problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

It is said that an integer $k$ is olympic if there exist four integers $a, b, c$ and $d$, all coprime with $k$, such that $k$ divides $a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4}+d^{4}$. Let $n$ be any integer.

Show that $n^{2}-2$ is olympic.

|

Let $p_{1}^{\alpha_{1}} \cdots p_{\ell}^{\alpha_{\ell}}$ be the prime factorization of $n^{2}-2$. Thanks to the Chinese Remainder Theorem, it suffices to show that each of the integers $p_{i}^{\alpha_{i}}$ is Olympic.

Suppose first that $p_{i}=2$. Since $n^{2}-2 \equiv\{2,3\}(\bmod 4)$, we know that $\alpha_{i} \leqslant 1$. Clearly, 2 is Olympic, since $1+1+1+1 \equiv 0(\bmod 2)$.

Now consider an odd prime divisor $p$ of $n^{2}-2$. Since 2 is not a square modulo 3 or 5, we know that $p \geqslant 7$. Furthermore, if $p^{\alpha}$ is Olympic, then $p$ is clearly so as well. Conversely, if $p$ is Olympic (and odd), Hensel's lemma shows that the fourth powers modulo $p^{k}$ are exactly the integers whose residues (modulo $p$) are fourth powers modulo $p$, and it follows that $p^{\alpha}$ is also Olympic.

We are thus reduced to showing that every prime $p \geqslant 7$ such that 2 is a square modulo $p$ is Olympic. We will proceed by case analysis, depending on the value of $p$ modulo 4 or 8. However, we first recall Fermat's little theorem, which states that the order $\omega_{p}(x)$ of an invertible element modulo $p$ must divide $p-1$. We also recall that $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$ contains an element of order $p-1$, as indicated by Theorem 17 of the POFM Arithmetic course on the properties of $\mathbb{Z} / \mathrm{n} \mathbb{Z}$. We deduce the following lemma.

Lemma: The $k$-th powers are the elements $x$ whose order $\omega_{p}(x)$ divides $(p-1) / \delta$, where $\delta=\operatorname{GCD}(k, p-1)$.

Proof: Let $z$ be an element of order $p-1$. The $k$-th powers are the elements of the form $z^{a k+b(p-1)}$, with $a$ and $b$ integers, i.e., the elements of the form $z^{\mathrm{c} \delta}$ with $c$ an integer. The order of these elements modulo $p$ clearly divides $(p-1) / \delta$.

Conversely, $\omega_{p}(x)$ divides $(p-1) / \delta$ if and only if $x$ is one of the roots of the polynomial $P(X)=1-X^{(\mathfrak{p}-1) / \delta}$. However, the elements of the form $z^{\mathfrak{c} \delta}$ already constitute $(p-1) / \delta$ roots of $P(X)$. Therefore, the $k$-th powers are exactly the roots of $P(X)$, which concludes the proof of the lemma.

We finally proceed with the case analysis announced above.

1. If $p \equiv 1(\bmod 8)$, and since -1 is of order 2, it is a fourth power. Since $0 \equiv 1+1+(-1)+(-1)(\bmod p)$, the integer $p$ is Olympic.

2. If $p \equiv 5(\bmod 8)$, then -1 is a square. Let $i$ and $-i$ be its square roots. They are of order 4, so they are not squares. However, $(1+i)^{2} \equiv 2 i(\bmod p)$. Since the set of squares is closed under product and inverse (and thus division), 2 is not a square, which actually means that $p$ does not divide $n^{2}-2$. This case is therefore impossible.

3. If $p \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, then being a fourth power is in fact the same as being a square. It suffices to show that 0 is a sum of four non-zero squares modulo $p$.

We will first show that it is a sum of $\ell$ non-zero squares, with $2 \leqslant \ell \leqslant 4$. Indeed, let $Q$ be the set of squares. Note that $|Q|=(p+1) / 2$, since every non-zero square has exactly two square roots modulo $p$. Thus, for any $k \in \mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$, and by the pigeonhole principle, the set $(k-Q) \cap Q$ is non-empty, which means that $k$ is a sum of two squares. If $k \neq 0$, one of these squares is even non-zero. But then, by writing $0 \equiv k+(-k)(\bmod p)$, we can indeed write 0 as a sum of four squares, at least two of which are non-zero.

Furthermore, by the identity $k^{2} \equiv(3 k / 5)^{2}+(4 k / 5)^{2}(\bmod p)$, every non-zero square is in fact a sum of two non-zero squares. Consequently, 0 is indeed a sum of four non-zero squares, which means that $p$ is Olympic.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

On dit qu'un entier $k$ est olympique s'il existe quatre entiers $a, b, c$ et $d$, tous premiers avec $k$, tels que $k$ divise $a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4}+d^{4}$. Soit $n$ un entier quelconque.

Montrer que $n^{2}-2$ est olympique.

|

Soit $p_{1}^{\alpha_{1}} \cdots p_{\ell}^{\alpha_{\ell}}$ la décomposition de $n^{2}-2$ en produits de facteurs premiers. Grâce au théorème Chinois, il nous suffit en fait de montrer que chacun des entiers $p_{i}^{\alpha_{i}}$ est olympique.

Supposons tout d'abord que $p_{i}=2$. Puisque $n^{2}-2 \equiv\{2,3\}(\bmod 4)$, on sait que $\alpha_{i} \leqslant 1$. Or, il est clair que 2 est olympique, puisque $1+1+1+1 \equiv 0(\bmod 2)$.

On considère maintenant un diviseur premier $p$ impair de $n^{2}-2$. Puisque 2 n'est pas carré modulo 3 ou 5 , on sait en fait que $p \geqslant 7$. Par ailleurs, si $p^{\alpha}$ est olympique, alors $p$ l'est clairement lui aussi. Réciproquement, si $p$ est olympique (et impair), le lemme de Hensel montre que les puissances $4{ }^{\text {èmes }}$ modulo $p^{k}$ sont exactement les entiers dont les résidus (modulo $p$ ) sont des puissances $4^{\text {èmes }}$ modulo $p$, et il s'ensuit que $p^{\alpha}$ est également olympique.

On se ramène donc à montrer que tout nombre premier $p \geqslant 7$ tel que 2 soit un carré modulo $p$ est olympique. On va procéder par disjonction de cas, selon la valeur de $p$ modulo 4 ou 8 . Cependant, on rappelle d'abord le petit théorème de Fermat, qui stipule que l'ordre $\omega_{p}(x)$ d'un élément inversible modulo $p$ doit diviser $p-1$. On rappelle également que $\mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$

contient un élément d'ordre $p-1$, comme l'indique le Théorème 17 du cours d'Arithmétique de la POFM sur les propriétés de $\mathbb{Z} / \mathrm{n} \mathbb{Z}$. On en déduit le lemme suivant.

Lemme : Les puissances $k^{\text {èmes }}$ sont les éléments $x$ dont l'ordre $\omega_{p}(x)$ divise $(p-1) / \delta$, où $\delta=\operatorname{PGCD}(k, p-1)$.

Démonstration : Soit $z$ un élément d'ordre $p-1$. Les puissances $k^{\text {èmes }}$ sont les éléments de la forme $z^{a k+b(p-1)}$, avec a et b entiers, c'est-à-dire les éléments de la forme $z^{\mathrm{c} \mathrm{\delta}}$ avec c entier. L'ordre de ces éléments modulo $p$ divise clairement $(p-1) / \delta$.

Réciproquement, $\omega_{p}(x)$ divise $(p-1) / \delta$ si et seulement si $x$ est une des racines du polynôme $P(X)=1-X^{(\mathfrak{p}-1) / \delta}$. Or, les éléments de la forme $z^{\mathfrak{c} \delta}$ constituent déjà $(p-1) / \delta$ racines de $P(X)$. Par conséquent, les puissances ${ }^{k e \text { èmes }}$ sont exactement les racines de $P(X)$, ce qui conclut la preuve du lemme.

On procède enfin à la disjonction de cas annoncée ci-dessus.

1. Si $p \equiv 1(\bmod 8)$, et puisque -1 est d'ordre 2 , c'est une puissance $4^{\text {ème }}$. Comme $0 \equiv$ $1+1+(-1)+(-1)(\bmod p)$, l'entier $p$ est olympique.

2. Si $p \equiv 5(\bmod 8)$, alors -1 est un carré. Soit $i$ et $-i$ ses racines carrées. Elles sont d'ordre 4 , donc ce ne sont pas des carrés. Or, $(1+i)^{2} \equiv 2 i(\bmod p)$. Puisque l'ensemble des carrés est clos par produit et par inverse (donc par division), 2 n'est donc pas un carré, ce qui signifiait en fait que $p$ ne divisait pas $n^{2}-2$. Ce cas s'avère donc impossible.

3. Si $p \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, alors être une puissance $4{ }^{\text {ème }}$ revient en fait à être un carré. Il suffit donc de montrer que 0 est somme de quatre carrés non nuls modulo $p$.

On va d'abord montrer que c'est une somme de $\ell$ carrés non nuls, avec $2 \leqslant \ell \leqslant 4$. En effet, soit Q l'ensemble des carrés. Notons que $|Q|=(p+1) / 2$, puisque tout carré non nul a exactement deux racines carrés modulo $p$. Ainsi, pour tout $k \in \mathbb{Z} / p \mathbb{Z}$, et par principe des tiroirs, $l^{\prime}$ ensemble $(k-Q) \cap Q$ est non vide, ce qui signifie que $k$ est somme de deux carrés. Si $k \neq 0$, l'un de ces carrés est même non nul. Mais alors, en écrivant $0 \equiv k+(-k)(\bmod p)$, on peut bien écrire 0 comme une somme de quatre carrés dont au moins deux sont non nuls.

Puis, en vertu de l'identité $k^{2} \equiv(3 k / 5)^{2}+(4 k / 5)^{2}(\bmod p)$, tout carré non nul est en fait somme de deux carrés non nuls. Par conséquent, 0 est bien somme de quatre carrés non nuls, ce qui signifie que $p$ est olympique.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2018-2019-Test_RMM_28_novembre_corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $x$ and $y$ be two real numbers. We define

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Prove that $M \geqslant 2$, and determine the cases of equality.

|

Among the three numbers $x y+1, x y-x-y+3$ and $-2 x y+x+y+2$, we denote $K$ as the smallest, $L$ as the second smallest, and $M$ as the largest. Therefore, $K \leqslant L \leqslant M$ and

$$

3 M \geqslant K+L+M=(x y+1)+(x y-x-y+3)+(-2 x y+x+y+2)=6,

$$

which means that $M \geqslant 2$.

Furthermore, if $M=2$, the inequalities $K \leqslant L \leqslant M$ are in fact equalities, which means that

$$

x y+1=x y-x-y+3=-2 x y+x+y+2=2

$$

Let $p$ be the product $x y$ and $s$ be the sum $x+y$. The equalities in equation (1) are satisfied if and only if $p=1$ and $s=2$.

The arithmetic-geometric mean inequality generally indicates that

$$

\frac{s^{2}}{4}=\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2} \geqslant x y=p

$$

with equality if and only if $x=y$. This result can also be seen if we note that

$$

\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}=\left(\frac{x-y}{2}\right)^{2}+x y

$$

Here, since we want to have $s^{2} / 4=1=p$, we must also have $x=y$, so that $x=y=1$.

Finally, conversely, if $x=y=1$, we can easily verify that

$$

x y+1=x y-x-y+3=-2 x y+x+y+2=2

$$

so that $M=2$ as well.

|

M=2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit $x$ et $y$ deux nombres réels. On pose

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Démontrer que $M \geqslant 2$, et déterminer les cas d'égalité.

|

Parmi les trois nombres $x y+1, x y-x-y+3$ et $-2 x y+x+y+2$, on note $K$ le plus petit, $L$ le deuxième plus petit et $M$ le plus grand. Alors $K \leqslant L \leqslant M$ donc

$$

3 M \geqslant K+L+M=(x y+1)+(x y-x-y+3)+(-2 x y+x+y+2)=6,

$$

ce qui signifie que $M \geqslant 2$.

En outre, si $M=2$, les inégalités $K \leqslant L \leqslant M$ sont en fait des égalités, ce qui signifie que

$$

x y+1=x y-x-y+3=-2 x y+x+y+2=2

$$

En notant $p$ le produit $x y$ et $s$ la somme $x+y$, les égalités de l'équation (1) sont vérifiées si et seulement si $p=1$ et $s=2$.

Or, l'inégalité arithmético-géométrique indique, de manière générale, que

$$

\frac{s^{2}}{4}=\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2} \geqslant x y=p

$$

avec égalité si et seulement si $x=y$. Ce résultat se retrouve bien si l'on remarque que

$$

\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}=\left(\frac{x-y}{2}\right)^{2}+x y

$$

Ici, puisque l'on souhaite avoir $s^{2} / 4=1=p$, il nous faut donc également avoir $x=y$, de sorte que $x=y=1$.

Enfin, réciproquement, on vérifie aisément, si $x=y=1$, que

$$

x y+1=x y-x-y+3=-2 x y+x+y+2=2

$$

de sorte que $M=2$ également.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Let $x$ and $y$ be two real numbers. We define

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Prove that $M \geqslant 2$, and determine the cases of equality.

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ Here is another way to prove that the equalities of equation (1) are satisfied if and only if $x=y=1$. First, if $x=y=1$, these equalities are clearly satisfied.

Conversely, if they are satisfied, then the equality $x y-x-y+3=2$ can be rewritten as $0=x y-x-y+1=(x-1)(y-1)$. Since $x$ and $y$ play symmetric roles, we can assume, without loss of generality, that $x=1$. For the equality $x y+1=2$ to be satisfied, it is then necessary that $y=1$, which concludes the proof here.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit $x$ et $y$ deux nombres réels. On pose

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Démontrer que $M \geqslant 2$, et déterminer les cas d'égalité.

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ Voici une autre manière de démontrer que les égalités de l'équation (1) sont vérifiées si et seulement si $x=y=1$. Tout d'abord, si $x=y=1$, ces égalités sont clairement vérifiées.

Réciproquement, si elles sont vérifiées, alors on peut réécrire l'égalité $x y-x-y+3=2$ comme $0=x y-x-y+1=(x-1)(y-1)$. Puisque $x$ et $y$ jouent des rôles symétriques, on peut supposer, sans perte de généralité, que $x=1$. Pour que l'égalité $x y+1=2$ soit vérifiée, il est alors nécessaire que $y=1$, ce qui conclut ici.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Let $x$ and $y$ be two real numbers. We define

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Prove that $M \geqslant 2$, and determine the cases of equality.

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ The idea of introducing the variables $p$ and $s$, as in the first solution, or directly using the equality $x y - x - y + 3 = 2$ to obtain a factorization, as in the second solution, might seem miraculous. Of course, this is not the case, and these approaches actually stem from what are known as Viète's formulas.

These formulas state that $x$ and $y$ are the two roots, possibly identical, of the polynomial

$$

P(X) = (X - x)(X - y) = X^2 - (x + y)X + xy = X^2 - sX + p.

$$

Since the equalities in equation (1) are symmetric in $x$ and $y$, a general result (which holds even if we had three unknowns $x, y$, and $z$, or even any number of unknowns) allows us to express them directly in terms of the values taken by the polynomial $P$.

For example, the equalities $p + 1 = 2$, $p - s + 3 = 2$, and $-2p + s + 2 = 2$ can be rewritten as $P(0) = 1$, $P(1) = 0$, and $P(1/2) = 1/4$. Here, the equality $P(1) = 0$ means precisely that $(x - 1)(y - 1) = 0$, which is the factorization used in our second solution.

We could also proceed more systematically. Indeed, since $P(1) = 0$, we know that the polynomial $P(X)$ is divisible by $X - 1$. We can therefore write it in the form $P(X) = (X - 1)(X - a)$, and then verify that $P(0) = a$, and thus that $P(X) = (X - 1)^2$.

If we had been less lucky and had not identified a root of our polynomial $P$, it would still have been possible to write $P$ as a Lagrange interpolation polynomial. Here, this method allows us to write

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(X) & = \frac{X - 1}{0 - 1} \frac{X - 1/2}{0 - 1/2} P(0) + \frac{X - 1}{1/2 - 1} \frac{X - 0}{1/2 - 0} P(1/2) + \frac{X - 1/2}{1 - 1/2} \frac{X - 0}{1 - 0} P(1) \\

& = 2(X - 1)(X - 1/2) - X(X - 1) = X^2 - 2X + 1 = (X - 1)^2

\end{aligned}

$$

from which it follows that the two roots of $P$ are $x = y = 1$.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was generally well solved. Few students noticed that the first inequality was a simple consequence of the fact that the maximum is greater than the arithmetic mean.

Be careful with handling inequalities: some students wrote that $xy < 1$ and $x + y \geq xy$ to conclude that $x + y \geq 1$, which is not true. Other students proved the required inequality but forgot to consider the equality cases, which was an important part of the exercise: unlike equality cases in classical inequalities, this one was harder to find, and asserting without proof that $x = y = 1$ was not sufficient.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit $x$ et $y$ deux nombres réels. On pose

$$

M=\max \{x y+1, x y-x-y+3,-2 x y+x+y+2\} .

$$

Démontrer que $M \geqslant 2$, et déterminer les cas d'égalité.

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ Avoir pensé à introduire les variables $p$ et $s$, comme dans la première solution, ou bien à utiliser directement l'égalité $x y-x-y+3=2$ pour obtenir une factorisation, comme dans la deuxième solution, pourrait passer pour miraculeux. Il n'en est bien sûr rien, et ces approchent découlent en fait de ce que l'on appelle les relations de Viète.

Ces relations consistent à dire que $x$ et $y$ sont les deux racines, éventuellement confondues, du polynôme

$$

P(X)=(X-x)(X-y)=X^{2}-(x+y) X+x y=X^{2}-s X+p .

$$

Puisque les égalités de l'équation (1) sont symétriques en $x$ et en $y$, un résultat général (valable même si on avait eu trois inconnues $x, y$ et $z$, ou même un nombre quelconque d'inconnues) permet en fait de démontrer qu'elles peuvent s'exprimer directement à partir des valeurs que prend le polynôme $P$.

Par exemple, les égalités $p+1=2, p-s+3=2$ et $-2 p+s+2=2$ peuvent se réécrire comme $P(0)=1, P(1)=0$ et $P(1 / 2)=1 / 4$. Ici, l'égalité $P(1)=0$ signifie précisément que $(x-1)(y-1)=0$, ce qui est la factorisation utilisée dans notre deuxième solution.

On pourrait également procéder de manière plus systématique. En effet, puisque $P(1)=0$, on sait que le polynôme $P(X)$ est divisible par $X-1$. On peut donc l'écrire sous la forme $P(X)=(X-1)(X-a)$, puis vérifier que $P(0)=a$, et donc que $P(X)=(X-1)^{2}$.

Si l'on avait été moins chanceux, et que l'on n'avait pas identifié de racine de notre polynôme $P$, il aurait toujours été possible d'écrire $P$ comme un polynôme d'interpolation de Lagrange. Ici, cette méthode nous permet d'écrire que

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(X) & =\frac{X-1}{0-1} \frac{X-1 / 2}{0-1 / 2} P(0)+\frac{X-1}{1 / 2-1} \frac{X-0}{1 / 2-0} P(1 / 2)+\frac{X-1 / 2}{1-1 / 2} \frac{X-0}{1-0} P(1) \\

& =2(X-1)(X-1 / 2)-X(X-1)=X^{2}-2 X+1=(X-1)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

d'où le fait que les deux racines de $P$ soient $x=y=1$.

Commentaire des correcteurs L'exercice a été plutôt bien résolu. Peu d'élèves ont vu que la première inégalité était une conséquence simple du fait que le maximum est plus grand que la moyenne arithmétique.

Attention au maniement des inégalités : certains élèves ont écrit que $x y<1$ et $x+y \geqslant x y$ pour en conclure que $x+y \geqslant 1$, ce qui n'est pas vrai. D'autres élèves ont démontré l'inégalité demandée mais oublié de regarder les cas d'égalité alors que c'était une partie importante de l'exercice : contrairement à des cas d'égalité dans des inégalités classiques, celui-là était plus dur à trouver, et affirmer sans preuve que $x=y=1$ ne suffisait pas.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

In the train, as they return from EGMOnd aan Zee, Clara and Edwige play the following game. Initially, the integer $n=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ is written on a piece of paper. Then, each in turn, starting with Clara, the players replace the integer $n$ by one of the numbers $k n / 10$, where $k$ is an integer between 1 and 9 inclusive. The first player to write a number that is not an integer loses, and her opponent wins.

Clara and Edwige are formidable players and play optimally. Which of the two will win?

|

Let's consider the number $n$ written on the piece of paper when player X is about to play, and before the game ends. We partially factorize $n$ as a product of prime numbers: $n=2^{x} \times 5^{y} \times m$, where $x$ and $y$ are natural numbers and $m$ is a non-zero natural number that is coprime with 2 and 5.

We will then prove the property $\mathcal{P}_{n}$ by induction on $n$: player X will lose if $x$ and $y$ are both even, and will win otherwise. First, $\mathcal{P}_{1}$ is obvious, since X will have to replace the number $n=1$ with a number between $1 / 10$ and $9 / 10$.

Let then $n \geqslant 1$ be any integer. Suppose $\mathcal{P}_{1}, \ldots, \mathcal{P}_{n}$, and we will prove $\mathcal{P}_{n+1}$.

$\triangleright$ If $x$ and/or $y$ is odd, we denote $r$ and $s$ as the remainders of $x$ and $y$ modulo 2. Then player X replaces the integer $n$ with the integer $n^{\prime}=n /\left(2^{r} \times 5^{s}\right)$. Since $n^{\prime}=2^{x-r} \times 5^{y-s} \times m$, the property $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ ensures that X's opponent will lose.

$\triangleright$ If $x$ and $y$ are both even, we still assume that X replaces $n$ with an integer $n^{\prime}$ (which is only possible if $x \geqslant 1$ or $y \geqslant 1$). If X replaces $n$ with the number $n^{\prime}=n / 2=2^{x-1} \times 5^{y} \times m$, then $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ ensures that X's opponent will win. Otherwise, we can write $n^{\prime}$ in the form $n^{\prime}=2^{x^{\prime}} \times 5^{y-1} \times m^{\prime}$ (with $m^{\prime}$ coprime with 2 and 5): regardless of the values of $x^{\prime}$ and $m^{\prime}$, the property $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ still ensures that X's opponent will lose.

We thus have the property $\mathcal{P}_{20!}$, where we have set $20!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$. In particular, we easily observe that $20!=2^{18} \times 5^{4} \times m$, where we have set $m=3^{8} \times 7^{2} \times 11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$. Since Clara, who plays first, $c^{\prime}$ is therefore Edwige who will win.

|

Edwige

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Dans le train, alors qu'elles rentrent de EGMOnd an Zee, Clara et Edwige jouent au jeu suivant. Initialement, l'entier $n=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ est écrit sur une feuille de papier. Puis, chacune à son tour, et en commençant par Clara, les joueuses remplacent l'entier $n$ par un des nombres $k n / 10$, où $k$ est un entier compris entre 1 et 9 inclus. La première joueuse à écrire un nombre qui n'est pas entier perd, et son adversaire gagne.

Clara et Edwige sont deux joueuses redoutables, et jouent donc de manière optimale. Laquelle des deux va-t-elle gagner?

|

Intéressons-nous au nombre $n$ écrit sur la feuille de papier au moment où la joueuse X s'apprête à jouer, et avant que la partie ne se termine. On factorise partiellement $n$ comme produit de nombres premiers : $n=2^{x} \times 5^{y} \times m$, où $x$ et $y$ sont des entiers naturels et $m$ est un entier naturel non nul premier avec 2 et 5 .

On va alors démontrer la propriété $\mathcal{P}_{n}$ par récurrence sur $n$ : la joueuse X perdra si $x$ et $y$ sont tous deux pairs, et gagnera dans le cas contraire. Tout d'abord, $\mathcal{P}_{1}$ est évidente, puisque X devra remplacer le nombre $n=1$ par un nombre compris entre $1 / 10$ et $9 / 10$.

Soit alors $n \geqslant 1$ un entier quelconque. On suppose $\mathcal{P}_{1}, \ldots, \mathcal{P}_{n}$, et on va démontrer $\mathcal{P}_{n+1}$.

$\triangleright$ Si $x$ et/ou $y$ est impair, on note $r$ et $s$ les restes de $x$ et $y$ modulo 2. Alors la joueuse X remplace l'entier $n$ par l'entier $n^{\prime}=n /\left(2^{r} \times 5^{s}\right)$. Puisque $n^{\prime}=2^{x-r} \times 5^{y-s} \times m$, la propriété $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ assure alors que l'adversaire de X perdra.

$\triangleright$ Si $x$ et $y$ sont pairs, on suppose tout de même que X remplace $n$ par un entier $n^{\prime}$ (ce qui n'est possible que si $x \geqslant 1$ ou $y \geqslant 1$ ). Si X remplace $n$ par le nombre $n^{\prime}=n / 2=$ $2^{x-1} \times 5^{y} \times m$, alors $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ assure que l'aversaire de $X$ gagnera. Sinon, on peut écrire $n^{\prime}$ sous la forme $n^{\prime}=2^{x^{\prime}} \times 5^{y-1} \times m^{\prime}$ (avec $m^{\prime}$ premier avec et 2 et 5 ): quelles que soient les valeurs de $x^{\prime}$ et de $m^{\prime}$, la propriété $\mathcal{P}_{n^{\prime}}$ assure quand même que l'adversaire de X perdra.

On dispose donc de la propriété $\mathcal{P}_{20!}$, où l'on a posé $20!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$. En particulier, on constate aisément que $20!=2^{18} \times 5^{4} \times m$, où l'on a posé $m=3^{8} \times 7^{2} \times 11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$. Puisque Clara qui joue la première, $c^{\prime}$ est donc Edwige qui gagnera.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

In the train, as they return from EGMOnd aan Zee, Clara and Edwige play the following game. Initially, the integer $n=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ is written on a piece of paper. Then, each in turn, starting with Clara, the players replace the integer $n$ by one of the numbers $k n / 10$, where $k$ is an integer between 1 and 9 inclusive. The first player to write a number that is not an integer loses, and her opponent wins.

Clara and Edwige are formidable players and play optimally. Which of the two will win?

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ We will once again provide a winning strategy for Edwige, which slightly differs from the previous one. This strategy is very simple (even if proving that it works is less so): if Clara has just transformed her number $n$ into a new number $n^{\prime}=k n / 10$, then Edwige will transform $n^{\prime}$ back into $n^{\prime \prime}=k n^{\prime} / 10$.

To show that this strategy will allow Edwige to win, and since the game will last at most $20!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ moves, it suffices to prove that $n^{\prime \prime}$ will necessarily be an integer. Thus, Edwige cannot lose, and she will therefore win.

First, we observe that the integer $20!$ is equal to $u^{2} \times v$, where we have set $u=2^{9} \times 2^{4} \times 5^{2} \times 7$ and $v=11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$. We will now prove that, if Edwige applies the strategy above, then each of the integers $n$ she leaves to Clara will be of the form $n=\hat{u}^{2} v$, with $\hat{u}$ an integer and $v=11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$.

This is already the case at the beginning of the game. Then, if Clara transforms an integer $n=\hat{u}^{2} v$ into another integer $n^{\prime}=k n / 10$, Edwige will transform $n^{\prime}$ into the number $n^{\prime \prime}=k n^{\prime} / 10=(k \hat{u} / 10)^{2} v$. It is therefore necessary to prove that $k \hat{u} / 10$ is an integer, that is, that 2 and 5 both divide $k \hat{u}$.

Since $n^{\prime}$ is an integer, and since $10 n^{\prime}=k n=k \hat{u}^{2} v$, we know that 2 and 5 both divide $k \hat{u}^{2} v$. However, 2 does not divide $v$, and therefore divides $k$ or $\hat{u}$: it therefore also divides $k \hat{u}$. Similarly, 5 does not divide $v$, and therefore divides $k$ or $\hat{u}$: it therefore also divides $k \hat{u}$. This concludes our proof.

Examiner's Comment Many students had good ideas about the problem, but few managed to obtain a real proof that Edwige has a winning strategy. Indeed, a number of students immediately gave Clara an "optimal strategy" from the start: to prove that Edwige wins, one must give a strategy to Edwige and verify that no matter what Clara does, Edwige will win. In particular, Clara has no reason to follow a strategy that seems to be the best at first glance (and which, quite often, is not).

Some students quickly considered that the only important values of $k$ were $k=1, k=2$, and $k=5$, as divisors of 10. However, $k=4$ and $k=8$ were just as important, allowing for 2-adic valuations that were otherwise inaccessible.

Moreover, several students understood that Edwige had an interest in leaving Clara at each step with an integer of the form $2^{x} 5^{y} m$, with $m$ an integer coprime with 10 and $x$ and $y$ even, but did not prove that Edwige could indeed leave Clara in such a state at each step; and especially that Edwige could play the move in question!

Finally, it would have been good to prove that the game ends in all cases, without which Edwige of course does not win.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Dans le train, alors qu'elles rentrent de EGMOnd an Zee, Clara et Edwige jouent au jeu suivant. Initialement, l'entier $n=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ est écrit sur une feuille de papier. Puis, chacune à son tour, et en commençant par Clara, les joueuses remplacent l'entier $n$ par un des nombres $k n / 10$, où $k$ est un entier compris entre 1 et 9 inclus. La première joueuse à écrire un nombre qui n'est pas entier perd, et son adversaire gagne.

Clara et Edwige sont deux joueuses redoutables, et jouent donc de manière optimale. Laquelle des deux va-t-elle gagner?

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ Nous allons de nouveau fournir une stratégie gagnante pour Edwige, qui diffère légèrement de la stratégie précédente. Cette stratégie est toute simple (même si montrer qu'elle convient l'est moins) : si Clara vient de transformer son nombre $n$ en un nouveau nombre $n^{\prime}=k n / 10$, alors Edwige transforme de nouveau $n^{\prime}$ en $n^{\prime \prime}=k n^{\prime} / 10$.

Pour montrer que cette stratégie permettra à Edwige de gagner, et puisque la partie durera au plus $20!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 20$ coups, il suffit de démontrer que $n^{\prime \prime}$ sera nécessairement un entier. Ainsi, Edwige ne pourra pas perdre, et elle gagnera donc.

Tout d'abord, on constate que l'entier 20! est égal à $u^{2} \times v$, où l'on a posé $u=2^{9} \times 2^{4} \times 5^{2} \times 7$ et $v=11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$. On va maintenant démontrer que, si Edwige applique la stratégie ci-dessus, alors chacun des entiers $n$ qu'elle laissera à Clara sera de la forme $n=\hat{u}^{2} v$, avec $\hat{u}$ entier et $v=11 \times 13 \times 17 \times 19$.

C'est déjà le cas au début du jeu. Puis, si Clara transforme un entier $n=\hat{u}^{2} v$ en un autre entier $n^{\prime}=k n / 10$, Edwige transformera $n^{\prime}$ en le nombre $n^{\prime \prime}=k n^{\prime} / 10=(k \hat{u} / 10)^{2} v$. Il s'agit donc de démontrer que $k \hat{u} / 10$ est un entier, c'est-à-dire que 2 et 5 divisent tous deux $k \hat{u}$.

Puisque $n^{\prime}$ est un entier, et comme $10 n^{\prime}=k n=k \hat{u}^{2} v$, on sait que 2 et 5 divisent tous deux $k \hat{u}^{2} v$. Or, 2 ne divise pas $v$, et divise donc $k$ ou $\hat{u}$ : il divise donc aussi $k \hat{u}$. De même, 5 ne divise pas $v$, et divise donc $k$ ou $\hat{u}$ : il divise donc aussi $k \hat{u}$. Cela conclut notre démonstration.

Commentaire des correcteurs Beaucoup d'élèves ont eu des bonnes idées sur le problème, mais peu ont réussi à obtenir une vraie preuve du fait qu'Edwige a une stratégie gagnante. En effet, un certain nombre d'élèves donne dès le départ une «stratégie optimale »à Clara : pour démontrer qu'Edwige gagne, il faut donner une stratégie à Edwige et vérifier quen peu importe ce que Clara faitn Edwige gagnera. En particulier, Clara n'a aucune raison de suivre une stratégie qui semble être la meilleure à vue d'œil (et qui, assez souvent, ne l'est pas).

Certains élèves ont rapidement considéré que seuls les seules valeurs de $k$ importantes étaient $k=1, k=2$ et $k=5$, en tant que diviseurs de 10 . Cependant, $k=4$ et $k=8$ étaient tout aussi importants, permettant d'obtenir des valuations 2-adiques inaccessibles autrement.

Par ailleurs, plusieurs élèves ont bien compris que Edwige avait intérêt à laisser Clara à chaque étape avec un entier de la forme $2^{x} 5^{y} m$, avec $m$ entier premier avec 10 et $x$ et $y$ pairs, mais n'ont pas prouvé que Edwige pouvait bien laisser Clara à chaque fois dans un tel état; et surtout qu'Edwige pouvait jouer le coup en question!

Enfin, il aurait été bien de prouver que la partie termine dans tous les cas, ce sans quoi Edwige ne gagne bien sûr pas.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Determine all natural numbers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

We start by decomposing each term into a product of prime factors. The equation then becomes

$$

3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}-3^{y} \cdot 2^{y}=3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}

$$

We will now handle different cases:

$\triangleright$ If $y>2 x$, then $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{2 x}\left(5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \times 2^{y}\right)$. Gauss's theorem then indicates that $3^{z}$ divides $3^{2 x}$ (since $5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \times 2^{y}$ is not divisible by 3, and is thus coprime with $3^{z}$) and that $3^{2 x}$ divides $3^{z}$ (since $673^{z}$ is not divisible by 3, and is thus coprime with $3^{2 x}$). We deduce that $z=2 x$, and the equation becomes

$$

673^{2 x}=5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \cdot 2^{y}

$$

However, since $673^{2 x} \geqslant 5^{x}$, this equation has no solution, and this case is therefore impossible.

$\triangleright$ If $y=2 x$, then $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{2 x}\left(5^{x}-2^{y}\right)$. As before, Gauss's theorem indicates that $3^{2 x}$ divides $3^{z}$. We deduce that $2 x \leqslant z$, and the equation becomes

$$

3^{z-2 x} \cdot 673^{z}=5^{x}-2^{y}

$$

However, since $673^{z} \geqslant 5^{z} \geqslant 5^{x}$, this equation has no solution either, and this case is therefore impossible.

$\triangleright$ If $y<2 x$, then $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{y}\left(3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}\right)$. Once again, since neither $673^{z}$ nor $3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}$ are divisible by 3, Gauss's theorem indicates that $3^{z}$ and $3^{y}$ divide each other. We deduce that $z=y$, and the equation becomes

$$

673^{y}=3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}

$$

We then distinguish several sub-cases:

$\triangleright$ If $y=0$, the equation becomes $2=3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}$, and of course has no solution.

$\triangleright$ If $y=1$, the equation becomes $675=3^{2 x-1} \cdot 5^{x}$. Since $675=3^{3} \times 5^{2}$, we deduce the existence of the solution $(x, y, z)=(2,1,1)$.

$\triangleright$ If $y \geqslant 2$, consider the equation modulo 4: it becomes $1 \equiv 3^{y}(\bmod 4)$, which means that $y$ is even.

Then, since we necessarily have $x \geqslant 1$, and if we consider the equation modulo 5, it becomes $(-2)^{y} \equiv-2^{y}(\bmod 5)$, which means that $y$ is odd. The equation therefore has no solution in this sub-case.

The unique solution to the equation is thus the triplet $(2,1,1)$.

|

(2,1,1)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers naturels $x, y$ et $z$ tels que

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

On commence par décomposer chaque terme en produit de facteurs premiers. L'équation devient alors

$$

3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}-3^{y} \cdot 2^{y}=3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}

$$

Nous allons maintenant traiter différents cas :

$\triangleright$ Si $y>2 x$, alors $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{2 x}\left(5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \times 2^{y}\right)$. Le théorème de Gauss indique alors que $3^{z}$ divise $3^{2 x}$ (car $5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \times 2^{y}$ n'est pas divisible par 3, doncest premier avec $3^{z}$ ) et que $3^{2 x}$ divise $3^{z}$ (car $673^{z}$ n'est pas divisible par 3 , donc est premier avec $3^{2 x}$. On en déduit que $z=2 x$, et l'équation devient

$$

673^{2 x}=5^{x}-3^{y-2 x} \cdot 2^{y}

$$

Mais, puisque $673^{2 x} \geqslant 5^{x}$, cette équation n'a en fait pas de solution, et ce cas est donc impossible.

$\triangleright$ Si $y=2 x$, alors $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{2 x}\left(5^{x}-2^{y}\right)$. Comme précédemment, le théorème de Gauss indique que $3^{2 x}$ divise $3^{z}$. On en déduit que $2 x \leqslant z$, et l'équation devient

$$

3^{z-2 x} \cdot 673^{z}=5^{x}-2^{y}

$$

Mais, puisque $673^{z} \geqslant 5^{z} \geqslant 5^{x}$, cette équation n'a pas de solution elle non plus, et ce cas est donc impossible.

$\triangleright$ Si $y<2 x$, alors $3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}=3^{y}\left(3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}\right)$. Une fois encore, puisque ni $673^{z} \mathrm{ni}$ $3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}$ ne sont divisibles par 3 , le théorème de Gauss indique que $3^{z}$ et $3^{y}$ se divisent mutuellement. On en déduit que $z=y$, et l'équation devient

$$

673^{y}=3^{2 x-y} \cdot 5^{x}-2^{y}

$$

On distingue alors plusieurs sous-cas :

$\triangleright$ Si $y=0$, l'équation devient $2=3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}$, et n'a bien sûr aucune solution.

$\triangleright$ Si $y=1$, l'équation devient $675=3^{2 x-1} \cdot 5^{x}$. Puisque $675=3^{3} \times 5^{2}$, on en déduit l'existence de la solution $(x, y, z)=(2,1,1)$.

$\triangleright$ Si $y \geqslant 2$, considérons notre équation modulo 4 : elle devient $1 \equiv 3^{y}(\bmod 4)$, ce qui signifie que $y$ est pair.

Puis, comme on a nécessairement $x \geqslant 1$, et si on considère l'équation modulo 5 , celle-ci devient $(-2)^{y} \equiv-2^{y}(\bmod 5)$, ce qui signifie que $y$ est impair. L'équation n'admet donc aucune solution dans ce sous-cas.

L'unique solution de l'équation est donc le triplet $(2,1,1)$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Determine all natural numbers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ We can directly treat the cases $y>2 x$ and $y=2 x$ at the same time, by presenting the arguments mentioned above in a slightly different order. First, since $2019^{z}<45^{x} \leqslant 2019^{x}$, we deduce that $z<x$. Furthermore, if one of the three integers $2 x, y$, and $z$ (we will call it $t$) is strictly smaller than the other two, then the integer $3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}-3^{y} \cdot 2^{y}-3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}$ is not divisible by $3^{t+1}$, which is impossible since it is supposed to be zero. Since we already know that $z<x \leqslant 2 x$, we deduce that $y=z$, and thus that $y=z<x$.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers naturels $x, y$ et $z$ tels que

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

$n^{\circ} 1$ On peut traiter directement les cas $y>2 x$ et $y=2 x$ en une seule fois, en reprentant les arguments mentionnés ci-dessus dans un ordre légèrement différent. Tout d'abord, puisque $2019^{z}<45^{x} \leqslant 2019^{x}$, on en déduit que $z<x$. En outre, si l'un des trois entiers $2 x, y$ et $z$ (on l'appellera $t$ ) est strictement plus petit que les deux autres, alors l'entier $3^{2 x} \cdot 5^{x}-3^{y} \cdot 2^{y}-3^{z} \cdot 673^{z}$ n'est pas divisible par $3^{t+1}$, ce qui est impossible puisqu'il est censé être nul. Puisque l'on sait déjà que $z<x \leqslant 2 x$, on en déduit que $y=z$, et donc que $y=z<x$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Determine all natural numbers $x, y$ and $z$ such that

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ We work directly from the equation

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

First, since $45^{x}>2019^{z}$, we know that $x \geqslant 1$. Considering the equation modulo 5, it rewrites as

$$

-1 \equiv-1^{y} \equiv(-1)^{z} \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

This means that $z$ is an odd integer.

Then, considering the equation modulo 4, and since $z$ is odd, it rewrites as

$$

1-2^{y} \equiv 45^{x}-6^{y} \equiv 2019^{z} \equiv(-1)^{z} \equiv-1 \quad(\bmod 4)

$$

This means that $y=1$.

Finally, since $x \geqslant 1$, considering the equation modulo 9, it rewrites as

$$

3 \equiv 45^{x}-6^{y} \equiv 3^{z} \quad(\bmod 9)

$$

This means that $z=1$.

The equation then becomes $45^{x}=6^{y}+2019^{z}=2025=45^{2}$, and the triplet $(x, y, z)=(2,1,1)$ appears as a solution to the equation in the statement.

In conclusion, the unique solution sought is the triplet $(2,1,1)$.

Comment from the graders The exercise was well solved. In particular, many students began by writing the small powers of 45, 6, and 2019, which allowed them to see remarkable relationships modulo 10, and then realize that looking at the equation modulo small numbers could be useful. Others correctly recognized that 45, 6, and 2019 are multiples of 3, which led them to use the concept of 3-adic valuation. In both cases, these are excellent reflexes that did not fail to bear fruit. However, it is regrettable that several students implicitly assumed $x, y$, and $z$ were non-zero, although nothing guaranteed this a priori: one must be careful to read the statement well to avoid losing points that are not easy to obtain otherwise!

|

(2,1,1)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers naturels $x, y$ et $z$ tels que

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ On travaille directement à partir de l'équation

$$

45^{x}-6^{y}=2019^{z}

$$

Tout d'abord, puisque $45^{x}>2019^{z}$, on sait que $x \geqslant 1$. Considérée modulo 5 , l'équation se réécrit

$$

-1 \equiv-1^{y} \equiv(-1)^{z} \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

Cela signifie que $z$ est un entier impair.

Puis, en considérant l'équation modulo 4, et puisque $z$ est impair, celle-ci se réécrit

$$

1-2^{y} \equiv 45^{x}-6^{y} \equiv 2019^{z} \equiv(-1)^{z} \equiv-1 \quad(\bmod 4)

$$

Cela signifie que $y=1$.

Enfin, puisque $x \geqslant 1$, en considérant l'équation modulo 9 , celle-ci se réécrit

$$

3 \equiv 45^{x}-6^{y} \equiv 3^{z} \quad(\bmod 9)

$$

Cela signifie que $z=1$.

L'équation devient alors $45^{x}=6^{y}+2019^{z}=2025=45^{2}$, et le triplet $(x, y, z)=(2,1,1)$ apparaît alors manifestement comme une solution de l'équation de l'énoncé.

En conclusion, l'unique solution recherchée est le triplet $(2,1,1)$.

Commentaire des correcteurs L'exercice a été bien résolu. En particulier, de nombreux élèves ont commencé par écrire les petites puissances de 45, 6 et 2019, ce qui leur a permis de voir des relations remarquables modulo 10 , puis de prendre conscience que regarder l'équation modulo de petits nombres pouvait être utile. D'autres ont reconnu, à juste titre, que 45, 6 et 2019 étaient des multiples de 3, ce qui les a poussés à utiliser la notion de valuation 3-adique. Dans les deux cas, il s'agit d'excellents réflexes, qui n'ont pas manqué de porter leurs fruits. On peut néanmoins regretter que plusieurs élèves aient implicitement supposé $x, y$ et $z$ non nuls, alors que rien ne venait le garantir a priori : il faut faire attention de bien lire l'énoncé pour éviter de perdre ainsi, par naïveté, des points pas faciles à obtenir par ailleurs!

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution alternative",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

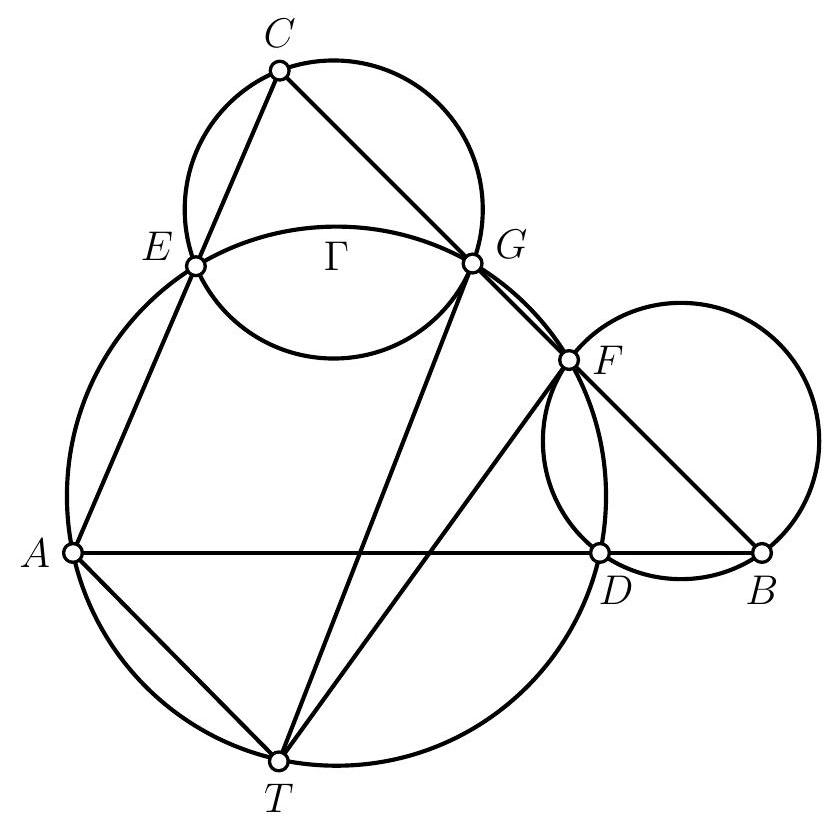

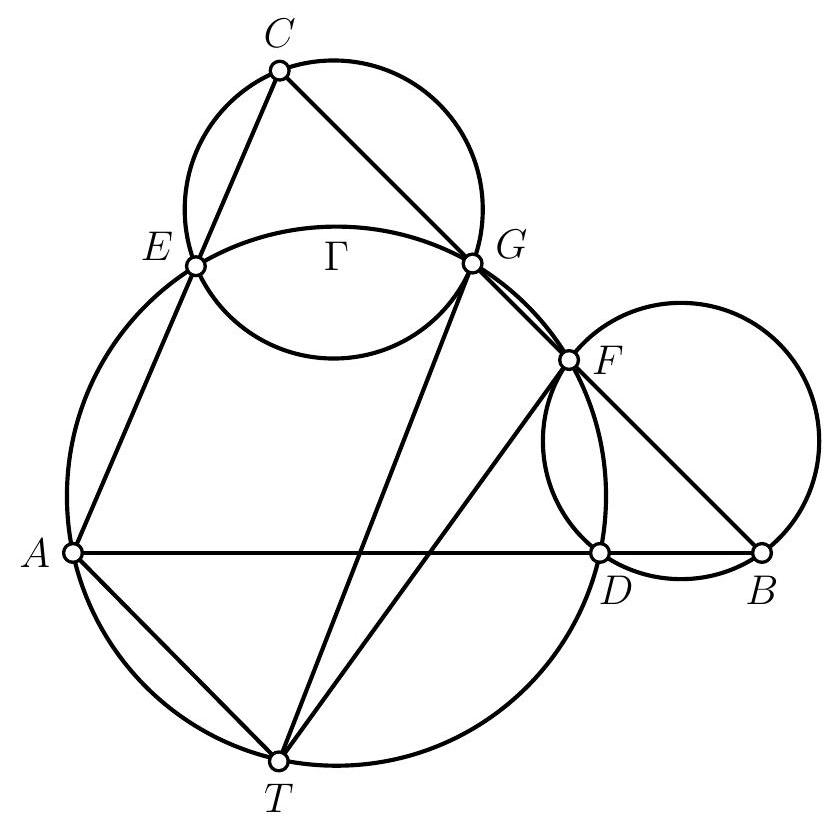

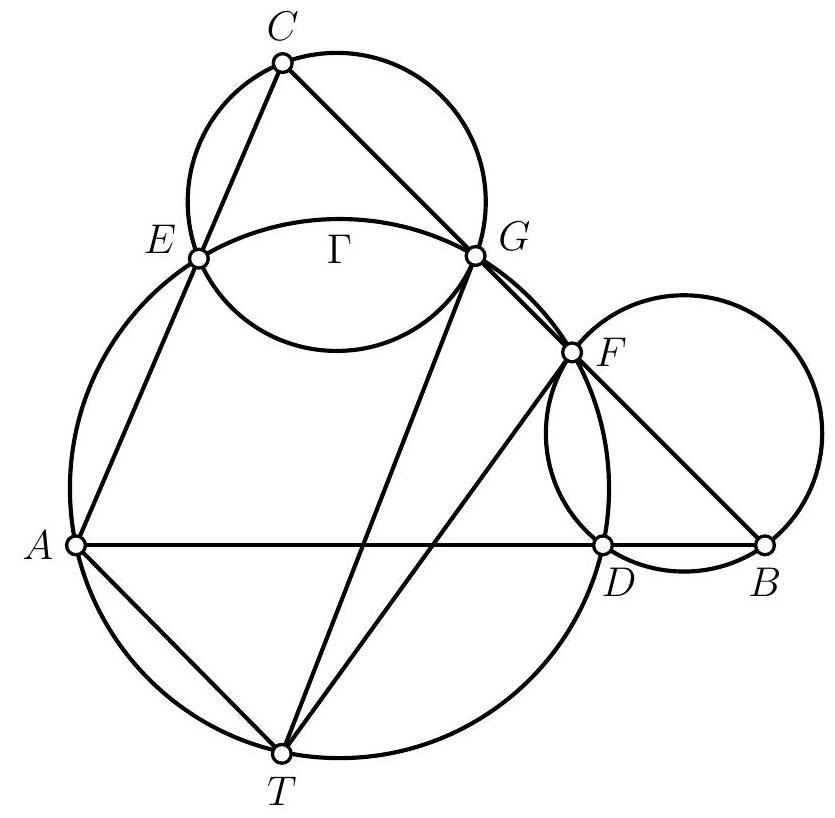

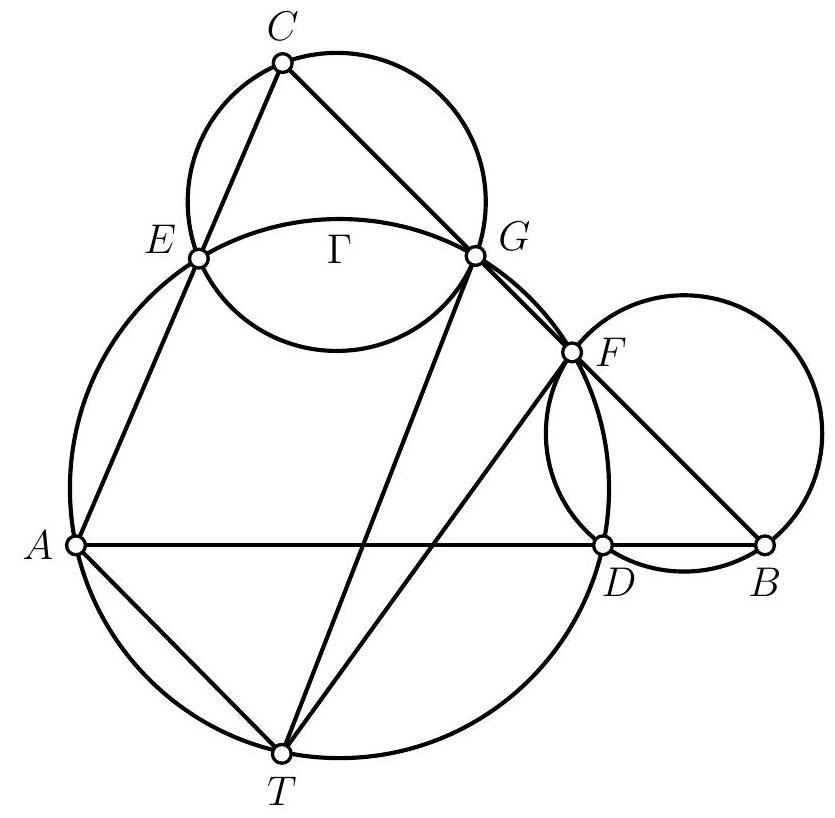

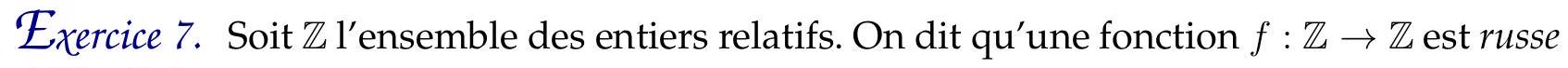

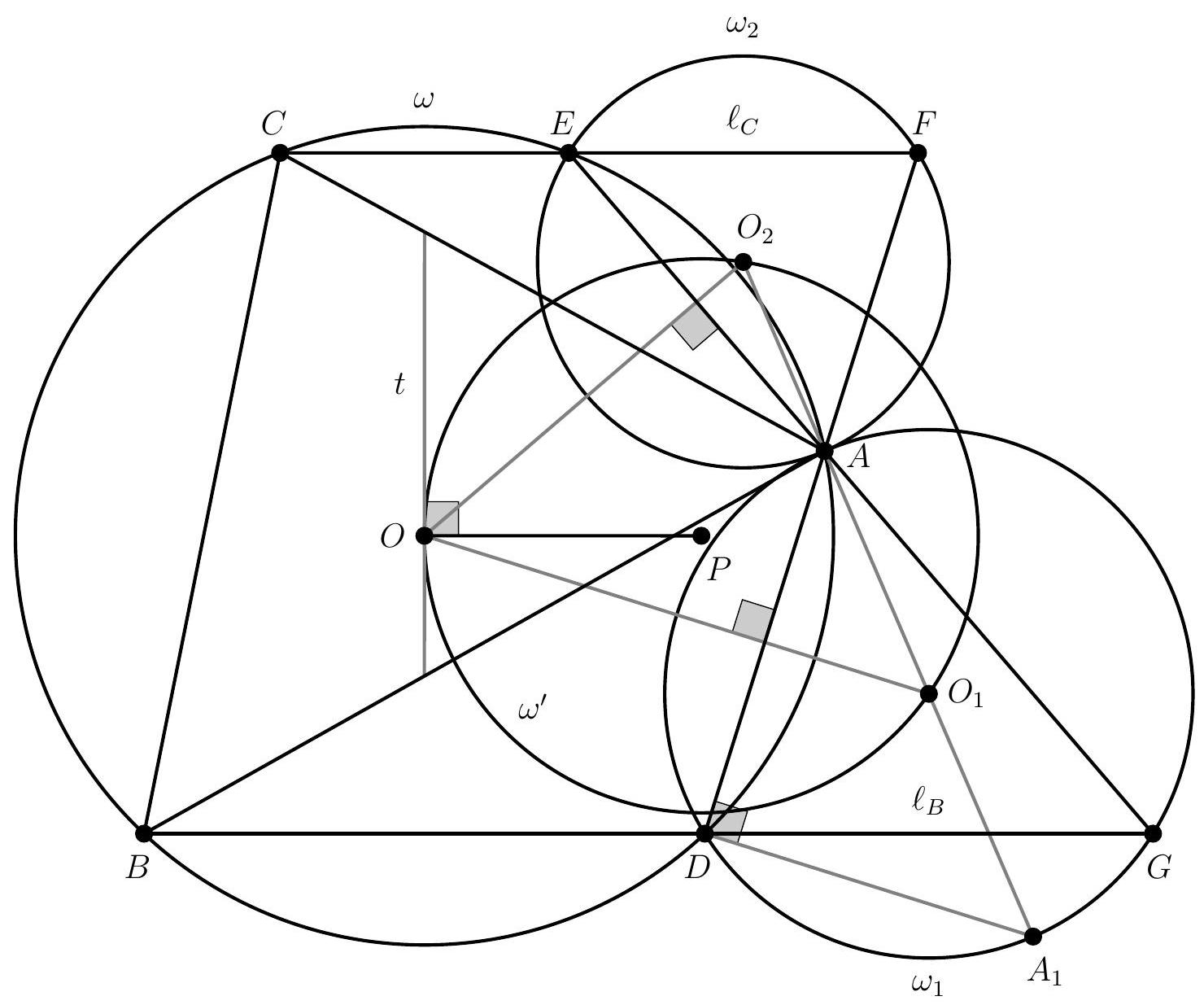

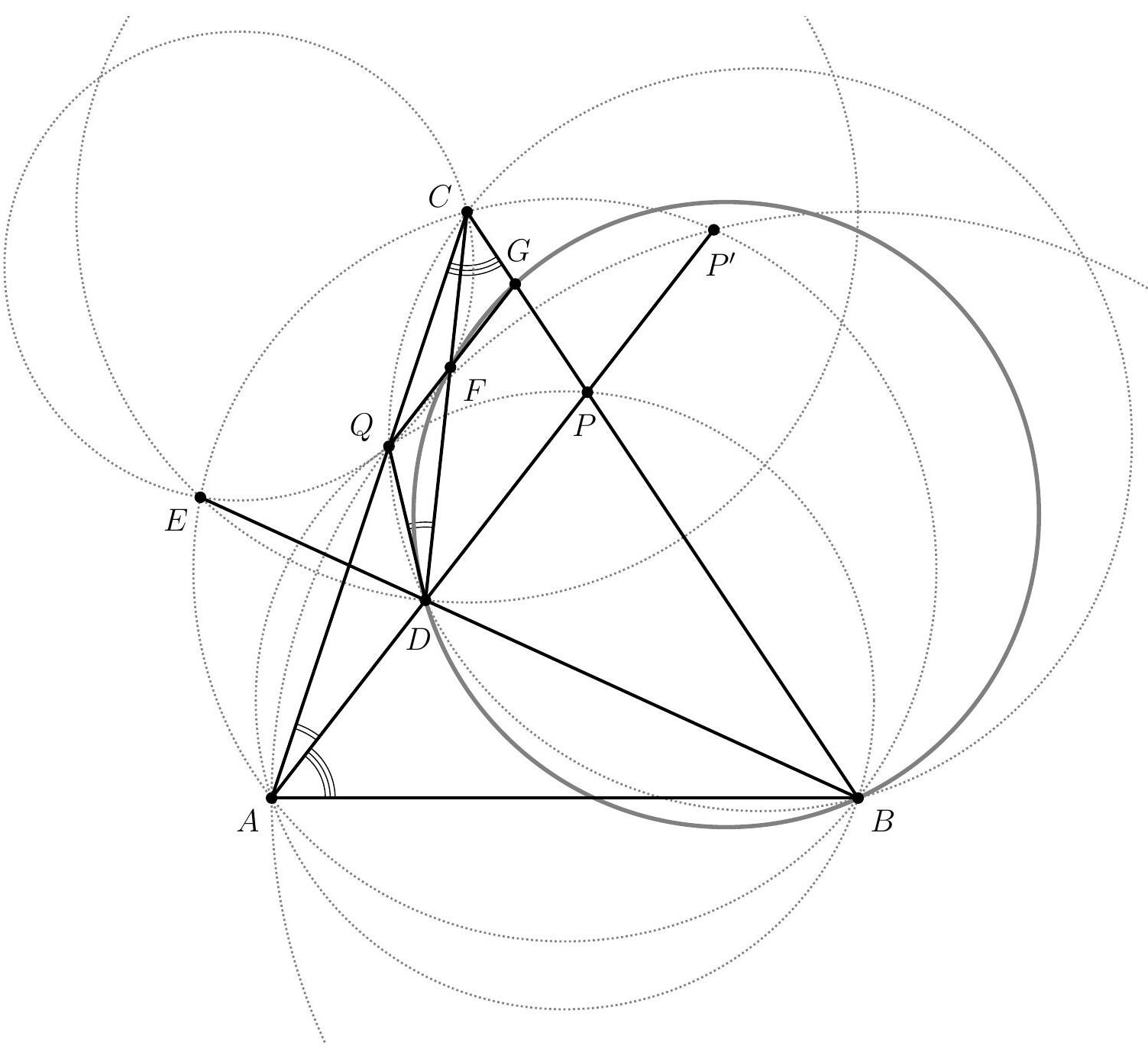

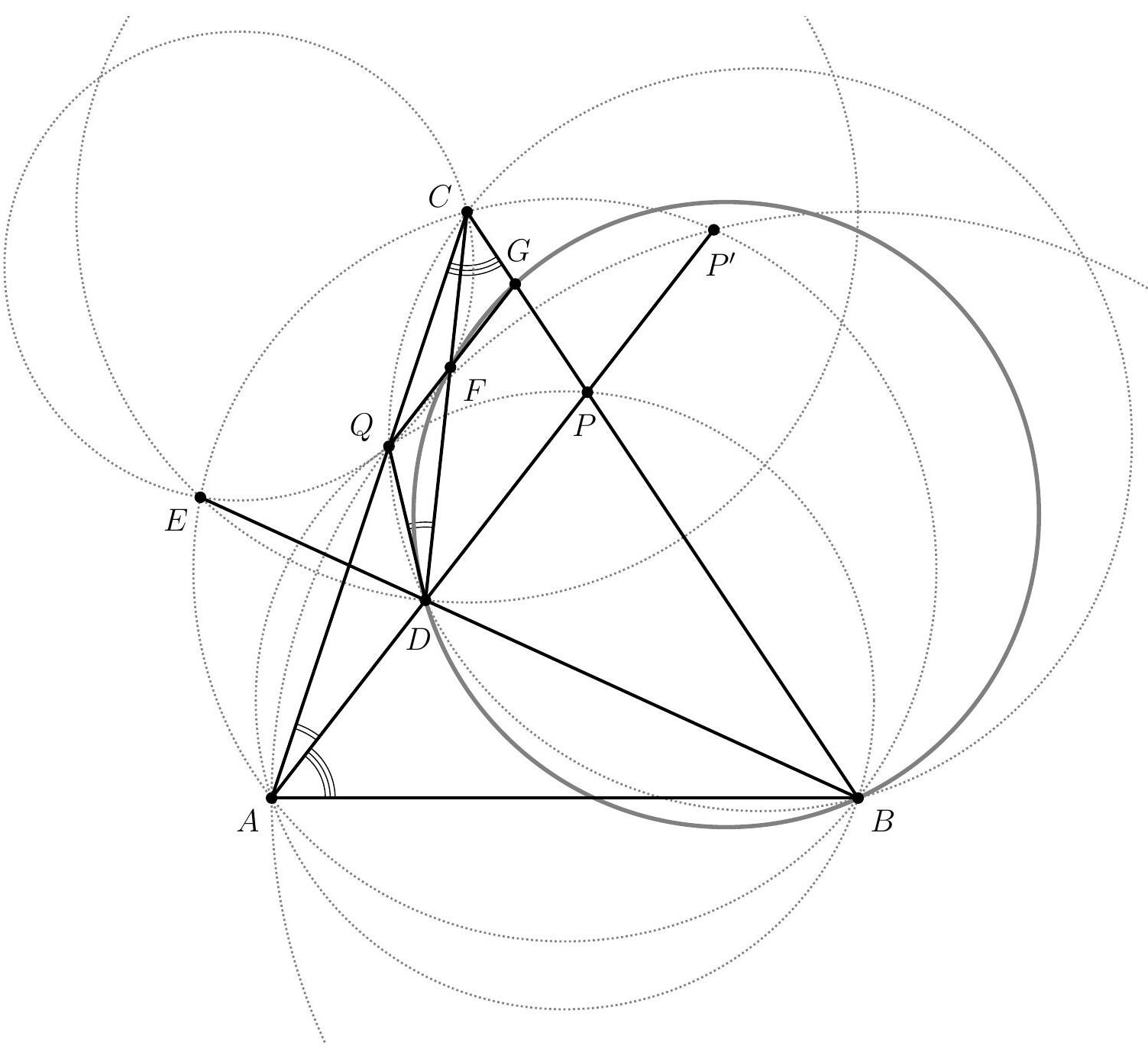

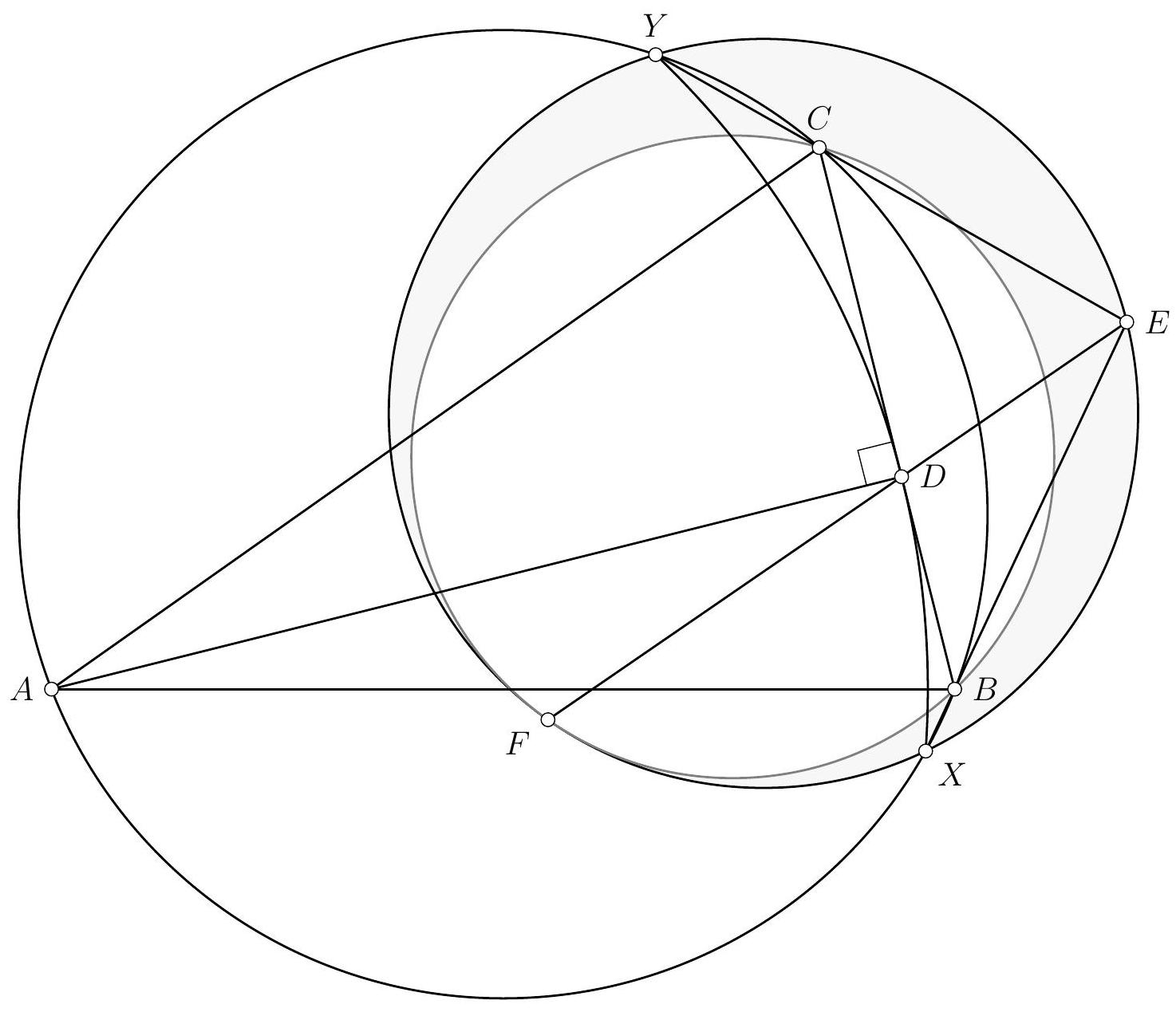

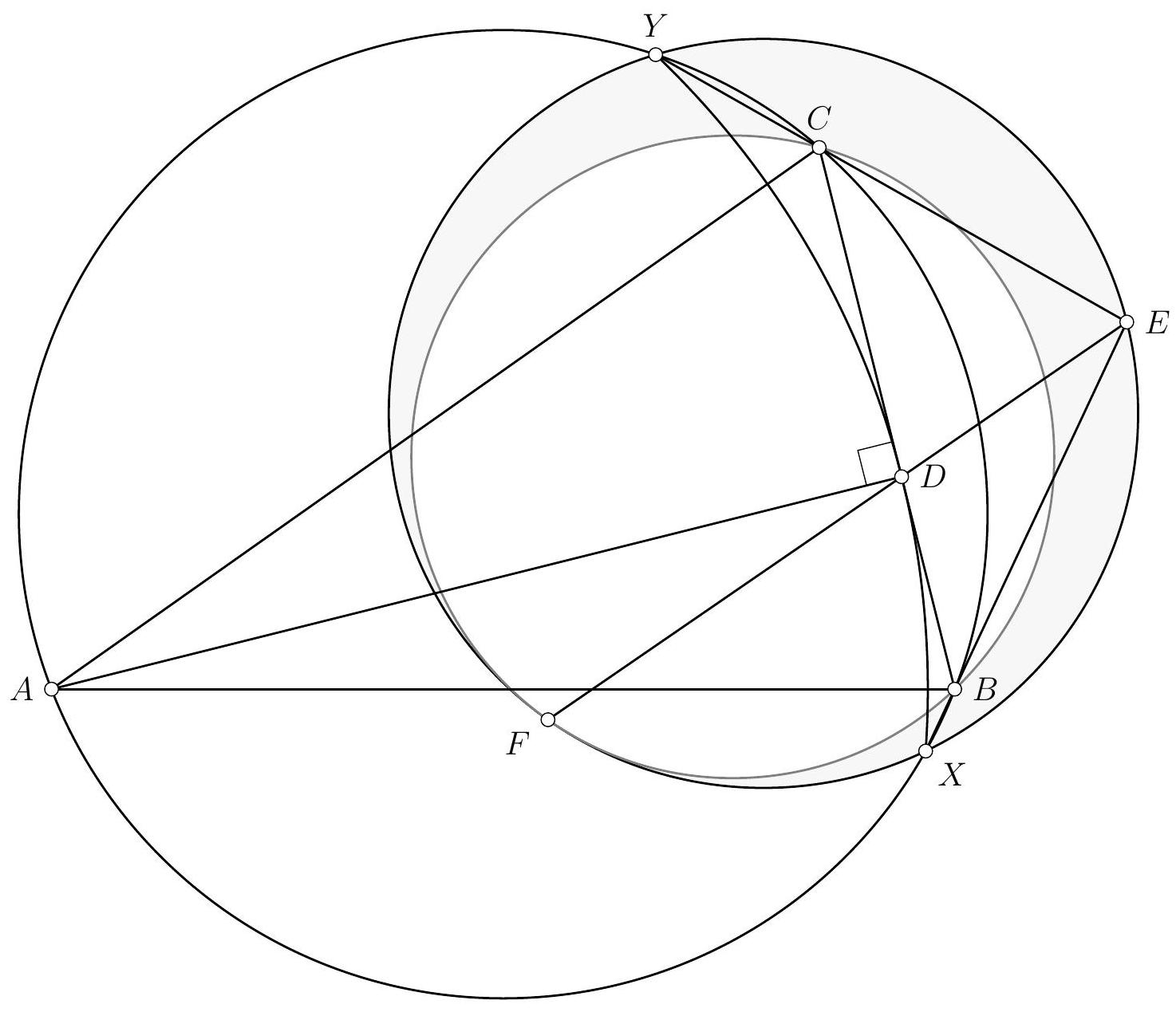

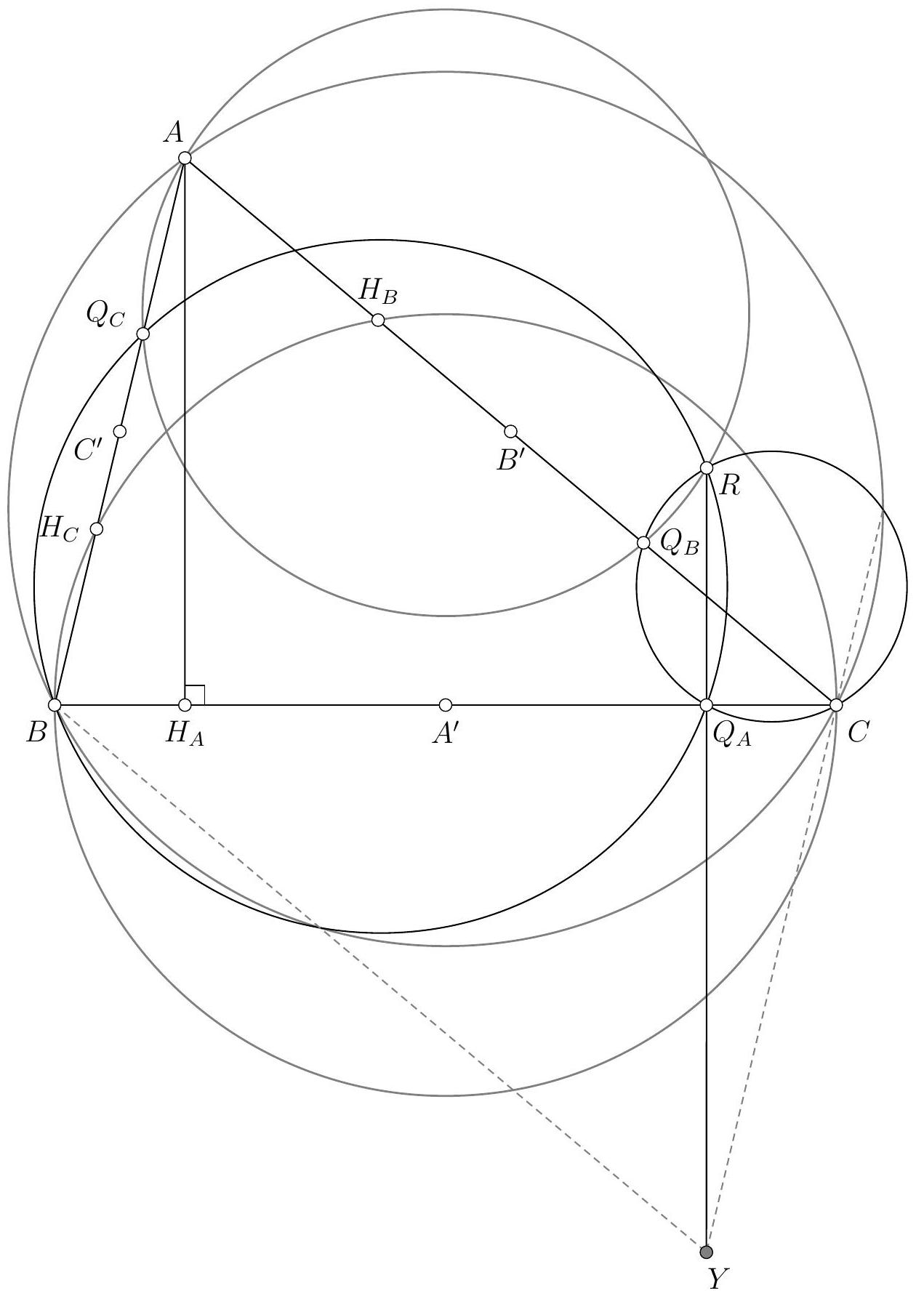

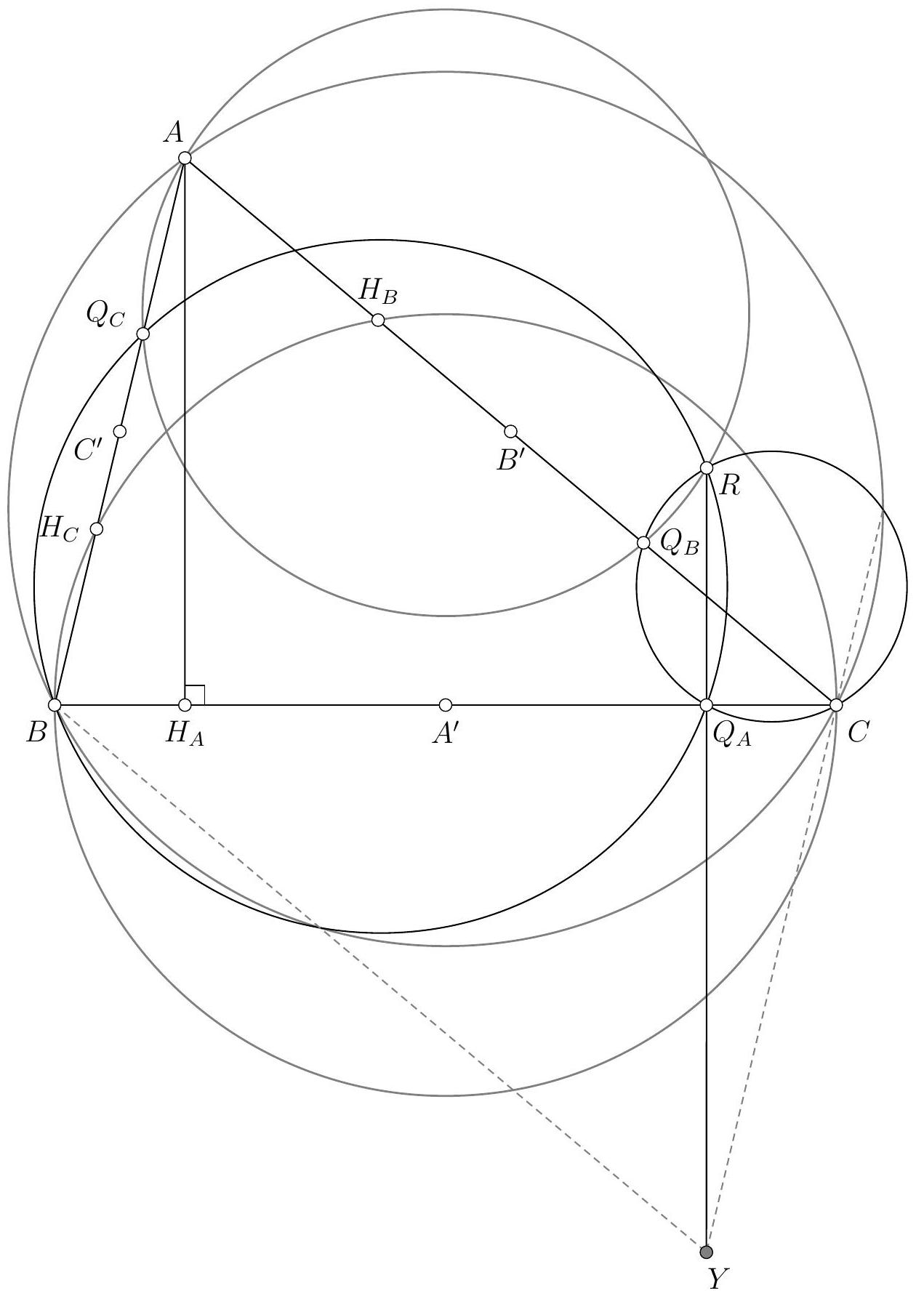

Let $ABC$ be a triangle and $\Gamma$ a circle passing through $A$. Suppose that $\Gamma$ intersects the segments $[AB]$ and $[AC]$ at two points, which we call $D$ and $E$ respectively, and that it intersects the segment $[BC]$ at two points, which we call $F$ and $G$, such that $F$ lies between $B$ and $G$. Let $T$ be the point of intersection between the tangent at $F$ to the circumcircle of $BDF$ and the tangent at $G$ to the circumcircle of $CEG$.

Prove that, if the points $A$ and $T$ are distinct, then $(AT)$ and $(BC)$ are parallel.

|

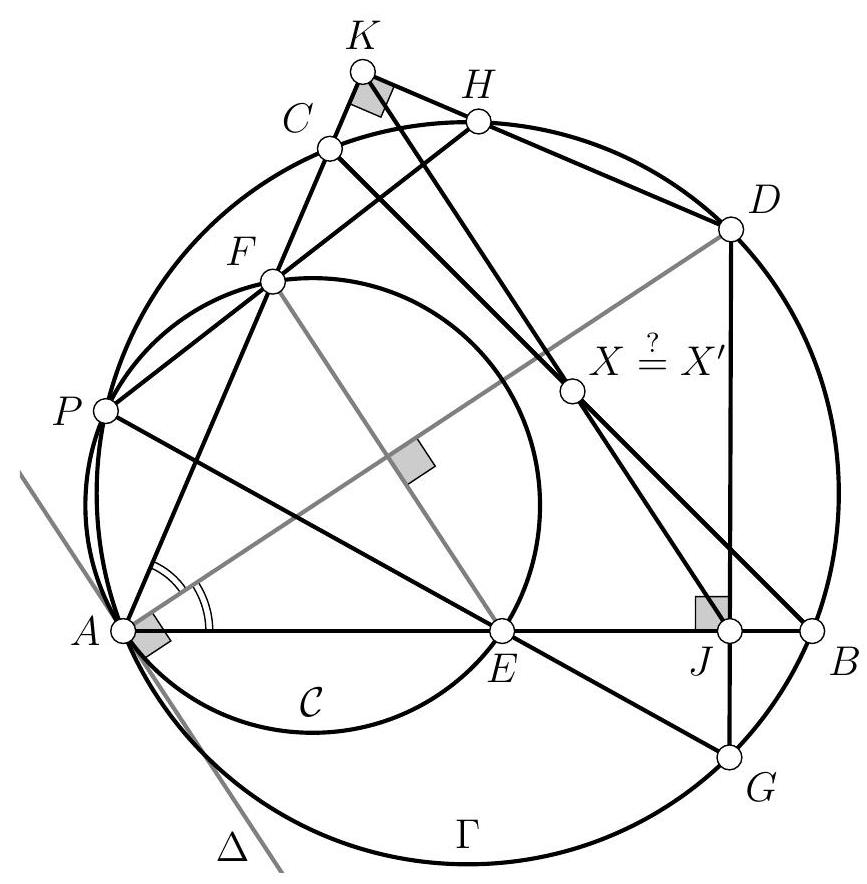

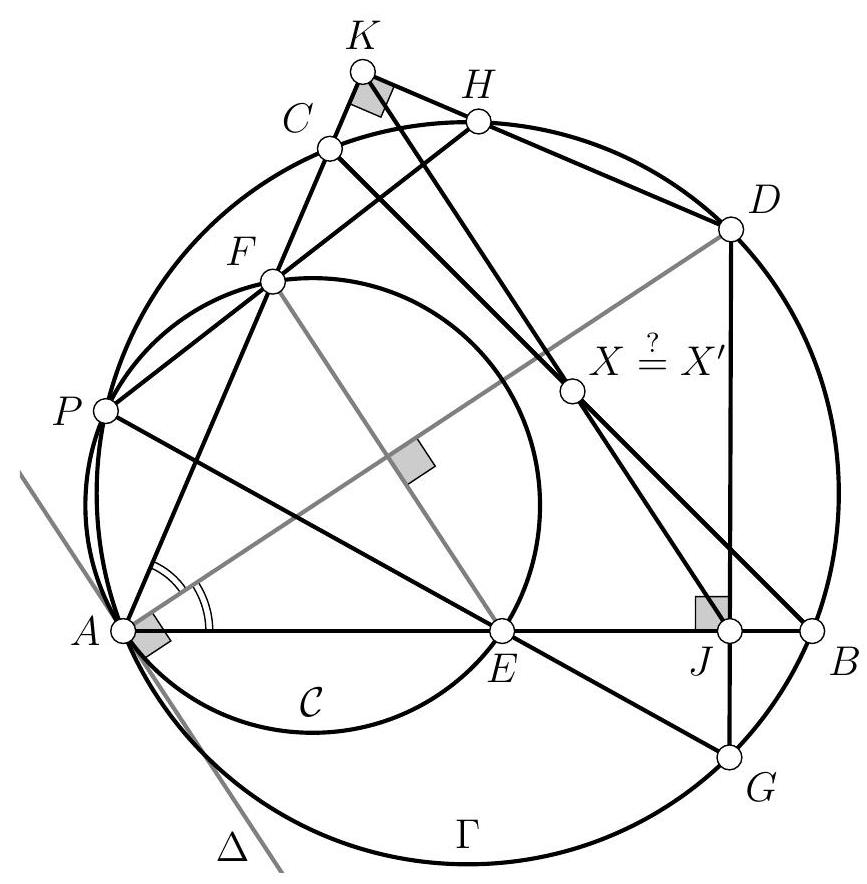

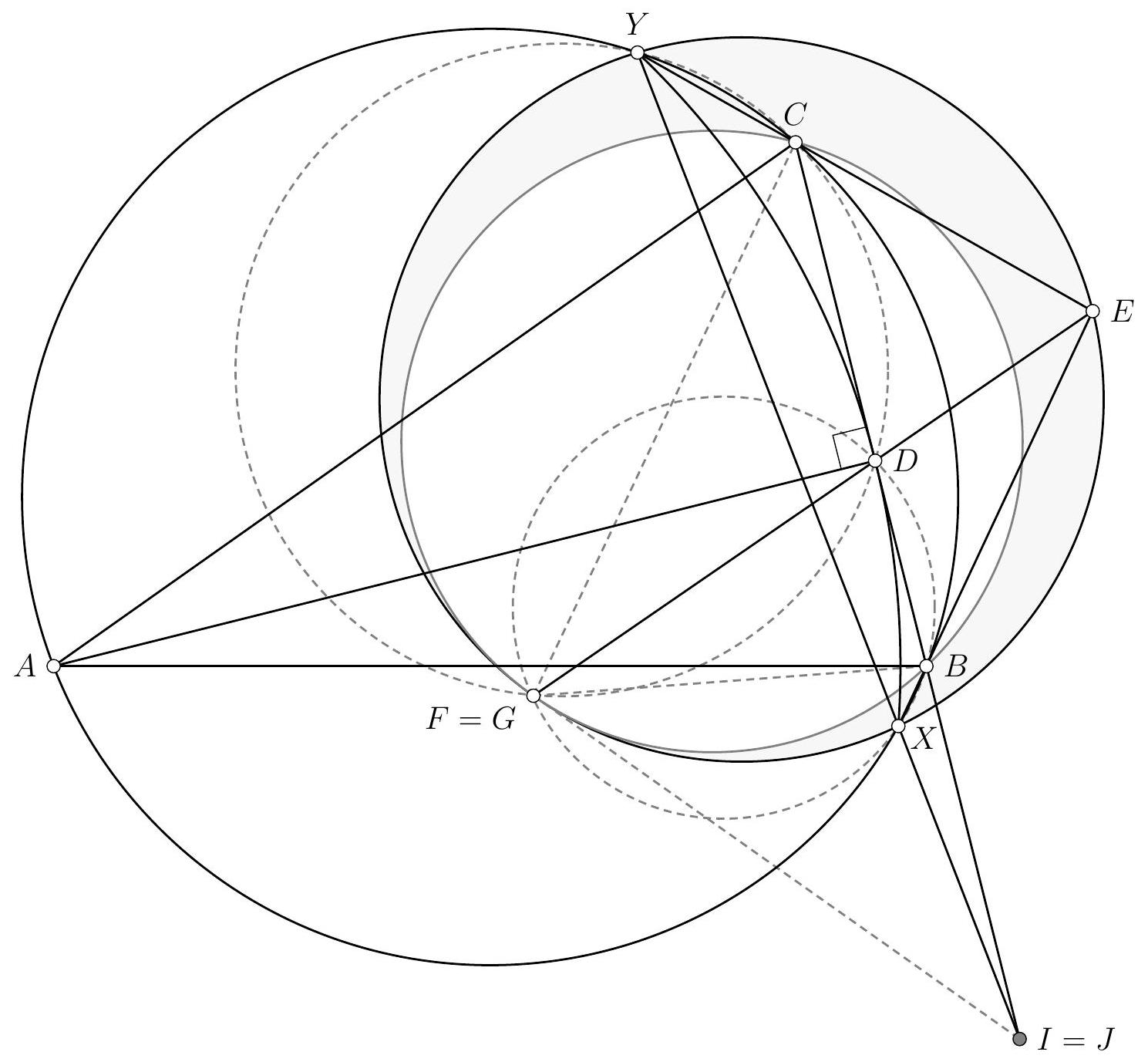

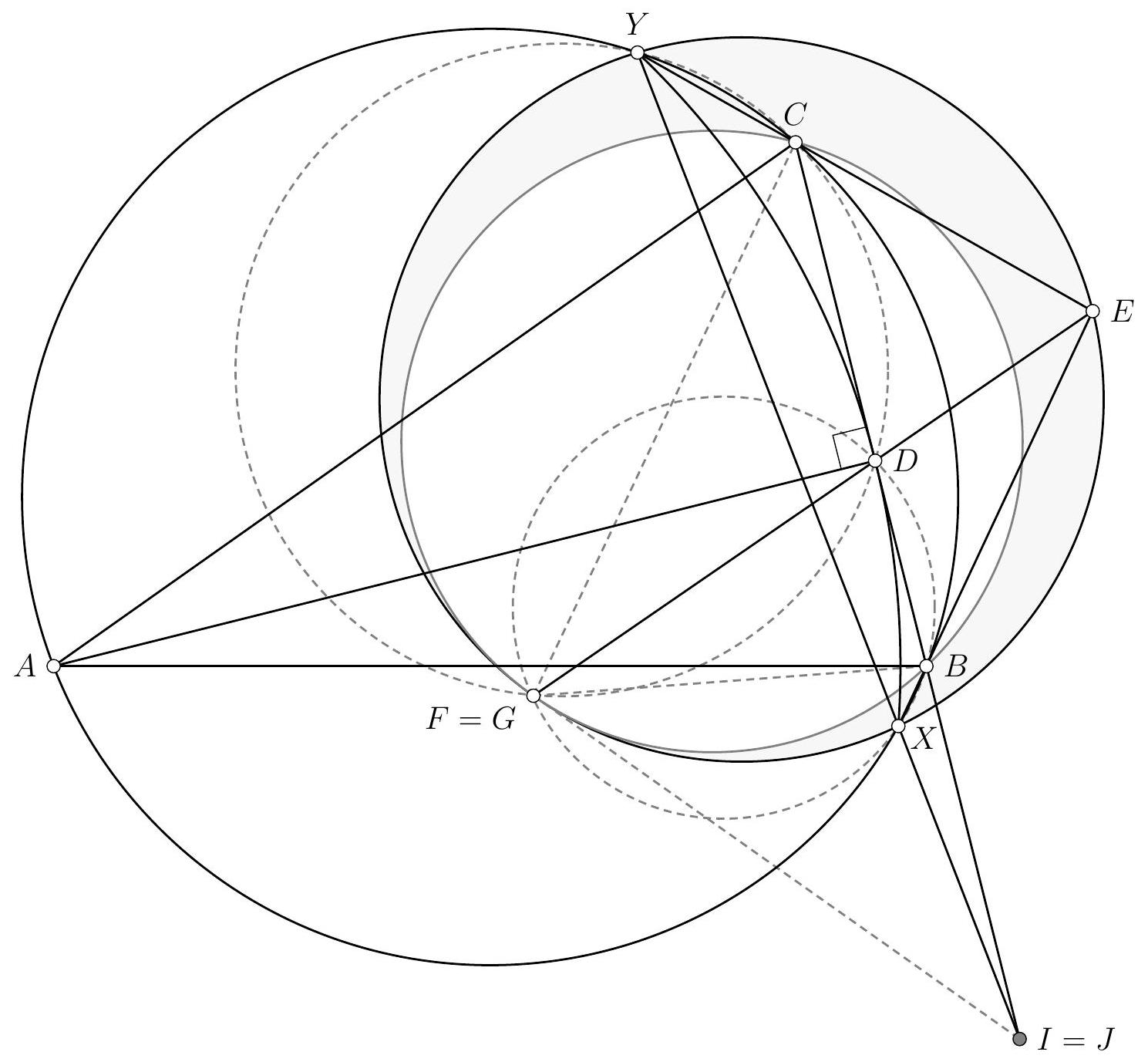

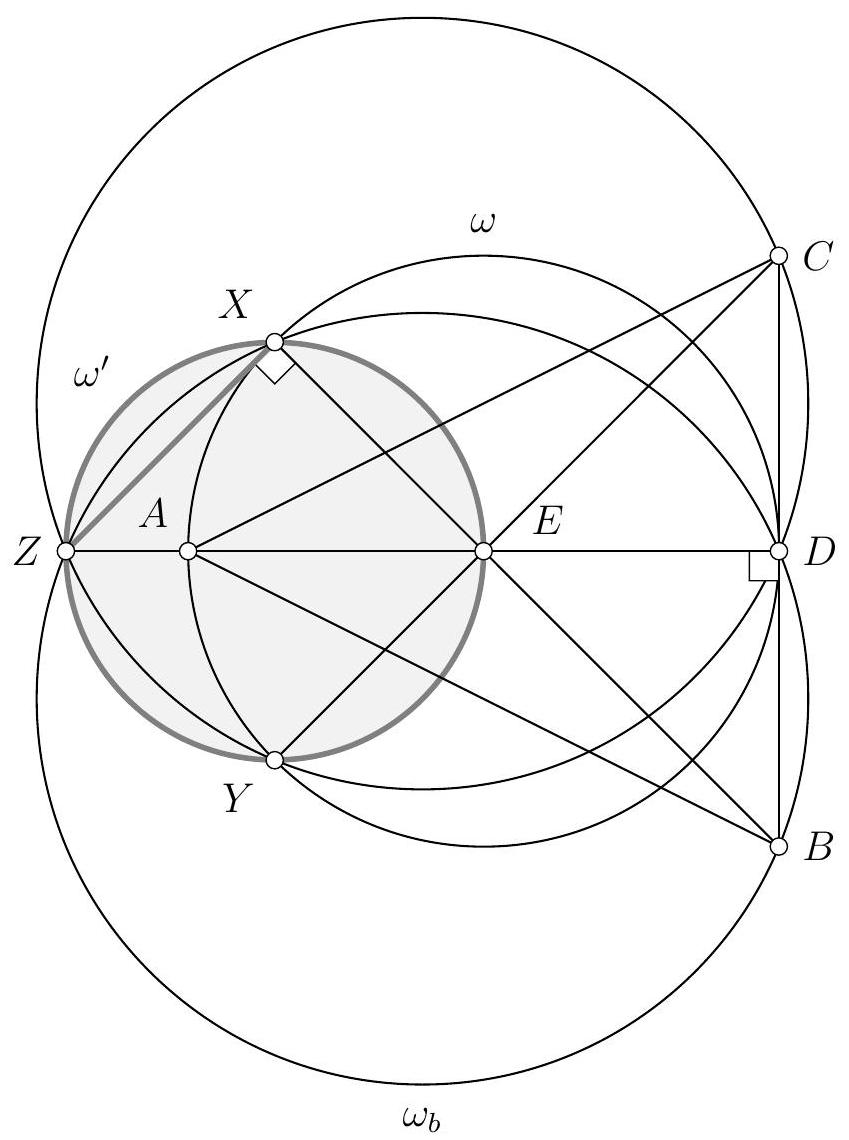

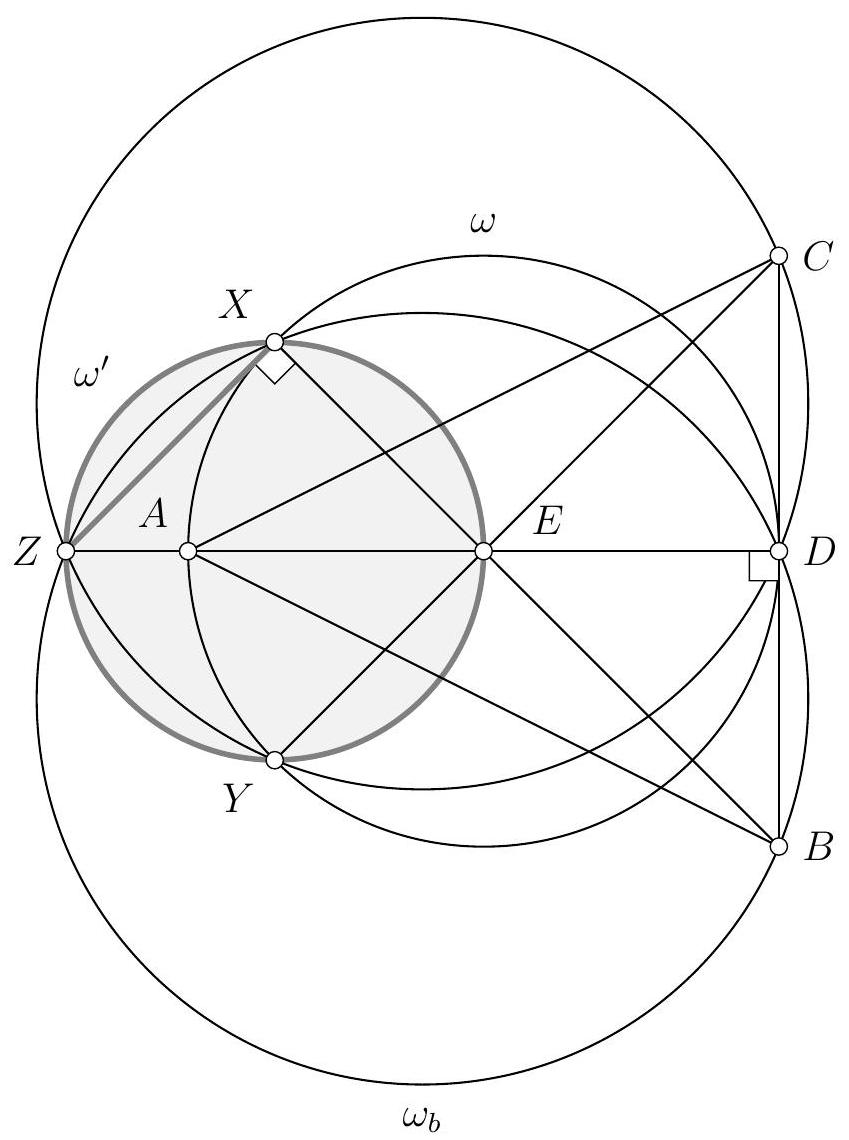

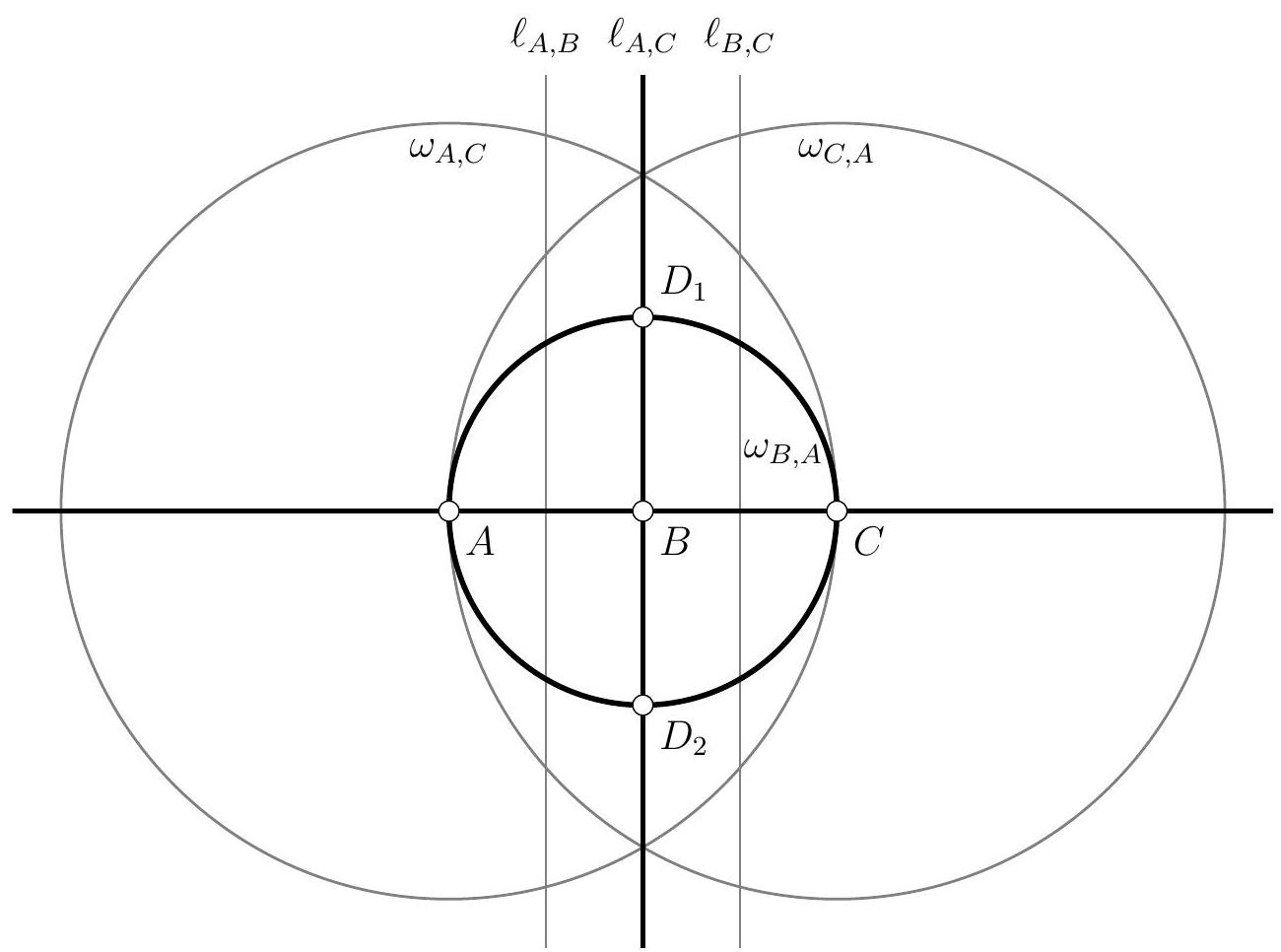

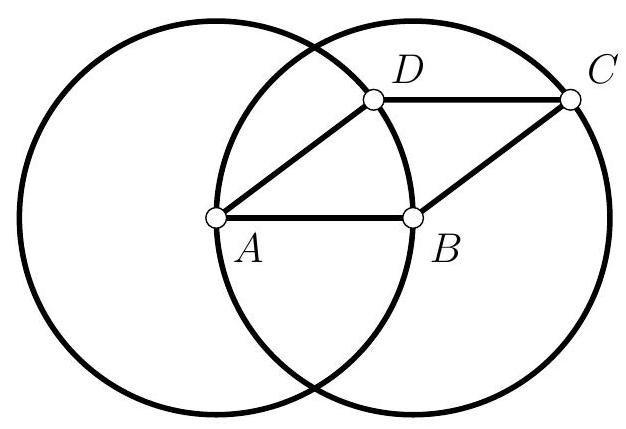

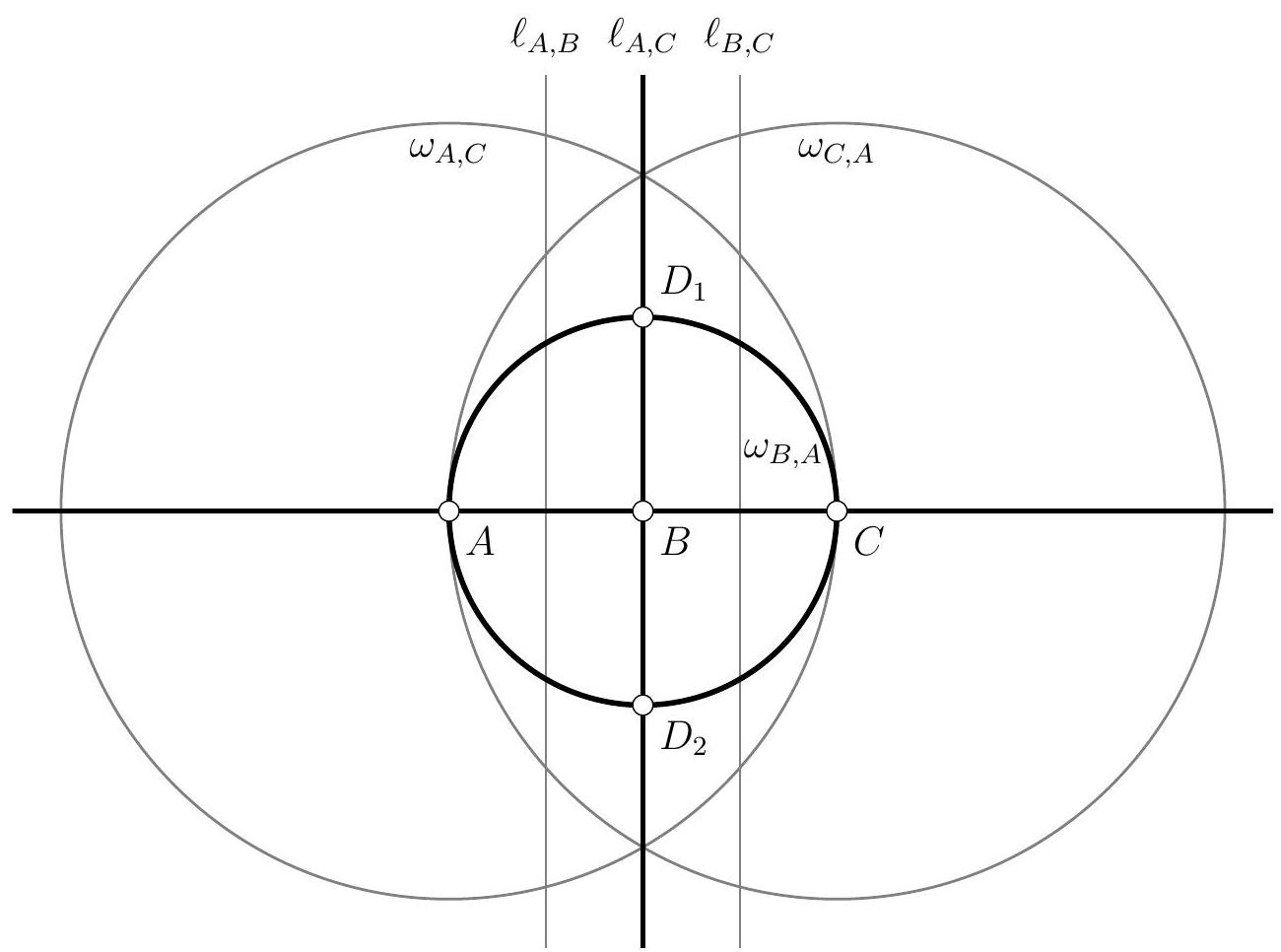

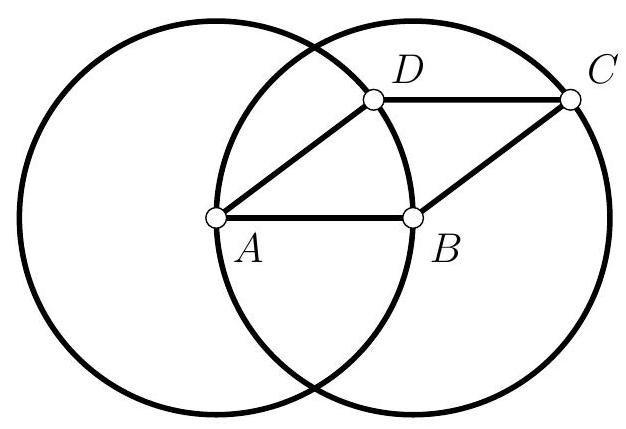

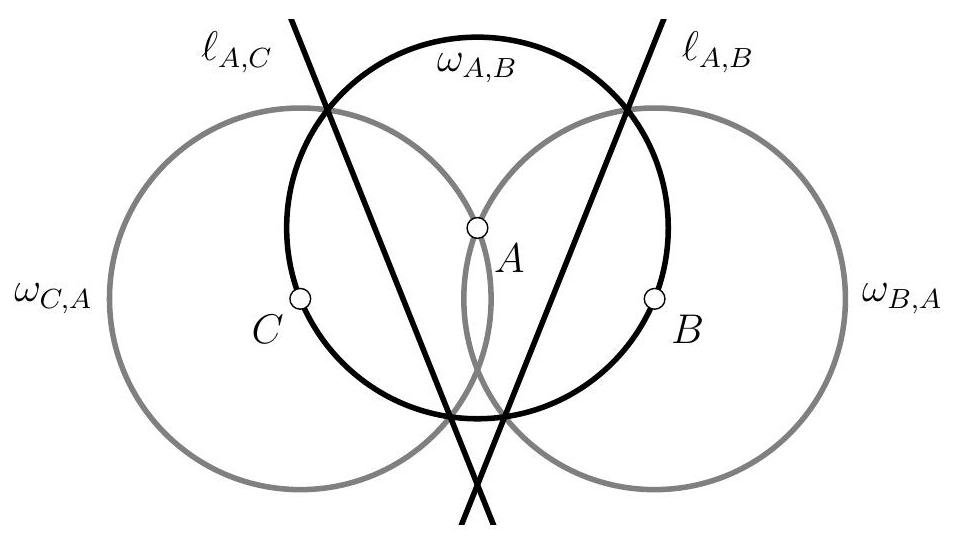

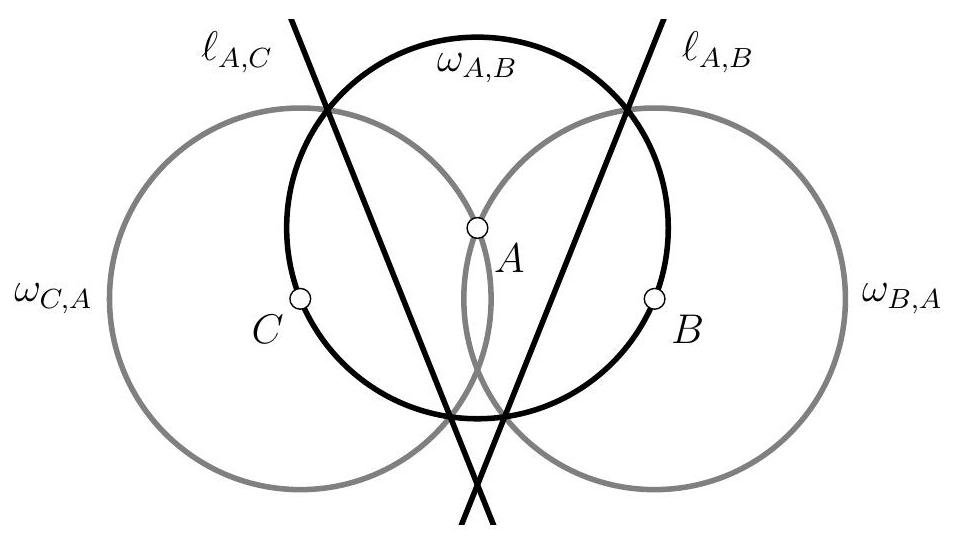

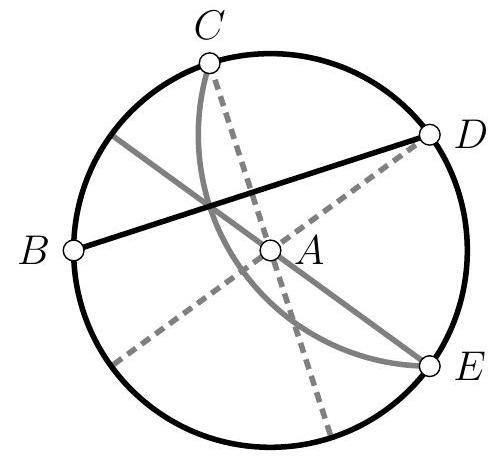

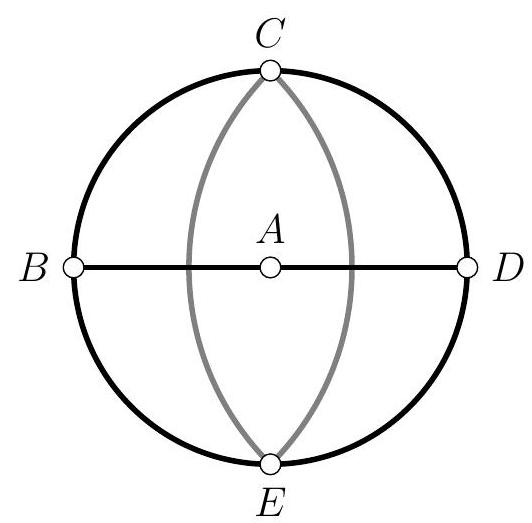

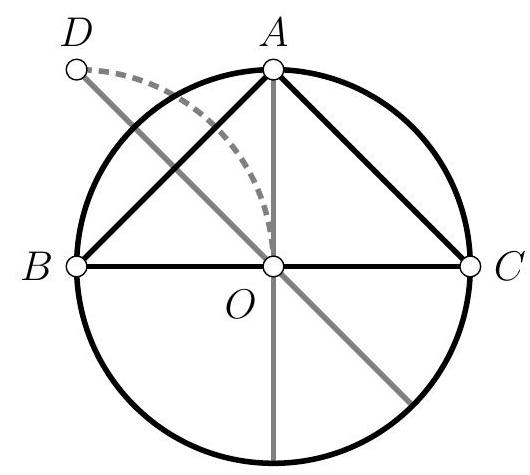

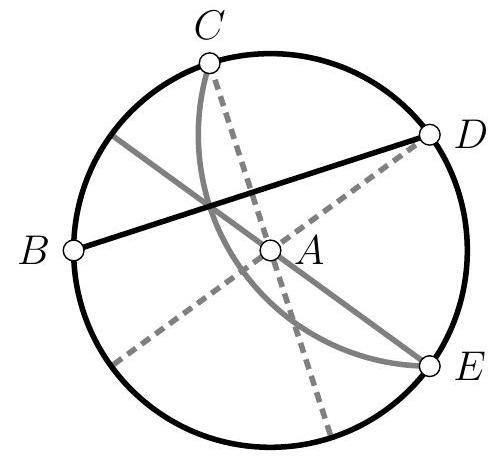

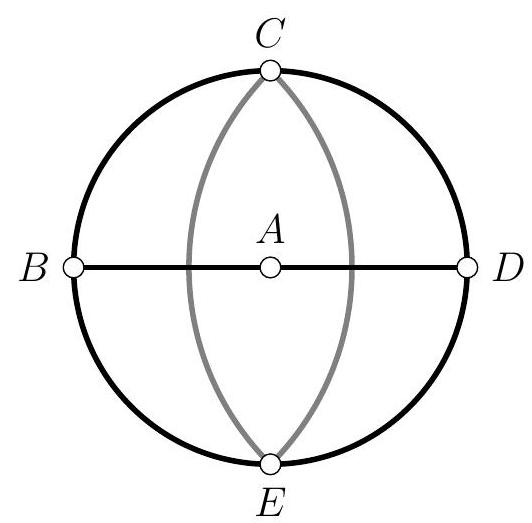

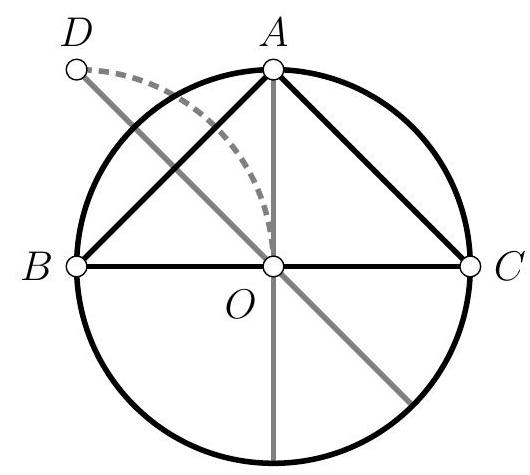

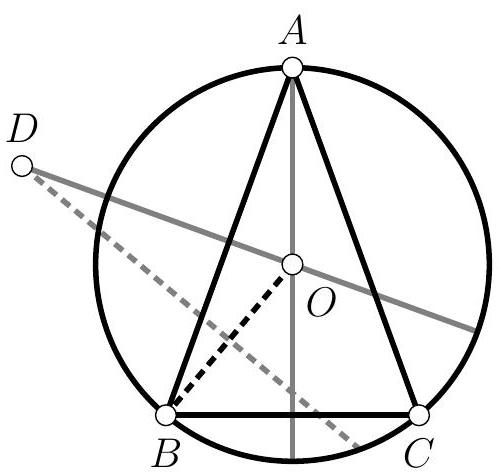

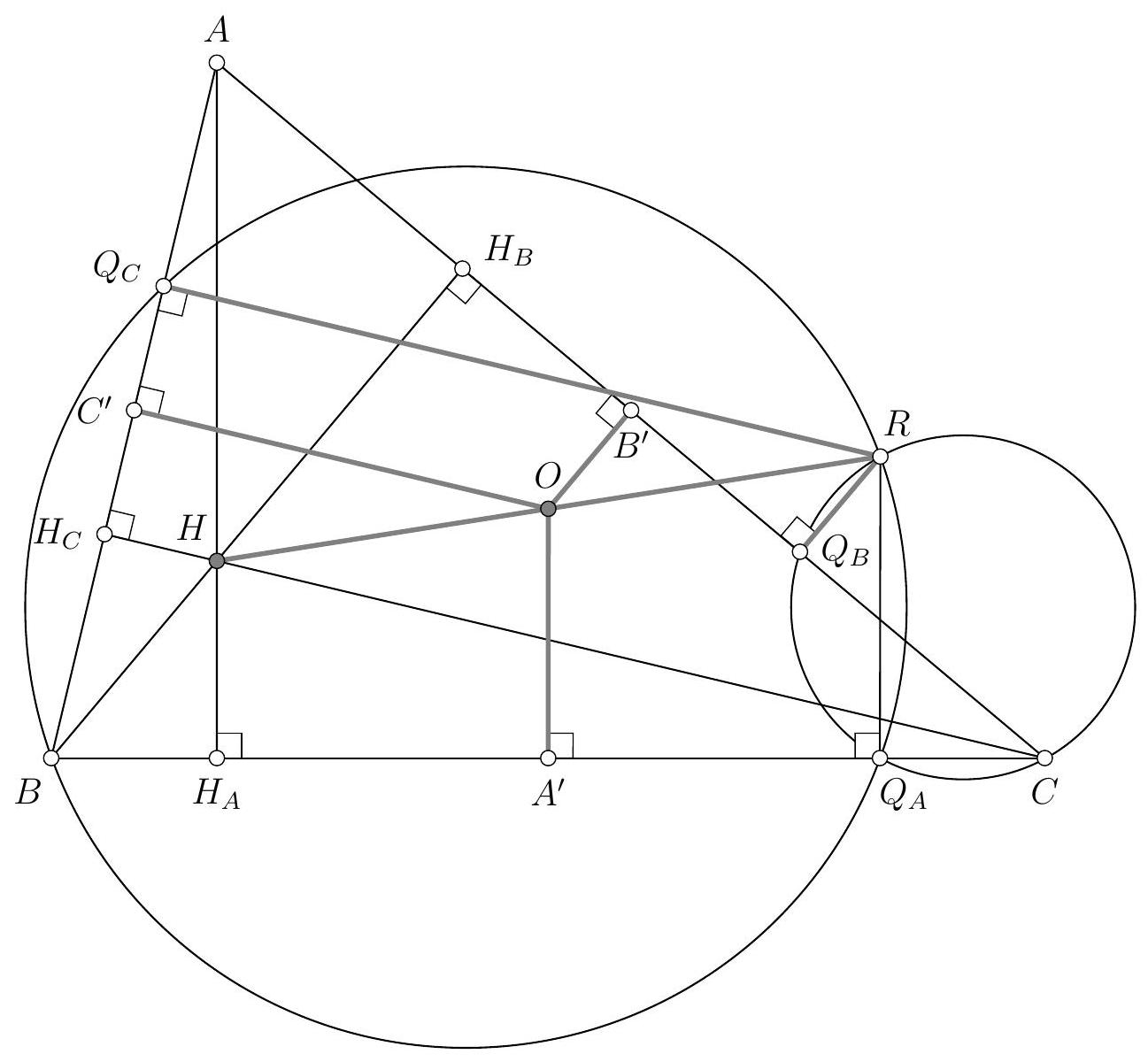

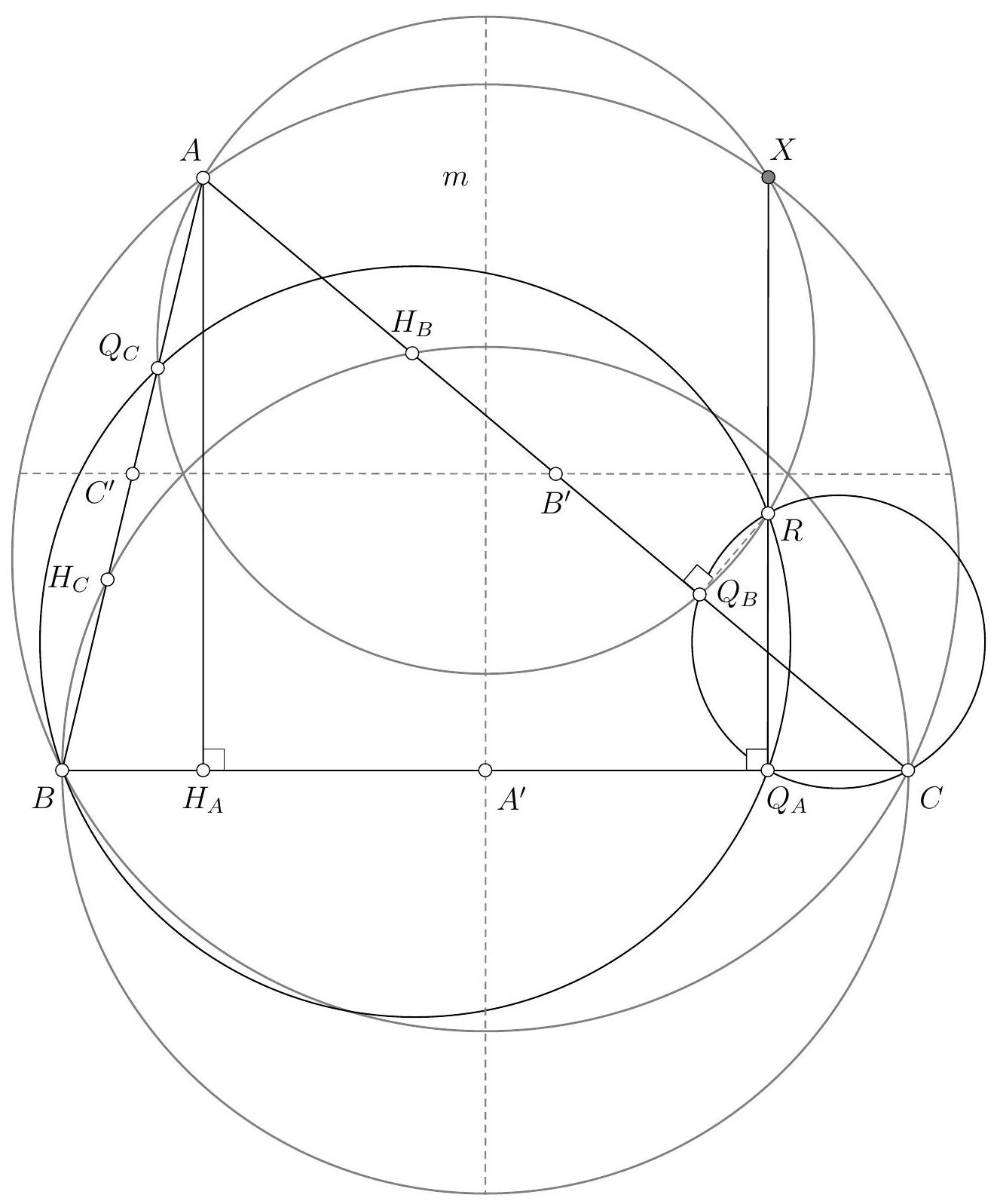

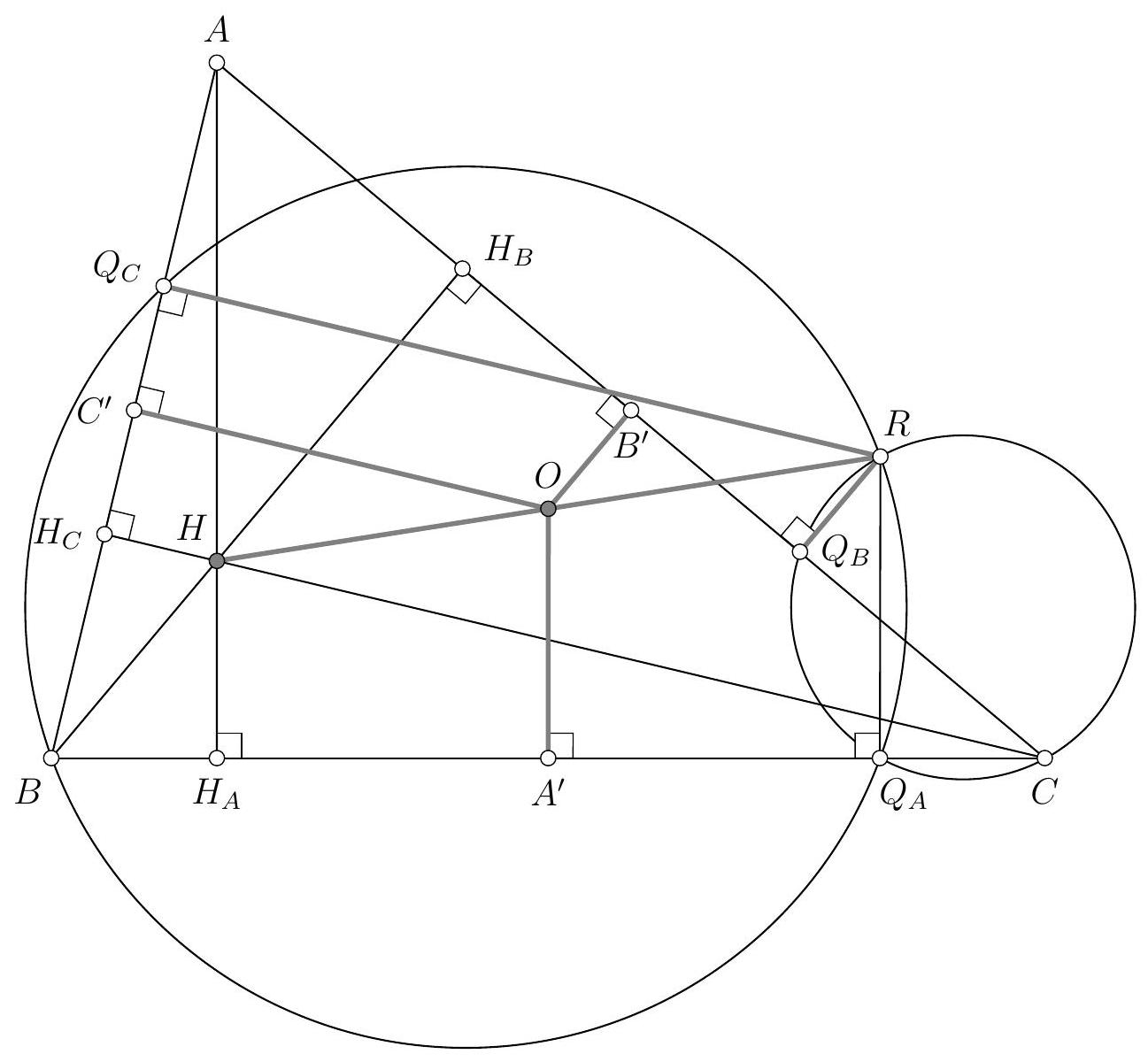

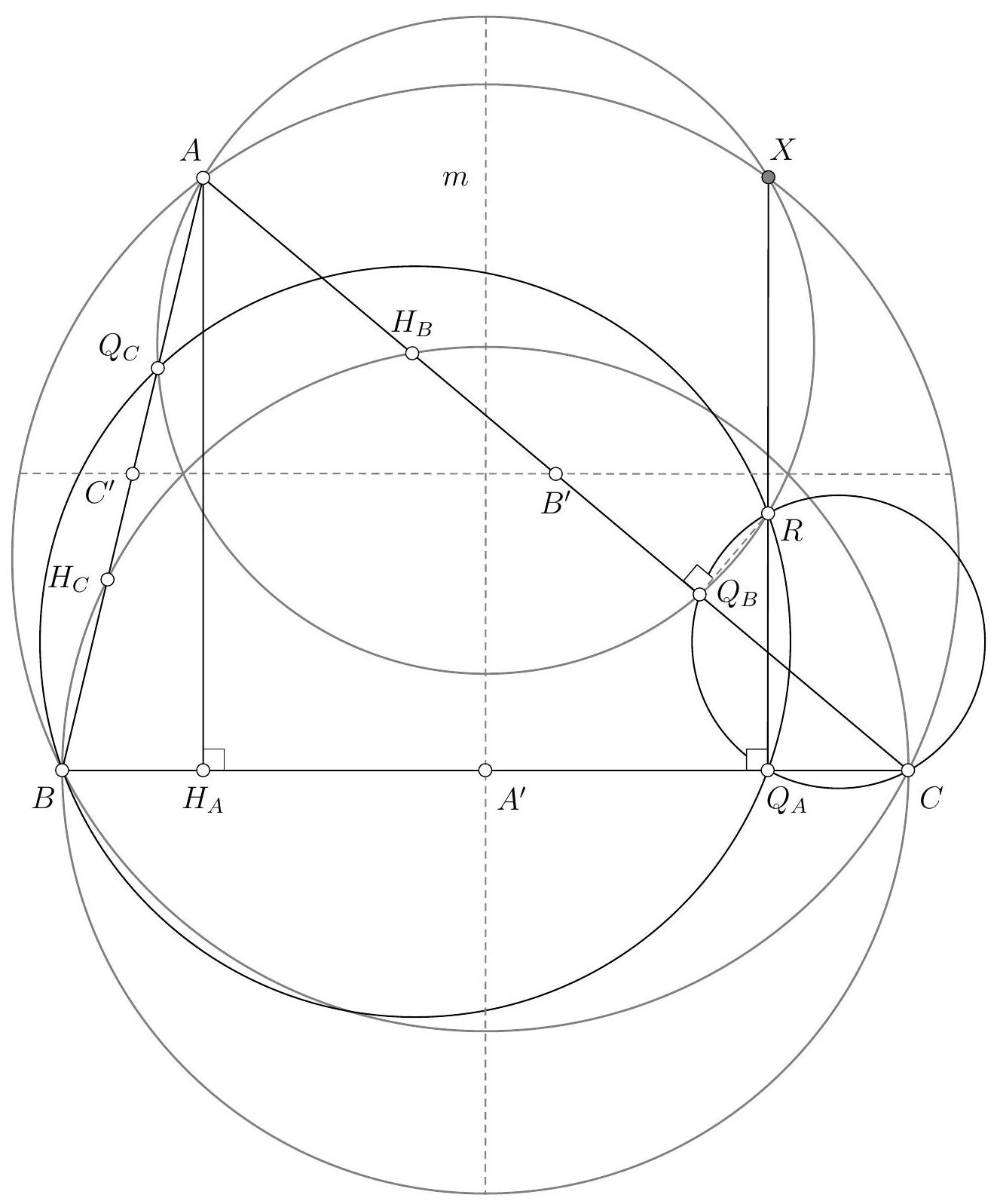

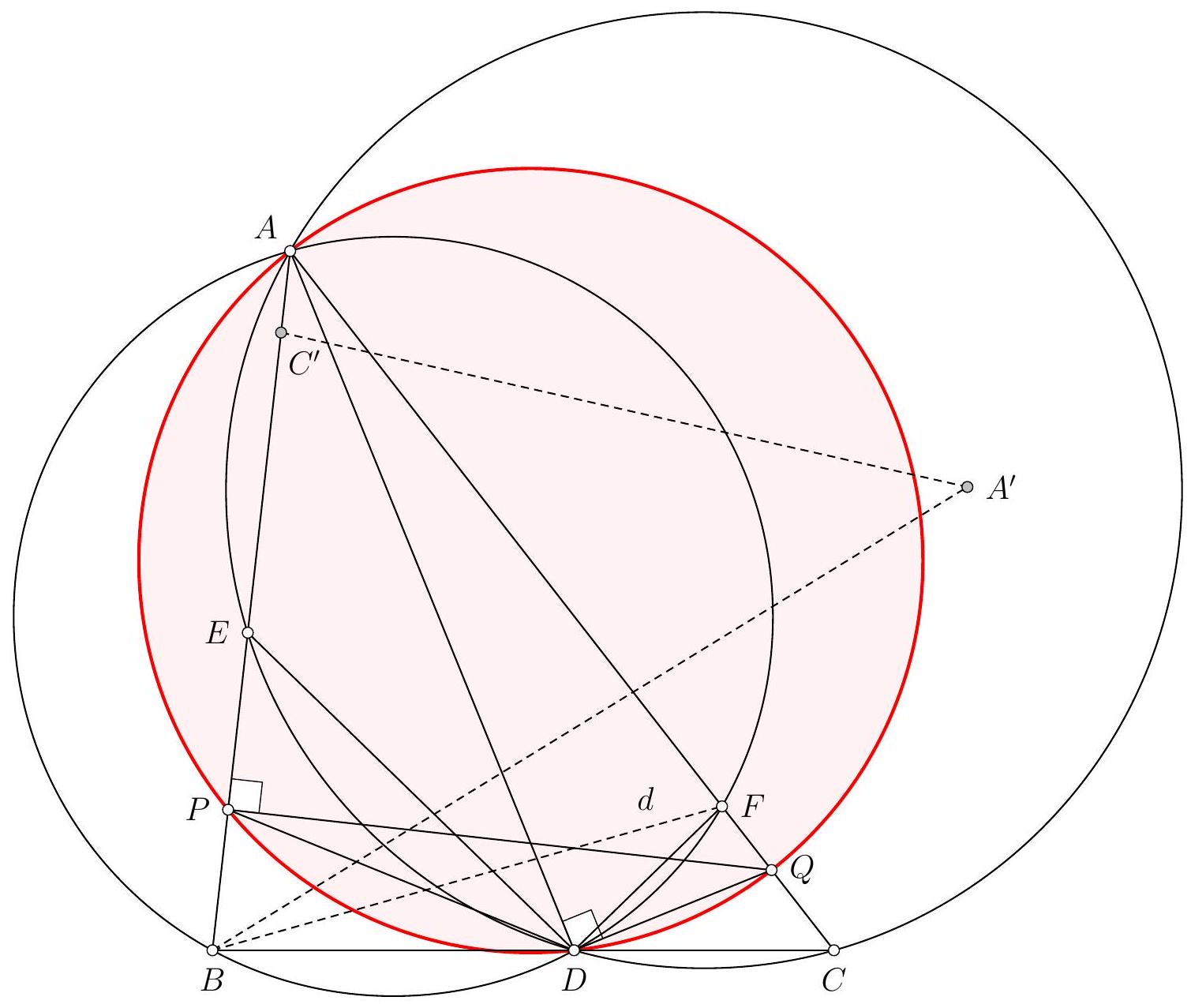

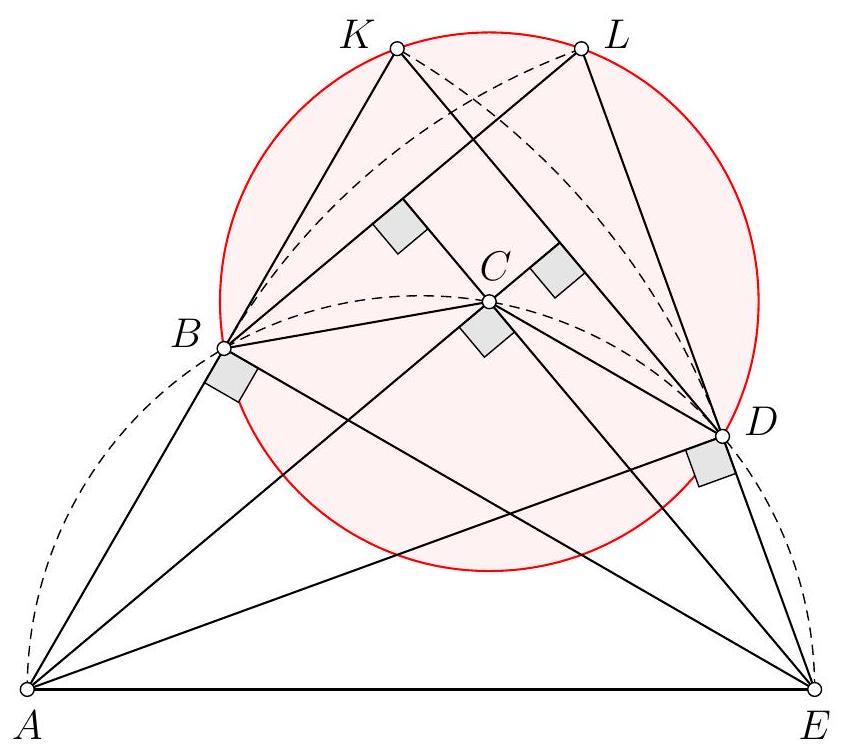

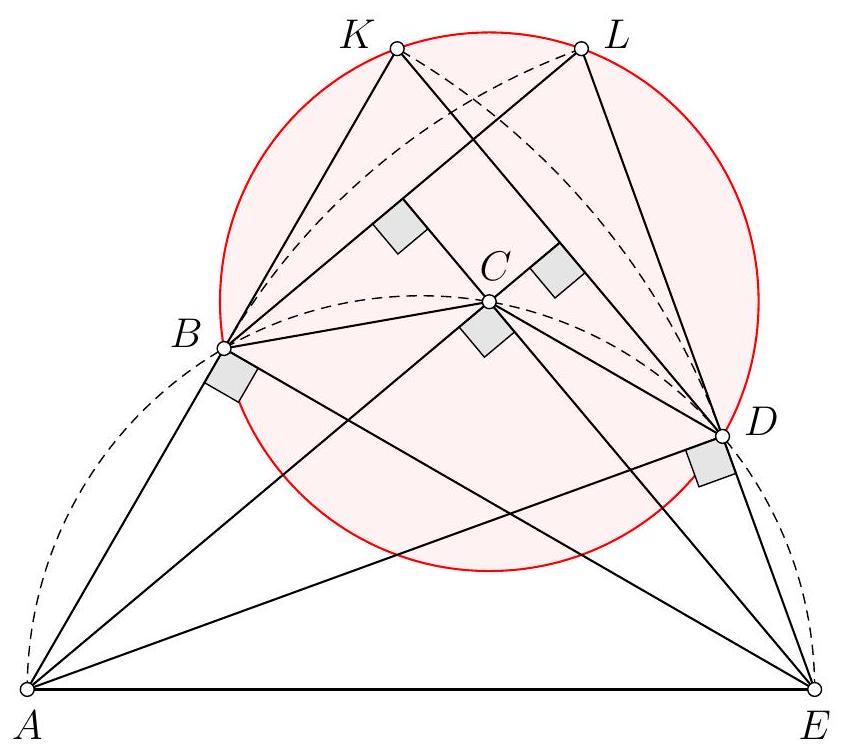

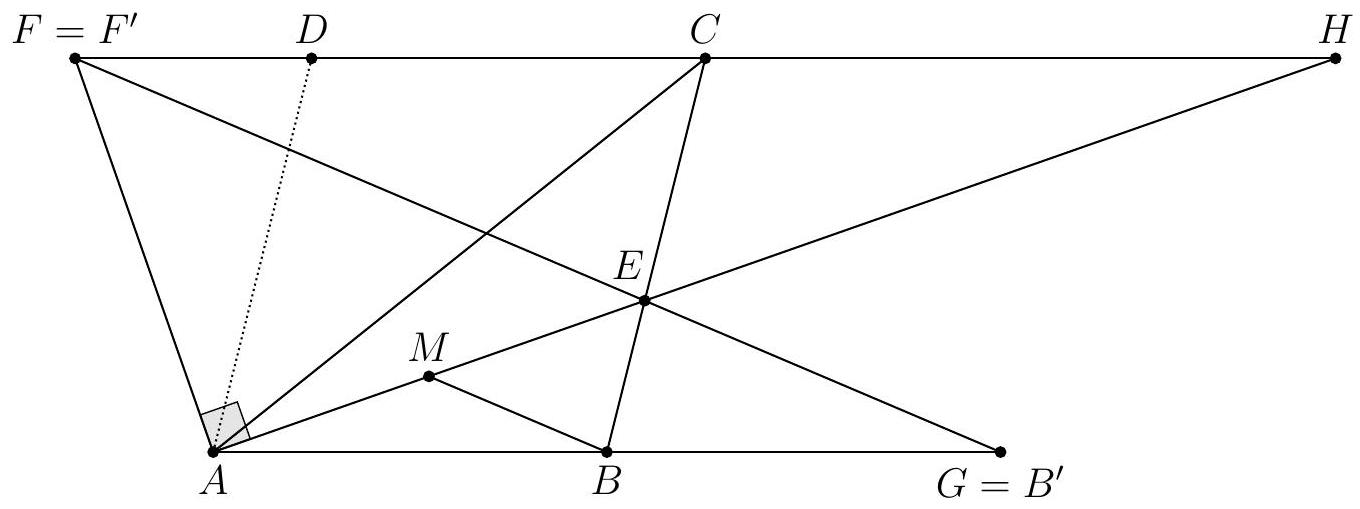

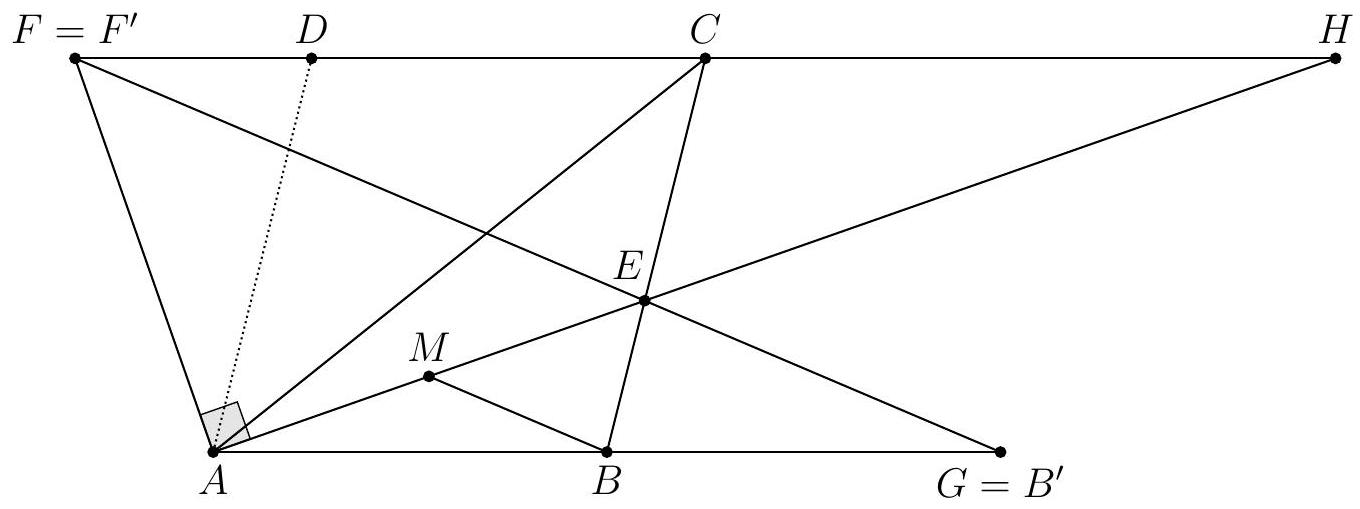

Let's start by drawing a figure.

A striking first observation is that $T$ appears to lie on the circle $\Gamma$. After verifying this on a second figure, we promptly set out to prove this first result. To do so, we embark on an angle chase using the properties of cyclic points and the limiting case of the inscribed angle theorem:

$$

\begin{aligned}

(T G, T F) & =(T G, B C)+(B C, T F)=(T G, C G)+(B F, T F)=(E G, E C)+(D B, D F) \\

& =(E G, A E)+(A D, D F)=(D G, A D)+(A D, D F)=(A D, D F)

\end{aligned}

$$

The points $A, F, G$, and $T$ are therefore concyclic, and $T$ lies on $\Gamma$. But then

$$

\begin{aligned}

(A T, B C) & =(A T, A F)+(A F, B C)=(G T, G F)+(A F, G F) \\

& =(G T, G C)+(A E, G E)=(E G, E C)+(C E, G E)=0^{\circ},

\end{aligned}

$$

which means precisely that the lines $(A T)$ and $(B C)$ are parallel.

Comment from the graders: The problem was correctly solved by 7 students. Some students, even if they did not completely solve the problem, used their figure to conjecture that the point $T$ lies on the circle $\Gamma$ and concluded by assuming this result. This approach was highly appreciated as it is the right attitude when facing a geometry problem.

## Senior Exercises

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle et $\Gamma$ un cercle passant par $A$. On suppose que $\Gamma$ recoupe les segments $[A B]$ et $[A C]$ en deux points, que l'on appelle respectivement $D$ et $E$, et qu'il coupe le segment $[B C]$ en deux points, que l'on appelle $F$ et $G$, de sorte que $F$ se trouve entre $B$ et $G$. Soit $T$ le point d'intersection entre la tangente en $F$ au cercle circonscrit à $B D F$ et la tangente en $G$ au cercle circonscrit à $C E G$.

Démontrer que, si les points $A$ et $T$ sont distincts, alors $(A T)$ et $(B C)$ sont parallèles.

|

Commençons par tracer une figure.

Une première remarque frappante est que $T$ semble être situé sur le cercle $\Gamma$. Après avoir vérifié qu'il l'était bien sur une deuxième figure, on s'empresse donc de démontrer ce premier résultat. Pour ce faire, on entame donc une chasse aux angles de droites, en utilisant les relations de cocyclicité et le cas limite du théorème de l'angle au centre :

$$

\begin{aligned}

(T G, T F) & =(T G, B C)+(B C, T F)=(T G, C G)+(B F, T F)=(E G, E C)+(D B, D F) \\

& =(E G, A E)+(A D, D F)=(D G, A D)+(A D, D F)=(A D, D F)

\end{aligned}

$$

Les points $A, F, G$ et $T$ sont donc cocycliques, et $T$ appartient à bien $\Gamma$. Mais alors

$$

\begin{aligned}

(A T, B C) & =(A T, A F)+(A F, B C)=(G T, G F)+(A F, G F) \\

& =(G T, G C)+(A E, G E)=(E G, E C)+(C E, G E)=0^{\circ},

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui signifie précisément que les droites $(A T)$ et $(B C)$ sont parallèles.

Commentaire des correcteurs L'exercice a été correctement résolu par 7 élèves. Quelques élèves, même s'ils n'ont pas complètement résolu le problème, ont utilisé leur figure pour conjecturer que le point $T$ appartenait au cercle $\Gamma$ et ont conclu en admettant ce résultat. Ce procédé a été grandement apprécié car c'est la bonne attitude face à un problème de géometrie.

## Exercices Senior

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

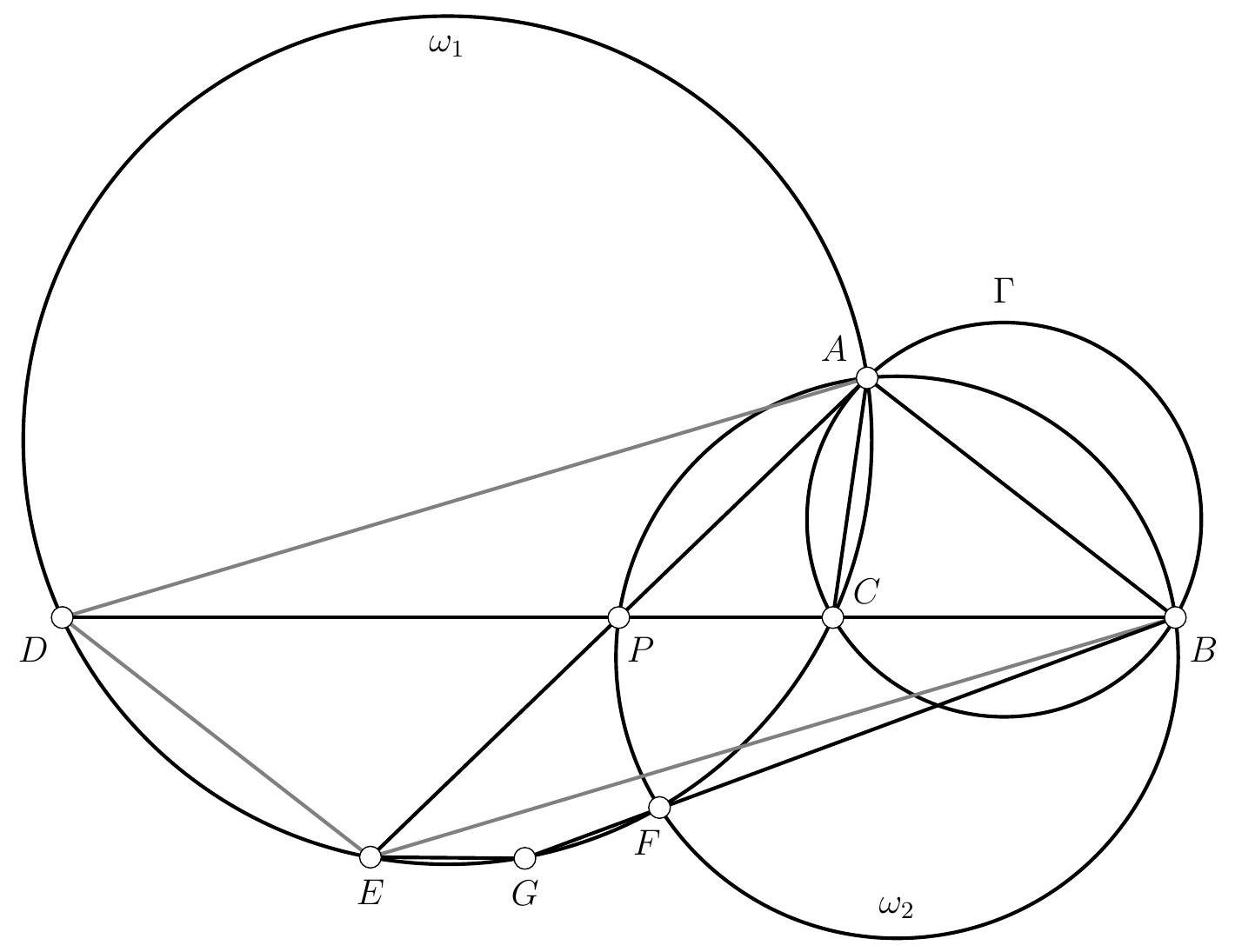

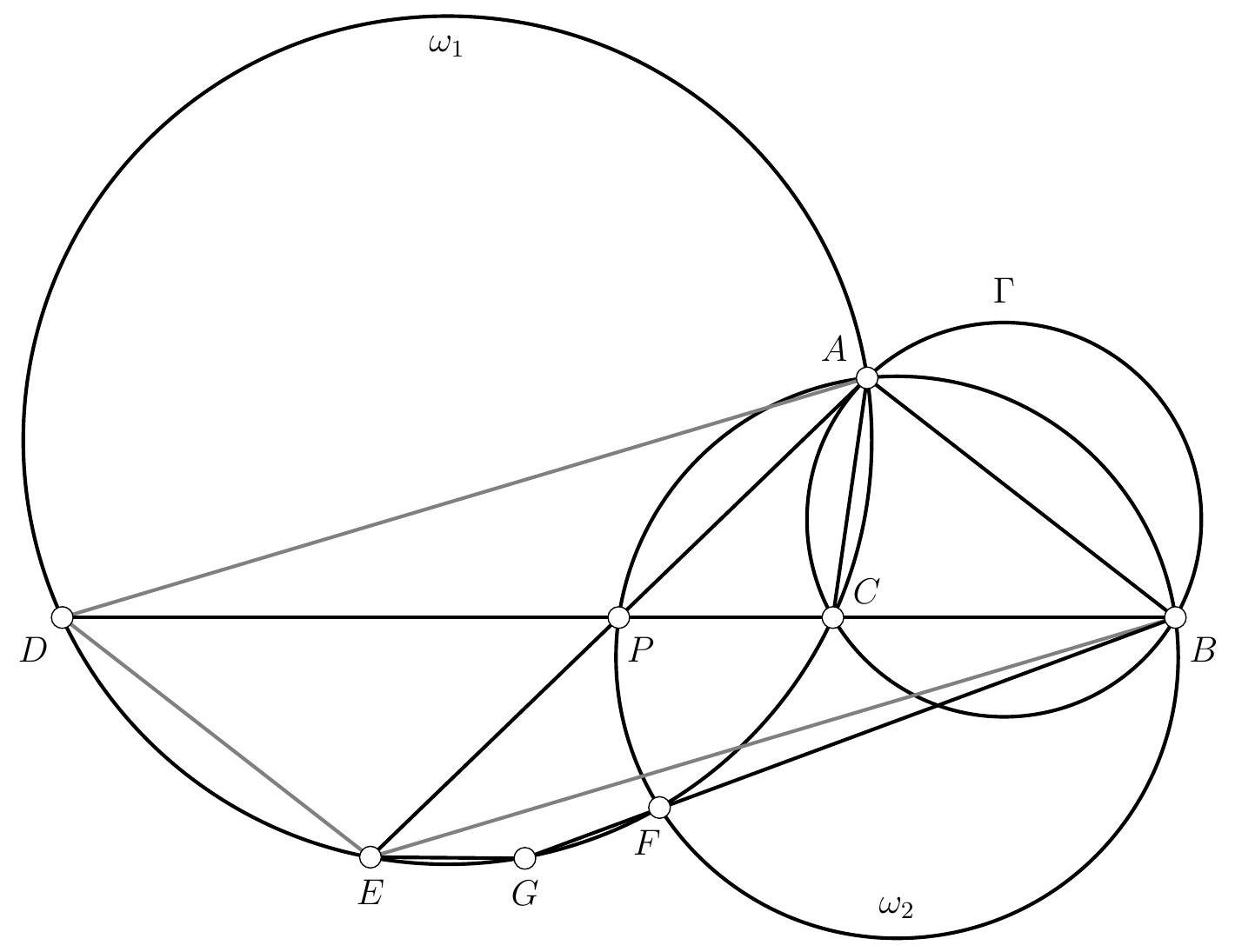

Let $ABC$ be a triangle and $\Gamma$ a circle passing through $A$. Suppose that $\Gamma$ intersects the segments $[AB]$ and $[AC]$ at two points, which we call $D$ and $E$ respectively, and that it intersects the segment $[BC]$ at two points, which we call $F$ and $G$, such that $F$ lies between $B$ and $G$. Let $T$ be the point of intersection between the tangent at $F$ to the circumcircle of $BDF$ and the tangent at $G$ to the circumcircle of $CEG$.

Prove that, if the points $A$ and $T$ are distinct, then $(AT)$ and $(BC)$ are parallel.

|

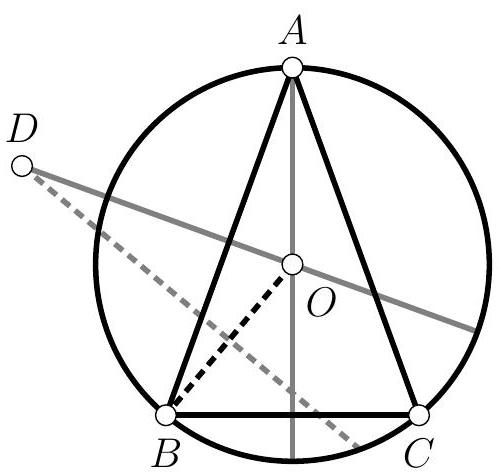

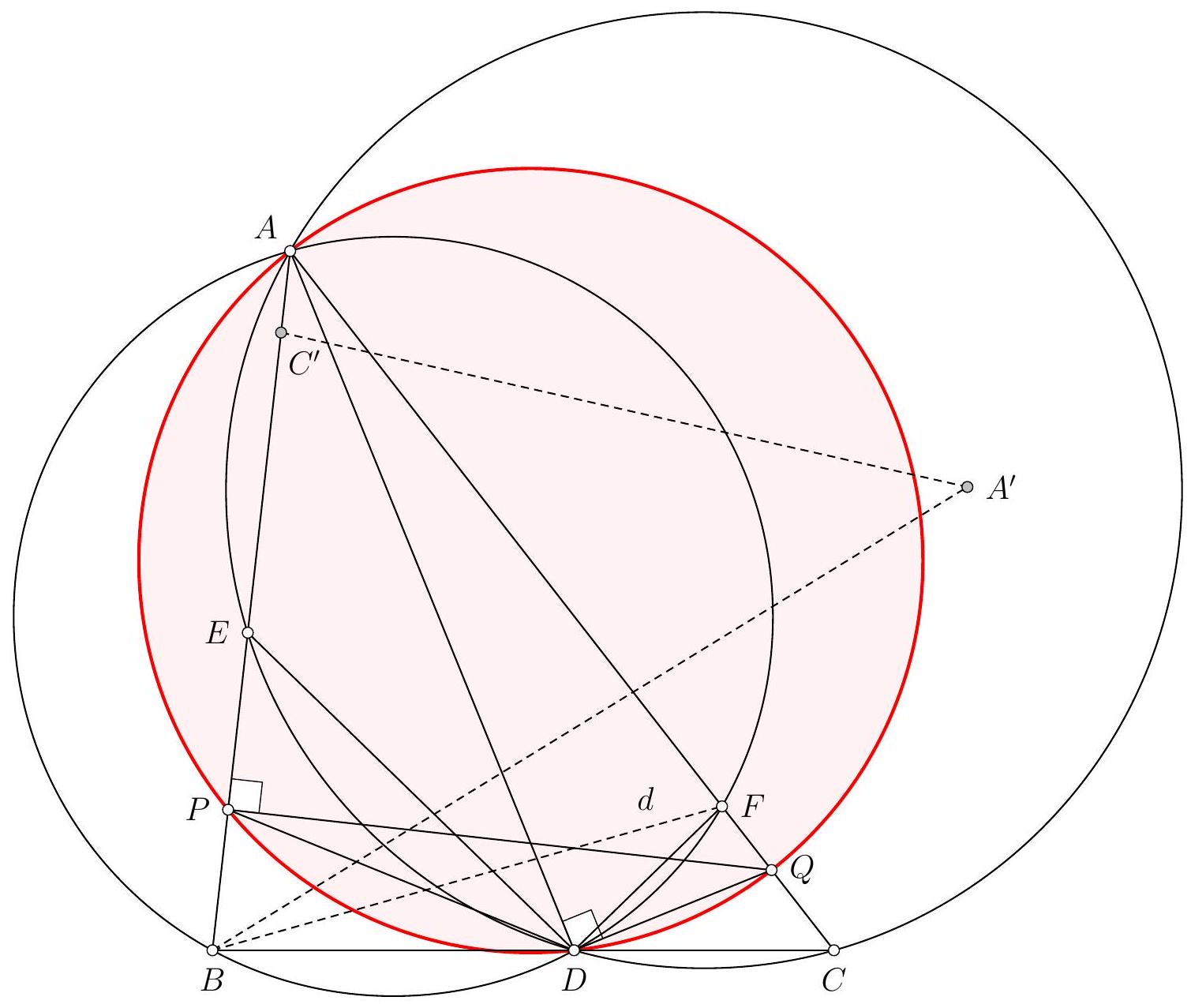

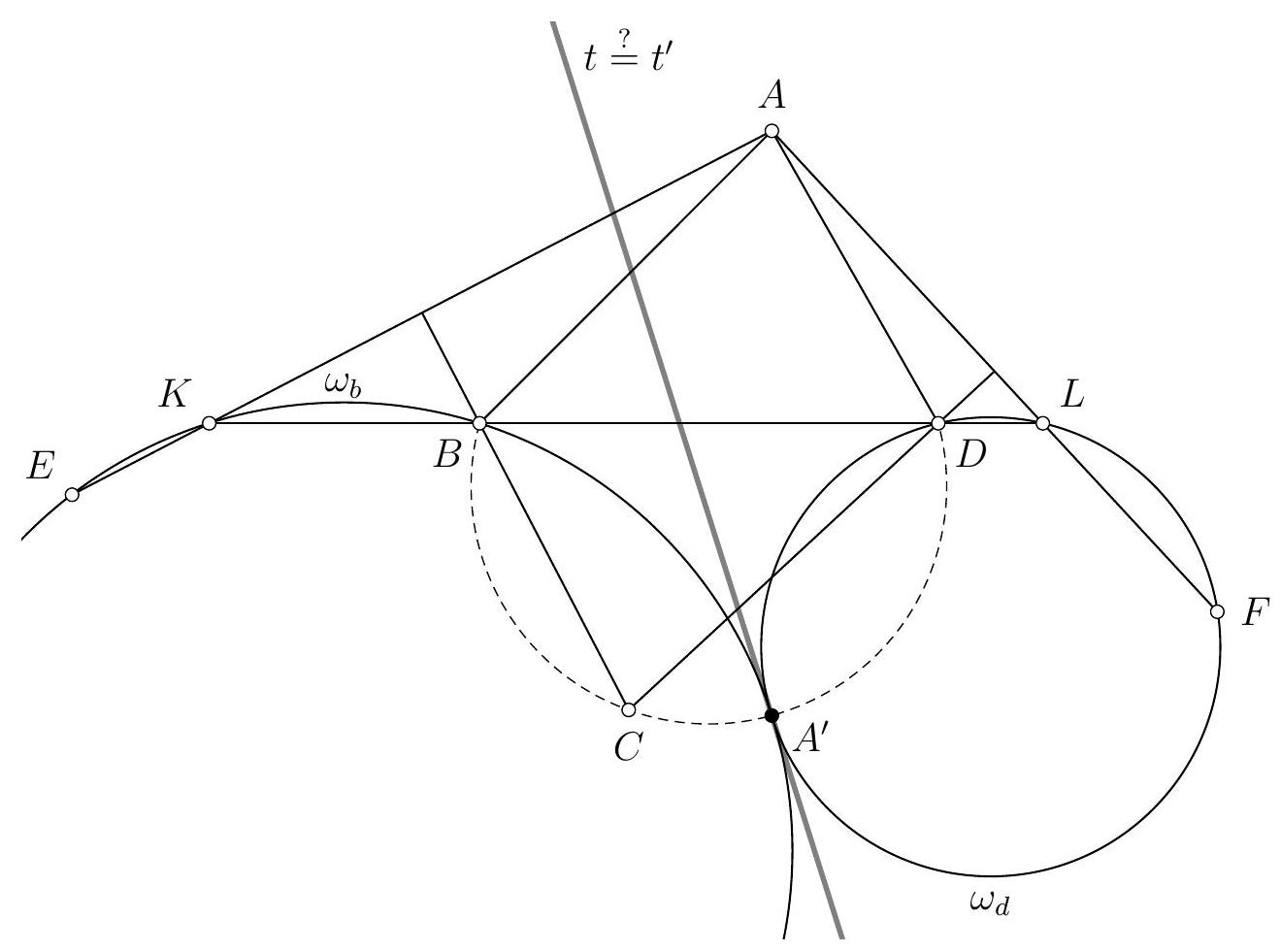

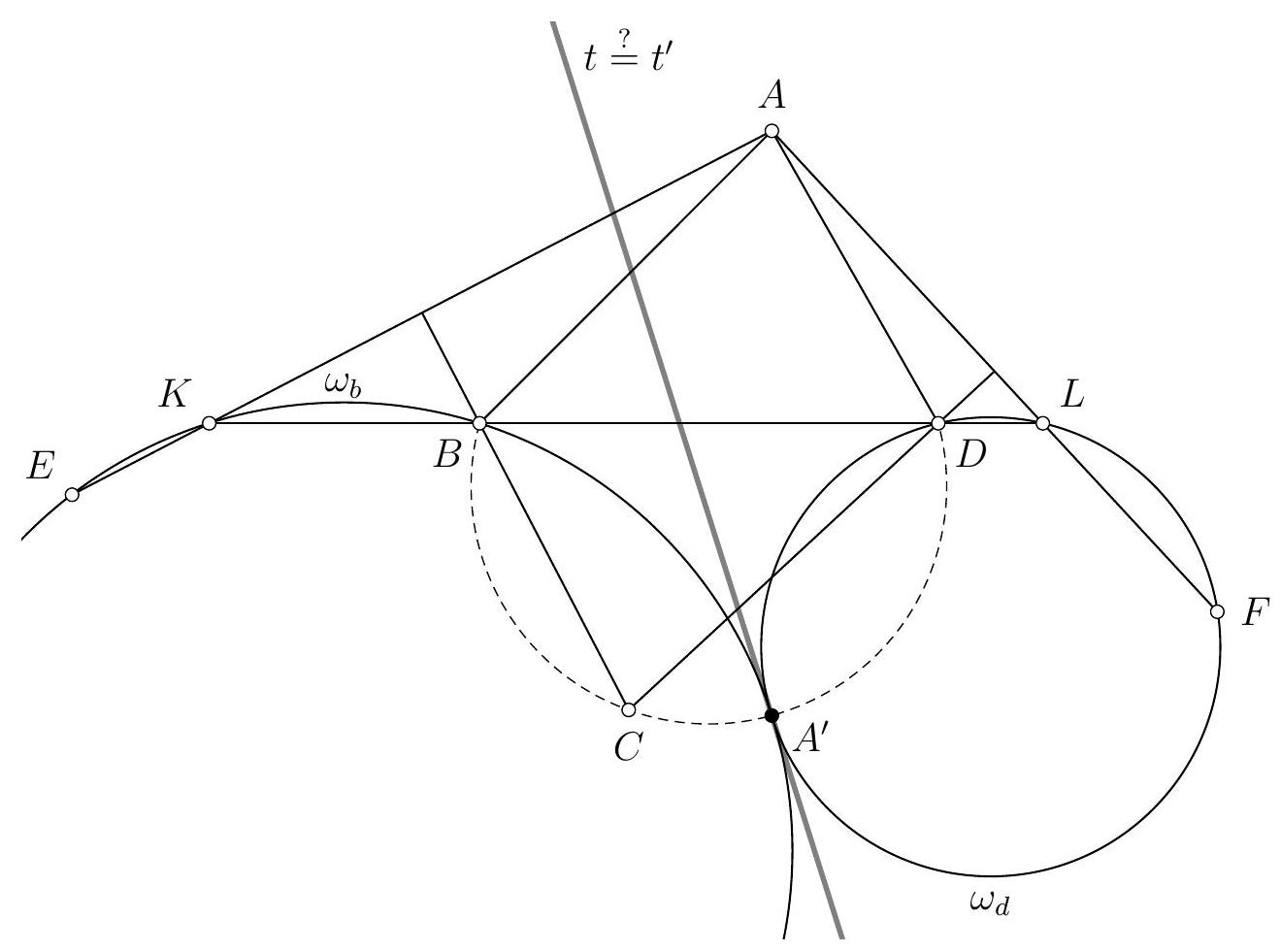

Let's start by drawing a figure.

A striking first observation is that $T$ appears to lie on the circle $\Gamma$. After verifying this on a second figure, we promptly set out to prove this first result. To do so, we embark on an angle chase using the properties of cyclic points and the limiting case of the inscribed angle theorem:

$$

\begin{aligned}

(T G, T F) & =(T G, B C)+(B C, T F)=(T G, C G)+(B F, T F)=(E G, E C)+(D B, D F) \\

& =(E G, A E)+(A D, D F)=(D G, A D)+(A D, D F)=(A D, D F) .

\end{aligned}

$$

The points $A, F, G$, and $T$ are therefore concyclic, and $T$ lies on $\Gamma$. But then

$$

\begin{aligned}

(A T, B C) & =(A T, A F)+(A F, B C)=(G T, G F)+(A F, G F) \\

& =(G T, G C)+(A E, G E)=(E G, E C)+(C E, G E)=0^{\circ},

\end{aligned}

$$

which precisely means that the lines $(A T)$ and $(B C)$ are parallel.

Comment from the graders: The exercise was very well done! The most efficient students noted that it was sufficient to show that the point $T'$, the intersection of the line parallel to the line $(B C)$ passing through the point $A$ with the circle $\Gamma$, lies on both tangents. It is a pity to note that several students submitted a very neat figure but did not attempt to make conjectures from this figure, even though the point $T$ clearly lies on the circle $\Gamma$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle et $\Gamma$ un cercle passant par $A$. On suppose que $\Gamma$ recoupe les segments $[A B]$ et $[A C]$ en deux points, que l'on appelle respectivement $D$ et $E$, et qu'il coupe le segment $[B C]$ en deux points, que l'on appelle $F$ et $G$, de sorte que $F$ se trouve entre $B$ et $G$. Soit $T$ le point d'intersection entre la tangente en $F$ au cercle circonscrit à $B D F$ et la tangente en $G$ au cercle circonscrit à $C E G$.

Démontrer que, si les points $A$ et $T$ sont distincts, alors $(A T)$ et $(B C)$ sont parallèles.

|

Commençons par tracer une figure.

Une première remarque frappante est que $T$ semble être situé sur le cercle $\Gamma$. Après avoir vérifié qu'il l'était bien sur une deuxième figure, on s'empresse donc de démontrer ce premier résultat. Pour ce faire, on entame donc une chasse aux angles de droites, en utilisant les relations de cocyclicité et le cas limite du théorème de l'angle au centre :

$$

\begin{aligned}

(T G, T F) & =(T G, B C)+(B C, T F)=(T G, C G)+(B F, T F)=(E G, E C)+(D B, D F) \\

& =(E G, A E)+(A D, D F)=(D G, A D)+(A D, D F)=(A D, D F) .

\end{aligned}

$$

Les points $A, F, G$ et $T$ sont donc cocycliques, et $T$ appartient à bien $\Gamma$. Mais alors

$$

\begin{aligned}

(A T, B C) & =(A T, A F)+(A F, B C)=(G T, G F)+(A F, G F) \\

& =(G T, G C)+(A E, G E)=(E G, E C)+(C E, G E)=0^{\circ},

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui signifie précisément que les droites $(A T)$ et $(B C)$ sont parallèles.

Commentaire des correcteurs L'exercice a été très bien réussi! Les élèves les plus efficaces ont noté qu'il suffisait de montrer que le point $T^{\prime} \mathrm{d}^{\prime}$ intersection de la droite parallèle à la droite $(B C)$ passant par le point $A$ avec le cercle $\Gamma$ appartenait aux deux tangentes. Il est dommage de constater que plusieurs élèves ont rendu une figure très propre mais n'ont pas cherché à effectuer de conjectures à partir de cette figure, alors même que le point $T$ appartient visiblement au cercle $\Gamma$.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Let $S$ be a set of integers. We say that $S$ is beautiful if it contains all integers of the form $2^{a}-2^{b}$, where $a$ and $b$ are non-zero natural numbers. We also say that $S$ is strong if, for any non-constant polynomial $P(X)$ with coefficients in $S$, the integer roots of $P(X)$ also belong to $S$.

Find all sets that are both beautiful and strong.

|

The set $\mathbb{Z}$ is clearly beautiful and strong. We will prove that it is the only one. To do this, consider a set $S$ that is beautiful and strong: we will actually prove, by strong induction on $n$, that the integers $n$ and $-n$ necessarily belong to $S$.

First, since $S$ is beautiful, it contains the integers $2^{1}-2^{1}=0, 2^{2}-2^{1}=2$, and $2^{1}-2^{2}=-2$. It also contains the integers 1 and -1, which are roots of the polynomials $2-2X$ and $2+2X$, respectively.

We now consider an integer $n \geqslant 3$ such that $-n-1, \ldots, n-1$ all belong to $S$. Let $\alpha$ be the 2-adic valuation of $n$, and $m$ be the odd integer such that $n=2^{\alpha} m$. By noting $\varphi(m)$ as the Euler's totient function of $m$, we observe that the integer $k=2^{\alpha+\varphi(m)+1}-2^{\alpha+1}$, which clearly belongs to $S$, is also a multiple of $2^{\alpha}$ and $m$, and thus of $n$.

Let $\overline{a_{\ell} a_{\ell-1} \ldots a_{0}}$ be the base-$n$ representation of $k / n$. All the integers $\pm a_{0}, \ldots, \pm a_{\ell}$ are between $1-n$ and $n-1$, and thus belong to $S$. By construction, $n$ is an integer root of the polynomial $P(X)=k-\sum_{i=0}^{\ell} a_{i} X^{i+1}$, whose coefficients are all in $S$, so $n$ is in $S$ as well. Similarly, $-n$ is an integer root of the polynomial $Q(X)=k-\sum_{i=0}^{\ell} a_{i}(-X)^{i+1}$, so $-n \in S$, which concludes the induction and the proof.

Remark: Given the statement, one could suspect that using polynomials of degree $d \geqslant 2$ might be useful, otherwise the creators of the statement would have directly chosen to define strong sets as sets stable under division. The remark below is mainly intended to illustrate the fact that if one seeks to drastically simplify a hypothesis in a mathematical statement, here with the goal of showing that $\mathbb{Z}$ would be the only beautiful set stable under division, it is very important to look for simple constructions that could invalidate this simplification.

We will in fact prove that there exists a set $S$ that is beautiful and stable under division, but different from $\mathbb{Z}$: this demonstrates that using polynomials of degree $d \geqslant 2$ was actually necessary to solve this problem. To construct this set, we need Zsygmondy's theorem and the known property that there exist Fermat numbers (i.e., integers of the form $2^{p}-1$) that are not prime, even if $p$ is large enough (below, we will need the inequality $p \geqslant 7$). For example, when $p=11$, $2^{11}-1=23 \times 89$. Indeed, write $2^{p}-1$ as the product $2^{p}-1=q \times r \times m$, where $q$ and $r$ are two primes, and $m$ is any integer. We then consider the set $S$ consisting of 0 and integers of the form

$$

\pm 2^{a} \prod_{k \geqslant 2}\left(2^{k}-1\right)^{\alpha_{k}}

$$

where the $\alpha_{k}$ are integers, only finitely many of which are non-zero. The set $S$ is clearly beautiful and stable under division.

Suppose now that $q \in S$: we then write $q$ as

$$

q=\prod_{k \geqslant 2}\left(2^{k}-1\right)^{\alpha_{k}}

$$

and let $\ell$ be the maximal index such that $\alpha_{\ell} \neq 0$. Since the order of 2 modulo $q$ and $r$ divides $p$, it is equal to $p$, so $\ell \geqslant p \geqslant 7$.

Zsygmondy's theorem then indicates that there exists a prime $s$ that divides $2^{\ell}-1$ and no integer $2^{k}-1$ for $1 \leqslant k \leqslant \ell-1$. We then note that

$$

v_{s}(q)=\sum_{k \geqslant 2} \alpha_{k} v_{s}\left(2^{k}-1\right)=\alpha_{\ell} v_{s}\left(2^{\ell}-1\right) \neq 0 .

$$

We deduce that $s=q$, so $\ell=p$, and that $v_{q}\left(2^{\ell}-1\right)=1$. This means in particular that $r \neq q$. But then, even for $\ell=p$, and instead of choosing $s=q$, we could have satisfied Zsygmondy's theorem by choosing $s=r$, leading to a contradiction. We therefore conclude that $q \notin S$, and thus that $S \neq \mathbb{Z}$.

Comment from the graders: This number theory problem was quite difficult as it required a trick: the simplest solution involved the base-$b$ decomposition of an integer. Only five students thought of this and they all received the maximum score. The grading scale valued this trick, making it impossible to score more than 3 if this base decomposition was not mentioned.

Almost all students realized that the only beautiful and strong set would be $\mathbb{Z}$, without necessarily knowing how to prove it.

Many students tried to show that every integer (sometimes restricted to odd or prime integers) has a multiple in $S$, which was essential for the subsequent steps. Many also showed that $S$ is symmetric with respect to 0 (i.e., if $n \in S$, then $-n \in S$), which allows avoiding dealing with negative integers in the subsequent steps.

Let's finally address some common errors:

$\triangleright$ Managing negative integers sometimes led to a significant error, especially when students attempted to prove by induction that $\llbracket 1, n \rrbracket \subseteq S$ for all $n \geqslant 1$. Some students introduced an integer $k \geqslant 1$ such that $n k \in S$, and they claimed that $n-k$ belonged to $S$ by induction hypothesis as an integer strictly less than $n$. However, these students did not rule out the case where $k \geqslant 2 n$, so it was possible to have $n-k \leqslant -n$, thus undermining their entire reasoning.

$\triangleright$ Some students noted that it sufficed for all primes to be in $S$ to conclude. This is true, but no known solution immediately proves this result. In this case, several students thought they had solved the problem by showing this result. They based their reasoning on the belief (erroneous, as indicated in the remark above) that if $n$ and $m$ are two distinct odd natural numbers, then the order of 2 modulo $n$ is different from the order of 2 modulo $m$. This error is equivalent to the misconception of Zsigmondy's theorem, which states that for $n \notin\{1,6\}$, $2^{n}-1$ has exactly one primitive prime divisor.

$\triangleright$ Finally, vague arguments like "we construct more and more integers by taking the integer roots of polynomials with coefficients in an increasingly large set" can help form an idea, but obviously do not earn any points.

It is worth noting that in a problem like this, explicitly verifying that small values of $n$ (e.g., $n=0, n=1$, and $n=2$) are in $S$ always earns a point, yet some students did not have this reflex.

Finally, many students proved that if $a b \in S$ and $a \in S$ is non-zero, then $b \in S$. This result, while correct, is misleading because it invites the use of only the degree 1 polynomials in the statement, which are clearly insufficient to conclude, as indicated in the remark above.

if the equality

$$

f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)

$$

is satisfied for all integers $x$ and $y$. An integer $v$ is said to be $f$-rare if the set of integers $x$ such that $f(x)=v$ is a finite and non-empty set.

a) Prove that there exists a Russian function $f$ for which there exists an $f$-rare integer.

b) Prove that for any Russian function $f$, there is at most one $f$-rare integer.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $S$ un ensemble d'entiers relatifs. On dit que $S$ est beau s'il contient tous les entiers de la forme $2^{a}-2^{b}$, où $a$ et $b$ sont des entiers naturels non nuls. On dit également que $S$ est fort si, pour tout polynôme $P(X)$ non constant et à coefficients dans $S$, les racines entières de $P(X)$ appartiennent également à $S$.

Trouver tous les ensembles qui sont à la fois beaux et forts.

|

L'ensemble $\mathbb{Z}$ est clairement beau et fort. Nous allons démontrer que c'est le seul. Pour ce faire, considérons un ensemble $S$ beau et fort : nous allons en fait prouver, par récurrence forte sur $n$, que les entiers $n$ et $-n$ appartiennent nécessairement à $S$.

Tout d'abord, puisque $S$ est beau, il contient les entiers $2^{1}-2^{1}=0,2^{2}-2^{1}=2$ et $2^{1}-2^{2}=-2$. Il contient donc aussi les entiers 1 et -1 , qui sont des racines respectives des polynômes $2-2 X$ et $2+2 X$.

On considère désormais un entier $n \geqslant 3$ tel que $-n-1, \ldots, n-1$ appartiennent tous à $S$. Soit $\alpha$ la valuation 2 -adique de $n$, et $m$ l'entier impair tel que $n=2^{\alpha} m$. En notant $\varphi(m)$ l'indicatrice d'Euler de $m$, on constate alors que l'entier $k=2^{\alpha+\varphi(m)+1}-2^{\alpha+1}$, qui appartient manifestement à $S$, est également un multiple de $2^{\alpha}$ et de $m$, donc de $n$.

Soit $\overline{a_{\ell} a_{\ell-1} \ldots a_{0}}$ l'écriture de $k / n$ en base $n$. Tous les entiers $\pm a_{0}, \ldots, \pm a_{\ell}$ sont compris entre $1-n$ et $n-1$, donc appartiennent à $S$. Par construction, $n$ est une racine entière du polynôme $P(X)=k-\sum_{i=0}^{\ell} a_{i} X^{i+1}$, dont tous les coefficients sont dans $S$, donc $n$ est dans $S$ lui aussi. De même, $-n$ est une racine entière du polynôme $Q(X)=k-\sum_{i=0}^{\ell} a_{i}(-X)^{i+1}$, donc $-n \in S$, ce qui conclut la récurrence et la démonstration.

Remarque: Au vu de l'énoncé, on pouvait se douter qu'utiliser des polynomes de degré $d \geqslant 2$ pourrait être utile, ce sans quoi les créateurs de l'énoncé auraient directement choisi de définir, tout simplement, les ensembles forts comme les ensembles stables par division. La remarque ci-dessous a pour but principal d'illustrer le fait que, si l'on cherche à simplifier drastiquement une hypothèse d'un énoncé mathématique, ici avec pour objectif de montrer que $\mathbb{Z}$ serait le seul ensemble beau stable par division, il est très important de chercher des constructions simples qui permettraient d'invalider cette simplification.

On va en fait démontrer qu'il existe un ensemble $S$ beau et stable par division, mais différent de $\mathbb{Z}$ : cela démontre qu'utiliser des polynomes de degré $d \geqslant 2$ était en fait nécessaire pour résoudre cet exercice. Pour construire cet ensemble, on a besoin du théorème de Zsygmondy ainsi que de la propriété connue suivante : il existe des nombres de Fermat (c'est-à-dire les entiers de la forme $2^{p}-1$ ) qui ne sont pas premiers, même si $p$ est assez grand (ci-dessous, on aura besoin de l'inégalité $p \geqslant 7$ ). C'est le cas, par exemple, quand $p=11$, car $2^{11}-1=23 \times 89$. En effet, écrivons $2^{p}-1$ comme le produit $2^{p}-1=q \times r \times m$, où $q$ et $r$ sont deux nombres premiers, et $m$ est un entier quelconque. On considère alors l'ensemble $S$ formé de 0 ainsi que des entiers de la forme

$$

\pm 2^{a} \prod_{k \geqslant 2}\left(2^{k}-1\right)^{\alpha_{k}}

$$

où les $\alpha_{k}$ sont des entiers relatifs dont seul un nombre fini est non nul. L'ensemble $S$ est manifestement beau et stable par division.

Supposons maintenant que $q \in S$ : on écrit alors $q$ sous la forme

$$

q=\prod_{k \geqslant 2}\left(2^{k}-1\right)^{\alpha_{k}}

$$

et on note $\ell$ l'indice maximal tel que $\alpha_{\ell} \neq 0$. Puisque l'ordre de 2 modulo $q$ et $r$ divise $p$, il est égal à $p$, de sorte que $\ell \geqslant p \geqslant 7$.

Le théorème de Zsygmondy indique alors qu'il existe un nombre premier $s$ qui divise $2^{\ell}-1$ et aucun entier $2^{k}-1$ pour $1 \leqslant k \leqslant \ell-1$. On remarque alors que

$$

v_{s}(q)=\sum_{k \geqslant 2} \alpha_{k} v_{s}\left(2^{k}-1\right)=\alpha_{\ell} v_{s}\left(2^{\ell}-1\right) \neq 0 .

$$

On en déduit que $s=q$, donc que $\ell=p$, et que $v_{q}\left(2^{\ell}-1\right)=1$. Cela signifie en particulier que $r \neq q$. Mais alors, même pour $\ell=p$, et au lieu de choisir $s=q$, on aurait pu satisfaire le théorème de Zsygmondy en choisissant $s=r$, obtenant ainsi une contradiction. On en conclut donc bien que $q \notin S$, et donc que $S \neq \mathbb{Z}$.

Commentaire des correcteurs Ce problème de théorie des nombres était assez difficile car nécessitait une astuce : la solution la plus simple faisait appel à la décomposition d'un entier en base $b$. Seuls cinq élèves y ont pensé et ils ont tous obtenu la note maximale. Le barème valorisait cette astuce, si bien qu'il était impossible d'avoir une note strictement supérieure à 3 si cet élément de décomposition en base n'était pas évoqué.

Quasiment tous les élèves se sont rendus compte que le seul ensemble beau et fort serait $\mathbb{Z}$, sans forcément savoir le prouver.

Beaucoup d'élèves ont pensé à montrer que tout entier (parfois en ne se restreignant qu'aux entiers impairs ou premiers) possédait un multiple dans $S$, ce qui était essentiel dans la suite. Beaucoup ont également montré que $S$ était symétrique par rapport à 0 (c'est-à-dire que, $n \in S$, alors $-n \in S$ ), ce qui permet d'éviter de se préoccuper des entiers négatifs dans la suite.

Revenons enfin sur quelques erreurs régulièrement rencontrées:

$\triangleright$ La gestion des entiers négatifs a parfois été source d'une erreur importante, notamment quand les élèves ont entrepris de démontrer par récurrence que $\llbracket 1, n \rrbracket \subseteq S$ pour tout $n \geqslant 1$. Certains élèves ont en effet introduit un entier $k \geqslant 1$ tel que $n k \in S$, et ils ont affirmé que $n-k$ appartenait par hypothèse de récurrence à $S$ en tant qu'entier strictement inférieur à $n$. Cependant, ces élèves n'ont pas écarté le cas où $k \geqslant 2 n$, de sorte que l'on pouvait avoir $n-k \leqslant-n$, remettant ainsi en cause tout leur raisonnement.

$\triangleright$ Quelques élèves ont remarqué qu'il suffisait que tous les nombres premiers soient dans $S$ pour conclure. C'est vrai, mais aucune solution connue ne prouve immédiatement ce résultat. En l'occurence, plusieurs élèves pensaient avoir résolu l'exercice en montrant ce résultat. Ils se fondaient sur la croyance (erronnée, comme indiqué dans la remarque ci-dessus) que, si $n$ et $m$ sont deux entiers naturels impairs distincts, alors l'ordre de 2 modulo $n$ est différent de celui de 2 modulo $m$. Cette erreur est équivalente à la méconnaissance du théorème de Zsigmondy consistant à croire que pour $n \notin\{1,6\}$, $2^{n}-1$ a exactement un diviseur premier primitif.

$\triangleright$ Enfin, les raisonnements vagues du style « on construit de plus en plus d'entiers en prenant les racines entières de polynômes à coefficients dans un ensemble de plus en plus grand » peuvent aider à se faire une idée, mais ne rapportent évidemment aucun point

Soulignons le fait que, dans un exercice comme celui-ci, vérifier explicitement que les petites valeurs de $n$ (par exemple $n=0, n=1$ et $n=2$ ) sont dans $S$ rapporte forcément un point, et pourtant quelques élèves n'ont pas eu ce réflexe.

Enfin, beaucoup d'élèves prouvent que si $a b \in S$ et $a \in S$ non nul, alors $b \in S$. Ce résultat certes correct est en fait trompeur, car il invite à n'utiliser que les polynômes de degré 1 de l'énoncé, qui ne suffisent manifestement pas à conclure, comme indiqué dans la remarque ci-dessus.

si l'égalité

$$

f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)

$$

est vérifiée pour tous les entiers $x$ et $y$. On dit également qu'un entier $v$ est $f$-rare si l'ensemble des entiers $x$ tels que $f(x)=v$ est un ensemble fini et non vide.

a) Démontrer qu'il existe une fonction $f$ russe pour laquelle il existe un entier $f$-rare.

b) Démontrer que, pour toute fonction $f$ russe, il existe au plus un entier $f$-rare.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Let $S$ be a set of integers. We say that $S$ is beautiful if it contains all integers of the form $2^{a}-2^{b}$, where $a$ and $b$ are non-zero natural numbers. We also say that $S$ is strong if, for any non-constant polynomial $P(X)$ with coefficients in $S$, the integer roots of $P(X)$ also belong to $S$.

Find all sets that are both beautiful and strong.

|

a) Let $f$ be the function defined by $f(0)=0$ and $f(n)=2^{v_{2}(n)+1}$, where $v_{2}(n)$ is the 2-adic valuation of $n$. First, it is clear that 0 is $f$-rare, since its only preimage under $f$ is 0 itself.

Furthermore, let $x$ and $y$ be two integers: by setting $v_{2}(0)=\infty$ and $\infty+1=\infty$, it appears that $v_{2}(f(x))=v_{2}(x)+1$, that $v_{2}(x+y)=\min \left\{v_{2}(x), v_{2}(y)\right\}$ if $v_{2}(x) \neq v_{2}(y)$, and that $v_{2}(x+y) \geqslant \min \left\{v_{2}(x), v_{2}(y)\right\}+1$ otherwise.

Finally, we have $f(x)=f(y)$ if and only if $v_{2}(x)=v_{2}(y)$. Consequently, $\triangleright$ if $v_{2}(x) \geqslant v_{2}(y)$, then

$$

v_{2}(f(x+y))=v_{2}(x+y)+1 \geqslant v_{2}(y)+1

$$

so $v_{2}(f(x+y)+y)=v_{2}(y)=v_{2}(f(x)+y)$ and $f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)$;

$\triangleright$ if $v_{2}(x)<v_{2}(y)$, then

$$

v_{2}(f(x+y))=v_{2}(x+y)+1=v_{2}(x)+1=v_{2}(f(x))

$$

so $f(x+y)=f(x)$ and $f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)$.

Thus, $f$ is a Russian function, which answers the question.

b) Let $v$ be a potential $f$-rare integer. We set $X_{v}=\{x \in \mathbb{Z}: f(x)=v\}$, then $a=\min \left(X_{v}\right)$ and $b=\max \left(X_{v}\right)$.

First, an immediate induction on $k$ shows that $f(f(x)+y)=f(f(x+k y)+y)$ for all integers $x, y$ and $k$. Therefore, if we set $y=a-f(x)$, then

$$

f(f(x+k y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)=f(a)=v

$$

so $f(x+k y)+y \in X_{v}$, which means that $f(x+k y) \geqslant a-y=f(x)$ for all $k \in \mathbb{Z}$. Similarly, if we set $z=b-f(x)$, then $f(x+\ell z)+z \in X_{v}$, which means that $f(x+\ell z) \leqslant b-z=f(x)$ for all $\ell \in \mathbb{Z}$.

The set $X_{f(x)}$ therefore contains the integer $x+m y z$ for all $m \in \mathbb{Z}$. Consequently, if the integer $r=f(x)$ is $f$-rare, it must be that $y z=0$, and thus that $r=f(x) \in\{a, b\} \subseteq X_{v}$. Thus, only the elements of $X_{v}$ can be $f$-rare.

But then, for any integer $w$ that would be $f$-rare, we know that $v$ belongs to both $X_{v}$ and $X_{w}$, which proves that $v=w$, as expected.

Comment from the graders This very difficult problem was substantially solved by three students. In doing so, they exceeded the expectations that the graders had formulated in view of the difficulty of the problem.

Moreover, several students proposed Russian functions that were in fact not: it is important to be meticulous when verifying that a function satisfies the conditions of a problem, especially if this verification is not obvious, as was the case here, and if it is supposed to provide a ready-made answer to a question in the problem.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $S$ un ensemble d'entiers relatifs. On dit que $S$ est beau s'il contient tous les entiers de la forme $2^{a}-2^{b}$, où $a$ et $b$ sont des entiers naturels non nuls. On dit également que $S$ est fort si, pour tout polynôme $P(X)$ non constant et à coefficients dans $S$, les racines entières de $P(X)$ appartiennent également à $S$.

Trouver tous les ensembles qui sont à la fois beaux et forts.

|

a) Soit $f$ la fonction définie par $f(0)=0$ et $f(n)=2^{v_{2}(n)+1}$, où $v_{2}(n)$ est la valuation 2 adique de $n$. Tout d'abord, il est clair que 0 est $f$-rare, puisque son seul antécédent par $f$ est 0 lui-même.

D'autre part, soit $x$ et $y$ deux entiers relatifs : en posant $v_{2}(0)=\infty$ et $\infty+1=\infty$, il apparaît que $v_{2}(f(x))=v_{2}(x)+1$, que $v_{2}(x+y)=\min \left\{v_{2}(x), v_{2}(y)\right\}$ si $v_{2}(x) \neq v_{2}(y)$, et que $v_{2}(x+y) \geqslant \min \left\{v_{2}(x), v_{2}(y)\right\}+1$ sinon.

Enfin, on a $f(x)=f(y)$ si et seulement si $v_{2}(x)=v_{2}(y)$. Par conséquent, $\triangleright \operatorname{si} v_{2}(x) \geqslant v_{2}(y)$, alors

$$

v_{2}(f(x+y))=v_{2}(x+y)+1 \geqslant v_{2}(y)+1

$$

donc $v_{2}(f(x+y)+y)=v_{2}(y)=v_{2}(f(x)+y)$ et $f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)$;

$\triangleright \operatorname{si} v_{2}(x)<v_{2}(y)$, alors

$$

v_{2}(f(x+y))=v_{2}(x+y)+1=v_{2}(x)+1=v_{2}(f(x))

$$

donc $f(x+y)=f(x)$ et $f(f(x+y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)$.

Ainsi, $f$ est une fonction russe, ce qui répond à la question.

b) Soit $v$ un éventuel entier $f$-rare. On pose $X_{v}=\{x \in \mathbb{Z}: f(x)=v\}$, puis $a=\min \left(X_{v}\right)$ et $b=\max \left(X_{v}\right)$.

Tout d'abord, une récurrence immédiate sur $k$ montre que $f(f(x)+y)=f(f(x+k y)+y)$ pour tous les entiers relatifs $x, y$ et $k$. Par conséquent, si on pose $y=a-f(x)$, alors

$$

f(f(x+k y)+y)=f(f(x)+y)=f(a)=v

$$

donc $f(x+k y)+y \in X_{v}$, de sorte que $f(x+k y) \geqslant a-y=f(x)$ pour tout $k \in \mathbb{Z}$. De même, si on pose $z=b-f(x)$, alors $f(x+\ell z)+z \in X_{v}$, de sorte que $f(x+\ell z) \leqslant b-z=f(x)$ pour tout $\ell \in \mathbb{Z}$.

L'ensemble $X_{f(x)}$ contient donc l'entier $x+m y z$ pour tout $m \in \mathbb{Z}$. Par conséquent, si l'entier $r=f(x)$ est $f$-rare, c'est que $y z=0$, et donc que $r=f(x) \in\{a, b\} \subseteq X_{v}$. Ainsi, seuls les éléments de $X_{v}$ sont susceptibles d'être $f$-rares.

Mais alors, pour tout entier $w$ qui serait $f$-rare, on sait que $v$ appartient à la fois à $X_{v}$ et à $X_{w}$, ce qui démontre que $v=w$, comme attendu.

Commentaire des correcteurs Ce problème très difficile a été substantiellement résolu par trois élèves. Ceux-ci ont, ce faisant, dépassé les attentes que les correcteurs avaient formulées au vu de la difficulté du problème.

Par ailleurs, plusieurs élèves ont proposé des fonctions russes qui n'en étaient en fait pas : il est important d'être méticuleux quand on vérifie qu'une fonction satisfait les conditions d'un énoncé, d'autant plus si cette vérification n'a rien d'évident, comme c'était le cas ici, et qu'elle est censée fournir une réponse toute faite à une question de l'énoncé.

|

{

"exam": "French_tests",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/tests/fr-2019-2020-Corrigé-Web-05-2020.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2019"

}

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ be the sequence of integers such that $a_{1}=1$ and, for all integers $n \geqslant 1$,

$$

a_{n+1}=a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+1

$$

Prove, for all integers $n \geqslant 1$, that $a_{n}^{2}+1$ divides $a_{n+1}^{2}+1$.

|

For all integers $n \geqslant 1$, let $b_{n}=a_{n}^{2}+1$. We conclude by directly observing that

$$

b_{n+1} \equiv\left(a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+1\right)^{2}+1 \equiv\left(b_{n}+a_{n}\right)^{2}+1 \equiv a_{n}^{2}+1 \equiv b_{n} \equiv 0 \quad\left(\bmod b_{n}\right)

$$

$\underline{\text { Alternative Solution } n^{\circ} 1}$ It suffices to observe, for all integers $n \geqslant 1$, that

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{n+1}^{2}+1 & =\left(a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+1\right)^{2}+1 \\

& =a_{n}^{4}+2 a_{n}^{3}+3 a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+2 \\

& =a_{n}^{2}\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)+2 a_{n}^{3}+2 a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+2 \\

& =a_{n}^{2}\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)+2 a_{n}\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)+2 a_{n}^{2}+2 \\

& =a_{n}^{2}\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)+2 a_{n}\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)+2\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right) \\

& =\left(a_{n}^{2}+2 a_{n}+2\right)\left(a_{n}^{2}+1\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

is indeed a multiple of $a_{n}^{2}+1$.

Comment from the graders The exercise was well solved. Some attempted induction, with little success, as it was difficult to obtain the result by induction. Few papers worked modulo $a_{n}^{2}+1$, which greatly simplified the calculations.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ la suite d'entiers telle que $a_{1}=1$ et, pour tout entier $n \geqslant 1$,

$$

a_{n+1}=a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+1

$$

Démontrer, pour tout entier $n \geqslant 1$, que $a_{n}^{2}+1$ divise $a_{n+1}^{2}+1$.

|

Pour tout entier $n \geqslant 1$, posons $b_{n}=a_{n}^{2}+1$. On conclut en constatant directement que

$$

b_{n+1} \equiv\left(a_{n}^{2}+a_{n}+1\right)^{2}+1 \equiv\left(b_{n}+a_{n}\right)^{2}+1 \equiv a_{n}^{2}+1 \equiv b_{n} \equiv 0 \quad\left(\bmod b_{n}\right)

$$