problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Do there exist strictly positive integers $a$ and $b$ such that $a^{n}+n^{b}$ and $b^{n}+n^{a}$ are coprime for all integers $n \geqslant 0$?

|

By contradiction: suppose there exist such integers $a$ and $b$.

By symmetry, we can assume that $a \geqslant b$.

If $d=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$, then for $n=d$, it is clear that $d$ divides $a^{d}+d^{b}$ and $b^{d}+d^{a}$. Since these two numbers are supposed to be coprime, it follows that $d=1$.

Let $N=a^{a}+b^{b}$. We have $N>1$ so there exists a prime number $p$ that divides $N$. Moreover, $p$ cannot divide $a$ without also dividing $b$, which contradicts $d=1$. Thus, $a$ is invertible modulo $p$ and there exists an integer $k \in\{0, \cdots, p-1\}$ such that $k a=b \bmod [p]$.

We then choose $n=k+p(a-b-k+p-1)$. By Fermat's little theorem, we get:

$$

a^{n}+n^{b} \equiv a^{k} \cdot a^{a-b-k+p-1}+k^{b} \equiv a^{a-b}+k^{b} \bmod [p]

$$

where $a^{b}\left(a^{n}+n^{b}\right) \equiv a^{a}+b^{b} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$,

and since $p$ does not divide $a$, we have $a^{n}+n^{b} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$.

Similarly, we have $b^{n}+n^{a} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$.

But then $p$ divides both $a^{n}+n^{b}$ and $b^{n}+n^{a}$, which contradicts their being coprime.

Finally, there do not exist such integers.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Existe-t-il des entiers strictement positifs $a$ et $b$ tels que $a^{n}+n^{b}$ et $b^{n}+n^{a}$ soient premiers entre eux pour tout entier $n \geqslant 0$ ?

|

Par l'absurde : supposons qu'il existe de tels entiers a et b.

Par symétrie, on peut supposer que $a \geqslant b$.

Si $d=\operatorname{pgcd}(a, b)$ alors, pour $n=d$, il est clair que $d$ divise $a^{d}+d^{b}$ et $b^{d}+d^{a}$. Or ces deux nombres étant censés être premiers entre eux, c'est que $d=1$.

Soit $N=a^{a}+b^{b}$. On a $N>1$ donc il existe un nombre premier $p$ qui divise $N$. De plus, $p$ ne peut diviser a sans quoi il devrait diviser également $b$, en contradiction avec $d=1$. Ainsi, $a$ est inversible modulo $p$ et il existe un entier $k \in\{0, \cdots, p-1\}$ tel que $k a=b \bmod [p]$.

On choisit alors $n=k+p(a-b-k+p-1)$. D'après le petit théorème de Fermat, il vient :

$$

a^{n}+n^{b} \equiv a^{k} \cdot a^{a-b-k+p-1}+k^{b} \equiv a^{a-b}+k^{b} \bmod [p]

$$

$d^{\prime}$ où $a^{b}\left(a^{n}+n^{b}\right) \equiv a^{a}+b^{b} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$,

et, puisque $p$ ne divise par $a$, on a alors $a^{n}+n^{b} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$.

On prouve de même, on a $b^{n}+n^{a} \equiv 0 \bmod [p]$.

Mais, alors $p$ divise à la fois $a^{n}+n^{b}$ et $b^{n}+n^{a}$, ce qui contredit qu'ils soient premiers entre eux.

Finalement, il n'existe pas de tels entiers.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

The Xantians are the inhabitants, potentially in infinite number, of the planet Xanta. Regarding themselves and their peers, the Xantians are capable of feeling two types of emotions, which they call love and respect. It has been observed that:

- Each Xantian loves one and only one Xantian, and respects one and only one Xantian.

- If $A$ loves $B$, then any Xantian who respects $A$ also loves $B$.

- If $A$ respects $B$, then any Xantian who loves $A$ also respects $B$.

- Each Xantian is loved by at least one Xantian.

Is it true that each Xantian respects the Xantian they love?

|

For each Xantian $x$, let $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ denote the Xantians loved and respected by $x$.

The first condition ensures that we have well-defined functions $f$ and $g$ from the set $X$ of Xantiens to itself.

The question is whether, for all $x$, we have $f(x)=g(x)$.

In fact, we will even prove that, for all $x$, we have $f(x)=g(x)=x$.

Let $x$ be a Xantian.

He respects $g(x)$, who, in turn, loves $f(g(x))$.

The second condition therefore ensures that $f(g(x))=f(x)$ for all $x$. (1)

Similarly, the third condition leads to $g(f(x))=g(x)$ for all $x$. (2)

Finally, the fourth condition means that $f$ is surjective.

Let $x$ be a Xantian. There therefore exists a Xantian $y$ such that $f(y)=x$.

We have $f(g(f(y)))=f(g(y))$ according to (2),

and thus, according to (1), it follows that $f(f(y))=f(y)$, or $f(x)=x$.

From (1), we immediately deduce that $g(x)=x$.

Ultimately, for all $x$, we have $f(x)=g(x)=x$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

Les Xantiens sont les habitants, en nombre éventuellement infini, de la planète Xanta. Vis-à-vis d'eux-mêmes et de leurs semblables, les Xantiens sont capables de ressentir deux types d'émotions, qu'ils appellent amour et respect. Il a été observé que:

- Chaque Xantien aime un et un seul Xantien, et respecte un et un seul Xantien.

- Si $A$ aime $B$, alors tout Xantien qui respecte $A$ aime également $B$.

- Si $A$ respecte $B$, alors tout Xantien qui aime $A$ respecte également $B$.

- Chaque Xantien est aimé d'au moins un Xantien.

Est-il vrai que chaque Xantien respecte le Xantien qu'il aime?

|

Pour chaque Xantien $x$, désignons respectivement par $f(x)$ et $g(x)$ les Xantiens aimés et respectés par $x$.

La première condition assure que l'on a bien défini des fonctions $f$ et $g$ de l'ensemble $X$ des Xantiens sur lui-même.

Il s'agit de savoir si, pour tout $x$, on a $f(x)=g(x)$.

En fait, nous allons même prouver que, pour tout $x$, on a $f(x)=g(x)=x$.

Soit $x$ un Xantien.

Il respecte $g(x)$ qui, de son côté, aime $f(g(x))$.

La seconde condition assure donc que $f(g(x))=f(x)$ pour tout $x$. (1)

De même, la troisième condition conduit à $g(f(x))=g(x)$ pour tout $x$. (2)

Enfin, la quatrième condition signifie que f est surjective.

Soit $x$ un Xantien. Il existe donc un Xantien $y$ tel que $f(y)=x$.

Or, on a $f(g(f(y)))=f(g(y))$ d'après (2)

et ainsi, d'après (1), il vient $f(f(y))=f(y)$, ou encore $f(x)=x$.

De (1), on déduit alors immédiatement que $g(x)=x$.

Finalement, pour tout $x$, on a bien $f(x)=g(x)=x$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Determine all strictly positive integers \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(4a+1\) and \(4b-1\) are coprime, and such that \(a+b\) divides \(16ab+1\).

|

Let's denote (C) as the condition in the statement. The integers $4 \mathbf{a}+1$ and $4 \mathrm{~b}-1$ are coprime if and only if $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ is coprime with $(4 a+1)+(4 b-1)=4(a+b)$. Since $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ is odd, it is automatically coprime with 4. We deduce that $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ and $4 \boldsymbol{b}-1$ are coprime if and only if $4 a+1$ is coprime with $a+b$.

On the other hand, $16 a b+1=16 a(a+b)+\left(1-16 a^{2}\right)=16 a(a+b)-(4 a-1)(1+4 a)$, so $a+b$ divides $16 a b+1$ if and only if $a+b$ divides $(4 a-1)(1+4 a)$. If $a+b$ is coprime with $1+4 a$, then this is equivalent to $a+b \mid 4 a-1$.

We deduce that (C) is equivalent to $\operatorname{pgcd}(a+b, 4 a+1)=1$ and $a+b \mid 4 a-1$.

On the other hand, let's show that if $a+b \mid 4 a-1$ then we automatically have $\operatorname{pgcd}(a+b, 4 a+1)=1$. Indeed, if a prime number $p$ divides $a+b$ and $4 a+1$, then it divides $4 a-1$ and $4 a+1$, so it divides $(4 a+1)-(4 a-1)=2$. Thus, $p=2$, and $2 \mid 4 a-1$. Impossible.

Finally, (C) is equivalent to $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b} \mid 4 \mathrm{a}-1$.

Since $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}>\mathrm{a}>\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{4}$, $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b} \mid 4 \mathrm{a}-1$ can only occur if $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=4 \mathrm{a}-1$ or $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{2}$ or $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{3}$.

The second case cannot occur because $4 a-1$ is odd.

(C) is therefore equivalent to $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=4 \mathrm{a}-1$ or $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{3}$, i.e., $\mathrm{b}=3 \mathrm{a}-1$ or $\mathrm{a}=3 \mathrm{~b}+1$.

|

b=3a-1 \text{ or } a=3b+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers strictement positifs a et $b$ tels que $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ et $4 \boldsymbol{b}-1$ soient premiers entre eux, et tels que $a+b$ divise $16 a b+1$.

|

Notons (C) la condition de l'énoncé. Les entiers $4 \mathbf{a}+1$ et $4 \mathrm{~b}-1$ sont premiers entre eux si et seulement si $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ est premier avec $(4 a+1)+(4 b-1)=4(a+b)$. Or, $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ est impair donc il est automatiquement premier avec 4 . On en déduit que $4 \boldsymbol{a}+1$ et $4 \boldsymbol{b}-1$ sont premiers entre eux si et seulement si $4 a+1$ est premier avec $a+b$.

D'autre part, $16 a b+1=16 a(a+b)+\left(1-16 a^{2}\right)=16 a(a+b)-(4 a-1)(1+4 a)$, donc $a+b$ divise $16 a b+1$ si et seulement si $a+b$ divise $(4 a-1)(1+4 a)$. Or, si $a+b$ est premier avec $1+4 a$ alors ceci équivaut à $a+b \mid 4 a-1$.

On en déduit que (C) équivaut à ce que $\operatorname{pgcd}(a+b, 4 a+1)=1$ et $a+b \mid 4 a-1$.

D'autre part, montrons que si $a+b \mid 4 a-1$ alors on a automatiquement $\operatorname{pgcd}(a+b, 4 a+1)=1$. En effet, si un nombre premier $p$ divise $a+b$ et $4 a+1$, alors il divise $4 a-1$ et $4 a+1$, donc il divise $(4 a+1)-(4 a-1)=2$. Il vient $p=2$, puis $2 \mid 4 a-1$. Impossible.

Finalement, (C) équivaut à $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b} \mid 4 \mathrm{a}-1$.

Or, $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}>\mathrm{a}>\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{4}$, donc $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b} \mid 4 \mathrm{a}-1$ ne peut se produire que si $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=4 \mathrm{a}-1$ ou $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{2}$ ou $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{3}$.

Le deuxième cas ne peut pas se produire car $4 a-1$ est impair.

(C) équivaut donc à $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=4 \mathrm{a}-1$ ou $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}=\frac{4 \mathrm{a}-1}{3}$, $\mathrm{c}^{\prime}$ est-à-dire $\mathrm{b}=3 \mathrm{a}-1$ ou $\mathrm{a}=3 \mathrm{~b}+1$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

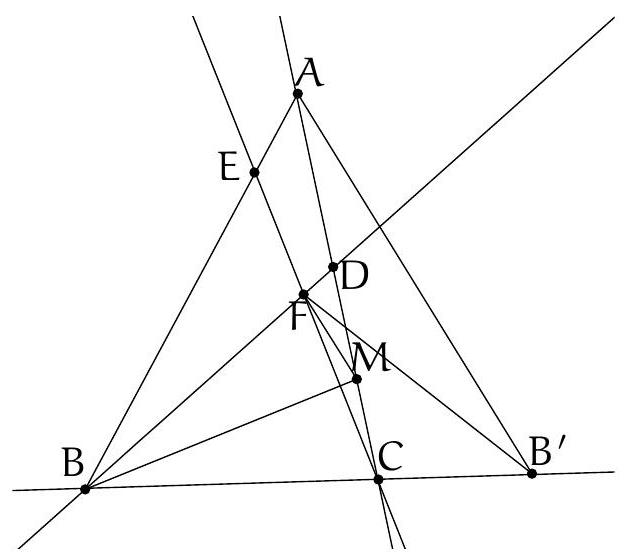

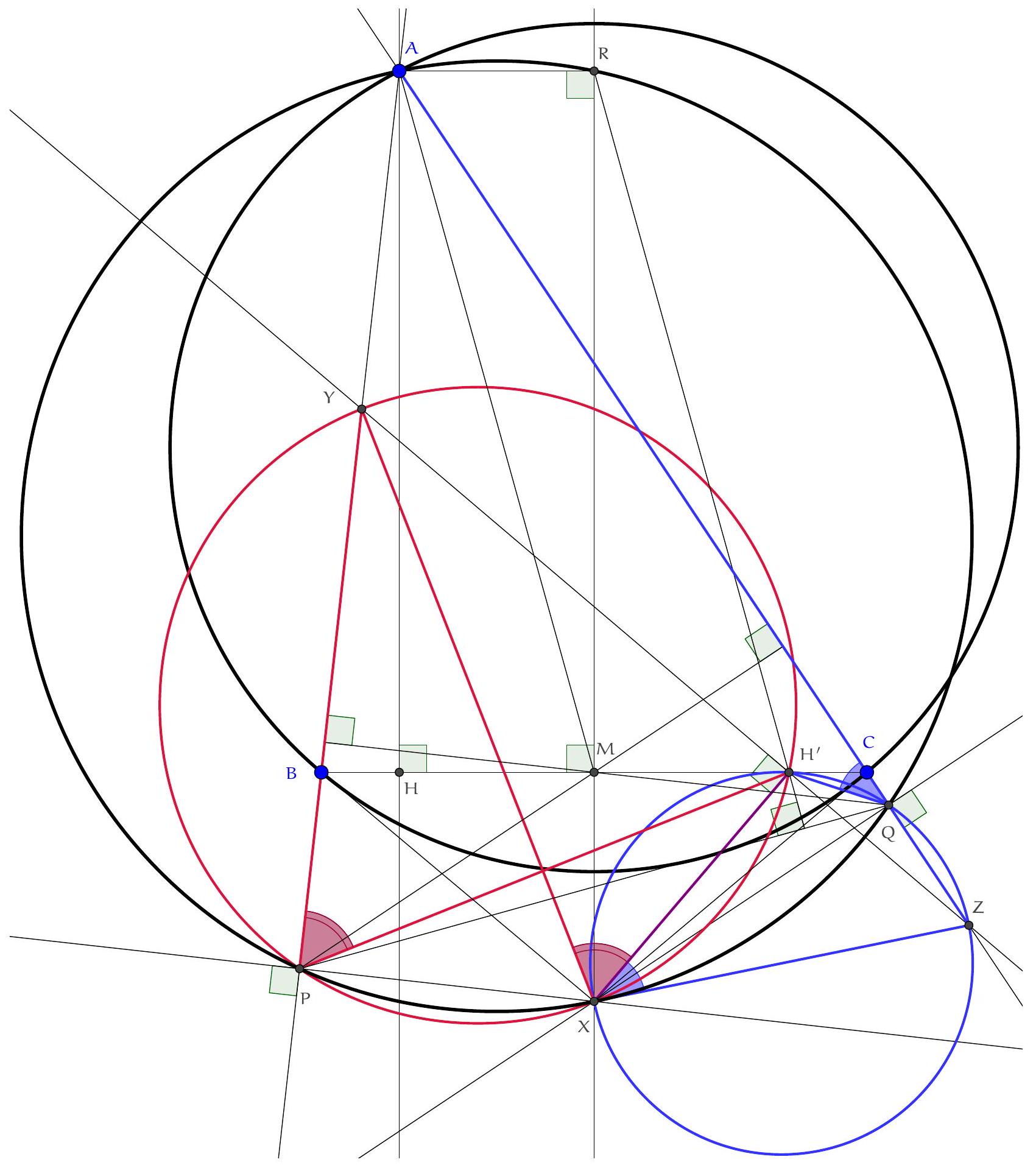

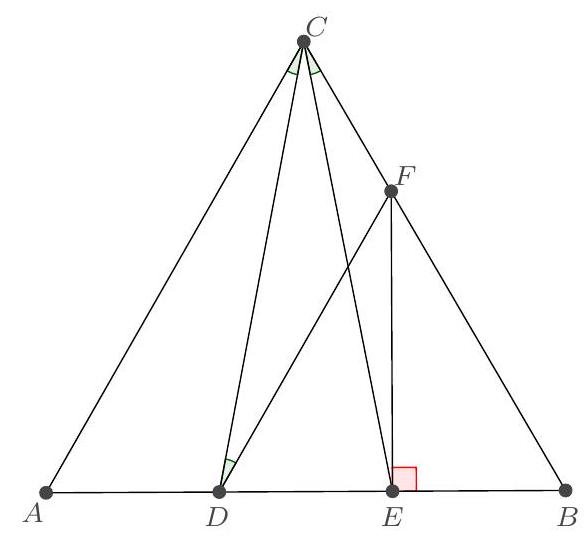

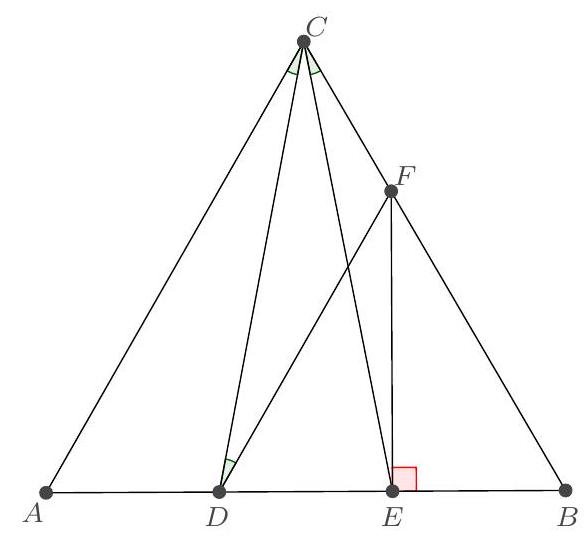

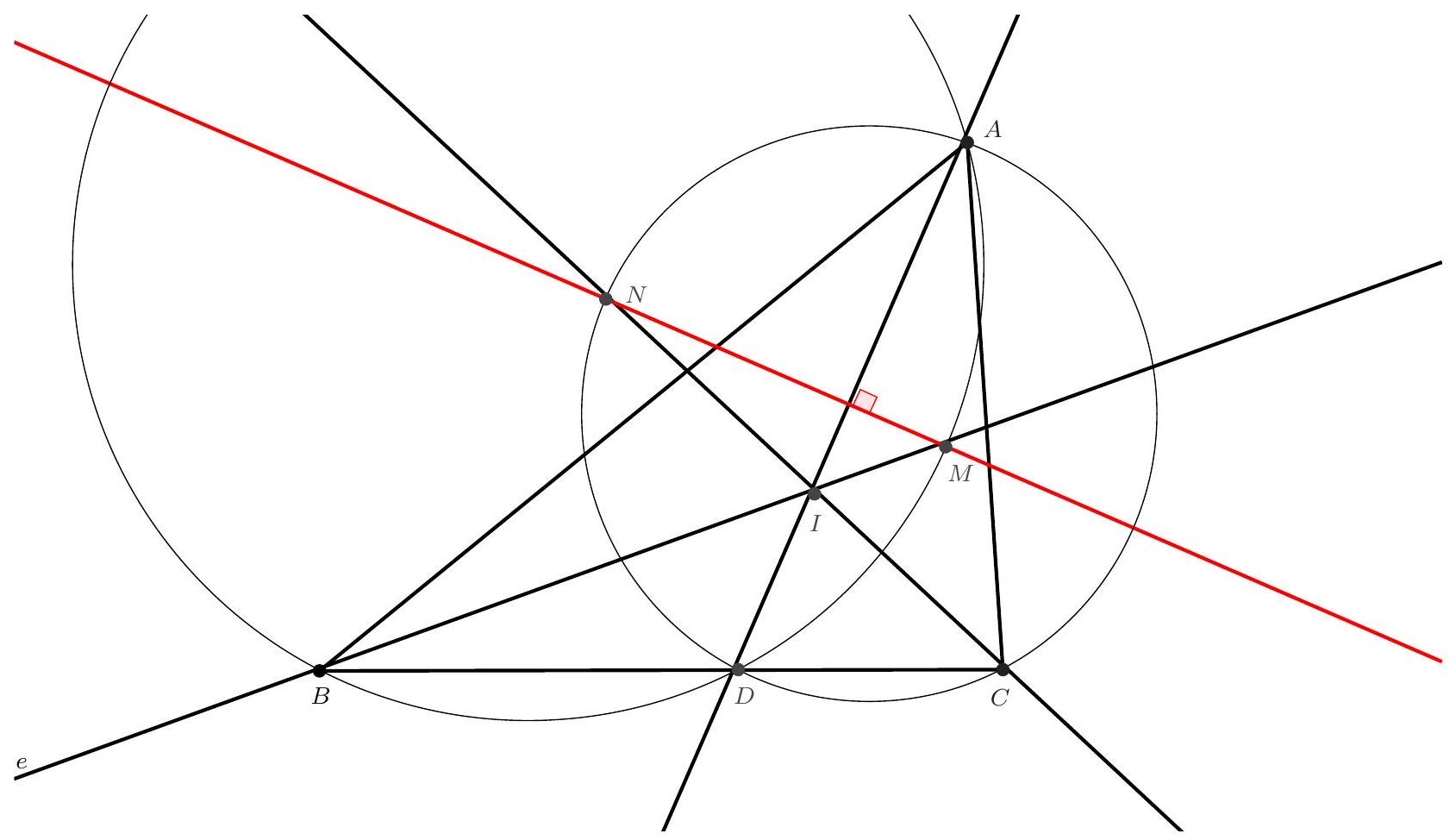

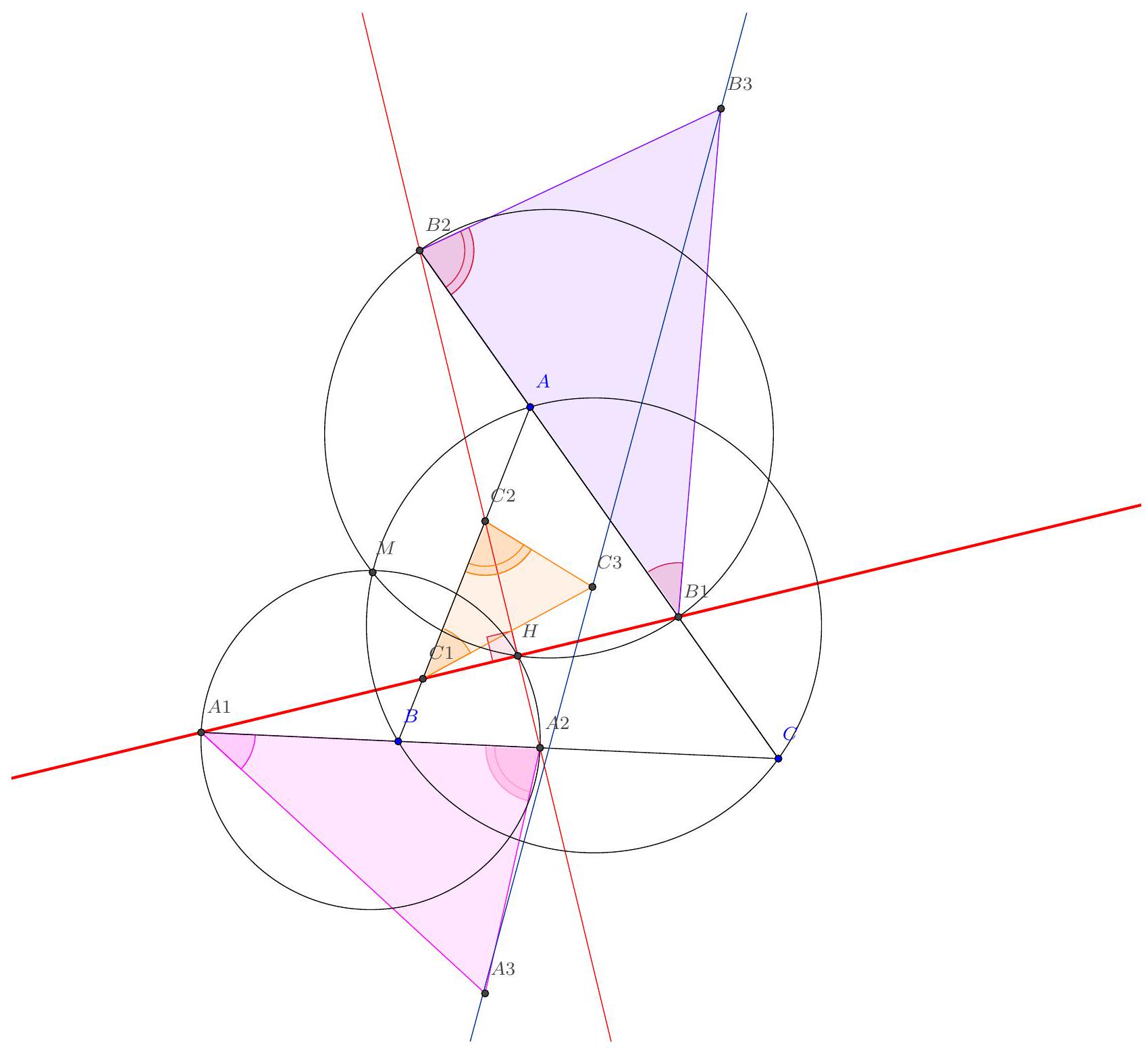

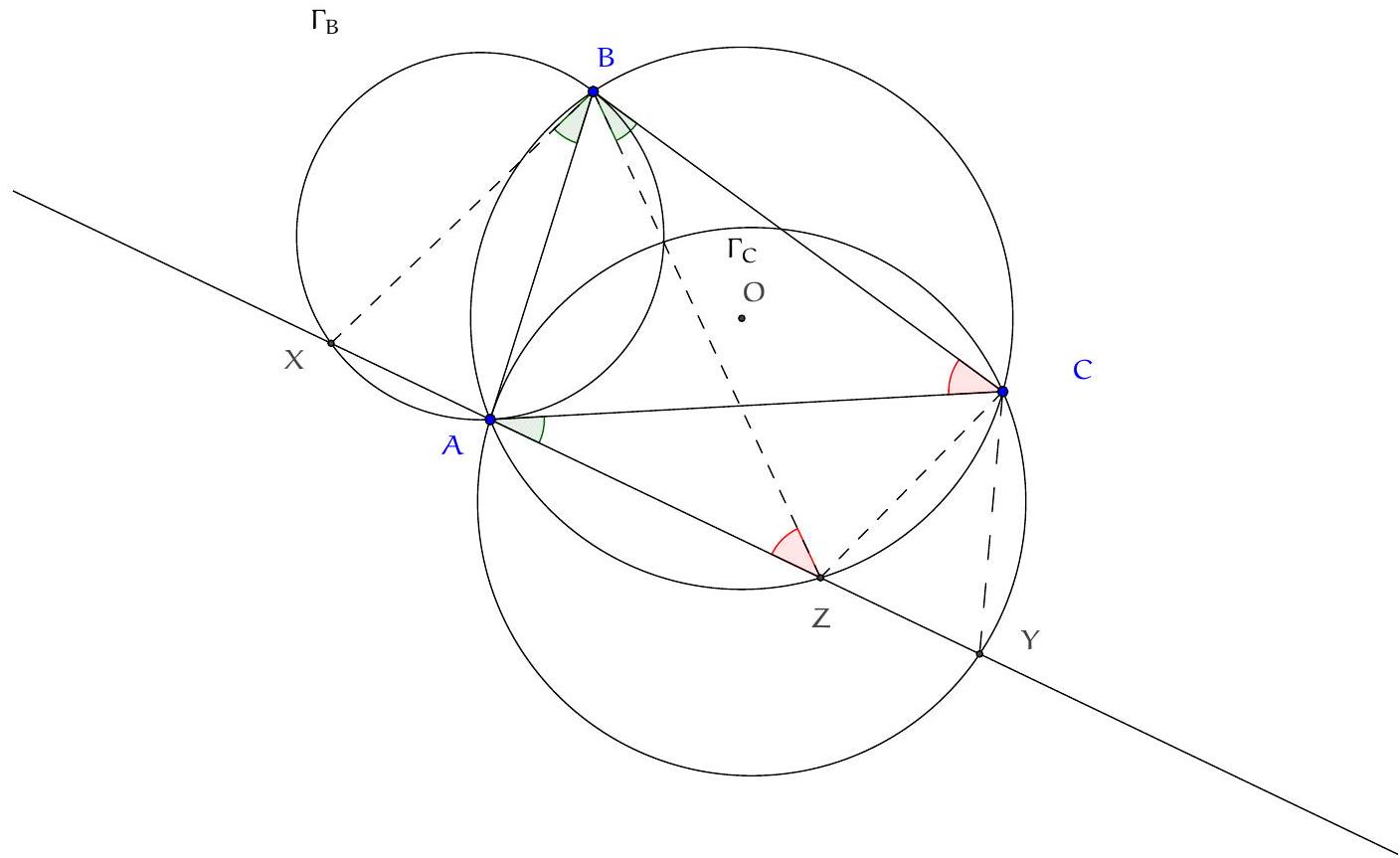

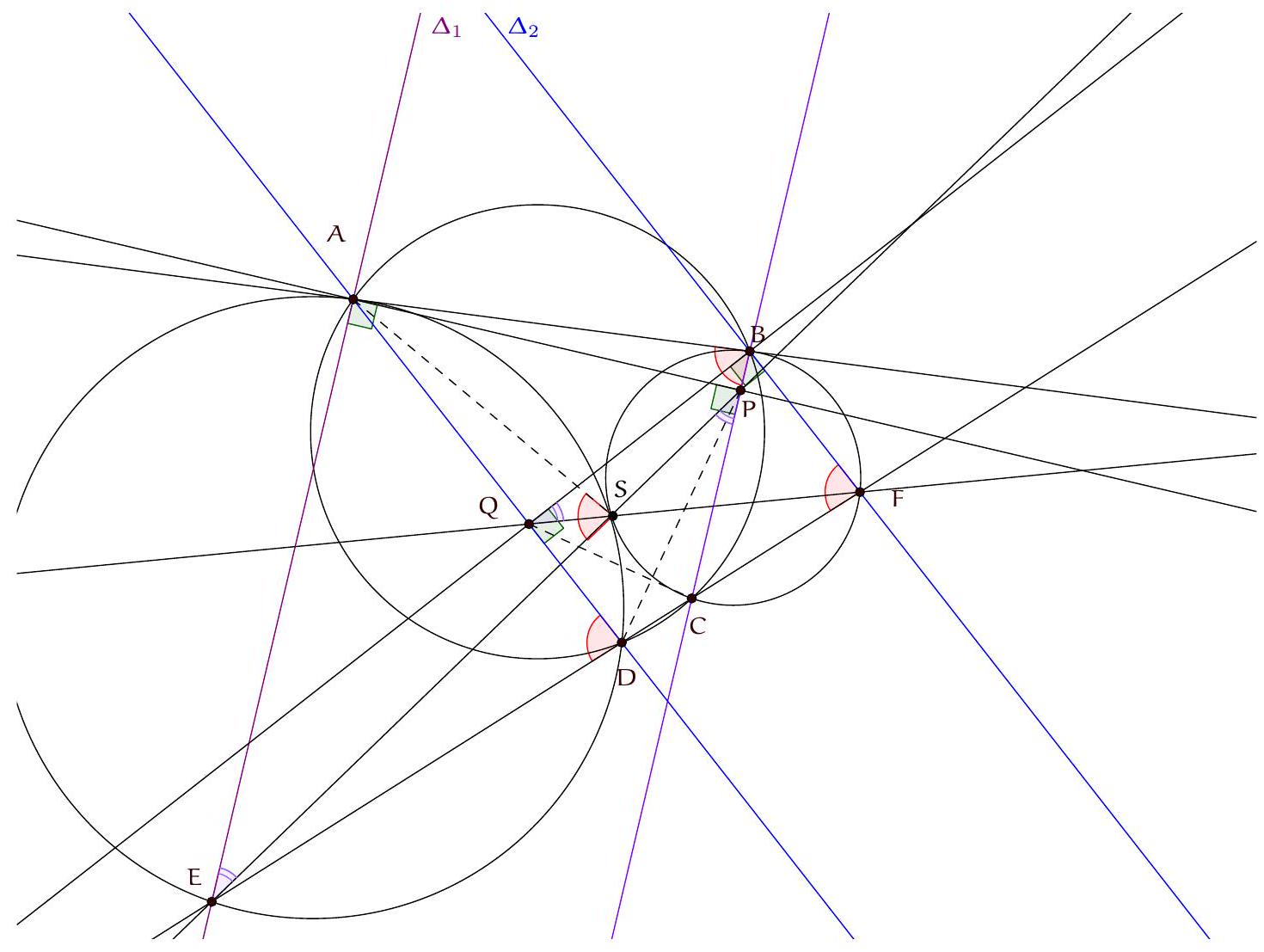

Let $ABC$ be a triangle such that $\widehat{A}=40^{\circ}$ and $\widehat{B}=60^{\circ}$. Let $D$ and $E$ be points on $[AC]$ and $[\mathrm{AB}]$ such that $\widehat{\mathrm{CBD}}=40^{\circ}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{ECB}}=70^{\circ}$. We denote $F$ as the intersection of $(BD)$ and $(CE)$. Show that $(A F) \perp(B C)$.

|

In $\widehat{\mathrm{BFC}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{CBF}}-\widehat{\mathrm{FCB}}=180^{\circ}-40^{\circ}-70^{\circ}=70^{\circ}=\widehat{\mathrm{FCB}}$, so BCF is isosceles at B. It follows that $B C=B F$.

Let $M$ be the intersection point between the bisector of $\widehat{C B F}$ and ( $A C$ ). We have $\widehat{B M A}=40^{\circ}=\widehat{B A M}$, so $M A=M B$.

On the other hand, $\widehat{B M C}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{C B M}-\widehat{M C B}=180^{\circ}-20^{\circ}-80^{\circ}=80^{\circ}=\widehat{M C B}$, so $B C=B M$.

From the above, we deduce that $M A=B F$.

Let $\mathrm{B}^{\prime} \in(\mathrm{BC})$ such that $A B^{\prime}$ is equilateral. Let $\Delta$ be the bisector of $\widehat{\mathrm{B}^{\prime} \mathrm{BA}}$. Since $\mathrm{BF}=\mathrm{BM}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{FBA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CBM}}$, the points $M$ and $F$ are symmetric with respect to $\Delta$. Also, $A$ and $B^{\prime}$ are symmetric with respect to $\Delta$, so $M A=\mathrm{FB}^{\prime}$.

Finally, $\mathrm{FB}^{\prime}=\mathrm{FB}$, so $F$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $\left[\mathrm{BB}^{\prime}\right]$, which is also the altitude ( $A F$ ) of the triangle $A B B^{\prime}$.

Another solution. Let $H$ be the projection of $F$ on $[B C]$ and $H^{\prime}$ the projection of $A$ on [BC]. It suffices to show that $\mathrm{H}=\mathrm{H}^{\prime}$. For this, it is enough to see that $\mathrm{BH}=\mathrm{BH}^{\prime}$.

We have $B^{\prime}=A B \cos 60$ and $B H=B F \cos 40=B C \cos 40$. Since $\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{\sin 80}{\sin 40}$, it suffices to show that $\sin 80 \cos 60=\sin 40 \cos 40$, which is equivalent (given that $\cos 60=\frac{1}{2}$) to $\sin 80=2 \sin 40 \cos 40$, which is true according to the general formula $\sin 2 x=2 \sin x \cos x$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle tel que $\widehat{A}=40^{\circ}$ et $\widehat{B}=60^{\circ}$. Soient $D$ et $E$ des points de [AC] et $[\mathrm{AB}]$ tels que $\widehat{\mathrm{CBD}}=40^{\circ}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{ECB}}=70^{\circ}$. On note F l'intersection de (BD) et (CE). Monter que $(A F) \perp(B C)$.

|

On a $\widehat{\mathrm{BFC}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{CBF}}-\widehat{\mathrm{FCB}}=180^{\circ}-40^{\circ}-70^{\circ}=70^{\circ}=\widehat{\mathrm{FCB}}$ donc BCF est isocèle en B . Il vient $B C=B F$.

Soit $M$ le point d'intersection entre la bissectrice de $\widehat{C B F}$ et ( $A C$ ). On a $\widehat{B M A}=40^{\circ}=\widehat{B A M}$ donc $M A=M B$.

D'autre part, $\widehat{B M C}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{C B M}-\widehat{M C B}=180^{\circ}-20^{\circ}-80^{\circ}=80^{\circ}=\widehat{M C B}$ donc $B C=B M$.

On déduit de ce qui précède que $M A=B F$.

Soit $\mathrm{B}^{\prime} \in(\mathrm{BC})$ tel que $A B^{\prime}$ est équilatéral. Soit $\Delta$ la bissectrice de $\widehat{\mathrm{B}^{\prime} \mathrm{BA}}$. Comme $\mathrm{BF}=\mathrm{BM}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{FBA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CBM}}$, les points $M$ et $F$ sont symétriques par rapport à $\Delta$. Or, $A$ et $B^{\prime}$ sont aussi symétriques par rapport à $\Delta$, donc $M A=\mathrm{FB}^{\prime}$.

Finalement, $\mathrm{FB}^{\prime}=\mathrm{FB}$, donc $F$ appartient à la médiatrice de $\left[\mathrm{BB}^{\prime}\right]$, qui est aussi la hauteur ( $A F$ ) du triangle $A B B^{\prime}$.

Autre solution. Notons $H$ le projeté de $F$ sur $[B C]$ et $H^{\prime}$ le projeté de $A$ sur [BC]. Il s'agit de montrer que $\mathrm{H}=\mathrm{H}^{\prime}$. Pour cela, il suffit de voir que $\mathrm{BH}=\mathrm{BH}^{\prime}$.

On a $B^{\prime}=A B \cos 60$ et $B H=B F \cos 40=B C \cos 40$. Comme $\frac{A B}{B C}=\frac{\sin 80}{\sin 40}$, il suffit de montrer que $\sin 80 \cos 60=\sin 40 \cos 40$, c'est-à-dire (compte tenu de $\cos 60=\frac{1}{2}$ ) que $\sin 80=$ $2 \sin 40 \cos 40$, ce qui est vrai d'après la formule générale $\sin 2 x=2 \sin x \cos x$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

For any strictly positive integer $x$, we denote $S(x)$ as the sum of the digits of its decimal representation.

Let $k>0$ be an integer. We define the sequence $\left(x_{n}\right)$ by $x_{1}=1$ and $x_{n+1}=S\left(k x_{n}\right)$ for all $n>0$.

Prove that $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$, for all $n>0$.

|

Lemme. For any integer $s \geqslant 0$, we have $10^{s} \geqslant(s+1)^{3}$.

Proof of the lemma. We reason by induction on $s$.

For $s=0$, we have $10^{0}=1=(0+1)^{3}$.

Suppose the inequality is true for the value $s$. Then:

$10^{\mathrm{s}+1} \geqslant 10(\mathrm{~s}+1)^{3}$ according to the induction hypothesis

$=10 s^{3}+30 s^{2}+30 s+10$

$\geqslant \mathrm{s}^{3}+6 \mathrm{~s}^{2}+12 \mathrm{~s}+8$

$=(s+2)^{3}$, which completes the proof.

If $x>0$ is an integer whose decimal representation uses $s+1$ digits, we have $S(x) \leqslant 9(s+1)$ and $10^{s} \leqslant x<10^{s+1}$. From the lemma, we have $s+1 \leqslant 10^{\frac{s}{3}}$, so $s+1 \leqslant x^{\frac{1}{3}}$ and thus $S(x) \leqslant 9 x^{\frac{1}{3}}$.

Now let's show by induction that $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$ for all $n$. The statement is clear for $n=1$. Suppose $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$, then $x_{n+1}=S\left(k x_{n}\right) \leqslant 9\left(k x_{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}<9(27 k \sqrt{k})^{\frac{1}{3}}=9 \times 3 \times \sqrt{k}=$ $27 \sqrt{\mathrm{k}}$, hence the result.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Pour tout entier strictement positif $x$, on note $S(x)$ la somme des chiffres de son écriture décimale.

Soit $k>0$ un entier. On définit la suite $\left(x_{n}\right)$ par $x_{1}=1$ et $x_{n+1}=S\left(k x_{n}\right)$ pour tout $n>0$.

Prouver que $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$, pour tout $n>0$.

|

Lemme. Pour tout entier $s \geqslant 0$, on a $10^{s} \geqslant(s+1)^{3}$.

Preuve du lemme. On raisonne par récurrence sur s.

Pour $s=0$, on a $10^{0}=1=(0+1)^{3}$.

Supposons l'inégalité vraie pour la valeur s. Alors :

$10^{\mathrm{s}+1} \geqslant 10(\mathrm{~s}+1)^{3}$ d'après l'hypothèse de récurrence

$=10 s^{3}+30 s^{2}+30 s+10$

$\geqslant \mathrm{s}^{3}+6 \mathrm{~s}^{2}+12 \mathrm{~s}+8$

$=(s+2)^{3}$, ce qui achève la preuve.

Si $x>0$ est un entier dont l'écriture décimale utilise $s+1$ chiffres, on a $S(x) \leqslant 9(s+1)$ et $10^{s} \leqslant x<10^{s+1}$. Or, d'après le lemme, on a $s+1 \leqslant 10^{\frac{s}{3}}$, donc $s+1 \leqslant x^{\frac{1}{3}}$ et ainsi $S(x) \leqslant 9 x^{\frac{1}{3}}$.

Montrons maintenant par récurrence que $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$ pour tout $n$. L'assertion est claire pour $n=1$. Supposons $x_{n}<27 \sqrt{k}$, alors $x_{n+1}=S\left(k x_{n}\right) \leqslant 9\left(k x_{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}<9(27 k \sqrt{k})^{\frac{1}{3}}=9 \times 3 \times \sqrt{k}=$ $27 \sqrt{\mathrm{k}}$, d'où le résultat.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 10.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 10",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be three strictly positive real numbers such that $a+b+c=9$. Show that

$$

\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9}+\frac{b^{3}+c^{3}}{b c+9}+\frac{c^{3}+a^{3}}{c a+9} \geqslant 9

$$

|

We are looking for a lower bound of the form $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9} \geqslant u(a+b)+v$, that is, $f(a) \geqslant 0$ where $f(a)=a^{3}+b^{3}-(u(a+b)+v)(a b+9)$.

By summing the three inequalities, we would deduce $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9}+\frac{b^{3}+c^{3}}{b c+9}+\frac{c^{3}+a^{3}}{c a+9} \geqslant 2 u(a+b+c)+3 v = 3(6 u+v)$, so it suffices that $6 u+v=3$.

On the other hand, if such a lower bound exists, since the inequality becomes an equality when $a = b = c = 3$, we must have $f(3)=0$ if $b=3$. Since $f(a) \geqslant 0$ for all $a$, we must necessarily have $f'(3)=0$ for $b=3$.

This imposes the condition $0=f'(3)=27-18 u-(6 u+v) \times 3=18(1-u)$, so $u=1$ and $v=-3$.

Let's show $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9} \geqslant(a+b)-3$. Since $a^{3}+b^{3} \geqslant \frac{(a+b)^{3}}{4}$ and $a b+9 \leqslant\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)^{2}+9$, it suffices to show that

$$

\frac{s^{3}}{s^{2}+36} \geqslant s-3

$$

where $s=a+b$. We reduce to a common denominator; the inequality simplifies to $3 s^{2}-36 s+108 \geqslant 0$, or equivalently $3(s-6)^{2} \geqslant 0$, which is true.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $a, b, c$ trois nombres réels strictement positifs tels que $a+b+c=9$. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9}+\frac{b^{3}+c^{3}}{b c+9}+\frac{c^{3}+a^{3}}{c a+9} \geqslant 9

$$

|

On cherche une minoration de la forme $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9} \geqslant u(a+b)+v, c^{\prime}$ est-àdire $f(a) \geqslant 0$ où $f(a)=a^{3}+b^{3}-(u(a+b)+v)(a b+9)$.

En sommant les trois inégalités, on en déduirait $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9}+\frac{b^{3}+c^{3}}{b c+9}+\frac{c^{3}+a^{3}}{c a+9} \geqslant 2 u(a+b+c)+3 v=$ $3(6 u+v)$, donc il suffit que $6 u+v=3$.

D'autre part, si une telle minoration existe, comme l'inégalité devient une égalité lorsque $\mathrm{a}=$ $\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=3$, on doit avoir $\mathrm{f}(3)=0$ si $\mathrm{b}=3$. Comme de plus $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{a}) \geqslant 0$ pour tout a , on doit nécessairement avoir $\mathrm{f}^{\prime}(3)=0$ pour $\mathrm{b}=3$.

Ceci impose la condition $0=f^{\prime}(3)=27-18 \mathbf{u}-(6 \mathbf{u}+\boldsymbol{v}) \times 3=18(1-\mathfrak{u})$, donc $\mathbf{u}=1$ et $v=-3$.

Montrons donc $\frac{a^{3}+b^{3}}{a b+9} \geqslant(a+b)-3$. Comme $a^{3}+b^{3} \geqslant \frac{(a+b)^{3}}{4}$ et $a b+9 \leqslant\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)^{2}+9$, il suffit de montrer que

$$

\frac{s^{3}}{s^{2}+36} \geqslant s-3

$$

où $s=a+b$. On réduit au même dénominateur; l'inégalité se simplifie en $3 s^{2}-36 s+108 \geqslant 0$, ou encore en $3(s-6)^{2} \geqslant 0$, ce qui est vrai.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 11.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 11",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Determine all integers $\mathrm{n}>0$ having the following property: "any strictly positive number that can be written as the sum of the squares of $n$ integers that are multiples of $n$ can also be written as the sum of the squares of $n$ integers, none of which is a multiple of $\mathrm{n}^{\prime \prime}$.

Determine all integers $\mathrm{n}>0$ having the following property: "any strictly positive number that can be written as the sum of the squares of $n$ integers that are multiples of $n$ can also be written as the sum of the squares of $n$ integers, none of which is a multiple of $\mathrm{n}^{\prime \prime}$.

|

An integer n having the desired property will be called good.

Let $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$ be a good integer. Then 2n is also good: indeed, let $\mathrm{m}=2 \mathrm{n}$ and let $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{m}$ be integers divisible by m. If two of these integers are non-zero, we can assume without loss of generality that they are $x_{1}$ and $x_{m}$. Since $n$ is good, there then exist integers $y_{i}$ not divisible by $n$ (and therefore not divisible by $m$) such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$ and $\sum_{i=n+1}^{2 n} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=n+1}^{2 n} y_{i}^{2}$. Thus, $\sum_{i=1}^{m} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} y_{i}^{2}$ with each $y_{i}$ not divisible by $m$.

If exactly one of the $x_{i}$ is non-zero, then $\sum_{i=1}^{m} x_{i}^{2}$ is of the form $(2 a)^{2}=a^{2}+a^{2}+a^{2}+a^{2}$ where $a>0$ is divisible by n, and we reason in the same way.

Lemma. Let $\mathrm{n}>0$ be an odd integer and $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$ be integers, at least one of which is not divisible by $n$. Then there exist integers $y_{1}, \cdots, y_{n}$ not divisible by $n$ such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$.

set $X=2 \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i}$.

If $n$ divides $X$, we replace $x_{1}$ by $-x_{1}$. The new value $X^{\prime}$ satisfies $X^{\prime}=X-4 x_{1}$. Since $n$ divides $X$ but not $4 x_{1}$ (recall that $n$ is assumed to be odd), it does not divide $X^{\prime}$. Thus, without loss of generality, we can assume that $n$ does not divide $X$.

It is easy to verify that $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(X-n x_{i}\right)^{2}$. By setting $y_{i}=X-n x_{i}$ for all $i$, the desired conclusion follows.

We can now prove that every $n \geqslant 3$ odd is good. Indeed, if $a>0$ is an integer that can be written as the sum of $n$ squares of integers all divisible by $n$, then, by considering the highest power of $n$ that divides these integers, there exists an integer $r>0$ and integers $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$, at least one of which is not divisible by $n$, such that $a=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r} x_{i}\right)^{2}$.

According to the lemma, there exist integers $y_{1}, \cdots, y_{n}$ not divisible by $n$ such that $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$, and thus $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r} x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r-1} y_{i}\right)^{2}$. Therefore, by applying the lemma $r$ times in succession, we are assured of the existence of integers $z_{1}, \cdots, z_{n}$ not divisible by $n$ such that $a=\sum_{i=1}^{n} z_{i}^{2}$. This proves that $n$ is good.

Since the double of any good integer is good, any integer that is not a power of 2 is good.

We now prove that 8 is good: Indeed, if $a$ is the sum of 8 squares of integers divisible by 8, then $a$ is divisible by 64. In particular, $a \geqslant 64$ and, according to Lagrange's four-square theorem, there exist integers $x_{1}, x_{2}$, $x_{3}, x_{4}$ such that $a=1^{2}+4^{2}+4^{2}+4^{2}+x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2}$. Note that, since $a \equiv 0 \bmod [8]$, we have $x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2} \equiv 7 \bmod [8]$. Since a square is congruent to 0, 1, or 4 modulo 8, the only way to obtain a sum of four squares congruent to 7 modulo 8 is to have $1,1,1,4$ in some order. Thus, none of the $x_{i}$ is divisible by 8, which concludes the proof.

Finally, we prove that 4 is not good. For this, it suffices to observe that $32=4^{2}+4^{2}+0^{2}+0^{2}$. On the other hand, to obtain $32=x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2}$, we must have $\left|x_{i}\right| \leqslant 5$ for all $i$. Moreover, to avoid multiples of 4, the only remaining possibilities are $\left|x_{i}\right|=1,2,3$ or 5. As above, reasoning modulo 8, the only possibility is to have $\left|x_{i}\right|=2$ for all $i$. But, we have $32 \neq 2^{2}+2^{2}+2^{2}+2^{2}$, which ensures that 4 is not good.

Thus, any divisor of 4 cannot be good.

Finally, all integers $\mathrm{n}>0$ are good except 1, 2, and 4.

|

all integers \mathrm{n}>0 are good except 1, 2, and 4

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers $\mathrm{n}>0$ ayant la propriété suivante: "tout nombre strictement positif qui s'écrit comme la somme des carrés de $n$ entiers multiples de $n$ peut également s'écrire comme la somme des carrés de $n$ entiers dont aucun n'est un multiple de $\mathrm{n}^{\prime \prime}$.

|

Un entier n ayant la propriété désirée sera dit bon.

Soit $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$ un entier bon. Alors 2 n est également bon : en effet, soit $\mathrm{m}=2 \mathrm{n}$ et soit $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{m}$ des entiers divisibles par m. Si deux de ces entiers sont non nuls, on peut supposer sans perte de généralité qu'il s'agit de $x_{1}$ et $x_{m}$. Puisque $n$ est bon, il existe alors des entiers $y_{i}$ non divisibles par $n$ (donc non divisibles par $m$ ) tels que $\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$ et $\sum_{i=n+1}^{2 n} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=n+1}^{2 n} y_{i}^{2}$. Ainsi, $\sum_{i=1}^{m} x_{i}^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} y_{i}^{2}$ avec chaque $y_{i}$ non divisible par $m$.

Si un et un seul des $x_{i}$ est non nul, alors $\sum_{i=1}^{m} x_{i}^{2}$ est de la forme $(2 a)^{2}=a^{2}+a^{2}+a^{2}+a^{2}$ où $a>0$ est divisible par n et on raisonne de la même manière.

Lemme. Soit $\mathrm{n}>0$ un entier impair et $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$ des entiers dont au moins un n'est pas divisible par $n$. Alors il existe des entiers $y_{1}, \cdots, y_{n}$ non divisibles par $n$ tels que $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$.

pose $X=2 \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i}$.

Si $n$ divise $X$, on remplace $x_{1}$ par $-x_{1}$. La nouvelle valeur $X^{\prime}$ vérifie $X^{\prime}=X-4 x_{1}$. Comme $n$ divise $X$ mais pas $4 x_{1}$ (rappelons que $n$ est supposé impair), il ne divise pas $X^{\prime}$. Ainsi, sans perte de généralité, on peut supposer que $n$ ne divise pas $X$.

Il est facile de vérifier que $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(X-n x_{i}\right)^{2}$. En posant $y_{i}=X-n x_{i}$ pour tout $i$, la conclusion souhaitée en découle.

On peut maintenant prouver que tout $n \geqslant 3$ impair est bon. En effet, si $a>0$ est un entier qui peut s'écrire comme la somme de $n$ carrés d'entiers tous divisibles par $n$ alors, en considérant la plus grande puissance de $n$ qui divise ces entiers, il existe donc un entier $r>0$ et des entiers $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$ dont au moins un n'est pas divisible par $n$ tels que $a=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r} x_{i}\right)^{2}$.

D'après le lemme, il existe des entiers $y_{1}, \cdots, y_{n}$ non divisibles par $n$ tels que $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$, et donc $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r} x_{i}\right)^{2}=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(n^{r-1} y_{i}\right)^{2}$. Ainsi, en appliquant le lemme $r$ fois de suite, on est assuré de l'existence d'entiers $z_{1}, \cdots, z_{n}$ non divisibles par $n$ tels que $a=\sum_{i=1}^{n} z_{i}^{2}$. Cela prouve que $n$ est bon.

Puisque le double de tout entier bon est bon, tout entier qui n'est pas une puissance de 2 est bon.

On prouve maintenant que 8 est bon : En effet, si a est la somme de 8 carrés d'entiers divisibles par 8 alors a est divisible par 64 . En particulier $a \geqslant 64 \mathrm{et}$, d'après le théorème des quatre carrés de Lagrange, il existe des entiers $x_{1}, x_{2}$, $x_{3}, x_{4}$ tels que $a=1^{2}+4^{2}+4^{2}+4^{2}+x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2}$. Notons que, puisque $a \equiv 0 \bmod [8]$, on a $x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2} \equiv 7 \bmod$ [8]. Or, un carré étant congru à 0,1 ou 4 modulo 8 , la seule façon d'obtenir une somme de quatre carrés congrue à 7 modulo 8 est d'avoir $1,1,1,4$ à l'ordre près. Ainsi, aucun des $x_{i}$ n'est divisible par 8 , ce qui conclut.

Enfin, on prouve que 4 n'est pas bon. Pour cela, il suffit de constater que $32=4^{2}+4^{2}+0^{2}+0^{2}$. D'autre part, pour obtenir $32=x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}+x_{3}^{2}+x_{4}^{2}$, on doit avoir $\left|x_{i}\right| \leqslant 5$ pour tout i. De plus, si l'on veut éviter les multiples de 4 , il ne reste plus que $\left|x_{i}\right|=1,2,3$ ou 5 . Or, comme ci-dessus en raisonnant modulo 8 , la seule possibilités est d'avoir $\left|x_{i}\right|=2$ pour tout $i$. Mais, on a $32 \neq$ $2^{2}+2^{2}+2^{2}+2^{2}$, ce qui assure que $4 \mathrm{n}^{\prime}$ est pas bon.

Ainsi, tout diviseur de 4 ne peut être bon.

Finalement, tous les entiers $\mathrm{n}>0$ sont bons sauf 1,2 et 4 .

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2014-2015-envoi-6-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 12",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Prove that there are only a finite number of prime numbers that can be written in the form $n^{3}+2 n+3$ with $n \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

Note that $n^{3}-n=n(n-1)(n+1)$ is a product of three consecutive integers. Since among three consecutive integers there is always a multiple of 3, we obtain that $n^{3}-n$ is divisible by 3, that is, $n^{3} \equiv n(\bmod 3)$. (This can also be seen using Fermat's little theorem.) Therefore, $n^{3}+2 n+3 \equiv n+2 n+3 \equiv 3 n+3 \equiv 0(\bmod 3)$, so $n^{3}+2 n+3$ is always divisible by 3. On the other hand, it can only be equal to 3 for a finite number of values of $n$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Prouver qu'il n'existe qu'un nombre fini de nombres premiers s'écrivant sous la forme $n^{3}+2 n+3$ avec $n \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

: Remarquons que $n^{3}-n=n(n-1)(n+1)$ est un produit de trois entiers consécutifs. Puisque parmi trois entiers consécutifs il y a toujours un multiple de 3 , on obtient que $n^{3}-n$ est divisible par 3, c'est-à-dire $n^{3} \equiv n(\bmod 3)$. (On peut le voir aussi en utilisant le petit théorème de Fermat.) On a donc $n^{3}+2 n+3 \equiv n+2 n+3 \equiv 3 n+3 \equiv 0(\bmod 3)$, donc $n^{3}+2 n+3$ est toujours divisible par 3 . D'autre part, il ne peut être égal à 3 que pour un nombre fini de valeurs de $n$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Solve $x^{4}-6 x^{2}+1=7 \times 2^{y}$ for $x$ and $y$ integers.

|

: The equation can be rewritten as $\left(x^{2}-3\right)^{2}=7 \times 2^{y}+8$. If $y \geq 3$, then the right side can be written as $8\left(7 \times 2^{y-3}+1\right)$. Since the left side is a square, its 2-adic valuation is even. Thus, $7 \times 2^{y-3}+1$ must be even, so $y=3$. In this case, $x^{2}-3=8$ so $x^{2}=11$, which is impossible. Therefore, $y \leq 2$. If $y=2$, we find $x= \pm 3$. For $y<0$, as well as for $y=0$ or $y=1$, there are no solutions. The only pairs of solutions are therefore $(x, y)=(3,2)$ and $(-3,2)$.

|

(3,2) \text{ and } (-3,2)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Résoudre $x^{4}-6 x^{2}+1=7 \times 2^{y}$ pour $x$ et $y$ entiers.

|

: L'équation se réécrit $\left(x^{2}-3\right)^{2}=7 \times 2^{y}+8$. Si $y \geq 3$, alors le côté droit s'écrit $8\left(7 \times 2^{y-3}+1\right)$. Le côté gauche étant un carré, sa valuation 2 -adique est paire. Ainsi, $7 \times 2^{y-3}+1$ doit être pair, donc $y=3$. Dans ce cas $x^{2}-3=8$ donc $x^{2}=11$, impossible. Donc $y \leq 2$. Si $y=2$, on trouve $x= \pm 3$. Pour $y<0$, ainsi que pour $y=0$ ou $y=1$ il n'y a pas de solution. Les seuls couples de solutions sont donc $(x, y)=(3,2)$ et $(-3,2)$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Find the smallest positive integer that cannot be written in the form $\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}$ for $a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

Let $E$ be the set of strictly positive integers that can be written in this form. Let's start by noting that

$$

\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}=2^{b-d} \frac{2^{a-b}-1}{2^{c-d}-1}

$$

Thus, if $x>0$ is written as $x=\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}$, then $b-d=v_{2}(x)$ and if we call $y$ the odd integer such that $x=2^{v_{2}(x)} y$, then $y$ can be written in the form $\frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{m}-1}$. In particular, the integer we are looking for is necessarily odd. On the other hand, we can immediately exclude integers of the form $2^{n}-1$, which are reached with $m=1$.

It is classical that if $2^{m}-1$ divides $2^{n}-1$, then $m$ divides $n$. Thus, by writing $n=m d, y$ is of the form

$$

y=\frac{2^{m d}-1}{2^{m}-1}=2^{(d-1) m}+2^{(d-2) m}+\ldots+2^{m}+1

$$

In other words, denoting $u=\underbrace{0 \ldots 0}_{m-1 \text { zeros }} 1$, the binary representation of $y$ is of the form $\overline{1 u \ldots u}^{2}$, with $u$ appearing $d-1$ times. The odd integers belonging to $E$ are exactly those having such a binary representation for well-chosen $m$ and $d$. The binary representations of the first odd integers that are not of the form $2^{n}-1$ are

$$

5=\overline{101}^{2}, 9={\overline{1001}^{2}}^{2}, 11={\overline{1011}^{2}}^{2}

$$

According to the criterion above, the smallest integer sought is 11.

Remark: This exercise can also be done by finding ways to write the integers 1 to 10 in this form, then showing that 11 cannot be written in this form: indeed, since 11 is odd, we can assume $b=d=1$. Then

$$

\left(2^{a}-1\right)=11\left(2^{c}-1\right)

$$

rewrites as

$$

10=2^{c} \times 11-2^{a}

$$

Since $10=2 \times 5$, we have $a=1$ or $c=1$. If $a=1$, we get $2^{c} \times 11=12$, which has no solution, and if $c=1$, we get $2^{a}=12$, which has no solution either. Therefore, 11 is the integer sought.

## 2 Common Exercises

|

11

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver le plus petit entier positif qui ne s'écrit pas sous la forme $\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}$ pour $a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{N}$.

|

: Soit E l'ensemble des entiers strictement positifs s'écrivant sous cette forme. Commençons par remarquer que

$$

\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}=2^{b-d} \frac{2^{a-b}-1}{2^{c-d}-1}

$$

Ainsi, si $x>0$ s'écrit $x=\frac{2^{a}-2^{b}}{2^{c}-2^{d}}$, alors $b-d=v_{2}(x)$ et si on appelle $y$ l'entier impair tel que $x=2^{v_{2}(x)} y$, alors $y$ s'écrit sous la forme $\frac{2^{n}-1}{2^{m}-1}$. En particulier, l'entier que nous cherchons est nécessairement impair. D'autre part, on peut tout de suite exclure les entiers de la forme $2^{n}-1$, atteints avec $m=1$.

Il est classique que si $2^{m}-1$ divise $2^{n}-1$, alors $m$ divise $n$. Ainsi, en écrivant $n=m d, y$ est de la forme

$$

y=\frac{2^{m d}-1}{2^{m}-1}=2^{(d-1) m}+2^{(d-2) m}+\ldots+2^{m}+1

$$

Autrement dit, en notant $u=\underbrace{0 \ldots 0}_{m-1 \text { zéros }} 1$, l'écriture en base 2 de $y$ est de la forme $\overline{1 u \ldots u}^{2}$, avec $u$ apparaissant $d-1$ fois. Les entiers impairs appartenant à $E$ sont exactement ceux ayant une telle écriture binaire pour $m$ et $d$ bien choisis. Les écritures binaires des premiers entiers impairs qui ne sont pas de la forme $2^{n}-1$ sont

$$

5=\overline{101}^{2}, 9={\overline{1001}^{2}}^{2}, 11={\overline{1011}^{2}}^{2}

$$

D'après le critère ci-dessus, le plus petit entier cherché est 11.

Remarque : cet exercice peut aussi se faire en trouvant des manières d'écrire les entiers 1 à 10 sous cette forme, puis en montrant que 11 ne s'écrit pas sous cette forme : en effet, vu que 11 est impair, on peut supposer $b=d=1$. Ensuite

$$

\left(2^{a}-1\right)=11\left(2^{c}-1\right)

$$

se réécrit

$$

10=2^{c} \times 11-2^{a}

$$

Puisque $10=2 \times 5$, nous avons $a=1$ ou $c=1$. Si $a=1$, on trouve $2^{c} \times 11=12$, qui n'a pas de solution, et si $c=1$, on trouve $2^{a}=12$, qui n'a pas de solution non plus. Donc 11 est l'entier cherché.

## 2 Exercices communs

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Find all triplets of prime numbers $(p, q, r)$ such that $(p+1)(q+2)(r+3)=4 p q r$.

|

If $p=2$ then we have $3(q+2)(r+3)=8 q r$ which implies $q=3$ or $r=3$. We then have the solution $(2,3,5)$.

If $q=2$ and $p, r>2$ then we have $(p+1)(r+3)=2 p r$. Since $p$ and $r$ are odd, the left-hand side is divisible by 4, while the right-hand side is divisible by 2, but not by 4, leading to a contradiction. Therefore, $p$ or $r$ must be 2, but no valid solution follows from this.

If $r=2$ then $5(p+1)(q+2)=8 p q$ and so $p$ or $q$ must be 5. We obtain the solution $(7,5,2)$.

Otherwise, $(p+1)$ is even and $(r+3)$ is even. Thus, we reduce to

$$

\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)(q+2)\left(\frac{r+3}{2}\right)=p q r .

$$

We have thus written $pqr$ as a product of three factors each strictly greater than 1. We deduce that $\left(\frac{p+1}{2}, q+2, \frac{r+3}{2}\right)$ is a permutation of $(p, q, r)$.

Clearly, $p \neq \frac{p+1}{2}$ since $p>\frac{p+1}{2}$.

If $p=\frac{r+3}{2}$, then since $q \neq q+2$, we must have $q=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{r+5}{4}$. Then $r=q+2=\frac{r+13}{4}$, and thus $r$ is not an integer.

If $p=q+2$, then there are two cases to consider:

- $r=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{q+3}{2}$ and $q=\frac{r+3}{2}=\frac{q+9}{4}$. So $q=3$ and we obtain the solution $(5,3,3)$.

- $r=\frac{r+3}{2}$ and $q=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{q+3}{2}$, which gives $r=q=3$. We then obtain the same solution $(5,3,3)$.

Finally, the only solutions are $(2,3,5),(7,5,2)$ and $(5,3,3)$.

|

(2,3,5),(7,5,2),(5,3,3)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver tous les triplets de nombres premiers $(p, q, r)$ tels que $(p+1)(q+2)(r+3)=4 p q r$.

|

: Si $p=2$ alors on a $3(q+2)(r+3)=8 q r$ ce qui implique $q=3$ ou $r=3$. On a alors la solution $(2,3,5)$.

Si $q=2$ et $p, r>2$ alors on a $(p+1)(r+3)=2 p r$. Puisque $p$ et $r$ sont impairs, le membre de gauche est divisible par 4 , alors que le membre de droite est divisible par 2 , mais pas par 4 , contradiction. Donc $p$ ou $r$ vaut 2 mais aucune solution valide n'en découle.

Si $r=2$ alors $5(p+1)(q+2)=8 p q$ et donc $p$ ou $q$ vaut 5 . On obtient la solution $(7,5,2)$.

Sinon, $(p+1)$ est pair et $(r+3)$ est pair. Donc on se ramène à

$$

\left(\frac{p+1}{2}\right)(q+2)\left(\frac{r+3}{2}\right)=p q r .

$$

Nous avons donc écrit pqr comme un produit de trois facteurs strictement plus grands que 1. On en déduit que $\left(\frac{p+1}{2}, q+2, \frac{r+3}{2}\right)$ est une permutation de $(p, q, r)$.

Clairement, $p \neq \frac{p+1}{2}$ puisque $p>\frac{p+1}{2}$.

Si $p=\frac{r+3}{2}$, alors puisque $q \neq q+2$, nous avons nécessairement $q=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{r+5}{4}$. Alors $r=q+2=\frac{r+13}{4}$, et donc $r$ n'est pas entier.

Si $p=q+2$, alors il y a deux cas à considérer :

$-r=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{q+3}{2}$ et $q=\frac{r+3}{2}=\frac{q+9}{4}$. Donc $q=3$ et on obtient la solution $(5,3,3)$.

$-r=\frac{r+3}{2}$ et $q=\frac{p+1}{2}=\frac{q+3}{2}$, ce qui donne $r=q=3$. On obtient alors cette même solution $(5,3,3)$.

Finalement, les seules solutions sont $(2,3,5),(7,6,2)$ et $(5,3,3)$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Find all strictly positive integers $n$ such that $2^{n-1} n+1$ is a perfect square.

|

We want to solve $2^{n-1} n+1=m^{2}$, that is, $2^{n-1} n=(m-1)(m+1)$. Since $n=1$ is not a solution, we have $n \geq 2$, and therefore $m$ must be odd, and $m-1$ and $m+1$ are even (in particular, $n \geq 3$). We set $k=\frac{m-1}{2}$. It then suffices to solve $2^{n-3} n=k(k+1)$. Among the integers $k$ and $k+1$, exactly one is even, and thus they are of the form $2^{n-3} d$ and $\frac{n}{d}$ with $d$ a divisor of $n$. A divisor of $n$ cannot be at a distance of 1 from an integer greater than $2^{n-3}$ if $n$ is too large. More precisely, we have $2^{n-3} d \geq 2^{n-3} \geq n+2$ if $n \geq 6$, so we must have $n \leq 5$. For $n=5$, we find $2^{4} \times 5+1=9^{2}$, so 5 is a solution. We verify that $2,3,4$ are not solutions. Therefore, $n=5$ is the only solution.

|

5

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver tous les entiers strictement positifs $n$ tels que $2^{n-1} n+1$ soit un carré parfait.

|

: On veut résoudre $2^{n-1} n+1=m^{2}$, c'est-à-dire $2^{n-1} n=(m-1)(m+1)$. Puisque $n=1$ n'est pas solution, on a $n \geq 2$, et donc $m$ est nécessairement impair, et $m-1$ et $m+1$ sont pairs (en particulier $n \geq 3$ ). On pose $k=\frac{m-1}{2}$. Il suffit alors de résoudre $2^{n-3} n=k(k+1)$. Parmi les entiers $k$ et $k+1$ exactement un est pair, et donc ils sont de la forme $2^{n-3} d$ et $\frac{n}{d}$ avec $d$ un diviseur de $n$. Or un diviseur de $n$ ne peut pas être à distance 1 d'un entier supérieur à $2^{n-3}$ si $n$ est trop grand. Plus précisément, on a $2^{n-3} d \geq 2^{n-3} \geq n+2$ si $n \geq 6$, donc on a nécessairement $n \leq 5$. Pour $n=5$, on trouve $2^{4} \times 5+1=9^{2}$, donc 5 est solution. On vérifie que $2,3,4$ ne sont pas solutions. Donc $n=5$ est la seule solution.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Let $x>1$ and $y$ be integers satisfying $2 x^{2}-1=y^{15}$. Show that $x$ is divisible by 5.

|

The integer $y$ is clearly odd and strictly greater than 1. We factorize the equation as follows:

$$

x^{2}=\left(\frac{y^{5}+1}{2}\right)\left(y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)

$$

Notice that

$$

y^{10}-y^{5}+1 \equiv 3\left(\bmod y^{5}+1\right)

$$

and thus $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y^{5}+1, y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)$ is equal to 1 or 3. If it were 1, then $y^{10}-y^{5}+1$ would be a square. However, for $y>0$ we have

$$

\left(y^{5}-1\right)^{2}=y^{10}-2 y^{5}+1<y^{10}-y^{5}+1<y^{10}=\left(y^{5}\right)^{2},

$$

which means that $y^{10}-y^{5}+1$ is strictly between two consecutive squares and cannot be a square itself. Therefore, $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y^{5}+1, y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)=3$, so there exist integers $a$ and $b$ such that

$$

y^{5}+1=6 a^{2} \quad \text { and } \quad y^{10}-y^{5}+1=3 b^{2} .

$$

We can factorize $(y+1)\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)=6 a^{2}$. Since $y^{5} \equiv-1(\bmod 3)$, we must have $y \equiv-1$ $(\bmod 3)$, so $y+1$ is divisible by 6. Similarly as above, we have

$$

y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1 \equiv 5(\bmod y+1)

$$

and thus $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y+1, y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)$ is equal to 1 or 5. If it is 5, then $a$ is divisible by 5 and so is $x$, and we are done. Suppose it is 1. Then $y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1$ is a square. In this case, $4\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)$ is also a square, which is impossible, because for $y>1$, we have

$$

\left(2 y^{2}-y\right)^{2}=4 y^{4}-4 y^{3}+y^{2}<4\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)<4 y^{4}-4 y^{3}+5 y^{2}-2 y+1=\left(2 y^{2}-y+1\right)^{2}

$$

## 3 Exercices groupe A

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soient $x>1$ et $y$ des entiers vérifiant $2 x^{2}-1=y^{15}$. Montrer que $x$ est divisible par 5 .

|

: L'entier $y$ est clairement impair et strictement plus grand que 1. On factorise l'équation sous la forme

$$

x^{2}=\left(\frac{y^{5}+1}{2}\right)\left(y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)

$$

Remarquons que

$$

y^{10}-y^{5}+1 \equiv 3\left(\bmod y^{5}+1\right)

$$

et que donc $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y^{5}+1, y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)$ est égal à 1 ou à 3 . S'il valait 1 , alors $y^{10}-y^{5}+1$ serait un carré. Or pour $y>0$ nous avons

$$

\left(y^{5}-1\right)^{2}=y^{10}-2 y^{5}+1<y^{10}-y^{5}+1<y^{10}=\left(y^{5}\right)^{2},

$$

c'est-à-dire que $y^{10}-y^{5}+1$ est strictement compris entre deux carrés consécutifs, et ne peut pas être lui-même un carré. Donc $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y^{5}+1, y^{10}-y^{5}+1\right)=3$, de sorte qu'il existe des entiers $a$ et $b$ tels que

$$

y^{5}+1=6 a^{2} \quad \text { et } \quad y^{10}-y^{5}+1=3 b^{2} .

$$

On peut factoriser $(y+1)\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)=6 a^{2}$. Puisque $y^{5} \equiv-1(\bmod 3)$, on a nécessairement $y \equiv-1$ $(\bmod 3)$, donc $y+1$ est divisible par 6 . De même que plus haut, on a

$$

y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1 \equiv 5(\bmod y+1)

$$

et donc $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(y+1, y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)$ est égal à 1 ou à 5 . S'il vaut 5 , alors $a$ est divisible par 5 et donc $x$ aussi, et nous avons terminé. Supposons donc qu'il vaut 1. Alors $y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1$ est un carré. Dans ce cas, $4\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)$ est aussi un carré, ce qui est impossible, car pour $y>1$, on a

$$

\left(2 y^{2}-y\right)^{2}=4 y^{4}-4 y^{3}+y^{2}<4\left(y^{4}-y^{3}+y^{2}-y+1\right)<4 y^{4}-4 y^{3}+5 y^{2}-2 y+1=\left(2 y^{2}-y+1\right)^{2}

$$

## 3 Exercices groupe A

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Characterize the integers $n \geq 2$ such that for any integer $a$ we have $a^{n+1}=a(\bmod n)$.

|

Here are the $n$ satisfying this property: $2,2 \cdot 3,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$.

To prove that this is exhaustive, we proceed as follows: we start by noting that $n$ has no square factor. Indeed, if $p^{2}$ divides $n$, then $p^{n+1}-p$ is divisible by $p^{2}$, which is not possible. Thus, $n$ must necessarily be a product $p_{1} \ldots p_{k}$ of distinct prime numbers. Consequently, by the Chinese Remainder Theorem, the condition in the statement is equivalent to $a^{n+1} \equiv a(\bmod p)$ for all integers $a$ and all $p \in\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}\right\}$. By choosing $a$ of order $p-1$ modulo $p$, we see that this is equivalent to $p-1$ dividing $n$ for all $p \in\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}\right\}$.

In summary: $n$ is a product of distinct primes $p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}$, and $p_{i}-1$ divides $n$ for all $i$. We deduce that for all $i, p_{i}-1$ is square-free and $p_{i}-1=q_{1} \ldots q_{m}$ where the $q_{j}$ are primes taken from the $p_{r}, r \neq i$.

Assuming without loss of generality that $p_{1}<p_{2}<\ldots<p_{k}$. From the above condition, we necessarily have $p_{1}=2$. If $k=1$, this gives the integer $n=2$. If $k>1$, then $p_{2}-1$ must be equal to 2, so $p_{2}=3$. If $k=2$, this gives the solution $n=6$. If $k>2$, we continue by saying that $p_{3}-1$ cannot be equal to 2 or 3, so it must be equal to $p_{1} p_{2}=6$, hence $p_{3}=7$. If $k=3$, this gives the solution $n=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7=42$. If $k>3$, we see that the only possible value for $p_{4}$ is $2 \times 3 \times 7+1=43$. For $k=4$, this gives the solution $n=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$. Finally, suppose that $k>4$. Then $p_{5}-1$ must be even and strictly greater than 43, so the only possible values are $2 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 7 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$. We check that none of these possibilities provide a prime $p_{5}$. Thus, we must have $k \leq 4$ and the solutions we have found are the only ones.

|

2, 2 \cdot 3, 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7, 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Caractériser les entiers $n \geq 2$ tels que pour tout entier $a$ on ait $a^{n+1}=a(\bmod n)$.

|

: Voici les $n$ vérifiant cette propriété : $2,2 \cdot 3,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$.

Pour prouver que c'est exhaustif on procède de la façon suivante : on commence par remarquer que $n$ n'a pas de facteur carré. En effet, si $p^{2}$ divise $n$, alors $p^{n+1}-p$ est divisible par $p^{2}$, ce qui n'est pas possible. Ainsi, $n$ est forcément un produit $p_{1} \ldots p_{k}$ de nombres premiers distincts. Par conséquent, par le lemme chinois la condition de l'énoncé est équivalente à $a^{n+1} \equiv a(\bmod p)$ pour tout entier $a$ et tout $p \in\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}\right\}$. En choisissant $a$ d'ordre $p-1$ modulo $p$, on obtient que cela est équivalent à ce que $p-1$ divise $n$ pour tout $p \in\left\{p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}\right\}$.

En résumé : $n$ est produit de premiers distincts $p_{1}, \ldots, p_{k}$, et $p_{i}-1$ divise $n$ pour tout $i$. On en déduit que pour tout $i, p_{i}-1$ est sans facteur carré et $p_{i}-1=q_{1} \ldots q_{m}$ où les $q_{j}$ sont des nombres premiers pris parmi les $p_{r}, r \neq i$.

Quitte à re-numéroter les $p_{i}$, on peut supposer que $p_{1}<p_{2}<\ldots<p_{k}$. D'après la condition ci-dessus, nous avons nécessairement $p_{1}=2$. Si $k=1$, cela nous donne l'entier $n=2$. Si $k>1$, alors $p_{2}-1$ est nécessairement égal à 2 , donc $p_{2}=3$. Si $k=2$, cela nous donne la solution $n=6$. Si $k>2$ on continue en disant que $p_{3}-1$ ne peut être égal à 2 ou 3 , donc il est égal à $p_{1} p_{2}=6$, d'où $p_{3}=7$. Si $k=3$, cela donne la solution $n=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7=42$. Si $k>3$, on voit que de même la seule valeur possible pour $p_{4}$ est $2 \times 3 \times 7+1=43$. Pour $k=4$, cela donne la solution $n=2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$. Enfin, supposons que $k>4$. Alors $p_{5}-1$ doit être pair et strictement supérieur à 43 , donc les seules valeurs possibles sont $2 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 7 \cdot 43,2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7 \cdot 43$. On vérifie qu'aucune de ces possibilités ne fournit un $p_{5}$ premier. Ainsi on a nécessairement $k \leq 4$ et les solutions que nous avons trouvées sont les seules.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Let $k \geq 3$ be an integer. We define the sequence $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n \geq k}$ by $a_{k}=2 k$, and

$$

a_{n}= \begin{cases}a_{n-1}+1 & \text { if } \operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right)=1 \\ 2 n & \text { otherwise. }\end{cases}

$$

Show that the sequence $\left(a_{n+1}-a_{n}\right)_{n \geq k}$ has infinitely many terms that are prime numbers.

|

: Let's start with an integer $n$ such that $a_{n}=2 n$. We will show by induction that if $p$ is the smallest prime factor of $n-1$, then for all $i \in\{0, \ldots, p-2\}, a_{n+i}=2 n+i$. Indeed, it is true for $i=0$, and if it is true for some $i<p-2$, then

$$

\operatorname{gcd}(n+i+1,2 n+i)=\operatorname{gcd}(n+i+1, n-1)=\operatorname{gcd}(i+2, n-1)=1

$$

since $i+2<p$, and thus $i+2$ is coprime with $n-1$ by the definition of $p$, which concludes the induction. Similarly, $\operatorname{gcd}(n+p-1,2 n+p-2)=\operatorname{gcd}(p, n-1)=p \neq 1$, and thus $a_{n+p-1}=2(n+p-1)$. In particular,

$$

a_{n+p-1}-a_{n+p-2}=2 n+2 p-2-(2 n+p-2)=p

$$

is prime.

Since $a_{k}=2 k$, we have thus shown that there are infinitely many $n$ satisfying $\operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right) \neq 1$, and that for such values of $n, a_{n}-a_{n-1}$ is prime.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $k \geq 3$ un entier. On définit la suite $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n \geq k}$ par $a_{k}=2 k$, et

$$

a_{n}= \begin{cases}a_{n-1}+1 & \text { si } \operatorname{pgcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right)=1 \\ 2 n & \text { sinon. }\end{cases}

$$

Montrer que la suite $\left(a_{n+1}-a_{n}\right)_{n \geq k}$ a une infinité de termes qui sont des nombres premiers.

|

: Partons d'un entier $n$ tel que $a_{n}=2 n$. Montrons par récurrence que si $p$ est le plus petit facteur premier de $n-1$, alors pour tout $i \in\{0, \ldots, p-2\}, a_{n+i}=2 n+i$. En effet, c'est vrai pour $i=0$, et si c'est vrai pour un certain $i<p-2$, alors

$$

\operatorname{pgcd}(n+i+1,2 n+i)=\operatorname{pgcd}(n+i+1, n-1)=\operatorname{pgcd}(i+2, n-1)=1

$$

car $i+2<p$, et donc $i+2$ est premier avec $n-1$ par définition de $p$, ce qui conclut la récurrence. De même, $\operatorname{pgcd}(n+p-1,2 n+p-2)=\operatorname{pgcd}(p, n-1)=p \neq 1$, et donc $a_{n+p-1}=2(n+p-1)$. En particulier,

$$

a_{n+p-1}-a_{n+p-2}=2 n+2 p-2-(2 n+p-2)=p

$$

est premier.

Puisque $a_{k}=2 k$, avons donc montré qu'il existe une infinité de $n$ satisfaisant $\operatorname{pgcd}\left(a_{n-1}, n\right) \neq 1$, et que pour de telles valeurs de $n, a_{n}-a_{n-1}$ est premier.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Let $t$ be a non-zero natural number. Show that there exists an integer $n>1$ coprime with $t$ such that for any integer $k \geq 1$, the integer $n^{k}+t$ is not a power (i.e., it is not of the form $m^{r}$ with $m \geq 1$ and $r \geq 2$).

|

To ensure that $n$ is coprime with $t$, we will look for it in the form $1 + ts$ where $s$ is an integer. We will then have $n^{k} + t \equiv 1 + t \pmod{s}$. In particular, if $s$ is divisible by $(t+1)$, then $n^{k} + t$ is also divisible by $(t+1)$.

First, we will handle the case where $t+1$ is not a power. In this case, it would suffice to ensure that we can choose $s$ such that $n^{k} + t$ is divisible by $t+1$, and that the quotient is coprime with $t+1$. For this, let's take $s = (t+1)^2$. Then $n = 1 + t(t+1)^2$, and

$$

n^{k} + t = \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{k} \binom{k}{i} t^i (t+1)^{2i}}_{\text{terms divisible by } (t+1)^2} + 1 + t = (t+1)(a(t+1) + 1)

$$

for some integer $a$, so we are done.

Now suppose that $t+1$ is a power: $t+1 = m^r$ with $m$ not a power. If we keep the same $n$ as above, we see that if $n^{k} + t = b^d$ is a power (with $d \geq 2$), then $t+1$ must necessarily be a $d$-th power, and thus $d$ divides $r$. Therefore, we have a bound on the $d$ such that $n^{k} + t$ is a $d$-th power for some $k$. We then observe that by replacing $n$ with its $r$-th power, i.e., by setting $n = n_0^r$ where $n_0 = 1 + t(t+1)^2$ (which does not change the fact that $t+1$ divides $n^{k} + t$, that the quotient is coprime with $t+1$, and that $n^{k} + t = b^d$ implies $d \mid r$ as above), we can write $t$ as the difference of two $d$-th powers:

$$

t = b^d - (n_0^{ke})^d

$$

where $e$ is the natural number such that $r = de$. This is not possible because $n_0$ is large relative to $t$. More precisely, we have:

$$

t = b^d - (n_0^{ke})^d = (b - n_0^{ke})(b^{d-1} + b^{d-2} n_0^{ke} + \ldots + b n_0^{ke(d-2)} + n_0^{ke(d-1)}) \geq n_0 > t

$$

contradiction. Therefore, for all $k$ and for all $d$, $n^{k} + t$ is not a $d$-th power, and we are done.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit $t$ un entier naturel non-nul. Montrer qu'il existe un entier $n>1$ premier avec $t$ tel que pour tout entier $k \geq 1$, l'entier $n^{k}+t$ ne soit pas une puissance (c'est-à-dire qu'il ne soit pas de la forme $m^{r}$ avec $m \geq 1$ et $r \geq 2$ ).

|

: Pour que $n$ soit premier avec $t$, on va le chercher sous la forme $1+t s$ où $s$ est entier. On aura alors $n^{k}+t \equiv 1+t(\bmod s)$. En particulier, si $s$ est divisible par $(t+1)$, alors $n^{k}+t$ l'est également.

On va d'abord traiter le cas où $t+1$ n'est pas une puissance. Dans ce cas, il suffirait de s'assurer qu'on peut choisir $s$ de telle sorte que $n^{k}+t$ soit divisible par $t+1$, et que le quotient soit premier avec $t+1$. Pour cela, prenons $s=(t+1)^{2}$. Alors $n=1+t(t+1)^{2}$, et

$$

n^{k}+t=\underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{k}\binom{k}{i} t^{i}(t+1)^{2 i}}_{\text {termes divisibles par }(t+1)^{2}}+1+t=(t+1)(a(t+1)+1)

$$

pour un certain entier $a$, donc on a gagné.

Supposons maintenant que $t+1$ soit une puissance : $t+1=m^{r}$ avec $m$ qui n'est pas une puissance. Si on garde le même $n$ que ci-dessus, on voit que si $n^{k}+t=b^{d}$ est une puissance (avec $d \geq 2$ ), alors $t+1$ est nécessairement une puissance $d$-ième, et donc $d$ divise $r$. Ainsi, nous avons une borne sur les $d$ tels que $n^{k}+t$ est puissance $d$-ième pour un certain $k$. On constate alors qu'en remplaçant $n$ par sa puissance $r$-ième, c'est-à-dire en posant $n=n_{0}^{r}$ où $n_{0}=1+t(t+1)^{2}$ (ce qui ne change pas le fait que $t+1$ divise $n^{k}+t$, que le quotient soit premier avec $t+1$, et que donc $n^{k}+t=b^{d}$ implique $d \mid r$ comme ci-dessus), on arrive à écrire $t$ comme une différence de deux puissances $d$-ièmes :

$$

t=b^{d}-\left(n_{0}^{k e}\right)^{d}

$$

où $e$ est l'entier naturel tel que $r=d e$. Cela n'est pas possible car $n_{0}$ est grand par rapport à $t$. Plus précisément, nous avons:

$$

t=b^{d}-\left(n_{0}^{k e}\right)^{d}=\left(b-n_{0}^{k e}\right)\left(b^{d-1}+b^{d-2} n_{0}^{k e}+\ldots+b n_{0}^{k e(d-2)}+n_{0}^{k e(d-1)}\right) \geq n_{0}>t

$$

contradiction. Donc pour tout $k$ et pour tout $d, n^{k}+t$ n'est pas une puissance $d$-ième et nous avons terminé.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

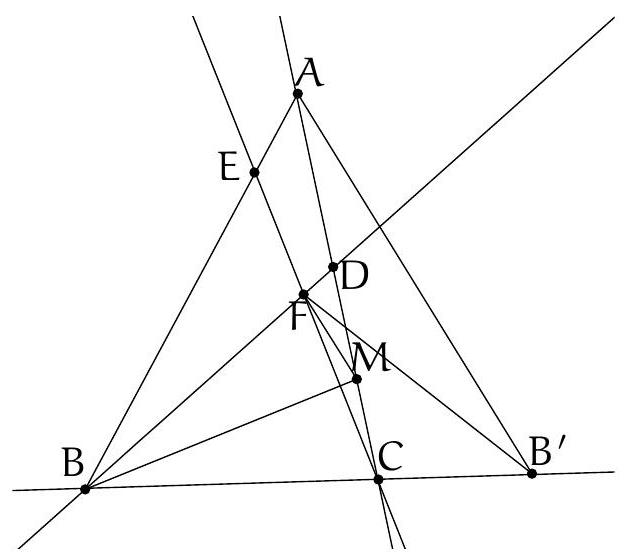

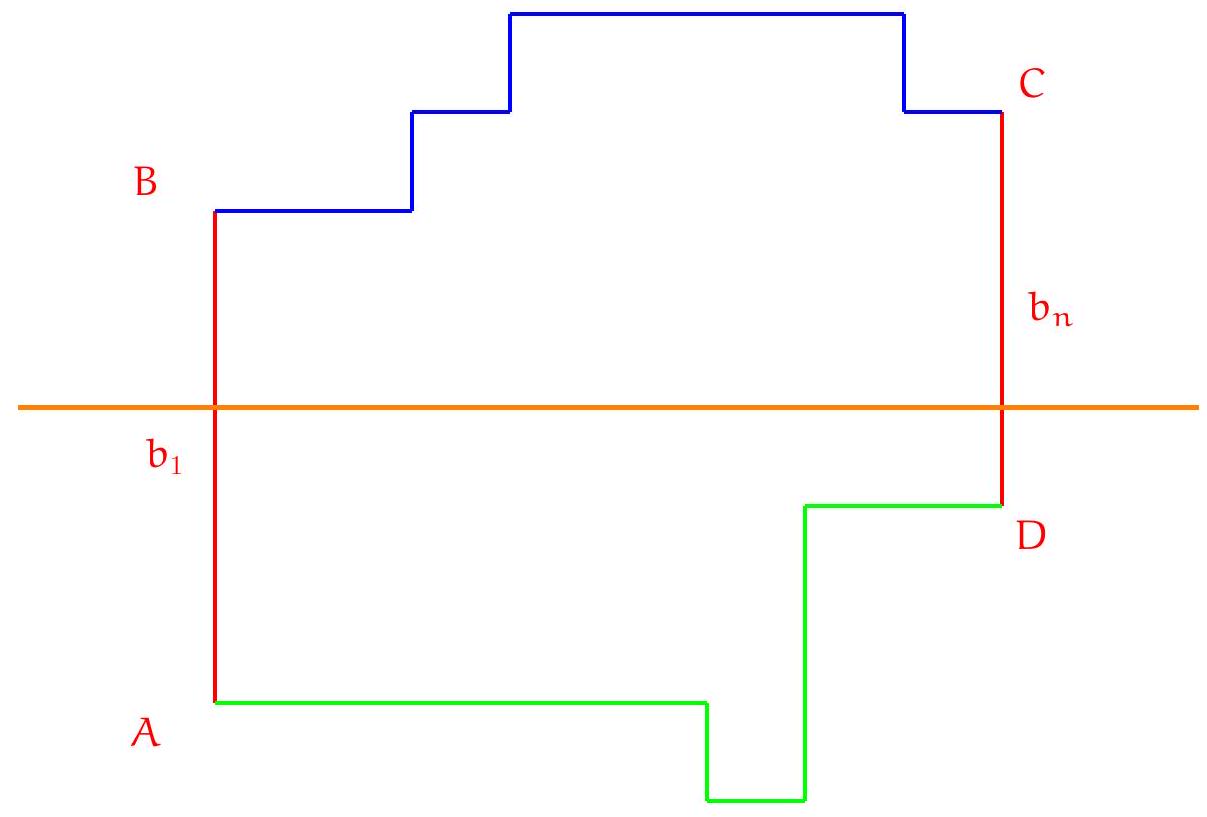

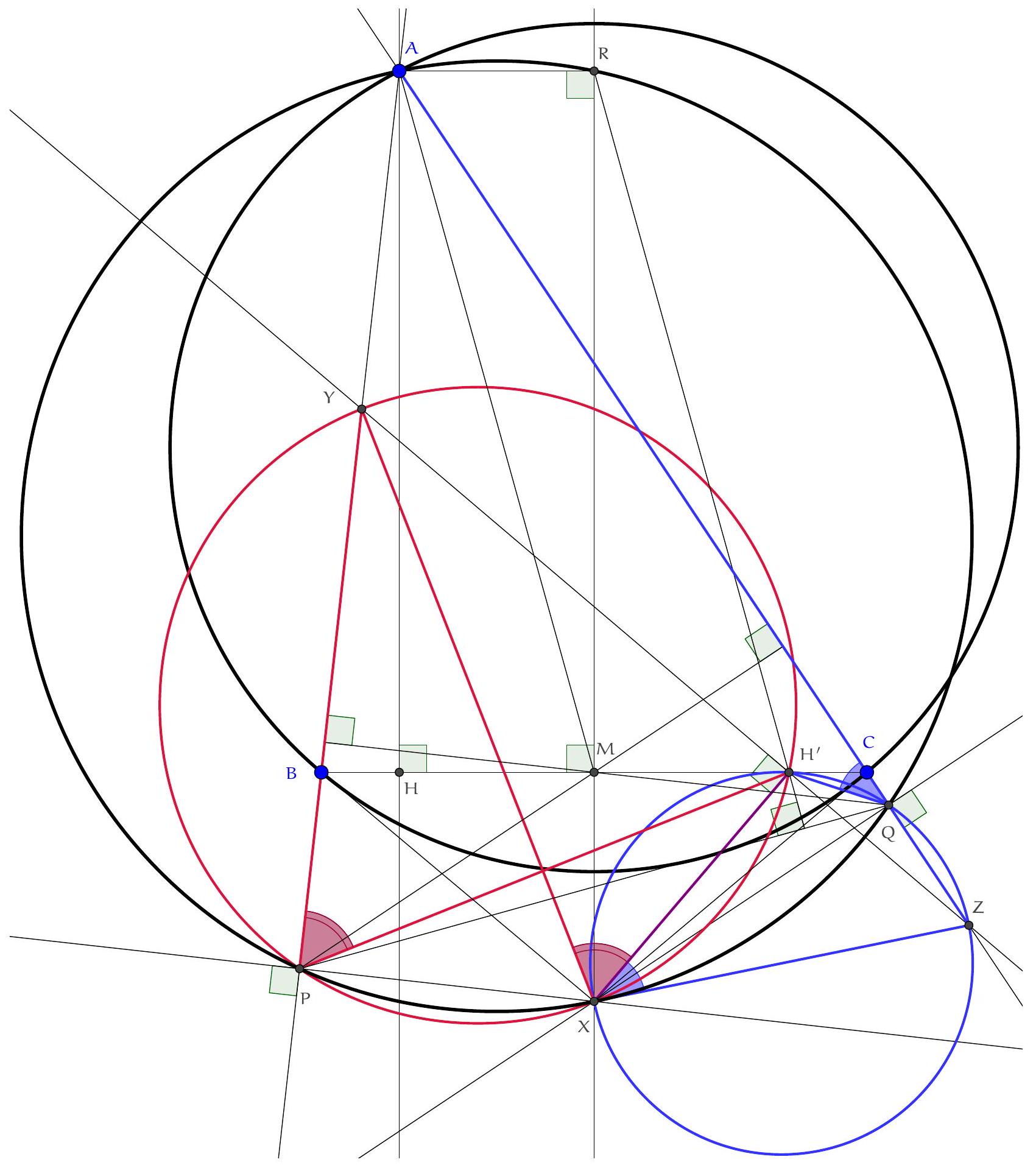

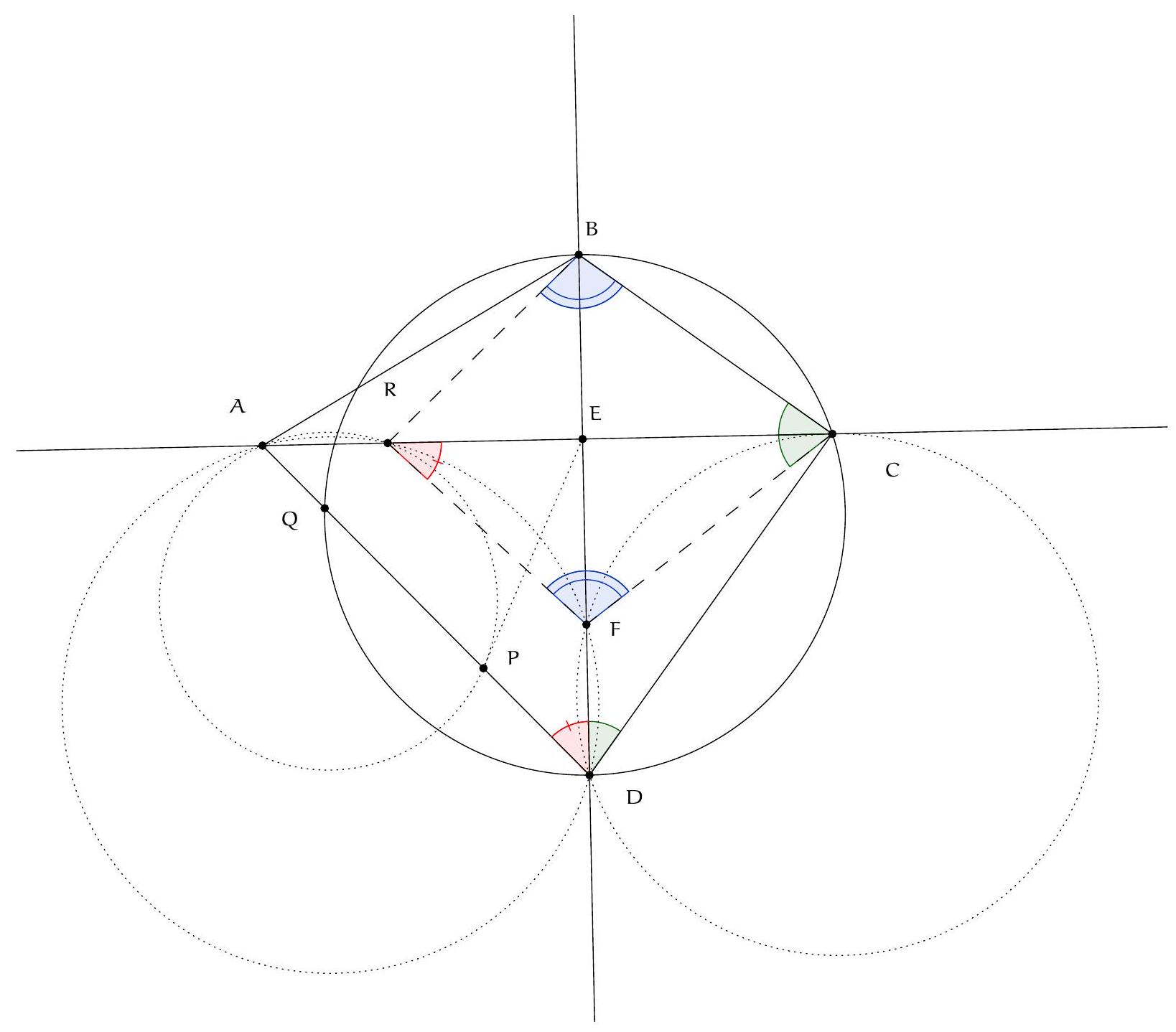

Let $A$ be a point outside a circle $\mathscr{C}$ with center $O$. A point $P$ moves on $\mathscr{C}$. Let $M$ be the intersection point between $(A P)$ and the bisector of $\widehat{P O A}$. Show that $M$ moves on a circle that we will describe.

|

Let $d=OA$ and $R$ be the radius of the circle.

According to the Angle Bisector Theorem, we have $MP/MA = OP/OA$, so $\frac{MA}{AP} = \frac{MA}{MA + MP} = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{MP}{MA}} = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{OP}{OA}} = \frac{OA}{OA + OP} = \frac{d}{d + R}$. Let $k$ be this value. Let $O'$ be the point on $[AO]$ such that $AO' = kAO$. According to Thales' Theorem, the lines $(O'M)$ and $(OP)$ are parallel, so $\frac{O'M}{OP} = \frac{AM}{AP} = k$, thus $O'M = kR$. This proves that $M$ describes the circle with center $O'$ and radius $kR$.

Notice that $AO' + kR = k(d + R) = d$, so this circle passes through $O$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A$ un point extérieur à un cercle $\mathscr{C}$ de centre $O$. Un point $P$ se déplace sur $\mathscr{C}$. Soit $M$ le point d'intersection entre $(A P)$ et la bissectrice de $\widehat{P O A}$. Montrer que $M$ se déplace sur un cercle que l'on décrira.

|

Notons $d=O A$ et $R$ le rayon du cercle.

D'après le théorème de la bissectrice, on a $M P / M A=O P / O A$, donc $\frac{M A}{A P}=\frac{M A}{M A+M P}=$ $\frac{1}{1+\frac{M P}{M A}}=\frac{1}{1+\frac{O P}{O A}}=\frac{O A}{O A+O P}=\frac{d}{d+R}$. Notons $k$ cette valeur. Soit $O^{\prime}$ le point de $[A O]$ tel que $A O^{\prime}=k A O$. D'après le théorème de Thalès, les droites $\left(O^{\prime} M\right)$ et $(O P)$ sont parallèles, donc $\frac{O^{\prime} M}{O P}=\frac{A M}{A P}=k$, donc $O^{\prime} M=k R$. Ceci prouve que $M$ décrit le cercle de centre $O^{\prime}$ et de rayon kR.

Remarquons que $A O^{\prime}+k R=k(d+R)=d$, donc ce cercle passe par $O$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

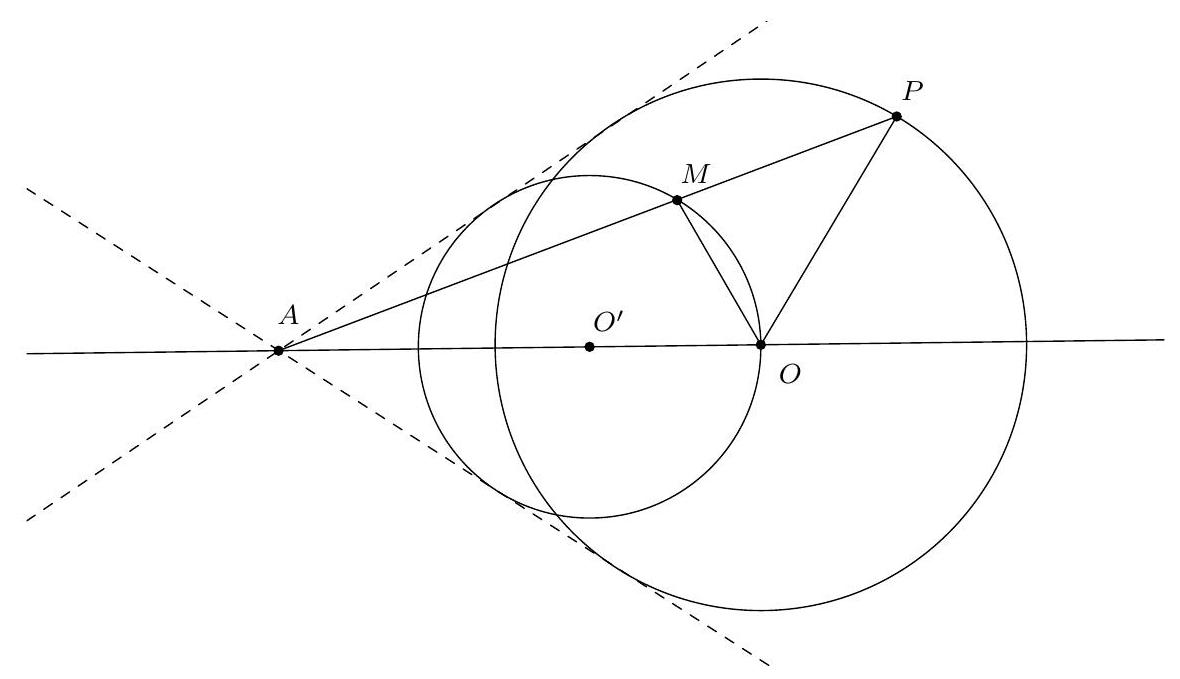

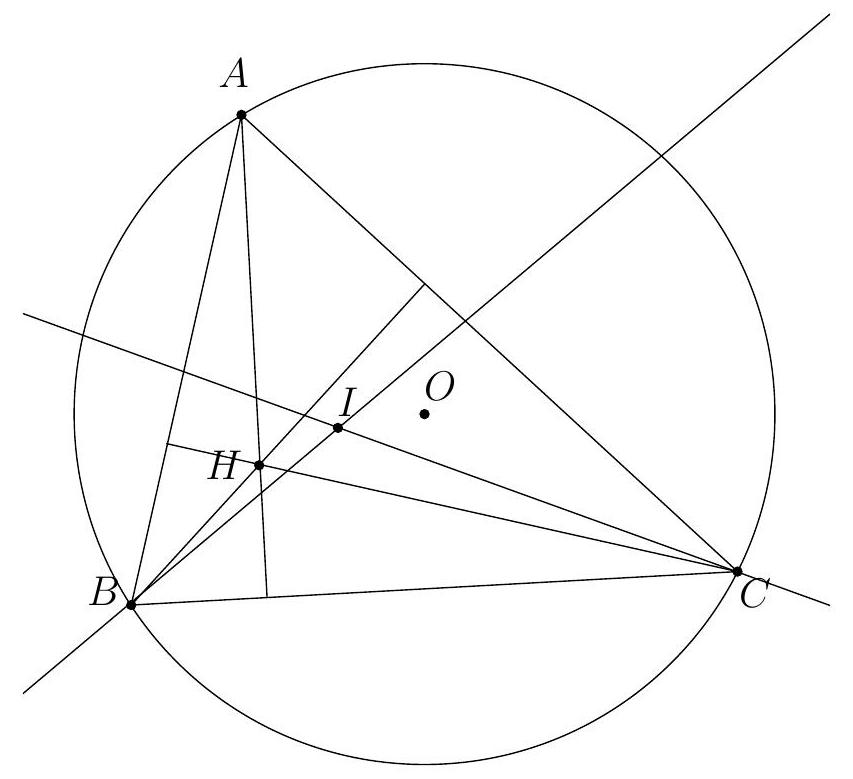

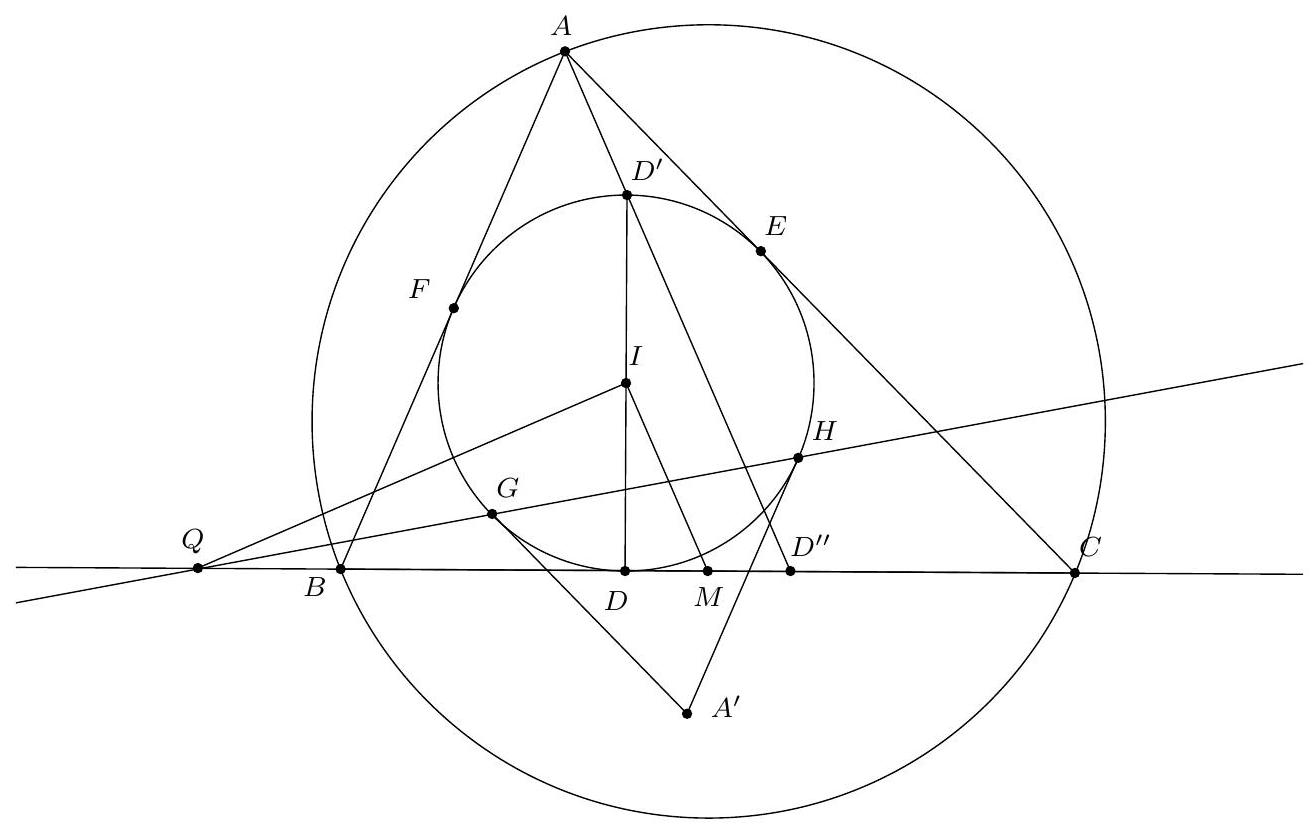

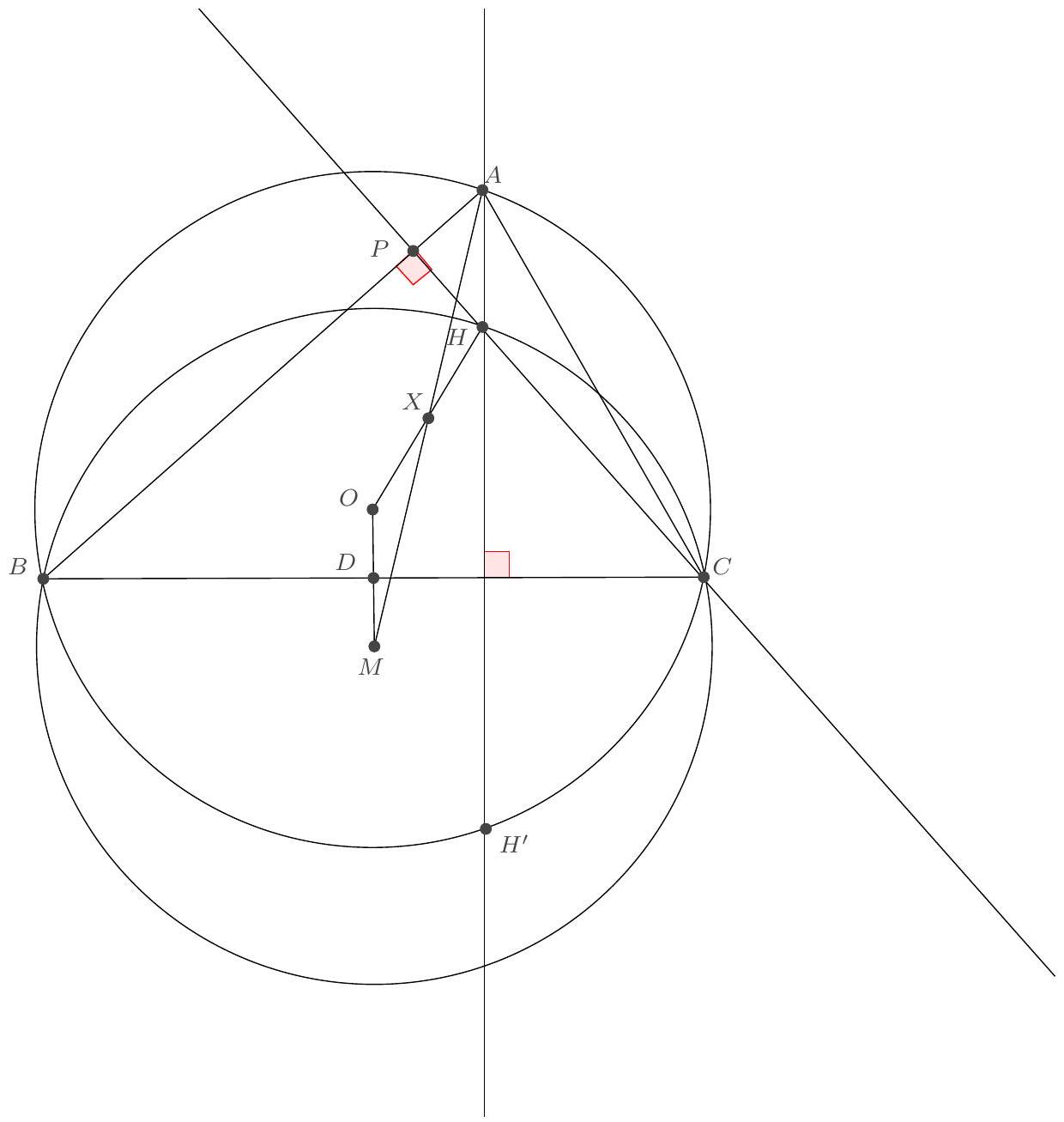

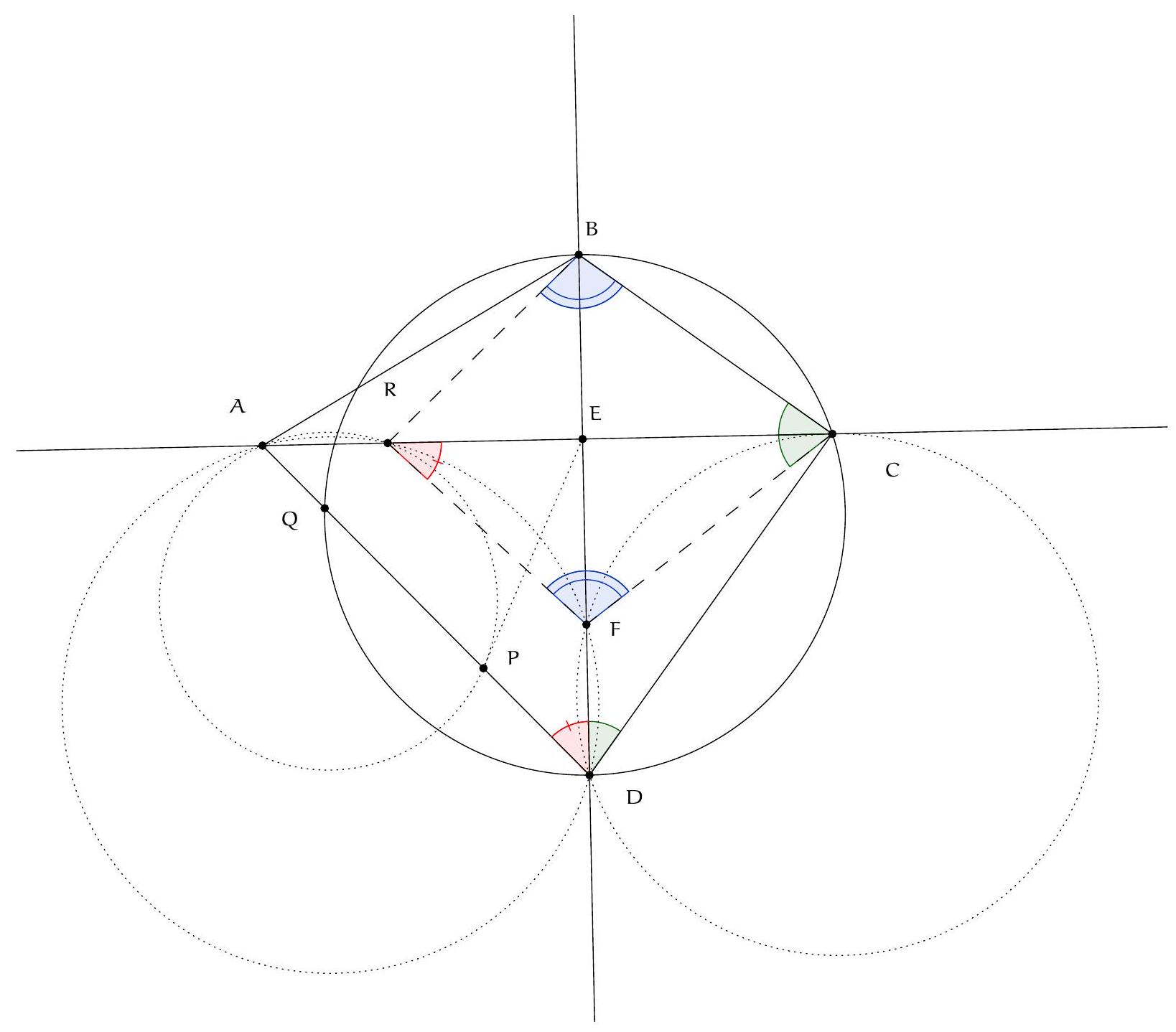

Let $ABC$ be a triangle such that $\widehat{A}=60^{\circ}$. We denote $O$ as the center of the circumcircle, $I$ as the center of the incircle, and $H$ as the orthocenter. Show that

1) $B, C, O, I, H$ are concyclic

2) $OIH$ is isosceles.

|

We use angles of lines. The angles are modulo $180^{\circ}$.

1) $(H B, H C)=(H B, A C)+(A C, A B)+(A B, H C)=D-(A B, A C)+D=-(A B, A C)=-60^{\circ}=$ $120^{\circ}=(O B, O C)$ (where we have denoted $D$ as the right angle), so $B, H, O, C$ are concyclic.

$(I B, I C)=(I B, B C)+(B C, I C)=-\widehat{B} / 2-\widehat{C} / 2=-120 / 2=-60^{\circ}=120^{\circ}$, so $I$ is also on this circle.

2) $(C O, C I)-(C I, C H)=(C O, C B)+(C B, C I)-(C I, C B)-(C B, C H)=(C O, C B)+$ $(C H, C B)+2(C B, C I)=(90-\widehat{A})+(90-\widehat{B})-\widehat{C}=0$, so $(C O, C I)=(C I, C H)$. Therefore, $(O I, O H)=(C I, C H)=(C O, C I)=(H O, H I)$, so $O I H$ is isosceles at $I$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle tel que $\widehat{A}=60^{\circ}$. On note $O$ le centre du cercle circonscrit, $I$ le centre du cercle inscrit et $H$ l'orthocentre. Montrer que

1) $B, C, O, I, H$ sont cocycliques

2) $O I H$ est isocèle.

|

On utilise les angles de droites. Les angles sont modulo $180^{\circ}$.

1) $(H B, H C)=(H B, A C)+(A C, A B)+(A B, H C)=D-(A B, A C)+D=-(A B, A C)=-60^{\circ}=$ $120^{\circ}=(O B, O C)$ (où on a noté $D$ l'angle droit), donc $B, H, O, C$ sont cocycliques.

$(I B, I C)=(I B, B C)+(B C, I C)=-\widehat{B} / 2-\widehat{C} / 2=-120 / 2=-60^{\circ}=120^{\circ}$, donc $I$ se trouve également sur ce cercle.

2) $(C O, C I)-(C I, C H)=(C O, C B)+(C B, C I)-(C I, C B)-(C B, C H)=(C O, C B)+$ $(C H, C B)+2(C B, C I)=(90-\widehat{A})+(90-\widehat{B})-\widehat{C}=0$, donc $(C O, C I)=(C I, C H)$. On a donc $(O I, O H)=(C I, C H)=(C O, C I)=(H O, H I)$, donc $O I H$ est isocèle en $I$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

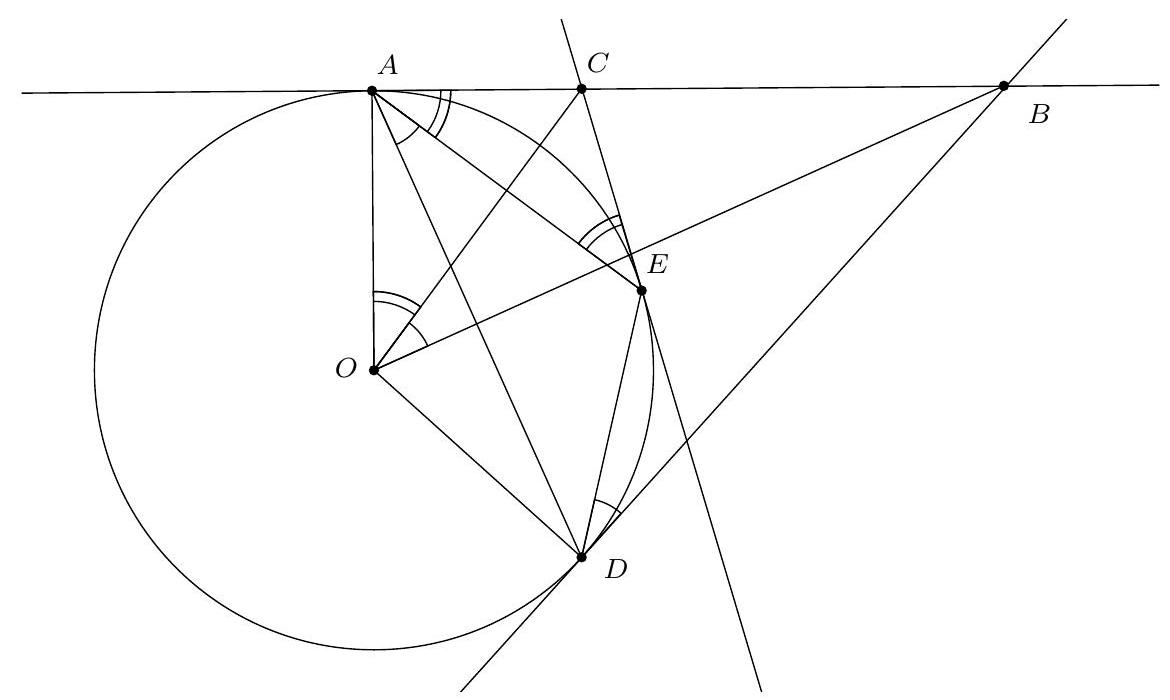

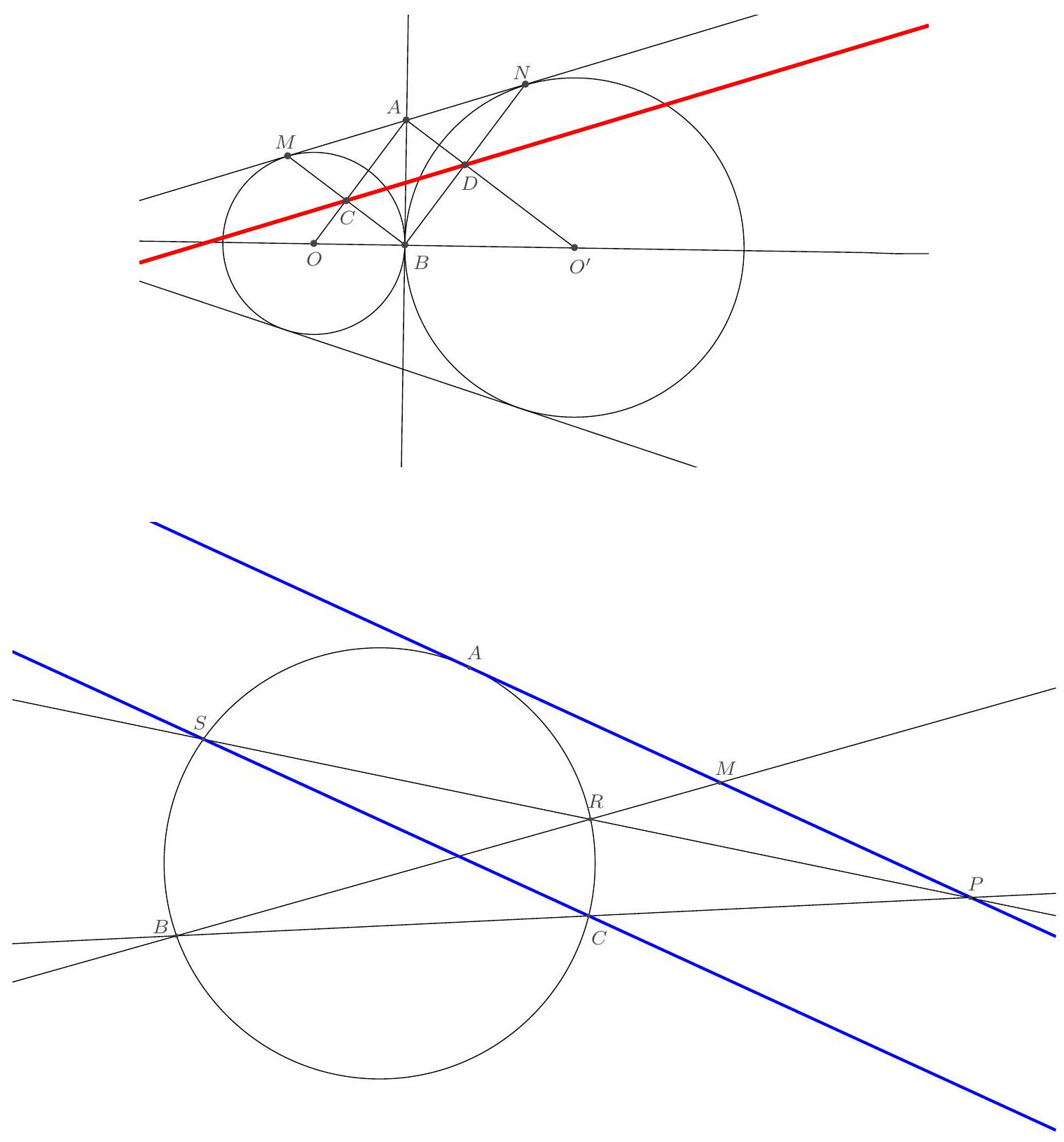

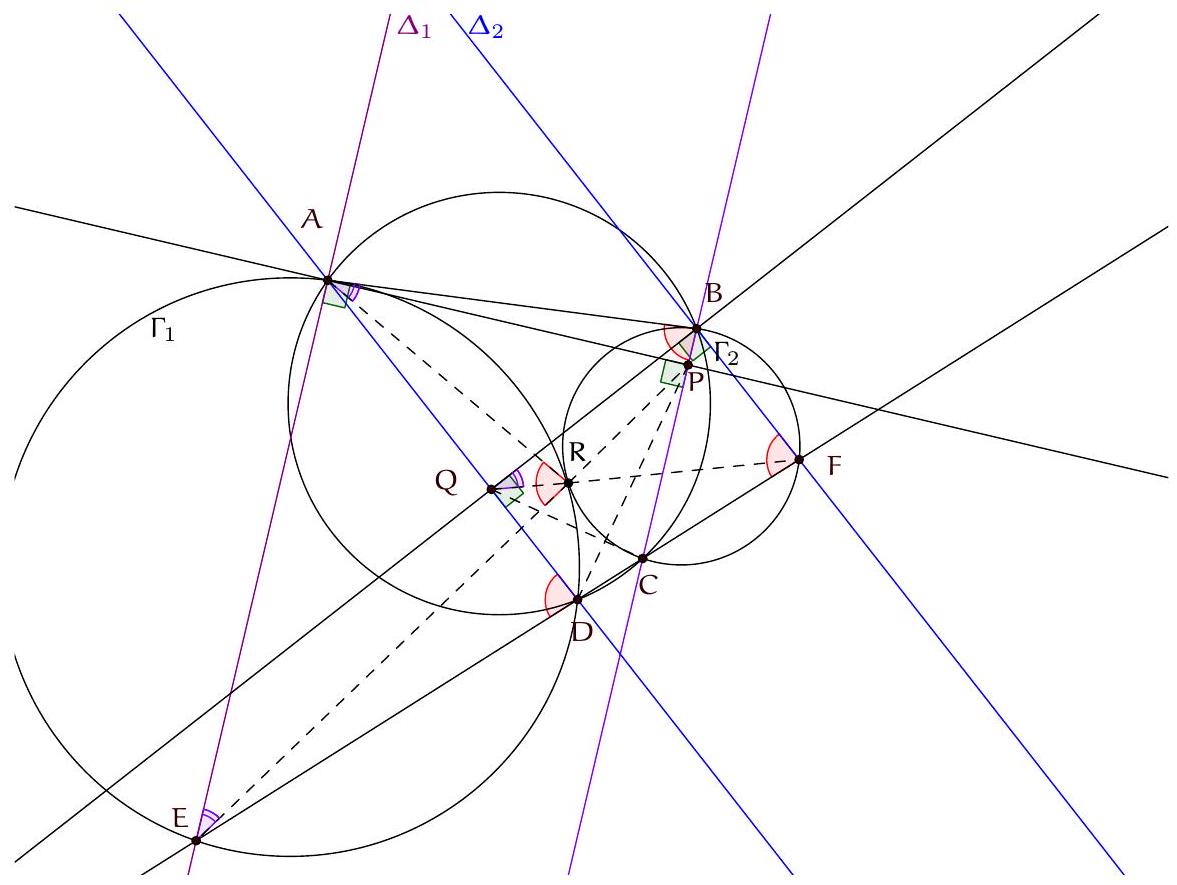

From a point $A$ on a circle with center $O$, a tangent to this circle is drawn, and two points $B$ and $C$ are taken on this tangent, with $C$ between $A$ and $B$. From $B$ and $C$, $(B D)$ and $(C E)$ are drawn tangent to the circle. Prove that $\widehat{B O C}=\widehat{D A E}$.

|

Let $\alpha=\widehat{B D E}$ and $\beta=\widehat{C E A}$. According to the inscribed angle theorem, we have $\alpha=\widehat{D A E}$.

Since $(C A)$ and $(C E)$ are the two tangents drawn from $C$, we have $\widehat{E A C}=\widehat{C E A}=\beta$. $\widehat{B O C}=\widehat{B O A}-\widehat{C O A}$. Now, $(B O) \perp(A D)$ and $(O A) \perp(A C)$, so $\widehat{B O A}=\widehat{D A C}=\alpha+\beta$, and similarly $\widehat{C O A}=\beta$, thus $\widehat{B O C}=\alpha=\widehat{D A E}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Par un point $A$ d'un cercle de centre $O$, on mène une tangente à ce cercle, et on prend deux points $B$ et $C$ sur cette tangente, avec $C$ entre $A$ et $B$. De $B$ et $C$, on mène $(B D)$ et $(C E)$ tangentes au cercle. Démontrer que $\widehat{B O C}=\widehat{D A E}$.

|

Notons $\alpha=\widehat{B D E}$ et $\beta=\widehat{C E A}$. D'après le théorème de l'angle inscrit, on a $\alpha=\widehat{D A E}$.

Comme $(C A)$ et $(C E)$ sont les deux tangentes menées à partir de $C$, on a $\widehat{E A C}=\widehat{C E A}=\beta$. $\widehat{B O C}=\widehat{B O A}-\widehat{C O A} . \mathrm{Or},(B O) \perp(A D)$ et $(O A) \perp(A C)$, donc $\widehat{B O A}=\widehat{D A C}=\alpha+\beta$, et de même $\widehat{C O A}=\beta$, donc $\widehat{B O C}=\alpha=\widehat{D A E}$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

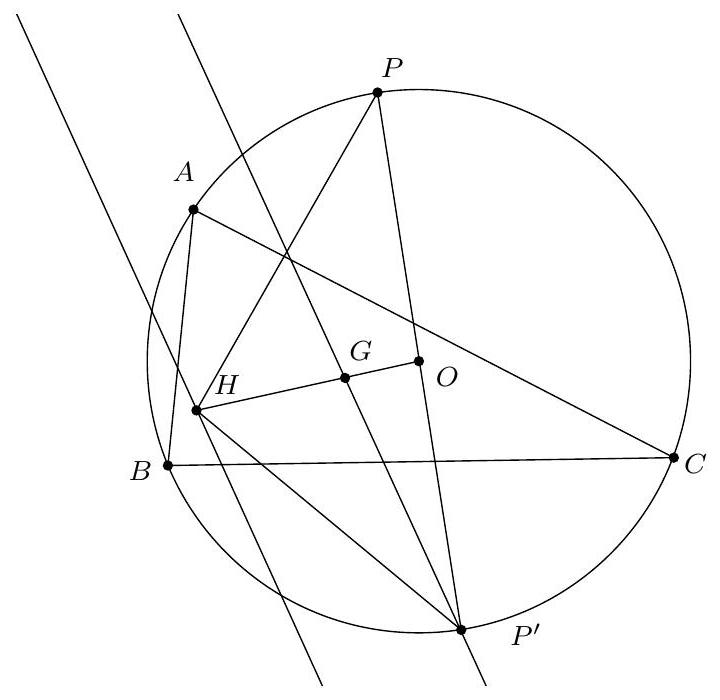

Let $ABC$ be a triangle. Let $P$ belong to the circumcircle. We know that the projections of $P$ onto $(BC)$, $(CA)$, and $(AB)$ are aligned on the line known as the Simson line. We assume that this line passes through the point diametrically opposite to $P$. Show that it also passes through the centroid of $ABC$.

|

Let $P^{\prime}$ be the point diametrically opposite to $P$. Let $\Delta$ be the Simson line. Let $h$ be the homothety with center $P$ and ratio 2. Then $h(\Delta)$ is the Steiner line. We know that it passes through the orthocenter $H$, so $\Delta$ passes through the midpoint of $[P H]$. We deduce that $\Delta$ is the median of $P P^{\prime} H$ from $P^{\prime}$.

Furthermore, (HO) is the median of $P P^{\prime} H$ from $H$. Since $\overrightarrow{H G}=\frac{2}{3} \overrightarrow{H O}$, the point $G$ is the centroid of $P H P^{\prime}$, so $\Delta$ passes through $G$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle. Soit $P$ appartenant au cercle circonscrit. On sait que les projetés de $P$ sur $(B C),(C A)$ et $(A B)$ sont alignés sur la droite dite de Simson. On suppose que cette droite passe par le point diamétralement opposé à $P$. Montrer qu'elle passe également par le centre de gravité de $A B C$.

|

Notons $P^{\prime}$ le point diamétralement opposé à $P$. Soit $\Delta$ la droite de Simson. Soit $h$ l'homothétie de centre $P$ et de rapport 2. Alors $h(\Delta)$ est la droite de Steiner. On sait qu'elle passe par l'orthocentre $H$, donc $\Delta$ passe par le milieu de $[P H]$. On en déduit que $\Delta$ est la médiane de $P P^{\prime} H$ issue de $P^{\prime}$.

Par ailleurs, (HO) est la médiane de $P P^{\prime} H$ issue de $H$. Comme $\overrightarrow{H G}=\frac{2}{3} \overrightarrow{H O}$, le point $G$ est le centre de gravité de $P H P^{\prime}$, donc $\Delta$ passe par $G$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

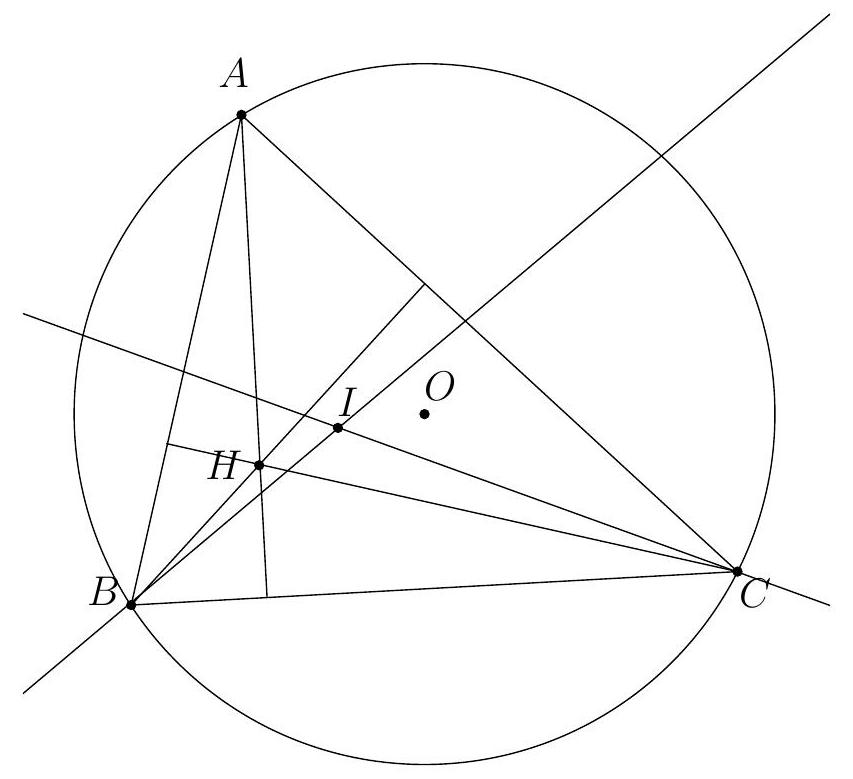

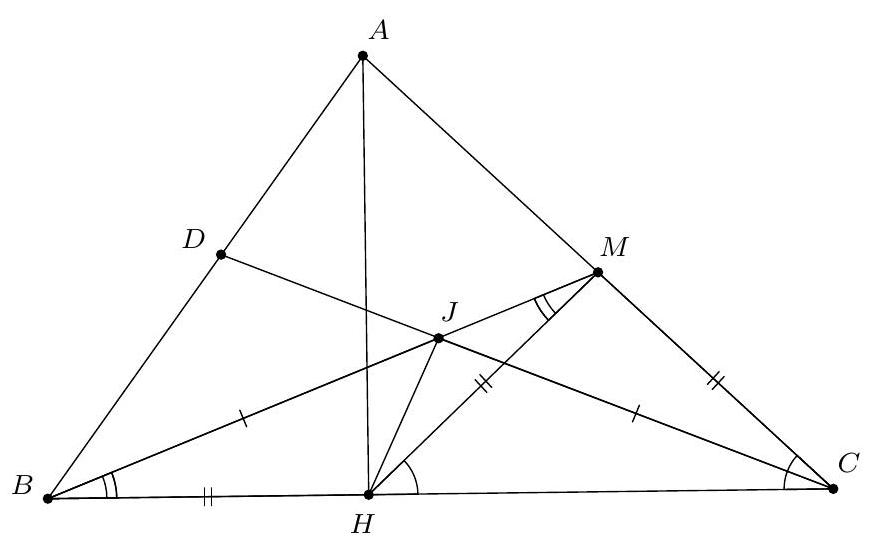

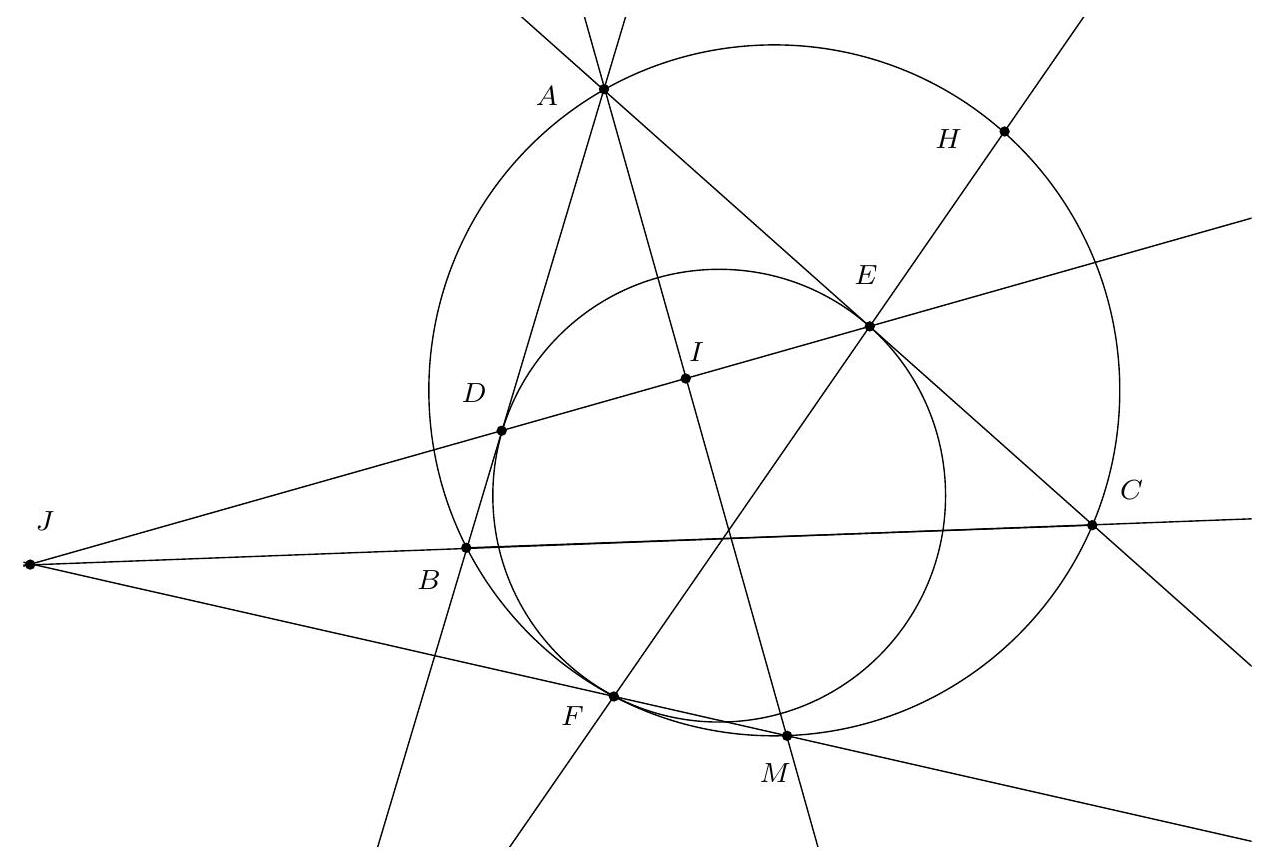

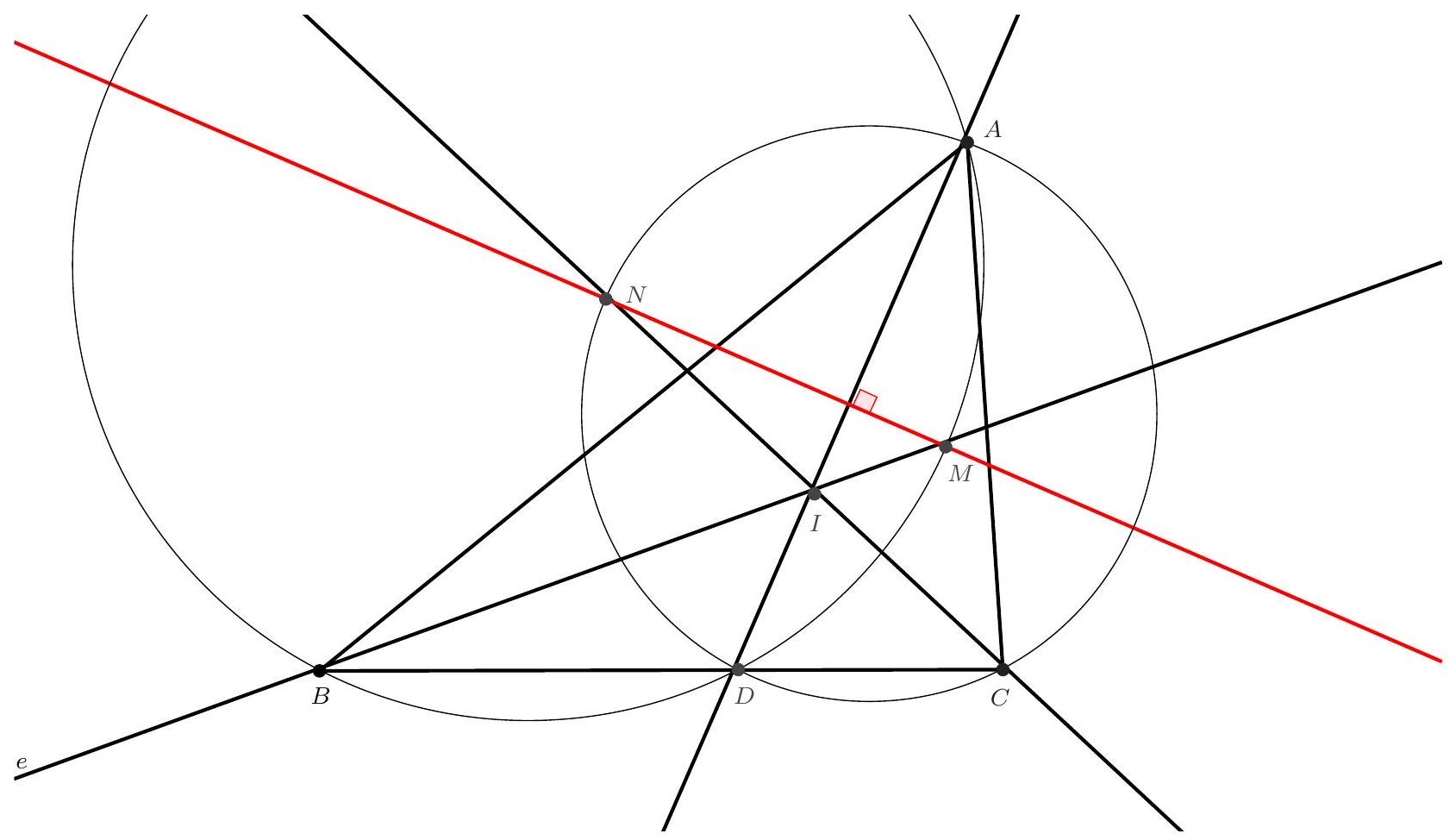

Let $ABC$ be a triangle. Suppose that the median $(BM)$ and the angle bisector $(CD)$ intersect at a point $J$ such that $JB=JC$. Let $H$ be the foot of the altitude from $A$. Show that $JM=JH$.

Soit $ABC$ un triangle. On suppose que la médiane $(BM)$ et la bissectrice $(CD)$ se coupent en un point $J$ tel que $JB=JC$. Soit $H$ le pied de la hauteur issue de $A$. Montrer que $JM=JH$.

(Note: The second part is the original French text, which is kept as requested.)

|

Let $\gamma=\widehat{A C B}$. We have $M A=M C=M H$, so $\widehat{C H M}=\gamma$.

We also have $\widehat{C H M}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{M H B}=\widehat{H B M}+\widehat{B M H}$.

Furthermore, $\widehat{H B M}=\widehat{D C B}=\gamma / 2$, so $\widehat{B M H}=\widehat{H M B}=\gamma / 2$.

We deduce that $B H=H M=M C$. The triangles $B H J$ and $C M J$ satisfy $B J=C J, \widehat{H B J}=$ $\widehat{M C J}$ and $B H=C M$ so they are congruent. Consequently, $J H=H M$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle. On suppose que la médiane $(B M)$ et la bissectrice $(C D)$ se coupent en un point $J$ tel que $J B=J C$. Soit $H$ le pied de la hauteur issue de $A$. Montrer que $J M=J H$.

|

Notons $\gamma=\widehat{A C B}$. On a $M A=M C=M H$, donc $\widehat{C H M}=\gamma$.

On a aussi $\widehat{C H M}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{M H B}=\widehat{H B M}+\widehat{B M H}$.

De plus, $\widehat{H B M}=\widehat{D C B}=\gamma / 2$, donc $\widehat{B M H}=\widehat{H M B}=\gamma / 2$.

On en déduit que $B H=H M=M C$. Les triangles $B H J$ et $C M J$ vérifient $B J=C J, \widehat{H B J}=$ $\widehat{M C J}$ et $B H=C M$ donc sont isométriques. Par conséquent, $J H=H M$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## \nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

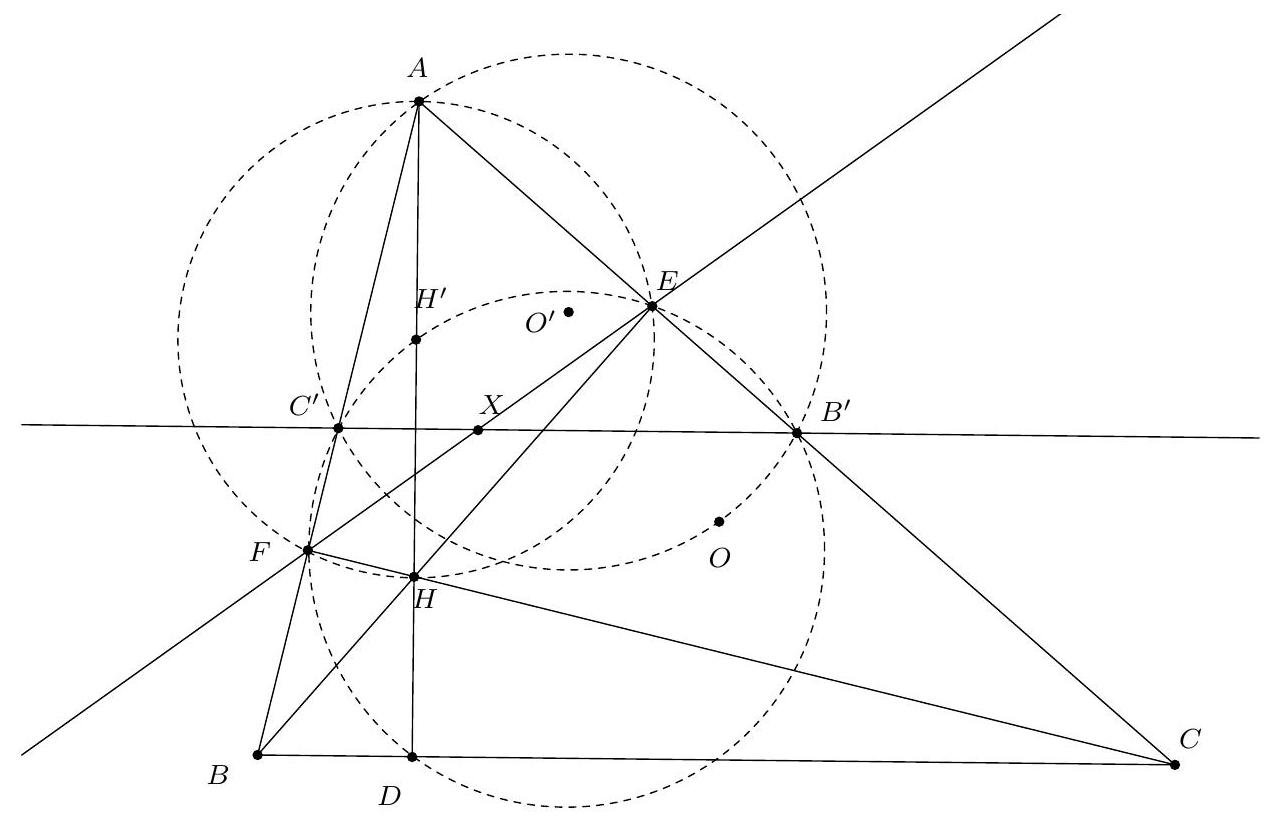

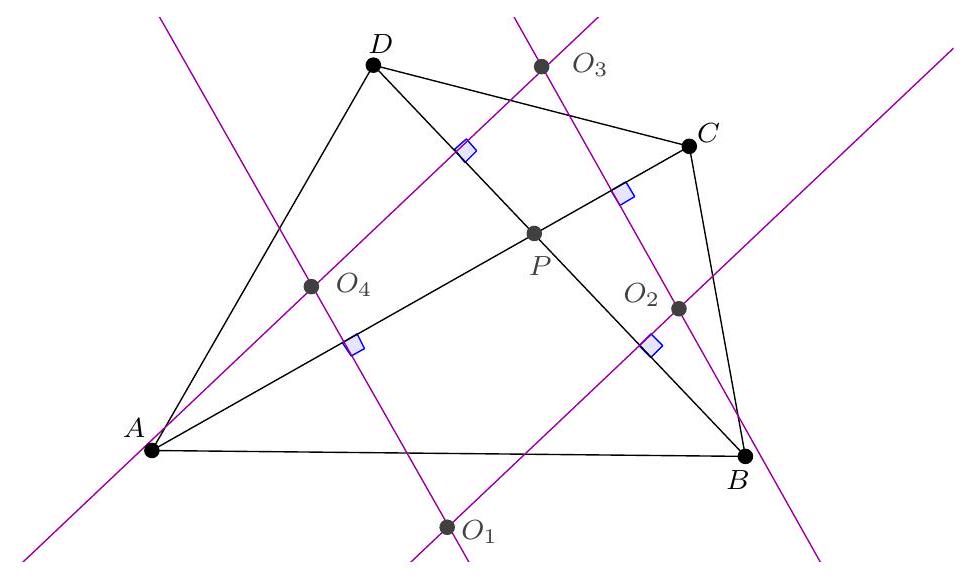

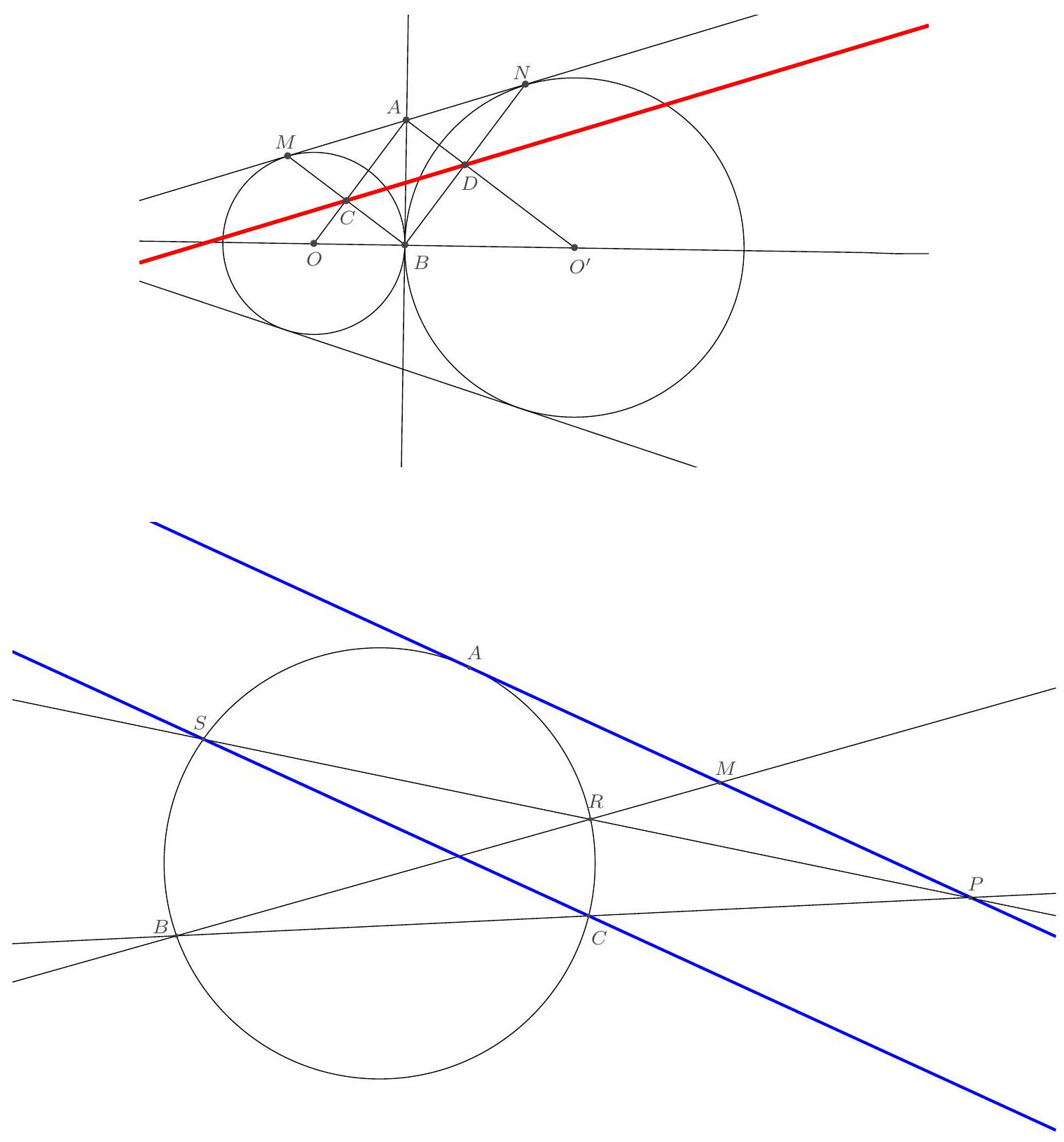

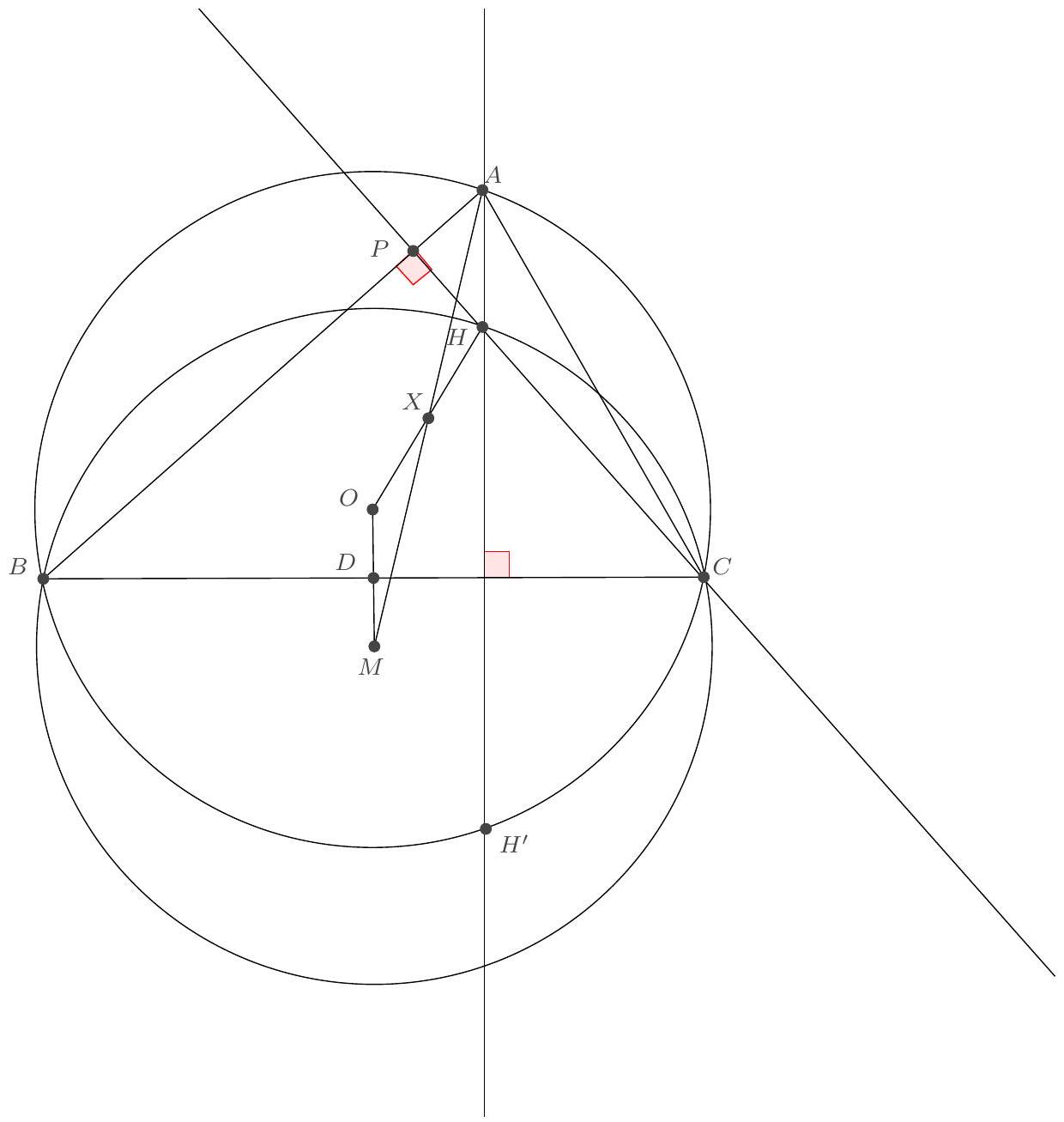

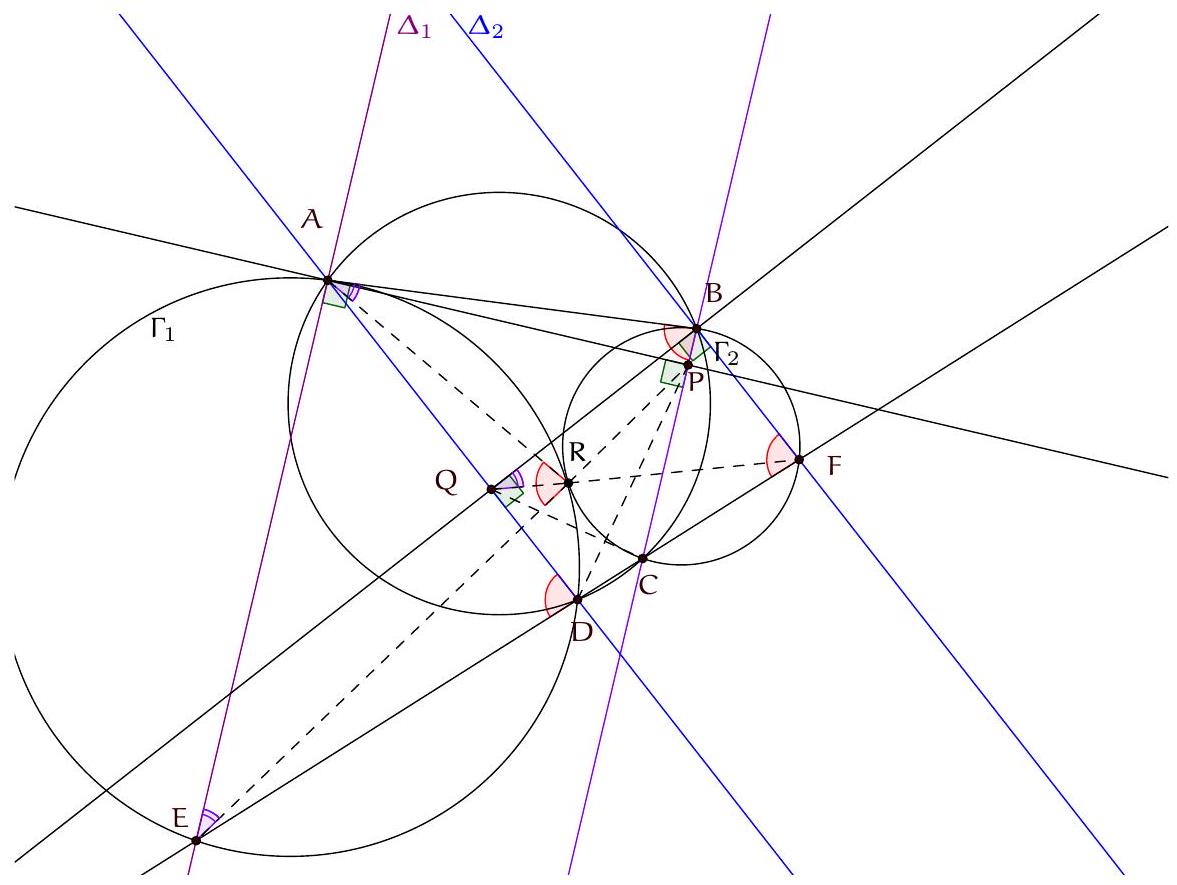

Let $ABC$ be a triangle, and $D, E, F$ the feet of the altitudes from $A, B, C$ respectively. We also define $H$ as the orthocenter of $ABC$, $O$ as the center of its circumcircle, and $X$ as the point on the line $(EF)$ that satisfies $XA = XD$. Show that the lines $(AX)$ and $(OH)$ are perpendicular.

|

We know that the radical axis of two circles is a line perpendicular to the line passing through the centers of the two circles.

The condition \( XA = XD \) means that \( X \) is on the perpendicular bisector of \([AD]\), which is none other than the midline \((B' C')\) (with \( B' \) and \( C' \) being the midpoints of \([AC]\) and \([AB]\)). We also know that the points \( A, E, F, H \) are concyclic according to the converse of the inscribed angle theorem. Furthermore, since \([AH]\) is a diameter of the circle passing through these four points, the midpoint \( H' \) of \([AH]\) is the center of this circle.

The center of the circle passing through \( A, B', C' \) is the midpoint \( O' \) of \([AO]\) (by the property of the homothety centered at \( A \) with a ratio of 1/2). We know that \((O' H')\) and \((OH)\) are parallel. The problem thus reduces to showing that \((AX)\) and \((O' H')\) are perpendicular. We will show here that \((AX)\) is actually the radical axis of the two circles mentioned earlier, which will complete the exercise according to the property mentioned at the beginning of the proof.

Since \( A \) is on both circles, it is indeed on their radical axis. We also know that \( B', C', E, F \) are concyclic on the Euler circle of triangle \( ABC \). Thus, we have the equality of lengths: \( XC' \times XB' = XE \times XF \), which means that \( X \) is indeed on the radical axis of our two circles.

Therefore, we have \((AX)\) and \((OH)\) being perpendicular.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle, et $D, E, F$ les pieds des hauteurs de $A, B, C$ respectivement. On définit aussi $H$ l'orthocentre de $A B C, O$ le centre de son cercle circonscrit, et $X$ le point de la droite $(E F)$ qui vérifie $X A=X D$. Montrer que les droites $(A X)$ et $(O H)$ sont perpendiculaires.

|

On sait que l'axe radical de deux cercles est une droite perpendiculaire à la droite passant par les centres des deux cercles.

La condition $X A=X D$ signifie que X est sur la médiatrice de $[A D]$, qui n'est autre que le droite des milieux $\left(B^{\prime} C^{\prime}\right)$ (avec $B^{\prime}$ et $C^{\prime}$ les milieux de $[A C]$ et de $[A B]$ ). On sait aussi que les points

$A, E, F, H$ sont cocycliques d'après la réciproque du théorème de l'angle inscrit. De, plus $[A H]$ étant un diamètre du cercle passant par ces quatre points, le milieu $H^{\prime}$ de $[A H]$ est le centre de ce cercle.

Le centre du cercle passant par $A, B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}$ est le milieu $O^{\prime}$ de $[A O]$ (par propriété de l'homothétie de centre $A$ et de rapport 1/2). On sait que $\left(O^{\prime} H^{\prime}\right)$ et $(O H)$ sont parallèles. Le problème revient donc à montrer que $(A X)$ et $\left(O^{\prime} H^{\prime}\right)$ sont perpendiculaires. Nous allons montrer ici que $(A X)$ est en fait l'axe radical des deux cercles évoqués précédemment, ce qui terminera l'exercice d'après la propriété évoquée au début de la preuve.

$A$ étant sur les deux cercles, est bien sur leur axe radical. On sait de plus que $B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}, E, F$ sont cocycliques sur le cercle d'Euler du triangle $A B C$. Ainsi on a l'égalité de longueurs : $X C^{\prime} \times X B^{\prime}=X E \times X F$, ce qui signifie que $X$ est bien sur l'axe radical de nos deux cercles.

Ainsi on a bien $(A X)$ et $(O H)$ qui sont perpendiculaires.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2015-2016-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2016"

}

|

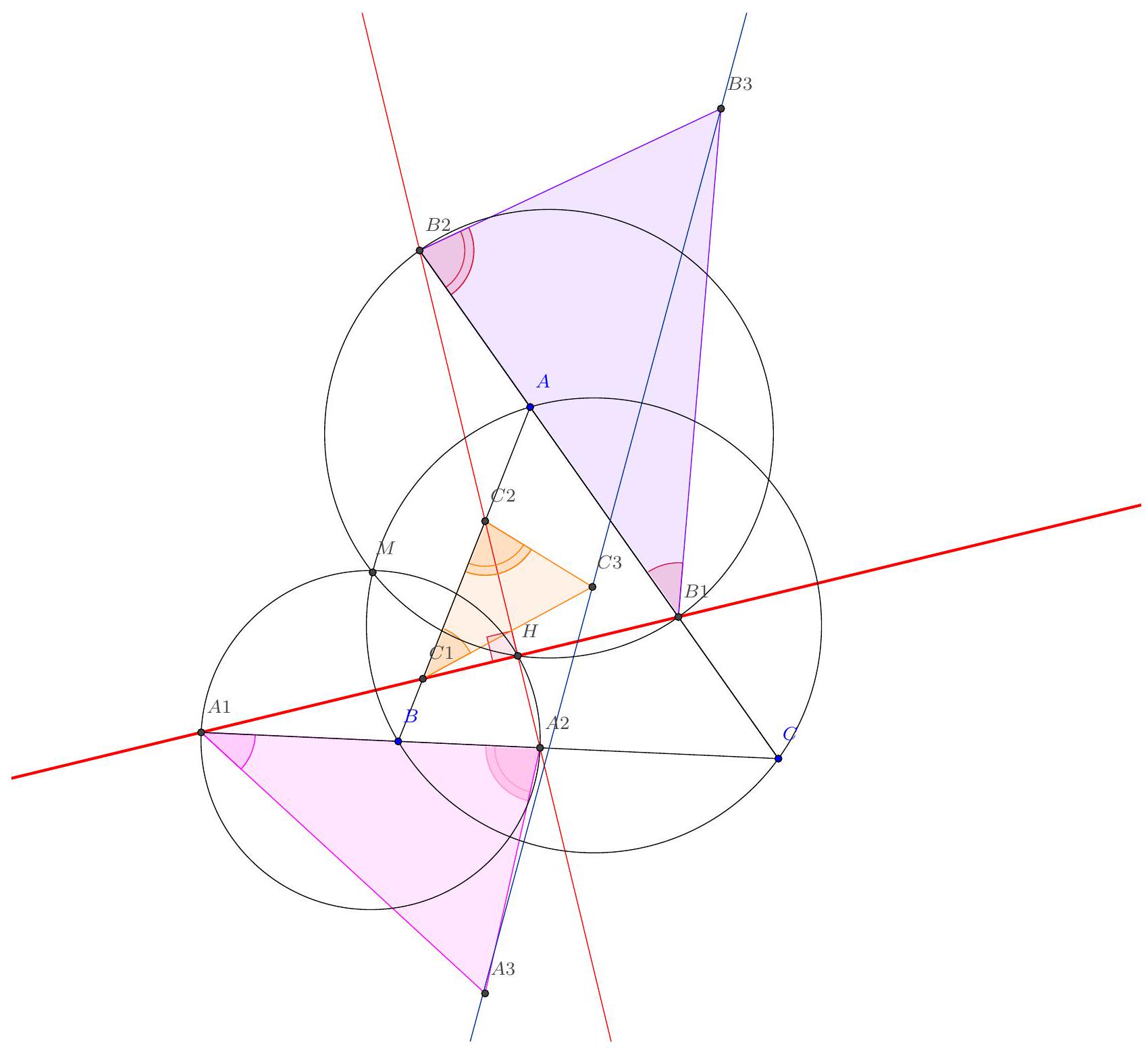

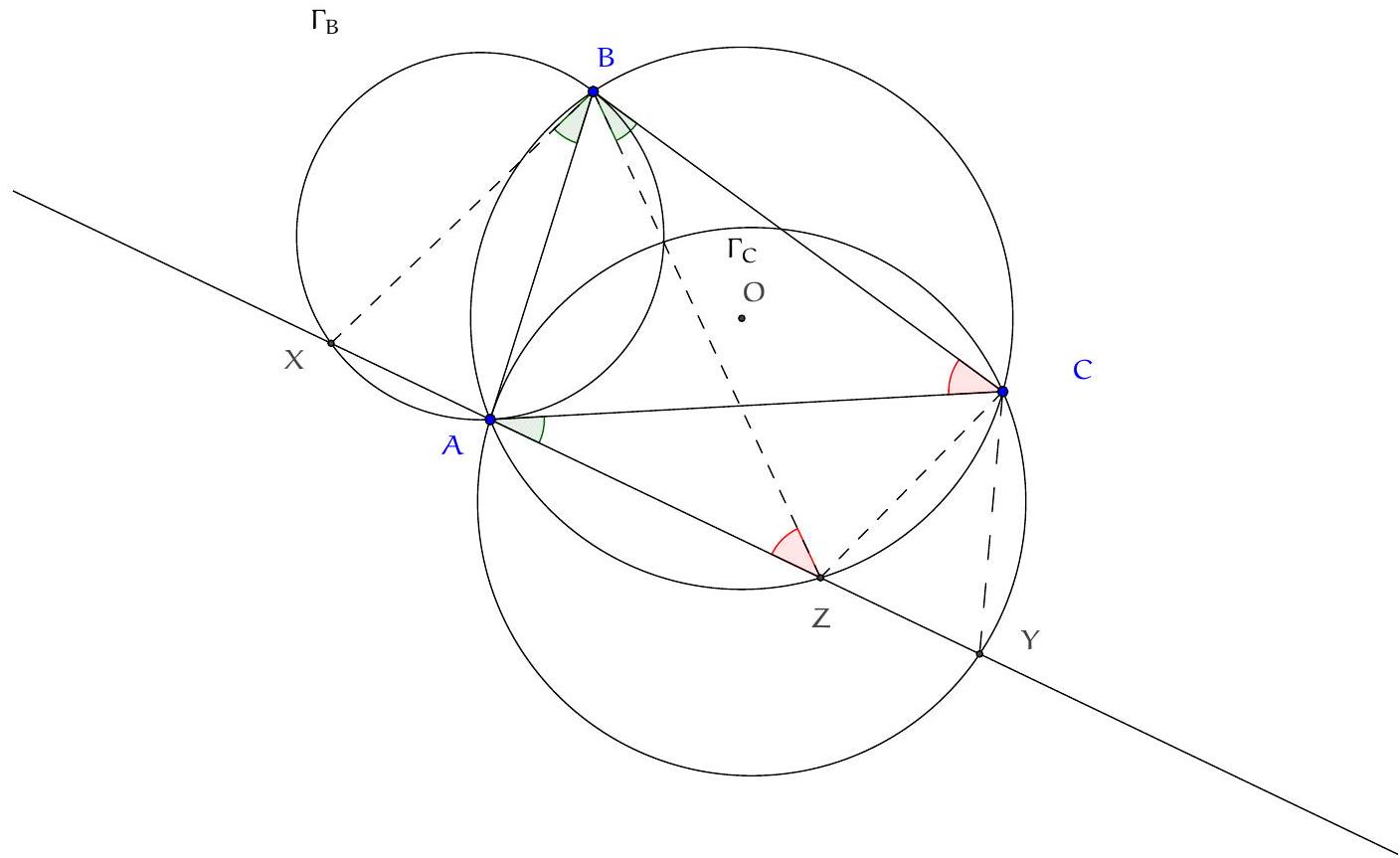

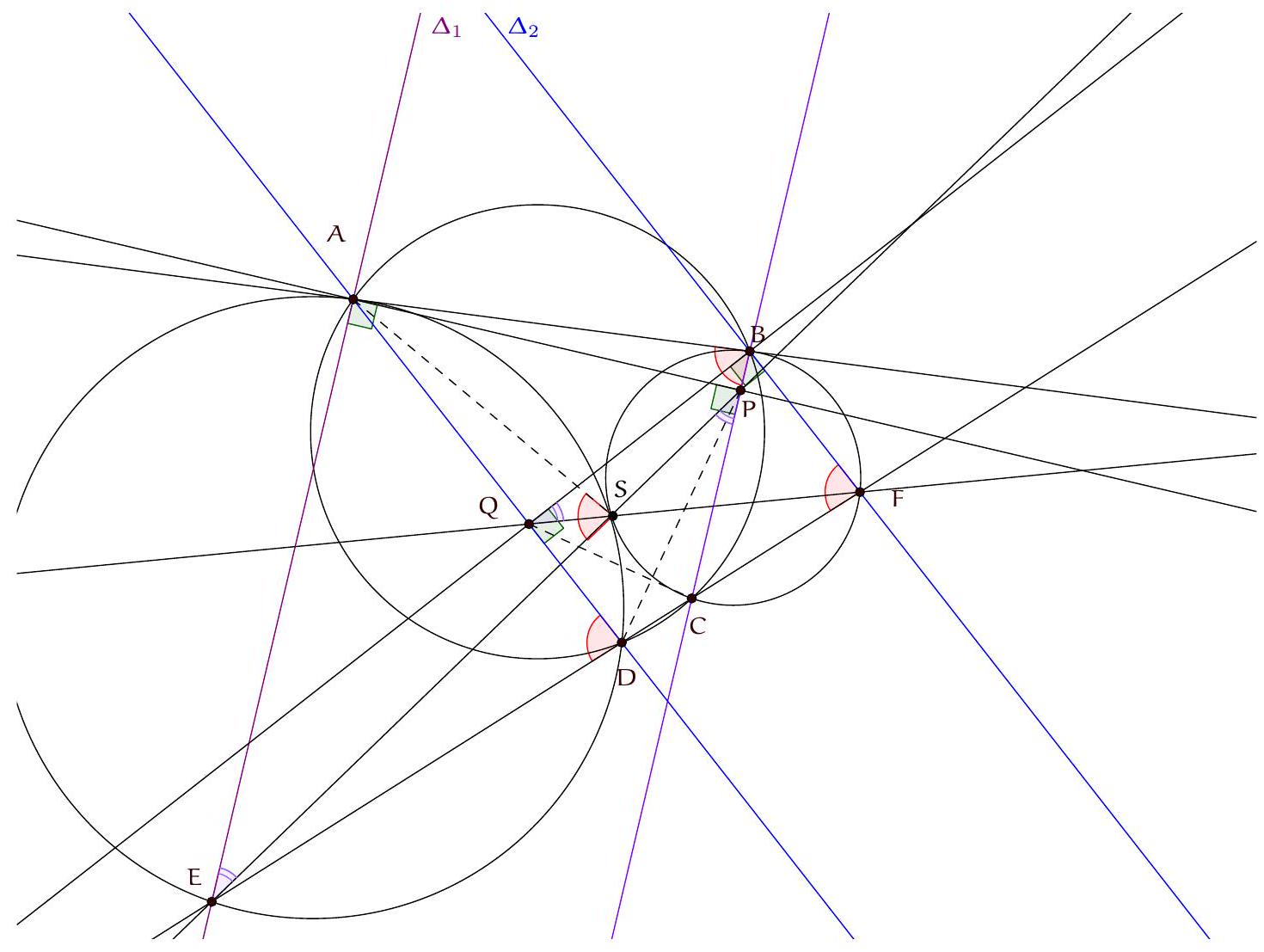

Let $ABC$ be a triangle, and $\Gamma$ its circumcircle. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $BC$ not containing $A$. A circle $\mathscr{C}$ is tangent to $[AB), [AC)$ at $D$ and $E$ respectively, and internally tangent to $\Gamma$ at $F$. Show that $(DE), (BC)$, and $(FM)$ are concurrent.

|

Let $I$ be the center of the incircle of $ABC$. The line $(EF)$ intersects $\Gamma$ at a point $H$. Let $J$ be the intersection of $(BC)$ with $(FM)$.

It is easy to see that $H$ is the midpoint of the arc $AC$ not containing $B$: indeed, the homothety centered at $F$ that maps $\mathscr{C}$ to $\Gamma$ maps $(AC)$ to the tangent at $H$ to $\Gamma$; this tangent is parallel to $(AC)$, which implies that $H$ is the midpoint of the arc, and consequently $B, I, H$ are collinear.

By applying Pascal's theorem to the hexagon $AMFHB C$, we obtain that $I, E, J$ are collinear. Similarly, $D, I, J$ are collinear. Thus, $(DE)$, $(BC)$, and $(FM)$ meet at $J$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle, et $\Gamma$ son cercle circonscrit. Soit $M$ le milieu de l'arc $B C$ ne contenant pas $A$. Un cercle $\mathscr{C}$ est tangent à $[A B),[A C)$ en $D$ et $E$ respectivement, et tangent intérieurement à $\Gamma$ en $F$. Montrer que $(D E),(B C)$ et $(F M)$ sont concourantes.

|

Soit $I$ le centre du cercle inscrit dans $A B C$. La droite $(E F)$ recoupe $\Gamma$ en un point $H$. Soit $J$ le point d'intersection de $(B C)$ avec $(F M)$.