problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

We are given 1999 coins. No two coins have the same weight. A machine is provided which allows us with one operation to determine, for any three coins, which one has the middle weight. Prove that the coin that is the 1000 -th by weight can be determined using no more than 1000000 operations and that this is the only coin whose position by weight can be determined using this machine.

|

It is possible to find the 1000 -th coin (i.e. the medium one among the 1999 coins). First we exclude the lightest and heaviest coin - for this we use 1997 weighings, putting the medium-weighted coin aside each time. Next we exclude the 2 -nd and 1998 -th coins using 1995 weighings, etc. In total we need

$$

1997+1995+1993+\ldots+3+1=999 \cdot 999<1000000

$$

weighings to determine the 1000 -th coin in such a way.

It is not possible to determine the position by weight of any other coin, since we cannot distinguish between the $k$-th and $(2000-k)$-th coin. To prove this, label the coins in some order as $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{1999}$. If a procedure for finding the $k$-th coin exists then it should work as follows. First we choose some three coins $a_{i_{1}}, a_{j_{1}}, a_{k_{1}}$, find the medium-weighted one among them, then choose again some three coins $a_{i_{2}}, a_{j_{2}}, a_{k_{2}}$ (possibly using the information obtained from the previous weighing) etc. The results of these

weighings can be written in a table like this:

| Coin 1 | Coin 2 | Coin 3 | Medium |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| $a_{i_{1}}$ | $a_{j_{1}}$ | $a_{k_{1}}$ | $a_{m_{1}}$ |

| $a_{i_{2}}$ | $a_{j_{2}}$ | $a_{k_{2}}$ | $a_{m_{2}}$ |

| $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ |

| $a_{i_{n}}$ | $a_{j_{n}}$ | $a_{k_{n}}$ | $a_{m_{n}}$ |

Suppose we make a decision " $a_{k}$ is the $k$-th coin" based on this table. Now let us exchange labels of the lightest and the heaviest coins, of the 2-nd and 1998 -th (by weight) coins etc. It is easy to see that, after this relabeling, each step in the procedure above gives the same result as before - but if $a_{k}$ was previously the $k$-th coin by weight, then now it is the $(2000-k)$-th coin, so the procedure yields a wrong coin which gives us the contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

We are given 1999 coins. No two coins have the same weight. A machine is provided which allows us with one operation to determine, for any three coins, which one has the middle weight. Prove that the coin that is the 1000 -th by weight can be determined using no more than 1000000 operations and that this is the only coin whose position by weight can be determined using this machine.

|

It is possible to find the 1000 -th coin (i.e. the medium one among the 1999 coins). First we exclude the lightest and heaviest coin - for this we use 1997 weighings, putting the medium-weighted coin aside each time. Next we exclude the 2 -nd and 1998 -th coins using 1995 weighings, etc. In total we need

$$

1997+1995+1993+\ldots+3+1=999 \cdot 999<1000000

$$

weighings to determine the 1000 -th coin in such a way.

It is not possible to determine the position by weight of any other coin, since we cannot distinguish between the $k$-th and $(2000-k)$-th coin. To prove this, label the coins in some order as $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{1999}$. If a procedure for finding the $k$-th coin exists then it should work as follows. First we choose some three coins $a_{i_{1}}, a_{j_{1}}, a_{k_{1}}$, find the medium-weighted one among them, then choose again some three coins $a_{i_{2}}, a_{j_{2}}, a_{k_{2}}$ (possibly using the information obtained from the previous weighing) etc. The results of these

weighings can be written in a table like this:

| Coin 1 | Coin 2 | Coin 3 | Medium |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| $a_{i_{1}}$ | $a_{j_{1}}$ | $a_{k_{1}}$ | $a_{m_{1}}$ |

| $a_{i_{2}}$ | $a_{j_{2}}$ | $a_{k_{2}}$ | $a_{m_{2}}$ |

| $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ | $\ldots$ |

| $a_{i_{n}}$ | $a_{j_{n}}$ | $a_{k_{n}}$ | $a_{m_{n}}$ |

Suppose we make a decision " $a_{k}$ is the $k$-th coin" based on this table. Now let us exchange labels of the lightest and the heaviest coins, of the 2-nd and 1998 -th (by weight) coins etc. It is easy to see that, after this relabeling, each step in the procedure above gives the same result as before - but if $a_{k}$ was previously the $k$-th coin by weight, then now it is the $(2000-k)$-th coin, so the procedure yields a wrong coin which gives us the contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\n8.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n8.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

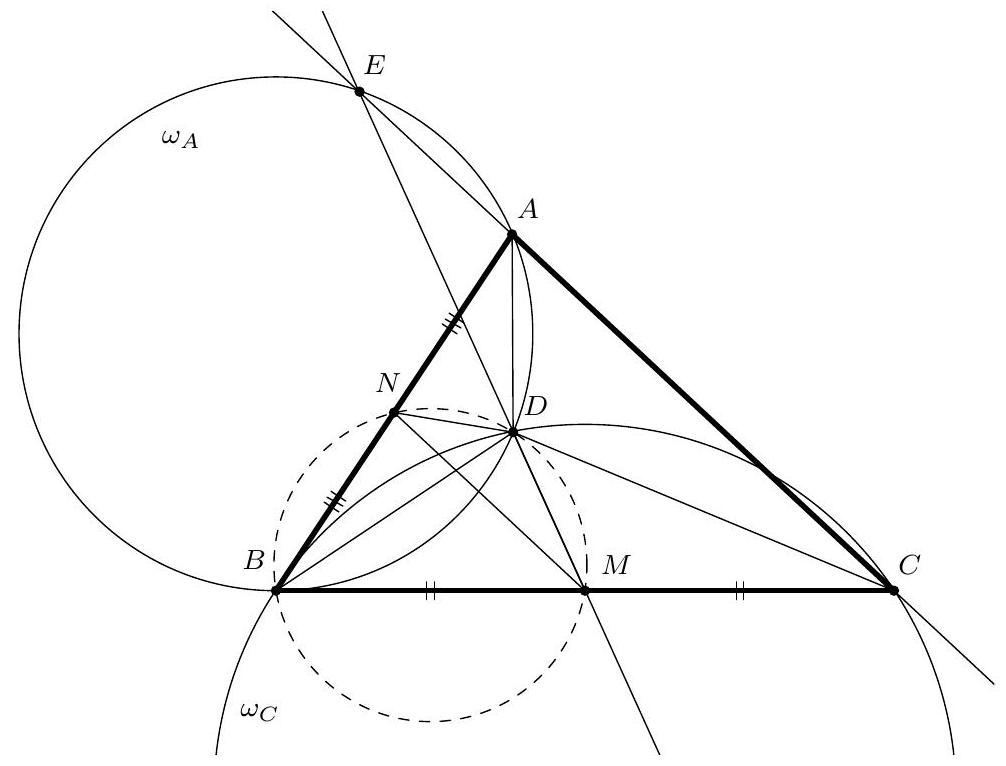

A cube with edge length 3 is divided into 27 unit cubes. The numbers $1,2, \ldots, 27$ are distributed arbitrarily over the unit cubes, with one number in each cube. We form the 27 possible row sums (there are nine such sums of three integers for each of the three directions parallel to the edges of the cube). At most how many of the 27 row sums can be odd?

|

Answer: 24.

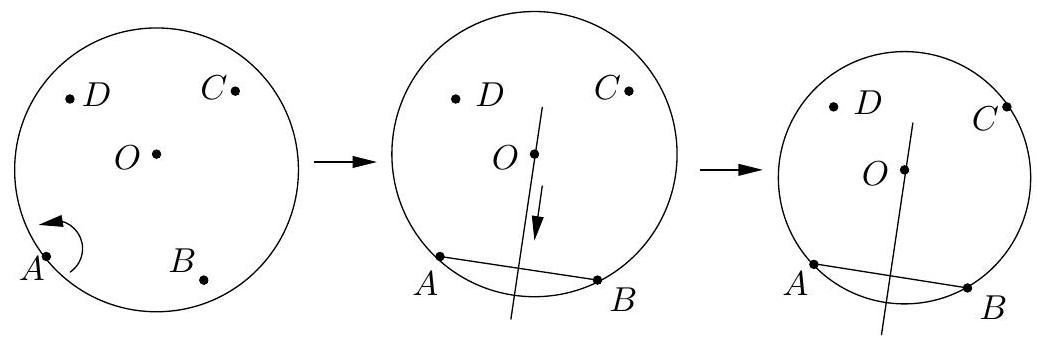

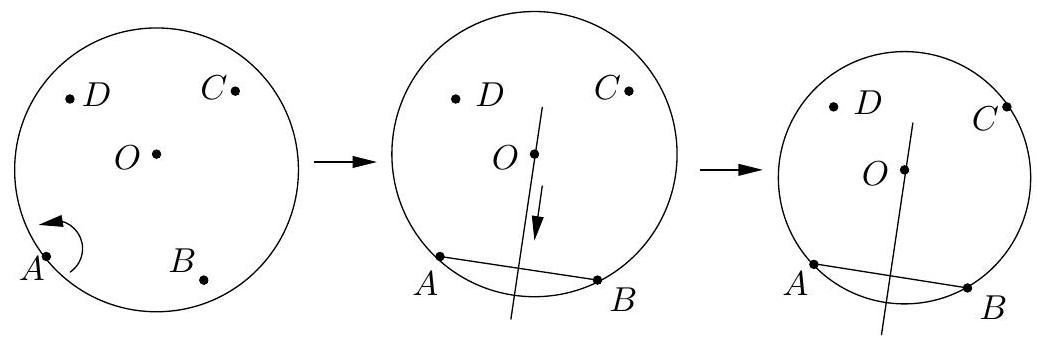

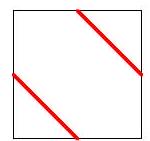

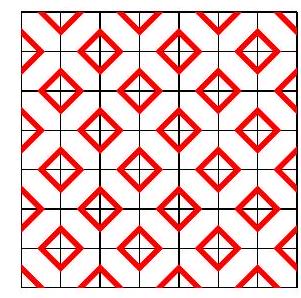

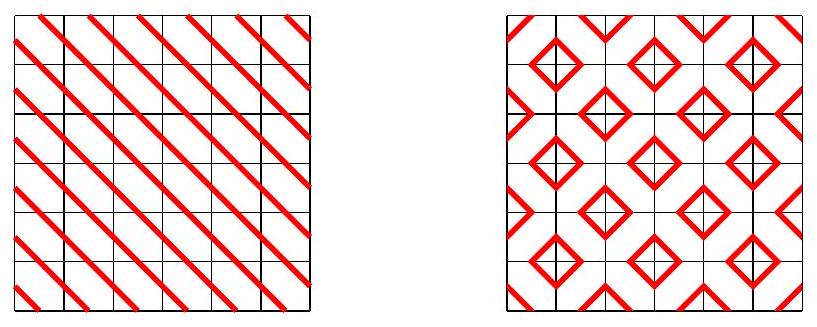

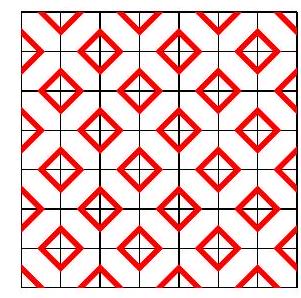

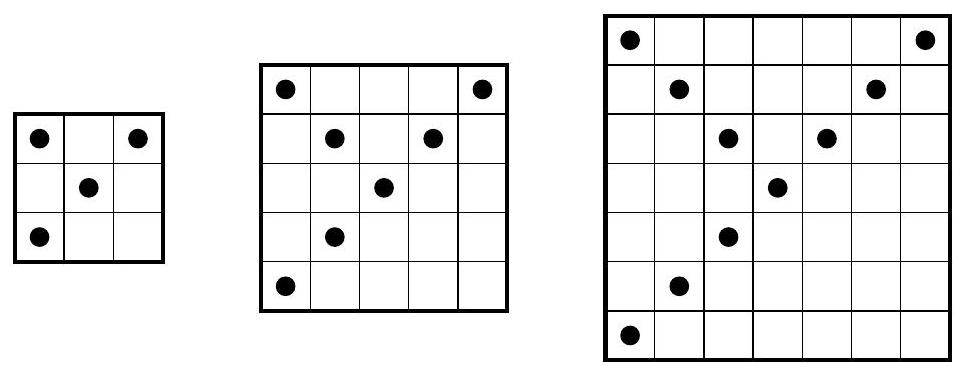

Since each unit cube contributes to exactly three of the row sums, then the total of all the 27 row sums is $3 \cdot(1+2+\ldots+27)=3 \cdot 14 \cdot 27$, which is even. Hence there must be an even number of odd row sums.

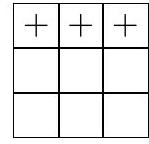

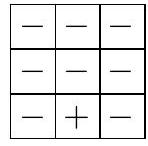

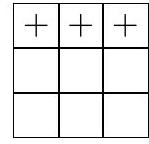

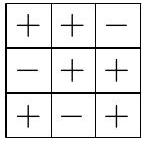

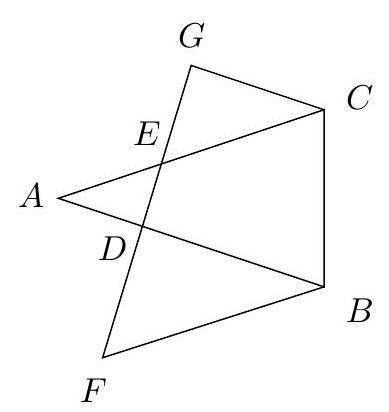

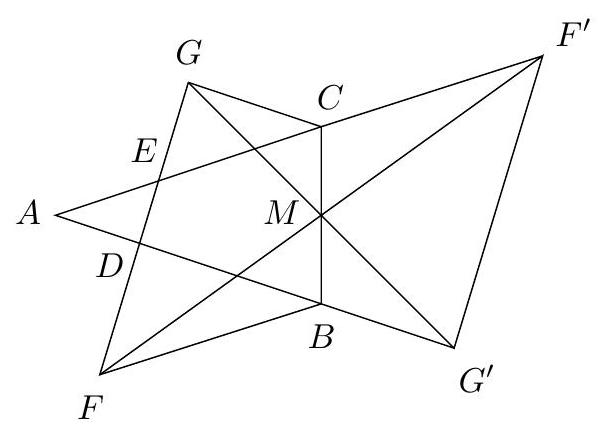

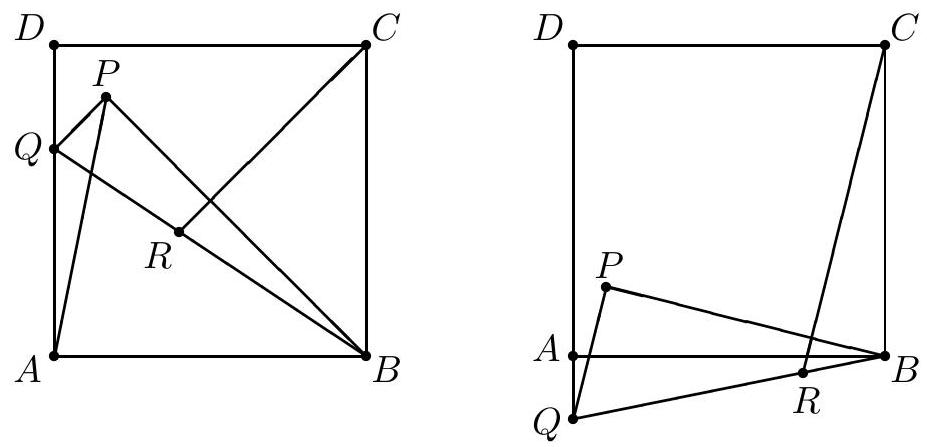

(a)

(b)

I

II

III

Figure 2

Figure 3

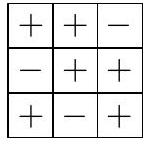

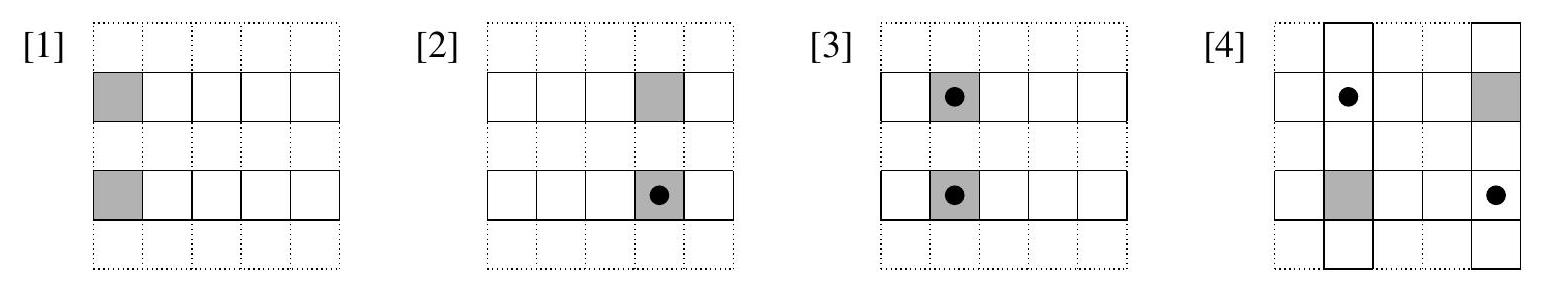

We shall prove that if one of the three levels of the cube (in any given direction) contains an even row sum, then there is another even row sum within that same level - hence there cannot be 26 odd row sums. Indeed, if this even row sum is formed by three even numbers (case (a) on Figure 2, where + denotes an even number and - denotes an odd number), then in order not to have even column sums (i.e. row sums in the perpendicular direction), we must have another even number in each of the three columns. But then the two remaining rows contain three even and three odd numbers, and hence their row sums cannot both be odd. Consider now the other case when the even row sum is formed by one even number and two odd numbers (case (b) on Figure 2). In order not to have even column sums, the column

containing the even number must contain another even number and an odd number, and each of the other two columns must have two numbers of the same parity. Hence the two other row sums have different parity, and one of them must be even.

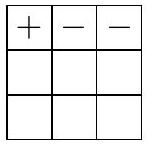

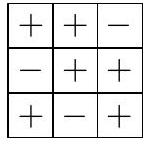

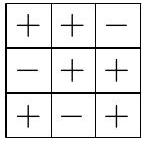

It remains to notice that we can achieve 24 odd row sums (see Figure 3, where the three levels of the cube are shown).

|

24

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A cube with edge length 3 is divided into 27 unit cubes. The numbers $1,2, \ldots, 27$ are distributed arbitrarily over the unit cubes, with one number in each cube. We form the 27 possible row sums (there are nine such sums of three integers for each of the three directions parallel to the edges of the cube). At most how many of the 27 row sums can be odd?

|

Answer: 24.

Since each unit cube contributes to exactly three of the row sums, then the total of all the 27 row sums is $3 \cdot(1+2+\ldots+27)=3 \cdot 14 \cdot 27$, which is even. Hence there must be an even number of odd row sums.

(a)

(b)

I

II

III

Figure 2

Figure 3

We shall prove that if one of the three levels of the cube (in any given direction) contains an even row sum, then there is another even row sum within that same level - hence there cannot be 26 odd row sums. Indeed, if this even row sum is formed by three even numbers (case (a) on Figure 2, where + denotes an even number and - denotes an odd number), then in order not to have even column sums (i.e. row sums in the perpendicular direction), we must have another even number in each of the three columns. But then the two remaining rows contain three even and three odd numbers, and hence their row sums cannot both be odd. Consider now the other case when the even row sum is formed by one even number and two odd numbers (case (b) on Figure 2). In order not to have even column sums, the column

containing the even number must contain another even number and an odd number, and each of the other two columns must have two numbers of the same parity. Hence the two other row sums have different parity, and one of them must be even.

It remains to notice that we can achieve 24 odd row sums (see Figure 3, where the three levels of the cube are shown).

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\n9.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n9.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Can the points of a disc of radius 1 (including its circumference) be partitioned into three subsets in such a way that no subset contains two points separated by distance 1 ?

|

Answer: no.

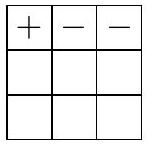

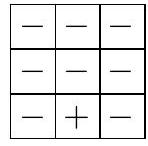

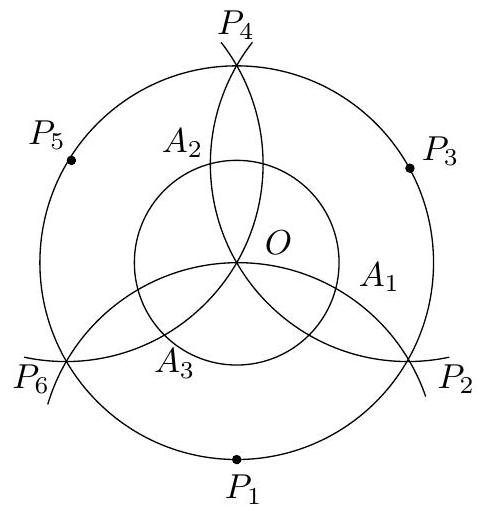

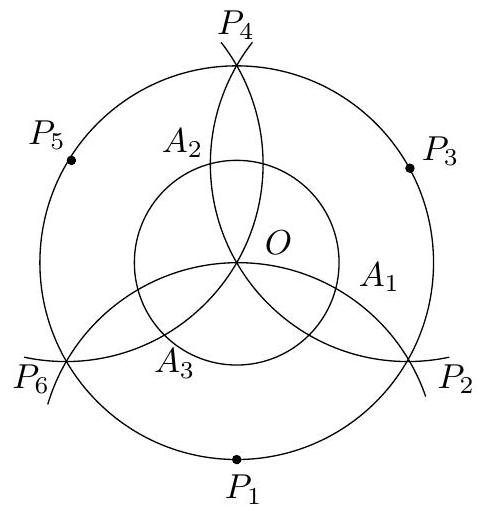

Let $O$ denote the centre of the disc, and $P_{1}, \ldots, P_{6}$ the vertices of an inscribed regular hexagon in the natural order (see Figure 4).

If the required partitioning exists, then $\{O\},\left\{P_{1}, P_{3}, P_{5}\right\}$ and $\left\{P_{2}, P_{4}, P_{6}\right\}$ are contained in different subsets. Now consider the circles of radius 1 centered in $P_{1}, P_{3}$ and $P_{5}$. The circle of radius $1 / \sqrt{3}$ centered in $O$ intersects these three circles in the vertices $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3}$ of an equilateral triangle of side length 1 . The vertices of this triangle belong to different subsets, but none of them can belong to the same subset as $P_{1}$ - a contradiction. Hence the required partitioning does not exist.

Figure 4

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Can the points of a disc of radius 1 (including its circumference) be partitioned into three subsets in such a way that no subset contains two points separated by distance 1 ?

|

Answer: no.

Let $O$ denote the centre of the disc, and $P_{1}, \ldots, P_{6}$ the vertices of an inscribed regular hexagon in the natural order (see Figure 4).

If the required partitioning exists, then $\{O\},\left\{P_{1}, P_{3}, P_{5}\right\}$ and $\left\{P_{2}, P_{4}, P_{6}\right\}$ are contained in different subsets. Now consider the circles of radius 1 centered in $P_{1}, P_{3}$ and $P_{5}$. The circle of radius $1 / \sqrt{3}$ centered in $O$ intersects these three circles in the vertices $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3}$ of an equilateral triangle of side length 1 . The vertices of this triangle belong to different subsets, but none of them can belong to the same subset as $P_{1}$ - a contradiction. Hence the required partitioning does not exist.

Figure 4

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\n10.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n10.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

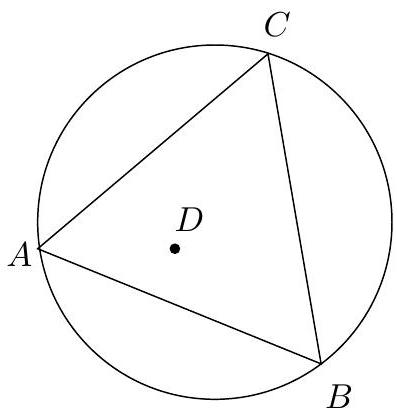

Prove that for any four points in the plane, no three of which are collinear, there exists a circle such that three of the four points are on the circumference and the fourth point is either on the circumference or inside the circle.

|

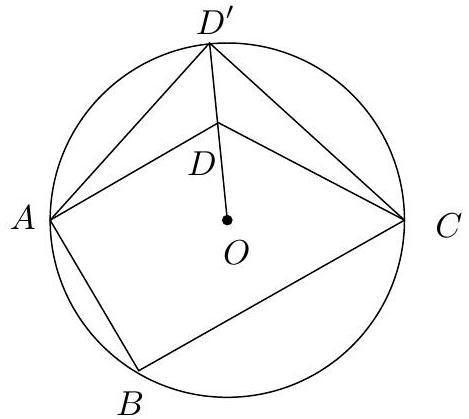

Consider a circle containing all these four points in its interior. First, decrease its radius until at least one of these points (say, $A$ ) will be on the circle. If the other three points are still in the interior of the circle, then rotate the circle around $A$ (with its radius unchanged) until at least one of the other three points (say, $B$ ) will also be on the circle. The centre of the circle now lies on the perpendicular bisector of the segment $A B$ - moving

the centre along that perpendicular bisector (and changing its radius at the same time, so that points $A$ and $B$ remain on the circle) we arrive at a situation where at least one of the remaining two points will also be on the circle (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

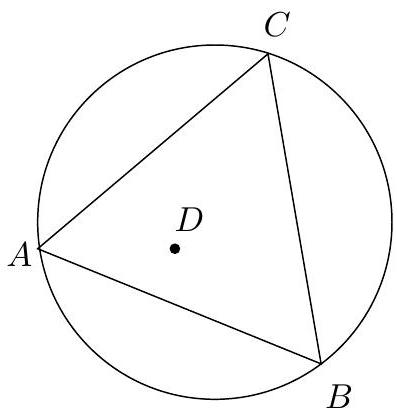

Alternative solution. The quadrangle with its vertices in the four points can be convex or non-convex.

If the quadrangle is non-convex, then one of the points lies in the interior of the triangle defined by the remaining three points (see Figure 6) - the circumcircle of that triangle has the required property.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Assume now that the quadrangle $A B C D$ (where $A, B, C, D$ are the four points) is convex. Then it has a pair of opposite angles, the sum of which is at least $180^{\circ}$ - assume these are at vertices $B$ and $D$ (see Figure 7). We shall prove that point $D$ lies either in the interior of the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ or on that circle. Indeed, let the ray drawn from the

circumcentre $O$ of triangle $A B C$ through point $D$ intersect the circumcircle in $D^{\prime}$ : since $\angle B+\angle D^{\prime}=180^{\circ}$ and $\angle B+\angle D \geqslant 180^{\circ}$, then $D$ cannot lie in the exterior of the circumcircle.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Prove that for any four points in the plane, no three of which are collinear, there exists a circle such that three of the four points are on the circumference and the fourth point is either on the circumference or inside the circle.

|

Consider a circle containing all these four points in its interior. First, decrease its radius until at least one of these points (say, $A$ ) will be on the circle. If the other three points are still in the interior of the circle, then rotate the circle around $A$ (with its radius unchanged) until at least one of the other three points (say, $B$ ) will also be on the circle. The centre of the circle now lies on the perpendicular bisector of the segment $A B$ - moving

the centre along that perpendicular bisector (and changing its radius at the same time, so that points $A$ and $B$ remain on the circle) we arrive at a situation where at least one of the remaining two points will also be on the circle (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Alternative solution. The quadrangle with its vertices in the four points can be convex or non-convex.

If the quadrangle is non-convex, then one of the points lies in the interior of the triangle defined by the remaining three points (see Figure 6) - the circumcircle of that triangle has the required property.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Assume now that the quadrangle $A B C D$ (where $A, B, C, D$ are the four points) is convex. Then it has a pair of opposite angles, the sum of which is at least $180^{\circ}$ - assume these are at vertices $B$ and $D$ (see Figure 7). We shall prove that point $D$ lies either in the interior of the circumcircle of triangle $A B C$ or on that circle. Indeed, let the ray drawn from the

circumcentre $O$ of triangle $A B C$ through point $D$ intersect the circumcircle in $D^{\prime}$ : since $\angle B+\angle D^{\prime}=180^{\circ}$ and $\angle B+\angle D \geqslant 180^{\circ}$, then $D$ cannot lie in the exterior of the circumcircle.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\n11.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n11.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

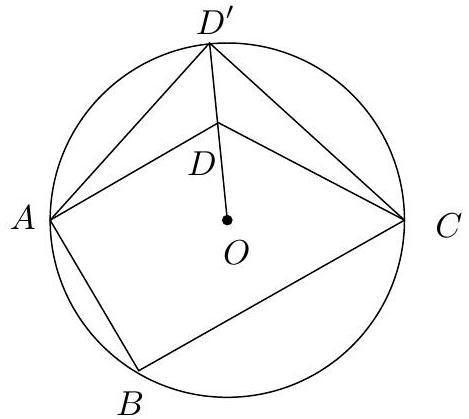

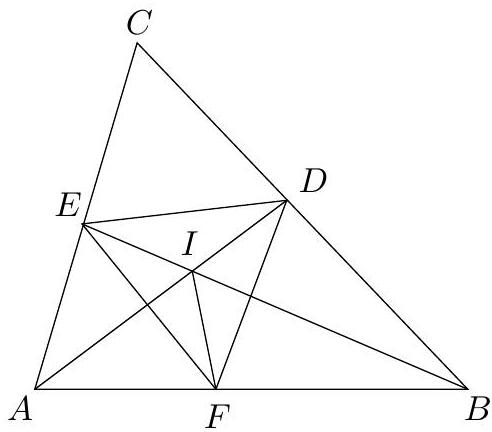

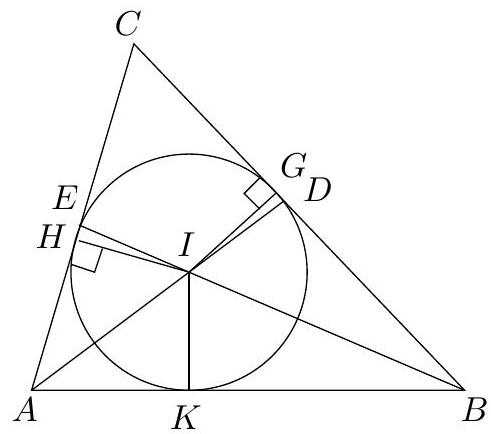

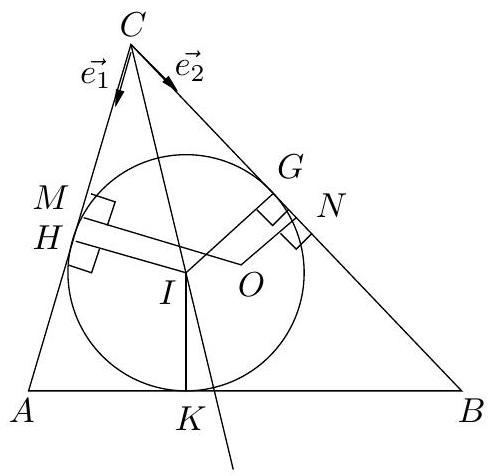

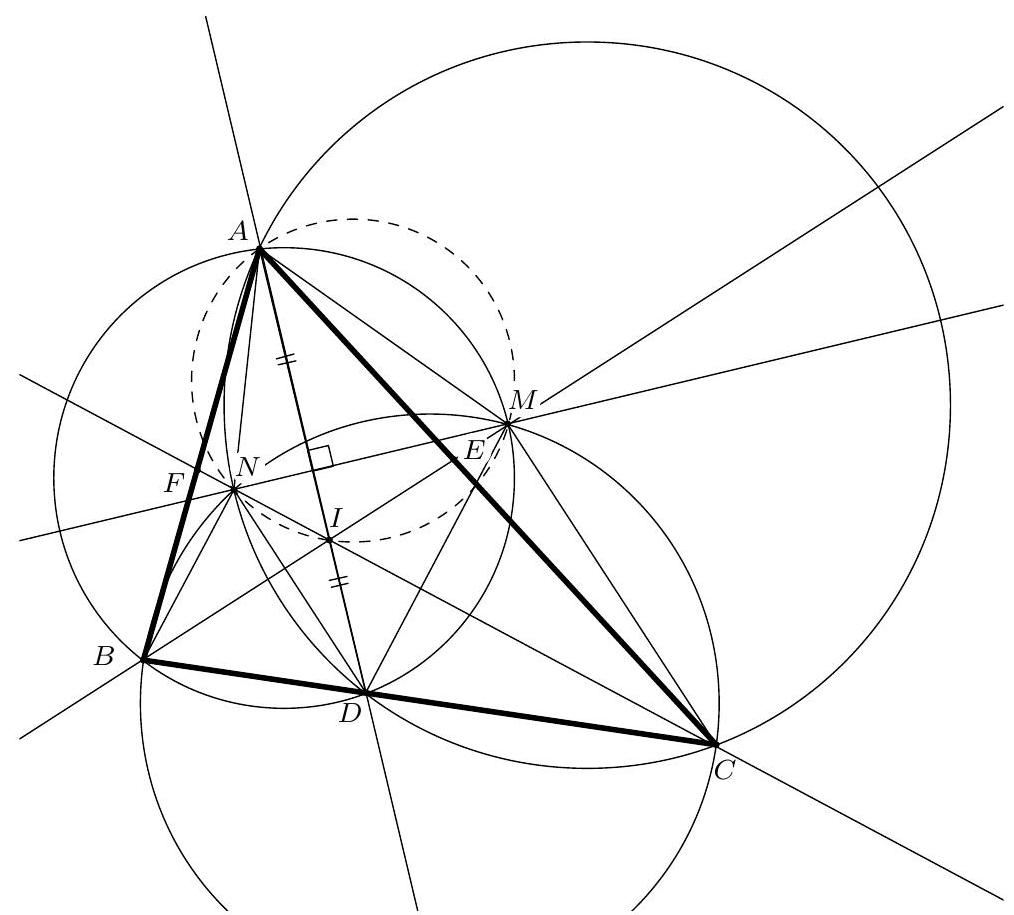

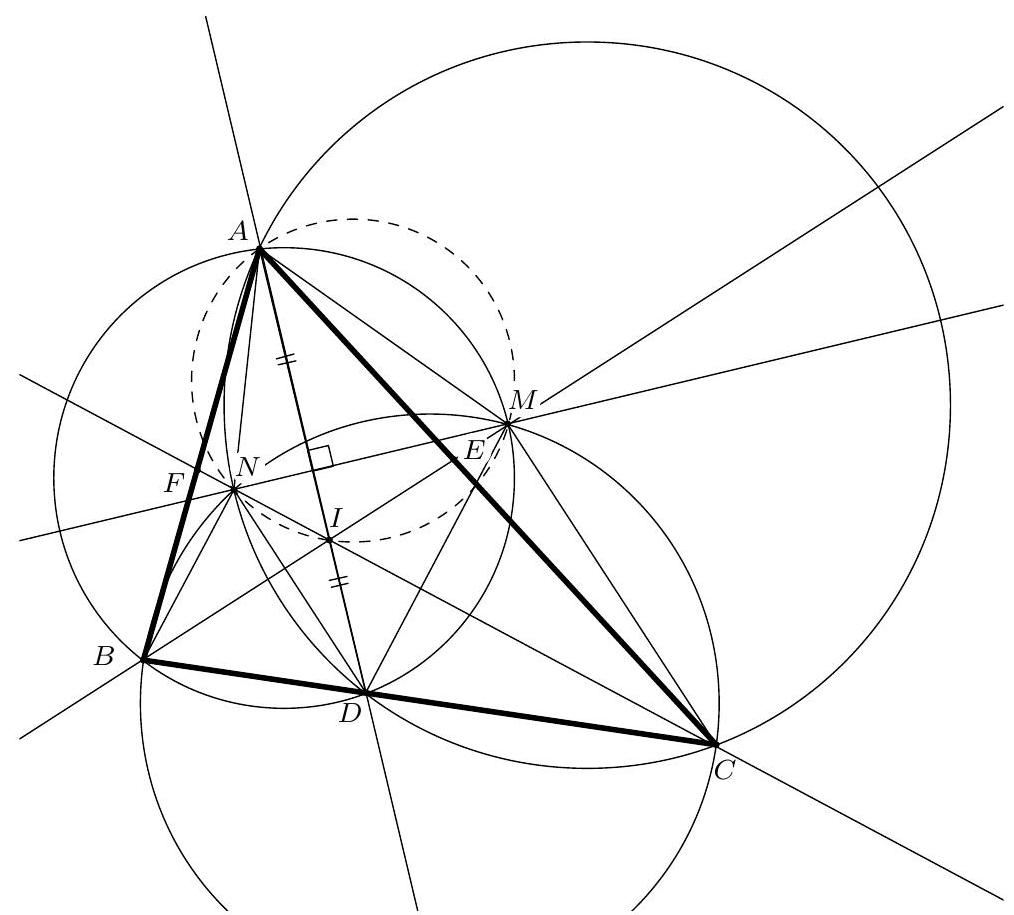

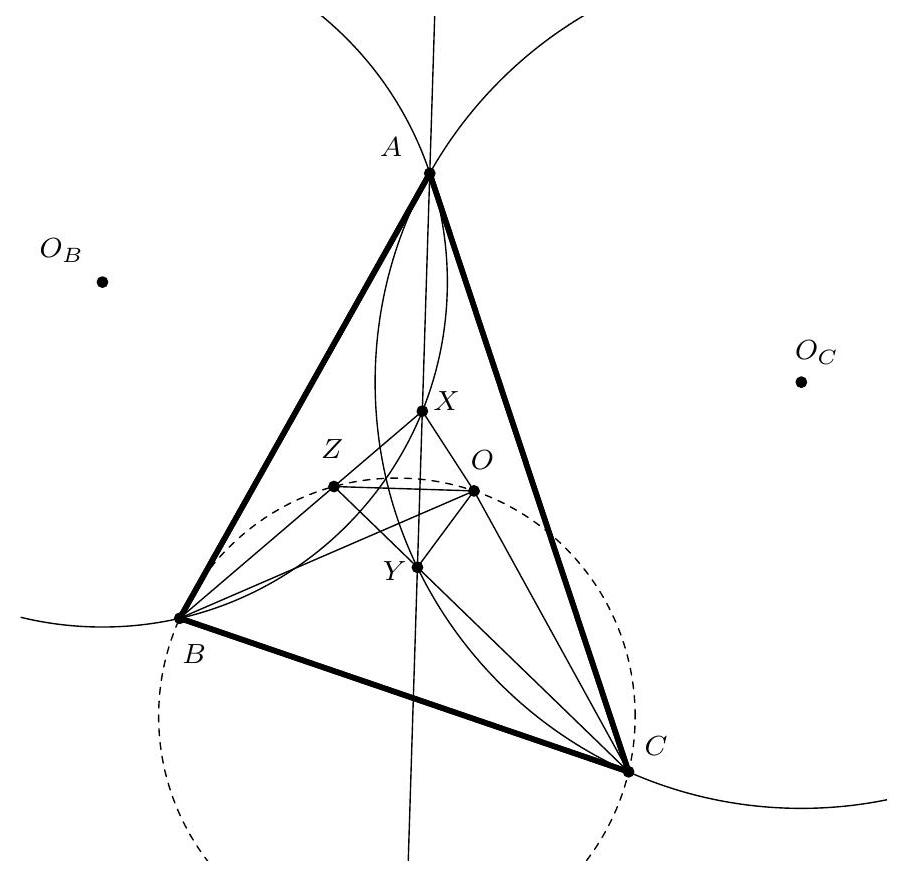

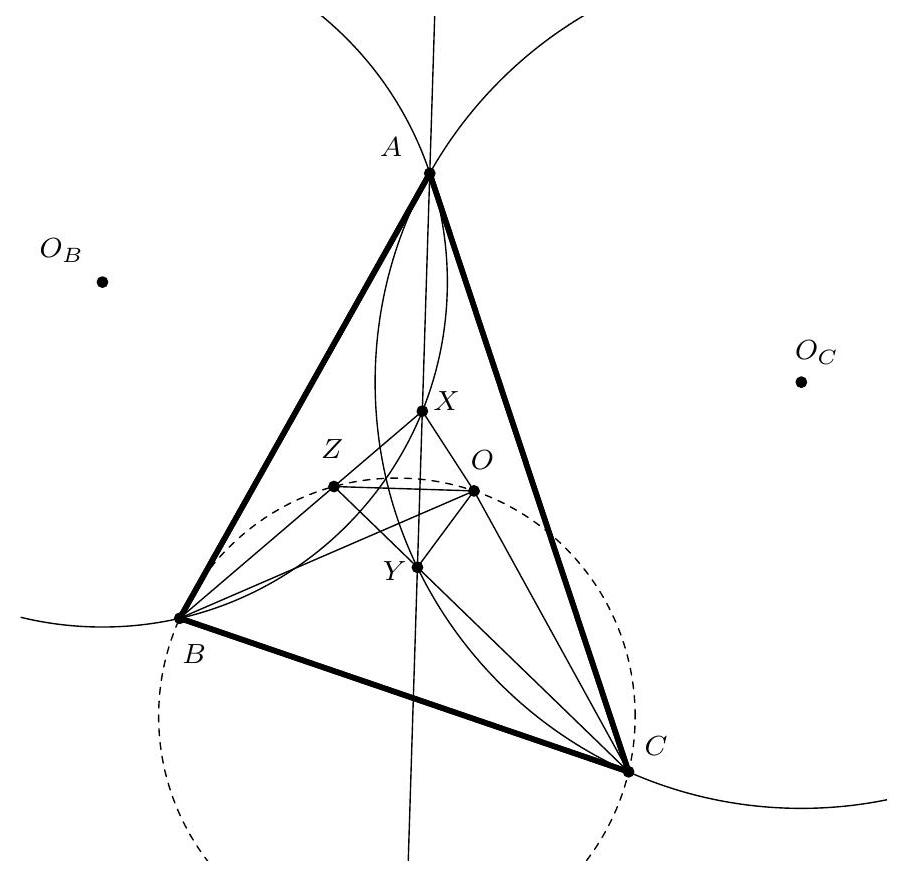

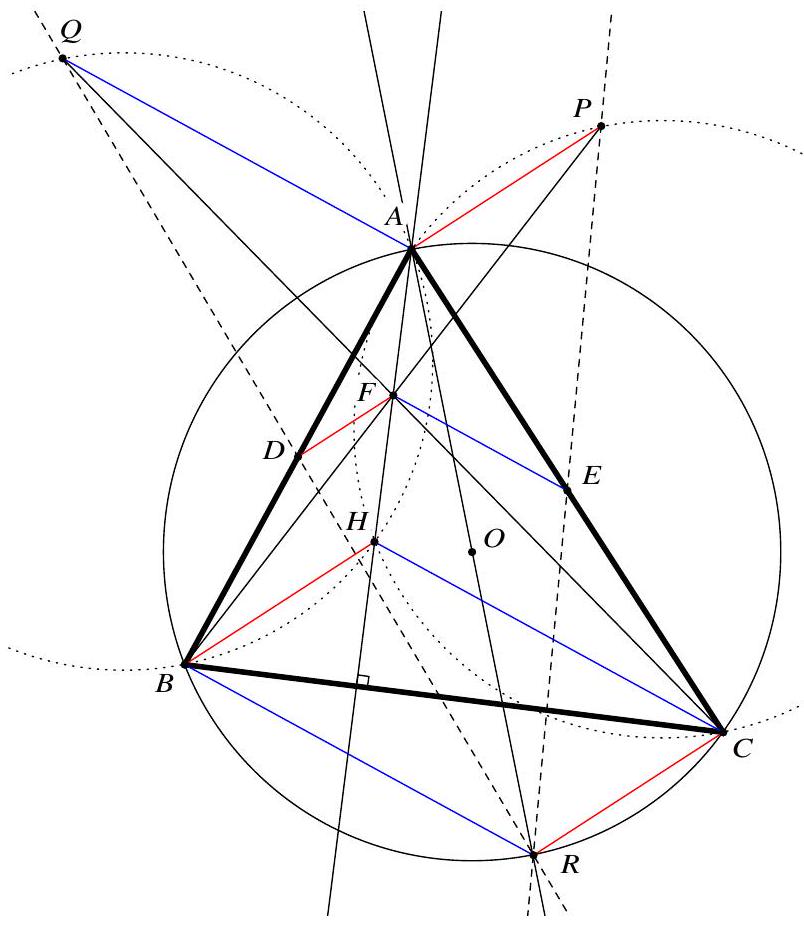

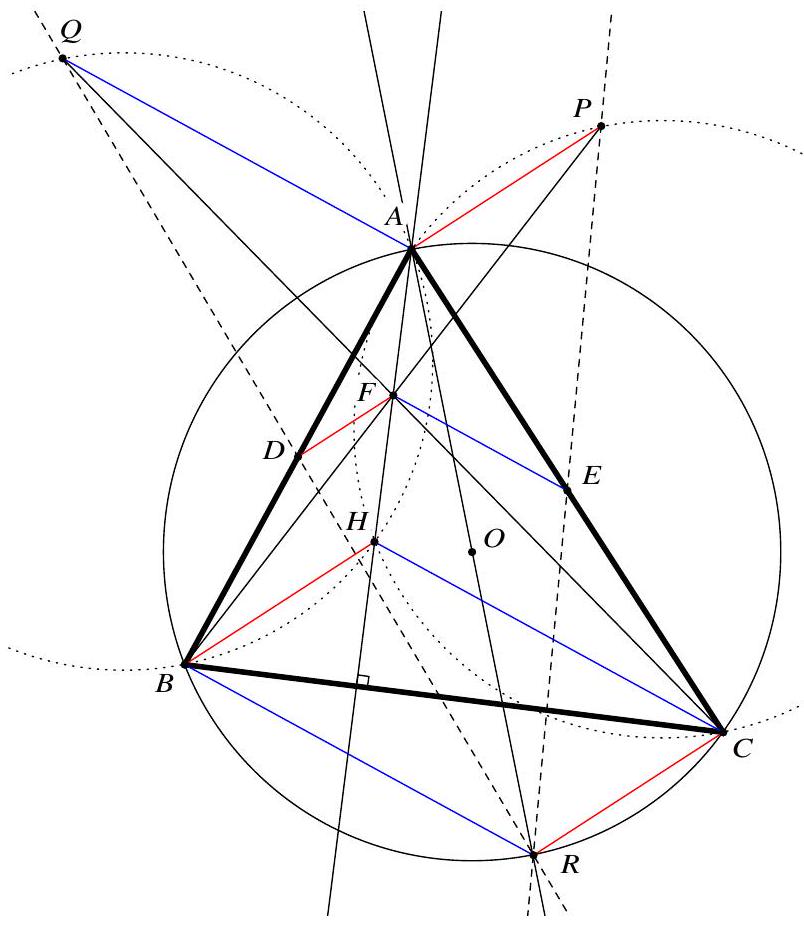

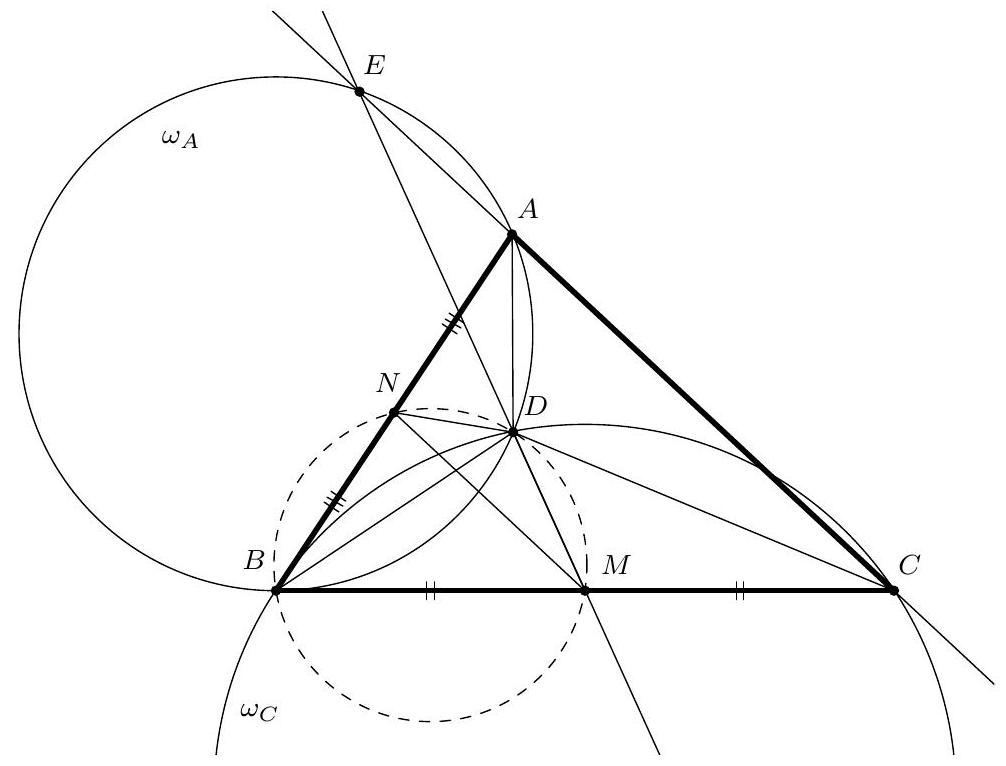

In a triangle $A B C$ it is given that $2|A B|=|A C|+|B C|$. Prove that the incentre of $A B C$, the circumcentre of $A B C$, and the midpoints of $A C$ and $B C$ are concyclic.

|

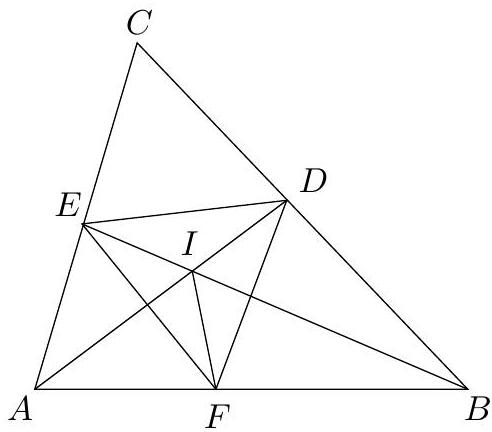

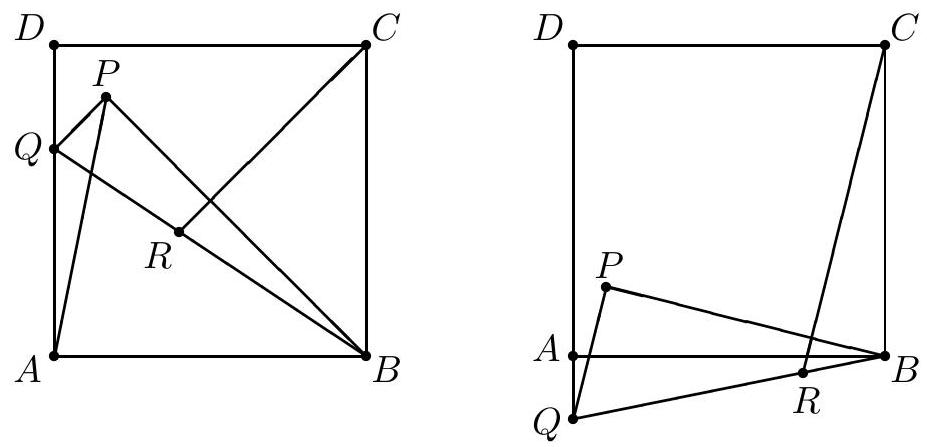

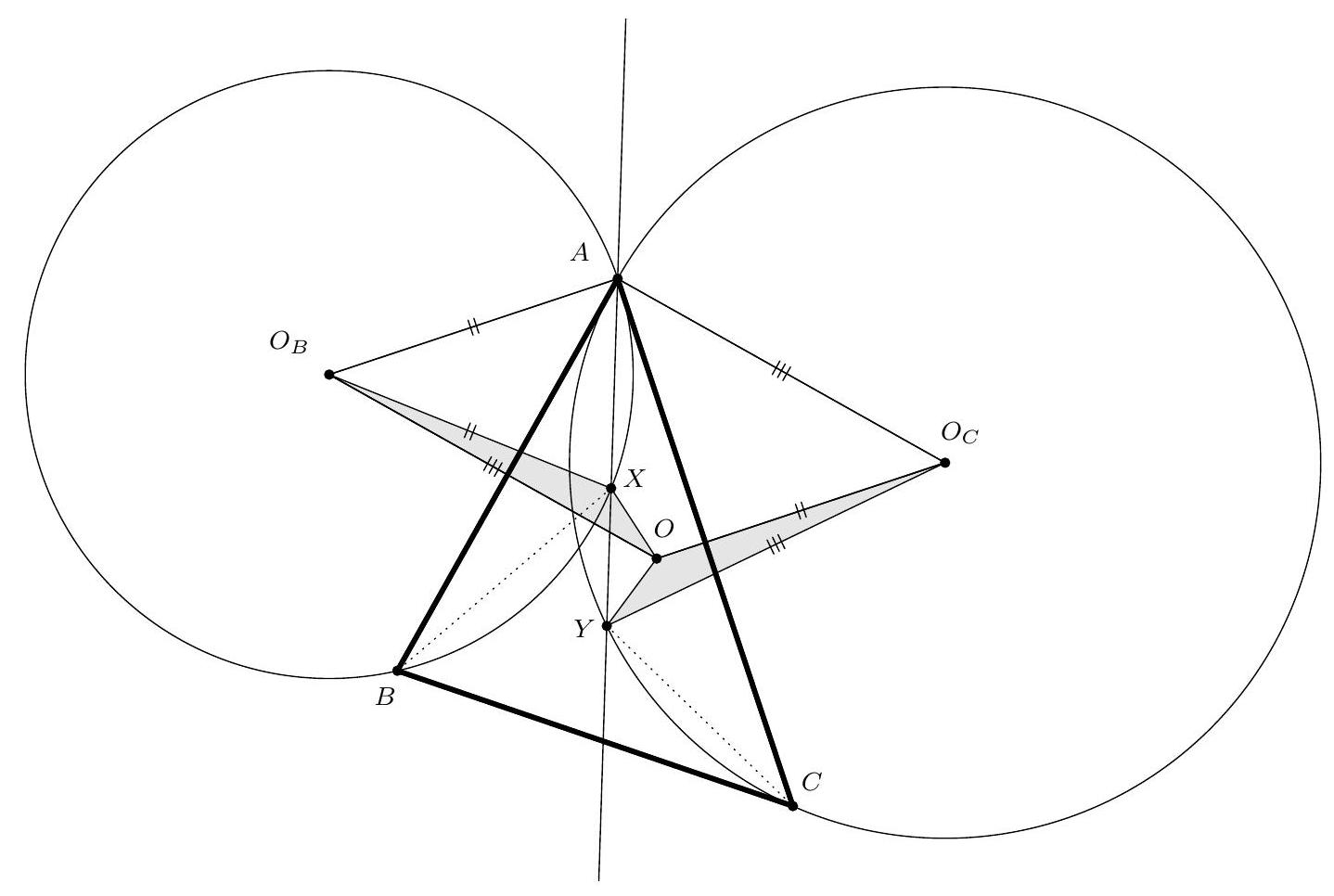

Let $N$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $M$ the midpoint of $A C$. Let $O$ be the circumcentre of $A B C$ and $I$ its incentre (see Figure 8). Since $\angle C M O=\angle C N O=90^{\circ}$, the points $C, N, O$ and $M$ are concyclic (regardless of whether $O$ lies inside the triangle $A B C$ ). We now have to show that the points $C, N, I$ and $M$ are also concyclic, i.e $I$ lies on the same circle as $C, N, O$ and $M$. It will be sufficient to show that $\angle N C M+\angle N I M=180^{\circ}$ in the quadrilateral $C N I M$. Since

$$

|A B|=\frac{|A C|+|B C|}{2}=|A M|+|B N|

$$

we can choose a point $D$ on the side $A B$ such that $|A D|=|A M|$ and $|B D|=|B N|$. Then triangle $A I M$ is congruent to triangle $A I D$, and similarly triangle $B I N$ is congruent to triangle $B I D$. Therefore

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle N C M+\angle N I M & =\angle N C M+\left(360^{\circ}-2 \angle A I D-2 \angle B I D\right)= \\

& =\angle B C A+360^{\circ}-2 \angle A I B= \\

& =\angle B C A+360^{\circ}-2 \cdot\left(180^{\circ}-\frac{\angle B A C}{2}-\frac{\angle A B C}{2}\right)= \\

& =\angle B C A+\angle A B C+\angle C A B=180^{\circ} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Figure 8

Figure 9

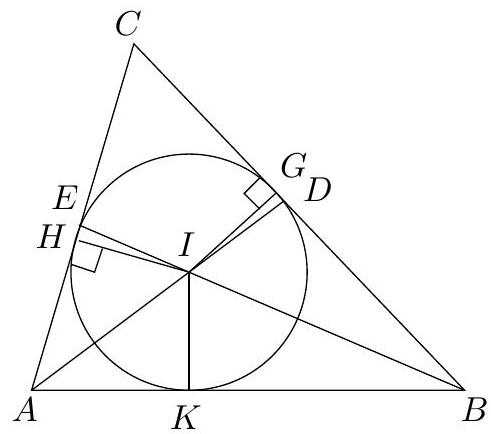

Alternative solution. Let $O$ be the circumcentre of $A B C$ and $I$ its in-

centre, and let $G, H$ and $K$ be the points where the incircle touches the sides $B C, A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle, respectively. Also, let $N$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $M$ the midpoint of $A C$ (see Figure 9). Since $\angle C M O=\angle C N O=90^{\circ}$, points $M$ and $N$ lie on the circle with diameter $O C$. We will show that point $I$ also lies on that circle. Indeed, we have

$$

|A H|+|B G|=|A K|+|B K|=|A B|=\frac{|A C|+|B C|}{2}=|A M|+|B N|,

$$

implying $|M H|=|N G|$. Since $M H$ and $N G$ are the perpendicular projections of $O I$ to the lines $A C$ and $B C$, respectively, then $I O$ must be either parallel or perpendicular to the bisector $C I$ of angle $A C B$. (To formally prove this, consider unit vectors $\overrightarrow{e_{1}}$ and $\overrightarrow{e_{2}}$ defined by the rays $C A$ and $C B$, and show that the condition $|M H|=|N G|$ is equivalent to $\left(\overrightarrow{e_{1}} \pm \overrightarrow{e_{2}}\right) \cdot \overrightarrow{I O}=0$.)

If $I O$ is perpendicular to $C I$, then $\angle C I O=90^{\circ}$ and we are done. If $I O$ is parallel to $C I$, the the circumcentre $O$ of triangle $A B C$ lies on the bisector $C I$ of angle $A C B$, whence $|A C|=|B C|$ and the condition $2|A B|=|A C|+|B C|$ implies that $A B C$ is an equilateral triangle. Hence in this case points $O$ and $I$ coincide and the claim of the problem holds trivially.

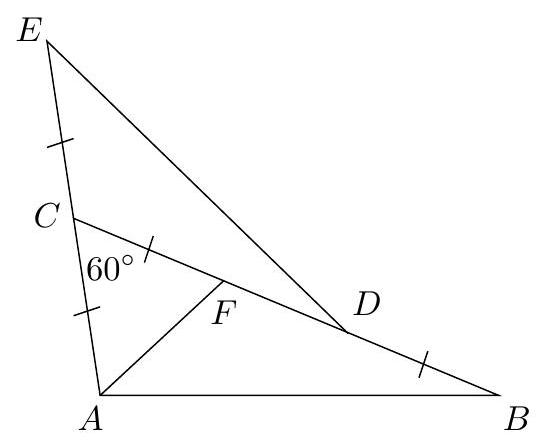

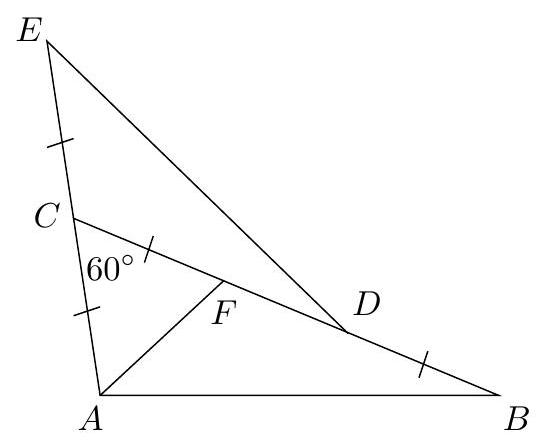

## 13. Answer: $60^{\circ}$.

Let $F$ be the point of the side $A B$ such that $|A F|=|A E|$ and $|B F|=|B D|$ (see Figure 10). The line $A D$ is the angle bisector of $\angle A$ in the isosceles triangle $A E F$. This implies that $A D$ is the perpendicular bisector of $E F$, whence $|D E|=|D F|$. Similarly we show that $|D E|=|E F|$. This proves that the triangle $D E F$ is equilateral, i.e. $\angle E F D=60^{\circ}$. Hence $\angle A F E+\angle B F D=120^{\circ}$, and also $\angle A E F+\angle B D F=120^{\circ}$. Thus $\angle C A B+\angle C B A=120^{\circ}$ and finally $\angle C=60^{\circ}$.

Alternative solution. Let $I$ be the incenter of triangle $A B C$, and let $G$, $H, K$ be the points where its incircle touches the sides $B C, A C, A B$ respectively (see Figure 11). Then

$$

|A E|+|B D|=|A B|=|A K|+|B K|=|A H|+|B G| \text {, }

$$

implying $|D G|=|E H|$. Hence the triangles $D I G$ ja $E I H$ are congruent,

and

$\angle D I E=\angle G I H=180^{\circ}-\angle C$.

Figure 10

Figure 11

On the other hand,

$$

\angle D I E=\angle A I B=180^{\circ}-\frac{\angle A+\angle B}{2} .

$$

Hence

$$

\angle C=\frac{\angle A+\angle B}{2}=90^{\circ}-\frac{\angle C}{2}

$$

which gives $\angle C=60^{\circ}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

In a triangle $A B C$ it is given that $2|A B|=|A C|+|B C|$. Prove that the incentre of $A B C$, the circumcentre of $A B C$, and the midpoints of $A C$ and $B C$ are concyclic.

|

Let $N$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $M$ the midpoint of $A C$. Let $O$ be the circumcentre of $A B C$ and $I$ its incentre (see Figure 8). Since $\angle C M O=\angle C N O=90^{\circ}$, the points $C, N, O$ and $M$ are concyclic (regardless of whether $O$ lies inside the triangle $A B C$ ). We now have to show that the points $C, N, I$ and $M$ are also concyclic, i.e $I$ lies on the same circle as $C, N, O$ and $M$. It will be sufficient to show that $\angle N C M+\angle N I M=180^{\circ}$ in the quadrilateral $C N I M$. Since

$$

|A B|=\frac{|A C|+|B C|}{2}=|A M|+|B N|

$$

we can choose a point $D$ on the side $A B$ such that $|A D|=|A M|$ and $|B D|=|B N|$. Then triangle $A I M$ is congruent to triangle $A I D$, and similarly triangle $B I N$ is congruent to triangle $B I D$. Therefore

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle N C M+\angle N I M & =\angle N C M+\left(360^{\circ}-2 \angle A I D-2 \angle B I D\right)= \\

& =\angle B C A+360^{\circ}-2 \angle A I B= \\

& =\angle B C A+360^{\circ}-2 \cdot\left(180^{\circ}-\frac{\angle B A C}{2}-\frac{\angle A B C}{2}\right)= \\

& =\angle B C A+\angle A B C+\angle C A B=180^{\circ} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Figure 8

Figure 9

Alternative solution. Let $O$ be the circumcentre of $A B C$ and $I$ its in-

centre, and let $G, H$ and $K$ be the points where the incircle touches the sides $B C, A C$ and $A B$ of the triangle, respectively. Also, let $N$ be the midpoint of $B C$ and $M$ the midpoint of $A C$ (see Figure 9). Since $\angle C M O=\angle C N O=90^{\circ}$, points $M$ and $N$ lie on the circle with diameter $O C$. We will show that point $I$ also lies on that circle. Indeed, we have

$$

|A H|+|B G|=|A K|+|B K|=|A B|=\frac{|A C|+|B C|}{2}=|A M|+|B N|,

$$

implying $|M H|=|N G|$. Since $M H$ and $N G$ are the perpendicular projections of $O I$ to the lines $A C$ and $B C$, respectively, then $I O$ must be either parallel or perpendicular to the bisector $C I$ of angle $A C B$. (To formally prove this, consider unit vectors $\overrightarrow{e_{1}}$ and $\overrightarrow{e_{2}}$ defined by the rays $C A$ and $C B$, and show that the condition $|M H|=|N G|$ is equivalent to $\left(\overrightarrow{e_{1}} \pm \overrightarrow{e_{2}}\right) \cdot \overrightarrow{I O}=0$.)

If $I O$ is perpendicular to $C I$, then $\angle C I O=90^{\circ}$ and we are done. If $I O$ is parallel to $C I$, the the circumcentre $O$ of triangle $A B C$ lies on the bisector $C I$ of angle $A C B$, whence $|A C|=|B C|$ and the condition $2|A B|=|A C|+|B C|$ implies that $A B C$ is an equilateral triangle. Hence in this case points $O$ and $I$ coincide and the claim of the problem holds trivially.

## 13. Answer: $60^{\circ}$.

Let $F$ be the point of the side $A B$ such that $|A F|=|A E|$ and $|B F|=|B D|$ (see Figure 10). The line $A D$ is the angle bisector of $\angle A$ in the isosceles triangle $A E F$. This implies that $A D$ is the perpendicular bisector of $E F$, whence $|D E|=|D F|$. Similarly we show that $|D E|=|E F|$. This proves that the triangle $D E F$ is equilateral, i.e. $\angle E F D=60^{\circ}$. Hence $\angle A F E+\angle B F D=120^{\circ}$, and also $\angle A E F+\angle B D F=120^{\circ}$. Thus $\angle C A B+\angle C B A=120^{\circ}$ and finally $\angle C=60^{\circ}$.

Alternative solution. Let $I$ be the incenter of triangle $A B C$, and let $G$, $H, K$ be the points where its incircle touches the sides $B C, A C, A B$ respectively (see Figure 11). Then

$$

|A E|+|B D|=|A B|=|A K|+|B K|=|A H|+|B G| \text {, }

$$

implying $|D G|=|E H|$. Hence the triangles $D I G$ ja $E I H$ are congruent,

and

$\angle D I E=\angle G I H=180^{\circ}-\angle C$.

Figure 10

Figure 11

On the other hand,

$$

\angle D I E=\angle A I B=180^{\circ}-\frac{\angle A+\angle B}{2} .

$$

Hence

$$

\angle C=\frac{\angle A+\angle B}{2}=90^{\circ}-\frac{\angle C}{2}

$$

which gives $\angle C=60^{\circ}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\n12.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n12.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

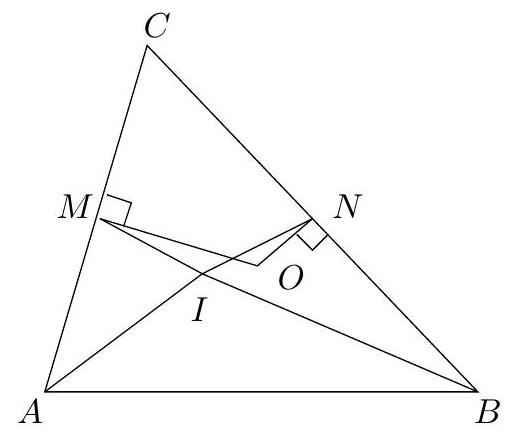

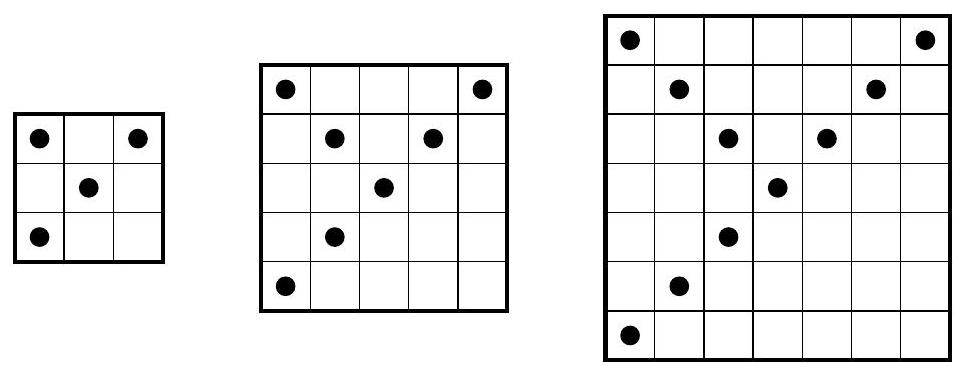

Let $A B C$ be an isosceles triangle with $|A B|=|A C|$. Points $D$ and $E$ lie on the sides $A B$ and $A C$, respectively. The line passing through $B$ and parallel to $A C$ meets the line $D E$ at $F$. The line passing through $C$ and parallel to $A B$ meets the line $D E$ at $G$. Prove that

$$

\frac{[D B C G]}{[F B C E]}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

where $[P Q R S]$ denotes the area of the quadrilateral $P Q R S$.

|

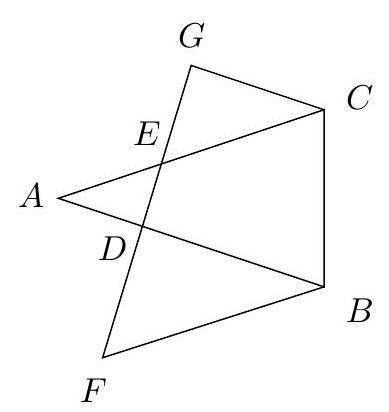

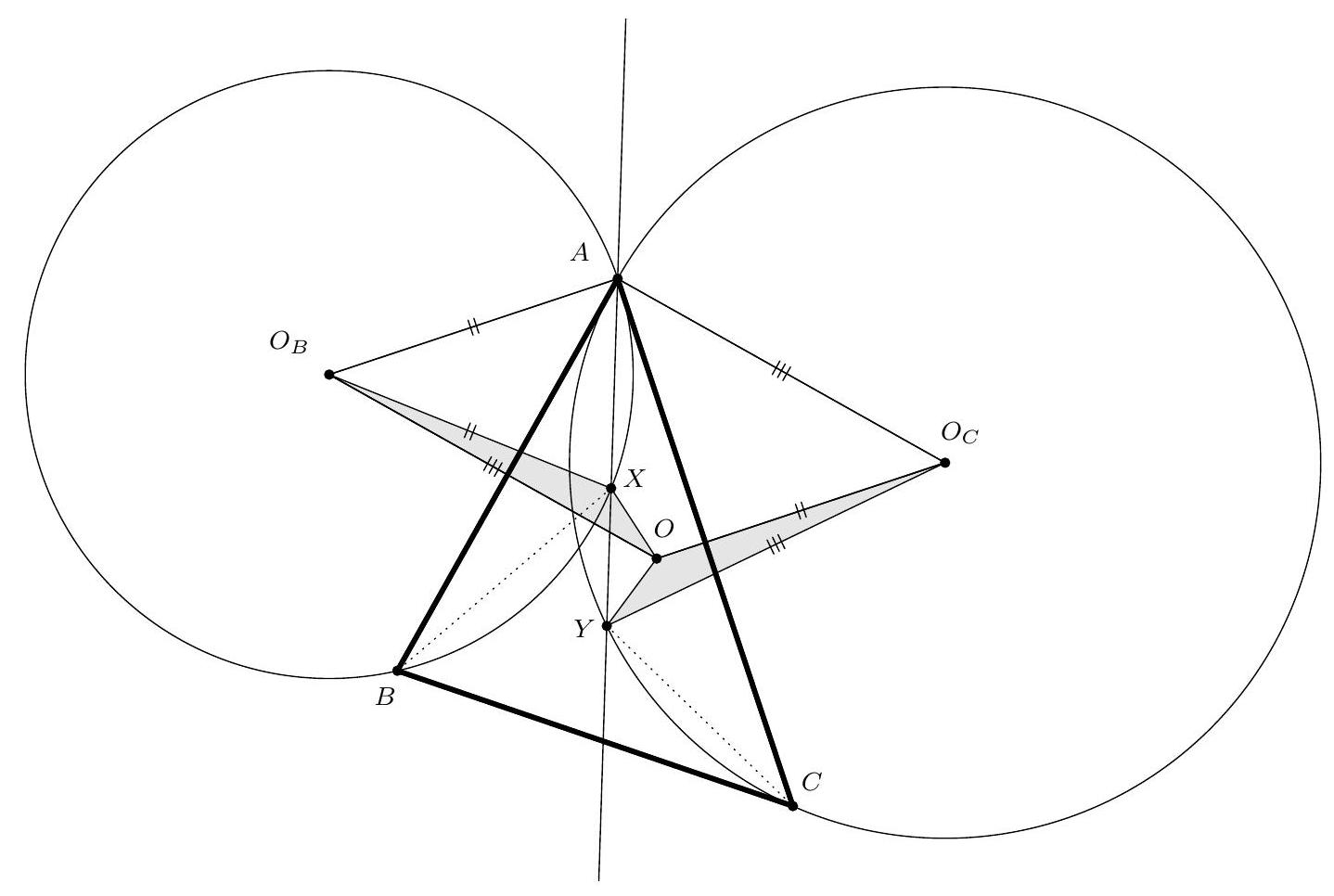

The quadrilaterals $D B C G$ and $F B C E$ are trapeziums. The area of a trapezium is equal to half the sum of the lengths of the parallel sides multiplied by the distance between them. But the distance between the parallel sides is the same for both of these trapeziums, since the distance from $B$ to $A C$ is equal to the distance from $C$ to $A B$. It therefore suffices to show that

$$

\frac{|B D|+|C G|}{|C E|+|B F|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

(see Figure 12). Now, since the triangles $B D F, A D E$ and $C G E$ are similar, we have

$$

\frac{|B D|}{|B F|}=\frac{|C G|}{|C E|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

which implies the required equality.

Figure 12

Figure 13

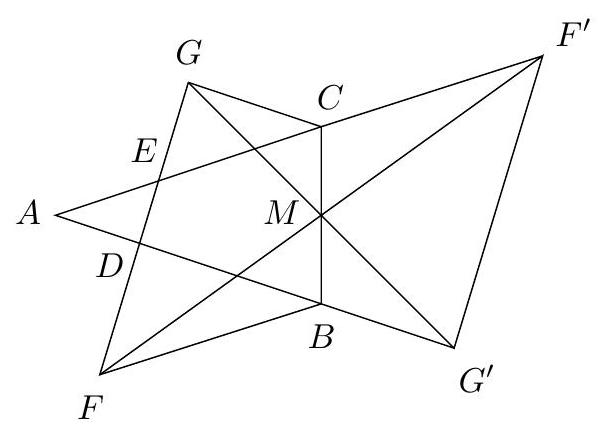

Alternative solution. As in the first solution, we need to show that

$$

\frac{|B D|+|C G|}{|B F|+|C E|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

Let $M$ be the midpoint of $B C$, and let $F^{\prime}$ and $G^{\prime}$ be the points symmetric to $F$ and $G$, respectively, relative to $M$ (see Figure 13). Since $C G$ is parallel to $A B$, then point $G^{\prime}$ lies on the line $A B$, and $\left|B G^{\prime}\right|=|C G|$. Similarly point $F^{\prime}$ lies on the line $A C$, and $\left|C F^{\prime}\right|=|B F|$. It remains to show that

$$

\frac{\left|D G^{\prime}\right|}{\left|E F^{\prime}\right|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

which follows from $D E$ and $F^{\prime} G^{\prime}$ being parallel.

Another solution. Express the areas of the quadrilaterals as

$$

[D B C G]=[A B C]-[A D E]+[E C G]

$$

and

$$

[F B C E]=[A B C]-[A D E]+[D B F]

$$

The required equality can now be proved by direct computation.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an isosceles triangle with $|A B|=|A C|$. Points $D$ and $E$ lie on the sides $A B$ and $A C$, respectively. The line passing through $B$ and parallel to $A C$ meets the line $D E$ at $F$. The line passing through $C$ and parallel to $A B$ meets the line $D E$ at $G$. Prove that

$$

\frac{[D B C G]}{[F B C E]}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

where $[P Q R S]$ denotes the area of the quadrilateral $P Q R S$.

|

The quadrilaterals $D B C G$ and $F B C E$ are trapeziums. The area of a trapezium is equal to half the sum of the lengths of the parallel sides multiplied by the distance between them. But the distance between the parallel sides is the same for both of these trapeziums, since the distance from $B$ to $A C$ is equal to the distance from $C$ to $A B$. It therefore suffices to show that

$$

\frac{|B D|+|C G|}{|C E|+|B F|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

(see Figure 12). Now, since the triangles $B D F, A D E$ and $C G E$ are similar, we have

$$

\frac{|B D|}{|B F|}=\frac{|C G|}{|C E|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

which implies the required equality.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Alternative solution. As in the first solution, we need to show that

$$

\frac{|B D|+|C G|}{|B F|+|C E|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

Let $M$ be the midpoint of $B C$, and let $F^{\prime}$ and $G^{\prime}$ be the points symmetric to $F$ and $G$, respectively, relative to $M$ (see Figure 13). Since $C G$ is parallel to $A B$, then point $G^{\prime}$ lies on the line $A B$, and $\left|B G^{\prime}\right|=|C G|$. Similarly point $F^{\prime}$ lies on the line $A C$, and $\left|C F^{\prime}\right|=|B F|$. It remains to show that

$$

\frac{\left|D G^{\prime}\right|}{\left|E F^{\prime}\right|}=\frac{|A D|}{|A E|}

$$

which follows from $D E$ and $F^{\prime} G^{\prime}$ being parallel.

Another solution. Express the areas of the quadrilaterals as

$$

[D B C G]=[A B C]-[A D E]+[E C G]

$$

and

$$

[F B C E]=[A B C]-[A D E]+[D B F]

$$

The required equality can now be proved by direct computation.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\n14.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n14.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle C=60^{\circ}$ and $|A C|<|B C|$. The point $D$ lies on the side $B C$ and satisfies $|B D|=|A C|$. The side $A C$ is extended to the point $E$ where $|A C|=|C E|$. Prove that $|A B|=|D E|$.

|

Consider a point $F$ on $B C$ such that $|C F|=|B D|$ (see Figure 14). Since $\angle A C F=60^{\circ}$, triangle $A C F$ is equilateral. Therefore $|A F|=|A C|=|C E|$

and $\angle A F B=\angle E C D=120^{\circ}$. Moreover, $|B F|=|C D|$. This implies that triangles $A F B$ and $E C D$ are congruent, and $|A B|=|D E|$.

Figure 14

Alternative solution. The cosine law in triangle $A B C$ implies

$$

\begin{aligned}

|A B|^{2} & =|A C|^{2}+|B C|^{2}-2 \cdot|A C| \cdot|B C| \cdot \cos \angle A C B= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+|B C|^{2}-|A C| \cdot|B C|= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+(|B D|+|D C|)^{2}-|A C| \cdot(|B D|+|D C|)= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+(|A C|+|D C|)^{2}-|A C| \cdot(|A C|+|D C|)= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+|D C|^{2}+|A C| \cdot|D C|

\end{aligned}

$$

On the other hand, the cosine law in triangle $C D E$ gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

|D E|^{2} & =|D C|^{2}+|C E|^{2}-2 \cdot|D C| \cdot|C E| \cdot \cos \angle D C E= \\

& =|D C|^{2}+|C E|^{2}+|D C| \cdot|E C|= \\

& =|D C|^{2}+|A C|^{2}+|D C| \cdot|A C| .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $|A B|=|D E|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with $\angle C=60^{\circ}$ and $|A C|<|B C|$. The point $D$ lies on the side $B C$ and satisfies $|B D|=|A C|$. The side $A C$ is extended to the point $E$ where $|A C|=|C E|$. Prove that $|A B|=|D E|$.

|

Consider a point $F$ on $B C$ such that $|C F|=|B D|$ (see Figure 14). Since $\angle A C F=60^{\circ}$, triangle $A C F$ is equilateral. Therefore $|A F|=|A C|=|C E|$

and $\angle A F B=\angle E C D=120^{\circ}$. Moreover, $|B F|=|C D|$. This implies that triangles $A F B$ and $E C D$ are congruent, and $|A B|=|D E|$.

Figure 14

Alternative solution. The cosine law in triangle $A B C$ implies

$$

\begin{aligned}

|A B|^{2} & =|A C|^{2}+|B C|^{2}-2 \cdot|A C| \cdot|B C| \cdot \cos \angle A C B= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+|B C|^{2}-|A C| \cdot|B C|= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+(|B D|+|D C|)^{2}-|A C| \cdot(|B D|+|D C|)= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+(|A C|+|D C|)^{2}-|A C| \cdot(|A C|+|D C|)= \\

& =|A C|^{2}+|D C|^{2}+|A C| \cdot|D C|

\end{aligned}

$$

On the other hand, the cosine law in triangle $C D E$ gives

$$

\begin{aligned}

|D E|^{2} & =|D C|^{2}+|C E|^{2}-2 \cdot|D C| \cdot|C E| \cdot \cos \angle D C E= \\

& =|D C|^{2}+|C E|^{2}+|D C| \cdot|E C|= \\

& =|D C|^{2}+|A C|^{2}+|D C| \cdot|A C| .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $|A B|=|D E|$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\n15.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n15.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Find the smallest positive integer $k$ which is representable in the form $k=19^{n}-5^{m}$ for some positive integers $m$ and $n$.

|

Answer: 14.

Assume that there are integers $n, m$ such that $k=19^{n}-5^{m}$ is a positive integer smaller than $19^{1}-5^{1}=14$. For obvious reasons, $n$ and $m$ must be positive.

Case 1: Assume that $n$ is even. Then the last digit of $k$ is 6 . Consequently, we have $19^{n}-5^{m}=6$. Considering this equation modulo 3 implies that $m$

must be even as well. With $n=2 n^{\prime}$ and $m=2 m^{\prime}$ the above equation can be restated as $\left(19^{n^{\prime}}+5^{m^{\prime}}\right)\left(19^{n^{\prime}}-5^{m^{\prime}}\right)=6$ which evidently has no solution in positive integers.

Case 2: Assume that $n$ is odd. Then the last digit of $k$ is 4 . Consequently, we have $19^{n}-5^{m}=4$. On the other hand, the remainder of $19^{n}-5^{m}$ modulo 3 is never 1 , a contradiction.

|

14

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Find the smallest positive integer $k$ which is representable in the form $k=19^{n}-5^{m}$ for some positive integers $m$ and $n$.

|

Answer: 14.

Assume that there are integers $n, m$ such that $k=19^{n}-5^{m}$ is a positive integer smaller than $19^{1}-5^{1}=14$. For obvious reasons, $n$ and $m$ must be positive.

Case 1: Assume that $n$ is even. Then the last digit of $k$ is 6 . Consequently, we have $19^{n}-5^{m}=6$. Considering this equation modulo 3 implies that $m$

must be even as well. With $n=2 n^{\prime}$ and $m=2 m^{\prime}$ the above equation can be restated as $\left(19^{n^{\prime}}+5^{m^{\prime}}\right)\left(19^{n^{\prime}}-5^{m^{\prime}}\right)=6$ which evidently has no solution in positive integers.

Case 2: Assume that $n$ is odd. Then the last digit of $k$ is 4 . Consequently, we have $19^{n}-5^{m}=4$. On the other hand, the remainder of $19^{n}-5^{m}$ modulo 3 is never 1 , a contradiction.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "16",

"problem_match": "\n16.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n16.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Does there exist a finite sequence of integers $c_{1}, \ldots, c_{n}$ such that all the numbers $a+c_{1}, \ldots, a+c_{n}$ are primes for more than one but not infinitely many different integers $a$ ?

|

Answer: yes.

Let $n=5$ and consider the integers $0,2,8,14,26$. Adding $a=3$ or $a=5$ to all of these integers we get primes. Since the numbers $0,2,8,14$ and 26 have pairwise different remainders modulo 5 then for any integer $a$ the numbers $a+0, a+2, a+8, a+14$ and $a+26$ have also pairwise different remainders modulo 5 ; therefore one of them is divisible by 5 . Hence if the numbers $a+0, a+2, a+8, a+14$ and $a+26$ are all primes then one of them must be equal to 5 , which is only true for $a=3$ and $a=5$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Does there exist a finite sequence of integers $c_{1}, \ldots, c_{n}$ such that all the numbers $a+c_{1}, \ldots, a+c_{n}$ are primes for more than one but not infinitely many different integers $a$ ?

|

Answer: yes.

Let $n=5$ and consider the integers $0,2,8,14,26$. Adding $a=3$ or $a=5$ to all of these integers we get primes. Since the numbers $0,2,8,14$ and 26 have pairwise different remainders modulo 5 then for any integer $a$ the numbers $a+0, a+2, a+8, a+14$ and $a+26$ have also pairwise different remainders modulo 5 ; therefore one of them is divisible by 5 . Hence if the numbers $a+0, a+2, a+8, a+14$ and $a+26$ are all primes then one of them must be equal to 5 , which is only true for $a=3$ and $a=5$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "17",

"problem_match": "\n17.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n17.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Let $m$ be a positive integer such that $m \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$. Show that there exists at most one factorization $m=a b$ where $a$ and $b$ are positive integers satisfying $0<a-b<\sqrt{5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}}$.

|

Squaring the second inequality gives $(a-b)^{2}<5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}$. Since $m=a b$, we have

$$

(a+b)^{2}<5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}+4 m=(\sqrt{4 m+1}+2)^{2}

$$

implying

$$

a+b<\sqrt{4 m+1}+2 \text {. }

$$

Since $a>b$, different factorizations $m=a b$ will give different values for the sum $a+b(a b=m, a+b=k, a>b$ has at most one solution in $(a, b))$. Since $m \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, we see that $a$ and $b$ must have different parity, and $a+b$ must be odd. Also note that

$$

a+b \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a b}=\sqrt{4 m}

$$

Since $4 m$ cannot be a square we have

$$

a+b \geqslant \sqrt{4 m+1} .

$$

Since $a+b$ is odd and the interval $[\sqrt{4 m+1}, \sqrt{4 m+1}+2)$ contains exactly one odd integer, then there can be at most one pair $(a, b)$ such that $a+b<\sqrt{4 m+1}+2$, or equivalently $a-b<\sqrt{5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $m$ be a positive integer such that $m \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$. Show that there exists at most one factorization $m=a b$ where $a$ and $b$ are positive integers satisfying $0<a-b<\sqrt{5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}}$.

|

Squaring the second inequality gives $(a-b)^{2}<5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}$. Since $m=a b$, we have

$$

(a+b)^{2}<5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}+4 m=(\sqrt{4 m+1}+2)^{2}

$$

implying

$$

a+b<\sqrt{4 m+1}+2 \text {. }

$$

Since $a>b$, different factorizations $m=a b$ will give different values for the sum $a+b(a b=m, a+b=k, a>b$ has at most one solution in $(a, b))$. Since $m \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, we see that $a$ and $b$ must have different parity, and $a+b$ must be odd. Also note that

$$

a+b \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a b}=\sqrt{4 m}

$$

Since $4 m$ cannot be a square we have

$$

a+b \geqslant \sqrt{4 m+1} .

$$

Since $a+b$ is odd and the interval $[\sqrt{4 m+1}, \sqrt{4 m+1}+2)$ contains exactly one odd integer, then there can be at most one pair $(a, b)$ such that $a+b<\sqrt{4 m+1}+2$, or equivalently $a-b<\sqrt{5+4 \sqrt{4 m+1}}$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "18",

"problem_match": "\n18.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n18.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Prove that there exist infinitely many even positive integers $k$ such that for every prime $p$ the number $p^{2}+k$ is composite.

|

Note that the square of any prime $p \neq 3$ is congruent to 1 modulo 3 . Hence the numbers $k=6 m+2$ will have the required property for any $p \neq 3$, as

$p^{2}+k$ will be divisible by 3 and hence composite.

In order to have $3^{2}+k$ also composite, we look for such values of $m$ for which $k=6 m+2$ is congruent to 1 modulo 5 - then $3^{2}+k$ will be divisible by 5 and hence composite. Taking $m=5 t+4$, we have $k=30 t+26$, which is congruent to 2 modulo 3 and congruent to 1 modulo 5 . Hence $p^{2}+(30 t+26)$ is composite for any positive integer $t$ and prime $p$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Prove that there exist infinitely many even positive integers $k$ such that for every prime $p$ the number $p^{2}+k$ is composite.

|

Note that the square of any prime $p \neq 3$ is congruent to 1 modulo 3 . Hence the numbers $k=6 m+2$ will have the required property for any $p \neq 3$, as

$p^{2}+k$ will be divisible by 3 and hence composite.

In order to have $3^{2}+k$ also composite, we look for such values of $m$ for which $k=6 m+2$ is congruent to 1 modulo 5 - then $3^{2}+k$ will be divisible by 5 and hence composite. Taking $m=5 t+4$, we have $k=30 t+26$, which is congruent to 2 modulo 3 and congruent to 1 modulo 5 . Hence $p^{2}+(30 t+26)$ is composite for any positive integer $t$ and prime $p$.

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "19",

"problem_match": "\n19.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n19.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ and $d$ be prime numbers such that $a>3 b>6 c>12 d$ and $a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}=1749$. Determine all possible values of $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}$.

## Solutions

|

Answer: the only possible value is 1999 .

Since $a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}$ is odd, one of the primes $a, b, c$ and $d$ must be 2 , and in view of $a>3 b>6 c>12 d$ we must have $d=2$. Now

$$

1749=a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}>9 b^{2}-b^{2}+4 d^{2}-d^{2}=8 b^{2}-12,

$$

implying $b \leqslant 13$. From $4<c<\frac{b}{2}$ we now have $c=5$ and $b$ must be either 11 or 13 . It remains to check that $1749+2^{2}-5^{2}+13^{2}=1897$ is not a square of an integer, and $1749+2^{2}-5^{2}+11^{2}=1849=43^{2}$. Hence $b=11$, $a=43$ and

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=43^{2}+11^{2}+5^{2}+2^{2}=1999

$$

|

1999

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $a, b, c$ and $d$ be prime numbers such that $a>3 b>6 c>12 d$ and $a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}=1749$. Determine all possible values of $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}$.

## Solutions

|

Answer: the only possible value is 1999 .

Since $a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}$ is odd, one of the primes $a, b, c$ and $d$ must be 2 , and in view of $a>3 b>6 c>12 d$ we must have $d=2$. Now

$$

1749=a^{2}-b^{2}+c^{2}-d^{2}>9 b^{2}-b^{2}+4 d^{2}-d^{2}=8 b^{2}-12,

$$

implying $b \leqslant 13$. From $4<c<\frac{b}{2}$ we now have $c=5$ and $b$ must be either 11 or 13 . It remains to check that $1749+2^{2}-5^{2}+13^{2}=1897$ is not a square of an integer, and $1749+2^{2}-5^{2}+11^{2}=1849=43^{2}$. Hence $b=11$, $a=43$ and

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}+d^{2}=43^{2}+11^{2}+5^{2}+2^{2}=1999

$$

|

{

"exam": "BalticWay",

"problem_label": "20",

"problem_match": "\n20.",

"resource_path": "BalticWay/segmented/en-bw99sol.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n20.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "1999"

}

|

A finite set of integers is called bad if its elements add up to 2010. A finite set of integers is a Benelux-set if none of its subsets is bad. Determine the smallest integer $n$ such that the set $\{502,503,504, \ldots, 2009\}$ can be partitioned into $n$ Benelux-sets.

(A partition of a set $S$ into $n$ subsets is a collection of $n$ pairwise disjoint subsets of $S$, the union of which equals $S$.)

|

As $502+1508=2010$, the set $S=\{502,503, \ldots, 2009\}$ is not a Benelux-set, so $n=1$ does not work. We will prove that $n=2$ does work, i.e. that $S$ can be partitioned into 2 Benelux-sets.

Define the following subsets of $S$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

& A=\{502,503, \ldots, 670\}, \\

& B=\{671,672, \ldots, 1005\}, \\

& C=\{1006,1007, \ldots, 1339\}, \\

& D=\{1340,1341, \ldots, 1508\}, \\

& E=\{1509,1510, \ldots, 2009\} .

\end{aligned}

$$

We will show that $A \cup C \cup E$ and $B \cup D$ are both Benelux-sets.

Note that there does not exist a bad subset of $S$ of one element, since that element would have to be 2010. Also, there does not exist a bad subset of $S$ of more than three elements, since the sum of four or more elements would be at least $502+503+504+505=2014>2010$. So any possible bad subset of $S$ contains two or three elements.

Consider a bad subset of two elements $a$ and $b$. As $a, b \geq 502$ and $a+b=2010$, we have $a, b \leq 2010-502=1508$. Furthermore, exactly one of $a$ and $b$ is smaller than 1005 and one is larger than 1005. So one of them, say $a$, is an element of $A \cup B$, and the other is an element of $C \cup D$. Suppose $a \in A$, then $b \geq 2010-670=1340$, so $b \in D$. On the other hand, suppose $a \in B$, then $b \leq 2010-671=1339$, so $b \in C$. Hence $\{a, b\}$ cannot be a subset of $A \cup C \cup E$, nor of $B \cup D$.

Now consider a bad subset of three elements $a, b$ and $c$. As $a, b, c \geq 502, a+b+c=2010$, and the three elements are pairwise distinct, we have $a, b, c \leq 2010-502-503=1005$. So $a, b, c \in A \cup B$. At least one of the elements, say $a$, is smaller than $\frac{2010}{3}=670$, and at least one of the elements, say $b$, is larger than 670 . So $a \in A$ and $b \in B$. We conclude that $\{a, b, c\}$ cannot be a subset of $A \cup C \cup E$, nor of $B \cup D$.

This proves that $A \cup C \cup E$ and $B \cup D$ are Benelux-sets, and therefore the smallest $n$ for which $S$ can be partitioned into $n$ Benelux-sets is $n=2$.

Remark. Observe that $A \cup C \cup E_{1}$ and $B \cup D \cup E_{2}$ are also Benelux-sets, where $\left\{E_{1}, E_{2}\right\}$ is any partition of $E$.

|

2

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

A finite set of integers is called bad if its elements add up to 2010. A finite set of integers is a Benelux-set if none of its subsets is bad. Determine the smallest integer $n$ such that the set $\{502,503,504, \ldots, 2009\}$ can be partitioned into $n$ Benelux-sets.

(A partition of a set $S$ into $n$ subsets is a collection of $n$ pairwise disjoint subsets of $S$, the union of which equals $S$.)

|

As $502+1508=2010$, the set $S=\{502,503, \ldots, 2009\}$ is not a Benelux-set, so $n=1$ does not work. We will prove that $n=2$ does work, i.e. that $S$ can be partitioned into 2 Benelux-sets.

Define the following subsets of $S$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

& A=\{502,503, \ldots, 670\}, \\

& B=\{671,672, \ldots, 1005\}, \\

& C=\{1006,1007, \ldots, 1339\}, \\

& D=\{1340,1341, \ldots, 1508\}, \\

& E=\{1509,1510, \ldots, 2009\} .

\end{aligned}

$$

We will show that $A \cup C \cup E$ and $B \cup D$ are both Benelux-sets.

Note that there does not exist a bad subset of $S$ of one element, since that element would have to be 2010. Also, there does not exist a bad subset of $S$ of more than three elements, since the sum of four or more elements would be at least $502+503+504+505=2014>2010$. So any possible bad subset of $S$ contains two or three elements.

Consider a bad subset of two elements $a$ and $b$. As $a, b \geq 502$ and $a+b=2010$, we have $a, b \leq 2010-502=1508$. Furthermore, exactly one of $a$ and $b$ is smaller than 1005 and one is larger than 1005. So one of them, say $a$, is an element of $A \cup B$, and the other is an element of $C \cup D$. Suppose $a \in A$, then $b \geq 2010-670=1340$, so $b \in D$. On the other hand, suppose $a \in B$, then $b \leq 2010-671=1339$, so $b \in C$. Hence $\{a, b\}$ cannot be a subset of $A \cup C \cup E$, nor of $B \cup D$.

Now consider a bad subset of three elements $a, b$ and $c$. As $a, b, c \geq 502, a+b+c=2010$, and the three elements are pairwise distinct, we have $a, b, c \leq 2010-502-503=1005$. So $a, b, c \in A \cup B$. At least one of the elements, say $a$, is smaller than $\frac{2010}{3}=670$, and at least one of the elements, say $b$, is larger than 670 . So $a \in A$ and $b \in B$. We conclude that $\{a, b, c\}$ cannot be a subset of $A \cup C \cup E$, nor of $B \cup D$.

This proves that $A \cup C \cup E$ and $B \cup D$ are Benelux-sets, and therefore the smallest $n$ for which $S$ can be partitioned into $n$ Benelux-sets is $n=2$.

Remark. Observe that $A \cup C \cup E_{1}$ and $B \cup D \cup E_{2}$ are also Benelux-sets, where $\left\{E_{1}, E_{2}\right\}$ is any partition of $E$.

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 1.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Find all polynomials $p(x)$ with real coefficients such that

$$

p(a+b-2 c)+p(b+c-2 a)+p(c+a-2 b)=3 p(a-b)+3 p(b-c)+3 p(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

. For $a=b=c$, we have $3 p(0)=9 p(0)$, hence $p(0)=0$. Now set $b=c=0$, then we have

$$

p(a)+p(-2 a)+p(a)=3 p(a)+3 p(-a)

$$

for all $a \in \mathbb{R}$. So we find a polynomial equation

$$

p(-2 x)=p(x)+3 p(-x)

$$

Note that the zero polynomial is a solution to this equation. Now suppose that $p$ is not the zero polynomial, and let $n \geq 0$ be the degree of $p$. Let $a_{n} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{n}$ in $p(x)$. At the left-hand side of (1), the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $(-2)^{n} \cdot a_{n}$, while at the right-hand side the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $a_{n}+3 \cdot(-1)^{n} \cdot a_{n}$. Hence $(-2)^{n}=1+3 \cdot(-1)^{n}$. For $n$ even, we find $2^{n}=4$, so $n=2$, and for $n$ odd, we find $-2^{n}=-2$, so $n=1$. As we already know that $p(0)=0$, we must have $p(x)=a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$, where $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are real numbers (possibly zero).

The polynomial $p(x)=x$ is a solution to our problem, as

$$

(a+b-2 c)+(b+c-2 a)+(c+a-2 b)=0=3(a-b)+3(b-c)+3(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$. Also, $p(x)=x^{2}$ is a solution, since

$$

\begin{aligned}

(a+b-2 c)^{2}+(b+c-2 a)^{2}+(c+a-2 b)^{2} & =6\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-6(a b+b c+c a) \\

& =3(a-b)^{2}+3(b-c)^{2}+3(c-a)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

Now note that if $p(x)$ is a solution to our problem, then so is $\lambda p(x)$ for all $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$. Also, if $p(x)$ and $q(x)$ are both solutions, then so is $p(x)+q(x)$. We conclude that for all real numbers $a_{2}$ and $a_{1}$ the polynomial $a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$ is a solution. Since we have already shown that there can be no other solutions, these are the only solutions.

|

a_{2} x^{2} + a_{1} x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find all polynomials $p(x)$ with real coefficients such that

$$

p(a+b-2 c)+p(b+c-2 a)+p(c+a-2 b)=3 p(a-b)+3 p(b-c)+3 p(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

. For $a=b=c$, we have $3 p(0)=9 p(0)$, hence $p(0)=0$. Now set $b=c=0$, then we have

$$

p(a)+p(-2 a)+p(a)=3 p(a)+3 p(-a)

$$

for all $a \in \mathbb{R}$. So we find a polynomial equation

$$

p(-2 x)=p(x)+3 p(-x)

$$

Note that the zero polynomial is a solution to this equation. Now suppose that $p$ is not the zero polynomial, and let $n \geq 0$ be the degree of $p$. Let $a_{n} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{n}$ in $p(x)$. At the left-hand side of (1), the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $(-2)^{n} \cdot a_{n}$, while at the right-hand side the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $a_{n}+3 \cdot(-1)^{n} \cdot a_{n}$. Hence $(-2)^{n}=1+3 \cdot(-1)^{n}$. For $n$ even, we find $2^{n}=4$, so $n=2$, and for $n$ odd, we find $-2^{n}=-2$, so $n=1$. As we already know that $p(0)=0$, we must have $p(x)=a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$, where $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are real numbers (possibly zero).

The polynomial $p(x)=x$ is a solution to our problem, as

$$

(a+b-2 c)+(b+c-2 a)+(c+a-2 b)=0=3(a-b)+3(b-c)+3(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$. Also, $p(x)=x^{2}$ is a solution, since

$$

\begin{aligned}

(a+b-2 c)^{2}+(b+c-2 a)^{2}+(c+a-2 b)^{2} & =6\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-6(a b+b c+c a) \\

& =3(a-b)^{2}+3(b-c)^{2}+3(c-a)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

Now note that if $p(x)$ is a solution to our problem, then so is $\lambda p(x)$ for all $\lambda \in \mathbb{R}$. Also, if $p(x)$ and $q(x)$ are both solutions, then so is $p(x)+q(x)$. We conclude that for all real numbers $a_{2}$ and $a_{1}$ the polynomial $a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$ is a solution. Since we have already shown that there can be no other solutions, these are the only solutions.

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

Find all polynomials $p(x)$ with real coefficients such that

$$

p(a+b-2 c)+p(b+c-2 a)+p(c+a-2 b)=3 p(a-b)+3 p(b-c)+3 p(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

. For $a=b=c$, we have $3 p(0)=9 p(0)$, hence $p(0)=0$. Now set $b=c=0$, then we have

$$

p(a)+p(-2 a)+p(a)=3 p(a)+3 p(-a)

$$

for all $a \in \mathbb{R}$. So we find a polynomial equation

$$

p(-2 x)=p(x)+3 p(-x)

$$

Define $q(x)=p(x)+p(-x)$, then we find that

$$

q(2 x)=p(2 x)+p(-2 x)=(p(-x)+3 p(x))+(p(x)+3 p(-x))=4 q(x)

$$

Note that the zero polynomial is a solution to this equation. Now suppose that $q$ is not the zero polynomial, and let $m \geq 0$ be the degree of $q$. Let $b_{m} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{m}$ in $q(x)$. At the left-hand side of (3), the coefficient of $x^{m}$ is $2^{m} \cdot b_{m}$, while at the right-hand side the coefficient of $x^{m}$ is $4 b_{m}$. Hence $m=2$. As $q(x)=p(x)+p(-x)$, the polynomial $q(x)$ does not contain any nonzero terms with odd exponent of $x$. Since also $q(0)=2 p(0)=0$, we conclude that

$$

q(x)=b_{2} x^{2}

$$

where $b_{2}$ is a real number (possibly zero).

From (2) we now deduce that $p(2 x)=p(-x)+3 p(x)=2 p(x)+q(x)$, so

$$

p(2 x)-2 p(x)=b_{2} x^{2}

$$

Suppose that that degree $n$ of $p$ is greater than 2 . Let $a_{n} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{n}$ in $p(x)$. At the left-hand side of (4), the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $\left(2^{n}-2\right) \cdot a_{n} \neq 0$. But the coefficient of $x^{n}$ at the right-hand side vanishes, yielding a contradiction. So the degree of $p$ is at most 2 . As we already know that $p(0)=0$, we must have $p(x)=a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$, where $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are real numbers (possibly zero).

We finally check that every polynomial of this form is indeed a solution (see solution 1 ).

|

p(x)=a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Find all polynomials $p(x)$ with real coefficients such that

$$

p(a+b-2 c)+p(b+c-2 a)+p(c+a-2 b)=3 p(a-b)+3 p(b-c)+3 p(c-a)

$$

for all $a, b, c \in \mathbb{R}$.

|

. For $a=b=c$, we have $3 p(0)=9 p(0)$, hence $p(0)=0$. Now set $b=c=0$, then we have

$$

p(a)+p(-2 a)+p(a)=3 p(a)+3 p(-a)

$$

for all $a \in \mathbb{R}$. So we find a polynomial equation

$$

p(-2 x)=p(x)+3 p(-x)

$$

Define $q(x)=p(x)+p(-x)$, then we find that

$$

q(2 x)=p(2 x)+p(-2 x)=(p(-x)+3 p(x))+(p(x)+3 p(-x))=4 q(x)

$$

Note that the zero polynomial is a solution to this equation. Now suppose that $q$ is not the zero polynomial, and let $m \geq 0$ be the degree of $q$. Let $b_{m} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{m}$ in $q(x)$. At the left-hand side of (3), the coefficient of $x^{m}$ is $2^{m} \cdot b_{m}$, while at the right-hand side the coefficient of $x^{m}$ is $4 b_{m}$. Hence $m=2$. As $q(x)=p(x)+p(-x)$, the polynomial $q(x)$ does not contain any nonzero terms with odd exponent of $x$. Since also $q(0)=2 p(0)=0$, we conclude that

$$

q(x)=b_{2} x^{2}

$$

where $b_{2}$ is a real number (possibly zero).

From (2) we now deduce that $p(2 x)=p(-x)+3 p(x)=2 p(x)+q(x)$, so

$$

p(2 x)-2 p(x)=b_{2} x^{2}

$$

Suppose that that degree $n$ of $p$ is greater than 2 . Let $a_{n} \neq 0$ be the coefficient of $x^{n}$ in $p(x)$. At the left-hand side of (4), the coefficient of $x^{n}$ is $\left(2^{n}-2\right) \cdot a_{n} \neq 0$. But the coefficient of $x^{n}$ at the right-hand side vanishes, yielding a contradiction. So the degree of $p$ is at most 2 . As we already know that $p(0)=0$, we must have $p(x)=a_{2} x^{2}+a_{1} x$, where $a_{1}$ and $a_{2}$ are real numbers (possibly zero).

We finally check that every polynomial of this form is indeed a solution (see solution 1 ).

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 2.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

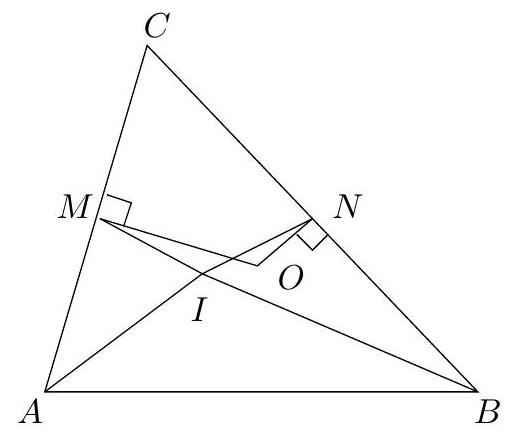

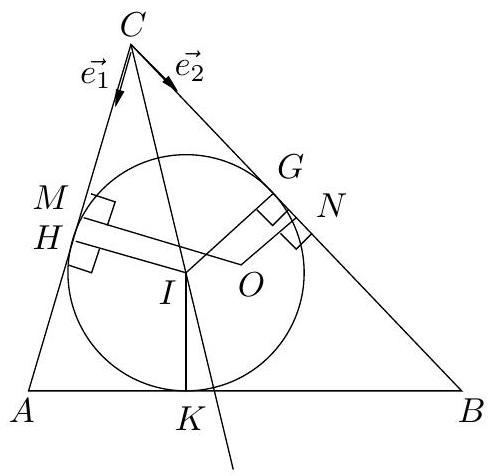

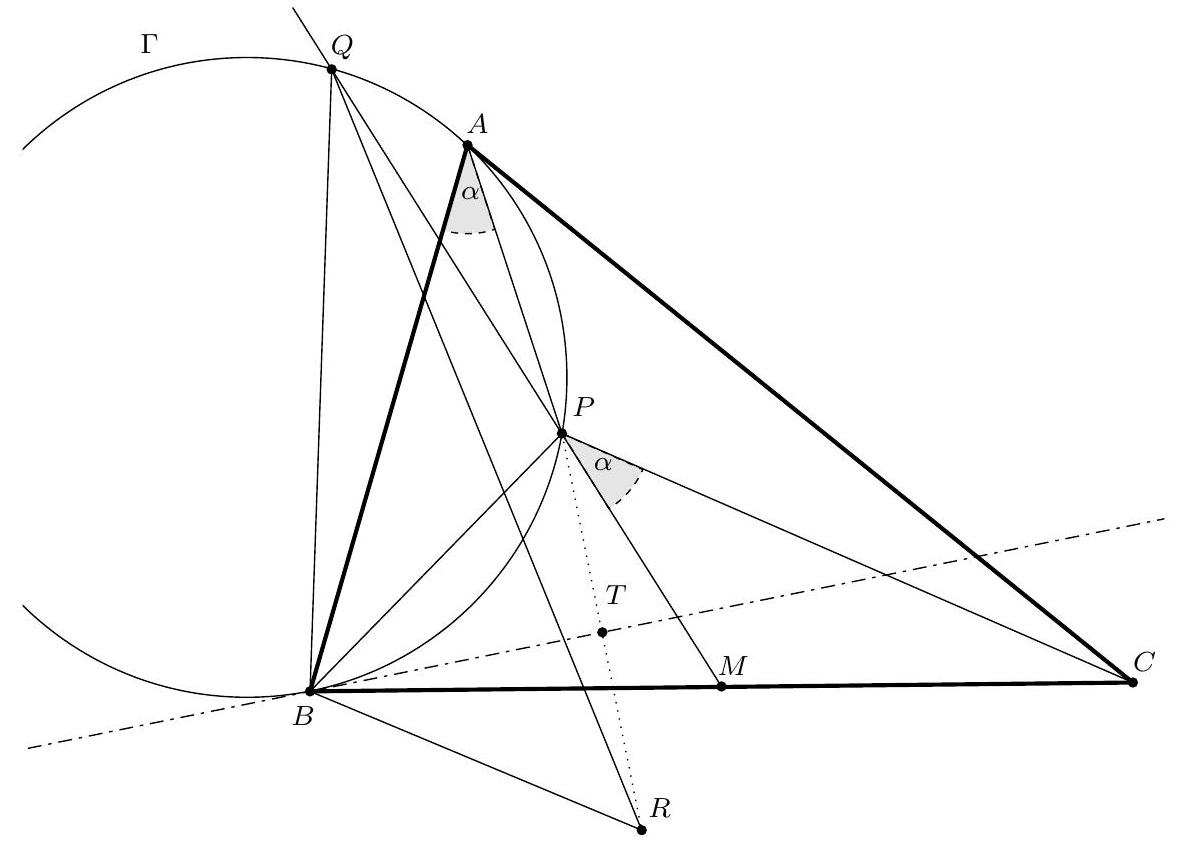

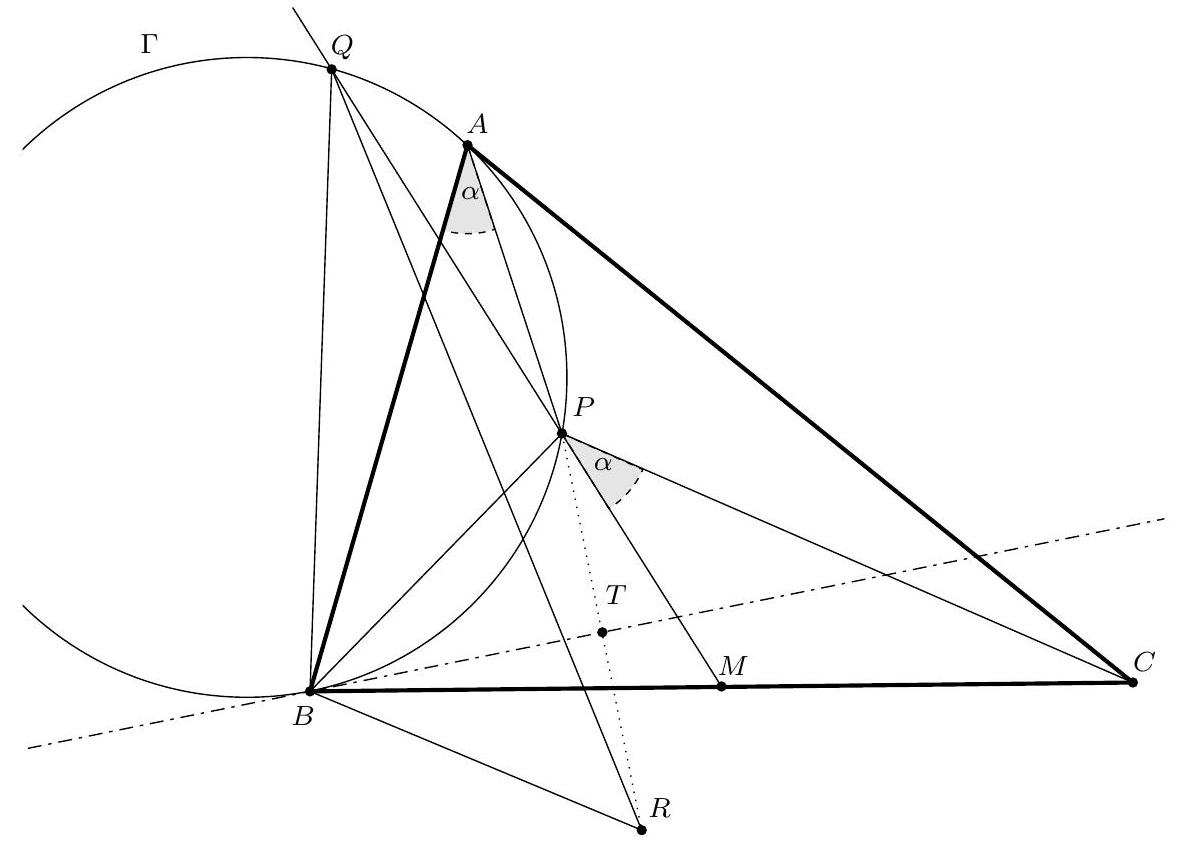

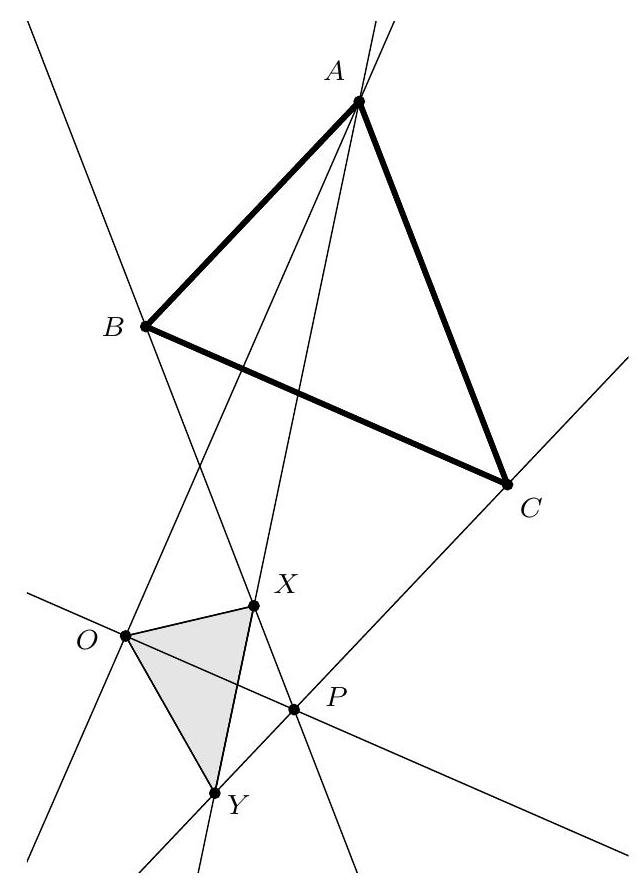

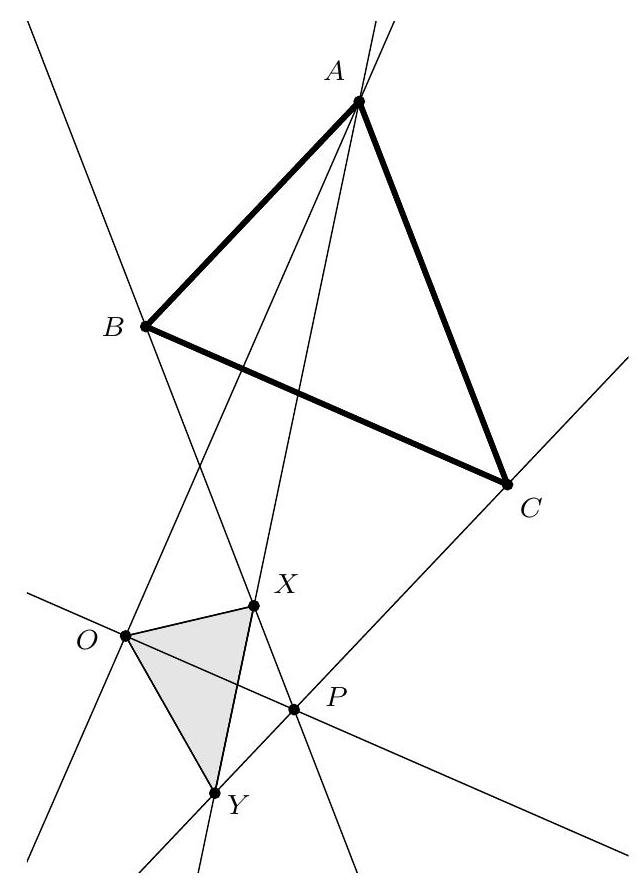

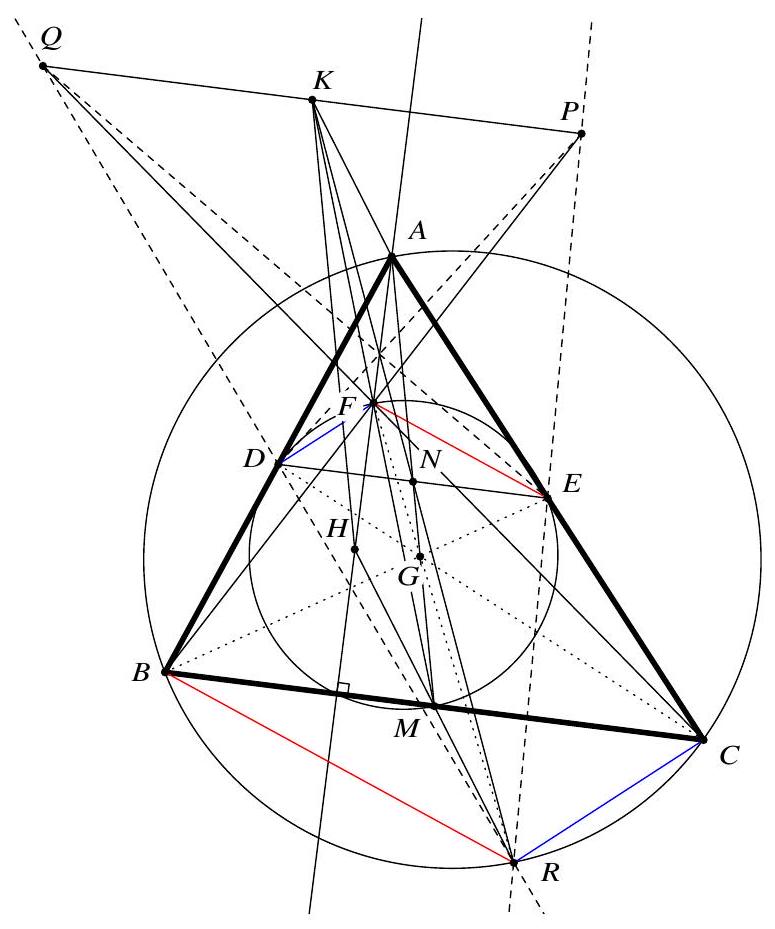

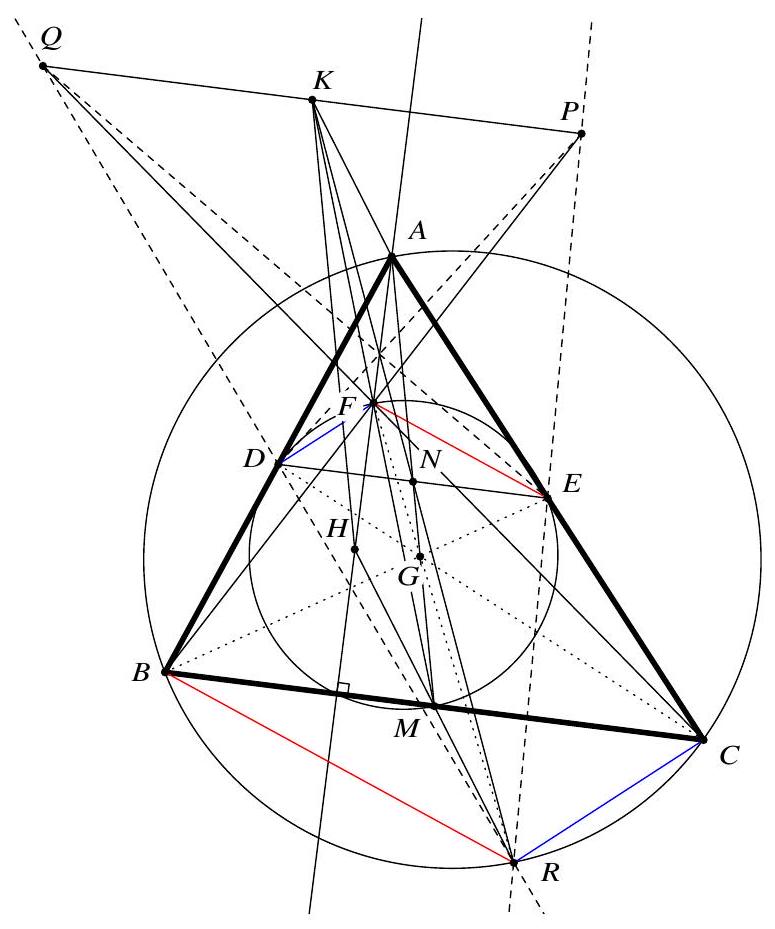

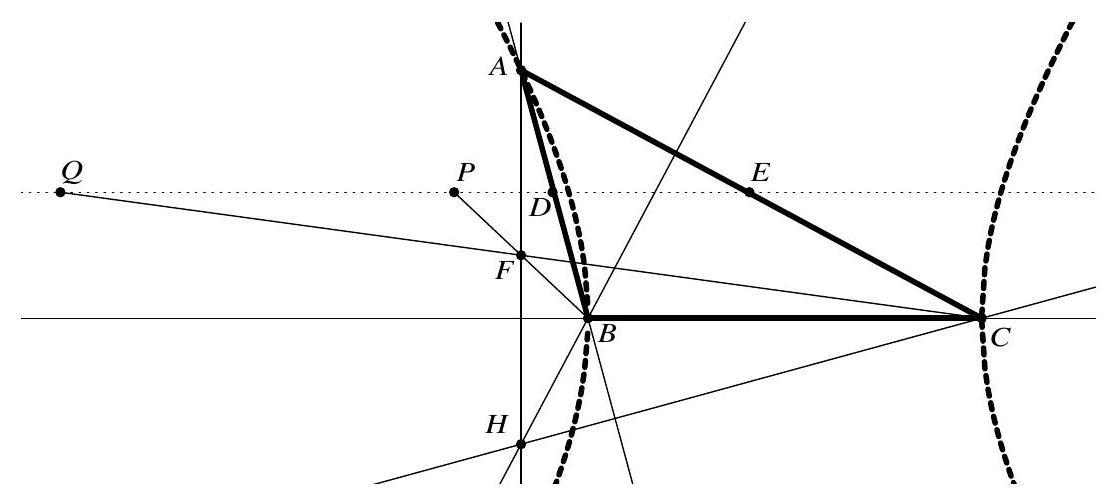

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

.

(a) Since $P, R$ and $Q$ are collinear, we have $\triangle P A Q \sim \triangle P B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|A Q|}{|B R|}=\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}

$$

Conversely, $P, T$ and $S$ are collinear if it holds that

$$

\frac{|A S|}{|B T|}=\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}

$$

So it suffices to prove

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B R|}=\frac{|A S|}{|A Q|}

$$

Since $\angle A B T=90^{\circ}=\angle A L B$ and $\angle T A B=\angle B A L$, we have $\triangle A B T \sim \triangle A L B$. And since $\angle A L B=90^{\circ}=\angle Q A B$ and $\angle L B A=\angle A B Q$, we have $\triangle A L B \sim \triangle Q A B$. Hence $\triangle A B T \sim \triangle Q A B$, so

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B A|}=\frac{|A B|}{|A Q|}

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A B R \sim \triangle A K B \sim \triangle S A B$, so

$$

\frac{|B R|}{|B A|}=\frac{|A B|}{|A S|}

$$

Combining both results, we get

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B R|}=\frac{|B T| /|B A|}{|B R| /|B A|}=\frac{|A B| /|A Q|}{|A B| /|A S|}=\frac{|A S|}{|A Q|}

$$

which had to be proved.

(b) Let the line $P K$ intersect $B R$ in $B_{1}$ and $A Q$ in $A_{1}$ and let the line $P L$ intersect $B R$ in $B_{2}$ and $A Q$ in $A_{2}$. Consider the points $A_{1}, A$ and $S$ on the line $A Q$, and the points $B_{1}, B$ and $T$ on the line $B R$. As $A Q \| B R$ and the three lines $A_{1} B_{1}, A B$ and $S T$ are concurrent (in $P$ ), we have

$$

A_{1} A: A S=B_{1} B: B T

$$

where all lengths are directed. Similarly, as $A_{1} B_{1}, A R$ and $S B$ are concurrent (in $K$ ), we have

$$

A_{1} A: A S=B_{1} R: R B

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{B B_{1}}{B T}=\frac{R B_{1}}{R B}=\frac{R B+B B_{1}}{R B}=1+\frac{B B_{1}}{R B}=1-\frac{B B_{1}}{B R}

$$

so

$$

B B_{1}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{B T}+\frac{1}{B R}} .

$$

Similary, using the lines $A_{2} B_{2}, A B$ and $Q R$ (concurrent in $P$ ) and the lines $A_{2} B_{2}$, $A T$ and $Q B$ (concurrent in $L$ ), we find

$$

B_{2} B: B R=A_{2} A: A Q=B_{2} T: T B

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{B B_{2}}{B R}=\frac{T B_{2}}{T B}=\frac{T B+B B_{2}}{T B}=1+\frac{B B_{2}}{T B}=1-\frac{B B_{2}}{B T}

$$

so

$$

B B_{2}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{B R}+\frac{1}{B T}}

$$

We conclude that $B_{1}=B_{2}$, which implies that $P, K$ and $L$ are collinear.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

.

(a) Since $P, R$ and $Q$ are collinear, we have $\triangle P A Q \sim \triangle P B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|A Q|}{|B R|}=\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}

$$

Conversely, $P, T$ and $S$ are collinear if it holds that

$$

\frac{|A S|}{|B T|}=\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}

$$

So it suffices to prove

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B R|}=\frac{|A S|}{|A Q|}

$$

Since $\angle A B T=90^{\circ}=\angle A L B$ and $\angle T A B=\angle B A L$, we have $\triangle A B T \sim \triangle A L B$. And since $\angle A L B=90^{\circ}=\angle Q A B$ and $\angle L B A=\angle A B Q$, we have $\triangle A L B \sim \triangle Q A B$. Hence $\triangle A B T \sim \triangle Q A B$, so

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B A|}=\frac{|A B|}{|A Q|}

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A B R \sim \triangle A K B \sim \triangle S A B$, so

$$

\frac{|B R|}{|B A|}=\frac{|A B|}{|A S|}

$$

Combining both results, we get

$$

\frac{|B T|}{|B R|}=\frac{|B T| /|B A|}{|B R| /|B A|}=\frac{|A B| /|A Q|}{|A B| /|A S|}=\frac{|A S|}{|A Q|}

$$

which had to be proved.

(b) Let the line $P K$ intersect $B R$ in $B_{1}$ and $A Q$ in $A_{1}$ and let the line $P L$ intersect $B R$ in $B_{2}$ and $A Q$ in $A_{2}$. Consider the points $A_{1}, A$ and $S$ on the line $A Q$, and the points $B_{1}, B$ and $T$ on the line $B R$. As $A Q \| B R$ and the three lines $A_{1} B_{1}, A B$ and $S T$ are concurrent (in $P$ ), we have

$$

A_{1} A: A S=B_{1} B: B T

$$

where all lengths are directed. Similarly, as $A_{1} B_{1}, A R$ and $S B$ are concurrent (in $K$ ), we have

$$

A_{1} A: A S=B_{1} R: R B

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{B B_{1}}{B T}=\frac{R B_{1}}{R B}=\frac{R B+B B_{1}}{R B}=1+\frac{B B_{1}}{R B}=1-\frac{B B_{1}}{B R}

$$

so

$$

B B_{1}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{B T}+\frac{1}{B R}} .

$$

Similary, using the lines $A_{2} B_{2}, A B$ and $Q R$ (concurrent in $P$ ) and the lines $A_{2} B_{2}$, $A T$ and $Q B$ (concurrent in $L$ ), we find

$$

B_{2} B: B R=A_{2} A: A Q=B_{2} T: T B

$$

This gives

$$

\frac{B B_{2}}{B R}=\frac{T B_{2}}{T B}=\frac{T B+B B_{2}}{T B}=1+\frac{B B_{2}}{T B}=1-\frac{B B_{2}}{B T}

$$

so

$$

B B_{2}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{B R}+\frac{1}{B T}}

$$

We conclude that $B_{1}=B_{2}$, which implies that $P, K$ and $L$ are collinear.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 1",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

.

(a) Define $X$ as the intersection of $A T$ and $B S$, and $Y$ as the intersection of $A R$ and $B Q$. To prove that $P, S$ and $T$ are collinear, we will use Menelaos' theorem in $\triangle A B X$, so we have to prove

$$

\frac{A P}{P B} \frac{B S}{S X} \frac{X T}{T A}=-1

$$

Note that $B$ is between $P$ and $A, X$ is between $S$ and $B$, and $X$ is between $T$ and $A$, so it suffices to prove that

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|}=1

$$

Because $A Q$ and $B R$ are parallel, we have $\triangle A Q P \sim \triangle B R P$, hence

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}=\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|}

$$

Also, since $\angle A S B=\angle K B R$ and $\angle B A S=90^{\circ}=\angle B K R$, we have $\triangle A S B \sim$ $\triangle K B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|B S|}{|R B|}=\frac{|A S|}{|K B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|B S|=\frac{|A S|}{|K B|}|R B| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A T B \sim \triangle Q A L$, hence

$$

\frac{|T A|}{|A Q|}=\frac{|T B|}{|A L|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|T A|=\frac{|T B|}{|A L|}|A Q| \text {. }

$$

As $\angle A S X=\angle A S B=90^{\circ}-\angle A B S=90^{\circ}-\angle A B K=\angle K A B=\angle Y A B$, and $\angle S A X=90^{\circ}-\angle X A B=90^{\circ}-\angle L A B=\angle A B L=\angle A B Y$, we have $\triangle S X A \sim$ $\triangle A Y B$, hence

$$

\frac{|S X|}{|A Y|}=\frac{|A S|}{|B A|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|S X|=\frac{|A S|}{|B A|}|A Y| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle B X T \sim \triangle A Y B$, hence

$$

\frac{|X T|}{|Y B|}=\frac{|B T|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|X T|=\frac{|B T|}{|A B|}|Y B| \text {. }

$$

By combining (5) - (9), we find

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|} & =\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|} \cdot \frac{|A S|}{|K B|}|R B| \cdot \frac{|B A|}{|A S||A Y|} \cdot \frac{|B T|}{|A B|}|Y B| \cdot \frac{|A L|}{|T B||A Q|} \\

& =\frac{|A L|}{|K B|} \frac{|Y B|}{|A Y|} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Since $\angle Y L A=90^{\circ}=\angle Y K B$ and $\angle A Y L=\angle B Y K$, we have $\triangle A Y L \sim \triangle B Y K$, hence

$$

\frac{|A L|}{|B K|}=\frac{|A Y|}{|B Y|}, \quad \text { so } \quad \frac{|A L|}{|B K|} \frac{|B Y|}{|A Y|}=1

$$

By combining (10) and (11), we find

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|}=1,

$$

as we wanted to prove.

(b) Again, we will use Menelaos' theorem in $\triangle A B X$, so we have to prove

$$

\frac{A P}{P B} \frac{B K}{K X} \frac{X L}{L A}=-1

$$

Note that $\frac{A P}{P B}<0$, and $\frac{B K}{K X}<0$ if and only if $\frac{X L}{L A}<0$, so it suffices to prove that

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B K|}{|K X|} \frac{|X L|}{|L A|}=1

$$

As $\angle B X L=\angle A X K$ and $\angle B L X=90^{\circ}=\angle A K X$, we have $\triangle B L X \sim \triangle A K X$, hence

$$

\frac{|X L|}{|X K|}=\frac{|B L|}{|A K|}

$$

Since $\angle A L B=90^{\circ}=\angle Q A B$, we have $\triangle A L B \sim \triangle Q A B$, hence

$$

\frac{|L A|}{|A Q|}=\frac{|L B|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|L A|=\frac{|L B|}{|A B|}|A Q| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A K B \sim \triangle A B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|B K|}{|R B|}=\frac{|A K|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|B K|=\frac{|A K|}{|A B|}|R B|

$$

By combining (5) and (12) - (14), we find

$$

\left.\frac{|A P|}{|P B|}\left|\frac{|B K|}{|K X|} \frac{|X L|}{|L A|}=\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|} \cdot \frac{|B L|}{|A K|} \cdot \frac{|A B|}{|L B||A Q|} \cdot \frac{|A K|}{|A B|}\right| R B \right\rvert\,=1,

$$

which is what we wanted to prove.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

.

(a) Define $X$ as the intersection of $A T$ and $B S$, and $Y$ as the intersection of $A R$ and $B Q$. To prove that $P, S$ and $T$ are collinear, we will use Menelaos' theorem in $\triangle A B X$, so we have to prove

$$

\frac{A P}{P B} \frac{B S}{S X} \frac{X T}{T A}=-1

$$

Note that $B$ is between $P$ and $A, X$ is between $S$ and $B$, and $X$ is between $T$ and $A$, so it suffices to prove that

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|}=1

$$

Because $A Q$ and $B R$ are parallel, we have $\triangle A Q P \sim \triangle B R P$, hence

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|B P|}=\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|}

$$

Also, since $\angle A S B=\angle K B R$ and $\angle B A S=90^{\circ}=\angle B K R$, we have $\triangle A S B \sim$ $\triangle K B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|B S|}{|R B|}=\frac{|A S|}{|K B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|B S|=\frac{|A S|}{|K B|}|R B| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A T B \sim \triangle Q A L$, hence

$$

\frac{|T A|}{|A Q|}=\frac{|T B|}{|A L|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|T A|=\frac{|T B|}{|A L|}|A Q| \text {. }

$$

As $\angle A S X=\angle A S B=90^{\circ}-\angle A B S=90^{\circ}-\angle A B K=\angle K A B=\angle Y A B$, and $\angle S A X=90^{\circ}-\angle X A B=90^{\circ}-\angle L A B=\angle A B L=\angle A B Y$, we have $\triangle S X A \sim$ $\triangle A Y B$, hence

$$

\frac{|S X|}{|A Y|}=\frac{|A S|}{|B A|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|S X|=\frac{|A S|}{|B A|}|A Y| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle B X T \sim \triangle A Y B$, hence

$$

\frac{|X T|}{|Y B|}=\frac{|B T|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|X T|=\frac{|B T|}{|A B|}|Y B| \text {. }

$$

By combining (5) - (9), we find

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|} & =\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|} \cdot \frac{|A S|}{|K B|}|R B| \cdot \frac{|B A|}{|A S||A Y|} \cdot \frac{|B T|}{|A B|}|Y B| \cdot \frac{|A L|}{|T B||A Q|} \\

& =\frac{|A L|}{|K B|} \frac{|Y B|}{|A Y|} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Since $\angle Y L A=90^{\circ}=\angle Y K B$ and $\angle A Y L=\angle B Y K$, we have $\triangle A Y L \sim \triangle B Y K$, hence

$$

\frac{|A L|}{|B K|}=\frac{|A Y|}{|B Y|}, \quad \text { so } \quad \frac{|A L|}{|B K|} \frac{|B Y|}{|A Y|}=1

$$

By combining (10) and (11), we find

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B S|}{|S X|} \frac{|X T|}{|T A|}=1,

$$

as we wanted to prove.

(b) Again, we will use Menelaos' theorem in $\triangle A B X$, so we have to prove

$$

\frac{A P}{P B} \frac{B K}{K X} \frac{X L}{L A}=-1

$$

Note that $\frac{A P}{P B}<0$, and $\frac{B K}{K X}<0$ if and only if $\frac{X L}{L A}<0$, so it suffices to prove that

$$

\frac{|A P|}{|P B|} \frac{|B K|}{|K X|} \frac{|X L|}{|L A|}=1

$$

As $\angle B X L=\angle A X K$ and $\angle B L X=90^{\circ}=\angle A K X$, we have $\triangle B L X \sim \triangle A K X$, hence

$$

\frac{|X L|}{|X K|}=\frac{|B L|}{|A K|}

$$

Since $\angle A L B=90^{\circ}=\angle Q A B$, we have $\triangle A L B \sim \triangle Q A B$, hence

$$

\frac{|L A|}{|A Q|}=\frac{|L B|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|L A|=\frac{|L B|}{|A B|}|A Q| \text {. }

$$

Similarly, we have $\triangle A K B \sim \triangle A B R$, hence

$$

\frac{|B K|}{|R B|}=\frac{|A K|}{|A B|}, \quad \text { so } \quad|B K|=\frac{|A K|}{|A B|}|R B|

$$

By combining (5) and (12) - (14), we find

$$

\left.\frac{|A P|}{|P B|}\left|\frac{|B K|}{|K X|} \frac{|X L|}{|L A|}=\frac{|Q A|}{|R B|} \cdot \frac{|B L|}{|A K|} \cdot \frac{|A B|}{|L B||A Q|} \cdot \frac{|A K|}{|A B|}\right| R B \right\rvert\,=1,

$$

which is what we wanted to prove.

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Solution 2",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

. As $\angle A K B=\angle A L B=90^{\circ}$, the points $K$ and $L$ belong to the circle with diameter $A B$. Since $\angle Q A B=\angle A B R=90^{\circ}$, the lines $A Q$ and $B R$ are tangents to this circle.

Apply Pascal's theorem to the points $A, A, K, L, B$ and $B$, all on the same circle. This yields that the intersection $Q$ of the tangent in $A$ and the line $B L$, the intersection $R$ of the tangent in $B$ and the line $A K$, and the intersection of $K L$ and $A B$ are collinear. So $K L$ passes through the intersection of $A B$ and $Q R$, which is point $P$. Hence $P, K$ and $L$ are collinear. This proves part b.

Now apply Pascal's theorem to the points $A, A, L, K, B$ and $B$. This yields that the intersection $S$ of the tangent in $A$ and the line $B K$, the intersection $T$ of the tangent in $B$ and the line $A L$, and the intersection $P$ of $K L$ and $A B$ are collinear. This proves part a.

#

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

. As $\angle A K B=\angle A L B=90^{\circ}$, the points $K$ and $L$ belong to the circle with diameter $A B$. Since $\angle Q A B=\angle A B R=90^{\circ}$, the lines $A Q$ and $B R$ are tangents to this circle.

Apply Pascal's theorem to the points $A, A, K, L, B$ and $B$, all on the same circle. This yields that the intersection $Q$ of the tangent in $A$ and the line $B L$, the intersection $R$ of the tangent in $B$ and the line $A K$, and the intersection of $K L$ and $A B$ are collinear. So $K L$ passes through the intersection of $A B$ and $Q R$, which is point $P$. Hence $P, K$ and $L$ are collinear. This proves part b.

Now apply Pascal's theorem to the points $A, A, L, K, B$ and $B$. This yields that the intersection $S$ of the tangent in $A$ and the line $B K$, the intersection $T$ of the tangent in $B$ and the line $A L$, and the intersection $P$ of $K L$ and $A B$ are collinear. This proves part a.

#

|

{

"exam": "Benelux_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nProblem 3.",

"resource_path": "Benelux_MO/segmented/Benelux_en-olympiad_en-bxmo-problems-2010-zz.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 3",

"tier": "T3",

"year": "2010"

}

|

On a line $l$ there are three different points $A, B$ and $P$ in that order. Let $a$ be the line through $A$ perpendicular to $l$, and let $b$ be the line through $B$ perpendicular to $l$. A line through $P$, not coinciding with $l$, intersects $a$ in $Q$ and $b$ in $R$. The line through $A$ perpendicular to $B Q$ intersects $B Q$ in $L$ and $B R$ in $T$. The line through $B$ perpendicular to $A R$ intersects $A R$ in $K$ and $A Q$ in $S$.

(a) Prove that $P, T, S$ are collinear.

(b) Prove that $P, K, L$ are collinear.

#

|

.

(a) W.l.o.g. we may assume that $A=(0,0)$ and $B=(1,0)$ and the line through $P$ is in the upper half plane, so $l$ is the $x$-axis, $a$ is the $y$-axis and $b$ is the line $x=1$. Take $P=(p, 0)(p>1)$ and $Q=(0, q)(q>0)$. Since $P Q$ is given by $\frac{x}{p}+\frac{y}{q}=1$, we find $R=\left(1, \frac{q(p-1)}{p}\right)$.

Now $A R$ is given by $y=\frac{q(p-1)}{p} x$, hence $B S$, the line perpendicular to $A R$ and passing through $B=(1,0)$, is given by $y=-\frac{p}{q(p-1)}(x-1)$. We find $S=\left(0, \frac{p}{q(p-1)}\right)$.

Moreover $B Q$ is given by $y=-q(x-1)$, hence $A T$, the line perpendicular to $B Q$ and passing through $A=(0,0)$, is given by $y=\frac{1}{q} x$. We find $T=\left(1, \frac{1}{q}\right)$. Since $\frac{|B T|}{|B P|}=\frac{1 / q}{p-1}=\frac{\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}{p}=\frac{|A S|}{|A P|}$, we conclude that $P, T$ and $S$ are collinear.

(b) Point $K$ is the intersection of $A R$ and $B S$. Solving for $x$ yields

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{q(p-1)}{p} x & =-\frac{p}{q(p-1)}(x-1) \\

\left(\frac{q(p-1)}{p}+\frac{p}{q(p-1)}\right) x & =\frac{p}{q(p-1)} \\

x & =\frac{\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}{\frac{q(p-1)}{p}+\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}

\end{aligned}

$$

so

$$

K=\left(\frac{\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}{\frac{q(p-1)}{p}+\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}, \frac{1}{\frac{q(p-1)}{p}+\frac{p}{q(p-1)}}\right)

$$

Point $L$ is the point of intersection of $A T$ and $B Q$. Solving for $x$ yields

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{q} x & =-q(x-1) \\

\left(\frac{1}{q}+q\right) x & =q \\

x & =\frac{q}{\frac{1}{q}+q}

\end{aligned}

$$

so

$$

L=\left(\frac{q}{\frac{1}{q}+q}, \frac{1}{\frac{1}{q}+q}\right)

$$