problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Find all integers $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n} \geq 0$ such that $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=5^{m}$.

|

We can factorize $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=(n-2)\left(n^{2}-n-1\right)$. For the equation to be true, it is necessary that the two factors are, up to a sign, powers of 5.

If $n-2$ is negative, since $n$ is positive, for $-(n-2)$ to be a power of 5, we must take $n=1$, and in this case $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=1$, so $m=0$, $n=1$ is a solution.

Otherwise, $\left(n^{2}-n-1\right)-(n-2)=n^{2}-2 n+1=(n-1)^{2}>0$, so $n^{2}-n-1$ is a power of 5 larger than $n-2$, thus $n-2$ divides $n^{2}-n-1=(n-2)(n+1)+1$, so $n-2$ divides 1, hence $n=3$, and in this case $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=5$, so $m=1, n=3$ is a solution.

Thus, the only solutions are $m=0, n=1$ and $m=1, n=3$.

|

m=0, n=1 \text{ and } m=1, n=3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver tous les entiers $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n} \geq 0$ tels que $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=5^{m}$.

|

On peut factoriser $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=(n-2)\left(n^{2}-n-1\right)$. Pour que l'équation soit vraie, il faut que les deux facteurs soient, au signe près, des puissances de 5.

Si $n-2$ est négatif, comme $n$ est positif, pour que $-(n-2)$ soit une puissance de 5 , il faut prendre $n=1$, et dans ce cas $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=1$, donc $m=0$, $n=1$ est solution.

Sinon, $\left(n^{2}-n-1\right)-(n-2)=n^{2}-2 n+1=(n-1)^{2}>0$, donc $n^{2}-n-1$ est une puissance de 5 plus grande que $n-2$, donc $n-2$ divise $n^{2}-n-1=(n-2)(n+1)+1$, donc $n-2$ divise 1 , donc $n=3$, et dans ce cas $n^{3}-3 n^{2}+n+2=5$, donc $m=1, n=3$ est solution.

Ainsi les seules solutions sont $m=0, n=1$ et $m=1, n=3$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi1-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Show that $n!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times n$ is divisible by $2^{n-1}$ if and only if $n$ is a power of 2.

|

For any prime number $p$, the $p$-adic valuation of an integer $n$ is defined as the largest integer, denoted $v_{p}(n)$, such that $p^{v_{p}(n)}$ divides $n$. The $p$-adic valuation of a product of integers is the sum of their $p$-adic valuations. For a real number $x$, we denote $\lfloor x\rfloor$ as the integer part of $x$, which is the greatest integer less than or equal to $x$.

We observe that $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ contains $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor$ multiples of $p$, $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p^{2}}\right\rfloor$ multiples of $p^{2}$, etc. From this, we derive Legendre's formula:

$$

v_{p}(n!)=\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p^{2}}\right\rfloor+\ldots

$$

For this exercise, we take $p=2$, and define $k$ as the integer such that $2^{k} \leq n < 2^{k+1}$. Then

$v_{2}(n!)=\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{4}\right\rfloor+\cdots+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2^{k}}\right\rfloor \leq \frac{n}{2}+\frac{n}{4}+\cdots+\frac{n}{2^{k}}=n\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\right) \leq n-1$.

For $n!$ to be divisible by $2^{n-1}$, i.e., for $v_{2}(n!) \geq n-1$, we must be in the cases of equality. In particular, it must be that $n\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\right)=n-1$, so $n=2^{k}$.

Conversely, if $n=2^{k}$, then we are in the cases of equality, so $2^{n-1}$ divides $n!$.

## Exercises Group A

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Montrer que $n!=1 \times 2 \times \cdots \times n$ est divisible par $2^{n-1}$ si et seulement si $n$ est une puissance de 2 .

|

On définit, pour tout nombre premier $p$, la valuation $p$-adique d'un entier $n$ comme le plus grand entier, noté $v_{p}(n)$, tel que $p^{v_{p}(n)}$ divise $n$. La valuation $p$-adique d'un produit d'entiers est la somme de leurs valuations $p$ adiques. Pour $x$ un nombre réel, on note $\lfloor x\rfloor$ la partie entière de $x$, c'est-à-dire le plus grand entier inférieur à $x$.

On observe que $\{1, \ldots, n\}$ contient $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor$ multiples de $p,\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p^{2}}\right\rfloor$ multiples de $p^{2}$, etc. On en déduit la formule de Legendre :

$$

v_{p}(n!)=\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{p^{2}}\right\rfloor+\ldots

$$

Pour cet exercice, on prend $p=2$, et on définit $k$ l'entier tel que $2^{k} \leq n<2^{k+1}$. Alors

$v_{2}(n!)=\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{4}\right\rfloor+\cdots+\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2^{k}}\right\rfloor \leq \frac{n}{2}+\frac{n}{4}+\cdots+\frac{n}{2^{k}}=n\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\right) \leq n-1$.

Pour que $n$ ! soit divisible par $2^{n-1}$, c'est-à-dire pour que $v_{2}(n!) \geq n-1$, il faut être dans les cas d'égalité. En particulier, il faut que $n\left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\right)=n-1$, donc que $n=2^{k}$.

Réciproquement, si $n=2^{k}$, alors on est dans les cas d'égalité, donc $2^{n-1}$ divise $n$ !.

## Exercices Groupe A

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi1-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find the pairs of integers $(x, y) \in \mathbb{Z}$ that are solutions to the equation $y^{2}=x^{5}-4$.

untranslated text:

Trouver les couples d'entiers $(x, y) \in \mathbb{Z}$ solutions de l'équation $y^{2}=x^{5}-4$.

|

By Fermat's little theorem, for any integer $x$ coprime with $11, x^{10} \equiv 1[11]$. Therefore, 11 divides $x^{10}-1=\left(x^{5}-1\right)\left(x^{5}+1\right)$. By Gauss's lemma, 11 divides $x^{5}-1$ or $x^{5}+1$. Thus, for any integer $x, x^{5}-4 \equiv-5[11]$ or $x^{5}-4 \equiv-3[11]$ or, in the case where 11 divides $x, x^{5}-4 \equiv-4[11]$.

For the left-hand term, we compute the quadratic residues modulo 11: $0^{2} \equiv 0[11], 1^{2}=(-1)^{2} \equiv 1[11], 2^{2}=(-2)^{2} \equiv 4[11], 3^{2}=(-3)^{2} \equiv-2[11]$, $4^{2}=(-4)^{2} \equiv 5[11]$, and $5^{2}=(-5)^{2} \equiv 3[11]$.

Thus $y^{2} \not \equiv x^{5}-4[11]$, so the equation has no solution.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver les couples d'entiers $(x, y) \in \mathbb{Z}$ solutions de l'équation $y^{2}=x^{5}-4$.

|

Par le petit théorème de Fermat, pour tout entier $x$ premier avec $11, x^{10} \equiv 1[11]$. Donc 11 divise $x^{10}-1=\left(x^{5}-1\right)\left(x^{5}+1\right)$. Par le lemme de Gauss, 11 divise $x^{5}-1$ ou $x^{5}+1$. Donc pour tout entier $x, x^{5}-4 \equiv-5[11]$ ou $x^{5}-4 \equiv-3[11]$ ou, dans le cas où 11 divise $x, x^{5}-4 \equiv-4[11]$.

Pour le terme de gauche, on calcule les résidus quadratiques modulo 11: $0^{2} \equiv 0[11], 1^{2}=(-1)^{2} \equiv 1[11], 2^{2}=(-2)^{2} \equiv 4[11], 3^{2}=(-3)^{2} \equiv-2[11]$, $4^{2}=(-4)^{2} \equiv 5[11]$, et $5^{2}=(-5)^{2} \equiv 3[11]$.

Ainsi $y^{2} \not \equiv x^{5}-4[11]$, donc l'équation n'a pas de solution.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi1-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Does there exist an infinite subset $A$ of $\mathbb{N}$ that satisfies the following property: any finite sum of distinct elements of $A$ is never a power of an integer (i.e., an integer of the form $a^{b}$ with $a$ and $b$ integers greater than or equal to 2)?

|

We are looking to construct a set $A=\left\{a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots\right\}$, where $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots\right)$ is an increasing sequence of integers. We choose the first element as $a_{0}=0$.

Let $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Suppose we have already found $a_{0}<\cdots<a_{n}$ such that the set $B$ of sums of distinct elements does not contain any power of an integer. We want to choose $a_{n+1}>a_{n}$ such that the set of sums of distinct elements of $\left\{a_{0}, \ldots a_{n+1}\right\}$ does not contain any power of an integer. It suffices that none of the $a_{n+1}+b$, with $b \in B$, is a power of an integer.

Let $N \in \mathbb{N}$. We bound the proportion $p(N)$ of powers of integers in $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$. There are fewer than $\sqrt{N}$ squares, fewer than $\sqrt[3]{N}$ cubes, and so on up to the $k$-th roots, where $k=\left\lfloor\log _{2}(N)\right\rfloor$. We can stop at $k$ because for all $b>k, 2^{b}>N$ so there are no $b$-th powers in $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$. Therefore,

$$

p(N) \leq \frac{\sqrt{N}+\sqrt[3]{N}+\cdots+\sqrt[k]{N}}{N-a_{n}} \leq \frac{\sqrt{N} \log _{2}(N)}{N-a_{n}} \underset{N \rightarrow+\infty}{\longrightarrow} 0 .

$$

Thus, for sufficiently large $N$, we can find $1+\max B$ consecutive numbers in $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$ that are not powers of integers. We choose for $a_{n+1}$ the smallest of these. Then none of the $a_{n+1}+b$, with $b \in B$, is a power of an integer.

Finally, we have constructed a set $A$ satisfying the required property.

Exercise 3: Let $P(n)$ denote the largest prime divisor of $n$. Show that there are infinitely many integers $n$ such that $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Existe-t-il un sous-ensemble infini $A$ de $\mathbb{N}$ qui vérifie la propriété suivante : toute somme finie d'éléments distincts de $A$ n'est jamais une puissance d'un entier (c'est-à-dire un entier de la forme $a^{b}$ avec $a$ et $b$ entiers supérieurs ou égaux à 2) ?

|

On cherche à construire un tel ensemble $A=\left\{a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots\right\}$, avec $\left(a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots\right)$ une suite croissante d'entiers. On choisit comme premier élément $a_{0}=0$.

Soit $n \in \mathbb{N}$. On suppose qu'on a déjà trouvé $a_{0}<\cdots<a_{n}$ tels que l'ensemble B des somme d'éléments distincts ne contienne pas de puissance d'un entier. On veut choisir $a_{n+1}>a_{n}$ tel que l'ensemble des sommes d'éléments distincts de $\left\{a_{0}, \ldots a_{n+1}\right\}$ ne contienne pas de puissance d'un entier. Il suffit qu'aucun des $a_{n+1}+b$, avec $b \in B$, ne soit une puissance d'un entier.

Soit $N \in \mathbb{N}$. Majorons la proportion $p(N)$ de puissances d'entiers dans $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$. Il y a moins de $\sqrt{N}$ carrés, moins de $\sqrt[3]{N}$ cubes, et ainsi de suites jusqu'aux racines $k$-ièmes, avec $k=\left\lfloor\log _{2}(N)\right\rfloor$. On peut s'arrêter à $k$ car pour tout $b>k, 2^{b}>N$ donc il n'y a pas de puissance $b$-ième dans $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$. Donc

$$

p(N) \leq \frac{\sqrt{N}+\sqrt[3]{N}+\cdots+\sqrt[k]{N}}{N-a_{n}} \leq \frac{\sqrt{N} \log _{2}(N)}{N-a_{n}} \underset{N \rightarrow+\infty}{\longrightarrow} 0 .

$$

Ainsi, pour $N$ assez grand, on peut trouver $1+\max B$ nombres consécutifs dans $\left\{a_{n}+1, \ldots, N\right\}$ qui ne sont pas des puissances d'entiers. On choisit pour $a_{n+1}$ le plus petit d'entre eux. Alors aucun des $a_{n+1}+b$, avec $b \in B$, n'est une puissance d'un entier.

Finalement, on a bien construit un ensemble $A$ satisfaisant la propriété demandée.

Exercices 3 On note $P(n)$ le plus grand diviseur premier de $n$. Montrer qu'il existe une infinité d'entiers $n$ tels que $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi1-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Does there exist an infinite subset $A$ of $\mathbb{N}$ that satisfies the following property: any finite sum of distinct elements of $A$ is never a power of an integer (i.e., an integer of the form $a^{b}$ with $a$ and $b$ integers greater than or equal to 2)?

|

Let $p$ be an odd prime number. We seek an integer $n$ of the form $p^{2^{k}}$, with $k$ an integer, such that $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$.

Let $k>l \geq 0$, we have

$$

\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}=\frac{p^{2^{l}}+1}{2}\left(p^{2^{k}-2^{l}}-p^{2^{k}-2 \cdot 2^{l}}+\cdots-p^{2 \cdot 2^{l}}+p^{2^{l}}-1\right)+1 .

$$

Thus, the $\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}, k \in \mathbb{N}$, are pairwise coprime. This implies that the $P\left(\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}\right)=P\left(p^{2^{k}}+1\right)$ are distinct integers. In particular, we can find $k$ such that $P\left(p^{2^{k}}+1\right) \geq p=P\left(p^{2^{k}}\right)$. Let $k_{p}$ be the smallest $k \geq 0$ satisfying this property. We choose $n=p^{2^{k_{p}}}$. We see that $P(n+1) \geq P(n)$, and since $n$ and $n+1$ are coprime, $P(n+1)>P(n)$. It remains to show that $P(n-1)<P(n)$. We write

$$

n-1=p^{2^{k_{p}}}-1=\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-1}}+1\right)\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-2}}+1\right) \ldots\left(p^{2}+1\right)(p+1)(p-1)

$$

thus

$$

P(n-1)=\max \left(P\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-1}}+1\right), \ldots, P(p+1), P(p-1)\right)<p=P(n)

$$

by the minimality of $k_{p}$ and because $P(p-1) \leq p-1<p$.

Finally, for any odd prime number $p$, we can find $n$ a power of $p$ such that $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$. Since there are infinitely many odd prime numbers, and since the powers of distinct prime numbers are distinct, there exist infinitely many such integers $n$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Existe-t-il un sous-ensemble infini $A$ de $\mathbb{N}$ qui vérifie la propriété suivante : toute somme finie d'éléments distincts de $A$ n'est jamais une puissance d'un entier (c'est-à-dire un entier de la forme $a^{b}$ avec $a$ et $b$ entiers supérieurs ou égaux à 2) ?

|

Soit $p$ un nombre premier impair. On cherche un entier $n$ de la forme $p^{2^{k}}$, avec $k$ entier, tel que $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$.

Soit $k>l \geq 0$, on a

$$

\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}=\frac{p^{2^{l}}+1}{2}\left(p^{2^{k}-2^{l}}-p^{2^{k}-2 \cdot 2^{l}}+\cdots-p^{2 \cdot 2^{l}}+p^{2^{l}}-1\right)+1 .

$$

Donc les $\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}, k \in \mathbb{N}$, sont deux à deux premiers entre eux. Cela implique que les $P\left(\frac{p^{2^{k}}+1}{2}\right)=P\left(p^{2^{k}}+1\right)$ sont des entiers distincts. En particulier, on peut trouver $k$ tel que $P\left(p^{2^{k}}+1\right) \geq p=P\left(p^{2^{k}}\right)$. Soit $k_{p}$ le plus petit $k \geq 0$ vérifiant cette propriété. On choisit $n=p^{2^{k_{p}}}$. On voit que $P(n+1) \geq P(n)$, or $n$ et $n+1$ sont premiers entre eux, donc $P(n+1)>P(n)$. Il reste à montrer que $P(n-1)<P(n)$. On écrit

$$

n-1=p^{2^{k_{p}}}-1=\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-1}}+1\right)\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-2}}+1\right) \ldots\left(p^{2}+1\right)(p+1)(p-1)

$$

donc

$$

P(n-1)=\max \left(P\left(p^{2^{k_{p}-1}}+1\right), \ldots, P(p+1), P(p-1)\right)<p=P(n)

$$

par minimalité de $k_{p}$ et parce que $P(p-1) \leq p-1<p$.

Finalement, pour tout nombre premier impair $p$, on peut trouver $n$ une puissance de $p$ telle que $P(n-1)<P(n)<P(n+1)$. Comme il y a une infinité de nombres premiers impairs, et comme les puissances de nombres premiers distincts sont distinctes, il existe une infinité de tels entiers $n$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi1-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

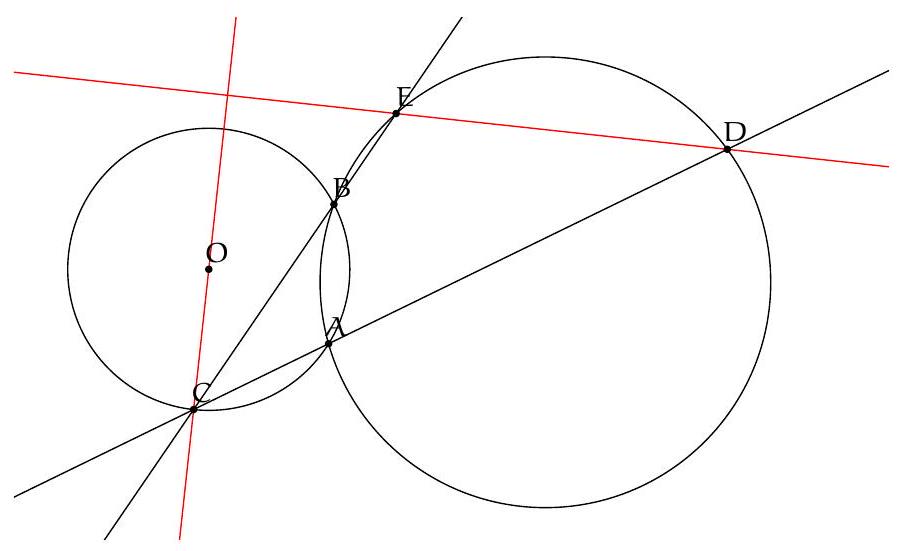

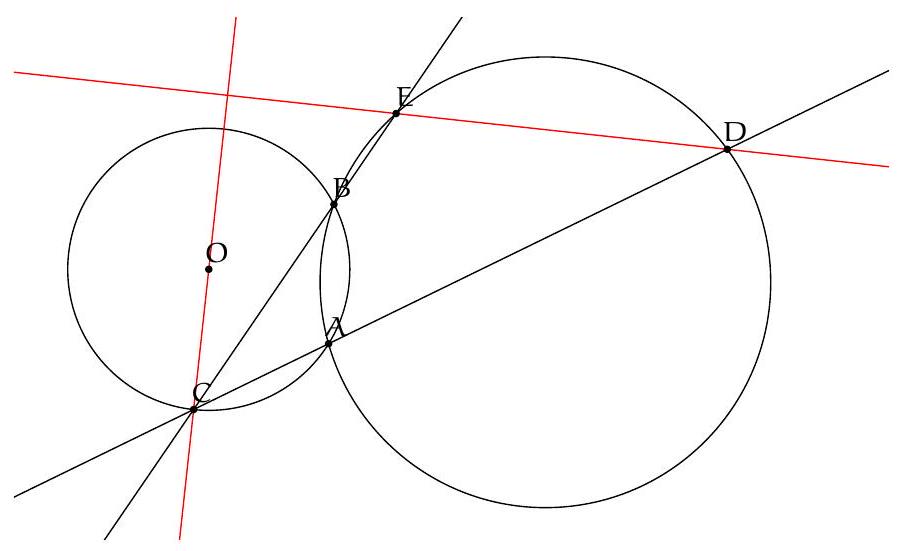

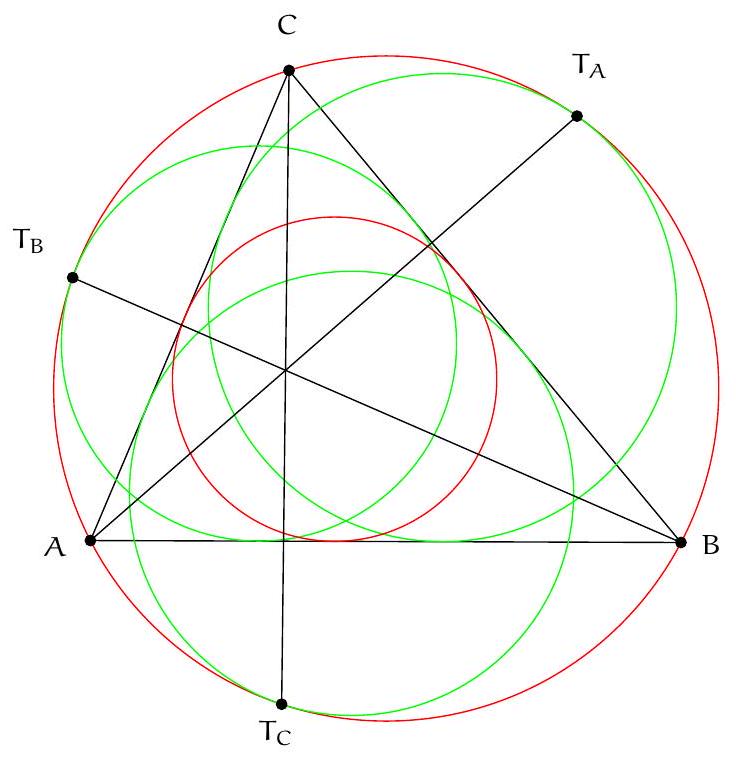

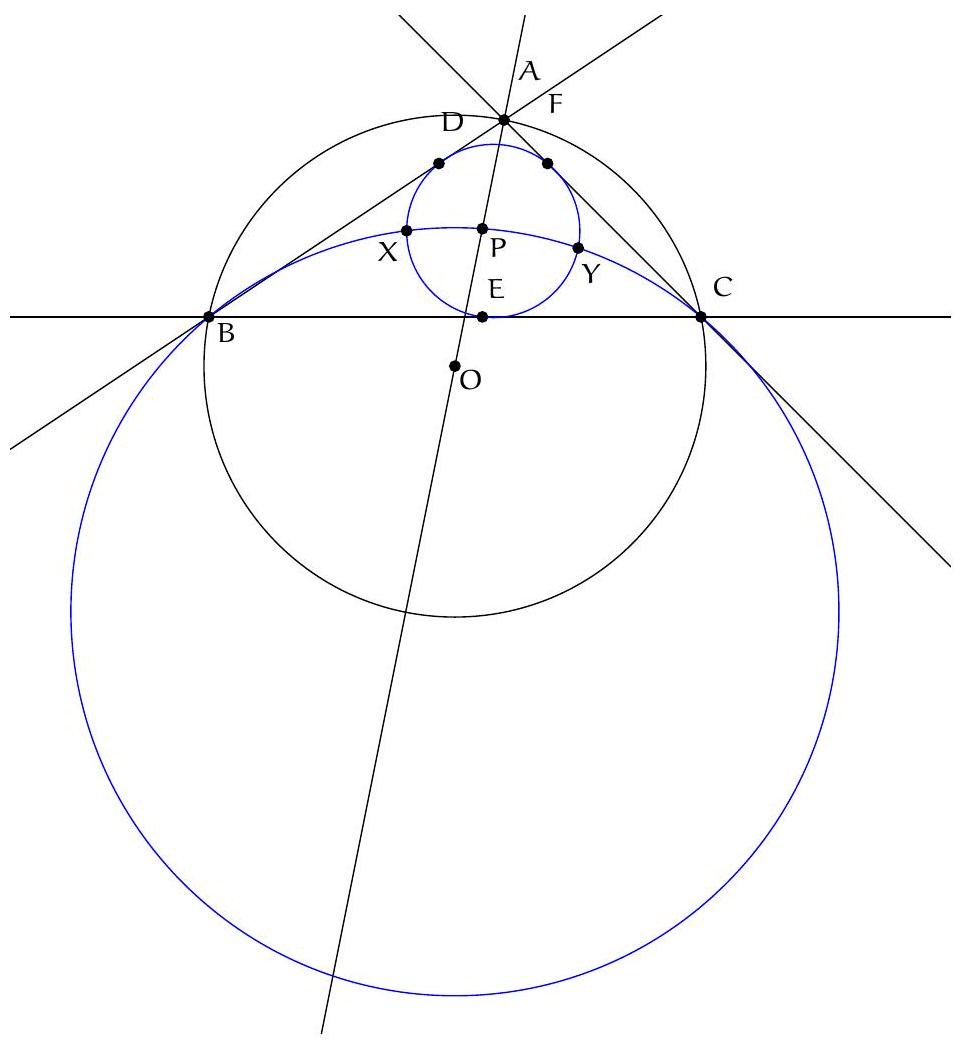

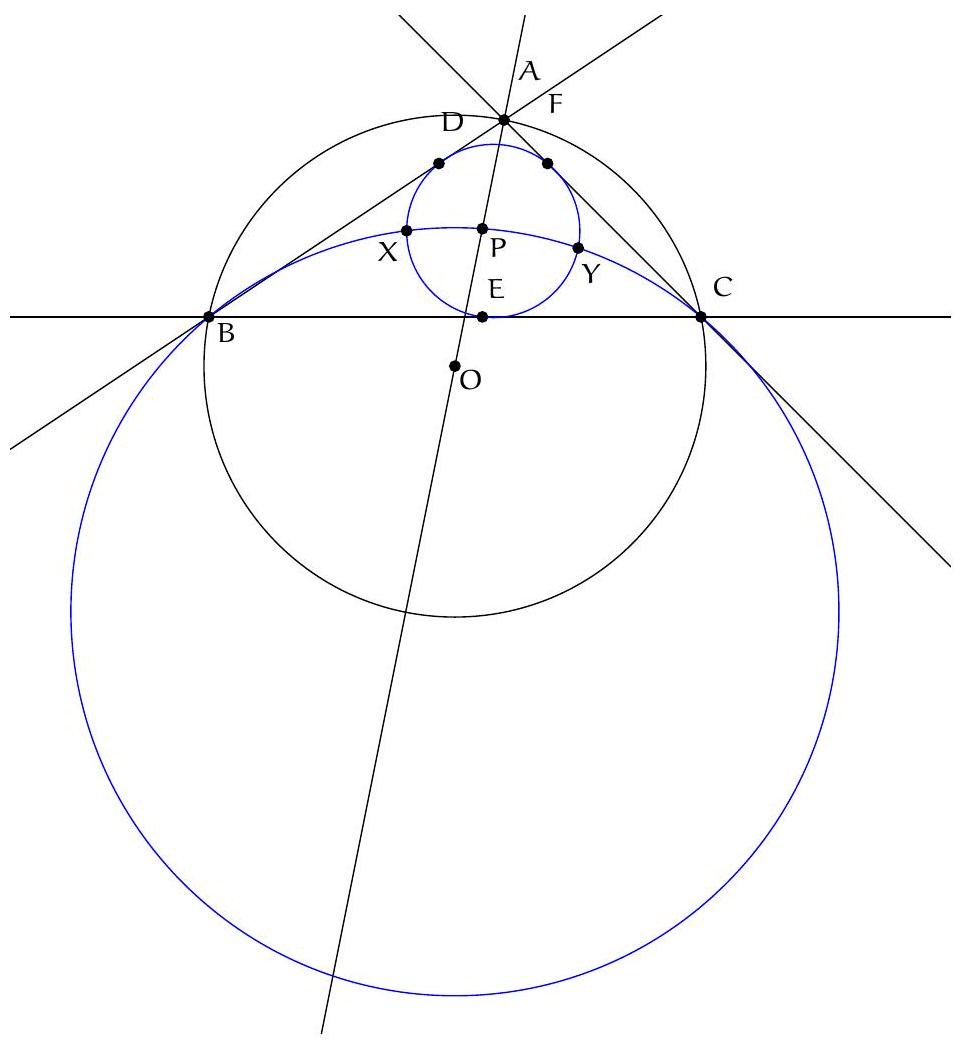

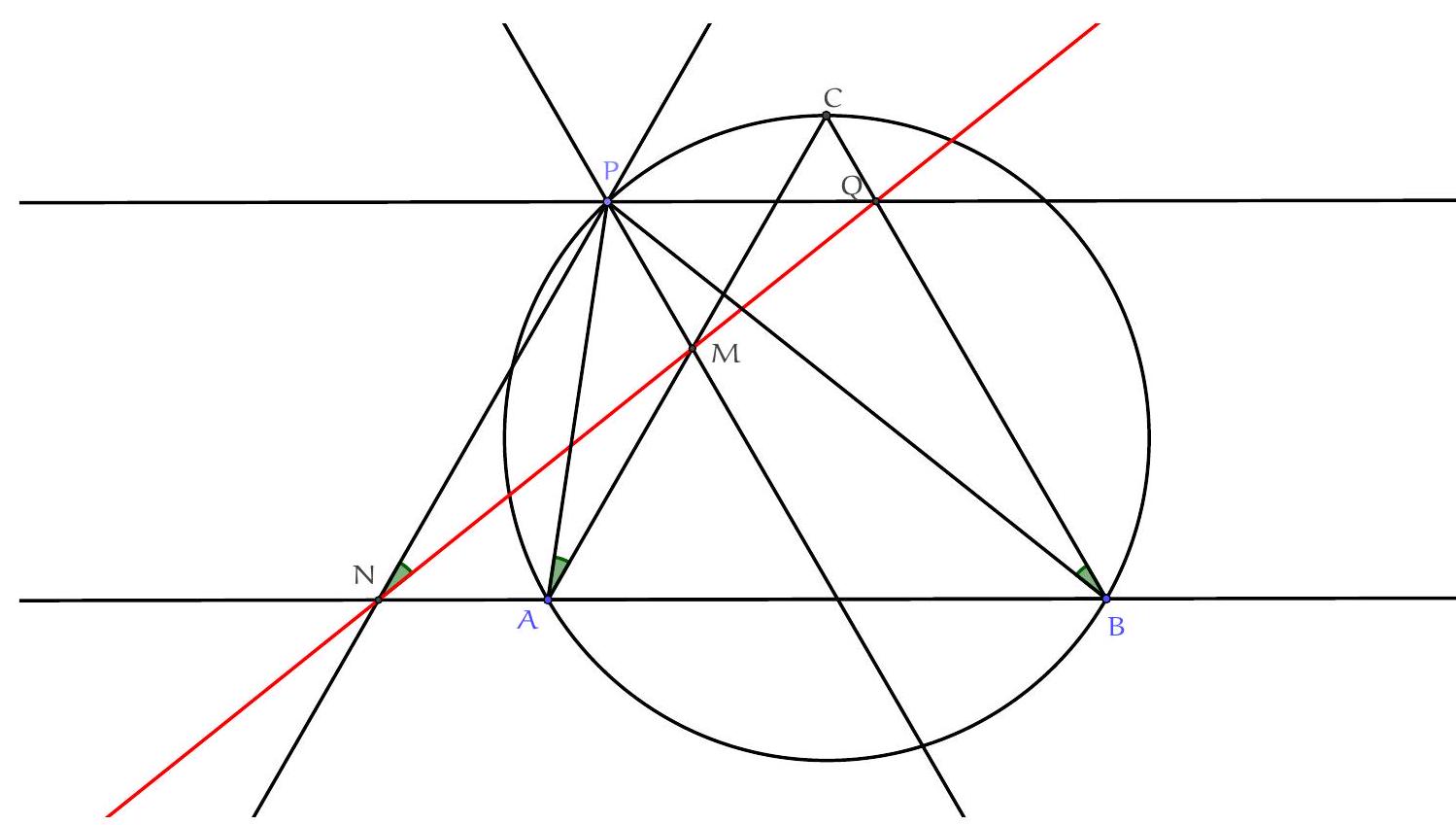

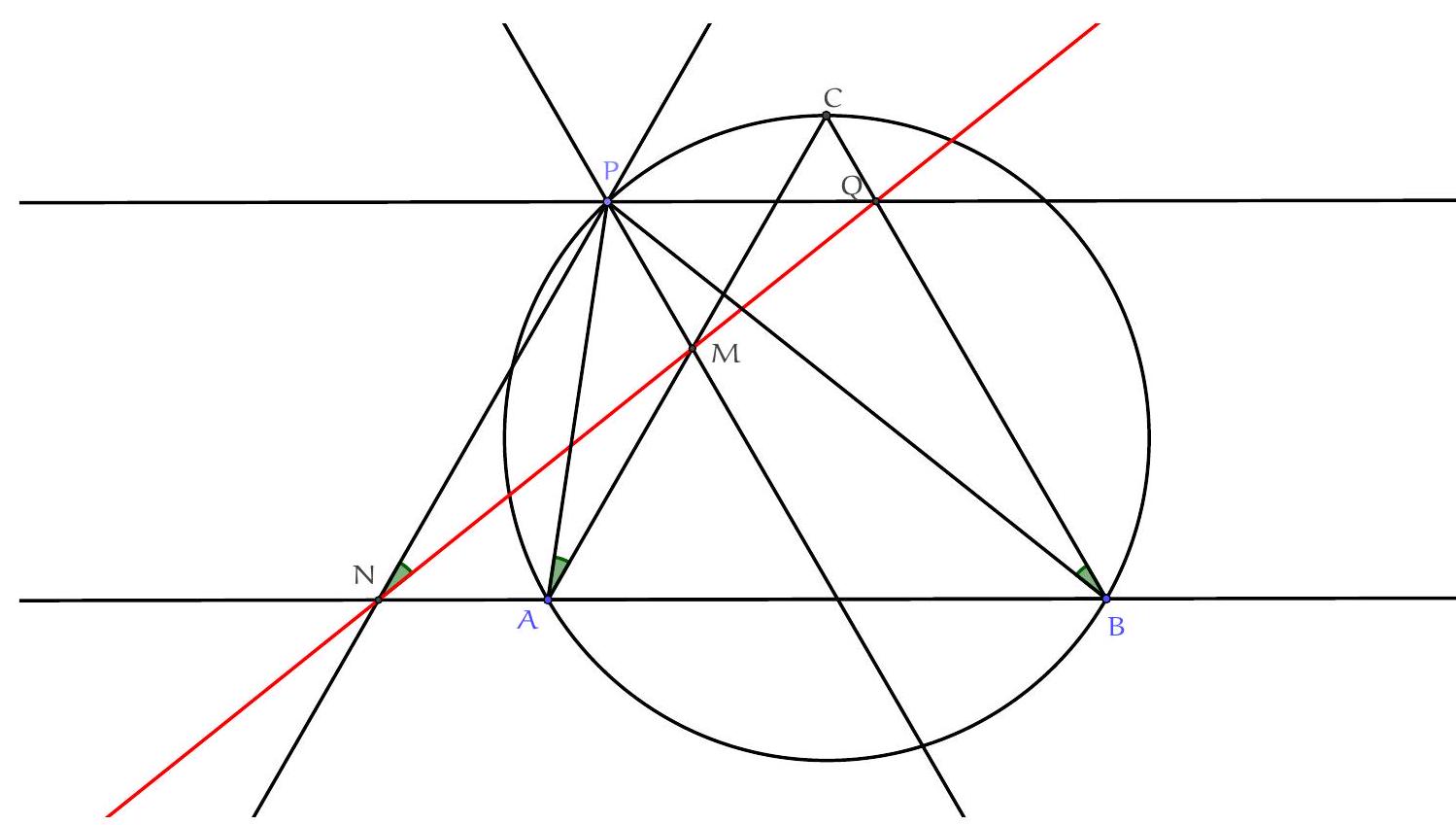

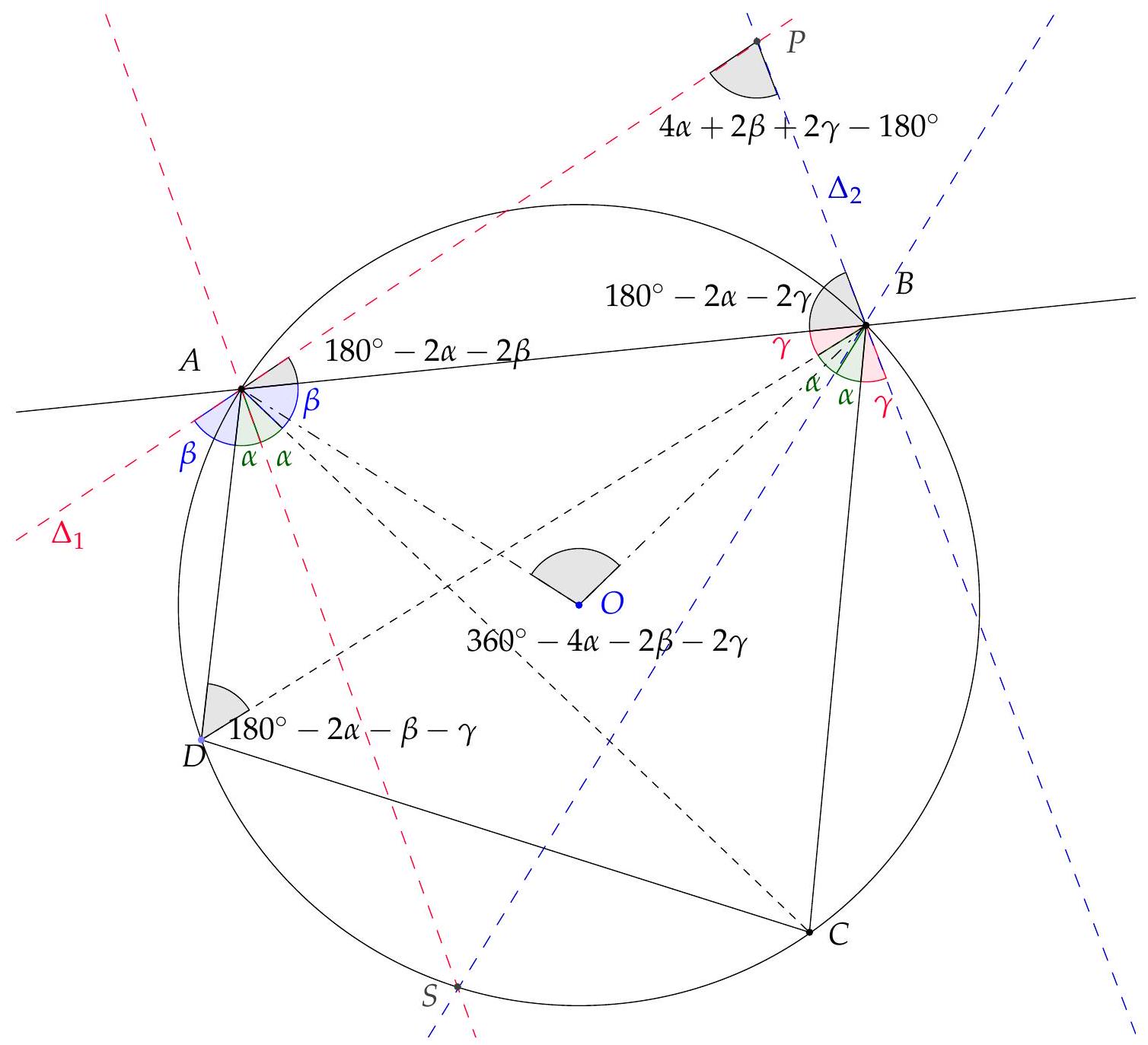

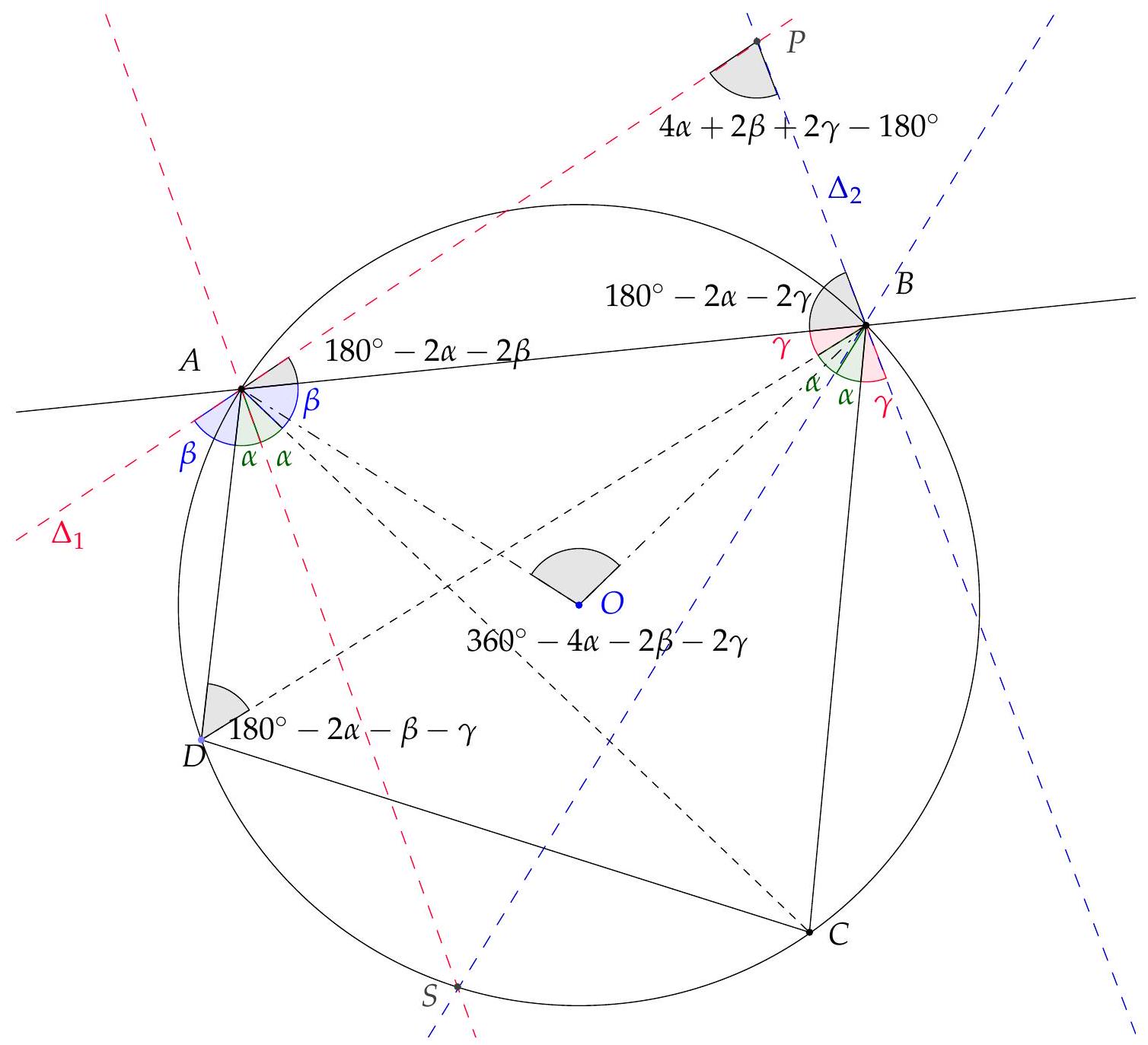

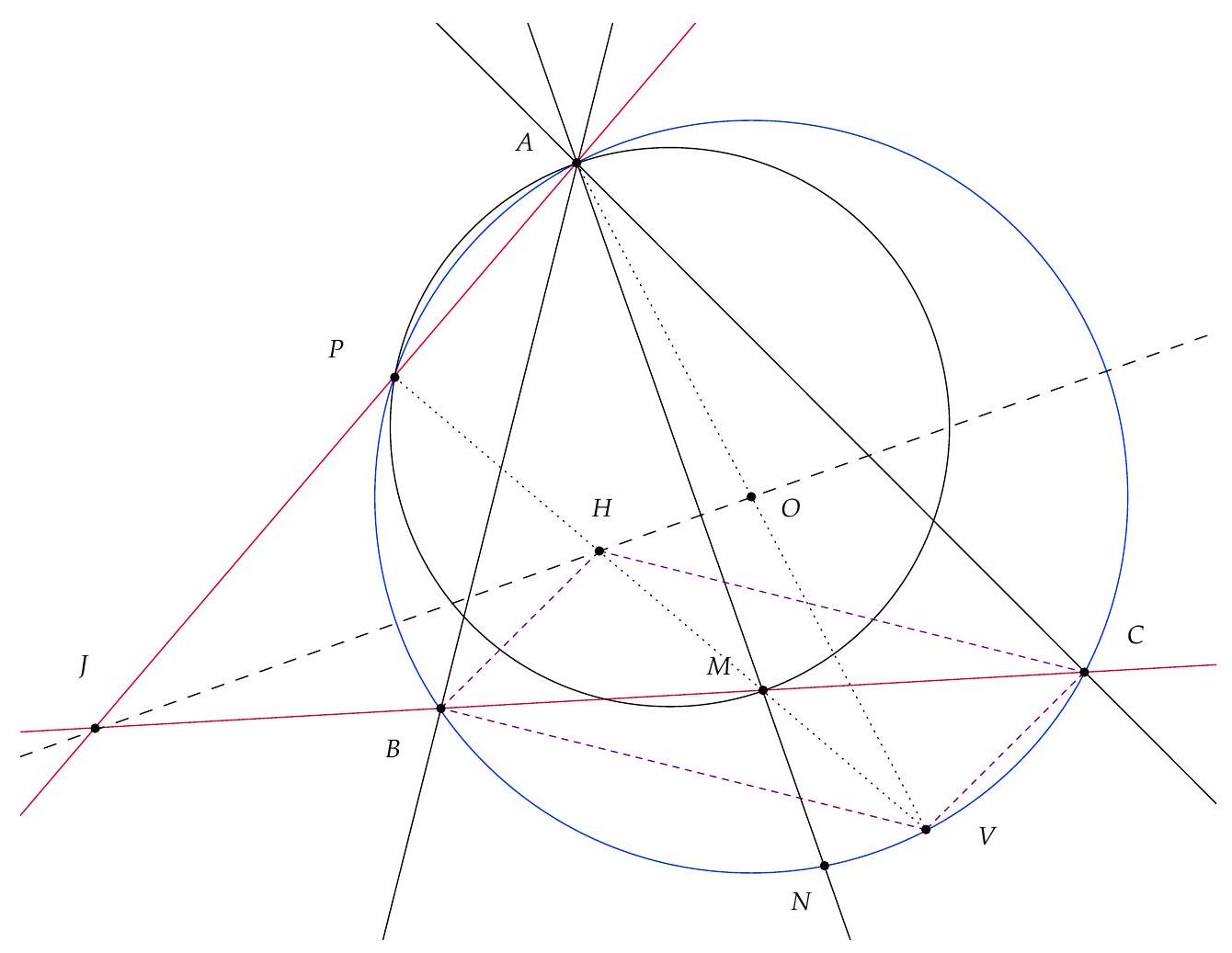

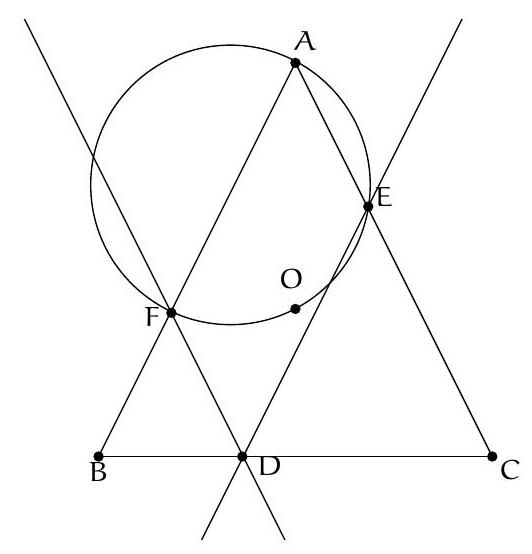

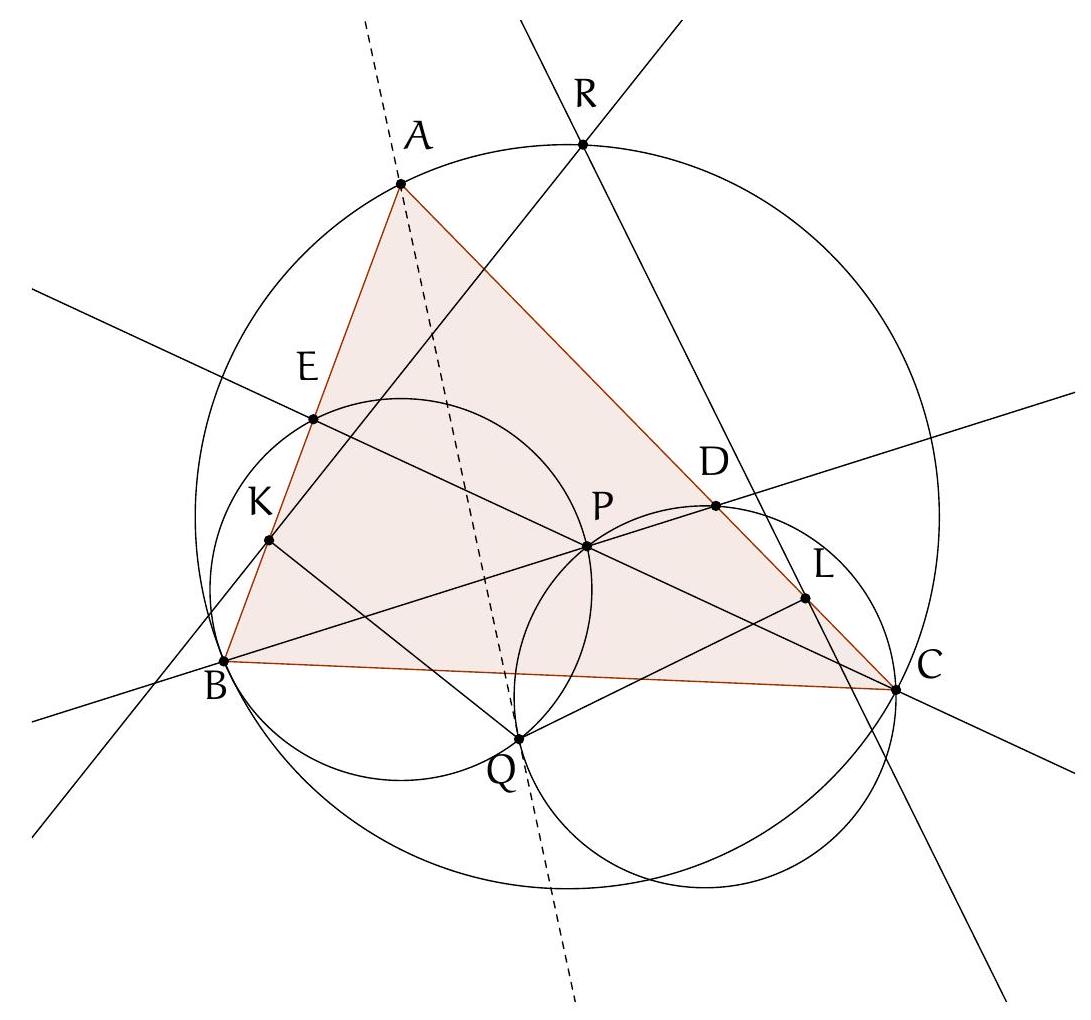

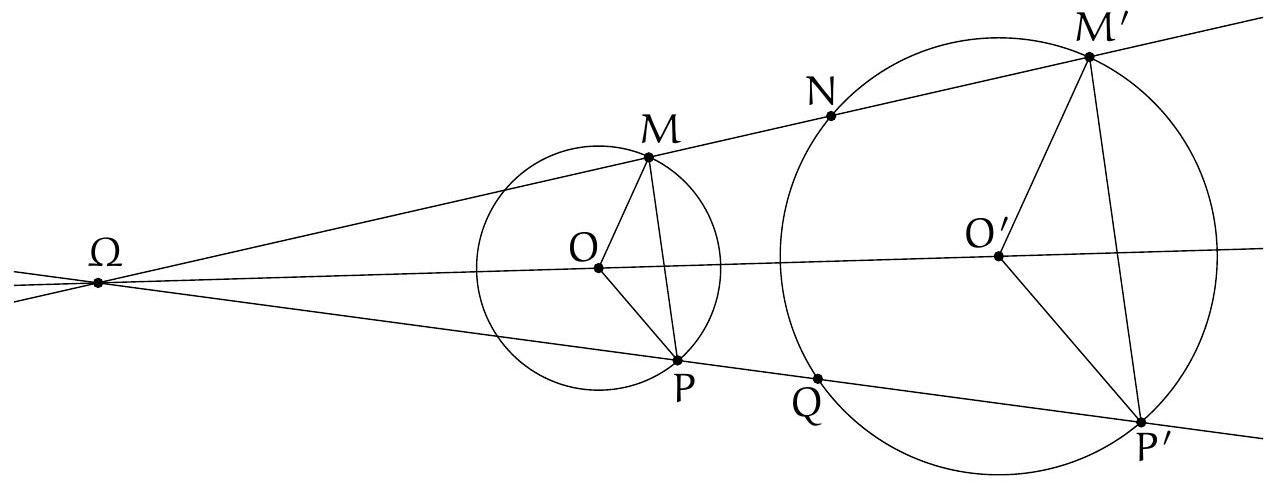

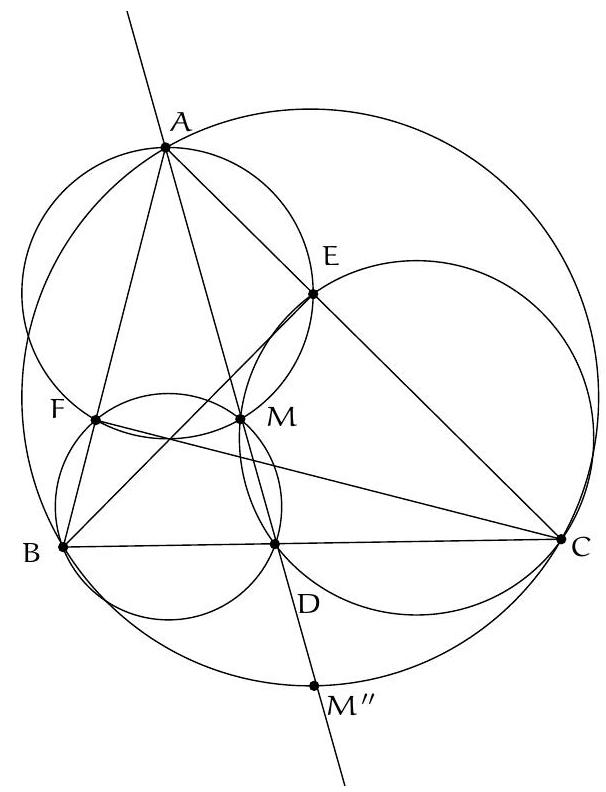

Let $\Gamma_{1}$ and $\Gamma_{2}$ be two circles intersecting at distinct points $A$ and $B$. Let $O$ be the center of $\Gamma_{1}$. Let $C$ be a point on $\Gamma_{1}$, and let $D, E$ be the intersections of $(AC)$ and $(BC)$ with $\Gamma_{2}$, respectively.

Show that $(OC)$ and $(DE)$ are perpendicular.

|

We proceed by angle chasing.

Here, we present a solution that is very (too) rigorous; it was not necessary to be so meticulous or to treat all these cases to receive the maximum score on this exercise.

Since we notice that the figure changes significantly depending on whether point $C$ is on the same side of the line (AB) as O or not, we have the choice between distinguishing cases in our angle chasing while being careful about orientation issues or working with directed angles of lines. The second method is often preferable, as long as we don't have to divide angles by two (the problem is that if we look at our directed angles of lines modulo 180 degrees and then divide by 2, we end up looking at directed angles of lines modulo 90 degrees, thus losing information). ${ }^{1}$ Here, we will mix both methods.

We calculate modulo 180 degrees:

$(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{DE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CD})+(\mathrm{CD}, \mathrm{DE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CD})+(\mathrm{AB}, \mathrm{BE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CA})+(\mathrm{CB}, \mathrm{AB})$.

Now, $2(O C, C A)+(O A, O C)=0$ and $2(C B, A B)=(O C, O A)$.

Therefore, $2(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{DE})=0$ modulo 180 degrees, so $(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{DE})$ is a multiple of 90 degrees (thus 0 or 90 degrees modulo 180), meaning that (OC) and (DE) are either parallel or perpendicular.

And here, we are stuck trying to exclude the parallel case. We can get out of this by case disjunction:

- If $A, C$, and the point diametrically opposite to $A$ on $\Gamma_{1}$ are in that order when read in the counterclockwise direction on the circle $\Gamma_{1}$, then $(O C, C A) = \widehat{O C A}$.

- Otherwise, $(OC, CA) = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{O C A}$.

- If $A, B, C$ are read in that order on the circle $\Gamma_{1}$ in the counterclockwise direction, then $(C B, A B) = \widehat{C B A}$.

- Otherwise, $(\mathrm{CB}, \mathrm{AB}) = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{CBA}}$.

- In all cases, $\widehat{C O A} = 180^{\circ} - 2 \widehat{O C A}$.

- But $\widehat{C O A} = 2 \widehat{C B A}$ if and only if $O$ and $B$ are on the same side of the line (AC).

- Conversely, if $O$ and $B$ are not on the same side of the line $(A C)$, then $\widehat{C O A} = 360^{\circ} - 2 \widehat{C B A}$.

The geometric angles have measures between 0 and 180 degrees.

If we treat all the cases presented above, by combining the equalities, we can show that the lines (OC) and (DE) are parallel.

[^0]Exercise 2. Let $A B C D$ be a convex quadrilateral. ${ }^{2}$ We are given two points $E, F$ such that $E, B, C, F$ are collinear in that order. We also assume that $\widehat{B A E} = \widehat{\mathrm{CDF}}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{EAF}} = \widehat{\mathrm{FDE}}$. Show that $\widehat{\mathrm{FAC}} = \widehat{\mathrm{EDB}}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $\Gamma_{1}$ et $\Gamma_{2}$ deux cercles se coupant en $A$ et $B$ distincts. Notons O le centre de $\Gamma_{1}$. Soit $C$ un point de $\Gamma_{1}$, soit $D, E$ les intersections respectives de (AC) et de (BC) avec $\Gamma_{2}$.

Montrer que (OC) et ( DE ) sont perpendiculaires.

|

On procède par chasse aux angles.

On présente ici une solution qui se veut très (trop) rigoureuse, il n'y avait pas besoin d'être aussi pointilleux ni de traiter tous ces cas pour recevoir la note maximale à cet exercice.

Comme on remarque que la figure change beaucoup selon que le point $C$ est du même côté de la droite ( AB ) que O ou non, on a le choix entre distinguer des cas dans notre chasse aux angles en faisant attention aux problèmes d'orientation ou travailler avec des angles orientés de droites. La deuxième méthode est souvent préférable, tant qu'on n'a pas à diviser des angles par deux (le problème est que, si on regarde nos angles orientés de droites modulo 180 degrés et qu'on divise par 2 , on se retrouve à regarder des angles orientés de droite modulo 90 degrés, donc on perd de l'information). ${ }^{1} \mathrm{Ici}$, on va panacher les deux méthodes.

On calcule modulo 180 degrés :

$(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{DE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CD})+(\mathrm{CD}, \mathrm{DE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CD})+(\mathrm{AB}, \mathrm{BE})=(\mathrm{OC}, \mathrm{CA})+(\mathrm{CB}, \mathrm{AB})$.

Or $2(O C, C A)+(O A, O C)=0$ et $2(C B, A B)=(O C, O A)$.

Donc 2 (OC, DE$)=0$ modulo 180 degrés, donc (OC, DE) est un multiple de 90 degrés (donc 0 ou 90 degrés modulo 180)donc (OC) et (DE) sont parallèles ou perpendiculaires.

Et là, on est embêtés pour exclure le cas parallèle. On peut s'en sortir par disjonction de cas:

- Si $A, C$ et le point diamétralement opposé à $A$ sur $\Gamma_{1}$ sont dans cet ordre quand on lit dans le sens trigonométrique (anti-horaire) sur le cercle $\Gamma_{1}$, alors $(O C, C A)=$ $\widehat{O C A}$

- Sinon, (OC, CA) $=180^{\circ}-\widehat{O C A}$

- Si $A, B, C$ se lisent dans cet ordre sur le cercle $\Gamma_{1}$ dans les sens trigonométrique, alors $(C B, A B)=\widehat{C B A}$.

- Sinon, $(\mathrm{CB}, \mathrm{AB})=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{CBA}}$.

- On a dans tous les cas $\widehat{C O A}=180^{\circ}-2 \widehat{O C A}$.

- Mais $\widehat{C O A}=2 \widehat{C B A}$ si et seulement si $O$ et $B$ sont du même côté de la droite (AC).

- En revanche, si $O$ et $B$ ne sont pas du même côté de la droite $(A C), \widehat{C O A}=$ $360^{\circ}-2 \widehat{C B A}$.

Les angles géométriques ayant des mesures entre 0 et 180 degrés.

Si on traite tous les cas présentés ci-dessus, en combinant les égalités, on arrive à montrer que les droites (OC) et (DE) sont parallèles.

[^0]Exercice 2. Soit un quadrilatère $A B C D$ convexe. ${ }^{2}$ On se donne $E, F$ deux points tels que $E, B, C, F$ soient alignés dans cet ordre. On suppose de plus que $\widehat{B A E}=$ $\widehat{\mathrm{CDF}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{EAF}}=\widehat{\mathrm{FDE}}$. Montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{FAC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{EDB}}$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $\Gamma_{1}$ and $\Gamma_{2}$ be two circles intersecting at distinct points $A$ and $B$. Let $O$ be the center of $\Gamma_{1}$. Let $C$ be a point on $\Gamma_{1}$, and let $D, E$ be the intersections of $(AC)$ and $(BC)$ with $\Gamma_{2}$, respectively.

Show that $(OC)$ and $(DE)$ are perpendicular.

|

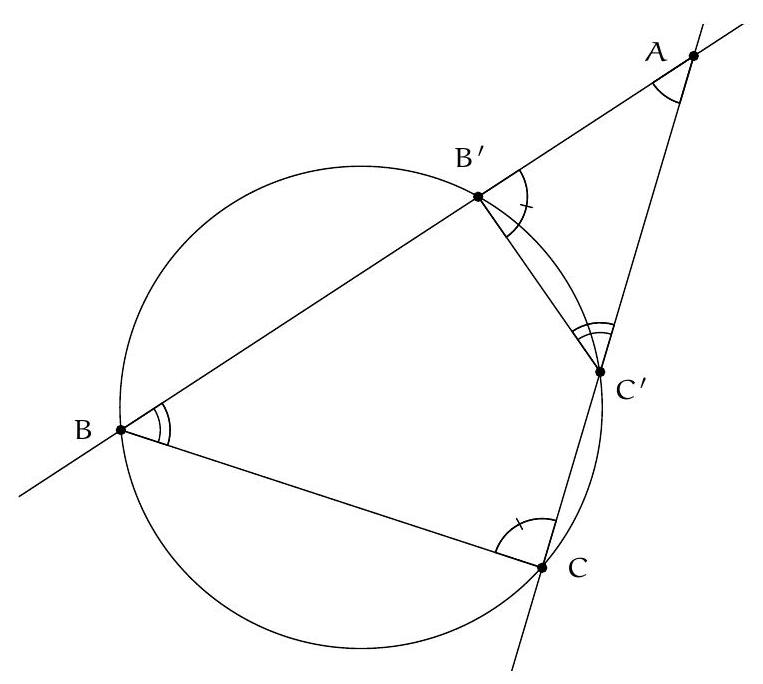

This is another angle chase. Since \(\widehat{F A E} = \widehat{FDE}\) and \(A, D\) are on the same side of \((EF)\), the points \(A, D, E, F\) are concyclic.

Furthermore, to show that \(\widehat{F A C} = \widehat{E D B}\), it suffices to show that \(\widehat{C A B} = \widehat{F A B} - \widehat{F A C}\) is equal to \(\widehat{CDB} = \widehat{CDE} - \widehat{EDB}\), in other words, that \(A, B, C, D\) are concyclic. To do this, we need to show that \(\widehat{D A B} + \widehat{D C B} = 180^{\circ}\). We have:

\[

\widehat{D A B} = \widehat{D A F} + \widehat{F A B} = \widehat{D E F} + \widehat{C D E} = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{ECD}

\]

which proves the concyclicity of \(A, B, C, D\) and thus the desired result.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $\Gamma_{1}$ et $\Gamma_{2}$ deux cercles se coupant en $A$ et $B$ distincts. Notons O le centre de $\Gamma_{1}$. Soit $C$ un point de $\Gamma_{1}$, soit $D, E$ les intersections respectives de (AC) et de (BC) avec $\Gamma_{2}$.

Montrer que (OC) et ( DE ) sont perpendiculaires.

|

C'est encore une chasse aux angles. Comme $\widehat{F A E}=\widehat{\mathrm{FDE}}$ et $A, D$ sont du même côté de (EF), les points $A, D, E, F$ sont cocycliques.

De plus, pour montrer que $\widehat{F A C}=\widehat{E D B}$, il suffit de montrer que $\widehat{C A B}=\widehat{F A B}-\widehat{F A C}$ est égal à $\widehat{\mathrm{CDB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CDE}}-\widehat{\mathrm{EDB}}$, autrement dit que $A, B, C, D$ sont cocycliques. Montrons pour cela que $\widehat{D A B}+\widehat{D C B}=180^{\circ}$. On a :

$$

\widehat{D A B}=\widehat{D A F}+\widehat{F A B}=\widehat{D E F}+\widehat{C D E}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ECD}}

$$

ce qui prouve la cocyclicité de $A, B, C, D$ et donc le résultat voulu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## \nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

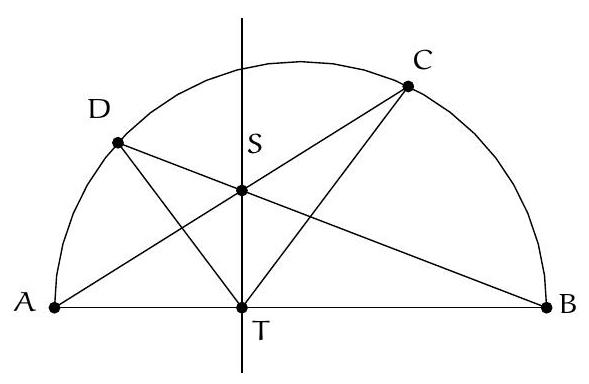

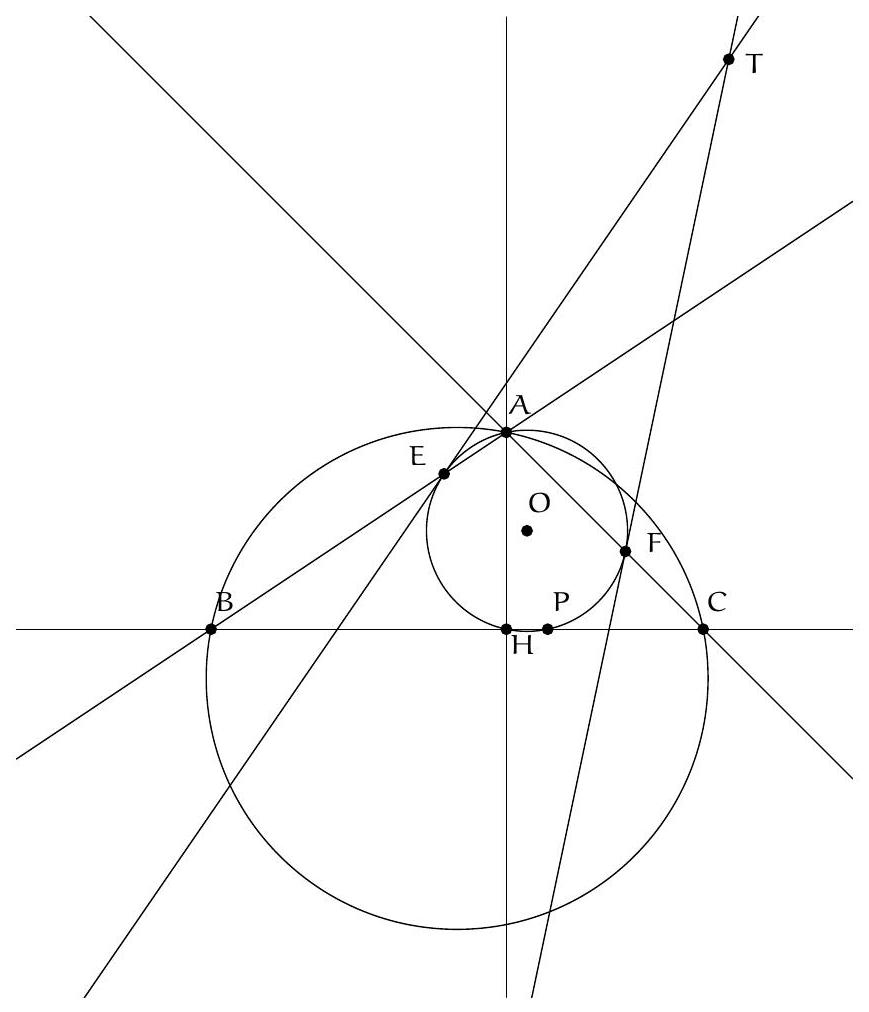

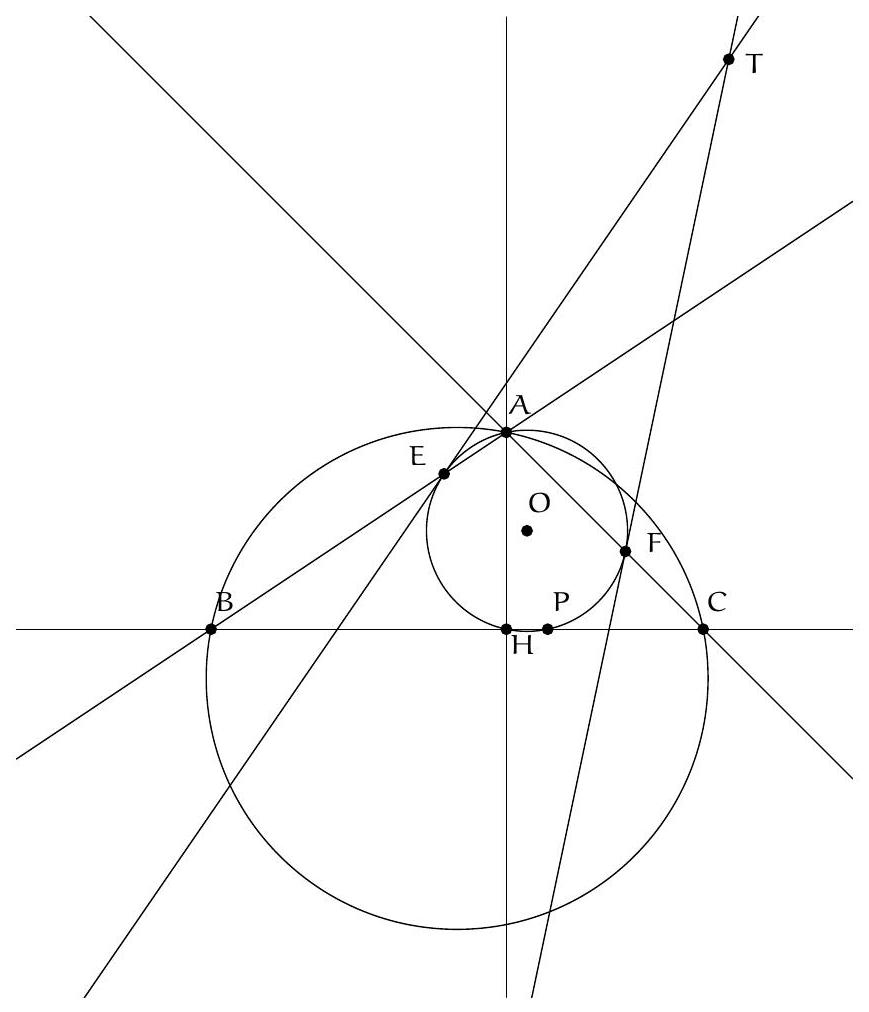

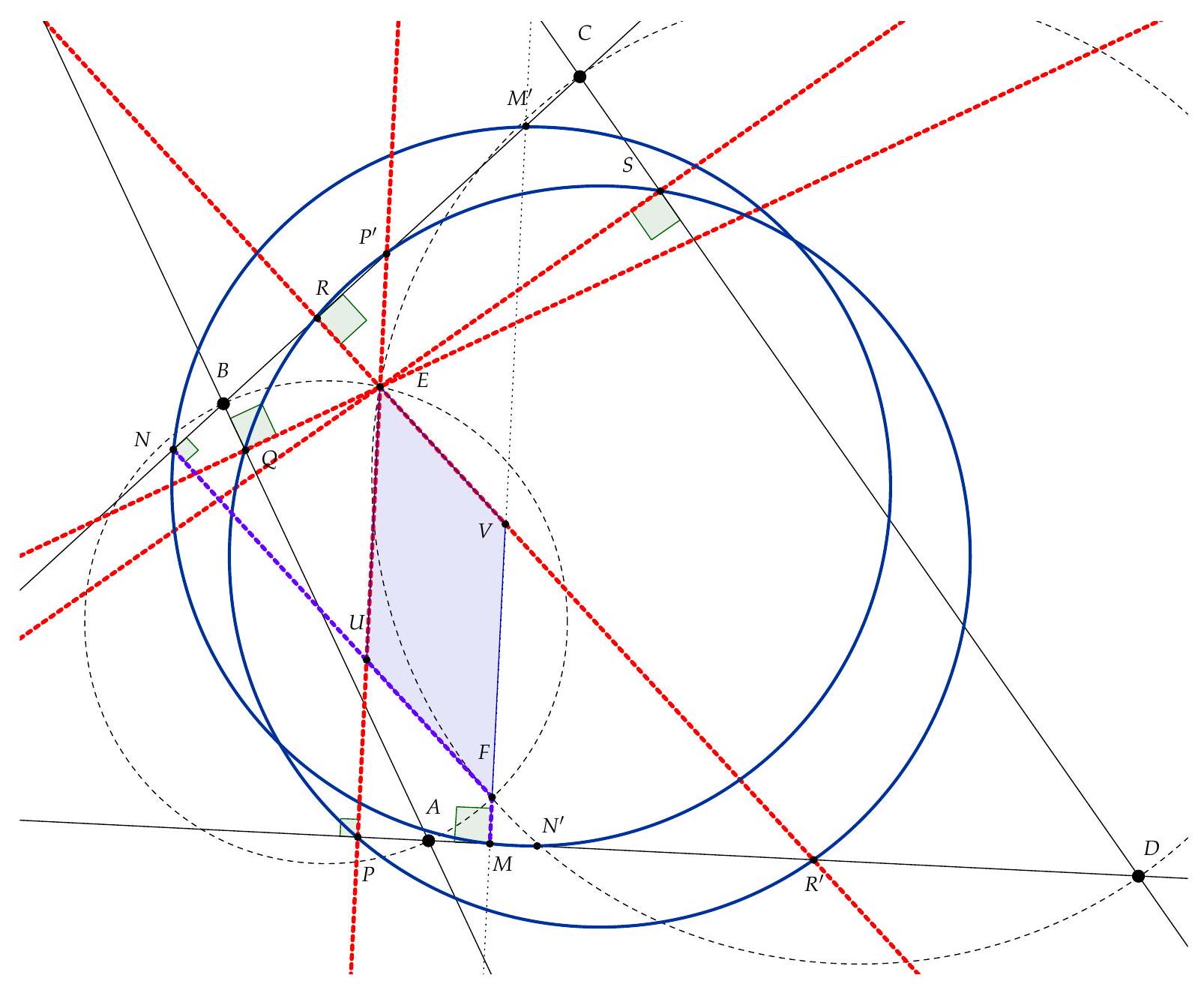

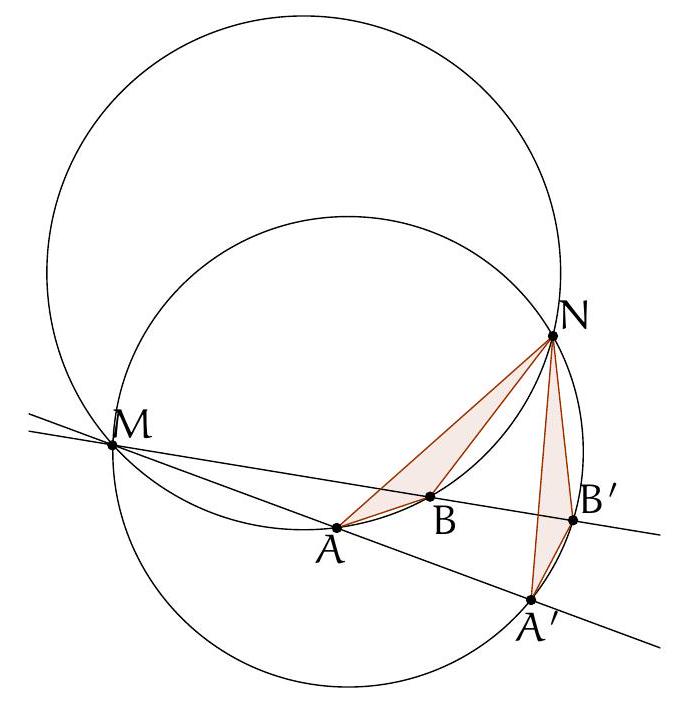

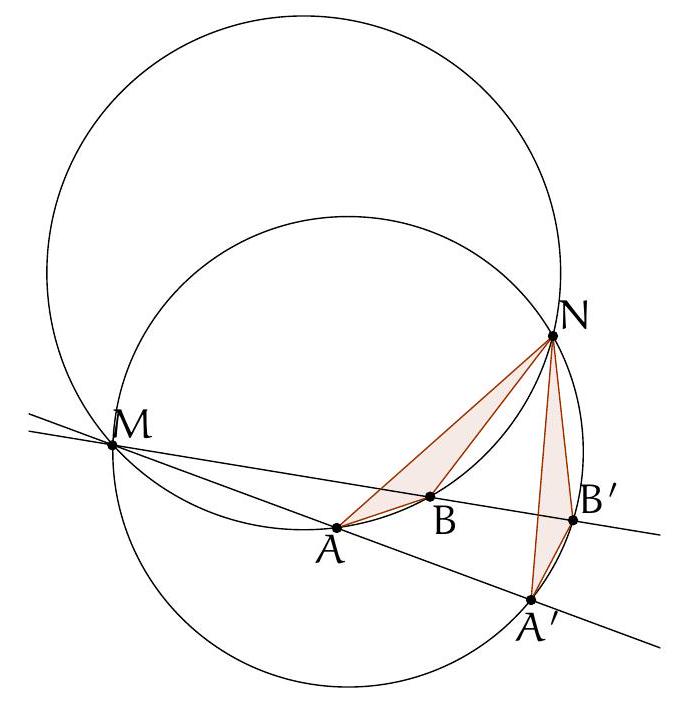

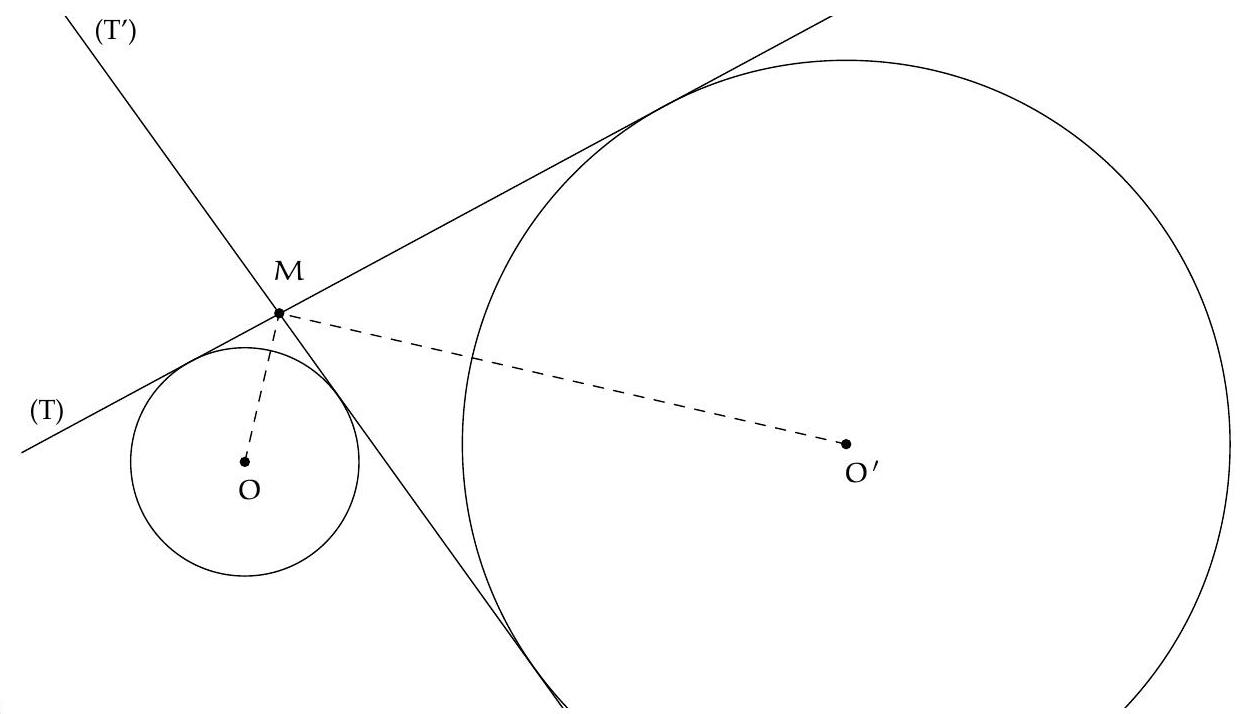

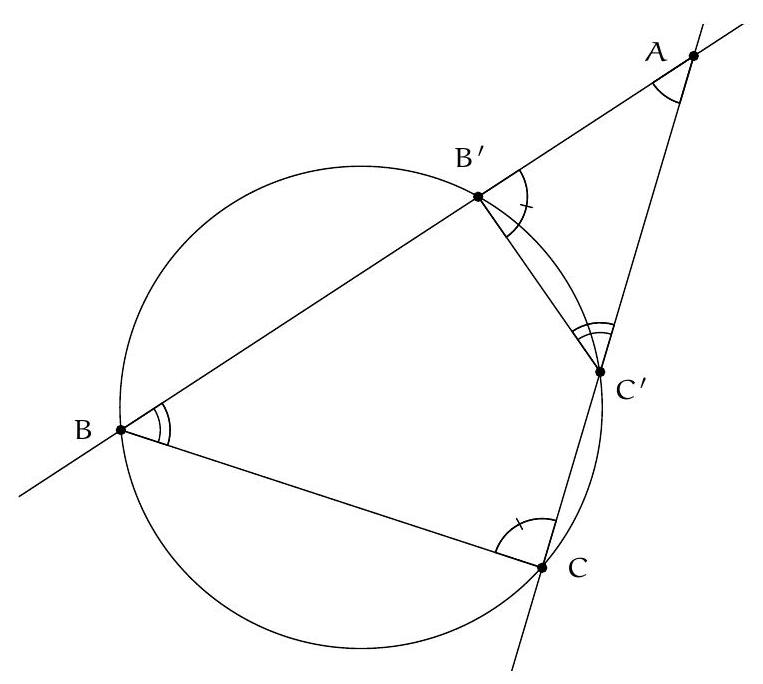

Let $[A B]$ be the diameter of a semicircle on which two points $C$ and $D$ are taken. Let $S$ be the intersection of $(A C)$ and $(B D)$, and $T$ the foot of the perpendicular from $S$ to $[A B]$.

[^1]Show that $(ST)$ is the bisector of the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{CTD}}$.

|

We solve this by angle chasing. The points \(A, D, S, T\) are concyclic (on the circle with diameter \([A S]\)) and similarly the points \(B, C, S, T\). Therefore, \(\widehat{S T D} = \widehat{S A D}\), and \(\widehat{S T C} = \widehat{S B C}\). Since \(\widehat{S A D} = \widehat{C A D} = \widehat{\mathrm{CBD}} = \widehat{\mathrm{SBC}}\) by the concyclicity of the points \(A, B, C, D\), we have \(\widehat{S T C} = \widehat{S T D}\).

We can also solve this problem using projective geometry. Indeed, we notice that \((ST)\) is the angle bisector of \(\widehat{\mathrm{CTD}}\) if and only if \((AB)\), \((ST)\), \((TD)\), \((TC)\) are harmonic (thanks to the 2/4 lemma). Let \(F\) be the intersection of \((BD)\) and \((TC)\). It suffices to show that \(B, S, D, F\) are harmonic, so it suffices to show that \(B, A, (C D) \cap (A B), T\) are harmonic. Now, \((C D) \cap (A B)\) is by construction on the polar of \(S\), so the polar of \((C D) \cap (A B)\) passes through \(S\). Moreover, it is perpendicular to \((A B)\), so \(c'\) is \((S T)\). This is why \((C D) \cap (A B), T, A, B\) are harmonic, which concludes the proof.

## Common Exercises

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $[A B]$ le diamètre d'un demi-cercle sur lequel on prend deux points $C$ et $D$. Soit $S$ l'intersection de ( $A C)$ et $(B D)$ et $T$ le pied de la perpendiculaire à $[A B]$ issue de $S$.

[^1]Montrer que (ST) est la bissectrice de l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{CTD}}$.

|

On s'en sort par chasse aux angles. Les points $A, D, S, T$ sont cocycliques (sur le cercle de diamètre $[A S])$ et de même les points $B, C, S, T$. Donc $\widehat{S T D}=\widehat{S A D}$, et $\widehat{S T C}=\widehat{S B C}$. Comme $\widehat{S A D}=\widehat{C A D}=\widehat{\mathrm{CBD}}=\widehat{\mathrm{SBC}}$ par cocyclicité des points $A, B, C, D$, on a bien $\widehat{S T C}=\widehat{S T D}$.

On peut aussi résoudre cet exercice avec de la géométrie projective. En effet, on remarque (ST) est la bissectrice de $\widehat{\mathrm{CTD}}$ si et seulement si (AB), (ST), (TD), (TC) sont harmoniques (grâce au lemme 2/4). Soit F l'intersection de (BD) et de (TC). Il suffit de montrer que $B, S, D, F$ sont harmoniques, donc il suffit de montrer que $B, A,(C D) \cap(A B), T$ sont harmoniques. Or $(C D) \cap(A B)$ est par construction sur la polaire de $S$ donc la polaire de $(C D) \cap(A B)$ passe par $S$. De plus, elle est perpendiculaire à $(A B)$, donc $c^{\prime}$ est $(S T)$. C'est pourquoi on a bien $(C D) \cap(A B), T, A$, $B$ harmoniques, ce qui conclut.

## Exercices Communs

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

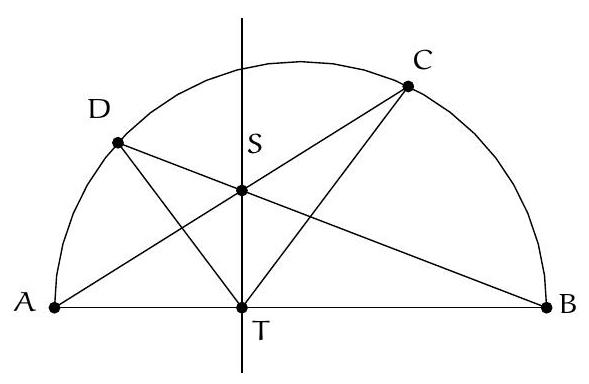

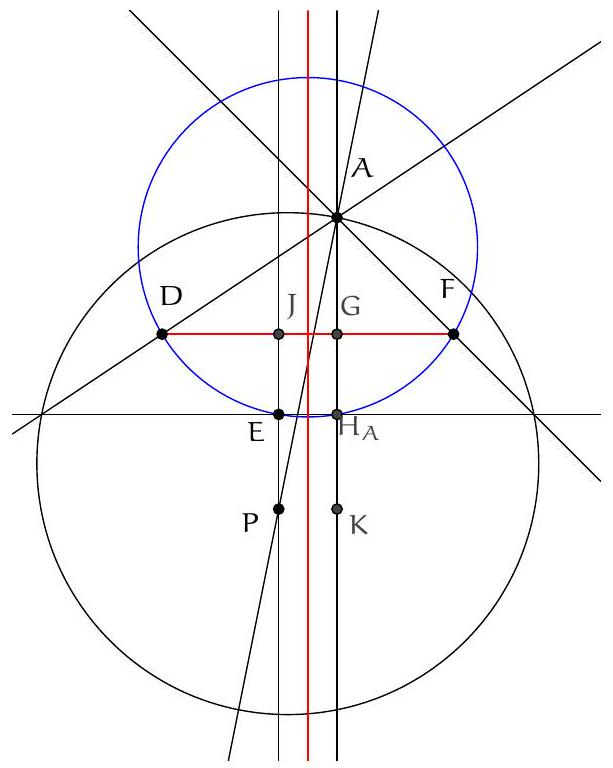

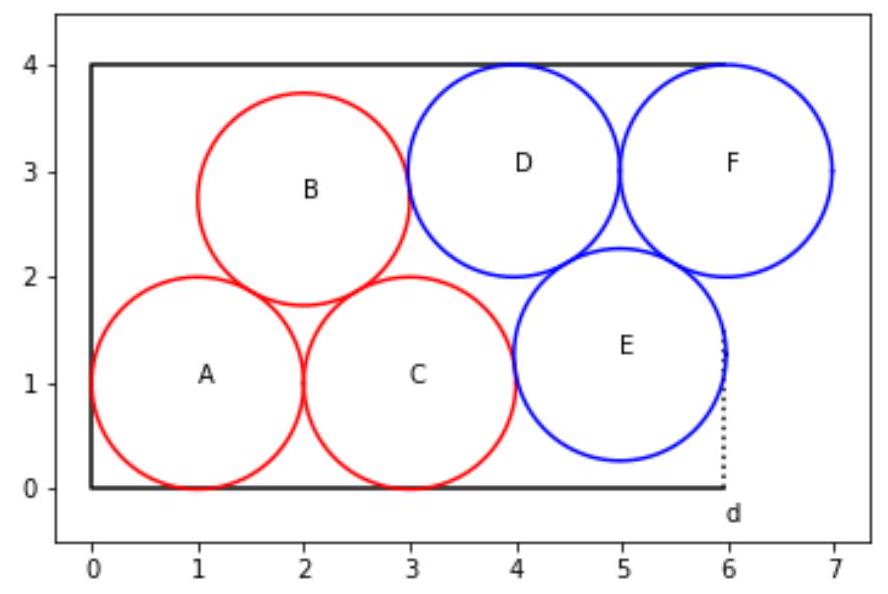

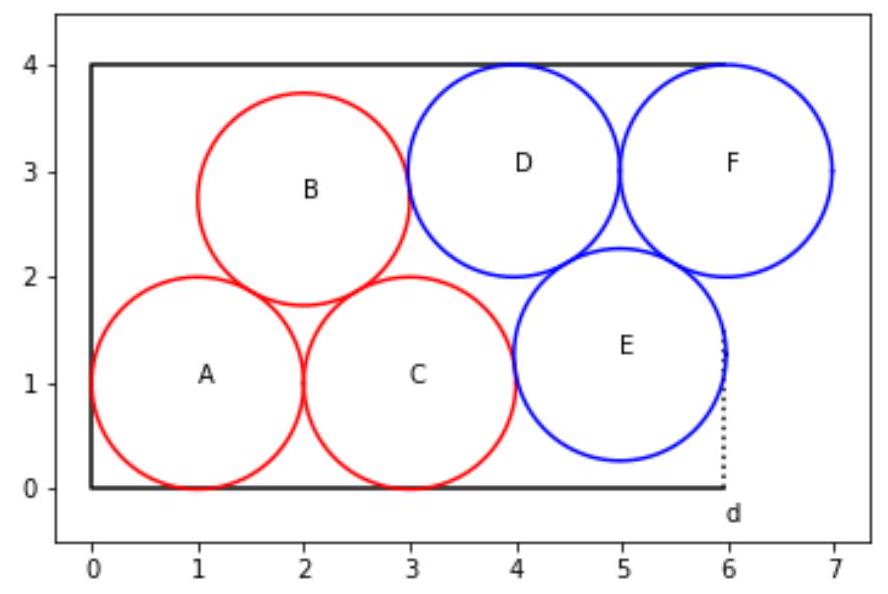

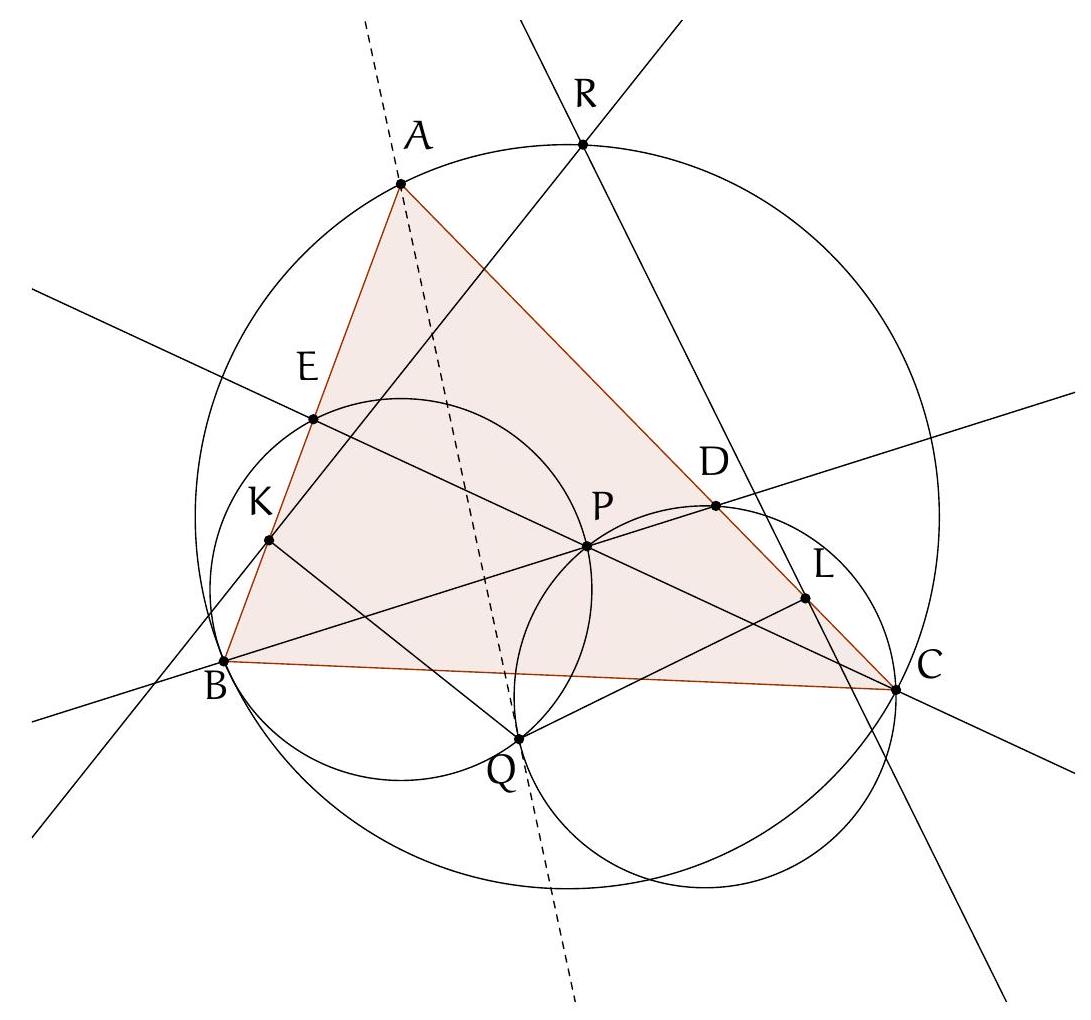

Let $ABC$ be a triangle such that $AB < AC$, $H$ its orthocenter, $\Gamma$ its circumcircle, and $d$ the tangent to $\Gamma$ at $A$. Consider the circle centered at $B$ passing through $A$. It intersects $d$ at $D$ and $(AC)$ at $E$.

Show that $D$, $E$, and $H$ are collinear.

|

First, we notice that the height from $B$ in $ABC$ is the perpendicular bisector of [AE]. Let $L$ be its intersection point with ($AC$). By the power of a point, $CE \cdot CA = CB^2 - AB^2 = CL^2 - AL^2 = CA \cdot (CL - AL)$, so $LA = LE$.

Therefore, HAE is isosceles at H. Thus, by angle chasing,

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{HEA}} = \widehat{\mathrm{HAC}} = 90^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{ACB}} = 90^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{DAB}} = \frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{ABD}} = \widehat{\mathrm{DEA}}.

$$

Therefore, D, E, H are collinear.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle tel que $A B<A C, H$ son orthocentre, $\Gamma$ son cercle circonscrit, d la tangente à $\Gamma$ en $A$. On considère le cercle de centre $B$ passant par $A$. Il coupe d en D et ( $A C$ ) en $E$.

Montrer que D, E, H sont alignés.

|

On remarque tout d'abord que la hauteur issue de $B$ dans $A B C$ est la médiatrice de [AE]. Soit en effet $L$ son point d'intersection avec ( $A C$ ). Par la puissance d'un point, $C E \cdot C A=C B^{2}-A B^{2}=C L^{2}-A L^{2}=C A \cdot(C L-A L)$ donc $L A=L E$.

Donc HAE est isocèle en H. Donc, par chasse aux angles,

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{HEA}}=\widehat{\mathrm{HAC}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ACB}}=90^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{DAB}}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{ABD}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DEA}} .

$$

Donc D, E, H sont alignés.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

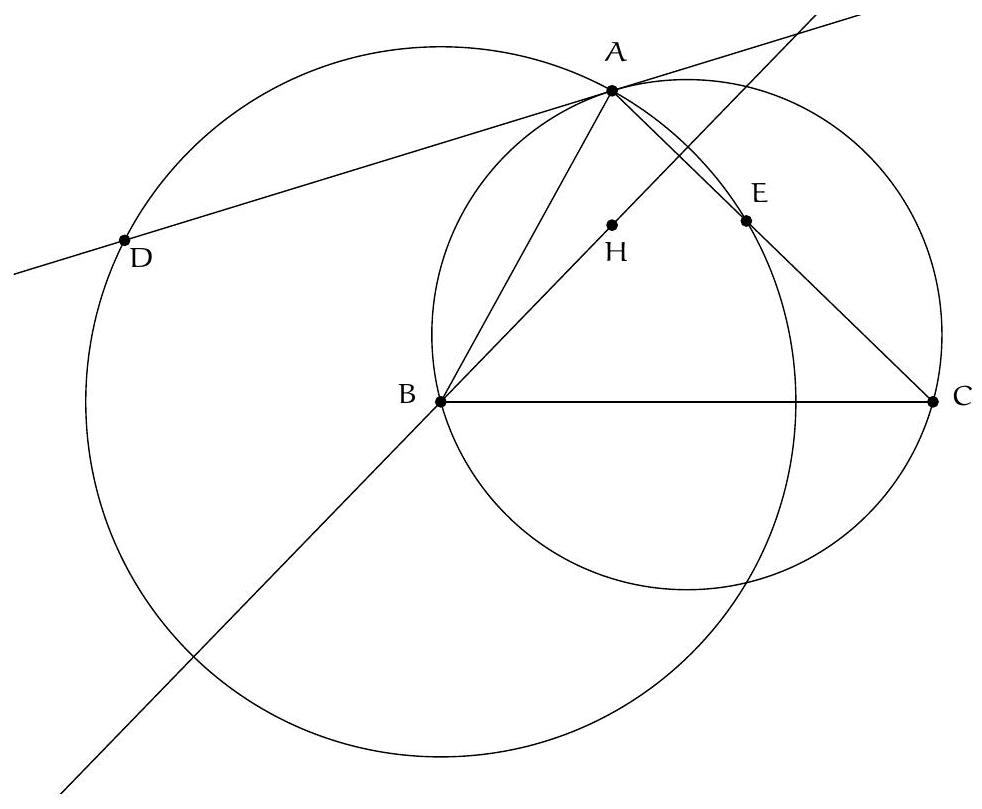

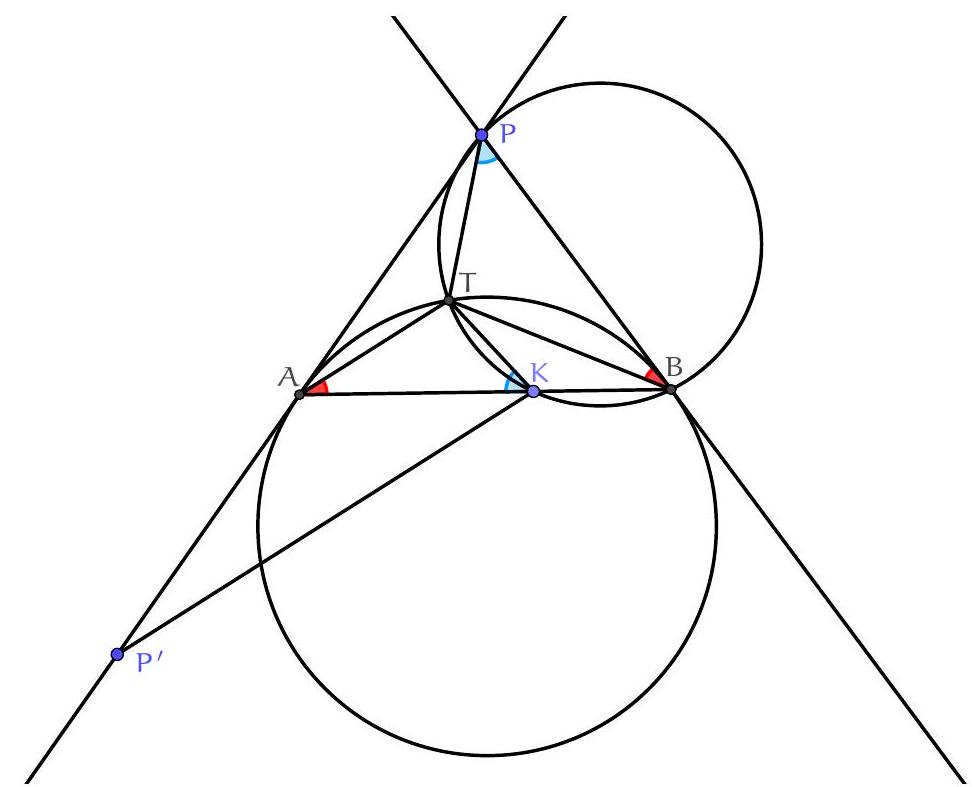

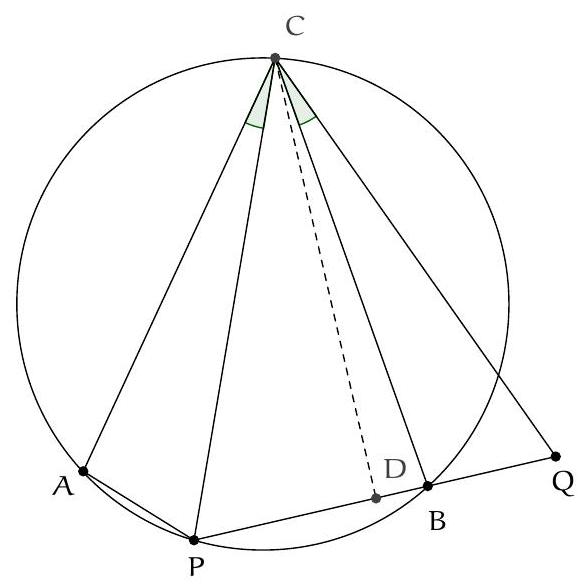

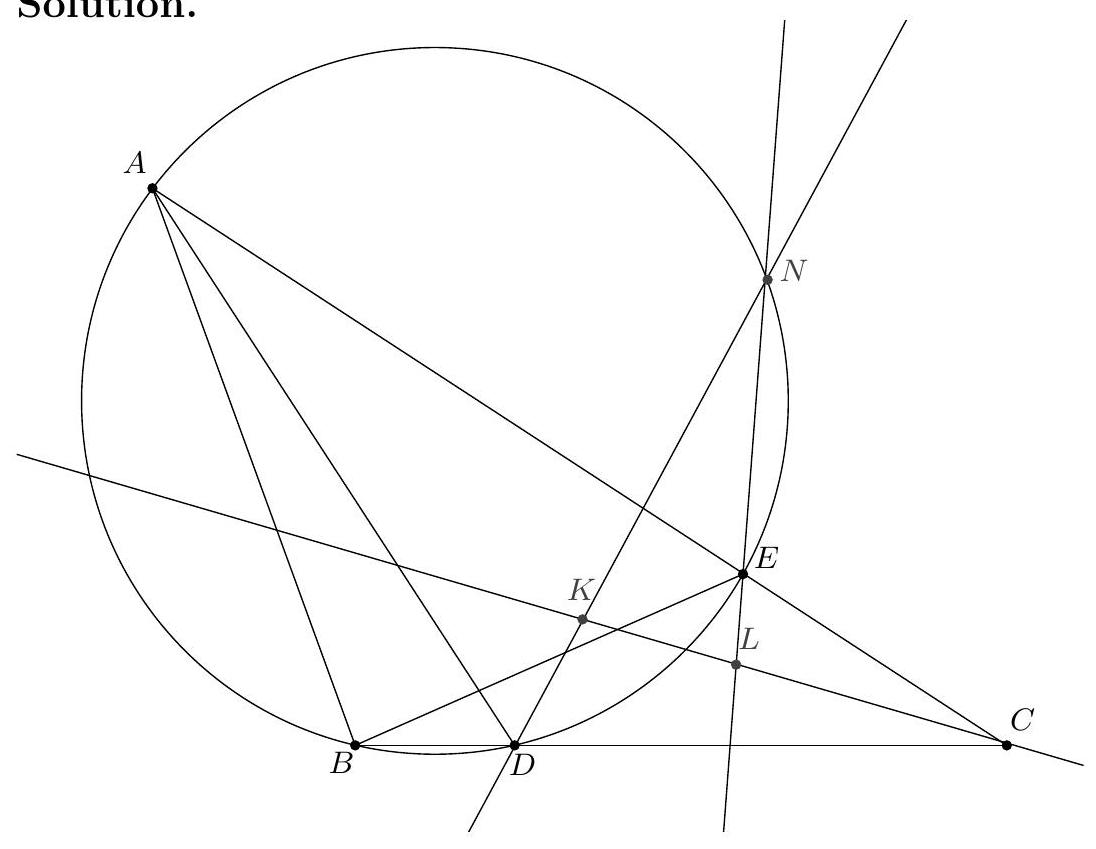

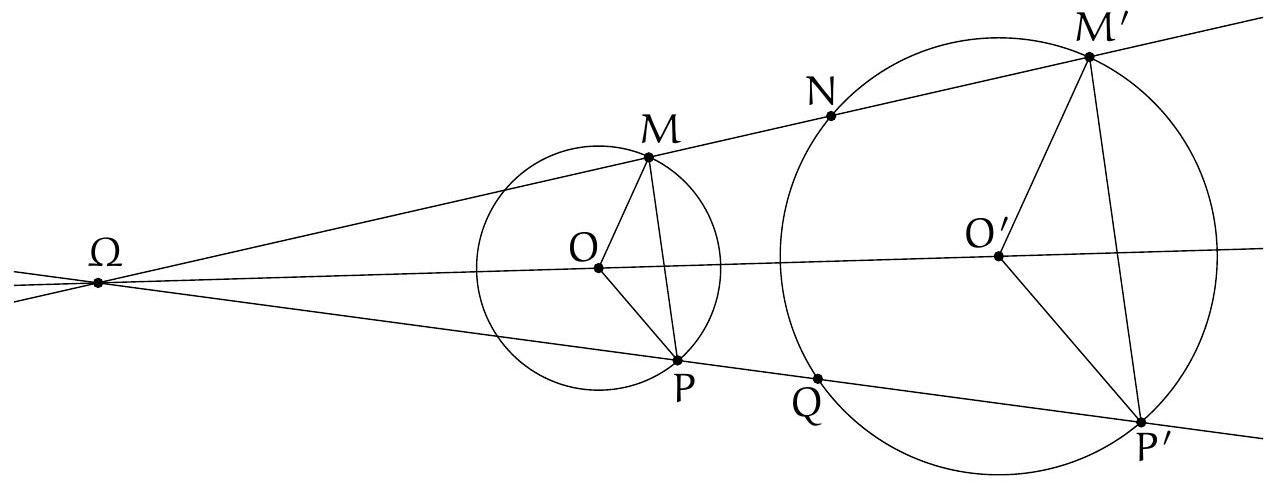

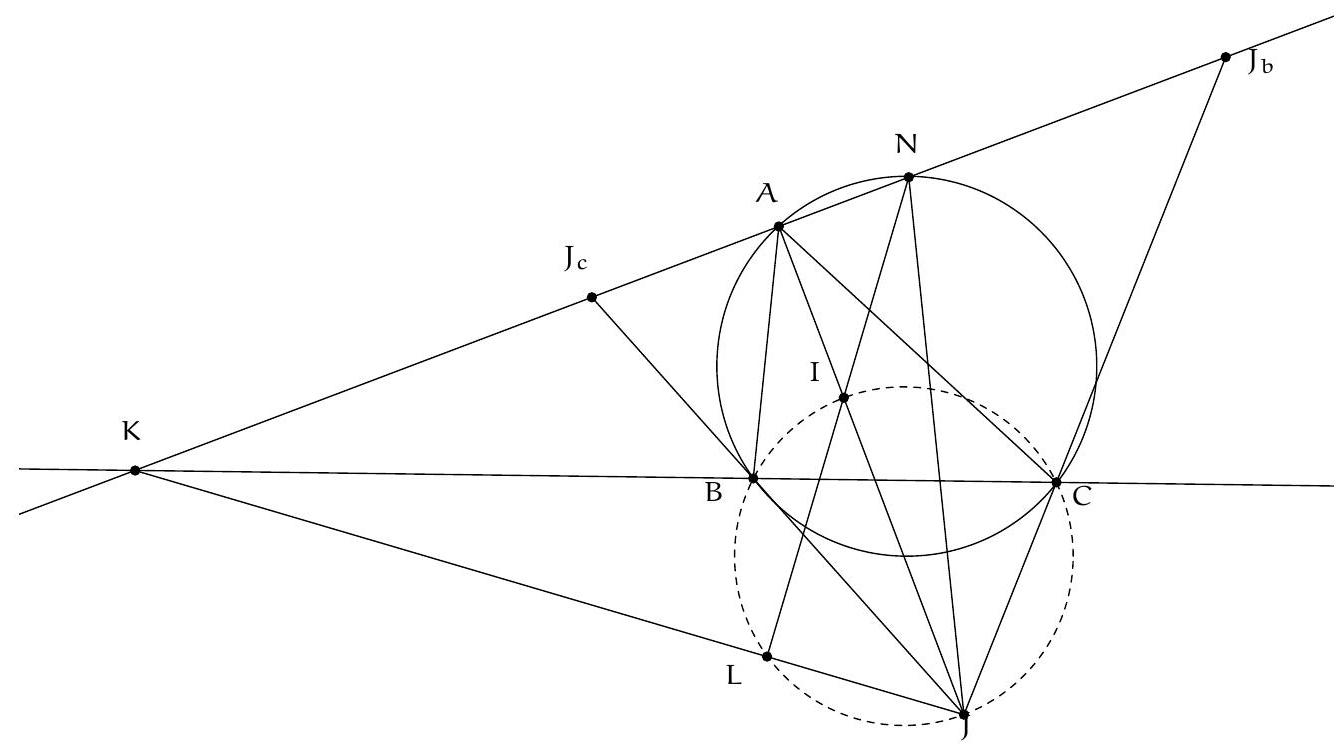

Let $ABC$ be a triangle, $\Gamma$ its circumcircle. Let $\omega_{A}$ be the circle internally tangent to $(AB)$, $(AC)$, and $\Gamma$. Denote $T_{A}$ as the point of tangency of $\Gamma$ with $\omega_{A}$. Similarly, define $T_{B}$ and $T_{C}$.

Show that $\left(A T_{A}\right)$, $\left(B T_{B}\right)$, and $\left(C T_{C}\right)$ are concurrent.

|

When we see many tangent circles, we should think about homotheties that exchange them. In this case, we have three positive homotheties with centers at \( \mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{A}}, \mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{B}}, \mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{C}} \) and which map \( \omega_{\mathrm{A}}, \omega_{\mathrm{B}} \) and \( \omega_{\mathrm{C}} \) to \( \Gamma \), respectively.

Moreover, since \( \omega_{\mathrm{A}} \) is tangent to (AB) and (AC), we also have a positive homothety with center \( A \) that maps \( \omega_{A} \) to the incircle \( \omega \) of \( \triangle ABC \). The same applies for \( B \) and \( C \).

The composition of two positive homotheties with centers \( \mathrm{O}_{1} \) and \( \mathrm{O}_{2} \) is a positive homothety whose center lies on the line \( \left(\mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{O}_{2}\right) \). Therefore, we have constructed three positive homotheties that all map \( \Gamma \) to \( \omega \), and their respective centers lie on \( \left(\mathrm{AT}_{\mathrm{A}}\right), \left(B \mathrm{BT}_{\mathrm{B}}\right) \) and \( \left(\mathrm{CT}_{\mathrm{C}}\right) \).

Since there is at most one positive homothety that maps one given circle to another, these three homotheties are actually the same homothety, with center \( Z \). Therefore, \( Z \in \left(A T_{A}\right), Z \in \left(B T_{B}\right) \) and \( Z \in \left(C T_{C}\right) \).

The lines \( \left(A T_{A}\right), \left(B T_{B}\right) \) and \( \left(C T_{C}\right) \) are thus concurrent.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle, $\Gamma$ son cercle circonscrit. Soit $\omega_{A}$ le cercle inscrit intérieurement à $(A B),(A C)$ et à $\Gamma$. On note $T_{A}$ le point de tangence de $\Gamma$ avec $\omega_{A}$. On définit de même $T_{B}$ et $T_{C}$.

Montrer que $\left(A T_{A}\right),\left(B T_{B}\right)$ et $\left(C T_{C}\right)$ sont concourantes.

|

Quand on voit beaucoup de cercles tangents, on doit penser aux homothéties qui les échangent. En l'occurrence, on a trois homothéties positives, de centre respectifs $\mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{A}}, \mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{B}}, \mathrm{T}_{\mathrm{C}}$ et qui envoient respectivement $\omega_{\mathrm{A}}, \omega_{\mathrm{B}}$ et $\omega_{\mathrm{C}}$ sur $\Gamma$.

De plus, $\omega_{\mathrm{A}}$ étant tangent à ( AB ) et ( AC ), on aussi une homothétie positive de centre $A$ qui envoie $\omega_{A}$ sur le cercle $\omega$ inscrit à $A B C$. De même pour $B$ et $C$.

Or la composée de deux homothéties positives de centres $\mathrm{O}_{1}$ et $\mathrm{O}_{2}$ est une homothétie positive dont le centre est sur la droite ( $\left.\mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{O}_{2}\right)$. On a donc construit trois homothéties positives qui envoient toutes $\Gamma$ sur $\omega$, et leurs centres respectifs appartiennent à $\left(\mathrm{AT}_{\mathrm{A}}\right),\left(B \mathrm{BT}_{\mathrm{B}}\right)$ et $\left(\mathrm{CT}_{\mathrm{C}}\right)$.

Comme il existe au plus une homothétie positive envoyant un cercle donné sur un autre cercle, ces trois homothéties sont en fait une seule et même homothétie, de centre $Z$. On a donc $Z \in\left(A T_{A}\right), Z \in\left(B T_{B}\right)$ et $Z \in\left(C T_{C}\right)$.

Les droites $\left(A T_{A},\left(B T_{B}\right)\right.$ et ( $C T_{C}$ sont donc concourantes.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

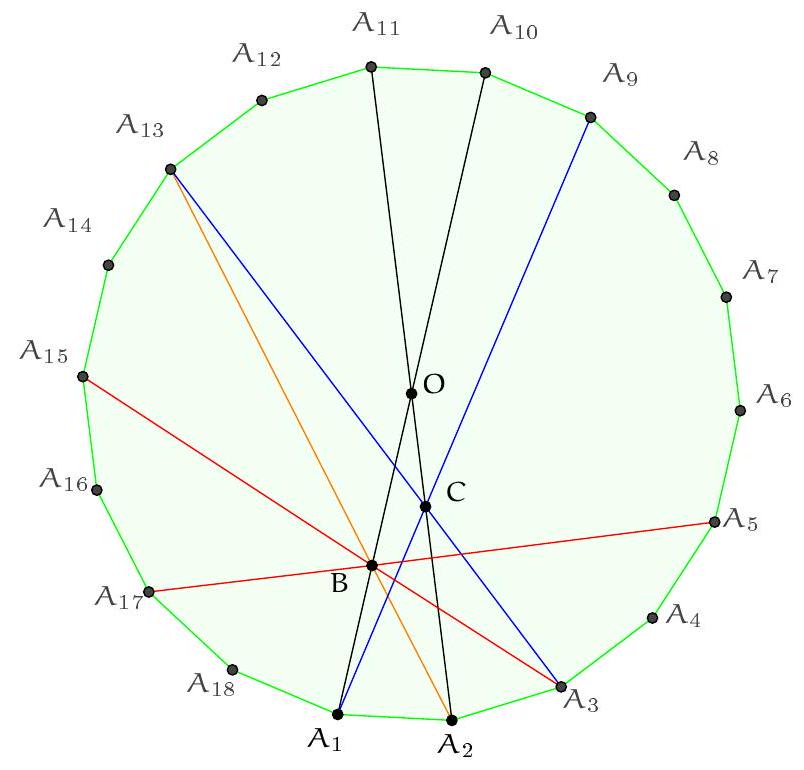

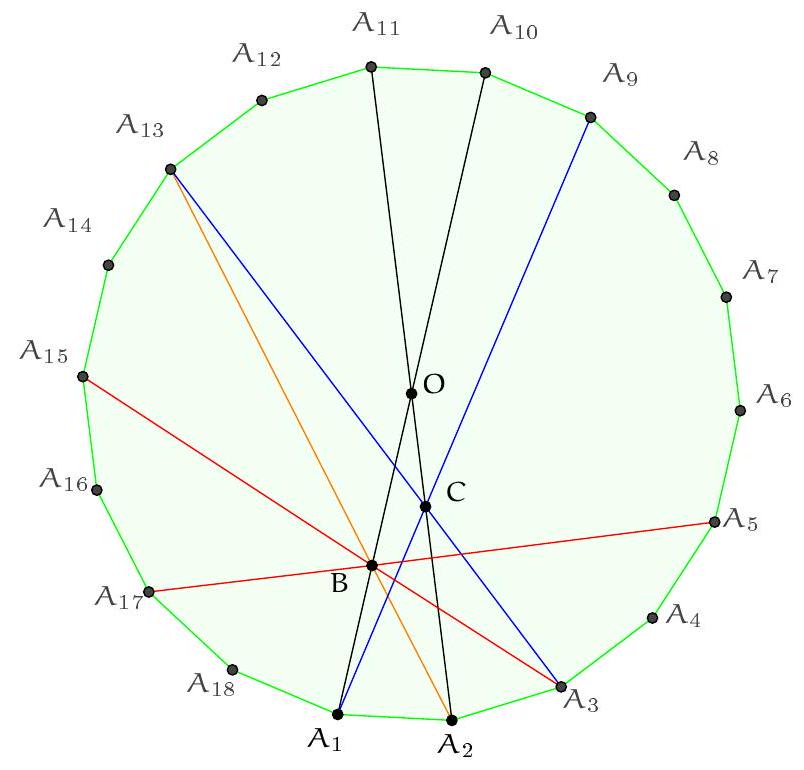

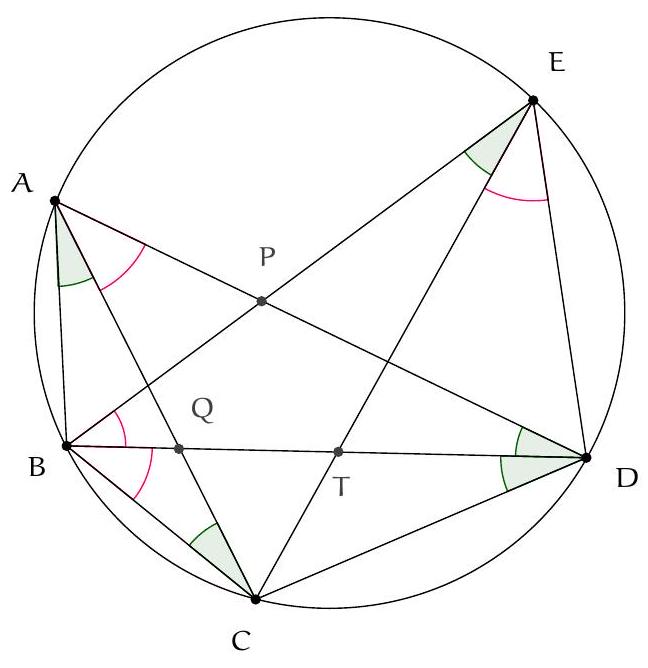

Let $O$ be the center of a regular 18-sided polygon with vertices $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{18}$. Let $B$ be the point on $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{1}\right]$ such that $\widehat{\mathrm{BA} A_{2} \mathrm{O}}=20^{\circ}$ and $C$ the point on $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right]$ such that $\widehat{\mathrm{CA}_{1} \mathrm{O}}=10^{\circ}$. Show that $\mathrm{BCA}_{2} \mathrm{~A}_{3}$ are concyclic.

|

We already extend the different existing lines: \(A_{1}, O, A_{10}\) are collinear, \(A_{2}, O, A_{11}\) are also collinear.

We then apply the inscribed angle theorem: any central angle that intercepts a segment of length \(A_{1} A_{2}\) is \(20^{\circ}\), and any inscribed angle that intercepts such a segment is \(10^{\circ}\). Therefore, \(A_{1}, C, A_{9}\) are collinear, and \(A_{2}, B, A_{13}\) are collinear.

By axial symmetry with respect to the axis \((OA_{2})\), it follows that \(A_{3}, C, A_{13}\) are collinear.

If we can show that \(A_{3}, B, A_{15}\) are collinear, then \(\widehat{CA_{3}B} = \widehat{A_{13}A_{3}A_{15}} = 20^{\circ} = \widehat{CA_{2}B}\), which establishes the required cocyclicity in this exercise.

Let's now show that \(A_{3}, B, A_{15}\) are indeed collinear. By axial symmetry with respect to the axis \((OA_{1})\), this is equivalent to showing that \(A_{17}, B, A_{5}\) are collinear.

We notice that \((A_{17}A_{5})\) is the perpendicular bisector of the segment \([OA_{2}]\): indeed, the triangle \(OA_{2}A_{5}\) is equilateral (since \(OA_{2} = OA_{5}\) and \(\widehat{A_{2}OA_{5}} = 60^{\circ}\)), so \(A_{5}\) is on the perpendicular bisector of \([OA_{2}]\), and the same applies to \(A_{17}\).

Since \(\triangle BO_{2}\) is isosceles at \(B\), \(B\) is also on the perpendicular bisector of \([OA_{2}]\), which establishes the desired collinearity and completes the solution.

## Exercises of Group A

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $O$ le centre d'un polygone régulier à 18 côtés de sommets $A_{1}, \ldots, A_{18}$. Soit $B$ le point de $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{1}\right]$ tel que $\widehat{\mathrm{BA} A_{2} \mathrm{O}}=20^{\circ}$ et C le point de $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right]$ tel que $\widehat{\mathrm{CA}_{1} \mathrm{O}}=10^{\circ}$. Montrer que $\mathrm{BCA}_{2} \mathrm{~A}_{3}$ sont cocycliques.

|

On prolonge déjà les différentes droites existantes: $A_{1}, O, A_{10}$ sont alignés, $A_{2}, 0, A_{11}$ aussi.

On applique ensuite le théorème de l'angle inscrit : tout angle au centre qui intercepte un segment de longueur $A_{1} A_{2}$ vaut $20^{\circ}$, tout angle inscrit qui intercepte un tel segment vaut $10^{\circ}$. Donc $A_{1}, C, A_{9}$ alignés, $A_{2}, B, A_{13}$ alignés.

Par symétrie axiale d'axe $\left(\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right)$, il vient $A_{3}, \mathrm{C}, \mathrm{A}_{13}$ alignés.

Si on parvient à montrer que $A_{3}, B, A_{1} 5$ alignés, alors $\widehat{\mathrm{CA}_{3} \mathrm{~B}}=\widehat{A_{13} \mathrm{~A}_{3} \mathcal{A}_{15}}=20^{\circ}=$ $\widehat{C A_{2} B}$, ce qui établit la cocyclicité demandée dans cet exercice.

Montrons maintenant qu'on a effectivement $A_{3}, B, A_{1} 5$ alignés. Par symétrie axiale d'axe $\left(\mathrm{OA}_{1}\right)$, cela équivaut à montrer que $A_{17}, \mathrm{~B}, A_{5}$ sont alignés.

Or, on remarque que ( $A_{17} A_{5}$ ) est la médiatrice du segment $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right]$ : en effet, le triangle $\mathrm{OA}_{2} A_{5}$ est équilatéral (comme $\mathrm{OA}_{2}=\mathrm{OA}_{5}$ et ${\widehat{A_{2} \mathrm{OA}}}_{5}=60^{\circ}$ ) donc $A_{5}$ est sur la médiatrice de $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right.$, de même pour $A_{17}$.

Comme $\mathrm{BO}_{2}$ est isocèle en $\mathrm{B}, \mathrm{B}$ est aussi sur la médiatrice de $\left[\mathrm{OA}_{2}\right]$, ce qui établit l'alignement voulu et termine la solution.

## Exercices du groupe A

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "## Exercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

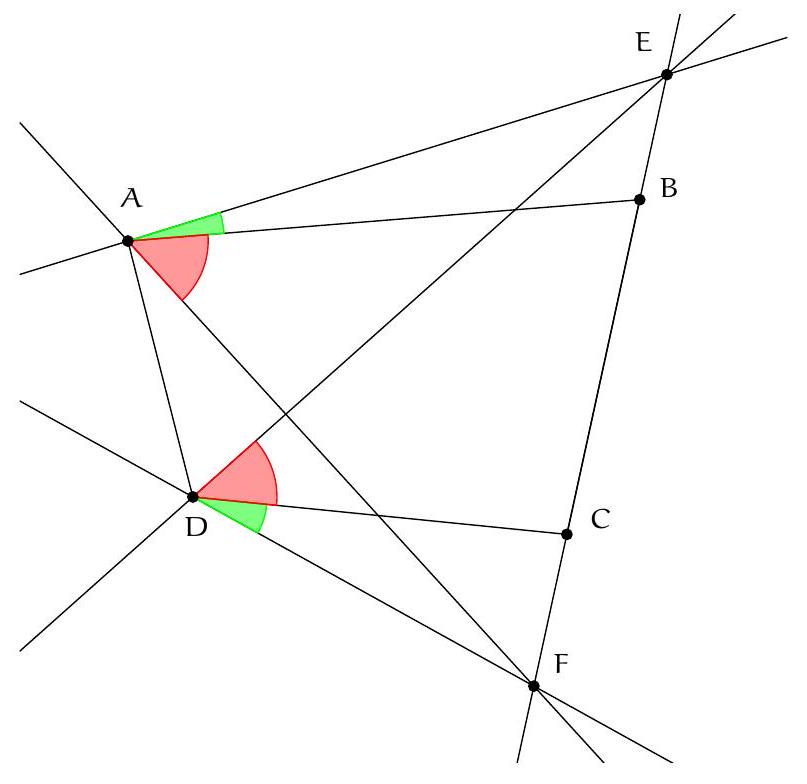

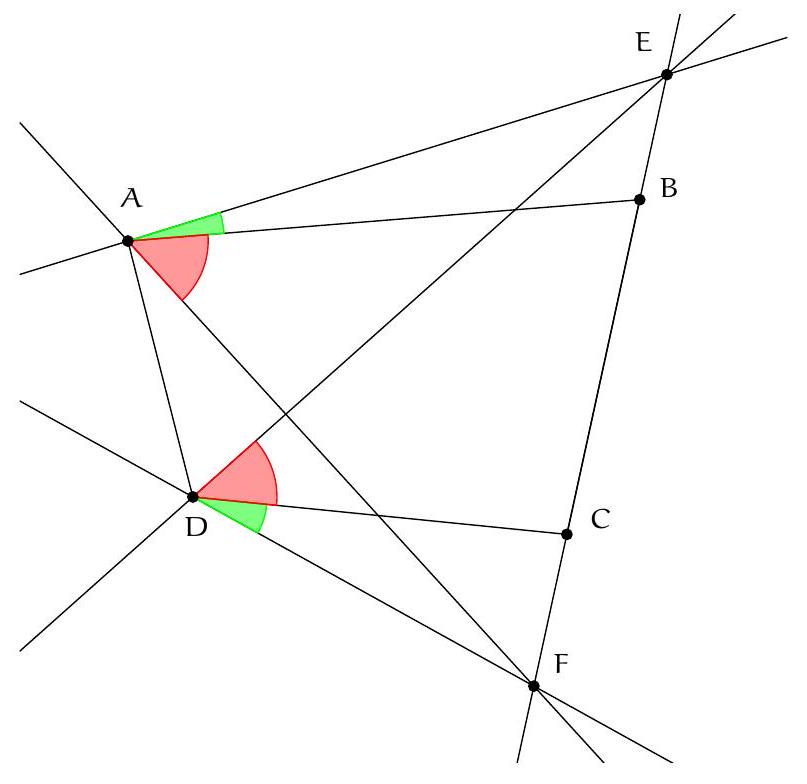

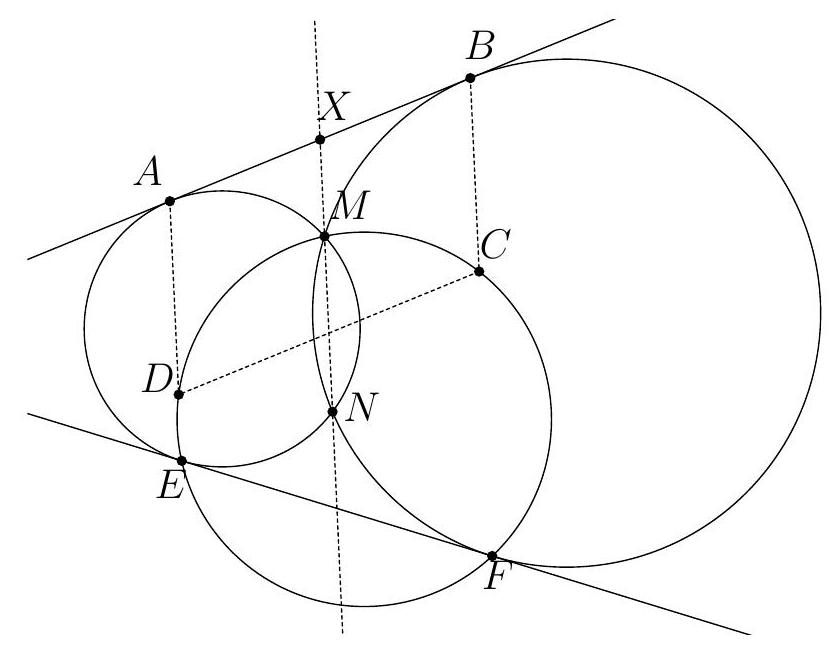

Let $ABC$ be a triangle such that $AB \neq AC$. Let $E$ be such that $AE = BE$ and $(BE)$ is perpendicular to $(BC)$, and let $F$ be such that $AF = CF$ and $(CF)$ is perpendicular to $(BC)$. Let $D$ be the point on $(BC)$ such that $(AD)$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $ABC$ at $A$.

Show that the points $D, E, F$ are collinear.

|

Suppose (without loss of generality) that $AB < AC$.

Let $O$ be the center of the circumcircle of $ABC$ and $G$ the point on the line $(AD)$ such that $(AB)$ is parallel to $(GC)$.

First, let's show that the angles $\widehat{BAD}$ and $\widehat{BCA}$ are of the same measure $\gamma$, and that the angles $\widehat{BOA}$ and $\widehat{CFA}$ are both of measure $2\gamma$. The only point that does not immediately follow from the inscribed angle theorem is the equality $\widehat{BOA} = \widehat{CFA}$.

Triangles $DBA$ and $DAC$ are similar, so there exists a similarity $s$ centered at $D$ that maps $B$ to $A$ and $A$ to $C$. Since $s$ preserves length ratios, it maps the perpendicular bisector of $[AB]$ to the perpendicular bisector of $[BC]$. It also maps the perpendicular to $(DA)$ passing through $A$ (which is $(AO)$, since $(AD)$ is tangent to the circle centered at $O$ passing through $A$) to the perpendicular to $(DC)$ passing through $C$ (which is $(CF)$). Therefore, $O$ is mapped to $F$. Since $s$ preserves the measures of geometric angles (note for those working with oriented angles, this is an indirect similarity!), $\widehat{BOA} = \widehat{AFC}$.

We deduce that $F$ is the center of the circumcircle of $AGC$. In particular, $F$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $[GC]$.

Now consider the homothety $h$ centered at $D$ that maps $B$ to $C$. Since the image of any line by $h$ is a parallel line, $(AB)$ is mapped to $(GC)$, and $(DA)$ is fixed, so $A$ is mapped to $G$. Since $h$ preserves length ratios, the perpendicular bisector of $[AB]$ is mapped to the perpendicular bisector of $[GC]$. Additionally, $(EB)$ is mapped to $(CF)$ due to the parallelism, so $E$ is mapped to $F$.

Therefore, $D$ (as the center of the homothety), $E$, and $F$ are collinear.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle tel que $A B \neq A C$. Soit $E$ tel que $A E=B E$ et $(B E)$ perpendiculaire à $(B C)$ et soit $F$ tel que $A F=C F$ et ( $C F)$ perpendiculaire à ( $B C$ ). Soit $D$ le point de $(B C)$ tel que $(A D)$ soit tangente au cercle circonscrit à $A B C$ en A.

Montrer que les points $D, E, F$ sont colinéaires.

|

Supposons (sans restreindre la généralité) que $A B<A C$.

Soit $O$ le centre du cercle circonscrit à $A B C$ et $G$ le point de la droite (AD) tel que $(\mathrm{AB})$ soit parallèle à (GC).

Montrons tout d'abord que les angles $\widehat{\mathrm{BAD}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{BCA}}$ sont de même mesure $\gamma$, et que les angles $\widehat{B O A}$ et $\widehat{C F A}$ sont tous les deux de mesure $2 \gamma$. Le seul point qui ne découle pas immédiatement du théorème de l'angle inscrit est l'égalité $\widehat{\mathrm{BOA}}=$ $\widehat{C F A}$.

Or DBA et DAC sont semblables, donc il existe une similitude $s$ de centre D qui envoie $B$ sur $A$ et $A$ sur $C$. Comme $s$ conserve les rapports de longueur, elle envoie la médiatrice de $[\mathrm{AB}]$ sur la médiatrice de $[\mathrm{BC}]$. Elle envoie aussi la perpendiculaire à ( $D A$ ) passant par $A$ (c'est-à-dire (AO), puisque ( $A D$ ) est tangente en $A$ au cercle de centre $O$ passant par $A$ ) sur la perpendiculaire à (DC) passant par C (c'est-à-dire (CF)). Donc O est envoyé sur F. Comme s conserve les mesure d'angles géométriques (attention pour ceux qui travaillent en angles orientés, c'est une similitude indirecte!), $\widehat{B O A}=\widehat{A F C}$.

On en déduit que $F$ est le centre du cercle circonscrit à $A G C$. En particulier, $F$ est sur la médiatrice de [GC].

On considère maintenant l'homothétie $h$ de centre $D$ qui envoie $B$ sur $C$. Comme l'image de toute droite par $h$ est une droite parallèle, $(A B)$ est envoyée sur (GC), et ( $D A$ ) est fixée donc $A$ est envoyé sur $G$. Comme $h$ conserve les rapports de longueurs, la médiatrice de $[A B]$ est envoyée sur la médiatrice de [GC]. De plus, (EB) est envoyée sur (CF) grâce au parallélisme, donc E est envoyé sur $F$.

Donc D (en tant que centre de l'homothétie), E et F sont alignés.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

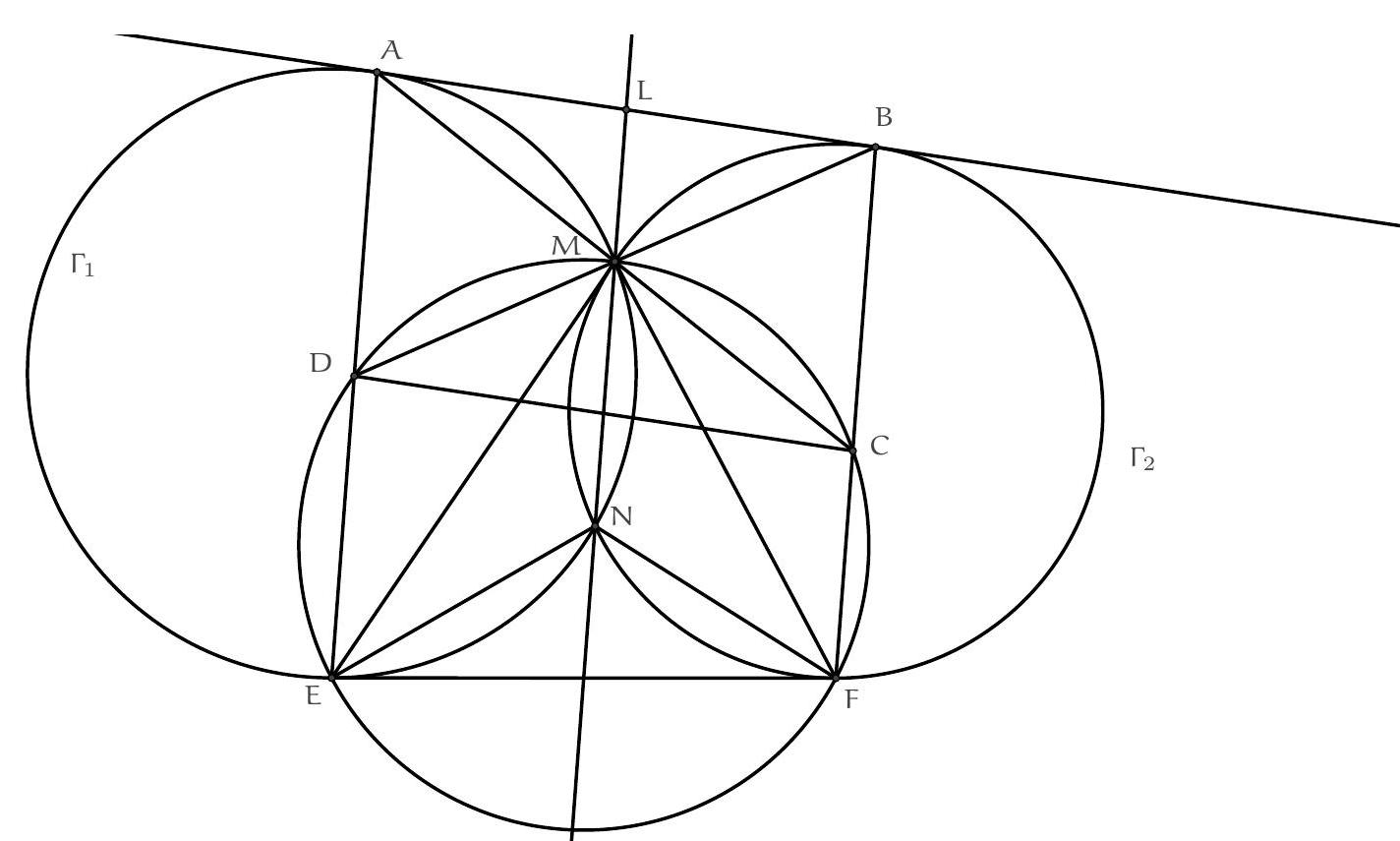

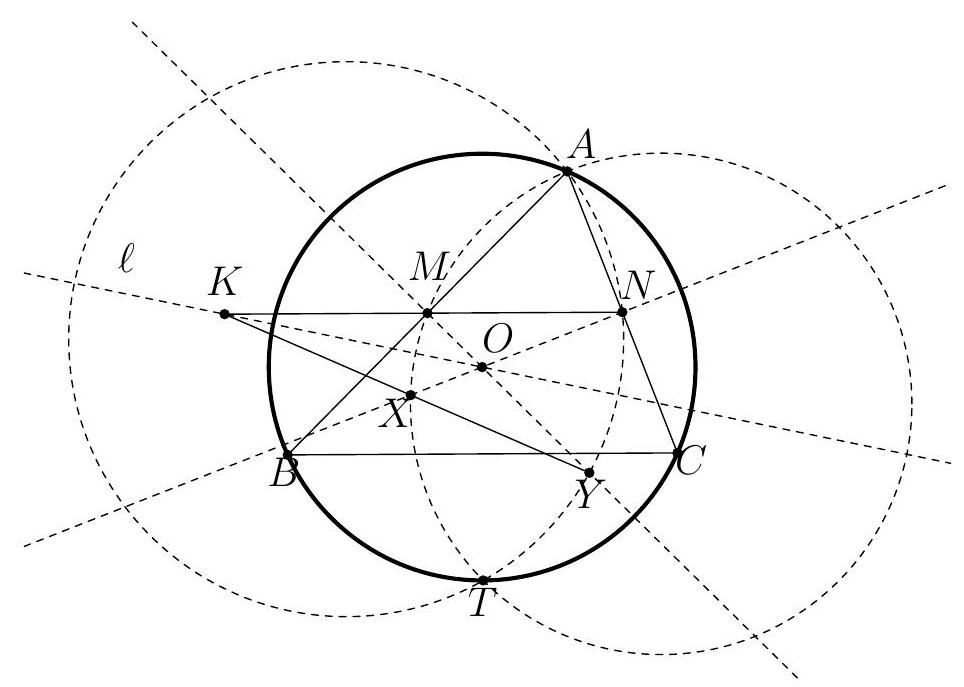

Let $ABC$ be a triangle.

For a given point $P$ on $(BC)$, we denote $E(P)$ and $F(P)$ as the second points of intersection of the lines $(AB)$ and $(AC)$ with the circle of diameter $[AP]$. Let $T(P)$ be the intersection of the tangents to this circle at $E(P)$ and $F(P)$.

Show that as $P$ varies on $(BC)$, the geometric locus of $T(P)$ is a line.

|

## Step 1: An important initial observation.

Let H be the foot of the altitude from A in triangle ABC. Let P and P' be two points on line (BC). We denote E = E(P), F = F(P), T = T(P), E' = E(P'), F' = F(P'), T' = T(P'). We also introduce O (respectively O') as the center of the circle with diameter [AP] (respectively [AP']).

Note that the circumcircles of EAF and E'AF' intersect at A and H. In particular, H is the Miquel point of the quadrilateral with sides (EE'), (E'F'), (F'F), (FE), meaning there exists a unique direct similarity s centered at H that maps E to E' and F to F'.

Furthermore, we have \(\widehat{EOF} = 2 \widehat{EHF} = 360^\circ - 2 \widehat{EAF} = 360^\circ - \widehat{BAC}\), which does not depend on P. Therefore, \(\widehat{EOF} = \widehat{E'O'F'}\), so the direct similarity s maps O to O'.

The point T is entirely defined by the data of E, O, F (via operations such as drawing a circle, taking a tangent, etc., which are preserved by similarities). Therefore, s also maps T to T'.

From this point, the hardest part is done.

Step 2: A technical game with similarities to conclude.

Let \(P_0\) be a point on (BC). We denote \(\sigma\) as the direct similarity centered at H that maps \(E(P_0)\) to \(T(P_0)\). Let P be a point on (BC). We denote \(\sigma_P\) as the direct similarity (centered at H) that maps \(E(P_0)\) to \(E(P)\). According to the previous discussion, it also maps \(T(P_0)\) to \(T(P)\).

Since the two similarities have the same center, \(\sigma_P \circ \sigma = \sigma \circ \sigma_P\). In particular, \(\sigma(E(P)) = \sigma \circ \sigma_P(E(P_0)) = \sigma_P(T(P_0)) = T(P)\).

Therefore, the locus of \(T(P)\) is the image by \(\sigma\) (which is a direct similarity) of the locus of \(E(P)\) (which is a line). This is therefore a line, as desired.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle.

Pour un point $P$ de ( $B C$ ) donné, on note $E(P)$ et $F(P)$ les deuxièmes points d'intersection des droites $(A B)$ et ( $A C$ ) avec le cercle de diamètre $[A P]$. Soit $T(P)$ l'intersection des tangentes à ce cercle en $E(P)$ et $F(P)$.

Montrer que quand $P$ varie sur ( $B C$ ), le lieu géométrique de $T(P)$ est une droite.

|

## Étape 1 : une première remarque importante.

Posons tout d'abord H le pied de la hauteur issue de $A$ dans $A B C$. Soient deux points $P$ et $P^{\prime}$ de la droite (BC). On note $E=E(P), F=F(P), T=T(P), E^{\prime}=$ $E\left(P^{\prime}\right), F^{\prime}=F\left(P^{\prime}\right), T^{\prime}=T\left(P^{\prime}\right)$. On introduit également $O$ (respectivement $O^{\prime}$ ) le centre du cercle de diamètre $[A P]$ (respectivement $\left.\left[A P^{\prime}\right]\right)$.

Remarquons que les cercles circonscrits à EAF et à $E^{\prime} A F^{\prime}$ se coupent en $A$ et H . En particulier, H est le point du Miquel du quadrilatère de côtés ( $\left.E E^{\prime}\right),\left(E^{\prime} F^{\prime}\right),\left(F^{\prime} F\right)$, (FE) autrement dit il existe une unique similitude directe $s$ de centre $H$ qui envoie $E$ sur $E^{\prime}$ et $F$ sur $F^{\prime}$.

D'autre part, on a $^{\mathrm{EOF}}=2 \widehat{\mathrm{EHF}}=360^{\circ}-2 \widehat{\mathrm{EAF}}=360^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BAC}}$, ce qui ne dépend pas de $P$. Donc $\widehat{\mathrm{EOF}}=\widehat{\mathrm{E}^{\prime} \mathrm{O}^{\prime} \mathrm{F}^{\prime}}$, donc la similitude directe $s$ envoie O sur $\mathrm{O}^{\prime}$.

Or, le point $T$ est entièrement défini par la donnée de $E, O, F$ (via des opérations de type tracer un cercle, prendre une tangente..., qui sont conservées par les similitudes). Donc s envoie aussi T sur $\mathrm{T}^{\prime}$.

À partir de là, le plus dur est fait.

Étape 2 : un jeu technique avec les similitudes pour conclure.

Soit $P_{0}$ un point de (BC). On note $\sigma$ la similitude directe de centre $H$ qui envoie $E\left(P_{0}\right)$ sur $T\left(P_{0}\right)$. Soit $P$ un point de (BC). On note $\sigma_{P}$ la similitude directe (de centre $H)$ qui envoie $E\left(P_{0}\right)$ sur $E(P)$. D'après ce qui précède, elle envoie aussi $T\left(P_{0}\right)$ sur T(P).

Comme les deux similitudes on le même centre $\sigma_{P} \circ \sigma=\sigma \circ \sigma_{P}$. En particulier, $\sigma(E(P))=\sigma \circ \sigma_{P}\left(E\left(P_{0}\right)\right)=\sigma_{P}\left(T\left(P_{0}\right)\right)=T(P)$.

Donc le lieu de $T(P)$ est l'image par $\sigma$ (qui est une similitude directe) du lieu de $E(P)$ (qui est une droite). C'est donc une droite, comme voulu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "## Exercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

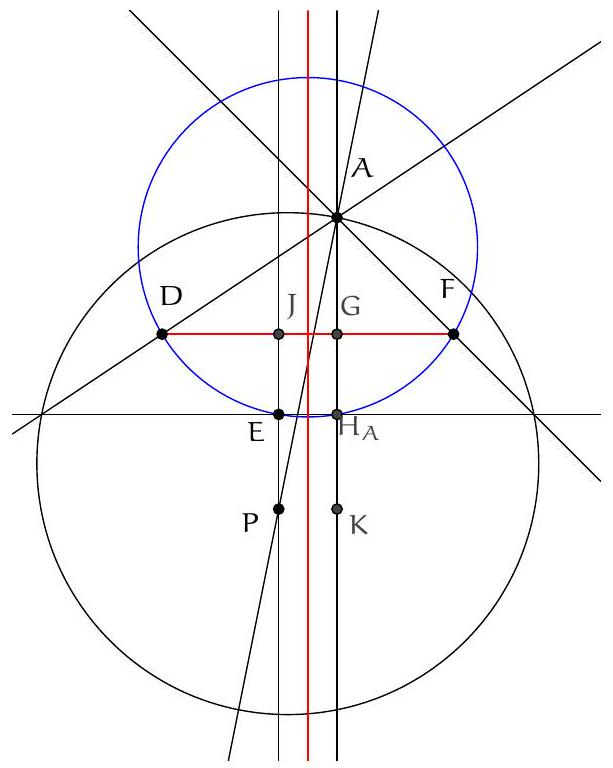

Let $ABC$ be a triangle, $O$ the center of its circumcircle. Let $P$ be a point on $(AO)$ and $D, E, F$ the orthogonal projections of $P$ on $(AB)$, $(BC)$, and $(CA)$. Let $X$ and $Y$ be the intersections of the circumcircles of $DEF$ and $BCP$.

Show that $\widehat{B A X}=\widehat{Y A C}$

|

## Step 1: Show that (DF) is parallel to (BC).

Let \( \mathrm{P}_{0} \) be the point diametrically opposite to \( A \) on the circumcircle of \( \triangle ABC \). \((P_{0} C)\) is perpendicular to \((A C)\) and thus parallel to \((\mathrm{PF})\), and \((\mathrm{P}_{0} B)\) is similarly parallel to \((\mathrm{PD})\).

Therefore, by the theorem of Thales, \(\frac{A D}{A B} = \frac{A P}{A P_{0}} = \frac{A F}{A C}\), implying that \((D F)\) is parallel to \((B C)\). Step 2: Show that \( H_{A} \), the foot of the altitude from \( A \), lies on (DEF).

Let \( G = (A H_{A} A) \cap (D F) \), \( J \) the orthogonal projection of \( P \) (and also of \( E \)) on \((D F)\), and \( K \) the orthogonal projection of \( P \) on \((A H_{A})\).

\( PKGJ \) is a rectangle, and \( P, K, D, F \) are concyclic on the circle with diameter \([PA]\). Therefore, \( PKFD \) is an isosceles trapezoid, so \((PJ)\) and \((KG)\) are symmetric with respect to the perpendicular bisector of \([DF]\).

Since \( EJGH \) is a rectangle and \((H_{A} G)\) and \((E J)\) are symmetric with respect to the perpendicular bisector of \((EF)\), \( D, H_{A}, E, F \) are concyclic.

Step 3: To conclude.

Step 1 shows that there exists an involution centered at \( A \) that swaps \( B \) and \( F \) on one hand, and \( C \) and \( D \) on the other. To conclude, it suffices to show that this involution swaps \( X \) and \( Y \), i.e., it maps the circumcircle of \( \triangle BCP \) to the circumcircle of \( \triangle DEF \).

The only difficulty is to show that the point to which the involution maps \( P \) lies on the circumcircle of \( \triangle DEF \).

Since \( P \) is a point on the circumcircle of \( \triangle ADF \) such that \((AP)\) and the circumcircle of \( \triangle ADF \) are perpendicular at \( P \), its image \( I \) is a point on the line \((BC)\) such that \((BC)\) and \((AI)\) are perpendicular at \( I \). Therefore, \( I = H_{A} \), and Step 2 allows us to conclude.

[^0]: 1. see the beginner geometry textbook for more details on directed angles of lines

[^1]: 2. i.e., the lines \((A B)\) and \((C D)\) are parallel or intersect outside the segments \([A B]\) and \([C D]\), and the lines \((B C)\) and \((D A)\) are parallel or intersect outside the segments \([BC]\) and \([DA]\)

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle, O le centre de son cercle circonscrit. Soit P un point sur (AO) et $D, E, F$ les projections orthogonales de $P$ sur ( $A B$ ), ( $B C$ ) et (CA). Soit $X$ et $Y$ les intersections des cercles circonscrits à DEF et à BCP.

Montrer que $\widehat{B A X}=\widehat{Y A C}$

|

## Étape 1 : Montrons que (DF) est parallèle à (BC).

Soit $\mathrm{P}_{0}$ le point diamétralement opposé à $A$ sur le cercle circonscrit à $A B C .\left(P_{0} C\right)$ est perpendiculaire à $(A C)$ donc parallèle à $(\mathrm{PF})$ et $\left(\mathrm{P}_{0} B\right)$ est de même parallèle à (PD).

Donc, d'après le théorème de Thalès, $\frac{A D}{A B}=\frac{A P}{A P_{0}}=\frac{A F}{A C}$, $d^{\prime}$ où ( $D F$ ) parallèle à ( $B C$ ). Étape 2 : Montrons que $H_{A}$, le pied de la hauteur issue de $A$ appartient à (DEF).

On pose $G=\left(A H_{A} A\right) \cap(D F), J$ la projection orthogonale de $P$ (celle de $E$ aussi) sur (DF) et $K$ la projection (orthogonale) de $P$ sur $\left(A H_{A}\right)$.

PKGJ est un rectangle, et $P, K, D, F$ sont cocycliques sur le cercle de diamètre [PA]. Donc PKFD est un trapèze isocèle, donc (PJ) et ( KG ) sont symétriques par rapport à la médiatrice de [DF].

Comme $E_{J G H}$ est un rectangle et $\left(H_{A} G\right)$ et $(E J)$ sont symétriques par rapport à la médiatrice de (EF), $D, H_{A}, E, F$ sont cocycliques.

Étape 3 : pour conclure.

L'étape 1 permet de montrer qu'il existe une involution de centre $A$ qui échange $B$ et $F$ d'une part, $C$ et $D$ d'autre part.Pour conclure, il suffit de montrer que cette involution échange $X$ et $Y$, c'est-à-dire qu'elle envoie le cercle circonscrit à BCP sur le cercle circonscrit à DEF.

La seule difficulté est de montrer que le point sur lequel l'involution envoie P appartient au cercle circonscrit à DEF.

Or $P$ est un point du cercle circonscrit à ADF tel que (AP) et le cercle circonscrit à $A D F$ sont perpendiculaires en $P$. Donc son image $I$ est un point de la droite (BC) tels que (BC) et (AI) sont perpendiculaires en I. Donc $I=H_{A}$, et l'étape 2 permet de conclure.

[^0]: 1. voir le poly de géométrie débutant pour plus de détails sur les angles orientés de droites

[^1]: 2. c'est-à-dire que les droites $(A B)$ et $(C D)$ sont parallèles ou se coupent à l'extérieur des segments $[A B]$ et $[C D]$ et les droites $(B C)$ et $(D A)$ sont parallèles ou se coupent à l'extérieur des segments [BC] et [DA]

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi2-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let \( a, b, c \) be strictly positive real numbers. Show that

$$

\frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{a c}+\frac{c}{a b} \geqslant \frac{2}{a}+\frac{2}{b}-\frac{2}{c}.

$$

Note, there is indeed a "minus" in the right-hand side!

|

By multiplying both sides by abc, the inequality to be shown can be rewritten as

$$

\mathrm{a}^{2}+\mathrm{b}^{2}+\mathrm{c}^{2} \geqslant 2 \mathrm{bc}+2 \mathrm{ac}-2 \mathrm{ab}

$$

By moving 2ab to the other side, we can factorize. The inequality to be shown becomes

$$

(a+b)^{2}+c^{2} \geqslant 2(a+b) c

$$

By moving everything to the left, the inequality is finally equivalent to

$$

(a+b-c)^{2} \geqslant 0

$$

which is always true. Moreover, we have equality if and only if $\mathrm{c}=\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient a, b, c des réels strictement positifs. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a}{b c}+\frac{b}{a c}+\frac{c}{a b} \geqslant \frac{2}{a}+\frac{2}{b}-\frac{2}{c} .

$$

Attention, il y a bien un "moins" dans le membre de droite!

|

En multipliant les deux membres par abc, l'inégalité à montrer se réécrit

$$

\mathrm{a}^{2}+\mathrm{b}^{2}+\mathrm{c}^{2} \geqslant 2 \mathrm{bc}+2 \mathrm{ac}-2 \mathrm{ab}

$$

En passant 2 ab de l'autre côté, on peut factoriser. L'inégalité à montrer devient

$$

(a+b)^{2}+c^{2} \geqslant 2(a+b) c

$$

En passant tout à gauche, l'inégalité est finalement équivalente à

$$

(a+b-c)^{2} \geqslant 0

$$

qui est bien toujours vraie. De plus, on a égalité si et seulement si $\mathrm{c}=\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

1. Let $a, b$ and $c$ be three real numbers such that

$$

|a| \geqslant|a+b|,|b| \geqslant|b+c| \text { and }|c| \geqslant|c+a| \text {. }

$$

Show that $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=0$.

2. Let $a, b, c$ and $d$ be four real numbers such that

$$

|a| \geqslant|a+b|,|b| \geqslant|b+c|,|c| \geqslant|c+d| \text { and }|d| \geqslant|d+a|

$$

Do we necessarily have $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=\mathrm{d}=0$?

|

1. Among the three numbers, there are at least two of the same sign. We can assume that these are $a$ and $b$ and that they are positive, the other cases being treated similarly. We then have

$$

a=|a| \geqslant|a+b|=a+b \geqslant a

$$

thus we have equality everywhere, so $b=0$. Since $|b| \geqslant|b+c|$, we have $0 \geqslant|c|$, so $c=0$. Finally, since $|c| \geqslant|c+a|$, we have $0 \geqslant|a|$, so $a=0$. Therefore, the three numbers are all zero.

2. No. For example, we can take $a=c=1$ and $b=d=-1$. We then have

$$

a+b=b+c=c+d=d+a=0

$$

so the condition is satisfied, even though the chosen numbers are non-zero.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

1. Soient $a, b$ et $c$ trois nombres réels tels que

$$

|a| \geqslant|a+b|,|b| \geqslant|b+c| \text { et }|c| \geqslant|c+a| \text {. }

$$

Montrer que $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=0$.

2. Soient $a, b, c$ et d quatre nombres réels tels que

$$

|a| \geqslant|a+b|,|b| \geqslant|b+c|,|c| \geqslant|c+d| \text { et }|d| \geqslant|d+a|

$$

A-t-on forcément $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=\mathrm{d}=0$ ?

|

1. Parmi les trois nombres, il y en a au moins deux de même signe. On peut supposer que ce sont $a$ et $b$ et qu'ils sont positifs, les autres cas se traitant de la même manière. On a alors

$$

a=|a| \geqslant|a+b|=a+b \geqslant a

$$

donc on a égalité partout, donc $b=0$. Comme $|b| \geqslant|b+c|$, on a donc $0 \geqslant|c|$, donc $c=0$. Finalement, comme $|c| \geqslant|c+a|$, on a $0 \geqslant|a|$ donc $a=0$ donc les trois nombres sont nuls.

2. Non. Par exemple, on peut prendre $a=c=1$ et $b=d=-1$. On a alors

$$

a+b=b+c=c+d=d+a=0

$$

donc la condition est vérifiée, bien que les nombres choisis soient non nuls.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find all functions $f$ from $\mathbb{R}$ to $\mathbb{R}$ such that, for all real numbers $x$ and $y$, we have

$$

f(x f(y))+x=f(x) f(y+1)

$$

|

By setting $x=0$, we obtain $f(0)=f(0) f(y+1)$ for all $y$, so either $f(0)=0$, or $f(y+1)=1$ for all $y$. In the second case, $f$ is constantly equal to 1, but then the equation becomes

$$

1+x=1 \times 1

$$

for all $x$, which is impossible. Therefore, we have $f(0)=0$. By setting $y=0$, we then obtain $x=f(x) f(1)$ for all $x$. In particular, by setting $x=1$, we get $1=f(1)^{2}$, so $f(1)$ is either 1 or -1.

If $f(1)=1$, then $x=f(x)$, so $f$ is the identity, which is indeed a solution. If $f(1)=-1$, we get $x=-f(x)$ for all $x$, so $f(x)=-x$ for all $x$, and we verify that this function is also a solution to the problem.

## Common Exercises

|

f(x) = x \text{ or } f(x) = -x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Trouver toutes les fonctions $f$ de $\mathbb{R}$ dans $\mathbb{R}$ telles que, pour tous réels $x$ et $y$, on ait

$$

f(x f(y))+x=f(x) f(y+1)

$$

|

En prenant $x=0$, on obtient $f(0)=f(0) f(y+1)$ pour tout $y$, donc soit $f(0)=0$, soit $f(y+1)=1$ pour tout $y$. Dans le second cas, $f$ est constante égale à 1 , mais alors l'équation devient

$$

1+x=1 \times 1

$$

pour tout $x$, ce qui est impossible. On a donc $f(0)=0$. En prenant $y=0$, on obtient alors $x=f(x) f(1)$ pour tout $x$. En particulier, en prenant $x=1$, on obtient $1=f(1)^{2}$ donc $f(1)$ vaut 1 ou -1 .

Si $f(1)=1$, alors $x=f(x)$ donc $f$ est l'identité, qui est bien solution. $\operatorname{Si} f(1)=-1$, on obtient $x=-f(x)$ pour tout $x$, donc $f(x)=-x$ pour tout $x$, et on vérifie que cette fonction aussi est bien solution du problème.

## Exercices Communs

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n \geqslant 1}$ be an increasing sequence of strictly positive integers and $k$ a strictly positive integer. Suppose that for some $r \geqslant 1$, we have $a \frac{r}{a_{r}}=k+1$. Show that there exists an integer $s \geqslant 1$ such that $\frac{s}{a_{s}}=k$.

|

Let $v_{n}=\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{ka}_{\mathrm{n}}$ for all $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$. The problem reduces to showing that there exists $s$ such that $v_{s}=0$.

We observe that $\nu_{1}=1-k a_{1} \leqslant 0$, that $\nu_{r}=r-k a_{r}=a_{r}>0$ and finally $\nu_{n+1}=$ $(n+1)-k a_{n+1}=n-k a_{n+1}+1 \leqslant n-k a_{n}+1=v_{n}+1$, since the sequence $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n}$ is increasing.

Intuitively, we have a sequence of integers starting from a negative number, reaching a strictly positive number, and can only increase by at most 1 at each step: it must reach 0. Let's prove it: let $s$ be the largest integer less than $r$ such that $v_{s} \leqslant 0$ (it exists because $\nu_{1} \leqslant 0$). Then, since $v_{r}>0$, we have $s<\mathrm{r}$, so $v_{s+1}>0$. Therefore, $v_{s+1} \geqslant 1$, so $0 \geqslant v_{s} \geqslant v_{s+1}-1 \geqslant 0$, hence $v_{s}=0$, so $\frac{s}{a_{s}}=k$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soient $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n \geqslant 1}$ une suite croissante d'entiers strictement positifs et $k$ un entier strictement positif. Supposons que pour un certain $r \geqslant 1$, on $a \frac{r}{a_{r}}=k+1$. Montrer qu'il existe un entier $s \geqslant 1$ tel que $\frac{s}{a_{s}}=k$.

|

Soit $v_{n}=\mathrm{n}-\mathrm{ka}_{\mathrm{n}}$ pour tout $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$. Le problème revient à montrer qu'il existe $s$ tel que $v_{s}=0$.

On observe que $\nu_{1}=1-k a_{1} \leqslant 0$, que $\nu_{r}=r-k a_{r}=a_{r}>0$ et qu'enfin $\nu_{n+1}=$ $(n+1)-k a_{n+1}=n-k a_{n+1}+1 \leqslant n-k a_{n}+1=v_{n}+1$, car la suite $\left(a_{n}\right)_{n}$ est croissante.

Intuitivement, on a donc une suite d'entiers qui part d'un nombre négatif, atteint un nombre strictement positif, et ne peut augmenter que d'au plus 1 à chaque fois : elle doit atteindre 0 . Prouvons-le : soit $s$ le plus grand entier inférieur à $r$ tel que $v_{s} \leqslant 0$ (il existe car $\nu_{1} \leqslant 0$ ). Alors, comme $v_{r}>0$, on a $s<\mathrm{r}$, donc $v_{s+1}>0$. On a donc $v_{s+1} \geqslant 1$, donc $0 \geqslant v_{s} \geqslant v_{s+1}-1 \geqslant 0$, donc $v_{s}=0$, de sorte que $\frac{s}{a_{s}}=k$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find all functions $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{R} \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that for all $x, y$ in $\mathbb{R}$,

$$

f(x+y)^{2}-f\left(2 x^{2}\right)=f(y+x) f(y-x)+2 x f(y)

$$

|

By setting $x=y=0$, we obtain that $f(0)^{2}-f(0)=f(0)^{2}$, hence $f(0)=0$. By taking $y=0$, we get

$$

f(x)^{2}=f\left(2 x^{2}\right)+f(x) f(-x)

$$

so $f^{2}$ is even, i.e., $f(x)^{2}=f(-x)^{2}$ for all $x$.

By replacing $x$ with $-x$ in the equation, we get

$$

f(y-x)^{2}-f\left(2 x^{2}\right)=f(y+x) f(y-x)-2 x f(y)

$$

By subtracting this equality from the original equation, it follows that

$$

f(y+x)^{2}-f(y-x)^{2}=4 x f(y)

$$

By swapping $x$ and $y$, we find

$$

f(y+x)^{2}-f(x-y)^{2}=4 y f(x)

$$

Since $f^{2}$ is even, we always have $f(y-x)^{2}=f(x-y)^{2}$, so for all real numbers $x, y$, $x f(y)=y f(x)$.

In particular, by taking $x=1$, we get $f(y)=y f(1)$ for all $y$, so $f$ is of the form $x \rightarrow a x$, with $a \in \mathbb{R}$. By taking $x=1$ and $y=0$, the original equation becomes $a^{2}-2 a=-a^{2}$, so $a=a^{2}$, hence $a=0$ or $a=1$. Thus, $f$ is the zero function or the identity.

Conversely, it is easy to verify that these functions are solutions.

|

f(x) = 0 \text{ or } f(x) = x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Trouver toutes les applications $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{R} \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}$ telles que pour tous $x, y$ dans $\mathbb{R}$,

$$

f(x+y)^{2}-f\left(2 x^{2}\right)=f(y+x) f(y-x)+2 x f(y)

$$

|

En posant $x=y=0$, on obtient que $f(0)^{2}-f(0)=f(0)^{2}$, donc $f(0)=0$. En prenant $y=0$, on obtient que

$$

f(x)^{2}=f\left(2 x^{2}\right)+f(x) f(-x)

$$

donc $f^{2}$ est paire, i.e. $f(x)^{2}=f(-x)^{2}$ pour tout $x$.

En remplaçant dans l'équation $x$ par $-x$, on obtient

$$

f(y-x)^{2}-f\left(2 x^{2}\right)=f(y+x) f(y-x)-2 x f(y)

$$

En soustrayant membre à membre cette égalité à celle de départ, il s'ensuit

$$

f(y+x)^{2}-f(y-x)^{2}=4 x f(y)

$$

En échangeant $x$ et $y$ on trouve

$$

f(y+x)^{2}-f(x-y)^{2}=4 y f(x)

$$

Comme $f^{2}$ est paire, on a toujours $f(y-x)^{2}=f(x-y)^{2}$ donc pour tous réels $x, y$, $x f(y)=y f(x)$.

En particulier, en prenant $x=1$, on obtient $f(y)=y f(1)$ pour tout $y$, donc $f$ est de la forme $x \rightarrow a x$, avec $a \in \mathbb{R}$. En prenant $x=1$ et $y=0$, l'équation de départ devient $a^{2}-2 a=-a^{2}$, donc $a=a^{2}$, donc $a=0$ ou $a=1$. Ainsi, $f$ est la fonction nulle ou l'identité.

Réciproquement, on vérifie sans difficulté que ces fonctions sont des solutions.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $a, b, c > 0$ such that $a^{2} + b^{2} + c^{2} + (a + b + c)^{2} \leqslant 4$. Show that

$$

\frac{a b + 1}{(a + b)^{2}} + \frac{b c + 1}{(b + c)^{2}} + \frac{c a + 1}{(c + a)^{2}} \geqslant 3

$$

|

By developing $(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c})^{2}$ and dividing everything by 2, the hypothesis can be rewritten as

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+a b+b c+c a \leqslant 2 .

$$

We now seek to homogenize the left-hand side of the inequality to be proven, that is, to ensure that all terms have the same degree. For this, we introduce a 2 in place of the 1 and use our hypothesis:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{a b+1}{(a+b)^{2}} & =\frac{1}{2} \frac{2 a b+2}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{1}{2} \frac{2 a b+a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+a b+b c+c a}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{c^{2}+a b+b c+c a}{(a+b)^{2}}\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Similarly, we obtain $\frac{b c+1}{(b+c)^{2}} \geqslant \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}$ and $\frac{c a+1}{(c+a)^{2}} \geqslant \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}$. By summing, the left-hand side is at least

$$

\frac{3}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}+\frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}+\frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}\right) .

$$

However, according to the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}+\frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}+\frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}} \\

\geqslant & 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}} \times \frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}} \times \frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}}=3

\end{aligned}

$$

thus the left-hand side is at least $\frac{3}{2}+\frac{3}{2}=3$, hence the result.

## Exercises of Group A

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $a, b, c>0$ tels que $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+(a+b+c)^{2} \leqslant 4$. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a b+1}{(a+b)^{2}}+\frac{b c+1}{(b+c)^{2}}+\frac{c a+1}{(c+a)^{2}} \geqslant 3

$$

|

En développant $(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c})^{2}$ et en divisant tout par 2, l'hypothèse se réécrit

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+a b+b c+c a \leqslant 2 .

$$

On cherche maintenant à homogénéiser le membre de gauche de l'inégalité à montrer, c'est-à-dire à faire en sorte que tous les termes aient le même degré. Pour cela, on fait apparaître un 2 à la place du 1 et on utilise notre hypothèse :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{a b+1}{(a+b)^{2}} & =\frac{1}{2} \frac{2 a b+2}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{1}{2} \frac{2 a b+a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+a b+b c+c a}{(a+b)^{2}} \\

& =\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{c^{2}+a b+b c+c a}{(a+b)^{2}}\right) \\

& =\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}

\end{aligned}

$$

De même, on obtient $\frac{b c+1}{(b+c)^{2}} \geqslant \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}$ et $\frac{c a+1}{(c+a)^{2}} \geqslant \frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}$. En sommant, le membre de gauche vaut au moins

$$

\frac{3}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}+\frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}+\frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}\right) .

$$

Or, d'après l'inégalité de la moyenne arithmético-géométrique, on a

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}}+\frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}}+\frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}} \\

\geqslant & 3 \sqrt[3]{\frac{(c+a)(c+b)}{(a+b)^{2}} \times \frac{(a+b)(a+c)}{(b+c)^{2}} \times \frac{(b+c)(b+a)}{(c+a)^{2}}}=3

\end{aligned}

$$

donc le membre de gauche vaut au moins $\frac{3}{2}+\frac{3}{2}=3$, d'où le résultat.

## Exercices du groupe A

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Find all polynomials with real coefficients \( P \) such that the polynomial

\[

(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)

\]

is constant.

|

We present two solutions: one that uses polynomial factorization, and another that is more computational.

Let's start with the solution by factorization. Suppose that $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-$ 1) $P(X)$ is constantly equal to $2 k$. By taking $X=-1$, we get $2 P(-1)=2 k$. By taking $X=1$, we get $2 P(0)=2 k$. Therefore, $P(0)=P(-1)=k$, so 0 and -1 are roots of $P-k$, so $P-k$ can be factored by $X$ and $X+1$. Consequently, there exists a polynomial $Q$ such that

$$

P(X)=X(X+1) Q(X)+k

$$

The condition can then be rewritten as follows: the polynomial

$$

(X-1) X(X+1)(Q(X-1)-Q(X))+2 k

$$

is constantly equal to $2 k$, so

$$

(X-1) X(X+1)(Q(X-1)-Q(X))=0

$$

Therefore, $Q(n)=Q(n-1)$ for all integers $n \geqslant 2$, so $Q$ takes the value $Q(2)$ infinitely many times, so $Q-Q(2)$ has infinitely many roots, so $Q$ is constant. Finally, $P$ is of the form

$$

P(X)=c X(X+1)+k

$$

where $c$ and $k$ are two real numbers. Conversely, if $P$ is of this form, it is easily verified that the given polynomial is constant, equal to $2 k$.

Let's move on to the computational solution. We denote $d$ as the degree of $P$, and write

$$

P(X)=a_{d} X^{d}+a_{d-1} X^{d-1}+\ldots

$$

with $a_{d} \neq 0$. The polynomial $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)$ is at most of degree $d+1$, and we will calculate the coefficients of degrees $d+1$ and $d$. We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(X-1) & =a_{d}(X-1)^{d}+a_{d-1}(X-1)^{d-1}+[\text { Polynomial of degree at most } d-2] \\

& =a_{d} X^{d}-d a_{d} X^{d-1}+a_{d-1} X^{d-1}+[\text { Polynomial of degree at most } d-2]

\end{aligned}

$$

by expanding $(X-1)^{\mathrm{d}}$ and $(\mathrm{X}-1)^{\mathrm{d}-1}$ using the binomial theorem. We deduce $(X+1) P(X-1)=a_{d} X^{d+1}-d a_{d} X^{d}+a_{d-1} X^{d}+a_{d} X^{d}+[$ Polynomial of degree at most $d-2]$ and, similarly,

$$

(X-1) P(X)=a_{d} X^{d+1}+a_{d-1} X^{d}-a_{d} X^{d}+[\text { Polynomial of degree at most } d-2]

$$

In $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)$, the coefficient of $X^{d+1}$ is therefore $a_{d}-a_{d}=0$, and the coefficient of $X^{d}$ is $(2-d) a_{d}$, with $a_{d}$. If $d>0$, since the polynomial must be constant, this coefficient must be zero. Since $a_{d}>0$ by definition, we must therefore have $d=2$, so $P$ is of degree 0 or 2, so of the form

$$

P(X)=a X^{2}+b X+c

$$

By substituting $P$ with this expression, we get that the following polynomial must be constant:

$$

(b-a) X+(a-b+2 c)

$$

This polynomial is constant if and only if $b-a=0$, i.e., $a=b$, which means $P$ is of the form

$$

P(X)=a X(X+1)+c

$$

with $a, c \in \mathbb{R}$, and we find the same solution as by the first method.

|

P(X)=a X(X+1)+c

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Trouver tous les polynômes à coefficients réels P tels que le polynôme

$$

(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)

$$

soit constant.

|

On présente deux solutions : une qui utilise une factorisation polynomiale, et une autre plus calculatoire.

Commençons par la solution par factorisation. Supposons que $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-$ 1) $P(X)$ est constant égal à $2 k$. En prenant $X=-1$, on obtient $2 P(-1)=2 k$. En prenant $X=1$, on obtient $2 \mathrm{P}(0)=2 \mathrm{k}$. On a donc $\mathrm{P}(0)=\mathrm{P}(-1)=k$, donc 0 et -1 sont des racines de $P-k$, donc $P-k$ se factorise par $X$ et $X+1$. Par conséquent, il existe un polynôme Q tel que

$$

P(X)=X(X+1) Q(X)+k

$$

La condition se réécrit alors de la manière suivante : le polynôme

$$

(X-1) X(X+1)(Q(X-1)-Q(X))+2 k

$$

est constant égal à $2 k$, donc

$$

(X-1) X(X+1)(Q(X-1)-Q(X))=0

$$

On a donc $Q(n)=Q(n-1)$ pour tout entier $n \geqslant 2$, donc $Q$ prend une infinité de fois la valeur $\mathrm{Q}(2)$, donc $\mathrm{Q}-\mathrm{Q}(2)$ a une infinité de racines, donc Q est constant. Finalement, P est donc de la forme

$$

P(X)=c X(X+1)+k

$$

où c et k sont deux nombres réels. Réciproquement, si P est de cette forme, on vérifie facilement que le polynôme donné est constant, égal à $2 k$.

Passons à la solution calculatoire. On note d le degré de P , et on écrit

$$

P(X)=a_{d} X^{d}+a_{d-1} X^{d-1}+\ldots

$$

avec $a_{d} \neq 0$. Le polynôme $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)$ est au plus de degré $d+1$, et on va calculer ses coefficients de degrés $d+1$ et $d$. On a

$$

\begin{aligned}

P(X-1) & =a_{d}(X-1)^{d}+a_{d-1}(X-1)^{d-1}+[\text { Polynôme de degré au plus } d-2] \\

& =a_{d} X^{d}-d a_{d} X^{d-1}+a_{d-1} X^{d-1}+[\text { Polynôme de degré au plus } d-2]

\end{aligned}

$$

en développant $(X-1)^{\mathrm{d}}$ et $(\mathrm{X}-1)^{\mathrm{d}-1}$ avec le binôme de Newton. On en déduit $(X+1) P(X-1)=a_{d} X^{d+1}-d a_{d} X^{d}+a_{d-1} X^{d}+a_{d} X^{d}+[$ Polynôme de degré au plus $d-2]$ et, similairement,

$$

(X-1) P(X)=a_{d} X^{d+1}+a_{d-1} X^{d}-a_{d} X^{d}+[\text { Polynôme de degré au plus } d-2]

$$

Dans $(X+1) P(X-1)-(X-1) P(X)$, le coefficient devant $X^{d+1}$ vaut donc $a_{d}-a_{d}=0$, et le coefficient devant $X^{d}$ vaut $(2-d) a_{d}$, avec $a_{d}$. Si $d>0$, comme le polynôme doit être constant, ce coefficient doit être nul. Comme $a_{d}>0$ par définition, on doit donc avoir $\mathrm{d}=2$, donc P est de degré 0 ou 2 , donc de la forme

$$

P(X)=a X^{2}+b X+c

$$

En remplaçant P par cette expression, on obtient que le polynôme suivant doit être constant :

$$

(b-a) X+(a-b+2 c)

$$

Ce dernier polynôme est constant si et seulement si $b-a=0$, soit $a=b$, c'est-à-dire si P est de la forme

$$

P(X)=a X(X+1)+c

$$

avec $a, c \in \mathbb{R}$, et on retrouve la même solution que par la première méthode.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-pofm-2017-2018-envoi3-corrige.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}$ be any real numbers. Show that

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n}\left|x_{i}+x_{j}\right| \geqslant n \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left|x_{i}\right| .

$$

|

Among the $n$ numbers, we assume that $r$ are positive (or zero), and $s=n-r$ are strictly negative. We denote $\left(a_{i}\right)_{1 \leqslant i \leqslant r}$ as the list of positive (or zero) numbers, and $\left(-b_{j}\right)_{1 \leqslant j \leqslant s}$ as the list of strictly negative numbers, such that all the $a_{i}$ and the $b_{j}$ are positive.

We define

$$

A=\sum_{i=1}^{r} a_{i}, B=\sum_{j=1}^{s} b_{j}

$$