problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

If we have a collection of points in space, we may reflect a point of the collection in another point of the collection and add the image of this to the collection.

If we start with a collection consisting of seven of the eight vertices of a cube, can we get the eighth vertex in the collection after a finite number of steps?

|

When we reflect a point $x$ on the number line in a point $y$, we get the reflected point $S_{y}(x)=y-(x-y)=2 y-x$. The same applies to points in space: if we reflect an arbitrary point $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ in a point $\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)$, we get $S_{\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)}\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)=\left(2 y_{1}-x_{1}, 2 y_{2}-x_{2}, 2 y_{3}-x_{3}\right)$.

We now consider only points with integer coordinates. No matter which grid point ( $y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}$ ) we choose, the coordinates of the image $S_{\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)}\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ of $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ all have the same parity as the coordinates of $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$. There are $2^{3}=8$ different possibilities for the parity combinations of the grid points. We can thus color the points of our grid with 8 colors, such that the color of a point is invariant under reflection in any grid point.

Consider now the cube with vertices $(0,0,0),(0,0,1),(0,1,0),(0,1,1),(1,0,0),(1,0,1)$, $(1,1,0),(1,1,1)$. These vertices each have a different color in the aforementioned coloring. Therefore, if one vertex is missing, we cannot obtain it by repeatedly reflecting one of the other vertices, because you only get points of a color you already had.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Geometry

|

Als we een verzameling punten in de ruimte hebben, mogen we een punt van de verzameling spiegelen in een ander punt van de verzameling en het beeld hiervan toevoegen aan de verzameling.

Als we beginnen met een verzameling bestaande uit zeven van de acht hoekpunten van een kubus, kunnen we dan het achtste hoekpunt in de verzameling krijgen na een eindig aantal stappen?

|

Als we op de getallenlijn een punt $x$ spiegelen in een punt $y$, dan krijgen we als spiegelbeeld het punt $S_{y}(x)=y-(x-y)=2 y-x$. Hetzelfde geldt voor punten in de ruimte: spiegelen we een willekeurig punt $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ in een punt $\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)$, dan krijgen we $S_{\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)}\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)=\left(2 y_{1}-x_{1}, 2 y_{2}-x_{2}, 2 y_{3}-x_{3}\right)$.

We bekijken nu alleen punten met gehele coördinaten. Hoe we het roosterpunt ( $y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}$ ) ook kiezen, de coördinaten van het beeld $S_{\left(y_{1}, y_{2}, y_{3}\right)}\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ van $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$ hebben alle drie dezelfde pariteit als de coördinaten van $\left(x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}\right)$. Er zijn $2^{3}=8$ verschillende mogelijkheden voor de pariteitscombinaties van de roosterpunten. We kunnen de punten van ons rooster dus kleuren met 8 kleuren, zodanig dat de kleur van een punt invariant is onder spiegeling in een willekeurig roosterpunt.

Beschouw nu de kubus met hoekpunten $(0,0,0),(0,0,1),(0,1,0),(0,1,1),(1,0,0),(1,0,1)$, $(1,1,0),(1,1,1)$. Deze hoekpunten hebben in bovengenoemde kleuring elk een andere kleur. Als er dus één hoekpunt ontbreekt, kunnen we deze niet verkijgen door het herhaald spiegelen van één van de andere hoekpunten, want je krijgt dan alleen maar punten van een kleur die je al had.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2006-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2006"

}

|

In a group of students, 50 students speak German, 50 students speak French, and 50 students speak Spanish. Some students speak more than one language.

Prove that the students can be divided into 5 groups such that in each group exactly 10 students speak German, 10 speak French, and 10 speak Spanish.

|

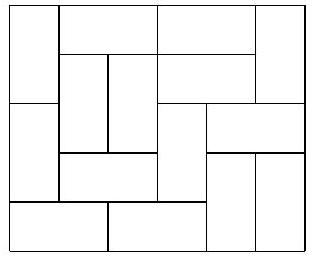

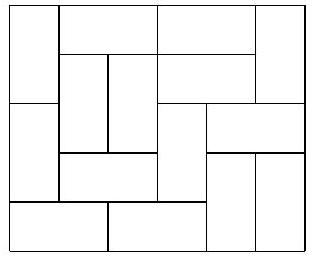

Students who do not speak any language can be disregarded, as we can distribute them arbitrarily over the groups.

We distinguish seven types of students, depending on the languages they speak: DFS, FS, SD, DF, D, F, and S, where, for example, an S-student speaks only Spanish.

Create a Venn diagram with the number of students (see figure 1 on page 6): $d$ DFS-students, $a$ FS-students, $b$ SD-students, and $c$ DF-students. Thus, there are $50-d-b-c$ D-students, $50-d-c-a$ F-students, and $50-d-a-b$ S-students. If we define $t=a+b+c+d$, then there are $50-t+a$ D-students, $50-t+b$ F-students, and $50-t+c$ S-students.

Assume, without loss of generality, that $a \leq b \leq c$. We will first form groups of 1 FS-student, 1 SD-student, and 1 DF-student. Together, these speak all three languages twice. After forming $a$ such groups, we have the following numbers left:

0 FS-students; $b-a \geq 0$ SD-students and $c-a \geq 0$ DF-students; $50-d-b-c$ D-students, $50-d-c-a$ F-students, and $50-d-a-b$ S-students. If we form $b-a$ groups of 1 SD-student and 1 F-student, and also $c-a$ groups of 1 DF-student and 1 S-student, we are left with $50-d-b-c$ D-students, $50-d-c-a-(b-a)=50-d-c-b$ F-students, and $50-d-a-b-(c-a)=50-d-b-c$ S-students, which form $50-d-b-c$ groups of 1 D-student, 1 F-student, and 1 S-student.

In all the groups formed so far, the three languages are spoken either once or twice. First, combine the groups where all three languages are spoken twice, until each language is spoken 10 times. Then continue adding groups where the languages are spoken once.

This results in groups where all three languages are spoken 10 times. Since each language is spoken 50 times, this leads to 5 such groups.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

In een groep van scholieren spreken 50 scholieren Duits, 50 scholieren Frans en 50 scholieren Spaans. Sommige scholieren spreken meer dan één taal.

Bewijs dat de scholieren in 5 groepen verdeeld kunnen worden zodat in elke groep precies 10 scholieren Duits spreken, 10 Frans en 10 Spaans.

|

Scholieren die geen enkele taal spreken kunnen we buiten beschouwing laten, want we kunnen ze willekeurig over de groepen verdelen.

We onderscheiden zeven typen scholieren, al naar gelang de talen die ze spreken: DFS, FS, SD, DF, D, F en S, waarbij bijvoorbeeld een S-scholier alleen Spaans spreekt.

Maak een Venn-diagram met de aantallen scholieren (zie figuur 1 op bladzijde 6): $d$ DFSscholieren, $a$ FS-scholieren, $b$ SD-scholieren en $c$ DF-scholieren. Dus zijn er $50-d-b-c$ D-scholieren, $50-d-c-a$ F-scholieren en $50-d-a-b$ S-scholieren. Definiëren we $t=a+b+c+d$, dan geldt dat er $50-t+a$ D-scholieren zijn, $50-t+b$ F-scholieren en $50-t+c$ S-scholieren.

Ga er z.b.d.a. van uit dat $a \leq b \leq c$. We gaan eerst groepjes maken van 1 FS-scholier, 1 SD-scholier en 1 DF-scholier. Deze spreken samen alle drie de talen twee maal. Nadat we $a$ van zulke groepjes hebben gemaakt, maken we $d$ groepjes bestaande uit 1 DFS-scholier. Nu houden we de volgende aantallen over:

0 FS-scholieren; $b-a \geq 0$ SD-scholieren en $c-a \geq 0$ DF-scholieren; $50-d-b-c$ Dscholieren, $50-d-c-a$ F-scholieren en $50-d-a-b$ S-scholieren. Maken we $b-a$ groepjes van 1 SD-scholier en 1 F-scholier en ook $c-a$ groepjes van 1 DF-scholier en 1 S-scholier, dan houden we $50-d-b-c$ D-scholieren, $50-d-c-a-(b-a)=50-d-c-b$ F-scholieren en $50-d-a-b-(c-a)=50-d-b-c$ S-scholieren over, die samen $50-d-b-c$ groepjes van 1 D-scholier, 1 F-scholier en 1 S-scholier vormen.

In alle tot nu toe gevormde groepjes worden de drie talen alle drie 1 keer, ofwel alle drie 2 keer gesproken. Voeg eerst de groepjes samen waarin alle drie de talen 2 keer worden gesproken, steeds totdat de talen 10 keer worden gesproken. Ga daarna verder met het toevoegen van groepjes waarin de talen 1 keer worden gesproken.

Dan krijgen we groepen waarin alle drie de talen 10 keer worden gesproken. Aangezien elke taal 50 keer wordt gesproken, leidt dit tot 5 van dergelijke groepen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2006-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Circles $\Gamma_{1}$ and $\Gamma_{2}$ intersect at $P$ and $Q$. Let $A$ be a point on $\Gamma_{1}$ not equal to $P$ or $Q$. The lines $A P$ and $A Q$ intersect $\Gamma_{2}$ again at $B$ and $C$ respectively.

Prove that the altitude from $A$ in triangle $A B C$ passes through a point that is independent of the choice of $A$.

|

By drawing several neat pictures, we have come to suspect that the mentioned altitude always passes through the center of $\Gamma_{1}$. We will now prove that this is indeed the case.

The foot of the altitude from $A$ to (the extension of) $B C$ we call $K$, and the other intersection of this altitude with $\Gamma_{1}$ we call $D$. To prove: $A D$ is a diameter of $\Gamma_{1}$.

There are several configurations possible. We call arc $P Q$ the part of $\Gamma_{1}$ that lies within $\Gamma_{2}$, and arc $Q P$ the other part of $\Gamma_{1}$. We first consider the case where $D$ lies on arc $P Q$ (see figure 2 on page 6). In this case, we have:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle D Q C + \angle P Q D = \angle P Q C & = \pi - \angle C B P \text{ (due to cyclic quadrilateral } P Q C B) \\

& = \pi - \angle K B P \text{ (same angle) } \\

& = \pi - \angle K B A \text{ (same angle) } \\

& = \angle B A K + \angle A K B \text{ (sum of angles in a triangle) } \\

& = \angle B A K + \frac{1}{2} \pi (A K \text{ was the altitude) } \\

& = \angle P A D + \frac{1}{2} \pi \text{ (same angle) } \\

& = \angle P Q D + \frac{1}{2} \pi \text{ (inscribed angle) }

\end{aligned}

$$

so $\angle D Q C = \frac{1}{2} \pi$. From $\angle A Q D + \angle D Q C = \angle A Q C = \pi$ (straight angle), it follows that $\angle A Q D = \frac{1}{2} \pi$, and by Thales' theorem, we can conclude that $A D$ is a diameter of $\Gamma_{1}$.

Now consider the case where $\angle B$ is obtuse and $B$ and $C$ still lie on the same side of $P Q$ (see figure 3 on page 6). In this case, we have:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle D Q C - \angle D Q P = \angle P Q C & = \pi - \angle C B P \text{ (due to cyclic quadrilateral } P Q C B) \\

& = \angle P B K \text{ (straight angle) } \\

& = \angle A B K \text{ (same angle) } \\

& = \pi - \angle K A B - \angle B K A \text{ (sum of angles in a triangle) } \\

& = \frac{1}{2} \pi - \angle K A B (A K \text{ was the altitude) } \\

& = \frac{1}{2} \pi - \angle D A P \text{ (same angle) } \\

& = \frac{1}{2} \pi - \angle D Q P \text{ (inscribed angle) }

\end{aligned}

$$

so $\angle D Q C = \frac{1}{2} \pi$. From $\angle A Q D + \angle D Q C = \angle A Q C = \pi$ it follows again that $\angle A Q D = \frac{1}{2} \pi$, and by Thales' theorem, we can conclude that $A D$ is a diameter of $\Gamma_{1}$.

All other configurations proceed analogously. By working with oriented angles, we would not need to use case distinctions.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Cirkels $\Gamma_{1}$ en $\Gamma_{2}$ snijden elkaar in $P$ en $Q$. Zij $A$ een punt op $\Gamma_{1}$ niet gelijk aan $P$ of $Q$. De lijnen $A P$ en $A Q$ snijden $\Gamma_{2}$ nogmaals in respectievelijk $B$ en $C$.

Bewijs dat de hoogtelijn uit $A$ in driehoek $A B C$ door een punt gaat dat onafhankelijk is van de keuze van $A$.

|

Door het tekenen van verscheidene nette plaatjes hebben we het vermoeden gekregen dat de genoemde hoogtelijn altijd door het middelpunt van $\Gamma_{1}$ gaat. Dat dat ook daadwerkelijk zo is, gaan we nu bewijzen.

Het voetpunt van de hoogtelijn uit $A$ op (het verlengde van) $B C$ noemen we $K$, en het andere snijpunt van deze hoogtelijn met $\Gamma_{1}$ noemen we $D$. Te bewijzen: $A D$ is een middellijn van $\Gamma_{1}$.

Er zijn verschillende configuraties mogelijk. We noemen boog $P Q$ het deel van $\Gamma_{1}$ dat binnen $\Gamma_{2}$ ligt, en boog $Q P$ het andere deel van $\Gamma_{1}$. We bekijken eerst het geval dat $D$ op boog $P Q$ ligt (zie figuur 2 op bladzijde 6). In dit geval geldt:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle D Q C+\angle P Q D=\angle P Q C & =\pi-\angle C B P(\text { wegens koordenvierhoek } P Q C B) \\

& =\pi-\angle K B P(\text { zelfde hoek }) \\

& =\pi-\angle K B A(\text { zelfde hoek }) \\

& =\angle B A K+\angle A K B \text { (hoekensom driehoek) } \\

& =\angle B A K+\frac{1}{2} \pi(A K \text { was hoogtelijn) } \\

& =\angle P A D+\frac{1}{2} \pi \text { (zelfde hoek) } \\

& =\angle P Q D+\frac{1}{2} \pi(\text { omtrekshoek })

\end{aligned}

$$

zodat $\angle D Q C=\frac{1}{2} \pi$. Uit $\angle A Q D+\angle D Q C=\angle A Q C=\pi$ (gestrekte hoek) volgt nu dat $\angle A Q D=\frac{1}{2} \pi$, zodat we wegens Thales kunnen concluderen dat $A D$ een middellijn is van $\Gamma_{1}$.

Bekijk nu het geval dat $\angle B$ stomp is en dat $B$ en $C$ nog wel aan dezelfde kant van $P Q$ liggen (zie figuur 3 op bladzijde 6). In dit geval geldt:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\angle D Q C-\angle D Q P=\angle P Q C & =\pi-\angle C B P(\text { wegens koordenvierhoek } P Q C B) \\

& =\angle P B K(\text { gestrekte hoek }) \\

& =\angle A B K(\text { zelfde hoek }) \\

& =\pi-\angle K A B-\angle B K A \text { (hoekensom driehoek) } \\

& =\frac{1}{2} \pi-\angle K A B(A K \text { was hoogtelijn) } \\

& =\frac{1}{2} \pi-\angle D A P \text { (zelfde hoek) } \\

& =\frac{1}{2} \pi-\angle D Q P(\text { omtrekshoek })

\end{aligned}

$$

zodat $\angle D Q C=\frac{1}{2} \pi$. Uit $\angle A Q D+\angle D Q C=\angle A Q C=\pi$ volgt wederom dat $\angle A Q D=\frac{1}{2} \pi$, zodat we wegens Thales kunnen concluderen dat $A D$ een middellijn is van $\Gamma_{1}$.

Alle andere configuraties gaan analoog. Door met georiënteerde hoeken te werken zouden we geen gevalsonderscheiding hoeven te gebruiken.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2006-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Let $\mathbb{R}_{>0}$ be the set of positive real numbers. Let $a \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$ be given. Find all functions $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that $f(a)=1$ and

$$

\forall x, y \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}: f(x) f(y)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{y}\right)=2 f(x y)

$$

|

Substituting $x=a$ and $y=1$ into (1) gives $f(a) f(1)+f\left(\frac{a}{a}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{1}\right)=2 f(a \cdot 1)$, which, due to $f(a)=1$, leads to $f(1)+f(1)=2$, thus

$$

f(1)=1

$$

Substituting $y=1$ into (1) gives $f(x) f(1)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{1}\right)=2 f(x \cdot 1)$, which, due to $f(a)=f(1)=1$, leads to $f(x)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right)=2 f(x)$, thus

$$

f(x)=f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) .

$$

But then (1) transforms into $f(x) f(y)+f(x) f(y)=2 f(x y)$, thus

$$

f(x) f(y)=f(x y)

$$

From (3) and (4) it follows that $f(x) f(x)=f(x) f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right)=f\left(x \cdot \frac{a}{x}\right)=f(a)=1$, so for every $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$, $f(x)=1$ or $f(x)=-1$.

Since we can write positive $x$ as $\sqrt{x} \sqrt{x}$, we find using (4) that $f(x)=$ $f(\sqrt{x} \sqrt{x})=f(\sqrt{x}) f(\sqrt{x})=( \pm 1)^{2}=1$, thus $f(x)=1$ for every $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$. We conclude that the only possibility for $f$ is apparently the constant function $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}: x \mapsto 1$.

Finally, we check whether the constant function $\forall x: f(x)=1$ indeed satisfies the conditions. The condition $f(a)=1$ is satisfied, while (1) becomes $1 \cdot 1+1 \cdot 1=2 \cdot 1$, which holds.

Thus, there is exactly one function $f$ that satisfies the given conditions, namely $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}: x \mapsto 1$.

|

f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}: x \mapsto 1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Zij $\mathbb{R}_{>0}$ de verzameling van positieve reële getallen. Laat $a \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$ gegeven zijn. Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ zodanig dat $f(a)=1$ en

$$

\forall x, y \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}: f(x) f(y)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{y}\right)=2 f(x y)

$$

|

Invullen van $x=a$ en $y=1$ in (1) geeft $f(a) f(1)+f\left(\frac{a}{a}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{1}\right)=2 f(a \cdot 1)$, wat wegens $f(a)=1$ leidt tot $f(1)+f(1)=2$, dus

$$

f(1)=1

$$

Invullen van $y=1$ in (1) geeft $f(x) f(1)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) f\left(\frac{a}{1}\right)=2 f(x \cdot 1)$, wat wegens $f(a)=f(1)=1$ leidt tot $f(x)+f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right)=2 f(x)$, dus

$$

f(x)=f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right) .

$$

Maar dan gaat (1) over in $f(x) f(y)+f(x) f(y)=2 f(x y)$, dus

$$

f(x) f(y)=f(x y)

$$

Uit (3) en (4) volgt dat $f(x) f(x)=f(x) f\left(\frac{a}{x}\right)=f\left(x \cdot \frac{a}{x}\right)=f(a)=1$, dus voor elke $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$ geldt $f(x)=1$ of $f(x)=-1$.

Aangezien we positieve $x$ kunnen schrijven als $\sqrt{x} \sqrt{x}$, vinden we m.b.v. (4) dat $f(x)=$ $f(\sqrt{x} \sqrt{x})=f(\sqrt{x}) f(\sqrt{x})=( \pm 1)^{2}=1$, dus $f(x)=1$ voor elke $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$. We concluderen dat de enige mogelijkheid voor $f$ blijkbaar de constante functie $f: \mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}: x \mapsto 1$ is.

Ten slotte controleren we of de constante functie $\forall x: f(x)=1$ daadwerkelijk voldoet. Aan $f(a)=1$ wordt voldaan, terwijl (1) neerkomt op $1 \cdot 1+1 \cdot 1=2 \cdot 1$, wat geldt.

Er is dus precies één functie $f$ die aan de gevraagde voorwaarden voldoet, namelijk $f$ : $\mathbb{R}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}: x \mapsto 1$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2006-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Let $\lfloor x\rfloor$ be the greatest integer less than or equal to $x$. Let $n \in \mathbb{N}, n \geq 7$ be given.

Prove that $\binom{n}{7}-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{7}\right\rfloor$ is divisible by 7.

|

Write $n=7 k+\ell$ for integers $k$ and $\ell$ with $0 \leq \ell \leq 6$, then it holds that $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{7}\right\rfloor=\left\lfloor k+\frac{\ell}{7}\right\rfloor=k$.

To prove: $\binom{n}{7} \equiv k(\bmod 7)$.

Proof: Writing out the binomial coefficient gives

$$

\binom{n}{7}=\frac{n!}{7!(n-7)!}=\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)(n-4)(n-5)(n-6)}{7 \cdot 6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}

$$

The factor $(n-\ell)$ in the numerator is equal to $7 k$, so

$\binom{n}{7}=\frac{7 k \cdot n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{7 \cdot 6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}=k \cdot \frac{n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}$,

where $(\widehat{n-\ell})$ means that we have omitted the factor $(n-\ell)$. Modulo 7, the numerator originally contained the 7 residue classes modulo 7, but now that we have omitted $(n-\ell) \equiv 0(\bmod 7)$, the numerator contains exactly the residue classes $1,2,3,4,5$ and 6, just like the denominator, which thus cancel each other out modulo the prime number 7. We are left with

$$

\binom{n}{7}=k \cdot \frac{n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1} \equiv k \cdot 1=k \quad(\bmod 7)

$$

which is what we wanted to prove.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $\lfloor x\rfloor$ het grootste gehele getal kleiner dan of gelijk aan $x$. Laat $n \in \mathbb{N}, n \geq 7$ gegeven zijn.

Bewijs dat $\binom{n}{7}-\left\lfloor\frac{n}{7}\right\rfloor$ deelbaar is door 7 .

|

Schrijf $n=7 k+\ell$ voor gehele $k$ en $\ell$ met $0 \leq \ell \leq 6$, dan geldt $\left\lfloor\frac{n}{7}\right\rfloor=\left\lfloor k+\frac{\ell}{7}\right\rfloor=k$.

Te bewijzen: $\binom{n}{7} \equiv k(\bmod 7)$.

Bewijs: Het uitschrijven van de binomiaalcoëfficiënt geeft

$$

\binom{n}{7}=\frac{n!}{7!(n-7)!}=\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)(n-4)(n-5)(n-6)}{7 \cdot 6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}

$$

De factor $(n-\ell)$ in de teller is gelijk aan $7 k$, zodat

$\binom{n}{7}=\frac{7 k \cdot n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{7 \cdot 6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}=k \cdot \frac{n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}$,

waar $(\widehat{n-\ell})$ betekent dat we de factor $(n-\ell)$ hebben weggelaten. Modulo 7 stonden in de teller de 7 restklassen modulo 7 , maar nu we $(n-\ell) \equiv 0(\bmod 7)$ hebben weggelaten staan in de teller precies de restklassen $1,2,3,4,5$ en 6 , net als in de noemer, die dus tegen elkaar wegvallen modulo het priemgetal 7 . We houden over dat

$$

\binom{n}{7}=k \cdot \frac{n(n-1) \cdots(\widehat{n-\ell}) \cdots(n-5)(n-6)}{6 \cdot 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1} \equiv k \cdot 1=k \quad(\bmod 7)

$$

hetgeen te bewijzen was.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "# Opgave 5.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2006-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Oplossing:",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2006"

}

|

Let $m$ be a positive integer. Prove that for all positive real numbers $a$ and $b$ the following holds:

$$

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m}+\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} \geq 2^{m+1}

$$

|

We use that $x+\frac{1}{x} \geq 2$ for all $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$. It holds that

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m}+\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} & =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^{i}+\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)^{i} \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^{i}+\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)^{i}\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{a^{i}}{b^{i}}+\frac{b^{i}}{a^{i}}\right) \\

& \geq \sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i} \cdot 2 \\

& =2^{m+1} .

\end{aligned}

$$

## Alternative solution.

Apply the inequality of the arithmetic and geometric means to 1 and $\frac{a}{b}$:

$$

1+\frac{a}{b} \geq 2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}

$$

so

$$

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m} \geq\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m}

$$

Similarly, of course,

$$

\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} \geq\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m}

$$

Now we apply the inequality of the arithmetic and geometric means again:

$$

\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m}+\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m} \geq 2 \sqrt{\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m} \cdot\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m}}=2^{m+1}

$$

This proves the desired result.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Zij $m$ een positief geheel getal. Bewijs dat voor alle positieve reële getallen $a$ en $b$ geldt:

$$

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m}+\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} \geq 2^{m+1}

$$

|

We gebruiken dat $x+\frac{1}{x} \geq 2$ voor alle $x \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}$. Er geldt

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m}+\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} & =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^{i}+\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)^{i} \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^{i}+\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)^{i}\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i}\left(\frac{a^{i}}{b^{i}}+\frac{b^{i}}{a^{i}}\right) \\

& \geq \sum_{i=0}^{m}\binom{m}{i} \cdot 2 \\

& =2^{m+1} .

\end{aligned}

$$

## Alternatieve oplossing.

Pas de ongelijkheid van het rekenkundig en meetkundig gemiddelde toe op 1 en $\frac{a}{b}$ :

$$

1+\frac{a}{b} \geq 2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}

$$

dus

$$

\left(1+\frac{a}{b}\right)^{m} \geq\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m}

$$

Analoog geldt natuurlijk

$$

\left(1+\frac{b}{a}\right)^{m} \geq\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m}

$$

Nu passen we opnieuw de ongelijkheid van het rekenkundig en meetkundig gemiddelde toe:

$$

\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m}+\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m} \geq 2 \sqrt{\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}\right)^{m} \cdot\left(2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{a}}\right)^{m}}=2^{m+1}

$$

Dit bewijst het gevraagde.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2007-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2007"

}

|

Four points $P, Q, R$, and $S$ lie in this order on a circle, such that $\angle P S R=90^{\circ}$. Let $H$ and $K$ be the feet of the perpendiculars from $Q$ to $P R$ and $P S$, respectively. Let $T$ be the intersection of $H K$ and $Q S$. Prove that $|S T|=|T Q|$.

|

Since $\angle P S R$ is a right angle, $P R$ is a diameter and thus $\angle P Q R$ is also a right angle. Furthermore, $P Q H K$ is a cyclic quadrilateral (and $P Q R S$ is obviously also one), so

$$

\angle Q S R=\angle Q P R=\angle Q P H=\angle Q K H

$$

Thus,

$$

\angle T K S=90^{\circ}-\angle Q K H=90^{\circ}-\angle Q S R=\angle Q S K

$$

Therefore, $\triangle T S K$ is isosceles with $|K T|=|T S|$. Furthermore, $\angle Q S R=\angle K Q S$, because $S R$ and $Q K$ are both perpendicular to $P S$, so

$$

\angle K Q S=\angle Q S R=\angle Q K H,

$$

which means that triangle $K Q T$ is also isosceles with $|T Q|=|T K|$. Therefore, $|T Q|=|T K|=|T S|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Vier punten $P, Q, R$ en $S$ liggen in deze volgorde op een cirkel, zodat $\angle P S R=90^{\circ}$. Zij $H$ en $K$ de voetpunten van de loodlijnen uit $Q$ op respectievelijk $P R$ en $P S$. Zij $T$ het snijpunt van $H K$ en $Q S$. Bewijs dat $|S T|=|T Q|$.

|

Omdat $\angle P S R$ recht is, is $P R$ een middellijn en is dus ook $\angle P Q R$ recht. Verder is $P Q H K$ een koordenvierhoek (en $P Q R S$ natuurlijk ook), dus

$$

\angle Q S R=\angle Q P R=\angle Q P H=\angle Q K H

$$

Dus

$$

\angle T K S=90^{\circ}-\angle Q K H=90^{\circ}-\angle Q S R=\angle Q S K

$$

Dus $\triangle T S K$ is gelijkbenig met $|K T|=|T S|$. Verder is $\angle Q S R=\angle K Q S$, omdat $S R$ en $Q K$ beide loodrecht op $P S$ staan, dus

$$

\angle K Q S=\angle Q S R=\angle Q K H,

$$

zodat ook driehoek $K Q T$ gelijkbenig is met $|T Q|=|T K|$. Dus $|T Q|=|T K|=|T S|$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2007-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2007"

}

|

You have 2007 cards. On each card, a positive integer less than 2008 is written. If you take a number (at least 1) of these cards, the sum of the numbers on the cards is not divisible by 2008. Prove that the same number is written on every card.

|

Do not assume. Let the numbers on the cards be $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{2007}$ where $n_{1} \neq n_{2}$. Let

$$

s_{i}=n_{1}+n_{2}+\ldots+n_{i},

$$

for $i=1,2, \ldots, 2007$. We now know that $s_{i} \equiv \equiv(\bmod 2008)$ for all $i$. Suppose $s_{i} \equiv s_{j}$ $(\bmod 2008)$ with $i<j$, then

$$

n_{i+1}+\ldots+n_{j} \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 2008)

$$

contradiction. Therefore, $s_{1}, \ldots, s_{2007}$ take on the values 1, 2, .., 2007 modulo 2008. Now consider $n_{2}$. We know that $n_{2} \not \equiv 0(\bmod 2008)$, so $n_{2} \equiv s_{i}(\bmod 2008)$ for some $i$. For $i=1$, this means $n_{2} \equiv n_{1}(\bmod 2008)$, which, given $n_{1}, n_{2} \in\{1, \ldots, 2007\}$, implies that $n_{1}=n_{2}$; contradiction. And for $i>1$, it means that the non-empty sum $s_{i}-n_{2}=n_{1}+n_{3}+n_{4}+\ldots+n_{i}$ is equal to 0 modulo 2008; again a contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Je hebt 2007 kaarten. Op elke kaart is een positief geheel getal kleiner dan 2008 geschreven. Als je een aantal (minstens 1) van deze kaarten neemt, is de som van de getallen op de kaarten niet deelbaar door 2008. Bewijs dat op elke kaart hetzelfde getal staat.

|

Stel niet. Noem de getallen op de kaarten $n_{1}, \ldots, n_{2007}$ waarbij $n_{1} \neq n_{2}$. Zij

$$

s_{i}=n_{1}+n_{2}+\ldots+n_{i},

$$

voor $i=1,2, \ldots, 2007$. We weten nu dat $s_{i} \equiv \equiv(\bmod 2008)$ voor alle $i$. Stel dat $s_{i} \equiv s_{j}$ $(\bmod 2008)$ met $i<j$, dan geldt

$$

n_{i+1}+\ldots+n_{j} \equiv 0 \quad(\bmod 2008)

$$

tegenspraak. Dus $s_{1}, \ldots, s_{2007}$ nemen modulo 2008 precies de waarden 1, 2, .., 2007 aan. Bekijk nu $n_{2}$. We weten dat $n_{2} \not \equiv 0(\bmod 2008)$, dus $n_{2} \equiv s_{i}(\bmod 2008)$ voor een of andere $i$. Voor $i=1$ staat hier $n_{2} \equiv n_{1}(\bmod 2008)$, wat wegens $n_{1}, n_{2} \in\{1, \ldots, 2007\}$ impliceert dat $n_{1}=n_{2}$; tegenspraak. En voor $i>1$ betekent het dat de niet-lege som $s_{i}-n_{2}=n_{1}+n_{3}+n_{4}+\ldots+n_{i}$ gelijk is aan 0 modulo 2008; wederom tegenspraak.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2007-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2007"

}

|

$\mathrm{Zij} n \geq 1$. Find all permutations $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ of $(1,2, \ldots, n)$ for which

$$

\frac{a_{k}^{2}}{a_{k+1}} \leq k+2 \quad \text { for } k=1,2, \ldots, n-1

$$

|

Suppose for some $i \leq n-1$ it holds that $a_{i}>i$. It follows that $\frac{a_{i}^{2}}{a_{i+1}} \leq i+2$, so

$$

a_{i+1} \geq \frac{a_{i}^{2}}{i+2} \geq \frac{(i+1)^{2}}{i+2}=\frac{i^{2}+2 i+1}{i+2}>i.

$$

If $a_{i} \geq i+2$, then in the same way $a_{i+1}>i+1$. If $a_{i}=i+1$, then $i+1$ is no longer available as a value for $a_{i+1}$, so $a_{i+1}>i+1$ also holds.

Thus, if $a_{i}>i$, then also $a_{i+1}>i+1$. Since $a_{n} \leq n$, there can be no $i$ such that $a_{i}>i$. It follows that $a_{i}=i$ for all $i$.

|

a_{i}=i

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

$\mathrm{Zij} n \geq 1$. Vind alle permutaties $\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}\right)$ van $(1,2, \ldots, n)$ waarvoor geldt

$$

\frac{a_{k}^{2}}{a_{k+1}} \leq k+2 \quad \text { voor } k=1,2, \ldots, n-1

$$

|

Stel dat voor zekere $i \leq n-1$ geldt dat $a_{i}>i$. Er geldt $\frac{a_{i}^{2}}{a_{i+1}} \leq i+2$, dus

$$

a_{i+1} \geq \frac{a_{i}^{2}}{i+2} \geq \frac{(i+1)^{2}}{i+2}=\frac{i^{2}+2 i+1}{i+2}>i .

$$

Als $a_{i} \geq i+2$, dan geldt op dezelfde manier $a_{i+1}>i+1$. Als $a_{i}=i+1$, dan is $i+1$ niet meer beschikbaar als waarde voor $a_{i+1}$, dus geldt ook $a_{i+1}>i+1$.

Dus als $a_{i}>i$, dan ook $a_{i+1}>i+1$. Aangezien $a_{n} \leq n$, kan er dus geen enkele $i$ zijn met $a_{i}>i$. Hieruit volgt dat $a_{i}=i$ voor alle $i$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2007-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2007"

}

|

Prove that there are infinitely many pairs of positive integers $(x, y)$ such that

$$

\frac{x+1}{y}+\frac{y+1}{x}=4 .

$$

|

We can rewrite the equation as $(x+1) x+(y+1) y=4 x y$, so

$$

x^{2}-(4 y-1) x+\left(y^{2}+y\right)=0 .

$$

If we see this as an equation in $x$ with parameter $y$, then for the two solutions $x_{0}$ and $x_{1}$, by Vieta's formulas, we have (i): $x_{0}+x_{1}=4 y-1$ and (ii): $x_{0} \cdot x_{1}=y^{2}+y$.

Suppose that $x_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$ and $y_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$ form an arbitrary solution. Then, for this value of $y_{0}$, there is another solution $x_{1}$, which is an integer by (i) and positive by (ii). For this other solution, we have by (i): $x_{1}=4 y_{0}-1-x_{0}$. In short, each solution pair $(x, y)$ leads to another solution pair $(4 y-1-x, y)$. The trick is to realize that then $(y, 4 y-1-x)$ is also a solution pair.

The pair $(1,1)$ is clearly a solution. Now consider the sequence $z_{1}=1, z_{2}=1$, and $z_{n+2}=$ $4 z_{n+1}-1-z_{n}(n \geq 1)$, then each pair $\left(z_{n}, z_{n+1}\right)$ is apparently a solution to the given equation.

Finally, we need to prove that this leads to all distinct solutions $\left(z_{n}, z_{n+1}\right)$. To do this, we prove by induction that $\forall n \geq 2: z_{n+1} \geq 2 z_{n} \wedge z_{n+1} \geq 1$.

For $n=2$, this is clearly true, as $z_{3}=2$ and $z_{2}=1$. Suppose it holds for some $n \geq 2$, so $z_{n+1} \geq 2 z_{n} \wedge z_{n+1} \geq 1$. Then $z_{n+2}=4 z_{n+1}-1-z_{n} \geq 4 z_{n+1}-z_{n+1}-z_{n+1}=2 z_{n+1} \geq 2>1$, so we see that it also holds for $n+1$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Bewijs dat er oneindig veel paren positieve gehele getallen $(x, y)$ zijn met

$$

\frac{x+1}{y}+\frac{y+1}{x}=4 .

$$

|

We kunnen de vergelijking herschrijven tot $(x+1) x+(y+1) y=4 x y$, dus

$$

x^{2}-(4 y-1) x+\left(y^{2}+y\right)=0 .

$$

Als we dit zien als een vergelijking in $x$ met parameter $y$, dan geldt er voor de twee oplossingen $x_{0}$ en $x_{1}$ wegens Vieta dat (i): $x_{0}+x_{1}=4 y-1$ en (ii): $x_{0} \cdot x_{1}=y^{2}+y$.

Stel nou dat $x_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$ en $y_{0} \in \mathbb{N}$ een willekeurige oplossing vormen. Dan is er bij deze waarde van $y_{0}$ dus nog een oplossing $x_{1}$, die wegens (i) weer geheel is, en wegens (ii) weer positief. Voor deze andere oplossing geldt wegens (i): $x_{1}=4 y_{0}-1-x_{0}$. Kortom, elk oplossingspaar $(x, y)$ leidt tot een oplossingspaar $(4 y-1-x, y)$. De truc is nou om te bedenken dat dan ook $(y, 4 y-1-x)$ een oplossingspaar is.

Het paar $(1,1)$ is duidelijk een oplossing. Beschouw nu de rij $z_{1}=1, z_{2}=1$, en $z_{n+2}=$ $4 z_{n+1}-1-z_{n}(n \geq 1)$, dan is elk paar $\left(z_{n}, z_{n+1}\right)$ dus blijkbaar een oplossing van de gegeven vergelijking.

Tot slot moeten we nog bewijzen dat dit tot echt allemaal verschillende oplossingen $\left(z_{n}, z_{n+1}\right)$ leidt. Hiertoe bewijzen we met inductie dat $\forall n \geq 2: z_{n+1} \geq 2 z_{n} \wedge z_{n+1} \geq 1$.

Voor $n=2$ is dit duidelijk, want $z_{3}=2$ en $z_{2}=1$. Stel het geldt voor zekere $n \geq 2$, dus $z_{n+1} \geq 2 z_{n} \wedge z_{n+1} \geq 1$. Dan $z_{n+2}=4 z_{n+1}-1-z_{n} \geq 4 z_{n+1}-z_{n+1}-z_{n+1}=2 z_{n+1} \geq 2>1$, dus zien we dat het ook geldt voor $n+1$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2007-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2007"

}

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ die voldoen aan

$$

f(f(f(n)))+f(f(n))+f(n)=3 n

$$

voor alle $n \in \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$.

|

Uit $f(m)=f(n)$ volgt $3 m=3 n$ dus $m=n$. Dus $f$ is injectief. Nu bewijzen we met volledige inductie naar $n$ dat $f(n)=n$ voor alle $n$.

Omdat $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ geldt $f(1) \geq 1, f(f(1)) \geq 1$ en $f(f(f(1))) \geq 1$. Vullen we nu $n=1$ in de functievergelijking in, dan zien we dat

$$

f(f(f(1)))+f(f(1))+f(1)=3,

$$

dus moet overal gelijkheid gelden: $f(1)=f(f(1))=f(f(f(1)))=1$.

Zij nu $k \geq 2$ en stel dat we voor alle $n<k$ bewezen hebben dat $f(n)=n$. Dan volgt uit de injectiviteit van $f$ dat voor alle $m \geq k$ geldt dat $f(m) \geq k$; de lagere functiewaardes worden immers al aangenomen. Dus in het bijzonder geldt $f(k) \geq k$ en dan ook $f(f(k)) \geq k$ en daarom ook $f(f(f(k))) \geq k$. Vullen we nu $n=k$ in de functievergelijking in, dan zien we dat

$$

f(f(f(k)))+f(f(k))+f(k)=3 k

$$

We zien dat ook nu weer overal gelijkheid moet gelden, dus $f(k)=k$. Dit voltooit de inductie.

De enige functie die kan voldoen is dus $f(n)=n$ voor alle $n$. Deze functie voldoet ook daadwerkelijk, want

$$

f(f(f(n)))+f(f(n))+f(n)=n+n+n=3 n

$$

|

f(n)=n

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ die voldoen aan

$$

f(f(f(n)))+f(f(n))+f(n)=3 n

$$

voor alle $n \in \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$.

|

Uit $f(m)=f(n)$ volgt $3 m=3 n$ dus $m=n$. Dus $f$ is injectief. Nu bewijzen we met volledige inductie naar $n$ dat $f(n)=n$ voor alle $n$.

Omdat $f: \mathbb{Z}_{>0} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ geldt $f(1) \geq 1, f(f(1)) \geq 1$ en $f(f(f(1))) \geq 1$. Vullen we nu $n=1$ in de functievergelijking in, dan zien we dat

$$

f(f(f(1)))+f(f(1))+f(1)=3,

$$

dus moet overal gelijkheid gelden: $f(1)=f(f(1))=f(f(f(1)))=1$.

Zij nu $k \geq 2$ en stel dat we voor alle $n<k$ bewezen hebben dat $f(n)=n$. Dan volgt uit de injectiviteit van $f$ dat voor alle $m \geq k$ geldt dat $f(m) \geq k$; de lagere functiewaardes worden immers al aangenomen. Dus in het bijzonder geldt $f(k) \geq k$ en dan ook $f(f(k)) \geq k$ en daarom ook $f(f(f(k))) \geq k$. Vullen we nu $n=k$ in de functievergelijking in, dan zien we dat

$$

f(f(f(k)))+f(f(k))+f(k)=3 k

$$

We zien dat ook nu weer overal gelijkheid moet gelden, dus $f(k)=k$. Dit voltooit de inductie.

De enige functie die kan voldoen is dus $f(n)=n$ voor alle $n$. Deze functie voldoet ook daadwerkelijk, want

$$

f(f(f(n)))+f(f(n))+f(n)=n+n+n=3 n

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\n1. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2008-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Julian and Johan are playing a game with an even number, say $2 n$, of cards ( $n \in \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ ). On each card, there is a positive integer. The cards are shuffled and laid out in a row on the table with the numbers visible. A player whose turn it is may take either the leftmost card or the rightmost card. The players take turns alternately.

Johan starts, so Julian picks the last card. Johan's score is the sum of the numbers on the $n$ cards he has picked, and the same goes for Julian. Prove that Johan can always achieve a score that is at least as high as Julian's.

|

Let $2 n$ be the number of cards and assume that the cards are arranged in a row as $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$. We prove by induction on $n$ that Johan can always ensure that he picks either all the odd cards $a_{1}, a_{3}, a_{5}, \ldots$ or all the even cards $a_{2}, a_{4}, a_{6}, \ldots$ For $n=1$, Johan picks card $a_{1}$ if he wants the odd cards and card $a_{2}$ if he wants the even cards. Suppose we have proven it for some $n$. Consider the cards $a_{1}$, $a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n+2}$. If Johan wants the odd cards, he picks $a_{1}$ first. Julian then picks either $a_{2}$ or $a_{2 n+2}$. After that, the remaining row is $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{2 n}$. In the first case, $b_{i}=a_{i+2}$ for all $i$, and according to the induction hypothesis, Johan can get all the odd $b_{i}$, which together with card $a_{1}$ gives him all the odd cards. In the second case, $b_{i}=a_{i+1}$ for all $i$, and according to the induction hypothesis, Johan can get all the even $b_{i}$, which together with card $a_{1}$ gives him all the odd cards. Therefore, Johan can ensure that he gets all the odd cards. Similarly, he can also ensure that he gets all the even cards. This completes the induction. Johan can now ensure that he scores at least as many points as Julian in the following way: if the sum of the numbers on the odd cards is at least as large as the sum of the numbers on the even cards, he chooses all the odd cards. Otherwise, he chooses all the even cards.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Julian en Johan spelen een spel met een even aantal, zeg $2 n$, kaarten ( $n \in \mathbb{Z}_{>0}$ ). Op elke kaart staat een positief geheel getal. De kaarten worden geschud en in een rij op tafel gelegd met de getallen zichtbaar. Een speler die aan de beurt is, mag ofwel de meest linker kaart ofwel de meest rechter kaart pakken. De spelers zijn om en om aan de beurt.

Johan begint, dus Julian pakt uiteindelijk de laatste kaart. De score van Johan is de som van de getallen op de $n$ kaarten die hij heeft gepakt en voor Julian net zo. Bewijs dat Johan altijd een minstens even hoge score als Julian kan behalen.

|

Zij $2 n$ het aantal kaarten en ga ervan uit dat de kaarten in de rij achtereenvolgens $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n}$ zijn. We bewijzen met inductie naar $n$ dat Johan dan altijd kan zorgen dat hij naar keuze alle oneven kaarten $a_{1}, a_{3}, a_{5}, \ldots$ pakt of juist alle even kaarten $a_{2}, a_{4}, a_{6}, \ldots$ Voor $n=1$ pakt Johan kaart $a_{1}$ als hij de oneven kaarten wil en kaart $a_{2}$ als hij de even kaarten wil. Stel we hebben het bewezen voor zekere $n$. Bekijk de kaarten $a_{1}$, $a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2 n+2}$. Als Johan de oneven kaarten wil, pakt hij eerst $a_{1}$. Julian pakt vervolgens $a_{2}$ of $a_{2 n+2}$. Daarna blijft over de rij $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{2 n}$. In het eerste geval geldt $b_{i}=a_{i+2}$ voor alle $i$ en kan Johan volgens de inductiehypothese alle oneven $b_{i}$ krijgen, wat hem samen met de kaart $a_{1}$ alle oneven kaarten oplevert. In het tweede geval geldt $b_{i}=a_{i+1}$ voor alle $i$ en kan Johan volgens de inductiehypothese alle even $b_{i}$ krijgen, wat hem samen met de kaart $a_{1}$ alle oneven kaarten oplevert. Johan kan dus zorgen dat hij alle oneven kaarten krijgt. Analoog kan hij ook zorgen dat hij alle even kaarten krijgt. Dit voltooit de inductie. Johan kan nu zorgen dat hij minstens evenveel punten scoort als Julian op de volgende manier: als de som van de getallen op de oneven kaarten minstens even groot is als de som van de getallen op de even kaarten, dan kiest hij alle oneven kaarten. Zo niet, dan kiest hij alle even kaarten.

#

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\n2. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2008-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $m, n$ be positive integers. Consider a sequence of positive integers $a_{1}$, $a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ that satisfies $m=a_{1} \geq a_{2} \geq \cdots \geq a_{n} \geq 1$. For $1 \leq i \leq m$ we define

$$

b_{i}=\#\left\{j \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}: a_{j} \geq i\right\}

$$

so $b_{i}$ is the number of $a_{j}$ in the sequence for which $a_{j} \geq i$. For $1 \leq j \leq n$ we define

$$

c_{j}=\#\left\{i \in\{1,2, \ldots, m\}: b_{i} \geq j\right\}

$$

so $c_{j}$ is the number of $b_{i}$ for which $b_{i} \geq j$.

Example: for the $a$-sequence 5, 3, 3, 2, 1, 1, the corresponding $b$-sequence is 6, 4, 3, 1, 1.

(a) Prove that $a_{j}=c_{j}$ for $1 \leq j \leq n$.

(b) Prove that for $1 \leq k \leq m$ it holds that: $\sum_{i=1}^{k} b_{i}=k \cdot b_{k}+\sum_{j=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{j}$.

|

(a) Solution 1. Note that for $1 \leq i \leq m$ and $1 \leq j \leq n$ we have:

| $a_{j} \geq i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| ---: | :--- |

| $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{j} \geq i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| at least $j$ of the $a'$'s are greater or equal to $i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $b_{i} \geq j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{i} \geq j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| at least $i$ of the $b'$'s are greater or equal to $j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $c_{j} \geq i$. | |

Let $j$ be given. First take $i=a_{j}$, then the first line is true, so the last one is too: $c_{j} \geq a_{j}$. Conversely, take $i=c_{j}$, then the last line is true, so the first one is too: $a_{j} \geq c_{j}$. It follows that $a_{j}=c_{j}$.

Solution 2. Due to the non-increasing property, we have $b_{i}=\max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\}$ and $c_{j}=\max \{i: b_{i} \geq j\}$. Therefore, for $1 \leq j \leq n$ we have

$$

c_{j}=\max \left\{i: b_{i} \geq j\right\}=\max \left\{i: \max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\} \geq j\right\}

$$

For a fixed $i$ we have:

$$

\max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\} \geq j \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad a_{j} \geq i

$$

so $c_{j}=\max \left\{i: a_{j} \geq i\right\}=a_{j}$.

(b) Solution 1. For $1 \leq k \leq m$ we have

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(b_{i}-b_{k}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(\#\left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\}-\#\left\{l: a_{l} \geq k\right\}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k} \#\left\{l: k>a_{l} \geq i\right\}

$$

Each element $a_{l}$ from the sequence (with $k>a_{l}$) is counted here exactly $a_{l}$ times (namely for each $i \leq a_{l}$), so this is nothing other than the sum of all such $a_{l}$. Now (see solution 1 of part a) $k \leq a_{l}$ if and only if $l \leq b_{k}$, so $k>a_{l}$ if and only if $l>b_{k}$, thus

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(b_{i}-b_{k}\right)=\sum_{l: k>a_{l}} a_{l}=\sum_{l=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{l}

$$

and the result to be proven follows directly from this.

Solution 2. We prove this by induction on $k$. For $k=1$ we have

$$

b_{1} \stackrel{?}{=} b_{1}+\sum_{j=b_{1}+1}^{n} a_{j}

$$

and this is true because $b_{1}=\#\left\{j: a_{j} \geq 1\right\}=n$, so the sum on the right-hand side is empty. Suppose now that we have proven it for some $k$ with $1 \leq k \leq m-1$. Then we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{i=1}^{k+1} b_{i} & =\sum_{i=1}^{k} b_{i}+b_{k+1} \\

& \stackrel{\mathrm{IH}}{=} k \cdot b_{k}+\sum_{j=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{j}+b_{k+1} \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j}+k\left(b_{k}-b_{k+1}\right)-\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{b_{k}} a_{j} \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j}+k\left(b_{k}-b_{k+1}\right)-\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{b_{k}} k \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j} .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Laat $m, n$ positieve gehele getallen zijn. Bekijk een rijtje positieve gehele getallen $a_{1}$, $a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ dat voldoet aan $m=a_{1} \geq a_{2} \geq \cdots \geq a_{n} \geq 1$. Voor $1 \leq i \leq m$ definiëren we

$$

b_{i}=\#\left\{j \in\{1,2, \ldots, n\}: a_{j} \geq i\right\}

$$

dus $b_{i}$ is het aantal getallen $a_{j}$ uit het rijtje waarvoor geldt $a_{j} \geq i$. Voor $1 \leq j \leq n$ definiëren we

$$

c_{j}=\#\left\{i \in\{1,2, \ldots, m\}: b_{i} \geq j\right\}

$$

dus $c_{j}$ is het aantal getallen $b_{i}$ waarvoor geldt $b_{i} \geq j$.

Voorbeeld: bij het a-rijtje 5, 3, 3, 2, 1, 1 hoort het b-rijtje 6, 4, 3, 1, 1 .

(a) Bewijs dat $a_{j}=c_{j}$ voor $1 \leq j \leq n$.

(b) Bewijs dat voor $1 \leq k \leq m$ geldt: $\sum_{i=1}^{k} b_{i}=k \cdot b_{k}+\sum_{j=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{j}$.

|

(a) Oplossing 1. Merk op dat voor $1 \leq i \leq m$ en $1 \leq j \leq n$ geldt:

| $a_{j} \geq i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| ---: | :--- |

| $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{j} \geq i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| minstens $j$ van de $a^{\prime}$ 'tjes zijn groter of gelijk aan $i$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $b_{i} \geq j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $b_{1}, b_{2}, \ldots, b_{i} \geq j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| minstens $i$ van de $b^{\prime}$ tjes zijn groter of gelijk aan $j$ | $\Longleftrightarrow$ |

| $c_{j} \geq i$. | |

Zij nu $j$ gegeven. Neem dan eerst $i=a_{j}$, dan is de eerste regel waar, dus de laatste ook: $c_{j} \geq a_{j}$. Neem andersom $i=c_{j}$, dan is de laatste regel waar, dus de eerste ook: $a_{j} \geq c_{j}$. Nu volgt $a_{j}=c_{j}$.

Oplossing 2. Wegens de niet-stijgendheid geldt $b_{i}=\max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\}$ en $c_{j}=\max \{i$ : $\left.b_{i} \geq j\right\}$. Dus voor $1 \leq j \leq n$ geldt

$$

c_{j}=\max \left\{i: b_{i} \geq j\right\}=\max \left\{i: \max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\} \geq j\right\}

$$

Voor een vaste $i$ geldt:

$$

\max \left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\} \geq j \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad a_{j} \geq i

$$

dus $c_{j}=\max \left\{i: a_{j} \geq i\right\}=a_{j}$.

(b) Oplossing 1. Voor $1 \leq k \leq m$ geldt

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(b_{i}-b_{k}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(\#\left\{l: a_{l} \geq i\right\}-\#\left\{l: a_{l} \geq k\right\}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k} \#\left\{l: k>a_{l} \geq i\right\}

$$

Elk element $a_{l}$ uit de rij (met $k>a_{l}$ ) wordt hierin precies $a_{l}$ maal geteld (namelijk voor elke $i \leq a_{l}$ ) dus dit is niets anders dan de som van al dergelijke $a_{l}$. Nu is (zie oplossing 1 van onderdeel a) $k \leq a_{l}$ dan en slechts dan als $l \leq b_{k}$, dus $k>a_{l}$ dan en slechts dan als $l>b_{k}$, dus

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(b_{i}-b_{k}\right)=\sum_{l: k>a_{l}} a_{l}=\sum_{l=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{l}

$$

en hier volgt het te bewijzen direct uit.

Oplossing 2. We bewijzen dit met inductie naar $k$. Voor $k=1$ staat er

$$

b_{1} \stackrel{?}{=} b_{1}+\sum_{j=b_{1}+1}^{n} a_{j}

$$

en dit is waar omdat $b_{1}=\#\left\{j: a_{j} \geq 1\right\}=n$, dus de som aan de rechterkant is leeg. Stel nu dat we het bewezen hebben voor zekere $k$ met $1 \leq k \leq m-1$. Dan geldt

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{i=1}^{k+1} b_{i} & =\sum_{i=1}^{k} b_{i}+b_{k+1} \\

& \stackrel{\mathrm{IH}}{=} k \cdot b_{k}+\sum_{j=b_{k}+1}^{n} a_{j}+b_{k+1} \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j}+k\left(b_{k}-b_{k+1}\right)-\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{b_{k}} a_{j} \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j}+k\left(b_{k}-b_{k+1}\right)-\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{b_{k}} k \\

& =(k+1) \cdot b_{k+1}+\sum_{j=b_{k+1}+1}^{n} a_{j} .

\end{aligned}

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\n3. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2008-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "# Opgave 3.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $n$ be an integer such that $\sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}$ is an integer.

Prove that $2+2 \sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}$ is the square of an integer.

|

Given that $1+12 n^{2}=a^{2}$. We can rewrite this as

$$

12 n^{2}=a^{2}-1=(a+1)(a-1)

$$

The left side is divisible by 2, so the right side must also be divisible by 2, hence $a$ is odd. Since the left side has an even number of factors of 2, both $a+1$ and $a-1$ must be divisible by an odd number of factors of 2 (one of them is divisible by exactly one factor of 2). Furthermore, $\operatorname{gcd}(a+1, a-1)=2$, so all odd prime factors that appear in $n$ must appear in exactly one of $a+1$ and $a-1$. For prime factors greater than 3, they appear an even number of times on the right; the prime factor 3 appears an odd number of times. In conclusion, there are two possibilities:

$$

a+1=6 b^{2} \quad \text { and } \quad a-1=2 c^{2}

$$

for some integers $b$ and $c$ with $b c=n$ or

$$

a+1=2 b^{2} \quad \text { and } \quad a-1=6 c^{2}

$$

for some integers $b$ and $c$ with $b c=n$. First, consider the first case. Then $a+1$ is divisible by 3 and thus $a-1 \equiv 1 \pmod{3}$. But this implies $c^{2} \equiv 2 \pmod{3}$, which is impossible. Therefore, the second case must hold. But then

$$

2+2 \sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}=2+2 a=2(a+1)=4 b^{2}=(2 b)^{2},

$$

which is what we needed to prove.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $n$ een geheel getal zo dat $\sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}$ een geheel getal is.

Bewijs dat $2+2 \sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}$ het kwadraat van een geheel getal is.

|

Zij a zo dat $1+12 n^{2}=a^{2}$. We kunnen dit herschrijven als

$$

12 n^{2}=a^{2}-1=(a+1)(a-1)

$$

De linkerkant is deelbaar door 2, dus de rechterkant ook, dus $a$ is oneven. Omdat links een even aantal factoren 2 staat, moeten zowel $a+1$ en $a-1$ deelbaar zijn door een oneven aantal factoren 2 (de een is namelijk deelbaar door precies één factor 2). Verder geldt $\operatorname{ggd}(a+1, a-1)=2$, dus alle oneven priemfactoren die voorkomen in $n$, komen voor in precies één van $a+1$ en $a-1$. Voor de priemfactoren groter dan 3 geldt dat ze rechts een even aantal keer voorkomen; de priemfactor 3 komt een oneven aantal keer voor. Concluderend zijn er twee mogelijkheden:

$$

a+1=6 b^{2} \quad \text { en } \quad a-1=2 c^{2}

$$

voor zekere gehele $b$ en $c$ met $b c=n$ of

$$

a+1=2 b^{2} \quad \text { en } \quad a-1=6 c^{2}

$$

voor zekere gehele $b$ en $c$ met $b c=n$. Bekijk eerst het eerste geval. Dan is $a+1$ deelbaar door 3 en dus $a-1 \equiv 1 \bmod 3$. Maar daaruit volgt $c^{2} \equiv 2 \bmod 3$ en dat is onmogelijk. Dus het tweede geval moet gelden. Maar dan is

$$

2+2 \sqrt{1+12 n^{2}}=2+2 a=2(a+1)=4 b^{2}=(2 b)^{2},

$$

en dat is wat we moesten bewijzen.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\n4. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2008-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $\triangle A B C$ be a right triangle with $\angle B=90^{\circ}$ and $|A B|>|B C|$; and let $\Gamma$ be the semicircle with diameter $A B$ on the side of $A B$ where $C$ also lies. Let point $P$ on $\Gamma$ such that $|B P|=|B C|$ and let $Q$ on line segment $A B$ such that $|A P|=|A Q|$. Prove that the midpoint of $C Q$ lies on $\Gamma$.

|

Solution 1. Let $S$ be the intersection of $\Gamma$ and $C Q$. We need to prove that $|Q S|=|S C|$.

The line $B C$ is a tangent to $\Gamma$, so $\angle C B P=\angle B A P=\angle Q A P$. Since triangles $C B P$ and $Q A P$ are both isosceles, they are similar. Let $\alpha=\angle B C P$, then

$$

\alpha=\angle B C P=\angle C P B=\angle Q P A=\angle A Q P

$$

We now see that

$$

\angle C P Q=\angle C P B+\angle B P Q=\angle Q P A+\angle B P Q=\angle B P A=90^{\circ} .

$$

Thus, $P$, like $B$, lies on the circle with diameter $C Q$. Point $S$ lies on this diameter, and we want to show that $S$ is the center of the circle, so it is sufficient to show that

$$

\angle B S P=2 \alpha=2 \angle B C P .

$$

In cyclic quadrilateral $Q B C P$, $\angle C P B=\angle C Q B$, so

$2 \alpha=\angle C Q B+\angle A Q P=180^{\circ}-\angle P Q C=180^{\circ}-\angle P B C=90^{\circ}+\angle Q B C-\angle P B C=90^{\circ}+\angle Q B P$.

In cyclic quadrilateral $A B S P$, where $A B$ is the diameter, we see

$$

90^{\circ}+\angle Q B P=90^{\circ}+\angle A B P=\angle B S A+\angle A S P=\angle B S P,

$$

so we can conclude

$$

2 \alpha=\angle B S P

$$

which is what we wanted to prove.

Solution 2. First note (as in the previous solution) that the two isosceles triangles are similar. Since $B C$ is perpendicular to $A B$, one triangle is rotated $90^{\circ}$ relative to the other. Let $l_{1}$ be the bisector of $\angle P B C$ and $l_{2}$ the bisector of $\angle P A Q$. These bisectors are now perpendicular to each other. Let $T$ be the intersection of $l_{1}$ and $l_{2}$. Then $\angle A T B=90^{\circ}$, so $T$ lies on $\Gamma$.

Now, $P$ is the image of $C$ under reflection in $l_{1}$ and $Q$ is the image of $P$ under reflection in $l_{2}$. The composition of these two reflections is the rotation about $T$ by $2 \cdot 90=180$ degrees. Under this rotation, $C$ maps to $Q$, so $C T Q$ is a straight line. Thus, $T=S$. Due to the rotation, $|T C|=|T Q|$ also holds, so $S$ is the midpoint of $C Q$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Laat $\triangle A B C$ een rechthoekige driehoek zijn met $\angle B=90^{\circ}$ en $|A B|>|B C|$; en zij $\Gamma$ de halve cirkel met middellijn $A B$ aan de kant van $A B$ waar ook $C$ ligt. Zij punt $P$ op $\Gamma$ zo dat $|B P|=|B C|$ en zij $Q$ op lijnstuk $A B$ zo dat $|A P|=|A Q|$. Bewijs dat het midden van $C Q$ op $\Gamma$ ligt.

|

Oplossing 1. Zij $S$ het snijpunt van $\Gamma$ en $C Q$. We moeten bewijzen dat $|Q S|=|S C|$.

De lijn $B C$ is een raaklijn aan $\Gamma$, dus geldt $\angle C B P=\angle B A P=\angle Q A P$. Omdat de driehoeken $C B P$ en $Q A P$ beide gelijkbenig zijn, zijn ze gelijkvormig. Zij $\alpha=\angle B C P$, dan geldt

$$

\alpha=\angle B C P=\angle C P B=\angle Q P A=\angle A Q P

$$

We zien nu dat

$$

\angle C P Q=\angle C P B+\angle B P Q=\angle Q P A+\angle B P Q=\angle B P A=90^{\circ} .

$$

Dus $P$ ligt, net als $B$, op de cirkel met middellijn $C Q$. Punt $S$ ligt op deze middellijn en we willen laten zien dat $S$ het middelpunt van de cirkel is, dus het is voldoende om te laten zien dat

$$

\angle B S P=2 \alpha=2 \angle B C P .

$$

In koordenvierhoek $Q B C P$ geldt $\angle C P B=\angle C Q B$, dus

$2 \alpha=\angle C Q B+\angle A Q P=180^{\circ}-\angle P Q C=180^{\circ}-\angle P B C=90^{\circ}+\angle Q B C-\angle P B C=90^{\circ}+\angle Q B P$.

In koordenvierhoek $A B S P$, waarin $A B$ de middellijn is, zien we

$$

90^{\circ}+\angle Q B P=90^{\circ}+\angle A B P=\angle B S A+\angle A S P=\angle B S P,

$$

zodat we kunnen concluderen

$$

2 \alpha=\angle B S P

$$

en dat is wat we wilden bewijzen.

Oplossing 2. Merk eerst op (net als in de vorige oplossing) dat de twee gelijkbenige driehoeken gelijkvormig zijn. Omdat $B C$ loodrecht op $A B$ staat, is de ene driehoek $90^{\circ}$ gedraaid ten opzichte van de andere. Zij $l_{1}$ de bissectrice van $\angle P B C$ en $l_{2}$ de bissectrice $\operatorname{van} \angle P A Q$. Deze bissectrices staan nu loodrecht op elkaar. Zij $T$ het snijpunt van $l_{1}$ en $l_{2}$. Dan geldt dus $\angle A T B=90^{\circ}$, dus $T$ ligt op $\Gamma$.

Nu is $P$ het beeld van $C$ onder spiegeling in $l_{1}$ en $Q$ is het beeld van $P$ onder spiegeling in $l_{2}$. De samenstelling van deze twee spiegelingen is de rotatie in $T$ om $2 \cdot 90=180$ graden. Onder deze rotatie gaat $C$ over in $Q$, dus $C T Q$ is een rechte lijn. Dus $T=S$. Wegens de rotatie geldt ook $|T C|=|T Q|$, dus $S$ is het midden van $C Q$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\n5. ",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2008-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOpgave 5.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2008"

}

|

Let $n \geq 10$ be an integer. We write $n$ in the decimal system. Let $S(n)$ be the sum of the digits of $n$. A stump of $n$ is a positive integer obtained by removing a number of (at least one, but not all) digits from the right end of $n$. For example: 23 is a stump of 2351. Let $T(n)$ be the sum of all stomps of $n$. Prove that $n = S(n) + 9 \cdot T(n)$.

|

From right to left, we assign the digits of $n$ with $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$. Therefore,

$$

n=a_{0}+10 a_{1}+\cdots+10^{k} a_{k} .

$$

A stump of $n$ consists of the digits $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ from right to left, where $1 \leq i \leq k$. Such a stump is then equal to $a_{i}+10 a_{i+1}+\cdots+10^{k-i} a_{k}$. If we sum this over all $i$, we get $T(n)$. We can then write $T(n)$ more conveniently by combining all terms with $a_{1}$, all terms with $a_{2}$, and so on (this is equivalent to swapping the summation signs: first summing over $i$ from 1 to $k$ and then for each $i$ summing over $j$ from $i$ to $k$, is the same as first summing over $j$ from 1 to $k$ and then for each $j$ summing over $i$ from 1 to $j$):

$$

\begin{gathered}

T(n)=\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(a_{i}+10 a_{i+1}+\cdots+10^{k-i} a_{k}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=i}^{k} 10^{j-i} a_{j} \\

=\sum_{j=1}^{k} \sum_{i=1}^{j} 10^{j-i} a_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left(1+10+\cdots+10^{j-1}\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{10^{j}-1}{10-1} a_{j} .

\end{gathered}

$$

In the last step, we used the sum formula for the geometric series. We now get

$$

9 \cdot T(n)=\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=0}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1\right) a_{j}

$$

Now consider that $S(n)=\sum_{j=0}^{k} a_{j}$. Therefore,

$$

S(n)+9 \cdot T(n)=\sum_{j=0}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1+1\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=0}^{k} 10^{j} a_{j}=n

$$

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Zij $n \geq 10$ een geheel getal. We schrijven $n$ in het tientallig stelsel. Zij $S(n)$ de som van de cijfers van $n$. Een stomp van $n$ is een positief geheel getal dat verkregen is door een aantal (minstens één, maar niet alle) cijfers van $n$ aan het rechteruiteinde weg te halen. Bijvoorbeeld: 23 is een stomp van 2351. $\mathrm{Zij} T(n)$ de som van alle stompen van $n$. Bewijs dat $n=S(n)+9 \cdot T(n)$.

|

Van rechts naar links geven we de cijfers van $n$ aan met $a_{0}, a_{1}, \ldots, a_{k}$. Er geldt dus

$$

n=a_{0}+10 a_{1}+\cdots+10^{k} a_{k} .

$$

Een stomp van $n$ bestaat van rechts naar links uit de cijfers $a_{i}, a_{i+1}, \ldots, a_{k}$ waarbij $1 \leq i \leq k$. Zo'n stomp is dan gelijk aan $a_{i}+10 a_{i+1}+\cdots+10^{k-i} a_{k}$. Als we dit sommeren over alle $i$, krijgen we $T(n)$. We kunnen vervolgens $T(n)$ makkelijker schrijven door alle termen met $a_{1}$ samen te nemen, alle termen met $a_{2}$, enzovoorts (dit komt hieronder neer op het verwisselen van de sommatietekens: eerst sommeren over $i$ van 1 tot en met $k$ en daarna per $i$ nog over $j$ van $i$ tot en met $k$, is hetzelfde als eerst sommeren over $j$ van 1 tot en met $k$ en daarna per $j$ nog over $i$ van 1 tot en met $j$ ):

$$

\begin{gathered}

T(n)=\sum_{i=1}^{k}\left(a_{i}+10 a_{i+1}+\cdots+10^{k-i} a_{k}\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{j=i}^{k} 10^{j-i} a_{j} \\

=\sum_{j=1}^{k} \sum_{i=1}^{j} 10^{j-i} a_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left(1+10+\cdots+10^{j-1}\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=1}^{k} \frac{10^{j}-1}{10-1} a_{j} .

\end{gathered}

$$

In de laatste stap hebben we de somformule voor de meetkundige reeks gebruikt. We krijgen nu

$$

9 \cdot T(n)=\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=0}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1\right) a_{j}

$$

Bedenk nu dat $S(n)=\sum_{j=0}^{k} a_{j}$. Er geldt dus

$$

S(n)+9 \cdot T(n)=\sum_{j=0}^{k}\left(10^{j}-1+1\right) a_{j}=\sum_{j=0}^{k} 10^{j} a_{j}=n

$$

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 1.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, point $P$ the midpoint of $B C$, and point $Q$ on segment $C A$ such that $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Let $S$ be the intersection of $B Q$ and $A P$. Prove that $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Draw a line through $P$ parallel to $A C$ and let $T$ be the intersection of this line with $B Q$. Then $P T$ is a midline in triangle $B C Q$, so $|P T|=\frac{1}{2}|C Q|=|Q A|$. Now $A T P Q$ is a quadrilateral with a pair of equal, parallel sides, so $A T P Q$ is a parallelogram. In a parallelogram, we know that the diagonals bisect each other, so $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een driehoek, punt $P$ het midden van $B C$ en punt $Q$ op lijnstuk $C A$ zodat $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Zij $S$ het snijpunt van $B Q$ en $A P$. Bewijs dat $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Trek een lijn door $P$ evenwijdig aan $A C$ en zij $T$ het snijpunt van deze lijn met $B Q$. Dan is $P T$ een middenparallel in driehoek $B C Q$, dus geldt $|P T|=\frac{1}{2}|C Q|=|Q A|$. Nu is $A T P Q$ een vierhoek met een paar even lange, evenwijdige zijden, dus $A T P Q$ is een parallellogram. Van een parallellogram weten we dat de diagonalen elkaar middendoor snijden, dus $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing I.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, point $P$ the midpoint of $B C$, and point $Q$ on segment $C A$ such that $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Let $S$ be the intersection of $B Q$ and $A P$. Prove that $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

We apply Menelaus' theorem in triangle $P C A$. We know that the points $B, S$ and $Q$ lie on one line, so

$$

-1=\frac{P B}{B C} \cdot \frac{C Q}{Q A} \cdot \frac{A S}{S P}=\frac{-1}{2} \cdot \frac{2}{1} \cdot \frac{A S}{S P}=-\frac{A S}{S P}

$$

Thus $\frac{A S}{S P}=1$, which implies that $S$ is the midpoint between $A$ and $P$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een driehoek, punt $P$ het midden van $B C$ en punt $Q$ op lijnstuk $C A$ zodat $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Zij $S$ het snijpunt van $B Q$ en $A P$. Bewijs dat $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

We passen de stelling van Menelaos toe in driehoek $P C A$. We weten dat de punten $B, S$ en $Q$ op één lijn liggen, dus

$$

-1=\frac{P B}{B C} \cdot \frac{C Q}{Q A} \cdot \frac{A S}{S P}=\frac{-1}{2} \cdot \frac{2}{1} \cdot \frac{A S}{S P}=-\frac{A S}{S P}

$$

Dus $\frac{A S}{S P}=1$, waaruit volgt dat $S$ midden tussen $A$ en $P$ ligt.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing II.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, point $P$ the midpoint of $B C$, and point $Q$ on segment $C A$ such that $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Let $S$ be the intersection of $B Q$ and $A P$. Prove that $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Let $M$ be the midpoint of $QC$ and let $x=[AQS]=[QMS]=[MCS]$ and $y=[CPS]=[PBS]$. Since $[CPA]=[PBA]$, it follows that $[ASB]=3x$. But then $[AQB]=x+3x$ while on the other hand $2[AQB]=[QCB]$, so $2x+2y=[QCB]=2[AQB]=8x$. Therefore, $y=3x$. But then $[ASB]=3x=y=[SPB]$, so $|AS|=|SP|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een driehoek, punt $P$ het midden van $B C$ en punt $Q$ op lijnstuk $C A$ zodat $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Zij $S$ het snijpunt van $B Q$ en $A P$. Bewijs dat $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Zij $M$ het midden van $Q C$ en noem $x=[A Q S]=[Q M S]=[M C S]$ en $y=[C P S]=[P B S]$. Omdat $[C P A]=[P B A]$ geldt dat $[A S B]=3 x$. Maar dan is $[A Q B]=x+3 x$ terwijl anderzijds $2[A Q B]=[Q C B]$, dus $2 x+2 y=[Q C B]=2[A Q B]=8 x$. Dus $y=3 x$. Maar dan $[A S B]=3 x=y=[S P B]$, dus $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing III.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Let $A B C$ be a triangle, point $P$ the midpoint of $B C$, and point $Q$ on segment $C A$ such that $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Let $S$ be the intersection of $B Q$ and $A P$. Prove that $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Let $R$ be the intersection of $CS$ and $AB$. According to Ceva's theorem, we have

$$

\frac{AR}{RB} \cdot \frac{BP}{PC} \cdot \frac{CQ}{QA}=1

$$

from which it follows that $2|AR|=|RB|$. Let $a=[PSC], b=[QSC], c=[QSA], d=[RSA]$, $e=[RSB]$, and $f=[PSB]$. Now we have

$$

b+a+f=2(c+d+e) \quad \text{and} \quad a+e+f=2(b+c+d)

$$

from which it follows that

$$

b-e=2e-2b

$$

so $b=e$. Furthermore, $2d=e$ and $2c=b$, so also $c=d$ and $c+d=e$. From $a+e+f=$ $2(b+c+d)$ we now get

$$

a+f=b+2c+2d=b+c+d+e,

$$

so

$$

2(a+f)=a+b+c+d+e+f=[ABC] .

$$

Thus $2|PS|=|PA|$, so $|PS|=|AS|$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Zij $A B C$ een driehoek, punt $P$ het midden van $B C$ en punt $Q$ op lijnstuk $C A$ zodat $|C Q|=2|Q A|$. Zij $S$ het snijpunt van $B Q$ en $A P$. Bewijs dat $|A S|=|S P|$.

|

Zij $R$ het snijpunt van $C S$ en $A B$. Volgens de stelling van Ceva geldt

$$

\frac{A R}{R B} \cdot \frac{B P}{P C} \cdot \frac{C Q}{Q A}=1

$$

waaruit volgt $2|A R|=|R B|$. Zij $a=[P S C], b=[Q S C], c=[Q S A], d=[R S A]$, $e=[R S B]$ en $f=[P S B]$. Nu geldt

$$

b+a+f=2(c+d+e) \quad \text { en } \quad a+e+f=2(b+c+d)

$$

waaruit volgt

$$

b-e=2 e-2 b

$$

dus $b=e$. Verder geldt $2 d=e$ en $2 c=b$, dus ook $c=d$ en $c+d=e$. Uit $a+e+f=$ $2(b+c+d)$ volgt nu

$$

a+f=b+2 c+2 d=b+c+d+e,

$$

dus

$$

2(a+f)=a+b+c+d+e+f=[A B C] .

$$

Dus $2|P S|=|P A|$, dus $|P S|=|A S|$.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 2.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing IV.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Let $a, b$ and $c$ be positive real numbers that satisfy $a+b+c \geq a b c$. Prove that

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \sqrt{3} a b c

$$

|

We know that $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq a b+b c+c a$ and thus $3\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right) \geq(a+b+c)^{2}$. Due to the inequality of the geometric and arithmetic mean, we have $a+b+c \geq 3(a b c)^{\frac{1}{3}}$ and on the other hand, it is given that $a+b+c \geq a b c$. Therefore, we have two inequalities:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a+b+c)^{2} \geq 3(a b c)^{\frac{2}{3}} \\

& a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a+b+c)^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a b c)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

We raise the first inequality to the power of $\frac{3}{4}$ and the second to the power of $\frac{1}{4}$ (and we are allowed to do this because everything is positive):

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{\frac{3}{4}} \geq 3^{\frac{3}{4}}(a b c)^{\frac{1}{2}} \\

& \left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{\frac{1}{4}} \geq 3^{-\frac{1}{4}}(a b c)^{\frac{1}{2}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Now we multiply these two and then we get

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 3^{\frac{1}{2}}(a b c)

$$

which is what we wanted.

|

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \sqrt{3} a b c

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Laat $a, b$ en $c$ positieve reële getallen zijn die voldoen aan $a+b+c \geq a b c$. Bewijs dat

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \sqrt{3} a b c

$$

|

We weten dat $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq a b+b c+c a$ en dus $3\left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right) \geq(a+b+c)^{2}$. Wegens de ongelijkheid van het meetkundig en rekenkundig gemiddelde geldt $a+b+c \geq$ $3(a b c)^{\frac{1}{3}}$ en anderzijds is gegeven dat $a+b+c \geq a b c$. Dus we hebben twee ongelijkheden:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a+b+c)^{2} \geq 3(a b c)^{\frac{2}{3}} \\

& a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a+b+c)^{2} \geq \frac{1}{3}(a b c)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

We doen de eerste ongelijkheid tot de macht $\frac{3}{4}$ en de tweede tot de macht $\frac{1}{4}$ (en dit mogen we doen omdat alles positief is):

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{\frac{3}{4}} \geq 3^{\frac{3}{4}}(a b c)^{\frac{1}{2}} \\

& \left(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}\right)^{\frac{1}{4}} \geq 3^{-\frac{1}{4}}(a b c)^{\frac{1}{2}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Nu vermenigvuldigen we deze beide en dan krijgen we

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2} \geq 3^{\frac{1}{2}}(a b c)

$$

wat het gevraagde is.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 3.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

Find all functions $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ that satisfy

$$

f(m+n)+f(m n-1)=f(m) f(n)+2

$$

for all $m, n \in \mathbb{Z}$.

|

First, assume there is a $c \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $f(n)=c$ for all $n$. Then we have $2c = c^2 + 2$, so $c^2 - 2c + 2 = 0$, which has no solution for $c$. Therefore, $f$ is not constant. Now substitute $m=0$. This gives $f(n) + f(-1) = f(n) f(0) + 2$, from which we conclude that $f(n)(1 - f(0))$ is a constant. Since $f(n)$ is not constant, it follows that $f(0) = 1$. From the same equation, we now get $f(-1) = 2$. Substitute $m=n=-1$, which gives $f(-2) + f(0) = f(-1)^2 + 2$, from which it follows that $f(-2) = 5$. Next, substitute $m=1$ and $n=-1$, then we get $f(0) + f(-2) = f(1) f(-1) + 2$, from which it follows that $f(1) = 2$.

Now substitute $m=1$, then we get $f(n+1) + f(n-1) = f(1) f(n) + 2$, or

$$

f(n+1) = 2f(n) + 2 - f(n-1).

$$

By induction, we can easily prove that $f(n) = n^2 + 1$ for all $n \geq 0$ and subsequently with the equation

$$

f(n-1) = 2f(n) + 2 - f(n+1)

$$

also for $n \leq 0$. Therefore, $f(n) = n^2 + 1$ for all $n$ and this function satisfies the conditions.

|

f(n) = n^2 + 1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Vind alle functies $f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}$ die voldoen aan

$$

f(m+n)+f(m n-1)=f(m) f(n)+2

$$

voor alle $m, n \in \mathbb{Z}$.

|

Stel eerst dat er een $c \in \mathbb{Z}$ is met $f(n)=c$ voor alle $n$. Dan hebben we $2 c=c^{2}+2$, dus $c^{2}-2 c+2=0$ en dat heeft geen oplossing voor $c$. Dus is $f$ niet constant. Vul nu in $m=0$. Dat geeft $f(n)+f(-1)=f(n) f(0)+2$, waaruit we concluderen dat $f(n)(1-f(0))$ een constante is. Omdat $f(n)$ niet constant is, volgt hieruit $f(0)=1$. Uit dezelfde vergelijking krijgen we nu $f(-1)=2$. Vul nu in $m=n=-1$, dat geeft $f(-2)+f(0)=f(-1)^{2}+2$, waaruit volgt $f(-2)=5$. Vul vervolgens in $m=1$ en $n=-1$, dan krijgen we $f(0)+f(-2)=f(1) f(-1)+2$, waaruit volgt $f(1)=2$.

Vul nu in $m=1$, dan krijgen we $f(n+1)+f(n-1)=f(1) f(n)+2$, ofwel

$$

f(n+1)=2 f(n)+2-f(n-1) .

$$

Met inductie bewijzen we nu gemakkelijk dat $f(n)=n^{2}+1$ voor alle $n \geq 0$ en vervolgens met de vergelijking

$$

f(n-1)=2 f(n)+2-f(n+1)

$$

ook voor $n \leq 0$. Dus $f(n)=n^{2}+1$ voor alle $n$ en deze functie voldoet.

|

{

"exam": "Dutch_TST",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nOpgave 4.",

"resource_path": "Dutch_TST/segmented/nl-2009-uitwerkingen.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nOplossing.",

"tier": "T1",

"year": "2009"

}

|

For a given $n$-gon with all sides of equal length, all vertices have rational coordinates. Prove that $n$ is even.

|

Let $\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right), \ldots,\left(x_{n}, y_{n}\right)$ be the coordinates of the vertices of the $n$-gon. Define $a_{i}=x_{i+1}-x_{i}, b_{i}=y_{i+1}-y_{i}$ for $i=1,2, \ldots, n$, where $x_{n+1}=x_{1}$ and $y_{n+1}=y_{1}$. Given that $a_{i}, b_{i} \in \mathbb{Q}$ and $\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} b_{i}=0$; and the sum $a_{i}^{2}+b_{i}^{2}$ is the same for all $i$. By multiplying away all denominators and dividing out any common factors of the numerators, we may assume that $a_{i}, b_{i} \in \mathbb{Z}$ and $\operatorname{gcd}\left(a_{1}, \ldots, a_{n}, b_{1}, \ldots, b_{n}\right)=1$. Let $c$ be the integer such that $a_{i}^{2}+b_{i}^{2}=c$ for all $i$.

First, assume that $c \equiv 1 \bmod 2$. Then for each $i$, exactly one of $a_{i}, b_{i}$ is odd. So out of all $2 n$ numbers $a_{i}, b_{i}$, exactly $n$ are even and $n$ are odd. Thus $0=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(a_{i}+b_{i}\right) \equiv n \bmod 2$. Therefore, $n$ is even.