problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

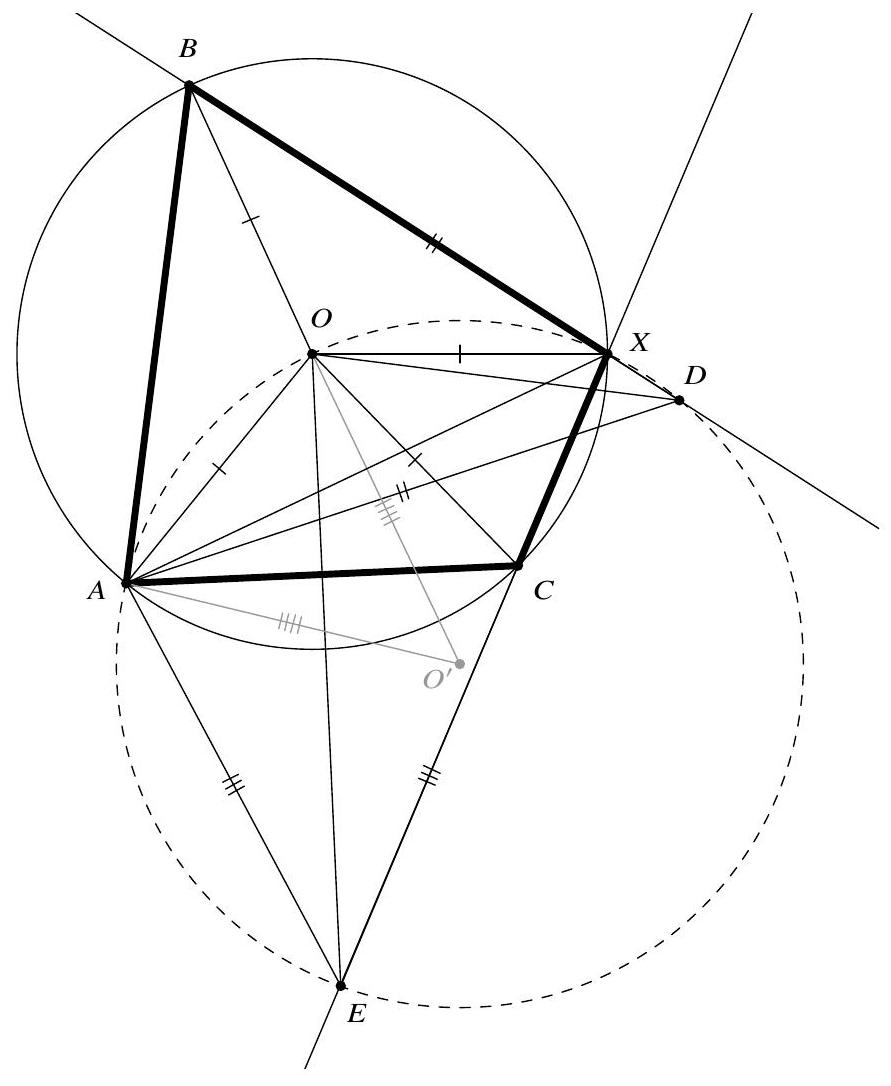

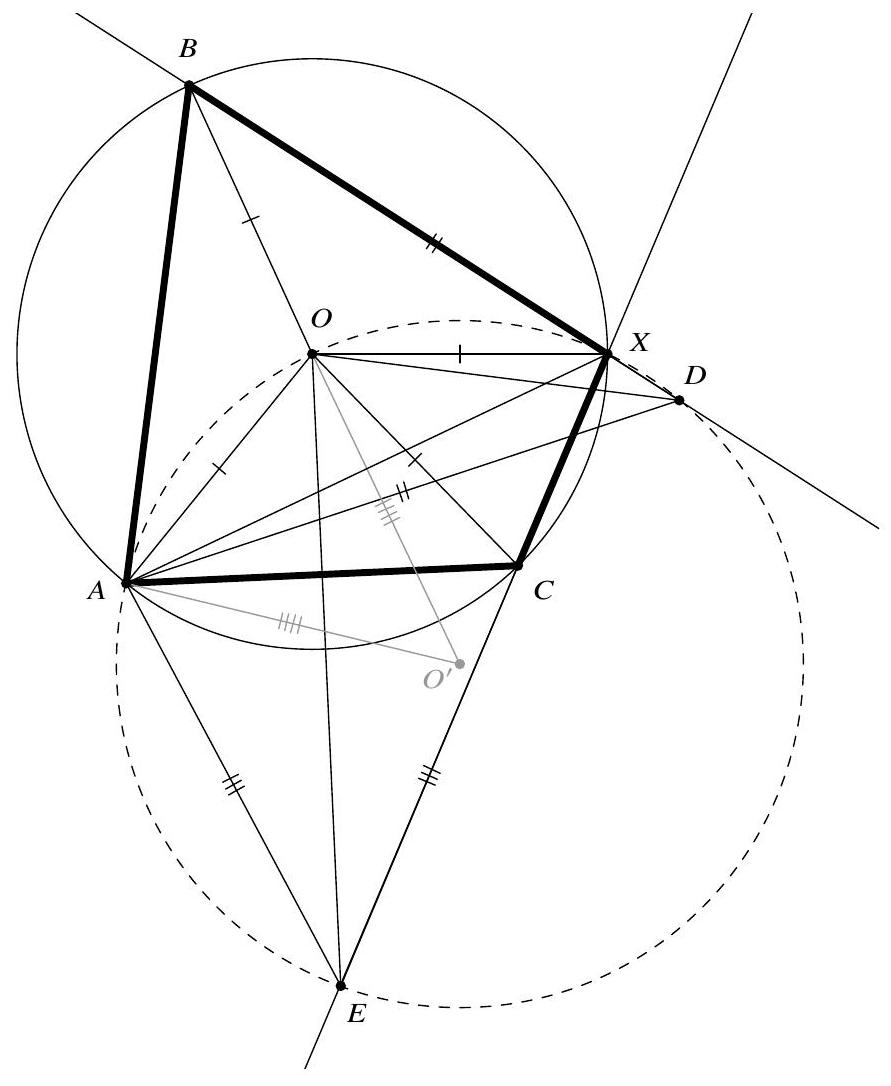

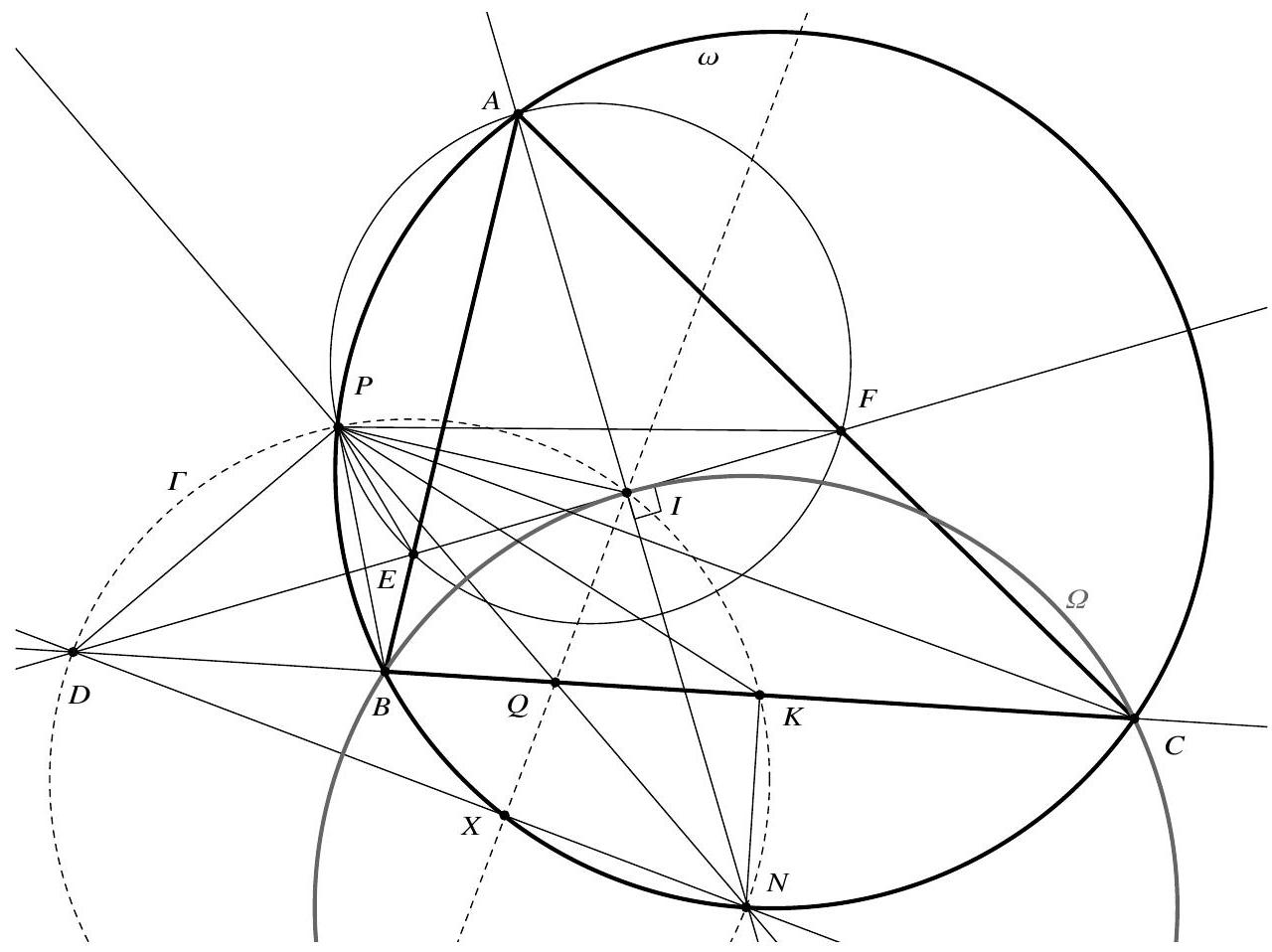

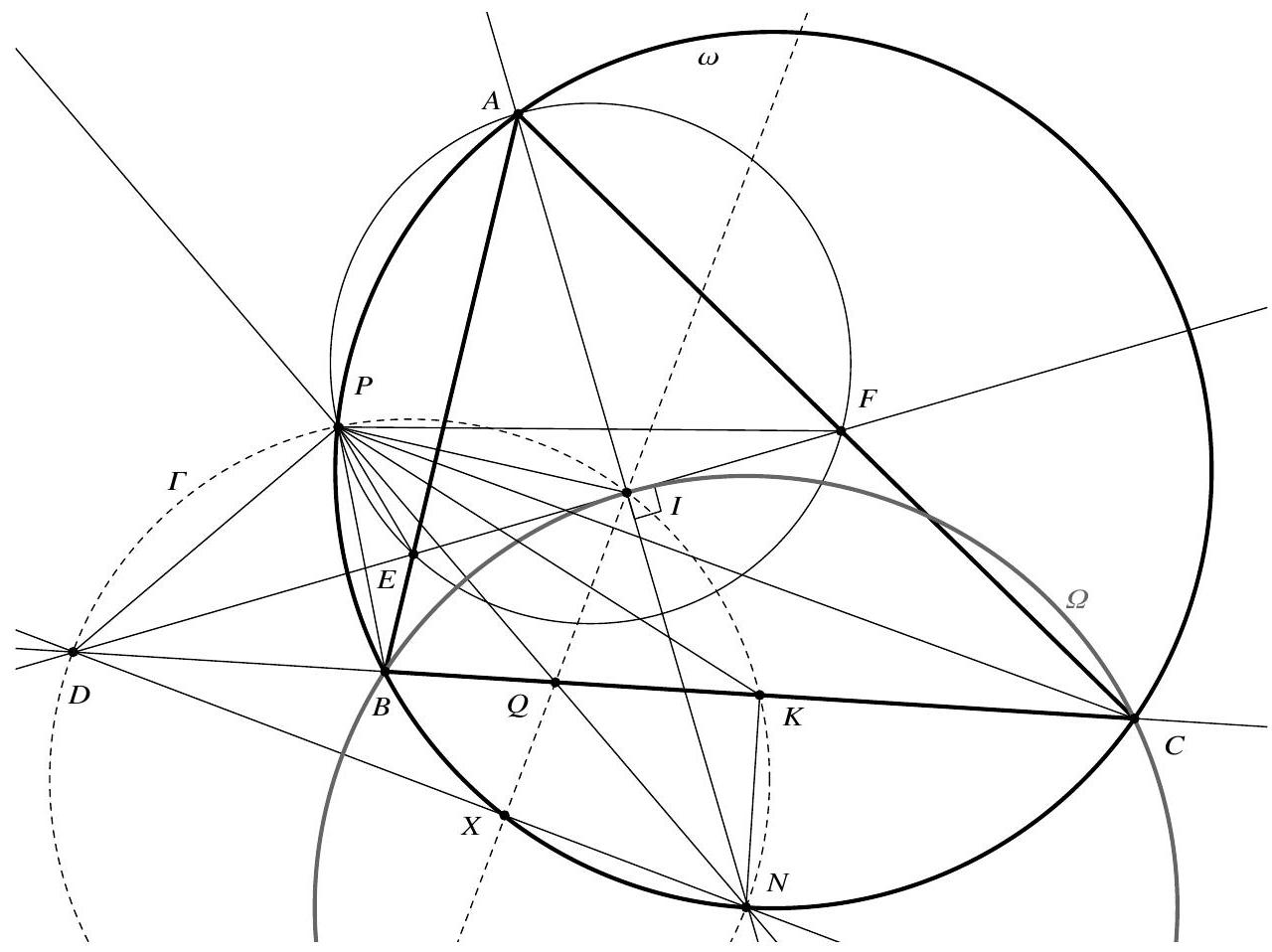

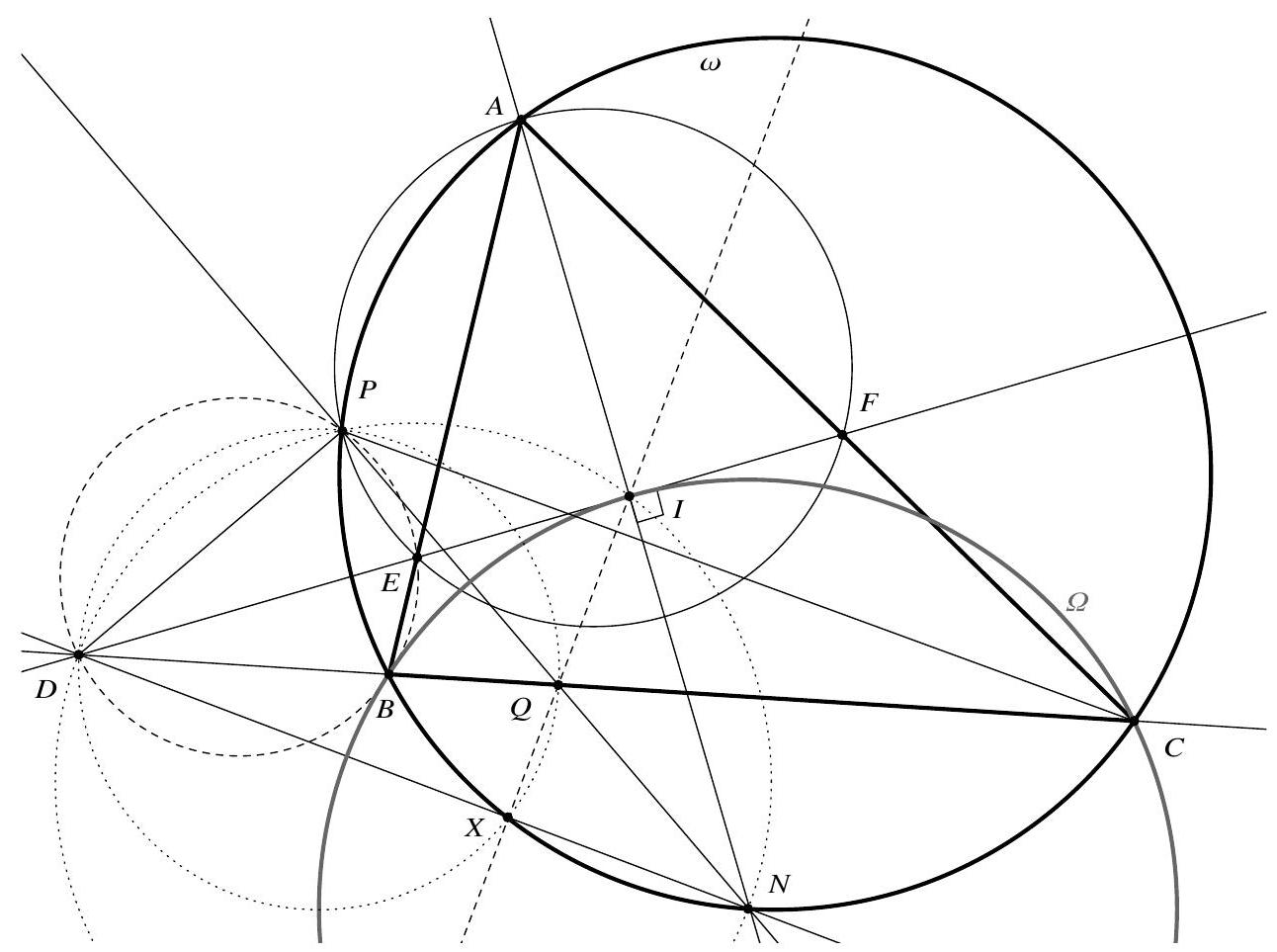

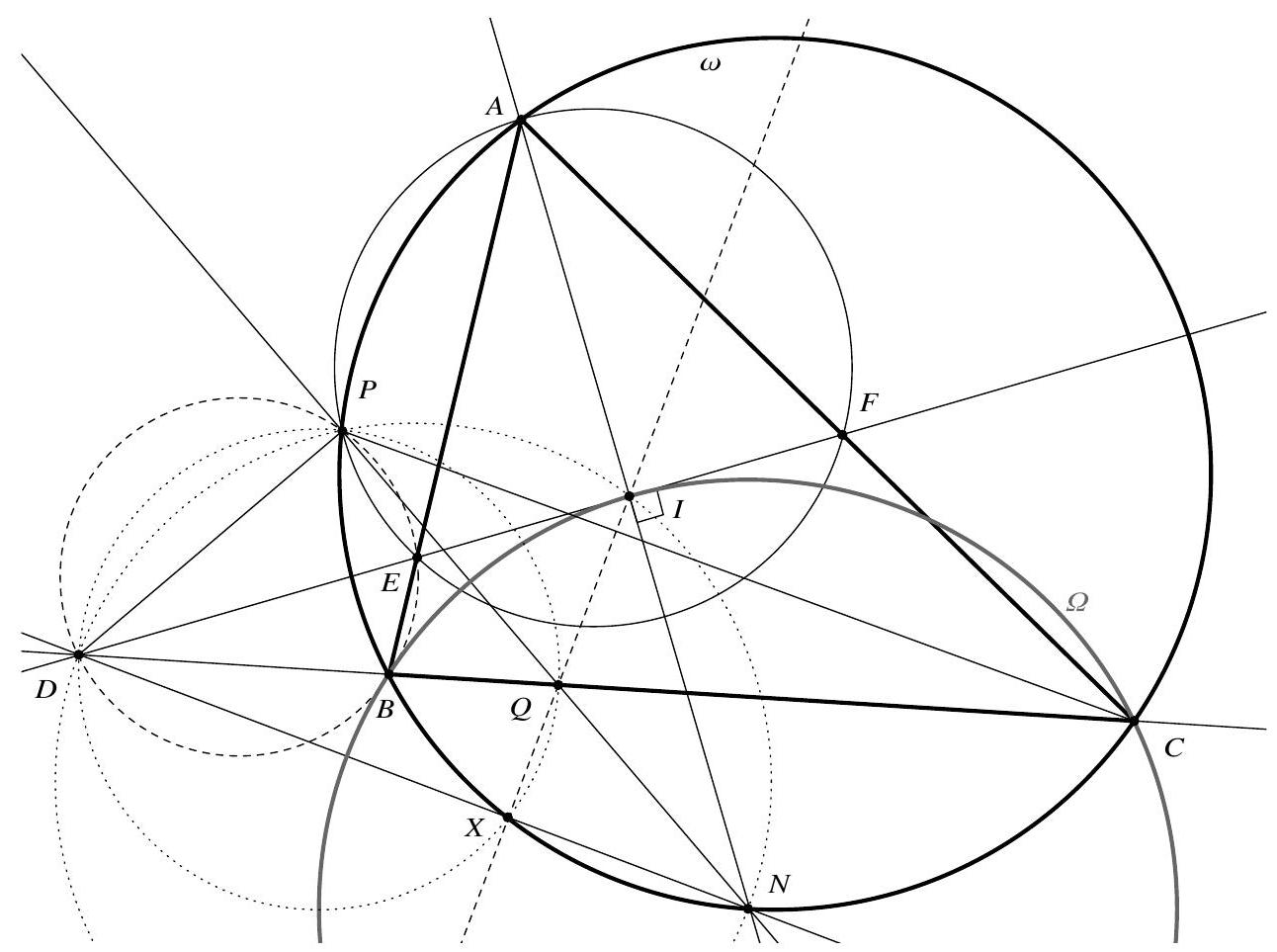

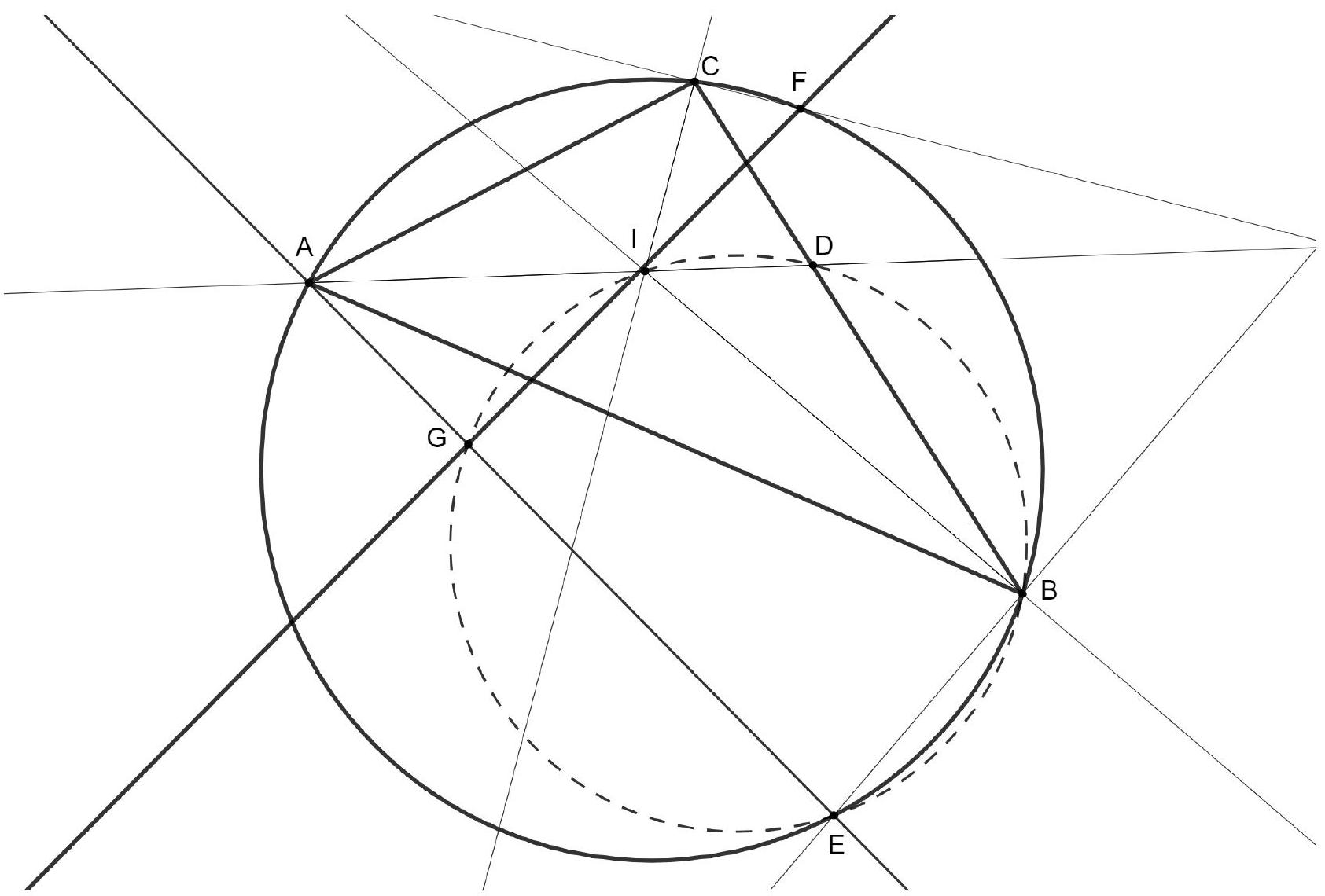

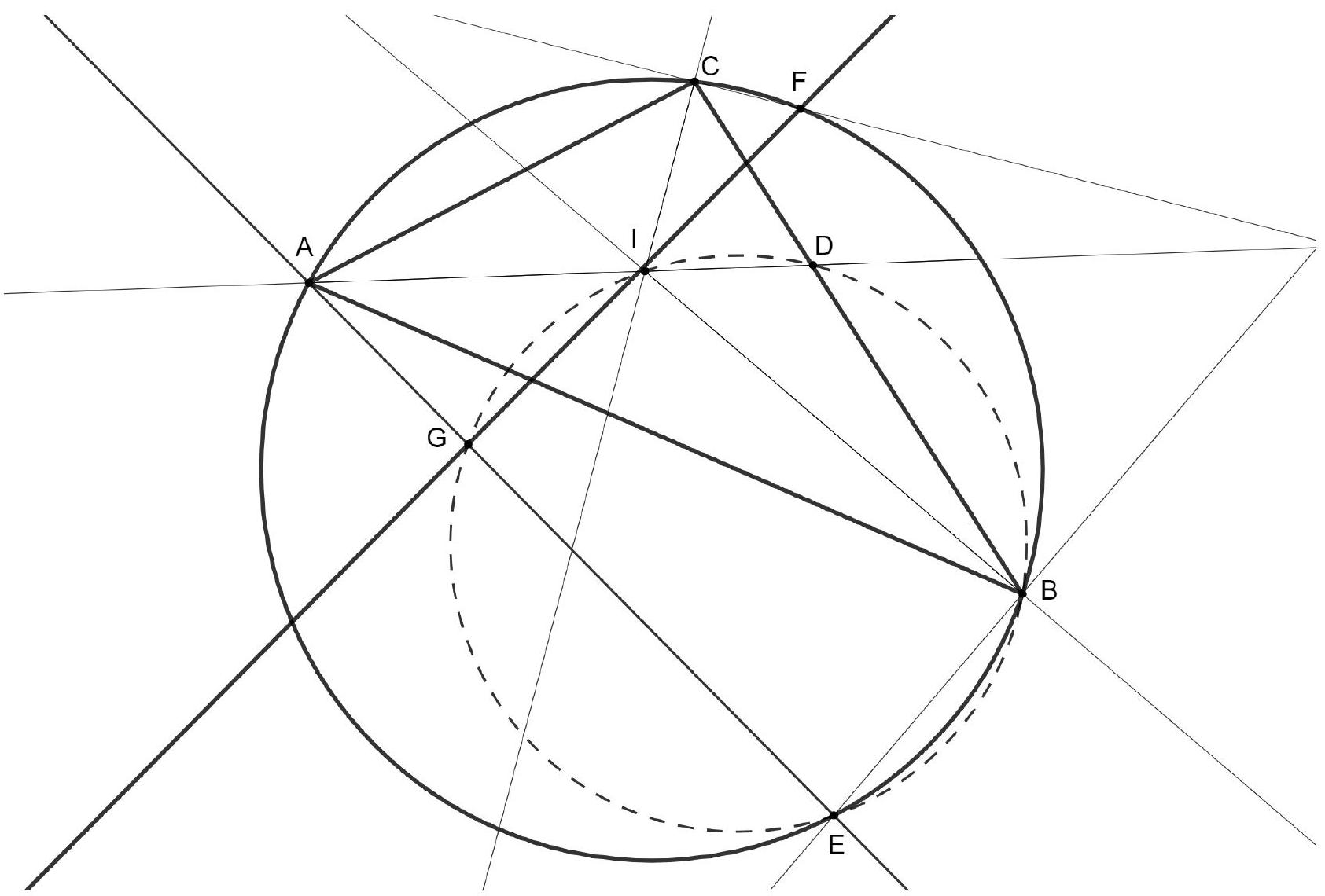

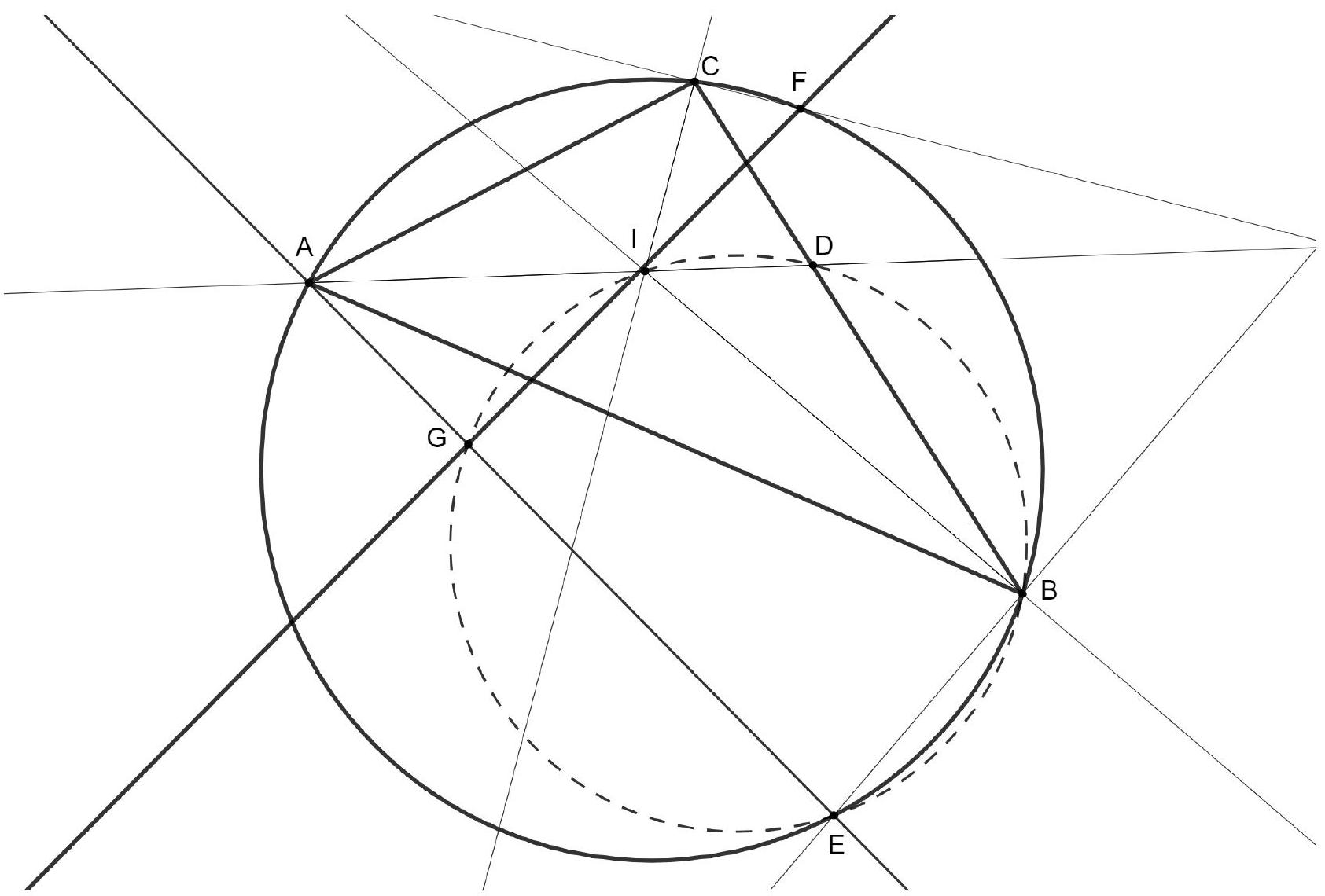

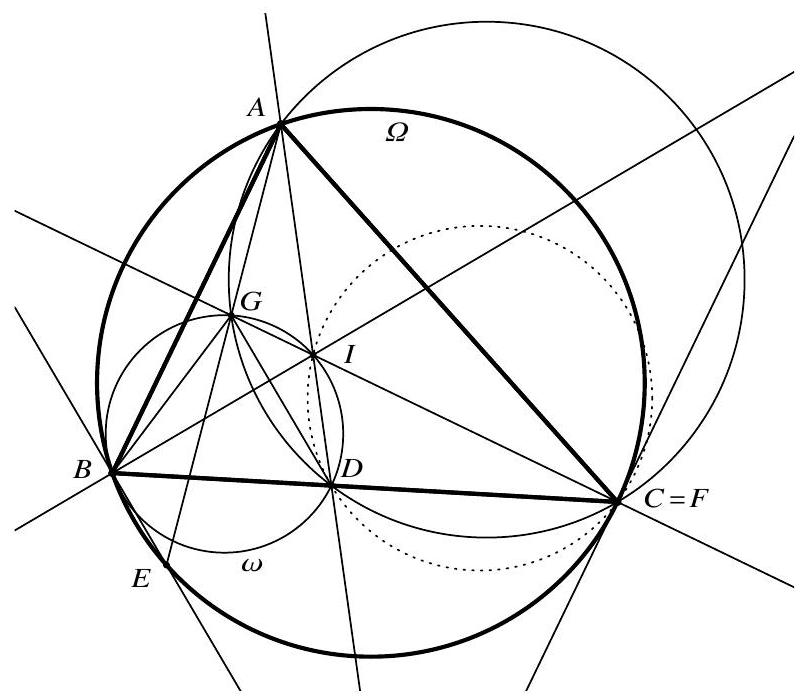

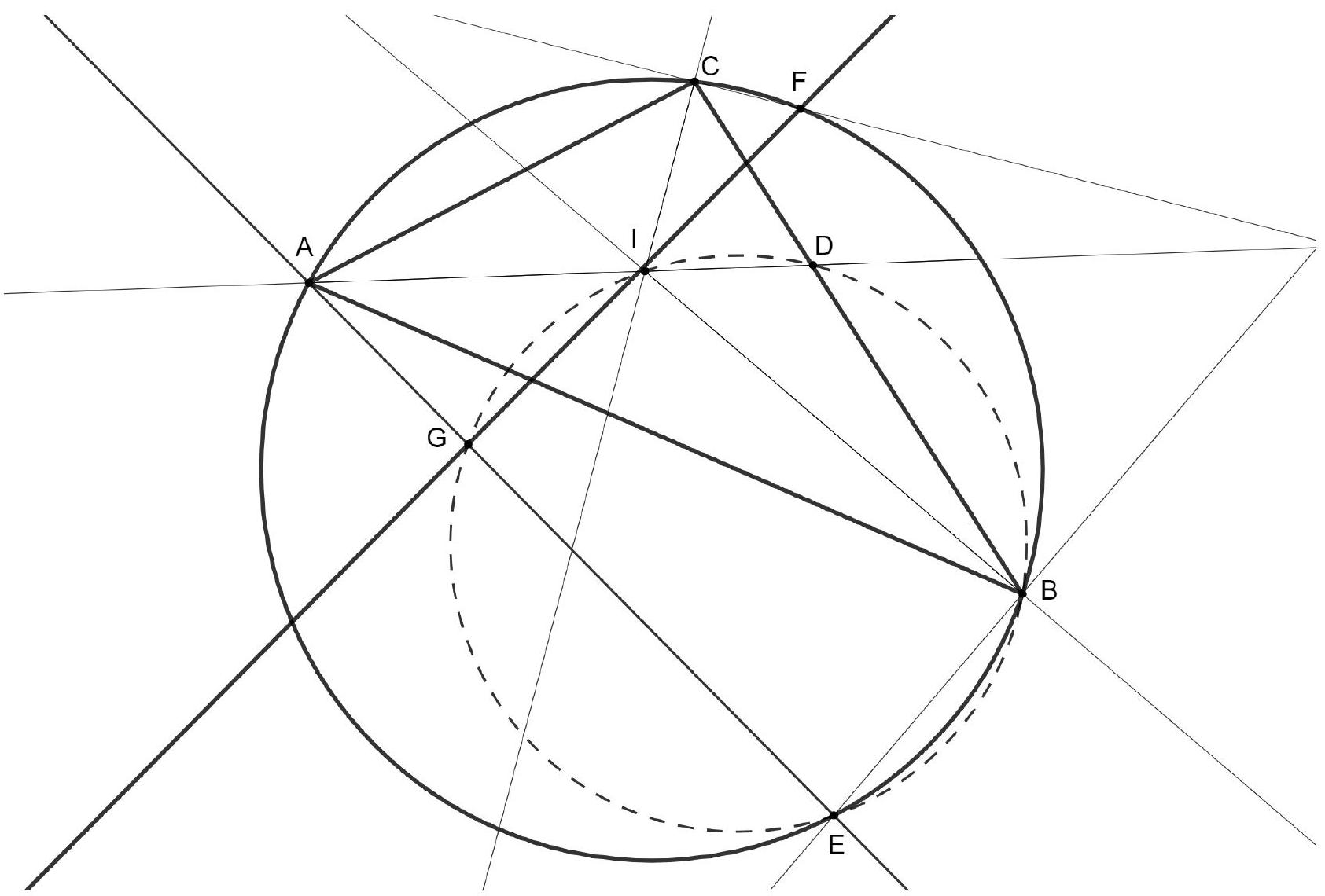

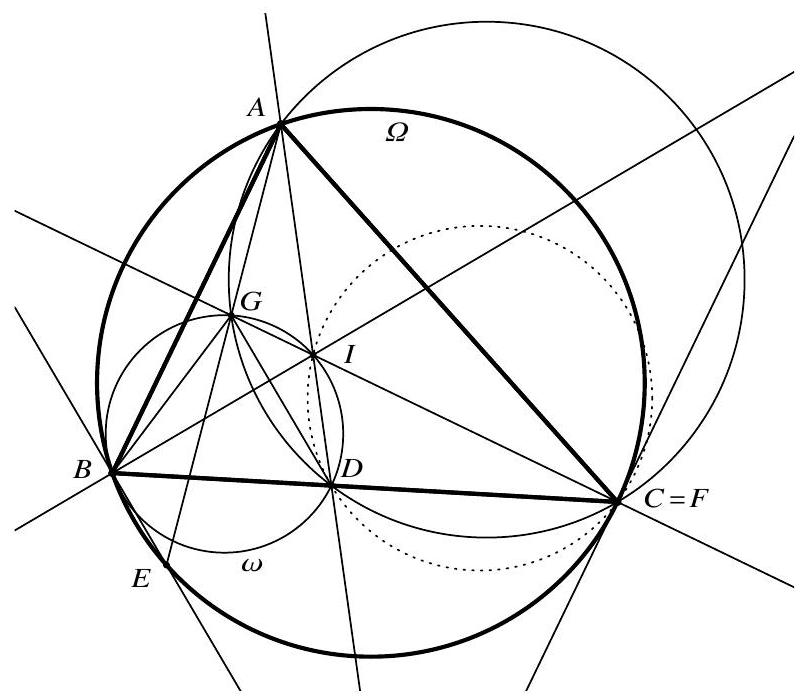

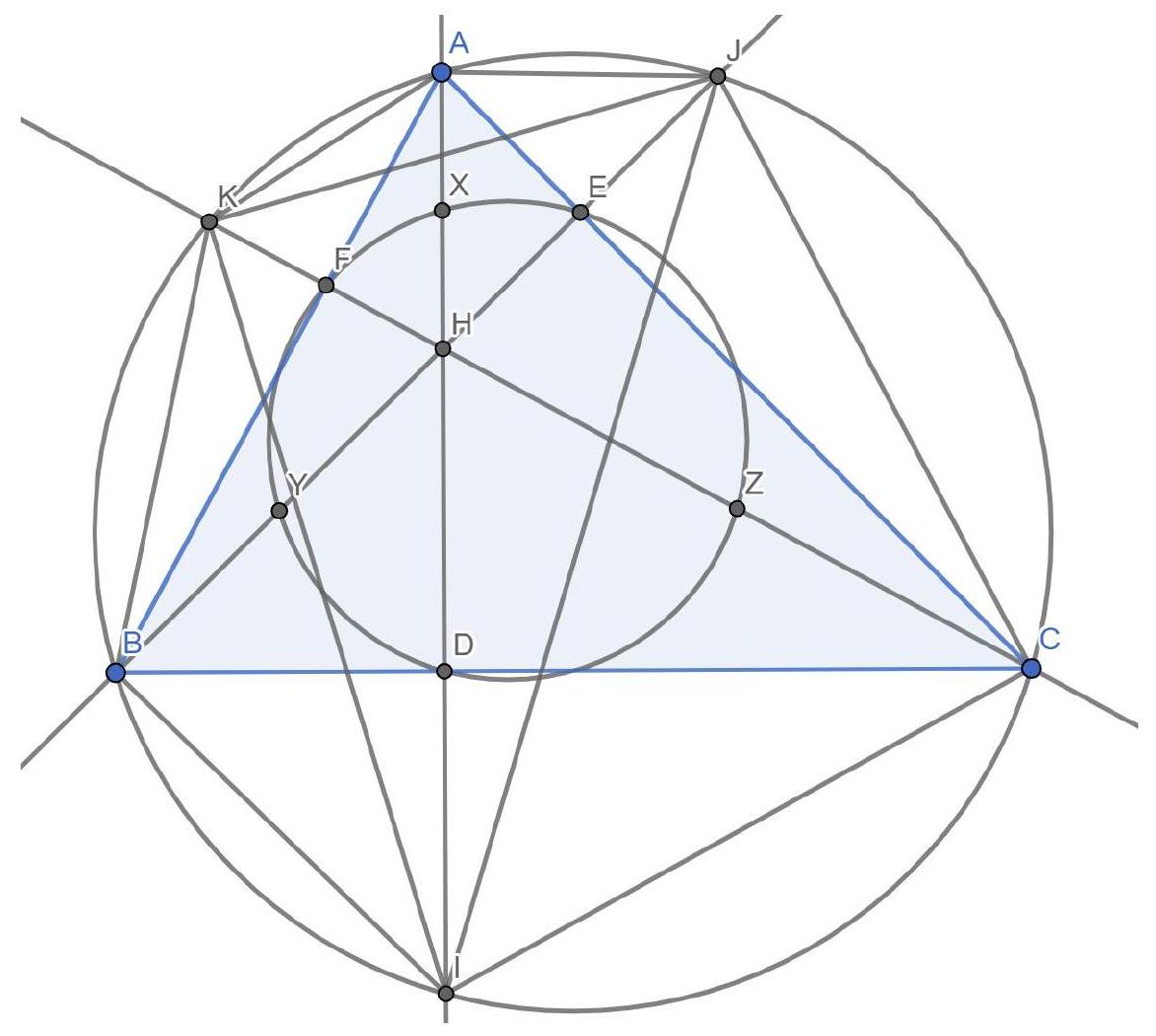

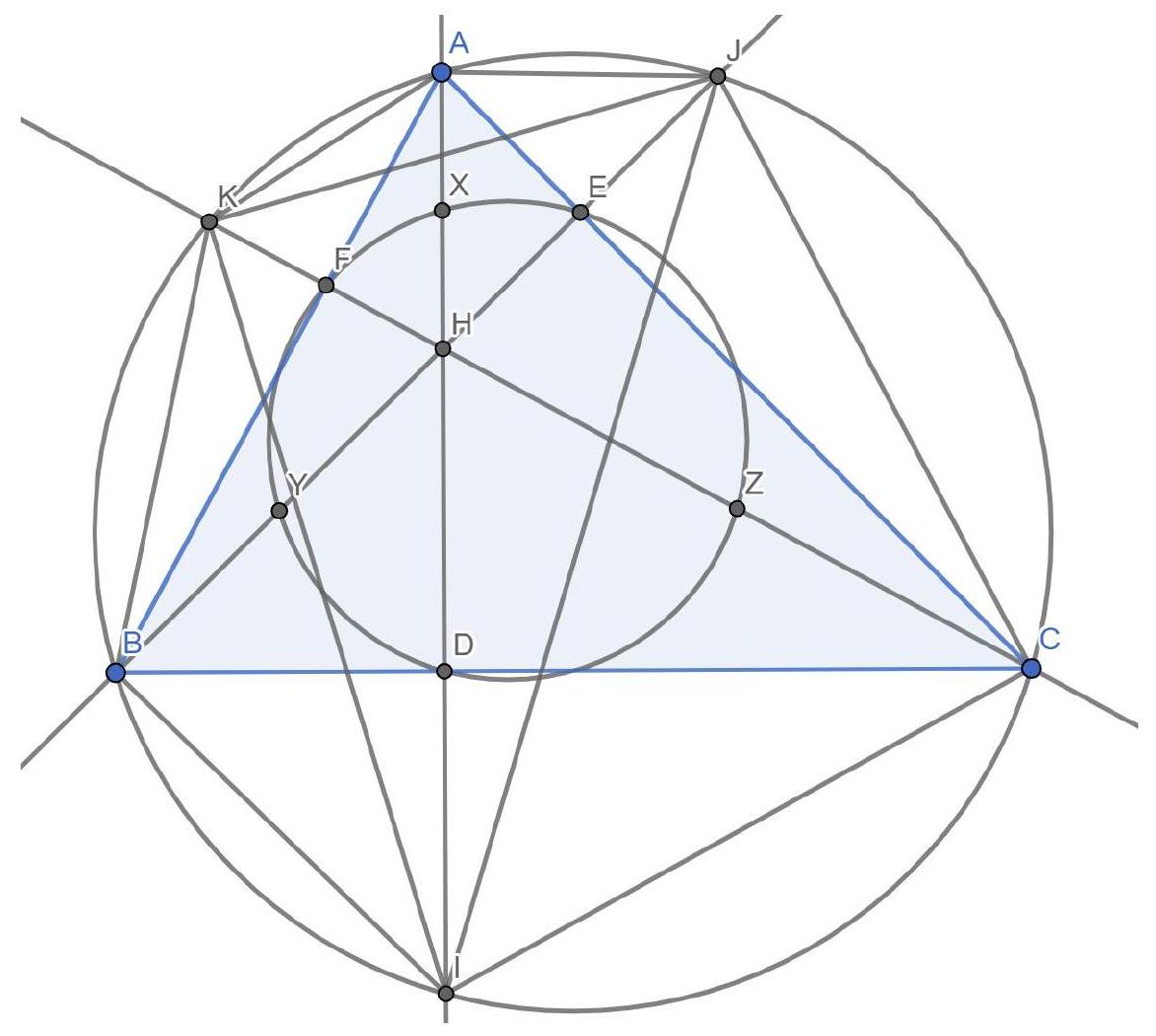

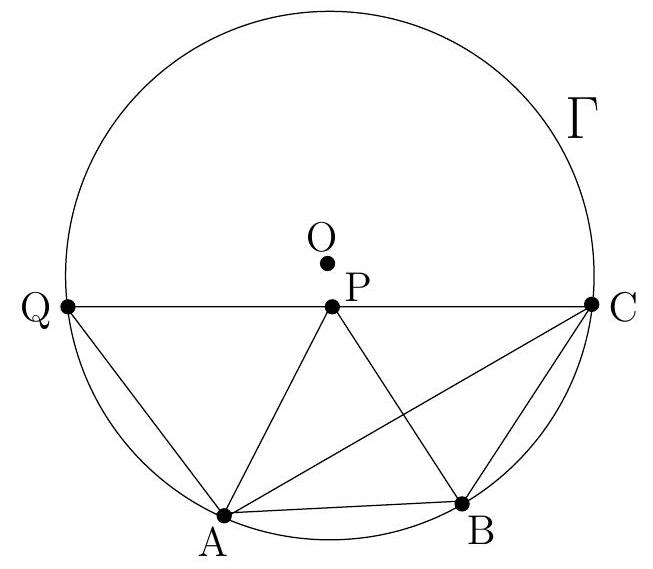

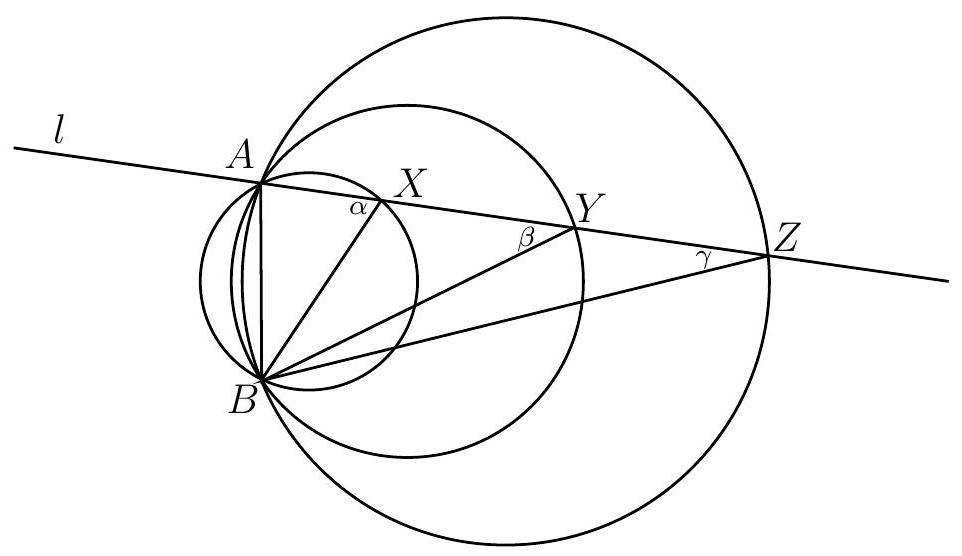

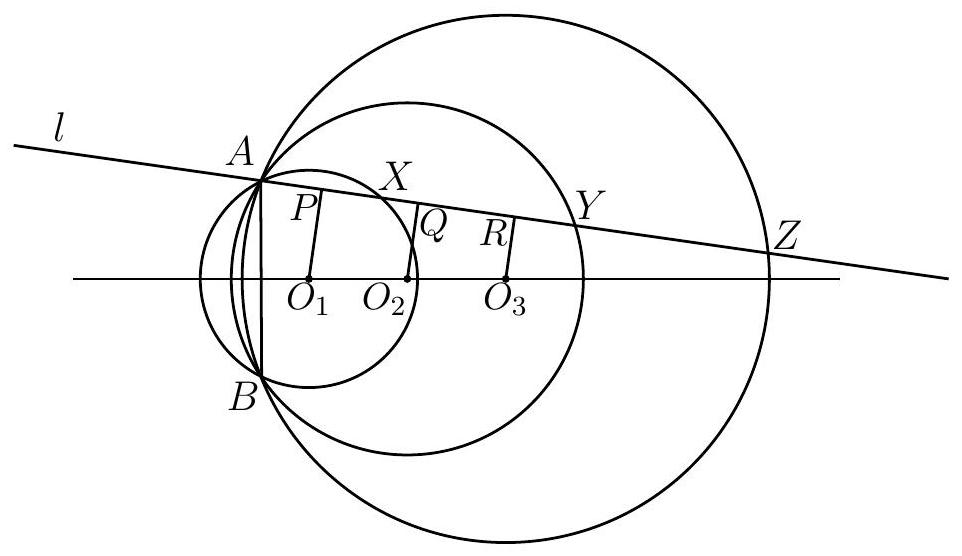

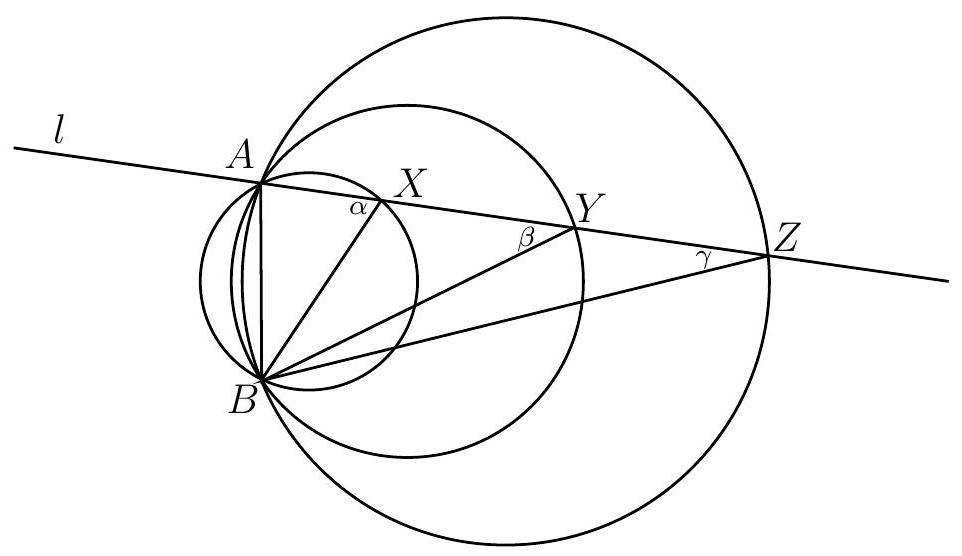

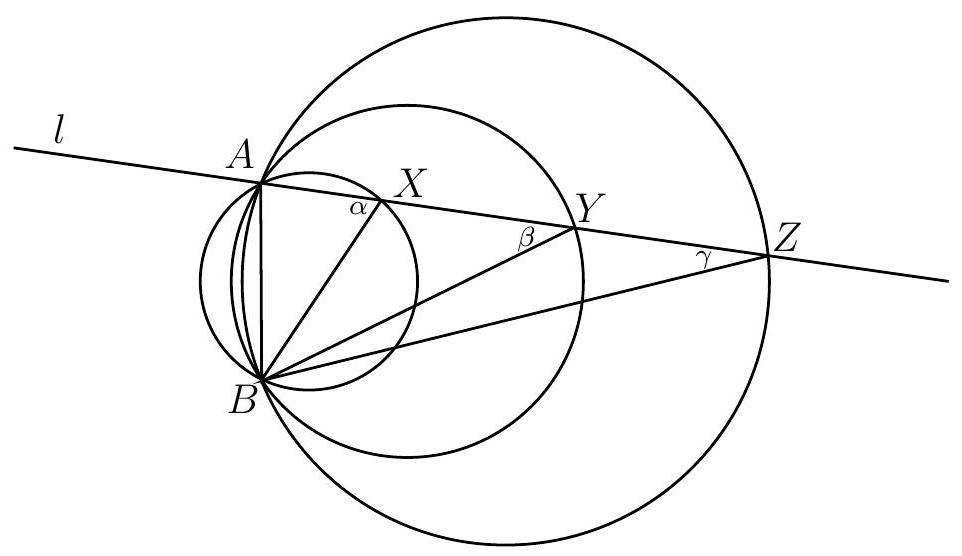

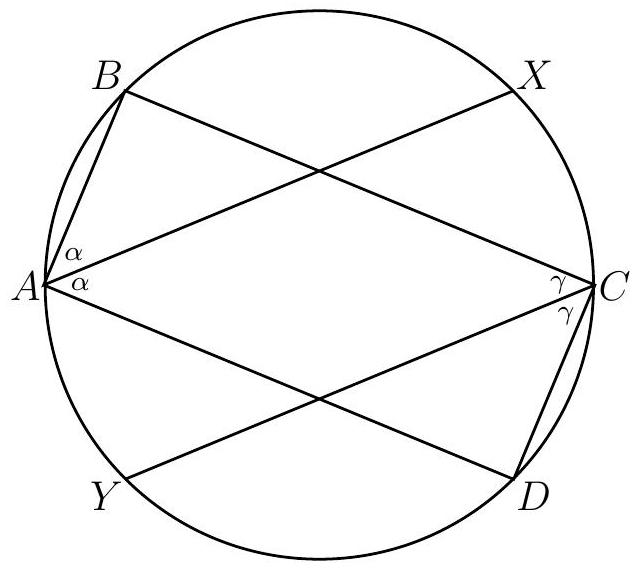

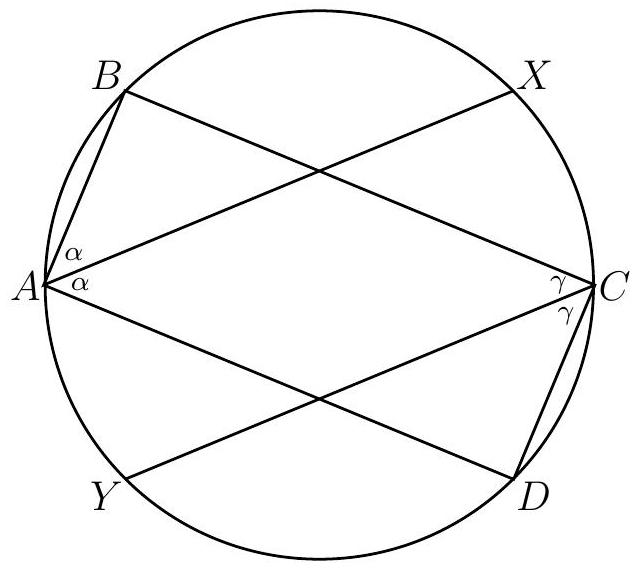

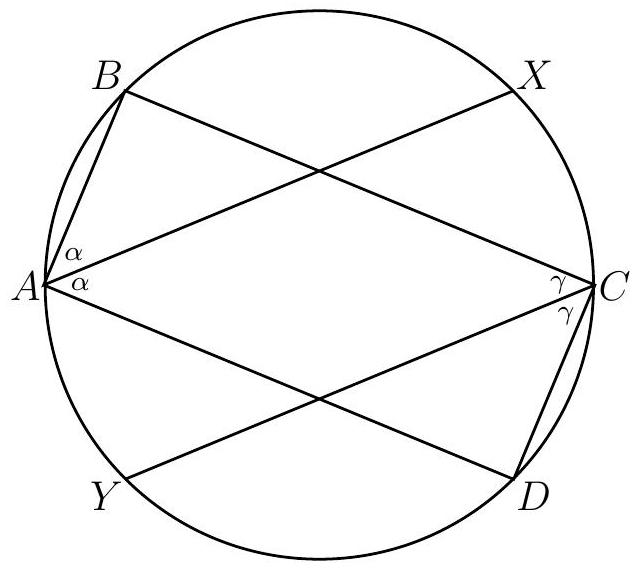

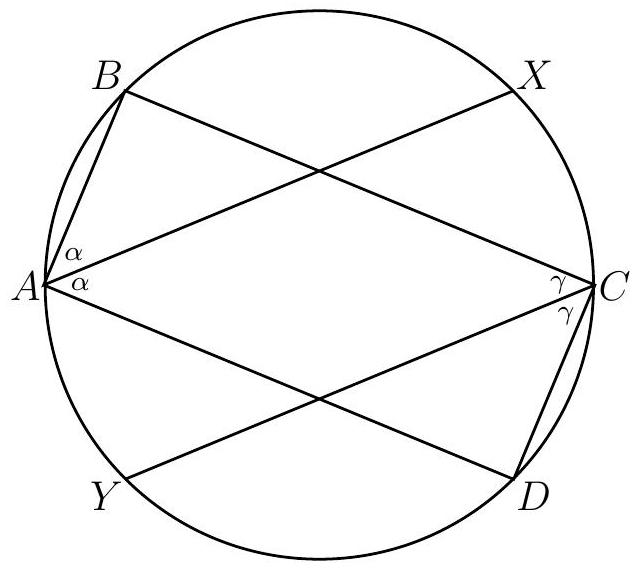

A cyclic quadrilateral $A B X C$ has circumcentre $O$. Let $D$ be a point on line $B X$ such that $|A D|=|B D|$. Let $E$ be a point on line $C X$ such that $|A E|=|C E|$. Prove that the circumcentre of triangle $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

First, note that $\angle A O X=2 \angle A B X=2\left(180^{\circ}-\angle A C X\right)=2 \angle A C E$ as $A B X C$ is cyclic. Secondly, both $\triangle D A B$ and $\triangle E A C$ are isosceles, which implies that $\angle A E X=\angle A E C=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A C E=180^{\circ}-\angle A O X$ and $\angle A D X=$ $\angle A D B=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A B D=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A B X=180^{\circ}-\angle A O X$. From this, see that respectively $A E X O$ and $A D X O$ are cyclic, i.e. $A E D X O$ is cyclic.

Hence, the circumcentre of $\triangle D E X$ is also the circumcentre of $A E D X O$. However, as in a circle any perpendicular bisector of a chord goes through the centre of the circle, we find that the circumcentre of $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

A cyclic quadrilateral $A B X C$ has circumcentre $O$. Let $D$ be a point on line $B X$ such that $|A D|=|B D|$. Let $E$ be a point on line $C X$ such that $|A E|=|C E|$. Prove that the circumcentre of triangle $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

First, note that $\angle A O X=2 \angle A B X=2\left(180^{\circ}-\angle A C X\right)=2 \angle A C E$ as $A B X C$ is cyclic. Secondly, both $\triangle D A B$ and $\triangle E A C$ are isosceles, which implies that $\angle A E X=\angle A E C=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A C E=180^{\circ}-\angle A O X$ and $\angle A D X=$ $\angle A D B=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A B D=180^{\circ}-2 \angle A B X=180^{\circ}-\angle A O X$. From this, see that respectively $A E X O$ and $A D X O$ are cyclic, i.e. $A E D X O$ is cyclic.

Hence, the circumcentre of $\triangle D E X$ is also the circumcentre of $A E D X O$. However, as in a circle any perpendicular bisector of a chord goes through the centre of the circle, we find that the circumcentre of $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2021-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2021"

}

|

A cyclic quadrilateral $A B X C$ has circumcentre $O$. Let $D$ be a point on line $B X$ such that $|A D|=|B D|$. Let $E$ be a point on line $C X$ such that $|A E|=|C E|$. Prove that the circumcentre of triangle $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

In this solution, we use directed angles $\measuredangle$. We have $\measuredangle A B D=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A C X=\measuredangle A C E$ and since $\triangle A B D$ and $\triangle A C E$ are both isosceles, we see that $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle A C E$ with equal orientation. This means that there exists a spiral symmetry $T$ with centre $A$ such that $T(B)=D$ and $T(C)=E$. Now let $O^{\prime}$ be the centre of $\odot D E X$. Then we find $\measuredangle D O^{\prime} E=2 \measuredangle D X E=2 \measuredangle B X C=\measuredangle B O C$. Moreover, $\triangle D O^{\prime} E$ and $\triangle B O C$ are isosceles, so we have $\triangle D O^{\prime} E \sim \triangle B O C$ with equal orientation. This means that $T$ must send $O$ to $O^{\prime}$, so in particular, $\triangle A O O^{\prime}$ is similar to $\triangle A B D$ and $\triangle A C E$. We conclude that $\left|A O^{\prime}\right|=\left|O O^{\prime}\right|$, from which the result follows.

# BxMO 2021: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

A cyclic quadrilateral $A B X C$ has circumcentre $O$. Let $D$ be a point on line $B X$ such that $|A D|=|B D|$. Let $E$ be a point on line $C X$ such that $|A E|=|C E|$. Prove that the circumcentre of triangle $\triangle D E X$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of $O A$.

#

|

In this solution, we use directed angles $\measuredangle$. We have $\measuredangle A B D=\measuredangle A B X=\measuredangle A C X=\measuredangle A C E$ and since $\triangle A B D$ and $\triangle A C E$ are both isosceles, we see that $\triangle A B D \sim \triangle A C E$ with equal orientation. This means that there exists a spiral symmetry $T$ with centre $A$ such that $T(B)=D$ and $T(C)=E$. Now let $O^{\prime}$ be the centre of $\odot D E X$. Then we find $\measuredangle D O^{\prime} E=2 \measuredangle D X E=2 \measuredangle B X C=\measuredangle B O C$. Moreover, $\triangle D O^{\prime} E$ and $\triangle B O C$ are isosceles, so we have $\triangle D O^{\prime} E \sim \triangle B O C$ with equal orientation. This means that $T$ must send $O$ to $O^{\prime}$, so in particular, $\triangle A O O^{\prime}$ is similar to $\triangle A B D$ and $\triangle A C E$. We conclude that $\left|A O^{\prime}\right|=\left|O O^{\prime}\right|$, from which the result follows.

# BxMO 2021: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2021-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2021"

}

|

A sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of positive integers satisfies $a_{1}>5$ and $a_{n+1}=5+6+\cdots+a_{n}$ for all positive integers $n$. Determine all prime numbers $p$ such that, regardless of the value of $a_{1}$, this sequence must contain a multiple of $p$.

#

|

We claim that the only prime number of which the sequence must contain a multiple is $p=2$. To prove this, we begin by noting that

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{a_{n}\left(a_{n}+1\right)}{2}-10=\frac{\left(a_{n}-4\right)\left(a_{n}+5\right)}{2}

$$

Let $p>2$ be an odd prime, and choose $a_{1} \equiv-4(\bmod p)$, so $2 a_{2} \equiv(-4-4)(-4+5) \equiv-8(\bmod p)$, whence $a_{2} \equiv-4(\bmod p)$, since $p$ is odd. By induction, $a_{n} \equiv-4(\bmod p) \not \equiv 0(\bmod p)$ for all $n$, and so the sequence need not contain a multiple of $p$.

We are left to show that the sequence must contain an even number. Suppose to the contrary that $a_{n}$ is odd for $n=1,2, \ldots$ We observe that

$$

a_{n+1}-a_{n}=\frac{a_{n}\left(a_{n}+1\right)}{2}-\frac{a_{n-1}\left(a_{n-1}+1\right)}{2}=\frac{a_{n}-a_{n-1}}{2}\left(a_{n}+a_{n-1}+1\right)

$$

By assumption, $a_{n}+a_{n-1}+1$ is odd for $n=1,2, \ldots$, so this shows that $v_{2}\left(a_{n+1}-a_{n}\right)=v_{2}\left(a_{n}-a_{n-1}\right)-1$, and so there exists $N$ such that $v_{2}\left(a_{N+1}-a_{N}\right)=0$. This is a contradiction, because $a_{n+1}-a_{n}$ is even for $n=1,2, \ldots$ by assumption, and thus completes the proof.

#

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of positive integers satisfies $a_{1}>5$ and $a_{n+1}=5+6+\cdots+a_{n}$ for all positive integers $n$. Determine all prime numbers $p$ such that, regardless of the value of $a_{1}$, this sequence must contain a multiple of $p$.

#

|

We claim that the only prime number of which the sequence must contain a multiple is $p=2$. To prove this, we begin by noting that

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{a_{n}\left(a_{n}+1\right)}{2}-10=\frac{\left(a_{n}-4\right)\left(a_{n}+5\right)}{2}

$$

Let $p>2$ be an odd prime, and choose $a_{1} \equiv-4(\bmod p)$, so $2 a_{2} \equiv(-4-4)(-4+5) \equiv-8(\bmod p)$, whence $a_{2} \equiv-4(\bmod p)$, since $p$ is odd. By induction, $a_{n} \equiv-4(\bmod p) \not \equiv 0(\bmod p)$ for all $n$, and so the sequence need not contain a multiple of $p$.

We are left to show that the sequence must contain an even number. Suppose to the contrary that $a_{n}$ is odd for $n=1,2, \ldots$ We observe that

$$

a_{n+1}-a_{n}=\frac{a_{n}\left(a_{n}+1\right)}{2}-\frac{a_{n-1}\left(a_{n-1}+1\right)}{2}=\frac{a_{n}-a_{n-1}}{2}\left(a_{n}+a_{n-1}+1\right)

$$

By assumption, $a_{n}+a_{n-1}+1$ is odd for $n=1,2, \ldots$, so this shows that $v_{2}\left(a_{n+1}-a_{n}\right)=v_{2}\left(a_{n}-a_{n-1}\right)-1$, and so there exists $N$ such that $v_{2}\left(a_{N+1}-a_{N}\right)=0$. This is a contradiction, because $a_{n+1}-a_{n}$ is even for $n=1,2, \ldots$ by assumption, and thus completes the proof.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2021-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2021"

}

|

A sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of positive integers satisfies $a_{1}>5$ and $a_{n+1}=5+6+\cdots+a_{n}$ for all positive integers $n$. Determine all prime numbers $p$ such that, regardless of the value of $a_{1}$, this sequence must contain a multiple of $p$.

#

|

For odd $p$, proceed as in solution 1 . Now let $p=2$, and suppose that every term of the sequence is odd. We claim that it follows that $a_{n} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{k}\right)$ for every integer $n \geq 1$ and every integer $k \geq 1$. We proceed per induction on $k$. For $k=1$ this simply states that $a_{n}$ is odd for all integers $n \geq 1$, as assumed. Now suppose it is true for $k=r$. Let $k=r+1$. Take any integer $n \geq 1$. Note that, by the induction hypothesis, $a_{n} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)$. Therefore there exists an integer $s$ such that $a_{n}=2^{r} s+5$. Now note that

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{\left(a_{n}-4\right)\left(a_{n}+5\right)}{2}=\frac{\left(2^{r} s+1\right)\left(2^{r} s+10\right)}{2}=\left(2^{r} s+1\right)\left(2^{r-1} s+5\right) \equiv 2^{r-1} s+5 \quad\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)

$$

By the induction hypothesis, $a_{n+1} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)$. Therefore $s$ is even, such that $a_{n}$ is of the form $2^{r+1} s+5$ for any integer $n \geq 1$, which concludes the induction. From this property, it follows that $a_{1}-5$ is divisible by $2^{k}$ for every integer $k \geq 1$, which is only possible if $a_{1}=5$. But $a_{1}>5$, so this is a contradiction.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

A sequence $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \ldots$ of positive integers satisfies $a_{1}>5$ and $a_{n+1}=5+6+\cdots+a_{n}$ for all positive integers $n$. Determine all prime numbers $p$ such that, regardless of the value of $a_{1}$, this sequence must contain a multiple of $p$.

#

|

For odd $p$, proceed as in solution 1 . Now let $p=2$, and suppose that every term of the sequence is odd. We claim that it follows that $a_{n} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{k}\right)$ for every integer $n \geq 1$ and every integer $k \geq 1$. We proceed per induction on $k$. For $k=1$ this simply states that $a_{n}$ is odd for all integers $n \geq 1$, as assumed. Now suppose it is true for $k=r$. Let $k=r+1$. Take any integer $n \geq 1$. Note that, by the induction hypothesis, $a_{n} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)$. Therefore there exists an integer $s$ such that $a_{n}=2^{r} s+5$. Now note that

$$

a_{n+1}=\frac{\left(a_{n}-4\right)\left(a_{n}+5\right)}{2}=\frac{\left(2^{r} s+1\right)\left(2^{r} s+10\right)}{2}=\left(2^{r} s+1\right)\left(2^{r-1} s+5\right) \equiv 2^{r-1} s+5 \quad\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)

$$

By the induction hypothesis, $a_{n+1} \equiv 5\left(\bmod 2^{r}\right)$. Therefore $s$ is even, such that $a_{n}$ is of the form $2^{r+1} s+5$ for any integer $n \geq 1$, which concludes the induction. From this property, it follows that $a_{1}-5$ is divisible by $2^{k}$ for every integer $k \geq 1$, which is only possible if $a_{1}=5$. But $a_{1}>5$, so this is a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2021-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2021"

}

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

The case $n=0$ is trivial; for $n>0$, the proof goes by induction on $n$. We need to make one preliminary observation:

Claim. For all reals $a, b, a+b x \leqslant \max \{a, a+b\}$ for all $x \in[0,1]$.

Proof. If $b \leqslant 0$, then $a+b x \leqslant a$ for all $x \in[0,1]$; otherwise, if $b>0, a+b x \leqslant a+b$ for all $x \in[0,1]$. This proves our claim.

This disposes of the base case $n=1$ of the induction: $a_{0}+a_{1} x \leqslant \max \left\{a_{0}, a_{0}+a_{1}\right\}$ for all $x \in[0,1]$. For $n \geqslant 2$, we note that, for all $x \in[0,1]$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} & =a_{0}+x\left(a_{1}+a_{2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-1}\right) \\

& \leqslant a_{0}+x\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}\right) \leqslant \max \left\{a_{0}, a_{0}+\left(a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}\right)\right\},

\end{aligned}

$$

for some $k \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ by the inductive hypothesis and our earlier claim. This completes the proof by induction.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

The case $n=0$ is trivial; for $n>0$, the proof goes by induction on $n$. We need to make one preliminary observation:

Claim. For all reals $a, b, a+b x \leqslant \max \{a, a+b\}$ for all $x \in[0,1]$.

Proof. If $b \leqslant 0$, then $a+b x \leqslant a$ for all $x \in[0,1]$; otherwise, if $b>0, a+b x \leqslant a+b$ for all $x \in[0,1]$. This proves our claim.

This disposes of the base case $n=1$ of the induction: $a_{0}+a_{1} x \leqslant \max \left\{a_{0}, a_{0}+a_{1}\right\}$ for all $x \in[0,1]$. For $n \geqslant 2$, we note that, for all $x \in[0,1]$,

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} & =a_{0}+x\left(a_{1}+a_{2} x+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n-1}\right) \\

& \leqslant a_{0}+x\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k}\right) \leqslant \max \left\{a_{0}, a_{0}+\left(a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}\right)\right\},

\end{aligned}

$$

for some $k \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ by the inductive hypothesis and our earlier claim. This completes the proof by induction.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

Define $s_{i}=a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{i}$ for $i \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$. Thus $a_{0}=s_{0}$ and $a_{i}=s_{i}-s_{i-1}$ for all $i \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} & =s_{0}+\left(s_{1}-s_{0}\right) x+\left(s_{2}-s_{1}\right) x^{2}+\ldots+\left(s_{n}-s_{n-1}\right) x^{n} \\

& =s_{0}(1-x)+s_{1}\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\ldots+s_{n-1}\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+s_{n} x^{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

Now choose $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that $s_{k}=\max \left\{s_{0}, s_{1}, \ldots, s_{n}\right\}$. Using the inequality $x^{i-1}-x^{i} \geqslant 0$, valid for all $i \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ and all $x \in[0,1]$, in the right-hand side above, it follows that

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant s_{k}(1- & x)+s_{k}\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\cdots+s_{k}\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+s_{k} x^{n} \\

& =s_{k}\left[(1-x)+\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\cdots+\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+x^{n}\right] \\

& =s_{k}=a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k} .

\end{aligned}

$$

This completes the proof.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

Define $s_{i}=a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{i}$ for $i \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$. Thus $a_{0}=s_{0}$ and $a_{i}=s_{i}-s_{i-1}$ for all $i \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$. Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} & =s_{0}+\left(s_{1}-s_{0}\right) x+\left(s_{2}-s_{1}\right) x^{2}+\ldots+\left(s_{n}-s_{n-1}\right) x^{n} \\

& =s_{0}(1-x)+s_{1}\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\ldots+s_{n-1}\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+s_{n} x^{n}

\end{aligned}

$$

Now choose $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that $s_{k}=\max \left\{s_{0}, s_{1}, \ldots, s_{n}\right\}$. Using the inequality $x^{i-1}-x^{i} \geqslant 0$, valid for all $i \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}$ and all $x \in[0,1]$, in the right-hand side above, it follows that

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant s_{k}(1- & x)+s_{k}\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\cdots+s_{k}\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+s_{k} x^{n} \\

& =s_{k}\left[(1-x)+\left(x-x^{2}\right)+\cdots+\left(x^{n-1}-x^{n}\right)+x^{n}\right] \\

& =s_{k}=a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k} .

\end{aligned}

$$

This completes the proof.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

The proof proceeds by induction on $n$. The base case $n=0$ is trivial. For $n \geqslant 1$, since $x \in[0,1]$, we have $x^{n} \leqslant x^{n-1}$. Thus, if $a_{n} \geqslant 0$, then $a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{n} x^{n-1}$, while, if $a_{n}<0$, then $a_{n} x^{n}<0$ trivially. This shows that $a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant \max \left\{0, a_{n} x^{n-1}\right\}$, whence

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+\max \left\{a_{n-1}, a_{n-1}+a_{n}\right\} x^{n-1}

$$

By the inductive hypothesis, the polynomial of degree $n-1$ on the right-hand side is bounded above by $a_{0}+\cdots+a_{k}$ for some $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n-2\}$ or $a_{0}+\cdots+a_{n-2}+\max \left\{a_{n-1}, a_{n-1}+a_{n}\right\}$. But the latter is equal to one of $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n-1}$ or $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}$; both are of the desired form, $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}$ for some $k \in\{n-1, n\}$. This completes the proof by induction.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Let $n \geqslant 0$ be an integer, and let $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}$ be real numbers. Show that there exists $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n\}$ such that

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+a_{2} x^{2}+\cdots+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}

$$

for all real numbers $x \in[0,1]$.

#

|

The proof proceeds by induction on $n$. The base case $n=0$ is trivial. For $n \geqslant 1$, since $x \in[0,1]$, we have $x^{n} \leqslant x^{n-1}$. Thus, if $a_{n} \geqslant 0$, then $a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{n} x^{n-1}$, while, if $a_{n}<0$, then $a_{n} x^{n}<0$ trivially. This shows that $a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant \max \left\{0, a_{n} x^{n-1}\right\}$, whence

$$

a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+a_{n} x^{n} \leqslant a_{0}+a_{1} x+\cdots+\max \left\{a_{n-1}, a_{n-1}+a_{n}\right\} x^{n-1}

$$

By the inductive hypothesis, the polynomial of degree $n-1$ on the right-hand side is bounded above by $a_{0}+\cdots+a_{k}$ for some $k \in\{0,1, \ldots, n-2\}$ or $a_{0}+\cdots+a_{n-2}+\max \left\{a_{n-1}, a_{n-1}+a_{n}\right\}$. But the latter is equal to one of $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n-1}$ or $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{n}$; both are of the desired form, $a_{0}+a_{1}+\cdots+a_{k}$ for some $k \in\{n-1, n\}$. This completes the proof by induction.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 3",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. There are $n$ ants walking along a line at constant nonzero speeds. Different ants need not walk at the same speed or walk in the same direction. Whenever two or more ants collide, all the ants involved in this collision instantly change directions. (Different ants need not be moving in opposite directions when they collide, since a faster ant may catch up with a slower one that is moving in the same direction.) The ants keep walking indefinitely.

Assuming that the total number of collisions is finite, determine the largest possible number of collisions in terms of $n$.

#

|

The order of the ants along the line does not change; denote by $v_{1}, v_{2}, \ldots, v_{n}$ the respective speeds of ants $1,2, \ldots, n$ in this order. If $v_{i-1}<v_{i}>v_{i+1}$ for some $i \in\{2, \ldots, n-1\}$, then, at each stage, ant $i$ can catch up with ants $i-1$ or $i+1$ irrespective of the latters' directions of motion, so the number of collisions is infinite. Hence, if the number of collisions is finite, then, up to switching the direction definining the order of the ants, (i) $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{n}$ or (ii) $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{k-1}>v_{k} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant v_{n}$ for some $k \in\{2, \ldots, n-1\}$. We need the following observation:

Claim. If $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{m}$, then ants $m-1$ and $m$ collide at most $m-1$ times.

Proof. The proof goes by induction on $m$, the case $m=1$ being trivial. Since $v_{m-1} \geqslant v_{m}$, ants $m-1$ and $m$ can only collide if the former is moving towards the latter. Hence, between successive collisions with ant $m$, ant $m-1$ must reverse direction by colliding with ant $m-2$. Since ants $m-1$ and $m-2$ collide at most $(m-1)-1=m-2$ times by the inductive hypothesis, ants $m$ and $m-1$ collide at most $(m-2)+1=m-1$ times.

Hence, in case (i), there are at most $0+1+\cdots+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions. In case (ii), applying the claim to ants $1,2, \ldots, k$ and also to ants $n, n-1, \ldots, k$ by switching their order, the number of collisions is at most $k(k-1) / 2+(n-k+1)(n-k) / 2=n(n-1) / 2-(k-1)(n-k)<n(n-1) / 2$.

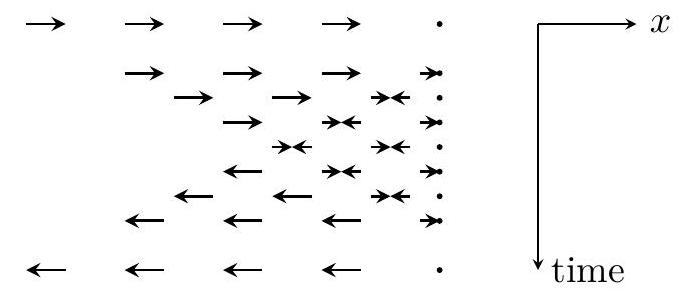

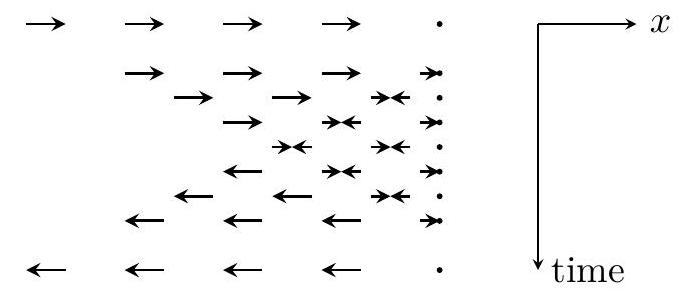

Now take a coordinate $x$ along the line, and put ants at $x=1,2, \ldots, n$ with positive initial velocities and speeds $v_{1}=\cdots=v_{n-1}=1, v_{n}=\varepsilon$, for some $\varepsilon$. For $\varepsilon=0$, collisions occur according to the pattern shown below for $n=5$, which clearly extends to all values of $n$ in such a way that ants $m$ and $m+1$ collide exactly $m$ times for $m=1,2, \ldots, n-1$. This yield $1+2+\cdots+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions in total. For all sufficiently small $\varepsilon>0$, the number of collisions remains equal to $n(n-1) / 2$.

This shows that the upper bound obtained above can be attained. If the number of collisions is finite, the largest possible number of collisions is therefore indeed $n(n-1) / 2$.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

n(n-1) / 2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. There are $n$ ants walking along a line at constant nonzero speeds. Different ants need not walk at the same speed or walk in the same direction. Whenever two or more ants collide, all the ants involved in this collision instantly change directions. (Different ants need not be moving in opposite directions when they collide, since a faster ant may catch up with a slower one that is moving in the same direction.) The ants keep walking indefinitely.

Assuming that the total number of collisions is finite, determine the largest possible number of collisions in terms of $n$.

#

|

The order of the ants along the line does not change; denote by $v_{1}, v_{2}, \ldots, v_{n}$ the respective speeds of ants $1,2, \ldots, n$ in this order. If $v_{i-1}<v_{i}>v_{i+1}$ for some $i \in\{2, \ldots, n-1\}$, then, at each stage, ant $i$ can catch up with ants $i-1$ or $i+1$ irrespective of the latters' directions of motion, so the number of collisions is infinite. Hence, if the number of collisions is finite, then, up to switching the direction definining the order of the ants, (i) $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{n}$ or (ii) $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{k-1}>v_{k} \leqslant \cdots \leqslant v_{n}$ for some $k \in\{2, \ldots, n-1\}$. We need the following observation:

Claim. If $v_{1} \geqslant \cdots \geqslant v_{m}$, then ants $m-1$ and $m$ collide at most $m-1$ times.

Proof. The proof goes by induction on $m$, the case $m=1$ being trivial. Since $v_{m-1} \geqslant v_{m}$, ants $m-1$ and $m$ can only collide if the former is moving towards the latter. Hence, between successive collisions with ant $m$, ant $m-1$ must reverse direction by colliding with ant $m-2$. Since ants $m-1$ and $m-2$ collide at most $(m-1)-1=m-2$ times by the inductive hypothesis, ants $m$ and $m-1$ collide at most $(m-2)+1=m-1$ times.

Hence, in case (i), there are at most $0+1+\cdots+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions. In case (ii), applying the claim to ants $1,2, \ldots, k$ and also to ants $n, n-1, \ldots, k$ by switching their order, the number of collisions is at most $k(k-1) / 2+(n-k+1)(n-k) / 2=n(n-1) / 2-(k-1)(n-k)<n(n-1) / 2$.

Now take a coordinate $x$ along the line, and put ants at $x=1,2, \ldots, n$ with positive initial velocities and speeds $v_{1}=\cdots=v_{n-1}=1, v_{n}=\varepsilon$, for some $\varepsilon$. For $\varepsilon=0$, collisions occur according to the pattern shown below for $n=5$, which clearly extends to all values of $n$ in such a way that ants $m$ and $m+1$ collide exactly $m$ times for $m=1,2, \ldots, n-1$. This yield $1+2+\cdots+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions in total. For all sufficiently small $\varepsilon>0$, the number of collisions remains equal to $n(n-1) / 2$.

This shows that the upper bound obtained above can be attained. If the number of collisions is finite, the largest possible number of collisions is therefore indeed $n(n-1) / 2$.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. There are $n$ ants walking along a line at constant nonzero speeds. Different ants need not walk at the same speed or walk in the same direction. Whenever two or more ants collide, all the ants involved in this collision instantly change directions. (Different ants need not be moving in opposite directions when they collide, since a faster ant may catch up with a slower one that is moving in the same direction.) The ants keep walking indefinitely.

Assuming that the total number of collisions is finite, determine the largest possible number of collisions in terms of $n$.

#

|

We show that there are at most $n(n-1) / 2$ collisions if the number of collisions is finite as in Solution 1.

To show that the upper bound of $n(n-1) / 2$ collisions can be attained, we construct, inductively, an example of $n$ ants colliding $n(n-1) / 2$ times, the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right, and after all collisions all ants move towards the left, with the possible exception of the rightmost ant. In every case, we will label the ants $1,2, \ldots, n$ from left to right. For $n=1$ this is trivial. For $n \geqslant 2$, we use the construction for $n-1$ ants (now labelled $2,3, \ldots, n$ ). We add ant 1 on the left, moving towards the right, faster than all other ants (so that the speeds of the ants still decrease from left to right), and in such a way that its first collision (with ant 2) happens after all $(n-1)(n-2) / 2$ collisions of the other $n-1$ ants. Now the following events happen (in this order) for $i=1,2, \ldots, n-2$ : ants $i$ and $i+1$ collide, after which ant $i$ moves to the left and ant $i+1$ moves to the right. These collisions do happen because the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right. Then ants $n-1$ and $n$ also collide, resulting in ant $n-1$ moving to the left. This shows that there are (at least) $(n-1)(n-2) / 2+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions. There are in fact no more collisions since the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right; alternatively, this follows from the upper bound proved previously. Since all ants except ant $n$ are moving towards the left after the collisions, this completes the inductive construction.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

n(n-1) / 2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $n$ be a positive integer. There are $n$ ants walking along a line at constant nonzero speeds. Different ants need not walk at the same speed or walk in the same direction. Whenever two or more ants collide, all the ants involved in this collision instantly change directions. (Different ants need not be moving in opposite directions when they collide, since a faster ant may catch up with a slower one that is moving in the same direction.) The ants keep walking indefinitely.

Assuming that the total number of collisions is finite, determine the largest possible number of collisions in terms of $n$.

#

|

We show that there are at most $n(n-1) / 2$ collisions if the number of collisions is finite as in Solution 1.

To show that the upper bound of $n(n-1) / 2$ collisions can be attained, we construct, inductively, an example of $n$ ants colliding $n(n-1) / 2$ times, the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right, and after all collisions all ants move towards the left, with the possible exception of the rightmost ant. In every case, we will label the ants $1,2, \ldots, n$ from left to right. For $n=1$ this is trivial. For $n \geqslant 2$, we use the construction for $n-1$ ants (now labelled $2,3, \ldots, n$ ). We add ant 1 on the left, moving towards the right, faster than all other ants (so that the speeds of the ants still decrease from left to right), and in such a way that its first collision (with ant 2) happens after all $(n-1)(n-2) / 2$ collisions of the other $n-1$ ants. Now the following events happen (in this order) for $i=1,2, \ldots, n-2$ : ants $i$ and $i+1$ collide, after which ant $i$ moves to the left and ant $i+1$ moves to the right. These collisions do happen because the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right. Then ants $n-1$ and $n$ also collide, resulting in ant $n-1$ moving to the left. This shows that there are (at least) $(n-1)(n-2) / 2+(n-1)=n(n-1) / 2$ collisions. There are in fact no more collisions since the speeds of the ants decrease from left to right; alternatively, this follows from the upper bound proved previously. Since all ants except ant $n$ are moving towards the left after the collisions, this completes the inductive construction.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

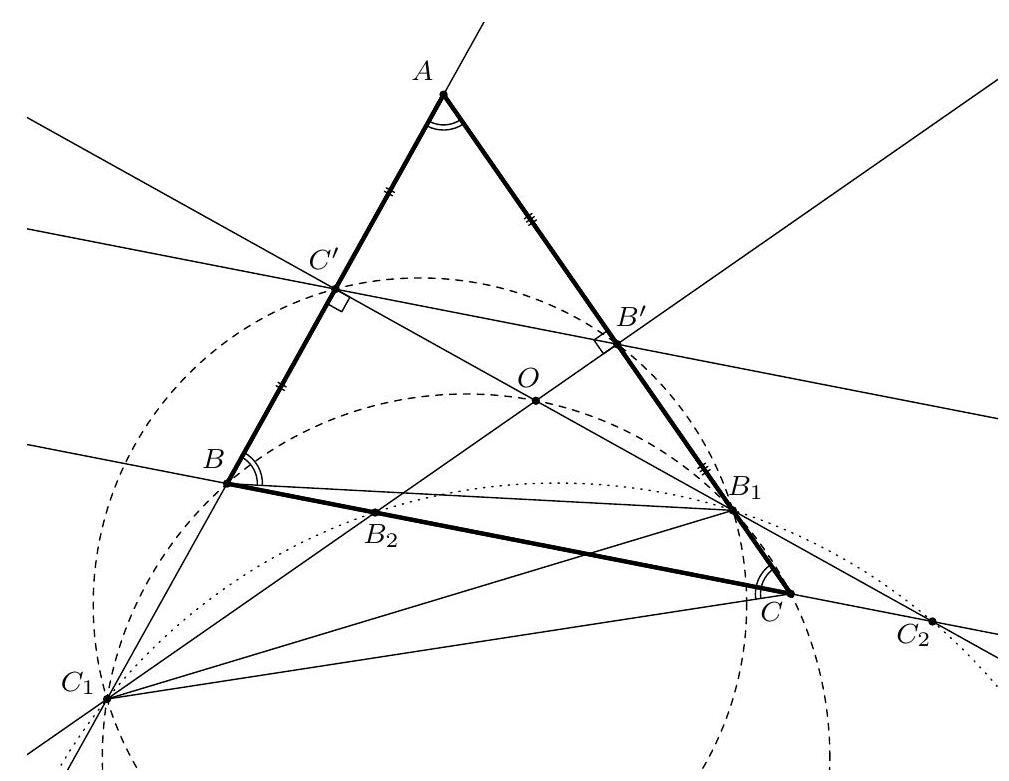

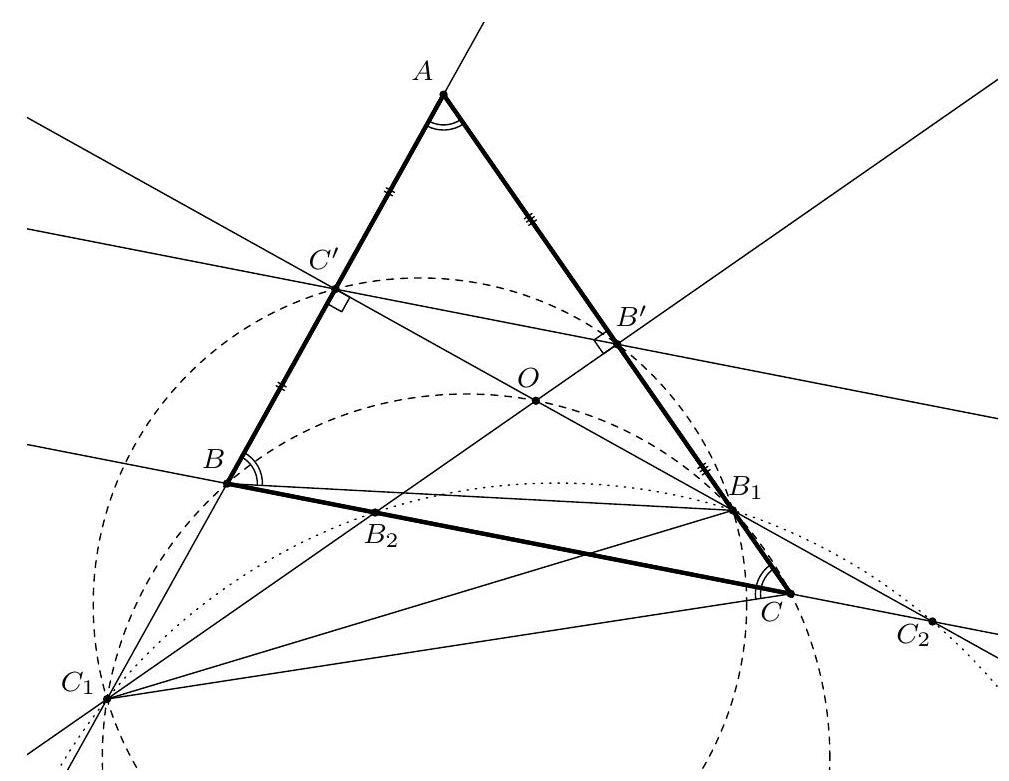

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ bisect segments $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, respectively, so their intersection $O$ is the circumcentre of $A B C$. Hence $\angle B O C=2 \angle A$ and $\angle C B O=\angle O C B=90^{\circ}-\angle A$. Now, by construction, $\angle O C_{1} B=90^{\circ}-\angle A=\angle O C B$, so $B C_{1} C O$ is cyclic. Similarly, $B C B_{1} O$ is cyclic by construction because $\angle O B_{1} C=180^{\circ}-\angle A B_{1} O=90^{\circ}+\angle A=180^{\circ}-\angle C B O$. In particular, $B C_{1} C B_{1}$ is cyclic, too.

Now $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B-\angle B_{2} C_{1} B$ and $\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C B-\angle C B_{1} C_{2}$. But $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B=\angle B_{1} C B$ since $B C_{1} C B_{1}$ is cyclic and $\angle B_{2} C_{1} B=\angle O C_{1} B=90^{\circ}-\angle A=180^{\circ}-\angle O B_{1} C=\angle C B_{1} C_{2}$. Hence $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}$, so $B_{1} B_{2} C_{1} C_{2}$ is cyclic, as required.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ bisect segments $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, respectively, so their intersection $O$ is the circumcentre of $A B C$. Hence $\angle B O C=2 \angle A$ and $\angle C B O=\angle O C B=90^{\circ}-\angle A$. Now, by construction, $\angle O C_{1} B=90^{\circ}-\angle A=\angle O C B$, so $B C_{1} C O$ is cyclic. Similarly, $B C B_{1} O$ is cyclic by construction because $\angle O B_{1} C=180^{\circ}-\angle A B_{1} O=90^{\circ}+\angle A=180^{\circ}-\angle C B O$. In particular, $B C_{1} C B_{1}$ is cyclic, too.

Now $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B-\angle B_{2} C_{1} B$ and $\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C B-\angle C B_{1} C_{2}$. But $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B=\angle B_{1} C B$ since $B C_{1} C B_{1}$ is cyclic and $\angle B_{2} C_{1} B=\angle O C_{1} B=90^{\circ}-\angle A=180^{\circ}-\angle O B_{1} C=\angle C B_{1} C_{2}$. Hence $\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2}=\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}$, so $B_{1} B_{2} C_{1} C_{2}$ is cyclic, as required.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

The isosceles triangles $A B_{1} B$ and $A C_{1} C$ have equal base angles $\angle B A B_{1}=\angle C_{1} A C=\angle A$, so are similar. In particular, $|A B| /\left|A B_{1}\right|=|A C| /\left|A C_{1}\right|$. Since $\angle B A C=\angle B_{1} A C_{1}=\angle A$, it follows that triangles $A B C$ and $A B_{1} C_{1}$ are similar, too. In particular, $\angle C B A=\angle A B_{1} C_{1}$.

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ are the respective perpendicular bisectors of $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, so meet them at their respective midpoints $C^{\prime}$ and $B^{\prime}$. Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2} & =\angle C^{\prime} C_{2} B=90^{\circ}-\angle C_{2} B C^{\prime}=90^{\circ}-\angle C B A=90^{\circ}-\angle A B_{1} C_{1}=90^{\circ}-\angle B^{\prime} B_{1} C_{1} \\

& =\angle B_{1} C_{1} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $B_{1} C_{2} C_{1} B_{2}$ is cyclic, which completes the proof.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

The isosceles triangles $A B_{1} B$ and $A C_{1} C$ have equal base angles $\angle B A B_{1}=\angle C_{1} A C=\angle A$, so are similar. In particular, $|A B| /\left|A B_{1}\right|=|A C| /\left|A C_{1}\right|$. Since $\angle B A C=\angle B_{1} A C_{1}=\angle A$, it follows that triangles $A B C$ and $A B_{1} C_{1}$ are similar, too. In particular, $\angle C B A=\angle A B_{1} C_{1}$.

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ are the respective perpendicular bisectors of $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, so meet them at their respective midpoints $C^{\prime}$ and $B^{\prime}$. Hence

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2} & =\angle C^{\prime} C_{2} B=90^{\circ}-\angle C_{2} B C^{\prime}=90^{\circ}-\angle C B A=90^{\circ}-\angle A B_{1} C_{1}=90^{\circ}-\angle B^{\prime} B_{1} C_{1} \\

& =\angle B_{1} C_{1} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $B_{1} C_{2} C_{1} B_{2}$ is cyclic, which completes the proof.

## BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ are the respective perpendicular bisectors of $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, so meet them at their respective midpoints $C^{\prime}$ and $B^{\prime}$. Since $\angle B_{1} C^{\prime} C_{1}=90^{\circ}=\angle C_{1} B^{\prime} B_{1}, B_{1} C_{1} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}$ is cyclic. Together with the fact that $B^{\prime} C^{\prime} \| B C$ by construction, this implies

$$

\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}=\angle C^{\prime} C_{2} B=\angle C_{2} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2},

$$

whence $B_{1} C_{2} C_{1} B_{2}$ is cyclic. This completes the proof.

# BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a scalene acute triangle. Let $B_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A C\right.$ such that $\left|A B_{1}\right|=\left|B B_{1}\right|$. Let $C_{1}$ be the point on ray $\left[A B\right.$ such that $\left|A C_{1}\right|=\left|C C_{1}\right|$. Let $B_{2}$ and $C_{2}$ be the points on line $B C$ such that $\left|A B_{2}\right|=\left|C B_{2}\right|$ and $\left|B C_{2}\right|=\left|A C_{2}\right|$. Prove that $B_{1}, C_{1}, B_{2}, C_{2}$ are concyclic.

#

|

By construction, lines $B_{1} C_{2}$ and $B_{2} C_{1}$ are the respective perpendicular bisectors of $[A B]$ and $[A C]$, so meet them at their respective midpoints $C^{\prime}$ and $B^{\prime}$. Since $\angle B_{1} C^{\prime} C_{1}=90^{\circ}=\angle C_{1} B^{\prime} B_{1}, B_{1} C_{1} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}$ is cyclic. Together with the fact that $B^{\prime} C^{\prime} \| B C$ by construction, this implies

$$

\angle B_{1} C_{2} B_{2}=\angle C^{\prime} C_{2} B=\angle C_{2} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C^{\prime} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B^{\prime}=\angle B_{1} C_{1} B_{2},

$$

whence $B_{1} C_{2} C_{1} B_{2}$ is cyclic. This completes the proof.

# BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 3",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there exists $n \in \mathbb{N}$ with two different prime factors $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q$ are perfect squares. In particular $n$ is not prime. Write $n-p=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. As $p \mid n$, it follows that $p \mid m$ and hence $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$ since $p$ is prime. Hence there exists $k \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-p=p^{2} k^{2}$. Similarly, there exists $\ell \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-q=q^{2} \ell^{2}$. We observe that $k, \ell \neq 0$ since $n$ is not prime.

Now we have $p-q=(n-q)-(n-p)=(\ell q-k p)(\ell q+k p)$. Since $p-q \neq 0, \ell q-k p \neq 0$, and hence $|p-q|=|k p-\ell q||k p+\ell q| \geqslant|k p+\ell q|=k p+\ell q$. This is a contradiction however, because, since $k, \ell \neq 0$, it is clear that $k p+\ell q \geqslant p+q>|p-q|$. Hence $S$ is good.

(b) Let $q$ be a prime, and let $Q=\left\{q, q^{3}, q^{5}, \ldots\right\}$ be the (infinite) set of odd powers of $q$, which is disjoint from $S$. We claim that $Q$ is good. Indeed, let $n \in \mathbb{N}$, and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p \in Q$, i.e. $n-p=q^{2 k+1}$ for some $k \in \mathbb{N}$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q^{2 k+1}$, and hence $p=q$. Thus $Q$ is good.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there exists $n \in \mathbb{N}$ with two different prime factors $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q$ are perfect squares. In particular $n$ is not prime. Write $n-p=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. As $p \mid n$, it follows that $p \mid m$ and hence $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$ since $p$ is prime. Hence there exists $k \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-p=p^{2} k^{2}$. Similarly, there exists $\ell \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-q=q^{2} \ell^{2}$. We observe that $k, \ell \neq 0$ since $n$ is not prime.

Now we have $p-q=(n-q)-(n-p)=(\ell q-k p)(\ell q+k p)$. Since $p-q \neq 0, \ell q-k p \neq 0$, and hence $|p-q|=|k p-\ell q||k p+\ell q| \geqslant|k p+\ell q|=k p+\ell q$. This is a contradiction however, because, since $k, \ell \neq 0$, it is clear that $k p+\ell q \geqslant p+q>|p-q|$. Hence $S$ is good.

(b) Let $q$ be a prime, and let $Q=\left\{q, q^{3}, q^{5}, \ldots\right\}$ be the (infinite) set of odd powers of $q$, which is disjoint from $S$. We claim that $Q$ is good. Indeed, let $n \in \mathbb{N}$, and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p \in Q$, i.e. $n-p=q^{2 k+1}$ for some $k \in \mathbb{N}$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q^{2 k+1}$, and hence $p=q$. Thus $Q$ is good.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=p(n / p-1)=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. Since $p \mid m^{2}$ and $p$ is prime, $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$, and hence $p \mid n / p-1<n / p$, so $p<\sqrt{n}$.

Now suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there are primes $p_{1}>p_{2}$ dividing $n$ such that $n-p_{1}<n-p_{2}$ are perfect squares. Then

$$

n-p_{2} \geqslant\left(\sqrt{n-p_{1}}+1\right)^{2}>n-p_{1}+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad p_{1}>p_{2}+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} \geqslant 2+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} .

$$

The last condition implies that $p_{1}>2 \sqrt{n-1}$. But $p_{1}<\sqrt{n}$ by the first part, so $\sqrt{n}>2 \sqrt{n-1}$, which is a contradiction for $n>1$; the cases $n=0$ and $n=1$ are trivial. Thus $S$ is good.

(b) We claim that the infinite set $P=\{3,5,7,11, \ldots\}$ of odd primes, which is disjoint from $S$, is good. Indeed, let $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=q$, for some odd prime $q$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q$, i.e. $p=q$, and hence $n=2 q$. Since $q$ is the only odd prime divisor of $n=2 q$, $P$ is good.

The set $P^{\prime}=\{2,3,5,7,11, \ldots\}$ of all primes is also good. The proof is similar: let $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=q$, for some prime $q$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q$, i.e. $p=q$, and hence $n=2 q$. If $q=2$, then 2 is the only prime divisor of $n$; if $q \neq 2$, then the only prime divisor of $n$, apart from $q$, is 2 . However, $n-2=2(q-1) \notin P^{\prime}$ since $q-1>1$. Hence $P^{\prime}$ is good.

# BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=p(n / p-1)=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. Since $p \mid m^{2}$ and $p$ is prime, $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$, and hence $p \mid n / p-1<n / p$, so $p<\sqrt{n}$.

Now suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there are primes $p_{1}>p_{2}$ dividing $n$ such that $n-p_{1}<n-p_{2}$ are perfect squares. Then

$$

n-p_{2} \geqslant\left(\sqrt{n-p_{1}}+1\right)^{2}>n-p_{1}+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad p_{1}>p_{2}+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} \geqslant 2+2 \sqrt{n-p_{1}} .

$$

The last condition implies that $p_{1}>2 \sqrt{n-1}$. But $p_{1}<\sqrt{n}$ by the first part, so $\sqrt{n}>2 \sqrt{n-1}$, which is a contradiction for $n>1$; the cases $n=0$ and $n=1$ are trivial. Thus $S$ is good.

(b) We claim that the infinite set $P=\{3,5,7,11, \ldots\}$ of odd primes, which is disjoint from $S$, is good. Indeed, let $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=q$, for some odd prime $q$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q$, i.e. $p=q$, and hence $n=2 q$. Since $q$ is the only odd prime divisor of $n=2 q$, $P$ is good.

The set $P^{\prime}=\{2,3,5,7,11, \ldots\}$ of all primes is also good. The proof is similar: let $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and let $p \mid n$ be a prime such that $n-p=q$, for some prime $q$. Then $p \mid n-p$, so $p \mid q$, i.e. $p=q$, and hence $n=2 q$. If $q=2$, then 2 is the only prime divisor of $n$; if $q \neq 2$, then the only prime divisor of $n$, apart from $q$, is 2 . However, $n-2=2(q-1) \notin P^{\prime}$ since $q-1>1$. Hence $P^{\prime}$ is good.

# BxMO 2022: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there exists $n \in \mathbb{N}$ with two different prime factors $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q$ are perfect squares. Write $n-p=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. As $p \mid n$, it follows that $p \mid m$ and hence $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$ since $p$ is prime. Hence there exists $k \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-p=p^{2} k^{2}$. Similarly, there exists $\ell \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-q=q^{2} \ell^{2}$. By construction, $n$ is not prime, so $n-p, n-q \neq 0$, whence $k, \ell \geqslant 1$.

Hence $p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q$. Hence $p^{2} k^{2}<p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q<q^{2} \ell^{2}+2 q \ell+1=(q \ell+1)^{2}$. Similarly, $q^{2} \ell^{2}<(p k+1)^{2}$, whence $q \ell-1<p k<q \ell+1$. It follows that $p k=q \ell$, so $p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q$ yields the contradiction $p=q$. Hence $S$ is good.

(b) Let $A$ be a finite good set such that $0 \notin A$, and let $m=\max A$. Let $a \geqslant 2 m+1$ be an integer. We claim that $A^{\prime}=A \cup\{a\}$ is good. Indeed, suppose to the contrary that there exist $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and primes $p, q \mid n$ with $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q \in A^{\prime}$. If $n<a$, then $n-p, n-q \in A$, which is a contradiction because $A$ is good. Hence $n \geqslant a$. Now $p \mid n-p$, so $n-p \geqslant p$ since $0 \notin A^{\prime}$. Thus $p \leqslant n / 2$ and hence $n-p \geqslant n / 2 \geqslant a / 2>m$. Similarly, $n-q>m$. It follows that $n-p=n-q=a$, which implies the contradiction $p=q$. Hence $A^{\prime}$ is good.

Now it is clear that any singleton set is good: indeed, if $A=\{a\}$, and $n \in \mathbb{N}$ has prime divisors $p, q$ such that $n-p, n-q \in A$, then $n-p=a=n-q$, so $p=q$. Starting from the singleton $T_{1}=\{2\}$, we use the above construction to obtain, iteratively, good sets $T_{2}, T_{3}, \ldots$ of $2,3, \ldots$ elements. It is clearly possibly to ensure that they are each disjoint from $S$ by not adding a perfect square at any stage. Then $T=T_{1} \cup T_{2} \cup \cdots$ is an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

A subset $A$ of the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}=\{0,1,2, \ldots\}$ is called good if every integer $n>0$ has at most one prime divisor $p$ such that $n-p \in A$.

(a) Show that the set $S=\{0,1,4,9, \ldots\}$ of perfect squares is good.

(b) Find an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

(Two sets are disjoint if they have no common elements.)

#

|

(a) Suppose to the contrary that $S$ is not good, so there exists $n \in \mathbb{N}$ with two different prime factors $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q$ are perfect squares. Write $n-p=m^{2}$, for some $m \in \mathbb{N}$. As $p \mid n$, it follows that $p \mid m$ and hence $p^{2} \mid m^{2}$ since $p$ is prime. Hence there exists $k \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-p=p^{2} k^{2}$. Similarly, there exists $\ell \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $n-q=q^{2} \ell^{2}$. By construction, $n$ is not prime, so $n-p, n-q \neq 0$, whence $k, \ell \geqslant 1$.

Hence $p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q$. Hence $p^{2} k^{2}<p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q<q^{2} \ell^{2}+2 q \ell+1=(q \ell+1)^{2}$. Similarly, $q^{2} \ell^{2}<(p k+1)^{2}$, whence $q \ell-1<p k<q \ell+1$. It follows that $p k=q \ell$, so $p^{2} k^{2}+p=q^{2} \ell^{2}+q$ yields the contradiction $p=q$. Hence $S$ is good.

(b) Let $A$ be a finite good set such that $0 \notin A$, and let $m=\max A$. Let $a \geqslant 2 m+1$ be an integer. We claim that $A^{\prime}=A \cup\{a\}$ is good. Indeed, suppose to the contrary that there exist $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and primes $p, q \mid n$ with $p \neq q$ such that $n-p, n-q \in A^{\prime}$. If $n<a$, then $n-p, n-q \in A$, which is a contradiction because $A$ is good. Hence $n \geqslant a$. Now $p \mid n-p$, so $n-p \geqslant p$ since $0 \notin A^{\prime}$. Thus $p \leqslant n / 2$ and hence $n-p \geqslant n / 2 \geqslant a / 2>m$. Similarly, $n-q>m$. It follows that $n-p=n-q=a$, which implies the contradiction $p=q$. Hence $A^{\prime}$ is good.

Now it is clear that any singleton set is good: indeed, if $A=\{a\}$, and $n \in \mathbb{N}$ has prime divisors $p, q$ such that $n-p, n-q \in A$, then $n-p=a=n-q$, so $p=q$. Starting from the singleton $T_{1}=\{2\}$, we use the above construction to obtain, iteratively, good sets $T_{2}, T_{3}, \ldots$ of $2,3, \ldots$ elements. It is clearly possibly to ensure that they are each disjoint from $S$ by not adding a perfect square at any stage. Then $T=T_{1} \cup T_{2} \cup \cdots$ is an infinite good set disjoint from $S$.

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Problem 4",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2022-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 3",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2022"

}

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that

$$

(x-y)(f(x)+f(y)) \leqslant f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right) \quad \text { for all } x, y \in \mathbb{R}

$$

#

|

Clearly, $f(x)=c x$ is a solution for each $c \in \mathbb{R}$ since $(x-y)(c x+c y)=c\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$. To show that there are no other solutions, we observe that

(1) $x=y: \quad 0 \leqslant f(0)$;

$x=1, y=0: \quad f(0)+f(1) \leqslant f(1) \Rightarrow f(0) \leqslant 0$, whence $f(0)=0 ;$

(2) $y=-x: \quad 2 x(f(x)+f(-x)) \leqslant f(0)=0$;

$x \rightarrow-x: \quad-2 x(f(-x)+f(x)) \leqslant 0 \Rightarrow 2 x(f(x)+f(-x)) \geqslant 0 ;$

thus $2 x(f(x)+f(-x))=0$ for all $x$, so $f(-x)=-f(x)$ for all $x \neq 0$, and hence for all $x$, since $f(0)=0$;

(3) $x \leftrightarrow y: \quad(y-x)(f(y)+f(x)) \leqslant f\left(y^{2}-x^{2}\right)=-f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right) \Rightarrow(x-y)(f(x)+f(y)) \geqslant f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$;

which is the given inequality with the inequality sign reversed, so $(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$ must hold for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$;

(4) $y \leftrightarrow-y: \quad(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)=f\left(x^{2}-(-y)^{2}\right)=(x+y)(f(x)+f(-y))=(x+y)(f(x)-f(y))$; expanding yields $f(x) y=f(y) x$ for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Taking $y=1$ in the last result, $f(x)=f(1) x$, i.e. $f(x)=c x$, where $c=f(1)$, for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. Since we have shown above that, conversely, all such functions are solutions, this completes the proof.

Alternative solution. A slight variation of this argument proves that $(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$ must hold for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$ as above, and then reaches $f(x)=c x$ as follows:

(4) $y= \pm 1: \quad(x \mp 1)(f(x) \pm f(1))=f\left(x^{2}-1\right)$ using $f(-1)=-f(1)$ from (2);

hence $(x-1)(f(x)+f(1))=(x+1)(f(x)-f(1)) \Rightarrow f(x)=f(1) x=c x$, where $c=f(1)$, on expanding.

# BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

f(x)=c x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that

$$

(x-y)(f(x)+f(y)) \leqslant f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right) \quad \text { for all } x, y \in \mathbb{R}

$$

#

|

Clearly, $f(x)=c x$ is a solution for each $c \in \mathbb{R}$ since $(x-y)(c x+c y)=c\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$. To show that there are no other solutions, we observe that

(1) $x=y: \quad 0 \leqslant f(0)$;

$x=1, y=0: \quad f(0)+f(1) \leqslant f(1) \Rightarrow f(0) \leqslant 0$, whence $f(0)=0 ;$

(2) $y=-x: \quad 2 x(f(x)+f(-x)) \leqslant f(0)=0$;

$x \rightarrow-x: \quad-2 x(f(-x)+f(x)) \leqslant 0 \Rightarrow 2 x(f(x)+f(-x)) \geqslant 0 ;$

thus $2 x(f(x)+f(-x))=0$ for all $x$, so $f(-x)=-f(x)$ for all $x \neq 0$, and hence for all $x$, since $f(0)=0$;

(3) $x \leftrightarrow y: \quad(y-x)(f(y)+f(x)) \leqslant f\left(y^{2}-x^{2}\right)=-f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right) \Rightarrow(x-y)(f(x)+f(y)) \geqslant f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$;

which is the given inequality with the inequality sign reversed, so $(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$ must hold for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$;

(4) $y \leftrightarrow-y: \quad(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)=f\left(x^{2}-(-y)^{2}\right)=(x+y)(f(x)+f(-y))=(x+y)(f(x)-f(y))$; expanding yields $f(x) y=f(y) x$ for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Taking $y=1$ in the last result, $f(x)=f(1) x$, i.e. $f(x)=c x$, where $c=f(1)$, for all $x \in \mathbb{R}$. Since we have shown above that, conversely, all such functions are solutions, this completes the proof.

Alternative solution. A slight variation of this argument proves that $(x-y)(f(x)+f(y))=f\left(x^{2}-y^{2}\right)$ must hold for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$ as above, and then reaches $f(x)=c x$ as follows:

(4) $y= \pm 1: \quad(x \mp 1)(f(x) \pm f(1))=f\left(x^{2}-1\right)$ using $f(-1)=-f(1)$ from (2);

hence $(x-1)(f(x)+f(1))=(x+1)(f(x)-f(1)) \Rightarrow f(x)=f(1) x=c x$, where $c=f(1)$, on expanding.

# BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Problem 1",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2023-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Determine all integers $k \geqslant 1$ with the following property: given $k$ different colours, if each integer is coloured in one of these $k$ colours, then there must exist integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{2023}$ of the same colour such that the differences $a_{2}-a_{1}, a_{3}-a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2023}-a_{2022}$ are all powers of 2 .

#

|

We claim that only $k=1$ and $k=2$ satisfy the required property. First, if $k \geqslant 3$, we colour each integer with its residue class modulo 3, so that, whenever two integers have the same colour, their difference is divisible by 3 , so is not a power of 2 . This shows that no $k \geqslant 3$ has the required property.

In the case $k=1$, the sequence defined by $a_{n}=2 n$ for $n=1,2, \ldots, 2023$ clearly has the required property. In the case $k=2$, we call the colours "red" and "blue", and construct, for each $n \geqslant 1$ and by induction, integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}$ of the same colour such that $a_{m+1}-a_{m}$ is a power of 2 for $m=1,2, \ldots, n-1$. The statement is trivial for $n=1$. For $n>1$, let $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}$ be red integers (without loss of generality) having the desired property. Consider the $n+1$ integers $b_{i}=a_{n}+2^{i}$, for $i=1,2, \ldots, n+1$. If one of these, say $b_{j}$, is red, then, as $b_{j}-a_{n}=2^{j}$, the $n+1$ red integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}<b_{j}$ have the desired property. Otherwise, $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{n+1}$ are all blue, and $b_{i+1}-b_{i}=\left(a_{n}+2^{i+1}\right)-\left(a_{n}+2^{i}\right)=2^{i}$ for $i=1,2, \ldots, n$, so the $n+1$ blue integers $b_{1}<b_{2}<\cdots<b_{n+1}$ have the desired property. This completes the inductive step and hence the proof.

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Determine all integers $k \geqslant 1$ with the following property: given $k$ different colours, if each integer is coloured in one of these $k$ colours, then there must exist integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{2023}$ of the same colour such that the differences $a_{2}-a_{1}, a_{3}-a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2023}-a_{2022}$ are all powers of 2 .

#

|

We claim that only $k=1$ and $k=2$ satisfy the required property. First, if $k \geqslant 3$, we colour each integer with its residue class modulo 3, so that, whenever two integers have the same colour, their difference is divisible by 3 , so is not a power of 2 . This shows that no $k \geqslant 3$ has the required property.

In the case $k=1$, the sequence defined by $a_{n}=2 n$ for $n=1,2, \ldots, 2023$ clearly has the required property. In the case $k=2$, we call the colours "red" and "blue", and construct, for each $n \geqslant 1$ and by induction, integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}$ of the same colour such that $a_{m+1}-a_{m}$ is a power of 2 for $m=1,2, \ldots, n-1$. The statement is trivial for $n=1$. For $n>1$, let $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}$ be red integers (without loss of generality) having the desired property. Consider the $n+1$ integers $b_{i}=a_{n}+2^{i}$, for $i=1,2, \ldots, n+1$. If one of these, say $b_{j}$, is red, then, as $b_{j}-a_{n}=2^{j}$, the $n+1$ red integers $a_{1}<a_{2}<\cdots<a_{n}<b_{j}$ have the desired property. Otherwise, $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{n+1}$ are all blue, and $b_{i+1}-b_{i}=\left(a_{n}+2^{i+1}\right)-\left(a_{n}+2^{i}\right)=2^{i}$ for $i=1,2, \ldots, n$, so the $n+1$ blue integers $b_{1}<b_{2}<\cdots<b_{n+1}$ have the desired property. This completes the inductive step and hence the proof.

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Problem 2",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2023-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution\n",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2023"

}

|

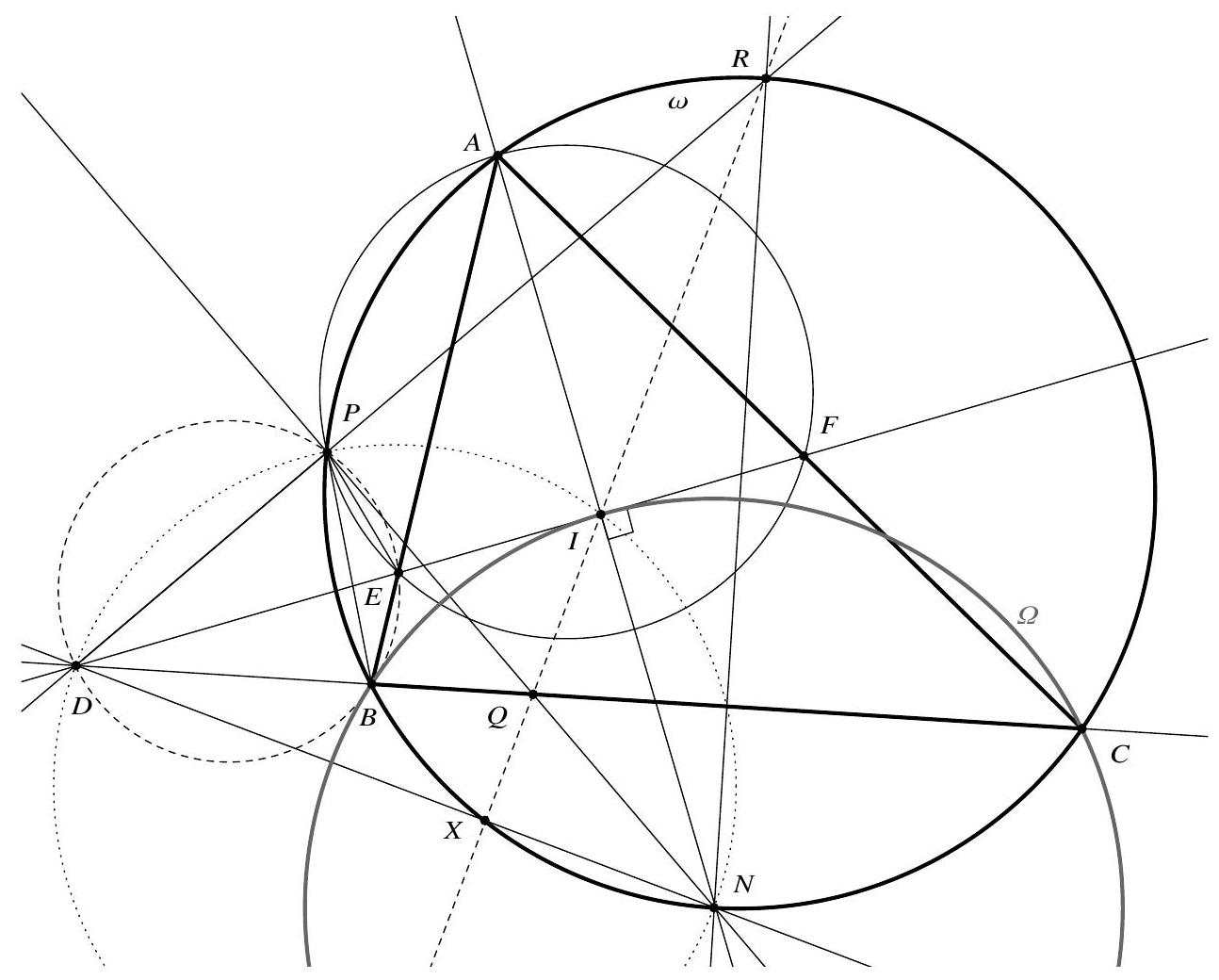

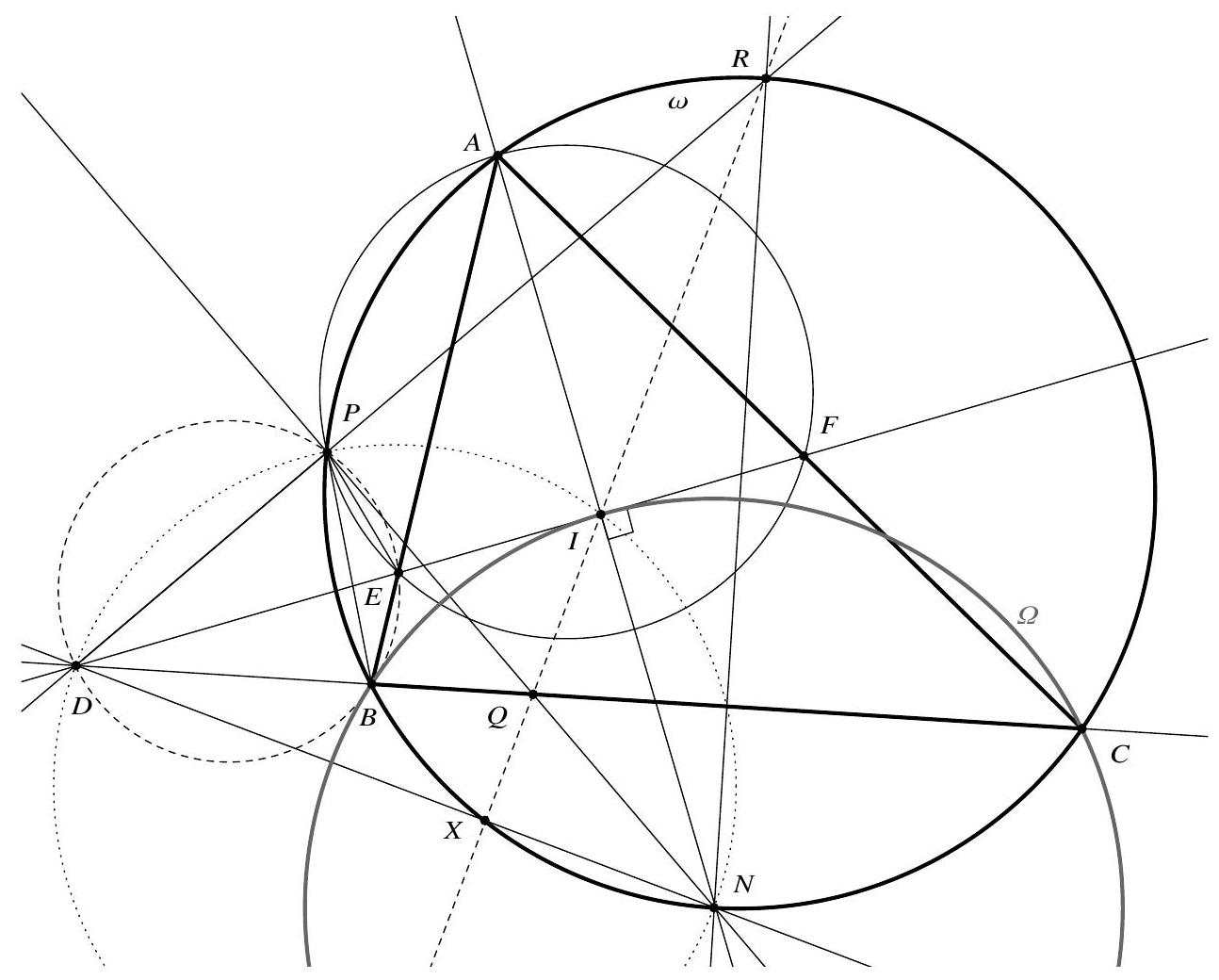

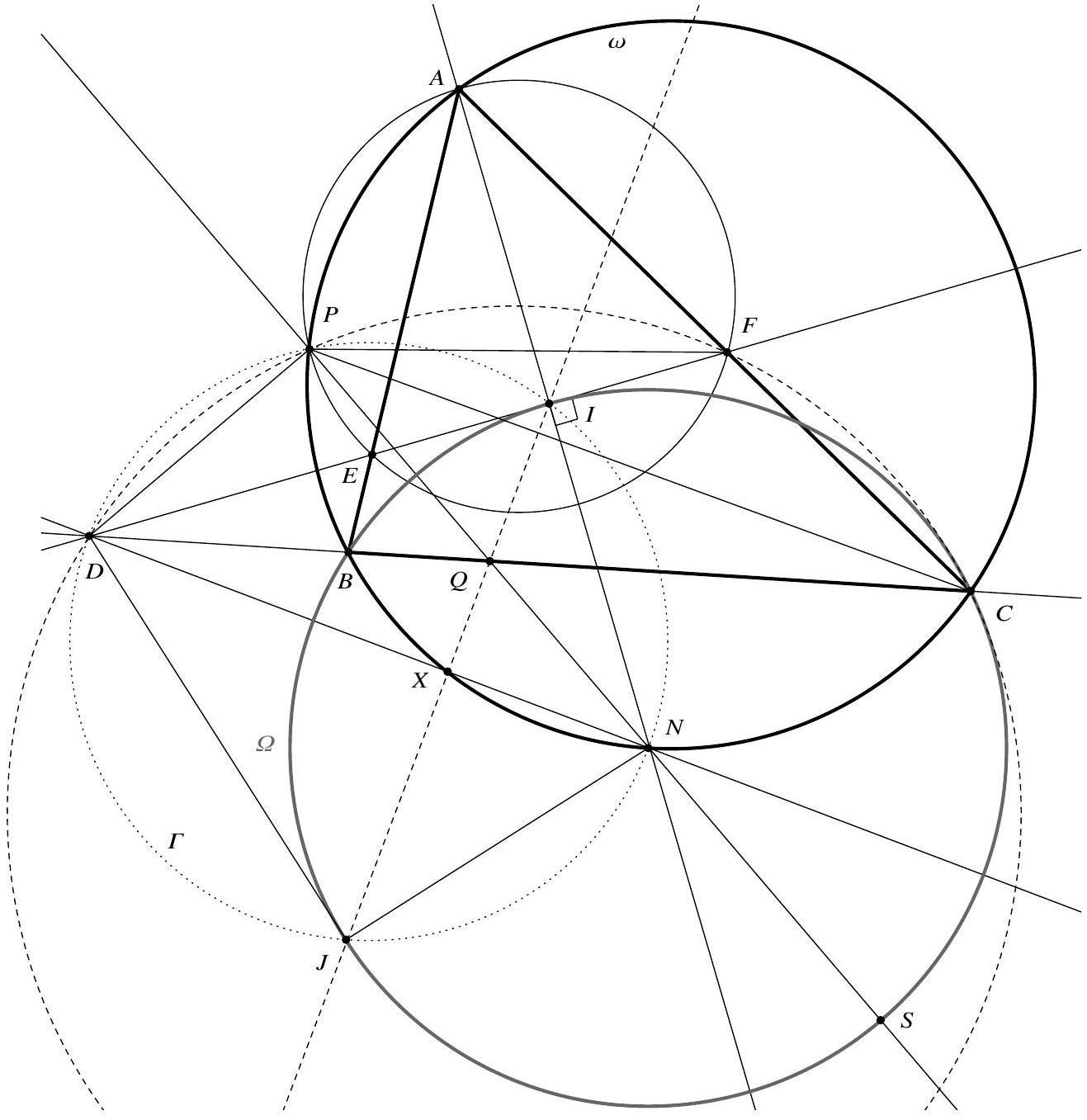

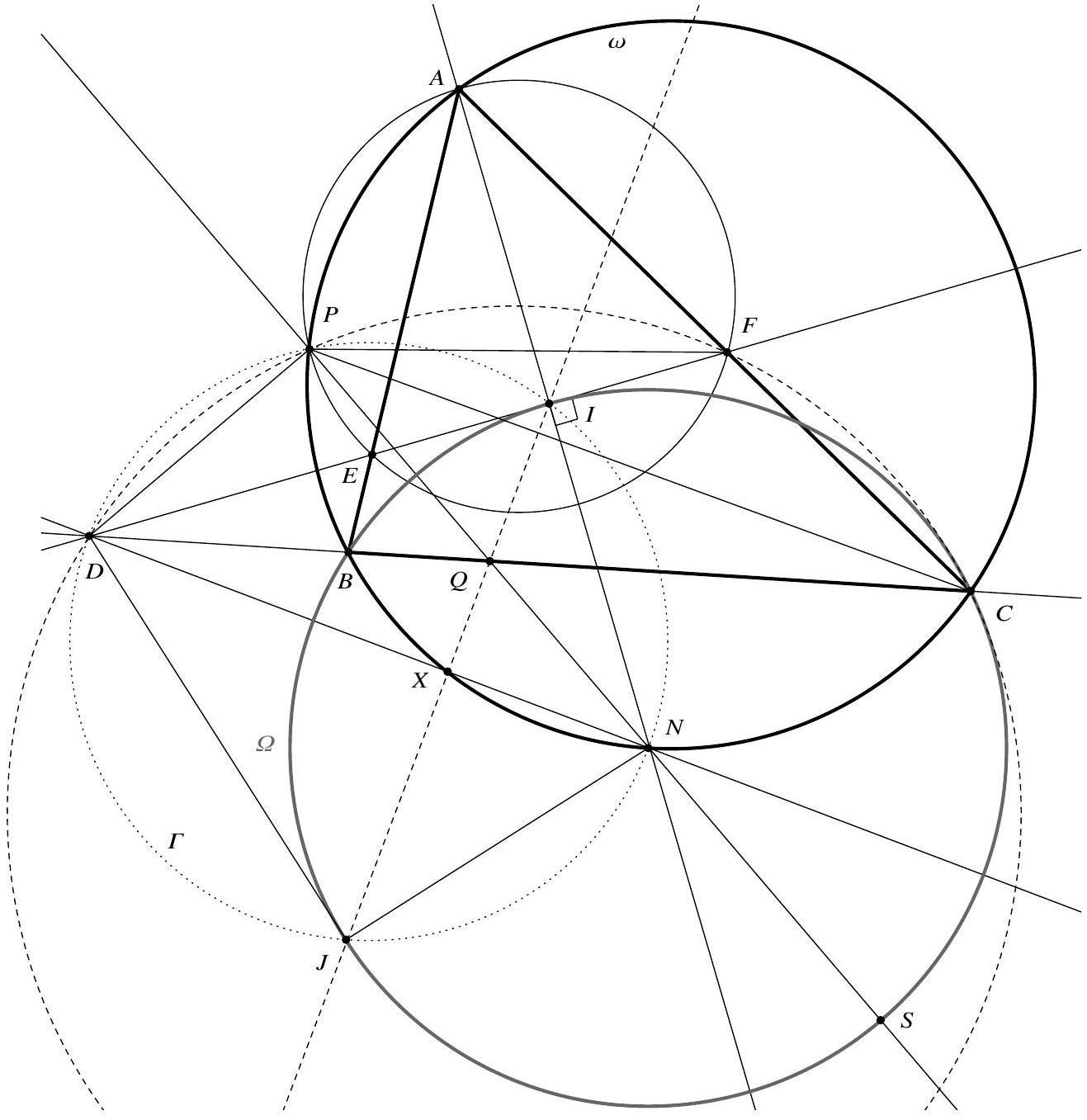

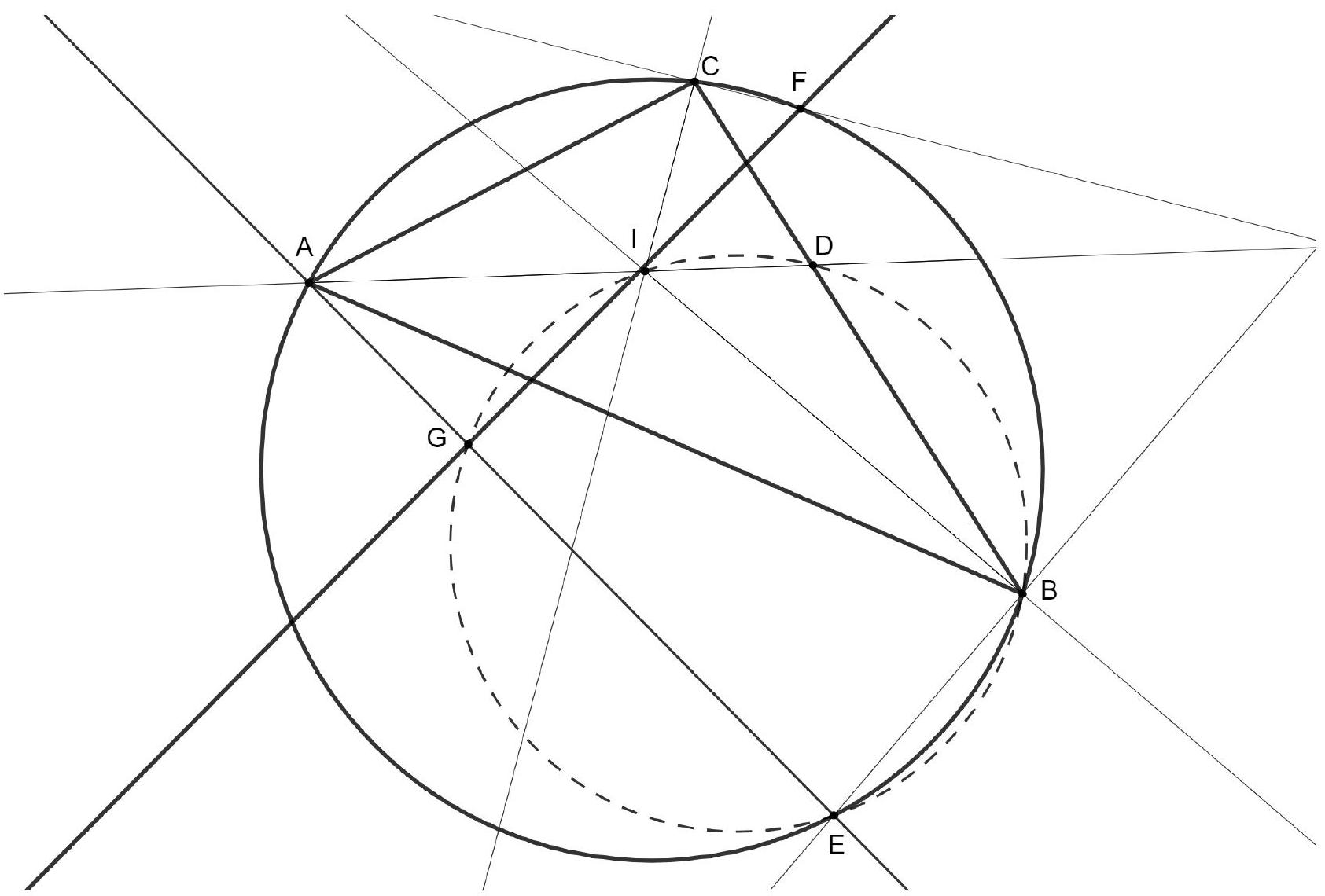

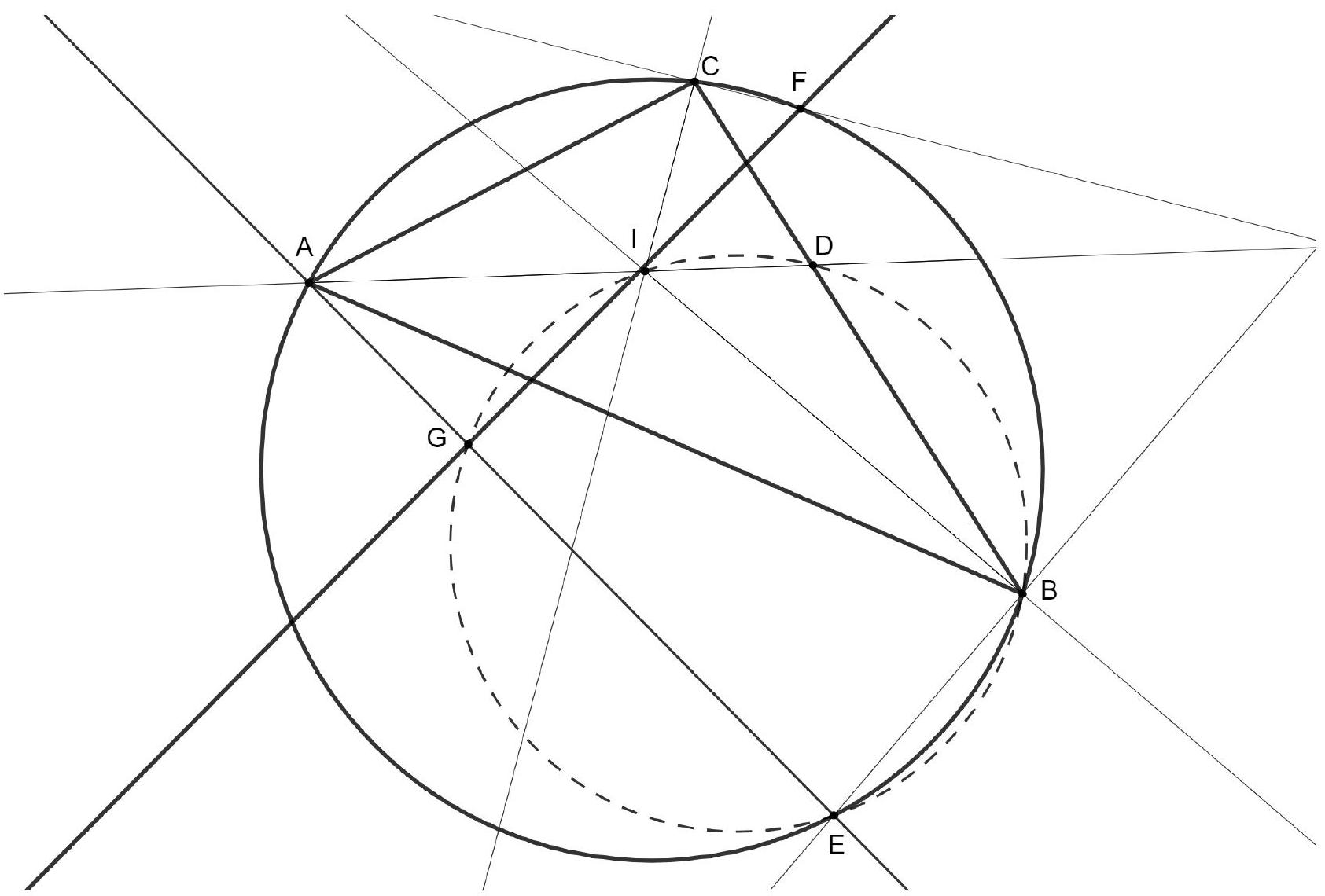

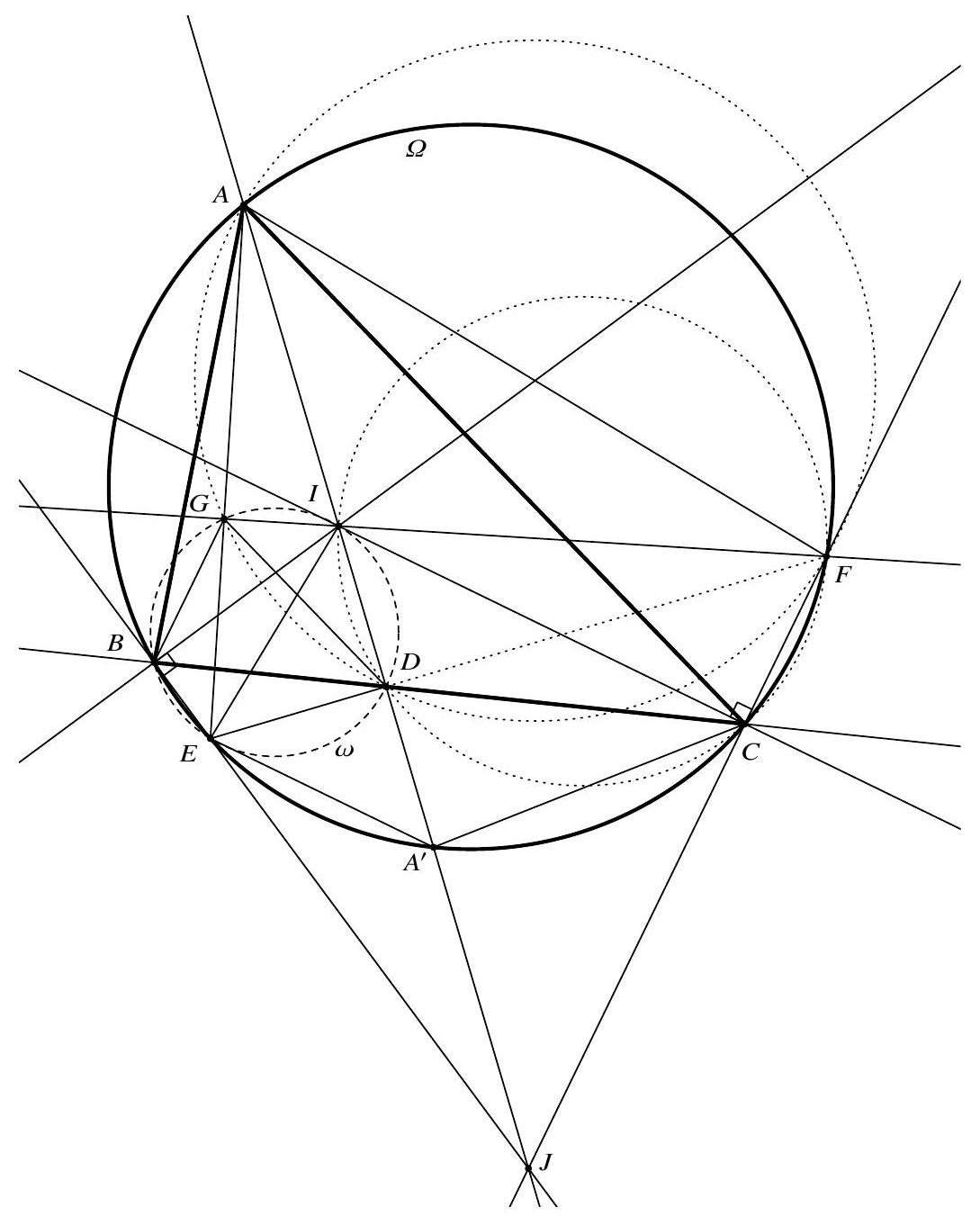

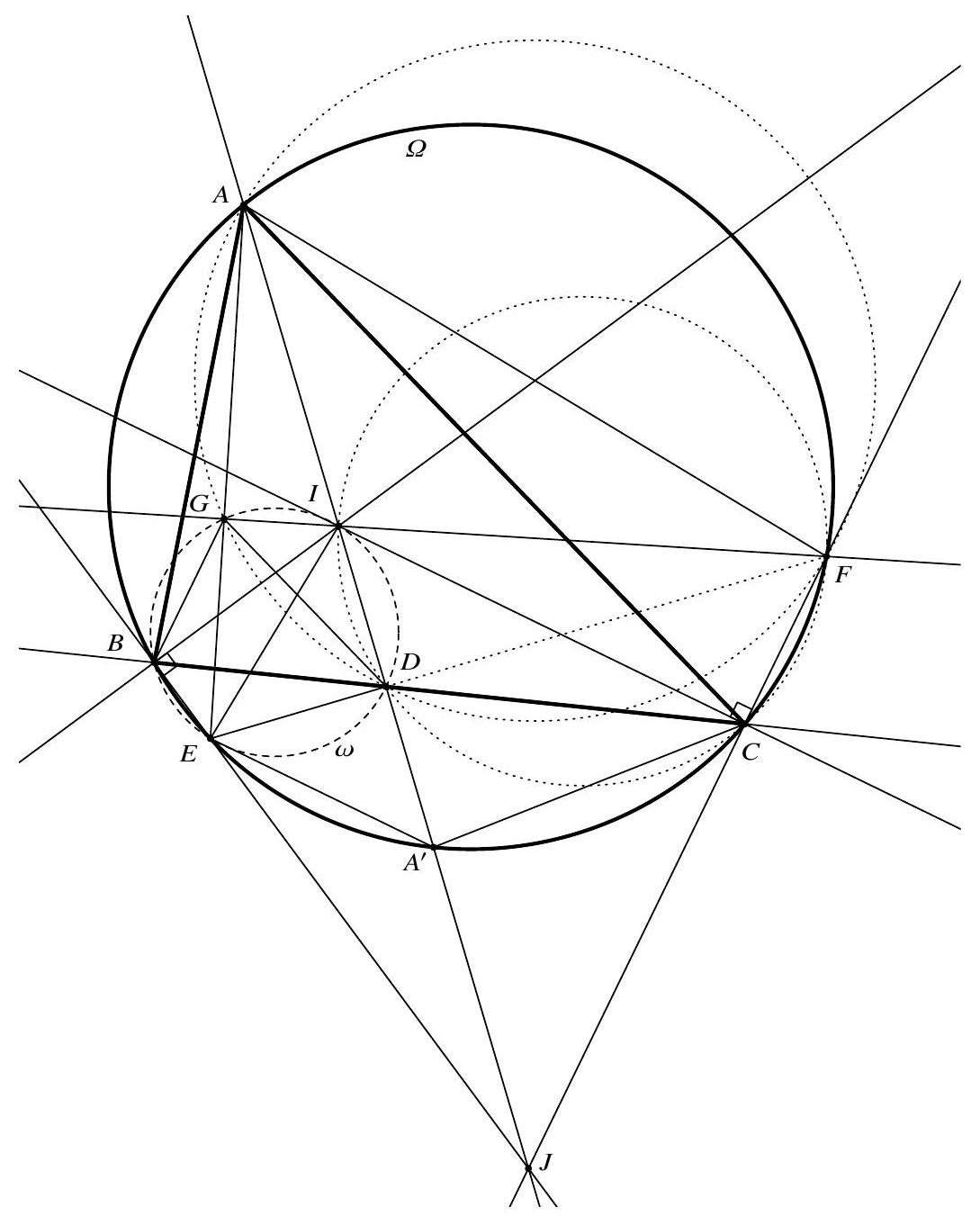

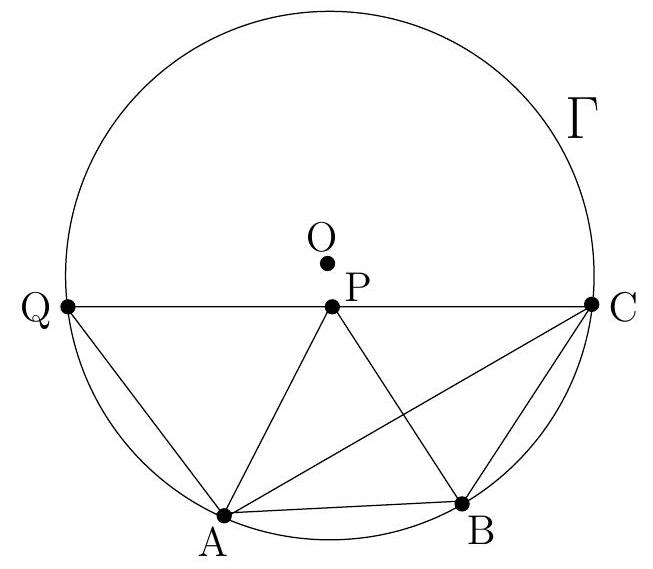

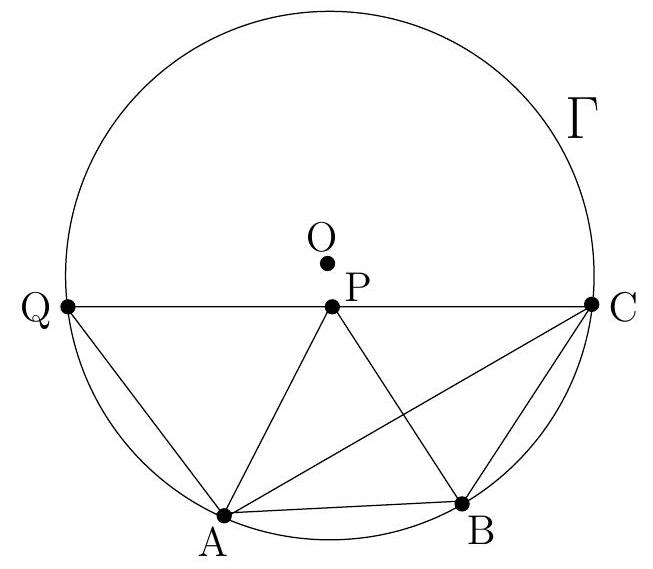

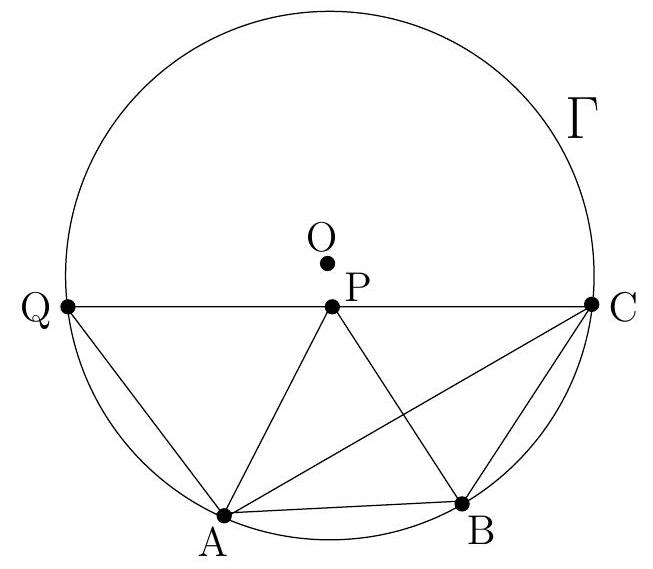

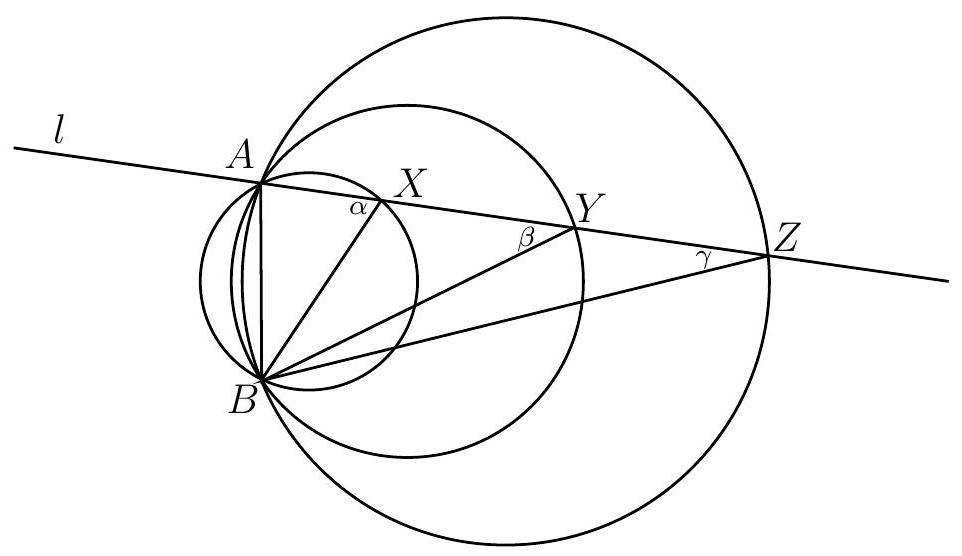

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

By construction, $A P E F$ and $A P B C$ are cyclic, and so

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle B D E & =\angle C D F=\angle A F D-\angle F C D=\angle A F E-\angle A C B=\left(180^{\circ}-\angle E P A\right)-\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B P A\right) \\

& =\angle B P A-\angle E P A=\angle B P E .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $D B E P$ is cyclic, too. It follows that $\angle I D P=\angle E D P=\angle E B P=\angle A B P=\angle A N P=\angle I N P$ since $A P B N$ is cyclic, and so $P D N I$ is also cyclic. In particular, $\angle D P N=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$. Let $R$ denote the second intersection of $D P$ and $\omega$, so $N Q \perp D R$. Then $\angle N P R=90^{\circ}$, so $R N$ is a diameter of $\omega$. It is well-known that $N$ is the midpoint of the arc $\widehat{B C}$ not containing $A$, whence $R N \perp B C$. Thus $D Q$ and $N Q$ are altitudes of triangle $R D N$, and so $Q$ is its orthocentre. This implies that $R Q \perp D N$, whence, since $R N$ is a diameter of $\omega$, the intersection $X$ of $R Q$ and $D N$ lies on $\omega$.

It is also well-known that $N$ is the centre of the circumcircle $\Omega$ of triangle $B C I$. Since $D I \perp I N$ by construction, $D I$ is tangent to $\Omega$ at $I$. As $D$ lies on the radical axis $B C$ of $\omega$ and $\Omega$, it follows that $|D I|^{2}=|D B||D C|=|D X||D N|$. Hence triangles $D N I$ and $D I X$ are similar; in particular, $\angle D X I=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$. All of this shows that $R, I, Q, X$ lie on a line perpendicular to $D N$ that intersects $D N$ at $X \in \omega$. This completes the proof.

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

By construction, $A P E F$ and $A P B C$ are cyclic, and so

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle B D E & =\angle C D F=\angle A F D-\angle F C D=\angle A F E-\angle A C B=\left(180^{\circ}-\angle E P A\right)-\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B P A\right) \\

& =\angle B P A-\angle E P A=\angle B P E .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $D B E P$ is cyclic, too. It follows that $\angle I D P=\angle E D P=\angle E B P=\angle A B P=\angle A N P=\angle I N P$ since $A P B N$ is cyclic, and so $P D N I$ is also cyclic. In particular, $\angle D P N=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$. Let $R$ denote the second intersection of $D P$ and $\omega$, so $N Q \perp D R$. Then $\angle N P R=90^{\circ}$, so $R N$ is a diameter of $\omega$. It is well-known that $N$ is the midpoint of the arc $\widehat{B C}$ not containing $A$, whence $R N \perp B C$. Thus $D Q$ and $N Q$ are altitudes of triangle $R D N$, and so $Q$ is its orthocentre. This implies that $R Q \perp D N$, whence, since $R N$ is a diameter of $\omega$, the intersection $X$ of $R Q$ and $D N$ lies on $\omega$.

It is also well-known that $N$ is the centre of the circumcircle $\Omega$ of triangle $B C I$. Since $D I \perp I N$ by construction, $D I$ is tangent to $\Omega$ at $I$. As $D$ lies on the radical axis $B C$ of $\omega$ and $\Omega$, it follows that $|D I|^{2}=|D B||D C|=|D X||D N|$. Hence triangles $D N I$ and $D I X$ are similar; in particular, $\angle D X I=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$. All of this shows that $R, I, Q, X$ lie on a line perpendicular to $D N$ that intersects $D N$ at $X \in \omega$. This completes the proof.

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2023-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

Let $K$ be the midpoint of segment [BC]. It is well-known that $N$ is the midpoint of the small arc $\widehat{B C}$ of $\omega$, so $B C \perp K N$. In particular, $\angle D K N=90^{\circ}$. But $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$ by construction, so $D I K N$ is cyclic, with circumcircle $\Gamma$. Moreover, $\angle P E F=180^{\circ}-\angle P A F=180^{\circ}-\angle P A B=\angle P B C$ and $\angle P F E=\angle P A E=\angle P A B=\angle P C B$ since $A F E P$ and $A C B P$ are cyclic, so triangles $P E F$ and $P B C$ are similar. Now, by construction, $I$ is the midpoint of segment $[E F]$, so, $K$ being the midpoint of $[B C]$, triangles $P I F$ and $P K C$ are similar, too. It follows that $\angle P I D=180^{\circ}-\angle P I F=180^{\circ}-\angle P K C=\angle P K D$, whence $P$ lies on $\Gamma$.

Let $\Omega$ be the circumcircle of triangle $B C I$. By construction, $Q$ lies on the radical axes $P N$ of $\omega, \Gamma$ and $B C$ of $\omega, \Omega$, so is the radical centre of $\omega, \Gamma, \Omega$. In particular, $I Q$ is the radical axis of $\Gamma, \Omega$, so is perpendicular to the line joining the centres of $\Gamma, \Omega$. Now it is well-known that $N$ is the centre of $\Omega$, and, since $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$, the centre of $\Gamma$ is the midpoint of segment $[D N]$. This shows that $I Q \perp D N$.

Finally, let $D N$ meet $\omega$ again at $X$. Since $D I \perp I N$ by construction and $N$ is the centre of $\Omega, D I$ is tangent to $\Omega$ at $I$. As $D$ lies on the radical axis $B C$ of $\omega, \Omega$, it follows that $|D I|^{2}=|D B||D C|=|D X||D N|$. Hence triangles $D N I$ and $D I X$ are similar; in particular, $\angle D X I=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$, i.e. $I X \perp D N$. Since $I Q \perp D N$, it follows that $X$ is the intersection of $I Q$ and $D N$. Since $X$ lies on $\omega$ by construction, this completes the proof.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

Let $K$ be the midpoint of segment [BC]. It is well-known that $N$ is the midpoint of the small arc $\widehat{B C}$ of $\omega$, so $B C \perp K N$. In particular, $\angle D K N=90^{\circ}$. But $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$ by construction, so $D I K N$ is cyclic, with circumcircle $\Gamma$. Moreover, $\angle P E F=180^{\circ}-\angle P A F=180^{\circ}-\angle P A B=\angle P B C$ and $\angle P F E=\angle P A E=\angle P A B=\angle P C B$ since $A F E P$ and $A C B P$ are cyclic, so triangles $P E F$ and $P B C$ are similar. Now, by construction, $I$ is the midpoint of segment $[E F]$, so, $K$ being the midpoint of $[B C]$, triangles $P I F$ and $P K C$ are similar, too. It follows that $\angle P I D=180^{\circ}-\angle P I F=180^{\circ}-\angle P K C=\angle P K D$, whence $P$ lies on $\Gamma$.

Let $\Omega$ be the circumcircle of triangle $B C I$. By construction, $Q$ lies on the radical axes $P N$ of $\omega, \Gamma$ and $B C$ of $\omega, \Omega$, so is the radical centre of $\omega, \Gamma, \Omega$. In particular, $I Q$ is the radical axis of $\Gamma, \Omega$, so is perpendicular to the line joining the centres of $\Gamma, \Omega$. Now it is well-known that $N$ is the centre of $\Omega$, and, since $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$, the centre of $\Gamma$ is the midpoint of segment $[D N]$. This shows that $I Q \perp D N$.

Finally, let $D N$ meet $\omega$ again at $X$. Since $D I \perp I N$ by construction and $N$ is the centre of $\Omega, D I$ is tangent to $\Omega$ at $I$. As $D$ lies on the radical axis $B C$ of $\omega, \Omega$, it follows that $|D I|^{2}=|D B||D C|=|D X||D N|$. Hence triangles $D N I$ and $D I X$ are similar; in particular, $\angle D X I=\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$, i.e. $I X \perp D N$. Since $I Q \perp D N$, it follows that $X$ is the intersection of $I Q$ and $D N$. Since $X$ lies on $\omega$ by construction, this completes the proof.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Problem 3",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2023-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2023"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

Since $A P E F$ and $A P B C$ are cyclic,

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle C P F & =\angle B P A-\angle B P C-\angle F P A=\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B C A\right)-\angle B A C-\angle F E A \\

& =\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B C A-\angle B A C\right)-\angle B E D=\angle C B A-\angle B E D=\angle C B E-\angle B E D=\angle B D E=\angle C D F,

\end{aligned}

$$

so $D P F C$ is cyclic, too. Thence $\angle C P D=\angle C F D=180^{\circ}-\angle I F A=90^{\circ}+\angle I A F=90^{\circ}+\angle C A N=90^{\circ}+\angle C P N$. Hence $\angle D P N=\angle C P D-\angle C P N=90^{\circ}$. Since $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$ by construction, it follows that DPIN is cyclic, with

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions

circumcircle $\Gamma$. Let $J$ be the second intersection of line $I Q$ and $\Gamma$. Moreover, it is well-known that $N$ is the centre of the circumcircle $\Omega$ of BIC. In particular, $|N I|=|N B|$, and so, since $N I P J$ and $N B P C$ are cyclic,

$$

\frac{|J Q|}{|J P|}=\frac{|N Q|}{|N I|}=\frac{|N Q|}{|N B|}=\frac{|C Q|}{|C P|}

$$

Let $S$ now be the point of intersection of $P N$ and $\Omega$ such that $P, N, S$ lie on line $P N$ in this order. By construction, $\angle Q P C=\angle N P C=\angle N A C=\angle B A N=\angle B C N=\angle Q C N$, so triangles $C Q N$ and $P C N$ are similar, whence

$$

\frac{|C Q|}{|C P|}=\frac{|N C|}{|N P|}=\frac{|N Q|}{|N C|}=\frac{|N C|+|N Q|}{|N C|+|N P|}=\frac{|N S|+|N Q|}{|N S|+|N P|}=\frac{|S Q|}{|S P|}

$$

Combining (1) and (2) shows that $C, J, S$ lie on a circle of Apollonius, the centre of which lies on the line through $P, Q, N, S$, so, since $|N C|=|N S|$ by construction, is $N$. In other words, $J$ lies on $\Omega$.

In particular, $|N I|=|N J|$. Now, by construction, $\angle D I N=\angle D J N=90^{\circ}$, so the right-angled triangles $D I N$ and $D J N$ are congruent, whence $D I N J$ is a kite. In particular, $I J \perp D N$. Since $Q$ lies on $I J$ by definition, this shows that $I Q \perp D N$. We can now conclude as in Solution 2.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with incentre $I$ and circumcircle $\omega$. Let $N$ denote the second point of intersection of line $A I$ and $\omega$. The line through $I$ perpendicular to $A I$ intersects line $B C$, segment $[A B]$, and segment $[A C]$ at the points $D, E$, and $F$, respectively. The circumcircle of triangle $A E F$ meets $\omega$ again at $P$, and lines $P N$ and $B C$ intersect at $Q$. Prove that lines $I Q$ and $D N$ intersect on $\omega$.

#

|

Since $A P E F$ and $A P B C$ are cyclic,

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle C P F & =\angle B P A-\angle B P C-\angle F P A=\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B C A\right)-\angle B A C-\angle F E A \\

& =\left(180^{\circ}-\angle B C A-\angle B A C\right)-\angle B E D=\angle C B A-\angle B E D=\angle C B E-\angle B E D=\angle B D E=\angle C D F,

\end{aligned}

$$

so $D P F C$ is cyclic, too. Thence $\angle C P D=\angle C F D=180^{\circ}-\angle I F A=90^{\circ}+\angle I A F=90^{\circ}+\angle C A N=90^{\circ}+\angle C P N$. Hence $\angle D P N=\angle C P D-\angle C P N=90^{\circ}$. Since $\angle D I N=90^{\circ}$ by construction, it follows that DPIN is cyclic, with

## BxMO 2023: Problems and Solutions