problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Determine all pairs $(x, y)$ of integers that satisfy the equation

$$

\sqrt[3]{7 x^{2}-13 x y+7 y^{2}}=|x-y|+1

$$

|

Equation (1) is symmetric in $x$ and $y$, so we can initially assume $x \geq y$. For $x \neq y$, for each solution $(x, y)$, $(y, x)$ is also a solution. With

$d=x-y \geq 0$ it follows that $\sqrt[3]{7 d^{2}+x y}=d+1$. Squaring yields $x^{2}-d x+\left(-d^{3}+4 d^{2}-3 d-1\right)=0$ with the discriminant $D=d^{2}-4\left(-d^{3}+4 d^{2}-3 d-1\right)=(d-2)^{2}(4 d+1) \geq 0$. Therefore, $x_{1 / 2}=\frac{d \pm(d-2) \sqrt{4 d+1}}{2}$. For $x$ to be an integer, $4 d+1$ must be a perfect square, and specifically the square of an odd number. The approach $4 d+1=(2 m+1)^{2}$ with $m \in\{0 ; 1 ; 2 ; \ldots\}$ yields $d=m^{2}+m$, so that $x_{1 / 2}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\left(m^{2}+m\right) \pm\left(m^{2}+m-2\right)(2 m+1)\right]$ results. This leads to $\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right)=\left(m^{3}+2 m^{2}-m-1, m^{3}+m^{2}-2 m-1\right)$ and for $m \neq 1$ to $\left(x_{2}, y_{2}\right)=\left(-m^{3}-m^{2}+2 m+1,-m^{3}-2 m^{2}+m+1\right)$ and the solutions $\left(y_{1}, x_{1}\right)$ and $\left(y_{2}, x_{2}\right)$ for $m>0$. A check confirms that these pairs are indeed solutions.

Hint: The simple special cases were found by most participants. Often, attempts were then made (in vain) to show that there are no further solutions using estimates.

|

(x_1, y_1) = (m^3 + 2m^2 - m - 1, m^3 + m^2 - 2m - 1), (x_2, y_2) = (-m^3 - m^2 + 2m + 1, -m^3 - 2m^2 + m + 1)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Man bestimme alle Paare ( $x, y$ ) ganzer Zahlen, welche die Gleichung

$$

\sqrt[3]{7 x^{2}-13 x y+7 y^{2}}=|x-y|+1

$$

erfüllen.

|

Die Gleichung (1) ist symmetrisch in $x$ und $y$, so dass wir zunächst $x \geq y$ annehmen können und für $x \neq y$ zu jeder Lösung $(x, y)$ auch $(y, x)$ als Lösung erhalten. Mit

$d=x-y \geq 0$ folgt $\sqrt[3]{7 d^{2}+x y}=d+1$. Potenzieren liefert $x^{2}-d x+\left(-d^{3}+4 d^{2}-3 d-1\right)=0$ mit der Diskriminante $D=d^{2}-4\left(-d^{3}+4 d^{2}-3 d-1\right)=(d-2)^{2}(4 d+1) \geq 0$. Es ist also $x_{1 / 2}=\frac{d \pm(d-2) \sqrt{4 d+1}}{2}$. Für die Ganzzahligkeit von $x$ muss $4 d+1$ eine Quadratzahl sein, und zwar das Quadrat einer ungeraden Zahl. Der Ansatz $4 d+1=(2 m+1)^{2}$ mit $m \in\{0 ; 1 ; 2 ; \ldots\}$ liefert $d=m^{2}+m$, so dass sich $x_{1 / 2}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\left(m^{2}+m\right) \pm\left(m^{2}+m-2\right)(2 m+1)\right]$ ergibt. Dies führt zu $\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right)=\left(m^{3}+2 m^{2}-m-1, m^{3}+m^{2}-2 m-1\right)$ und für $m \neq 1 \mathrm{zu}$ $\left(x_{2}, y_{2}\right)=\left(-m^{3}-m^{2}+2 m+1,-m^{3}-2 m^{2}+m+1\right)$ und den Lösungen $\left(y_{1}, x_{1}\right)$ bzw. $\left(y_{2}, x_{2}\right)$ für $m>0$. Eine Probe bestätigt, dass diese Paare tatsächlich Lösungen sind.

Hinweis: Die einfachen Spezialfälle wurden von den meisten Teilnehmern gefunden. Häufig wurde dann (vergeblich) versucht, mit Abschätzungen zu zeigen, dass es keine weiteren Lösungen gibt.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2015-loes_awkl_15.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

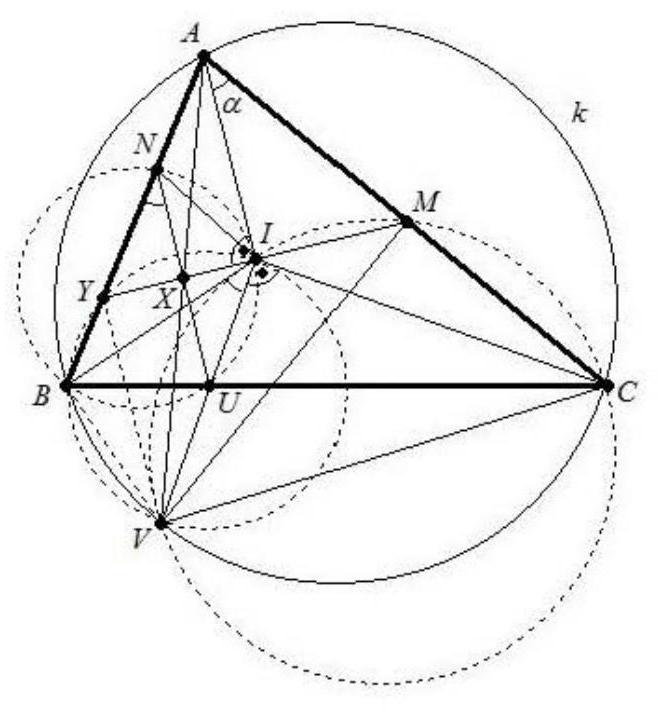

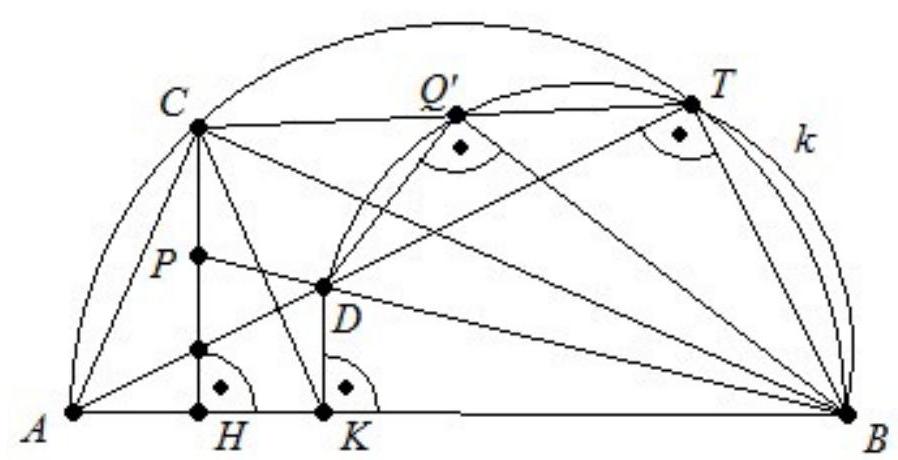

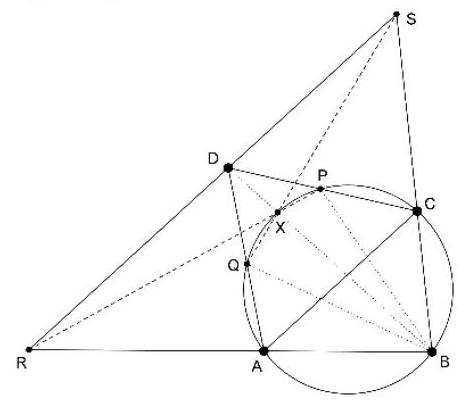

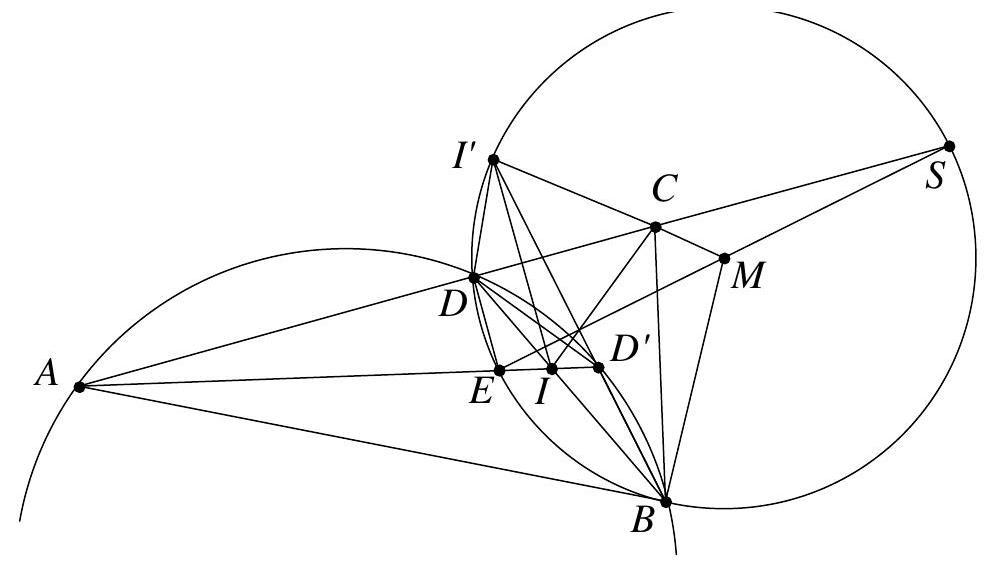

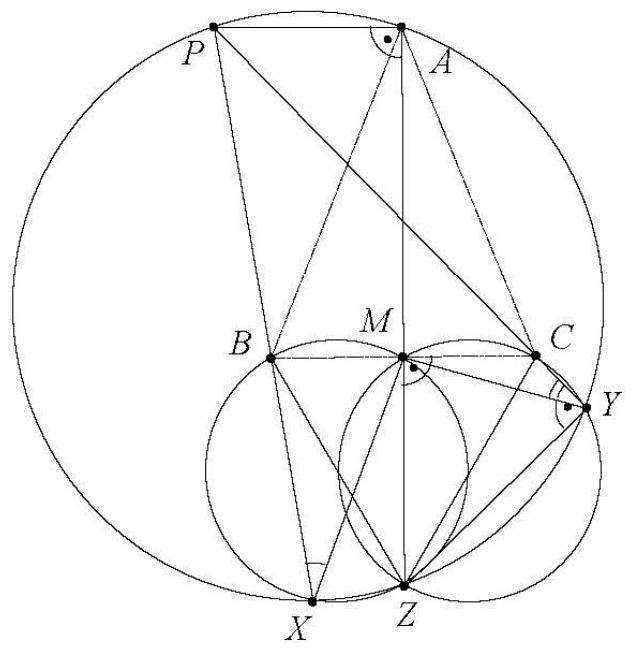

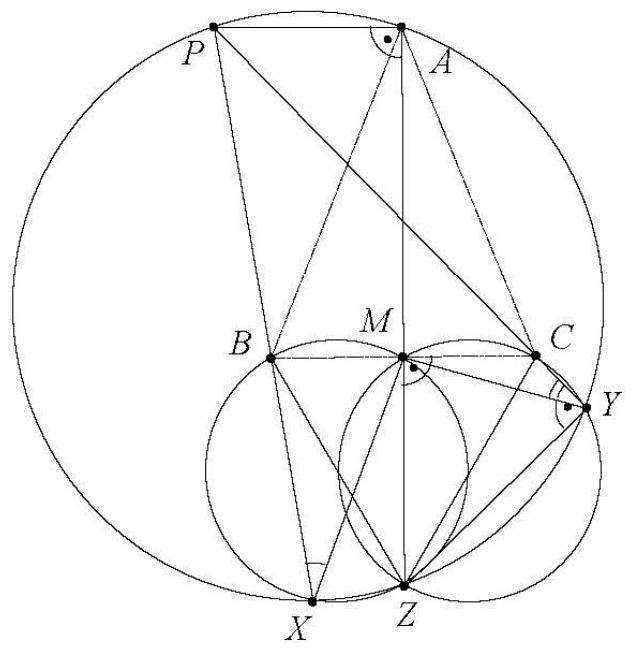

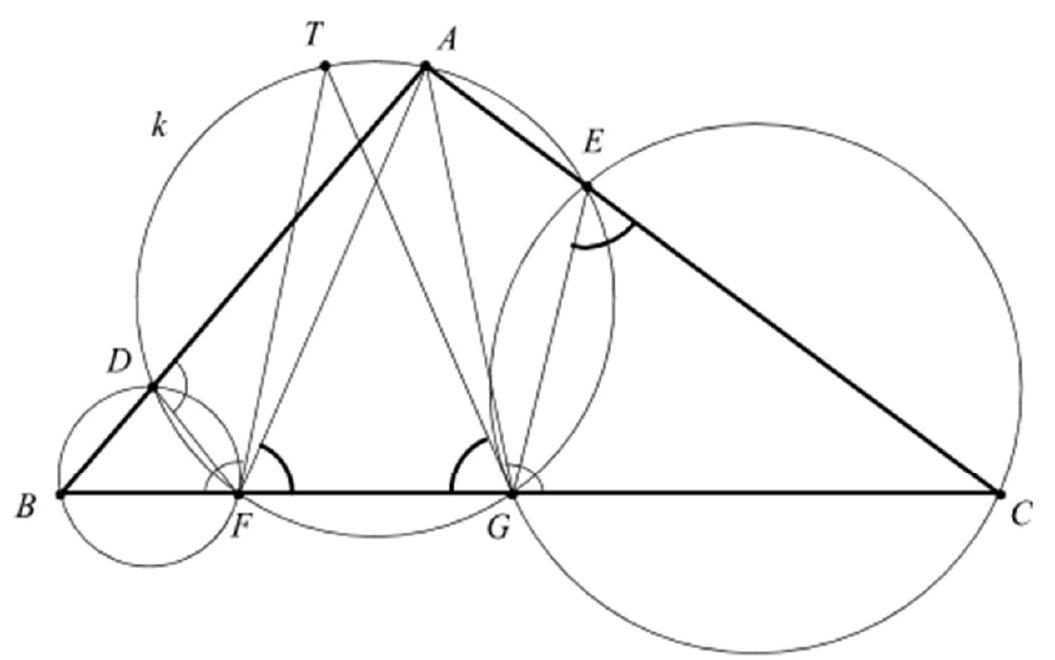

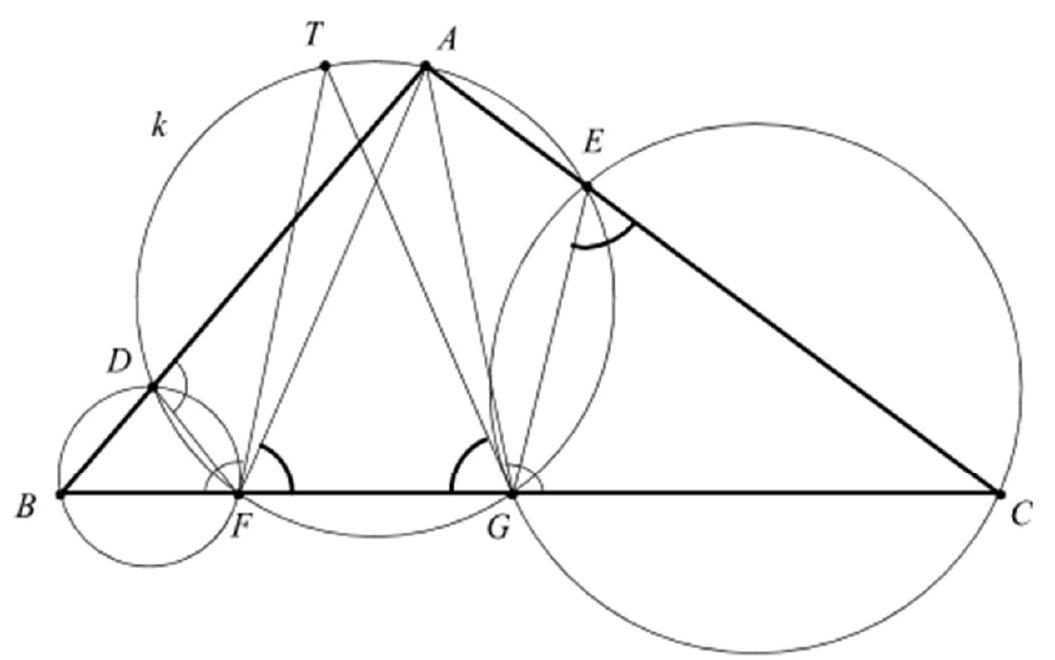

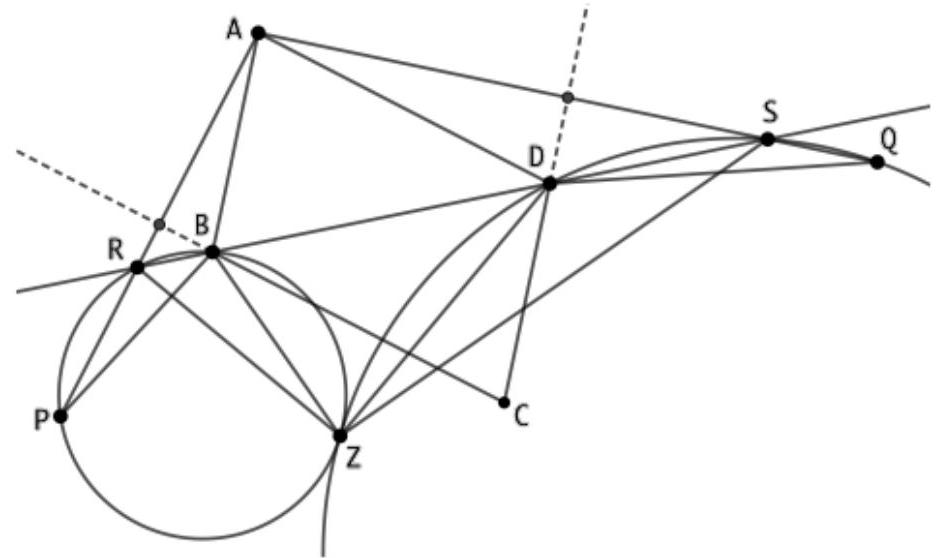

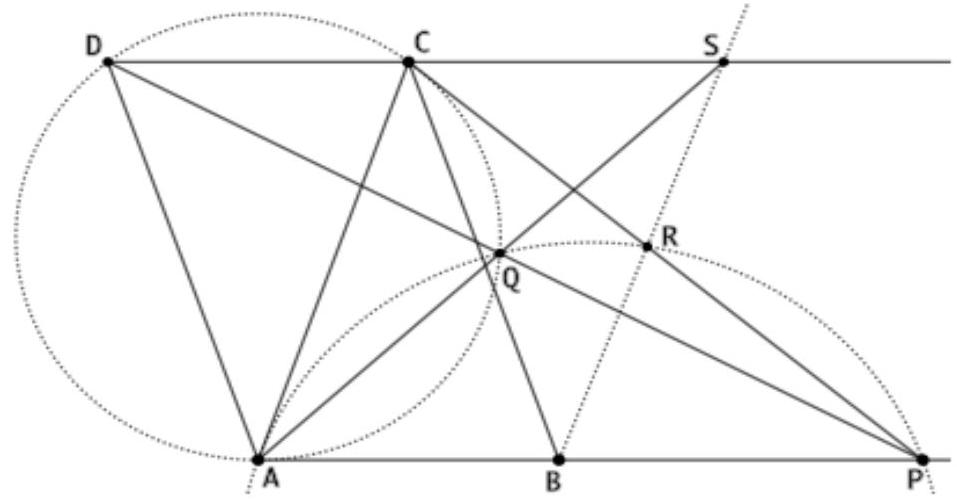

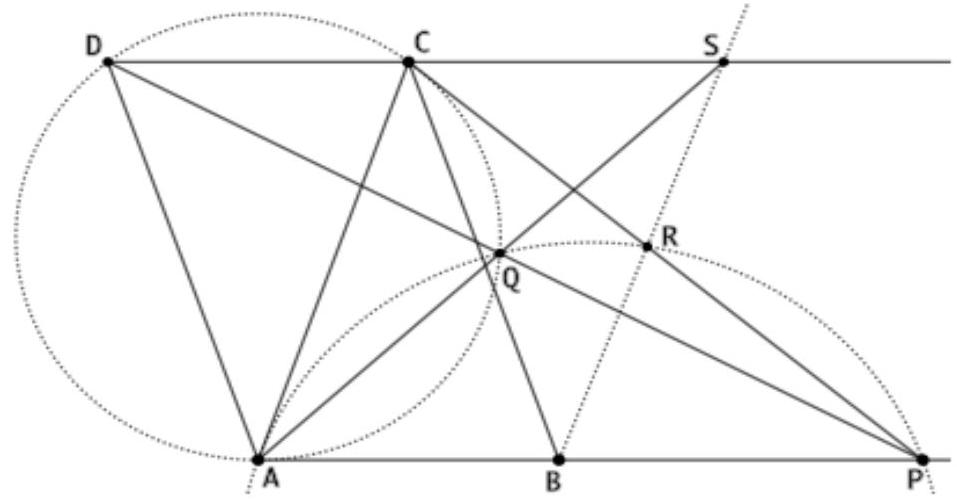

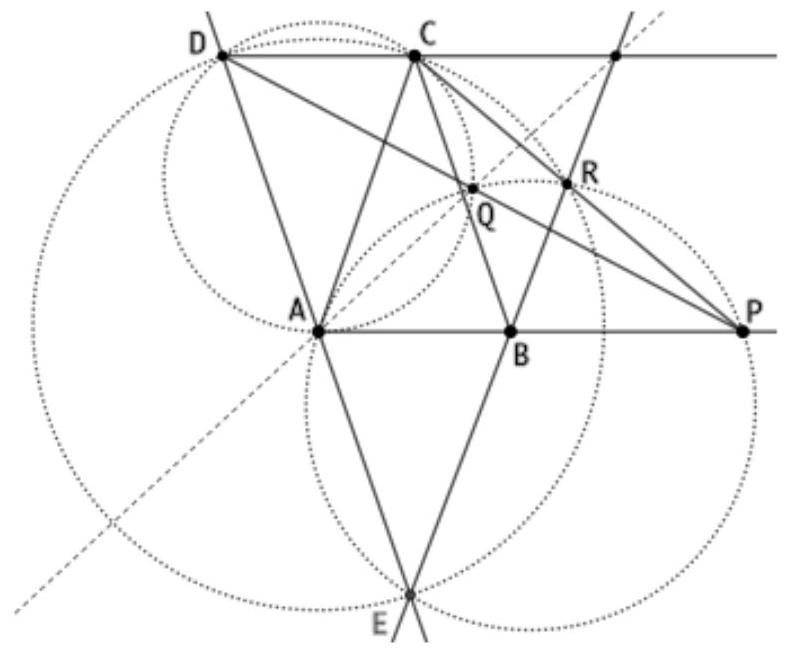

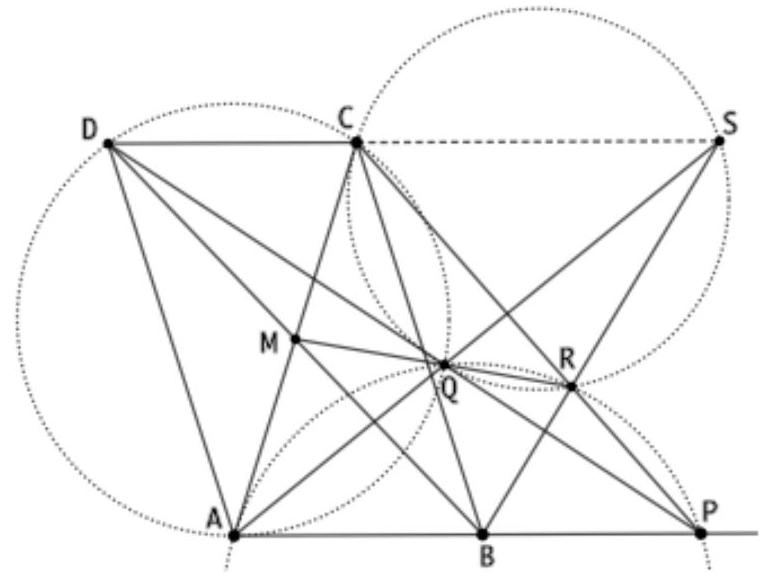

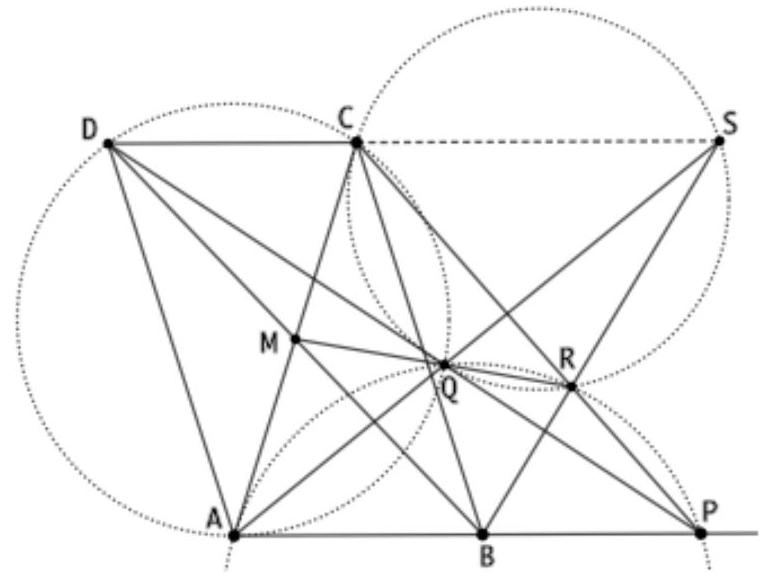

Let $ABC$ be an acute-angled triangle with circumcircle $k$ and incenter $I$. The perpendicular to $CI$ through $I$ intersects the side $BC$ at $U$ and $k$ at $V$, where $V$ and $A$ lie on opposite sides of $BC$. The parallel to $AI$ through $U$ intersects $AV$ at point $X$.

Prove: If the lines $XI$ and $AI$ are perpendicular to each other, then $XI$ intersects the side $AC$ at its midpoint $M$.

|

In the figure, $M$ is initially only the intersection of $X I$ and $A C$. $N$ is the intersection of $X U$ and $A B$, and $Y$ is the intersection of $X I$ and $A B$. The half interior angles of triangle $A B C$ are denoted by $\alpha, \beta$ and $\gamma$ respectively. Since $\angle U I C=90^{\circ}$, it follows that $\angle C U I=\alpha+\beta$ and therefore $\angle B N U=\angle B A I=\angle B I U=\alpha$, so the points $B, U, I$ and $N$ lie on a circle. Therefore, $\overline{\Pi U}=\overline{I N}$ (chords corresponding to $\beta$) and since $X \perp N U$, it follows that $\overline{N X}=\overline{X U}$. Applying the intercept theorem leads to $\frac{\overline{V X}}{\overline{V A}}=\frac{\overline{X U}}{\overline{A I}}=\frac{\overline{N X}}{\overline{A I}}=\frac{\overline{Y X}}{\overline{Y I}}$, from which $Y V \| A I$ follows. Thus, $\angle B Y V=\alpha=\angle B N$, so

the points $B, V, I$ and $Y$ lie on a circle. Therefore, $\angle V B I=\angle V Y I=90^{\circ}$. Since the bisectors of the interior and exterior angles at a vertex in a triangle are always perpendicular, $B V$ is the bisector of the exterior angle at $B$. In the cyclic quadrilateral $A B V C$ (circumcircle of $A B C$), we recognize that $\angle V A C=\angle V B C=\alpha+\gamma$ and $\angle A C V=180^{\circ}-\angle V B A=180^{\circ}-(\alpha+2 \beta+\gamma)=\alpha+\gamma$, so $\angle V A C=\angle A C V$. Thus, triangle $A V C$ is isosceles with the apex at $V$. To show that $M$ is the midpoint of $A C$, it suffices to prove that $\angle V M C=90^{\circ}$. For this, we use in the cyclic quadrilaterals $B V I Y$ and $A B V C$ that $\angle V I M=180^{\circ}-\angle Y I V=\angle V B Y=\angle V B A=180^{\circ}-\angle A C V$, so $V C M I$ is also a cyclic quadrilateral. This yields $\angle V M C=\angle V I C=90^{\circ}$.

Hint: Some participants attempted a chase of angles, which, however, remains unsuccessful without a chase of cyclic quadrilaterals. Analytical approaches could not be successfully completed.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C$ ein spitzwinkliges Dreieck mit dem Umkreis $k$ und dem Inkreismittelpunkt $I$. Die Orthogonale zu $C I$ durch I schneide die Seite $B C$ in $U$ und $k$ in $V$, wobei $V$ und $A$ auf verschiedenen Seiten von $B C$ liegen. Die Parallele zu $A I$ durch $U$ schneide $A V$ im Punkt $X$.

Man beweise: Wenn die Geraden $X I$ und $A I$ orthogonal zueinander sind, dann schneidet $X I$ die Seite $A C$ in ihrem Mittelpunkt $M$.

|

In der Figur ist $M$ zunächst nur der Schnittpunkt von $X I$ und $A C . N$ ist der Schnittpunkt von $X U$ und $A B$ und $Y$ der Schnittpunkt von $X I$ und $A B$. Die halben Innenwinkel des Dreiecks $A B C$ sind mit $\alpha, \beta$ bzw. $\gamma$ bezeichnet. Wegen $\Varangle U I C=90^{\circ}$ ist $\Varangle C U I=\alpha+\beta$ und daher $\Varangle B N U=\Varangle B A I=\Varangle B I U=\alpha$, so dass die Punkte $B, U, I$ und $N$ auf einem Kreis liegen. Deshalb gilt $\overline{\Pi U}=\overline{I N}$ (Sehnen $\mathrm{zu} \beta$ ) und wegen $X \perp N U$ folgt $\overline{N X}=\overline{X U}$. Anwendung der Strahlensätze führt auf $\frac{\overline{V X}}{\overline{V A}}=\frac{\overline{X U}}{\overline{A I}}=\frac{\overline{N X}}{\overline{A I}}=\frac{\overline{Y X}}{\overline{Y I}}$, woraus $Y V \| A I$ folgt. Also ist auch $\Varangle B Y V=\alpha=\Varangle B N$, so

dass die Punkte $B, V, I$ und $Y$ auf einem Kreis

liegen. Daher ist $\Varangle V B I=\Varangle V Y I=90^{\circ}$. Da die Halbierenden von Innen- und Außenwinkel an einer Ecke im Dreieck stets orthogonal sind, ist $B V$ die Halbierende des Außenwinkels bei $B$. Im Sehnenviereck $A B V C$ (Umkreis von $A B C$ ) erkennen wir daher $\Varangle V A C=\Varangle V B C=\alpha+\gamma$ und $\Varangle A C V=180^{\circ}-\Varangle V B A=180^{\circ}-(\alpha+2 \beta+\gamma)=\alpha+\gamma$, also $\Varangle V A C=\Varangle A C V$. Das Dreieck $A V C$ ist somit gleichschenklig mit der Spitze $V$. Um nun zu zeigen, dass $M$ der Mittelpunkt von $A C$ ist, reicht der Nachweis von $\varangle V M C=90^{\circ}$. Dazu verwenden wir in den Sehnenvierecken $B V I Y$ und $A B V C$, dass $\Varangle V I M=180^{\circ}-\Varangle Y I V=\Varangle V B Y=\Varangle V B A=180^{\circ}-\Varangle A C V$ ist, so dass auch $V C M I$ ein Sehnenviereck ist. Dies liefert $\Varangle V M C=\Varangle V I C=90^{\circ}$.

Hinweis: Einige Teilnehmer haben eine Winkeljagd versucht, die jedoch ohne eine Jagd nach Sehnenvierecken erfolglos bleibt. Analytische Ansätze konnten nicht erfolgreich abgeschlossen werden.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2015-loes_awkl_15.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

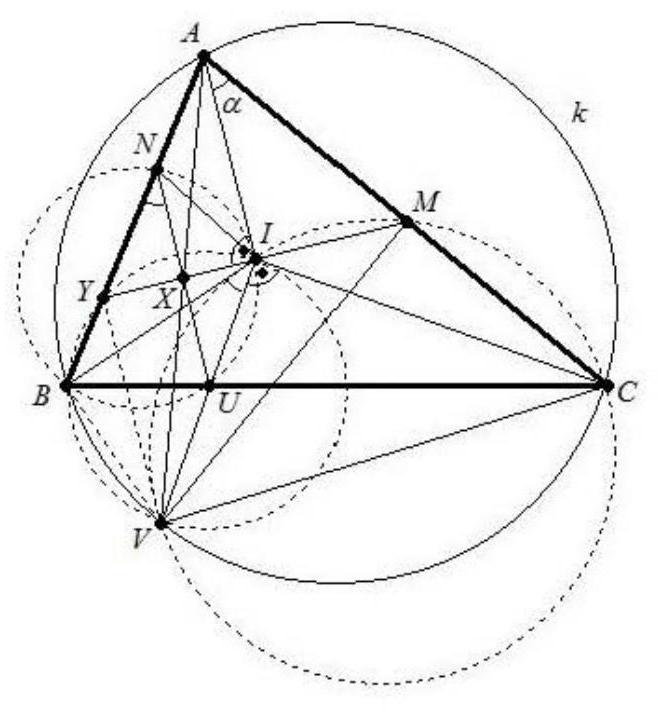

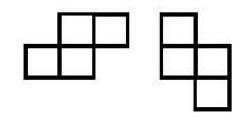

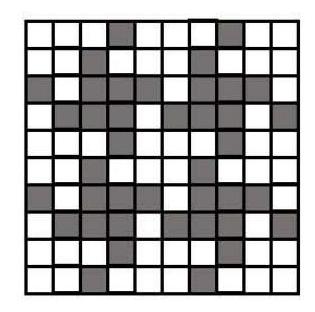

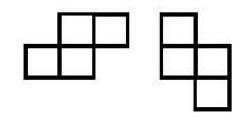

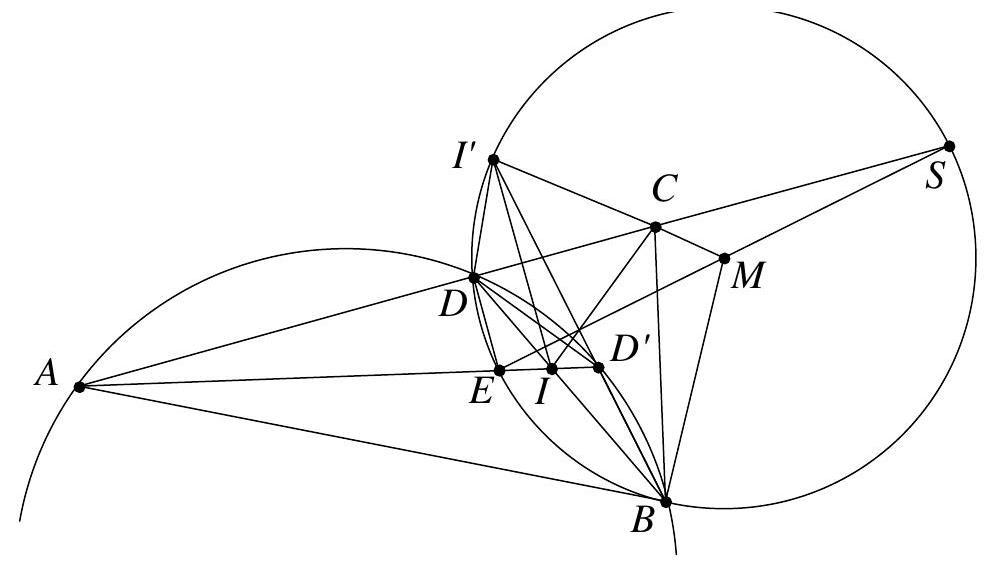

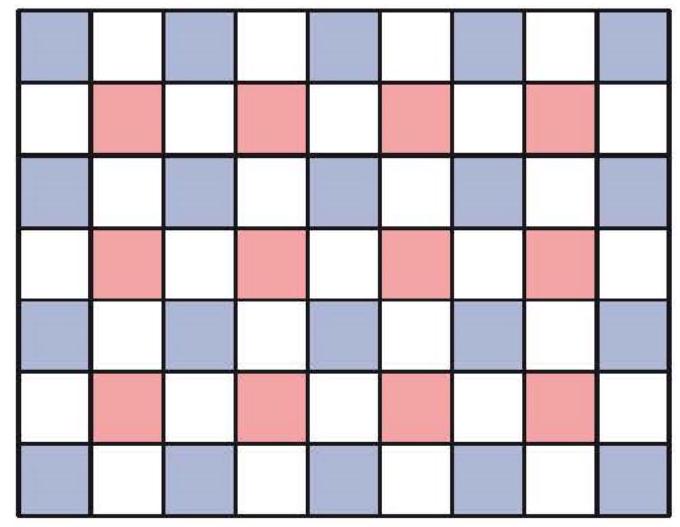

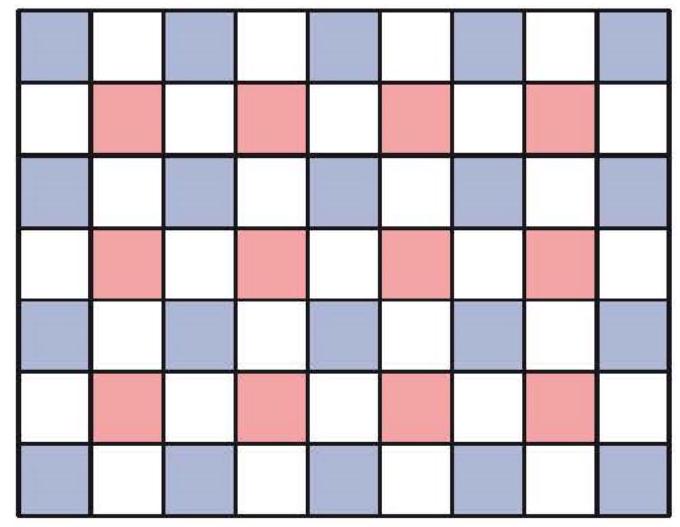

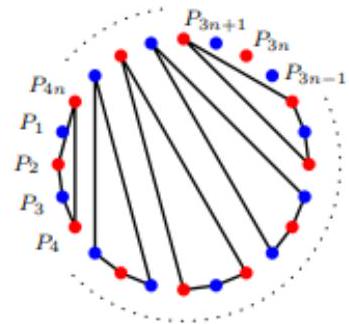

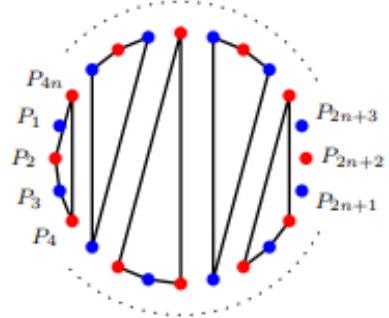

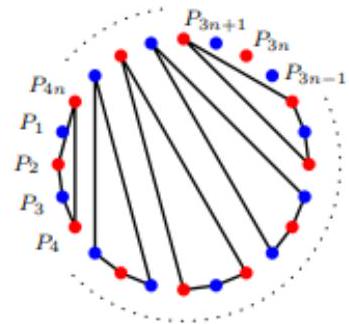

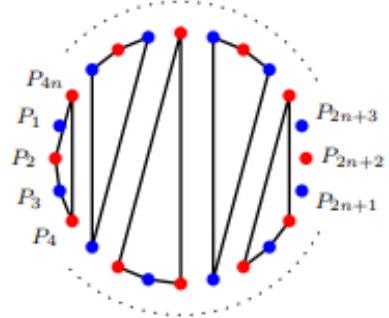

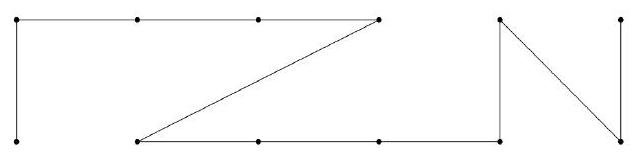

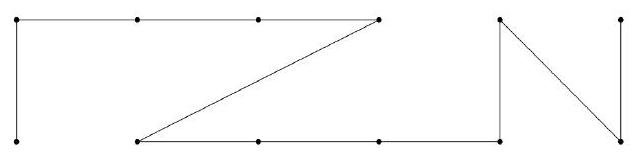

From two 2x1 domino tiles, one can construct a tetromino by placing the two domino tiles along their longer sides such that the midpoint of the longer side of one domino tile is a vertex of the other domino tile. This results in two different types of tetrominos in terms of their orientation, which we will call $S$- and $Z$-tetrominos.

$S$-tetrominos:

$Z$-tetrominos:

A lattice polygon $P$ is a simply connected area whose boundary lines lie only on the grid lines of the integer coordinate grid. A tiling of $P$ is a complete and non-overlapping covering of $P$ with pieces that do not partially lie outside of $P$.

We now assume that a lattice polygon $P$ can only be tiled with $S$-tetrominos. Prove: If a tiling of $P$ with $S$- and $Z$-tetrominos is also possible, then the number of $Z$-tetrominos used is always even.

|

We can assume that $P$ consists of parts of the unit squares of the integer coordinate grid, as colored in the image. Under this coloring, each $S$-tetromino covers an even number of black squares, and each $Z$-tetromino covers an odd number of these. Since $P$ can be completely paved with $S$-tetrominos, it contains an even number of black squares. Therefore, if a tiling with $S$- and $Z$-tetrominos is possible, this even number also requires an even number of $Z$-tetrominos.

Hint: There are other coloring approaches, such as with two colorings. The argument that $P$ must be completely decomposable into axis-symmetric parts where two $S$-tetrominos can be replaced by two $Z$-tetrominos, like all approaches based on local properties of $P$, is not conclusive and only covers special cases $a b$.

|

proof

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Aus zwei 2x1-Dominosteinen kann man ein Tetromino konstruieren, indem man die beiden Dominosteine längs ihrer längeren Seiten so aneinanderlegt, dass der Mittelpunkt der längeren Seite des einen Dominosteins ein Eckpunkt des anderen Dominosteins ist. Dabei ergeben sich zwei hinsichtlich ihrer Orientierung verschiedene Typen von Tetrominos, die wir als $S$ - bzw. $Z$-Tetromino bezeichnen wollen.

$S$-Tetrominos:

Z-Tetrominos:

Ein Gitterpunktpolygon P ist eine einfach zusammenhängende Fläche, deren Randlinien nur auf Gitterlinien des ebenen ganzzahligen Koordinatengitters liegen. Eine Pflasterung von $P$ ist eine vollständige und überlappungsfreie Überdeckung von $P$ mit Flächenstücken, die auch nicht teilweise außerhalb von $P$ liegen.

Wir nehmen nun an, dass ein Gitterpunktpolygon $P$ nur mit $S$-Tetrominos gepflastert werden kann. Man beweise: Wenn auch eine Pflasterung von $P$ mit $S$ - und $Z$-Tetrominos möglich ist, dann ist die Anzahl der dabei verwendeten $Z$-Tetrominos stets gerade.

|

Wir können annehmen, dass $P$ aus einem Teil der Einheitsquadrate des ganzzahligen Koordinatengitters besteht, die wie abgebildet eingefärbt sind. Unter dieser Färbung bedeckt jedes $S$-Tetromino eine gerade Anzahl schwarzer Quadrate und jedes $Z$-Tetromino eine ungerade Anzahl von diesen. Da $P$ vollständig mit $S$-Tetrominos gepflastert werden kann, enthält es eine gerade Anzahl schwarzer Quadrate. Wenn also eine Pflasterung mit $S$ - und $Z$-Tetrominos möglich ist, erfordert diese gerade Anzahl auch eine gerade Anzahl von Z-Tetrominos.

Hinweis: Es gibt weitere Färbungsansätze, z.B. mit zwei Färbungen. Das Argument, $P$ müsse vollständig in achsensymmetrische Teile zerlegbar sein, in denen dann zwei $S$-Tetrominos durch zwei $Z$-Tetrominos ersetzt werden können, ist wie alle Ansätze, die auf lokalen Eigenschaften von $P$ beruhen, nicht zwingend und deckt nur Spezialfälle $a b$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2015-loes_awkl_15.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2015"

}

|

Determine all positive integers $m$ with the following property:

The sequence $a_{0}, a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ with $a_{0}=\frac{2 m+1}{2}$ and $a_{k+1}=a_{k}\left\lfloor a_{k}\right\rfloor$ for $k=0,1,2, \ldots$ contains at least one integer.

Hint: $\lfloor x\rfloor$ denotes the greatest integer part (integer function) of $x$.

|

It holds that $a_{0}=m+\frac{1}{2}$ and $a_{1}=a_{0}\left\lfloor a_{0}\right\rfloor=\left(m+\frac{1}{2}\right) \cdot m=m^{2}+\frac{m}{2}$. This expression is obviously an integer for even $m$, so the desired property of the sequence is present here.

Furthermore, for $m=1$, we have $a_{0}=\frac{3}{2},\left\lfloor a_{0}\right\rfloor=1$, and for $a_{k}=\frac{3}{2}$, it always follows that $a_{k+1}=\frac{3}{2} \cdot 1=\frac{3}{2}$. Thus, there is no integer term in the sequence.

Now let $m \geq 3$ be odd. There exists a unique representation $m=2^{p} \cdot n_{0}+1$ with $p \geq 1, n_{0}$ odd and $p, n_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$. Thus, $a_{0}=2^{p} n_{0}+\frac{3}{2}$, and for $a_{k}=2^{p} n_{k}+\frac{3}{2}$ ( $n_{k}$ odd), it follows that $a_{k+1}=\left(2^{p} n_{k}+\frac{3}{2}\right)\left(2^{p} n_{k}+1\right)=2^{p-1}\left(2^{p+1} n_{k}^{2}+5 n_{k}\right)+\frac{3}{2}$, where the term in parentheses is odd. Therefore, there exists a representation $a_{k+1}=2^{p-1} n_{k+1}+\frac{3}{2}$ with odd $n_{k+1}$. Increasing $k$ by 1 simultaneously decreases $p$ by 1, so $a_{k+p}=2^{0} n_{k+p}+\frac{3}{2}$ holds and $\left\lfloor a_{k+p}\right\rfloor$ is even. Then $a_{k+p+1}$ is an integer, and thus the desired property of the sequence is also present for every $m \geq 3$. Therefore, all positive integers except 1 belong to the desired set.

Hint: The occasional practice of calculating with "fractional residue classes" modulo a power of two often led to errors, such as the incorrect answer that no numbers with a remainder of 1 modulo 8 belong to the set.

|

all positive integers except 1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Man bestimme alle positiven ganzen Zahlen $m$ mit folgender Eigenschaft:

Die Folge $a_{0}, a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ mit $a_{0}=\frac{2 m+1}{2}$ und $a_{k+1}=a_{k}\left\lfloor a_{k}\right\rfloor$ für $k=0,1,2, \ldots$ enthält wenigstens eine ganze Zahl.

Hinweis: $\lfloor x\rfloor$ bezeichnet den größten ganzen Teil (integer-Funktion) von $x$.

|

Es gilt $a_{0}=m+\frac{1}{2}$ und $a_{1}=a_{0}\left\lfloor a_{0}\right\rfloor=\left(m+\frac{1}{2}\right) \cdot m=m^{2}+\frac{m}{2}$. Dieser Ausdruck ist für gerades $m$ offensichtlich ganz, so dass hier die gesuchte Eigenschaft der Folge vorliegt.

Weiterhin gilt bei $m=1$, dass $a_{0}=\frac{3}{2},\left\lfloor a_{0}\right\rfloor=1$ und für $a_{k}=\frac{3}{2}$ stets auch $a_{k+1}=\frac{3}{2} \cdot 1=\frac{3}{2}$ ist. Hier gibt es also kein ganzzahliges Folgenglied.

Nun sei $m \geq 3$ ungerade. Es existiert die eindeutige Darstellung $m=2^{p} \cdot n_{0}+1$ mit $p \geq 1, n_{0}$ ungerade und $p, n_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$. Somit gilt $a_{0}=2^{p} n_{0}+\frac{3}{2}$, und für $a_{k}=2^{p} n_{k}+\frac{3}{2}$ ( $n_{k}$ ungerade) folgt $a_{k+1}=\left(2^{p} n_{k}+\frac{3}{2}\right)\left(2^{p} n_{k}+1\right)=2^{p-1}\left(2^{p+1} n_{k}^{2}+5 n_{k}\right)+\frac{3}{2}$, wobei die Klammer ungerade ist. Also existiert eine Darstellung $a_{k+1}=2^{p-1} n_{k+1}+\frac{3}{2}$ mit ungeradem $n_{k+1}$. Durch Erhöhen von $k$ um 1 wird also gleichzeitig $p$ um 1 vermindert, so dass $a_{k+p}=2^{0} n_{k+p}+\frac{3}{2}$ gilt und $\left\lfloor a_{k+p}\right\rfloor$ gerade ist. Dann ist $a_{k+p+1}$ eine ganze Zahl, und so liegt auch für jedes $m \geq 3$ die gesuchte Eigenschaft der Folge vor. Damit gehören alle positiven ganzen Zahlen außer 1 zur gesuchten Menge.

Hinweis: Das gelegentlich praktizierte Rechnen mit „gebrochenen Restklassen" modulo einer Zweierpotenz führte häufig zu Fehlern wie etwa der falschen Antwort, dass keine Zahlen mit Rest 1 mod 8 zur Menge gehören.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2016-loes_awkl_16.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Determine all functions $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ that satisfy the equation $f(x-f(y))=f(f(x))-f(y)-1$ for all $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$.

|

The equation (1) is precisely satisfied by the functions $f_{1}: x \rightarrow-1$ and $f_{2}: x \rightarrow x+1$. By substitution, it is easily confirmed that both functions are solutions.

Now let $f$ be a function that satisfies (1) for all $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$. By substituting $x=0$ and $y=f(0)$, we obtain with $z=-f(f(0))$ that $f(z)=-1$. Substituting $y=z$ into (1) leads to $f(x+1)=f(f(x))$ for all $x \in \mathbb{Z}$.

Thus, we simplify (1) to $f(x-f(y))=f(x+1)-f(y)-1$.

Substituting $y=x$ into (3) and using (2), we get $f(x+1)-f(x)=f(x-f(x))+1=f(f(x-1-f(x)))+1$.

Since from (3) it follows that $f(x-1-f(x))=f(x)-f(x)-1=-1$, this simplifies to $f(x+1)=f(x)+f(-1)+1=f(x)+c$ with a constant $c$. Therefore, $f$ is linear and satisfies the form $f(x)=c x+b$ with $b=f(0)$. Substituting this into (2) yields $c x+c+b=c^{2} x+c b+b$ for all $x \in \mathbb{Z}$. For $x=0$ and $x=1$, we get $c+b=c b+b$ and $c^{2}=c$; from this, it follows that $c=0$ or $c=1$. From $c=1$ we get $b=1$ and thus $f_{2}$; from $c=0$ it follows that $f$ is constant, and with (1) we get $b=-1$, so $f_{1}$. This completes the proof.

Hint: Often, restrictions were imposed at the beginning (e.g., that $x=f(y)$, i.e., belongs to the range), which were later "forgotten". The statement $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ was sometimes misinterpreted to mean that the range includes all integers.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Man bestimme alle Funktionen $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$, die für alle $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$ die Gleichung $f(x-f(y))=f(f(x))-f(y)-1$

erfüllen.

|

Die Gleichung (1) wird genau von den Funktionen $f_{1}: x \rightarrow-1$ und $f_{2}: x \rightarrow x+1$ erfüllt. Durch Einsetzen wird leicht bestätigt, dass beide Funktionen Lösungen sind.

Nun sei $f$ eine Funktion, die (1) für alle $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$ erfüllt. Durch Einsetzen von $x=0$ und $y=f(0)$ erhalten wir mit $z=-f(f(0))$, dass $f(z)=-1$ ist. Einsetzen von $y=z$ in (1) führt auf $f(x+1)=f(f(x))$ für alle $x \in \mathbb{Z}$

Damit vereinfachen wir (1) zu $f(x-f(y))=f(x+1)-f(y)-1$

Mit $y=x$ in (3) und mit (2) ist $f(x+1)-f(x)=f(x-f(x))+1=f(f(x-1-f(x)))+1$.

Weil aus (3) folgt: $f(x-1-f(x))=f(x)-f(x)-1=-1$, vereinfacht sich dies zu $f(x+1)=f(x)+f(-1)+1=f(x)+c$ mit konstantem $c$. Daher ist $f$ linear und genügt dem Ansatz $f(x)=c x+b$ mit $b=f(0)$. Dies in (2) eingesetzt liefert $c x+c+b=c^{2} x+c b+b$ für alle $x \in \mathbb{Z}$. Für $x=0$ und $x=1$ erhalten wir $c+b=c b+b$ sowie $c^{2}=c$; daraus folgt $c=0$ oder $c=1$. Aus $c=1$ folgt $b=1$ und wir erhalten $f_{2}$; aus $c=0$ folgt, dass $f$ konstant ist, und mit (1) ergibt sich $b=-1$, also $f_{1}$. Damit ist alles gezeigt.

Hinweis: Oft wurden zu Beginn Einschränkungen vorgenommen (z.B. dass $x=f(y)$ ist, also zur Wertemenge gehört), die später „vergessen" wurden. Die Angabe $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ wurde gelegentlich so missverstanden, dass die Wertemenge alle ganzen Zahlen umfasst.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2016-loes_awkl_16.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2016"

}

|

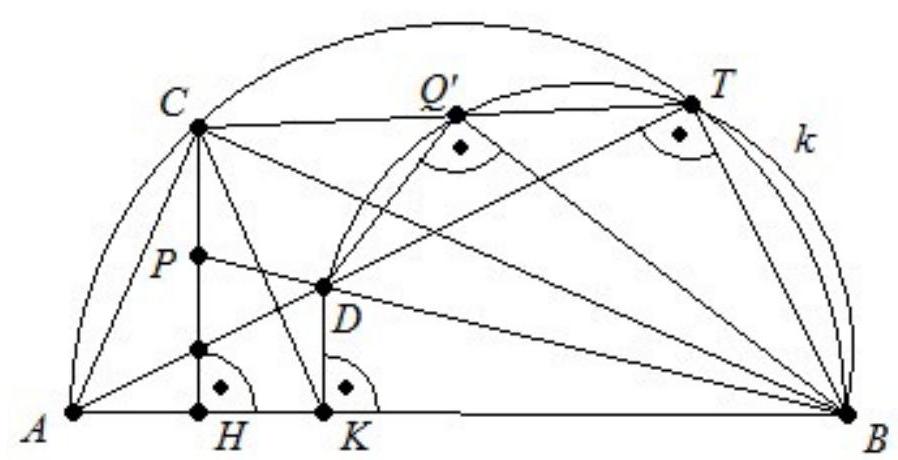

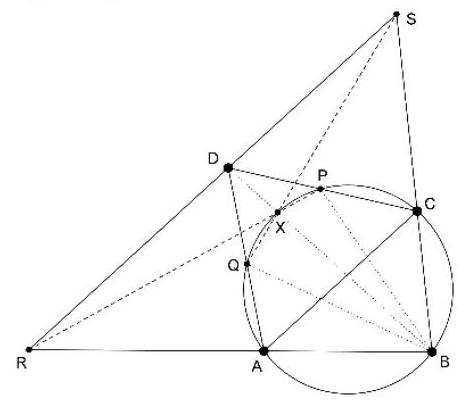

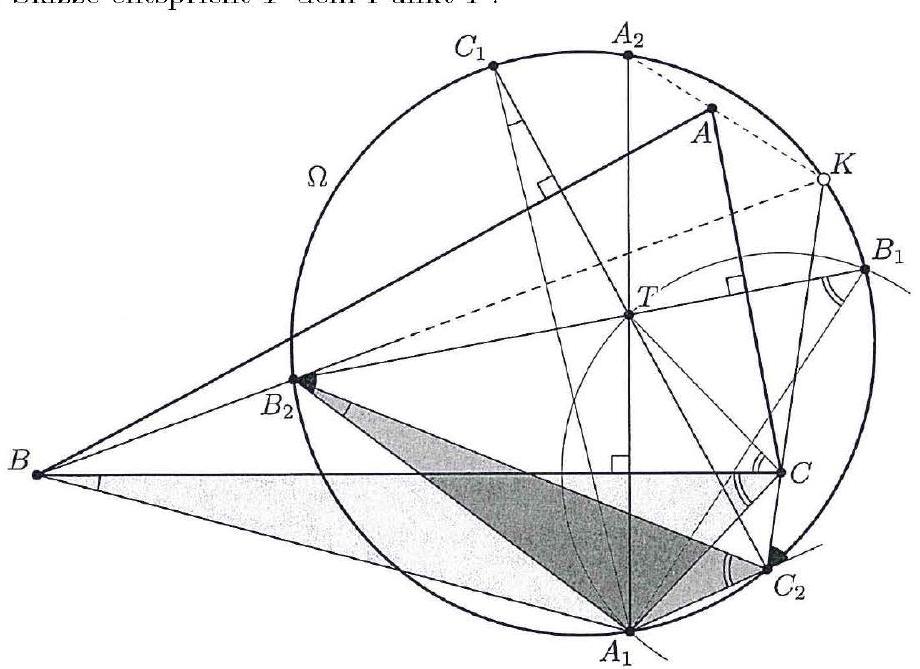

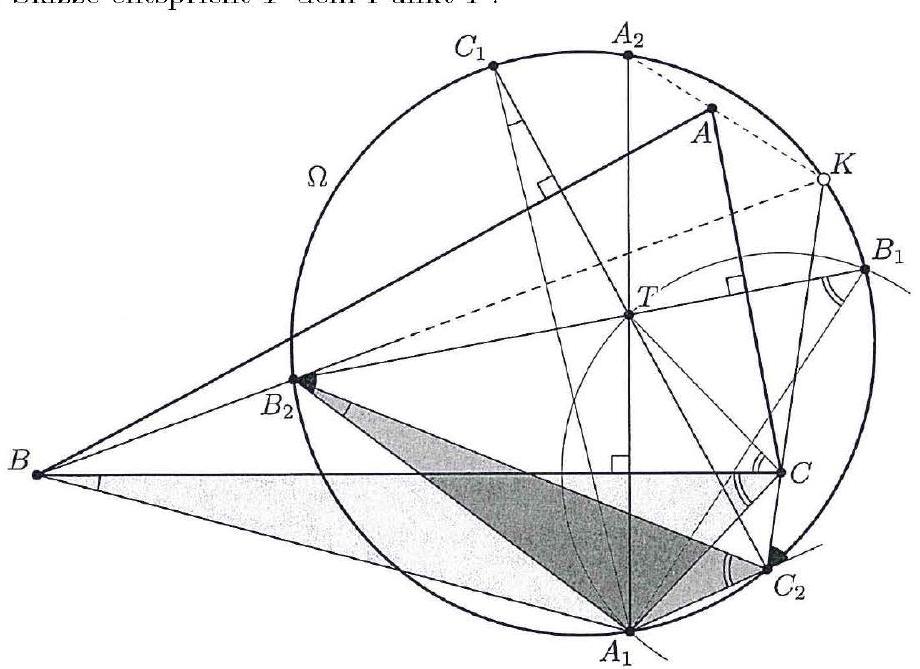

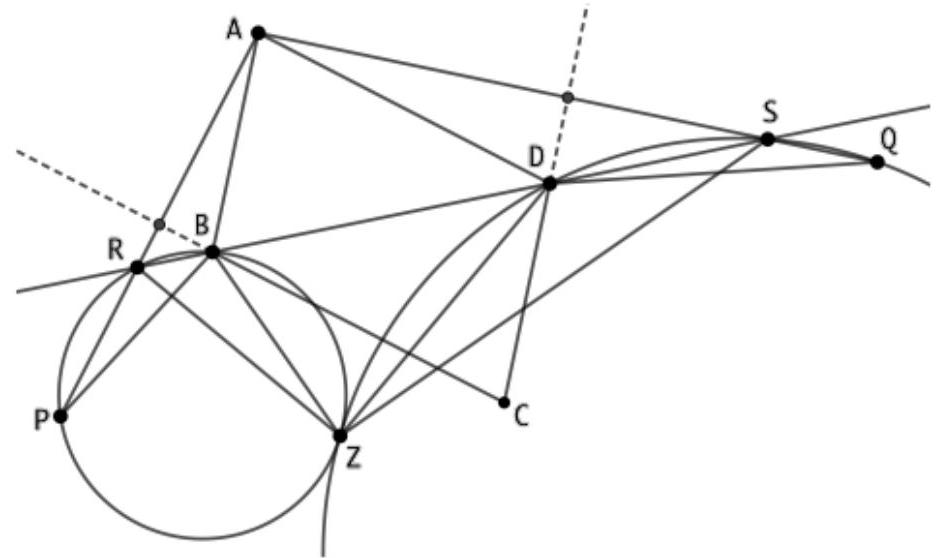

Let $ABC$ be a right triangle with $\varangle ACB = \gamma = 90^{\circ}$. Furthermore, let $H$ be the foot of the altitude from $C$ to $AB$.

Now, we choose a point $D$ inside the triangle $HBC$ such that $CH$ bisects the segment $AD$, and denote the intersection of $CH$ and $BD$ by $P$. We construct the semicircle $k$ with $BD$ as its diameter, which is intersected by $BC$. A line through $P$ is tangent to $k$ at the point $Q$. Prove that the lines $CQ$ and $AD$ always intersect on $k$.

|

Let $K$ be the foot of the perpendicular from $D$ to $AB$ and $T$ the intersection of $AD$ with $k$. Since $\varangle A T B = \varangle A C B = 90^{\circ}$, $T$ also lies on the circumcircle of $ABC$. Because $C H \| D K$, it follows that $|A H| = |H K|$.

To prove that $C, Q$, and $T$ are collinear, we consider the intersection $Q'$ of $CT$ with $k$ and need only show that $P Q' k$ is tangent, or that $\varangle P Q' D = \varangle Q' B D$.

Since $B T Q' D$ is a cyclic quadrilateral and the triangles $A H C$ and $H K C$ are congruent, we have

$\varangle Q' B D = \varangle Q' T D = \varangle C T A = \varangle C B A = \varangle A C H = \varangle H C K$. Therefore, the right triangles $C H K$ and $B Q' D$ are similar, which implies $|H K| / |C K| = |Q' D| / |B D|$, hence $|H K| \cdot |B D| = |C K| \cdot |Q' D|$ (1). Since $P H \| D K$, we have $|P D| / |B D| = |H K| / |B K|$, thus $|P D| \cdot |B K| = |H K| \cdot |B D|$ (2). Comparing (1) and (2) leads to $|P D| \cdot |B K| = |C K| \cdot |Q' D|$ and thus $|P D| / |Q' D| = |C K| / |B K|$. Therefore, and because $\varangle C K A = \varangle K A C = \varangle B D Q'$, the triangles $C K B$ and $P D Q'$ are similar. Hence, $\varangle P Q' D = \varangle C B A = \varangle Q' B D$, which is what we needed to show.

Hint: A pure angle chase does not lead to the goal; however, there are other proof possibilities, such as utilizing a suitable homothety with center $B$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C$ ein rechtwinkliges Dreieck mit $\varangle A C B=\gamma=90^{\circ}$. Ferner sei $H$ der Fußpunkt der Höhe von $C$ auf $A B$.

Nun wählen wir einen Punkt $D$ so im Inneren des Dreiecks $H B C$, dass $C H$ die Strecke $A D$ halbiert, und bezeichnen den Schnittpunkt von $C H$ und $B D$ mit $P$. Über der Strecke $B D$ als Durchmesser errichten wir denjenigen Halbkreis $k$, der von $B C$ geschnitten wird. Eine Gerade durch $P$ berührt $k$ im Punkt $Q$. Man beweise, dass sich die Geraden $C Q$ und $A D$ stets auf $k$ schneiden.

|

Wie in der Figur sei $K$ der Fußpunkt des Lotes von $D$ auf $A B$ und $T$ der Schnittpunkt von $A D$ mit $k$. Wegen $\varangle A T B=\varangle A C B=90^{\circ}$ liegt $T$ auch auf dem Umkreis von $A B C$. Wegen $C H \| D K$ gilt $|A H|=|H K|$.

Um nachzuweisen, dass $C, Q$ und $T$ kollinear sind, betrachten wir den Schnittpunkt $Q^{\prime}$ von $C T$ mit $k$ und müssen nur zeigen, dass $P Q^{\prime} k$ berührt, bzw. dass $\varangle P Q^{\prime} D=\varangle Q^{\prime} B D$ ist.

Weil $B T Q^{\prime} D$ ein Sehnenviereck ist und die Dreiecke $A H C$ und $H K C$ kongruent sind, gilt

$\varangle Q^{\prime} B D=\varangle Q ' T D=\varangle C T A=\varangle C B A=\varangle A C H=\varangle H C K$. Also sind die rechtwinkligen Dreiecke $C H K$ und $B Q^{\prime} D$ ähnlich, woraus $|H K| /|C K|=\left|Q^{\prime} D\right| /|B D|$ folgt, also $|H K| \cdot|B D|=|C K| \cdot\left|Q^{\prime} D\right|$ (1). Wegen $P H \| D K$ gilt $|P D| /|B D|=|H K| /|B K|$, also $|P D| \cdot|B K|=|H K| \cdot|B D|$ (2). Der Vergleich von (1) und (2) führt auf $|P D| \cdot|B K|=|C K| \cdot\left|Q^{\prime} D\right|$ und somit $|P D| /\left|Q^{\prime} D\right|=|C K| /|B K|$. Deswegen und weil $\varangle C K A=\varangle K A C=\varangle B D Q^{\prime}$ ist, sind die Dreiecke $C K B$ und $P D Q^{\prime}$ ähnlich. Daher gilt $\varangle P Q^{\prime} D=\varangle C B A=\varangle Q^{\prime} B D$, was zu zeigen war.

Hinweis: Eine reine Winkeljagd führt nicht zu Ziel; allerdings gibt es andere Beweismöglichkeiten, wie etwa Ausnutzen einer geeigneten Drehstreckung mit Zentrum $B$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2016-loes_awkl_16.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2016"

}

|

Given positive integers $k$ and $n$ with $n>k$. By a binary word of length $n$, we mean a sequence of $n$ elements, each being 0 or 1. Anja selects one of all possible binary words of length $n$. Then she writes down all binary words of length $n$ that differ from her chosen word at exactly $k$ positions on a board. Afterwards, Bernhard enters the room. Anja tells him the value of $k$ and then he examines the binary words on the board. He tries to guess the binary word initially chosen by Anja. What is (in dependence on $k$ and $n$) the minimum number of attempts Bernhard needs to guess the binary word with certainty?

|

The answer is: If $n \neq 2k$, Bernhard can always guess the word chosen by Anja on the first attempt. In the case $n=2k$, he needs two attempts to guess the word with certainty. We denote the word chosen by Anja at the beginning with $u$.

Case 1: $n \neq 2k$. Let $1 \leq i \leq n$ be arbitrary. Of all $\binom{n}{k}$ words on the board, exactly $\binom{n-1}{k}$ agree with $u$ at the $i$-th position, and $\binom{n-1}{k-1}$ differ from $u$ at the $i$-th position. Simple calculation shows that in the case $n \neq 2k$, $\binom{n-1}{k} \neq \binom{n-1}{k-1}$ also holds, meaning Bernhard can deduce the $i$-th position of $u$ by examining the $i$-th positions of all words on the board. Since this works for all $i=1, \ldots, n$, Bernhard can uniquely determine the word $u$ chosen by Anja at the beginning and guess it correctly on the first attempt.

Case 2: $n=2k$. We first show that Bernhard cannot uniquely determine $u$, meaning he might need more than one attempt. Suppose Anja had chosen the (unique) binary word $\bar{u}$ that differs from her actual word $u$ at all positions. An arbitrary binary word of length $n$ agrees with $u$ in exactly $k=n/2$ positions if and only if it agrees with $\bar{u}$ in exactly $k=n/2$ positions. This means that Anja would have written exactly the same binary words on the board. This implies that Bernhard has no way to distinguish between $u$ and $\bar{u}$ and might guess Anja's word incorrectly on his first attempt. We now show that Bernhard can always succeed in two attempts. It suffices to prove that for any binary word $w$ of length $n$ that is different from both $u$ and $\bar{u}$, the set of all binary words of length $n$ that differ from $w$ in exactly $k=n/2$ positions is not identical to the set of words on the board. Without loss of generality, we can assume that $w$ differs from $u$ in exactly $a$ positions, where $0 < a \leq k=n/2$ (otherwise consider $\bar{u}$ instead of $u$). Then we can change exactly $k$ of the remaining $n-a \geq k$ positions and obtain a word $w'$ that differs from $w$ in exactly $k$ positions but differs from $u$ in $a+k > k$ positions, meaning it is not on the board.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Gegeben seien positive ganze Zahlen $k$ und $n$ mit $n>k$. Unter einem Binärwort der Länge $n$ verstehen wir eine Folge aus $n$ Folgengliedern, die alle 0 oder 1 sind. Anja wählt unter allen möglichen Binärwörtern der Länge $n$ eines aus. Dann schreibt sie alle Binärwörter der Länge $n$, die sich von ihrem gewählten Wort an genau $k$ Stellen unterscheiden, an eine Tafel. Anschließend betritt Bernhard den Raum. Anja nennt ihm den Wert von $k$ und danach betrachtet er die Binärwörter an der Tafel. Er versucht nun das zu Beginn von Anja gewählte Binärwort zu erraten. Was ist (in Abhängigkeit von $k$ und $n$ ) die minimale Anzahl an Versuchen, die Bernhard benötigt um das Binärwort mit Sicherheit zu erraten?

|

Die Antwort lautet: Falls $n \neq 2 k$ kann Bernhard das von Anja gewählte Wort stets im ersten Versuch erraten, im Fall $n=2 k$ braucht er zwei Versuche um das Wort mit Sicherheit zu erraten. Wir bezeichnen das von Anja zu Beginn gewählte Wort mit $u$.

Fall 1: $n \neq 2 k$. Es sei $1 \leq i \leq n$ beliebig. Von allen $\binom{n}{k}$ Wörtern an der Tafel stimmen genau $\binom{n-1}{k}$ an der $i$-ten Stelle mit $u$ überein und $\binom{n-1}{k-1}$ sind an der $i$-ten Stelle verschieden von $u$. Einfaches Nachrechnen zeigt, dass im Fall $n \neq 2 k$ auch $\binom{n-1}{k} \neq\binom{ n-1}{k-1}$ gilt, das heißt Bernhard kann durch das Betrachten der $i$-ten Stellen aller Wörter an der Tafel auf die $i$-te Stelle von $u$ schließen. Da dies für alle $i=1, \ldots, n$ funktioniert, kann Bernhard das von Anja zu Beginn gewählte Wort $u$ eindeutig bestimmen und errät es auf diese Weise im ersten Versuch. Fall $2: n=2 k$. Wir zeigen zunächst, dass Bernhard nicht eindeutig auf $u$ schließen kann, also möglicherweise mehr als einen Versuche benötigt. Angenommen, Anja hätte das (eindeutige) Binärwort $\bar{u}$ gewählt, dass sich an allen Stellen von ihrem tatsächlichen Wort $u$ unterscheidet. Ein beliebiges Binärwort der Länge $n$ stimmt genau dann in $k=n / 2$ Stellen mit $u$ überein, wenn es in $k=n / 2$ Stellen mit $\bar{u}$ übereinstimmt, das heißt Anja hätte in diesem Fall exakt die gleichen Binärwörter an die Tafel geschrieben. Dies bedeutet, dass Bernhard keine Möglichkeit hat zwischen $u$ und $\bar{u}$ zu unterscheiden und in seinem ersten Versuch Anjas Wort zu raten möglicherweise falsch liegt. Wir zeigen nun, dass Bernhard in zwei Versuchen stets Erfolg haben kann. Dazu genügt es zu beweisen, dass für jedes von $u$ und $\bar{u}$ verschiedene Binärwort $w$ der Länge $n$ die Menge aller Binärwörter der Länge $n$, die sich an genau $k=n / 2$ Stellen von $w$ unterscheiden, nicht identisch mit der Menge der Wörter an der Tafel ist. Dazu dürfen wir ohne Beschränkung der Allgemeinheit annehmen dass sich $w$ von $u$ an genau $a$ Stellen unterscheidet, wobei $0<a \leq k=n / 2$ (sonst betrachte $\bar{u}$ statt $u$ ). Dann können wir genau $k$ der übrigen $n-a \geq k$ Stellen abändern und erhalten ein Wort $w^{\prime}$, das sich an genau $k$ Stellen von $w$ unterscheidet, aber an $a+k>k$ Stellen von $u$, das heißt es steht nicht an der Tafel.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "1. Aufgabe.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Let $ABCD$ be a convex quadrilateral. The diagonal $BD$ bisects the angle $\measuredangle CBA$. The circumcircle of triangle $ABC$ intersects the segments $\overline{CD}$ and $\overline{DA}$ at the interior points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. The line through point $D$ parallel to the line $AC$ intersects the lines $BA$ and $BC$ at the points $R$ and $S$, respectively. Prove that the four points $P, Q, R$, and $S$ lie on a common circle.

|

Step 1: Since $\measuredangle B R D = \measuredangle B A C = \measuredangle B P C = \pi - \measuredangle D P B$, $B P D R$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Similarly, it can be shown that $B S D Q$ is also a cyclic quadrilateral. Step 2: Let $X$ be defined as the intersection of $B D$ with the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Then, $\measuredangle D P X = \pi - \measuredangle X P C = \measuredangle C B X = 1 / 2 \measuredangle C B A$. Since from Step 1, $\measuredangle D P R = \measuredangle D B R = 1 / 2 \measuredangle D B A$ also holds, $X$ lies on $P R$. Similarly, it can be shown that $X$ also lies on $Q S$. Step 3: We combine these insights and calculate (using the chord theorem) $|P X| \cdot |X R| = |B X| \cdot |X D| = |Q X| \cdot |X S|$. Using the converse of the chord theorem, the claim follows.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C D$ ein konvexes Viereck. Die Diagonale $B D$ halbiere den Winkel $\measuredangle C B A$. Der Umkreis des Dreiecks $A B C$ schneide die Strecken $\overline{C D}$ und $\overline{D A}$ in den inneren Punkten $P$ bzw. $Q$. Die durch den Punkt $D$ verlaufende Parallele zur Geraden $A C$ schneide die Geraden $B A$ und $B C$ in den Punkten $R$ bzw. $S$. Man beweise, dass die vier Punkte $P, Q, R$ und $S$ auf einem gemeinsamen Kreis liegen.

|

Schritt 1: Wegen $\measuredangle B R D=\measuredangle B A C=\measuredangle B P C=\pi-\measuredangle D P B$ ist $B P D R$ ein Sehnenviereck. Analog zeigt man, dass auch $B S D Q$ ein Sehnenviereck ist. Schritt 2: Es sei $X$ definiert als der Schnittpunkt von $B D$ mit dem Umkreis des Dreiecks $A B C$. Dann gilt $\measuredangle D P X=\pi-\measuredangle X P C=\measuredangle C B X=1 / 2 \measuredangle C B A$. Da nach Schritt 1 auch $\measuredangle D P R=\measuredangle D B R=1 / 2 \measuredangle D B A$ gilt, liegt $X$ auf $P R$. Analog zeigt man, dass $X$ auch auf $Q S$ liegt. Schritt 3: Wir kombinieren die Erkenntnisse und rechnen (mithilfe des Sehnensatzes) $|P X| \cdot|X R|=|B X| \cdot|X D|=|Q X| \cdot|X S|$. Mit der Umkehrung des Sehnensatzes folgt nun die Behauptung.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "2. Aufgabe.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Die Menge der positiven ganzen Zahlen sei mit $\mathbb{N}$ bezeichnet. Man bestimme alle Funktionen $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}$ mit der folgenden Eigenschaft: Für alle positiven ganzen Zahlen $m$ und $n$ ist die Zahl $f(m)+f(n)-m n$ von 0 verschieden und ist ein Teiler der Zahl $m f(m)+n f(n)$.

|

Antwort: Es gibt genau eine Funktion, die die beschriebene Bedingung erfüllt, nämlich $f(k)=k^{2}$ für alle $k$. Zum Beweis sei $f$ wie verlangt. Schritt 1: Einsetzen von $m=n=1$ liefert $2 f(1)-1 \mid 2 f(1)$, also auch $2 f(1)-1 \mid 2 f(1)-(2 f(1)-1)=1$ und damit $2 f(1)-1=1$, also $f(1)=1$. Schritt 2: Von nun an stehe $p$ stets für eine Primzahl mit $p \geq 7$. Einsetzen von $m=n=p$ liefert $2 f(p)-p^{2} \mid 2 p f(p)$ und damit auch $2 f(p)-p^{2} \mid 2 p f(p)-p\left(2 f(p)-p^{2}\right)=p^{3}$, also

$$

2 f(p)-p^{2} \in\left\{-p^{3},-p^{2},-p,-1,1, p, p^{2}, p^{3}\right\}

$$

Da $f(p)>0$ folgt

$$

f(p) \in\left\{\frac{p^{2}-p}{2}, \frac{p^{2}-1}{2}, \frac{p^{2}+1}{2}, \frac{p^{2}+p}{2}, p^{2}, \frac{p^{3}+p^{2}}{2}\right\} .

$$

Schritt 3: Wir setzen $m=1, n=p$ und erhalten $f(p)+1-p \mid p f(p)+1$, also auch $f(p)+1-p \mid p f(p)+1-p(f(p)+1-p)=p^{2}-p+1$. Angenommen, es gilt $f(p) \neq p^{2}$. Dann folgt (beachte, dass $p^{2}-p+1$ ungerade ist) notwendigerweise $f(p)+1-p \leq 1 / 3\left(p^{2}-p+1\right)$. Nach Schritt 2 gilt jedoch $f(p) \geq\left(p^{2}-p\right) / 2$, es folgt also

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{p^{2}-p}{2}+1-p & \leq \frac{p^{2}-p+1}{3} \\

3 p^{2}-3 p+6-6 p & \leq 2 p^{2}-2 p+1 \\

p^{2}+5 & \leq 7 p

\end{aligned}

$$

was für $p \geq 7$ nicht der Fall ist. Also war die obige Annahme falsch und es muss $f(p)=p^{2}$ gelten. Schritt 4: Es sei $n \in \mathbb{N}$ beliebig. Wir setzen $m=p$ und erhalten $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid$ $p^{3}+n f(n)$, also auch $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid p^{3}+n f(n)-n\left(f(n)-p^{2}-p n\right)=p\left(p^{2}-p n+n^{2}\right)$. Für alle hinreichend großen Primzahlen $p$ ist $f(n)$ und damit auch die linke Seite des letzten Ausdrucks nicht durch $p$ teilbar, daher folgt $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid p^{2}-p n+n^{2}$ und somit auch $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid\left(f(n)+p^{2}-p n\right)-\left(p^{2}-p n+n^{2}\right)=f(n)-n^{2}$. Da die linke Seite beliebig groß werden kann (es gibt unendlich viele Primzahlen) folgt $f(n)-n^{2}=0$ und damit $f(n)=n^{2}$. Schritt 5: Die Probe bestätigt dass $f(k)=k^{2}$ für alle $k \in \mathbb{N}$ tatsächlich die Bedingung erfüllt: Es gilt $f(m)+f(n)-m n=m^{2}+n^{2}-m n \geq 2 m n-m n=m n>0$, und außerdem gilt $\left(m^{2}+n^{2}-m n\right)(m+n)=m^{3}+n^{3}=m f(m)+n f(n)$, das heißt $f(m)+f(n)-m n$ ist von 0 verschieden und ist ein Teiler der Zahl $m f(m)+n f(n)$.

|

f(k)=k^{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Die Menge der positiven ganzen Zahlen sei mit $\mathbb{N}$ bezeichnet. Man bestimme alle Funktionen $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}$ mit der folgenden Eigenschaft: Für alle positiven ganzen Zahlen $m$ und $n$ ist die Zahl $f(m)+f(n)-m n$ von 0 verschieden und ist ein Teiler der Zahl $m f(m)+n f(n)$.

|

Antwort: Es gibt genau eine Funktion, die die beschriebene Bedingung erfüllt, nämlich $f(k)=k^{2}$ für alle $k$. Zum Beweis sei $f$ wie verlangt. Schritt 1: Einsetzen von $m=n=1$ liefert $2 f(1)-1 \mid 2 f(1)$, also auch $2 f(1)-1 \mid 2 f(1)-(2 f(1)-1)=1$ und damit $2 f(1)-1=1$, also $f(1)=1$. Schritt 2: Von nun an stehe $p$ stets für eine Primzahl mit $p \geq 7$. Einsetzen von $m=n=p$ liefert $2 f(p)-p^{2} \mid 2 p f(p)$ und damit auch $2 f(p)-p^{2} \mid 2 p f(p)-p\left(2 f(p)-p^{2}\right)=p^{3}$, also

$$

2 f(p)-p^{2} \in\left\{-p^{3},-p^{2},-p,-1,1, p, p^{2}, p^{3}\right\}

$$

Da $f(p)>0$ folgt

$$

f(p) \in\left\{\frac{p^{2}-p}{2}, \frac{p^{2}-1}{2}, \frac{p^{2}+1}{2}, \frac{p^{2}+p}{2}, p^{2}, \frac{p^{3}+p^{2}}{2}\right\} .

$$

Schritt 3: Wir setzen $m=1, n=p$ und erhalten $f(p)+1-p \mid p f(p)+1$, also auch $f(p)+1-p \mid p f(p)+1-p(f(p)+1-p)=p^{2}-p+1$. Angenommen, es gilt $f(p) \neq p^{2}$. Dann folgt (beachte, dass $p^{2}-p+1$ ungerade ist) notwendigerweise $f(p)+1-p \leq 1 / 3\left(p^{2}-p+1\right)$. Nach Schritt 2 gilt jedoch $f(p) \geq\left(p^{2}-p\right) / 2$, es folgt also

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{p^{2}-p}{2}+1-p & \leq \frac{p^{2}-p+1}{3} \\

3 p^{2}-3 p+6-6 p & \leq 2 p^{2}-2 p+1 \\

p^{2}+5 & \leq 7 p

\end{aligned}

$$

was für $p \geq 7$ nicht der Fall ist. Also war die obige Annahme falsch und es muss $f(p)=p^{2}$ gelten. Schritt 4: Es sei $n \in \mathbb{N}$ beliebig. Wir setzen $m=p$ und erhalten $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid$ $p^{3}+n f(n)$, also auch $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid p^{3}+n f(n)-n\left(f(n)-p^{2}-p n\right)=p\left(p^{2}-p n+n^{2}\right)$. Für alle hinreichend großen Primzahlen $p$ ist $f(n)$ und damit auch die linke Seite des letzten Ausdrucks nicht durch $p$ teilbar, daher folgt $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid p^{2}-p n+n^{2}$ und somit auch $f(n)+p^{2}-p n \mid\left(f(n)+p^{2}-p n\right)-\left(p^{2}-p n+n^{2}\right)=f(n)-n^{2}$. Da die linke Seite beliebig groß werden kann (es gibt unendlich viele Primzahlen) folgt $f(n)-n^{2}=0$ und damit $f(n)=n^{2}$. Schritt 5: Die Probe bestätigt dass $f(k)=k^{2}$ für alle $k \in \mathbb{N}$ tatsächlich die Bedingung erfüllt: Es gilt $f(m)+f(n)-m n=m^{2}+n^{2}-m n \geq 2 m n-m n=m n>0$, und außerdem gilt $\left(m^{2}+n^{2}-m n\right)(m+n)=m^{3}+n^{3}=m f(m)+n f(n)$, das heißt $f(m)+f(n)-m n$ ist von 0 verschieden und ist ein Teiler der Zahl $m f(m)+n f(n)$.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "3. Aufgabe.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Determine the smallest real constant $C$ with the following property:

For any five arbitrary positive real numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, a_{5}$, which do not necessarily have to be distinct, there always exist pairwise different indices $i, j, k, l$ such that

$\left|\frac{a_{i}}{a_{j}}-\frac{a_{k}}{a_{l}}\right| \leq C$ holds.

|

The desired value is $C=\frac{1}{2}$.

First, we prove that $C \leq \frac{1}{2}$. To do this, we assume without loss of generality (oBdA) that $a_{1} \leq a_{2} \leq a_{3} \leq a_{4} \leq a_{5}$ and consider the five fractions $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}, \frac{a_{3}}{a_{4}}, \frac{a_{1}}{a_{5}}, \frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}, \frac{a_{4}}{a_{5}}$. By the pigeonhole principle, at least three of these fractions lie in one of the intervals ]0, $\frac{1}{2}$ ] or $\left.] \frac{1}{2}, 1\right]$. Among these, two fractions are consecutive in the list or the first and the last fraction are included. In any case, the positive difference between these two fractions is less than $\frac{1}{2}$, and the four involved indices are pairwise distinct.

Now we show that $C \geq \frac{1}{2}$. For this, consider the example 1, 2, 2, 2, $r$, where $r$ is a very large number. With these numbers, we can form the fractions $\frac{1}{r}, \frac{2}{r}, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{2}{2}, \frac{2}{1}, \frac{r}{2}, \frac{r}{1}$, ordered by size. According to the problem statement, $\frac{1}{r}$ and $\frac{2}{r}$ cannot both be chosen. Therefore, the smallest positive difference is $\frac{1}{2}-\frac{2}{r}$, which approaches the value $\frac{1}{2}$ from below as $r \rightarrow \infty$. $\square$

|

\frac{1}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Man bestimme die kleinste reelle Konstante $C$ mit folgender Eigenschaft:

Für fünf beliebige positive reelle Zahlen $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, a_{5}$, die nicht unbedingt verschieden sein müssen, lassen sich stets paarweise verschiedene Indizes $i, j, k, l$ finden, so dass

$\left|\frac{a_{i}}{a_{j}}-\frac{a_{k}}{a_{l}}\right| \leq C$ gilt.

|

Der gesuchte Wert ist $C=\frac{1}{2}$.

Zunächst beweisen wir, dass $C \leq \frac{1}{2}$ gilt. Dazu nehmen wir oBdA $a_{1} \leq a_{2} \leq a_{3} \leq a_{4} \leq a_{5}$ an und betrachten die fünf Brüche $\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}, \frac{a_{3}}{a_{4}}, \frac{a_{1}}{a_{5}}, \frac{a_{2}}{a_{3}}, \frac{a_{4}}{a_{5}}$. Nach dem Schubfachprinzip liegen in einem der Intervalle ]0, $\frac{1}{2}$ ] bzw. $\left.] \frac{1}{2}, 1\right]$ drei verschiedene dieser Brüche, wobei zwei von diesen in der Aufzählung direkt aufeinanderfolgen oder der erste und der letzte Bruch dabei sind. Jedenfalls ist die positive Differenz dieser beiden Brüche kleiner als $\frac{1}{2}$ und die vier beteiligten Indizes sind paarweise verschieden.

Nun zeigen wir, dass $C \geq \frac{1}{2}$ gilt. Dazu betrachten das Beispiel 1, 2, 2, 2 , $r$, wobei $r$ eine Riesenzahl sein soll. Mit diesen Zahlen lassen sich - der Größe nach geordnet - die Brüche $\frac{1}{r}, \frac{2}{r}, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{2}{2}, \frac{2}{1}, \frac{r}{2}, \frac{r}{1}$ bilden, wobei nach der Aufgabenstellung $\frac{1}{r}$ und $\frac{2}{r}$ nicht gleichzeitig gewählt werden dürfen. Daher ist die kleinste positive Differenz gleich $\frac{1}{2}-\frac{2}{r}$, und dies nähert sich für $r \rightarrow \infty$ dem Wert $\frac{1}{2}$ von unten beliebig gut an. $\square$

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer that is coprime to 6. We color the vertices of a regular $n$-gon with three colors such that for each color, the number of vertices colored with it is odd.

Prove that there always exists an isosceles triangle whose vertices belong to the vertices of the $n$-gon and are all colored differently.

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}$ be the numbers of isosceles triangles whose vertices contain exactly 1, 2, and 3 colors, respectively. We assume that $a_{3}=0$. The colors are red, green, and blue, where $r, g$, and $b$ denote the (odd) number of vertices colored with each respective color. We now determine the number $a$ of pairs $(\Delta, v)$, where $\Delta$ is an isosceles triangle with more than one vertex color and $v$ is a side of this triangle whose endpoints are colored differently, in two ways.

Due to $a_{3}=0$, the vertices of such a triangle must be colored with exactly two colors, one of which belongs to two vertices that are endpoints of a side $v$. Thus, each triangle contributes two pairs, and it follows that $a=2 a_{2}$.

For any two vertices $A$ and $B$, there are exactly three different vertices $C$ that form an isosceles triangle with $A$ and $B$: either $A B=A C$ or $A B=B C$ or $A C=B C$. None of these possibilities can coincide, otherwise $A B C$ would be equilateral and $n$ would be divisible by 3. $A C=B C$ exists because $n$ is odd, and thus the perpendicular bisector of $A B$ passes through exactly one other vertex. Therefore, starting from two differently colored vertices $A$ and $B$, we have $a=3(r g+g b+b r)$. This term is odd by assumption, in contradiction to $a=2 a_{2}$. Hence, $a_{3} \neq 0$ must hold.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Es sei $n$ eine positive ganze Zahl, die teilerfremd zu 6 ist. Wir färben die Ecken eines regulären $n$-Ecks so mit drei Farben, dass für jede Farbe die Anzahl der mit ihr gefärbten Ecken ungerade ist.

Man beweise, dass es dann stets ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck gibt, dessen Ecken zu den Ecken des $n$ Ecks gehören und alle verschieden gefärbt sind.

|

Es seien $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}$ die Anzahlen der gleichschenkligen Dreiecke, in deren Eckpunkten genau 1, 2 bzw. 3 Farben vorkommen. Wir nehmen an, dass $a_{3}=0$ gelte. Die Farben seien rot, grün und blau, wobei $r, g$ und $b$ die (ungerade) Anzahl der jeweils so gefärbten Ecken bezeichnet. Wir bestimmen nun auf zwei Arten die Anzahl $a$ der Paare ( $\Delta, v$ ), wobei $\Delta$ ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck mit mehr als einer Eckenfarbe und $v$ eine Seitenkante dieses Dreiecks ist, deren Endpunkte mit verschiedenen Farben belegt sind.

Wegen $a_{3}=0$ müssen die Eckpunkte eines solchen Dreiecks mit genau zwei Farben belegt sein, von denen eine zu zwei Ecken gehört, die jeweils Endpunkte einer Seitenkante $v$ sind. Also trägt jedes Dreieck zwei Paare bei und es ist $a=2 a_{2}$.

Zu je zwei Eckpunkten $A$ und $B$ gibt genau drei verschiedene Eckpunkte $C$, die mit $A$ und $B$ ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck bilden: entweder ist $A B=A C$ oder $A B=B C$ oder $A C=B C$. Dabei können keine dieser Möglichkeiten zusammenfallen, weil sonst $A B C$ gleichseitig und $n$ durch 3 teilbar wäre. $A C=B C$ existiert, weil $n$ ungerade ist und daher die Mittelsenkrechte von $A B$ durch genau einen weiteren Eckpunkt verläuft. Daher gilt, ausgehend von zwei verschieden gefärbten Eckpunkten $A$ und $B$, dass $a=3(r g+g b+b r)$ ist. Dieser Term ist nach Voraussetzung ungerade, im Widerspruch zu $a=2 a_{2}$. Daher muss $a_{3} \neq 0$ gelten.

[^0]

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

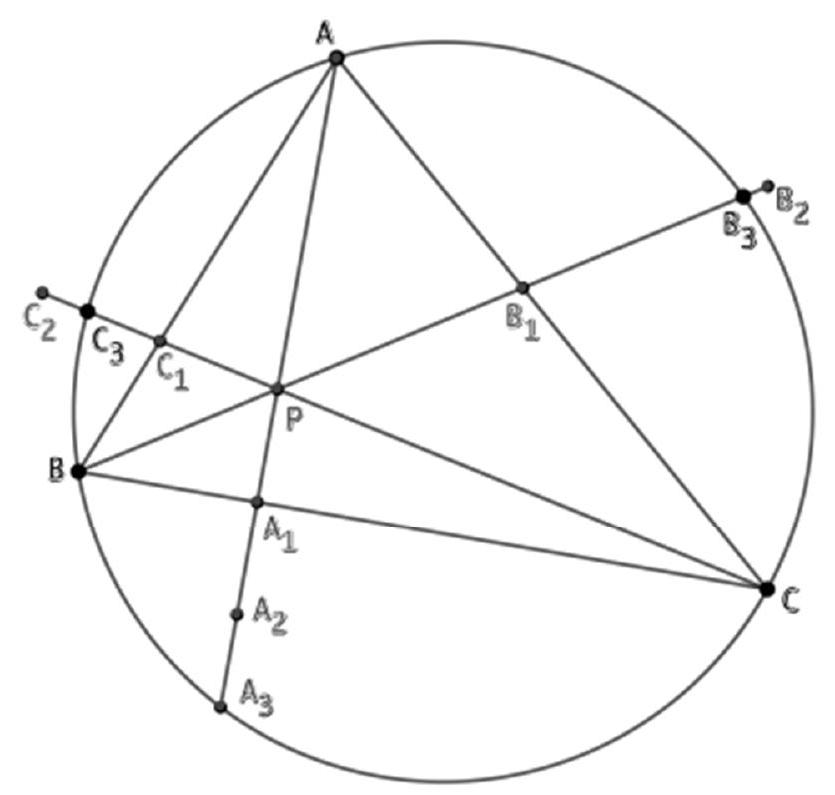

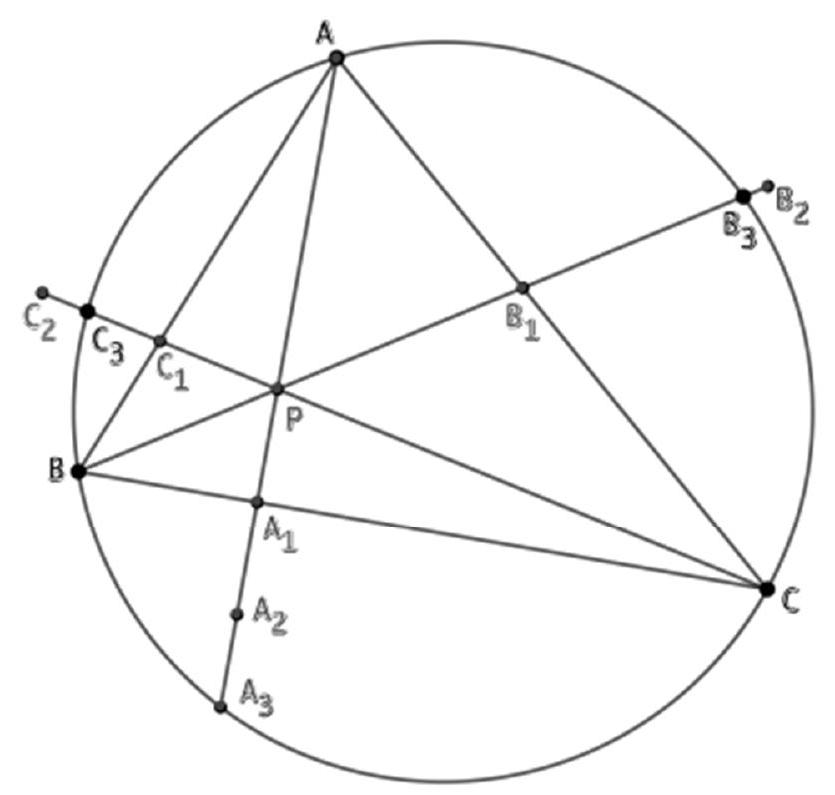

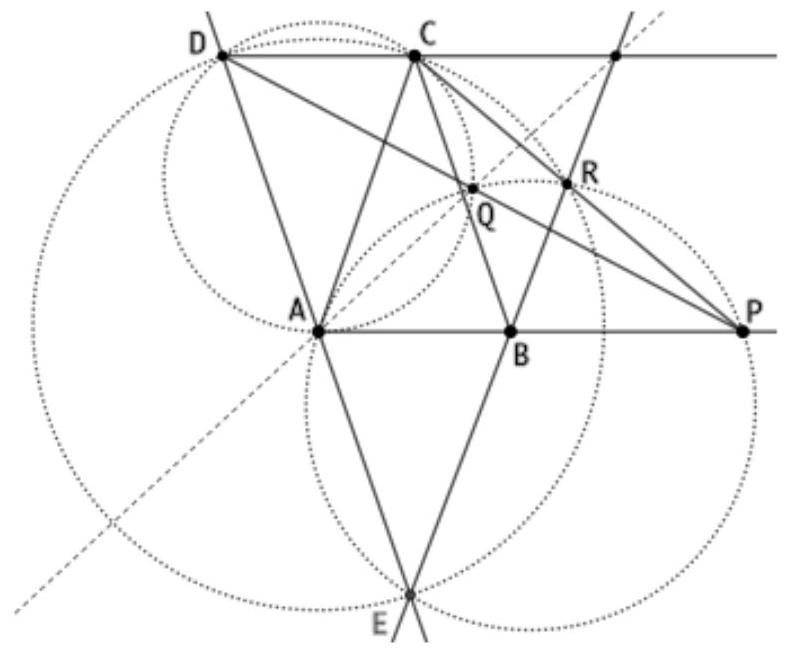

Let $ABC$ be a triangle with $AB = AC \neq BC$. Furthermore, let $I$ be the incenter of $ABC$.

The line $BI$ intersects $AC$ at point $D$, and the perpendicular to $AC$ through $D$ intersects $AI$ at point $E$. Prove that the reflection of $I$ over the line $AC$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $BDE$.

|

First, we prove the following lemma (already using the appropriate notation for the problem): The perpendicular bisector of a side $B I I^{\prime}$ and the angle bisector through the third vertex $D$ intersect on the circumcircle of any non-isosceles triangle $B I^{\prime} D$. ("South Pole Theorem") Proof of the lemma: Let $M$ be the center of the circumcircle of $B I^{\prime} D$ and $S$ the intersection point of the angle bisector with the circumcircle, different from $D$. Then $\angle B M I I^{\prime}$, as a central angle, is twice as large as $\angle B D I^{\prime}$, and $\angle S D I^{\prime}$ is half as large as $\angle B D I^{\prime}$. Since the perpendicular bisector of $B I^{\prime}$ bisects both arcs of the circumcircle corresponding to this chord, it must pass through $S$.

Corollary: Let the other intersection point of the perpendicular bisector of $B I^{\prime}$ with the circumcircle be $E$. Then, according to the lemma, $D$ lies on the Thales circle over $E S$, and $\angle E D S = 90^{\circ}$. Therefore, $D E$ is the external angle bisector of $\angle B D I^{\prime}$. The converse also holds: If for a point $E$ on the external angle bisector of $\angle B D I^{\prime}$, $B E = E I^{\prime}$ also holds, then $E$ lies on the circumcircle of $B I^{\prime} D$.

For the main proof, we denote the reflection point of $I$ as $I^{\prime}$ and the second intersection point of $A I$ with the circumcircle of triangle $A B D$ as $D^{\prime}$. Since $A D^{\prime}$ is the angle bisector of $\angle B A D$, $D^{\prime}$ is the midpoint of the arc $B D$, and thus $D D^{\prime} = B D^{\prime} = C D^{\prime}$.

Using the inscribed angle theorem for the chord $A D$ and appropriate angle bisectors, we get $\angle D D^{\prime} E = \angle D D^{\prime} A = \angle D B A = \angle C B I = \angle I C B$. Since $D^{\prime}$, due to the equal distances, is the circumcenter of triangle $B C D$, we have $\angle E D D^{\prime} = 90^{\circ} - \angle D^{\prime} D C = \angle C B D = \angle C B I$, and thus the triangles $E D^{\prime} D$ and $I B C$ are similar. This implies $\frac{B C}{C I} = \frac{B C}{C I} = \frac{D D^{\prime}}{D^{\prime} E} = \frac{B D^{\prime}}{D^{\prime} E}$.

Furthermore, $\angle I^{\prime} C B = \angle A C B + \angle I^{\prime} C A = \angle A C B + \angle A C I = \angle A C B + \angle C B D = \angle B D A = \angle B D^{\prime} E$, and therefore the triangles $B C I^{\prime}$ and $B D^{\prime} E$ are similar, as are $B C D^{\prime}$ and $B I^{\prime} E$, because the rotation-dilation centered at $B$ that maps $B C I^{\prime}$ to $B D^{\prime} E$ also maps $C D^{\prime}$ to $I^{\prime} E$.

Since $B C D^{\prime}$ is isosceles, $B E = E I^{\prime}$ also holds.

Now, $D E \perp A C$, and by the corollary, $E$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $B I^{\prime} D$.

Note: There are many other solution approaches to this problem, but none of them can be solved with simple angle chasing. All analytical solution attempts failed due to the increasingly complex terms. In the sketch, $M I^{\prime}$ and $D S$ intersect at $C$; this is indeed always the case.

[^0]: Note: Many solution approaches using a procedure to color new points appropriately contained gaps because loops or multiple assignments were not fully investigated.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C$ ein Dreieck mit $A B=A C \neq B C$. Ferner sei $I$ der Inkreismittelpunkt von $A B C$.

Die Gerade $B I$ schneidet $A C$ im Punkt $D$, und die Orthogonale zu $A C$ durch $D$ schneidet $A I$ im Punkt $E$. Man beweise, dass der Spiegelpunkt von $I$ bei Spiegelung an der Achse $A C$ auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks BDE liegt.

|

Zunächst beweisen wir (schon mit den zur Aufgabe passenden Bezeichnungen) folgendes Lemma: Die Mittelsenkrechte einer Seite $B I I^{\prime}$ und die Winkelhalbierende durch den dritten Eckpunkt $D$ schneiden sich auf dem Umkreis jedes nicht gleichschenkligen Dreiecks $B I^{\prime} D$. („Südpolsatz") Beweis des Lemmas: Es sei $M$ der Mittelpunkt des Umkreises von $B I^{\prime} D$ und $S$ der von $D$ verschiedene Schnittpunkt der Winkelhalbierenden mit dem Umkreis. Dann ist $\square B M I I^{\prime}$ als Mittelpunktswinkel doppelt so groß wie $\square B D I^{\prime}$ und $\square S D I^{\prime}$ halb so groß wie $\square B D I^{\prime}$. Da aber die Mittelsenkrechte von $B I^{\prime}$ beide Bögen des Umkreises zu dieser Sehne halbiert, muss sie durch $S$ gehen.

Korollar: Der andere Schnittpunkt der Mittelsenkrechten von $B I$ ' mit dem Umkreis sei $E$. Dann liegt nach dem Lemma $D$ auf dem Thaleskreis über $E S$ und es ist $\square E D S=90^{\circ}$ Somit ist $D E$ die äußere Winkelhalbierende von $\square B D I^{\prime}$. Die Umkehrung gilt ebenfalls: Wenn für den Punkt $E$ auf der äußeren Winkelhalbierenden von $\square B D I^{\prime}$ auch $B E=E I '$ gilt, dann liegt $E$ auf dem Umkreis von $B I^{\prime} D$.

Für den Hauptbeweis bezeichnen wir den Spiegelpunkt von $I$ mit $I^{\prime}$ und den zweiten Schnittpunkt von $A I$ und dem Umkreis des Dreiecks $A B D$ mit $D^{\prime}$. Weil $A D^{\prime}$ die Winkelhalbierende von $\square B A D$ ist, liegt $D^{\prime}$ in der Mitte des Bogens $B D$ und so gilt $D D^{\prime}=B D^{\prime}=C D^{\prime}$.

Unter Verwendung des Umfangswinkelsatzes über der Sehne $A D$ sowie geeigneter Winkelhalbierender erhalten wir $\square D D^{\prime} E=\square D D^{\prime} A=\square D B A=\square C B I=\square I C B$. Weil $D^{\prime}$ wegen der gleichen Abstände der Umkreismittelpunkt des Dreiecks $B C D$ ist, gilt $\square E D D^{\prime}=90^{\circ}-\square D^{\prime} D C=\square C B D=\square C B I$, also sind wegen $\square C B I=\square I C B$ die Dreiecke $E D^{\prime} D$ und $I B C$ ähnlich. Daraus folgt $\frac{B C}{C I}=\frac{B C}{C I}=\frac{D D^{\prime}}{D^{\prime} E}=\frac{B D^{\prime}}{D^{\prime} E}$.

Außerdem gilt $\square I^{\prime} C B=\square A C B+\square I^{\prime} C A=\square A C B+\square A C I=\square A C B+\square C B D=\square B D A=\square B D^{\prime} E$, und daher sind die Dreiecke $B C I^{\prime}$ und $B D^{\prime} E$ ähnlich, ebenso sind $B C D^{\prime}$ und $B I^{\prime} E$ ähnliche Dreiecke, denn bei der Drehstreckung um $B$, die $B C I^{\prime}$ in $B D^{\prime} E$ überführt, geht $C D^{\prime}$ in $I^{\prime} E$ über.

Weil aber $B C D^{\prime}$ gleichschenklig ist, gilt auch $B E=E I^{\prime}$.

Nun ist $D E \perp A C$, und nach dem Korollar liegt $E$ auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks $B I^{\prime} D$. .

Hinweis: Es gibt viele weitere Lösungswege zu diesem Problem, die jedoch alle nicht mit einer einfachen Winkeljagd auskommen. Sämtliche analytischen Lösungsansätze waren wegen der immer komplexer werdenden Terme zum Scheitern verurteilt. In der Skizze schneiden sich MI* und $D S$ in $C$; dies ist tatsächlich immer so.

[^0]: Hinweis: Viele Lösungsansätze über eine Prozedur, mit der man immer neue Punkte geeignet färbt, enthielten Lücken, weil Schleifen oder Mehrfachbelegungen nicht vollständig untersucht worden sind.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 3",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2017-loes_awkl_17.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2017"

}

|

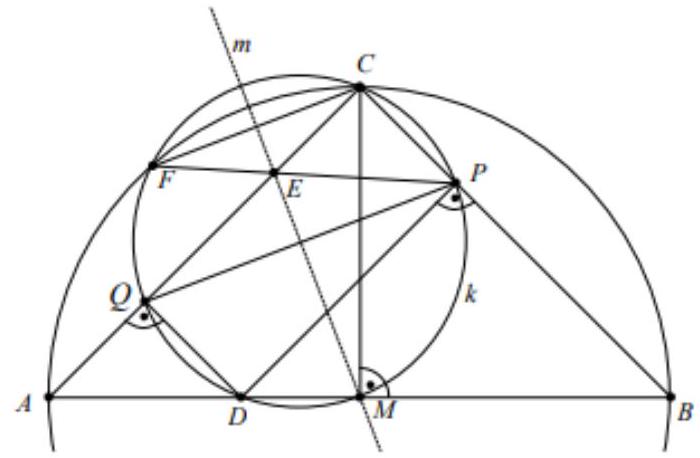

A rectangle $\mathcal{R}$ with odd integer side lengths is divided into rectangles, all of which have integer side lengths. Prove that for at least one of these rectangles, the distances to each of the four sides of $\mathcal{R}$ are all even or all odd.

|

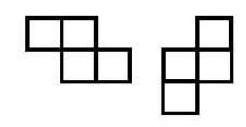

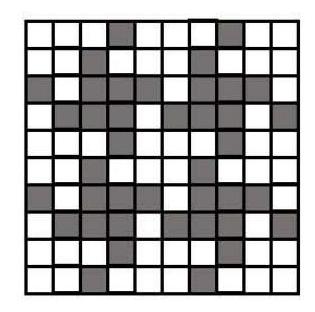

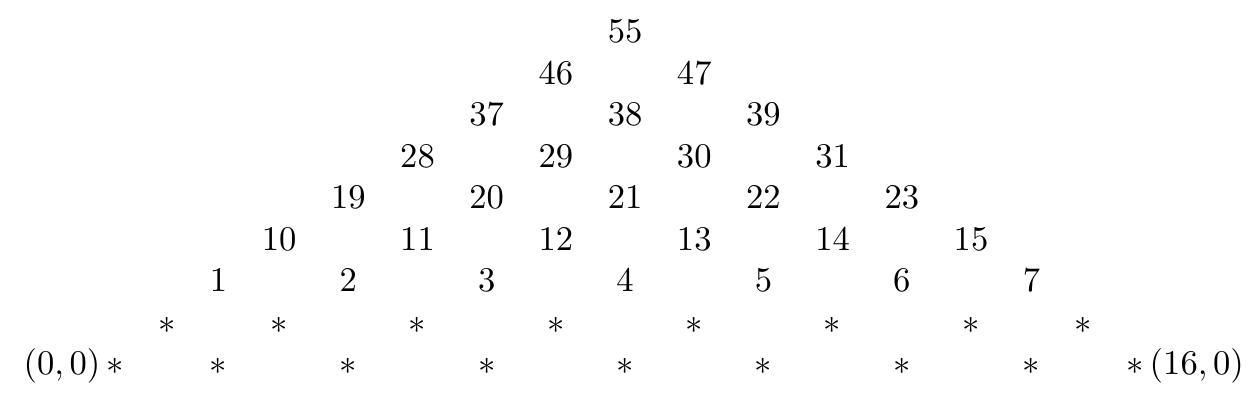

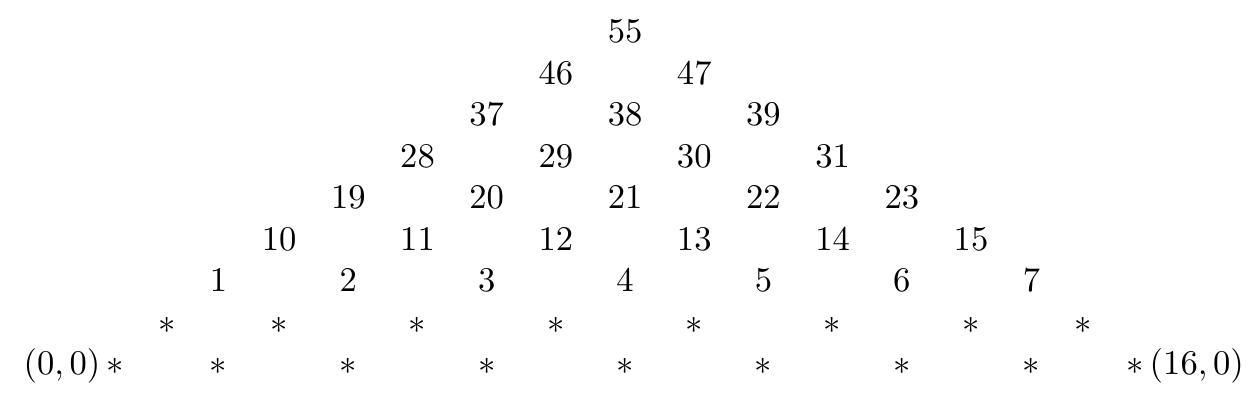

We divide $\mathcal{R}$ into unit squares and color some of these unit squares in red or blue, as shown in the following illustration.

Since $\mathcal{R}$ has odd side lengths by assumption, all four corner squares of $\mathcal{R}$ are colored blue, and there are more colored than uncolored squares in total. Therefore, at least one of the rectangles $\mathcal{R}_{1}, \ldots, \mathcal{R}_{k}$ into which $\mathcal{R}$ is divided must also contain more colored than uncolored squares, let $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ be such a rectangle. Then $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ has odd side lengths and all four corner squares of $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ are colored. This implies that all four corner squares of $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ must have the same color. If they are blue, $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ has even distances to all four sides of $\mathcal{R}$; if they are red, $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ has odd distances to all four sides of $\mathcal{R}$. In either case, $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ satisfies the required condition.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Ein Rechteck $\mathcal{R}$ mit ungeraden ganzzahligen Seitenlängen ist in Rechtecke unterteilt, die alle ganzahlige Seitenlängen haben. Man beweise, dass für mindestens eines dieser Rechtecke die Abstände zu jeder der vier Seiten von $\mathcal{R}$ alle gerade oder alle ungerade sind.

|

Wir unterteilen $\mathcal{R}$ in Einheitsquadrate und färben einige dieser Einheitsquadrate in rot oder blau ein, entsprechend der folgenden Illustration.

Da $\mathcal{R}$ laut Voraussetzung ungerade Seitenlängen hat, sind alle vier Eckfelder von $\mathcal{R}$ blau gefärbt, und es gibt insgesamt mehr gefäbte als ungefärbte Felder. Somit enthält auch mindestens eines der Rechtecke $\mathcal{R}_{1}, \ldots, \mathcal{R}_{k}$, in die $\mathcal{R}$ unterteilt wurde, mehr gefärbte als ungefärbte Felder, sei $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ ein solches. Dann hat $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ ungerade Seitenlängen und alle vier Eckfelder von $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ sind gefärbt. Daraus folgt, dass alle vier Eckfelder von $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ dieselbe Farbe tragen müssen. Falls sie blau sind, hat $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ gerade Abstände zu allen vier Seiten von $\mathcal{R}$; falls sie rot sind hat $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ ungerade Abstände zu allen vier Seiten von $\mathcal{R}$. In jedem Fall erfüllt $\mathcal{R}_{i}$ die geforderte Bedingung.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nAufgabe 1.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2018-loes_awkl_18.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $d$ be a positive integer and $\left(a_{i}\right)_{i=1,2,3, \ldots}$ be a sequence of positive integers. We assume that the following two conditions are satisfied:

- Every positive integer appears exactly once in the sequence.

- For all indices $i \geq 10^{100}$, $\left|a_{i+1}-a_{i}\right| \leq 2 d$.

Prove that there exist infinitely many indices $j$ for which $\left|a_{j}-j\right|<d$.

|

Assume the claim is not satisfied. Then there exists an index $N>10^{100}$ such that for all $i \geq N$ either $a_{i} \leq i-d$ or $a_{i} \geq i+d$ holds. In the first case, because $i \geq N>10^{100}$, according to the second condition on the sequence, we also have

$$

a_{i+1} \leq a_{i}+2 d \leq i-d+2 d=(i+1)+(d-1)

$$

so it must be that $a_{i+1} \leq(i+1)-d$. By induction, it follows that $a_{i} \leq j-d$ for all $j \geq i$.

Thus, we have shown:

(A) Either $a_{i} \geq i+d$ for all $i \geq N$, or

(B) there exists an $M \geq N$ such that $a_{i} \leq i-d$ for all $i \geq M$.

First, assume (A) is satisfied. The numbers $1, \ldots, N$ must, according to the first condition on the sequence, all appear in the sequence. However, $a_{i} \geq i+d > i \geq N$ for all $i \geq N$, meaning there are only the $N-1$ sequence terms $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{N-1}$ that can take on any of these values. By the pigeonhole principle, a contradiction arises.

Now, assume (B) is satisfied. Let $k=\max \left\{M, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M}\right\}$. Then the $k$ sequence terms $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ are all less than $k$, because for $i=1, \ldots M-1$ we have $a_{i} \leq$ $\max \left\{a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M-1}\right\} \leq k$ and for $i=M, \ldots, k$ we have $a_{i} \leq i-d < i \leq k$. These $k$ numbers are thus all in the set $\{1,2, \ldots, k-1\}$. By the pigeonhole principle, there exist two indices $1 \leq i<j \leq k$ such that $a_{i}=a_{j}$, which contradicts the first condition on the sequence.

Since we have obtained a contradiction in each case, the claim holds.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Es sei eine positive ganze Zahl $d$ und eine Folge $\left(a_{i}\right)_{i=1,2,3, \ldots}$ positiver ganzer Zahlen gegeben. Wir nehmen an, dass folgende zwei Bedingungen erfüllt sind:

- Jede positive ganze Zahl taucht genau einmal in der Folge auf.

- Für alle Indizes $i \geq 10^{100}$ gilt $\left|a_{i+1}-a_{i}\right| \leq 2 d$.

Man beweise, dass unendlich viele Indizes $j$ existieren, für die $\left|a_{j}-j\right|<d$ gilt.

|

Angenommen, die Behauptung wäre nicht erfüllt. Dann existiert ein Index $N>10^{100}$, sodass für alle $i \geq N$ entweder $a_{i} \leq i-d$ oder $a_{i} \geq i+d$ gilt. Im ersten Fall gilt wegen $i \geq N>10^{100}$ laut der zweiten Voraussetzung an die Folge auch

$$

a_{i+1} \leq a_{i}+2 d \leq i-d+2 d=(i+1)+(d-1)

$$

es muss also $a_{i+1} \leq(i+1)-d$ gelten. Induktiv folgt damit $a_{i} \leq j-d$ für alle $j \geq i$.

Damit haben wir gezeigt:

(A) Entweder es gilt $a_{i} \geq i+d$ für alle $i \geq N$, oder

(B) es existiert ein $M \geq N$, sodass $a_{i} \leq i-d$ für alle $i \geq M$ gilt.

Nehmen wir zunächst an, (A) sei erfüllt. Die Zahlen $1, \ldots, N$ müssen laut der ersten Voraussetzung an die Folge alle einmal in der Folge auftauchen. Nun gilt jedoch $a_{i} \geq i+d>i \geq N$ für alle $i \geq N$, das heißt es gibt nur die $N-1$ Folgenglieder $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{N-1}$, die einen dieser Werte annehmen können. Nach dem Schubfachprinzip ergibt sich ein Widerspruch.

Nehmen wir nun an, (B) sei erfüllt. Es sei $k=\max \left\{M, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M}\right\}$. Dann sind die $k$ Folgenglieder $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ alle kleiner als $k$, denn für $i=1, \ldots M-1$ gilt $a_{i} \leq$ $\max \left\{a_{1}, \ldots, a_{M-1}\right\} \leq k$ und für $i=M, \ldots, k$ gilt $a_{i} \leq i-d<i \leq k$. Diese $k$ Zahlen liegen damit alle in der Menge $\{1,2, \ldots, k-1\}$. Nach dem Schubfachprinzip existieren daher zwei Indizes $1 \leq i<j \leq k$ mit $a_{i}=a_{j}$, was er ersten Voraussetzung an die Folge widerspricht.

Da wir in jedem Fall einen Widerspruch erhalten haben, gilt die Behauptung.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nAufgabe 2.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2018-loes_awkl_18.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $ABC$ be a triangle. The excircle $\omega$ opposite to point $A$ touches the segment $\overline{BC}$ and the rays $AC$ and $AB$ at points $D$, $E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $AEF$ intersects the line $BC$ at points $P$ and $Q$. Finally, let $M$ be the midpoint of the segment $\overline{AD}$. Prove that $\omega$ and the circumcircle of triangle $MPQ$ are tangent.

|

Let $J$ be the center of the incircle $\omega$. Then $J E \perp A E$ and $J F \perp A F$, so the Thales circle $\Omega$ of $\overline{A J}$ passes through $E$ and $F$, and thus also through $P$ and $Q$. The ray $A D$ intersects $\Omega$ and $\omega$ again at $N$ and $T$ respectively.

Then $J N$ is the perpendicular from $J$ to $D T$, so $N$ is the midpoint of the segment $\overline{D T}$. By the chord theorem, we have

$$

|D M| \cdot |D T| = \frac{1}{2} \cdot |D A| \cdot |D T| = |D A| \cdot |D N| = |D P| \cdot |D Q|

$$

Thus, by the converse of the chord theorem, the point $T$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $M P Q$. Now consider the image point of $N$ under inversion with respect to the circle $\omega$, denoted by $Z$. Since the Thales circles over $\overline{J D}$ and $\overline{J T}$ both pass through the point $N$, $Z$ lies on the images of these circles, which are the tangents through $D$ and $T$ to $\omega$. The points $B, C, P$, and $Q$ also lie on the first of these lines. Furthermore, $N$ lies on the circle $\Omega$, which inverts to the line $E F$, so $Z$ also lies on the line $E F$. Therefore, by the secant theorem,

$$

|Z T|^{2} = |Z E| \cdot |Z F| = |Z P| \cdot |Z Q|,

$$

and by the converse of the secant theorem, $Z T$ is also tangent to the circumcircle of triangle $M P Q$. This proves that this circle and $\omega$ touch at the point $T$.

## Solutions to the 2nd Selection Exam 2017/2018

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C$ ein Dreieck. Der dem Punkt $A$ gegenüberliegende Ankreis $\omega$ berühre die Strecke $\overline{B C}$ sowie die Strahlen $A C$ und $A B$ in den Punkten $D, E$ bzw. $F$. Der Umkreis des Dreiecks $A E F$ schneide die Gerade $B C$ in den Punkten $P$ und $Q$. Schließlich sei $M$ der Mittelpunkt der Strecke $\overline{A D}$. Man beweise, dass sich $\omega$ und der Umkreis des Dreiecks $M P Q$ berühren

|

Es sei $J$ der Mittelpunkt des Ankreises $\omega$. Dann gilt $J E \perp A E$ und $J F \perp$ $A F$, der Thaleskreis $\Omega$ von $\overline{A J}$ verläuft also durch $E$ und $F$, und damit auch durch $P$ und $Q$. Der Strahl $A D$ schneide $\Omega$ und $\omega$ erneut in $N$ bzw. $T$.

Dann ist $J N$ die Lotgerade von $J$ auf $D T$, also ist $N$ der Mittelpunkt der Strecke $\overline{D T}$. Damit gilt laut dem Sehnensatz

$$

|D M| \cdot|D T|=1 / 2 \cdot|D A| \cdot|D T|=|D A| \cdot|D N|=|D P| \cdot|D Q|

$$

der Punkt $T$ liegt nach der Umkehrung des Sehnensatzes also auf dem Umkreis des Dreiecks $M P Q$. Wir betrachten nun den Bildpunkt von $N$ bei Inversion am Kreis $\omega$, dieser sei mit $Z$ bezeichnet. Da die Thaleskreise über $\overline{J D}$ und $\overline{J T}$ beide durch den Punkt $N$ verlaufen, liegt $Z$ auf den Bildern dieser Kreise, also den Tangenten durch $D$ und $T$ an $\omega$. Auf ersterer Geraden liegen auch $B, C, P$ und $Q$. Ferner liegt $N$ auf dem Kreis $\Omega$, der bei der betrachteten Inversion in die Gerade $E F$ übergeht, also liegt auch $Z$ auf der Geraden $E F$. Damit gilt nach dem Sekantensatz

$$

|Z T|^{2}=|Z E| \cdot|Z F|=|Z P| \cdot|Z Q|,

$$

nach der Umkehrung des Sekantensatzes tangiert $Z T$ daher auch den Umkreis des Dreiecks $M P Q$. Damit haben wir beweisen, dass sich dieser Kreis und $\omega$ im Punkt $T$ berühren.

## Lösungen zur 2. Auswahlklausur 2017/2018

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nAufgabe 3.",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2018-loes_awkl_18.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}, k$ and $M$ be positive integers with the properties

$$

\frac{1}{a_{1}}+\frac{1}{a_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{1}{a_{n}}=k \quad \text { and } \quad a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}=M .

$$

Prove: For $M>1$, the polynomial

$$

P(x)=M(x+1)^{k}-\left(x+a_{1}\right)\left(x+a_{2}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right)

$$

has no positive solutions.

|

We show $P(x)<0$ for all $x>0$, i.e., $M(x+1)^{k}<\left(x+a_{1}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right) \Leftrightarrow$ $a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{1}}+\frac{1}{a_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{1}{a_{n}}}<\left(x+a_{1}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right) \Leftrightarrow \prod_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}}<\prod_{i=1}^{n}\left(x+a_{i}\right)$.

To do this, we show that for each $i\left((1 \leq i \leq n)\right.$ the relation $a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}} \leq x+a_{i}(1)$ holds and for at least one $i$ even $a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}}<x+a_{i}$ is true. The claim then follows by multiplication for all $i$.

From the AM-GM inequality for the numbers $x+1,1,1, \ldots, 1\left(a_{i}-1\right.$ summands 1$)$, we get $\frac{x+a_{i}}{a_{i}} \geq \sqrt[a]{x+1}$, which, after multiplication by $a_{i}$, precisely yields (1). The equality sign holds exactly for $a_{i}=1$, which cannot be true for all $i$, because then $M=1$, contradicting the assumption $M>1$. Since all transformations are valid for the given values, everything is shown.

Hint: Further proof approaches using the Bernoulli inequality, the binomial theorem, Jensen's inequality, or analysis are possible. The term "solution" in the problem statement, of course, stands synonymously for "root".

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Es seien $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}, k$ und $M$ positive ganze Zahlen mit den Eigenschaften

$$

\frac{1}{a_{1}}+\frac{1}{a_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{1}{a_{n}}=k \quad \text { und } \quad a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}=M .

$$

Man beweise: Für $M>1$ hat das Polynom

$$

P(x)=M(x+1)^{k}-\left(x+a_{1}\right)\left(x+a_{2}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right)

$$

keine positiven Lösungen.

|

Wir zeigen $P(x)<0$ für alle $x>0$, also $M(x+1)^{k}<\left(x+a_{1}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right) \Leftrightarrow$ $a_{1} a_{2} \ldots a_{n}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{1}}+\frac{1}{a_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{1}{a_{n}}}<\left(x+a_{1}\right) \ldots\left(x+a_{n}\right) \Leftrightarrow \prod_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}}<\prod_{i=1}^{n}\left(x+a_{i}\right)$.

Dazu zeigen wir, dass für jedes $i\left((1 \leq i \leq n)\right.$ die Beziehung $a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}} \leq x+a_{i}(1)$ gilt und für wenigstens ein $i$ sogar $a_{i}(x+1)^{\frac{1}{a_{i}}}<x+a_{i}$ ist. Die Behauptung folgt dann durch Multiplikation für alle $i$.

Aus der AM-GM-Ungleichung für die Zahlen $x+1,1,1, \ldots, 1\left(a_{i}-1\right.$ Summanden 1$)$ folgt $\frac{x+a_{i}}{a_{i}} \geq \sqrt[a]{x+1}$, was nach Multiplikation mit $a_{i}$ gerade (1) ergibt. Das Gleichheitszeichen gilt genau für $a_{i}=1$, was nicht für alle $i$ sein kann, denn dann wäre $M=1$, im Widerspruch zur Voraussetzung $M>1$. Da für die gegebenen Werte alle Umformungen erlaubt sind, ist alles gezeigt.

Hinweis: Weitere Beweisansätze über die Bernoulli-Ungleichung, den binomischen Satz, die Jensensche Ungleichung oder Analysis sind möglich. Der Begriff „Lösung" in der Aufgabenstellung steht natürlich synonym zu „Nullstelle".

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 1",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2018-loes_awkl_18.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Let $A B C D E$ be a convex pentagon with the properties

$$

\overline{A B}=\overline{B C}=\overline{C D}, \angle B A E=\angle D C B \text { and } \angle E D C=\angle C B A .

$$

Prove that the perpendicular from $E$ to $B C$ passes through the intersection of $A C$ and $B D$.

|

Due to the conditions, $\triangle A B C$ and $\triangle B C D$ are isosceles. Therefore, the perpendicular bisector of $A C$ passes through $B$ and the perpendicular bisector of $B D$ passes through $C$. Both intersect at point $I$ (see figure).

Because $B D \perp C I$ and $A C \perp B I$, $A C$ and $B D$ intersect at the orthocenter of triangle $B C I$, and it follows that $I H \perp B C$. If we can show that $E I \perp B C$, the claim follows because there can only be one perpendicular to $B C$ through $I$. Since $B I$ and $C I$ are also angle bisectors of $\angle C B A$ and $\angle D C B$ respectively, it follows that $\overline{I A}=\overline{I C}$ and $\overline{I B}=\overline{I D}$. Because $\overline{A B}=\overline{B C}=\overline{C D}$, the triangles $A B I, B C I$, and $C D I$ are congruent. Therefore, $\angle B A I=\angle I C B=\frac{1}{2} \angle D C B=\frac{1}{2} \angle B A E$, so $I A$ is the angle bisector of $\angle B A E$. Similarly, $I D$ is the angle bisector of $\angle E D C$.

The composition of the reflections in $A I, B I, C I, D I$, and $E I$ is a reflection with fixed points $E$ and $I$. Therefore, $I$ also lies on the angle bisector of $\angle A E D$.

Now, $\angle A E D=540^{\circ}-2 \angle C B A-2 \angle B A E$, and thus in quadrilateral $A B I E$:

$\angle B I E=360^{\circ}-\angle B A E-\angle I B A-\angle A E I=360^{\circ}-\angle B A E-\frac{1}{2} \angle C B A-\left(270^{\circ}-\angle C B A-\angle B A E\right)$

$=90^{\circ}+\frac{1}{2} \angle C B A=90^{\circ}+\angle C B I$. By the exterior angle theorem, it follows that $E I \perp B C$. ㅁ.

Hint: There are other solution paths using the intersection points of the extensions of suitable sides, using trigonometry, or (usually very laborious) analytic geometry. Errors partly arose from using the claim in the proof, such as not distinguishing between the lines $E T$ and $I T$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Es sei $A B C D E$ ein konvexes Fünfeck mit den Eigenschaften

$$

\overline{A B}=\overline{B C}=\overline{C D}, \angle B A E=\angle D C B \text { und } \angle E D C=\angle C B A .

$$

Man beweise, dass die Lotgerade von $E$ auf $B C$ durch den Schnittpunkt von $A C$ und $B D$ verläuft.

|

Wegen der Voraussetzungen sind $\triangle A B C$ und $\triangle B C D$ gleichschenklig. Daher geht die Mittelsenkrechte zu $A C$ durch $B$ und die Mittelsenkrechte zu $B D$ durch $C$. Beide schneiden sich im Punkt $I$ (siehe Figur).

Wegen $B D \perp C I$ und $A C \perp B I$ schneiden sich $A C$ und $B D$ im Höhenschnittpunkt des Dreiecks $B C I$ und es folgt $I H \perp B C$. Wenn wir nun zeigen können, dass $E I \perp B C$ ist, folgt die Behauptung, weil es durch $I$ nur eine Orthogonale zu $B C$ geben kann. Weil $B I$ und $C I$ auch Winkelhalbierende von $\angle C B A$ bzw. $\angle D C B$ sind, folgt $\overline{I A}=\overline{I C}$ sowie $\overline{I B}=\overline{I D}$. Wegen $\overline{A B}=\overline{B C}=\overline{C D}$ sind die Dreiecke $A B I, B C I$ und $C D I$ kongruent. Daher ist $\angle B A I=\angle I C B=\frac{1}{2} \angle D C B=\frac{1}{2} \angle B A E$, so dass $I A$ Winkelhalbierende von $\angle B A E$ ist. Analog gilt, dass $I D$ Winkelhalbierende von $\angle E D C$ ist.

Die Verkettung der Achsenspiegelungen an $A I, B I, C I, D I$ und $E I$ ist eine Achsenspiegelung mit den Fixpunkten $E$ und $I$. Daher liegt $I$ auch auf der Winkelhalbierenden von $\angle A E D$.

Nun gilt $\angle A E D=540^{\circ}-2 \angle C B A-2 \angle B A E$, und damit folgt im Viereck $A B I E$ :

$\angle B I E=360^{\circ}-\angle B A E-\angle I B A-\angle A E I=360^{\circ}-\angle B A E-\frac{1}{2} \angle C B A-\left(270^{\circ}-\angle C B A-\angle B A E\right)$

$=90^{\circ}+\frac{1}{2} \angle C B A=90^{\circ}+\angle C B I$. Mit dem Außenwinkelsatz folgt $E I \perp B C$. ㅁ.

Hinweis: Es gibt andere Lösungswege über die Schnittpunkte der Verlängerungen geeigneter Seiten, mithilfe von

Trigonometrie oder (in der Regel sehr aufwändig) analytischer Geometrie. Fehler entstanden z.T. durch Verwendung der Behauptung im Beweis, etwa durch Nicht-Unterscheiden der Geraden $E T$ und IT.

|

{

"exam": "Germany_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Aufgabe 2",

"resource_path": "Germany_TST/segmented/de-2018-loes_awkl_18.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nLösung:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2018"

}

|

Determine all integers $n \geq 2$ with the following property:

For any not necessarily distinct integers $m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{n}$, whose sum is not divisible by $n$, there exists an index $i(1 \leq i \leq n)$, such that none of the numbers

$$

m_{i}, m_{i}+m_{i+1}, m_{i}+m_{i+1}+m_{i+2}, \ldots, m_{i}+m_{i+1}+\ldots+m_{i+n-1}

$$

is divisible by $n$. (Here, $m_{i}=m_{i-n}$ for $i>n$.)

|

The sought numbers are exactly the prime numbers.

Part Proof 1: No non-prime number satisfies all conditions.

Let $n=a \cdot b$ with $1<a, b<n$ be a decomposition of $n$ into two proper divisors. We choose $m_{i}=a$ for $1 \leq i<n$ and $m_{n}=0$. Then the sum $m_{1}+m_{2}+\ldots+m_{n}=(n-1) a$ is obviously not divisible by $n$, since neither factor is divisible by $n$.

Now we choose for any index $i$ the index $j=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}b & \text { for } 1 \leq i \leq n-b \\ b+1 & \text { for } n-b<i \leq n\end{array}\right.$ and obtain $m_{i}+m_{i+1}+\ldots+m_{i+j-1}=a \cdot b=n \equiv 0 \bmod n$. With this counterexample, the part proof is complete.

Part Proof 2: Every prime number satisfies all conditions.

Let $n$ now be a prime number. For a proof by contradiction, assume that for the numbers $m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{n}$, whose sum is not divisible by $n$, there is a number $j(1 \leq j \leq n)$ for every index $i(1 \leq i \leq n)$ such that the sum $m_{l}+m_{i+1}+\ldots+m_{i+j-1}$ is divisible by $n$. Here, even $j \neq n$ holds, because the sum of all $m_{i}$ is not divisible by $n$.

Now we construct for $0 \leq k \leq n-1$ a finite sequence of integers $i_{0}, i_{1}, \ldots, i_{n}$ with $i_{k+1}-i_{k} \leq n-1$ (1), by choosing $m_{i_{k}+1}+m_{i_{k}+2}+\ldots+m_{i_{k+1}} \equiv 0 \bmod n$. The starting index $i_{0}$ is arbitrary and the new index $i_{k+1}$ is the smallest possible after $i_{k}$ when proceeding cyclically $\bmod n$.

By the pigeonhole principle, there are two different numbers $i_{r}$ and $i_{s}$ in the sequence of these $n+1$ indices with $0 \leq r<s \leq n$ that are congruent $\bmod n$. With them, $\sum_{j=r}^{s-1}\left(m_{i_{j}+1}+m_{i_{j+2}}+\ldots+m_{i_{j+1}}\right) \equiv 0 \bmod n$ holds, because this is true for each bracketed sum.

On the other hand, from $i_{s} \equiv i_{r} \bmod n$, it follows that there is a positive integer $d$ with $i_{s}-i_{r}=d \cdot n$. Due to (1), $i_{s}-i_{r} \leq(n-1) n$, so $d \leq n-1$ follows. Then $\sum_{j=r}^{s-1}\left(m_{i_{j}+1}+m_{i_{j+2}}+\ldots+m_{i_{j+1}}\right)=d\left(m_{1}+m_{2}+\ldots+m_{n}\right)$

cannot be a multiple of $n$, because $n$ is prime and neither $d$ nor $m_{1}+m_{2}+\ldots+m_{n}$ are multiples of $n$ - contradiction! $\square$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Man bestimme alle ganzen Zahlen $n \geq 2$ mit der folgenden Eigenschaft:

Für beliebige, nicht notwendigerweise verschiedene ganze Zahlen $m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{n}$, deren Summe nicht durch $n$ teilbar ist, existiert ein Index $i(1 \leq i \leq n)$, so dass keine der Zahlen

$$

m_{i}, m_{i}+m_{i+1}, m_{i}+m_{i+1}+m_{i+2}, \ldots, m_{i}+m_{i+1}+\ldots+m_{i+n-1}

$$

durch $n$ teilbar ist. (Dabei sei $m_{i}=m_{i-n}$ für $i>n$.)

|