problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Determine the value of $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{k=0}^{n}\binom{n}{k}^{-1}$.

|

2 Let $S_{n}$ denote the sum in the limit. For $n \geq 1$, we have $S_{n} \geq\binom{ n}{0}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n}^{-1}=2$. On the other hand, for $n \geq 3$, we have

$$

S_{n}=\binom{n}{0}^{-1}+\binom{n}{1}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n-1}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n}^{-1}+\sum_{k=2}^{n-2}\binom{n}{k}^{-1} \leq 2+\frac{2}{n}+(n-3)\binom{n}{2}^{-1}

$$

which goes to 2 as $n \rightarrow \infty$. Therefore, $S_{n} \rightarrow 2$.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Determine the value of $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \sum_{k=0}^{n}\binom{n}{k}^{-1}$.

|

2 Let $S_{n}$ denote the sum in the limit. For $n \geq 1$, we have $S_{n} \geq\binom{ n}{0}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n}^{-1}=2$. On the other hand, for $n \geq 3$, we have

$$

S_{n}=\binom{n}{0}^{-1}+\binom{n}{1}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n-1}^{-1}+\binom{n}{n}^{-1}+\sum_{k=2}^{n-2}\binom{n}{k}^{-1} \leq 2+\frac{2}{n}+(n-3)\binom{n}{2}^{-1}

$$

which goes to 2 as $n \rightarrow \infty$. Therefore, $S_{n} \rightarrow 2$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Find $p$ so that $\lim _{x \rightarrow \infty} x^{p}(\sqrt[3]{x+1}+\sqrt[3]{x-1}-2 \sqrt[3]{x})$ is some non-zero real number.

|

$\sqrt{\frac{5}{3}}$ Make the substitution $t=\frac{1}{x}$. Then the limit equals to

$$

\lim _{t \rightarrow 0} t^{-p}\left(\sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}+1}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}-1}-2 \sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}}\right)=\lim _{t \rightarrow 0} t^{-p-\frac{1}{3}}(\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2)

$$

We need the degree of the first nonzero term in the MacLaurin expansion of $\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2$. We have

$$

\sqrt[3]{1+t}=1+\frac{1}{3} t-\frac{1}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right), \quad \sqrt[3]{1-t}=1-\frac{1}{3} t-\frac{1}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right)

$$

It follows that $\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2=-\frac{2}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right)$. By consider the degree of the leading term, it follows that $-p-\frac{1}{3}=-2$. So $p=\frac{5}{3}$.

|

\frac{5}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Find $p$ so that $\lim _{x \rightarrow \infty} x^{p}(\sqrt[3]{x+1}+\sqrt[3]{x-1}-2 \sqrt[3]{x})$ is some non-zero real number.

|

$\sqrt{\frac{5}{3}}$ Make the substitution $t=\frac{1}{x}$. Then the limit equals to

$$

\lim _{t \rightarrow 0} t^{-p}\left(\sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}+1}+\sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}-1}-2 \sqrt[3]{\frac{1}{t}}\right)=\lim _{t \rightarrow 0} t^{-p-\frac{1}{3}}(\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2)

$$

We need the degree of the first nonzero term in the MacLaurin expansion of $\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2$. We have

$$

\sqrt[3]{1+t}=1+\frac{1}{3} t-\frac{1}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right), \quad \sqrt[3]{1-t}=1-\frac{1}{3} t-\frac{1}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right)

$$

It follows that $\sqrt[3]{1+t}+\sqrt[3]{1-t}-2=-\frac{2}{9} t^{2}+o\left(t^{2}\right)$. By consider the degree of the leading term, it follows that $-p-\frac{1}{3}=-2$. So $p=\frac{5}{3}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $T=\int_{0}^{\ln 2} \frac{2 e^{3 x}+e^{2 x}-1}{e^{3 x}+e^{2 x}-e^{x}+1} d x$. Evaluate $e^{T}$.

|

$\frac{11}{4}$ Divide the top and bottom by $e^{x}$ to obtain that

$$

T=\int_{0}^{\ln 2} \frac{2 e^{2 x}+e^{x}-e^{-x}}{e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}} d x

$$

Notice that $2 e^{2 x}+e^{x}-e^{-x}$ is the derivative of $e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}$, and so

$$

T=\left[\ln \left|e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}\right|\right]_{0}^{\ln 2}=\ln \left(4+2-1+\frac{1}{2}\right)-\ln 2=\ln \left(\frac{11}{4}\right)

$$

Therefore, $e^{T}=\frac{11}{4}$.

|

\frac{11}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Let $T=\int_{0}^{\ln 2} \frac{2 e^{3 x}+e^{2 x}-1}{e^{3 x}+e^{2 x}-e^{x}+1} d x$. Evaluate $e^{T}$.

|

$\frac{11}{4}$ Divide the top and bottom by $e^{x}$ to obtain that

$$

T=\int_{0}^{\ln 2} \frac{2 e^{2 x}+e^{x}-e^{-x}}{e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}} d x

$$

Notice that $2 e^{2 x}+e^{x}-e^{-x}$ is the derivative of $e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}$, and so

$$

T=\left[\ln \left|e^{2 x}+e^{x}-1+e^{-x}\right|\right]_{0}^{\ln 2}=\ln \left(4+2-1+\frac{1}{2}\right)-\ln 2=\ln \left(\frac{11}{4}\right)

$$

Therefore, $e^{T}=\frac{11}{4}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. $[7]$",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Evaluate the limit $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} n^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)}\left(1^{1} \cdot 2^{2} \cdots \cdots n^{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{n^{2}}}$.

|

$e^{-1 / 4}$ Taking the logarithm of the expression inside the limit, we find that it is

$$

-\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right) \ln n+\frac{1}{n^{2}} \sum_{k=1}^{n} k \ln k=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{k}{n} \ln \left(\frac{k}{n}\right)

$$

We can recognize this as the as Riemann sum expansion for the integral $\int_{0}^{1} x \ln x d x$, and thus the limit of the above sum as $n \rightarrow \infty$ equals to the value of this integral. Evaluating this integral using integration by parts, we find that

$$

\int_{0}^{1} x \ln x d x=\left.\frac{1}{2} x^{2} \ln x\right|_{0} ^{1}-\int_{0}^{1} \frac{x}{2} d x=-\frac{1}{4}

$$

Therefore, the original limit is $e^{-1 / 4}$.

|

e^{-1 / 4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Evaluate the limit $\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} n^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)}\left(1^{1} \cdot 2^{2} \cdots \cdots n^{n}\right)^{\frac{1}{n^{2}}}$.

|

$e^{-1 / 4}$ Taking the logarithm of the expression inside the limit, we find that it is

$$

-\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right) \ln n+\frac{1}{n^{2}} \sum_{k=1}^{n} k \ln k=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{k}{n} \ln \left(\frac{k}{n}\right)

$$

We can recognize this as the as Riemann sum expansion for the integral $\int_{0}^{1} x \ln x d x$, and thus the limit of the above sum as $n \rightarrow \infty$ equals to the value of this integral. Evaluating this integral using integration by parts, we find that

$$

\int_{0}^{1} x \ln x d x=\left.\frac{1}{2} x^{2} \ln x\right|_{0} ^{1}-\int_{0}^{1} \frac{x}{2} d x=-\frac{1}{4}

$$

Therefore, the original limit is $e^{-1 / 4}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Evaluate the integral $\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \ln (1-x) d x$.

|

$2-\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$ We have the MacLaurin expansion $\ln (1-x)=-x-\frac{x^{2}}{2}-\frac{x^{3}}{3}-\cdots$. So

$$

\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \ln (1-x) d x=-\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{x^{n}}{n} d x=-\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n} \int_{0}^{1} x^{n} \ln x d x

$$

Using integration by parts, we get

$$

\int_{0}^{1} x^{n} \ln x d x=\left.\frac{x^{n+1} \ln x}{n+1}\right|_{0} ^{1}-\int_{0}^{1} \frac{x^{n}}{n+1} d x=-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}

$$

(We used the fact that $\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} x^{n} \ln x=0$ for $n>0$, which can be proven using l'Hôpital's rule.) Therefore, the original integral equals to

$$

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n(n+1)^{2}}=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}\right)

$$

Telescoping the sum and using the well-known identity $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^{2}}=\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$, we see that the above sum is equal to $2-\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$.

|

2-\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Calculus

|

Evaluate the integral $\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \ln (1-x) d x$.

|

$2-\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$ We have the MacLaurin expansion $\ln (1-x)=-x-\frac{x^{2}}{2}-\frac{x^{3}}{3}-\cdots$. So

$$

\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \ln (1-x) d x=-\int_{0}^{1} \ln x \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{x^{n}}{n} d x=-\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n} \int_{0}^{1} x^{n} \ln x d x

$$

Using integration by parts, we get

$$

\int_{0}^{1} x^{n} \ln x d x=\left.\frac{x^{n+1} \ln x}{n+1}\right|_{0} ^{1}-\int_{0}^{1} \frac{x^{n}}{n+1} d x=-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}

$$

(We used the fact that $\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} x^{n} \ln x=0$ for $n>0$, which can be proven using l'Hôpital's rule.) Therefore, the original integral equals to

$$

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n(n+1)^{2}}=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}-\frac{1}{(n+1)^{2}}\right)

$$

Telescoping the sum and using the well-known identity $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^{2}}=\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$, we see that the above sum is equal to $2-\frac{\pi^{2}}{6}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [8]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-calc-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

A $3 \times 3 \times 3$ cube composed of 27 unit cubes rests on a horizontal plane. Determine the number of ways of selecting two distinct unit cubes from a $3 \times 3 \times 1$ block (the order is irrelevant) with the property that the line joining the centers of the two cubes makes a $45^{\circ}$ angle with the horizontal plane.

|

60 There are 6 such slices, and each slice gives 10 valid pairs (with no overcounting). Therefore, there are 60 such pairs.

|

60

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A $3 \times 3 \times 3$ cube composed of 27 unit cubes rests on a horizontal plane. Determine the number of ways of selecting two distinct unit cubes from a $3 \times 3 \times 1$ block (the order is irrelevant) with the property that the line joining the centers of the two cubes makes a $45^{\circ}$ angle with the horizontal plane.

|

60 There are 6 such slices, and each slice gives 10 valid pairs (with no overcounting). Therefore, there are 60 such pairs.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $S=\{1,2, \ldots, 2008\}$. For any nonempty subset $A \subset S$, define $m(A)$ to be the median of $A$ (when $A$ has an even number of elements, $m(A)$ is the average of the middle two elements). Determine the average of $m(A)$, when $A$ is taken over all nonempty subsets of $S$.

|

$\frac{-2009}{2}$ For any subset $A$, we can define the "reflected subset" $A^{\prime}=\{i \mid 2009-i \in A\}$. Then $m(A)=2009-m\left(A^{\prime}\right)$. Note that as $A$ is taken over all nonempty subsets of $S, A^{\prime}$ goes through all the nonempty subsets of $S$ as well. Thus, the average of $m(A)$ is equal to the average of $\frac{m(A)+m\left(A^{\prime}\right)}{2}$, which is the constant $\frac{2009}{2}$.

Remark: : This argument is very analogous to the famous argument that Gauss used to sum the series $1+2+\cdots+100$.

|

\frac{2009}{2}

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $S=\{1,2, \ldots, 2008\}$. For any nonempty subset $A \subset S$, define $m(A)$ to be the median of $A$ (when $A$ has an even number of elements, $m(A)$ is the average of the middle two elements). Determine the average of $m(A)$, when $A$ is taken over all nonempty subsets of $S$.

|

$\frac{-2009}{2}$ For any subset $A$, we can define the "reflected subset" $A^{\prime}=\{i \mid 2009-i \in A\}$. Then $m(A)=2009-m\left(A^{\prime}\right)$. Note that as $A$ is taken over all nonempty subsets of $S, A^{\prime}$ goes through all the nonempty subsets of $S$ as well. Thus, the average of $m(A)$ is equal to the average of $\frac{m(A)+m\left(A^{\prime}\right)}{2}$, which is the constant $\frac{2009}{2}$.

Remark: : This argument is very analogous to the famous argument that Gauss used to sum the series $1+2+\cdots+100$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Farmer John has 5 cows, 4 pigs, and 7 horses. How many ways can he pair up the animals so that every pair consists of animals of different species? Assume that all animals are distinguishable from each other. (Please write your answer as an integer, without any incomplete computations.)

|

100800 Since there are 9 cow and pigs combined and 7 horses, there must be a pair with 1 cow and 1 pig, and all the other pairs must contain a horse. There are $4 \times 5$ ways of selecting the cow-pig pair, and 7! ways to select the partners for the horses. It follows that the answer is $4 \times 5 \times 7!=100800$.

|

100800

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Farmer John has 5 cows, 4 pigs, and 7 horses. How many ways can he pair up the animals so that every pair consists of animals of different species? Assume that all animals are distinguishable from each other. (Please write your answer as an integer, without any incomplete computations.)

|

100800 Since there are 9 cow and pigs combined and 7 horses, there must be a pair with 1 cow and 1 pig, and all the other pairs must contain a horse. There are $4 \times 5$ ways of selecting the cow-pig pair, and 7! ways to select the partners for the horses. It follows that the answer is $4 \times 5 \times 7!=100800$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Kermit the frog enjoys hopping around the infinite square grid in his backyard. It takes him 1 Joule of energy to hop one step north or one step south, and 1 Joule of energy to hop one step east or one step west. He wakes up one morning on the grid with 100 Joules of energy, and hops till he falls asleep with 0 energy. How many different places could he have gone to sleep?

|

10201

It is easy to see that the coordinates of the frog's final position must have the same parity. Suppose that the frog went to sleep at $(x, y)$. Then, we have that $-100 \leq y \leq 100$ and $|x| \leq 100-|y|$, so $x$ can take on the values $-100+|y|,-98+|y|, \ldots, 100-|y|$. There are $101-|y|$ such values, so the total number of such locations is

$$

\sum_{y=-100}^{100} 101-|y|=201 \cdot 101-2 \cdot \frac{100(100+1)}{2}=101^{2}=10201

$$

|

10201

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Kermit the frog enjoys hopping around the infinite square grid in his backyard. It takes him 1 Joule of energy to hop one step north or one step south, and 1 Joule of energy to hop one step east or one step west. He wakes up one morning on the grid with 100 Joules of energy, and hops till he falls asleep with 0 energy. How many different places could he have gone to sleep?

|

10201

It is easy to see that the coordinates of the frog's final position must have the same parity. Suppose that the frog went to sleep at $(x, y)$. Then, we have that $-100 \leq y \leq 100$ and $|x| \leq 100-|y|$, so $x$ can take on the values $-100+|y|,-98+|y|, \ldots, 100-|y|$. There are $101-|y|$ such values, so the total number of such locations is

$$

\sum_{y=-100}^{100} 101-|y|=201 \cdot 101-2 \cdot \frac{100(100+1)}{2}=101^{2}=10201

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n4. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $S$ be the smallest subset of the integers with the property that $0 \in S$ and for any $x \in S$, we have $3 x \in S$ and $3 x+1 \in S$. Determine the number of non-negative integers in $S$ less than 2008.

|

128 Write the elements of $S$ in their ternary expansion (i.e. base 3). Then the second condition translates into, if $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k}} \in S$, then $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k} 0}$ and $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k} 1}$ are also in $S$. It follows that $S$ is the set of nonnegative integers whose tertiary representation contains only the digits 0 and 1. Since $2 \cdot 3^{6}<2008<3^{7}$, there are $2^{7}=128$ such elements less than 2008 . Therefore, there are 128 such non-negative elements.

|

128

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $S$ be the smallest subset of the integers with the property that $0 \in S$ and for any $x \in S$, we have $3 x \in S$ and $3 x+1 \in S$. Determine the number of non-negative integers in $S$ less than 2008.

|

128 Write the elements of $S$ in their ternary expansion (i.e. base 3). Then the second condition translates into, if $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k}} \in S$, then $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k} 0}$ and $\overline{d_{1} d_{2} \cdots d_{k} 1}$ are also in $S$. It follows that $S$ is the set of nonnegative integers whose tertiary representation contains only the digits 0 and 1. Since $2 \cdot 3^{6}<2008<3^{7}$, there are $2^{7}=128$ such elements less than 2008 . Therefore, there are 128 such non-negative elements.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

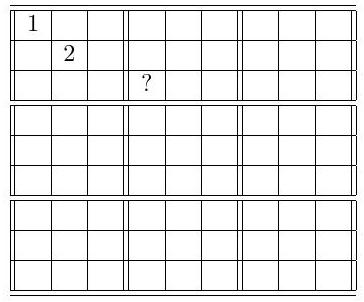

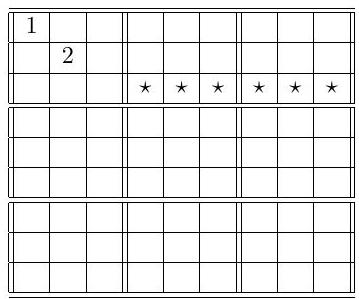

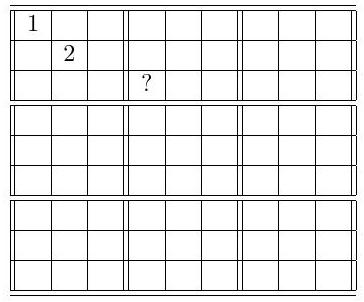

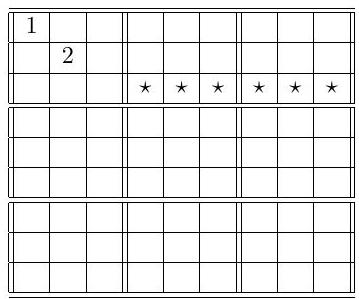

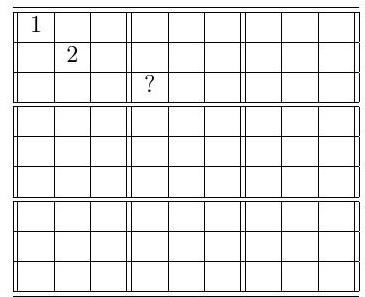

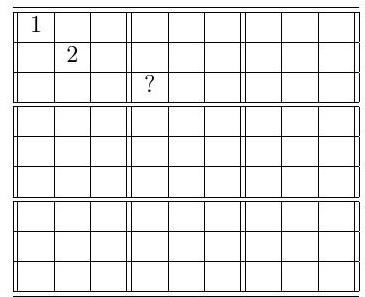

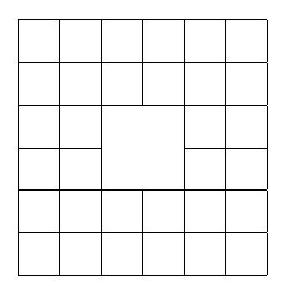

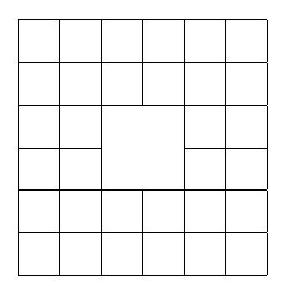

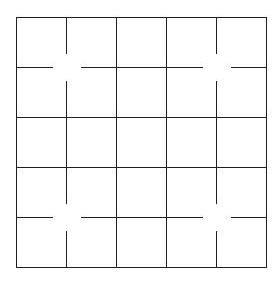

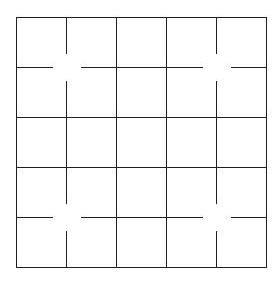

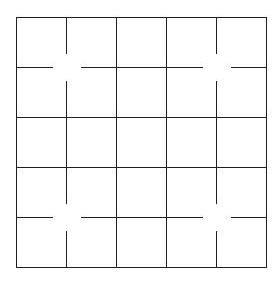

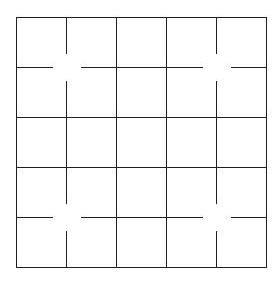

A Sudoku matrix is defined as a $9 \times 9$ array with entries from $\{1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ and with the constraint that each row, each column, and each of the nine $3 \times 3$ boxes that tile the array contains each digit from 1 to 9 exactly once. A Sudoku matrix is chosen at random (so that every Sudoku matrix has equal probability of being chosen). We know two of squares in this matrix, as shown. What is the probability that the square marked by? contains the digit 3 ?

|

$\quad \frac{2}{21}$ The third row must contain the digit 1, and it cannot appear in the leftmost three squares. Therefore, the digit 1 must fall into one of the six squares shown below that are marked with $\star$. By symmetry, each starred square has an equal probability of containing the digit 1 (To see this more precisely, note that swapping columns 4 and 5 gives another Sudoku matrix, so the probability that the 4 th column $\star$ has the 1 is the same as the probability that the 5 th column $\star$ has the 1 . Similarly, switching the 4-5-6th columns with the 7-8-9th columns yields another Sudoku matrix, which implies in particular that the probability that the 4 th column $\star$ has the 1 is the same as the probability that the 7 th column $\star$ has the 1 . The rest of the argument follows analogously.) Therefore, the probability that the ? square contains 1 is $1 / 6$.

Similarly the probability that the digit 2 appears at? is also $1 / 6$. By symmetry, the square ? has equal probability of containing the digits $3,4,5,6,7,8,9$. It follows that this probability is $\left(1-\frac{1}{6}-\frac{1}{6}\right) / 7=$ $\frac{2}{21}$.

|

\frac{2}{21}

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

A Sudoku matrix is defined as a $9 \times 9$ array with entries from $\{1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ and with the constraint that each row, each column, and each of the nine $3 \times 3$ boxes that tile the array contains each digit from 1 to 9 exactly once. A Sudoku matrix is chosen at random (so that every Sudoku matrix has equal probability of being chosen). We know two of squares in this matrix, as shown. What is the probability that the square marked by? contains the digit 3 ?

|

$\quad \frac{2}{21}$ The third row must contain the digit 1, and it cannot appear in the leftmost three squares. Therefore, the digit 1 must fall into one of the six squares shown below that are marked with $\star$. By symmetry, each starred square has an equal probability of containing the digit 1 (To see this more precisely, note that swapping columns 4 and 5 gives another Sudoku matrix, so the probability that the 4 th column $\star$ has the 1 is the same as the probability that the 5 th column $\star$ has the 1 . Similarly, switching the 4-5-6th columns with the 7-8-9th columns yields another Sudoku matrix, which implies in particular that the probability that the 4 th column $\star$ has the 1 is the same as the probability that the 7 th column $\star$ has the 1 . The rest of the argument follows analogously.) Therefore, the probability that the ? square contains 1 is $1 / 6$.

Similarly the probability that the digit 2 appears at? is also $1 / 6$. By symmetry, the square ? has equal probability of containing the digits $3,4,5,6,7,8,9$. It follows that this probability is $\left(1-\frac{1}{6}-\frac{1}{6}\right) / 7=$ $\frac{2}{21}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

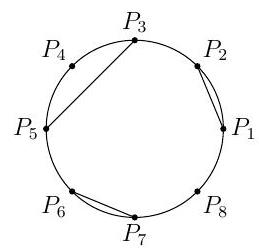

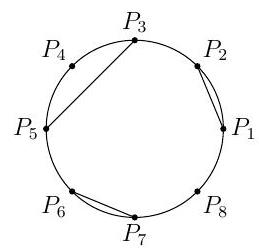

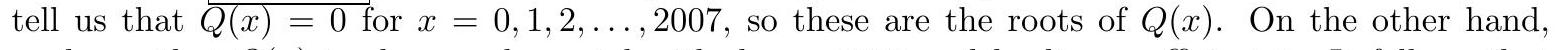

Let $P_{1}, P_{2}, \ldots, P_{8}$ be 8 distinct points on a circle. Determine the number of possible configurations made by drawing a set of line segments connecting pairs of these 8 points, such that: (1) each $P_{i}$ is the endpoint of at most one segment and (2) two no segments intersect. (The configuration with no edges drawn is allowed. An example of a valid configuration is shown below.)

|

323 Let $f(n)$ denote the number of valid configurations when there are $n$ points on the circle. Let $P$ be one of the points. If $P$ is not the end point of an edge, then there are $f(n-1)$ ways to connect the remaining $n-1$ points. If $P$ belongs to an edge that separates the circle so that there are $k$ points on one side and $n-k-2$ points on the other side, then there are $f(k) f(n-k-2)$ ways of finishing the configuration. Thus, $f(n)$ satisfies the recurrence relation

$$

f(n)=f(n-1)+f(0) f(n-2)+f(1) f(n-3)+f(2) f(n-4)+\cdots+f(n-2) f(0), n \geq 2

$$

The initial conditions are $f(0)=f(1)=1$. Using the recursion, we find that $f(2)=2, f(3)=4, f(4)=$ $9, f(5)=21, f(6)=51, f(7)=127, f(8)=323$.

Remark: These numbers are known as the Motzkin numbers. This is sequence A001006 in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (http://www.research.att.com/~njas/sequences/A001006). In

Richard Stanley's Enumerative Combinatorics Volume 2, one can find 13 different interpretations of Motzkin numbers in exercise 6.38.

|

323

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $P_{1}, P_{2}, \ldots, P_{8}$ be 8 distinct points on a circle. Determine the number of possible configurations made by drawing a set of line segments connecting pairs of these 8 points, such that: (1) each $P_{i}$ is the endpoint of at most one segment and (2) two no segments intersect. (The configuration with no edges drawn is allowed. An example of a valid configuration is shown below.)

|

323 Let $f(n)$ denote the number of valid configurations when there are $n$ points on the circle. Let $P$ be one of the points. If $P$ is not the end point of an edge, then there are $f(n-1)$ ways to connect the remaining $n-1$ points. If $P$ belongs to an edge that separates the circle so that there are $k$ points on one side and $n-k-2$ points on the other side, then there are $f(k) f(n-k-2)$ ways of finishing the configuration. Thus, $f(n)$ satisfies the recurrence relation

$$

f(n)=f(n-1)+f(0) f(n-2)+f(1) f(n-3)+f(2) f(n-4)+\cdots+f(n-2) f(0), n \geq 2

$$

The initial conditions are $f(0)=f(1)=1$. Using the recursion, we find that $f(2)=2, f(3)=4, f(4)=$ $9, f(5)=21, f(6)=51, f(7)=127, f(8)=323$.

Remark: These numbers are known as the Motzkin numbers. This is sequence A001006 in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (http://www.research.att.com/~njas/sequences/A001006). In

Richard Stanley's Enumerative Combinatorics Volume 2, one can find 13 different interpretations of Motzkin numbers in exercise 6.38.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

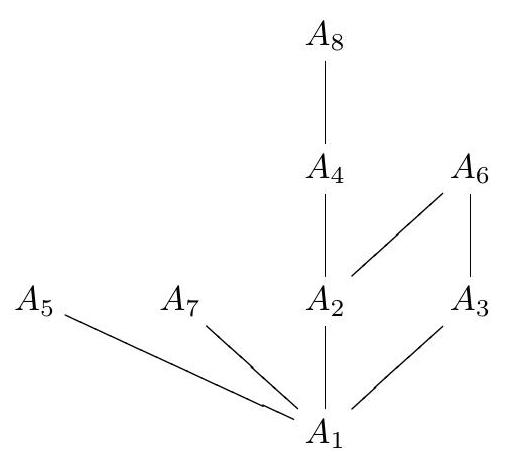

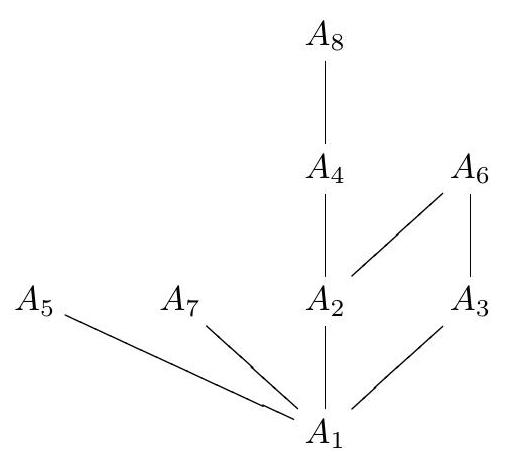

Determine the number of ways to select a sequence of 8 sets $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{8}$, such that each is a subset (possibly empty) of $\{1,2\}$, and $A_{m}$ contains $A_{n}$ if $m$ divides $n$.

|

2025 Consider an arbitrary $x \in\{1,2\}$, and let us consider the number of ways for $x$ to be in some of the sets so that the constraints are satisfied. We divide into a few cases:

- Case: $x \notin A_{1}$. Then $x$ cannot be in any of the sets. So there is one possibility.

- Case: $x \in A_{1}$ but $x \notin A_{2}$. Then the only other sets that $x$ could be in are $A_{3}, A_{5}, A_{7}$, and $x$ could be in some collection of them. There are 8 possibilities in this case.

- Case: $x \in A_{2}$. Then $x \in A_{1}$ automatically. There are 4 independent choices to be make here: (1) whether $x \in A_{5} ;(2)$ whether $x \in A_{7}$; (3) whether $x \in A_{3}$, and if yes, whether $x \in A_{6}$; (4) whether $x \in A_{4}$, and if yes, whether $x \in A_{8}$. There are $2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 3=36$ choices here.

Therefore, there are $1+8+36=45$ ways to place $x$ into some of the sets. Since the choices for $x=1$ and $x=2$ are made independently, we see that the total number of possibilities is $45^{2}=2025$.

Remark: The solution could be guided by the following diagram. Set $A$ is above $B$ and connected to $B$ if and only if $A \subset B$. Such diagrams are known as Hasse diagrams, which are used to depict partially ordered sets.

|

2025

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Determine the number of ways to select a sequence of 8 sets $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{8}$, such that each is a subset (possibly empty) of $\{1,2\}$, and $A_{m}$ contains $A_{n}$ if $m$ divides $n$.

|

2025 Consider an arbitrary $x \in\{1,2\}$, and let us consider the number of ways for $x$ to be in some of the sets so that the constraints are satisfied. We divide into a few cases:

- Case: $x \notin A_{1}$. Then $x$ cannot be in any of the sets. So there is one possibility.

- Case: $x \in A_{1}$ but $x \notin A_{2}$. Then the only other sets that $x$ could be in are $A_{3}, A_{5}, A_{7}$, and $x$ could be in some collection of them. There are 8 possibilities in this case.

- Case: $x \in A_{2}$. Then $x \in A_{1}$ automatically. There are 4 independent choices to be make here: (1) whether $x \in A_{5} ;(2)$ whether $x \in A_{7}$; (3) whether $x \in A_{3}$, and if yes, whether $x \in A_{6}$; (4) whether $x \in A_{4}$, and if yes, whether $x \in A_{8}$. There are $2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 3=36$ choices here.

Therefore, there are $1+8+36=45$ ways to place $x$ into some of the sets. Since the choices for $x=1$ and $x=2$ are made independently, we see that the total number of possibilities is $45^{2}=2025$.

Remark: The solution could be guided by the following diagram. Set $A$ is above $B$ and connected to $B$ if and only if $A \subset B$. Such diagrams are known as Hasse diagrams, which are used to depict partially ordered sets.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

On an infinite chessboard (whose squares are labeled by $(x, y)$, where $x$ and $y$ range over all integers), a king is placed at $(0,0)$. On each turn, it has probability of 0.1 of moving to each of the four edgeneighboring squares, and a probability of 0.05 of moving to each of the four diagonally-neighboring squares, and a probability of 0.4 of not moving. After 2008 turns, determine the probability that the king is on a square with both coordinates even. An exact answer is required.

|

| $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{3}{4 \cdot 5^{2008}}$ |

| :---: |

| Since only the parity of the coordinates are relevant, it is equivalent to | consider a situation where the king moves $(1,0)$ with probability 0.2 , moves $(0,1)$ with probability 0.2 , moves $(1,1)$ with probability 0.2 , and stays put with probability 0.4 . This can be analyzed using the generating function

$$

f(x, y)=(0.4+2 \times 0.1 x+2 \times 0.1 y+4 \times 0.05 x y)^{2008}=\frac{(2+x+y+x y)^{2008}}{5^{2008}} .

$$

We wish to find the sum of the coefficients of the terms $x^{a} y^{b}$, where both $a$ and $b$ are even. This is simply equal to $\frac{1}{4}(f(1,1)+f(1,-1)+f(-1,1)+f(-1,-1))$. We have $f(1,1)=1$ and $f(1,-1)=$ $f(-1,1)=f(-1,-1)=1 / 5^{2008}$. Therefore, the answer is

$$

\frac{1}{4}(f(1,1)+f(1,-1)+f(-1,1)+f(-1,-1))=\frac{1}{4}\left(1+\frac{3}{5^{2008}}\right)=\frac{1}{4}+\frac{3}{4 \cdot 5^{2008}}

$$

|

\frac{1}{4}+\frac{3}{4 \cdot 5^{2008}}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On an infinite chessboard (whose squares are labeled by $(x, y)$, where $x$ and $y$ range over all integers), a king is placed at $(0,0)$. On each turn, it has probability of 0.1 of moving to each of the four edgeneighboring squares, and a probability of 0.05 of moving to each of the four diagonally-neighboring squares, and a probability of 0.4 of not moving. After 2008 turns, determine the probability that the king is on a square with both coordinates even. An exact answer is required.

|

| $\frac{1}{4}+\frac{3}{4 \cdot 5^{2008}}$ |

| :---: |

| Since only the parity of the coordinates are relevant, it is equivalent to | consider a situation where the king moves $(1,0)$ with probability 0.2 , moves $(0,1)$ with probability 0.2 , moves $(1,1)$ with probability 0.2 , and stays put with probability 0.4 . This can be analyzed using the generating function

$$

f(x, y)=(0.4+2 \times 0.1 x+2 \times 0.1 y+4 \times 0.05 x y)^{2008}=\frac{(2+x+y+x y)^{2008}}{5^{2008}} .

$$

We wish to find the sum of the coefficients of the terms $x^{a} y^{b}$, where both $a$ and $b$ are even. This is simply equal to $\frac{1}{4}(f(1,1)+f(1,-1)+f(-1,1)+f(-1,-1))$. We have $f(1,1)=1$ and $f(1,-1)=$ $f(-1,1)=f(-1,-1)=1 / 5^{2008}$. Therefore, the answer is

$$

\frac{1}{4}(f(1,1)+f(1,-1)+f(-1,1)+f(-1,-1))=\frac{1}{4}\left(1+\frac{3}{5^{2008}}\right)=\frac{1}{4}+\frac{3}{4 \cdot 5^{2008}}

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Determine the number of 8-tuples of nonnegative integers $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, b_{1}, b_{2}, b_{3}, b_{4}\right)$ satisfying $0 \leq$ $a_{k} \leq k$, for each $k=1,2,3,4$, and $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{4}+2 b_{1}+3 b_{2}+4 b_{3}+5 b_{4}=19$.

|

1540 For each $k=1,2,3,4$, note that set of pairs $\left(a_{k}, b_{k}\right)$ with $0 \leq a_{k} \leq k$ maps bijectively to the set of nonnegative integers through the map $\left(a_{k}, b_{k}\right) \mapsto a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$, as $a_{k}$ is simply the remainder of $a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$ upon division by $k+1$. By letting $x_{k}=a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$, we see that the problem is equivalent to finding the number of quadruples of nonnegative integers $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}, x_{4}\right)$ such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}=19$. This is the same as finding the number of quadruples of positive integers $\left(x_{1}+1, x_{2}+1, x_{3}+1, x_{4}+1\right)$ such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}=23$. By a standard "dots and bars" argument, we see that the answer is $\binom{22}{3}=1540$.

A generating functions solution is also available. It's not hard to see that the answer is the coefficient of $x^{19}$ in

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1+x)\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)\left(1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}\right)\left(1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}+x^{4}\right) \\

& \quad\left(1+x^{2}+x^{4}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{3}+x^{6}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{4}+x^{8}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{5}+x^{10}+\cdots\right) \\

= & \left(\frac{1-x^{2}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{3}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{4}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{5}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{2}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{3}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{4}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{5}}\right) \\

= & \frac{1}{(1-x)^{4}}=(1-x)^{-4} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Using binomial theorem, we find that the coefficient of $x^{19}$ in $(1-x)^{-4}$ is $(-1)^{19}\binom{-4}{19}=\binom{22}{19}=1540$.

|

1540

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Determine the number of 8-tuples of nonnegative integers $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, b_{1}, b_{2}, b_{3}, b_{4}\right)$ satisfying $0 \leq$ $a_{k} \leq k$, for each $k=1,2,3,4$, and $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{4}+2 b_{1}+3 b_{2}+4 b_{3}+5 b_{4}=19$.

|

1540 For each $k=1,2,3,4$, note that set of pairs $\left(a_{k}, b_{k}\right)$ with $0 \leq a_{k} \leq k$ maps bijectively to the set of nonnegative integers through the map $\left(a_{k}, b_{k}\right) \mapsto a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$, as $a_{k}$ is simply the remainder of $a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$ upon division by $k+1$. By letting $x_{k}=a_{k}+(k+1) b_{k}$, we see that the problem is equivalent to finding the number of quadruples of nonnegative integers $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}, x_{4}\right)$ such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}=19$. This is the same as finding the number of quadruples of positive integers $\left(x_{1}+1, x_{2}+1, x_{3}+1, x_{4}+1\right)$ such that $x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}+x_{4}=23$. By a standard "dots and bars" argument, we see that the answer is $\binom{22}{3}=1540$.

A generating functions solution is also available. It's not hard to see that the answer is the coefficient of $x^{19}$ in

$$

\begin{aligned}

& (1+x)\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)\left(1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}\right)\left(1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}+x^{4}\right) \\

& \quad\left(1+x^{2}+x^{4}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{3}+x^{6}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{4}+x^{8}+\cdots\right)\left(1+x^{5}+x^{10}+\cdots\right) \\

= & \left(\frac{1-x^{2}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{3}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{4}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1-x^{5}}{1-x}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{2}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{3}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{4}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1-x^{5}}\right) \\

= & \frac{1}{(1-x)^{4}}=(1-x)^{-4} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Using binomial theorem, we find that the coefficient of $x^{19}$ in $(1-x)^{-4}$ is $(-1)^{19}\binom{-4}{19}=\binom{22}{19}=1540$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [7]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-comb-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $A B C D$ be a unit square (that is, the labels $A, B, C, D$ appear in that order around the square). Let $X$ be a point outside of the square such that the distance from $X$ to $A C$ is equal to the distance from $X$ to $B D$, and also that $A X=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$. Determine the value of $C X^{2}$.

|

$\quad \frac{5}{2}$

Since $X$ is equidistant from $A C$ and $B D$, it must lie on either the perpendicular bisector of $A B$ or the perpendicular bisector of $A D$. It turns that the two cases yield the same answer, so we will just assume the first case. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $A B$ and $N$ the midpoint of $C D$. Then, $X M$ is perpendicular to $A B$, so $X M=\frac{1}{2}$ and thus $X N=\frac{3}{2}, N C=\frac{1}{2}$. By the Pythagorean Theorem we find $X C=\frac{\sqrt{10}}{2}$ and the answer follows.

|

\frac{5}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a unit square (that is, the labels $A, B, C, D$ appear in that order around the square). Let $X$ be a point outside of the square such that the distance from $X$ to $A C$ is equal to the distance from $X$ to $B D$, and also that $A X=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$. Determine the value of $C X^{2}$.

|

$\quad \frac{5}{2}$

Since $X$ is equidistant from $A C$ and $B D$, it must lie on either the perpendicular bisector of $A B$ or the perpendicular bisector of $A D$. It turns that the two cases yield the same answer, so we will just assume the first case. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $A B$ and $N$ the midpoint of $C D$. Then, $X M$ is perpendicular to $A B$, so $X M=\frac{1}{2}$ and thus $X N=\frac{3}{2}, N C=\frac{1}{2}$. By the Pythagorean Theorem we find $X C=\frac{\sqrt{10}}{2}$ and the answer follows.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [2]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ such that $107 n$ has the same last two digits as $n$.

|

50 The two numbers have the same last two digits if and only if 100 divides their difference $106 n$, which happens if and only if 50 divides $n$.

|

50

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the smallest positive integer $n$ such that $107 n$ has the same last two digits as $n$.

|

50 The two numbers have the same last two digits if and only if 100 divides their difference $106 n$, which happens if and only if 50 divides $n$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

There are 5 dogs, 4 cats, and 7 bowls of milk at an animal gathering. Dogs and cats are distinguishable, but all bowls of milk are the same. In how many ways can every dog and cat be paired with either a member of the other species or a bowl of milk such that all the bowls of milk are taken?

|

20 Since there are 9 dogs and cats combined and 7 bowls of milk, there can only be one dog-cat pair, and all the other pairs must contain a bowl of milk. There are $4 \times 5$ ways of selecting the dog-cat pair, and only one way of picking the other pairs, since the bowls of milk are indistinguishable, so the answer is $4 \times 5=20$.

|

20

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

There are 5 dogs, 4 cats, and 7 bowls of milk at an animal gathering. Dogs and cats are distinguishable, but all bowls of milk are the same. In how many ways can every dog and cat be paired with either a member of the other species or a bowl of milk such that all the bowls of milk are taken?

|

20 Since there are 9 dogs and cats combined and 7 bowls of milk, there can only be one dog-cat pair, and all the other pairs must contain a bowl of milk. There are $4 \times 5$ ways of selecting the dog-cat pair, and only one way of picking the other pairs, since the bowls of milk are indistinguishable, so the answer is $4 \times 5=20$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Positive real numbers $x, y$ satisfy the equations $x^{2}+y^{2}=1$ and $x^{4}+y^{4}=\frac{17}{18}$. Find $x y$.

|

$\frac{1}{6}$ Same as Algebra Test problem 1.

|

\frac{1}{6}

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Positive real numbers $x, y$ satisfy the equations $x^{2}+y^{2}=1$ and $x^{4}+y^{4}=\frac{17}{18}$. Find $x y$.

|

$\frac{1}{6}$ Same as Algebra Test problem 1.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

The function $f$ satisfies

$$

f(x)+f(2 x+y)+5 x y=f(3 x-y)+2 x^{2}+1

$$

for all real numbers $x, y$. Determine the value of $f(10)$.

|

$\quad-49$ Same as Algebra Test problem 4.

|

-49

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

The function $f$ satisfies

$$

f(x)+f(2 x+y)+5 x y=f(3 x-y)+2 x^{2}+1

$$

for all real numbers $x, y$. Determine the value of $f(10)$.

|

$\quad-49$ Same as Algebra Test problem 4.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

In a triangle $A B C$, take point $D$ on $B C$ such that $D B=14, D A=13, D C=4$, and the circumcircle of $A D B$ is congruent to the circumcircle of $A D C$. What is the area of triangle $A B C$ ?

|

108 Same as Geometry Test problem 4.

|

108

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

In a triangle $A B C$, take point $D$ on $B C$ such that $D B=14, D A=13, D C=4$, and the circumcircle of $A D B$ is congruent to the circumcircle of $A D C$. What is the area of triangle $A B C$ ?

|

108 Same as Geometry Test problem 4.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n6. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

The equation $x^{3}-9 x^{2}+8 x+2=0$ has three real roots $p, q, r$. Find $\frac{1}{p^{2}}+\frac{1}{q^{2}}+\frac{1}{r^{2}}$.

|

25 From Vieta's relations, we have $p+q+r=9, p q+q r+p r=8$ and $p q r=-2$. So

$$

\frac{1}{p^{2}}+\frac{1}{q^{2}}+\frac{1}{r^{2}}=\frac{(p q+q r+r p)^{2}-2(p+q+r)(p q r)}{(p q r)^{2}}=\frac{8^{2}-2 \cdot 9 \cdot(-2)}{(-2)^{2}}=25

$$

|

25

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

The equation $x^{3}-9 x^{2}+8 x+2=0$ has three real roots $p, q, r$. Find $\frac{1}{p^{2}}+\frac{1}{q^{2}}+\frac{1}{r^{2}}$.

|

25 From Vieta's relations, we have $p+q+r=9, p q+q r+p r=8$ and $p q r=-2$. So

$$

\frac{1}{p^{2}}+\frac{1}{q^{2}}+\frac{1}{r^{2}}=\frac{(p q+q r+r p)^{2}-2(p+q+r)(p q r)}{(p q r)^{2}}=\frac{8^{2}-2 \cdot 9 \cdot(-2)}{(-2)^{2}}=25

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $S$ be the smallest subset of the integers with the property that $0 \in S$ and for any $x \in S$, we have $3 x \in S$ and $3 x+1 \in S$. Determine the number of positive integers in $S$ less than 2008.

|

127 Same as Combinatorics Problem 5.

|

127

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $S$ be the smallest subset of the integers with the property that $0 \in S$ and for any $x \in S$, we have $3 x \in S$ and $3 x+1 \in S$. Determine the number of positive integers in $S$ less than 2008.

|

127 Same as Combinatorics Problem 5.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

A Sudoku matrix is defined as a $9 \times 9$ array with entries from $\{1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ and with the constraint that each row, each column, and each of the nine $3 \times 3$ boxes that tile the array contains each digit from 1 to 9 exactly once. A Sudoku matrix is chosen at random (so that every Sudoku matrix has equal probability of being chosen). We know two of squares in this matrix, as shown. What is the probability that the square marked by ? contains the digit 3 ?

|

$\frac{2}{21}$ Same as Combinatorics Test problem 6.

|

\frac{2}{21}

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

A Sudoku matrix is defined as a $9 \times 9$ array with entries from $\{1,2, \ldots, 9\}$ and with the constraint that each row, each column, and each of the nine $3 \times 3$ boxes that tile the array contains each digit from 1 to 9 exactly once. A Sudoku matrix is chosen at random (so that every Sudoku matrix has equal probability of being chosen). We know two of squares in this matrix, as shown. What is the probability that the square marked by ? contains the digit 3 ?

|

$\frac{2}{21}$ Same as Combinatorics Test problem 6.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle with side length 2 , and let $\Gamma$ be a circle with radius $\frac{1}{2}$ centered at the center of the equilateral triangle. Determine the length of the shortest path that starts somewhere on $\Gamma$, visits all three sides of $A B C$, and ends somewhere on $\Gamma$ (not necessarily at the starting point). Express your answer in the form of $\sqrt{p}-q$, where $p$ and $q$ are rational numbers written as reduced fractions.

|

$\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1$ Same as Geometry Test problem 8.

|

\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle with side length 2 , and let $\Gamma$ be a circle with radius $\frac{1}{2}$ centered at the center of the equilateral triangle. Determine the length of the shortest path that starts somewhere on $\Gamma$, visits all three sides of $A B C$, and ends somewhere on $\Gamma$ (not necessarily at the starting point). Express your answer in the form of $\sqrt{p}-q$, where $p$ and $q$ are rational numbers written as reduced fractions.

|

$\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1$ Same as Geometry Test problem 8.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n10. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Four students from Harvard, one of them named Jack, and five students from MIT, one of them named Jill, are going to see a Boston Celtics game. However, they found out that only 5 tickets remain, so 4 of them must go back. Suppose that at least one student from each school must go see the game, and at least one of Jack and Jill must go see the game, how many ways are there of choosing which 5 people can see the game?

|

104 Let us count the number of way of distributing the tickets so that one of the conditions is violated. There is 1 way to give all the tickets to MIT students, and $\binom{7}{5}$ ways to give all the tickets to the 7 students other than Jack and Jill. Therefore, the total number of valid ways is $\binom{9}{5}-1-\binom{7}{5}=104$.

|

104

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Four students from Harvard, one of them named Jack, and five students from MIT, one of them named Jill, are going to see a Boston Celtics game. However, they found out that only 5 tickets remain, so 4 of them must go back. Suppose that at least one student from each school must go see the game, and at least one of Jack and Jill must go see the game, how many ways are there of choosing which 5 people can see the game?

|

104 Let us count the number of way of distributing the tickets so that one of the conditions is violated. There is 1 way to give all the tickets to MIT students, and $\binom{7}{5}$ ways to give all the tickets to the 7 students other than Jack and Jill. Therefore, the total number of valid ways is $\binom{9}{5}-1-\binom{7}{5}=104$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [2]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle. Let $\Omega$ be a circle inscribed in $A B C$ and let $\omega$ be a circle tangent externally to $\Omega$ as well as to sides $A B$ and $A C$. Determine the ratio of the radius of $\Omega$ to the radius of $\omega$.

|

3 Same as Geometry Test problem 2.

|

3

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle. Let $\Omega$ be a circle inscribed in $A B C$ and let $\omega$ be a circle tangent externally to $\Omega$ as well as to sides $A B$ and $A C$. Determine the ratio of the radius of $\Omega$ to the radius of $\omega$.

|

3 Same as Geometry Test problem 2.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [2]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

A $3 \times 3 \times 3$ cube composed of 27 unit cubes rests on a horizontal plane. Determine the number of ways of selecting two distinct unit cubes (order is irrelevant) from a $3 \times 3 \times 1$ block with the property that the line joining the centers of the two cubes makes a $45^{\circ}$ angle with the horizontal plane.

|

60 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 1.

|

60

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A $3 \times 3 \times 3$ cube composed of 27 unit cubes rests on a horizontal plane. Determine the number of ways of selecting two distinct unit cubes (order is irrelevant) from a $3 \times 3 \times 1$ block with the property that the line joining the centers of the two cubes makes a $45^{\circ}$ angle with the horizontal plane.

|

60 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 1.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Suppose that $a, b, c, d$ are real numbers satisfying $a \geq b \geq c \geq d \geq 0, a^{2}+d^{2}=1, b^{2}+c^{2}=1$, and $a c+b d=1 / 3$. Find the value of $a b-c d$.

|

$\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$ We have

$$

(a b-c d)^{2}=\left(a^{2}+d^{2}\right)\left(b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-(a c+b d)^{2}=(1)(1)-\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}=\frac{8}{9}

$$

Since $a \geq b \geq c \geq d \geq 0, a b-c d \geq 0$, so $a b-c d=\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$.

Comment: Another way to solve this problem is to use the trigonometric substitutions $a=\sin \theta$, $b=\sin \phi, c=\cos \phi, d=\cos \theta$.

|

\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Suppose that $a, b, c, d$ are real numbers satisfying $a \geq b \geq c \geq d \geq 0, a^{2}+d^{2}=1, b^{2}+c^{2}=1$, and $a c+b d=1 / 3$. Find the value of $a b-c d$.

|

$\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$ We have

$$

(a b-c d)^{2}=\left(a^{2}+d^{2}\right)\left(b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-(a c+b d)^{2}=(1)(1)-\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)^{2}=\frac{8}{9}

$$

Since $a \geq b \geq c \geq d \geq 0, a b-c d \geq 0$, so $a b-c d=\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3}$.

Comment: Another way to solve this problem is to use the trigonometric substitutions $a=\sin \theta$, $b=\sin \phi, c=\cos \phi, d=\cos \theta$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Kermit the frog enjoys hopping around the infinite square grid in his backyard. It takes him 1 Joule of energy to hop one step north or one step south, and 1 Joule of energy to hop one step east or one step west. He wakes up one morning on the grid with 100 Joules of energy, and hops till he falls asleep with 0 energy. How many different places could he have gone to sleep?

|

10201 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 4.

|

10201

|

Yes

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Kermit the frog enjoys hopping around the infinite square grid in his backyard. It takes him 1 Joule of energy to hop one step north or one step south, and 1 Joule of energy to hop one step east or one step west. He wakes up one morning on the grid with 100 Joules of energy, and hops till he falls asleep with 0 energy. How many different places could he have gone to sleep?

|

10201 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 4.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Determine all real numbers $a$ such that the inequality $\left|x^{2}+2 a x+3 a\right| \leq 2$ has exactly one solution in $x$.

|

1,2 Same as Algebra Test problem 3.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Determine all real numbers $a$ such that the inequality $\left|x^{2}+2 a x+3 a\right| \leq 2$ has exactly one solution in $x$.

|

1,2 Same as Algebra Test problem 3.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

A root of unity is a complex number that is a solution to $z^{n}=1$ for some positive integer $n$. Determine the number of roots of unity that are also roots of $z^{2}+a z+b=0$ for some integers $a$ and $b$.

|

8 Same as Algebra Test problem 6.

|

8

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

A root of unity is a complex number that is a solution to $z^{n}=1$ for some positive integer $n$. Determine the number of roots of unity that are also roots of $z^{2}+a z+b=0$ for some integers $a$ and $b$.

|

8 Same as Algebra Test problem 6.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

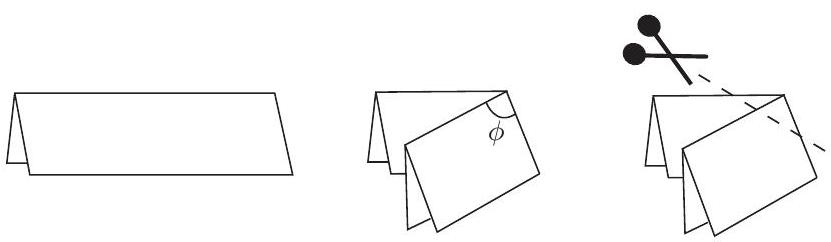

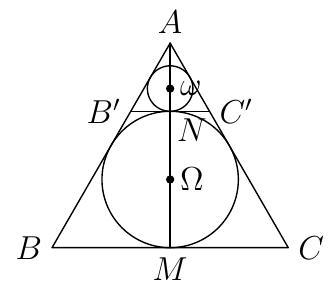

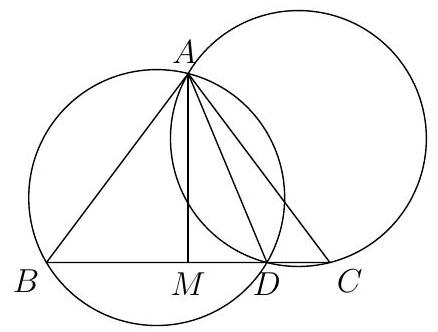

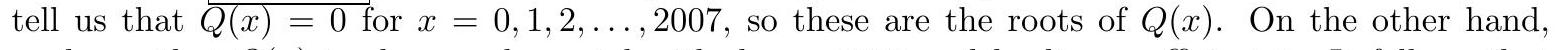

A piece of paper is folded in half. A second fold is made such that the angle marked below has measure $\phi\left(0^{\circ}<\phi<90^{\circ}\right)$, and a cut is made as shown below.

When the piece of paper is unfolded, the resulting hole is a polygon. Let $O$ be one of its vertices. Suppose that all the other vertices of the hole lie on a circle centered at $O$, and also that $\angle X O Y=144^{\circ}$, where $X$ and $Y$ are the the vertices of the hole adjacent to $O$. Find the value(s) of $\phi$ (in degrees).

|

$81^{\circ}$ Same as Geometry Test problem 5.

|

81^{\circ}

|

Incomplete

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A piece of paper is folded in half. A second fold is made such that the angle marked below has measure $\phi\left(0^{\circ}<\phi<90^{\circ}\right)$, and a cut is made as shown below.

When the piece of paper is unfolded, the resulting hole is a polygon. Let $O$ be one of its vertices. Suppose that all the other vertices of the hole lie on a circle centered at $O$, and also that $\angle X O Y=144^{\circ}$, where $X$ and $Y$ are the the vertices of the hole adjacent to $O$. Find the value(s) of $\phi$ (in degrees).

|

$81^{\circ}$ Same as Geometry Test problem 5.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

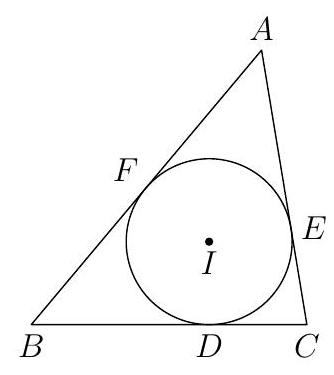

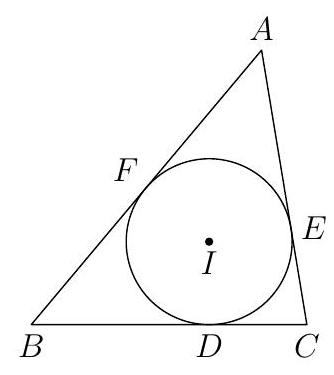

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, and $I$ its incenter. Let the incircle of $A B C$ touch side $B C$ at $D$, and let lines $B I$ and $C I$ meet the circle with diameter $A I$ at points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. Given $B I=$ $6, C I=5, D I=3$, determine the value of $(D P / D Q)^{2}$.

|

$\frac{75}{64}$ Same as Geometry Test problem 9.

|

\frac{75}{64}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, and $I$ its incenter. Let the incircle of $A B C$ touch side $B C$ at $D$, and let lines $B I$ and $C I$ meet the circle with diameter $A I$ at points $P$ and $Q$, respectively. Given $B I=$ $6, C I=5, D I=3$, determine the value of $(D P / D Q)^{2}$.

|

$\frac{75}{64}$ Same as Geometry Test problem 9.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Determine the number of 8-tuples of nonnegative integers ( $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, b_{1}, b_{2}, b_{3}, b_{4}$ ) satisfying $0 \leq$ $a_{k} \leq k$, for each $k=1,2,3,4$, and $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{4}+2 b_{1}+3 b_{2}+4 b_{3}+5 b_{4}=19$.

|

1540 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 10.

|

1540

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Determine the number of 8-tuples of nonnegative integers ( $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, a_{4}, b_{1}, b_{2}, b_{3}, b_{4}$ ) satisfying $0 \leq$ $a_{k} \leq k$, for each $k=1,2,3,4$, and $a_{1}+a_{2}+a_{3}+a_{4}+2 b_{1}+3 b_{2}+4 b_{3}+5 b_{4}=19$.

|

1540 Same as Combinatorics Test problem 10.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-gen2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

How many different values can $\angle A B C$ take, where $A, B, C$ are distinct vertices of a cube?

|

5 . In a unit cube, there are 3 types of triangles, with side lengths $(1,1, \sqrt{2}),(1, \sqrt{2}, \sqrt{3})$ and $(\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2})$. Together they generate 5 different angle values.

|

5

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

How many different values can $\angle A B C$ take, where $A, B, C$ are distinct vertices of a cube?

|

5 . In a unit cube, there are 3 types of triangles, with side lengths $(1,1, \sqrt{2}),(1, \sqrt{2}, \sqrt{3})$ and $(\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2})$. Together they generate 5 different angle values.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

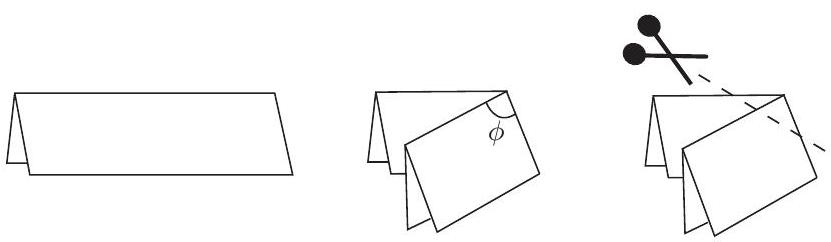

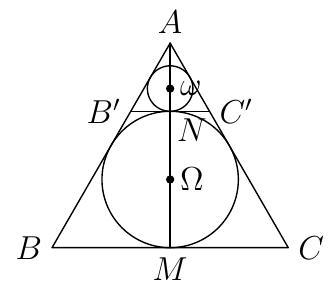

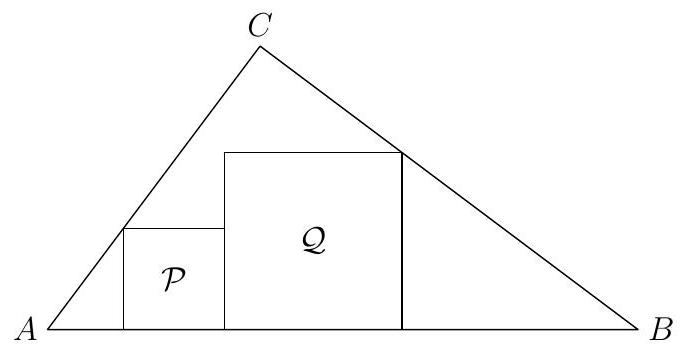

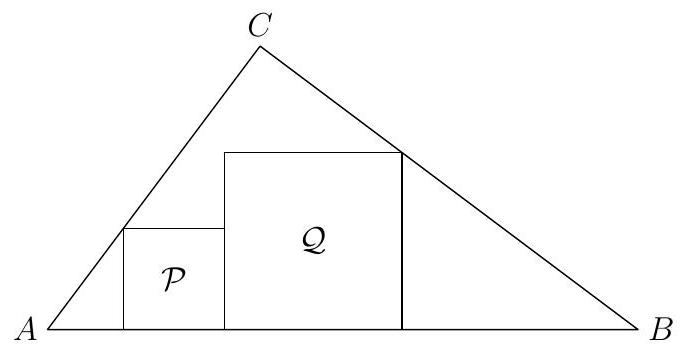

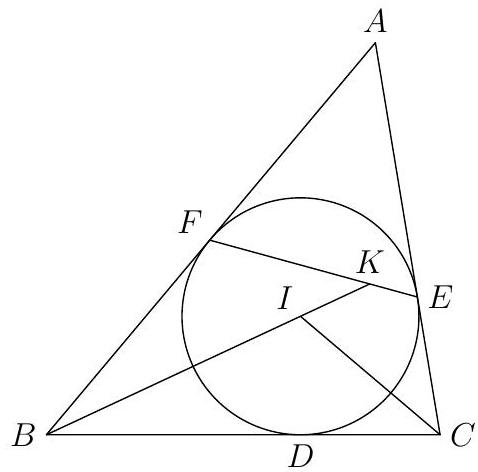

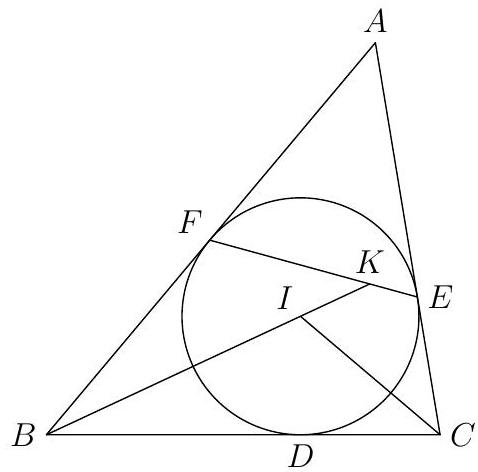

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle. Let $\Omega$ be its incircle (circle inscribed in the triangle) and let $\omega$ be a circle tangent externally to $\Omega$ as well as to sides $A B$ and $A C$. Determine the ratio of the radius of $\Omega$ to the radius of $\omega$.

|

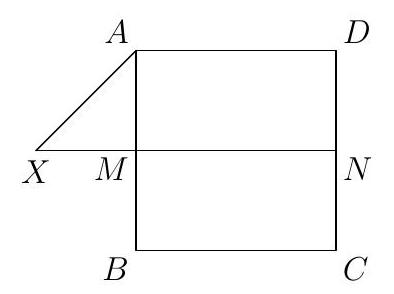

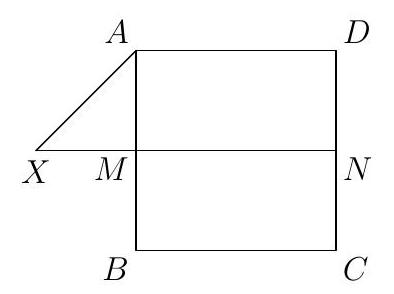

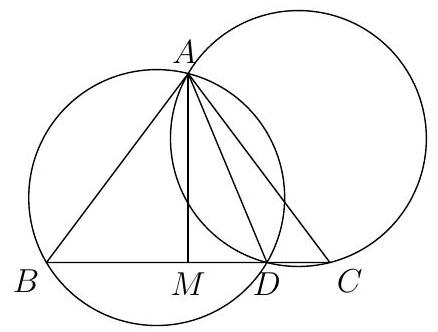

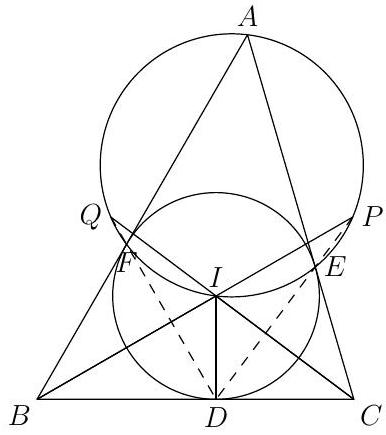

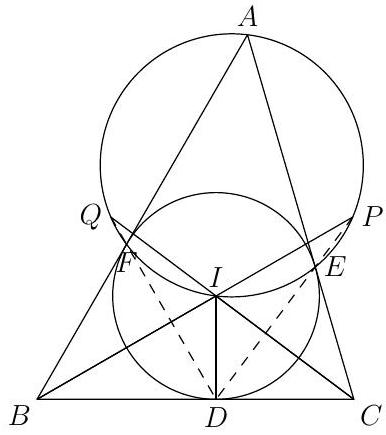

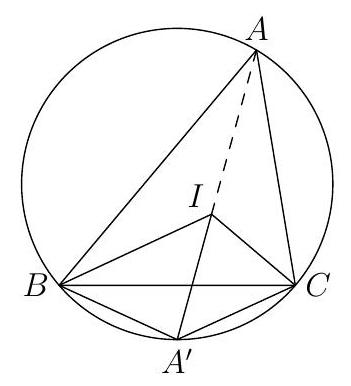

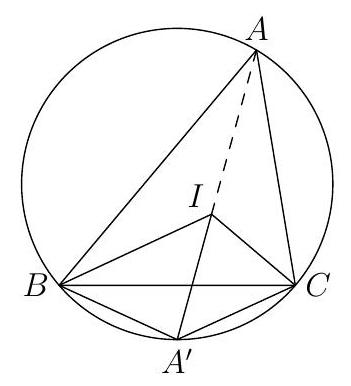

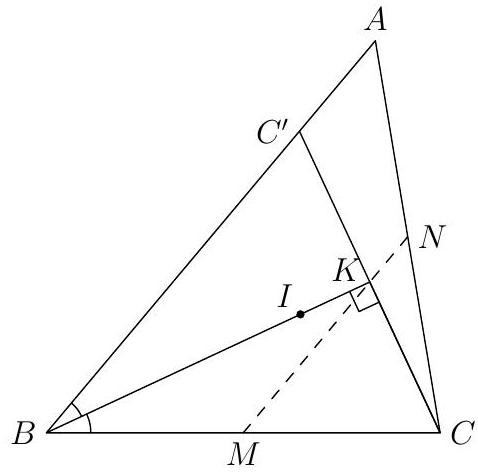

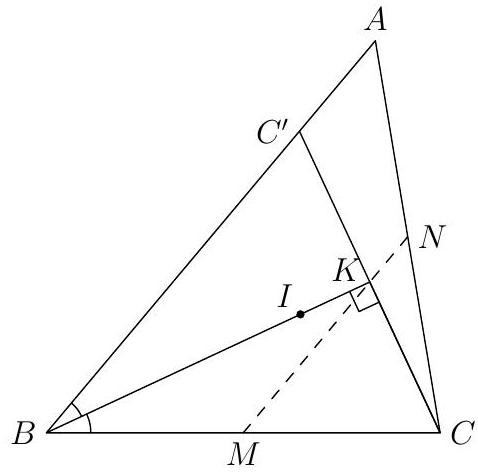

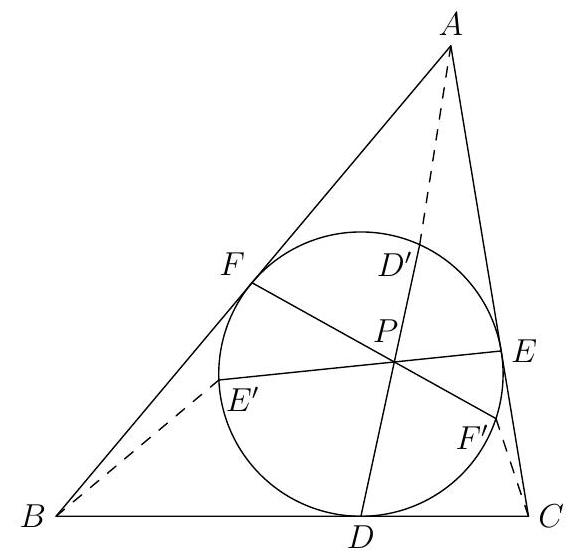

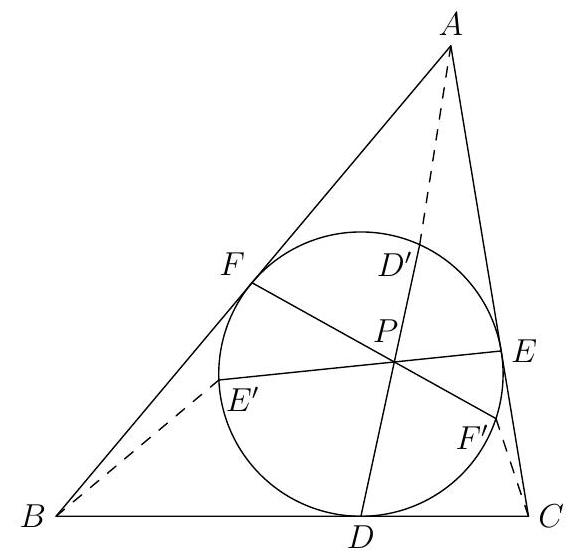

$\quad 3$ Label the diagram as shown below, where $\Omega$ and $\omega$ also denote the center of the corresponding circles. Note that $A M$ is a median and $\Omega$ is the centroid of the equilateral triangle. So $A M=3 M \Omega$. Since $M \Omega=N \Omega$, it follows that $A M / A N=3$, and triangle $A B C$ is the image of triangle $A B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ after a scaling by a factor of 3 , and so the two incircles must also be related by a scale factor of 3 .

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle. Let $\Omega$ be its incircle (circle inscribed in the triangle) and let $\omega$ be a circle tangent externally to $\Omega$ as well as to sides $A B$ and $A C$. Determine the ratio of the radius of $\Omega$ to the radius of $\omega$.

|

$\quad 3$ Label the diagram as shown below, where $\Omega$ and $\omega$ also denote the center of the corresponding circles. Note that $A M$ is a median and $\Omega$ is the centroid of the equilateral triangle. So $A M=3 M \Omega$. Since $M \Omega=N \Omega$, it follows that $A M / A N=3$, and triangle $A B C$ is the image of triangle $A B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ after a scaling by a factor of 3 , and so the two incircles must also be related by a scale factor of 3 .

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. [3]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

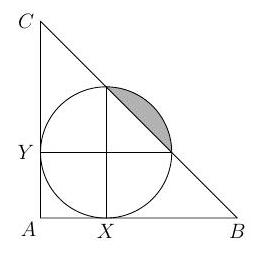

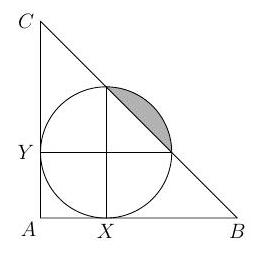

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle B A C=90^{\circ}$. A circle is tangent to the sides $A B$ and $A C$ at $X$ and $Y$ respectively, such that the points on the circle diametrically opposite $X$ and $Y$ both lie on the side $B C$. Given that $A B=6$, find the area of the portion of the circle that lies outside the triangle.

|

$\pi-2$ Let $O$ be the center of the circle, and $r$ its radius, and let $X^{\prime}$ and $Y^{\prime}$ be the points diametrically opposite $X$ and $Y$, respectively. We have $O X^{\prime}=O Y^{\prime}=r$, and $\angle X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}=90^{\circ}$. Since triangles $X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}$ and $B A C$ are similar, we see that $A B=A C$. Let $X^{\prime \prime}$ be the projection of $Y^{\prime}$ onto $A B$. Since $X^{\prime \prime} B Y^{\prime}$ is similar to $A B C$, and $X^{\prime \prime} Y^{\prime}=r$, we have $X^{\prime \prime} B=r$. It follows that $A B=3 r$, so $r=2$.

Then, the desired area is the area of the quarter circle minus that of the triangle $X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}$. And the answer is $\frac{1}{4} \pi r^{2}-\frac{1}{2} r^{2}=\pi-2$.

|

\pi-2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle B A C=90^{\circ}$. A circle is tangent to the sides $A B$ and $A C$ at $X$ and $Y$ respectively, such that the points on the circle diametrically opposite $X$ and $Y$ both lie on the side $B C$. Given that $A B=6$, find the area of the portion of the circle that lies outside the triangle.

|

$\pi-2$ Let $O$ be the center of the circle, and $r$ its radius, and let $X^{\prime}$ and $Y^{\prime}$ be the points diametrically opposite $X$ and $Y$, respectively. We have $O X^{\prime}=O Y^{\prime}=r$, and $\angle X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}=90^{\circ}$. Since triangles $X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}$ and $B A C$ are similar, we see that $A B=A C$. Let $X^{\prime \prime}$ be the projection of $Y^{\prime}$ onto $A B$. Since $X^{\prime \prime} B Y^{\prime}$ is similar to $A B C$, and $X^{\prime \prime} Y^{\prime}=r$, we have $X^{\prime \prime} B=r$. It follows that $A B=3 r$, so $r=2$.

Then, the desired area is the area of the quarter circle minus that of the triangle $X^{\prime} O Y^{\prime}$. And the answer is $\frac{1}{4} \pi r^{2}-\frac{1}{2} r^{2}=\pi-2$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

In a triangle $A B C$, take point $D$ on $B C$ such that $D B=14, D A=13, D C=4$, and the circumcircle of $A D B$ is congruent to the circumcircle of $A D C$. What is the area of triangle $A B C$ ?

|

108

The fact that the two circumcircles are congruent means that the chord $A D$ must subtend the same angle in both circles. That is, $\angle A B C=\angle A C B$, so $A B C$ is isosceles. Drop the perpendicular $M$ from $A$ to $B C$; we know $M C=9$ and so $M D=5$ and by Pythagoras on $A M D, A M=12$. Therefore, the area of $A B C$ is $\frac{1}{2}(A M)(B C)=\frac{1}{2}(12)(18)=108$.

|

108

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

In a triangle $A B C$, take point $D$ on $B C$ such that $D B=14, D A=13, D C=4$, and the circumcircle of $A D B$ is congruent to the circumcircle of $A D C$. What is the area of triangle $A B C$ ?

|

108

The fact that the two circumcircles are congruent means that the chord $A D$ must subtend the same angle in both circles. That is, $\angle A B C=\angle A C B$, so $A B C$ is isosceles. Drop the perpendicular $M$ from $A$ to $B C$; we know $M C=9$ and so $M D=5$ and by Pythagoras on $A M D, A M=12$. Therefore, the area of $A B C$ is $\frac{1}{2}(A M)(B C)=\frac{1}{2}(12)(18)=108$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. [4]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

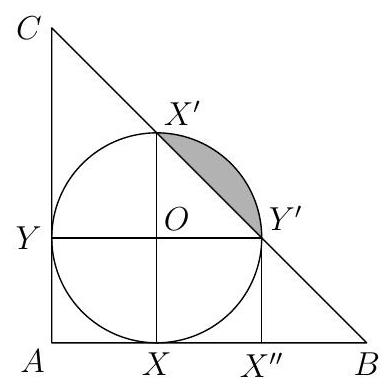

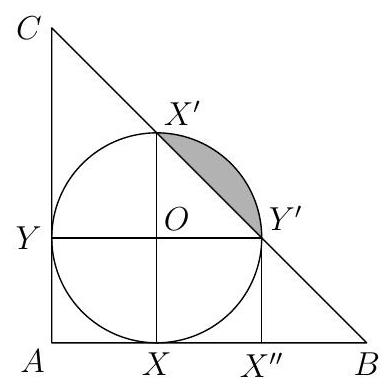

A piece of paper is folded in half. A second fold is made such that the angle marked below has measure $\phi\left(0^{\circ}<\phi<90^{\circ}\right)$, and a cut is made as shown below.

When the piece of paper is unfolded, the resulting hole is a polygon. Let $O$ be one of its vertices. Suppose that all the other vertices of the hole lie on a circle centered at $O$, and also that $\angle X O Y=144^{\circ}$, where $X$ and $Y$ are the the vertices of the hole adjacent to $O$. Find the value(s) of $\phi$ (in degrees).

|

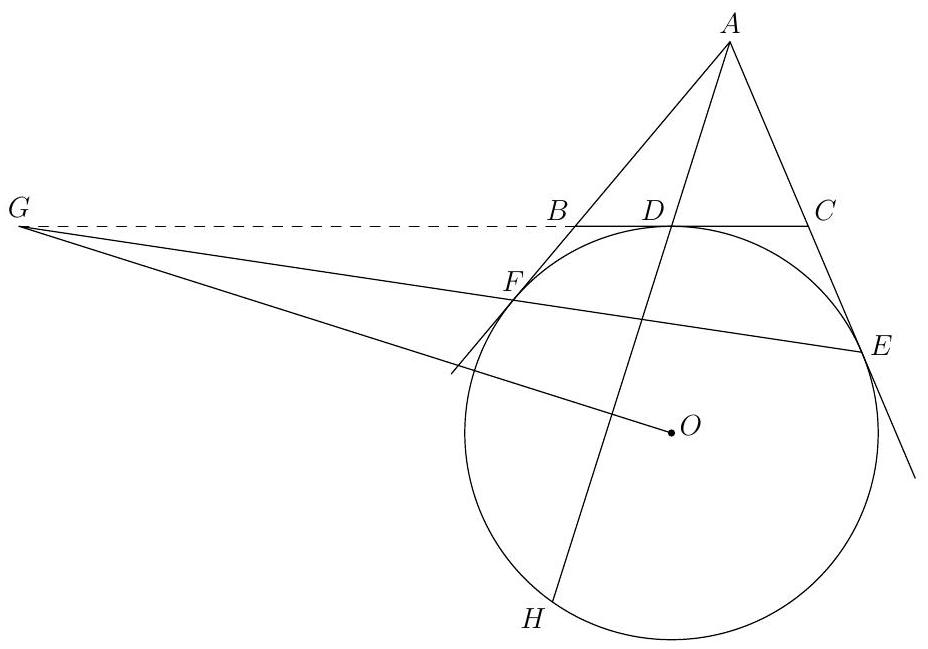

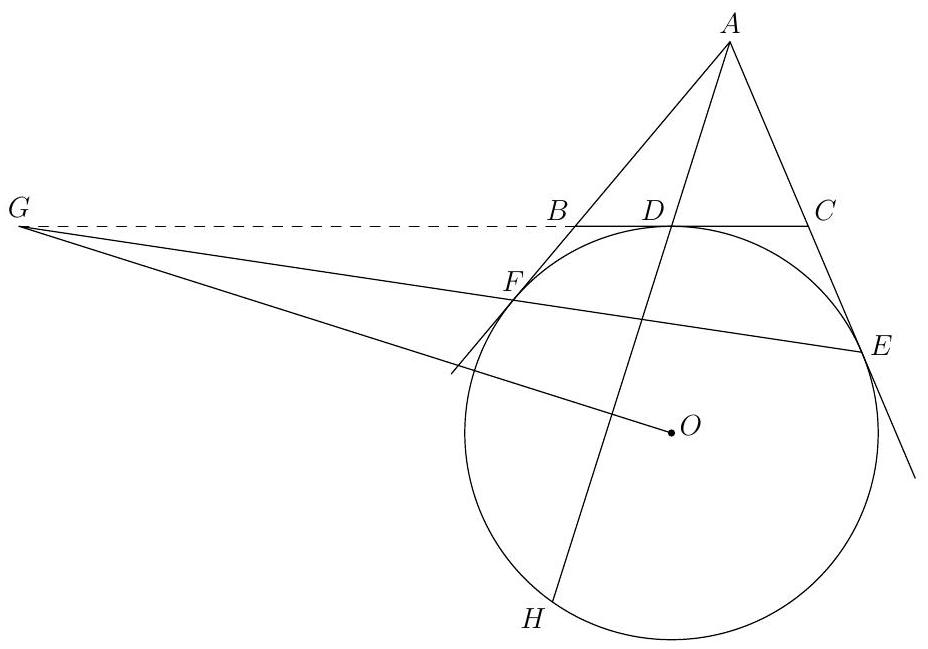

$81^{\circ}$ Try actually folding a piece of paper. We see that the cut out area is a kite, as shown below. The fold was made on $A C$, and then $B E$ and $D E$. Since $D C$ was folded onto $D A$, we have $\angle A D E=\angle C D E$.

Either $A$ or $C$ is the center of the circle. If it's $A$, then $\angle B A D=144^{\circ}$, so $\angle C A D=72^{\circ}$. Using $C A=D A$, we see that $\angle A C D=\angle A D C=54^{\circ}$. So $\angle E D A=27^{\circ}$, and thus $\phi=72^{\circ}+27^{\circ}=99^{\circ}$, which is inadmissible, as $\phi<90^{\circ}$.

So $C$ is the center of the circle. Then, $\angle C A D=\angle C D A=54^{\circ}, \angle A D E=27^{\circ}$, and $\phi=54^{\circ}+27^{\circ}=81^{\circ}$.

|

81^{\circ}

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A piece of paper is folded in half. A second fold is made such that the angle marked below has measure $\phi\left(0^{\circ}<\phi<90^{\circ}\right)$, and a cut is made as shown below.

When the piece of paper is unfolded, the resulting hole is a polygon. Let $O$ be one of its vertices. Suppose that all the other vertices of the hole lie on a circle centered at $O$, and also that $\angle X O Y=144^{\circ}$, where $X$ and $Y$ are the the vertices of the hole adjacent to $O$. Find the value(s) of $\phi$ (in degrees).

|

$81^{\circ}$ Try actually folding a piece of paper. We see that the cut out area is a kite, as shown below. The fold was made on $A C$, and then $B E$ and $D E$. Since $D C$ was folded onto $D A$, we have $\angle A D E=\angle C D E$.

Either $A$ or $C$ is the center of the circle. If it's $A$, then $\angle B A D=144^{\circ}$, so $\angle C A D=72^{\circ}$. Using $C A=D A$, we see that $\angle A C D=\angle A D C=54^{\circ}$. So $\angle E D A=27^{\circ}$, and thus $\phi=72^{\circ}+27^{\circ}=99^{\circ}$, which is inadmissible, as $\phi<90^{\circ}$.

So $C$ is the center of the circle. Then, $\angle C A D=\angle C D A=54^{\circ}, \angle A D E=27^{\circ}$, and $\phi=54^{\circ}+27^{\circ}=81^{\circ}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle A=45^{\circ}$. Let $P$ be a point on side $B C$ with $P B=3$ and $P C=5$. Let $O$ be the circumcenter of $A B C$. Determine the length $O P$.

|

$\sqrt{\sqrt{17}}$ Using extended Sine law, we find the circumradius of $A B C$ to be $R=\frac{B C}{2 \sin A}=4 \sqrt{2}$. By considering the power of point $P$, we find that $R^{2}-O P^{2}=P B \cdot P C=15$. So $O P=\sqrt{R^{2}-15}=$ $\sqrt{16 \cdot 2-15}=\sqrt{17}$.

|

\sqrt{17}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle A=45^{\circ}$. Let $P$ be a point on side $B C$ with $P B=3$ and $P C=5$. Let $O$ be the circumcenter of $A B C$. Determine the length $O P$.

|

$\sqrt{\sqrt{17}}$ Using extended Sine law, we find the circumradius of $A B C$ to be $R=\frac{B C}{2 \sin A}=4 \sqrt{2}$. By considering the power of point $P$, we find that $R^{2}-O P^{2}=P B \cdot P C=15$. So $O P=\sqrt{R^{2}-15}=$ $\sqrt{16 \cdot 2-15}=\sqrt{17}$.

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6. [5]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

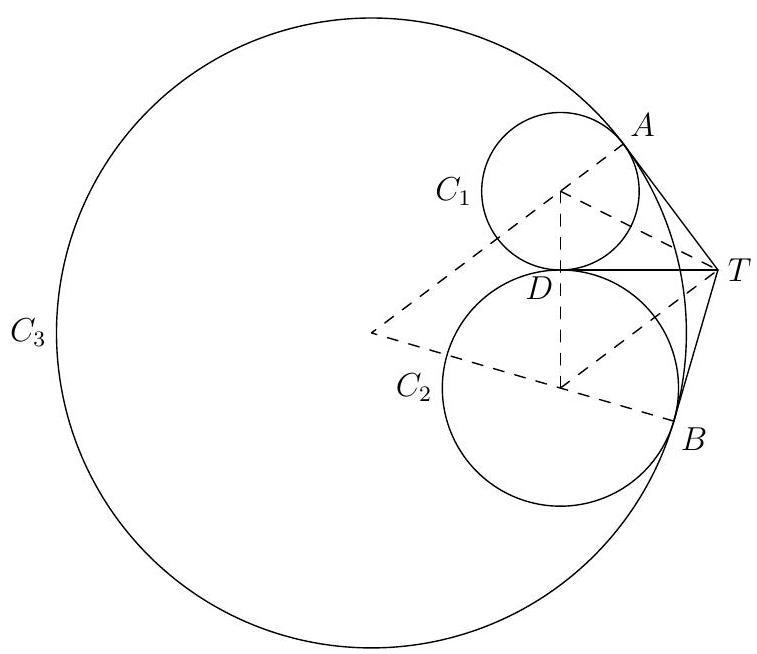

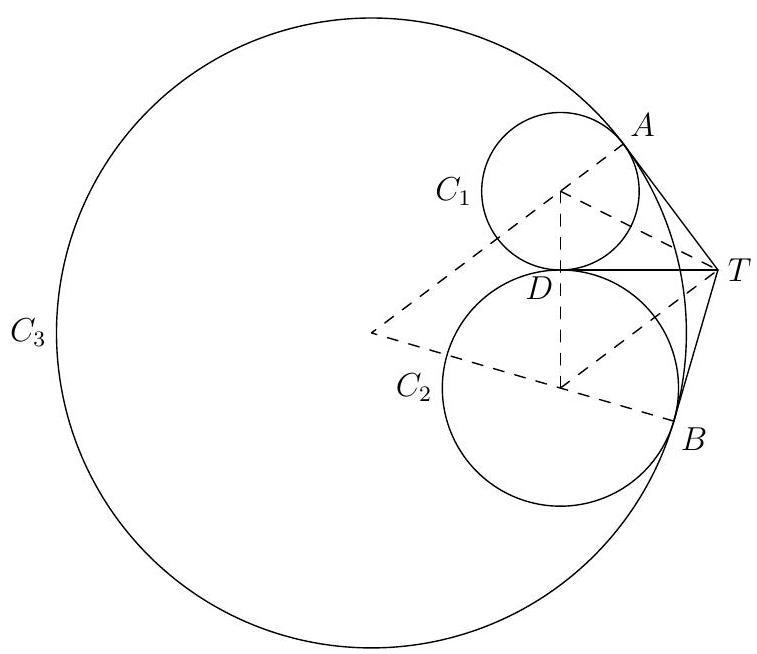

Let $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ be externally tangent circles with radius 2 and 3 , respectively. Let $C_{3}$ be a circle internally tangent to both $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ at points $A$ and $B$, respectively. The tangents to $C_{3}$ at $A$ and $B$ meet at $T$, and $T A=4$. Determine the radius of $C_{3}$.

|

8 Let $D$ be the point of tangency between $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$. We see that $T$ is the radical center of the three circles, and so it must lie on the radical axis of $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$, which happens to be their common tangent $T D$. So $T D=4$.

We have

$$

\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2}=\frac{2}{T D}=\frac{1}{2}, \quad \text { and } \quad \tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}=\frac{3}{T D}=\frac{3}{4} .

$$

Thus, the radius of $C_{3}$ equals to

$$

\begin{aligned}

T A \tan \frac{\angle A T B}{2} & =4 \tan \left(\frac{\angle A T D+\angle B T D}{2}\right) \\

& =4 \cdot \frac{\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2}+\tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}}{1-\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2} \tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}} \\

& =4 \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{2}+\frac{3}{4}}{1-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4}} \\

& =8 .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

8

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ be externally tangent circles with radius 2 and 3 , respectively. Let $C_{3}$ be a circle internally tangent to both $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ at points $A$ and $B$, respectively. The tangents to $C_{3}$ at $A$ and $B$ meet at $T$, and $T A=4$. Determine the radius of $C_{3}$.

|

8 Let $D$ be the point of tangency between $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$. We see that $T$ is the radical center of the three circles, and so it must lie on the radical axis of $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$, which happens to be their common tangent $T D$. So $T D=4$.

We have

$$

\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2}=\frac{2}{T D}=\frac{1}{2}, \quad \text { and } \quad \tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}=\frac{3}{T D}=\frac{3}{4} .

$$

Thus, the radius of $C_{3}$ equals to

$$

\begin{aligned}

T A \tan \frac{\angle A T B}{2} & =4 \tan \left(\frac{\angle A T D+\angle B T D}{2}\right) \\

& =4 \cdot \frac{\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2}+\tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}}{1-\tan \frac{\angle A T D}{2} \tan \frac{\angle B T D}{2}} \\

& =4 \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{2}+\frac{3}{4}}{1-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4}} \\

& =8 .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "HMMT",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7. [6]",

"resource_path": "HarvardMIT/segmented/en-112-2008-feb-geo-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nAnswer: ",

"tier": "T4",

"year": "2008"

}

|

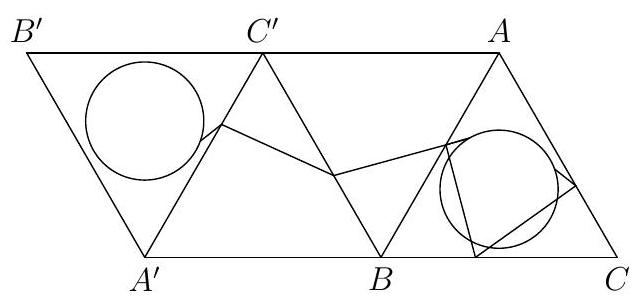

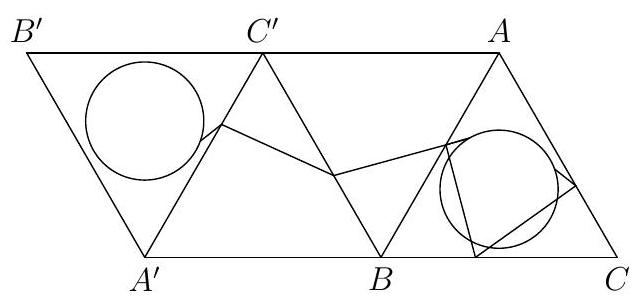

Let $A B C$ be an equilateral triangle with side length 2 , and let $\Gamma$ be a circle with radius $\frac{1}{2}$ centered at the center of the equilateral triangle. Determine the length of the shortest path that starts somewhere on $\Gamma$, visits all three sides of $A B C$, and ends somewhere on $\Gamma$ (not necessarily at the starting point). Express your answer in the form of $\sqrt{p}-q$, where $p$ and $q$ are rational numbers written as reduced fractions.

|

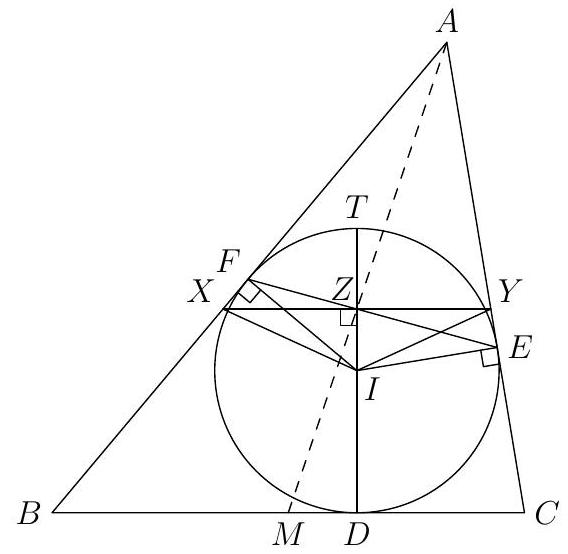

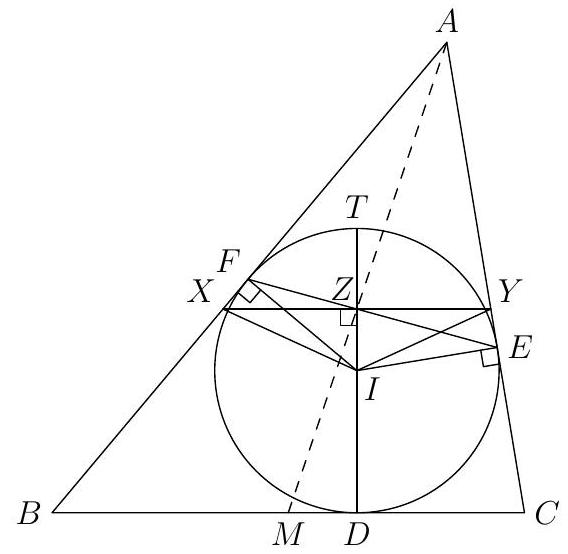

$\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1$ Suppose that the path visits sides $A B, B C, C A$ in this order. Construct points $A^{\prime}, B^{\prime}, C^{\prime}$ so that $C^{\prime}$ is the reflection of $C$ across $A B, A^{\prime}$ is the reflection of $A$ across $B C^{\prime}$, and $B^{\prime}$ is the reflection of $B$ across $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. Finally, let $\Gamma^{\prime}$ be the circle with radius $\frac{1}{2}$ centered at the center of $A^{\prime} B^{\prime} C^{\prime}$. Note that $\Gamma^{\prime}$ is the image of $\Gamma$ after the three reflections: $A B, B C^{\prime}, C^{\prime} A^{\prime}$.

When the path hits $A B$, let us reflect the rest of the path across $A B$ and follow this reflected path. When we hit $B C^{\prime}$, let us reflect the rest of the path across $B C^{\prime}$, and follow the new path. And when we hit $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$, reflect the rest of the path across $A^{\prime} C^{\prime}$ and follow the new path. We must eventually end up at $\Gamma^{\prime}$.

It is easy to see that the shortest path connecting some point on $\Gamma$ to some point on $\Gamma^{\prime}$ lies on the line connecting the centers of the two circles. We can easily find the distance between the two centers to be $\sqrt{3^{2}+\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)^{2}}=\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}$. Therefore, the length of the shortest path connecting $\Gamma$ to $\Gamma^{\prime}$ has length $\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1$. By reflecting this path three times back into $A B C$, we get a path that satisfies our conditions.

|

\sqrt{\frac{28}{3}}-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|