problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In the regular 18-gon $\quad \mathrm{A}_{1} \mathrm{~A}_{2} . \mathrm{A}_{18}$ with circumcenter M, P is the intersection of $A_{1} A_{7}$ with $M A_{2}$ and $Q$ is the intersection of $A_{2} A_{13}$ with $M A_{1}$. Calculate the angle $\angle \mathrm{MPQ}$.

## 2. Selection Exam

|

empty

Translate the text above into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

| null |

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Im regulären 18-Eck $\quad \mathrm{A}_{1} \mathrm{~A}_{2} . \mathrm{A}_{18}$ mit den Umkreismittelpunkt M ist P der Schnitt von $A_{1} A_{7}$ mit $M A_{2}$ und $Q$ der Schnitt von $A_{2} A_{13}$ mit $M A_{1}$. Man berechne den Winkel $\angle \mathrm{MPQ}$.

## 2. Auswahlklausur

|

empty

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2001-aufgaben_awb_01.jsonl",

"solution_match": "",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2001"

}

|

Given positive integers $a, b, c$ with the property $b > 2a$ and $c > 2b$.

Show that there always exists a real number $r$ with the following property:

The fractional parts of the numbers $ra, rb, rc$ all lie in the interval $\left.\rfloor \frac{1}{3} ; \frac{2}{3}\right\rfloor$.

(Hint: The fractional part of a number is the difference between the number and its integer part.)

|

empty

Translate the text above into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

| null |

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Gegeben seien positive ganze Zahlen $a, b, c$ mit der Eigenschaft $b>2 a$ und $c>2 b$.

Man zeige, dass es dann stets eine reelle Zahl $r$ mit folgender Eigenschaft gibt:

Die gebrochenen Teile der Zahlen $r a, r b, r c$ liegen alle im Intervall $\left.\rfloor \frac{1}{3} ; \frac{2}{3}\right\rfloor$.

(Hinweis: Der gebrochene Teil einer Zahl ist die Differenz zwischen der Zahl und ihrem ganzen Teil.)

|

empty

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2001-aufgaben_awb_01.jsonl",

"solution_match": "",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2001"

}

|

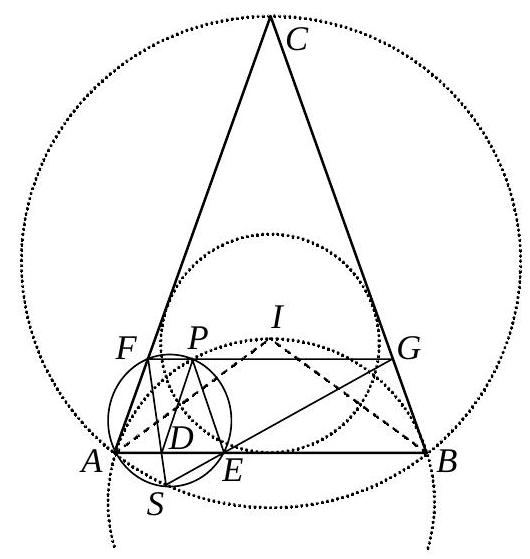

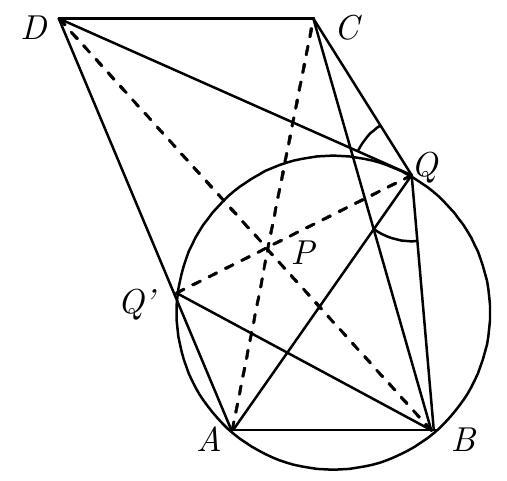

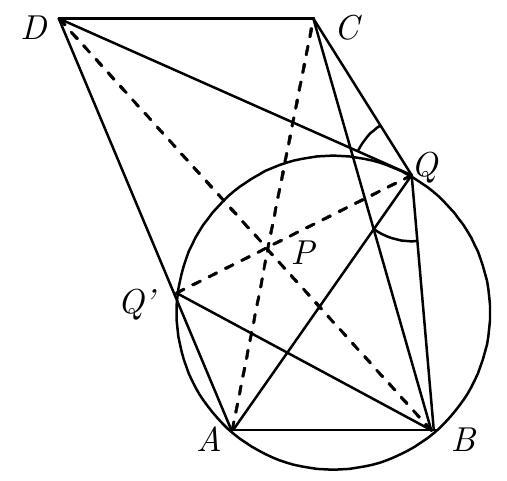

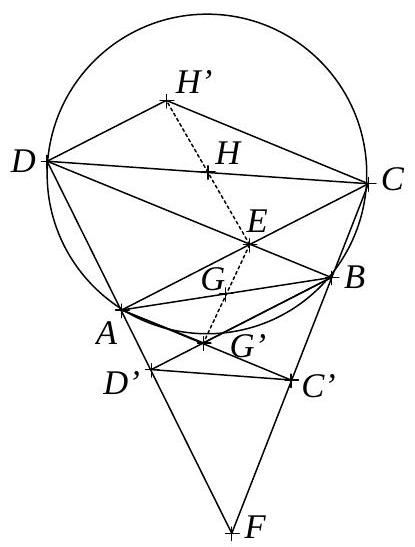

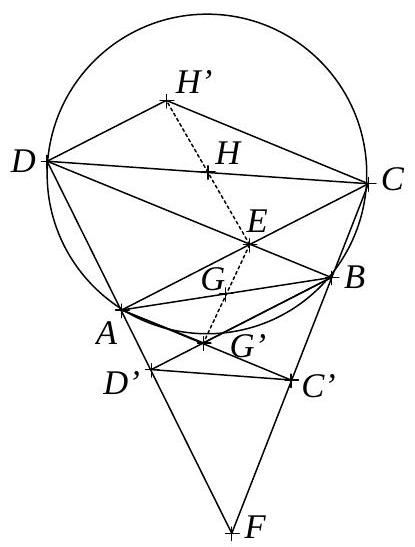

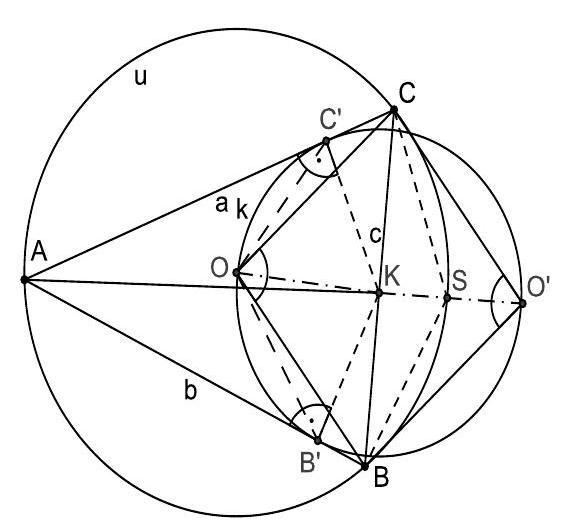

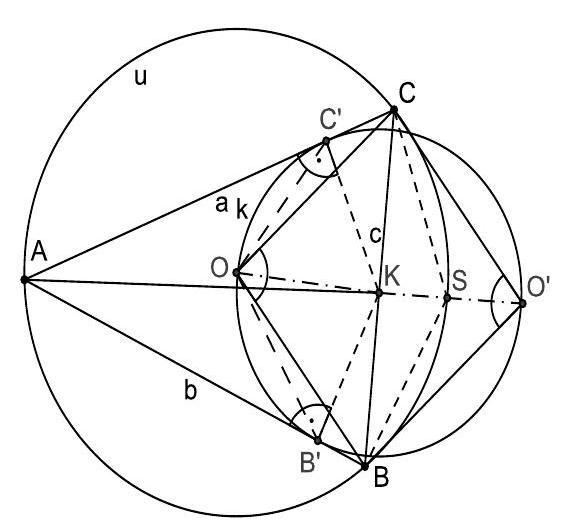

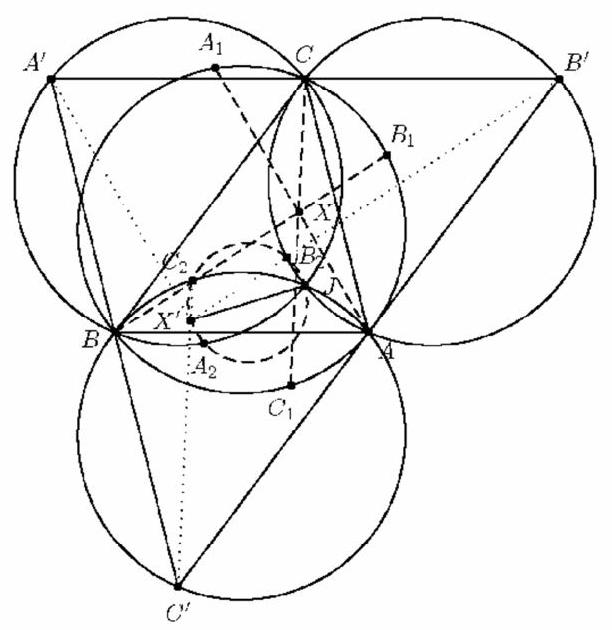

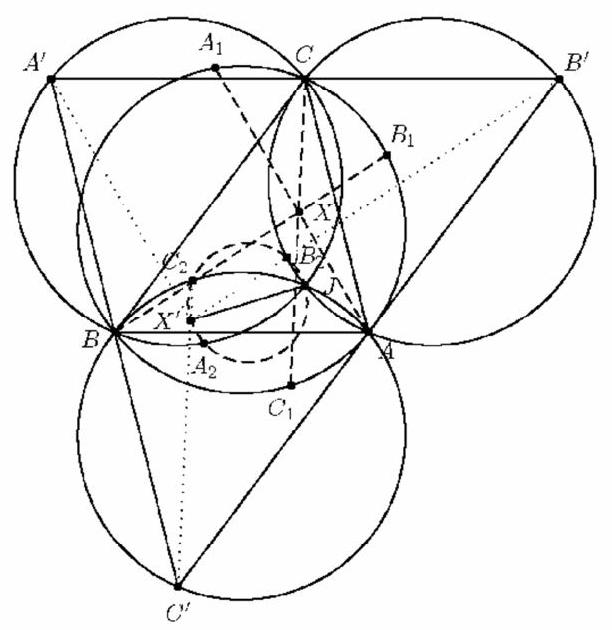

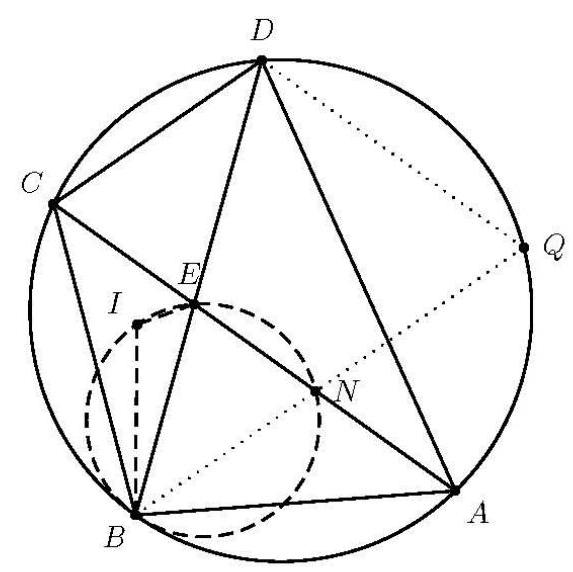

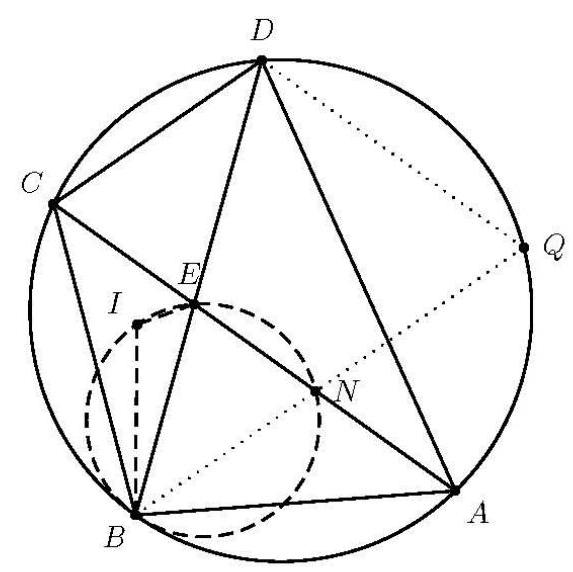

We consider two circles in the plane that intersect at two distinct points $X$ and $Y$.

Prove that there are four fixed points in this plane with the following property: For any circle that lies in the intersection of the two given circles and touches these at points $A$ and $B$ and intersects the line $X Y$ at points $C$ and $D$, each of the lines $A C, A D, B C$, and $B D$ passes through one of these four points.

|

empty

Translate the text above into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

| null |

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Wir betrachten zwei Kreise in der Ebene, welche sich in den beiden verschiedenen Punkten $X$ und $Y$ schneiden.

Man beweise, dass es in dieser Ebene vier feste Punkte mit folgender Eigenschaft gibt: Für jeden Kreis, der im Durchschnitt der beiden gegebenen Kreise liegt und diese in den Punkten $A$ und $B$ berührt sowie die Gerade $X Y$ in den Punkten $C$ und $D$ schneidet, geht jede der Geraden $A C, A D, B C$ und $B D$ durch einen dieser vier Punkte.

|

empty

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2001-aufgaben_awb_01.jsonl",

"solution_match": "",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2001"

}

|

For every positive integer $n$, let $d(n)$ denote the number of all positive divisors of $n$. (Examples: $d(2)=2, d(6)=4, d(9)=3$.)

Determine all positive integers $n$ with the property $(d(n))^{3}=4 n$.

|

empty

Translate the text above into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Für jede positive ganze Zahl $n$ bezeichne $d(n)$ die Anzahl aller positiver Teiler von $n$. (Beispiele: $d(2)=2, d(6)=4, d(9)=3$.)

Man bestimme alle positiven ganzen Zahlen $n$ mit der Eigenschaft $(d(n))^{3}=4 n$.

|

empty

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2001-aufgaben_awb_01.jsonl",

"solution_match": "",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2001"

}

|

Determine the number of all numbers of the form $x^{2}+y^{2}(x, y \in\{1,2,3, \ldots, 1000\})$, which are divisible by 121.

|

The possible remainders when a square number is divided by 11 are 0, 1, 4, 9, 5, and 3. Since, except for zero, no complementary remainders modulo 11 occur, both $x^{2}$ and $y^{2}$, and consequently $x$ and $y$, must be divisible by 11.

Among the numbers from 1 to 1000, there are exactly [1000/11] = 90 multiples of 11. Therefore, there are at most 90.89/2 = 4005 numbers divisible by 121 of the form $x^{2}+y^{2}$ with $x \neq y$, and exactly 90 numbers divisible by 121 of the form $x^{2}+x^{2}$. Consequently, there can be at most 4095 numbers of the mentioned form. However, their number is actually lower, as there are many numbers that allow different representations as the sum of two squares. Unfortunately, the problem setter did not consider this when formulating the problem. All the more delightful was the fact that some participants provided very interesting solution approaches.

|

4095

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Man ermittle die Anzahl aller Zahlen der Form $x^{2}+y^{2}(x, y \in\{1,2,3, \ldots, 1000\})$, die durch 121 teilbar sind.

|

Die Reste, die eine Quadratzahl bei der Division durch 11 haben kann, sind 0, 1, 4, 9, 5 und 3. Da aber, außer zur Null, keine komplementären Reste modulo 11 auftreten, müssen sowohl $x^{2}$ als auch $y^{2}$ und folglich auch $x$ und $y$ durch 11 teilbar sein.

Unter den Zahlen von 1 bis 1000 gibt es genau [1000/11] = 90 Vielfache von 11. Es gibt demnach höchstens 90.89/2 = 4005 durch 121 teilbare Zahlen der Form $x^{2}+y^{2}$ mit $x \neq y$, und genau 90 durch 121 teilbare Zahlen der Form $x^{2}+x^{2}$. Folglich kann es höchstens 4095 Zahlen der genannten Form geben. Ihre Anzahl ist allerdings geringer, da es viele Zahlen gibt, die unterschiedliche Darstellungen als Summe zweier Quadrate erlauben. Leider hatte das der Aufgabensteller bei der Formulierung der Aufgabe nicht bedacht. Umso erfreulicher war die Tatsache, dass einige Teilnehmer sehr interessante Lösungsansätze lieferten.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl1_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

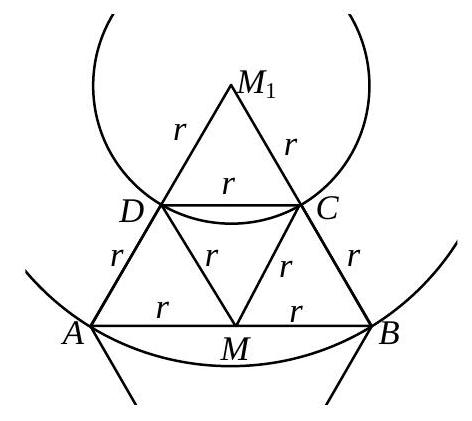

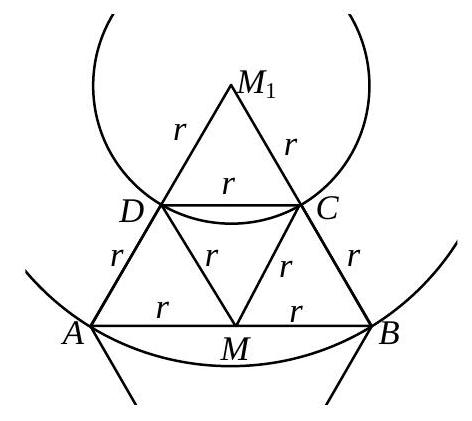

Prove: If \( x, y, z \) are the lengths of the angle bisectors of a triangle with a perimeter of 6, then

$$

\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac{1}{y^2}+\frac{1}{z^2} \geq 1

$$

|

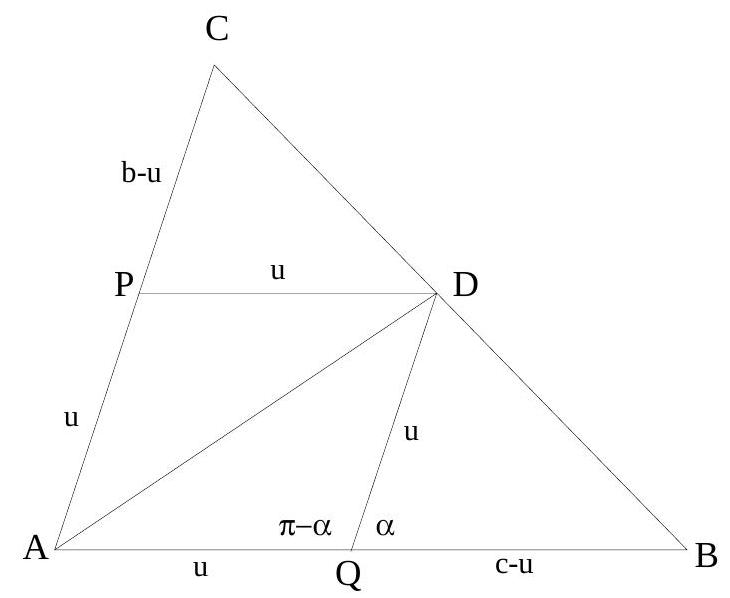

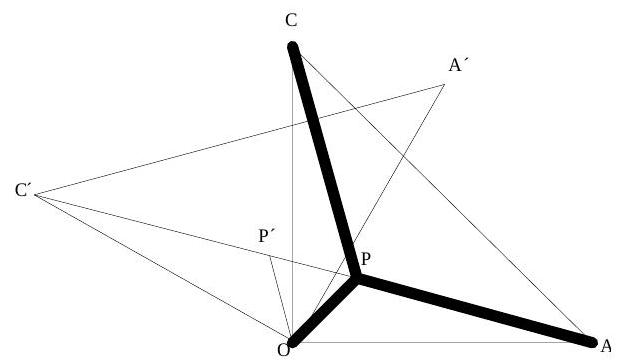

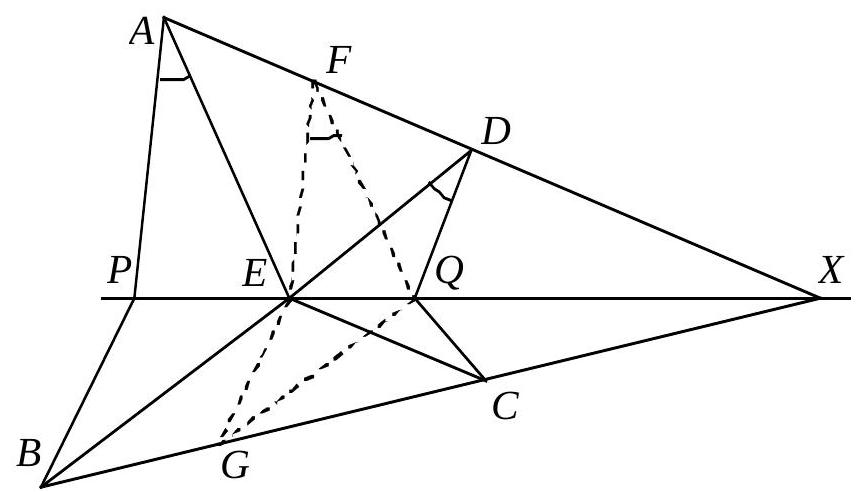

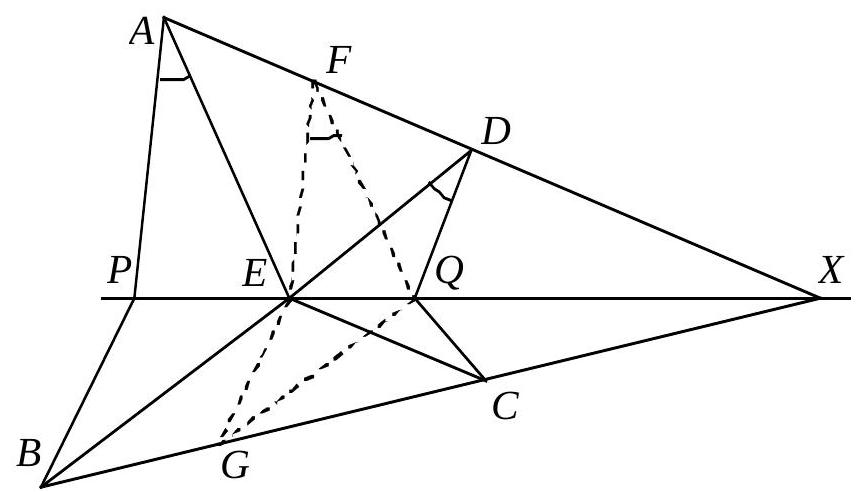

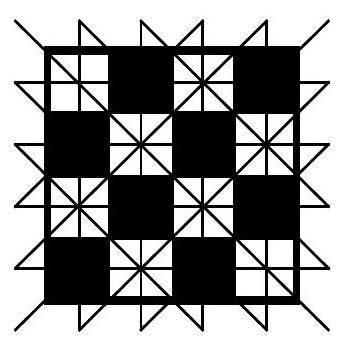

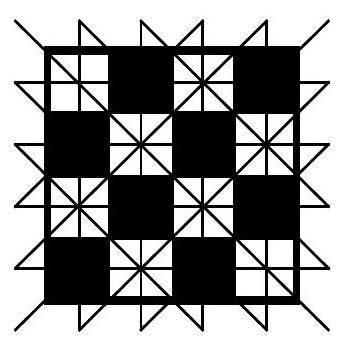

Consider the adjacent figure.

DP and DQ are the parallels through D to AB and

AC. Since $A D=x$ is the angle bisector of $\alpha$, AQDP is a rhombus, whose side length is denoted by $u$.

From the similarity of triangles PDC and QBD, it follows that $\frac{u}{c-u}=\frac{b-u}{u}$, from which we obtain $u=\frac{bc}{b+c}$.

Applying the Law of Cosines in triangle AQD leads to

\[

\begin{aligned}

x^{2}=2 u^{2}-2 u^{2} \cos (\pi-\alpha) & =2 u^{2}(1+\cos \alpha) \\

=2 u^{2}\left(1+\frac{b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2 b c}\right)=2 u^{2} & \frac{(b+c)^{2}-a^{2}}{2 b c}= \\

& =\frac{b c}{(b+c)^{2}}(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)

\end{aligned}

\]

With $(b+c)^{2} \geq 4 b c$ and $a+b+c=6$, it follows that $x^{2} \leq 1.5(-a+b+c)$.

Similarly, we get $y^{2} \leq 1.5(a-b+c)$ and $z^{2} \leq 1.5(a+b-c)$.

From the inequality between the arithmetic and geometric means of three positive numbers, we get $\left(\frac{1}{x^{2}}+\frac{1}{y^{2}}+\frac{1}{z^{2}}\right)\left(x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}\right) \geq 9$ and from this, finally,

\[

\frac{1}{x^{2}}+\frac{1}{y^{2}}+\frac{1}{z^{2}} \geq \frac{9}{x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}} \geq \frac{9}{1.5 \cdot 6}=1

\]

where the equality sign holds only for $x=y=z$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Man beweise: Sind x, y, z die Längen der Winkelhalbierenden eines Dreiecks mit dem Umfang 6, dann gilt

$$

\frac{1}{\mathrm{x}^{2}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{y}^{2}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{z}^{2}} \geq 1

$$

|

Man beachte nebenstehende Figur.

DP und DQ sind die Parallelen durch D zu AB und

AC. Da $A D=x$ die Winkelhalbierende von $\alpha$ ist, ist AQDP eine Raute, deren Seitenlänge mit $u$ bezeichnet wurde.

Aus der Ähnlichkeit der Dreiecke PDC mit QBD folgt $\frac{\mathrm{u}}{\mathrm{c}-\mathrm{u}}=\frac{\mathrm{b}-\mathrm{u}}{\mathrm{u}}$, woraus man $u=\frac{b c}{b+c}$ erhält.

Der Kosinussatz im Dreieck AQD führt zu

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{x}^{2}=2 \mathrm{u}^{2}-2 \mathrm{u}^{2} \cos (\pi-\alpha) & =2 \mathrm{u}^{2}(1+\cos \alpha) \\

=2 u^{2}\left(1+\frac{b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2 b c}\right)=2 u^{2} & \frac{(b+c)^{2}-a^{2}}{2 b c}= \\

& =\frac{b c}{(b+c)^{2}}(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)

\end{aligned}

$$

Mit $(b+c)^{2} \geq 4 b c$ und $a+b+c=6$ folgt $x^{2} \leq 1,5(-a+b+c)$.

Ähnlich ergibt sich $y^{2} \leq 1,5(a-b+c)$ und $z^{2} \leq 1,5(a+b-c)$.

Aus der Ungleichung zwischen dem arithmetischen und geometrischen Mittel dreier positiver Zahlen, ergibt sich $\left(\frac{1}{x^{2}}+\frac{1}{y^{2}}+\frac{1}{z^{2}}\right)\left(x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}\right) \geq 9$ und hieraus schließlich

$$

\frac{1}{x^{2}}+\frac{1}{y^{2}}+\frac{1}{z^{2}} \geq \frac{9}{x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}} \geq \frac{9}{1,5 \cdot 6}=1

$$

wobei das Gleichheitszeichen nur für $x=y=z$ gilt.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl1_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

Find all solutions of the equation $\quad x^{2 y}+(x+1)^{2 y}=(x+2)^{2 y}$ with $x, y \in N$.

|

One can easily see that neither $x$ nor $y$ can be zero.

For $y=1$, from $x^{2}+(x+1)^{2}=(x+2)^{2}$, we obtain the equation $x^{2}-2 x-3=0$, of which only the solution $x=3$ is valid.

Now let $y>1$.

Since $x$ and $x+2$ have the same parity, $x+1$ is an even number and thus $x$ is an odd number.

With $x=2 k-1(k \in \mathbb{N})$, we get the equation

(\#) $\quad(2 k-1)^{2 y}+(2 k)^{2 y}=(2 k+1)^{2 y}$

from which, by expanding, we obtain:

$$

(2 k)^{2 y}-2 y(2 k)^{2 y-1}+\ldots-2 y 2 k+1+(2 k)^{2 y}=(2 k)^{2 y}+2 y(2 k)^{2 y-1}+\ldots+2 y 2 k+1

$$

Since $y>1$, it follows that $2 y \geq 3$. If we now move all terms in $yk$ to one side and factor out $(2k)^{3}$ on the other side, we get:

$$

8 yk=(2 k)^{3}\left[2\binom{2 y}{3}+2\binom{2 y}{5}(2 k)^{2}+\ldots-(2 k)^{2 y-3}\right]

$$

from which it follows that $y$ is a multiple of $k$.

By dividing equation (\#) by $(2k)^{2 y}$, we get:

$$

\left(1-\frac{1}{2 k}\right)^{2 y}+1=\left(1+\frac{1}{2 k}\right)^{2 y}

$$

where the left side is less than 2. The right side, however, is greater than $1+\frac{2 y}{2 k} \geq 2$, which cannot be, since $y$ is a multiple of $k$.

Therefore, the given equation has only the solution $x=3$ and $y=1$.

That there are no solutions for $y > 1$ was clear to most participants, as it represents a special case of Fermat's Last Theorem, which has since been proven. Unfortunately, only a few managed to provide a complete proof of this special case.

|

x=3, y=1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Man ermittle alle Lösungen der Gleichung $\quad x^{2 y}+(x+1)^{2 y}=(x+2)^{2 y}$ mit $x, y \in N$.

|

Man erkennt leicht, dass weder $x$, noch $y$, Null sein können.

Für $y=1$ erhält man aus $x^{2}+(x+1)^{2}=(x+2)^{2}$ die Gleichung $x^{2}-2 x-3=0$, von der nur die Lösung $x=3$ in Frage kommt.

Sei nun $y>1$.

Da $x$ und $x+2$ dieselbe Parität haben, ist $x+1$ eine gerade und demnach $x$ eine ungerade Zahl.

Mit $x=2 k-1(k \in N)$ ergibt sich die Gleichung

(\#) $\quad(2 k-1)^{2 y}+(2 k)^{2 y}=(2 k+1)^{2 y}$

woraus man durch Ausmultiplizieren folgendes erhält:

$$

(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}}-2 \mathrm{y}(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}-1}+\ldots-2 \mathrm{y} 2 \mathrm{~h}+1+(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}}=(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}}+2 \mathrm{y}(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}-1}+\ldots+2 \mathrm{y} 2 \mathrm{k}+1

$$

Da $y>1$, ist auch $2 \mathrm{y} \geq 3$. Lässt man nun alle Glieder in yk auf einer Seite und faktorisiert auf der anderen Seite (2k) ${ }^{3}$, dann erhält man:

$$

8 \mathrm{yk}=(2 \mathrm{k})^{3}\left[2\binom{2 \mathrm{y}}{3}+2\binom{2 \mathrm{y}}{5}(2 \mathrm{k})^{2}+\ldots-(2 \mathrm{k})^{2 \mathrm{y}-3}\right]

$$

woraus folgt, dass y ein Vielfaches von k ist.

Durch Division der Gleichung (\#) durch (2k) ${ }^{2 y}$ ergibt sich:

$$

\left(1-\frac{1}{2 k}\right)^{2 y}+1=\left(1+\frac{1}{2 k}\right)^{2 y}

$$

wobei die linke Seite kleiner als 2 ist. Die rechte Seite ist allerdings größer als $1+\frac{2 y}{2 k} \geq 2$, was nicht sein kann, da y ein Vielfaches von $k$ ist.

Die gegebene Gleichung hat demnach nur die Lösung $x=3$ und $\mathrm{y}=1$.

Dass es für y > 1 keine Lösungen geben kann, war den meisten Teilnehmern klar, da sich ein Sonderfall für den großen Satz von Fermat ergibt, der mittlerweile bewiesen ist. Leider gelang nur wenigen ein vollständiger Beweis dieses Sonderfalles.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl1_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

Let $P$ be the set of all ordered pairs $(p, q)$ of non-negative integers. Determine all functions $f: P \rightarrow \mathrm{IR}$ with the property

$$

f(p, q)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}

0 \quad \text { if } p q=0 \\

1+\frac{1}{2} f(p+1, q-1)+\frac{1}{2} f(p-1, q+1) \text { otherwise }

\end{array} .\right.

$$

|

The only such function is $f(p, q)=p \cdot q$.

This function clearly satisfies the first condition for $p=0$ or $q=0$. For $p q \neq 0$, we have $1+\frac{1}{2} f(p+1, q-1)+\frac{1}{2} f(p-1, q+1)=1+\frac{1}{2}(p+1)(q-1)+\frac{1}{2}(p-1)(q+1)=p q$, so the second condition is also satisfied.

Now it must be shown that there is no other function with these properties. To do this, we set $f(p, q)=p q+g(p, q)$. For $p q \neq 0$, the second condition yields $p q+g(p, q)=1+\frac{1}{2}((p+1)(q-1)+g(p+1, q-1)+(p-1)(q+1)+g(p-1, q+1))$, thus $g(p, q)=\frac{1}{2}(g(p+1, q-1)+g(p-1, q+1))$. Therefore, the numbers $g(0, p+q)$, $g(1, p+q-1), g(2, p+q-2), \ldots, g(p+q-1,1), g(p+q, 0)$ form an arithmetic sequence. Since their outer terms $g(0, p+q)$ and $g(p+q, 0)$ are both zero, each term in the sequence is zero. Consequently, $g(p, q)=0$ for all non-negative integers, and thus $f(p, q)=p \cdot q$ is the only solution.

Note: The second part of the proof is the more significant one. It is not enough to merely exclude certain types of functions, as some participants have attempted.

|

f(p, q)=p \cdot q

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Es sei $P$ die Menge aller geordneter Paare $(p, q)$ von nichtnegativen ganzen Zahlen. Man bestimme alle Funktionen $f: P \rightarrow \mathrm{IR}$ mit der Eigenschaft

$$

f(p, q)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}

0 \quad \text { wenn } p q=0 \\

1+\frac{1}{2} f(p+1, q-1)+\frac{1}{2} f(p-1, q+1) \text { sonst }

\end{array} .\right.

$$

|

Die einzige solche Funktion ist $f(p, q)=p \cdot q$.

Diese Funktion erfüllt offensichtlich für $p=0$ oder $q=0$ die erste Bedingung. Für $p q \neq 0$ gilt $1+\frac{1}{2} f(p+1, q-1)+\frac{1}{2} f(p-1, q+1)=1+\frac{1}{2}(p+1)(q-1)+\frac{1}{2}(p-1)(q+1)=p q$, so dass auch die zweite Bedingung erfültt ist.

Nun muss noch gezeigt werden, dass es keine andere Funktion mit diesen Eigenschaften gibt. Dazu setzen wir $f(p, q)=p q+g(p, q)$. Für $p q \neq 0$ ergibt sich aus der zweiten

Bedingung $p q+g(p, q)=1+\frac{1}{2}((p+1)(q-1)+g(p+1, q-1)+(p-1)(q+1)+g(p-1, q+1))$, also $g(p, q)=\frac{1}{2}(g(p+1, q-1)+g(p-1, q+1))$. Daher bilden die Zahlen $g(0, p+q)$, $g(1, p+q-1), g(2, p+q-2), \ldots, g(p+q-1,1), g(p+q, 0)$ eine arithmetische Folge. Da ihre Außenglieder $g(0, p+q)$ und $g(p+q, 0)$ gleich Null sind, hat jedes Folgenglied den Wert Null. Folglich ist $g(p, q)=0$ für alle nichtnegativen ganzen Zahlen und daher $f(p, q)=p \cdot q$ die einzige Lösung.

Anmerkung: Der zweite Teil des Beweises ist der bedeutendere. Dabei reicht es nicht, nur bestimmte Typen von Funktionen auszuschließen, wie es einige Teilnehmer versucht haben.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl2_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

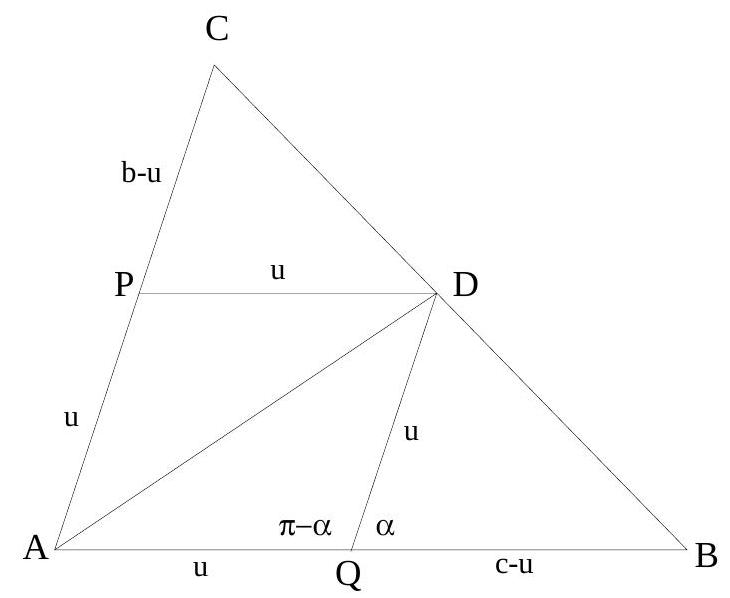

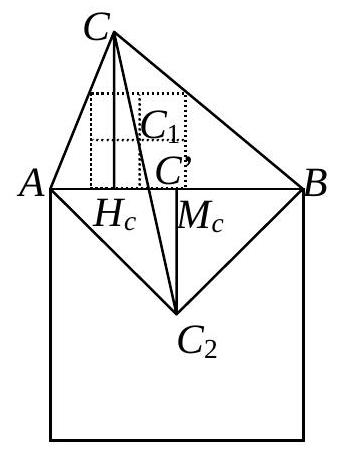

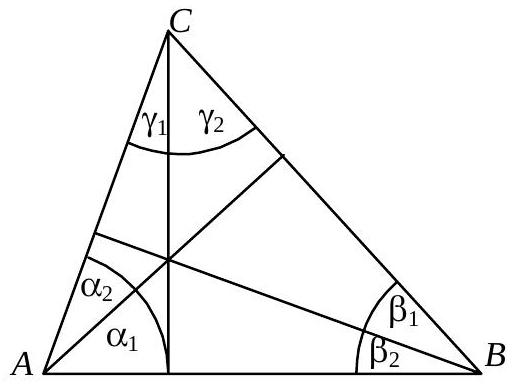

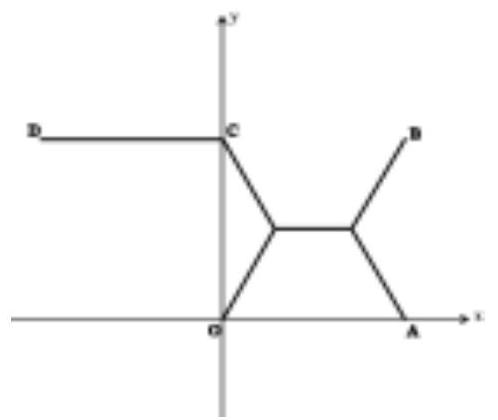

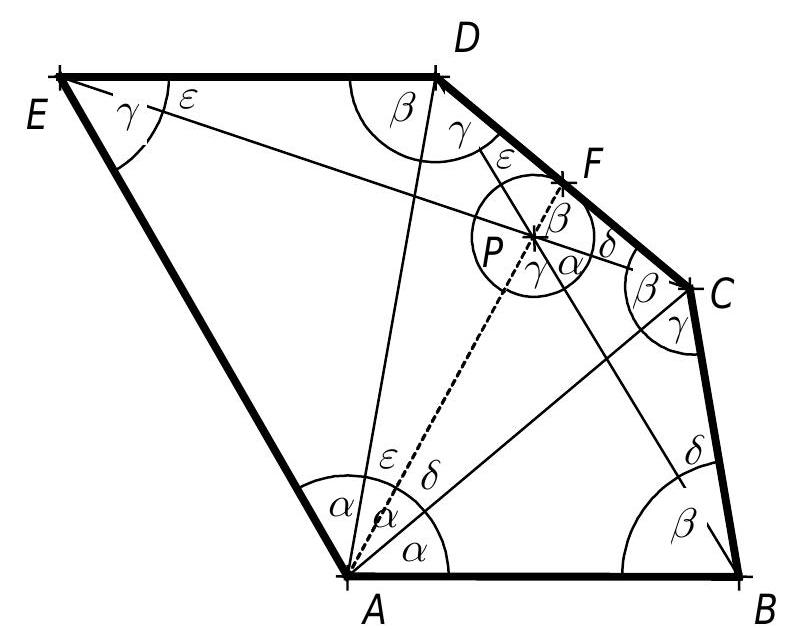

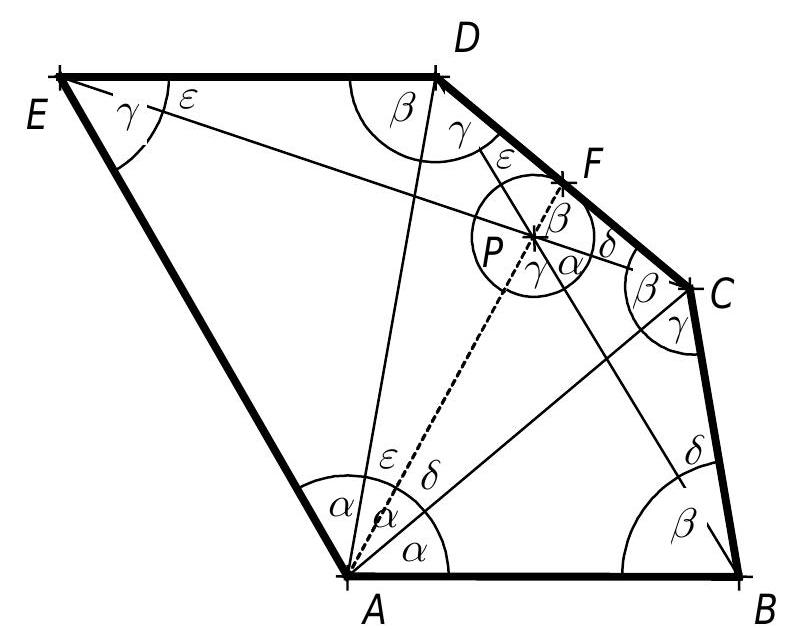

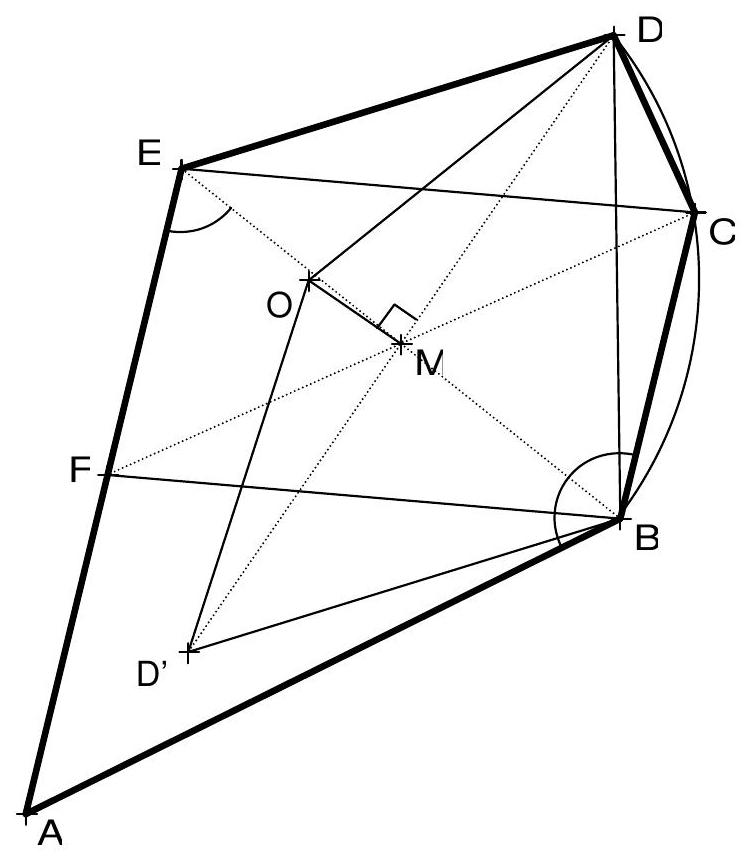

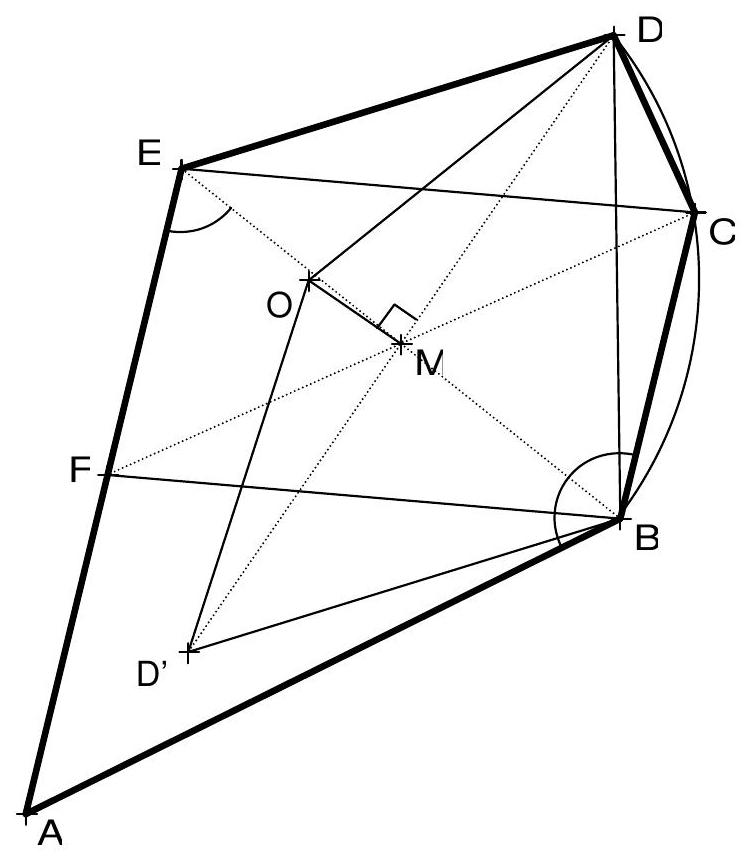

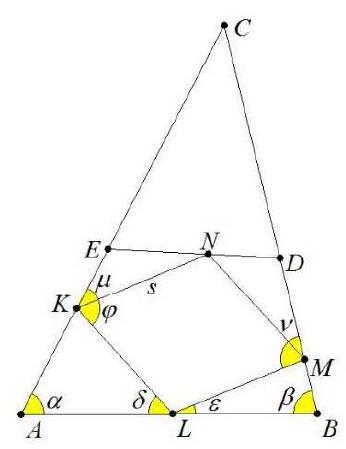

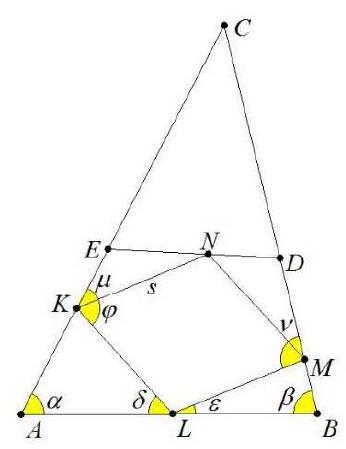

In an acute-angled triangle $A B C$, a square with center $A_{1}$ is inscribed such that two vertices lie on $B C$ and one each on $A B$ and $A C$. Analogously, the squares with centers $B_{1}$ and $C_{1}$ are defined.

Prove that the lines $A A_{1}, B B_{1}$, and $C C_{1}$ have a common intersection point.

|

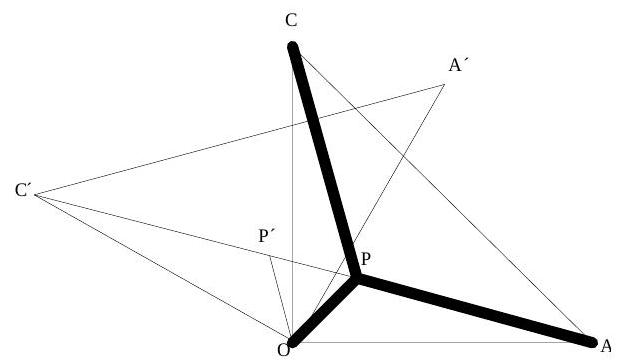

In addition to the given figure, we consider the square constructed outwardly over the side $AB$ with the center $C_{2}$. Since there is a central dilation that transforms the inscribed square with center $C_{1}$ into the outwardly constructed square, $C, C_{1}$, and $C_{2}$ lie on a straight line.

The height $h_{c}$ intersects $AB$ at $H_{c}$, and let $\left|A H_{c}\right|=p,\left|H_{c} B\right|=q$. Furthermore, let $M_{c}$ be the midpoint of $AB$ and $C^{\prime}$ be the intersection of $C C_{2}$ with $AB$. Finally, set $\left|A C^{\prime}\right|=c_{1}$ and $\left|C^{\prime} B\right|=c_{2}$. All subsegments of $AB$ exist due to the acute angles of triangle $ABC$. For the other sides of the triangle, corresponding points and segments are defined analogously.

By the intercept theorems, $\frac{\left|H_{c} C^{\prime}\right|}{\left|C H_{c}\right|}=\frac{\left|C^{\prime} M_{c}\right|}{\left|M_{c} C_{2}\right|}$, i.e., $\frac{c_{1}-p}{h_{c}}=\frac{\frac{1}{2} c-c_{1}}{\frac{1}{2} c} \Rightarrow c_{1}=\frac{c\left(p+h_{c}\right)}{c+2 h_{c}}$.

Similarly, $c_{2}=\frac{c\left(q+h_{c}\right)}{c+2 h_{c}}$ and we obtain $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\frac{p}{h_{c}}+1}{\frac{q}{h_{c}}+1}$. (For $\alpha=\beta$, $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=1$. )

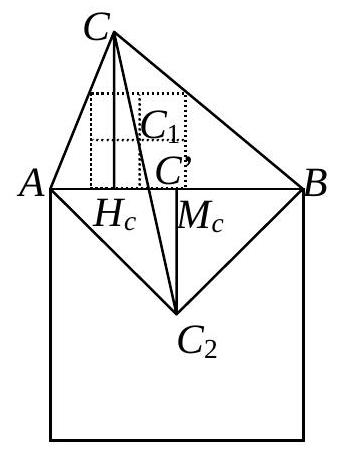

The angles between the heights and the respective adjacent sides are cyclically denoted by $\gamma_{1}, \gamma_{2}$, $\alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}$, and $\beta_{1}, \beta_{2}$. Then, $\alpha_{1}=\gamma_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\beta\right), \quad \beta_{1}=\alpha_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\gamma\right)$, and $\gamma_{1}=\beta_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\alpha\right)$. Furthermore, $\frac{p}{h_{c}}=\tan \gamma_{1}$ and $\frac{q}{h_{c}}=\tan \gamma_{2}$, so $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\tan \gamma_{1}+1}{\tan \gamma_{2}+1}$. Similarly, $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{\tan \alpha_{1}+1}{\tan \alpha_{2}+1}$ and $\frac{b_{1}}{b_{2}}=\frac{\tan \beta_{1}+1}{\tan \beta_{2}+1}$. Therefore,

\[

\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}} \cdot \frac{b_{1}}{b_{2}} \cdot \frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\left(\tan \alpha_{1}+1\right)\left(\tan \beta_{1}+1\right)\left(\tan \gamma_{1}+1\right)}{\left(\tan \alpha_{2}+1\right)\left(\tan \beta_{2}+1\right)\left(\tan \gamma_{2}+1\right)}=\frac{\tan \alpha_{1}+1}{\tan \gamma_{2}+1} \cdot \frac{\tan \beta_{1}+1}{\tan \alpha_{2}+1} \cdot \frac{\tan \gamma_{1}+1}{\tan \beta_{2}+1}=1 \cdot 1 \cdot 1=1.

\]

By the converse of Ceva's theorem, the lines $A A^{\prime}=A A_{1}$, $B B^{\prime}=B B_{1}$, and $C C^{\prime}=C C_{1}$ intersect at a point.

Note: Some participants conjectured that the lines $A A_{1}$ etc. are the angle bisectors of the given triangle. This conjecture is false, as can be seen from a very acute, nearly right-angled triangle. Ceva's theorem is not necessary for the proof; there are other solution methods, such as using spiral dilations.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

In ein spitzwinkliges Dreieck $A B C$ wird ein Quadrat mit Mittelpunkt $A_{1}$ so einbeschrieben, dass zwei Ecken auf $B C$ und je eine auf $A B$ bzw. $A C$ liegen. Analog sind die Quadrate mit den Mittelpunkten $B_{1}$ bzw. $C_{1}$ definiert.

Man beweise, dass die Geraden $A A_{1}, B B_{1}$ und $C C_{1}$ einen gemeinsamen Schnittpunkt haben.

|

Zusätzlich zur gegebenen Figur betrachten wir das nach außen errichtete Quadrat über der Seite $A B$ mit dem Mittelpunkt $C_{2}$. Da es eine zentrische Streckung gibt, welche das einbeschriebene Quadrat mit Mittelpunkt $C_{1}$ in das nach außen errichtete Quadrat überführt, liegen $C, C_{1}$ und $C_{2}$ auf einer Geraden.

Die Höhe $h_{c}$ schneidet $A B$ in $H_{c}$ und es sei $\left|A H_{c}\right|=p,\left|H_{c} B\right|=q$. Ferner sei $M_{c}$ der Mittelpunkt von $A B$ und $C^{\prime}$ der Schnittpunkt von $C C_{2}$ mit $A B$. Schließlich setzen wir $\left|A C^{\prime}\right|=c_{1}$ und $\left|C^{\prime} B\right|=c_{2}$. Alle Teilstrecken von $A B$ existieren wegen der Spitzwinkligkeit des Dreiecks $A B C$. Für die anderen Dreiecksseiten seien entsprechende

Punkte und Abschnitte analog definiert.

Nach den Strahlensätzen gilt $\frac{\left|H_{c} C^{\prime}\right|}{\left|C H_{c}\right|}=\frac{\left|C^{\prime} M_{c}\right|}{\left|M_{c} C_{2}\right|}$, d.h. $\frac{c_{1}-p}{h_{c}}=\frac{\frac{1}{2} c-c_{1}}{\frac{1}{2} c} \Rightarrow c_{1}=\frac{c\left(p+h_{c}\right)}{c+2 h_{c}}$.

Analog ist $c_{2}=\frac{c\left(q+h_{c}\right)}{c+2 h_{c}}$ und wir erhalten $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\frac{p}{h_{c}}+1}{\frac{q}{h_{c}}+1}$. (Für $\alpha=\beta$ ist $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=1$. )

Die Winkel zwischen den Höhen und den jeweils anliegenden beiden Seiten seien zyklisch mit $\gamma_{1}, \gamma_{2}$ bzw. $\alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}$ bzw. $\beta_{1}, \beta_{2}$ bezeichnet. Dann gilt $\alpha_{1}=\gamma_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\beta\right), \quad \beta_{1}=\alpha_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\gamma\right)$ und $\gamma_{1}=\beta_{2}\left(=90^{\circ}-\alpha\right)$. Ferner ist $\frac{p}{h_{c}}=\tan \gamma_{1}$ und $\frac{q}{h_{c}}=\tan \gamma_{2}$, also $\frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\tan \gamma_{1}+1}{\tan \gamma_{2}+1}$. Analog gilt $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}=\frac{\tan \alpha_{1}+1}{\tan \alpha_{2}+1}$ und $\frac{b_{1}}{b_{2}}=\frac{\tan \beta_{1}+1}{\tan \beta_{2}+1}$. Damit ist

$\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}} \cdot \frac{b_{1}}{b_{2}} \cdot \frac{c_{1}}{c_{2}}=\frac{\left(\tan \alpha_{1}+1\right)\left(\tan \beta_{1}+1\right)\left(\tan \gamma_{1}+1\right)}{\left(\tan \alpha_{2}+1\right)\left(\tan \beta_{2}+1\right)\left(\tan \gamma_{2}+1\right)}=\frac{\tan \alpha_{1}+1}{\tan \gamma_{2}+1} \cdot \frac{\tan \beta_{1}+1}{\tan \alpha_{2}+1} \cdot \frac{\tan \gamma_{1}+1}{\tan \beta_{2}+1}=1 \cdot 1 \cdot 1=1$.

Nach der Umkehrung des Satzes von Ceva schneiden sich daher die Geraden $A A^{\prime}=A A_{1}$, $B B^{\prime}=B B_{1}$ und $C C^{\prime}=C C_{1}$ in einem Punkt.

Anmerkung: Einige Teilnehmer haben vermutet, die Geraden $A A_{1}$ etc. seien die Winkelhalbierenden des gegebenen Dreiecks. Diese Vermutung ist falsch, wie man an einem sehr spitzen, fast rechtwinkligen Dreieck sieht. Der Satz von Ceva ist zum Beweis nicht notwendig; es gibt andere Lösungsmöglichkeiten, z.B. mit Drehstreckungen.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl2_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

Prove that there is no positive integer $n$ with the following property: For $k=1,2, \ldots, 9$ the leftmost digit - in decimal notation - of $(n+k)!$ is $k$.

|

We assume that there is a number $n$ with the required property. Then none of the factorials can be a power of ten, because from 3! onwards all factorials are divisible by 3 and the first factorials obviously do not have the required property. None of the numbers $n+2, \ldots, n+9$ can be a power of ten either, because otherwise the leading digit of two consecutive factorials in the considered sequence would be the same. Thus, there is a $j$ such that $10^{j}<n+2<\ldots<n+9<10^{j+1}$ (1). Because $(n+8)!$ ends with an 8 and $(n+9)!$ with a 9, there are natural numbers $a$ and $b$ with $9 \cdot 10^{a}<(n+9)!<10^{a+1}$ and $8 \cdot 10^{b}<(n+8)!<9 \cdot 10^{b}$, which leads to $10^{a-b}<n+9<\frac{5}{4} \cdot 10^{a-b}$.

From (1) it follows that $j=a-b$ and $10^{j}<n+2<\ldots<n+9<\frac{5}{4} \cdot 10^{j}$ (2).

Since $(n+1)!$ starts with a 1, there is an $m$ such that $10^{m}<(n+1)!<2 \cdot 10^{m}$, while from (2) it follows: $10^{3 j}<(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)<\left(\frac{5}{4}\right)^{3} \cdot 10^{3 j}$. Multiplying the last two inequalities yields $10^{3 j+m}<(n+4)!<2 \cdot \frac{125}{64} \cdot 10^{3 j+m}$, which can be weakened to $10^{3 j+m}<(n+4)!<4 \cdot 10^{3 j+m}$ because $\frac{250}{64}<4$. This implies that the number $(n+4)!$ would not start with 4, but with 1, 2, or 3 - in contradiction to the assumption.

Note: Most participants who attempted this or similar estimates were also successful. However, this problem sometimes led to very unclear presentations.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Man beweise, dass es keine positive ganze Zahl $n$ mit der folgenden Eigenschaft gibt: Für $k=1,2, \ldots, 9$ ist die - in dezimaler Schreibweise - linke Ziffer von $(n+k)$ ! gleich $k$.

|

Wir nehmen an, dass es eine Zahl $n$ mit der verlangten Eigenschaft gibt. Dann kann keine der Fakultäten eine Zehnerpotenz sein, weil ab 3! alle Fakultäten durch 3 teilbar sind und die ersten Fakultäten offensichtlich nicht die verlangte Eigenschaft haben. Es kann auch keine der Zahlen $n+2, \ldots, n+9$ eine Zehnerpotenz sein, weil sonst die Anfangsziffer zweier aufeinanderfolgender Fakultäten in der betrachteten Folge dieselbe wäre. Somit gibt es ein $j$ mit $10^{j}<n+2<\ldots<n+9<10^{j+1}$ (1). Weil $(n+8)$ ! mit einer 8 und $(n+9)$ ! mit einer 9 endet, gibt es natürliche Zahlen a und $b$ mit $9 \cdot 10^{a}<(n+9)!<10^{a+1}$ und $8 \cdot 10^{b}<(n+8)!<9 \cdot 10^{b}$, was auf $10^{a-b}<n+9<\frac{5}{4} \cdot 10^{a-b}$ führt.

Mit (1) folgt $j=a-b$ und $10^{j}<n+2<\ldots<n+9<\frac{5}{4} \cdot 10^{j}$ (2).

Da $(n+1)$ ! mit 1 anfängt, gibt es ein $m$ mit $10^{m}<(n+1)!<2 \cdot 10^{m}$, während aus (2) folgt: $10^{3 j}<(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)<\left(\frac{5}{4}\right)^{3} \cdot 10^{3 j}$. Multiplikation der beiden letzten Ungleichungen liefert $10^{3 j+m}<(n+4)!<2 \cdot \frac{125}{64} \cdot 10^{3 j+m}$, was wegen $\frac{250}{64}<4 \mathrm{zu} 10^{3 j+m}<(n+4)!<4 \cdot 10^{3 j+m}$ abgeschwächt werden kann. Daraus folgt, dass die Zahl $(n+4)$ ! nicht mit 4, sondern mit 1, 2 oder 3 beginnen würde - im Widerspruch zur Voraussetzung.

Anmerkung: Die meisten Teilnehmer, die sich auf diese oder ähnliche Abschätzungen eingelassen hatten, waren dann auch erfolgreich. Allerdings gab es gerade bei dieser Aufgabe z.T. sehr unübersichtliche Darstellungen.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2002-loes_awkl2_02.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2002"

}

|

In chess, the winner receives 1 point and the loser 0 points. In the event of a draw (remis), each player receives $1 / 2$ point.

Fourteen chess players, no two of whom were the same age, participated in a tournament where each played against every other. After the tournament, a ranking list was created. In the case of two players with the same number of points, the younger one received a better ranking.

After the tournament, Jan noticed that the top three players had a total number of points exactly equal to the total number of points of the last nine players. Jörg added that the number of games that ended in a draw was maximized. Determine the number of drawn games.

|

The total number of points of the last nine players is at least (9*8):2 = 36 points (because if each of the nine played only against another of the nine, then there would already be 36 points in total, as one point is awarded in each match). The total number of points of the top three, however, is at most $13+12+11=36$ points, if they win all their games against the remaining 13 players.

It follows that the last nine players do not win any of their games against the others, and the top three win all their games, although they can play to a draw against each other.

The number of drawn matches (which, according to Jörg, is maximized!) must therefore be $3+1+36=40$.

|

40

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Beim Schachspiel erhält der Sieger 1 Punkt und der Besiegte 0 Punkte. Bei Unentschieden (Remis) erhält jeder der Spieler $1 / 2$ Punkt.

Vierzehn Schachspieler, von denen keine zwei gleich alt waren, trugen einen Wettbewerb aus, in dem jeder gegen jeden spielte. Nach Abschluss des Wettbewerbs wurde eine Rangliste erstellt. Von zwei Spielern mit gleicher Punktezahl, erhält der Jüngere eine bessere Platzierung.

Nach dem Wettbewerb stellte Jan fest, dass die drei Bestplatzierten insgesamt genau so viele Punkte erhielten wie die Gesamtzahl der Punkte der letzten neun Spieler. Jörg bemerkte dazu, dass dabei die Zahl der unentschieden ausgegangenen Spiele maximal war. Man ermittle die Anzahl der unentschiedenen Spiele.

|

Die Gesamtzahl der Punkte der letzten neun Spieler beträgt mindestens (9.8):2 = 36 Punkte (denn wenn nur jeder der neun gegen einen anderen der neun spielen würde, dann wären es, da in jeder Partie ein Punkt vergeben wird, insgesamt schon 36 Punkte). Die Gesamtzahl der drei Erstplatzierten ist aber höchstens $13+12+11=36$ Punkte, falls sie alle Spiele gegen die restlichen 13 Spieler gewinnen würden.

Es folgt also, dass die letzten neun Spieler keines der Spiele mit den anderen gewinnen und die drei ersten, alle, wobei sie untereinander durchaus unentschieden spielen können.

Die Anzahl der unentschieden gespielten Partien (die ja gemäß Jörg maximal ist!) muss also $3+1+36=40$ sein.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl1_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

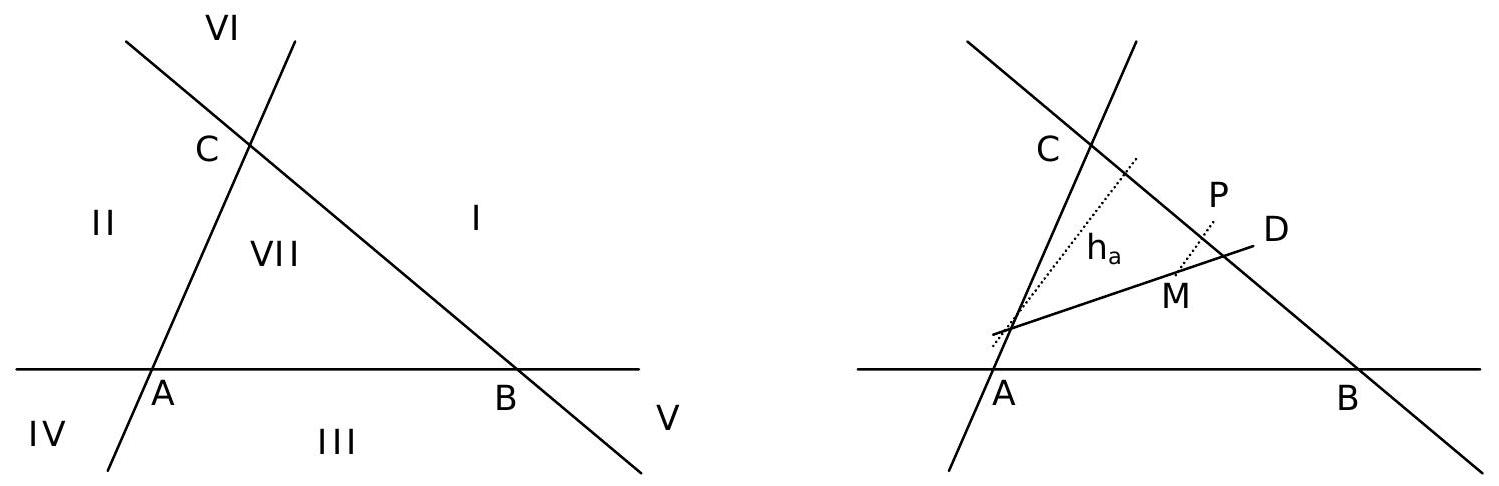

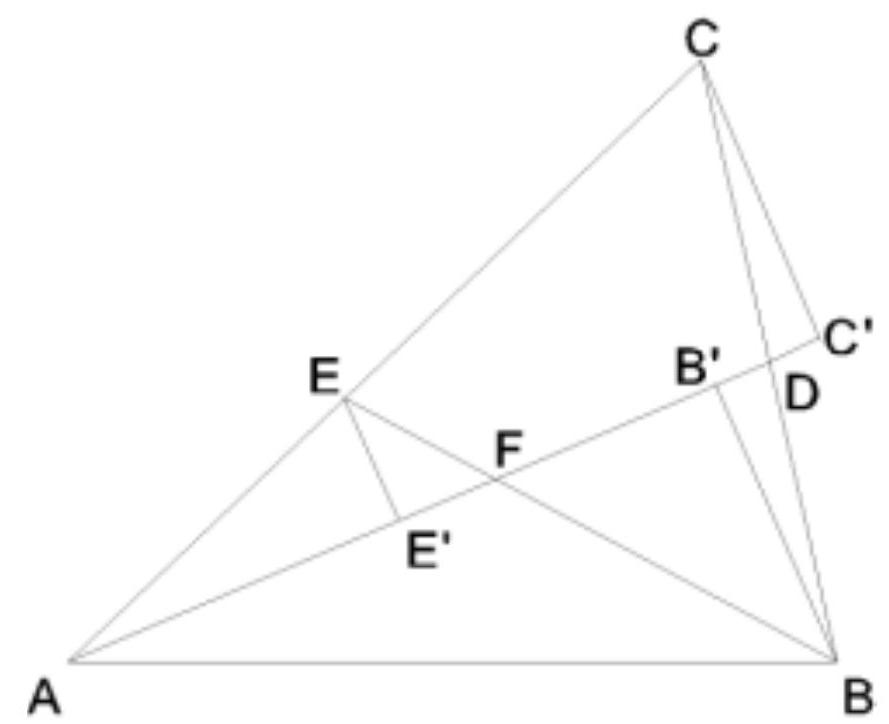

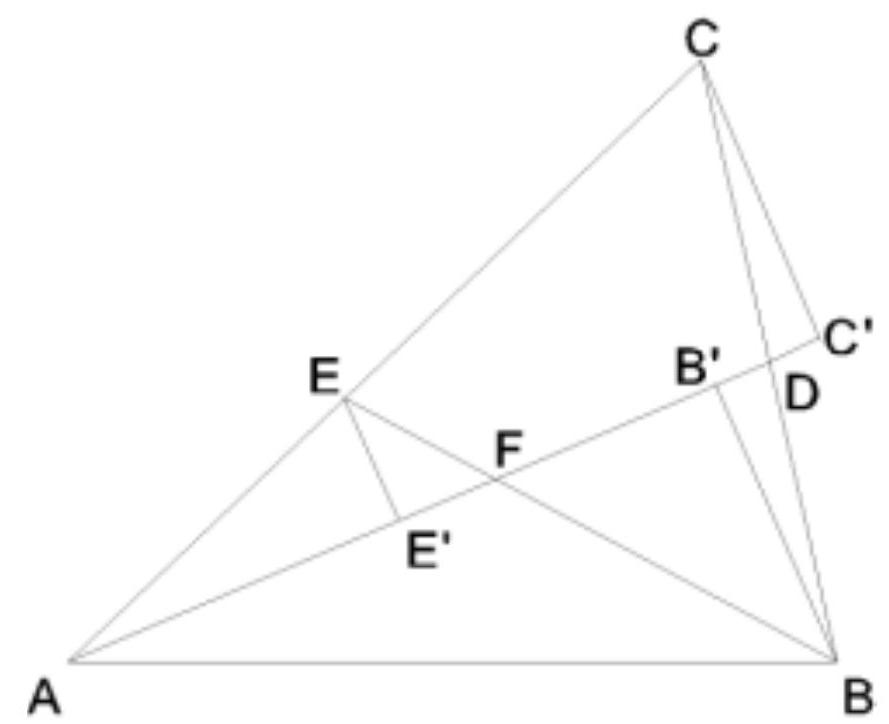

Gegeben ist ein Dreieck ABC und ein Punkt M so, dass die Geraden MA, MB, MC die Geraden BC, CA, AB (in dieser Reihenfolge) in D, E beziehungsweise F schneiden.

Man beweise, dass es dann stets die Zahlen $\varepsilon_{1}, \varepsilon_{2}, \varepsilon_{3}$ aus $\{-1,1\}$ gibt, so dass gilt:

$\varepsilon_{1} \cdot \frac{M D}{A D}+\varepsilon_{2} \cdot \frac{M E}{B E}+\varepsilon_{3} \cdot \frac{M F}{C F}=1$

|

Punkt $M$ ( $M \notin\{A, B, C\})$ kann entweder auf einer der vorgegebenen Geraden, oder in einer der sieben Gebiete liegen, in denen die Ebene des Dreiecks ABC durch die Geraden $A B, B C, C A$ geteilt wird.

Es ist stets

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{M D}{A D}=\frac{M P}{h_{a}}=\frac{0,5 \cdot M P \cdot B C}{0,5 \cdot h_{a} \cdot B C}=\frac{F(M B C)}{F(A B C)}, \\

& \text { (Strahlensatz) }

\end{aligned}

$$

wobei $P \in B C$ und $M P \perp B C$ und $F(X Y Z)$ der Inhalt des Dreiecks XYZ ist. Ähnliches gilt für die anderen Verhältnisse.

Liegt M im Inneren oder am Rande des Dreiecks $A B C$, dann ist also:

$$

\frac{M D}{A D}+\frac{M E}{B E}+\frac{M F}{C F}=\frac{F(M B C)}{F(A B C)}+\frac{F(M C A)}{F(A B C)}+\frac{F(M A B)}{F(A B C)}=1

$$

woraus $\varepsilon_{1}=\varepsilon_{2}=\varepsilon_{3}=1$ folgt.

Ähnliche Überlegungen führen auch dann ans Ziel, wenn M außerhalb des Dreiecks ABC liegt, nur dass $\varepsilon_{1}, \varepsilon_{2}$ bzw. $\varepsilon_{3}=-1$, falls $M$ im Bereich I, II bzw. III liegt. Sollte $M$ in den Bereichen IV, V bzw. VI liegen, dann sind genau zwei der $\varepsilon_{i}$ gleich -1 .

Etwas eleganter und straffer lässt sich der Beweis führen, falls man orientierte Strecken oder Flächen verwendet.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Gegeben ist ein Dreieck ABC und ein Punkt M so, dass die Geraden MA, MB, MC die Geraden BC, CA, AB (in dieser Reihenfolge) in D, E beziehungsweise F schneiden.

Man beweise, dass es dann stets die Zahlen $\varepsilon_{1}, \varepsilon_{2}, \varepsilon_{3}$ aus $\{-1,1\}$ gibt, so dass gilt:

$\varepsilon_{1} \cdot \frac{M D}{A D}+\varepsilon_{2} \cdot \frac{M E}{B E}+\varepsilon_{3} \cdot \frac{M F}{C F}=1$

|

Punkt $M$ ( $M \notin\{A, B, C\})$ kann entweder auf einer der vorgegebenen Geraden, oder in einer der sieben Gebiete liegen, in denen die Ebene des Dreiecks ABC durch die Geraden $A B, B C, C A$ geteilt wird.

Es ist stets

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{M D}{A D}=\frac{M P}{h_{a}}=\frac{0,5 \cdot M P \cdot B C}{0,5 \cdot h_{a} \cdot B C}=\frac{F(M B C)}{F(A B C)}, \\

& \text { (Strahlensatz) }

\end{aligned}

$$

wobei $P \in B C$ und $M P \perp B C$ und $F(X Y Z)$ der Inhalt des Dreiecks XYZ ist. Ähnliches gilt für die anderen Verhältnisse.

Liegt M im Inneren oder am Rande des Dreiecks $A B C$, dann ist also:

$$

\frac{M D}{A D}+\frac{M E}{B E}+\frac{M F}{C F}=\frac{F(M B C)}{F(A B C)}+\frac{F(M C A)}{F(A B C)}+\frac{F(M A B)}{F(A B C)}=1

$$

woraus $\varepsilon_{1}=\varepsilon_{2}=\varepsilon_{3}=1$ folgt.

Ähnliche Überlegungen führen auch dann ans Ziel, wenn M außerhalb des Dreiecks ABC liegt, nur dass $\varepsilon_{1}, \varepsilon_{2}$ bzw. $\varepsilon_{3}=-1$, falls $M$ im Bereich I, II bzw. III liegt. Sollte $M$ in den Bereichen IV, V bzw. VI liegen, dann sind genau zwei der $\varepsilon_{i}$ gleich -1 .

Etwas eleganter und straffer lässt sich der Beweis führen, falls man orientierte Strecken oder Flächen verwendet.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl1_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Let \( N \) be a natural number and \( x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n} \) be other natural numbers less than \( N \) such that the least common multiple of any two of these \( n \) numbers is greater than \( N \).

Prove that the sum of the reciprocals of these \( n \) numbers is always less than 2; that is,

$$

\frac{1}{x_{1}}+\frac{1}{x_{2}}+\cdots+\frac{1}{x_{n}}<2

$$

|

Since the least common multiple (LCM) of $x_i$ and $x_j$ is greater than N, there are no two numbers among $1, 2, \ldots, N$ that are multiples of both $x_i$ and $x_j$.

Among the multiples of the natural number $x$, there are two such that $kx \leq N < (k+1)x$, which implies $k \leq \frac{N}{x} < k+1$. The number of multiples of $x$ that are less than N is therefore the integer part of $\frac{N}{x}$, which is equal to $\left[\frac{N}{x}\right]$.

For the numbers $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n$, it follows that $\left[\frac{N}{x_1}\right] + \left[\frac{N}{x_2}\right] + \cdots + \left[\frac{N}{x_n}\right] < N$.

On the other hand, $\left[\frac{N}{x_i}\right] > \frac{N}{x_i} - 1$, and thus $\frac{N}{x_1} + \frac{N}{x_2} + \cdots + \frac{N}{x_n} - n < N$.

Since $n < N$, it follows that:

$\frac{N}{x_1} + \frac{N}{x_2} + \cdots + \frac{N}{x_n} < 2N$, which finally leads to $\frac{1}{x_1} + \frac{1}{x_2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{x_n} < 2$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Sei N eine natürliche Zahl und $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \mathrm{x}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ weitere natürliche Zahlen kleiner als N und so, dass das kleinste gemeinsame Vielfache von beliebigen zwei dieser n Zahlen größer als N ist.

Man beweise, dass die Summe der Kehrwerte dieser n Zahlen stets kleiner 2 ist; also

$$

\frac{1}{x_{1}}+\frac{1}{x_{2}}+\cdots+\frac{1}{x_{n}}<2

$$

|

Da das kgV von $\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{i}}$ und $\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{j}}$ größer als N ist, gibt es unter den Zahlen $1,2, \ldots, \mathrm{~N}$ keine zwei, die sowohl Vielfache von $\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{i}}$, als auch von $\mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{j}}$ sind.

Unter den Vielfachen der natürlichen Zahl $x$ gibt es zwei so, dass $k x \leq N<(k+1) x$, woraus $\mathrm{k} \leq \frac{N}{x}<\mathrm{k}+1$ folgt. Die Anzahl der Vielfachen von x , die kleiner N sind, ist demnach der ganzzahlige Teil von $\frac{N}{X}$, also gleich $\left[\frac{N}{x}\right]$.

Für die Zahlen $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \mathrm{x}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ gilt folglich $\left[\frac{N}{x_{1}}\right]+\left[\frac{N}{x_{2}}\right]+\cdots+\left[\frac{N}{x_{n}}\right]<N$.

Andrerseits ist $\left[\frac{N}{x_{i}}\right]>\frac{N}{x_{i}}-1$ und demnach $\frac{N}{x_{1}}+\frac{N}{x_{2}}+\cdots+\frac{N}{x_{n}}-n<N$.

Da aber $\mathrm{n}<\mathrm{N}$ ist folgt:

$\frac{N}{x_{1}}+\frac{N}{x_{2}}+\cdots+\frac{N}{x_{n}}<2 N$, was schließlich zu $\frac{1}{x_{1}}+\frac{1}{x_{2}}+\cdots+\frac{1}{x_{n}}<2$ führt.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl1_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

Determine all functions $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ with the property

$$

f(f(x)+y)=2 x+f(f(y)-x)

$$

for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

For any real number $z$, we set $a=f(z), b=z+f(0), n=f\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)$, and $m=f(0)-\frac{a+b}{2}$. Since $\mathbb{D}_{f}=\mathbb{R}$, $a, b, n$, and $m$ are well-defined. Substituting $x=0$, $y=z$ into $(*)$ yields $f(z+f(0))=f(f(z))$, so $f(a)=f(b)$ (I).

Substituting $x=m$ and $y=a$ or $y=b$ into $(*)$ yields $\left\{\begin{array}{l}f(f(m)+a)=2 m+f(f(a)-m) \\ f(f(m)+b)=2 m+f(f(b)-m)\end{array}\right.$, which, due to (I), can be summarized as $f(f(m)+a)=f(f(m)+b)$ (II).

Substituting $x=a$ or $x=b$ and $y=n$ into $(*)$ yields $\left\{\begin{array}{l}f(f(a)+n)=2 a+f(f(n)-a) \\ f(f(b)+n)=2 b+f(f(n)-b)\end{array}\right.$, which, due to (I), can be summarized as $2 a+f(f(n)-a)=2 b+f(f(n)-b)$ (III). Substituting $x=\frac{a+b}{2}, y=0$ into $(*)$ yields $f\left(f\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)\right)=a+b+f\left(f(0)-\frac{a+b}{2}\right)$, so $f(n)=a+b+f(m)$ or, in other words, $f(n)-a=f(m)+b$ and $f(n)-b=f(m)+a$. This, combined with (III), immediately gives $2 a+f(f(m)+b)=2 b+f(f(m)+a)$, from which, with (II), we conclude $a=b$, so $f(z)=z+f(0)$. This shows that any function $f$ that satisfies $(*)$ must have the form $f(x)=x+c \quad(c=$ const. ). Substituting into $(*)$ confirms that any $f$ of this form indeed satisfies the given equation: $f(f(x)+y)=x+y+2 c=2 x+f(f(y)-x)$.

Note: Additional properties of $f$, such as injectivity, monotonicity, or differentiability, should not be assumed but must be proven.

|

f(x)=x+c

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Man bestimme alle Funktionen $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ mit der Eigenschaft

$$

f(f(x)+y)=2 x+f(f(y)-x)

$$

für alle $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

Für eine beliebige reelle Zahl $z$ setzen wir $a=f(z), b=z+f(0), n=f\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)$ und $m=f(0)-\frac{a+b}{2}$. Wegen $\mathbb{D}_{f}=\mathbb{R}$ sind $a, b, n$ und $m$ wohlbestimmt. Einsetzen von $x=0$, $y=z$ in $(*)$ liefert $f(z+f(0))=f(f(z))$, also $f(a)=f(b)$ (I).

Einsetzen von $x=m$ und $y=a$ bzw. $y=b$ in $\left(^{*}\right)$ liefert $\left\{\begin{array}{l}f(f(m)+a)=2 m+f(f(a)-m) \\ f(f(m)+b)=2 m+f(f(b)-m)\end{array}\right.$, was wir wegen (I) zu $f(f(m)+a)=f(f(m)+b$ ) (II) zusammenfassen können.

Einsetzen von $x=a$ bzw. $x=b$ und $y=n$ in $\left(^{*}\right.$ )liefert $\left\{\begin{array}{l}f(f(a)+n)=2 a+f(f(n)-a) \\ f(f(b)+n)=2 b+f(f(n)-b)\end{array}\right.$, was wir wegen (I) zu $2 a+f(f(n)-a)=2 b+f(f(n)-b$ ) (III) zusammenfassen können. Einsetzen von $x=\frac{a+b}{2}, y=0$ in (*) liefert $f\left(f\left(\frac{a+b}{2}\right)\right)=a+b+f\left(f(0)-\frac{a+b}{2}\right)$, also $f(n)=a+b+f(m)$ oder, anders formuliert, $f(n)-a=f(m)+b$ bzw. $f(n)-b=f(m)+a$. Dies liefert mit (III) sofort $2 a+f(f(m)+b))=2 b+f(f(m)+a)$, woraus mit (II) nun $a=b$ folgt, also $f(z)=z+f(0)$. Damit ist gezeigt, dass jede Funktion $f$, die (*) erfüllt, die Form $f(x)=x+c \quad(c=$ konst. ) haben muss. Einsetzen in (*) bestätigt, dass jedes $f$ dieser Form die gegebene Gleichung tatsächlich erfüllt: $f(f(x)+y)=x+y+2 c=2 x+f(f(y)-x)$.

Anmerkung: Zusätzliche Eigenschaften von $f$, wie etwa Injektivität, Monotonie oder Differenzierbarkeit, dürfen nicht vorausgesetzt, sondern müssen bewiesen werden.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl2_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

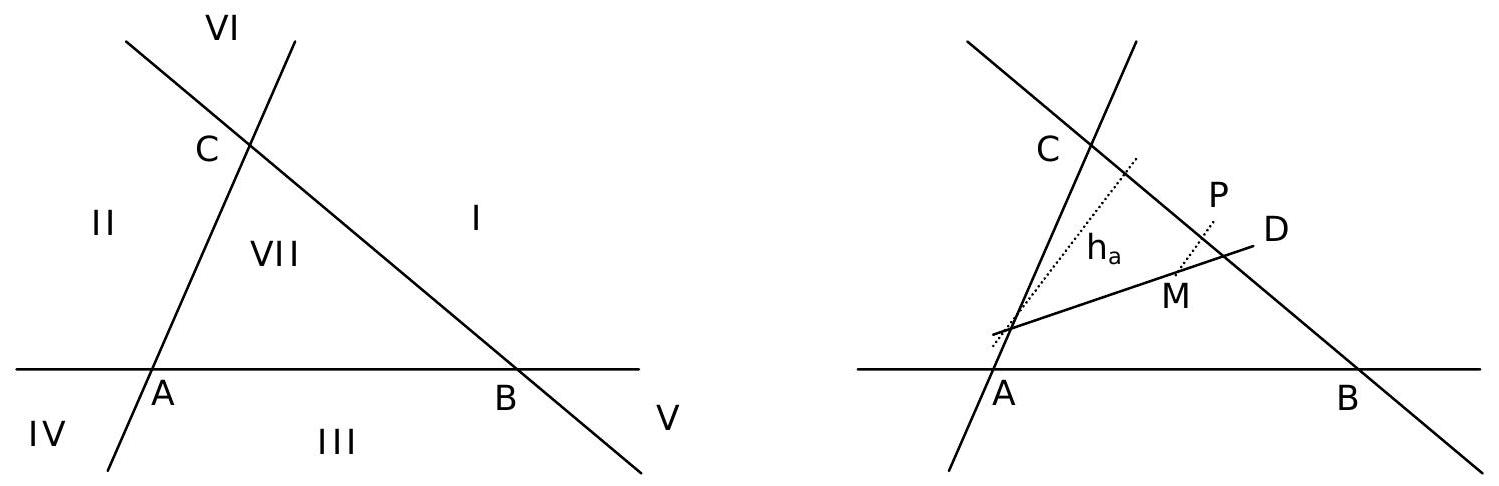

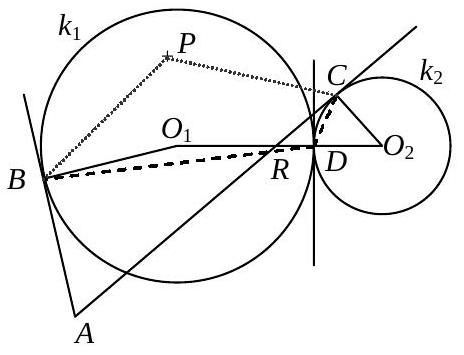

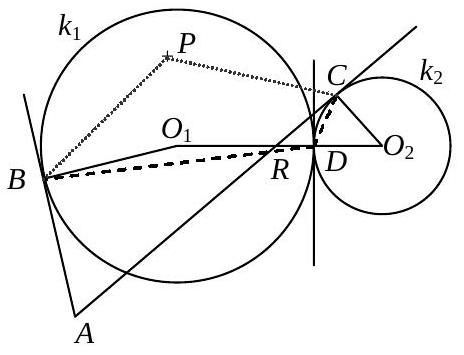

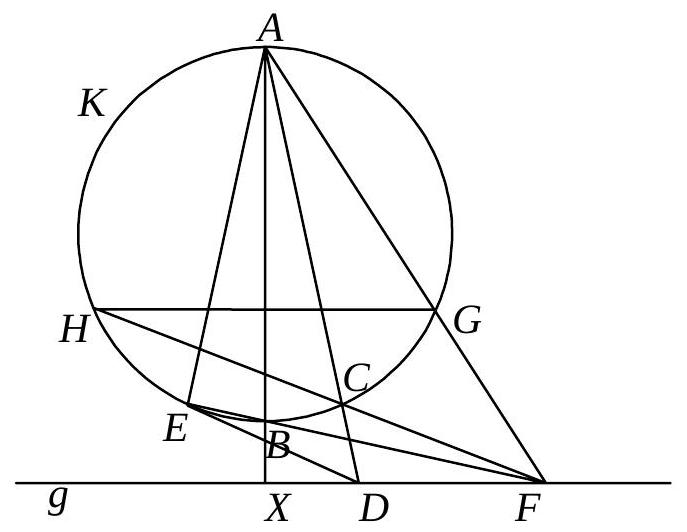

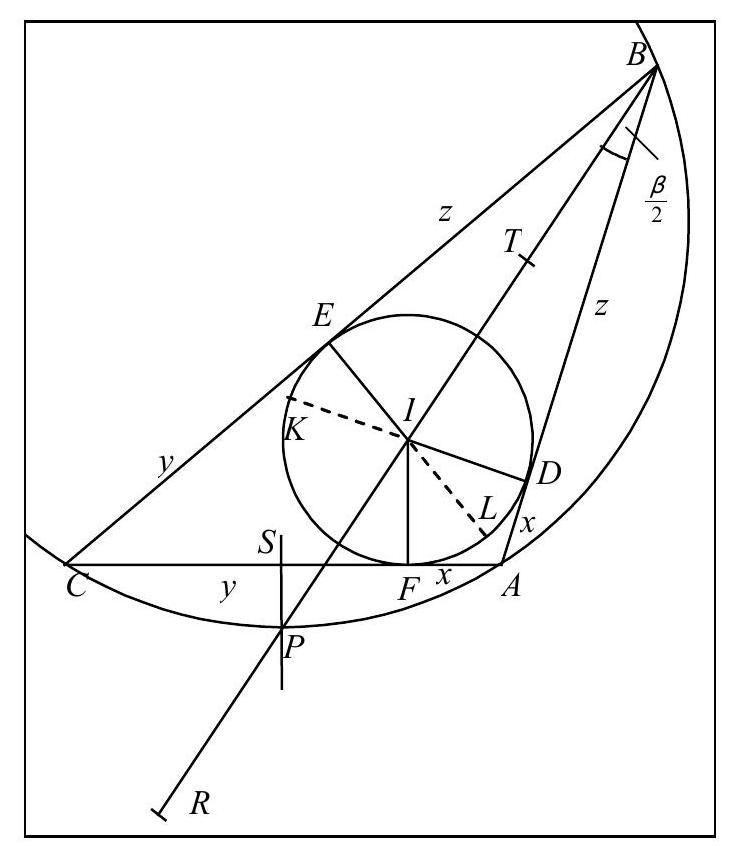

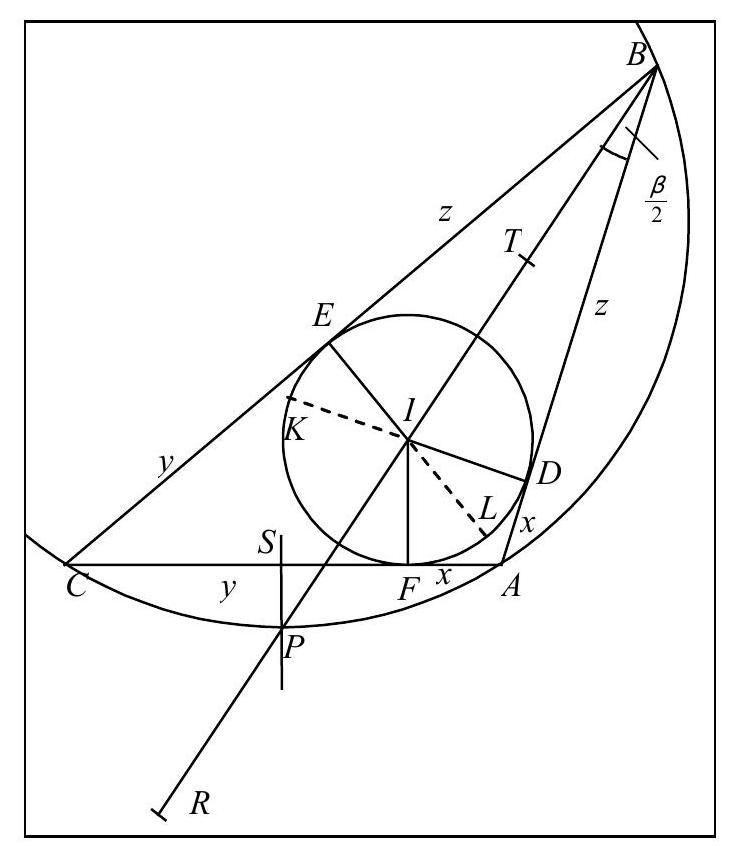

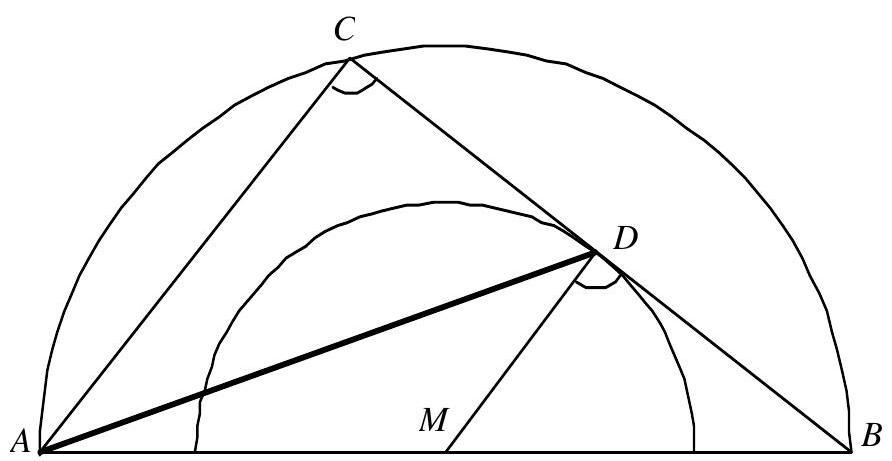

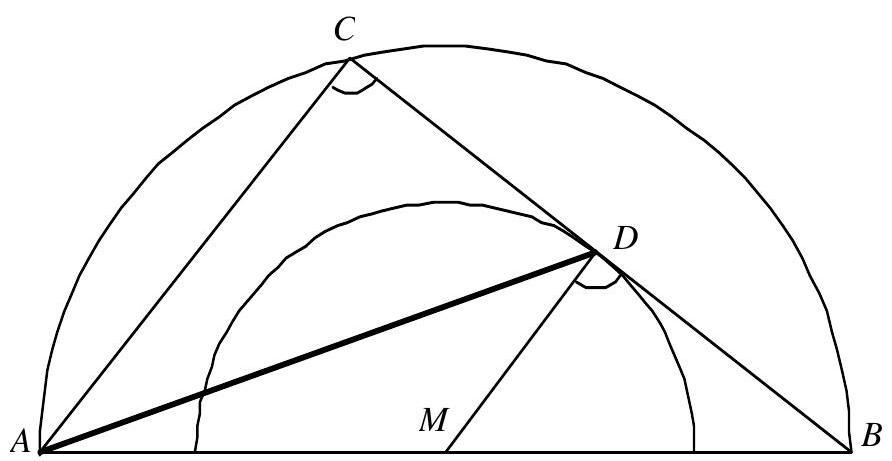

Let $B$ be any point on a circle $k_{1}$ and let $A$ be a point different from $B$ on the tangent to $k_{1}$ at $B$. Furthermore, let $C$ be a point outside $k_{1}$ with the property that the segment $A C$ intersects $k_{1}$ at two distinct points. Finally, let $k_{2}$ be the circle that touches the line $(A C)$ at $C$ and touches the circle $k_{1}$ at a point $D$ which lies on the opposite side of $(A C)$ from $B$.

Prove that the circumcenter of triangle $BCD$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$.

|

We denote the centers of the circles $k_{1}$ and $k_{2}$ with $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$, respectively. The solution assumes that $\angle C D B$ is obtuse (see Fig.); otherwise, some angles need to be swapped modulo $180^{\circ}$.

Let $P$ be the circumcenter of triangle BDC; then, by the central angle theorem,

$\angle B P C=2 \cdot\left(180^{\circ}-\angle C D B\right)=360^{\circ}-2 \cdot \angle C D B$ (1).

$P$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ if $A C P B$ is a cyclic quadrilateral; this is true if $\angle B P C=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B$.

To prove this, we calculate $\angle C D B$. Since $k_{1}$ and $k_{2}$ touch at $D$, $D$ lies on the segment $O_{1} O_{2}$ and we have $\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle O_{1} D B-\angle O_{2} D C$ (2). Since $k_{1}$ touches the line ( $A B$ ), $\angle A B O_{1}=90^{\circ}$, so $\angle A B D+\angle D B O_{1}=90^{\circ}$. Since $B$ and $D$ lie on $k_{1}$, triangle $B D O_{1}$ is isosceles with $\angle O_{1} D B=\angle D B O_{1}$. Thus, $\angle O_{1} D B=90^{\circ}-\angle A B D$ (3). Since $k_{2}$ touches the line ( $A C$ ), $\angle A C O_{2}=90^{\circ}$, so $\angle A C D+\angle D C O_{2}=90^{\circ}$. Since $C$ and $D$ lie on $k_{2}$, triangle $\mathrm{CDO}_{2}$ is isosceles with $\angle \mathrm{O}_{2} D C=\angle D C O_{2}$. Thus, $\angle O_{2} D C=90^{\circ}-\angle A C D$ (4). Substituting (3) and (4) into (2) yields $\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\left(90^{\circ}-\angle A B D\right)-\left(90^{\circ}-\angle A C D\right)=180^{\circ}-\angle A B D+\angle A C D$ (5).

Now consider the intersection point $R$ of $(A C)$ and ( $B D$ ) and deduce

$\angle A B D=\angle A B R=180^{\circ}-\angle R A B-\angle B R A=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B-\angle B R A$ and

$\angle A C D=\angle R C D=180^{\circ}-\angle C D R-\angle D R C=180^{\circ}-\angle C D B-\angle B R A$. From (5) we get

$\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle C A B-\angle C D B$, so $2 \cdot \angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle C A B$. Substituting into (1) yields $\angle B P C=360^{\circ}-\left(180^{\circ}+\angle C A B\right)=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B$. This completes the proof.

Note: Since $k_{1}$ is intersected by the segment $A C$, $k_{2}$ cannot touch the line ( $\left.A C\right)$ from $A$ before intersecting with $k_{1}$. Also, $C$ cannot be chosen specially.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $B$ ein beliebiger Punkt auf einem Kreis $k_{1}$ und es sei $A$ ein von $B$ verschiedener Punkt auf der Tangente an $k_{1}$ in $B$. Ferner sei $C$ ein Punkt außerhalb von $k_{1}$ mit der Eigenschaft, dass die Strecke $A C$ den Kreis $k_{1}$ in zwei verschiedenen Punkten schneidet. Schließlich sei $k_{2}$ der Kreis, der die Gerade ( $A C$ ) in $C$ berührt und den Kreis $k_{1}$ in einem Punkt $D$ berührt, welcher auf der anderen Seite von ( $A C$ ) liegt wie $B$.

Man beweise, dass der Umkreismittelpunkt des Dreiecks BCD auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks $A B C$ liegt.

|

Wir bezeichnen die Mittelpunkte der Kreise $k_{1}$ und $k_{2}$ mit $O_{1}$ bzw. $O_{2}$. Die Lösung setzt nun voraus, dass $\angle C D B$ stumpf ist (siehe Fig.); andernfalls sind lediglich einige Winkel modulo $180^{\circ}$ zu vertauschen.

Es sei $P$ der Umkreismittelpunkt des Dreiecks BDC; dann ist nach dem Satz vom Mittelpunktswinkel

$\angle B P C=2 \cdot\left(180^{\circ}-\angle C D B\right)=360^{\circ}-2 \cdot \angle C D B$ (1).

$P$ liegt dann auf dem Umkreis von Dreieck $A B C$, wenn $A C P B$ ein Sehnenviereck ist; dies gilt dann, wenn $\angle B P C=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B$ ist.

Um dies zu beweisen, berechnen wir $\angle C D B$. Da $k_{1}$ und $k_{2}$ sich in $D$ berühren, liegt $D$ auf der Strecke $O_{1} O_{2}$ und es gilt $\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle O_{1} D B-\angle O_{2} D C$ (2). Da $k_{1}$ die Gerade ( $A B$ ) berührt, ist $\angle A B O_{1}=90^{\circ}$, also $\angle A B D+\angle D B O_{1}=90^{\circ}$. Da $B$ und $D$ auf $k_{1}$ liegen, ist das Dreieck $B D O_{1}$ gleichschenklig mit $\angle O_{1} D B=\angle D B O_{1}$. Somit ist $\angle O_{1} D B=90^{\circ}-\angle A B D$ (3). Da $k_{2}$ die Gerade ( $A C$ ) berührt, ist $\angle A C O_{2}=90^{\circ}$, also $\angle A C D+\angle D C O_{2}=90^{\circ}$. Da $C$ und $D$ auf $k_{2}$ liegen, ist das Dreieck $\mathrm{CDO}_{2}$ gleichschenklig mit $\angle \mathrm{O}_{2} D C=\angle D C O_{2}$. Somit ist $\angle O_{2} D C=90^{\circ}-\angle A C D$ (4). Einsetzen von (3) und (4) in (2) liefert $\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\left(90^{\circ}-\angle A B D\right)-\left(90^{\circ}-\angle A C D\right)=180^{\circ}-\angle A B D+\angle A C D$ (5).

Nun betrachten wir den Schnittpunkt $R$ von $(A C)$ und ( $B D$ ) und folgern

$\angle A B D=\angle A B R=180^{\circ}-\angle R A B-\angle B R A=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B-\angle B R A$ sowie

$\angle A C D=\angle R C D=180^{\circ}-\angle C D R-\angle D R C=180^{\circ}-\angle C D B-\angle B R A$. Aus (5) ergibt sich

$\angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle C A B-\angle C D B$, also $2 \cdot \angle C D B=180^{\circ}+\angle C A B$. Einsetzen in (1) liefert $\angle B P C=360^{\circ}-\left(180^{\circ}+\angle C A B\right)=180^{\circ}-\angle C A B$. Damit ist alles gezeigt.

Anmerkung: Da $k_{1}$ von der Strecke $A C$ geschnitten wird, kann $k_{2}$ die Gerade ( $\left.A C\right)$ nicht - von $A$ aus vor dem Schnitt mit $k_{1}$ berühren. Auch darf $C$ nicht speziell gewählt werden.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl2_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

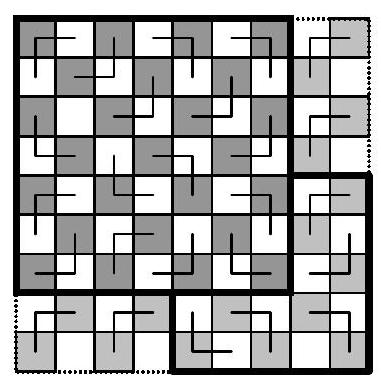

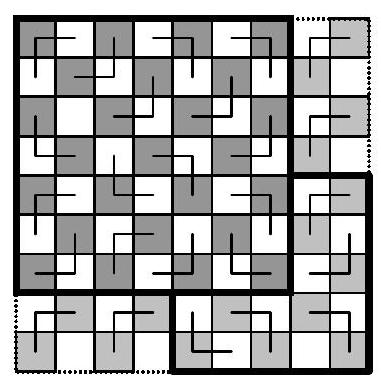

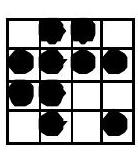

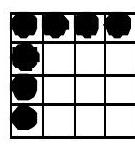

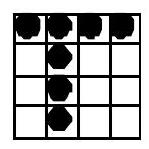

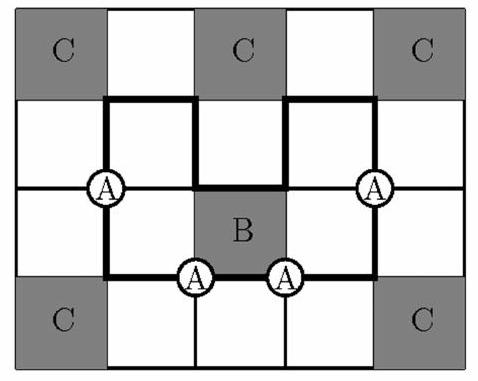

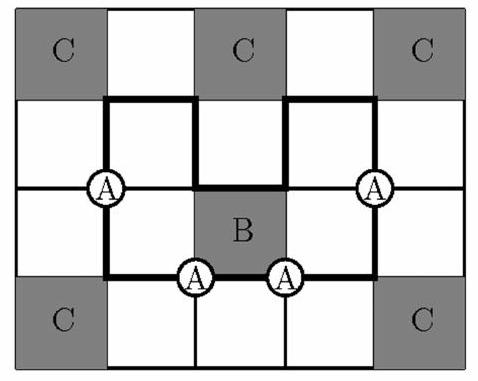

Let $n$ be an odd natural number. The fields of an $n \times n$ chessboard are alternately colored black and white, with the corner fields being black. Furthermore, a triomino is defined as an L-shaped figure consisting of three connected unit squares.

a) For which values of $n$ is it possible to cover all black fields of the chessboard with non-overlapping triominoes?

b) What is the minimum number of triominoes required for the covering when it is possible?

Hint: Two triominoes overlap if they share at least one unit square.

|

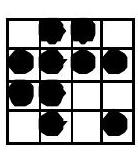

a) and b): We count the rows of the chessboard from the top. The $n \times n$ chessboard has $\frac{n+1}{2}$ rows with odd numbers, and in each of these rows, there are $\frac{n+1}{2}$ black squares. Each of these $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ black squares must be covered by a different triomino, so at least $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ triominoes are required. Since each consists of 3 squares, due to the no-overlap rule, it must hold that: $3\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2} \leq n^{2}$. For 1, 3, and 5, this gives $3 \leq 1$, $12 \leq 9$, $27 \leq 25$. Therefore, for $n<7$, the required covering is not possible.

The figure shows, as an anchor, a covering for $n=7$ with $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}=16$ triominoes and the step $n \rightarrow n+2$, which proves the existence of a covering for every $n \geq 7$. In this step, an "L" shape, 5 fields wide and high, is added to the right bottom corner of the $n \times n$ chessboard, whose covering with $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ stones is assumed, and then completed with $2 \times 2$ fields, each with a matching triomino. The "L" contains 5 triominoes, and the two $2 \times (n-5)$ rectangles together contain $n-3$ triominoes. Thus, there are $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2} + n - 3 + 5 = \frac{n^{2} + 6n + 9}{4} = \left(\frac{n+3}{2}\right)^{2}$ triominoes, the minimum number for the $(n+2) \times (n+2)$ chessboard. By complete induction, the claim follows.

Note: Only all black squares should be covered; white squares can remain uncovered. Of course, the triominoes do not extend beyond the chessboard. A complete solution also includes proving that the added triominoes in the step $n \rightarrow n+2$ are compatible with the minimum number, as well as mentioning $n=1$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Es sei $n$ eine ungerade natürliche Zahl. Die Felder eines $n \times n$-Schachbretts seien abwechselnd schwarz und weiß gefärbt, wobei die Eckfelder schwarz sind. Ferner sei ein Trimino definiert als eine L-förmige Figur aus drei verbundenen Einheitsquadraten.

a) Für welche Werte von $n$ ist es möglich, alle schwarzen Felder des Schachbretts durch nicht überlappende Triminos zu überdecken?

b) Welches ist bei möglicher Überdeckung die minimale Anzahl der jeweils benötigten Triminos?

Hinweis: Zwei Triminos überlappen sich, wenn sie wenigstens ein Einheitsquadrat gemeinsam bedecken.

|

a) und b): Wir zählen die Reihen des Schachbretts von oben. Das $n \times n$-Schachbrett hat $\frac{n+1}{2}$ Reihen mit ungerader Nummer und in jeder dieser Reihen $\frac{n+1}{2}$ schwarze Felder. Jedes dieser $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ schwarzen Quadrate muss von einem anderen Trimino überdeckt werden, daher sind wenigstens $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ Triminos erforderlich. Da jedes aus 3 Quadraten besteht, muss wegen des Überlappungsverbots gelten: $3\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2} \leq n^{2}$. Für 1,3 und 5 folgt $3 \leq 1$, $12 \leq 9,27 \leq 25$. Also ist für $n<7$ eine verlangte Überdeckung nicht möglich.

Die Figur zeigt als Verankerung eine Überdeckung für $n=7$ mit $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}=16$ Triminos und den Schritt $n \rightarrow n+2$, mit dem für jedes $n \geq 7$ die Existenz einer Überdeckung bewiesen ist. Bei diesem Schritt wird dem $n \times n$-Schachbrett, dessen Überdeckung mit $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}$ Steinen vorausgesetzt ist, in der rechten unteren Ecke ein „L" angesetzt, das 5 Felder breit und hoch ist, und anschließend durch $2 \times 2$-Felder mit je einem passenden Trimino ergänzt. Das „L" enthält 5 Triminos und die beiden $2 \times(n-5)$-Rechtecke zusammen $n-3$ Triminos. Es

ergeben sich also $\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)^{2}+n-3+5=\frac{n^{2}+6 n+9}{4}=\left(\frac{n+3}{2}\right)^{2}$ Triminos, die Mindestzahl für das $(n+2) \times(n+2)-$ Schachbrett. Mit vollständiger Induktion folgt die Behauptung.

Anmerkung: Nur alle schwarzen Felder sollten überdeckt werden; es können also weiße Felder frei bleiben. Selbstverständlich ragen die Triminos nicht über das Schachbrett hinaus. Zu einer vollständigen Lösung gehört auch der Nachweis, dass beim Schritt $n \rightarrow n+2$ die hinzugefügten Triminos mit der minimalen Anzahl verträglich sind, sowie die Erwähnung von $n=1$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2003-loes_awkl2_03.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2003"

}

|

A function $f$ is given by $f(x)+f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)=1+x$ for $x \in \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$.

Determine a formula for $f$.

|

Let $x \in \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$ and $y=1-\frac{1}{x}$ and $z=\frac{1}{1-x}$. It is easy to see that together with $x$, $y$ and thus also $z$ belong to $\mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$. Substituting $y$ and $z$ into the original equation leads to:

$$

f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)+f\left(\frac{1}{1-x}\right)=2-\frac{1}{x} \text { and } f\left(\frac{1}{1-x}\right)+f(x)=1+\frac{1}{1-x}

$$

Subtracting the last two relations gives:

$$

f(x)-f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)=\frac{1}{1-x}+\frac{1}{x}-1

$$

and adding this to the original equation finally results in

$$

f(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{1-x}+\frac{1}{x}+x\right)=\frac{-x^{3}+x^{2}+1}{2 x(1-x)}

$$

|

\frac{-x^{3}+x^{2}+1}{2 x(1-x)}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Eine Funktion $f$ ist gegeben durch $f(x)+f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)=1+x$ für $x \in \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$.

Man ermittle eine Formel für $f$.

|

Sei $x \in \mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$ und $y=1-\frac{1}{x}$ und $z=\frac{1}{1-x}$. Es ist leicht einzusehen, dass zusammen mit $x$ auch $y$ und damit auch $z$ zu $\mathbb{R} \backslash\{0,1\}$ gehören. Einsetzen von $y$ und $z$ in die Ausgangsgleichung führt zu:

$$

f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)+f\left(\frac{1}{1-x}\right)=2-\frac{1}{x} \text { und } f\left(\frac{1}{1-x}\right)+f(x)=1+\frac{1}{1-x}

$$

Durch Subtraktion der beiden letzten Beziehungen erhält man:

$$

f(x)-f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)=\frac{1}{1-x}+\frac{1}{x}-1

$$

und nach Addition zur Ausgangsgleichung führt das schließlich zu

$$

f(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{1-x}+\frac{1}{x}+x\right)=\frac{-x^{3}+x^{2}+1}{2 x(1-x)}

$$

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl1_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

In triangle $A B C$, $A D (D \in B C)$ is a median, $E$ is a point on $A C$, and $F$ is the intersection of $B E$ with $A D$.

Prove: If $\frac{B F}{F E}=\frac{B C}{A B}+1$, then $B E$ is an angle bisector.

|

Let $B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}, E^{\prime}$ be the projections of $B, C$, and $E$ onto the line $A D$. The right triangles $\triangle D B B^{\prime}$ and $\triangle D C C^{\prime}$ are congruent, since $D$ is the midpoint of $B C$ and the acute angles at $D$ are equal. This implies that $B B^{\prime}=C C^{\prime}$.

In the triangle $\triangle A C^{\prime} C$, $E E^{\prime}$ is parallel to $C C^{\prime}$, and thus

$$

\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{C C^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}}=\frac{B B^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}}.

$$

The right triangles $\triangle B B^{\prime} F$ and $\triangle E E^{\prime} F$ are similar, as the angles at $F$ are equal. This implies $\frac{B B^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}}=\frac{B F}{F E}$, which, together with the previous relationship, leads to $\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{B F}{E F}$.

Replacing $\frac{B F}{E F}$ in the initial relationship with $\frac{A C}{A E}$, we get:

$\frac{B C}{A B}+1=\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{B C+A B}{A B}$, which simplifies to $\frac{A C-A E}{A E}=\frac{B C}{A B}$ and finally to $\frac{E C}{A E}=\frac{B C}{A B}$.

According to the converse of the Angle Bisector Theorem, $B E=w_{\beta}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Im Dreieck $A B C$ ist $A D(D \in B C)$ eine Seitenhalbierende, $E$ ein Punkt auf $A C$ und $F$ der Schnittpunkt von $B E$ mit $A D$.

Man beweise: Falls $\frac{B F}{F E}=\frac{B C}{A B}+1$, dann ist $B E$ eine Winkelhalbierende.

|

Seien $B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}, E^{\prime}$ die Projektionen von $B, C$ und $E$ auf die Gerade $A D$. Die rechtwinkligen Dreiecke $\triangle D B B^{\prime}$ und $\triangle D C C^{\prime}$ sind kongruent, da $D$ der Mittelpunkt von $B C$ ist und die spitzen Winkel bei $D$ gleich groß sind. Daraus folgt, dass $B B^{\prime}=C C^{\prime}$.

Im Dreieck $\triangle A C^{\prime} C$ ist $E E^{\prime}$ parallel zu $C C^{\prime}$ und folglich

$$

\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{C C^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}}=\frac{B B^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}} .

$$

Die rechtwinkligen Dreiecke $\triangle B B^{\prime} F$ und $\triangle E E^{\prime} F$ sind ähnlich, da die Winkel bei $F$ gleich sind. Daraus folgt $\frac{B B^{\prime}}{E E^{\prime}}=\frac{B F}{F E}$, was zusammen mit der vorletzten Beziehung zu $\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{B F}{E F}$ führt.

Ersetzt man nun $\frac{B F}{E F}$ in der Ausgangsbeziehung durch $\frac{A C}{A E}$, ergibt sich:

$\frac{B C}{A B}+1=\frac{A C}{A E}=\frac{B C+A B}{A B}$, was zu $\frac{A C-A E}{A E}=\frac{B C}{A B}$ und schließlich zu $\frac{E C}{A E}=\frac{B C}{A B}$ führt.

Gemäß der Umkehrung des Satzes der Winkelhalbierenden ist $B E=w_{\beta}$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl1_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Given are the six real numbers $a, b, c$ and $x, y, z$ such that

a) $0 < b - c < a < b + c$

b) $a x + b y + c z = 0$

Determine (with justification!) the sign of $a y z + b x z + c x y$.

|

From $0<b-c<a<b+c$ it follows that $a, b$, and $c$ are positive. Furthermore, one can construct a triangle with segments of these lengths. This implies that the numbers $-a+b+c, \quad a-b+c$ and $a+b-c$ are positive.

From $a x+b y+c z=0$ it follows that $x=-\frac{b y+c z}{a}$.

We obtain

$$

a y z+b z x+c x y=a y z-\frac{1}{a}(b y+c z)(b z+c y)=-\frac{1}{a}\left(b^{2} y z+b c y^{2}+c b z^{2}+c^{2} y z-a^{2} y z\right)

$$

It suffices to show that the term in the last parentheses is not negative.

A simple rearrangement yields

$$

b^{2} y z+b c y^{2}+c b z^{2}+c^{2} y z-a^{2} y z=b c y^{2}+b c z^{2}+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) y z

$$

Since $a$ and $c$ are positive, one can multiply the term by $4 b c$ without changing the sign. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the sign of $4 b^{2} c^{2} y^{2}+4 b^{2} c^{2} z^{2}+4 b c\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) y z$. By adding and subtracting $\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2} z^{2}$, we get the following step by step:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& 4 b^{2} c^{2} y^{2}+4 b c y z\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) z^{2}+\left[4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}\right] z^{2}= \\

& =\left[2 b c y+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) z\right]^{2}+\left[4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}\right] z^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

The sign of the last term is not negative, as the first part is a square and in the second part $4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}=(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)$ is positive. The number $a y z+b z x+c x y$ is therefore not positive.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Gegeben sind die sechs reellen Zahlen $a, b, c$ und $x, y, z$ so, dass

a) $0<b-c<a<b+c$

b) $a x+b y+c z=0$

Man ermittle (mit Begründung!) das Vorzeichen von $a y z+b x z+c x y$.

|

Aus $0<b-c<a<b+c$ folgt, dass $a, b$ und $c$ positiv sind. Außerdem kann man mit Strecken dieser Längen ein Dreieck konstruieren. Daraus folgt, dass die Zahlen $-a+b+c, \quad a-b+c$ und $a+b-c$ positiv sind.

Aus $a x+b y+c z=0$ folgt $x=-\frac{b y+c z}{a}$.

Es ergibt sich

$$

a y z+b z x+c x y=a y z-\frac{1}{a}(b y+c z)(b z+c y)=-\frac{1}{a}\left(b^{2} y z+b c y^{2}+c b z^{2}+c^{2} y z-a^{2} y z\right)

$$

Es reicht zu zeigen, dass der Term in der letzten Klammer nicht negativ ist.

Eine einfache Umformung ergibt

$$

b^{2} y z+b c y^{2}+c b z^{2}+c^{2} y z-a^{2} y z=b c y^{2}+b c z^{2}+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) y z

$$

Da $a$ und $c$ positiv sind, kann man den Term mit $4 b c$ multiplizieren, ohne dass sich das Vorzeichen ändert. Es ist also das Vorzeichen von $4 b^{2} c^{2} y^{2}+4 b^{2} c^{2} z^{2}+4 b c\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) y z$ zu untersuchen. Durch Addition und Subtraktion von $\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2} z^{2}$ ergibt sich der Reihe nach:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& 4 b^{2} c^{2} y^{2}+4 b c y z\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) z^{2}+\left[4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}\right] z^{2}= \\

& =\left[2 b c y+\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right) z\right]^{2}+\left[4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}\right] z^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Das Vorzeichen des letzten Terms ist nicht negativ, da der erste Teil ein Quadrat ist und im zweiten Teil $4 b^{2} c^{2}-\left(b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}\right)^{2}=(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)$ positiv ist. Die Zahl $a y z+b z x+c x y$ ist folglich nicht positiv.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl1_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

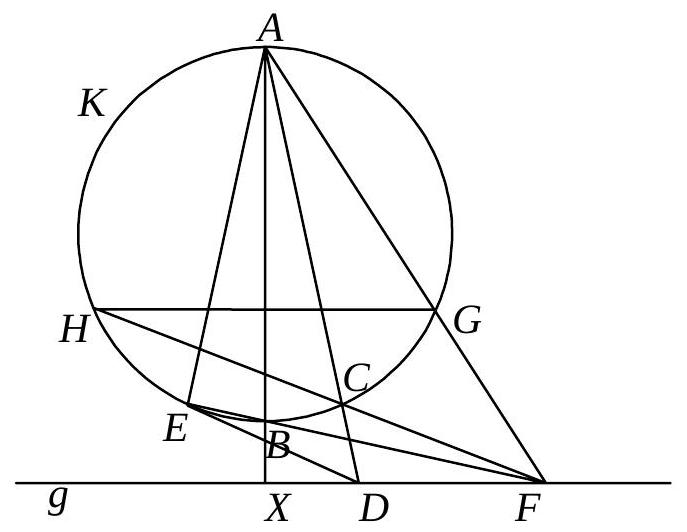

In the plane, there are $n$ closed disks $\mathrm{K}_{1}, \mathrm{~K}_{2}, \ldots ; \mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{n}}$ with the same radius $r$. Each point in the plane is contained in at most 2003 of these disks. Prove that each disk $K_{\mathrm{i}}$ intersects at most 14020 other disks.

|

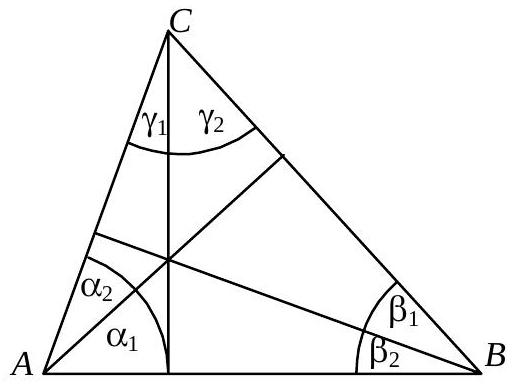

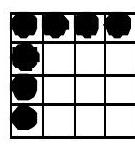

We conduct a proof by contradiction. In addition to the assumption, we assume that a circular disk (w.l.o.g. let this be $K_{1}$) intersects at least 14021 other circular disks. The centers of these disks then obviously all lie within a circular disk of radius $2r$ around the center $M_{1}$ of $K_{1}$. If 2003 or more of the centers of these other disks were to lie within or on the boundary of $K_{1}$, then these disks would all contain $M_{1}$. Thus, $M_{1}$ would be contained in more than 2003 disks, since $M_{1}$ is also contained in $K_{1}$. Therefore, at least 14021 - 2002 $=12019$ centers of the other disks must lie in an annulus with inner radius $r$ and outer radius $2r$ around $M_{1}$. Dividing this annulus into 6 equal sectors with an internal angle of $60^{\circ}$, it follows by the pigeonhole principle that at least 2004 of these centers must lie in at least one sector.

In the diagram, this sector is shown with the midpoint $M$ of the segment $AB$. From $\left|A M_{1}\right|=\left|B M_{1}\right|=2r$ and $\angle A M_{1} B = 60^{\circ}$, it follows that $\triangle A B M_{1}$ is equilateral. Thus, $M D$ and $MC$ are its midlines, and it follows that

$|M A|=|M B|=|M C|=|M D|=r$. Therefore, the sector lies entirely within a circle around $M$ with radius $r$. Each of the at least 2004 disks with centers in this sector thus contains the point $M$. Hence, $M$ is contained in at least 2004 disks - a contradiction to the assumption.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

In der Ebene liegen n abgeschlossene Kreisscheiben $\mathrm{K}_{1}, \mathrm{~K}_{2}, \ldots ; \mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{n}}$ mit gleichem Radius r . Jeder Punkt der Ebene ist dabei in höchstens 2003 dieser Kreisscheiben enthalten. Man beweise, dass jede Kreisscheibe $K_{\mathrm{i}}$ höchstens 14020 andere Kreisscheiben schneidet.

|

Wir führen einen Beweis durch Widerspruch. Dazu nehmen wir zusätzlich zur Voraussetzung an, dass eine Kreisscheibe (oBdA sei dies $K_{1}$ ) mindestens 14021 andere Kreisscheiben schneidet. Die Mittelpunkte dieser Scheiben liegen dann offensichtlich alle in einer Kreisscheibe mit Radius $2 r$ um den Mittelpunkt $M_{1}$ von $K_{1}$. Lägen 2003 oder mehr der Mittelpunkte dieser anderen Kreisscheiben in oder auf dem Rand von $K_{1}$, so würden diese Scheiben alle $M_{1}$ enthalten. Damit würde $M_{1}$ in mehr als 2003 Kreisscheiben enthalten sein, da $M_{1}$ auch in $K_{1}$ enthalten ist. Also müssen mindestens 14021 - 2002 $=12019$ Mittelpunkte der anderen Kreisscheiben in einem Kreisring mit innerem Radius r und äußerem Radius $2 r$ um $M_{1}$ liegen. Teilen wir diesen Ring in 6 gleich große Sektoren mit Innenwinkel $60^{\circ}$, so liegen nach dem Schubfachprinzip in mindestens einem Sektor wenigstens 2004 dieser Mittelpunkte.

In der Zeichnung ist dieser Sektor mit dem Mittelpunkt $M$ der Strecke $A B$ dargestellt. Aus $\left|A M_{1}\right|=\left|B M_{1}\right|=2 r$ und $\angle A M_{1} B=$ $60^{\circ}$ folgt, dass $\triangle A B M_{1}$ gleichseitig ist. Also sind $M D$ und MC seine Mittelparallelen und es folgt

$|M A|=|M B|=|M C|=|M D|=r$. Daher liegt der Sektor vollständig in einem Kreis um M mit Radius r. Jede der wenigstens 2004 Kreisscheiben mit Mittelpunkten in diesem Sektor enthält also den Punkt M. Damit ist M aber in

wenigstens 2004 Kreisscheiben enthalten - ein Widerspruch zur Annahme.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl2_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Given are $n$ real numbers $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \mathrm{x}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ and $\mathrm{y}_{1}, \mathrm{y}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{y}_{\mathrm{n}}$. The elements of an $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ matrix A are defined as follows: ( $1 \leq \mathrm{i}, \mathrm{j} \leq \mathrm{n}$ )

$$

a_{i j}= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } x_{i}+y_{j} \geq 0 \\ 0 & \text { if } x_{i}+y_{j}<0\end{cases}

$$

Furthermore, let B be an $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$ matrix with elements 0 or 1, such that the sum of the elements in each row and each column of B is equal to the sum of the elements in the corresponding row or column of A.

Prove that then $\mathrm{A}=\mathrm{B}$ holds.

|

We assume that there is a matrix $B$ of the required type with $B \neq A$. Now we consider in $A$ only those elements $a_{ij}$ that differ from the corresponding elements $b_{ij}$. There must be at least one such element. All other elements of $A$ are deleted. Then, within each row and column, the number of remaining zeros is equal to the number of remaining ones, since these counts in $B$ are simply swapped for the same row or column sum. Thus, each number $x_i$ appears in the remaining arrangement just as often as a summand in a sum $x_i + y_j < 0$ as it does in a sum $x_i + y_j \geq 0$. The same applies to each number $y_j$.

Now we add up all sums $x_i + y_j < 0$ with $a_{ij} \neq b_{ij}$. The sum of these sums is necessarily $< 0$. Similarly, we add up all sums $x_i + y_j \geq 0$ with $a_{ij} \neq b_{ij}$. The sum of these sums is necessarily $\geq 0$. However, since each of the numbers $x_i$ and $y_j$ appears equally often in both sums, these sums must have the same value, which is a contradiction! Therefore, there can be no different elements in $A$ and $B$, and it follows that $A = B$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Gegeben seien jeweils n reelle Zahlen $\mathrm{x}_{1}, \mathrm{x}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{x}_{\mathrm{n}}$ bzw. $\mathrm{y}_{1}, \mathrm{y}_{2}, \ldots, \mathrm{y}_{\mathrm{n}}$. Die Elemente einer $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$-Matrix A seien folgendermaßen definiert: ( $1 \leq \mathrm{i}, \mathrm{j} \leq \mathrm{n}$ )

$$

a_{i j}= \begin{cases}1 & \text { wenn } x_{i}+y_{j} \geq 0 \\ 0 & \text { wenn } x_{i}+y_{j}<0\end{cases}

$$

Weiter sei B eine $\mathrm{n} \times \mathrm{n}$-Matrix mit Elementen 0 oder 1, so dass die Summe der Elemente in jeder Zeile und jeder Spalte von B gleich der Summe der Elemente in der entsprechenden Zeile bzw. Spalte von A ist.

Man beweise, dass dann $\mathrm{A}=\mathrm{B}$ gilt.

|

Wir nehmen an, dass es eine Matrix $B$ der geforderten Art gebe mit $B \neq A$. Nun betrachten wir in A nur noch diejenigen Elemente $a_{i j}$, die sich von den entsprechenden Elementen $b_{i j}$ unterscheiden. Es muss mindestens ein solches Element geben. Alle anderen Elemente von A werden gestrichen. Dann ist innerhalb jeder Zeile bzw. Spalte die Anzahl der verbleibenden Nullen gleich der Anzahl der verbleibenden Einsen, da diese

Anzahlen in B bei gleicher Zeilen- bzw. Spaltensumme gerade vertauscht sind. Also tritt jede Zahl $x_{i}$ in der verbleibenden Anordnung genauso oft als Summand einer Summe $x_{i}+y_{j}<0$ auf wie als Summand einer Summe $x_{i}+y_{j} \geq 0$. Das Gleiche gilt für jede Zahl $y_{j}$.

Nun addieren wir alle Summen $x_{i}+y_{j}<0$ mit $a_{i j} \neq b_{i j}$. Die Summe dieser Summen ist zwangsläufig $<0$. Ebenso addieren wir alle Summen $x_{i}+y_{j} \geq 0$ mit $a_{i j} \neq b_{i j}$. Die Summe dieser Summen ist zwangsläufig $\geq 0$. Da aber jede der Zahlen $x_{i}$ und $y_{j}$ gleich häufig in beiden Summen auftritt, müssen diese Summen den gleichen Wert haben Widerspruch! Daher kann es keine verschiedenen Elemente in A und B geben und es gilt $A=B$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl2_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Lösung\n",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

Let $ABC$ be an isosceles triangle with $\overline{AC} = \overline{BC}$ and incenter $I$. Furthermore, let $P$ be a point inside $ABC$ on the circumcircle of triangle $BIA$. The parallels to $CA$ and $CB$ through $P$ intersect $AB$ at $D$ and $E$ respectively. The parallel to $AB$ through $P$ intersects $CA$ and $CB$ at $F$ and $G$ respectively.

Show that the lines $DF$ and $EG$ intersect on the circumcircle of triangle $ABC$.

|

Due to $\angle F P E=\angle F G B=180^{\circ}-\angle C B A=180^{\circ}-\angle B A C=180^{\circ}-\angle F A E$ (parallelism and isosceles property), FAEP is a cyclic quadrilateral. Similarly, GPDB is also a cyclic quadrilateral. Their two circumcircles intersect at P and another point, which we denote as S. Now it follows that $\angle E S P=\angle E A P=\angle B A P=180^{\circ}-\angle A P B-\angle P B A$ $=180^{\circ}-\angle A I B-\angle P B A=\angle B A I+\angle I B A-\angle P B A=2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} \angle C B A-\angle P B A=\angle C B P=\angle G B P$ $=\angle G S P$ (inscribed angles and symmetry). Therefore, S lies on the line EG; similarly, S, D, and F are collinear. Hence, S is the intersection of DF and EG. It remains to prove that this point lies on the circumcircle of ABC.

Indeed, we have

$\angle B S A=\angle P S A+\angle B S P=180^{\circ}-\angle A F P+180^{\circ}-\angle P G B=$ $\angle G F C+\angle C G F=180^{\circ}-\angle F C G=180^{\circ}-\angle A C B$. Thus, ASBC is a cyclic quadrilateral, which is what we needed to prove.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C$ ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck mit $\overline{A C}=\overline{B C}$ und Inkreismittelpunkt I. Ferner sei $P$ ein Punkt im Inneren von ABC auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks BIA. Die Parallelen zu $C A$ und $C B$ durch $P$ schneiden $A B$ in $D$ bzw. E. Die Parallele zu AB durch P schneidet CA und $C B$ in $F$ bzw. G.

Man zeige, dass sich die Geraden DF und EG auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks ABC schneiden.

|

Wegen $\angle F P E=\angle F G B=180^{\circ}-\angle C B A=180^{\circ}-\angle B A C=180^{\circ}-\angle F A E$ (Parallelität und Gleichschenkligkeit) ist FAEP ein Sehnenviereck. Analog erweist sich GPDB als Sehnenviereck. Ihre beiden Umkreise schneiden sich in P und einem weiteren Punkt, den wir mit S bezeichnen. Nun folgt weiter $\angle E S P=\angle E A P=\angle B A P=180^{\circ}-\angle A P B-\angle P B A$ $=180^{\circ}-\angle A I B-\angle P B A=\angle B A I+\angle I B A-\angle P B A=2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} \angle C B A-\angle P B A=\angle C B P=\angle G B P$ $=\angle G S P$ (Umfangswinkel und Symmetrie). Also liegt S auf der Geraden EG; entsprechend sind S, D und F kollinear. Deshalb ist S der Schnittpunkt von DF und EG. Es bleibt zu beweisen, dass dieser Punkt auf dem Umkreis von ABC liegt.

In der Tat gilt

$\angle B S A=\angle P S A+\angle B S P=180^{\circ}-\angle A F P+180^{\circ}-\angle P G B=$ $\angle G F C+\angle C G F=180^{\circ}-\angle F C G=180^{\circ}-\angle A C B$. Somit ist ASBC ein Sehnenviereck, was zu beweisen war.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2004-loes_awkl2_04.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2004"

}

|

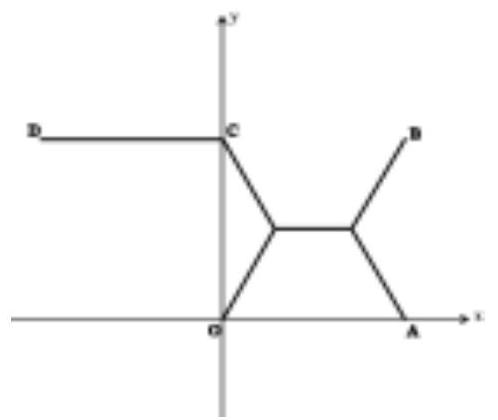

Gegeben sind die positiven reellen Zahle $a$ und $b$ und die natürliche Zahl $n$.

Man ermittle in Abhängigkeit von $a, b$ und $n$ das größte der $n+1$ Glieder in der Entwicklung von $(a+b)^{n}$.

|

Das $k$-te Glied $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{k})$ in der Entwicklung von $(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b})^{\mathrm{n}}$ ist gegeben durch die Formel: $G(k)=\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1}$, wobei $\binom{n}{0}=1$ und $1 \leq \mathrm{k} \leq \mathrm{n}+1$.

Da es endlich viele Glieder gibt und jede endliche Zahlenmenge (mindestens) ein maximales Element enthält, wird untersucht unter welchen Bedingungen das k-te Element maximal ist. Dafür müssen die folgenden Beziehungen gleichzeitig erfüllt sein: $\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1} \geq\binom{ n}{k} \cdot a^{n-k} \cdot b^{k}$ und $\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1} \geq\binom{ n}{k-2} \cdot a^{n-k+2} \cdot b^{k-2}$, wobei im letzten Fall $k \geq 2$ sein muss und eine dieser Ungleichungen streng ist (einfacher Nachweis!).

Das führt einerseits $\mathrm{zu} \frac{1}{n-k+1} \cdot a \geq \frac{1}{k} \cdot b$ und andererseits $\mathrm{zu} \frac{1}{k-1} \cdot b \geq \frac{1}{n-k+2} \cdot a$, woraus sowohl $\mathrm{n}+1 \geq \mathrm{k} \geq \frac{n b+b}{a+b}$, als auch $1 \leq \mathrm{k} \leq \frac{n b+2 b+a}{a+b}=\frac{n b+b}{a+b}+1$ folgt.

Falls $\mathrm{i}=\frac{n b+b}{a+b}$ nicht ganzzahlig ist, ist $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i})$ das größte Glied, andernfalls sind $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i})$ und $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i}+1)$ maximal.

Weitere maximale Glieder kann es nicht geben.

|

\frac{n b+b}{a+b}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Gegeben sind die positiven reellen Zahle $a$ und $b$ und die natürliche Zahl $n$.

Man ermittle in Abhängigkeit von $a, b$ und $n$ das größte der $n+1$ Glieder in der Entwicklung von $(a+b)^{n}$.

|

Das $k$-te Glied $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{k})$ in der Entwicklung von $(\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b})^{\mathrm{n}}$ ist gegeben durch die Formel: $G(k)=\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1}$, wobei $\binom{n}{0}=1$ und $1 \leq \mathrm{k} \leq \mathrm{n}+1$.

Da es endlich viele Glieder gibt und jede endliche Zahlenmenge (mindestens) ein maximales Element enthält, wird untersucht unter welchen Bedingungen das k-te Element maximal ist. Dafür müssen die folgenden Beziehungen gleichzeitig erfüllt sein: $\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1} \geq\binom{ n}{k} \cdot a^{n-k} \cdot b^{k}$ und $\binom{n}{k-1} \cdot a^{n-k+1} \cdot b^{k-1} \geq\binom{ n}{k-2} \cdot a^{n-k+2} \cdot b^{k-2}$, wobei im letzten Fall $k \geq 2$ sein muss und eine dieser Ungleichungen streng ist (einfacher Nachweis!).

Das führt einerseits $\mathrm{zu} \frac{1}{n-k+1} \cdot a \geq \frac{1}{k} \cdot b$ und andererseits $\mathrm{zu} \frac{1}{k-1} \cdot b \geq \frac{1}{n-k+2} \cdot a$, woraus sowohl $\mathrm{n}+1 \geq \mathrm{k} \geq \frac{n b+b}{a+b}$, als auch $1 \leq \mathrm{k} \leq \frac{n b+2 b+a}{a+b}=\frac{n b+b}{a+b}+1$ folgt.

Falls $\mathrm{i}=\frac{n b+b}{a+b}$ nicht ganzzahlig ist, ist $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i})$ das größte Glied, andernfalls sind $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i})$ und $\mathrm{G}(\mathrm{i}+1)$ maximal.

Weitere maximale Glieder kann es nicht geben.