problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

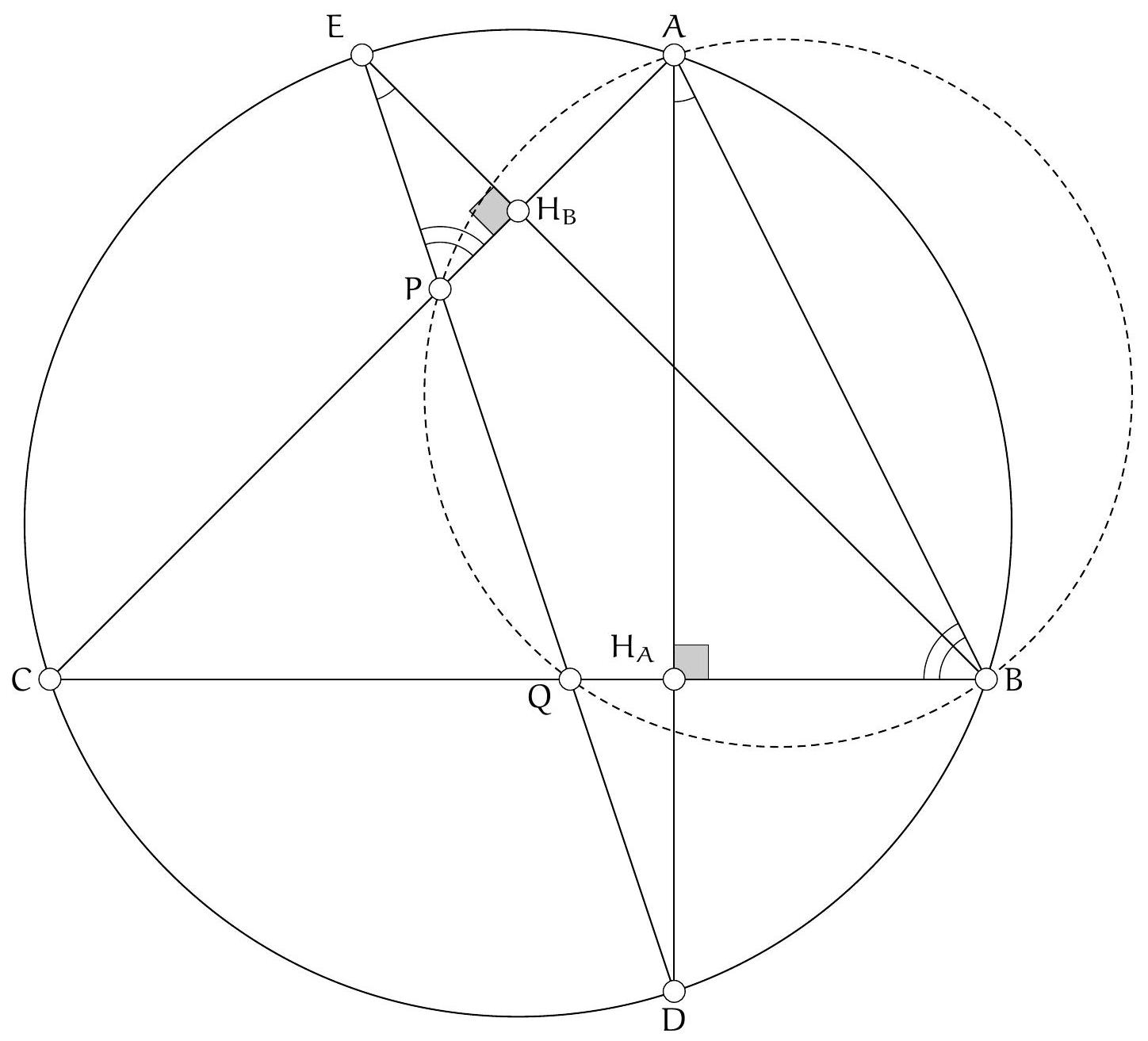

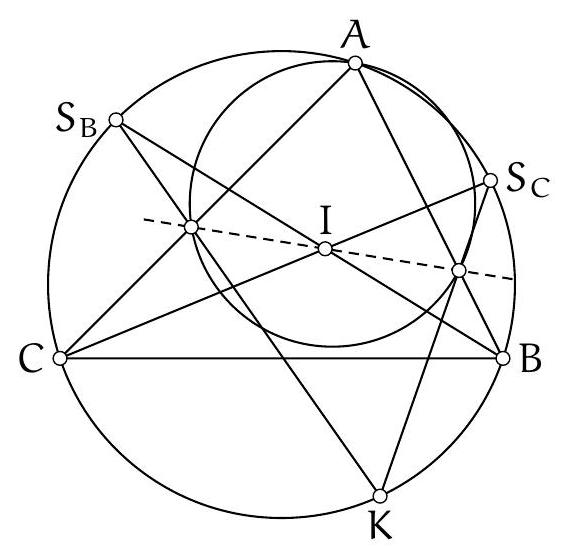

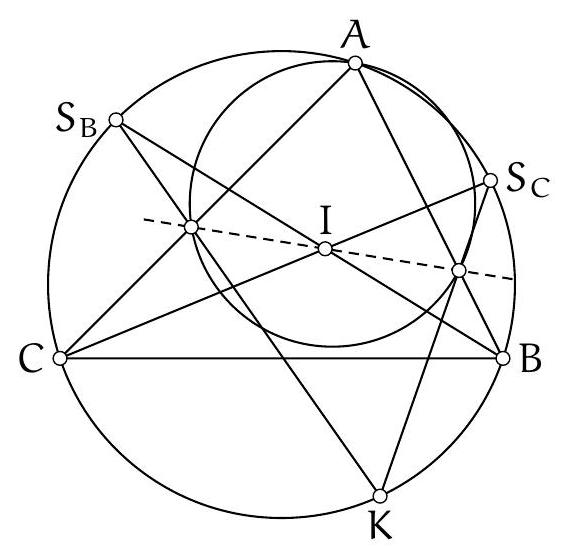

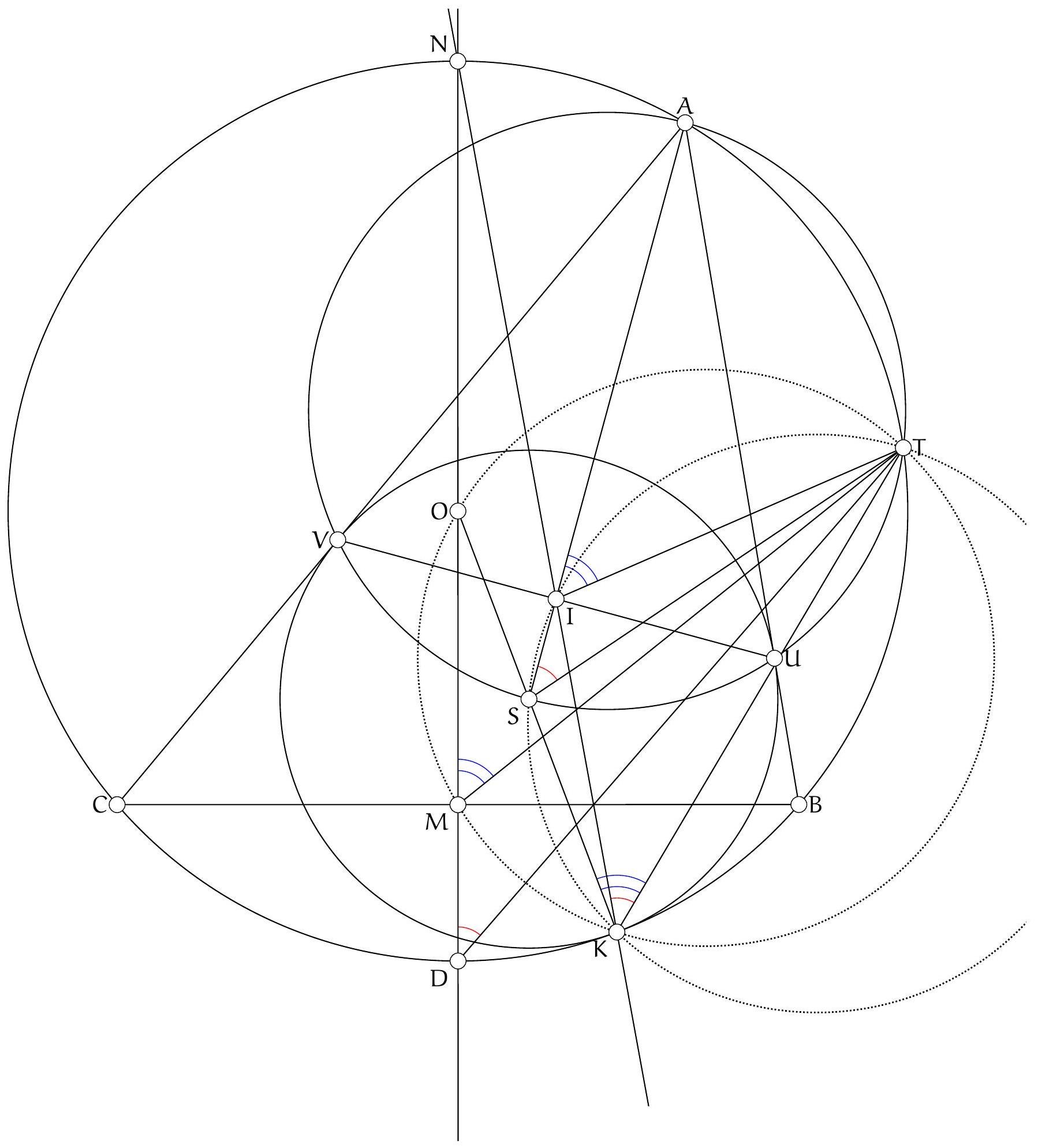

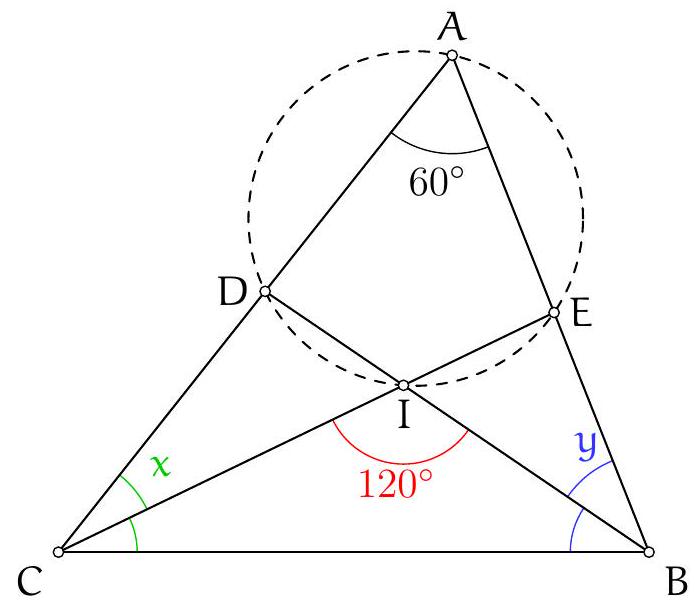

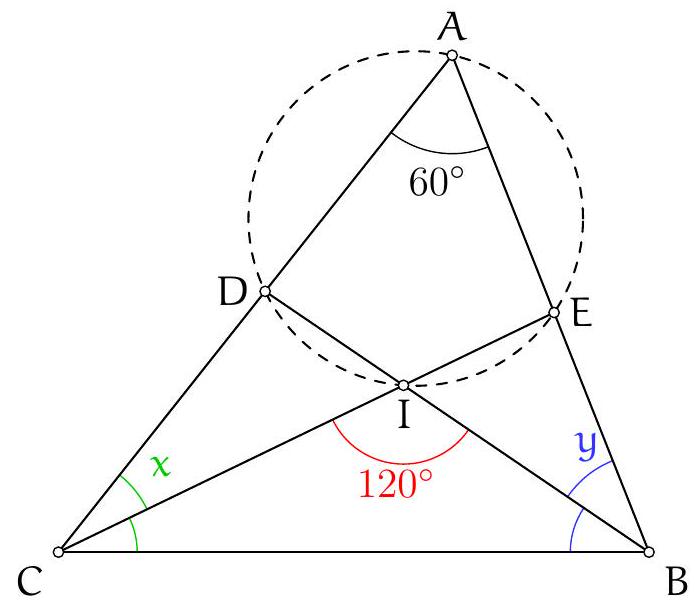

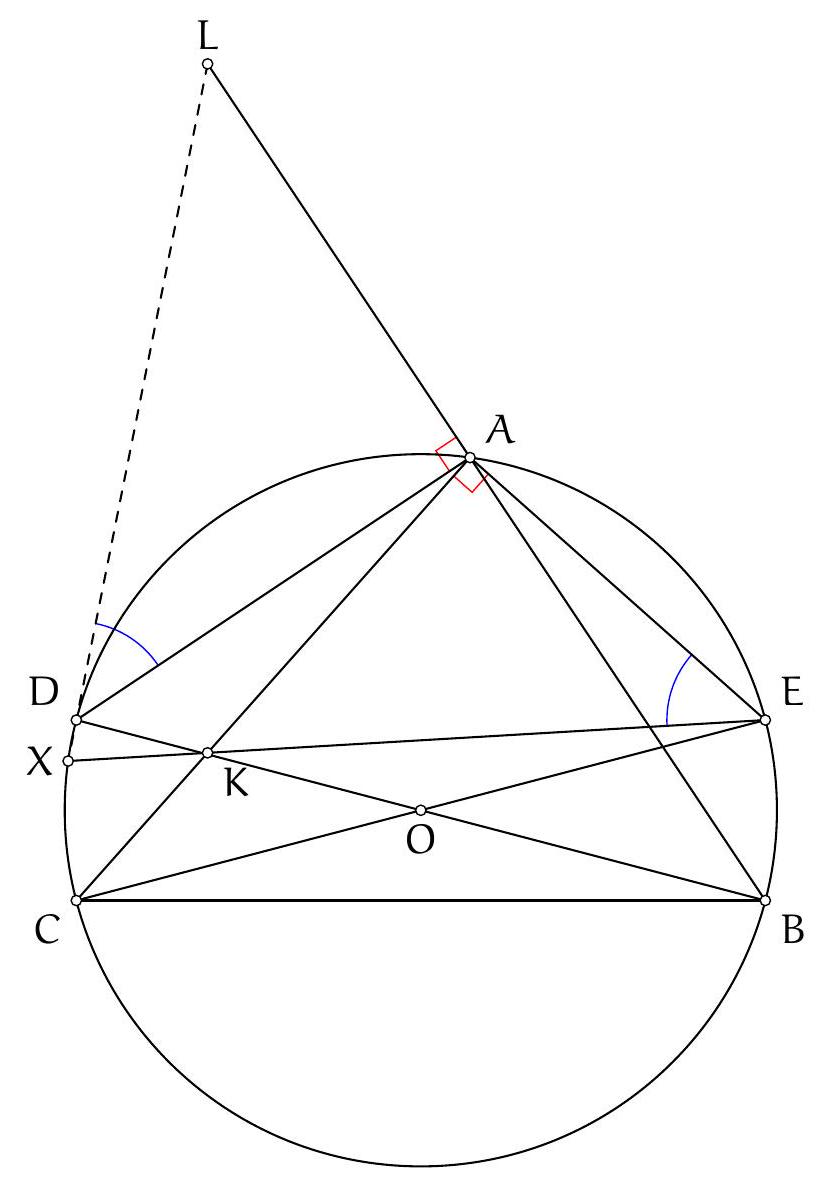

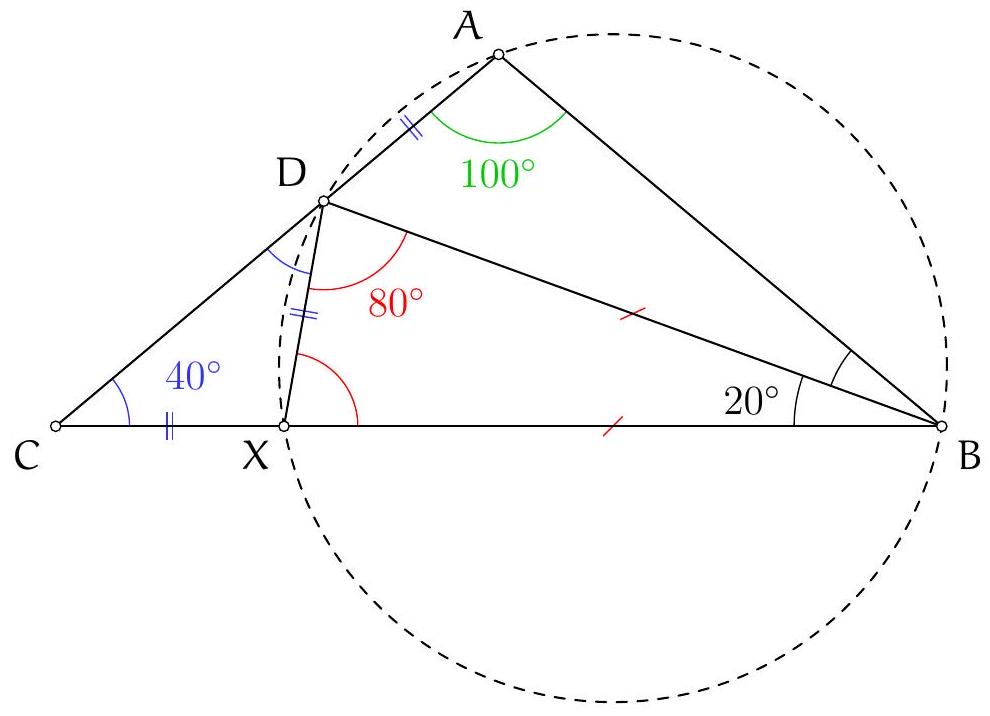

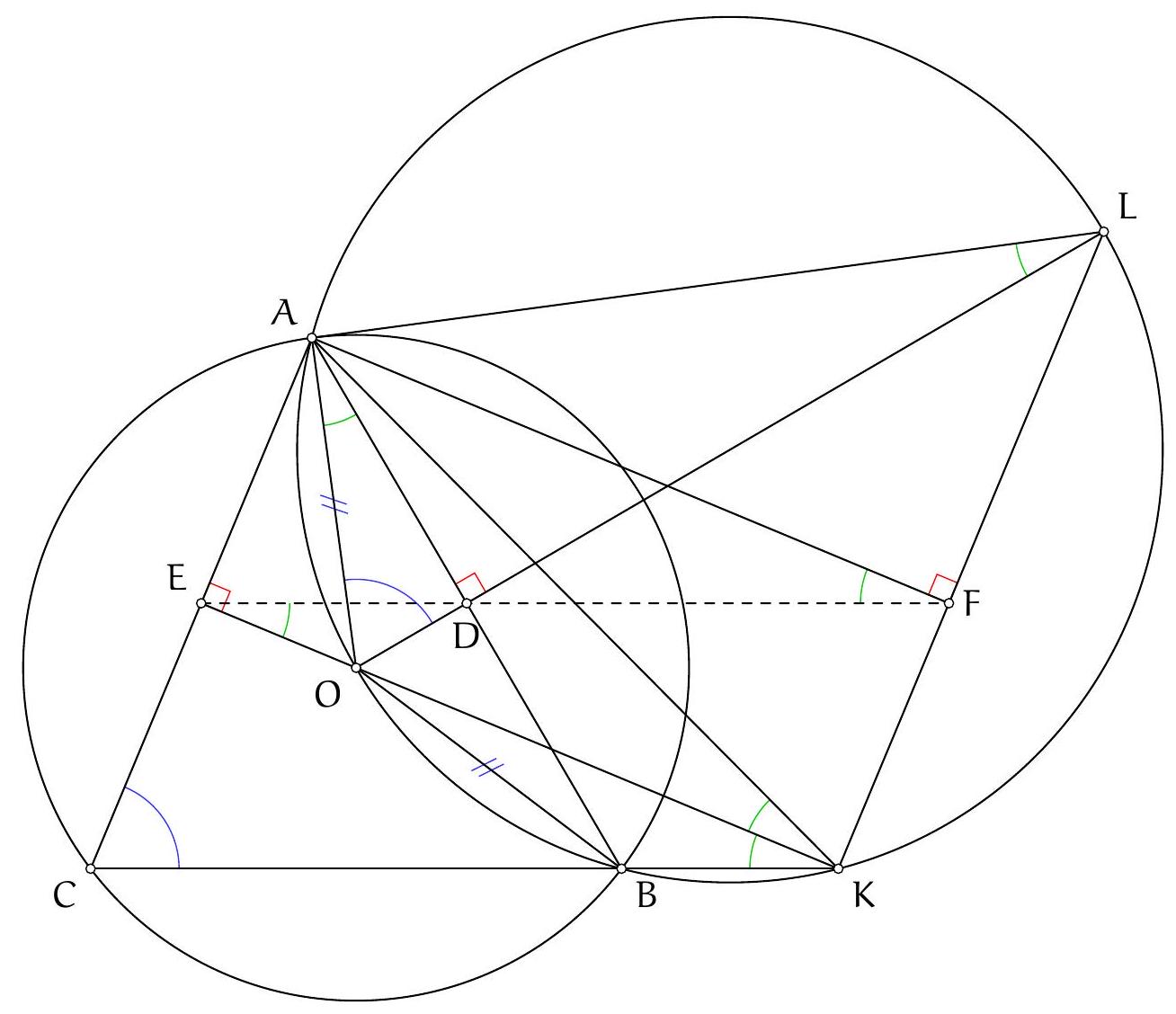

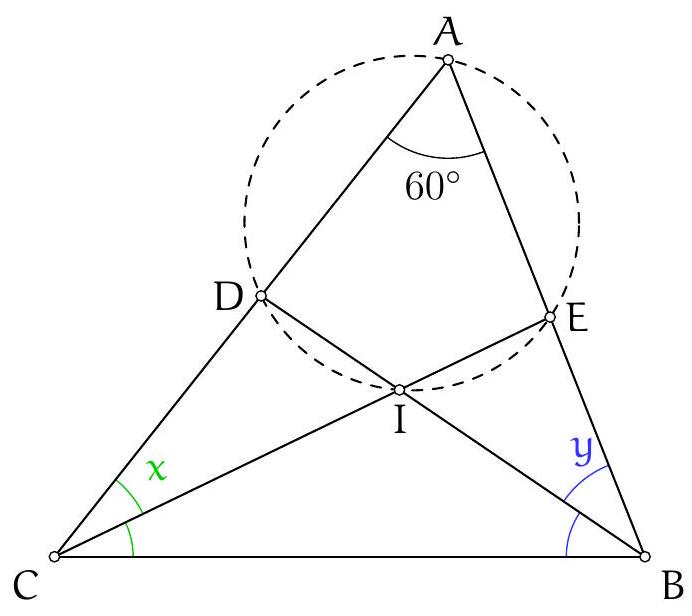

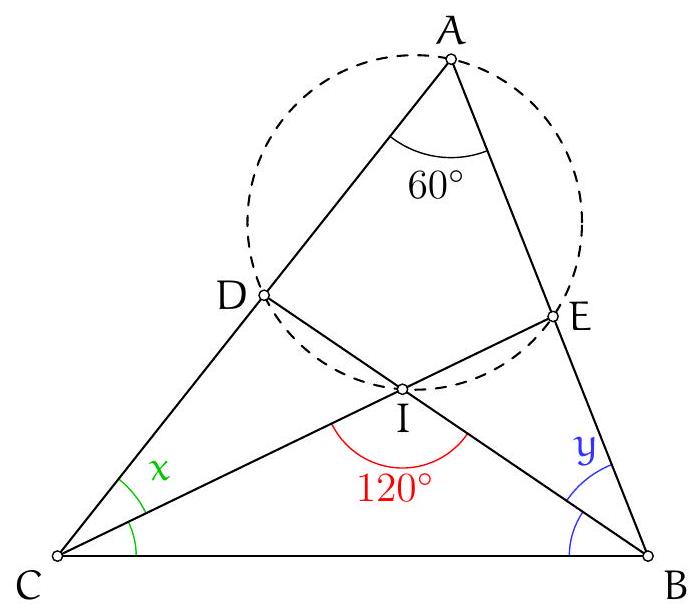

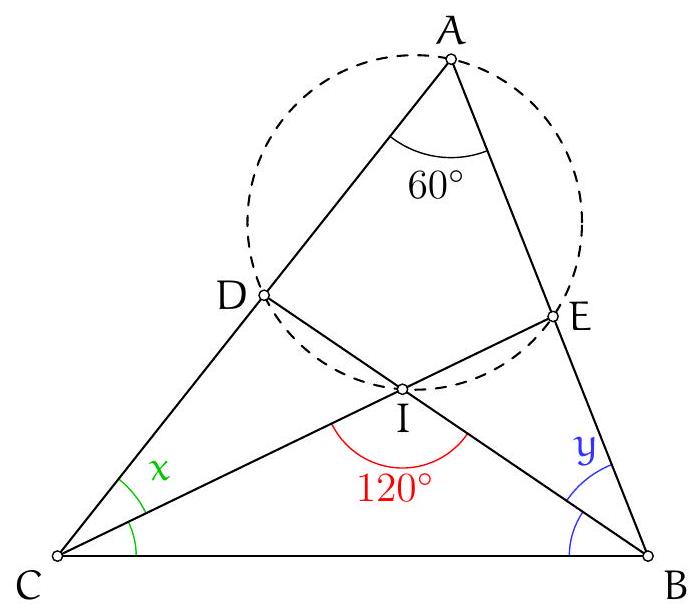

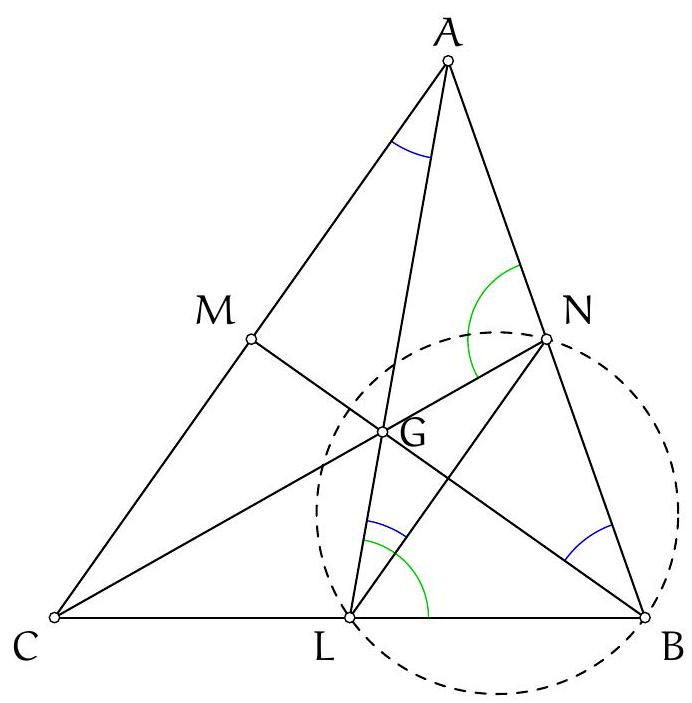

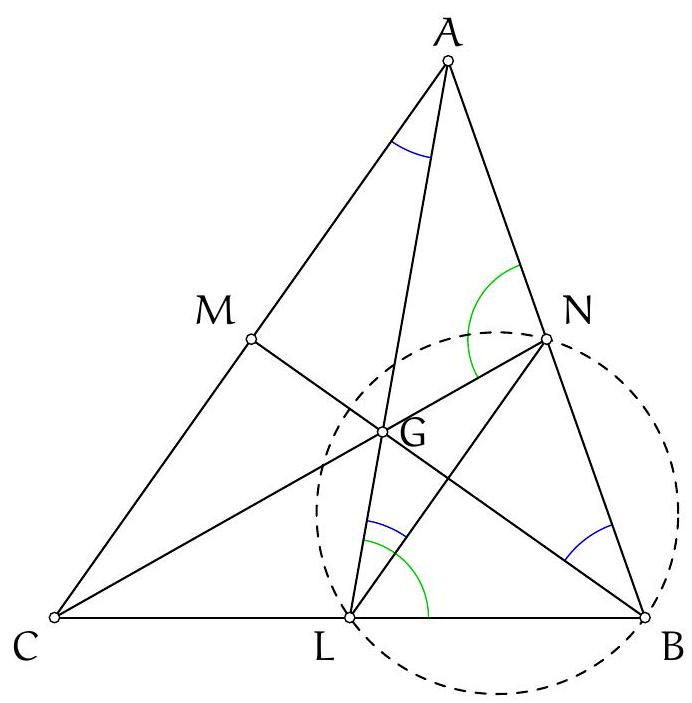

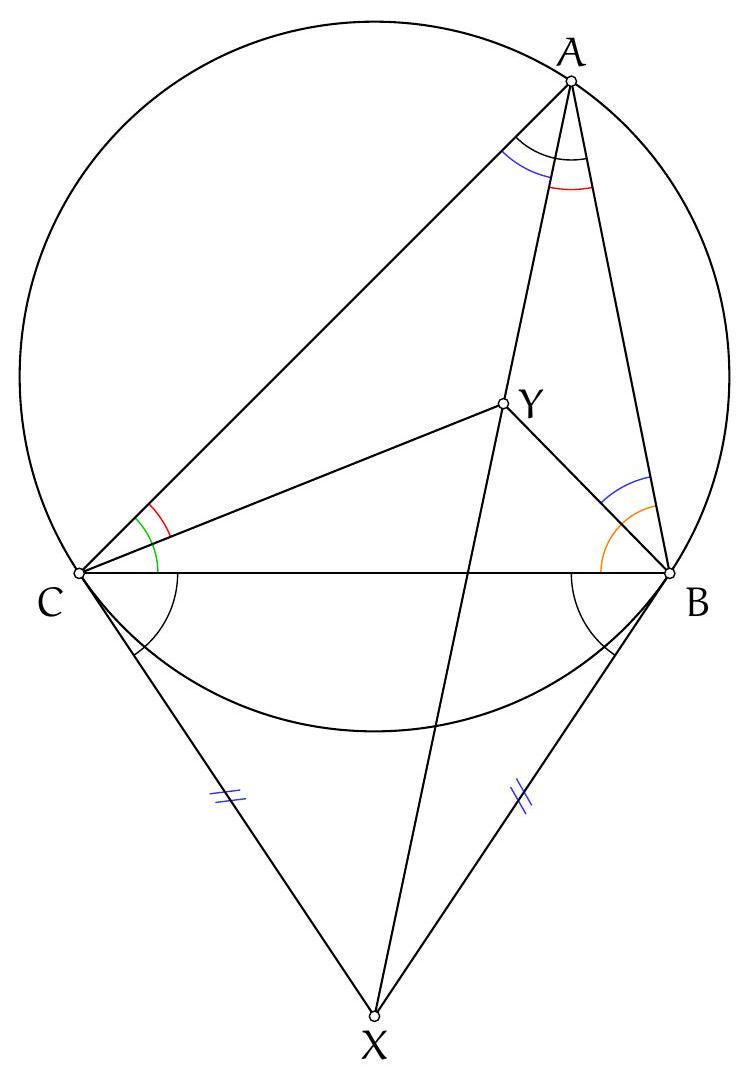

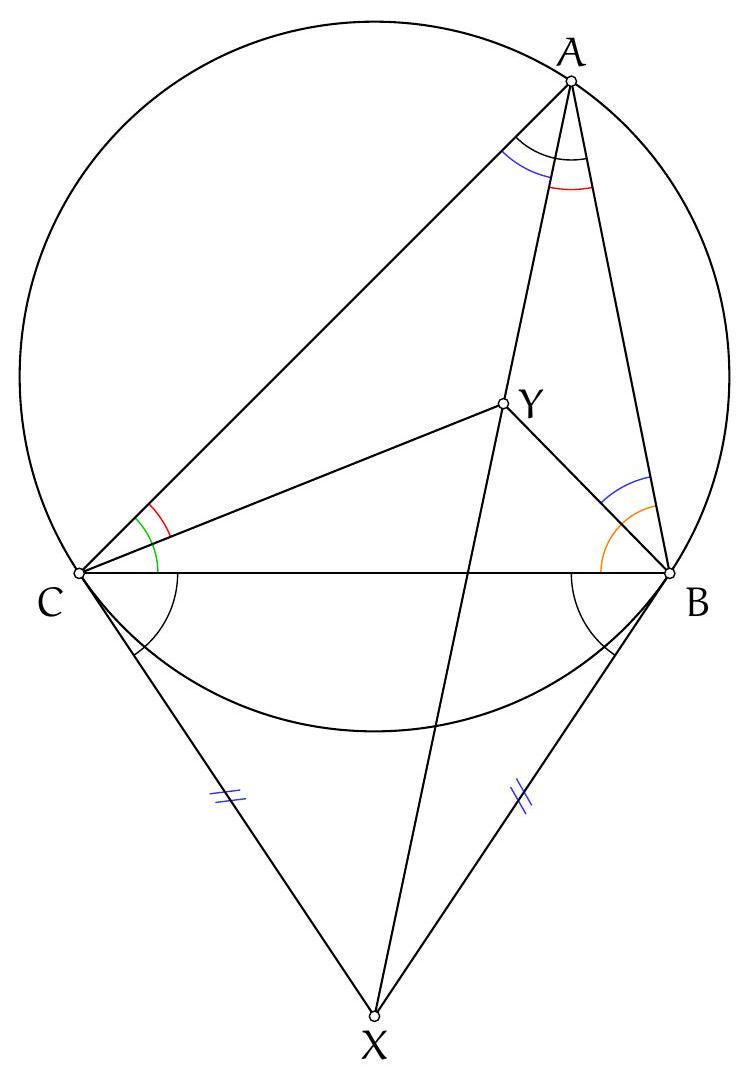

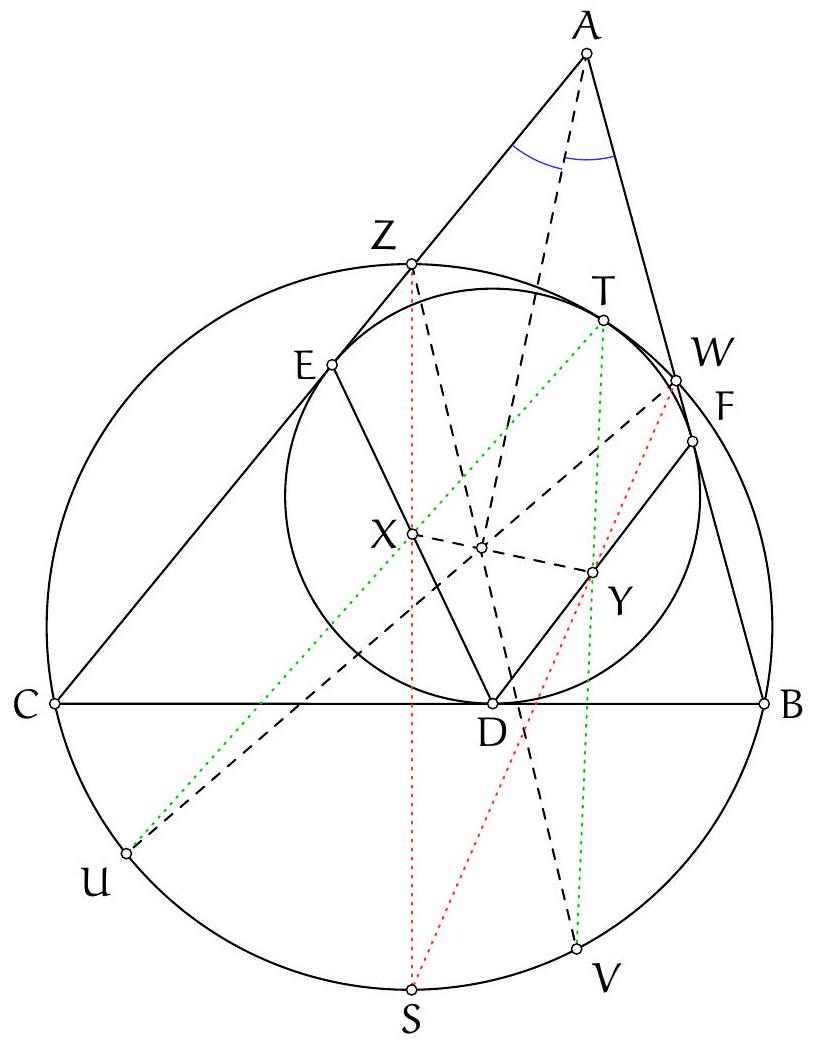

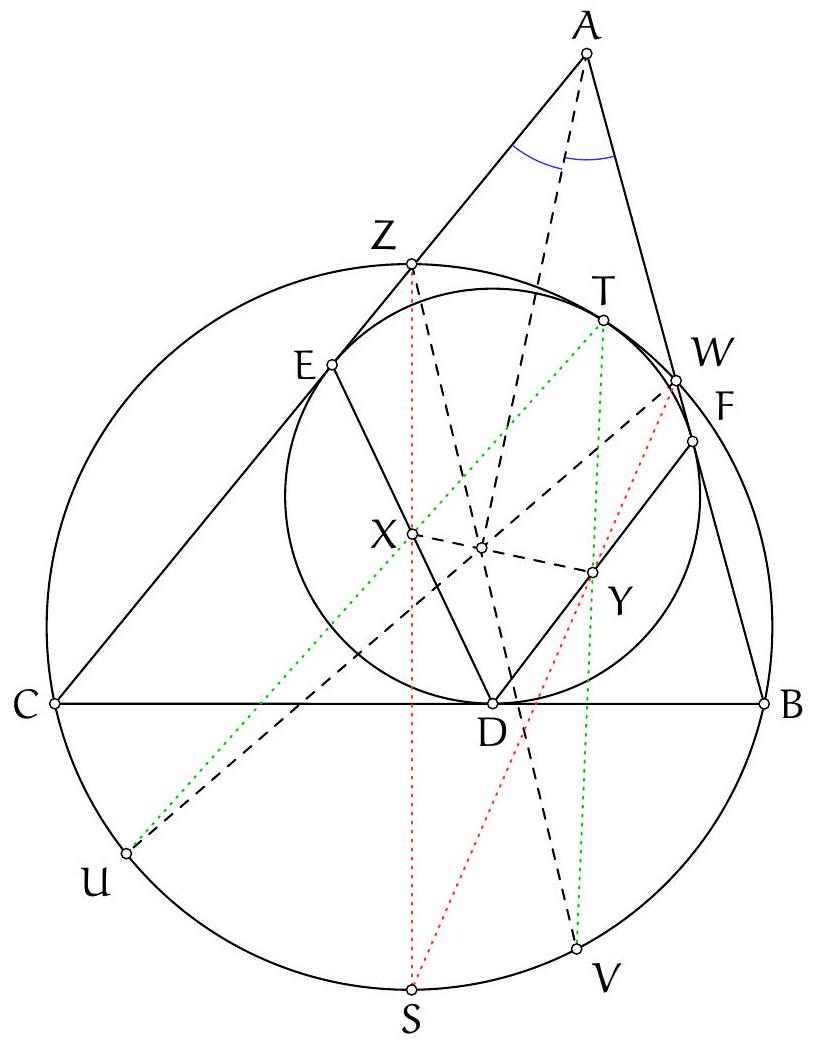

Let $ABC$ be a triangle with acute angles. The altitude from $A$ intersects the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$ at a point $D$. The altitude from $B$ intersects the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$ at a point $E$. The line $(ED)$ intersects the sides $[AC]$ and $[BC]$ at points $P$ and $Q$ respectively. Show that the points $P, Q, B$ and $A$ are concyclic.

|

Let's determine which angles seem easy to access. For example, it seems complicated to obtain the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{PBQ}}$ or the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{PBA}}$. On the other hand, we already know the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$, so it seems reasonable to try to show that $\widehat{\mathrm{QPA}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$.

Now, $180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{QPA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{EPA}}$, so we try to show that $\widehat{\mathrm{EPA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$. Two right angles are given: if we let $H_{B}$ be the foot of the altitude from vertex $B$ and $H_{A}$ be the foot of the altitude from vertex $A$, then the angles $\widehat{A H_{A} B}$ and $\widehat{B H_{B} A}$ are right angles.

We have not yet used the hypothesis that points $E$ and $D$ are on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. This hypothesis translates into an angle equality using the inscribed angle theorem. This gives notably $\widehat{\mathrm{DEB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}$.

By reporting these angle equalities on the figure, we find that $\widehat{\mathrm{PEH}_{B}}=\widehat{\mathrm{H}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{AB}}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{PH}_{B} \mathrm{E}}=\widehat{\mathrm{BH}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{A}}$. The triangles $\mathrm{PEH}_{B}$ and $\mathrm{BAH}_{\mathrm{A}}$ are therefore similar (there are two pairs of equal angles). Thus, $\widehat{\mathrm{EPH}_{\mathrm{B}}}=\widehat{\mathrm{ABH}_{\mathrm{A}}}$, which is the equality we wanted to prove.

Comment from the graders: The exercise is very well done, and the students have shown several effective ways of looking at the problem.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle dont les angles sont aigus. La hauteur issue de $A$ recoupe le cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$ en un point $D$. La hauteur issue de $B$ recoupe le cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$ en un point $E$. La droite (ED) coupe les côtés $[A C]$ et $[B C]$ respectivement en les points $P$ et $Q$. Montrer que les points $P, Q, B$ et $A$ sont cocycliques.

|

Déterminons quels sont les angles qui semblent faciles d'accès. Par exemple, il semble compliqué de pouvoir obtenir l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{PBQ}}$ ou l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{PBA}}$. En revanche, on connait déjà l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$ donc il semble raisonnable d'essayer de montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{QPA}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$.

Or, $180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{QPA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{EPA}}$, on essaye donc de montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{EPA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{QBA}}$. Deux angles droits nous sont donnés : si on pose $H_{B}$ le pied de la hauteur issue du sommet $B$ et $H_{A}$ le pied de la hauteur issue du sommet $A$, alors les angles $\widehat{A H_{A} B}$ et $\widehat{B H_{B} A}$ sont droits.

On n'a pas encore utilisé l'hypothèse que les points $E$ et $D$ étaient sur le cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$. Cette hypothèse se traduit par une égalité d'angle à l'aide du théorème de l'angle inscrit. Ceci donne notemment $\widehat{\mathrm{DEB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}$.

En reportant ces différentes égalités d'angles sur la figure, on trouve donc que $\widehat{\mathrm{PEH}_{B}}=\widehat{\mathrm{H}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{AB}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{PH}_{B} \mathrm{E}}=\widehat{\mathrm{BH}_{\mathrm{A}} \mathrm{A}}$. Les triangles $\mathrm{PEH}_{B}$ et $\mathrm{BAH}_{\mathrm{A}}$ sont donc sembables (il y a deux paires d'angles égaux deux à deux). Ainsi, $\widehat{\mathrm{EPH}_{\mathrm{B}}}=\widehat{\mathrm{ABH}_{\mathrm{A}}}$ qui est l'égalité que l'on souhaitait démontrer.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice est très bien réussi et les élèves ont montré plusieurs façons efficaces de voir les choses.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

The cells of an $8 \times 8$ chessboard are white. A move consists of swapping the colors of the cells of a $3 \times 1$ or $1 \times 3$ rectangle (white cells become black and black cells become white). Is it possible to achieve the configuration where all cells of the chessboard are black in a finite number of moves?

|

The statement presents a finite sequence of operations, and the problem asks whether it is possible to go from the initial situation to a certain final situation. A first idea in this case is to look for an invariant.

One can possibly try by hand to see if it is possible to end up with a configuration where all the squares are black. After several attempts, one realizes that one cannot achieve the desired configuration, and one can therefore conjecture that the answer to the exercise is negative.

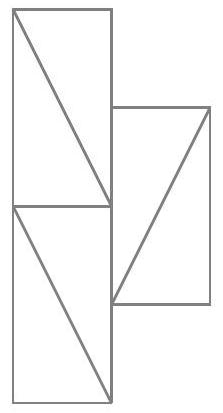

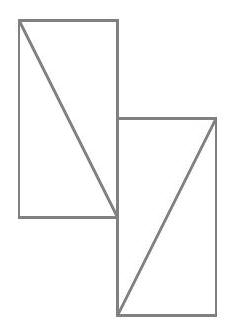

Here, the support of the statement is a chessboard, so we will look for a coloring invariant, that is, we will look for a clever coloring of the chessboard that highlights the invariant. What are the characteristics of a good coloring? First of all, since the considered rectangles have 3 squares, one can look for a coloring that has at most 3 colors. Also, one can look for a coloring such that each rectangle $3 \times 1$ or $1 \times 3$ has one square of each color. We therefore adopt the following coloring (where we have replaced the colors with numbers, given that the exercise already talks about the colors of the squares).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

What does this coloring tell us? Each rectangle $3 \times 1$ or $1 \times 3$ has exactly one square of each number. Therefore, when one changes the colors of a rectangle, exactly one square of each number changes color. Since the numbers of squares of number 1, 2, and 3 are not the same, this encourages us to count at each step the number of white squares of each number.

Let $\mathrm{N}_{1}$ be the number of white squares containing the number 1, called type 1, $\mathrm{~N}_{2}$ the number of white squares of type 2, and $\mathrm{N}_{3}$ the number of white squares of type 3. In the initial situation, $\mathrm{N}_{1}=\mathrm{N}_{3}=21$ and $\mathrm{N}_{2}=22$, these numbers are not all equal. We will therefore be interested in the evolution of the difference between the numbers $N_{1}$ and $N_{2}$. Changing the color of the squares of a rectangle $3 \times 1$ or $1 \times 3$ simultaneously decreases or increases each of the numbers $N_{1}, N_{2}$, and $N_{3}$. In particular, the difference $N_{1}-N_{2}$, at each step, increases by $2, 0$, or $-2$. In particular, its parity does not change. Now $\mathrm{N}_{1}-\mathrm{N}_{2}$ is odd at the start. In the final situation required, $N_{1}-N_{2}=0.0$ is even, so the number $N_{1}-N_{2}$ cannot be zero after a finite number of steps. Therefore, it is not possible to end up with a completely black chessboard. Comment from the examiners: The exercise was not approached by many students. The exercise is, however, a very instructive exercise on invariants by coloring.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Les cases d'un échiquier $8 \times 8$ sont blanches. Un coup consiste à échanger les couleurs des cases d'un rectangle $3 \times 1$ ou $1 \times 3$ (les cases blanches deviennent noires et les cases noires deviennent blanches). Est-il possible d'aboutir en un nombre fini de coups à la configuration où toutes les cases de l'échiquier sont noires?

|

L'énoncé présente une suite finie d'opérations et le problème demande s'il est possible de partir de la situation initiale pour arriver à une certaine situation finale. Une première idée dans ce cas est de chercher un invariant.

On peut éventuellement essayer à la main de voir s'il est possible d'aboutir à une configuration où toutes les cases sont noires. Après plusieurs essais, on se rend compte qu' on n'arrive pas à aboutir la configuration désirée et on peut donc conjecturer que la réponse à l'exercice est négative.

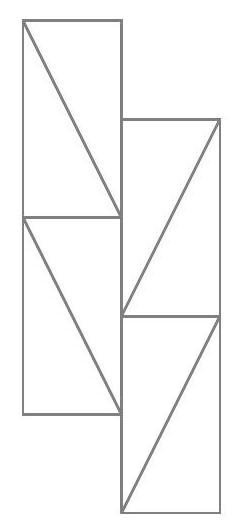

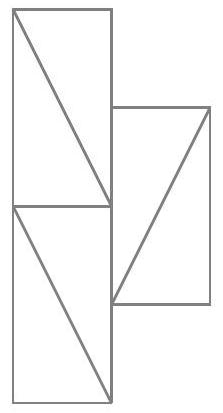

Ici, le support de l'énoncé est un échiquier, on va donc chercher un invariant de coloriage, c'est-à-dire que nous allons chercher un coloriage astucieux de l'échiquier qui mette en évidence l'invariant. Quelles sont les caractéristiques d'un bon coloriage ? Tout d'abord, puisque les rectangles considérés possèdent 3 cases, on peut chercher un coloriage qui possède au plus 3 couleurs. Aussi, on peut chercher un coloriage tel que chaque rectangle $3 \times 1$ ou $1 \times 3$ possède une case de chaque couleur. On adopte donc le coloriage suivant (où on a remplacé les couleurs par des numéros, étant donné que l'exercice parle déjà de couleurs de cases).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Que nous apprend ce coloriage ? Chaque rectangle $3 \times 1$ ou $1 \times 3$ possède exactement une case de chaque numéro. Donc lorsque l'on change les couleurs d'un rectangle, exactement une case de chaque numéro change de couleur. Puisque les nombres de cases de numéro 1,2 et 3 ne sont pas identiques, ceci nous encourage à compter à chaque étape le nombre de cases blanches de chaque numéro.

Soit $\mathrm{N}_{1}$ le nombre de cases blanches contenant le numéro 1, dites de type $1, \mathrm{~N}_{2}$ le nombre de cases blanches de types 2 et $\mathrm{N}_{3}$ le nombre de cases blanches de type 3. Dans la situation initiale, $\mathrm{N}_{1}=\mathrm{N}_{3}=21$ et $\mathrm{N}_{2}=22$, ces nombres ne sont pas tous égaux. On va donc s'intéresser à l'évolution de la différence entre les nombres $N_{1}$ et $N_{2}$. Changer la couleur des cases d'un rectangle $3 \times 1$ ou $1 \times 3$ fait en même temps diminuer ou augmenter chacun des nombres $N_{1}, N_{2}$ et $N_{3}$. En particulier, la différence $N_{1}-N_{2}$, à chaque étape, augmente de $2,0 \mathrm{ou}-2$. En particulier, sa parité ne change pas. Or $\mathrm{N}_{1}-\mathrm{N}_{2}$ est impair au départ. Dans la situation finale demandée, $N_{1}-N_{2}=0.0$ est pair, donc le nombre $N_{1}-N_{2}$ ne peut être nul au bout d'un nombre fini d'étape. On ne peut donc pas arriver à un échiquier entièrement noir. Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice n'a pas été abordé par beaucoup d'élèves. L'exercice est cela dit un exercice d'invariant par coloriage très instructif.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Determine all triplets $(x, y, z)$ of natural numbers satisfying the equation:

$$

2^{x}+3^{y}=z^{2}

$$

|

First, let's analyze the problem: we have a Diophantine equation with a power of 2, a power of 3, and a square. We quickly test small values of \( z \) to find solutions. We can observe that \( 2^{0} + 3^{1} = 2^{2} \), \( 2^{3} + 3^{0} = 3^{2} \), and \( 2^{4} + 3^{2} = 5^{2} \). Since we have a few solutions, we won't find immediate contradictions by simply looking modulo something.

However, we have a square, so it is natural to look modulo 4 or modulo 3 to try to get information about \( x \) and \( y \). Ideally, we would like to show that either \( x \) or \( y \) is even, as this would give us another square in the equation, allowing us to factorize. We will look modulo 4, and first consider the case where 4 divides \( 2^{x} \), i.e., the case \( x \geq 2 \).

Suppose \( x \geq 2 \). Since a square is congruent to 0 or 1 modulo 4, \( z^{2} \) is congruent to 0 or 1 modulo 4, and thus \( 3^{y} \) is also congruent to 0 or 1 modulo 4. Since \( 3^{y} \) is not divisible by 4, we must have \( 3^{y} \equiv 1 \pmod{4} \). Since \( 3^{2} \equiv 9 \equiv 1 \pmod{4} \), we must have \( y \) even (if \( y = 2k + 1 \), then \( 3^{y} \equiv 9^{k} \times 3 \equiv 3 \pmod{4} \)). Let \( y = 2k \) where \( k \) is an integer. We get \( 2^{x} = z^{2} - (3^{k})^{2} = (z - 3^{k})(z + 3^{k}) \). Note that \( z + 3^{k} \) is strictly positive, so

because they divide \( 2^{x} \).

Here we have two terms whose product is \( 2^{x} \). We want to show that one of them cannot be very large. To do this, we will consider the gcd of \( z + 3^{k} \) and \( z - 3^{k} \) and compute it using the fact that it divides their sum, difference, and product.

Let \( d \) be the gcd of \( (z - 3^{k}) \) and \( (z + 3^{k}) \). Then \( d \) divides \( (z + 3^{k}) - (z - 3^{k}) = 2 \times 3^{k} \), but \( d \) also divides \( 2^{x} \), so \( d \) divides 2. Since \( z + 3^{k} \equiv z - 3^{k} \pmod{2} \), if \( d = 1 \), then \( (z - 3^{k}) \) and \( (z + 3^{k}) \) are odd, so \( 2^{x} \) is also odd, which contradicts the fact that \( x \geq 2 \). Therefore, \( d = 2 \).

In particular, since \( (z - 3^{k}) \) and \( (z + 3^{k}) \) are powers of 2 with gcd 2, the smaller of the two is 2. Since \( z + 3^{k} > z - 3^{k} \), we have \( z = 3^{k} + 2 \). Considering the gcd here is not necessary; we could have directly arrived at this by setting \( z + 3^{k} = 2^{a} \) and \( z - 3^{k} = 2^{b} \), observing that \( a > b \), and writing \( 2 \times 3^{k} = 2^{a} - 2^{b} = 2^{b}(2^{a-b} - 1) \), but it is a good reflex when we have a product to look at the gcd of the factors.

From this, we deduce that \( z + 3^{k} = 2^{x-1} \) and \( z - 3^{k} = 2 \), so by taking the difference \( 2 \times 3^{k} + 2 = 2^{x-1} \) and thus \( 3^{k} + 1 = 2^{x-2} \). This equation is quite well-known, but if we don't know it, since we have powers of 2 and 3, it is relevant to look modulo 2, 4, 8, or 3, 9. Since \( 3 + 1 = 2^{2} \), looking modulo 4 and 3 won't conclude immediately, so we look modulo 8.

If \( x \geq 5 \), 8 divides \( 2^{x-2} \), so 8 divides \( 3^{k} + 1 \). However, the powers of 3 modulo 8 are 1 or 3, so \( 3^{k} + 1 \) is 2 or 4 modulo 8 and is not divisible by 8, which gives a contradiction. Therefore, we must have \( x = 2, 3, \) or 4.

For \( x = 2 \), \( 1 = 1 + 3^{k} \) so \( 3^{k} = 0 \), which is impossible. For \( x = 3 \), \( 1 + 3^{k} = 2 \) so \( 3^{k} = 1 \) and \( k = 0 \), thus \( y = 0 \). For \( x = 4 \), \( 1 + 3^{k} = 4 \) so \( 3^{k} = 3 \), thus \( k = 1 \) and \( y = 2 \).

Conversely, if \( (x, y) = (3, 0) \), then \( z^{2} = 2^{x} + 3^{y} = 9 = 3^{2} \) so \( z = \pm 3 \) and the triplet \( (3, 0, 3) \) is a solution. If \( (x, y) = (4, 2) \), then \( z^{2} = 2^{x} + 3^{y} = 25 = 5^{2} \) so \( z = 5 \) and the triplet \( (4, 2, 5) \) is a solution.

It remains to treat the case where \( x = 0 \) and the case where \( x = 1 \). For the case where \( x = 0 \), we have \( 2^{x} = 1 \), which is a square, so we will factorize and reuse the gcd technique. If \( x = 0 \), the equation becomes \( 3^{y} = z^{2} - 1 = (z - 1)(z + 1) \). The gcd of \( z - 1 \) and \( z + 1 \) divides \( 3^{y} \) and divides \( z + 1 - (z - 1) = 2 \), so it must be 1. Since \( 3^{y} = (z - 1)(z + 1) \), \( z - 1 \) and \( z + 1 \) are positive powers of 3 (since \( z + 1 > 0 \) and thus \( z - 1 > 0 \), their product is strictly positive), the smallest of the two must be 1, so \( z - 1 = 1 \) and \( z = 2 \). We get \( 3^{y} = z^{2} - 1 = 3 \) so \( y = 1 \). Conversely, \( (0, 1, 2) \) is a solution because \( 1 + 3 = 2^{2} \).

For the case \( x = 1 \), we don't see any solutions, so we need to find a relevant modulo to evaluate the equation. Since there is a power of 3 and a square, we can look modulo 3. If \( x = 1 \), the equation becomes \( 2 + 3^{y} = z^{2} \). If \( y = 0 \), the equation becomes \( z^{2} = 3 \), which has no integer solutions. Therefore, \( y > 0 \) and \( z^{2} \equiv 2 \pmod{3} \). However, a square modulo 3 is congruent to 0 or 1, so there are no solutions for \( x = 1 \). The solutions are therefore \( (0, 1, 2) \), \( (3, 0, 3) \), and \( (4, 2, 5) \).

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally well done. However, it is necessary to verify the solutions obtained and justify everything that is stated: for example, it is necessary to justify that if two powers of 2 are 2 units apart, they must be 2 and 4 (this can be easily done by looking modulo 4).

|

(0, 1, 2), (3, 0, 3), (4, 2, 5)

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les triplets $(x, y, z)$ d'entiers naturels satisfaisant l'équation:

$$

2^{x}+3^{y}=z^{2}

$$

|

Tout d'abord, analysons le problème : on a une équation diophantienne avec une puissance 2 , une puissance de 3 et un carré. On s'empresse donc de tester les petites valeurs de $z$ et de trouver la solution. On peut remarquer que $2^{0}+3^{1}=2^{2}, 2^{3}+3^{0}=3^{2}$ et $2^{4}+3^{2}=5^{2}$. A priori comme on a quelques solutions, on ne va pas trouver de contradictions immédiates simplement en regardant modulo quelque chose.

Néanmoins on a un carré, donc il est naturel de regarder modulo 4 ou modulo 3 et d'essayer d'obtenir des informations sur $x$ et $y$. Idéalement, on aimerait obtenir que soit $x$ soit $y$ est pair, comme ça on aurait un autre carré dans l'équation ce qui nous permettrait de factoriser. On va donc regarder modulo 4, pour cela on a envie de traitrer en premier le cas où 4 divise $2^{\mathrm{x}}$, i.e. le cas $x \geqslant 2$.

Supposons $x \geqslant 2$. Comme un carré est congru à 0 ou 1 modulo $4, z^{2}$ est congru à 0 ou 1 modulo 4 , donc $3^{y}$ aussi. Comme il n'est pas divisible par 4 , on a forcément $3^{y} \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$. Comme $3^{2} \equiv 9 \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 4)$, on a nécessairement $y$ pair $\left(\right.$ si $\left.y=2 k+1,3^{y} \equiv 9^{k} \times 3 \equiv 3(\bmod 4)\right)$. Posons $y=2 k$ avec $k$ entier, on obtient $2^{\mathrm{x}}=z^{2}-\left(3^{k}\right)^{2}=\left(z-3^{k}\right)\left(z+3^{k}\right)$. Notons que $z+3^{k}$ est strictement positif, donc

car elles divisent $2^{x}$.

Ici on a deux termes dont le produit vaut $2^{x}$, on aimerait montrer que l'un d'entre eux ne peut pas être très grand. Pour cela on va considérer le pgcd de $z+3^{k}$ et $z-3^{k}$ et le calculer en utilisant qu'il divise leur somme, différence et produit.

Soit d le pgcd de $\left(z-3^{k}\right)$ et $\left(z+3^{k}\right)$, alors $d$ divise $\left(z+3^{k}\right)-\left(z-3^{k}\right)=2 \times 3^{k}$, mais $d$ divise aussi $2^{\mathrm{x}}$ donc $d$ divise 2 . Comme $z+3^{k} \equiv z-3^{k}(\bmod 2)$, si d vaut $1,\left(z-3^{k}\right)$ et $\left(z+3^{k}\right)$ sont impairs donc $2^{\mathrm{x}}$ aussi, ce qui contredit le fait que $x \geqslant 2$. On a donc $\mathrm{d}=2$

En particulier comme $\left(z-3^{k}\right)$ et $\left(z+3^{k}\right)$ sont des puissances de 2 de pgcd 2 , le plus petit des deux vaut 2 donc comme $z+3^{k}>z-3^{k}, z=3^{k}+2$. Considérer le pgcd ici n'est pas nécessaire, on aurait pu directement aboutir à cela en posant $z+3^{\mathrm{k}}=2^{\mathrm{a}}, z-3^{\mathrm{k}}=2^{\mathrm{b}}$, observé que $\mathrm{a}>\mathrm{b}$ et écrit $2 \times 3^{\mathrm{k}}=2^{\mathrm{a}}-2^{\mathrm{b}}=2^{\mathrm{b}}\left(2^{\mathrm{a}-\mathrm{b}}-1\right)$, mais un bon réflexe quand on a un produit est de regarder le pgcd des facteurs.

De ceci, on déduit que $z+3^{k}=2^{x-1}$ et $z-3^{k}=2$, donc en faisant la différence $2 \times 3^{k}+2=2^{x-1}$ donc $3^{\mathrm{k}}+1=2^{\mathrm{x}-2}$. Cette équation est assez connue, mais si on ne la connait pas, comme on a des puissances de 2 et de 3 , il est pertinent de regarder modulo $2,4,8$ ou 3,9 . Comme $3+1=2^{2}$, regarder modulo 4 et 3 ne conclura pas tout de suite, on regarde donc modulo 8 .

Si $x \geqslant 5,8$ divise $2^{x-2}$ donc 8 divise $3^{x}+1$. Or les puissances de 3 modulo 8 valent 1 ou 3 donc $3^{x}-1$ vaut 2 ou 4 modulo 8 et n'est pas divisible par 8 , ce qui donne une contradiction. On a donc forcément $x=2,3$ ou 4 .

Pour $x=2,1=1+3^{k}$ donc $3^{k}=0$ ce qui est impossible. Pour $x=3,1+3^{k}=2$ donc $3^{k}=1$ donc $k=0$ et $y=0$. Pour $x=4,1+3^{k}=4$ donc $3^{k}=3$, on a donc $k=1$ soit $y=2$.

Réciproquement, si $(x, y)=(3,0), z^{2}=2^{x}+3^{y}=9=3^{2}$ donc $z= \pm 3$ et le triplet $(3,0,3)$ convient. Si $(x, y)=(4,2), z^{2}=2^{x}+3^{y}=25=5^{2}$ donc $z=5$ et le triplet $(4,2,5)$ convient.

Il reste donc à traiter le cas où $x=0$ et celui où $x=1$. Pour le cas où $x=0$, on a $2^{x}=1$ qui est un carré, on va donc factoriser et réutiliser la technique du pgcd. Si $x=0$, l'équation se réécrit $3^{y}=z^{2}-1=(z-1)(z+1)$. Le pgcd de $z-1$ et $z+1$ divise $3^{y}$ et divise $z+1-(z-1)=2$ donc il vaut nécessairement 1 . Comme $3^{y}=(z-1)(z+1), z-1$ et $z+1$ sont des puissances de 3 positives (car $z+1>0$ donc $z-1>0$ leur produit étant strictement positif) de pgcd 1 , le plus petit des deux

vaut nécessairement 1 donc $z-1=1, z=2$. On obtient $3^{y}=z^{2}-1=3$ donc $y=1$. Réciproquement $(0,1,2)$ est solution car $1+3=2^{2}$.

Pour le cas $x=1$, on ne voit pas de solution, il faut donc trouver un modulo pertinent pour évaluer l'équation, comme il y a une puissance de 3 et un carré, on peut regarder modulo 3 . $\mathrm{Si} x=1$ l'équation devient $2+3^{y}=z^{2}$. Si $y=0$ l'équation devient $z^{2}=3$ qui n'a pas de solution entière. On a donc $y>0$ donc $z^{2} \equiv 2(\bmod 3)$. Or un carré modulo 3 est congru à 0 ou 1 , il n'y a donc pas de solution pour $x=1$. Les solutions sont donc $(0,1,2),(3,0,3)$ et $(4,2,5)$.

Commentaire des correcteurs: Exercice globalement bien réussi. Il faut néanmoins penser à vérifier les solutions obtenues et justifier tout ce qui est affirmé : par exemple il faut justifier que si deux puissances de 2 sont distance de 2 ce sont forcément 2 et 4 (on peut le faire facilement en regardant modulo 4).

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

A grid of size $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ contains $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ cells. Each cell contains a natural number between 1 and $\boldsymbol{n}$, such that each integer in the set $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ appears exactly $n$ times in the grid. Show that there exists a column or a row of the grid containing at least $\sqrt{n}$ different numbers.

|

Let's first look at what happens in what seems to be the 'worst case': if each row/column does not contain many numbers, each number will be present a lot. In particular, for any $i$, the number of $i$ seems to be written in few rows and columns. But a priori, if the number $i$ appears too much in a row, it will appear in many columns and vice versa. A priori, the worst case seems to be the one where each number appears in as many columns as rows, and since each number appears $n$ times, the square must be of dimension $\sqrt{n}$, so $i$ appears in at least $2 \sqrt{n}$ rows and columns.

Of course, this analysis is by no means a proof, but we see two important ideas: first, the number of distinct numbers in each row/column seems to be related to the number of rows/columns in which each number appears. Second, for any $i$ between 1 and $n$, the number $i$ appears at least on $2 \sqrt{n}$ rows and columns. We will therefore try to formalize this.

Let $a_{c, i}$ for $c$ a column or a row and $i$ an integer between 1 and $n$ be the number of times $i$ appears in $c$, let $c_{i}$ (resp. $l_{i}$) be the number of columns (resp. rows) to which $i$ belongs. Let $C$ be the set of columns and $L$ the set of rows.

Note that the hypothesis that $i$ appears $n$ times translates as $c_{i} \times l_{i} \geqslant n$ because $i$ appears in at most $c_{i} l_{i}$ cells.

Note that for any $i$, $l_{i}+c_{i}$ being the number of rows or columns where $i$ appears, it is $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}$. The number of distinct elements in column $c$ is, in turn, $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i}$. In particular, we see that the $a_{c, i}$ play an important role in the problem.

Now it remains to relate the number of appearances of $i$ in the different rows/columns to the number of numbers in each row. For this, we will look at the sum of the $a_{c, i}$ (we sum over $i$ from 1 to $n$ and over $c$ columns and rows) and use the two previous interpretations.

We thus obtain $\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}+l_{i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}} \geqslant 2 n \sqrt{n}$.

We deduce that $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}}=2 n \sqrt{n}$.

In particular, since there are $2 n$ rows or columns, there exists $c$ rows or columns such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sqrt{n}$ i.e., $c$ contains at least $\sqrt{n}$ different numbers.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was very difficult and only one student succeeded. It was necessary to try to relate the number of numbers per row to the number of columns/rows where a number appears, and few students had this idea.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Une grille de taille $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ contient $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ cases. Chaque case contient un entier naturel compris entre 1 et $\boldsymbol{n}$, de telle sorte que chaque entier de l'ensemble $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ apparaît exactement $n$ fois dans la grille. Montrer qu'il existe une colonne ou une ligne de la grille contenant au moins $\sqrt{n}$ nombres différents.

|

Essayons d'abord de regarder ce qui se passe dans ce qui semble être 'le pire cas" : si chaque ligne/colonne ne contient pas beaucoup de numéros, chaque numéro va y être beaucoup présent. En particulier, pour tout $i$, le nombre de $i$ semble être écrit dans peu de lignes et de colonnes. Mais à priori si le numéro $i$ apparait trop dans une ligne, il apparaitra dans beaucoup de colonnes et inversement. A priori, le pire cas semble être celui où chaque numéro apparaît dans autant de colonnes que de lignes et comme chaque numéro apparaît $n$ fois, le carré doit être de dimension $\sqrt{n}$, donc $i$ apparait dans au moins $2 \sqrt{n}$ lignes et colonnes.

Bien sûr, cette analyse ne constitue en rien une preuve, mais on voit deux idées importantes : premièrement, le nombre de numéros distincts dans chaque ligne/colonne semble avoir un lien avec le nombre de lignes/colonnes où chaque numéro apparaît. Deuxièmement, pour tout $i$ entre 1 et $n$, le nombre $i$ apparait au moins sur $2 \sqrt{n}$ lignes et colonnes. On va donc essayer de formaliser ça.

Notons $a_{c, i}$ pour $c$ une colonne ou une ligne et $i$ un entier entre 1 et $n$ le nombre de fois qu'apparait $i$ dans $c$, notons $c_{i}$ (resp. $l_{i}$ ) le nombre de colonnes (resp. lignes) à laquelle $i$ appartient. On note C l'ensemble des colonnes $L$ celui des lignes.

Notons que l'hypothèse du fait que $i$ apparait $n$ fois se traduit comme $c_{i} \times l_{i} \geqslant n$ car $i$ apparait dans au plus $c_{i} l_{i}$ cases.

Notons que pour tout $i$, $l_{i}+c_{i}$ étant le nombre de ligne ou de colonne où apparait $i$, il vaut $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}$. Le nombre d'éléments distincts dans la colonne $c$ vaut, quant à lui, $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i}$. En particulier, on voit bien que les $a_{c, i}$ jouent un rôle important dans le problème.

Maintenant il reste à relier le nombre d'apparitions de i dans les différentes lignes/colonnes au nombre de numéros dans chaque ligne. Pour cela on va regarder la somme des $a_{c, i}$ (on somme sur $i$ entre 1 et $n$ et sur c colonne et ligne) et utiliser les deux interprétations précédentes.

On obtient ainsi $\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}+l_{i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}} \geqslant 2 n \sqrt{n}$.

On en déduit que $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}}=2 n \sqrt{n}$.

En particulier, comme il y a $2 n$ lignes ou colonnes, il existe $c$ colonnes ou lignes telles que $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sqrt{n}$ i.e. c contient au moins $\sqrt{\mathrm{n}}$ numéros différents.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice était très dur et seul un élève l'a réussi. Il fallait essayer de relier le nombre de numéros par ligne aux nombres de colonnes/lignes où apparait un numéro et rares sont ceux qui ont eu l'idée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

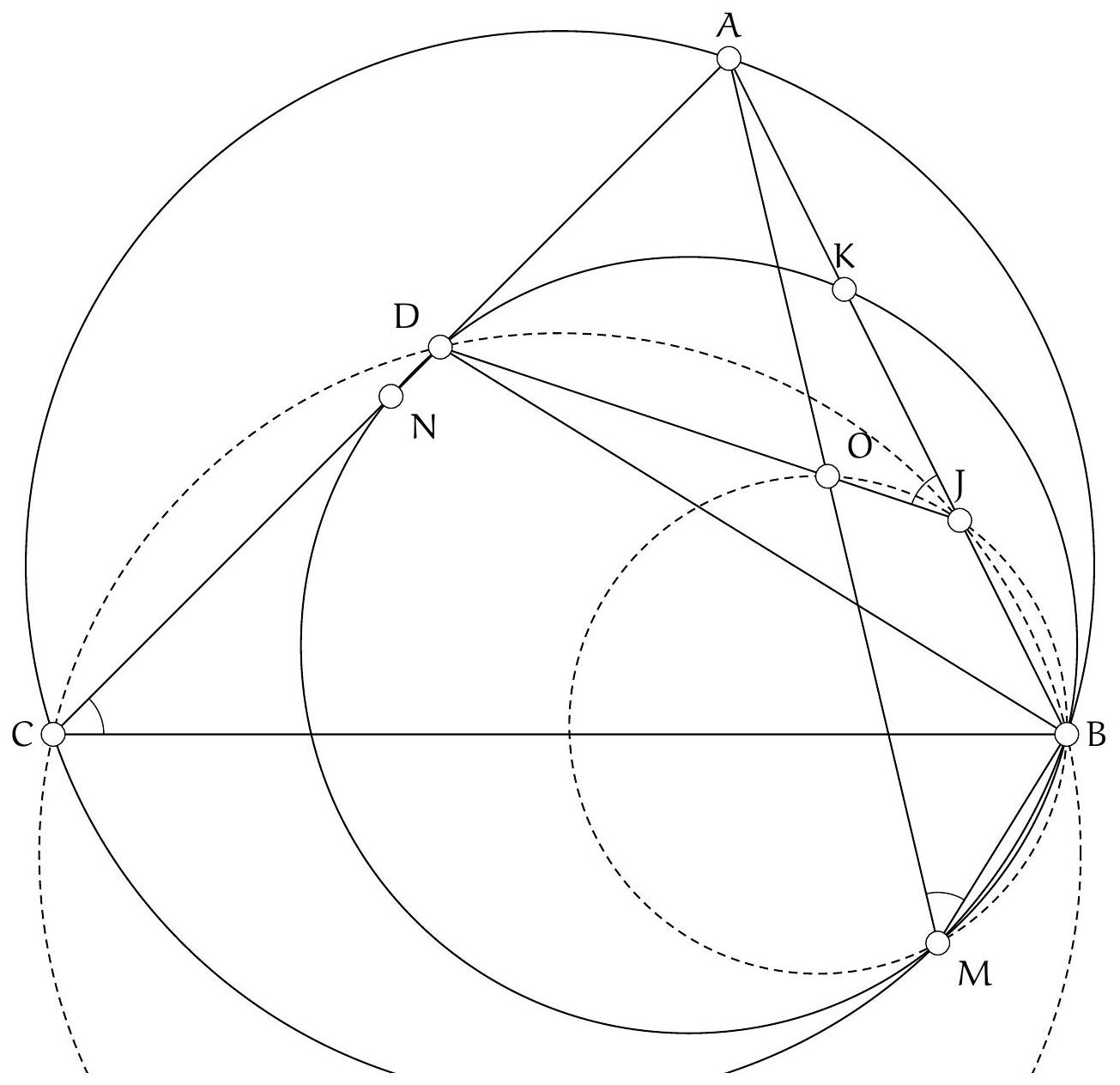

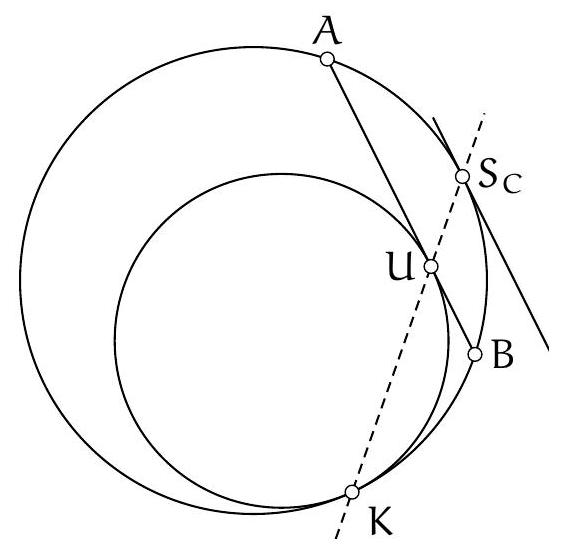

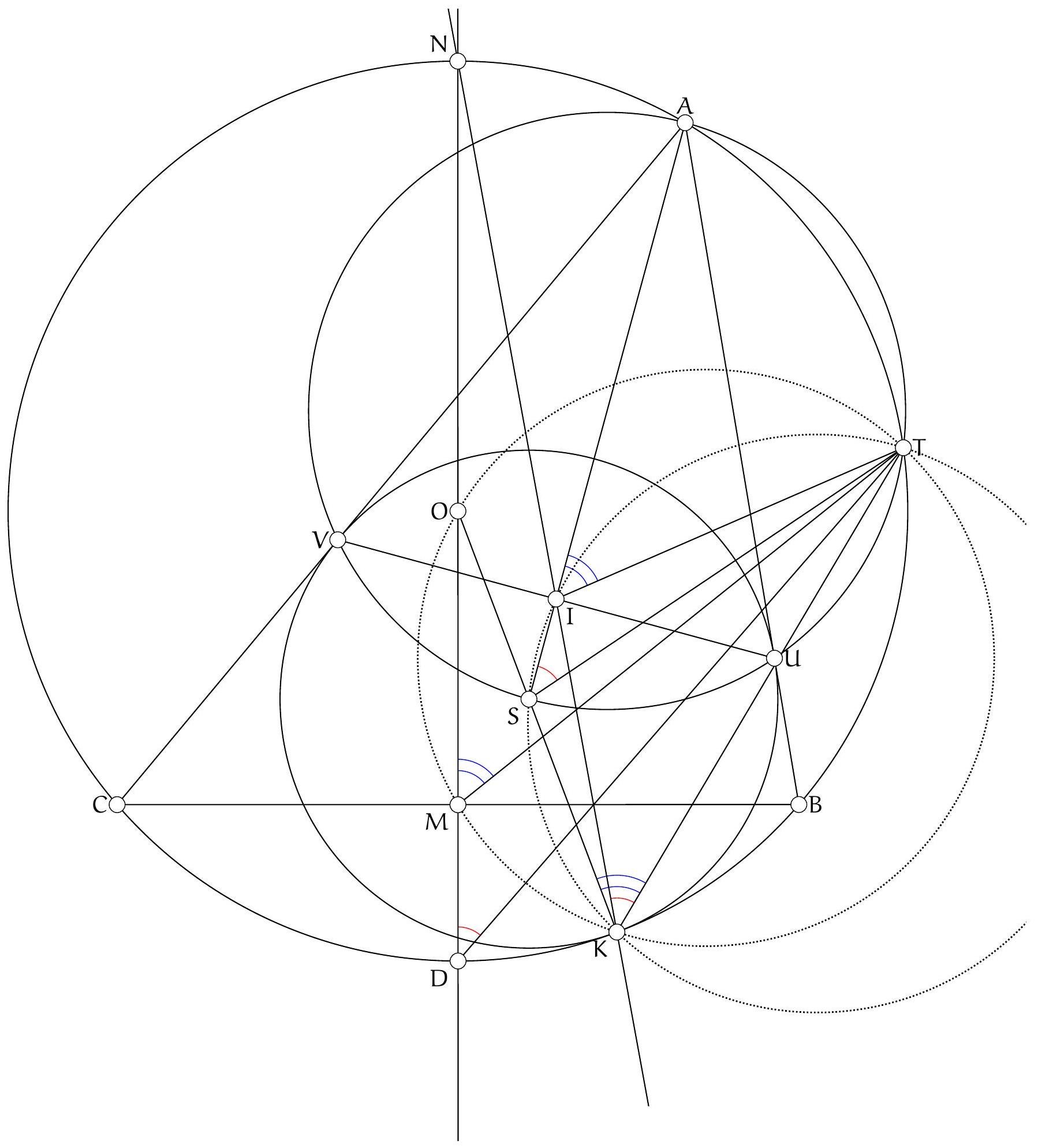

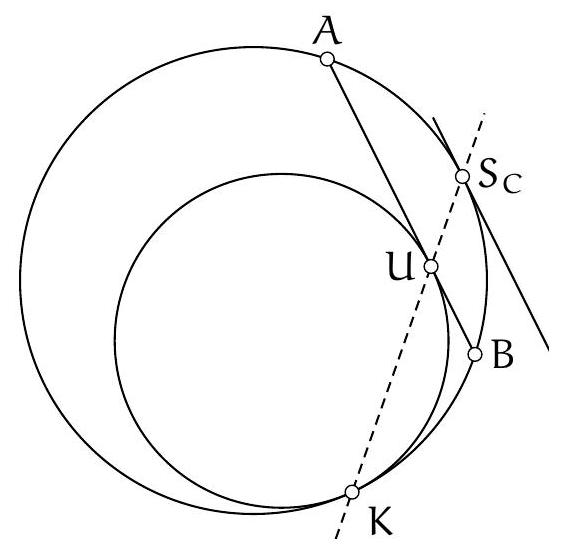

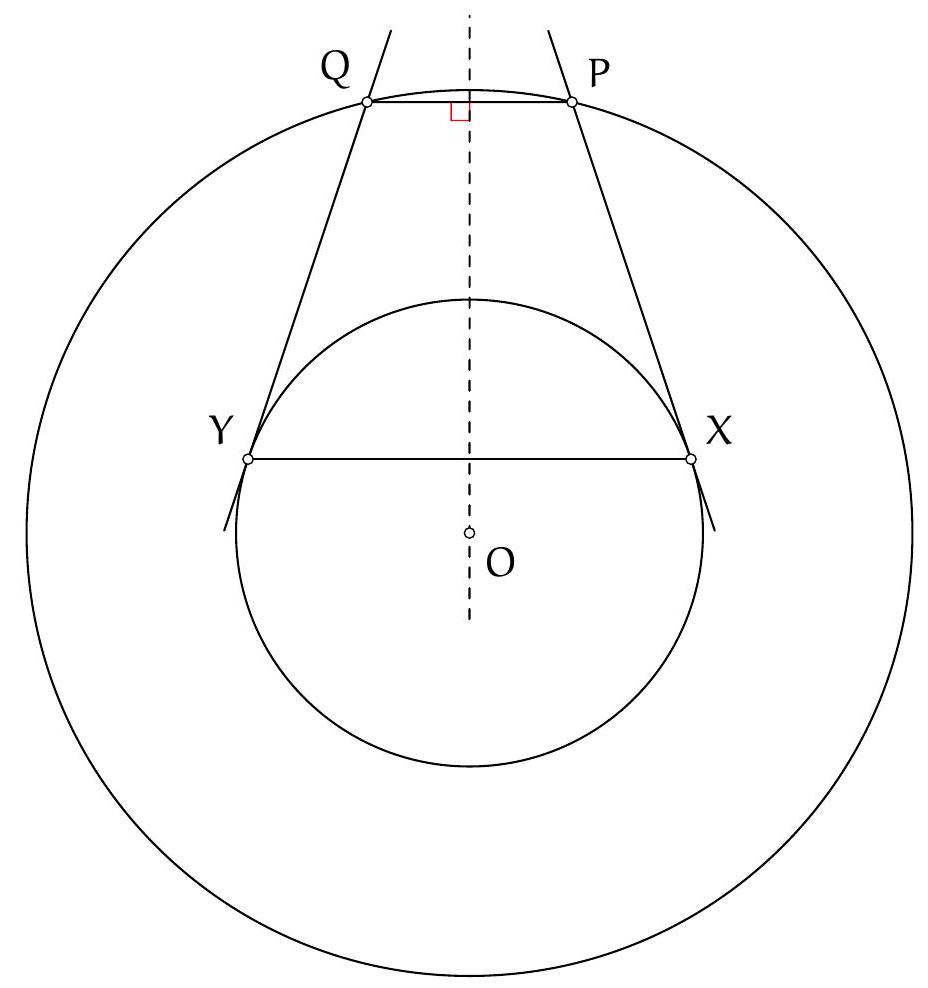

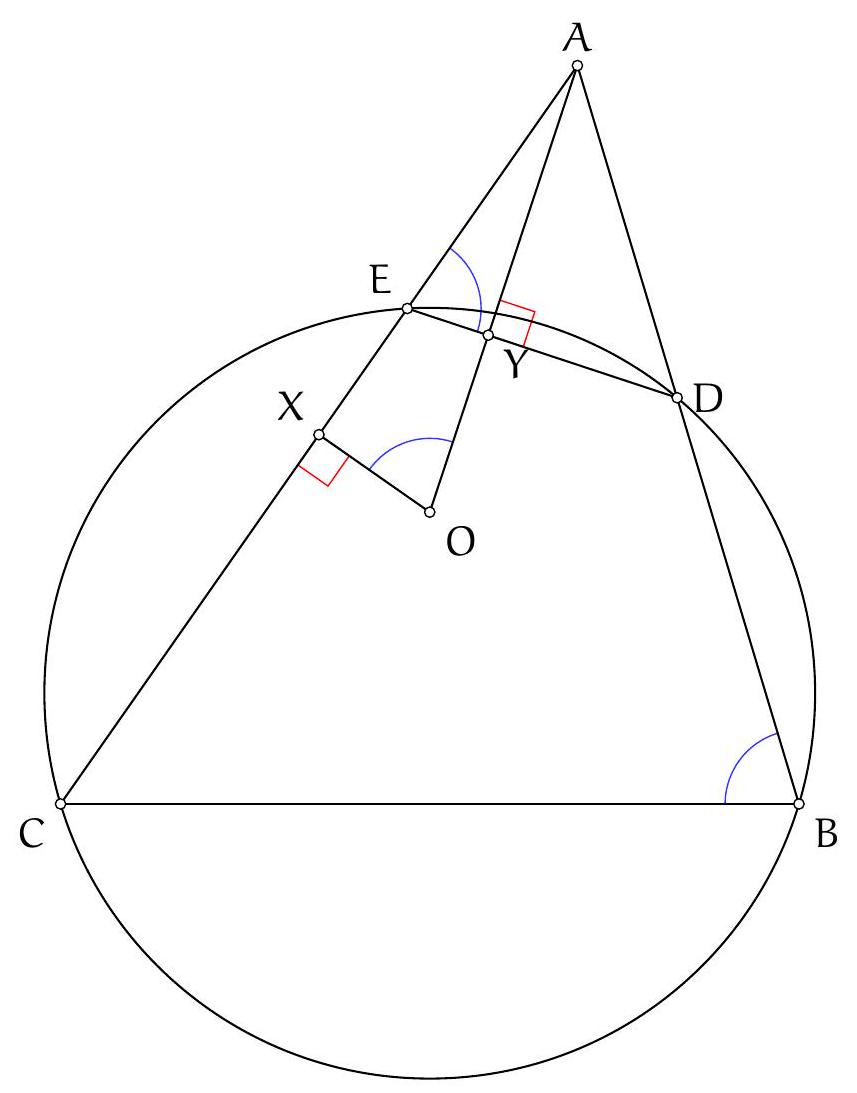

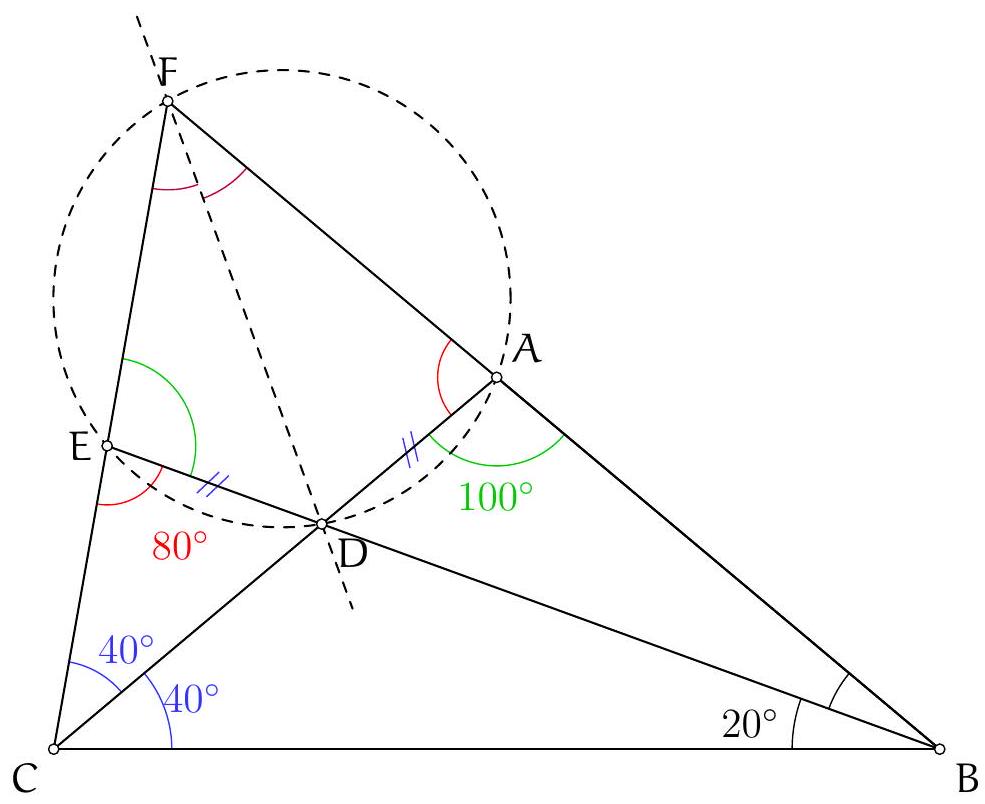

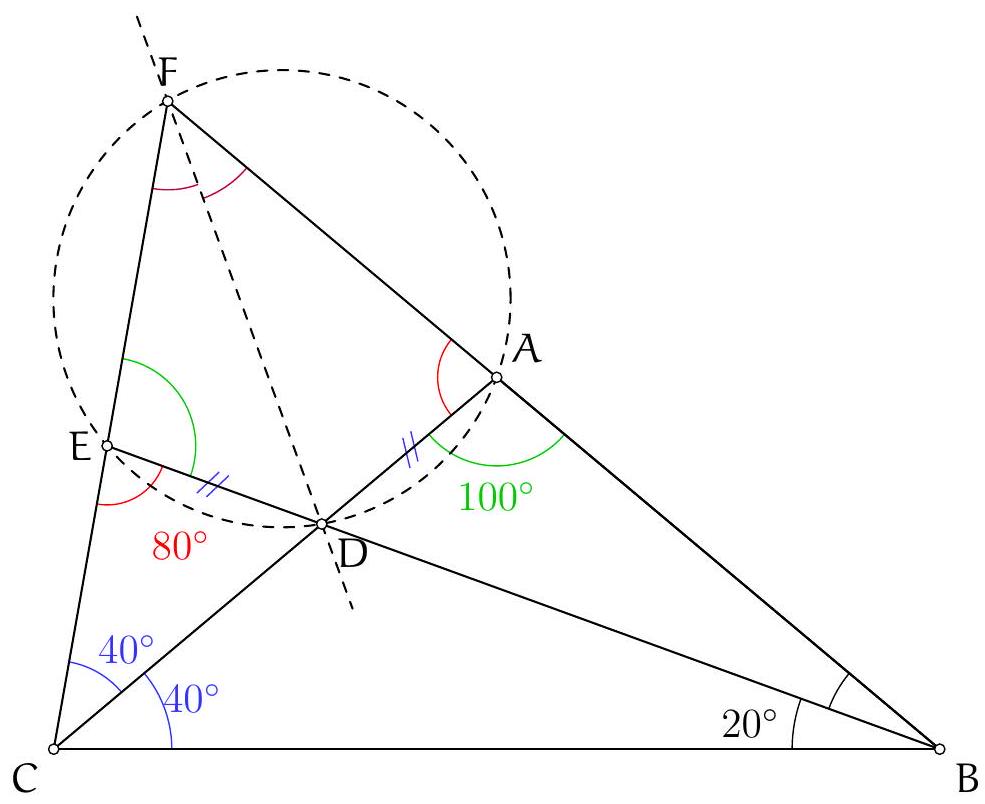

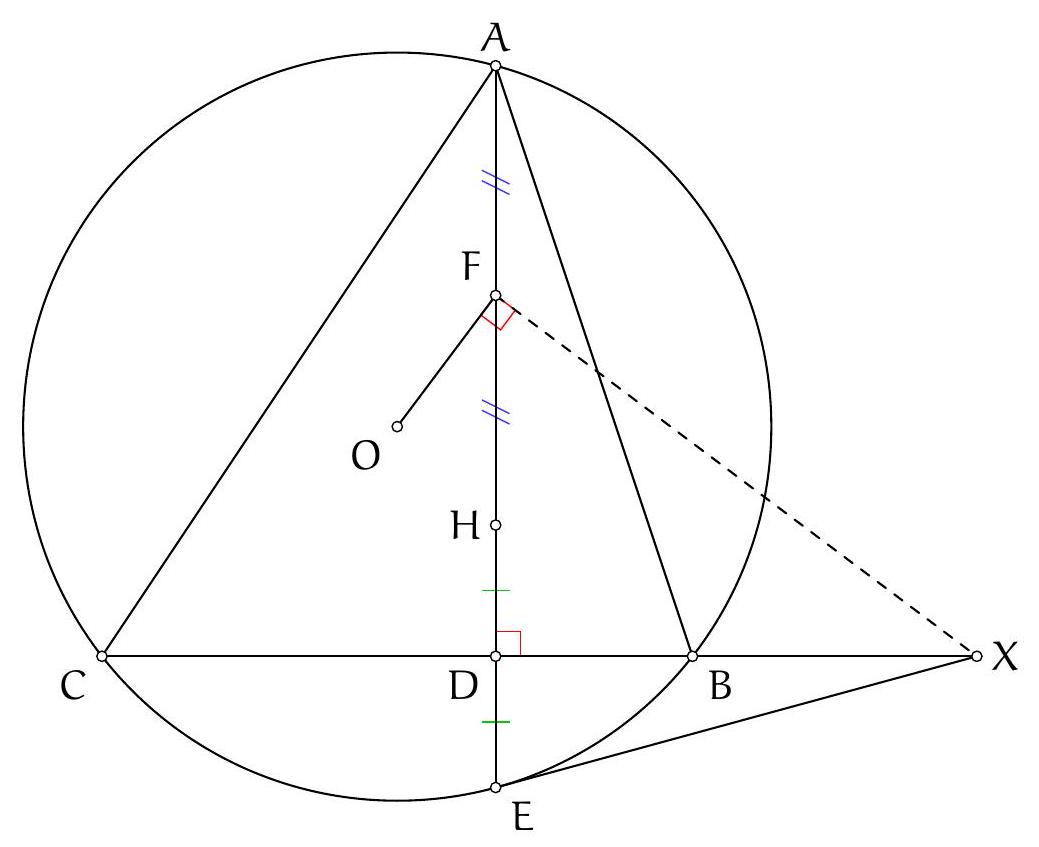

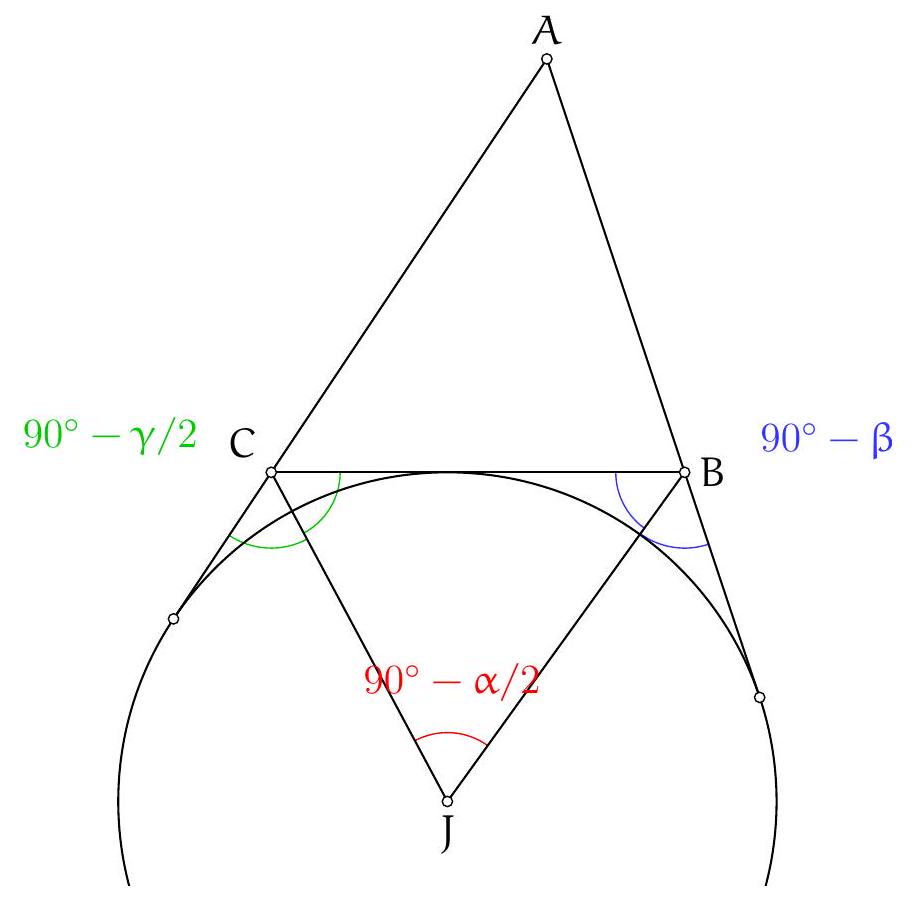

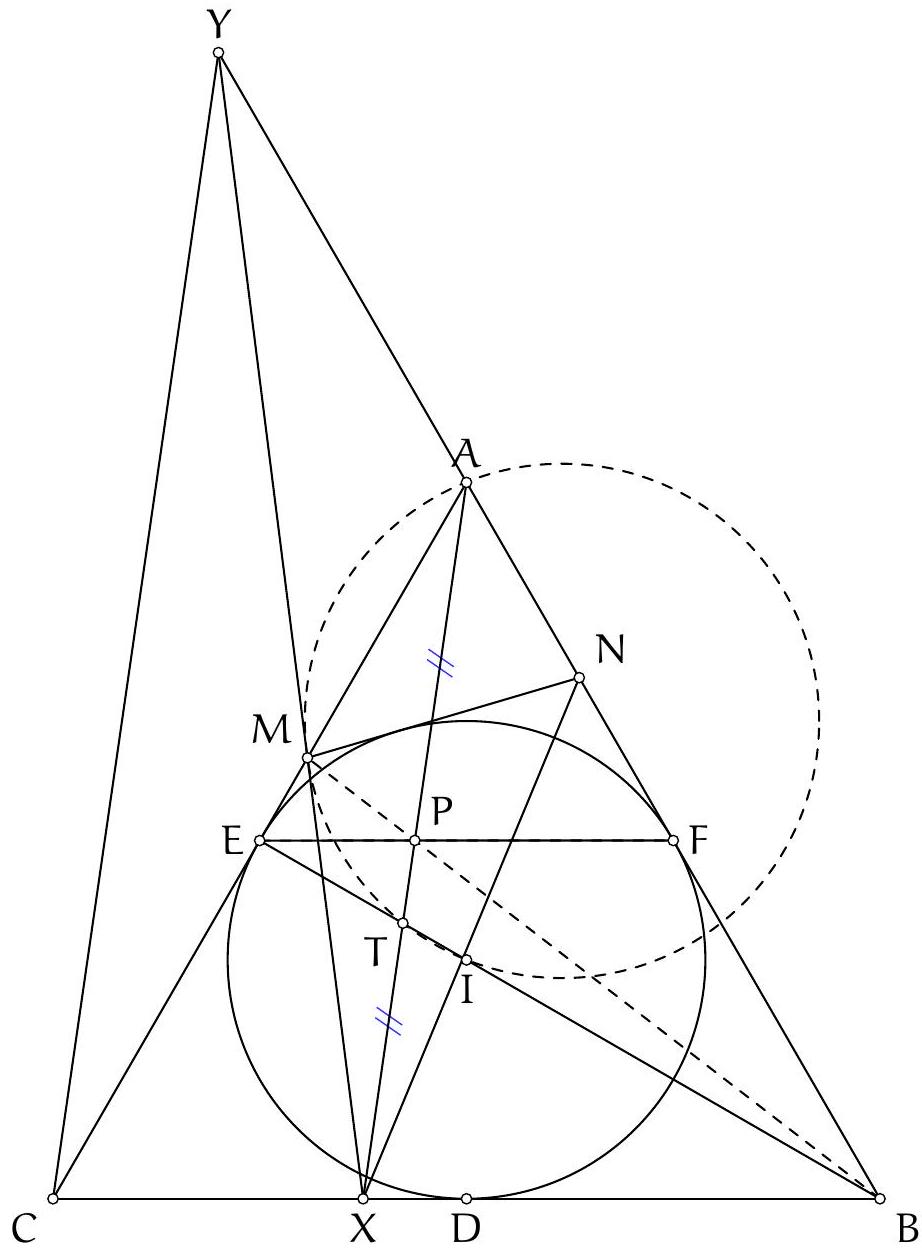

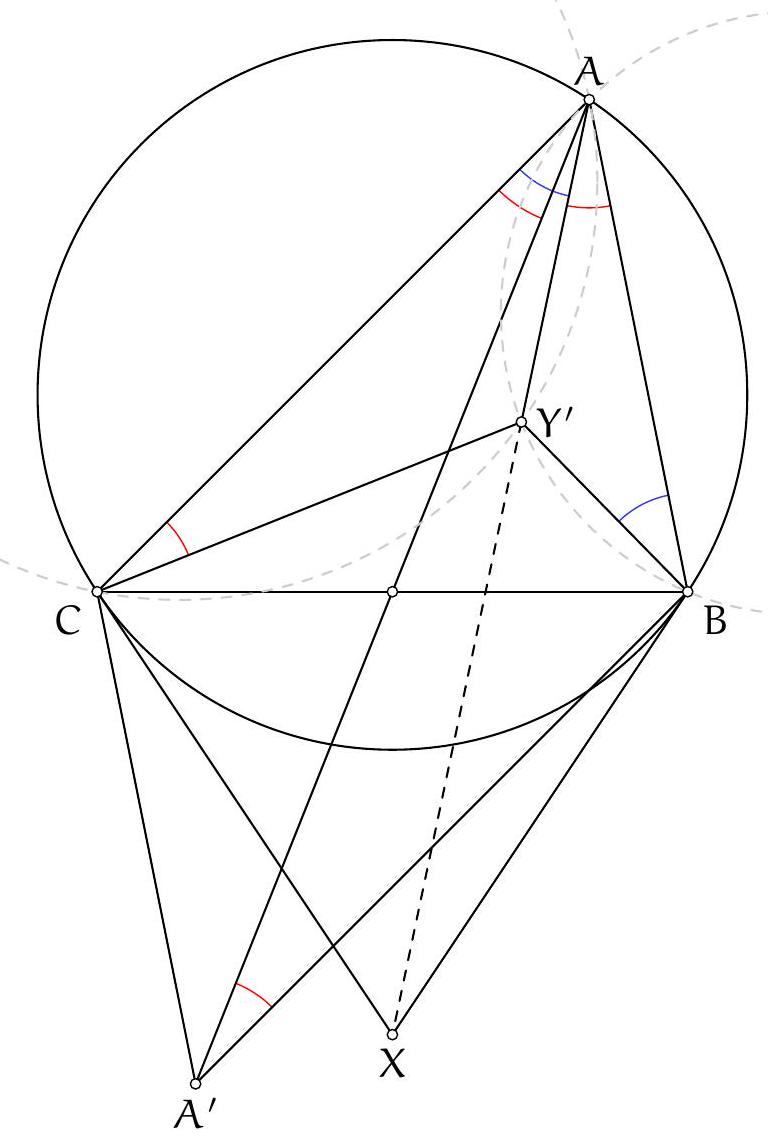

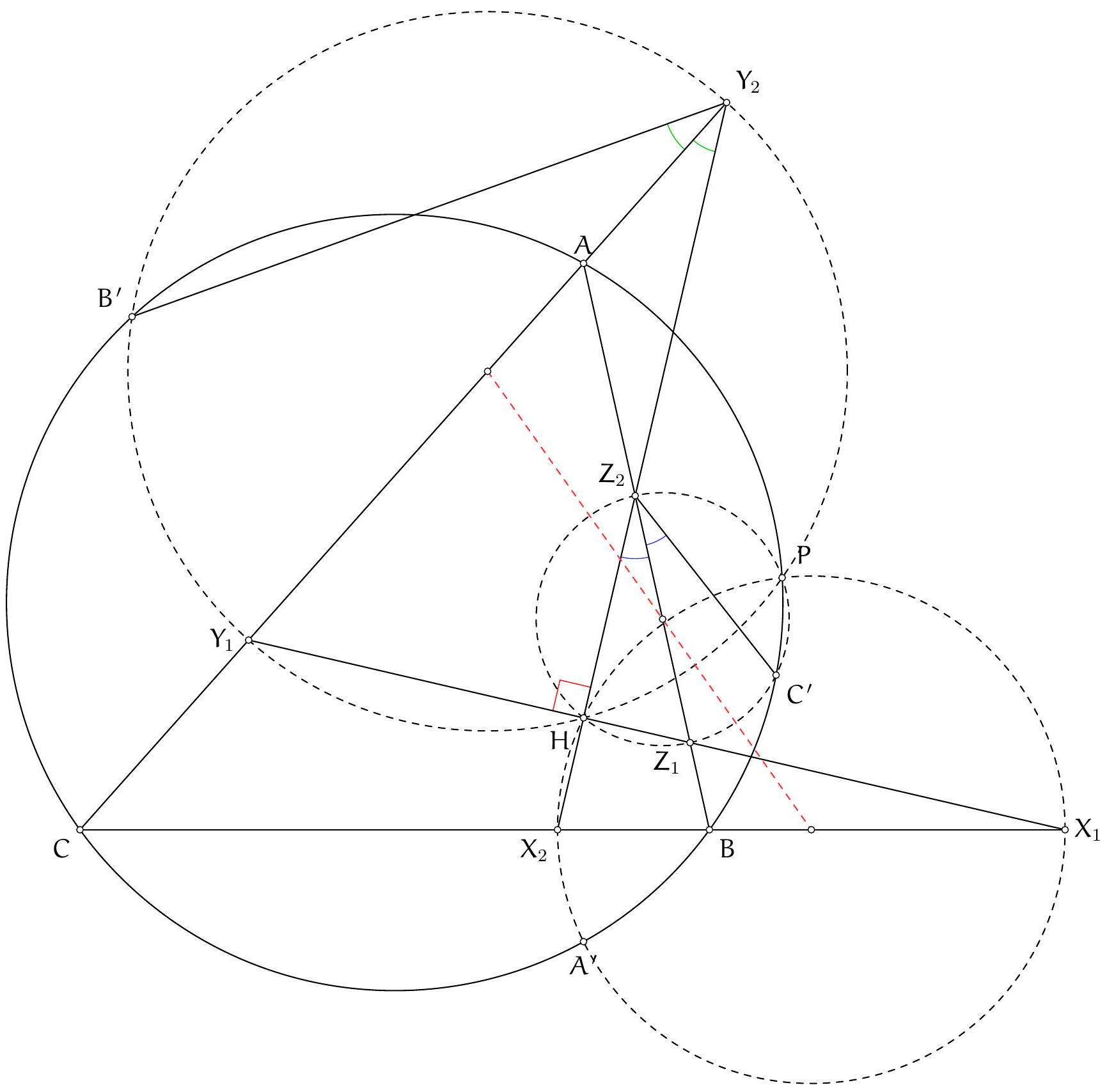

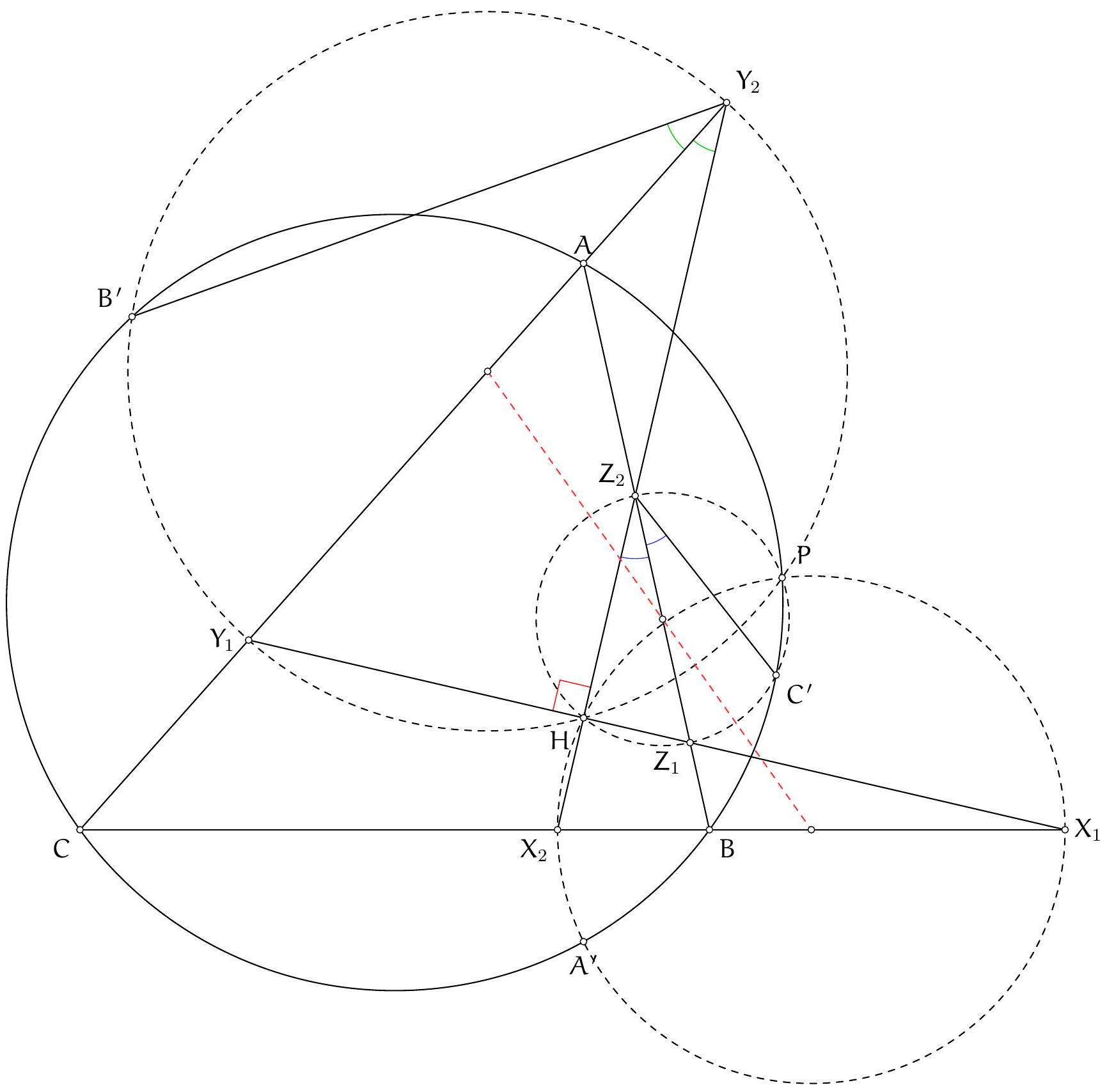

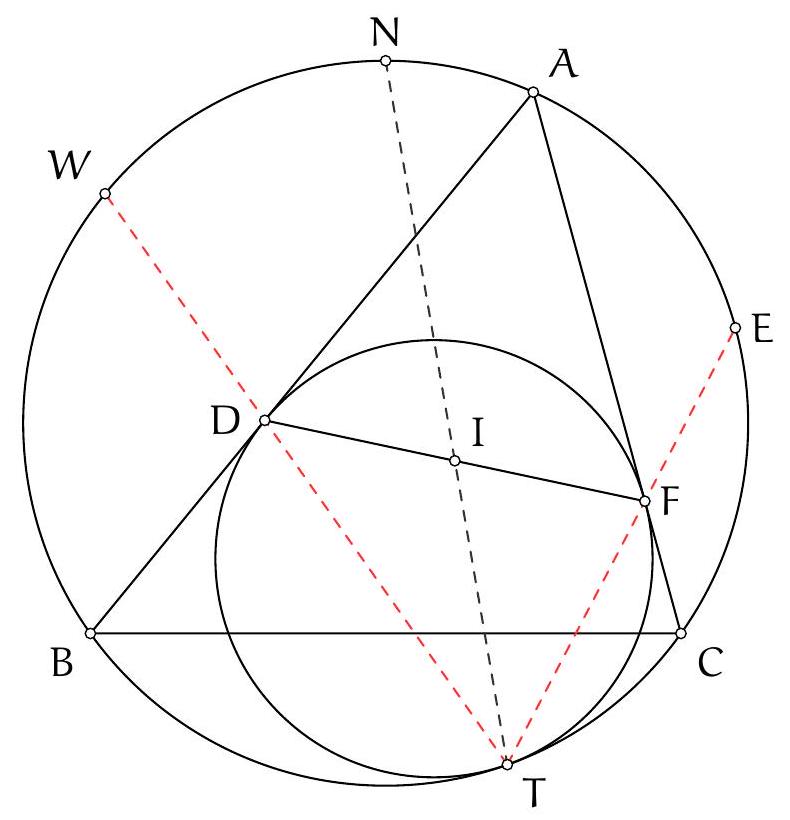

Let $ABC$ be a non-isosceles triangle at $B$. Let $D$ be the foot of the angle bisector of $\angle ABC$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $\widehat{AC}$ containing $B$ on the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$. The circumcircle of triangle $BDM$ intersects the segment $[AB]$ at a point $K$ distinct from $B$. Let $J$ be the symmetric point of $A$ with respect to point $K$. The line $(DJ)$ intersects the line $(AM)$ at a point $O$. Show that the points $J, B, M$, and $O$ are concyclic.

|

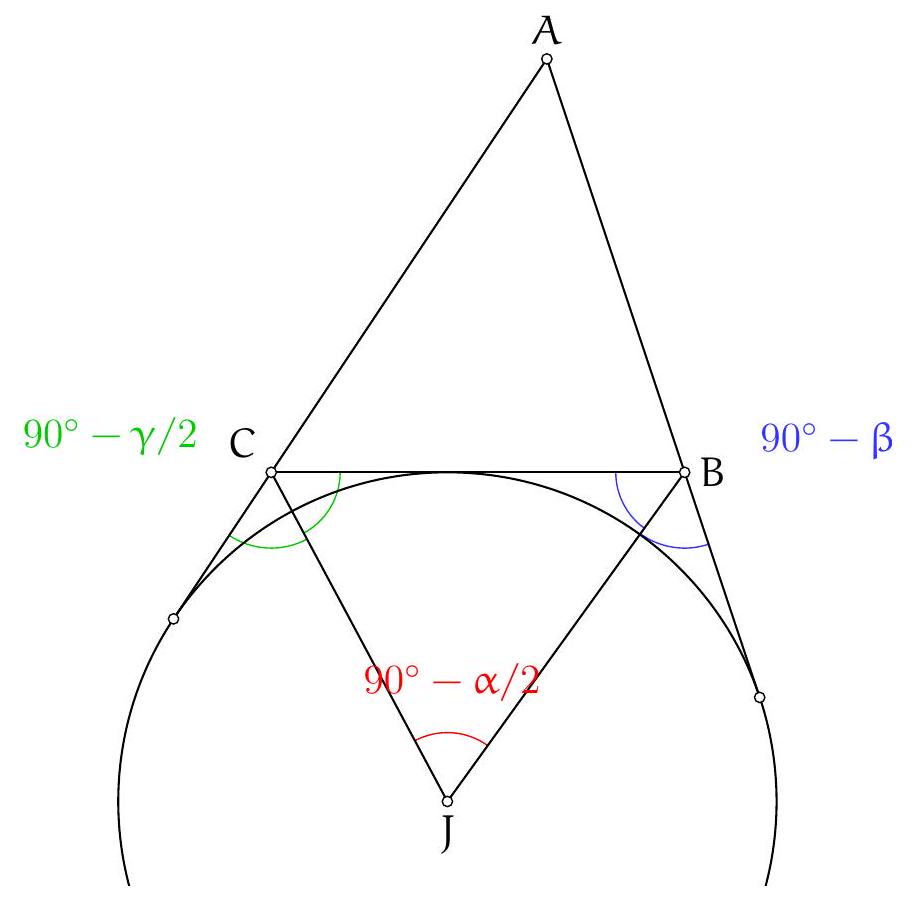

First, we recognize in the figure some known points: point $M$ is the midpoint of the arc $A C$ containing $B$, which is the North Pole of point $B$ in triangle $A B C$, meaning it is the intersection of the external bisector of angle $\widehat{A B C}$, the perpendicular bisector of segment $[A C]$, and the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Therefore, the angle $\widehat{D B M}$ is a right angle (by definition of the external bisector). The fact that $M$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of segment $[A C]$ also invites us to consider this bisector. Let $N$ be the midpoint of segment $[A C]$. Then $\widehat{\mathrm{DNM}}=90^{\circ}$. We deduce that points $B, M, N$, and $D$ are concyclic, and $D$ lies on the circle passing through points $B, K$, and $D$.

New concyclic points provide two pieces of information: one about angles using the inscribed angle theorem and one about lengths using the power of a point. Since most points lie on two lines intersecting at vertex $A$, we will use the power of point $A$ with respect to various circles.

Notably, by the power of a point, $A K \cdot A B=A D \cdot A N$. Therefore,

$$

A J \cdot A B=2 A K \cdot A B=2 A D \cdot A N=A D \cdot A C

$$

Thus, points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{C}, \mathrm{B}$, and $J$ are concyclic by the converse of the power of a point. To conclude, we will use directed angles to avoid having to handle different possible configurations separately.

We now have all the tools to perform an angle chase. The angles that are difficult to access are $\widehat{\mathrm{OMJ}}, \widehat{\mathrm{OBJ}}, \widehat{M J B} \ldots$ On the other hand, angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DJB}}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{OMB}}$ seem easier to obtain using the circles present in the figure.

Since points D, C, B, and O are concyclic, we find

$$

(J B, J O)=(J B, J D)=(C B, C D)=(C B, C A)=(M B, M A)=(M B, M O)

$$

Thus, quadrilateral JBMO is indeed cyclic.

Comment from the graders: The problem was not approached by many students and was solved by two students. Some students noted that point $M$ is the North Pole of point $B$, which is a very good reflex.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle non isocèle en $B$. Soit $D$ le pied de la bissectrice de l'angle $\widehat{A B C}$. Soit $M$ le milieu de l'arc $\widehat{A C}$ contenant $B$ sur le cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$. Le cercle circonscrit au triangle $B D M$ coupe la segment $[A B]$ en un point $K$ distinct de $B$. Soit $J$ le symétrique du point $A$ par rapport au point K . La droite (DJ) intersecte la droite ( $A M$ ) en un point O . Montrer que les points $\mathrm{J}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{M}$ et O sont cocycliques.

|

Tout d'abord, on reconnaît dans la figure quelques points connus : le point $M$ est le milieu de l'arc $A C$ contenant $B$, il s'agit donc du pôle Nord du point $B$ dans le triangle $A B C$, c'est-à-dire qu'il est le point d'intersection de la bissectrice extérieure de l'angle $\widehat{A B C}$, de la médiatrice du segment $[A C]$ et du cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$. On obtient donc que l'angle $\widehat{D B M}$ est droit (par définition de la bissectrice extérieure). Le fait que $M$ appartient à la médiatrice du segment $[A C]$ nous invite également à considérer cette médiatrice. Soit N le milieu du segment $[A C]$. Alors $\widehat{\mathrm{DNM}}=90^{\circ}$. On déduit donc que les points $B, M, N$ et $D$ sont cocycliques et $D$ appartient au cercle passant par les pointe $B, K$ et $D$.

De nouveaux points cocycliques apportent deux informations : une information sur les angles grâce au théorème de l'angle inscrit et une information sur les longueurs grâce à la puissance d'un point. Puisque la majorité des points se trouve sur deux droites se coupant en le sommet $A$, nous allons utiliser la puissance du point $A$ par rapport à divers cercles.

Notamment, par puissance d'un point $A K \cdot A B=A D \cdot A N$. Donc

$$

A J \cdot A B=2 A K \cdot A B=2 A D \cdot A N=A D \cdot A C

$$

donc les points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{C}, \mathrm{B}$ et J sont cocycliques d'après la réciproque de la puissance d'un point. Pour conclure, nous allons utiliser les angles orientés, pour éviter d'avoir à traiter séparément les différentes configurations possibles.

Nous avons à présent tous les outils pour effectuer une chasse aux angles. Des angles difficiles d'accès sont les angles $\widehat{\mathrm{OMJ}}, \widehat{\mathrm{OBJ}}, \widehat{M J B} \ldots$ En revanche, les angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DJB}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{OMB}}$ semblent plus faciles à obtenir à l'aide des cercles présents sur la figure.

Puisque les points D, C, B et O sont cocycliques, on trouve

$$

(J B, J O)=(J B, J D)=(C B, C D)=(C B, C A)=(M B, M A)=(M B, M O)

$$

donc le quadrilatère JBMO est bien cyclique.

Commentaire des correcteurs : L'exercice n'a pas été abordé par beaucoup d'élèves et il a été résolu par deux élèves. Quelques élèves ont noté que le point $M$ est le pôle Nord du point $B$, ce qui est un très bon réflexe.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Determine the smallest integer $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$ such that there exist strictly positive integers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ such that

$$

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \mid\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1

$$

|

Let's analyze the problem. In this problem, we are looking for the smallest integer \( n \) satisfying a certain property. Suppose we want to show that the smallest integer sought is the integer \( c \). To show that \( c \) is indeed the smallest integer, we must on the one hand show that if an integer \( n \) satisfies the property, then \( n \geqslant c \), and on the other hand, we must show that we can find \( c \) integers satisfying the divisibility relation.

Since there is a divisibility relation, we can expect to use various ideas:

- If \( a \mid b \) then \( a \) divides the linear combinations of \( a \) and \( b \)

- If \( a \mid b \) and \( a \) and \( b \) are strictly positive, then \( a \mid b \)

- If \( a \mid b \), the divisors of \( a \) also divide \( b \)

Once this initial analysis is done, we can start by looking for integers \( a_{i} \) satisfying the property for small values of \( n \), for example, for \( n=2,3 \) or even 4 if we are brave, before realizing that this method will not allow us to determine \( n \).

However, having searched for \( a_{i} \) for small values of \( n \) allows us to find potential properties that the \( a_{i} \) must satisfy. For example, we may have noticed that the integers \( a_{i} \) cannot all be even, since in that case the sum of the \( a_{i}^{2} \) would be even but \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \) is odd. We then realize that what matters in this argument is not the parity of the \( a_{i} \) but the parity of the sum.

We obtain that \( a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n} \) is odd. Otherwise, since \( a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \equiv a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n} \bmod 2 \), \( a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n} \) is also even, but then \( a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \) is even and divides \( \left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \) which is odd, which is absurd.

We deduce that \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \) is even. The previous parity argument invites us to refine this study. We will therefore look to see if \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \) is divisible by 4, 8, etc. The presence of multiple squares invites us to look at each term with well-chosen moduli.

For example, modulo 4, \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2} \equiv 1 \) so 4 divides \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \). Let's not stop here; we also know that the squares of odd numbers can only be 1 modulo 8. Thus, \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \) is divisible by 8. Since 8 is coprime with \( a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \) which is odd, we deduce that

\[

8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \mid \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1

\]

Another remark that we can make about the statement is that it involves the sum of squares of numbers on one side and the square of the sum of numbers on the other side. This suggests the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality or the inequality of arithmetic and quadratic means. We can therefore try to compare the quantities \( 8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \) and \( \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \).

This idea of comparing the terms is consistent with what we are trying to show. The divisibility obtained gives that \( 8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \leqslant \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \). In the inequality of arithmetic and quadratic means, the square of the sum is smaller than the sum of the squares of the elements multiplied by the number of variables. We suspect that the inequality obtained will be false for \( n \) too small, which will provide the desired bound. More precisely,

\[

8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \leqslant \left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \leqslant n\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right)-1 < n\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right)

\]

where the middle inequality corresponds to the inequality of arithmetic and quadratic means. We finally obtain that \( n > 8 \) so \( n \geqslant 9 \).

Conversely, we seek 9 integers satisfying the property. We can expect that small integers will work. We can therefore look for \( a_{i} \) equal to 1 or 2. Finally, we find that by taking \( a_{1}=\cdots=a_{7}=1 \) and \( a_{8}=a_{9}=2 \), we have 15 which divides \( 11^{2}-1=120=15 \times 8 \).

The expected answer is therefore \( n=9 \).

Comment from the graders: The problem was solved by only one student. This is an instructive and very complete exercise, involving both arithmetic arguments and inequalities.

|

9

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer le plus petit entier $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$ tel qu'il existe des entiers strictement positifs $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ tels que

$$

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \mid\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1

$$

|

Analysons le problème. Dans ce problème, on cherche le plus petit entier n satisfaisant une certaine propriété. Supposons que l'on veuille montrer que le plus petit entier recherché est l'entier c. Pour montrer que c'est bien le plus petit entier, on doit d'une part montrer que si un entier n satisfait la propriété, alors $n \geqslant c$ et on doit montrer d'autre part que l'on peut trouver $c$ entiers satisfaisant la relation de divisibilité.

Pusiqu'il y a une relation de divisibilité, on peut s'attendre à utiliser divers idées :

- Si $a \mid b$ alors $a$ divise les combinaisons linéaires de $a$ et $b$

- Si $a \mid b$ et que $a$ et $b$ sont strictement positifs, alors $a \mid b$

- Si $a \mid b$, les diviseurs de $a$ divisent également $b$

Une fois cette première analyse effectuée, on peut commencer par regarder si on trouve des entiers $a_{i}$ satisfaisant la propriété pour des petites valeurs de $n$, par exemple pour $n=2,3$ ou même 4 si on est courageux, avant de se convaincre que cette méthode ne permettra pas de déterminer n .

Néanmoins, avoir cherché des $a_{i}$ pour des petites valeurs de $n$ nous permet de trouver d'éventuelles propriétés que doivent satisfaire les $a_{i}$. Par exemple, on a pu remarquer que les entiers $a_{i}$ ne peuvent pas tous être pairs, puisque dans ce cas la somme des $a_{i}^{2}$ serait paire mais $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$ est impair. On se rend alors compte que ce qui importe dans cet argument, ce n'est pas la parité des $a_{i}$ qui entre en jeu mais la parité de la somme.

On obtient que $a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}$ est impair. Dans le cas contraire, puisque $a_{1}^{2}+a_{2}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2} \equiv$ $a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n} \bmod 2, a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}$ est pair également mais alors $a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}$ est pair et divise $\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$ qui est impair, ce qui est absurde.

On déduit que $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$ est pair. L'argument de parité précédent nous invite à préciser cette étude. On va donc chercher si $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$ est divisible par $4,8 \ldots$. La présence des multiples carré nous invite à regarder chaque terme avec des modulos bien choisis.

Par exemple, modulo $4,\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2} \equiv 1$ donc 4 divise $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$. Ne nous arrêtons pas en si bon chemin, nous savons également que les carrés des nombres impairs ne peuvent que valoir 1 modulo 8. Ainsi, $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$ est divisible par 8 . Or 8 est premier avec $a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}$ qui est impair. On déduit de tout cela que

$$

8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \mid\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1

$$

Enfin, une autre remarque que l'on peut formuler sur l'énoncé est qu'il implique la somme des carrés de nombres d'un côté et le carré de la somme des nombres de l'autre côté. Ceci fait penser à l'inégalité de Cauchy-Schwarz, ou à l'inégalité des moyennes arithmétiques et quadratiques. On peut donc essayer de comparer les quantités $8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right)$ et $\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$.

Cette idée de comparer les termes est cohérente avec ce que l'on cherche à montrer. La divisibilité obtenue donne que $8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \leqslant\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1$. Or, dans l'inégalité des moyennes arithmétique et quadratique, le carré de la somme est plus petit que la somme des carrés des éléments multipliée par le

nombre de variables. On se doute donc que l'inégalité obtenue va être fausse pour n trop petit, ce qui va nous fournir la borne souhaitée. Plus précisement,

$$

8\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right) \leqslant\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2}-1 \leqslant n\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right)-1<n\left(a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{n}^{2}\right)

$$

où l'inégalité au milieu correspond à l'inégalité des moyennes arithmétiques et quadratiques. On obtient finalement que $\mathrm{n}>8$ donc $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 9$.

Réciproquement, on cherche 9 entiers satisfaisant la propriété. On peut s'attendre à ce que de petits entiers fonctionnent. On peut donc chercher des $a_{i}$ valant 1 ou 2 . Finalement, on trouve qu'en prenant $a_{1}=\cdots=a_{7}=1$ et $a_{8}=a_{9}=2$, on a bien 15 qui divise $11^{2}-1=120=15 \times 8$.

La réponse attendue est donc $\mathrm{n}=9$.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice n'a été résolu que par un élève. C'est un exercice instructif et très complet, faisant appel à des arguments arithmétiques et des inégalités.

## Exercices Seniors

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $\left(x_{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ be a real sequence such that $x_{0}=0$ and $x_{1}=1$ and for all $n \geqslant 0, x_{n+2}=$ $3 x_{n+1}-2 x_{n}$. We also set $y_{n}=x_{n}^{2}+2^{n+2}$ for all natural numbers $n$. Show that for all integers $n>0, y_{n}$ is the square of an odd integer.

|

We start by testing the statement for small values of \( n \). We therefore calculate the first values of the sequences \(\left(x_{n}\right)\) and \(\left(y_{n}\right)\). For example, we find \( x_{2}=3 \), \( x_{4}=7 \), \( x_{5}=15 \ldots \) We can therefore conjecture that \( x_{n}=2^{n}-1 \). We promptly set out to prove this by induction.

The result is already true for ranks 0 and 1. If we assume \( x_{n}=2^{n}-1 \) and \( x_{n+1}=2^{n+1}-1 \), we have \( x_{n+2} = 3 x_{n+1} - 2 x_{n} = 3 \times 2^{n+1} - 3 - 2 \times 2^{n} + 2 = (3-1) \times 2^{n+1} - 1 = 2^{n+2} - 1 \), which completes the induction. We then substitute this expression for \( x_{n} \) into the expression for \( y_{n} \). All that remains is to manipulate this new expression algebraically:

\[

y_{n} = \left(2^{n}-1\right)^{2} + 2^{n+2} = 2^{2 n} - 2^{n+1} + 1 + 2^{n+2} = 2^{2 n} - 2^{n+1} + 1 + 2 \times 2^{n+1} = 2^{2 n} + 2^{n+1} + 1 = \left(2^{n} + 1\right)^{2}

\]

This shows that \( y_{n} \) is the square of an odd integer.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was solved by all the students who tackled it!

|

y_{n} = \left(2^{n} + 1\right)^{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit $\left(x_{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ une suite réelle telle que $x_{0}=0$ et $x_{1}=1$ et pour tout $n \geqslant 0, x_{n+2}=$ $3 x_{n+1}-2 x_{n}$. On pose également $y_{n}=x_{n}^{2}+2^{n+2}$ pour tout entier naturel $n$. Montrer que pour tout entier $n>0, y_{n}$ est le carré d'un entier impair.

|

On commence par tester l'énoncé pour des petites valeurs de n . On calcule donc les premières valeurs des suites $\left(x_{n}\right)$ et $\left(y_{n}\right)$. On trouve par exemple $x_{2}=3, x_{4}=7$, $x_{5}=15 \ldots$ On peut donc conjecturer que $x_{n}=2^{n}-1$. On s'empresse de le démontrer par récurrence.

Le résultat est déjà au rang 0 et 1 . Si on suppose $x_{n}=2^{n}-1$ et $x_{n+1}=2^{n+1}-1$, on a $x_{n+2}=$ $3 x_{n+1}-2 x_{n}=3 \times 2^{n+1}-3-2 \times 2^{n}+2=(3-1) \times 2^{n+1}-1=2^{n+2}-1$ ce qui achève la récurrence. On injecte alors cette expression de $x_{n}$ dans l'expression de $y_{n}$. Il ne nous reste plus qu'à manipuler algébriquement cette nouvelle expression :

$$

y_{n}=\left(2^{n}-1\right)^{2}+2^{n+2}=2^{2 n}-2^{n+1}+1+2^{n+2}=2^{2 n}-2^{n+1}+1+2 \times 2^{n+1}=2^{2 n}+2^{n+1}+1=\left(2^{n}+1\right)^{2}

$$

Ceci montre bien que $y_{n}$ est le carré d'un entier impair.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice a été résolu par tous les élèves qui l'ont abordé !

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 10.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 10",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Find all functions $f$ from $\mathbb{R}$ to $\mathbb{R}$ such that for every pair $(x, y)$ of real numbers:

$$

f(f(x)) + f(f(y)) = 2y + f(x - y)

$$

|

Let's analyze the problem: here we are dealing with a functional equation with two variables. The first thing to do is to try some classic substitutions: $x=y=0$, $x=0, y=0, x=y$. Since we have a $f(x-y)$, it is very tempting to see what it gives for $x=y$. Let's set $C=f(0)$, for $x=y$, we get $2 f(f(x))=2 x+C$ which simplifies to $f(f(x))=x+\frac{C}{2}$.

Now that we have a more manageable expression for $f(f(x))$, we can substitute it back into the original equation and see what it gives.

Substituting back into the original equation, we have $x+y+C=2 y+f(x-y)$, which simplifies to $f(x-y)=x-y+C$. For $y=0$, we get $f(x)=x+C$ for all real $x$. Now, we need to determine $C$ before performing the verification, so we try to see what constraint the equation $f(f(x))=x+\frac{C}{2}$ imposes on $C$.

In particular, $f(f(x))=f(x+C)=x+2 C$, so $2 C=\frac{C}{2}$, which gives $4 C=C$, and thus $3 C=0$, so $C=0$. Therefore, we have $f(x)=x$ for all real $x$. Now we must not forget to verify that the function we found is indeed a solution! Conversely, the identity function works because in this case, $f(f(x))+f(f(y))=f(x)+f(y)=x+y=2 y+x-y=2 y+f(x-y)$ for all real $x, y$.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was very well done. Be careful not to conclude that $f$ is the identity when you find $f(X)=X$ with $X$ depending on $x$ and $y$ (you need to verify that $X$ can take all real values).

|

f(x)=x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Trouver toutes les fonctions $f$ de $\mathbb{R}$ dans $\mathbb{R}$ telles que pour tout couple $(x, y)$ de réels :

$$

f(f(x))+f(f(y))=2 y+f(x-y)

$$

|

Analysons le problème : ici on est face à une équation fonctionnelle, avec deux variables. La première chose à faire est d'essayer les quelques substitutions classiques : $x=y=0$, $x=0, y=0, x=y$. Ici comme on a un $f(x-y)$, il est très tentant de regarder ce que ça donne pour $x=y$. Posons donc $C=f(0)$, pour $x=y$, on obtient $2 f(f(x))=2 x+C$ soit $f(f(x))=x+\frac{C}{2}$.

Maintenant qu'on a une expression plus maniable de $f(f(x))$, on peut la réinjecter dans l'équation et regarder ce que ça donne.

En réinjectant dans l'équation initiale, on a donc $x+y+C=2 y+f(x-y)$ soit $f(x-y)=x-y+C$, pour $y=0$ on a donc $f(x)=x+C$ pour tout réel $x$. Maintenant, il faudrait déterminer $C$ avant d'effectuer la vérification, on essaie donc de voir quelle contrainte l'équation $f(f(x))=x+\frac{C}{2}$ donne sur $C$.

En particulier $f(f(x))=f(x+C)=x+2 C$ donc $2 C=\frac{C}{2}$ donc $4 C=C, 3 C=0$ donc $C=0$, on a donc $f(x)=x$ pour tout réel $x$. Maintenant on n'oublie pas de vérifier que la fonction trouvée est bien solution ! Réciproquement la fonction identité convient car dans ce cas, $f(f(x))+f(f(y))=f(x)+f(y)=$ $x+y=2 y+x-y=2 y+f(x-y)$ pour tout $x, y$ réels.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice a été très bien réussi. Il faut faire attention à ne pas conclure que $f$ est l'identité lorsque l'on trouve $f(X)=X$ avec $X$ dépendant de $x$ et $y$ (il faut vérifier que $X$ peut prendre toutes les valeurs réelles).

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 11.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 11",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

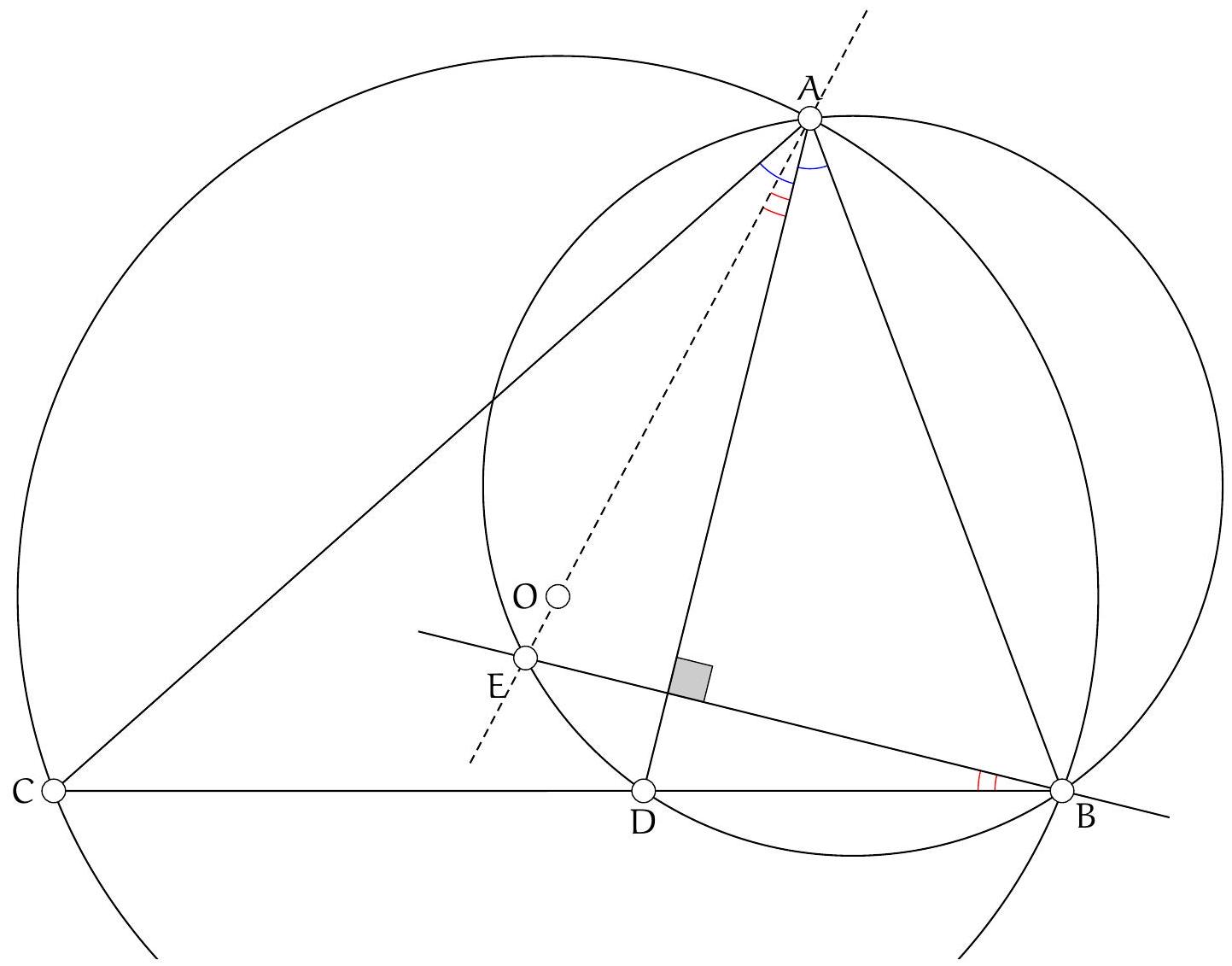

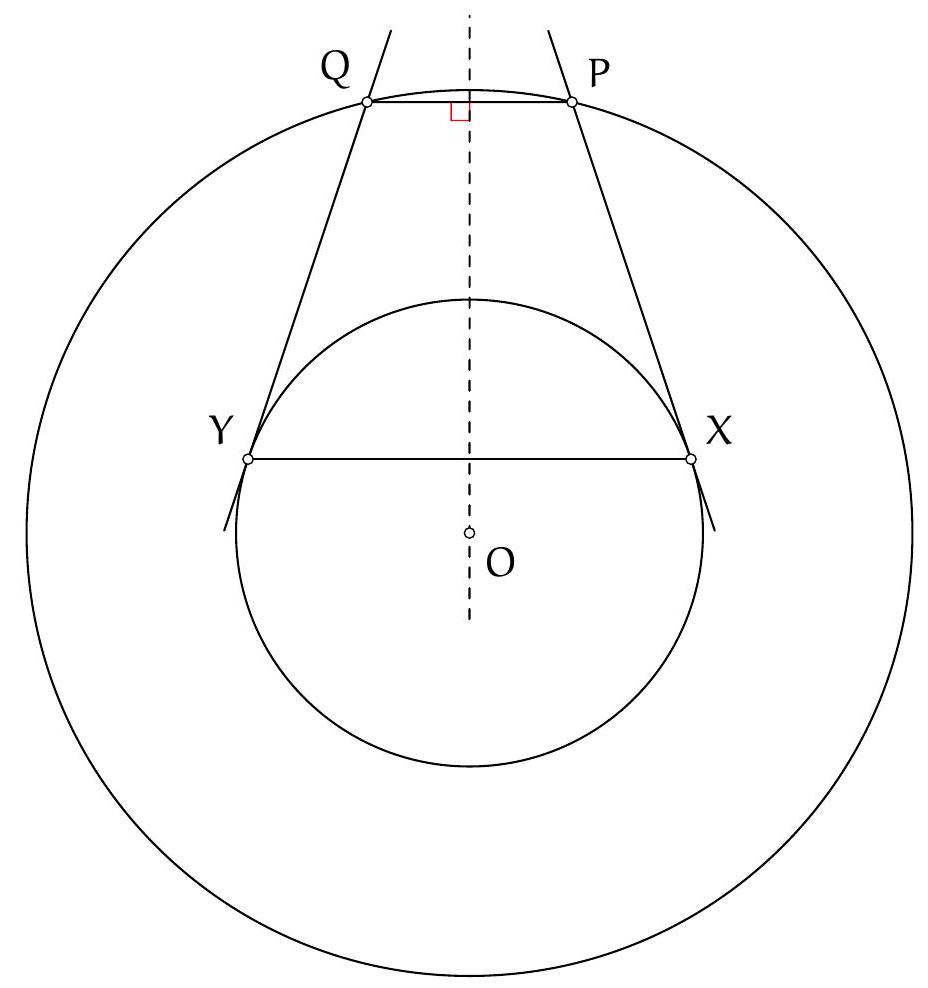

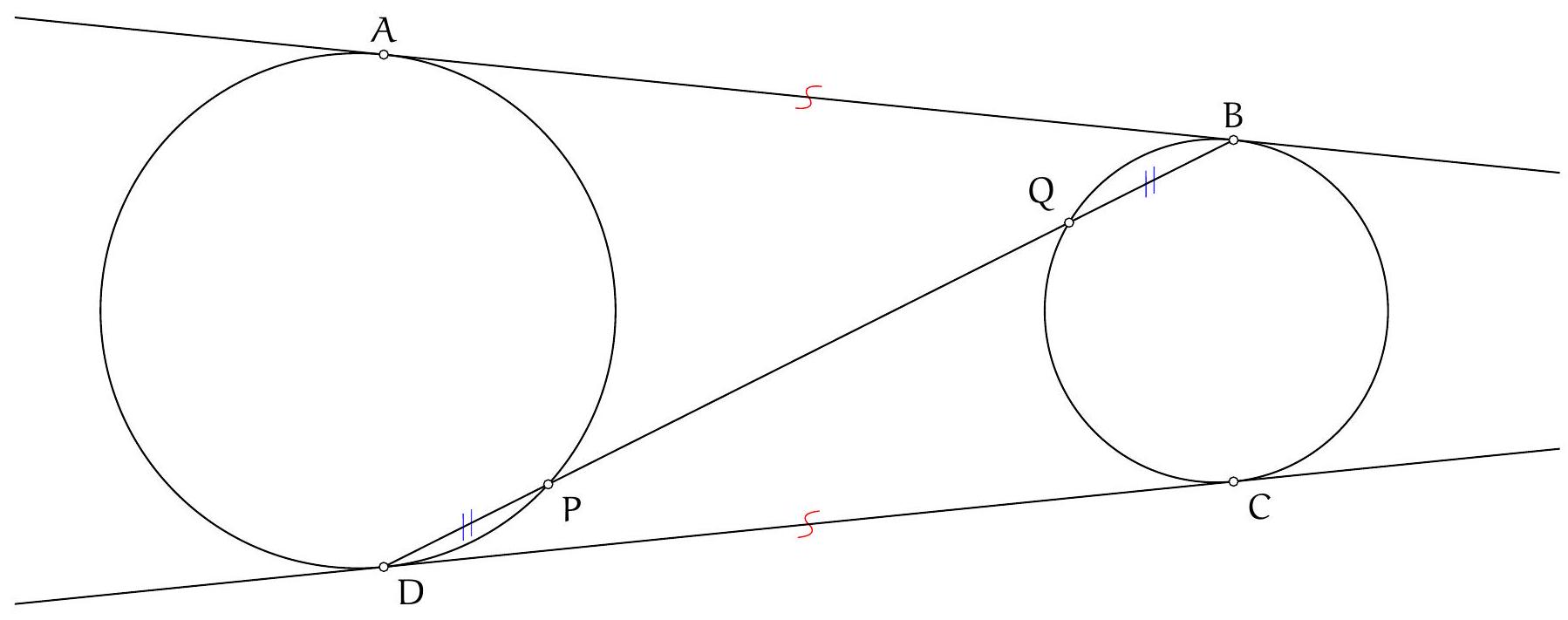

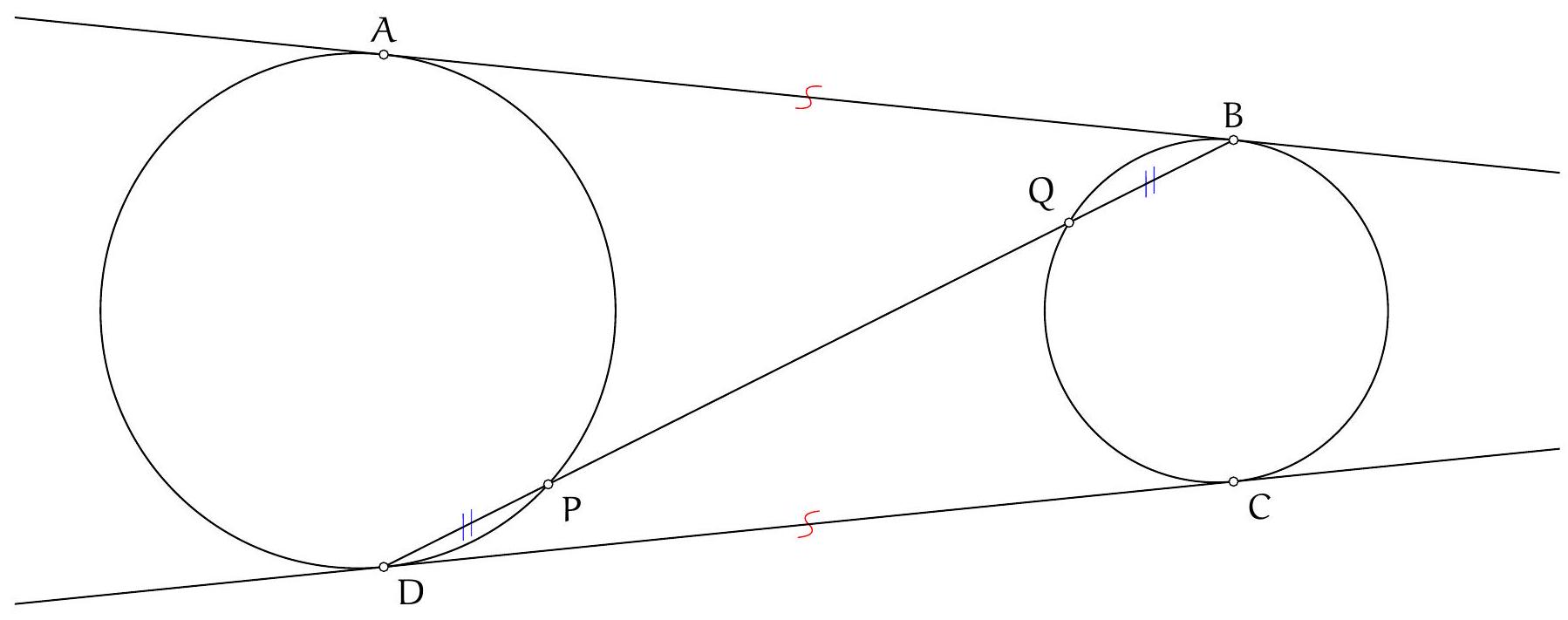

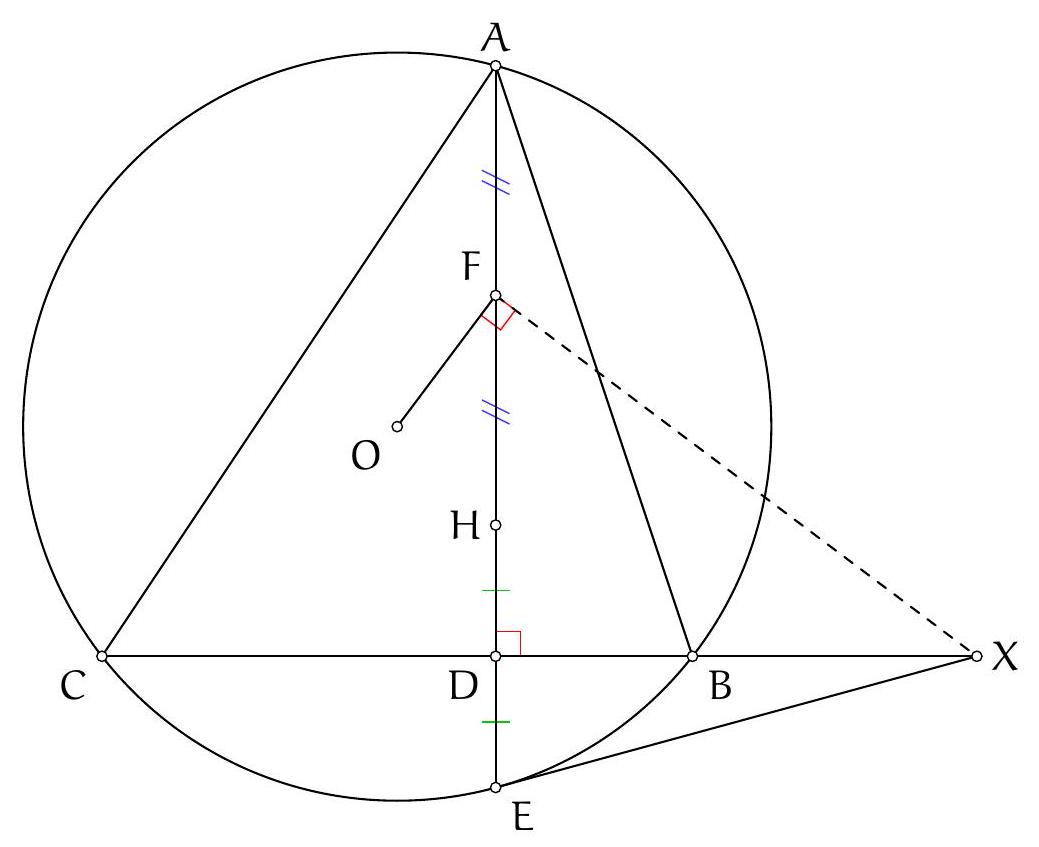

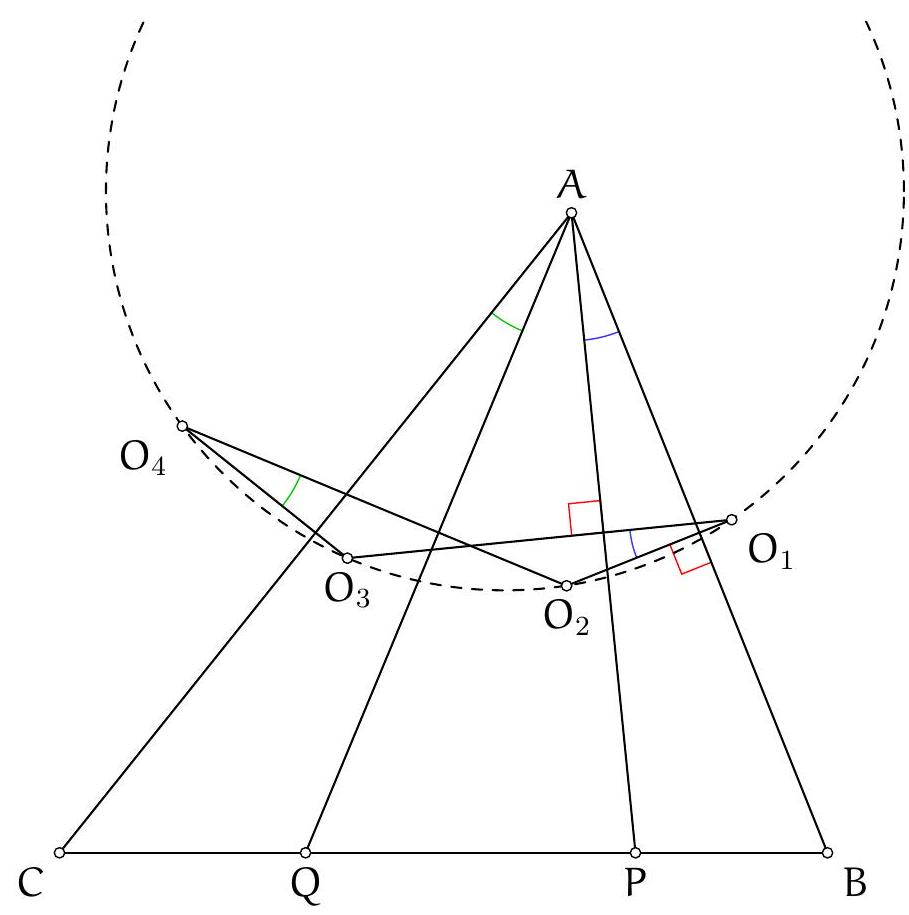

Let $ABC$ be an acute-angled triangle. Let $D$ be the foot of the angle bisector of $\widehat{BAC}$. The perpendicular to the line $(AD)$ passing through the point $B$ intersects the circumcircle of triangle $ADB$ at a point $E$. Let $O$ be the center of the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$. Show that the points $A$, $O$, and $E$ are collinear.

|

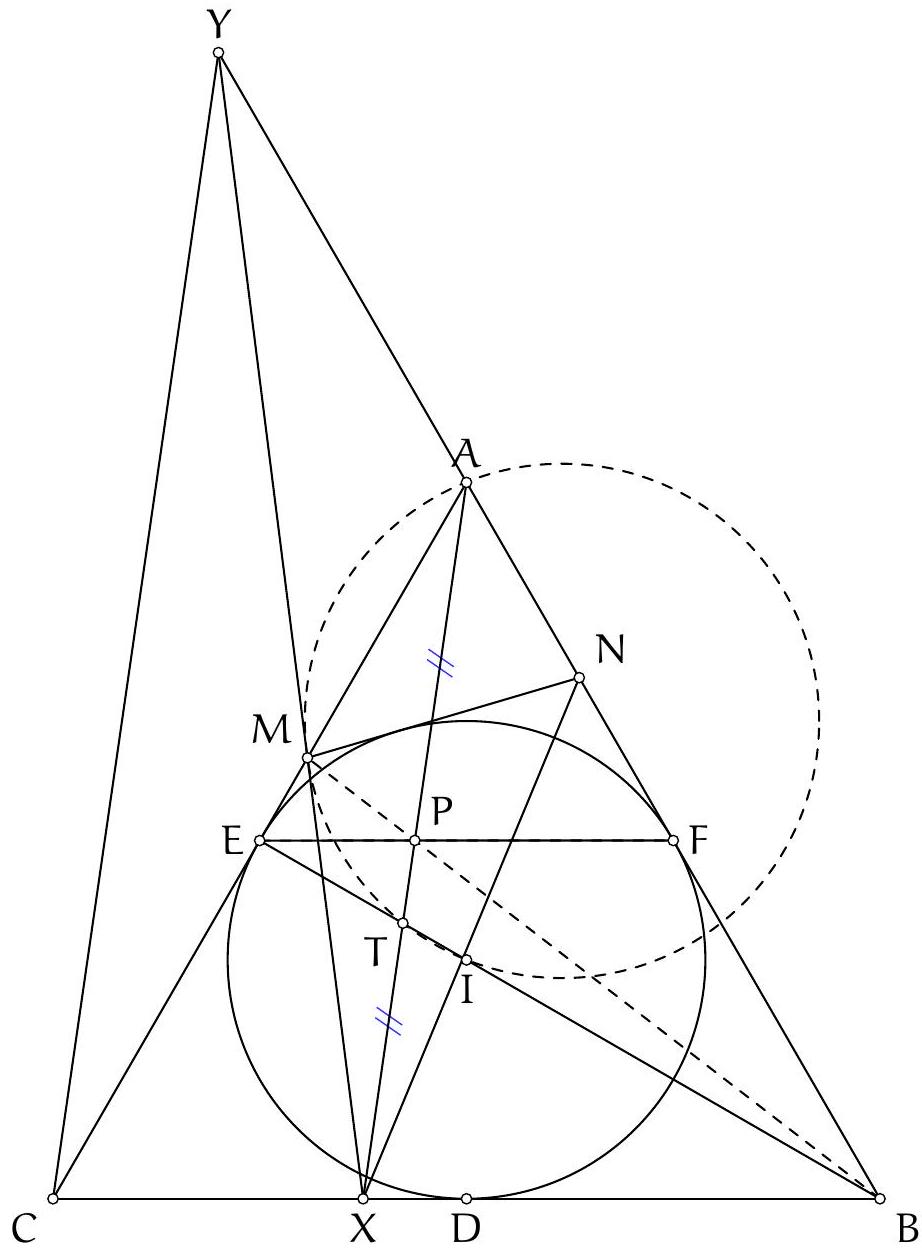

Let's examine the angles we can easily obtain. Since points $A, E, D$, and $B$ are on the same circle, we should be able to use the inscribed angle theorem to get an equality involving $\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}$. Since the line $(\mathrm{BE})$ is perpendicular to the line $(\mathrm{AD})$, we should be able to calculate the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{EBA}}$. Of course, we also know the angle $\widehat{O A B}$. It seems reasonable to show the collinearity of points $A, O$, and $E$ by showing that $\widehat{O A B}=\widehat{\mathrm{EAB}}$. We calculate these two angles separately in terms of the angles of triangle $A B C$.

On the one hand, according to the central angle theorem and since triangle $A O B$ is isosceles at $O$, we have

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{OAB}}=\frac{1}{2}\left(180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{AOB}}\right)=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}

$$

On the other hand, $\widehat{E A B}=\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}$. Using the inscribed angle theorem and the fact that $\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}$, we get:

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{EBD}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}

$$

Since the sum of the angles in triangle $ADC$ is $180^{\circ}$, we have $\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DCA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}$. Thus,

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\left(\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}\right)+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}

$$

and we find that $\widehat{O A B}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{A C B}=\widehat{E A B}$, so points $A, O$, and $E$ are collinear. Comment from the graders: The exercise is well done. However, many students submitted a very complicated proof.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle aux angles aigus. Soit $D$ le pied de la bissectrice de l'angle $\widehat{B A C}$. La perpendiculaire à la droite $(A D)$ passant par le point $B$ recoupe le cercle circonscrit au triangle $A D B$ en un point $E$. Soit $O$ le centre du cercle circonscrit au triangle $A B C$. Montrer que les points $A, O$ et $E$ sont alignés.

|

Examinons les angles que nous pouvons obtenir facilement. Puisque les points $A, E, D$ et $B$ sont sur un même cercle, on doit pouvoir utilise le théorème de l'angle inscrit pour avoir une égalité portant sur $\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}$. Puisque la droite $(\mathrm{BE})$ est perpendiculaire à la droite $(\mathrm{AD})$, on doit pouvoir calculer l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{EBA}}$. Enfin, on connaît bien sûr l'angle $\widehat{O A B}$. Il semble donc raisonnable de montrer l'alignement des points $A, O$ et $E$ en montrant que $\widehat{O A B}=\widehat{\mathrm{EAB}}$. On calcule séparément ces deux angles en fonction des angles du triangle $A B C$.

D'une part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre et puisque le triangle $A O B$ est isocèle en O , on a

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{OAB}}=\frac{1}{2}\left(180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{AOB}}\right)=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}

$$

D'autre part, $\widehat{E A B}=\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}$. On utilise alors le théorème de l'angle inscrit et le fait que $\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}=$ $\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}$, on obtient :

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{EAD}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{EBD}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}

$$

Or la somme des angles du triangle ADC fait $180^{\circ}$ donc $\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DCA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{DAC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}$. Ainsi

$$

90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BDA}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\left(\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}\right)+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}

$$

et on trouve bien que $\widehat{O A B}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{A C B}=\widehat{E A B}$ donc les points $A, O$ et $E$ sont alignés. Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice est bien réussi. Cependant, plusieurs élèves ont rendu un preuve très compliquée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 13.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 13",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

A grid of size $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ contains $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ cells. Each cell contains a natural number between 1 and $\boldsymbol{n}$, such that each integer in the set $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ appears exactly $n$ times in the grid. Show that there exists a column or a row of the grid containing at least $\sqrt{n}$ different numbers.

|

Let's first look at what happens in what seems to be the 'worst case': if each row/column does not contain many numbers, each number will be present a lot. In particular, for any $i$, the number of $i$ seems to be written in few rows and columns. But a priori, if the number $i$ appears too much in a row, it will appear in many columns and vice versa. A priori, the worst case seems to be the one where each number appears in as many columns as rows, and since each number appears $n$ times, the square must be of dimension $\sqrt{n}$, so $i$ appears in at least $2 \sqrt{n}$ rows and columns.

Of course, this analysis is by no means a proof, but we see two important ideas: first, the number of distinct numbers in each row/column seems to be linked to the number of rows/columns in which each number appears. Second, for any $i$ between 1 and $n$, the number $i$ appears at least on $2 \sqrt{n}$ rows and columns. We will therefore try to formalize this.

Let $a_{c, i}$ for $c$ a column or a row and $i$ an integer between 1 and $n$ be the number of times $i$ appears in $c$, let $c_{i}$ (resp. $l_{i}$) be the number of columns (resp. rows) to which $i$ belongs. Let $C$ be the set of columns and $L$ the set of rows.

Note that the hypothesis that $i$ appears $n$ times translates as $c_{i} \times l_{i} \geqslant n$ because $i$ appears in at most $c_{i} l_{i}$ cells.

Note that for any $i$, $l_{i}+c_{i}$ being the number of rows or columns where $i$ appears, it is $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}$. The number of distinct elements in column $c$ is, in turn, $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i}$. In particular, we see that the $a_{c, i}$ play an important role in the problem.

Now it remains to relate the number of appearances of $i$ in the different rows/columns to the number of numbers in each row. For this, we will look at the sum of the $a_{c, i}$ (we sum over $i$ from 1 to $n$ and over $c$ columns and rows) and use the two previous interpretations.

We thus obtain $\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}+l_{i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}} \geqslant 2 n \sqrt{n}$.

We deduce that $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}}=2 n \sqrt{n}$.

In particular, since there are $2 n$ rows or columns, there exists $c$ rows or columns such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sqrt{n}$ i.e., $c$ contains at least $\sqrt{n}$ different numbers.

Graders' comments: The exercise was generally well done by those who tackled it, but it is important to be clear in explanations and precise in the definitions of the different objects introduced.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Une grille de taille $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ contient $\mathrm{n}^{2}$ cases. Chaque case contient un entier naturel compris entre 1 et $\boldsymbol{n}$, de telle sorte que chaque entier de l'ensemble $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ apparaît exactement $n$ fois dans la grille. Montrer qu'il existe une colonne ou une ligne de la grille contenant au moins $\sqrt{n}$ nombres différents.

|

Essayons d'abord de regarder ce qui se passe dans ce qui semble être 'le pire cas" : si chaque ligne/colonne ne contient pas beaucoup de numéros, chaque numéro va y être beaucoup présent. En particulier, pour tout $i$, le nombre de $i$ semble être écrit dans peu de lignes et de colonnes. Mais à priori si le numéro $i$ apparait trop dans une ligne, il apparaitra dans beaucoup de colonnes et inversement. A priori, le pire cas semble être celui où chaque numéro apparaît dans autant de colonnes que de lignes et comme chaque numéro apparaît $n$ fois, le carré doit être de dimension $\sqrt{n}$, donc $i$ apparait dans au moins $2 \sqrt{n}$ lignes et colonnes.

Bien sûr, cette analyse ne constitue en rien une preuve, mais on voit deux idées importantes : premièrement, le nombre de numéros distincts dans chaque ligne/colonne semble avoir un lien avec le nombre de lignes/colonnes où chaque numéro apparaît. Deuxièmement, pour tout $i$ entre 1 et $n$, le nombre $i$ apparait au moins sur $2 \sqrt{n}$ lignes et colonnes. On va donc essayer de formaliser ça.

Notons $a_{c, i}$ pour $c$ une colonne ou une ligne et $i$ un entier entre 1 et $n$ le nombre de fois qu'apparait $i$ dans $c$, notons $c_{i}$ (resp. $l_{i}$ ) le nombre de colonnes (resp. lignes) à laquelle $i$ appartient. On note C l'ensemble des colonnes $L$ celui des lignes.

Notons que l'hypothèse du fait que $i$ apparait $n$ fois se traduit comme $c_{i} \times l_{i} \geqslant n$ car $i$ apparait dans au plus $c_{i} l_{i}$ cases.

Notons que pour tout $i$, $l_{i}+c_{i}$ étant le nombre de ligne ou de colonne où apparait $i$, il vaut $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}$. Le nombre d'éléments distincts dans la colonne $c$ vaut, quant à lui, $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i}$. En particulier, on voit bien que les $a_{c, i}$ jouent un rôle important dans le problème.

Maintenant il reste à relier le nombre d'apparitions de $i$ dans les différentes lignes/colonnes au nombre de numéros dans chaque ligne. Pour cela on va regarder la somme des $a_{c, i}$ (on somme sur $i$ entre 1 et $n$ et sur c colonne et ligne) et utiliser les deux interprétations précédentes.

On obtient ainsi $\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{c \in C \cup L} a_{c, i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}+l_{i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}} \geqslant 2 n \sqrt{n}$.

On en déduit que $\sum_{c \in C \cup L} \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} 2 \sqrt{c_{i} l_{i}}=2 n \sqrt{n}$.

En particulier, comme il y a $2 n$ lignes ou colonnes, il existe $c$ colonnes ou lignes telles que $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{c, i} \geqslant \sqrt{n}$ i.e. c contient au moins $\sqrt{\mathrm{n}}$ numéros différents.

Commentaire des correcteurs: L'exercice a été globalement bien réussi par ceux qui l'ont traité, mais il faut faire attention à être clair dans ses explications et être précis dans les définitions des différents objets introduits.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 14.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-commenté-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 14",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Find all integers $n \geqslant 1$ such that for every prime $p<n, n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p n$ is not divisible by a square different from 1.

|

Let's analyze the problem: we are looking for integers \( n \) that satisfy a certain property. We can start by finding the small values of \( n \) that work: by testing integers \( n \) between 1 and 20, we find \(\{1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 13\}\).

One of the first things to do when facing this problem is to understand the meaning of \( n - \left\lfloor \frac{n}{p} \right\rfloor p \). Since \(\frac{n}{p}\) is the division of \( n \) by \( p \), we can try to see if this quantity can be interpreted from the Euclidean division.

Note that \( n - \left\lfloor \frac{n}{p} \right\rfloor p \) is the remainder of the Euclidean division of \( n \) by \( p \). Indeed, if \( n = pq + r \) with \( q \) an integer and \( 0 \leq r \leq p-1 \), we have \(\left\lfloor \frac{n}{p} \right\rfloor = \left\lfloor q + \frac{r}{p} \right\rfloor = q\), so \( n - \left\lfloor \frac{n}{p} \right\rfloor p = r \).

Next, we observe that all the solutions found except 1 are prime numbers: we will try to show that an integer \( n \) satisfying the property must be prime, for example, by taking \( p \) as one of its divisors.

Let \( n > 1 \) be an integer satisfying the property. We deduce from this that if \( n \) is not prime, and if \( p < n \) is a prime divisor of \( n \), then \( n - \left\lfloor \frac{n}{p} \right\rfloor p = 0 \) is divisible by 4, which is a perfect square, leading to a contradiction.

Now, what can we do to advance: let's analyze what the property can give us. If \( n \geq 12 \), for \( p = 2 \) the remainder of the Euclidean division is 1, for \( p = 3 \) it is 1 or 2, so this does not help. For \( p = 5 \), we get that the remainder cannot be 4, for \( p = 7 \), the remainder cannot be 4, for \( p = 8 \) the remainder cannot be 4, 8, or 9. A priori, continuing like this indefinitely seems complicated, as we will just have a very large system, which will probably have solutions (since there are infinitely many numbers congruent to 1 modulo \( p_1 \times \ldots \times p_k \), looking at the remainders by the first \( k \) prime numbers seems less useful). However, 4 seems to play an important role: 4 cannot be a remainder of the division of \( n \) by \( p \). In particular, if \( p \geq 5 \), \( p \) cannot divide \( n - 4 \)! It seems interesting to look at what \( n - 4 \) can be, and similarly what \( n - 8 \) and \( n - 9 \) can be, as these cannot have prime factors greater than 10. To avoid cases where these quantities are negative, we assume \( n \geq 11 \).

Let \( n \) be a prime number greater than or equal to 11 satisfying the statement. Let \( p \) divide \( n - 4 \), we have \( p < n \). If \( p \geq 5 \), the remainder of the Euclidean division of \( p \) by 5 is 4 and it is divisible by 4, which is a square different from 1, leading to a contradiction. Moreover, \( p \) cannot be 2 because otherwise 2 divides \( n - 4 \) and thus 2 divides \( n \), which means \( n \) is not prime. Therefore, \( n - 4 = 3^x \) with \( x \) a positive integer because \( n - 4 > 1 \).

By making the same reasoning for \( n - 8 \) and \( n - 9 \), they cannot be divisible by \( p \) if \( p \geq 10 \).

Now let's analyze the prime factors of \( n - 8 \) and \( n - 9 \): they can be divisible by 2, 3, 5, 7. For the factor 3, since 3 divides \( n - 4 \), \( n \equiv 1 \pmod{3} \), so \( n - 8 \equiv 2 \pmod{3} \) and \( n - 9 \equiv 1 \pmod{3} \), these are not divisible by 3.

Moreover, \( n - 8 \) is not divisible by 2 because \( n \) is not. Since \( n - 8 \) and \( n - 9 \) are coprime, three cases present themselves to us: either \( n - 8 \) is a power of 5, or it is a power of 7, or \( n - 8 \) is divisible by 5 and 7, in which case \( n - 9 \) is a power of 2.

- If \( n - 8 = 5^y \) with \( y \) a positive integer, we have \( n - 4 = 5^y + 4 = 3^x \).

Here, since 4 is a square, we would like to show that \( 3^x \) is a square to factorize the equation. For this, we look modulo 4 because we have squares and \( 5 \equiv 1 \pmod{4} \).

Looking modulo 4, we have \( 3^x \equiv 1^y \equiv 1 \pmod{4} \). Otherwise, since the order of 3 modulo 4 is 2, 2 divides \( x \) so \( x \) is even. Let \( x = 2k \), we have \( (3^k - 2)(3^k + 2) = 5^y \) so \( 3^k - 2 \) is positive and \( 3^k - 2 \) and \( 3^k + 2 \) are powers of 5. Here we have a product of terms equal to a power of 2, so we try to compute their gcd to hope to bound one of the terms. In particular, the gcd of \( 3^k + 2 \) and \( 3^k - 2 \) divides \( (3^k + 2) - (3^k - 2) = 4 \) which is not divisible by 5, and it divides their product, i.e., \( 5^y \), so it is 1. Since \( 3^k - 2 \) and \( 3^k + 2 \) are powers of 2 with gcd 1, the smallest one is 1, so we have \( 3^k - 2 = 1 \) which gives \( k = 1 \) so \( x = 2 \). We get \( n = 3^x + 4 = 9 + 4 = 13 \).

- If \( n - 8 = 7^y \) with \( y \) a positive integer, we have \( n - 4 = 7^y + 4 = 3^x \).

Since 4 is a square, we would like to show that \( x \) is even to factorize. For this, we look modulo 7. Note that if \( y = 0 \), there is no solution to this equation. Otherwise, we have \( 3^x \equiv 4 \pmod{7} \), and the powers of 3 modulo 7 are \( 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5, 1 \), so the order of 3 is 6 and we have \( x \equiv 4 \pmod{6} \) so \( x \) is even. Let \( x = 2k \), we have \( (3^k - 2)(3^k + 2) = 7^y \) so \( 3^k - 2 \) is positive and \( 3^k - 2 \) and \( 3^k + 2 \) are powers of 7.

In particular, the gcd of \( 3^k + 2 \) and \( 3^k - 2 \) divides \( (3^k + 2) - (3^k - 2) = 4 \) which is not divisible by 7, and it divides \( 7^y \) so it is 1. Since \( 3^k - 2 \) and \( 3^k + 2 \) are powers of 2 with gcd 1, the smallest one is 1, so we have \( 3^k - 2 = 1 \) so \( k = 1 \) so \( x = 2 \), we get \( 7^y = 3^x - 4 = 5 \) which is impossible.

- Otherwise, \( n - 9 = 2^y \) with \( y \) a positive integer, we have \( n - 4 = 2^y + 5 = 3^x \). Note that since \( n - 4 \geq 7 \), we have \( x \geq 1 \) and \( y \geq 1 \).

Here we do not have a square a priori, but we can try to get information about the parity of \( x \) and \( y \). Since we have powers of 2 and 3, we will look modulo 3 and 4. Note that if \( y = 1 \), the equation becomes \( 3^x = 7 \), there is no solution. Since \( x \geq 1 \) and looking modulo 3, we have \( 2^y \equiv -5 \equiv 1 \pmod{3} \) and the order of 2 modulo 3 is 2, so \( y \) is even. Since \( y \geq 2 \), we have \( 3^x \equiv 1 \pmod{4} \) and since the order of 3 modulo 4 is 2, \( x \) is even. We write \( x = 2b \), \( y = 2c \), we have \( 5 = (3^b - 2^c)(3^b + 2^c) \) so \( 3^b - 2^c \) is positive and since \( 3^b - 2^c < 3^b + 2^c \), \( 3^b - 2^c \) and \( 3^b + 2^c \) are 1 and 5 respectively. We deduce that \( 3^b \times 2 = (3^b + 2^c) + (3^b - 2^c) = 6 \) so \( b = 1 \) so \( x = 2 \), we fall back into the previous case \( n = 13 \).

In particular, we have obtained that \( n = 13 \) or \( n < 11 \) and \( n \) is prime, i.e., \( n \) is \( 2, 3, 5, 7 \) or 13. Let's verify that these are solutions:

- There is no prime number strictly less than 1 and 2, so 1 and 2 are solutions.

- The remainder of the division of 3 by 2 is 1, which has no square factors, so 3 is a solution.

- The remainders of the Euclidean divisions of 5 by 2 and 3 are 1 and 2, which have no square factors, so 5 is a solution.

- The remainders of the Euclidean divisions of 7 by 2, 3, and 5 are 1, 1, and 2, which have no square factors, so 7 is a solution.

- The remainders of the Euclidean divisions of 13 by 2, 3, 5, 7, and 11 are 1, 1, 3, 6, and 2, which have no square factors, so 13 is a solution.

The set of solutions is therefore \(\{1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 13\}\).

Comment from the graders: This arithmetic problem was solved by few students, all of whom showed that they are extremely comfortable. The other students who approached the problem simply noted that if \( n \geq 2 \) is a solution, then it is prime, which was a good start, but there were still many steps missing before reaching the solution.

|

\{1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 13\}

|

Incomplete

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver tous les entiers $n \geqslant 1$ tel que pour tout nombre premier $p<n, n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p n$ 'est pas divisible par un carré différent de 1.

|

Analysons le problème : on cherche les entiers $n$ vérifiant une certaine propriété. On peut déjà commencer par chercher les petites valeurs de n qui conviennent : en testant les entiers $n$ entre 1 et 20 on trouve $\{1,2,3,5,7,13\}$.

Une des premières choses à faire devant ce problème est de réussir à donner un sens à $n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p$. $\frac{n}{p}$ étant la division de $n$ par $p$ on peut essayer de regarder si cette quantité ne s'interprète pas à partir de la division euclidienne.

Notons que $n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p$ est le reste de la division euclidienne de $n$ par $p$. En effet si $n=p q+r$ avec $q$ entier et $0 \leqslant r \leqslant p-1$, on a $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor=\left\lfloor q+\frac{r}{p}\right\rfloor=q$ donc $n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p=r$.

Ensuite, on note que toutes les solutions trouvées sauf 1 sont des nombres premiers : on va donc essayer de montrer qu'un entier $n$ vérifiant la propriété est forcément premier, par exemple en prenant $p$ un de ses diviseurs.

Soit $n>1$ un entier vérifiant la propriété. On déduit de ceci que si $n$ n'est pas premier, si $p<n$ est un diviseur premier de $n$, alors $n-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor p=0$ est divisible par 4 qui est un carré parfait, contradiction.

Maintenant que peut-on faire pour avancer : analysons ce que la propriété peut nous donner. Si $\boldsymbol{n} \geqslant 12$, pour $p=2$ le reste de la division euclidienne vaut 1 , pour $p=3$ il vaut 1 ou 2 , donc cela n'apporte rien. Pour $p=5$, on obtient que le reste ne peut valoir 4 , pour $p=7$, le reste ne peut valoir 4 , pour $p=8$ le reste ne peut valoir ni 4 ni 8 ni 9 . A priori, continuer comme ça indéfiniment semble compliqué, vu qu'on aura juste un très gros système, qui admettra probablement des solutions (comme il y a une infinité de nombre congru à 1 modulo $p_{1} \times \ldots p_{k}$, le fait de regarder les restes par les $k$ premiers nombre premiers semble peu utile). Par contre, 4 semble jouer un rôle important : 4 ne peut pas être un reste de la divison de $n$ par $p$. En particulier si $p \geqslant 5, p$ ne peut diviser $n-4$ ! Il semble donc intéressant de regarder ce que peut valoir $n-4$, et de même ce que peuvent valoir $n-8$ et $n-9$ car ceux-ci ne peuvent pas avoir de facteur premier plus grand que 10 . Pour éviter les cas où ces quantités sont négatives, on supposer $n \geqslant 11$.

Soit n premier supérieur ou égal à 11 vérifiant l'énoncé. Soit p divisant $\boldsymbol{n}-4$, on a $\mathrm{p}<\mathrm{n}$. Si $\mathrm{p} \geqslant 5$, le reste de la division euclidienne de p par 5 vaut 4 et il est divisible par 4 qui est un carré différent de 1, ce qui donne une contradiction. De plus, $p$ ne peut valoir 2 car sinon 2 divise $n-4$ donc 2 divise $n, n$ 'est dans ce cas pas premier. Ainsi $\mathrm{n}-4=3^{x}$ avec $x$ un entier strictement positif car $\mathrm{n}-4>1$.

En faisant le même raisonnement $\mathrm{n}-8$ et $\mathrm{n}-9$ ne sont pas divisibles par $p$ si $p \geqslant 10$.

Maintenant analysons les facteurs premiers de $\boldsymbol{n}-8$ et $\mathrm{n}-9$ : ils peuvent être divisibles par 2, 3, 5, 7. Pour le facteur 3 , comme 3 divise $n-4, n \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$, donc $n-8 \equiv 2(\bmod 3)$ et $n-9 \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 3)$, ceux-ci ne sont pas divisibles par 3.

De plus $n-8$ n'est pas divisible par 2 car $n$ ne l'est pas. Comme $n-8$ et $n-9$ sont premiers entre eux, trois cas se présentent à nous : soit $\mathrm{n}-8$ est une puissance de 5 , soit c'est une puissance de 7 , soit $\mathrm{n}-8$ est divisible par 5 et 7 , dans ce cas $n-9$ est une puissance de 2 .

- $\operatorname{Sin}-8=5^{y}$ avec $y$ entier positif, on a $n-4=5^{y}+4=3^{x}$.

Ici 4 étant un carré, on aimerait montrer que $3^{x}$ est un carré pour factoriser l'équation. Pour cela, on regarde modulo 4 car on a des carrés et $5 \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$.

Regardons modulo 4 , on a $3^{x} \equiv 1^{y} \equiv(\bmod 4)$. Sinon comme l'ordre de 3 modulo 4 est 2 , 2 divise $x$ donc $x$ est pair. Posons $x=2 k$, on a $\left(3^{k}-2\right)\left(3^{k}+2\right)=5^{y}$ donc $3^{k}-2$ est positif et $3^{k}-2$ et $3^{k}+2$ sont des puissances de 5 . Ici on a un produit de terme valant une puissance de 2 , on essaie donc de calculer leur pgcd pour espérer borner un des termes. En particulier, le pgcd de $3^{\mathrm{k}}+2$ et $3^{\mathrm{k}}-2$ divise $\left(3^{\mathrm{k}}+2\right)-\left(3^{\mathrm{k}}-2\right)=4$ qui n'est pas divisible par 5 , et il divise leur produit c'est-à-dire $5^{y}$, il vaut donc 1 . Comme $3^{k}-2$ et $3^{k}+2$ sont des puissances de 2 de pgcd 1 , la plus petite vaut 1 , on a donc $3^{\mathrm{k}}-2=1$ soit $\mathrm{k}=1$ soit $\chi=2$. On obtient $\mathrm{n}=3^{\mathrm{x}}+4=9+4=13$.

- $\operatorname{Sin}-8=7^{y}$ avec $y$ entier positif, on a $\mathrm{n}-4=7^{y}+4=3^{x}$.

Comme 4 est un carré, on aimerait réussir à montrer que $x$ est pair pour factoriser, pour cela on regarde modulo 7 . Notons que si $y=0$, il n'y a pas de solution à cette équation. Sinon on a $3^{\mathrm{x}} \equiv 4(\bmod 7)$, or les puissances de 3 modulo 7 valent $1,3,2,6,4,5,1$, l'ordre de 3 vaut donc 6 et on a forcément $x \equiv 4(\bmod 6)$ donc $x$ est pair. Posons $x=2 k$, on a $\left(3^{k}-2\right)\left(3^{k}+2\right)=7^{y}$ donc $3^{k}-2$ est positif et $3^{k}-2$ et $3^{k}+2$ sont des puissances de 7 .