problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$ such that $A B<A C$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ of $\omega$ containing the point $A$, and let $X \neq M$ be the other point on $\omega$ such that $A X=A M$. Points $E$ and $F$ are chosen on sides $A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle $A B C$, respectively, such that $E X=E C$ and $F X=F B$. Prove that $A E=A F$.

|

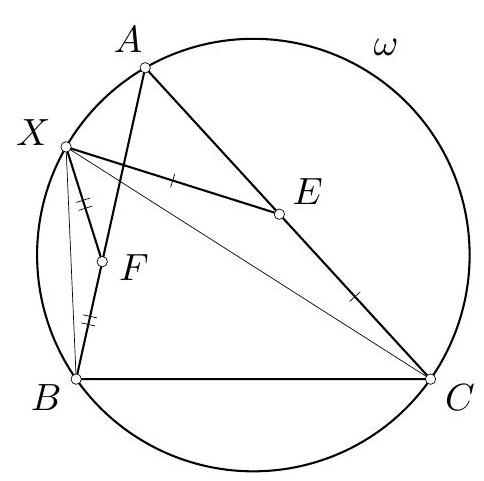

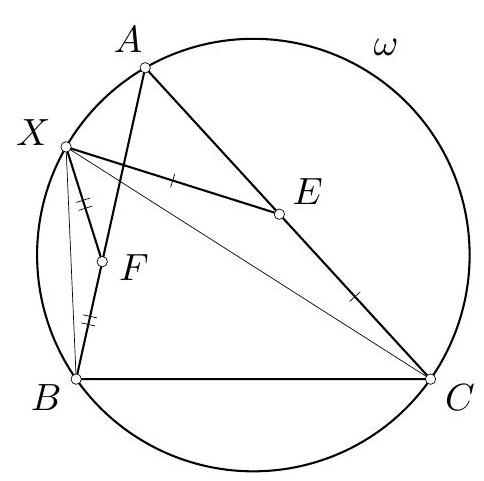

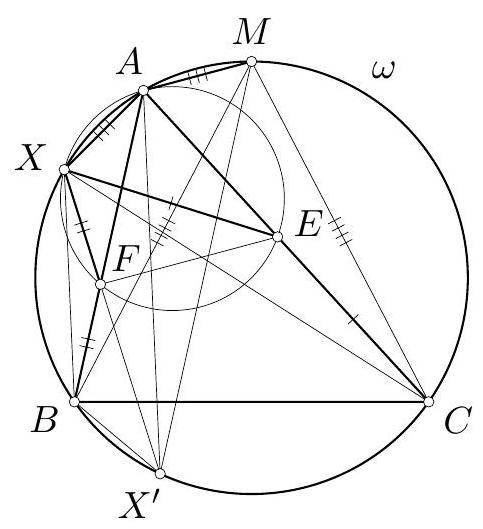

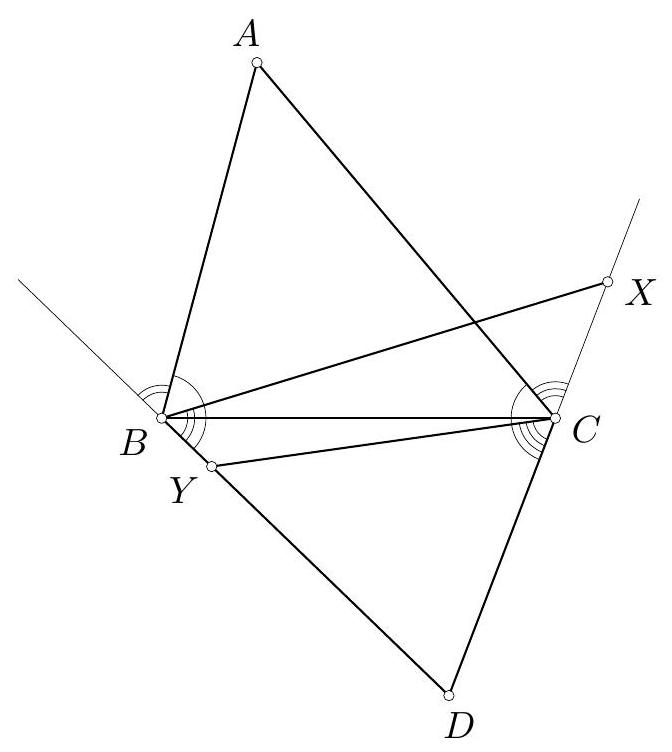

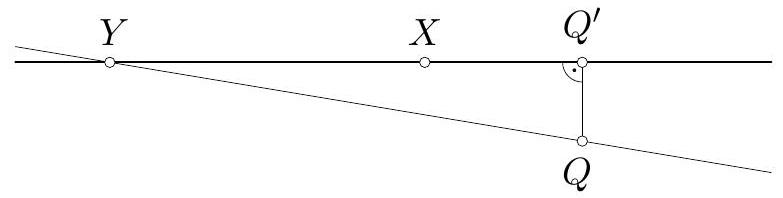

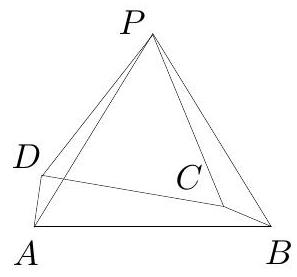

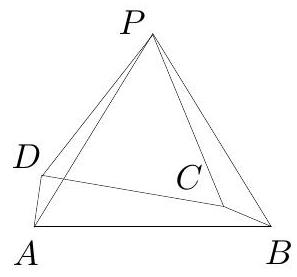

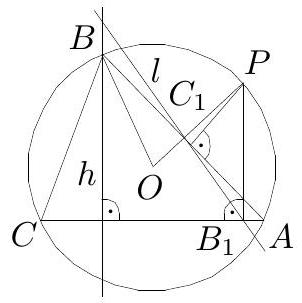

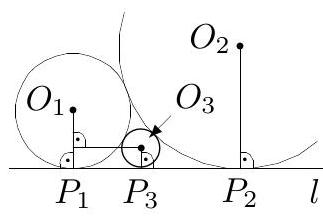

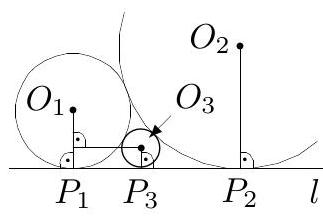

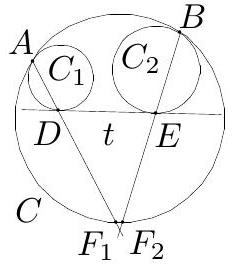

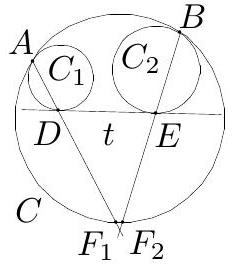

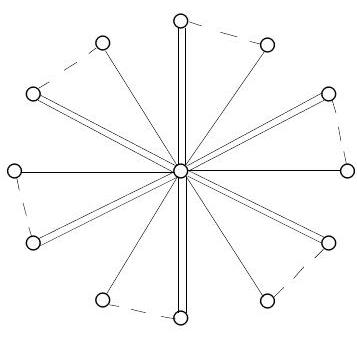

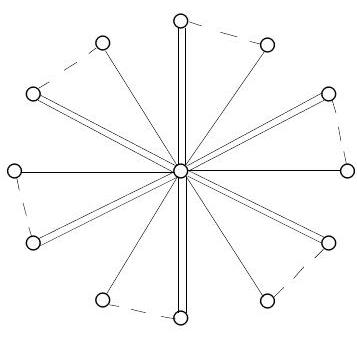

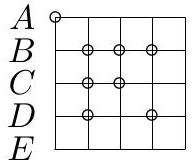

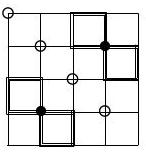

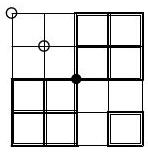

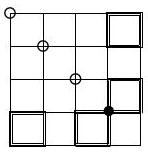

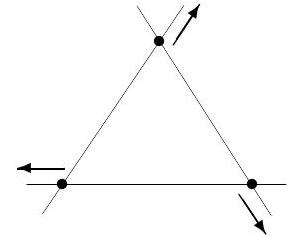

Triangles $X F B$ and $X E C$ are isosceles (Fig. 12). Note that $X$ lies on the shorter arc $A B$ of $\omega$ since otherwise the perpendicular bisector of $B X$ could not intersect side $A B$. Hence $\angle X B F=\angle X B A=\angle X C A=\angle X C E$ which implies that triangles $X F B$ and $X E C$ are similar. Therefore $\angle X F A=\angle X E A$. Hence $A E F X$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.

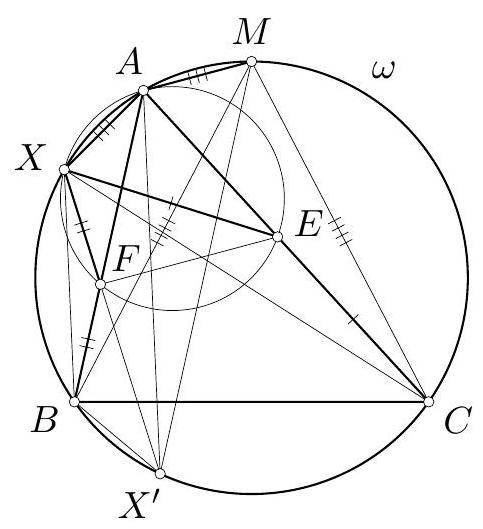

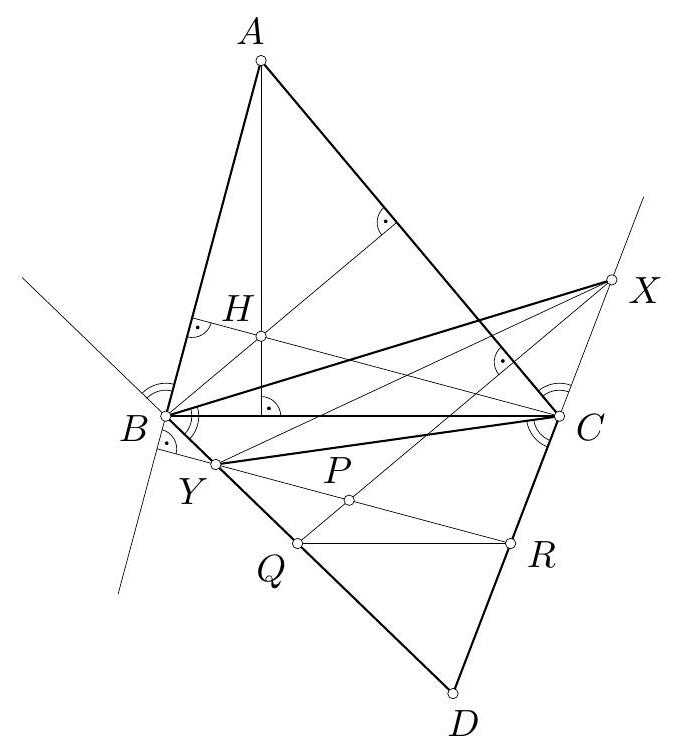

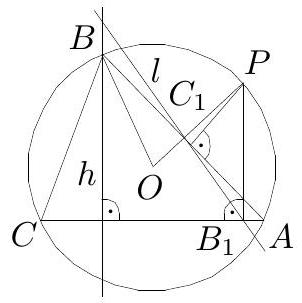

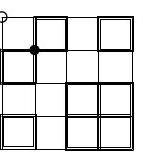

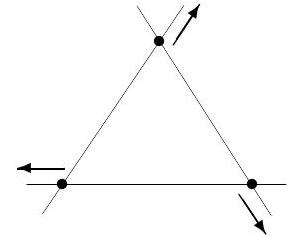

Let $X F$ intersect $\omega$ again at $X^{\prime} \neq X$ (Fig. 13). By $\angle B X X^{\prime}=\angle B X F=\angle X B F=\angle X B A$, arcs $B X^{\prime}$ and $A X$ of $\omega$ are equal, i.e. $B X^{\prime}=A X$. Since $A X=A M$, it follows that $B X^{\prime}=A M$. So $A B X^{\prime} M$ is an isosceles trapezoid which implies also $A X^{\prime}=B M$, i.e. arcs $A X^{\prime}$ and $B M$ of $\omega$ are equal. Therefore

$$

\angle A E F=180^{\circ}-\angle A X F=180^{\circ}-\angle A X X^{\prime}=180^{\circ}-\angle M A B=\angle M C B .

$$

By considering the second intersection point of $X E$ with $\omega$, we can analgously prove the equality $\angle E F A=\angle C B M$. Since arcs $M B$ and $M C$ of $\omega$ are equal, $\angle M C B=\angle C B M$, so $\angle A E F=\angle E F A$. Hence $A E=A F$, as desired.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$ such that $A B<A C$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ of $\omega$ containing the point $A$, and let $X \neq M$ be the other point on $\omega$ such that $A X=A M$. Points $E$ and $F$ are chosen on sides $A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle $A B C$, respectively, such that $E X=E C$ and $F X=F B$. Prove that $A E=A F$.

|

Triangles $X F B$ and $X E C$ are isosceles (Fig. 12). Note that $X$ lies on the shorter arc $A B$ of $\omega$ since otherwise the perpendicular bisector of $B X$ could not intersect side $A B$. Hence $\angle X B F=\angle X B A=\angle X C A=\angle X C E$ which implies that triangles $X F B$ and $X E C$ are similar. Therefore $\angle X F A=\angle X E A$. Hence $A E F X$ is a cyclic quadrilateral.

Let $X F$ intersect $\omega$ again at $X^{\prime} \neq X$ (Fig. 13). By $\angle B X X^{\prime}=\angle B X F=\angle X B F=\angle X B A$, arcs $B X^{\prime}$ and $A X$ of $\omega$ are equal, i.e. $B X^{\prime}=A X$. Since $A X=A M$, it follows that $B X^{\prime}=A M$. So $A B X^{\prime} M$ is an isosceles trapezoid which implies also $A X^{\prime}=B M$, i.e. arcs $A X^{\prime}$ and $B M$ of $\omega$ are equal. Therefore

$$

\angle A E F=180^{\circ}-\angle A X F=180^{\circ}-\angle A X X^{\prime}=180^{\circ}-\angle M A B=\angle M C B .

$$

By considering the second intersection point of $X E$ with $\omega$, we can analgously prove the equality $\angle E F A=\angle C B M$. Since arcs $M B$ and $M C$ of $\omega$ are equal, $\angle M C B=\angle C B M$, so $\angle A E F=\angle E F A$. Hence $A E=A F$, as desired.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$ such that $A B<A C$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ of $\omega$ containing the point $A$, and let $X \neq M$ be the other point on $\omega$ such that $A X=A M$. Points $E$ and $F$ are chosen on sides $A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle $A B C$, respectively, such that $E X=E C$ and $F X=F B$. Prove that $A E=A F$.

|

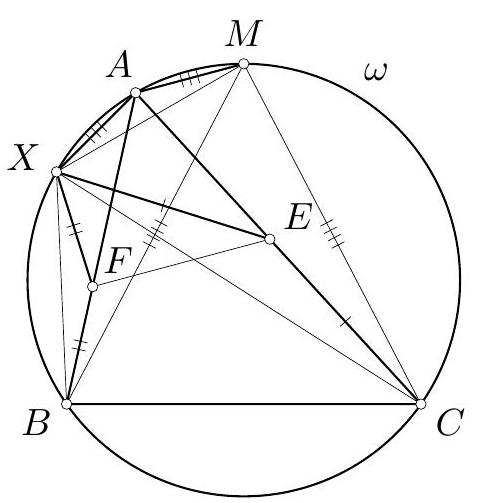

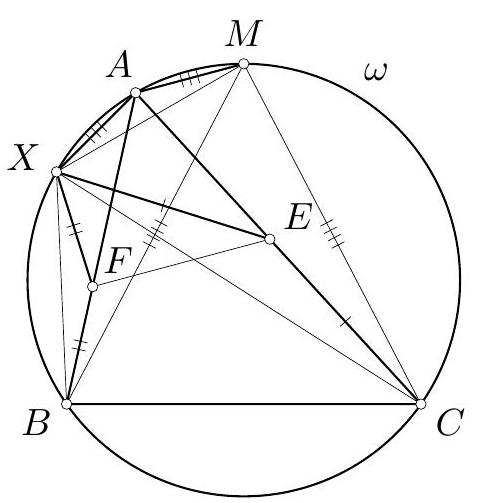

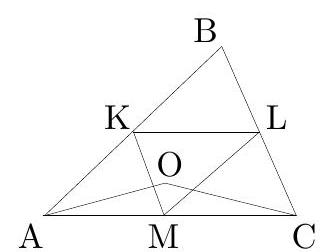

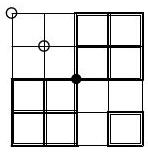

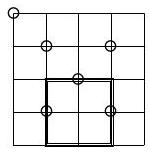

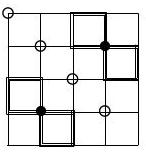

Triangles $X F B, X E C$ and $X A M$ are isosceles (Fig. 144. In addition, note that $\measuredangle F B X=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A M X$ and $\measuredangle F B X=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A C X=\measuredangle E C X$, from which it follows that triangles $X F B, X E C$ and $X A M$ are directly similar (i.e., similar with the same orientation).

Denote $\frac{X F}{X B}=\frac{X E}{X C}=\frac{X A}{X M}=k$ and $\measuredangle B X F=\measuredangle C X E=\measuredangle M X A=\alpha$. Then the rotation with center $X$ by angle $\alpha$ along with scaling by ratio $k$ maps points $B, C, M$ to points $F, E, A$, respectively. Thus triangle $A F E$ is similar to triangle $M B C$ by spiral similarity. But $M B=M C$ as $M$ is the midpoint of arc $B C$. Hence also $A E=A F$.

Remark: The problem can be approached using complex numbers, taking $\omega$ as a unit circle.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

|

A E=A F

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$ such that $A B<A C$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the arc $B C$ of $\omega$ containing the point $A$, and let $X \neq M$ be the other point on $\omega$ such that $A X=A M$. Points $E$ and $F$ are chosen on sides $A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle $A B C$, respectively, such that $E X=E C$ and $F X=F B$. Prove that $A E=A F$.

|

Triangles $X F B, X E C$ and $X A M$ are isosceles (Fig. 144. In addition, note that $\measuredangle F B X=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A M X$ and $\measuredangle F B X=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A C X=\measuredangle E C X$, from which it follows that triangles $X F B, X E C$ and $X A M$ are directly similar (i.e., similar with the same orientation).

Denote $\frac{X F}{X B}=\frac{X E}{X C}=\frac{X A}{X M}=k$ and $\measuredangle B X F=\measuredangle C X E=\measuredangle M X A=\alpha$. Then the rotation with center $X$ by angle $\alpha$ along with scaling by ratio $k$ maps points $B, C, M$ to points $F, E, A$, respectively. Thus triangle $A F E$ is similar to triangle $M B C$ by spiral similarity. But $M B=M C$ as $M$ is the midpoint of arc $B C$. Hence also $A E=A F$.

Remark: The problem can be approached using complex numbers, taking $\omega$ as a unit circle.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with orthocentre $H$. Let $D$ be a point outside the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ such that $\angle A B D=\angle D C A$. The reflection of $A B$ in $B D$ intersects $C D$ at $X$. The reflection of $A C$ in $C D$ intersects $B D$ at $Y$. The lines through $X$ and $Y$ perpendicular to $A C$ and $A B$, respectively, intersect at $P$. Prove that points $D, P$ and $H$ are collinear.

|

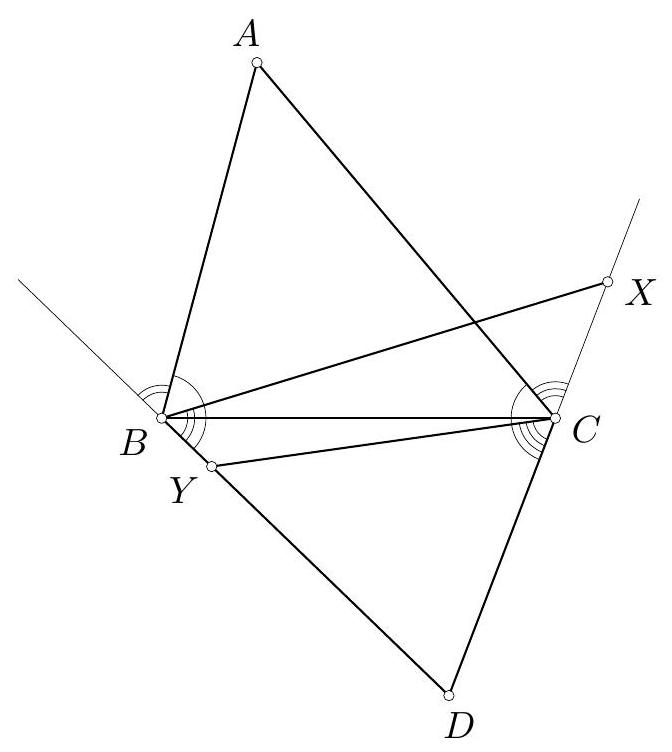

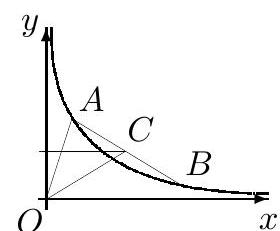

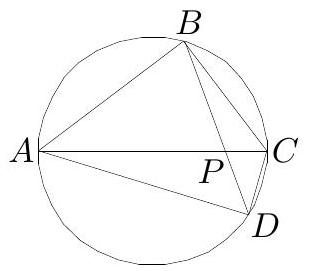

From the reflections, we have

$$

\angle D B X=180^{\circ}-\angle D B A=180^{\circ}-\angle D C A=\angle D C Y

$$

(Fig. 15), so points $B, C, X, Y$ are concyclic.

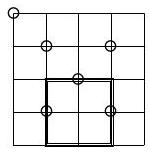

Define $Q=X P \cap B D$ and $R=Y P \cap C D$ (Fig. 16). Then due to the right angles, we find $\angle D Y R=\angle D X Q$. Hence points $Q, R, X, Y$ are concyclic, too.

Consequently, $\angle D Q R=\angle D X Y=\angle D B C$, so $B C \| Q R$. Since also $B H \| P Q$ and $C H \| P R$, it follows that triangle $B H C$ is a homothetic image of triangle $Q P R$ with center $D$. Hence $D, P$ and $H$ are collinear.

Figure 15

Figure 16

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with orthocentre $H$. Let $D$ be a point outside the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ such that $\angle A B D=\angle D C A$. The reflection of $A B$ in $B D$ intersects $C D$ at $X$. The reflection of $A C$ in $C D$ intersects $B D$ at $Y$. The lines through $X$ and $Y$ perpendicular to $A C$ and $A B$, respectively, intersect at $P$. Prove that points $D, P$ and $H$ are collinear.

|

From the reflections, we have

$$

\angle D B X=180^{\circ}-\angle D B A=180^{\circ}-\angle D C A=\angle D C Y

$$

(Fig. 15), so points $B, C, X, Y$ are concyclic.

Define $Q=X P \cap B D$ and $R=Y P \cap C D$ (Fig. 16). Then due to the right angles, we find $\angle D Y R=\angle D X Q$. Hence points $Q, R, X, Y$ are concyclic, too.

Consequently, $\angle D Q R=\angle D X Y=\angle D B C$, so $B C \| Q R$. Since also $B H \| P Q$ and $C H \| P R$, it follows that triangle $B H C$ is a homothetic image of triangle $Q P R$ with center $D$. Hence $D, P$ and $H$ are collinear.

Figure 15

Figure 16

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\n13.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

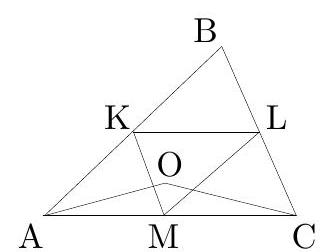

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$. The altitudes $A D, B E$ and $C F$ of the triangle $A B C$ intersect at point $H$. A point $K$ is chosen on the line $E F$ such that $K H \| B C$. Prove that the reflection of $H$ in $K D$ lies on $\omega$.

|

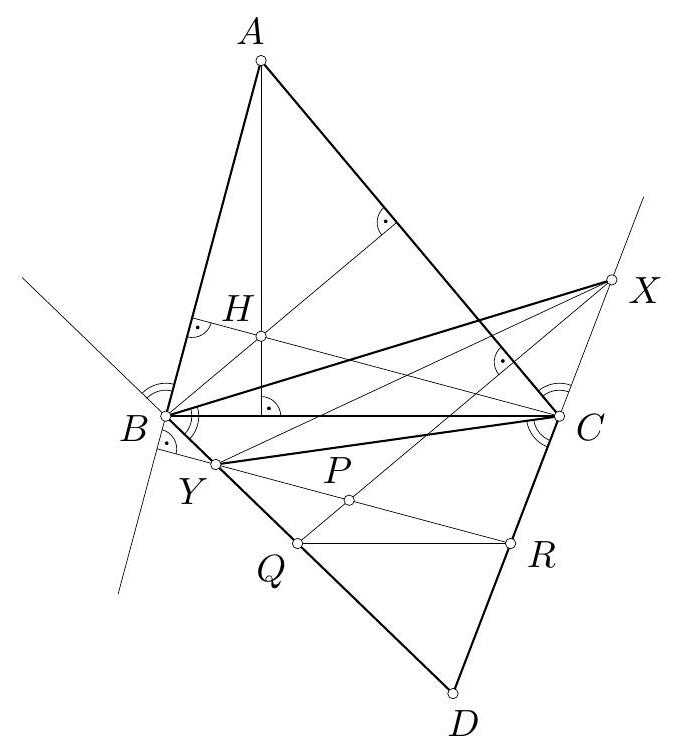

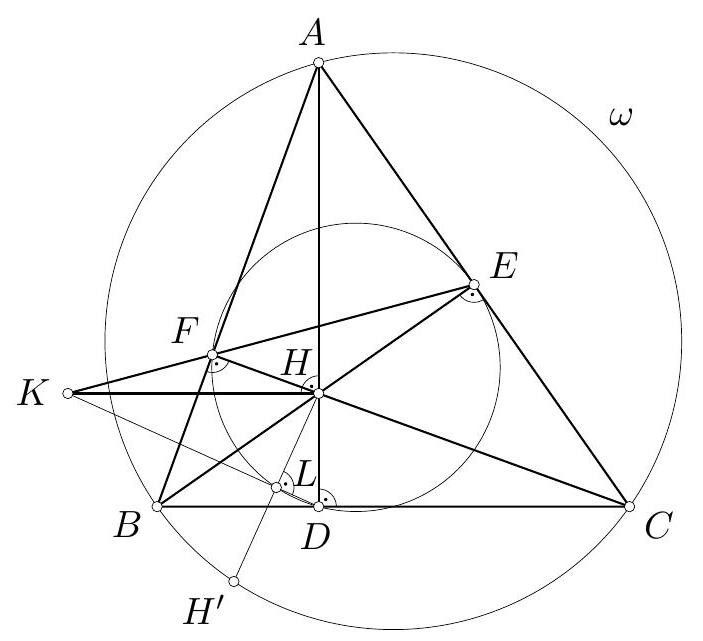

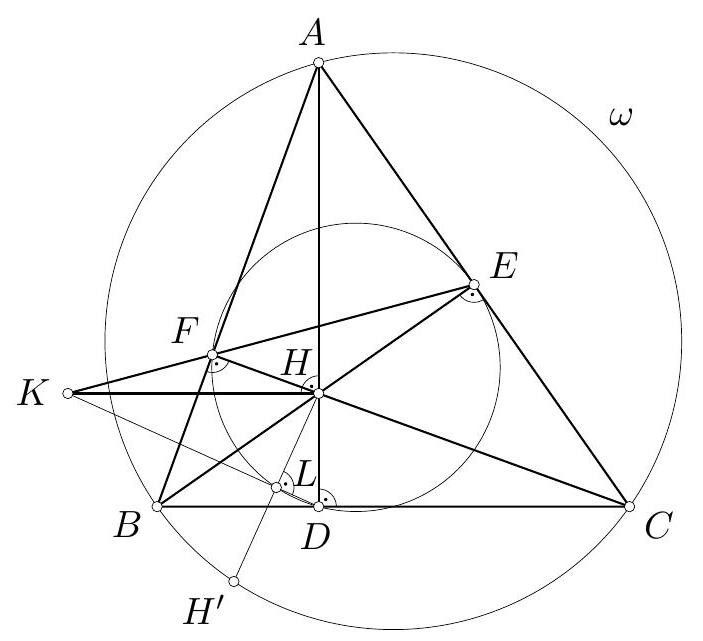

Since $\angle A E H=90^{\circ}=\angle A F H$, we know that $A E H F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral and $A H$ is a diameter of its circumcircle. As $K H \| B C$ and $A H \perp B C$, we have $\angle K H A=90^{\circ}$, so $K H$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $A E H F$.

Denote by $H^{\prime}$ the reflection of $H$ in $K D$ and by $L$ the intersection of lines $K D$ and $H H^{\prime}$ (Fig. 17). Clearly $\angle H L D=90^{\circ}$ and from the equality $\angle K H D=180^{\circ}-\angle H L D$ it follows that $K H$ is also tangent to the circumcircle of $D L H$. From the power of the point $K$ with respect to the circumcircles of $A E H F$ and $D L H$ we obtain $K E \cdot K F=K H^{2}=K L \cdot K D$. Hence points $E, F, D, L$ lie on a common circle.

By a known fact of triangle geometry, reflections of $H$ in the points $D, E$ and $F$ lie on $\omega$. Hence the homothety with center $H$ and ratio 2 maps the circumcircle of triangle $D E F$ to $\omega$. As this homothety maps $L$ to $H^{\prime}$ and $L$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $D E F$, the point $H^{\prime}$ must lie on $\omega$.

Remark: The problem can be approached using computational methods, namely complex numbers and Cartesian coordinates.

Figure 17

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute triangle with circumcircle $\omega$. The altitudes $A D, B E$ and $C F$ of the triangle $A B C$ intersect at point $H$. A point $K$ is chosen on the line $E F$ such that $K H \| B C$. Prove that the reflection of $H$ in $K D$ lies on $\omega$.

|

Since $\angle A E H=90^{\circ}=\angle A F H$, we know that $A E H F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral and $A H$ is a diameter of its circumcircle. As $K H \| B C$ and $A H \perp B C$, we have $\angle K H A=90^{\circ}$, so $K H$ is tangent to the circumcircle of $A E H F$.

Denote by $H^{\prime}$ the reflection of $H$ in $K D$ and by $L$ the intersection of lines $K D$ and $H H^{\prime}$ (Fig. 17). Clearly $\angle H L D=90^{\circ}$ and from the equality $\angle K H D=180^{\circ}-\angle H L D$ it follows that $K H$ is also tangent to the circumcircle of $D L H$. From the power of the point $K$ with respect to the circumcircles of $A E H F$ and $D L H$ we obtain $K E \cdot K F=K H^{2}=K L \cdot K D$. Hence points $E, F, D, L$ lie on a common circle.

By a known fact of triangle geometry, reflections of $H$ in the points $D, E$ and $F$ lie on $\omega$. Hence the homothety with center $H$ and ratio 2 maps the circumcircle of triangle $D E F$ to $\omega$. As this homothety maps $L$ to $H^{\prime}$ and $L$ lies on the circumcircle of triangle $D E F$, the point $H^{\prime}$ must lie on $\omega$.

Remark: The problem can be approached using computational methods, namely complex numbers and Cartesian coordinates.

Figure 17

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

There is a set of $N \geq 3$ points in the plane, such that no three of them are collinear. Three points $A$, $B, C$ in the set are said to form a Baltic triangle if no other point in the set lies on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Assume that there exists at least one Baltic triangle.

Show that there exist at least $\frac{N}{3}$ Baltic triangles.

|

If $N=3$, the number of Baltic triangles is 1 which is $\frac{N}{3}$.

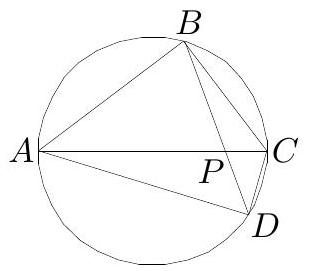

To show that there always exist at least $\frac{N}{3}$ Baltic triangles, we prove that every point is a vertex of at least one Baltic triangle. This implies the desired result because every Baltic triangle consists of exactly 3 points.

First we prove a useful lemma: Given $n \geq 2$ points in the plane, either all are collinear or there exists a line passing through exactly 2 points.

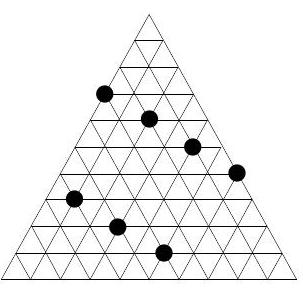

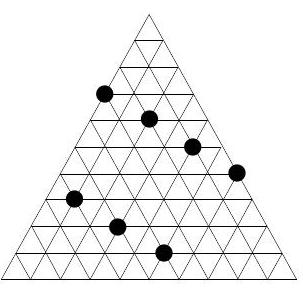

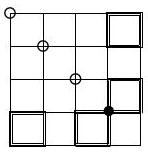

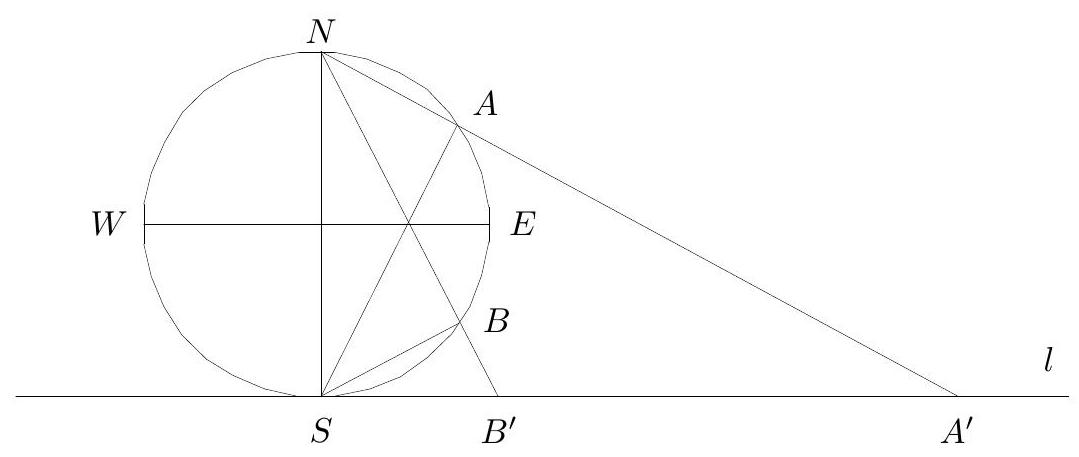

Proof: Take a line $l$ going through at least 2 points, and a point $Q$ not on the line $l$ such that the distance from $Q$ to $l$ is minimal over all such pairs. Denote $Q^{\prime}$ as the projection of $Q$ to $l$. If $l$ contains at least 3 points, two of them must be on the same side of $Q^{\prime}$ (or coincide with $Q^{\prime}$ ). Say those points are $X$ and $Y$, with $X$ lying between $Y$ and $Q^{\prime}$ (Fig. 18). But then the distance from $X$ to the line $Q Y$ is smaller than $Q Q^{\prime}$ and this contradicts minimality.

Figure 18

Now assume $N \geq 4$ and apply an inversion of the plane with center $O$ where $O$ is any point in the given set. Consider the $N-1$ other points after the inversion. By our lemma, there exists a line going through exactly 2 of them, because if they were all collinear, all points would have been concyclic before the inversion, contradicting the assumption about the existence of a Baltic triangle. Denote these points as $P$ and $Q$. The line $P Q$ cannot go through $O$, because this would mean that these 3 points were collinear before the inversion. But then before the inversion, no other point lied on the circumcircle of triangle $O P Q$, meaning that $O, P, Q$ formed a Baltic triangle.

So every single point in the given set is a vertex of at least one Baltic triangle and we are done.

Remark: The lemma proved in the solution is known as the Sylvester-Gallai theorem.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

There is a set of $N \geq 3$ points in the plane, such that no three of them are collinear. Three points $A$, $B, C$ in the set are said to form a Baltic triangle if no other point in the set lies on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Assume that there exists at least one Baltic triangle.

Show that there exist at least $\frac{N}{3}$ Baltic triangles.

|

If $N=3$, the number of Baltic triangles is 1 which is $\frac{N}{3}$.

To show that there always exist at least $\frac{N}{3}$ Baltic triangles, we prove that every point is a vertex of at least one Baltic triangle. This implies the desired result because every Baltic triangle consists of exactly 3 points.

First we prove a useful lemma: Given $n \geq 2$ points in the plane, either all are collinear or there exists a line passing through exactly 2 points.

Proof: Take a line $l$ going through at least 2 points, and a point $Q$ not on the line $l$ such that the distance from $Q$ to $l$ is minimal over all such pairs. Denote $Q^{\prime}$ as the projection of $Q$ to $l$. If $l$ contains at least 3 points, two of them must be on the same side of $Q^{\prime}$ (or coincide with $Q^{\prime}$ ). Say those points are $X$ and $Y$, with $X$ lying between $Y$ and $Q^{\prime}$ (Fig. 18). But then the distance from $X$ to the line $Q Y$ is smaller than $Q Q^{\prime}$ and this contradicts minimality.

Figure 18

Now assume $N \geq 4$ and apply an inversion of the plane with center $O$ where $O$ is any point in the given set. Consider the $N-1$ other points after the inversion. By our lemma, there exists a line going through exactly 2 of them, because if they were all collinear, all points would have been concyclic before the inversion, contradicting the assumption about the existence of a Baltic triangle. Denote these points as $P$ and $Q$. The line $P Q$ cannot go through $O$, because this would mean that these 3 points were collinear before the inversion. But then before the inversion, no other point lied on the circumcircle of triangle $O P Q$, meaning that $O, P, Q$ formed a Baltic triangle.

So every single point in the given set is a vertex of at least one Baltic triangle and we are done.

Remark: The lemma proved in the solution is known as the Sylvester-Gallai theorem.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Determine all composite positive integers $n$ such that, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$.

Answer: 10.

|

Call a positive integer $n$ powerless if, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$. The solution is composed of proofs of three claims.

Claim 1: If $n$ is powerless, then each positive divisor $d$ of $n$ can be written as $k^{2}+1$ for some integer $k$.

Proof: We will prove this by strong induction on the divisors of $n$. First, we have that $1=0^{2}+1$. Now let $d=k^{m}+1>1$ be a divisor of $n$, and assume that all divisors less than $d$ can be written on the desired form. If $m$ is even, we are done, and if $m$ is odd, we have

$$

d=(k+1)\left(k^{m-1}-k^{m-2}+\cdots+1\right) .

$$

Then, either $k+1=d$, meaning that $k^{m}=k$ so $k=1$ and $d=1^{2}+1$, or $k+1$ is a divisor of $n$ stricly less than $d$, so we can write $k+1=l^{2}+1$ for some integer $l$. Hence $d=\left(l^{2}\right)^{m}+1=\left(l^{m}\right)^{2}+1$.

Claim 2: If $n$ is powerless, then $n$ is square-free.

Proof: Suppose for contradiction that there is a prime $p$ such that $p^{2} \mid n$. Then by Claim 1 we may write $p^{2}=l^{2}+1$. As the difference of square numbers are sums of consecutive odd integers, this leaves only the solution $l=0, p=1$, a contradiction.

Claim 3: The only composite powerless positive integer is 10.

We will give two proofs for this claim.

Proof 1: Suppose $n$ is a composite powerless number with prime divisors $p<q$. By Claim 1, we write $p=a^{2}+1, q=b^{2}+1$ and $p q=c^{2}+1$. Then we have $c^{2}<p q<q^{2}$, so $c<q$. However, as $b^{2}+1=q \mid c^{2}+1$, we have $c^{2} \equiv-1 \equiv b^{2}(\bmod q)$, so $c \equiv \pm b(\bmod q)$ and thus either $c=b$ or $c=q-b$. In the first case, we get $p=1$, a contradiction. In the second case, we get

$$

p q=c^{2}+1=(q-b)^{2}+1=q^{2}-2 b q+b^{2}+1=q^{2}-2 b q+q=(q-2 b+1) q

$$

so $p=q-2 b+1$ and thus $p$ is even. Therefore, $p=2$, and so $b^{2}+1=q=2 b+1$, which means $b=2$, and thus $q=5$. By Claim 2, this implies $n=10$, and since $1=0^{2}+1,2=1^{2}+1,5=2^{2}+1$ and $10=3^{2}+1$, this is indeed a powerless number.

Proof 2: Again, let $p \neq q$ be prime divisors of $n$ and write $p=a^{2}+1, q=b^{2}+1$ and $p q=c^{2}+1$. Factorizing in gaussian integers, this yields

$$

(a+\mathrm{i})(a-\mathrm{i})(b+\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i})=(c+\mathrm{i})(c-\mathrm{i})

$$

We note that all the factors on the left, and none of the factors on the right, are gaussian primes. Thus, each factor on the right must be the product of two factors on the left. As $(a+i)(a-i)$ and $(b+i)(b-i)$ both are real, the unique factorization of $\mathbb{Z}[\mathrm{i}]$ leaves us without loss of generality with three cases:

$$

c+\mathrm{i}=(a+\mathrm{i})(b+\mathrm{i}), \quad c+\mathrm{i}=(a-\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i}), \quad c+\mathrm{i}=(a+\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i})

$$

In the first two cases, we have $a+b= \pm 1$, both contradictions. In the third case, we get $b-a=1$, and thus, $q=a^{2}+2 a+2$. As this makes $q-p$ odd, we get $p=2$ meaning $a=1$ so that $q=5$. Now we finish as in proof 1.

Remark: Claim 2 can also be proven independently of Claim 1 with the help of Mihailescu's theorem.

Do there exist infinitely many quadruples $(a, b, c, d)$ of positive integers such that the number $a^{a!}+$ $b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$ is prime and $2 \leq d \leq c \leq b \leq a \leq d^{2024} ?$

Answer: No.

|

10

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Determine all composite positive integers $n$ such that, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$.

Answer: 10.

|

Call a positive integer $n$ powerless if, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$. The solution is composed of proofs of three claims.

Claim 1: If $n$ is powerless, then each positive divisor $d$ of $n$ can be written as $k^{2}+1$ for some integer $k$.

Proof: We will prove this by strong induction on the divisors of $n$. First, we have that $1=0^{2}+1$. Now let $d=k^{m}+1>1$ be a divisor of $n$, and assume that all divisors less than $d$ can be written on the desired form. If $m$ is even, we are done, and if $m$ is odd, we have

$$

d=(k+1)\left(k^{m-1}-k^{m-2}+\cdots+1\right) .

$$

Then, either $k+1=d$, meaning that $k^{m}=k$ so $k=1$ and $d=1^{2}+1$, or $k+1$ is a divisor of $n$ stricly less than $d$, so we can write $k+1=l^{2}+1$ for some integer $l$. Hence $d=\left(l^{2}\right)^{m}+1=\left(l^{m}\right)^{2}+1$.

Claim 2: If $n$ is powerless, then $n$ is square-free.

Proof: Suppose for contradiction that there is a prime $p$ such that $p^{2} \mid n$. Then by Claim 1 we may write $p^{2}=l^{2}+1$. As the difference of square numbers are sums of consecutive odd integers, this leaves only the solution $l=0, p=1$, a contradiction.

Claim 3: The only composite powerless positive integer is 10.

We will give two proofs for this claim.

Proof 1: Suppose $n$ is a composite powerless number with prime divisors $p<q$. By Claim 1, we write $p=a^{2}+1, q=b^{2}+1$ and $p q=c^{2}+1$. Then we have $c^{2}<p q<q^{2}$, so $c<q$. However, as $b^{2}+1=q \mid c^{2}+1$, we have $c^{2} \equiv-1 \equiv b^{2}(\bmod q)$, so $c \equiv \pm b(\bmod q)$ and thus either $c=b$ or $c=q-b$. In the first case, we get $p=1$, a contradiction. In the second case, we get

$$

p q=c^{2}+1=(q-b)^{2}+1=q^{2}-2 b q+b^{2}+1=q^{2}-2 b q+q=(q-2 b+1) q

$$

so $p=q-2 b+1$ and thus $p$ is even. Therefore, $p=2$, and so $b^{2}+1=q=2 b+1$, which means $b=2$, and thus $q=5$. By Claim 2, this implies $n=10$, and since $1=0^{2}+1,2=1^{2}+1,5=2^{2}+1$ and $10=3^{2}+1$, this is indeed a powerless number.

Proof 2: Again, let $p \neq q$ be prime divisors of $n$ and write $p=a^{2}+1, q=b^{2}+1$ and $p q=c^{2}+1$. Factorizing in gaussian integers, this yields

$$

(a+\mathrm{i})(a-\mathrm{i})(b+\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i})=(c+\mathrm{i})(c-\mathrm{i})

$$

We note that all the factors on the left, and none of the factors on the right, are gaussian primes. Thus, each factor on the right must be the product of two factors on the left. As $(a+i)(a-i)$ and $(b+i)(b-i)$ both are real, the unique factorization of $\mathbb{Z}[\mathrm{i}]$ leaves us without loss of generality with three cases:

$$

c+\mathrm{i}=(a+\mathrm{i})(b+\mathrm{i}), \quad c+\mathrm{i}=(a-\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i}), \quad c+\mathrm{i}=(a+\mathrm{i})(b-\mathrm{i})

$$

In the first two cases, we have $a+b= \pm 1$, both contradictions. In the third case, we get $b-a=1$, and thus, $q=a^{2}+2 a+2$. As this makes $q-p$ odd, we get $p=2$ meaning $a=1$ so that $q=5$. Now we finish as in proof 1.

Remark: Claim 2 can also be proven independently of Claim 1 with the help of Mihailescu's theorem.

Do there exist infinitely many quadruples $(a, b, c, d)$ of positive integers such that the number $a^{a!}+$ $b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$ is prime and $2 \leq d \leq c \leq b \leq a \leq d^{2024} ?$

Answer: No.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Determine all composite positive integers $n$ such that, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$.

Answer: 10.

|

Assume that there exists a prime $p<d$ such that $p \nmid a b c d$. Then, since $p-1 \mid d$ ! and $p \nmid d$, by Fermat's little theorem $d^{d!} \equiv\left(d^{p-1}\right)^{\frac{d!}{p-1}} \equiv 1(\bmod p)$. By the same argument $a^{a!} \equiv b^{b!} \equiv c^{c!} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod p)$, and therefore $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!} \equiv 1+1-1-1 \equiv 0(\bmod p)$.

Now we prove that for big enough $d$, the product $P$ of primes less than $d$ is at least $d^{10000}$. Assume $d>2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$. Notice that by Bertrand's postulate, the biggest prime less than $d$ is at least $\frac{d}{2}$, the second biggest is at least $\frac{d}{4}$ etc., and 10001-th biggest is at least $\frac{d}{2^{10001}}$. So

$$

P \geq \frac{d}{2} \frac{d}{4} \cdots \frac{d}{2^{10001}}=\frac{d^{10001}}{2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}} \geq d^{10000}

$$

Now note that the number of quadruples where $d<2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$ is finite, because all the number are bounded above by $d^{2024}$ and hence by $2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}} \cdot 2024$. When $d \geq 2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$ we have $a b c d \leq$ $d^{1+3 \cdot 2024}<d^{7000}$ and since $P \geq d^{10000}$, there exist at least two primes $p$ and $q$, less than $d$, that do not divide $a b c d$. But then by our first result, we have $p q \mid a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$, so it cannot be prime.

Remark: The solution can be modified as follows. We can proceed in the first paragraph to conclude that $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$ is not prime. Indeed, if $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}=p$ where $p<d$ then definitely $a>d$ (otherwise $a=b=c=d$ and $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}=0$ ). Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

d & >p=a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!} \geq a^{a!}-d^{d!}=\left(a^{(d+1) \cdot \ldots \cdot a}\right)^{d!}-d^{d!} \\

& \geq\left(a^{d+1}\right)^{d!}-d^{d!} \geq a^{d+1}-d>d^{d+1}-d>d^{2}-d=(d-1) d \geq d

\end{aligned}

$$

contradiction. Then in the last paragraph, there is no need to find two primes less than $d$ that do not divide $a b c d$, one is enough.

|

10

|

Incomplete

|

Incomplete

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Determine all composite positive integers $n$ such that, for each positive divisor $d$ of $n$, there are integers $k \geq 0$ and $m \geq 2$ such that $d=k^{m}+1$.

Answer: 10.

|

Assume that there exists a prime $p<d$ such that $p \nmid a b c d$. Then, since $p-1 \mid d$ ! and $p \nmid d$, by Fermat's little theorem $d^{d!} \equiv\left(d^{p-1}\right)^{\frac{d!}{p-1}} \equiv 1(\bmod p)$. By the same argument $a^{a!} \equiv b^{b!} \equiv c^{c!} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod p)$, and therefore $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!} \equiv 1+1-1-1 \equiv 0(\bmod p)$.

Now we prove that for big enough $d$, the product $P$ of primes less than $d$ is at least $d^{10000}$. Assume $d>2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$. Notice that by Bertrand's postulate, the biggest prime less than $d$ is at least $\frac{d}{2}$, the second biggest is at least $\frac{d}{4}$ etc., and 10001-th biggest is at least $\frac{d}{2^{10001}}$. So

$$

P \geq \frac{d}{2} \frac{d}{4} \cdots \frac{d}{2^{10001}}=\frac{d^{10001}}{2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}} \geq d^{10000}

$$

Now note that the number of quadruples where $d<2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$ is finite, because all the number are bounded above by $d^{2024}$ and hence by $2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}} \cdot 2024$. When $d \geq 2^{\frac{10001 \cdot 10002}{2}}$ we have $a b c d \leq$ $d^{1+3 \cdot 2024}<d^{7000}$ and since $P \geq d^{10000}$, there exist at least two primes $p$ and $q$, less than $d$, that do not divide $a b c d$. But then by our first result, we have $p q \mid a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$, so it cannot be prime.

Remark: The solution can be modified as follows. We can proceed in the first paragraph to conclude that $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}$ is not prime. Indeed, if $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}=p$ where $p<d$ then definitely $a>d$ (otherwise $a=b=c=d$ and $a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!}=0$ ). Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

d & >p=a^{a!}+b^{b!}-c^{c!}-d^{d!} \geq a^{a!}-d^{d!}=\left(a^{(d+1) \cdot \ldots \cdot a}\right)^{d!}-d^{d!} \\

& \geq\left(a^{d+1}\right)^{d!}-d^{d!} \geq a^{d+1}-d>d^{d+1}-d>d^{2}-d=(d-1) d \geq d

\end{aligned}

$$

contradiction. Then in the last paragraph, there is no need to find two primes less than $d$ that do not divide $a b c d$, one is enough.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

An infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ of positive integers is such that $a_{n} \geq 2$ and $a_{n+2}$ divides $a_{n+1}+a_{n}$ for all $n \geq 1$. Prove that there exists a prime which divides infinitely many terms of the sequence.

|

Assume that every prime divides only finitely many terms of the sequence. In particular this means that there exists an integer $N>1$ such that $2 \nmid a_{n}$ for all $n \geq N$. Let $M=\max \left(a_{N}, a_{N+1}\right)$ We will now show by induction that $a_{n} \leq M$ for all $n \geq N$. This is obvious for $n=N$ and $n=N+1$. Now let $n \geq N+2$ be arbitrary and assume that $a_{n-1}, a_{n-2} \leq M$. By the definition of $N$, it is clear that $a_{n-2}, a_{n-1}, a_{n}$ are all odd and so $a_{n} \neq a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$, but we know that $a_{n} \mid a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$ and therefore

$$

a_{n} \leq \frac{a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}}{2} \leq \max \left(a_{n-1}, a_{n-2}\right) \leq M

$$

by the induction hypothesis. This completes the induction.

This shows that the sequence is bounded and therefore there are only finitely many primes which divide a term of the sequence. However there are infinitely many terms, that all have a prime divisor, hence some prime must divide infinitely many terms of the sequence.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

An infinite sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots$ of positive integers is such that $a_{n} \geq 2$ and $a_{n+2}$ divides $a_{n+1}+a_{n}$ for all $n \geq 1$. Prove that there exists a prime which divides infinitely many terms of the sequence.

|

Assume that every prime divides only finitely many terms of the sequence. In particular this means that there exists an integer $N>1$ such that $2 \nmid a_{n}$ for all $n \geq N$. Let $M=\max \left(a_{N}, a_{N+1}\right)$ We will now show by induction that $a_{n} \leq M$ for all $n \geq N$. This is obvious for $n=N$ and $n=N+1$. Now let $n \geq N+2$ be arbitrary and assume that $a_{n-1}, a_{n-2} \leq M$. By the definition of $N$, it is clear that $a_{n-2}, a_{n-1}, a_{n}$ are all odd and so $a_{n} \neq a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$, but we know that $a_{n} \mid a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}$ and therefore

$$

a_{n} \leq \frac{a_{n-1}+a_{n-2}}{2} \leq \max \left(a_{n-1}, a_{n-2}\right) \leq M

$$

by the induction hypothesis. This completes the induction.

This shows that the sequence is bounded and therefore there are only finitely many primes which divide a term of the sequence. However there are infinitely many terms, that all have a prime divisor, hence some prime must divide infinitely many terms of the sequence.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Does there exist a positive integer $N$ which is divisible by at least 2024 distinct primes and whose positive divisors $1=d_{1}<d_{2}<\ldots<d_{k}=N$ are such that the number

$$

\frac{d_{2}}{d_{1}}+\frac{d_{3}}{d_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{d_{k}}{d_{k-1}}

$$

is an integer?

Answer: Yes.

|

For arbitrary positive integer $N$, we will write $f(N)=\frac{d_{2}}{d_{1}}+\frac{d_{3}}{d_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{d_{k}}{d_{k-1}}$ where $1=d_{1}<d_{2}<\ldots<d_{k}=N$ are all positive divisors of $N$. Let us prove by induction that for any positive integer $M$ there is a positive integer $N$ with exactly $M$ different prime divisors such that $f(N)$ is an integer.

- Base case: If $M=1$, this is clearly true (any prime power $N>1$ works).

- Induction step: Assume that the claim holds for $M$ prime divisors. Let $N$ be a positive integer with exactly $M$ prime divisors such that $f(N)$ is an integer. Pick a prime $p>N$. We claim that there is some choice of $\alpha$ such that $f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)$ is an integer. Note that since $p>N$, the divisors of $N \cdot p^{\alpha}$ in the ascending order are

$$

\begin{aligned}

& d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots, d_{k} \\

& p d_{1}, p d_{2}, \ldots, p d_{k} \\

& \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \\

& p^{\alpha} d_{1}, p^{\alpha} d_{2}, \ldots, p^{\alpha} d_{k}

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence we get that

$$

f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)=(\alpha+1) f(N)+\alpha \cdot \frac{p d_{1}}{d_{k}}

$$

The term $(\alpha+1) f(N)$ is an integer by the choice of $N$. If we pick $\alpha=N$ then $\alpha \cdot \frac{p d_{1}}{d_{k}}=N \cdot \frac{p}{N}=p$ is an integer, too. Thus $f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)$ is an integer and we are done.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Does there exist a positive integer $N$ which is divisible by at least 2024 distinct primes and whose positive divisors $1=d_{1}<d_{2}<\ldots<d_{k}=N$ are such that the number

$$

\frac{d_{2}}{d_{1}}+\frac{d_{3}}{d_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{d_{k}}{d_{k-1}}

$$

is an integer?

Answer: Yes.

|

For arbitrary positive integer $N$, we will write $f(N)=\frac{d_{2}}{d_{1}}+\frac{d_{3}}{d_{2}}+\ldots+\frac{d_{k}}{d_{k-1}}$ where $1=d_{1}<d_{2}<\ldots<d_{k}=N$ are all positive divisors of $N$. Let us prove by induction that for any positive integer $M$ there is a positive integer $N$ with exactly $M$ different prime divisors such that $f(N)$ is an integer.

- Base case: If $M=1$, this is clearly true (any prime power $N>1$ works).

- Induction step: Assume that the claim holds for $M$ prime divisors. Let $N$ be a positive integer with exactly $M$ prime divisors such that $f(N)$ is an integer. Pick a prime $p>N$. We claim that there is some choice of $\alpha$ such that $f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)$ is an integer. Note that since $p>N$, the divisors of $N \cdot p^{\alpha}$ in the ascending order are

$$

\begin{aligned}

& d_{1}, d_{2}, \ldots, d_{k} \\

& p d_{1}, p d_{2}, \ldots, p d_{k} \\

& \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \\

& p^{\alpha} d_{1}, p^{\alpha} d_{2}, \ldots, p^{\alpha} d_{k}

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence we get that

$$

f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)=(\alpha+1) f(N)+\alpha \cdot \frac{p d_{1}}{d_{k}}

$$

The term $(\alpha+1) f(N)$ is an integer by the choice of $N$. If we pick $\alpha=N$ then $\alpha \cdot \frac{p d_{1}}{d_{k}}=N \cdot \frac{p}{N}=p$ is an integer, too. Thus $f\left(N \cdot p^{\alpha}\right)$ is an integer and we are done.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "\n19.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Positive integers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{aligned}

(a b-1)^{2} & =c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b+1 \\

a^{2}+b^{2} & =c^{2}+a b

\end{aligned}\right.

$$

(a) Prove that $c+1$ is a perfect square.

(b) Find all such triples $(a, b, c)$.

Answer: (b) $a=b=c=3$.

|

(a) Rearranging terms in the first equation gives

$$

a^{2} b^{2}-2 a b=c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b

$$

By substituting $a b=a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}$ into the right-hand side and rearranging the terms we get

$$

a^{2} b^{2}+c^{2}=(c+1)\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+2 a b

$$

By adding $2 a b c$ to both sides and factorizing we get

$$

(a b+c)^{2}=(c+1)(a+b)^{2}

$$

Now it is obvious that $c+1$ has to be a square of an integer.

(b) Let us say $c+1=d^{2}$, where $d>1$ and is an integer. Then substituting this into the equation (10) and taking the square root of both sides (we can do that as all the terms are positive) we get

$$

a b+d^{2}-1=d(a+b)

$$

We can rearrange it to $(a-d)(b-d)=1$, which immediately tells us that either $a=b=d+1$ or $a=b=d-1$. Note that in either case $a=b$. Substituting this into the second equation of the given system we get $a^{2}=c^{2}$, implying $a=c$ (as $\left.a, c>0\right)$.

- If $a=b=d-1$, then $a=c$ gives $d-1=d^{2}-1$, so $d=0$ or $d=1$, neither of which gives a positive $c$, so cannot be a solution.

- If $a=b=d+1$, then $a=c$ gives $d+1=d^{2}-1$, so $d^{2}-d-2=0$. The only positive solution is $d=2$ which gives $a=b=c=3$. Substituting it once again into both equations we indeed get a solution.

|

a=b=c=3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Positive integers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{aligned}

(a b-1)^{2} & =c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b+1 \\

a^{2}+b^{2} & =c^{2}+a b

\end{aligned}\right.

$$

(a) Prove that $c+1$ is a perfect square.

(b) Find all such triples $(a, b, c)$.

Answer: (b) $a=b=c=3$.

|

(a) Rearranging terms in the first equation gives

$$

a^{2} b^{2}-2 a b=c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b

$$

By substituting $a b=a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}$ into the right-hand side and rearranging the terms we get

$$

a^{2} b^{2}+c^{2}=(c+1)\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+2 a b

$$

By adding $2 a b c$ to both sides and factorizing we get

$$

(a b+c)^{2}=(c+1)(a+b)^{2}

$$

Now it is obvious that $c+1$ has to be a square of an integer.

(b) Let us say $c+1=d^{2}$, where $d>1$ and is an integer. Then substituting this into the equation (10) and taking the square root of both sides (we can do that as all the terms are positive) we get

$$

a b+d^{2}-1=d(a+b)

$$

We can rearrange it to $(a-d)(b-d)=1$, which immediately tells us that either $a=b=d+1$ or $a=b=d-1$. Note that in either case $a=b$. Substituting this into the second equation of the given system we get $a^{2}=c^{2}$, implying $a=c$ (as $\left.a, c>0\right)$.

- If $a=b=d-1$, then $a=c$ gives $d-1=d^{2}-1$, so $d=0$ or $d=1$, neither of which gives a positive $c$, so cannot be a solution.

- If $a=b=d+1$, then $a=c$ gives $d+1=d^{2}-1$, so $d^{2}-d-2=0$. The only positive solution is $d=2$ which gives $a=b=c=3$. Substituting it once again into both equations we indeed get a solution.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Positive integers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{aligned}

(a b-1)^{2} & =c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b+1 \\

a^{2}+b^{2} & =c^{2}+a b

\end{aligned}\right.

$$

(a) Prove that $c+1$ is a perfect square.

(b) Find all such triples $(a, b, c)$.

Answer: (b) $a=b=c=3$.

|

(a) Substituting $a^{2}+b^{2}$ from the second equation to the first one gives

$$

(a b-1)^{2}=c\left(c^{2}+a b\right)+a b+1

$$

Rearranging terms in the obtained equation gives

$$

(a b)^{2}-(c+3) a b-c^{3}=0

$$

which we can consider as a quadratic equation in $a b$. Its discriminant is

$$

D=(c+3)^{2}+4 c^{3}=4 c^{3}+c^{2}+6 c+9=(c+1)\left(4 c^{2}-3 c+9\right)=(c+1)\left(4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)\right)

$$

To have solutions in integers, $D$ must be a perfect square. Note that $c+1$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ can have no common odd prime factors. Hence $\operatorname{gcd}\left(c+1,4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)\right)$ is a power of 2 , so $c+1$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ are either both perfect squares or both twice of some perfect squares. In the first case, we are done. In the second case, note that

$$

4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1) \equiv 4(c-1)^{2}=(2(c-1))^{2} \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

so $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ must be $0,1,4$ modulo 5 . On the other hand, twice of a perfect square is $0,2,3$ modulo 5 . Consequently, $c+1 \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1) \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$, the latter of which implies $c-1 \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$. This leads to contradiction since $c-1$ and $c+1$ cannot be both divisible by 5 .

(b) By the solution of part (a), both $c+1$ and $4 c^{2}-3 c+9$ are perfect squares. However, due to $c>0$ we have $(2 c-1)^{2}=4 c^{2}-4 c+1<4 c^{2}-3 c+9$, and for $c>3$ we also have $(2 c)^{2}=4 c^{2}>4 c^{2}-3 c+9$. Thus $4 c^{2}-3 c+9$ is located between two consecutive perfect squares, which gives a contradiction with it being a square itself.

Out of $c=1,2,3$, only $c=3$ makes $c+1$ a perfect square. In this case, the quadratic equation $(a b)^{2}-(c+3) a b-c^{3}=0$ yields $a b=9$, so $a=1, b=9$ or $a=3, b=3$ or $a=9, b=1$. Out of those, only $a=3, b=3$ satisfies the equations.

Remark: Part (a) of the problem can be solved yet another way. By substituting $a^{2}+b^{2}$ from the second equation to the first one, we obtain

$$

(a b-1)^{2}=c\left(c^{2}+a b\right)+a b+1=c^{3}+1+a b c+a b=(c+1)\left(c^{2}-c+1+a b\right)

$$

Whenever an integer $n$ divides $c+1$, it also divides $a b-1$. Therefore $c \equiv-1(\bmod n)$ and $a b \equiv 1$ $(\bmod n)$. But then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 4(\bmod n)$, i.e., $n$ divides $c^{2}-c+1+a b-4$. Thus the greatest common divisor of $c+1$ and $c^{2}-c+1+a b$ divides 4 , i.e., it is either 1,2 or 4 . In the first and third case we are done. If their greatest common divisor is 2 , then clearly all three of $a, b, c$ are odd, so $a^{2} \equiv b^{2} \equiv c^{2} \equiv 1(\bmod 8)$. Thus from the second equation we have $a b=a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 8)$, so $(a b-1)^{2}$ is divisible by 64 . Now, if $c \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$, then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, which means that $(c+1)\left(c^{2}-c+1+a b\right) \equiv 4(\bmod 8)$, giving a contradiction with $(a b-1)^{2}$ being divisible by 64 . If instead $c \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$. This means that both $c+1$ and $c^{2}-c+1+a b$ are divisible by 4 , giving a contradiction with the assumption that their greatest common divisor is 2 . Therefore $c+1$ must be a perfect square.

|

a=b=c=3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Positive integers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{aligned}

(a b-1)^{2} & =c\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)+a b+1 \\

a^{2}+b^{2} & =c^{2}+a b

\end{aligned}\right.

$$

(a) Prove that $c+1$ is a perfect square.

(b) Find all such triples $(a, b, c)$.

Answer: (b) $a=b=c=3$.

|

(a) Substituting $a^{2}+b^{2}$ from the second equation to the first one gives

$$

(a b-1)^{2}=c\left(c^{2}+a b\right)+a b+1

$$

Rearranging terms in the obtained equation gives

$$

(a b)^{2}-(c+3) a b-c^{3}=0

$$

which we can consider as a quadratic equation in $a b$. Its discriminant is

$$

D=(c+3)^{2}+4 c^{3}=4 c^{3}+c^{2}+6 c+9=(c+1)\left(4 c^{2}-3 c+9\right)=(c+1)\left(4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)\right)

$$

To have solutions in integers, $D$ must be a perfect square. Note that $c+1$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ can have no common odd prime factors. Hence $\operatorname{gcd}\left(c+1,4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)\right)$ is a power of 2 , so $c+1$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ are either both perfect squares or both twice of some perfect squares. In the first case, we are done. In the second case, note that

$$

4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1) \equiv 4(c-1)^{2}=(2(c-1))^{2} \quad(\bmod 5)

$$

so $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1)$ must be $0,1,4$ modulo 5 . On the other hand, twice of a perfect square is $0,2,3$ modulo 5 . Consequently, $c+1 \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$ and $4(c-1)^{2}+5(c+1) \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$, the latter of which implies $c-1 \equiv 0(\bmod 5)$. This leads to contradiction since $c-1$ and $c+1$ cannot be both divisible by 5 .

(b) By the solution of part (a), both $c+1$ and $4 c^{2}-3 c+9$ are perfect squares. However, due to $c>0$ we have $(2 c-1)^{2}=4 c^{2}-4 c+1<4 c^{2}-3 c+9$, and for $c>3$ we also have $(2 c)^{2}=4 c^{2}>4 c^{2}-3 c+9$. Thus $4 c^{2}-3 c+9$ is located between two consecutive perfect squares, which gives a contradiction with it being a square itself.

Out of $c=1,2,3$, only $c=3$ makes $c+1$ a perfect square. In this case, the quadratic equation $(a b)^{2}-(c+3) a b-c^{3}=0$ yields $a b=9$, so $a=1, b=9$ or $a=3, b=3$ or $a=9, b=1$. Out of those, only $a=3, b=3$ satisfies the equations.

Remark: Part (a) of the problem can be solved yet another way. By substituting $a^{2}+b^{2}$ from the second equation to the first one, we obtain

$$

(a b-1)^{2}=c\left(c^{2}+a b\right)+a b+1=c^{3}+1+a b c+a b=(c+1)\left(c^{2}-c+1+a b\right)

$$

Whenever an integer $n$ divides $c+1$, it also divides $a b-1$. Therefore $c \equiv-1(\bmod n)$ and $a b \equiv 1$ $(\bmod n)$. But then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 4(\bmod n)$, i.e., $n$ divides $c^{2}-c+1+a b-4$. Thus the greatest common divisor of $c+1$ and $c^{2}-c+1+a b$ divides 4 , i.e., it is either 1,2 or 4 . In the first and third case we are done. If their greatest common divisor is 2 , then clearly all three of $a, b, c$ are odd, so $a^{2} \equiv b^{2} \equiv c^{2} \equiv 1(\bmod 8)$. Thus from the second equation we have $a b=a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2} \equiv 1$ $(\bmod 8)$, so $(a b-1)^{2}$ is divisible by 64 . Now, if $c \equiv 1(\bmod 4)$, then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, which means that $(c+1)\left(c^{2}-c+1+a b\right) \equiv 4(\bmod 8)$, giving a contradiction with $(a b-1)^{2}$ being divisible by 64 . If instead $c \equiv 3(\bmod 4)$, then $c^{2}-c+1+a b \equiv 0(\bmod 4)$. This means that both $c+1$ and $c^{2}-c+1+a b$ are divisible by 4 , giving a contradiction with the assumption that their greatest common divisor is 2 . Therefore $c+1$ must be a perfect square.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw24sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2:",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2024"

}

|

Integers $1,2, \ldots, n$ are written (in some order) on the circumference of a circle. What is the smallest possible sum of moduli of the differences of neighbouring numbers?

|

Let $a_{1}=1, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{k}=n, a_{k+1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be the order in which the numbers $1,2, \ldots, n$ are written around the circle. Then the sum of moduli of the differences of neighbouring numbers is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left|1-a_{2}\right|+\left|a_{2}-a_{3}\right|+\cdots+\left|a_{k}-n\right|+\left|n-a_{k+1}\right|+\cdots+\left|a_{n}-1\right| \\

& \geq\left|1-a_{2}+a_{2}-a_{3}+\cdots+a_{k}-n\right|+\left|n-a_{k+1}+\cdots+a_{n}-1\right| \\

& =|1-n|+|n-1|=2 n-2 .

\end{aligned}

$$

This minimum is achieved if the numbers are written around the circle in increasing order.

|

2n-2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Integers $1,2, \ldots, n$ are written (in some order) on the circumference of a circle. What is the smallest possible sum of moduli of the differences of neighbouring numbers?

|

Let $a_{1}=1, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{k}=n, a_{k+1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be the order in which the numbers $1,2, \ldots, n$ are written around the circle. Then the sum of moduli of the differences of neighbouring numbers is

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left|1-a_{2}\right|+\left|a_{2}-a_{3}\right|+\cdots+\left|a_{k}-n\right|+\left|n-a_{k+1}\right|+\cdots+\left|a_{n}-1\right| \\

& \geq\left|1-a_{2}+a_{2}-a_{3}+\cdots+a_{k}-n\right|+\left|n-a_{k+1}+\cdots+a_{n}-1\right| \\

& =|1-n|+|n-1|=2 n-2 .

\end{aligned}

$$

This minimum is achieved if the numbers are written around the circle in increasing order.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

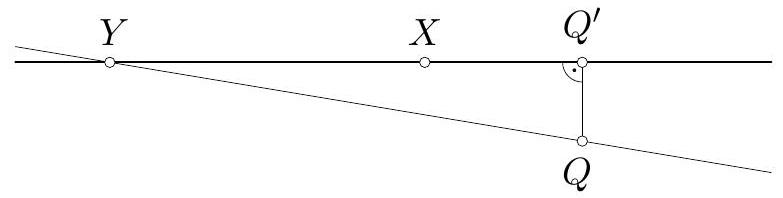

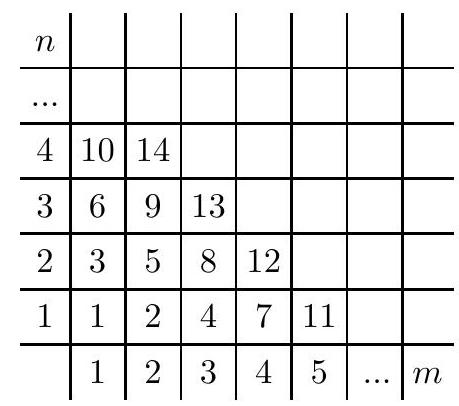

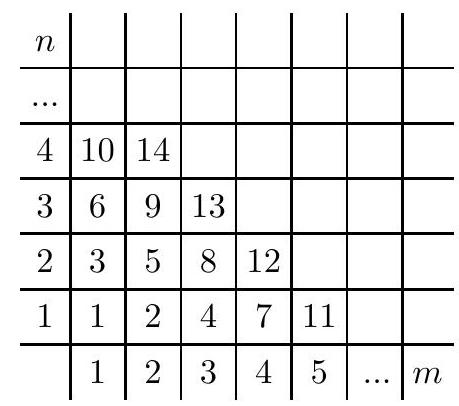

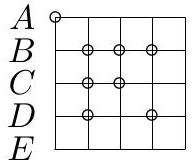

The squares of a squared paper are enumerated as follows:

Devise a polynomial $p(m, n)$ of two variables $m, n$ such that for any positive integers $m$ and $n$ the number written in the square with coordinates $(m, n)$ will be equal to $p(m, n)$.

|

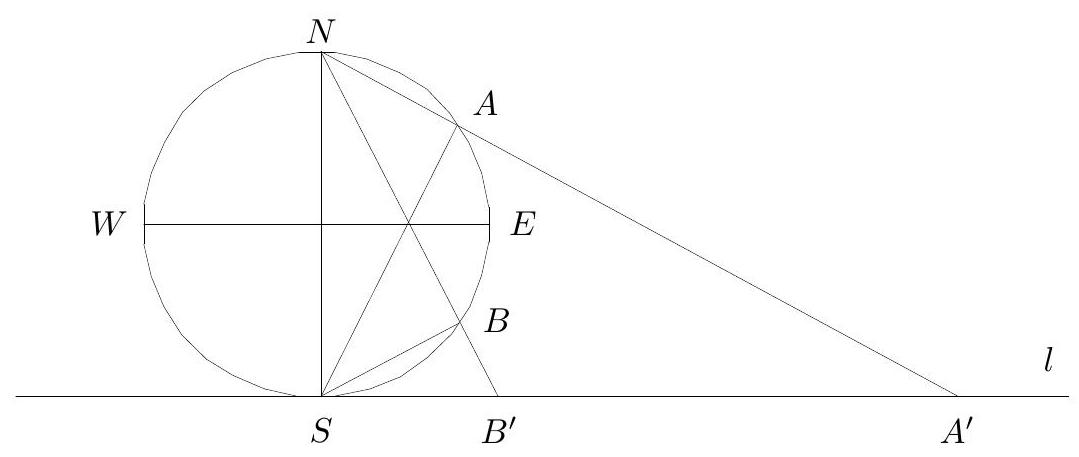

Since the square with the coordinates $(m, n)$ is $n$th on the $(n+m-1)$-th diagonal, it contains the number

$$

P(m, n)=\sum_{i=1}^{n+m-2} i+n=\frac{(n+m-1)(n+m-2)}{2}+n

$$

|

\frac{(n+m-1)(n+m-2)}{2}+n

|

Incomplete

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

The squares of a squared paper are enumerated as follows:

Devise a polynomial $p(m, n)$ of two variables $m, n$ such that for any positive integers $m$ and $n$ the number written in the square with coordinates $(m, n)$ will be equal to $p(m, n)$.

|

Since the square with the coordinates $(m, n)$ is $n$th on the $(n+m-1)$-th diagonal, it contains the number

$$

P(m, n)=\sum_{i=1}^{n+m-2} i+n=\frac{(n+m-1)(n+m-2)}{2}+n

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Let $a_{0}>0, c>0$ and

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{a_{n}+c}{1-a_{n} c}, \quad n=0,1, \ldots

$$

Is it possible that the first 1990 terms $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{1989}$ are all positive but $a_{1990}<0$ ?

|

Obviously we can find angles $0<\alpha, \beta<90^{\circ}$ such that $\tan \alpha>0, \tan (\alpha+\beta)>0, \ldots$, $\tan (\alpha+1989 \beta)>0$ but $\tan (\alpha+1990 \beta)<0$. Now it suffices to note that if we take $a_{0}=\tan \alpha$ and $c=\tan \beta$ then $a_{n}=\tan (\alpha+n \beta)$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $a_{0}>0, c>0$ and

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{a_{n}+c}{1-a_{n} c}, \quad n=0,1, \ldots

$$

Is it possible that the first 1990 terms $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{1989}$ are all positive but $a_{1990}<0$ ?

|

Obviously we can find angles $0<\alpha, \beta<90^{\circ}$ such that $\tan \alpha>0, \tan (\alpha+\beta)>0, \ldots$, $\tan (\alpha+1989 \beta)>0$ but $\tan (\alpha+1990 \beta)<0$. Now it suffices to note that if we take $a_{0}=\tan \alpha$ and $c=\tan \beta$ then $a_{n}=\tan (\alpha+n \beta)$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Prove that, for any real $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$,

$$

\sum_{i, j=1}^{n} \frac{a_{i} a_{j}}{i+j-1} \geq 0

$$

|

Consider the polynomial $P(x)=a_{1}+a_{2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-1}$. Then $P^{2}(x)=\sum_{k, l=1}^{n} a_{k} a_{l} x^{k+l-2}$ and $\int_{0}^{1} P^{2}(x) d x=\sum_{k, l=1}^{n} \frac{a_{k} a_{l}}{k+l-1}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Prove that, for any real $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$,

$$

\sum_{i, j=1}^{n} \frac{a_{i} a_{j}}{i+j-1} \geq 0

$$

|

Consider the polynomial $P(x)=a_{1}+a_{2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-1}$. Then $P^{2}(x)=\sum_{k, l=1}^{n} a_{k} a_{l} x^{k+l-2}$ and $\int_{0}^{1} P^{2}(x) d x=\sum_{k, l=1}^{n} \frac{a_{k} a_{l}}{k+l-1}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Let $*$ denote an operation, assigning a real number $a * b$ to each pair of real numbers ( $a, b)$ (e.g., $a * b=$ $a+b^{2}-17$ ). Devise an equation which is true (for all possible values of variables) provided the operation $*$ is commutative or associative and which can be false otherwise.

|

A suitable equation is $x *(x * x)=(x * x) * x$ which is obviously true if $*$ is any commutative or associative operation but does not hold in general, e.g., $1-(1-1) \neq(1-1)-1$.

|

1-(1-1) \neq (1-1)-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Let $*$ denote an operation, assigning a real number $a * b$ to each pair of real numbers ( $a, b)$ (e.g., $a * b=$ $a+b^{2}-17$ ). Devise an equation which is true (for all possible values of variables) provided the operation $*$ is commutative or associative and which can be false otherwise.

|

A suitable equation is $x *(x * x)=(x * x) * x$ which is obviously true if $*$ is any commutative or associative operation but does not hold in general, e.g., $1-(1-1) \neq(1-1)-1$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Let $A B C D$ be a quadrangle, $|A D|=|B C|, \angle A+\angle B=120^{\circ}$ and let $P$ be a point exterior to the quadrangle such that $P$ and $A$ lie at opposite sides of the line $D C$ and the triangle $D P C$ is equilateral. Prove that the triangle $A P B$ is also equilateral.

|

Note that $\angle A D C+\angle C D P+\angle B C D+\angle D C P=360^{\circ}$ (see Figure 1). Thus $\angle A D P=360^{\circ}-$ $\angle B C D-\angle D C P=\angle B C P$. As we have $|D P|=|C P|$ and $|A D|=|B C|$, the triangles $A D P$ and $B C P$ are congruent and $|A P|=|B P|$. Moreover, $\angle A P B=60^{\circ}$ since $\angle D P C=60^{\circ}$ and $\angle D P A=\angle C P B$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C D$ be a quadrangle, $|A D|=|B C|, \angle A+\angle B=120^{\circ}$ and let $P$ be a point exterior to the quadrangle such that $P$ and $A$ lie at opposite sides of the line $D C$ and the triangle $D P C$ is equilateral. Prove that the triangle $A P B$ is also equilateral.

|

Note that $\angle A D C+\angle C D P+\angle B C D+\angle D C P=360^{\circ}$ (see Figure 1). Thus $\angle A D P=360^{\circ}-$ $\angle B C D-\angle D C P=\angle B C P$. As we have $|D P|=|C P|$ and $|A D|=|B C|$, the triangles $A D P$ and $B C P$ are congruent and $|A P|=|B P|$. Moreover, $\angle A P B=60^{\circ}$ since $\angle D P C=60^{\circ}$ and $\angle D P A=\angle C P B$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

The midpoint of each side of a convex pentagon is connected by a segment with the intersection point of the medians of the triangle formed by the remaining three vertices of the pentagon. Prove that all five such segments intersect at one point.

|

Let $A, B, C, D$ and $E$ be the vertices of the pentagon (in order), and take any point $O$ as origin. Let $M$ be the intersection point of the medians of the triangle $C D E$, and let $N$ be the midpoint of the segment $A B$. We have

$$

\overline{O M}=\frac{1}{3}(\overline{O C}+\overline{O D}+\overline{O E})

$$

and

$$

\overline{O N}=\frac{1}{2}(\overline{O A}+\overline{O B})

$$

The segment $N M$ may be written as

$$

\overline{O N}+t(\overline{O M}-\overline{O N}), \quad 0 \leq t \leq 1

$$

Taking $t=\frac{3}{5}$ we get the point

$$

P=\frac{1}{5}(\overline{O A}+\overline{O B}+\overline{O C}+\overline{O D}+\overline{O E}),

$$

the centre of gravity of the pentagon. Choosing a different side of the pentagon, we clearly get the same point $P$, which thus lies on all such line segments.

Remark. The problem expresses the idea of subdividing a system of five equal masses placed at the vertices of the pentagon into two subsystems, one of which consists of the two masses at the endpoints of the side under consideration, and one consisting of the three remaining masses. The segment mentioned in the problem connects the centres of gravity of these two subsystems, and hence it contains the centre of gravity of the whole system.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

The midpoint of each side of a convex pentagon is connected by a segment with the intersection point of the medians of the triangle formed by the remaining three vertices of the pentagon. Prove that all five such segments intersect at one point.

|

Let $A, B, C, D$ and $E$ be the vertices of the pentagon (in order), and take any point $O$ as origin. Let $M$ be the intersection point of the medians of the triangle $C D E$, and let $N$ be the midpoint of the segment $A B$. We have

$$

\overline{O M}=\frac{1}{3}(\overline{O C}+\overline{O D}+\overline{O E})

$$

and

$$

\overline{O N}=\frac{1}{2}(\overline{O A}+\overline{O B})

$$

The segment $N M$ may be written as

$$

\overline{O N}+t(\overline{O M}-\overline{O N}), \quad 0 \leq t \leq 1

$$

Taking $t=\frac{3}{5}$ we get the point

$$

P=\frac{1}{5}(\overline{O A}+\overline{O B}+\overline{O C}+\overline{O D}+\overline{O E}),

$$

the centre of gravity of the pentagon. Choosing a different side of the pentagon, we clearly get the same point $P$, which thus lies on all such line segments.

Remark. The problem expresses the idea of subdividing a system of five equal masses placed at the vertices of the pentagon into two subsystems, one of which consists of the two masses at the endpoints of the side under consideration, and one consisting of the three remaining masses. The segment mentioned in the problem connects the centres of gravity of these two subsystems, and hence it contains the centre of gravity of the whole system.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Let $P$ be a point on the circumcircle of a triangle $A B C$. It is known that the base points of the perpendiculars drawn from $P$ onto the lines $A B, B C$ and $C A$ lie on one straight line (called a Simson line). Prove that the Simson lines of two diametrically opposite points $P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ are perpendicular.

|

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of the triangle $A B C$ and $\angle B$ be its maximal angle (so that $\angle A$ and $\angle C$ are necessarily acute). Further, let $B_{1}$ and $C_{1}$ be the base points of the perpendiculars drawn from the point $P$ to the sides $A C$ and $A B$ respectively and let $\alpha$ be the angle between the Simson line $l$ of point $P$ and the height $h$ of the triangle drawn to the side $A C$. It is sufficient to prove that $\alpha=\frac{1}{2} \angle P O B$. To show this, first note that the points $P, C_{1}, B_{1}, A$ all belong to a certain circle. Now we have to consider several sub-cases depending on the order of these points on that circle and the location of point $P$ on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Figure 2 shows one of these cases - here we have $\alpha=\angle P B_{1} C_{1}=\angle P B_{1} C_{1}=$ $\angle P A B=\frac{1}{2} \angle P O B$. The other cases can be treated in a similar manner.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $P$ be a point on the circumcircle of a triangle $A B C$. It is known that the base points of the perpendiculars drawn from $P$ onto the lines $A B, B C$ and $C A$ lie on one straight line (called a Simson line). Prove that the Simson lines of two diametrically opposite points $P_{1}$ and $P_{2}$ are perpendicular.

|

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of the triangle $A B C$ and $\angle B$ be its maximal angle (so that $\angle A$ and $\angle C$ are necessarily acute). Further, let $B_{1}$ and $C_{1}$ be the base points of the perpendiculars drawn from the point $P$ to the sides $A C$ and $A B$ respectively and let $\alpha$ be the angle between the Simson line $l$ of point $P$ and the height $h$ of the triangle drawn to the side $A C$. It is sufficient to prove that $\alpha=\frac{1}{2} \angle P O B$. To show this, first note that the points $P, C_{1}, B_{1}, A$ all belong to a certain circle. Now we have to consider several sub-cases depending on the order of these points on that circle and the location of point $P$ on the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$. Figure 2 shows one of these cases - here we have $\alpha=\angle P B_{1} C_{1}=\angle P B_{1} C_{1}=$ $\angle P A B=\frac{1}{2} \angle P O B$. The other cases can be treated in a similar manner.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

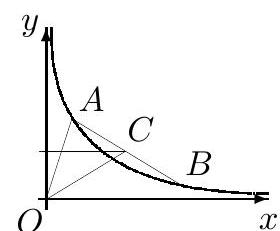

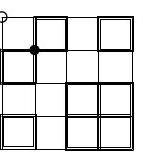

Two equal triangles are inscribed into an ellipse. Are they necessarily symmetrical with respect either to the axes or to the centre of the ellipse?

|

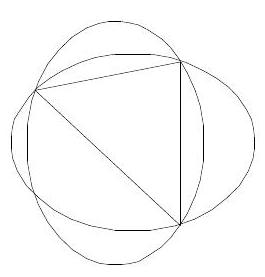

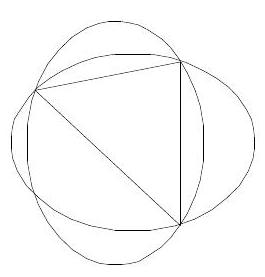

No, not necessarily (see Figure 3 where the two ellipses are equal).

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Problem not solved

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Two equal triangles are inscribed into an ellipse. Are they necessarily symmetrical with respect either to the axes or to the centre of the ellipse?

|

No, not necessarily (see Figure 3 where the two ellipses are equal).

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

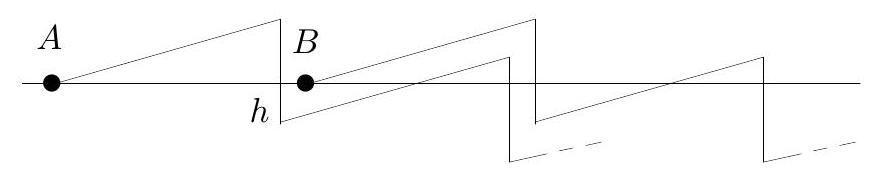

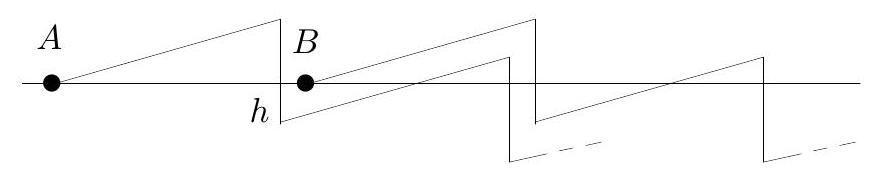

A segment $A B$ of unit length is marked on the straight line $t$. The segment is then moved on the plane so that it remains parallel to $t$ at all times, the traces of the points $A$ and $B$ do not intersect and finally the segment returns onto $t$. How far can the point $A$ now be from its initial position?

|

The point $A$ can move any distance from its initial position - see Figure 4 and note that we can make the height $h$ arbitrarily small.

Figure 4

|

any\ distance

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

A segment $A B$ of unit length is marked on the straight line $t$. The segment is then moved on the plane so that it remains parallel to $t$ at all times, the traces of the points $A$ and $B$ do not intersect and finally the segment returns onto $t$. How far can the point $A$ now be from its initial position?

|

The point $A$ can move any distance from its initial position - see Figure 4 and note that we can make the height $h$ arbitrarily small.

Figure 4

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Prove that the modulus of an integer root of a polynomial with integer coefficients cannot exceed the maximum of the moduli of the coefficients.

|

For a non-zero polynomial $P(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+a_{1} x+a_{0}$ with integer coefficients, let $k$ be the smallest index such that $a_{k} \neq 0$. Let $c$ be an integer root of $P(x)$. If $c=0$, the statement is obvious. If $c \neq 0$, then using $P(c)=0$ we get $a_{k}=-x\left(a_{k+1}+a_{k+2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-k-1}\right)$. Hence $c$ divides $a_{k}$, and since $a_{k} \neq 0$ we must have $|c| \leq\left|a_{k}\right|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prove that the modulus of an integer root of a polynomial with integer coefficients cannot exceed the maximum of the moduli of the coefficients.

|

For a non-zero polynomial $P(x)=a_{n} x^{n}+\cdots+a_{1} x+a_{0}$ with integer coefficients, let $k$ be the smallest index such that $a_{k} \neq 0$. Let $c$ be an integer root of $P(x)$. If $c=0$, the statement is obvious. If $c \neq 0$, then using $P(c)=0$ we get $a_{k}=-x\left(a_{k+1}+a_{k+2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-k-1}\right)$. Hence $c$ divides $a_{k}$, and since $a_{k} \neq 0$ we must have $|c| \leq\left|a_{k}\right|$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\n11.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Let $m$ and $n$ be positive integers. Prove that $25 m+3 n$ is divisible by 83 if and only if $3 m+7 n$ is divisible by 83 .

|

Use the equality $2 \cdot(25 x+3 y)+11 \cdot(3 x+7 y)=83 x+83 y$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $m$ and $n$ be positive integers. Prove that $25 m+3 n$ is divisible by 83 if and only if $3 m+7 n$ is divisible by 83 .

|

Use the equality $2 \cdot(25 x+3 y)+11 \cdot(3 x+7 y)=83 x+83 y$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Prove that the equation $x^{2}-7 y^{2}=1$ has infinitely many solutions in natural numbers.

|

For any solution $(m, n)$ of the equation we have $m^{2}-7 n^{2}=1$ and

$$

1=\left(m^{2}-7 n^{2}\right)^{2}=\left(m^{2}+7 n^{2}\right)^{2}-7 \cdot(2 m n)^{2} .

$$

Thus $\left(m^{2}+7 n^{2}, 2 m n\right)$ is also a solution. Therefore it is sufficient to note that the equation $x^{2}-7 y^{2}=1$ has at least one solution, for example $x=8, y=3$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Prove that the equation $x^{2}-7 y^{2}=1$ has infinitely many solutions in natural numbers.

|

For any solution $(m, n)$ of the equation we have $m^{2}-7 n^{2}=1$ and

$$

1=\left(m^{2}-7 n^{2}\right)^{2}=\left(m^{2}+7 n^{2}\right)^{2}-7 \cdot(2 m n)^{2} .

$$

Thus $\left(m^{2}+7 n^{2}, 2 m n\right)$ is also a solution. Therefore it is sufficient to note that the equation $x^{2}-7 y^{2}=1$ has at least one solution, for example $x=8, y=3$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\n13.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Do there exist 1990 relatively prime numbers such that all possible sums of two or more of these numbers are composite numbers?

|

Such numbers do exist. Let $M=1990$ ! and consider the sequence of numbers $1+M, 1+2 M$, $1+3 M, \ldots$ For any natural number $2 \leq k \leq 1990$, any sum of exactly $k$ of these numbers (not necessarily different) is divisible by $k$, and hence is composite. number. It remains to show that we can choose 1990 numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{1990}$ from this sequence which are relatively prime. Indeed, let $a_{1}=1+M$, $a_{2}=1+2 M$ and for $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ already chosen take $a_{n+1}=1+a_{1} \cdots a_{n} \cdot M$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Do there exist 1990 relatively prime numbers such that all possible sums of two or more of these numbers are composite numbers?

|

Such numbers do exist. Let $M=1990$ ! and consider the sequence of numbers $1+M, 1+2 M$, $1+3 M, \ldots$ For any natural number $2 \leq k \leq 1990$, any sum of exactly $k$ of these numbers (not necessarily different) is divisible by $k$, and hence is composite. number. It remains to show that we can choose 1990 numbers $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{1990}$ from this sequence which are relatively prime. Indeed, let $a_{1}=1+M$, $a_{2}=1+2 M$ and for $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ already chosen take $a_{n+1}=1+a_{1} \cdots a_{n} \cdot M$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Prove that none of the numbers

$$

F_{n}=2^{2^{n}}+1, \quad n=0,1,2, \ldots,

$$

is a cube of an integer.

|

Assume there exist such natural numbers $k$ and $n$ that $2^{2^{n}}+1=k^{3}$. Then $k$ must be an odd number and we have $2^{2^{n}}=k^{3}-1=(k-1)\left(k^{2}+k+1\right)$. Hence $k-1=2^{s}$ and $k^{2}+k+1=2^{t}$ where $s$ and $t$ are some positive integers. Now $2^{2 s}=(k-1)^{2}=k^{2}-2 k+1$ and $2^{t}-2^{2 s}=3 k$. But $2^{t}-2^{2 s}$ is even while $3 k$ is odd, a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Prove that none of the numbers

$$

F_{n}=2^{2^{n}}+1, \quad n=0,1,2, \ldots,

$$

is a cube of an integer.

|

Assume there exist such natural numbers $k$ and $n$ that $2^{2^{n}}+1=k^{3}$. Then $k$ must be an odd number and we have $2^{2^{n}}=k^{3}-1=(k-1)\left(k^{2}+k+1\right)$. Hence $k-1=2^{s}$ and $k^{2}+k+1=2^{t}$ where $s$ and $t$ are some positive integers. Now $2^{2 s}=(k-1)^{2}=k^{2}-2 k+1$ and $2^{t}-2^{2 s}=3 k$. But $2^{t}-2^{2 s}$ is even while $3 k$ is odd, a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

A closed polygonal line is drawn on squared paper so that its links lie on the lines of the paper (the sides of the squares are equal to 1). The lengths of all links are odd numbers. Prove that the number of links is divisible by 4 .

|

There must be an equal number of horizontal and vertical links, and hence it suffices to show that the number of vertical links is even. Let's pass the whole polygonal line in a chosen direction and mark each vertical link as "up" or "down" according to the direction we pass it. As the sum of lengths of the "up" links is equal to that of the "down" ones and each link is of odd length, we have an even or odd number of links of both kinds depending on the parity of the sum of their lengths.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

A closed polygonal line is drawn on squared paper so that its links lie on the lines of the paper (the sides of the squares are equal to 1). The lengths of all links are odd numbers. Prove that the number of links is divisible by 4 .

|

There must be an equal number of horizontal and vertical links, and hence it suffices to show that the number of vertical links is even. Let's pass the whole polygonal line in a chosen direction and mark each vertical link as "up" or "down" according to the direction we pass it. As the sum of lengths of the "up" links is equal to that of the "down" ones and each link is of odd length, we have an even or odd number of links of both kinds depending on the parity of the sum of their lengths.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

In two piles there are 72 and 30 sweets respectively. Two students take, one after another, some sweets from one of the piles. Each time the number of sweets taken from a pile must be an integer multiple of the number of sweets in the other pile. Is it the beginner of the game or his adversary who can always assure taking the last sweet from one of the piles?

|

Note that one of the players must have a winning strategy. Assume that it is the player making the second move who has it. Then his strategy will assure taking the last sweet also in the case when the beginner takes $2 \cdot 30$ sweets as his first move. But now, if the beginner takes $1 \cdot 30$ sweets then the second player has no choice but to take another 30 sweets from the same pile, and hence the beginner can use the same strategy to assure taking the last sweet himself. This contradiction shows that it must be the beginner who has the winning strategy.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

In two piles there are 72 and 30 sweets respectively. Two students take, one after another, some sweets from one of the piles. Each time the number of sweets taken from a pile must be an integer multiple of the number of sweets in the other pile. Is it the beginner of the game or his adversary who can always assure taking the last sweet from one of the piles?

|

Note that one of the players must have a winning strategy. Assume that it is the player making the second move who has it. Then his strategy will assure taking the last sweet also in the case when the beginner takes $2 \cdot 30$ sweets as his first move. But now, if the beginner takes $1 \cdot 30$ sweets then the second player has no choice but to take another 30 sweets from the same pile, and hence the beginner can use the same strategy to assure taking the last sweet himself. This contradiction shows that it must be the beginner who has the winning strategy.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\n17.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1990"

}

|

Positive integers $1,2, \ldots, 100,101$ are written in the cells of a $101 \times 101$ square grid so that each number is repeated 101 times. Prove that there exists either a column or a row containing at least 11 different numbers.

|

Let $a_{k}$ denote the total number of rows and columns containing the number $k$ at least once. As $i \cdot(20-i)<101$ for any natural number $i$, we have $a_{k} \geq 21$ for all $k=1,2, \ldots, 101$. Hence $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{101} \geq 21 \cdot 101=2121$. On the other hand, assuming any row and any column contains no more than 10 different numbers we have $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{101} \leq 202 \cdot 10=2020$, a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Positive integers $1,2, \ldots, 100,101$ are written in the cells of a $101 \times 101$ square grid so that each number is repeated 101 times. Prove that there exists either a column or a row containing at least 11 different numbers.

|

Let $a_{k}$ denote the total number of rows and columns containing the number $k$ at least once. As $i \cdot(20-i)<101$ for any natural number $i$, we have $a_{k} \geq 21$ for all $k=1,2, \ldots, 101$. Hence $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{101} \geq 21 \cdot 101=2121$. On the other hand, assuming any row and any column contains no more than 10 different numbers we have $a_{1}+\cdots+a_{101} \leq 202 \cdot 10=2020$, a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw90sol.jsonl",