problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let $n \geqslant 3$ be an integer. We color 2 n vertices of a $4 \mathrm{n}+1$-gon. Show that there exist three colored vertices that form an isosceles triangle.

|

We proceed by contradiction, assuming that no triplet of colored vertices forms an isosceles triangle.

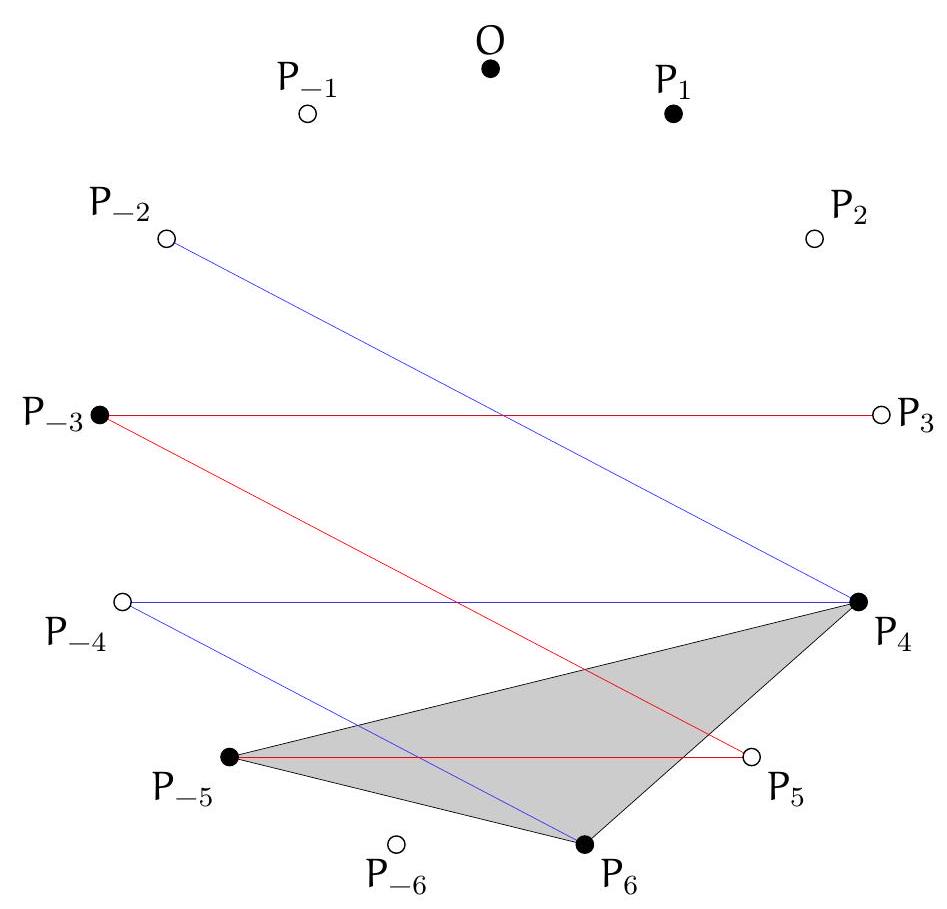

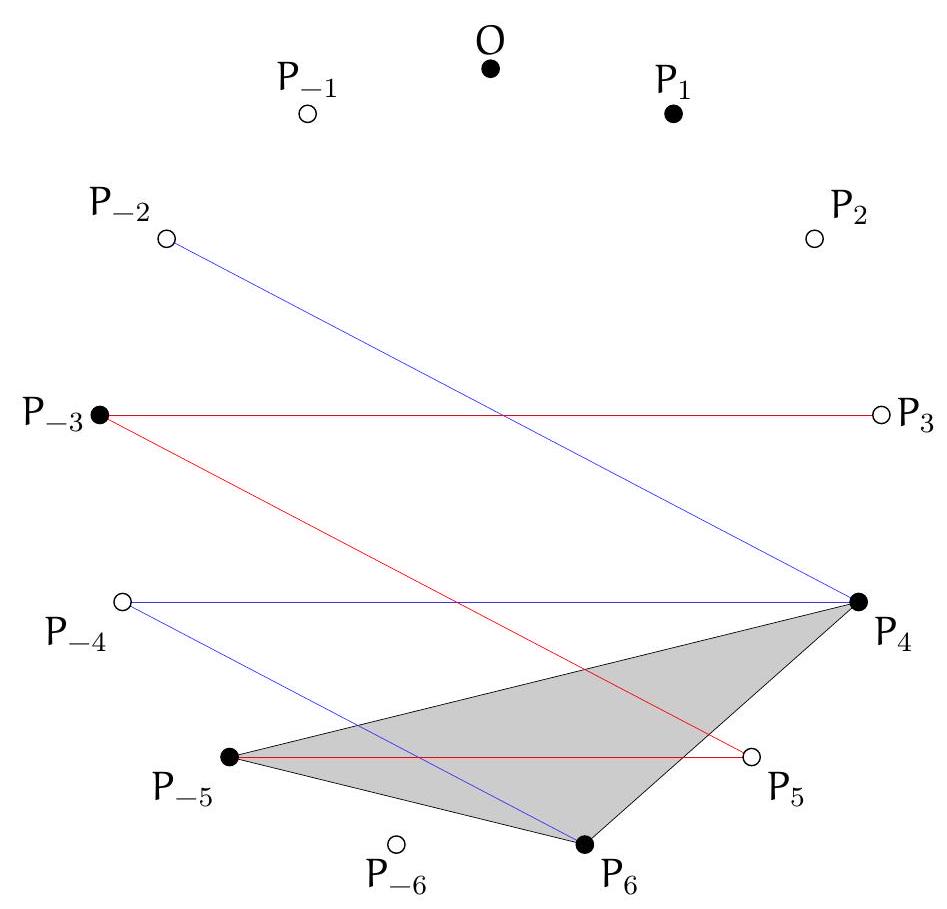

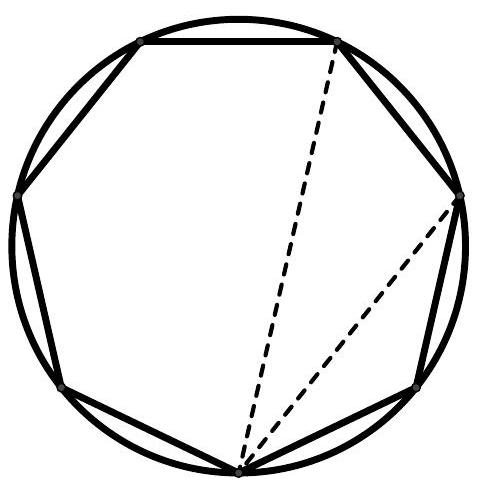

First, fix a colored vertex \( O \) and denote \( \mathrm{OP}_{1} \ldots \mathrm{P}_{2 n} \mathrm{P}_{-2 n} \ldots \mathrm{P}_{-1} \) as the rest of the polygon. Since the triangle \( O P_{i} P_{-i} \) is isosceles for \( 1 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n \), at most one of the two vertices \( P_{i} \) and \( P_{-i} \) is colored.

Suppose that two consecutive vertices are never both colored. In particular, \( \mathrm{P}_{1} \) and \( \mathrm{P}_{-1} \) are not colored because they are adjacent to \( O \) which is colored. But then each of the \( 2 \mathrm{n}-1 \) pairs \( ( \mathrm{P}_{i}, \mathrm{P}_{-i} ) \) of remaining vertices contains at most one colored vertex, and at least \( 2 \mathrm{n}-1 \) vertices among the \( P_{i} \) are colored. We conclude that each pair \( \left(P_{i}, P_{-i}\right) \) with \( i \geqslant 2 \) contains exactly one colored vertex. Thus, either \( P_{i} \) or \( P_{-i} \) is colored for \( i \geqslant 2 \).

Suppose that \( \mathrm{P}_{2 n} \) is colored. Then \( \mathrm{P}_{2 n-1} \) is not colored, so \( \mathrm{P}_{-2 n+1} \) is colored. But then \( \mathrm{P}_{-2 n+2} \) is not colored, so \( P_{2 n-2} \) is colored. The triangle \( P_{2 n-2}, P_{2 n}, P_{-2 n+1} \) being isosceles and colored, we find a contradiction.

We have shown that there exist two consecutive colored vertices, say \( O \) and \( P_{1} \). The vertices \( P_{-1} \) and \( P_{2} \) are then not colored, under penalty of creating an isosceles triangle with \( O \) and \( P_{1} \). Similarly, the triangle \( \mathrm{OP}_{1} \mathrm{P}_{-2 n} \) is isosceles at \( \mathrm{P}_{-2 n} \) which is not colored.

Consider then the following sequence of vertices, of length \( 2(n-1): P_{3}, P_{-3}, \ldots, P_{2 i-1}, P_{-2 i+1}, \ldots, P_{2 n-1}, P_{-2 n+1} \)

Two consecutive vertices of this sequence form an isosceles triangle with \( O \) or with \( P_{1} \), and cannot both be colored.

The same applies to the sequence \( P_{-2}, P_{4}, \ldots, P_{-2 i} P_{2 i+2}, \ldots, P_{-2 n+2}, P_{2 n} \).

These two sequences therefore contain at most half of the colored vertices each. But since they contain together exactly \( 2 \mathrm{n}-2 \) colored vertices, the previous inequalities are saturated and in each sequence, exactly one vertex out of two is colored.

If \( P_{3} \) is colored, then \( \mathrm{P}_{5} \) is colored and the triangle \( \mathrm{P}_{1} \mathrm{P}_{3} \mathrm{P}_{5} \) is isosceles and colored. Similarly, if \( \mathrm{P}_{-2} \) is colored, then \( \mathrm{P}_{-4} \) is colored and the triangle \( \mathrm{OP}_{-2} \mathrm{P}_{-4} \) is isosceles and colored. We deduce that \( \mathrm{P}_{-2 n+1}, \mathrm{P}_{2 n} \) and \( \mathrm{P}_{2 n-2} \) are colored and form an isosceles triangle, which concludes.

Comment from the graders: The problem admitted many solutions and was, overall, well solved by those who attempted it.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Soit $n \geqslant 3$ un entier. On colorie 2 n sommets d'un $4 \mathrm{n}+1$-gone régulier. Montrer qu'il existe trois sommets coloriés qui forment un triangle isocèle.

|

On porcède par l'absurde en supposant qu'aucun triplet de sommets coloriés ne forme de triangle isocèle.

Dans un premier temps, fixons un sommet colorié O et notons $\mathrm{OP}_{1} \ldots \mathrm{P}_{2 n} \mathrm{P}_{-2 n} \ldots \mathrm{P}_{-1}$ le reste du polygone. Puisque le triangle $O P_{i} P_{-i}$ est isocèle pour $1 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n$, au plus l'un des deux sommets $P_{i}$ et $P_{-i}$ est colorié.

Supposons que deux sommets consécutifs ne sont jamais tous les deux coloriés. En particulier, $\mathrm{P}_{1}$ et $\mathrm{P}_{-1}$ ne sont pas coloriés car ils sont adjacents à O qui est colorié. Mais alors chacune des $2 \mathrm{n}-1$ paires ( $\mathrm{P}_{i}, \mathrm{P}_{-i}$ ) de sommets restants contient au plus un point colorié, et au moins $2 \mathrm{n}-1$ sommets parmis les $P_{i}$ sont coloriés. On conclut que chaque paire $\left(P_{i}, P_{-i}\right)$ avec $i \geqslant 2$ contient exactement un sommet colorié. Ainsi, soit $P_{i}$ soit $P_{-i}$ est colorié pour $i \geqslant 2$.

Supposons que $\mathrm{P}_{2 n}$ est colorié. Alors $\mathrm{P}_{2 n-1}$ n'est pas colorié, donc $\mathrm{P}_{-2 n+1}$ est colorié. Mais alors $\mathrm{P}_{-2 n+2}$ n'est pas colorié, donc $P_{2 n-2}$ est colorié. Le triangle $P_{2 n-2}, P_{2 n}, P_{-2 n+1}$ étant isocèle et colorié, on trouve une contradiction.

On a montré qu'il existe deux sommets consécutifs coloriés, disons 0 et $P_{1}$. Les sommets $P_{-1}$ et $P_{2}$ ne sont alors pas coloriés, sous peine de créer un triangle isocèle avec $O$ et $P_{1}$. De même, le triangle $\mathrm{OP}_{1} \mathrm{P}_{-2 n}$ est isocèle en $\mathrm{P}_{-2 n}$ dont $\mathrm{P}_{-2 n} \mathrm{n}$ 'est pas colorié.

Considérons alors la suite de sommets suivante, de longueur $2(n-1): P_{3}, P_{-3}, \ldots, P_{2 i-1}, P_{-2 i+1}, \ldots, P_{2 n-1}, P_{-2 n+1}$

Deux sommets consécutifs de cette suite forment un triangle isocèle avec $O$ ou avec $P_{1}$, et ne peuvent pas être tous les deux coloriés.

Il en va de même pour la suite $P_{-2}, P_{4}, \ldots, P_{-2 i} P_{2 i+2}, \ldots, P_{-2 n+2}, P_{2 n}$.

Ces deux suites contiennent donc chacune au plus une moitié de sommets coloriés. Mais comme elles contiennent ensemble exactement $2 \mathrm{n}-2$ sommets coloriés, les inégalités précédents sont saturées et dans chaque suite, exactement un sommet sur deux est colorié.

Si $P_{3}$ est colorié, alors $\mathrm{P}_{5}$ est colorié et le triangle $\mathrm{P}_{1} \mathrm{P}_{3} \mathrm{P}_{5}$ est isocèle colorié. De même, si $\mathrm{P}_{-2}$ est colorié, alors $\mathrm{P}_{-4}$ est colorié et le triangle $\mathrm{OP}_{-2} \mathrm{P}_{-4}$ est isocèle colorié. On déduit que $\mathrm{P}_{-2 n+1}, \mathrm{P}_{2 n}$ et $\mathrm{P}_{2 n-2}$ sont coloriés et forment un triangle isocèle, ce qui conclut.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème admettait de nombreuses solutions et a été, dans l'ensemble, bien résolu par ceux qui l'ont cherché.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 15.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-4-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 15",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Consider a regular 2022-gon with side length 1. The points are numbered $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{2022}$ in a certain order. Initially, Elie starts from point $A_{1}$, then jumps from point to point to $A_{2}$, then from $A_{2}$ to $A_{3}$, and so on, each time taking the shortest arc. When he reaches $A_{2022}$, he finally returns to $A_{1}$. Determine the maximum value of the sum of the lengths of the arcs that Elie has traveled, among all possible numberings of the points.

|

Response: $\mathrm{If} N=1011$, The maximum value is $2\left(\mathrm{~N}^{2}-\mathrm{N}+1\right)$.

The problem asks to find the maximum value of a sum of lengths, which necessarily involves two parts. First, we show that the path traveled by Elie is necessarily of length less than $2\left(\mathrm{~N}^{2}-\mathrm{N}+1\right)$, this part is called the analysis. Second, we provide an example of a numbering for which the path traveled is exactly of length $2\left(N^{2}-N+1\right)$, this step is called the construction.

Analysis: In the following, we keep the notation $N=1011$. We also denote $\underline{P Q}$ as the length of the shortest arc connecting P and Q, and $\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}$ as the length of the longest arc. Consider a numbering $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{2 N}$ in any order. We also set $A_{2 N+1}=A_{1}$.

Since estimating each segment $A_{i} A_{i+1}$ by its minimum length is too rough, we will instead lower-bound the sum $A_{1} \overline{A_{2}+\ldots}+A_{2 N} A_{1}$ by upper-bounding groups of terms. More precisely, we will look at the path traveled between two consecutive odd vertices.

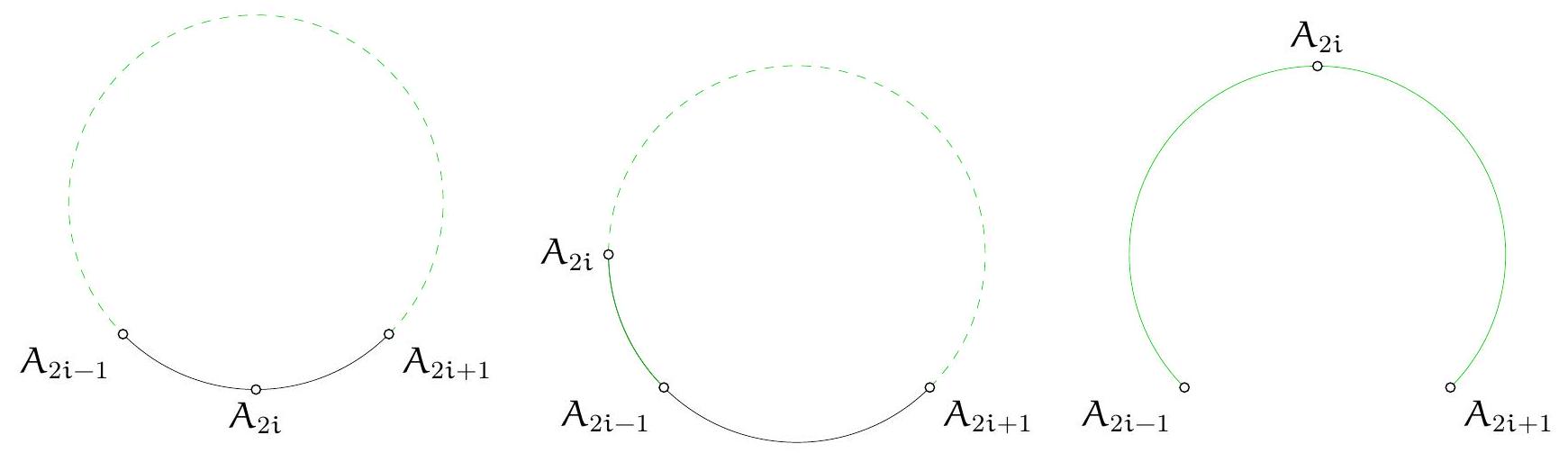

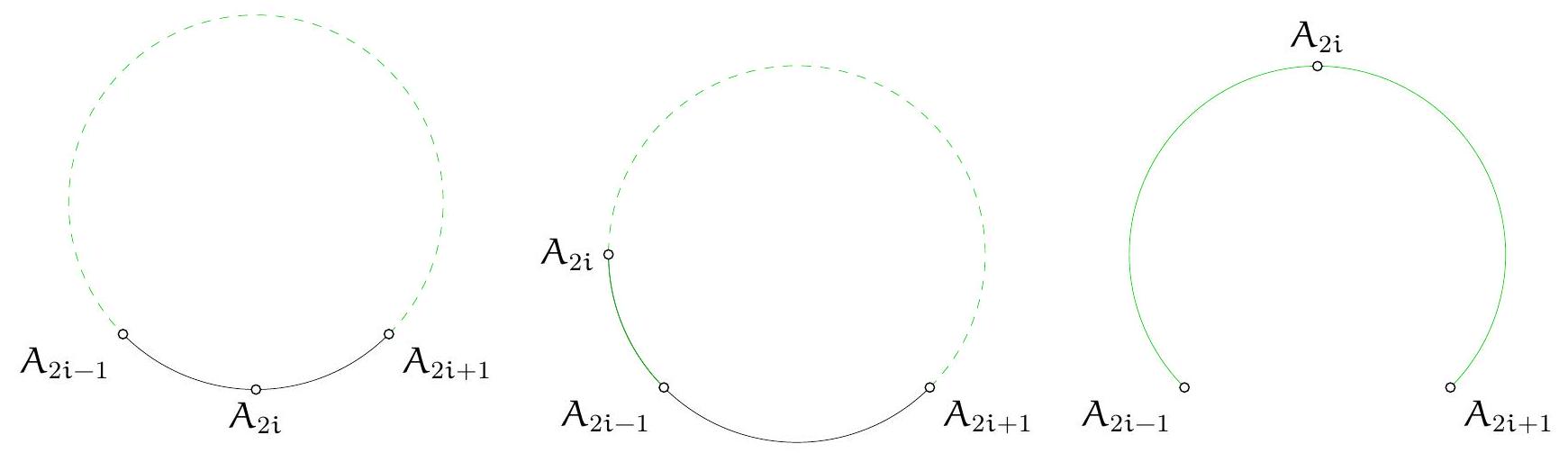

Let $1 \leqslant i \leqslant N$. We want to show that $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$, in other words, that passing through $A_{2 i}$ is less costly than taking the large arc $A_{2 i-1} \mathcal{A}_{2 i+1}$. The desire to prove such an inequality can come from attempts on small cases.

If $A_{2 i}$ is on the small arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}$, then $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. Suppose now that $A_{2 i}$ is on the large arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}$. If the small arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$ does not contain $A_{2 i-1}$ or if the small arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}$ does not contain $A_{2 i+1}$, then $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. If now $A_{2 i-1}$ is on the small arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$, then $A_{2 i+1}$ is on the large arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}$ and $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}+$ $\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\overline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. The case where $A_{2 i-1}$ is on the small arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$ is treated similarly.

We therefore have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} & \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}} \\

& =\left(2 \mathrm{~N}-\underline{A_{1} A_{3}}\right)+\ldots+\left(2 N-\underline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}\right) \\

& \left.=2 N^{2}-\underline{\left(A_{1} A_{3}\right.}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N-1}} \overline{A_{1}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

It is therefore sufficient to minimize the sum $\underline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}$. For this, note that there exist two odd-numbered vertices $A$ and B at a distance of at least $\mathrm{N}-1$ (since there are N odd vertices). As the sum is cyclic, we can assume that $A=A_{1}$ (by renumbering the vertices if necessary). But then the path $A_{1} \ldots A_{2 N-1} A_{1}$ requires traveling an arc $\underline{A_{1} B}$ to go from $A_{1}$ to $B$ and then an arc $B A_{1}$ to go from $B$ to $A_{1}$. Such a path is therefore at least twice the length of the small arc $A B$, which is $2(N-1)$.

It follows that

$$

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}} \geqslant 2 N^{2}-2(N-1)=2\left(N^{2}-N+1\right)

$$

Construction: Conversely, number the vertices in the order $A_{1} A_{3} \ldots A_{2 N-1} A_{2} \ldots A_{2 N}$. The path of Elie is then of length

$$

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}=\underbrace{N+N-1+\ldots+N+N-1}_{N-1 \text { times }}+N+1=2 N^{2}-2 N+2

$$

Graders' Comments: The problem was not solved by many students. Many students found a construction that achieves the correct bound, but among those who attempted the problem, too many students still try to justify that one cannot do better by one of the two arguments:

- Either by saying that at each step, the point $A_{k}$ is placed in the "optimal" position. But performing the "best" operation at each step is not a guarantee of arriving at the best configuration. Here, placing the point $A_{k}$ diametrically opposite to the point $A_{k+1}$ forces, at the end, to have $A_{2022}$ and $A_{1}$ adjacent. Who says that not systematically placing the points $A_{k}$ and $A_{k+1}$ as far apart as possible does not allow increasing the distance between $A_{1}$ and $A_{2022}$ to have a greater total distance?

- Or by saying that if points are swapped on the found configuration, the distance is not increased. This reasoning also does not prove that the configuration is a global maximum, but only proves that the configuration is a local maximum.

We hope that upon reading this comment, students will no longer make these two common reasoning errors.

|

2(N^2 - N + 1)

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

On considère un 2022-gone régulier de côté 1 . Les points sont numérotés $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{2022}$ dans un certain ordre. Au départ, Elie part du point $A_{1}$, puis saute de point en point vers le point $A_{2}$, puis de $A_{2}$ vers $A_{3}$ etc... chaque fois en prenant l'arc le plus court. Lorsqu'il atteint $A_{2022}$, il rejoint finalement $A_{1}$. Déterminer la valeur maximale de la somme des longueurs des arcs qu'a parcouru Elie, parmi toutes les numérotations de points possibles.

|

Réponse: $\mathrm{Si} N=1011$, La valeur maximale est $2\left(\mathrm{~N}^{2}-\mathrm{N}+1\right)$.

Le problème demande de trouver la valeur maximale d'une somme de longueurs, il contient nécessairement deux parties. Dans un premier temps, on montre que le chemin parcouru par Elie est forcément de longueur inférieure à $2\left(\mathrm{~N}^{2}-\mathrm{N}+1\right)$, cette partie s'appelle l'analyse. Dans un second temps, on donne l'exemple d'une numérotation pour laquelle le chemin parcouru est exactement de longueur $2\left(N^{2}-N+1\right)$, cette étape s'appelle la construction.

Analyse : Dans la suite, on garde la notation $N=1011$. On note également $\underline{P Q}$ la longueur de l'arc le plus court reliant P et Q et $\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}$ la longueur de l'arc le plus long. Considérons une numérotation $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{2 N}$ dans un ordre quelconque. On pose aussi $A_{2 N+1}=A_{1}$.

Puisque majorer chaque portion $A_{i} A_{i+1}$ par sa longueur minimale est une estimation trop grossière, on va plutôt minorer la somme $A_{1} \overline{A_{2}+\ldots}+A_{2 N} A_{1}$ en majorant des paquets de terme. Plus précisément, nous allons regarder le chemin parcouru entre deux sommets impairs consécutifs.

Soit $1 \leqslant i \leqslant N$. On désire montrer que $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$, autrement dit, que passer par $A_{2 i}$ est moins coûteux que prendre le grand arc $A_{2 i-1} \mathcal{A}_{2 i+1}$. La volonté de démontrer une telle inégalité peut venir de tentatives sur des petits cas.

Si $A_{2 i}$ est sur le petit arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}$, alors $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. Supposons désormais que $A_{2 i}$ est sur le grand arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}$. Si le petit arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$ ne contient pas $A_{2 i-1}$ ou si le petit arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}$ ne contient pas $A_{2 i+1}$, alors $\underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. Si maintenant $A_{2 i-1}$ est sur le petit arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$, alors $A_{2 i+1}$ est sur le grand arc $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}$ et $A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}+$ $\underline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}} \leqslant \underline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i}}+\overline{A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}}=\overline{A_{2 i-1} A_{2 i+1}}$. Le cas où $A_{2 i-1}$ est sur le petit arc $A_{2 i} A_{2 i+1}$ se traite de façon similaire.

On a donc

$$

\begin{aligned}

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} & \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}} \\

& =\left(2 \mathrm{~N}-\underline{A_{1} A_{3}}\right)+\ldots+\left(2 N-\underline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}\right) \\

& \left.=2 N^{2}-\underline{\left(A_{1} A_{3}\right.}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N-1}} \overline{A_{1}}\right) .

\end{aligned}

$$

Il suffit donc de minimiser la somme $\underline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}$. Pour cela, notons qu'il existe deux sommets $A$ et B de numéro impair à distance au moins $\mathrm{N}-1$ (car il y a N sommets impairs). Comme la somme

est cyclique, on peut supposer que $A=A_{1}$ (quitte à renuméroter les sommets). Mais alors le chemin $A_{1} \ldots A_{2 N-1} A_{1}$ nécessite de parcourir un arc $\underline{A_{1} B}$ pour aller de $A_{1}$ vers $B$ puis un arc $B A_{1}$ pour aller de $B$ vers $A_{1}$. Un tel chemin est donc de longueur au moins le double du petit arc $A B$, soit $2(N-1)$.

Il vient

$$

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}} \geqslant 2 N^{2}-2(N-1)=2\left(N^{2}-N+1\right)

$$

Construction : Réciproquement, numérotons les sommets dans l'ordre $A_{1} A_{3} \ldots A_{2 N-1} A_{2} \ldots A_{2 N}$. Le chemin d'Elie est alors de longueur

$$

\underline{A_{1} A_{2}}+\ldots+\underline{A_{2 N} A_{1}} \leqslant \overline{A_{1} A_{3}}+\ldots+\overline{A_{2 N-1} A_{1}}=\underbrace{N+N-1+\ldots+N+N-1}_{N-1 \text { fois }}+N+1=2 N^{2}-2 N+2

$$

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème n'a pas été beaucoup résolu. Beaucoup d'élèves ont trouvé une construction réalisant la bonne borne, mais parmi ceux qui ont cherché l'exercice, trop d'élèves encore tentent de justifier qu'on ne peut pas faire mieux par l'un des deux arguments :

- Soit en disant qu'à chaque étape on place le point $A_{k}$ à l'endroit "optimal". Mais effectuer la "meilleure" opération à chaque fois n'est pas gage d'arriver à la meilleure configuration. Ici, placer le point $A_{k}$ diamétralement opposé au point $A_{k+1}$ impose à la fin d'avoir $A_{2022}$ et $A_{1}$ adjacents. Qui nous dit que ne pas systématiquement placer les points $A_{k}$ et $A_{k+1}$ le plus éloigné possible ne permet pas d'augmenter la distance entre $A_{1}$ et $A_{2022}$ pour avoir une plus grande distance totale?

- Soit en disant que si l'on échange des points sur la configuration trouvée, on n'augmente pas la distance. Là aussi, ce raisonnement ne permet pas de prouver que la configuration est un maximum global, mais seulement de prouver que la configuration est un maximum local.

Nous espérons qu'à la lecture de ce commentaire, les élèves ne commettront plus ces deux erreurs communes de raisonnement.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 16.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-4-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 16",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Consider 51 strictly positive integers with a sum of 100 on a line. Show that for any integer $1 \leqslant k<100$, there exist consecutive integers with a sum of $k$ or $100-k$.

|

We slightly rephrase the statement to make it more visual: imagine a circle with a circumference of 100, graduated from 0 to 99. On this circle, 51 graduations are marked in black and the other 49 are marked with dotted lines. Without loss of generality, we mark the graduation 0 in black. Our positive integers correspond to the lengths between the black graduations. It is easy to verify that this is a bijective representation of the problem. For any $k$, by the pigeonhole principle, since the function that maps $j$ to $j+k$ is injective (modulo 100), there exists a black graduation $j$ such that its image $j+k$ is also black. Two cases arise. Either the segment $[j, j+k]$ does not cross 0, and then we have the desired integers. Or it crosses 0, and then $[j+k, j]$ does not cross 0 and is of length $n-k$. In both cases, we have found consecutive integers with a sum of $k$ or $n-k$.

Graders' comment: The exercise is well handled.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

On considère 51 entiers strictement positifs de somme 100 sur une ligne. Montrer que pour tout entier $1 \leqslant k<100$, il existe des entiers consécutifs de somme $k$ ou $100-k$.

|

On reformule légèrement l'énoncé pour le rendre plus visuel : on se représente un cercle de périmètre 100 gradué (de 0 à 99 par exemple) sur-lequel on a marqué en noir 51 graduations et en pointillés les 49 autres. Sans perte de généralité on marque en noir la graduation 0. Nos entiers positifs correspondent aux longueurs entre les graduations noires. On vérifie facilement qu'il s'agit d'une représentation bijective du problème. Pour tout $k$, par principe des tiroirs, comme l'application qui à $j$ associe $j+k$ est injective (modulo 100), il existe une graduation marquée en noir $j$ telle que son image $j+k$ l'est aussi. Deux cas se présentent alors. Soit le segment $[j, j+k]$ ne coupe pas 0 et alors on a bien les entiers souhaités. Soit il coupe 0 et alors $[j+k, j]$ ne coupe pas 0 et est de longueur $n-k$. Dans les deux cas, on a trouvé des entiers consécutifs de somme $k$ ou $n-k$.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice est plutôt bien traité.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 17.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-4-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 17",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $\mathrm{C}_{1}, \mathrm{C}_{2}, \ldots \mathrm{C}_{\mathrm{n}}$ be circles of the same radius arranged in the plane such that they are never tangent to each other and there always exists a path passing through the circles to go from a point on one of them to another (in other words, the circles are connected). Denoting $S$ as the set of intersection points of the circles, show that $|S| \geqslant n$.

|

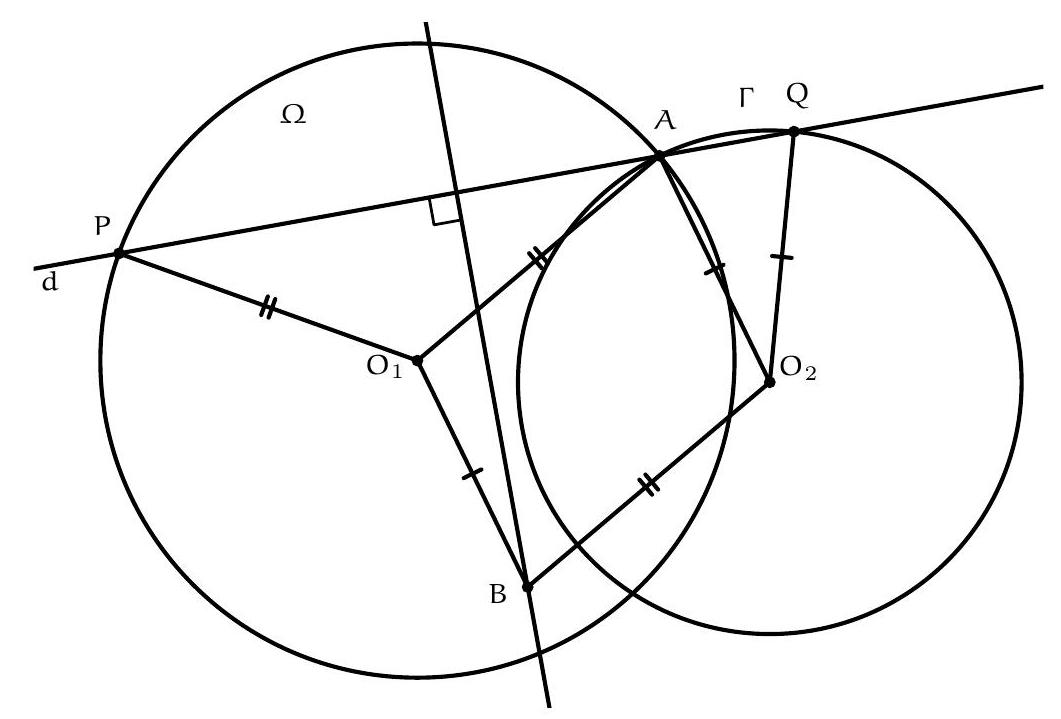

First, we rephrase the problem in terms of graphs. We denote by \( C \) the set of centers of the circles and \( S \) the set of intersection points which form the vertices of a graph \( G \). We connect by an edge every pair \( (c, s) \in C \times S \) if \( s \) belongs to the circle centered at \( c \). Notice then that for every edge \( (c, s) \), \( \operatorname{deg}(c) \geqslant \operatorname{deg}(s) \). Indeed, according to the statement, for every point \( c_{i} \) connected to \( s \) other than \( c \), we can associate another intersection point of \( c_{i} \) with \( c \) since the circles are not tangent. Given \( c_{i} \) and \( c_{j} \) distinct, these second points \( s_{i} \) and \( s_{j} \) cannot be the same since all circles have the same radius. Now that the problem is reformulated, we can reason solely on the graph: \( G \) is a bipartite graph between \( C \) and \( S \) such that for every edge \( (c, s) \), \( \operatorname{deg}(c) \geqslant \operatorname{deg}(s) \). It easily follows that \( |C| \leqslant |S| \). Indeed, denoting \( A \) the set of edges and \( a = (c_{a}, s_{a}) \) these edges: \( |C| = \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \frac{1}{\operatorname{deg}(c_{a})} \leqslant \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \frac{1}{\operatorname{deg}(s_{a})} = S \), which concludes.

Graders' comments: The problem was attempted by few students and solved by only one. Attempting a proof by induction was doomed to fail: indeed, one can add a circle without necessarily adding an intersection point to the figure formed.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soient $\mathrm{C}_{1}, \mathrm{C}_{2}, \ldots \mathrm{C}_{\mathrm{n}}$ des cercles de même rayon disposés dans le plan de sorte qu'ils ne soient jamais tangents 2 à 2 et qu'il existe toujours un chemin passant par les cercles pour aller d'un point de l'un d'entre eux à un autre (autrement dit, les cercles sont connectés). En notant S l'ensemble des points d'intersection des cercles, montrer que $|S| \geqslant n$.

|

Dans un premier temps, on reformule le problème en termes de graphes. On note C l'ensemble des centres des cercles et S l'ensemble des points d'intersections qui constituent les sommets d'un graphe $G$. On relie par une arête tout couple ( $c, s) \in C \times S$ si $s$ appartient au cercle de centre $c$. Remarquons alors que pour toute arête $(c, s), \operatorname{deg}(c) \geqslant \operatorname{deg}(s)$. En effet, d'après l'énoncé, à tout point $c_{i}$ relié à $s$ autre que c on peut associer un autre point d'intersection de $\mathrm{c}_{\mathrm{i}}$ avec c car les cercles ne sont pas tangents. Étant donnés $\boldsymbol{c}_{\boldsymbol{i}}$ et $\boldsymbol{c}_{\boldsymbol{j}}$ distincts, ces deuxièmes points $s_{i}$ et $s_{j}$ ne peuvent pas être confondus puisque tous les cercles sont de même rayons. Maintenant que le problème est reformulé, on peut raisonner uniquement sur le graphe : $G$ est un graphe bipartite entre $C$ et $S$ tel que pour toute arête $(c, s), \operatorname{deg}(c) \geqslant \operatorname{deg}(s)$. Il vient aisément que $|C| \leqslant|S|$ En effet, en notant A l'ensemble des arêtes et $a=\left(c_{a}, s_{a}\right)$ ces arêtes $:|C|=\sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \frac{1}{\operatorname{deg}\left(c_{a}\right)} \leqslant \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \frac{1}{\operatorname{deg}\left(s_{a}\right)}=S$ ce qui conclut.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Le problème a été peu tenté, et résolu par un seul élève. Faire une récurrence était voué à l'échec : en effet, on peut rajouter un cercle, sans pour autant rajouter de point d'intersection à la figure formée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 18.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-4-2023-2024.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 18",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Find all triplets of positive integers $(x, y, z)$ satisfying the equation

$$

x! + 2^y = z!

$$

|

Let $(x, y, z)$ be a solution triplet.

First, we aim to reduce the number of values that $x$ can take. Note that $x! < z!$ so $x < z$. In particular, $x!$ divides $z!$ and $x!$, so $x!$ divides $z! - x! = 2^y$. Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $x \geq 3$, in this case 3 divides $x!$ but does not divide $2^y$, which makes it impossible for $x!$ to divide $2^y$. Thus, $x = 0, 1$ or 2.

We now perform a case disjunction between $x! = 1$ so $x = 0$ or 1, or $x! = 2$ so $x = 2$.

- Case $x = 0$ or 1: the equation becomes $1 + 2^y = z!$. We then perform a second case disjunction:

- Case $y = 0$: we find $z = 2$. Conversely, $(0,0,2)$ and $(1,0,2)$ are indeed solutions.

- Case $y \geq 1$: thus $1 + 2^y \geq 3$ and $1 + 2^y$ is odd. However, $z!$ is even if $z \geq 2$, and equals 0 or 1 if $z = 1$, neither of which can satisfy our equation. Thus, if we assume $y \geq 1$, there are no solutions.

- Case $x = 2$: We distinguish according to the values of $y$:

- Case $y = 0$: we get $3 = z!$ which has no solutions (since $2! < 3 < 3!$).

- Case $y = 1$: we get $4 = z!$ which has no solutions (since $2! < 3 < 3!$).

- Case $y \geq 2$: we get that 2 divides $2^y + 2$, but 4 does not divide $2^y + 2$. Thus, 2 divides $z!$ but 4 does not divide $z!$, so $z = 2$ or 3. Since $2^y + 2 \geq 4 + 2 = 6$, we get $z = 3$, so $2 + 2^y = 6$, thus $2^y = 4$ and $y = 2$. Conversely, $(2,2,3)$ is indeed a solution since $2 + 4 = 6$.

Thus, the solutions are the triplets $(0,0,2), (1,0,2)$, and $(2,2,3)$.

Comment from the graders: The exercise, rather simple, was approached by a large number of students. Most managed to find the correct set of solutions and thought to use moduli or divisibility, which is very good. However, many errors were made, consisting in neglecting to properly handle the small cases. For example, many papers hastily claimed that a power of 2 is even, which is false for $2^0 = 1$. Attention must be paid to such details. It is also recalled that 0 is a positive integer.

|

(0,0,2), (1,0,2), (2,2,3)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver toutes les triplets d'entiers positifs $(x, y, z)$ satisfaisant l'équation

$$

x!+2^{y}=z!

$$

|

Soit ( $x, y, z$ ) un triplet solution.

On cherche dans un premier temps à réduire le nombre de valeurs que $x$ peut prendre. Pour ce faire notons que $x$ ! < $<$ ! donc $x<z$. En particulier, $x$ ! divise $z$ ! et $x$ !, donc $x$ ! divise $z$ ! $-x!=2^{y}$. Supposons par l'absurde que $x \geqslant 3$, dans ce cas 3 divise $x$ ! mais ne divise pas $2^{y}$, ce qui rend impossible le fait que $x$ ! divise $2^{y}$. Ainsi $x=0,1$ ou 2 .

On effectue maintenant une disjonction de cas entre $x!=1$ donc $x=0$ ou 1 , ou bien $x!=2$ donc $x=2$.

- Cas $x=0$ ou 1 : l'équation devient $1+2^{y}=z$ !. On effectue alors une deuxième disjonction de cas

- Cas $y=0$ : on trouve $z=2$. Réciproquement, $(0,0,2)$ et $(1,0,2)$ sont bien solution.

- Cas $y \geqslant 1$ : ainsi $1+2^{y} \geqslant 3$ et $1+2^{y}$ est impair. Or $z$ ! est pair si $z \geqslant 2$, et vaut 0 ou 1 si $z=1$, aucun des deux cas ne peut donc satisfaire notre équation. Ainsi, si on suppose que $y \geqslant 1$, il n'y a pas de solution.

- Cas $x=2$ : On distingue encore selon les valeurs de $y$ :

- Cas $\mathrm{y}=0$ : on obtient $3=z$ ! qui n'a pas de solutions (car $2!<3<3$ !).

- Cas $\mathrm{y}=1$ : on obtient $4=z$ ! qui n'a pas de solutions (car $2!<3<3$ !).

- Cas $y \geqslant 2$ : on obtient que 2 divise $2^{y}+2$, mais que 4 ne divise pas $2^{y}+2$. Ainsi 2 divise $z$ ! mais 4 ne divise pas $z$ !, donc $z=2$ ou 3 . Comme de plus $2^{y}+2 \geqslant 4+2=6$, on obtient $z=3$, donc $2+2^{y}=6$, donc $2^{y}=4$ donc $y=2$. Réciproquement, $(2,2,3)$ est bien solution $\mathrm{car} 2+4=6$.

Ainsi les solutions sont les triplets $(0,0,2),(1,0,2)$ et $(2,2,3)$.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice, plutôt simple, a été abordé par un grand nombre d'élèves. La plupart ont réussi à trouver le bon ensemble de solutions, et ont bien pensé à utiliser les modulos ou la divisibilité, ce qui est très bien. Cependant, de nombreuses erreurs ont été commises, consistant à négliger de traiter proprement les petits cas. Par exemple, de nombreuses copies affirmaient hâtivement qu'une puissance de 2 est paire, ce qui est faux pour $2^{0}=1$. Il faut faire attention à ce genre de détails. On rappelle également que 0 est un entier positif.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $ABC$ be an equilateral triangle and $P$ a point on the circumcircle of this triangle but distinct from $A$, $B$, and $C$. The lines passing through $P$ and parallel to $(BC)$, $(CA)$, and $(AB)$ intersect the lines $(CA)$, $(AB)$, and $(BC)$ at $M$, $N$, and $Q$ respectively. Show that the points $M$, $N$, and $Q$ are collinear.

|

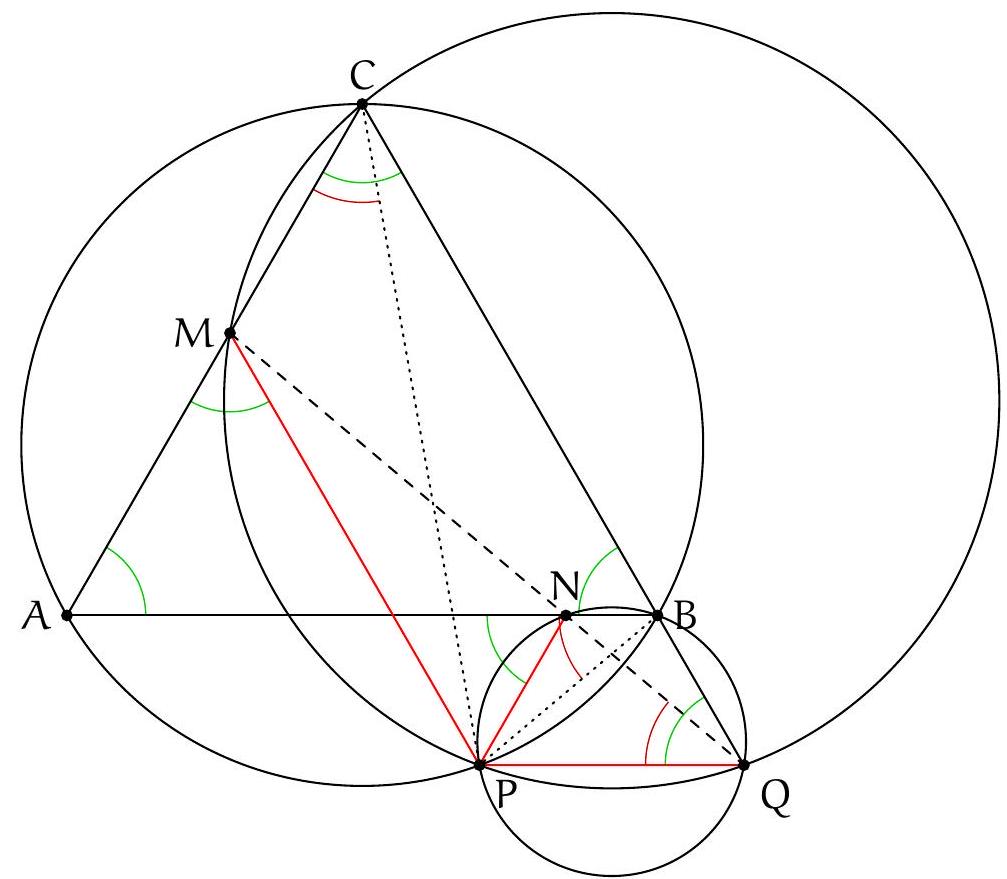

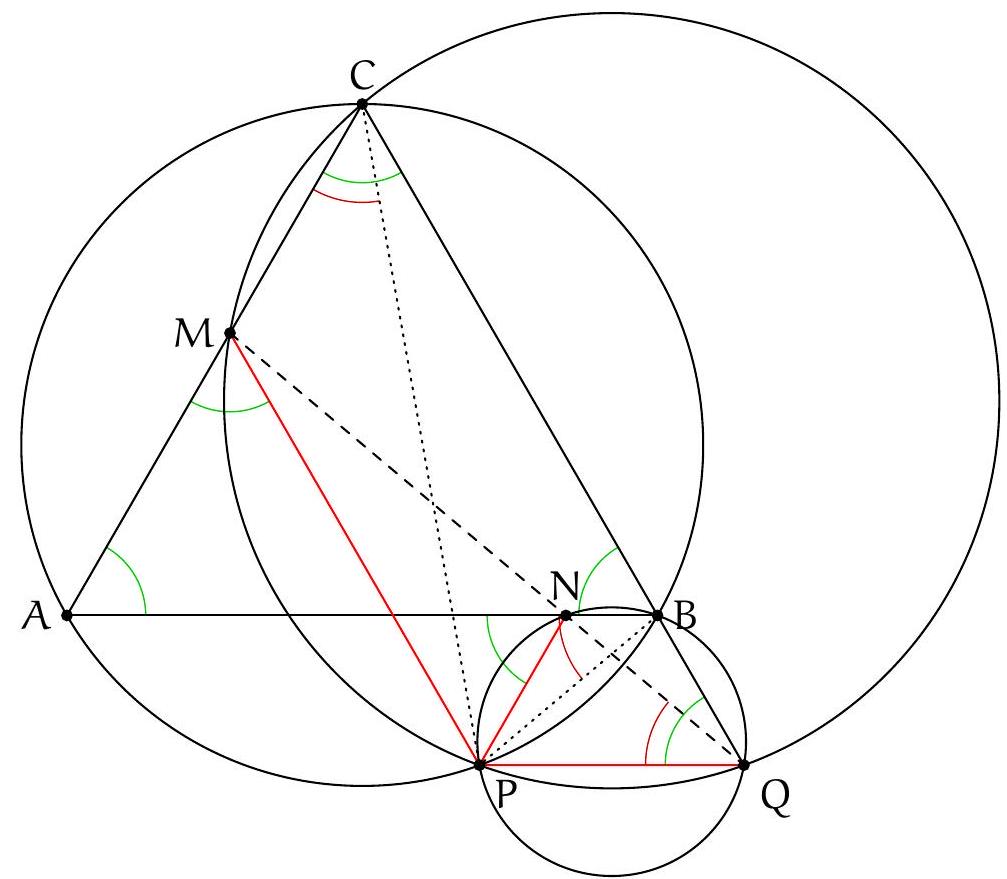

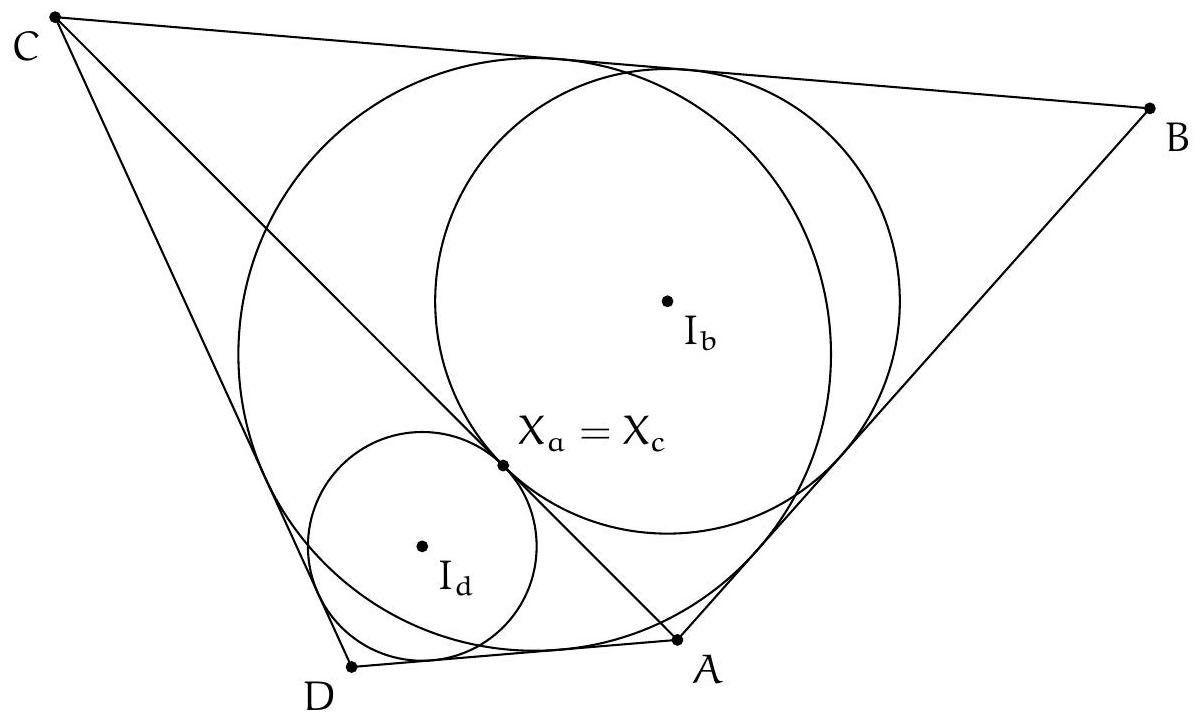

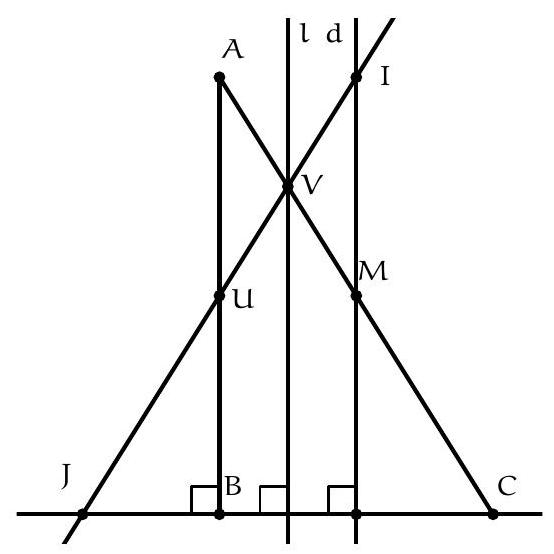

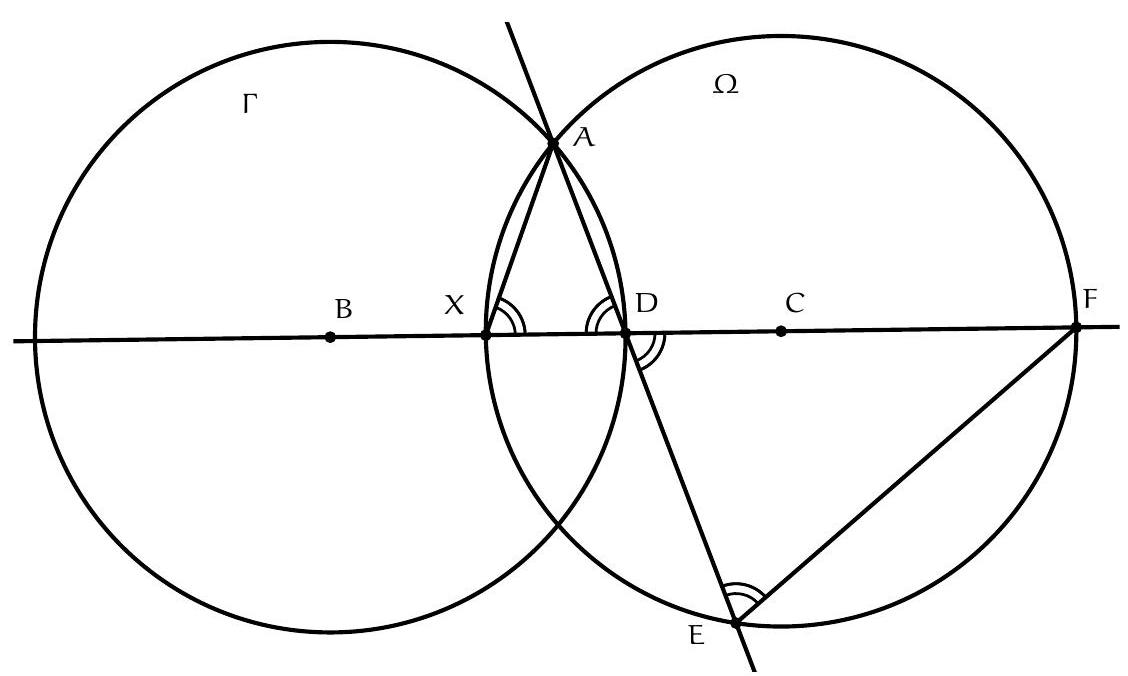

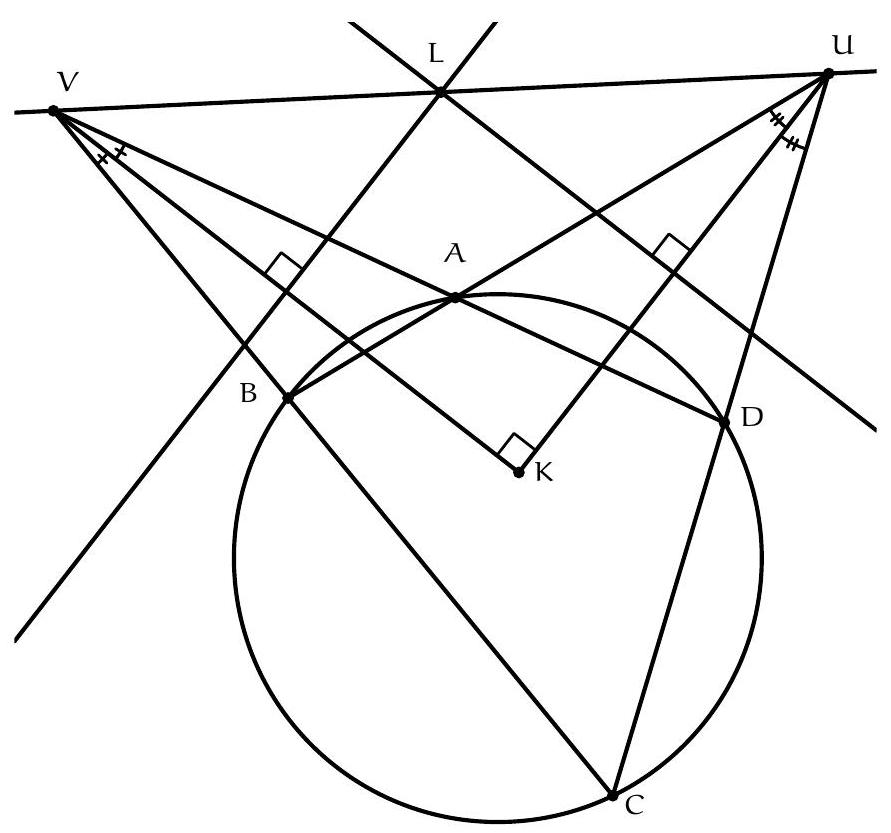

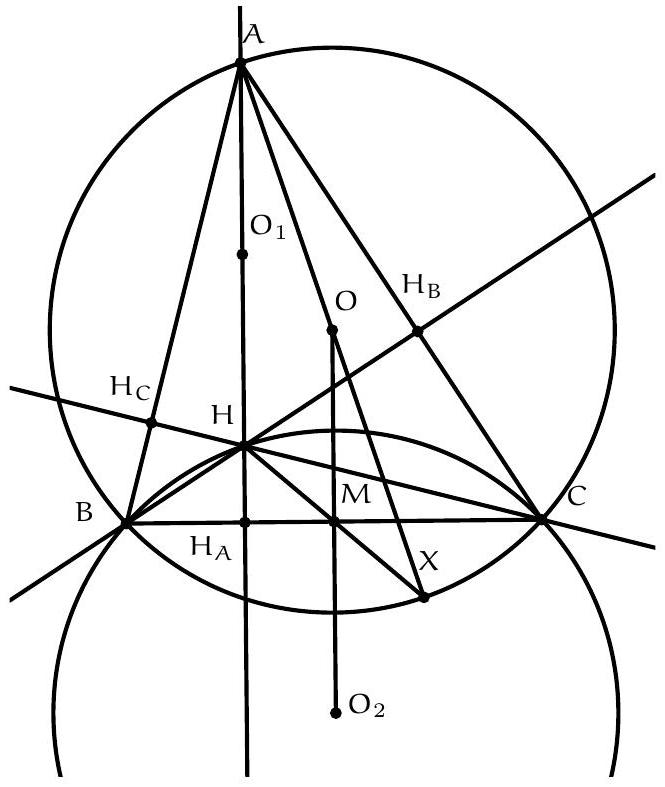

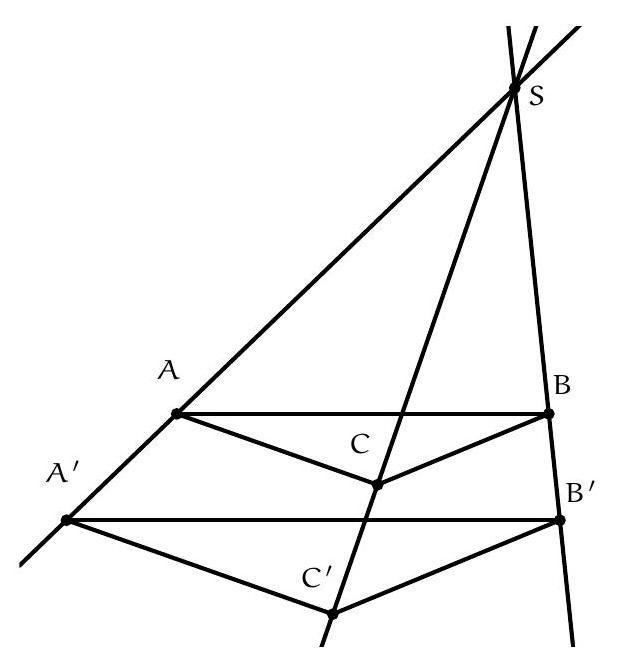

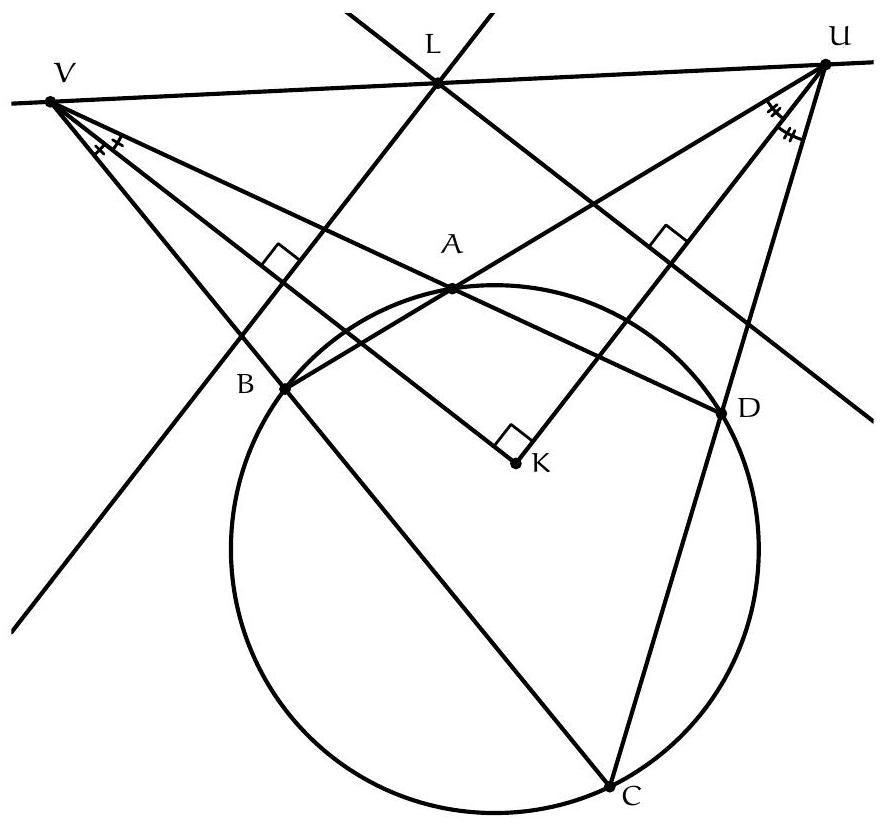

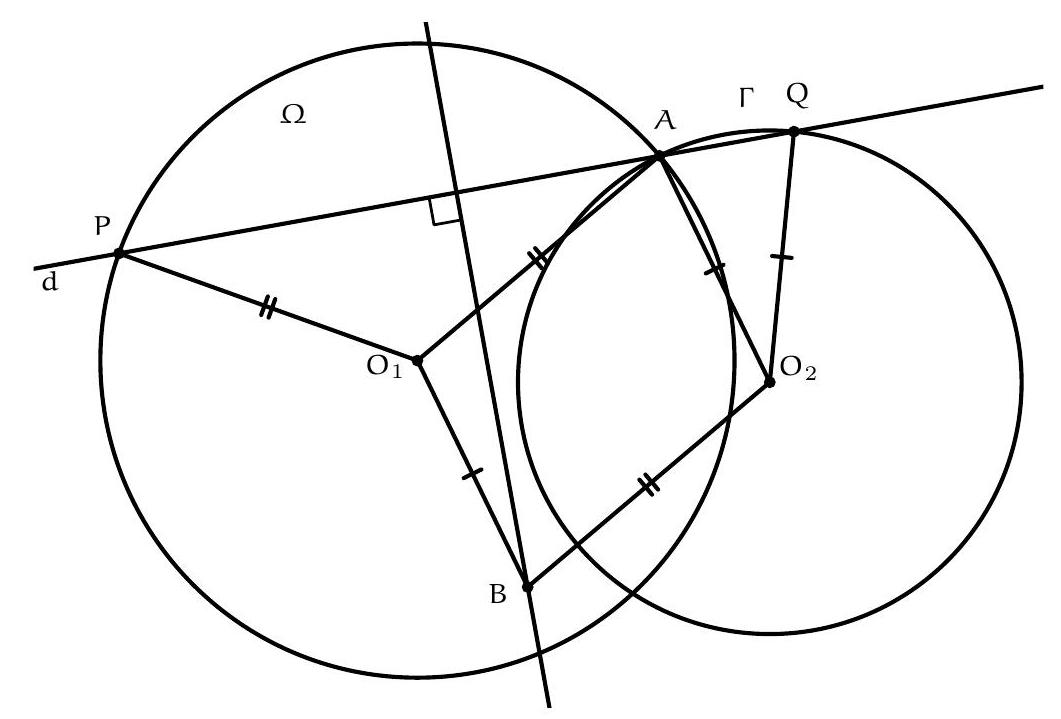

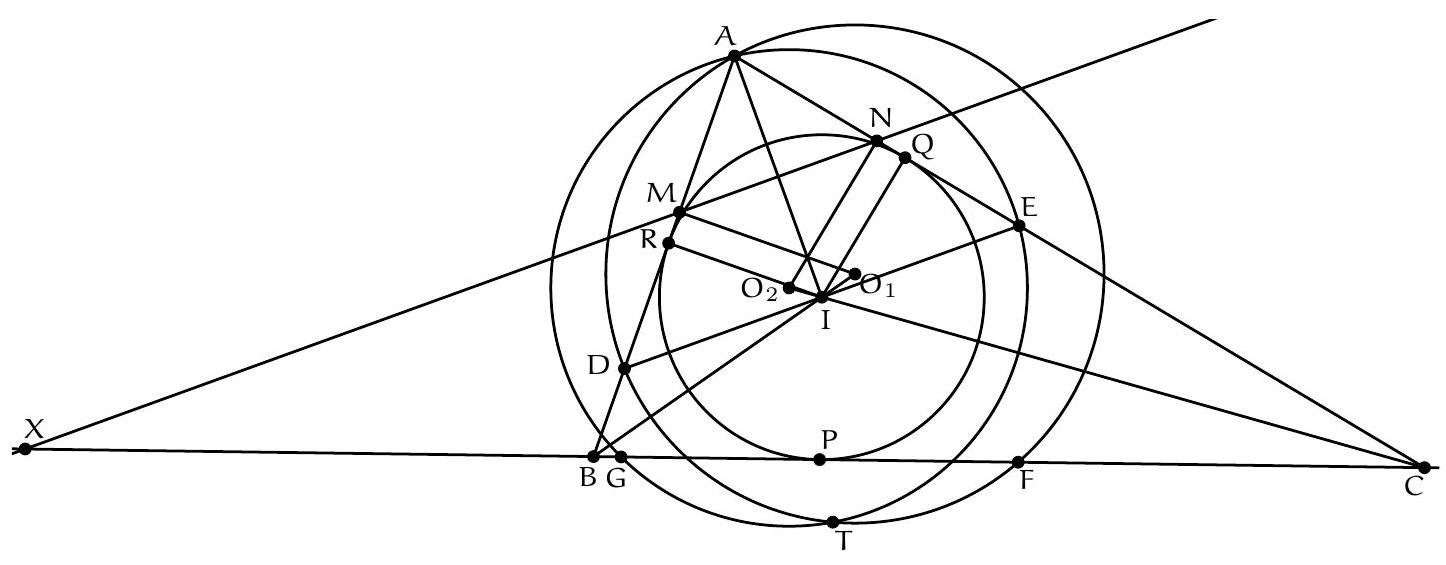

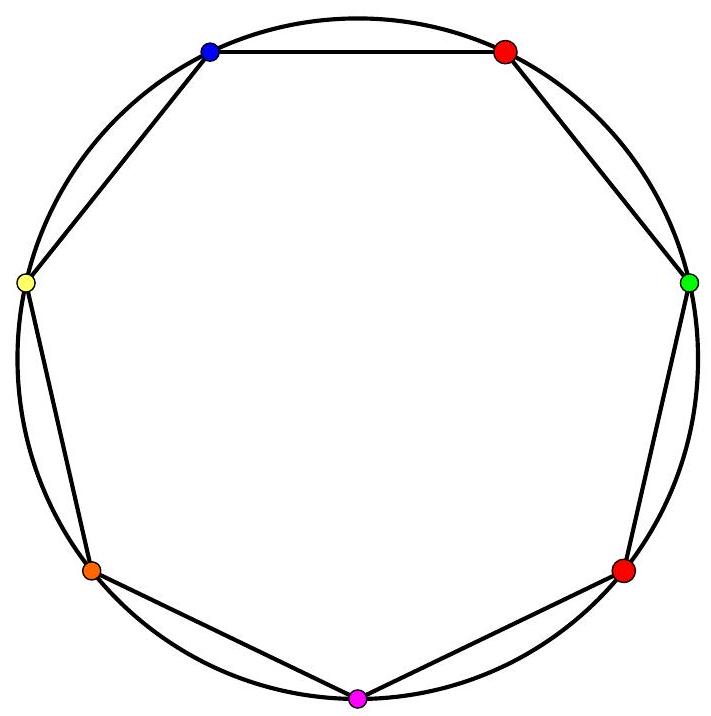

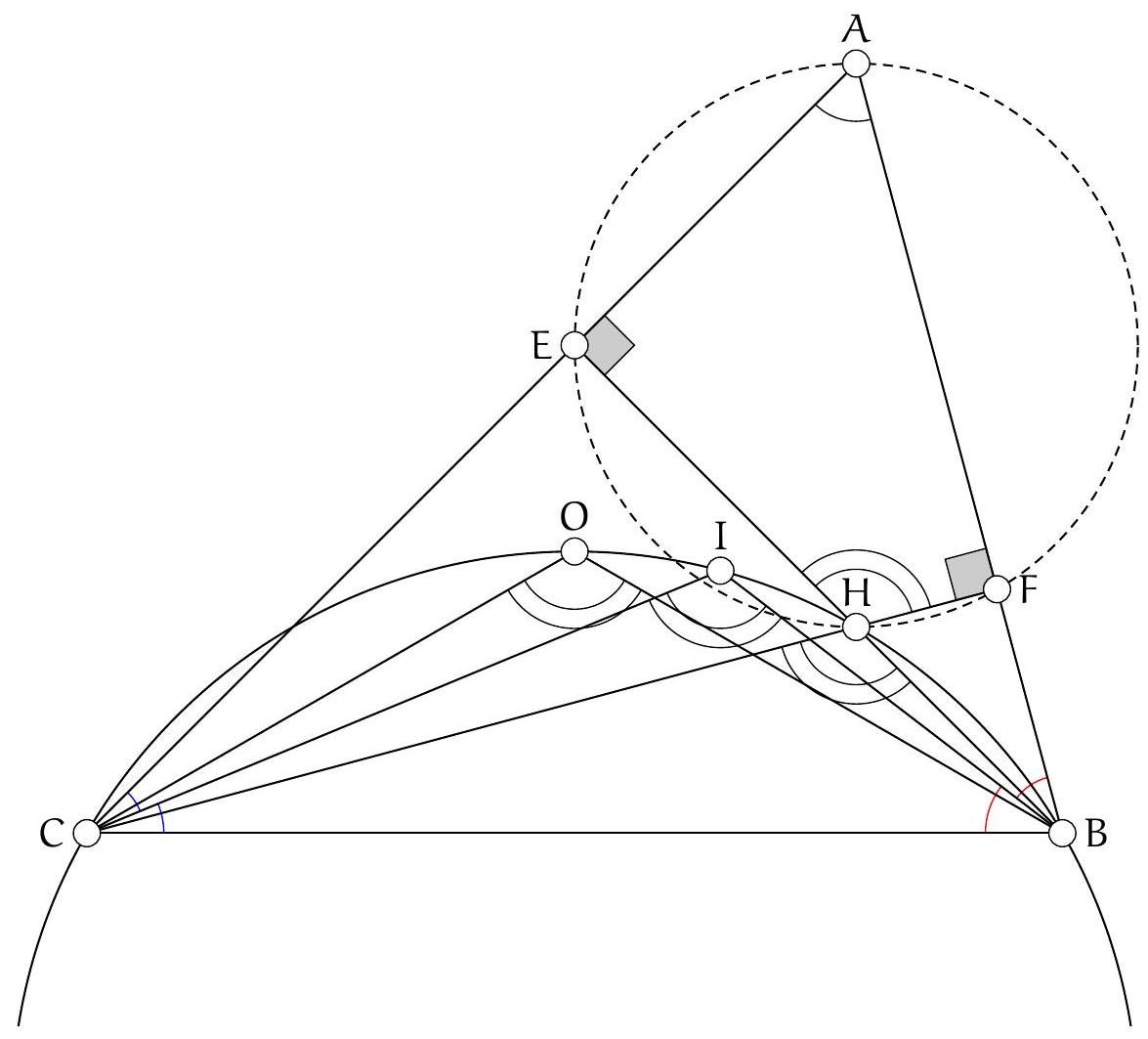

Consider the following figure:

Let's show that \(P, N, B, Q\) are concyclic. Since \((PN)\) is parallel to \((AC)\), and \((NB)\) is parallel to \((AB)\), \(\widehat{ANP} = \widehat{CAB} = 60^\circ\). Since \((PQ)\) is parallel to \((AB)\), \(\widehat{PQB} = \widehat{ABC} = 60^\circ\). Thus, \(P, N, B, Q\) are concyclic. Therefore, \(\widehat{PQN} = \widehat{PBN} = \widehat{PBA}\).

Let's show that \(P, M, C, Q\) are concyclic. Since \((PM)\) is parallel to \((BC)\), \(\widehat{AMP} = \widehat{ACB} = 60^\circ\). Since \(\widehat{PQC} = \widehat{PQB} = 60^\circ\), \(P, M, C, Q\) are concyclic. Therefore, \(\widehat{PQM} = \widehat{PCM} = \widehat{PCA}\). By the concyclicity of \(A, P, B, C\), \(\widehat{PQM} = \widehat{PCA} = \widehat{PBA} = \widehat{PQN}\), so \(Q, N, M\) are collinear.

Graders' comments: Well solved overall. Many proofs are a bit too long. Some reasoning errors (alignment of points cannot be used to prove they are actually aligned).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle equilatéral et P un point sur le cercle circonscrit de ce triangle mais distincs de $A$, $B$ et $C$. Les droites passant par $P$ et parallèles à $(B C),(C A)$ et $(A B)$ intersectent les droites (CA), (AB) et (BC) en $M$, $N$ et $Q$ respectivement. Montrer que les points $M, N$ et $Q$ sont alignés.

|

On se place dans le cas de la figure suivante :

Montrons que $P, N, B, Q$ sont cocycliques. Comme $(P N)$ est parallèle à $(A C)$, et $(N B)$ est parallèle à $(\mathrm{AB}), \widehat{A N P}=\widehat{C A B}=60$. Comme $(\mathrm{PQ})$ est parallèle à $(\mathrm{AB}), \widehat{\mathrm{PQB}}=\widehat{A B C}=60$. Ainsi $\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{N}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{Q}$ sont cocycliques. Ainsi $\widehat{\mathrm{PQN}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PBN}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PBA}}$.

Montrons que $P, M, C, Q$ sont cocycliques. Comme $(P M)$ est parallèle à $(B C), \widehat{A M P}=\widehat{A C B}=60$. Or $\widehat{\mathrm{PQC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PQB}}=60$. Ainsi $\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{M}, \mathrm{C}, \mathrm{Q}$ sont cocycliques. Ainsi $\widehat{\mathrm{PQM}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PCM}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PCA}}$. Par cocyclité de $A, P, B, C, \widehat{P Q M}=\widehat{P C A}=\widehat{P B A}=\widehat{P Q N}$ donc $Q, N, M$ sont alignés.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Bien résolu dans l'ensemble. Beaucoup de preuves qui sont un peu trop longues. Quelques erreurs de raisonnement (on ne peut pas utiliser que les points sont alignés pour montrer qu'ils le sont effectivement).

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $x, y, z$ be three positive real numbers, such that $x \leqslant 1$. Prove that:

$$

x y + y + 2 z \geqslant 4 \sqrt{x y z}

$$

|

Note that since $x \leqslant 1, x y+y \geqslant x y+x y=2 x y$. In particular, by the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality,

$$

x y+y+2 z \geqslant 2 x y+2 z=2(x y+z) \geqslant 4 \sqrt{x y z}

$$

which gives the desired inequality.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was quite simple and was approached by many students, and almost all of them succeeded. However, I encourage students to carefully proofread their work before submitting, to ensure that inequalities are written correctly and that no cases have been overlooked (for example, by simplifying an equation by $y z$ when $y z$ could be zero).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $x, y, z$ trois réels positifs, tel que $x \leqslant 1$. Démontrer que:

$$

x y+y+2 z \geqslant 4 \sqrt{x y z}

$$

|

Notons que comme $x \leqslant 1, x y+y \geqslant x y+x y=2 x y$. En particulier par inégalité arithmético-géométrique

$$

x y+y+2 z \geqslant 2 x y+2 z=2(x y+z) \geqslant 4 \sqrt{x y z}

$$

ce qui donne l'inégalité voulue.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice était assez simple et a été abordé par de nombreux élèves, et réussi par presque chacun d'entre eux. J'invite toutefois les élèves à bien se relire lorsqu'ils soumettent une copie, afin de vérifier que les inégalités sont écrites correctement et que des cas n'ont pas été oubliés (par exemple en simplifiant une équation par $y z$ alors que $y z$ peut être nul).

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

2024 students, all of different heights, need to line up in a single file. However, each student does not want to have both a shorter student in front of them and a shorter student behind them. How many ways are there to form such a line?

|

Let's look at the tallest student: if they are not placed at the very beginning or the very end of the line, they are between two students who are shorter than them. Thus, the tallest student must be placed at the end or at the beginning.

By this reasoning, and by looking at small cases, we can conjecture that if we need to place $n \geqslant 1$ students all of different heights with the constraint given in the statement, there are $2^{\text {n-1 }}$ possibilities. Let's prove this by induction on $n$.

Initialization: for $\mathrm{n}=1$ student, there is only one possible line and $1=2^{\mathrm{n}-1}$.

Hereditary: suppose the hypothesis is true at rank $n$ for a $n \geqslant 1$, let's show that it is true at rank $n+1$. The tallest student is necessarily placed either at the very beginning or at the very end. If we remove this student from the line, the line of $n$ people still satisfies the statement: there are therefore potentially $2^{n-1}$ possibilities for the line without the tallest person. If we add the tallest person at the front or the back of the line, the line still satisfies the statement (since the person next to the tallest will not be between two people who are shorter), as there are two choices for placing the tallest person, there are $2^{\mathfrak{n}}=2^{\mathfrak{n + 1 - 1}}$ possibilities to form the line, which concludes the induction.

Thus, by applying the property for $\mathrm{n}=2024$, there are $2^{2023}$ possibilities.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was very well done overall, with few errors. Two main methods of proof were used: the first is similar to what the statement suggests, and involves seeing how to place the students, one by one. The second involves understanding what the "shape" of the distribution of students will be, in a V shape, and counting these configurations using various arguments.

|

2^{2023}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

2024 élèves, tous de taille différente, doivent se placer en file indienne. Cependant, chaque élève ne souhaite pas avoir à la fois devant lui et derrière lui un élève plus petit que lui. Combien y a-t-il de façons de former une telle file indienne?

|

Regardons l'élève de plus grande taille : s'il n'est pas placé au tout début ou à la toute fin de la file, il est entre deux élèves plus petits que lui. Ainsi l'élève le plus grand doit être placé à la fin ou au début.

Via ce raisonnement, et en regardant les petits cas on peut conjecturer que si on doit placer $n \geqslant 1$ élèves tous de taille différente avec la contrainte de l'énoncé, il y a $2^{\text {n-1 }}$ possibilités. Montrons cela par récurrence sur n .

Initialisation : pour $\mathrm{n}=1$ élèves, il n'y a qu'une file possible et $1=2^{\mathrm{n}-1}$.

Hérédité : supposons l'hypothèse vraie au rang $n$ pour un $n \geqslant 1$, montrons qu'elle l'est au rang $n+1$. L'élève le plus grand est frocément placé soit au tout début, soit à la toute fin. Si on l'enlève de la file, la file de $n$ personnes vérifie toujours l'énoncé : il y a donc potentiellement $2^{n-1}$ possibilité pour la file sans la personne la plus grande. Si on rajoute la personne la plus grande devant ou derrière la file vérifie toujours l'énoncé (car la personne à côté du plus grand ne sera pas entre deux personnes plus petites), comme il y a deux choix de placements du plus grand, il y a $2^{\mathfrak{n}}=2^{\mathfrak{n + 1 - 1}}$ possibilités pour former la file, ce qui conclut la récurrence.

Ainsi en appliquant la propriété pour $\mathrm{n}=2024$, il y a $2^{2023}$ possibilités.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Exercice très bien réussi dans l'ensemble, avec peu d'erreurs. Deux méthodes de preuve principales ont été employées : la première est semblable à ce que fait l'énoncé, et consiste à voir comment placer les élèves, un par un. La seconde consiste à comprendre quelle va être la "forme" de la répartition des élèves, en V , et à compter ces configurations par divers arguments.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

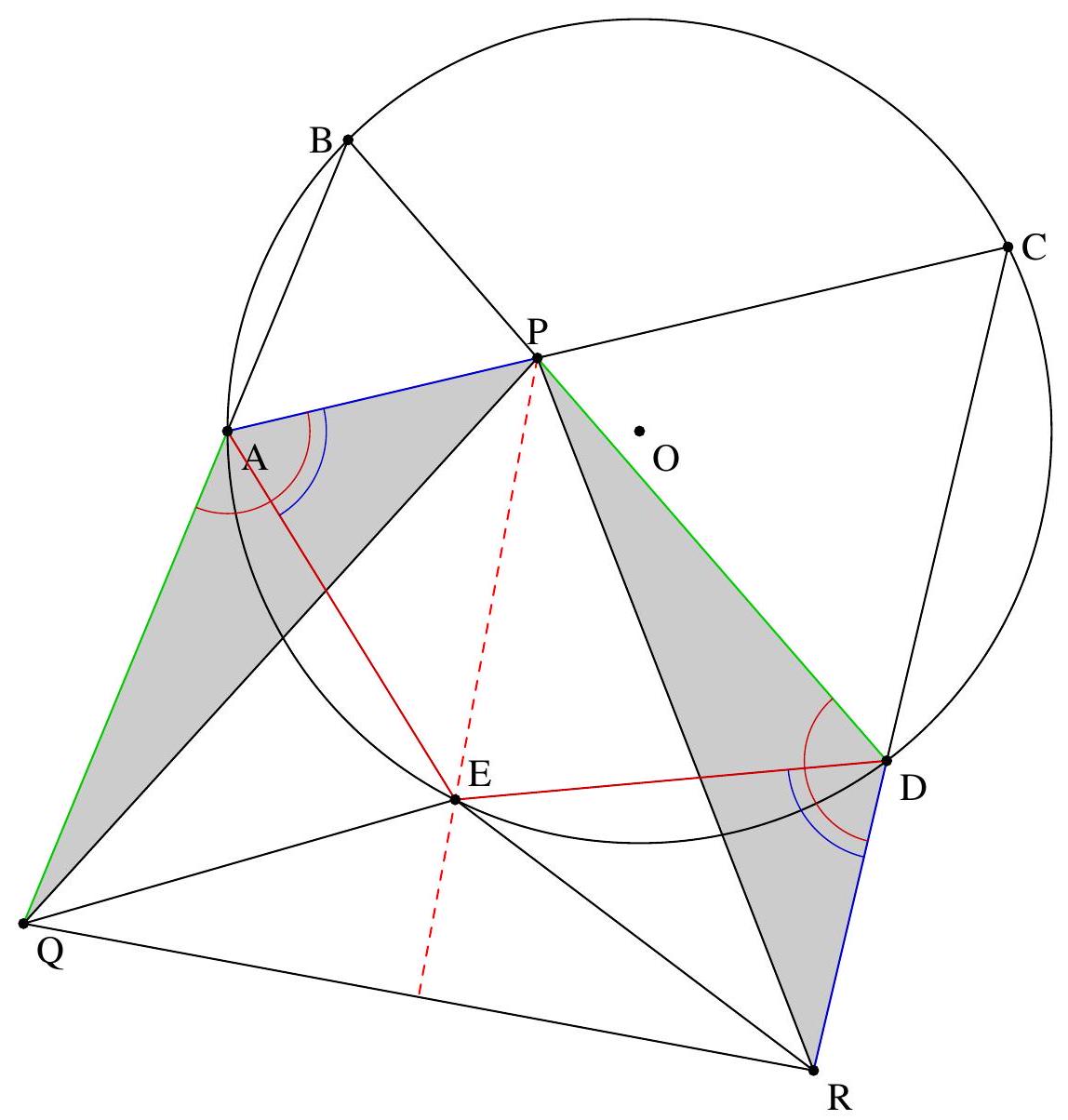

Let $A, B, C, D$ and $E$ be five points in this order on a circle such that $A E=D E$. Let $P$ be the point of intersection of $(A C)$ and $(B D)$. Let $Q$ be the point on the ray $[B A)$ such that $A Q=D P$. Let $R$ be the point on the ray $[C D)$ such that $D R=A P$. Show that the lines $(P E)$ and $(Q R)$ are perpendicular.

|

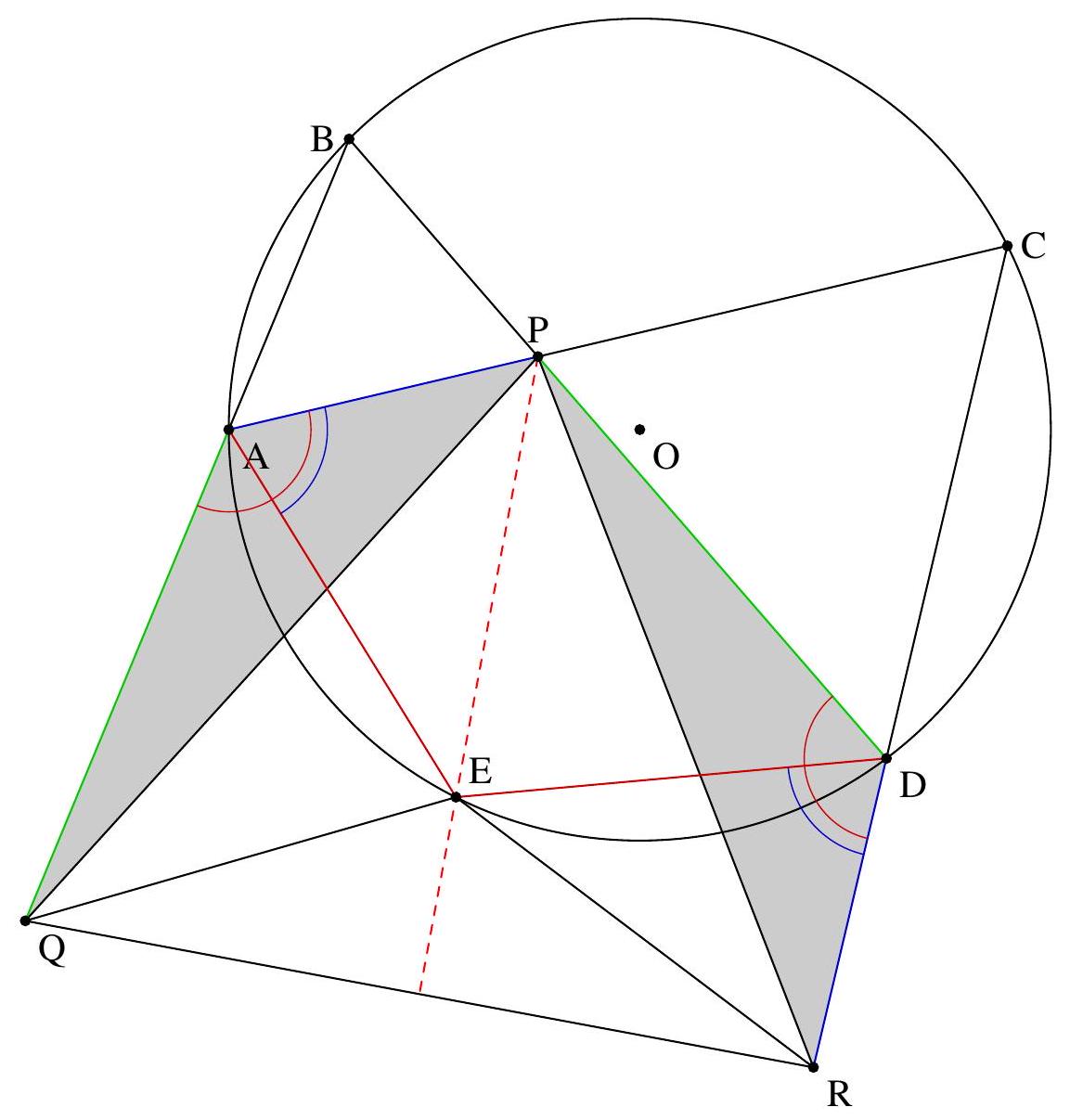

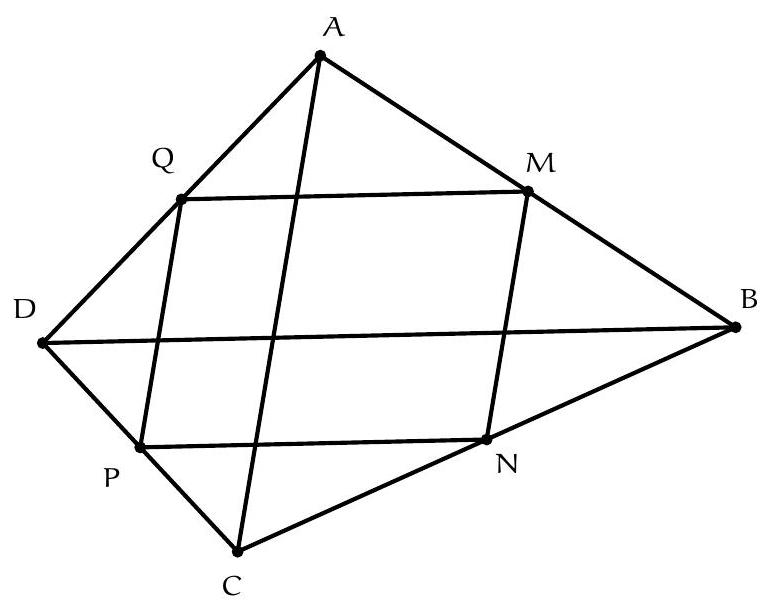

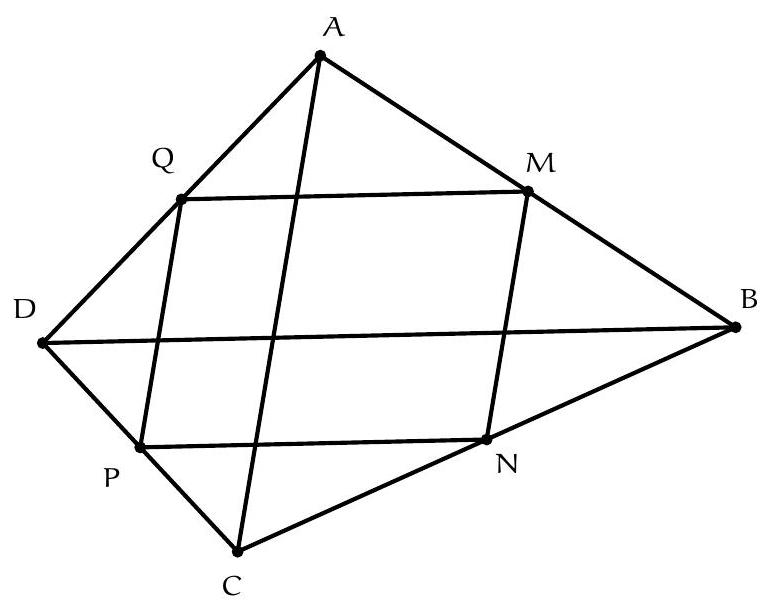

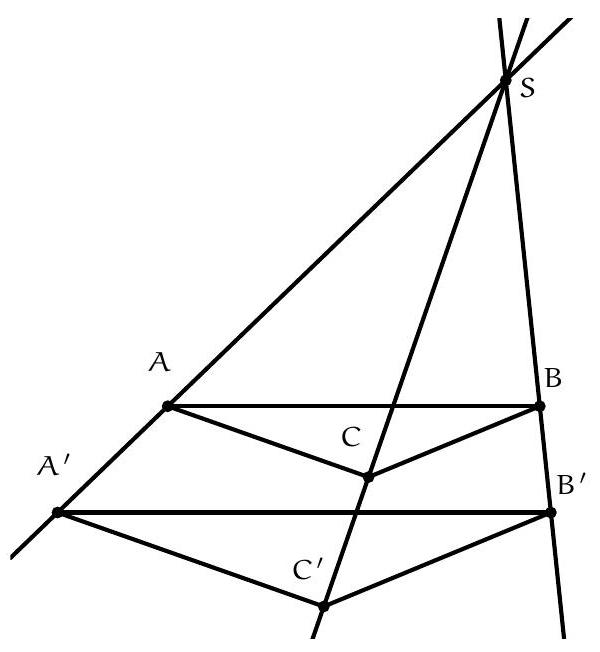

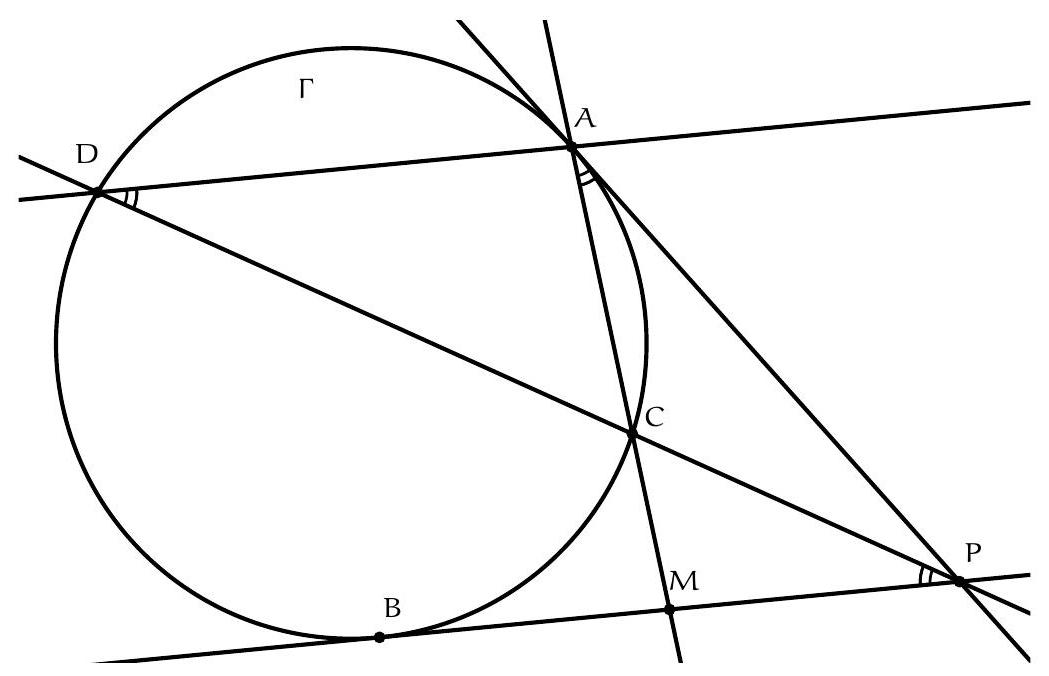

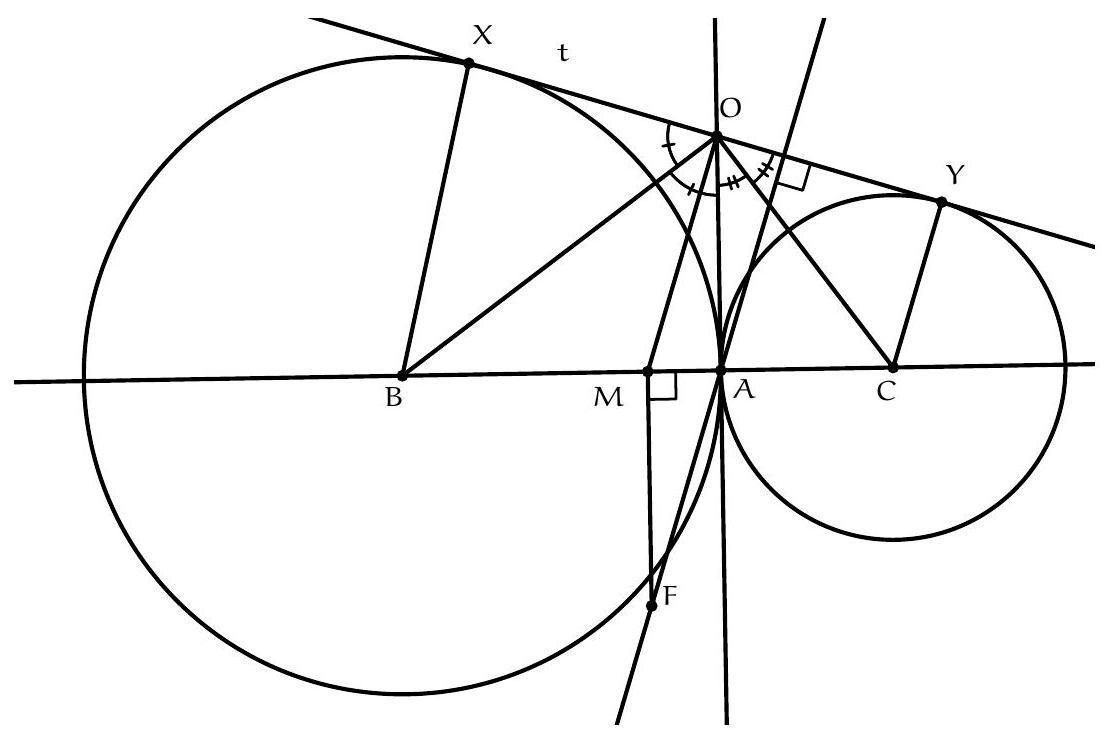

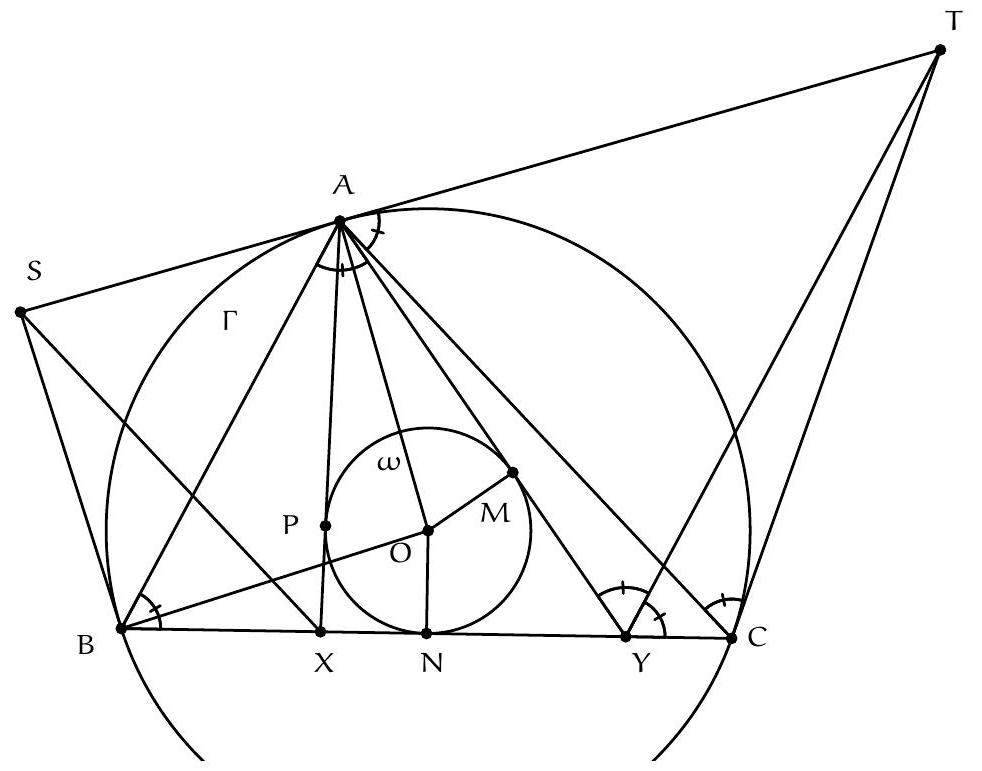

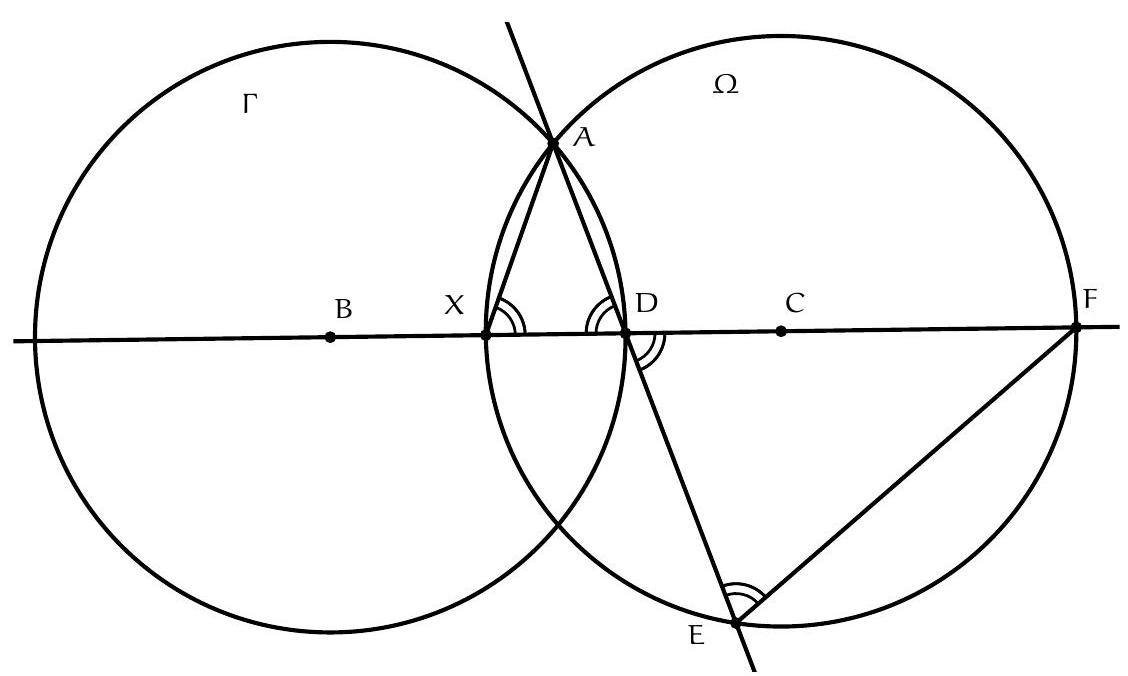

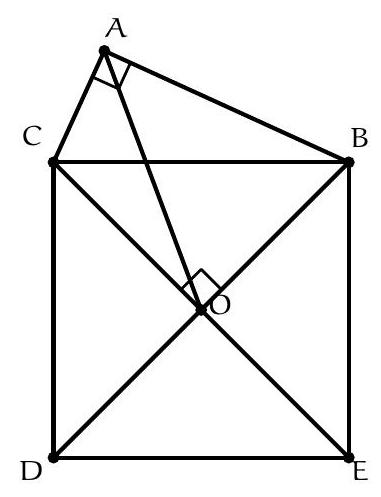

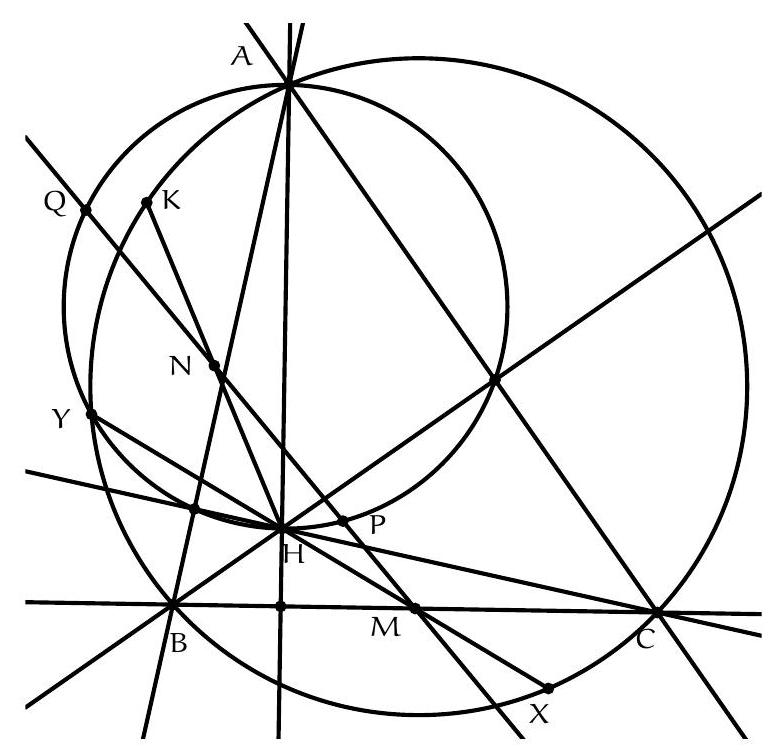

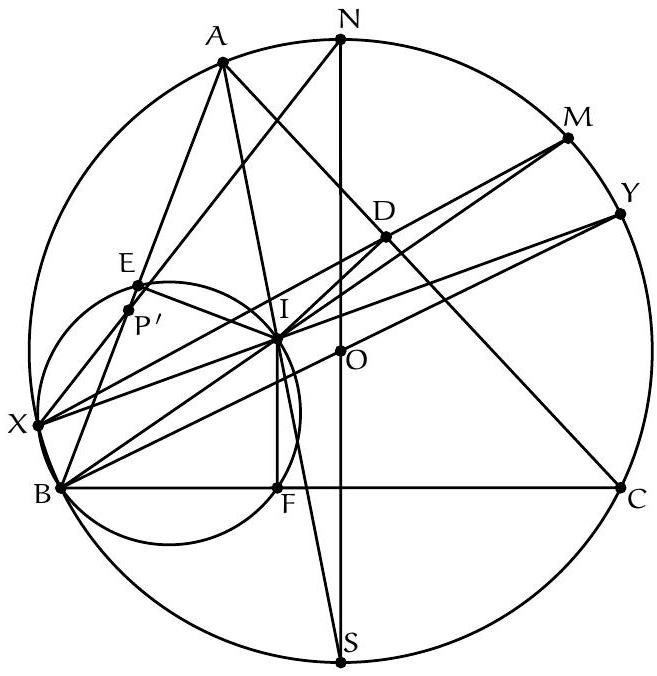

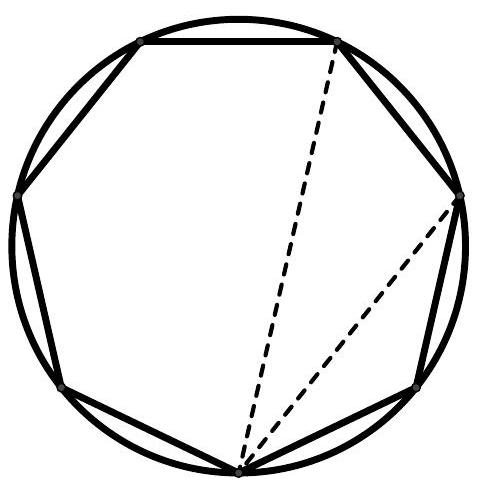

In the case of the following figure:

In this statement, we have many equal lengths $(A Q=D P, D R=A P, A E=D E)$. As shown in the figure, it is helpful to color the equal lengths to identify potential congruent triangles and make progress in the problem.

The triangles DRP and AQP appear to be congruent: let's prove it. First, note that $\mathrm{DR}=A \mathrm{~A}$ and $\mathrm{DP}=\mathrm{AR}$ by hypothesis. Additionally, $\widehat{\mathrm{RDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CAB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{PAB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAQ}}$. Thus, the triangles DRP and AQP are congruent.

In particular, $P Q=P R$, so $P$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $(Q R)$.

The triangles $D E R$ and $A E P$ appear to be congruent: let's prove it. We have $D E=A E$ and $D R=A P$. Additionally, $\widehat{\mathrm{EDR}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{EDC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CAE}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAE}}$. Thus, the triangles DER and AEP are congruent, and $E P=E R$.

Similarly, the triangles $A E Q$ and $D E P$ are congruent (since $A, Q$ play a symmetric role to $D, R$), so $E P=E Q$, and thus $E R=E Q: E$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $(Q R)$.

Therefore, the perpendicular bisector of $(Q R)$ is $(E P)$, so $(E P)$ and $(Q R)$ are perpendicular.

Comment from the graders: The exercise is very well done.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soient $A, B, C, D$ et $E$ cinq points dans cet ordre sur un cercle tels que $A E=D E$. Soit $P$ le point d'intersection de $(A C)$ et $(B D)$. Soit $Q$ le point de la demi-droite $[B A)$ tel que $A Q=D P$. Soit $R$ le point de la demi-droite $[C D)$ tel que $D R=A P$. Montrer que les droites $(P E)$ et $(Q R)$ sont perpendiculaires.

|

On se place dans le cas de la figure suivante:

Dans cet énoncé on a de nombreuses égalités de longueur $(A Q=D P, D R=A P, A E=D E$. Comme sur la figure, il ne faut pas hésiter à colorier les longueurs égales pour voir des potentiels triangles isométriques, et avancer dans le problème).

Les triangles DRP et AQP ont l'air d'être isométriques : prouvons-le. Notons déjà que $\mathrm{DR}=A \mathrm{~A}$ et $\mathrm{DP}=\mathrm{AR}$ par hypothèse. De plus $\widehat{\mathrm{RDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CAB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{PAB}}=$ $\widehat{\mathrm{PAQ}}$. Ainsi les triangles DRP et AQP sont isométriques.

En particulier $P Q=P R$, donc $P$ est sur la médiatrice de $(Q R)$.

Les triangles $D E R$ et $A E P$ ont l'air d'être isométriques : prouvons-le. On a $D E=A E$ et $D R=A P$. De plus $\widehat{\mathrm{EDR}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{EDC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CAE}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAE}}$. Ainsi les triangles DER et AEP sont isométriques et $E P=E R$.

De même les triangles $A E Q$ et $D E P$ sont isométriques ( $\operatorname{car} A, Q$ jouent un rôle symétrique à $D, R$ ), ainsi $E P=E Q$, donc $E R=E Q: E$ est sur la médiatrice de $(Q R)$.

Ainsi la médiatrice de ( $Q R$ ) est ( $E P$ ), donc ( $E P$ ) et $(Q R)$ sont perpendiculaires.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice est très bien réussi.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Is it possible to find a block of 1000 consecutive positive integers that contains exactly 5 prime numbers?

|

At first glance, it seems difficult to guarantee exactly 5 prime numbers in a block of 1000 consecutive integers: no elementary arithmetic theorem allows ensuring closely spaced prime numbers without other primes between them. Therefore, we can try to determine how many prime numbers can be found in a block of 1000 consecutive numbers.

First, it is relatively well-known that one can find 1000 consecutive numbers, none of which are prime. Indeed, $1001!+2, \ldots, 1001!+1001$ are not prime: if $2 \leqslant i \leqslant 1001, 1001!+i$ is divisible by $i$ and strictly greater than $i$, so it is not prime.

We can also note that between 1 and 1000 there are many prime numbers: at least more than 5, since $2,3,5,7,11,13$ are prime.

Let $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n})$ be the number of prime numbers in the set $\{n, \ldots, n+999\}$. The natural next step after our two previous remarks is to wonder how to evaluate the number $P(n)$ as $n$ ranges over $\mathbb{N}^{*}$. To go from $\{n, \ldots, n+999\}$ to $\{n+1, \ldots, n+1+999\}$, we add $n+1000$ and remove $n$. Thus, we add at most one prime number and remove at most one prime number: we have

$$

\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n}+1)-\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n}) \in\{-1,0,1\}

$$

Thus $P$ varies by at most 1, and we know that $P(1)>5>P(1001!+2)$. It seems quite intuitive that this implies there exists an integer $k$ such that $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k})=5$, we will prove this.

Let $k$ be the smallest integer such that $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k}) \leqslant 5$. We know that $\mathrm{k}>1$, so $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k}-1)>5$ by minimality. Thus, we must have $P(k)=P(k-1)-1$ (to have $P(k) \leqslant 5$), so $P(k)>4$. Thus $P(k) \geqslant 5$, and by definition $P(k) \leqslant 5$, so $P(k)=5$.

Thus the answer to the statement is yes: there does exist a block of 1000 consecutive integers with exactly five prime numbers.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally well handled, but few students managed to properly formulate the fact that there exist 1000 consecutive composite numbers.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Est-il possible de trouver un bloc de 1000 nombres entiers strictement positifs consécutifs qui contient exactement 5 nombres premiers?

|

A première vue, il semble difficile de garantir exactement 5 nombre premier dans un bloc de 1000 entiers consécutifs : aucun théorème d'arithmétique élémentaire permet de s'assurer d'avoir des nombres premiers rapprochés, mais pas d'autres nombres premier entre eux. On peut donc essayer de se demander combien de nombres premiers on peut trouver dans un bloc de 1000 nombres consécutifs.

Déjà, il est relativement connu qu'on peut trouver 1000 nombres consécutifs dont aucun n'est premier. En effet, $1001!+2, \ldots, 1001!+1001$ ne sont pas premiers : si $2 \leqslant i \leqslant 1001,1001!+i$ est divisible par $i$ et strictement plus grand que $i$, donc il n'est pas premier.

On peut aussi remarquer qu'entre 1 et 1000 il y a beaucoup de nombres premiers : en tout cas strictement plus que 5 , vu que $2,3,5,7,11,13$ sont premiers.

Notons $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n})$ le nombre de nombres premiers dans l'ensemble $\{n, \ldots, n+999\}$. L'étape naturelle après nos deux remarques précédentes est de se demander comment évalue le nombre $P(n)$ lorsque $n$ parcourt $\mathbb{N}^{*}$. Pour passer de $\{n, \ldots, n+999\}$ à $\{n+1, \ldots, n+1+999\}$, on rajoute $n+1000$ et on enlève $n$. Ainsi on ajoute au plus un nombre premier, et on enlève au plus un nombre premier : on a donc

$$

\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n}+1)-\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{n}) \in\{-1,0,1\}

$$

Ainsi $P$ ne varie que de 1 en 1 , et on sait que $P(1)>5>P(1001!+2)$. Il semble assez intuitif que cela implique qu'il existe un entier k tel que $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k})=5$, nous allons prouver cela.

Soit $k$ le premier entier tel que $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k}) \leqslant 5$. On sait que $\mathrm{k}>1$, donc $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{k}-1)>5$ par minimalité. Ainsi, on a forcément $P(k)=P(k-1)-1$ (pour avoir $P(k) \leqslant 5$ ), donc $P(k)>4$. Ainsi $P(k) \geqslant 5$, or par définition $P(k) \leqslant 5$, donc $P(k)=5$.

Ainsi la réponse à l'énoncé est oui : il existe bien un bloc de 1000 entiers consécutifs avec exactement cinq entiers premiers.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice a globalement été bien traité, mais peu d'élèves ont réussi à bien formuler le fait qu'il existe 1000 nombres composés consécutifs.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

It is said that an integer $k>1$ is superb if there exist $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}, \mathrm{a}$ three strictly positive integers such that

$$

5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+49=\mathrm{a}^{\mathrm{k}}

$$

Determine the smallest superb integer.

|

Suppose $k=2$ is superb: there exist three strictly positive integers $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}, \mathrm{a}$ such that $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+49=a^{2}$. By looking modulo 3, $5^{\mathrm{m}}+1 \equiv 2^{\mathrm{m}}+1 \equiv \mathrm{a}^{2}(\bmod 3)$. The powers of 2 modulo 9 alternate between 2 if m is odd, and 1 if m is even, so $2^{\mathrm{m}}+1$ is either 2 or 0 modulo 3. Since squares modulo 3 are 0 and 1, we deduce that $2^{\mathrm{m}}+1$ is 0 modulo 3, hence $m$ is odd. By looking modulo 7, we get $5^{\mathrm{m}} \equiv \boldsymbol{a}^{2}(\bmod 7)$. The squares modulo 7 are $0,1,2,4$, and the powers of 5 alternate between $1,5,4,6,2,3$. Thus $5^{\mathrm{m}}$ is 0, 1, 2, or 4 if and only if $m$ is 0, 2, or 4 modulo 6, which is impossible since $m$ is odd. Thus $k \neq 2$.

Suppose $k=3$ is superb: there exist three strictly positive integers $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}$, a such that $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+49=a^{3}$. By looking modulo 7, $5^{\mathrm{m}} \equiv \mathrm{a}^{3}$. The cubes modulo 7 are $0,1,6$. The powers of 5 modulo 7 alternate between $1,5,4,6,2,3$. Thus we get that $m \equiv 0(\bmod 6)$ or $m \equiv 3(\bmod 6)$: in all cases, 3 divides m. We then look modulo 9: we have $5^{\mathrm{m}}+4 \equiv \mathrm{a}^{3}$. Since m is divisible by 3, $5^{m}$ and $a^{3}$ are cubes. The cubes modulo 9 are $0,1,8$. Thus $5^{m}-a^{3}$ can be 0, 1, 2, 7, 8 modulo 9, but not 4, which is contradictory. Thus $k \neq 3$.

Suppose $k=3$ is superb: there exist three strictly positive integers $\mathbf{m}, \mathrm{n}$, a such that $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+49=a^{4}=\left(a^{2}\right)^{2}$. In particular, 2 is superb, which is contradictory.

Note that 5 is superb: by taking $\mathbf{a}=3$, we have $\mathbf{a}^{\mathrm{k}}=3^{5}=243=5^{1}+63 \times 3+49$ so 5 is superb. Thus 5 is the smallest superb integer.

Comment from the graders: The problem was solved by few students, who did it well.

|

5

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

On dit qu'un entier $k>1$ est superbe s'il existe $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}, \mathrm{a}$ trois entiers strictement positifs tels que

$$

5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+49=\mathrm{a}^{\mathrm{k}}

$$

Déterminer le plus petit entier superbe.

|

Supposons que $k=2$ est superbe : il existe trois entiers strictement positifs $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}, \mathrm{a}$ tels que $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+$ $49=a^{2}$. En regardant modulo $3,5^{\mathrm{m}}+1 \equiv 2^{\mathrm{m}}+1 \equiv \mathrm{a}^{2}(\bmod 3)$. Or les puissances de 2 modulo 9 valent alternativement 2 si m est impair, puis 1 si m est pair, donc $2^{\mathrm{m}}+1$ vaut soit 2 soit 0 modulo 3 . Comme les carrés modulo 3 sont 0 et 1 , on en déduit que $2^{\mathrm{m}}+1$ vaut 0 modulo 3 , donc que $m$ est impair. En regardant modulo 7 , on obtient que $5^{\mathrm{m}} \equiv \boldsymbol{a}^{2}(\bmod 7)$. Or les carrés modulo 7 sont $0,1,2,4$, et les puissances de 5 alternent entre $1,5,4,6,2,3$. Ainsi $5^{\mathrm{m}}$ vaut $0,1,2$ ou 4 si et seulement si $m$ vaut 0,2 ou 4 modulo 6 , ce qui est impossible car $m$ est pair. Ainsi $k \neq 2$.

Supposons que $\mathrm{k}=3$ est superbe : il existe trois entiers strictement positifs $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}$, a tels que $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+$ $49=a^{3}$. En regardant modulo $7,5^{\mathrm{m}} \equiv \mathrm{a}^{3}$. Or les cubes modulo 7 sont $0,1,6$. Et les puissances de 5 modulo 7 alternent entre $1,5,4,6,2,3$. Ainsi on obtient que $m \equiv 0(\bmod 6)$ ou $m \equiv 3(\bmod 6)$ : dans tous les cas 3 divise m . On regarde alors modulo 9 : on a $5^{\mathrm{m}}+4 \equiv \mathrm{a}^{3}$. Or comme m est divisible par 3 , $5^{m}$ et $a^{3}$ sont des cubes. Les cubes modulo 9 sont $0,1,8$. Ainsi $5^{m}-a^{3}$ peut valoir $0,1,2,7,8$ modulo 9 , mais pas 4 ce qui est contradictoire. Ainsi $k \neq 3$.

Supposons que $k=3$ est superbe : il existe trois entiers strictement positifs $\mathbf{m}, \mathrm{n}$, a tels que $5^{\mathrm{m}}+63 \mathrm{n}+$ $49=a^{4}=\left(a^{2}\right)^{2}$. En particulier, 2 est superbe ce qui est contradictoire.

Notons que 5 est superbe : en prenant $\mathbf{a}=3$, on a $\mathbf{a}^{\mathrm{k}}=3^{5}=243=5^{1}+63 \times 3+49$ donc 5 est superbe. Ainsi 5 est le plus petit entier superbe.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice a été traité par peu d'élèves, qui l'ont bien résolu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $x, y, z$ be three real numbers satisfying $x+y+z=2$ and $xy+yz+zx=1$. Determine the maximum value that $x-y$ can take.

|

Let $(x, y, z)$ be a triplet satisfying the statement. By swapping $x$ and the maximum of the triplet, and then $z$ and the minimum of the triplet, we can assume $x \geqslant z \geqslant y$, while increasing $x-y$.

Since $x+y+z=2$, we have $4=(x+y+z)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}+2(x y+y z+x z)=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}+2$, thus $x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}=2$.

In particular, $(x-y)^{2}+(y-z)^{2}+(x-z)^{2}=2\left(x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}\right)-2(x y+y z+x z)=2$. By the arithmetic-quadratic inequality, $(x-z)^{2}+(z-y)^{2} \geqslant \frac{(x-z+z-y)^{2}}{2}=\frac{(x-y)^{2}}{2}$, so $2 \geqslant(x-y)^{2}+\frac{(x-y)^{2}}{2}=\frac{3(x-y)^{2}}{2}$, thus $(x-y) \leqslant \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$.

Let's try to show that this value is attainable. If we have $x-y=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$, then we have equality in the arithmetic-quadratic inequality: thus $x-z=z-y$, so since their sum is $x-y$, $x-z=z-y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$. In particular, since $x+y+z=3 z+(z-x)+(z-y)=3 z$, we have $z=\frac{2}{3}, x=\frac{2}{3}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$ and $y=\frac{2}{3}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$. Conversely, for these values of $x, y, z$, we indeed have:

$-x+y+z=3 \times \frac{2}{3}=2$

$-x y+y z+z x=x y+(x+y) z=\left(\frac{2}{3}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)\left(\frac{2}{3}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}+\frac{4}{3} \times \frac{2}{3}=\frac{4}{9}-\frac{1}{3}+\frac{8}{9}=\frac{9}{9}=1\right)$

$-x-y=2 \times \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$

Thus $(x, y, z)$ satisfies the conditions of the statement, and $x-y=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$, so the maximum value that $x-y$ can take is $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$.

Graders' comment: The exercise was not approached much. The main mistake is forgetting to find $x, y, z$ for which equality holds.

|

\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Soit $x, y, z$ trois nombres réels vérifiant $x+y+z=2$ et $x y+y z+z x=1$. Déterminer la valeur maximale que peut prendre $x-y$.

|

Soit ( $x, y, z$ ) un triplet vérifiant l'énoncé. Quitte à échanger $x$ et le maximum du triplet, puis $z$ et le minimum du triplet, on peut supposer $x \geqslant z \geqslant y$, tout en augmentant $x-y$.

Comme $x+y+z=2$, on a $4=(x+y+z)^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}+2(x y+y z+x z)=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}+2$, donc $x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}=2$.

En particulier $(x-y)^{2}+(y-z)^{2}+(x-z)^{2}=2\left(x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}\right)-2(x y+y z+x z)=2$. Or par inégalité arithmético quadratique, $(x-z)^{2}+(z-y)^{2} \geqslant \frac{(x-z+z-y)^{2}}{2}=\frac{(x-y)^{2}}{2}$, donc $2 \geqslant(x-y)^{2}+\frac{(x-y)^{2}}{2}=$ $\frac{3(x-y)^{2}}{2}$, donc $(x-y) \leqslant \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$.

Essayons de montrer que cette valeur est atteignable. Si on a $x-y=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$, alors on a égalité dans l'inégalité arithmético quadratique : ainsi $x-z=z-y$, donc comme leur somme vaut $x-y, x-z=z-y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$. En particulier, comme $x+y+z=3 z+(z-x)+(z-y)=3 z$, on a $z=\frac{2}{3}, x=\frac{2}{3}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$ et $y=\frac{2}{3}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}$. Réciproquement, pour ces valeurs de $x, y, z$, on a bien :

$-x+y+z=3 \times \frac{2}{3}=2$

$-x y+y z+z x=x y+(x+y) z=\left(\frac{2}{3}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)\left(\frac{2}{3}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}+\frac{4}{3} \times \frac{2}{3}=\frac{4}{9}-\frac{1}{3}+\frac{8}{9}=\frac{9}{9}=1\right.$

$-x-y=2 \times \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$

Ainsi $(x, y, z)$ vérifie les conditions de l'énoncé, et $x-y=\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$, donc la valeur maximale que peut prendre $x-y$ est $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice a été assez peu abordé. La principale erreur est d'oublier de trouver des $x, y, z$ pour lesquels on a égalité.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

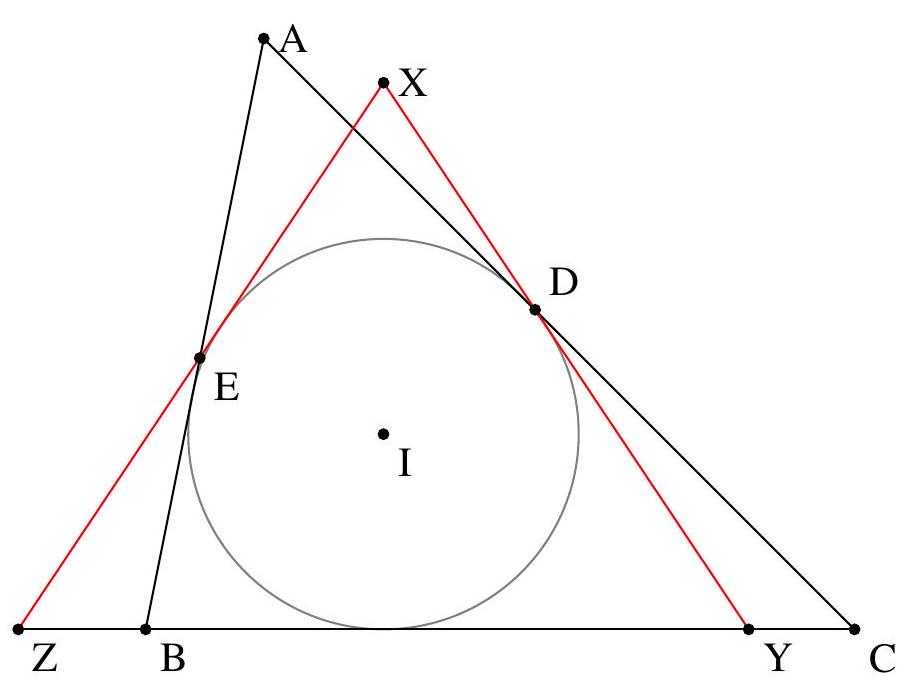

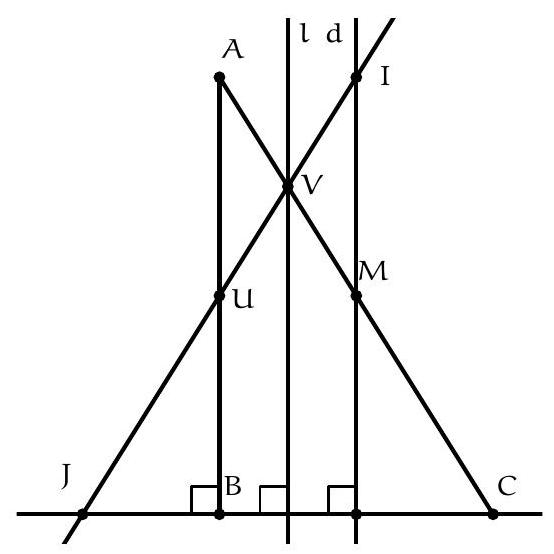

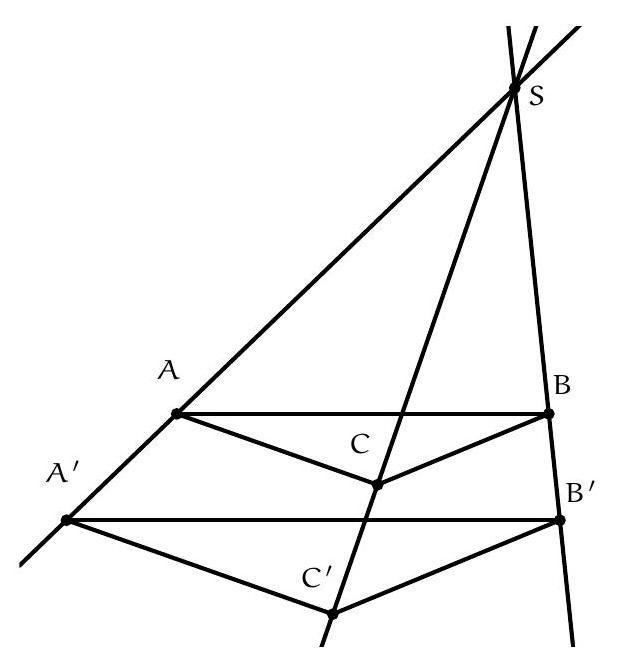

Let $ABC$ be a triangle and $I$ the center of the inscribed circle. We denote $D$ and $E$ as the feet of the angle bisectors from $B$ and $C$. Let $X$ be the intersection of the reflections of $(AB)$ and $(AC)$ with respect to $(CE)$ and $(BD)$. Show that the lines $(XI)$ and $(BC)$ are perpendicular.

|

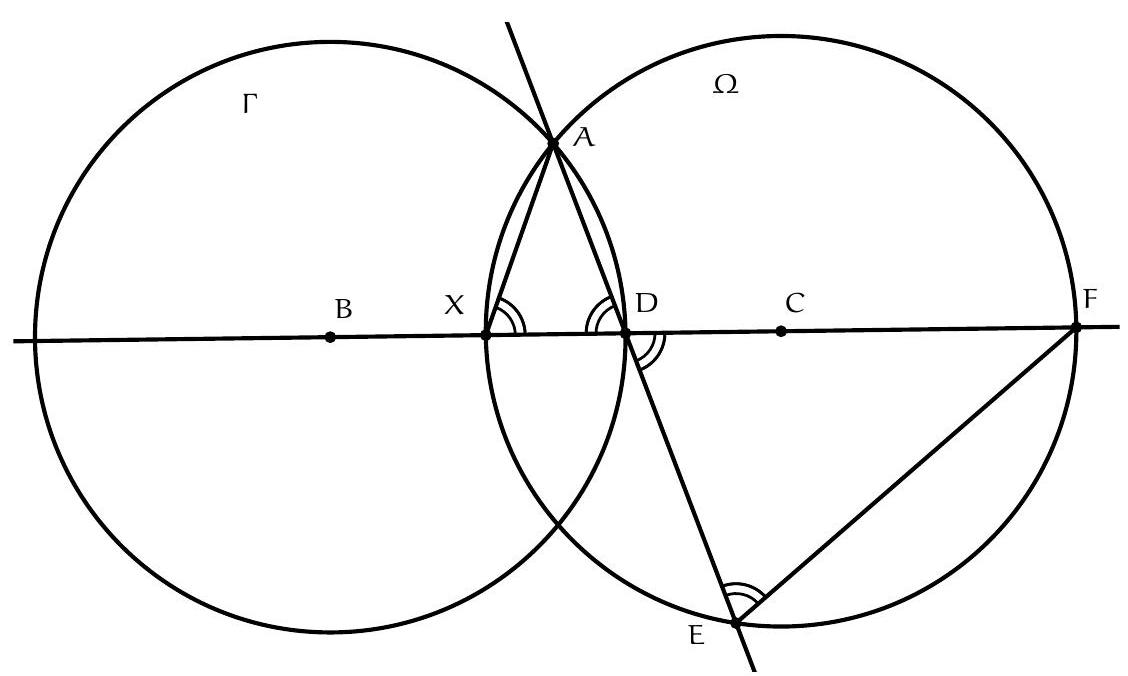

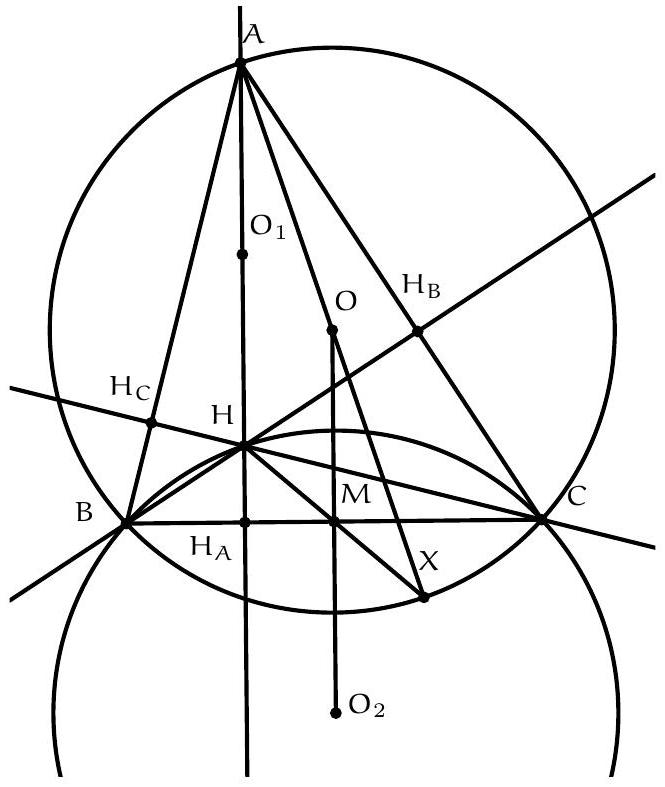

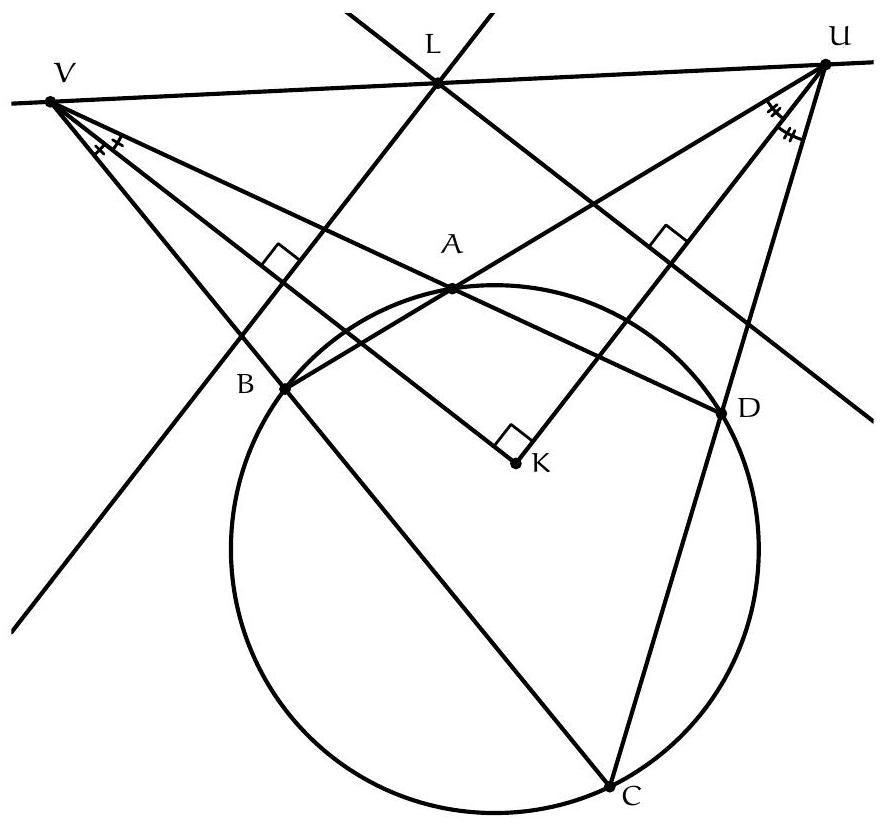

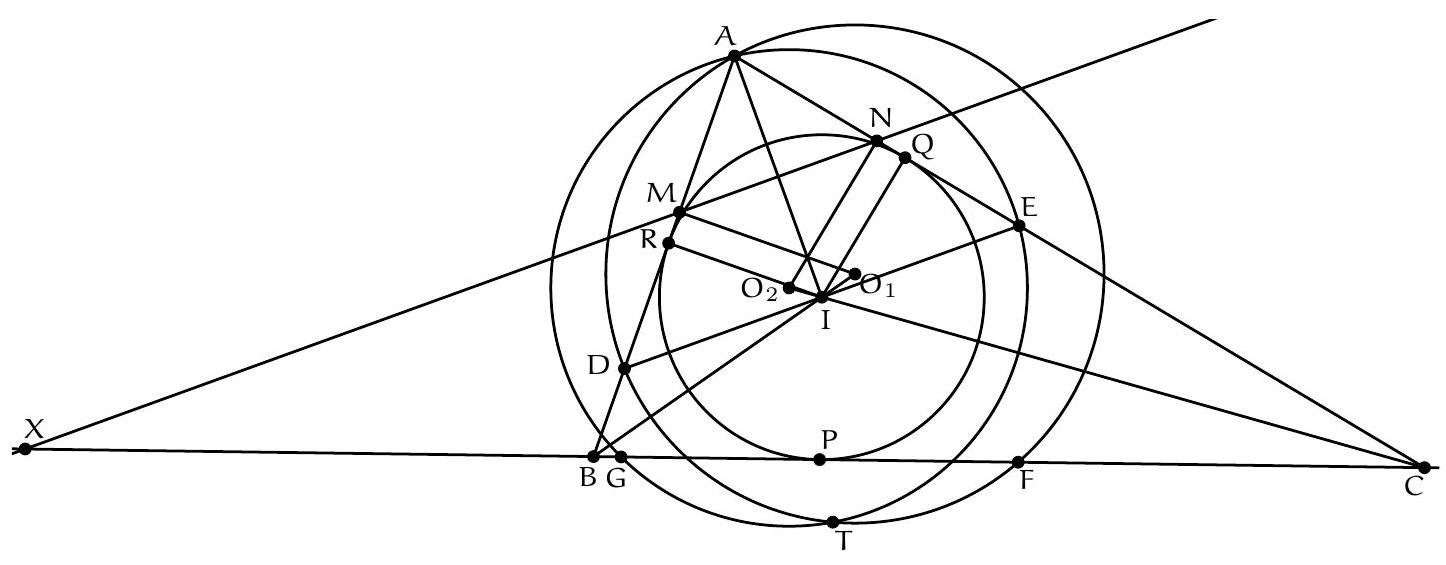

Let $Y$ and $Z$ be the intersections of $(DX)$ and $(EX)$ with the line $(BC)$. We will show that the triangle $ZXY$ is isosceles at $X$ and that $I$ is the center of its inscribed circle. If we manage to prove these properties, the conclusion of the exercise will follow. Indeed, the line $(XI)$ is then the bisector of the isosceles triangle $XYZ$ at $X$, and therefore it is also the altitude.

Let $\omega$ be the inscribed circle of triangle $ABC$. We know that the line $(AB)$ is tangent to $\omega$. Since the line $(CI)$ is an axis of symmetry of $\omega$, it follows that the line $(XE)$ is also tangent to $\omega$. Similarly, the line $(DX)$ is tangent to $\omega$. By definition, the line $(YZ)$ is the line $(BC)$ and is therefore also tangent to $\omega$. This shows that $\omega$ is the inscribed circle of triangle $XYZ$. In particular, the line $(XI)$ is the bisector from $X$.

We complete the proof of the exercise by showing that $\widehat{XZY} = \widehat{XYZ}$. Let $\alpha$ be the angle at $A$ in triangle $ABC$. We then have,

\[

\begin{aligned}

\widehat{\mathrm{XZY}} & = \widehat{\mathrm{EZC}} \\

& = \widehat{\mathrm{XEC}} - \widehat{\mathrm{ECZ}} \\

& = \widehat{\mathrm{AEC}} - \widehat{\mathrm{ECA}} \\

& = \widehat{\mathrm{EAC}} = \alpha.

\end{aligned}

\]

Similarly, $\widehat{XYZ} = \alpha$, which shows that triangle $ZYX$ is isosceles at $X$ and concludes the proof of the exercise.

Comment from the graders: This geometry problem was approached by very few students. Most of them succeeded well, using various methods. The simplest methods of resolution in this problem were those that made the most use of symmetry arguments. One can only recommend, when faced with a figure that presents such symmetries, to try to exploit them.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle et $I$ le centre du cercle inscrit. On note $D$ et $E$ les pieds des bissectrices issues de $B$ et $C$. Soit $X$ l'intersection des symétriques de $(A B)$ et $(A C)$ par rapport à $(C E)$ et $(B D)$. Montrer que les droites (XI) et (BC) sont perpendiculaires.

|

Notons $Y$ et $Z$ les intersections respectives de (DX) et (EX) avec la droite (BC). On va montrer que le triangle ZXY est isocèle en $X$ et que I est le centre de son cercle inscrit. Si on arrive à montrer ces propriétés, la conclusion de l'exercice suivrait. En effet, la droite (XI) est alors la bissectrice du triangle $X Y Z$ isocèle en $X$, donc en également la hauteur.

Soit $\omega$ le cercle inscrit du triangle $A B C$, on sait donc que la droite $(A B)$ est tangente à $\omega$, comme la droite $(\mathrm{CI})$ est un axe de symétrie de $\omega$ il suit que la droite (XE) est également tangente à $\omega$. De la même manière, la droite (DX) est tangente à $\omega$. Par définition la droite (YZ) est la droite (BC) donc également tangente à $\omega$. Cela montre que $\omega$ est le cercle inscrit du triangle XYZ. En particulier, la droite (XI) est la bissetrice issue de $X$.

On finit la preuve de l'exercice en montrant que $\widehat{X Z Y}=\widehat{X Y Z}$. On note $\alpha$ l'angle en $A$ dans le triangle ABC. On a alors,

$$

\begin{aligned}

\widehat{\mathrm{XZY}} & =\widehat{\mathrm{EZC}} \\

& =\widehat{\mathrm{XEC}}-\widehat{\mathrm{ECZ}} \\

& =\widehat{\mathrm{AEC}}-\widehat{\mathrm{ECA}} \\

& =\widehat{\mathrm{EAC}}=\alpha .

\end{aligned}

$$

De la même manière $\widehat{X Y Z}=\alpha$ ce qui montre bien que le triangle ZYX est isocèle en $X$ et conclut la preuve de l'exercice.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Cet exercice de géométrie a été abordé par très peu d'élèves. La plupart d'entre eux l'ont bien réussi, par diverses méthodes. Les méthodes de résolution les plus simples, dans cet exercice, étaient celles qui faisaient le plus appel aux arguments de symétrie. On ne peut que conseiller, face à une figure qui présente de telles symétries, de chercher à les exploiter.

## Exercices Seniors

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Find all triplets of positive integers $(x, y, z)$ satisfying the equation

$$

x! + 2^y = z!

$$

|

Let $(x, y, z)$ be a solution triplet.

First, we aim to reduce the number of values that $x$ can take. Note that $x! < z!$ so $x < z$. In particular, $x!$ divides $z!$ and $x!$, so $x!$ divides $z! - x! = 2^y$. Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $x \geq 3$, in this case 3 divides $x!$ but does not divide $2^y$, which makes it impossible for $x!$ to divide $2^y$. Thus, $x = 0, 1$ or 2.

We now perform a case disjunction between $x! = 1$ so $x = 0$ or 1, or $x! = 2$ so $x = 2$.

- Case $x = 0$ or 1: the equation becomes $1 + 2^y = z!$. We then perform a second case disjunction:

- Case $y = 0$: we find $z = 2$. Conversely, $(0,0,2)$ and $(1,0,2)$ are indeed solutions.

- Case $y \geq 1$: thus $1 + 2^y \geq 3$ and $1 + 2^y$ is odd. However, $z!$ is even if $z \geq 2$, and equals 0 or 1 if $z = 1$, neither of which can satisfy our equation. Thus, if we assume $y \geq 1$, there are no solutions.

- **Case** $x = 2$: We distinguish further according to the values of $y$:

- Case $y = 0$: we get $3 = z!$ which has no solutions (since $2! < 3 < 3!$).

- Case $y = 1$: we get $4 = z!$ which has no solutions (since $2! < 3 < 3!$).

- Case $y \geq 2$: we get that 2 divides $2^y + 2$, but 4 does not divide $2^y + 2$. Thus, 2 divides $z!$ but 4 does not divide $z!$, so $z = 2$ or 3. Since $2^y + 2 \geq 4 + 2 = 6$, we get $z = 3$, so $2 + 2^y = 6$, thus $2^y = 4$ and $y = 2$. Conversely, $(2,2,3)$ is indeed a solution because $2 + 4 = 6$.

Thus, the solutions are the triplets $(0,0,2)$, $(1,0,2)$, and $(2,2,3)$.

Comment from the graders: Almost all students who attempted the problem understood it well. However, solving the equation without errors was more challenging: many students forgot some cases (typically the case $x = 0$; it is also worth noting that $0! = 1$), made hasty generalizations (for example, that $1 + 2^{y-1}$ is always odd - which is true only if $y \geq 2$, and the case $y \leq 1$ must be treated), or forgot to verify that the triplets they found were solutions (a common mistake; it is always necessary to do so, even if it only involves saying "we verify conversely that [...] are indeed solutions"). Some students did not justify certain more general arguments ("the only factorials with a difference of 1 are 2 and 1", or "the only factorials that are powers of 2 are 2 and 1"), or did so very vaguely (by talking about "rate of growth", which is not applicable here). Such statements must always be justified (especially since the argument can be made in one or two sentences). Finally, a surprisingly large number of papers contain minor inconsistencies or oversights, generally not penalized: we invite candidates to carefully proofread their papers before submitting them.

|

(0,0,2), (1,0,2), (2,2,3)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver toutes les triplets d'entiers positifs $(x, y, z)$ satisfaisant l'équation

$$

x!+2^{y}=z!

$$

|

Soit ( $x, y, z$ ) un triplet solution.

On cherche dans un premier temps à réduire le nombre de valeurs que $x$ peut prendre. Pour ce faire notons que $x!<z$ ! donc $x<z$. En particulier, $x$ ! divise $z$ ! et $x$ !, donc $x$ ! divise $z$ ! $-x!=2^{y}$. Supposons par l'absurde que $x \geqslant 3$, dans ce cas 3 divise $x$ ! mais ne divise pas $2^{y}$, ce qui rend impossible le fait que $x$ ! divise $2^{y}$. Ainsi $x=0,1$ ou 2 .

On effectue maintenant une disjonction de cas entre $x!=1$ donc $x=0$ ou 1 , ou bien $x!=2$ donc $x=2$.

- Cas $x=0$ ou 1 : l'équation devient $1+2^{y}=z$ !. On effectue alors une deuxième disjonction de cas

- Cas $y=0$ : on trouve $z=2$. Réciproquement, $(0,0,2)$ et $(1,0,2)$ sont bien solution.

- Cas $y \geqslant 1$ : ainsi $1+2^{y} \geqslant 3$ et $1+2^{y}$ est impair. Or $z$ ! est pair si $z \geqslant 2$, et vaut 0 ou 1 si $z=1$, aucun des deux cas ne peut donc satisfaire notre équation. Ainsi, si on suppose que $y \geqslant 1$, il n'y a pas de solution.

- $\boldsymbol{C a s} x=2$ : On distingue encore selon les valeurs de $y$ :

- Cas $y=0$ : on obtient $3=z$ ! qui n'a pas de solutions (car $2!<3<3$ !).

- Cas $y=1$ : on obtient $4=z$ ! qui n'a pas de solutions (car $2!<3<3$ !).

- Cas $y \geqslant 2$ : on obtient que 2 divise $2^{y}+2$, mais que 4 ne divise pas $2^{y}+2$. Ainsi 2 divise $z$ ! mais 4 ne divise pas $z$ !, donc $z=2$ ou 3 . Comme de plus $2^{y}+2 \geqslant 4+2=6$, on obtient $z=3$, donc $2+2^{y}=6$, donc $2^{y}=4$ donc $y=2$. Réciproquement, $(2,2,3)$ est bien solution car $2+4=6$.

Ainsi les solutions sont les triplets $(0,0,2),(1,0,2)$ et $(2,2,3)$.

Commentaire des correcteurs : La quasi-totalité des élèves ayant traité l'exercice l'ont bien compris. Mais résoudre l'équation sans faute était plus compliqué : bien des élèves ont oublié des cas (typiquement, le cas $x=0$; on rappelle d'ailleurs que $0!=1$ ), fait des généralisations hâtives (par exemple que $1+2^{y-1}$ était toujours impair - ce qui n'est vrai que si $y \geqslant 2$, et il faut traiter le cas $y \leqslant 1$ ), ou oublié de vérifier que les triplets qu'ils ont trouvés étaient des solutions (faute assez répandue; il faut toujours le faire, même s'il ne s'agit que de dire "on vérifie réciproquement que [...] sont bien des solutions"). Quelques élèves n'ont pas justifié certains arguments plus généraux ("les seules factorielles de différence 1 sont 2 et 1 ", ou "les seules factorielles qui sont des puissances de 2 sont 2 et 1 "), ou l'ont fait très vaguement (en parlant de "vitesse de croissance", qui n'est pas un concept applicable ici). Ce genre d'affirmation doit toujours être justifié (surtout dans la mesure où l'argument tient en une ou deux phrases). Enfin, un nombre surprenant de copies contient de légères incohérences ou des étourderies, en général non sanctionnées : nous invitons les candidats à bien se relire avant d'envoyer les copies.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 10.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 10",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Félix wants to color the integers from 1 to 2023 such that if $a, b$ are two distinct integers between 1 and 2023 and $a$ divides $\mathbf{b}$, then $a$ and $b$ are of different colors. What is the minimum number of colors Félix needs?

|

We can try to color the numbers greedily: 1 can be colored with a color we denote as $a$, 2 and 3 with the same color $b$ (but not color $a$), then 4 and 6 with color $c$ (we can also color 5 and 7 with color $c$), etc. It seems that an efficient coloring is to color all numbers $n$ such that $2^{k} \leqslant n<2^{k+1}$ with color $k+1$, as long as $n \leqslant 2023$. Thus, we color $[1,2[$ with color $1$, $[2,4[$ with color $2$, ..., $[1024,2023]$ with color $11$. If $a \neq b$ are of the same color $k \in \{1, \ldots, 11\}$, then $0<\frac{a}{b}<\frac{2^{k+1}}{2^{k}}=2$, so if $b$ divides $a$, then $\frac{a}{b}$ is an integer and must be 1. Thus, $a=b$, which is a contradiction. Therefore, our coloring satisfies the condition of the problem and requires 11 colors.

Conversely, if a coloring satisfies the problem statement, the numbers $2^{0}=1, 2^{1}, \ldots, 2^{10}$ are between 1 and 2023, and if we take $a \neq b$ among these 11 numbers, either $a$ divides $b$ or $b$ divides $a$. Thus, these 11 numbers must be of different colors. Therefore, at least 11 colors are needed.

Thus, the minimum number of colors required is 11.

Comment from the graders: The exercise is very well done. As in any problem where we need to find the minimum number such that, it is important to split the proof into two parts: why $n=11$ colors are sufficient, and why if $n \leqslant 10$, $n$ colors are not sufficient.

|

11

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Félix souhaite colorier les entiers de 1 à 2023 tels que si $a, b$ sont deux entiers distincts entre 1 et 2023 et a divise $\mathbf{b}$, alors a et $b$ sont de couleur différentes. Quel est le nombre minimal de couleur dont Félix a besoin?

|

On peut essayer de colorier de manière gloutonne les nombres : 1 peut être colorié d'une couleur qu'on note $a$, 2 et 3 de la même couleur $b$ (mais pas de la couleur $a$ ), puis 4,6 de la couleur $c$ (on peut aussi colorier 5 et 7 de la couleur c), etc. Il semble donc qu'une coloriation performante soit pour tout $k$ de colorier les nombres $n$ vérifiant $2^{k} \leqslant n<2^{k+1}$ de la couleur $k+1$, tant que $n \leqslant 2023$. Ainsi on colorie $[1,2[$ de couleur $1,[2,4[$ de couleur $2, \ldots,[1024,2023]$ de couleur 11 . Si $a \neq b$ sont de la même couleur $\mathrm{k} \in\{1, \ldots, 11\}$ alors $0<\frac{\mathrm{a}}{\mathrm{b}}<\frac{2^{k+1}}{2^{k}}=2$, donc si b divise a , alors $\frac{\mathrm{a}}{\mathrm{b}}$ est entier donc vaut 1 . On a alors $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}$ ce qui est contradictoire. Ainsi notre coloriage vérifie bien la condition de l'énoncé, et nécessite 11 couleurs.

Réciproquement si un coloriage vérifie l'énoncé, les nombres $2^{0}=1,2^{1}, \ldots, 2^{10}$ sont entre 1 et 2023 , et si on prend $a \neq b$ parmi ces 11 nombres, soit $a$ divise $b$, soit $b$ divise $a$. Ainsi ces 11 nombres sont de couleurs différentes. Il faut donc au moins 11 couleurs.

Ainsi le nombre minimal de couleurs requises est 11.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice est très bien réussi. Comme dans tout exercice où on demande de trouver le nombre minimal tel que, il est important de découper la preuve en deux parties : pourquoi $n=11$ couleurs suffisent, et pourquoi si $n \leqslant 10, n$ couleurs ne suffisent pas.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 11.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 11",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

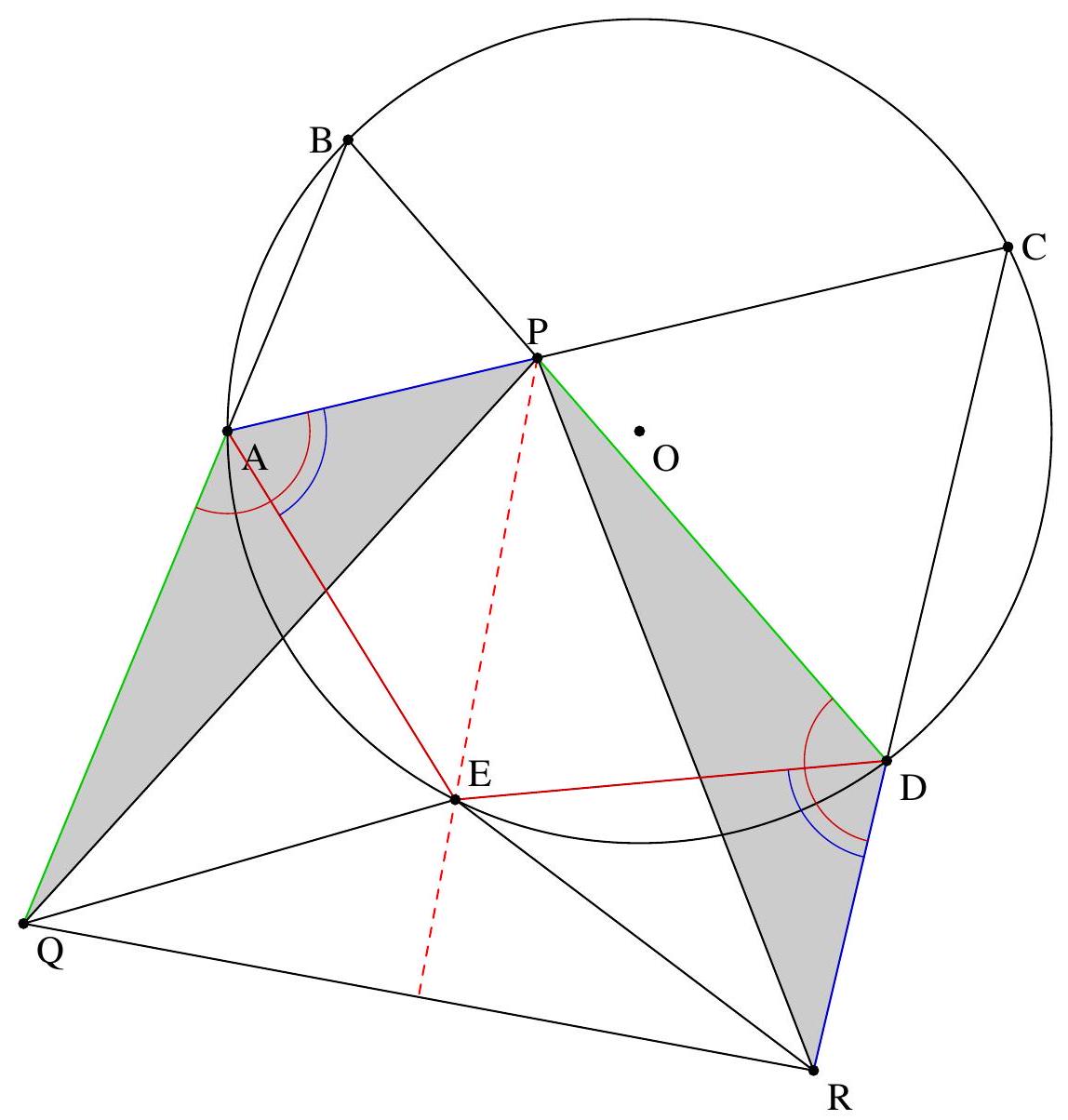

Let $A, B, C, D$ and $E$ be five points in this order on a circle such that $A E=D E$. Let $P$ be the point of intersection of $(A C)$ and $(B D)$. Let $Q$ be the point on the ray $[B A)$ such that $A Q=D P$. Let $R$ be the point on the ray $[C D)$ such that $D R=A P$. Show that the lines $(P E)$ and $(Q R)$ are perpendicular.

|

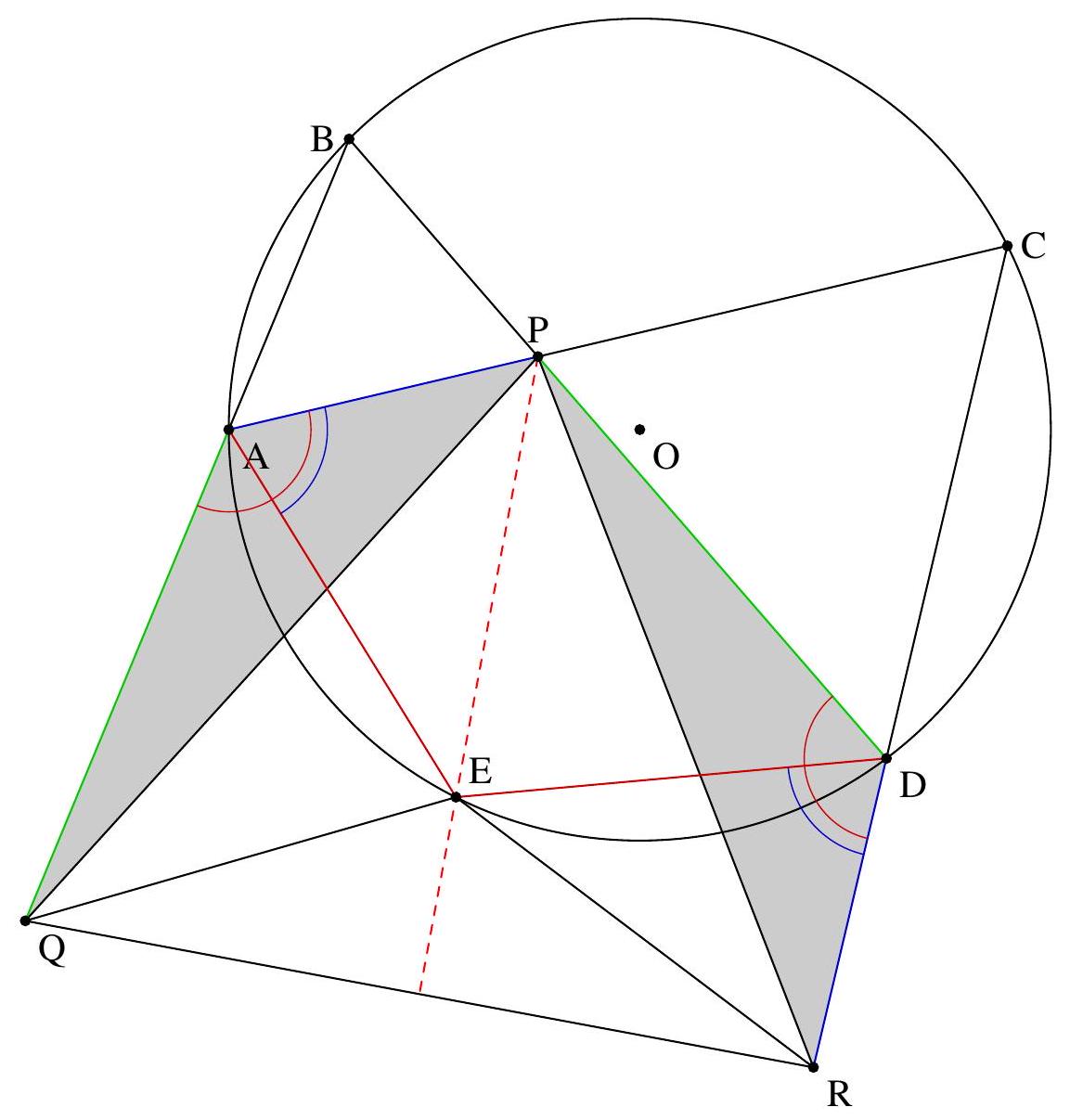

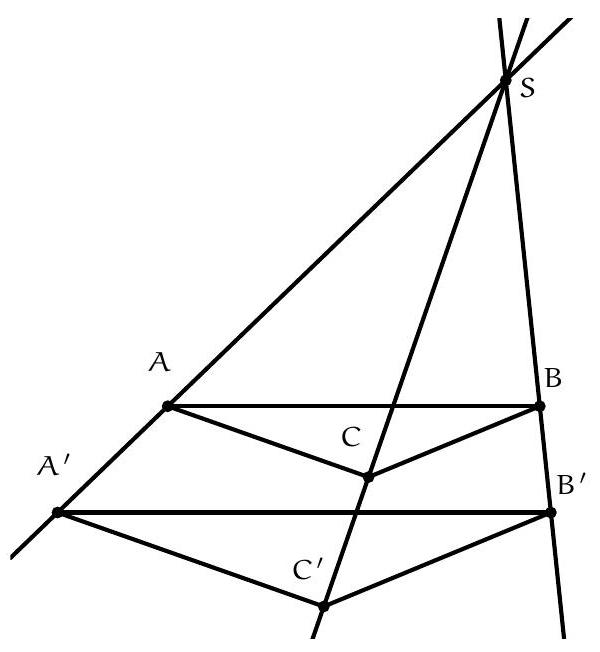

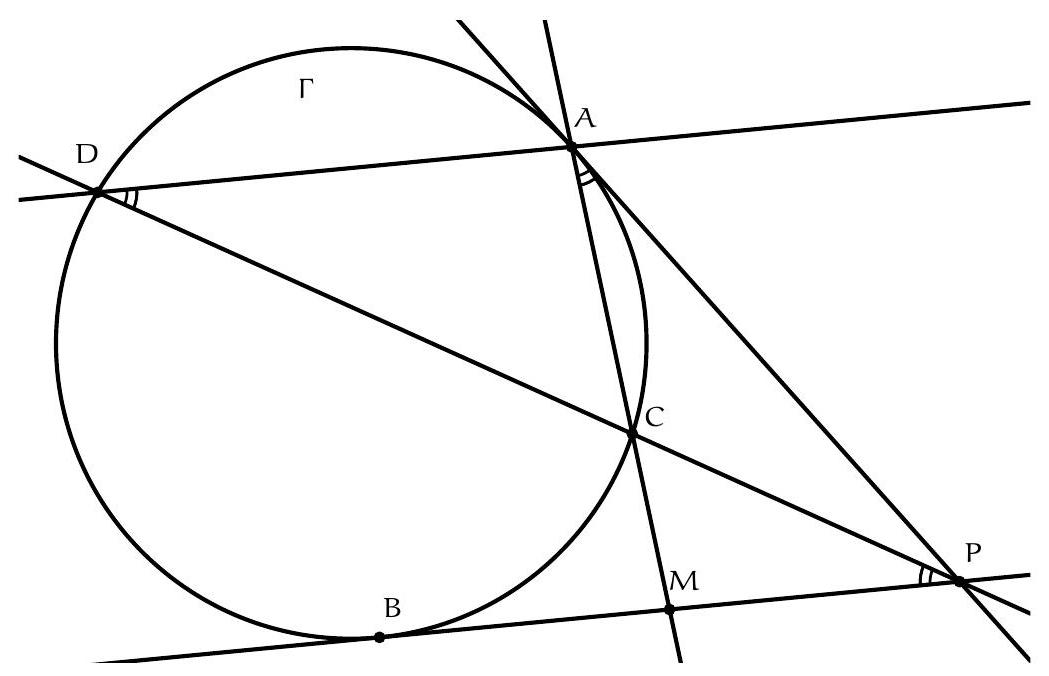

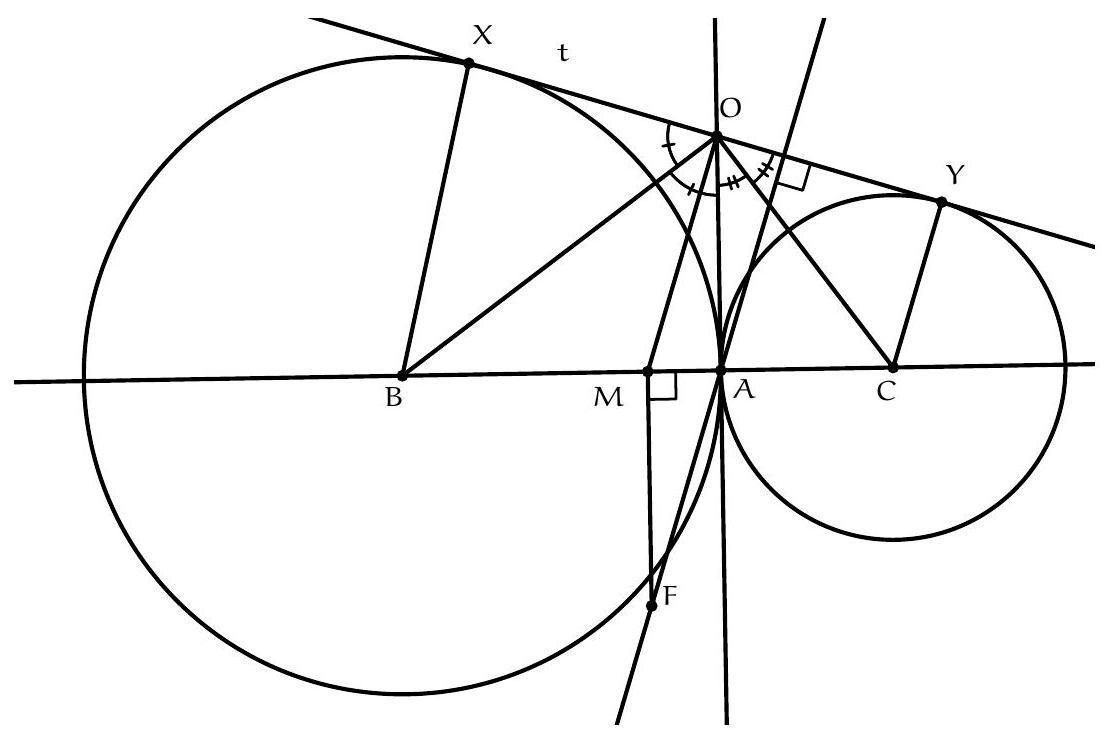

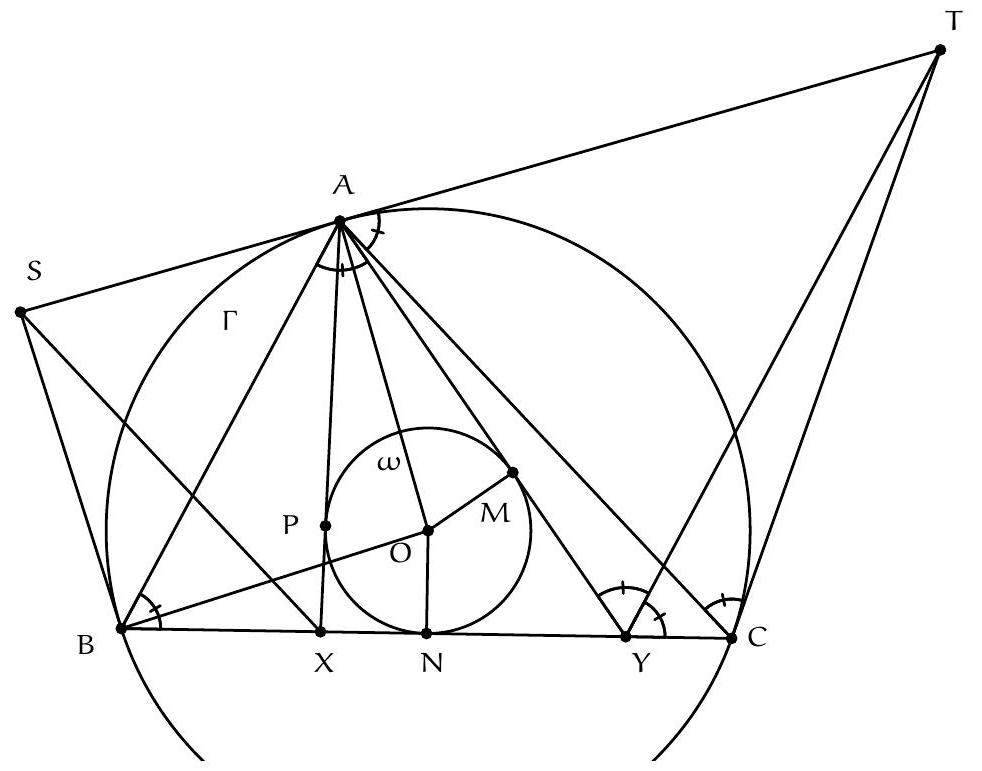

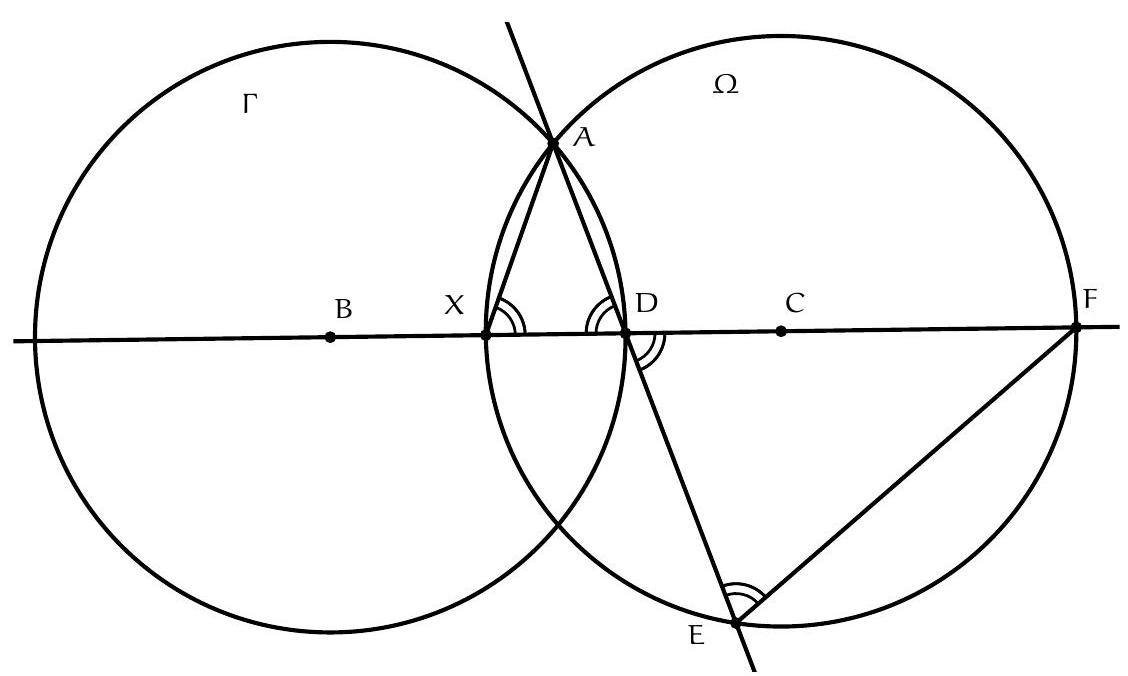

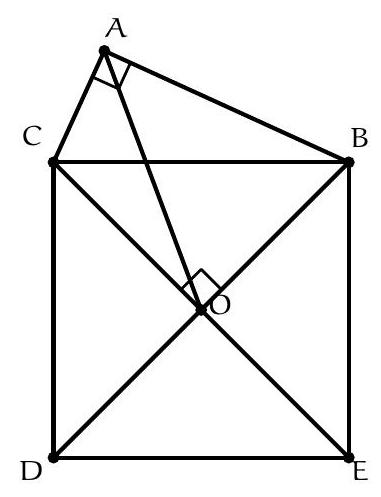

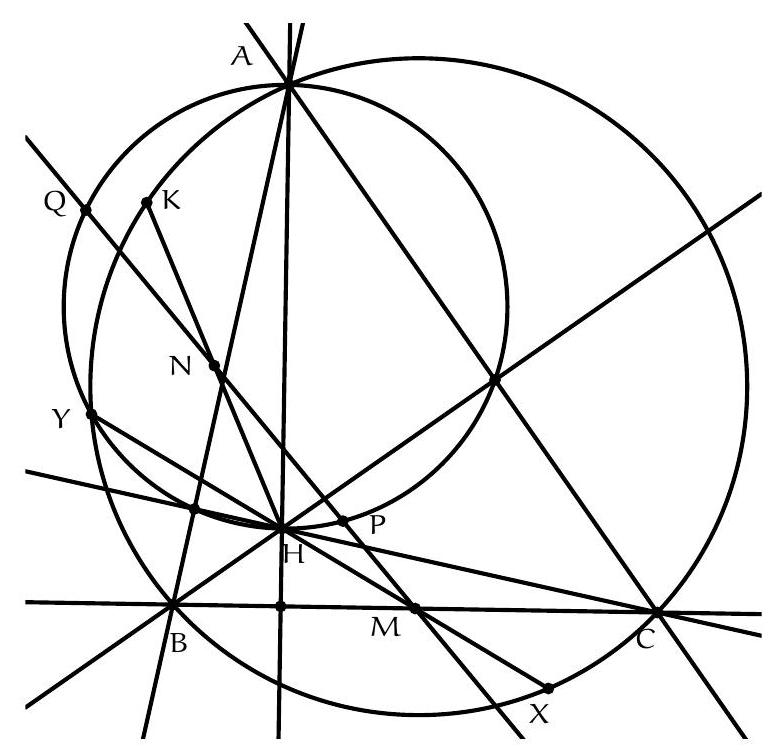

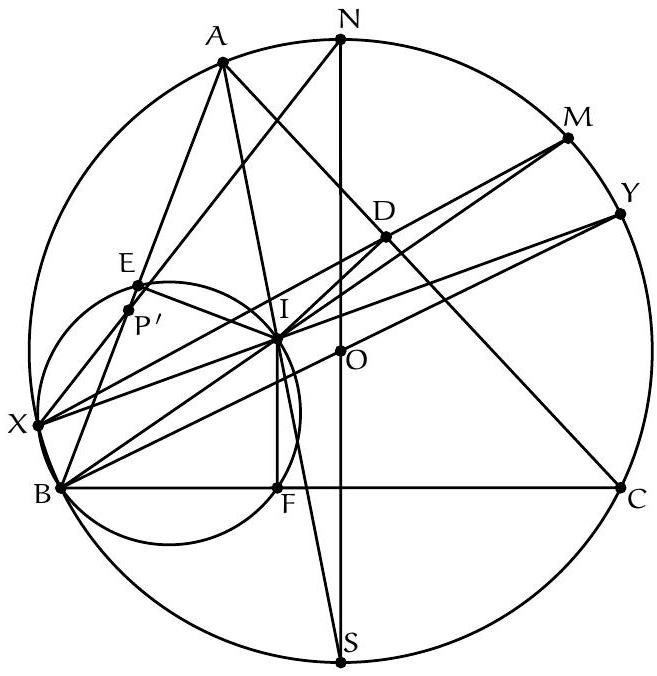

In the case of the following figure:

In this statement, we have many equal lengths ($A Q = D P$, $D R = A P$, $A E = D E$). As shown in the figure, it is helpful to color the equal lengths to identify potential congruent triangles and make progress in the problem.

The triangles DRP and AQP appear to be congruent: let's prove it. First, note that $\mathrm{DR} = A Q$ and $\mathrm{DP} = A R$ by hypothesis. Additionally, $\widehat{\mathrm{RDP}} = 180 - \widehat{\mathrm{CDP}} = 180 - \widehat{\mathrm{CDB}} = 180 - \widehat{\mathrm{CAB}} = 180 - \widehat{\mathrm{PAB}} = \widehat{\mathrm{PAQ}}$. Thus, the triangles DRP and AQP are congruent.

In particular, $P Q = P R$, so $P$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $(Q R)$.

The triangles DER and AEP also appear to be congruent: let's prove it. We have $D E = A E$ and $D R = A P$. Additionally, $\widehat{\mathrm{EDR}} = 180 - \widehat{\mathrm{EDC}} = \widehat{\mathrm{CAE}} = \widehat{\mathrm{PAE}}$. Thus, the triangles DER and AEP are congruent, and $E P = E R$.

Similarly, the triangles AEQ and DEP are congruent (since $A, Q$ play a symmetric role to $D, R$), so $E P = E Q$, and thus $E R = E Q$: $E$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $(Q R)$.

Therefore, the perpendicular bisector of $(QR)$ is $(EP)$, so $(EP)$ and $(QR)$ are perpendicular.

Comment from the graders: This problem was successfully solved by a large majority of students who attempted it. The main issue was imprecision in vocabulary: two triangles with all equal lengths are called congruent rather than equal or identical. The concept of similar triangles is weaker than the previous one and only indicates the equality of angles (and thus also the ratios of lengths, but not the lengths themselves).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soient $A, B, C, D$ et $E$ cinq points dans cet ordre sur un cercle tels que $A E=D E$. Soit $P$ le point d'intersection de ( $A C)$ et $(B D)$. Soit $Q$ le point de la demi-droite $[B A)$ tel que $A Q=D P$. Soit $R$ le point de la demi-droite [CD) tel que $D R=A P$. Montrer que les droites $(P E)$ et $(Q R)$ sont perpendiculaires.

|

On se place dans le cas de la figure suivante :

Dans cet énoncé on a de nombreuses égalités de longueur ( $A Q=D P, D R=A P, A E=D E$. Comme sur la figure, il ne faut pas hésiter à colorier les longueurs égales pour voir des potentiels triangles isométriques, et avancer dans le problème).

Les triangles DRP et $A Q P$ ont l'air d'être isométriques : prouvons-le. Notons déjà que $\mathrm{DR}=A Q$ et $\mathrm{DP}=A R$ par hypothèse. De plus $\widehat{\mathrm{RDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDP}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CDB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{CAB}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{PAB}}=$ $\widehat{P A Q}$. Ainsi les triangles DRP et AQP sont isométriques.

En particulier $P Q=P R$, donc $P$ est sur la médiatrice de $(Q R)$.

Les triangles DER et $A E P$ ont l'air d'être isométriques : prouvons-le. On a $D E=A E$ et $D R=A P$. De plus $\widehat{\mathrm{EDR}}=180-\widehat{\mathrm{EDC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CAE}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAE}}$. Ainsi les triangles DER et AEP sont isométriques et $E P=E R$.

De même les triangles $A E Q$ et $D E P$ sont isométriques (car $A, Q$ jouent un rôle symétrique à $D, R$ ), ainsi $E P=E Q$, donc $E R=E Q: E$ est sur la médiatrice de $(Q R)$.

Ains i la médiatrice de (QR) est (EP), donc (EP) et $(Q R)$ sont perpendiculaires.

Commentaire des correcteurs : Cet exercice a été réussi par une large majorité des élèves l'ayant traité. Le principal problème était une imprécision dans le vocabulaire : deux triangles dont toutes les longueurs

sont égales sont dits isométriques plutôt qu'égaux ou identiques. Quant à la notion de triangles semblables, elle est plus faible que la précédente, et traduit simplement l'égalité des angles (et donc aussi des rapports de longueurs, mais pas des longueurs elles-mêmes).

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrige-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 12",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

It is said that a polynomial $P$ is fantastic if there exist real numbers $\mathrm{a}_{0}, \ldots, \mathrm{a}_{2022}$ such that

$$

P(X)=X^{2023}+a_{2022} X^{2022}+\cdots+a_{1} X+a_{0}

$$

if it has 2023 roots $r_{1}, \ldots, r_{2023}$ (not necessarily distinct) in $[0,1]$, and if $P(0)+P(1)=0$. Determine the maximum value that $\mathrm{r}_{1} \cdot \mathrm{r}_{2} \cdots \mathrm{r}_{2023}$ can take for a fantastic polynomial.

|