problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

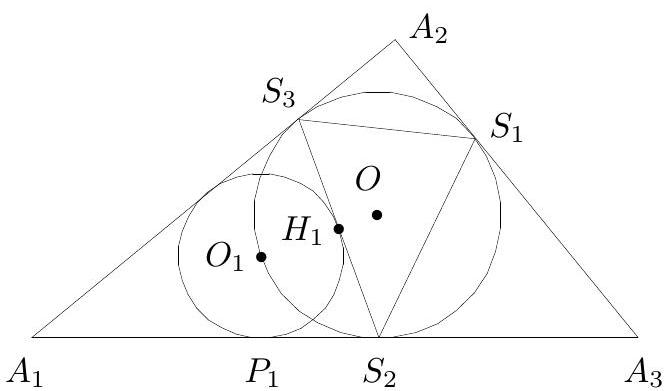

The inscribed circle of the triangle $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$ touches the sides $A_{2} A_{3}, A_{3} A_{1}$ and $A_{1} A_{2}$ at points $S_{1}, S_{2}, S_{3}$, respectively. Let $O_{1}, O_{2}, O_{3}$ be the centres of the inscribed circles of triangles $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}, A_{2} S_{3} S_{1}$ and $A_{3} S_{1} S_{2}$, respectively. Prove that the straight lines $O_{1} S_{1}, O_{2} S_{2}$ and $O_{3} S_{3}$ intersect at one point.

|

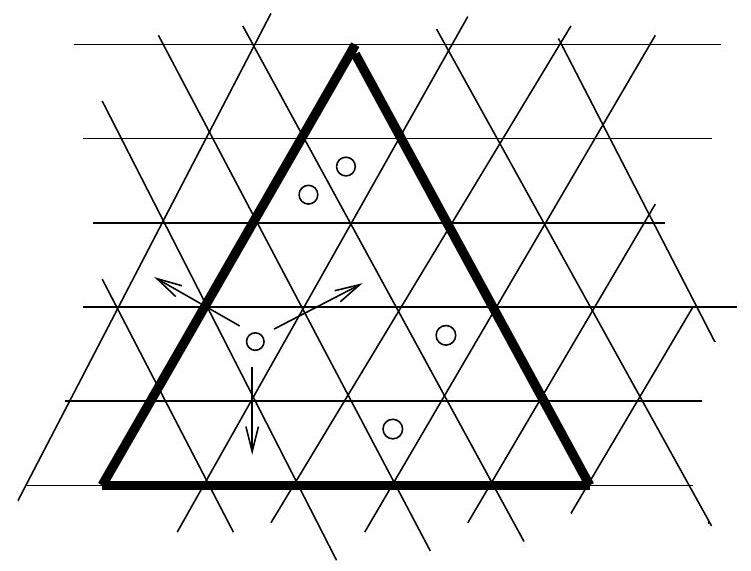

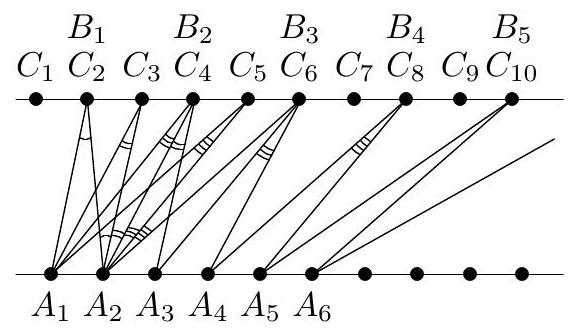

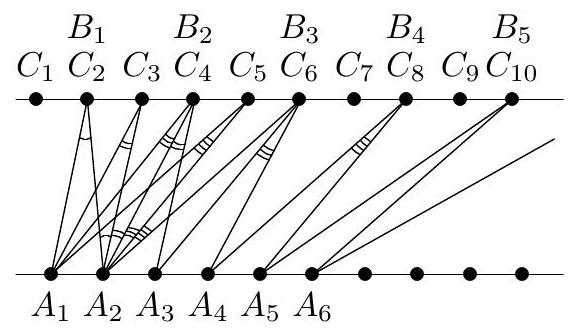

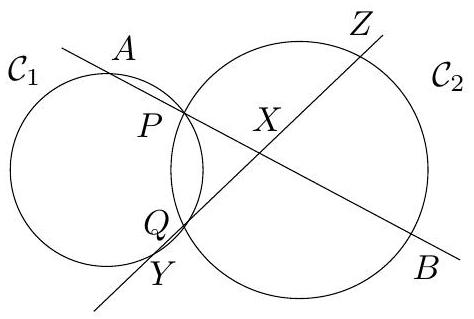

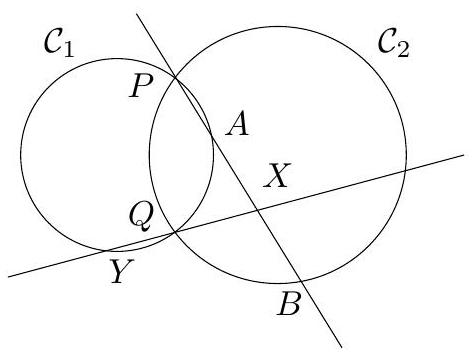

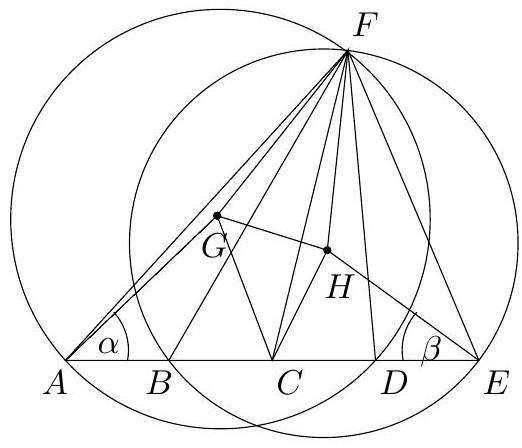

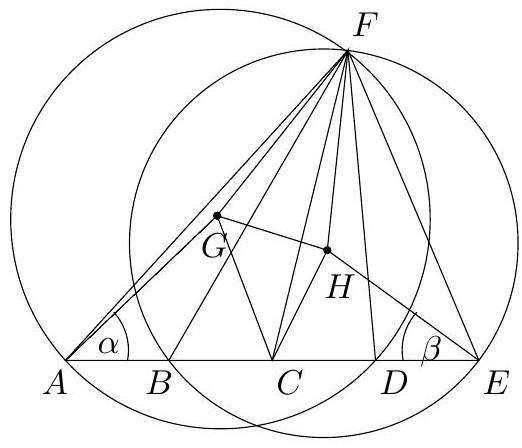

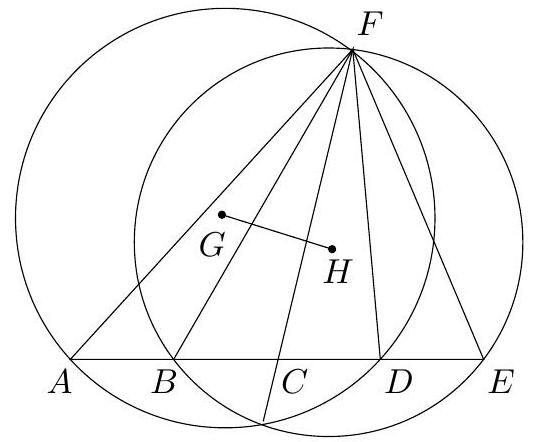

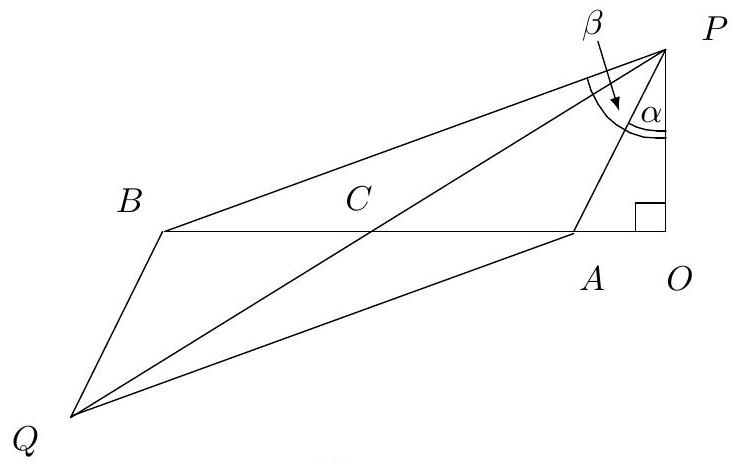

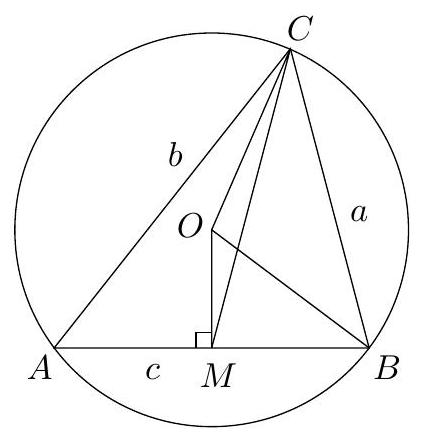

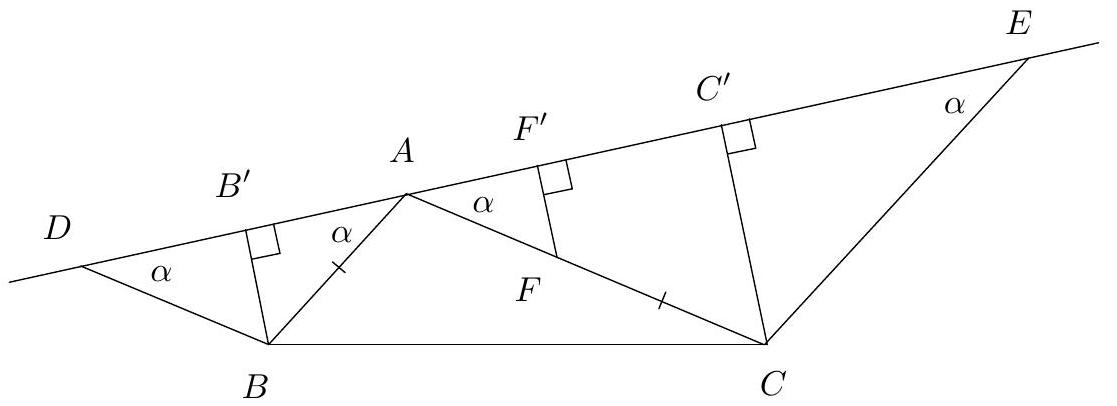

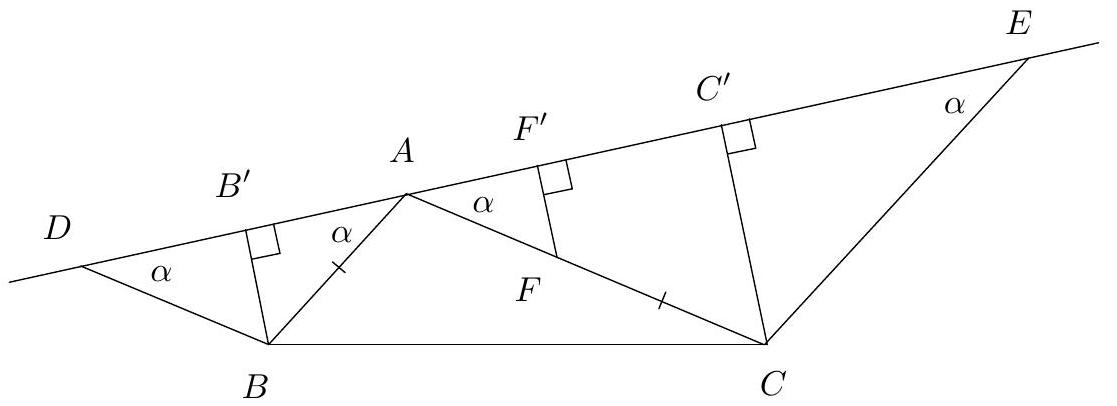

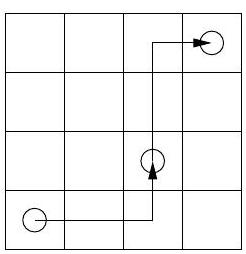

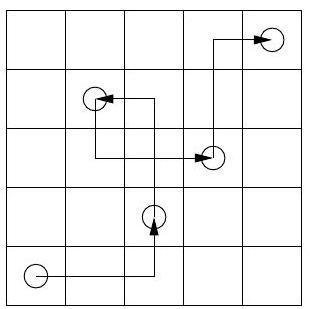

We shall prove that the lines $S_{1} O_{1}, S_{2} O_{2}, S_{3} O_{3}$ are the bisectors of the angles of the triangle $S_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$. Let $O$ and $r$ be the centre and radius of the inscribed circle $C$ of the triangle $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$. Further, let $P_{1}$ and $H_{1}$ be the points where the inscribed circle of the triangle $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$ (with the centre $O_{1}$ and radius $r_{1}$ ) touches its sides $A_{1} S_{2}$ and $S_{2} S_{3}$, respectively (see Figure 2). To show that $S_{1} O_{1}$ is the bisector of the angle $\angle S_{3} S_{1} S_{2}$ it is sufficient to prove that $O_{1}$ lies on the circumference of circle $C$, for in this case the arcs $O_{1} S_{2}$ and $O_{1} S_{3}$ will obviously be equal. To prove this, first note that as $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$ is an isosceles triangle the point $H_{1}$, as well as $O_{1}$, lies on the straight line $A_{1} O$. Now, it suffices to show that $\left|O H_{1}\right|=r-r_{1}$. Indeed, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{r-r_{1}}{r}=1-\frac{r_{1}}{r}=1-\frac{\left|O_{1} P_{1}\right|}{\left|O S_{2}\right|}=1-\frac{\left|P_{1} A_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|-\left|P_{1} A_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|} \\

& =\frac{\left|S_{2} P_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|S_{2} H_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|O H_{1}\right|}{\left|O S_{2}\right|}=\frac{\left|O H_{1}\right|}{r} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Figure 2

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

The inscribed circle of the triangle $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$ touches the sides $A_{2} A_{3}, A_{3} A_{1}$ and $A_{1} A_{2}$ at points $S_{1}, S_{2}, S_{3}$, respectively. Let $O_{1}, O_{2}, O_{3}$ be the centres of the inscribed circles of triangles $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}, A_{2} S_{3} S_{1}$ and $A_{3} S_{1} S_{2}$, respectively. Prove that the straight lines $O_{1} S_{1}, O_{2} S_{2}$ and $O_{3} S_{3}$ intersect at one point.

|

We shall prove that the lines $S_{1} O_{1}, S_{2} O_{2}, S_{3} O_{3}$ are the bisectors of the angles of the triangle $S_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$. Let $O$ and $r$ be the centre and radius of the inscribed circle $C$ of the triangle $A_{1} A_{2} A_{3}$. Further, let $P_{1}$ and $H_{1}$ be the points where the inscribed circle of the triangle $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$ (with the centre $O_{1}$ and radius $r_{1}$ ) touches its sides $A_{1} S_{2}$ and $S_{2} S_{3}$, respectively (see Figure 2). To show that $S_{1} O_{1}$ is the bisector of the angle $\angle S_{3} S_{1} S_{2}$ it is sufficient to prove that $O_{1}$ lies on the circumference of circle $C$, for in this case the arcs $O_{1} S_{2}$ and $O_{1} S_{3}$ will obviously be equal. To prove this, first note that as $A_{1} S_{2} S_{3}$ is an isosceles triangle the point $H_{1}$, as well as $O_{1}$, lies on the straight line $A_{1} O$. Now, it suffices to show that $\left|O H_{1}\right|=r-r_{1}$. Indeed, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{r-r_{1}}{r}=1-\frac{r_{1}}{r}=1-\frac{\left|O_{1} P_{1}\right|}{\left|O S_{2}\right|}=1-\frac{\left|P_{1} A_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|-\left|P_{1} A_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|} \\

& =\frac{\left|S_{2} P_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|S_{2} H_{1}\right|}{\left|S_{2} A_{1}\right|}=\frac{\left|O H_{1}\right|}{\left|O S_{2}\right|}=\frac{\left|O H_{1}\right|}{r} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Figure 2

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

Find the smallest number $a$ such that a square of side $a$ can contain five disks of radius 1 so that no two of the disks have a common interior point.

|

Let $P Q R S$ be a square which has the property described in the problem. Clearly, $a>2$. Let $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ be the square inside $P Q R S$ whose sides are at distance 1 from the sides of $P Q R S$, and, consequently, are of length $a-2$. Since all the five disks are inside $P Q R S$, their centres are inside $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$. Divide $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ into four congruent squares of side length $\frac{a}{2}-1$. By the pigeonhole principle, at least two of the five centres are in the same small square. Their distance, then, is at most $\sqrt{2}\left(\frac{a}{2}-1\right)$. Since the distance has to be at least 2 , we have $a \geq 2+2 \sqrt{2}$. On the other hand, if $a=2+2 \sqrt{2}$, we can place the five disks in such a way that one is centred at the centre of $P Q R S$ and the other four have centres at $P^{\prime}, Q^{\prime}$, $R^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime}$.

|

2+2\sqrt{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Find the smallest number $a$ such that a square of side $a$ can contain five disks of radius 1 so that no two of the disks have a common interior point.

|

Let $P Q R S$ be a square which has the property described in the problem. Clearly, $a>2$. Let $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ be the square inside $P Q R S$ whose sides are at distance 1 from the sides of $P Q R S$, and, consequently, are of length $a-2$. Since all the five disks are inside $P Q R S$, their centres are inside $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$. Divide $P^{\prime} Q^{\prime} R^{\prime} S^{\prime}$ into four congruent squares of side length $\frac{a}{2}-1$. By the pigeonhole principle, at least two of the five centres are in the same small square. Their distance, then, is at most $\sqrt{2}\left(\frac{a}{2}-1\right)$. Since the distance has to be at least 2 , we have $a \geq 2+2 \sqrt{2}$. On the other hand, if $a=2+2 \sqrt{2}$, we can place the five disks in such a way that one is centred at the centre of $P Q R S$ and the other four have centres at $P^{\prime}, Q^{\prime}$, $R^{\prime}$ and $S^{\prime}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\n13.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

Let $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ be the angles of a triangle opposite to its sides with lengths $a, b$ and $c$, respectively. Prove the inequality

$$

a \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\beta}+\frac{1}{\gamma}\right)+b \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\gamma}+\frac{1}{\alpha}\right)+c \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}\right) \geq 2 \cdot\left(\frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{b}{\beta}+\frac{c}{\gamma}\right) \cdot

$$

|

Clearly, the inequality $a>b$ implies $\alpha>\beta$ and similarly $a<b$ implies $\alpha<\beta$, hence $(a-b)(\alpha-\beta) \geq$ 0 and $a \alpha+b \beta \geq a \beta+b \alpha$. Dividing the last equality by $\alpha \beta$ we get

$$

\frac{a}{\beta}+\frac{b}{\alpha} \geq \frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{b}{\beta}

$$

Similarly we get

$$

\frac{a}{\gamma}+\frac{c}{\alpha} \geq \frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{c}{\gamma}

$$

and

$$

\frac{b}{\gamma}+\frac{c}{\beta} \geq \frac{b}{\beta}+\frac{c}{\gamma}

$$

To finish the proof it suffices to add the inequalities (6)-(8).

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ be the angles of a triangle opposite to its sides with lengths $a, b$ and $c$, respectively. Prove the inequality

$$

a \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\beta}+\frac{1}{\gamma}\right)+b \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\gamma}+\frac{1}{\alpha}\right)+c \cdot\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+\frac{1}{\beta}\right) \geq 2 \cdot\left(\frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{b}{\beta}+\frac{c}{\gamma}\right) \cdot

$$

|

Clearly, the inequality $a>b$ implies $\alpha>\beta$ and similarly $a<b$ implies $\alpha<\beta$, hence $(a-b)(\alpha-\beta) \geq$ 0 and $a \alpha+b \beta \geq a \beta+b \alpha$. Dividing the last equality by $\alpha \beta$ we get

$$

\frac{a}{\beta}+\frac{b}{\alpha} \geq \frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{b}{\beta}

$$

Similarly we get

$$

\frac{a}{\gamma}+\frac{c}{\alpha} \geq \frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{c}{\gamma}

$$

and

$$

\frac{b}{\gamma}+\frac{c}{\beta} \geq \frac{b}{\beta}+\frac{c}{\gamma}

$$

To finish the proof it suffices to add the inequalities (6)-(8).

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

Does there exist a triangle such that the lengths of all its sides and altitudes are integers and its perimeter is equal to 1995 ?

|

Consider a triangle $A B C$ with all its sides and heights having integer lengths. From the cosine theorem we conclude that $\cos \angle A, \cos \angle B$ and $\cos \angle C$ are rational numbers. Let $A H$ be one of the heights of the triangle $A B C$, with the point $H$ lying on the straight line determined by the side $B C$. Then $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ must be rational and hence integer (consider the Pythagorean theorem for the triangles $A B H$ and $A C H$ ). Now, if $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ have different parity then $|A B|$ and $|A C|$ also have different parity and $|B C|$ is odd. If $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ have the same parity then $|A B|$ and $|A C|$ also have the same parity and $|B C|$ is even. In both cases the perimeter of triangle $A B C$ is an even number and hence cannot be equal to 1995

Remark. In the solution we only used the fact that all three sides and one height of the triangle $A B C$ are integers.

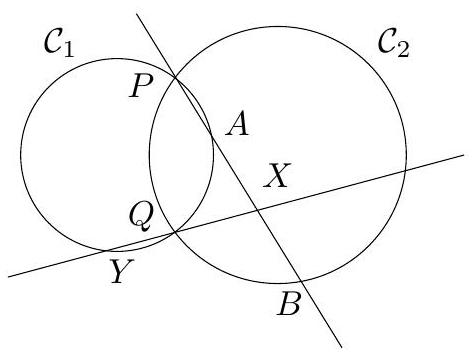

Figure 3

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Does there exist a triangle such that the lengths of all its sides and altitudes are integers and its perimeter is equal to 1995 ?

|

Consider a triangle $A B C$ with all its sides and heights having integer lengths. From the cosine theorem we conclude that $\cos \angle A, \cos \angle B$ and $\cos \angle C$ are rational numbers. Let $A H$ be one of the heights of the triangle $A B C$, with the point $H$ lying on the straight line determined by the side $B C$. Then $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ must be rational and hence integer (consider the Pythagorean theorem for the triangles $A B H$ and $A C H$ ). Now, if $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ have different parity then $|A B|$ and $|A C|$ also have different parity and $|B C|$ is odd. If $|B H|$ and $|C H|$ have the same parity then $|A B|$ and $|A C|$ also have the same parity and $|B C|$ is even. In both cases the perimeter of triangle $A B C$ is an even number and hence cannot be equal to 1995

Remark. In the solution we only used the fact that all three sides and one height of the triangle $A B C$ are integers.

Figure 3

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

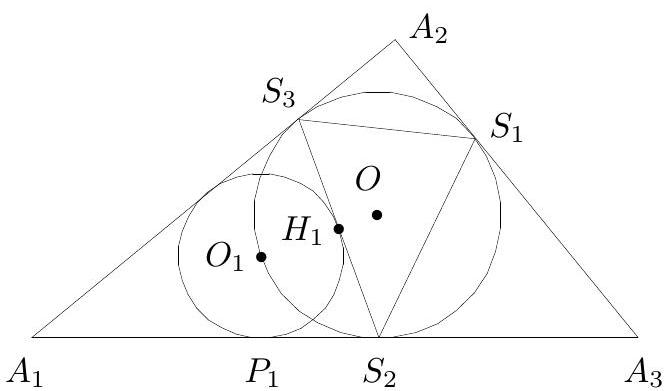

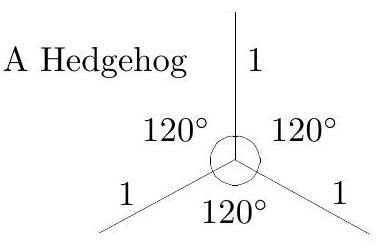

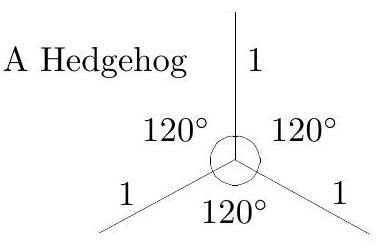

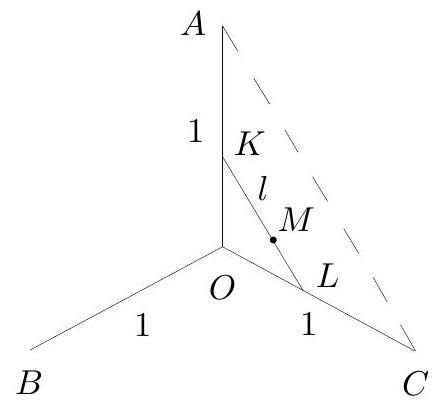

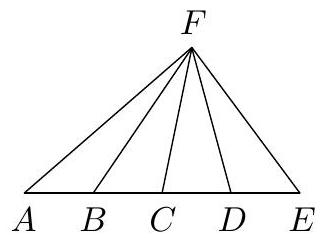

The Wonder Island is inhabited by Hedgehogs. Each Hedgehog consists of three segments of unit length having a common endpoint, with all three angles between them equal to $120^{\circ}$ (see Figure 3). Given that all Hedgehogs are lying flat on the island and no two of them touch each other, prove that there is a finite number of Hedgehogs on Wonder Island.

|

It suffices to prove that if the distance between the centres of two Hedgehogs is less than 0.2, then these Hedgehogs intersect. To show this, consider two Hedgehogs with their centres at points $O$ and $M$, respectively, such that $|O M|<0.2$. Let $A, B$ and $C$ be the endpoints of the needles of the first Hedgehog (see Figure 4) and draw a straight line $l$ parallel to $A C$ through the point $M$. As $|A C|=\sqrt{3}$ implies $|K L| \leq$ $\frac{0.2}{0.5}|A C|<1$ and the second Hedgehog has at least one of its needles pointing inside the triangle $O K L$, this needle intersects the first Hedgehog.

Remark. If the Hedgehogs can move their needles so that the angles between them can take any positive value then there can be an infinite number of Hedgehogs on the Wonder Island.

Figure 4

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

The Wonder Island is inhabited by Hedgehogs. Each Hedgehog consists of three segments of unit length having a common endpoint, with all three angles between them equal to $120^{\circ}$ (see Figure 3). Given that all Hedgehogs are lying flat on the island and no two of them touch each other, prove that there is a finite number of Hedgehogs on Wonder Island.

|

It suffices to prove that if the distance between the centres of two Hedgehogs is less than 0.2, then these Hedgehogs intersect. To show this, consider two Hedgehogs with their centres at points $O$ and $M$, respectively, such that $|O M|<0.2$. Let $A, B$ and $C$ be the endpoints of the needles of the first Hedgehog (see Figure 4) and draw a straight line $l$ parallel to $A C$ through the point $M$. As $|A C|=\sqrt{3}$ implies $|K L| \leq$ $\frac{0.2}{0.5}|A C|<1$ and the second Hedgehog has at least one of its needles pointing inside the triangle $O K L$, this needle intersects the first Hedgehog.

Remark. If the Hedgehogs can move their needles so that the angles between them can take any positive value then there can be an infinite number of Hedgehogs on the Wonder Island.

Figure 4

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

In a certain kingdom, the king has decided to build 25 new towns on 13 uninhabited islands so that on each island there will be at least one town. Direct ferry connections will be established between any pair of new towns which are on different islands. Determine the least possible number of these connections.

|

Let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{13}$ be the numbers of towns on each island. Suppose there exist numbers $i$ and $j$ such that $a_{i} \geq a_{j}>1$ and consider an arbitrary town $A$ on the $j$-th island. The number of ferry connections from town $A$ is equal to $25-a_{j}$. On the other hand, if we "move" town $A$ to the $i$-th island then there will be $25-\left(a_{i}+1\right)$ connections from town $A$ while no other connections will be affected by this move. Hence, the smallest number of connections will be achieved if there are 13 towns on one island and one town on each of the other 12 islands. In this case there will be $13 \cdot 12+\frac{12 \cdot 11}{2}=222$ connections.

|

222

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In a certain kingdom, the king has decided to build 25 new towns on 13 uninhabited islands so that on each island there will be at least one town. Direct ferry connections will be established between any pair of new towns which are on different islands. Determine the least possible number of these connections.

|

Let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{13}$ be the numbers of towns on each island. Suppose there exist numbers $i$ and $j$ such that $a_{i} \geq a_{j}>1$ and consider an arbitrary town $A$ on the $j$-th island. The number of ferry connections from town $A$ is equal to $25-a_{j}$. On the other hand, if we "move" town $A$ to the $i$-th island then there will be $25-\left(a_{i}+1\right)$ connections from town $A$ while no other connections will be affected by this move. Hence, the smallest number of connections will be achieved if there are 13 towns on one island and one town on each of the other 12 islands. In this case there will be $13 \cdot 12+\frac{12 \cdot 11}{2}=222$ connections.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\n17.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

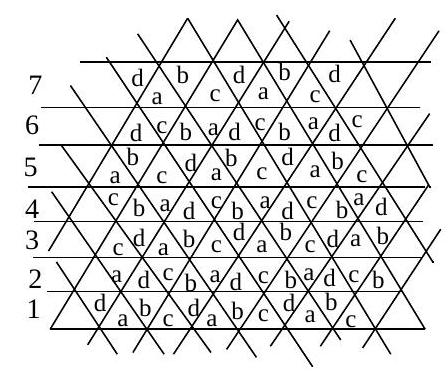

There are $n$ lines $(n>2)$ given in the plane. No two of the lines are parallel and no three of them intersect at one point. Every point of intersection of these lines is labelled with a natural number between 1 and $n-1$. Prove that, if and only if $n$ is even, it is possible to assign the labels in such a way that every line has all the numbers from 1 to $n-1$ at its points of intersection with the other $n-1$ lines.

|

Suppose we have assigned the labels in the required manner. When a point has label 1 then there can be no more occurrences of label 1 on the two lines that intersect at that point. Therefore the number of intersection points labelled with 1 has to be exactly $\frac{n}{2}$, and so $n$ must be even. Now, let $n$ be an even number and denote the $n$ lines by $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots, l_{n}$. First write the lines $l_{i}$ in the following table:

$$

\begin{array}{llllll}

& & l_{3} & l_{4} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+1} \\

l_{1} & l_{2} & & & & \\

& & l_{n} & l_{n-1} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+2}

\end{array}

$$

and then rotate the picture $n-1$ times:

$$

\begin{array}{llllll}

& & l_{2} & l_{3} & \ldots & l_{n / 2} \\

l_{1} & l_{n} & l_{n-1} & l_{n-2} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+1} \\

& & & & & \\

& & l_{n} & l_{2} & \ldots & l_{n / 2-1} \\

l_{1} & l_{n-1} & & & & l_{n / 2}

\end{array}

$$

etc.

According to these tables, we can join the lines in pairs in $n-1$ different ways $-l_{1}$ with the line next to it and every other line with the line directly above or under it. Now we can assign the label $i$ to all the intersection points of the pairs of lines shown in the $i$ th table.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

There are $n$ lines $(n>2)$ given in the plane. No two of the lines are parallel and no three of them intersect at one point. Every point of intersection of these lines is labelled with a natural number between 1 and $n-1$. Prove that, if and only if $n$ is even, it is possible to assign the labels in such a way that every line has all the numbers from 1 to $n-1$ at its points of intersection with the other $n-1$ lines.

|

Suppose we have assigned the labels in the required manner. When a point has label 1 then there can be no more occurrences of label 1 on the two lines that intersect at that point. Therefore the number of intersection points labelled with 1 has to be exactly $\frac{n}{2}$, and so $n$ must be even. Now, let $n$ be an even number and denote the $n$ lines by $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots, l_{n}$. First write the lines $l_{i}$ in the following table:

$$

\begin{array}{llllll}

& & l_{3} & l_{4} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+1} \\

l_{1} & l_{2} & & & & \\

& & l_{n} & l_{n-1} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+2}

\end{array}

$$

and then rotate the picture $n-1$ times:

$$

\begin{array}{llllll}

& & l_{2} & l_{3} & \ldots & l_{n / 2} \\

l_{1} & l_{n} & l_{n-1} & l_{n-2} & \ldots & l_{n / 2+1} \\

& & & & & \\

& & l_{n} & l_{2} & \ldots & l_{n / 2-1} \\

l_{1} & l_{n-1} & & & & l_{n / 2}

\end{array}

$$

etc.

According to these tables, we can join the lines in pairs in $n-1$ different ways $-l_{1}$ with the line next to it and every other line with the line directly above or under it. Now we can assign the label $i$ to all the intersection points of the pairs of lines shown in the $i$ th table.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

The Wonder Island Intelligence Service has 16 spies in Tartu. Each of them watches on some of his colleagues. It is known that if spy $A$ watches on spy $B$ then $B$ does not watch on $A$. Moreover, any 10 spies can be numbered in such a way that the first spy watches on the second, the second watches on the third, .., the tenth watches on the first. Prove that any 11 spies can also be numbered in a similar manner.

|

We call two spies $A$ and $B$ neutral to each other if neither $A$ watches on $B$ nor $B$ watches on $A$.

Denote the spies $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{16}$. Let $a_{i}, b_{i}$ and $c_{i}$ denote the number of spies that watch on $A_{i}$, the number of that are watched by $A_{i}$ and the number of spies neutral to $A_{i}$, respectively. Clearly, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{i}+b_{i}+c_{i} & =15, \\

a_{i}+c_{i} & \leq 8, \\

b_{i}+c_{i} & \leq 8

\end{aligned}

$$

for any $i=1, \ldots, 16$ (if any of the last two inequalities does not hold then there exist 10 spies who cannot be numbered in the required manner). Combining the relations above we find $c_{i} \leq 1$. Hence, for any spy, the number of his neutral colleagues is 0 or 1 .

Now suppose there is a group of 11 spies that cannot be numbered as required. Let $B$ be an arbitrary spy in this group. Number the other 10 spies as $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ so that $C_{1}$ watches on $C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ watches on $C_{1}$. Suppose there is no spy neutral to $B$ among $C_{1}, \ldots, C_{10}$. Then, if $C_{1}$ watches on $B$ then $B$ cannot watch on $C_{2}$, as otherwise $C_{1}, B, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ would form an 11-cycle. So $C_{2}$ watches on $B$, etc. As some of the spies $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ must watch on $B$ we get all of them watching on $B$, a contradiction. Therefore, each of the 11 spies must have exactly one spy neutral to him among the other 10 - but this is impossible.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

The Wonder Island Intelligence Service has 16 spies in Tartu. Each of them watches on some of his colleagues. It is known that if spy $A$ watches on spy $B$ then $B$ does not watch on $A$. Moreover, any 10 spies can be numbered in such a way that the first spy watches on the second, the second watches on the third, .., the tenth watches on the first. Prove that any 11 spies can also be numbered in a similar manner.

|

We call two spies $A$ and $B$ neutral to each other if neither $A$ watches on $B$ nor $B$ watches on $A$.

Denote the spies $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{16}$. Let $a_{i}, b_{i}$ and $c_{i}$ denote the number of spies that watch on $A_{i}$, the number of that are watched by $A_{i}$ and the number of spies neutral to $A_{i}$, respectively. Clearly, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{i}+b_{i}+c_{i} & =15, \\

a_{i}+c_{i} & \leq 8, \\

b_{i}+c_{i} & \leq 8

\end{aligned}

$$

for any $i=1, \ldots, 16$ (if any of the last two inequalities does not hold then there exist 10 spies who cannot be numbered in the required manner). Combining the relations above we find $c_{i} \leq 1$. Hence, for any spy, the number of his neutral colleagues is 0 or 1 .

Now suppose there is a group of 11 spies that cannot be numbered as required. Let $B$ be an arbitrary spy in this group. Number the other 10 spies as $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ so that $C_{1}$ watches on $C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ watches on $C_{1}$. Suppose there is no spy neutral to $B$ among $C_{1}, \ldots, C_{10}$. Then, if $C_{1}$ watches on $B$ then $B$ cannot watch on $C_{2}$, as otherwise $C_{1}, B, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ would form an 11-cycle. So $C_{2}$ watches on $B$, etc. As some of the spies $C_{1}, C_{2}, \ldots, C_{10}$ must watch on $B$ we get all of them watching on $B$, a contradiction. Therefore, each of the 11 spies must have exactly one spy neutral to him among the other 10 - but this is impossible.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "\n19.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

An equilateral triangle is divided into 9000000 congruent equilateral triangles by lines parallel to its sides. Each vertex of the small triangles is coloured in one of three colours. Prove that there exist three points of the same colour being the vertices of a triangle with its sides parallel to the sides of the original triangle.

|

Consider the side $A B$ of the big triangle $A B C$ as "horizontal" and suppose the statement of the problem does not hold. The side $A B$ contains 3001 vertices $A=A_{0}, A_{1}, \ldots, A_{3000}=B$ of 3 colours. Hence, there are at least 1001 vertices of one colour, e.g., red. For any two red vertices $A_{k}$ and $A_{n}$ there exists a unique vertex $B_{k n}$ such that the triangle $B_{k n} A_{k} A_{n}$ is equilateral. That vertex $B_{k n}$ cannot be red. For different pairs $(k, n)$ the corresponding vertices $B_{k n}$ are different, so we have at least $\left(\begin{array}{c}1001 \\ 2\end{array}\right)>500000$ vertices of type $B_{k n}$ that cannot be red. As all these vertices are situated on 3000 horizontal lines, there exists a line $L$ which contains more than 160 vertices of type $B_{k n}$, each of them coloured in one of the two remaining colours. Hence there exist at least 81 vertices of the same colour, e.g., blue, on line $L$. For every two blue vertices $B_{k n}$ and $B_{m l}$ on line $L$ there exists a unique vertex $C_{k n m l}$ such that:

(i) $C_{k n m l}$ lies above the line $L$;

(ii) The triangle $C_{k n m l} B_{k n} B_{m l}$ is equilateral;

(iii) $C_{k n m l}=B_{p q}$ where $p=\min (k, m)$ and $q=\max (n, l)$.

Different pairs of vertices $B_{k n}$ belonging to line $L$ define different vertices $C_{k n m l}$. So we have at least $\left(\begin{array}{c}81 \\ 2\end{array}\right)>3200$ vertices of type $C_{k n m l}$ that can be neither blue nor red. As the number of these vertices exceeds the number of horizontal lines, there must be two vertices $C_{k n m l}$ and $C_{p q r s}$ on one horizontal line. Now, these two vertices define a new vertex $D_{\text {knmlpqrs }}$ that cannot have any of the three colours, a contradiction.

Remark. The minimal size of the big triangle that can be handled by this proof is 2557 .

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

An equilateral triangle is divided into 9000000 congruent equilateral triangles by lines parallel to its sides. Each vertex of the small triangles is coloured in one of three colours. Prove that there exist three points of the same colour being the vertices of a triangle with its sides parallel to the sides of the original triangle.

|

Consider the side $A B$ of the big triangle $A B C$ as "horizontal" and suppose the statement of the problem does not hold. The side $A B$ contains 3001 vertices $A=A_{0}, A_{1}, \ldots, A_{3000}=B$ of 3 colours. Hence, there are at least 1001 vertices of one colour, e.g., red. For any two red vertices $A_{k}$ and $A_{n}$ there exists a unique vertex $B_{k n}$ such that the triangle $B_{k n} A_{k} A_{n}$ is equilateral. That vertex $B_{k n}$ cannot be red. For different pairs $(k, n)$ the corresponding vertices $B_{k n}$ are different, so we have at least $\left(\begin{array}{c}1001 \\ 2\end{array}\right)>500000$ vertices of type $B_{k n}$ that cannot be red. As all these vertices are situated on 3000 horizontal lines, there exists a line $L$ which contains more than 160 vertices of type $B_{k n}$, each of them coloured in one of the two remaining colours. Hence there exist at least 81 vertices of the same colour, e.g., blue, on line $L$. For every two blue vertices $B_{k n}$ and $B_{m l}$ on line $L$ there exists a unique vertex $C_{k n m l}$ such that:

(i) $C_{k n m l}$ lies above the line $L$;

(ii) The triangle $C_{k n m l} B_{k n} B_{m l}$ is equilateral;

(iii) $C_{k n m l}=B_{p q}$ where $p=\min (k, m)$ and $q=\max (n, l)$.

Different pairs of vertices $B_{k n}$ belonging to line $L$ define different vertices $C_{k n m l}$. So we have at least $\left(\begin{array}{c}81 \\ 2\end{array}\right)>3200$ vertices of type $C_{k n m l}$ that can be neither blue nor red. As the number of these vertices exceeds the number of horizontal lines, there must be two vertices $C_{k n m l}$ and $C_{p q r s}$ on one horizontal line. Now, these two vertices define a new vertex $D_{\text {knmlpqrs }}$ that cannot have any of the three colours, a contradiction.

Remark. The minimal size of the big triangle that can be handled by this proof is 2557 .

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw94sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1994"

}

|

Find all triples $(x, y, z)$ of positive integers satisfying the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

x^{2}=2(y+z) \\

x^{6}=y^{6}+z^{6}+31\left(y^{2}+z^{2}\right)

\end{array}\right.

$$

|

From the first equation it follows that $x$ is even. The second equation implies $x>y$ and $x>z$. Hence $4 x>2(y+z)=x^{2}$, and therefore $x=2$ and $y+z=2$, so $y=z=1$. It is easy to check that the triple $(2,1,1)$ satisfies the given system of equations.

|

(2,1,1)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find all triples $(x, y, z)$ of positive integers satisfying the system of equations

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

x^{2}=2(y+z) \\

x^{6}=y^{6}+z^{6}+31\left(y^{2}+z^{2}\right)

\end{array}\right.

$$

|

From the first equation it follows that $x$ is even. The second equation implies $x>y$ and $x>z$. Hence $4 x>2(y+z)=x^{2}$, and therefore $x=2$ and $y+z=2$, so $y=z=1$. It is easy to check that the triple $(2,1,1)$ satisfies the given system of equations.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Let $a$ and $k$ be positive integers such that $a^{2}+k$ divides $(a-1) a(a+1)$. Prove that $k \geq a$.

|

We have $(a-1) a(a+1)=a\left(a^{2}+k\right)-(k+1) a$. Hence $a^{2}+k$ divides $(k+1) a$, and thus $k+1 \geq a$, or equivalently, $k \geq a$.

|

k \geq a

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $a$ and $k$ be positive integers such that $a^{2}+k$ divides $(a-1) a(a+1)$. Prove that $k \geq a$.

|

We have $(a-1) a(a+1)=a\left(a^{2}+k\right)-(k+1) a$. Hence $a^{2}+k$ divides $(k+1) a$, and thus $k+1 \geq a$, or equivalently, $k \geq a$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

The positive integers $a, b, c$ are pairwise relatively prime, $a$ and $c$ are odd and the numbers satisfy the equation $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$. Prove that $b+c$ is a square of an integer.

|

Since $a$ and $c$ are odd, $b$ must be even. We have $a^{2}=c^{2}-b^{2}=(c+b)(c-b)$. Let $d=\operatorname{gcd}(c+b, c-b)$. Then $d$ divides $(c+b)+(c-b)=2 c$ and $(c+b)-(c-b)=2 b$. Since $c+b$ and $c-b$ are odd, $d$ is odd, and hence $d$ divides both $b$ and $c$. But $b$ and $c$ are relatively prime, so $d=1$, i.e., $c+b$ and $c-b$ are also relatively prime. Since $(c+b)(c-b)=a^{2}$ is a square, it follows that $c+b$ and $c-b$ are also squares. In particular, $b+c$ is a square as required.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

The positive integers $a, b, c$ are pairwise relatively prime, $a$ and $c$ are odd and the numbers satisfy the equation $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$. Prove that $b+c$ is a square of an integer.

|

Since $a$ and $c$ are odd, $b$ must be even. We have $a^{2}=c^{2}-b^{2}=(c+b)(c-b)$. Let $d=\operatorname{gcd}(c+b, c-b)$. Then $d$ divides $(c+b)+(c-b)=2 c$ and $(c+b)-(c-b)=2 b$. Since $c+b$ and $c-b$ are odd, $d$ is odd, and hence $d$ divides both $b$ and $c$. But $b$ and $c$ are relatively prime, so $d=1$, i.e., $c+b$ and $c-b$ are also relatively prime. Since $(c+b)(c-b)=a^{2}$ is a square, it follows that $c+b$ and $c-b$ are also squares. In particular, $b+c$ is a square as required.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

John is older than Mary. He notices that if he switches the two digits of his age (an integer), he gets Mary's age. Moreover, the difference between the squares of their ages is the square of an integer. How old are Mary and John?

|

Let John's age be $10 a+b$ where $0 \leq a, b \leq 9$. Then Mary's age is $10 b+a$, and hence $a>b$. Now

$$

(10 a+b)^{2}-(10 b+a)^{2}=9 \cdot 11(a+b)(a-b) .

$$

Since this is the square of an integer, $a+b$ or $a-b$ must be divisible by 11 . The only possibility is clearly $a+b=11$. Hence $a-b$ must be a square. A case study yields the only possibility $a=6, b=5$. Thus John is 65 and Mary 56 years old.

|

65, 56

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

John is older than Mary. He notices that if he switches the two digits of his age (an integer), he gets Mary's age. Moreover, the difference between the squares of their ages is the square of an integer. How old are Mary and John?

|

Let John's age be $10 a+b$ where $0 \leq a, b \leq 9$. Then Mary's age is $10 b+a$, and hence $a>b$. Now

$$

(10 a+b)^{2}-(10 b+a)^{2}=9 \cdot 11(a+b)(a-b) .

$$

Since this is the square of an integer, $a+b$ or $a-b$ must be divisible by 11 . The only possibility is clearly $a+b=11$. Hence $a-b$ must be a square. A case study yields the only possibility $a=6, b=5$. Thus John is 65 and Mary 56 years old.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Let $a<b<c$ be three positive integers. Prove that among any $2 c$ consecutive positive integers there exist three different numbers $x, y, z$ such that $a b c$ divides $x y z$.

|

First we show that among any $b$ consecutive numbers there are two different numbers $x$ and $y$ such that $a b$ divides $x y$. Among the $b$ consecutive numbers there is clearly a number $x^{\prime}$ divisible by $b$, and a number $y^{\prime}$ divisible by $a$. If $x^{\prime} \neq y^{\prime}$, we can take $x=x^{\prime}$ and $y=y^{\prime}$, and we are done. Now assume that $x^{\prime}=y^{\prime}$. Then $x^{\prime}$ is divisible by $e$, the least common multiple of $a$ and $b$. Let $d=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$. As $a<b$, we have $d \leq \frac{1}{2} b$. Hence there is a number $z^{\prime} \neq x^{\prime}$ among the $b$ consecutive numbers such that $z^{\prime}$ is divisible by $d$. Hence $x^{\prime} z^{\prime}$ is divisible by $d e$. But $d e=a b$, so we can take $x=x^{\prime}$ and $y=z^{\prime}$.

Now divide the $2 c$ consecutive numbers into two groups of $c$ consecutive numbers. In the first group, by the above reasoning, there exist distinct numbers $x$ and $y$ such that $a b$ divides $x y$. The second group contains a number $z$ divisible by $c$. Then $a b c$ divides $x y z$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $a<b<c$ be three positive integers. Prove that among any $2 c$ consecutive positive integers there exist three different numbers $x, y, z$ such that $a b c$ divides $x y z$.

|

First we show that among any $b$ consecutive numbers there are two different numbers $x$ and $y$ such that $a b$ divides $x y$. Among the $b$ consecutive numbers there is clearly a number $x^{\prime}$ divisible by $b$, and a number $y^{\prime}$ divisible by $a$. If $x^{\prime} \neq y^{\prime}$, we can take $x=x^{\prime}$ and $y=y^{\prime}$, and we are done. Now assume that $x^{\prime}=y^{\prime}$. Then $x^{\prime}$ is divisible by $e$, the least common multiple of $a$ and $b$. Let $d=\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)$. As $a<b$, we have $d \leq \frac{1}{2} b$. Hence there is a number $z^{\prime} \neq x^{\prime}$ among the $b$ consecutive numbers such that $z^{\prime}$ is divisible by $d$. Hence $x^{\prime} z^{\prime}$ is divisible by $d e$. But $d e=a b$, so we can take $x=x^{\prime}$ and $y=z^{\prime}$.

Now divide the $2 c$ consecutive numbers into two groups of $c$ consecutive numbers. In the first group, by the above reasoning, there exist distinct numbers $x$ and $y$ such that $a b$ divides $x y$. The second group contains a number $z$ divisible by $c$. Then $a b c$ divides $x y z$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Prove that for positive $a, b, c, d$

$$

\frac{a+c}{a+b}+\frac{b+d}{b+c}+\frac{c+a}{c+d}+\frac{d+b}{d+a} \geq 4 .

$$

|

The inequality between the arithmetic and harmonic mean gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a+c}{a+b}+\frac{c+a}{c+d} \geq \frac{4}{\frac{a+b}{a+c}+\frac{c+d}{c+a}}=4 \cdot \frac{a+c}{a+b+c+d} \\

& \frac{b+d}{b+c}+\frac{d+b}{d+a} \geq \frac{4}{\frac{b+c}{b+d}+\frac{d+a}{d+b}}=4 \cdot \frac{b+d}{a+b+c+d}

\end{aligned}

$$

and adding these inequalities yields the required inequality.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Prove that for positive $a, b, c, d$

$$

\frac{a+c}{a+b}+\frac{b+d}{b+c}+\frac{c+a}{c+d}+\frac{d+b}{d+a} \geq 4 .

$$

|

The inequality between the arithmetic and harmonic mean gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{a+c}{a+b}+\frac{c+a}{c+d} \geq \frac{4}{\frac{a+b}{a+c}+\frac{c+d}{c+a}}=4 \cdot \frac{a+c}{a+b+c+d} \\

& \frac{b+d}{b+c}+\frac{d+b}{d+a} \geq \frac{4}{\frac{b+c}{b+d}+\frac{d+a}{d+b}}=4 \cdot \frac{b+d}{a+b+c+d}

\end{aligned}

$$

and adding these inequalities yields the required inequality.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\n6.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Prove that $\sin ^{3} 18^{\circ}+\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ}=1 / 8$.

|

We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sin ^{3} 18^{\circ}+\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} & =\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ}\left(\sin 18^{\circ}+\sin 90^{\circ}\right)=\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cdot 2 \sin 54^{\circ} \cos 36^{\circ}=2 \sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ} \\

& =\frac{2 \sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ}}{\cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{\sin ^{2} 36^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ}}{2 \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{\sin ^{2} 72^{\circ}}{8 \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{8} .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

\frac{1}{8}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prove that $\sin ^{3} 18^{\circ}+\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ}=1 / 8$.

|

We have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sin ^{3} 18^{\circ}+\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} & =\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ}\left(\sin 18^{\circ}+\sin 90^{\circ}\right)=\sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cdot 2 \sin 54^{\circ} \cos 36^{\circ}=2 \sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ} \\

& =\frac{2 \sin ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ}}{\cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{\sin ^{2} 36^{\circ} \cos ^{2} 36^{\circ}}{2 \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{\sin ^{2} 72^{\circ}}{8 \cos ^{2} 18^{\circ}}=\frac{1}{8} .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\n7.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

The real numbers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the inequalities $|a| \geq|b+c|,|b| \geq|c+a|$ and $|c| \geq|a+b|$. Prove that $a+b+c=0$.

|

Squaring both sides of the given inequalities we get

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

a^{2} \geq(b+c)^{2} \\

b^{2} \geq(c+a)^{2} \\

c^{2} \geq(a+b)^{2}

\end{array}\right.

$$

Adding these three inequalities and rearranging, we get $(a+b+c)^{2} \leq 0$. Clearly equality must hold, and we have $a+b+c=0$.

|

a+b+c=0

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

The real numbers $a, b$ and $c$ satisfy the inequalities $|a| \geq|b+c|,|b| \geq|c+a|$ and $|c| \geq|a+b|$. Prove that $a+b+c=0$.

|

Squaring both sides of the given inequalities we get

$$

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

a^{2} \geq(b+c)^{2} \\

b^{2} \geq(c+a)^{2} \\

c^{2} \geq(a+b)^{2}

\end{array}\right.

$$

Adding these three inequalities and rearranging, we get $(a+b+c)^{2} \leq 0$. Clearly equality must hold, and we have $a+b+c=0$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Prove that

$$

\frac{1995}{2}-\frac{1994}{3}+\frac{1993}{4}-\cdots-\frac{2}{1995}+\frac{1}{1996}=\frac{1}{999}+\frac{3}{1000}+\cdots+\frac{1995}{1996} .

$$

|

Denote the left-hand side of the equation by $L$, and the right-hand side by $R$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

L & =\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k+1}\left(\frac{1997}{k+1}-1\right)=1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k+1} \cdot \frac{1}{k+1}=1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k} \cdot \frac{1}{k}+1996, \\

R & =\sum_{k=1}^{998}\left(\frac{2 k+1996}{998+k}-\frac{1997}{998+k}\right)=1996-1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998} .

\end{aligned}

$$

We must verify that $\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k-1} \cdot \frac{1}{k}=\sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998}$. But this follows from the calculation

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k-1} \cdot \frac{1}{k}=\sum_{k=1}^{1996} \frac{1}{k}-2 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{2 k}=\sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998}

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prove that

$$

\frac{1995}{2}-\frac{1994}{3}+\frac{1993}{4}-\cdots-\frac{2}{1995}+\frac{1}{1996}=\frac{1}{999}+\frac{3}{1000}+\cdots+\frac{1995}{1996} .

$$

|

Denote the left-hand side of the equation by $L$, and the right-hand side by $R$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

L & =\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k+1}\left(\frac{1997}{k+1}-1\right)=1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k+1} \cdot \frac{1}{k+1}=1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k} \cdot \frac{1}{k}+1996, \\

R & =\sum_{k=1}^{998}\left(\frac{2 k+1996}{998+k}-\frac{1997}{998+k}\right)=1996-1997 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998} .

\end{aligned}

$$

We must verify that $\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k-1} \cdot \frac{1}{k}=\sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998}$. But this follows from the calculation

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{1996}(-1)^{k-1} \cdot \frac{1}{k}=\sum_{k=1}^{1996} \frac{1}{k}-2 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{2 k}=\sum_{k=1}^{998} \frac{1}{k+998}

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Find all real-valued functions $f$ defined on the set of all non-zero real numbers such that:

(i) $f(1)=1$,

(ii) $f\left(\frac{1}{x+y}\right)=f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)+f\left(\frac{1}{y}\right)$ for all non-zero $x, y, x+y$,

(iii) $(x+y) f(x+y)=x y f(x) f(y)$ for all non-zero $x, y, x+y$.

|

Substituting $x=y=\frac{1}{2} z$ in (ii) we get

$$

f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)=2 f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)

$$

for all $z \neq 0$. Substituting $x=y=\frac{1}{z}$ in (iii) yields

$$

\frac{2}{z} f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z^{2}}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2}

$$

for all $z \neq 0$, and hence

$$

2 f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2} .

$$

From (1) and (2) we get

$$

f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2},

$$

or, equivalently,

$$

f(x)=x(f(x))^{2}

$$

for all $x \neq 0$. If $f(x)=0$ for some $x$, then by (iii) we would have

$$

f(1)=(x+(1-x)) f(x+(1-x))=(1-x) f(x) f(1-x)=0

$$

which contradicts the condition (i). Hence $f(x) \neq 0$ for all $x$, and (3) implies $x f(x)=1$ for all $x$, and thus $f(x)=\frac{1}{x}$. It is easily verified that this function satisfies the given conditions.

|

f(x)=\frac{1}{x}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find all real-valued functions $f$ defined on the set of all non-zero real numbers such that:

(i) $f(1)=1$,

(ii) $f\left(\frac{1}{x+y}\right)=f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)+f\left(\frac{1}{y}\right)$ for all non-zero $x, y, x+y$,

(iii) $(x+y) f(x+y)=x y f(x) f(y)$ for all non-zero $x, y, x+y$.

|

Substituting $x=y=\frac{1}{2} z$ in (ii) we get

$$

f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)=2 f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)

$$

for all $z \neq 0$. Substituting $x=y=\frac{1}{z}$ in (iii) yields

$$

\frac{2}{z} f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z^{2}}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2}

$$

for all $z \neq 0$, and hence

$$

2 f\left(\frac{2}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2} .

$$

From (1) and (2) we get

$$

f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)=\frac{1}{z}\left(f\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)\right)^{2},

$$

or, equivalently,

$$

f(x)=x(f(x))^{2}

$$

for all $x \neq 0$. If $f(x)=0$ for some $x$, then by (iii) we would have

$$

f(1)=(x+(1-x)) f(x+(1-x))=(1-x) f(x) f(1-x)=0

$$

which contradicts the condition (i). Hence $f(x) \neq 0$ for all $x$, and (3) implies $x f(x)=1$ for all $x$, and thus $f(x)=\frac{1}{x}$. It is easily verified that this function satisfies the given conditions.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

In how many ways can the set of integers $\{1,2, \ldots, 1995\}$ be partitioned into three nonempty sets so that none of these sets contains two consecutive integers?

|

We construct the three subsets by adding the numbers successively, and disregard at first the condition that the sets must be non-empty. The numbers 1 and 2 must belong to two different subsets, say $A$ and $B$. We then have two choices for each of the numbers $3,4, \ldots, 1995$, and different choices lead to different partitions. Hence there are $2^{1993}$ such partitions, one of which has an empty part. The number of partitions satisfying the requirements of the problem is therefore $2^{1993}-1$.

|

2^{1993}-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

In how many ways can the set of integers $\{1,2, \ldots, 1995\}$ be partitioned into three nonempty sets so that none of these sets contains two consecutive integers?

|

We construct the three subsets by adding the numbers successively, and disregard at first the condition that the sets must be non-empty. The numbers 1 and 2 must belong to two different subsets, say $A$ and $B$. We then have two choices for each of the numbers $3,4, \ldots, 1995$, and different choices lead to different partitions. Hence there are $2^{1993}$ such partitions, one of which has an empty part. The number of partitions satisfying the requirements of the problem is therefore $2^{1993}-1$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\n11.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Assume we have 95 boxes and 19 balls distributed in these boxes in an arbitrary manner. We take six new balls at a time and place them in six of the boxes, one ball in each of the six. Can we, by repeating this process a suitable number of times, achieve a situation in which each of the 95 boxes contains an equal number of balls?

|

Since $6 \cdot 16=96$, we can put 16 times 6 balls in the boxes so that the number of balls in one of the boxes increases by two, while in all other boxes it increases by one. Repeating this procedure, we can either diminish the difference between the number of balls in the box which has most balls and the number of balls in the box with the least number of balls, or diminish the number of boxes having the least number of balls, until all boxes have the same number of balls.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Assume we have 95 boxes and 19 balls distributed in these boxes in an arbitrary manner. We take six new balls at a time and place them in six of the boxes, one ball in each of the six. Can we, by repeating this process a suitable number of times, achieve a situation in which each of the 95 boxes contains an equal number of balls?

|

Since $6 \cdot 16=96$, we can put 16 times 6 balls in the boxes so that the number of balls in one of the boxes increases by two, while in all other boxes it increases by one. Repeating this procedure, we can either diminish the difference between the number of balls in the box which has most balls and the number of balls in the box with the least number of balls, or diminish the number of boxes having the least number of balls, until all boxes have the same number of balls.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Consider the following two person game. A number of pebbles are situated on the table. Two players make their moves alternately. A move consists of taking off the table $x$ pebbles where $x$ is the square of any positive integer. The player who is unable to make a move loses. Prove that there are infinitely many initial situations in which the second player can win no matter how his opponent plays.

|

Suppose that there is an $n$ such that the first player always wins if there are initially more than $n$ pebbles. Consider the initial situation with $n^{2}+n+1$ pebbles. Since $(n+1)^{2}>n^{2}+n+1$, the first player can take at most $n^{2}$ pebbles, leaving at least $n+1$ pebbles on the table. By the assumption, the second player now wins. This contradiction proves that there are infinitely many situations in which the second player wins no matter how the first player plays.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Consider the following two person game. A number of pebbles are situated on the table. Two players make their moves alternately. A move consists of taking off the table $x$ pebbles where $x$ is the square of any positive integer. The player who is unable to make a move loses. Prove that there are infinitely many initial situations in which the second player can win no matter how his opponent plays.

|

Suppose that there is an $n$ such that the first player always wins if there are initially more than $n$ pebbles. Consider the initial situation with $n^{2}+n+1$ pebbles. Since $(n+1)^{2}>n^{2}+n+1$, the first player can take at most $n^{2}$ pebbles, leaving at least $n+1$ pebbles on the table. By the assumption, the second player now wins. This contradiction proves that there are infinitely many situations in which the second player wins no matter how the first player plays.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\n13.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

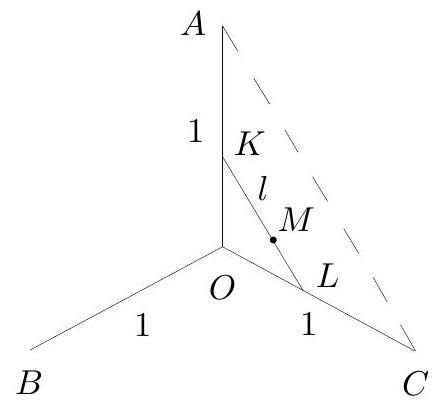

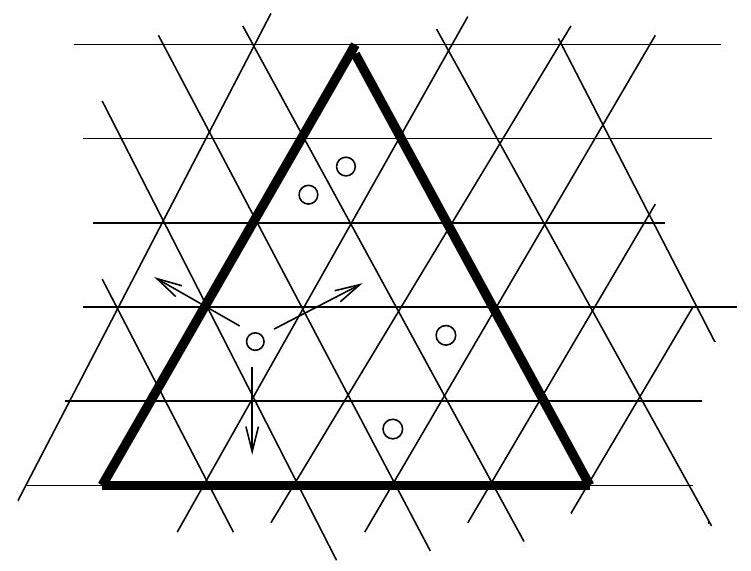

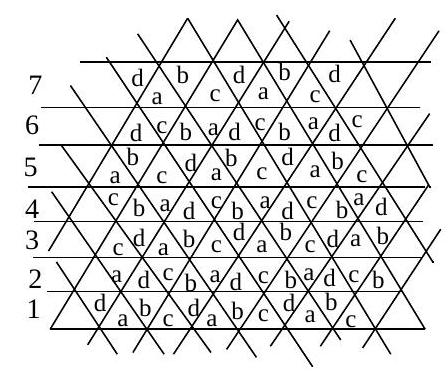

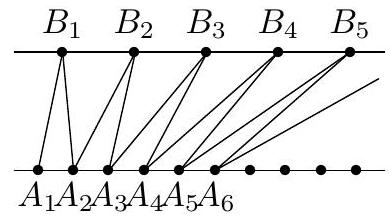

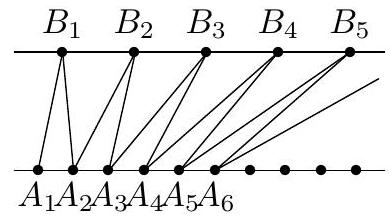

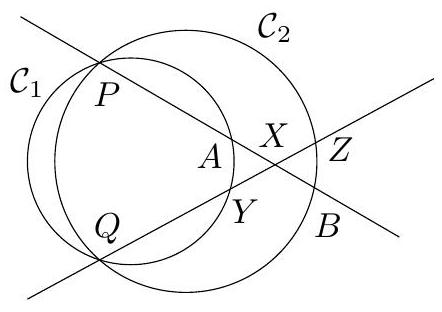

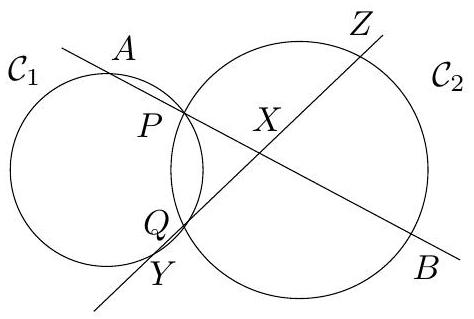

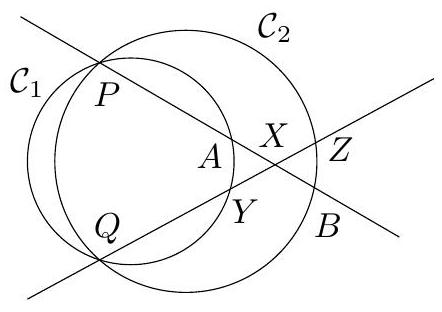

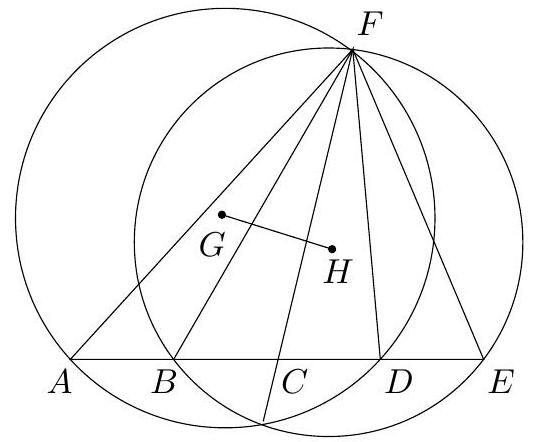

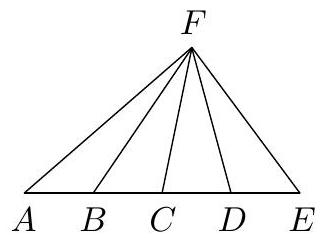

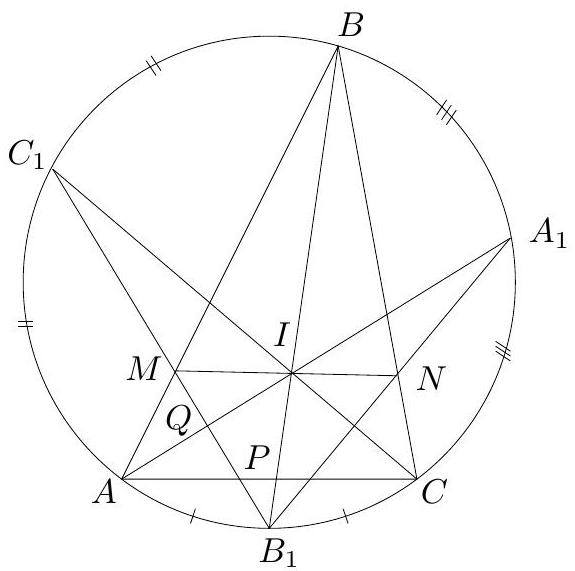

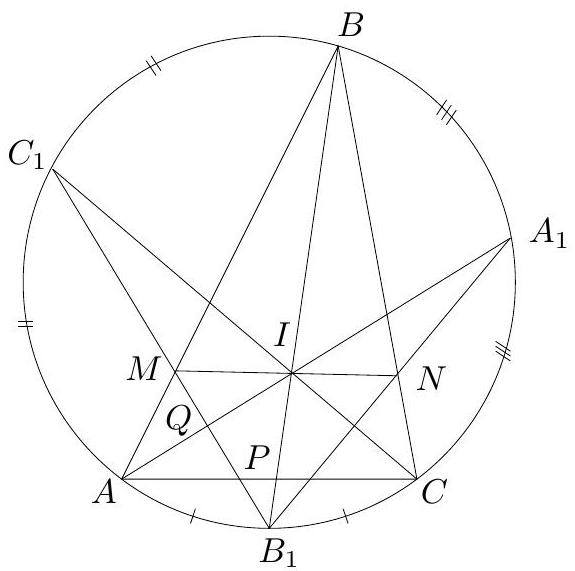

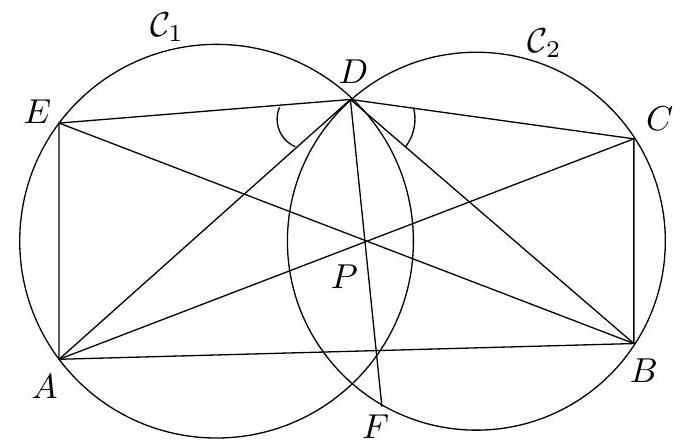

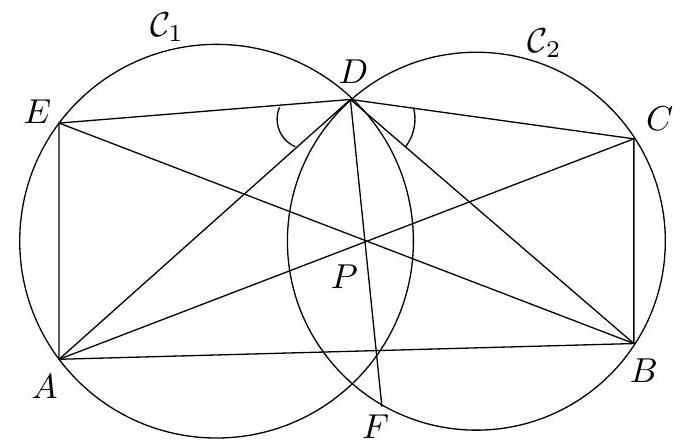

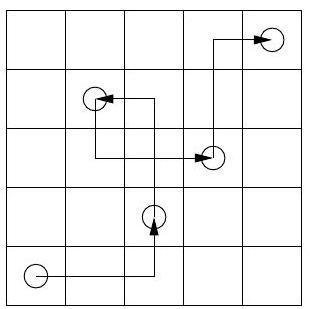

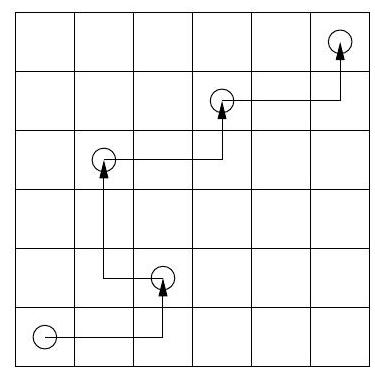

There are $n$ fleas on an infinite sheet of triangulated paper. Initially the fleas are in different small triangles, all of which are inside some equilateral triangle consisting of $n^{2}$ small triangles (see Figure 1 for a possible initial configuration with $n=5$ ). Once a second each flea jumps from its triangle to one of the three small triangles as indicated in the figure. For which positive integers $n$ does there exist an initial configuration such that after a finite number of jumps all the $n$ fleas can meet in a single small triangle?

Figure 1

|

The small triangles can be coloured in four colours as shown in Figure 2. Then each flea can only reach triangles of a single colour. Moreover, number the horizontal rows are numbered as in Figure 2, and note that with each move a flea jumps from a triangle in an even-numbered row to a triangle in an odd-numbered row, or vice versa. Hence, if all the fleas are to meet in one small triangle, then they must initially be located in triangles of the same colour and in rows of the same parity. On the other hand, if these conditions are met, then the fleas can end up all in some designated triangle (of the right colour and parity). When a flea reaches this triangle, it can jump back and forth between the designated triangle and one of its neighbours until the other fleas arrive.

It remains to find the values of $n$ for which the big triangle contains at least $n$ small triangles of one colour, in rows of the same parity. For any odd $n$ there are at least $1+2+\cdots+\frac{n+1}{2}=\frac{1}{8}\left(n^{2}+4 n+3\right) \geq n$ such triangles. For even $n \geq 6$ we also have at least $1+2+\cdots+\frac{n}{2}=\frac{1}{8}\left(n^{2}+2 n\right) \geq n$ triangles of the required kind. Finally, it is easy to check that for $n=2$ and $n=4$ the necessary set of small triangles cannot be found.

Hence it is possible for the fleas to meet in one small triangle for all $n$ except 2 and 4 .

Figure 2

|

n \neq 2, 4

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

There are $n$ fleas on an infinite sheet of triangulated paper. Initially the fleas are in different small triangles, all of which are inside some equilateral triangle consisting of $n^{2}$ small triangles (see Figure 1 for a possible initial configuration with $n=5$ ). Once a second each flea jumps from its triangle to one of the three small triangles as indicated in the figure. For which positive integers $n$ does there exist an initial configuration such that after a finite number of jumps all the $n$ fleas can meet in a single small triangle?

Figure 1

|

The small triangles can be coloured in four colours as shown in Figure 2. Then each flea can only reach triangles of a single colour. Moreover, number the horizontal rows are numbered as in Figure 2, and note that with each move a flea jumps from a triangle in an even-numbered row to a triangle in an odd-numbered row, or vice versa. Hence, if all the fleas are to meet in one small triangle, then they must initially be located in triangles of the same colour and in rows of the same parity. On the other hand, if these conditions are met, then the fleas can end up all in some designated triangle (of the right colour and parity). When a flea reaches this triangle, it can jump back and forth between the designated triangle and one of its neighbours until the other fleas arrive.

It remains to find the values of $n$ for which the big triangle contains at least $n$ small triangles of one colour, in rows of the same parity. For any odd $n$ there are at least $1+2+\cdots+\frac{n+1}{2}=\frac{1}{8}\left(n^{2}+4 n+3\right) \geq n$ such triangles. For even $n \geq 6$ we also have at least $1+2+\cdots+\frac{n}{2}=\frac{1}{8}\left(n^{2}+2 n\right) \geq n$ triangles of the required kind. Finally, it is easy to check that for $n=2$ and $n=4$ the necessary set of small triangles cannot be found.

Hence it is possible for the fleas to meet in one small triangle for all $n$ except 2 and 4 .

Figure 2

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

A polygon with $2 n+1$ vertices is given. Show that it is possible to label the vertices and midpoints of the sides of the polygon, using all the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 4 n+2$, so that the sums of the three numbers assigned to each side are all equal.

|

First, label the midpoints of the sides of the polygon with the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 2 n+1$, in clockwise order. Then, beginning with the vertex between the sides labelled by 1 and 2 , label every second vertex in clockwise order with the numbers $4 n+2,4 n+1, \ldots, 2 n+2$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

A polygon with $2 n+1$ vertices is given. Show that it is possible to label the vertices and midpoints of the sides of the polygon, using all the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 4 n+2$, so that the sums of the three numbers assigned to each side are all equal.

|

First, label the midpoints of the sides of the polygon with the numbers $1,2, \ldots, 2 n+1$, in clockwise order. Then, beginning with the vertex between the sides labelled by 1 and 2 , label every second vertex in clockwise order with the numbers $4 n+2,4 n+1, \ldots, 2 n+2$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

In the triangle $A B C$, let $l$ be the bisector of the external angle at $C$. The line through the midpoint $O$ of the segment $A B$ parallel to $l$ meets the line $A C$ at $E$. Determine $|C E|$, if $|A C|=7$ and $|C B|=4$.

|

Let $F$ be the intersection point of $l$ and the line $A B$. Since $|A C|>|B C|$, the point $E$ lies on the segment $A C$, and $F$ lies on the ray $A B$. Let the line through $B$ parallel to $A C$ meet $C F$ at $G$. Then the triangles $A F C$ and $B F G$ are similar. Moreover, we have $\angle B G C=\angle B C G$, and hence the triangle $C B G$ is isosceles with $|B C|=|B G|$. Hence $\frac{|F A|}{|F B|}=\frac{|A C|}{|B G|}=\frac{|A C|}{|B C|}=\frac{7}{4}$. Therefore $\frac{|A O|}{|A F|}=\frac{3}{2} / 7=\frac{3}{14}$. Since the triangles $A C F$ and $A E O$ are similar, $\frac{|A E|}{|A C|}=\frac{|A O|}{|A F|}=\frac{3}{14}$, whence $|A E|=\frac{3}{2}$ and $|E C|=\frac{11}{2}$.

|

\frac{11}{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

In the triangle $A B C$, let $l$ be the bisector of the external angle at $C$. The line through the midpoint $O$ of the segment $A B$ parallel to $l$ meets the line $A C$ at $E$. Determine $|C E|$, if $|A C|=7$ and $|C B|=4$.

|

Let $F$ be the intersection point of $l$ and the line $A B$. Since $|A C|>|B C|$, the point $E$ lies on the segment $A C$, and $F$ lies on the ray $A B$. Let the line through $B$ parallel to $A C$ meet $C F$ at $G$. Then the triangles $A F C$ and $B F G$ are similar. Moreover, we have $\angle B G C=\angle B C G$, and hence the triangle $C B G$ is isosceles with $|B C|=|B G|$. Hence $\frac{|F A|}{|F B|}=\frac{|A C|}{|B G|}=\frac{|A C|}{|B C|}=\frac{7}{4}$. Therefore $\frac{|A O|}{|A F|}=\frac{3}{2} / 7=\frac{3}{14}$. Since the triangles $A C F$ and $A E O$ are similar, $\frac{|A E|}{|A C|}=\frac{|A O|}{|A F|}=\frac{3}{14}$, whence $|A E|=\frac{3}{2}$ and $|E C|=\frac{11}{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Prove that there exists a number $\alpha$ such that for any triangle $A B C$ the inequality

$$

\max \left(h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}\right) \leq \alpha \cdot \min \left(m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}\right)

$$

holds, where $h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}$ denote the lengths of the altitudes and $m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}$ denote the lengths of the medians. Find the smallest possible value of $\alpha$.

|

Let $h=\max \left(h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}\right)$ and $m=\min \left(m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}\right)$. If the longest height and the shortest median are drawn from the same vertex, then obviously $h \leq m$. Now let the longest height and shortest median be $A D$ and $B E$, respectively, with $|A D|=h$ and $|B E|=m$. Let $F$ be the point on the line $B C$ such that $E F$ is parallel to $A D$. Then $m=|E B| \geq|E F|=\frac{h}{2}$, whence $h \leq 2 m$. For an example with $h=2 m$, consider a triangle where $D$ lies on the ray $C B$ with $|C B|=|B D|$. Hence the smallest such value is $\alpha=2$.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Prove that there exists a number $\alpha$ such that for any triangle $A B C$ the inequality

$$

\max \left(h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}\right) \leq \alpha \cdot \min \left(m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}\right)

$$

holds, where $h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}$ denote the lengths of the altitudes and $m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}$ denote the lengths of the medians. Find the smallest possible value of $\alpha$.

|

Let $h=\max \left(h_{A}, h_{B}, h_{C}\right)$ and $m=\min \left(m_{A}, m_{B}, m_{C}\right)$. If the longest height and the shortest median are drawn from the same vertex, then obviously $h \leq m$. Now let the longest height and shortest median be $A D$ and $B E$, respectively, with $|A D|=h$ and $|B E|=m$. Let $F$ be the point on the line $B C$ such that $E F$ is parallel to $A D$. Then $m=|E B| \geq|E F|=\frac{h}{2}$, whence $h \leq 2 m$. For an example with $h=2 m$, consider a triangle where $D$ lies on the ray $C B$ with $|C B|=|B D|$. Hence the smallest such value is $\alpha=2$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\n17.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

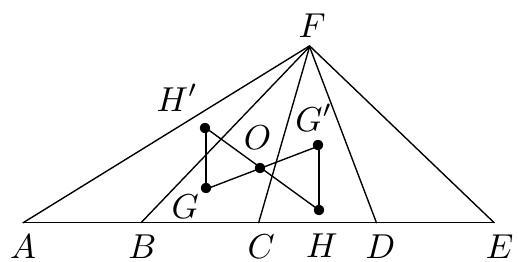

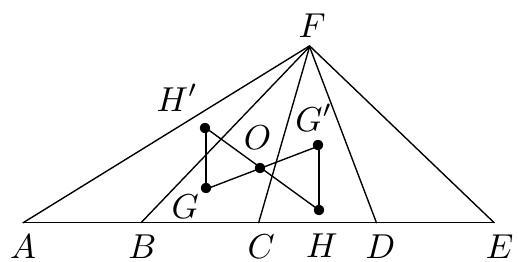

Let $M$ be the midpoint of the side $A C$ of a triangle $A B C$ and let $H$ be the foot point of the altitude from $B$. Let $P$ and $Q$ be the orthogonal projections of $A$ and $C$ on the bisector of angle $B$. Prove that the four points $M, H, P$ and $Q$ lie on the same circle.

|

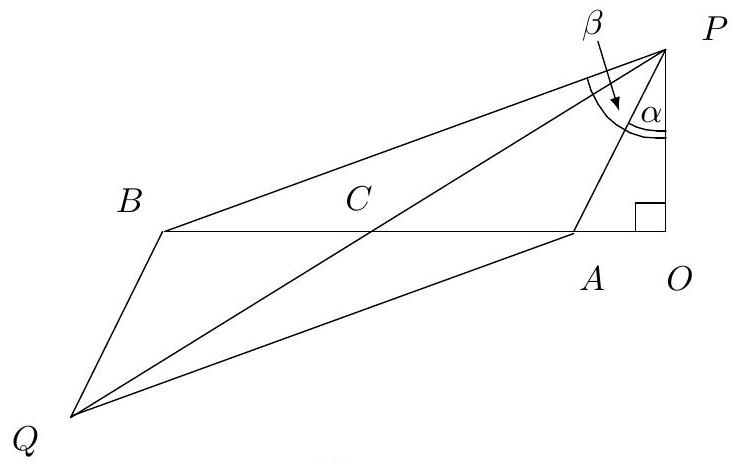

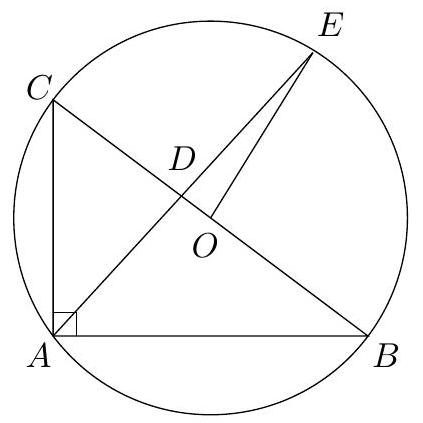

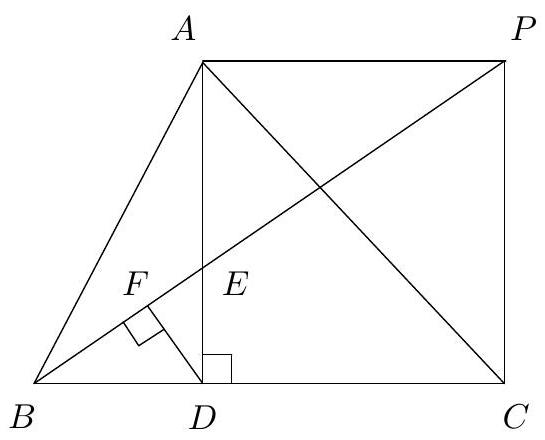

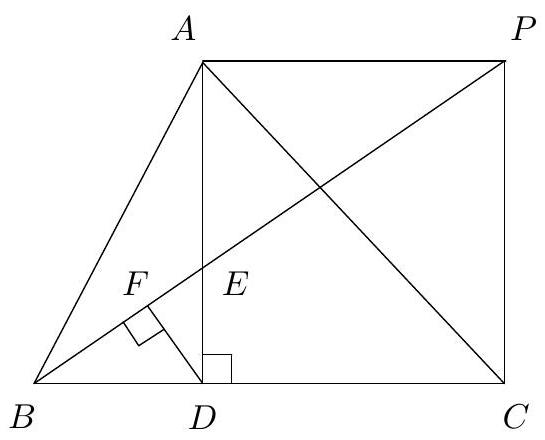

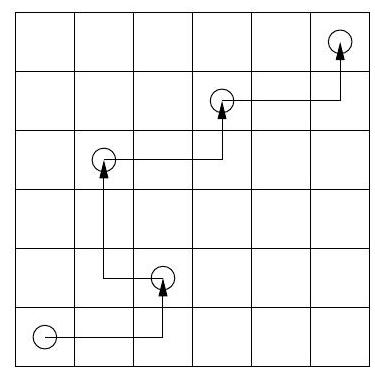

If $|A B|=|B C|$, the points $M, H, P$ and $Q$ coincide and the circle degenerates to a point. We will assume that $|A B|<|B C|$, so that $P$ lies inside the triangle $A B C$, and $Q$ lies outside of it.

Let the line $A P$ intersect $B C$ at $P_{1}$, and let $C Q$ intersect $A B$ at $Q_{1}$. Then $|A P|=\left|P P_{1}\right|$ (since $\triangle A P B \cong$ $\left.\triangle P_{1} P B\right)$, and therefore $M P \| B C$. Similarly, $M Q \| A B$. Therefore $\angle A M Q=\angle B A C$. We have two cases:

(i) $\angle B A C \leq 90^{\circ}$. Then $A, H, P$ and $B$ lie on a circle in this order. Hence $\angle H P Q=180^{\circ}-\angle H P B=$ $\angle B A C=\angle H M Q$. Therefore $H, P, M$ and $Q$ lie on a circle.

(ii) $\angle B A C>90^{\circ}$. Then $A, H, B$ and $P$ lie on a circle in this order. Hence $\angle H P Q=180^{\circ}-\angle H P B=$ $180^{\circ}-\angle H A B=\angle B A C=\angle H M Q$, and therefore $H, P, M$ and $Q$ lie on a circle.

Figure 3

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $M$ be the midpoint of the side $A C$ of a triangle $A B C$ and let $H$ be the foot point of the altitude from $B$. Let $P$ and $Q$ be the orthogonal projections of $A$ and $C$ on the bisector of angle $B$. Prove that the four points $M, H, P$ and $Q$ lie on the same circle.

|

If $|A B|=|B C|$, the points $M, H, P$ and $Q$ coincide and the circle degenerates to a point. We will assume that $|A B|<|B C|$, so that $P$ lies inside the triangle $A B C$, and $Q$ lies outside of it.

Let the line $A P$ intersect $B C$ at $P_{1}$, and let $C Q$ intersect $A B$ at $Q_{1}$. Then $|A P|=\left|P P_{1}\right|$ (since $\triangle A P B \cong$ $\left.\triangle P_{1} P B\right)$, and therefore $M P \| B C$. Similarly, $M Q \| A B$. Therefore $\angle A M Q=\angle B A C$. We have two cases:

(i) $\angle B A C \leq 90^{\circ}$. Then $A, H, P$ and $B$ lie on a circle in this order. Hence $\angle H P Q=180^{\circ}-\angle H P B=$ $\angle B A C=\angle H M Q$. Therefore $H, P, M$ and $Q$ lie on a circle.

(ii) $\angle B A C>90^{\circ}$. Then $A, H, B$ and $P$ lie on a circle in this order. Hence $\angle H P Q=180^{\circ}-\angle H P B=$ $180^{\circ}-\angle H A B=\angle B A C=\angle H M Q$, and therefore $H, P, M$ and $Q$ lie on a circle.

Figure 3

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

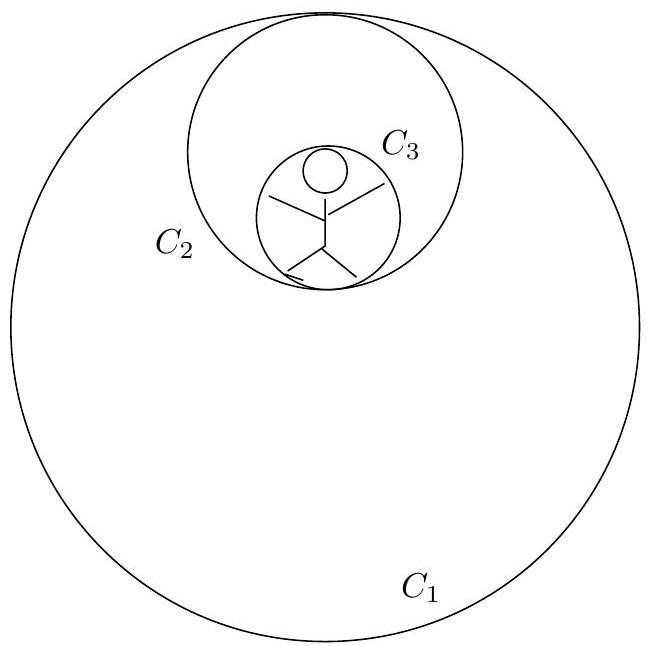

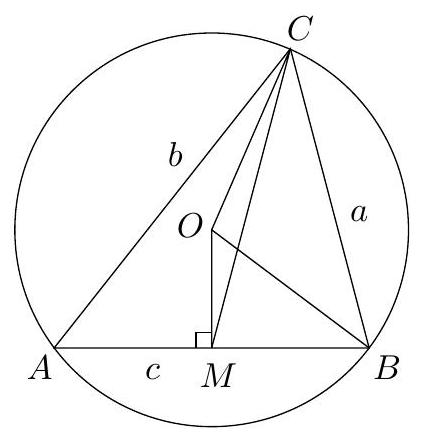

The following construction is used for training astronauts: A circle $C_{2}$ of radius $2 R$ rolls along the inside of another, fixed circle $C_{1}$ of radius $n R$, where $n$ is an integer greater than 2 . The astronaut is fastened to a third circle $C_{3}$ of radius $R$ which rolls along the inside of circle $C_{2}$ in such a way that the touching point of the circles $C_{2}$ and $C_{3}$ remains at maximum distance from the touching point of the circles $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ at all times (see Figure 3).

How many revolutions (relative to the ground) does the astronaut perform together with the circle $C_{3}$ while the circle $C_{2}$ completes one full lap around the inside of circle $C_{1}$ ?

|

Consider a circle $C_{4}$ with radius $R$ that rolls inside $C_{2}$ in such a way that the two circles always touch in the point opposite to the touching point of $C_{2}$ and $C_{3}$. Then the circles $C_{3}$ and $C_{4}$ follow each other and make the same number of revolutions, and so we will assume that the astronaut is inside the circle $C_{4}$ instead. But the touching point of $C_{2}$ and $C_{4}$ coincides with the touching point of $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$. Hence the circles $C_{4}$ and $C_{1}$ always touch each other, and we can disregard the circle $C_{2}$ completely.

Suppose the circle $C_{4}$ rolls inside $C_{1}$ in counterclockwise direction. Then the astronaut revolves in clockwise direction. If the circle $C_{4}$ had rolled along a straight line of length $2 \pi n R$ (instead of the inside of $C_{1}$ ), the circle $C_{4}$ would have made $n$ revolutions during its movement. As the path of the circle $C_{4}$ makes a $360^{\circ}$ counterclockwise turn itself, the total number of revolutions of the astronaut relative to the ground is $n-1$.

Remark: The radius of the intermediate circle $C_{2}$ is irrelevant. Moreover, for any number of intermediate circles the answer remains the same, depending only on the radii of the outermost and innermost circles.

|

n-1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

The following construction is used for training astronauts: A circle $C_{2}$ of radius $2 R$ rolls along the inside of another, fixed circle $C_{1}$ of radius $n R$, where $n$ is an integer greater than 2 . The astronaut is fastened to a third circle $C_{3}$ of radius $R$ which rolls along the inside of circle $C_{2}$ in such a way that the touching point of the circles $C_{2}$ and $C_{3}$ remains at maximum distance from the touching point of the circles $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$ at all times (see Figure 3).

How many revolutions (relative to the ground) does the astronaut perform together with the circle $C_{3}$ while the circle $C_{2}$ completes one full lap around the inside of circle $C_{1}$ ?

|

Consider a circle $C_{4}$ with radius $R$ that rolls inside $C_{2}$ in such a way that the two circles always touch in the point opposite to the touching point of $C_{2}$ and $C_{3}$. Then the circles $C_{3}$ and $C_{4}$ follow each other and make the same number of revolutions, and so we will assume that the astronaut is inside the circle $C_{4}$ instead. But the touching point of $C_{2}$ and $C_{4}$ coincides with the touching point of $C_{1}$ and $C_{2}$. Hence the circles $C_{4}$ and $C_{1}$ always touch each other, and we can disregard the circle $C_{2}$ completely.

Suppose the circle $C_{4}$ rolls inside $C_{1}$ in counterclockwise direction. Then the astronaut revolves in clockwise direction. If the circle $C_{4}$ had rolled along a straight line of length $2 \pi n R$ (instead of the inside of $C_{1}$ ), the circle $C_{4}$ would have made $n$ revolutions during its movement. As the path of the circle $C_{4}$ makes a $360^{\circ}$ counterclockwise turn itself, the total number of revolutions of the astronaut relative to the ground is $n-1$.

Remark: The radius of the intermediate circle $C_{2}$ is irrelevant. Moreover, for any number of intermediate circles the answer remains the same, depending only on the radii of the outermost and innermost circles.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "\n19.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Prove that if both coordinates of every vertex of a convex pentagon are integers, then the area of this pentagon is not less than $\frac{5}{2}$.

|

There are two vertices $A_{1}$ and $A_{2}$ of the pentagon that have their first coordinates of the parity, and their second coordinates of the same parity. Therefore the midpoint $M$ of $A_{1} A_{2}$ has integer coordinates. There are two possibilities:

(i) The considered vertices are not consecutive. Then $M$ lies inside the pentagon (because it is convex) and is the common vertex of five triangles having as their bases the sides of the pentagon. The area of any one of these triangles is not less than $\frac{1}{2}$, so the area of the pentagon is at least $\frac{5}{2}$.

(ii) The considered vertices are consecutive. Since the pentagon is convex, the side $A_{1} A_{2}$ is not simultaneously parallel to $A_{3} A_{4}$ and $A_{4} A_{5}$. Suppose that the segments $A_{1} A_{2}$ and $A_{3} A_{4}$ are not parallel. Then the triangles $A_{2} A_{3} A_{4}, M A_{3} A_{4}$ and $A-1 A_{3} A_{4}$ have different areas, since their altitudes dropped onto the side $A_{3} A_{4}$ form a monotone sequence. At least one of these triangles has area not less than $\frac{3}{2}$, and the pentagon has area not less than $\frac{5}{2}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Prove that if both coordinates of every vertex of a convex pentagon are integers, then the area of this pentagon is not less than $\frac{5}{2}$.

|

There are two vertices $A_{1}$ and $A_{2}$ of the pentagon that have their first coordinates of the parity, and their second coordinates of the same parity. Therefore the midpoint $M$ of $A_{1} A_{2}$ has integer coordinates. There are two possibilities:

(i) The considered vertices are not consecutive. Then $M$ lies inside the pentagon (because it is convex) and is the common vertex of five triangles having as their bases the sides of the pentagon. The area of any one of these triangles is not less than $\frac{1}{2}$, so the area of the pentagon is at least $\frac{5}{2}$.

(ii) The considered vertices are consecutive. Since the pentagon is convex, the side $A_{1} A_{2}$ is not simultaneously parallel to $A_{3} A_{4}$ and $A_{4} A_{5}$. Suppose that the segments $A_{1} A_{2}$ and $A_{3} A_{4}$ are not parallel. Then the triangles $A_{2} A_{3} A_{4}, M A_{3} A_{4}$ and $A-1 A_{3} A_{4}$ have different areas, since their altitudes dropped onto the side $A_{3} A_{4}$ form a monotone sequence. At least one of these triangles has area not less than $\frac{3}{2}$, and the pentagon has area not less than $\frac{5}{2}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw95sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1995"

}

|

Let $\alpha$ be the angle between two lines containing the diagonals of a regular 1996-gon, and let $\beta \neq 0$ be another such angle. Prove that $\alpha / \beta$ is a rational number.

|

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of the 1996-gon. Consider two diagonals $A B$ and $C D$. There is a rotation around $O$ that takes the point $C$ to $A$ and $D$ to a point $D^{\prime}$. Clearly the angle of this rotation is a multiple of $2 \varphi=2 \pi / 1996$.

The angle $B A D^{\prime}$ is the inscribed angle on the $\operatorname{arc} B D^{\prime}$, and hence is an integral multiple of $\varphi$, the inscribed angle on the arc between any two adjacent vertices of the 1996-gon. Hence the angle between $A B$ and $C D$ is also an integral multiple of $\varphi$.

Since both $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are integral multiples of $\varphi, \alpha / \beta$ is a rational number.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $\alpha$ be the angle between two lines containing the diagonals of a regular 1996-gon, and let $\beta \neq 0$ be another such angle. Prove that $\alpha / \beta$ is a rational number.

|

Let $O$ be the circumcentre of the 1996-gon. Consider two diagonals $A B$ and $C D$. There is a rotation around $O$ that takes the point $C$ to $A$ and $D$ to a point $D^{\prime}$. Clearly the angle of this rotation is a multiple of $2 \varphi=2 \pi / 1996$.

The angle $B A D^{\prime}$ is the inscribed angle on the $\operatorname{arc} B D^{\prime}$, and hence is an integral multiple of $\varphi$, the inscribed angle on the arc between any two adjacent vertices of the 1996-gon. Hence the angle between $A B$ and $C D$ is also an integral multiple of $\varphi$.

Since both $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are integral multiples of $\varphi, \alpha / \beta$ is a rational number.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw96sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1996"

}

|

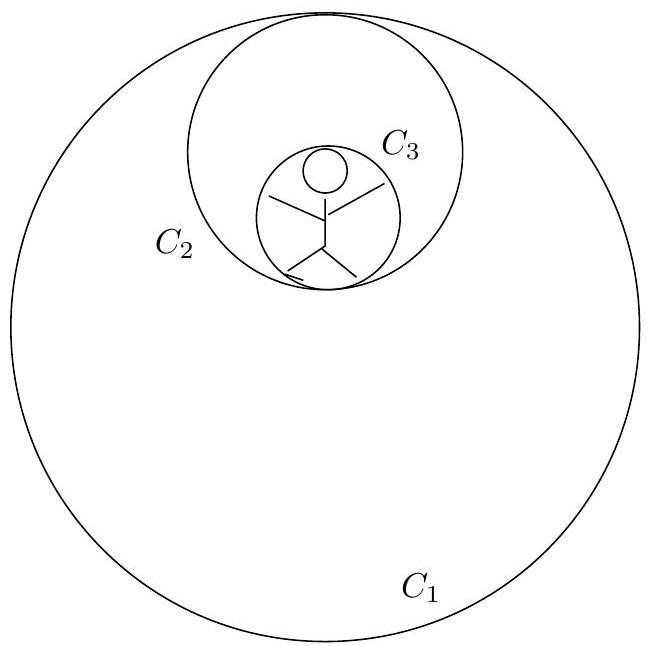

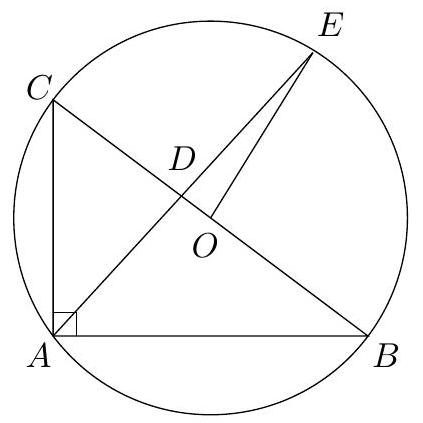

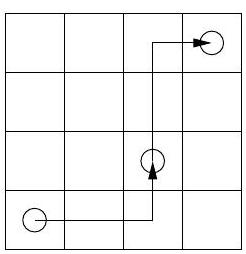

In the figure below, you see three half-circles. The circle $C$ is tangent to two of the half-circles and to the line $P Q$ perpendicular to the diameter $A B$. The area of the shaded region is $39 \pi$, and the area of the circle $C$ is $9 \pi$. Find the length of the diameter $A B$.

Figure 1

|

Let $r$ and $s$ be the radii of the half-circles with diameters $A P$ and $B P$. Then we have

$$

39 \pi=\frac{\pi}{2}\left((r+s)^{2}-r^{2}-s^{2}\right)-9 \pi

$$

hence $r s=48$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of the diameter $A B, N$ be the midpoint of $P B, O$ be the centre of the circle $C$, and let $F$ be the orthogonal projection of $O$ on $A B$. Since the radius of $C$ is 3 , we have $|M O|=r+s-3,|M F|=r-s+3,|O N|=s+3$, and $|F N|=s-3$.

Applying the Pythagorean theorem to the triangles $M F O$ and $N F O$ yields

$$

(r+s-3)^{2}-(r-s+3)^{2}=|O F|^{2}=(s+3)^{2}-(s-3)^{2},

$$

which implies $r(s-3)=3 s$, so that $3(r+s)=r s=48$. Hence $|A B|=2(r+s)=32$.

|

32

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

In the figure below, you see three half-circles. The circle $C$ is tangent to two of the half-circles and to the line $P Q$ perpendicular to the diameter $A B$. The area of the shaded region is $39 \pi$, and the area of the circle $C$ is $9 \pi$. Find the length of the diameter $A B$.

Figure 1

|