problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Let $T$ be the set of all positive integer divisors of $2004^{100}$. What is the largest possible number of elements that a subset $S$ of $T$ can have if no element of $S$ is an integer multiple of any other element of $S$ ?

|

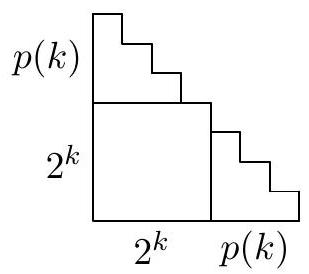

Assume throughout that $a, b, c$ are nonnegative integers. Since the prime factorization of 2004 is $2004=2^{2} \cdot 3 \cdot 167$,

$$

T=\left\{2^{a} 3^{b} 167^{c} \mid 0 \leq a \leq 200,0 \leq b, c \leq 100\right\}

$$

Let

$$

S=\left\{2^{200-b-c} 3^{b} 167^{c} \mid 0 \leq b, c \leq 100\right\}

$$

For any $0 \leq b, c \leq 100$, we have $0 \leq 200-b-c \leq 200$, so $S$ is a subset of $T$. Since there are 101 possible values for $b$ and 101 possible values for $c, S$ contains $101^{2}$ elements. We will show that no element of $S$ is a multiple of another and that no larger subset of $T$ satisfies this condition.

Suppose $2^{200-b-c} 3^{b} 167^{c}$ is an integer multiple of $2^{200-j-k} 3^{j} 167^{k}$. Then

$$

200-b-c \geq 200-j-k, \quad b \geq j, \quad c \geq k

$$

But this first inequality implies $b+c \leq j+k$, which together with $b \geq j, c \geq k$ gives $b=j$ and $c=k$. Hence no element of $S$ is an integer multiple of another element of $S$.

Let $U$ be a subset of $T$ with more than $101^{2}$ elements. Since there are only $101^{2}$ distinct pairs $(b, c)$ with $0 \leq b, c \leq 100$, then (by the pigeonhole principle) $U$ must contain two elements $u_{1}=2^{a_{1}} 3^{b_{1}} 167^{c_{1}}$ and $u_{2}=2^{a_{2}} 3^{b_{2}} 167^{c_{2}}$, with $b_{1}=b_{2}$ and $c_{1}=c_{2}$, but $a_{1} \neq a_{2}$. If $a_{1}>a_{2}$, then $u_{1}$ is a multiple of $u_{2}$ and if $a_{1}<a_{2}$, then $u_{2}$ is a multiple of $u_{1}$. Hence $U$ does not satisfy the desired condition.

Therefore the largest possible number of elements that such a subset of $T$ can have is $101^{2}=10201$.

|

10201

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let $T$ be the set of all positive integer divisors of $2004^{100}$. What is the largest possible number of elements that a subset $S$ of $T$ can have if no element of $S$ is an integer multiple of any other element of $S$ ?

|

Assume throughout that $a, b, c$ are nonnegative integers. Since the prime factorization of 2004 is $2004=2^{2} \cdot 3 \cdot 167$,

$$

T=\left\{2^{a} 3^{b} 167^{c} \mid 0 \leq a \leq 200,0 \leq b, c \leq 100\right\}

$$

Let

$$

S=\left\{2^{200-b-c} 3^{b} 167^{c} \mid 0 \leq b, c \leq 100\right\}

$$

For any $0 \leq b, c \leq 100$, we have $0 \leq 200-b-c \leq 200$, so $S$ is a subset of $T$. Since there are 101 possible values for $b$ and 101 possible values for $c, S$ contains $101^{2}$ elements. We will show that no element of $S$ is a multiple of another and that no larger subset of $T$ satisfies this condition.

Suppose $2^{200-b-c} 3^{b} 167^{c}$ is an integer multiple of $2^{200-j-k} 3^{j} 167^{k}$. Then

$$

200-b-c \geq 200-j-k, \quad b \geq j, \quad c \geq k

$$

But this first inequality implies $b+c \leq j+k$, which together with $b \geq j, c \geq k$ gives $b=j$ and $c=k$. Hence no element of $S$ is an integer multiple of another element of $S$.

Let $U$ be a subset of $T$ with more than $101^{2}$ elements. Since there are only $101^{2}$ distinct pairs $(b, c)$ with $0 \leq b, c \leq 100$, then (by the pigeonhole principle) $U$ must contain two elements $u_{1}=2^{a_{1}} 3^{b_{1}} 167^{c_{1}}$ and $u_{2}=2^{a_{2}} 3^{b_{2}} 167^{c_{2}}$, with $b_{1}=b_{2}$ and $c_{1}=c_{2}$, but $a_{1} \neq a_{2}$. If $a_{1}>a_{2}$, then $u_{1}$ is a multiple of $u_{2}$ and if $a_{1}<a_{2}$, then $u_{2}$ is a multiple of $u_{1}$. Hence $U$ does not satisfy the desired condition.

Therefore the largest possible number of elements that such a subset of $T$ can have is $101^{2}=10201$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2004.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution\n\n",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2004"

}

|

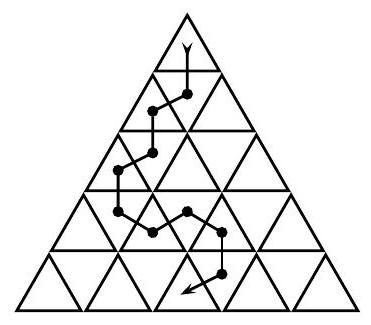

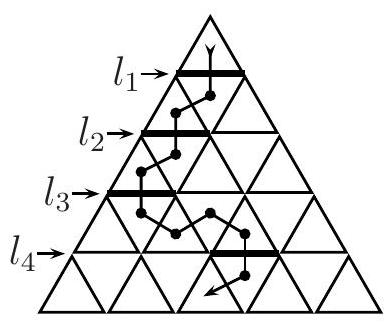

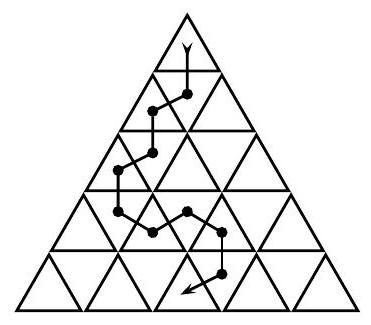

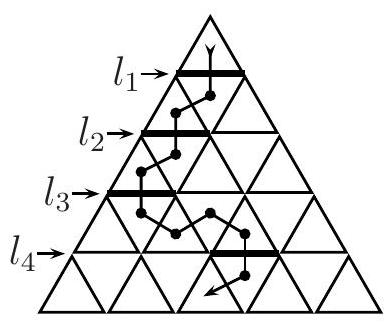

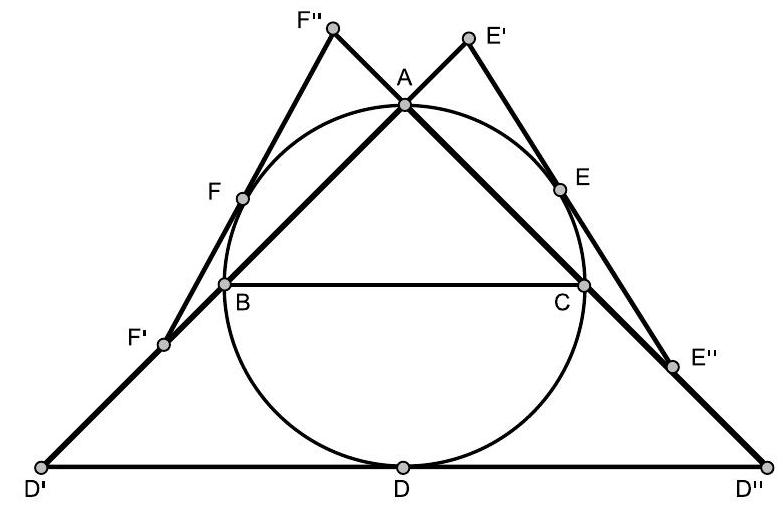

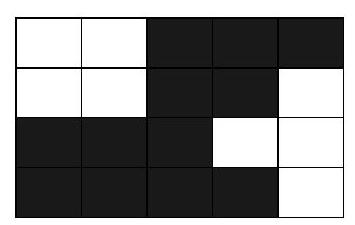

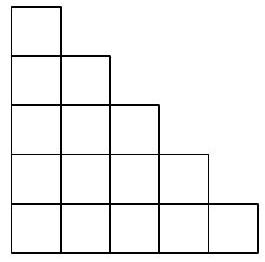

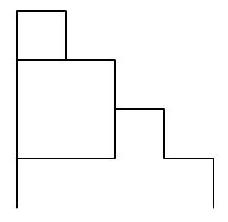

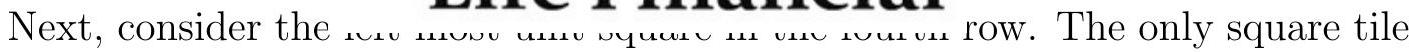

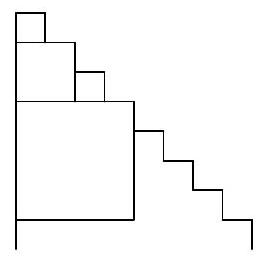

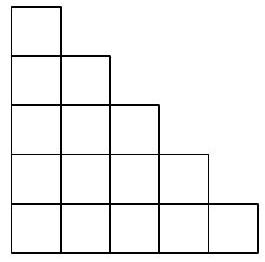

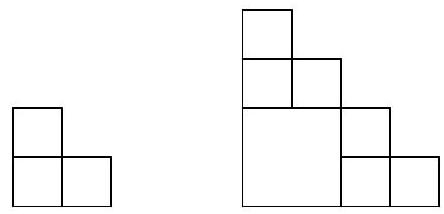

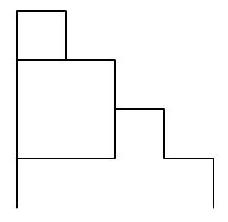

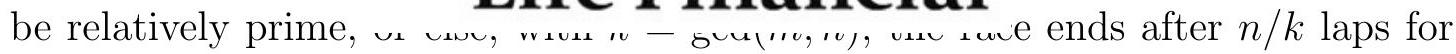

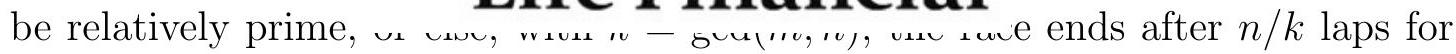

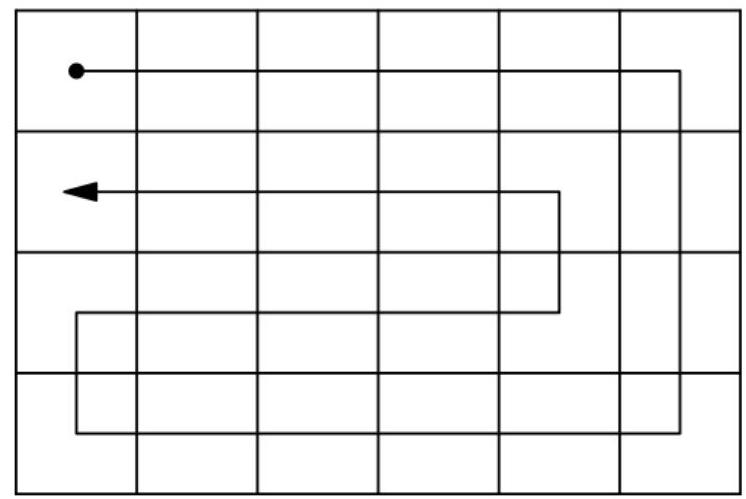

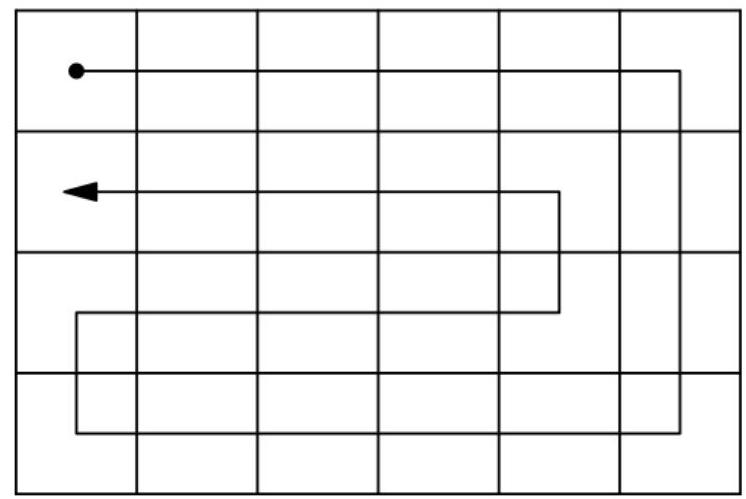

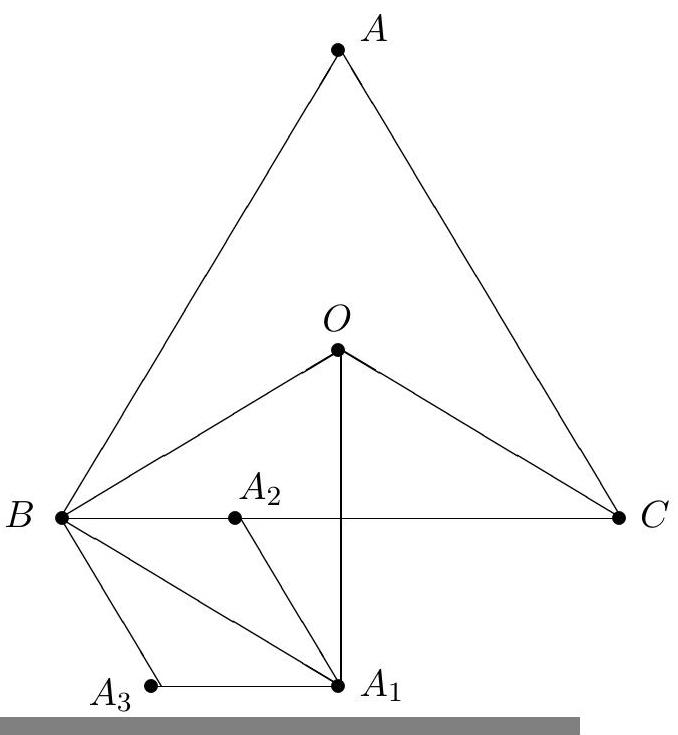

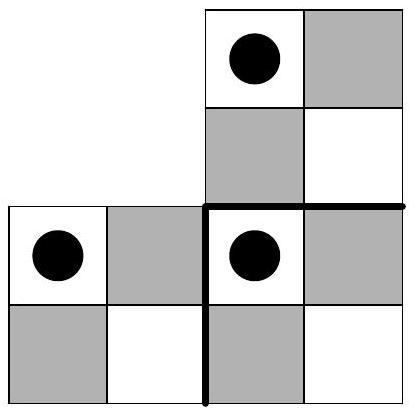

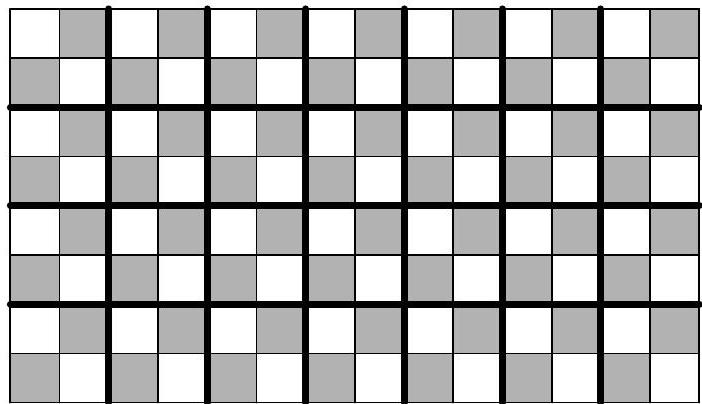

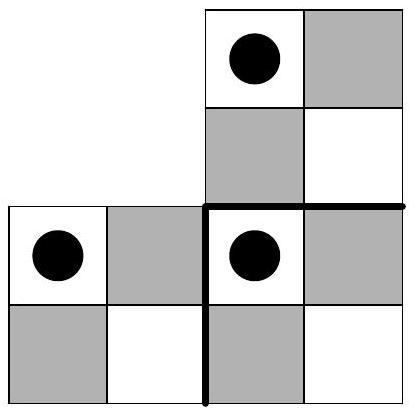

Consider an equilateral triangle of side length $n$, which is divided into unit triangles, as shown. Let $f(n)$ be the number of paths from the triangle in the top row to the middle triangle in the bottom row, such that adjacent triangles in our path share a common edge and the path never travels up (from a lower row to a higher row) or revisits a triangle. An example of one such path is illustrated below for $n=5$. Determine the value of $f(2005)$.

|

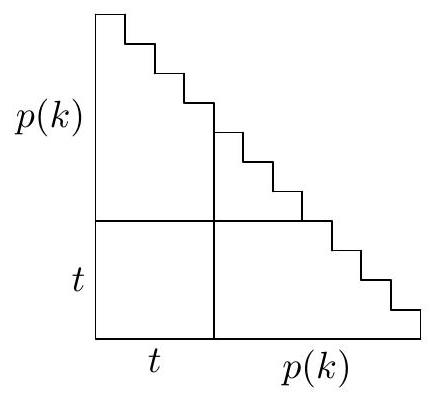

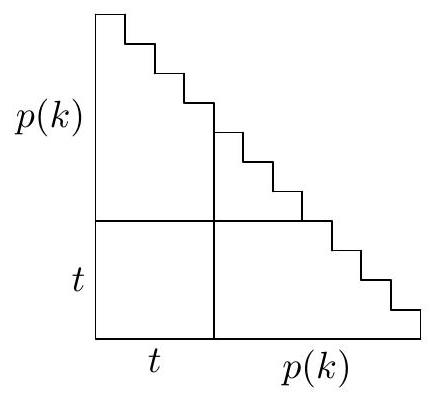

We shall show that $f(n)=(n-1)$ !.

Label the horizontal line segments in the triangle $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots$ as in the diagram below. Since the path goes from the top triangle to a triangle in the bottom row and never travels up, the path must cross each of $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots, l_{n-1}$ exactly once. The diagonal lines in the triangle divide $l_{k}$ into $k$ unit line segments and the path must cross exactly one of these $k$ segments for each $k$. (In the diagram below, these line segments have been highlighted.) The path is completely determined by the set of $n-1$ line segments which are crossed. So as the path moves from the $k$ th row to the $(k+1)$ st row, there are $k$ possible line segments where the path could cross $l_{k}$. Since there are $1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots(n-1)=(n-1)$ ! ways that the path could cross the $n-1$ horizontal lines, and each one corresponds to a unique path, we get $f(n)=(n-1)$ !.

Therefore $f(2005)=(2004)$ !.

|

2004!

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Consider an equilateral triangle of side length $n$, which is divided into unit triangles, as shown. Let $f(n)$ be the number of paths from the triangle in the top row to the middle triangle in the bottom row, such that adjacent triangles in our path share a common edge and the path never travels up (from a lower row to a higher row) or revisits a triangle. An example of one such path is illustrated below for $n=5$. Determine the value of $f(2005)$.

|

We shall show that $f(n)=(n-1)$ !.

Label the horizontal line segments in the triangle $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots$ as in the diagram below. Since the path goes from the top triangle to a triangle in the bottom row and never travels up, the path must cross each of $l_{1}, l_{2}, \ldots, l_{n-1}$ exactly once. The diagonal lines in the triangle divide $l_{k}$ into $k$ unit line segments and the path must cross exactly one of these $k$ segments for each $k$. (In the diagram below, these line segments have been highlighted.) The path is completely determined by the set of $n-1$ line segments which are crossed. So as the path moves from the $k$ th row to the $(k+1)$ st row, there are $k$ possible line segments where the path could cross $l_{k}$. Since there are $1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdots(n-1)=(n-1)$ ! ways that the path could cross the $n-1$ horizontal lines, and each one corresponds to a unique path, we get $f(n)=(n-1)$ !.

Therefore $f(2005)=(2004)$ !.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution\n\n",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

Defining $\theta$ as in Solution 1, we have $c / a+c / b=\sec \theta+\csc \theta$. By the AM-GM inequality, we have $(\sec \theta+\csc \theta) / 2 \geq \sqrt{\sec \theta \csc \theta}$. So

$$

c / a+c / b \geq \frac{2}{\sqrt{\sin \theta \cos \theta}}=\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{\sin 2 \theta}} \geq 2 \sqrt{2}

$$

Since $a, b, c$ are integers, we have $c / a+c / b>2 \sqrt{2}$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

Defining $\theta$ as in Solution 1, we have $c / a+c / b=\sec \theta+\csc \theta$. By the AM-GM inequality, we have $(\sec \theta+\csc \theta) / 2 \geq \sqrt{\sec \theta \csc \theta}$. So

$$

c / a+c / b \geq \frac{2}{\sqrt{\sin \theta \cos \theta}}=\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{\sin 2 \theta}} \geq 2 \sqrt{2}

$$

Since $a, b, c$ are integers, we have $c / a+c / b>2 \sqrt{2}$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

By simplifying and using the AM-GM inequality,

$$

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2}=c^{2}\left(\frac{a+b}{a b}\right)^{2}=\frac{\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)(a+b)^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}} \geq \frac{2 \sqrt{a^{2} b^{2}}(2 \sqrt{a b})^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}}=8

$$

with equality only if $a=b$. By using the same argument as in Solution $1, a$ cannot equal $b$ and the inequality is strict.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

By simplifying and using the AM-GM inequality,

$$

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2}=c^{2}\left(\frac{a+b}{a b}\right)^{2}=\frac{\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)(a+b)^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}} \geq \frac{2 \sqrt{a^{2} b^{2}}(2 \sqrt{a b})^{2}}{a^{2} b^{2}}=8

$$

with equality only if $a=b$. By using the same argument as in Solution $1, a$ cannot equal $b$ and the inequality is strict.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\frac{c^{2}}{a^{2}}+\frac{c^{2}}{b^{2}}+\frac{2 c^{2}}{a b}=1+\frac{b^{2}}{a^{2}}+\frac{a^{2}}{b^{2}}+1+\frac{2\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)}{a b} \\

& =2+\left(\frac{a}{b}-\frac{b}{a}\right)^{2}+2+\frac{2}{a b}\left((a-b)^{2}+2 a b\right) \\

& =4+\left(\frac{a}{b}-\frac{b}{a}\right)^{2}+\frac{2(a-b)^{2}}{a b}+4 \geq 8,

\end{aligned}

$$

with equality only if $a=b$, which (as argued previously) cannot occur.

## b) Solution 1

Since $c / a+c / b$ is rational, $(c / a+c / b)^{2}$ can only be an integer if $c / a+c / b$ is an integer. Suppose $c / a+c / b=m$. We may assume that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. (If not, divide the common factor from $(a, b, c)$, leaving $m$ unchanged.)

Since $c(a+b)=m a b$ and $\operatorname{gcd}(a, a+b)=1$, $a$ must divide $c$, say $c=a k$. This gives $a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2} k^{2}$ which implies $b^{2}=\left(k^{2}-1\right) a^{2}$. But then $a$ divides $b$ contradicting the fact that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. Therefore $(c / a+c / b)^{2}$ is not equal to any integer $n$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\frac{c^{2}}{a^{2}}+\frac{c^{2}}{b^{2}}+\frac{2 c^{2}}{a b}=1+\frac{b^{2}}{a^{2}}+\frac{a^{2}}{b^{2}}+1+\frac{2\left(a^{2}+b^{2}\right)}{a b} \\

& =2+\left(\frac{a}{b}-\frac{b}{a}\right)^{2}+2+\frac{2}{a b}\left((a-b)^{2}+2 a b\right) \\

& =4+\left(\frac{a}{b}-\frac{b}{a}\right)^{2}+\frac{2(a-b)^{2}}{a b}+4 \geq 8,

\end{aligned}

$$

with equality only if $a=b$, which (as argued previously) cannot occur.

## b) Solution 1

Since $c / a+c / b$ is rational, $(c / a+c / b)^{2}$ can only be an integer if $c / a+c / b$ is an integer. Suppose $c / a+c / b=m$. We may assume that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. (If not, divide the common factor from $(a, b, c)$, leaving $m$ unchanged.)

Since $c(a+b)=m a b$ and $\operatorname{gcd}(a, a+b)=1$, $a$ must divide $c$, say $c=a k$. This gives $a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2} k^{2}$ which implies $b^{2}=\left(k^{2}-1\right) a^{2}$. But then $a$ divides $b$ contradicting the fact that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. Therefore $(c / a+c / b)^{2}$ is not equal to any integer $n$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

We begin as in Solution 1, supposing that $c / a+c / b=m$ with $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. Hence $a$ and $b$ are not both even. It is also the case that $a$ and $b$ are not both odd, for then $c^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2} \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, and perfect squares are congruent to either 0 or 1 modulo 4. So one of $a, b$ is odd and the other is even. Therefore $c$ must be odd.

Now $c / a+c / b=m$ implies $c(a+b)=m a b$, which cannot be true because $c(a+b)$ is odd and mab is even.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple, i.e., a triplet of positive integers with $a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}$.

a) Prove that $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

b) Prove that there does not exist any integer $n$ for which we can find a Pythagorean triple $(a, b, c)$ satisfying $(c / a+c / b)^{2}=n$.

## a) Solution 1

Let $(a, b, c)$ be a Pythagorean triple. View $a, b$ as lengths of the legs of a right angled triangle with hypotenuse of length $c$; let $\theta$ be the angle determined by the sides with lengths $a$ and $c$. Then

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{c}{a}+\frac{c}{b}\right)^{2} & =\left(\frac{1}{\cos \theta}+\frac{1}{\sin \theta}\right)^{2}=\frac{\sin ^{2} \theta+\cos ^{2} \theta+2 \sin \theta \cos \theta}{(\sin \theta \cos \theta)^{2}} \\

& =4\left(\frac{1+\sin 2 \theta}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}\right)=\frac{4}{\sin ^{2} 2 \theta}+\frac{4}{\sin 2 \theta}

\end{aligned}

$$

Note that because $0<\theta<90^{\circ}$, we have $0<\sin 2 \theta \leq 1$, with equality only if $\theta=45^{\circ}$. But then $a=b$ and we obtain $\sqrt{2}=c / a$, contradicting $a, c$ both being integers. Thus, $0<\sin 2 \theta<1$ which gives $(c / a+c / b)^{2}>8$.

|

We begin as in Solution 1, supposing that $c / a+c / b=m$ with $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b)=1$. Hence $a$ and $b$ are not both even. It is also the case that $a$ and $b$ are not both odd, for then $c^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2} \equiv 2(\bmod 4)$, and perfect squares are congruent to either 0 or 1 modulo 4. So one of $a, b$ is odd and the other is even. Therefore $c$ must be odd.

Now $c / a+c / b=m$ implies $c(a+b)=m a b$, which cannot be true because $c(a+b)$ is odd and mab is even.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

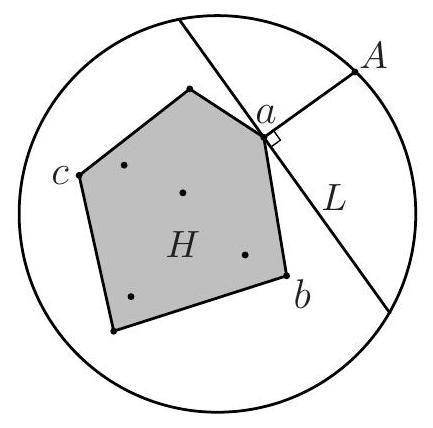

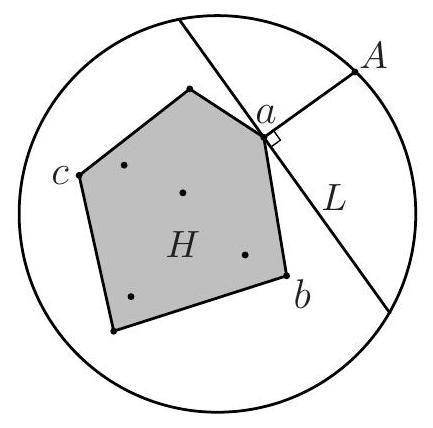

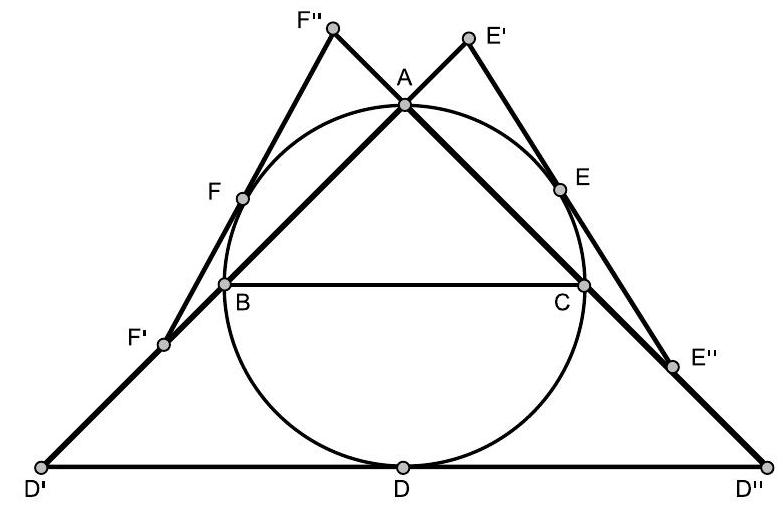

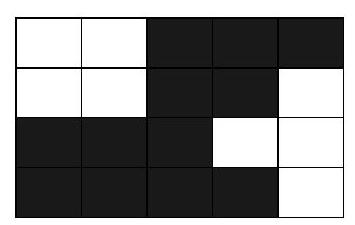

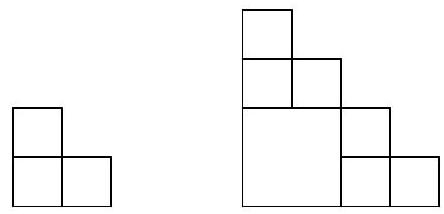

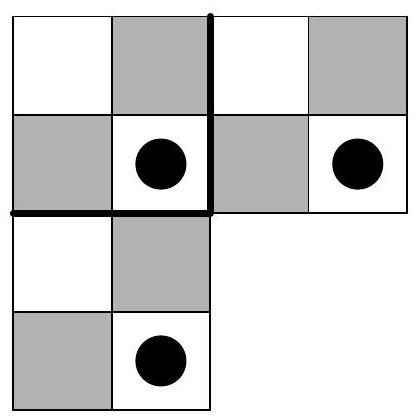

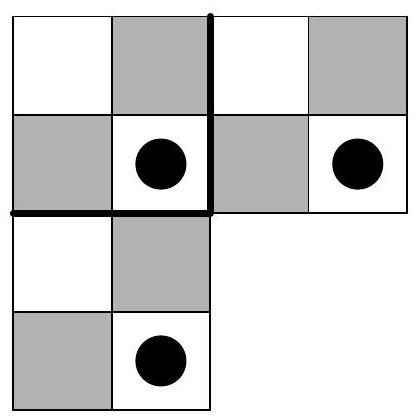

Let $S$ be a set of $n \geq 3$ points in the interior of a circle.

a) Show that there are three distinct points $a, b, c \in S$ and three distinct points $A, B, C$ on the circle such that $a$ is (strictly) closer to $A$ than any other point in $S, b$ is closer to $B$ than any other point in $S$ and $c$ is closer to $C$ than any other point in $S$.

b) Show that for no value of $n$ can four such points in $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) be guaranteed.

|

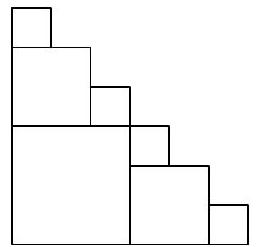

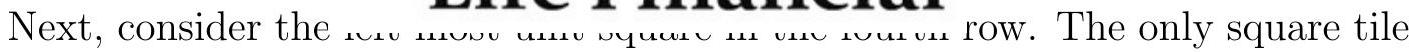

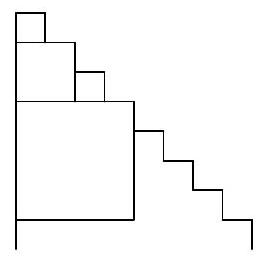

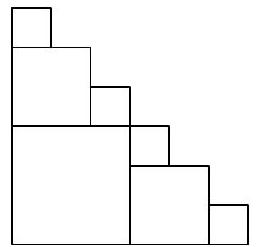

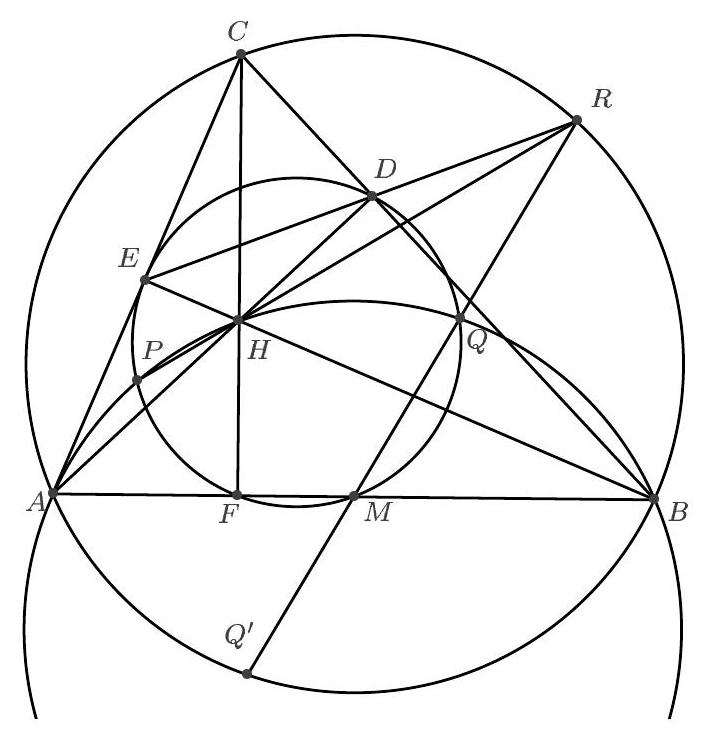

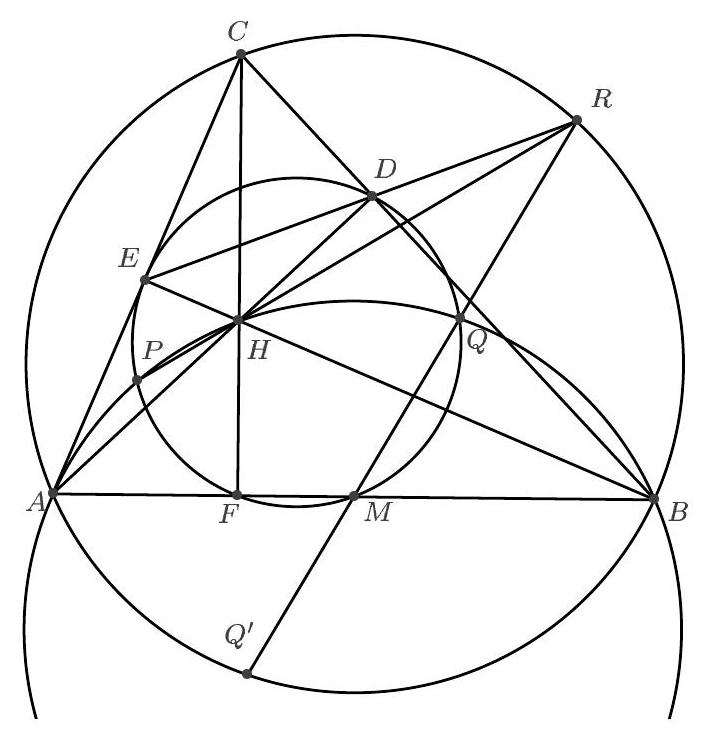

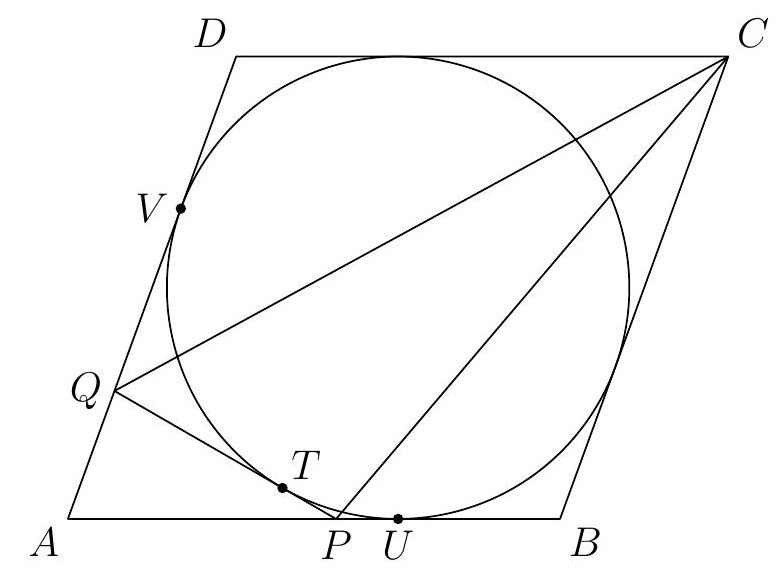

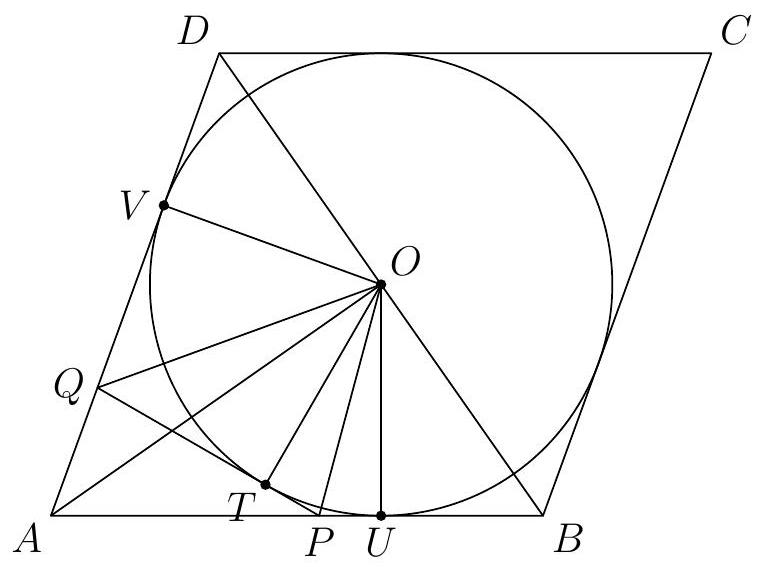

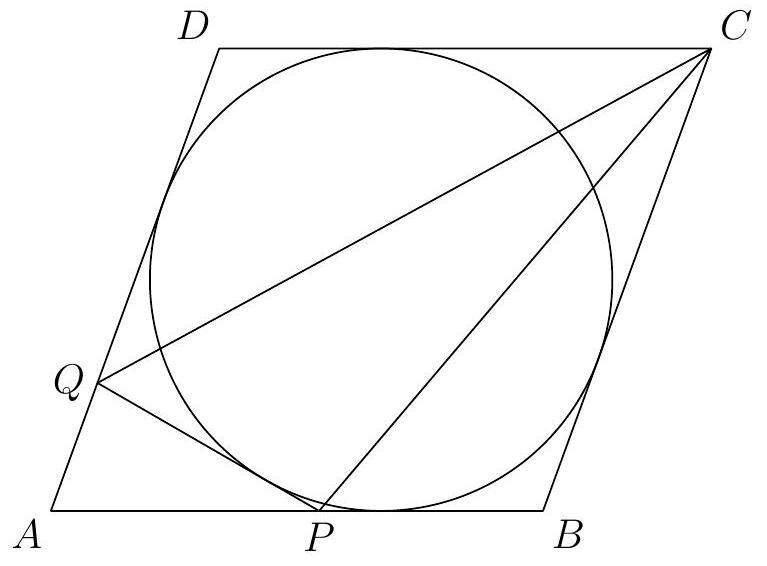

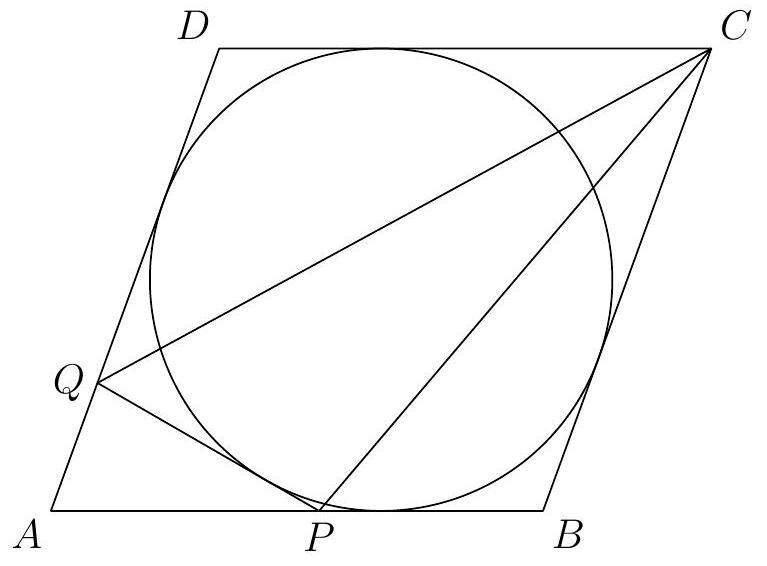

a) Let $H$ be the smallest convex set of points in the plane which contains $S . \dagger$ Take 3 points $a, b, c \in S$ which lie on the boundary of $H$. (There must always be at least 3 (but not necessarily 4) such points.)

Since $a$ lies on the boundary of the convex region $H$, we can construct a chord $L$ such that no two points of $H$ lie on opposite sides of $L$. Of the two points where the perpendicular to $L$ at $a$ meets the circle, choose one which is on a side of $L$ not containing any points of $H$ and call this point $A$. Certainly $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point on $L$ or on the other side of $L$. Hence $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point of $S$. We can find the required points $B$ and $C$ in an analogous way and the proof is complete.

[Note that this argument still holds if all the points of $S$ lie on a line.]

(a)

(b)

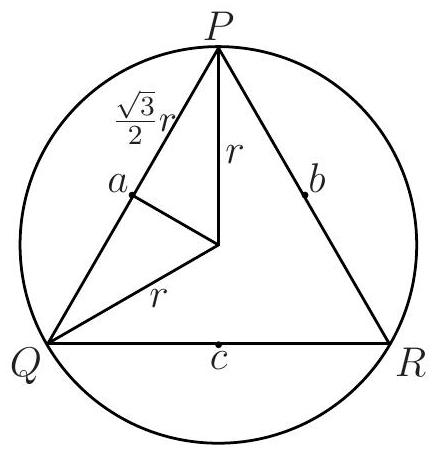

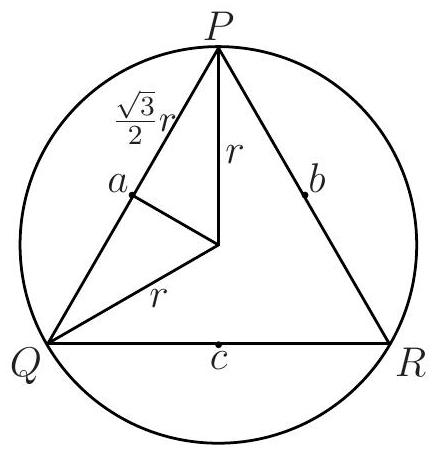

b) Let $P Q R$ be an equilateral triangle inscribed in the circle and let $a, b, c$ be midpoints of the three sides of $\triangle P Q R$. If $r$ is the radius of the circle, then every point on the circle is within $(\sqrt{3} / 2) r$ of one of $a, b$ or $c$. (See figure (b) above.) Now $\sqrt{3} / 2<9 / 10$, so if $S$ consists of $a, b, c$ and a cluster of points within $r / 10$ of the centre of the circle, then we cannot select 4 points from $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) having the desired property.[^0]

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $S$ be a set of $n \geq 3$ points in the interior of a circle.

a) Show that there are three distinct points $a, b, c \in S$ and three distinct points $A, B, C$ on the circle such that $a$ is (strictly) closer to $A$ than any other point in $S, b$ is closer to $B$ than any other point in $S$ and $c$ is closer to $C$ than any other point in $S$.

b) Show that for no value of $n$ can four such points in $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) be guaranteed.

|

a) Let $H$ be the smallest convex set of points in the plane which contains $S . \dagger$ Take 3 points $a, b, c \in S$ which lie on the boundary of $H$. (There must always be at least 3 (but not necessarily 4) such points.)

Since $a$ lies on the boundary of the convex region $H$, we can construct a chord $L$ such that no two points of $H$ lie on opposite sides of $L$. Of the two points where the perpendicular to $L$ at $a$ meets the circle, choose one which is on a side of $L$ not containing any points of $H$ and call this point $A$. Certainly $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point on $L$ or on the other side of $L$. Hence $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point of $S$. We can find the required points $B$ and $C$ in an analogous way and the proof is complete.

[Note that this argument still holds if all the points of $S$ lie on a line.]

(a)

(b)

b) Let $P Q R$ be an equilateral triangle inscribed in the circle and let $a, b, c$ be midpoints of the three sides of $\triangle P Q R$. If $r$ is the radius of the circle, then every point on the circle is within $(\sqrt{3} / 2) r$ of one of $a, b$ or $c$. (See figure (b) above.) Now $\sqrt{3} / 2<9 / 10$, so if $S$ consists of $a, b, c$ and a cluster of points within $r / 10$ of the centre of the circle, then we cannot select 4 points from $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) having the desired property.[^0]

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $S$ be a set of $n \geq 3$ points in the interior of a circle.

a) Show that there are three distinct points $a, b, c \in S$ and three distinct points $A, B, C$ on the circle such that $a$ is (strictly) closer to $A$ than any other point in $S, b$ is closer to $B$ than any other point in $S$ and $c$ is closer to $C$ than any other point in $S$.

b) Show that for no value of $n$ can four such points in $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) be guaranteed.

|

a) If all the points of $S$ lie on a line $L$, then choose any 3 of them to be $a, b, c$. Let $A$ be a point on the circle which meets the perpendicular to $L$ at $a$. Clearly $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point on $L$, and hence closer than other other point in $S$. We find $B$ and $C$ in an analogous way.

Otherwise, choose $a, b, c$ from $S$ so that the triangle formed by these points has maximal area. Construct the altitude from the side $b c$ to the point $a$ and extend this line until it meets the circle at $A$. We claim that $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point in $S$.

Suppose not. Let $x$ be a point in $S$ for which the distance from $A$ to $x$ is less than the distance from $A$ to $a$. Then the perpendicular distance from $x$ to the line $b c$ must be greater than the perpendicular distance from $a$ to the line $b c$. But then the triangle formed by the points $x, b, c$ has greater area than the triangle formed by $a, b, c$, contradicting the original choice of these 3 points. Therefore $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point in $S$.

The points $B$ and $C$ are found by constructing similar altitudes through $b$ and $c$, respectively.

b) See Solution 1.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Let $S$ be a set of $n \geq 3$ points in the interior of a circle.

a) Show that there are three distinct points $a, b, c \in S$ and three distinct points $A, B, C$ on the circle such that $a$ is (strictly) closer to $A$ than any other point in $S, b$ is closer to $B$ than any other point in $S$ and $c$ is closer to $C$ than any other point in $S$.

b) Show that for no value of $n$ can four such points in $S$ (and corresponding points on the circle) be guaranteed.

|

a) If all the points of $S$ lie on a line $L$, then choose any 3 of them to be $a, b, c$. Let $A$ be a point on the circle which meets the perpendicular to $L$ at $a$. Clearly $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point on $L$, and hence closer than other other point in $S$. We find $B$ and $C$ in an analogous way.

Otherwise, choose $a, b, c$ from $S$ so that the triangle formed by these points has maximal area. Construct the altitude from the side $b c$ to the point $a$ and extend this line until it meets the circle at $A$. We claim that $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point in $S$.

Suppose not. Let $x$ be a point in $S$ for which the distance from $A$ to $x$ is less than the distance from $A$ to $a$. Then the perpendicular distance from $x$ to the line $b c$ must be greater than the perpendicular distance from $a$ to the line $b c$. But then the triangle formed by the points $x, b, c$ has greater area than the triangle formed by $a, b, c$, contradicting the original choice of these 3 points. Therefore $A$ is closer to $a$ than to any other point in $S$.

The points $B$ and $C$ are found by constructing similar altitudes through $b$ and $c$, respectively.

b) See Solution 1.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

Since similar triangles give the same value of $K P / R^{3}$, we can fix $R=1$ and maximize $K P$ over all triangles inscribed in the unit circle. Fix points $A$ and $B$ on the unit circle. The locus of points $C$ with a given perimeter $P$ is an ellipse that meets the circle in at most four points. The area $K$ is maximized (for a fixed $P$ ) when $C$ is chosen on the perpendicular bisector of $A B$, so we get a maximum value for $K P$ if $C$ is where the perpendicular bisector of $A B$ meets the circle. Thus the maximum value of $K P$ for a given $A B$ occurs when $A B C$ is an isosceles triangle. Repeating this argument with $B C$ fixed, we have that the maximum occurs when $A B C$ is an equilateral triangle.

Consider an equilateral triangle with side length $a$. It has $P=3 a$. It has height equal to $a \sqrt{3} / 2$ giving $K=a^{2} \sqrt{3} / 4$. ¿From the extended law of sines, $2 R=a / \sin (60)$ giving $R=a / \sqrt{3}$. Therefore the maximum value we seek is

$$

K P / R^{3}=\left(\frac{a^{2} \sqrt{3}}{4}\right)(3 a)\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{a}\right)^{3}=\frac{27}{4} .

$$

|

\frac{27}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

Since similar triangles give the same value of $K P / R^{3}$, we can fix $R=1$ and maximize $K P$ over all triangles inscribed in the unit circle. Fix points $A$ and $B$ on the unit circle. The locus of points $C$ with a given perimeter $P$ is an ellipse that meets the circle in at most four points. The area $K$ is maximized (for a fixed $P$ ) when $C$ is chosen on the perpendicular bisector of $A B$, so we get a maximum value for $K P$ if $C$ is where the perpendicular bisector of $A B$ meets the circle. Thus the maximum value of $K P$ for a given $A B$ occurs when $A B C$ is an isosceles triangle. Repeating this argument with $B C$ fixed, we have that the maximum occurs when $A B C$ is an equilateral triangle.

Consider an equilateral triangle with side length $a$. It has $P=3 a$. It has height equal to $a \sqrt{3} / 2$ giving $K=a^{2} \sqrt{3} / 4$. ¿From the extended law of sines, $2 R=a / \sin (60)$ giving $R=a / \sqrt{3}$. Therefore the maximum value we seek is

$$

K P / R^{3}=\left(\frac{a^{2} \sqrt{3}}{4}\right)(3 a)\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{a}\right)^{3}=\frac{27}{4} .

$$

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

From the extended law of sines, the lengths of the sides of the triangle are $2 R \sin A$, $2 R \sin B$ and $2 R \sin C$. So

$$

P=2 R(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C) \text { and } K=\frac{1}{2}(2 R \sin A)(2 R \sin B)(\sin C),

$$

giving

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A \sin B \sin C(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)

$$

We wish to find the maximum value of this expression over all $A+B+C=180^{\circ}$. Using well-known identities for sums and products of sine functions, we can write

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A\left(\frac{\cos (B-C)}{2}-\frac{\cos (B+C)}{2}\right)\left(\sin A+2 \sin \left(\frac{B+C}{2}\right) \cos \left(\frac{B-C}{2}\right)\right) .

$$

If we first consider $A$ to be fixed, then $B+C$ is fixed also and this expression takes its maximum value when $\cos (B-C)$ and $\cos \left(\frac{B-C}{2}\right)$ equal 1 ; i.e. when $B=C$. In a similar way, one can show that for any fixed value of $B, K P / R^{3}$ is maximized when $A=C$. Therefore the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$ occurs when $A=B=C=60^{\circ}$, and it is now an easy task to substitute this into the above expression to obtain the maximum value of $27 / 4$.

|

\frac{27}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

From the extended law of sines, the lengths of the sides of the triangle are $2 R \sin A$, $2 R \sin B$ and $2 R \sin C$. So

$$

P=2 R(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C) \text { and } K=\frac{1}{2}(2 R \sin A)(2 R \sin B)(\sin C),

$$

giving

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A \sin B \sin C(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)

$$

We wish to find the maximum value of this expression over all $A+B+C=180^{\circ}$. Using well-known identities for sums and products of sine functions, we can write

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A\left(\frac{\cos (B-C)}{2}-\frac{\cos (B+C)}{2}\right)\left(\sin A+2 \sin \left(\frac{B+C}{2}\right) \cos \left(\frac{B-C}{2}\right)\right) .

$$

If we first consider $A$ to be fixed, then $B+C$ is fixed also and this expression takes its maximum value when $\cos (B-C)$ and $\cos \left(\frac{B-C}{2}\right)$ equal 1 ; i.e. when $B=C$. In a similar way, one can show that for any fixed value of $B, K P / R^{3}$ is maximized when $A=C$. Therefore the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$ occurs when $A=B=C=60^{\circ}$, and it is now an easy task to substitute this into the above expression to obtain the maximum value of $27 / 4$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

As in Solution 2, we obtain

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A \sin B \sin C(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)

$$

From the AM-GM inequality, we have

$$

\sin A \sin B \sin C \leq\left(\frac{\sin A+\sin B+\sin C}{3}\right)^{3},

$$

giving

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}} \leq \frac{4}{27}(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)^{4}

$$

with equality when $\sin A=\sin B=\sin C$. Since the sine function is concave on the interval from 0 to $\pi$, Jensen's inequality gives

$$

\frac{\sin A+\sin B+\sin C}{3} \leq \sin \left(\frac{A+B+C}{3}\right)=\sin \frac{\pi}{3}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} .

$$

Since equality occurs here when $\sin A=\sin B=\sin C$ also, we can conclude that the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$ is $\frac{4}{27}\left(\frac{3 \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{4}=27 / 4$.

|

\frac{27}{4}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle with circumradius $R$, perimeter $P$ and area $K$. Determine the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$.

|

As in Solution 2, we obtain

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}}=4 \sin A \sin B \sin C(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)

$$

From the AM-GM inequality, we have

$$

\sin A \sin B \sin C \leq\left(\frac{\sin A+\sin B+\sin C}{3}\right)^{3},

$$

giving

$$

\frac{K P}{R^{3}} \leq \frac{4}{27}(\sin A+\sin B+\sin C)^{4}

$$

with equality when $\sin A=\sin B=\sin C$. Since the sine function is concave on the interval from 0 to $\pi$, Jensen's inequality gives

$$

\frac{\sin A+\sin B+\sin C}{3} \leq \sin \left(\frac{A+B+C}{3}\right)=\sin \frac{\pi}{3}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} .

$$

Since equality occurs here when $\sin A=\sin B=\sin C$ also, we can conclude that the maximum value of $K P / R^{3}$ is $\frac{4}{27}\left(\frac{3 \sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{4}=27 / 4$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let's say that an ordered triple of positive integers $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful if $a \leq b \leq c$, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, and $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. For example, $(1,2,2)$ is 5 -powerful.

a) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

b) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful.

[Note that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)$ is the greatest common divisor of $a, b$ and $c$.]

|

Let $T_{n}=a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ and consider the polynomial

$$

P(x)=(x-a)(x-b)(x-c)=x^{3}-(a+b+c) x^{2}+(a b+a c+b c) x-a b c .

$$

Since $P(a)=0$, we get $a^{3}=(a+b+c) a^{2}-(a b+a c+b c) a+a b c$ and multiplying both sides by $a^{n-3}$ we obtain $a^{n}=(a+b+c) a^{n-1}-(a b+a c+b c) a^{n-2}+(a b c) a^{n-3}$. Applying the same reasoning, we can obtain similar expressions for $b^{n}$ and $c^{n}$ and adding the three identities we get that $T_{n}$ satisfies the following 3 -term recurrence:

$$

T_{n}=(a+b+c) T_{n-1}-(a b+a c+b c) T_{n-2}+(a b c) T_{n-3} \text {, for all } n \geq 3

$$

¿From this we see that if $T_{n-2}$ and $T_{n-3}$ are divisible by $a+b+c$, then so is $T_{n}$. This immediately resolves part (b) - there are no ordered triples which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful-and reduces the number of cases to be considered in part (a): since all triples are 1-powerful, the recurrence implies that any ordered triple which is both 2 -powerful and 3 -powerful is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

Putting $n=3$ in the recurrence, we have

$$

a^{3}+b^{3}+c^{3}=(a+b+c)\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-(a b+a c+b c)(a+b+c)+3 a b c

$$

which implies that $(a, b, c)$ is 3 -powerful if and only if $3 a b c$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. Since

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=(a+b+c)^{2}-2(a b+a c+b c),

$$

$(a, b, c)$ is 2 -powerful if and only if $2(a b+a c+b c)$ is divisible by $a+b+c$.

Suppose a prime $p \geq 5$ divides $a+b+c$. Then $p$ divides $a b c$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1, p$ divides exactly one of $a, b$ or $c$; but then $p$ doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

Suppose $3^{2}$ divides $a+b+c$. Then 3 divides $a b c$, implying 3 divides exactly one of $a$, $b$ or $c$. But then 3 doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

Suppose $2^{2}$ divides $a+b+c$. Then 4 divides $a b c$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, at most one of $a, b$ or $c$ is even, implying one of $a, b, c$ is divisible by 4 and the others are odd. But then $a b+a c+b c$ is odd and 4 doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

So if $(a, b, c)$ is 2 - and 3 -powerful, then $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 or any prime greater than 3. Since $a+b+c$ is at least $3, a+b+c$ is either 3 or 6 . It is now a simple matter to check the possibilities and conclude that the only triples which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$ are $(1,1,1)$ and $(1,1,4)$.

|

(1,1,1) \text{ and } (1,1,4)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let's say that an ordered triple of positive integers $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful if $a \leq b \leq c$, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, and $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. For example, $(1,2,2)$ is 5 -powerful.

a) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

b) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful.

[Note that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)$ is the greatest common divisor of $a, b$ and $c$.]

|

Let $T_{n}=a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ and consider the polynomial

$$

P(x)=(x-a)(x-b)(x-c)=x^{3}-(a+b+c) x^{2}+(a b+a c+b c) x-a b c .

$$

Since $P(a)=0$, we get $a^{3}=(a+b+c) a^{2}-(a b+a c+b c) a+a b c$ and multiplying both sides by $a^{n-3}$ we obtain $a^{n}=(a+b+c) a^{n-1}-(a b+a c+b c) a^{n-2}+(a b c) a^{n-3}$. Applying the same reasoning, we can obtain similar expressions for $b^{n}$ and $c^{n}$ and adding the three identities we get that $T_{n}$ satisfies the following 3 -term recurrence:

$$

T_{n}=(a+b+c) T_{n-1}-(a b+a c+b c) T_{n-2}+(a b c) T_{n-3} \text {, for all } n \geq 3

$$

¿From this we see that if $T_{n-2}$ and $T_{n-3}$ are divisible by $a+b+c$, then so is $T_{n}$. This immediately resolves part (b) - there are no ordered triples which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful-and reduces the number of cases to be considered in part (a): since all triples are 1-powerful, the recurrence implies that any ordered triple which is both 2 -powerful and 3 -powerful is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

Putting $n=3$ in the recurrence, we have

$$

a^{3}+b^{3}+c^{3}=(a+b+c)\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)-(a b+a c+b c)(a+b+c)+3 a b c

$$

which implies that $(a, b, c)$ is 3 -powerful if and only if $3 a b c$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. Since

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=(a+b+c)^{2}-2(a b+a c+b c),

$$

$(a, b, c)$ is 2 -powerful if and only if $2(a b+a c+b c)$ is divisible by $a+b+c$.

Suppose a prime $p \geq 5$ divides $a+b+c$. Then $p$ divides $a b c$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1, p$ divides exactly one of $a, b$ or $c$; but then $p$ doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

Suppose $3^{2}$ divides $a+b+c$. Then 3 divides $a b c$, implying 3 divides exactly one of $a$, $b$ or $c$. But then 3 doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

Suppose $2^{2}$ divides $a+b+c$. Then 4 divides $a b c$. Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, at most one of $a, b$ or $c$ is even, implying one of $a, b, c$ is divisible by 4 and the others are odd. But then $a b+a c+b c$ is odd and 4 doesn't divide $2(a b+a c+b c)$.

So if $(a, b, c)$ is 2 - and 3 -powerful, then $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 or any prime greater than 3. Since $a+b+c$ is at least $3, a+b+c$ is either 3 or 6 . It is now a simple matter to check the possibilities and conclude that the only triples which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$ are $(1,1,1)$ and $(1,1,4)$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let's say that an ordered triple of positive integers $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful if $a \leq b \leq c$, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, and $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. For example, $(1,2,2)$ is 5 -powerful.

a) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

b) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful.

[Note that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)$ is the greatest common divisor of $a, b$ and $c$.]

|

Let $p$ be a prime. By Fermat's Little Theorem,

$$

a^{p-1} \equiv \begin{cases}1(\bmod p), & \text { if } p \text { doesn't divide } a \\ 0(\bmod p), & \text { if } p \text { divides } a\end{cases}

$$

Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, we have that $a^{p-1}+b^{p-1}+c^{p-1} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod p)$. Therefore if $p$ is a prime divisor of $a^{p-1}+b^{p-1}+c^{p-1}$, then $p$ equals 2 or 3 . So if $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$, then the only primes which can divide $a+b+c$ are 2 or 3 .

We can proceed in a similar fashion to show that $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 .

Since

$$

a^{2} \equiv \begin{cases}0(\bmod 4), & \text { if } p \text { is even; } \\ 1(\bmod 4), & \text { if } p \text { is odd }\end{cases}

$$

and $a, b, c$ aren't all even, we have that $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod 4)$.

By expanding $(3 k)^{3},(3 k+1)^{3}$ and $(3 k+2)^{3}$, we find that $a^{3}$ is congruent to 0,1 or -1 modulo 9. Hence

$$

a^{6} \equiv \begin{cases}0(\bmod 9), & \text { if } 3 \text { divides } a ; \\ 1(\bmod 9), & \text { if } 3 \text { doesn't divide } a .\end{cases}

$$

Since $a, b, c$ aren't all divisible by 3 , we have that $a^{6}+b^{6}+c^{6} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod 9)$.

So $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}$ is not divisible by 4 and $a^{6}+b^{6}+c^{6}$ is not divisible by 9 . Thus if $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$, then $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 . Therefore $a+b+c$ is either 3 or 6 and checking all possibilities, we conclude that the only triples which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$ are $(1,1,1)$ and $(1,1,4)$.

See Solution 1 for the (b) part.

[^0]: ${ }^{\dagger}$ By the way, $H$ is called the convex hull of $S$. If the points of $S$ lie on a line, then $H$ will be the shortest line segment containing the points of $S$. Otherwise, $H$ is a polygon whose vertices are all elements of $S$ and such that all other points in $S$ lie inside or on this polygon.

|

(1,1,1) \text{ and } (1,1,4)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Let's say that an ordered triple of positive integers $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful if $a \leq b \leq c$, $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, and $a^{n}+b^{n}+c^{n}$ is divisible by $a+b+c$. For example, $(1,2,2)$ is 5 -powerful.

a) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$.

b) Determine all ordered triples (if any) which are 2004-powerful and 2005-powerful, but not 2007-powerful.

[Note that $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)$ is the greatest common divisor of $a, b$ and $c$.]

|

Let $p$ be a prime. By Fermat's Little Theorem,

$$

a^{p-1} \equiv \begin{cases}1(\bmod p), & \text { if } p \text { doesn't divide } a \\ 0(\bmod p), & \text { if } p \text { divides } a\end{cases}

$$

Since $\operatorname{gcd}(a, b, c)=1$, we have that $a^{p-1}+b^{p-1}+c^{p-1} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod p)$. Therefore if $p$ is a prime divisor of $a^{p-1}+b^{p-1}+c^{p-1}$, then $p$ equals 2 or 3 . So if $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$, then the only primes which can divide $a+b+c$ are 2 or 3 .

We can proceed in a similar fashion to show that $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 .

Since

$$

a^{2} \equiv \begin{cases}0(\bmod 4), & \text { if } p \text { is even; } \\ 1(\bmod 4), & \text { if } p \text { is odd }\end{cases}

$$

and $a, b, c$ aren't all even, we have that $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod 4)$.

By expanding $(3 k)^{3},(3 k+1)^{3}$ and $(3 k+2)^{3}$, we find that $a^{3}$ is congruent to 0,1 or -1 modulo 9. Hence

$$

a^{6} \equiv \begin{cases}0(\bmod 9), & \text { if } 3 \text { divides } a ; \\ 1(\bmod 9), & \text { if } 3 \text { doesn't divide } a .\end{cases}

$$

Since $a, b, c$ aren't all divisible by 3 , we have that $a^{6}+b^{6}+c^{6} \equiv 1,2$ or $3(\bmod 9)$.

So $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}$ is not divisible by 4 and $a^{6}+b^{6}+c^{6}$ is not divisible by 9 . Thus if $(a, b, c)$ is $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$, then $a+b+c$ is not divisible by 4 or 9 . Therefore $a+b+c$ is either 3 or 6 and checking all possibilities, we conclude that the only triples which are $n$-powerful for all $n \geq 1$ are $(1,1,1)$ and $(1,1,4)$.

See Solution 1 for the (b) part.

[^0]: ${ }^{\dagger}$ By the way, $H$ is called the convex hull of $S$. If the points of $S$ lie on a line, then $H$ will be the shortest line segment containing the points of $S$. Otherwise, $H$ is a polygon whose vertices are all elements of $S$ and such that all other points in $S$ lie inside or on this polygon.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2005.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\n## Solution 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2005"

}

|

Let $f(n, k)$ be the number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to $n$ children so that each child receives at most 2 candies. For example, if $n=3$, then $f(3,7)=0, f(3,6)=1$ and $f(3,4)=6$.

Determine the value of

$$

f(2006,1)+f(2006,4)+f(2006,7)+\cdots+f(2006,1000)+f(2006,1003) .

$$

Comment. Unfortunately, there was an error in the statement of this problem. It was intended that the sum should continue to $f(2006,4012)$.

|

The number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to 2006 children is equal to the number of ways of distributing 0 to a particular child and $k$ to the rest, plus the number of ways of distributing 1 to the particular child and $k-1$ to the rest, plus the number of ways of distributing 2 to the particular child and $k-2$ to the rest. Thus $f(2006, k)=$ $f(2005, k)+f(2005, k-1)+f(2005, k-2)$, so that the required sum is

$$

1+\sum_{k=1}^{1003} f(2005, k)

$$

In evaluating $f(n, k)$, suppose that there are $r$ children who receive 2 candies; these $r$ children can be chosen in $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ r\end{array}\right)$ ways. Then there are $k-2 r$ candies from which at most one is given to each of $n-r$ children. Hence

$$

f(n, k)=\sum_{r=0}^{\lfloor k / 2\rfloor}\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

n-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

n-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)

$$

with $\left(\begin{array}{l}x \\ y\end{array}\right)=0$ when $x<y$ and when $y<0$. The answer is

$$

\sum_{k=0}^{1003} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

r

\end{array}\right) \sum_{k=0}^{1003}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)

$$

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $f(n, k)$ be the number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to $n$ children so that each child receives at most 2 candies. For example, if $n=3$, then $f(3,7)=0, f(3,6)=1$ and $f(3,4)=6$.

Determine the value of

$$

f(2006,1)+f(2006,4)+f(2006,7)+\cdots+f(2006,1000)+f(2006,1003) .

$$

Comment. Unfortunately, there was an error in the statement of this problem. It was intended that the sum should continue to $f(2006,4012)$.

|

The number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to 2006 children is equal to the number of ways of distributing 0 to a particular child and $k$ to the rest, plus the number of ways of distributing 1 to the particular child and $k-1$ to the rest, plus the number of ways of distributing 2 to the particular child and $k-2$ to the rest. Thus $f(2006, k)=$ $f(2005, k)+f(2005, k-1)+f(2005, k-2)$, so that the required sum is

$$

1+\sum_{k=1}^{1003} f(2005, k)

$$

In evaluating $f(n, k)$, suppose that there are $r$ children who receive 2 candies; these $r$ children can be chosen in $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \\ r\end{array}\right)$ ways. Then there are $k-2 r$ candies from which at most one is given to each of $n-r$ children. Hence

$$

f(n, k)=\sum_{r=0}^{\lfloor k / 2\rfloor}\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

n-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

n-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)

$$

with $\left(\begin{array}{l}x \\ y\end{array}\right)=0$ when $x<y$ and when $y<0$. The answer is

$$

\sum_{k=0}^{1003} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

r

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

r

\end{array}\right) \sum_{k=0}^{1003}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005-r \\

k-2 r

\end{array}\right)

$$

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Let $f(n, k)$ be the number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to $n$ children so that each child receives at most 2 candies. For example, if $n=3$, then $f(3,7)=0, f(3,6)=1$ and $f(3,4)=6$.

Determine the value of

$$

f(2006,1)+f(2006,4)+f(2006,7)+\cdots+f(2006,1000)+f(2006,1003) .

$$

Comment. Unfortunately, there was an error in the statement of this problem. It was intended that the sum should continue to $f(2006,4012)$.

|

The desired number is the sum of the coefficients of the terms of degree not exceeding 1003 in the expansion of $\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)^{2005}$, which is equal to the coefficient of $x^{1003}$ in the expansion of

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)^{2005}\left(1+x+\cdots+x^{1003}\right) & =\left[\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2005}\right]\left(1-x^{1004}\right)(1-x)^{-1} \\

& =\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006}-\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006} x^{1004}

\end{aligned}

$$

Since the degree of every term in the expansion of the second member on the right exceeds 1003, we are looking for the coefficient of $x^{1003}$ in the expansion of the first member:

$$

\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006}=\sum_{i=0}^{2005}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right) x^{3 i} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty}(-1)^{j}\left(\begin{array}{c}

-2006 \\

j

\end{array}\right) x^{j}

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

& =\sum_{i=0}^{2005} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005+j \\

j

\end{array}\right) x^{3 i+j} \\

& =\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{2005}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005+k-3 i \\

2005

\end{array}\right)\right) x^{k} .

\end{aligned}

$$

The desired number is

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{334}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

3008-3 i \\

2005

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{334}(-1)^{i} \frac{(3008-3 i) !}{i !(2005-i) !(1003-3 i) !} .

$$

(Note that $\left(\begin{array}{c}3008-3 i \\ 2005\end{array}\right)=0$ when $i \geq 335$.)

|

\sum_{i=1}^{334}(-1)^{i} \frac{(3008-3 i) !}{i !(2005-i) !(1003-3 i) !}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Let $f(n, k)$ be the number of ways of distributing $k$ candies to $n$ children so that each child receives at most 2 candies. For example, if $n=3$, then $f(3,7)=0, f(3,6)=1$ and $f(3,4)=6$.

Determine the value of

$$

f(2006,1)+f(2006,4)+f(2006,7)+\cdots+f(2006,1000)+f(2006,1003) .

$$

Comment. Unfortunately, there was an error in the statement of this problem. It was intended that the sum should continue to $f(2006,4012)$.

|

The desired number is the sum of the coefficients of the terms of degree not exceeding 1003 in the expansion of $\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)^{2005}$, which is equal to the coefficient of $x^{1003}$ in the expansion of

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+x+x^{2}\right)^{2005}\left(1+x+\cdots+x^{1003}\right) & =\left[\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2005}\right]\left(1-x^{1004}\right)(1-x)^{-1} \\

& =\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006}-\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006} x^{1004}

\end{aligned}

$$

Since the degree of every term in the expansion of the second member on the right exceeds 1003, we are looking for the coefficient of $x^{1003}$ in the expansion of the first member:

$$

\left(1-x^{3}\right)^{2005}(1-x)^{-2006}=\sum_{i=0}^{2005}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right) x^{3 i} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty}(-1)^{j}\left(\begin{array}{c}

-2006 \\

j

\end{array}\right) x^{j}

$$

$$

\begin{aligned}

& =\sum_{i=0}^{2005} \sum_{j=0}^{\infty}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005+j \\

j

\end{array}\right) x^{3 i+j} \\

& =\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{2005}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005+k-3 i \\

2005

\end{array}\right)\right) x^{k} .

\end{aligned}

$$

The desired number is

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{334}(-1)^{i}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2005 \\

i

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

3008-3 i \\

2005

\end{array}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{334}(-1)^{i} \frac{(3008-3 i) !}{i !(2005-i) !(1003-3 i) !} .

$$

(Note that $\left(\begin{array}{c}3008-3 i \\ 2005\end{array}\right)=0$ when $i \geq 335$.)

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

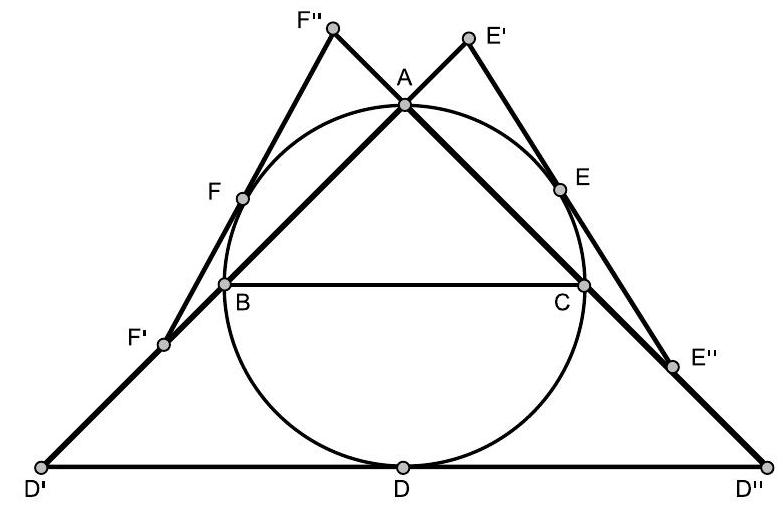

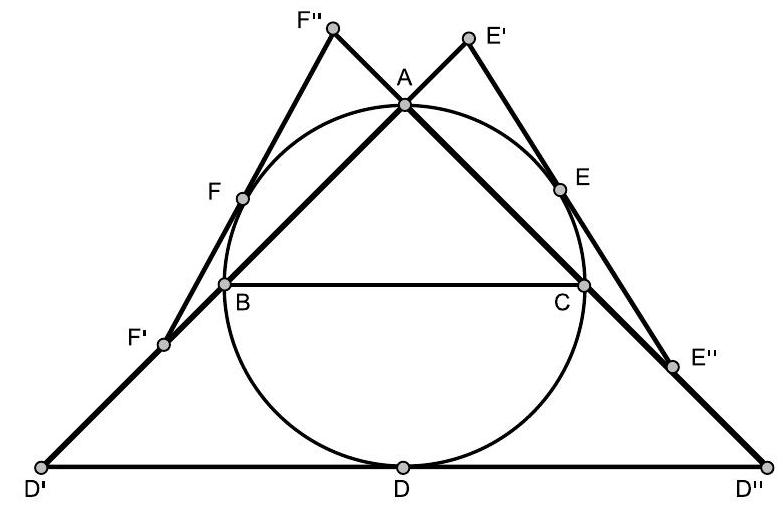

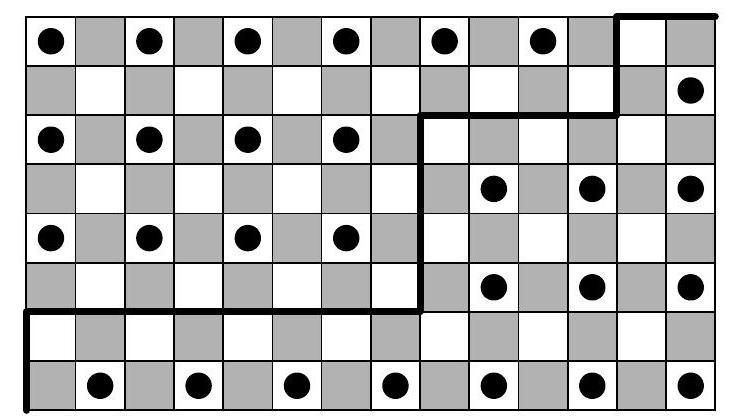

Let $A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle. Inscribe a rectangle $D E F G$ in this triangle so that $D$ is on $A B, E$ is on $A C$ and both $F$ and $G$ are on $B C$. Describe the locus of (i.e., the curve occupied by) the intersections of the diagonals of all possible rectangles $D E F G$.

|

The locus is the line segment joining the midpoint $M$ of $B C$ to the midpoint $K$ of the altitude $A H$. Note that a segment $D E$ with $D$ on $A B$ and $E$ on $A C$ determines an inscribed rectangle; the midpoint $F$ of $D E$ lies on the median $A M$, while the midpoint of the perpendicular from $F$ to $B C$ is the centre of the rectangle. This lies on the median $M K$ of the triangle $A M H$.

Conversely, any point $P$ on $M K$ is the centre of a rectangle with base along $B C$ whose height is double the distance from $K$ to $B C$.

|

not found

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Let $A B C$ be an acute-angled triangle. Inscribe a rectangle $D E F G$ in this triangle so that $D$ is on $A B, E$ is on $A C$ and both $F$ and $G$ are on $B C$. Describe the locus of (i.e., the curve occupied by) the intersections of the diagonals of all possible rectangles $D E F G$.

|

The locus is the line segment joining the midpoint $M$ of $B C$ to the midpoint $K$ of the altitude $A H$. Note that a segment $D E$ with $D$ on $A B$ and $E$ on $A C$ determines an inscribed rectangle; the midpoint $F$ of $D E$ lies on the median $A M$, while the midpoint of the perpendicular from $F$ to $B C$ is the centre of the rectangle. This lies on the median $M K$ of the triangle $A M H$.

Conversely, any point $P$ on $M K$ is the centre of a rectangle with base along $B C$ whose height is double the distance from $K$ to $B C$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

In a rectangular array of nonnegative real numbers with $m$ rows and $n$ columns, each row and each column contains at least one positive element. Moreover, if a row and a column intersect in a positive element, then the sums of their elements are the same. Prove that $m=n$.

|

Consider first the case where all the rows have the same positive sum $s$; this covers the particular situation in which $m=1$. Then each column, sharing a positive element with some row, must also have the sum $s$. Then the sum of all the entries in the matrix is $m s=n s$, whence $m=n$.

We prove the general case by induction on $m$. The case $m=1$ is already covered. Suppose that we have an $m \times n$ array not all of whose rows have the same sum. Let $r<m$ of the rows have the sum $s$, and each of the of the other rows have a different sum. Then every column sharing a positive entry with one of these rows must also have sum $s$, and these are the only columns with the sum $s$. Suppose there are $c$ columns with sum $s$. The situation is essentially unchanged if we permute the rows and then the column so that the first $r$ rows have the sum $s$ and the first $c$ columns have the sum $s$. Since all the entries of the first $r$ rows not in the first $c$ columns and in the first $c$ columns not in the first $r$ rows must be 0 , we can partition the array into a $r \times c$ array in which all rows and columns have sum $s$ and which satisfies the hypothesis of the problem, two rectangular arrays of zeros in the upper right and lower left and a rectangular $(m-r) \times(n-c)$ array in the lower right that satisfies the conditions of the problem. By the induction hypothesis, we see that $r=c$ and so $m=n$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

In a rectangular array of nonnegative real numbers with $m$ rows and $n$ columns, each row and each column contains at least one positive element. Moreover, if a row and a column intersect in a positive element, then the sums of their elements are the same. Prove that $m=n$.

|

Consider first the case where all the rows have the same positive sum $s$; this covers the particular situation in which $m=1$. Then each column, sharing a positive element with some row, must also have the sum $s$. Then the sum of all the entries in the matrix is $m s=n s$, whence $m=n$.

We prove the general case by induction on $m$. The case $m=1$ is already covered. Suppose that we have an $m \times n$ array not all of whose rows have the same sum. Let $r<m$ of the rows have the sum $s$, and each of the of the other rows have a different sum. Then every column sharing a positive entry with one of these rows must also have sum $s$, and these are the only columns with the sum $s$. Suppose there are $c$ columns with sum $s$. The situation is essentially unchanged if we permute the rows and then the column so that the first $r$ rows have the sum $s$ and the first $c$ columns have the sum $s$. Since all the entries of the first $r$ rows not in the first $c$ columns and in the first $c$ columns not in the first $r$ rows must be 0 , we can partition the array into a $r \times c$ array in which all rows and columns have sum $s$ and which satisfies the hypothesis of the problem, two rectangular arrays of zeros in the upper right and lower left and a rectangular $(m-r) \times(n-c)$ array in the lower right that satisfies the conditions of the problem. By the induction hypothesis, we see that $r=c$ and so $m=n$.

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

In a rectangular array of nonnegative real numbers with $m$ rows and $n$ columns, each row and each column contains at least one positive element. Moreover, if a row and a column intersect in a positive element, then the sums of their elements are the same. Prove that $m=n$.

|

[Y. Zhao] Let the term in the $i$ th row and the $j$ th column of the array be denoted by $a_{i j}$, and let $S=\{(i, j)$ : $\left.a_{i j}>0\right\}$. Suppose that $r_{i}$ is the sum of the $i$ th row and $c_{j}$ the sum of the $j$ th column. Then $r_{i}=c_{j}$ whenever $(i, j) \in S$. Then we have that

$$

\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}

$$

We evaluate the sums on either side independently.

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} \frac{1}{r_{i}} \sum_{j=1}^{n} a_{i j}=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left(\frac{1}{r_{i}}\right) r_{i}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} 1=m . \\

& \sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{j=1}^{n} \frac{1}{c_{j}} \sum_{i=1}^{m} a_{i j}=\sum_{j=1}^{n}\left(\frac{1}{c_{j}}\right) c_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{n} 1=n .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $m=n$.

Comment. The second solution can be made cleaner and more elegant by defining $u_{i j}=a_{i j} / r_{i}$ for all $(i, j)$. When $a_{i j}=0$, then $u_{i j}=0$. When $a_{i j}>0$, then, by hypothesis, $u_{i j}=a_{i j} / c_{j}$, a relation that in fact holds for all $(i, j)$. We find that

$$

\sum_{j=1}^{n} u_{i j}=1 \quad \text { and } \quad \sum_{i=1}^{n} u_{i j}=1

$$

for $1 \leq i \leq m$ and $1 \leq j \leq n$, so that $\left(u_{i j}\right)$ is an $m \times n$ array whose row sums and column sums are all equal to 1 . Hence

$$

m=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left(\sum_{j=1}^{n} u_{i j}\right)=\sum\left\{u_{i j}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{j=1}^{n}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{m} u_{i j}\right)=n

$$

(being the sum of all the entries in the array).

|

m=n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

In a rectangular array of nonnegative real numbers with $m$ rows and $n$ columns, each row and each column contains at least one positive element. Moreover, if a row and a column intersect in a positive element, then the sums of their elements are the same. Prove that $m=n$.

|

[Y. Zhao] Let the term in the $i$ th row and the $j$ th column of the array be denoted by $a_{i j}$, and let $S=\{(i, j)$ : $\left.a_{i j}>0\right\}$. Suppose that $r_{i}$ is the sum of the $i$ th row and $c_{j}$ the sum of the $j$ th column. Then $r_{i}=c_{j}$ whenever $(i, j) \in S$. Then we have that

$$

\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}

$$

We evaluate the sums on either side independently.

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{r_{i}}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} \frac{1}{r_{i}} \sum_{j=1}^{n} a_{i j}=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left(\frac{1}{r_{i}}\right) r_{i}=\sum_{i=1}^{m} 1=m . \\

& \sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}:(i, j) \in S\right\}=\sum\left\{\frac{a_{i j}}{c_{j}}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{j=1}^{n} \frac{1}{c_{j}} \sum_{i=1}^{m} a_{i j}=\sum_{j=1}^{n}\left(\frac{1}{c_{j}}\right) c_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{n} 1=n .

\end{aligned}

$$

Hence $m=n$.

Comment. The second solution can be made cleaner and more elegant by defining $u_{i j}=a_{i j} / r_{i}$ for all $(i, j)$. When $a_{i j}=0$, then $u_{i j}=0$. When $a_{i j}>0$, then, by hypothesis, $u_{i j}=a_{i j} / c_{j}$, a relation that in fact holds for all $(i, j)$. We find that

$$

\sum_{j=1}^{n} u_{i j}=1 \quad \text { and } \quad \sum_{i=1}^{n} u_{i j}=1

$$

for $1 \leq i \leq m$ and $1 \leq j \leq n$, so that $\left(u_{i j}\right)$ is an $m \times n$ array whose row sums and column sums are all equal to 1 . Hence

$$

m=\sum_{i=1}^{m}\left(\sum_{j=1}^{n} u_{i j}\right)=\sum\left\{u_{i j}: 1 \leq i \leq m, 1 \leq j \leq n\right\}=\sum_{j=1}^{n}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{m} u_{i j}\right)=n

$$

(being the sum of all the entries in the array).

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 2.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Consider a round-robin tournament with $2 n+1$ teams, where each team plays each other team exactly once. We say that three teams $X, Y$ and $Z$, form a cycle triplet if $X$ beats $Y, Y$ beats $Z$, and $Z$ beats $X$. There are no ties.

(a) Determine the minimum number of cycle triplets possible.

(b) Determine the maximum number of cycle triplets possible.

|

(a) The minimum is 0 , which is achieved by a tournament in which team $T_{i}$ beats $T_{j}$ if and only if $i>j$.

(b) Any set of three teams constitutes either a cycle triplet or a "dominated triplet" in which one team beats the other two; let there be $c$ of the former and $d$ of the latter. Then $c+d=\left(\begin{array}{c}2 n+1 \\ 3\end{array}\right)$. Suppose that team $T_{i}$ beats $x_{i}$ other teams; then it is the winning team in exactly $\left(\begin{array}{c}x_{i} \\ 2\end{array}\right)$ dominated triples. Observe that $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}=\left(\begin{array}{c}2 n+1 \\ 2\end{array}\right)$, the total number of games. Hence

$$

d=\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1}\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{i} \\

2

\end{array}\right)=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}^{2}-\frac{1}{2}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

2

\end{array}\right)

$$

By the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality, $(2 n+1) \sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}^{2} \geq\left(\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}\right)^{2}=n^{2}(2 n+1)^{2}$, whence

$$

c=\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

3

\end{array}\right)-\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1}\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{i} \\

2

\end{array}\right) \leq\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

3

\end{array}\right)-\frac{n^{2}(2 n+1)}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

2

\end{array}\right)=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6} .

$$

To realize the upper bound, let the teams be $T_{1}=T_{2 n+2}, T_{2}=T_{2 n+3}$. $\cdots, T_{i}=T_{2 n+1+i}, \cdots, T_{2 n+1}=T_{4 n+2}$. For each $i$, let team $T_{i}$ beat $T_{i+1}, T_{i+2}, \cdots, T_{i+n}$ and lose to $T_{i+n+1}, \cdots, T_{i+2 n}$. We need to check that this is a consistent assignment of wins and losses, since the result for each pair of teams is defined twice. This can be seen by noting that $(2 n+1+i)-(i+j)=2 n+1-j \geq n+1$ for $1 \leq j \leq n$. The cycle triplets are $\left(T_{i}, T_{i+j}, T_{i+j+k}\right)$ where $1 \leq j \leq n$ and $(2 n+1+i)-(i+j+k) \leq n$, i.e., when $1 \leq j \leq n$ and $n+1-j \leq k \leq n$. For each $i$, this counts $1+2+\cdots+n=\frac{1}{2} n(n+1)$ cycle triplets. When we range over all $i$, each cycle triplet gets counted three times, so the number of cycle triplets is

$$

\frac{2 n+1}{3}\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6} .

$$

|

\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Consider a round-robin tournament with $2 n+1$ teams, where each team plays each other team exactly once. We say that three teams $X, Y$ and $Z$, form a cycle triplet if $X$ beats $Y, Y$ beats $Z$, and $Z$ beats $X$. There are no ties.

(a) Determine the minimum number of cycle triplets possible.

(b) Determine the maximum number of cycle triplets possible.

|

(a) The minimum is 0 , which is achieved by a tournament in which team $T_{i}$ beats $T_{j}$ if and only if $i>j$.

(b) Any set of three teams constitutes either a cycle triplet or a "dominated triplet" in which one team beats the other two; let there be $c$ of the former and $d$ of the latter. Then $c+d=\left(\begin{array}{c}2 n+1 \\ 3\end{array}\right)$. Suppose that team $T_{i}$ beats $x_{i}$ other teams; then it is the winning team in exactly $\left(\begin{array}{c}x_{i} \\ 2\end{array}\right)$ dominated triples. Observe that $\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}=\left(\begin{array}{c}2 n+1 \\ 2\end{array}\right)$, the total number of games. Hence

$$

d=\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1}\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{i} \\

2

\end{array}\right)=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}^{2}-\frac{1}{2}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

2

\end{array}\right)

$$

By the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality, $(2 n+1) \sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}^{2} \geq\left(\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1} x_{i}\right)^{2}=n^{2}(2 n+1)^{2}$, whence

$$

c=\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

3

\end{array}\right)-\sum_{i=1}^{2 n+1}\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{i} \\

2

\end{array}\right) \leq\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

3

\end{array}\right)-\frac{n^{2}(2 n+1)}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

2

\end{array}\right)=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6} .

$$

To realize the upper bound, let the teams be $T_{1}=T_{2 n+2}, T_{2}=T_{2 n+3}$. $\cdots, T_{i}=T_{2 n+1+i}, \cdots, T_{2 n+1}=T_{4 n+2}$. For each $i$, let team $T_{i}$ beat $T_{i+1}, T_{i+2}, \cdots, T_{i+n}$ and lose to $T_{i+n+1}, \cdots, T_{i+2 n}$. We need to check that this is a consistent assignment of wins and losses, since the result for each pair of teams is defined twice. This can be seen by noting that $(2 n+1+i)-(i+j)=2 n+1-j \geq n+1$ for $1 \leq j \leq n$. The cycle triplets are $\left(T_{i}, T_{i+j}, T_{i+j+k}\right)$ where $1 \leq j \leq n$ and $(2 n+1+i)-(i+j+k) \leq n$, i.e., when $1 \leq j \leq n$ and $n+1-j \leq k \leq n$. For each $i$, this counts $1+2+\cdots+n=\frac{1}{2} n(n+1)$ cycle triplets. When we range over all $i$, each cycle triplet gets counted three times, so the number of cycle triplets is

$$

\frac{2 n+1}{3}\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)=\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6} .

$$

|

{

"exam": "Canada_MO",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4.",

"resource_path": "Canada_MO/segmented/en-sol2006.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution 1.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Consider a round-robin tournament with $2 n+1$ teams, where each team plays each other team exactly once. We say that three teams $X, Y$ and $Z$, form a cycle triplet if $X$ beats $Y, Y$ beats $Z$, and $Z$ beats $X$. There are no ties.

(a) Determine the minimum number of cycle triplets possible.

(b) Determine the maximum number of cycle triplets possible.

|

[S. Eastwood] (b) Let $t$ be the number of cycle triplets and $u$ be the number of ordered triplets of teams $(X, Y, Z)$ where $X$ beats $Y$ and $Y$ beats $Z$. Each cycle triplet generates three ordered triplets while other triplets generate exactly one. The total number of triplets is

$$

\left(\begin{array}{c}

2 n+1 \\

3

\end{array}\right)=\frac{n\left(4 n^{2}-1\right)}{3} .

$$

The number of triples that are not cycle is

$$

\frac{n\left(4 n^{2}-1\right)}{3}-t

$$

Hence

$$