problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Determine all polynomials P and Q with integer coefficients such that, if the sequence $\left(x_{n}\right)$ is defined by $x_{0}=2015, x_{2 n+1}=P\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ and $x_{2 n+2}=\mathrm{Q}\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ for all $n \geqslant 0$, then every positive integer $\mathrm{m}>0$ divides at least one non-zero term of the sequence.

|

Let P and Q be two such polynomials.

We will say that a sequence $\left(\mathrm{y}_{\mathrm{n}}\right)$ of integers has property D if every integer $\mathrm{m}>0$ divides at least one non-zero term of this sequence. We will say that a polynomial T with integer coefficients has property D if there exists an integer a such that the sequence $\left(x_{n}\right)$ defined by $x_{0}=a$ and $x_{n+1}=T\left(x_{n}\right)$ has property D.

We now begin with three lemmas.

Lemma 1. Let $(x_{n})$ be a sequence of integers and let $k$ be a non-zero natural number. Then $(x_{n})$ has property D if and only if one of the $k$ sequences $\left(x_{k n}\right),\left(x_{k n+1}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{k n+k-1}\right)$ has property D.

Proof of Lemma 1. Suppose first that none of the $k$ sequences $\left(x_{k n}\right),\left(x_{k n+1}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{k n+k-1}\right)$ has property D. Then, for each integer $\ell \in\{0,1, \ldots, k-1\}$, there exists an integer $M_{\ell}$ that does not divide any non-zero term of the sequence $(x_{k n+\ell})$. In particular, the integer $\prod_{\ell=0}^{k-1} M_{\ell}$ cannot divide any non-zero term of the sequence $\left(x_{n}\right)$, which therefore cannot have property D either.

Conversely, if a sequence $\left(x_{k n+\ell}\right)$ has property D, then clearly $\left(x_{n}\right)$ also has property D.

Lemma 2. Let T be a polynomial with integer coefficients, of degree d and leading coefficient $\rho$. If T has property D, then $\mathrm{d}=1$ and $|\rho|<4$.

Proof of Lemma 2. If T is constant, the sequence $(x_{n})$ takes only a finite number of distinct values, which prevents it from having property D. We now proceed by contradiction, and assume that $d \geqslant 2$ or that $d=1$ and $|\rho| \geqslant 4$. Then there exists a real number $c>0$ such that

$$

|\mathrm{T}(\mathrm{x})|>3|x| \text { for all } x \text { such that }|x|>c \text {. (1) }

$$

Note that there are only a finite number of integers in [-c; c] and that each of them can only be reached a finite number of times by T. Thus, there exists an integer $N \geqslant 0$ such that $\left|x_{N}\right|>c$. An immediate induction using (1) shows that then $\left|x_{i}\right|>c$ for all $i \geqslant N$.

Moreover, without loss of generality, we can choose $N$ to be minimal with this property. We then have

$$

\left|x_{i}\right| \leqslant c \text { for all } i<N, \text { and }\left|x_{i}\right|>c \text { for all } i \geqslant N \text {. (2) }

$$

In particular, from (1) and (2), we deduce that $\left|x_{N+1}\right|>\max \left(c,\left|x_{0}\right|, \cdots,\left|x_{N}\right|\right)$.

Let $m=\left|x_{N+1}-x_{N}\right|$, which is a strictly positive integer. Then:

$m \geqslant\left|x_{N+1}\right|-\left|x_{N}\right|>2\left|x_{N}\right|>\max \left(\left|x_{0}\right|, \cdots,\left|x_{N}\right|\right)$, which ensures that $m$ does not divide any non-zero $x_{i}$ when $i \leqslant N$. But then $m$ does not divide $x_{N+1}$ either.

On the other hand, since T has integer coefficients, $x_{n+1}-x_{n}=T\left(x_{n}\right)-T\left(x_{n-1}\right)$ is divisible by $x_{n}-x_{n-1}$ for all $n \geqslant 1$. In particular, for all $n \geqslant N$, $x_{n+1}-x_{n}$ is divisible by $m$, and thus

$$

x_{n+1}-x_{N+1}=\left(x_{n+1}-x_{n}\right)+\left(x_{n}-x_{n-1}\right)+\cdots+\left(x_{N+2}-x_{N+1}\right)

$$

is also divisible by $m$. But, since $m$ does not divide $x_{N+1}$, it does not divide $x_{n}$ for all $n \geqslant N+1$ either. Finally, $m$ does not divide any non-zero term of the sequence, in contradiction with the hypothesis that $\left(x_{n}\right)$ has property D.

Lemma 3. Let $T(X)=\rho X+\theta$ be a polynomial with integer coefficients. If T has property D, then $\rho=1$.

Proof of Lemma 3. If T has property D, let $x_{0}$ be an integer such that the sequence $(x_{n})$ defined by $x_{n+1}=T\left(x_{n}\right)$ has property D. According to Lemma 1, one of the sequences $\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ and $\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ has property D, and satisfies $x_{n+2}=T\left(T\left(x_{n}\right)\right)$. The polynomial $T(T(X))$ therefore also has property D.

Now, $T(T(X))$ has leading coefficient $\rho^{2}$. Lemma 2 then shows that $\rho^{2}<4$, so $\rho \in\{-1,0,1\}$. Since $\rho$ is the leading coefficient of T, we necessarily have $\rho \neq 0$. Moreover, if $\rho=-1$, then $T(T(X))=X$ does not have property D. It follows that $\rho=1$.

Let's return to the exercise.

We set $H(X)=P(Q(X))$ and $K(X)=Q(P(X))$.

According to Lemma 1, one of the two sequences $(x_{2 k})$ and $(x_{2 k+1})$ has property D, so one of the polynomials H and K has property D, since $x_{2 k+2}=H(x_{2 k})$ and $x_{2 k+3}=K(x_{2 k+1})$.

Since $\operatorname{deg} H=(\operatorname{deg} P) \cdot(\operatorname{deg} Q)=\operatorname{deg} K$, Lemma 2 indicates that $\operatorname{deg} H=\operatorname{deg} P=\operatorname{deg} Q=\operatorname{deg} K=1$. Let us then write $P(X)=a X+b$ and $Q(X)=c X+d$. We then have $H(X)=a c X+a d+b$ and $K(X)=a c X+b c+d$, so Lemma 3 indicates that $a=c= \pm 1$.

Finally, note that $x_{2 n}=2015+(a d+b) n$ and that $x_{2 n+1}=(a 2015+d)+(b c+d) n$. Now, an arithmetic sequence $\left(y_{n}\right)$ with common difference $r$ has property D if and only if $r$ divides $y_{0}$:

- if $y_{0}=q r$, and if $m \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$, then $q^{2} m-q \geqslant 0$ and $m$ divides $y_{q^{2} m-q}=q^{2} m r$;

- if $r$ does not divide $y_{0}$, then $r$ does not divide any integer $y_{n}$.

Now, Lemma 1 indicates that $\left(x_{n}\right)$ has property D if and only if $\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ or $\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ has property D. In the first case, this means that $a d+b$ divides $x_{0}=2005$. In the second case, this means that $b c+d$ divides $x_{1}=2005 c+d$. Note that $|a d+b|=|b c+d|$.

The pairs of polynomials $(P(X), Q(X))$ we are looking for are therefore the pairs $(P(X), Q(X))=(\varepsilon X+b, \varepsilon X+d)$ such that $\varepsilon= \pm 1$ and $b+\varepsilon d$ divides 2005 or $2005+\varepsilon d$.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les polynômes P et Q à coefficients entiers tels que, si l'on définit la suite $\left(x_{n}\right)$ par $x_{0}=2015, x_{2 n+1}=P\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ et $x_{2 n+2}=\mathrm{Q}\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ pour tout $n \geqslant 0$, alors tout entier $\mathrm{m}>0$ divise au moins un terme non nul de la suite.

|

Soit P et Q deux tels polynômes.

On dira qu'une suite $\left(\mathrm{y}_{\mathrm{n}}\right)$ d'entiers possède la propriété D si tout entier $\mathrm{m}>0$ divise au moins un terme non nul de cette suite. On dira qu'un polynôme T à coefficients entiers possède la propriété D s'il existe un entier a tel que la suite $\left(x_{n}\right)$ définie par $x_{0}=a$ et $x_{n+1}=T\left(x_{n}\right)$ possède la propriété D.

Nous débutons maintenant par trois lemmes.

Lemme 1. Soit ( $x_{n}$ ) une suite d'entiers et soit $k$ un entier naturel non nul. Alors ( $x_{n}$ ) possède la propriété D si et seulement si l'une des $k$ suites $\left(x_{k n}\right),\left(x_{k n+1}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{k n+k-1}\right)$ possède la propriété D.

Preuve du lemme 1. Supposons d'abord qu'aucune des $k$ suites $\left(x_{k n}\right),\left(x_{k n+1}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{k n+k-1}\right)$ ne possède la propriété $D$. Alors, pour chaque entier $\ell \in\{0,1, \ldots, k-1\}$, il existe un entier $M_{\ell}$ qui ne divise aucun terme non nul de la suite ( $x_{k n+\ell}$ ). En particulier, l'entier $\prod_{\ell=0}^{k-1} M_{\ell}$ ne peut donc diviser aucun terme non nul de la suite $\left(x_{n}\right)$, qui ne peut posséder la propriété D non plus.

Réciproquement, si une suite $\left(x_{k n+\ell}\right)$ a la propriété $D$, alors clairement $\left(x_{n}\right)$ a la propriété $D$ aussi.

Lemme 2. Soit T un polynôme à coefficients entiers, de degré d et de coefficient dominant $\rho$. Si R possède la propriété D , alors $\mathrm{d}=1$ et $|\rho|<4$.

Preuve du lemme 2. Si T est constant, la suite ( $x_{n}$ ) ne prend qu'un nombre fini de valeurs distinctes, ce qui lui interdit d'avoir la propriété D. Procédons maintenant par l'absurde, et supposons que $d \geqslant 2$ ou que $d=1$ et $|\rho| \geqslant 4$. Il existe alors un réel $c>0$ tel que

$$

|\mathrm{T}(\mathrm{x})|>3|x| \text { pour tout } x \text { tel que }|x|>c \text {. (1) }

$$

On note qu'il n'existe qu'un nombre fini d'entiers dans [-c; c] et que chacun d'eux ne peut être atteint qu'un nombre fini de fois par $T$. Ainsi, il existe un entier $N \geqslant 0$ tel que $\left|x_{N}\right|>c$. Une récurrence immédiate à l'aide de (1) montre qu'alors $\left|x_{i}\right|>c$ pour tout $i \geqslant N$.

De plus, sans perte de généralité, on peut choisir $N$ minimal ayant cette propriété. On a donc

$$

\left|x_{i}\right| \leqslant c \text { pour tout } i<N, \text { et }\left|x_{i}\right|>c \text { pour tout } i \geqslant N \text {. (2) }

$$

En particulier, de (1) et (2), on déduit que $\left|x_{N+1}\right|>\max \left(c,\left|x_{0}\right|, \cdots,\left|x_{N}\right|\right)$.

Posons $m=\left|x_{N+1}-x_{N}\right|$, qui est bien un entier strictement positif. Alors:

$m \geqslant\left|x_{N+1}\right|-\left|x_{N}\right|>2\left|x_{N}\right|>\max \left(\left|x_{0}\right|, \cdots,\left|x_{N}\right|\right)$, ce qui assure $m$ ne divise aucun $x_{i}$ non nul lorsque $i \leqslant N$. Mais alors $m$ ne divise pas $x_{N+1}$ non plus.

D'autre part, puisque $T$ est à coefficients entiers, $x_{n+1}-x_{n}=T\left(x_{n}\right)-T\left(x_{n-1}\right)$ est divisible par $x_{n}-x_{n-1}$ pour tout $n \geqslant 1$. En particulier, pour tout $n \geqslant N$, on a $x_{n+1}-x_{n}$ divisible par $m$, et donc

$$

x_{n+1}-x_{N+1}=\left(x_{n+1}-x_{n}\right)+\left(x_{n}-x_{n-1}\right)+\cdots+\left(x_{N+2}-x_{N+1}\right)

$$

est lui aussi divisible par $m$. Mais, $m$ ne divisant pas $x_{N+1}$, il ne divise donc pas non plus $x_{n}$ pour tout $n \geqslant N+1$. Finalement, $m$ ne divise aucun terme non nul de la suite, en contradiction avec l'hypothèse que $\left(x_{n}\right)$ possède la propriété $D$.

Lemme 3. Soit $T(X)=\rho X+\theta$ un polynôme à coefficients entiers. Si $T$ possède la propriété $D$, alors $\rho=1$.

Preuve du lemme 3. Si T possède la propriété D , soit $x_{0}$ un entier tel que la suite ( $x_{n}$ ) définie par $x_{n+1}=T\left(x_{n}\right)$ ait la propriété $D$. D'après le lemme 1, l'une des suites $\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ et $\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ a la propriété $D$, et satisfait bien $x_{n+2}=T\left(T\left(x_{n}\right)\right)$. Le polynôme $T(T(X))$ a donc également la propriété D .

Or, $T(T(X))$ est de coefficient dominant $\rho^{2}$. Le lemme 2 montre donc que $\rho^{2}<4$, donc que $\rho \in\{-1,0,1\}$. Puisque $\rho$ est un coefficient dominant de $T$, on a nécessairement $\rho \neq 0$. De plus, si $\rho=-1$, alors $T(T(X))=X$ n'a pas la propriété $D$. Il s'ensuit que $\rho=1$.

Revenons maintenant à l'exercice.

On pose $H(X)=P(Q(X))$ et $K(X)=Q(P(X))$.

D'après le lemme 1, l'une des deux suites ( $\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}}$ ) et $\left(\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}+1}\right)$ possède la propriété D , donc l'un des polynômes H et K possède la propriété D , car $\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}+2}=\mathrm{H}\left(\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}}\right)$ et $\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}+3}=\mathrm{K}\left(\mathrm{x}_{2 \mathrm{k}+1}\right)$.

Puisque $\operatorname{deg} H=(\operatorname{deg} P) \cdot(\operatorname{deg} Q)=\operatorname{deg} K$, le lemme 2 indique que $\operatorname{deg} H=\operatorname{deg} P=\operatorname{deg} \mathbf{Q}=$ $\operatorname{deg} K=1$. Notons alors $P(X)=a X+b$ et $Q(X)=c X+d$. On a alors $H(X)=a c X+a d+b$ et $K(X)=a c X+b c+d$, donc le lemme 3 indique que $a=c= \pm 1$.

Finalement, notons que $x_{2 n}=2015+(a d+b) n$ et que $x_{2 n+1}=(a 2015+d)+(b c+d) n$. Or, une suite arithmétique $\left(y_{n}\right)$ de raison $r$ a la propriété $D$ si et seulement si $r$ divise $y_{0}$ :

- si $y_{0}=q r$, et si $m \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$, alors $q^{2} m-q \geqslant 0$ et $m$ divise $y_{q^{2} m-q}=q^{2} m r$;

- si $r$ ne divise pas $y_{0}$, alors $r$ ne divise aucun entier $y_{n}$.

Or, le lemme 1 inidique que $\left(x_{n}\right)$ a la propriété $D$ si et seulement si $\left(x_{2 n}\right)$ ou $\left(x_{2 n+1}\right)$ a la propriété $D$. Dans le premier cas, cela signifie que $a d+b$ divise $x_{0}=2005$. Dans le second cas, cela signifie que $b c+d$ divise $x_{1}=2005 c+d$. Or, notons que $|a d+b|=|b c+d|$.

Les paires des polynômes $(P(X), Q(X))$ recherchées sont donc les paires $(P(X), Q(X))=$ $(\varepsilon X+b, \varepsilon X+d)$ telles que $\varepsilon= \pm 1$ et $b+\varepsilon$ d divise 2005 ou $2005+\varepsilon d$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-fevrier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Determine all real numbers $x, y, z$ satisfying the following system of equations: $x=\sqrt{2 y+3}, y=\sqrt{2 z+3}, z=\sqrt{2 x+3}$.

|

It is clear that the numbers $x, y, z$ must be strictly positive. The first two equations give $x^{2}=2 y+3$ and $y^{2}=2 z+3$. By subtracting them, we obtain $x^{2}-y^{2}=2(y-z)$. From this, we deduce that if $x \leqslant y$ then $y \leqslant z$, and similarly if $y \leqslant z$ then $z \leqslant x$. Therefore, if $x \leqslant y$, we have $x \leqslant y \leqslant z \leqslant x$, which implies that $x=y=z$.

We can similarly show that if $x \geqslant y$ then $x=y=z$. Therefore, in all cases, $x, y, z$ are equal, and their common value satisfies the equation $x^{2}=2 x+3$, which can also be written as $(x-3)(x+1)=0$. Since $x$ is strictly positive, it must be that $x=y=z=3$. Conversely, it is immediately verified that $x=y=z=3$ is indeed a solution to the system.

|

x=y=z=3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Déterminer tous les nombres réels $x, y, z$ satisfaisant le système d'équations suivant : $x=\sqrt{2 y+3}, y=\sqrt{2 z+3}, z=\sqrt{2 x+3}$.

|

Il est évident que les nombres $x, y, z$ doivent être strictement positifs. Les deux premières équations donnent $x^{2}=2 y+3$ et $y^{2}=2 z+3$. En les soustrayant, on obtient $x^{2}-y^{2}=2(y-z)$. On en déduit que si $x \leqslant y$ alors $y \leqslant z$, et de même si $y \leqslant z$ alors $z \leqslant x$. Donc si $x \leqslant y$, on a $x \leqslant y \leqslant z \leqslant x$, ce qui impose que $x=y=z$.

On montre de même que si $x \geqslant y$ alors $x=y=z$. Donc dans tous les cas, $x, y, z$ sont égaux, et leur valeur commune satisfait l'équation $x^{2}=2 x+3$, qui s'écrit encore $(x-3)(x+1)=0$. Or, $x$ est strictement positif, donc nécessairement $x=y=z=3$. Réciproquement, on vérifie immédiatement que $x=y=z=3$ est bien solution du système.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $n$ and $k$ be strictly positive integers. There are $n k$ objects (of the same size) and $k$ boxes that can each hold $n$ objects. Each object is colored in one of $k$ possible colors. Show that it is possible to arrange the objects in the boxes so that each box contains objects of at most 2 different colors.

|

We show this by induction on $k$. If $k=1$, the statement is obvious. Suppose the property holds for all integers $<k$.

If one of the colors $c$ is taken exactly $n$ times, we place all objects of color $c$ in the last box. The induction hypothesis allows us to place the remaining $n(k-1)$ objects in the first $k-1$ boxes such that each box contains objects of at most 2 different colors.

Suppose, therefore, that no color is taken exactly $n$ times. If all colors are taken $\leqslant n-1$ times, then there are at most $(n-1) k$ objects in total, which contradicts the hypothesis. Therefore, one of the colors $c_{1}$ is taken $\geqslant n+1$ times. Similarly, one of the colors $c_{2}$ is taken $\leqslant n-1$ times.

We then place all objects of color $c_{2}$ in the last box. We complete this box with objects of color $c_{1}$. The induction hypothesis allows us to place the remaining $n(k-1)$ objects in the first $k-1$ boxes such that each box contains objects of at most 2 different colors.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Soient $n$ et $k$ des entiers strictement positifs. Il y a $n k$ objets (de même taille) et $k$ boîtes qui peuvent contenir chacune $n$ objets. Chaque objet est colorié en une couleur parmi $k$ couleurs possibles. Montrer qu'il est possible de ranger les objets dans les boîtes de sorte que chaque boîte contienne des objets d'au plus 2 couleurs différentes.

|

On le montre par récurrence sur $k$. Si $k=1 c^{\prime}$ est évident. Supposons la propriété vraie pour tous les entiers $<k$.

Si l'une des couleurs $c$ est prise exactement $n$ fois, on range tous les objets dont la couleur est $c$ dans la dernière boîte. L'hypothèse de récurrence permet de ranger les $n(k-1)$ objets restants dans les $k-1$ premières boîtes de sorte que chaque boîte contienne des objets d'au plus 2 couleurs différentes.

Supposons donc qu'aucune couleur ne soit prise exactement $n$ fois. Si toutes les couleurs sont prises $\leqslant n-1$ fois, alors il y a au plus $(n-1) k$ objets au total, ce qui contredit l'hypothèse. Donc l'une des couleurs $c_{1}$ est prise $\geqslant n+1$ fois. De même, l'une des couleurs $c_{2}$ est prise $\leqslant n-1$ fois.

On place alors tous les objets de couleur $c_{2}$ dans la dernière boîte. On complète cette boîte avec des objets de couleur $c_{1}$. L'hypothèse de récurrence permet de ranger les $n(k-1)$ objets restants dans les $k-1$ premières boîtes de sorte que chaque boîte contienne des objets d'au plus 2 couleurs différentes.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

It is said that a strictly positive integer $n$ is amusing if for every strictly positive divisor $d$ of $n$, the integer $d+2$ is prime. Determine all the amusing integers that have the maximum number of divisors.

|

Let $n$ be an amusing integer and $p$ a prime divisor of $n$. Then $p$ is odd, since $p+2$ is prime.

Suppose that $p \geqslant 5$. Then $p+2$ is prime, and $p+2>3$, so $p+2$ is not divisible by 3. We deduce that $p$ is not congruent to 1 modulo 3. It is clear that $p$ is not congruent to 0 modulo 3, so $p \equiv 2(\bmod 3)$. Suppose that $p^{2} \mid n$. Then $p^{2} \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$, so $p^{2}+2 \equiv 0$ $(\bmod 3)$. Furthermore, $p^{2}+2$ is prime, so $p^{2}+2=3$, which is impossible.

We deduce from the above that if $p \geqslant 5$ is a prime divisor of $n$, then $p^{2}$ does not divide $n$.

Similarly, if $p_{1}$ and $p_{2}$ are distinct prime divisors $\geqslant 5$ of $n$, then $p_{1} p_{2}$ divides $n$, so $p_{1} p_{2}+2$ is divisible by 3, which is impossible.

Therefore, every amusing integer $n$ is of the form $n=3^{k}$ or $3^{k} p$ where $p$ is prime.

We check that $3+2, 3^{2}+2, 3^{3}+2$, and $3^{4}+2$ are prime, but $3^{5}+2$ is not, so $k \leqslant 4$. The amusing integers of the form $3^{k}$ therefore have at most 5 divisors.

If $n=3^{4} \times 5=405$, then $n+2$ is not prime, so $n$ is not amusing.

If $n=3^{k} p$ with $p \geqslant 7$ prime, and $k \geqslant 3$, then the numbers $p, 3 p, 9 p, 27 p$ are divisors of $n$ congruent to $p, 3 p, 4 p, 2 p$ modulo 5. None is congruent to 0 modulo 5, and the congruences of these four numbers modulo 5 are distinct, so in some order they are $1, 2, 3, 4$. We deduce that there is a divisor $d \geqslant 7$ of $n$ such that $d \equiv 3(\bmod 5)$. We have $d+2>5$ and $5 \mid d$, which implies that $d$ is not prime.

We deduce from the above that the amusing integers of the form $3^{k} p$ satisfy $k \leqslant 2$ or $(k \leqslant 3$ and $p=5$), so have at most 8 divisors, with equality only when $k=3$ and $p=5$. Conversely, we check that $3^{3} \times 5$ is amusing, so the unique amusing integer having a maximum number of divisors is $3^{3} \times 5=135$.

|

135

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

On dit qu'un entier strictement positif $n$ est amusant si pour tout diviseur strictement positif $d$ de $n$, l'entier $d+2$ est premier. Déterminer tous les entiers amusants dont le nombre de diviseurs est maximum.

|

Soit $n$ un entier amusant et $p$ un diviseur premier de $n$. Alors $p$ est impair, puisque $p+2$ est premier.

Supposons que $p \geqslant 5$. Alors $p+2$ est premier, et $p+2>3$, donc $p+2$ n'est pas divisible par 3. On en déduit que $p$ n'est pas congru à 1 modulo 3 . Il est clair que $p \mathrm{n}^{\prime}$ est pas congru à 0 modulo 3 , donc $p \equiv 2(\bmod 3)$. Supposons que $p^{2} \mid n$. Alors $p^{2} \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$, donc $p^{2}+2 \equiv 0$ $(\bmod 3)$. De plus, $p^{2}+2$ est premier, donc $p^{2}+2=3$, ce qui est impossible.

On déduit de ce qui précède que si $p \geqslant 5$ est un diviseur premier de $n$, alors $p^{2}$ ne divise pas $n$.

De même, si $p_{1}$ et $p_{2}$ sont des diviseurs premiers distincts $\geqslant 5$ de $n$, alors $p_{1} p_{2}$ divise $n$, donc $p_{1} p_{2}+2$ est divisible par 3 , ce qui est impossible.

Par conséquent, tout entier amusant $n$ est de la forme $n=3^{k}$ ou bien $3^{k} p$ où $p$ est premier.

On vérifie que $3+2,3^{2}+2,3^{3}+2$ et $3^{4}+2$ sont premiers mais $3^{5}+2$ ne l'est pas, donc $k \leqslant 4$. Les entiers amusants de la forme $3^{k}$ ont donc au plus 5 diviseurs.

Si $n=3^{4} \times 5=405$, alors $n+2$ n'est pas premier donc $n$ n'est pas amusant.

Si $n=3^{k} p$ avec $p \geqslant 7$ premier, et $k \geqslant 3$, alors les nombres $p, 3 p, 9 p, 27 p$ sont des diviseurs de $n$ congrus à $p, 3 p, 4 p, 2 p$ modulo 5 . Aucun n'est congru à 0 modulo 5 , et les congruences de ces quatre nombres modulo 5 sont deux à deux distinctes, donc à l'ordre près valent $1,2,3,4$. On en déduit qu'il existe un diviseur $d \geqslant 7$ de $n$ tel que $d \equiv 3(\bmod 5)$. On a donc $d+2>5$ et $5 \mid d$, ce qui entraîne que $d$ n'est pas premier.

On déduit de ce qui précède que les entiers amusants de la forme $3^{k} p$ vérifient $k \leqslant 2$ ou bien $(k \leqslant 3$ et $p=5$ ), donc ont au plus 8 diviseurs, avec égalité seulement lorsque $k=3$ et $p=5$. Réciproquement, on vérifie que $3^{3} \times 5$ est amusant, donc l'unique entier ammusant ayant un nombre maximal de diviseurs est $3^{3} \times 5=135$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

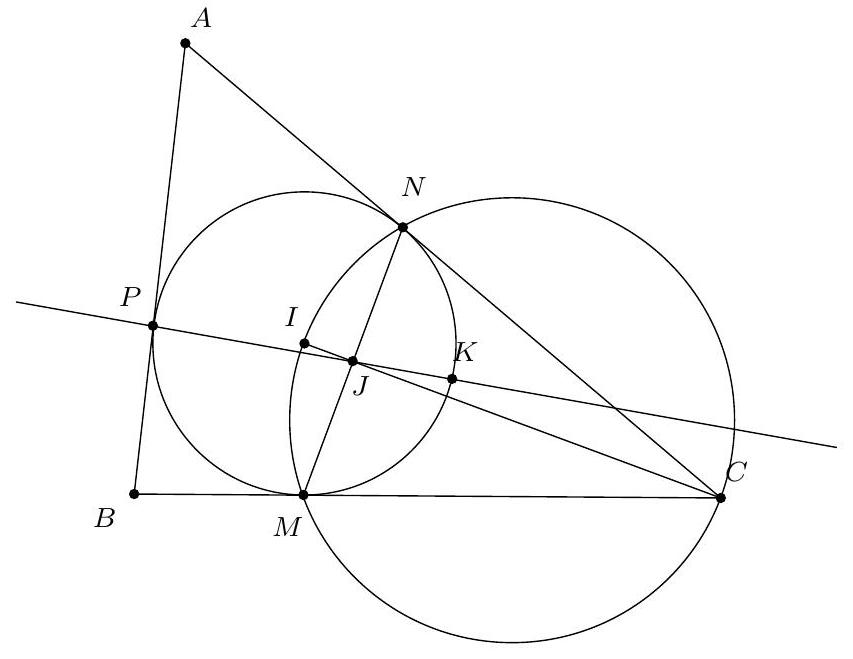

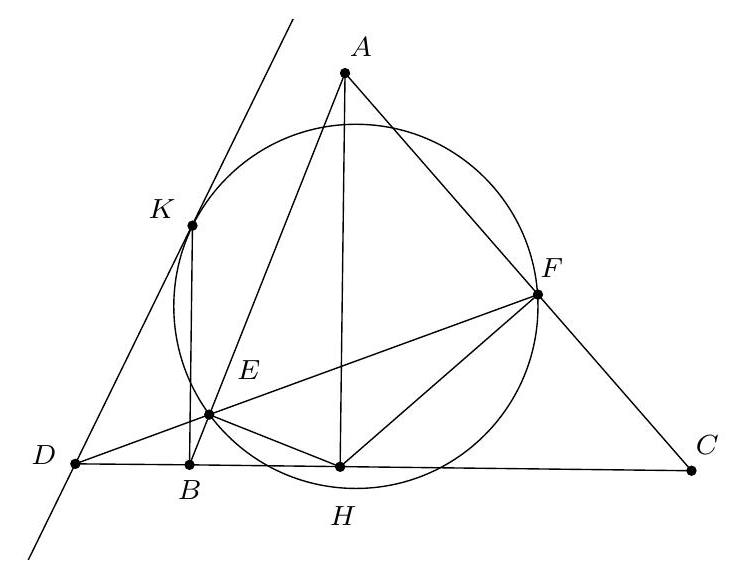

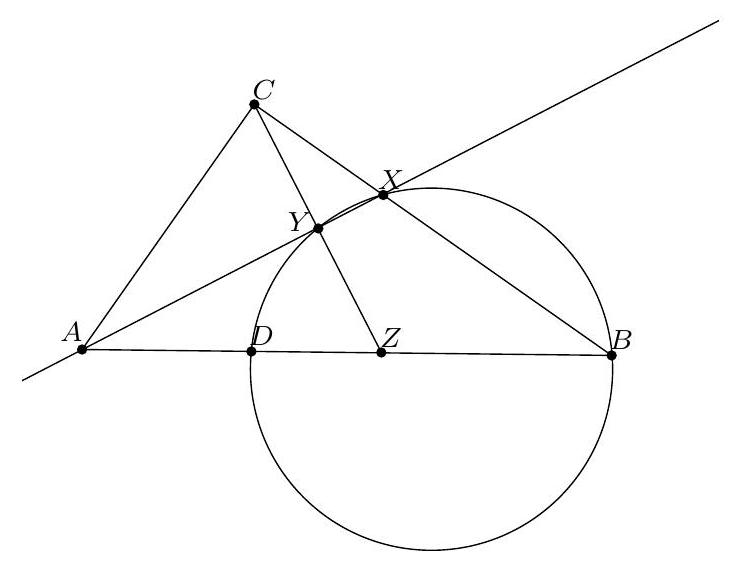

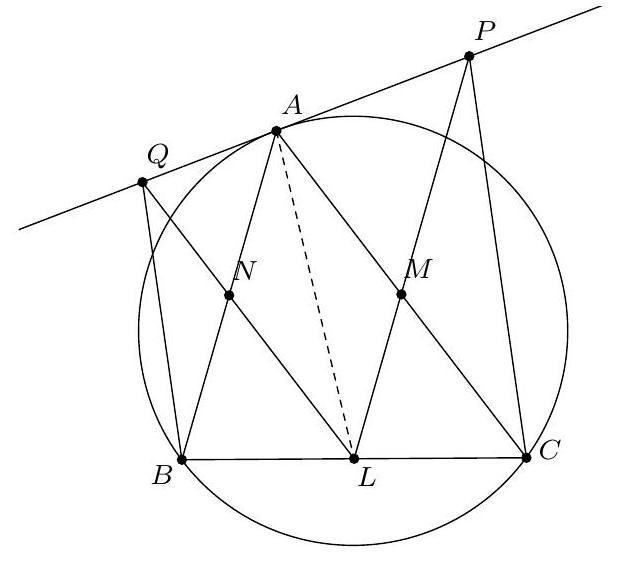

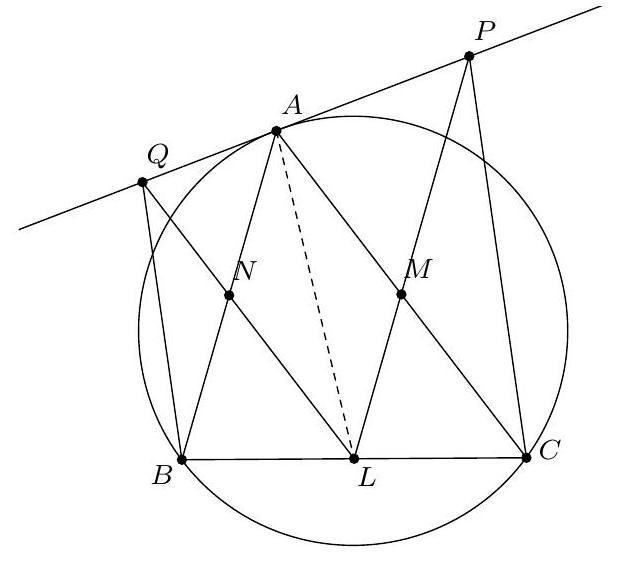

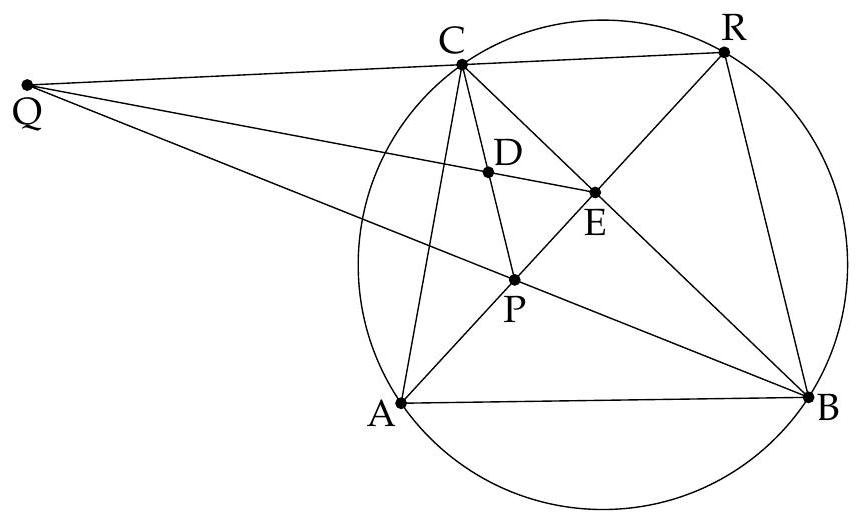

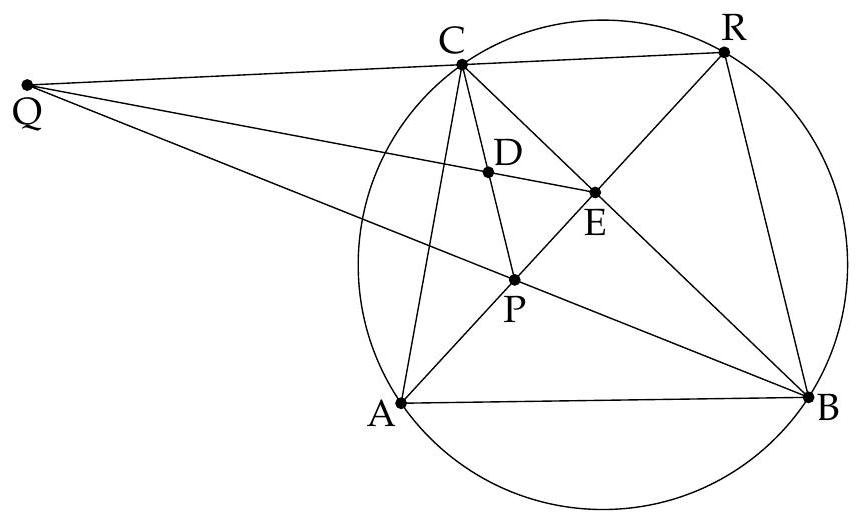

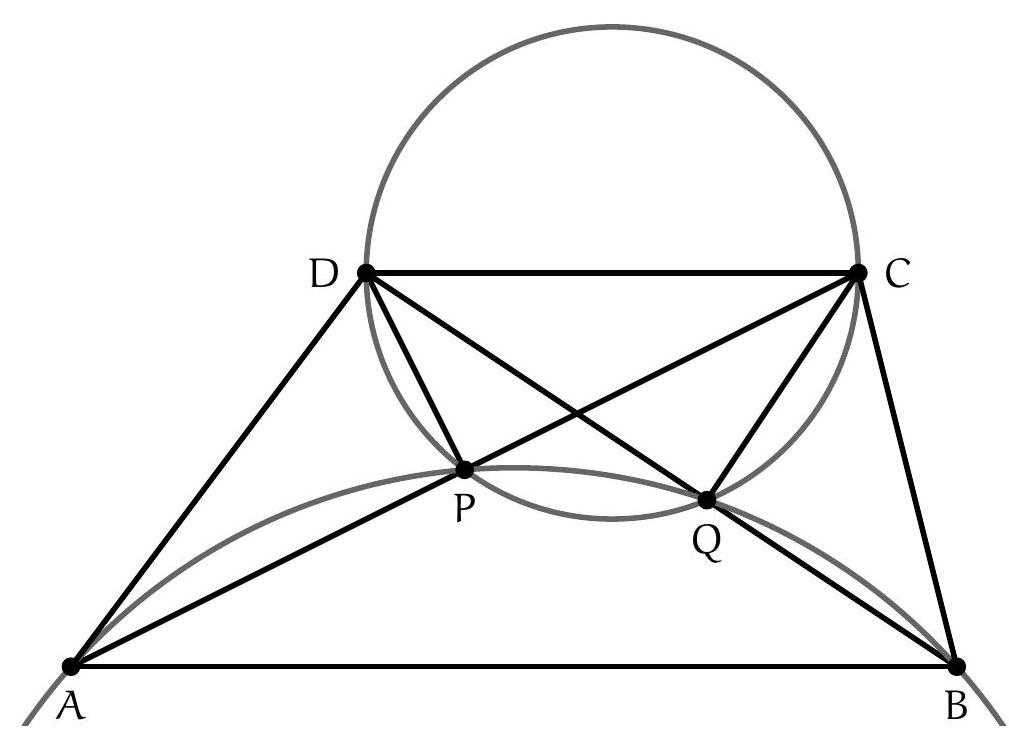

Let $ABC$ be a non-isosceles triangle. Let $\omega$ be the incircle and $I$ its center. We denote $M, N, P$ as the points of tangency of $\omega$ with the sides $[BC], [CA], [AB]$. Let $J$ be the intersection point between $(MN)$ and $(IC)$. The line $(PJ)$ intersects $\omega$ again at $K$. Show that

a) $CKIP$ is cyclic;

b) $(CI)$ is the bisector of $\widehat{PC K}$.

|

a) Since $(I N) \perp(N C)$ and $(I M) \perp(M C)$, the points $M$ and $N$ are located on the circle with diameter [IC], so $I, M, C, N$ are concyclic.

From the power of a point with respect to this circle, we have $J I \cdot J C = J M \cdot J N$. On the other hand, using the power with respect to the inscribed circle, we have $J M \cdot J N = J K \cdot J P$, so finally $J I \cdot J C = J K \cdot J P$, which implies that $P, I, K, C$ are concyclic.

b) From part a), we have $\widehat{I C P} = \widehat{I K P}$ and $\widehat{K C I} = \widehat{K P I}$. Since $I P K$ is isosceles at $I$, we have $\widehat{I K P} = \widehat{K P I}$, which implies that $\widehat{I C P} = \widehat{K C I}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle non isocèle. Soit $\omega$ le cercle inscrit et $I$ son centre. On note $M, N, P$ les points de contact de $\omega$ avec les côtés $[B C],[C A],[A B]$. Soit $J$ le point d'intersection entre $(M N)$ et $(I C)$. La droite $(P J)$ recoupe $\omega$ en $K$. Montrer que

a) $C K I P$ est cyclique;

b) $(C I)$ est la bissectrice de $\widehat{P C K}$.

|

a) Comme $(I N) \perp(N C)$ et $(I M) \perp(M C)$, les points $M$ et $N$ sont situés sur le cercle de diamètre [IC], donc $I, M, C, N$ sont cocycliques.

D'après la puissance d'un point par rapport à ce cercle, on a $J I \cdot J C=J M \cdot J N$. D'autre part, en utilisant la puissance par rapport au cercle inscrit, on a $J M \cdot J N=J K \cdot J P$, donc finalement $J I \cdot J C=J K \cdot J P$, ce qui entraîne que $P, I, K, C$ sont cocycliques.

b) D'après la question a), on a $\widehat{I C P}=\widehat{I K P}$ et $\widehat{K C I}=\widehat{K P I}$. Or, $I P K$ est isocèle en $I$, donc $\widehat{I K P}=\widehat{K P I}$, ce qui entraîne que $\widehat{I C P}=\widehat{K C I}$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

a) Prove that for all strictly positive real numbers $a, b, k$ such that $a < b$, we have

$$

\frac{a}{b} < \frac{a+k}{b+k}

$$

b) Prove that

$$

\frac{1}{100} + \frac{4}{101} + \frac{7}{102} + \frac{10}{103} + \cdots + \frac{148}{149} > 25

$$

|

a) Since $a k < b k$, then $a b + a k < a b + b k$. This can be written as $a(b+k) < b(a+k)$, or equivalently $\frac{a}{b} < \frac{a+k}{b+k}$.

b) Let $A = \frac{1}{100} + \frac{4}{101} + \frac{7}{102} + \frac{10}{103} + \cdots + \frac{148}{149}$. By applying the above, we deduce

$$

A > \frac{1}{100} + \frac{3}{100} + \frac{5}{100} + \frac{7}{100} + \cdots + \frac{99}{100} = \frac{50 + 2(0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + 49)}{100}

$$

It is sufficient to verify that the latter term equals 25, either by manually calculating the numerator or by using the formula

$$

1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}

$$

which gives

$$

\frac{50 + 2(0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots + 49)}{100} = \frac{50 + 49 \times 50}{100} = 25

$$

|

25

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

a) Prouver que, pour tous réels strictement positifs $a, b, k$ tels que $a<b$, on a

$$

\frac{a}{b}<\frac{a+k}{b+k}

$$

b) Prouver que

$$

\frac{1}{100}+\frac{4}{101}+\frac{7}{102}+\frac{10}{103}+\cdots+\frac{148}{149}>25

$$

|

a) On a $a k<b k$, donc $a b+a k<a b+b k$. Ceci s'écrit $a(b+k)<b(a+k)$, ou encore $\frac{a}{b}<\frac{a+k}{b+k}$.

b) Soit $A=\frac{1}{100}+\frac{4}{101}+\frac{7}{102}+\frac{10}{103}+\cdots+\frac{148}{149}$. En appliquant ce qui précède, on en déduit

$$

A>\frac{1}{100}+\frac{3}{100}+\frac{5}{100}+\frac{7}{100}+\cdots+\frac{99}{100}=\frac{50+2(0+1+2+3+\cdots+49)}{100}

$$

Il suffit donc de vérifier que ce dernier terme vaut 25 , soit en calculant à la main le numérateur, soit en utilisant la formule

$$

1+2+3+\cdots+n=\frac{n(n+1)}{2}

$$

qui donne

$$

\frac{50+2(0+1+2+3+\cdots+49)}{100}=\frac{50+49 \times 50}{100}=25

$$

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

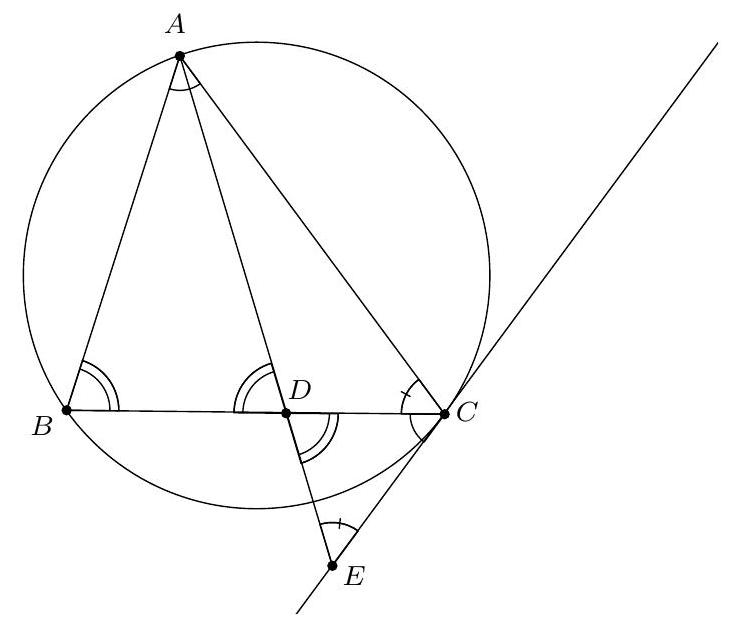

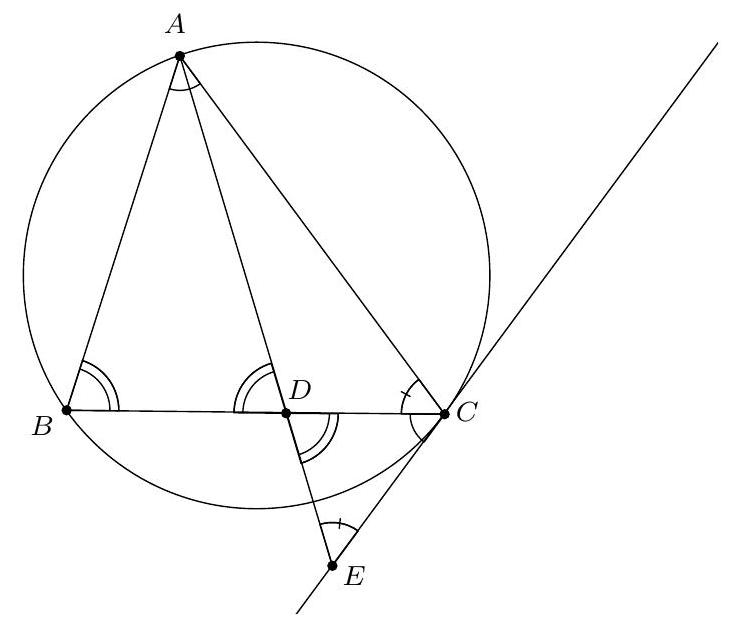

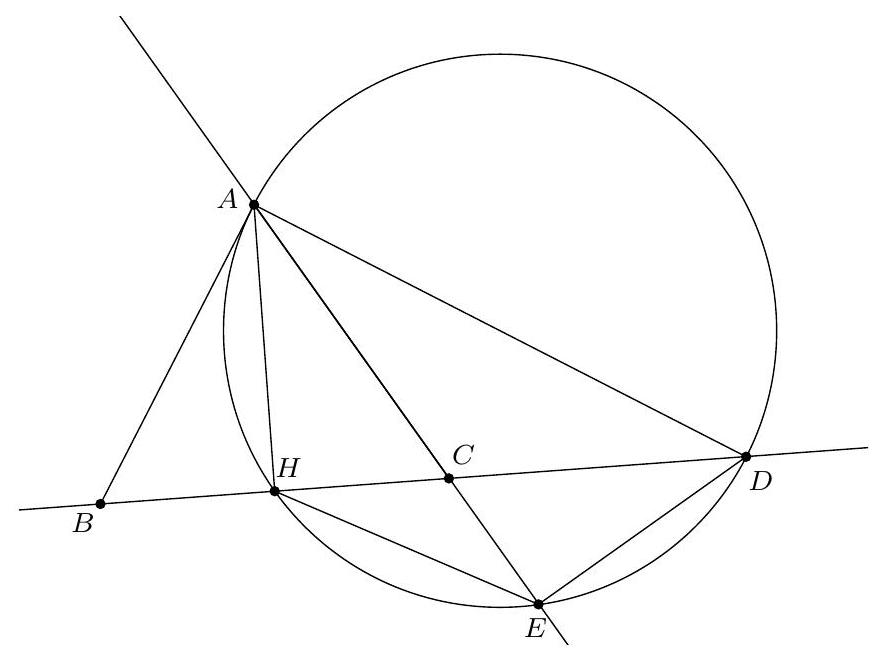

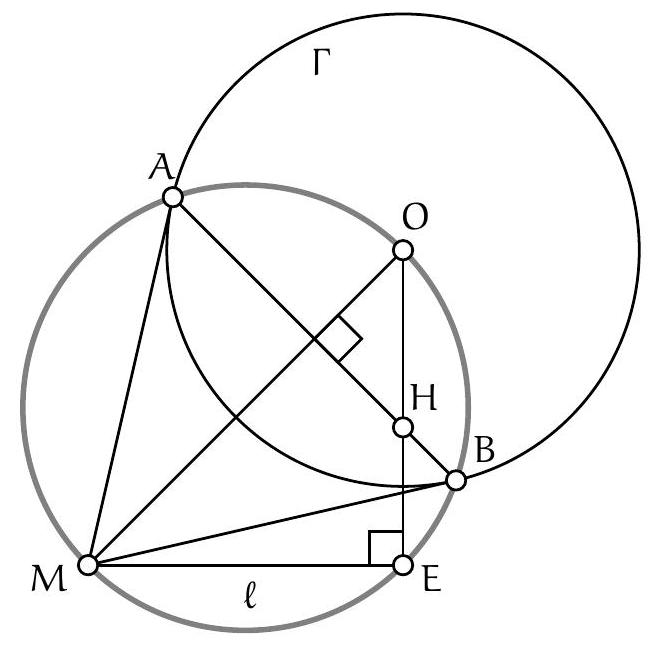

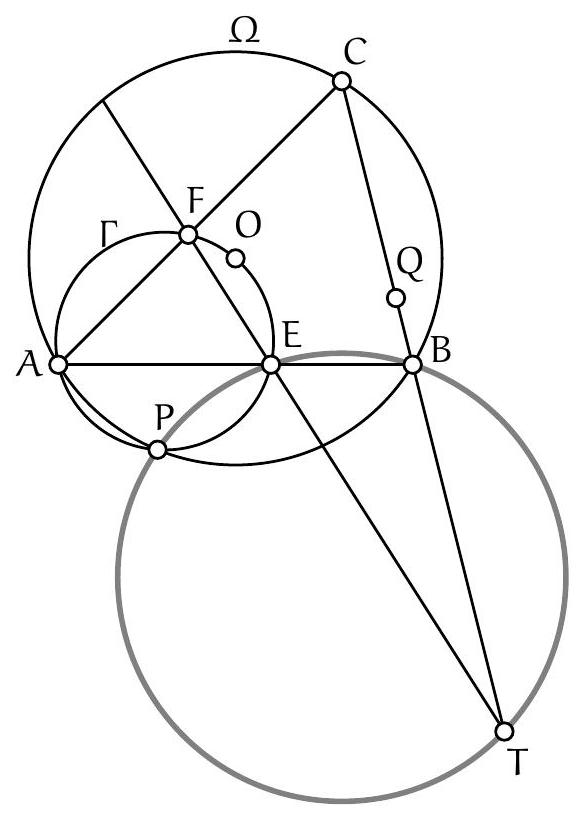

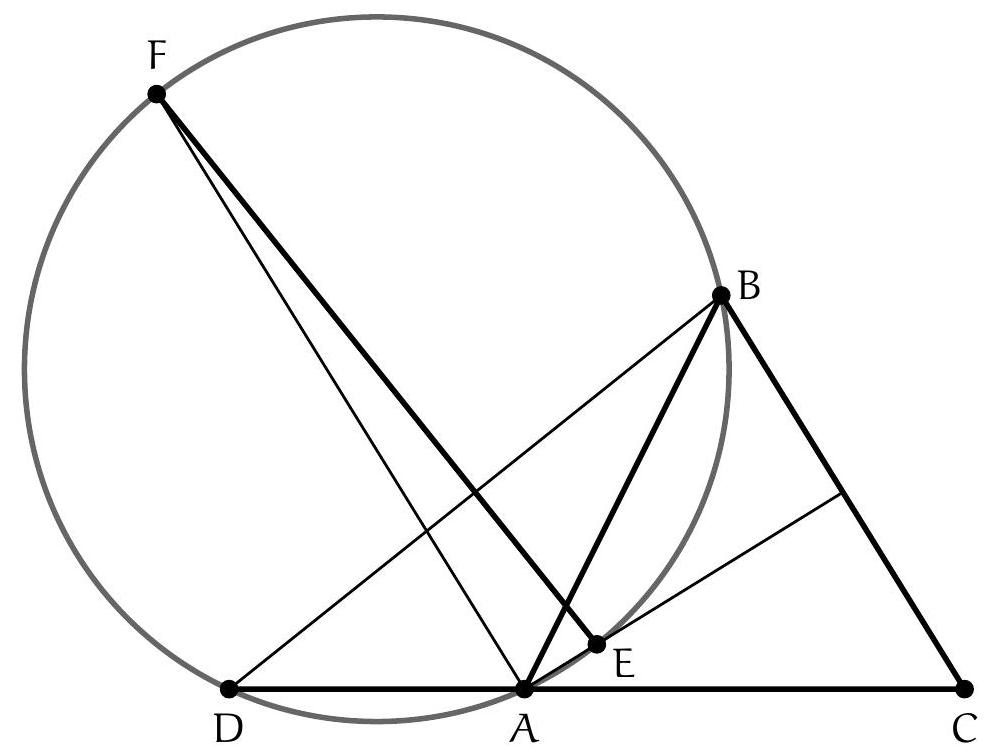

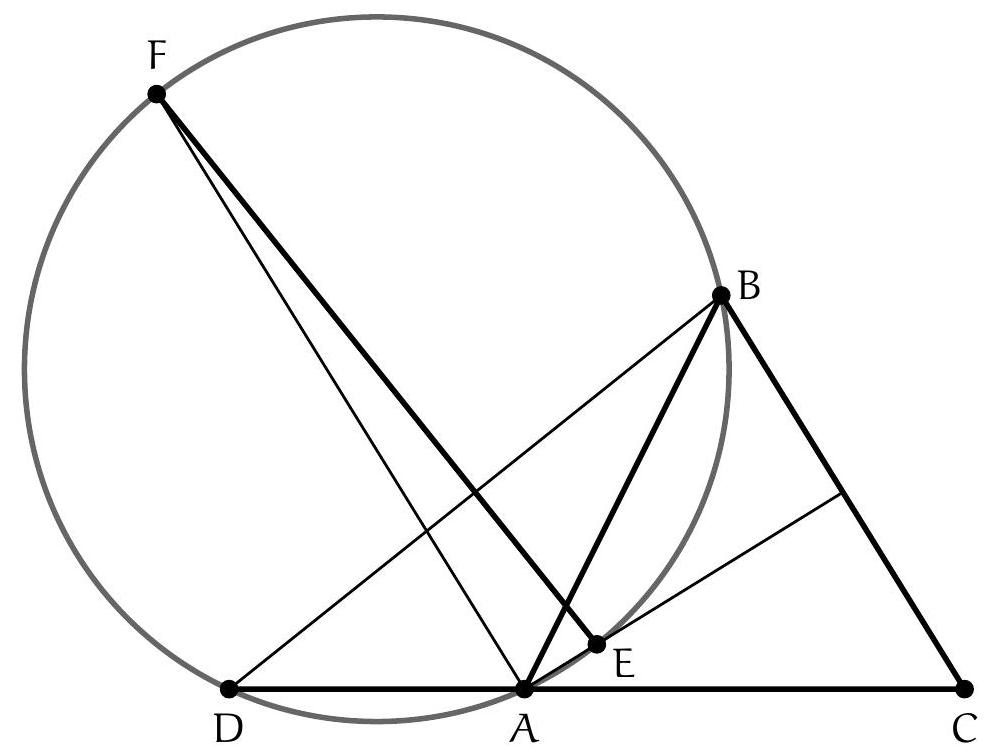

Let $ABC$ be an acute triangle such that $AC > AB$, $D$ on $(BC)$ such that $AD = AB$ and $D$ different from $B$. Let $\Gamma$ be the circumcircle of $ABC$, $\Delta$ the tangent to $\Gamma$ at $C$, and $E$ the intersection of $(AD)$ and $\Delta$.

Show that $CD^2 = AD \cdot DE - BD \cdot DC$.

|

Given that $\widehat{E D C}=\widehat{A D B}=\widehat{C B A}$ and $\widehat{D C E}=\widehat{B A C}$, triangles $A B C$ and $C D E$ are similar. Therefore, we have $\frac{A B}{C D}=\frac{B C}{D E}$, so

$$

A D \cdot D E - B D \cdot D C = A B \cdot D E - B D \cdot D C = B C \cdot C D - B D \cdot C D = (B C - B D) C D = C D^{2} .

$$

|

CD^2 = AD \cdot DE - BD \cdot DC

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle acutangle tel que $A C>A B, D \operatorname{sur}(B C)$ tel que $A D=A B$ et $D$ différent de $B$. Soit $\Gamma$ le cercle circonscrit à $A B C, \Delta$ la tangente à $\Gamma$ en $C, E$ l'intersection de $(A D)$ et $\Delta$.

Montrer que $C D^{2}=A D \cdot D E-B D \cdot D C$.

|

On a $\widehat{E D C}=\widehat{A D B}=\widehat{C B A}$ et $\widehat{D C E}=\widehat{B A C}$ donc $A B C$ et $C D E$ sont semblables. On en déduit que $\frac{A B}{C D}=\frac{B C}{D E}$, donc

$$

A D \cdot D E-B D \cdot D C=A B \cdot D E-B D \cdot D C=B C \cdot C D-B D \cdot C D=(B C-B D) C D=C D^{2} .

$$

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $n$ be a strictly positive integer such that $n(n+2015)$ is the square of an integer.

a) Prove that $n$ is not a prime number.

b) Give an example of such an integer $n$.

|

a) Suppose that $n$ is prime and there exists an integer $m$ satisfying $n(n+2015)=m^{2}$. Then $n$ divides $m^{2}$, so $n$ divides $m$. We can therefore write $m=n r$. It follows that $n(n+2015)=n^{2} r^{2}$, and then $n+2015=n r^{2}$. Consequently, $2015=n r^{2}-n=n\left(r^{2}-1\right)$ is divisible by $n$.

Since $2015=5 \times 13 \times 31$, $n$ must be one of the integers 5, 13, 31.

If $n=5$ then $r^{2}-1=13 \times 31=403$, which is impossible because 404 is not a perfect square. Similarly, $5 \times 31+1=156$ and $5 \times 13+1=66$ are not perfect squares, which rules out the cases $n=13$ and $n=31$.

b) We seek integers $n$ and $m$ such that

$$

(2 m)^{2}=4 n(n+2015)=(2 n)^{2}+2 \times(2 n) \times 2015=(2 n+2015)^{2}-2015^{2}

$$

This is equivalent to $2015^{2}=(2 n+2015)^{2}-(2 m)^{2}=(2 n+2015+2 m)(2 n+2015-2 m)$.

Let $a=2015 \times 5$ and $b=\frac{2015}{5}$. It suffices that

$$

2 n+2015+2 m=a \text { and } 2 n+2015-2 m=b

$$

By adding these equations, we find that $4 n+4030=a+b=403 \times 25+403$, so $\underline{n=1612}$, and by subtracting we get $4 m=a-b=403 \times 24$ so $m=403 \times 6$.

|

1612

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $n$ un entier strictement positif tel que $n(n+2015)$ est le carré d'un entier.

a) Prouver que $n$ n'est pas un nombre premier.

b) Donner un exemple d'un tel entier $n$.

|

a) Supposons que $n$ est premier et qu'il existe un entier $m$ vérifiant $n(n+2015)=m^{2}$. Alors $n$ divise $m^{2}$, donc $n$ divise $m$. On peut donc écrire $m=n r$. Il vient $n(n+2015)=n^{2} r^{2}$, puis $n+2015=n r^{2}$. Par conséquent, $2015=n r^{2}-n=n\left(r^{2}-1\right)$ est divisible par $n$.

Or, $2015=5 \times 13 \times 31$, donc $n$ est l'un des entiers 5, 13, 31 .

Si $n=5$ alors $r^{2}-1=13 \times 31=403$, ce qui est impossible car 404 n'est pas un carré parfait. De même, $5 \times 31+1=156$ et $5 \times 13+1=66$ ne sont pas des carrés parfaits, ce qui exclut les cas $n=13$ et $n=31$.

b) On cherche $n$ et $m$ entiers tels que

$$

(2 m)^{2}=4 n(n+2015)=(2 n)^{2}+2 \times(2 n) \times 2015=(2 n+2015)^{2}-2015^{2}

$$

Ceci équivaut à $2015^{2}=(2 n+2015)^{2}-(2 m)^{2}=(2 n+2015+2 m)(2 n+2015-2 m)$.

Soient $a=2015 \times 5$ et $b=\frac{2015}{5}$. Il suffit donc que

$$

2 n+2015+2 m=a \text { et } 2 n+2015-2 m=b

$$

En additionnant ces égalités, on trouve que $4 n+4030=a+b=403 \times 25+403$, donc $\underline{n=1612}$, et en soustrayant on obtient $4 m=a-b=403 \times 24$ donc $m=403 \times 6$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

We want to color the three-element parts of $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\}$, such that if two of these parts have no element in common, then they must be of different colors. What is the minimum number of colors needed to achieve this goal?

|

Consider the sequence of sets $\{1,2,3\},\{4,5,6\},\{1,2,7\},\{3,4,6\},\{1,5,7\},\{2,3,6\},\{4,5,7\}$, $\{1,2,3\}$.

Each set must have a different color from the next, so there must be at least two colors. If there were exactly two colors, then the colors would have to alternate, which is impossible because the last set is the same as the first and should be of the opposite color.

Conversely, let's show that three colors suffice:

- We color blue the sets that contain at least two elements among 1, 2, 3.

- We color green the sets not colored blue and that contain at least two elements among 4, 5, 6.

- We color red the sets not colored blue or green.

It is clear that two blue sets have an element in common among 1, 2, 3; similarly, two green sets have an element in common among 4, 5, 6. Finally, any red set contains three elements, which necessarily includes the element 7: two red sets therefore also have an element in common.

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On veut colorier les parties à trois éléments de $\{1,2,3,4,5,6,7\}$, de sorte que si deux de ces parties n'ont pas d'élément en commun alors elles soient de couleurs différentes. Quel est le nombre minimum de couleurs pour réaliser cet objectif?

|

Considérons la suite de parties $\{1,2,3\},\{4,5,6\},\{1,2,7\},\{3,4,6\},\{1,5,7\},\{2,3,6\},\{4,5,7\}$, $\{1,2,3\}$.

Chaque partie doit avoir une couleur différente de la suivante, donc déjà il y a au moins deux couleurs. S'il n'y avait qu'exactement deux couleurs, alors les couleurs devraient alterner, ce qui est impossible car la dernière partie est la même que la première et devrait être de couleur opposée.

Réciproquement, montrons que trois couleurs suffisent:

- On colorie en bleu les parties qui contiennent au moins deux éléments parmi 1, 2, 3.

- On colorie en vert les parties non coloriées en bleu et qui contiennent au moins deux éléments parmi 4, 5, 6 .

- On colorie en rouge les parties non coloriées en bleu ou en vert.

Il est évident que deux parties bleues ont un élément en commun parmi 1, 2, 3 ; de même, deux parties vertes ont un élément en commun parmi $4,5,6$. Enfin, toute partie rouge contient trois éléments, dont contient nécessairement l'élément 7 : deux parties rouges ont donc également un élément en commun.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

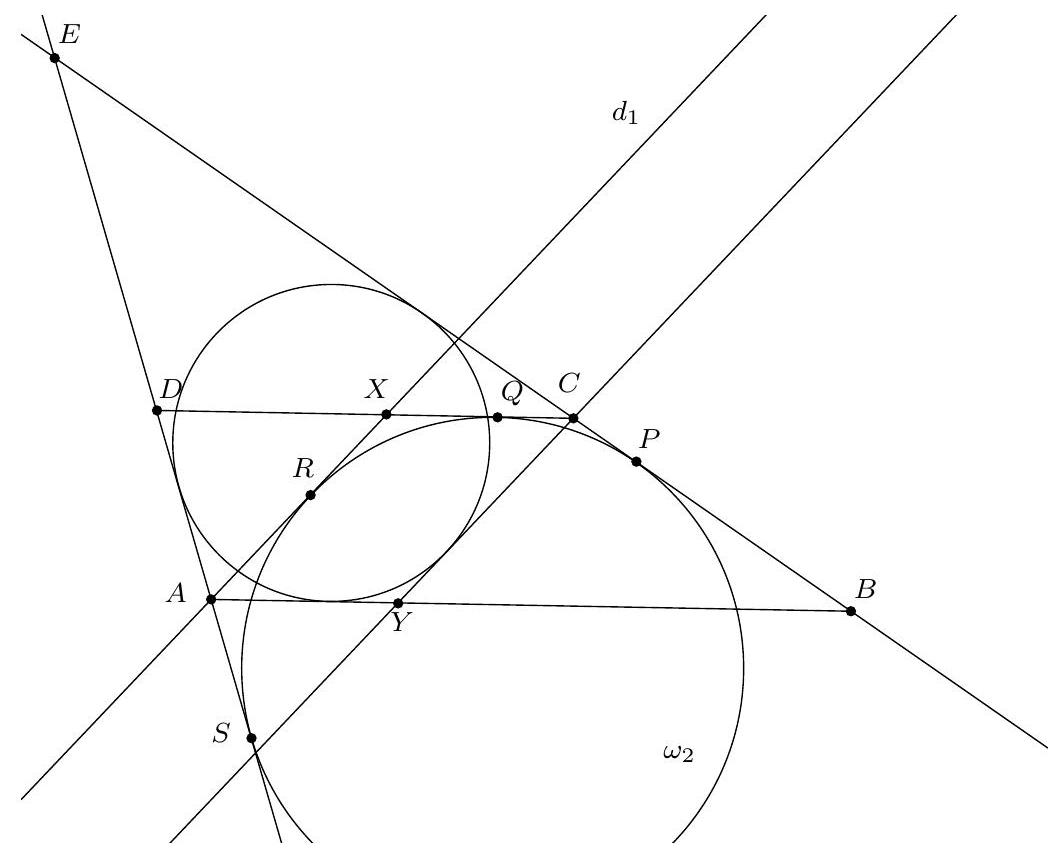

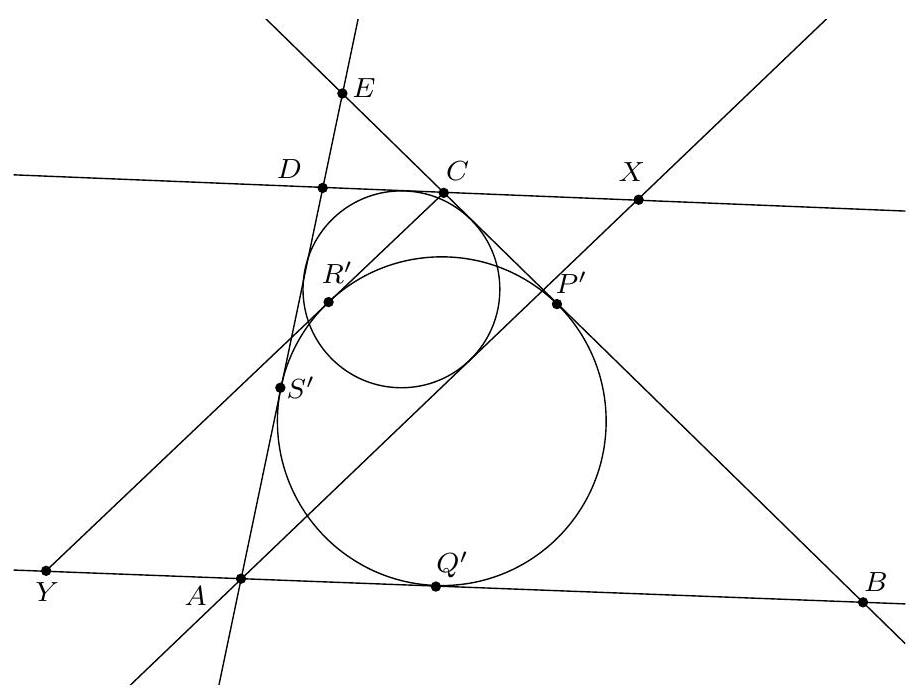

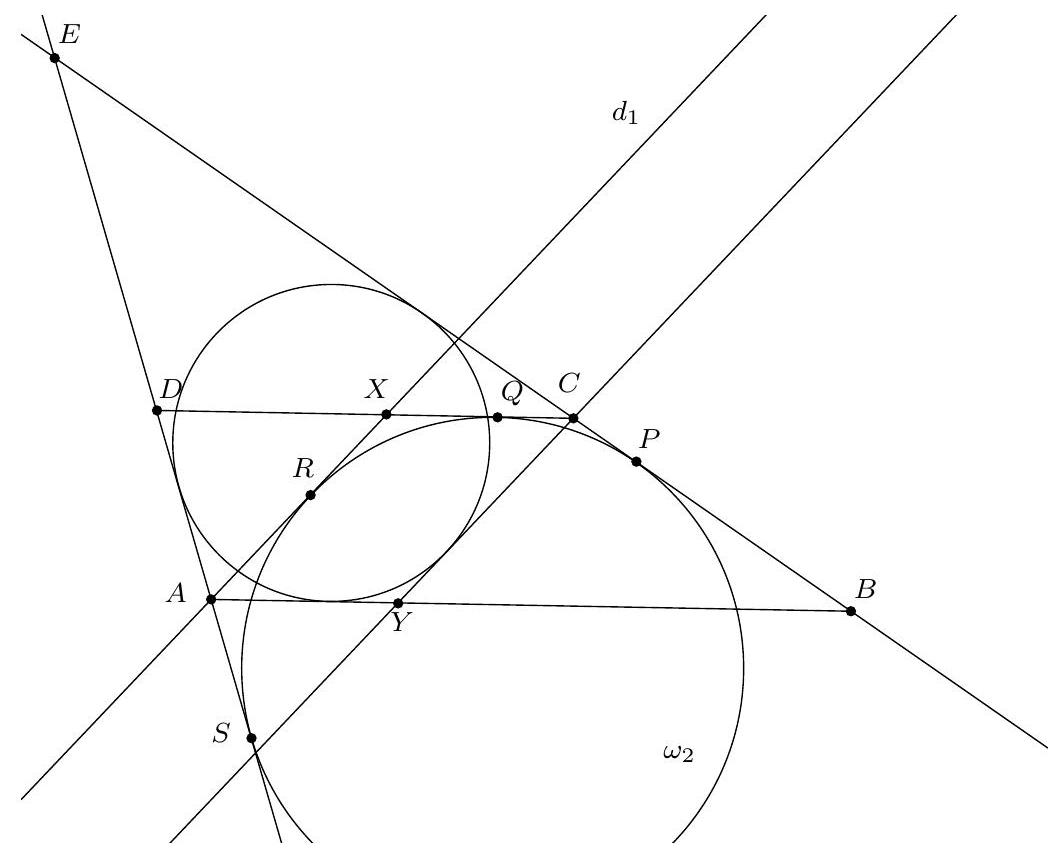

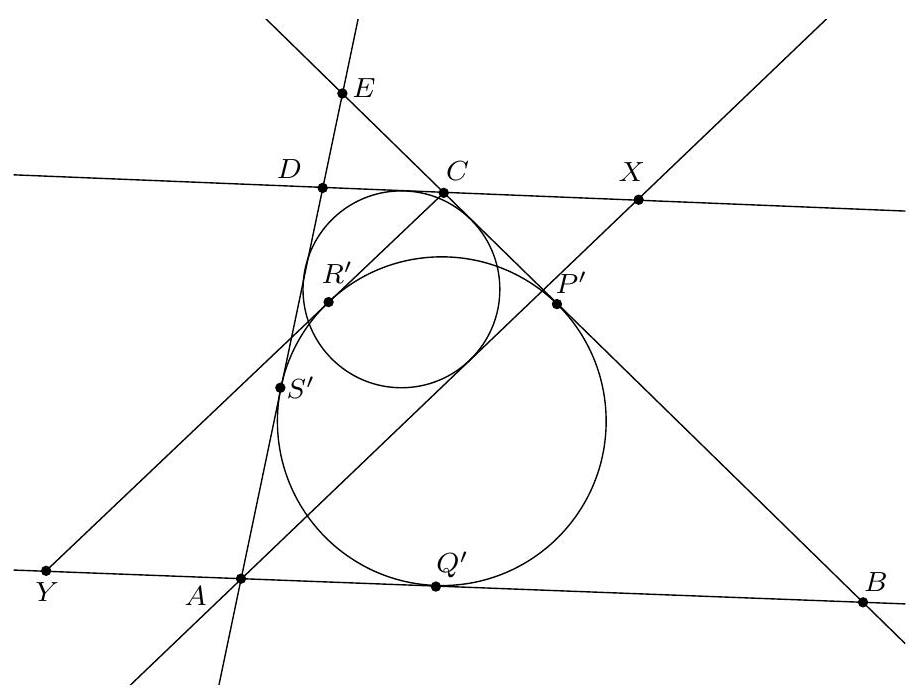

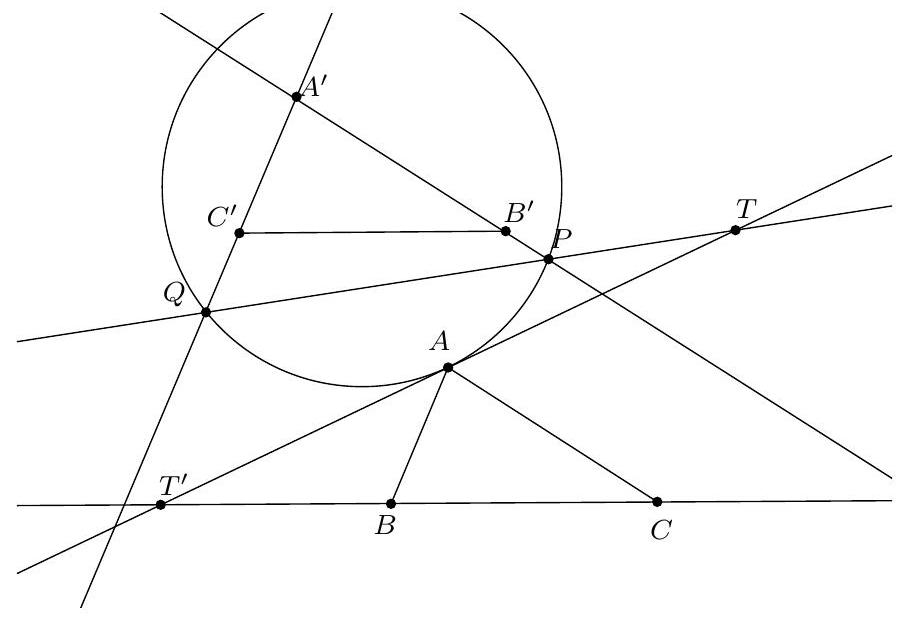

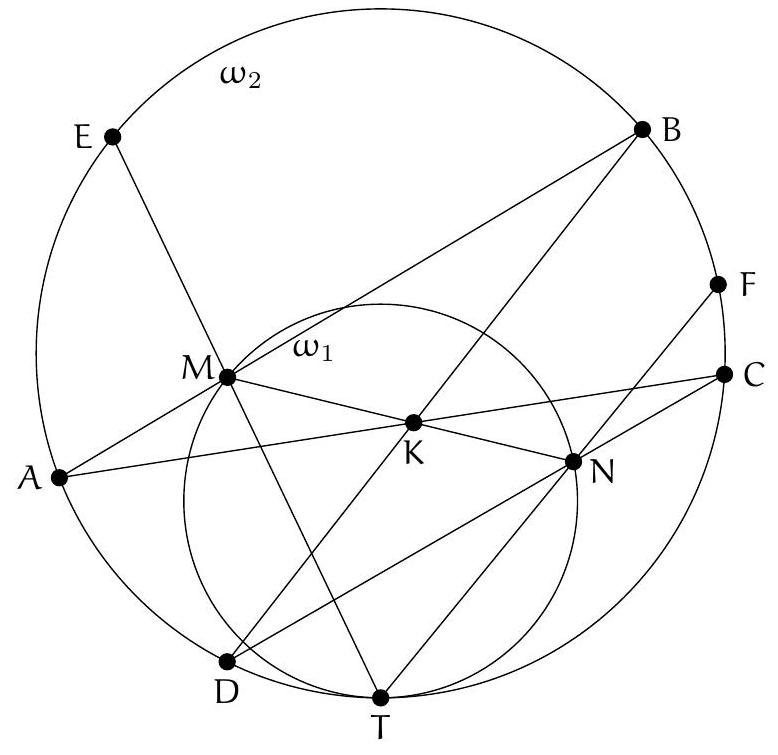

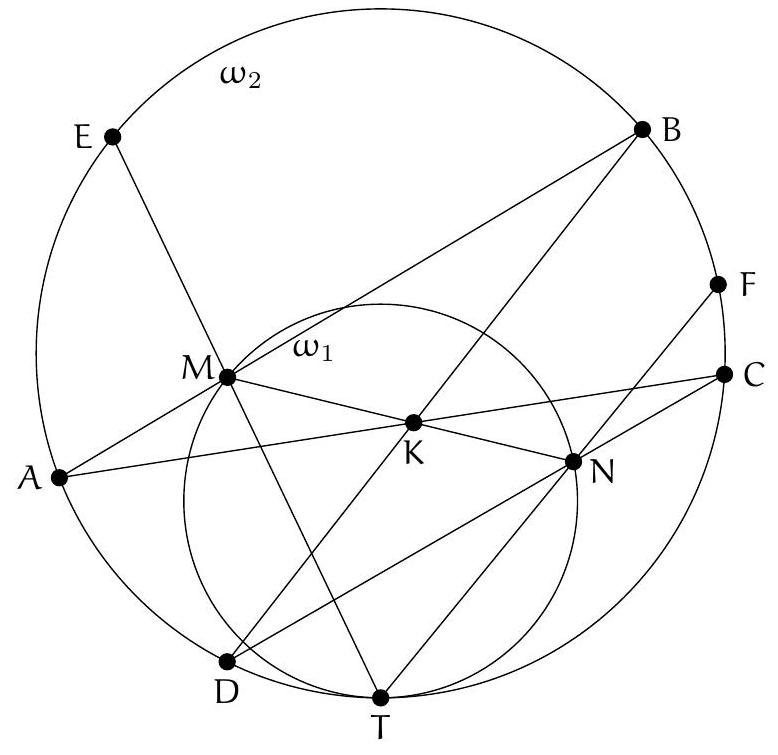

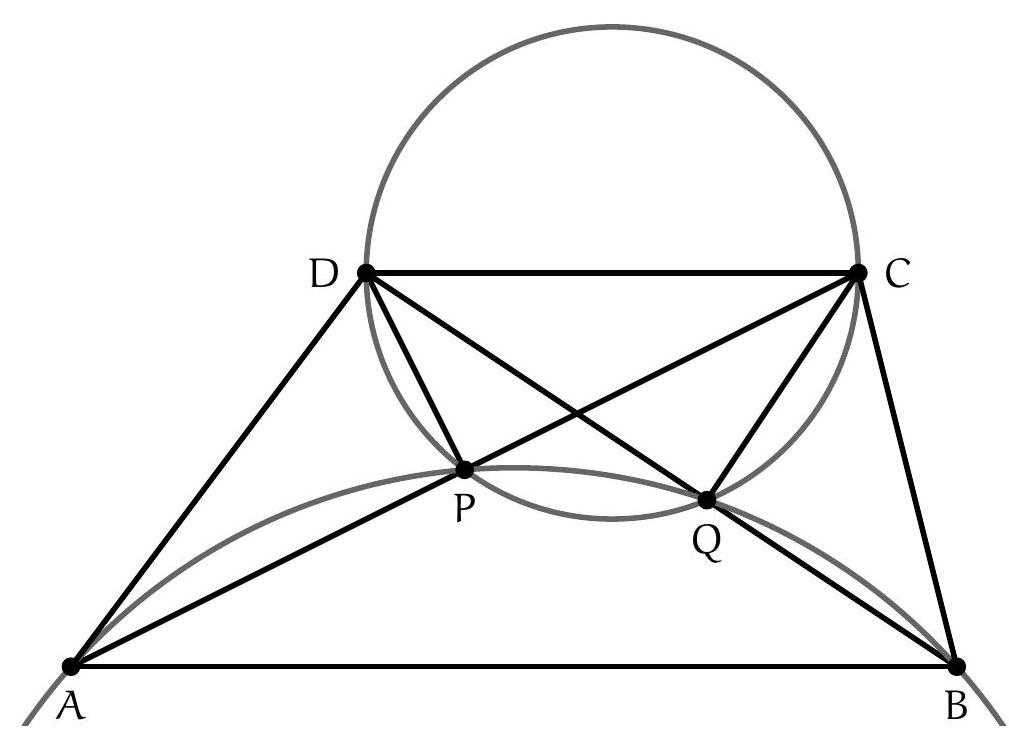

Let $ABCD$ be a trapezoid such that $(AB) / /(CD)$. Two circles $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ are located inside the trapezoid such that $\omega_{1}$ is tangent to $(DA)$, $(AB)$, $(BC)$ and $\omega_{2}$ is tangent to $(BC)$, $(CD)$, $(DA)$. Let $d_{1}$ be a line passing through $A$, other than $(AD)$, tangent to $\omega_{2}$. Let $d_{2}$ be a line passing through $C$, other than $(CB)$, tangent to $\omega_{1}$. Show that $d_{1} / / d_{2}$.

|

By continuity, we can assume that $A B \neq C D$. Furthermore, by swapping $A$ and $B$ with $C$ and $D$, as well as $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$, we can assume $A B > C D$.

Let $E$ be the intersection of $(A D)$ and $(B C)$. Suppose that $(C D)$ intersects $\omega_{1}$.

We denote $P, Q, R, S$ as the points of tangency of $\omega_{2}$ with $(B C), (C D), d_{1}, (D A)$. Let $X$ be the intersection of $(C D)$ with $d_{1}$. Let $d_{2}^{\prime}$ be the line parallel to $d_{1}$ passing through $C$ and $Y = (A B) \cap d_{2}^{\prime}$. We orient the lines such that the algebraic measures $\overline{E A}, \overrightarrow{A B}, \overline{B C}, \overline{D C}, \overline{A X}, \overline{Y C}$ are positive.

\[

\begin{aligned}

(E A + Y C) - (C E + A Y) & = (\overline{E A} + \overline{Y C}) - (\overline{C E} + \overline{A Y}) \\

& = \overline{E S} + \overline{S A} + \overline{A X} - \overline{C P} - \overline{P E} - \overline{X C} \\

& = \overline{S A} + \overline{A X} - \overline{C P} - \overline{X C} \text{ since } \overline{E S} = \overline{P E} \\

& = \overline{R A} + \overline{A X} - \overline{X Q} = \overline{R X} - \overline{X Q} = 0

\end{aligned}

\]

Thus, $E A Y C$ is circumscribed. It follows that $d_{2}^{\prime} = (C Y) = d_{2}$, so $d_{1} \parallel d_{2}$.

If now $(C D)$ does not intersect $\omega_{1}$, we define this time $d_{1}^{\prime}$ as the line parallel to $d_{2}$ passing through $A$, $X = (C D) \cap d_{1}^{\prime}$, and $Y = (A B) \cap d_{2}$. We show as above that $E A X C$ is circumscribed (the proof is left to the reader).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C D$ un trapèze tel que $(A B) / /(C D)$. Deux cercles $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$ sont situés à l'intérieur du trapèze de sorte que $\omega_{1}$ est tangent à $(D A),(A B),(B C)$ et $\omega_{2}$ est tangent à $(B C),(C D),(D A)$. Soit $d_{1}$ une droite passant par $A$, autre que $(A D)$, tangente à $\omega_{2}$. Soit $d_{2}$ une droite passant par $C$, autre que $(C B)$, tangente à $\omega_{1}$. Montrer que $d_{1} / / d_{2}$.

|

Par continuité, on peut supposer que $A B \neq C D$. De plus, quitte à échanger $A$ et $B$ avec $C$ et $D$, ainsi que $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$, on peut supposer $A B>C D$.

Soit $E$ l'intersection de $(A D)$ et $(B C)$. Supposons que $(C D)$ coupe $\omega_{1}$.

On note $P, Q, R, S$ les points de contact de $\omega_{2}$ avec $(B C),(C D), d_{1},(D A)$. Soit $X$ l'intersection de $(C D)$ avec $d_{1}$. Soit $d_{2}^{\prime}$ la parallèle à $d_{1}$ passant par $C$ et $Y=(A B) \cap d_{2}^{\prime}$. On oriente les droites de sorte que les mesures algébriques $\overline{E A}, \overrightarrow{A B}, \overline{B C}, \overline{D C}, \overline{A X}, \overline{Y C}$ soient positives.

$$

\begin{aligned}

(E A+Y C)-(C E+A Y) & =(\overline{E A}+\overline{Y C})-(\overline{C E}+\overline{A Y}) \\

& =\overline{E S}+\overline{S A}+\overline{A X}-\overline{C P}-\overline{P E}-\overline{X C} \\

& =\overline{S A}+\overline{A X}-\overline{C P}-\overline{X C} \operatorname{car} \overline{E S}=\overline{P E} \\

& =\overline{R A}+\overline{A X}-\overline{X Q}=\overline{R X}-\overline{X Q}=0

\end{aligned}

$$

donc $E A Y C$ est circonscriptible. Il vient $d_{2}^{\prime}=(C Y)=d_{2}$, donc $d_{1} / / d_{2}$.

Si maintenant $(C D)$ ne coupe pas $\omega_{1}$, on définit cette fois $d_{1}^{\prime}$ la parallèle à $d_{2}$ passant par $A$, $X=(C D) \cap d_{1}^{\prime}$ et $Y=(A B) \cap d_{2}$. On montre comme ci-dessus que EAXC est circonscriptible (la preuve est laissée au lecteur).

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be strictly positive integers. For all $k=1,2, \ldots, n$, we denote

$$

m_{k}=\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq k} \frac{a_{k-\ell+1}+a_{k-\ell+2}+\cdots+a_{k}}{\ell} .

$$

Show that for any $\alpha>0$, the number of integers $k$ such that $m_{k}>\alpha$ is strictly less than $\frac{a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}}{\alpha}$.

|

Let $k_{1}$ be the largest integer $k$ such that $m_{k}>\alpha$. There exists $\ell_{1}$ such that $a_{k_{1}-\ell_{1}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{1}}>\ell_{1} \alpha$.

Let $k_{2}$ be the largest integer $\leqslant k_{1}-\ell_{1}$ such that $m_{k}>\alpha$. There exists $\ell_{2}$ such that $a_{k_{2}-\ell_{2}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{2}}>\ell_{2} \alpha$. ...

We thus construct a finite sequence $k_{1}>k_{2}>\cdots>k_{r}$ such that any integer $k$ satisfying $m_{k}>\alpha$ is found in one of the intervals $I_{j}=\llbracket k_{j}-\ell_{j}+1, k_{j} \rrbracket$. Moreover, these intervals are pairwise disjoint.

Consequently, the number of integers $k$ such that $m_{k}>\alpha$ is less than or equal to the sum of the lengths of the intervals, namely $\ell_{1}+\cdots+\ell_{r}$.

Now, $\sum_{j=1}^{r} \ell_{j}<\frac{1}{\alpha} \sum_{j}\left(a_{k_{j}-\ell_{j}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{j}}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{\alpha}\left(a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}\right)$. QED.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ des entiers strictement positifs. Pour tout $k=1,2, \ldots, n$, on note

$$

m_{k}=\max _{1 \leq \ell \leq k} \frac{a_{k-\ell+1}+a_{k-\ell+2}+\cdots+a_{k}}{\ell} .

$$

Montrer que pour tout $\alpha>0$, le nombre d'entiers $k$ tel que $m_{k}>\alpha$ est strictement plus petit que $\frac{a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{n}}{\alpha}$.

|

Soit $k_{1}$ le plus grand entier $k$ tel que $m_{k}>\alpha$. Il existe $\ell_{1}$ tel que $a_{k_{1}-\ell_{1}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{1}}>\ell_{1} \alpha$.

Soit $k_{2}$ le plus grand entier $\leqslant k_{1}-\ell_{1}$ tel que $m_{k}>\alpha$. Il existe $\ell_{2}$ tel que $a_{k_{2}-\ell_{2}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{2}}>\ell_{2} \alpha$. ...

On construit ainsi une suite finie $k_{1}>k_{2}>\cdots>k_{r}$ telle que tout entier $k$ vérifiant $m_{k}>\alpha$ se trouve dans l'un des intervalles $I_{j}=\llbracket k_{j}-\ell_{j}+1, k_{j} \rrbracket$. De plus, ces intervalles sont deux à deux disjoints.

Par conséquent, le nombre d'entiers $k$ tels que $m_{k}>\alpha$ est inférieur ou égal à la somme des longueurs des intervalles, à savoir $\ell_{1}+\cdots+\ell_{r}$.

Or, $\sum_{j=1}^{r} \ell_{j}<\frac{1}{\alpha} \sum_{j}\left(a_{k_{j}-\ell_{j}+1}+\cdots+a_{k_{j}}\right) \leqslant \frac{1}{\alpha}\left(a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}\right)$. CQFD.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $a, b, c, n$ be integers, with $n \geq 2$. Let $p$ be a prime number that divides $a^{2}+a b+b^{2}$ and $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$, but does not divide $a+b+c$.

Prove that $n$ and $p-1$ are not coprime.

|

If $p$ divides $a$ and $b$, then $p$ divides $c^{n}$, hence $p$ divides $c$, which contradicts the last assertion. Therefore, by possibly swapping $a$ and $b$, we assume that $p$ does not divide $b$. By possibly multiplying $a, b, c$ by an inverse of $b$ modulo $p$, we can assume that $b=1$ and thus

$$

p \mid a^{2}+a+1, \quad p \mid a^{n}+1+c^{n}, \quad p \nmid a+1+c.

$$

Since $a^{2}+a+1$ is odd, $p$ is also odd.

Since $p$ divides $\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)(a-1)=a^{3}-1$, the order of $a$ modulo $p$ is 1 or 3.

First case: $a \equiv 1 \pmod{p}$. Then $p=3$, so $c^{n} \equiv -1 - a^{n} \equiv 1 \pmod{3}$.

In particular, $c$ is invertible modulo 3, so $c \equiv \pm 1 \pmod{3}$. Since $p \nmid a+1+c$, we must have $c \equiv -1 \pmod{3}$. Finally, since $c^{n} \equiv 1 \pmod{3}$, the integer $n$ is even, hence not coprime with $p-1$.

Second case: the order of $a$ modulo $p$ is 3. Since the order of $a$ modulo $p$ also divides $p-1$ by Fermat's little theorem, we have $3 \mid p-1$.

Suppose that $n$ is coprime with $p-1$. Then $x \mapsto x^{n}$ is a bijection from $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ to itself:

- if $n \equiv 1 \pmod{3}$ then $c^{n} \equiv -a^{n} - 1 \equiv -a - 1 \equiv a^{2} \equiv (a^{2})^{n} \pmod{p}$, so by the bijectivity of $x \mapsto x^{n}$ in $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ we have $c \equiv a^{2} \equiv -a - 1 \pmod{p}$: contradiction!

- if $n \equiv 2 \pmod{3}$ then $c^{n} \equiv -a^{n} - 1 \equiv -a^{2} - 1 \equiv a \equiv (a^{2})^{n} \pmod{p}$, so by the bijectivity of $x \mapsto x^{n}$ in $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ we have $c \equiv a^{2} \equiv -a - 1 \pmod{p}$: contradiction!

We conclude that $n \equiv 0 \pmod{3}$, so 3 is a common divisor of $n$ and $p-1$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $a, b, c, n$ des entiers, avec $n \geq 2$. Soit $p$ un nombre premier qui divise $a^{2}+a b+b^{2}$ et $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$, mais qui ne divise pas $a+b+c$.

Prouver que $n$ et $p-1$ ne sont pas premiers entre eux.

|

Si $p$ divise $a$ et $b$, alors $p$ divise $c^{n}$ donc $p$ divise $c$, ce qui contredit la dernière assertion. Donc, quitte à échanger $a$ et $b$, on suppose que $p$ ne divise pas $b$. Quitte à multiplier $a, b, c$ par un inverse de $b$ modulo $p$, on peut supposer que $b=1$ et donc

$$

p\left|a^{2}+a+1, \quad p\right| a^{n}+1+c^{n}, \quad p \nmid a+1+c .

$$

Comme $a^{2}+a+1$ est impair, $p$ l'est aussi.

Comme $p$ divise $\left(a^{2}+a+1\right)(a-1)=a^{3}-1$, l'ordre de $a$ modulo $p$ est 1 ou 3 .

Premier cas: $a \equiv 1(\bmod p)$. Alors $p=3$, donc $c^{n} \equiv-1-a^{n} \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$.

En particulier, $c$ est inversible modulo 3 , donc $c \equiv \pm 1(\bmod 3)$. Comme $p \nmid a+1+c$, on a nécessairement $c \equiv-1(\bmod 3)$. Enfin, comme $c^{n} \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$, l'entier $n$ est pair donc n'est pas premier avec $p-1$.

Deuxième cas: l'ordre de $a$ modulo $p$ est 3 . Comme par ailleurs l'ordre de $a$ modulo $p$ divise $p-1$ en vertu du petit théorème de Fermat, on a $3 \mid p-1$.

Supposons que $n$ est premier avec $p-1$. Alors $x \mapsto x^{n}$ est une bijection de $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ sur lui-même :

- si $n \equiv 1(\bmod 3)$ alors $c^{n} \equiv-a^{n}-1 \equiv-a-1 \equiv a^{2} \equiv\left(a^{2}\right)^{n}(\bmod p)$ donc par bijectivité de $x \mapsto x^{n}$ dans $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ on a $c \equiv a^{2} \equiv-a-1(\bmod p):$ contradiction!

- si $n \equiv 2(\bmod 3)$ alors $c^{n} \equiv-a^{n}-1 \equiv-a^{2}-1 \equiv a \equiv\left(a^{2}\right)^{n}(\bmod p)$ donc par bijectivité de $x \mapsto x^{n}$ dans $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ on a $c \equiv a^{2} \equiv-a-1(\bmod p):$ contradiction!

On en déduit que $n \equiv 0(\bmod 3)$, donc 3 est un diviseur commun de $n$ et de $p-1$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2014-2015-ofm-2014-2015-test-janvier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$ be real numbers such that $a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{2 n}=0$.

Prove that there exist at least $2 n-1$ pairs $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ with $i<j$ such that $a_{i}+a_{j} \geqslant 0$.

|

Without loss of generality, we can assume that $a_{1} \leq a_{2} \leq \cdots \leq a_{2 n}$. We distinguish two cases:

- If $a_{n}+a_{2 n-1} \geq 0$ then we have $a_{i}+a_{2 n-1} \geq 0$ for $i=n, \cdots, 2 n-2$, and $a_{i}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$ for $i=n \cdots, 2 n-1$. This provides at least $2 n-1$ non-negative sums.

- If $a_{n}+a_{2 n-1}<0$ then

$$

a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n-1}+a_{n+1}+\cdots a_{2 n-2}+a_{2 n}>0

$$

On the other hand, we have $0>a_{n}+a_{2 n-1} \geq a_{n-1}+a_{2 n-2} \geq \cdots \geq a_{2}+a_{n+1}$, so

$$

a_{2}+a_{3}+\cdots+a_{n-1}+a_{n+1}+\cdots+a_{2 n-2}<0

$$

From (1) and (2), we deduce that $a_{1}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$, which ensures that $a_{i}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$ for $i=1, \cdots 2 n-1$.

Another solution. Let $b_{1} \leqslant b_{2} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant b_{\ell}$ be the non-negative integers among $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$. First case: $\ell>n$. Then there are at least $\frac{\ell(\ell-1)}{2} \geq \frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ pairs $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ with $i<j, a_{i} \geqslant 0$ and $a_{j} \geqslant 0$. Now, $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}-(2 n-1)=\frac{n^{2}-3 n+2}{2}=\frac{(n-1)(n-2)}{2} \geqslant 0$, so there are at least $2 n-1$ pairs $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ with $i<j$ such that $a_{i}+a_{j} \geqslant 0$.

Second case: $\ell \leqslant n$. Let $c_{1} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant c_{\ell}$ be the smallest integers among $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$. Since $\ell \leqslant n$, we have $c_{\ell}<0$. Moreover, $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n} a_{i}$ is equal to the sum of $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i}\right)$ and negative terms, so $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i}\right) \geqslant 0$. Now, $b_{\ell}+c_{\ell} \geqslant b_{i}+c_{i}$ for all $i$, so $b_{\ell}+c_{\ell} \geqslant 0$.

We thus form $2 n-\ell$ pairs $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ by taking $a_{j}=b_{\ell}$ and $a_{i}$ other than $c_{1}, \ldots, c_{\ell-1}, b_{\ell}$.

Furthermore, for all $k=1, \ldots, \ell-1$, we have $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i+k}\right) \geqslant 0$ (where by convention $c_{\ell+1}=c_{1}$, $c_{\ell+2}=c_{2}$, etc.), so for all $k$ there exists $i$ such that $b_{i}+c_{i+k} \geqslant 0$. This provides $\ell-1$ additional pairs.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$ des réels tels que $a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{2 n}=0$.

Prouver qu'il existe au moins $2 n-1$ couples $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ avec $i<j$ tels que $a_{i}+a_{j} \geqslant 0$.

|

Sans perte de généralité, on peut supposer que $a_{1} \leq a_{2} \leq \cdots \leq a_{2 n}$. On distingue deux cas :

- Si $a_{n}+a_{2 n-1} \geq 0$ alors on a $a_{i}+a_{2 n-1} \geq 0$ pour $i=n, \cdots, 2 n-2$, et $a_{i}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$ pour $i=n \cdots, 2 n-1$. Cela fournit bien $2 n-1$ sommes positives ou nulles.

- Si $a_{n}+a_{2 n-1}<0$ alors

$$

a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n-1}+a_{n+1}+\cdots a_{2 n-2}+a_{2 n}>0

$$

D'autre part, on a $0>a_{n}+a_{2 n-1} \geq a_{n-1}+a_{2 n-2} \geq \cdots \geq a_{2}+a_{n+1}$, donc

$$

a_{2}+a_{3}+\cdots+a_{n-1}+a_{n+1}+\cdots+a_{2 n-2}<0

$$

De (1) et (2), on déduit que $a_{1}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$, ce qui assure que $a_{i}+a_{2 n} \geq 0$ pour $i=1, \cdots 2 n-1$.

Autre solution. Notons $b_{1} \leqslant b_{2} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant b_{\ell}$ les entiers positifs ou nuls parmi $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$. Premier cas: $\ell>n$. Alors il y a au moins $\frac{\ell(\ell-1)}{2} \geq \frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ couples $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ avec $i<j, a_{i} \geqslant 0$ et $a_{j} \geqslant 0$. Or, $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}-(2 n-1)=\frac{n^{2}-3 n+2}{2}=\frac{(n-1)(n-2)}{2} \geqslant 0$, donc il y a au moins $2 n-1$ couples $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ avec $i<j$ tels que $a_{i}+a_{j} \geqslant 0$.

Deuxième cas : $\ell \leqslant n$. Notons $c_{1} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant c_{\ell}$ les plus petits entiers parmi $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$. Comme $\ell \leqslant n$, on a $c_{\ell}<0$. De plus, $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n} a_{i}$ est égal à la somme de $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i}\right)$ et de termes négatifs, donc $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i}\right) \geqslant 0$. Or, $b_{\ell}+c_{\ell} \geqslant b_{i}+c_{i}$ pour tout $i$, donc $b_{\ell}+c_{\ell} \geqslant 0$.

On forme ainsi déjà $2 n-\ell$ couples $\left(a_{i}, a_{j}\right)$ en prenant $a_{j}=b_{\ell}$ et $a_{i}$ autre que $c_{1}, \ldots, c_{\ell-1}, b_{\ell}$.

De plus, pour tout $k=1, \ldots, \ell-1$, on a $\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}\left(b_{i}+c_{i+k}\right) \geqslant 0$ (où par convention $c_{\ell+1}=c_{1}$, $c_{\ell+2}=c_{2}$, etc.), donc pour tout $k$ il existe $i$ tel que $b_{i}+c_{i+k} \geqslant 0$. Ceci fournit encore $\ell-1$ couples supplémentaires.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-decembre-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

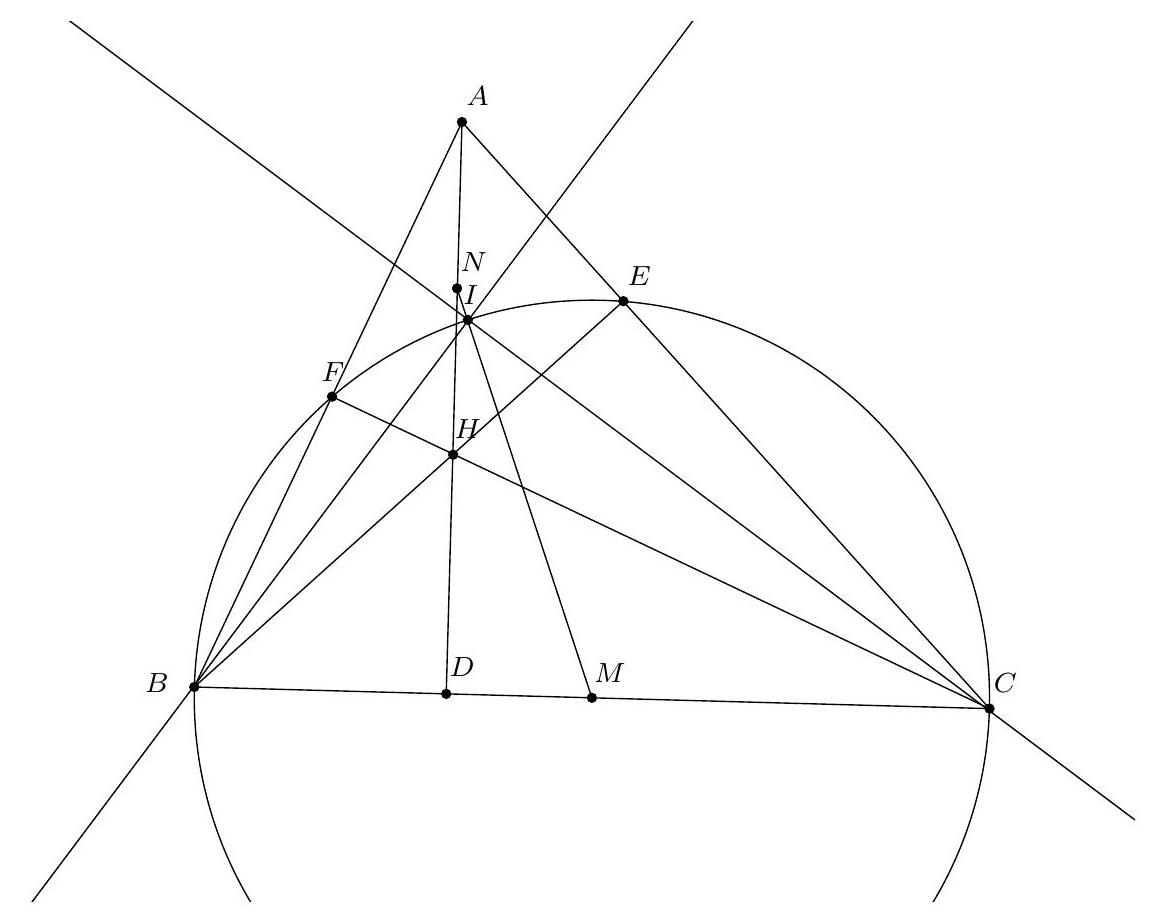

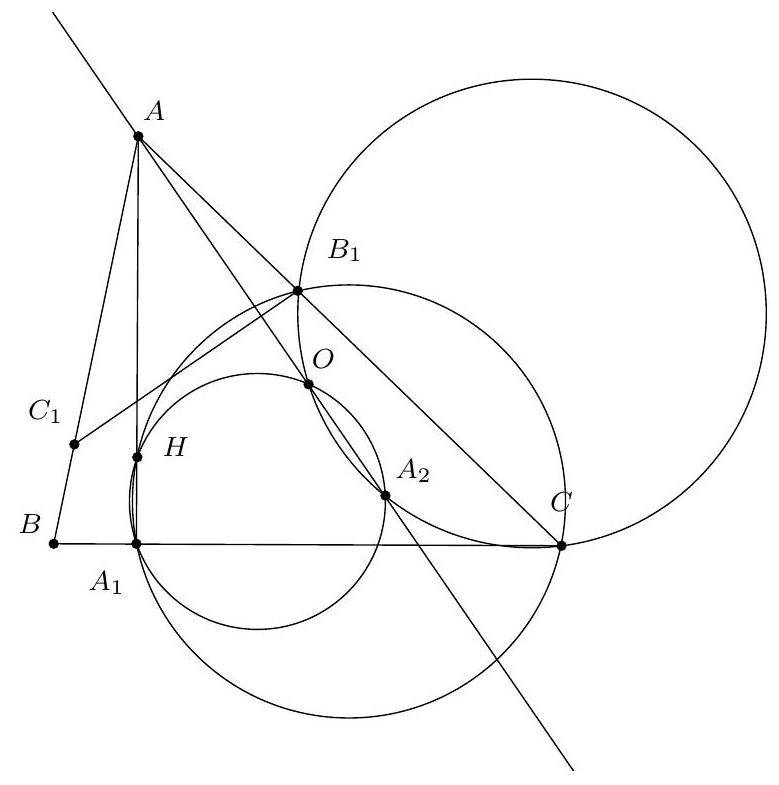

Let $ABC$ be a triangle with all angles acute, and $H$ its orthocenter. The bisectors of $\widehat{ABH}$ and $\widehat{ACH}$ intersect at a point $I$. Show that $I$ is collinear with the midpoints of $[BC]$ and $[AH]$.

|

Let $D, E, F$ be the feet of the altitudes, $O$ the center of the circumcircle, $M$ the midpoint of $[B C]$, and $N$ the midpoint of $[A H]$. We have $2 \overrightarrow{M N}=2 \overrightarrow{O N}-2 \overrightarrow{O M}=\overrightarrow{O A}+\overrightarrow{O H}-\overrightarrow{O B}-\overrightarrow{O C}$.

Since $\overrightarrow{O H}=\overrightarrow{O A}+\overrightarrow{O B}+\overrightarrow{O C}$, it follows that $\overrightarrow{M N}=\overrightarrow{O A}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that $(M I)$ is parallel to $(O A)$.

Since $B C F$ is a right triangle at $F$, the point $F$ lies on the circle centered at $M$ passing through $B$ and $C$. The same applies to point $E$. The angle bisector of $\widehat{A B H}$ passes through the midpoint of the arc $E F$, and similarly for the angle bisector of $\widehat{A C H}$, so $I$ is the midpoint of the arc $E F$. Denoting $C^{\prime}$ as the midpoint of $[A B]$, we deduce the angle equalities $(M I, M B)=2(C I, C B)=$ $(C E, C B)+(C F, C B)=(C A, C B)+(C F, A B)+(A B, C B)$.

On the other hand, $(O A, M B)=\left(O A, O C^{\prime}\right)+\left(O C^{\prime}, A B\right)+(A B, M B)=(C A, C B)+(C F, A B)+$ $(A B, C B)$ because $\left(O C^{\prime}\right)$ and $(C F)$ are parallel.

Therefore, $(O A, M B)=(M I, M B)$, which proves that $(O A)$ and $(M I)$ are parallel.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle dont tous les angles sont aigus, et $H$ son orthocentre. Les bissectrices de $\widehat{A B H}$ et $\widehat{A C H}$ se coupent en un point $I$. Montrer que $I$ est aligné avec les milieux de $[B C]$ et de $[A H]$.

|

Notons $D, E, F$ les pieds des hauteurs, $O$ le centre du cercle circonscrit, $M$ le milieu de $[B C]$ et $N$ le milieu de $[A H]$. On a $2 \overrightarrow{M N}=2 \overrightarrow{O N}-2 \overrightarrow{O M}=\overrightarrow{O A}+\overrightarrow{O H}-\overrightarrow{O B}-\overrightarrow{O C}$.

Or, $\overrightarrow{O H}=\overrightarrow{O A}+\overrightarrow{O B}+\overrightarrow{O C}$ donc $\overrightarrow{M N}=\overrightarrow{O A}$. Par conséquent, il suffit de montrer que ( $M I$ ) est parallèle à $(O A)$.

Comme $B C F$ est un triangle rectangle en $F$, le point $F$ est situé sur le cercle de centre $M$ passant par $B$ et $C$. Il en va de même pour le point $E$. La bissectrice de $\widehat{A B H}$ passe par le milieu de l'arc $E F$, et de même pour la bissectrice de $\widehat{A C H}$, donc $I$ est le milieu de l'arc $E F$. En notant $C^{\prime}$ le milieu de $[A B]$, on en déduit les égalités d'angles de droites $(M I, M B)=2(C I, C B)=$ $(C E, C B)+(C F, C B)=(C A, C B)+(C F, A B)+(A B, C B)$.

D'autre part, $(O A, M B)=\left(O A, O C^{\prime}\right)+\left(O C^{\prime}, A B\right)+(A B, M B)=(C A, C B)+(C F, A B)+$ $(A B, C B)$ car $\left(O C^{\prime}\right)$ et $(C F)$ sont parallèles.

Par conséquent, $(O A, M B)=(M I, M B)$, ce qui prouve que $(O A)$ et $(M I)$ sont parallèles.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-decembre-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

For any integer $n \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$, we denote $v_{3}(n)$ as the 3-adic valuation of $n$, which is the greatest integer $k$ such that $n$ is divisible by $3^{k}$. We set $u_{1}=2$ and $u_{n}=4 v_{3}(n)+2-\frac{2}{u_{n-1}}$ for all $n \geqslant 2$ (provided that $u_{n-1}$ is defined and non-zero).

Show that, for any positive rational number $q$, there exists a unique integer $n \geqslant 1$ such that $u_{n}=q$.

|

First, note that $u_{1}=2, u_{2}=1, u_{3}=3, u_{4}=\frac{3}{2}, u_{5}=\frac{2}{3}$ and $u_{6}=3$. We prove by induction that, for all integers $n \geq 2$, we have $0<u_{n}$ and

$$

0<u_{3 n-1}<1<u_{3 n-2}<2<u_{3 n}=2+u_{n}:

$$

this is already true for $n=2$.

Since $u_{3 n}=u_{n}+2$, we show successively that $u_{3 n+1}, u_{3 n+2}$ and $u_{3 n+3}$ are well defined, with

$$

\begin{aligned}

& u_{3 n+1}=2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n}}=1+\frac{u_{n}}{2+u_{n}}, \text { so } 1<u_{3 n+1}<2 ; \\

& u_{3 n+2}=2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n+1}}=1+\frac{u_{n}}{1+u_{n}}, \text { so } 0<u_{3 n+2}<1 ; \\

& u_{3 n+3}=4 v_{3}(3(n+1))+2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n+2}}=4 v_{3}(n)+4-\frac{2}{u_{n}}=2+u_{n+1} .

\end{aligned}

$$

This concludes the induction.

Now, consider the function $\varphi:\{x \in \mathbb{Q}: 0<x$ and $x \notin\{1,2\}\} \mapsto\{x \in \mathbb{Q}: 0<x\}$ such that

$$

\begin{aligned}

\varphi: & x \mapsto \frac{x}{1-x} \text { if } 0<x<1 ; \\

& x \mapsto 2 \frac{x-1}{2-x} \text { if } 1<x<2 ; \\

& x \mapsto x-2 \text { if } 2<x

\end{aligned}

$$

Furthermore, for any irreducible fraction $\frac{p}{q}$, with $p \geq 0$ and $q>0$, we set $\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|=p+q$. Then:

- $\left\|\varphi\left(\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|\frac{p}{q-p}\right\|=p<p+q=\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ if $0<p<q$;

- $\left\|\varphi\left(1+\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|2 \frac{p}{q-p}\right\| \leq 2 q<(p+q)+q=\left\|1+\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ if $0<p<q$;

- $\left\|\varphi\left(2+\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|=p+q<(p+2 q)+q=\left\|2+\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ if $0<p$ and $0<q$.

In all cases, if $x$ is a positive rational number such that $x \notin\{1,2\}$, we have $\|\varphi(x)\|<\|x\|$. Now, for any positive rational number $x$ and for all integers $n \geq 1$:

- if $0<x<1$, then $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n+2}=x$;

- if $1<x<2$, then $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n+1}=x$;

- if $2<x$, then $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n}=x$.

An induction on $\|x\|$ immediately shows that, for any positive rational number $x$, there exists a unique integer $n \geq 1$ such that $u_{n}=x$, which concludes the exercise.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Pour tout entier $n \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$, on note $v_{3}(n)$ la valuation 3 -adique de $n$, c'est-à-dire le plus grand entier $k$ tel que $n$ est divisible par $3^{k}$. On pose $u_{1}=2$ et $u_{n}=4 v_{3}(n)+2-\frac{2}{u_{n-1}}$ pour tout $n \geqslant 2$ (si tant est que $u_{n-1}$ soit défini et non nul).

Montrer que, pour tout nombre rationnel strictement positif $q$, il existe un et un seul entier $n \geqslant 1$ tel que $u_{n}=q$.

|

Tout d'abord, notons que $u_{1}=2, u_{2}=1, u_{3}=3, u_{4}=\frac{3}{2}, u_{5}=\frac{2}{3}$ et $u_{6}=3$. On prouve par récurrence que, pour tout entier $n \geq 2$, on a $0<u_{n}$ et

$$

0<u_{3 n-1}<1<u_{3 n-2}<2<u_{3 n}=2+u_{n}:

$$

c'est déjà vrai pour $n=2$.

Puisque $u_{3 n}=u_{n}+2$, on montre successivement que $u_{3 n+1}, u_{3 n+2}$ et $u_{3 n+3}$ sont bien définis, avec

$$

\begin{aligned}

& u_{3 n+1}=2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n}}=1+\frac{u_{n}}{2+u_{n}}, \text { donc } 1<u_{3 n+1}<2 ; \\

& u_{3 n+2}=2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n+1}}=1+\frac{u_{n}}{1+u_{n}}, \text { donc } 0<u_{3 n+2}<1 ; \\

& u_{3 n+3}=4 v_{3}(3(n+1))+2-\frac{2}{u_{3 n+2}}=4 v_{3}(n)+4-\frac{2}{u_{n}}=2+u_{n+1} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Ceci conclut la récurrence.

Maintenant, considérons la fonction $\varphi:\{x \in \mathbb{Q}: 0<x$ et $x \notin\{1,2\}\} \mapsto\{x \in \mathbb{Q}: 0<x\}$ telle que

$$

\begin{aligned}

\varphi: & x \mapsto \frac{x}{1-x} \text { si } 0<x<1 ; \\

& x \mapsto 2 \frac{x-1}{2-x} \text { si } 1<x<2 ; \\

& x \mapsto x-2 \text { si } 2<x

\end{aligned}

$$

En outre, pour toute fraction irréductible $\frac{p}{q}$, avec $p \geq 0$ et $q>0$, on pose $\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|=p+q$. Alors :

- $\left\|\varphi\left(\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|\frac{p}{q-p}\right\|=p<p+q=\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ si $0<p<q$ ;

- $\left\|\varphi\left(1+\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|2 \frac{p}{q-p}\right\| \leq 2 q<(p+q)+q=\left\|1+\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ si $0<p<q$ ;

- $\left\|\varphi\left(2+\frac{p}{q}\right)\right\|=\left\|\frac{p}{q}\right\|=p+q<(p+2 q)+q=\left\|2+\frac{p}{q}\right\|$ si $0<p$ et $0<q$.

Dans tous les cas, si $x$ est un rationnel strictement positif tel que $x \notin\{1,2\}$, on a $\|\varphi(x)\|<\|x\|$. Or, pour tout rationnel strictement positif $x$ et pour tout entier $n \geq 1$ :

- si $0<x<1$, alors $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n+2}=x ;$

- si $1<x<2$, alors $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n+1}=x$;

- si $2<x$, alors $u_{n}=\varphi(x) \Leftrightarrow u_{3 n}=x$.

Une récurrence sur $\|x\|$ montre donc immédiatement que, pour tout rationnel strictement positif $x$, il existe un entier unique entier $n \geq 1$ tel que $u_{n}=x$, ce qui conclut l'exercice.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-decembre-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Prove that for all integers $n \geq 2$, we have: $\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{1}{\sqrt[k]{(2 k)!}} \geq \frac{n-1}{2 n+2}$.

N.B. If $a>0$, we denote $\sqrt[k]{a}$ the unique positive real number $b$ such that $b^{k}=a$.

|

We reason by induction on $n \geq 2$.

For $n=2$, we have $\frac{1}{\sqrt{24}} > \frac{1}{6}$.

Suppose the desired inequality holds for the value $n-1 \geq 2$. For the value $n$, the right-hand side increases by $\frac{n-1}{2 n+2} - \frac{n-2}{2 n} = \frac{1}{n(n+1)}$.

According to the induction hypothesis, it suffices to prove that $\frac{1}{\sqrt[n]{(2 n)!}} \geq \frac{1}{n(n+1)}$.

For $k=1,2, \cdots, n$, we have $(n-k)(n-k+1) \geq 0$, so $0 \leq k(2 n-k+1) \leq n(n+1)$.

By multiplying these inequalities term by term, we get $(2 n)! \leq (n(n+1))^{n}$, from which the conclusion follows.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Prouver que, pour tout entier $n \geq 2$, on a : $\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{1}{\sqrt[k]{(2 k)!}} \geq \frac{n-1}{2 n+2}$.

N.B. Si $a>0$, on note $\sqrt[k]{a}$ l'unique nombre réel $b>0$ tel que $b^{k}=a$.

|

On raisonne par récurrence sur $n \geq 2$.

Pour $n=2$, on a bien $\frac{1}{\sqrt{24}}>\frac{1}{6}$.

Supposons que l'inégalité désirée soit vraie pour la valeur $n-1 \geq 2$. Pour la valeur $n$, le membre de droite augmente de $\frac{n-1}{2 n+2}-\frac{n-2}{2 n}=\frac{1}{n(n+1)}$.

D'après l'hypothèse de récurrence, il suffit donc de prouver que $\frac{1}{\sqrt[n]{(2 n)!}} \geq \frac{1}{n(n+1)}$.

Or, pour $k=1,2, \cdots, n$, on a $(n-k)(n-k+1) \geq 0$, donc $0 \leq k(2 n-k+1) \leq n(n+1)$.

En multipliant ces inégalités membre à membre, il vient $(2 n)!\leq(n(n+1))^{n}$, $\mathrm{d}^{\prime}$ où la conclusion.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-fevrier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Let $ABC$ be a non-right triangle such that $AB < AC$. We denote $H$ as the projection of $A$ onto $(BC)$, and $E, F$ as the projections of $H$ onto $(AB)$ and $(AC)$, respectively. The line $(EF)$ intersects $(BC)$ at point $D$. Consider the semicircle with diameter $[CD]$ located in the same half-plane delimited by $(CD)$ as $A$. Let $K$ be the point on this semicircle that projects onto $B$. Show that $(DK)$ is tangent to the circle $KEF$.

|

As $A E H F$ are concyclic (on the circle with diameter $[A H]$), we have $(E F, E A)=(H F, H A)=$ $(H F, C A)+(C A, C B)+(C B, H A)=(C A, C B)=(C F, C B)$, so $(E F, E B)=(C F, C B)$. Therefore, $B, E, F, C$ are concyclic. From the power of a point with respect to a circle, we have $D E \cdot D F=D B \cdot D C$. On the other hand, since $D K C$ is a right triangle at $K$, the triangles $D K B$ and $D C K$ are similar, which implies $\frac{D K}{D B}=\frac{D C}{D K}$, or equivalently $D K^{2}=D B \cdot D C$.

Thus, $D K^{2}=D E \cdot D F$, and therefore, from the power of $D$ with respect to the circle $K E F$, we conclude that $(D K)$ is tangent to the circle $K E F$ at $K$.

Remark: The choice of the semicircle is not important.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle non rectangle tel que $A B<A C$. On note $H$ le projeté de $A$ sur $(B C)$, et $E, F$ les projetés respectifs de $H$ sur $(A B)$ et $(A C)$. La droite $(E F)$ coupe $(B C)$ au point $D$. On considère le demi-cercle de diamètre $[C D]$ situé dans le même demi-plan délimité par $(C D)$ que $A$. Soit $K$ le point de ce demi-cercle qui se projette sur $B$. Montrer que $(D K)$ est tangente au cercle $K E F$.

|

Comme $A E H F$ sont cocycliques (sur le cercle de diamètre $[A H]$ ), on a $(E F, E A)=(H F, H A)=$ $(H F, C A)+(C A, C B)+(C B, H A)=(C A, C B)=(C F, C B)$, donc $(E F, E B)=(C F, C B)$. Par conséquent, $B, E, F, C$ sont cocycliques. D'après la puissance d'un point par rapport à un cercle, on a $D E \cdot D F=D B \cdot D C$. D'autre part, comme $D K C$ est rectangle en $K$, les triangles $D K B$ et $D C K$ sont semblables, ce qui implique $\frac{D K}{D B}=\frac{D C}{D K}$, ou encore $D K^{2}=D B \cdot D C$.

Il vient $D K^{2}=D E \cdot D F$, et donc d'après la puissance de $D$ par rapport au cercle $K E F$, on en déduit que $(D K)$ est tangente en $K$ au cercle $K E F$.

Remarque : le choix du demi-cercle n'a pas d'importance.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-fevrier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Let $n \geq 1$ be an integer. A group of $2 n$ people meet. Each of these people has at least $n$ friends in this group (in particular, if $A$ is a friend of $B$ then $B$ is a friend of $A$, and one is not a friend with oneself). Prove that it is possible to arrange these $2 n$ people around a round table so that each person is between two of their friends.

|

Consider an arbitrary arrangement of guests:

AB.... $A$.

where $A, B$ denote different people, but the two $A$s represent the same person (we are around a round table).

In what follows, we will consider the arrangement as a sequence of people, ordered from left to right.

If two neighbors are not friends, we will say that it is a tension.

If there is no tension, it is over.

If there is a tension, by circular symmetry, we can always assume that $A$ and $B$ are not friends.

Since $B$ has at least $n$ friends, plus himself, we deduce that $B$ has at most $n-1$ "enemies".

Suppose that in the arrangement above and after $B$, we never find two neighbors $A'$ and $B'$ (in this order) who are friends respectively of $A$ and $B$.

Then, since such an arrangement does not occur before $B$ either, we deduce that it never appears, and therefore to the right of each friend of $A$ must be an enemy of $B$. Thus, the number of enemies of $B$ is at least equal to the number of friends of $A$, which implies $n-1 \geq n$. Contradiction.

Therefore, we can find two neighbors $A'$ and $B'$ (in this order) who are friends respectively of $A$ and $B$.

The arrangement is then of the form:

$$

A B \ldots A' B' \ldots A

$$

Under these conditions, we can eliminate the tension between $A$ and $B$ by reversing the order of the people between $B$ and $A'$:

$$

A\left(B \ldots A'\right) B' \ldots A \rightarrow A\left(A' \ldots B\right) B' \ldots A

$$

This provides a new arrangement but with at least one less tension than in the previous one, since clearly the modification does not create any new tension (however, it can eliminate a potential tension between $A'$ and $B'$).

By repeating this procedure as many times as necessary (a finite number of times in any case, since the initial number of tensions is finite), we eliminate all tensions, and the goal is achieved.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Soit $n \geq 1$ un entier. Un groupe de $2 n$ personnes se réunit. Chacune de ces personnes possède au moins $n$ amies dans ce groupe (en particulier, si $A$ est amie avec $B$ alors $B$ est amie avec $A$, et on n'est pas ami avec soi-même). Prouver que l'on peut disposer ces $2 n$ personnes autour d'une table ronde de sorte que chacune soit entre deux de ses amies.

|

Considérons une disposition arbitraire des invités :

AB.... $A$.

où $A, B$ désignent des personnes différentes, mais les deux $A$ représentent la même personne (on est autour d'une table ronde).

Dans ce qui suit, on considérera la disposition comme une suite de personnes, ordonnée de gauche à droite.

Si deux voisins ne sont pas amis, on dira que c'est une tension.

S'il n'y a aucune tension, c'est fini.

S'il existe une tension, par symétrie circulaire, on peut toujours supposer que $A$ et $B$ ne sont pas amis.

Comme $B$ a au moins $n$ amis, plus lui-même, on en déduit que $B$ a au plus $n-1$ "ennemis".

Supposons que dans la disposition ci-dessus et après $B$, on ne trouve jamais deux voisins $A^{\prime}$ et $B^{\prime}$ (dans cet ordre) qui sont amies respectivement de $A$ et de $B$.

Alors, comme une telle disposition n'arrive pas non plus avant $B$, on en déduit qu'elle n'apparaît jamais, et donc qu'à droite de chaque ami de $A$ doit se trouver un ennemi de $B$. Donc, le nombre d'ennemis de $B$ est au moins égal au nombre d'amis de $A$, ce qui implique $n-1 \geq n$. Contradiction.

Par suite, on peut trouver deux voisins $A^{\prime}$ et $B^{\prime}$ (dans cet ordre) qui sont amies respectivement de $A$ et de $B$.

La disposition est alors de la forme :

$$

A B \ldots A^{\prime} B^{\prime} \ldots A

$$

Dans ces conditions, on peut éliminer la tension entre $A$ et $B$ en renversant l'ordre des personnes entre $B$ et $A^{\prime}$ :

$$

A\left(B \ldots A^{\prime}\right) B^{\prime} \ldots A \rightarrow A\left(A^{\prime} \ldots B\right) B^{\prime} \ldots A

$$

Cela fournit une nouvelle disposition mais avec au moins une tension de moins que dans la précédente, puisque clairement la modification ne crée pas de nouvelle tension (par contre, elle peut éliminer une tension éventuelle entre $A^{\prime}$ et $B^{\prime}$ ).

En répétant cette procédure autant que nécessaire (un nombre fini de fois en tout cas, puisque le nombre initial de tensions est fini), on fait disparaître toutes les tensions, et l'objectif est atteint.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-fevrier-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

The cells of a 10 by 10 grid are colored in white and black. A coloring of these cells is said to be homogeneous if it contains a $3 \times 3$ monochromatic square, and inhomogeneous otherwise. Show that there are more inhomogeneous colorings than homogeneous colorings.

|

There are $2^{100}$ possible colorings. If $c$ is a $3 \times 3$ square, the number of colorings such that $c$ is monochrome is equal to $2 \times 2^{91}=2^{92}$. There are 64 $3 \times 3$ squares, so there are at most $64 \times 2^{92}=2^{98}$ homogeneous colorings.

|

2^{98}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Les cases d'une grille à 10 lignes et 10 colonnes sont coloriées en blanc et en noir. Un coloriage de ces cases est dit homogène s'il contient un carré $3 \times 3$ monochrome, et inhomogène sinon. Montrer qu'il existe plus de coloriages inhomogènes que de coloriages homogènes.

|

Il y a $2^{100}$ coloriages possibles. Si $c$ est un carré $3 \times 3$, le nombre de coloriages tels que $c$ soit monochrome est égal à $2 \times 2^{91}=2^{92}$. Or, il y a 64 carrés $3 \times 3$, donc il y a au plus $64 \times 2^{92}=2^{98}$ coloriages homogènes.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Show that if $a, b, c$ are positive real numbers satisfying $a+b+c=1$ then

$$

\frac{7+2 b}{1+a}+\frac{7+2 c}{1+b}+\frac{7+2 a}{1+c} \geqslant \frac{69}{4}

$$

|

Given $7+2 b=5+2(1+b)$, we write the left-hand side in the form

$$

5\left(\frac{1}{1+a}+\frac{1}{1+b}+\frac{1}{1+c}\right)+2\left(\frac{1+b}{1+a}+\frac{1+c}{1+b}+\frac{1+a}{1+c}\right)

$$

Using the inequality $\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geqslant \frac{9}{x+y+z}$, we bound the first term from below by $\frac{45}{4}$.

Using the inequality $x+y+z \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x y z}$, we bound the second term from below by 6. The assertion to be proved follows.

|

\frac{69}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Montrer que si $a, b, c$ sont des nombres réels positifs vérifiant $a+b+c=1$ alors

$$

\frac{7+2 b}{1+a}+\frac{7+2 c}{1+b}+\frac{7+2 a}{1+c} \geqslant \frac{69}{4}

$$

|

Comme $7+2 b=5+2(1+b)$, on écrit le membre de gauche sous la forme

$$

5\left(\frac{1}{1+a}+\frac{1}{1+b}+\frac{1}{1+c}\right)+2\left(\frac{1+b}{1+a}+\frac{1+c}{1+b}+\frac{1+a}{1+c}\right)

$$

En utilisant l'inégalité $\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}+\frac{1}{z} \geqslant \frac{9}{x+y+z}$, on minore le premier terme par $\frac{45}{4}$.

En utilisant l'inégalité $x+y+z \geqslant 3 \sqrt[3]{x y z}$, on minore le second terme par 6 . L'assertion à démontrer en découle.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2015-2016-ofm-2015-2016-test-fevrier-junior-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

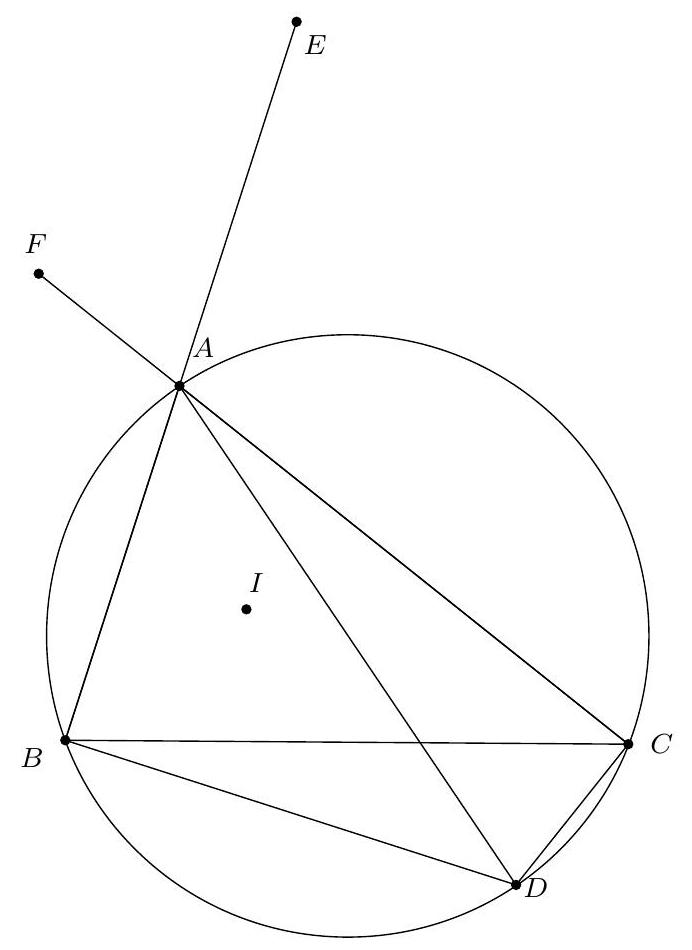

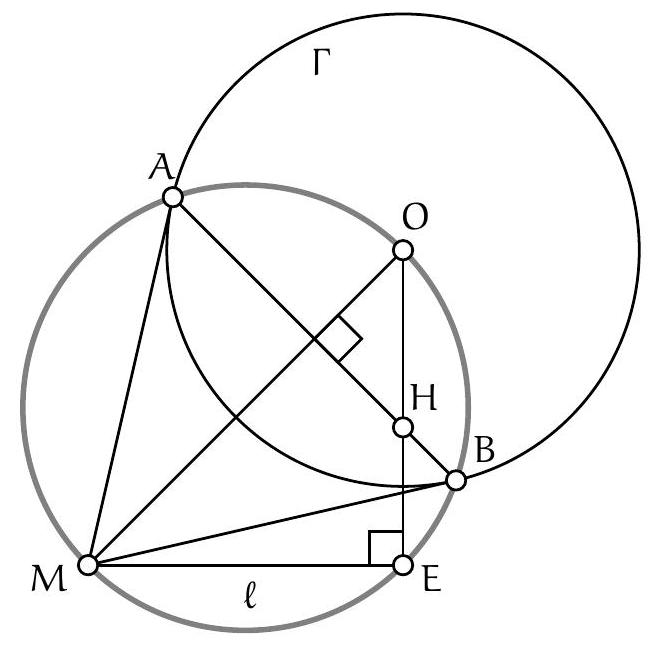

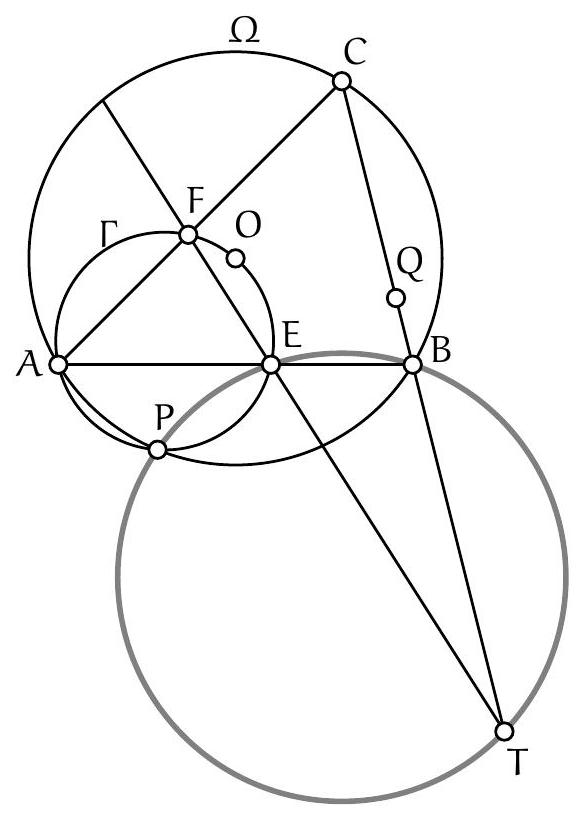

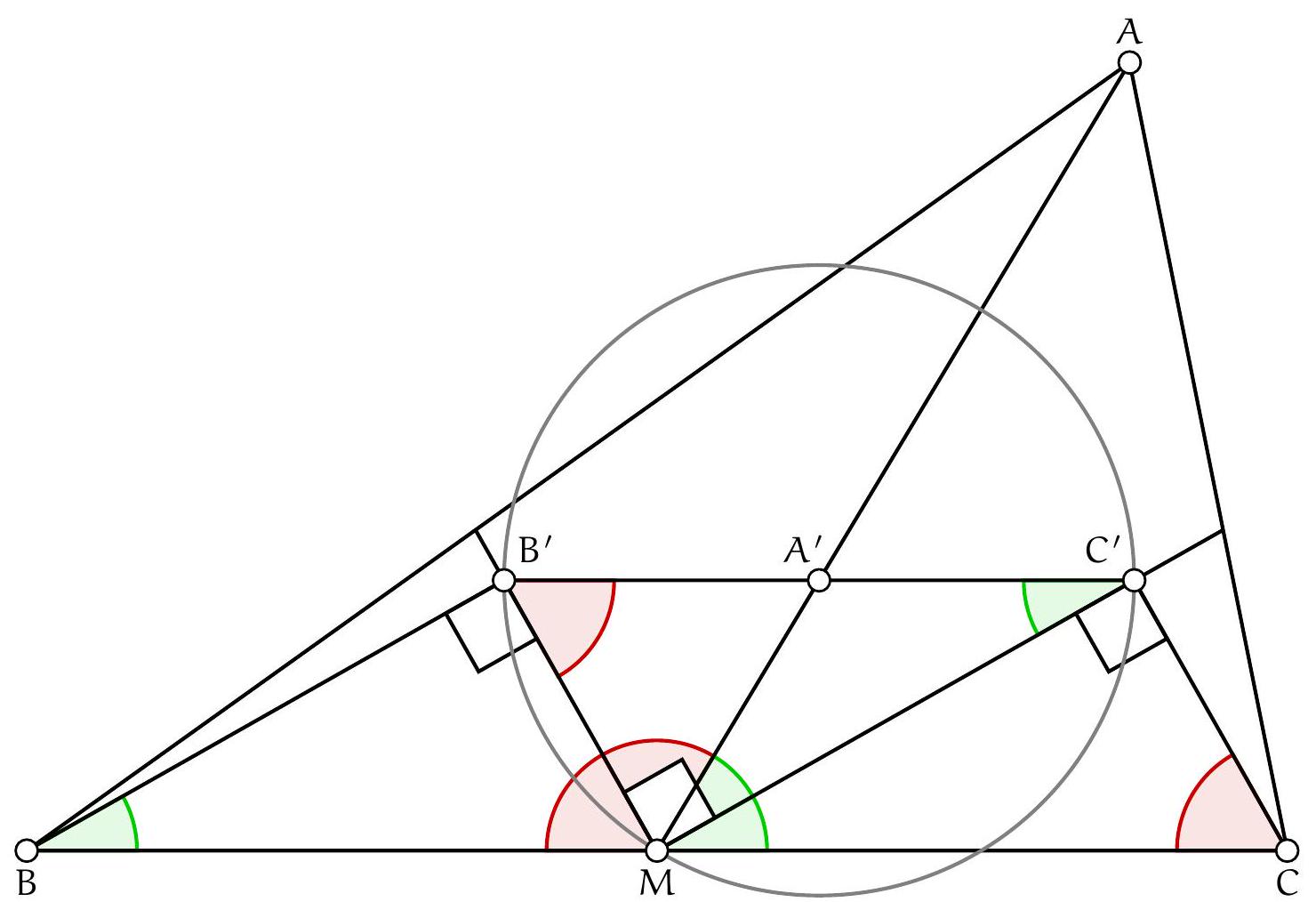

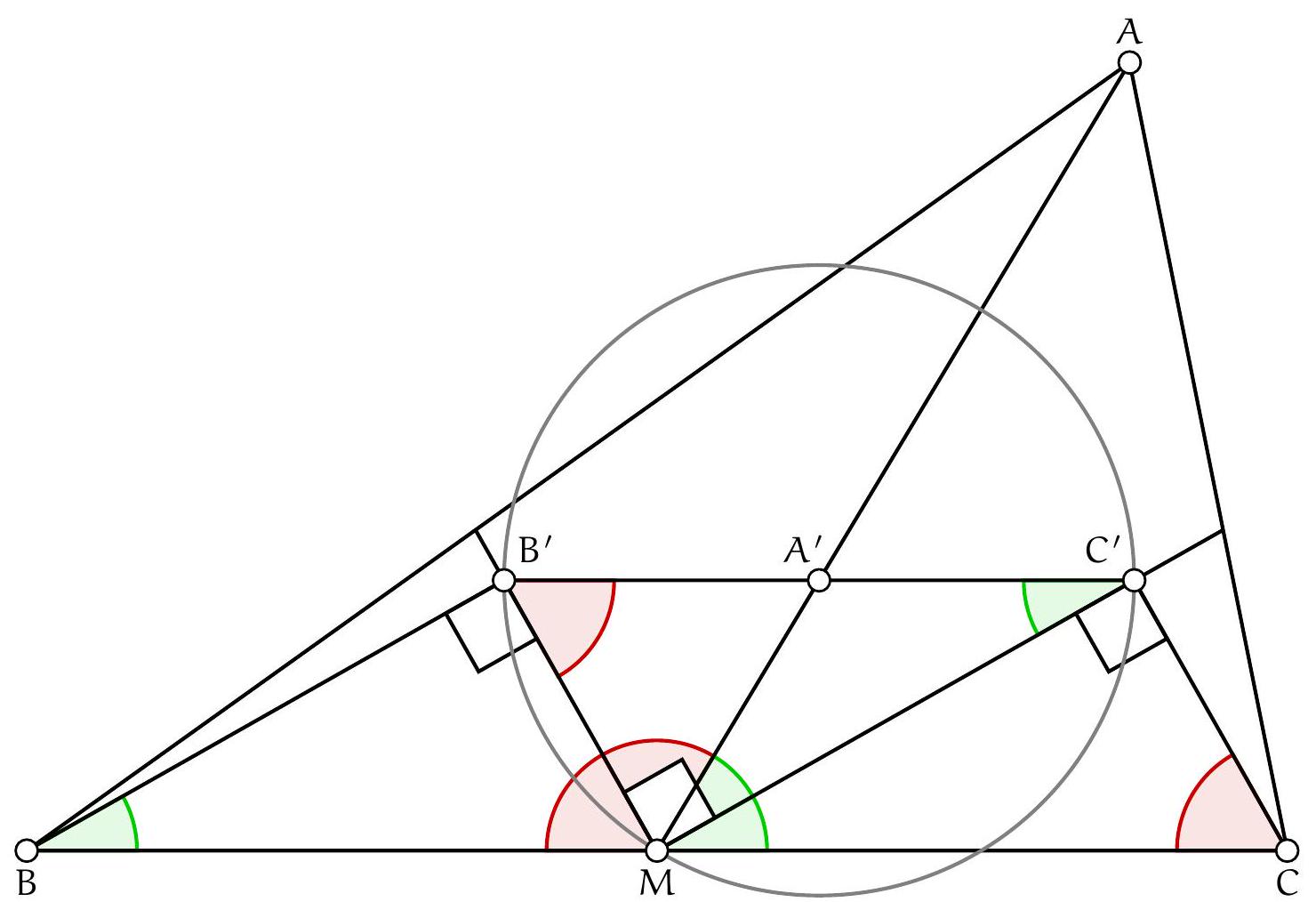

Let $ABC$ be a triangle, and $M$ the midpoint of $[BC]$. We denote $I_{b}$ and $I_{c}$ as the centers of the incircles of $AMB$ and $AMC$. Show that the second point of intersection of the circumcircles of triangles $ABI_{b}$ and $ACI_{c}$ lies on the line $(AM)$.

|

Let $T$ be the intersection between the circle with diameter $[B C]$ and the ray $\left[M A\right)$. It suffices to show that $T$ lies on the circle $A B I_{b}$ (by symmetry of the roles of $B$ and $C$, this will show that it also lies on the circle $A C I_{c}$).

Since $\widehat{B T C}$ is a right angle, we have $\widehat{A T B}=90^{\circ}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A M B}=\widehat{A I_{b} B}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle, et $M$ le milieu de $[B C]$. On note $I_{b}$ et $I_{c}$ les centres des cercles inscrits à $A M B$ et $A M C$. Montrer que le second point d'intersection des cercles circonscrits aux triangles $A B I_{b}$ et $A C I_{c}$ se situe sur la droite $(A M)$.

|