problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Determine all pairs of integers $(x, y)$ such that $x^{2}+73=y^{2}$.

|

As is often the case with a Diophantine equation, one seeks to rearrange the equation so as to have products of factors on both sides of the equality. When perfect squares are present, one can use the remarkable identity \( y^{2}-x^{2}=(y-x)(y+x) \). This allows rewriting the equation as:

\[

73=(y-x)(y+x)

\]

Thus, the number \( y-x \) is a divisor of 73. The divisors of 73 are \( 73, 1, -1, -73 \). We then distinguish four cases:

Case \( \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 1: \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=73 \). Then \( \mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=1 \). This leads to \( \mathrm{y}=73+\mathrm{x}=73+(1-\mathrm{y}) \), so \( \mathrm{y}=37 \) and \( x=-36 \). Conversely, we indeed have \( (-36)^{2}+73=37^{2} \), so the pair \( (-36,37) \) is indeed a solution.

Case \( \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 2: y-x=1 \). Then \( x+y=73 \). This leads to \( y=1+x=1+(73-y) \), so \( y=37 \) and \( x=36 \). Conversely, we indeed have \( 36^{2}+73=37^{2} \), so the pair \( (36,37) \) is indeed a solution.

Case \( \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 3: \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=-1 \). Then \( \mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=-73 \). This leads to \( \mathrm{y}=-1+\mathrm{x}=-1+(-73-\mathrm{y}) \), so \( y=-37 \) and \( x=-36 \). Conversely, we indeed have \( (-36)^{2}+73=(-37)^{2} \), so the pair \( (-36,-37) \) is indeed a solution.

\(\underline{\text { Case } \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 4:} \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=-73 \). Then \( \mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=-1 \). This leads to \( \mathrm{y}=-73+\mathrm{x}=-73+(-1-\mathrm{y}) \), so \( y=-37 \) and \( x=36 \). Conversely, we indeed have \( 36^{2}+73=(-37)^{2} \), so the pair \( (36,-37) \) is indeed a solution.

The solution pairs are therefore \( (-36,-37), (-36,37), (36,-37) \) and \( (36,37) \).

## Comments from the graders:

The exercise was generally well done, with a few recurring errors:

- Assuming the integers are positive.

- Forgetting cases in the factorization (forgetting to take the opposites / to swap the factors)

|

(-36,-37), (-36,37), (36,-37), (36,37)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les couples d'entiers $(x, y)$ tels que $x^{2}+73=y^{2}$.

|

Comme souvent pour une équation diophantienne, on cherche à réarranger l'équation de sorte à avoir des produits de facteurs des deux côtés de l'égalité. Lorsque l'on est en présence de carrés parfaits, on peut utiliser l'identité remarquable $y^{2}-x^{2}=(y-x)(y+x)$. Ceci permet de réécrire l'équation sous la forme :

$$

73=(y-x)(y+x)

$$

Ainsi, le nombre $y-x$ est un diviseur de 73 . Or les diviseurs de 73 sont $73,1,-1,-73$. On distingue alors quatre cas:

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 1: \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=73$. Alors $\mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=1$. Ceci conduit à $\mathrm{y}=73+\mathrm{x}=73+(1-\mathrm{y})$, soit $\mathrm{y}=37$ et $x=-36$. Réciproquement, on a bien $(-36)^{2}+73=37^{2}$, donc le couple $(-36,37)$ est bien solution.

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 2: y-x=1$. Alors $x+y=73$. Ceci conduit à $y=1+x=1+(73-y)$, soit $y=37$ et $x=36$. Réciproquement, on a bien $36^{2}+73=37^{2}$, donc le couple $(36,37)$ est bien solution.

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 3: \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=-1$. Alors $\mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=-73$. Ceci conduit à $\mathrm{y}=-1+\mathrm{x}=-1+(-73-\mathrm{y})$, soit $y=-37$ et $x=-36$. Réciproquement, on a bien $(-36)^{2}+73=(-37)^{2}$, donc le couple $(-36,-37)$ est bien solution.

$\underline{\text { Cas } \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 4:} \mathrm{y}-\mathrm{x}=-73$. Alors $\mathrm{x}+\mathrm{y}=-1$. Ceci conduit à $\mathrm{y}=-73+\mathrm{x}=-73+(-1-\mathrm{y})$, soit $y=-37$ et $x=36$. Réciproquement, on a bien $36^{2}+73=(-37)^{2}$, donc le couple $(36,-37)$ est bien solution.

Les couples solutions sont donc $(-36,-37),(-36,37),(36,-37)$ et $(36,37)$.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice bien réussi dans l'ensemble, avec quelques erreurs récurrentes :

- Supposer que les entiers sont positifs.

- Oublier des cas dans la factorisation (oublier de prendre les opposés / d'échanger les facteurs)

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let \( a \) be a strictly positive real number and \( n \geqslant 1 \) an integer. Show that

$$

\frac{a^{n}}{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}<\frac{1}{2 n}

$$

|

Since the difficulty lies in the denominator of the right-hand side, and for greater comfort, we can seek to show the inverse relation, namely:

$$

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}}>2 n

$$

The idea behind the following solution is to "homogenize" the numerator of the left-hand side, that is, to compare this numerator, in which the \(a\)s are raised to distinct powers, to an expression composed solely of \(a\)s raised to the same power. To do this, we seek to pair certain terms and apply the inequality of means. Let's see: for \(0 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n\), we have \(a^{i}+a^{2 n-i} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a^{i} a^{2 n-i}} = 2 a^{n}\). Thus:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}} & =\frac{\left(1+a^{2 n}\right)+\left(a+a^{2 n-1}\right)+\ldots+\left(a^{n-1}+a^{n+1}\right)+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{\overbrace{2 a^{n}+2 a^{n}+\ldots+2 a^{n}}^{n \text{ terms }}+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =\frac{(2 n+1) a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =2 n+1 \\

& >2 n

\end{aligned}

$$

which provides the desired inequality.

## Comments from the graders:

The exercise is very well solved! The students have well understood how to use the mean inequality.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit a un réel strictement positif et $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$ un entier. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a^{n}}{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}<\frac{1}{2 n}

$$

|

Puisque la difficulté réside dans le dénominateur du membre de droite, et pour plus de confort, on peut chercher à montrer la relation inverse, à savoir :

$$

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}}>2 n

$$

L'idée derrière la solution qui suit est "d'homogénéiser" le numérateur du membre de gauche, c'est-àdire de comparer ce numérateur dans lequel les a sont élevés à des puissances distinctes à une expression composée uniquement de a élevés à la même puissance. Pour cela, on cherche à coupler certains termes et appliquer l'inégalité des moyennes. Voyons plutôt : pour $0 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n$, on a $a^{i}+a^{2 n-i} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a^{i} a^{2 n-i}}=$ $2 a^{n}$. Ainsi :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}} & =\frac{\left(1+a^{2 n}\right)+\left(a+a^{2 n-1}\right)+\ldots+\left(a^{n-1}+a^{n+1}\right)+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{\overbrace{2 a^{n}+2 a^{n}+\ldots+2 a^{n}}^{n \text { termes }}+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =\frac{(2 n+1) a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =2 n+1 \\

& >2 n

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui fournit l'inégalité voulue.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

L'exercice est très bien résolu! Les élèves ont bien compris comment utiliser l'inégalité de la moyenne.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

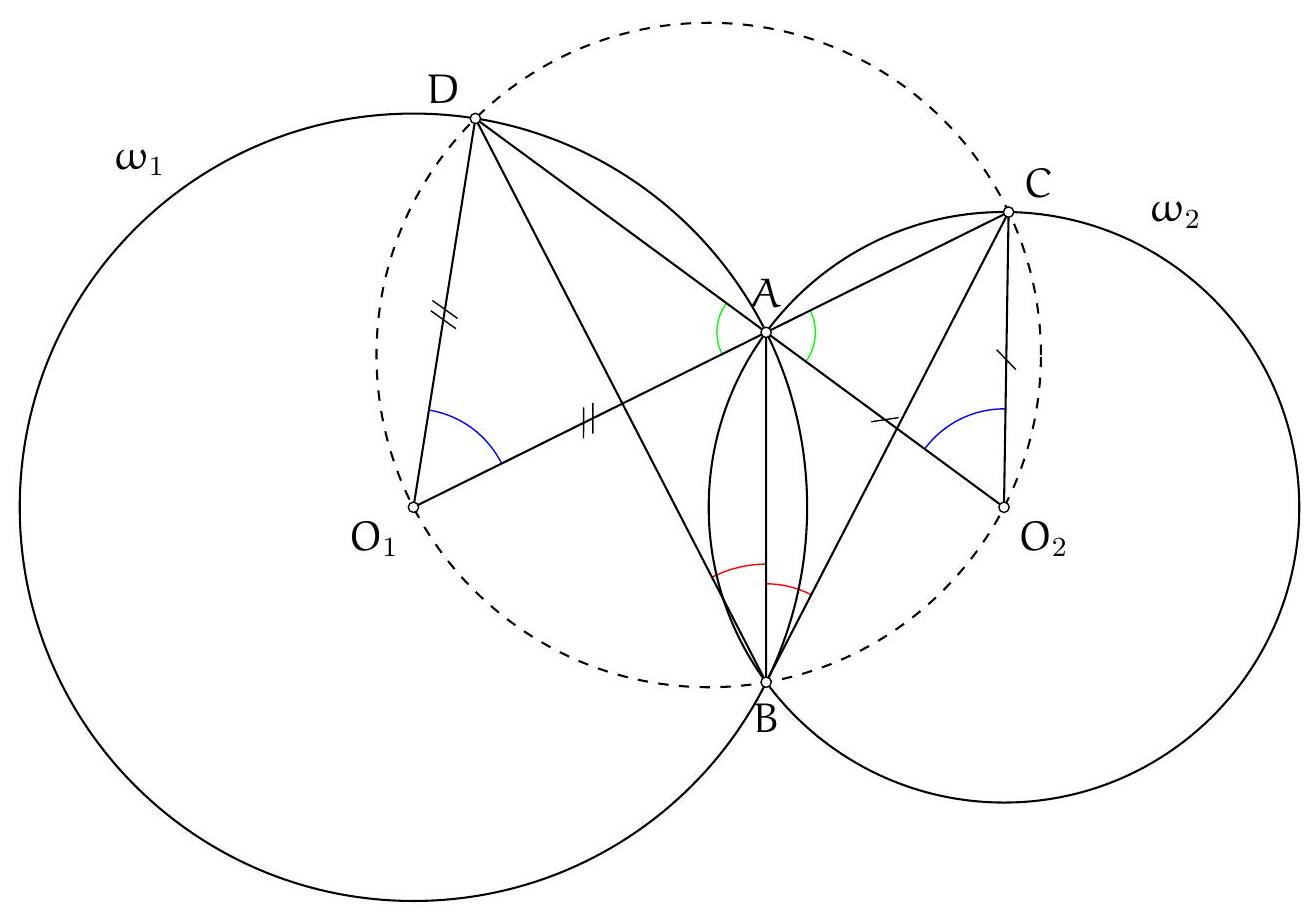

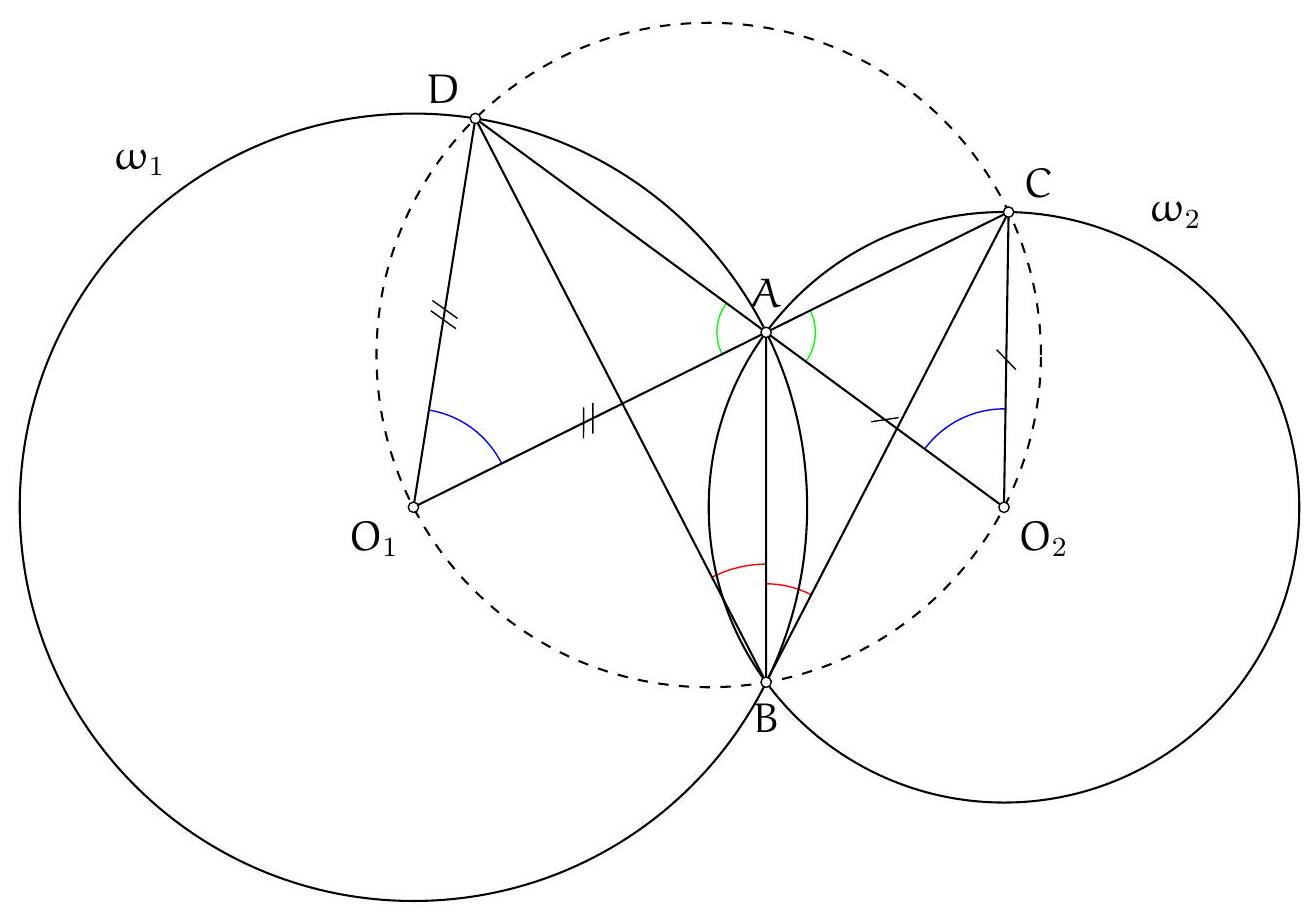

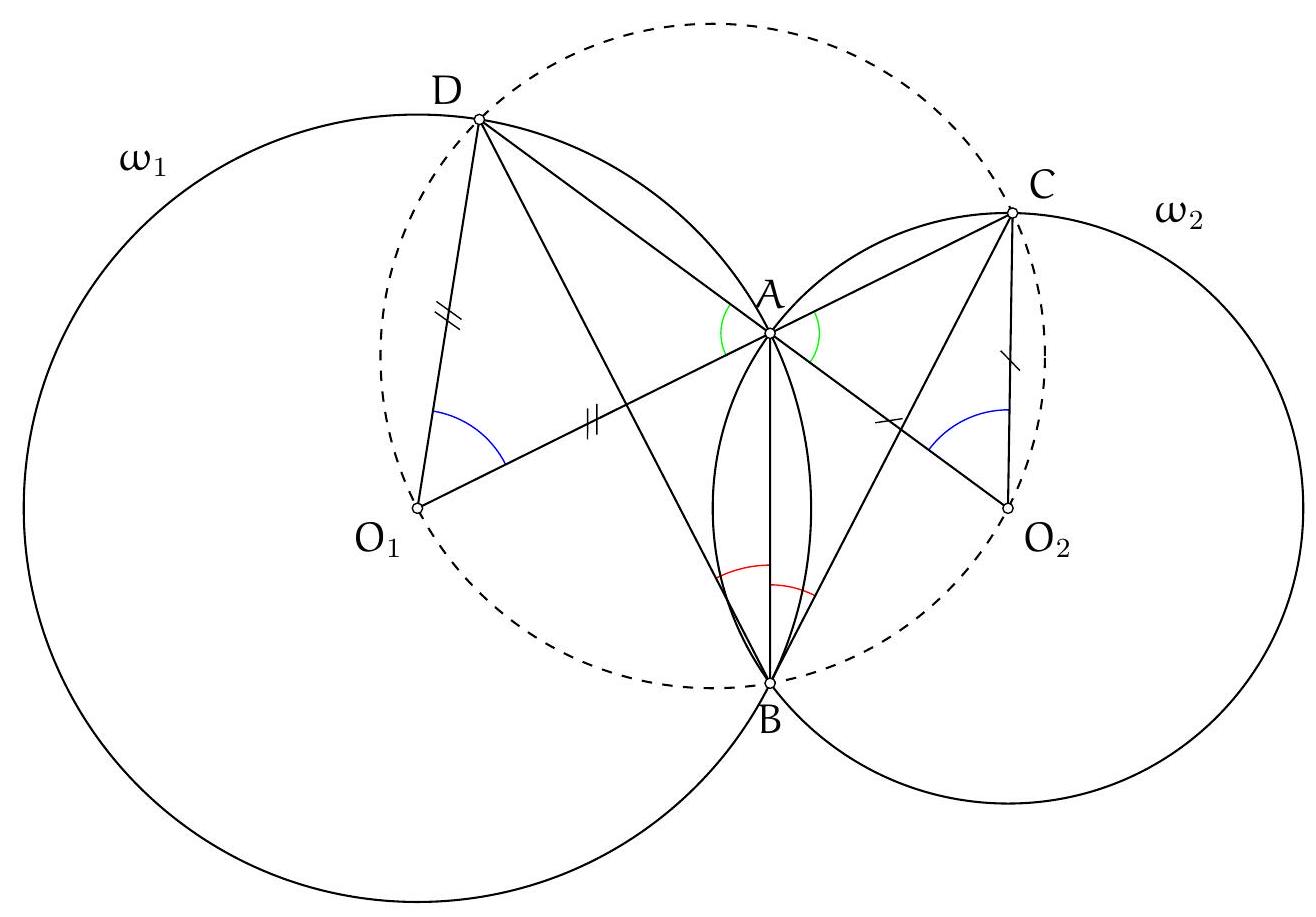

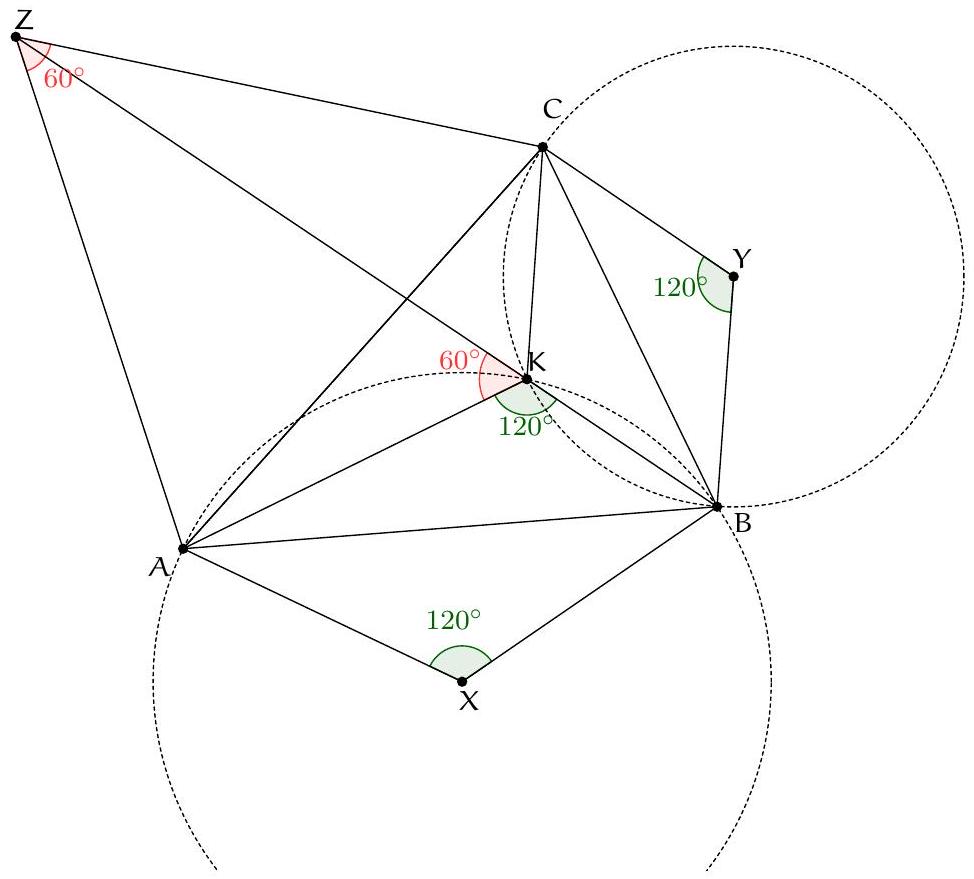

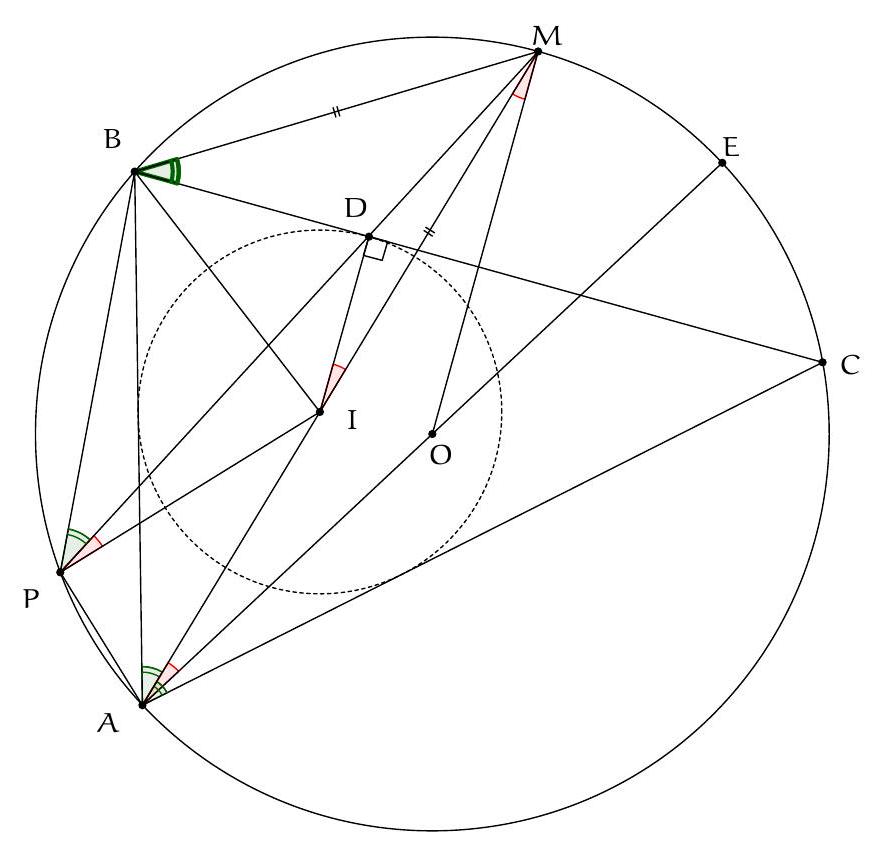

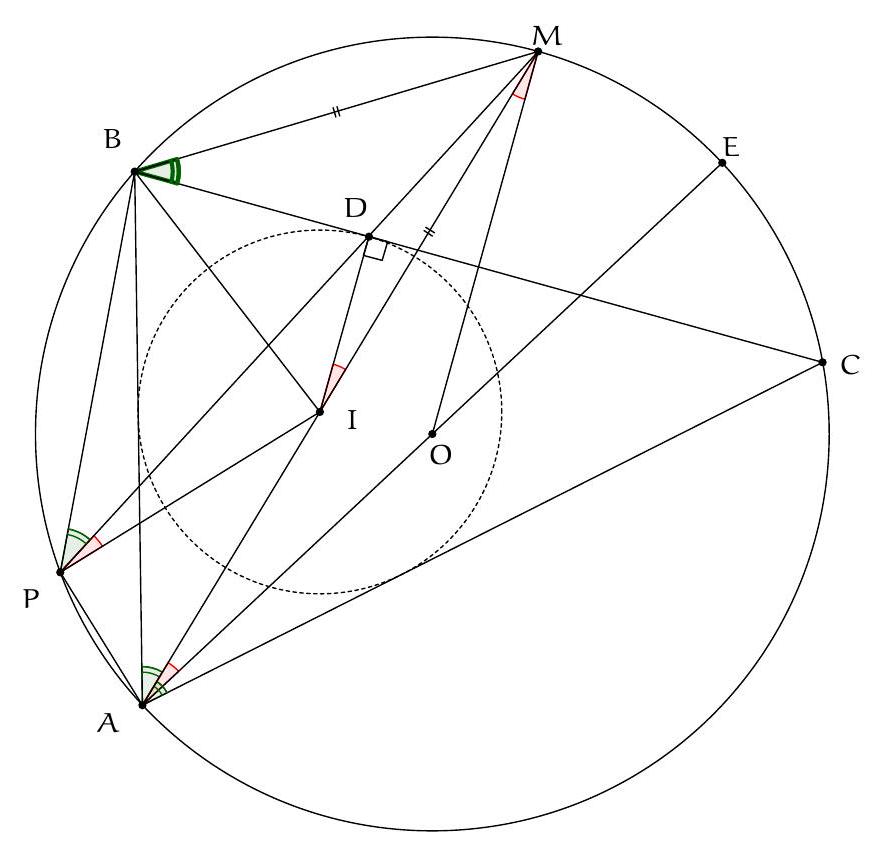

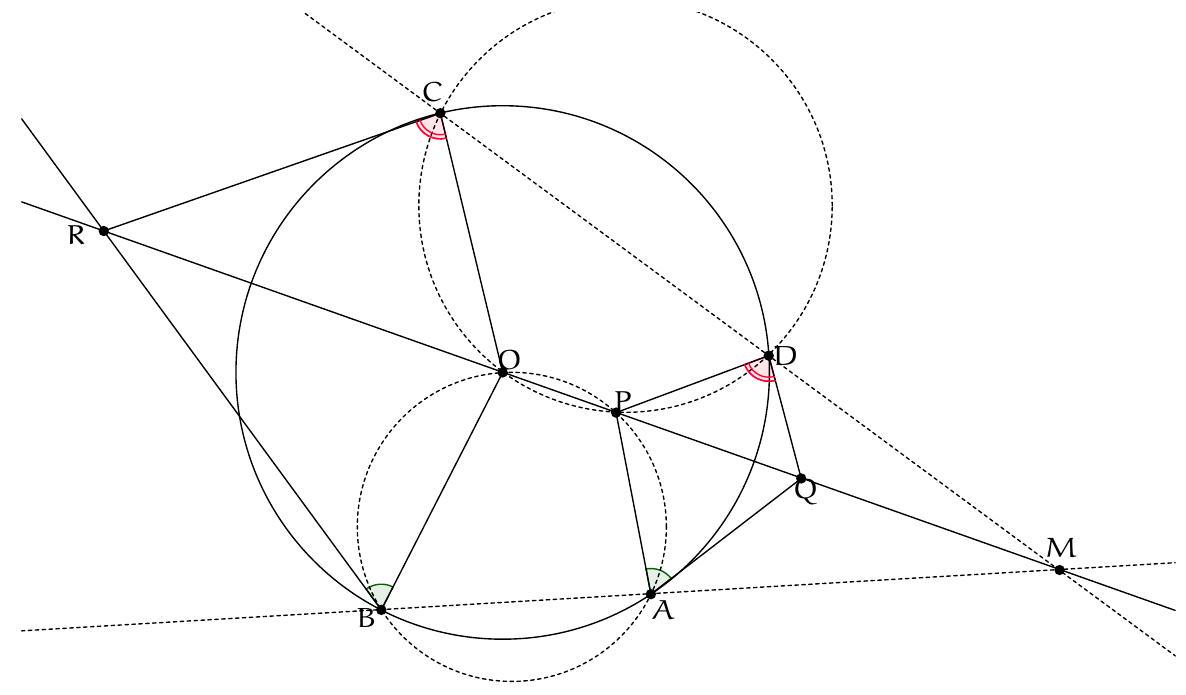

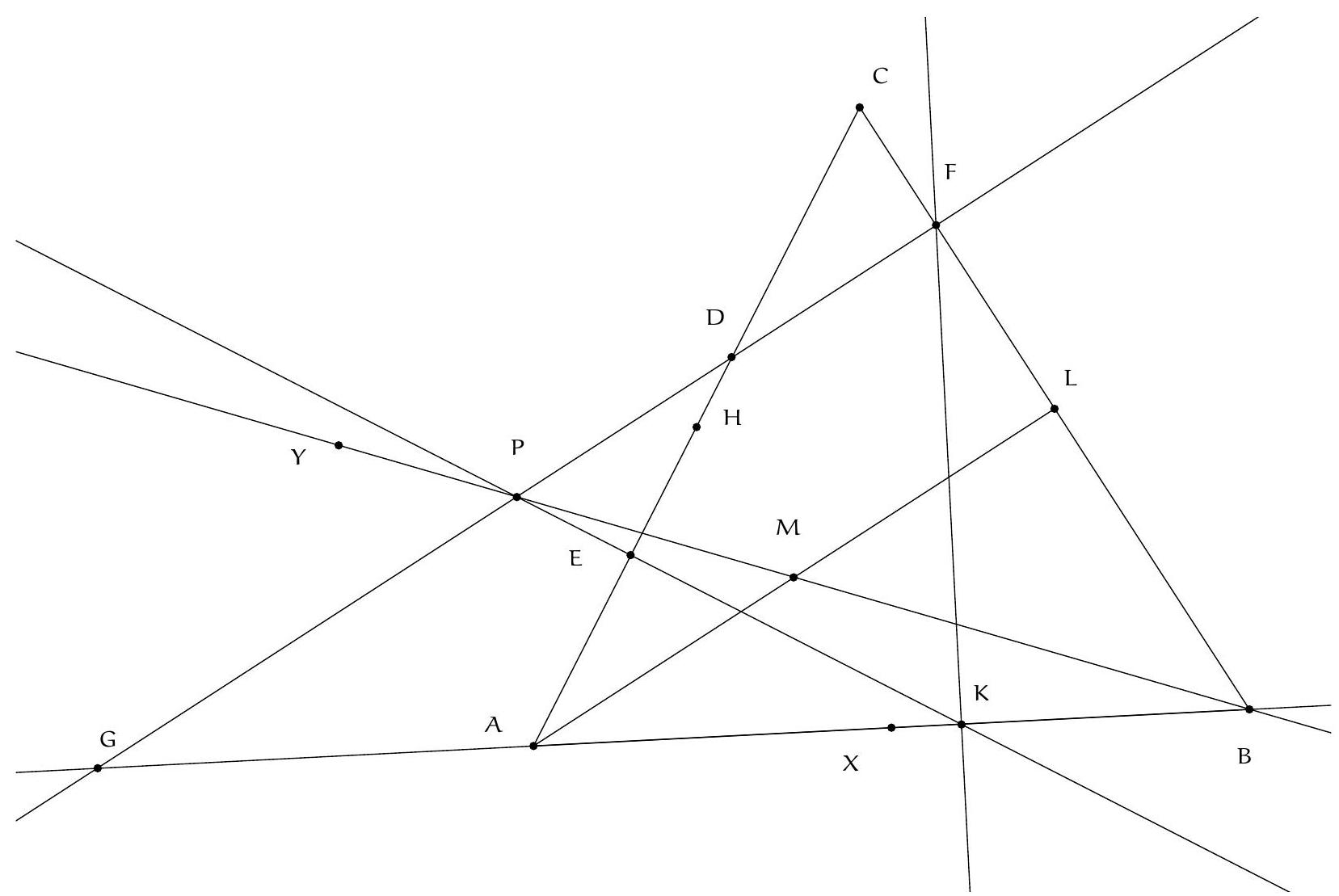

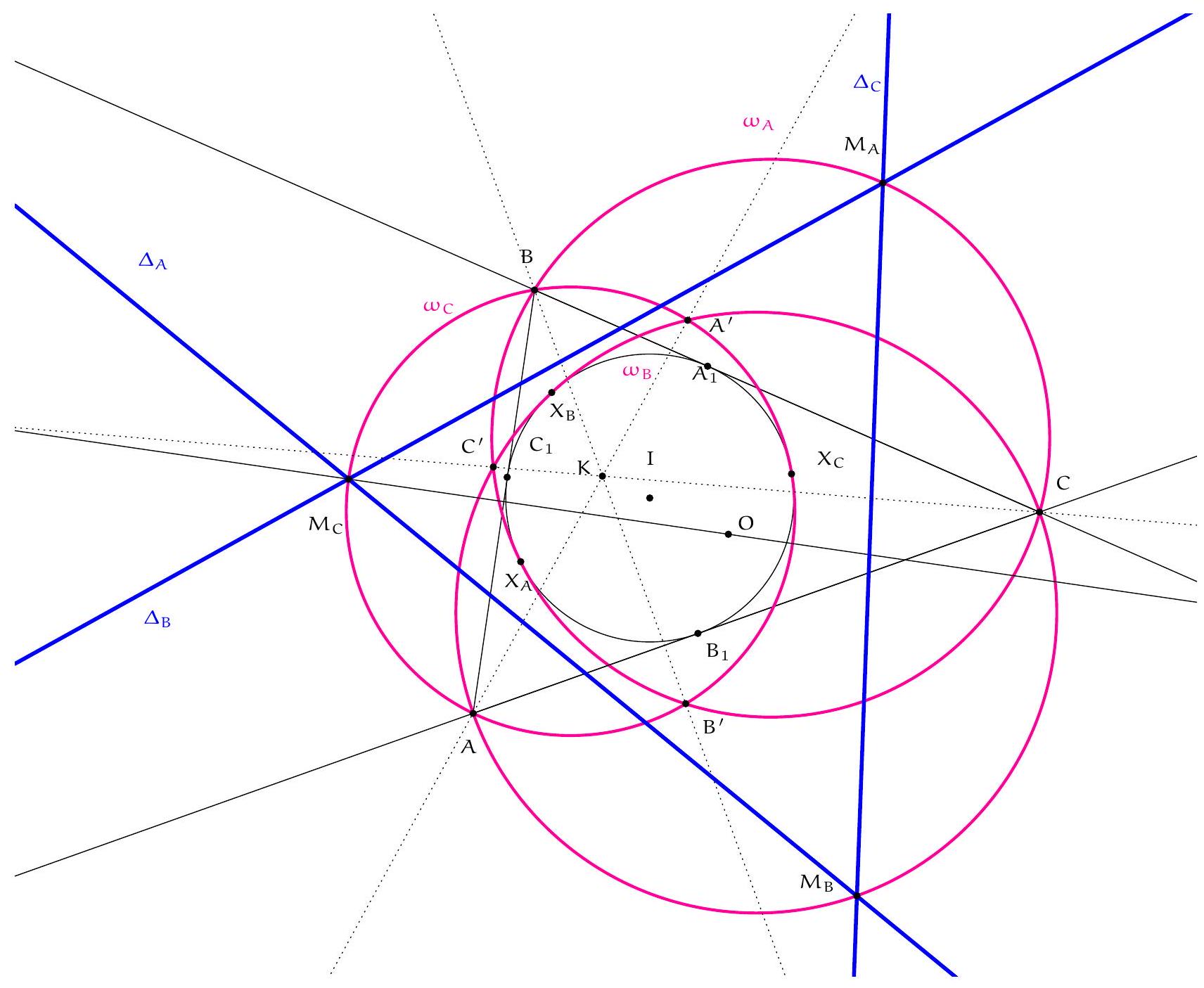

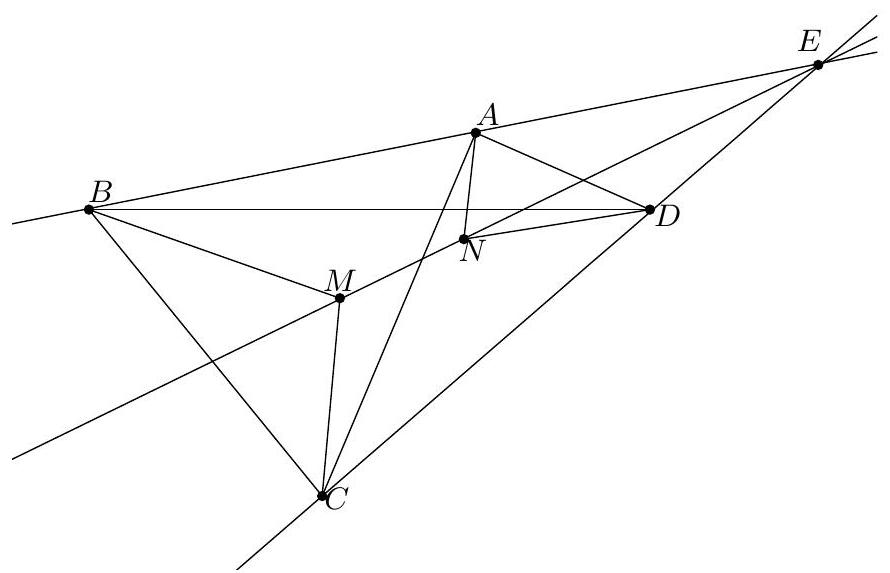

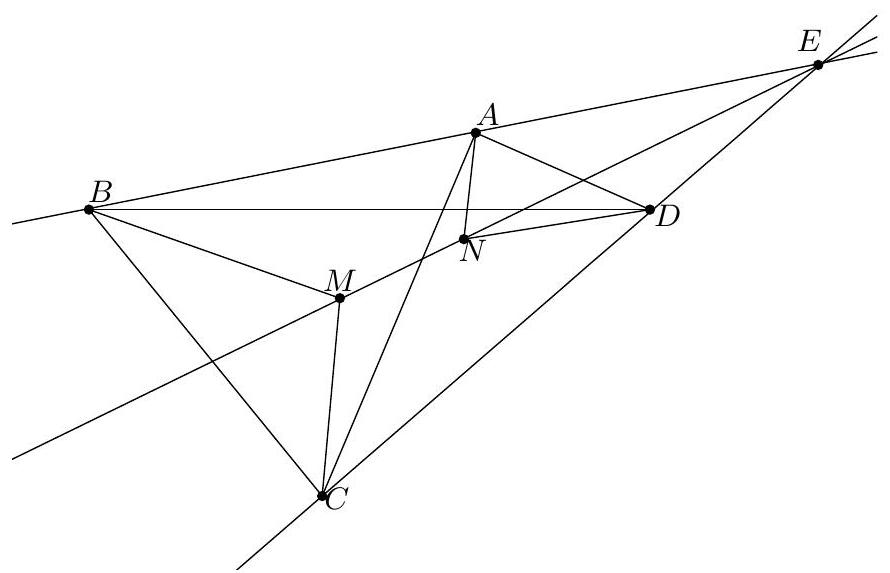

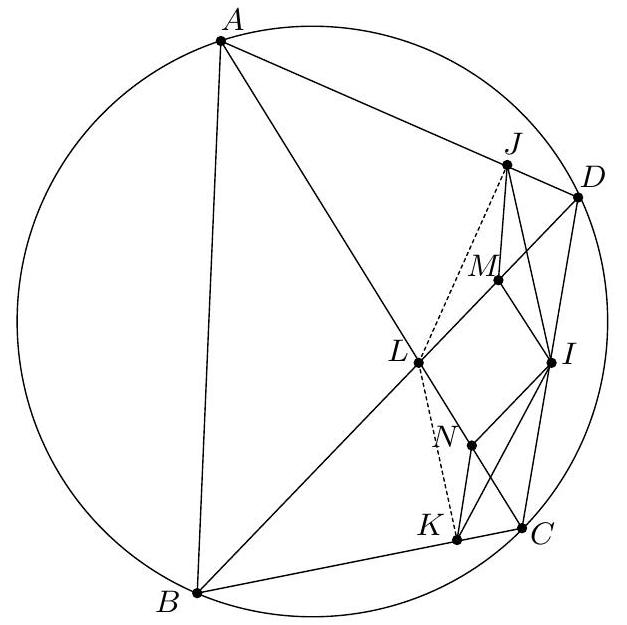

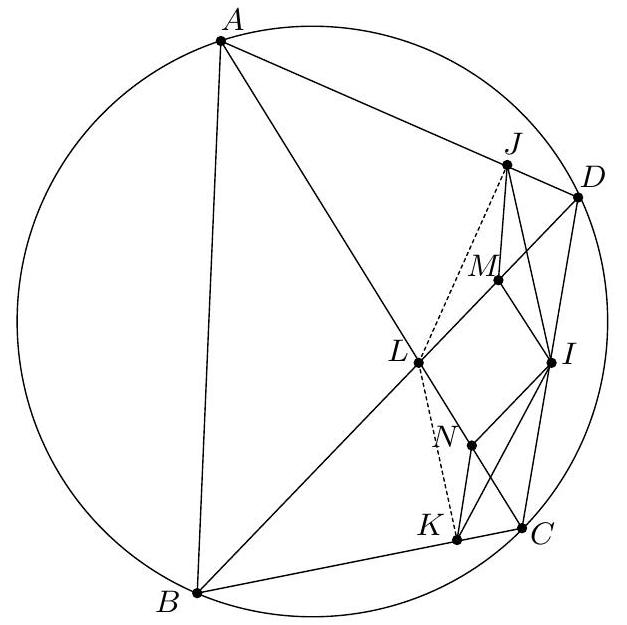

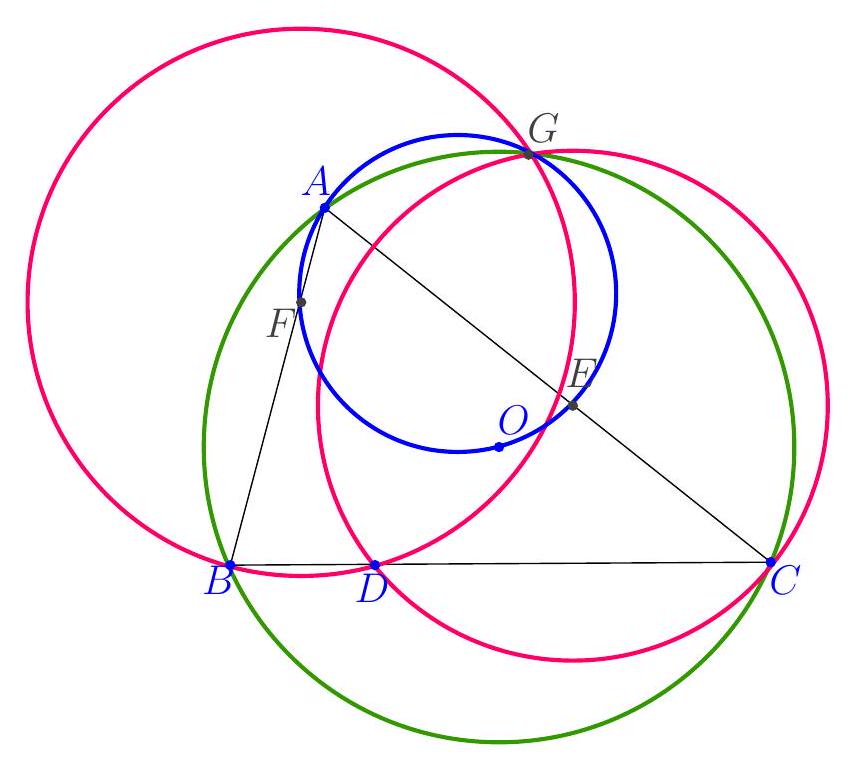

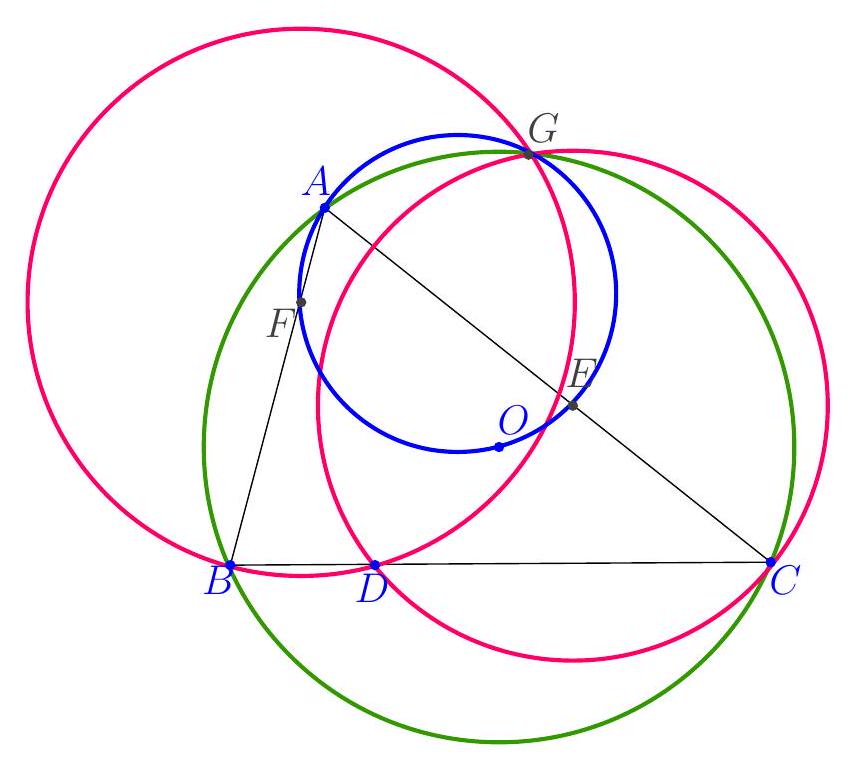

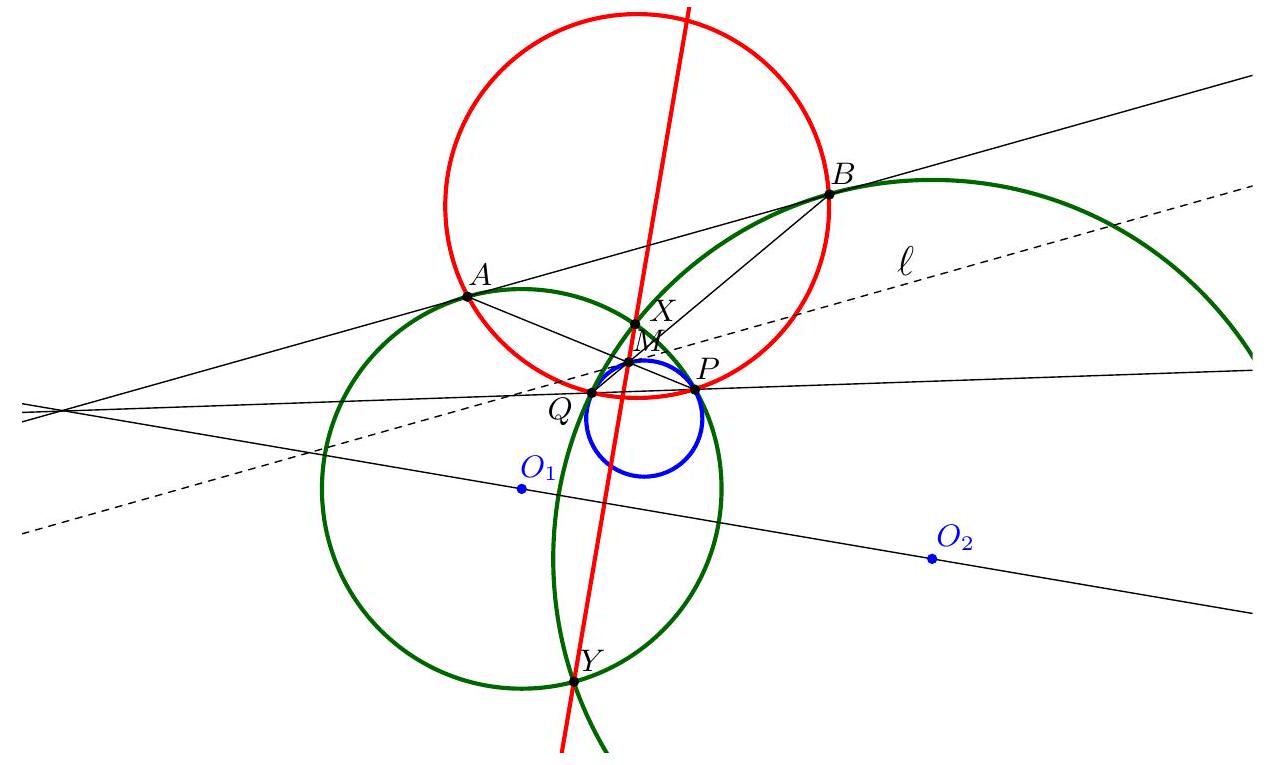

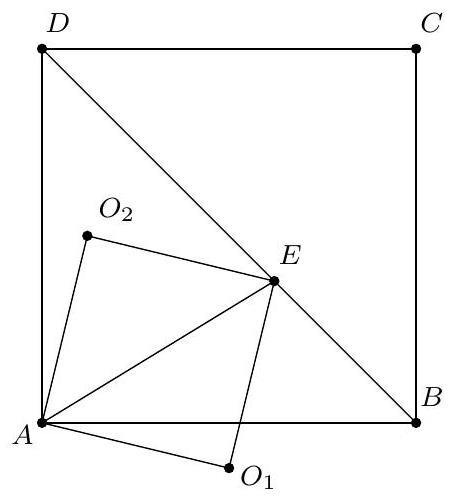

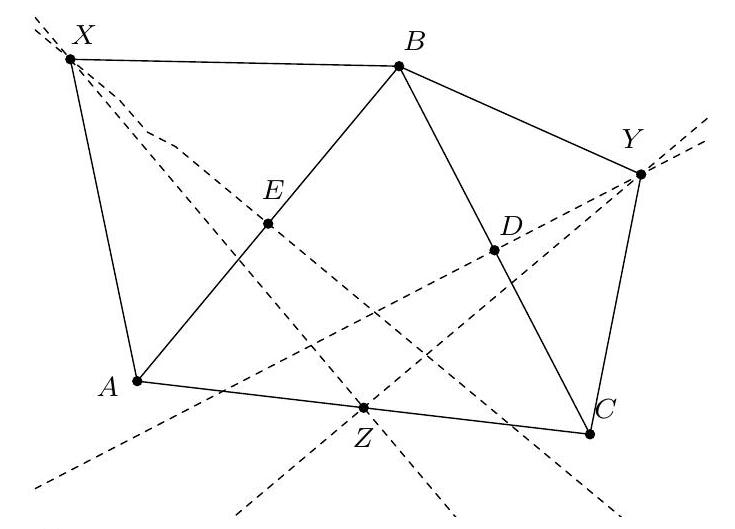

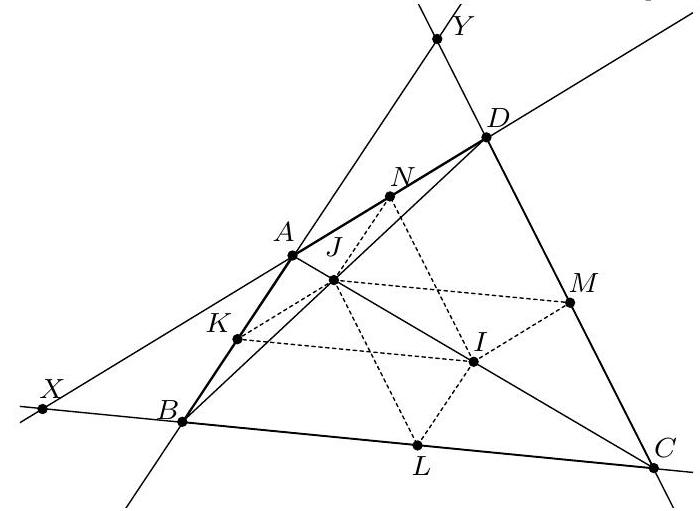

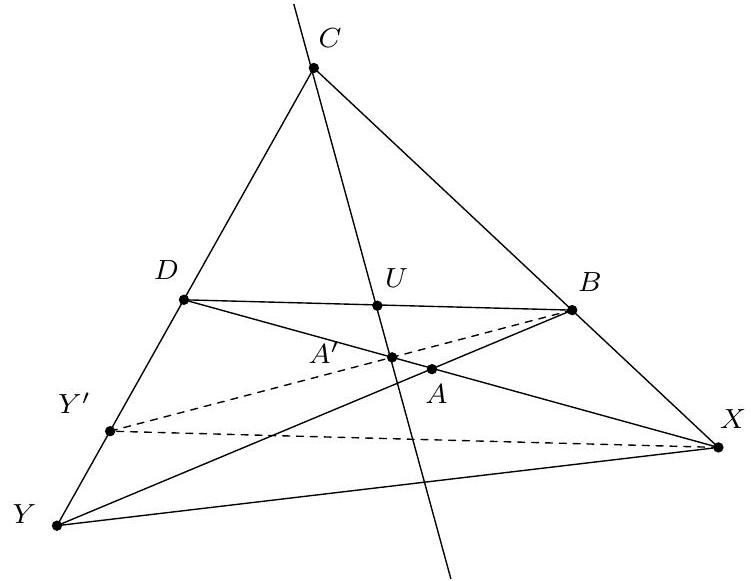

Let $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ be two circles with centers $O_{1}$ and $O_{2}$, respectively. Suppose that $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ intersect at points $A$ and $B$. The line $\left(O_{1} A\right)$ intersects the circle $\omega_{2}$ again at $C$, while the line $\left(O_{2} A\right)$ intersects the circle $\omega_{1}$ again at $D$. Show that the points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{O}_{1}, \mathrm{~B}, \mathrm{O}_{2}$, and $C$ lie on the same circle.

|

Note that since the angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DAO}_{1}}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{CAO}_{2}}$ are vertically opposite, they are equal. On the other hand, since points $A$ and $D$ belong to the circle $\omega_{1}$, the triangle $A O_{1} D$ is isosceles at $O_{1}$. Similarly, the triangle $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ is isosceles at $\mathrm{O}_{2}$. Therefore, triangles $\mathrm{DO}_{1} A$ and $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ are isosceles triangles with the same base angles, so they are similar. This implies that $\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} A}$, and thus

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO} \mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{D}}

$$

so the points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$, and D are concyclic.

Furthermore, we can decompose the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}$ into the sum $\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{ABC}}$. On the one hand, according to the inscribed angle theorem in the circle $\omega_{1}$, we have $\widehat{A B D}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}$. On the other hand, according to the inscribed angle theorem in the circle $\omega_{1}$, we have $\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A_{2} C}$. Thus,

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{1} \mathrm{D}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{2} \mathrm{C}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}

$$

which allows us to conclude that point B belongs to the circle passing through the points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$, and D.

## Comments from the graders:

Very well solved exercise.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soient $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$ deux cercles de centres respectifs $O_{1}$ et $O_{2}$. On suppose que $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$ se coupent en les points $A$ et $B$. La droite $\left(O_{1} A\right)$ recoupe le cercle $\omega_{2}$ en $C$ tandis que la droite $\left(O_{2} A\right)$ recoupe le cercle $\omega_{1}$ en D . Montrer que les points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{O}_{1}, \mathrm{~B}, \mathrm{O}_{2}$ et C appartiennent à un même cercle.

|

Notons que puisque les angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DAO}_{1}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{CAO}_{2}}$ sont opposés par le sommet, ils sont égaux. D'autre part, puisque les points $A$ et $D$ appartiennent au cercle $\omega_{1}$, le triangle $A O_{1} D$ est isocèle en $O_{1}$. De même, le triangle $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ est isocèle en $\mathrm{O}_{2}$. Les triangles $\mathrm{DO}_{1} A$ et $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ sont donc des triangels isocèle avec les mêmes angles à la base, ils sont donc semblables. Ceci implique que $\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} A}$, et donc que

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO} \mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{D}}

$$

si bien que les points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$ et D sont cocycliques.

Par ailleurs, on peut découper l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}$ en la somme $\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{ABC}}$. D'une part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre dans le cercle $\omega_{1}$, on a $\widehat{A B D}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}$. D'autre part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre dans le cercle $\omega_{1}$, on a $\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A_{2} C}$. Ainsi

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{1} \mathrm{D}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{2} \mathrm{C}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}

$$

ce qui permet de conclure que le point B appartient au cercle passant par les points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$ et D .

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice très bien résolu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Aurélien writes 11 natural numbers on the board. Show that he can choose some of these numbers and place + and - signs between them in such a way that the result is divisible by 2021.

|

We can see the choice of certain integers with + and - signs as a choice of certain integers that we will count positively and certain integers that we will count negatively. The numbers that Aurélien can obtain are numbers that can be written as the difference between two sums of several starting integers. We can note that the converse is also true: if a and b can be written as the sum of certain integers, then Aurélien can obtain $a-b$ by putting a plus sign in front of the integers that are in $a$ and a minus sign in front of those that are in $b$. If the same starting integer is used to obtain both a and $b$, Aurélien cannot write both a plus and a minus sign, but he can simply not write the integer at all, which has the same effect as adding and then removing it. Therefore, all differences between two sums of integers from the table are results that Aurélien can obtain. Saying that a difference between two sums is divisible by 2021 is equivalent to saying that the two sums were congruent modulo 2021. We have $2^{11}=2048>2021$ sums, so according to the pigeonhole principle, two are congruent modulo 2021.

## Comments from the graders:

An extremely well-executed exercise by those who tackled it. The solutions are almost all analogous to the corrected solution.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Aurélien écrit 11 entiers naturels au tableau. Montrer qu'il peut choisir certains de ces entiers et placer des signes + et - entre eux de telle sorte que le résultat soit divisible par 2021.

|

On peut voir un choix de certains entiers avec des signes + et - comme un choix de certains entiers que l'on va compter positivement et de certains entiers que l'on va compter négativement. Les nombres qu'Aurélien peut obtenir sont des nombres qui s'écrivent comme la différence entre deux sommes de plusieurs entiers de départ. On peut remarquer que la réciproque est aussi vrai, si a et b s'écrivent comme somme de certains entiers, alors Aurélien peut obtenir $a-b$ en mettant un signe plus devant les entiers qui sont dans $a$ et un signe $b$ devant ceux qui sont dans $b$. Si le même entier de départ est utilisé pour obtenir à la fois a et $b$, Aurélien ne peut pas écrire devant un signe - et + , mais il peut simplement de pas écrire l'entier tout court, ce qui a le même effet que l'ajouter puis l'enlever. Toutes les différences entre deux sommes d'entiers du tableau sont donc des résultats qu'Aurélien peut obtenir. Dire qu'une différence entre deux sommes est dvisible par 2021 revient à dire que les deux sommes étaient congrues modulo 2021. On dispose de $2^{11}=2048>2021$ sommes, donc d'après le principe des tiroirs, deux sont congrues modulo 2021.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice extrêmement bien réussi par ceux qui l'ont traité. Les solutions sont presque toutes analogues à celle du corrigé.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $x, y, z$ be strictly positive real numbers such that

$$

x+\frac{y}{z}=y+\frac{z}{x}=z+\frac{x}{y}=2

$$

Determine all possible values that the number $x+y+z$ can take.

|

In such a problem, one must seek to examine each equation separately but also to relate them. In practice, this involves looking at the equation obtained when performing the sum or product of two or more equations. Another idea is to apply known inequalities on one side or the other of the equation. Indeed, often the equalities present in the problems are only possible when the variables satisfy the equality case of a well-known inequality.

Let's start with a separate examination. We consider the first equation $x+\frac{y}{z}=2$. According to the inequality of means, we have

$$

2=x+\frac{y}{z} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{x \cdot \frac{y}{z}}

$$

which gives $\sqrt{\frac{x y}{z}} \leqslant 1$. Similarly, the second equation $y+\frac{z}{x}=2$ gives $\sqrt{\frac{y z}{x}} \leqslant 1$. By multiplying these two inequalities, we obtain

$$

1 \geqslant \sqrt{\frac{x y}{z}} \cdot \sqrt{\frac{y z}{x}}=y

$$

Thus $y \leqslant 1$, and similarly we find that $x \leqslant 1$ and $z \leqslant 1$. We now seek to apply these estimates or to prove inverse estimates (for example, $y \geqslant 1$, which would imply that $y=1$).

Note that the relation $x+\frac{y}{z}=2$ can be rewritten as $x z+y=2 z$. Similarly, we obtain $y x+z=2 x$ and $y z+x=2 y$. By summing these three relations, we find that $x z+y x+y z+x+y+z=2(x+y+z)$, or equivalently $x y+y z+z x=x+y+z$. But then

$$

x+y+z=x y+y z+z x \leqslant x \cdot 1+y \cdot 1+z \cdot 1=x+y+z

$$

Our inequality is in fact an equality. And since $x, y$, and $z$ are non-zero, each of the inequalities used in the line above is in fact an equality. Therefore, we have $x=y=z=1$ and $x+y+z=3$. This value is indeed attainable since the triplet $(1,1,1)$ satisfies the system given in the problem, which completes our problem.

## Comments from the graders:

A well-executed exercise. The methods of resolution are extremely varied. Some students made the mistake of considering the problem symmetric, whereas it is only cyclic.

|

3

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Soient $x, y, z$ des réels strictement positifs tels que

$$

x+\frac{y}{z}=y+\frac{z}{x}=z+\frac{x}{y}=2

$$

Déterminer toutes les valeurs possibles que peut prendre le nombre $x+y+z$.

|

Dans un tel problème, il faut chercher à examiner chaque équation séparément mais aussi à les mettre en relation. En pratique, cela consiste à regarder l'équation obtenue lorsque l'on effectue la somme ou le produit de deux ou plusieurs équations. Une autre idée est d'appliquer des inégalités connues d'un côté ou de l'autre de l'équation. En effet, souvent les égalités présentes dans les problèmes ne sont possibles que lorsque les variables vérifient le cas d'égalité d'une inégalité bien connue.

Commençons par un examen séparé. On considère la première équation $x+\frac{y}{z}=2$. D'après l'inégalité des moyennes, on a

$$

2=x+\frac{y}{z} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{x \cdot \frac{y}{z}}

$$

soit $\sqrt{\frac{x y}{z}} \leqslant 1$. De même, la deuxième équation $y+\frac{z}{x}=2$ donne $\sqrt{\frac{y z}{x}} \leqslant 1$. En multipliant ces deux inégalités, on obtient

$$

1 \geqslant \sqrt{\frac{x y}{z}} \cdot \sqrt{\frac{y z}{x}}=y

$$

Ainsi $y \leqslant 1$, et de même on trouve que $x \leqslant 1$ et $z \leqslant 1$. On cherche désormais à appliquer ces estimations ou à prouver des estimations inverses (par exemple $y \geqslant 1$, ce qui imposerait que $y=1$ ).

Notons que la relation $x+\frac{y}{z}=2$ se réécrit $x z+y=2 z$. On obtient de même que $y x+z=2 x$ et $y z+x=2 y$. En sommant ces trois relations, on trouve que $x z+y x+y z+x+y+z=2(x+y+z)$, ou encore $x y+y z+z x=x+y+z$. Mais alors

$$

x+y+z=x y+y z+z x \leqslant x \cdot 1+y \cdot 1+z \cdot 1=x+y+z

$$

Notre inégalité est en fait une égalité. Et puisque $x, y$ et $z$ sont non nuls, chacune des inégalités utilisées dans la ligne ci-dessus est en fait une égalité. On a donc $x=y=z=1$ et $x+y+z=3$. Cette valeur est bien atteignable puisque le triplet $(1,1,1)$ vérifie bien le système de l'énoncé, ce qui termine notre problème.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice plutôt bien réussi. Les méthodes de résolution sont extrêmement variées. Certains élèves ont commis l'erreur de considérer que le problème est symétrique, alors qu'il n'est que cyclique.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Find all pairs $(x, y)$ of strictly positive integers such that $x y \mid x^{2}+2 y-1$.

|

On the one hand, we can write $x|x y| x^{2}+2 y-1$ so $x \mid 2 y-1$. Therefore, there exists $n$ such that $2 y-1=nx$. Necessarily, $n$ and $x$ are odd.

On the other hand, the divisibility relation from the statement gives us an inequality: we know that $x y>0$, so

$$

x y \leqslant x^{2}+2 y-1

$$

By multiplying this relation by 2 to simplify the calculations and combining the two, we get

$$

x(n x+1) \leqslant 2 x^{2}+2(n x+1)-2

$$

Rearranging the terms,

$$

(n-2) x^{2} \leqslant(2 n-1) x

$$

Since $x>0$,

$$

x \leqslant \frac{2 n-1}{n-2}=2+\frac{3}{n-2}

$$

Remembering that $n$ and $x$ are necessarily odd, we distinguish several cases.

Case $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 1: n \geqslant 7$. Then

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}<3

$$

So $x=1$. Conversely, all pairs $(1, y)$ are solutions.

Case $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 2: \mathrm{n}=5$. Then

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}=3

$$

So $x=1$ or $x=3$. All pairs with $x=1$ are solutions. If $x=3$, we have $2 y-1=n x=5 \cdot 3=15$ so $y=8$. We verify that $(3,8)$ is a solution: $24 \mid 24$.

$\underline{\text { Case } \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 3:} \mathbf{n}=3$. Then

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}=5

$$

So $x=1$ or $x=3$. All pairs with $x=1$ are solutions. If $x=3$, we have $2 y-1=n x=3 \cdot 3=9$ so $y=5$. We verify that $(3,5)$ is not a solution: $15 \nmid 24$. If $x=5$ we have $2 y-1=n x=5 \cdot 3=15$ so $y=8$. We verify that $(5,8)$ is a solution: $40 \mid 40$.

Case $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 4: \mathbf{n}=1$. Then $x=2 y-1$. Then

$$

x y=2 y^{2}-y \mid 4 y^{2}-2 y=(2 y-1)^{2}+2 y-1=x^{2}+2 y+1

$$

So all pairs of the form $(2 y-1, y)$ are solutions.

## Comments from the graders:

The exercise is rather well done by the students who tackled it. Despite the somewhat tedious disjunction of cases, very few omissions are noted. Some still have difficulty with the concept of divisibility, notably how to interpret an expression of the type $a \mid b c$.

|

(1, y), (3, 8), (5, 8), (2y-1, y)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Trouver tous les couples $(x, y)$ d'entiers strictement positifs tels que $x y \mid x^{2}+2 y-1$.

|

D'une part, on peut écrire $x|x y| x^{2}+2 y-1$ donc $x \mid 2 y-1$. Donc il existe n tel que $2 \mathrm{y}-1=\mathrm{nx}$. Forcément, n et $x$ sont impairs.

D'autre part, la relation de divisibilité de l'énoncé nous donne une inégalité : on sait que $x y>0$, donc

$$

x y \leqslant x^{2}+2 y-1

$$

En multipliant cette relation par 2 pour simplifier les calculs et en combinant les deux, on obtient

$$

x(n x+1) \leqslant 2 x^{2}+2(n x+1)-2

$$

En reorganisant les termes,

$$

(n-2) x^{2} \leqslant(2 n-1) x

$$

Soit, comme $x>0$

$$

x \leqslant \frac{2 n-1}{n-2}=2+\frac{3}{n-2}

$$

En se souvenant que n et $x$ sont forcément impairs, on distingue plusieurs cas.

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 1: n \geqslant 7$. Alors

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}<3

$$

Donc $x=1$. Réciproquement, tous les couples $(1, y)$ sont solution.

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 2: \mathrm{n}=5$. Alors

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}=3

$$

Donc $x=1$ ou $x=3$. Tous les couples avec $x=1$ sont solutions. Si $x=3$, on a $2 y-1=\mathfrak{n} x=$ $5 \cdot 3=15$ donc $y=8$. On vérifie $(3,8)$ est solution : $24 \mid 24$.

$\underline{\text { Cas } \mathrm{n}^{\circ} 3:} \mathbf{n}=3$. Alors

$$

x \leqslant 2+\frac{3}{n-2}=5

$$

Donc $x=1$ ou $x=3$. Tous les couples avec $x=1$ sont solutions. Si $x=3$, on a $2 y-1=$ $\mathrm{n} x=3 \cdot 3=9$ donc $y=5$. On vérifie que $(3,5)$ n'est pas solution : $15 \nmid 24 . \operatorname{Si} x=5$ on a $2 \mathrm{y}-1=\mathrm{n} x=5 \cdot 3=15$ donc $y=8$. On vérifie que $(5,8)$ est solution : $40 \mid 40$.

Cas $\mathrm{n}^{\circ} 4: \mathbf{n}=1$. Alors $x=2 y-1$. Alors

$$

x y=2 y^{2}-y \mid 4 y^{2}-2 y=(2 y-1)^{2}+2 y-1=x^{2}+2 y+1

$$

Donc tous les couples de la forme $(2 y-1, y)$ sont solutions.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

L'exercice est plutôt bien réussi par les élèves qui l'ont traité. Malgré la disjonction de cas relativement fastidieuse, on relève très peu d'oublis. Certains ont encore du mal avec la notion de divisibilité, notamment comment interpréter une expression du type $a \mid b c$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $n \geqslant 1$ be a strictly positive integer. On a wall, $n$ nails are hammered in. Each pair of nails is connected by a colored string using one of the $n$ colors. We say the wall is colored if for every triplet of distinct colors $a, b, c$, there exist three nails such that the three strings connecting these nails are of colors $a, b$, and $c$.

- Does a colored wall exist for $\mathrm{n}=6$?

- Does a colored wall exist for $\mathrm{n}=7$?

|

In fact, it is the parity of $n$ that is crucial.

Case $n$ even: There are $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$, so on average there are $\frac{n-1}{2}$ strings of each color. Since this number is not an integer, there are colors with more strings than the average and some with fewer. We could just as well choose an underrepresented color and compare the number of color triplets containing this color with the number of string triplets containing a string of this color to obtain a contradiction. Here, we will take the opposite approach: we consider an overrepresented color. There are at least $\frac{n+1}{2}$ strings of this color, so there are at least $n+1$ ends of strings of this color. According to the pigeonhole principle, there exists a vertex with two ends of strings of this color. Therefore, there exists a triplet of strings containing this color twice, and thus corresponding to no color triplet. However, there are $\binom{n}{3}$ string triplets that must fill the $\binom{n}{3}$ possible color triplets, leaving no room for wasting string triplets. It is therefore impossible to obtain a colored wall for $n$ even.

Case $n$ odd: Here, the previous reasoning indicates that for each color, there must be $\frac{n-1}{2}$ strings connecting $n-1$ distinct points and leaving one point unconnected by this color. We find the following construction: we number the nails in $\mathbb{Z} / n \mathbb{Z}$ and the colors as well. Then, we assign the color $i+j$ to the string between nail $i$ and nail $j$. This construction seems promising because it is completely symmetric and satisfies the desired property. Indeed, it is easy to verify that the color triplet of strings $a, b, c$ is achieved by taking the nails $\frac{a+b}{2}, \frac{a+c}{2}, \frac{b+c}{2}$.

Graders' Comments:

The exercise is well solved. Some found only one of the two cases, but were rewarded.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

Soit $n \geqslant 1$ un entier strictement positif. Sur un mur, $n$ clous sont plantés. Chaque paire de clous est reliée par une corde coloriée à l'aide d'une des n couleurs. On dit que le mur est coloré si pour tout triplet de couleurs deux à deux distinctes $a, b, c$, il existe trois clous tels que les trois cordes reliant ces clous soient de couleur $a, b$ et $c$.

- Existe-t-il un mur coloré pour $\mathrm{n}=6$ ?

- Existe-t-il un mur coloré pour $\mathrm{n}=7$ ?

|

C'est en fait la parité de n qui est cruciale.

Cas n pair : Il y a $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$ donc en moyenne il y a $\frac{n-1}{2}$ cordes de chaque couleur. Ce nombre n'étant pas entier, il y a des couleurs avec plus de cordes que la moyenne et des avec moins. On pourrait tout-à-fait choisir une couleur sous-représentée et comparer le nombre de triplets de couleurs comportant cette couleur avec le nombre de triplets de cordes comportant une corde de cette couleur pour obtenir un contradiction. On va ici choisir l'approche opposée : on considère une couleur sur-représentée. Il y a au moins $\frac{n+1}{2}$ cordes de cette couleur, donc au moins $n+1$ extrémités de cordes de cette couleur. D'après le principe des tiroirs, il existe un sommet ayant deux extrémités de cordes de cette couleur. Il existe donc un triplet de cordes comportant deux fois cette couleur, et ne correspondant donc à aucun triplet de couleur. Cependant il y a $\binom{n}{3}$ triplets de cordes qui doivent remplir les $\binom{n}{3}$ triplets de couleurs possibles, il n'y a aucune marge pour gâcher des triplets de cordes. Il est donc impossible d'obtenir un mur coloré pour $n$ pair.

Cas n impair : Ici le raisonnement précédent nous indique juste que pour chaque couleur il faut $\frac{\mathrm{n}-1}{2}$ cordes reliant $n-1$ points distincts et laissant un unique point ne relié par cette couleur. On trouve la construction suivante : on numérote les clous dans $\mathbb{Z} / \mathrm{n} \mathbb{Z}$ et les couleurs aussi. Ensuite, on donne à la corde entre le clou $i$ et le clou $j$ la couleur $i+j$. Cette construction semble prometteuse car elle est totalement symétrique et vérifie la propriété voulue. En effet, on vérifie facilement que le triplet de couleur de corde $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c}$ est atteint en prenant les clous $\frac{\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}}{2}, \frac{\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{c}}{2}, \frac{\mathrm{~b}+\mathrm{c}}{2}$

Commentaires des correcteurs:

L'exercice est bien résolu. Certains n'ont trouvé qu'un cas sur les deux, mais ont été récompensé.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

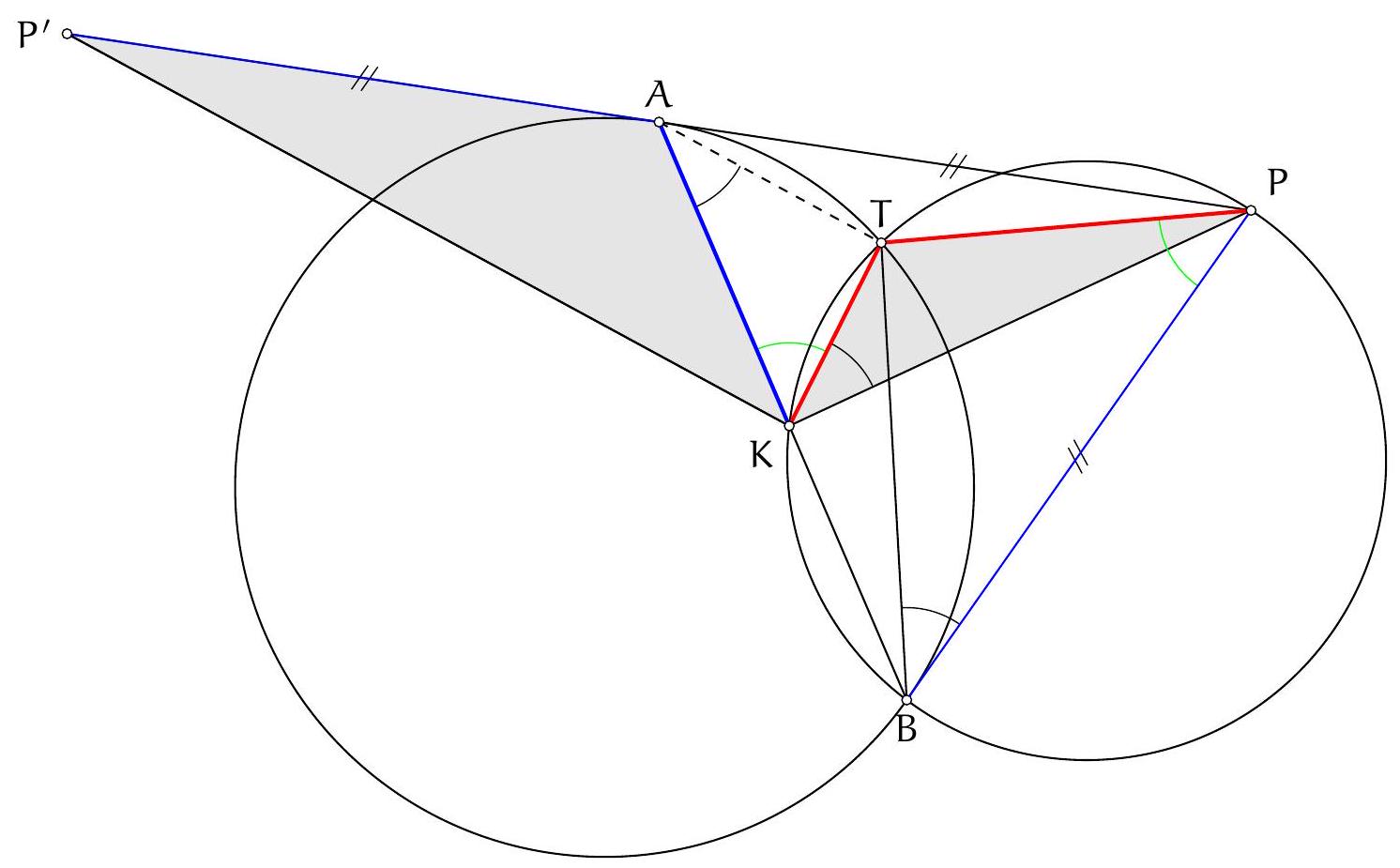

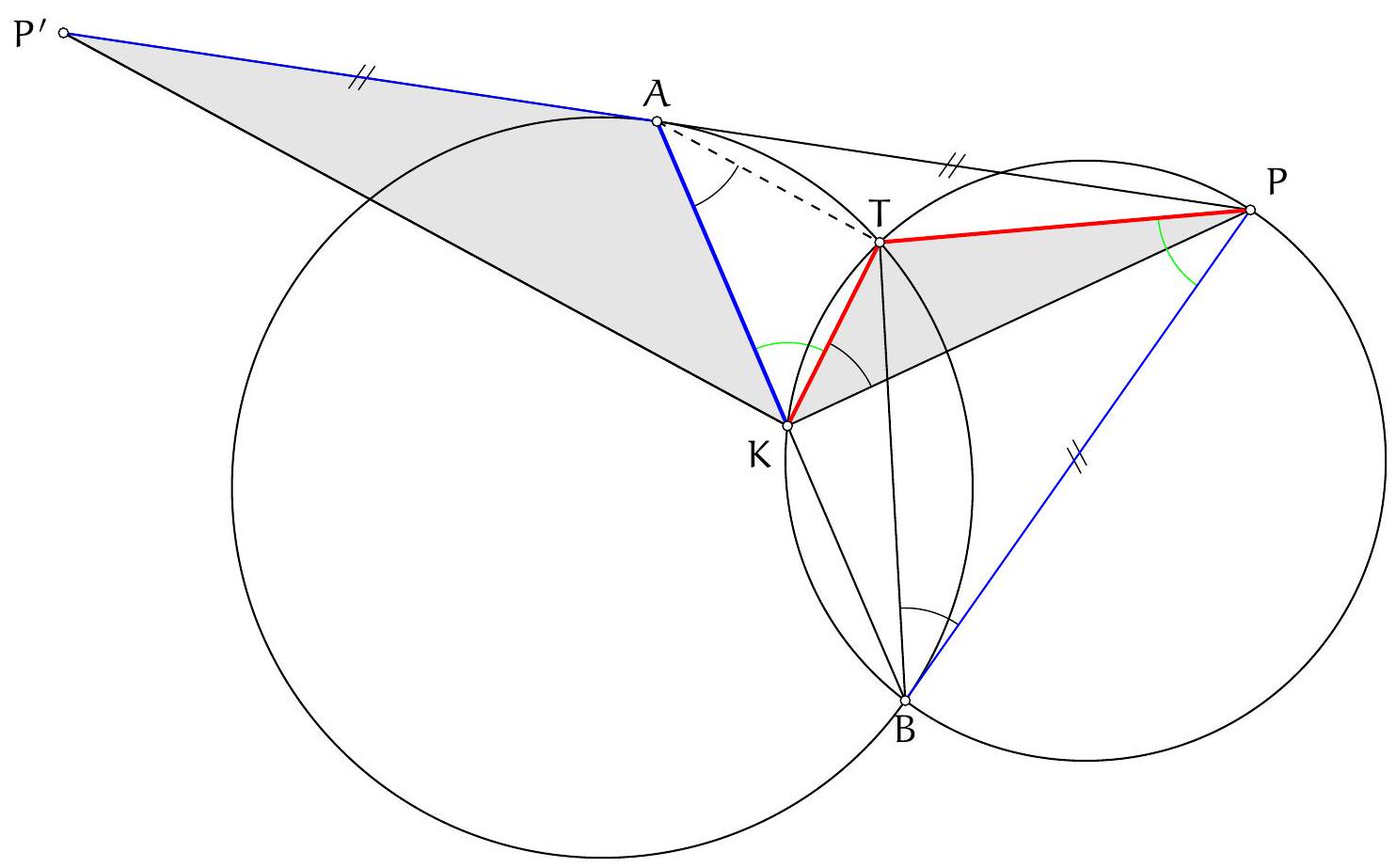

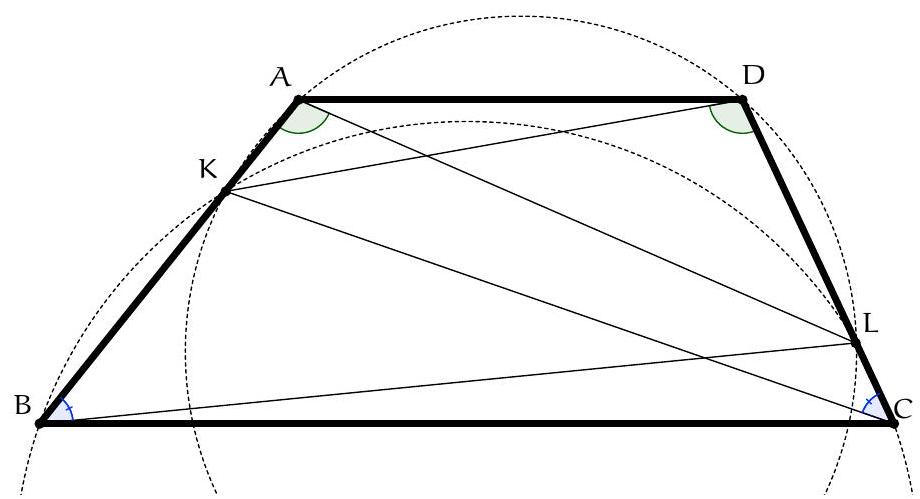

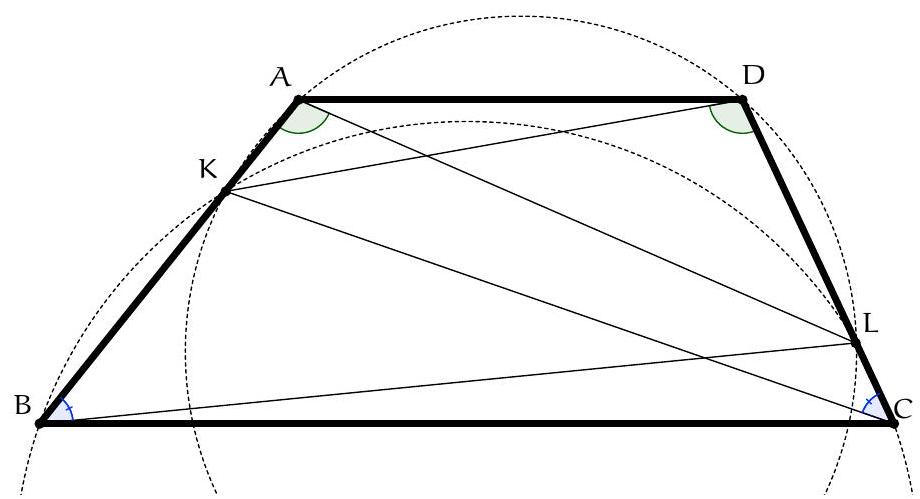

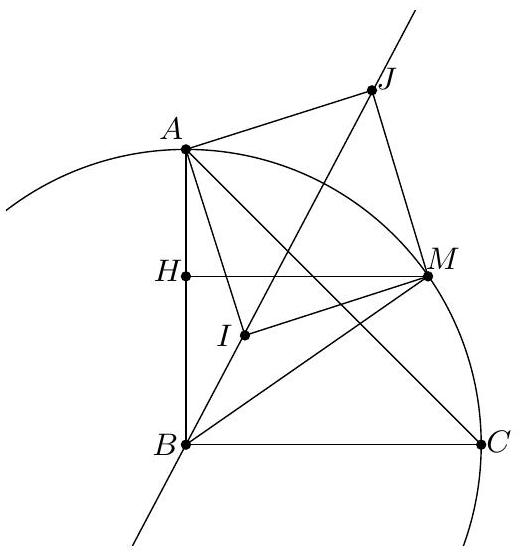

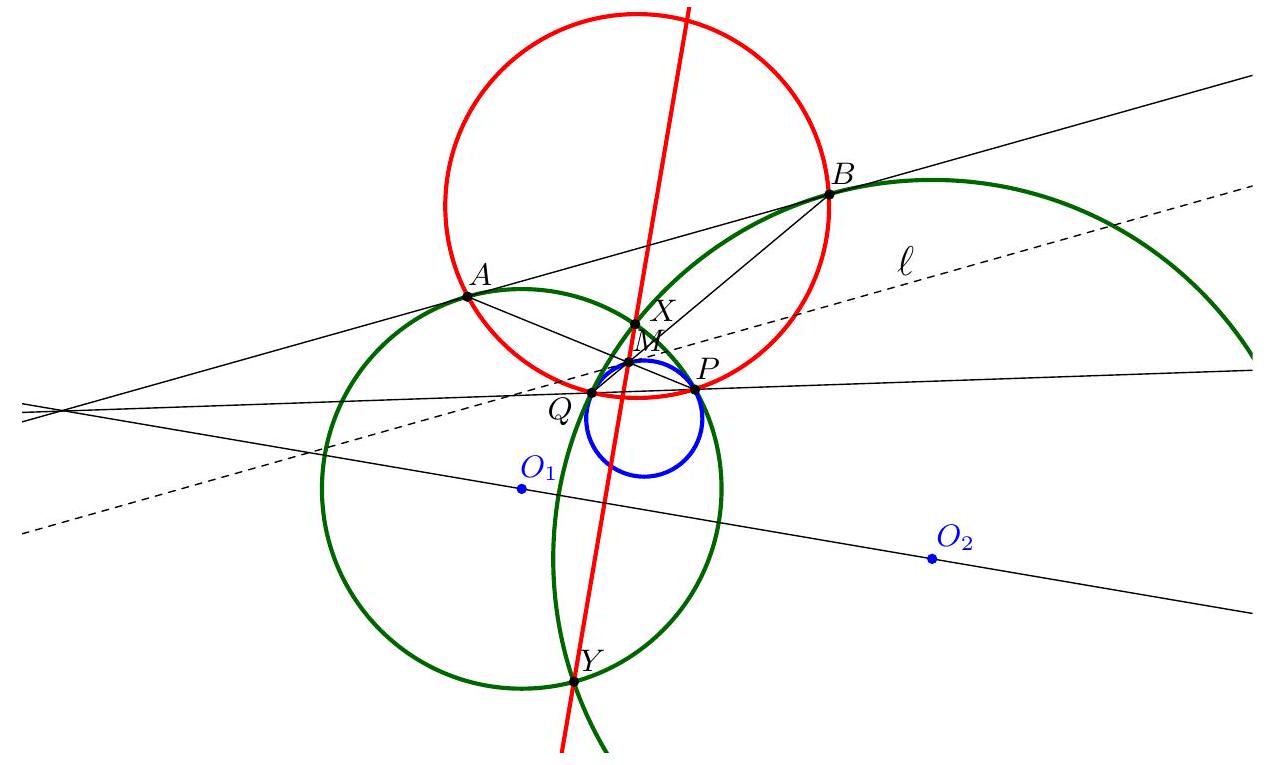

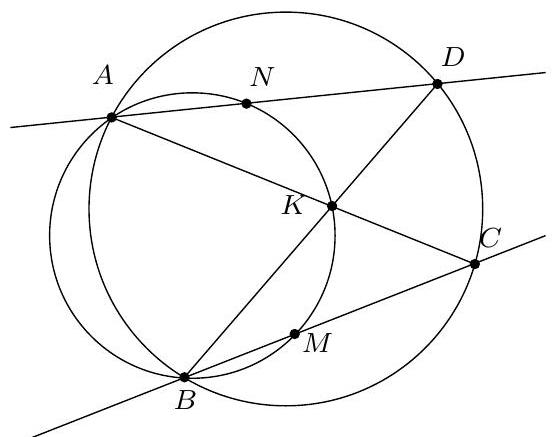

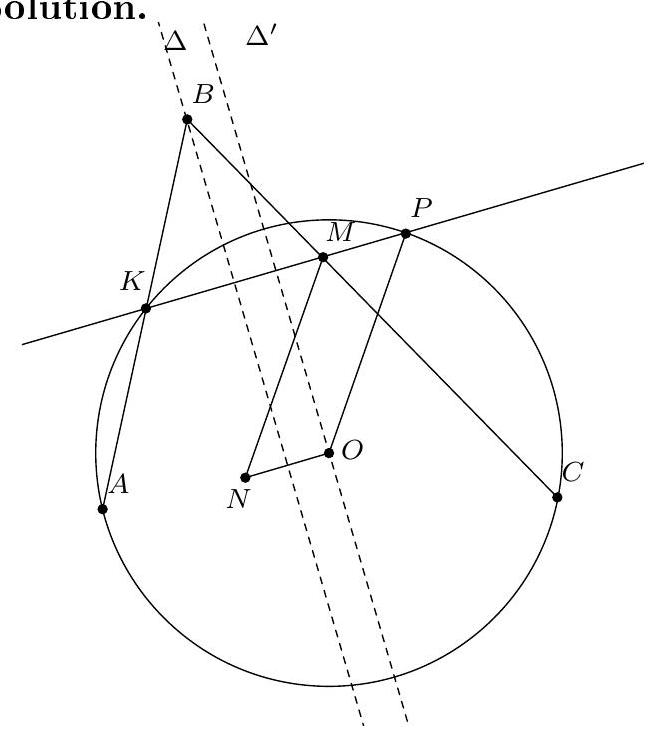

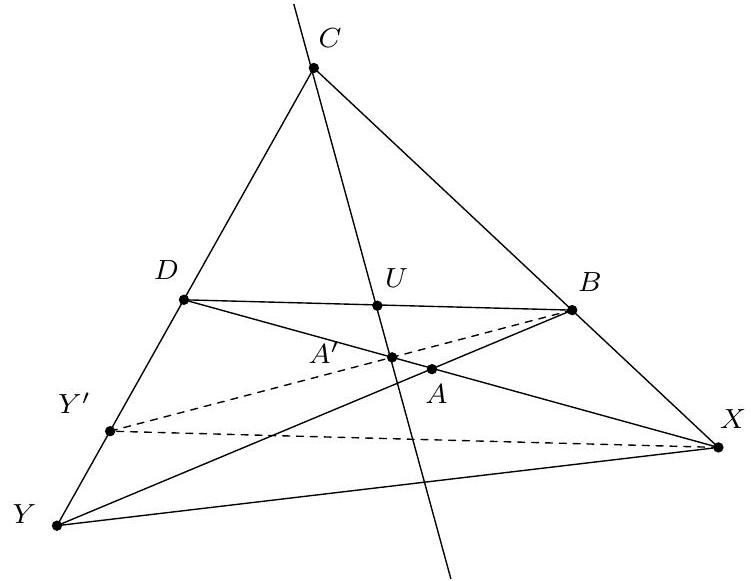

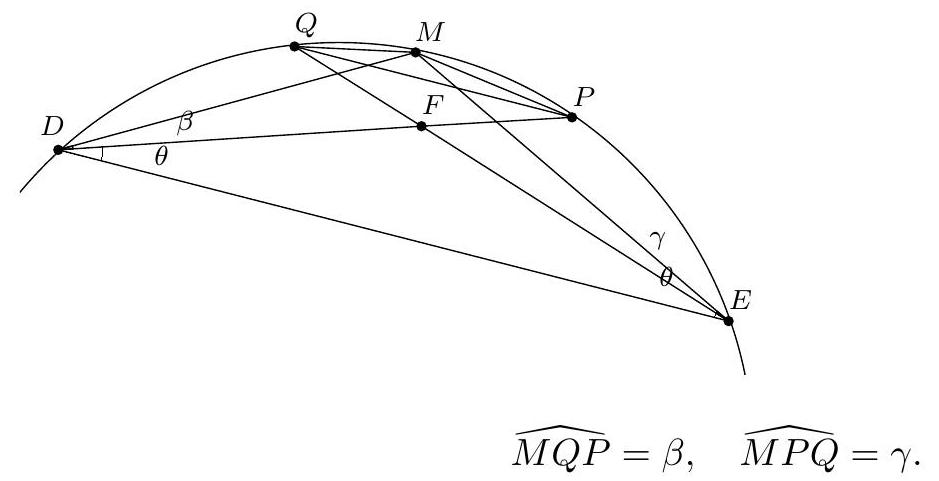

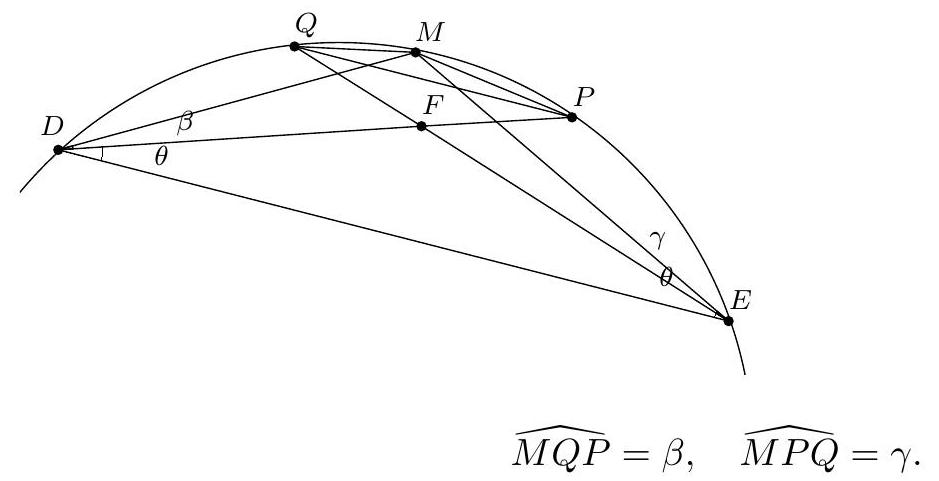

Let $\Gamma$ be a circle and $P$ a point outside $\Gamma$. The tangents to $\Gamma$ from $P$ touch $\Gamma$ at $A$ and $B$. Let $K$ be a point distinct from $A$ and $B$ on the segment $[A B]$. The circumcircle of triangle $P B K$ intersects the circle $\Gamma$ at point $T$. Let $P'$ be the symmetric point of $P$ with respect to point $A$. Show that $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$.

|

According to the inscribed angle theorem, $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that $\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$. The figure suggests that triangles PKT and $P^{\prime}$ KA are similar, so we will try to prove this result, which will imply the desired angle equality.

To show that $\triangle P K T \sim \triangle P^{\prime} K A$, there are several possibilities. For example, we can show that $\widehat{T P K} = \widehat{K^{\prime} A}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{KAP}}$. However, when trying to calculate the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{TPK}}$, we realize that the equality $\widehat{\mathrm{TPK}}=\widehat{\mathrm{KP}^{\prime} A}$ is equivalent to the statement to be proven. Therefore, we will show that $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{AK}}$ and that $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}}=\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{AP}^{\prime}}$.

To show that $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{AK}}$, we first note that triangle $A P B$ is isosceles at $P$ because the lines ( $A P$ ) and ( $B P$ ) are tangent at $A$ and $B$ to the circle $\Gamma$. By applying the inscribed angle theorem in the circle passing through $P, B, K$ and $T$, we find:

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{KBP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ABP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BAP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAK}}

$$

It remains to show that $\frac{K T}{K A}=\frac{T P}{A P^{\prime}}$. Since $A P^{\prime}=A P=B P$, it suffices to show that $\frac{K T}{K A}=\frac{T P}{B P}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that triangles AKT and BPT are similar. To do this, it suffices to show that the angles of these two triangles are equal in pairs.

On the one hand, by the inscribed angle theorem, $\widehat{A K T}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{TPB}}$. On the other hand, by the tangent angle theorem, $\widehat{\mathrm{TAK}} = \widehat{\mathrm{TAB}} = \widehat{\mathrm{TBP}}$.

Therefore, triangles $A K T$ and BPT are similar as desired.

## Comments from the graders:

A good success relative to the estimated difficulty of the exercise. Some students, who did not completely solve the exercise, shared their ideas on the problem, which was greatly appreciated.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $\Gamma$ un cercle et P un point à l'extérieur de $\Gamma$. Les tangentes à $\Gamma$ issues de P touchent $\Gamma$ en $A$ et $B$. Soit $K$ un point distinct de $A$ et $B$ sur le segment $[A B]$. Le cercle circonscrit au triangle $P B K$ recoupe le cercle $\Gamma$ au point $T$. Soit $P^{\prime}$ le symétrique du point $P$ par rapport au point $A$. Montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$.

|

D'après le théorème de l'angle inscrit, $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}$. Ainsi, il suffit de montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$. La figure semble suggérer que les triangles PKT et $P^{\prime}$ KA sont semblables, nous allons donc essayer de montrer ce résultat, qui impliquera bien l'égalité d'angle voulue.

Pour montrer que $\triangle P K T \sim \triangle P^{\prime} K A$, on a plusieurs possibilités. Par exemple, on peut montrer que $\widehat{T P K}=$ $\widehat{K^{\prime} A}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{KAP}}$. Toutefois, lorsque l'on essaye de calculer l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{TPK}}$, on se rend compte que l'égalité $\widehat{\mathrm{TPK}}=\widehat{\mathrm{KP}^{\prime} A}$ est équivalente à l'énoncé à démontrer. On va donc montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{AK}}$ et que $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}}=\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{AP}^{\prime}}$.

Pour montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} A \mathrm{AK}}$, il faut d'abord remarquer que le triangle $A P B$ est isocèle en $P$ puisque les droites ( $A P$ ) et ( $B P$ ) sont tangentes en $A$ et $B$ au cercle $\Gamma$. En appliquant le théorème de l'angle inscrit dans le cercle passat par $P, B, K$ et $T$, on trouve :

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{KBP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ABP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BAP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAK}}

$$

Il reste donc à montrer que $\frac{K T}{K A}=\frac{T P}{A P^{\prime}}$. Puisque $A P^{\prime}=A P=B P$, il suffit de montrer que $\frac{K T}{K A}=\frac{T P}{B P}$. Il suffit donc de montrer que les triangles AKT et BPT sont semblables. Pour cela, il suffit de montrer que les angles de ces deux triangles sont deux à deux égaux.

D'une part, par angle inscrit, $\widehat{A K T}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{TPB}}$. D'autre part par angle tangentiel, $\widehat{\mathrm{TAK}}=$ $\widehat{\mathrm{TAB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{TBP}}$.

Donc les triangles $A K T$ et BPT sont semblables comme voulu.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Une bonne réussite relativement à la difficulté estimée de l'exercice. Quelques élèves, qui n'ont pas résolu complètement l'exercice, on tenu à partager leurs idées sur le problème, ce qui a été grandement apprécié.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{101}$ be real numbers in the interval $[-2 ; 10]$ such that

$$

a_{1}+\ldots+a_{101}=0

$$

Show that

$$

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{101}^{2} \leqslant 2020

$$

|

When dealing with inequalities on real numbers that are not necessarily positive, it is essential to separate the positive and negative variables. This simple idea often constitutes the starting point in the solution and can lead to interesting developments, in addition to preventing certain errors when manipulating inequalities with negative numbers.

The second idea, when the variables play symmetric roles, is to impose an order on the reals. In addition to sometimes yielding interesting results for the problem, this greatly simplifies the writing of the solution.

By renumbering the variables, we assume that $a_{1} \leqslant a_{2} \leqslant \ldots \leqslant a_{100} \leqslant a_{101}$. If all the reals are zero, then the sum of their squares is zero and is therefore less than 2020. We now assume that one of the reals is non-zero. Since the sum of the $a_{i}$ is zero, this implies that at least one real is strictly positive and another is strictly negative. We then denote $p$ the index such that $a_{p}<0 \leqslant a_{p+1}$.

Let's rewrite the zero sum hypothesis in the form

$$

-\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{p}\right)=a_{p+1}+\ldots+a_{101}

$$

We will now seek to make this hypothesis appear in the sum to be calculated. For this, we will also use the fact that if $1 \leqslant i \leqslant p$, then $a_{i} \geqslant-2$ and that if $p+1 \leqslant i \leqslant 101$, then $a_{i} \leqslant 10$. We have:

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{101}^{2} & =\underbrace{a_{1} \cdot a_{1}}_{\leqslant-2 a_{1}}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{p} \cdot a_{p}}_{\leqslant-2 a_{p}}+\underbrace{a_{p+1} \cdot a_{p+1}}_{\leqslant 10 a_{p+1}}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{101} \cdot a_{101}}_{\leqslant 10 a_{101}} \\

& \leqslant-2 a_{1}+\ldots+\left(-2 a_{p}\right)+10 a_{p+1}+\ldots+10 a_{101} \\

& =2\left(-\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{p}\right)\right)+10\left(a_{p+1}+\ldots+a_{101}\right) \\

& =2(\underbrace{a_{p+1}}_{\leqslant 10}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{101}}_{\leqslant 10})+10(-(\underbrace{a_{1}}_{\geqslant-2}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{p}}_{\geqslant-2})) \\

& \leqslant 2 \cdot 10 \cdot(101-p)+10 \cdot 2 \cdot p \\

& =2020

\end{aligned}

$$

which is the desired inequality.

## Comments from the Examiners:

Some students noticed that, for $-2 \leqslant a_{i} \leqslant 10$, we have $\left(a_{i}+2\right)\left(a_{i}-10\right) \leqslant 0$, and used this to arrive at a proof very efficiently. Others chose to construct the values of $a_{i}$ that maximize the sum of the squares; in this case, it was of course essential to prove the optimality of the construction to obtain the majority of the points.

## Senior Exercises

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soient $a_{1}, \ldots, a_{101}$ des réels appartenant à l'intervalle $[-2 ; 10]$ tels que

$$

a_{1}+\ldots+a_{101}=0

$$

Montrer que

$$

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{101}^{2} \leqslant 2020

$$

|

Lorsque l'on effectue des inégalités sur des réels qui ne sont pas forcément positifs, il est essentiel de séparer les variables positives et négatives. Cette idée simple constitue souvent l'idée de départ dans la solution et peut mener à des développements intéressants, en plus de prévenir certaines erreurs lors de manipulations d'inégalités avec des nombres négatifs.

La deuxième idée, lorsque les variables jouent des rôles symétriques, est d'imposer un ordre aux réels. En plus de permettre, parfois, d'obtenir des résultats intéressants pour le problème, cela simplifie grandement la rédaction de la solution.

Quitte à renuméroter les variables, on suppose donc que $a_{1} \leqslant a_{2} \leqslant \ldots \leqslant a_{100} \leqslant a_{101}$. Si tous les réels sont nuls, alors la somme de leur carré est nulle et donc bien inférieure à 2020. On suppose désormais que l'un des réels est non nul. Puisque la somme des $a_{i}$ est nulle, cela impose qu'au moins un réel est strictement positif et un autre strictement négatif. On note alors $p$ l'indice vérifiant $a_{p}<0 \leqslant a_{p+1}$.

Réécrivons dès à présent l'hypothèse de la somme nulle sous la forme

$$

-\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{p}\right)=a_{p+1}+\ldots+a_{101}

$$

On va désormais chercher à faire apparaître cette hypothèse dans la somme à calculer. Pour cela, on va également se servir du fait que si $1 \leqslant i \leqslant p$, alors $a_{i} \geqslant-2$ et que si $p+1 \leqslant i \leqslant 101$, alors $a_{i} \leqslant 10$. On a :

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{1}^{2}+\ldots+a_{101}^{2} & =\underbrace{a_{1} \cdot a_{1}}_{\leqslant-2 a_{1}}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{p} \cdot a_{p}}_{\leqslant-2 a_{p}}+\underbrace{a_{p+1} \cdot a_{p+1}}_{\leqslant 10 a_{p+1}}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{101} \cdot a_{101}}_{\leqslant 10 a_{101}} \\

& \leqslant-2 a_{1}+\ldots+\left(-2 a_{p}\right)+10 a_{p+1}+\ldots+10 a_{101} \\

& =2\left(-\left(a_{1}+\ldots+a_{p}\right)\right)+10\left(a_{p+1}+\ldots+a_{101}\right) \\

& =2(\underbrace{a_{p+1}}_{\leqslant 10}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{101}}_{\leqslant 10})+10(-(\underbrace{a_{1}}_{\geqslant-2}+\ldots+\underbrace{a_{p}}_{\geqslant-2})) \\

& \leqslant 2 \cdot 10 \cdot(101-p)+10 \cdot 2 \cdot p \\

& =2020

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui est l'inégalité voulue.

## Commentaires des correcteurs :

Certains élèves ont remarqué que, pour $-2 \leqslant a_{i} \leqslant 10$, on a $\left(a_{i}+2\right)\left(a_{i}-10\right) \leqslant 0$, et s'en sont servi pour aboutir à une preuve de façon très efficace. D'autres ont choisi de construire les valeurs de $a_{i}$ maximisant la somme des carrés; dans ce cas, il était bien sûr indispensable de prouver l'optimalité de la construction pour obtenir la majorité des points.

## Exercices Seniors

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $a$ be a strictly positive real number and $n \geqslant 1$ an integer. Show that

$$

\frac{a^{n}}{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}<\frac{1}{2 n}

$$

|

Since the difficulty lies in the denominator of the right-hand side, and for greater comfort, we can seek to show the inverse relationship, namely:

$$

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}}>2 n

$$

The idea behind the following solution is to "homogenize" the numerator of the left-hand side, that is, to compare this numerator, in which the $a$ are raised to distinct powers, to an expression composed solely of $a$ raised to the same power. To do this, we seek to pair certain terms and apply the inequality of arithmetic and geometric means. Let's see: for $0 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n$, we have $a^{i}+a^{2 n-i} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a^{i} a^{2 n-i}}=$ $2 a^{n}$. Thus:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}} & =\frac{\left(1+a^{2 n}\right)+\left(a+a^{2 n-1}\right)+\ldots+\left(a^{n-1}+a^{n+1}\right)+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{\overbrace{2 a^{n}+2 a^{n}+\ldots+2 a^{n}}^{n \text { terms }}+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =\frac{(2 n+1) a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =2 n+1 \\

& >2 n

\end{aligned}

$$

which provides the desired inequality.

Comments from the graders:

The exercise was very well solved overall. Many students were able to directly apply the AM-GM inequality to $2n+1$ terms, while most others managed to get by with the AM-GM inequality for two terms.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit a un réel strictement positif et $n \geqslant 1$ un entier. Montrer que

$$

\frac{a^{n}}{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}<\frac{1}{2 n}

$$

|

Puisque la difficulté réside dans le dénominateur du membre de droite, et pour plus de confort, on peut chercher à montrer la relation inverse, à savoir :

$$

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}}>2 n

$$

L'idée derrière la solution qui suit est "d'homogénéiser" le numérateur du membre de gauche, c'est-àdire de comparer ce numérateur dans lequel les a sont élevés à des puissances distinctes à une expression composée uniquement de a élevés à la même puissance. Pour cela, on cherche à coupler certains termes et appliquer l'inégalité des moyennes. Voyons plutôt : pour $0 \leqslant i \leqslant 2 n$, on a $a^{i}+a^{2 n-i} \geqslant 2 \sqrt{a^{i} a^{2 n-i}}=$ $2 a^{n}$. Ainsi :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1+a+\ldots+a^{2 n}}{a^{n}} & =\frac{\left(1+a^{2 n}\right)+\left(a+a^{2 n-1}\right)+\ldots+\left(a^{n-1}+a^{n+1}\right)+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& \geqslant \frac{\overbrace{2 a^{n}+2 a^{n}+\ldots+2 a^{n}}^{n \text { termes }}+a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =\frac{(2 n+1) a^{n}}{a^{n}} \\

& =2 n+1 \\

& >2 n

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui fournit l'inégalité voulue.

Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice très bien résolu dans l'ensemble. De nombreux élèves ont su appliquer l'IAG directement à $2 \mathrm{n}+1$ termes, les autres ont pour la plupart réussi à s'en sortir avec l'IAG à deux termes.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "10",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 10.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 10",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Determine all integers $a$ such that $a-3$ divides $a^{3}-3$.

Determine all integers $a$ such that $a-3$ divides $a^{3}-3$.

|

We know that $a-3 \mid a^{3}-3^{3}$, so it divides the difference

$$

a-3 \mid a^{3}-3-\left(a^{3}-3^{3}\right)=27-3=24

$$

Conversely, it is sufficient that $a-3$ divides 24 for it to divide $24+a^{3}-3^{3}=a^{3}-3$. The solutions are therefore exactly the divisors of 24 to which we add 3. We have therefore

$$

a-3 \in\{-24,-12,-8,-6,-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,6,8,12,24\}

$$

and $a \in\{-21,-9,-5,-3,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5,6,9,11,15,27\}$.

## Comments from the graders:

The exercise was very well solved overall; the most common mistake is forgetting some divisors of 24.

|

a \in\{-21,-9,-5,-3,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5,6,9,11,15,27\}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Number Theory

|

Déterminer tous les entiers a tels que $a-3$ divise $a^{3}-3$.

|

On sait que $a-3 \mid a^{3}-3^{3}$, donc il divise la différence

$$

a-3 \mid a^{3}-3-\left(a^{3}-3^{3}\right)=27-3=24

$$

Réciproquement, il suffit que $a-3$ divise 24 pour qu'il divise $24+a^{3}-3^{3}=a^{3}-3$. Les solutions sont donc exactement les diviseurs de 24 auxquels on ajoute 3 . On a donc

$$

a-3 \in\{-24,-12,-8,-6,-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,6,8,12,24\}

$$

et $a \in\{-21,-9,-5,-3,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5,6,9,11,15,27\}$.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice très bien résolu dans l'ensemble ; l'erreur la plus fréquente est l'oubli de certains diviseurs de 24.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "11",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 11.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 11",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

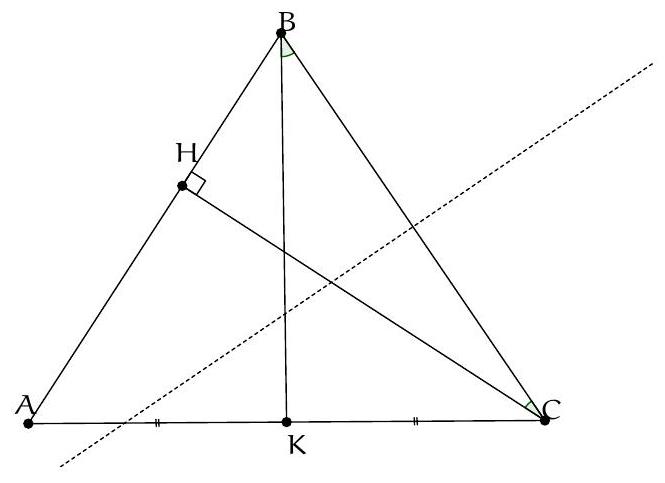

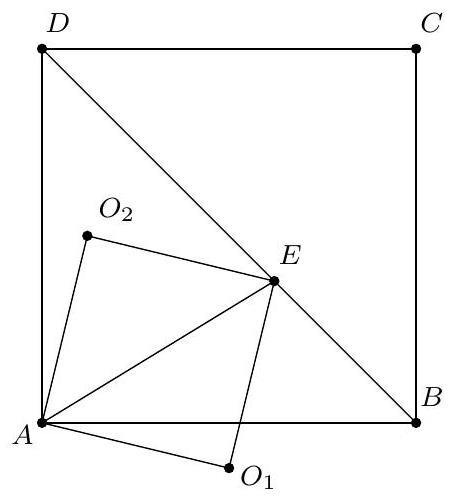

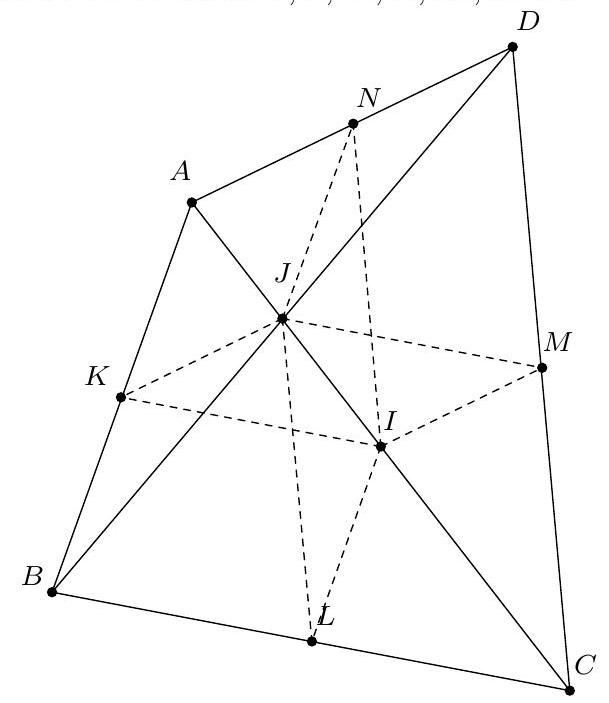

Let $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ be two circles with centers $\mathrm{O}_{1}$ and $\mathrm{O}_{2}$, respectively. Suppose that $\omega_{1}$ and $\omega_{2}$ intersect at points $A$ and $B$. The line $\left(O_{1} A\right)$ intersects the circle $\omega_{2}$ again at $C$, while the line $\left(O_{2} A\right)$ intersects the circle $\omega_{1}$ again at $D$. Show that the points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{O}_{1}, \mathrm{~B}, \mathrm{O}_{2}$, and $C$ lie on the same circle.

|

Let us note that since the angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DAO}_{1}}$ and $\widehat{\mathrm{CAO}_{2}}$ are vertically opposite, they are equal. On the other hand, since points $A$ and $D$ belong to the circle $\omega_{1}$, the triangle $A O_{1} D$ is isosceles at $O_{1}$. Similarly, the triangle $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ is isosceles at $\mathrm{O}_{2}$. Therefore, triangles $\mathrm{DO}_{1} A$ and $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ are isosceles triangles with the same base angles, so they are similar. This implies that $\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}$, and thus

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO} \mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{D}}

$$

so the points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$, and D are concyclic.

Furthermore, we can decompose the angle $\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}$ into the sum $\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{ABC}}$. On the one hand, according to the inscribed angle theorem in the circle $\omega_{1}$, we have $\widehat{A B D}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}$. On the other hand, according to the inscribed angle theorem in the circle $\omega_{1}$, we have $\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{2} C}$. Thus,

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{1} \mathrm{D}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{2} \mathrm{C}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}

$$

which allows us to conclude that point B belongs to the circle passing through the points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$, and D.

## Comments from the graders:

Very well solved exercise.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soient $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$ deux cercles de centres respectifs $\mathrm{O}_{1}$ et $\mathrm{O}_{2}$. On suppose que $\omega_{1}$ et $\omega_{2}$ se coupent en les points $A$ et $B$. La droite $\left(O_{1} A\right)$ recoupe le cercle $\omega_{2}$ en $C$ tandis que la droite $\left(O_{2} A\right)$ recoupe le cercle $\omega_{1}$ en D . Montrer que les points $\mathrm{D}, \mathrm{O}_{1}, \mathrm{~B}, \mathrm{O}_{2}$ et C appartiennent à un même cercle.

|

Notons que puisque les angles $\widehat{\mathrm{DAO}_{1}}$ et $\widehat{\mathrm{CAO}_{2}}$ sont opposés par le sommet, ils sont égaux. D'autre part, puisque les points $A$ et $D$ appartiennent au cercle $\omega_{1}$, le triangle $A O_{1} D$ est isocèle en $O_{1}$. De même, le triangle $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ est isocèle en $\mathrm{O}_{2}$. Les triangles $\mathrm{DO}_{1} A$ et $\mathrm{CO}_{2} A$ sont donc des triangels isocèle avec les mêmes angles à la base, ils sont donc semblables. Ceci implique que $\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}$, et donc que

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO} \mathrm{O}_{1} \mathrm{D}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{~A}}=\widehat{\mathrm{CO}_{2} \mathrm{D}}

$$

si bien que les points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$ et D sont cocycliques.

Par ailleurs, on peut découper l'angle $\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}$ en la somme $\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{\mathrm{ABC}}$. D'une part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre dans le cercle $\omega_{1}$, on a $\widehat{A B D}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}$. D'autre part, d'après le théorème de l'angle au centre dans le cercle $\omega_{1}$, on a $\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{2} C}$. Ainsi

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{DBC}}=\widehat{\mathrm{DBA}}+\widehat{A B C}=\frac{1}{2} \widehat{A O_{1} \mathrm{D}}+\frac{1}{2} \widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{2} \mathrm{C}}=\widehat{\mathrm{AO}_{1} \mathrm{D}}

$$

ce qui permet de conclure que le point B appartient au cercle passant par les points $\mathrm{C}, \mathrm{O}_{2}, \mathrm{O}_{1}$ et D .

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

Exercice très bien résolu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "12",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 12.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 12",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $(a_n)$ be a strictly increasing sequence of positive integers such that $a_1 = 1$ and for all $n \geq 1, a_{n+1} \leq 2n$. Show that for every integer $n \geq 1$, there exist two indices $p$ and $q$ such that $a_p - a_q = n$.

|

Let $n \geqslant 1$ be an integer. We will use the pigeonhole principle. Construct our pigeonholes in such a way that if two numbers are in the same pigeonhole, they satisfy the property stated in the problem. For this, we consider the following pigeonholes: we group the integers from 1 to $2n$ into pairs of the form $\{i, n+i\}$ for $i$ between 1 and $n$, which constitutes $n$ pigeonholes. These pigeonholes are disjoint from each other, and if two terms of the sequence are in the same pigeonhole, this gives two indices $p$ and $q$ such that $a_{p}-a_{q}=n$, because all terms of a strictly increasing sequence are distinct.

Since the sequence $(a_{m})$ is increasing and since $a_{n+1} \leqslant 2n$, $a_{m} \in \llbracket 1,2n \rrbracket$ for $m \in \llbracket 1, n+1 \rrbracket$. Therefore, the first $n+1$ terms of the sequence are in the interval $\llbracket 1,2n \rrbracket$. By the pigeonhole principle, there are two distinct terms that belong to the same set $\{i, n+i\}$ for some $i$, which is the desired result.

## Comments from the graders:

Very well treated exercise.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soit ( $a_{n}$ ) une suite strictement croissante d'entiers positifs telle que $a_{1}=1$ et pour tout $n \geqslant 1, a_{n+1} \leqslant 2 n$. Montrer que pour tout entier $n \geqslant 1$, il existe deux indices $p$ et $q$ tels que $a_{p}-a_{q}=n$.

|

Soit $n \geqslant 1$ un entier. On va utiliser le principe des tiroirs. Construisons nos tiroirs deux sorte que si deux nombres sont dans un même tiroirs, ils vérifient la propriété de l'énoncé. Pour cela, on considère les tiroirs suivants : on réunit les entiers de 1 à $2 n$ en les couples de la forme $\{i, n+i\}$ pour $i$ entre 1 et $n$, ce qui constitue $n$ tiroirs. Ces tiroirs sont bien disjoints deux à deux, et si deux termes de la suite sont dans un même tiroir, cela donne les deux indices $p$ et $q$ tels que $a_{p}-a_{q}=n$, car tous les termes d'une suite strictement croissante sont distincts.

Or, puisque la suite ( $a_{m}$ ) est croissante et puisque $a_{n+1} \leqslant 2 n, a_{m} \in \llbracket 1,2 n \rrbracket$ pour $m \in \llbracket 1, n+1 \rrbracket$. Donc les $n+1$ premiers termes de la suites sont dans l'intervalle $\llbracket 1,2 n \rrbracket$. Par le principe des tiroirs, il y a deux termes distincts qui appartiennent au même ensemble $\{i, n+i\}$ pour un certain $i$, ce qui est le résultat voulu.

## Commentaires des correcteurs :

Exercice très bien traité.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "13",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 13.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 13",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

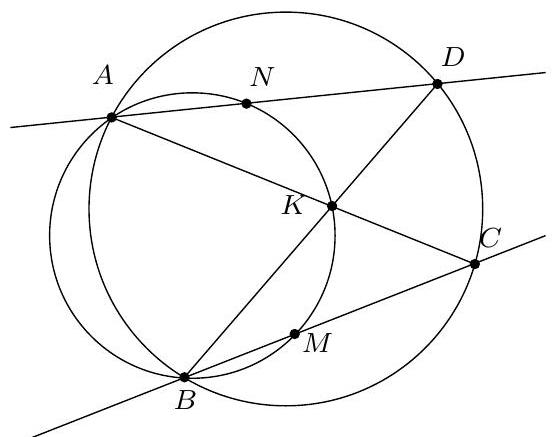

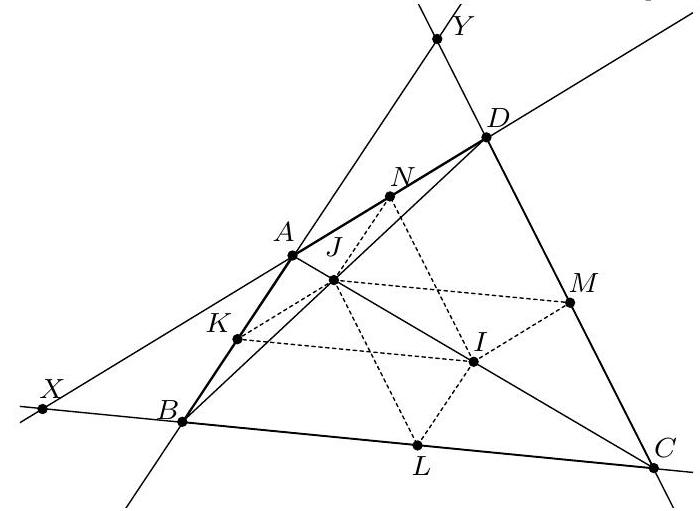

Let $\Gamma$ be a circle and $P$ a point outside $\Gamma$. The tangents to $\Gamma$ from $P$ touch $\Gamma$ at $A$ and $B$. Let $K$ be a point distinct from $A$ and $B$ on the segment $[A B]$. The circumcircle of triangle $PBK$ intersects the circle $\Gamma$ at point $T$. Let $P'$ be the symmetric point of $P$ with respect to point $A$. Show that $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}'\mathrm{KA}}$.

|

According to the inscribed angle theorem, $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that $\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$. The figure suggests that triangles PKT and $\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}$ are similar, so we will try to prove this result, which will imply the desired angle equality.

To show that $\triangle P K T \sim \triangle P^{\prime} K A$, we have several options. For example, we can show that $\widehat{T P K} = \widehat{K P^{\prime} A}$ and $\widehat{K T P} = \widehat{K A P}$. However, when we try to calculate the angle $\widehat{T P K}$, we realize that the equality $\widehat{T P K} = \widehat{K P^{\prime} A}$ is equivalent to the statement we want to prove. Therefore, we will show that $\widehat{K T P} = \widehat{P^{\prime} A K}$ and that $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}} = \frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{AP}^{\prime}}$.

To show that $\widehat{K T P} = \widehat{P^{\prime} A K}$, we first need to note that triangle $A P B$ is isosceles at $P$ because the lines ($A P$) and ($B P$) are tangent at $A$ and $B$ to the circle $\Gamma$. By applying the inscribed angle theorem in the circle passing through $\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{K}$, and T, we find:

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}} = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{KBP}} = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{ABP}} = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{BAP}} = \widehat{\mathrm{PAK}}

$$

It remains to show that $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}} = \frac{\mathrm{TP}}{A \mathrm{P}^{\prime}}$. Since $A P^{\prime} = A P = B P$, it suffices to show that $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}} = \frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{BP}}$. Therefore, it suffices to show that triangles AKT and BPT are similar. To do this, it suffices to show that the angles of these two triangles are equal in pairs.

On the one hand, by the inscribed angle theorem, $\widehat{A K T} = 180^{\circ} - \widehat{\mathrm{BKT}} = \widehat{\mathrm{TPB}}$. On the other hand, by the tangent angle theorem, $\widehat{\mathrm{TAK}} = \widehat{\mathrm{TAB}} = \widehat{\mathrm{TBP}}$.

Therefore, triangles AKT and BPT are similar as desired.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $\Gamma$ un cercle et $P$ un point à l'extérieur de $\Gamma$. Les tangentes à $\Gamma$ issues de $P$ touchent $\Gamma$ en $A$ et $B$. Soit $K$ un point distinct de $A$ et $B$ sur le segment $[A B]$. Le cercle circonscrit au triangle PBK recoupe le cercle $\Gamma$ au point $T$. Soit $\mathrm{P}^{\prime}$ le symétrique du point $P$ par rapport au point $A$. Montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$.

|

D'après le théorème de l'angle inscrit, $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}$. Ainsi, il suffit de montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{PKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$. La figure semble suggérer que les triangles PKT et $\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}$ sont semblables, nous allons donc essayer de montrer ce résultat, qui impliquera bien l'égalité d'angle voulue.

Pour montrer que $\triangle P K T \sim \triangle P^{\prime} K A$, on a plusieurs possibilités. Par exemple, on peut montrer que $\widehat{T P K}=$ $\widehat{K P^{\prime} A}$ et $\widehat{K T P}=\widehat{K A P}$. Toutefois, lorsque l'on essaye de calculer l'angle $\widehat{T P K}$, on se rend compte que l'égalité $\widehat{T P K}=\widehat{K P^{\prime} A}$ est équivalente à l'énoncé à démontrer. On va donc montrer que $\widehat{K T P}=\widehat{P^{\prime} A K}$ et que $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}}=\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{AP}^{\prime}}$.

Pour montrer que $\widehat{K T P}=\widehat{P^{\prime} A K}$, il faut d'abord remarquer que le triangle $A P B$ est isocèle en $P$ puisque les droites ( $A P$ ) et ( $B P$ ) sont tangentes en $A$ et $B$ au cercle $\Gamma$. En appliquant le théorème de l'angle inscrit dans le cercle passant par $\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{K}$ et T , on trouve :

$$

\widehat{\mathrm{KTP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{KBP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{ABP}}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BAP}}=\widehat{\mathrm{PAK}}

$$

Il reste donc à montrer que $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}}=\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{A \mathrm{P}^{\prime}}$. Puisque $A P^{\prime}=A P=B P$, il suffit de montrer que $\frac{\mathrm{KT}}{\mathrm{KA}}=\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{BP}}$. Il suffit donc de montrer que les triangles AKT et BPT sont semblables. Pour cela, il suffit de montrer que les angles de ces deux triangles sont deux à deux égaux.

D'une part, par angle inscrit, $\widehat{A K T}=180^{\circ}-\widehat{\mathrm{BKT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{TPB}}$. D' autre part, par angle tangentiel, $\widehat{\mathrm{TAK}}=$ $\widehat{\mathrm{TAB}}=\widehat{\mathrm{TBP}}$.

Donc les triangles AKT et BPT sont semblables comme voulu.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 14.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 14",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $\Gamma$ be a circle and $P$ a point outside $\Gamma$. The tangents to $\Gamma$ from $P$ touch $\Gamma$ at $A$ and $B$. Let $K$ be a point distinct from $A$ and $B$ on the segment $[A B]$. The circumcircle of triangle $PBK$ intersects the circle $\Gamma$ at point $T$. Let $P'$ be the symmetric point of $P$ with respect to point $A$. Show that $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}'\mathrm{KA}}$.

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ :

In case of an allergy to angle chasing, it is also possible to progress in the problem with advanced ideas. The problem naturally presents itself as dynamic: keeping $\Omega, P, A, B, P^{\prime}$ fixed, we can move $K$ projectively. Then $T$ also moves projectively, as the circle $PBK$ having two fixed points $P$ and $B$ has a non-fixed intersection with the line $(AB)$ and with $\Omega$, so it can pass projectively to $K$ or to $T$. Moreover, the angles to be measured are between a fixed line and a line that moves projectively, so the equality of angles means that the point at infinity of the first projective line is mapped to the point at infinity of the second by a well-chosen rotation (or by a symmetry if the angles were in the opposite direction). The problem is well projective, let's look for three special cases.

We can send $K$ to infinity, then by tangency $T$ ends up at $B$ and the two angles that should be equal are zero.

We can send $K$ to $A$, then $T$ also ends up at $A$ and the two angles that should be equal are equal because triangle $PAB$ is isosceles at $P$.

We still need one more special case using the fact that $P^{\prime}$ is not only on the line $(PA)$ but is also symmetric. We can place $K$ on the symmetric of $B$ with respect to $A$ to construct a parallelogram. The angle chasing is then not quite immediate, but easier than in the original problem, as it does not require an idea to use the midpoint condition since it suffices to consider the parallelogram. It is left as an exercise to the reader.

## Comments from the graders:

The exercise was very well done, and the proofs using the tricks around the midpoints of segments were particularly appreciated.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $\Gamma$ un cercle et $P$ un point à l'extérieur de $\Gamma$. Les tangentes à $\Gamma$ issues de $P$ touchent $\Gamma$ en $A$ et $B$. Soit $K$ un point distinct de $A$ et $B$ sur le segment $[A B]$. Le cercle circonscrit au triangle PBK recoupe le cercle $\Gamma$ au point $T$. Soit $\mathrm{P}^{\prime}$ le symétrique du point $P$ par rapport au point $A$. Montrer que $\widehat{\mathrm{PBT}}=\widehat{\mathrm{P}^{\prime} \mathrm{KA}}$.

|

$n^{\circ} 2$ :

En cas d'allergie à la chasse aux angles, il est aussi possible de progresser dans le problème avec des idées avancées. Le problème se présente naturellement comme dynamique : en gardant fixe $\Omega, P, A, B, P^{\prime}$ on peut faire bouger K projectivement. Alors la T bouge aussi projectivement car le cercle PBK ayant deux points fixes P et B il a une intersection non fixe avec la droite $(\mathrm{AB})$ et avec $\Omega$, donc peut passer projectivement à $K$ ou à $T$. De plus, les angles à mesurer sont entre une droite fixe et une droite qui bouge projectivement chacun, l'égalité d'angle revient donc à dire que le point à l'infini de la première droite projective est envoyé sur le point à l'infini de la deuxième par une rotation bien choisie (ou par une symétrie si les angles avaient été dans l'autre sens). Le problème est bien projectif, cherchons trois cas particuliers.

On peut envoyer K à l'infini, alors par tangence $T$ se retrouve en $B$ et les deux angles qui doivent être égaux sont nuls.

On peut envoyer K sur $A$, alors T se retrouve aussi en $A$ et les deux angles qui doivent être égaux sont égaux car le triangle PAB est isocèle en P .

Il nous manque encore un cas particulier utilisant le fait que $\mathrm{P}^{\prime}$ soit non seulement sur la droite ( $P A$ ) mais bien symétrique. On peut placer K sur le symétrique de B par rapport à $A$ pour construire un parallélogramme. La chasse aux angles n'est alors pas tout à fait immédiate, mais plus facile que dans le problème original, car elle ne nécessite pas d'idée pour utiliser la condition de milieu puisqu'il suffit de considérer le parallélogramme. Elle est laissée en exercice au lecteur.

## Commentaires des correcteurs:

L'exercice a été très bien réussi, et les preuves utilisant les astuces autour des milieux de segments ont été particulièrement appréciées.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "14",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 14.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution ",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

Let $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}$ and $\times$ be strictly positive integers. Show that

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)

$$

|

By exchanging $m$ and $n$, we can assume that $m \leqslant n$. We then proceed by induction on $n$ with $m$ fixed.

Initialization: If $\mathrm{m}=\mathrm{n}$, the equality is trivial.

Induction: Suppose the equality is true for some $n \geqslant m$ and let's show that the equality is true for $n+1$. The left-hand side becomes

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right)

$$

Let's examine the terms on the right-hand side, which are of the form $\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right)$. We have

$$

\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right)-\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if }\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1 \\ 0 & \text { otherwise }\end{cases}

$$

Now, $\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1$ if and only if $x \geqslant(n+1) i$, or equivalently $i \leqslant\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor$. Therefore, the number of $i$ in $\llbracket 1, m \rrbracket$ for which $\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1$ is precisely $\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right)$. We deduce that

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right) & =\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=1}^{n+1} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

where the second equality comes from the induction hypothesis. This completes the induction and concludes the exercise.

$\underline{\text { Alternative Solution: }}$ A very clever solution involves double counting, noting that both sides of the equality count the same object, namely the number of pairs $(a, b)$ such that $a \leqslant m, b \leqslant n$ and $a b \leqslant x$.

Indeed, let's count this number of objects in a first way. The choice of a pair $(a, b) \in$ $\llbracket 1, \mathrm{~m} \rrbracket \times \llbracket 1, n \rrbracket$ such that $\mathrm{ab} \leqslant x$ is characterized first by the choice of $a$ in $\llbracket 1, m \rrbracket$. Then, since $a b \leqslant x$, we have $b \leqslant\left\lfloor\frac{x}{a}\right\rfloor$. Therefore, $b \leqslant \min (\lfloor x / a\rfloor, n)$ and there are $\min (\lfloor x / a\rfloor, n)$ choices for $b$ if $a$ is fixed. Thus, we have in total

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)

$$

such pairs $(a, b)$.

By starting with the choice of $b$ rather than $a$, a similar reasoning allows us to assert that there are

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)

$$

such pairs of integers $(a, b)$. The two terms are therefore equal.

Comments from the graders:

The exercise was well handled by many students, relative to its estimated difficulty.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Number Theory

|

Soient $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}$ et $\times$ des entiers strictement positifs. Montrer que

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)=\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)

$$

|

Quitte à échanger $m$ et $n$, on peut supposer que $m \leqslant n$. On procède alors par récurrence sur $n$ à $m$ fixé.

Initialisation : Si $\mathrm{m}=\mathrm{n}$, l'égalité est triviale.

Hérédité : Supposons l'égalité vraie pour un certain $n \geqslant m$ et cherchons à montrer que l'égalité est vraie pour $n+1$. Le membre de gauche devient

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right)

$$

Examinons les termes du membre de droite, qui sont de la forme $\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right)$. On a

$$

\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right)-\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)= \begin{cases}1 & \text { si }\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1 \\ 0 & \text { sinon }\end{cases}

$$

Or, $\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1$ si et seulement si $x \geqslant(n+1) i$, ou encore $i \leqslant\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor$. Donc le nombre de $i$ de $\llbracket 1, m \rrbracket$ pour lesquels $\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor \geqslant n+1$ est précisément $\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right)$. On déduit que

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n+1\right) & =\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)+\min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{n+1}\right\rfloor, m\right) \\

& =\sum_{i=1}^{n+1} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

où la deuxième égalité provient de l'hypothèse de récurrence. Ceci achève la récurrence et conclut l'exercice.

$\underline{\text { Solution alternative: }}$ Une solution très astucieuse consiste à procéder par double comptage, en remarquant que les deux membres de l'égalité servent à compter le même objet, à savoir le nombre de paires $(a, b)$ telles que $a \leqslant m, b \leqslant n$ et $a b \leqslant x$.

Cherchons en effet à compter ce nombre d'objet d'une première façon. Le choix d'une paire $(a, b) \in$ $\llbracket 1, \mathrm{~m} \rrbracket \times \llbracket 1, n \rrbracket$ telle que $\mathrm{ab} \leqslant x$ se caractérise dans un premier temps par le choix de $a$ dans $\llbracket 1, m \rrbracket$. Puis, puisque $a b \leqslant x$, on $a b \leqslant\left\lfloor\frac{x}{a}\right\rfloor$. Donc $b \leqslant \min (\lfloor x / a\rfloor, n)$ et il y a $\min (\lfloor x / a\rfloor, n)$ choix pour $b$ si a est fixé. On a donc en tout

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{m} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, n\right)

$$

telles paires $(a, b)$.

En commençant par choisir b plutôt que $a$, un raisonnement similaire nous permet d'affirmer qu'il y a

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} \min \left(\left\lfloor\frac{x}{i}\right\rfloor, m\right)

$$

telles paires d'entiers $(a, b)$. Les deux termes sont donc égaux.

Commentaires des correcteurs:

L'exercice a été bien traité et par beaucoup d'élèves, relativement à sa difficulté estimée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "15",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 15.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-corrigé-envoi-5.jsonl",

"solution_match": "## Solution de l'exercice 15",

"tier": "T2",

"year": null

}

|

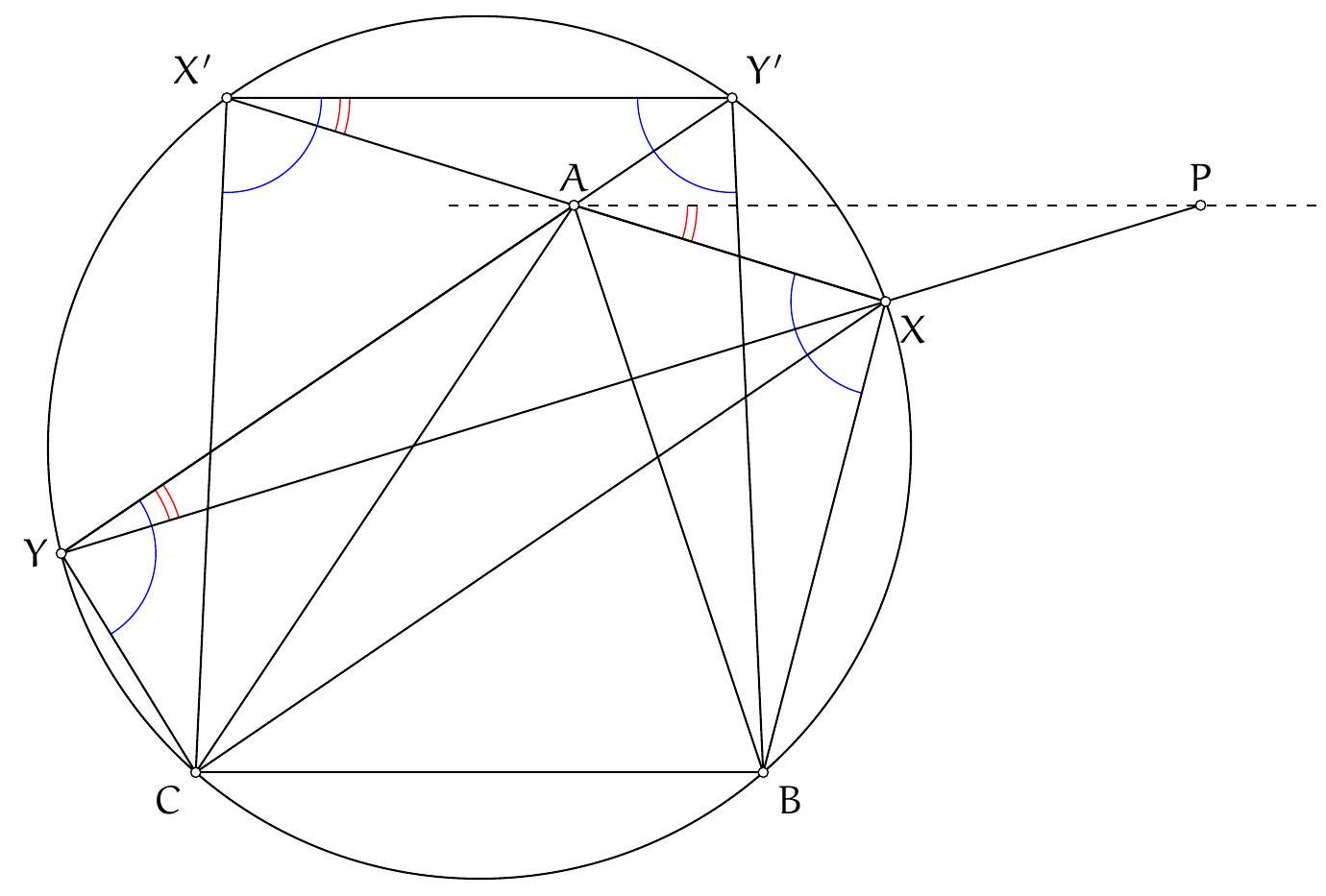

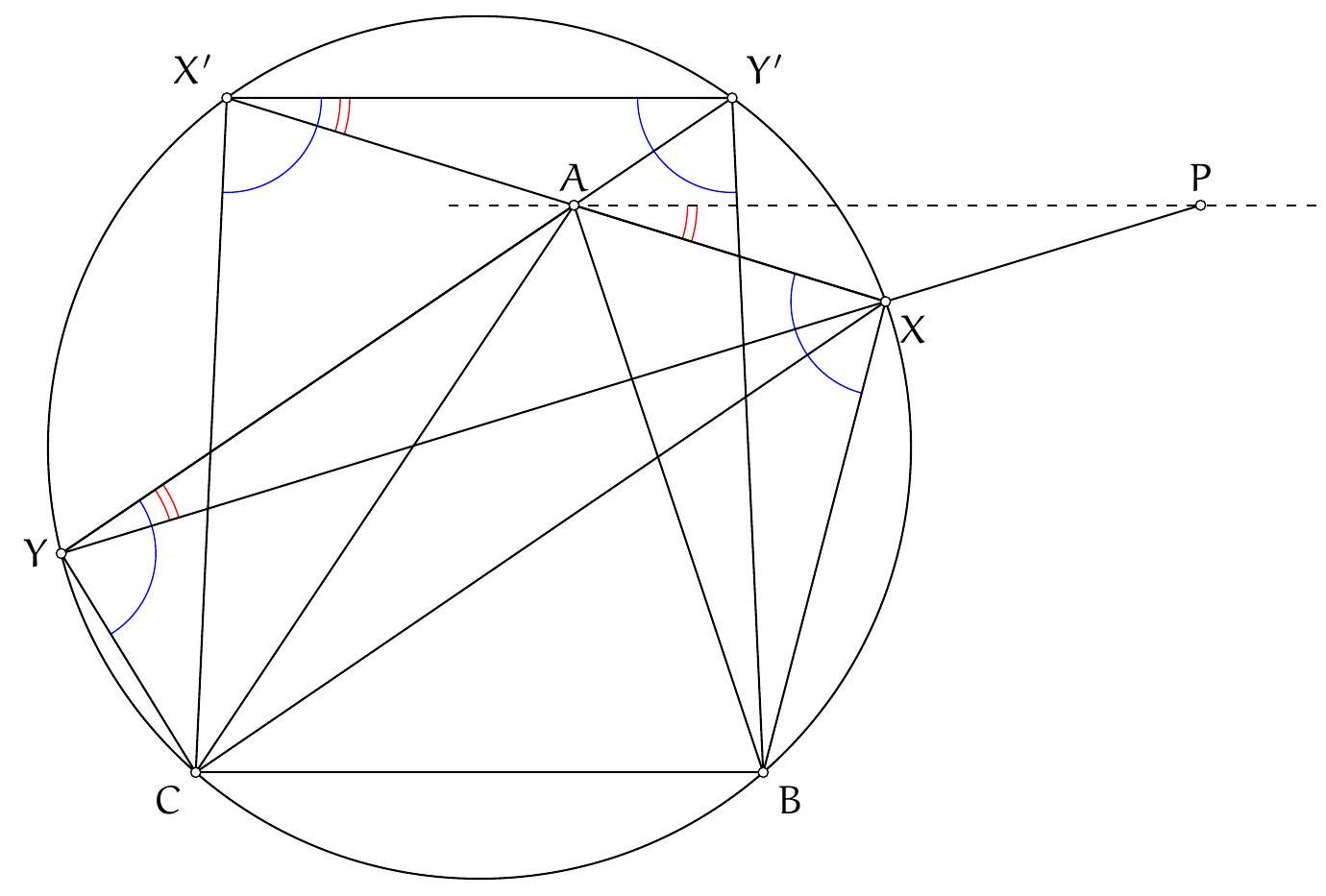

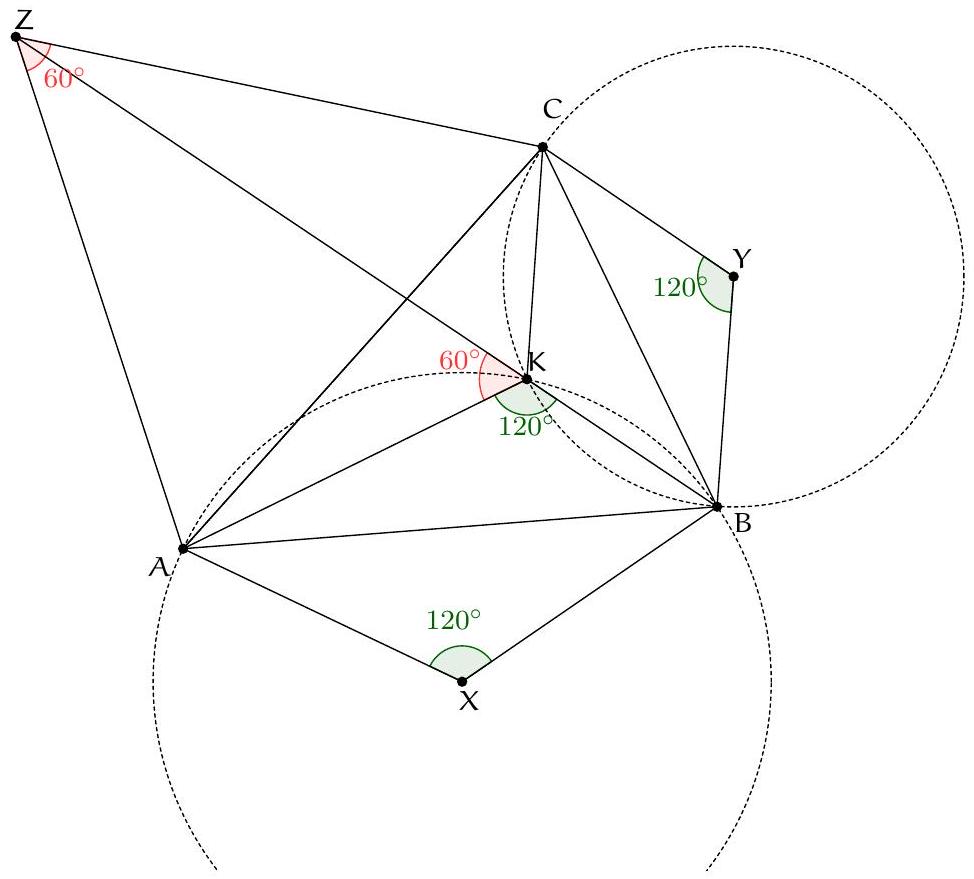

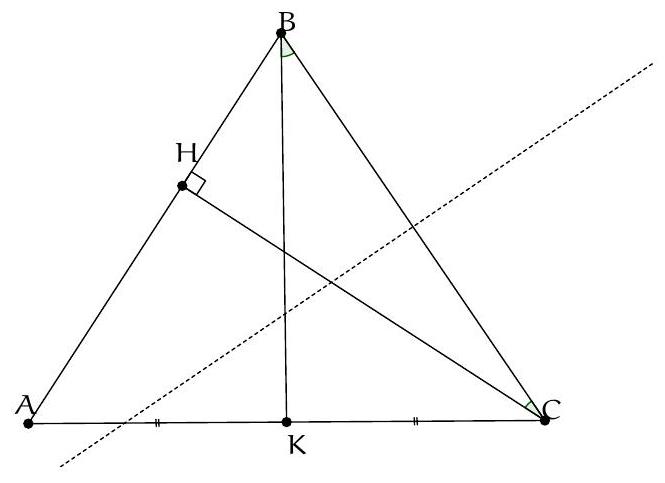

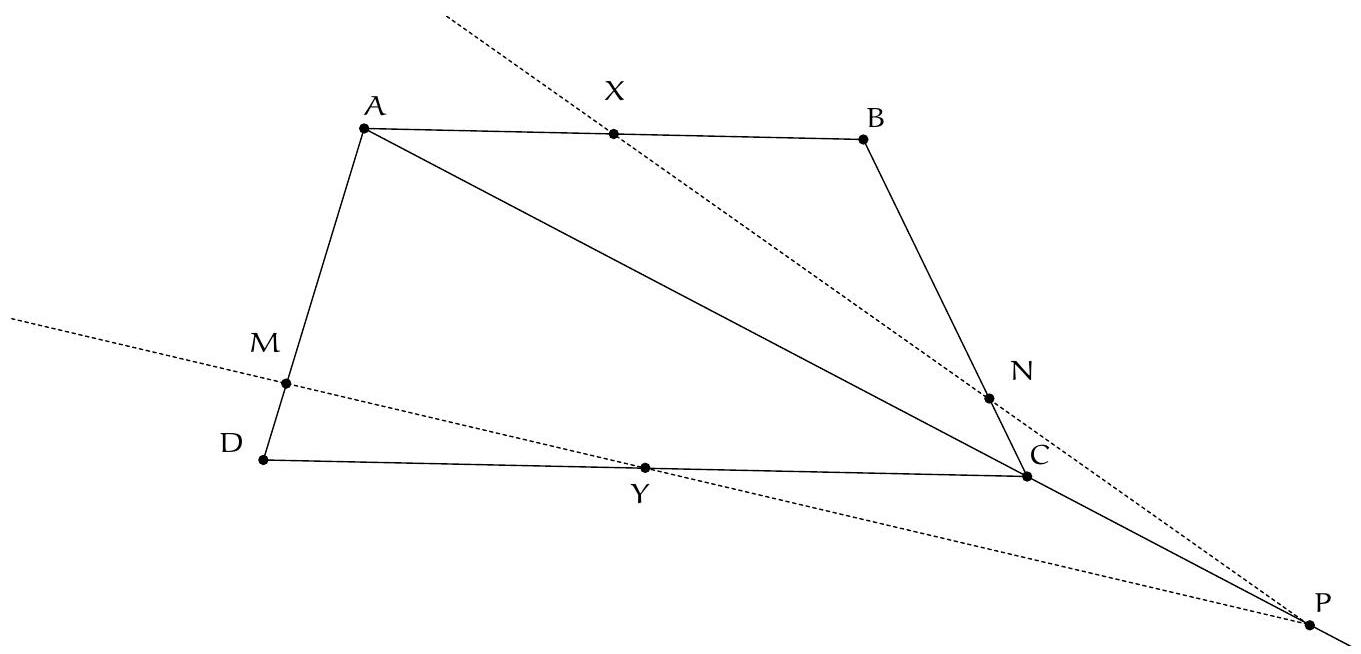

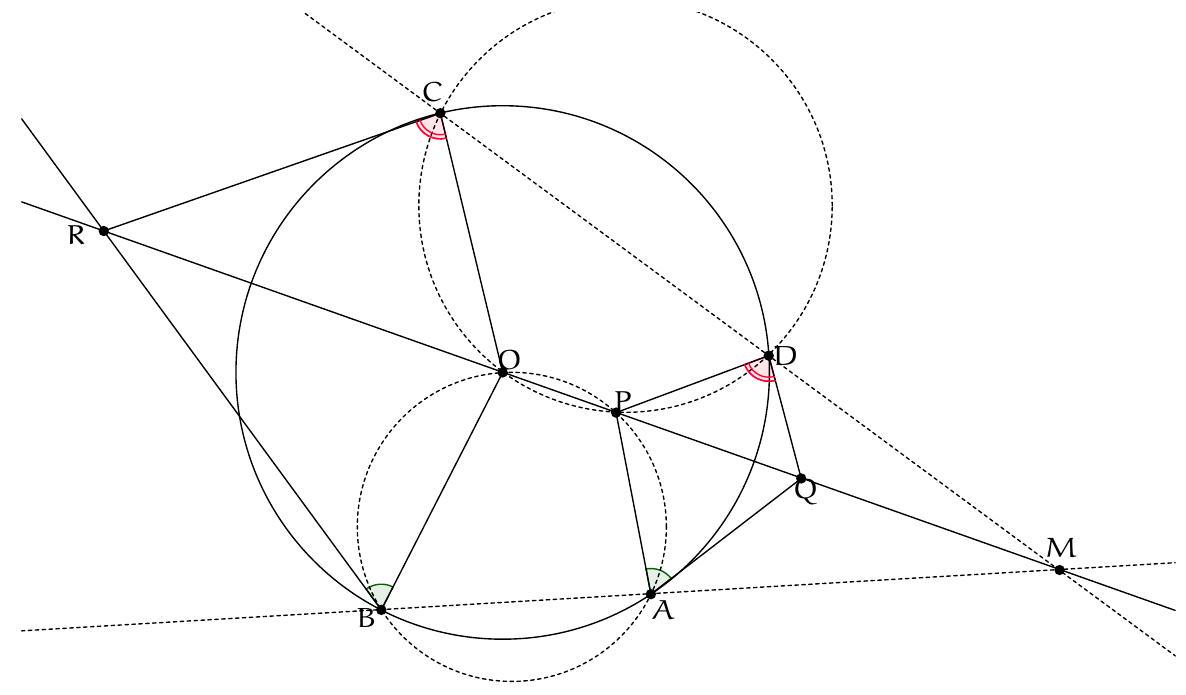

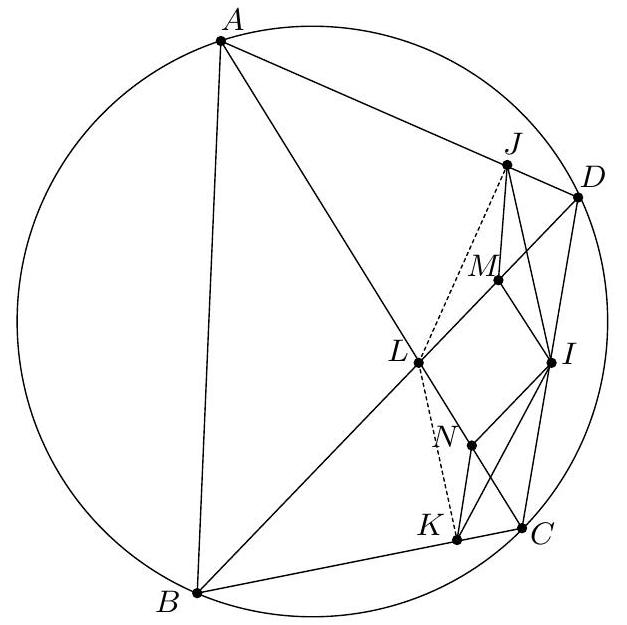

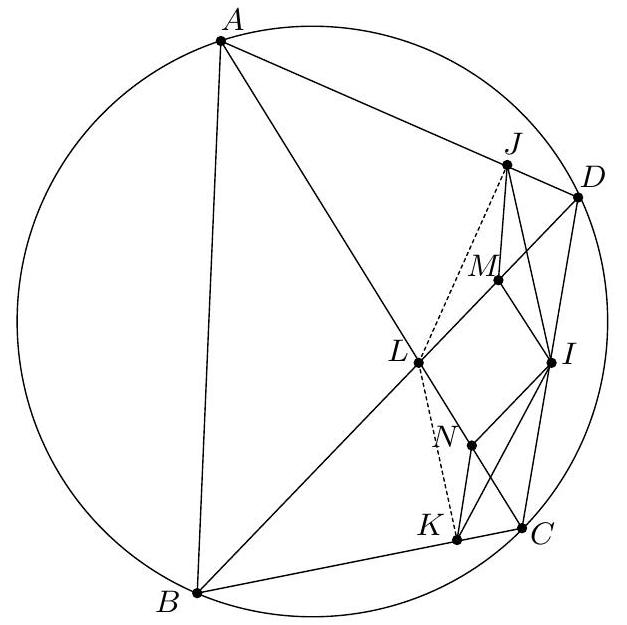

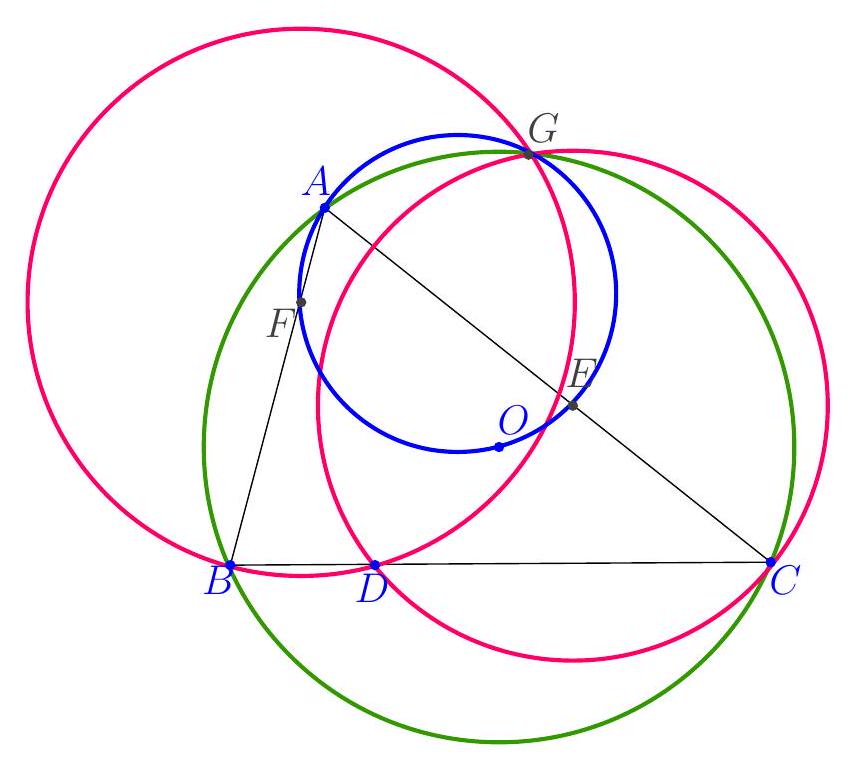

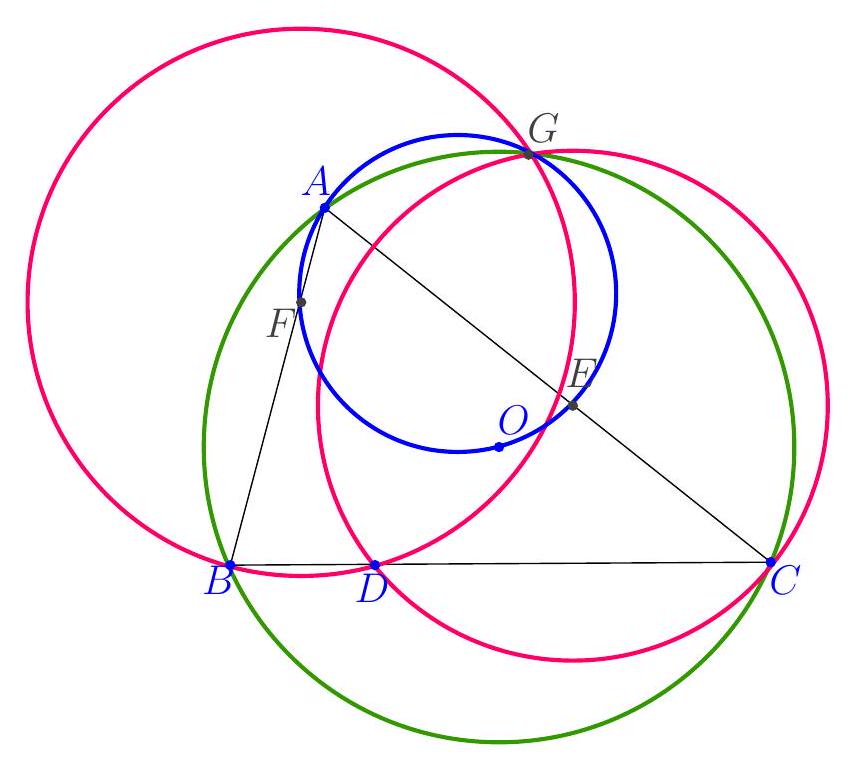

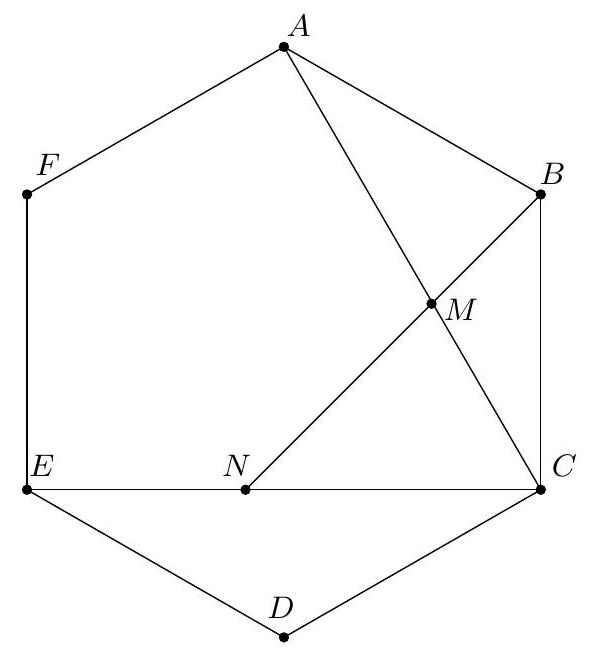

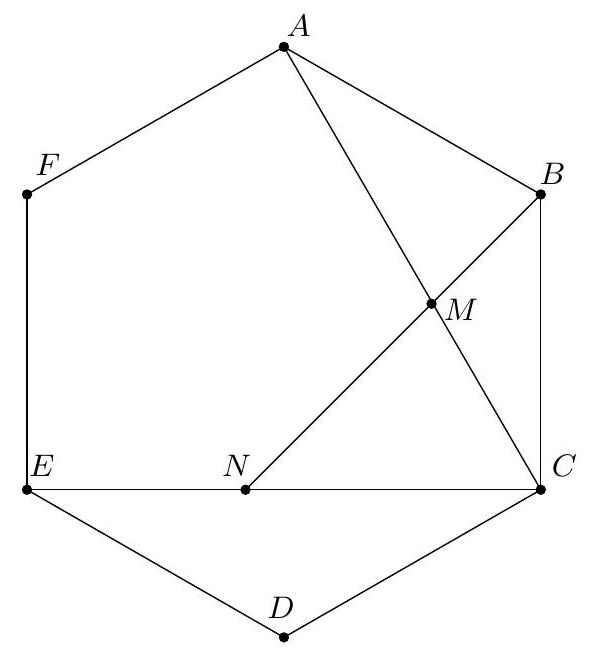

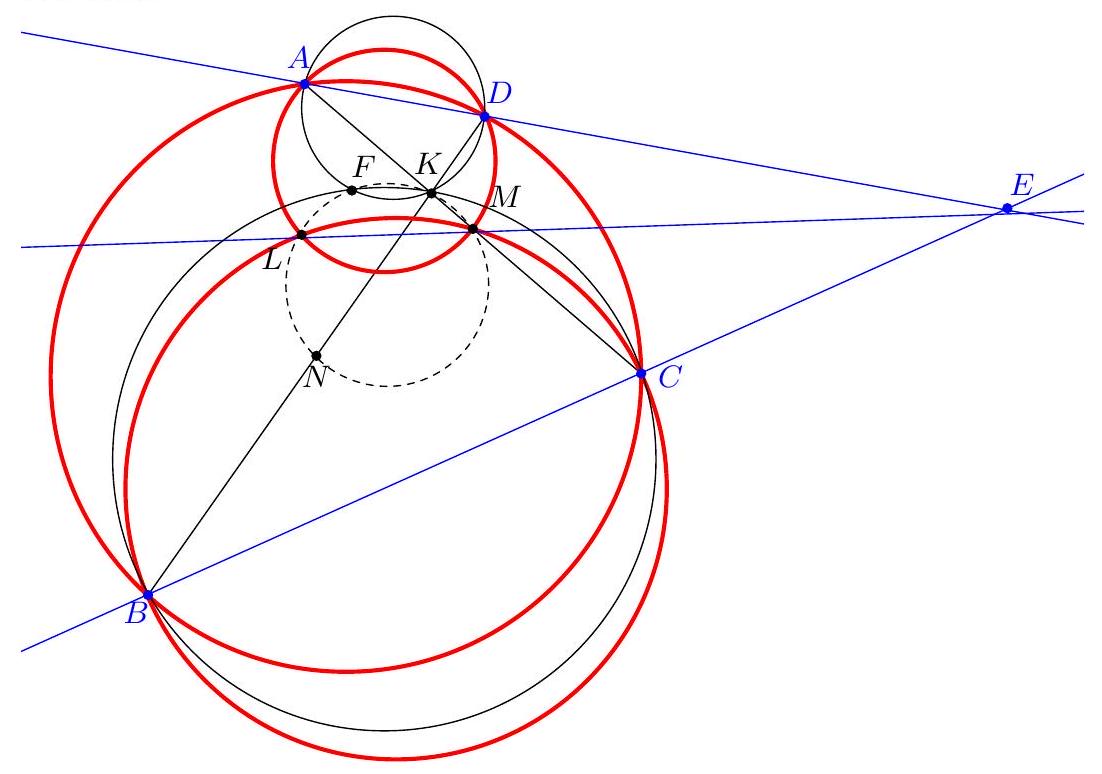

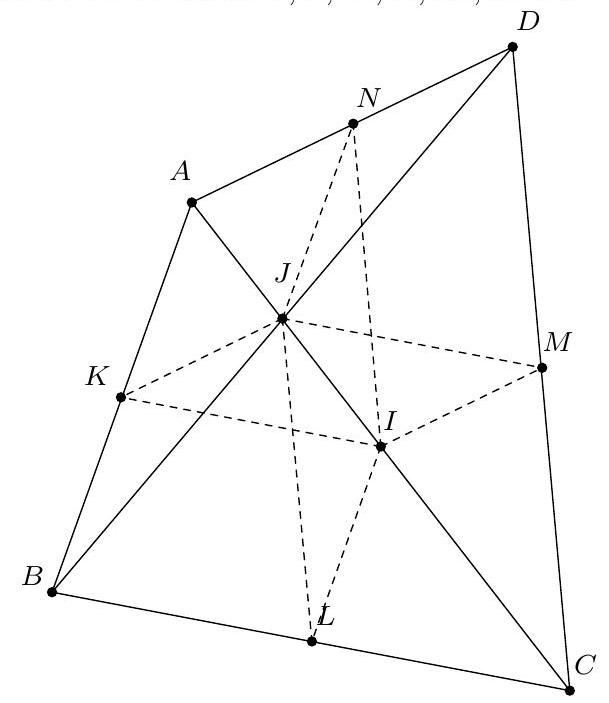

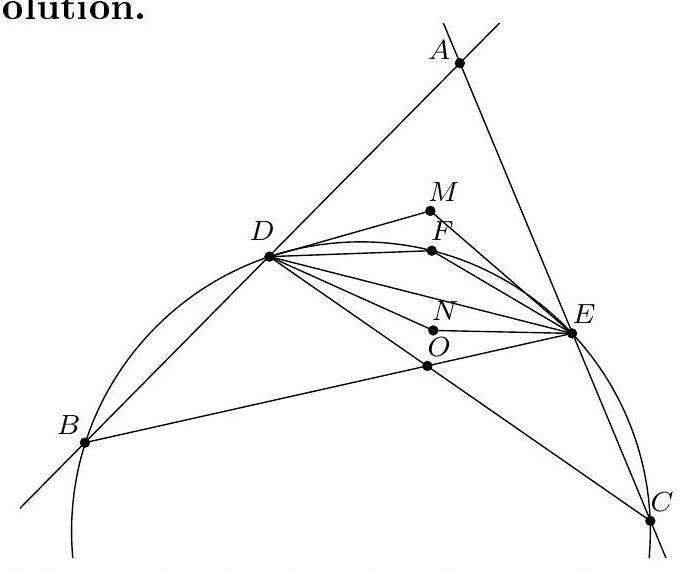

Let $ABC$ be a triangle in which $AB < AC$. Let $\omega$ be a circle passing through $B$ and $C$ and suppose that the point $A$ is inside the circle $\omega$. Let $X$ and $Y$ be points on $\omega$ such that $\widehat{BXA} = \widehat{AYC}$. We assume that $X$ and $C$ are on opposite sides of the line $(AB)$ and that $Y$ and $B$ are on opposite sides of the line $(AC)$. Show that, as $X$ and $Y$ vary on the circle $\omega$, the line $(XY)$ passes through a fixed point.

|

First, we will seek to draw an exact figure, hoping that the reasoning used for the drawing will enlighten us about the dynamics of the figure.

To draw the figure, we aim to take advantage of the hypothesis that the points $X, B, C$, and $Y$ lie on the same circle, using the inscribed angle theorem. Suppose the figure is drawn. We extend the line $(X A)$ and denote $X^{\prime}$ as the second intersection point of $(X A)$ with $\omega$, and similarly, $Y^{\prime}$ as the second intersection point of $(Y A)$ with $\omega$.

The inscribed angle theorem and the hypothesis about $X$ and $Y$ impose the following equality:

$$

\widehat{C X^{\prime} Y^{\prime}} = \widehat{C Y^{\prime}} = \widehat{C Y^{\prime}} = \widehat{A X B} = \widehat{X^{\prime} X B} = \widehat{X^{\prime} Y^{\prime} B}

$$

Thus, the quadrilateral $B C X^{\prime} Y^{\prime}$ is an isosceles trapezoid, and the lines $(X^{\prime} Y^{\prime})$ and $(B C)$ are parallel.

We can deduce a protocol for drawing the figure: Place a point $X$ on the circle $\omega$ and extend the line $(A X)$ to obtain the point $X^{\prime}$. Then obtain the point $Y^{\prime}$ by drawing the line parallel to $(B C)$ passing through $X^{\prime}$. Finally, obtain the point $Y$ by extending the line $(Y^{\prime} A)$.

Now, let's solve the exercise. Since we can draw an exact figure, we can draw the figure for two different positions of the point $X$, denoted as $X_{1}$ and $X_{2}$, draw the associated points $Y_{1}$ and $Y_{2}$, and conjecture the position of the fixed point using the intersection of the lines $(X_{1} Y_{1})$ and $(X_{2} Y_{2})$. It is striking that the intersection point obtained lies on the line parallel to $(B C)$ passing through the point $A$.

Let $P$ be the intersection of the line $(X Y)$ with the line parallel to $(B C)$ passing through $A$. Since the lines $(X^{\prime} Y^{\prime})$ and $(A P)$ are parallel, we find:

$$

\widehat{X A P} = \widehat{X X^{\prime} Y^{\prime}} = \widehat{X Y Y^{\prime}} = \widehat{X Y A}

$$

Thus, the line $(A P)$ is tangent to the circumcircle of the triangle $A X Y$. Therefore, according to the power of a point:

$$

\mathrm{PA}^2 = \mathrm{PX} \cdot \mathrm{PY} = \mathcal{P}_{\omega}(\mathrm{P})

$$

The position of the point $P$ on the line parallel to $(B C)$ passing through $A$ is uniquely determined by the power of the point $P$ with respect to the circle $\omega$, which does not depend on $X$ and $Y$. This is what we wanted to prove.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Soit $A B C$ un triangle dans lequel $A B<A C$. Soit $\omega$ un cercle passant par $B$ et $C$ et on suppose que le point $A$ se trouve à l'intérieur du cercle $\omega$. Soient $X$ et $Y$ des points de $\omega$ tels que $\widehat{B X A}=\widehat{A Y C}$. On suppose que $X$ et $C$ sont situés de part et d'autre de la droite $(A B)$ et que $Y$ et $B$ sont situés de part et d'autre de la droite (AC). Montrer que, lorsque $X$ et $Y$ varient sur le cercle $\omega$, la droite (XY) passe par un point fixe.

|

Tout d'abord, nous allons chercher à tracer une figure exacte, en espérant que les raisonnements mis en oeuvre pour le tracé nous éclairerons sur la dynamique de la figure.