problem

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| answer

stringlengths 1

250

⌀ | problem_is_valid

stringclasses 4

values | solution_is_valid

stringclasses 3

values | question_type

stringclasses 4

values | problem_type

stringclasses 8

values | problem_raw

stringlengths 14

10.4k

| solution_raw

stringlengths 1

24.1k

| metadata

dict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

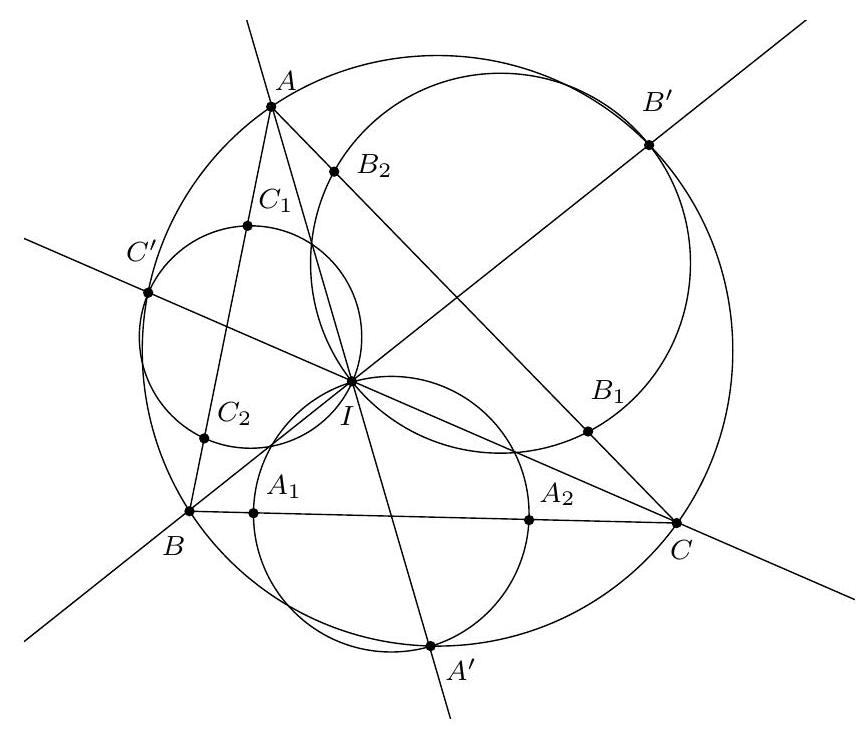

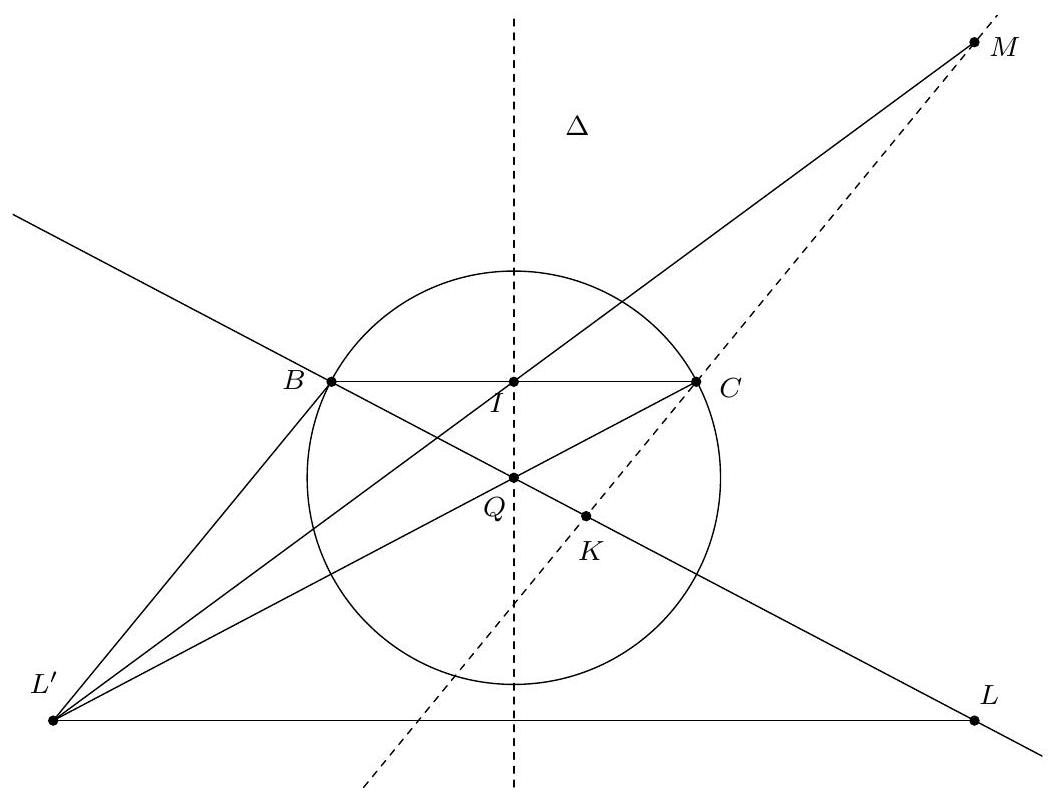

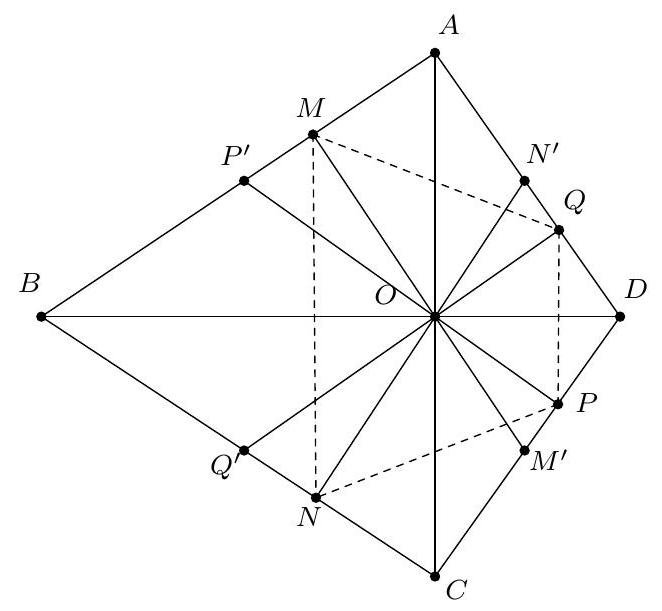

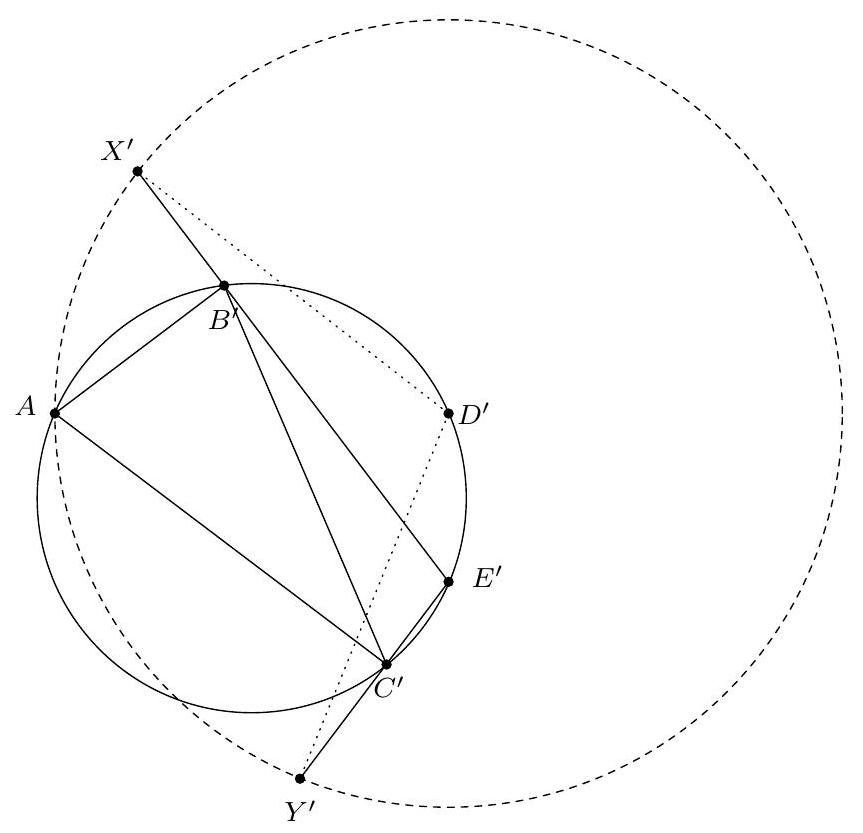

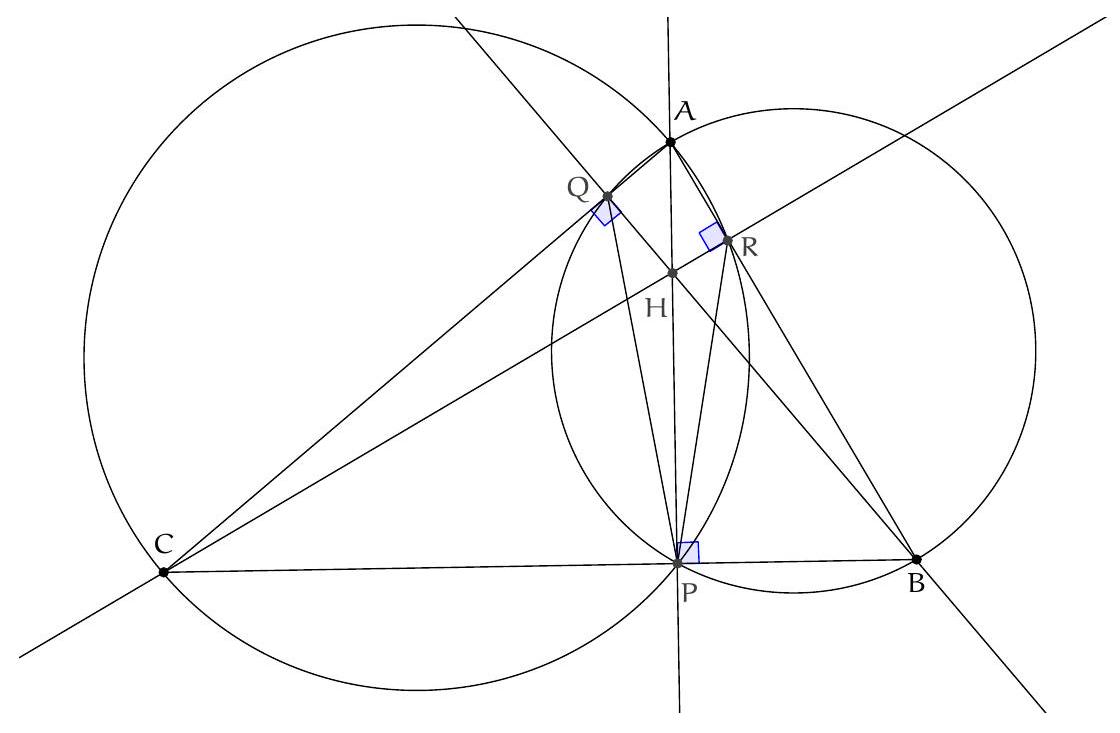

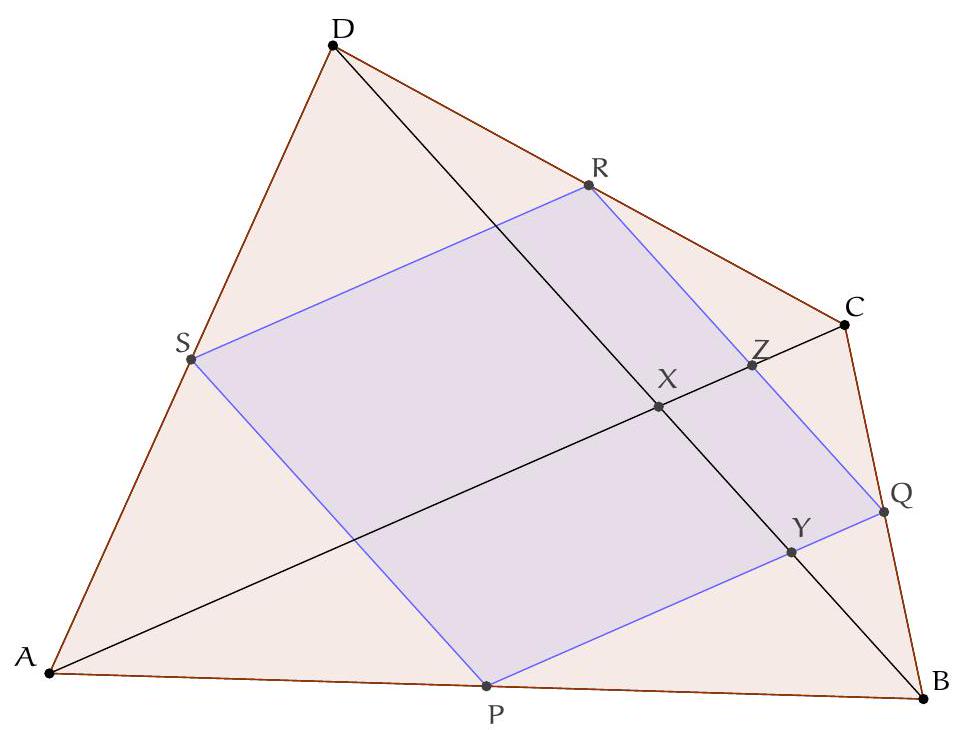

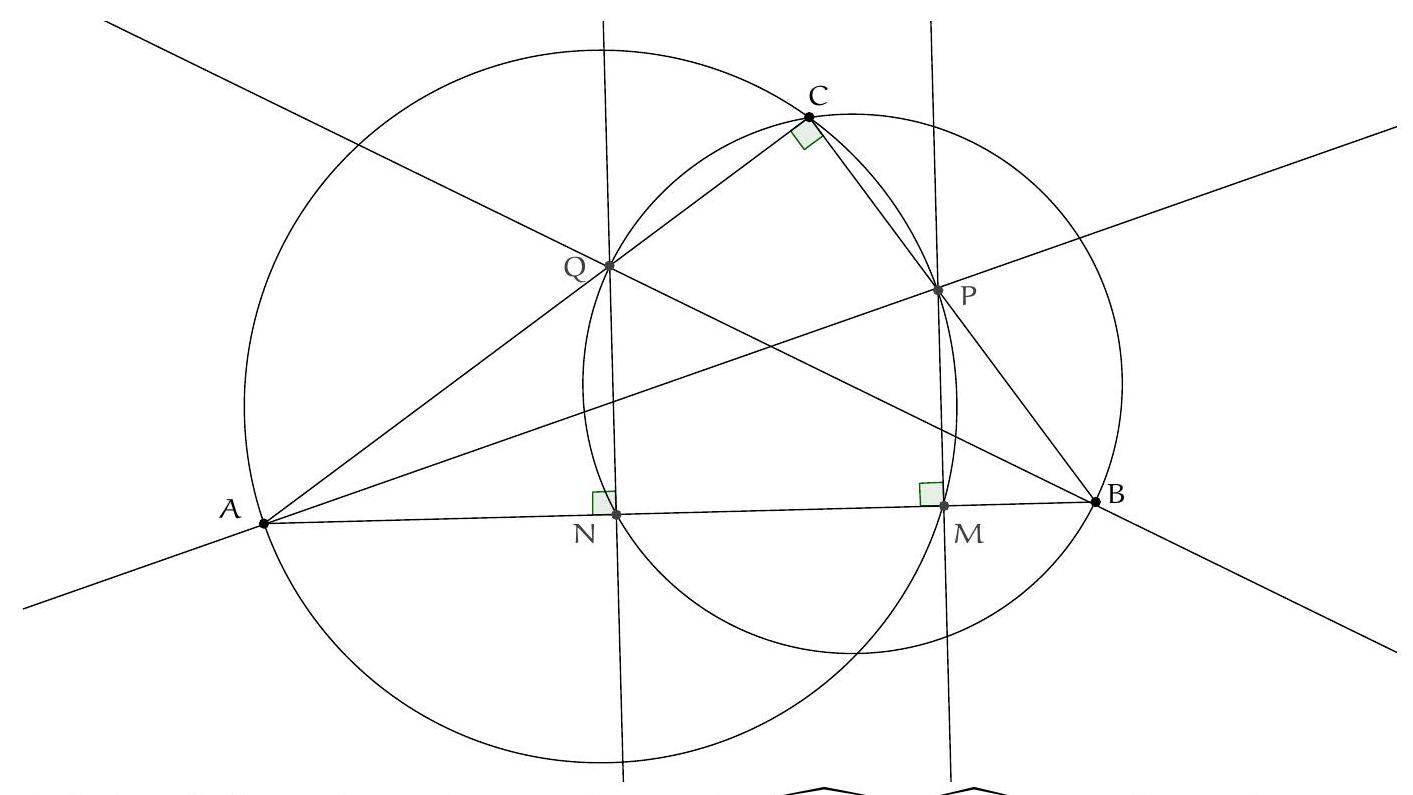

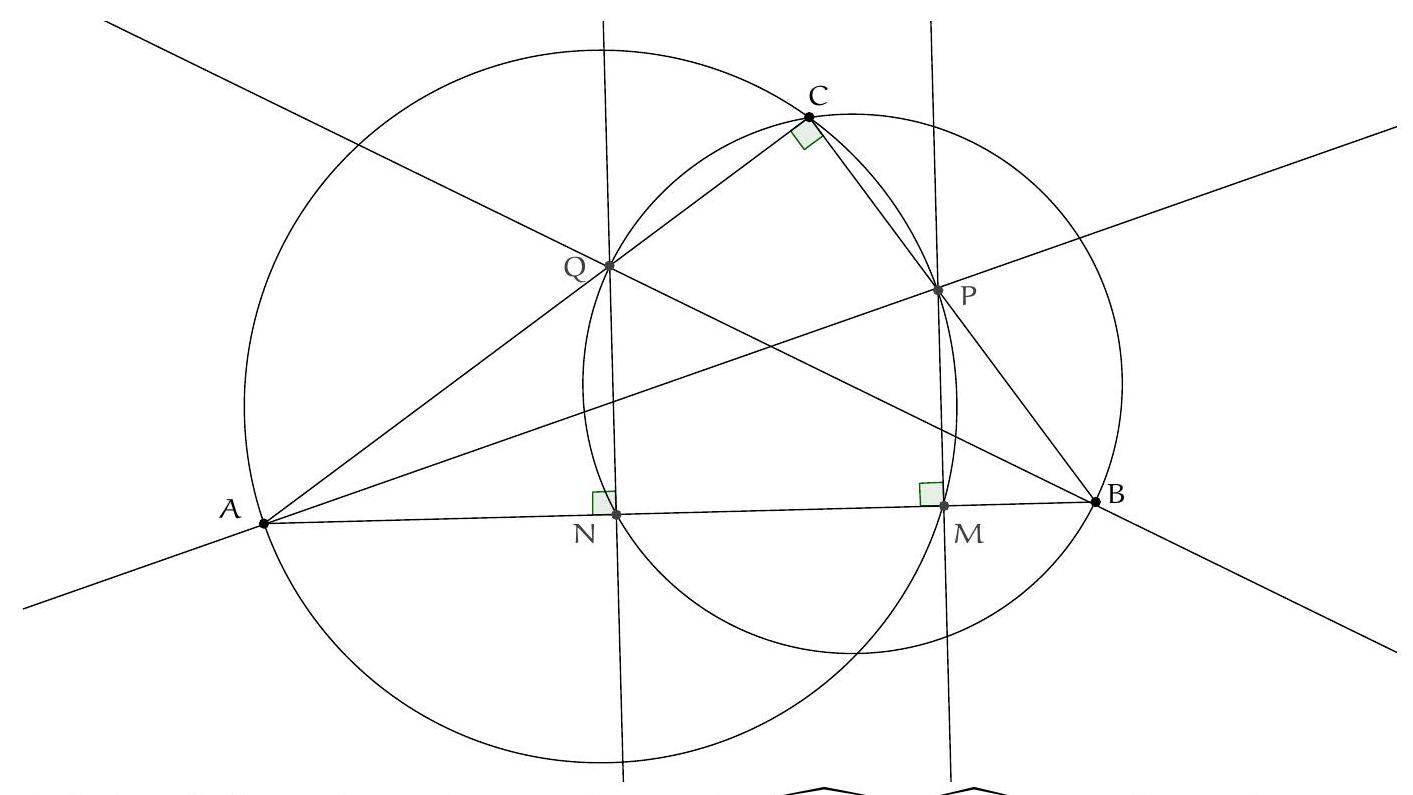

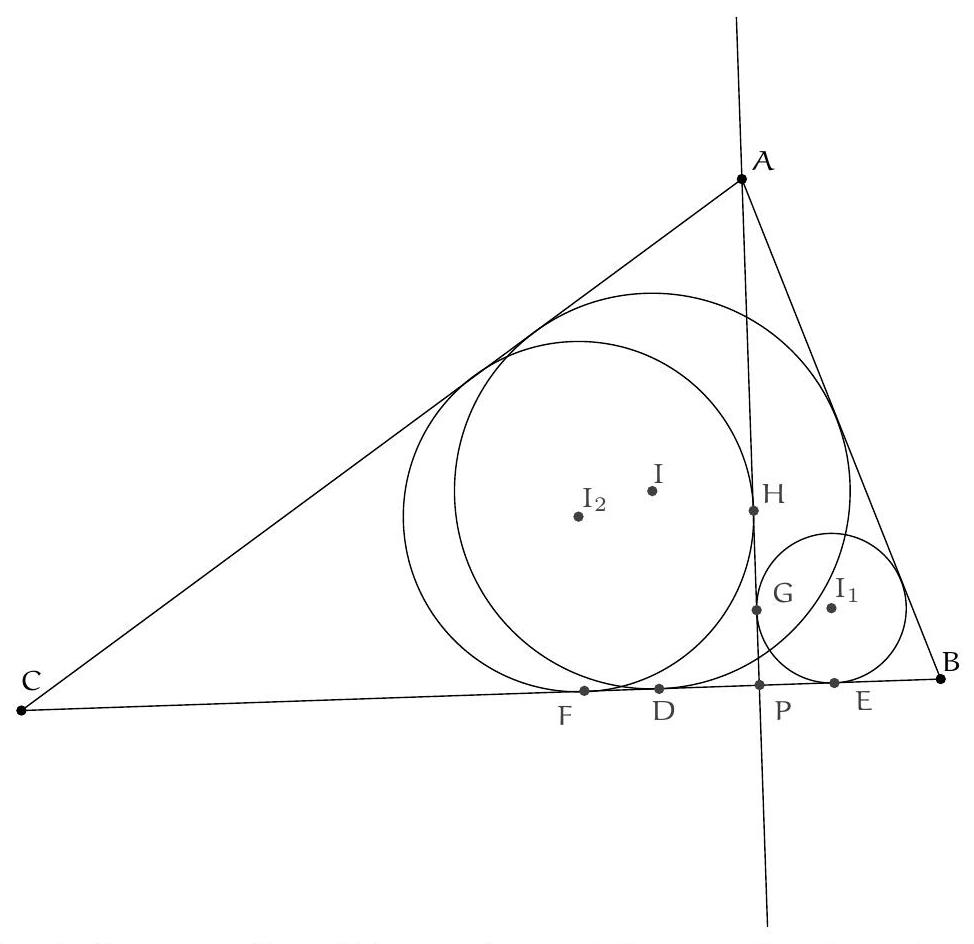

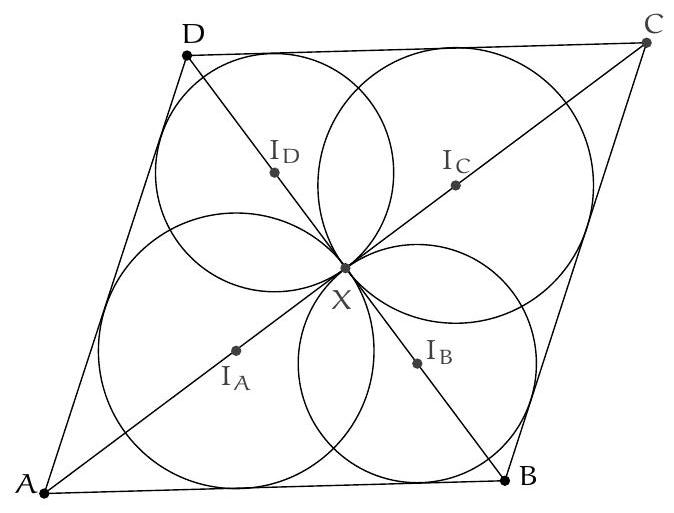

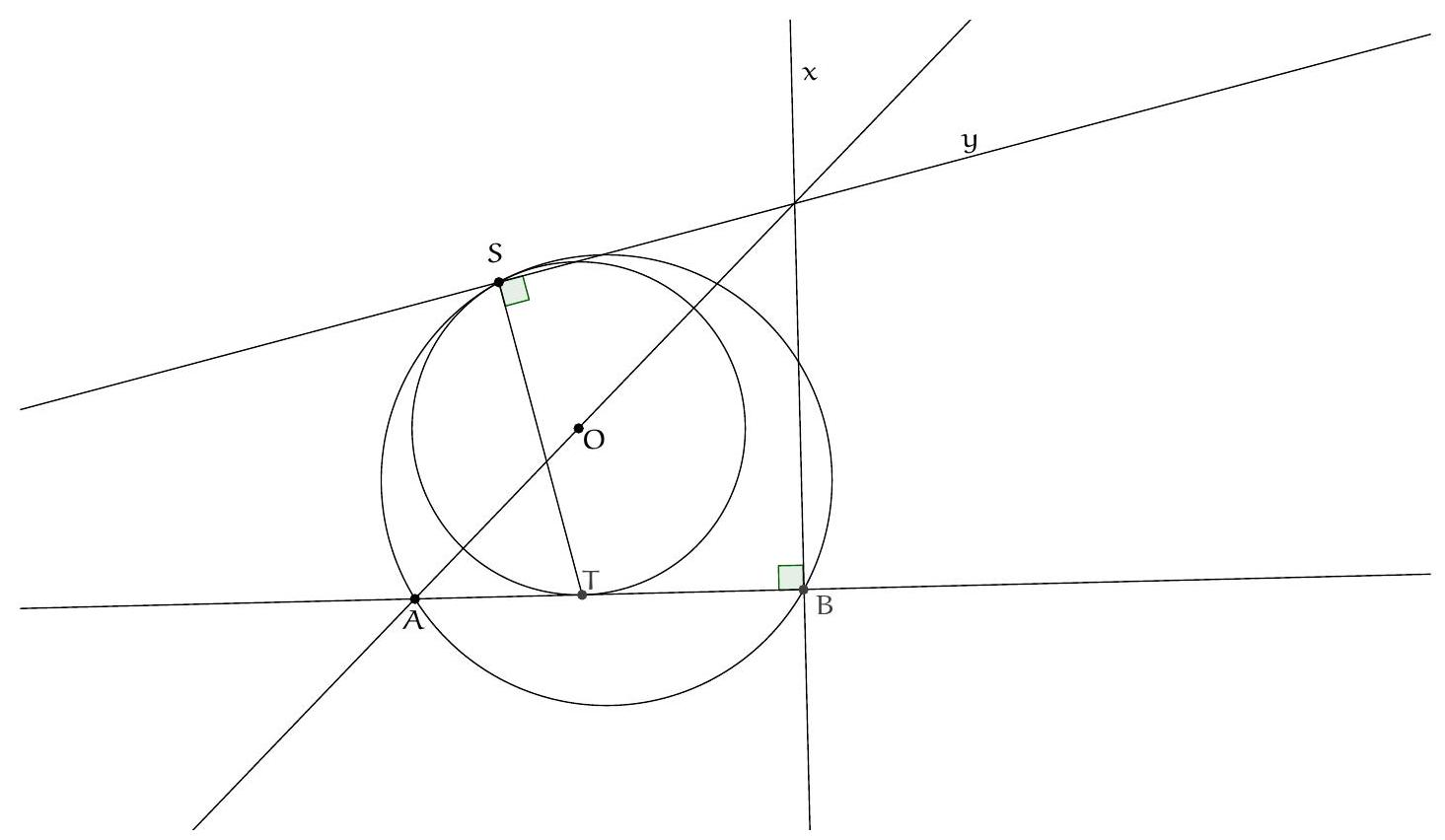

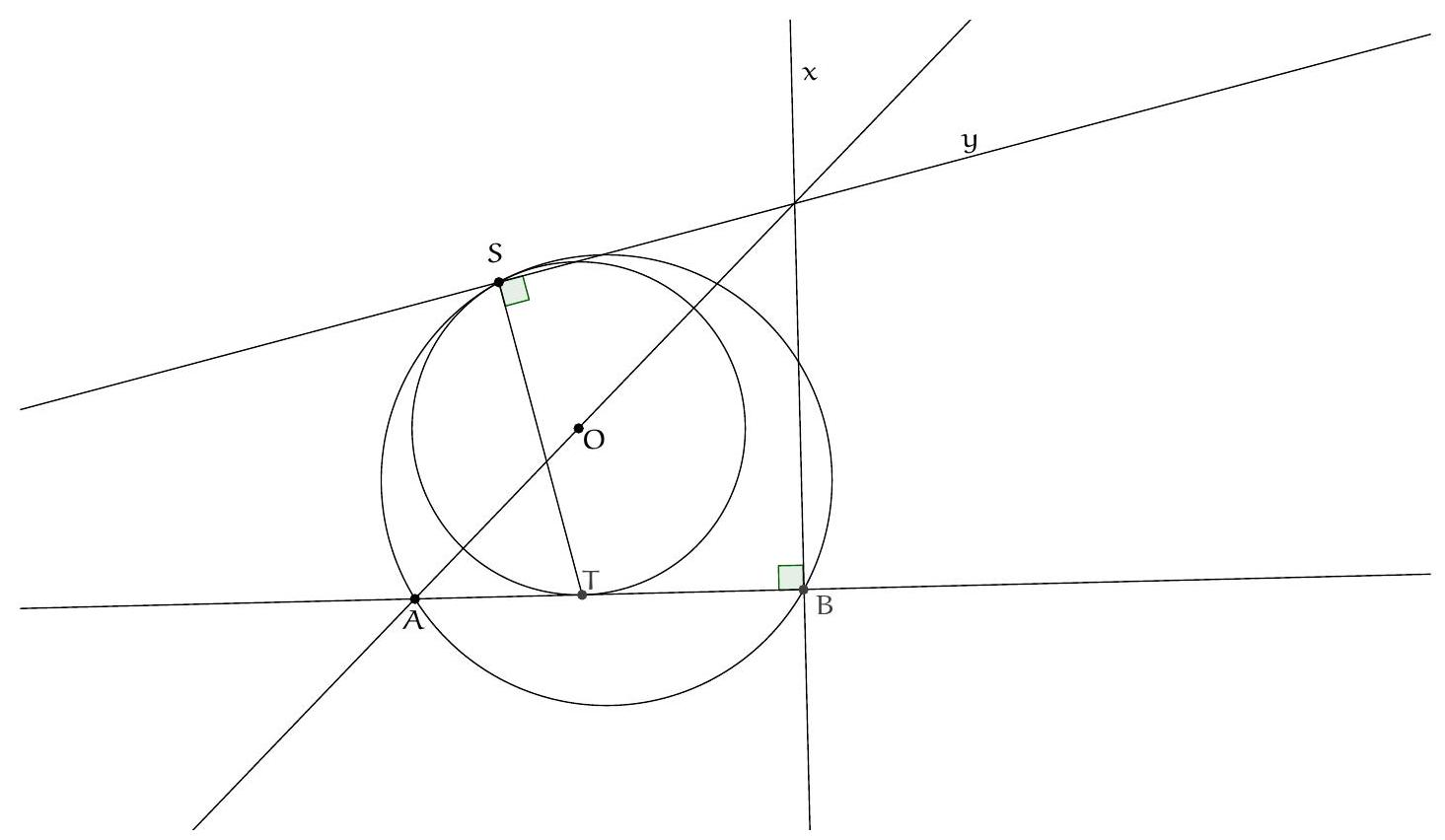

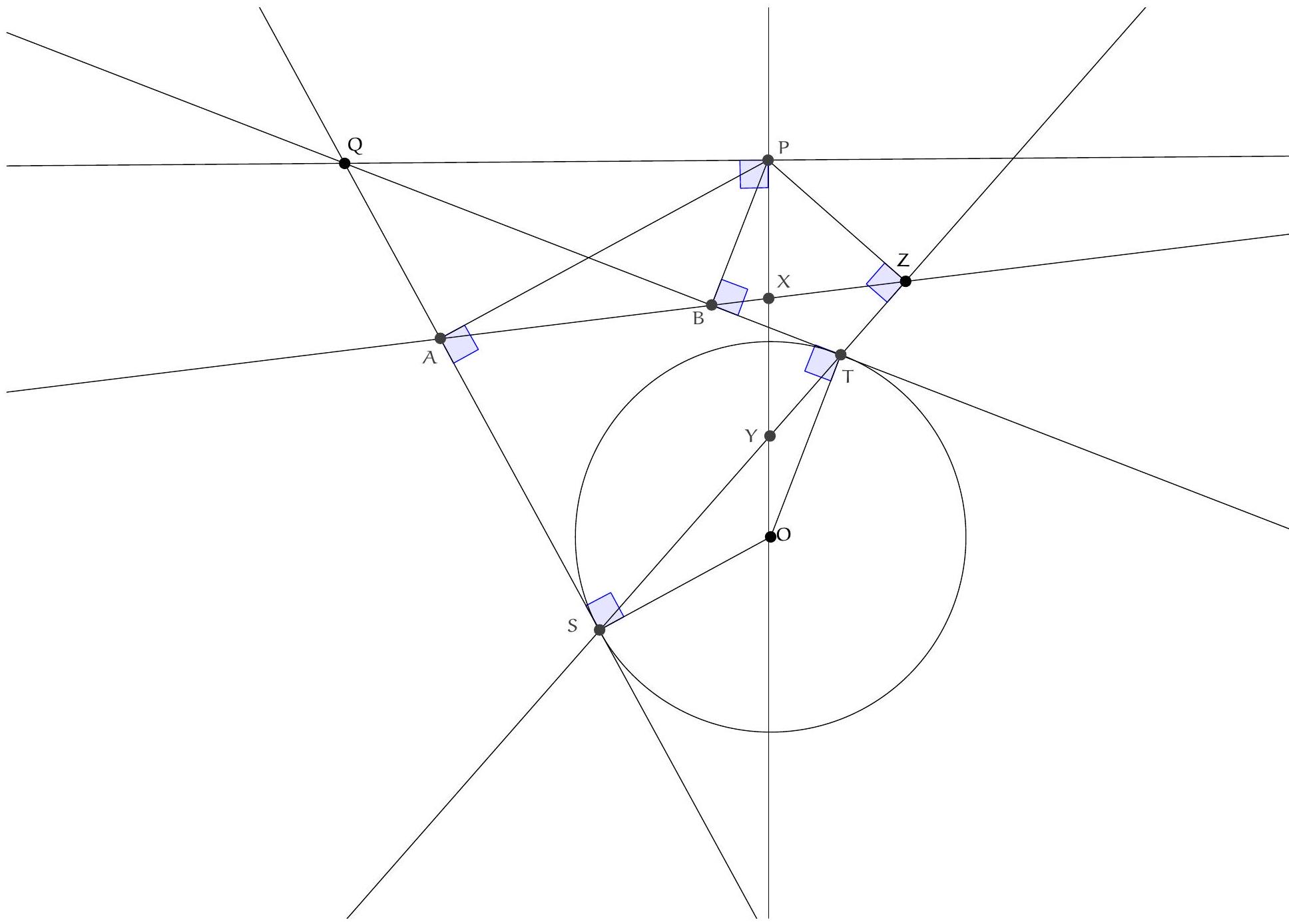

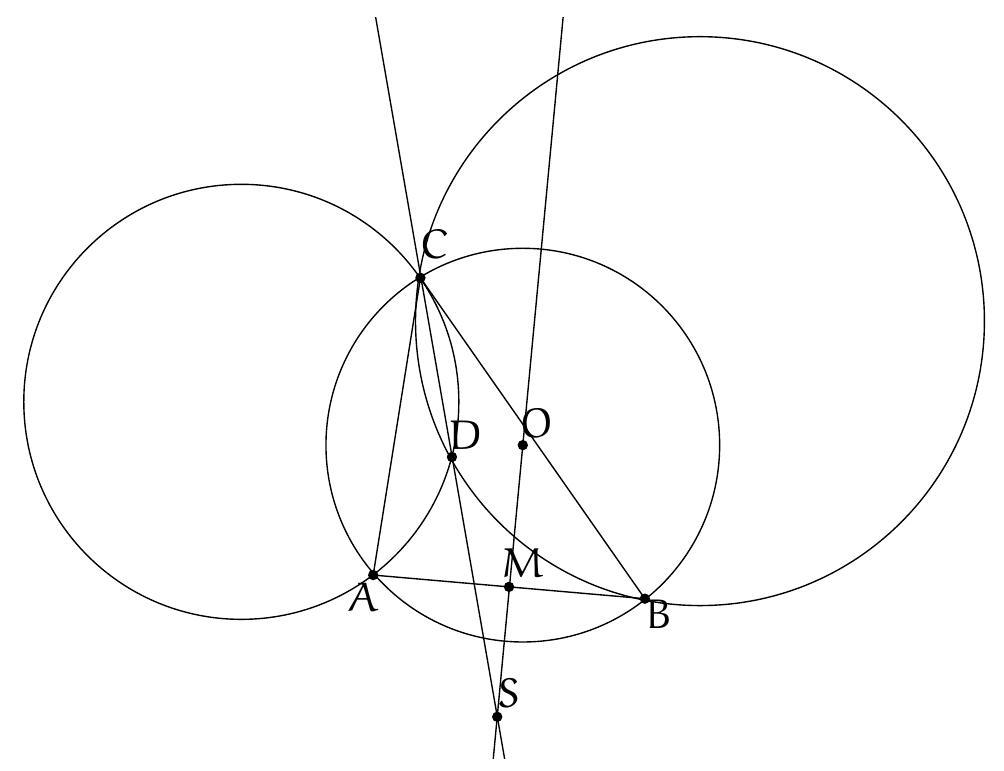

A circle with center $O$ is inscribed in a quadrilateral $ABCD$ whose sides are not parallel. Show that the point $O$ coincides with the intersection point of the medians of the quadrilateral if and only if $OA \cdot OC = OB \cdot OD$. (A median line of the quadrilateral is a line connecting the midpoints of opposite sides.)

|

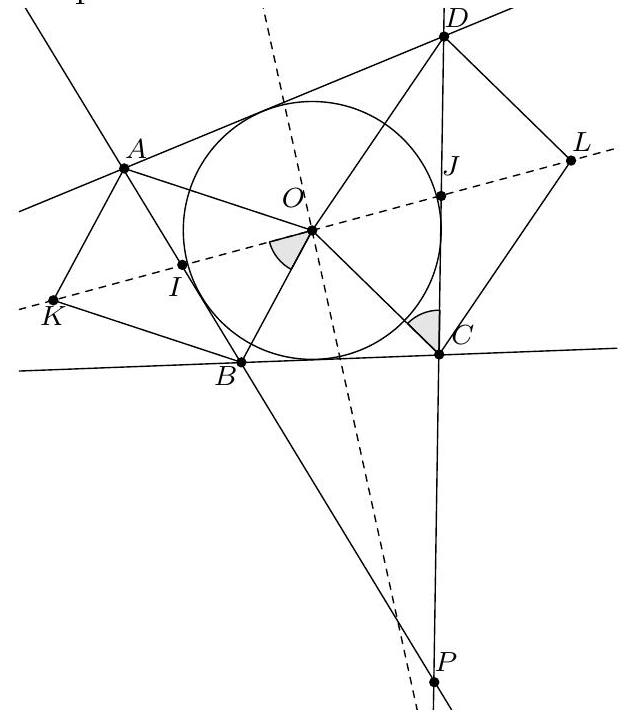

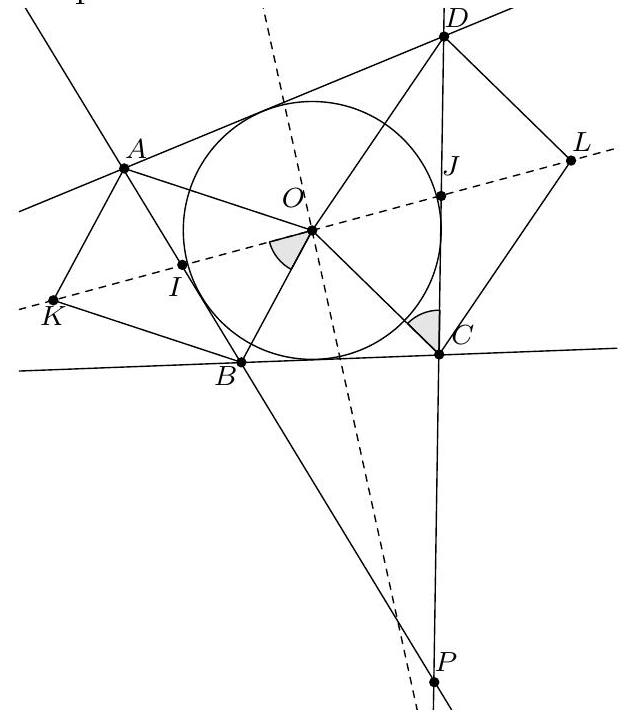

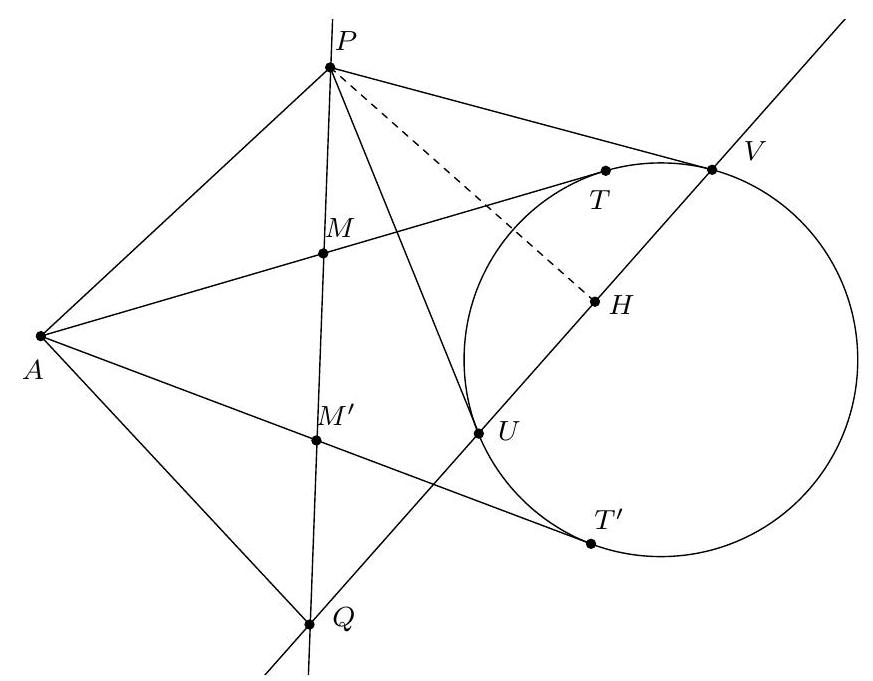

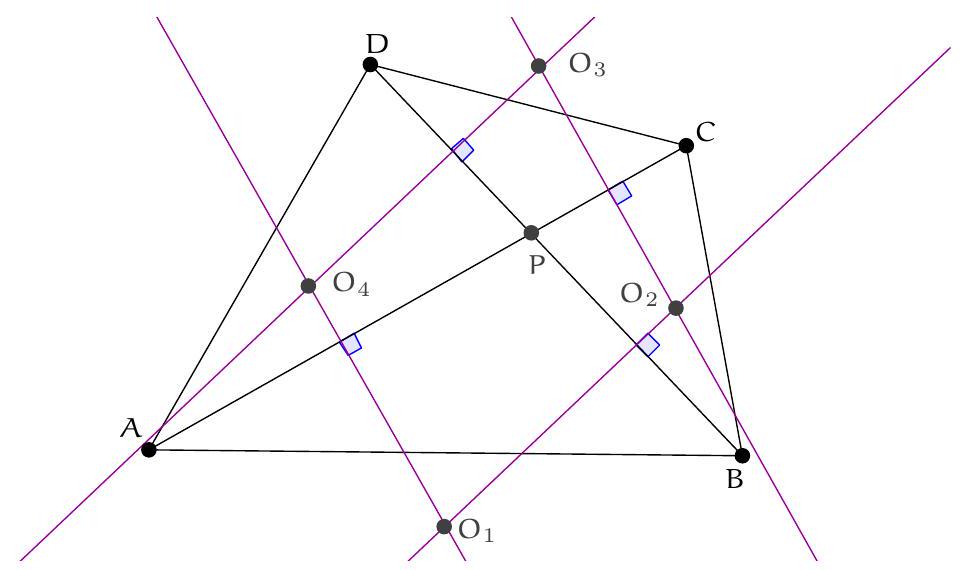

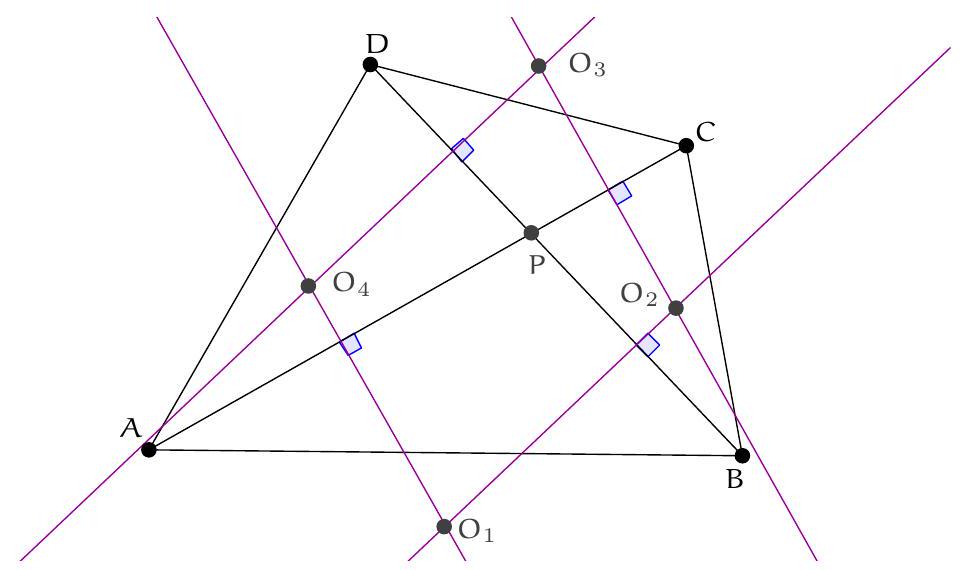

Let $I$ and $J$ be the midpoints of the sides $[A B]$ and $[C D]$ respectively. The lines $(A B)$ and $(C D)$ intersect at point $P$. Without loss of generality, we can assume that $P$ is the intersection of the rays $[A B)$ and $[C D)$.

1) Suppose that $O$ is the intersection of the medians of the quadrilateral $A B C D$. Then $O$ is the midpoint of the segment $[I J]$, because the midpoints of the sides of a quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram. Thus, $[P O]$ is the bisector and median from $P$ of the triangle $I P J$, so $I P J$ is isosceles at $P$ and $\widehat{B I O}=\widehat{C J O}$. Furthermore,

$$

\widehat{I B O}+\widehat{J C O}=\frac{1}{2}(\widehat{A B C}+\widehat{B C D})=\frac{1}{2}(\pi+\widehat{B P C})=\pi-\widehat{P I J}=\widehat{I B O}+\widehat{I O B}

$$

Then $\widehat{J C O}=\widehat{I O B}$ and the triangles $O I B$ and $C J O$ are similar. We obtain that $\frac{O B}{O C}=$ $\frac{I B}{J O}$. Similarly, we have $\frac{O A}{O D}=\frac{I A}{J O}$. Since $I B=I A$, we get $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$.

2) Now suppose that $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$. We note that

$$

\begin{aligned}

\widehat{A O B}+\widehat{C O D} & =(\pi-\widehat{O A B}-\widehat{O B A})+(\pi-\widehat{O C D}-\widehat{O D C}) \\

& =\pi-\frac{1}{2}(\widehat{D A B}+\widehat{A B C}+\widehat{B C D}+\widehat{C D A})=\pi

\end{aligned}

$$

Therefore, if we construct the parallelograms $O A K B$ and $C O D L$ from the triangles $O A B$ and $O C D$, these parallelograms will be similar, because $\frac{O A}{A K}=\frac{O A}{O B}=$ $\frac{D O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{D L}$. In particular, the triangles $O I B$ and $C J O$ are also similar, because they correspond to each other in the similar parallelograms $O A K B$ and $C O D L$. It follows that

$$

\widehat{I O B}=\widehat{O C J}=\widehat{O C B}, \quad \widehat{C O J}=\widehat{I B O}=\widehat{O B C}

$$

We obtain that

$$

\widehat{I O B}+\widehat{B O C}+\widehat{C O J}=\widehat{O C B}+\widehat{B O C}+\widehat{O B C}=\pi,

$$

so $O$ lies on $(I J)$. Similarly, $O$ lies on the other median of the quadrilateral $A B C D$.

Another solution. We can solve the problem using an analytical method with complex numbers. The calculations are lengthy but not impractical.

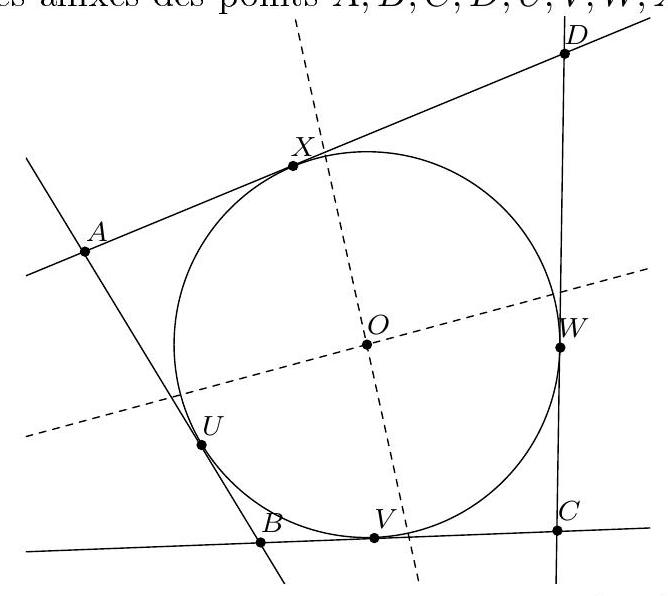

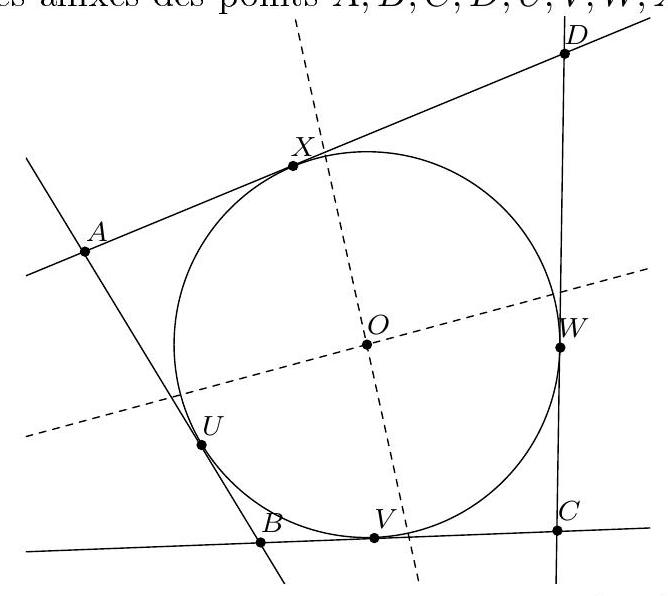

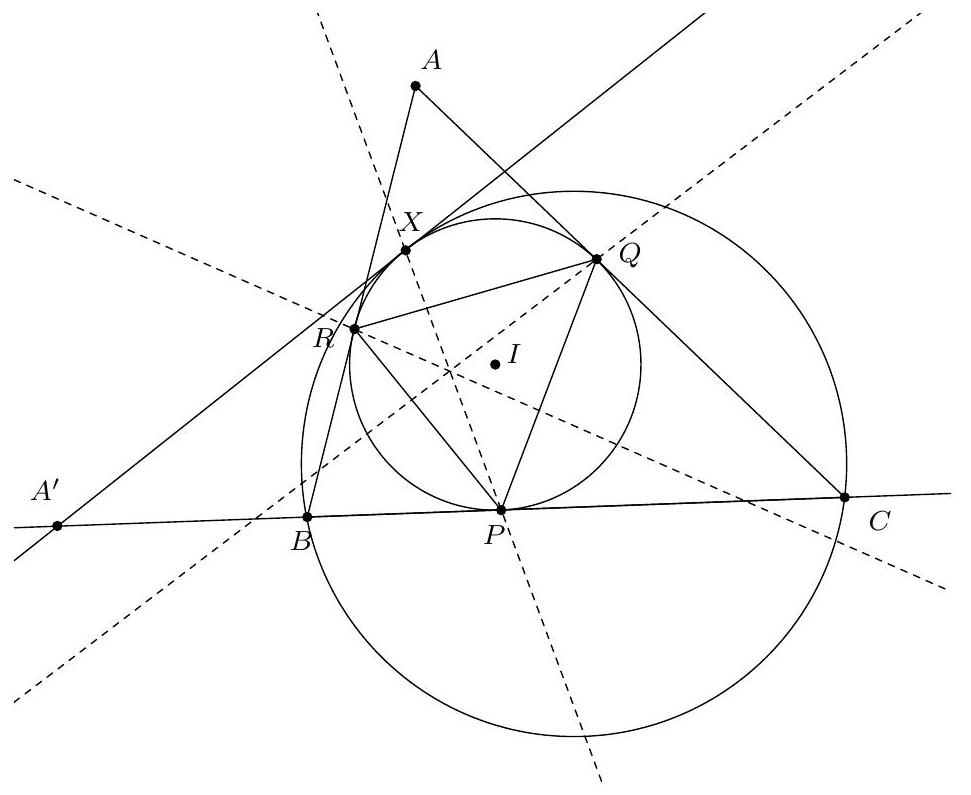

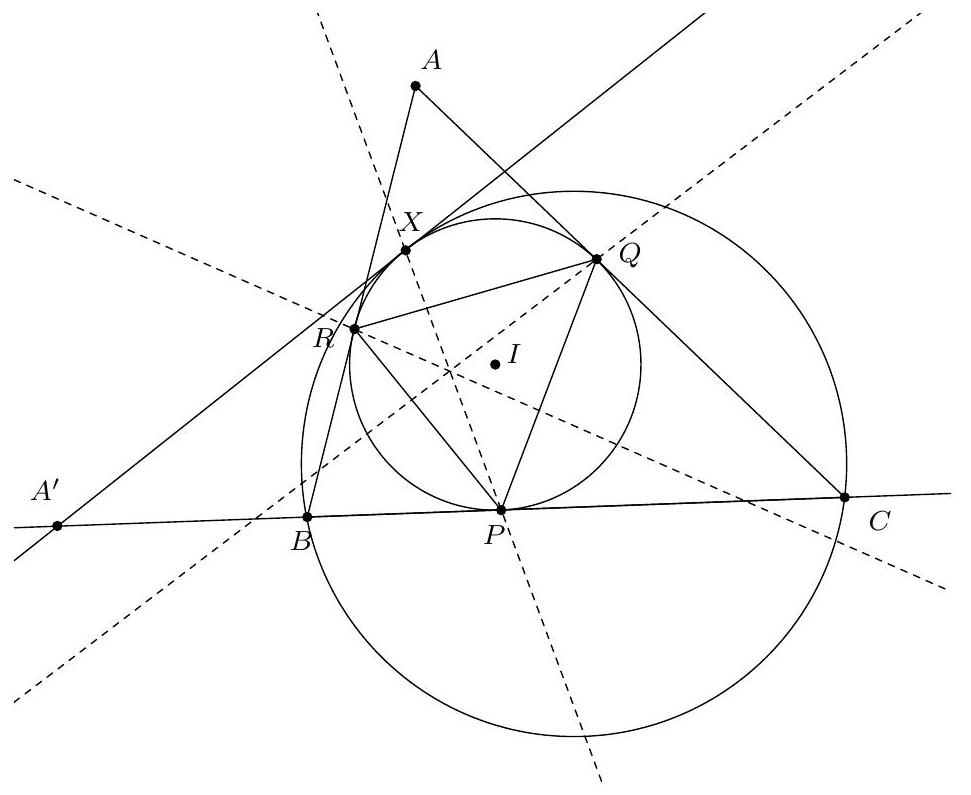

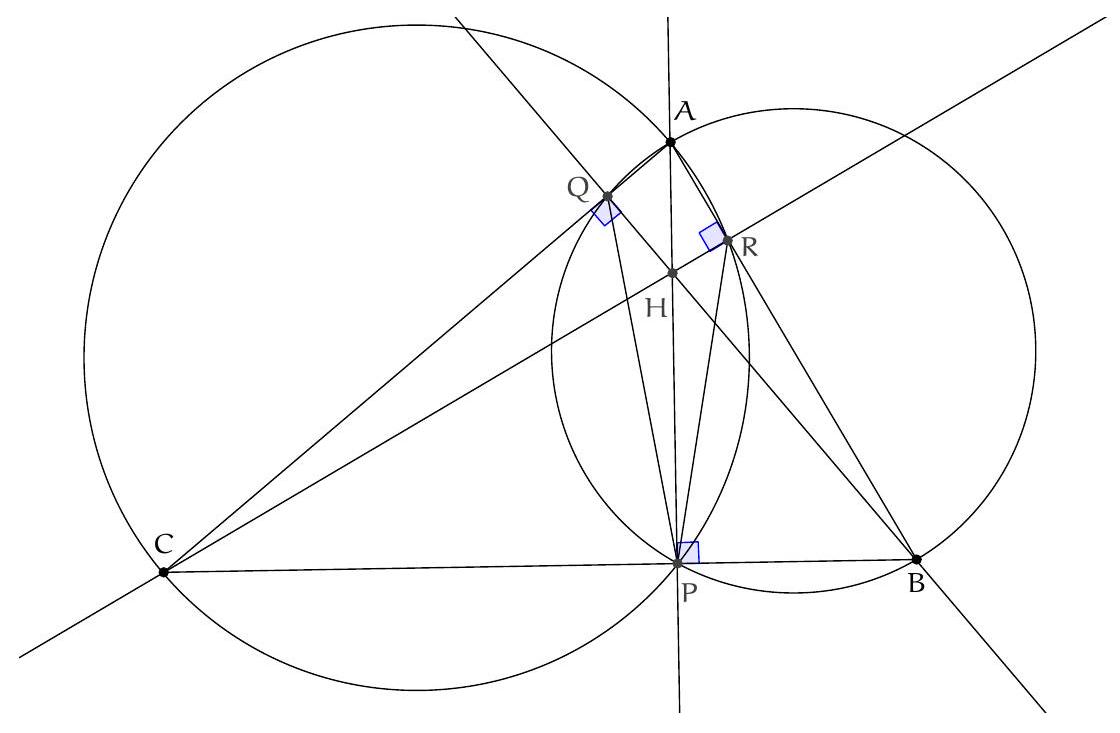

Let $U, V, W, X$ be the points of tangency of the lines $(A B),(B C),(C D)$ and $(D A)$ with the circle. We can assume that the circle is centered at 0 and has a radius of 1. Let $a, b, c, d, u, v, w, x$ be the affixes of the points $A, B, C, D, U, V, W, X$.

A point with affix $z$ lies on $(A B)$ if and only if $z-u$ is perpendicular to $u$, which can be written as $0=\bar{u}(z-u)+u(\bar{z}-\bar{u})$, or equivalently $\bar{u} z+u \bar{z}=2$. Since $\bar{u}=1 / u$, this can be written as $z+u^{2} \bar{z}=2 u$. Similarly, the equation of the line $(A D)$ is $z+x^{2} \bar{z}=2 x$. By combining these two equations, we find that

$$

a=\frac{2 u x}{u+x} .

$$

Similarly, we have $b=\frac{2 u v}{u+v}, c=\frac{2 v w}{v+w}$ and $d=\frac{2 w x}{w+x}$.

We calculate that $4 O A^{-2}=|u+x|^{2}=2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x$. We have similar expressions for $4 O B^{-2}$, etc. Therefore,

$$

\begin{aligned}

O A \cdot O C & =O B \cdot O D \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad(2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x)(2+v \bar{w}+\bar{v} w)=(2+u \bar{v}+\bar{u} v)(2+w \bar{x}+\bar{w} x) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad u x(2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x) v w(2+v \bar{w}+\bar{v} w)=u v(2+u \bar{v}+\bar{u} v) w x(2+w \bar{x}+\bar{w} x) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad\left(2 u x+u^{2}+x^{2}\right)\left(2 v w+v^{2}+w^{2}\right)=\left(2 u v+u^{2}+v^{2}\right)\left(2 w x+x^{2}+w^{2}\right) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 u v^{2} x+2 u w^{2} x+2 u^{2} v w+u^{2} v^{2}+2 v w x^{2}+w^{2} x^{2} \\

& =2 u v x^{2}+2 u v w^{2}+2 u^{2} w x+u^{2} x^{2}+2 v^{2} w x+v^{2} w^{2} \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2(u-w) v^{2} x-2(u-w) u w x+2(u-w) u v w \\

& \quad-2(u-w) v x^{2}+(u-w)(u+w) v^{2}-(u-w)(u+w) x^{2}=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2 v^{2} x-2 u w x+2 u v w-2 v x^{2}+u v^{2}+v^{2} w-u x^{2}-w x^{2}=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 v x(v-x)+(v-x) w(v+x)+2 u w(v-x)+u(v+x)(v-x)=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2 u w+2 x v+(x+v)(u+w)=0 .

\end{aligned}

$$

On the other hand, $O$ lies on the line passing through the midpoints of $[A D]$ and $[B C]$ if and only if $0, \frac{a+d}{2}$ and $\frac{b+c}{2}$ are collinear, which means that $\frac{a+d}{b+c}$ is real, i.e.,

$$

\frac{\frac{u x}{u+x}+\frac{x w}{x+w}}{\frac{u v}{u+v}+\frac{v w}{v+w}}=\frac{\frac{1}{u+x}+\frac{1}{w+x}}{\frac{1}{u+v}+\frac{1}{v+w}}

$$

We multiply the numerators of each side by $(u+x)(x+w)$ and the denominators by $(u+v)(v+w)$, which gives successively

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{x[u(x+w)+w(u+x)]}{v[u(v+w)+w(u+v)]}=\frac{2 x+(u+w)}{2 v+(u+w)} \\

& \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad x[2 u w+u(u+w)][2 v+(u+w)]=v[2 u w+v(u+w)][2 x+(u+w)] \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 x u w(u+w)+2 x^{2} v(u+w)+x^{2}(u+w)^{2} \\

& \quad=2 v u w(u+w)+2 x v^{2}(u+w)+v^{2}(u+w)^{2} \\

& \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2(x-v) u w(u+w)+2(x-v) x v(u+w)+(x-v)(x+v)(u+w)^{2}=0

\end{aligned}

$$

Since the opposite sides are not parallel, we have $u+w \neq 0$. By simplifying by $(x-v)(u+w)$, we obtain the condition $2 u w+2 x v+(x+v)(u+w)=0$ which is the same as the previous one.

We conclude that $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$ if and only if $O$ lies on the line passing through the midpoints of $[A D]$ and $[B C]$. Similarly, we show that $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$ if and only if $O$ lies on the line passing through the midpoints of $[A B]$ and $[C D]$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Geometry

|

Un cercle de centre $O$ est inscrit dans un quadrilatère $A B C D$ dont les côtés ne sont pas parallèles. Montrer que le point $O$ coïncide avec le point d'intersection des lignes médianes du quadrilatère si et seulement si $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$. (Une ligne médiane du quadrilatère est une droite reliant les milieux des côtés opposés.)

|

Soient $I$ et $J$ les milieux des côtés $[A B]$ et $[C D]$ respectivement. Les droites $(A B)$ et $(C D)$ se coupent au point $P$. Sans perte de généralité, on peut supposer que $P$ est le point d'intersection des demi-droites $[A B)$ et $[C D)$.

1) Supposons que $O$ est le point d'intersection des lignes médianes du quadrilatère $A B C D$. Alors $O$ est le milieu du segment $[I J]$, parce que les milieux des côtés d'un quadrilatère sont les sommets d'un parallélogramme. Puis, $[P O]$ est la bissectrice et la médiane issus de $P$ du triangle $I P J$, donc $I P J$ est isocèle en $P$ et $\widehat{B I O}=\widehat{C J O}$. En outre,

$$

\widehat{I B O}+\widehat{J C O}=\frac{1}{2}(\widehat{A B C}+\widehat{B C D})=\frac{1}{2}(\pi+\widehat{B P C})=\pi-\widehat{P I J}=\widehat{I B O}+\widehat{I O B}

$$

Alors $\widehat{J C O}=\widehat{I O B}$ et les triangles $O I B$ et $C J O$ sont semblables. On obtient que $\frac{O B}{O C}=$ $\frac{I B}{J O}$. De même, on a $\frac{O A}{O D}=\frac{I A}{J O}$. Comme $I B=I A$, on obtient $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$.

2) On suppose maintenant que $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$. On note que

$$

\begin{aligned}

\widehat{A O B}+\widehat{C O D} & =(\pi-\widehat{O A B}-\widehat{O B A})+(\pi-\widehat{O C D}-\widehat{O D C}) \\

& =\pi-\frac{1}{2}(\widehat{D A B}+\widehat{A B C}+\widehat{B C D}+\widehat{C D A})=\pi

\end{aligned}

$$

Par conséquent, si on construit les parallélogrammes $O A K B$ et $C O D L$ à partir des triangles $O A B$ et $O C D$, ces parallélogrammes seront semblables, parce que $\frac{O A}{A K}=\frac{O A}{O B}=$ $\frac{D O}{O C}=\frac{D O}{D L}$. En particulier, les triangles $O I B$ et $C J O$ sont également semblables, parce qu'ils se correspondent mutuellement dans les parallélogrammes semblables $O A K B$ et $C O D L . \mathrm{Il}$ vient

$$

\widehat{I O B}=\widehat{O C J}=\widehat{O C B}, \quad \widehat{C O J}=\widehat{I B O}=\widehat{O B C}

$$

On obtient que

$$

\widehat{I O B}+\widehat{B O C}+\widehat{C O J}=\widehat{O C B}+\widehat{B O C}+\widehat{O B C}=\pi,

$$

donc $O$ se trouve sur $(I J)$. De même, $O$ se trouve sur l'autre ligne médiane du quadrilatère $A B C D$.

Autre solution. On peut résoudre l'exercice par une méthode analytique utilisant les nombres complexes. Les calculs sont longs mais pas impraticables.

Notons $U, V, W, X$ les points de contact des droites $(A B),(B C),(C D)$ et $(D A)$ avec le cercle. On peut supposer que le cercle est de centre 0 et de rayon 1 . Notons $a, b, c, d, u, v, w, x$ les affixes des points $A, B, C, D, U, V, W, X$.

Un point d'affixe $z$ appartient à $(A B)$ si et seulement si $z-u$ est perpendiculaire à $u$, ce qui s'écrit $0=\bar{u}(z-u)+u(\bar{z}-\bar{u})$, ou encore $\bar{u} z+u \bar{z}=2$. Comme $\bar{u}=1 / u$, ceci s'écrit encore $z+u^{2} \bar{z}=2 u$. De même, l'équation de la droite $(A D)$ est $z+x^{2} \bar{z}=2 x$. En combinant ces deux équations, on trouve que

$$

a=\frac{2 u x}{u+x} .

$$

De même, on a $b=\frac{2 u v}{u+v}, c=\frac{2 v w}{v+w}$ et $d=\frac{2 w x}{w+x}$.

On calcule que $4 O A^{-2}=|u+x|^{2}=2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x$. On a des expressions analogues pour $4 O B^{-2}$, etc. Par conséquent,

$$

\begin{aligned}

O A \cdot O C & =O B \cdot O D \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad(2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x)(2+v \bar{w}+\bar{v} w)=(2+u \bar{v}+\bar{u} v)(2+w \bar{x}+\bar{w} x) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad u x(2+u \bar{x}+\bar{u} x) v w(2+v \bar{w}+\bar{v} w)=u v(2+u \bar{v}+\bar{u} v) w x(2+w \bar{x}+\bar{w} x) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad\left(2 u x+u^{2}+x^{2}\right)\left(2 v w+v^{2}+w^{2}\right)=\left(2 u v+u^{2}+v^{2}\right)\left(2 w x+x^{2}+w^{2}\right) \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 u v^{2} x+2 u w^{2} x+2 u^{2} v w+u^{2} v^{2}+2 v w x^{2}+w^{2} x^{2} \\

& =2 u v x^{2}+2 u v w^{2}+2 u^{2} w x+u^{2} x^{2}+2 v^{2} w x+v^{2} w^{2} \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2(u-w) v^{2} x-2(u-w) u w x+2(u-w) u v w \\

& \quad-2(u-w) v x^{2}+(u-w)(u+w) v^{2}-(u-w)(u+w) x^{2}=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2 v^{2} x-2 u w x+2 u v w-2 v x^{2}+u v^{2}+v^{2} w-u x^{2}-w x^{2}=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 v x(v-x)+(v-x) w(v+x)+2 u w(v-x)+u(v+x)(v-x)=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2 v x+v w+v x+2 u w+u v+u x=0 \\

& \Longleftrightarrow 2(u w+x v)+(x+v)(u+w)=0 .

\end{aligned}

$$

D'autre part, $O$ appartient à la droite passant par les milieux de $[A D]$ et de $[B C]$ si et seulement si $0, \frac{a+d}{2}$ et $\frac{b+c}{2}$ sont alignés, ce qui se traduit par le fait que $\frac{a+d}{b+c}$ est réel, c'est-à-dire

$$

\frac{\frac{u x}{u+x}+\frac{x w}{x+w}}{\frac{u v}{u+v}+\frac{v w}{v+w}}=\frac{\frac{1}{u+x}+\frac{1}{w+x}}{\frac{1}{u+v}+\frac{1}{v+w}}

$$

On multiplie les numérateurs de chaque membre par $(u+x)(x+w)$ et les dénominateurs par $(u+v)(v+w)$, ce qui donne successivement

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \frac{x[u(x+w)+w(u+x)]}{v[u(v+w)+w(u+v)]}=\frac{2 x+(u+w)}{2 v+(u+w)} \\

& \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad x[2 u w+u(u+w)][2 v+(u+w)]=v[2 u w+v(u+w)][2 x+(u+w)] \\

& \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2 x u w(u+w)+2 x^{2} v(u+w)+x^{2}(u+w)^{2} \\

& \quad=2 v u w(u+w)+2 x v^{2}(u+w)+v^{2}(u+w)^{2} \\

& \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad 2(x-v) u w(u+w)+2(x-v) x v(u+w)+(x-v)(x+v)(u+w)^{2}=0

\end{aligned}

$$

Comme les côtés opposés ne sont pas parallèles, on a $u+w \neq 0$. En simplifiant par $(x-v)(u+w)$, on obtient la condition $2 u w+2 x v+(x+v)(u+w)=0$ qui est la même que la précédente.

On en conclut que $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$ si et seulement si $O$ appartient à la droite passant par les milieux de $[A D]$ et de $[B C]$. De même, on montre que $O A \cdot O C=O B \cdot O D$ si et seulement si $O$ appartient à la droite passant par les milieux de $[A B]$ et de $[C D]$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-1-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution.",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

It is said that a 9-digit number is interesting if each digit from 1 to 9 appears exactly once, the digits from 1 to 5 appear in order but the digits from 1 to 6 do not, for example 189236457.

How many interesting numbers are there?

|

To build an interesting number, we can first place the digits from 1 to 5, then intercalate the 6 somewhere, then the 7, the 8, and the 9. The order of the digits from 1 to 5 is fixed. Then, the 6 can be placed anywhere except after the 5 because the digits from 1 to 6 would not be in order. Therefore, there are 5 ways to place the 6. Next, the 7 can be placed anywhere, so there are 7 ways to place it, and similarly, 8 ways to place the 8 and 9 ways to place the 9.

Thus, there are $5 * 7 * 8 * 9=2520$ interesting numbers.

|

2520

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On dit qu'un nombre à 9 chiffres est intéressant si chaque chiffre de 1 à 9 y apparaît une unique fois, que les chiffres de 1 à 5 y apparaissent dans l'ordre mais pas les chiffres de 1 à 6 , par exemple 189236457 .

Combien y a-t-il de nombres intéressants?

|

Pour construire un nombre intéressant, on peut placer d'abord les chiffres de 1 à 5 , puis intercaler le 6 quelque part, puis le 7 , le 8 et le 9 . L'ordre des chiffres de 1 à 5 est imposé. Ensuite, le 6 peut être placé n'importe où sauf après le 5 car les chiffres de 1 à 6 ne sont pas dans l'ordre. Il y a donc 5 manières de placer le 6 . Ensuite, on peut placer le 7 n'importe où, donc il y a 7 manières de le placer, et de même 8 manières de placer le 8 et 9 pour le 9.

Il y a donc $5 * 7 * 8 * 9=2520$ nombres intéressants.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

In a country, there are n cities. Any two cities are always connected either by a highway or by a train line. Show that one of the two means of transportation allows any city to be connected to any other.

|

We reason by induction on $n$: for $n=1$ or $n=2$, the result is immediate. Suppose we have shown it at rank $n$, and consider $n+1$ cities:

We isolate one of the cities, let's call it Paris, for example. Then one of the two means of transport allows connecting all the cities except Paris. Suppose it is the car:

- if Paris is connected to a city by a highway, for example, Lyon, we can go from Paris to Lyon by car, then to any other city according to the induction hypothesis.

- otherwise, Paris is connected to all the cities by a train line, so we can go from any city to any city by train via Paris.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Dans un pays, il y a n villes. Deux villes quelconques sont toujours reliées soit par une autoroute, soit par une ligne de train. Montrer qu'un des deux moyens de transport permet de relier n'importe quelle ville à n'importe quelle autre.

|

On raisonne par récurrence sur $n$ : pour $n=1$ ou $n=2$, le résultat est immédiat. Supposons qu'on l'a montré au rang $n$, et considérons $n+1$ villes :

On isole une des villes, appelons-la par exemple Paris. Alors un des deux moyens de transports permet de relier entre elles toutes les villes sauf Paris. Supposons que c'est la voiture:

- si Paris est relié à une ville par une autoroute par exemple Lyon, on peut en voiture aller de Paris à Lyon, puis à n'importe quelle autre ville d'après l'hypothèse de récurrence.

- sinon, Paris est relié à toutes les villes par une ligne de train, donc on peut aller de n'importe quelle ville à n'importe quelle ville en train en passant par Paris.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Scientists participate in a conference, each scientist being either a mathematician or a physicist. Of course, physicists always lie, and mathematicians always tell the truth, except when they make a mistake. During the final dinner, all are seated in a circle around a table, and each one claims to be sitting between a mathematician and a physicist. It turns out that exactly one distracted mathematician made a mistake. How many physicists are at the conference?

|

If 2 physicists are sitting side by side, since they lied, they are not between a physicist and a mathematician, so each is between two physicists, and so on, so the conference only hosts physicists, which is absurd because there is at least one mathematician (the one who was wrong...). Each physicist is therefore between two mathematicians.

On the other hand, each mathematician is between a mathematician and a physicist, except the one who was wrong. Let's call him Thomas: if Thomas is between two physicists, then everywhere else there is an alternation of two mathematicians, one physicist... But then, if there are $k$ pairs of mathematicians side by side, there are $2 k+1$ mathematicians and $k+1$ physicists, so $3 k+2$ scientists, which is absurd because $3 k+2 \neq 2014$.

Thomas is therefore between two mathematicians, so we have three mathematicians side by side, and the others in pairs. If there are $k$ pairs, then we have $2 k+3$ mathematicians and $k+1$ physicists, so $3 k+4=2014$ so $k=670$ and there are 671 physicists.

## Common Exercises

|

671

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Logic and Puzzles

|

scientifiques participent à un congrès, chaque scientifique étant soit un mathématicien, soit un physicien. Bien sûr, les physiciens mentent toujours et les mathématiciens disent toujours la vérité, sauf quand ils se trompent. Lors du dîner final, tous sont assis en rond autour d'une table, et chacun prétend se trouver entre un mathématicien et un physicien. Il se trouve qu'exactement un mathématicien distrait s'est trompé. Combien y a-t-il de physiciens au congrès?

|

Si 2 physiciens sont assis côté à côté, comme ils ont menti, ils ne sont pas entre un physicien et un mathématicien, donc chacun est entre deux physiciens, et ainsi de suite, donc le congrès n'accueille que des physiciens, ce qui est absurde car il y a au moins un mathématicien (celui qui s'est trompé...). Chaque physicien est donc entre deux mathématiciens.

D'autre part, chaque mathématicien est entre un mathématicien et un physicien, sauf celui qui s'est trompé. Appelons-le Thomas : si Thomas est entre deux physiciens, alors on a partout ailleurs une alternance de deux mathématiciens, un physicien... Mais alors, si il y a k paires de mathématiciens côte à côte, il y a $2 k+1$ mathématiciens et $k+1$ physiciens, donc $3 k+2$ scientifiques, ce qui est absurde car $3 k+2 \neq 2014$.

Thomas est donc entre deux mathématiciens, donc on a trois mathématiciens côté à côte, et les autres par paires. Si il y a $k$ paires, alors on a $2 k+3$ mathématiciens et $k+1$ physiciens donc $3 k+4=2014$ donc $k=670$ et il y a 671 physiciens.

## Exercices communs

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "32014",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 32014",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Show that every polyhedron has two faces with the same number of vertices.

|

Let $n$ be the number of faces of the polyhedron, and let $F$ be a fixed face: the edges of $F$ separate $F$ from different faces, so the number of edges of $F$ is less than or equal to the number of faces other than $F$. Moreover, $F$ has at least 3 edges. Each face has as many edges as vertices, so every face has a number of vertices between 3 and $n-1$, which gives $n-3$ possibilities. According to the pigeonhole principle, there therefore exist two faces that have the same number of vertices.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Montrer que tout polyèdre a deux faces qui ont le même nombre de sommets.

|

Soit $n$ le nombre de faces du polyèdre, et soit $F$ une face fixée : les arêtes de $F$ séparent $F$ de faces toutes différentes, donc le nombre d'arêtes de $F$ est inférieur ou égal au nombre de faces autres que $F$. De plus, $F$ a au moins 3 arêtes. Chaque face a autant d'arêtes que de sommet, donc toute face a un nombre de sommets compris entre 3 et $n-1$, soit $n-3$ possibilités. D'après le principe des tiroirs, il existe donc deux faces qui ont le même nombre de sommets.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $\mathrm{n} \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$. Show that it is possible to partition $\{1,2, \ldots, \mathrm{n}\}$ into two subsets $A$ and $B$ such that the sum of the elements of $A$ is equal to the product of the elements of $B$.

|

A priori, set $B$ must be much smaller than $A$. We will therefore look for a $B$ with a small number of elements. By testing small values of $n$, we can think of looking for $B$ in the form $\{1, a, b\}$ with $a, b \neq 1$ and $a \neq b$.

We then have $\prod_{x \in B} x = a b$, and:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{x \in \mathcal{A}} & = \sum_{x=1}^{n} x - 1 - a - b \\

& = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - a - b - 1

\end{aligned}

$$

We want $\frac{n(n+1)}{2} = a b + a + b + 1 = (a+1)(b+1)$, so it suffices to write $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ as a product. If $n$ is even, we can take $a+1 = \frac{n}{2}$ and $b+1 = n+1$, which gives $a = \frac{n}{2} - 1$ and $b = n$. If $n$ is odd, we take $a = \frac{n-1}{2}$ and $b = n-1$. In both cases, the assumption $n \geqslant 5$ allows us to easily verify that 1, $a$, and $b$ are pairwise distinct.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Soit $\mathrm{n} \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$. Montrer qu'il est possible de partitionner $\{1,2, \ldots, \mathrm{n}\}$ en deux sousensembles $A$ et $B$ tels que la somme des éléments de $A$ soit égale au produit des éléments de B.

|

A priori, l'ensemble B doit être bien plus petit que A. On va donc chercher un $B$ avec un petit nombre d'éléments. En testant des petites valeurs de $n$, on peut penser à chercher $B$ sous la forme $\{1, a, b\}$ avec $a, b \neq 1$ et $a \neq b$.

On a alors $\prod_{x \in B} x=a b$, et :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{x \in \mathcal{A}} & =\sum_{x=1}^{n} x-1-a-b \\

& =\frac{n(n+1)}{2}-a-b-1

\end{aligned}

$$

On veut donc $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}=a b+a+b+1=(a+1)(b+1)$, donc il suffit d'écrire $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$ comme un produit. Or, si $n$ est pair, on peut prendre $a+1=\frac{n}{2}$ et $b+1=n+1$, soit $a=\frac{n}{2}-1$ et $b=n$. Si $n$ est impair, on prend $a=\frac{n-1}{2}$ et $b=n-1$. Dans les deux cas, l'hypothèse $n \geqslant 5$ permet de vérifier facilement que 1, a et $b$ sont deux à deux distincts.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

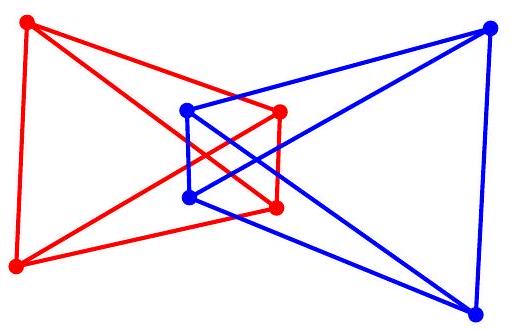

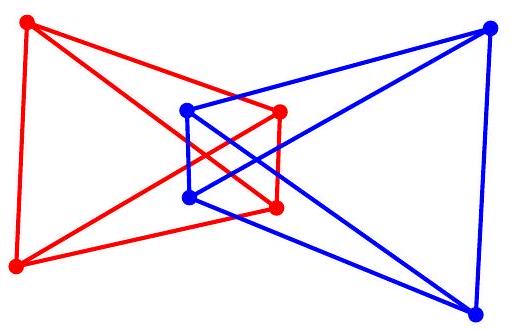

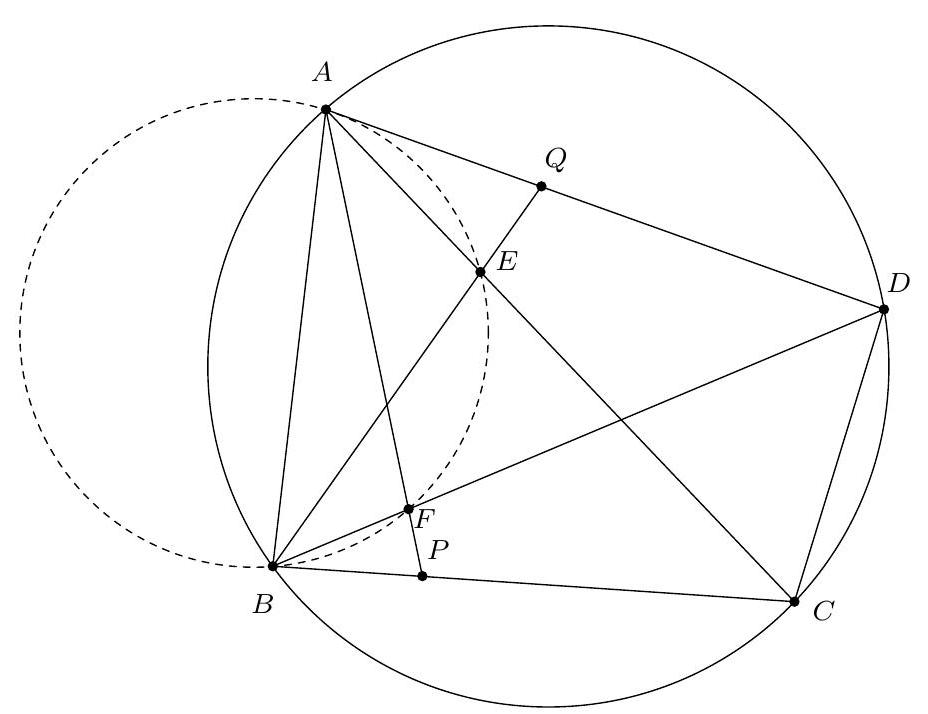

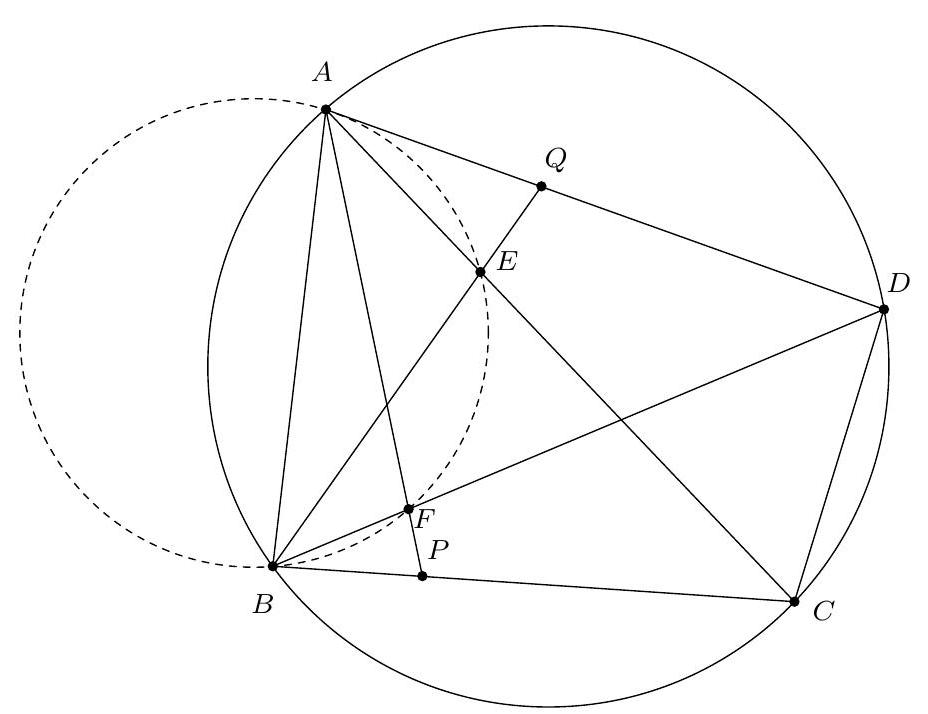

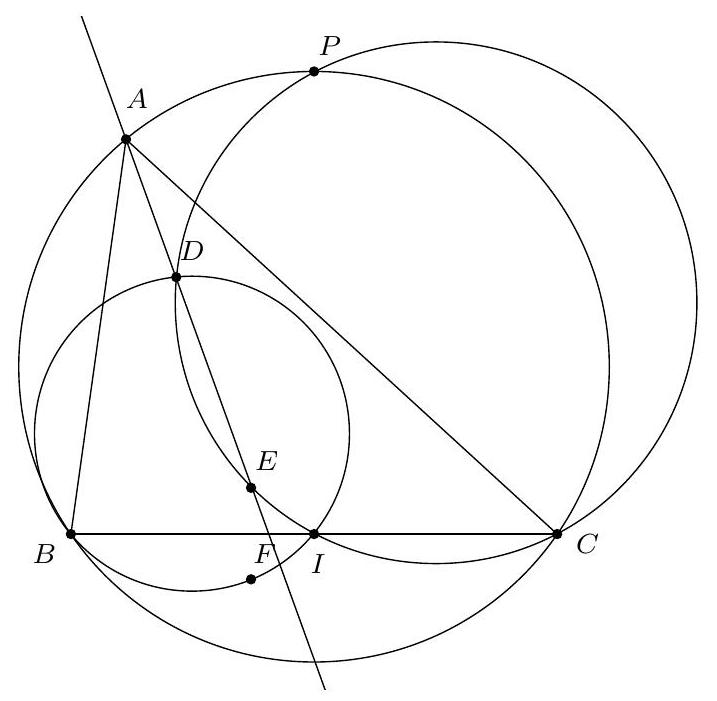

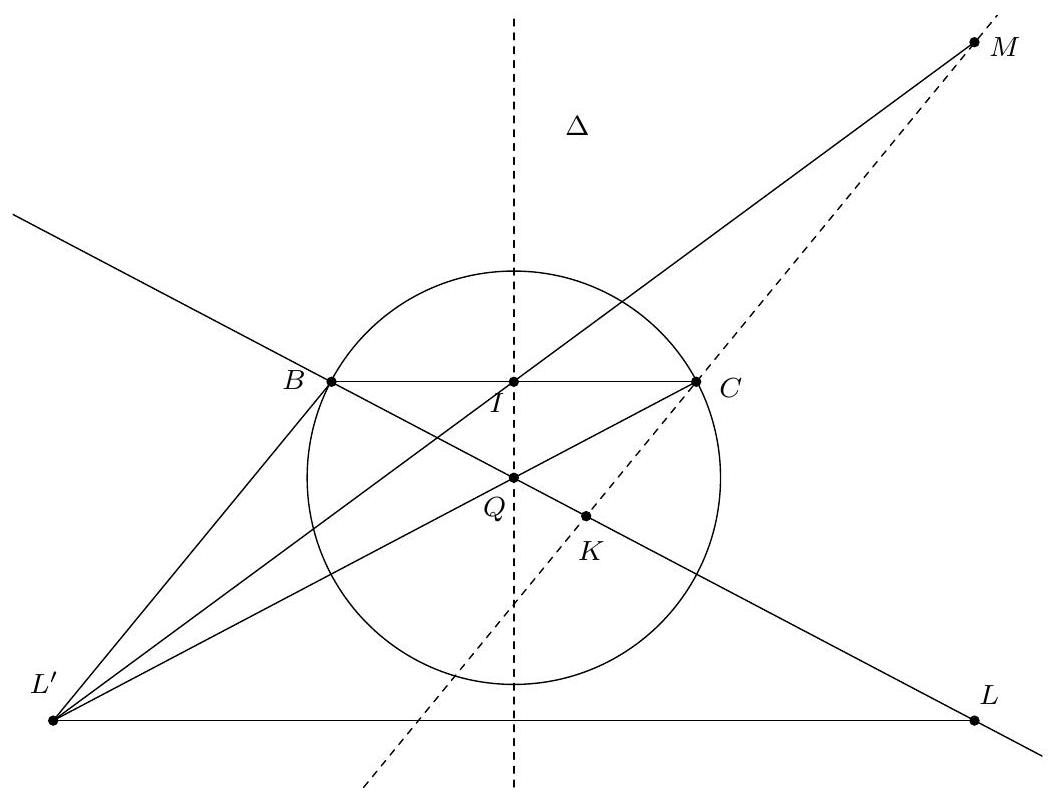

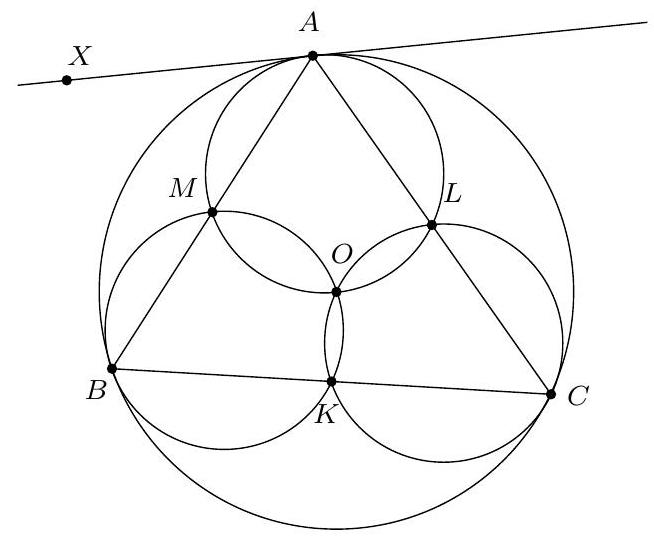

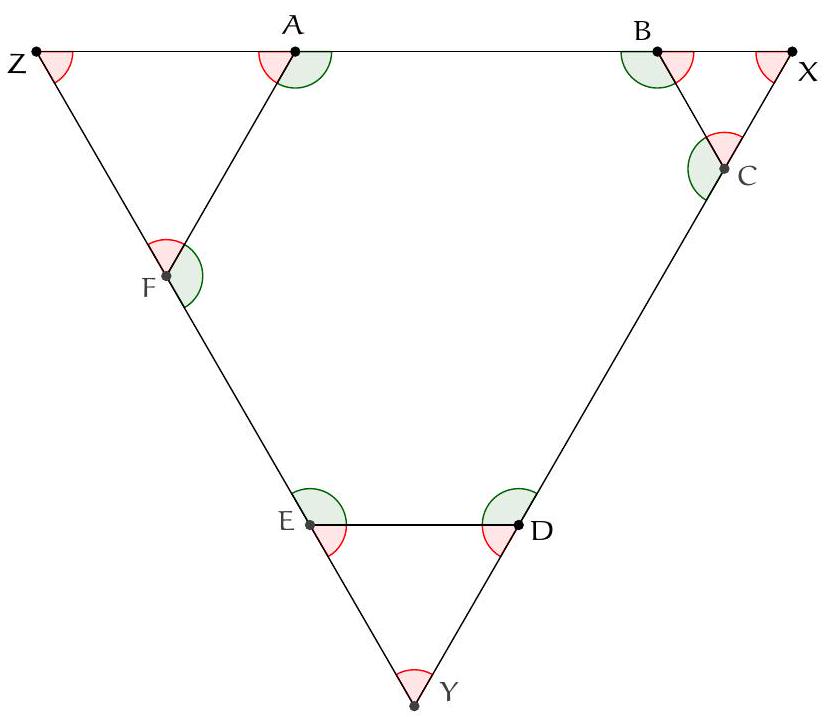

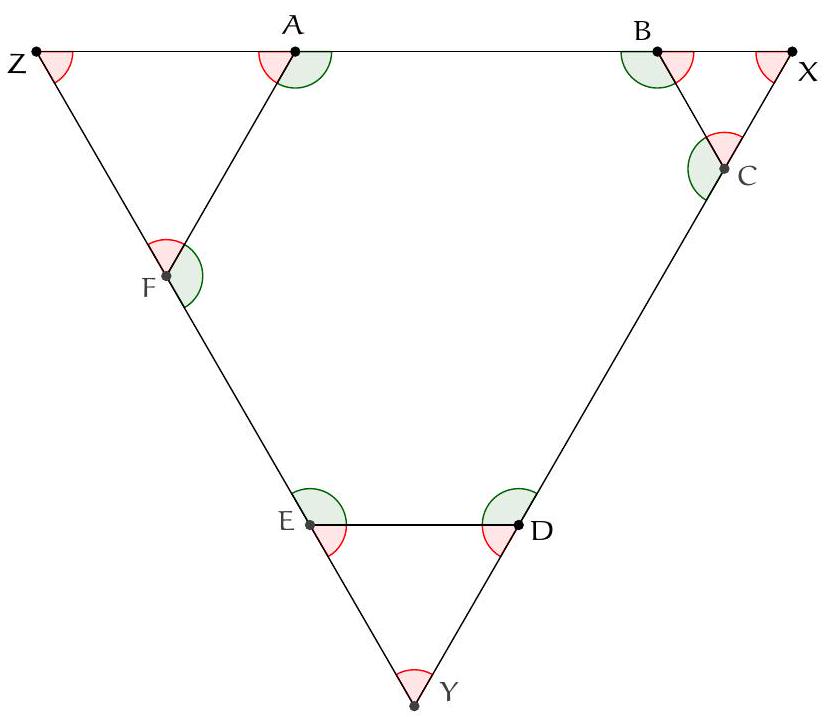

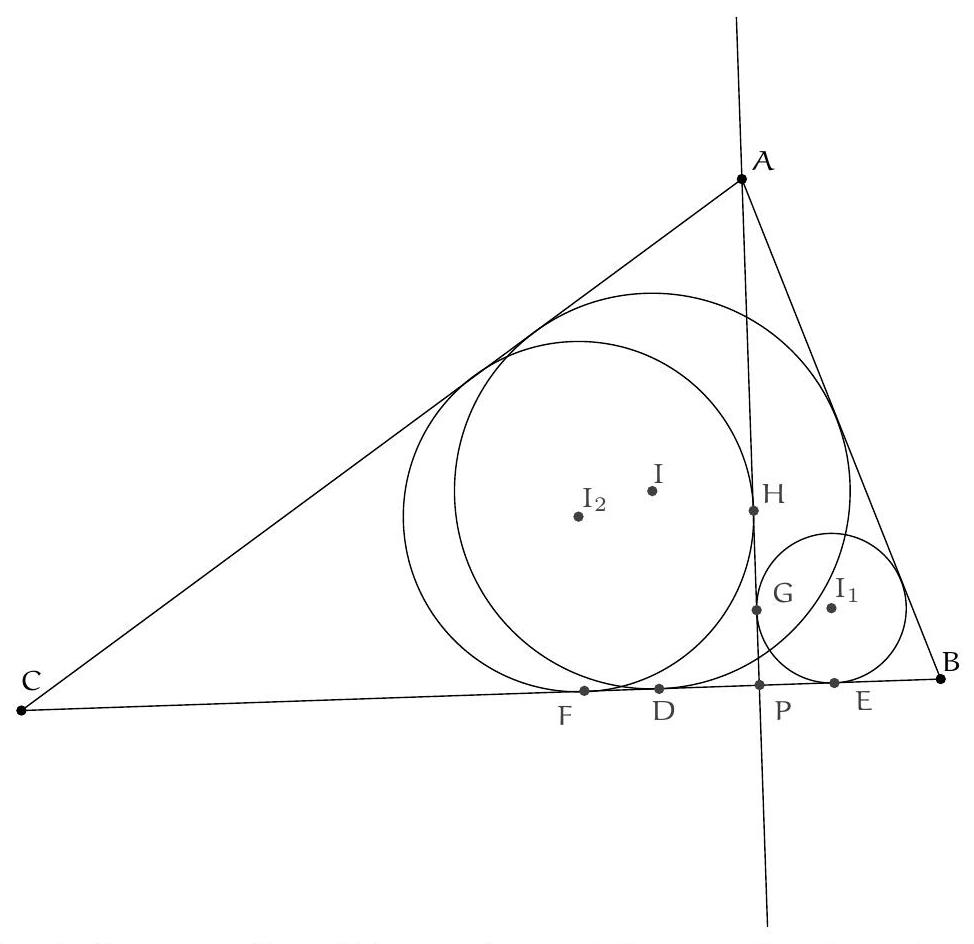

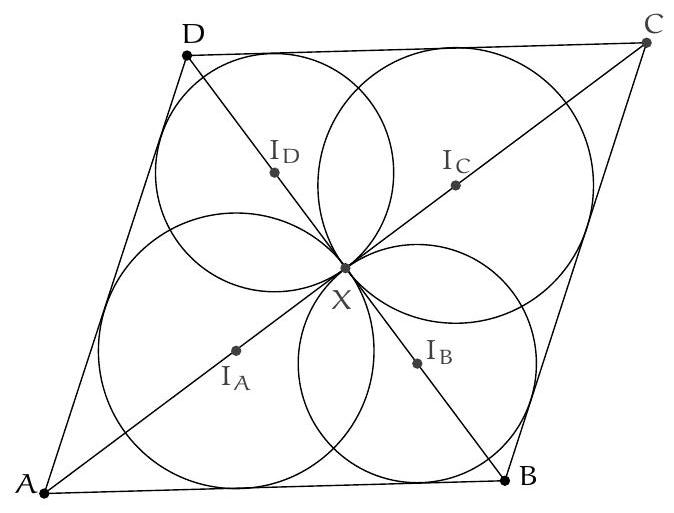

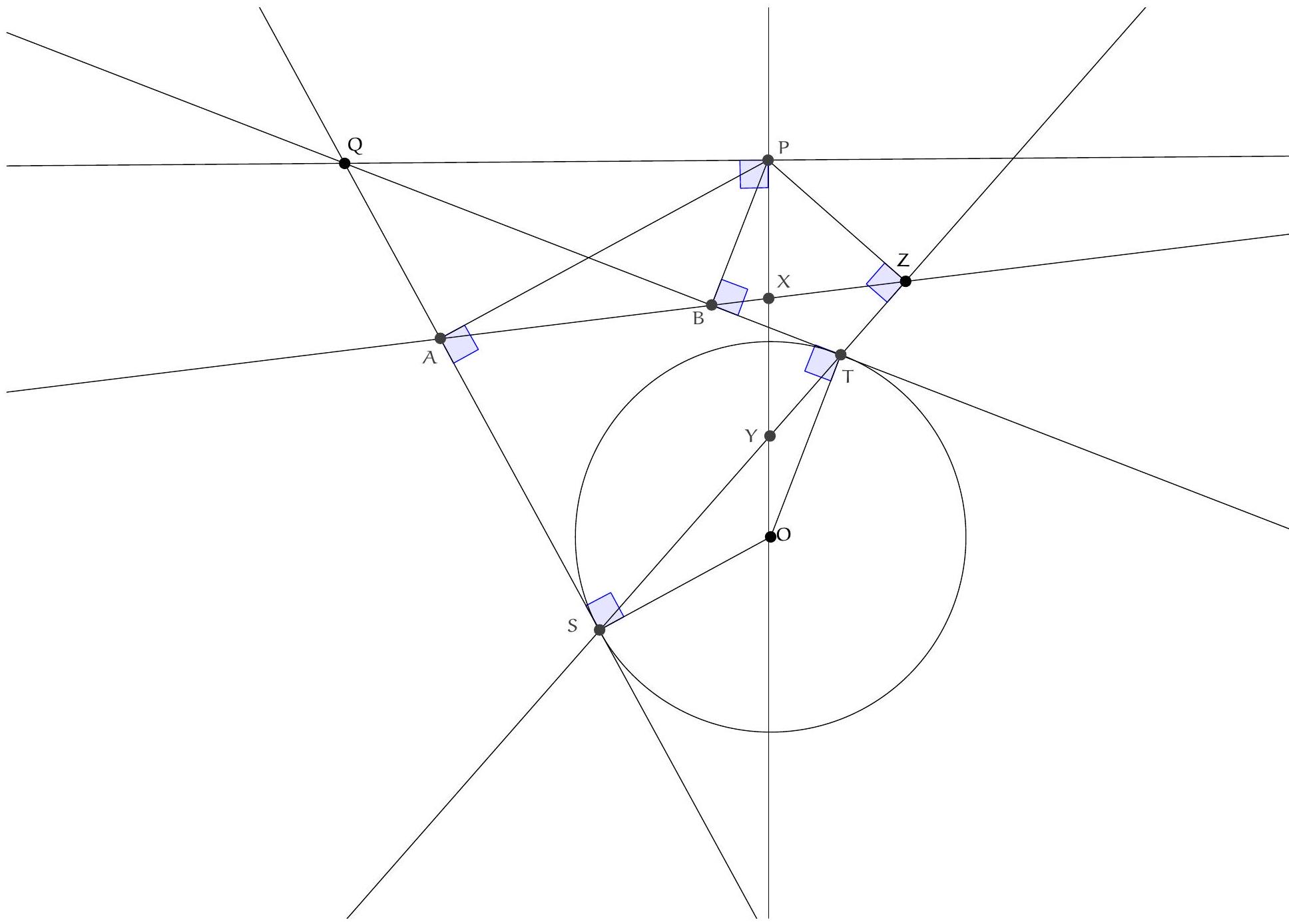

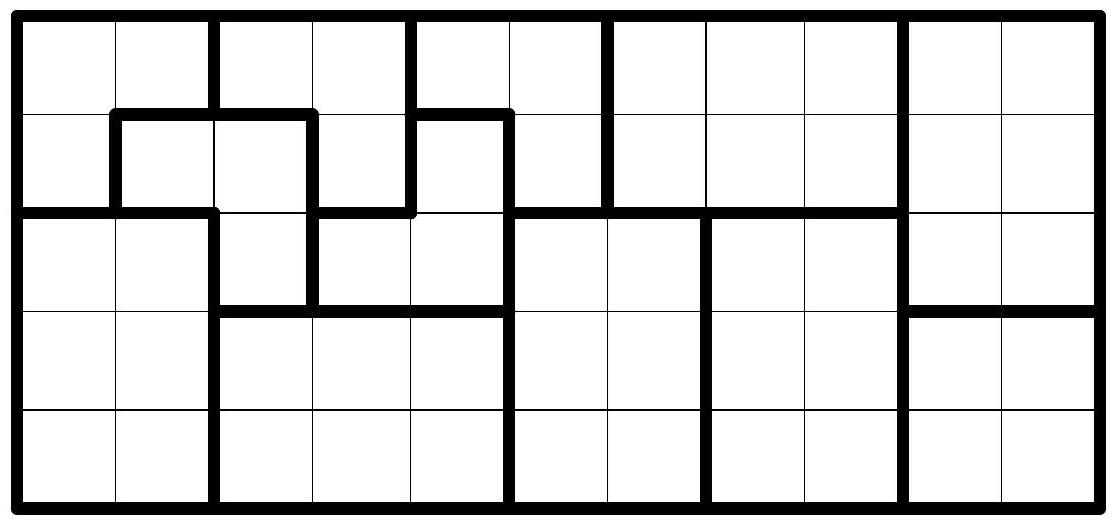

We are given $n$ points in the plane, such that no three of them are ever collinear. Each point is colored either red or blue. We assume that there is exactly one blue point inside each triangle whose vertices are red, and one red point inside each triangle whose vertices are blue.

What is the largest possible value of $n$?

## Exercise Group A

|

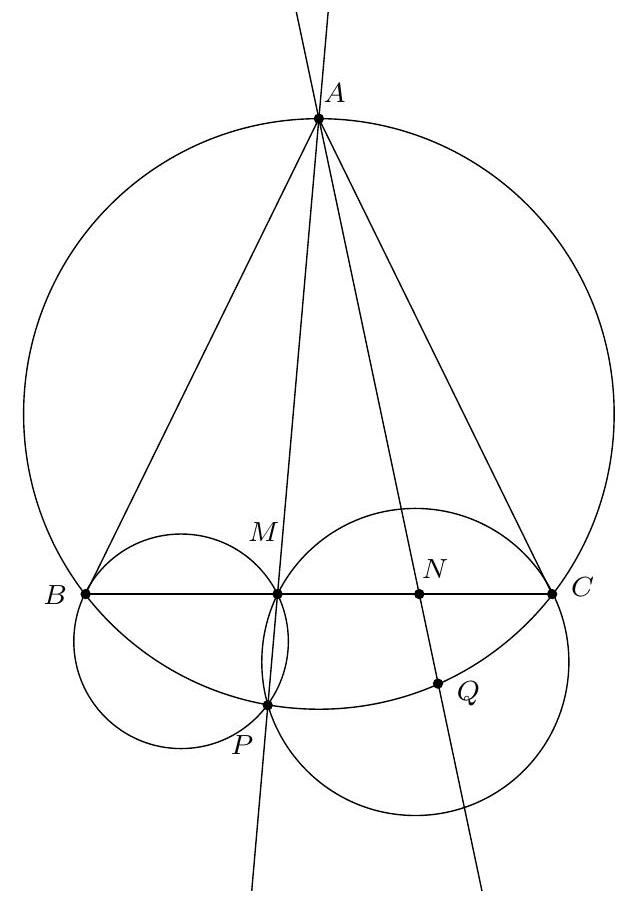

First, we show that the blue points form a convex polygon: if this were not the case, we could find a blue point inside a blue polygon, and by cutting this polygon into triangles, we could find a blue point inside a blue triangle. The large blue triangle must contain a single red point, but we can cut it into three triangles, each containing a single red point, which is absurd.

The blue points therefore form a convex polygon, as do the red points. Moreover, there can be at most 2 red points inside the blue polygon, because if there were 3, they would form a triangle with no blue point inside.

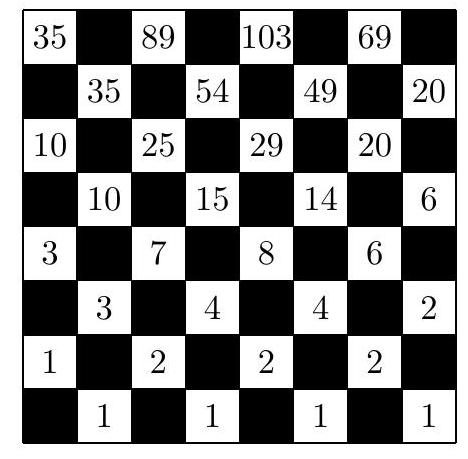

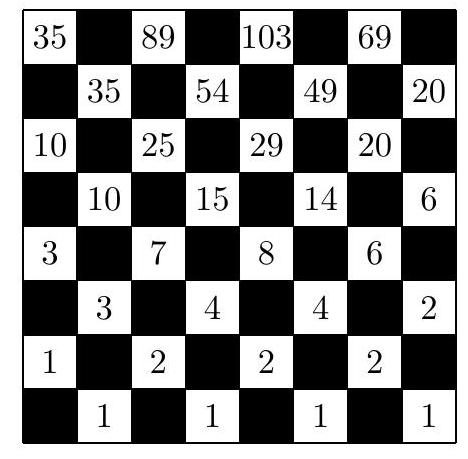

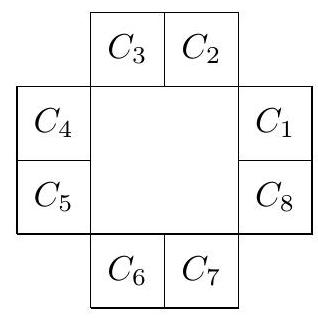

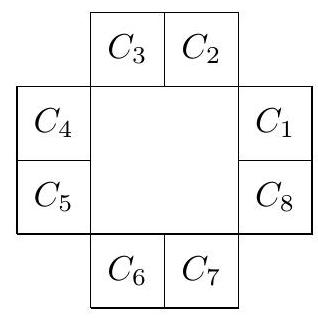

Finally, if $k$ is the number of blue points, we can cut the blue polygon into $k-2$ triangles, each of which must contain a red point, so $k-2 \leqslant 2$ and $k \leqslant 4$. Similarly, there can be at most 4 red points, so $\mathrm{n} \leqslant 8$. We can then verify that the following configuration with 8 points works:

|

8

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Combinatorics

|

On se donne $n$ points du plan, tels que trois quelconques d'entre eux ne sont jamais alignés. Chacun est colorié en rouge ou en bleu. On suppose qu'il y a exactement un point bleu à l'intérieur de chaque triangle dont les sommets sont rouges, et un point rouge à l'intérieur de chaque triangle dont les sommets sont bleus.

Quelle est la plus grande valeur possible de n?

## Exercices groupe A

|

On montre d'abord que les points bleus forment un polygone convexe: si ce n'était pas le cas, on pourrait trouver un point bleu à l'intérieur d'un polygone bleu, donc on en découpant ce polygone en triangles, on pourrait trouver un point bleu à l'intérieur d'un triangle bleu. Le grand triangle bleu doit contenir un unique point rouge, mais on peut le découper en trois triangles qui contiennent chacun un unique point rouge, ce qui est absurde.

Les points bleus forment donc un polygone convexe, de même que les rouges. De plus, il y a au maximum 2 points rouges à l'intérieur du polygone bleu, car s'il y en avait 3 ils formeraient un triangle sans point bleu à l'intérieur.

Enfin, si $k$ est le nombre de points bleus, on peut découper le polygone bleu en $k-2$ triangles, qui chacun doivent contenir un point rouge, donc $k-2 \leqslant 2$ et $k \leqslant 4$. De même, il y a au plus 4 points rouges donc $\mathrm{n} \leqslant 8$. On peut alors vérifier que la configuration à 8 points suivante convient:

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $E$ be a set of cardinality $n$ and $\mathscr{F}$ a set of subsets of $E$ with $|\mathscr{F}|=$ $2^{\text{n-1}}$ such that for all $A, B$ and $C$ in $\mathscr{F}, A \cap B \cap C$ is non-empty.

Show that the intersection of all elements of $\mathscr{F}$ is non-empty.

|

If $A \subset E$, we will denote $A^{c}$ its complement: the set of subsets of $E$ is partitioned into $2^{n-1}$ doubletons of the form $\left\{A, A^{c}\right\}$ where $A \subset E$. Now, it is impossible for both elements of a doubleton to be in $\mathscr{F}$, because their intersection is empty, so $\mathscr{F}$ contains exactly one element from each doubleton.

Let $A$ and $B$ be in $\mathscr{F}$: we will show that $A \cap B \in \mathscr{F}$. According to what we have just said, it suffices to show that $(A \cap B)^{c} \notin \mathscr{F}$. This is true because $A \cap B \cap (A \cap B)^{c}$ is empty.

By induction on $k$, we deduce that for all $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{k}$ in $\mathscr{F}, A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k} \in \mathscr{F}$. Indeed, it is true for $k=2$ and if we have shown it for $k$, then:

$$

A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k}=\left(A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k-1}\right) \cap A_{k}

$$

is the intersection of two elements of $\mathscr{F}$, so it is in $\mathscr{F}$.

Since $\mathscr{F}$ is finite, the intersection of all elements of $\mathscr{F}$ is in $\mathscr{F}$. However, the empty set cannot be in $\mathscr{F}$ because its intersection with itself is empty, so the intersection of all elements of $\mathscr{F}$ is not empty.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Combinatorics

|

Soient E un ensemble de cardinal n et $\mathscr{F}$ un ensemble de parties de E avec $|\mathscr{F}|=$ $2^{\text {n-1 }}$ tel que pour tous $A, B$ et $C$ dans $\mathscr{F}, A \cap B \cap C$ est non vide.

Montrer que l'intersection de tous les éléments de $\mathscr{F}$ est non vide.

|

Si $A \subset E$, on notera $A^{c}$ son complémentaire: l'ensemble des parties de $E$ est partitionné en $2^{n-1}$ doubletons de la forme $\left\{A, A^{c}\right\}$ où $A \subset E$. Or, il est impossible que les deux éléments d'un doubleton soient dans $\mathscr{F}$, car leur intersection est vide, donc $\mathscr{F}$ contient exactement un élément de chaque doubleton.

Soient donc $A$ et $B$ dans $\mathscr{F}$ : on va montrer que $A \cap B \in \mathscr{F}$. D'après ce qu'on vient de dire, il suffit de montrer $(A \cap B)^{c} \notin \mathscr{F}$. Or, ceci est vrai car $A \cap B \cap(A \cap B)^{c}$ est vide.

Par récurrence sur $k$, on en déduit que pour tous $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{k}$ de $\mathscr{F}, A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k} \in \mathscr{F}$. En effet, c'est vrai pour $k=2$ et si on l'a montré pour $k$, alors :

$$

A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k}=\left(A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap \ldots \cap A_{k-1}\right) \cap A_{k}

$$

est l'intersection de deux éléments de $\mathscr{F}$, donc est dans $\mathscr{F}$.

Comme $\mathscr{F}$ est fini, l'intersection de tous les éléments de $\mathscr{F}$ est dans $\mathscr{F}$. Or, l'ensemble vide ne peut pas être dans $\mathscr{F}$ car son intersection avec lui-même est vide, donc l'intersection de tous les éléments de $\mathscr{F}$ n'est pas vide.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-2-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 9",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Do there exist real numbers $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c}, \mathrm{d}>0$ and $e, f, \mathrm{~g}, \mathrm{~h}<0$ simultaneously satisfying

$$

a e+b c>0, e f+c g>0, f d+g h>0 \text { and } d a+h b>0 ?

$$

|

No, such real numbers do not exist. By contradiction: suppose such real numbers do exist. We start by rewriting the inequalities, but with only positive terms. We then have

$$

b c > a(-e) \text{ and } (-e)(-f) > c(-g) \text{ and } (-g)(-h) > (-f) d \text{ and } da > (-h) b

$$

If we multiply all these inequalities term by term (and since everything is positive, there is no danger), we get \( abcdefgh > abcbdefgh \), leading to the desired contradiction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Existe-t-il des réels $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c}, \mathrm{d}>0$ et $e, f, \mathrm{~g}, \mathrm{~h}<0$ vérifiant simultanément

$$

a e+b c>0, e f+c g>0, f d+g h>0 \text { et } d a+h b>0 ?

$$

|

Non, il n'en existe pas. Par l'absurde : supposons qu'il existe de tels réels.On commence par réécrire les inégalités, mais avec uniquement des termes positifs. On a donc

$$

b c>a(-e) \text { et }(-e)(-f)>c(-g) \text { et }(-g)(-h)>(-f) d \text { et da }>(-h) b

$$

Si l'on multiplie toutes ces inégalités membres à membres (et, comme tout est positif, il n'y a aucun danger), il vient abcdefgh > abcbdefgh, d'où la contradiction cherchée.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "1",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 1.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 1",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $a, b, c$ be real numbers such that $-1 \leqslant a x^{2}+b x+c \leqslant 1$ for $x=-1, x=0$ and $x=1$. Prove that

$$

-\frac{5}{4} \leqslant a x^{2}+b x+c \leqslant \frac{5}{4} \text { for all real } x \in[-1,1]

$$

|

Let $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})=\mathrm{ax}^{2}+\mathrm{bx}+\mathrm{c}$. Then $\mathrm{P}(-1)=\mathrm{a}-\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}, \mathrm{P}(0)=\mathrm{c}$ and $\mathrm{P}(1)=$ $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}$. And, according to the statement, we have $|\mathrm{P}(-1)| \leqslant 1,|\mathrm{P}(0)| \leqslant 1$ and $|\mathrm{P}(1)| \leqslant 1$.

Now, for any real $\chi$, we can directly verify that

$$

P(x)=\frac{x(x+1)}{2} P(1)-\frac{x(1-x)}{2} P(-1)+\left(1-x^{2}\right) P(0)

$$

- Let $x \in[0 ; 1]$. According to (1) and the triangle inequality, we get

$$

\begin{aligned}

|\mathrm{P}(x)| & \leqslant \frac{x(x+1)}{2}|\mathrm{P}(1)|+\frac{x(1-x)}{2}|\mathrm{P}(-1)|+\left(1-x^{2}\right)|\mathrm{P}(0)| \\

& \leqslant \frac{x(x+1)}{2}+\frac{x(1-x)}{2}+\left(1-x^{2}\right) \\

& =-x^{2}+x+1 \\

& =\frac{5}{4}-\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus, $|P(x)| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$.

- Let $x \in[-1 ; 0]$. According to (1) and the triangle inequality, we get this time

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \leqslant-\frac{x(x+1)}{2}|P(1)|-\frac{x(1-x)}{2}|P(-1)|+\left(1-x^{2}\right)|P(0)| \\

& \leqslant-\frac{x(x+1)}{2}-\frac{x(1-x)}{2}+\left(1-x^{2}\right) \\

& =-x^{2}-x+1 \\

& =\frac{5}{4}-\left(x+\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus, $|\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$, again.

Finally, for all $x \in[-1 ; 1]$, we have $|\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $a, b, c$ des réels tels que $-1 \leqslant a x^{2}+b x+c \leqslant 1$ pour $x=-1, x=0$ et $x=1$. Prouver que

$$

-\frac{5}{4} \leqslant a x^{2}+b x+c \leqslant \frac{5}{4} \text { pour tout réel } x \in[-1,1]

$$

|

Posons $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})=\mathrm{ax}{ }^{2}+\mathrm{bx}+\mathrm{c}$. Alors $\mathrm{P}(-1)=\mathrm{a}-\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}, \mathrm{P}(0)=\mathrm{c}$ et $\mathrm{P}(1)=$ $\mathrm{a}+\mathrm{b}+\mathrm{c}$. Et, d'après l'énoncé, on a $|\mathrm{P}(-1)| \leqslant 1,|\mathrm{P}(0)| \leqslant 1$ et $|\mathrm{P}(1)| \leqslant 1$.

Or, pour tout réel $\chi$, on vérifie directement que

$$

P(x)=\frac{x(x+1)}{2} P(1)-\frac{x(1-x)}{2} P(-1)+\left(1-x^{2}\right) P(0)

$$

- Soit $x \in[0 ; 1]$. D'après (1) et l'inégalité triangulaire, il vient

$$

\begin{aligned}

|\mathrm{P}(x)| & \leqslant \frac{x(x+1)}{2}|\mathrm{P}(1)|+\frac{x(1-x)}{2}|\mathrm{P}(-1)|+\left(1-x^{2}\right)|\mathrm{P}(0)| \\

& \leqslant \frac{x(x+1)}{2}+\frac{x(1-x)}{2}+\left(1-x^{2}\right) \\

& =-x^{2}+x+1 \\

& =\frac{5}{4}-\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Et ainsi $|P(x)| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$.

- Soit $x \in[-1 ; 0]$. D'après (1) et l'inégalité triangulaire, il vient cette fois

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \leqslant-\frac{x(x+1)}{2}|P(1)|-\frac{x(1-x)}{2}|P(-1)|+\left(1-x^{2}\right)|P(0)| \\

& \leqslant-\frac{x(x+1)}{2}-\frac{x(1-x)}{2}+\left(1-x^{2}\right) \\

& =-x^{2}-x+1 \\

& =\frac{5}{4}-\left(x+\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Et ainsi $|\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$, à nouveau.

Finalement, pour tout $x \in[-1 ; 1]$, on a $|\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})| \leqslant \frac{5}{4}$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "2",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 2.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 2",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Prove that, for all real $a \geqslant 0$, we have

$$

a^{3}+2 \geqslant a^{2}+2 \sqrt{a}

$$

|

For all real $a \geqslant 0$, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a^{3}-a^{2}-2 \sqrt{a}+2 & =a^{2}(a-1)-2(\sqrt{a}-1) \\

& =a^{2}(\sqrt{a}-1)(\sqrt{a}+1)-2(\sqrt{a}-1) \\

& =(\sqrt{a}-1)\left(a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1)-2\right) .(1)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now:

- If $a \geqslant 1$ then $\sqrt{a} \geqslant 1$ and $a^{2} \geqslant 1$. Thus, we have $\sqrt{a}-1 \geqslant 0$ and $a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1) \geqslant 2$. Therefore, each of the factors in (1) is positive, which ensures that the product is positive.

- If $a \leqslant 1$ then $\sqrt{a} \leqslant 1$ and $a^{2} \leqslant 1$. Thus, we have $\sqrt{a}-1 \leqslant 0$ and $a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1) \leqslant 2$. Therefore, each of the two factors in (1) is negative, and the product is thus still positive.

Finally, for all real $a \geqslant 0$, we have $a^{3}-a^{2}-2 \sqrt{a}+2 \geqslant 0$ or equivalently $a^{3}+2 \geqslant a^{2}+2 \sqrt{a}$.

## Common Exercises

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Prouver que, pour tout réel $a \geqslant 0$, on a

$$

a^{3}+2 \geqslant a^{2}+2 \sqrt{a}

$$

|

Pour tout réel $a \geqslant 0$, on a

$$

\begin{aligned}

a^{3}-a^{2}-2 \sqrt{a}+2 & =a^{2}(a-1)-2(\sqrt{a}-1) \\

& =a^{2}(\sqrt{a}-1)(\sqrt{a}+1)-2(\sqrt{a}-1) \\

& =(\sqrt{a}-1)\left(a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1)-2\right) .(1)

\end{aligned}

$$

Or:

- Si $a \geqslant 1$ alors $\sqrt{a} \geqslant 1$ et $a^{2} \geqslant 1$. Ainsi, on a $\sqrt{a}-1 \geqslant 0$ et $a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1) \geqslant 2$. Par suite, chacun des facteurs de (1) est positif, ce qui assure que le produit est positif.

- Si $a \leqslant 1$ alors $\sqrt{a} \leqslant 1$ et $a^{2} \leqslant 1$. Ainsi, on a $\sqrt{a}-1 \leqslant 0$ et $a^{2}(\sqrt{a}+1) \leqslant 2$. Par suite, chacun des deux facteurs de (1) est négatif, et le produit est donc encore positif.

Finalement, pour tout réel $a \geqslant 0$, on a $a^{3}-a^{2}-2 \sqrt{a}+2 \geqslant 0$ ou encore $a^{3}+2 \geqslant a^{2}+2 \sqrt{a}$.

## Exercices Communs

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "3",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 3.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 3",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Prove that if $n$ is a strictly positive integer, the expression

$$

\frac{\sqrt{n+\sqrt{0}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{1}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{2}}+\cdots \sqrt{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-1}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{n^{2}}}}{\sqrt{n-\sqrt{0}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{1}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{2}}+\cdots \sqrt{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-1}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{n^{2}}}}

$$

is independent of $n$.

|

By squaring each of the two members, we deduce that, for all real numbers $a, b$ such that $0 \leqslant b \leqslant a$, we have

$$

\sqrt{a+\sqrt{a^{2}-b^{2}}}=\sqrt{\frac{a+b}{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{a-b}{2}}

$$

In particular, for all natural numbers $n$ and $m$, with $m \leqslant n^{2}$, we have

$$

\sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}

$$

Let $\mathrm{n}>0$ be an integer. We therefore have

$$

\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}+\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}

$$

Thus, after reindexing:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}} & =\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{m}}{2}}+\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{m}}{2}} \\

& =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}

\end{aligned}

$$

Thus $\left(1-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}$

and therefore $\frac{\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}}{\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}}=1+\sqrt{2}$, which is indeed a value.

|

1+\sqrt{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Prouver que si $n$ est un entier strictement positif, l'expression

$$

\frac{\sqrt{n+\sqrt{0}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{1}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{2}}+\cdots \sqrt{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-1}}+\sqrt{n+\sqrt{n^{2}}}}{\sqrt{n-\sqrt{0}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{1}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{2}}+\cdots \sqrt{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-1}}+\sqrt{n-\sqrt{n^{2}}}}

$$

est indépendante de n .

|

En calculant le carré de chacun des deux membres, on déduit que, pour tous réels $a, b$ tels que $0 \leqslant b \leqslant a$, on a

$$

\sqrt{a+\sqrt{a^{2}-b^{2}}}=\sqrt{\frac{a+b}{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{a-b}{2}}

$$

En particulier, pour tous entiers naturels $n$ et $m$, avec $m \leqslant n^{2}$, on a

$$

\sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}

$$

Soit $\mathrm{n}>0$ un entier. On a donc

$$

\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}+\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{n^{2}-m}}{2}}

$$

D'où, après réindexation :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}} & =\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n+\sqrt{m}}{2}}+\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{\frac{n-\sqrt{m}}{2}} \\

& =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}

\end{aligned}

$$

$\operatorname{Ainsi}\left(1-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right) \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}$

et donc $\frac{\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n+\sqrt{m}}}{\sum_{m=0}^{n^{2}} \sqrt{n-\sqrt{m}}}=1+\sqrt{2}$, qui est bien une valeur

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "4",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 4.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 4",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $(a_{n})$ be a sequence defined by $a_{1}, a_{2} \in [0,100]$ and

$$

a_{n+1}=a_{n}+\frac{a_{n-1}}{n^{2}-1} \quad \text { for all integer } n \geqslant 2

$$

Does there exist an integer $n$ such that $a_{n}>2013$?

|

The answer is no.

More precisely, let us show by induction that $a_{n} \leqslant 400$, for all $n \geqslant 0$.

The inequality is true for $n=1$ and $n=2$, according to the statement.

Suppose it is true for all $k \leqslant n$ for some integer $n \geqslant 2$.

For all $k \in\{2, \cdots, n\}$, we have $a_{k+1}=a_{k}+\frac{a_{k-1}}{k^{2}-1}$. By summing these relations member by member and after simplifying the common terms, we get:

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{n+1} & =a_{2}+\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{a_{k-1}}{k^{2}-1} \\

& \leqslant 100+\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{400}{k^{2}-1}, \text { according to the induction hypothesis and the statement } \\

& =100+200 \sum_{k=2}^{n}\left(\frac{1}{k-1}-\frac{1}{k+1}\right) \\

& =100+200\left(1+\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}\right) \text { after simplification by dominoes } \\

& =400-\frac{200}{n}-\frac{200}{n+1}

\end{aligned}

$$

and thus $a_{n+1} \leqslant 400$, which completes the induction.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Soit ( $a_{n}$ ) une suite définie par $a_{1}, a_{2} \in[0,100]$ et

$$

a_{n+1}=a_{n}+\frac{a_{n-1}}{n^{2}-1} \quad \text { pour tout enter } n \geqslant 2

$$

Existe-t-il un entier $n$ tel que $a_{n}>2013$ ?

|

La réponse est non.

Plus précisément, montrons par récurrence que l'on a $a_{n} \leqslant 400$, pour tout $n \geqslant 0$.

L'inégalité est vraie pour $\mathrm{n}=1$ et $\mathrm{n}=2$, d'après l'énoncé.

Supposons qu'elle soit vraie pour tout $k \leqslant n$ pour un certain entier $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$.

Pour tout $k \in\{2, \cdots, n\}$, on a $a_{k+1}=a_{k}+\frac{a_{k-1}}{k^{2}-1}$. En sommant, membre à membre, ces relations et après simplification des termes communs, il vient:

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{n+1} & =a_{2}+\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{a_{k-1}}{k^{2}-1} \\

& \leqslant 100+\sum_{k=2}^{n} \frac{400}{k^{2}-1}, \text { d'après l'hypothèse de récurrence et l'énoncé } \\

& =100+200 \sum_{k=2}^{n}\left(\frac{1}{k-1}-\frac{1}{k+1}\right) \\

& =100+200\left(1+\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1}\right) \text { après simplification par dominos } \\

& =400-\frac{200}{n}-\frac{200}{n+1}

\end{aligned}

$$

et donc $a_{n+1} \leqslant 400$, ce qui achève la récurrence.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "5",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 5.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 5",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Determine the greatest possible value and the smallest possible value of

$$

\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}}

$$

when $a, b, c$ are strictly positive real numbers satisfying $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=6$.

|

First, we note that for the expression to make sense, it is required that $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c} \in$ [0; 2].

According to the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we have

$\left(\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}}\right)^{2} \leqslant 3\left(4-a^{2}+4-b^{2}+4-c^{2}\right)=18$,

i.e., $\sqrt{4-\mathrm{a}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{b}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{c}^{2}} \leqslant 3 \sqrt{2}$, with equality for $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=\sqrt{2}$.

Thus, the maximum possible value is $3 \sqrt{2}$.

Now let's find the minimum value:

Without loss of generality, we can assume that $a \leqslant b \leqslant c$.

From $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=6$, we deduce that $3 a^{2} \leqslant 6$, hence $0 \leqslant a^{2} \leqslant 2$.

On the other hand, if $x, y \geqslant 0$, it is clear that $\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{y} \leqslant \sqrt{x+y}$, with equality if and only if $x=0$ or $\mathrm{y}=0$.

It follows that

$\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}} \geqslant \sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{8-b^{2}-c^{2}}=\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{2+a^{2}}$,

and, since $0 \leqslant 4-\mathrm{c}^{2} \leqslant 4-\mathrm{b}^{2}$, equality holds if and only if $4-\mathrm{c}^{2}=0$, i.e., $\mathrm{c}=2$.

It remains to find the minimum of the expression $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})=\sqrt{4-\mathrm{x}}+\sqrt{2+\mathrm{x}}$, when $x \in[0 ; 2]$. Since everything is positive, this is equivalent to finding the minimum of $(f(x))^{2}=6+2 \sqrt{(4-x)(2+x)}$, under the same conditions.

Since $(4-x)(2+x)=-x^{2}+2 x+8=9-(x-1)^{2}$, the minimum value of $\sqrt{(4-x)(2+x)}$ is $\sqrt{8}$, with equality for $x=0$.

Thus, we have $(\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x}))^{2} \geqslant 6+2 \sqrt{8}=(2+\sqrt{2})^{2}$, or $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x}) \geqslant 2+\sqrt{2}$, with equality for $\mathrm{x}=0$.

Therefore, $\sqrt{4-\mathrm{a}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{b}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{c}^{2}} \geqslant 2+\sqrt{2}$, with equality in particular for $(\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c})=$ $(0, \sqrt{2}, 2)$.

This ensures that the smallest value sought is $2+\sqrt{2}$.

## Exercises of Group A

|

3\sqrt{2} \text{ and } 2+\sqrt{2}

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Inequalities

|

Déterminer la plus grande valeur possible et la plus petite valeur possible de

$$

\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}}

$$

lorsque $a, b, c$ sont des réels strictement positifs vérifiant $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=6$.

|

Tout d'abord, on note que si l'on veut que l'expression ait un sens, il faut $\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c} \in$ [0; 2].

D'après l'inégalité de Cauchy-Schwarz, on a

$\left(\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}}\right)^{2} \leqslant 3\left(4-a^{2}+4-b^{2}+4-c^{2}\right)=18$,

c.à.d. $\sqrt{4-\mathrm{a}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{b}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{c}^{2}} \leqslant 3 \sqrt{2}$, avec égalité pour $\mathrm{a}=\mathrm{b}=\mathrm{c}=\sqrt{2}$.

Ainsi, la plus grande valeur possible est $3 \sqrt{2}$.

Cherchons maintenant la valeur minimale :

Sans perte de généralité, on peut supposer que $a \leqslant b \leqslant c$.

De $a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2}=6$, on déduit alors que $3 a^{2} \leqslant 6$, soit donc $0 \leqslant a^{2} \leqslant 2$.

D'autre part, si $x, y \geqslant 0$, on a clairement $\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{y} \leqslant \sqrt{x+y}$, avec égalité si et seulement si $x=0$ ou $\mathrm{y}=0$.

Il vient alors

$\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{4-b^{2}}+\sqrt{4-c^{2}} \geqslant \sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{8-b^{2}-c^{2}}=\sqrt{4-a^{2}}+\sqrt{2+a^{2}}$,

et, puisque $0 \leqslant 4-\mathrm{c}^{2} \leqslant 4-\mathrm{b}^{2}$, égalité a lieu si et seulement si $4-\mathrm{c}^{2}=0$, c.à $\mathrm{d} . \mathrm{c}=2$.

Il reste donc à trouver le minimum de l'expression $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})=\sqrt{4-\mathrm{x}}+\sqrt{2+\mathrm{x}}$, lorsque $x \in[0 ; 2]$. Or, puisque tout est positif, cela revient à trouver le minimum de $(f(x))^{2}=6+2 \sqrt{(4-x)(2+x)}$, sous les mêmes conditions.

Comme $(4-x)(2+x)=-x^{2}+2 x+8=9-(x-1)^{2}$, la valeur minimale de $\sqrt{(4-x)(2+x)}$ est $\sqrt{8}$, avec égalité pour $x=0$.

Ainsi, on a $(\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x}))^{2} \geqslant 6+2 \sqrt{8}=(2+\sqrt{2})^{2}$, ou encore $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x}) \geqslant 2+\sqrt{2}$, avec égalité pour $\mathrm{x}=0$.

Par suite, on a $\sqrt{4-\mathrm{a}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{b}^{2}}+\sqrt{4-\mathrm{c}^{2}} \geqslant 2+\sqrt{2}$, avec égalité en particulier pour $(\mathrm{a}, \mathrm{b}, \mathrm{c})=$ $(0, \sqrt{2}, 2)$.

Cela assure que la plus petite valeur cherchée est $2+\sqrt{2}$.

## Exercices du groupe A

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "6",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 6.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 6",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Determine all functions $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{R} \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+*}$ that satisfy the following three conditions for all real numbers $x$ and $y$:

i) $f\left(x^{2}\right)=f(x)^{2}-2 x f(x)$,

ii) $f(-x)=f(x-1)$,

iii) if $1<x<y$ then $f(x)<f(y)$.

|

We will prove that the only solution is $\mathrm{f}: x \longrightarrow x^{2}+x+1$.

Let $f$ be a potential solution to the problem.

From i), for $x=0$, we deduce that $f(0)=f^{2}(0)$. And, since $f(0)>0$, we have $f(0)=1$.

Let $x$ be a real number. Using i) for the values $x$ and $-x$, we get

$f(x)^{2}-2 x f(x)=f\left(x^{2}\right)=f(-x)^{2}+2 x f(-x)$,

or equivalently $(f(x)-f(-x))(f(x)+f(-x))=2 x(f(x)+f(-x))$.

Since $f$ takes strictly positive values, we have $f(x)+f(-x) \neq 0$,

and thus $f(x)-f(-x)=2 x$.

Finally, and from ii), we have

$$

f(x)=f(x-1)+2 x \text {, for all real } x .(1)

$$

In particular, we easily deduce from (1) that, for all integers $n \geqslant 0$, we have

$$

\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=\mathrm{f}(0)+2(\mathrm{n}+(\mathrm{n}-1)+\cdots+1)=\mathrm{n}^{2}+\mathrm{n}+1

$$

From ii), we then obtain that

$$

f(n)=n^{2}+n+1 \text { for all integers } n

$$

Let $x$ be a real number and $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 0$ an integer.

For all integers $k$, we have $f(x+k)=2 x+2 k+f(x+k-1)$.

After summing these relations for $k=0,1, \cdots, n$ and simplifying the common terms, we get

$\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x}+\mathfrak{n})=2 \mathbf{n} x+2(\mathfrak{n}+(\mathfrak{n}-1)+\cdots+1)+\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x})$.

Thus:

$$

f(x+n)=f(x)+2 n x+n^{2}+n, \text { for all real } x \text { and all integers } n \geqslant 0 \text {. (2) }

$$

This will allow us to conclude for positive rationals:

Let $x=\frac{m}{n}$, with $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}>0$ integers.

From (2), we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{f}\left((x+\mathrm{n})^{2}\right) & =\mathrm{f}\left(x^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) \\

& =\mathrm{f}\left(x^{2}\right)+2\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) \mathrm{x}^{2}+\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right)^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2} \\

& =\mathrm{f}^{2}(x)-2 \mathrm{xf}(x)+2\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) x^{2}+\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right)^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

But, from i) and (2), we also have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathbf{f}\left((x+n)^{2}\right) & =f^{2}(x+n)+2(x+n) f(x+n) \\

& =\left(f(x)+2 m+n^{2}+n\right)^{2}-2(x+n)\left(f(x)+2 m+n^{2}+n\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

By identifying the last two expressions of $f\left((x+n)^{2}\right)$, and after a thrilling calculation, we obtain that

$$

f(x)=x^{2}+x+1, \text { for all positive rationals } x

$$

Let $x>1$ be a real number.

We know that there exist two sequences of positive rationals, $\left(u_{n}\right)$ and $\left(v_{n}\right)$, which converge to $x$ and such that $u_{n} \leqslant w \leqslant v_{n}$ for all integers $n$.

Since, from iii), the function $f$ is strictly increasing on $] 1 ;+\infty\left[\right.$, for all integers $n$, we have $f\left(u_{n}\right)<$ $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})<\mathrm{f}\left(v_{\mathrm{n}}\right)$,

or equivalently $u_{n}^{2}+u_{n}+1<f(x)<v_{n}^{2}+v_{n}+1$.

By letting $n$ tend to $+\infty$, and according to the squeeze theorem, we then get $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$.

$$

\text { Thus, we have } f(x)=x^{2}+x+1 \text {, for all real } x>1 \text { (3) }

$$

Let's now deliver the final blow.

Let $x$ be a real number.

We choose an integer $\mathrm{n}>0$ such that $x+n>1$.

From (2) and (3), we deduce that

$\mathbf{f}(x+\mathfrak{n})=(x+\mathfrak{n})^{2}+(x+\mathfrak{n})+1$ and $\mathbf{f}(x+\mathfrak{n})=\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x})+2 \mathfrak{n} x+\mathfrak{n}^{2}+\mathfrak{n}$.

By identifying these two expressions, and after some more calculations, we get $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$.

Finally, we have $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$, for all real $x$.

It is routine to verify that this function is indeed a solution to the problem.

|

f(x)=x^{2}+x+1

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

math-word-problem

|

Algebra

|

Déterminer toutes les fonctions $\mathrm{f}: \mathbb{R} \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+*}$ qui vérifient les trois conditions suivantes pour tous réels $x$ et $y$ :

i) $f\left(x^{2}\right)=f(x)^{2}-2 x f(x)$,

ii) $f(-x)=f(x-1)$,

iii) si $1<x<y$ alors $f(x)<f(y)$.

|

Nous allons prouver que la seule solution est $\mathrm{f}: x \longrightarrow x^{2}+x+1$.

Soit $f$ une solution éventuelle du problème.

De i ), pour $x=0$, on déduit que $f(0)=f^{2}(0)$. Et, comme $f(0)>0$, on a donc $f(0)=1$.

Soit $x$ un réel. En utilisant i) pour les valeurs $x$ et $-x$, il vient

$f(x)^{2}-2 x f(x)=f\left(x^{2}\right)=f(-x)^{2}+2 x f(-x)$,

ou encore $(f(x)-f(-x))(f(x)+f(-x))=2 x(f(x)+f(-x))$.

Puisque $f$ est à valeurs strictement positives, on a $f(x)+f(-x) \neq 0$,

et donc $f(x)-f(-x)=2 x$.

Finalement, et d'après ii), on a

$$

f(x)=f(x-1)+2 x \text {, pour tout réel } x .(1)

$$

En particulier, on déduit facilement de (1) que, pour tout entier $n \geqslant 0$, on a

$$

\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{n})=\mathrm{f}(0)+2(\mathrm{n}+(\mathrm{n}-1)+\cdots+1)=\mathrm{n}^{2}+\mathrm{n}+1

$$

De ii), on obtient alors que

$$

f(n)=n^{2}+n+1 \text { pour tout entier } n

$$

Soit $x$ un réel et $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 0$ un entier.

Pour tout entier $k$, on a $f(x+k)=2 x+2 k+f(x+k-1)$.

Après sommation membre à membre de toutes ces relations pour $k=0,1, \cdots, n$, et simplification des termes communs, il vient

$\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x}+\mathfrak{n})=2 \mathbf{n} x+2(\mathfrak{n}+(\mathfrak{n}-1)+\cdots+1)+\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x})$.

Et ainsi :

$$

f(x+n)=f(x)+2 n x+n^{2}+n, \text { pour tout réel } x \text { et tout entier } n \geqslant 0 \text {. (2) }

$$

Cela va nous permettre de conclure sur les rationnels positifs :

Soit $x=\frac{m}{n}$, avec $\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{n}>0$ entiers.

D'après (2), on a

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{f}\left((x+\mathrm{n})^{2}\right) & =\mathrm{f}\left(x^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) \\

& =\mathrm{f}\left(x^{2}\right)+2\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) \mathrm{x}^{2}+\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right)^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2} \\

& =\mathrm{f}^{2}(x)-2 \mathrm{xf}(x)+2\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right) x^{2}+\left(2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}\right)^{2}+2 \mathrm{~m}+\mathrm{n}^{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

Mais, d'après i) et (2), on a également

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathbf{f}\left((x+n)^{2}\right) & =f^{2}(x+n)+2(x+n) f(x+n) \\

& =\left(f(x)+2 m+n^{2}+n\right)^{2}-2(x+n)\left(f(x)+2 m+n^{2}+n\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

En identifiant les deux dernières expressions de $f\left((x+n)^{2}\right)$, et après un calcul passionnant, on obtient que

$$

f(x)=x^{2}+x+1, \text { pour tout rationnel } x>0

$$

Soit $x>1$ un réel.

On sait qu'il existe deux suites de rationnels positifs, $\left(u_{n}\right)$ et $\left(v_{n}\right)$, qui convergent vers $x$ et telles que $u_{n} \leqslant w \leqslant v_{n}$ pour tout entier $n$.

Or, d'après iii), la fonction $f$ est strictement croissante sur $] 1 ;+\infty\left[\right.$ donc, pour tout entier $n$, on a $f\left(u_{n}\right)<$ $\mathrm{f}(\mathrm{x})<\mathrm{f}\left(v_{\mathrm{n}}\right)$,

ou encore $u_{n}^{2}+u_{n}+1<f(x)<v_{n}^{2}+v_{n}+1$.

En faisant tendre $n$ vers $+\infty$, et d'après le théorème des gendarmes, il vient alors $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$.

$$

\text { Ainsi, on a } f(x)=x^{2}+x+1 \text {, pour tout réel } x>1 \text { (3) }

$$

Donnons maintenant le coup de grâce.

Soit $x$ un réel.

On choisit un entier $\mathrm{n}>0$ tel que $x+n>1$.

De (2) et (3), on déduit que

$\mathbf{f}(x+\mathfrak{n})=(x+\mathfrak{n})^{2}+(x+\mathfrak{n})+1$ et $\mathbf{f}(x+\mathfrak{n})=\mathbf{f}(\mathrm{x})+2 \mathfrak{n} x+\mathfrak{n}^{2}+\mathfrak{n}$.

En identifiant ces deux expressions, et après encore quelques calculs, il vient $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$.

Et finalement, on a $f(x)=x^{2}+x+1$, pour tout réel $x$.

Ce n'est que routine que de vérifier que cette fonction est bien une solution du problème.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "7",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 7.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 7",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let P and Q be two polynomials with real coefficients, of degrees $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 0$. Suppose that the coefficient of $x^{n}$ of each of these two polynomials is equal to 1 and that, for all real $x$, we have $P(P(x))=$ $\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})$ ).

Prove that $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{Q}$.

|

The result is evident if $\mathrm{n}=0$. In what follows, we therefore assume that $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$.

By contradiction: suppose that the polynomial $\mathrm{R}=\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{Q}$ is not the zero polynomial.

Let $k$ be the degree of R.

Since $P$ and $Q$ are both of degree $n$, and have the same leading coefficient, we have $k \in\{0, \cdots, n-1\}$. Furthermore, we have

$$

P(P(x))-Q(Q(x))=[Q(P(x))-Q(Q(x))]+R(P(x))

$$

Let $Q(x)=x^{n}+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+\cdots+a_{1} x+a_{0}$.

We notice that then

$$

\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x}))-\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))=\left[\mathrm{P}^{n}(x)-\mathrm{Q}^{n}(x)\right]+\mathrm{a}_{n-1}\left[\mathrm{P}^{n-1}(x)-\mathrm{Q}^{n-1}(x)\right]+\cdots+\mathrm{a}_{1}[\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})-\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})]

$$

and each term of this sum other than $\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]$ is of degree at most $n(n-1)$. On the other hand, we have

$$

\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]=R(x)\left[P^{n-1}(x)+P^{n-2}(x) Q(x)+\cdots+Q^{n-1}(x)\right]

$$

which ensures that $\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]$ is of degree $n(n-1)+k$ and has a leading coefficient equal to $n$ (we recall that $P$ and $Q$ both have a leading coefficient equal to 1).

- Suppose that $k>0$.

Then, the polynomial $Q(P(x))-Q(Q(x))$ is of degree $n(n-1)+k$.

On the other hand, the degree of $R(P(x))$ is $k n$, and we have $k n \leqslant n(n-1)<n(n-1)+k$.

From (1), we deduce that $P(P(x))-Q(Q(x))$ is of degree $n(n-1)+k$, and therefore non-zero, in contradiction with the statement.

- It remains to study the case where $k=0$, i.e., when $R$ is constant.

Let $c$ be this constant. Our initial hypothesis ensures that $c \neq 0$.

From $P(P(x))=Q(Q(x))$, it follows that $\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})+\mathrm{c})=\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))-\mathrm{c}$.

Since $Q$ is not constant, this means that the equality $Q(y+c)=Q(y)-c$ is true for an infinite number of real numbers $y$. Since these are polynomials, this means that it is true for all real numbers $y$.

An immediate induction then leads to $Q(j c)=a_{0}-j c$ for all integers $j \geqslant 0$.

As above, the equality $Q(x)=-x+a_{0}$ being true for an infinite number of values (since $c \neq 0$), it is therefore true for all $x$. This contradicts that $Q$ has a leading coefficient equal to 1.

Thus, in all cases, we have obtained a contradiction. This ensures that $R$ is indeed the zero polynomial, and completes the proof.

## Another solution.

The result is easy to show if $\mathfrak{n}=0$ or $\mathfrak{n}=1$. In what follows, we therefore assume that $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$. Let $R=P-Q$ and suppose by contradiction that it is non-zero. Without loss of generality, we can assume that the leading coefficient of $R$ is strictly positive.

Lemma 1. For any polynomial $R$ with a strictly positive leading coefficient, there exists a real number $a$ such that for all $x \geqslant a$ we have $R(x)>0$.

Indeed, $R(x)$ can be written in the form $c x^{m}\left(1+\frac{c_{1}}{x}+\cdots+\frac{c_{m}}{x^{m}}\right)$ with $c>0$. The term in parentheses tends to 1 as $x \rightarrow+\infty$, so it is strictly positive for $x$ sufficiently large.

Lemma 2. For any polynomial $P$ of degree $\geqslant 1$ with a strictly positive leading coefficient, there exists $a$ such that $P$ is strictly increasing on $[a, +\infty[$.

Indeed, the derivative polynomial $P^{\prime}$ satisfies the conditions of Lemma 1, so $P^{\prime}(x)$ is strictly positive for $x$ sufficiently large.

Returning to the exercise. From the two preceding lemmas, there exists $a$ such that on $[a, +\infty[$, $P$ and $Q$ are strictly increasing, and $R$ and $R \circ Q$ are strictly positive.

We then have for all $x \geqslant a$:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})) & >\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{Q}(x)) \quad \text { since } \mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})>\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}) \\

& =\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))+\mathrm{R}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})) \\

& >\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))

\end{aligned}

$$

which contradicts $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x}))=\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))$.

|

proof

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Algebra

|

Soit P et Q deux polynômes à coefficients réels, de degrés $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 0$. On suppose que le coefficient de $x^{n}$ de chacun de ces deux polynômes est égal à 1 et que, pour tout réel $x$, on a $P(P(x))=$ $\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})$ ).

Prouver que $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{Q}$.

|

Le résultat est évident si $\mathrm{n}=0$. Dans ce qui suit, on suppose donc que $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 1$.

Par l'absurde : supposons que le polynôme $\mathrm{R}=\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{Q}$ ne soit pas le polynôme nul.

Soit $k$ le degré de R.

Puisque $P$ et $Q$ sont tous deux de degré $n$, et de même coefficient dominant, on a $k \in\{0, \cdots, n-1\}$. De plus, on a

$$

P(P(x))-Q(Q(x))=[Q(P(x))-Q(Q(x))]+R(P(x))

$$

Posons $Q(x)=x^{n}+a_{n-1} x^{n-1}+\cdots+a_{1} x+a_{0}$.

On remarque qu'alors

$$

\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x}))-\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))=\left[\mathrm{P}^{n}(x)-\mathrm{Q}^{n}(x)\right]+\mathrm{a}_{n-1}\left[\mathrm{P}^{n-1}(x)-\mathrm{Q}^{n-1}(x)\right]+\cdots+\mathrm{a}_{1}[\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})-\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})]

$$

et chacun des termes de cette somme autre que $\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]$ est de degré au plus $n(n-1)$. D'autre part, on a

$$

\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]=R(x)\left[P^{n-1}(x)+P^{n-2}(x) Q(x)+\cdots+Q^{n-1}(x)\right]

$$

ce qui assure que $\left[P^{n}(x)-Q^{n}(x)\right]$ est de degré $n(n-1)+k$ et de coefficient dominant égal à $n$ (on rappelle que $P$ et $Q$ sont tous les deux de coefficient dominant égal à 1 ).

- On suppose que $k>0$.

Alors, le polynôme $Q(P(x))-Q(Q(x))$ est de degré $n(n-1)+k$.

D'autre part, le degré de $R(P(x))$ est $k n$, et on a $k n \leqslant n(n-1)<n(n-1)+k$.

De (1), on déduit que $P(P(x))-Q(Q(x))$ est de degré $n(n-1)+k$, et donc non nul, en contradiction avec l'énoncé.

- Il reste à étudier le cas où $k=0$, c'est-à-dire lorsque $R$ est constant.

Notons c cette constante. Notre hypothèse initiale assure que $c \neq 0$.

$\operatorname{De} P(P(x))=Q(Q(x))$, il vient $\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})+\mathrm{c})=\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))-\mathrm{c}$.

Puisque $Q$ n'est pas constant, c'est donc que l'égalité $Q(y+c)=Q(y)-c$ est vraie pour une infinité de réels $y$. S'agissant de polynômes, c'est donc qu'elle est vraie pour tout réel $y$.

Une récurrence immédiate conduit alors à $Q(j c)=a_{0}-j c$ pour tout entier $j \geqslant 0$.

Comme ci-dessus, l'égalité $Q(x)=-x+a_{0}$ étant vraie pour une infinité de valeurs (puisque $c \neq 0$ ), elle est donc vraie pour tout $x$. Cela contredit que $Q$ est de coefficient dominant égal à 1 .

Ainsi, dans tous les cas, on a obtenu une contradiction. Cela assure que $R$ est bien le polynôme nul, et achève la démonstration.

## Autre solution.

Le résultat est facile à montrer si $\mathfrak{n}=0$ ou $\mathfrak{n}=1$. Dans ce qui suit, on suppose donc que $\mathrm{n} \geqslant 2$. Notons $R=P-Q$ et supposons par l'absurde qu'il est non nul. Quitte à permuter les rôles de P et de Q , on peut supposer que le coefficient dominant de $R$ est strictement positif.

Lemme 1. Pour tout polynôme R ayant un coefficient dominant strictement positif, il existe un réel a tel que pour tout $x \geqslant a$ on a $R(x)>0$.

En effet, $R(x)$ peut s'écrire sous la forme $c x^{m}\left(1+\frac{c_{1}}{x}+\cdots+\frac{c_{m}}{x^{m}}\right)$ avec $c>0$. Le terme entre parenthèses tend vers 1 lorsque $x \rightarrow+\infty$, donc est strictement positif pour $x$ assez grand.

Lemme 2. Pour tout polynôme $P$ de degré $\geqslant 1$ ayant un coefficient dominant strictement positif, il existe a tel que P est strictement croissant sur [a, $+\infty$ [.

En effet, le polynôme dérivé $P^{\prime}$ vérifie les conditions du lemme 1 donc $P^{\prime}(x)$ est strictement positif pour $x$ assez grand.

Revenons à l'exercice. D'après les deux lemmes précédents, il existe a tel que sur [a, $+\infty[, P$ et $Q$ sont strictement croissants, et $R$ et $R \circ Q$ sont strictement positifs.

On a alors pour tout $x \geqslant a$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})) & >\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{Q}(x)) \quad \text { puisque } \mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x})>\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}) \\

& =\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))+\mathrm{R}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x})) \\

& >\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))

\end{aligned}

$$

ce qui contredit $\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{P}(\mathrm{x}))=\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{Q}(\mathrm{x}))$.

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "8",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 8.",

"resource_path": "French/segmented/envois/fr-ofm-2013-2014-envoi-3-solutions.jsonl",

"solution_match": "\nSolution de l'exercice 8",

"tier": "T2",

"year": "2014"

}

|

Let $n>0$ be an integer and $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$ be strictly positive real numbers. Prove that:

$$

\begin{gathered}

\max _{x_{1}>0, \cdots, x_{n}>0} \min \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)= \\

\min _{x_{1}>0, \cdots, x_{n}>0} \max \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)=2 \cos \left(\frac{\pi}{n+2}\right) .

\end{gathered}

$$

|

Let $U$ be the set of $n$-tuples of strictly positive real numbers. For $x=\left(x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}\right) \in U$, we define

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \quad m(x)=\min \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right) \\

& \text { and } M(x)=\max \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Our strategy will be to prove that there exists $a \in U$ such that $m(a)=M(a)$ and that, for all $x \in U$, we have $m(x) \leqslant m(a)$ and $M(a) \leqslant M(x)$.

Let $a=\left(a_{1}, \cdots, a_{n}\right) \in U$.

The condition $m(a)=M(a)$ can be written as

$$

a_{1}=\frac{1}{a_{1}}+a_{2}=\cdots=\frac{1}{a_{n-1}}+a_{n}=\frac{1}{a_{n}} .

$$

But, let's assume for now that we have already found $a \in U$ such that $m(a)=M(a)$.

By contradiction: Suppose there exists $x \in U$ such that $m(x)>m(a)$.

We then prove by induction on $k$ that $x_{k}>\mathfrak{a}_{k}$ for all $k \in\{1, \cdots, \mathfrak{n}\}$:

First, we have $x_{1} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=a_{1}$.

Furthermore, if $x_{k}>a_{k}$ for some $k \in\{1, \cdots, n-1\}$, then

$$

\frac{1}{x_{k}}+x_{k+1} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=\frac{1}{a_{k}}+a_{k+1}

$$

By the induction hypothesis, we have $\frac{1}{x_{k}}<\frac{1}{a_{k}}$, hence $x_{k+1}>a_{k+1}$, which completes the induction.

In particular, we have $x_{n}>a_{n}$.

But, $\frac{1}{x_{n}} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=\frac{1}{a_{n}}$, hence $x_{n}<a_{n}$. Contradiction.

Thus, for all $x \in U$, we have $m(x) \leqslant m(a)$.

We similarly prove that $M(a) \leqslant M(x)$ for all $x \in U$.

Under these conditions, we have $\max _{x \in U}\{m(x)\}=\mathfrak{m}(a)=M(a)=\min _{x \in U}\{M(x)\}$, as desired.

To conclude, it remains to find $a \in U$ satisfying (1).

Let's show how to find such an $a$ without relying too much on the statement:

Suppose such an $a$ exists. We denote $\alpha>0$ the common value in (1).

It is easy to verify that then, for all $k$, we have $a_{k}=\frac{b_{k}}{b_{k-1}}$, where $b_{0}=1, b_{1}=\alpha$, and $b_{j}=\alpha b_{j-1}-b_{j-2}$ for $j \geqslant 2$. (2)

Since $\alpha=\frac{1}{a_{n}}$, we must have $b_{n-1}=\alpha b_{n}$, which means that $b_{n+1}=0$.

Let's return to $\alpha$. In fact, we even have $\alpha<2$:

Indeed, suppose $\alpha \geqslant 2$. Then, $a_{1}=\alpha \geqslant 2$ and, by a straightforward induction, we deduce that $a_{k}=\alpha-\frac{1}{a_{k-1}} \geqslant 1+\frac{1}{k}$.

In particular, we have $a_{n} \geqslant 1+\frac{1}{n}>1$ and $a_{n}=\frac{1}{\alpha}<1$, contradiction.

We can therefore set $\alpha=2 \cos (t)$ where $t \in] 0, \frac{\pi}{2}[$.

Given the well-known formula

$$

2 \cos (a) \sin (b)=\sin (b+a)+\sin (b-a)

$$

another straightforward induction from (2) leads to

$$

b_{k}=\frac{\sin ((k+1) t)}{\sin (t)} \text { for all } k \geqslant 0

$$

The condition $b_{n+1}=0$ then imposes $t=\frac{\pi}{n+2}$. Thus, we have $\alpha=2 \cos \left(\frac{\pi}{n+2}\right)$ and $a=\left(a_{1}, \cdots, a_{n}\right)$ where $a_{k}=\frac{\sin \left(\frac{(k+1) \pi}{n+2}\right)}{\sin \left(\frac{k \pi}{n+2}\right)}$.

Conversely, it is easily verified that, under these conditions, the chain of equalities (1) holds.

$\mathcal{F i n}$

|

2 \cos \left(\frac{\pi}{n+2}\right)

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

proof

|

Inequalities

|

Soit $n>0$ un entier et $x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}$ des réels strictement positifs. Prouver que :

$$

\begin{gathered}

\max _{x_{1}>0, \cdots, x_{n}>0} \min \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)= \\

\min _{x_{1}>0, \cdots, x_{n}>0} \max \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)=2 \cos \left(\frac{\pi}{n+2}\right) .

\end{gathered}

$$

|

Soit Ul'ensemble des n -uplets de réels strictement positifs. Pour $x=\left(x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}\right) \in U$, on pose

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \quad m(x)=\min \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right) \\

& \text { et } M(x)=\max \left(x_{1}, \frac{1}{x_{1}}+x_{2}, \cdots, \frac{1}{x_{n-1}}+x_{n}, \frac{1}{x_{n}}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Notre stratégie va consister à prouver qu'il existe $a \in U$ tel que $m(a)=M(a)$ et que, pour tout $x \in U$, on a $m(x) \leqslant m(a)$ et $M(a) \leqslant M(x)$.

Soit $a=\left(a_{1}, \cdots, a_{n}\right) \in U$.

La condition $m(a)=M(a)$ s'écrit

$$

a_{1}=\frac{1}{a_{1}}+a_{2}=\cdots=\frac{1}{a_{n-1}}+a_{n}=\frac{1}{a_{n}} .

$$

Mais, admettons pour le moment que l'on ait déjà trouvé $a \in U$ tel que $m(a)=M(a)$.

Par l'absurde : On suppose qu'il existe $x \in U$ tel que $m(x)>m(a)$.

On prouve alors par récurrence sur $k$ que $x_{k}>\mathfrak{a}_{k}$ pour tout $k \in\{1, \cdots, \mathfrak{n}\}$ :

Déjà, on a $x_{1} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=a_{1}$.

D'autre part, si $x_{k}>a_{k}$ pour un certain $k \in\{1, \cdots, n-1\}$, alors

$$

\frac{1}{x_{k}}+x_{k+1} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=\frac{1}{a_{k}}+a_{k+1}

$$

Or, d'après l'hypothèse de récurrence, on a $\frac{1}{x_{k}}<\frac{1}{a_{k}}$, d'où $x_{k+1}>a_{k+1}$, ce qui achève la récurrence.

En particulier, on a donc $x_{n}>a_{n}$.

Mais, $\frac{1}{x_{n}} \geqslant m(x)>m(a)=\frac{1}{a_{n}}$, d'où $x_{n}<a_{n}$. Contradiction.

Ainsi, pour tout $x \in U$, on a $m(x) \leqslant m(a)$.

On démontre de même que $M(a) \leqslant M(x)$, pour tout $x \in U$.

Dans ces conditions, on a $\max _{x \in U}\{m(x)\}=\mathfrak{m}(a)=M(a)=\min _{x \in U}\{M(x)\}$, comme désiré.

Pour conclure, il ne reste donc plus qu'à trouver $a \in U$ vérifiant (1).

Montrons comment trouver un tel a sans trop s'aider de l'énoncé :

Supposons qu'un tel a existe. On note $\alpha>0$ la valeur commune dans (1).

On vérifie sans difficulté qu'alors, pour tout $k$, on a $a_{k}=\frac{b_{k}}{b_{k-1}}$, où $b_{0}=1, b_{1}=\alpha$, et $b_{j}=\alpha b_{j-1}-b_{j-2}$ pour $j \geqslant 2$. (2)

Comme $\alpha=\frac{1}{a_{n}}$, on doit avoir $b_{n-1}=\alpha b_{n}$, ce qui signifie que $b_{n+1}=0$.

Revenons sur $\alpha$. En fait, on a même $\alpha<2$ :

En effet, supposons que $\alpha \geqslant 2$. Alors, $a_{1}=\alpha \geqslant 2$ et, par une récurrence sans difficulté, on déduit que $a_{k}=\alpha-\frac{1}{a_{k-1}} \geqslant 1+\frac{1}{k}$.

En particulier, on a $a_{n} \geqslant 1+\frac{1}{n}>1$ et $a_{n}=\frac{1}{\alpha}<1$, contradiction.

On peut donc poser $\alpha=2 \cos (t)$ où $t \in] 0, \frac{\pi}{2}[$.

Compte-tenu de la formule bien connue

$$

2 \cos (a) \sin (b)=\sin (b+a)+\sin (b-a)

$$

une autre récurrence sans difficulté à partir de (2) conduit alors à

$$

b_{k}=\frac{\sin ((k+1) t)}{\sin (t)} \text { pour tout } k \geqslant 0

$$

La condition $b_{n+1}=0$ impose alors $t=\frac{\pi}{n+2}$. Ainsi, on a $\alpha=2 \cos \left(\frac{\pi}{n+2}\right)$ et $a=\left(a_{1}, \cdots, a_{n}\right)$ où $a_{k}=\frac{\sin \left(\frac{(k+1) \pi}{n+2}\right)}{\sin \left(\frac{k \pi}{n+2}\right)}$.

Réciproquement, on vérifie aisément que, dans ces conditions, la chaîne d'égalités (1) est vraie.

$\mathcal{F i n}$

|

{

"exam": "French_envois",

"problem_label": "9",

"problem_match": "\nExercice 9.",