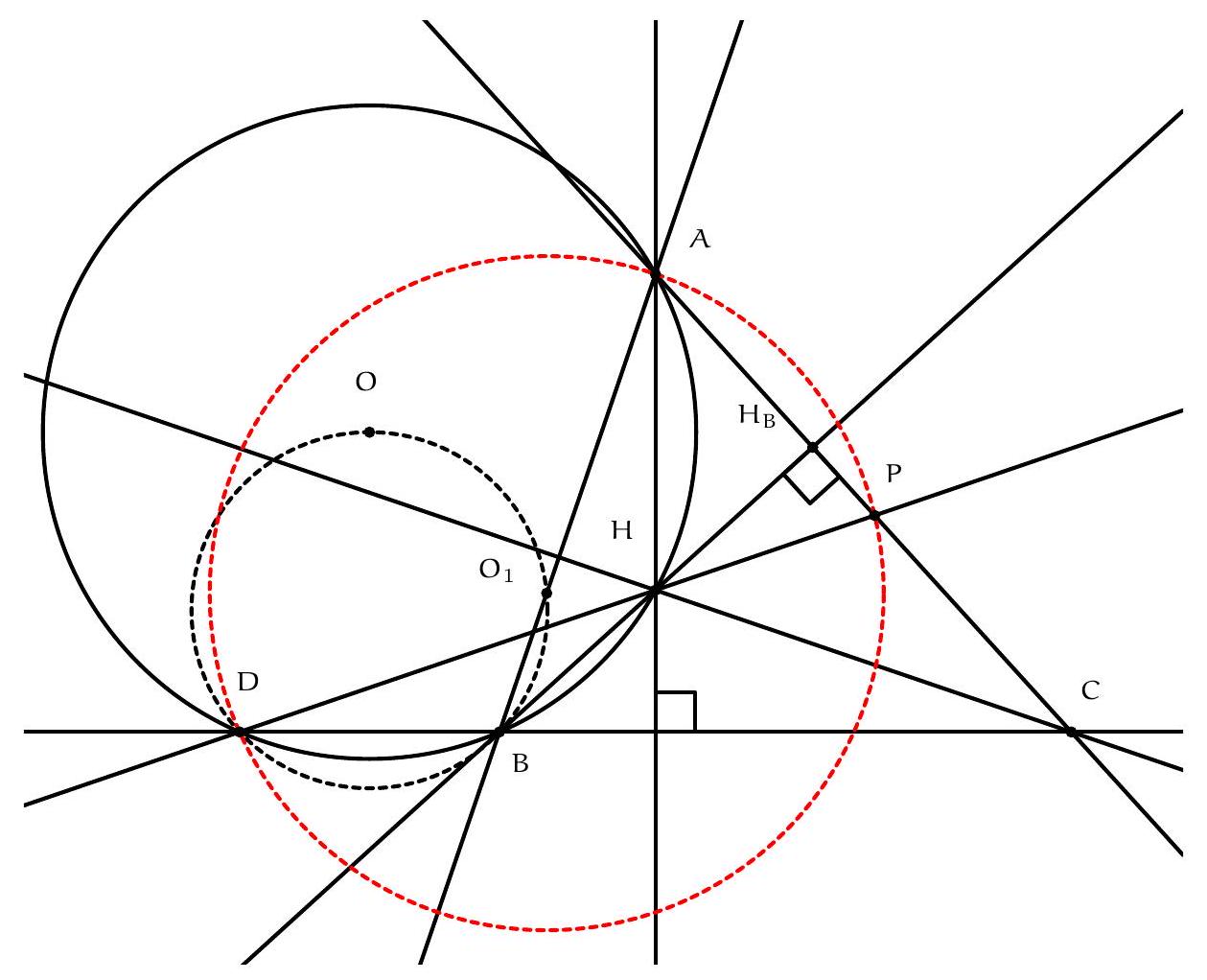

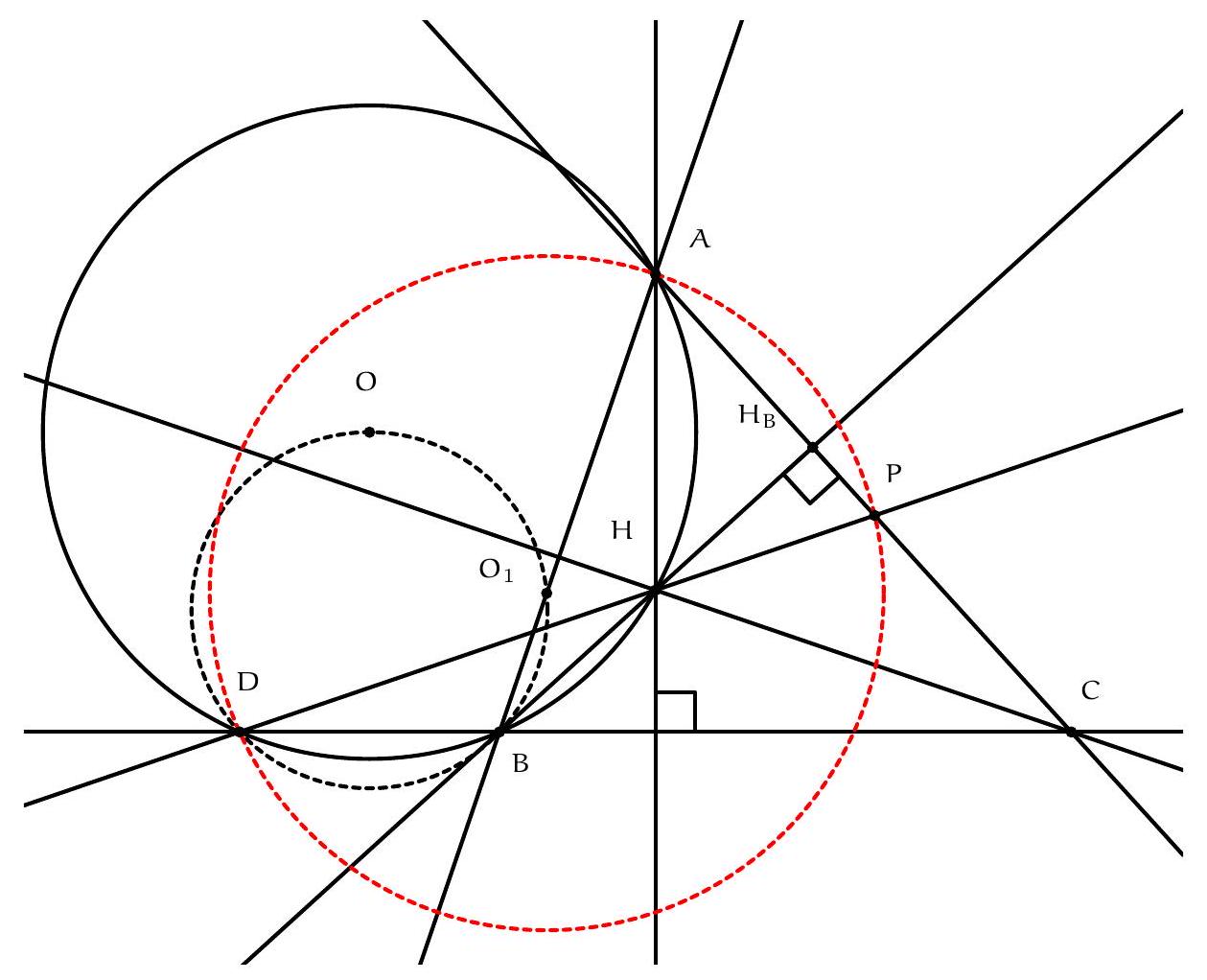

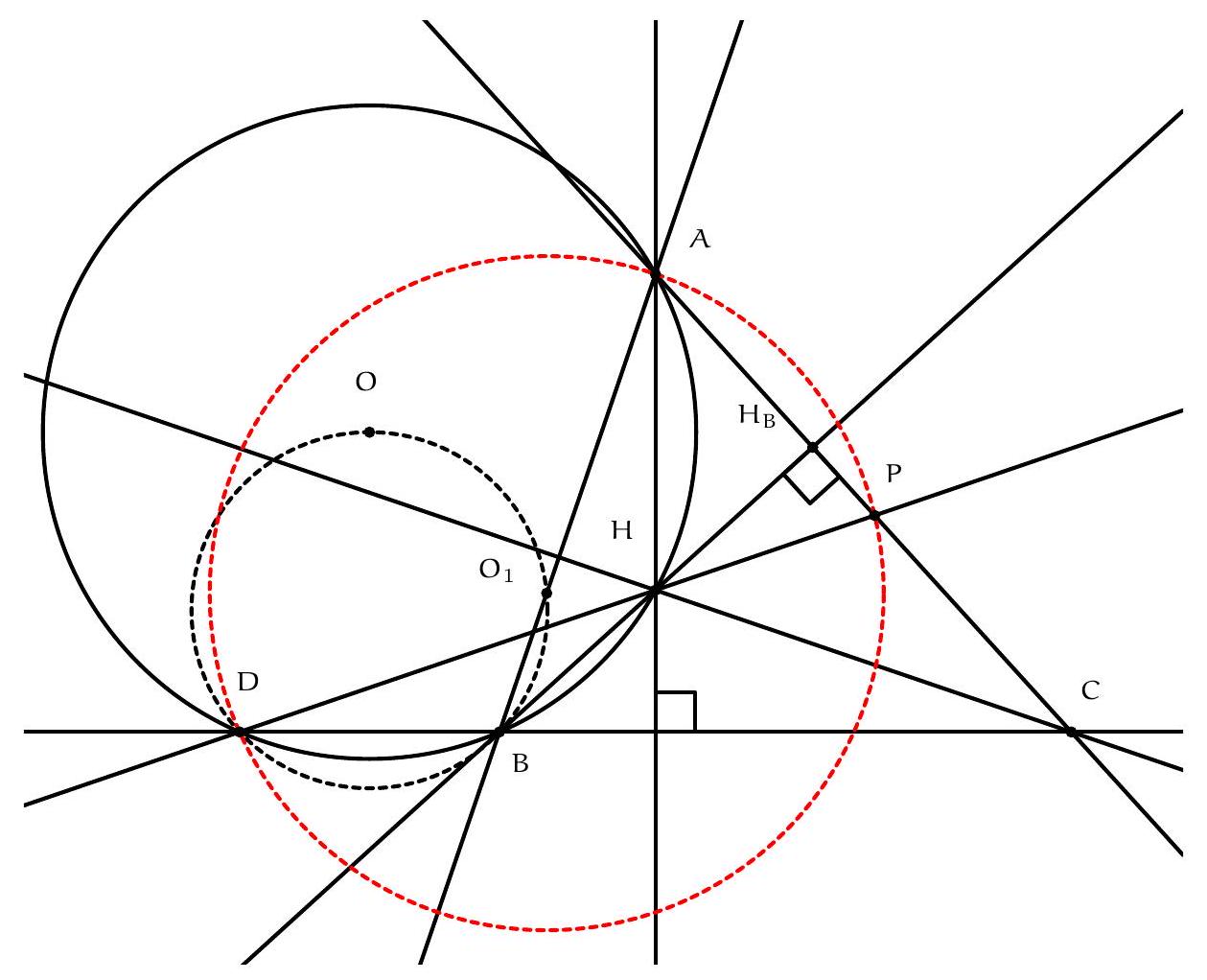

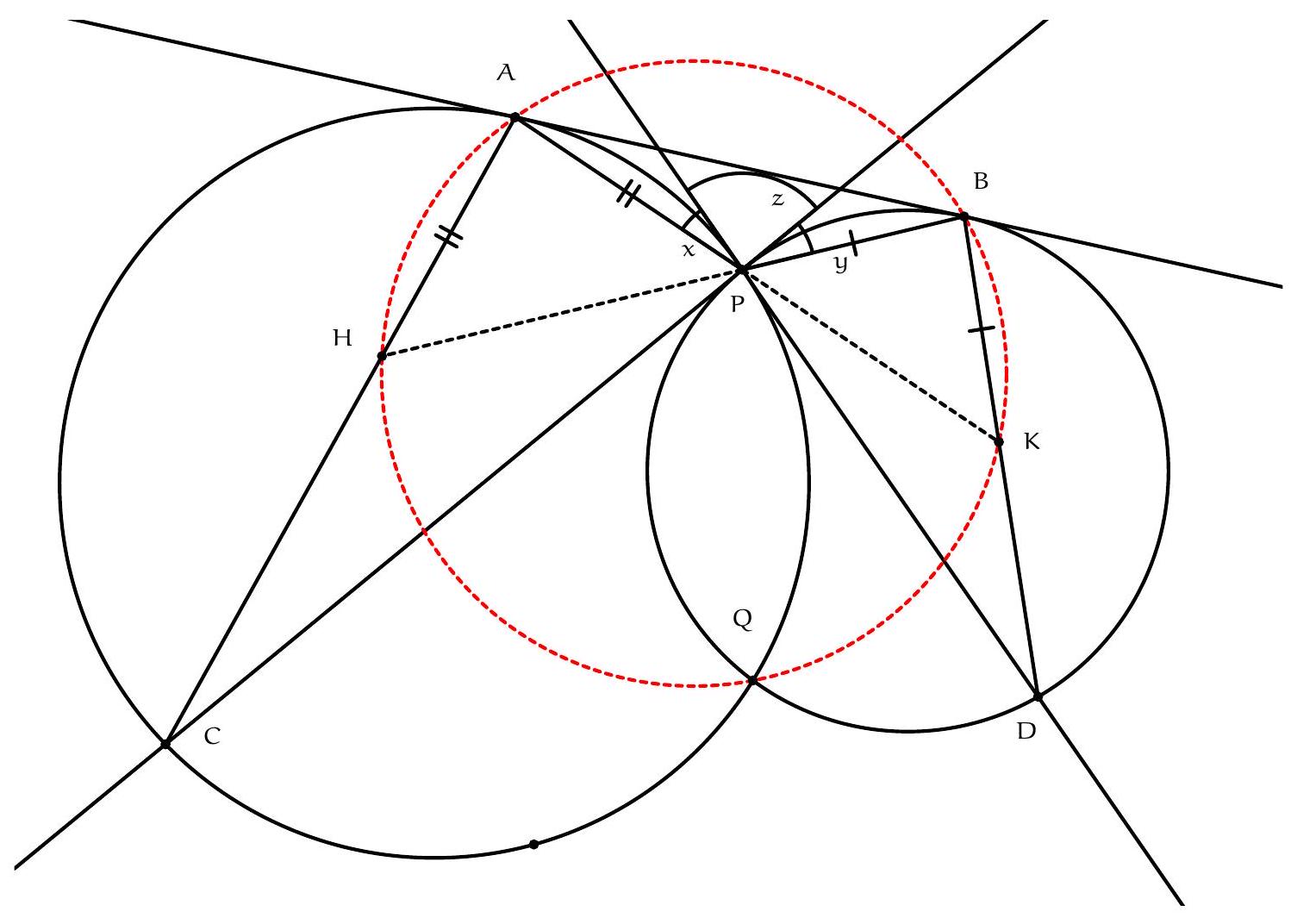

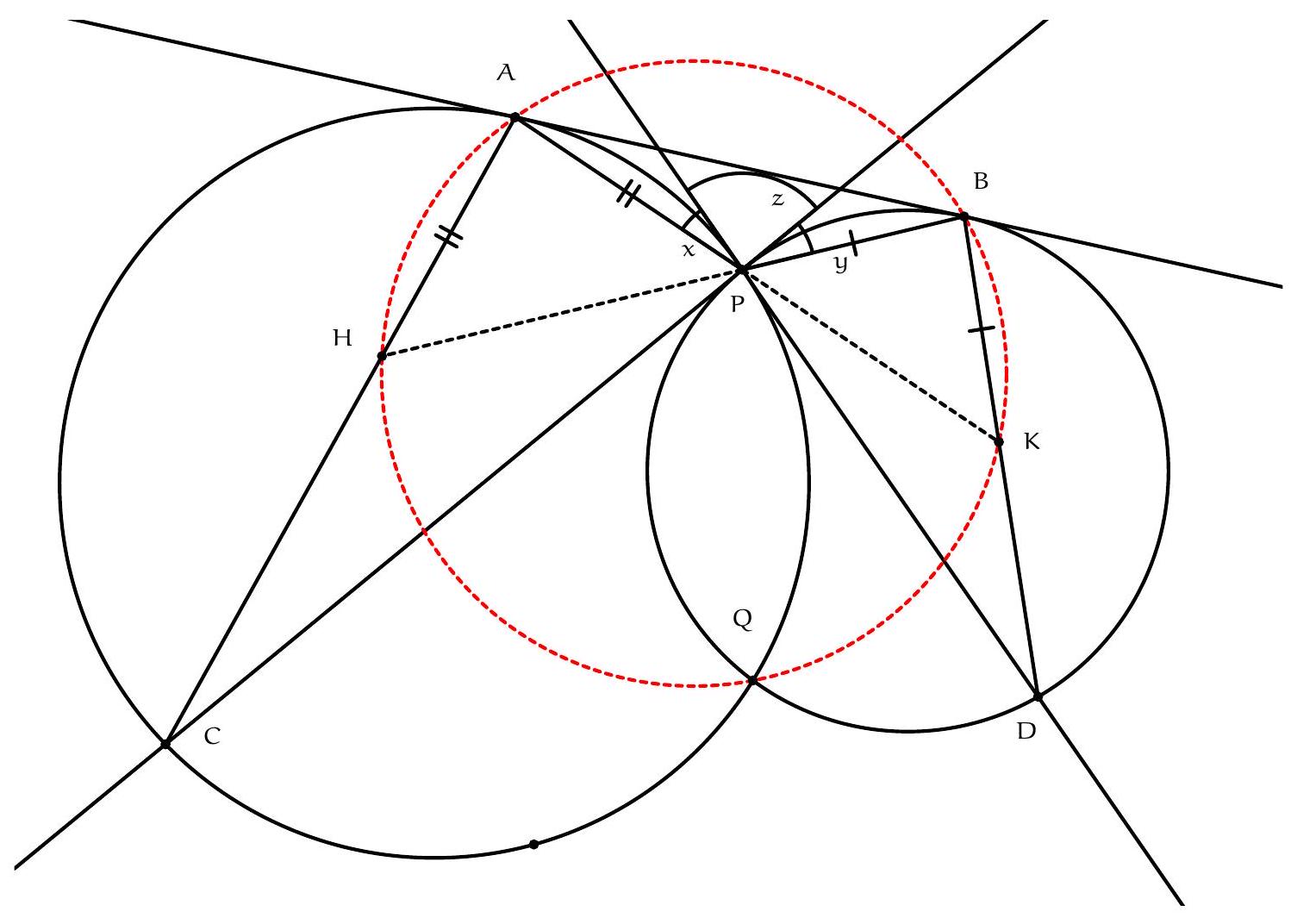

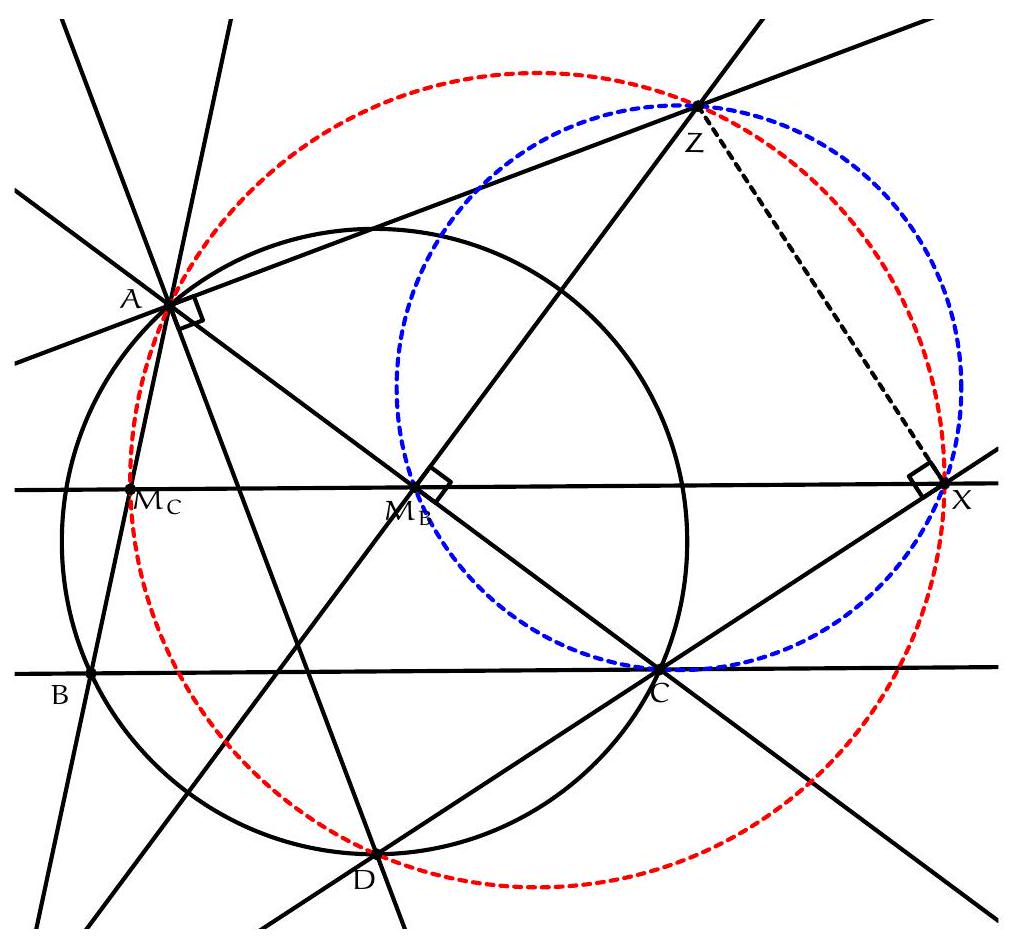

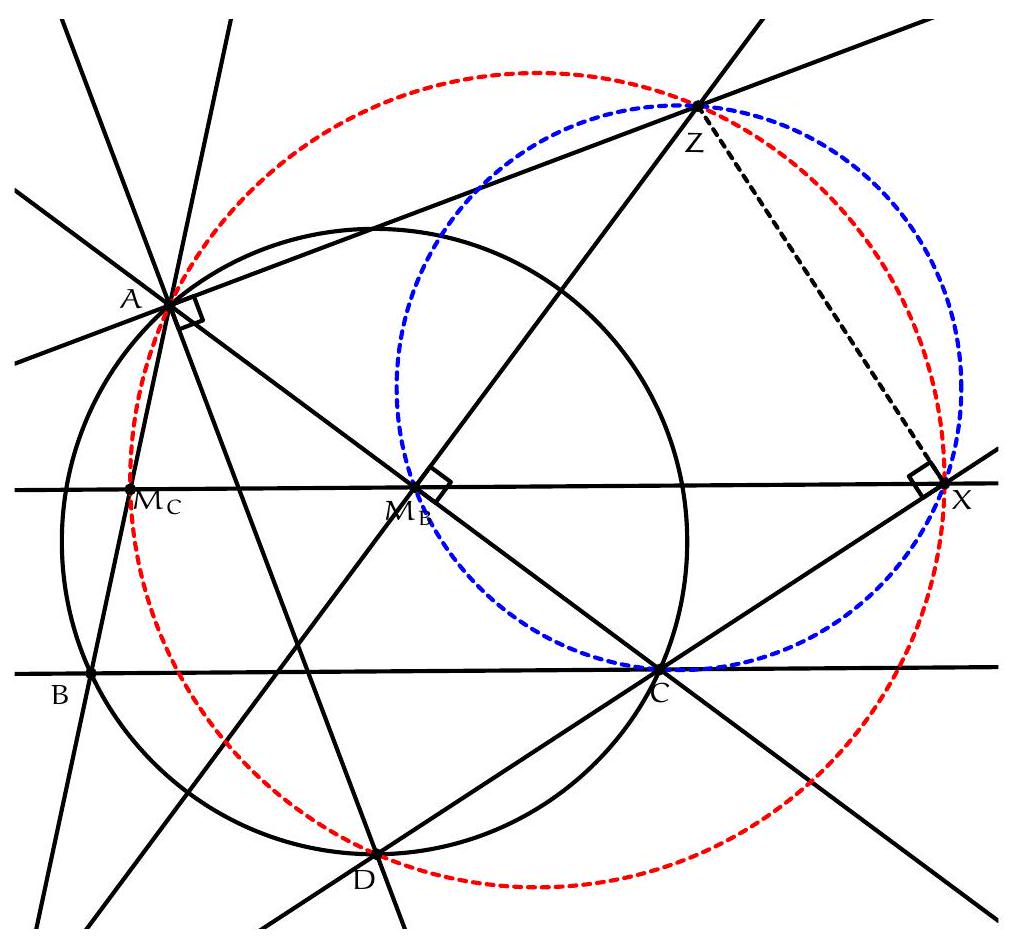

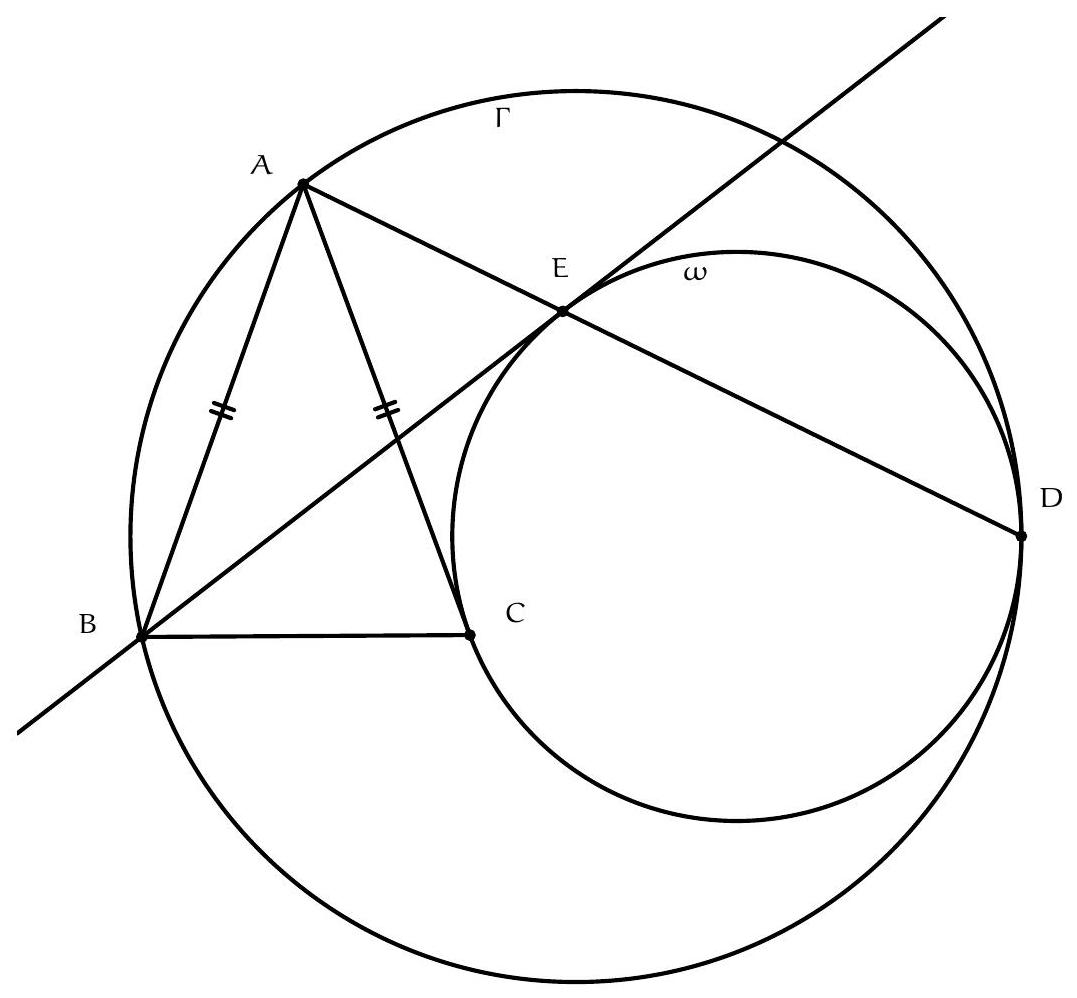

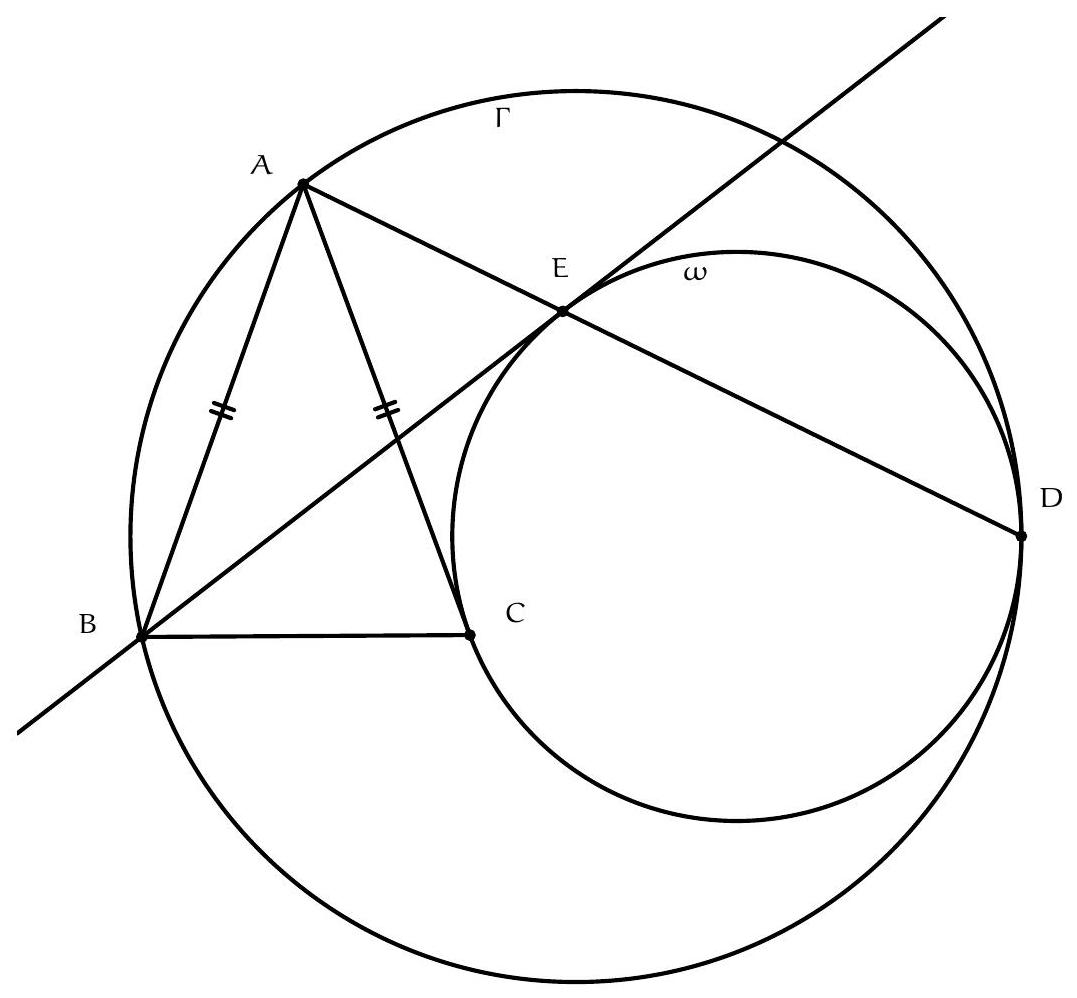

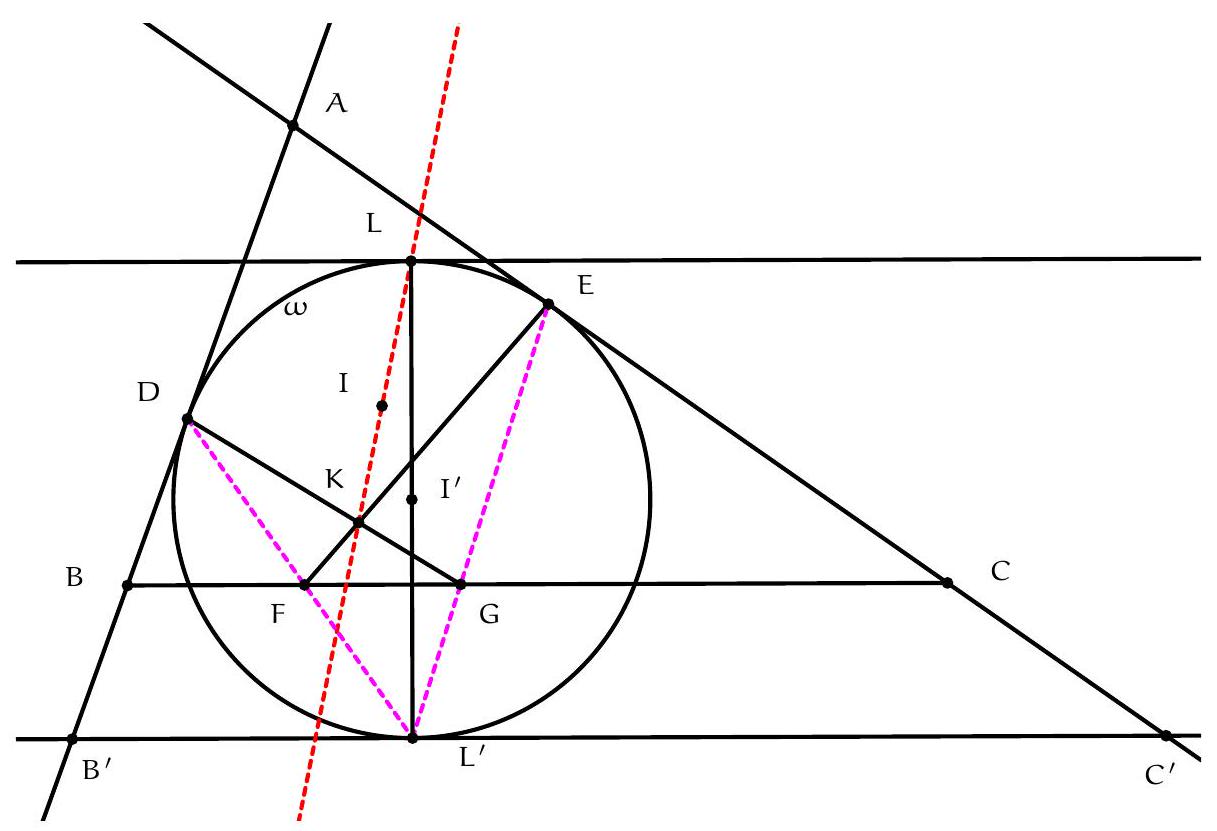

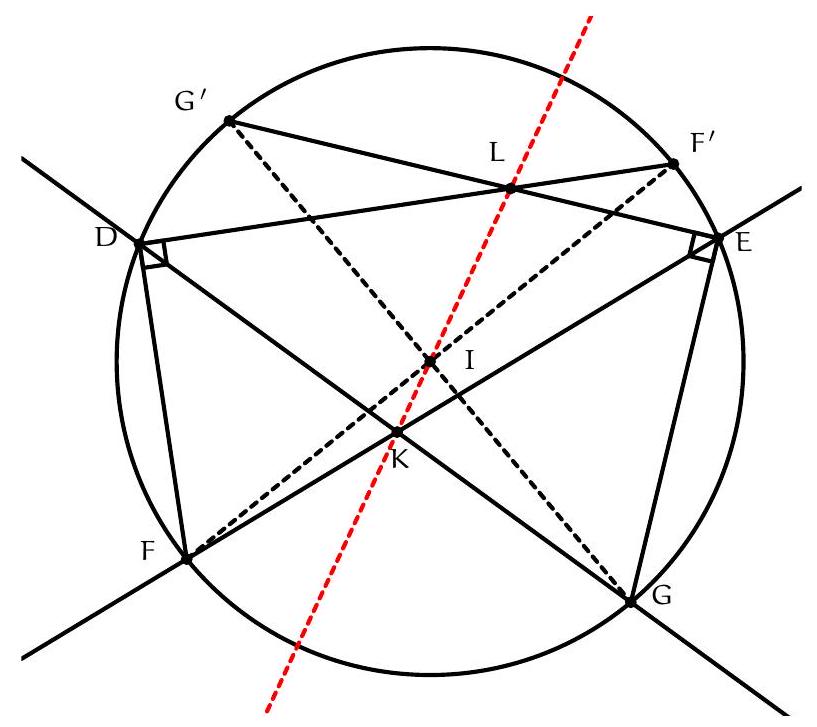

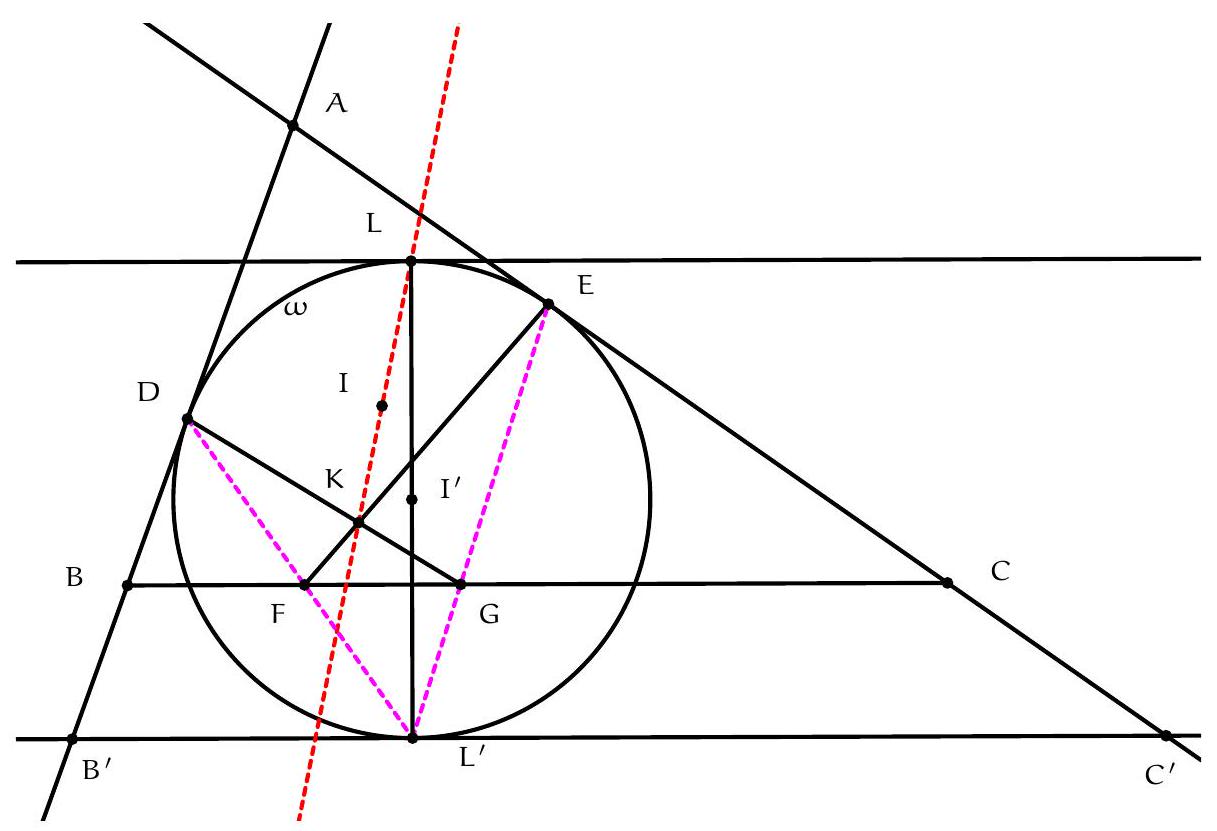

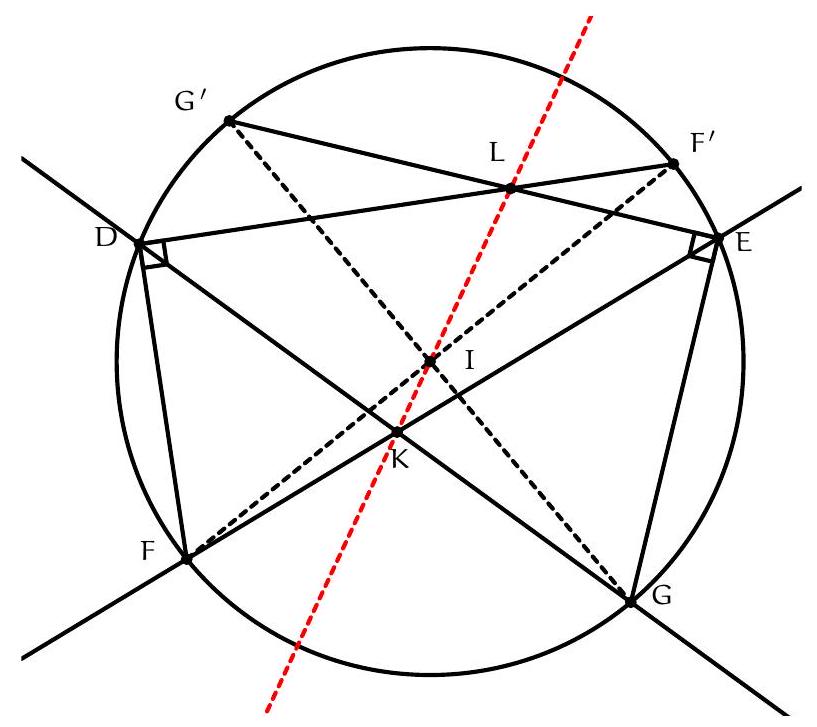

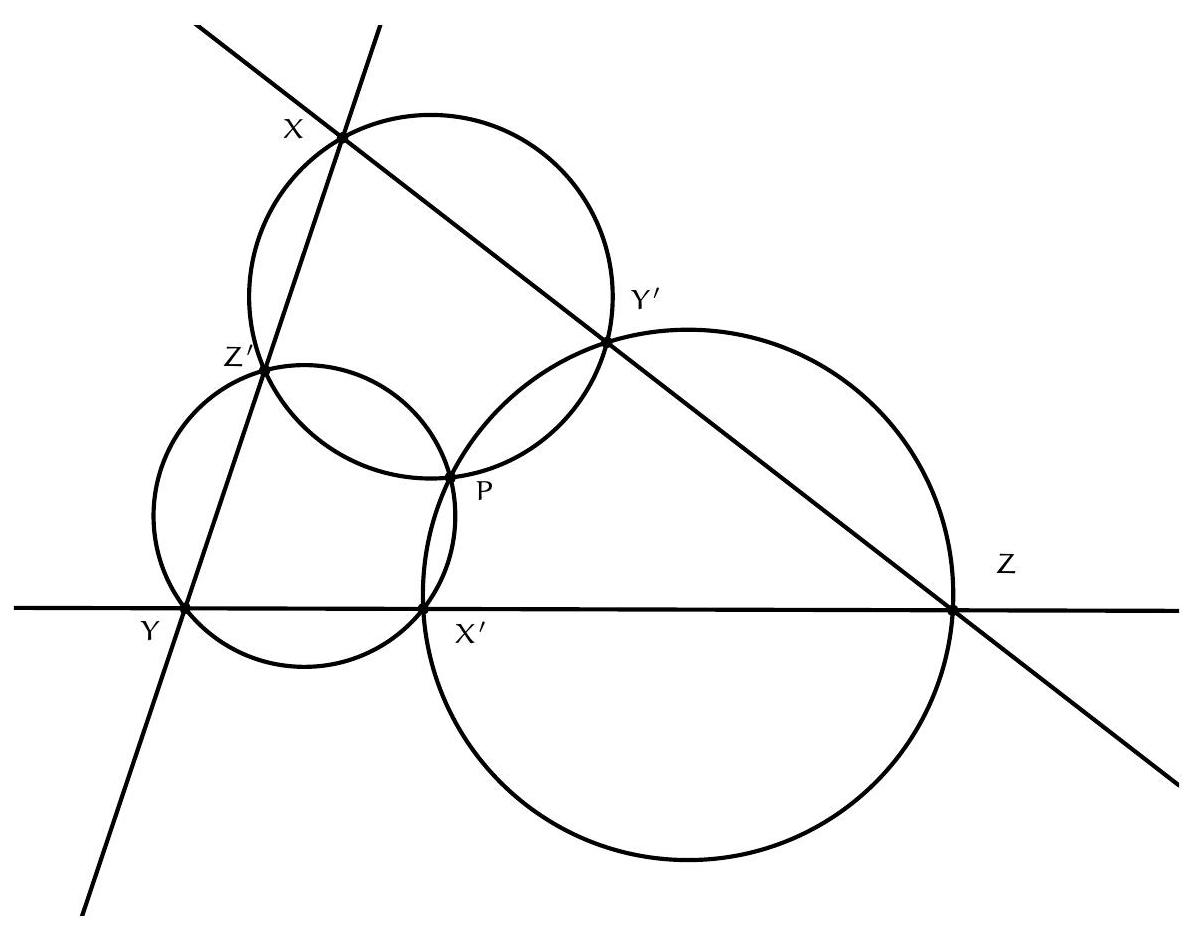

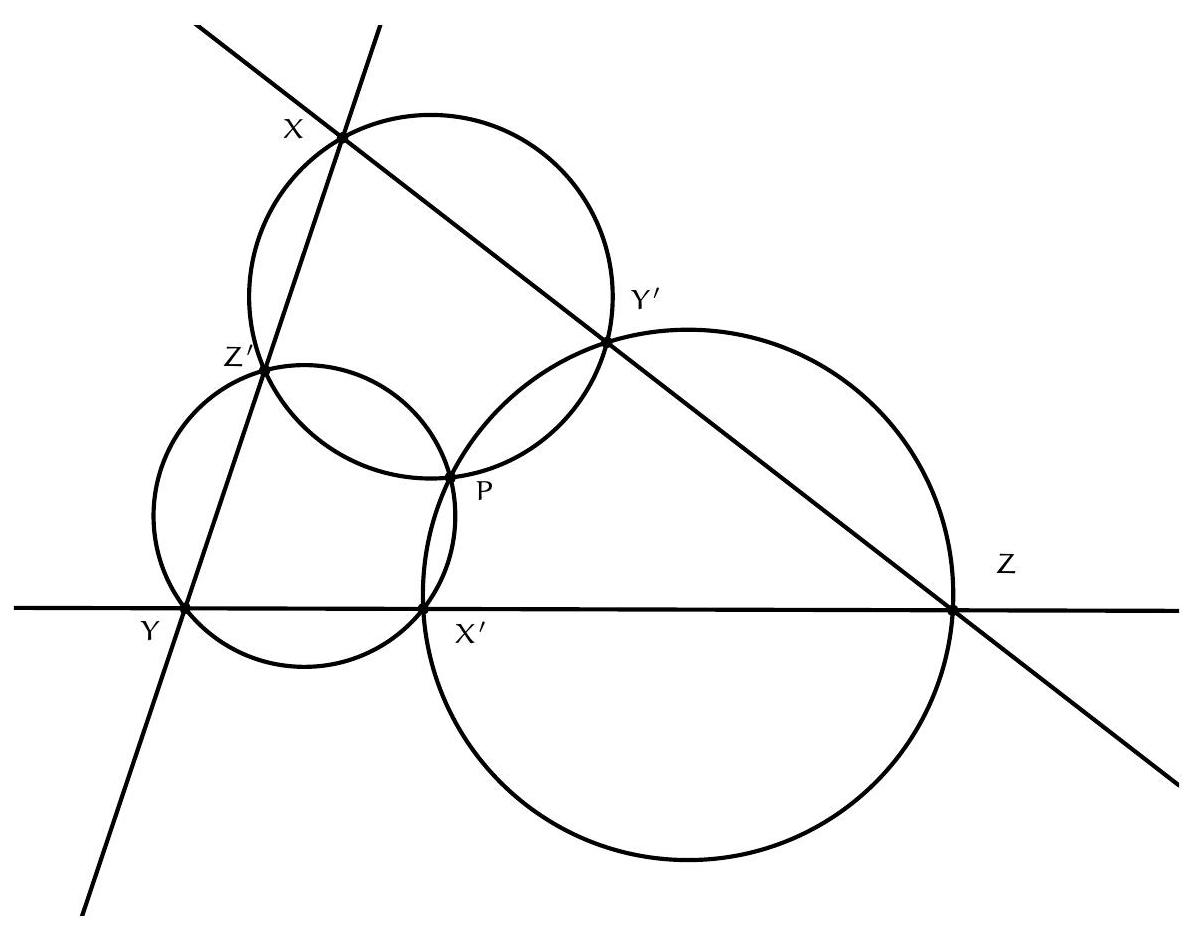

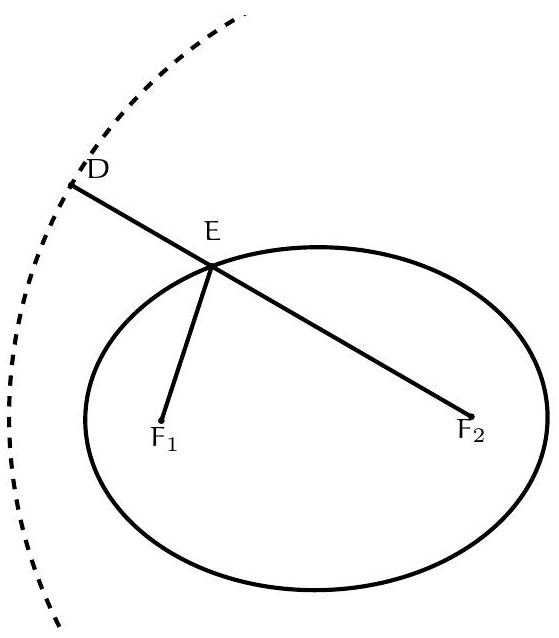

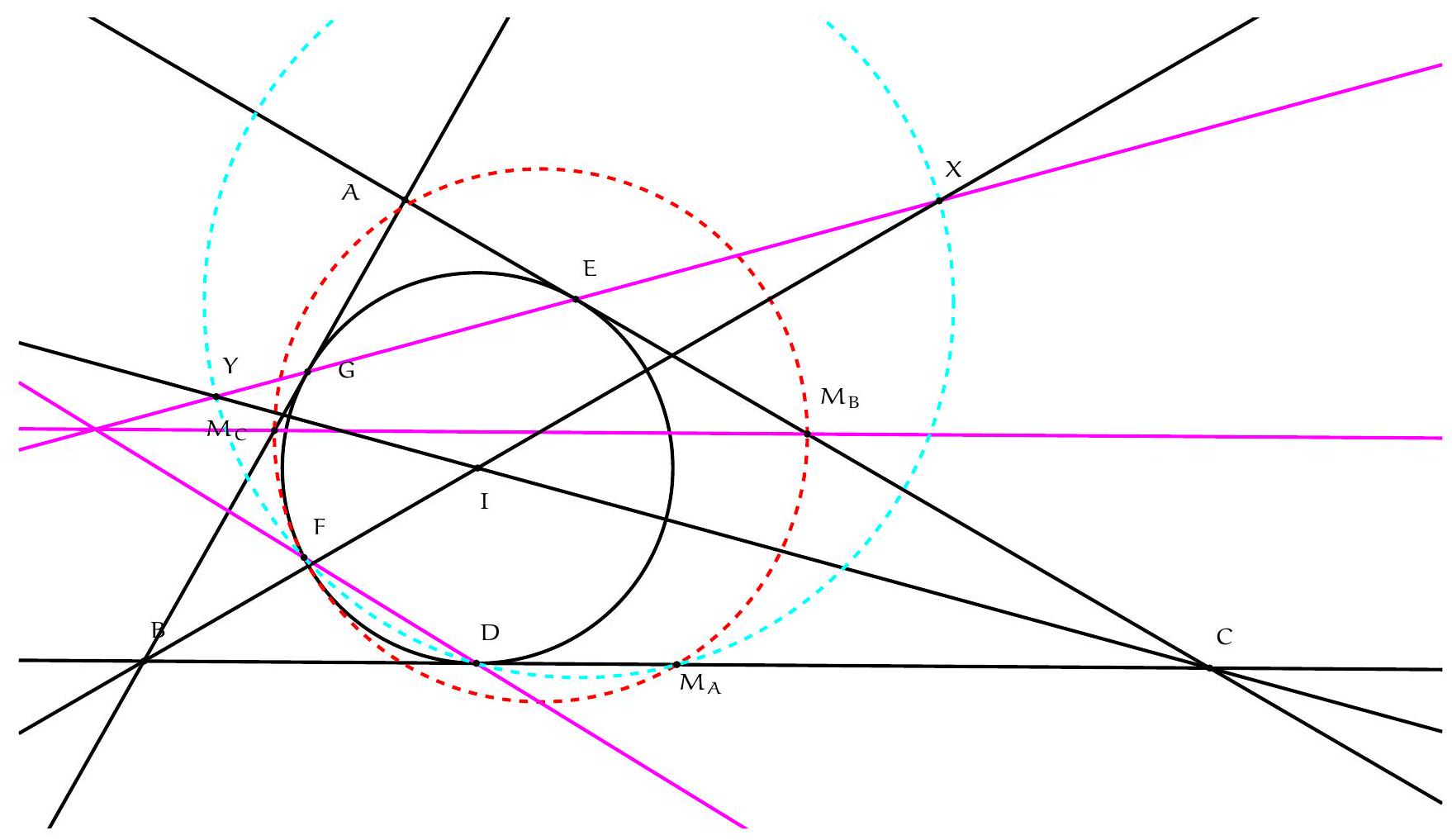

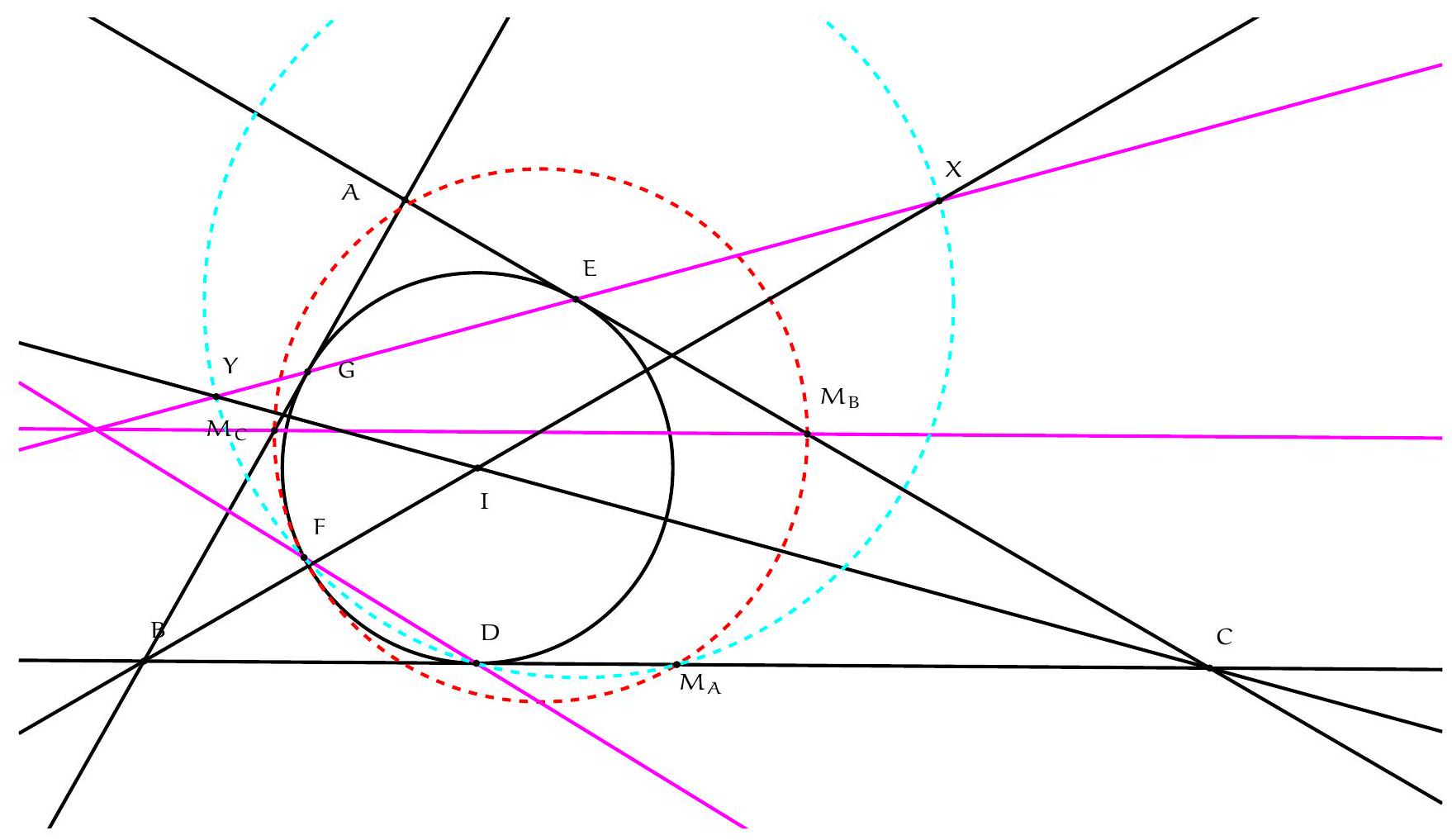

Let $ABC$ be a triangle and let $A_{1}, B_{1}$, and $C_{1}$ be the points of contact of the $A$-excircle, denoted by $\omega_{A}$, with the side $BC$ and the rays $[AC)$ and $[AB)$, respectively. Let $P$ be the midpoint of the segment $\left[B_{1} C_{1}\right]$. The line $\left(A_{1} P\right)$ intersects the circle $\omega_{A}$ again at point $X$. The tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$ at point $A$ and the tangent to the circle $\omega_{A}$ at point $X$ intersect at $R$. Show that $RX = RP$.

|

By drawing the circle centered at $R$ with radius $R A$, we notice that it also passes through $P$. Therefore, we will instead introduce $R^{\prime}$ as the center of the circumcircle of triangle $A P X$ and show that the lines $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ and ( $X R^{\prime}$ ) are respectively tangent to the circumcircles of triangles $A B C$ and $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

For this, note that since $P$ is the midpoint of the segment $\left[B_{1} C_{1}\right]$ and the line $\left(A I_{A}\right)$ is its perpendicular bisector, the points $A, P$ and $I_{A}$ are collinear. Moreover, since $\widehat{I_{A} B_{1} A}=90^{\circ}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{I_{A} C_{1} A}$, the points $B_{1}, I_{A}, C_{1}$ and $A$ are concyclic. By the power of a point, we have:

$$

\mathrm{PA} \times \mathrm{PI}_{\mathrm{A}}=\mathrm{PB}_{1} \times \mathrm{PC}_{1}=\mathrm{PA}_{1} \times \mathrm{PX}

$$

Thus, the points $A_{1}, I_{A}, X$ and $A$ are concyclic by the converse of the power of a point.

Now, let's show that $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ is tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. On the one hand, by the inscribed angle theorem:

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{PAR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{PXA}}.

$$

But using the concyclicity of the points $A_{1}, I_{A}, X$ and $A$, we find

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{PAR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathcal{A}_{1} X A}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathcal{A}_{1} \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} A}.

$$

Let $D$ be the foot of the angle bisector of $\widehat{B A C}$ and $S$ the South pole of vertex $A$ in $A B C$. $D$ and $S$ are collinear with $A$ and $I_{A}$. Then

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{A_{1} I_{A} A}=\widehat{C D I_{A}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{A B C}-\frac{1}{2} \widehat{B A C}=\widehat{A B C}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A C B}=\widehat{A C P}

$$

Thus, $\widehat{P_{A R}}{ }^{\prime}=\widehat{A C P}$, so the line $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ is tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$.

Now, let's show that the line ( $R^{\prime} X$ ) is tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$. We also have by the inscribed angle theorem:

$$

\widehat{A_{1} X R^{\prime}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PXR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{PAX}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{A} A X}

$$

Then, by the inscribed angle in the circle passing through $A, A_{1}, I_{A}$ and $X$, and using that the triangle $I_{A} \mathcal{A}_{1} X$ is isosceles at $\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}}$, we have

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} A X}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{~A}_{1} X}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{~A}_{1} \mathrm{I}_{A} X}=\widehat{\mathrm{A}_{1} \mathrm{~B}_{1} X}

$$

where we used the inscribed angle theorem in the circle $\omega_{A}$. Thus, the line ( $\left.R^{\prime} X\right)$ is tangent to $\omega_{A}$ and $R=R^{\prime}$, which concludes.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle et soient $A_{1}, B_{1}$ et $C_{1}$ les points de contact resepctifs du cercle $A$-exinscrit, noté $\omega_{A}$, avec le côté $B C$ et les demi-droites $[A C)$ et $[A B$ ). Soit $P$ le milieu du segment $\left[B_{1} C_{1}\right]$. La droite $\left(A_{1} P\right)$ recoupe le cercle $\omega_{A}$ au point $X$. La tangente au cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$ au point $A$ et la tangente au cercle $\omega_{A}$ au point $X$ se coupent en $R$. Montrer que $R X=R P$.

|

En traçant le cercle de centre $R$ de rayon $R A$, on s'aperçoit que celui-ci passe également par $P$. On va donc plutôt introduire $R^{\prime}$ le centre du cercle circonscrit au triangle $A P X$ et montre que les droites $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ et ( $X R^{\prime}$ ) sont respectivement tangentes aux cercles circonscrits au triangle $A B C$ et au triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

Pour cela, notons que puisque $P$ est le milieu du segment $\left[B_{1} C_{1}\right]$ dont la droite $\left(A I_{A}\right)$ est la médiatrice, les points $A, P$ et $I_{A}$ sont alignés. De plus, puisque $\widehat{I_{A} B_{1} A}=90^{\circ}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{I_{A} C_{1} A}$, les points $B_{1}, I_{A}, C_{1}$ et $A$ sont cocycliques. Par puissance d'un point, on a :

$$

\mathrm{PA} \times \mathrm{PI}_{\mathrm{A}}=\mathrm{PB}_{1} \times \mathrm{PC}_{1}=\mathrm{PA}_{1} \times \mathrm{PX}

$$

de sorte que les points $A_{1}, I_{A}, X$ et $A$ sont cocycliques par la réciproque de la puissance d'un point.

Montrons à présent que $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ est tangente au cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$. D'une part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre :

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{PAR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{PXA}} .

$$

Mais en utilisant la cocyclicité des points $A_{1}, I_{A}, X$ et $A$, on a trouve

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{PAR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathcal{A}_{1} X A}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathcal{A}_{1} \mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} A} .

$$

Soit alors $D$ le pied de la bissectrice de l'angle $\widehat{B A C}$ et $S$ le pôle Sud su sommet $A$ dans $A B C$. $D$ et $S$ sont alignés avec $A$ et $I_{A}$. Alors

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{A_{1} I_{A} A}=\widehat{C D I_{A}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{A B C}-\frac{1}{2} \widehat{B A C}=\widehat{A B C}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A C B}=\widehat{A C P}

$$

Ainsi, $\widehat{P_{A R}}{ }^{\prime}=\widehat{A C P}$, donc la droite $\left(A R^{\prime}\right)$ est tangente au cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$.

Montrons que la droite ( $R^{\prime} X$ ) est tangente au cercle circonscrit au triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$. On a là aussi par angle au centre :

$$

\widehat{A_{1} X R^{\prime}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PXR}^{\prime}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{PAX}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{A} A X}

$$

Puis, par angle inscrit dans le cercle passant par $A, A_{1}, I_{A}$ et $X$, et en utilisant que le triangle $I_{A} \mathcal{A}_{1} X$ est isocèle en $\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}}$, on a

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} A X}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{I}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{~A}_{1} X}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{~A}_{1} \mathrm{I}_{A} X}=\widehat{\mathrm{A}_{1} \mathrm{~B}_{1} X}

$$

où l'on a utilisé le théorème de l'angle au centre dans le cercle $\omega_{A}$. Ainsi, la droite ( $\left.R^{\prime} X\right)$ est tangente à $\omega_{A}$ et $R=R^{\prime}$, ce qui conclut.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 18.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-5-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 18",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $x$ and $y$ be two positive real numbers. Show that

$$

\left(x^{2}+x+1\right)\left(y^{2}+y+1\right) \geqslant 9 x y .

$$

What are the cases of equality?

|

We apply the arithmetic-geometric inequality to get

$$

\begin{gathered}

x^{2}+x+1 \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{3}}=3 x \\

y^{2}+y+1 \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{y^{3}}=3 y

\end{gathered}

$$

By multiplying these two inequalities, which are positive, we obtain the inequality stated in the problem. Since $x^{2}+x+1$ and $y^{2}+y+1$ are strictly positive, we have equality when we have equality in both arithmetic-geometric inequalities. This happens when $x^{2}=x=1$ and $y^{2}=y=1$, and thus we have equality for $x=y=1$.

Comment from the graders: In general, the exercise was very well solved. Several people forget to consider the equality case.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $x$ et $y$ deux réels positifs. Montrer que

$$

\left(x^{2}+x+1\right)\left(y^{2}+y+1\right) \geqslant 9 x y .

$$

Quels sont les cas d'égalité?

|

On applique l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique pour avoir

$$

\begin{gathered}

x^{2}+x+1 \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{3}}=3 x \\

y^{2}+y+1 \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{y^{3}}=3 y

\end{gathered}

$$

En multipliant ces deux inégalités, qui sont à termes positifs, on obtient l'inégalité de l'énoncé. Comme $x^{2}+x+1$ et $y^{2}+y+1$ sont strictement positifs, on a égalité lorsque l'on a égalité dans les deux inégalités arithmético-géométriques. Mais ceci arrive lorsque $x^{2}=x=1$ et $y^{2}=y=1$, et on a donc égalité pour $x=y=1$.

Commentaire des correcteurs: De manière générale, l'exercice a été très bien résolu. Plusieurs personnes oublient de faire le cas d'égalité.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $a$ and $b$ be two real numbers. Suppose that $2a + a^2 = 2b + b^2$. Show that if $a$ is an integer (not necessarily positive), then $b$ is also an integer.

|

We rewrite the equality

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 a-2 b=b^{2}-a^{2} \\

2(a-b)=-(a+b)(a-b)

\end{gathered}

$$

Then either $\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{a}$, and in this case b is an integer, or

$$

2=-a-b

$$

from which

$$

\mathrm{b}=-2-\mathrm{a}

$$

and $b$ is still an integer.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally well handled, with a few reasoning errors. Almost all students avoided the trap $a+1=-(b+1)$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soient $a$ et $b$ deux réels. Supposons que $2 a+a^{2}=2 b+b^{2}$. Montrer que si $a$ est un entier (pas forcément positif), alors b est aussi un entier.

|

On réécrit l'égalité

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 a-2 b=b^{2}-a^{2} \\

2(a-b)=-(a+b)(a-b)

\end{gathered}

$$

Alors soit $\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{a}$, et alors b est un entier, soit

$$

2=-a-b

$$

d'où

$$

\mathrm{b}=-2-\mathrm{a}

$$

et $b$ est encore un entier.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Exercice bien traité dans l'ensemble, avec quelques erreurs de raisonnement. Presque tous les élèves ont évité le piège $a+1=-(b+1)$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Show that there do not exist strictly positive real numbers $x, y, z$ such that

$$

\left(2 x^{2}+y z\right)\left(2 y^{2}+x z\right)\left(2 z^{2}+x y\right)=26 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}

$$

|

We could try to simply apply the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality to each of the factors on the left side, but this gives that the left term is greater than or equal to \(16 \sqrt{2} x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}\), which is not enough to conclude (since \(16 \sqrt{2} < 26\)). In fact, this is because we cannot have equality in all three arithmetic-geometric mean inequalities at the same time. We would like the case \(x=y=z\) to be a case of equality in the arithmetic-geometric mean inequalities we apply.

For example, take the first term \(2 x^{2} + y z\). We split it into \(x^{2} + x^{2} + y z\) (so that each of the terms is equal if \(x=y=z\)), then we can apply the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality:

\[

2 x^{2} + y z \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{2} \cdot x^{2} \cdot y z} = 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{4} y z}

\]

By applying the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality to all the positive terms, we have

\[

\left(2 x^{2} + y z\right)\left(2 y^{2} + x z\right)\left(2 z^{2} + x y\right) \geqslant 27 \sqrt[3]{x^{4} y z \cdot y^{4} x z \cdot z^{4} y z} = 27 \sqrt[3]{x^{6} y^{6} z^{6}} = 27 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}

\]

which is strictly greater than \(26 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}\), so we cannot have equality.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally successful. Good use of the AM-GM inequality, except for a few errors in reasoning.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Montrer qu'il n'existe pas de réels $x, y, z$ strictement positifs tels que

$$

\left(2 x^{2}+y z\right)\left(2 y^{2}+x z\right)\left(2 z^{2}+x y\right)=26 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}

$$

|

On pourrait essayer de simplement appliquer l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique sur chacun des facteurs du côté gauche, mais ceci donne que le terme de gauche est supérieur ou égal à $16 \sqrt{2} x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}$ ce qui ne suffit pas pour conclure (car $16 \sqrt{2}<26$ ). En fait, ceci vient du fait que l'on ne peut pas avoir égalité dans les trois inégalités arithmético-géométriques à la fois. On aimerait bien que le cas $x=y=z$ soit un cas d'égalité des inégalités arithmético-géométrique que l'on applique.

Prenons par exemple le premier terme $2 x^{2}+y z$. On le sépare en $x^{2}+x^{2}+y z$ (de façon à ce que chacun des termes soit égaux si $x=y=z$ ), on peut alors appliquer l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique :

$$

2 x^{2}+y z \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x^{2} \cdot x^{2} \cdot y z}=3 \sqrt[3]{x^{4} y z}

$$

En appliquant l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique sur tous les termes qui sont positifs, on a

$$

\left(2 x^{2}+y z\right)\left(2 y^{2}+x z\right)\left(2 z^{2}+x y\right) \geqslant 27 \sqrt[3]{x^{4} y z \cdot y^{4} x z \cdot z^{4} y z}=27 \sqrt[3]{x^{6} y^{6} z^{6}}=27 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}

$$

ce qui est strictement supérieur à $26 x^{2} y^{2} z^{2}$, on ne peut donc pas avoir égalité.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Exercice réussi dans l'ensemble. Bonnes utilsations de l'IAG, sauf quelques erreurs de raisonnement.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Show that for all real numbers $x, y, z$, we have

$$

\frac{x^{2}-y^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{y^{2}-z^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}-x^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} \leqslant 0 .

$$

|

We rewrite the inequality as

$$

\frac{x^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{y^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} \leqslant \frac{y^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{x^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} .

$$

Since the inequality is not symmetric, we cannot assume without loss of generality that $x^{2} \leqslant y^{2} \leqslant z^{2}$. However, note that the sequences $\left(x^{2}, y^{2}, z^{2}\right)$ and $\left(\frac{1}{2 x^{2}+1}, \frac{1}{2 y^{2}+1}, \frac{1}{2 z^{2}+1}\right)$ are arranged in reverse order (the largest of the first sequence corresponds to the smallest of the second sequence, for example). Therefore, we can apply the rearrangement inequality, which directly implies the inequality in the statement.

Comment from the graders: Students who approached the problem generally did well. They proposed three types of solutions. Some used the rearrangement inequality (also known as the turnstile inequality), similar to the solution provided. The most common mistake was to claim that the inequality is symmetric, which is clearly not the case, and to assume an order. While this is not critical in the context of the rearrangement inequality, such imprecisions are dangerous: a few students, by illegally assuming a convenient order, dispensed with using the rearrangement inequality, and their reasoning was entirely incorrect. Others used the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality directly and effectively after slightly transforming the problem. Unfortunately, about half of the students eliminated the fractions, expanded, and then used the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality term by term. Let us recall that this strategy is risky because a single calculation error can completely invalidate the solution, and more challenging problems (such as problem 6) are difficult to solve this way.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Montrer que pour tous les réels $x, y, z$, on a

$$

\frac{x^{2}-y^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{y^{2}-z^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}-x^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} \leqslant 0 .

$$

|

On réécrit l'inégalité en

$$

\frac{x^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{y^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} \leqslant \frac{y^{2}}{2 x^{2}+1}+\frac{z^{2}}{2 y^{2}+1}+\frac{x^{2}}{2 z^{2}+1} .

$$

L'inégalité n'étant pas symétrique, on ne peut pas supposer sans perte de généralité que $x^{2} \leqslant y^{2} \leqslant$ $z^{2}$. Cependant, remarquons que les suites $\left(x^{2}, y^{2}, z^{2}\right)$ et $\left(\frac{1}{2 x^{2}+1}, \frac{1}{2 y^{2}+1}, \frac{1}{2 z^{2}+1}\right)$ sont rangées dans l'ordre inverse (le plus grand de la première suite correspond au plus petit de la deuxième suite par exemple). On peut donc appliquer l'inégalité de réordonnement qui implique directement l'inégalité de l'énoncé.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Les élèves ayant abordé le problème l'ont plutôt bien réussi. Ils ont proposé trois types de solutions. Certains passent par l'inégalité de réarrangement (aussi appelée inégalité du tourniquet), à l'instar du corrigé. L'erreur la plus fréquente est alors de dire que l'inégalité est symétrique, ce qui n'est manifestement pas le cas, et de supposer un ordre. Dans le cadre de l'inégalité de réarrangement ceci n'est pas dramatique, mais ce type d'imprécisions reste dangereux : quelques élèves, en supposant illégalement un ordre commode, se sont dispensés d'utiliser l'inégalité de réarrangement, et leur raisonnement est tout à fait erroné. D'autres utilisent directement et efficacement l'inégalité arithméticogéométrique après avoir un peu transformé le problème. Une regrettable moitié enfin, se débarasse des fractions, développe, puis utilise l'IAG termes à termes. Rappelons que cette stratégie est hasardeuse car une faute de calcul rend complètement invalide la solution, et que les problèmes un peu plus durs (comme le problème 6) sont difficiles à résoudre ainsi.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $n \geqslant 2$ and $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n} \in[0,1]$ be real numbers. Determine the maximum value that the smallest of the numbers

$$

a_{1}-a_{1} a_{2}, a_{2}-a_{2} a_{3}, \ldots, a_{n}-a_{n} a_{1}

$$

can take.

|

Let $i$ be such that $a_{i}$ is minimal. Then we have $a_{i+1} \geqslant a_{i}$ (where $a_{n+1}=a_{1}$) and thus by the arithmetic-geometric inequality on $a_{i}$ and $1-a_{i}$, we obtain

$$

a_{i}-a_{i} a_{i+1} \leqslant a_{i}-a_{i}^{2}=a_{i}\left(1-a_{i}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(a_{i}+1-a_{i}\right)^{2}=\frac{1}{4}

$$

so the minimum of the numbers is at most $\frac{1}{4}$. It remains to verify that we can find $a_{i}$ such that the minimum is equal to $\frac{1}{4}$. If all the $a_{i}$ are equal to $\frac{1}{2}$, then all the $a_{i}-a_{i} a_{i+1}$ are equal to $\frac{1}{4}$ and the minimum is indeed $\frac{1}{4}$.

Comment from the graders: The problem was generally well done. It contained two steps: proving that the expression is always less than 0.25 and providing an example where this bound is achieved. Some students forget one or the other of these two steps and thus lose valuable points.

|

\frac{1}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $n \geqslant 2$ et $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n} \in[0,1]$ des réels. Déterminer la valeur maximale que peut prendre le plus petit des nombres

$$

a_{1}-a_{1} a_{2}, a_{2}-a_{2} a_{3}, \ldots, a_{n}-a_{n} a_{1}

$$

|

Soit $i$ tel que $a_{i}$ soit minimal. Alors on a $a_{i+1} \geqslant a_{i}$ (où $a_{n+1}=a_{1}$ ) et donc par inégalité arithmético-géométrique sur $a_{i}$ et $1-a_{i}$, on obtient

$$

a_{i}-a_{i} a_{i+1} \leqslant a_{i}-a_{i}^{2}=a_{i}\left(1-a_{i}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(a_{i}+1-a_{i}\right)^{2}=\frac{1}{4}

$$

donc le minimum des nombres vaut au plus $\frac{1}{4}$. Il reste à vérifier que l'on peut trouver des $a_{i}$ tel que le minimum soit égal à $\frac{1}{4}$. Si tous les $a_{i}$ valent $\frac{1}{2}$, alors tous les $a_{i}-a_{i} a_{i+1}$ valent $\frac{1}{4}$ et le minimum vaut bien $\frac{1}{4}$.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème est bien réussi dans l'ensemble. Il contenait deux étapes: prouver que l'expresison est toujours plus petite que 0.25 et donner un exemple en lequel cette borne est atteinte. Quelques élèves oublient l'une ou l'autre de ces deux étapes et perdent alors de précieux points.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be three strictly positive real numbers. Show that

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 2

$$

|

We start by applying the arithmetic-geometric inequality to the three terms in the statement:

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{\left(a^{4}+1\right)\left(b^{4}+1\right)\left(c^{4}+1\right)}{\left(b^{3}+b^{2}+b\right)\left(c^{3}+c^{2}+c\right)\left(a^{3}+a^{2}+a\right)}}

$$

We aim to find a lower bound for the quotients $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}$. For this, we apply arithmetic-geometric inequalities:

$$

\begin{aligned}

a^{3}+a^{2}+a & \leqslant \frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+a^{2}\right)+a^{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(a^{2}+1\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)+2 a^{2} \\

& \leqslant \frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)+\left(a^{4}+1\right)=\frac{3}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

and thus $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{2}{3}$. We have the same for $b$ and $c$, and therefore

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{3}}=2

$$

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $a, b, c$ trois réels strictement positifs. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 2

$$

|

On commence par appliquer l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique aux trois termes de l'énoncé :

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{\left(a^{4}+1\right)\left(b^{4}+1\right)\left(c^{4}+1\right)}{\left(b^{3}+b^{2}+b\right)\left(c^{3}+c^{2}+c\right)\left(a^{3}+a^{2}+a\right)}}

$$

On cherche donc à minorer les quotients $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}$. Pour cela, on applique des inégalités arithméticogéométriques :

$$

\begin{aligned}

a^{3}+a^{2}+a & \leqslant \frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+a^{2}\right)+a^{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(a^{2}+1\right)=\frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)+2 a^{2} \\

& \leqslant \frac{1}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)+\left(a^{4}+1\right)=\frac{3}{2}\left(a^{4}+1\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

et ainsi $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{2}{3}$. On a de même pour $b$ et $c$, et donc

$$

\frac{\mathrm{a}^{4}+1}{\mathrm{~b}^{3}+\mathrm{b}^{2}+\mathrm{b}}+\frac{\mathrm{b}^{4}+1}{\mathrm{c}^{3}+\mathrm{c}^{2}+\mathrm{c}}+\frac{\mathrm{c}^{4}+1}{\mathrm{a}^{3}+\mathrm{a}^{2}+\mathrm{a}} \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{3}}=2

$$

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "## Exercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be three strictly positive real numbers. Show that

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 2

$$

|

:

We can also think about it using the rearrangement inequality. The inequality is not symmetric, so we cannot assume without loss of generality that $a \geqslant b \geqslant c$ or something similar.

However, by strict monotonicity, $\left(a^{4}+1, b^{4}+1, c^{4}+1\right)$ is in the same order as $(a, b, c)$. Similarly, $\left(a^{3}+a^{2}+a, b^{3}+b^{2}+b, c^{3}+c^{2}+c\right)$ is also in the same order, and $\left(\frac{1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}, \frac{1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}, \frac{1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}\right)$ is in the reverse order. Thus, by the rearrangement inequality,

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}

$$

is the minimum value that can be taken by a sum of products of terms from $\left(a^{4}+1, b^{4}+1, c^{4}+1\right)$ with terms from $\left(\frac{1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}, \frac{1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}, \frac{1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}\right)$. In particular here:

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}

$$

We can now show as before that $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{2}{3}$ and conclude by

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 3 \cdot \frac{2}{3}=2

$$

Graders' comments: The problem is very well done. However, many students believe that we can assume $a \geqslant b \geqslant c$ because 'the inequality is symmetric'. However, the inequality is not symmetric: if we swap $b$ and $c$, the inequality is drastically changed. Fortunately, here by chance, the reasoning was easily rectifiable (see solution 2 in the answer key). However, the few copies that multiplied and expanded everything did not succeed, once again demonstrating that thinking before haphazardly expanding everything is always a good idea.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $a, b, c$ trois réels strictement positifs. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 2

$$

|

:

On peut également réfléchir avec l'inégalité de réarrangement. L'inégalité n'est pas symétrique, on ne peut donc pas supposer sans perte de généralités $a \geqslant b \geqslant c$ ou quelque chose de similaire.

Cependant, par stricte croissance, $\left(a^{4}+1, b^{4}+1, c^{4}+1\right)$ est dans le même ordre que $(a, b, c)$. De même, $\left(a^{3}+a^{2}+a, b^{3}+b^{2}+b, c^{3}+c^{2}+c\right)$ est également dans le même ordre et $\left(\frac{1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}, \frac{1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}, \frac{1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}\right)$ est dans le sens inverse. Ainsi, par inégalité de réarrangement,

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}

$$

est la valeur minimale que peut prendre une somme de produit de termes de $\left(a^{4}+1, b^{4}+1, c^{4}+1\right)$ avec des termes de $\left(\frac{1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}, \frac{1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}, \frac{1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}\right)$. En particulier ici :

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}

$$

On peut maintenant comme précédemment montrer $\frac{a^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant \frac{2}{3}$ et conclure par

$$

\frac{a^{4}+1}{b^{3}+b^{2}+b}+\frac{b^{4}+1}{c^{3}+c^{2}+c}+\frac{c^{4}+1}{a^{3}+a^{2}+a} \geqslant 3 \cdot \frac{2}{3}=2

$$

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème est très bien réussi. Cependant, beaucoup d'élèves croient qu'on peut supposer $a \geqslant b \geqslant c$ car 'l'inégalité est symétrique". Or l'inégalité n'est pas symétrique : si on change b et c l'inégalité est drastiquement changée. Heureusement qu'ici par chance, le raisonnement était rectifiable facilement (cf la solution 2 du corrigé). Cependant, les quelques copies qui ont tout multiplié et développé n'ont pas réussi, témoignant encore une fois du fait que réfléchir avant de tout développer hasardeusement est toujours une bonne idée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "## Exercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution alternative",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $a, b, c, d$ be four real numbers such that $|a|>1,|b|>1,|c|>1$ and $|d|>1$. Suppose that $(a+1)(b+1)(c+1)(d+1)=(a-1)(b-1)(c-1)(d-1)$. Show that

$$

\frac{1}{a-1}+\frac{1}{b-1}+\frac{1}{c-1}+\frac{1}{d-1}>0

$$

|

We know from the statement that none of $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c}, \mathrm{d}$ equals 1. The condition in the statement can be written as

$$

\frac{a+1}{a-1} \frac{b+1}{b-1} \frac{c+1}{c-1} \frac{d+1}{d-1}=1

$$

Notice that since $|a|>1$, we have either $a>1$ and thus $a+1>0$ and $a-1>0$, or $a<-1$ and thus $a+1<0$ and $a-1<0$. Therefore, in all cases $\frac{a+1}{a-1}$ is positive, and the same applies to $b, c, d$. We can therefore apply the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality to the product above to get

$$

\frac{\mathrm{a}+1}{\mathrm{a}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{b}+1}{\mathrm{~b}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{c}+1}{\mathrm{c}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{d}+1}{\mathrm{~d}-1} \geqslant 4 \sqrt[4]{\frac{\mathrm{a}+1}{\mathrm{a}-1} \frac{\mathrm{~b}+1}{\mathrm{~b}-1} \frac{\mathrm{c}+1}{\mathrm{c}-1} \frac{\mathrm{~d}+1}{\mathrm{~d}-1}}=4

$$

We can rewrite this as

$$

\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{a}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{~b}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{c}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{~d}-1}\right) \geqslant 4

$$

and thus

$$

\frac{1}{a-1}+\frac{1}{b-1}+\frac{1}{c-1}+\frac{1}{d-1} \geqslant 0

$$

However, the statement asks us to show that the inequality is strict. Therefore, we need to consider the case of equality in the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality. Equality holds if and only if

$$

\frac{a+1}{a-1}=\frac{b+1}{b-1}=\frac{c+1}{c-1}=\frac{d+1}{d-1}

$$

Since the product of these four terms is 1, these terms must all be 1 or all be -1. In the first case, we have $a+1=a-1$, which is impossible. In the second case, we have $a+1=1-a$ and thus $a=0$, which is also impossible because $|a|>1$. Therefore, equality cannot hold, and the inequality is indeed strict as stated.

Comment from the graders: The problem is rarely approached. Some students attempted complicated calculations, and surprisingly few managed to make it work. In inequalities, it is crucial to try to bring out the hypotheses rather than brute-forcing the calculations.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soient $a, b, c, d$ quatre réels tels que $|a|>1,|b|>1,|c|>1$ et $|d|>1$. Supposons que $(a+1)(b+1)(c+1)(d+1)=(a-1)(b-1)(c-1)(d-1)$. Montrer que

$$

\frac{1}{a-1}+\frac{1}{b-1}+\frac{1}{c-1}+\frac{1}{d-1}>0

$$

|

On sait d'après l'énoncé que aucun des $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c}, \mathrm{d}$ ne vaut 1 . La condition de l'énoncé s'écrit alors

$$

\frac{a+1}{a-1} \frac{b+1}{b-1} \frac{c+1}{c-1} \frac{d+1}{d-1}=1

$$

Remarquons que comme $|a|>1$, alors on a soit $a>1$ et donc $a+1>0$ et $a-1>0$, ou alors $a<-1$ et donc $a+1<0$ et $a-1<0$. Ainsi, dans tous les cas $\frac{a+1}{a-1}$ est positif, et de même pour $b, c, d$. On peut donc appliquer l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique sur le produit précédent pour avoir

$$

\frac{\mathrm{a}+1}{\mathrm{a}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{b}+1}{\mathrm{~b}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{c}+1}{\mathrm{c}-1}+\frac{\mathrm{d}+1}{\mathrm{~d}-1} \geqslant 4 \sqrt[4]{\frac{\mathrm{a}+1}{\mathrm{a}-1} \frac{\mathrm{~b}+1}{\mathrm{~b}-1} \frac{\mathrm{c}+1}{\mathrm{c}-1} \frac{\mathrm{~d}+1}{\mathrm{~d}-1}}=4

$$

On réécrit ceci sous la forme

$$

\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{a}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{~b}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{c}-1}\right)+\left(1+\frac{2}{\mathrm{~d}-1}\right) \geqslant 4

$$

et donc

$$

\frac{1}{a-1}+\frac{1}{b-1}+\frac{1}{c-1}+\frac{1}{d-1} \geqslant 0

$$

Mais l'énoncé nous demande de montrer que l'inégalité est stricte, on s'intéresse donc au cas d'égalité dans l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique. On a égalité si et seulement si

$$

\frac{a+1}{a-1}=\frac{b+1}{b-1}=\frac{c+1}{c-1}=\frac{d+1}{d-1}

$$

Comme le produit de ces quatre termes vaut 1 , nécessairement ces termes valent tous 1 ou tous -1 . Dans le premier cas, on a $a+1=a-1$ ce qui est impossible. Dans le deuxième cas, on a $a+1=1-a$ et donc $a=0$, ce qui est aussi impossible car $|a|>1$. Ainsi, on ne peut pas avoir égalité et l'inégalité est bien stricte comme dans l'énoncé.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème est peu abordé. Certains se sont lancés dans des calculs compliqués, et étonnamment très peu ont réussi à faire fonctionner cela. En inégalité, il est crucial d'essayer de faire apparaître les hypothèses plutôt que de bourriner les calculs.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$ be an integer and $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ be positive real numbers. Show that

$$

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{(n+1)^{2}}{4 n}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{2}

$$

What are the cases of equality?

|

The trick is to apply the arithmetic-geometric inequality to the left side of the inequality, but with coefficients $\sqrt{n}$ and $\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}$:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots\right. & \left.+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right)=\sqrt{n}\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right) \frac{1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}}{\sqrt{n}} \\

& \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(\sqrt{n}\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)+\frac{1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}}{\sqrt{n}}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

For each $i$, the coefficient of $x_{i}$ is $\frac{\sqrt{n}}{i}+\frac{i}{\sqrt{n}}$. The function $t \mapsto t+\frac{1}{t}$ is decreasing for $t<1$ and increasing for $t>1$. Indeed, for example, for $1<x<y$, we have $xy>1$ and thus:

$$

y-x>\frac{y-x}{xy}=\frac{1}{x}-\frac{1}{y}

$$

Thus, the maximum coefficient is achieved at $i=1$ or $i=n$. In each case, we find a coefficient $\sqrt{n}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}=\frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}$, and therefore

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)\right)^{2} \\

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{(n+1)^{2}}{4 n}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

We are interested in the cases of equality. For $1<i<n$, the inequality $\frac{\sqrt{n}}{i}+\frac{i}{\sqrt{n}} \leqslant \frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}$ is strict, so necessarily $x_{i}$ must be equal to 0. Then, we need to have equality in the arithmetic-geometric inequality, which is written as

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sqrt{n}\left(x_{1}+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right) & =\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\left(x_{1}+n x_{n}\right) \\

\left(\sqrt{n}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\right) x_{1} & =\left(\sqrt{n}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\right) x_{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

If $n=1$, we always have equality (there is only one $x_{i}$), otherwise we have the condition $x_{1}=x_{n}$. Conversely, we can verify that if $x_{1}=x_{n}$ and all other $x_{i}$ are zero, we indeed have equality in the inequality of the statement.

Comment from the graders: The problem is rarely approached, and even less solved. Very few copies deal with the cases of equality, although this is part of the statement and could earn points. Be sure to know the statements of known inequalities well, as misapplying an inequality can ruin an entire proof.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$ un entier et $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ des réels positifs. Montrer que

$$

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{(n+1)^{2}}{4 n}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{2}

$$

Quels sont les cas d'égalité?

|

L'astuce est d'appliquer une inégalité arithmético-géométrique au côté gauche de l'inégalité, mais avec des coefficients $\sqrt{n}$ et $\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots\right. & \left.+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right)=\sqrt{n}\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right) \frac{1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}}{\sqrt{n}} \\

& \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(\sqrt{n}\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)+\frac{1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}}{\sqrt{n}}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Pour chaque $i$, le coefficient de $x_{i}$ est $\frac{\sqrt{n}}{i}+\frac{i}{\sqrt{n}}$. La fonction $t \mapsto t+\frac{1}{t}$ est décroissante pour $t<1$ et croissante pour $\mathrm{t}>1$. En effet, par exemple pour $1<x<y$, on a $x y>1$ et donc:

$$

y-x>\frac{y-x}{x y}=\frac{1}{x}-\frac{1}{y}

$$

Ainsi, le coefficient maximal est atteint en $i=1$ ou $i=n$. Dans chaque cas, on trouve un coefficient $\sqrt{n}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}=\frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}$, et donc

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)\right)^{2} \\

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{1}+\frac{x_{2}}{2}+\ldots+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right)\left(1 \cdot x_{1}+2 \cdot x_{2}+\ldots+n \cdot x_{n}\right) \leqslant \frac{(n+1)^{2}}{4 n}\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

On s'intéresse aux cas d'égalité. Pour $1<i<n$, l'inégalité $\frac{\sqrt{n}}{i}+\frac{i}{\sqrt{n}} \leqslant \frac{n+1}{\sqrt{n}}$ est stricte, donc nécessairement $x_{i}$ doit être égal à 0 . Ensuite, il faut avoir égalité dans l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique, ce qui s'écrit

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sqrt{n}\left(x_{1}+\frac{x_{n}}{n}\right) & =\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\left(x_{1}+n x_{n}\right) \\

\left(\sqrt{n}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\right) x_{1} & =\left(\sqrt{n}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\right) x_{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

Si $n=1$, on a toujours égalité (il n'y a qu'un seul $x_{i}$ ), sinon on a la condition $x_{1}=x_{n}$. Réciproquement, on peut vérifier que si $x_{1}=x_{n}$ et tous les autres $x_{i}$ sont nuls, on a bien égalité dans l'inégalité de l'énoncé.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème est peu abordé, et encore moins résolu. Très peu de copies traitent les cas d'égalité, alors que cela fait partie de l'énoncé, et pouvait faire gagner des points. Veillez à bien connaître les énoncés des inégalités connues, mal appliquer une inégalité peut fausser toute une preuve.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $c$ be a non-negative integer. Find all sequences of strictly positive integers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ such that for every strictly positive integer $n$, $a_{n}$ is equal to the number of integers $i$ satisfying $a_{i} \leqslant a_{n+1}+c$.

|

Let $\left(a_{n}\right)$ be a sequence satisfying the conditions of the statement for the constant $c$. We start by showing that the sequence is increasing. Indeed, suppose by contradiction that there exists an integer $n$ such that $a_{n}>a_{n+1}$. Then, according to the hypothesis of the statement, there are strictly more $a_{i}$ less than or equal to $a_{n+1}+c$ than $a_{i}$ less than or equal to $a_{n+2}+c$. This means that necessarily $a_{n+2}<a_{n+1}$. Continuing in this way, we find that the sequence of $a_{i}$ is strictly decreasing from rank $n$. Since it takes strictly positive integer values, this is absurd.

Now let's show that the sequence is first constant up to a certain rank, then strictly increasing. Indeed, suppose that $a_{i}=a_{j}$ with $i<j$. Then if $i>1, a_{i-1}$ and $a_{j-1}$ are both the number of $a_{k}$ less than or equal to $a_{i}+c=a_{j}+c$, and thus $a_{i-1}=a_{j-1}$. Since we have $i \leqslant j-1<j$, we have $a_{j}=a_{i} \leqslant a_{j-1} \leqslant a_{j}$ and thus $a_{i-1}=a_{j-1}=a_{j}$ and thus $a_{i-1}=a_{j}$. We continue by successively decreasing $i$ by 1 until we have $a_{j}=a_{1}$. The whole sequence cannot be equal to $a_{1}$, because by hypothesis only $a_{1}$ terms of the sequence are less than or equal to $a_{2}+c=a_{1}+c>a_{1}$. Thus, the sequence is constant and equal to $a_{1}$ up to a certain rank $N$, then increases strictly.

Let $n \geqslant N$, then we know that there are $a_{n}$ elements of the sequence less than or equal to $a_{n+1}+c$. These elements are the first $n$ $a_{i}$ (by increasing), as well as the elements $a_{n+1}, a_{n+2}, \ldots, a_{n+k}$ for some $k$. Thus, $k$ is given by the inequalities $a_{n+k} \leqslant a_{n+1}+c$ and $a_{n+k+1}>a_{n+1}+c$. Since the sequence is strictly increasing after rank $N$, necessarily

$$

a_{n+k} \geqslant a_{n+k-1}+1 \geqslant a_{n+k-2}+2 \geqslant \ldots \geqslant a_{n+1}+k-1

$$

hence $a_{n+1}+c \geqslant a_{n+k} \geqslant a_{n+1}+k-1$ and $k \leqslant c+1$. Thus, the number $a_{n}$ of elements of the sequence less than or equal to $a_{n+1}+c$ is at most

$$

a_{n}=n+k \leqslant n+c+1

$$

On the other hand, we know that $a_{n+k+1}$ is at least $a_{n+1}+c+1 \geqslant a_{n}+c+2=n+k+c+2$. We thus have $a_{n+k+1} \geqslant n+k+c+2$ which is the same upper bound as the upper bound above but for $a_{n+k+1}$. Then for all $m \geqslant n+k+1$, we have

$$

m+c+1 \geqslant a_{m} \geqslant a_{n+k+1}+(m-(n+k+1)) \geqslant n+k+c+2+m-n-k-1=m+c+1

$$

and thus $a_{m}=m+c+1$ for all $m$ sufficiently large.

Let's show that this equality is true for all $m$. If by contradiction it were false, let $M$ be maximal such that $a_{M} \neq M+c+1$. Then $a_{M}$ is the number of terms of the sequence less than or equal to $a_{M+1}+c=$ $M+2 c+2$, which are the $M$ terms $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M}$ as well as the terms $a_{M+1}, \ldots, a_{M+c+1}=M+2 c+2$, and thus

$$

a_{M}=M+(c+1)

$$

which is absurd. Thus, for all $n, a_{n}=n+c+1$.

Let's check that this solution works well. Let $n \geqslant 1$ be an integer. Then $a_{n+1}+c=n+2 c+2$ and the integers $i$ such that $a_{i}=\mathfrak{i}+\boldsymbol{c}+1 \leqslant n+2 c+2$ are the $i$ less than or equal to $n+c+1$, there are $n+c+1=a_{n}$, as desired.

Comment from the graders: The problem is very little approached, and rarely solved. Remarks on the behavior of the sequence were worth points. Be sure to check the candidate solutions. Also, be rigorous in handling inequalities.

|

a_{n}=n+c+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Soit c un entier positif ou nul. Trouver toutes les suites d'entiers strictement positifs $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ telles que pour tout entier strictement positif $n, a_{n}$ soit égal au nombre d'entiers $i$ vérifiant $a_{i} \leqslant a_{n+1}+c$.

|

Soit $\left(a_{n}\right)$ une suite vérifiant les conditions de l'énoncé pour la constante $c$. On commence par montrer que la suite est croissante. En effet, supposons par l'absurde qu'il existe un entier $n$ tel que $a_{n}>a_{n+1}$. Alors d'après l'hypothèse de l'énoncé, il y a strictement plus de $a_{i}$ inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{n+1}+c$ que de $a_{i}$ inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{n+2}+c$. Ceci signifie que nécessairement $a_{n+2}<a_{n+1}$. En continuant ainsi, on trouve que la suite des $a_{i}$ est strictement décroissante à partir du rang $n$. Comme elle est à valeurs entières strictement positives, c'est absurde.

Montrons maintenant que la suite est d'abord constante jusqu'à un certain rang, puis strictement croissante. Supposons en effet que $a_{i}=a_{j}$ avec $i<j$. Alors si $i>1, a_{i-1}$ et $a_{j-1}$ sont tous les deux les nombres de $a_{k}$ inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{i}+c=a_{j}+c$, et donc $a_{i-1}=a_{j-1}$. Comme on a $i \leqslant j-1<j$, on a $a_{j}=a_{i} \leqslant a_{j-1} \leqslant a_{j}$ et donc $a_{i-1}=a_{j-1}=a_{j}$ et donc $a_{i-1}=a_{j}$. On continue en diminuant successivement $i$ de 1 jusqu'à avoir $a_{j}=a_{1}$. Toute la suite ne peut pas être égale à $a_{1}$, car par hypothèse seulement $a_{1}$ termes de la suite sont inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{2}+c=a_{1}+c>a_{1}$. Ainsi, la suite est constante égale à $a_{1}$ jusqu'à un certain rang $N$, puis croît strictement.

Soit $n \geqslant N$, alors on sait qu'il y a $a_{n}$ éléments de la suite inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{n+1}+c$. Ces éléments sont les $n$ premiers $a_{i}$ (par croissance), ainsi que les éléments $a_{n+1}, a_{n+2}, \ldots, a_{n+k}$ pour un certain $k$. Ainsi, $k$ est donné par les inégalités $a_{n+k} \leqslant a_{n+1}+c$ et $a_{n+k+1}>a_{n+1}+c$. Comme la suite est strictement croissante après le rang N , nécessairement

$$

a_{n+k} \geqslant a_{n+k-1}+1 \geqslant a_{n+k-2}+2 \geqslant \ldots \geqslant a_{n+1}+k-1

$$

d'où $a_{n+1}+c \geqslant a_{n+k} \geqslant a_{n+1}+k-1$ et $k \leqslant c+1$. Ainsi, le nombre $a_{n}$ d'éléments de la suite inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{n+1}+c$ est au plus

$$

a_{n}=n+k \leqslant n+c+1

$$

D'un autre côté, on sait que $a_{n+k+1}$ vaut au moins $a_{n+1}+c+1 \geqslant a_{n}+c+2=n+k+c+2$. On a donc $a_{n+k+1} \geqslant n+k+c+2$ ce qui est la même borne que la borne supérieure ci-dessus mais pour $a_{n+k+1}$. Alors pour tout $m \geqslant n+k+1$, on a

$$

m+c+1 \geqslant a_{m} \geqslant a_{n+k+1}+(m-(n+k+1)) \geqslant n+k+c+2+m-n-k-1=m+c+1

$$

et donc $a_{m}=m+c+1$ pour tout $m$ suffisamment grand.

Montrons que cette égalité est vraie pour tout $m$. Si par l'absurde elle était fausse, soit $M$ maximal tel que $a_{M} \neq M+c+1$. Alors $a_{M}$ est le nombre de termes de la suite inférieurs ou égaux à $a_{M+1}+c=$ $M+2 c+2$, qui sont les $M$ termes $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M}$ ainsi que les termes $a_{M+1}, \ldots, a_{M+c+1}=M+2 c+2$, et donc

$$

a_{M}=M+(c+1)

$$

ce qui est absurde. Ainsi, pour tout $\mathrm{n}, \mathrm{a}_{\mathrm{n}}=\mathrm{n}+\mathrm{c}+1$.

Vérifions que cette solution fonctionne bien. Soit $n \geqslant 1$ entier. Alors $a_{n+1}+c=n+2 c+2$ et les entiers $i$ tels que $a_{i}=\mathfrak{i}+\boldsymbol{c}+1 \leqslant n+2 c+2$ sont les $i$ inférieurs ou égaux à $n+c+1$, il y en a $n+c+1=a_{n}$, comme voulu.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème est très peu abordé, et très rarement résolu. Les remarques sur le comportement de la suite valaient des points. Attention à bien vérifier les solutions candidates. Attention aussi à rester rigoureux dans la manipulation des inégalités.

## Exercices Seniors

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $a$ and $b$ be two real numbers. Suppose that $2a + a^2 = 2b + b^2$. Show that if $a$ is an integer (not necessarily positive), then $b$ is also an integer.

|

We rewrite the equality

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 a-2 b=b^{2}-a^{2} \\

2(a-b)=-(a+b)(a-b)

\end{gathered}

$$

Then either $\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{a}$, and in this case, b is an integer, or

$$

2=-a-b

$$

from which

$$

\mathrm{b}=-2-\mathrm{a}

$$

and $b$ is still an integer.

Comment from the graders: The problem was successfully solved by almost everyone. Be careful of calculation errors for those who went through it a bit too quickly.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soient $a$ et $b$ deux réels. Supposons que $2 a+a^{2}=2 b+b^{2}$. Montrer que si $a$ est un entier (pas forcément positif), alors b est aussi un entier.

|

On réécrit l'égalité

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 a-2 b=b^{2}-a^{2} \\

2(a-b)=-(a+b)(a-b)

\end{gathered}

$$

Alors soit $\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{a}$, et alors b est un entier, soit

$$

2=-a-b

$$

d'où

$$

\mathrm{b}=-2-\mathrm{a}

$$

et $b$ est encore un entier.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Le problème était réussi par presque tous. Attention aux erreurs de calcul pour ceux qui sont passés un peu vite.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 10.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 10",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

For a real number $x$, we denote $\lfloor x\rfloor$ as the greatest integer less than or equal to $x$ (for example, $\lfloor 2.7\rfloor=2$, $\lfloor\pi\rfloor=3$, and $\lfloor-1.5\rfloor=-2$). We also denote $\{x\}=x-\lfloor x\rfloor$.

Find all real numbers $x$ such that

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}<x-1

$$

|

We rewrite $x=\lfloor x\rfloor+\{x\}$ on the right-hand side and move all terms to the left so that the inequality becomes

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}-\lfloor x\rfloor-\{x\}+1<0

$$

or equivalently,

$$

(\lfloor x\rfloor-1)(\{x\}-1)<0

$$

Notice that for any real $x$, we have $0 \leqslant\{x\}<1$ and thus $\{x\}-1<0$. Therefore, the inequality is equivalent to

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor-1>0

$$

or $\lfloor x\rfloor>1$. This precisely means that $x \geqslant 2$. We can verify that conversely, if $x \geqslant 2$, then $x$ satisfies the inequality in the problem statement.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was initially difficult to approach because a term involving $\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}$ is quite unusual, but it was well handled by those who tackled it. One could reason by equivalence as done in the solution. It is important in this case to maintain the reasoning by equivalence throughout (or explain that the converse is true). In particular, this is one of the cases where it is necessary to use $\Leftrightarrow$ signs between each line of mathematics. One could also better visualize the problem by considering a case disjunction, which generally used the same ideas.

|

x \geqslant 2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Pour un réel $x$, on note $\lfloor x\rfloor$ le plus grand entier relatif inférieur ou égal à $x$ (par exemple, $\lfloor 2,7\rfloor=2,\lfloor\pi\rfloor=3$ et $\lfloor-1,5\rfloor=-2$ ). On note aussi $\{x\rfloor=x-\lfloor x\rfloor$.

Trouver tous les réels $x$ tels que

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}<x-1

$$

|

On réécrit $x=\lfloor x\rfloor+\{x\}$ dans le terme de droite et on met tous les termes à gauche pour que l'inégalité devienne

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}-\lfloor x\rfloor-\{x\}+1<0

$$

ou encore

$$

(\lfloor x\rfloor-1)(\{x\}-1)<0

$$

Remarquons que pour tout $x$ réel, on a $0 \leqslant\{x\}<1$ et donc $\{x\}-1<0$. Alors l'inégalité est équivalente à

$$

\lfloor x\rfloor-1>0

$$

ou encore $\lfloor x\rfloor>1$. Ceci veut précisément dire que $x \geqslant 2$. On peut vérifier que réciproquement, si $x \geqslant 2$, alors $x$ vérifie bien l'inégalié de l'énoncé.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice était difficile à aborder initialement car un terme en $\lfloor x\rfloor\{x\}$ est assez inhabituel, mais plutôt bien appréhendé par ceux qui l'ont traité. On pouvait raisonner par équivalence comme cela est fait dans le corrigé. Il faut faire attention dans ce cas à bien garder le résonnement par équivalence tout du long (ou expliquer que la réciproque est vraie). En particulier c'est un des cas où il faut mettre des signes $\Leftrightarrow$ entre chaque ligne mathématique. On pouvait également pour mieux se représenter les choses faire une disjonction de cas qui utilisait en général les mêmes idées.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 11.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 11",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

The sequence $(a_{n})$ is defined by $a_{1}=1$ and

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Show that for all integers $m \geqslant 3$, we have $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

We set $P_{n}=\prod^{n} a_{k}$. We have

$$

\frac{P_{n}}{P_{n-1}}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{P_{n-1}}

$$

which gives

$$

n P_{n}=P_{n-1}+n

$$

We then set $M_{n}=n!P_{n}$. We deduce

$$

M_{n}=M_{n-1}+n!

$$

We deduce that $M_{n}=\sum k!$. We then deduce

$$

a_{n}=\frac{P_{n}}{P_{n-1}}=\frac{\frac{1}{n!} \sum k!}{\frac{1}{(n-1)!} \sum k!}

$$

It remains to show that

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{n} k!\leqslant \sum_{k=1}^{n-1} n \times k!

$$

which comes from using $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 3$ to have notably $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2+1$ and

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{n} k!\leqslant 1+2+\sum_{k=3}^{n} n \times(k-1)!\leqslant n+n \sum_{k=2}^{n-1} k!

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

La suite ( $a_{n}$ ) est définie par $a_{1}=1$ et

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Montrer que pour tout entier $m \geqslant 3$, on a $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

On pose $P_{n}=\prod^{n} a_{k}$. On a

$$

\frac{P_{n}}{P_{n-1}}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{P_{n-1}}

$$

ce qui donne

$$

n P_{n}=P_{n-1}+n

$$

On pose alors $M_{n}=n!P_{n}$. On déduit

$$

M_{n}=M_{n-1}+n!

$$

On déduit que $M_{n}=\sum k!$. On déduit alors

$$

a_{n}=\frac{P_{n}}{P_{n-1}}=\frac{\frac{1}{n!} \sum k!}{\frac{1}{(n-1)!} \sum k!}

$$

Il reste à montrer que

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{n} k!\leqslant \sum_{k=1}^{n-1} n \times k!

$$

ce qui vient en utilisant $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 3$ pour avoir notamment $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2+1$ et

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{n} k!\leqslant 1+2+\sum_{k=3}^{n} n \times(k-1)!\leqslant n+n \sum_{k=2}^{n-1} k!

$$

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 12",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

The sequence $(a_{n})$ is defined by $a_{1}=1$ and

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Show that for all integers $m \geqslant 3$, we have $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

:

Starting from the equation on the $P_{n}$, we want to show that $a_{n} \leqslant 1$ for $n \geqslant 3$, that is, $P_{n} \leqslant P_{n-1}$. This can be rewritten as

$$

\begin{gathered}

\frac{1}{n} P_{n-1}+1 \leqslant P_{n-1} \\

P_{n-1} \geqslant \frac{n}{n-1} .

\end{gathered}

$$

We aim to prove this inequality by induction. For $n=3$, we have

$$

P_{2}=\frac{1}{2}+1=\frac{3}{2}=\frac{3}{3-1} .

$$

If the result is true at rank $n$, then at rank $n+1$,

$$

P_{n}=\frac{1}{n} P_{n-1}+1 \geqslant \frac{1}{n} \frac{n}{n-1}+1=\frac{n}{n-1} \geqslant \frac{n+1}{n}

$$

which concludes the induction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

La suite ( $a_{n}$ ) est définie par $a_{1}=1$ et

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Montrer que pour tout entier $m \geqslant 3$, on a $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

:

A partir de l'équation sur les $P_{n}$, on veut donc montrer que $a_{n} \leqslant 1$ pour $n \geqslant 3$, c'est-à-dire que $P_{n} \leqslant P_{n-1}$. Ceci se réécrit

$$

\begin{gathered}

\frac{1}{n} P_{n-1}+1 \leqslant P_{n-1} \\

P_{n-1} \geqslant \frac{n}{n-1} .

\end{gathered}

$$

On cherche donc à montrer cette inégalité par récurence. Pour $\mathrm{n}=3$, on a bien

$$

\mathrm{P}_{2}=\frac{1}{2}+1=\frac{3}{2}=\frac{3}{3-1} .

$$

Si le résultat est vrai au rang n , on a, au rang $\mathrm{n}+1$,

$$

P_{n}=\frac{1}{n} P_{n-1}+1 \geqslant \frac{1}{n} \frac{n}{n-1}+1=\frac{n}{n-1} \geqslant \frac{n+1}{n}

$$

ce qui conclut la récurrence.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution alternative",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

The sequence $(a_{n})$ is defined by $a_{1}=1$ and

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Show that for all integers $m \geqslant 3$, we have $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

2 :

On a $a_{n+1}-\frac{1}{n}=\frac{1}{a_{1} \ldots a_{n}}$. Thus:

$$

a_{n+1}-\frac{1}{n}=\frac{1}{a_{1} \ldots a_{n-1}} \frac{1}{a_{n}}=\left(a_{n}-\frac{1}{n-1}\right) \frac{1}{a_{n}}

$$

Therefore, $a_{n+1}=1-\frac{1}{a_{n}(n-1)}+\frac{1}{n}$. We can calculate the first few terms to find that $a_{3}=1$. We can then prove by induction on $n$ that $a_{n} \leqslant 1$.

If the result is true at rank $n$, then $a_{n+1}=1-\frac{1}{a_{n}(n-1)}+\frac{1}{n} \leqslant 1-\frac{1}{n-1}+\frac{1}{n} \leqslant 1$. This concludes the proof.

Comment from the graders: Most of those who tackled the exercise understood it well. The main task was to transform the strong recurrence relation into a simple recurrence relation and then use induction. Some students provided reasoning that required handling the first few terms manually. This should not be overlooked, especially since it can help detect a reasoning error.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

La suite ( $a_{n}$ ) est définie par $a_{1}=1$ et

$$

a_{n}=\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{a_{1} \cdot \ldots \cdot a_{n-1}}

$$

Montrer que pour tout entier $m \geqslant 3$, on a $a_{m} \leqslant 1$.

|

2 :

On a $a_{n+1}-\frac{1}{n}=\frac{1}{a_{1} \ldots a_{n}}$. Ainsi :

$$

a_{n+1}-\frac{1}{n}=\frac{1}{a_{1} \ldots a_{n-1}} \frac{1}{a_{n}}=\left(a_{n}-\frac{1}{n-1}\right) \frac{1}{a_{n}}

$$

Dès lors $a_{n+1}=1-\frac{1}{a_{n}(n-1)}+\frac{1}{n}$. On peut calculer les premiers termes pour avoir $a_{3}=1$. On peut ensuite prouver par récurrence sur $n$ que $a_{n} \leqslant 1$.

Si le résultat est vrai au rang $n, a_{n+1}=1-\frac{1}{a_{n}(n-1)}+\frac{1}{n} \leqslant 1-\frac{1}{n-1}+\frac{1}{n} \leqslant 1$. Ce qui conclut.

Commentaire des correcteurs : La plupart de ceux qui ont abordé l'exercice l'ont bien compris. Il s'agissait principalement de transformer la relation de récurrence forte en une relation de récurrence simple puis de faire une récurrence. Certains élèves ont donné des raisonnements qui demandaient de traiter les premiers termes à la main. Il ne faut pas oublier de le faire, surtout que cela peut permettre de déceler une erreur de raisonnement.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Determine all functions $f$ from $\mathbb{R}$ to $\mathbb{R}$ such that for all real $x, y$:

$$

f(x) f(y) f(x-y)=x^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(x)

$$

|

Let $f$ be a solution of the equation.

For $x=y=0$, we have:

$$

\mathbf{f}(0)^{3}=0

$$

Thus, $f(0)=0$. We exclude the function $f \equiv 0$ which is indeed a solution of the problem.

Now, consider a number $x$ such that $f(x)=0$. Then for any $y$:

$$

0=x^{2} f(y)-0

$$

Since we have excluded the case $f \equiv 0$, we can find $y$ such that $f(y) \neq 0$ and thus $x=0$. Therefore, if $f(x)=0$, we have $x=0$.

We can now observe that swapping $x$ and $y$ in the equation changes the right-hand term to its opposite, so we have:

$$

f(x) f(y) f(x-y)=x^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(x)=-\left(y^{2} f(x)-x^{2} f(y)\right)=-f(y) f(x) f(y-x)

$$

Thus, for $x$ and $y$ non-zero, we have $f(x-y)=-f(y-x)$. By setting $y=2x$ with $x \neq 0$, we obtain that for all $x \neq 0, f(-x)=-f(x)$. Since $f(0)=0$, $f$ is odd.

We can now take $x=2y$, and the given equality with the oddness gives:

$$

f(2 y) f(y)^{2}=4 y^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(2 y)

$$

On the other hand, with $x=-y$:

$$

f(y)^{2} f(2 y)=2 y^{2} f(y)

$$

Using these two equalities, we have:

$$

f(2 y) y^{2}=2 y^{2} f(y)

$$

If $y$ is non-zero, we have $f(y) \neq 0$, and thus the previous equality can be written as $f(2y)=2f(y)$, and equation (1) becomes:

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 f(y)^{3}=2 y^{2} f(y) \\

f(y)^{2}=y^{2}

\end{gathered}

$$

We thus find $f(y)= \pm y$. Note that, a priori, the sign could depend on $y$. Suppose, by contradiction, that $a$ and $b$ are two non-zero real numbers such that $f(a)=a$ and $f(b)=-b$. Taking $x=b$ and $y=a$, we get:

$$

-a b f(a-b)=a b(a+b)

$$

Since $a$ and $b$ are non-zero, $f(a-b)=-(a+b)$. But $f(a-b)= \pm(a-b)$, and depending on the sign, we get either $a=0$ or $b=0$, which is absurd. For $x=0$, we have both $f(x)=x$ and $f(x)=-x$, so necessarily $f$ is of the form: $f(x)=0$ for all $x$, or $f(x)=-x$ for all $x$, or $f(x)=x$ for all $x$.

These three functions are indeed solutions.

Comment from the graders: The problem was attempted by a significant number of students, often with the right ideas for substitutions. Many need to be more careful about not dividing by 0, even when the 0 is hidden in an $f(x)$ or other value. This often leads to arguments that fall back on their feet, but for the wrong reasons. Another very common mistake is that of "multigraphs": if we know that $\mathrm{f}(x)^{2}=x^{2}$ for all $x$, we cannot immediately conclude that $f$ is the identity function or its negative. Indeed, the function could arbitrarily alternate between $+x$ and $-x$.

|

f(x)=0, f(x)=x, f(x)=-x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Déterminer toutes les fonctions f de $\mathbb{R}$ dans $\mathbb{R}$ telles que pour tous $x, y$ réels :

$$

f(x) f(y) f(x-y)=x^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(x)

$$

|

Soit f une solution de l'équation.

Pour $x=y=0$, on $a$ :

$$

\mathbf{f}(0)^{3}=0

$$

Ainsi, $f(0)=0$. On exclut la fonction $f \equiv 0$ qui est effectivement solution du problème.

On considère maintenant, un nombre $x$ tel que $f(x)=0$. On a alors pour un $y$ quelconque :

$$

0=x^{2} f(y)-0

$$

Comme on a exclu le cas $f \equiv 0$, on peut trouver $y$ tel que $f(y) \neq 0$ et donc $x=0$. Ainsi, si $f(x)=0$, on $\mathrm{a} x=0$ 。

On peut maintenant remarquer qu'échanger $x$ et $y$ dans l'équation, change le terme de droite en son oppposé, on a donc:

$$

f(x) f(y) f(x-y)=x^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(x)=-\left(y^{2} f(x)-x^{2} f(y)\right)=-f(y) f(x) f(y-x)

$$

Ainsi pour $x$ et $y$ non nuls, on a $f(x-y)=-f(y-x)$. En posant $y=2 x$ avec $x \neq 0$, on obtient que pour tout $x \neq 0, f(-x)=-f(x)$. Comme $f(0)=0, f$ est impaire.

On peut maintenant prendre $x=2 y$, l'égalité de l'énoncé avec l'imparité donnent :

$$

f(2 y) f(y)^{2}=4 y^{2} f(y)-y^{2} f(2 y)

$$

D'autre part, avec $x=-\mathrm{y}$ :

$$

f(y)^{2} f(2 y)=2 y^{2} f(y)

$$

En utilisant ces deux égalités, on a :

$$

f(2 y) y^{2}=2 y^{2} f(y)

$$

Si $y$ est non nul, on a $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{y}) \neq 0$, et donc l'égalité précédente s'écrit $\mathrm{f}(2 \mathrm{y})=2 \mathrm{f}(\mathrm{y})$, et l'équation (1) s'écrit

$$

\begin{gathered}

2 f(y)^{3}=2 y^{2} f(y) \\

f(y)^{2}=y^{2}

\end{gathered}

$$

On trouve donc $f(y)= \pm y$. Attention, a priori, le signe pourrait dépendre de $y$. Soit, par l'absurde, a et $b$ deux réels non nuls tels que $f(a)=a$ et $f(b)=-b$. En prenant $x=b$ et $y=a$, on obtient:

$$

-a b f(a-b)=a b(a+b)

$$

Comme $a$ et $b$ sont non nuls, $f(a-b)=-(a+b)$. Mais $f(a-b)= \pm(a-b)$, et en fonction du signe on obtient soit $a=0$, soit $b=0$, ce qui est absurde. Pour $x=0$, on a à la fois $f(x)=x$ et $f(x)=-x$, donc nécessairement $f$ est de la forme : $f(x)=0$ pour tous $x$, ou $f(x)=-x$ pour tous $x$, ou $f(x)=x$ pour tous $x$.

Ces trois fonctions sont bien solutions.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Le problème a été tenté par un nombre important d'élèves, souvent avec les bonnes idées de substitutions. Un grand nombre doit faire plus attention à ne pas diviser par 0 , même quand ce 0 se cache dans un $f(x)$ ou autre valeur. Cela mène à des raisonnements qui souvent retombent sur leur pattes, mais pour les mauvaises raisons. Une autre erreur très fréquente est celle des "multigraphes" : si l'on sait que $\mathrm{f}(x)^{2}=x^{2}$ pour tout $x$, alors on ne peut pas immédiatement conclure que $f$ est plus ou moins la fonction identité. En effet la fonction pourrait alterner de façon arbitraire entre $+x$ et $-x$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 13.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-Corrige-envoi-algebre-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 13",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Emile has created an exercise for Benoît. He announces that he has secretly chosen a unitary polynomial $P$ of degree 2023 with integer coefficients, that is, of the form

$$

P(X)=X^{2023}+a_{2022} X^{2022}+a_{2021} X^{2021}+\ldots+a_{1} X+a_{0}

$$

where $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2022}$ are integers. He gives Benoît $k$ integers $n_{1}, n_{2}, \ldots, n_{k}$, where $k$ is a positive integer, as well as the value of the product $P\left(n_{1}\right) P\left(n_{2}\right) \ldots P\left(n_{k}\right)$. From this information, Benoît must try to determine the polynomial $P$.

Find the smallest integer $k$ such that Emile can find $P$ and $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{k}$ to ensure that the only polynomial matching the information given to Benoît is $P$.

|

Let's show that the minimal $k$ is $k=2023$. Indeed, suppose first that $k<2023$ and that Émile chooses $P$ and $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{k}$. Let

$$

Q = P + (X - n_{1})(X - n_{2}) \ldots (X - n_{k})

$$

which is a polynomial with integer coefficients, always monic of degree 2023, and different from $P$. Then $P$ and $Q$ are equal at each $n_{i}$, and therefore the products $P(n_{1}) \ldots P(n_{k})$ and $Q(n_{1}) \ldots Q(n_{k})$ are equal, so Benoît cannot determine the value of the polynomial $P$.

Now suppose that $k=2023$. Émile can then choose $n_{1}=3, n_{2}=6, \ldots, n_{2023}=3 \cdot 2023$ and set

$$

P = (X-3)(X-6) \ldots (X-3 \cdot 2023) + 1

$$

Then the product $P(n_{1}) P(n_{2}) \ldots P(n_{k})$ is 1. Let $Q$ be a polynomial with integer coefficients, monic of degree 2023, such that the product $Q(n_{1}) \ldots Q(n_{k})$ is equal to 1; we need to show that necessarily $Q=P$. Since all the $Q(n_{i})$ are integers, they are all either 1 or -1. However, we can note that since the $n_{i}$ are divisible by 3, for all $i$, $Q(n_{i})$ is congruent to the constant term of $Q$. Since 1 and -1 are not congruent modulo 3, all the $Q(n_{i})$ are equal. Since 2023 is odd, they cannot all be equal to -1, so they are all 1. Then $P - Q$ is a polynomial of degree at most 2022 (since the terms of order 2023 cancel out) and is zero at each of the 2023 values of the $n_{i}$, so $Q = P$, which concludes.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally well understood, and many students thought to create a polynomial $P$ such that the product $P(n_{1}) P(n_{2}) \ldots P(n_{k}) = 1$, which was the right way to solve the exercise. However, be careful to better justify the arguments of polynomial division with integer coefficients; some students were a bit too quick on this step.

|

2023

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Emile a créé un exercice pour Benoît. Il lui annonce qu'il a choisi secrètement un polynôme P unitaire de degré 2023 à coefficients entiers, c'est-à-dire de la forme

$$

P(X)=X^{2023}+a_{2022} X^{2022}+a_{2021} X^{2021}+\ldots+a_{1} X+a_{0}

$$

où $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2022}$ sont des entiers relatifs. Il donne à Benoît $k$ entiers $n_{1}, n_{2}, \ldots, n_{k}$, où $k$ est un entier positif, ainsi que la valeur du produit $P\left(n_{1}\right) P\left(n_{2}\right) \ldots P\left(n_{k}\right)$. A partir de ces connaissances, Benoît doit essayer de retrouver le polynôme P .

Trouver l'entier $k$ minimal tel que Emile puisse trouver $P$ et $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{k}$ afin de s'assurer que le seul polynôme coincidant avec les informations données à Benoît soit P .

|

Montrons que le $k$ minimal est $k=2023$. En effet, supposons d'abord que $k<2023$ et qu'Emile choisisse $P$ et $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{k}$. Posons

$$

\mathrm{Q}=\mathrm{P}+\left(\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{n}_{1}\right)\left(\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{n}_{2}\right) \ldots\left(\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{n}_{\mathrm{k}}\right)

$$

qui est un polynôme à coefficients entiers, toujours unitaire de degré 2023, et différent de P . Alors P et $Q$ sont égaux en chaque $n_{i}$, et donc les produits $P\left(n_{1}\right) \ldots P\left(n_{k}\right)$ et $Q\left(n_{1}\right) \ldots Q\left(n_{k}\right)$ sont égaux, donc Benoît ne peut pas retrouver la valeur du polynôme $P$.

Supposons maintenant que $k=2023$. Emile peut alors choisir $n_{1}=3, n_{2}=6, \ldots, n_{2023}=3 \cdot 2023$ et poser

$$

P=(X-3)(X-6) \ldots(X-3 \cdot 2023)+1

$$